Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 04/35/08. The contractual start date was in October 2006. The draft report began editorial review in May 2012 and was accepted for publication in August 2013. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Andrew McCaddon is a scientific advisor and shareholder of COBALZ Ltd – a private limited company developing novel B vitamin and antioxidant supplements.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2014. This work was produced by Bedson et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Plain English summary

Depression is common and serious. Only half of sufferers respond well to antidepressants. There is reason to hope that folic acid, which helps mothers and babies in pregnancy, will help. We conducted the clinical trial known as FolATED to test whether adding folic acid to antidepressants makes them work better and also gives good value for money. We also studied genetic and other scientific aspects of depression.

We aimed to recruit 450 adults from across Wales with confirmed moderate or severe depression for which they were taking or about to start antidepressants, but without other serious illness. Our target was for 360 (80%) of them to complete carefully designed questionnaires about their mental health on three occasions over 6 months. We actually recruited 475, and analysed 440 (93%) of them. Once a day for 12 weeks these participants added an extra pill to their antidepressants. For half of them, chosen at random, this pill contained 5 mg of folic acid. For the other half this pill looked the same but did not contain any folic acid. Only one person knew who had which pill.

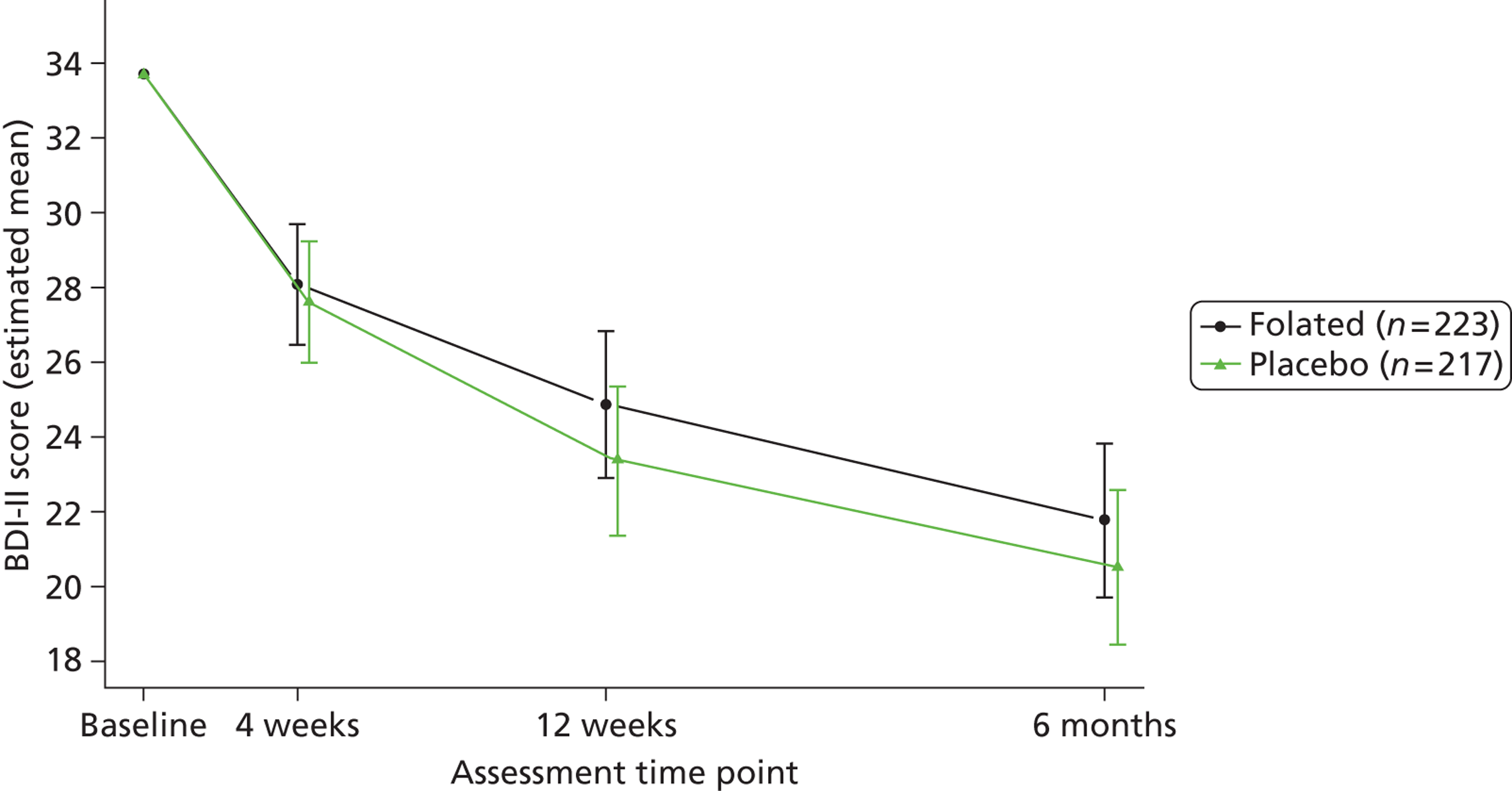

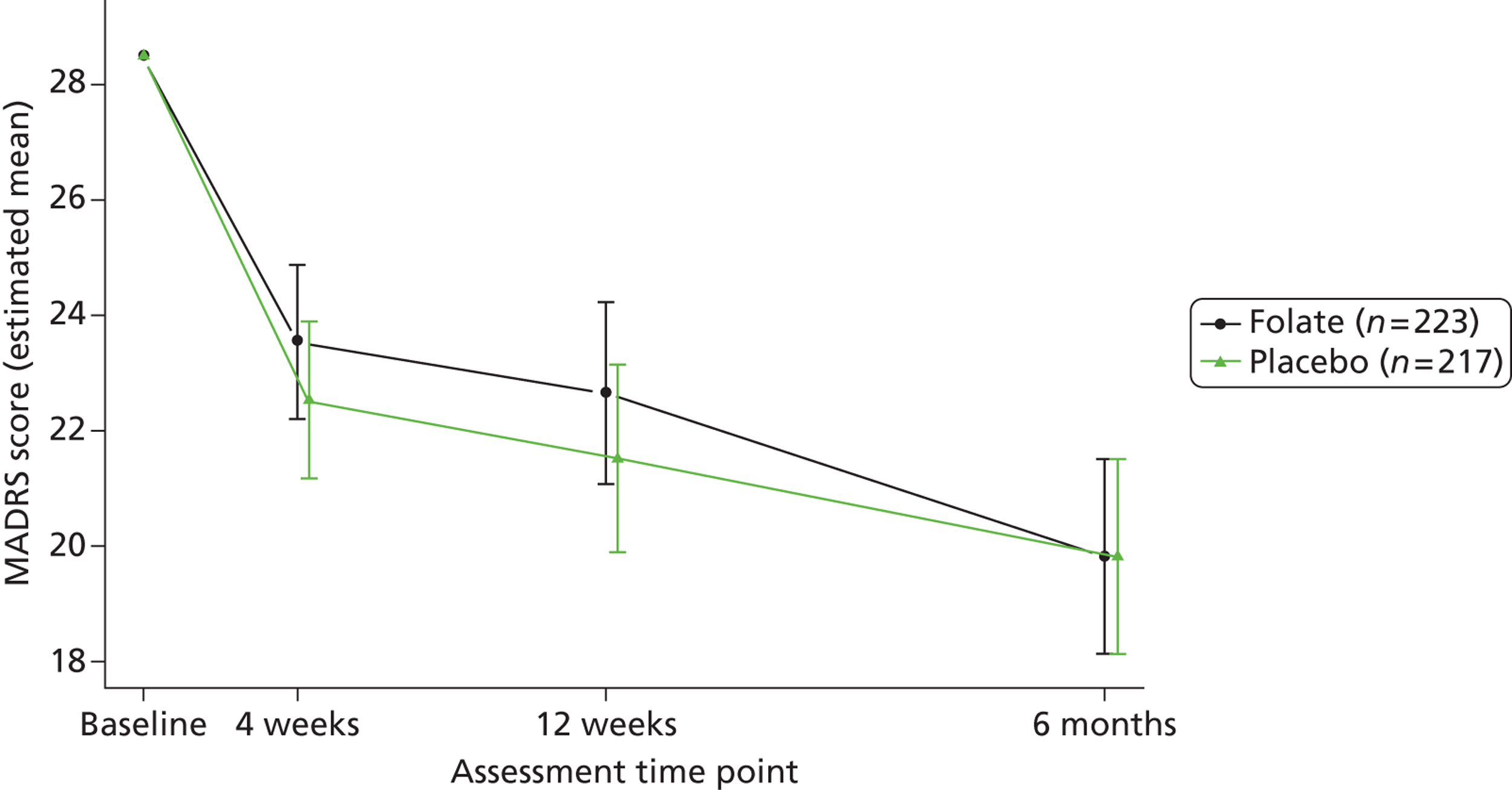

Unfortunately the reported health of those who received active pills did not improve any more than the health of those who took inactive pills. So there is now no reason to believe that folic acid strengthens antidepressants. Fortunately recent research suggests that methylfolate may be better at this. So FolATED has undermined guidelines that advocate folic acid for depression, but suggested another way forward.

Chapter 1 Introduction

Background

Prevalence of depression

Depression is one of the main mental health disorders presenting in primary care. 1 The prevalence of major depression in the general population ranges from 3% to 10% with more than 150 million people at a time suffering from depression across the world. 2 In the UK prevalence of depression in 2009–10 was 11% in England, 11.5% in Northern Ireland, 8.6% in Scotland, and 7.9% in Wales. 3 Unipolar depression leads to 12.15% of years lived with disability, and is ranked as the third leading contributor to the global burden of diseases. 2 Indeed depression is currently the second cause of disability worldwide for males and females between the ages of 15 and 44 years and is predicted to reach second place for all ages by 2020. 4 Depression has become the leading cause of disability in Europe, leading to a loss of one in every 10 healthy years of life, and the leading cause of early retirement. 5 Depression and stress are now the commonest reported causes for sickness absence from work in the UK6 with over 100 million working days lost across Europe at a cost of 1% Gross Domestic Product (GDP). 7 A higher prevalence of depression is observed in women than men across the 18- to 64-year age range with women up to 2.5 times more likely to develop depression. 8

Characteristics of depression

The core symptoms of depression are low mood and loss of interest or enjoyment in usually pleasurable activities. Associated symptoms include disturbances to sleep and appetite, reduced energy and concentration, negative thoughts of guilt or worthlessness and suicidal ideation. The International Statistical Classification of Diseases & Related Health Problems (ICD-10) states that for a diagnosis of depression at least five symptoms need to be present, including at least one of the core symptoms, at an intensity that causes functional impairment and for a minimum duration of 2 weeks. Depression is classified as mild, moderate or severe according to the number of symptoms present and degree of functional impairment, and the grading of severity is of direct relevance to the treatment approaches recommended. 9 Depression is associated with increased mortality linked to suicide, alcohol and drug misuse, and increased rates of cardiovascular disease. 10 Depression thus burdens individuals, families, the NHS, and the national economy. 11 One UK study estimated the total cost of depression to the UK in 2000 at £9 billion; at that time, before the introduction of Improving Access to Psychological Therapies (also known as IAPT) in NHS England, the direct cost of treatment, mainly antidepressant medication (ADM), was £370 million; and indirect costs of 110 million working days lost to depression accounted for the vast majority of the total cost. 12 The sub-optimal treatment of depressive disorders is therefore of great public health concern.

Treatments for depression

In accordance with the joint report of the World Health Organization (WHO) and World Organization of National Colleges & Associations of Family Doctors (WONCA)1 and the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidance9 the majority of people with depression are identified, treated and managed within primary care. Treatment aims to relieve symptoms, restore functioning and, in the long term, prevent relapse. The goal of treatment is complete remission which is associated with better functioning and reduced risk of relapse. 13 While there is some evidence that people with depressive symptoms improve over time without treatment,14,15 a significant proportion follow a chronic course with significant levels of depressive symptoms and functional continuing for several years. 16,17

Antidepressants are recommended as a treatment option for moderate to severe depression either in combination with psychotherapy9 or as monotherapy. 18 Owing to their greater tolerability selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) are recommended as first-line treatment in primary care. 9 Patients treated with an SSRI are seven times more likely to complete a therapeutic course than those treated with tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs). 19 In clinical trials of antidepressants typically 50% of patients with depression respond to active treatment, while one-third respond to placebo20 with the placebo response appearing to increase over time in clinical trials. 21 With first-line treatments about one-third of patients achieve remission from depression, increasing to two-thirds with refinement of treatment. 22 A study of mental disorders in 14 centres worldwide found that 50% of patients continued to have a diagnosis of depression after 1 year23 with at least 10% having persistent or chronic depression. 24 Furthermore, at least 50% of people will go on to have at least one further episode of depression following their first episode of major depression. 25 The risk of further recurrences after second and third episodes rises to 70% and 90% respectively. 25 Cumulative rates of recurrence remain linear over long periods of follow-up (30–40 years), indicating a constant risk of recurrence over the lifespan. 26 Therefore recurrence rates increase with length of follow-up, and for the majority of patients depression is a recurrent condition.

Depression is a prevalent global health problem resulting in high levels of disability. While effective treatments are available outcomes remain sub-optimal with a significant proportion of patients failing to achieve remission and experiencing chronic illness, early relapse and multiple recurrences across the lifespan. There remains a pressing need for research to optimise outcomes from antidepressant treatment.

Review of the literature

Depression and folate

Over recent years there has been a growing interest and an increasing body of evidence exploring the relationship between B vitamins, in particular folate, and depression. 27–30 Folate is a naturally occurring B vitamin and can be found in leafy green vegetables, fruits, dried beans and peas. 31 Folic acid is the synthetic form of folate, which is inexpensive and found in supplements and fortified food. 31,32

There is evidence to suggest that low folate intake is associated with symptoms of depression. 33–36 Studies report that up to one-third of patients with depressive illness have decreased serum and red cell folate levels. 37 Many people with depression have lower concentrations of folate than people with other psychiatric disorders or no psychiatric disorder. 34,38,39 Associations between folate deficiency and depressive symptoms, symptom severity and treatment outcomes in adults and the older adult population have been reported. 38,40–44 Low folate intake may also increase the risk of recurrent depression33 and depression in later life. 43 Gilbody and colleagues conducted a systematic review of observational epidemiological studies investigating the relationship between low folate status and depression. 45 They concluded that low folate status was associated with depression but could not conclude that that was a causal relationship. Though low folate may result from poor nutrition or socio-economic disadvantage, confounders are common in chronic mental illness. Other recent evidence suggests that low folate may be a consequence rather than a cause of depressive symptoms. 46 While there is weak evidence that increased folate intake may prevent depressive symptoms,35,47 this is not a consistent finding. 48 In one randomised controlled trial (RCT), for example, giving folate (2 mg) with vitamins B12 and B6 did not reduce severity of depressive symptoms. 49

The role of homocysteine

Folate is absorbed and transported in the blood in the form of 5-methyltetrahydrofolate (5-MTHF)50 and is measured in the blood as either serum folate or red cell folate. 50

Homocysteine is a highly sensitive marker of folate status51 and functional folate deficiency is indicated by elevated homocysteine. Tiemeier et al. found a significant relationship between depression and hyperhomocysteinemia, folate and B12 deficiency. 52 Observational studies indicate that patients with depression have increased plasma total homocysteine concentrations. 53,54 A recent meta-analysis showed that older adults with a high total homocysteine concentration have an increased risk of depression [odds ratio (OR) = 1.70; 95% confidence interval (CI) from 1.38 to 2.08]. 55

There are important relationships between folic acid and vitamin B12 that have implications for how folate can be used therapeutically. For people who are deficient in vitamin B12, exposure to high levels of folate can result in subacute combined degeneration of the spinal cord, which may be linked to impaired methionine biosynthesis. 56 As methylmalonyl CoA mutase, a vitamin B12-dependent enzyme, converts methylmalonyl-CoA to succinyl-CoA, blood methylmalonic acid (MMA) levels increase with suboptimal B12 status. The cross-sectional study of > 10,000 participants in the US National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) observed a novel relationship between MMA and folate:57 in patients with low B12 (< 148 pmol/l ≈ 200 ng/l) MMA increased significantly with increasing serum folate. This finding is due, either to adverse oxidative effects of unmetabolised folic acid on B12 homeostasis, or inability of patients with low B12 to retain intracellular folate. 58

Antidepressant treatment and folate

Folate is an essential cofactor for the biosynthesis of both serotonin (5-hydroxytryptamine or 5-HT) and noradrenaline. Thus folate deficiency leads to impaired serotonin synthesis in the human brain. 59 This may provide a theoretical model for claims that folate can play a role in the treatment and prevention of depression. 60 Virtually all antidepressants are thought to act by prolonging the activity of serotonin or noradrenaline in neurotransmission or by modulating monoamine receptor sensitivity. 61 Lower folate levels have been associated with poorer antidepressant response. 62 Further evidence suggests that baseline levels of folate within the normal range predict antidepressant response. 63

This raises the possibility of folate being used to augment antidepressants. Initial small feasibility studies seemed to confirm the potential of this augmentation strategy. 32 A Cochrane review and meta-analysis50,64 explored the role of folate augmentation in depression. Only two RCTs were identified (combined n = 151), both of which suggest possible beneficial effects of folate augmentation. 65,66 Two further small trials have given contradictory results. One study, 67 with a clinical sample of 42 patients with major depressive disorder, reported that 10 mg of escitalopram (Cipralex®, Lundbeck) alone produced greater improvement than the combination of escitalopram and folic acid (2.5 mg/day). The other study, 68 with a clinical sample of 27, reported a greater reduction in depressive symptoms when 20 mg of fluoxetine (non-proprietary) was augmented with folic acid (10 mg/day) than when augmented with placebo. However, emerging evidence within an older depressed population suggests there may be no benefit from folate augmentation of antidepressants. 69 Despite this negative finding in the elderly there is still interest in a potential augmentation role for the B vitamins in general, with the currently recruiting B-VITAGE trial exploring B vitamin supplementation in later life. 70 These data convey mixed messages about the use of folic acid to improve ADM. To advance this debate about the clinical effectiveness of folic acid, we plan to update the Cochrane systematic review to include this and other recently reported studies of augmentation by folic acid. 50

Folate, depression and genetics

There has recently been much research aimed at identifying genetic aspects of depression and antidepressant therapy. Indeed, a number of large genome-wide association studies, and some subsequent meta-analyses, have identified genetic polymorphisms associated with both risk of depression71–73 and response to antidepressant therapy. 74,75 However, these studies have been unable to demonstrate consistent and reproducible genetic associations.

