Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 06/07/01. The contractual start date was in February 2006. The draft report began editorial review in June 2013 and was accepted for publication in October 2013. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Neil Marlow reports personal fees from Novartis, personal fees from Elsevier, outside the submitted work. Tim Coleman reports personal fees from Pierre Fabre Laboratories, France, outside the submitted work.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2014. This work was produced by Cooper et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Introduction

The problem

Maternal smoking during pregnancy is the most important, and preventable, cause of adverse pregnancy outcomes including placental abruption, miscarriage, birth before 37 weeks’ gestation (pre-term birth) and low birthweight (LBW). 1 Pre-term birth is the principal cause of neonatal death and morbidity, with up to 50% of infants’ neurodevelopmental problems being attributable to this. 2 Similarly, LBW births are a marker of ill health and are associated with the future development of coronary heart disease, type 2 diabetes and obesity. 3

Tobacco smoking in pregnancy is a worldwide public health problem. The UK’s estimated rate of pre-natal smoking is 12%4 and rates are similar in most developed countries, including Australia (17%),5 Denmark (16%),6 the USA (11%)7 and Germany (13%). 8 Some other European countries, such as Spain9 and Poland,10 have considerably higher rates of maternal smoking in pregnancy, reaching around 30%. Although the prevalence of smoking in pregnancy appears generally to be reducing in high-income countries, in low- and middle-income countries, rates of maternal smoking in pregnancy are believed to be increasing. 11 It is predicted that in the future, higher rates of maternal smoking in low- and middle-income countries will substantially transfer the health burden from smoking during pregnancy to these nations. 12 Additionally, in high-income countries, rates of smoking in pregnancy remain highest among younger women and those who are more socially disadvantaged. 4 As the children of mothers who smoke are twice as likely to become smokers,13 smoking in pregnancy perpetuates cycles of deprivation and health inequalities across generations that permanent smoking cessation initiated in pregnancy could reduce.

Treatments for smoking cessation in pregnancy

Stopping smoking in pregnancy not only benefits maternal health but has positive impacts on infant outcomes and effective cessation interventions which are used by pregnant women reduce numbers of LBW and pre-term births. 14 Presumably, because the harms of smoking and the benefits of stopping are widely known, many smokers stop when they are planning a pregnancy or soon after conceiving; for example, in England and Wales, around 50% of smokers manage to stop smoking during at least part of their pregnancy. 4 For pregnant women who are unable to stop smoking without assistance, there are only two proven cessation interventions which could help them with this: behavioural14 and self-help15 smoking cessation support. Intensive behavioural support, which is delivered outside women’s routine antenatal care, can reduce smoking in later pregnancy14 [pooled risk ratio (RR) for reduction in smoking prevalence after behavioural support 0.94, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.93 to 0.96], as can self-help cessation interventions15 [odds ratio (OR) for cessation following self-help intervention 1.83, 95% CI 1.23 to 2.73]. Behavioural support usually involves psychologically orientated counselling that can broadly be described as ‘cognitive–behavioural therapy’. However, for this intervention to have an effect, women must attend appointments with health professionals in addition to their routine antenatal care; however, in countries such as England, where such support has been freely available for some time, relatively few pregnant smokers have made use of this. Using the NHS Stop Smoking Service (SSS)16 and maternity statistics17 combined with national survey data,4 one can estimate that, in 2011, only 14% of English pregnant smokers set quit dates using such support and as few as 6% subsequently managed to stop smoking for at least 4 weeks. Self-help support, including books, manuals, text messaging and DVDs, involves structured interventions that may be introduced briefly to smokers by health professionals, but are primarily designed for motivated quitters to work through on their own. Self-help interventions are not likely to appeal to all smokers and do require a certain level of cognitive ability for successful use.

Outside of pregnancy there are more cessation interventions of proven efficacy available to assist smokers, including nicotine replacement therapy (NRT),18 bupropion (Zyban®, GSK)19 and varenicline (Champix®, Pfizer). 20 NRT works by substituting the nicotine inhaled in tobacco smoke, which is accompanied by many other toxins, for ‘clean’ medicinal nicotine (e.g. transdermal patches or lozenges). Using NRT after becoming abstinent permits the smoker to lessen or avoid withdrawal symptoms and, eventually, as the amount or dose of NRT reduces, these are eliminated. Bupropion is an antidepressant with an uncertain mechanism of action, but is thought to promote smoking cessation by antagonising nicotinic acetylcholine receptors. Varenicline is an alpha-4 beta-2 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor partial agonist; it binds to nicotinic receptors and is thought to act by preventing the pleasurable sensations that smokers experience after smoking, making them less likely to do so and, hence, more likely to achieve cessation. Unfortunately, neither varenicline nor bupropion is approved for use in pregnancy. Also, possibly owing to fears that either drug might cause fetal harm, there are insufficient studies in pregnancy to draw any conclusions about the efficacy of safety of either drug for use by pregnant smokers.

Nicotine is the active ingredient of NRT and its impacts in pregnancy have been much more thoroughly researched. 21 Nicotine is a known neurotoxin and may be expected to affect developing fetal nerve tissues. This may explain observed associations between behavioural problems and attention deficit disorder among smokers’ children. 22,23 However, while tobacco combustion creates and releases many potential fatal toxins in addition to nicotine, NRT delivers nicotine alone. Consequently, there is an international, expert consensus that maternal use of NRT in pregnancy should be safer for the fetus than continued smoking. 24 It should be noted that this consensus, while logical, is theoretically based and is not underpinned by research evidence. Nevertheless, this consensus has had an impact internationally on the use of NRT in pregnancy and has contributed to a relaxation in indications for NRT prescribing during pregnancy in some countries. For example, since 2003 in the UK, the British National Formulary25 (the manual used to guide prescribing in the UK NHS) has listed pregnancy as a ‘caution’ rather than a ‘contraindication’ to using NRT. Additionally, in 2005, the UK Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA) issued guidance that specifically stated that pregnant women who had not managed to stop smoking using other means could be prescribed NRT. Many other countries take similar approaches; the authoritative website, www.treatobacco.net, hosts all nations’ smoking cessation guidelines and the vast majority of those written in English recommend cautious use of NRT for smoking cessation in pregnancy. 26

Current evidence for nicotine-replacement therapy use in pregnancy

Health policy recommendations for NRT use in pregnancy have developed in the absence of scientific evidence. In 2004, when the study described in this report [the Smoking Nicotine And Pregnancy (SNAP) trial] was commissioned, only three trials had investigated NRT for smoking cessation in pregnancy27–29 and the largest of these29 was excluded from a later meta-analysis30 and Cochrane review31 because its design made it impossible to attribute treatment effects to NRT. Pooling of data from these three studies, including the trial which was not included in later reviews, suggested that NRT used in pregnancy had borderline effectiveness for reducing smoking in later pregnancy (pooled RR 0.94, 95% CI 0.89 to 1.00). 32 In addition, one of these studies had found that slightly heavier and, therefore, potentially healthier, infants were born to women who had been randomised to NRT. 27 While the SNAP trial was running, three further trials investigating the efficacy and safety of NRT for smoking cessation in pregnancy were published. 33–35 However, a systematic review and meta-analysis that included these three more recent trials and also the two previous relevant studies27,28 found no evidence that that NRT was effective for smoking cessation in pregnancy (pooled RR for cessation after NRT 1.63, 95% CI 0.85 to 3.14). 30 This lack of evidence for the use of NRT in pregnancy comes from trials conducted in Canada, the USA, Denmark and Australia, which randomised a total of 695 women. 27,28,33–35

Unfortunately, despite the knowledge that nicotine is potentially fetotoxic, there is little evidence available to assess whether or not using NRT in pregnancy is safe. Of the five trials above that reported before the SNAP trial concluded, only three monitored maternal or infant birth outcomes27,34,35 and none collected data on infants’ outcomes after delivery. Given this paucity of empirical data, meta-analyses investigating the impact of NRT on infants’ birth outcomes have been inconclusive30 and more data are required. In addition, as nicotine could be one of the tobacco smoke constituents responsible for the cognitive and behavioural problems seen in infants born to smokers,22 studies that assess the impact of NRT used for cessation in pregnancy on early infant outcomes are also needed. It remains likely that nicotine is not solely responsible for these adverse effects; indeed, it may have no such impacts, and other toxins in tobacco smoke could be partially, or perhaps even completely responsible for them. However, this should not be assumed.

In summary, smoking in pregnancy is an extremely harmful behaviour and an increasing public health problem internationally. There are only two cessation interventions of proven efficacy for use in pregnancy and no licensed drug cessation treatments have been shown to be safe or effective in pregnancy. There is a consensus in favour of using NRT in pregnancy, but NRT remains of unproven efficacy and its impacts on infants born to mothers who use it in pregnancy require determining. Consequently, the SNAP trial, a double-blind, randomised placebo-controlled trial of NRT used for smoking cessation in pregnancy, was planned and is described within this report.

Objectives

The overall aim of the study was to investigate whether or not NRT is more effective than placebo in achieving smoking cessation for women between 12 and 24 weeks pregnant, who currently smoke five or more cigarettes per day and who smoked at least 10 cigarettes per day before pregnancy.

The specific study objectives were to compare:

-

the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness for achieving biochemically validated smoking cessation of 15 mg per 16 hours transdermal nicotine patches with placebo patches in women at delivery

-

the effects of maternal NRT patch use with placebo patch use during pregnancy on (1) disability, behaviour and development and (2) respiratory symptoms in infants at 2 years of age.

Chapter 2 Methods

Trial design

This was a phase IV, multicentre, double-blind, randomised (1 : 1 allocation and stratified by site), placebo-controlled, parallel-group trial of standard-dose (15 mg per 16 hours) NRT patches. Participants were monitored from their recruitment at between 12 and 24 weeks’ gestation until the delivery of their babies and then followed up by questionnaire for a further 2 years.

Participants and recruitment

Eligibility criteria

Eligible women were aged 16–50 years, between 12 and 24 weeks’ pregnant, smoked at least 10 cigarettes per day before pregnancy and continued to smoke at least five cigarettes per day. The eligible women also had an exhaled carbon monoxide (CO) concentration of at least 8 parts per million (p.p.m.). They were excluded if they had contraindications to the use of NRT including severe cardiovascular disease, unstable angina, cardiac arrhythmias, recent cardiovascular accident or transient ischaemic attack, chronic generalised skin disorders or known sensitivity to nicotine patches, chemical or alcohol dependence, known major fetal abnormalities, or were unable to give informed consent. Women could enrol in the trial only once but could participate in other non-conflicting research projects.

Recruiting centres

Participants were recruited from seven hospital antenatal clinics in the Midlands and north-west England. Initially, these were at Nottingham University Hospitals NHS Trust City Hospital campus, Nottingham University Hospitals NHS Trust Queen’s Medical Centre (QMC) campus, Sherwood Forest Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust (King’s Mill Hospital) and University Hospital of North Staffordshire NHS Trust (City General Site). Three further sites were added later to improve recruitment rates: Mid Cheshire Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust (Leighton Hospital), East Cheshire NHS Trust (Macclesfield District General Hospital) and Derby Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust (Derby City General, later to become Royal Derby Hospital).

Research midwives

In each centre, research midwives (RMs) undertook all trial-related procedures. RMs were trained in research procedures by the trial manager with input from the chief investigator and attended monthly staff update meetings. In addition, Clare Mannion, one of the trial co-investigators and a UK expert trainer of smoking cessation professionals, provided the RMs with training, to English national standards, in delivery of behavioural support to pregnant women. 36

Recruitment and consent

We used three methods of identifying and recruiting eligible women who were interested in stopping smoking.

