Notes

Article history

This issue of the Health Technology Assessment journal series contains a project commissioned/managed by the Methodology research programme (MRP). The Medical Research Council (MRC) is working with NIHR to deliver the single joint health strategy and the MRP was launched in 2008 as part of the delivery model. MRC is lead funding partner for MRP and part of this programme is the joint MRC–NIHR funding panel ‘The Methodology Research Programme Panel’.

To strengthen the evidence base for health research, the MRP oversees and implements the evolving strategy for high quality methodological research. In addition to the MRC and NIHR funding partners, the MRP takes into account the needs of other stakeholders including the devolved administrations, industry R&D, and regulatory/advisory agencies and other public bodies. The MRP funds investigator-led and needs-led research proposals from across the UK. In addition to the standard MRC and RCUK terms and conditions, projects commissioned/managed by the MRP are expected to provide a detailed report on the research findings and may publish the findings in the HTA journal, if supported by NIHR funds.

The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2014. This work was produced by O’Cathain et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Introduction

The use of qualitative research with randomised controlled trials (RCTs) in the health field is not new. There are excellent examples and discussions published in the 1990s. 1,2 In the 2000s, the Medical Research Council (MRC) framework for the development and evaluation of complex interventions, although focusing on neither qualitative research nor trials, highlighted the utility of using a variety of methods at different phases of the evaluation process, including qualitative research. 3–5

The contribution of qualitative research to randomised controlled trials

Researchers have internationally described the contribution qualitative research can make to trials in the health field. 2,6–8 These include general statements about ‘harnessing the benefits of trials’ as well as more specific contributions around explaining outcomes or variation in outcomes, verifying outcomes from standardised instruments, explaining how mechanisms work in a theoretical model, developing good recruitment and consent procedures, understanding how an intervention works in practice, drawing attention to outcomes important to patients and practitioners, communicating findings, helping to interpret the trial results, understanding why an intervention was or was not successful, optimising the implementation of an intervention in a pilot trial and challenging the underlying theory of the intervention. Researchers have also described detailed examples of some of these contributions; explicitly showing the value of the qualitative research to the specific trial it was undertaken with. 1,9

Complex interventions

There is an increasing understanding that many of the interventions evaluated in the health field are complex, requiring focus on the fidelity and quality of implementation of the intervention, clarification of the causal mechanisms and exploration of any variation in outcomes. 5 Thus, qualitative research is likely to be essential at some stage of developing or evaluating complex interventions. It may also be useful for simpler interventions such as those in drug trials for which the complexity may not be related to the intervention itself but to the lives of the people who will take the drug or the environment in which the trial of that drug operates.

Context

There is increasing reference in the literature on interventions and trials to the importance of understanding the effect of the context in which an intervention is delivered within a trial10 and the role of qualitative research in facilitating this understanding. 7,11 Those designing interventions need to understand the context in which they will operate and when reporting trials, researchers need to describe the context in which the intervention was evaluated so that users of that research can transfer findings to their own context. 4 Indeed, Hawe et al. 12 describe a ‘process and context evaluation’. Wells et al. 10 explore the role of context in trials rather than the role of qualitative research per se; nonetheless, their study is highly relevant to the role of qualitative research with trials. Through the use of multiple case studies of trials of complex interventions, they identified that context is important to understanding the mechanism and generalisability of complex interventions, for instance, context may shape the intervention and fidelity to the intervention, the scale of the problem the intervention seeks to address may be context specific and practitioners’ enthusiasm for the intervention may affect the quality of the trial as well as the intervention. They also point out that some of the assumptions underpinning trials may be compromised owing to tensions between the ideal of a trial and the reality of implementing it in the real world and propose that the concept of reflexivity would encourage more realistic accounts of trials which may ultimately lead to better understanding of effectiveness studies. This highlights the utility of qualitative research not simply for trials of complex interventions but trials and interventions operating in complex environments.

Process evaluations

Process evaluations have been conducted since the mid-1980s to improve understanding of applied interventions and in particular to consider conditions under which the intervention is effective, for whom it is effective and the key mechanisms by which the intervention works. 13 Linnan and Steckler13 propose that process evaluations can be used for both positive and negative trials to understand which components of the intervention contributed to its effectiveness or to understand why the trial was unsuccessful. They list seven key components of a process evaluation: context, reach, dose delivered, dose received, fidelity, implementation and recruitment. Oakley et al. 14 list a similar range of issues that process evaluations can address alongside trials, including understanding implementation of the intervention, contextual factors that affect an intervention, dose of intervention, variation in outcomes and interpretation of the trial findings. These issues overlap with the contribution qualitative research can make to trials when the qualitative research occurs during rather than before or after the trial. However, it is important to understand that process evaluations can be fully quantitative, fully qualitative or mixed methods, drawing on combinations of surveys, documents, observation and interview and, therefore, they should not be conflated with qualitative research. 14 Because qualitative research can be a key component of process evaluations, and, indeed, Oakley et al. 14 argue that process evaluations should be both qualitative and quantitative, it was important to consider process evaluations when assessing the contribution of qualitative research to trials.

The rationale for the QUAlitative Research in Trials study (maximising the value of QUAlitative Research with Trials)

Researchers have identified the potential value of undertaking qualitative research with trials and there are examples of its application in the literature. 1,9 However, there is a need to take stock of this whole endeavour and consider how qualitative research is being used in practice and whether or not its potential is being maximised. The impetus for the QUAlitative Research in Trials (QUART) study came from a sense that there were problems with gaining value from this work. A member of our team had participated in the commissioning of trials in health care in the UK and raised concerns about how useful the planned qualitative research would be for the trial with which it was being commissioned because researchers sometimes failed to be explicit about the work the qualitative research was doing for the specific trial. For example, qualitative research with the aim of ‘exploring patients’ and health professionals’ experiences of the intervention’ raised the question of how this would enhance, add value or impact on the specific trial it was being commissioned with. This prompted the development of the QUART study, with the aim of assessing the contribution qualitative research undertaken with trials makes to the specific trial. The concern was related to our team’s more general interest in maximising the potential of mixed methods research. 15 However, our perspective in the QUART study was different because, rather than being interested in the whole mixed methods study of a RCT and qualitative research, we were interested in maximising the value of the qualitative research for the specific trial. Our focus was on the utility of the qualitative research,16 viewing qualitative research within an ‘enhancement model’,17 whereby we were interested in how qualitative research enhances the trial, rather than how it makes an independent contribution to knowledge. Flemming et al. 7 describe this as ‘enhancing evidence from trials’.

Existing frameworks for the use of qualitative research with randomised controlled trials

Researchers have described a variety of contributions of qualitative research to trials and intervention studies. Frameworks are useful because they can help novice researchers to learn about these contributions and more experienced researchers to select from the full range of contributions when designing studies. We found two existing frameworks of the use of qualitative research with trials:

-

A temporal framework of the contribution of qualitative research before, during and after a trial. 2,6,8 These authors offer a list of contributions of qualitative research at these three time points of a trial.

-

The MRC framework18 of phases of an evaluation (pre-trial, pilot trial, definitive trial, implementation) has been used by Jansen et al. 11 to document the contribution of qualitative research to the development of community-based interventions in primary care.

Flemming et al. 7 do not put forward a framework but structure their consideration of how mixed methods research can generate evidence for palliative care around study planning, recruitment, conduct and implementation. This draws on a combination of the two frameworks presented above. These frameworks were based on the authors’ research experience, practical examples of the use of qualitative research and trials, and the authors’ perceptions of the potential contribution of qualitative research to trials. We wanted to develop a framework inductively, based on empirical evidence of the contribution made, recognising that the most appropriate framework might be one of the two already in existence.

Focus on specific trials

Qualitative research can be undertaken to explore trials in general. For example, qualitative interviews can be undertaken with key trial stakeholders about strategies to improve recruitment to trials generally. This can be a useful endeavour but was not the focus of the QUART study, for which the interest was the value of qualitative research undertaken with specific trials.

Defining value

In the QUART study, we define the value of qualitative research undertaken with a specific trial as the ‘work’ the qualitative research does for, or the ‘impact’ it has on, that trial. For example, it contributes to optimising the intervention prior to the main trial or it explains the trial findings. However, when we undertook the first component of the QUART study – the systematic mapping review of journal articles reporting the qualitative research – few articles described the impact of the qualitative research on the specific trial. Instead, the authors described the conclusions of the qualitative research, sometimes explicitly articulating the value of the qualitative research for the specific trial or sometimes for future trials or the work that trials are engaged in, namely the provision of evidence of effectiveness of health interventions (we call this ‘the trial endeavour’ within this report). So, although the QUART study focus was on the value of the qualitative research to the specific trial, we had to widen our definition of value when assessing articles reporting the qualitative research. In addition, as the authors of these articles did not necessarily articulate the value for the specific trial or the trial endeavour, or that any value was attained in practice, we sometimes found ourselves having to make a subjective assessment of the ‘potential value’ of that qualitative research.