Only a few studies have described an association between risk of depression and genetic variation of genes of the one-carbon folate and methionine biosynthesis pathways. Most have focused on, and identified, an association with depression and the frequently characterised c.677C > T polymorphism (rs1801133) of the methyltetrahydrofolate reductase (MTR) gene. 76,77 This variant encodes a valine to alanine amino acid substitution at residue 222. The variant protein has reduced catalytic activity and thermolability and is associated with elevated homocysteine levels under conditions of impaired folate status. Others, in addition to MTR c.677C > T, have also described the p.D919G variant (rs1805087) of the MTR gene as a statistically significant risk factor for moderate and severe depression in postmenopausal women. 78 The MTR gene encodes the protein methyltetrahydrofolate reductase, which is a key enzyme in the biosynthesis of homocysteine to methionine.

Furthermore, it has recently been reported that the MTR c.677C > T polymorphism modifies the protective effect of folic acid against depression after pregnancy. 79 Others have demonstrated an association between c.677C > T and folate and homocysteine concentrations. 80 These observations further support the hypothesis that genetic variation in the one-carbon folate pathway may affect folic acid efficacy as an adjuvant to antidepressant therapy by altering folate bioavailability and increasing homocysteine levels.

Summary

Depression is a prevalent and debilitating mental health disorder. It often follows a chronic or recurrent course across the lifespan. Antidepressants are the recommended treatment for moderate to severe depression. Only half of people will respond to first-line treatment, and only one-third will achieve remission. Further research is needed to investigate ways of augmenting antidepressants to boost treatment response and rates of remission.

Evidence suggests that folic acid may be a useful adjunct to antidepressant treatment for four reasons:

-

Patients with depression often have a functional folate deficiency.

-

The severity of deficiency, indicated by elevated homocysteine, correlates with depression severity.

-

Low folate is associated with poor antidepressant response.

-

Folate is required for the synthesis of neurotransmitters in the pathogenesis and treatment of depression.

Objectives

The Cochrane review by Taylor and colleagues concluded that adequately powered randomised trials were needed to investigate the therapeutic potential of folate augmentation of antidepressants. 50 The National Institute of Health Research Health Technology Assessment (NIHR HTA) programme commissioned FolATED to address this gap in the literature.

The main objectives of FolATED were to assess the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of adding folic acid to the antidepressant treatment of moderate to severe depression. Our secondary objectives were to explore whether baseline folate and homocysteine predict response to treatment, and investigate whether response to treatment depends on genetic polymorphisms related to folate metabolism.

Chapter 2 Methods

Trial design

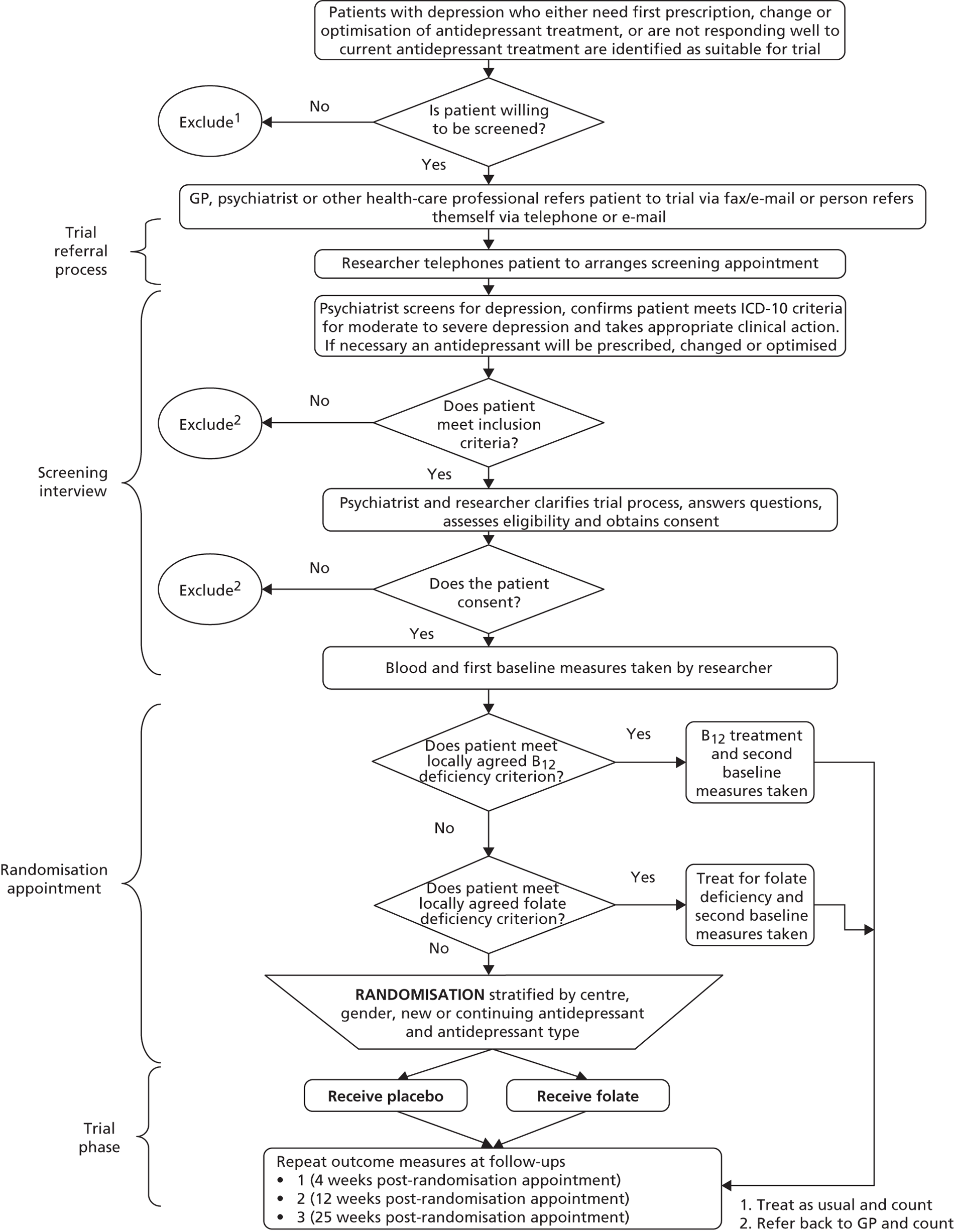

FolATED was a three-centre, double-blind and placebo-controlled, but otherwise pragmatic, randomised trial of folic acid augmentation of antidepressant treatment for people with moderate to severe depression. Participants were allocated to folic acid or matching placebo in equal proportions. Assessment took place at weeks –2 (to screen for eligibility and initiate ADM if needed); –1 (to check by telephone for tolerability of antidepressants); 0 (baseline – to randomise to folate or placebo); and 4, 12 and 25 weeks (to assess outcomes). Figure 1 shows the flow diagram for the trial. 81,82

FIGURE 1.

Flow diagram of the trial.

Participants

Settings

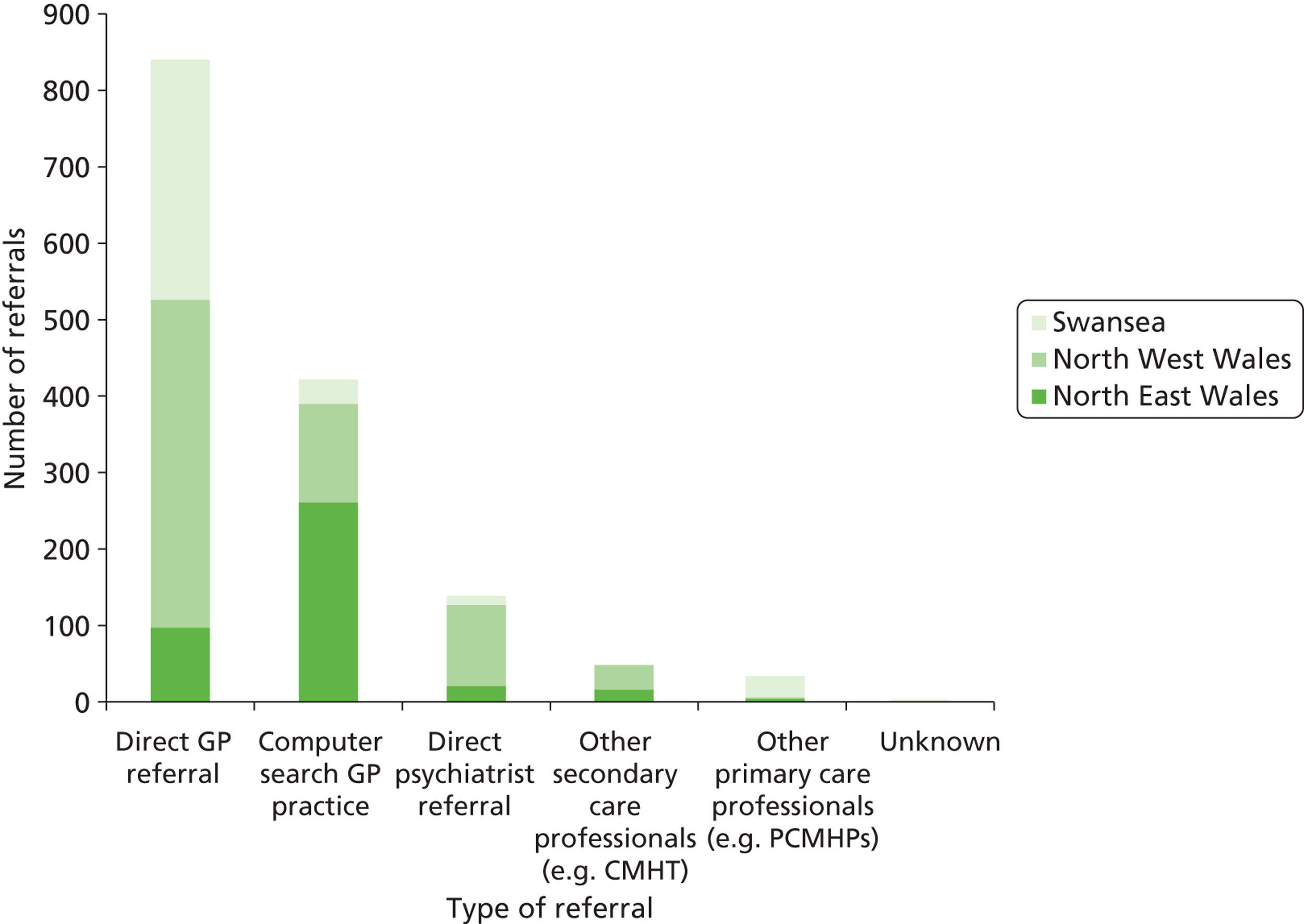

We recruited participants from primary and secondary care at three centres across Wales between July 2007 and November 2010. The sites were North East Wales, North West Wales and Swansea; and covered a population of about 1.35 million people in 2009. 83 We screened potential participants referred by their primary or secondary care clinicians or themselves for eligibility – in a variety of settings including general practice, secondary mental health services, research clinics, and patients’ homes.

Informed consent

All potential participants received a copy of the information sheet and consent form (see Appendix 1) from their referring clinician or the research team at least 24 hours before screening to ensure they had time to consider the study. Trial psychiatrists or screening nurses checked that eligible patients fully understood the study and gave them the opportunity to ask questions. To all potential participants we stressed that taking part in the study was voluntary and that their clinical care would not change if they did not want to take part in the trial.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Trial psychiatrists could assess eligibility of any potential participant. For self-referred participants registered mental health nurses liaising with a trial psychiatrist could also assess eligibility.

Potential participants were eligible to take part in the trial if they met all these criteria:

-

presenting with moderate to severe depressive symptoms confirmed by a trial psychiatrist during the screening interview and reporting a score of at least 19 on the Beck Depression Inventory version 2 (BDI-II) at screening, and at least 17 at baseline84

-

being treated with ADM, or about to commence ADM treatment

-

aged at least 18 years

-

able to give informed consent, and

-

able to complete the research assessments.

We excluded potential participants from the trial if they:

-

a. were folate deficient

-

b. were B12 deficient

-

c. had taken supplements containing folic acid within 2 months

-

d. suffered from psychosis

-

e. suffered from bipolar disorder

-

f. were participating in other clinical research

-

g. were pregnant or planning to become pregnant

-

h. were taking anticonvulsants

-

i. had a serious, advanced or terminal illness with a life expectancy of less than 1 year

-

j. had recently started treatment for a medical condition that had not yet been stabilised, or

-

k. had a diagnosis of, or treatment for, any malignant disease or related condition like intestinal polyposis.

Sample size

We originally powered FolATED to detect a difference between the two treatment groups of three points on the BDI-II at 25 weeks, judging that a clinically important difference. As we estimated the standard deviation (SD) of BDI-II scores in the trial population at 10.7, our protocol proposed a completed sample size of 400 at 25 weeks to yield 80% power to detect this difference using a significance level of 5%. As interim analysis of baseline BDI-II scores showed that their SD was about 10, we revised the target completed sample size to 358 at 25 weeks. The original protocol allowed 10% loss at each of the three follow-up assessments, thus requiring to randomise 549 to achieve 400 completers at 25 weeks. As interim analysis also showed that retention at 25 weeks was 79% rather than the 73% expected, the new target of 358 completers needed a randomised sample of 453.

Randomisation

At screening the screener took a blood sample to assess B12 and folate status, and arranged a further appointment within 14 days to confirm the B12 and folate results. We excluded participants who were B12 or folate deficient from the main trial but offered them the opportunity to continue in the ‘comprehensive cohort’ of recruited patients.

Eligible participants completed the baseline assessments and the recruiting centre telephoned the randomisation centre at NWORTH, Bangor University. NWORTH used dynamic allocation to protect against subversion while ensuring that each arm of the trial was balanced for the stratification variables. For each participant the adaptive algorithm recalculated the likelihood of their allocation between treatment groups from the distribution of stratification variables among participants already recruited and allocated. This process keeps the balance between strata within acceptable limits of the target allocation ratio of 1 : 1 while maintaining unpredictability. 85 The selected stratification variables were:

-

centre (North East Wales, North West Wales or Swansea)

-

sex (male or female)

-

timing of ADM (new or continuing)

-

type of ADM (SSRI or other)

-

whether participant had received counselling for depression (ever or never).

Intervention

By the time participants entered the trial, we ensured they were receiving antidepressant treatment optimised to therapeutic dosages – equivalent to SSRI of at least 20 mg per day or TCA of at least 150 mg per day. Most had received an antidepressant prescription from their general practitioner (GP) before referral to the trial. For patients not on ADM, trial psychiatrists initiated ADM to meet clinical need and patient preference in accordance with routine practice. For patients on sub-therapeutic ADM, trial psychiatrists optimised the treatment regime according to the British National Formulary (BNF),86 namely citalopram dose of at least 20 mg per day or equivalent. For participants who had been receiving a therapeutic dose of ADM, we encouraged trial psychiatrists to optimise dose according to the BNF, for example by increasing citalopram dosage to 40 mg per day, or change the antidepressant, again depending on clinical need and patient preference.

Participants received a 12-week supply of either 5 mg folic acid or placebo in addition to their ADM. We selected the 5-mg dose of folic acid because that is effective for other indications,87 carries a low risk of adverse events (AEs), and is routinely used to treat folate deficiency. 31

Bilcare (formerly DHP Ltd) supplied the trial drugs and achieved the blinding needed by the trial by the process of over-encapsulation. They placed each tablet inside a size ‘1’ opaque hard gelatin capsule and added lactose BP, an ingredient of the tablet, to fill the capsule. To produce placebo for the trial they filled the same capsules with lactose. They packed capsules into high-density polyethylene bottles with tamper-evident child-resistant screw caps. They tested to confirm that the over-encapsulated tablet complied with the British Pharmacopoeia88 standard for disintegration in vitro. They also checked each batch for the presence or absence of 5 mg folic acid.

Blinding

The North Wales Organisation for Randomised Trials in Health coded the identically packaged folic acid and placebo randomly for each stratification group. Each patient’s prescription indicated his or her trial number and package serial number generated by NWORTH, thus determining the appropriate trial package. NWORTH and the local pharmacies held the key to the randomisation codes. The telephone numbers of those pharmacies were available to break codes in emergency.

This ensured that throughout recruitment treatment allocations were unknown to participants, healthcare professionals, investigators, and researchers. We broke randomisation codes for two participants. One was diagnosed with lower oesophageal cancer, and the other collapsed with agitation, breathing difficulty, raised pulse, and reduced consciousness. On both occasions the local pharmacist revealed the code from a scratch card. This ensured that we revealed only the individual allocation, only to those who needed to know.

An independent GP monitored blood results, notably to check for B12 and folate deficiency at follow-up. To avoid accidental unblinding researchers engaged in clinical data collection or analysis did not have access to these blood results. Furthermore we separated pharmacogenetic and biochemistry analysis from clinical effectiveness analysis, and combined these results only when analyses were complete. Formal unblinding of the randomisation codes took place at the joint final meeting of the Trial Steering Committee (TSC) and the Data Monitoring and Ethics Committee (DMEC) on 10 October 2011.