-

Community midwives usually ask women about smoking status at their booking appointment and then refer those who would like help to stop smoking to their local NHS SSS. In some recruiting areas, women referred to NHS SSS were asked if they would be interested in finding out about the trial and the RM contacted any who expressed interest. Those who were not interested or eligible for enrolment, but who wanted to stop smoking, were seen by the NHS SSS as per normal practice.

-

Leaflets containing brief information about the trial were sent to women before their antenatal clinic or routine ultrasonography scan appointments. Women attending these clinics were then asked to complete a screening questionnaire to identify those who were eligible and interested (see Appendix 1).

-

Some women who had seen information leaflets or posters advertising the study in hospitals contacted the RMs directly.

Potentially eligible women who expressed interest in the trial were given a participant information sheet (PIS) and, after having chance to consider this for at least 24 hours and discuss with a RM, gave their written informed consent before trial data were collected. In addition to trial participation, women were asked to give consent for researchers to have access to their and their child’s medical records, for information held by the NHS to be used to keep in touch with them and to follow their health status, and also for storage of blood samples for possible use in future research. For most trial participants, consent and baseline data collection took place in their homes.

Interventions

The only difference in interventions delivered to trial groups was in the type of transdermal patches allocated to women. In the intervention group, these were active nicotine patches (15 mg per 16 hours NRT transdermal patches), whereas women in the control group received visually identical placebo patches.

At enrolment, RMs delivered behavioural support lasting up to 1 hour. During counselling, RMs applied techniques to encourage cognitive and behavioural changes among smokers such that smoking cessation could be successfully achieved. The initial session focused on behavioural advice and tips for smokers, including preparation for quitting and how to avoid smoking lapses once a quit attempt had begun in addition to instruction and advice on how to use patches (which could be either placebo or nicotine). During the session, participants were required to set a quit date within 2 weeks from which follow-up was timed. A manual used by RMs to guide the support sessions (‘The SNAP trial’s guide to stopping smoking during pregnancy’: see Appendix 2) was written by Clare Mannion and included some techniques from the US ‘Smoking Cessation and Reduction in Pregnancy Treatment’ trials37 that were believed to be relevant to UK smokers. As is consistent with good smoking cessation practice, this manual, which contained tips and suggestions for becoming smoke-free, was left with women so that they could refer to it after their support session. Subsequently, participants were randomised to equal-sized groups receiving either a 4-week supply of 15 mg per 16 hours NRT transdermal patches or visually identical placebos (United Pharmaceuticals, Amman, Jordan), which women were instructed to start on their quit dates. One month after quitting, those not smoking, validated by CO measurement of < 8 p.p.m.,38 were issued with another 4-week patch supply if they wanted it. In addition to behavioural support delivered at enrolment, RMs provided three further behavioural support sessions to all participants. Telephone behavioural support was delivered on participants’ quit dates, at 3 days afterwards and at 1 month afterwards; those women who collected a second month’s supply of NRT also received face-to-face support from the RM at the time this was delivered to them. These sessions involved reinforcement of earlier behavioural sessions, with an added focus on ways of avoiding relapse now that quit attempts had begun.

Provision of additional behavioural support and nicotine-replacement therapy to trial participants and availability of nicotine-replacement therapy to non-participants

Prior to starting the trial, we visited local NHS SSSs in the recruiting areas and discussed their service provision, as it was intended that these would provide behavioural support to women enrolled onto the trial. Primary care trusts (PCTs) in all of the trial’s recruiting areas had NHS SSSs for pregnant women, but several PCTs had recently undergone local reorganisations and there was considerable variation in the delivery of cessation services. Some services were already issuing NRT to pregnant women, despite the absence of evidence for its effectiveness. We hoped to get agreement from PCTs that, for the duration of the trial, NRT would be issued only to pregnant women within the trial, thereby ensuring that local availability did not jeopardise recruitment and/or retention of participants or interpretation of trial findings. The outcome of these visits meant that, in most trial areas (all except Derby), women’s contact details were shared with their local NHS SSS, which agreed to contact participants and offer them additional behavioural support. They also agreed that they would not normally offer participants any non-trial NRT products. Women were encouraged to ask for further behavioural support as necessary, and RMs or NHS SSS staff, guided by the manual, delivered any additional support that participants required. In Derby, where participants’ contact details were not shared with the NHS SSS, RMs provided additional support. The provision of additional behavioural support to participants and the availability of NRT to participants and non-participants who contacted the NHS SSS are shown in Table 1, which illustrates the context in which trial recruitment occurred.

| Trial centre | PCTs hosting NHS SSS within the area of each trial centre | Provision of additional behavioural support | NRT availability within PCT | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Trial participants | Non-participants | |||

| Nottingham University Hospitals NHS Trust (City Hospital and QMC campuses) | Nottingham City PCT (Nottingham City New Leaf) | Nottingham City New Leaf (Stop Smoking) Service | Not offered or prescribed NRT; if any enquired about NRT, referred back to a trial researcher for further discussion | NRT still offered as judged appropriate to non-trial pregnant women |

| Nottinghamshire County PCT (Nottinghamshire County New Leaf) | Nottinghamshire County New Leaf (Stop Smoking) Service | NRT not prescribed to any pregnant women through the service for the duration of the trial | NRT not prescribed to any pregnant women through the service for the duration of the trial | |

| Derbyshire County PCT (few participants only from the Nottingham University Hospitals NHS Trust centres) | By RMs | No agreements made; NRT available via local NHS SSS | No changes to NRT provision; available via local NHS SSS | |

| Sherwood Forest Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust (King’s Mill Hospital) | Nottinghamshire County PCT (Nottinghamshire County New Leaf) | Nottinghamshire County New Leaf (Stop Smoking) Service | NRT not prescribed to any pregnant women through the service for the duration of the trial | NRT not prescribed to any pregnant women through the service for the duration of the trial |

| University Hospital of North Staffordshire NHS Trust (City General site) | Stoke PCT (North Staffordshire NHS SSS) | RMs until 1 month, then passed to North Staffordshire NHS SSS for further support if required | No NRT prescribed to women enrolled onto the trial | NRT prescribed only to pregnant women not eligible or not interested in participating in the trial |

| Mid Cheshire Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust (Leighton Hospital) | Central and Eastern Cheshire PCT (Central and Eastern Cheshire NHS SSS) | Central and Eastern Cheshire NHS SSS | All eligible women informed and referred to trial. NRT not offered or prescribed to any pregnant women enrolled in the trial | NRT initially not prescribed to any pregnant women; later changed so available to women not eligible or interested in participating in the trial |

| East Cheshire NHS Trust (Macclesfield District General Hospital) | Central and Eastern Cheshire PCT (Central and Eastern Cheshire NHS SSS) | Central and Eastern Cheshire NHS SSS | All eligible women informed and referred to trial. NRT not offered or prescribed to any pregnant women enrolled in the trial | NRT initially not available to any pregnant women; later changed so available to women not eligible or interested in participating in the trial |

| Derby Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust (Derby City General Hospital) | Derby City and Derbyshire County PCTs (Fresh Start) | By RMs | No agreements made; trial participants not referred to NHS SSS | No changes to NRT provision; available via local NHS SSS |

Randomisation and blinding

Eligibility criteria were entered into a secure online database before internet-based randomisation that was stratified by recruiting site and used a computer-generated, pseudorandom code using random permuted blocks of randomly varying size, with a 1 : 1 allocation ratio, which was created by the Nottingham Clinical Trials Unit (NCTU) and held on a secure server in accordance with their standard operating procedures. Following randomisation, the database issued participants with a unique identifier and allocated a trial treatment-pack number to them. Identically packaged treatments, previously prepared by one central pharmacy (QMC pharmacy, Nottingham University Hospitals NHS Trust), were dispensed by local pharmacies. All pharmacists, research staff and trial participants were blinded to treatment allocations.

In addition, during the follow-up period in the 2 years after ascertainment of the primary outcome at delivery, participants and anyone involved in following them up and entering data remained blind to the treatment allocation.

Data collection to delivery

Baseline

At baseline, RMs collected women’s demographic and contact details: ‘Heaviness of Smoking Index’,39 a measure of nicotine addiction recorded on a scale of 0 (lower) to 6 (higher nicotine addiction); number of daily cigarettes smoked before pregnancy; partner’s smoking status; gestation; ethnicity; age completed full-time education; parity; use of NRT in current pregnancy; height and weight. Women were also asked to provide an exhaled CO measurement, blood and saliva samples for cotinine estimation and a blood sample for future deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) extraction (any studies using the DNA samples would require further funding and relevant ethical approvals).

One month

One month after the quit date, RMs telephoned participants and asked for details about their smoking status. This included whether or not they had smoked since their agreed quit date and, if so, how often this had occured and whether or not they had smoked in the previous 24 hours. RMs also asked about the number of times they had received additional behavioural support and whether this had been face to face, by telephone or by mobile telephone text message; the number of trial patches they had used (i.e. adherence); and whether or not they had obtained and used any additional NRT outside of the trial. Those who reported not smoking were visited for CO validation and a saliva sample (for cotinine measurement) was obtained from any women who were still using trial patches and not smoking. Non-contactable women were sent a postal questionnaire.

Delivery

When participants were admitted to hospital in established labour prior to childbirth, or as soon as possible afterwards, as at the 1-month contact, RMs or delivery suite staff ascertained smoking status, use of trial and ‘non-trial’ NRT, including reported numbers of patches used and additional behavioural support received. Exhaled CO measurements and saliva cotinine samples were obtained from women who reported not smoking for at least 24 hours before delivery. RMs telephoned those missed while in hospital, and any who reported abstinence were visited at home for biochemical validation within a maximum of 4 weeks after delivery. Maternal and infant birth outcomes were obtained from medical records. Maternal outcomes included hypertension (> 140/90 mmHg) measured on two or more occasions during pregnancy, miscarriage or stillbirth, labour onset (spontaneous, induced or no labour), mode of delivery (spontaneous vaginal, assisted vaginal or caesarean section) and antenatal or postnatal hospital admissions. Infant data and outcomes collected at delivery or after discharge included date of birth, name, hospital and NHS numbers, sex, birthweight, gestational age at birth, number of births (with number and birth order if multiple birth), live birth or stillbirth, arterial cord-blood pH (either ≥ 7 or < 7), Apgar score (either ≥ 7 or < 7), intraventricular haemorrhage, neonatal convulsions, admissions to neonatal intensive care units (NICUs) and any congenital abnormalities.

Adverse event monitoring

During each contact with participants, RMs enquired about adverse events (AEs) or symptoms the participant had experienced. RMs also obtained this information from monthly examination of medical records. They then summarised the descriptions in the case report forms and on the study database. Descriptions were used to code the AEs according to standard terms in the Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities (MedDRA®) version 13.1 [www.meddra.org/; MedDRA is the international medical terminology developed under the auspices of the International Conference on Harmonisation of Technical Requirements for Registration of Pharmaceuticals for Human Use (ICH). MedDRA trademark is owned by International Federation of Pharmaceutical Manufacturers and Associations on behalf of ICH]. The incidence of events was analysed according to the MedDRA System Organ Class categorisation and preferred terms. Information about deaths after delivery was obtained from the NHS Health and Social Care Information Centre’s Data Linkage Service (previously Office for National Statistics) with whom all trial participants and their infants had been flagged. After starting the trial, it was realised that many relatively common pregnancy-related events were being reported as serious adverse events (SAEs), including pregnancy-related hospital admissions, premature birth and LBW and, on clinical review, none of these had been considered to be related to the study drug. The Trial Steering Committee (TSC) and the sponsor, therefore, advised that it would be appropriate to amend the protocol so that only maternal and fetal/infant deaths and hospital admissions unrelated to the underlying pregnancy would be reported as SAEs, and ethical approval was received for this. We continued to collect and monitor these along with other AEs, and the Data Monitoring Committee (DMC) reviewed data showing the distribution of all AEs and SAEs within trial groups at their meetings.

