Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was commissioned and funded by the HTA programme on behalf of NICE as project number 10/109/01. The protocol was agreed in February 2011. The assessment report began editorial review in February 2013 and was accepted for publication in July 2013. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

none

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2014. This work was produced by Colquitt et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Background

This technology assessment has been undertaken on the request of the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Health Technology Assessment (HTA) programme to inform the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) appraisal Implantable Cardioverter Defibrillators for the Treatment of Arrhythmias and Cardiac Resynchronisation Therapy for the Treatment of Heart Failure (Review of TA95 and TA120). 1

Description of the underlying health problem

This assessment encompasses people at risk of sudden cardiac death (SCD) as a result of ventricular arrhythmias (abnormal heart rhythms) and people with heart failure (HF) as a result of left ventricular systolic dysfunction (LVSD) and cardiac dyssynchrony. For the purposes of this assessment, and in line with the NICE scope,1 three populations are considered:

-

people at increased risk of SCD as a result of ventricular arrhythmias despite receiving optimal pharmacological therapy (OPT)

-

people with HF as a result of LVSD and cardiac dyssynchrony despite receiving OPT

-

people with both conditions described above.

In practice, however, these are not distinct populations and there is considerable overlap between the groups, such that people with HF from LVSD are at risk of SCD from ventricular arrhythmia.

Sudden cardiac death

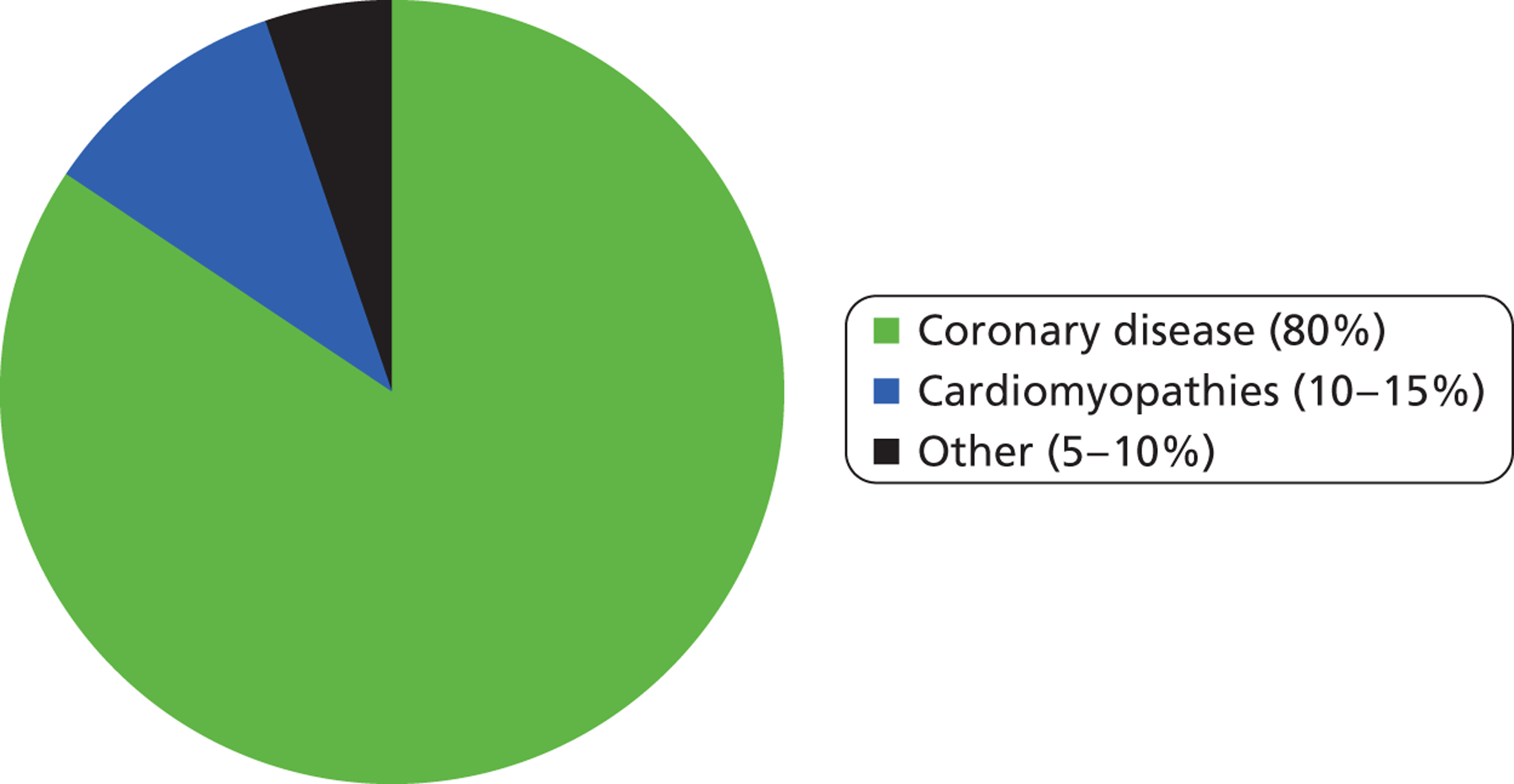

The widely accepted definition of SCD is a sudden and unexpected death from cardiac causes within an hour of the onset of symptoms. 2 Coronary heart disease (CHD) (narrowing or blocking of the coronary arteries) is the most common clinical finding associated with SCD, with about 80% of such deaths linked to this condition (Figure 1). CHD causes SCD mainly because it can lead to ventricular tachycardia (VT), which is an abnormally fast heart rhythm originating in one of the ventricles, and ventricular fibrillation (VF), which is an unco-ordinated and erratic contraction of the heart muscle of the ventricles. Patients with cardiomyopathies (diseases of heart muscle) account for a further 10–15% of cases of SCD and there is likely to be significant overlap between this group and those with CHD (i.e. some patients will have both conditions). The remaining 5–10% of SCD cases are associated with other disorders, either structurally abnormal congenital cardiac conditions or structurally normal but electrically abnormal hearts. 3

Deaths in England and Wales from CHD in 2010 numbered 140,301 (Table 1). It is thought that approximately 50% of all CHD-related deaths are SCDs. 6 The cause of SCD is frequently VT or VF, but may also be due to asystole (cessation of electrical activity in the heart) or causes other than arrhythmias (e.g. ischaemia)8,9 Commonly, VT develops initially followed by degeneration to VF, which then leads to the development of asystole. 10 According to guidelines of the American College of Cardiology, the American Heart Association and the European Society of Cardiology for the management of patients with ventricular arrhythmias and the prevention of SCD,7 VF is the rhythm recorded at the time of sudden cardiac arrest in 75–80% of cases. There is evidence that the incidence of VT/VF events has declined over time, perhaps reflecting an impact of treatment strategies targeted at coronary artery disease. 11–14

| Cause of death | Total | Men | Women |

|---|---|---|---|

| aCHD4 | 140,301 | 81,405 | 58,896 |

| SCDb | 70,151 | 40,703 | 29,448 |

| VFc | 52,613–56,121 | 30,527–32,562 | 22,086–23,558 |

People known to be at risk of SCD include those who have experienced a previous event that they survived, such as life-threatening arrhythmia (accounting for 5–10% of SCDs), haemodynamic abnormalities including HF (7–15% of SCDs) and acute coronary syndromes such as myocardial infarction (MI) and angina pectoris (≤ 20% of SCDs). 6 However, in ≥ 30% of SCDs, CHD had not been previously diagnosed in the patient, and in one-third of SCDs the patients were known to have cardiac disease but were considered to be at low risk for SCD. 6

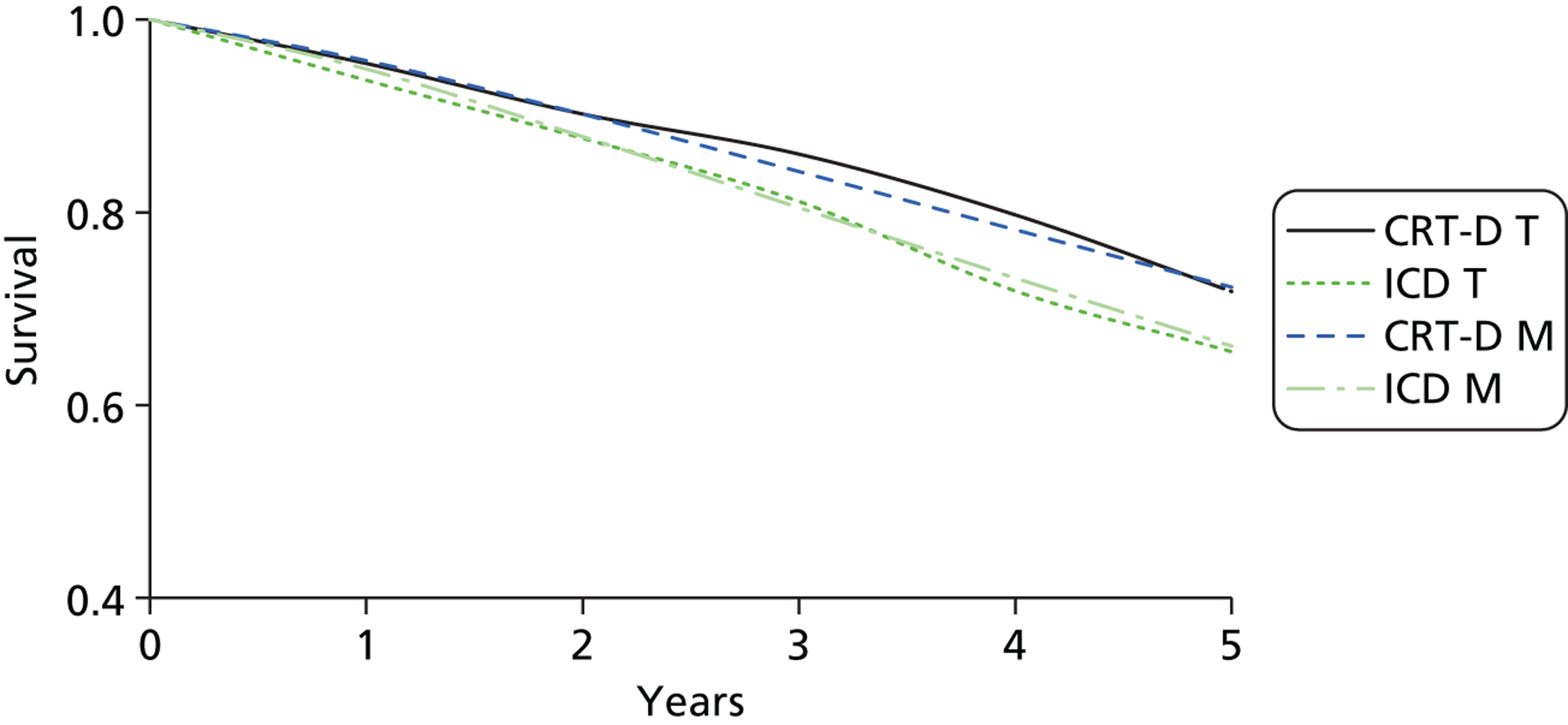

A recent systematic review of 67 studies worldwide15 estimated that the average survival rate for adults following an out-of-hospital cardiac arrest was 7%. Depending on the clinical scenario, a small proportion of people who do survive a first life-threatening cardiac episode may remain at high risk of further episodes (e.g. if VF is due to left ventricular dysfunction). Secondary prevention (prevention of an additional life-threatening event) may therefore be required. When appropriate treatment and secondary preventative strategies are implemented, recent studies have reported 5-year survival ranging from 69% to 100%,16,17 although these may overestimate survival. It is important to recognise the multiple causes of the electrical process of VF, as not all patients with VF will be amenable to implantable cardiac defibrillator (ICD) therapy. For example, VF or VT occurring as a primary electrical process in Brugada syndrome would be expected to respond well to ICD therapy, whereas VF due to massive heart damage in a major acute MI may not. Deciding on the rational use of ICD therapy can be complex, as the risk of arrhythmic death and therefore the potential benefit from ICD therapy varies between pathologies (e.g. ischaemic heart disease, non-ischaemic cardiomyopathy or electrical disease) and also with the progression of the disease (e.g. the impact of ICD may vary depending on the time after an MI that the therapy is started).

Preventing a first life-threatening event (primary prevention of SCD) is challenging because it requires identifying people with a sufficient level of risk for primary prevention to be appropriate. There are multiple risk factors for SCD, which include increasing age, hereditary factors, being in the top 10% of risk for coronary atherogenesis, the presence of inflammatory markers (e.g. C-reactive protein), hypertension, left ventricular hypertrophy, intraventricular conduction abnormalities [e.g. left bundle branch block (LBBB)], obesity, diabetes and lifestyle factors (e.g. smoking, excessive alcohol consumption, lack of physical activity, social and economic stressors). 7 Currently no optimal strategy for risk stratification exists. 18

Heart failure

Heart failure is a clinical syndrome characterised by symptoms (breathlessness and fatigue) and signs (fluid retention) caused by failure of the heart to pump adequately. It is usually a chronic condition predominantly affecting people aged > 50 years and has a poor prognosis. 19 Coronary artery disease (ischaemic heart disease) has been identified as the most common cause of HF in two UK studies. 20,21 Other causes of HF are LVSD, hypertension, valve disease, atrial fibrillation or flutter, cardiomyopathy (either hypertrophic or restrictive) or cor pulmonale (pulmonary heart disease). The cause of HF was unknown in approximately one-third of cases in the two UK studies. 20,21 The NICE scope for this appraisal1 focuses on HF that is a result of LVSD. LVSD is an impairment in the ability of the left ventricle to pump blood into the circulation during contraction (systole). 19

The prognosis for HF patients is poor, with deterioration in quality of life (QoL) and reduced life expectancy. 19 In addition, HF patients may also be at risk of SCD. Patients with HF and LVSD from the Echocardiographic Heart of England Screening Study (ECHOES) cohort had a 5-year survival rate of 53%,22 and 3.8% of the deaths that occurred among those with HF and LVSD were sudden deaths,22 although SCD may be underestimated in this study. The 10-year survival in this study for those with HF and LVSD was 27.4%. 23 The severity of HF graded according to the New York Heart Association (NYHA) classification system is an indicator of prognosis. 24–27 This system has four classes to which patients can be assigned, with severity increasing with class number from I to IV (Table 2); however, it is worth noting that clinicians may differ in the way that they interpret and assign these classes. 28

| Class | Comfort at rest? | Limitation to physical activity? | Effect of physical activity |

|---|---|---|---|

| I | Yes | None | No undue fatigue, palpitations, dyspnoea or angina pain |

| II | Yes | Slight | Ordinary physical activity can result in fatigue, palpitations, dyspnoea or angina pain |

| III | Yes | Marked | Less than ordinary activity causes fatigue, palpitations, dyspnoea or angina pain |

| IV | May have HF or angina symptoms even at rest | Always | Unable to carry out any physical activity without new or increasing discomfort |

The most recent estimates for the incidence of HF in the UK come from the General Practice Research Database (GPRD). 29 In 2009 these data indicated that the incidence of HF was higher in Wales (men 44.6 and women 24.9 per 100,000 person-years) than in England (men 37.5 and women 23.0 per 100,000 person-years). The incidence of HF increased with age, being highest in those aged > 75 years (e.g. in England, men 326.0 and women 256.2 per 100,000 person-years), and incidence rates are higher in men than in women at all ages. From these data and those for Scotland and Northern Ireland, it has been estimated that there are > 27,000 new cases of HF in the UK each year. 29

The corresponding estimates for the prevalence of HF in the UK derived from the GPRD29 are similar in England and Wales (for all ages in men: 0.9% in England and 1.0% in Wales; for all ages in women: 0.7% in England and Wales). In total, this corresponds to almost 160,000 cases in England and Wales in 2009. Data from the ECHOES cohort have indicated that, of the total number of HF cases identified, approximately 50% have HF with LVSD. 22 Applying this proportion to the prevalence data for England and Wales from the GRPD would suggest that there were approximately 80,000 cases of HF with LVSD in 2009.

Description of the technology under assessment

The current technology assessment concerns specific types of cardiac implantable electronic devices for the prophylaxis and/or treatment of conduction system disease that use one or more of the following approaches to restore normal heart rhythm:

-

‘pacing’ – a series of low-voltage electrical impulses delivered at a fast rate to correct the heart rhythm

-

cardioversion’ – one or more small electric shocks delivered to the heart to restore a normal rhythm

-

‘defibrillation’ – one or more large electric shocks delivered to the heart to restore a normal rhythm.

Cardiac resynchronisation therapy (CRT) devices are a specific type of cardiac pacemaker that have three conducting leads (connected to the right atrium and both ventricles) and are used to correct inconsistency of the heartbeat between the right and left sides of the heart (dyssynchrony), referred to as biventricular pacing. These devices are known as CRT-pacers (CRT-Ps) (or biventricular pacers).

Implantable cardioverter defibrillators are used to provide cardioversion and/or defibrillation shocks to correct more serious dysfunction of the heart rhythm, including VT, VF and asystole, any one of which may be associated with SCD. ‘Single chamber’ ICDs have a single conducting lead connected only to the right ventricle; ‘dual chamber’ ICDs have two leads connected to the right atrium and the right ventricle. In addition to their cardioversion and defibrillation ability, modern ICDs provide the functionality of a standard pacemaker to treat slow heart rhythms (if necessary) by pacing the right-hand chamber(s) of the heart.

Modern types of CRT device may combine the functionality of both a CRT-P and an ICD and these are referred to as CRT-defibrillators (CRT-Ds).

Cardiac resynchronisation therapy is aimed at a specific subset of the HF population with evidence of delayed left ventricular activation (as manifest by prolongation of the QRS complex). Because this population is a priori at risk of arrhythmic death, CRT can be combined with an ICD. ICDs and CRT-D devices are appropriate for patients with a high risk of SCD, whereas CRT-P devices are appropriate in patients with less serious cardiac arrhythmias. However, as noted earlier, heart disease is a complex and progressive condition and patients who are initially implanted with a CRT-P may subsequently develop heart disease and be at risk of SCD, and an upgrade from a CRT-P to a CRT-D or an ICD may be appropriate. 30

Although they may differ in function, CRT and ICD devices are similar in size and structure – about the size of a pocket watch (capacity 30–40 ml, weight around 70 g, thickness approximately 13 mm) – and consist of a battery-powered pulse generator controlled by a microcomputer. They are implanted under the skin, typically just below the collar bone on the left or right side of the chest, and (depending on the device type) have one or more leads (tiny wires) that are routed through veins to the heart’s chambers for sensing electrical activity and for providing the corrective pacing, cardioversion and/or defibrillation impulses. Modern CRT and ICD devices store a record of the heart’s electrical activity and contain a wireless transmitter/receiver to enable the device to be programmed and interrogated from an external computer using wireless telemetry. Readings from a device may be transmitted by telephone, enabling the cardiologist to remotely check the performance of the device while the patient is at home.

Early devices were implanted using the transthoracic method, but current CRT and ICD devices are placed under the skin in the pectoral region with transvenous insertion of the leads into the heart under local anaesthesia, using high-resolution X-ray angiography to guide the placing of the leads. The procedure for primary prevention typically requires a maximum of a 1-night stay in hospital. For secondary prevention the length of stay will depend on any underlying health problems. The longevity of CRT and ICD devices is limited by their battery life, which is in the range of 4–7 years, depending on a number of factors including the pacing mode, pacing percentage and capacitor recharge interval. 31–33 Replacement of batteries alone is not feasible, so when the battery is due for renewal the pulse generator unit has to be replaced, in a minor surgical procedure. When possible the connecting leads are left in situ and only the generator unit itself is replaced, although eventually one or more of the connecting leads may also require replacement.

Modern devices can be specifically programmed to deliver resynchronisation pacing independently to the atria and ventricles of the heart to maximise synchronisation. The devices can also be programmed according to which of the heart’s chambers they monitor (sense) to detect existing electrical activity. The ability of CRT and ICD devices to recognise different types of arrhythmia may enable them to deliver more appropriate therapy, in particular lessening the incidence of inappropriate shocks. Several coding systems (typically comprising three to five letters) have been developed to indicate the programmed pacing/sensing modes. A widely used code developed by the Heart Rhythm Society (HRS) and the British Pacing and Electrophysiology Group (BPEG) consists of three letters to describe the pacing chamber [atrium, A; ventricle, V; or dual (i.e. both), D], three letters to describe the sensed chamber (A, V or D) and a further three letters to describe whether pacing is inhibited (I) or triggered (T) in response to the sensed beat or, if dual pacing and sensing are programmed, whether dual (D) inhibition and triggering (for the different chambers) occurs. As an example, the code ‘VVI’ would indicate ventricular pacing (shocks are delivered to the ventricle), ventricular sensing (electrical activity is monitored in the ventricle) and that pacing is inhibited if an electrical beat is sensed in the ventricle. To illustrate a more complex example, the code ‘DDD’ would indicate a device programmed for dual-chamber pacing and sensing. In this case the atrium would be stimulated if sinus bradycardia is detected. Both atrium and ventricle would be stimulated if bradycardia exists independently in both chambers. If heart block exists with normal sinus function the ventricle would be paced in synchrony with the atrium and, if sinus rhythm exists, pacing would be totally inhibited.

The most recent development in cardiac implantable electronic devices is the subcutaneous ICD (S-ICD), which was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in April 2012. The S-ICD is positioned just under the skin, outside the rib cage, and can be implanted under local anaesthesia. The electronics and batteries of the S-ICD enable it to deliver enough energy to defibrillate the heart without the need for a connecting lead to the heart, which avoids lead-related complications including the risk of dangerous infections (other potential procedural complications are considered below). A disadvantage of the S-ICD, however, is that it cannot provide long-term pacing. A RCT comparing S-ICD with transvenous ICD (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier NCT01296022)34 is currently under way and is due to complete in March 2015 and a registry study of S-ICD (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier NCT01085435)35 is due to complete in December 2016.

Potential procedural complications

The most challenging technical aspect of a CRT device implantation is the optimal placement of the third lead in the coronary sinus vein. The final position of the left ventricular pacing lead depends on the anatomy of the cardiac venous system, as well as the performance and stability of the pacing lead and the need to avoid phrenic nerve stimulation. 36 The left phrenic nerve (which sends signals between the brain and the diaphragm) may be stimulated by the left ventricular pacing lead, causing uncomfortable diaphragmatic twitch, which could prevent optimal left ventricular lead placement and can hinder left ventricular stimulation. Phrenic nerve stimulation occurs in around 20% of patients with bipolar leads. 37 A recent systematic review of implantation-related complications in 11 ICD and seven CRT trials suggests that the most common complications include coronary vein dissection (1.3%) and coronary vein perforation (1.3%), with coronary vein-related complications occurring in only 2.0% of patients. 38 This low rate is attributed to the growing experience of physicians combined with technical progress. The overall incidence of lead dislodgement for non-thoracotomy ICDs was 1.8%, with higher rates of lead dislodgement in the CRT trials, which varied from 2.9% to 10.6%. The reported overall rate of leads dislodged during and after 3095 successful implantations was 5.9%. A recent study in the USA,39 which was based on the National Cardiovascular Data Registry, found that, after adjusting for diagnostic test results and comorbidities, dual-chamber ICDs were associated with a 40% greater odds of procedural complications and a 45% greater odds of mortality than single-chamber ICDs, illustrating a greater risk of procedural complications with the more complex types of ICD device. Another recent study in the USA40 examined 16-year trends from 1993 to 2008 in the incidence of infections related to cardiac implantable electronic devices, based on data from the National Inpatient Sample (NIS). There has been a marked increase in infection incidence, notably since 2004, and this has been associated with an increase in in-hospital mortality and increased treatment costs. The reasons for the increased incidence of device-related infections are unclear, but could be related to the increased use of ICD and CRT devices relative to traditional pacemakers. Because of the demands placed on the battery, the longevity of ICD and CRT devices is lower than that of traditional pacemakers, and the need for more frequent surgical replacement of ICD and CRT devices might at least in part explain why the number of device-related infections has increased. 40

Setting, cost and equipment

Cardiac resynchronisation therapy and ICD device implants are carried out in local hospital or cardiac centres and can take from 1 to 3 hours depending on the type of device. Implantation of biventricular or resynchronisation devices is more complicated and takes longer than implantation of other ICDs. Implantation procedures are usually performed by senior cardiologists with specialist training in the technique, supported by cardiac technicians and nurses. Follow-up visits for patients can be as often as every 3–12 months, requiring support from senior cardiologists, cardiac nurses and technicians. According to the HRS/European Heart Rhythm Association (EHRA) Expert Consensus on the Monitoring of Cardiovascular Implantable Electronic Devices,41 whereas neither direct nor remote monitoring follow-up visits should be longer than 12 months, 6-monthly follow-up for ICD and CRT-D devices is recommended. The increasing complexity of devices could impact on the time needed for follow-up visits.

