Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 08/116/10. The contractual start date was in March 2011. The draft report began editorial review in May 2013 and was accepted for publication in January 2014. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Anne Greenough has held grants from various ventilator manufacturers and received honoraria for giving lectures and advising various ventilator manufacturers.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2014. This work was produced by Greenough et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Background

One in 200 infants in the UK are born extremely prematurely, that is before 29 weeks of gestation. Advances in neonatal care have meant that 75% of such babies survive, but many have long-term respiratory and/or functional problems; for example, up to 40% develop bronchopulmonary dysplasia (BPD). 1 Affected infants have frequent hospital admissions in the first 2 years, particularly for respiratory infections. 2 In one series, one-quarter of BPD infants had three or more readmissions. 2 Supplementary oxygen at home may be required for many months. 3 BPD infants who required home oxygen had greater health-care utilisation than those who did not, with an associated doubling of their cost of care throughout the preschool years;4 the families’ quality of life has also been reported to be poorer. 5 At preschool and school age, troublesome recurrent respiratory symptoms are common. In one cohort of children who had BPD, 28% coughed more than once per week and 7% wheezed more than once per week in the preschool years,4 and in a cohort of 7- to 8-year-olds, whereas only 7% of term controls were wheezing, 30% of BPD children and 24% of prematurely born children without BPD were also affected. 6 Troublesome symptoms and lung function abnormalities are even seen in young adults who had BPD. 7,8 Nine per cent of very prematurely born infants have serious disability at 2 years of age. 9 At school age, BPD is associated with poor cognitive and academic achievement, which is the predominant problem leading to educational special needs support. This poor cognitive and academic achievement, together with motor, attention and behavioural problems, contribute to functional deficits that may persist to adult life. 9

Infants born extremely prematurely usually require respiratory support which, although often life-saving, is frequently associated with lung damage which leads to the long-term respiratory problems described above. As a consequence, new ventilation modes, including high-frequency oscillation (HFO), have been developed with the hope of reducing that adverse outcome. During HFO, a constant pressure is applied to optimise oxygenation and volume delivery is minimised. Unfortunately, if used inappropriately, HFO can increase severe intracranial haemorrhage and periventricular leukomalacia, which lead to adverse neurodevelopmental outcomes, including cerebral palsy, with an associated high cost of care. It was, therefore, essential that HFO use was assessed in an appropriately designed randomised controlled trial and hence the United Kingdom Oscillation Study (UKOS) was performed.

United Kingdom Oscillation Study

The UKOS was a multicentre, randomised trial undertaken to determine whether or not use of HFO or conventional ventilation (CV) from within 1 hour of birth would reduce mortality and the incidence of BPD. (The earlier results of UKOS discussed below were published separately elsewhere.)1,10,11

Infants were eligible for the study if their gestational age was between 23 weeks and 28 weeks plus 6 days, they were born in a participating centre and they required endotracheal intubation from birth and ongoing intensive care. Infants were excluded if they had to be transferred to another hospital for intensive care shortly after birth or had a major congenital malformation.

A total of 25 centres participated in the study – 22 in the UK and one each in Australia, Ireland and Singapore. To ensure that each centre had adequate experience with high-frequency oscillatory ventilation (HFOV), we required participating centres to have used this type of ventilatory support in a minimum of 20infants before the study began. The quality of collected data was monitored and the statistical analyses were performed at the co-ordinating centre (St. George’s Hospital, London, UK). Both the South Thames Multicentre Research Ethics Committee, London, UK, and the Local Research Ethics Committee at each participating centre approved the protocol.

Women at high risk of delivering an infant before 29 weeks of gestation were invited, before delivery, to participate in the trial, and oral or written assent was obtained. Randomisation occurred either when delivery was imminent or immediately after the infant was born. Written confirmation of consent was obtained from one or both parents within 24 hours after the birth, as directed by the Multicentre Research Ethics Committee. If consent was refused, the infant was excluded and the mode of ventilation was left to the discretion of the clinician.

After assent or consent had been obtained, infants were randomly assigned, in blocks of four, to either CV or HFOV, with stratification according to gestational age (two strata) and according to centre (25 strata). Procedures were implemented to ensure balanced assignment within strata at each participating centre. Each centre kept a log of all eligible infants and reasons for non-recruitment.

Within 1 hour after birth, eligible infants were assigned to receive either CV or HFOV as their primary mode of respiratory support. Unless the infant could be extubated electively, switching from the assigned mode of ventilation was permitted only during the first 120 hours after birth, if the clinical condition for a minimum of 1 hour met the criteria for treatment failure. These criteria were a partial pressure of oxygen (PaO2) of < 49 mmHg in an infant receiving a fraction of inspired oxygen (FiO2) of 1.0 following changes in the mean airway pressure or peak inspiratory pressure, or a partial pressure of carbon dioxide (PaCO2) of > 60 mmHg despite interventions to improve ventilation, or both. If the infant still required ventilation after 120 hours of age, clinicians were free to use whichever mode of ventilation they wished. No changes in clinical management except those indicated below were specified as part of the trial. Conventional ventilation was delivered by time-cycled, pressure-limited ventilators starting with a rate of 60 breaths per minute and an inspiratory time of 0.4 seconds. Subsequently, ventilator settings were adjusted at the discretion of the attending clinician to maintain a PaO2 between 49 and 75 mmHg and a PaCO2 between 34 and 53 mmHg. HFOV, with optimisation of lung volume, was delivered by one of three models of high-frequency oscillator [the Dräger Babylog 8000 (Dräger Medical, Lubeck, Germany), the SensorMedics 3100A (CareFusion, San Diego, CA, USA), or the SLE 2000HFO (SLE Ltd, South Croydon, UK)], all of which have been shown to have similar performance characteristics at the frequencies recommended in this trial. Ventilation was begun at a mean airway pressure of 6–8 cmH2O and a frequency of 10 Hz, and the amplitude was increased until the infant’s chest was seen to be ‘bouncing’. The ratio of inspiration to expiration was fixed at either 1 : 1 (with the Dräger or SLE ventilator) or 1 : 2 (with the SensorMedics ventilator), in accordance with the manufacturers’ recommendations. The FiO2 was initially set to ensure adequate oxygenation (PaO2 > 48 mmHg), and, when the FiO2 was > 0.3, the mean airway pressure was increased by 0.5–1.0 cmH2O every 10–15 minutes until it was possible to decrease the FiO2. The FiO2 was reduced to 0.3 before the mean airway pressure was decreased, provided that the lungs were not hyperinflated (a condition defined by the flattening of the diaphragm below the margin of the ninth rib on chest radiography). Settings were then adjusted to maintain a PaO2 between 49 and 75 mmHg and a PaCO2 between 34 and 53 mmHg. Oxygenation was managed by adjustment of the mean airway pressure and the FiO2; PaCO2 was managed by adjustment of the oscillatory amplitude, but if difficulties in the management of the PaCO2 persisted after a change in the amplitude alone, the ventilator frequency was also adjusted. If pulmonary interstitial emphysema developed, the strategy was changed to one of low volume and high FiO2 with the reduction in the mean airway pressure to the lowest level compatible with a PaO2 of 49–75 mmHg, even if this strategy resulted in an increase in the FiO2 to the range of 0.7–0.9. No simultaneous positive-pressure breathing was used. The protocol recommended that infants receive exogenous surfactant as soon as possible after birth. A subsequent dose (given approximately 12 hours later) was recommended for infants receiving CV if the FiO2 was > 0.3 and for infants receiving HFOV if the mean airway pressure was > 10 cmH2O.

Definition of outcomes and sample size calculations

The primary outcome measure was a composite of death or chronic lung disease (defined by a dependence on supplemental oxygen) at 36 weeks of postmenstrual age. Secondary outcome measures were the age at death, the age at hospital discharge, major abnormality on cranial ultrasonography, air leak, failure of treatment, failure on hearing testing, necrotising enterocolitis, patent ductus arteriosus requiring treatment, treatment with postnatal systemic corticosteroids, pulmonary haemorrhage, and retinopathy of prematurity. A sample of 800–1200 infants was needed, given the assumptions that 30% of the study population would have a gestational age of 23–25 weeks, 70% would have a gestational age of 26–28 weeks and that the incidence of the primary outcome would be 75% for the lower-gestational-age group and 48% for the higher-gestational-age group. With a sample of this size, the study had 90% power (at a significance level of 0.05) to detect a difference between treatment groups of 9–11 percentage points.

Statistical analysis

An independent committee reviewed statistical analyses performed 12 and 18 months after recruitment began and found no reason to stop the trial early. Analyses were adjusted to preserve an overall level of significance of 0.05. For the secondary outcomes (both main effects and interactions), we used the Bonferroni method to correct for multiple testing, which resulted in the use of a p-value of 0.004 to indicate significance. All reported p-values are uncorrected unless otherwise stated.

Unadjusted relative risks or hazard ratios, as appropriate, with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated to estimate the relative effect of HFOV as compared with that of CV for all outcomes. Logistic regression or Cox regression was used to investigate treatment effects, with the use of gestational age (23–25 weeks or 26–28 weeks) and location (UK and Ireland, Australia or Singapore) as covariates. Interaction terms were fit in the model in order to assess differences in treatment effects according to gestational age and location. Baseline variables with the potential to be important prognostic factors were identified in advance of the analysis. We decided to include them in the model only if a clinically important imbalance was observed. All statistical analyses were performed according to the intention-to-treat principle, with the use of Stata software (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA; version 12).