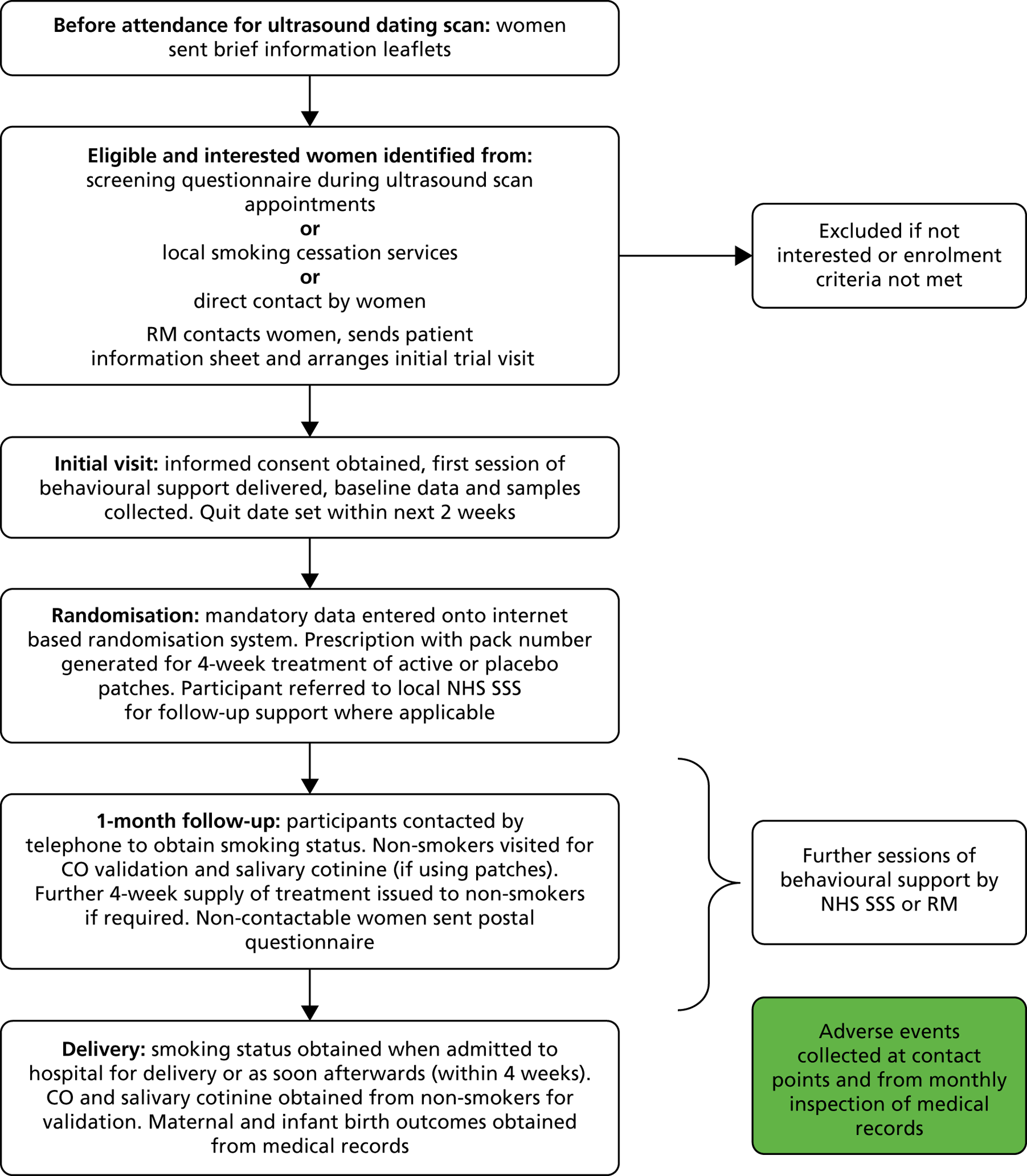

Figure 1 is a flow chart showing the data collection process from recruitment until delivery.

FIGURE 1.

Trial flow from recruitment to delivery.

Data collection and follow-up after delivery

After primary outcome data were collected, participants were followed up by postal questionnaire at 6 months, 1 year and 2 years after delivery of their infants. Questionnaires were not sent after maternal or infant deaths, if no birth details were available, if the participant had withdrawn consent for follow-up, or if no contact details could be obtained for the participant and if they were not registered with a general practitioner (GP). The NHS Health and Social Care Information Centre sent the trial office a report including information on any participant and infant deaths every 3 months. However, because of a delay in receiving the death report, a questionnaire was sent inadvertently to a participant whose infant had died; we subsequently sent the NHS Health and Social Care Information Centre a list of participants and infants who were due to be sent questionnaires for them to check every month. For non-respondents, or if questionnaires had been returned undelivered, the trial office contacted alternative family members using contact details that the participant had provided when they enrolled onto the trial and, if necessary, the participant’s GP or PCT were contacted to obtain their current contact details. During the follow-up period in the 2 years after ascertainment of the primary outcome at delivery, all those involved in following-up participants and in entering data remained blind to the treatment allocation.