The average cost of the devices, including leads, has been estimated at £9692 for the ICD device, £3411 for CRT-P and £12,293 for CRT-D (see Chapter 5, Parameters common to all populations, and see Table 109 for further details). In addition to the cost of the device itself, high-quality digital X-ray equipment is necessary for coronary sinus angiography and positioning of the left ventricular pacing lead, as well as an external ICD programmer (a telemetry computer commercially produced and marketed for use with the device41) to enable the cardiologist to adjust the settings of the ICD after surgery or at follow-up visits as required.

Management of the disease

Existing guidelines for SCD and HF include NICE guidance on ICDs for arrhythmias42 and CRT for HF,43 and a NICE clinical guideline on the management of chronic HF. 44 Guidelines on the use of CRT have also been published by the European Society of Cardiology,45 the Heart Failure Society of America46 and the American College of Cardiology Foundation and the American Heart Association. 47 A 10-year National Service Framework for Coronary Heart Disease was published by the UK Department of Health in 2000,48 but this did not make specific recommendations on the use of CRT or ICD devices and is now out of date. Given the absence of a national framework, Heart Rhythm UK has recently developed standards for the implantation and follow-up of CRT devices. 49

Sudden cardiac death

Diagnosis of sudden cardiac death

As SCD can happen without warning, it is important for general practitioners and secondary care providers to be aware of risk factors so that patients at high risk of SCD can be identified and referred for cardiac evaluation. A range of diagnostic tests may be used to identify risk of SCD. An electrocardiogram (ECG) can detect abnormalities in the heart’s electrical activity and may reveal evidence of heart damage from CHD, or signs of a previous or current heart attack. Electrophysiological testing is sometimes used to identify the origins of an arrhythmia and programmed electrical stimulation (PES) of the heart may be used to stimulate the heart to induce the arrhythmia. An electrophysiological or PES study may be used before implantation of an ICD to confirm the need for an ICD or for diagnostic work-up. Other tests that may be used to identify SCD risk include ultrasound echocardiography and cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (to image or film different parts or the whole of the heart), blood tests (to check concentrations of chemicals involved in heart function, e.g. potassium and magnesium) and cardiac catheterisation (e.g. if blood samples from within the heart are required, or to inject dye for angiographic studies).

Implantable devices for sudden cardiac death

Ventricular arrhythmias, particularly sustained VT and VF, are life-threatening events. For patients who meet specified treatment criteria, the NICE guidance issued in 2006 [technology appraisal (TA)9542] recommends that ICD (or CRT-D) therapy is recommended for primary prevention (prevention of a first life-threatening arrhythmic event) and secondary prevention (prevention of an additional life-threatening event in survivors of sudden cardiac events or patients with recurrent unstable rhythms) of SCD. Patients with sustained ventricular arrhythmias associated with haemodynamic compromise in the presence of LVSD should be considered for ICD therapy after reversible factors are addressed. Patients with LVSD and who have recently had a MI or patients who have a cardiac condition that is associated with a high risk of sudden death should also be considered for ICD therapy in addition to OPT. OPT (as described below) is used as an adjunct or provided for those patients for whom an ICD would not be appropriate (e.g. those with a severely limited prognosis).

Specific recommendations of the NICE guidance42 (which does not cover non-ischaemic dilated cardiomyopathy) are that ICDs may be used as primary prevention for patients who have a history of previous (≤ 4 weeks) MI and either left ventricular dysfunction with a left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) < 35% (no worse than NYHA class III) and non-sustained VT on Holter (24-hour ECG) monitoring and inducible VT on electrophysiological testing or left ventricular dysfunction with a LVEF of < 30% (no worse than NYHA class III) and a QRS duration of ≥ 120 milliseconds; or who have a familial cardiac condition with a high risk of sudden death, including long QT syndrome, hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, Brugada syndrome or arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia, or have undergone surgical repair of congenital heart disease.

Implantable cardioverter defibrillators as secondary prevention for arrhythmias are recommended for individuals who present, in the absence of a treatable cause, with one of the following: survived a cardiac arrest due to either VT or VF; spontaneous sustained VT causing syncope or significant haemodynamic compromise; sustained VT without syncope or cardiac arrest and who have an associated reduction in ejection fraction (LVEF < 35%) (no worse than NYHA class III). 42

Optimal pharmacological therapy for sudden cardiac death

Chronic prophylactic antiarrhythmic drug (AAD) therapy is aimed at suppressing the development of arrhythmias in patients at high risk of SCD. The class III drugs such as amiodarone are used for specific indications. These drugs may enhance the maintenance of sinus rhythm but cannot terminate an arrhythmia once it is initiated. A meta-analysis based on 8522 patients from 15 trials found that amiodarone reduced the risk of SCD by 29% and cardiovascular death (CVD) by 18% in patients at risk of SCD. 50 However, amiodarone therapy was neutral with respect to all-cause mortality and was associated with a high discontinuation rate and significant end-organ adverse reactions including hepatic, pulmonary and thyroid toxicity, with a two- and fivefold increased risk of pulmonary and thyroid toxicity respectively50 Other drugs that may be included in the OPT of SCD are angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors (recommended for all patients with LVSD to improve ventricular geometry and function), aldosterone receptor antagonists (for people resistant to other drug therapy) and beta-blockers (to reverse ventricular remodelling) among others. 51

Heart failure

Diagnosis of heart failure

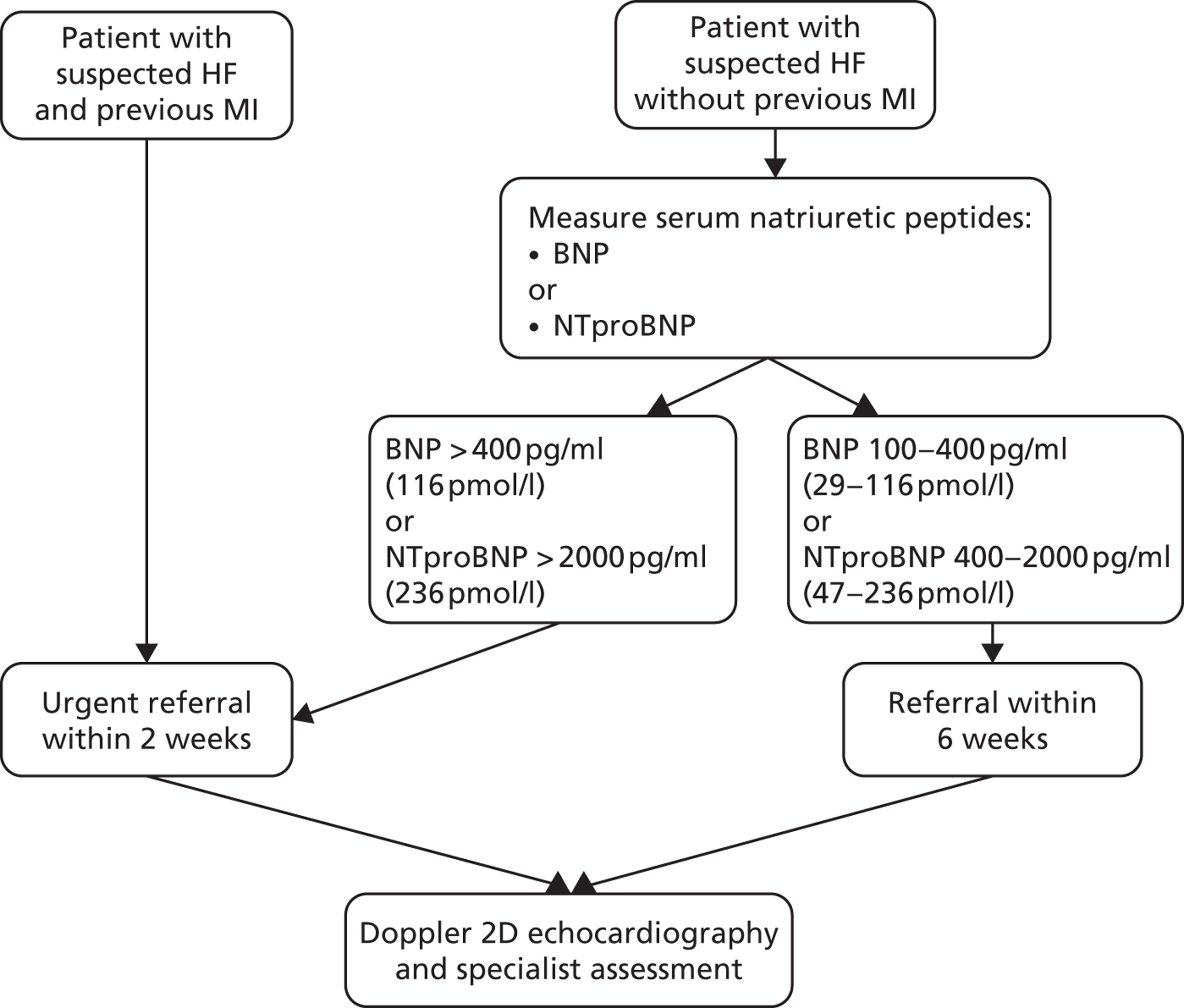

The NICE clinical guideline CG108, Chronic Heart Failure: Management of Chronic Heart Failure in Adults in Primary and Secondary Care,44 provides a diagnostic pathway for HF, the key elements of which are shown in Figure 2. Serum natriuretic peptides (SNPs; protein substances secreted by the wall of the heart when it is stretched or under increased pressure) should be measured in people with suspected HF without MI, although the guideline cautions that levels of SNPs can be reduced by certain conditions (e.g. obesity) or treatments (e.g. diuretics, ACE inhibitors, beta-blockers). Conversely, other conditions [e.g. left ventricular hypertropy, renal dysfunction, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD)] can cause high levels of SNPs. Therefore, an ECG and other tests (e.g. chest radiography, blood tests, urinalysis, spirometry) may be required to evaluate other possible diagnoses. Transthoracic Doppler two-dimensional echocardiography is used to assess the function (systolic and diastolic) of the left ventricle, to detect intracardiac shunts and to exclude important valve disease. If a poor image is obtained, other imaging methods (e.g. radionuclide angiography, cardiac magnetic resonance imaging or transoesophageal Doppler two-dimensional echocardiography) can be considered.

FIGURE 2.

Key elements in the NICE HF guideline diagnostic pathway. 52 BNP, B-type natriuretic peptide; NTproBNP, N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide.

Management of heart failure

A patient presenting with the typical signs and symptoms of HF should receive specialist assessment including echocardiography. 44 If HF is diagnosed the goals of treatment are to reduce mortality and improve the health outcome of the patient. In clinical practice, pharmacological agents are routinely used as the first-line therapy in managing HF44 (details of OPT for HF are given in Optimal pharmacological therapy for heart failure).

In addition to drug therapy, according to the NICE clinical guideline,44 individuals should be encouraged to participate in exercise-based cardiac rehabilitation (including a psychological and educational component), to give up smoking if applicable or be referred to a smoking cessation service, and to abstain from alcohol consumption if they have alcohol-related HF. Similarly, the European Society of Cardiology recommends that individuals with HF should be enrolled in a multidisciplinary care management programme. 53

Implantable devices for heart failure

As the severity of HF symptoms increases, a patient’s symptoms may no longer be controlled by OPT or lifestyle changes. There are multiple syndromes associated with HF that could predispose patients to the need for further intervention. In patients with HF, the existence of a modifiable risk factor such as arrhythmias may constitute a rationale for the use of multiple interventions. The NICE pathway for chronic HF52 indicates that, when symptoms are not controlled by OPT, treatment with CRT-P or CRT-D can be considered for patients meeting specific criteria.

Current NICE guidance issued in 2007 (TA12043) recommends CRT-P as a treatment option for individuals with HF who fulfil all of the following criteria: are currently experiencing or have recently experienced NYHA class III–IV symptoms; are in sinus rhythm – either with a QRS duration of ≥ 150 milliseconds estimated by standard ECG or with a QRS duration of 120–149 milliseconds estimated by ECG and mechanical dyssynchrony that is confirmed by echocardiography; have a LVEF of ≤ 35%; are receiving OPT. CRT-D may be considered for individuals who fulfil the criteria for implantation of a CRT-P device and who also separately fulfil the criteria for the use of an ICD device (see Implantable devices for sudden cardiac death).

Comments received from a clinical expert indicate that CRT is increasingly being considered for people without symptoms with the aim of improving prognosis by modifying the natural history of HF. Another interventional procedure that may be considered for patients with severe refractory symptoms is cardiac transplant. For those awaiting a donor heart, short-term circulatory support with a left ventricular assist device may be indicated. 54

Optimal pharmacological therapy for heart failure

Optimal medical drug therapy for HF can include ACE inhibitors, diuretics (for the relief of congestive symptoms and fluid retention), beta-blockers, aldosterone antagonists, digoxin (if symptoms continue despite the use of ACE inhibitors), amiodarone, anticoagulants (to reduce the risk of stroke), aspirin (to reduce the risk of vascular events), statins (to reduce the risk of MI and stroke), inotropic agents (to stimulate the heart muscle) and calcium channel blockers (for comorbid hypertension and angina).

The NICE 2010 clinical guideline44 suggests that medical drug therapy for HF has two aims – first, to improve morbidity (by reducing symptoms, improving exercise tolerance, reducing hospital admissions and improving QoL) and, second, to improve prognosis (by reducing all-cause mortality or HF-related mortality). According to the guideline, first-line treatment should include both ACE inhibitors and beta-blockers licensed for HF for all individuals with HF due to LVSD.

If an individual remains symptomatic despite optimal therapy with an ACE inhibitor and a beta-blocker, second-line treatment recommendations are to add one of the following: an aldosterone antagonist licensed for HF [especially if the patient has moderate to severe HF (NYHA class III–IV) or has had an MI within the past month] or an angiotensin II receptor antagonist (also known as an angiotensin receptor blocker or ARB) licensed for HF [especially if the patient has mild to moderate HF (NYHA class II–III)] or hydralazine in combination with nitrate [especially if the patient is of African or Caribbean origin and has moderate to severe HF (NYHA class III–IV)]. 44

Pharmacological recommendations for all types of HF include diuretics, calcium channel blockers, amiodarone, anticoagulants, aspirin and inotropic agents (such as dobutamine, milrinone or enoximone). ACE inhibitor therapy should not be initiated in individuals with a clinical suspicion of haemodynamically significant valve disease. 44

Current service provision

Current service provision is difficult to ascertain as the most recent audits of the use of CRT devices and ICDs in England and Wales55,56 suggest that there is considerable regional variation in implant rates. There is also a lack of information on patient referral patterns for the receipt of resynchronisation and defibrillation devices in the NHS. 57

The National Heart Failure Audit April 2010–March 201158 did not capture any information on the use of CRT devices or ICDs, but recommended that such data should be collected in future audits.

The most recent study to have reported the use of CRT devices and ICDs was the Cardiac Rhythm Management: UK National Clinical Audit 2010,55 which compared the rates of implantation of bradycardia pacemakers, ICDs and CRT devices during 2000–10 in comparison with national targets (a recent update of the audit56 provides additional data for January–December 2011 but is an interim version pending final publication). The audit collected data from 28 cardiac networks (regional groups of hospitals providing implants of pacemakers, CRT devices and ICDs) in England. There is clearly wide regional variation in the rates of implantation, with some cardiovascular networks having achieved or exceeded national target implant rates during 2010 and other networks not (Table 3). However, there is some debate about what the national targets should be. For example, a target of 100 ICD implants per million patients per annum has been proposed55 but other estimates that assume adherence to published guidelines suggest that the annual implant rate for ICDs should be higher, between 105 and 504 per million patients. 57 The wide regional variation in implant rates appears to suggest underuse in those regions with low implant rates. 57 The audit55 noted that the ratio of CRT-P implants to CRT-D implants and the ratio of ICD to CRT-D implants were highly variable among the cardiac networks in England, but it is not possible to determine the extent to which this variation reflects differences in local clinical practice and/or differences between patient populations. A study of ICD referral patterns in a single cardiac network in southern England57 found that implant rates were higher in areas where the local hospital was a regional cardiac centre compared with district general hospitals (with or without a device specialist), suggesting that some of the observed regional variation may reflect the structure of cardiac networks (the number and type of hospitals they include) and their patient referral pathways. 57 The discrepancy observed within the study of cardiac networks was greatest with respect to the use of ICDs for coronary artery disease primary prevention indications, and the authors suggested that this most likely reflects underuse of the therapy in the district hospitals rather than overuse in the regional cardiac centre. 57 A related study in the same cardiac network retrospectively investigated the management of ICD-implanted patients who developed HF. 59 Such patients may potentially benefit by being upgraded from an ICD to a CRT device. However, only a low proportion of these patients were found to have received an upgrade, raising the question of whether a CRT device might have been a more appropriate initial choice than an ICD for this patient subgroup. 59

| Device type | Averagea (range) no. of implants per million patients, adjusted for age and sex | National target (no. of implants per million patients, adjusted for age and sex) |

|---|---|---|

| ICD | 72 (34–131) | 100 |

| All CRT devices (CRT-P + CRT-D) | 114 (68–182) | 130 |

| All defibrillator devices (ICD + CRT-D) | 131 (81–197) | Not reported |

The audit55 reported data on the types of physiological pacing that were employed and also some data on the presenting symptoms and ECG patterns in patients with implants. As there is substantial overlap in the indications for resynchronisation and defibrillation devices,59 the choice of clinicians between ICD, CRT-D and CRT-P devices may in some cases have been arbitrary,55 and the audit did not discriminate between all of the possible pacing and defibrillation modes that can be programmed in modern implantable devices. Overall, in England during 2010, an ICD was the device type employed most frequently for syncope/cardiac arrest with VT/VF; CRT-D devices were the most frequent type implanted for HF with VT/VF; and CRT-P devices were the most frequent type employed in patients who had HF without VT/VF. Both CRT-D and ICD devices, but rarely CRT-P devices, were used for prophylaxis (Table 4). All device types were implanted more often in men than in women (80.1% of ICD, 83.4% of CRT-D and 68.4% of CRT-P devices were implanted in men). In 2011, a much higher proportion of CRT-D devices were implanted for primary prevention than for secondary prevention (78.3% vs. 21.7% respectively), although the proportions of ICDs implanted for primary and secondary prevention were similar (48.3% and 51.4% respectively). 55

| Presenting symptom and ECG | ICD (%) | CRT-D (%) | CRT-P (%) | Total (rounded) (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Syncope/cardiac arrest and VT/VF | 79.3 | 20.4 | 0.2 | 100 |

| HF and VT/VF | 29.8 | 68.2 | 1.9 | 100 |

| HF and any rhythm except VT/VF | 3.9 | 20.6 | 75.5 | 100 |

| Prophylactic (no symptoms) – all presenting ECGs | 48.5 | 48.8 | 2.7 | 100 |

The demand for device implants will increase because of a growing ageing population. In addition, there are increasing demands to expand the use of CRT devices, that is, to include individuals with NYHA class I–II symptoms, an ejection fraction of < 30% and a QRS interval wider than 130 milliseconds. This will increase the burden on existing services within cardiology, as well as raising the importance of device costs. The UK National Clinical Audit55 confirms that there has been a substantial increase in the number of CRT and ICD devices implanted in England and Wales during 2000–10. The interim update of the audit56 suggests, however, that, although more ICDs per million patients were implanted in England in 2011 than in 2010, the rate of increase has slowed and, overall, the total number of CRT implants per million patients was similar during 2010 and 2011.

In addition to the variation within the UK (see Table 3), there is considerable variation in the utilisation of implantable defibrillators across Europe,55 and ICD/CRT-D implant rates are considerably higher in the USA than in Europe. 60 The UK has approximately 0.7 ICD implant centres per million population, which is lower than in France, Germany, Italy and the USA. 60 It has been suggested that lower utilisation rates may reflect three main factors: a shortage of implant centres and electrophysiologists; poorly developed referral strategies/care pathways; and problems with specialist health-care investment. 60 The recently collected data55,60 suggest that systematic planning of ICD services is lacking in the UK, with underutilisation of CRT and ICD devices, although it is unclear if this impacts on the equality of service provision.

Chapter 2 Definition of the decision problem

This chapter states the key factors that will be addressed by this assessment and defines the scope of the assessment in terms of these key factors in line with the definitions provided in the NICE scope. 61 This assessment updates and expands on two previous technology assessment reports (TARs), The Clinical and Cost-Effectiveness of Implantable Cardioverter Defibrillators: a Systematic Review62 (which itself was an update of a TAR published in 200063) and The Clinical Effectiveness and Cost-Effectiveness of Cardiac Resynchronisation (Biventricular Pacing) for Heart Failure: Systematic Review and Economic Model. 64 The key differences between the present assessment and the previous assessments are outlined below and summarised in Appendix 1.

Decision problem

The interventions included within the scope of this assessment are ICD, CRT-P and CRT-D devices, each in addition to OPT.

Three populations are defined by the NICE scope:61

-

people at increased risk of SCD as a result of ventricular arrhythmias despite OPT

-

people with HF as a result of LVSD and cardiac dyssynchrony despite OPT

-

people with both conditions described above.

The first group, people at risk of SCD as a result of ventricular arrhythmias, includes and expands on the population considered in the previous ICD TAR. 62 For the present assessment this population is not restricted by NYHA classification and there is no specified cut-off for LVEF. The second group, people with HF as a result of LVSD and cardiac dyssynchrony, includes and expands on the population considered in the previous CRT TAR. 64 As in the previous TAR, this population is not restricted by NYHA classification in the present assessment, but unlike the previous TAR there is no specified cut-off for LVEF. The third group, people with both conditions, was not considered in the previous TARs. 62,64 People with cardiomyopathy are not excluded from consideration in this assessment.

Although the three populations are considered separately within the report for the purposes of this assessment, it is acknowledged that in practice these are not distinct groupings and there is considerable overlap between the groups: people with HF due to LVSD are at risk of SCD from ventricular arrhythmia.

The NICE scope61 did not indicate whether any subgroups of patients were of interest. No subgroups were predefined in the earlier guidance (TA9542), but subgroup analyses were reported in some included studies by LVEF, QRS duration and history of HF requiring treatment. Subgroups that were thought to be of interest in TA12043 and were therefore predefined were age, atrial fibrillation, NYHA class, degree of LVSD, degree of dyssynchrony and ischaemic and non-ischaemic HF. Relevant subgroups for the current assessment may also include renal failure. If sufficient evidence is available, consideration will be given to these subgroups.