Data collection

We collected data at screening, baseline and randomisation, and 4, 12 and 25 weeks after randomisation, using the trial case report forms (CRFs). Though we aimed to collect the data on the day due, this was not always possible. Hence there was a window for each data collection (Table 1).

| Data collection | Due date (days since randomisation) | Window |

|---|---|---|

| Screening for eligibility | –14 days | ± 10 days |

| Randomisation | 0 | Origin |

| 4-week follow-up | 28 days | + 14 days |

| 12-week follow-up | 84 days | ± 14 days |

| 25-week follow-up | 175 days | ± 28 days |

We designed some questionnaires for completion by researchers or clinicians, and others by participants. The preferred mode was face to face. When that was not possible, we permitted completion over the telephone and mailed the questionnaire to the participant in advance.

Primary outcome measure

The main outcome measure was self-rated symptom severity as measured by the Beck Depression Inventory version 2 (BDI-II). 84 The BDI-II consists of 21 items, each rated on a four-point scale ranging from 0 to 3; a total score of 1–13 indicates no depression, 14–18 mild depression, 19–28 moderate depression, and 29–63 severe depression. As BDI-II scores at 25 weeks are useful in assessing participants’ medium-term recovery, that was the basis of our original power calculation (see Sample size, above). When updating that calculation, we also designated the primary outcome as the area under the curve (‘AUC’ for short) of mean BDI-II scores between randomisation and the 25-week follow-up, because this summarises participants’ recovery across the whole of that period. 84 Though there was less prior information on AUCs, notably on clinically important differences, we judged that the combination of well-behaved BDI-II scores and the mathematically robust trapezium method of estimating AUCs89 would make 358 an appropriate target sample size (see Sample size, above). In the event we were able to analyse many more than 358 trial participants. Because the actual follow-up time could vary by up to 4 weeks from the target of 25 weeks (see Table 1), we converted the area under the curve to a more meaningful ‘AUC average’, which represents a participant’s BDI-II (or other outcome) score averaged over that participant’s follow-up period.

Secondary outcome measures

Symptom severity

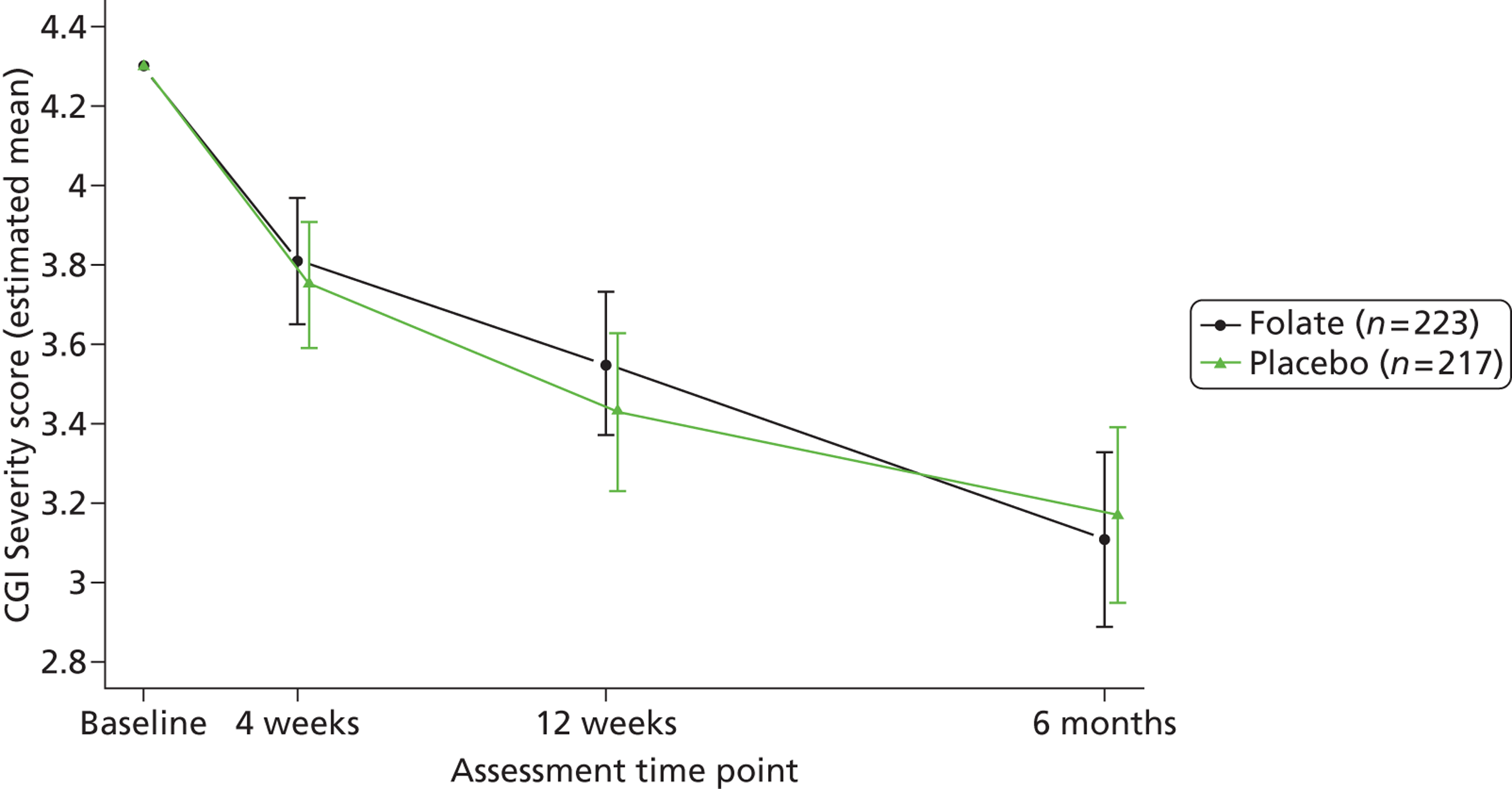

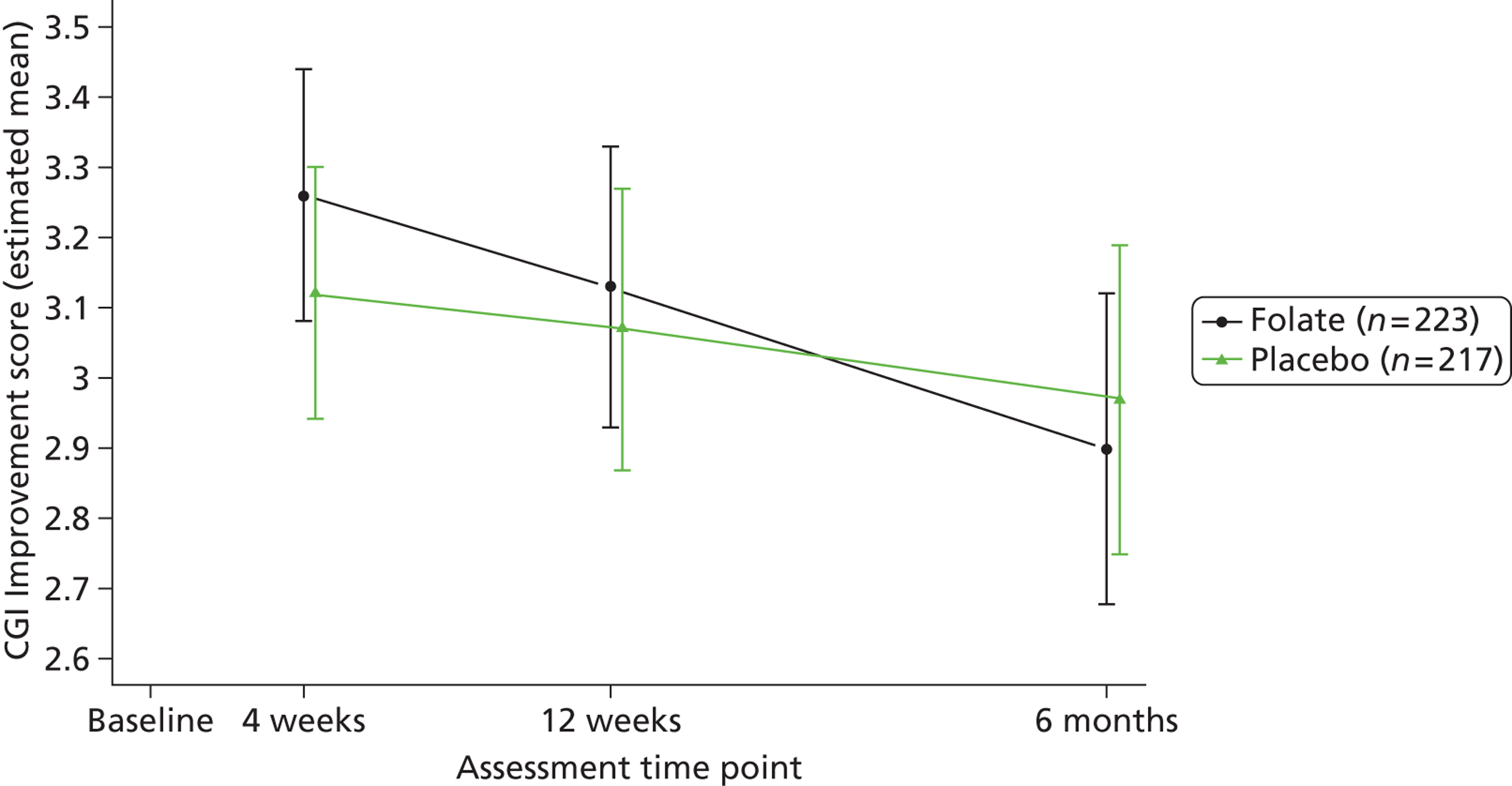

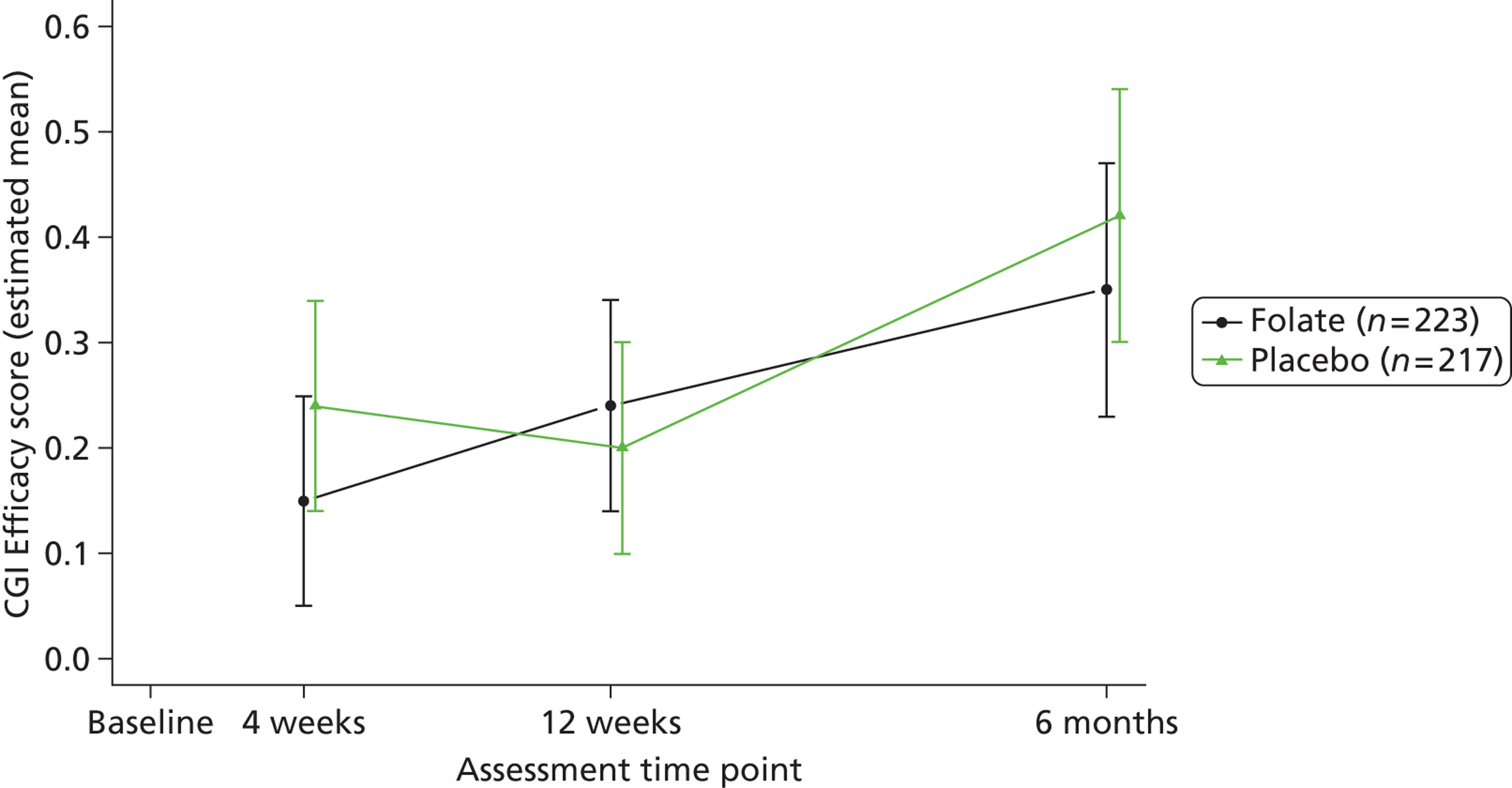

Clinicians rated symptom severity using the Montgomery–Åsberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS) and the Clinical Global Impression (CGI) of change at baseline and 4, 12 and 25 weeks. The MADRS90 consists of 10 items each rated on a seven-point scale (0–6), which yield a total score between 0 and 60. The CGI91 comprises three separate clinician-rated items: an ordinal scale of current severity of illness between 1 and 7; an ordinal scale of global improvement since recruitment between 1 and 7; and an efficacy index ranging from 0.25 to 4.0 derived from a 4 × 4 matrix plotting therapeutic effect against side effects.

Researchers at all centres received training in completing the rated scales (MADRS and CGI) from standard training videos. To estimate inter-rater reliability, we collated researchers’ ratings of these videos on several occasions.