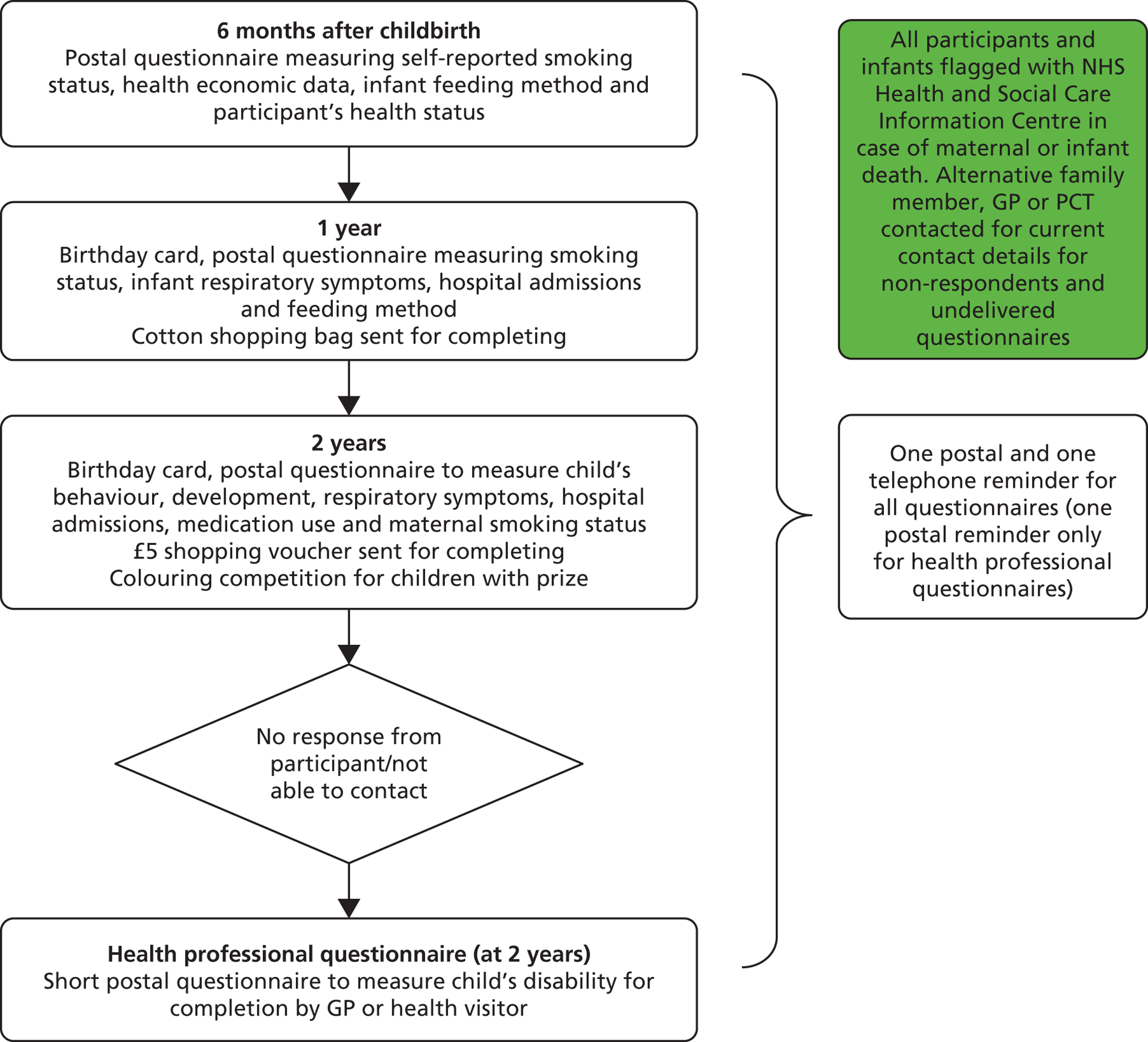

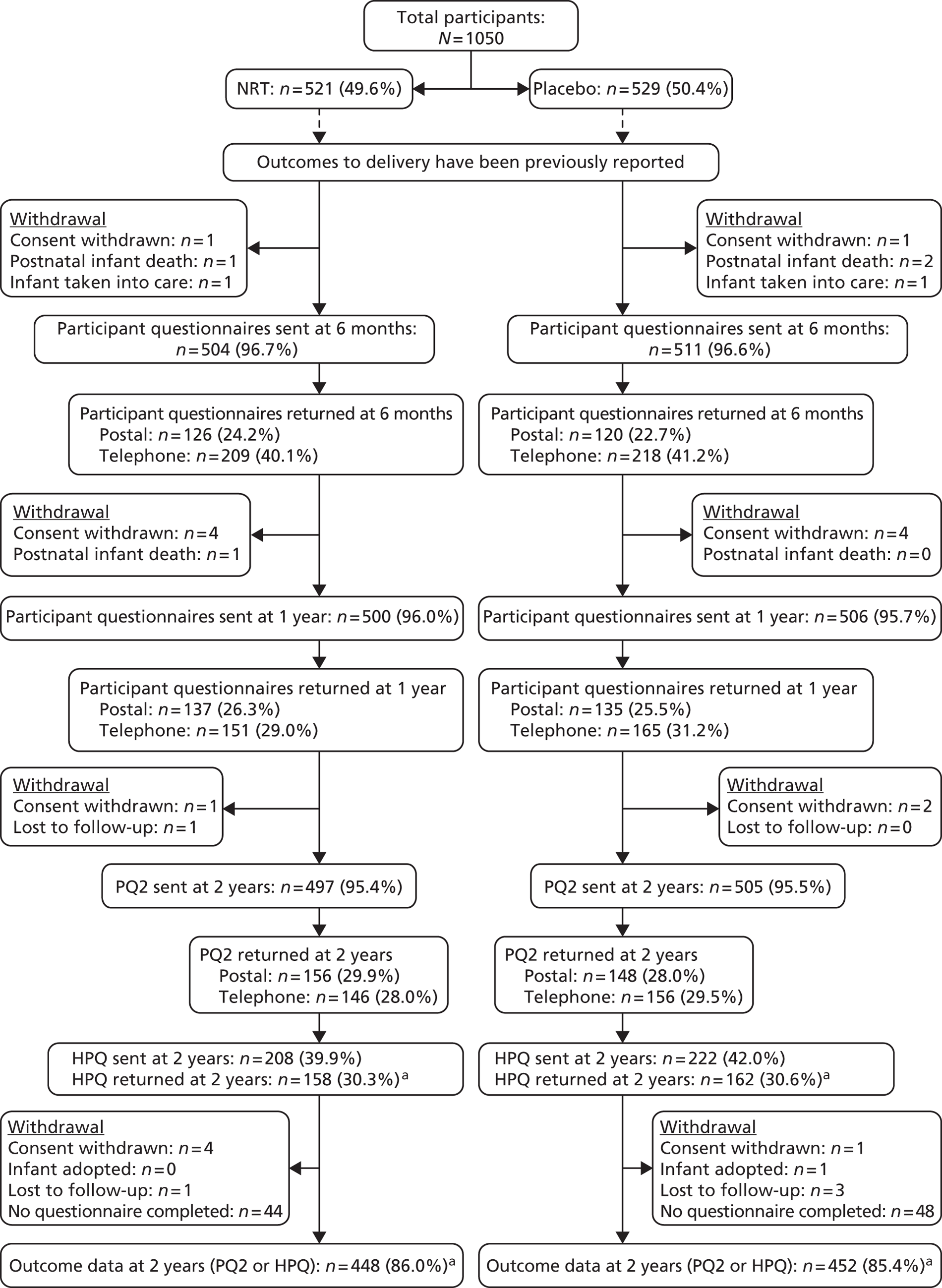

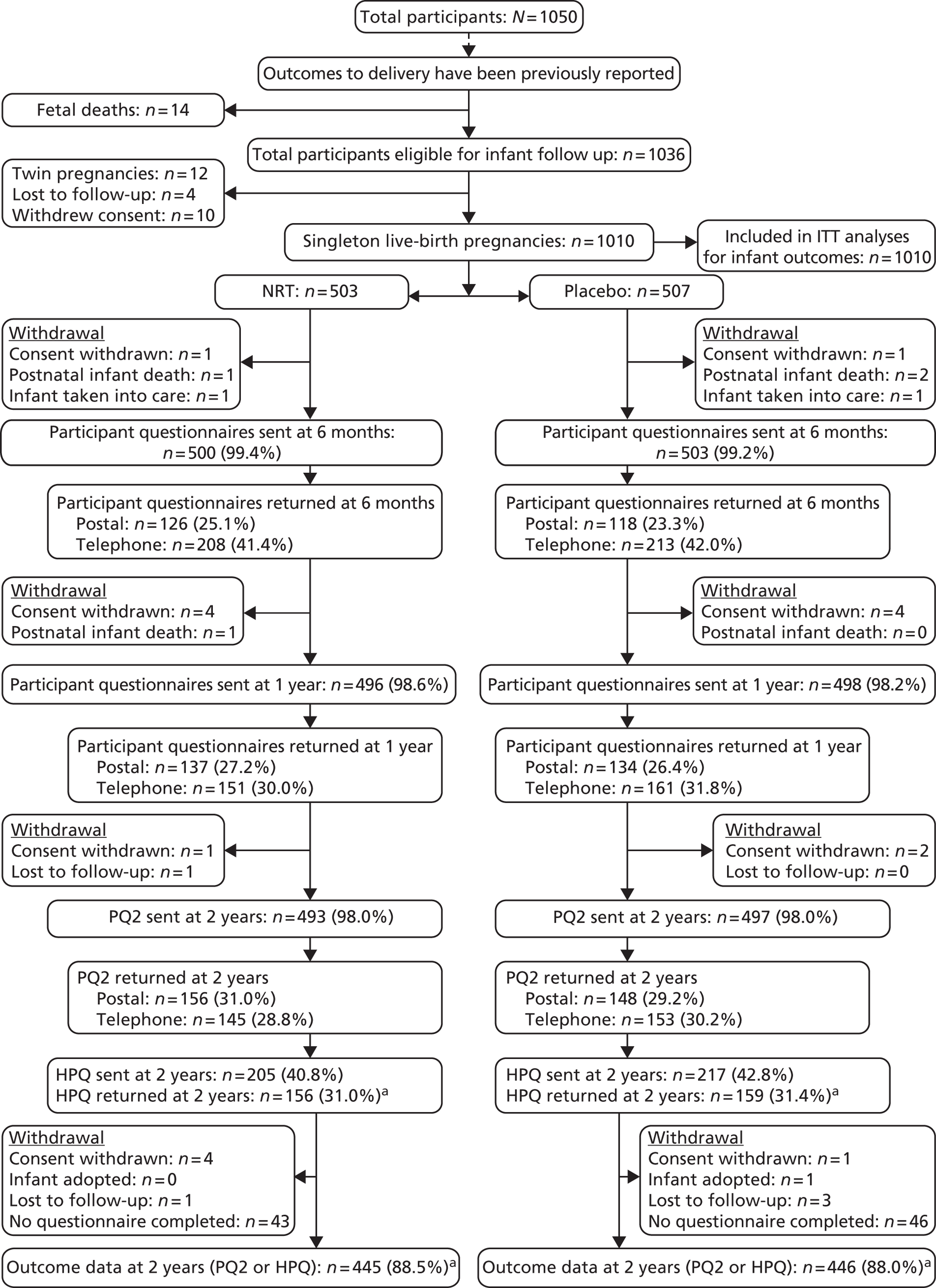

A flow chart outlining the follow-up process from delivery until the infants’ second birthdays is shown in Figure 2.

FIGURE 2.

Trial follow-up from delivery to infants’ second birthdays.

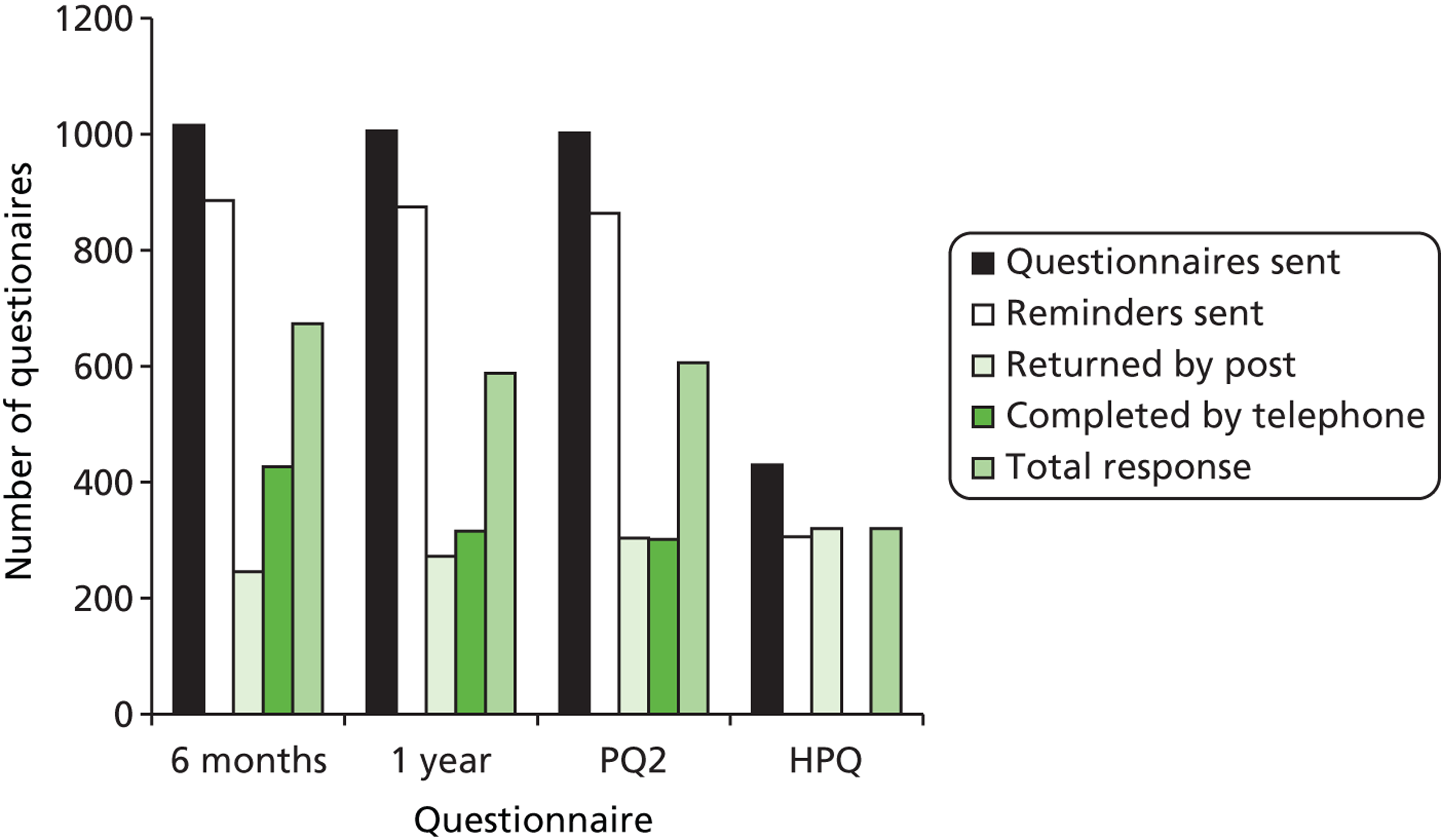

The evidence base for questionnaire design was taken into account when composing instruments40 and the following evidence-based methods to improve postal returns of questionnaires were used to maximise response rates. 41 At each follow-up point, participants were sent a postal questionnaire followed by one postal reminder after 2 weeks. After a further 2 weeks, participants were telephoned and asked to complete the questionnaire over the telephone with an appointment made to call them back when necessary. To maintain contact between researchers and participants, the trial office sent greetings cards following childbirth, at Christmas and on the child’s first and second birthdays and participants were sent cards reminding them to inform the team of any address changes. At 1 year, a cotton shopping bag was sent to participants on completion of the questionnaire; at 2 years, participants were given a £5 shopping voucher for questionnaire completion and there was a colouring competition that children of respondents could enter. The colouring competition had a £50 shopping voucher prize, with a winner chosen three times per year.

Six months after childbirth

The following information was collected from participants 6 months after delivery: current smoking status, smoking status since childbirth, maternal use of NRT and NHS SSSs since childbirth, length of any maternal hospital inpatient stay after delivery lasting > 24 hours, length of any infant inpatient stay in special care after birth, numbers of additional infant hospital admissions for respiratory illness or other causes, infant feeding method and a health status measure – the European Quality of Life-5 Dimensions (EQ-5D). 42

One year after childbirth

A shorter questionnaire was sent at 1 year, primarily to maintain contact with the participant, but also to collect the following information: current smoking status, smoking status since birth of infant, infant’s respiratory symptoms, infant hospital admissions for respiratory illness and other causes, and infant feeding method.

Two years after childbirth

At 2 years, a questionnaire sent to participants, the 2-year ‘participant questionnaire’ (PQ2) asked about maternal smoking behaviour and infant development. The PQ2 used items from the Ages and Stages Questionnaire®, Third Edition (ASQ-3™),43,44 which has been developed for assessing child development at 2 years and is valid for use from 23 months until 25 months and 15 days. It was designed to be completed by parents and to distinguish between children with suspected developmental delay and those for whom development is within the normal range. In a US population, the ASQ-3 has been reported to have a sensitivity of 92.2% and a specificity of 71.9% for detecting developmental delay at 24-months. 45 With permission from the authors and publishers, the wording of some questions was slightly adapted for our UK population. Items 1–30 on the PQ2 consisted of all 30 ASQ-3 items on child development covering five domains: communication, gross motor, fine motor, problem solving and personal–social development. Seven additional PQ2 items (i.e. PQ2 items 31–36 and 44), also taken from the ASQ-3, were mixed ‘yes’ or ‘no’/free text questions investigating both general and specific parental concerns relating to infant health and development. The PQ2 also contained items that were not from the ASQ-3 asking about infant hospital admissions, parental reports of infants’ respiratory symptoms and any medication taken for these.

Health professional questionnaire

If, at 2 years, participants did not respond to the PQ2 questionnaire, the health professional questionnaire (HPQ) was posted to their GPs. This shorter questionnaire was designed to be easily completed using medical or health visitors’ records and health professionals completing HPQs required little knowledge of the infants. If GPs could not complete HPQs, they were asked to forward these to health visitors. The HPQ contained items that corresponded to those on the PQ2 and were also intended to measure children’s disability and general health in a manner consistent with the ASQ-3. 46–48 This included open-response questions that corresponded to ‘non-domain’ ASQ-3 items included on the PQ2.