Maximising value

Jansen et al. 11 identified how the value of qualitative research may not currently be maximised in practice. They studied 33 trials in which qualitative research was used to develop an intervention and identified that it was rarely used to improve or tailor interventions to fit with primary care, so that interventions were delivered as planned rather than adjusted to local circumstances. We took a similar approach to Jansen et al. 11 by considering what researchers were doing and reporting in practice and considering any gaps in this practice that would allow those producing and applying research findings to maximise the value of this qualitative research. We took this approach because there is no agreed consensus on the value that should be attained from undertaking qualitative research with trials.

The boundaries of the QUAlitative Research in Trials study

The QUART study focused on:

-

RCTs in health rather than in other fields such as social or educational research

-

qualitative research undertaken in the context of specific trials rather than the body of research for which qualitative research is used to explore trials as a social process or to explore an aspect of trials more generally

-

the qualitative research component rather than the whole study or the trial

-

all interventions, including complex interventions

-

research published in English.

Aims and objectives

Aim

To identify the range of ways qualitative research is used with specific trials and how to maximise its value to the specific trial.

Objectives

-

To map and quantify the range of ways qualitative research is used with trials.

-

To identify good practice and ways of maximising the value of the qualitative research in this context.

-

To explore researchers’ perspectives on the current practice of combining qualitative research and trials.

Chapter 2 Design and overview of methods

Design

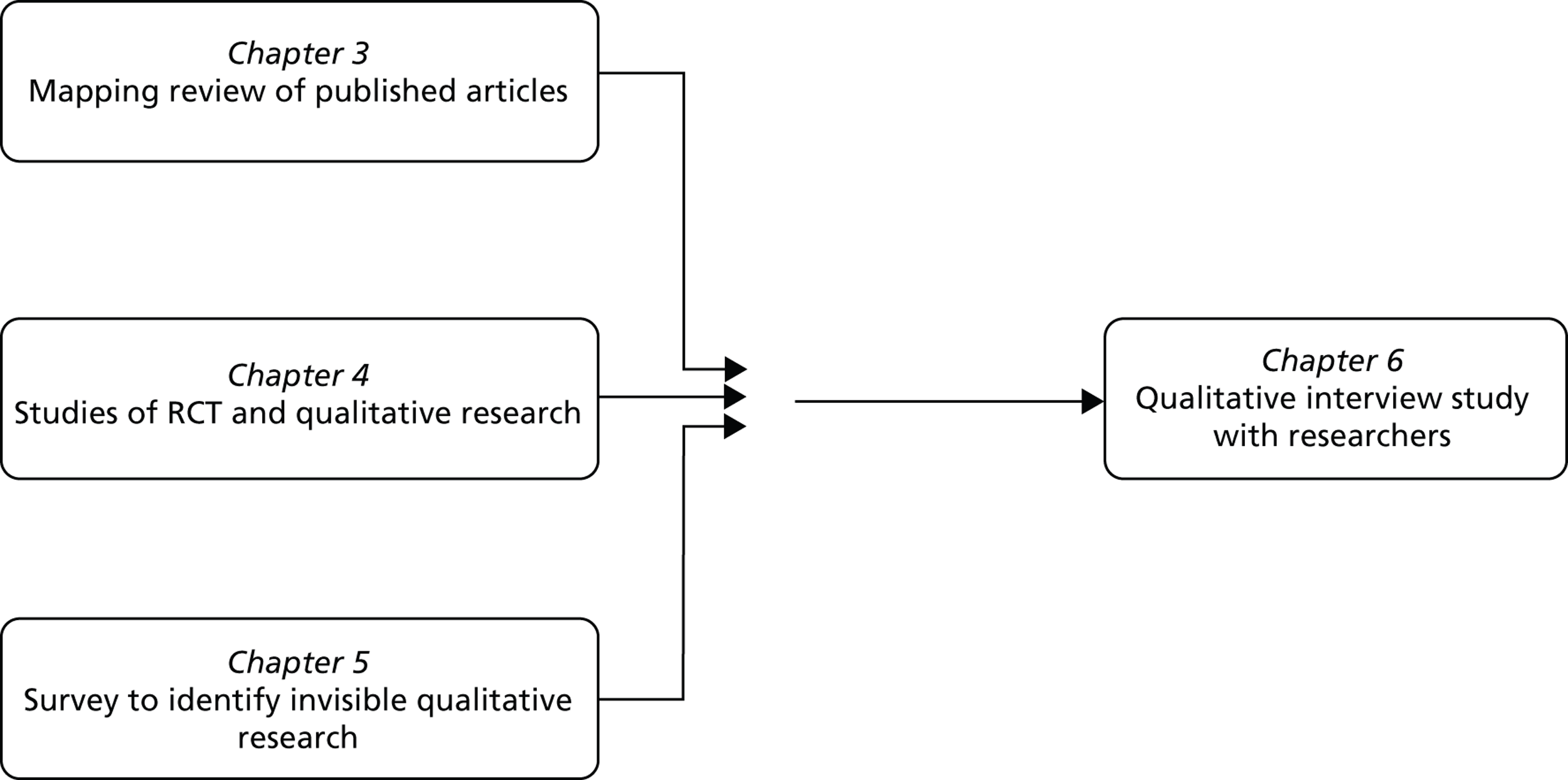

The proposal for the QUART study can be seen in Appendix 1 . We undertook a sequential mixed methods study with four components. First, a systematic mapping review of peer-reviewed journal articles reporting qualitative research undertaken with specific trials; second, a review of the documentation of studies which combined trials and qualitative research; third, a survey of lead investigators of trials that appeared not to have used qualitative research, and these three components were followed by a fourth component of a qualitative interview study of researchers identified from these articles and studies.

Methods

Systematic mapping review of published journal articles

We undertook a database search of peer-reviewed journals between January 2008 and September 2010 for articles reporting qualitative research undertaken with specific trials. The aim was to map the range of contributions of the qualitative research to the specific trial and identify good practice and ways of maximising value.

Review of studies

Not all qualitative research undertaken with trials is published in peer-reviewed journals. 8 We undertook a systematic search of the metaRegister of Controlled Trials (mRCT), a database of registered trials, to identify trials funded in the UK and ongoing between 2001 and 2010 that reported the use of qualitative methods on the trial database. The aim was to explore the potential contribution of the qualitative research to the specific trial and consider good practice in terms of how it was presented in proposals and reports. This also offered insights into recent practice because some studies started in 2010, whereas studies in the mapping review started much earlier than this.

Survey of lead investigators

We anticipated that qualitative research undertaken with trials would not necessarily be described on the mRCT database. Therefore, we undertook a survey of lead investigators of trials with no apparent qualitative research on the mRCT database of registered trials funded in the UK. The aim was to identify ‘invisible’ qualitative research and its contribution to the specific trial.

A qualitative interview study with researchers

We undertook a semistructured telephone interview study with researchers purposively sampled from the first three components of the study. The aim was to explore researchers’ perceptions of how to maximise the value of qualitative research with trials and the facilitators and barriers to this.

Report structure

We report the methods, findings and discussions of each component in separate chapters ( Figure 1 ). Then we integrate these in Chapter 7 and discuss the integrated findings in Chapter 8 .

FIGURE 1.

Mixed methods design as reported in separate chapters.

Public and patient involvement

We held a meeting with two members of the public as part of our public and patient involvement (PPI) for the QUART study. Both were identified because they had been PPI representatives on trials. One person had been an active PPI member of a mixed methods pilot trial and another a PPI member of a drug trial and, it transpired, had also recruited participants into trials as part of their job. We met during the early stages of the mapping review and asked them to read two articles reporting qualitative research undertaken with trials and discuss the content of these articles with the QUART team. They were extremely positive about the need to include qualitative research with trials because, for them, the qualitative research paid attention to the views and needs of people, bringing to the fore the human beings that recruit to, or participate within, trials. This meeting shaped our understanding of the value of the qualitative research and highlighted the need for our team to ensure that we paid full attention to the positive aspects of the research we read.