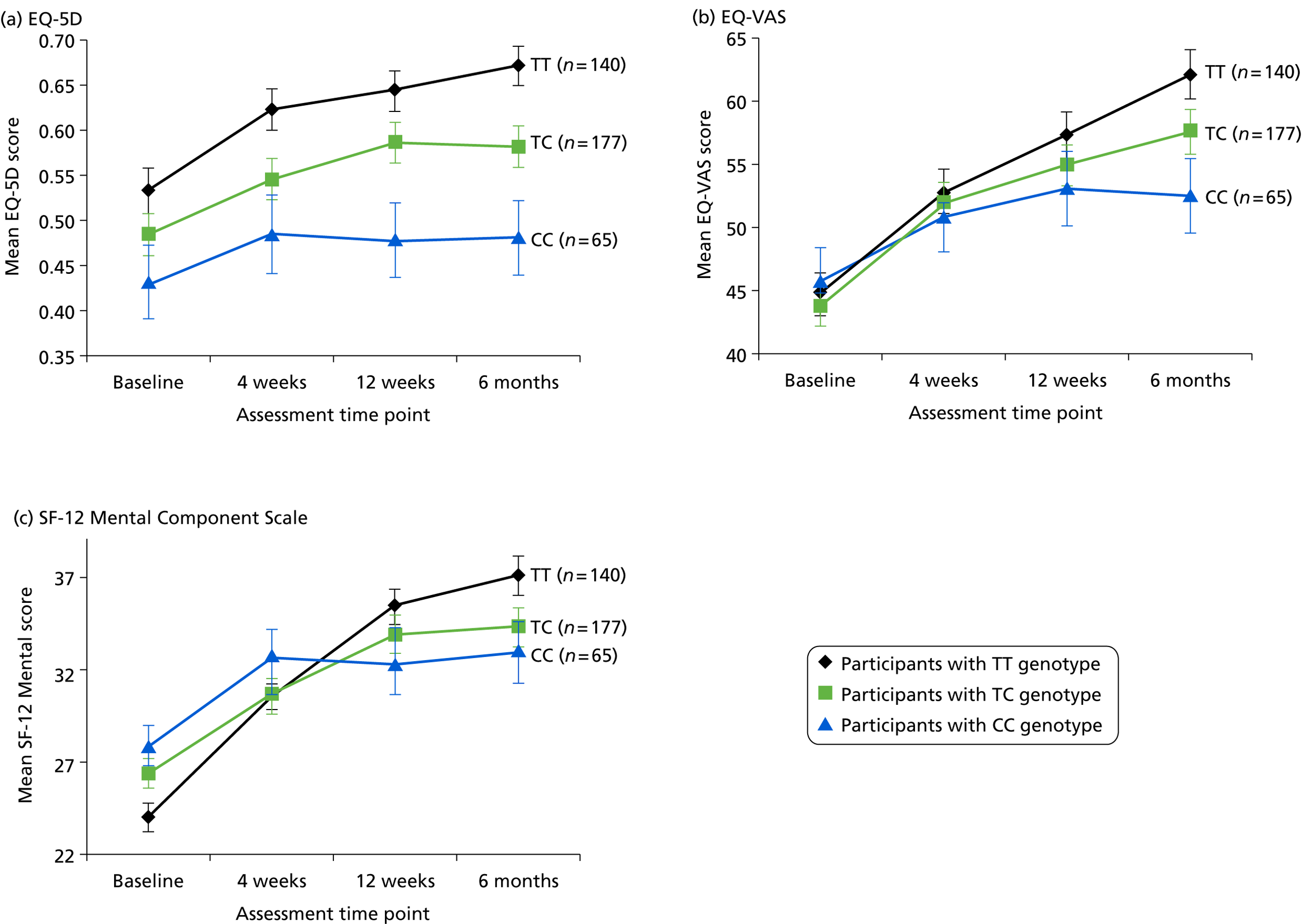

Health status

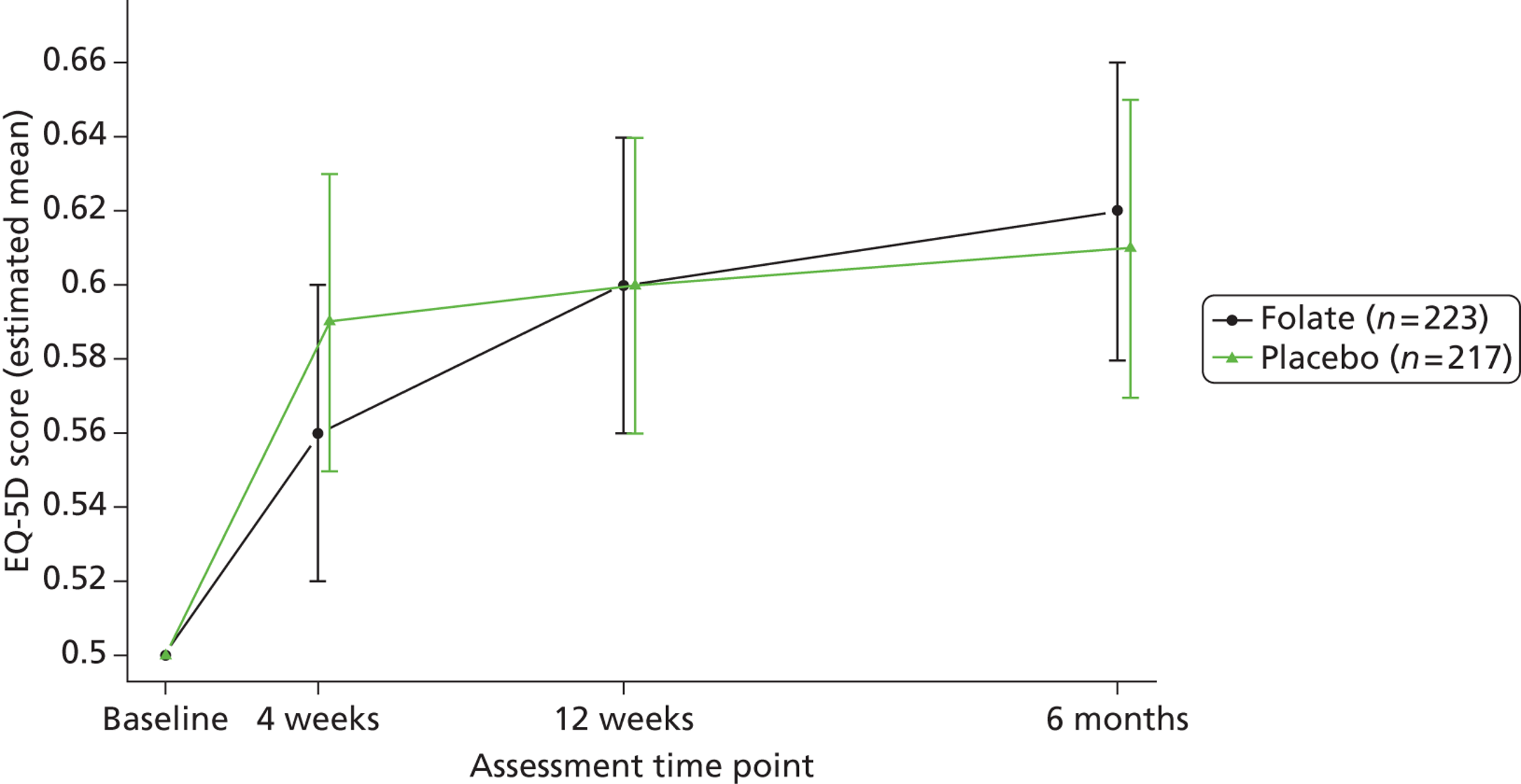

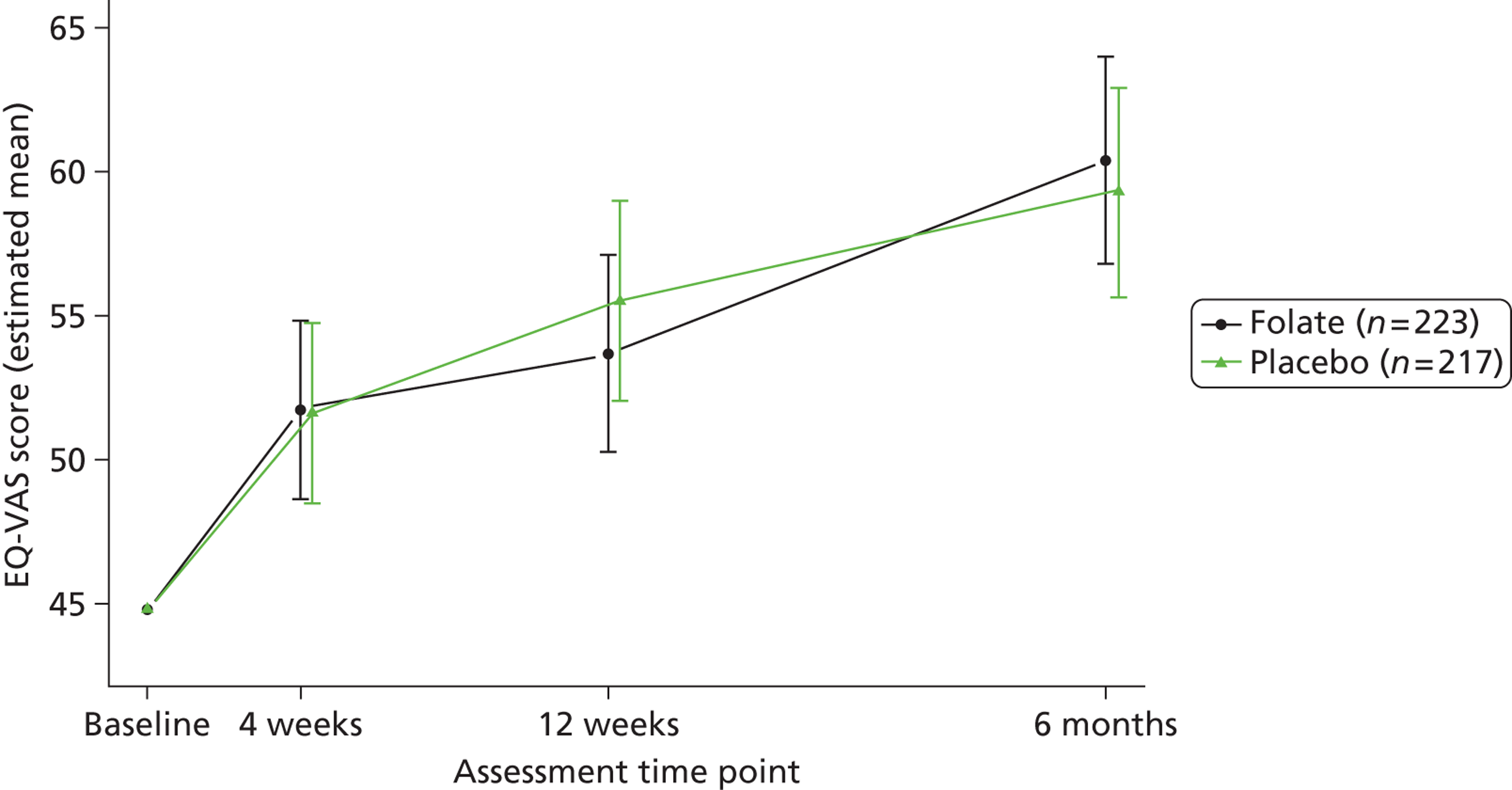

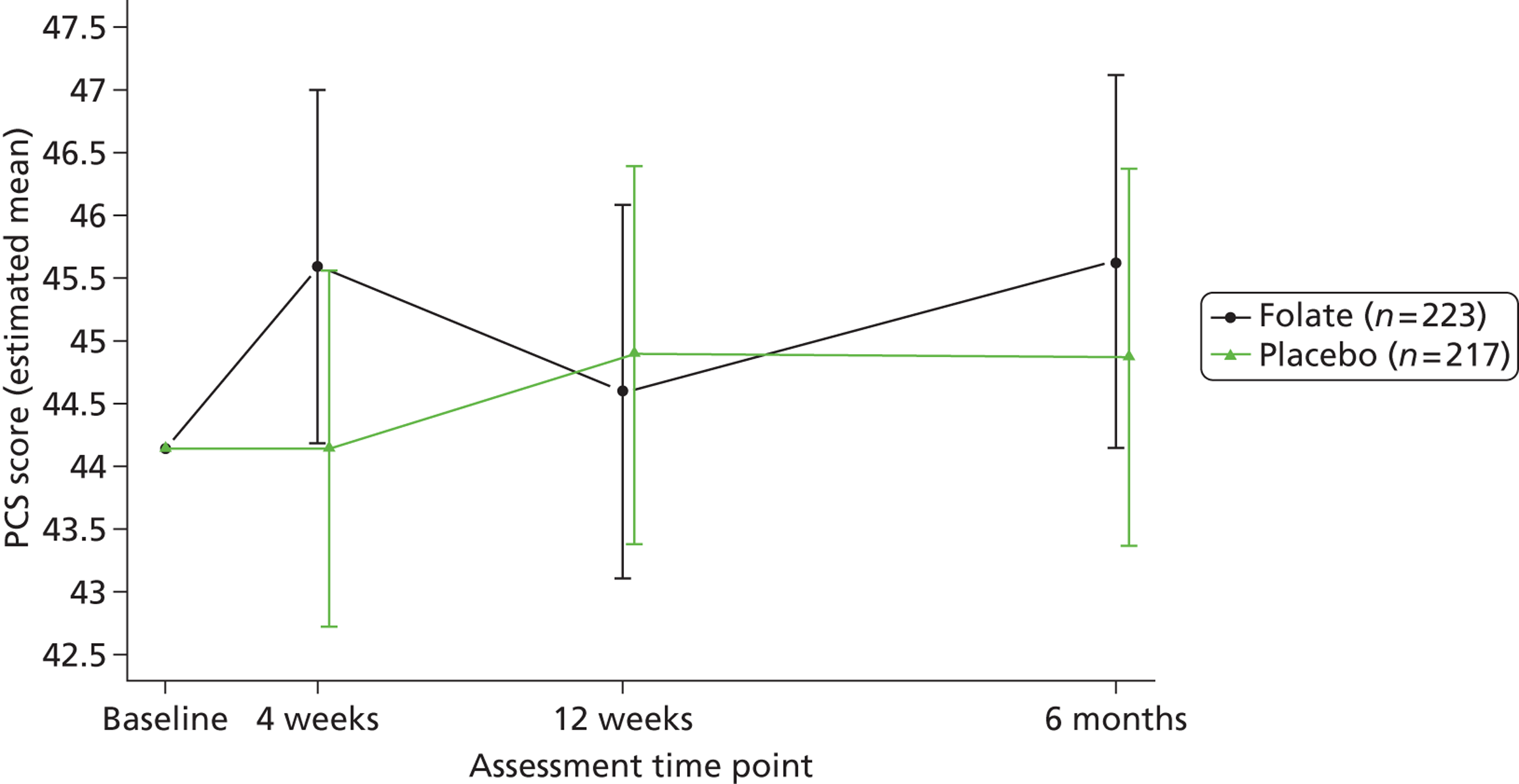

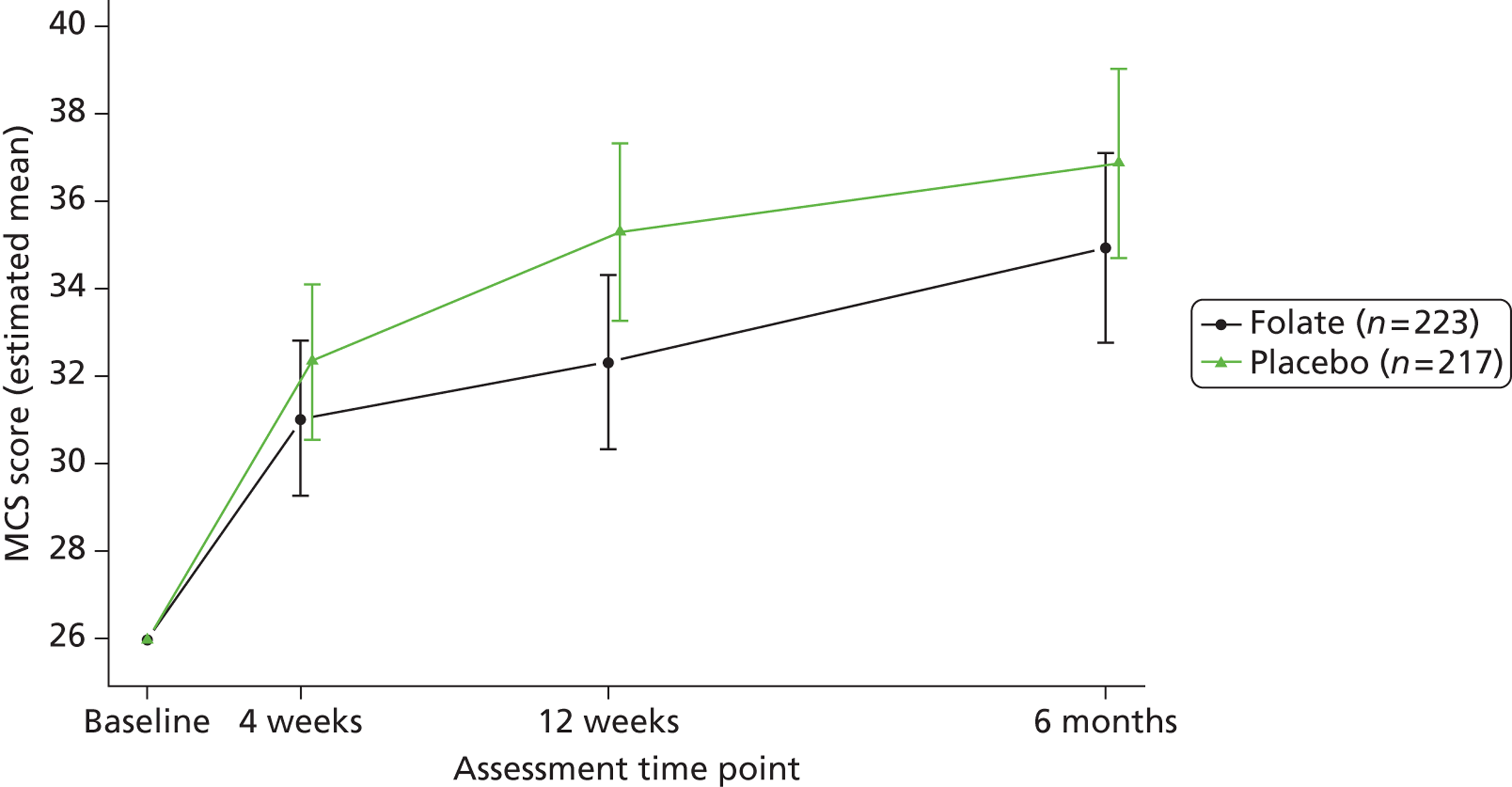

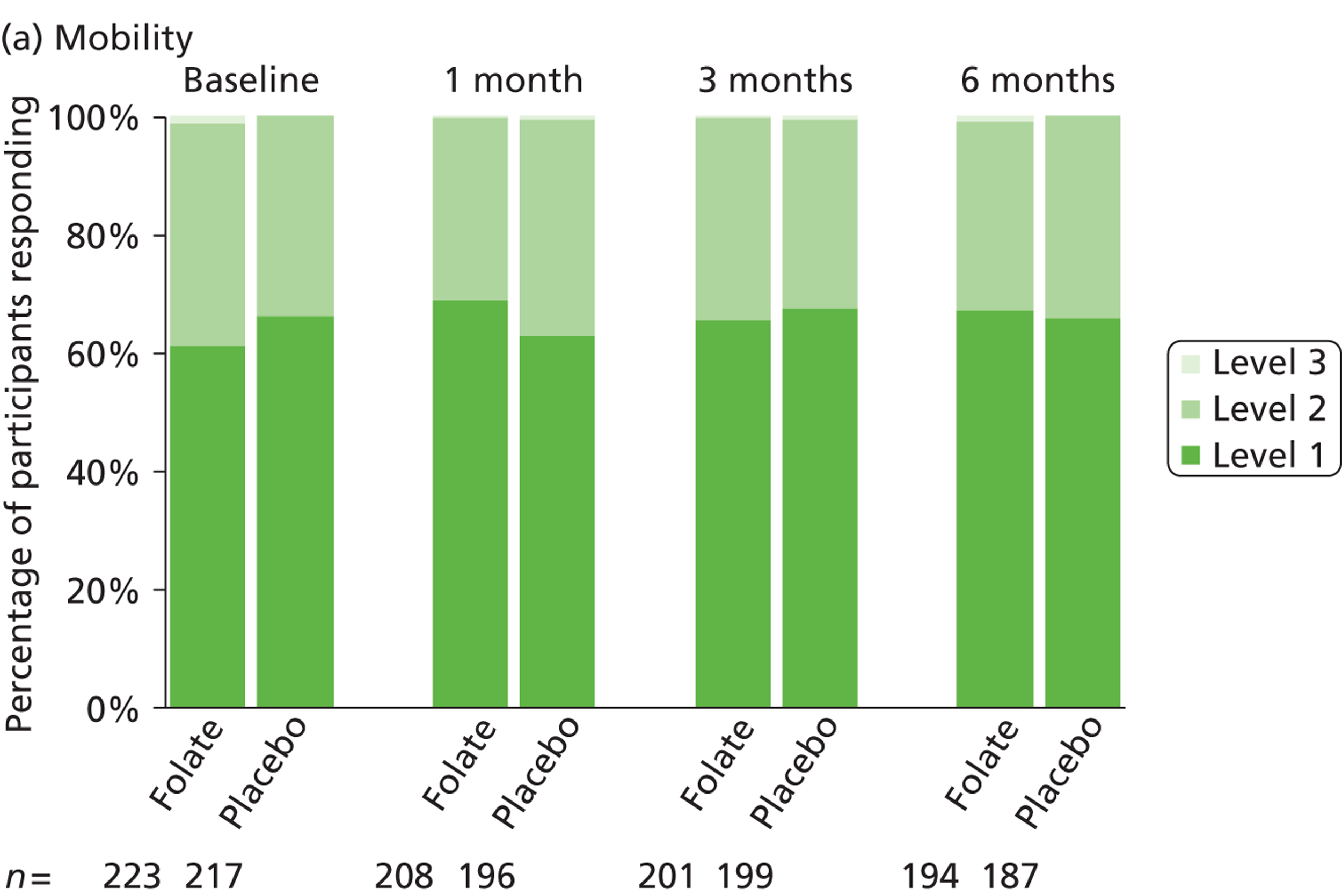

Participants reported their mental and physical health by version 2 of the UK 12-item Short Form Health Survey (SF-12) and their quality of life by the EQ-5D, both at baseline, 4, 12 and 25 weeks. The SF-12 is a functional measure of quality of life comprising 10 five-point items and two three-point items. 92 Using scoring algorithms designed to achieve standardisation to a mean of 50 and a SD of 10 in the 1998 general US population, these items yield separate physical and mental component scores (PCS-12 and MCS-12). Though we used EQ-5D as a secondary measure of clinical effectiveness, its main purpose was to measure health utility for economic analysis. 93

Proportion of participants with moderate depression

Though we adopted the standard definition of moderate depression as a BDI-II score of 19 or more, we estimated the proportion of participants with moderate depression by statistical inference from the observed distribution of BDI-II scores. This technique is more robust to random variation than mere counting.