For any participants for whom we received both the completed PQ2 and HPQ, only responses from PQ2 were used in analyses.

The system we used to map the question responses to outcomes is outlined in the Derivation of composite ‘impairment’ outcome for infants section and in the statistical analysis plan (SAP) (this can be accessed at http://eprints.nottingham.ac.uk/3283/).

Outcome measures and definitions

Primary outcome to delivery

The primary outcome was self-reported, prolonged and total abstinence from smoking between the quit date and delivery, validated by exhaled CO and salivary cotinine (COT) at childbirth. Occasional minor lapses (no more than five cigarettes in total between the quit date and delivery) were not counted as a return to smoking; this is consistent with standard criteria for assessing outcome in cessation studies. 49 CO readings of ≤ 8 p.p.m. and COT of < 10 ng/ml indicated not smoking. 38 The method used for deriving the primary outcome from responses at 1 month and delivery is detailed in Box 1.

For a positive response (i.e. abstinent from smoking), the following were required:

at 1 month: ‘smoked since quit date’ = ‘no’ or ‘missing’ or ‘how often have you smoked’ = ‘five times or less’ or ‘at least weekly but less than daily’ or ‘missing’ (i.e. any response other than ‘on most days or frequently’)

and

at delivery: ‘smoked in last 24 hours’ = ‘no’ and ‘smoked since quit date’ = ‘no’ and CO result is between 0 and 8 and/or COTa,b < 10 ng/ml or ‘how often have you smoked’ = ‘five times or less’ and CO result is between 0 and 8 and/or COT < 10 ng/ml.

a Some participants will only have CO measurements and, for these women, readings in the stated reference range are defined as a positive primary outcome (even without COT). Most trial participants will have both CO and COT measurements and, for these women, BOTH readings must fall within defined ranges to count as having a positive outcome.

b At the outset of the trial, CO only was used to validate abstinence from smoking at delivery, but at DMC/TSC request this was changed and COT was added. Consequently, for most participants, both CO and COT were available at delivery. Therefore, either CO or COT could be used individually for validation, but if both were available then they both needed to indicate abstinence for a positive outcome.

Secondary outcomes

-

Smoking outcomes monitored until delivery

-

self-reported, prolonged abstinence from smoking between the quit date and 1 month

-

self-reported, prolonged abstinence from smoking between the quit date and 1 month with biochemical validation (exhaled CO) (this outcome was not listed in the trial protocol).

-

self-reported, prolonged abstinence from smoking between the quit date and delivery

-

self-reported, prolonged abstinence from smoking between the quit date and delivery, with biochemical validation of this at both 1-month follow-up and delivery

-

self-reported smoking cessation for the previous 24-hour period at delivery validated by exhaled CO and saliva cotinine estimation.

-

-

Smoking outcomes monitored after delivery

-

self-reported, prolonged abstinence from smoking between the quit date and 6 months after delivery

-

self-reported smoking cessation for the previous 7-day period at 6 months after delivery.

-

-

Birth and maternal outcomes

-

miscarriage (non-live birth prior to 24 weeks’ gestation) and stillbirth (non-live birth at 24 weeks’ gestation or later)

-

neonatal death (i.e. from live birth to 28 days)

-

post-neonatal death (29 days to 2 years)

-

individualised birthweight z-score (i.e. birthweight adjust for gestational age, maternal height, maternal weight at booking and ethnic group)

-

unadjusted birthweight and birthweight as z-score

-

Apgar score

-

cord blood pH

-

gestational age at birth

-

intraventricular haemorrhage

-

neonatal enterocolitis

-

neonatal convulsions

-

congenital abnormality

-

NICU admission

-

infant ventilated > 24 hours

-

elective termination

-

elective termination undertaken for fetal morbidity judged incompatible with fetal/infant survival

-

maternal mortality

-

mode of delivery

-

hypertension in pregnancy (> 140/90 mmHg at least twice).

-

Outcomes 2 years after delivery

-

Infant impairment

-

Defined as presence of disability and/or behaviour and development problem(s) and categorised as:

-

survival with no impairment: two of the outcomes in the protocol at 2 years were (1) behaviour and development and (2) disability. These outcomes were combined for analysis and reporting purposes and the mapping of protocol outcomes on to those listed above is fully described in the next section (see Derivation of composite ‘impairment’ outcome for infants) and the SAP (http://eprints.nottingham.ac.uk/3283/)

-

survival with definite impairment (this outcome was not listed in the trial protocol)

-

survival with suspected impairment (this outcome was not listed in the trial protocol).

-

-

Survival with ‘no impairment’ was the primary outcome at 2 years.

-

-

Infant respiratory symptoms

-

Smoking outcomes

-

self-reported, prolonged abstinence from smoking between quit date and 2 years after delivery

-

self-reported smoking cessation for previous 7-day period at 2 years after delivery.

-

Derivation of composite ‘impairment’ outcome for infants

Overview

Full details of how these outcomes were derived from questionnaire responses can be found in the SAP (http://eprints.nottingham.ac.uk/3283/), but a summary follows. This process was discussed with the TSC and the independent TSC statistician approved the SAP before analyses began.

Rationale

At the outset of the trial, we proposed two discrete infant outcomes at 2 years and these were (1) behaviour and development and (2) disability. However, there was no expectation that infants born within the trial would have particularly high rates of disability or developmental problems; therefore, when preparing the SAP for the follow-up analyses, the decision was taken to amalgamate data on both outcomes into one composite outcome. The rationale was that this would permit the trial to demonstrate with greater confidence whether or not NRT is safe for use in pregnancy, as judged in terms of infant development at 2 years.

Impairments were categorised in a mutually exclusive way so that all infants for whom questionnaires had been returned were allocated to just one of the following categories: ‘survival with no impairment’, ‘definite developmental impairment’ or ‘suspected developmental impairment’. This categorisation was based on responses to selected PQ2 and HPQ items, including the ASQ-3 domains. The scoring of the domains is explained in the following section [Scoring of Ages and Stages Questionnaire (2-year participant questionnaire) domain scores], followed by an explanation of how these domain scores and other PQ2/HPQ responses were collated to form outcomes. In some cases, one or more members of the research team inspected hard copies of questionnaires to allocate outcomes after making judgements about free-text responses and, in all such cases, assessors were blind to participants’ treatment allocations.

Scoring of Ages and Stages Questionnaire (2-year participant questionnaire) domain scores

Ages and Stages Questionnaire items from the PQ2 that are components of ASQ-3 domains were scored and these individual item scores were summed to give overall ‘domain’ scores, as described in the ASQ-3 User Guide. 45 Overall ‘domain’ scores were then compared with standard thresholds/cut-off points to determine whether domain scores should be categorised as ‘normal’, ‘abnormal’ or ‘borderline’. In clinical practice, any infants with ‘abnormal’ scores for any ASQ-3 domain would be considered to have ‘failed’ the ASQ-3 and would be recommended to undergo a more detailed assessment for development delay and those with borderline scores would be closely monitored.

Primary outcome: survival with no impairment

We classified infants as having ‘survived with no impairment’ if scores were normal for all ASQ-3 domains included on the PQ2 AND no problems were reported in PQ2 items 31–35 (i.e. free-text response questions also taken from the ASQ-3). If the PQ2 was not completed but a HPQ had been returned, this was used instead and ‘survival with no impairment’ was considered to have occurred when no HPQ responses indicated potential developmental problems.

Definite and suspected impairment

-

‘Definite’ developmental impairment: we classified infants as having developmental impairment if scores were at or below the cut-point in any ASQ-3 domain(s) or, if no participant questionnaire had been completed, if the HPQ indicated severe problems for any of questions 1–4 and/or severe disability was indicated by the response to question 9 and/or severe development delay was indicated in response to question 10.

-

‘Suspected’ developmental impairment: we classified infants as having suspected developmental impairment if all ASQ-3 scores were above the cut-point, but one or more domains scores fell within the borderline range and/or this classification was used if responses to either the PQ2 or HPQ reported concerns about developmental impairment that were judged to represent potential impairment. ‘Yes’ responses to PQ2 items questions 31–37 or HPQ questions 1–6 were examined by the research team; if these were judged to potentially reflect valid developmental impairments, infants were placed in the ‘suspected impairment’ category and/or any response stating that a child had mild or moderate disability on HPQ question 9 and/or mild or moderate development delay on HPQ question 10 was classed as suspected developmental impairment.

It should be noted that HPQ/PQ2 items dealing with feeding and behaviour problems were not used in derivation of these early child outcomes; these kinds of problems are frequently reported and have a variety of causes. A priori, we decided not to consider reports of these problems as indicative of impairment. In addition, as questions 1–4 were yes/no responses with free text, the severity of problems could be difficult to establish. Therefore, we used caution and if there were doubts about the severity of problems we classified them as ‘suspected’ impairment.

Derivation of infant respiratory problems

Infants were judged to have a respiratory problem if, at 2 years, any of questions 38–42 of the PQ2 and/or question 7 of the HPQ indicated this. On the PQ2, these questions included hospital admissions for respiratory problems, problems with chest or breathing (yes/no, free text), wheeze or whistling in chest (yes/no, frequency), doctor diagnosed asthma (yes/no), asthma medications taken (yes/no, inhaler description free text). The HPQ asked whether or not the child has problems with their chest or breathing (yes/no, free text).

Maternal smoking outcomes after delivery

We assessed these in a manner consistent with Russell Criteria49 and with smoking outcomes reported at delivery. The derivation of smoking outcomes is described below:

-

Positive outcome for ‘Self-reported, prolonged abstinence from smoking between quit date and 2 years after delivery’: the participant must have met the criteria for prolonged abstinence at delivery (i.e. positive primary outcome), plus one of the following responses

-

‘smoked since 2-year-old was born’ = ‘No’

-

or

-

‘how often have you smoked’ = ‘five times or less’

-

If any participant questionnaires were completed at 6 and/or 12 months, these should all have had the same responses as above for a positive outcome.

-

-

Smoked in last week (self-reported smoking cessation for previous 7-day period at 2 years after delivery):

-

‘smoked since two year old was born’ = ‘No’

-

or ‘smoked in last week’ = ‘No’

-

-

Smoked in last 2 years (self-reported prolonged abstinence from smoking between delivery and 2 years) (this outcome was not listed in the trial protocol)

-

‘smoked since two year old was born’ = ‘No’

-

or

-

‘how often have you smoked’ = ‘5 times or less’

-

If any participant questionnaires had been completed at 6 and/or 12 months, these should all have had the same responses as above for a positive outcome.

-

Outcomes collected on 6-month and 1-year questionnaires

Smoking status and respiratory outcome items were included on 6-month and 1-year questionnaires. These were not listed in the study protocol and only smoking outcomes are reported later. In addition, at 6 months, the EQ-5D questionnaire items were also used and questionnaire items asked about length of stay in hospital and/or special care unit after delivery, infant hospital admissions and medications taken; these data were intended for the Health economics analysis (see Chapter 4).

The 6-month and 1-year questionnaires included questions about breast and bottle-feeding and, again, these items were not included in the original study protocol and data are not presented in this report.

Sample size

We planned to recruit 525 women into each arm of the study. A trial with 500 women in each arm would detect an absolute difference of 9% in smoking cessation rates between the two groups immediately before childbirth, with a two-sided significance level of 5% and a power of 93%. It was anticipated that up to 5% of women would be lost to follow-up, and the sample size (of 500) was inflated by a factor of 1.05 to allow for this. This size of study allowed smaller treatment effects to be detected with lower power. For example, there would be 80% power to detect an absolute difference in cessation rates of 7%.