The relevant comparisons for this assessment are as follows:

-

for people at increased risk of SCD as a result of ventricular arrhythmias despite OPT, ICD will be compared with standard care (OPT without ICD)

-

for people with HF as a result of LVSD and cardiac dyssynchrony despite OPT, CRT-P and CRT-D will be compared with each other or with standard care (OPT without CRT)

-

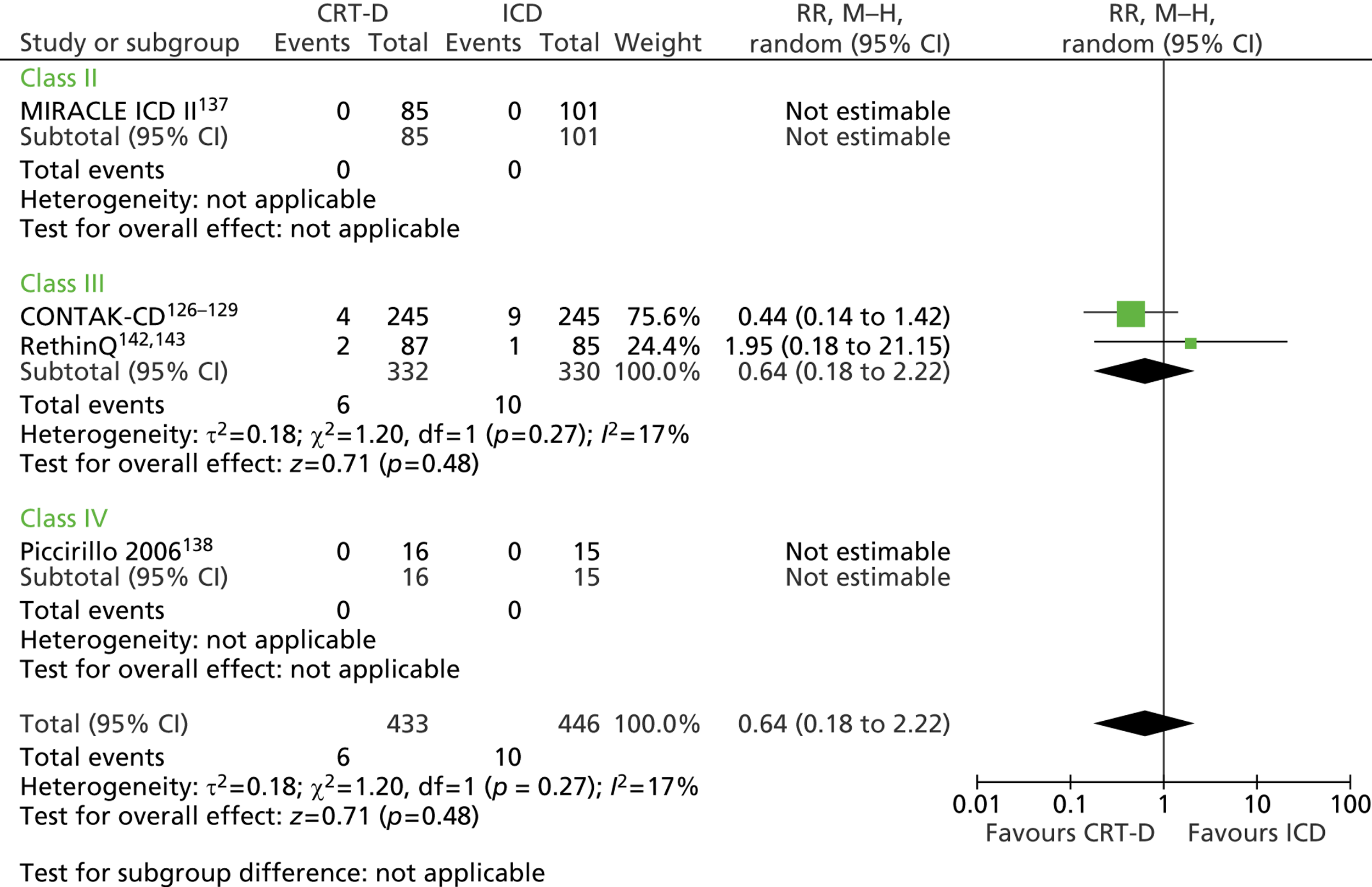

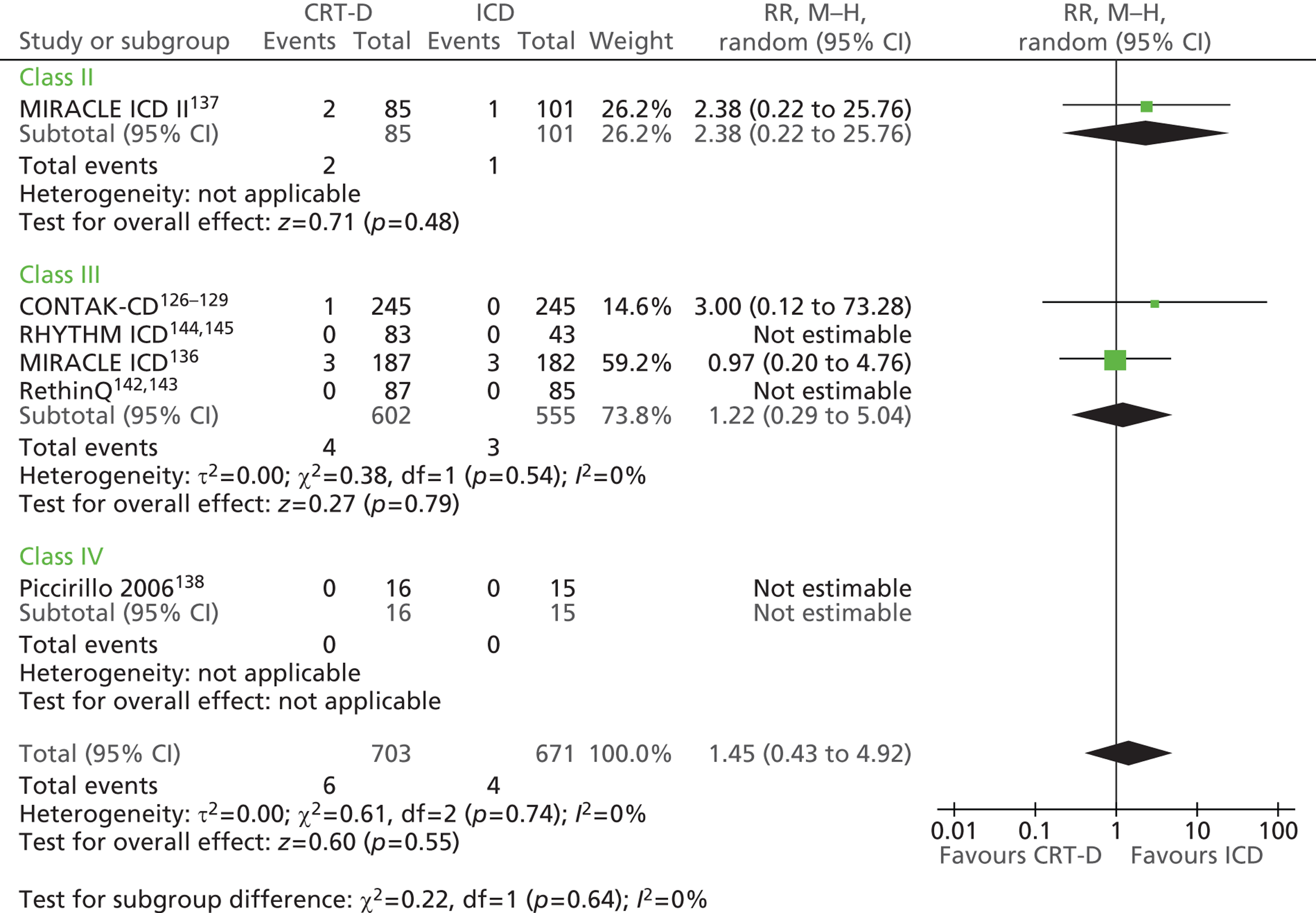

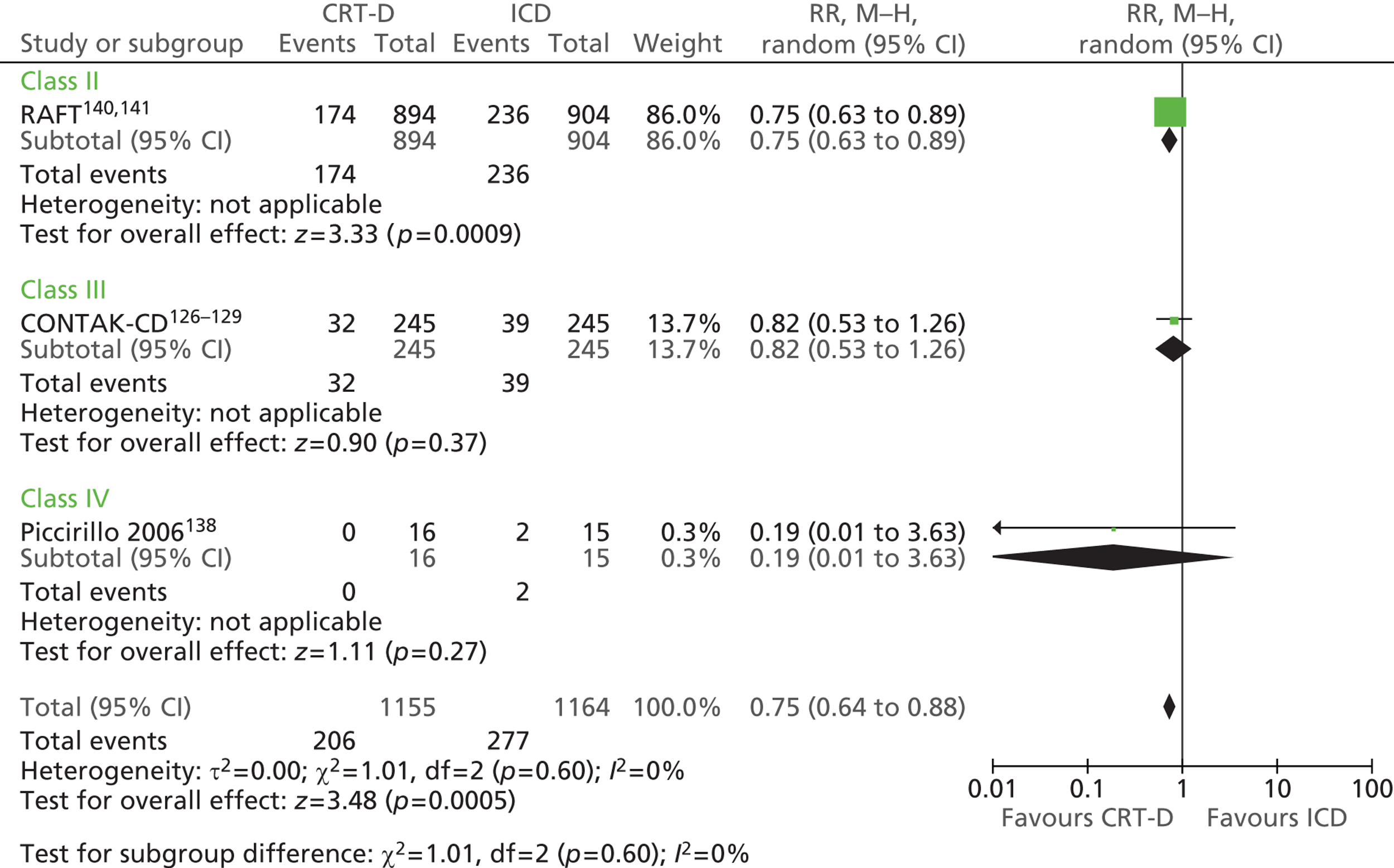

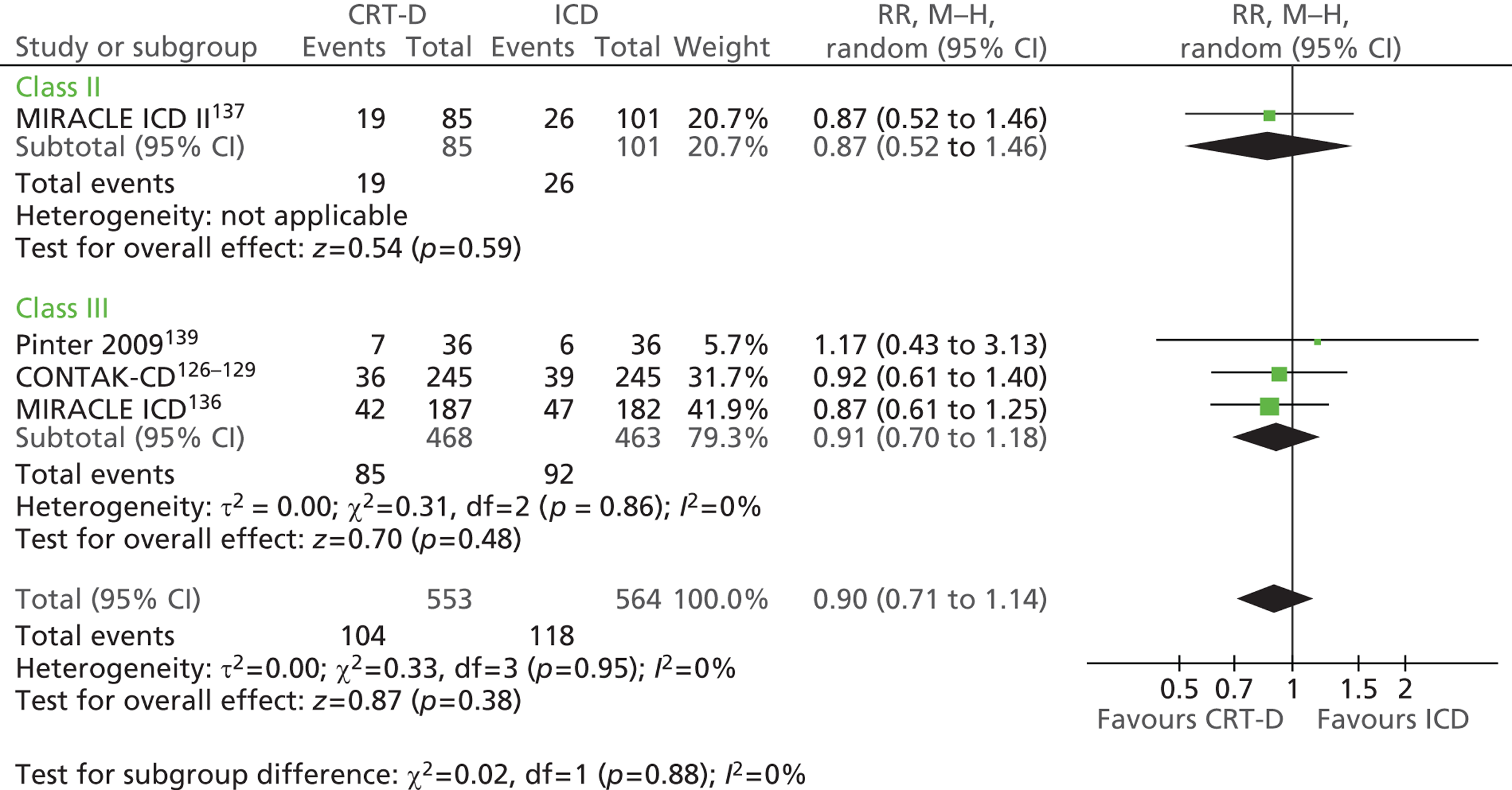

for people with both conditions described above, CRT-D will be compared with ICD, CRT-P or standard care (OPT alone).

The clinical outcomes of interest include mortality (including progressive HF mortality, non-HF mortality, all-cause mortality and SCD), health-related quality of life (HRQoL), symptoms and complications related to tachyarrhythmias and/or HF, HF hospitalisations, change in NYHA class, change in LVEF, and adverse effects of treatment. Outcomes for the assessment of cost-effectiveness will include direct costs based on estimates of health-care resources associated with the interventions as well as consequences of the interventions, such as treatment of adverse events.

Overall aims and objectives of the assessment

The aims of this health technology assessment are threefold:

-

to assess the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of ICDs in addition to OPT for the treatment of people who are at increased risk of SCD as a result of ventricular arrhythmias despite receiving OPT

-

to assess the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of CRT-P or CRT-D in addition to OPT for the treatment of people with HF as a result of LVSD and cardiac dyssynchrony despite receiving OPT

-

to assess the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of CRT-D in addition to OPT for the treatment of people who have an increased risk of both SCD as a result of ventricular arrhythmias and HF as a result of LVSD and cardiac dyssynchrony despite OPT.

Chapter 3 Methods for the systematic reviews of clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness

The a priori methods for systematically reviewing the evidence of clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness were described in the research protocol, which was sent to the advisory group and to NICE for comment. Although helpful comments were received relating to the general content of the research protocol, there were none that identified specific problems with the methodology of the review. The methods outlined in the protocol are briefly summarised below.

Identification of studies

A search strategy was developed, tested and refined by an experienced information scientist. The strategy identified clinical effectiveness studies of ICDs for arrhythmias and CRT for the treatment of HF. Additional search strategies identified studies reporting on the cost-effectiveness of ICDs and CRT, and studies reporting on the epidemiology and natural history of arrhythmias and HF. Searches to inform cost-effectiveness modelling were also conducted. Sources of information and search terms are provided in Appendix 2. The most recent search was carried out in November 2012.

The following electronic databases were searched: The Cochrane Library including the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (CDSR), the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, the Centre for Reviews and Dissemination (CRD) (University of York) Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effectiveness (DARE), the NHS Economic Evaluation Database (NHS EED) and the Health Technology Assessment (HTA) database; MEDLINE (Ovid); EMBASE (Ovid); MEDLINE In-Process and Other Non-Indexed Citations (Ovid); Web of Science with Conference Proceedings: Science Citation Index Expanded (SCIE) and Conference Proceedings Citation Index – Science (CPCI) (ISI Web of Knowledge); Biosis Previews (ISI Web of Knowledge); Zetoc (Mimas); NIHR Clinical Research Network Portfolio; ClinicalTrials.gov; and Current Controlled Trials. Searches were carried out from database inception to the present for studies in the English language. Searches were limited to randomised controlled trials (RCTs) for the assessment of clinical effectiveness and to full economic evaluations for the assessment of cost-effectiveness. Bibliographies of retrieved papers and the manufacturers’ submission (MS) to NICE were assessed for relevant studies that met the inclusion criteria, and the expert advisory group was contacted to identify additional published and unpublished evidence.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

The inclusion criteria for population, interventions and comparators are summarised in Table 5.

| Population | People at increased risk of SCD as a result of ventricular arrhythmias despite OPT | People with HF as a result of LVSD and cardiac dyssynchrony despite OPT | People with both conditions described to the left |

| Interventions | ICD in addition to OPT | CRT-P or CRT-D in addition to OPT | CRT-D in addition to OPT |

| Comparators | Standard care (OPT without ICD) | CRT-P vs. CRT-D; standard care (OPT without CRT) | ICDs; CRT-P; standard care (OPT alone) |

Population

-

People at increased risk of SCD as a result of ventricular arrhythmias despite OPT.

-

People with HF as a result of LVSD and cardiac dyssynchrony despite OPT.

-

People with both conditions described above.

Left ventricular systolic dysfunction was defined as a reduced LVEF using the cut-off provided by the publications (an arbitrary cut-off was not imposed by this review). Similarly, cardiac dyssynchrony was as defined by the publications, usually a prolonged QRS interval. Trials clearly stating that participants had a reduced LVEF, cardiac dyssynchrony and an indication for an ICD were considered as having both conditions.

Interventions

The interventions under consideration for each patient group are:

-

for people at increased risk of SCD: ICDs in addition to OPT

-

for people with HF: CRT-P or CRT-D in addition to OPT

-

for people with both conditions: CRT-D in addition to OPT.

Comparators

The comparators under consideration for each patient group are:

-

for people at increased risk of SCD: standard care (OPT without ICD)

-

for people with HF: CRT-P or CRT-D were compared with each other; standard care (OPT without CRT)

-

for people with both conditions: ICDs; CRT-P; standard care (OPT alone).

When screening studies for inclusion it became apparent that the pharmacological therapy in some of the older studies might not be considered optimal by current standards. After consultation with NICE and clinical experts, it was decided that trials in which the pharmacological therapy in either the intervention arm or the comparator arm was not optimal (i.e. was not current best practice based on clinical opinion) would be included in the systematic review.

Outcomes

Studies must have included one or more of the following outcome measures to be eligible for inclusion in this review:

-

mortality (including progressive HF mortality, non-HF mortality, all-cause mortality and SCD)

-

adverse effects of treatment

-

HRQoL

-

symptoms and complications related to tachyarrhythmias and/or HF

-

HF hospitalisations

-

change in NYHA class

-

change in LVEF.

Study design

-

For the systematic review of clinical effectiveness, only RCTs were eligible.

-

Studies published as abstracts or conference presentations from 2010 onwards were included only if sufficient details were presented to allow an appraisal of the methodology and the assessment of results to be undertaken.

-

Systematic reviews of the clinical effectiveness of ICDs and CRT were used as a source of references.

-

For the systematic review of cost-effectiveness, studies were included only if they reported the results of full economic evaluations [cost-effectiveness analyses (reporting cost per life-year gained), cost–utility analyses or cost–benefit analyses].

-

For the systematic review of QoL, primary studies or QoL data collected as part of a trial using the European Quality of Life-5 Dimensions (EQ-5D) (not visual analogue scale), and specified by NYHA class for people with HF, were included.

-

Non-English-language studies were excluded.

Screening and data extraction process

Studies were selected for inclusion in the systematic review of clinical effectiveness through a two-stage process using the criteria defined earlier. The titles and abstracts of studies identified by the search strategy were screened by two reviewers to identify all citations that potentially met the inclusion criteria. Full papers of potentially relevant studies were retrieved and assessed by two independent reviewers using a standardised eligibility form. Full papers or abstracts describing the same study were linked together, with the article reporting key outcomes designated as the primary publication. Data from included studies were extracted by one reviewer using a standardised data extraction form and checked by a second reviewer. At each stage, any disagreements were resolved by discussion, with the involvement of a third reviewer when necessary.

Titles and abstracts identified by the search strategies for the systematic reviews of cost-effectiveness and QoL were assessed for potential eligibility by two health economists using predetermined inclusion criteria. Full papers were assessed for inclusion by two reviewers.

Critical appraisal

The risk of bias of the clinical effectiveness studies was assessed according to criteria devised by The Cochrane Collaboration. 65 Criteria were applied by one reviewer and checked by a second reviewer, with differences in opinion resolved by consensus and by consultation with a third reviewer if necessary. Economic evaluations were appraised using criteria based on those recommended by Drummond and Jefferson,66 the requirements of the NICE reference case67 and the suggested guideline for good practice in decision-analytic modelling by Philips and colleagues68 (see Appendix 3). Published studies carried out from the UK NHS and Personal Social Services (PSS) perspective were examined in more detail.