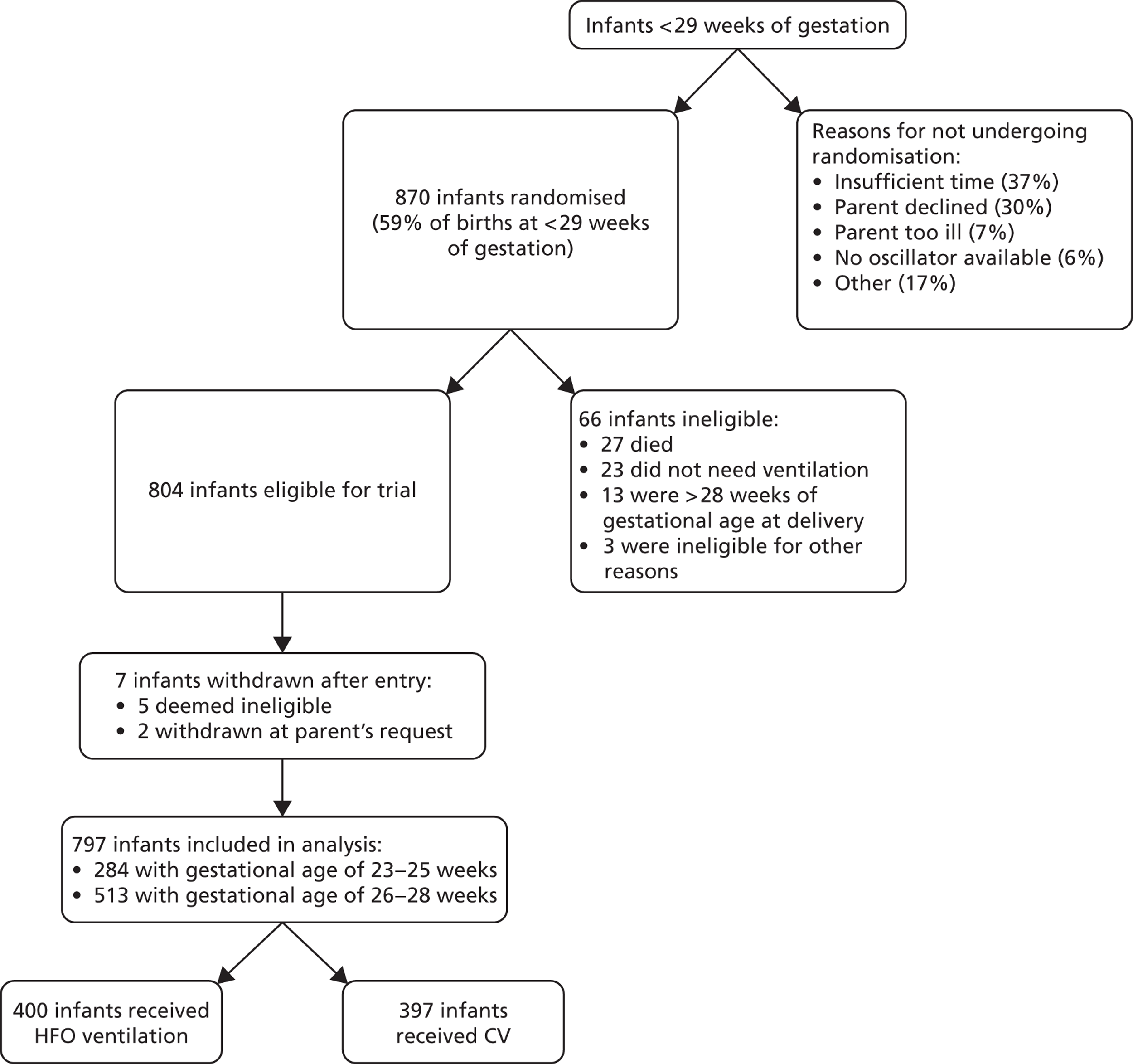

Between August 1998 and January 2001, 870 infants underwent randomisation; 804 were subsequently enrolled in the trial and data from 797 were analysed ( Figure 1 ).

FIGURE 1.

United Kingdom Oscillation Study Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) flow diagram.

The two treatment groups were well balanced in terms of maternal characteristics. A total of 91% of the women received antenatal corticosteroids. The groups were also closely matched in terms of characteristics of the infants; 96% of infants were given surfactant replacement therapy at a median of 28 minutes after birth (range 0–1232 minutes).

Results

Primary outcome

The composite primary outcome of death or chronic lung disease (defined by dependence on supplemental oxygen at 36 weeks of postmenstrual age) occurred in 66% of infants assigned to HFO and 68% of those assigned to CV [relative risk (RR) 0.98 (95% CI 0.89 to 1.08), p = 0.71] ( Table 1 ). Similar proportions of infants died (25% HFO vs. 26% CV) or had chronic lung disease (41% in each group). When the analysis was stratified according to gestational age, there were similar findings with respect to the primary outcome and the frequency of each component (p = 0.46 for the interaction between gestational age and mode of ventilation). Overall, 33% of the infants were alive without dependence on supplemental oxygen at 36 weeks of postmenstrual age: 12% of those who were born between 23 and 25 weeks gestational age and 45% of those who were born between 26 and 28 weeks gestational age. There were no significant differences in the secondary outcomes except regarding major cerebral abnormality, which was significantly lower in the HFO group ( Table 2 ).

| Infants by outcome | Number/total (%) | HFO/CV | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CV | HFO | RR | 95% CI | |

| All infants | ||||

| Died or O2 dependent at 36 weeks CGA | 268/397 (68) | 265/400 (66) | 0.98 | 0.89 to 1.08 |

| Died | 105/397 (26) | 100/400 (25) | ||

| Survived: O2 dependent | 163/397 (41) | 165/400 (41) | ||

| Survived: not O2 dependent | 129/397 (32) | 135/400 (34) | ||

| 23–25 weeks | ||||

| Died or O2 dependent at 36 weeks CGA | 119/136 (88) | 130/148 (88) | 1.00 | 0.92 to 1.10 |

| Died | 60/136 (44) | 61/148 (41) | ||

| Survived: O2 dependent | 59/136 (43) | 69/148 (47) | ||

| Survived: not O2 dependent | 17/136 (13) | 18/148 (12) | ||

| 26–28 weeks | ||||

| Died or O2 dependent at 36 weeks CGA | 149/261 (57) | 135/252 (54) | 0.94 | 0.80 to 1.10 |

| Died | 45/261 (17) | 39/252 (15) | ||

| Survived: O2 dependent | 104/261 (40) | 96/252 (38) | ||

| Survived: not O2 dependent | 112/261 (43) | 117/252 (46) | ||

| Outcome | Number/total (%) unless specified otherwise | HFO/CV | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CV | HFO | RR | 95% CI | |

| Age at death (median, days, IQR) | 6 (2–19) | 6 (1–19) | 0.85 | 0.64 to 1.13 |

| Number of days in hospital for survivors [median, days (IQR)] | 89 (70–112) | 94 (73–114) | ||

| Failure of treatment | 41/397 (10) | 41/400 (10) | 0.99 | 0.66 to 1.50 |

| Any air leak | 72/395 (18) | 64/399 (16) | 0.88 | 0.65 to 1.20 |

| Pulmonary haemorrhage (requiring change in ventilator settings) | 55/390 (14) | 44/395 (11) | 0.79 | 0.55 to 1.14 |

| Postnatal systemic steroids (any) | 94/340 (28) | 104/339 (31) | 1.11 | 0.88 to 1.40 |

| Patent ductus arteriosus requiring treatment | 129/394 (33) | 137/399 (34) | 1.05 | 0.86 to 1.28 |

| Any major cerebral abnormality | 75/393 (19) | 54/393 (14) | 0.72 | 0.52 to 0.99 |

| Retinopathy of prematurity (2+ or worse) | 42/396 (11) | 43/400 (11) | 1.01 | 0.68 to 1.51 |

| Failed hearing test | 33/151 (22) | 29/136 (21) | 0.98 | 0.63 to 1.52 |

| Necrotising enterocolitis | 33/393 (8.4) | 47/394 (12) | 1.42 | 0.93 to 2.17 |

Overall, those results do not provide evidence of a difference in the outcomes of infants supported by HFO or CV. The possible adverse effect of HFO on neurological outcomes, however, was not observed and indeed the proportion of infants with major cerebral abnormalities was significantly lower in the HFO group. 1

Pulmonary function at follow-up of very preterm infants from the United Kingdom Oscillation Study

There were similar rates of chronic lung disease, defined as oxygen dependency at 36 weeks postmenstrual age (BPD), in the two ventilator groups of UKOS,1 as reported above. A diagnosis of BPD, however, has been poorly associated with long-term respiratory outcome. Potential differences in lung function between the groups could become apparent as the infants grew older. Indeed, it has been reported that airway function may deteriorate during the first year after birth in prematurely born infants, regardless of whether or not they had initial lung disease. 12,13 A previous randomised study14 had included respiratory follow-up and measurement of pulmonary function in infancy. 15 No differences in lung function in infancy were found. 15 Infants in that study, however, were relatively mature compared with those recruited into UKOS; in addition, they did not receive antenatal steroids or exogenous surfactant and no strategies to optimise lung volume on HFO were employed. 16 The aim, therefore, of this study10 was to test the hypothesis that infants who had been exposed to antenatal steroids and exogenous surfactant and randomised to HFO in the UKOS trial would have superior pulmonary function at follow-up to those ventilated conventionally.

Pulmonary function assessments at 1 year corrected age were performed at a single centre in London, UK [King’s College Hospital (KCH)], and a subgroup of trial infants was recruited from the participating centres that were within reasonable travelling distance from that centre. Informed written consent from infants’ parents was obtained before testing, and the study was approved by both the South Thames Multicentre Research Ethics Committee and the Local Research Ethics Committee of KCH NHS Trust.

Infants were tested between the ages of 11 and 14 months corrected age. Before their appointment, parents were asked to complete a 2-week respiratory symptom diary card. Appointments were deferred if the infant developed symptoms of a respiratory tract infection during this period. All infants were seen in the paediatric respiratory laboratory at KCH. On arrival, a history was taken, and each infant was weighed, measured and examined. Parents were asked not to reveal the mode of ventilation to which their child had been initially assigned. The testing procedure consisted of measurement of tidal breathing parameters, functional residual capacity (FRC) by whole-body plethysmography (FRCpleth), inspiratory and expiratory airway resistance (R aw), and FRC by helium gas dilution (FRCHe). Additional detail on the method for making these measurements is provided in the online supplement.

Pulmonary function testing methodology

Infants were sedated with 80–120 mg/kg chloral hydrate, and monitored by pulse oximetry (Datex-Ohmeda 3800, Hatfield, UK) throughout the pulmonary function testing and afterwards until they were awake. Once asleep, the infant was laid supine in the plethysmograph (Department of Medical Engineering, Hammersmith Hospital, London, UK), which had a total volume of 90 l and included a heated, humidified rebreathing system. The infant breathed through an appropriately sized Rendell-Baker facemask, sealed around the nose and mouth with silicone putty. Pressure at the airway opening (Pao) was measured using a differential pressure transducer (range ± 5 kPa, MP45, Validyne Engineering Corporation, Northridge, CA, USA) connected to a port in the mask support. The mask support also incorporated a thermistor measuring airway temperature and was connected to a heated pneumotachograph (Fleisch, Switzerland) to measure airflow. The pneumotachograph was attached to a differential pressure transducer (range ± 0.2 kPa, MP 45, Validyne Engineering Corporation, Northridge, CA, USA). Pressure changes within the plethysmograph were measured using a differential pressure transducer (range ± 0.2 kPa, MP45, Validyne Engineering Corporation, Northridge CA, USA). All signals were amplified (CD18 carrier amplifiers, Validyne Engineering Corporation, Northridge, CA, USA) and the flow signal integrated electrically to give tidal volume (FV 156 integrator, Validyne Engineering Corporation, Northridge, CA, USA). The resultant four channels of data were acquired, analysed and displayed in real time on a personal computer (Gateway GP7–500, Dublin, Ireland) running a computer program custom designed using LabWindows software (National Instruments, Austin, TX, USA) with analogue-to-digital sampling at 200 Hz (PC-LPM-16PnP, National Instruments, Austin, TX, USA). All channels were calibrated prior to each patient test, as previously described. 17

Following application of the facemask, a minimum of 20 breaths were recorded for analysis of tidal breathing, including calculation of the time taken to achieve peak expiratory flow, expressed as a proportion of expiratory time (tPTEF : tE), and respiratory rate. FRCpleth was then calculated from a minimum of three end-inspiratory occlusions. 18,19 A time-based trace of all four data channels and an x/y plot of plethysmographic volume shift during airway occlusion (V pleth)/Pao during each occlusion were displayed by the computer. Occlusions were considered acceptable if V pleth and Pao were in phase and no airflow was evident. 20 The infant was then switched to the rebreathing bag. Individual breaths acquired during periods of rebreathing were displayed as x/y plots of V pleth/flow by the computer. Only technically acceptable breaths, that is the loop was closed or nearly closed at points of zero flow, were used in the analysis. 21 R aw was calculated electronically using an established formula20 by applying a regression line to the selected portion of the loop. R aw was calculated during initial inspiration between 0% and 50% maximal inspiratory flow, and during expiration between 0% and 50% maximal expiratory flow. 17 During all R aw measurements, the computer calculated the apparatus resistance of the selected portion of the individual breath by relating Pao to flow and then subtracting this value from the total measured resistance. 22

On completion of the plethysmographic measurements, FRCHe was measured while the infant lay undisturbed on the base of the plethysmograph, using the same mask with silicone putty. During the initial stages of the study, FRCHe was determined using a water-sealed spirometer (Pulmonet III, Gould, Bilthoven, the Netherlands), as described previously. 23 Most infants were tested using the EBS 2615 system (Equilibrated Bio Systems, New York, NY, USA), which consisted of a 500-ml rebreathing bag in a closed heliox circuit. The system was modified to produce a time-based display of flow and tidal volume, allowing accurate switching into the circuit at end expiration. 24 An online display of the helium dilution curve allowed precise determination of gas equilibration. For both FRCHe techniques, the mean of two recordings that were within 10% of each other was taken. 25 The FRCHe of 12 infants was measured using both devices in order to assess comparability, with a median difference of 4.8% (range 0.3–11.4%) between devices.