A Cochrane review showed that approximately 10% of women who are still smoking at the time of their first antenatal visit stop smoking with usual care, and a further 6–7% will stop as a result of a formal smoking cessation programme using intensive behavioural counselling. 32 Therefore, in our control group (placebo plus intensive behavioural counselling), a smoking cessation rate of around 16% was anticipated. The most recent Cochrane review of the efficacy of NRT outside of pregnancy had reported a treatment effect (OR) for transdermal patches of 1.74 (95% CI 1.57 to 1.93). 50 Consequently, if NRT were similarly effective in pregnancy, one could expect a smoking cessation rate of approximately 25% in the treatment group (NRT plus intensive behavioural counselling).

Tables in the SAP show the consequences to study power if the treatment effects in the trial were smaller or overall quit rate was lower than expected (http://eprints.nottingham.ac.uk/3283/).

Statistical methods

The SAP for the primary analysis was finalised before any analyses started. For analyses to be conducted on follow-up data, the analysis plan was added to and finalised during the follow-up period, before any follow-up analyses commenced. (The SAP containing both primary and follow-up analyses can be found at http://eprints.nottingham.ac.uk/3283/). Data cleaning and preparatory work were performed blind to study arm allocation and all analyses of outcomes recorded at delivery were performed blind to study arm allocation, with treatment codes revealed after these were completed. However, it was not possible to perform all follow-up analyses blind. Statistical analyses were performed using SAS software version 9.1.3 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA) and Stata/SE version 11.2 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA).

Analysis to primary outcome point (delivery)

Analysis was on an intention-to-treat (ITT) basis and participants who, for any reason, had missing outcome data were assumed to be smoking. The proportion of women who reported prolonged abstinence from smoking immediately before childbirth was compared between treatment groups by logistic regression and adjusted for recruitment centre as a stratification variable. Statistical significance was assessed using the likelihood ratio test. The primary analysis adjusted for no further variables as multivariate analysis results, and therefore overall conclusions, can be sensitive to decisions concerning which variables to adjust for and how these are specified. Nevertheless, we planned a secondary analysis adjusting for baseline COT (continuous variable), maternal education (in years) and partners’ smoking status (binary variable), as adjusting for potentially important prognostic factors can improve the precision of treatment effect estimates. 51 Other smoking cessation outcomes were analysed similarly.

Fetal and maternal birth outcomes were compared on an ITT basis. For binary outcomes, ORs were obtained using logistic regression adjusted for recruitment centre and also using the likelihood ratio test (with Fisher’s exact test used and stratification by centre ignored when numbers of events were small). For continuous outcomes, we compared means between groups with adjustment for recruitment centre using multiple linear regression.

For fetal outcomes, primary analysis was of singleton births only to allow for the fact that observations will be non-independent and that non-singleton births are likely to have different birth outcomes. However, we undertook a sensitivity analysis including multiple births, with clustering of outcomes accounted for using an approach previously published. This adapts the methodology previously created for use with cluster randomised controlled trials (RCTs), assuming that each woman is regarded as the ‘cluster’ and her number of offspring the cluster size. 52

In all analyses, a p-value of < 0.05 was taken to indicate statistical significance and 95% CIs were calculated.

Analysis at the 2-year follow-up point

The ASQ-3 does not require adjustment of an infant’s age to allow for prematurity once he or she reaches 24 months of age; therefore, as the questionnaire was sent shortly before the child’s second birthday, no adjustment to infant ages was made in analyses.

Maternal characteristics at baseline and delivery and infant birth outcomes at delivery were compared between those participants and infants who did and did not have outcomes ascertained at 2 years after delivery. We also compared maternal and infant characteristics according to whether follow-up at 2 years was by PQ2, HPQ or neither.

Analysis of early childhood outcomes was on an ITT basis with participants analysed in the treatment groups to which they were randomised. Participants with no live birth (i.e. miscarriage, stillbirth or elective termination) or those where the pregnancy outcome was unknown were excluded from the ITT analysis, but postnatal infant deaths were included in the denominator for developmental outcomes. The primary analysis was restricted to singleton births to allow for the fact that observations will be non-independent and that multiple births may have very different outcomes. For the primary outcome, survival with no impairment, a complete case analysis was compared with an analysis using multiple imputation to deal with missing values. Multiple imputation was carried out using the ‘mi’ commands in Stata and in our multiple imputation we included all of the complete baseline and the treatment code, and used 20 imputations. Using this approach, multiple imputation was also used for the other developmental outcomes: suspected and definite developmental impairment. The infant impairment and respiratory outcomes at 2 years were analysed as binary indicators of presence or absence of the outcome. The ORs for the effect of treatment group were obtained by logistic regression adjusting for centre as the stratification factor. In a subsidiary analysis, multiple births were included and clustering accounted for by the same method as in analysis at delivery. We also conducted sensitivity analyses comparing the results of analyses based on parental responses only and those based on a combination of parental and health professional responses.

Smoking outcomes were also analysed on an ITT basis, with all women analysed in the treatment groups to which they were randomised and all non-respondents assumed to be smoking. ORs for the effect of treatment group on smoking cessation outcomes were also obtained by logistic regression. As at delivery, the primary analysis adjusted only for centre, but we carried out sensitivity analysis that also adjusted for baseline COT, partner’s smoking status and age at finishing education.

We tested the assumption that those missing at follow-up were smokers by exploring alternative associations for the relationship between smoking status and ‘missingness’. 53 In this analysis, we defined the OR for the association between quitting and being missing as the informatively missing odds ratio (IMOR) and we looked at the effect on the size of the treatment effect on smoking abstinence outcome by varying the size of this OR between 0 and 1. In the main analysis, the assumption that those missing at follow-up are smokers is equivalent to assuming that IMOR equals 0 (i.e. that all those who are missing are smokers). We altered this OR up to IMOR equals 1, which is equivalent to assuming that there is no association between being missing data and smoking status. We carried out this analysis using the mean score method to estimate the treatment effect under the pattern mixture model, logit[E(y|r,my)] = α1 + β1r + myδ, where my is an indicator of whether the outcome is missing or otherwise, r is the treatment effect, and exponential (δ) [the OR between outcome y and my (IMOR)] is varied in the range 0–1. 54 α1 and β1 are estimated using the subgroup with outcome data, missing values of y (the outcome) are replaced by invlogit(α1 + β1r + δ), the mean of this new y variable is calculated for the intervention and control arms (say a1 and a0), and ORs calculated from these mean values accordingly [a1/(1 – a1)]/[a0/1 – a0)].

Secondary analysis

A priori, we planned to investigate whether or not there was any relationship between self-reported nicotine patch use in pregnancy and the presence or absence of developmental impairment in infants at 2 years. For this, we conducted an exploratory regression analysis with absence of impairment at 2 years as the dependent variable and the number of nicotine patches women reported having used when asked at delivery as an explanatory variable. ‘Suspected’ and ‘definite’ impairment categories were combined into one group representing infants who did not have impairment-free survival at 2 years. We investigated the possibility that baseline maternal characteristics may have a confounding effect on any relationship and adjusted for confounders as appropriate. For those in the placebo group, we set adherence with nicotine patches as zero. Additionally, if data on adherence were not reported at delivery, we imputed 0 days use of nicotine patches.

Trial management and conduct

The trial was co-ordinated from a central trial office located within the University of Nottingham, with the day-to-day running supervised and organised by a local trial management group and trial manager. The trial was sponsored by the University of Nottingham and conducted in accordance with good clinical practice (GCP) guidelines. All research staff received GCP and research governance training in addition to the study-specific training. Monthly research staff meetings were held in Nottingham, which all RMs were encouraged to attend; the aim was to keep them motivated, updated and trained, as well as to give them the opportunity to network with each other.

In addition to GCP and research governance training, all RMs were trained to English national standards in delivering smoking cessation advice, with particular emphasis on the issues faced by pregnant smokers. RMs completed the 2-day training before they started recruiting, with additional refresher training during the trial. The general aim of training was to provide RMs with an understanding of the basic epidemiology of smoking behaviour, the motivations behind this, harm caused by smoking and environmental tobacco smoke exposure, why people smoke and key barriers to quitting experienced by those smokers who attempt cessation. Skills-focused sessions also aimed to equip RMs with the counselling skills required to help smokers to begin thinking differently about their habit (cognitive change) and to apply recognised techniques to overcoming their addiction (behavioural change). RMs were trained to put emphasis on the value of behavioural approaches for cessation in pregnancy, on the uncertainty regarding the efficacy of NRT and the inappropriateness of using either bupropion or varenicline in pregnancy. In addition, they were trained to counsel participants in the appropriate use of patches (i.e. as if all were issued with active patches) and to instruct them not to smoke or use non-trial NRT preparations in addition to trial medications.

The NCTU provided a web-based database and randomisation system, data management reports and MedDRA coding of AEs. The system was held on a secure server in the NCTU, had a full electronic audit trail and full back-ups of the database were made every 24 hours. Baseline and follow-up data were collected on paper case report forms (CRFs) or questionnaires and then inputted onto the database by the RM or trial administrator. The database included validation checks on data fields, whereby responses not meeting expected criteria would be flagged so that data entry errors were minimised. The trial administrator or trial manager checked all database entries contributing to the outcomes at delivery against the CRF and clarified any queries with RMs. In addition, 10% of follow-up questionnaires were checked against database entries.

The independent TSC and the DMC met once or twice per year to monitor and supervise the progress and conduct of the trial and to review any safety or data issues. The DMC received blinded outcome data each time it met. Stopping rules were established such that if quit rates in the whole sample fell below 4%, or if recruitment rates fell below 25% of the target, then they would consider recommending that the trial be stopped.

Oxfordshire Research Committee A granted national research ethical approval, with additional local approvals for each recruitment centre and Clinical Trial Authorisation (CTA) approval from the MHRA (CTA number: 03057/0002/001-0001). The protocol was published,55 with several approved amendments made to the original protocol after the start of recruitment; details of these amendments are given below (see Protocol amendments) and the final protocol can be found in Appendix 3. The trial was registered on the ISRCRN database (ISRCTN07249128) and was assigned a EudraCT number (2004-002621-46). The NHS National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Primary Care Research Network adopted the study.

Bulk supplies of the NRT and placebo patches were manufactured by United Pharmaceuticals, purchased at market rates and imported into the EU via Almac Ltd, Clinical Trial Services, Craigavon, Northern Ireland. QMC Clinical Trials Pharmacy at Nottingham University Hospitals NHS Trust managed quality control testing, packaging and labelling of participant packs. To ensure stability for the whole study period, the patches needed to be stored refrigerated at 2–8 °C before being dispensed to participants. However, as the drug was stable at temperatures of < 25 °C for 3 months, and only 1 month’s supply of patches was issued at a time, it was not necessary for participants to store them in a refrigerator.

Baseline and 1-month saliva samples were analysed at laboratories within the Centre for Oncology and Molecular Medicine, Division of Medical Sciences at the University of Dundee, UK, under the overall supervision of Professor Michael Coughtrie (a co-investigator). Baseline blood samples were analysed by ABS Laboratories Ltd, Welwyn Garden City, Hertfordshire, UK, and saliva samples taken at delivery were analysed by Salimetrics Europe Ltd, Newmarket, Suffolk, UK.

Protocol amendments

Brief details of protocol amendments made after the start of recruitment, but prior to breaking treatment allocation codes, are listed below.

-

We originally anticipated that women would be sent the PIS before their clinic appointments so that they could then be recruited and consented when they attended for their antenatal scan appointment. However, it was soon realised that, overall, this was not a practical option and that most women were being enrolled on home visits. Therefore, rather than posting the PIS to all women, we added the option of just sending leaflets containing brief information about the trial, with the full PIS later posted to women who had been identified and contacted using the screening questionnaire.