Adverse events and side effects

Though we asked centres to report all AEs, we focused on serious adverse events (SAEs) including inpatient admissions, attempted or completed suicide, and other mortality. We asked centre principal investigators to assess whether folic acid could possibly have caused each SAE, and whether it was an expected consequence. The chief investigators reviewed these data blind to the random allocations.

We assessed side effects through the UKU side effects scale,94 which sums scores on 48 distinct side effects – 10 ‘psychic’, 8 ‘neurologic’, 11 ‘autonomic’ and 19 other – and adds two global items. It rates each item on a four-point scale ranging from 0 to 3, yielding system-specific scores out of 30, 24, 33 and 57, two global scores out of three, and a total score out of 150.

Adherence to the trial drug

We assessed adherence to the trial medication from dispensing records; returned tablet count at 12 weeks; folate and homocysteine levels at 12 weeks; and the Morisky Questionnaire95 administered only at 12 weeks. This instrument asks four binary questions about adherence, and reports the number of positive responses as a score between 0 and 4.

Folate status and B12 status

We measured red cell folate at baseline; and serum folate, homocysteine and B12 from blood samples collected at baseline, 12 and 25 weeks. We sent all of those samples to local NHS laboratories on the day of collection. For homocysteine analysis we centrifuged venous blood within 30 minutes of collection and stored the plasma at –20 °C until analysis. We assayed all samples from individual participants in the same batch to minimise the effect of inter-batch variation. We measured plasma total homocysteine using a one-step immunoassay following reduction with dithiothreitol, commercially available from the Abbott Diagnostics ARCHITECT system. The average intra-batch coefficient of variation (CV) for homocysteine was less than 3%.

Suicidality

We rated suicidality by Section C of the Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI)96 at baseline and 4, 12 and 25 weeks. Summing the scores allocated to ‘yes’ responses yields a total score between 0 and 33, which the MINI criteria categorise into low risk (0–5), moderate risk (6–9) or high risk (≥ 10).

Other data

We collected basic demographic information for each participant including sex, age, ethnicity, employment status, marital status and number of dependent children. We also recorded smoking and alcohol consumption, which are known to affect homocysteine levels.

Follow-up

Thus we thoroughly assessed participants at 4, 12 and 25 weeks after randomisation. Antidepressants show a delayed and variable onset of clinical improvements in depression. 97–99 Previous trials suggest that 50% of those who eventually respond to ADM start to respond within 2 weeks, 75% within 4 weeks, and almost all within 6 weeks. 100 Hence we scheduled the first assessment at week 4, 6 weeks after the start or optimisation of antidepressant treatment. Non-response at 4 weeks may lead to changes in the ADM in accordance with the BNF and NICE guidelines. Hence the second assessment at 12 weeks could measure both continuing and late responses to ADM and folate augmentation. The third assessment at 25 weeks addressed any changes in effectiveness after the end of folic acid therapy, but during ADM, since that is the minimum duration of maintenance antidepressant treatment. 18

Quality assurance

The conduct of this trial followed the principles of good clinical practice (GCP) outlined by the ICH-GCP and complied with EU directive 2001/20/EC. 101 The research also adhered to the Medical Research Council (MRC) guidelines for clinical trials102–104 and the Research Governance Frameworks for England and Wales. 105–107 In particular we anonymised all research data and stored them securely. All research team members received general training in GCP and trial-specific training in the protocol, recruiting participants, taking blood, completing CRFs, conducting assessments, and reporting AEs. We also developed a fieldworker’s manual to maintain consistency between sites.

Independent Trial monitoring

We established a TSC and a DMEC to oversee FolATED through biannual meetings or telephone conferences. The TSC comprised an independent chair, three independent members, and five members of the FolATED trial management team. The DMEC comprised an independent chair and two independent members, with the trial statistician in attendance (see Appendix 2).

Approvals

The Multicentre Research Ethics Committee (MREC) for Wales gave initial ethical approval on 6 November 2006, and the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA) issued the Clinical Trial Authorisation (CTA) on 21 December 2006. Appendix 3 lists the dates of approvals for individual centres.

Summary of changes to the project protocol

Appendix 4 lists all substantial changes to the protocol approved by TSC, DMEC, MHRA, MREC, and primary and secondary care R&D Departments.

Statistical methods

Statistical analysis plan

Before starting analysis we developed our analysis plan for approval by the DMEC (see Appendix 5).

Trial populations

‘Analysed’ population

Randomisation allocated all participants to one of the two treatments. The CONSORT guidelines require that the main analysis be ‘by treatment allocated’. Ideally, therefore, this population should comprise all randomised participants. In practice only participants who contributed at least one BDI-II measured after baseline can usefully contribute. To get the most from their data, we used established methods to impute their missing data.

Complete case population

This population comprises only those participants whose outcome data are complete. It provides a sensitivity analysis of two issues: whether primary and secondary findings are sensitive to the absence of missing data, and the methods we used to impute those missing data.

‘Randomised’ population

At first sight it is difficult to draw inferences about this population because some contributed no data after baseline, even on the BDI-II. Because we know the baseline characteristics of all these participants, however, it is possible to reweight the ‘analysed population’ so that they match the characteristics of the randomised population, notably allocated treatment, stratifying variables and baseline BDI-II.

Imputation of missing data for ‘analysis by treatment allocated’

We excluded participants without follow-up data from the primary analysis ‘by treatment allocated’. For each variable we summarised missing data by reason (mainly participant withdrew; questionnaire not returned; page missing; item missing). Where < 10% of data were missing, we treated them as if they were missing completely at random (MCAR). 108 If > 10% of data were missing, we explored the missing data and tabulated them by the stratification variables both as reported at randomisation and as validated after quality assurance; by participant demographics; and by other important covariates. Rather than exclude participants missing some data, we chose to impute these data (see Appendix 5).

Missing items within a subscale

For missing items within a subscale we took account of methodological publications about the instrument. To impute missing items we used the principle that, if < 25% of the items within a subscale were missing for a participant at a time point, one should impute them by the weighted mean of the completed items, but if > 50% of the items within a subscale were missing for a participant at a time point, one should treat that subscale as wholly missing and impute it accordingly.

Missing subscales

Where between 25% and 50% of the items within a subscale were missing, we proceeded thus: if < 40% of the subscales for a participant at a time point were missing, we imputed all missing subscales by a single application of the general regression model for missing data imputation used in SPSS (Statistical Product and Service Solutions, SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA),109 taking account of all validated stratification variables. If > 40% of the subscales for a participant at a time point were missing, but < 20% of participants experienced that problem, we imputed all missing subscales by a single multivariate imputation across all time points that also took account of all validated stratification variables. Fortunately these rules covered the whole of FolATED.

Missing time points

If one of the four time points for a participant was missing, we imputed all subscales within that time point by five iterations of the repeated-measures model for missing data imputation used in SPSS using all other subscales at all time points together with age, gender, centre and group. 107

Data description and transformation

Initially we summarised data by allocated treatment and centre. Rather than test for statistical differences between allocated groups at baseline, we adjusted for any imbalance by analysis of covariance. Our analysis plan assumed that residual variation from our statistical models follows Normal distributions. This is a robust assumption in the sense that only a substantial deviation would invalidate each analysis. So we plotted and reviewed residual distributions. As none of these was substantial, we did not need to transform data to improve consistency with the assumption of Normality. Hence we present all data as collected.

Methods for analysing outcomes

All of our statistical tests were two-sided with a significance level of 5%.

Continuous outcomes with baseline and more than one follow-up

We used the AUC average, not only to summarise treatment outcome across the whole of the 25 weeks of data collection, but also to take account of the correlation between successive measurements for the same participant. We calculated the AUC average by using the trapezium rule89,110 to weight the outcome scores at baseline and the three actual follow-up points. From the imputed data set we estimated the average score for each participant over his or her total follow-up period as the area under the EQ-5D utility curve divided by the duration of follow-up, using the trapezoidal rule specified by the formula:

where Uj is the utility attributed to the jth measurement, T is the duration in days of the participant’s study period, tj is the time in days at which the jth measurement takes place for that participant,111 and values j = 0, 1, 2 and 3 correspond to the baseline and three subsequent follow-ups respectively. We used similar formulae to calculate AUC averages for BDI-II, MADRS and SF-12 physical and mental component scores.

As covariates in these analyses we used the validated stratification variables – centre, sex, new or continuing case, type of antidepressant and previous counselling. For the individual time points, which contribute to and illustrate the AUC, we used analysis of covariance to adjust for the corresponding baseline score.

Continuous outcome with no baseline and only one follow-up (Morisky scale)

We used analysis of covariance with baseline depression scores and validated stratification variables as covariates, to test whether medication adherence, measured on the Morisky scale, differs significantly between the two treatment arms. If so, we would have added the Morisky score and ADMs recorded by GPs to the usual covariates.

Dichotomous outcomes (serious adverse events and adverse events)

We used logistic regression of (S)AE compared with no (S)AE over each participant’s time in the trial to test whether the proportion of (S)AEs differs between treatment arms, using baseline scores and validated stratification variables as covariates. We transformed all estimated fixed effects back from their logistic form and summarised them by OR, standard error, 95% CI, and significance level.

Covariates to be adjusted within the statistical model

We kept baseline depression scores and validated stratification variables as covariates throughout. We also explored covariates of potential scientific relevance, including demographic (notably age, ethnicity, marital status, number of dependants and employment status, coded in accordance with usual demographic practice) and clinical (e.g. referral source, smoking, alcohol consumption and medication adherence, measured by both Morisky scale and recorded prescriptions). We fitted and retained these if they showed evidence of an effect at a significance level of 10%.

Interactions to be tested

Within each analysis we tested for interaction between treatment and centre, not least because of substantial differences in psychiatric practice and recruitment policy. On finding no evidence of interaction we estimated the treatment effect for each centre. We also tested for interactions between treatment and significant covariates.

Deviations from protocol

During the trial there were two protocol deviations that resulted in systematic missing data – one within a centre at one time point, the other within a single instrument early in the trial. First, early in the trial 13 participants in one centre did not receive appointments for visits at 4 weeks as the centre was under pressure from a large number of referrals; fortunately preventive action prevented any recurrence. Second, early in the trial 83 participants completed an incorrect version of the MADRS instrument: 40 at screening; 29 at randomisation; eight at 4 weeks; and six at 12 weeks. As both were administrative errors balanced between treatment groups, however, sensitivity analysis suggested that neither resulted in systematic bias. We therefore invoked our standard missing data procedures (see Imputation of missing data for ‘analysis by treatment allocated’, above).

Sensitivity analyses

We applied three main sensitivity analyses – to the BDI-II as primary outcome in the first instance, with the intention of applying them to other outcome measures if the BDI-II proved sensitive to alternative assumptions. First we used ‘complete case’ analysis to test the sensitivity of findings to the absence of missing data; and the methods we used to impute those missing data. Secondly we used multi-level modelling with the same covariates, also known as repeated measures analysis of variance, to test the sensitivity of findings to our choice of AUC as main method of analysis; we estimated parameters for three fixed factors – the three time points (4, 12 and 25 weeks), centre and treatment group. Finally we reweighted the ‘analysed population’ to match the characteristics of the ‘randomised population’, and test the sensitivity of findings to non-response. To do so, we matched the participants completely lost to follow-up to participants from the analysed population. First we linked them by allocated treatment, centre and gender. Then we used a hierarchical cluster analysis to identify the best set of variables to match the non-responders to members of the responding trial population – age, marital status, reported alcohol intake, and BDI-II at screening and at baseline. We conducted this procedure both on raw data and on imputed data.

Biochemical analyses

The first of our secondary objectives was to explore whether baseline folate and homocysteine predict response to treatment – the difference between baseline and follow-up. We followed participants at 12 weeks, as they completed the trial medication, and at 25 weeks, the usual endpoint of antidepressant trials. Though many of our analyses of effectiveness use simple linear regression, this is less well suited to analyse topics where multicollinearity, that is multiple correlation, plays a major role. Instead we use repeated measures analysis of variance, which examines all four time points (i.e. baseline and 4, 12 and 25 weeks) simultaneously by fitting all four measures and adjusting for stratification variables, baseline measurements, biochemistry, demography and other covariates.

Health economics methods

Introduction

There are no economic evaluations of folic acid in managing depression. If shown to be effective, however, folic acid could represent a highly cost-effective treatment option. As it costs only 3 pence a day, the main cost drivers are likely to be hospital admissions, use of health and personal social services, ADM, and other aspects of care which might change following therapeutic benefit.

The aim of the economic analysis was therefore to assess whether the addition of 5 mg folic acid, once daily for 12 weeks, in new or existing users of antidepressants, represents a cost-effective use of healthcare resources. We limited this analysis to trial-generated estimates of costs and benefits, without modelling wider effects.

Perspective

In line with the NICE reference case,112 we adopted the costing perspective of the National Health Service (NHS) and Personal Social Services (PSS). We estimated all costs in 2009–10 prices.

Data sources

Resource use

We derived participants’ use of services from:

-

self-completed questionnaires

-

GPs’ records of prescribed medications, and

-

our register of serious adverse events (SAEs), specifically for hospital admissions.

We based our resource use questionnaire on that used in the Assessing Health Economics of Anti-Depressants (AHEAD) trial of the cost-effectiveness of tricyclic antidepressants, selective serotonin re-uptake inhibitors and lofepramine. 113 It comprises four sections, relating to patients’ use of general practice and generic community nursing services, social services, psychiatric hospital and community services, and other health services, notably hospital admissions and attendances, including at Emergency Departments (Table 2). Research professionals completed the questionnaire by asking participants to recall their use of these services for the 3 months before the baseline visit, and 12 and 25 weeks thereafter.

| Item | Unit | Cost | Comments and assumptions | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| General practice and community pharmacy and nursing services | ||||

| GP consultation | Visit | £36 | 11.7 minutes/consultation, including direct care staff costs and qualification costs | 119 |

| GP home visit | Visit | £120 | 23.4 minutes/visit, including travel, direct care staff costs and qualification costs | 119 |

| GP telephone contact | Call | £22 | 7.1 minutes/call, including direct care staff costs and qualification costs | 119 |

| Practice nurse at surgery | Visit | £12 | 15.5 minutes/consultation, including qualification costs | 119 |

| District nurse at home | Visit | £27 | 20 minutes/visit, including qualification costs | 119 |

| Counsellor at surgery | Visit | £71 | 96.6 minutes/consultation | 119 |

| Health visitor | Visit | £37 | 20 minutes/visit | 119 |

| Vitamin B12 test | Test | £1.29 | NHS reference cost code DAP841 | 116 |

| Pharmacy dispensing fee | Prescription item | £3.03 | Average NHS cost/item dispensed, assuming all prescribed items dispensed | 115 |

| Social services | ||||

| Social worker (home or office) | Visit | £213 | 1 hour face-to-face contact | 119 |

| Home help | Contact | £75 | 3 hours/week of local authority home care | 119 |

| Care assistant | Contact | £214 | 10 hours/week of local authority community care | 119 |

| Day centre | Day | £36 | Based on community care package | 119 |

| Psychiatric hospital and community services | ||||

| Consultant psychiatrist at hospital | Visit | £205 | NHS reference cost code PS25B | 116 |

| Consultant psychiatrist at home | Visit | £328 | Cost/hour of patient contact, including qualification costs | 119 |

| Clinical psychologist | Visit | £81 | Cost/hour of client contact | 119 |

| Community psychiatric nurse | Visit | £56 | Cost/per hour of client contact | 119 |

| Other services | ||||

| Day hospital | Day | £99 | NHS reference cost code DCF41 | 116 |

| Emergency Department | Visit | £116 | NHS reference cost code 180 | 116 |

| Hospital clinic | Visit | £199 | NHS reference cost code 430 | 116 |

| Mental health inpatient stay | Night | £302 | NHS reference cost code MHIPA2 | 116 |

| Occupational health services | Visit | £46 | Hospital occupational therapist | 119 |

| NHS Direct | Contact | £21.37 | Cost/nurse adviser contact | 120 |

| Ambulance or paramedic | Contact | £246 | NHS reference cost code PS25A | 116 |

We sought details of participants’ prescribed medicines, over the 25 weeks they were in the trial, from their GPs. Two pharmacy technicians compiled a database of prescription data, normally supplied as printouts or screen dumps, and a pharmacist checked it for accuracy. We also checked data on hospital admissions, obtained directly from participants, against our SAE register.