Sample size

A pulmonary function subset sample size of 100 infants had been calculated when the UKOS trial was designed, based on previously determined variability of pulmonary function measurements and a clinically relevant difference between the two groups that we wished to be able to detect. This sample size would have enabled detection of a difference of 0.56 standard deviations (SDs) between the groups, with 80% power at the 5% significance level. The actual sample size fell below this target (discussed later here) and, allowing for the unequal group sizes, enabled detection of 0.65 SDs between the groups.

Statistical analysis

Mean values with 95% CIs for the differences between groups were calculated for all data. The pulmonary function data did not follow a normal distribution and logarithmic transformation did not correct the skewness. However, the group sizes were over 30, and the SDs were similar in the two groups. In this situation, the t-test is fairly robust to slight deviations from normality and, thus, we chose to present 95% CIs for differences between means based on the t method. To check the robustness of the t-test and CI method, we also calculated p-values using the Mann–Whitney rank test. These p-values were virtually identical to those calculated using the t-test, and statistical significance (or non significance) was entirely consistent. Statistical analysis was performed using Stata software.

Results

Subjects

From the 12 centres that participated in this follow-up study, 185 infants were eligible for pulmonary function testing. From these, parents of 149 infants were invited to attend for testing. The remaining 36 infants either were living too far away from London or had been lost to follow-up. The parents of 90 infants agreed to participate in the follow-up study. However, 10 failed to attend their appointments, three (one CV and two HFOV) were repeatedly unwell or remained dependent on supplemental oxygen, and one could not be successfully sedated. This left 76 infants who formed the study group.

The studied infants had slightly lower mean birthweight and gestational age than the remainder of the trial survivors, as indicated by 95% CIs that excluded zero but were otherwise similar with respect to a range of sociodemographic and clinical parameters. Follow-up data were not available for all 592 survivors of the trial. The follow-up data were obtained exclusively from standardised respiratory questionnaires completed at 6 and 12 months’ corrected age by each infant’s own paediatrician.

When split according to randomised mode of ventilation, the two pulmonary function groups were well matched for a range of baseline characteristics, with no statistically significant differences. At follow-up, data were obtained when each infant attended for pulmonary function testing.

Pulmonary function

Most infants had complete pulmonary function results. On some occasions, technically acceptable recordings were not obtained, or the infant woke before measurements were complete. Measurements of FRCpleth were missing for two infants (one in each group) and of FRCHe for four infants (one CV and three HFOV). One or other type of FRC measurement was available for all infants. Airway resistance measurements were missing for six infants (three in each group) and tidal breathing parameters for five infants (three CV and two HFOV).

Results

The study was conducted in a subset of 76 UKOS infants whose parents were willing to participate and were able to travel to KCH. There were no statistically significant differences in pulmonary function between the two groups ( Table 3 ).

| Lung function method | CV (n = 34) | HFO (n = 42) | Difference in means (HFO – CV) | 95% CI for difference in means | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD), median | Mean (SD), median | ||||

| FRCpleth (ml/kg) | 26.9 (6.3), 25.4 | 26.5 (6.4), 25.8 | –0.4 | –3.4 to 2.5 | 0.76 |

| FRCHe (ml/kg) | 24.1 (5.4), 23.0 | 23.5 (5.7), 22.2 | –0.6 | –3.2 to 2.1 | 0.67 |

| FRCHe : FRCpleth | 0.90 (0.11), 0.90 | 0.90 (0.13), 0.91 | 0.0 | –0.06 to 0.06 | 0.93 |

| Inspiratory R aw [kPa/(l/s)] | 3.3 (1.3), 3.0 | 3.4 (1.6), 3.0 | 0.1 | –0.6 to 0.8 | 0.72 |

| Expiratory R aw [kPa/(l/s)] | 4.4 (2.8), 3.3 | 4.1 (2.5), 3.3 | –0.3 | –1.6 to 1.1 | 0.66 |

| tPTEF : tE | 0.21 (0.07), 0.22 | 0.24 (0.06), 0.22 | 0.03 | –0.01 to 0.06 | 0.15 |

| Respiratory rate (breaths/minute) | 31.2 (6.0), 30.8 | 33.9 (8.0), 33.1 | 2.7 | –0.7 to 6.1 | 0.12 |

These results do not provide evidence that lung function at follow-up is influenced by neonatal ventilation support for extremely prematurely born infants. It is important, however, to note that small airway function was only assessed by measurement of gas trapping and it would be important to assess the UKOS graduates when they are old enough to perform more comprehensive lung function assessments.

Respiratory and neurological outcomes at 2 years of age of infants from the United Kingdom Oscillation Study11

In this study,11 the outcome for surviving infants up to 2 years of age corrected for prematurity who had been entered into UKOS was assessed to determine whether ventilatory modality was associated with either increased longer-term respiratory or neurodevelopmental morbidity.

Study population

Of the 592 surviving infants who were entered into the study and discharged home, seven subsequently died, no outcome forms were returned for 164, and outcome information was available for 428 from 22 centres in the UK and one each from Australia, Ireland and Singapore. Infants were followed by their local paediatrician until 2 years of age corrected for prematurity. Questionnaires were mailed to the local paediatrician responsible for follow-up when each infant reached 21 months post-term age, with a request that the child be evaluated as close to 24 months post-term age as possible and within the ‘window’ of 22–28 months. Up to two reminders were sent to paediatricians when questionnaires had not been returned to the co-ordinating centre by 25 months post-term age. If questionnaires were still not returned, in the UK, the child’s local health visitor was telephoned and asked to complete the forms.

Paediatricians were asked to complete two forms. A respiratory questionnaire requested details about frequency of cough and wheeze and their relationship to infection, use of respiratory drugs, home oxygen, and hospital admissions (for both respiratory and other reasons). Social and demographic information, including family history of smoking and atopy, was also recorded. A neurodevelopmental questionnaire recorded information on health status and anthropometry.

In addition, parents were separately mailed a questionnaire that included questions in three areas: non-verbal cognitive development (derived from items in the Bayley scales of infant development26) and vocabulary and language (derived from the MacArthur language scales27). The original questionnaire was validated in a term population and modified for this study to incorporate better sensitivity at lower developmental scores. 28 A total score of 49 achieved 81% sensitivity and 81% specificity for a Bayley scale mental development index of 70 (more than two SDs below the mean). 28

Statistical methods

The original trial was powered to detect a 12% difference in disability rates (estimated rate 17%) or a 14% difference in respiratory symptoms (estimates: 50% during first year; 33% during second year). We compared baseline infant, maternal and socioeconomic variables between the two randomisation groups, to confirm that deaths or loss of children to follow-up had not affected the balance. To investigate any potential bias due to the omission of subjects with missing data or data obtained outside the specified window, we compared important neonatal outcomes in the three possible groups of subjects: (1) those whose questionnaires were completed within the specified window (22–28 months post term); (2) those whose questionnaires were completed outside the window; and (3) those whose questionnaires had not been returned. Analysis was on an intention-to-treat basis using the follow-up data obtained exclusively within the 22–28-month window.

Results

Respiratory and neurodevelopmental questionnaires completed by paediatricians were returned for 428 (73%) children, of which 373 (87% of those returned) were within the specified age window. Parents returned developmental questionnaires within the specified age window for 288 children (49% of survivors to discharge) The proportion of infants with oxygen dependency at 36 weeks postmenstrual age, supplemental oxygen at discharge, or major abnormality on cranial ultrasound scanning did not differ significantly between those infants with information returned inside the follow-up window, outside the window or those without follow-up data. There was a good balance in infant and maternal characteristics between the two ventilation groups among children with follow-up data. Specifically, they were well matched in terms of the major determinants of outcome: birthweight, gestational age, sex of infant or major abnormality on cranial ultrasound scan.

The frequency of reported respiratory symptoms was high: half of parents reported that their child suffered from coughing, of whom 31% coughed frequently (more than once a week); and 37% reported wheezing, of whom 30% wheezed frequently. Overall, 41% had received inhaled medication ( Table 4 ). There were no significant differences in respiratory outcomes between the two groups, although there were trends favouring the HFO group in respiratory morbidity (see Table 4 ), but not in hospital admissions ( Table 5 ).

| Respiratory outcomes | CV | HFO | HFO/CV | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number/total (%) | Number/total (%) | RR | 95% CI | |

| Chest symptoms | ||||

| Suffer from coughing | 98/194 (51) | 84/172 (49) | 0.97 | 0.79 to 1.19 |

| Coughs > once a week | 33/97 (34) | 21/81 (26) | 0.76 | 0.48 to 1.21 |

| Coughs once a week, > once a month | 15/97 (15) | 17/81 (21) | ||

| Coughs once a month or less | 49/97 (51) | 43/81 (53) | ||

| Coughs with exercise | 28/76 (37) | 15/61 (25) | 0.67 | 0.39 to 1.13 |

| Coughs with infection | 88/98 (90) | 68/81 (84) | 0.93 | 0.83 to 1.05 |

| Suffer from wheezing | 75/187 (40) | 56/167 (34) | 0.84 | 0.63 to 1.10 |

| Wheezes > once a week | 21/72 (29) | 16/53 (30) | 1.04 | 0.60 to 1.79 |

| Wheezes once a week, > once a month | 12/72 (17) | 6/53 (11) | ||

| Wheezes once a month or less | 39/72 (54) | 31/53 (58) | ||

| Wheezes with exercise | 26/60 (43) | 13/42 (31) | 0.71 | 0.42 to 1.22 |

| Wheezes with infection | 66/73 (90) | 50/56 (89) | 0.99 | 0.88 to 1.11 |

| Chest medicines | ||||

| Chest medicine in the last 12 months | 115/192 (60) | 94/171 (55) | 0.92 | 0.77 to 1.10 |

| Bronchodilators | 82/192 (43) | 63/171 (37) | 0.86 | 0.67 to 1.11 |

| Inhaled steroids | 50/192 (26) | 36/171 (21) | 0.81 | 0.56 to 1.18 |

| Other | ||||

| On home oxygen now | 4/194 (2.1) | 2/173 (1.2) | 0.56 | 0.10 to 3.02 |

| Outcome | CV | HFO | RR HFO/CV | 95% CI or p-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number/total or mean (SD) | % or range | Number/total or mean (SD) | % or range | |||

| Respiratory admission ever | 112/264 | 42 | 118/276 | 43 | 1.01 | 0.83 to 1.23 |

| Mean (SD) rangea | 2.4 (2.3) | 1–14 | 2.3 (2.3) | 1–14 | p = 0.65 | |

| Respiratory admission in last 12 months | 27/179 | 15 | 24/157 | 15 | 1.01 | 0.61 to 1.68 |

| Mean (SD) rangea | 1.3 (0.6) | 1–3 | 1.4 (1.0) | 1–5 | p = 0.81 | |

| Surgical admission ever | 59/264 | 22 | 59/276 | 21 | 0.96 | 0.70 to 1.32 |

| Mean (SD) rangea | 1.4 (0.7) | 1–4 | 1.5 (1.1) | 1–7 | p = 0.82 | |

| ICU admission ever | 25/264 | 9.5 | 23/276 | 8.3 | 0.88 | 0.51 to 1.51 |

| Mean (SD) rangea | 1.3 (0.6) | 1–3 | 1.1 (0.5) | 1–3 | p = 0.13 | |

Overall, 9% of children had severe disability and 38% had other disabilities at 2 years of age. There were no significant differences in neurological outcomes between the two ventilation groups ( Table 6 ).