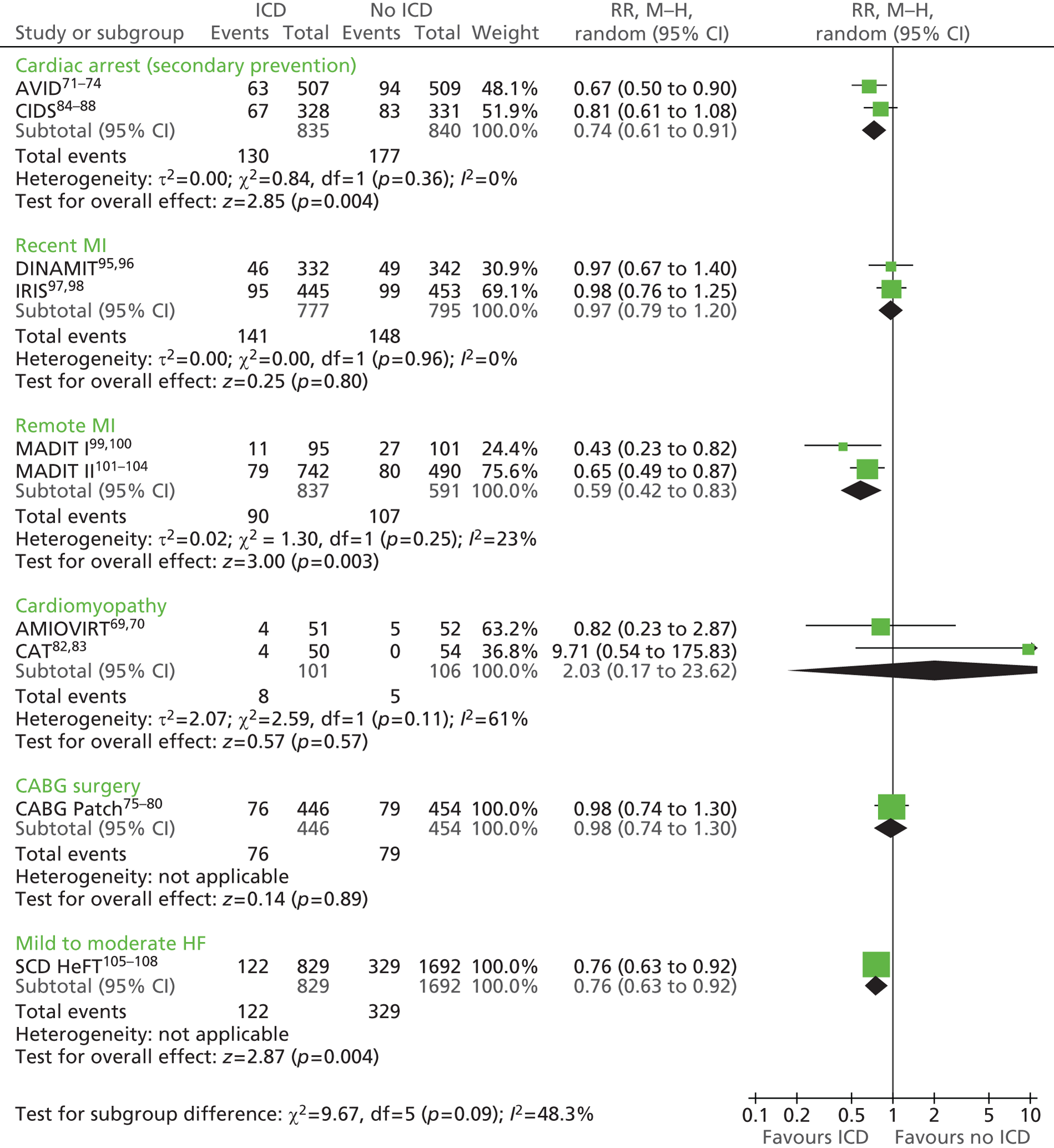

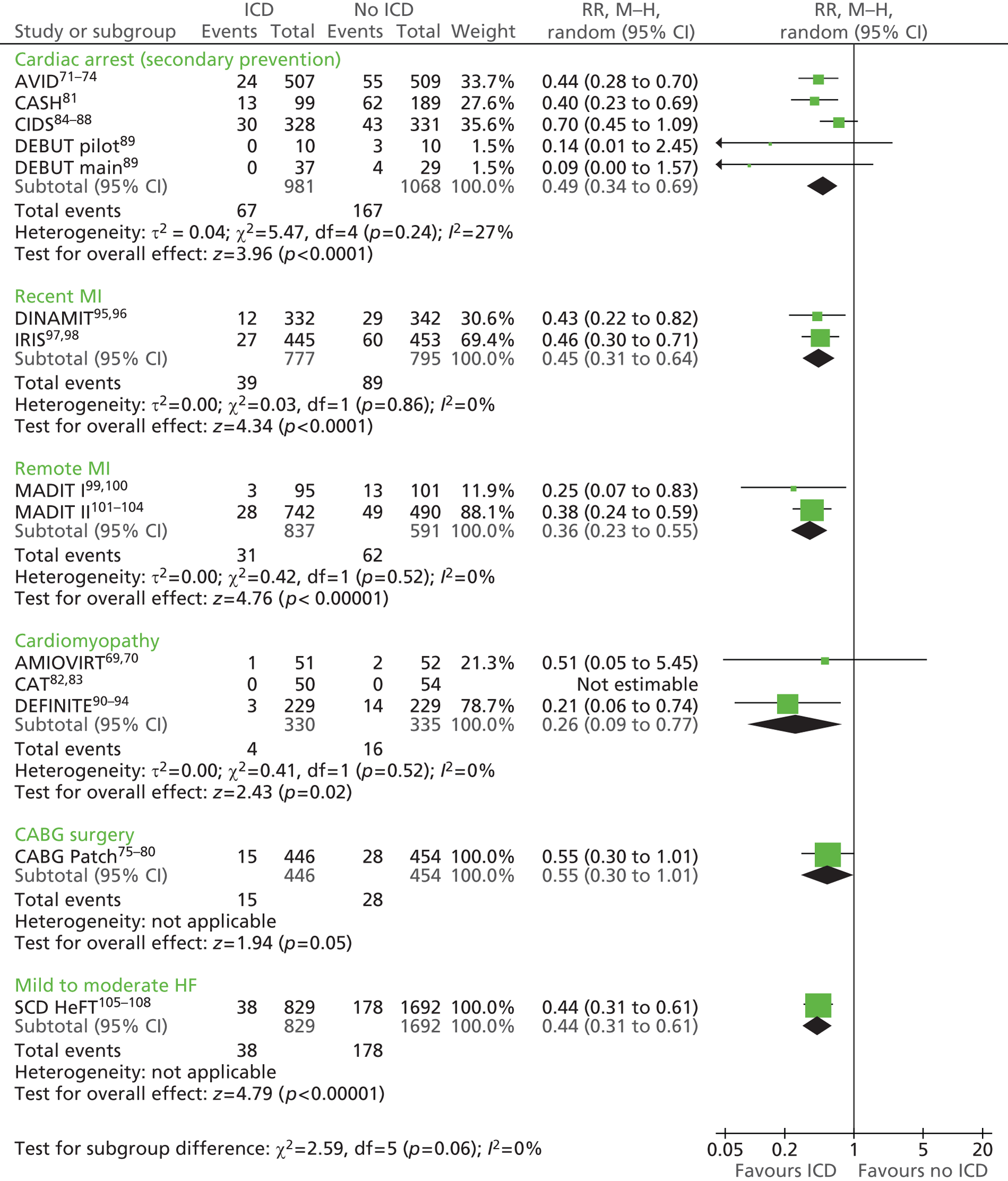

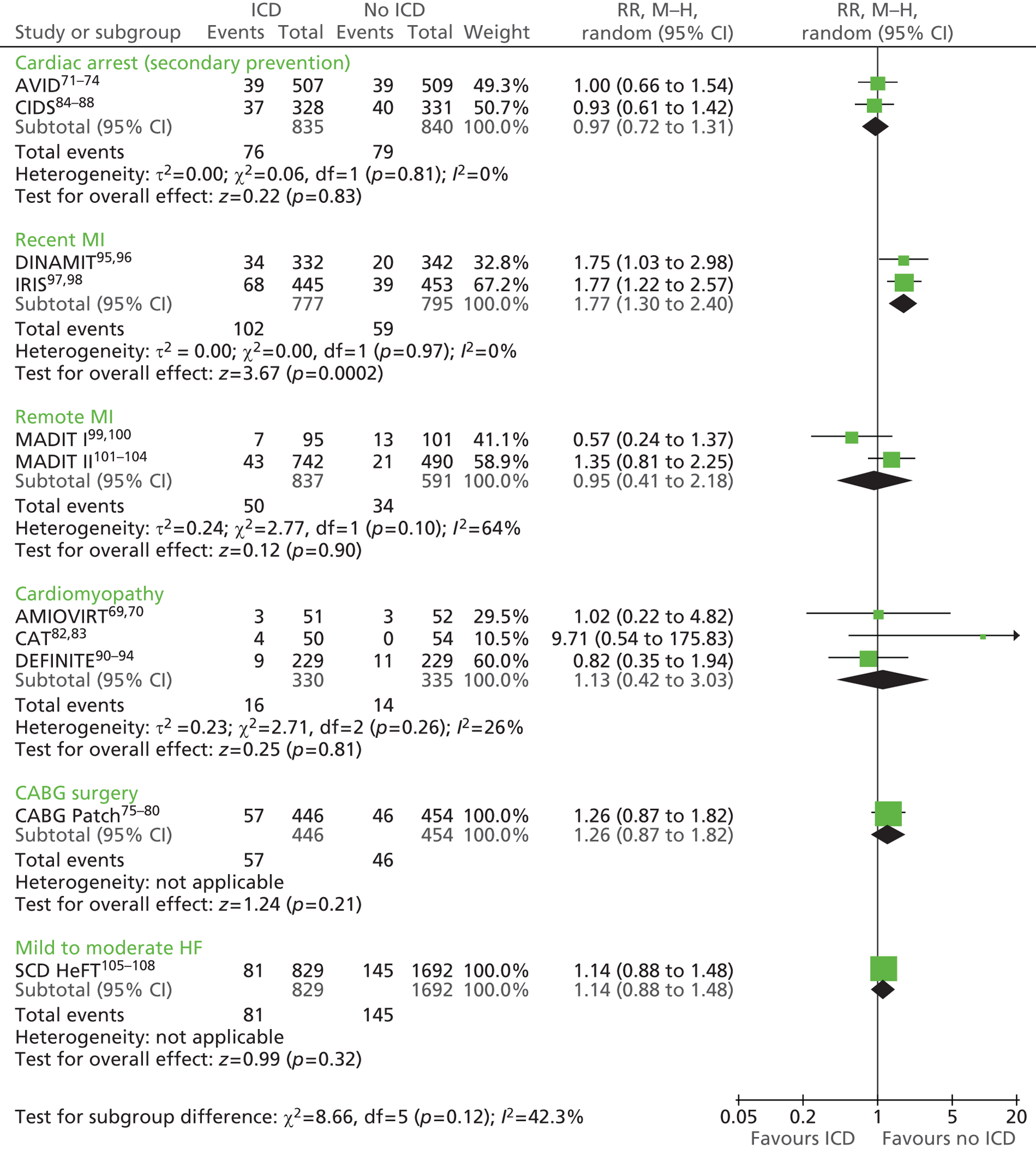

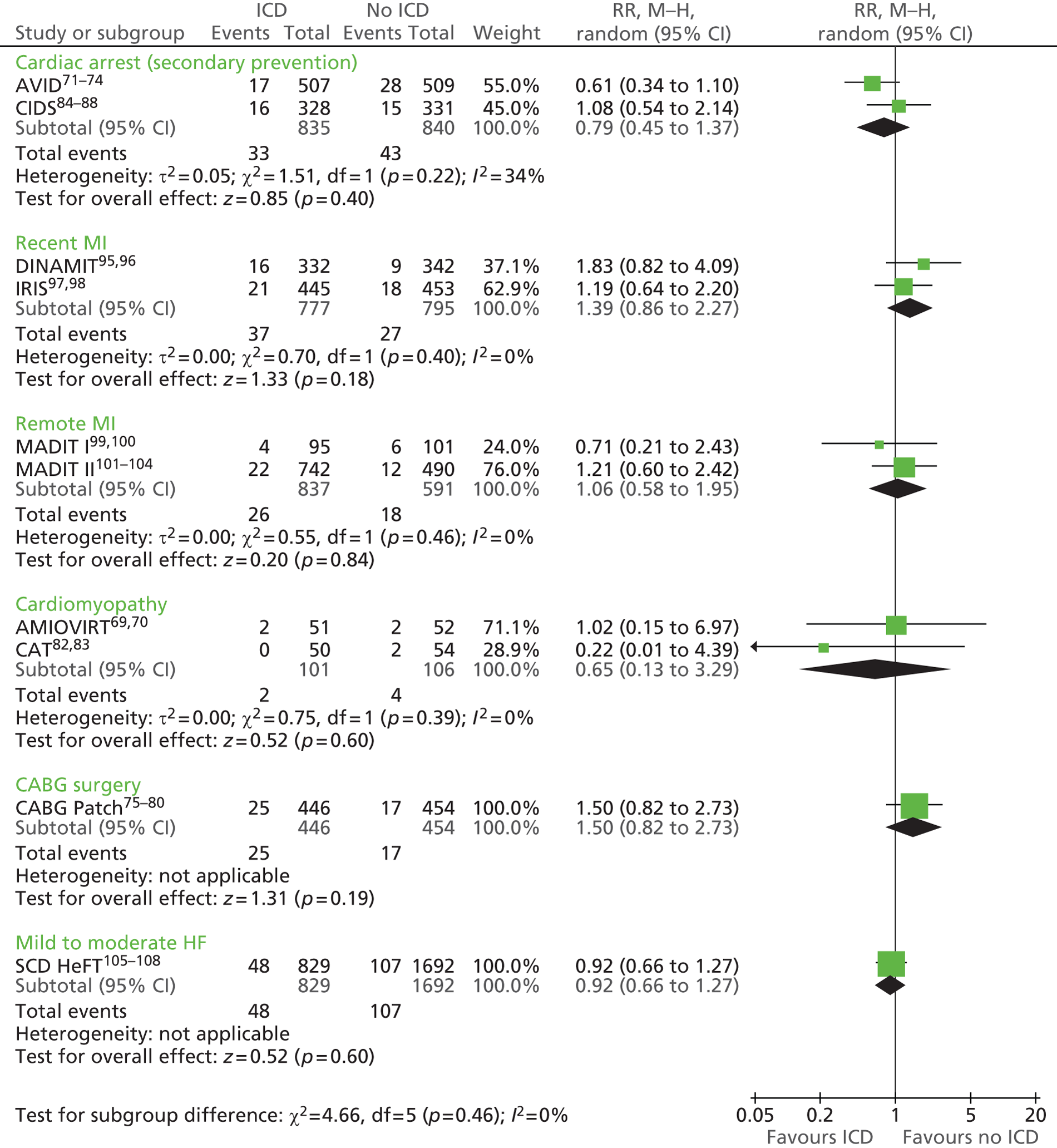

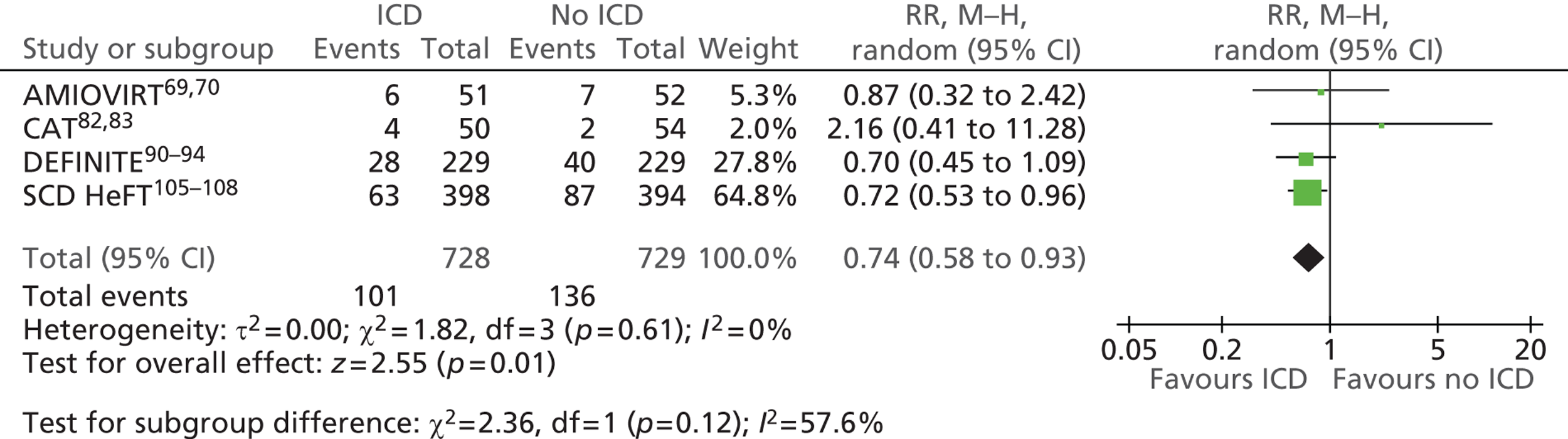

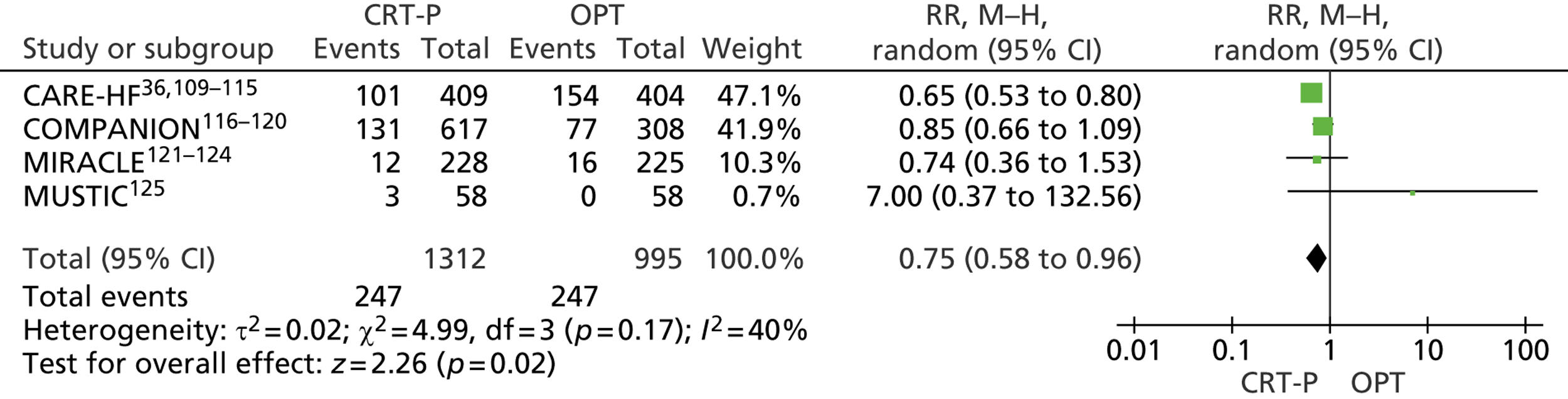

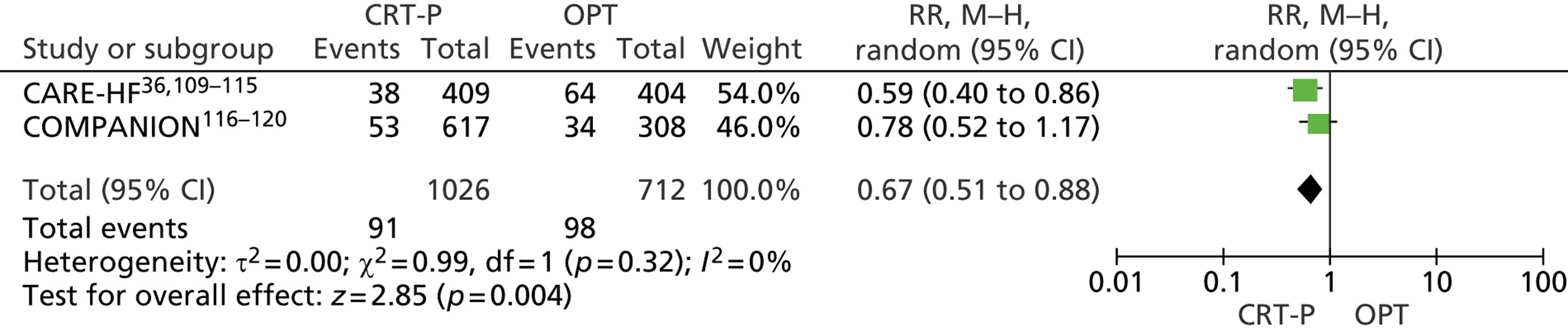

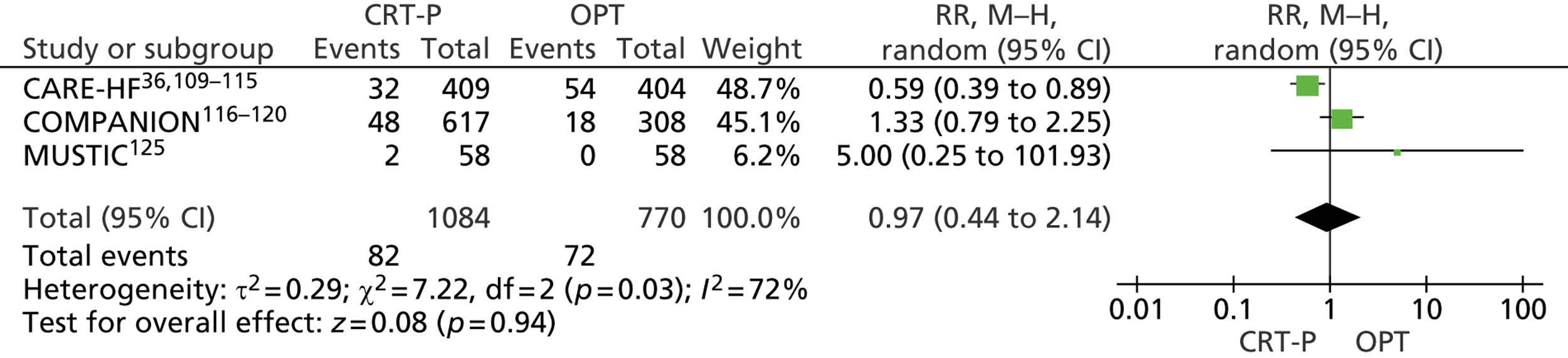

Method of data synthesis

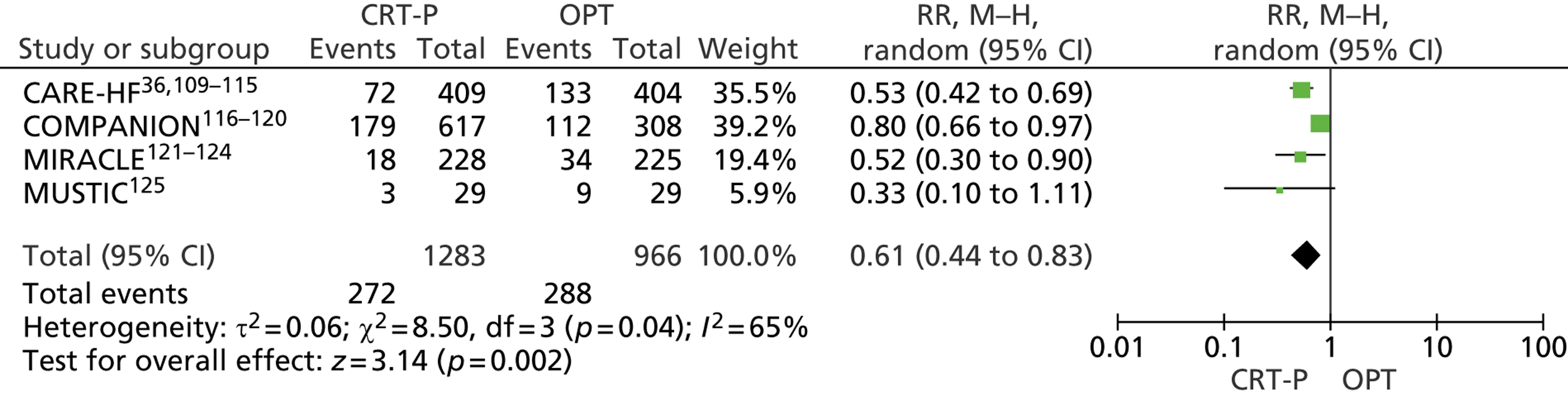

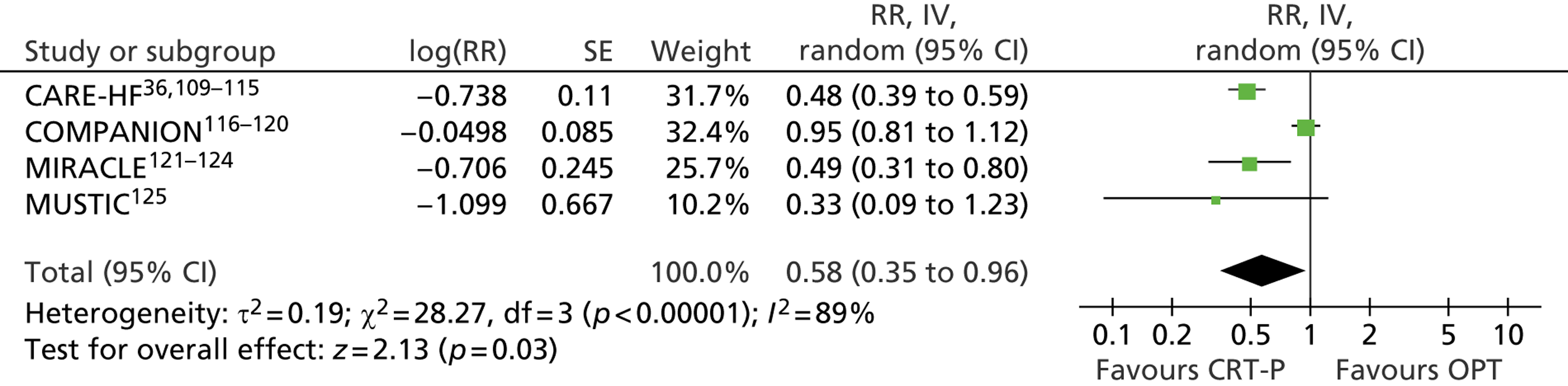

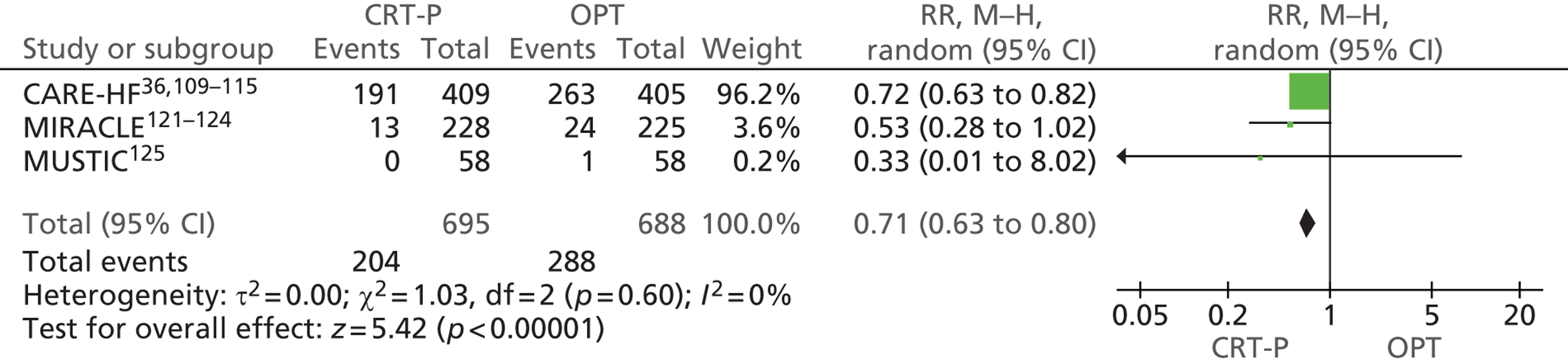

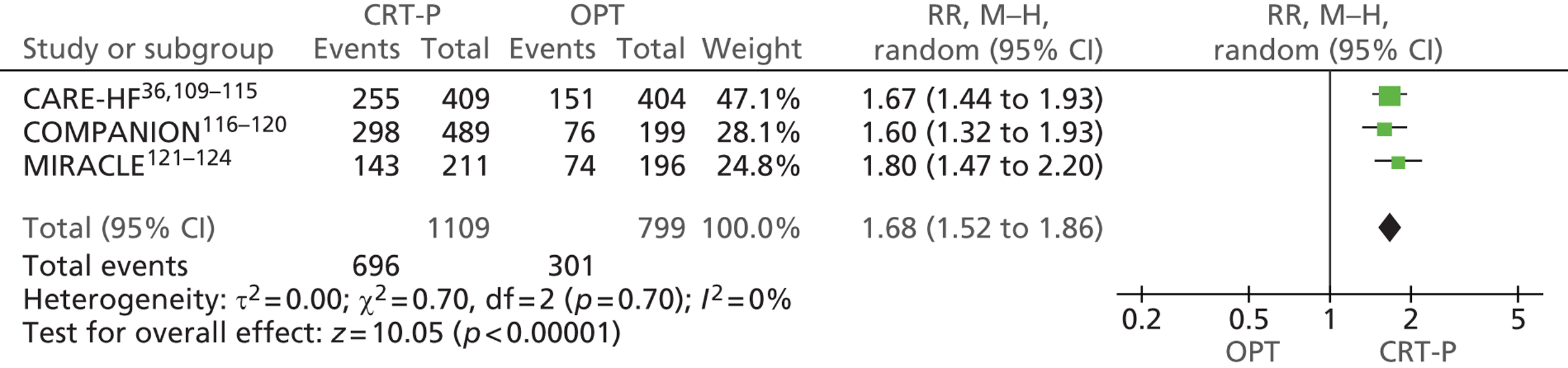

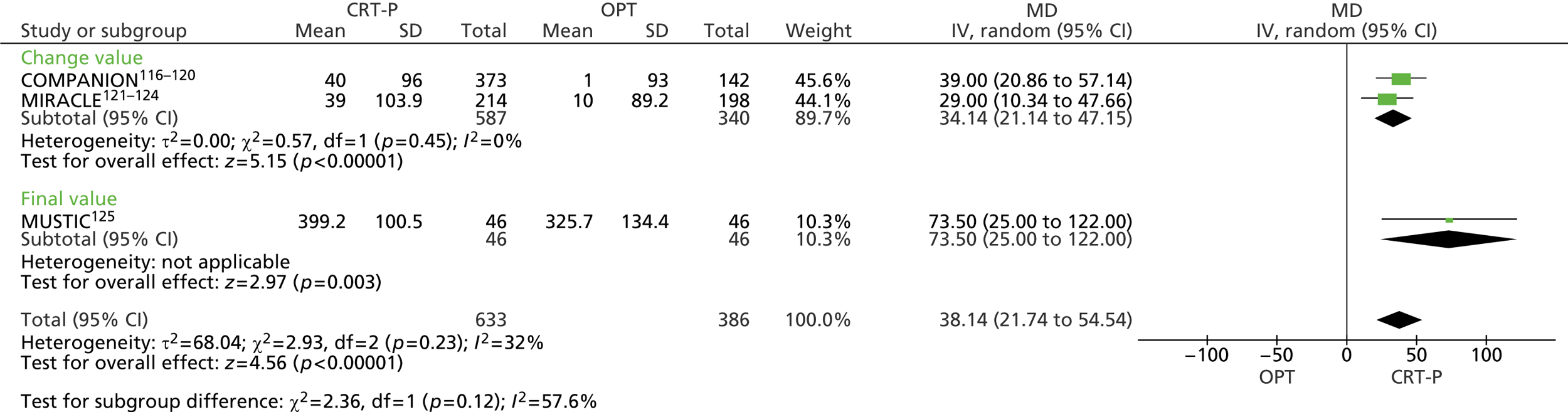

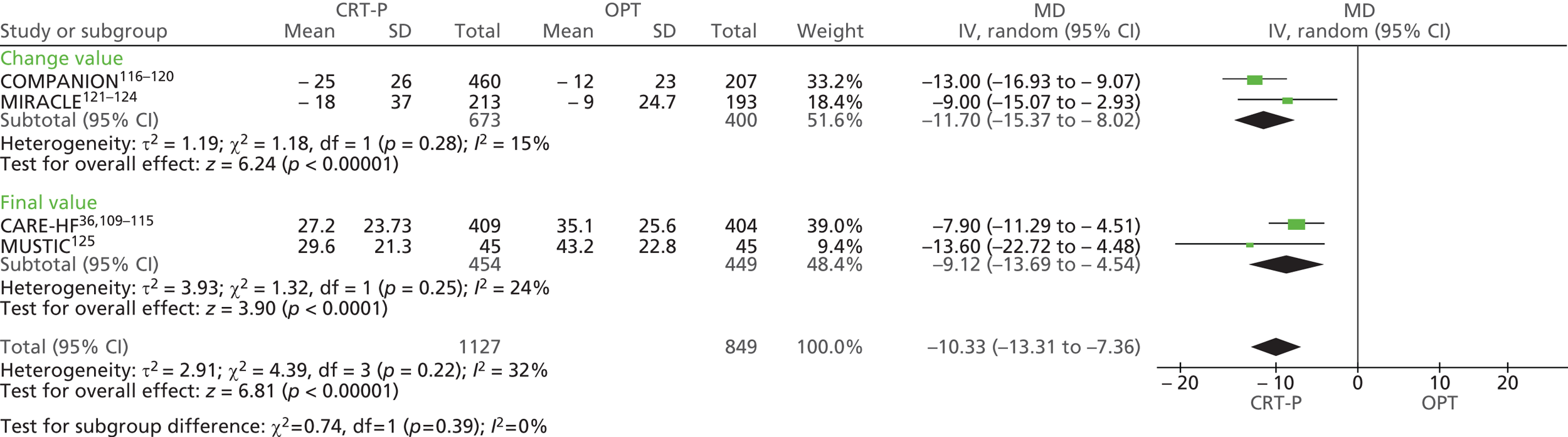

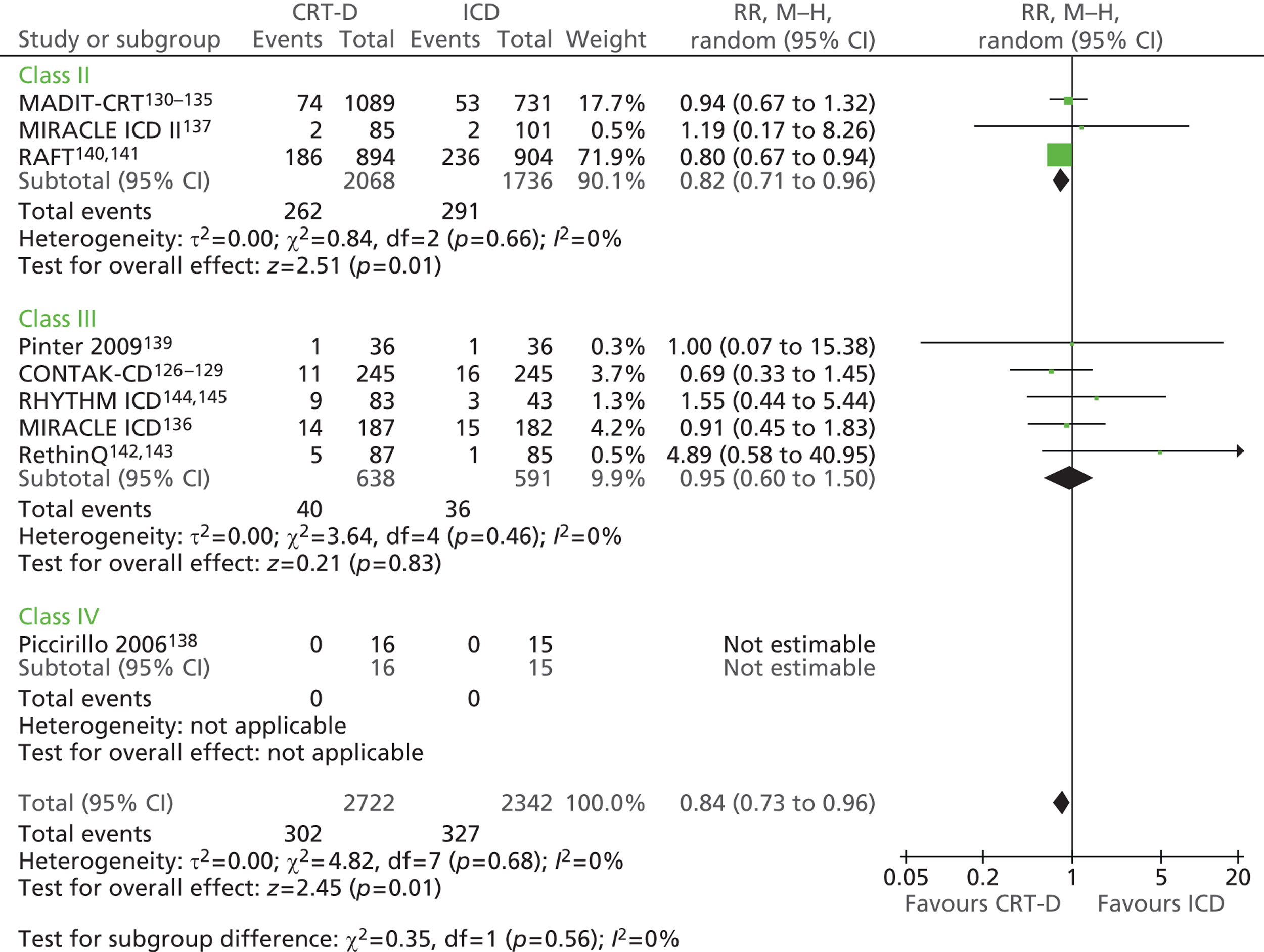

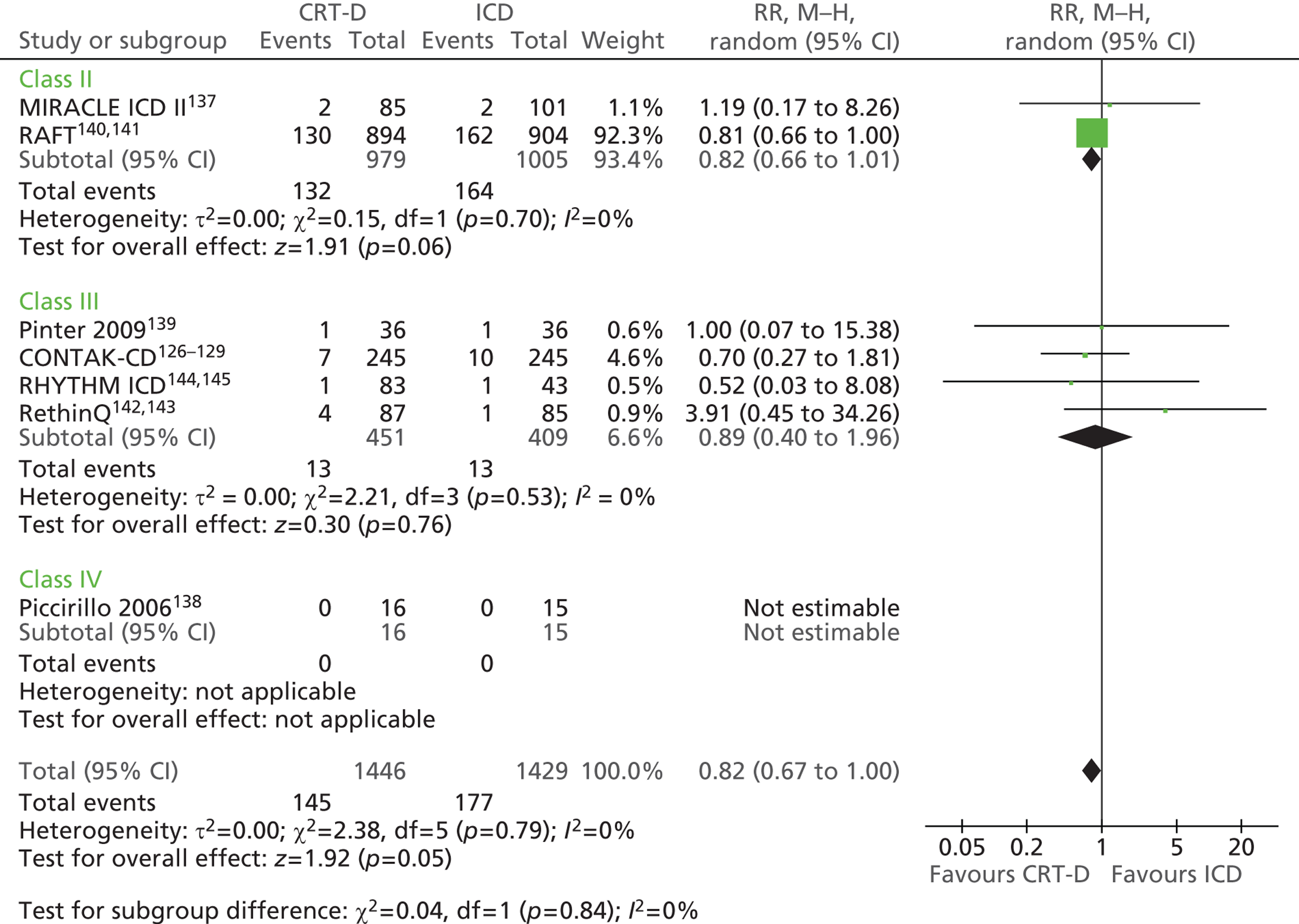

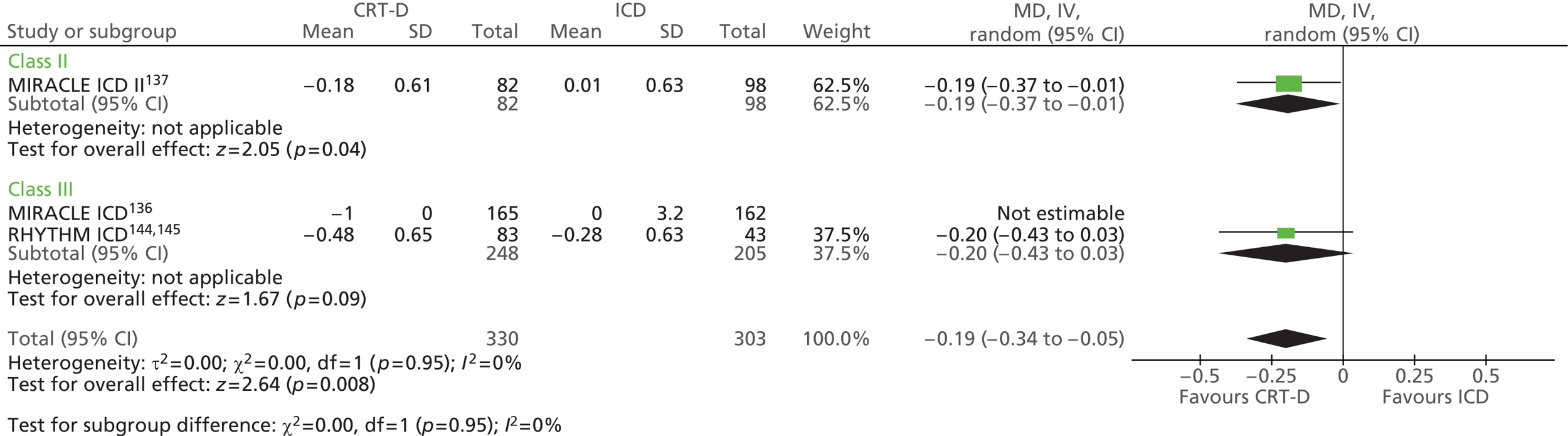

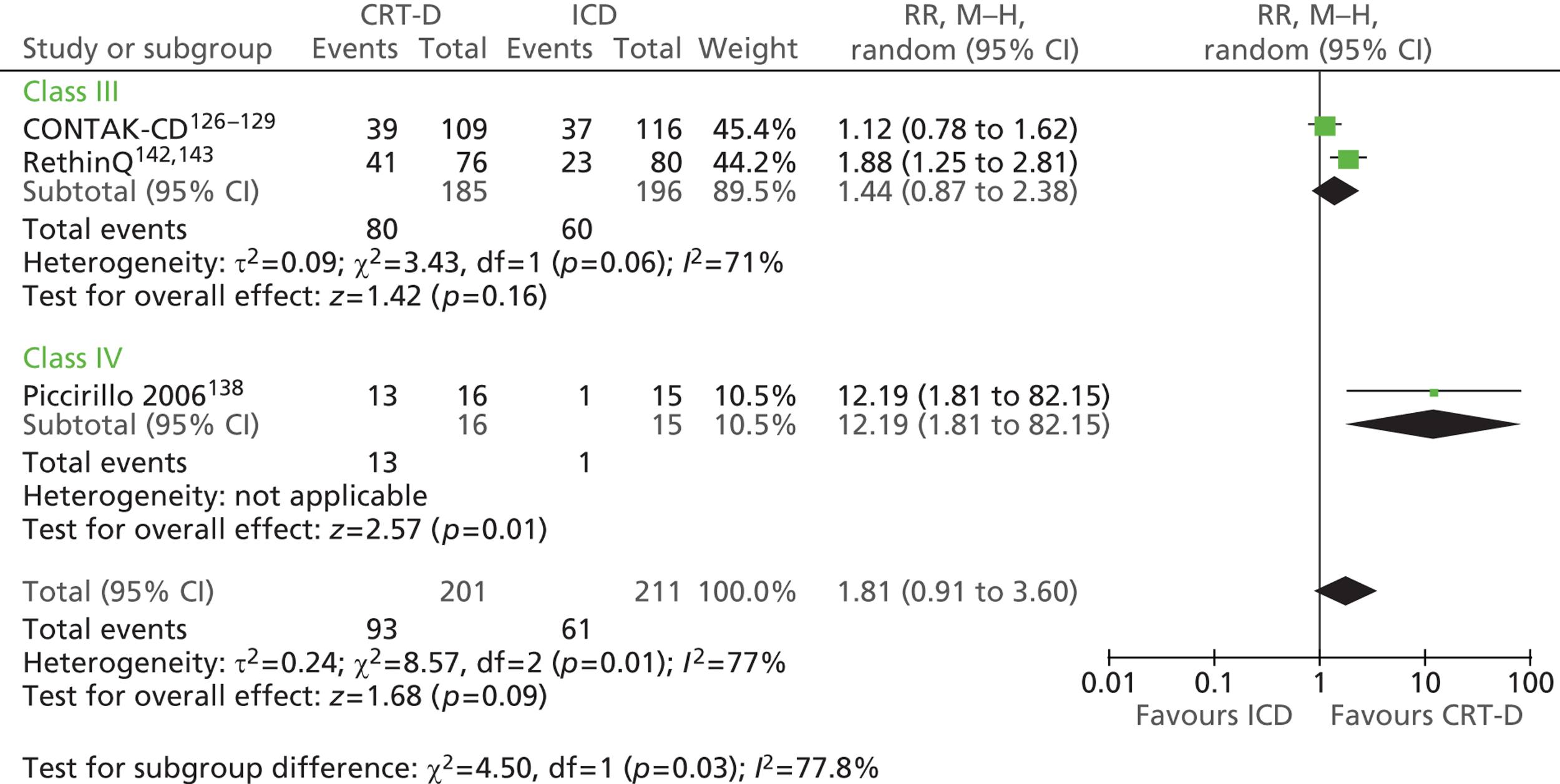

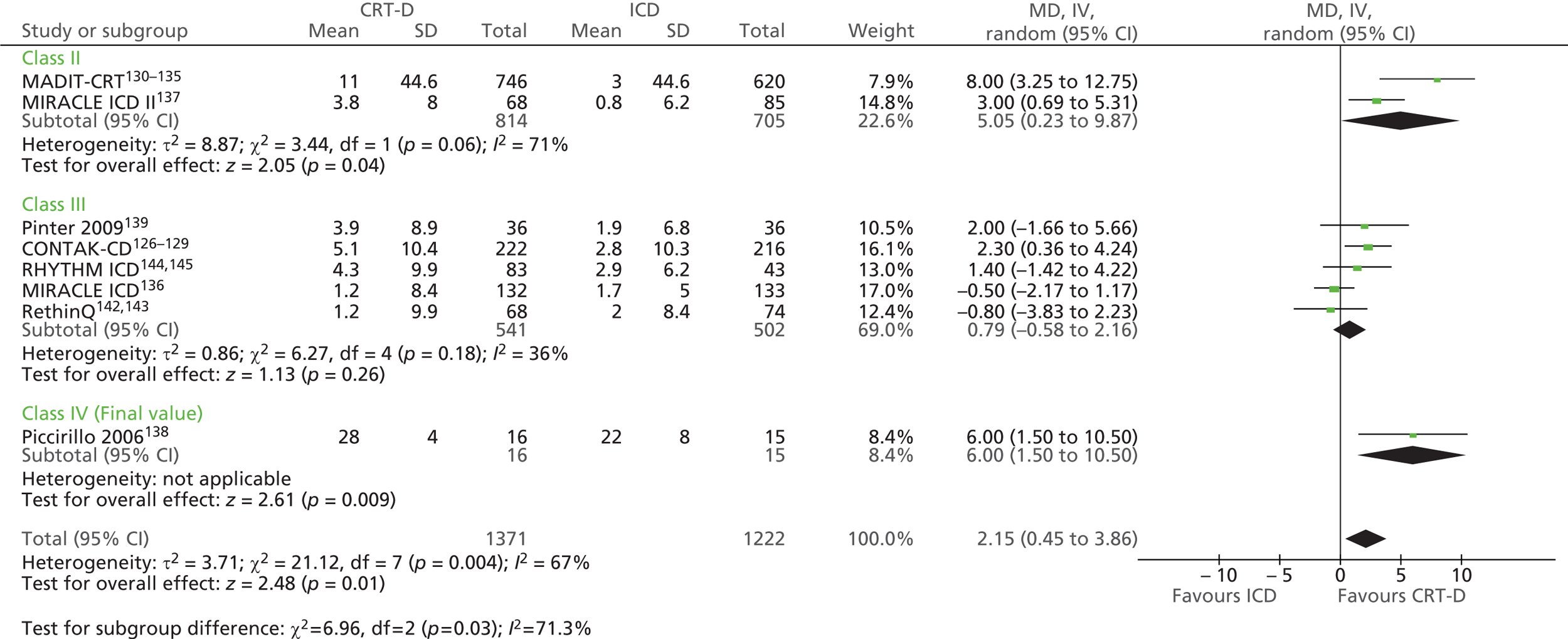

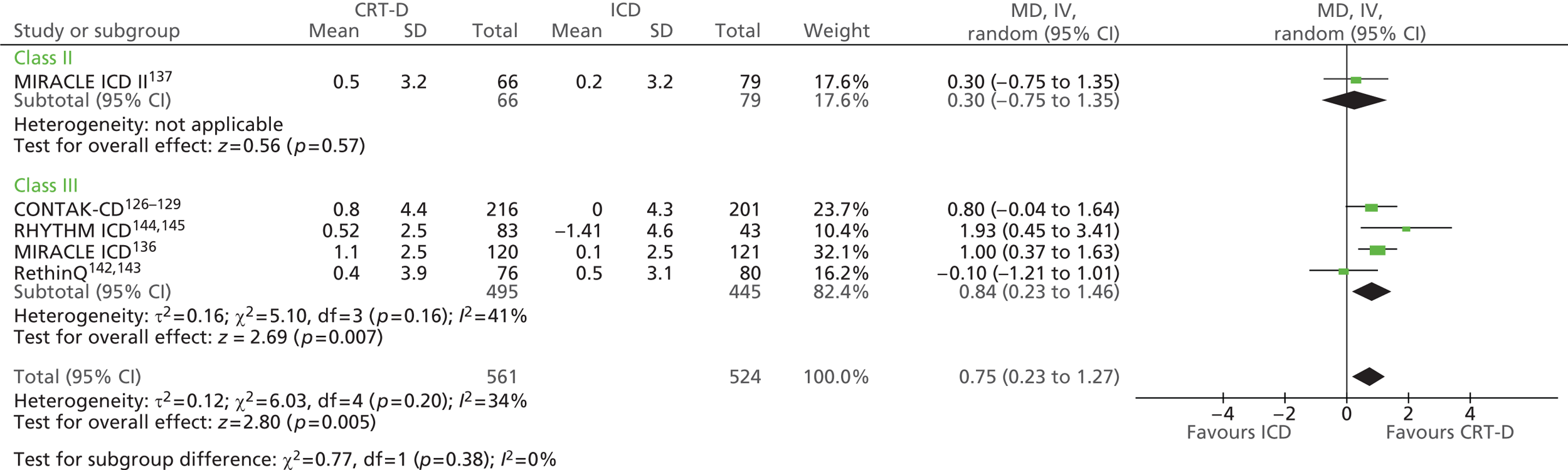

Clinical effectiveness data were synthesised through a narrative review with tabulation of the results of included studies. When data were of sufficient quality and homogeneity, meta-analysis of the clinical effectiveness studies was performed to estimate the risk ratio (RR) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for relevant outcomes. The random-effects method was used. Meta-analysis was performed using Review Manager 5 (RevMan; The Cochrane Collaboration, The Nordic Cochrane Centre, Copenhagen, Denmark). Statistical heterogeneity was assessed using the chi-squared test and degrees of freedom (df), and the I2 statistic. When standard deviations (SDs) were not presented in the published papers, these were calculated from the available statistics [CIs, standard errors (SEs) or p-values]. 65 A minority of papers reported median values with 95% CIs; in these cases, rather than omitting the trial from a meta-analysis, it was assumed that the data were symmetrical (and so the median would be similar to the mean value) and the median was used directly in the meta-analysis.

This report contains reference to confidential information provided as part of the NICE appraisal process. This information has been removed from the report and the results, discussions and conclusions of the report do not include the confidential information. These sections are clearly marked in the report.

Chapter 4 Clinical effectiveness

Overall quantity of evidence identified

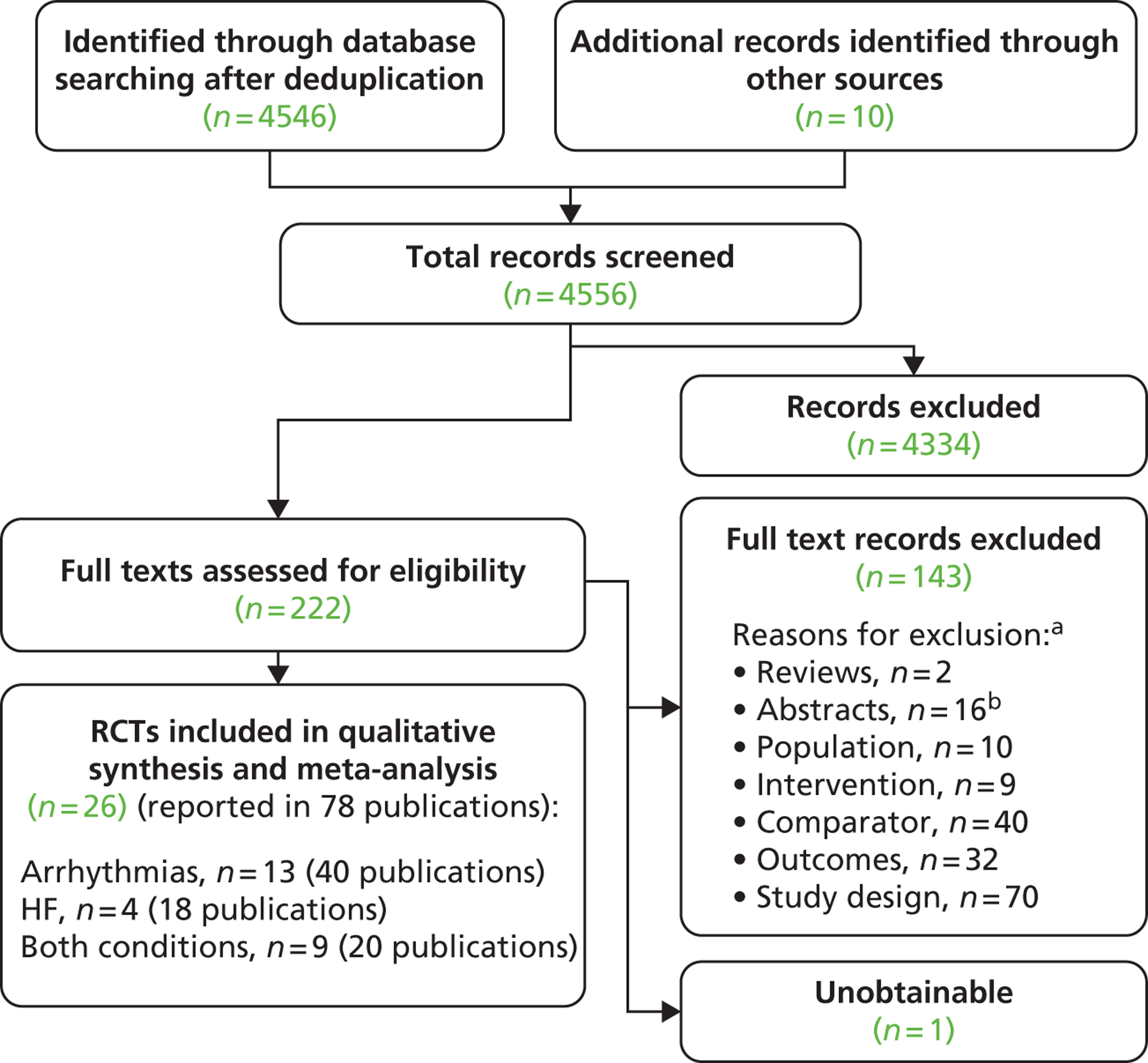

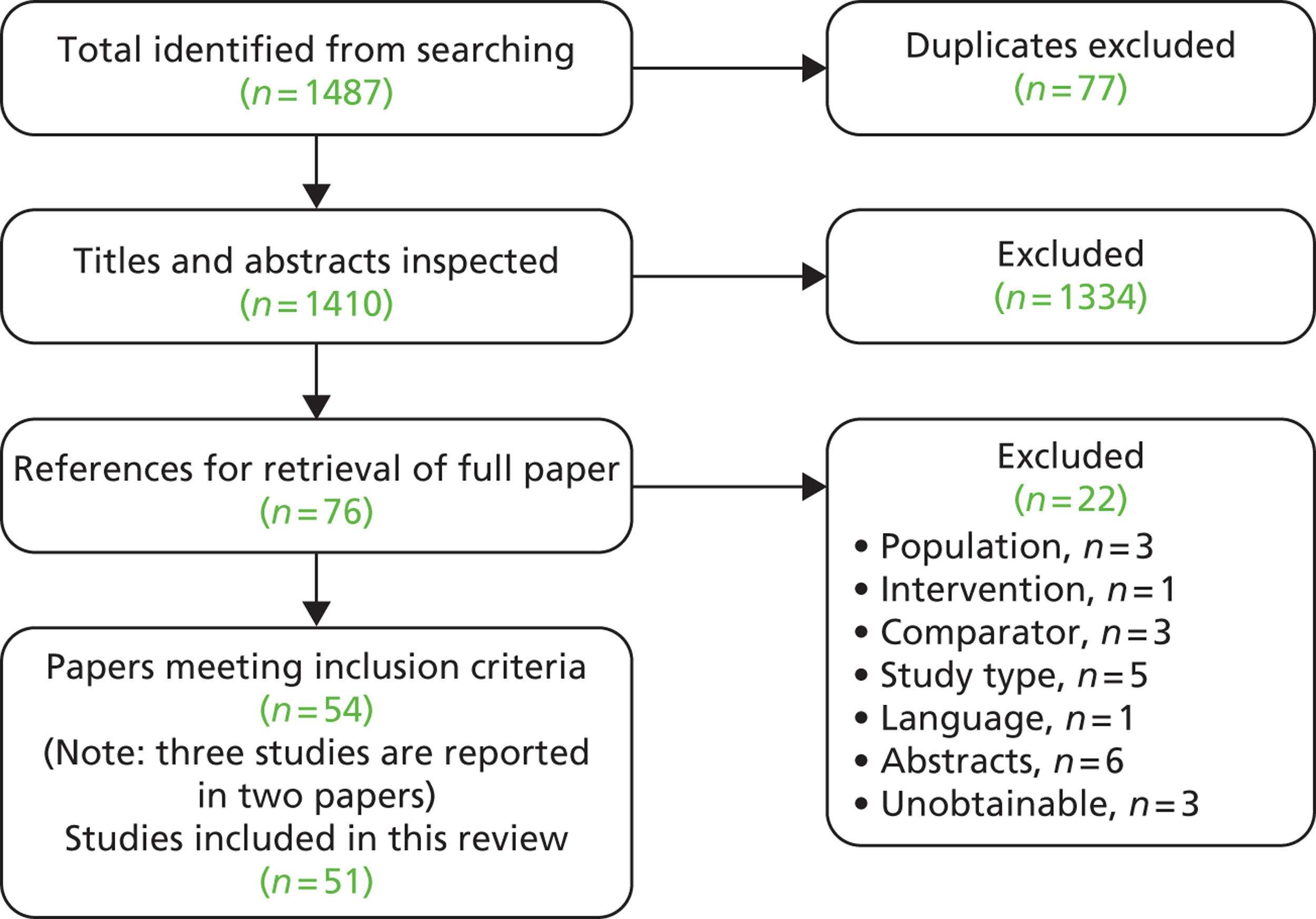

Searches identified a total of 4556 references after deduplication and full texts of 222 references were retrieved after screening titles and abstracts. The number of references excluded at each stage of the systematic review is shown in Figure 3. Selected references that were retrieved but later excluded are listed in Appendix 4 with reasons for exclusion. Papers were often excluded for more than one reason, with the most common reason being study design (70 papers), followed by comparator (40 papers) and outcomes (32 papers). Although not formally assessed, the level of agreement between reviewers for screening was considered good.

FIGURE 3.

Flow chart of identification of studies. a, Studies could be excluded for more than one reason; b, 16 of the abstracts/conference presentations were published from 2010 onwards (see Appendix 4) and were excluded as there were insufficient details included to allow an appraisal of the methodology and an assessment of the results as per the protocol.

Searches identified five relevant trials in progress, summaries of which can be found in Appendix 5.