Unit costs

The costs of the intervention were: folic acid 5 mg – 84 tablets costing £2.67;114 dispensing fee equal to NHS average of £3.03;115 and serum vitamin B12 testing from the NHS reference costs for biochemistry. 116

We derived the unit costs of other resources from standard sources (see Table 2). We took drug costs from the Prescription Cost Analysis,117 which derives products’ net ingredient costs (i.e. excluding discounts and dispensing costs) from actual NHS expenditure. 118 We took the cost of pharmacy dispensing from a report commissioned by the Department of Health to estimate the cost of providing community pharmacies. 115 We retrieved the costs of healthcare professionals’ time from the Unit Costs of Health and Social Care 2010. 119 These include salaries and expenses, costs of training and qualifications, and capital and overhead costs. We took hospital costs from the NHS reference costs,117 which underpin the calculation of the tariff for ‘payment by results’ in England.

Health outcomes

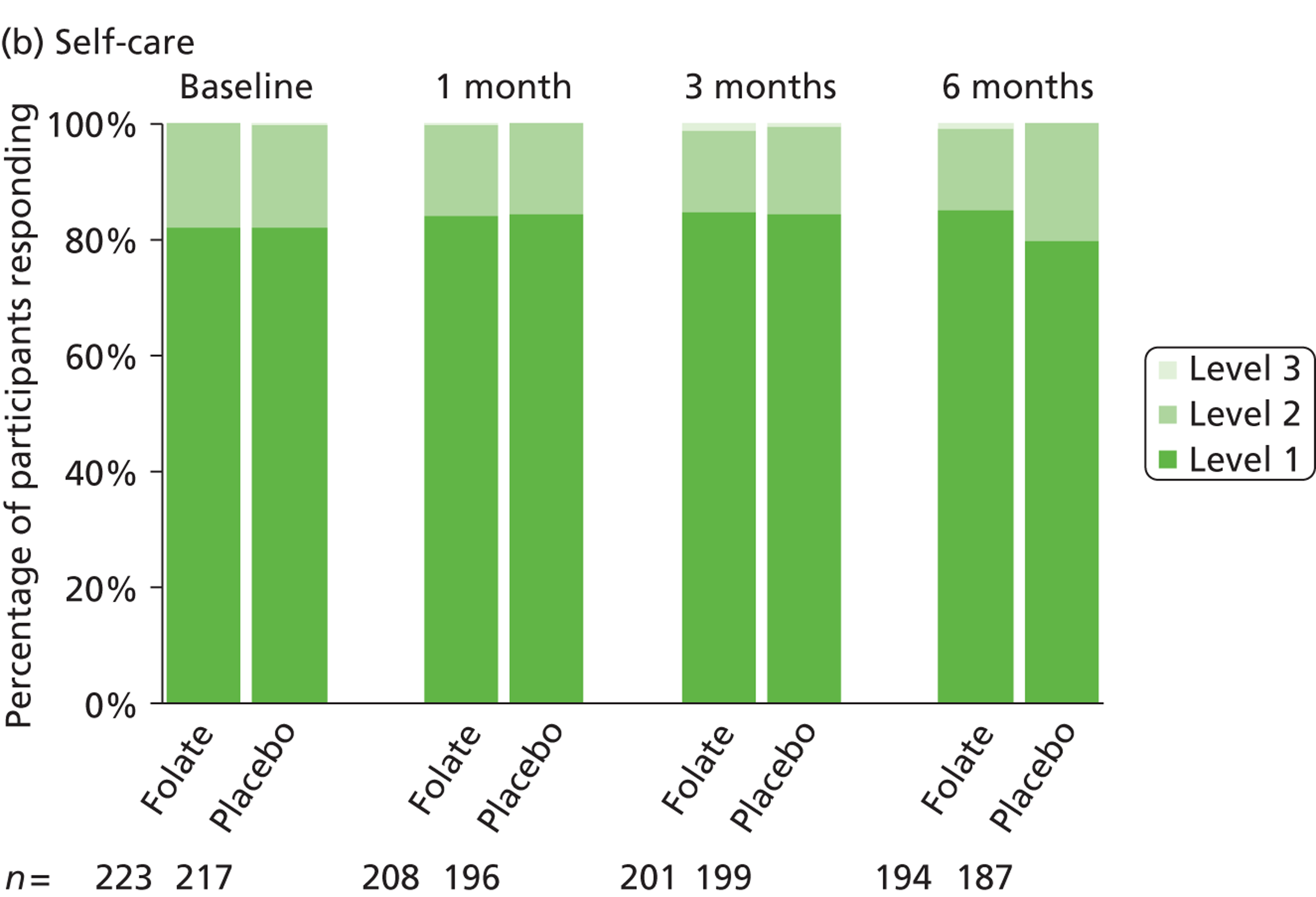

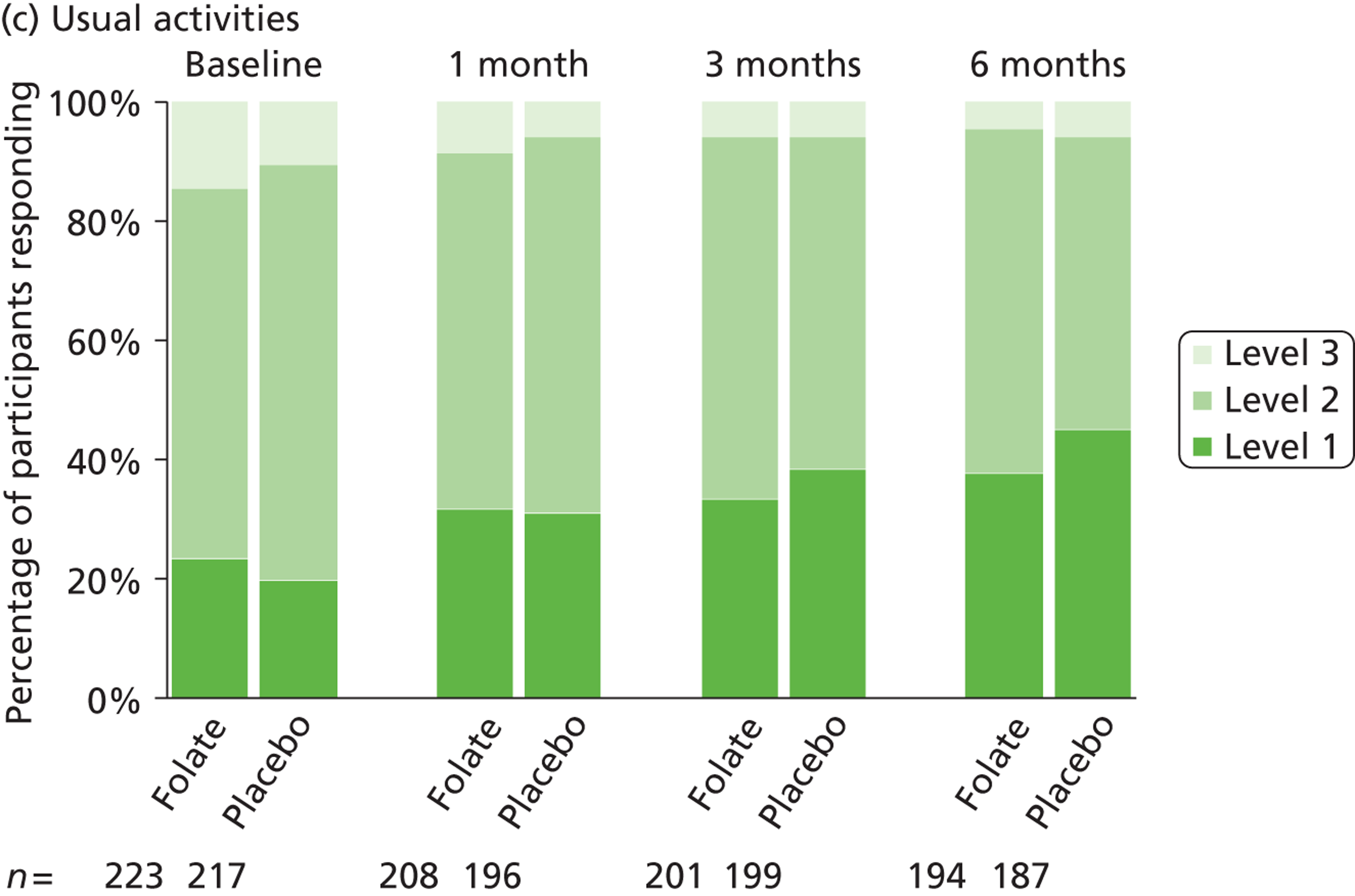

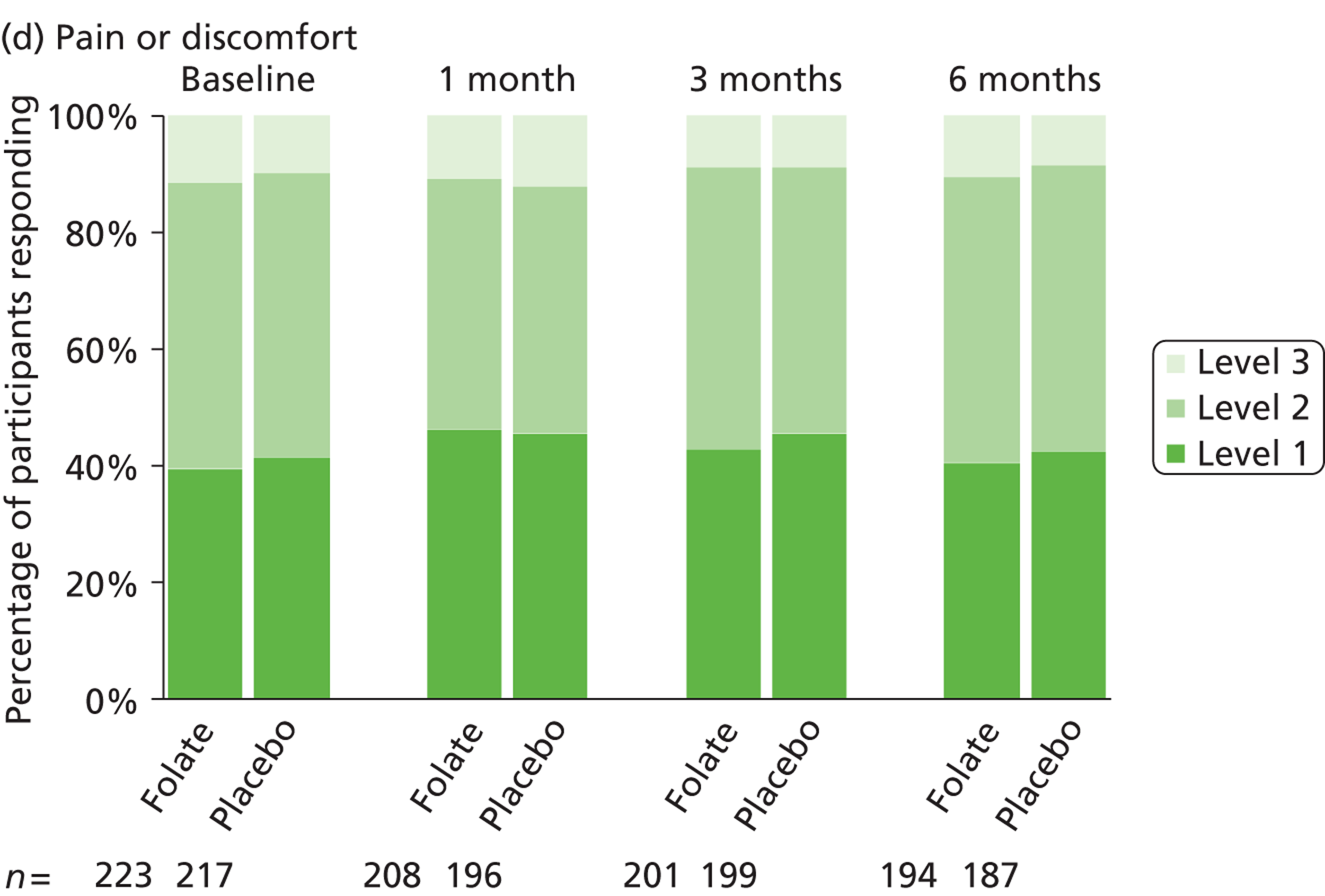

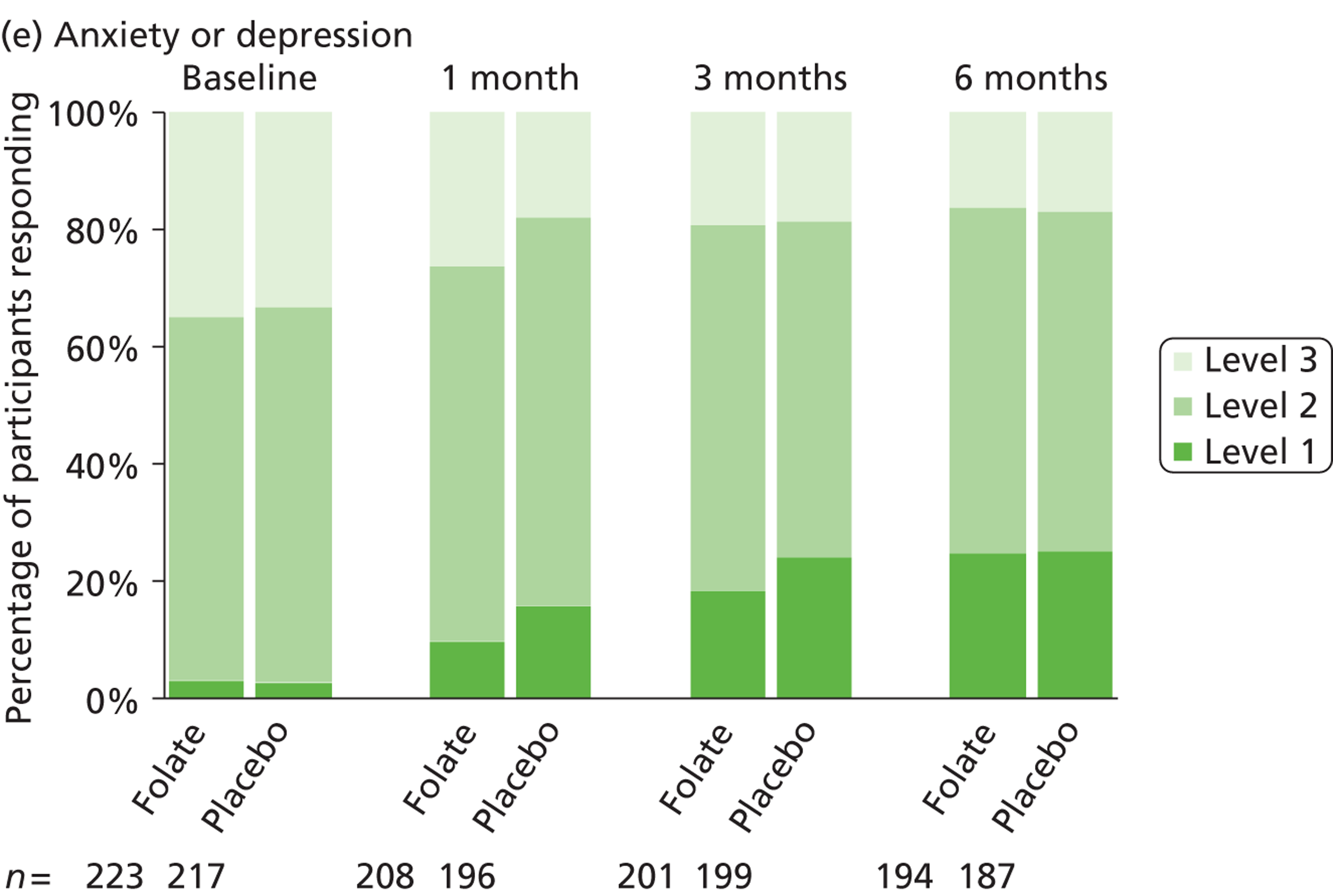

The primary measure of health outcome for economic analysis was the quality-adjusted life-year (QALY), estimated from the EQ-5D questionnaire administered at baseline and 4, 12 and 25 weeks. This assesses health-related quality of life on five dimensions – mobility, self-care, usual activities, pain-discomfort and anxiety-depression. The three possible responses on each dimension are ‘no problems’, ‘moderate problems’ and ‘extreme problems’. We converted participants’ responses into a single, preference-based utility using on the UK tariff. 121

Secondary measures of health outcome for economic analysis included the EQ-VAS, the UK Short Form Health Survey – 6 Dimensions (SF-6D) and BDI-II, all completed at the same times as the EQ-5D. The EQ-VAS is a vertical 20-cm visual analogue scale for recording participants’ rating of their current health-related quality of life. The SF-6D derives an alternative preference-based utility from SF-12 responses using weights estimated from a sample of the general population by the standard gamble technique. 122

For the cost-effectiveness analysis, we calculated the number of weeks free from moderate or severe depression (defined as a BDI-II score < 13)123 by statistical inference from the observed distribution of BDI-II scores, assuming linear interpolation between time points (baseline, 4, 12 and 25 weeks).

Data analysis

We combined data on costs and outcomes in the ‘treatment allocated’ population (see Statistical methods, Imputation of missing date for analysis by treatment allocated, Missing items within a subscale, above) over 25 weeks to estimate an incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER) for comparison against accepted thresholds. Primary analysis was on the data set in which we had imputed missing data in the manner described above (see Statistical methods, Trial populations).