| Outcome | CV | HFO | RR (HFO/CV) or difference in means | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number/total (%) | Number/total (%) | |||

| Neuromotor | ||||

| No or poor head control | 1/189 (0.5) | 0/170 (0.0) | SD | |

| Unable to sit unsupported | 3/185 (1.6) | 4/168 (2.4) | 1.47 | 0.33 to 6.46 |

| Unable to stand, requires support | 14/189 (7.4) | 12/168 (7.1) | 0.96 | 0.46 to 2.03 |

| Unable to walk, non-fluent gait | 23/190 (12.0) | 16/169 (9.5) | 0.78 | 0.43 to 1.43 |

| Unable to use left hand, not pincer grip | 7/179 (3.9) | 10/165 (6.1) | 1.55 | 0.60 to 3.98 |

| Unable to use right hand, not pincer grip | 6/185 (3.2) | 6/167 (3.6) | 1.11 | 0.36 to 3.37 |

| Unable to do/difficulty with bimanual tasks | 7/188 (3.7) | 14/168 (8.3) | 2.24 | 0.93 to 5.41 |

| Has convulsions (± treatment) | 6/189 (3.2) | 14/167 (8.4) | 2.64 | 1.04 to 6.72 |

| Vision | ||||

| Squint | 23/189 (12.0) | 22/171 (13.0) | 1.06 | 0.61 to 1.83 |

| Parent report – reduced vision | 14/189 (7.4) | 5/163 (3.1) | 0.41 | 0.15 to 1.12 |

| Parent report – abnormal eye movements | 7/188 (3.7) | 8/165 (4.8) | 1.30 | 0.48 to 3.51 |

| Hearing | ||||

| Hearing loss (± aids) | 15/188 (8.0) | 11/170 (6.4) | 0.81 | 0.38 to 1.72 |

| Other domains | ||||

| Does not understands signs or words | 0/185 (0.0) | 3/168 (1.8) | n/a | |

| Tube feeding | 4/191 (2.1) | 1/172 (0.6) | 0.28 | 0.03 to 2.46 |

| Overall disability grading | ||||

| Severe disabilitya | 16/191 (8.4) | 15/172 (8.7) | 0.93 | 0.74 to 1.16 |

| Other disability | 76/191 (40.0) | 62/172 (36.0) | ||

| No disability | 99/191 (52.0) | 95/172 (55.0) | ||

| Any disability | ||||

| 23–25 weeks’ gestation | 25/47 (54) | 24/51 (47) | 0.88 | 0.60 to 1.31 |

| 26–28 weeks’ gestation | 67/144 (46) | 53/121 (44) | 0.94 | 0.72 to 1.23 |

| Cognitive development | ||||

| Parent report composite score < 49 | 40/151 (26) | 41/137 (30) | 1.13 | 0.78 to 1.63 |

| Parent report composite mean (SD)b | 76 (37) | 75 (38) | –1.7 | –10.40 to 7.00 |

| Growth | ||||

| 23–25 weeks’ gestation | ||||

| Height SDS mean (SD) | –0.67 (0.98) | –0.76 (1.03) | –0.09 | –0.50 to 0.33 |

| Weight SDS mean (SD) | –0.80 (1.41) | –0.90 (1.16) | –0.10 | –0.63 to 0.43 |

| Head circumference SDS mean (SD) | –1.59 (1.44) | –1.46 (1.28) | 0.13 | –0.45 to 0.70 |

| 26–28 weeks’ gestation | ||||

| Height SDS mean (SD) | –0.53 (1.10) | –0.40 (1.09) | 0.13 | –0.16 to 0.42 |

| Weight SDS mean (SD) | –0.73 (1.24) | –0.54 (1.26) | 0.19 | –0.13 to 0.51 |

| Head circumference SDS mean (SD) | –1.28 (1.50) | –1.14 (1.42) | 0.15 | –0.25 to 0.54 |

Chapter 2 United Kingdom Oscillation Study follow-up study

Introduction

Recent meta-analyses of randomised trials of new modes of ventilation have demonstrated that only HFO use was associated with a significant reduction in BPD, but the effect was modest. 29 In that meta-analysis of 15 trials, overall, there were no significant differences in severe intracranial haemorrhage or periventricular leukomalacia rates, but the effects were inconsistent across the trials. Following the adverse results of one trial,30 a type of oscillator was withdrawn. Nevertheless, a survey showed that 40% of UK neonatal units regularly ventilating babies use HFO in addition to, or in place of, CV. 31 Before even more neonatal units adopt HFO into their routine practice, it is essential to determine, using clinically meaningful assessments, that is respiratory and neurodevelopmental status at school age, whether or not HFO is at least as safe and efficacious as CV techniques. Only if similar or better outcomes are found would it be appropriate to continue to use HFO.

The clinical implications of the systematic review29 are difficult to interpret, as the diagnosis of BPD does not correlate well with long-term pulmonary outcomes in prematurely born children. A better predictive measure is lung function assessment at follow-up, but this has rarely been incorporated into randomised trials of HFO. At school age, the data on lung function are limited and conflicting. Small airway function may decline over the first year after birth in prematurely born infants. 12 Whether or not there is catch-up growth has not been examined, but the results of a non-randomised study suggested that the decline does not occur if prematurely born infants are initially supported by high-volume HFO rather than CV. 13 Thus, it is important to determine whether or not the use of high-volume HFO in a randomised trial in infants at highest risk for adverse long-term respiratory outcomes, that is those born very prematurely, is associated with better lung function, particularly small airway function and other respiratory outcomes at school age. Longitudinal assessment of lung function is also required to determine if the use of HFO from birth influences catch-up growth in lung function.

Although, the meta-analysis of HFO trials demonstrated no significant excess of neurodevelopmental abnormalities,29 in some studies HFO has been associated with increases in severe intracranial haemorrhage and periventricular leukomalacia. The associations are biologically plausible as high-volume HFO could cause lung overdistension compromising cardiac output and cerebral perfusion. In addition, HFO could increase hypocarbia, which can also result in less severe, but clinically important, degrees of brain injury. Thus, it is important when assessing long-term respiratory outcomes of infants entered into randomised trials of HFO to also determine their long-term neurodevelopmental outcomes. Such data are essential to determine if HFO should continue to be used and be introduced even further into clinical practice or, conversely, its use be discontinued for very prematurely born infants, even if there are favourable respiratory outcomes.

Pulmonary hypertension (PH) complicates severe BPD, but even raised pulmonary vascular resistance (PVR), which can be present in older patients with BPD, can result in morbidity. There is some evidence that the degree of PVR may also depend on ventilator strategy, as it may be lower if fast rates and low tidal volumes rather than slow rates and high tidal volumes are used. Thus, it was important to determine if HFO use in very prematurely born infants might reduce the risk of PVR at school age. Diagnosis of PH is often difficult because the symptoms may be subtle and masked by coexisting respiratory problems. 32 Doppler echocardiography is commonly used to screen for PH in clinical practice and has been used to screen for PH in other groups of patients such as those with sickle cell disease. 33 The children in this study were assessed using Doppler echocardiography, which is an accurate and non-invasive technique. 33,34 Although tricuspid regurgitation is seen in only about 33% of normal children, if there is PH, 80% of patients will have tricuspid regurgitation which can be quantified by Doppler. 35

The aim of this follow-up study was to determine the long-term outcomes of children who had been recruited into UKOS and, in particular, to test the hypothesis that use of HFO in the newborn period would be associated with superior small airway function at school age. In addition, we wished to assess the effects of HFO compared with CV on a broad range of respiratory health and educational outcomes at age 11–14 years in children born very prematurely. The results of those follow-up assessments of children from the randomised trial would robustly inform the true risk–benefit ratio of use of HFO in very prematurely born infants. A null (no difference) finding would be as important clinically as any difference that might be observed, as it would resolve the uncertainty surrounding the long-term effects of HFO and CV and determine whether or not HFO could be safely used to support very prematurely born infants. A subsidiary aim was to track the lung function in the subset of children previously assessed at 1 year, as those results would highlight whether or not changes in lung function over time differed according to ventilation mode.

Study design

Comprehensive lung function and cardiac assessments were undertaken when the children were 11–14 years of age at KCH NHS Foundation Trust, London, UK. All assessments were made by a research fellow and research nurse blind to the child’s randomised mode of ventilation. Respiratory, health-related quality of life and functional assessment questionnaires were completed (see Appendix 1 ). Parents and their children who were unable to attend the London centre completed the questionnaires only.

Recruitment of children into the study and parent input

The UKOS children were followed to 2 years of age. Since then we have maintained contact with the families by sending birthday cards to the UK-based children. This included an information sheet, a stamped-addressed envelope and a request to inform us of any change in contact details. We also provided information about the study on our website. Families have spontaneously kept in touch with us and many have informed us of changes in their contact details. When funding for the follow-up at age 11–14 years was obtained, a newsletter was sent to all families. A mother of a UKOS child has been involved in the study design and its conduct as a member of the steering committee. Her input has been invaluable in advising us on recruitment strategies and communication with families.

