Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 10/28/01. The contractual start date was in May 2012. The draft report began editorial review in June 2013 and was accepted for publication in November 2013. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

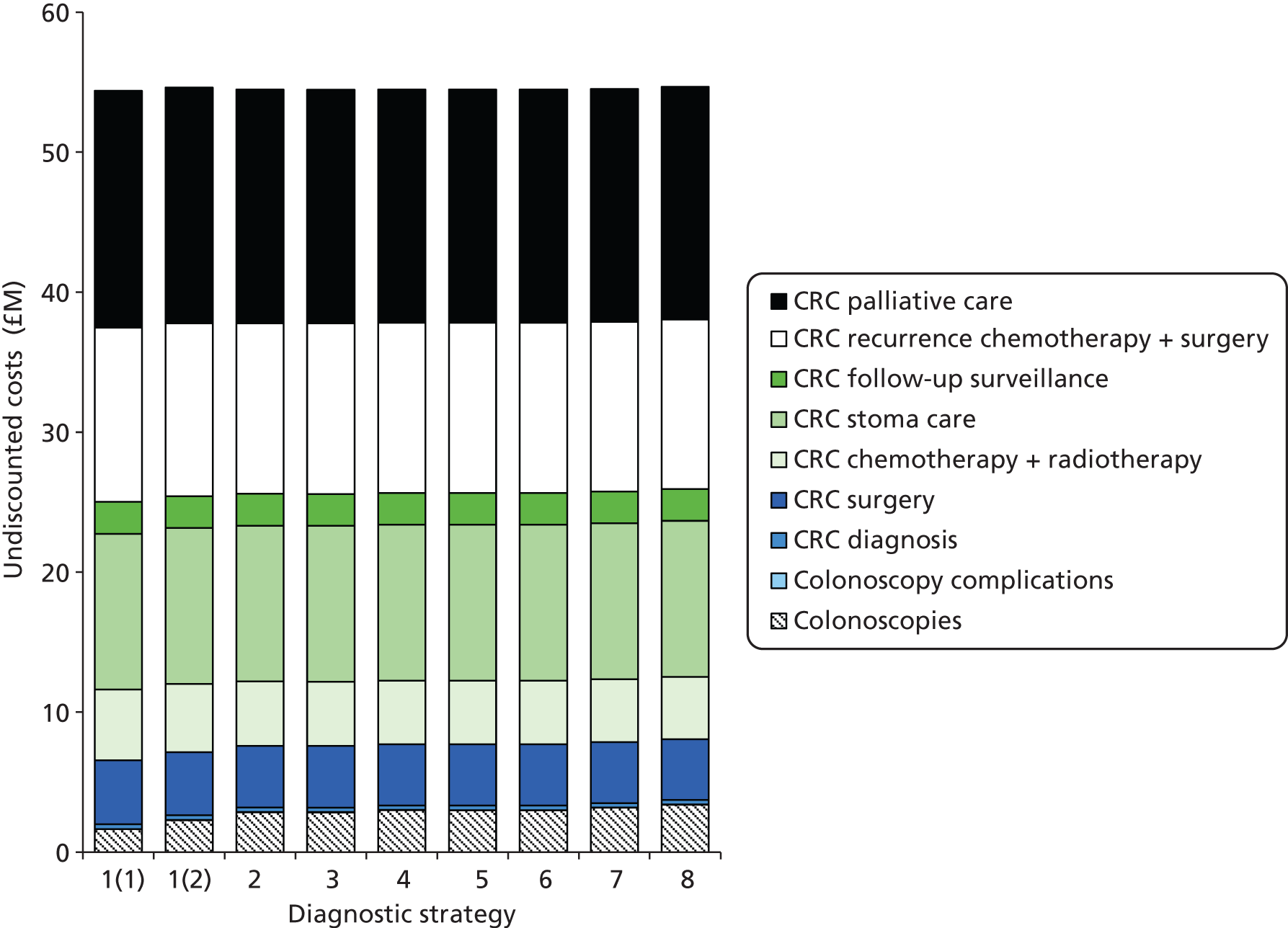

none

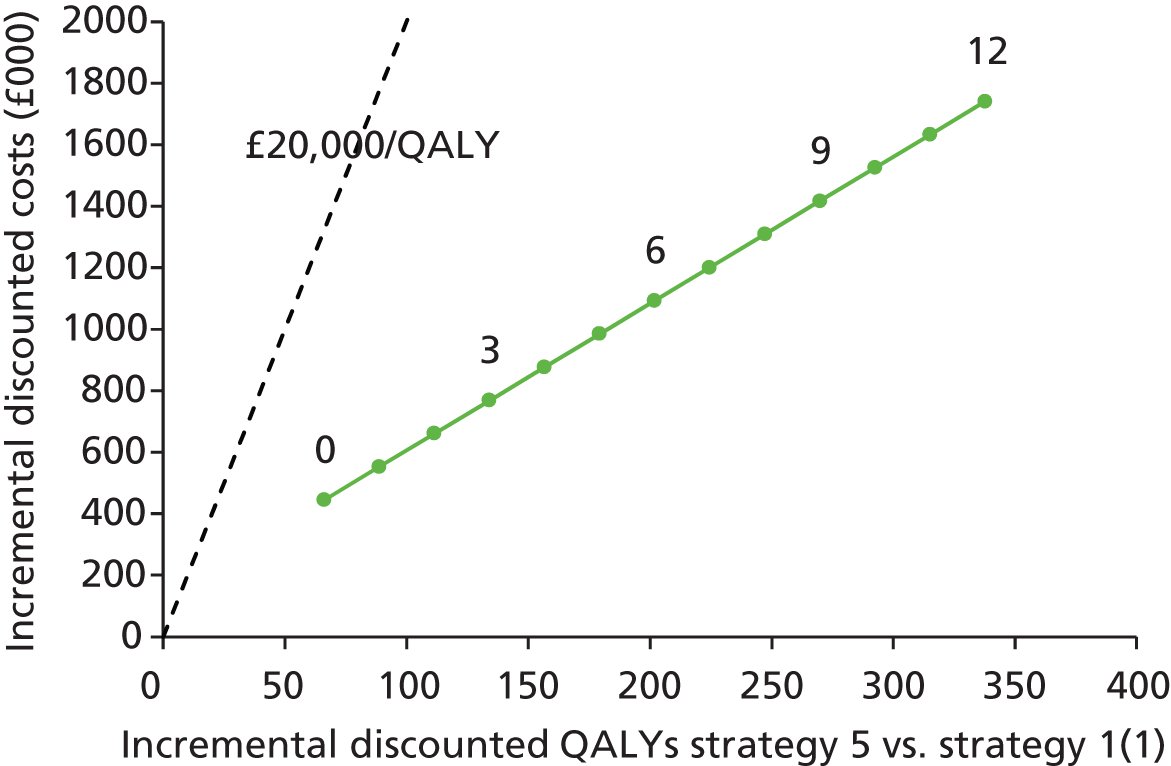

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2014. This work was produced by Snowsill et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Background

Nature of disease

Lynch syndrome (LS) is the most common form of genetically defined, hereditary colorectal cancer (CRC), accounting for 1–3% of all such tumours. Historically, a variety of names have been used for the disease, originally identified by Aldred Scott Warthin in 1913 and then rediscovered by Henry T Lynch in 1966. Lynch coined the terms ‘site-specific colon cancer’ and ‘family cancer’ syndromes. During a workshop in Amsterdam in 1989, the participants agreed upon the name hereditary non-polyposis colorectal cancer (HNPCC), as at that time the syndrome was unknown to most doctors. 1 The appropriateness of the name was discussed again at the international collaborative group on HNPCC meeting in Bethesda, MD, in 2004 where, as the syndrome is also associated with many other tumours, it was proposed that the name ‘Lynch syndrome’ should be reintroduced. 1

Lynch syndrome is inherited as an autosomal dominant disorder, whereby if one parent has the disease, there is a 50% chance that each of his or her children will inherit it. It is characterised by an increased risk of CRC and cancers of the endometrium, ovary, stomach, small intestine, hepatobiliary tract, urinary tract, brain and skin among others, with the lifetime cancer risk highest for CRC (Table 1).

| Cancer | Estimated lifetime cancer risk for individuals with LS (%) | Estimated lifetime cancer risk in the general population (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Colorectal by age 70 years | Men: 382 | 5–63 |