Chapter 3 A systematic mapping review of published qualitative research undertaken with specific randomised controlled trials

Aim

We undertook a review of peer-reviewed journal articles reporting the qualitative research undertaken with a specific trial in order to map the contribution of aspects of trials addressed by the qualitative research. We then sought to identify good practice and missed opportunities within articles to understand how to maximise the value of qualitative research undertaken with specific trials when reporting the qualitative research in a journal article.

We identified problems with our intended approach early in this process. We had assumed that these articles would explicitly state the contribution the qualitative research had made to the specific trial, for example optimised recruitment processes or explained trial findings. However, we found that this rarely occurred and that the contribution was often directed at future trials and the trial endeavour of generating evidence of effectiveness of health interventions. We also found that authors did not necessarily articulate the contribution and we had to draw this out ourselves. As there was rarely evidence that this value had occurred, we refer to potential value throughout this chapter. In this chapter we address two issues:

-

the aspect of the trial addressed by the qualitative research

-

its potential value.

First, we identified the aspect of the trial addressed by the qualitative research by considering the stated aim of the qualitative research in the article. This was often general rather than specific so we discarded this approach and considered the actual focus of the journal article. For example, a stated aim might be ‘to interview participants who have experienced the intervention in a pilot trial to explore their views of the intervention’ but the focus of the article was ‘identifying problems with the feasibility of the intervention’. Second, we considered the potential value first in relation to the trial and then we attempted to abstract this to consider value to the trial endeavour. For example, the impact on a trial of identifying problems with the feasibility of an intervention might be the intervention was refined for use in the main trial and its abstracted potential value might be ‘optimising the intervention for the main trial’ and ‘saving money by not undertaking a large expensive trial of a suboptimal intervention’.

Methods

Systematic mapping review

We undertook a ‘mapping review’ or ‘systematic map’ of published journal articles reporting qualitative research undertaken with specific RCTs. 19 The aim of this type of review is to map out and categorise existing literature on a particular topic, with further review work expected. Formal quality appraisal is not expected and synthesis is graphical or tabular. We called our review a ‘systematic mapping review’ because labels for different types of reviews are not consistent. 19 This review involved a systematic search for published articles reporting qualitative research undertaken with specific trials and categorisation of the uses made of qualitative research into an inductively developed framework. This was followed by detailed synthesis of articles within each category to identify the potential value and ways in which value had been maximised, followed by synthesis of these issues across all categories. We did not aim to synthesise findings from these studies.

Mapping review search strategy

Our plan was to search for articles published between 2001 and September 2010, which was the last full month prior to our search. We searched the following databases: MEDLINE, PreMEDLINE, EMBASE, The Cochrane Library, Health Technology Assessment (HTA), PsycINFO, CINAHL, British Nursing Index, Social Sciences Citation Index and Applied Social Sciences Index and Abstracts. We used two sets of search terms, one to identify RCTs and one to identify qualitative research, searching for journal articles that included both sets of terms. The search terms for RCTs are well documented. We adapted The Cochrane Highly Sensitive Search Strategy for identifying randomised trials in MEDLINE. 20 The search terms for qualitative research were more challenging. We started with a qualitative research filter21 but this returned many articles that were irrelevant to our study. We made decisions about the terms to use for the final search in an iterative manner, balancing the need for comprehensiveness and relevance. 20 We tested a range of terms in MEDLINE and held team discussions about the specificity and sensitivity of different terms. The final search strategy is reported in Appendix 2 . We identified 15,208 references, which was reduced to 10,822 after electronic removal of duplicates. We downloaded these references to a data management software program Endnote X5.0.1 for windows (Thomson Reuters, CA, USA).

Mapping review inclusion and exclusion criteria

Our inclusion criteria were English-language articles published between 2001 and September 2010 reporting the findings of empirical qualitative research studies undertaken before, during or after a specific RCT in the field of health. These could include qualitative research reported within a mixed methods article. Our exclusion criteria were:

-

not a journal article (e.g. conference proceedings, book chapter)

-

no abstract available

-

not a specific RCT (e.g. qualitative research about hypothetical RCTs or RCTs in general)

-

not qualitative research

-

not health related

-

not a report of findings of empirical research (e.g. published protocol, methodological paper, editorial)

-

not reported in English

-

not human research.

Screening references and abstracts for the mapping review

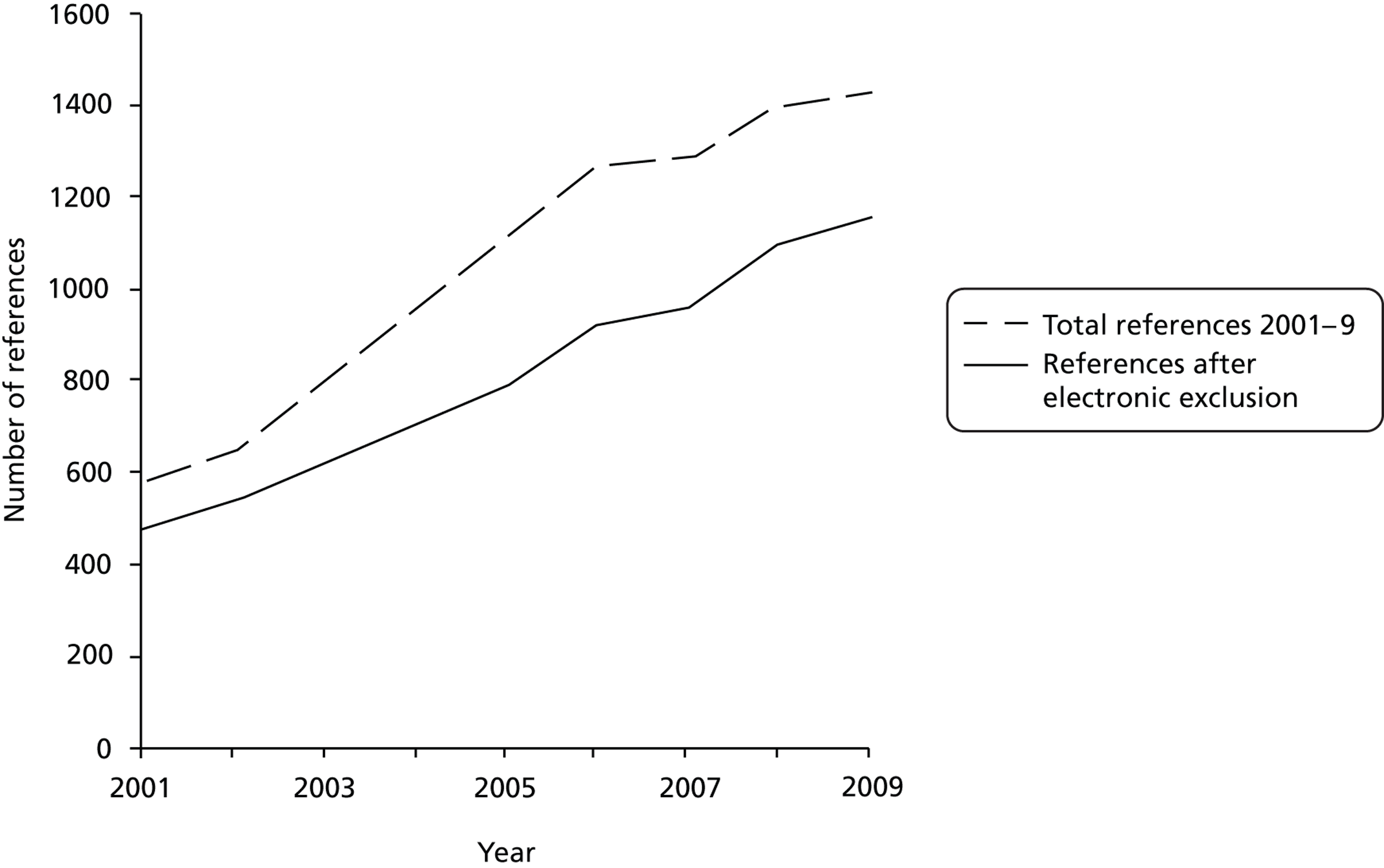

We applied the exclusion criteria electronically to the 10,822 references and abstracts. The numbers of references identified increased each year ( Figure 2 ). We do not report 2010 in Figure 2 because we did not search the full year.

FIGURE 2.

Numbers of references identified in an electronic search for qualitative research undertaken with RCTs between 2001 and 2009.