Assessments

Respiratory function and atopy assessment

Airway function was assessed by spirometry [forced expiratory flow at 75%, 50% or 25% vital capacity (FEF75, FEF50 or FEF25), forced expiratory flow at one minute (FEV1) and peak expiratory flow (PEF)], to generate information on the larger airways (specifically PEF) and smaller airways (specifically FEF25). A minimum of three flow–volume loops with results 10% of each other were recorded, and the flow–volume loop with the highest FEV1 analysed. As those techniques indirectly measure airway resistance and are effort dependent, direct assessment was also made by impulse oscillometry, which is not effort dependent. In addition, inhomogeneity of ventilation distribution, a sensitive index of small airway abnormalities, was assessed by a multiple breath technique, measuring indices of gas mixing including the lung clearance index (LCI). Lung volumes were assessed by measurements of FRCHe and FVC. Plethysmographic assessment of FRCpleth, total lung capacity (TLC) and residual volume (RV) were made and gas trapping assessed by calculating the FRCHe to FRCpleth ratio and, hence, small airway abnormalities further identified. Measurements were made at least twice and mean values within 10% of each other were recorded. Total lung gas transfer, alveolar volume (VA) and gas transfer per unit volume were assessed using the single breath gas transfer technique. All lung function results were standardised for sex and height using the reference ranges of Rosenthal et al. 36,37 and Nowowiejska et al. 38 Airway hyperreactivity was assessed by a bronchial challenge tailored to the child’s baseline lung function. Children with a baseline FEV1 ≤ 70% of predicted received a bronchodilator and their FEV1 and FRC were remeasured. Children with a FEV1> 70% of that predicted underwent a cold-air challenge. This involved the child breathing through a face mask, supplied with subfreezing air (–15 °C), for 4 minutes at 60% of their maximum voluntary ventilation, as measured by a target ventilation meter. FEV1 was measured prior to, and then every, 2 minutes for 12 minutes after the cold-air challenge had finished. 39 A response to the challenge was a change in FEV1 of at least 10%.

The fraction of exhaled nitric oxide (FeNO) was measured with an online computerised system (HypAir™FeNO system, running ExpAir software version 1.29; Medisoft, Sorinnes, Belgium) following American Thoracic Society recommendations. 40 Subjects inhaled NO-free air through the mouth to TLC and exhaled through an expiratory resistor to maintain an expiratory pressure of 20 cmH2O and target flow of 50 ml/second for at least 6–7 seconds. 41 The FeNO was calculated as the mean of three measurements that agreed to within 10% of the mean value.

Atopy was assessed by skin-prick testing and from the family history. Skin-prick testing was undertaken to a panel of common inhalant allergens including mixed grass pollen, Dermatophagoides pteronyssinus, Dermatophagoides farinae, dog and cat. A positive (histamine) and a negative control were used. The skin-prick tests were considered positive if the wheal reaction was 3 mm greater than the negative control.

Pulmonary hypertension

The children were assessed using Doppler echocardiography, PH was defined as the mean pulmonary artery pressure (mPAP) > 25 mmHg. 41 The mPAP was calculated as mean right ventricular (RVENT) minus the right atrial (RA) pressure plus the estimated RA pressure. Continuous-wave Doppler was used to determine the peak velocity of the tricuspid regurgitation jet and the time velocity integral was traced to obtain the mean RVENT–RA gradient. All results were reported as the average of three measurements.

Other data collected

Height, weight, blood pressure and demographic details at assessment were collected. Hospital admissions were determined from parental report. Admissions before 2 years of age had already been recorded in the UKOS database. Urine samples were analysed for cotinine levels.

Questionnaires (see Appendix 1)

The Health Utilities Index version 3 (HUI-3) was completed and questions were also asked of respiratory health, symptoms, medicine usage and neurological illnesses such as seizures. Parents were additionally asked whether or not their child had previous hospital admissions (hospital admissions up to 2 years of age had already been included on the UKOS database). The parents and child completed the questionnaires independently. The Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ) was completed by the child, their parent and their teacher. School performance over a range of subjects was determined by a questionnaire completed by the child’s teacher, as was special needs support requirement.

Sample size

The primary outcome was small airway function. A sample size of 320 allowed a difference of 0.36 SDs in the mean lung function results to be detected with 90% power at the 5% significance level. Differences in lung function of ≥1.00 SD have been demonstrated in children with and without adverse respiratory outcomes; thus, our sample size allowed detection of a clinically important difference in lung function. Secondary outcomes were other aspects of lung function, respiratory health and symptoms, multiattribute health status as assessed by HUI-3, the results of the SDQ, special educational needs (SEN) support and subject-specific educational attainment.

Statistical analysis

The study was analysed as a two parallel-group study in keeping with the original design. The general modelling approach was to use a mixed model for both continuous and binary outcomes with the mother/pregnancy as the random effect to allow for clustering due to the relatively high proportion of multiple births common in very preterm populations. Methodological work involving simulations by one of the UKOS investigators (JP) and colleagues has shown that for data sets with a similar structure to UKOS, that is with most children being singleton births (i.e. a cluster of size one), but with a proportion of children who are twins, triplets or quads, the best estimates are obtained from using a mixed model, even if the proportions of multiples is relatively low. 42 For the binary data, the Laplace method was used within Stata as our ongoing simulations have indicated that this method gives the most reliable estimates. All study outcome analyses were adjusted for observed baseline imbalances between the two ventilation groups by incorporating the unbalanced factors as fixed effects in the multifactorial model. Unadjusted and adjusted analyses have been presented to show the effects of adjustment as estimates with 95% CIs. As we had a clearly predefined single primary outcome, FEF75, we have not adjusted for multiple testing of the secondary outcomes. In a few cases with very small proportions for secondary outcomes, for example, cerebral palsy, affecting 30 children overall, the mixed model with covariates would not converge and so a one-level logistic model was used with the clustering allowed for by obtaining a robust standard error. Where numbers of a binary event were very small, an adjusted analysis was impossible using any method and so, in such cases, a simple chi-squared test was used to provide an indicative p-value.

Neonatal baseline data were compared for the children recruited and not recruited at age 11–14 years to determine the representativeness of the group with follow-up data. Neonatal and follow-up data in the sample recruited for follow-up were compared by ventilation group to check for imbalance by group due to differential recruitment.

The primary analysis was to compare FEF75 z-score by mode of ventilation at birth. The z-scores normalised lung function for the sex and height of the child using standard formulae incorporated into the lung function measuring equipment.

As some lung function results had a skewed distribution, those data were transformed, most frequently using a logarithmic transformation. A further sensitivity analysis was performed to adjust lung function for cotinine level and pubertal stage regardless of their statistical significance. This was done as cotinine is an indicator of exposure to environmental tobacco smoke and thus potentially affects respiratory function and pubertal stage is linked to growth rate. A further sensitivity analysis was performed on key secondary outcomes derived from the questionnaire data to include only those children with both lung function and questionnaire data as, as anticipated, some families were only able to complete questionnaires by mail and not able to attend for assessment.

Differences in mean lung function are often difficult to interpret clinically and, so, for the primary outcome we also calculated the proportions of children in each ventilator group who had results below the tenth centile as a criterion for ‘poor’ lung function. This was possible because the lung function z-scores follow a normal distribution. The fuller rationale and methods for this are given in Peacock et al. 43

Dealing with missing data

Some children were unable to complete all lung function tests and, so, multiple imputation using chained equations was used to impute missing data. The following variables, in addition to all lung function variables, were used in the imputation: ventilation group, birthweight, gestational age group, use of surfactant, multiple birth, mother’s ethnicity, child’s current height, a binary health indicator (any report of the following wheeze, antibiotics, chest medicine, hospital admission, seizure, diabetes, cerebral palsy, hydrocephalus, gastrostomy, bowel stoma indicating ‘yes’) and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) inattention score. Fifty data sets were imputed, and the imputation assumed that given these covariates, the data were missing at random. A further sensitivity analysis of the primary outcome was performed adjusting for the factors related to non-recruitment, namely ethnicity, Index of Multiple Deprivation (IMD) and maternal smoking during pregnancy. 44

Intraclass correlation coefficients

These have been calculated to aid other researchers.

Software

An online data collection system for clinical studies (MedSciNet; MedSciNet AB, Stockholm, Sweden) was used for data collection and data management. Statistical analysis was conducted using Stata.

Results

Recruitment

Seven hundred and ninety-seven infants were recruited into UKOS from 25 centres; 22 were in England, Scotland or Wales and one in each of Australia, Ireland and Singapore. Infants from the 22 UK centres were followed up at the age of 6, 12 and 24 months and a subset of 76 UK-based children, who were able to travel to KCH, underwent lung function assessment at age 12 months.

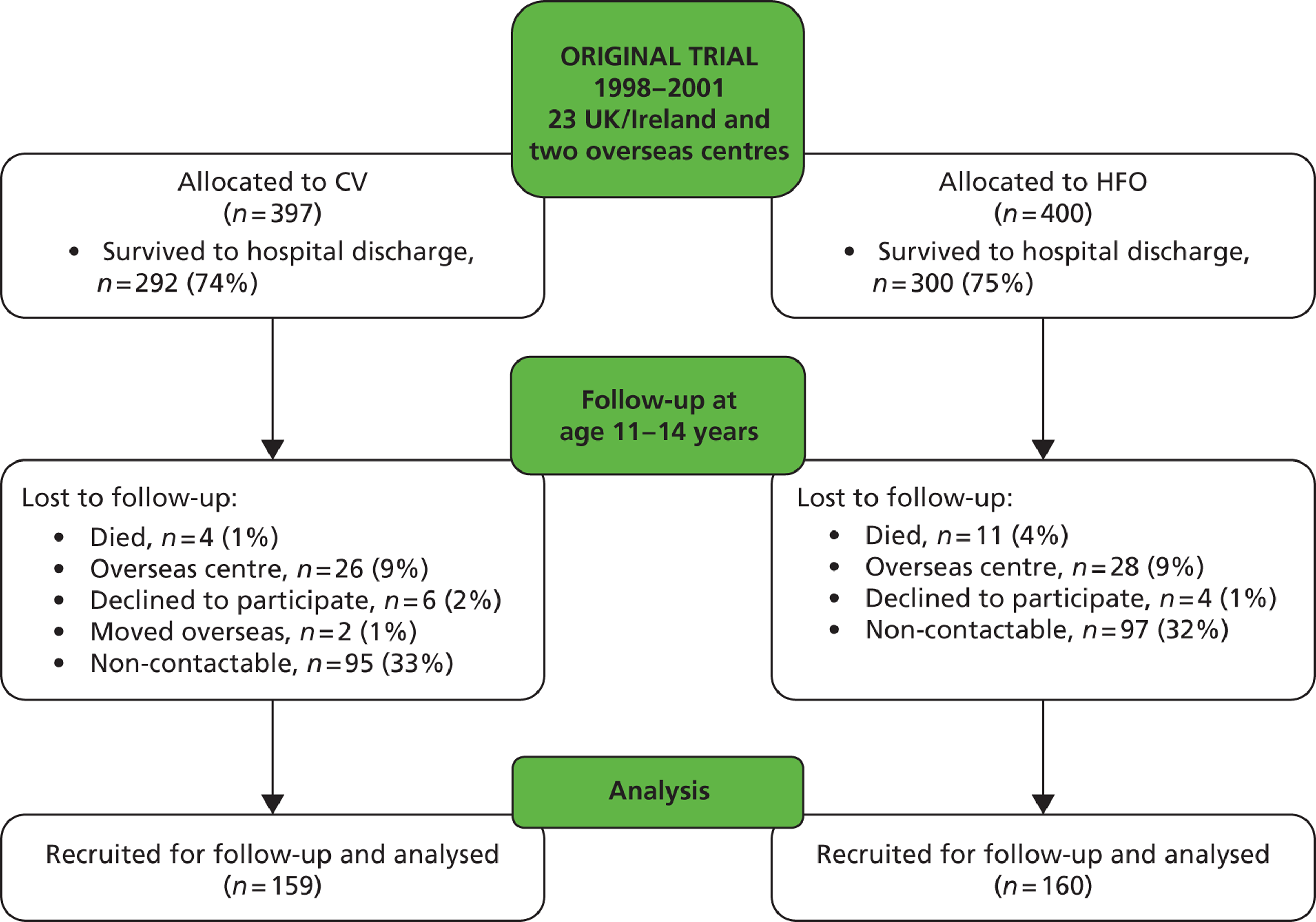

The target group for the current study included all 538 children in England, Scotland, Wales and Ireland surviving to hospital discharge ( Figure 2 ). Fifteen children had subsequently died and 57, despite vigorous efforts, could not be traced, and so the maximum available sample was 466. One hundred and forty-eight children either declined follow-up or failed to reply to multiple letters and telephone calls. A total of 319 children are the subject of this report. The planned sample size was 320 children completing all elements of the study. However, while our total was virtually at target (n = 319), only 256 of these completed full lung function tests as well as completing questionnaires, leaving 59 who took part by completing the detailed questionnaires but not the assessments, and four who completed the assessments but did not return the questionnaires. Comparison of the baseline characteristics of those who were and were not recruited demonstrated significant differences with regard to only the mother’s ethnic group, children who were recruited were more likely to have a Caucasian mother and less likely to have a mother who smoked during pregnancy (24% vs. 38%) ( Table 7 ). Differences in the birthweight z-score were of borderline significance; recruited children had on average a lower z-score than those not recruited (mean z = –0.59 vs. –0.41).