Twenty-six eligible RCTs were identified (Table 6); many of these trials were reported in several publications (a total of 78 papers). Thirteen RCTs were considered to involve people at increased risk of SCD as a result of ventricular arrhythmias (see People at risk of sudden cardiac death as a result of ventricular arrhythmias), four trials were considered to involve people with HF as a result of LVSD and cardiac dyssynchrony (see People with heart failure as a result of left ventricular systolic dysfunction and cardiac dyssynchrony) and nine RCTs were considered to involve people with both of these conditions (see People with both conditions). Further details on the quantity and quality of research for each of these populations are described in the following sections.

| Study | Publicationa |

|---|---|

| People at increased risk of SCD as a result of ventricular arrhythmias | |

| AMIOVIRT | Strickberger et al. 2003,69 Wijetunga and Strickberger 200370 |

| AVID | AVID investigators 199771 and 1999,72 Hallstrom 1995,73 Schron et al. 200274 |

| CABG Patch | Bigger 1997,75 CABG Patch Trial Investigators and Coordinators 1993,76 Bigger et al. 199877 and 1999,78 Spotnitz et al. 1998,79 Namerow et al. 199980 |

| CASH | Kuck et al. 2000 81 |

| CAT | Bänsch et al. 2002,82 German Dilated Cardiomyopathy Study investigators 199283 |

| CIDS | Connolly et al. 200084 and 1993,85 Sheldon et al. 2000,86 Irvine et al. 2002,87 Bokhari et al. 200488 |

| DEBUT | Nademanee et al. 2003 89 |

| DEFINITE | Kadish et al. 200490 and 2000,91 Schaechter et al. 2003,92 Ellenbogen et al. 2006,93 Passman et al. 200794 |

| DINAMIT | Hohnloser et al. 200495 and 200096 |

| IRIS | Steinbeck et al. 200997 and 200498 |

| MADIT I | Moss et al. 1996,99 MADIT Executive Committee 1991100 |

| MADIT II | Moss et al. 2002101 and 1999,102 Greenberg et al. 2004,103 Noyes et al. 2007104 |

| SCD-HeFT | Bardy et al. 2005,105 Mitchell et al. 2008,106 Mark et al. 2008,107 Packer et al. 2009108 |

| People with HF as a result of LVSD and cardiac dyssynchrony | |

| CARE-HF | Cleland et al. 2005,109 2001,110 2006,111 2007112 and 2009,113 Gras et al. 2007,36 Gervais et al. 2009,114 Ghio et al. 2009115 |

| COMPANION | Bristow et al. 2004116 and 2000,117 US Food and Drug Administration 2004,118 Carson et al. 2005,119 Anand et al. 2009120 |

| MIRACLE | Abraham et al. 2002121 and 2000,122 US Food and Drug Administration 2001,123 St John Sutton et al. 2003124 |

| MUSTIC | Cazeau et al. 2001 125 |

| People with both conditions described above | |

| CONTAK-CD | Higgins et al. 2003,126 Saxon et al. 1999,127 Lozano et al. 2000,128 US Food and Drug Administration 2002129 |

| MADIT-CRT | Moss et al. 2009130 and 2005,131 Solomon et al. 2010,132 Goldenberg et al. 2011,133,134 Arshad et al. 2011135 |

| MIRACLE ICD | Young et al. 2003 136 |

| MIRACLE ICD II | Abraham et al. 2004 137 |

| Piccirillo 2006 | Piccirillo et al. 2006 138 |

| Pinter 2009 | Pinter et al. 2009 139 |

| RAFT | Tang et al. 2010140 and 2009141 |

| RethinQ | Beshai et al. 2007,142 Beshai and Grimm 2007143 |

| RHYTHM ICD | US Food and Drug Administration 2004144 and 2005145 |

People at risk of sudden cardiac death as a result of ventricular arrhythmias

Quantity and quality of research available

Eleven of the 13 RCTs included reported their findings in more than one paper; a summary of the included papers for each trial can be seen in Table 7. Seven of these RCTs plus one additional RCT [the Multicenter Unsustained Tachycardia Trial (MUSTT)146] were included in the 2005 TAR,62 as can be seen in Table 7. One further RCT [the Midlands Trial of Empirical Amiodarone versus Electrophysiology-Guided Interventions and Implantable Cardioverter-Defibrillators (MAVERIC)147] was noted in the 2005 TAR62 as in progress at that time. The interventions in the MUSTT146 and MAVERIC147 trials did not meet the scope of the present review; however, as these were included in the previous TARs62,63 they are discussed in Subgroup analyses reported by included randomised controlled trials. A list of other excluded studies can be seen in Appendix 4.