Analysis of costs

We estimated costs over 25 weeks for each participant by aggregating across resource categories. To draw inferences from this skewed distribution, we used ‘bootstrapping’, that is resampling with replacement and re-estimating sample means for each replicate. We used 10,000 replicates, corrected for bias and skewness by the technique known as ‘bias correction and acceleration’, and generated 95% CIs. We inferred whether differences in mean costs between treatment and control groups were statistically significant from those bootstrapped CIs. 124 To adjust for differences at baseline and in duration of follow-up, we used the regression model:125

where patient i in treatment group gi has a pre-baseline cost of Ci and a time between randomisation and final follow up of Ti and β1 represents the difference in costs after adjusting for imbalance in mean costs before baseline. We used the logarithmic transformation to address the natural skewness of costs, and transformed the results of the regression back to recover the differential cost. As there were essentially no differences in demographic variables between groups, we did not need to adjust for any other variable.

Analysis of health outcomes

While the AUC average Uav is the measure analysed in effectiveness tables (see Methods for analysing outcomes: Continuous outcomes with baseline and more than one follow-up above), economic analysis uses QALY: the area under the utility curve over the participant’s follow-up period in years. Hence:

where Uav is the participant’s AUC average utility and T is the duration in days of the participant’s study period. However, as this period may vary from 21 to 29 weeks, we adjusted QALYs, like costs, for duration as well as baseline.

To adjust QALYs for differences in baseline utility and duration of follow-up, we used the regression model:126

where patient i in treatment group gi has baseline utility of Bi [equal to U0 in equation (1) above] and time between randomisation and final follow-up of Ti; and β1 represents the difference in QALYs after adjusting for imbalance in mean utility at baseline. As again there were essentially no differences in demographic variables between the two groups, we did not need to adjust for any other variable. We applied the same procedure to other measures of health outcome.

For all economic measures of health outcome we used 10,000 replicates to generate non-parametric bootstrapped 95% CIs, again corrected for bias and skewness, for the differences in means between treatment and control groups.

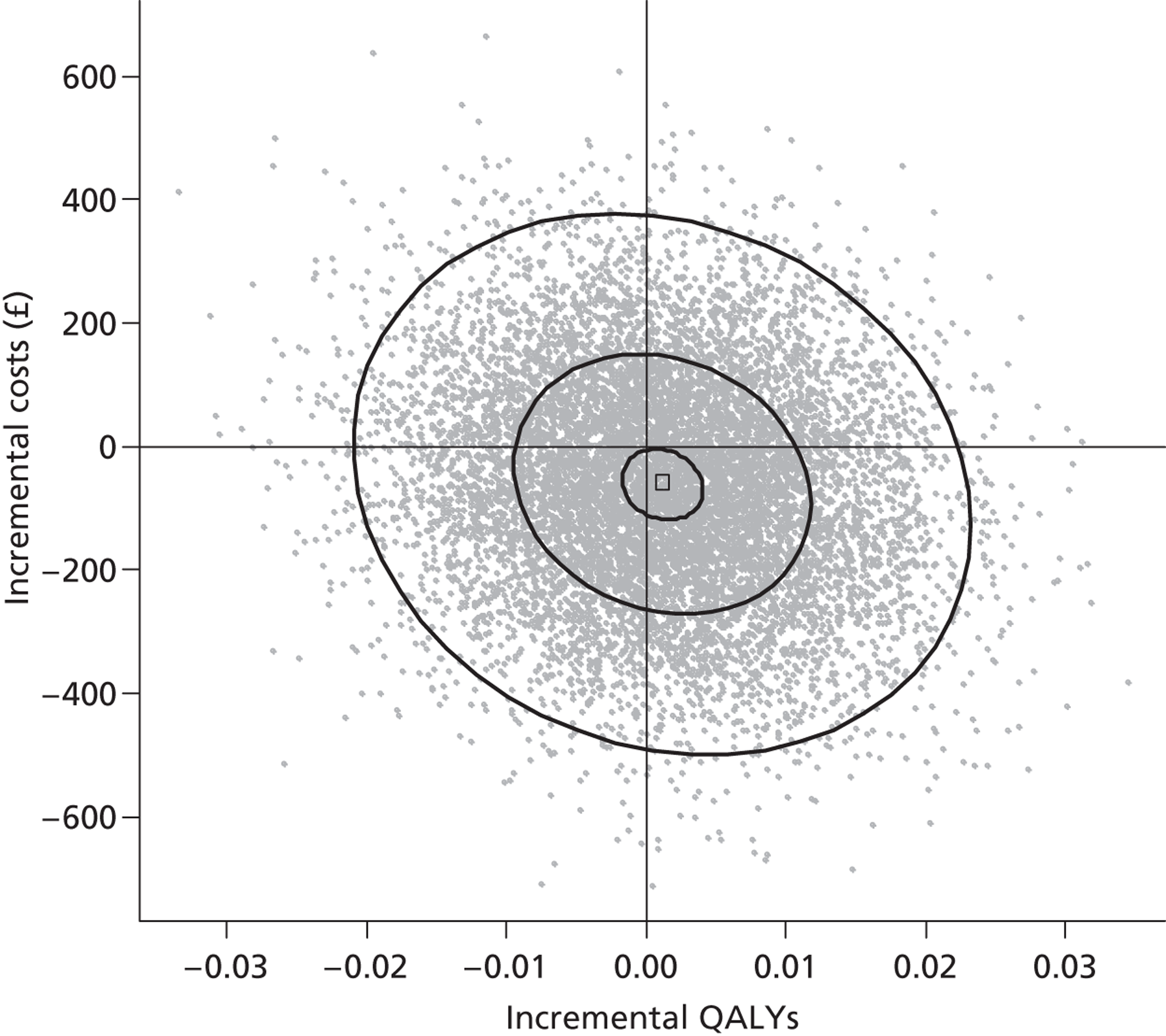

Cost–utility analysis

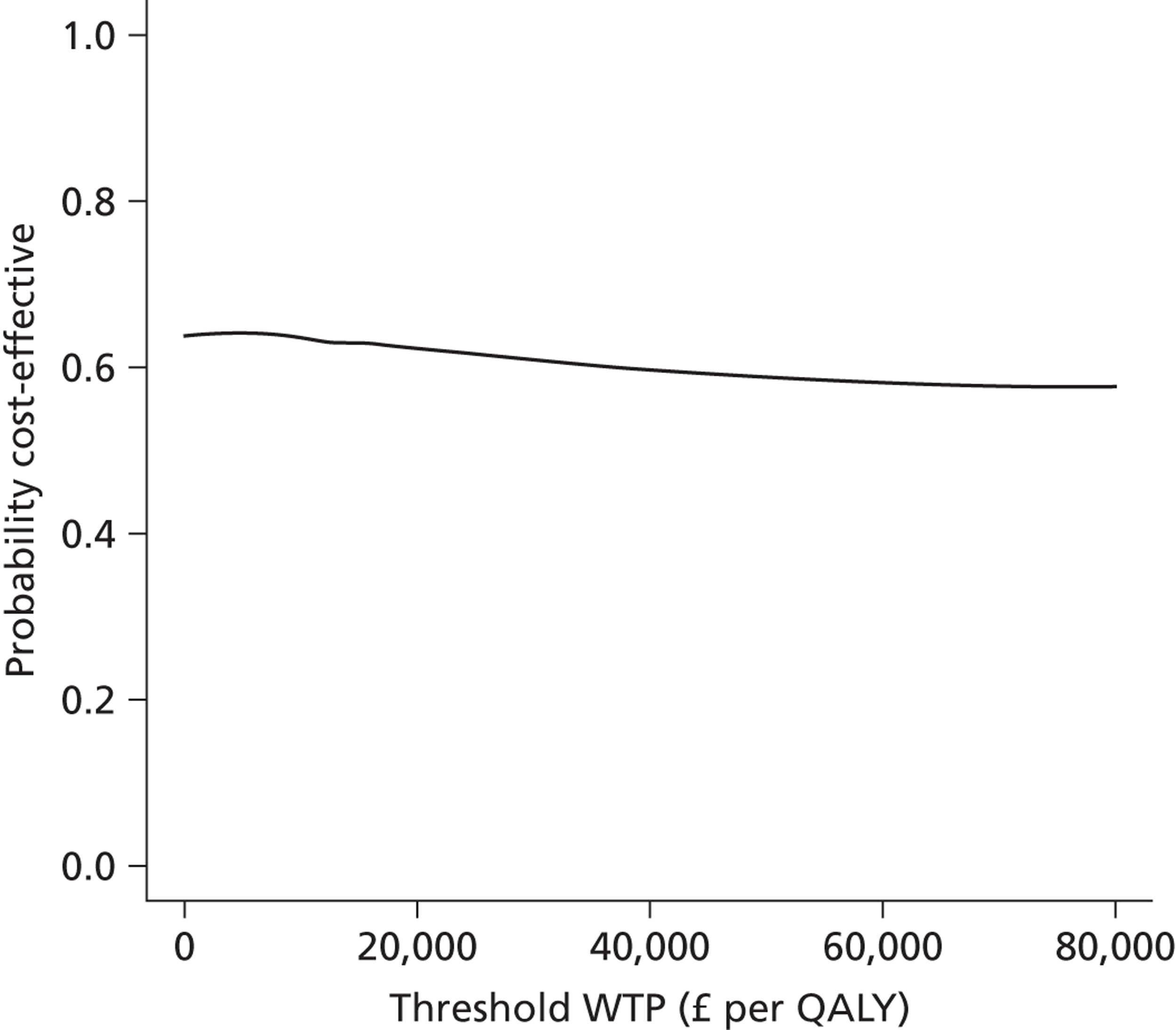

Comparing two treatments results in one of four scenarios. The intervention ‘dominates’ if it saves costs and improves health outcomes. The intervention ‘is dominated’ if it increases costs and outcomes deteriorate. More commonly the intervention improves outcomes at greater cost, or saves costs at the expense of outcomes. Then one must estimate an incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER) by dividing the difference in adjusted mean costs (ΔC) by the difference in adjusted mean benefits (ΔB). NICE is more likely to recommend an intervention for use by the NHS if the ICER falls below the threshold for cost-effectiveness, which ranges from £20,000 to £30,000 per QALY. 112

We used non-parametric bootstrapping to map the joint distribution of costs and outcomes on the cost-effectiveness plane and generate cost-effectiveness acceptability curves to show the probability that the intervention was cost-effective across a range of thresholds of cost-effectiveness.

Sensitivity analysis

To examine the extent to which the ICERs are sensitive to basic assumptions, we used two alternative approaches to measuring utility – the EQ-VAS and the SF-6D, and restricted analysis to all participants who gave complete EQ-5D responses. We used R software111 for all analyses.

Genetic methods

Our aim was to test whether genetic polymorphisms affect the efficacy of folic acid in combination with ADM, with a view to using them as predictive markers of adjuvant folic acid efficacy. There is strong evidence to suggests that folic acid can play a role in the treatment and prevention of depression. 60 It is the effect of genetic variability on this role that we aim to investigate. This study focuses on variability in genes encoding proteins and enzymes implicated in the carbon folate and methionine synthesis pathways, rather on genome-wide analysis. 127 We justify this approach by the folic acid intervention in this study and the weight of evidence to suggest decreased folate is associated with depressive illness. 41,77,128

Given the level of complexity of the one-carbon folate pathway,127 the genetic characteristics of FolATED trial participants span a comprehensive set of folate pathway genes beyond the commonly analysed methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase (MTHFR) polymorphisms. Similar pathway-wide candidate gene approaches to genotyping have previously successfully identified genetic risk factors for several clinical phenotypes including colorectal,129,130 breast,131 and bladder cancers,132 and cleft lip or palate. 133

DNA isolation

We extracted genomic DNA from 5 ml of whole blood using the Chemagic Magnetic Module (MSM) 1 system according to the manufacturer’s protocol (Chemagen Biopolymer-Technologie AG, Baesweiler, Germany). We eluted samples in 500 µl of the manufacturer’s elution buffer.

Single nucleotide polymorphism selection

We compiled a list of 25 candidate genes127 associated with either the one-carbon folate or methionine synthesis pathways. We identified 48 non-synonymous single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) within these genes from the Single Nucleotide Polymorpism Database [dbSNP;134 www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/SNP (accessed May 2008)] and selected for analysis those with minor allele frequency greater than 5%. We included a further 100 SNPs from the HapMap (http://hapmap.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov) population of Utah residents with ancestry from northern and western Europe which, when analysed by Haploview software version 402 (www.broadinstitute.org/haploview/haploview), tagged at least one other SNP. We added a 19 base pair (bp) deletion polymorphism of intron 1 of the dihydrofolate reductase gene (DHFR) and a 28 base pair double or triple tandem repeat polymorphism of the thymidylate synthase (TYMS) gene because both have been extensively characterised in clinical studies. 127

Genotyping

We designed multiplex assays for the MALDI-TOF-based Sequenom iPLEX system (Sequenom Inc., San Diego, CA, USA) using the software at https://mysequenom.com/default.aspx. We included 140 SNPs in five-assay plexes ranging from 11 to 35 SNPs in size. We excluded five SNPs which we could not incorporate in assays because of proximal nucleotide sequence constraints and another three SNPs which we could not include at a minimum plexing level of > 10 SNPs per assay (see Appendix 6, Table 35).

We genotyped patients for these 140 SNPs according to the manufacturer’s protocol using 40 ng/reaction genomic DNA. We obtained sequence-specific polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and extension reaction oligonucleotides from Metabion GmbH (Martinsried, Germany). Table 36 of Appendix 6 defines the corresponding primer and probe sequences.

We typed the 19 bp deletion polymorphism from the dihydrofolate reductase gene (DHFR) and the 28 bp tandem repeat polymorphism from the thymidylate synthase (TYMS) gene using previously published protocols and PCR primer sequences21,22 with minor modification. Briefly the 25-µl PCR reaction consisted of 20 ng genomic DNA, 5 pmol each of primer and 18 µl 1.1× ReddyMix™ PCR mastermix (Abgene Ltd, Epsom, UK).

We resolved all PCR products with ethidium bromide staining on a 3% agarose gel. For the DHFR 19 bp deletion, a 92 bp product identified the deletion allele and a 113 bp product identified the insertion allele. For the TYMS tandem repeat a 144 bp product distinguished the triple repeat allele from the double (116 bp).

We undertook all genotyping with 10% of DNA samples duplicated as well as positive and negative controls to confirm genotype calling accuracy and concordance.

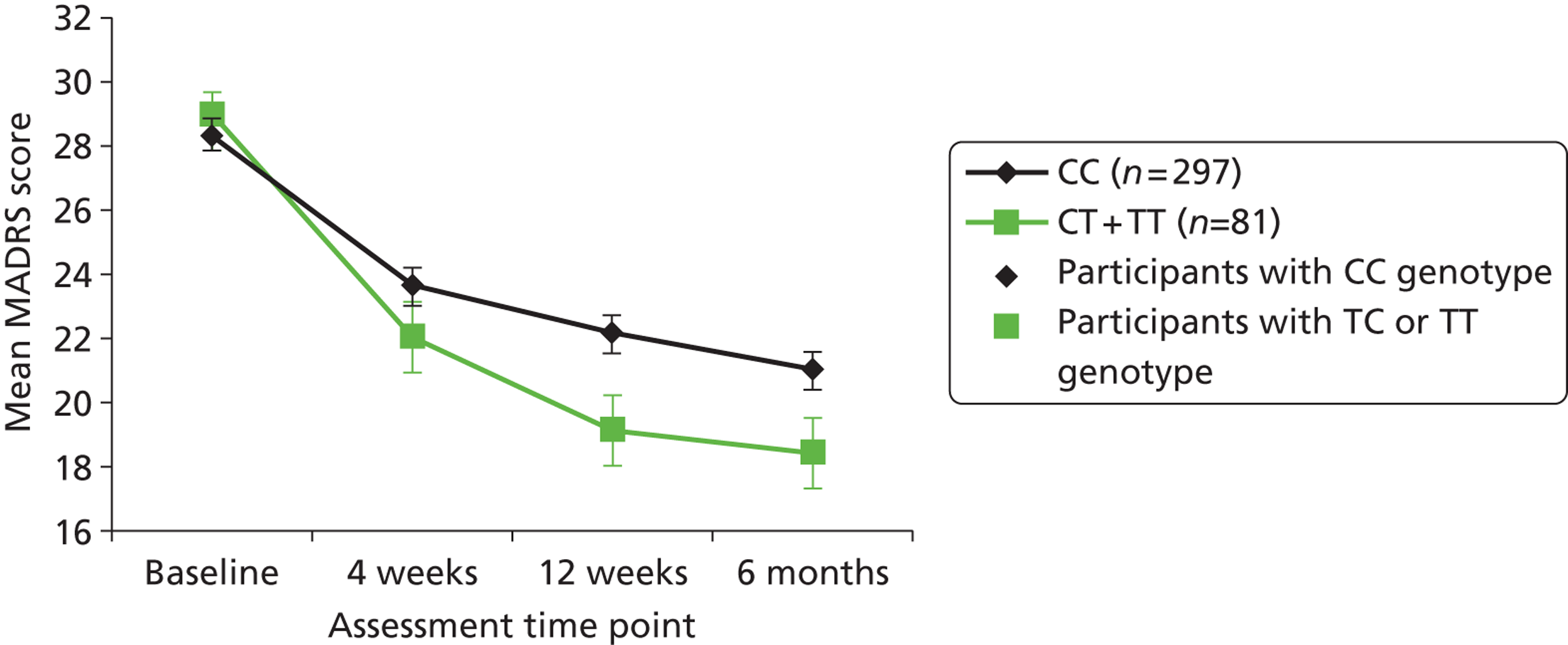

Genetics outcomes

For this genetic sub-study, the primary outcome was self-rated symptom severity on the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI-II) at baseline, and 4, 12 and 25 weeks, consistent with the trial’s primary outcome. Secondary outcomes were:

-

symptom severity rated by clinicians on the MADRS and the CGI of change (also at baseline and 4, 12 and 25 weeks)

-

mental and physical aspects of self-reported health status on the SF-12 (ditto)

-

side effects assessed by the UKU side effects scale and reported AEs (ditto), and

-

proportion of patients with self-rated moderate or severe depression (i.e. BDI-II score ≥ 19) at 25 weeks.