FIGURE 2.

United Kingdom Oscillation Study Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) flow diagram.

| Baseline characteristics | Recruited | Not recruited | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| N | 319 | 204 | |

| Male sex | 162/319 (51) | 109/204 (53) | 0.550 |

| Mother’s ethnicity | |||

| White | 285/318 (90.0) | 149/203 (73.0) | < 0.001 overall |

| Black | 21/318 (6.6) | 35/203 (17.0) | |

| Other | 12/318 (3.8) | 19/203 (9.3) | |

| IMD median (range)a | 15.2 (1.0–68.1) | 28.2 (1.1–70.0) | < 0.001 |

| Birthweight (g) | 895 (209) | 914 (204) | 0.310 |

| Birthweight z-score (range) | –0.59 (–3.45 to 2.41) | –0.41 (–3.28 to 2.17) | 0.050 |

| Gestational age (weeks) | 26.9 (1.33) | 26.7 (1.39) | 0.350 |

| Multiple birth | 76/319 (24) | 45/204 (22) | 0.640 |

| Surfactant given | 310/319 (97) | 203/204 (99) | 0.097 |

| Mother smoked during pregnancy | 69/292 (24) | 72/188 (38) | 0.001 |

| Postnatal steroids | 84/314 (27) | 61/203 (30) | 0.420 |

| Oxygen dependency at 36 weeks postmenstrual age | 183/319 (57) | 121/204 (59) | 0.660 |

| Oxygen dependency at 28 days | 262/319 (82) | 164/204 (80) | 0.620 |

| Oxygen dependent at discharge | 71/315 (23) | 44/204 (22) | 0.800 |

Baseline characteristics

There were four maternal and neonatal characteristics factors that differed significantly between the two ventilation groups: the CV group had a higher mean birthweight (923 g vs. 867 g), were born slightly later (mean gestational age 27.0 weeks vs. 26.7 weeks), included a greater proportion who were born at 26–28 weeks of gestation (81% vs. 68%) and included a greater proportion who received surfactant (99% vs. 95%) ( Table 8 ).

| Maternal and neonatal characteristics | Mode of ventilation | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| CV | HFO | ||

| N | 159 | 160 | |

| Male sex | 85/159 (53) | 77/160 (48) | 0.340 |

| Mother’s ethnic group | |||

| White | 142/158 (90.0) | 143/160 (89.0) | |

| Black | 11/158 (7.0) | 10/160 (6.3) | |

| Other | 5/158 (3.2) | 7/160 (4.4) | 0.920 overall |

| At birth | |||

| Birthweight (g) | 923 (206) | 867 (209) | 0.016 |

| Birthweight z-score (range) | –0.55 (–2.94 to 1.73) | –0.62 (–3.45 to 2.41) | 0.520 |

| Gestational age, weeks | 27.0 (1.18) | 26.7 (1.45) | 0.043 |

| Gestational group | |||

| Born at 23–25 weeks of gestation | 30/159 (19) | 52/160 (33) | |

| Born at 26–28 weeks of gestation | 129/159 (81) | 108/160 (68) | 0.005 |

| Multiple birth | 39/159 (25) | 37/160 (23) | 0.770 |

| Surfactant given | 158/159 (99) | 152/160 (95) | 0.036 |

| Mother smoked during pregnancy | 31/146 (21) | 38/146 (26) | 0.340 |

| Postnatal steroids | 36/157 (23) | 48/157 (31) | 0.130 |

| Oxygen dependency at 36 weeks postmenstual age | 95/159 (60) | 88/160 (55) | 0.390 |

| Oxygen dependency at 28 days | 131/159 (82) | 131/160 (82) | 0.900 |

| Oxygen dependent at discharge | 34/156 (22) | 37/159 (23) | 0.750 |

There were no significant differences between the two groups in their characteristics when they were assessed at 11–14 years of age ( Table 9 ).

| Characteristics | Mode of ventilation | p-value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CV | HFO | ||||

| For those who completed full assessmenta | |||||

| Age (years) | 121 | 12.5 (0.60) | 129 | 12.6 (0.62) | 0.660 |

| Range | 11.2–14.4 | 11.5–14.4 | |||

| Weight (kg) (range) | 121 | 44.4 (23.4–102.0) | 129 | 44.9 (19.0–86.7) | 0.530 |

| Boy | 45.4 (25.0–102.0) | 43.3 (19.0–86.7) | 0.650 | ||

| Girl | 43.1 (23.4–57.0) | 46.5 (29.0–72.0) | 0.100 | ||

| Height (cm) (range) | 121 | 153 (129–173) | 129 | 151 (124–172) | 0.260 |

| Boy | 153 (138–173) | 151 (124–172) | 0.120 | ||

| Girl | 152 (129–169) | 152 (137–164) | 0.850 | ||

| BMI median (kg/m2) (range) | 121 | 17.8 (12.8–34.5) | 121 | 18.9 (11.9–30.6) | 0.150 |

| Boy | 17.7 (12.8–34.5) | 17.8 (11.9–29.3) | 0.760 | ||

| Girl | 19.0 (14.1–23.6) | 19.3 (14.4–30.6) | 0.068 | ||

| Haemoglobin (g/dl) | 118 | 12.7 (1.25) | 124 | 12.7 (1.13) | 0.980 |

| Oxygen saturation (%) | 119 | 98.3 (1.11) | 127 | 98.3 (1.21) | 0.970 |

| Blood pressure systolic (mmHg) | 89 | 118.4 (9.18) | 98 | 118.0 (10.80) | 0.820 |

| Blood pressure diastolic (mmHg) | 89 | 74.5 (8.79) | 98 | 74.4 (9.40) | 0.940 |

| Current smoking exposure | |||||

| Cotinine range (ng/ml) | 116 | < 10, 154 | 115 | < 10, 168 | |

| Undetectable (< 10 ng/ml) | 86/106 (80) | 92/115 (80) | 0.840 overall | ||

| Passive smoker (10–15 ng/ml) | 4/106 (4) | 3/115 (3) | |||

| Active smoker (> 15 ng/ml) | 17/106 (16) | 20/115 (17) | |||

| For those who completed questionnaires only | |||||

| Pubertal statusb | 148 | 155 | |||

| Reached stage 3 in physical or hair development | 109/146 (75) | 110/152 (72) | 0.740 | ||

| Do not know | 5/146 (3.4) | 8/152 (5.3) | |||

| Family smoke | 148 | 44/149 (30) | 153 | 51/152 (34) | 0.450 |

| House has problems with damp or mould | 148 | 10/150 (6.7) | 155 | 13/154 (8.4) | 0.560 |