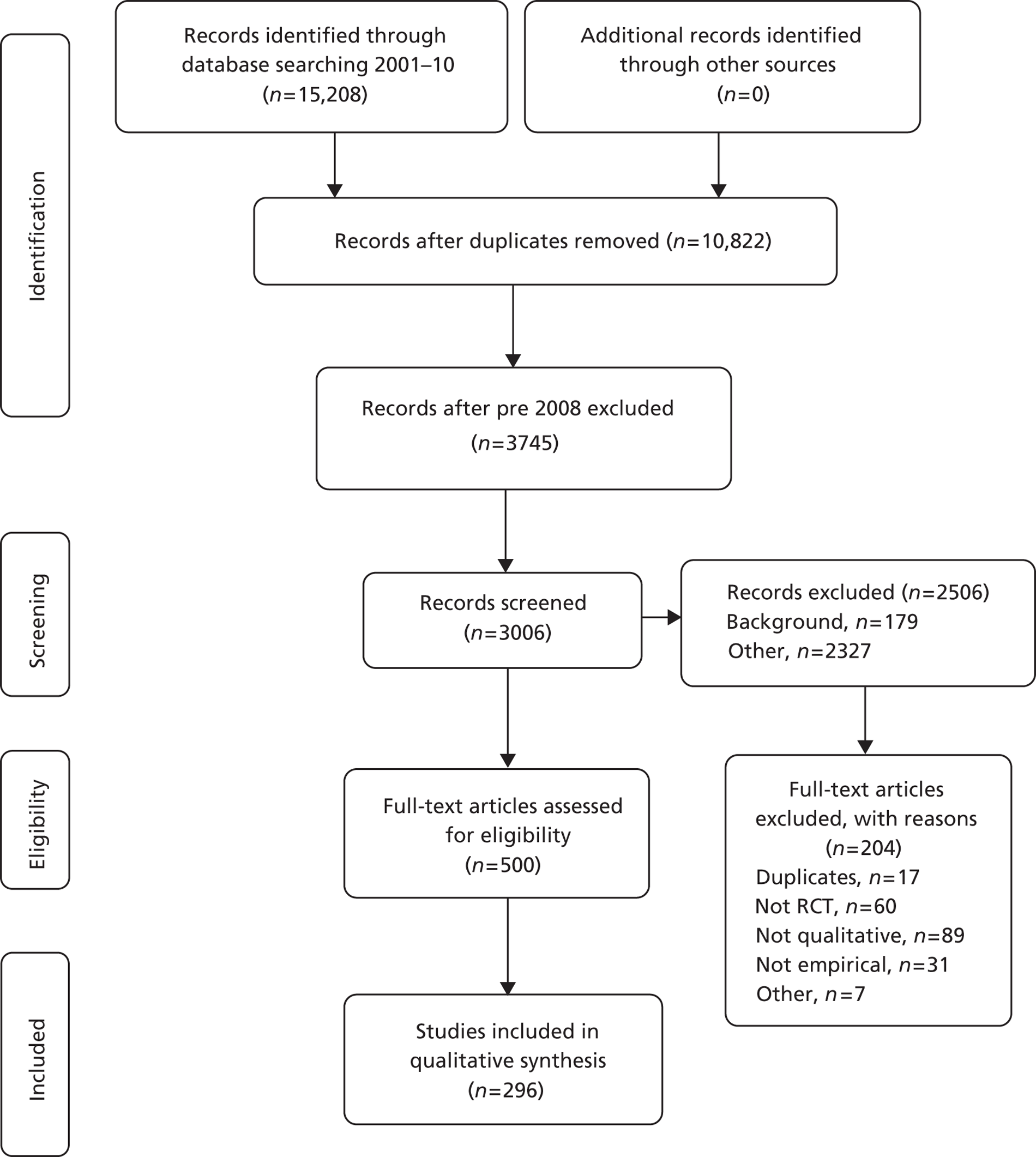

Owing to the large number of references identified, we made the decision to focus on articles published between January 2008 and September 2010. The rationale was that the most recently published articles would offer the most useful insights to future researchers. This resulted in 3745 references and abstracts, with 739 excluded by electronic application of exclusion criteria ( Table 1 ). One of the research team (SJD) read the abstracts of the remaining 3006 references and excluded a further 2506. The most common reasons for exclusion were that the abstract did not refer to a RCT, did not use qualitative research or did not report empirical research ( Figure 3 and see Table 1 ). There were 500 abstracts after this screening process. Two members of the research team (KJT and AO) reviewed a sample of 100 excluded abstracts to check the reliability of the exclusion process. Each read 50 abstracts and placed them into the exclusion categories. Of the 100 abstracts reviewed, all were categorised as exclusions. There was some disagreement about which exclusion category was most appropriate for 16 abstracts. These disagreements were resolved with discussion between team members. Further screening was undertaken on full articles (see Categorisation based on full articles).

| Criterion | Electronic screening of 3745 references | Screening of abstracts of 3006 articles | Screening of 500 full articles |

|---|---|---|---|

| Duplicates | 0 | 8 | 17 |

| Not a journal article | 29 | 2 | 0 |

| No abstract | 65 | 0 | – |

| Not RCT | 2 | 1102 | 60 |

| Not qualitative research | 1 | 609 | 89 |

| Not health related | 2 | 69 | 0 |

| Not empirical | 640 | 708 | 31 |

| Other: not English, not human, full article not found | 0 | 8 | 7 |

| Total exclusions | 739 | 2506 | 204 |

FIGURE 3.

The PRISMA flow diagram for articles 2008–10.

Preliminary categorisation of abstracts using the stated aim of the qualitative research

We did not set out with a plan of how we would develop our map or framework. As we proceeded, we realised that the approach we were taking was similar to the five stages of ‘framework analysis’, an approach to analysing qualitative data. 22 The stages of framework analysis are ‘familiarisation’ with the data, ‘identifying a thematic framework’, ‘indexing’ by applying the framework systematically to the data, ‘charting’ by putting data related to a theme together and ‘mapping and interpretation’ to think about the meaning of the findings in relation to original purpose of the research.

As a starting point for the categorisation of qualitative research we undertook the first three stages of ‘framework analysis’. We familiarised ourselves with the articles by reading a small set of abstracts (n = 122). We identified a thematic framework by using the stated aim of the qualitative research within the abstract to identify categories and subcategories of a ‘preliminary framework’. We also considered the potential of the temporal framework6,8 and the MRC framework for the evaluation of complex interventions3 as our overarching framework. We found that the information given in the abstracts did not include details necessary for mapping onto these frameworks. After team discussions, we finalised our preliminary framework and one team member (SJD) ‘indexed’ by applying it to the stated aim of the qualitative research in our 500 abstracts, open to emergent categories which were then added to the framework ( Table 2 ). The purpose of this initial categorisation was to create meaningful categories to enable a second, more in-depth, process of categorisation at a later stage.

| Category | Subcategory | Numbers of abstracts |

|---|---|---|

| Intervention | Patient views of intervention in RCT | 114 |

| Professional views of intervention in RCT | 35 | |

| Develop the intervention | 94 | |

| Build explanatory model of how intervention works | 12 | |

| Factors influencing intervention delivery | 19 | |

| Evaluation of intervention | 38 | |

| Design and conduct | Recruitment for RCT | 50 |

| Being part of trial | 25 | |

| Would patients participate in trial? | 19 | |

| Trial design (acceptability of some designs) | 11 | |

| Outcomes | Variation in outcomes | 14 |

| Accuracy of outcome measures | 15 | |

| Additional outcomes following trial | 22 | |

| Outcome tool development | 18 | |

| Disease | Patient views of disease | 20 |

| Professional views of disease | 5 | |

| Dissemination | Dissemination of trial results | 4 |

| Unclassifiable | Do not know | 10 |

Categorisation based on full articles

We obtained copies of full articles for the 500 included abstracts. All members of the team read articles from across the categories before selecting a category to lead on and engaging in a process similar to framework analysis:

Step 1: familiarisation – we read the full articles in the category, including those that had been moved from another category by other team members.

Step 2: further exclusion – we excluded some articles on further reading, for example those that did not report qualitative research. Application of exclusion criteria became challenging and these challenges are discussed in Challenges applying the framework. We excluded another 204 articles at this stage (see Table 1 and Figure 3 ).