Genetics statistical methods

Before the analyses of association, we tested each SNP for Hardy–Weinberg Equilibrium, and excluded those found to deviate at a significance level of 0.1%. We also excluded SNPs which did not meet all our genotype quality criteria:

-

a. minor allele frequency greater than 1%

-

b. genotyping rate greater than 95% per SNP, and

-

c. samples more than 90% of SNPs called.

We fitted three mixed models to all five outcomes for each included SNP. The first (‘baseline model’) included the baseline value of the outcome, covariates representing the three time points (4, 12 and 25 weeks), three validated stratifying variables – centre, type of antidepressant, new or continuing patient – and treatment received, that is whether participants supplemented their medication with folic acid or not. We also tested non-genetic factors known to be generally associated with outcome (age, gender, marital status, employment status, number of dependents, smoking and alcohol consumption, previous counselling and treatment adherence as assessed by the Morisky scale) for univariate association with each outcome and included them in the model if the significance level was less than 10%.

The second (‘SNP’) model was identical to the first with the addition of the SNP as covariate. The third (‘interaction’) model was identical to the second with the addition of interaction between SNP and treatment received. To test for statistical significance of SNP main effects, we used likelihood ratio tests to compare the specific SNP model with the baseline model. To test for statistical significance of the SNP-folated interaction, we again used the likelihood ratio test to compare the specific interaction model with the specific SNP model. Each test tried two models – one making no assumption about the underlying mode of inheritance, the other assuming an additive mode of inheritance – and used the lower significance level for each SNP.

To take account of the multiple comparisons due to four tests on each of more than 100 SNPs, we estimated the false discovery rate (‘FDR’) for each comparison, and treated FDRs less than 5% as statistically significant associations. We used the statistical software packages: R;111 PLINK version 1.07 from http://pngu.mgh.harvard.edu/~purcell/plink/; and PASW version 18135,136 for these analyses.

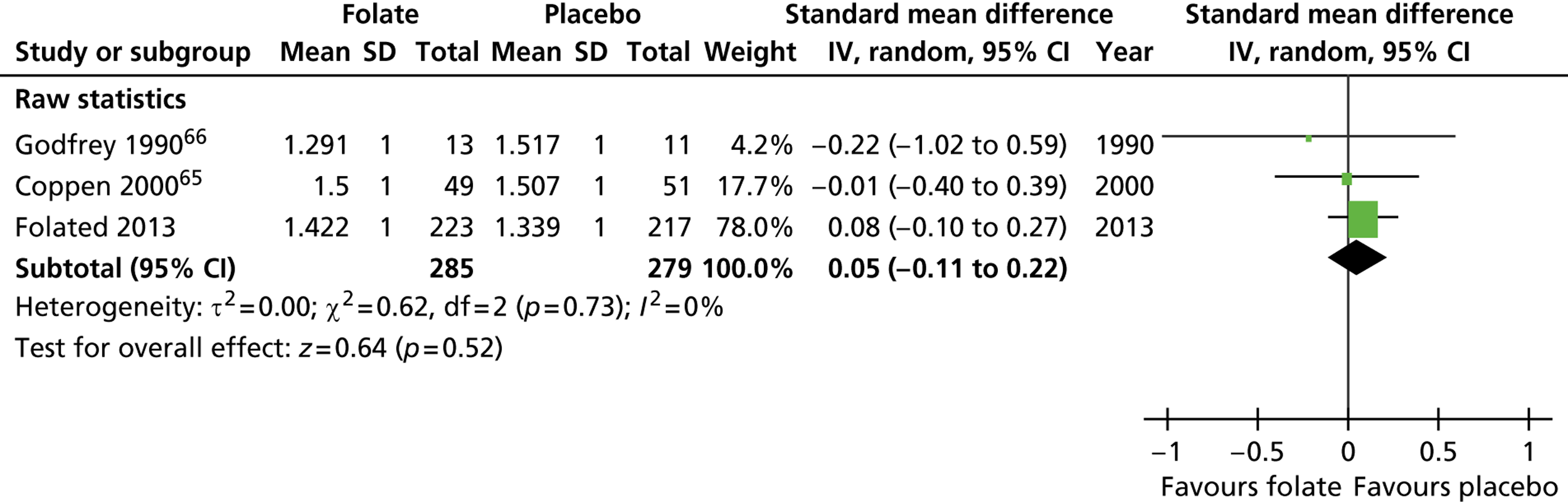

Systematic review of the effectiveness of folate in augmenting antidepressant medication

Introduction

At the start of the FolATED trial understanding of the benefits of folate augmentation of ADM stemmed from a recent Cochrane systematic review. 50,64 The authors concluded that there was limited evidence that adding folate to ADM was helpful, and recommended larger trials to test this hypothesis thoroughly. That recommendation led directly to the funding of FolATED.

Method

Data sources and study selection

We updated the current Cochrane systematic review50 following analysis of the FolATED trial. The authors of that review searched the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials and MEDLINE from 1966 until May 2005. In August 2012 we reran their search for randomised trials evaluating folate in any form to augment ADM in treating depression. We followed the Cochrane systematic review search strategy in PubMed until December 2011 but without language restrictions. Consistent with the design of FolATED we selected randomised trials evaluating folate to augment antidepressants in treating depressive disorder rather than folate as sole therapy.

Data extraction and synthesis

Two of us (BRC and ITR) independently assessed potential trials for eligibility and quality, and extracted data. The Cochrane systematic review had used the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HDRS) as primary outcome. 50 In contrast the FolATED trial used the Beck Depression Index (BDI-II). To compare these instruments we converted both to standard Normal distributions with a SD of 1 and mean equal to the trial effect size, namely the mean difference between trial groups divided by trial SD. We gave each trial a weight inversely proportional to the variance with which it estimated that difference. We used a random-effects model to estimate the standardised mean difference and associated 95% CI. We assessed the heterogeneity of findings by the I2-statistic. 137

Chapter 3 Results

Recruitment: identification and eligibility

We recruited participants in three centres: North East Wales, North West Wales and Swansea. The first randomisations took place in North West Wales in July 2007, in Swansea in August 2007, and in North East Wales in October 2007. We randomised the final participant in November 2010 and completed follow-up in May 2011.

Figure 2 shows that FolATED received 1488 referrals; screened 863, of whom 635 consented to take part; randomised 479, of whom four were in error and removed from analysis; and analysed 440 (92% of the 475 valid randomisations). Though the four randomised in error had BDI-II scores of at least 19 at –2 weeks, these had fallen below 17 at randomisation, so they should have been excluded. The reasons why 625 referred patients did not reach screening were: 44% did not wish to take part; 26% did not respond to the research team; 16.5% were ineligible; and 13.5% did not attend the screening appointment.

FIGURE 2.

‘CONSORT diagram’ of flow of participants through trial. Note: Hence we included 223 + 217 = 440 participants in primary analysis.

At screening to assess eligibility for the trial, the primary reason for exclusion was that people did not meet the trial specified criteria for moderate to severe depression (54%). The other criteria that excluded more than 5% of those screened were: presence of malignancy or similar disorder (10%); not currently taking antidepressants (9%); and taking anticonvulsants (7%).

Randomisation interviews took place 2 weeks after screening when blood test results were available to verify eligibility to enter the trial. Of the 635 people who had consented to take part, we could not randomise 156: 68 people dropped out between screening and randomisation and a further 42 at the randomisation interview, of whom 36 scored too low on the BDI-II. Forty-six people entered the comprehensive cohort and 20 who were eligible to do so declined. Table 3 cross-tabulates reasons for losses by stage of recruitment and Appendix 7 does so by centre.

| Reason for not randomising | Between referral and screening | Screening | Randomisation | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-specified exclusion criteria | ||||

| Are under 18 years | 4 | 0 | 0 | 4 |

| Not depressed by ICD – 10 criteria | 0 | 122 | 36 | 158 |

| Folate deficient | 0 | 1 | 15 | 16 |

| B12 deficient | 2 | 0 | 8 | 10 |

| Have taken folate supplementation | 14 | 8 | 2 | 24 |

| Suffered from psychosis | 3 | 2 | 0 | 5 |

| Bipolar disorder | 2 | 4 | 0 | 6 |

| Are already in another research trial | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| Are pregnant or planning to be so | 9 | 0 | 0 | 9 |

| Taking anticonvulsants | 5 | 16 | 1 | 22 |

| Serious, advanced or terminal illness | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Treatment for a medical condition not yet stabilised | 1 | 2 | 0 | 3 |

| Taking lithium | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Have had diagnosis of malignant disease | 19 | 22 | 2 | 43 |

| Subtotal | 62 | 177 | 64 | 303 |

| Other exclusions | ||||

| Not on antidepressants | 36 | 21 | 9 | 66 |

| Other | 5 | 14 | 5 | 24 |

| Subtotal | 41 | 35 | 14 | 90 |

| Refusal | 277 | 16 | 17 | 310 |

| Did not attend appointment | 84 | 0 | 15 | 99 |

| Could not contact | 161 | 0 | 0 | 161 |

| Subtotal | 522 | 16 | 32 | 570 |

| Comprehensive cohort | 0 | 0 | 46 | 46 |

| Total | 625 | 228 | 156 | 1009 |

Centre differences in recruitment patterns

North West Wales received 47% of the referrals to the trial and randomised 50% of the final sample. North East Wales and Swansea received and randomised very similar proportions of the total – 27% and 26% respectively of referrals received and 25% of the randomised sample each). Table 4 summarises these flows by centre.

| Reason for not randomising | North East Wales | North West Wales | Swansea | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number referred | 400 | 698 | 390 | 1488 |

| Trial exclusion criteria | 15 | 31 | 16 | 62 |

| Other exclusions | 15 | 17 | 9 | 41 |

| Refusal | 91 | 128 | 58 | 227 |

| Did not attend | 21 | 29 | 34 | 84 |

| Could not contact | 26 | 75 | 60 | 161 |

| Number screened | 232 | 418 | 213 | 863 |

| Trial exclusion criteria | 57 | 75 | 45 | 177 |

| Other exclusions | 7 | 25 | 3 | 35 |

| Refusal | 4 | 12 | 0 | 16 |

| Other loss | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Number consented | 164 | 306 | 165 | 635 |

| Trial exclusion criteria | 6 | 42 | 16 | 64 |

| Other exclusions | 1 | 9 | 4 | 14 |

| Refusal | 9 | 4 | 4 | 17 |

| Did not attend | 3 | 6 | 6 | 15 |

| To comprehensive cohort | 24 | 7 | 15 | 46 |

| Number randomised | 121 | 238 | 120 | 479 |

Loss to follow-up

We randomised 475 participants (excluding four randomised in error): 237 to receive folic acid and 238 to receive placebo. In the folic acid group 15 people withdrew and 26 were lost to follow-up by 25 weeks. In the placebo group 18 people withdrew and 32 were lost to follow-up by 25 weeks. Table 5 shows the reasons for loss at each stage.

| Type of drop-out | Reason for drop-out | Folate | Placebo | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4 weeks | 12 weeks | 25 weeks | Total | 4 weeks | 12 weeks | 25 weeks | Total | ||

| Withdrawals | Too many personal commitments | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| Felt better | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | |

| Stopped taking antidepressants | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 2 | |

| Pregnant | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | |

| No reason given or did not want to take part | 3 | 4 | 0 | 7 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 3 | |

| Withdrew owing to adverse side effects | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Had an abnormal electrocardiogram | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | |

| Participant elderly and too ill to take part | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | |

| Unable to contact because moved out of area | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 4 | 3 | 7 | |

| Newly diagnosed with bipolar disorder | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Started folic acid supplements – asked to withdraw | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| New diagnosis of multiple sclerosis | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Subtotal | 8 | 6 | 1 | 15 | 10 | 5 | 3 | 18 | |

| Lost to follow-up | Did not attend any further follow-up appointments | 6 | 11 | 9 | 26 | 11 | 10 | 11 | 32 |

| DNAd but attended at least one further follow-up | 15 | 5 | 0 | 20 | 21 | 3 | 0 | 24 | |

| Total | 29 | 22 | 10 | 61 | 42 | 18 | 14 | 74 | |

Participant drop-out and missing data

There were no follow-up data for 35 randomised participants; 18 withdrew before the 4-week follow-up (8 folic acid group, 10 placebo group) and 17 did not attend any appointments (6 folic acid group, 11 placebo group). Thus 14 dropped out of the folic acid group and 21 out of the placebo group. We removed these from further analysis. Therefore 440 entered the main analysis, 223 from the folic acid group and 217 from the placebo group. If these evaluable participants missed follow-up appointments, we imputed their data in accordance with Chapter 2, Statistical methods, Trial populations, above (Table 6). However we imputed no baseline measures.

| Follow-up | Folate (n = 223) | Placebo (n = 217) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Completed | Imputed | Completed | Imputed | |

| 4 weeks | 208 | 15 | 196 | 21 |

| 12 weeks | 201 | 22 | 199 | 18 |

| 25 weeks | 196 | 27 | 188 | 29 |

Of the 440 evaluable participants 36 (8%) missed follow-up at 4 weeks, 40 (9%) at 12 weeks, and 56 (13%) at 25 weeks. Thus 10% of follow-up assessments were missing. Sixty-two participants missed one assessment: 33 at 4 weeks, 6 at 12 weeks and 23 at 25 weeks. Thirty-five participants missed two assessments: 2 at 4 and 12 weeks; 1 at 4 and 25 weeks; and 32 at 12 and 25 weeks. Thus 343 (78%) participants undertook all three assessments.

For the eight main outcome measures (BDI-II, MADRS, CGI, SF-12, EQ-5D, EQ-VAS, MINI and Morisky) a full data set over the four times would have comprised 102,520 data items. Only 2572 (2.5%) were missing, of which 2476 (2.4%) items were in missing subscales or times while 96 (0.1%) items were isolated missing values within otherwise complete subscales. Reassuringly there was no hint of significant differences between trial groups in either respect.

The missing item rate for seven of these measures is fairly consistent: BDI-II, EQ-5D, EQ-VAS, and MINI all 2.3%; MADRS 2.4%; SF-12 3.2% and CGI 3.3%. In contrast the Morisky data had a missing item rate of 10%, not explained by being collected only at 12 weeks. Predictably the pattern of missing data differed very significantly between centres: North West Wales, the best recruiting centre, missed more 4-week data than other centres, but fewer at 25 weeks. This pattern was due to heavy workload early in the trial when several 4-week appointments were missed; fortunately routine monitoring recognised and rectified the problem. Reassuringly there was no significant difference between centres in the proportion followed up.

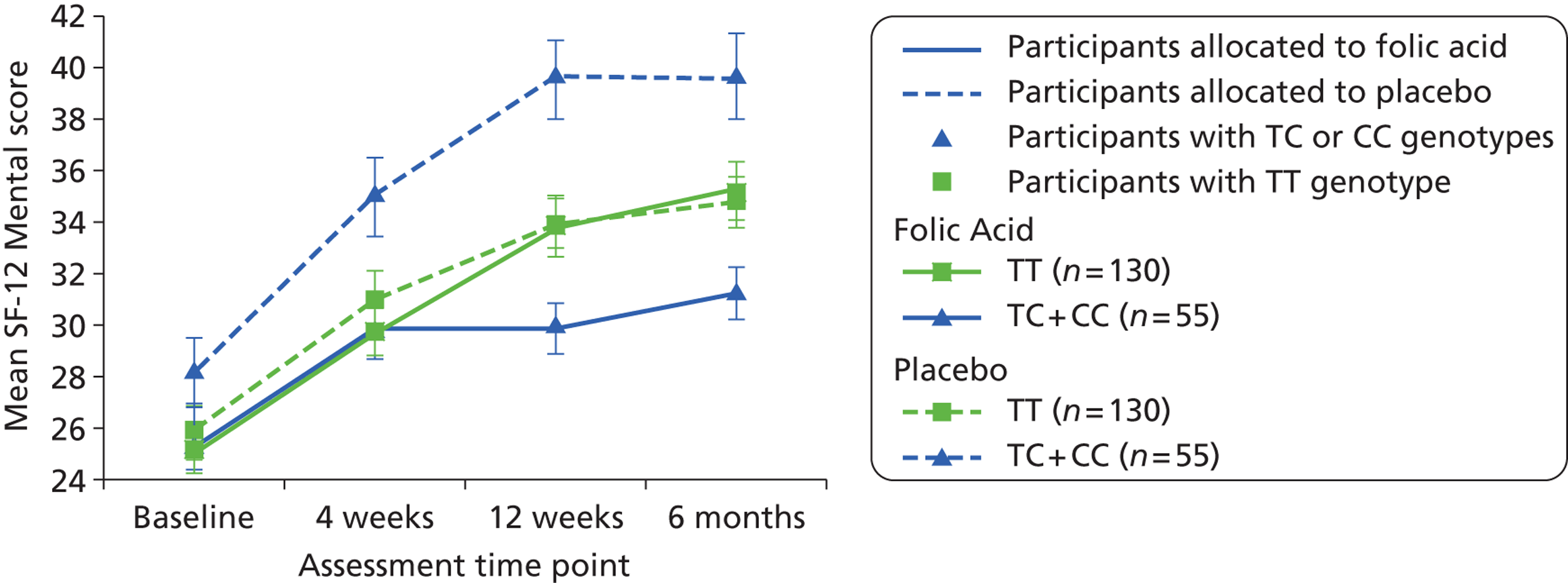

Validation of stratification variables