| Family has asthma | 149 | 76/150 (51) | 155 | 72/154 (47) | 0.500 |

| Home owner | 147 | 105/148 (71) | 155 | 114/154 (74) | 0.550 |

| IMD median (range)c | 114 | 15.4 (2.6–68.0) | 123 | 14.8 (1.0–67.9) | 0.660 |

Lung function and allergy assessment results

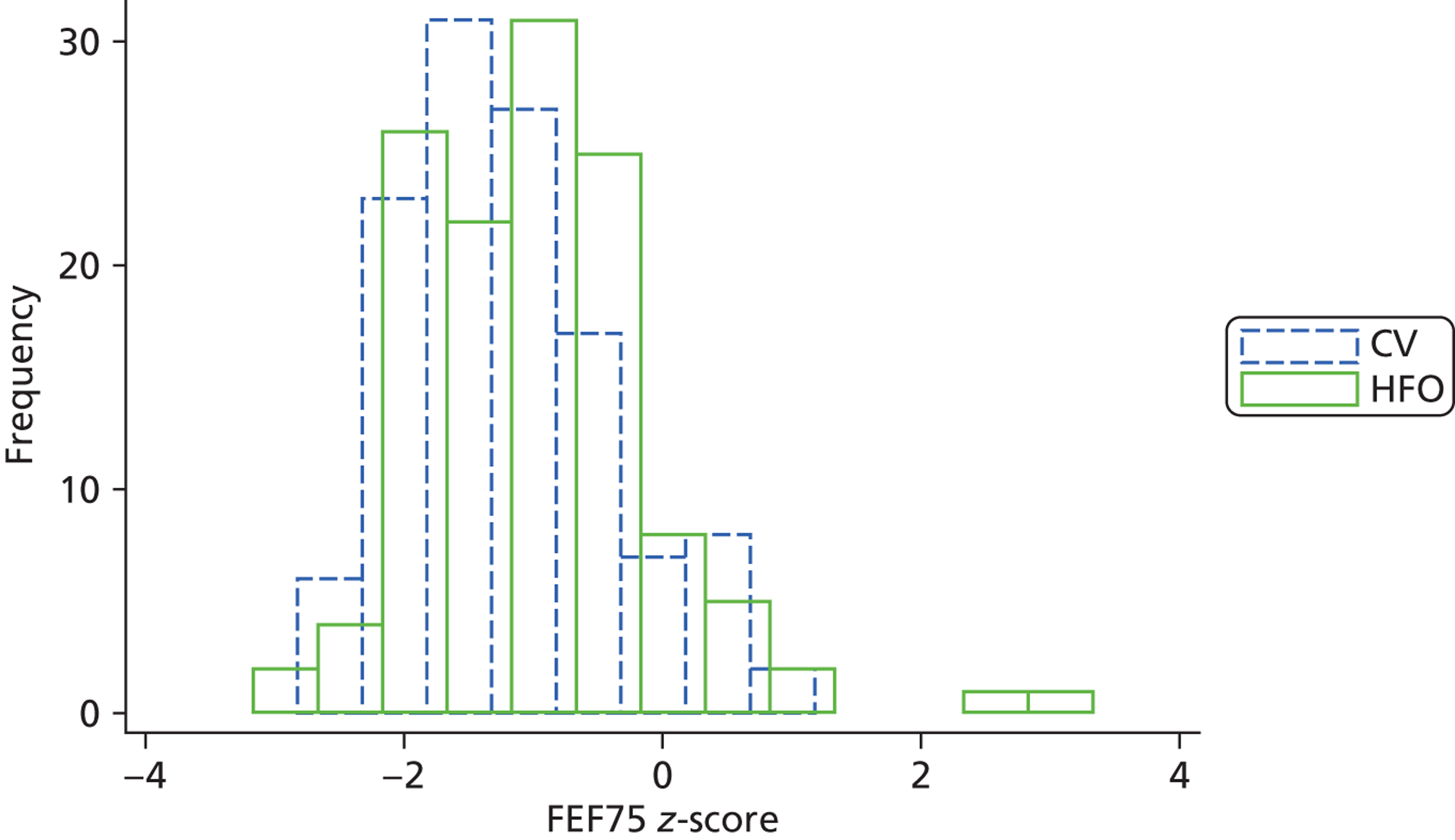

There was a statistically significant difference in the primary outcome small airway function, FEF75; the z-score was higher in the HFO group (mean FEF75 z-score was –1.19 vs. –0.97) ( Table 10 ). This difference was significant in both the unadjusted model that allowed for multiple births, but did not include any covariates, and in the fully adjusted model which additionally adjusted for the baseline neonatal factors that had shown imbalance between the groups. The adjusted difference in mean z-scores was 0.23 (95% CI 0.02 to 0.45). The percentage of children with lung function below the tenth centile was 46% in the CV compared with 37% in the HFO group. There were similar differences in mean lung function between the groups for both FEF50 and FEF25. The histograms for FEF75 shows that the two groups had a similar shape distribution and the CV distribution is simply shifted downwards, that is to say there was a reduction in FEF75 in all children ( Figure 3 ).

| Lung function tests | CV | HFO | Unadjusted difference or ORa (95% CI) | Adjusted difference or ORa (95% CI) | p-value for adjusted analysis | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | 121 | 129 | |||||

| FEF75 z-score | 248 | –1.19 (0.80) | –0.97 (0.95) | 0.21(0.00 to 0.42) | 0.23 (0.02 to 0.45) | 0.035 | |

| FEF50 z-score | 248 | –1.37 (0.85) | –1.07 (0.93) | 0.28 (0.07 to 0.49) | 0.30 (0.09 to 0.52) | 0.006 | |

| FEF25 z-score | 248 | –1.16 (0.95) | –0.84 (0.90) | 0.27 (0.05 to 0.49) | 0.29 (0.07 to 0.51) | 0.011 | |

| FEF25–75 z-score | 231 | –1.58 (1.05) | –1.34 (1.09) | 0.18 (–0.07 to 0.44) | 0.21 (–0.04 to 0.47) | 0.100 | |

| FEV1 z-score | 248 | –0.95 (1.02) | –0.60 (1.08) | 0.31 (0.06 to 0.56) | 0.35 (0.09 to 0.60) | 0.008 | |

| FVC z-score | 248 | –0.44 (0.89) | –0.29 (1.05) | 0.11 (–0.12 to 0.35) | 0.13 (–0.10 to 0.37) | 0.270 | |

| FEV1/FVC z-score | 248 | –1.75 (1.78) | –1.16 (1.75) | 0.54 (0.12 to 0.95) | 0.58 (0.16 to 0.99) | 0.007 | |

| PEF % predicted | 247 | 80.3 (15.0) | 86.3 (15.5) | 5.58 (1.97 to 9.18) | 5.85 (2.21 to 9.49) | 0.002 | |

| Gas transfer | |||||||

| D L,CO z-score | 210 | –1.10 (0.92) | –0.81 (1.19) | 0.30 (0.02 to 0.57) | 0.31 (0.04 to 0.58) | 0.023 | |

| VA (l) | 210 | 3.44 (0.66) | 3.40 (0.59) | –0.05 (–0.19 to 0.10) | –0.05 (–0.20 to 0.09) | 0.480 | |

| D L,CO/VA (mmol/minute/kPa/l) | 210 | 1.73 (0.20) | 1.76 (0.21) | 0.04 (–0.01 to 0.09) | 0.04 (–0.01 to 0.09) | 0.110 | |

| RV z-score | 211 | 0.46 (1.19) | 0.31 (1.35) | –0.05 (–0.38 to 0.27) | –0.09 (–0.42 to 0.24) | 0.600 | |

| TLC z-score | 213 | 0.20 (1.00) | 0.36 (1.13) | 0.16 (–0.11 to 0.44) | 0.16 (–0.12 to 0.43) | 0.260 | |

| FRCpleth z-score | 218 | –0.07 (1.26) | –0.11 (1.28) | –0.10 (–0.42 to 0.23) | –0.08 (–0.41 to 0.25) | 0.630 | |

| VCmax z-score | 213 | –0.50 (0.88) | –0.17 (1.09) | 0.29 (0.03 to 0.55) | 0.31 (0.05 to 0.57) | 0.020 | |

| FRCHe z-score | 229 | –0.62 (1.10) | –0.75 (1.05) | –0.15 (–0.41 to 0.10) | –0.18 (–0.44 to 0.08) | 0.190 | |

| LCI | 155 | 7.50 (1.18) | 7.62 (1.39) | 0.16 (–0.21 to 0.53) | 0.17 (–0.21 to 0.54) | 0.390 | |

| FRCSF6 (l) | 163 | 1.77 (0.43) | 1.73 (0.42) | –0.04 (–0.16 to 0.08) | –0.04 (–0.16 to 0.08) | 0.530 | |

| R5Hz % predicted | 237 | 99.6 (23) | 92.5 (21) | –7.02 (–12.30 to –1.70) | –7.13 (–12.50 to –1.76) | 0.009 | |

| R20Hz % predicted | 237 | 95.5 (24) | 90.2 (22) | –5.65 (–11.20 to –0.08) | –5.22 (–10.70 to 0.24) | 0.061 | |

| Airways reactivity | |||||||

| Cold air challenge, positive response | 193 | 24/95 (25%) | 20/98 (20%) | 0.76 (0.39 to 1.49)a | 0.76 (0.38 to 1.53)a | 0.450 | |

| Bronchodilator, positive response | 37 | 7/21 (33%) | 716 (44%) | 1.56 (0.41 to 5.99)a | 1.75 (0.38 to 7.98)a | 0.470 | |

| FeNO (p.p.b.)b | 207 | 15.4 (1.88) | 14.7 (1.91) | 0.96 (0.80 to 1.14) | 0.98 (0.83 to 1.17) | 0.840 | |

| Skin-prick test, positive | 188 | 9/92 (9.8%) | 11/96 (11.5%) | 1.19 (0.43 to 3.28) | 1.34 (0.45 to 3.99) | 0.600 | |

| Number of positives | 1 | 5/9 | 8/11 | ||||

| 2 | 4/9 | 2/11 | |||||

| 3 | 0/9 | 1/11 | |||||

FIGURE 3.

Distribution of FEF75 z-score by ventilation group. Dotted blue line indicates CV group. Solid green line indicates HFO group.

There were significant differences between the ventilation groups with regard to a number of the other lung function results: FEV1 (difference = 0.35 SDs), FEV1 : FVC (0.58 SDs), PEF (5.85% points), diffusing capacity of the lung for carbon monoxide (D L,CO) (0.31 SDs), VCmax (0.31 SDs) and respiratory resistance at 5 Hz (R5Hz) (7.13% points) (see Table 10 ).

The results were all worse on average in the CV group. There were no significant differences with regard to airway hyper-reactivity and exhaled nitric oxide between the two groups.

Sensitivity analyses were performed on the lung function measurement results; pubertal stage and cotinine levels were added to the fully adjusted model ( Table 11 ). This further analysis demonstrated findings consistent with the previous analysis, with significant differences in the primary outcome and the above secondary outcomes with similar effect sizes. The results of multiple imputation used to address the incomplete lung function data demonstrated similar effect sizes between the HFO and CV groups ( Table 12 ), and the further analysis that adjusted for differences in the sample assessed and those not follow-up also gave almost identical effect sizes ( Table 13 , sensitivity analysis 2).

| Lung function test | Basic modela | Sensitivity analysisb | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adjusted difference (95% CI) | p-value | Adjusted difference (95% CI) | p-value | |

| FEF75 z-score | 0.23 (0.02 to 0.45) | 0.035 | 0.30 (0.06 to 0.53) | 0.013 |

| FEF50 z-score | 0.30 (0.09 to 0.52) | 0.006 | 0.30 (0.06 to 0.53) | 0.013 |

| FEF25 z-score | 0.29 (0.07 to 0.51) | 0.011 | 0.25 (0.02 to 0.49) | 0.034 |

| FEF25–75 z-score | 0.21 (–0.04 to 0.47) | 0.100 | 0.17 (–0.11 to 0.45) | 0.240 |

| FEV1 z-score | 0.35 (0.09 to 0.60) | 0.008 | 0.32 (0.04 to 0.61) | 0.027 |

| FVC z-score | 0.13 (–0.10 to 0.37) | 0.270 | 0.10 (–0.16 to 0.36) | 0.460 |

| FEV1/FVC z-score | 0.58 (0.16 to 0.99) | 0.007 | 0.45 (0.02 to 0.88) | 0.041 |

| PEF (% predicted) | 5.85 (2.21 to 9.49) | 0.002 | 6.88 (2.77 to 11.0) | 0.001 |

| D L,CO z-score | 0.31 (0.04 to 0.58) | 0.023 | 0.35 (0.04 to 0.65) | 0.028 |

| VA (l) | –0.05 (–0.20 to 0.09) | 0.480 | –0.07 (–0.21 to 0.08) | 0.360 |

| D L,CO/VA (mmol/minute/kPa/l) | 0.04 (–0.01 to 0.09) | 0.110 | 0.03 (–0.03 to 0.08) | 0.330 |

| RV z-score | –0.09 (–0.42 to 0.24) | 0.600 | –0.03 (–0.37 to 0.31) | 0.850 |

| FRCpleth z-score | –0.08 (–0.41 to 0.25) | 0.630 | –0.09 (–0.44 to 0.26) | 0.620 |

| VCmax z-score | 0.31 (0.05 to 0.57) | 0.020 | 0.31 (0.02 to 0.60) | 0.037 |

| FRCHe z-score | –0.18 (–0.44 to 0.08) | 0.190 | –0.22 (–0.51 to 0.08) | 0.150 |

| LCI | 0.17 (–0.21 to 0.54) | 0.390 | 0.13 (–0.33 to 0.58) | 0.580 |

| FRCSF6 (l) | –0.04 (–0.16 to 0.08) | 0.530 | –0.06 (–0.18 to 0.07) | 0.370 |

| R5Hz (% predicted) | –7.13 (–12.5 0 to –1.76) | 0.009 | –7.45 (–13.40 to –1.50) | 0.014 |

| R20Hz (% predicted) | –5.22 (–10.70 to 0.24) | 0.061 | –5.42 (–11.30 to 0.43) | 0.069 |