Step 3: identification of a thematic framework through recategorisation and development of categories and subcategories – we recategorised any articles that, after full reading, did not appear to fit into the allocated category or subcategory. We considered whether subcategories were right and changed their titles, their order in the category and added or collapsed subcategories. We held in-depth discussions about a number of articles to help us define the unique characteristics of a particular subcategory. At this stage we felt that the preliminary categorisation based on the stated aim of the article did not necessarily describe the focus actually taken by the qualitative research presented in the article. For example, articles that were originally categorised as ‘patient view of intervention’ were put into new categories such as identifying the ‘perceived value and benefits of intervention’. This recategorisation stage required a considerable amount of discussion between team members, with all members reading abstracts and articles, and discussing disagreements in terms of allocating articles to categories.

Step 4: ‘indexing’ or allocation of articles – each article was allocated mainly to one subcategory but some had more than one focus and were categorised into two or more subcategories.

Step 5: data extraction or ‘charting’ – we undertook formal data extraction for up to six articles from each subcategory. For subcategories with more than six articles, we randomly selected articles with the exception of the ‘intervention’ category. Because this category had very large subcategories, we undertook purposive sampling to ensure we displayed the range of articles within each subcategory. During data extraction, we described authorship, the qualitative methods, the RCT, the intervention, the stated aim of the qualitative research, the aspect of the trial addressed by the qualitative research and the potential value of the qualitative research for the trial endeavour (see Step 6). Reflections on good practice and ways in which the value of the qualitative research for RCTs could have been maximised were largely based on these data extractions of six articles per subcategory. However, these reflections were also informed by our wider reading of all the articles within that subcategory. This step was similar to the ‘charting’ stage of framework analysis for which data within a theme are studied in depth. Matrices of subthemes and interviewees are created in the standard approach to framework analysis. We created figures based on descriptive data and display them in the findings.

Step 6: identifying potential value for articles in the data extraction – we had intended to extract the value of the qualitative research to the specific trial. During team discussions, we identified that the value of the qualitative research was not necessarily explicitly articulated within the articles. When it was not explicit, we made a subjective assessment of potential value based on reading the article and our own subjective assessment of issues we had identified in background reading in Chapter 1 . In practice, authors of these articles implicitly discussed value through how they framed the article in the introduction and the issues they alluded to in the discussion. We considered these to be potential value rather than actual value because authors rarely evidenced impact that occurred in practice. We developed a tick box set of values for the data extraction form but mainly used a free text box to record potential value.

Step 7: identifying exemplars – for each subcategory, we attempted to identify an article that we judged as undertaking that type of work well. Key considerations were how explicit authors were about the impact of the qualitative research on the specific trial or the message for the wider trial endeavour and the depth of insights described in the article.

Step 8: describing the type of intervention – finally, two members of the team worked together to categorise the intervention for articles in the data extraction (AO and KJT). Each independently categorised the intervention into ‘drug or device’ or ‘complex intervention’. This was a crude categorisation based on a brief description of an intervention in the qualitative article. Our approach was to identify RCTs of drugs and devices (including surgery and acupuncture) and then categorise any others as complex interventions because of the lack of detail required to classify an intervention as complex with any confidence. We then compared our categorisations and discussed disagreements to reach consensus.

Challenges applying the framework

We met four key challenges during this categorisation process and resolved them during team discussions as follows.

Maintaining perspective

Qualitative research generates knowledge and has value outside the context of RCTs. As stated earlier, our goal was to categorise the contribution of qualitative research to the trial endeavour. This felt uncomfortable at times because we were ignoring the strengths and value of qualitative research in its own right. We resolved this difficulty by ensuring that we were transparent about the perspective we were taking.

Defining ‘specific randomised control trial’

We met three challenges here. First, some trials were referred to as a ‘clinical trial’ or ‘trial’ and it was not clear if they were RCTs; therefore, we took a generous approach to including these articles. Second, sometimes the qualitative research was undertaken regarding a set of trials rather than a specific trial, for example a programme of trials on asthma in a single medical centre involved in trial recruitment. We did not want to include the vast literature for which qualitative research is used to explore different aspects of trials in general but decided to include articles based on sets of trials about a specific disease or patient group, for example undertaken in a neonatal trials unit, because of the possibility that the qualitative research could impact on that set of trials. Third, we were clear that hypothetical trials were excluded but made an explicit decision to include any hypothetical trials we identified in our two ‘in principle’ subcategories in which there was evidence of a commitment to undertake a trial if the intervention or trial design were acceptable ( Table 3 shows final categories including ‘acceptability of the intervention in principle’ and ‘acceptability of the trial in principle’). Therefore, there was some blurring of our boundaries and in data extraction we identified these as ‘grey’ articles.

| Category | Subcategory | n (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Intervention content and delivery | 254 (71) | |

| Intervention development | 48 (13) | |

| Intervention components | 10 (3) | |

| Models, mechanisms and underlying theory development | 23 (6) | |

| Perceived value and benefits of intervention | 42 (12) | |

| Acceptability of intervention in principle | 32 (9) | |

| Feasibility and acceptability of intervention in practice | 83 (23) | |

| Fidelity, reach and dose of intervention | 12 (3) | |

| Implementation of the intervention in the real world | 4 (1) | |

| Trial design, conduct and processes | 54 (15) | |

| Recruitment and retention | 11 (3) | |

| Diversity of participants | 7 (2) | |

| Trial participation | 4 (1) | |

| Acceptability of the trial in principle | 5 (1) | |

| Acceptability of the trial in practice | 4 (1) | |

| Ethical conduct | 16 (4) | |

| Adaptation of trial conduct to local context | 2 (1) | |

| Impact of trial on staff, researchers or participants | 5 (1) | |

| Outcomes | 5 (1) | |

| Breadth of outcomes | 1 (< 1) | |

| Variation in outcomes | 4 (1) | |

| Measures | 10 (3) | |

| Accuracy of measures | 7 (2) | |

| Completion of measures | 1 (< 1) | |

| Development of measures | 2 (1) | |

| Condition | Experience of the disease, behaviour or beliefs | 33 (9) |

| Total uses | 356 (100) | |

Defining ‘qualitative research’

We could not rely on the article authors’ use of the term ‘qualitative research’; for example, some authors called surveys a qualitative method. We defined qualitative research as qualitative data collection (interviews, focus groups, observation, documents) and analysis (textual analysis, usually supported by quotes). We found many articles based on open questions in surveys or unstructured interviews reduced to quantitative findings reported as percentages. We generally excluded these but found it difficult to decide on this boundary for some articles. For example, an open question on a survey resulted in a detailed textual analysis so we included it. Again, there was some blurring of our boundaries and in data extraction we identified these as ‘grey’ articles.

Distinguishing the contribution of the qualitative research from other methods and approaches

Some articles reported mixed methods research and we had to work hard to distinguish findings based on the qualitative rather than the quantitative research. We felt we were generally successful but that it was much harder to distinguish the contribution of qualitative research within articles reporting participatory action research.

Quality appraisal

Quality appraisal is not essential for mapping reviews. 19 We stated in our proposal that we would consider quality but our aim was not to judge the quality of the qualitative research. However, we did commit to explicitly reviewing our exemplars using accepted quality criteria. We revisited this during the study and discussed the benefits of either applying a quality assessment checklist to all articles or to only those we selected as exemplars. We identified the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme checklist for the appraisal of qualitative research as a simple and well-regarded checklist. 23 We decided not to apply it to all 296 articles for two reasons. First, the methodological quality of these types of articles has already been assessed for 30 qualitative studies undertaken with RCTs. 8 That study found that there was not sufficient information in one-third of these 30 studies to assess methodological quality and considerable weaknesses were found for the rest, including inadequate description of sampling and analysis. Second, our interest was different – we wanted to assess quality defined as the contribution the qualitative research made to the trial endeavour and identify quality issues specific to this. We decided not to apply quality criteria to our exemplars because we wanted the keep the focus on quality in terms of the impact of the qualitative research on the specific trial or the message for the wider trial endeavour.

Synthesis within and across subcategories

We identified good practice and ways of maximising value within each subcategory by reading the articles and identifying issues that were present in some articles and missing from others. Then we asked questions within the whole subcategory: why did researchers do the qualitative research? Did it seem like a useful thing to do? What did some researchers do that felt helpful? What could have been done to improve the value of the research for the trial endeavour? Finally, we identified commonly occurring themes across the subcategories. This was similar to the final stage of framework analysis, ‘mapping and interpretation’, in which researchers consider relationships between themes in the context of the original research question.

Findings

We present the findings in four sections:

-

framework of the use of qualitative research with trials

-

detailed description of framework subcategories with examples

-

the potential value of qualitative research with trials

-

the rationale for the QUART study (maximising the value of QUAlitative Research with Trials).