| Study | 2005 TAR62 (reason for exclusion) | Present TAR (participants) | Publicationa |

|---|---|---|---|

| Secondary prevention | |||

| AVID | Included | Included (cardiac arrest) | AVID investigators 199771 and 1999,72 Hallstrom 1995,73 Schron et al. 200274 |

| CASH | Included | Included (cardiac arrest) | Kuck et al. 2000 81 |

| CIDS | Included | Included (cardiac arrest) | Connolly et al. 200084 and 1993,85 Sheldon et al. 2000,86 Irvine et al. 2002,87 Bokhari et al. 200488 |

| DEBUT | Excluded (participants) | Included (sudden unexpected death syndrome) | Nademanee et al. 2003 89 |

| Primary prevention | |||

| DINAMIT | In progress | Included (early post MI) | Hohnloser et al. 200495 and 200096 |

| IRIS | New | Included (early post MI) | Steinbeck et al. 200997 and 200498 |

| MADIT I | Included | Included (remote from MI) | Moss et al. 1996,99 MADIT Executive Committee 1991100 |

| MADIT II | Included | Included (remote from MI) | Moss et al. 2002101 and 1999,102 Greenberg et al. 2004,103 Noyes et al. 2007104 |

| AMIOVIRT | Excluded (participants) | Included (cardiomyopathy) | Strickberger et al. 2003,69 Wijetunga and Strickberger 200370 |

| CAT | Included | Included (cardiomyopathy) | Bänsch et al. 2002,82 German Dilated Cardiomyopathy Study investigators 199283 |

| DEFINITE | Excluded (participants) | Included (cardiomyopathy) | Kadish et al. 200490 and 2000,91 Schaechter et al. 2003,92 Ellenbogen et al. 2006,93 Passman et al. 200794 |

| CABG Patch | Included | Included (need for CABG) | Bigger 1997,75 CABG Patch Trial Investigators and Coordinators 1993;76 Bigger et al. 199877 and 1999,78 Spotnitz et al. 1998,79 Namerow et al. 199980 |

| MUSTT | Included | Excluded because of intervention | Buxton et al. 1999,146 Lee et al. 2002148 |

| SCD-HeFT | In progress, in NICE TA9542 | Included (HF) | Bardy et al. 2005,105 Mitchell et al. 2008,106 Mark et al. 2008,107 Packer et al. 2009108 |

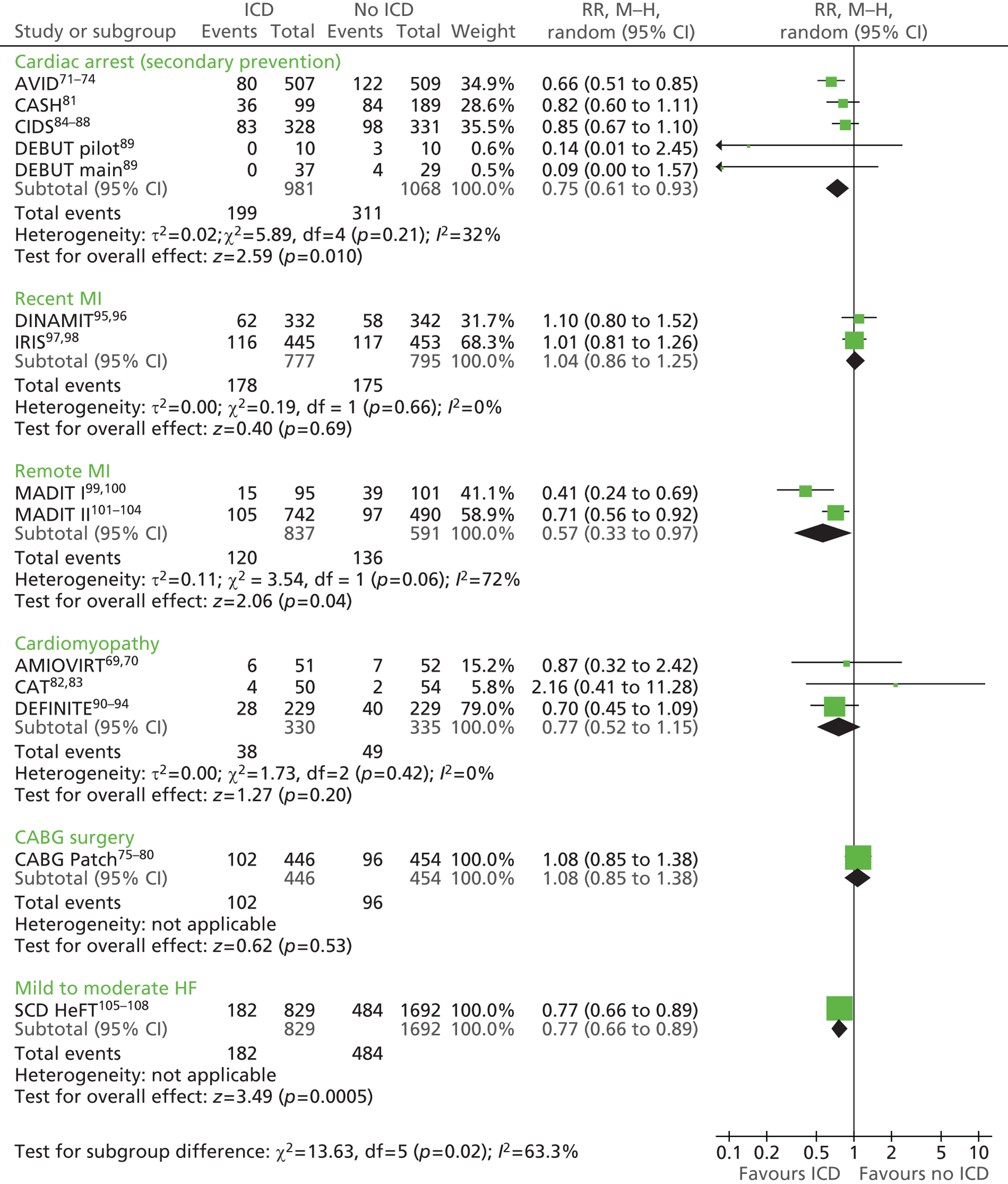

The RCTs used different criteria to identify groups at ‘high risk’ of SCD from ventricular arrhythmia. The Antiarrhythmics Versus Implantable Defibrillators (AVID),71 Cardiac Arrest Study Hamburg (CASH),81 Canadian Implantable Defibrillator Study (CIDS)84 and Defibrillator versus Beta-Blockers for Unexplained Death in Thailand (DEBUT)89 trials included people who had had a previous ventricular arrhythmia or who had been resuscitated from cardiac arrest. Four studies included people with either a recent MI [Defibrillator in Acute Myocardial Infarction Trial (DINAMIT)95 and the Immediate Risk Stratification Improves Survival (IRIS) trial97] or a MI > 3–4 weeks before study entry [Multicenter Automatic Defibrillator Implantation Trial I (MADIT I),99 MADIT II101]. The Amiodarone Versus Implantable Cardioverter-Defibrillator Randomized Trial (AMIOVIRT),69 Cardiomyopathy Trial (CAT)82 and Defibrillators in Non-Ischemic Cardiomyopathy Treatment Evaluation (DEFINITE)90 trial included people with cardiomyopathy. The Coronary Artery Bypass Graft Patch (CABG Patch) trial75 recruited patients scheduled for coronary artery bypass graft surgery and at high risk for sudden death, and the Sudden Cardiac Death in Heart Failure Trial (SCD-HeFT)105 recruited a broad population of patients with mild to moderate HF. The results will be discussed according to the ‘high-risk’ group of the participants.