-

Small changes were made to the protocol to clarify trial processes and allow for minor variations in practice in the different centres due to different local arrangements in, for example, prescribing and dispensing practices, local clinic arrangements, follow-up cessation support and time spent in hospital after delivery.

-

Ambiguities in the primary outcome measure were addressed and clarified in the protocol, including the time window in which data collected could be used for analysis, how self-report and biochemical validation data of smoking cessation contributed to a positive primary outcome and what constitutes ‘prolonged abstinence from smoking’. Secondary outcomes were clarified to distinguish and define fetal death at different gestations, i.e. miscarriage and stillbirth.

-

We obtained ethical approval to send a ‘congratulations on the birth of your baby’ card to women after delivery.

-

The content of the questionnaires sent at 6 months, 1 year and 2 years after delivery was finalised and approved, along with a questionnaire to be sent to participants when they could not be contacted 1 month after their quit date. We also decided to include incentives of shopping vouchers and a colouring competition to help improve response rates for the 2-year questionnaires. 41

-

Once the trial started, we realised that as many pregnancy-related conditions required hospital admissions this was resulting in a large number of SAE reports, none of which were felt to be related to the study drug. Therefore, the sponsor and TSC recommended that we should extend the list of conditions in the protocol that did not need to be reported as a SAE (any deaths of the mother or fetus/infant were still reported). All these AEs were still collected and reviewed by the DMC so that unforeseen impacts of NRT could be monitored.

-

Following further stability data from the manufacturer of the nicotine and placebo patches used in the study, the shelf life was extended from 24 to 42 months.

Trial extensions

The HTA granted two time extensions to the application, adding a total of 12 months to the original length of the trial. This was necessary as the start of recruitment was slightly delayed and the overall recruitment period took 10 months longer than the original estimate of 24 months. Careful budgeting of trial resources funded the majority of this extension, but a small addition to the budget was also awarded.

Chapter 3 Results

Recruitment and follow-up of outcomes at delivery

Recruitment and flow of participants through the trial

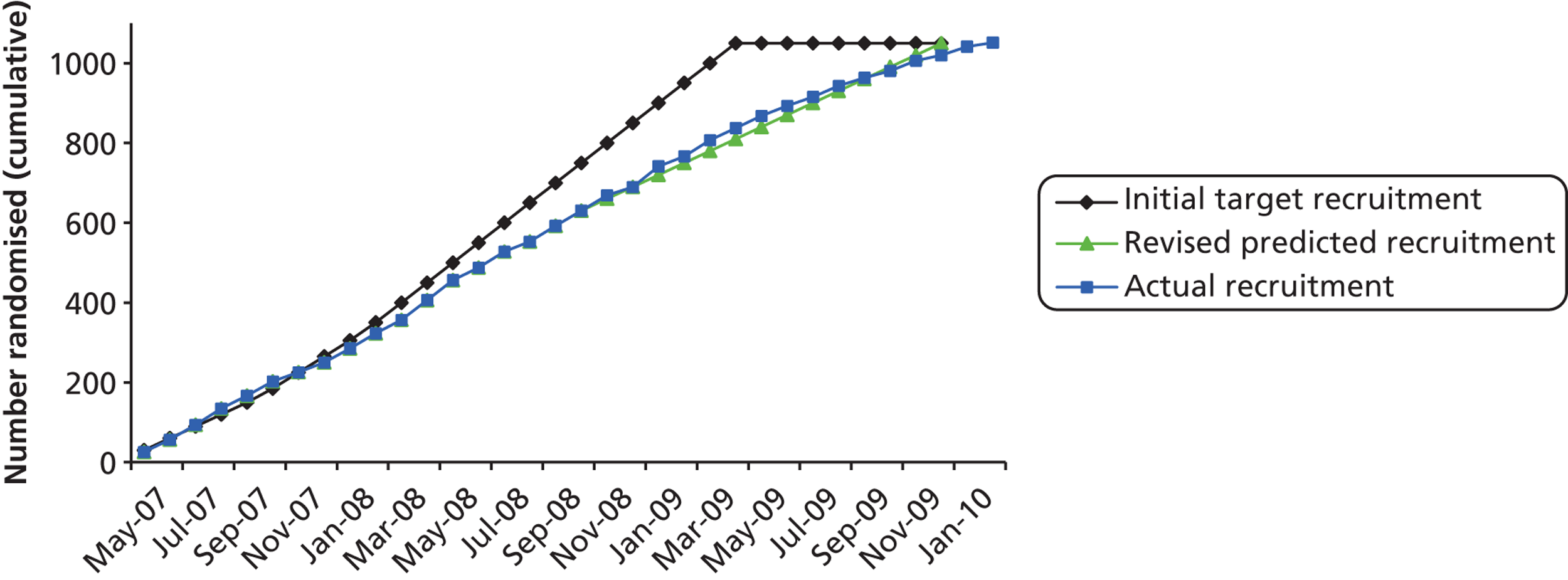

Participants were recruited between May 2007 and February 2010 (Figure 3 and Table 2). We initially estimated that recruitment would take 24 months, but after the first 6 months, target figures were revised in line with actual recruitment figures and the recruitment period extended by 10 months.

FIGURE 3.

Cumulative trial recruitment.

| Centre | NRT (n) | Placebo (n) | Total (N = 1050), n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nottingham University Hospitals NHS Trust (QMC campus) | 61 | 62 | 123 (11.7) |

| Nottingham University Hospitals NHS Trust (City Hospital campus) | 62 | 66 | 128 (12.2) |

| Sherwood Forest Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust (King’s Mill Hospital) | 108 | 108 | 216 (20.6) |

| University Hospital of North Staffordshire (City General Site) | 127 | 130 | 257 (24.5) |

| Mid Cheshire Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust (Leighton Hospital) | 83 | 84 | 167 (15.9) |

| East Cheshire NHS Trust (Macclesfield District General Hospital) | 40 | 40 | 80 (7.6) |

| Derby Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust (Derby City General – later to become Royal Derby Hospital) | 40 | 39 | 79 (7.5) |

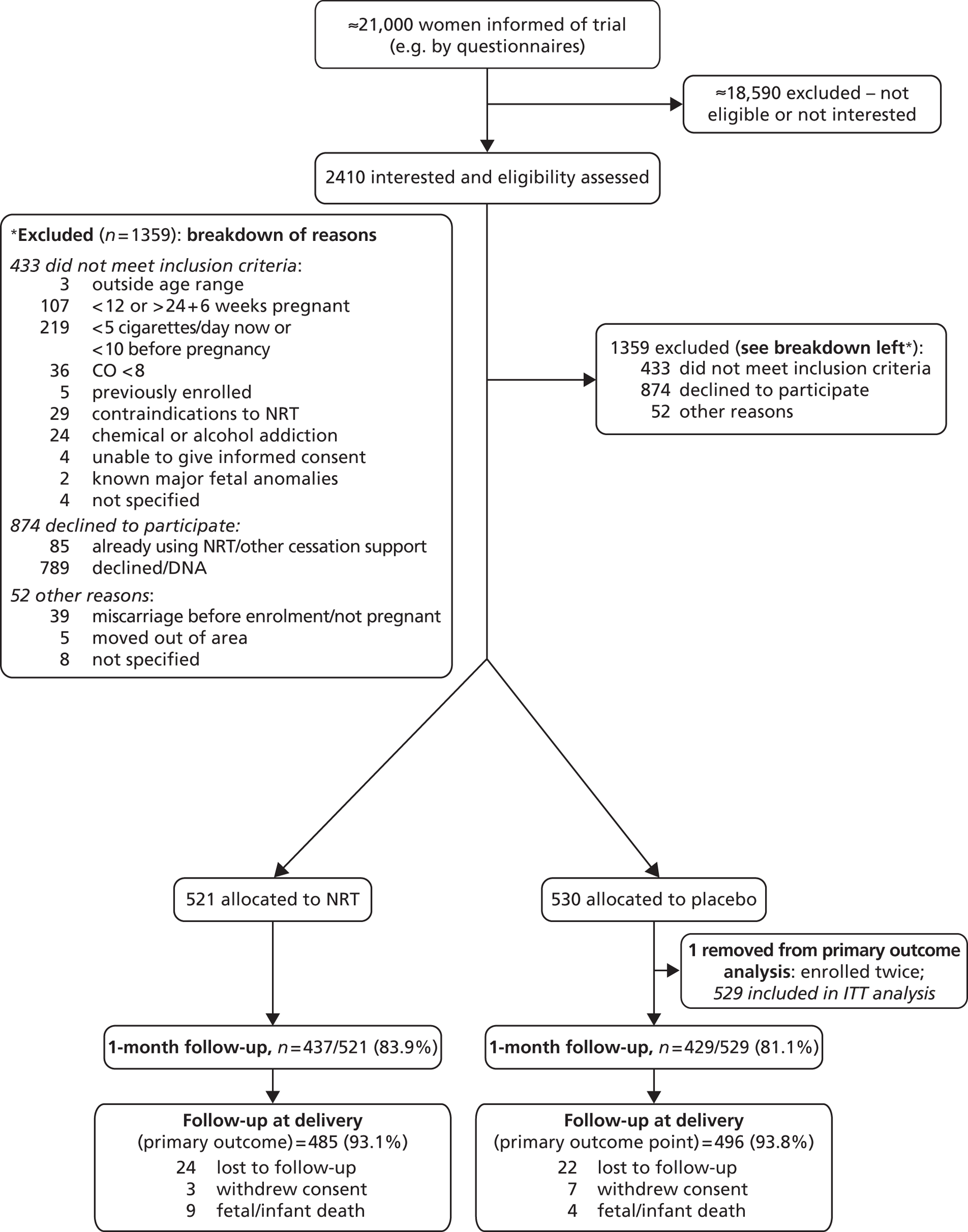

The Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) diagram (Figure 4) summarises the process of recruitment and flow of participants through the study to the primary follow-up point. Approximately 21,000 women were informed of the trial by questionnaires that were distributed and completed in antenatal clinics. The majority of these (around 18,590) were excluded without further contact either because the screening questionnaire showed that they were not eligible (usually because they were not smokers), or because they had no interest in joining the trial.

FIGURE 4.

The CONSORT diagram showing flow of participants to delivery. From Coleman et al. 56 Copyright © 2012 Massachusetts Medical Society. Reprinted with permission. DNA, did not attend.

Of the 2410 women who expressed interest in the trial and were assessed for eligibility, 1051 (43.6%) were randomised: 521 were assigned to receive NRT and 530 were assigned to receive placebo patches (see Figure 4). One woman was mistakenly enrolled for a second time in a subsequent pregnancy; her second enrolment in the placebo group was removed from all analyses, giving a final sample size of 1050 (529 in the placebo group).

Protocol breaches were discovered for 13 other participants, but after consideration of violation details it was decided that these were not serious and would have no significant impact on trial participants or the scientific integrity of the trial. These participants, therefore, remained in the trial and their data were used in analyses; details of these protocol breaches are given in Appendix 4.

Two additional problems affecting 27 participants occurred within one site pharmacy, but, again, these were judged to have no significant impact on participants or trial integrity, and details are given in Appendix 4.

Of 1050 pregnancies, 1038 were singleton and 12 were twin.

At 1 month after their quit date, 866 women (82.5%) provided outcome data and, of these, 573 (66.2%) responded by telephone, 19 (2.2%) responded by questionnaire and 274 (31.6%) attended face-to-face consultations with RMs.

At delivery, 981 (93.4%) participants provided smoking outcome data, but 46 (4.4%) who could not be contacted within the necessary time frame, 10 (1.0%) who withdrew consent and 13 (1.2%) who experienced fetal or infant death (including one elective termination) were not asked for their smoking status.