Framework of the use of qualitative research with trials

Size and characteristics of the evidence base

We identified 296 articles published between January 2008 and September 2010. The references of these articles are listed in Appendix 3 . There was no evidence of increasing numbers per year in this short time period: 113 articles in 2008, 105 in 2009 and 78 in the first nine months of 2010 (equivalent to 104 in a full year).

Most of the first authors were based in the USA (107 articles) and the UK (97 articles), with others based in Scandinavian countries (21 articles), Australia (20 articles), Canada (15 articles), South Africa (seven articles), New Zealand (five articles), Spain (five articles) and a range of other countries in Africa (six articles), Asia (six articles) and Europe (seven articles). The journals these articles were published in are listed in Appendix 4 .

Framework of the focus of the qualitative research

As we read the full articles and discussed the content within the team, the framework presented in Table 2 developed into five broad categories related to:

-

the intervention being tested

-

the trial design and conduct

-

outcomes

-

measures used within the trial

-

the condition studied in the trial.

Subcategories also developed further; for example, the subcategories of ‘patient views of the intervention’ and ‘professional views of the intervention’ disappeared because we were interested in the insights offered by these views for the trial. For example, we developed a subcategory of ‘acceptability of the intervention in principle’ that was always based on exploring the views of patients and/or professionals. At this stage, some articles were reclassified to a different category when the focus of the full article conflicted with the focus described in the abstract. Some articles were classified into two or more subcategories, usually within the same category. We identified 22 discrete subcategories within the five broad categories and identified 356 incidents of these within the 296 articles ( Table 3 ).

Distribution within subcategories

The majority of the articles focused on the intervention (66%, 196/296), with few articles focusing on measures and outcomes (see Table 3 ). This imbalance between categories may reflect practice or may be due to some activities undertaken in relation to trials not being published or not being identified by our search strategy. The subcategories that each of the 296 articles were allocated to are shown in Appendix 3 at the end of each reference.

Timing of the qualitative research

A total of 28% (82/296) of articles reported qualitative research undertaken at the pre-trial stage, i.e. as part of a pilot, feasibility or early-phase trial or study in preparation for the main trial. Some activities would be expected to occur only prior to the main trial, such as intervention development, and all of these articles were undertaken pre-trial. However, others that may also be expected to occur prior to the trial, such as ‘acceptability of the intervention in principle’, occurred frequently during the main trial. This is discussed in more detail in the next section on the individual subcategories (see Detailed description of framework subcategories with examples).

It was not possible to categorise articles using the temporal framework before, during and after the trial6,8 because it was unclear in many articles when the data collection for the qualitative research was undertaken in terms of during or after the trial. Sometimes data collection was undertaken after the intervention ended, after the last outcome was measured, or after the trial findings were known. Sometimes the data analysis was undertaken at these different stages based on data collected during the trial. Often it was not clear precisely when the data collection or analysis was undertaken.

Detailed description of framework subcategories with examples

In this section we explore each of the 22 subcategories identified in Table 3 in detail. We based this on reading all the articles and the detailed data extraction on up to six articles per subcategory and extracting data on 104 articles in total. These subcategory assessments were subjective, inductive and emergent, shaped by the articles we found and by our values and interests. Within each subcategory we:

-

describe the subcategory

-

give examples of articles within it (see the relevant table within each subcategory)

-

identify which of the examples focused on drugs or devices and which on complex interventions (see the relevant table within each subcategory)

-

indicate an exemplar in the figure of examples

-

explore the potential value of using qualitative research to this purpose

-

offer suggestions for good practice.

Category 1: content and delivery of the trial intervention

The first category focused on the intervention being tested in the trial and was by far the largest category, accounting for 254 of the 356 uses of the qualitative research (71%). Qualitative research was used to explore eight aspects of the content and delivery of trial interventions from development through to implementation in the real world (see Table 3 ):

-

intervention development

-

intervention components

-

models, mechanisms and underlying theory development

-

perceived value and benefits of intervention

-

acceptability of intervention in principle

-

feasibility and acceptability of intervention in practice

-

fidelity, reach and dose of intervention

-

implementation of the intervention in the real world.

Development of the trial intervention

Qualitative research to support intervention development may be undertaken as part of a formal evaluation framework that advocates the use of theoretical and feasibility modelling prior to testing an intervention in a trial,3 or it may be undertaken without a formal framework, with the clear intention to create, or refine, all or part of an intervention for testing within a trial. Our criterion for including studies in this subcategory was that the qualitative findings reported substantive development of the intervention content or delivery. We expected these interventions to be complex interventions involving behavioural aspects of care delivery or receipt. We identified 48 articles, all of which included qualitative research undertaken prior to a planned main trial. Many of these studies used mixed methods research and some described other pre-trial work in conjunction with the intervention development, such as testing possible outcome measures for use in the full trial and trial design issues such as recruitment and retention. We selected six examples purposively to include a range of interventions: clinical, educational and professional. These are described in Table 4 . The focus of the qualitative research was always clearly related to the specific trial and the qualitative methods included interviews, focus groups and non-participant observation. The research subjects were drawn from members of the public, potential trial participants and professionals involved in the delivery of the proposed intervention.

| Study | Country | Trial | Aim of qualitative research | Qualitative methods and sample | Value of qualitative research for the specific trial and the trial endeavour |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Davies et al. 200924 | USA | Community-based pragmatic RCT comparing health/social support and parenting interventions for mothers living with HIV (C) | To ensure the intervention met the cultural and situational needs of the target recipients in terms of content and delivery process | Semistructured interviews with seven service providers and two focus groups with clinic patients and clinic advisory group members | Several intervention elements were developed in direct response to the qualitative findings. At time of publishing, the full trial was under way. Strengthens trial relevance by ensuring intervention is culturally appropriate and sensitive to the needs of recipients, carers and those delivering care |

| Gulbrandsen et al. 200825 | Norway | Pragmatic RCT of ‘Four Habits’ a clinical communication tool designed and evaluated in USA for use in Norway (C) | As part of mixed methods research to identify ways to tailor the intervention content to meet the needs of local health-care practice | Three focus groups with local physicians who had been given the intervention training | Confirmed cultural alignment and informed elements of the training programme for use in the planned trial. Strengthens trial relevance by ensuring intervention is sensitive to the needs of those delivering care and locally appropriate. Improves internal validity of trial by reducing the risk of poor implementation affecting the effectiveness of the intervention |

| Jefford et al. 200826 | Australia | RCT of standard correspondence compared with tailored chemotherapy information for GPs (C) | To identify information needs of GPs treating patients receiving chemotherapy | Focus groups (10 GPs as intervention recipients) and semistructured interviews | Directly informed information content and mode of communication in the trial. Strengthens trial relevance by optimising intervention in line with perceived needs of recipients. Engenders stakeholders’ support for the trial |

| Marciel et al. 201027 | USA | Planned multicentre RCT of mobile telephone intervention to improve adherence to treatment by adolescents with cystic fibrosis (C) | As part of mixed methods research to refine the intervention taking account of patient and provider perspectives | Focus group with 17 health-care professionals and semistructured interviews with 18 patients and 12 parents | Changes to the intervention delivery as a result of the focus group concerns. Interviews confirmed acceptability of intervention. Strengthens trial relevance by maximising cultural appropriateness of the intervention. Strengthens trial relevance by optimising intervention in line with perceived needs of recipients, carers and those delivering care. Engenders stakeholders’ support for the trial |

| Nagel et al. 200928 | Australia | RCT of a brief intervention for indigenous people with chronic mental illness and substance dependence (C) | To understand local perspectives of mental illness and mental health to develop a culturally adapted brief intervention | Group and individual interviews, and observation, within a participatory action research model engaging local aboriginal health workers and recovered patients. This continued alongside the trial | Incorporated into the design of the intervention but clear evidence of the process for this not provided in this paper, which reports the trial results. Strengthens trial relevance by maximising cultural appropriateness of the intervention. Strengthens trial relevance by optimising intervention in line with perceived needs of recipients, carers and those delivering care. Engenders stakeholders’ support |

| Redfern et al. 200829 | UK | Planned RCT of prevention advice to improve risk factor management after stroke (C) | Part of mixed methods research exploring patient experiences and understanding of secondary prevention and observational work to understand context and process | 20 semistructured interviews with potential intervention recipients. Non-participant observation at two hospitals to explore delivery, process and context | Development phase of MRC framework. Strengthens trial relevance by optimising intervention in line with perceived needs of recipients. Improves internal validity of trial by reducing the risk of poor implementation affecting the effectiveness of the intervention |

Intervention development undertaken in a pre-trial context can strengthen the relevance of a trial by optimising the intervention and/or its delivery from the perspective of recipients and providers. The rationale for this use of qualitative research fell into three categories:

-

The need to optimise an existing intervention that has some clinical or practice history in order to ensure that the ‘best’ intervention is tested in the trial. Multiple versions of an existing intervention may be in use with no identifiable ‘gold standard’ and the problem may be presented as needing to develop an optimised intervention.