Characteristics of the included studies

Study characteristics are summarised in Tables 8–10 and participant characteristics are summarised in Tables 11–13. Additional details can be found in Appendix 7.

| Parameter | AVID71 | CASH81 | CIDS84 | DEBUT89 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study design | RCT | RCT | RCT | RCT (pilot and main study) |

| Target population | Resuscitated from near-fatal VF; or symptomatic sustained VT with haemodynamic compromise | Resuscitated from cardiac arrest secondary to documented sustained ventricular arrhythmia | Previous sustained ventricular arrhythmia | SUDS survivors or probable survivors |

| Intervention | ICD + medical therapy | ICD + medical therapy | ICD + AAD for symptomatic VT | ICD + beta-blocker or amiodarone if frequent shocks |

| Comparator | AAD + medical therapy | AAD (amiodarone or metoprolol) + medical therapy | Amiodarone + AAD for symptomatic VT | Beta-blocker (long-acting propranolol); other beta-blockers if intolerable side effects |

| Country (no. of centres) | USA (53), Canada (3) | Germany (multicentre, number unclear) | Canada (19), Australia (3), USA (2) | Thailand (unclear) |

| Sample size (randomised) | 1016 | 288 | 659 | Pilot 20, main trial 66 |

| Length of follow-up | Mean 18.2 (SD 12.2) months | Mean 57 (SD 34) months | Mean 3 years | Maximum 3 years |

| Key inclusion criteria | VF, VT with syncope or VT without syncope but with ejection fraction ≤ 0.40 and systolic blood pressure < 80 mmHg; chest pain or near syncope.73 If patients underwent revascularisation their ejection fraction had to be ≤ 0.40 | Not reported. Rate was the only criterion selected for detection of a sustained ventricular arrhythmia | Any of following in the absence of either recent acute MI (≤ 72 hours) or electrolyte imbalance: documented VF; out-of-hospital cardiac arrest requiring defibrillation or cardioversion; documented, sustained VT causing syncope; other documented sustained VT at a rate ≥ 150 bpm causing presyncope or angina in a patient with a LVEF ≤ 35%; or unmonitored syncope with subsequent documentation of either spontaneous VT ≥ 10 seconds or sustained (≥ 30 seconds) monomorphic VT induced by programmed ventricular stimulation | SUDS survivor: a healthy subject without structural heart disease who had survived unexpected VF or cardiac arrest after successful resuscitation Probable SUDS survivor: a subject without structural heart disease who experienced symptoms indicative of the clinical presentation of SUDs, especially during sleep. ECG abnormalities showing RBBB-like pattern with ST elevation in right precordial leads and inducible VT/VF in electrophysiological testing |

| Parameter | DINAMIT95 | IRIS97 | MADIT I99 | MADIT II101 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Target population | Recent MI (6–40 days); reduced LVEF and impaired cardiac autonomic function | Recent MI (≤ 31 days) and predefined markers of elevated risk | Previous MI and left ventricular dysfunction | High-risk cardiac patients with previous MI and advanced left ventricular dysfunction |

| Study design | RCT | RCT | RCT | RCT |

| Intervention | ICD + OPT | ICD + OPT | ICD + conventional medical therapy | ICD + conventional medical therapy |

| Comparator | OPT | OPT | Conventional medical therapy | Conventional medical therapy |

| Country (no. of centres) | Canada (25), Germany (21), France, (8), UK (4), Poland (4), Slovakia (2), Austria (2), Sweden (2), USA (2), the Czech Republic (1), Switzerland (1), Italy (1) | Austria, the Czech Republic, Germany, Hungary, Poland, the Russian Federation, Slovakia (total 92) | USA (30), Europe (2) | USA (71), Europe (5) |

| Sample size | 674 | 898 | 196 | 1232 |

| Length of follow-up | Mean 30 (SD 13) months | Average 37 (range 0 to 106) months | Average 27 (range < 1 to 60) months | Average 20 months (range 6 days to 53 months) |

| Key inclusion criteria | Recent MI (6–40 days previously); LVEF ≤ 0.35; SD of normal-to-normal RR intervals of ≤ 70 milliseconds or a mean R–R interval of ≤ 750 milliseconds (heart rate ≥ 80 bpm) over a 24-hour period as assessed by 24-hour Holter monitoring performed at least 3 days after the infarction | Predefined markers of elevated risk – at least one of heart rate ≥ 90 bpm on first available ECG (within 48 hours of MI) and LVEF ≤ 40% (on one of days 5–31 after the MI); non-sustained VT of three or more consecutive ventricular premature beats during Holter ECG monitoring, with a heart rate ≥ 150 bpm (on days 5–31) | NYHA class I, II or III; LVEF ≤ 0.35; Q-wave or enzyme-positive MI > 3 weeks before entry; a documented episode of asymptomatic, unsustained VT unrelated to an acute MI; no indications for CABG or coronary angioplasty within past 3 months; sustained VT or fibrillation reproducibly induced and not suppressed after the intravenous administration of procainamide (or equivalent) | LVEF ≤ 0.30 in last 3 months; MI > 1 month before study entry |

| Parameter | Cardiomyopathy | CABG surgery | HF | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AMIOVIRT69 | CAT82 | DEFINITE90 | CABG Patch75 | SCD-HeFT105 | |

| Target population | Non-ischaemic (DCM) and asymptomatic non-sustained VT | Recent-onset idiopathic DCM and impaired LVEF and without documented symptomatic VT | Non-ischaemic cardiomyopathy and moderate to severe left ventricular dysfunction | Patients scheduled for CABG surgery and at risk for sudden death (LVEF < 0.36 and abnormalities on ECG) | Broad population of patients with mild to moderate HF |

| Study design | RCT | RCT (pilot) | RCT | RCT | RCT |

| Intervention | ICD + OPT | ICD + OPT | ICD + OPT | ICD + OPT | ICD + OPT |

| Comparator | Amiodarone + OPT | OPT | OPTa | OPT; no specific therapy for ventricular arrhythmia | Amiodarone or placebo (two groups) + OPT |

| Country (no. of centres) | USA (10) | Germany (15) | USA (44), Israel (4) | USA (35), Germany (2) | USA (99%), Canada, New Zealand (total 148) |

| Sample size | 103 | 104 | 458 | 900 | 2521 |

| Length of follow-up | Mean 2 (SD 1.3) years | 2 years | Mean 29 (SD 14.4) months | Mean 32 months | Median 45.5 (range 24 to 72.6) months |

| Key inclusion criteria | Non-ischaemic DCM (left ventricular dysfunction in the absence of, or disproportionate to the severity of, CAD); LVEF ≤ 0.35; asymptomatic non-sustained VT; NYHA class I–III | NYHA class II or III; LVEF ≤ 30%; aged 18–70 years; symptomatic DCM ≤ 9 months | LVEF < 36%; presence of ambient arrhythmias; history of symptomatic HF; presence of non-ischaemic DCM | Scheduled for CABG surgery; LVEF < 0.36; marker of arrhythmia: abnormalities on ECG | NYHA class II or III; chronic, stable CHF from ischaemic or non-ischaemic causes; LVEF ≤ 35%; ischaemic CHF defined as LVSD associated with marked stenosis or a documented history of MI; non-ischaemic CHF defined as LVSD without marked stenosis |

| Parameter | AVID71 | CASH81 | CIDS84 | DEBUT (pilot trial)89 | DEBUT (main trial)89 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ICD | AAD | ICD | AAD | ICD | AAD | ICD | Beta-blocker | ICD | Beta-blocker | ||

| Amiodarone | Metoprolol | ||||||||||

| Sample size, n | 507 | 509 | 99 | 92 | 97 | 328 | 331 | 10 | 10 | 37 | 29 |

| Age (years), mean (SD) or [SEM] | 65 (11) | 65 (10) | 58 (11) | 59 (10) | 56 (11) | 63.3. (9.2) | 63.8 (9.9) | 44 [11] | 48 [15] | 40 [11] | 40 [14] |

| Sex, % male | 78 | 81 | 79 | 82 | 79 | 85.4 | 83.7 | 100 | 100 | 95 | 100 |

| Index arrhythmia VF, % | 44.6 | 45.0 | 84a | 45.1b | 50.1b | 70 | 60 | 24.3 | 37.9 | ||

| Index arrhythmia VT, % | 55.4 | 55.0 | 16a | 39.7b | 37.5b | 0 | 0 | 5.4 | 6.9 | ||

| Ischaemic heart disease, % | 81 | 81 | 73 | 77 | 70 | 82.9 | 82.2 | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Dilated cardiomyopathy, % | NR | NR | 12 | 10 | 14 | 8.5 | 10.6 | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Previous MI, % | 67 | 67 | NR | NR | NR | 77.1 | 75.8 | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| No CHF, % | 45 | 40 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 51.2 | 49.5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| NYHA I, % | 48 | 48 | 23 | 25 | 32 | 37.8 | 39.9 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| NYHA II, % | 59 | 57 | 55 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||||

| NYHA III, % | 7 | 12 | 18 | 18 | 13 | 11.0 | 10.6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| NYHA IV, % | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||||

| LVEF, mean (SD) or [SEM] | 0.32 (0.13) | 0.31 (0.13) | 0.46 (0.19) | 0.44 (0.17) | 0.47 (0.17) | 34.3 (14.5) | 33.3 (14.1) | 67 [12] | 69 [6] | 66 [10] | 67 [7] |

| Heart rate (bpm) | 77 (18) | 78 (17) | 81 (17) | 80 (17) | 76 (16) | NR | NR | 67 [12] | 64 [7] | 64 [11] | 66 [12] |

| QT interval (milliseconds), mean (SD) or [SEM] | 441 (40) | 445 (39) | 437 (42) | 430 (51) | 430 (48) | NR | NR | 396 [51] | 387 [31] | 404 [43] | 394 [31] |

| QRS interval (milliseconds), mean (SD) or [SEM] | 116 (26) | 117 (26) | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | 98 [29] | 92 [12] | 99 [30] | 95 [16] |

| BBB (unspecified), % | 23 | 25 | 17 | 23 | 19 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Parameter | DINAMIT95 | IRIS97 | MADIT I99 | MADIT II101 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ICD | OPT | ICD | OPT | ICD | OPT | ICD | OPT | |

| Sample size, n | 332 | 342 | 445 | 453 | 95 | 101 | 742 | 490 |

| Age (years), mean (SD) | 61.5 (10.9) | 62.1 (10.6) | 62.8 (10.5) | 62.4 (10.6) | 62 (9) | 64 (9) | 64 (10) | 65 (10) |

| Sex, % male | 75.9 | 76.6 | 77.5 | 75.9 | 92 | 92 | 84 | 85 |

| Arrhythmia, % | NR | NR | NSVT 22.2 | NSVT 24.1 | VT 100 | VT 100 | NR | NR |

| NYHA I, % | 13.5 | 12.0 | 28a | 37 | 33 | 35 | 39 | |

| NYHA II, % | 60.9 | 58.7 | 60a | 63 | 67 | 35 | 34 | |

| NYHA III, % | 25.6 | 29.3 | 12a | 25 | 23 | |||

| NYHA IV, % | 0 | 0 | 0.1a | 0 | 0 | 5 | 4 | |

| LVEF (%), mean (SD) | 28 (5) | 28 (5) | 34.6 (9.3) | 34.5 (9.4) | 27 (7) | 25 (7) | 23 (5) | 23 (6) |

| QRS interval (milliseconds), mean (SD) | 107 (24) | 105 (23) | NR | NR | NR | NR | 50% ≥ 120 milliseconds | 51% ≥ 120 milliseconds |

| LBBB/RBBB, % | NR | NR | 10.1/NR | 6.4/NR | 7/NR | 8/NR | 19/9 | 18/7 |

| Parameter | Cardiomyopathy | CABG surgery | HF | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AMIOVIRT69 | CAT82 | DEFINITE90 | CABG Patch75 | SCD-HeFT105 | |||||||

| ICD | Amiodarone | ICD | Control | ICD + OPT | OPT | ICD | Control | ICD | Amiodarone | Placebo | |

| Sample size, n | 51 | 52 | 50 | 54 | 229 | 229 | 446 | 454 | 829 | 845 | 847 |

| Age (years), mean (SD) or [range] | 58 (11) | 60 (12) | 52 (12) | 52 (10) | 58.4 [20.3–83.9] | 58.1 [21.8–78.7] | 64 (9) | 63 (9) | 60.1 [51.9–69.2]a | 60.4 [51.7–68.3]a | 59.7 [51.2–67.8]a |

| Sex, % male | 67 | 74 | 86 | 74 | 72.5 | 69.9 | 86.5 | 82.2 | 77 | 76 | 77 |

| Index arrhythmia, % | NSVT 100 | NSVT 100 | NSVT 53.1 | NSVT 58.0 | NSVT 22.3, PVCs 9.2, both 68.6 | NSVT 22.7, PVCs 9.6, both 67.7 | NR | NR | NSVT 25 | NSVT 23 | NSVT 21 |

| Ischaemic heart disease, %b | 4.9 | 11 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Duration of cardiomyopathy, mean (SD) or [median, range] | 2.9 (4.0) years | 3.5 (3.9) years | [3.0 months] | [2.5 months] | [2.39, 0.00–21.33 yearsc] | [3.27, 0.0–38.5 yearsc] | |||||

| NYHA class, % | |||||||||||

| I | 18 | 13 | 0 | 0 | 25.3 | 17.9 | NR | NR | 0 | ||

| II | 64 | 63 | 66.7 | 64.1 | 54.2 | 60.7 | 71 | 74 | 70 | ||

| III | 16 | 24 | 33.3 | 35.8 | 20.5 | 21.4 | 30 | ||||

| IV | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | NR | NR | 0 | ||

| LVEF (%), mean (SD) or [range] | 22 (10) | 23 (8) | 24 (6) | 25 (8) | 20.9 [7–35] | 21.8 [10–35] | 27 (6) | 27 (6) | 24.0 [19.0–30.0]a | 25.0 [20.0–30.0]a | 25.0 [20.0–30.0]a |

| QRS interval (milliseconds), mean (SD) or [range] | NR | NR | 102 (29) | 114 (29) | 114.7 [78–196] | 115.5 [79–192] | 71%d | 74%d | NR | NR | NR |