For most participants who reported that they were non-smokers, biochemical validation was obtained. The validation rates at 1 month were 89% (116/131) in the NRT group and 85% (63/74) in the placebo group. At delivery, validation rates were 89% (58/65 women) in the NRT group and 92% (45/49) in the placebo group.

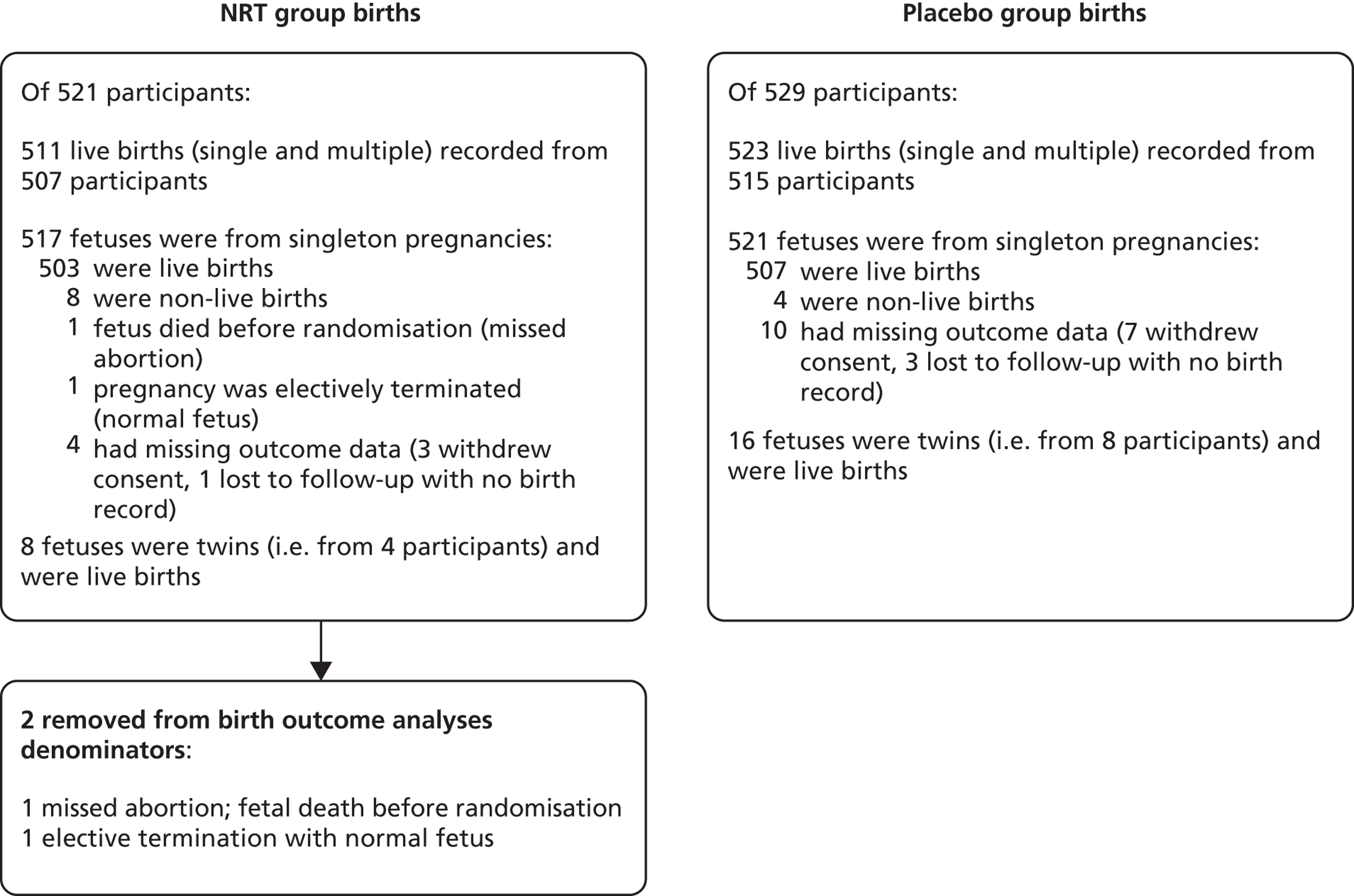

The ascertainment rate for birth outcomes was more complete than smoking outcomes as these were obtained from participants’ hospital notes. Figure 5 summarises numbers of births within participants and completeness of birth outcome ascertainment.

FIGURE 5.

Completeness of birth outcome data. From Coleman et al. 56 Copyright © 2012 Massachusetts Medical Society. Reprinted with permission.

Further details on the numbers of participants who were followed up and for whom outcome data were obtained at 1 month and at delivery are presented by study centre in Table 3.

| Outcome ascertainment | Nottingham – QMC | Nottingham – City | King’s Mill | North Staffs | Leighton | Macclesfield | Derby | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1-month visit, n (%) | ||||||||

| In person | 36 (29.3) | 33 (25.8) | 41 (19.0) | 52 (20.2) | 75 (44.9) | 20 (25.0) | 17 (21.5) | 274 (26.1) |

| Telephone or returned questionnaire | 71 (57.7) | 80 (62.5) | 123 (56.9) | 156 (60.7) | 68 (40.7) | 41 (51.3) | 53 (67.1) | 592 (56.4) |

| No contact at 1 month | 16 (13.0) | 15 (11.7) | 52 (24.1) | 49 (19.1) | 24 (14.4) | 19 (23.8) | 9 (11.4) | 184 (17.5) |

| Total | 123 | 128 | 216 | 257 | 167 | 80 | 79 | 1050 (100) |

| Final trial status, n (%) | ||||||||

| Outcome data obtained | 115 (93.5) | 118 (92.2) | 210 (97.2) | 232 (90.3) | 158 (94.6) | 72 (90.0) | 76 (96.2) | 981 (93.4) |

| Fetal/infant deatha | 2 (1.6) | 2 (1.6) | 1 (0.5) | 3 (1.2) | 3 (1.8) | 1 (1.3) | 1 (1.3) | 13 (1.2) |

| Lost to follow-up or withdrew consent | 6 (4.9) | 8 (6.3) | 5 (2.3) | 22 (8.6) | 6 (3.6) | 7 (8.8) | 2 (2.5) | 56 (5.3) |

| Total | 123 | 128 | 216 | 257 | 167 | 80 | 79 | 1050 (100) |

Baseline characteristics

Sociodemographic characteristics, smoking behaviour, obstetric history and participants’ prior use of NRT were similar in both trial groups (Table 4). Women had a mean age of 26 years and joined the trial at a mean gestational age of 16 weeks. Participants were heavy smokers and around one-third smoked within 5 minutes of waking and the median number of cigarettes smoked per day at randomisation was 14.

| Characteristic | NRT (N = 521) | Placebo (N = 529) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean age (years), (SD) | 26.4 (6.2) | 26.2 (6.1) | |

| Median number of cigarettes smoked daily before pregnancy (IQR) | 20 (15–20) | 20 (15–20) | |

| Median number of cigarettes smoked daily at randomisation (IQR) | 13 (10–20) | 15 (10–20) | |

| Mean gestational age at baseline (weeks) (SD) | 16.2 (3.6) | 16.3 (3.5) | |

| Ethnic group, n (%) | White British | 503 (96.5) | 515 (97.4) |

| Other | 18 (3.5) | 14 (2.6) | |

| Mean age left full-time educationb (years) (SD) | 16.2 (1.4) | 16.3 (1.7) | |

| Parity,c n (%) | 0–1 | 356 (68.3) | 363 (68.6) |

| 2–3 | 129 (24.8) | 142 (26.9) | |

| ≥ 4 | 36 (6.9) | 24 (4.5) | |

| Median baseline cotinine levels (ng/ml) (IQR) | 123.1 (80.1–179.8) | 121.2 (77.2–175.9) | |

| Time to first cigarette (minutes), n (%) | 0–15 | 281 (54.0) | 285 (53.9) |

| > 15–60 | 199 (38.2) | 198 (37.4) | |

| > 60 | 41 (7.9) | 46 (8.7) | |

| Women with partner who smokes,d n/women with a partner, n (%) | 356/481 (74.0) | 360/482 (74.7) | |

| Mean height (cm)e (SD) | 163.2 (6.8) | 163.0 (6.5) | |

| Mean weight (kg)f (SD) | 71.7 (18.2) | 71.6 (17.2) | |

| Previous preterm birth,g n (%) | 42 (8.1) | 50 (9.5) | |

| Length of first behavioural support session (minutes), n (%) | ≤ 30 | 84 (16.1) | 81 (15.3) |

| 31–60 | 428 (82.1) | 433 (81.9) | |

| > 60 | 9 (1.7) | 15 (2.8) | |

| Use of NRT within pregnancy and prior to enrolment,h n (%) | 23 (4.4) | 24 (4.5) | |

Primary outcome measure at delivery

The rate of prolonged abstinence at delivery with validation was 9.4% in the NRT group and 7.6% in the placebo group (OR for abstinence with NRT 1.26, 95% CI 0.82 to 1.96) (Table 5).

| Outcome | n (%) | OR (95% CI)a | Adjusted OR (95% CI)b | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NRT (N = 521) | Placebo (N = 529) | |||

| Primary | ||||

| Prolonged self-reported abstinence from smoking between quit date and delivery with COT and/or CO validationc,d | 49 (9.4) | 40 (7.6) | 1.26 (0.82 to 1.96) | 1.27 (0.82 to 1.98) |

| Secondary | ||||

| Prolonged abstinence from quit date to delivery without validation | 65 (12.5) | 49 (9.3) | 1.40 (0.94 to 2.07) | 1.41 (0.95 to 2.09) |

| Abstinence to 1 month after quit date without validation | 131 (25.1) | 74 (14.0) | 2.07 (1.51 to 2.85) | 2.13 (1.54 to 2.95) |

| Abstinence to 1 month after quit date with CO validatione | 111 (21.3) | 62 (11.7) | 2.05 (1.46 to 2.88) | 2.10 (1.49 to 2.97) |

| Prolonged abstinence to delivery with validation at 1 month after quit date and delivery | 42 (8.1) | 32 (6.0) | 1.36 (0.84 to 2.19) | 1.37 (0.84 to 2.22) |

| Point prevalence cessation (> 24-hour quit) at delivery with CO validation | 63 (12.1) | 53 (10.0) | 1.23 (0.84 to 1.82) | 1.24 (0.84 to 1.85) |

| Point prevalence cessation (> 24-hour quit) at delivery without validation | 104 (20.0) | 89 (16.8) | 1.24 (0.90 to 1.70) | 1.25 (0.90 to 1.72) |

Secondary outcome measures at delivery

Smoking outcomes at delivery

For self-reported (i.e. non-validated) abstinence, there was a slightly larger but still non-significant difference in quit rates: 12.5% with NRT compared with 9.3% with placebo (OR 1.40, 95% CI 0.94 to 2.07) (see Table 5). At 1 month, the validated abstinence rate was significantly higher in the NRT group than in the placebo group (21.3% vs. 11.7%, respectively; OR 2.05, 95% CI 1.46 to 2.88). Similar findings were found for adjusted analyses with all smoking outcomes.

Birth outcomes at delivery

Table 6 shows outcomes for singleton births including deaths, mean birthweight and rates of preterm birth, LBW and congenital abnormalities, and these were mainly similar in the two study groups. However, there were significantly more deliveries by caesarean section in the NRT group than in the placebo group (20.7% vs. 15.3%). Analyses that included twin births gave very similar findings.

| Fetal outcomes (singleton births only) | NRT (N = 515) n/N (%) |

Placebo (N = 521) n/N (%) |

OR (95% CI)b |

|---|---|---|---|

| Miscarriagec | 3/515 (0.6) | 2/521 (0.4) | 1.52 (0.25 to 9.13) |

| Stillbirthc | 5/512 (1.0) | 2/519 (0.4) | 2.59 (0.50 to 13.4) |