-

The need to adapt an existing intervention for use in a different context:

-

– A new clinical or practice context, for example a similar programme of care for a different patient group or a hospital service delivered in primary care.

-

– A different geographical context for which the goal is to adapt a successful intervention developed in one country for use in another country where health services and health-care delivery differ (e.g. Gulbrandsen’s ‘Four Habits’25).

-

– A different cultural context that may require adapting a mainstream intervention for use with a specific minority group or subgroup of a clinical population (e.g. Nagel’s Torres Strait Islanders28 or Marciel’s adolescents with cystic fibrosis27).

-

-

The need to develop a ‘de novo’ intervention, based on perceived clinical or practice need and, often, a theoretical understanding of the nature of the required intervention. 26,29

The driver for undertaking qualitative research in this context was not clinical appropriateness, but rather the need to explore the intervention as part of a matrix of health-related social behaviour on the part of patients, carers, health professionals or communities. That is to say, articles described participants in terms of their social and behavioural characteristics and explore experiences and beliefs from the perspective of a community of recipients or carers, a community of professionals delivering the intervention, or a particular context of delivery (primary care, community care, web-based care). Key to this was the way in which the research participants were defined and the issues particular to the group that were predicted to be relevant. Examples of this included women living with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) who were also fulfilling the role of mothers,24 people with mental health problems who were also part of a minority indigenous group with specific cultural characteristics,28 or physicians who delivered care within the context of a particular national culture and its health-care system. 25

In order to achieve the research goal of identifying the best possible (or most appropriate) intervention for testing in a full trial, the need to attend to the health-related behaviours and beliefs of relevant groups (to be accessed via their experiences and perspectives) was the starting point and rationale for most of the qualitative research undertaken in this subcategory, whether the intervention was being designed de novo, being optimised or being adapted for use in a new context. In addition, some studies reported the importance of qualitative research in the development phase of a trial in terms of the opportunity to engender ‘stakeholder support’ for the trial process. 26–28 This was described as operating both at an individual level (patient and professional) and at a community level. 26–28

-

Be clear that changes were made to the intervention

-

In some cases, the qualitative findings resulted in a demonstrated change being made to the intervention content or delivery. In others, confirmation of acceptability was the real objective of the study. Good practice would entail making a clear distinction between these two aims within articles.

-

-

Ensure changes to the intervention are grounded in the data

-

When the aim of the qualitative research was to develop the intervention for a planned trial, it was important for researchers to demonstrate the mechanisms by which the qualitative data influenced the final intervention design. For this to happen it was necessary for the changes to be convincingly grounded in the data. This did not always occur, perhaps owing to limited article word count because in papers reporting the development of the intervention alongside the trial results, very little space was allocated to the qualitative component and its impact was usually reported rather than demonstrated.

-

-

Place within an evaluative framework

-

The MRC framework for the development and evaluation of complex interventions offers endorsement for the practice of undertaking qualitative research to support intervention development. 3 A conceptual framework for the qualitative research, such as the MRC framework, was not used in the majority of articles in this subcategory. One advantage of using such a framework may be to raise the profile and status of the qualitative research contributing to intervention development and to ensure that its contribution is documented. For example, referencing and using the MRC framework, the authors of one paper were able to claim that their goal was the development of ‘the definitive risk-factor management intervention’. 29

-

Describing the trial intervention and elaborating its components

In this subcategory, the qualitative research supported a description of a trial intervention, or one or more components of a complex intervention. We included articles for which qualitative methods were employed to generate essential data for the description, usually taking into account recipients’ experiences during the trial. These descriptive accounts could be based on mixed methods research, combining qualitative data about patients’ experiences with quantitative data relating to satisfaction measures. We identified 10 articles, all undertaken at the full trial stage. Some of them also reported qualitative research undertaken to meet other objectives such as assessing the acceptability of the intervention. We selected six examples purposively to include a range of interventions: clinical, educational and professional ( Table 5 ). The qualitative methods included interviews and audio recordings of consultations. The research subjects were drawn from members of the public, intervention recipients, and professionals involved in the delivery of the intervention.

| Study | Country | Trial | Aim of qualitative research | Qualitative methods and sample | Value of qualitative research for the specific trial and the trial endeavour |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Foster et al. 201030 | USA/UK/Uganda | Cluster RCT of home-based antiretroviral therapy compared with facility-based antiretroviral therapy (DD) | As part of mixed methods research, to describe one component of the intervention in both arms of the trial (the use of medicine companions to encourage adherence) | Longitudinal interviews with 40 participants from both arms | Described the role of medicine companions as a component of the intervention from the perspective of participants. Describes an over-looked or taken-for-granted component of a complex intervention. Informs intervention content for future trials |

| Gambling and Long 201031 | UK | RCT of telephone-based support for behavioural change amongst patients with type 2 diabetes (C) | To explore recipients’ experiences of the ‘packaging’ of advice | Taped samples of telephone counselling sessions and interviews with nine intervention recipients | Explored the way advice was given and received and described the personalised and responsive dynamics as generic components of telephone counselling. Describes generic components within a complex intervention. Informs intervention content for future trials |

| Macpherson and Thomas 200832 | UK | Pragmatic RCT of acupuncture care compared with usual care for persistent lower back pain (DD) | To describe the intervention as delivered from the perspective of the providers | Semistructured interviews with six acupuncturists who delivered care in the trial | Disaggregated components of the intervention and identified self-help advice as an integral process of acupuncture care. Describes a potentially hidden component of a complex intervention. Informs intervention content for future trials |

| McQueen et al. 200933 | USA | RCT of a tailored interactive intervention compared with use of a generic website to increase colorectal cancer screening in primary care (C) | To explore the content and process of physician–patient discussions about screening during a wellness visit | Audio-taped consultations involving 76 patients and eight physicians, all participating in the RCT | Described process of shared decision-making as a component of the intervention delivery. Describes a generic component within a complex intervention. Informs intervention content for future trials |

| Romo et al. 200934 | Spain | Open RCT of hospital-based heroin prescription compared with methadone prescription for long-term socially excluded opiate addicts for whom other treatments have failed (DD) | To explore patients’ and relatives’ experience of the intervention as delivered within the trial | In-depth semistructured interviews with 21 patients receiving intervention and paired family members | Explored the experience of receiving prescription heroin in a hospital setting and described the resulting medicalisation of addiction as a separate component of the intervention. Describes a potentially hidden component of a complex intervention. Informs intervention content for future trials |

| Teti et al. 201035 | USA | RCT of group education + peer-led support groups compared with brief education messages to increase HIV status disclosure and condom use amongst women living with HIV/AIDS (C) | To examine how women experienced the intervention | Semistructured interviews with 18 participants after the intervention was delivered | Described the content of components of the intervention (e.g. group discussions) and explored the relationship between components. Describes components of a novel and complex intervention to allow replicability in the real world |

A lot of space may be needed within a report to describe in detail the components of a complex or multifaceted intervention delivered to recipients. This may not be possible within the structure of a conventional trial report, or valued enough to ensure that a limited word count includes intervention description. The MRC framework for complex interventions3 supports this process at an early stage of evaluation, but all 10 articles undertook this description alongside the main trial (see Table 5 ). Qualitative research undertaken alongside a trial can provide a rich account of elements of the intervention in detail, enhancing understanding of how the intervention plays out in the experimental delivery context of the trial. In the articles reviewed here, there were two main reasons for using qualitative research:

-

to describe and make available an unfamiliar or complex intervention using the experiences and perspectives of trial participants35

-

to increase understanding of individual components of a complex intervention and make them available for further exploration or testing. 30,32–34

Researchers chose to focus on a particular component of a complex intervention for a number of reasons. Macpherson and Thomas32 focused on an underexplored component, looking at acupuncture practitioners’ intention to deliver self-care advice alongside needling. This article raised a question regarding the integral nature of this aspect of the intervention as delivered and the implications of this for future trials of acupuncture care. Romo et al. 34 explored patient and family experiences of receiving prescription heroin in a hospital setting, and identified the perceived medicalisation of addiction (in contrast to criminalisation) as a component of the intervention in its own right. In contrast, Foster et al. 30 focused on an element of the intervention that was common to both arms of the trial (the use of medication companions) and highlighted the fact that this ‘taken-for-granted‘ component was integral to both home- and facility-based delivery of antiretroviral therapy and that its mechanisms of action would benefit from further research. Qualitative research was also used to explore components of complex interventions relating to what might be described as generic strategies, such as ‘shared-decision making’ in the context of advising about different cancer screening options within a consultation33 or the way health behaviour advice is ‘packaged’, rather than its specific content. 31

Accounts of complex interventions used in trials run the risk of reflecting the research protocol, rather than what was delivered in practice. Quantitative research methods may be employed to verify measurable elements of delivery, but qualitative methods, such as non-participant observation or in-depth interviews, can provide rich descriptive accounts of how the intervention was delivered on the ground during the trial, from the perspectives of recipients or providers. This descriptive function may form part of what is described as a ‘process evaluation’, although none of the articles we describe here used that term.