| LBBB/RBBB, % | 16/42 | 8/53 | 24/2 | 37/0 | 19.7/3.5 | 19.7/3.1 | 10/NR | 12/NR | NR | NR | NR |

Intervention and comparators

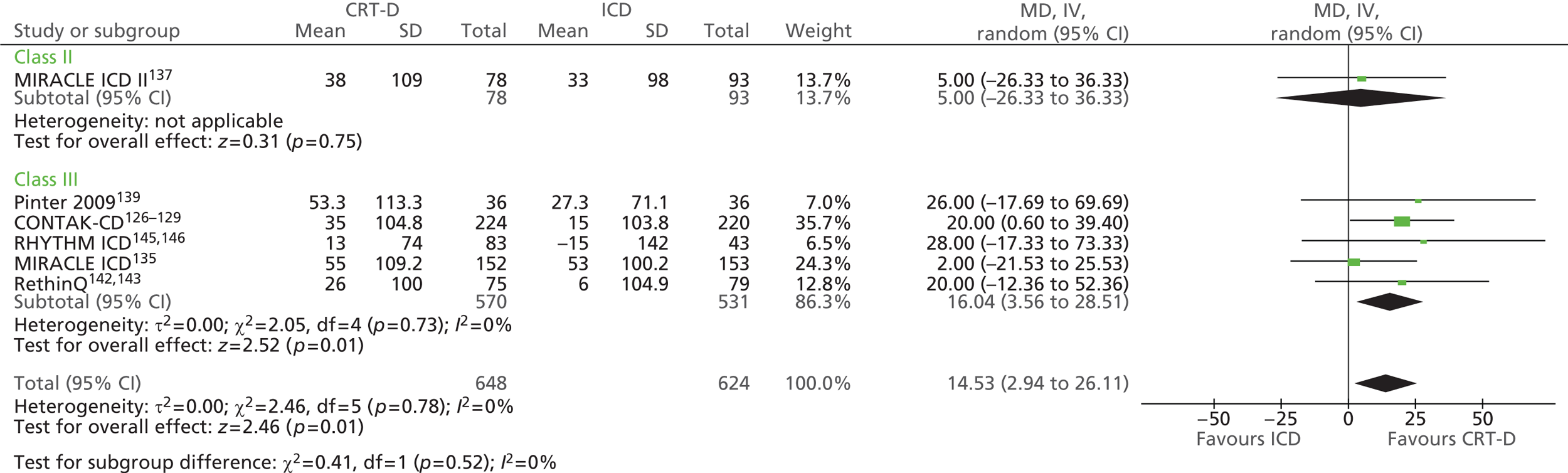

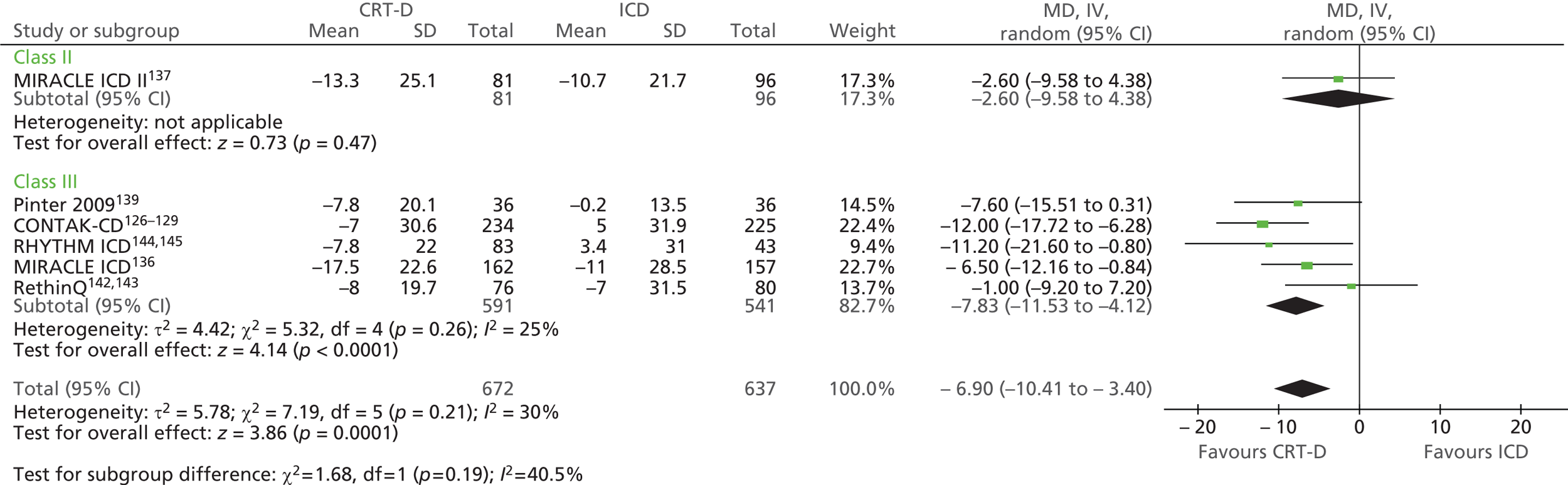

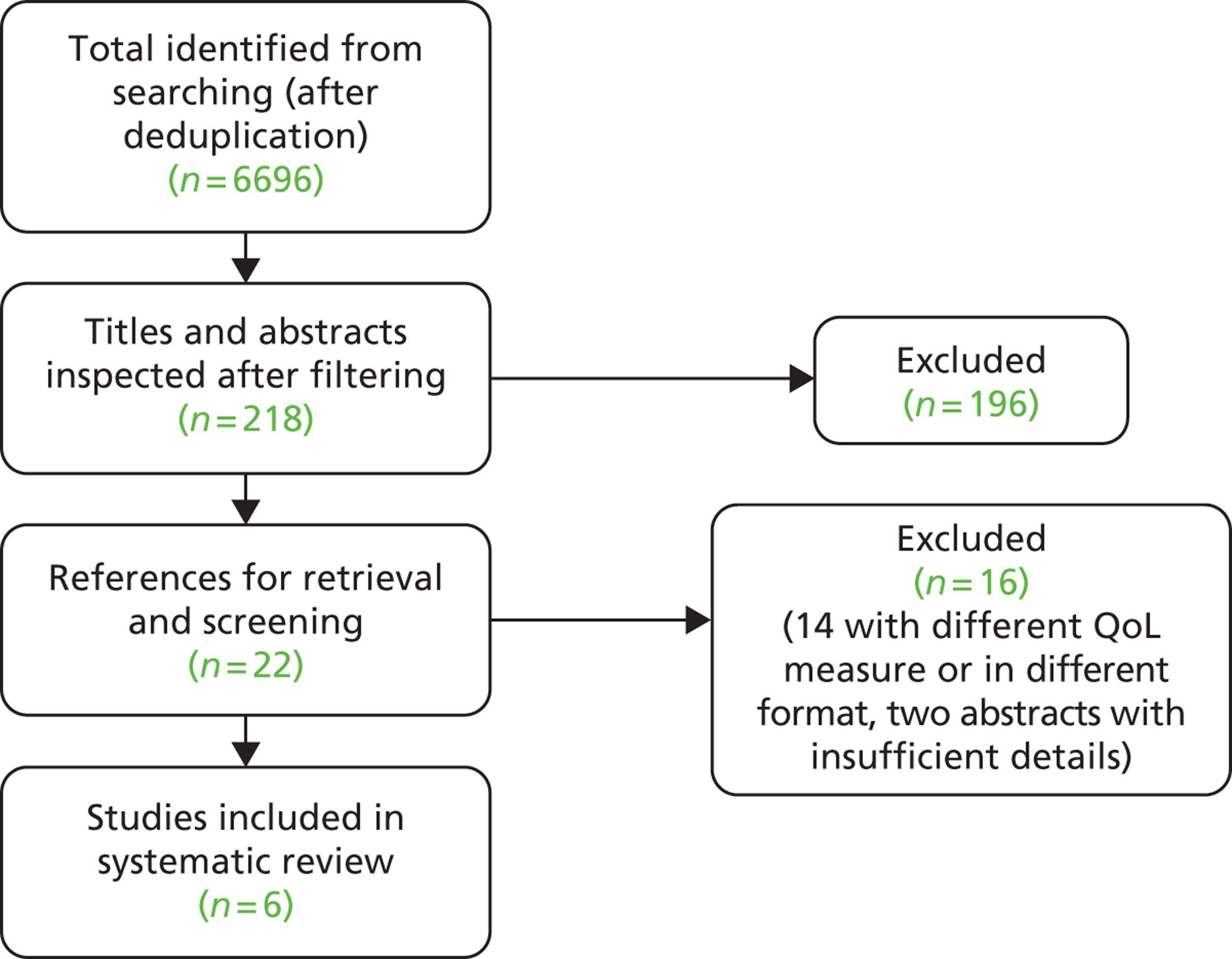

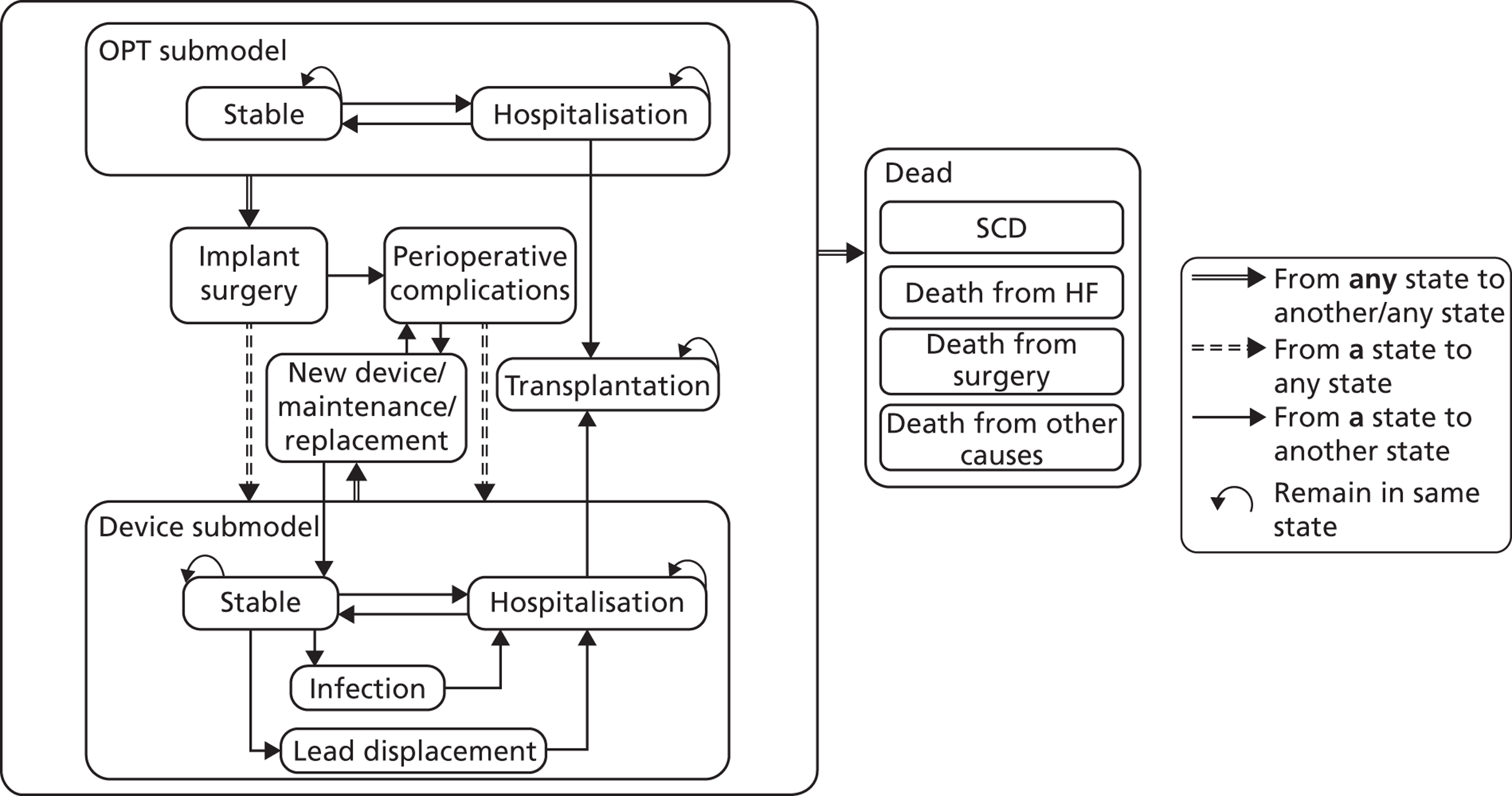

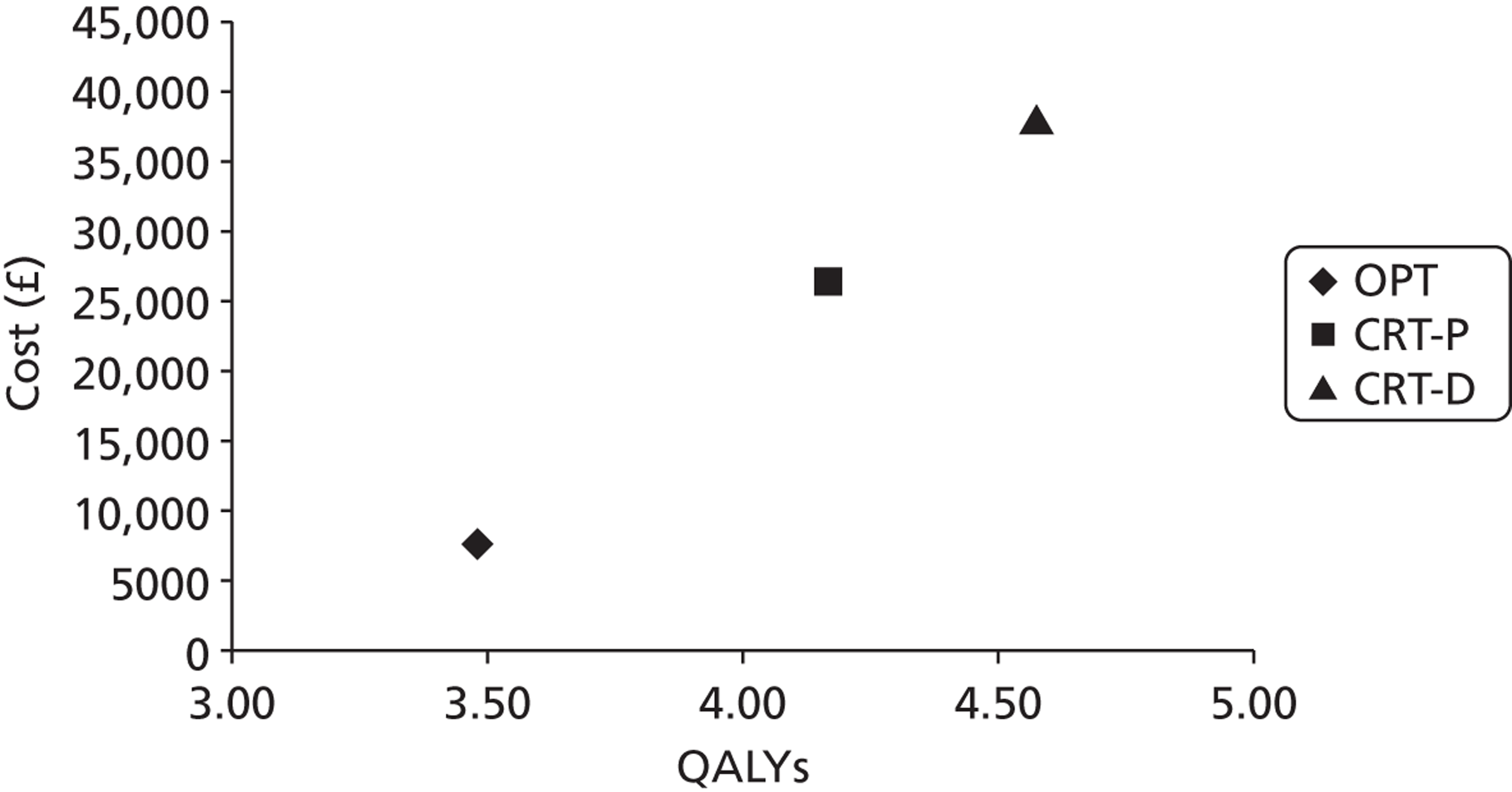

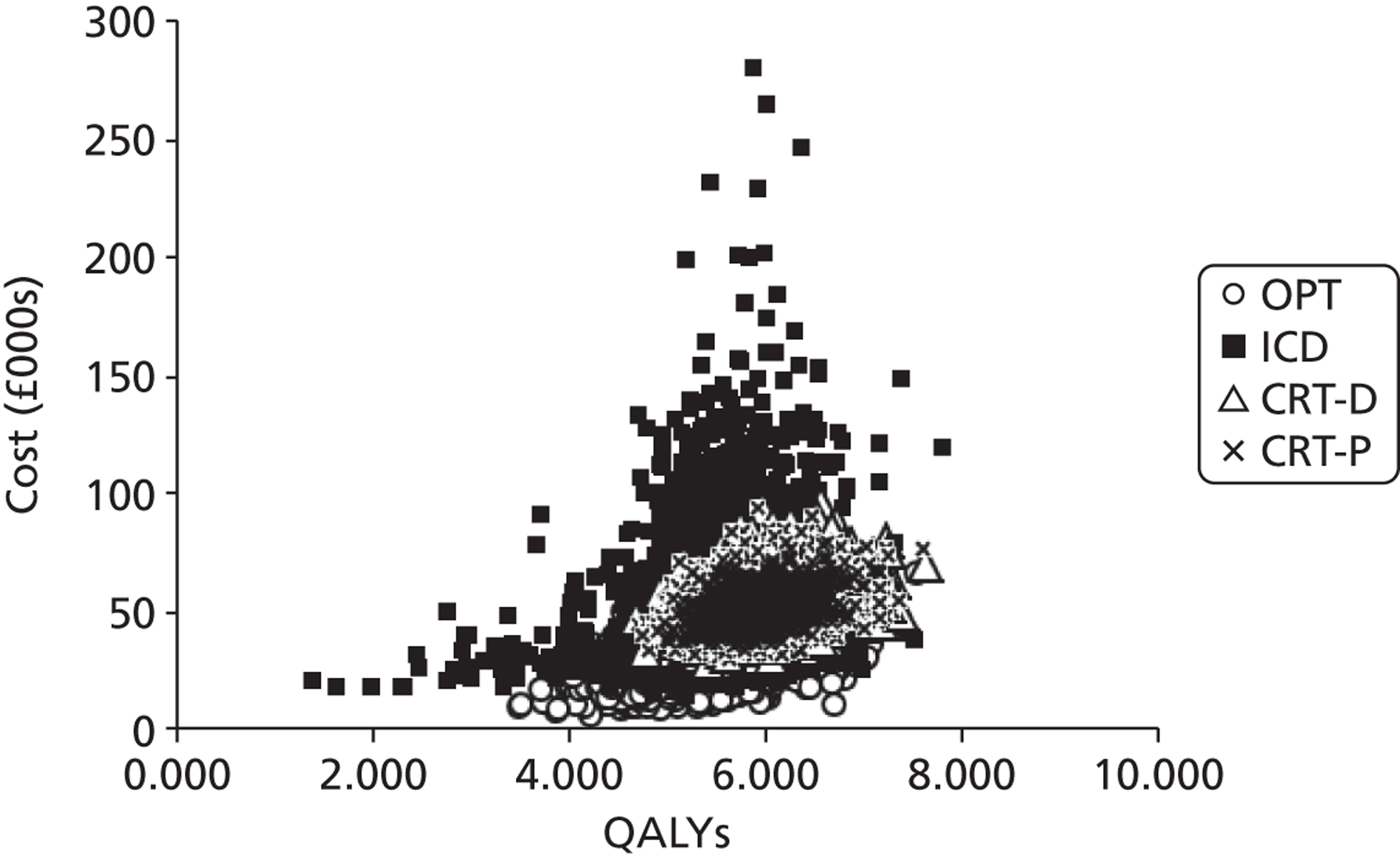

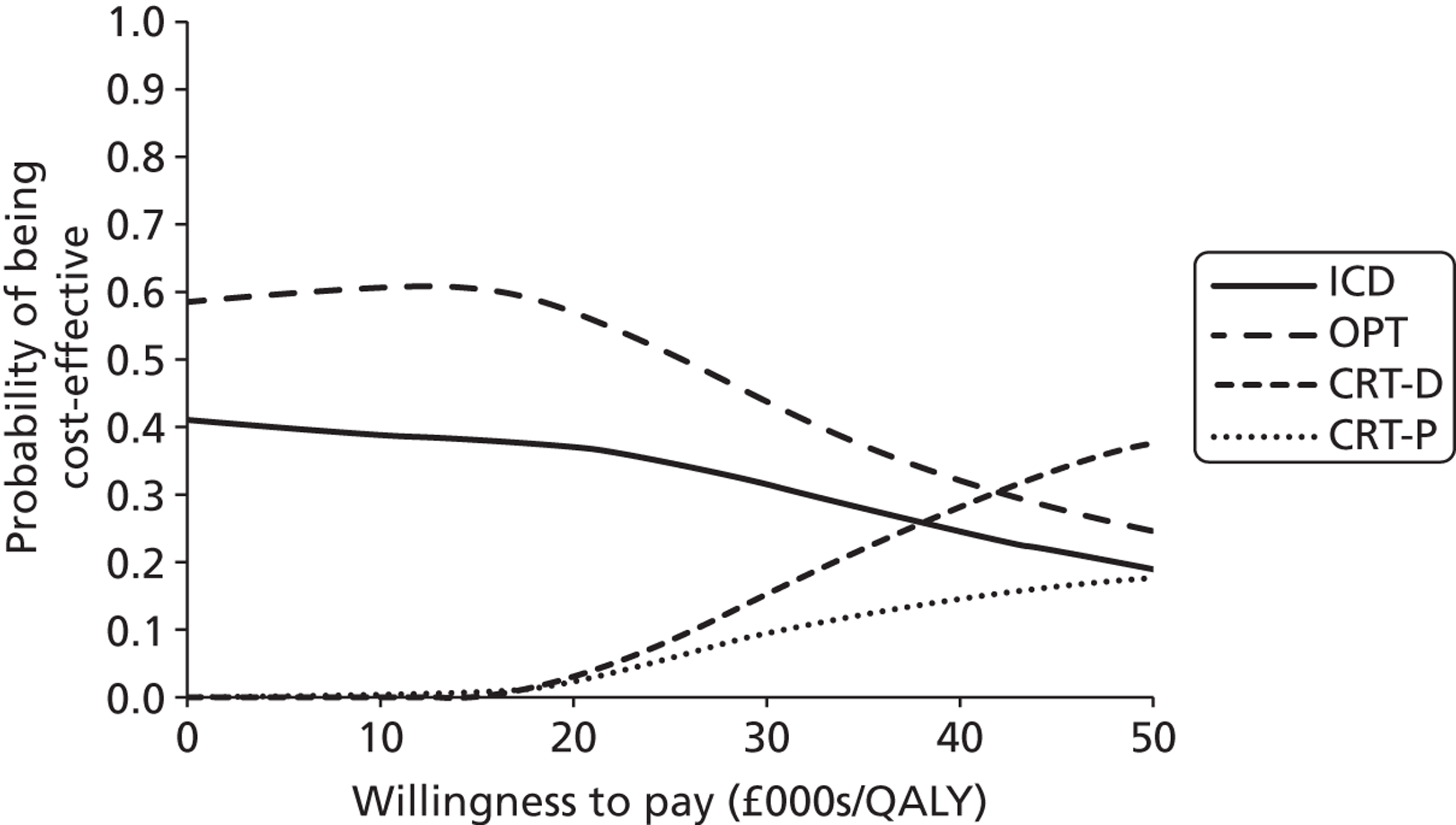

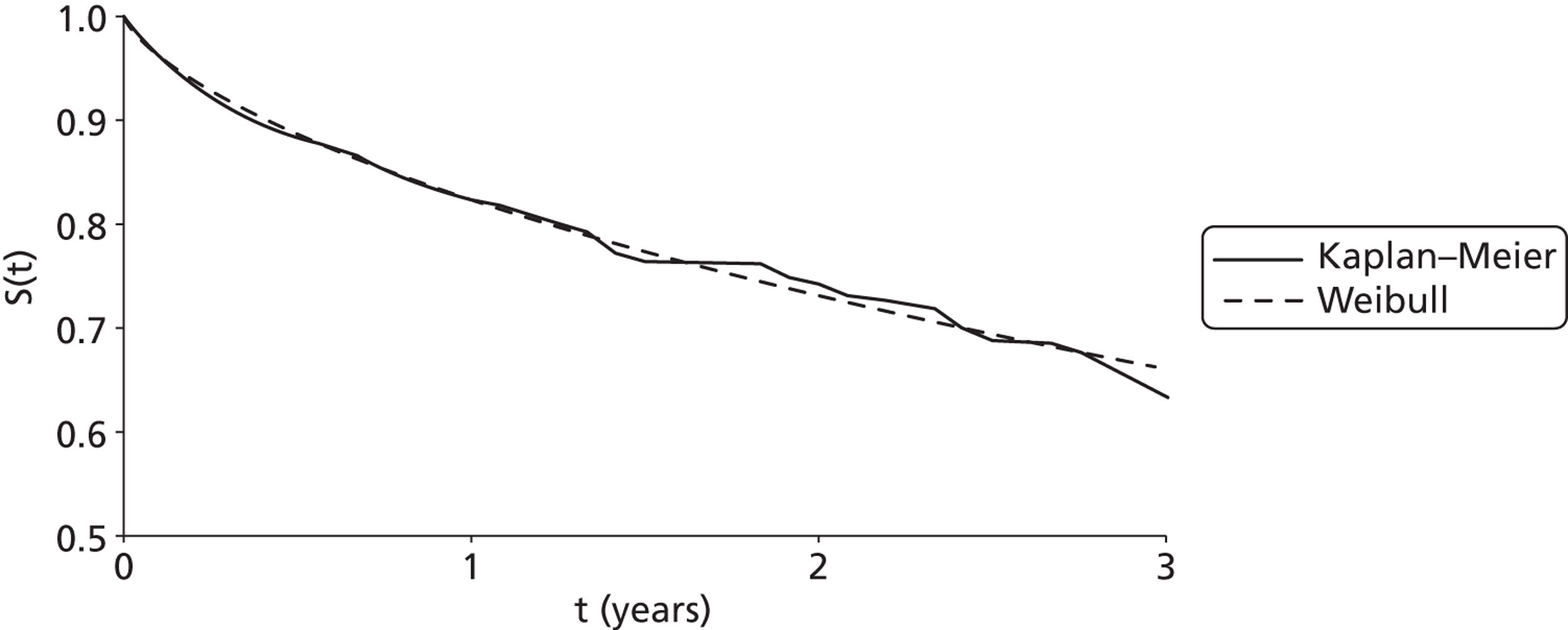

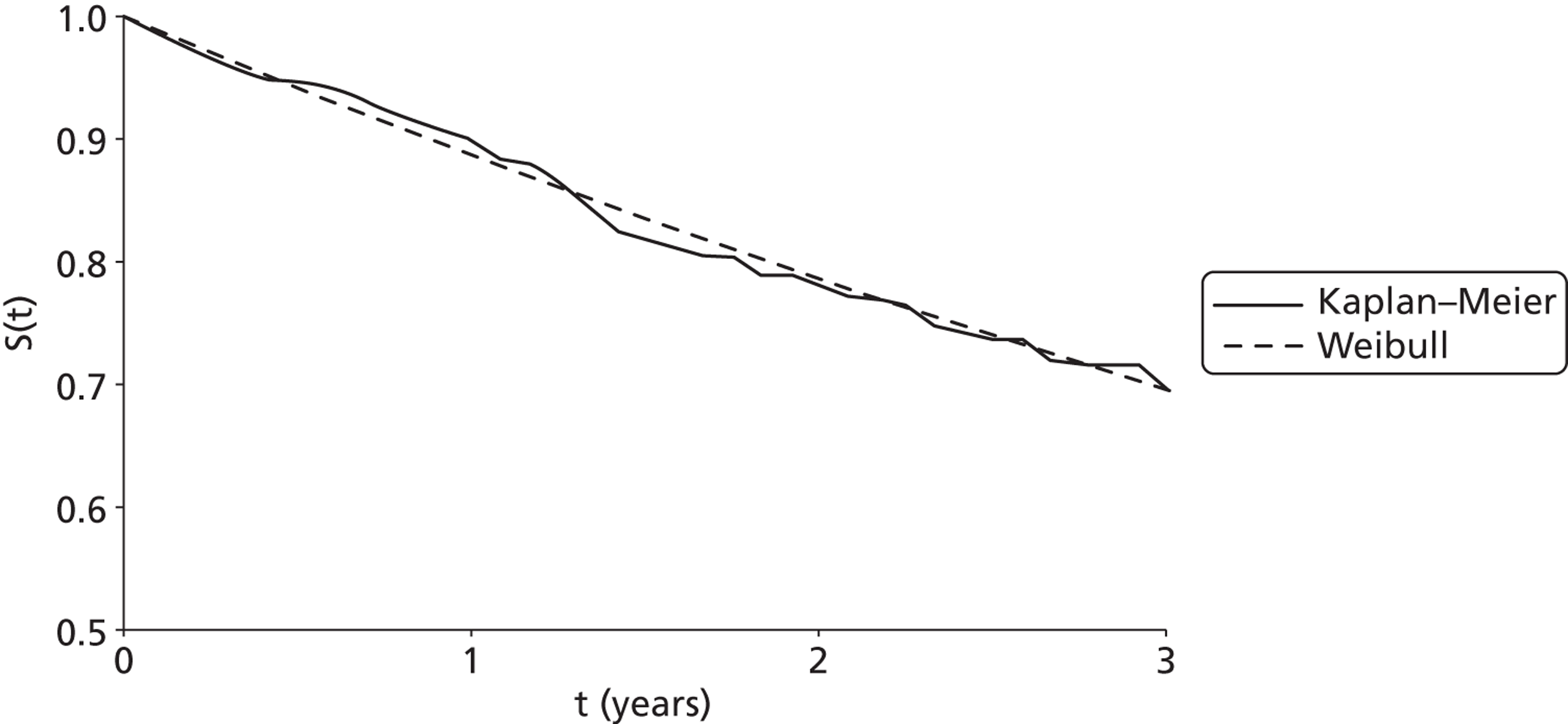

The NICE scope and systematic review protocol defined the intervention for this group of people as ‘ICDs in addition to OPT’ and the comparator as ‘standard care (OPT without an ICD)’. Concepts of OPT have changed over time and OPT varies depending on the population (e.g. previous VF, post MI, HF), making a standard definition of OPT difficult. Standards of reporting have also changed, making it difficult in some instances to be clear what participants have received. As a consequence it was decided, and agreed with NICE, to include studies that compared ICDs (with or without OPT) with the different types of medical therapy, reporting the details of the pharmacological therapy used. The studies included were eligible on all other selection criteria.