| FeNO (p.p.b.)c | 0.98 (0.83 to 1.17) | 0.84 0 | 0.94 (0.78 to 1.14) | 0.550 |

| Lung function test | Available data | Imputed data | Complete cases (basic modela) adjusted difference (95% CI) | p-value | Imputed datab adjusted difference (95% CI) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FEF75 z-score | 248 | – | 0.23 (0.02 to 0.45) | 0.035 | – | – |

| FEF50 z-score | 248 | – | 0.30 (0.09 to 0.52) | 0.006 | – | – |

| FEF25 z-score | 248 | – | 0.29 (0.07 to 0.51) | 0.011 | – | – |

| FEF25–75 z-score | 231 | 17 | 0.21 (–0.04 to 0.47) | 0.100 | 0.20 (–0.05 to 0.45) | 0.12 |

| FEV1 z-score | 248 | – | 0.35 (0.09 to 0.60) | 0.008 | – | – |

| FVC z-score | 248 | – | 0.13 (–0.10 to 0.37) | 0.270 | – | – |

| FEV1/FVC z-score | 248 | – | 0.58 (0.16 to 0.99) | 0.007 | – | – |

| PEF (% predicted) | 247 | 1 | 5.85 (2.21 to 9.49) | 0.002 | 5.85 (2.22 to 9.48) | 0.002 |

| D L,CO z-score | 209 | 39 | 0.31 (0.04 to 0.58) | 0.023 | 0.29 (0.02 to 0.56) | 0.037 |

| VA (l) | 209 | 39 | –0.05 (–0.20 to 0.09) | 0.480 | –0.08 (–0.21 to 0.06) | 0.280 |

| D L,CO/VA (mmol/minute/kPa/l) | 210 | Not imputed | 0.04 (–0.01 to 0.09) | 0.110 | – | – |

| RV z-score | 211 | 37 | –0.09 (–0.42 to 0.24) | 0.600 | –0.20 (–0.53 to 0.13) | 0.240 |

| TLC z-score | 212 | 36 | 0.16 (–0.12 to 0.43) | 0.260 | 0.11 (–0.16 to 0.37) | 0.430 |

| FRCpleth z-score | 217 | 31 | –0.08 (–0.41 to 0.25) | 0.630 | –0.11 (–0.43 to 0.21) | 0.500 |

| VCmax z-score | 212 | 36 | 0.31 (0.05 to 0.57) | 0.020 | 0.25 (0.00 to 0.50) | 0.046 |

| FRCHe z-score | 228 | 20 | –0.18 (–0.44 to 0.08) | 0.190 | –0.16 (–0.42 to 0.10) | 0.230 |

| LCI | 153 | 95 | 0.17 (–0.21 to 0.54) | 0.390 | 0.04 (–0.41 to 0.49) | 0.870 |

| FRCSF6 (l) | 161 | 87 | –0.04 (–0.16 to 0.08) | 0.530 | –0.08 (–0.20 to 0.04) | 0.180 |

| R5Hz (% predicted) | 235 | 13 | –7.13 (–12.50 to –1.76) | 0.009 | –7.63 (–13.10 to –2.14) | 0.006 |

| R20Hz (% predicted) | 235 | 13 | –5.22 (–10.70 to 0.24) | 0.061 | –5.49 (–11.20 to 0.23) | 0.060 |

| FeNO (p.p.b.)c | 206 | 42 | 0.98 (0.83 to 1.17) | 0.840 | 0.99 (0.83 to 1.19) | 0.940 |

| Lung function test | Basic model adjusted difference (95% CI) | p-value | Sensitivity analysis 1 adjusted difference (95% CI) | p-value | Sensitivity analysis 2 adjusted difference (95% CI) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FEF75 z-score | 0.23 (0.02 to 0.45) | 0.035 | 0.27 (0.04 to 0.50) | 0.0230 | 0.27 (0.04 to 0.50) | 0.022 |

| FEF50 z-score | 0.30 (0.09 to 0.52) | 0.006 | 0.26 (0.03 to 0.49) | 0.027 | 0.34 (0.11 to 0.57) | 0.004 |

| FEF25 z-score | 0.29 (0.07 to 0.51) | 0.011 | 0.21 (–0.02 to 0.44) | 0.070 | 0.34 (0.11 to 0.58) | 0.005 |

| FEF25–75 z-score | 0.21 (–0.04 to 0.47) | 0.100 | 0.14 (–0.13 to 0.41) | 0.300 | 0.29 (0.02 to 0.57) | 0.034 |

| FEV1 z-score | 0.35 (0.09 to 0.60) | 0.008 | 0.28 (0.00 to 0.56) | 0.053 | 0.41 (0.14 to 0.67) | 0.003 |

| FVC z-score | 0.13 (–0.10 to 0.37) | 0.270 | 0.08 (–0.18 to 0.34) | 0.550 | 0.17 (–0.07 to 0.41) | 0.170 |

| FEV1/FVC z-score | 0.58 (0.16 to 0.99) | 0.007 | 0.40 (–0.02 to 0.83) | 0.062 | 0.69 (0.24 to 1.14) | 0.003 |

| PEF (% predicted) | 5.85 (2.21 to 9.49) | 0.002 | 6.54 (2.44 to 10.60) | 0.002 | 6.64 (2.73 to 10.5) | 0.001 |

| D L,CO z-score | 0.31 (0.04 to 0.58) | 0.023 | 0.34 (0.03 to 0.65) | 0.030 | 0.34 (0.05 to 0.62) | 0.021 |

| VA (l) | –0.05 (–0.20 to 0.09) | 0.480 | –0.06 (–0.21 to 0.08) | 0.410 | –0.02 (–0.17 to 0.14) | 0.820 |

| D L,CO/VA (mmol/minute/kPa/l) | 0.04 (–0.01 to 0.09) | 0.110 | 0.02 (–0.03 to 0.08) | 0.410 | 0.05 (0.00 to 0.11) | 0.069 |

| RV z-score | –0.09 (–0.42 to 0.24) | 0.600 | 0.01 (–0.32 to 0.34) | 0.950 | –0.09 (–0.44 to 0.26) | 0.620 |

| TLC z-score | 0.16 (–0.12 to 0.43) | 0.260 | 0.20 (–0.10 to 0.49) | 0.200 | 0.17 (–0.12 to 0.45) | 0.250 |

| FRCpleth z-score | –0.08 (–0.41 to 0.25) | 0.630 | –0.07 (–0.42 to 0.28) | 0.700 | –0.10 (–0.45 to 0.24) | 0.560 |

| VCmax z-score | 0.31 (0.05 to 0.57) | 0.020 | 0.30 (0.01 to 0.59) | 0.043 | 0.36 (0.10 to 0.61) | 0.007 |

| FRCHe z-score | –0.18 (–0.44 to 0.08) | 0.190 | –0.20 (–0.50 to 0.09) | 0.170 | –0.21 (–0.48 to 0.07) | 0.140 |

| LCI | 0.17 (–0.21 to 0.54) | 0.390 | 0.21 (–0.22 to 0.65) | 0.340 | 0.29 (–0.10 to 0.68) | 0.140 |

| FRCSF6 (l) | –0.04 (–0.16 to 0.08) | 0.530 | –0.06 (–0.19 to 0.06) | 0.340 | –0.05 (–0.18 to 0.08) | 0.450 |

| R5Hz (% predicted) | –7.13 (–12.50 to –1.76) | 0.009 | –7.23 (–13.20 to –1.29) | 0.017 | –8.28 (–14.10 to –2.46) | 0.005 |

| R20Hz (% predicted) | –5.22 (–10.70 to 0.24) | 0.061 | –5.36 (–11.20 to 0.51) | 0.073 | –5.88 (–11.90 to 0.17) | 0.057 |

| FeNO (p.p.b.) | 0.98 (0.83 to 1.17)a | 0.840a | 0.92 (0.76 to 1.11)a | 0.390 | 0.99 (0.81 to 1.20)a | 0.890 |

Analysis of the lung function results of children who had also been assessed at 1 year demonstrated that their small airway function had deteriorated, as demonstrated by an increase in gas trapping.

Further details of the imputation modelling

The following variables, in addition to all lung function variables, were used in the imputation: ventilation group, birthweight, gestational age group, use of surfactant, multiple birth, mother’s ethnicity, child’s current height, a binary health indicator (any report of the following: wheeze, antibiotics, chest medicine, hospital admission, seizure, diabetes, cerebral palsy, hydrocephalus, gastrostomy, bowel stoma indicating ‘yes’) and ADHD inattention score. Fifty data sets were imputed and the imputation assumed that, given these covariates, the data were missing at random.

Respiratory morbidity in the past 12 months and health problems

There were no significant differences between ventilation groups with regard to respiratory morbidity in the last 12 months or health problems as documented by the parent-completed questionnaire and the effect sizes were nearly all very close to 1 ( Table 14 ). The reasons why the child was admitted to hospital are given in Table 15 and the reasons why the child was under the care of a doctor are given in Table 16 .

| Respiratory morbidity in past 12 months | CV | HFO | Unadjusted OR (HFO/CV) (95% CI) | Adjusted OR (HFO/CV) (95% CI) | p-value for adjusted analysis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wheeze | 22/150 (15) | 23/154 (15) | 1.02 (0.55 to 1.89) | 1.01 (0.53 to 1.90) | 0.98 |

| Number of wheeze attacksa | |||||

| Daily | 1/22 (4.6) | 5/22 (23) | 0.76 overallb | ||

| Weekly | 1/22 (4.6) | 2/22 (9.1) | |||

| Monthly | 4/22 (18) | 4/22 (18) | |||

| < monthly | 16/22 (73) | 11/22 (50) | |||

| If wheeze, sleep disturbed by wheeze | |||||

| Never woken with wheeze | 15/22 (68) | 14/23 (61) | |||

| Seldom wakes (< 1 night/week) | 6/22 (27) | 6/23 (26) | |||

| Frequently wakes (≥ 1 night/week) | 1/22 (4.6) | 3/23 (13) | |||

| Antibiotics for chest problems | |||||

| Yes | 22/150 (15) | 18/154 (12) | 0.76 (0.38 to 1.54) | 0.69 (0.34 to 1.43) | 0.32c |

| No | 123/150 (82) | 132/154 (86) | |||

| Do not know | 5/150 (3.3) | 4/154 (2.6) | |||

| If yes, number of courses of antibioticsd | |||||

| One course of antibiotics | 11/21 (52) | 11/15 (73) | |||

| Two courses of antibiotics | 6/21 (29) | 1/15 (6.7) | |||

| Two or more courses of antibiotics | 4/21 (19) | 3/15 (20) | |||

| Other medicines for chest problems | |||||

| Yes | 24/150 (16) | 23/152 (15) | 0.94 (0.51 to 1.75) | 0.94 (0.50 to 1.77) | 0.85c |

| No | 125/150 (83) | 127/152 (84) | |||

| Do not know | 1/150 (0.7) | 2/152 (1.3) | |||

| Admission to hospital (see Table 15 ) | 15/150 (10) | 18/152 (12) | 1.21 (0.60 to 2.44) | 0.95 (0.45 to 1.99) | 0.89 |

| Chest problems | 4 | 0 | |||

| Number of admissions (range) | 1–6 | – | |||

| Surgery | 8 | 13 | |||

| Number of admissions (range) | 1–2 | 1–2 | |||

| Other | 8 | 5 | |||

| Number of admissions (range) | 1–3 | 1 | |||