In each of our examples, the qualitative research appeared to provide an opportunity to focus attention on one or more components of a complex intervention, the significance of which might otherwise remain hidden or over-looked in a pragmatic trial. Although some of these articles discussed their findings in terms of possible mechanisms of action, the main purpose was to provide a rich and detailed account of different components of the intervention, based on the participants’ experiences. Using qualitative research data in this way is sometimes seen as ‘poor’ qualitative research because it does not extend itself into interpretive analysis or theory building. However, this tendency to undervalue the potential contribution of rich description has been recognised,36 especially in terms of its ability to ‘challenge taken-for-granted assumptions about the nature of the setting or group under study’. 37

-

Be clear about the origin of the research question

-

In our sample of articles, the genesis of the qualitative research question was sometimes unclear. The stronger articles gave a clear account of the reason for the focus on particular components and indicated whether this was an emergent issue or one that was identified as a research focus early in the trial.

-

-

Place within an evaluative framework

-

Describing, elucidating and highlighting hidden or overlooked components of a complex intervention using qualitative methods is a useful research output that has value for future intervention development, but many of the articles lacked a wider framework for presenting this type of analysis. Use of the MRC framework for the development and evaluation of complex interventions was rare and it may be that this framework could help provide this type of research with a useful rationale and contextual reference point.

-

-

Consider findings in relation to mechanisms of action

-

Descriptive accounts developed through qualitative data may also lend themselves to further development relating to an exploration of mechanisms of action or the explicit development of theoretical concepts underpinning interventions. Some of these articles moved towards this type of analysis, but this was not their aim.

-

-

Make explicit links to the main trial

-

Links to the main trial tended to be limited to the background and methods sections of articles, with little or no attempt to link this research back to the trial in the discussion or conclusion. This raised concerns about whether or not the research had any impact on the trial and also limited its utility for future trials.

-

Models, mechanisms and underlying theory development of the intervention

This subcategory was distinguished from the ‘intervention components’ focus described above by going one step further and attempting to develop underlying concepts and behavioural theories, as well as exploring mechanisms of action. Articles in this subcategory described an explicit aim to develop the conceptual thinking behind the intervention, using the rich data provided by the experience of delivering an intervention within a trial context. In practice, a few articles sat between this subcategory and the previous one, making some reference to theory or mechanisms of action, but falling short of developing these ideas using the qualitative data collected. This subcategory was also distinguished from the next subcategory Exploring perceived value and benefits of the trial intervention, which identifies additional (unmeasured) benefits from the perspective of the trial participants. When articles in this subcategory identify unmeasured benefits, they go on to explore their role as (sometimes hidden) mechanisms for change, and locate these findings in a theoretical framework, thus attempting to integrate any such additional benefits into an explanatory model of the mechanism of action of the intervention.

We identified 23 articles in this subcategory, with only one undertaken at the pre-trial stage. We selected six examples purposively to include examples of the range of topics: treatment, process and context mechanisms. The six articles focused on a range of interventions: clinical, educational and professional ( Table 6 ). The qualitative methods used in these six examples included interviews, focus groups and observation, and the research subjects included trial participants and wider stakeholders.

| Study | Country | Trial | Aim of qualitative research | Qualitative methods and sample | Value of qualitative research for the specific trial and the trial endeavour |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Byng et al. 200838 | UK | Cluster RCT of a multifaceted facilitation process (Mental Health Link) to improve care of patients with long-term mental illness (C) | To investigate how a complex health services intervention led to developments in shared care for people with long-term mental illness | Interviews with 46 practitioners and managers from 12 cluster sites to create 12 case studies, analysed using a Realistic Evaluation framework | Identified core functions of shared care and developed a theoretical model linking intervention specific, external and generic mechanisms to improve health care. Unpicks the complexity of an intervention and develops a theoretically informed model of mechanisms of action. Develops an explanatory model of the intervention and/or its delivery to inform the interpretation of the trial results |

| aHoddinott et al. 201039 | UK | Cluster RCT of community breastfeeding support groups to increase breastfeeding rates (C) | To support the development of an explanatory model of the intervention mechanisms and why success was or was not achieved. Part of a mixed methods study to explore anticipated variations in intervention success at cluster level | 64 ethnographic, in-depth interviews, 13 focus groups and 17 observations to produce seven locality case studies, informed by a realist approach | Aided the development of a model of the intervention located in context that helped to explain the observed variation in outcomes at cluster level. Develops a model showing how context and the complex systems within which an intervention occurs can be an important mechanism of change. Develops an explanatory model of the intervention and/or it’s delivery to inform the interpretation of the trial results |

| Liu et al. 200840 | Taiwan | RCT of a body–mind–spirit therapy (including positive psychology and qi-gong exercises) compared with usual care for cancer patients with symptoms of depression and anxiety (C) | To explore treatment mechanisms and provide a more comprehensive understanding of the therapy | Focus group with 12 intervention group participants | Identified eight theoretically informed domains of the treatment effects of group therapy and highlighted the importance of culturally sensitive approaches to therapy. Develops a theoretically informed model of treatment effects from a patient perspective |

| Kaptchuk et al. 200941 | USA | RCT of the placebo effect in patients undergoing acupuncture for symptoms of irritable bowel syndrome (C) | To explore the experiences of patients undergoing placebo-enhanced treatment in the context of a trial | Repeated semistructured interviews with 12 patients in the intervention group | Identified a spectrum of factors associated with the placebo effect and concluded that any single theory or model of placebo is inadequate to explain its reported benefits. Evaluates existing theories of mechanisms of action and develops new insights or models |

| O’Sullivan et al. 201042 | Canada | RCT of theory-based physical activity counsellor to increase activity as a preventative strategy (C) | To identify aspects of the intervention perceived to be instrumental in eliciting desired behaviour changes | Repeated semistructured interviews with 15 patients in the intervention group | Identified aspects of the intervention seen as helpful and linked these to the underlying theory informing the intervention design (Self Determination Theory). Explores perceived mechanisms of action to endorse the theory underlying the intervention |

| Rogers et al. 200943 | UK | RCT of self-management group-based intervention (The Expert Patients Programme) for people with long-term conditions (C) | To explore the concept of social comparison as a mechanism that facilitates or limits the success of self-skills training groups | In-depth interviews with 23 participants before and after the intervention | Described the importance of social comparison as an underlying feature of group-based self-care skills training. Develops a concept or underlying theory that underpins the operation of an intervention |

Qualitative research with this focus appeared to be motivated by a desire to acknowledge the role of complexity in many interventions being trialled, owing either to the multifaceted nature of the intervention or to the complex social structures and contexts in which interventions took place. The qualitative research was intrinsically evaluative and entailed an exploration of the intervention using the perspective of the participants and wider stakeholders. When the goal was an explanatory model of the intervention,38,39 the qualitative research was part of a broader mixed methods approach. Alternatively, the focus was on ‘generic’ mechanisms rather than on those deemed to be specific to the trial intervention, in which case the message was less for the trial itself and more for a ‘class’ of intervention, such as ‘self-management’43 or ‘placebo effects’. 41 Additionally, the research was sometimes designed to address a recognised body of theoretical work, such as theories of behavioural change. Researchers undertaking research in this subcategory reported a number of related reasons for doing so:

-

To unpick the complexity of an intervention and develop a theoretically informed model of mechanisms of action by modelling the relationship between the elements.

-

To refine interventions by identifying the most ‘effective’ components from participants’ accounts, with reference to underlying theories from the social sciences.

-