| Women: 312 | ||

| Endometrial | Women: 332 | Women: 2–33 |

| Gastric | 0.72 | 13 |

| Ovarian | Women: 92 | Women: 1–23 |

| Small bowel | 0.62 | 0.013 |

| Bladder | 43 | 1–33 |

| Urinary tract | 1.9–8.45 | 46,7 |

| Brain | 43 | 0.63 |

| Kidney, renal pelvis | 33 | 13 |

| Biliary tract | 0.62 | 0.53 |

| Pancreas | 0.4–3.75 | 1.48 |

| Prostate | Men: 9.1–30.05 | Men: 13.28 |

| Breast | Women: 5.4–14.45 | Women: 12.98 |

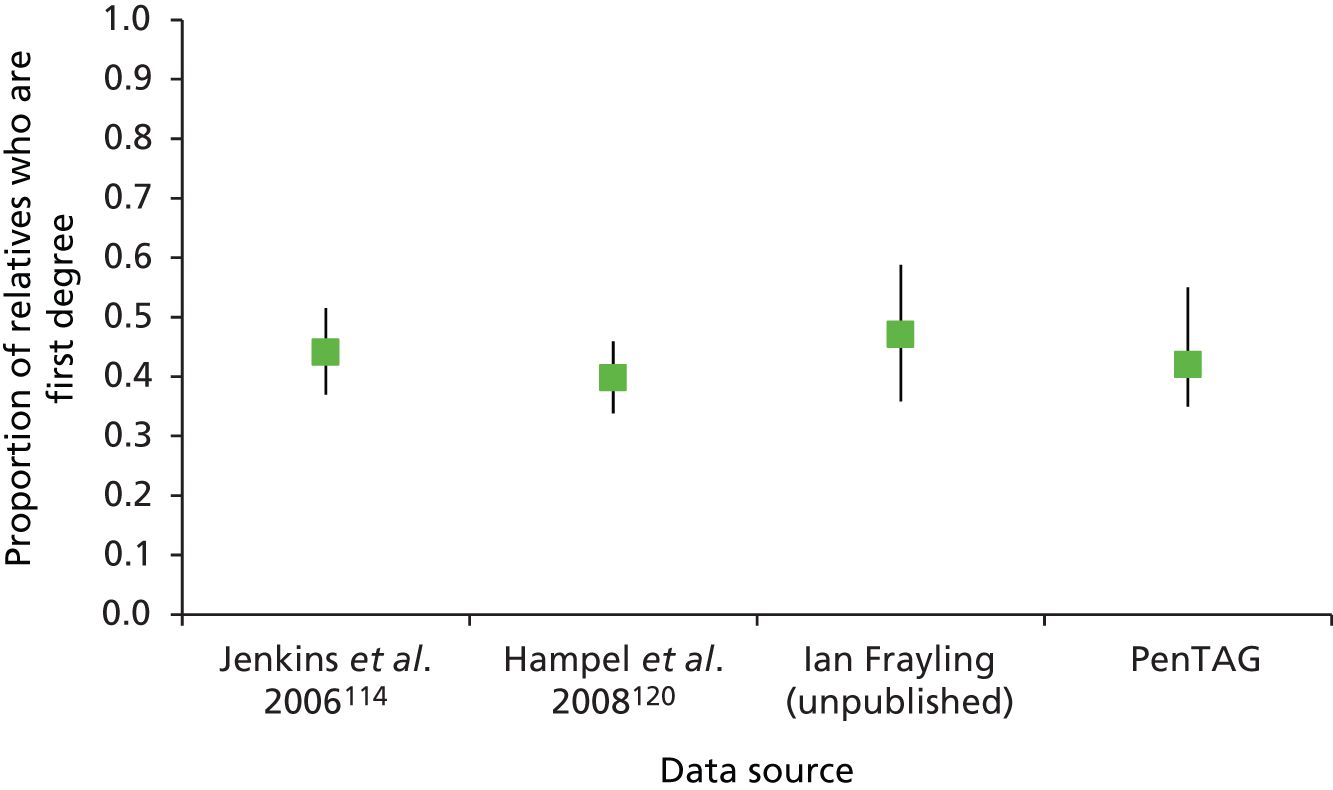

Overall, LS accounts for between 0.3% and 2.4% of CRCs, and its prevalence in the general population is of the order of 1 : 3100 (although this may be subject to underestimation due to the current lack of systematic testing). 9,10 The risk of a second primary CRC in individuals with LS is high (estimated at 16% within 10 years) and the risk of a LS cancer in a first- or second-degree family member is approximately 45% for men and 35% for women by age 70 years. 1

Lynch syndrome is caused by mutations in deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) mismatch repair (MMR) genes, namely MutL homologue 1 (MLH1), MutS homologues 2 and 6 (MSH2 and MSH6) and postmeiotic segregation increased 2 (PMS2). 4,11 Loss of DNA MMR activity in a cell, due to mutations in both alleles of one of the MMR genes, leads to an inability to repair base–base mismatches and small insertions and deletions, resulting in genetic mutations which may then progress to cancer. 12 Mutations occur all over the genome, but especially in repetitive DNA sequences, such as microsatellites. These cause abnormal patterns of microsatellite repeats to be observed when DNA is amplified from a tumour with defective MMR compared with DNA amplified from surrounding normal tissue. This phenomenon is known as microsatellite instability (MSI).

Based on data from 12,624 observations worldwide, MLH1 accounts for 39%, MSH2 34%, MSH6 20% and PMS2 8% of entries in the International Society for Gastrointestinal Hereditary Tumours (InSiGHT) database (www.insight-group.org/mutations/). However, all such estimates are subject to bias, because these are generally mutations found in families referred to genetics clinics, subject to fulfilment of local referral guidelines.

Diagnosis/testing

Currently, the Amsterdam criteria (AC) II and Revised Bethesda criteria, as seen in Table 2, may be used to assist with diagnosis of LS. In 1989, the AC were proposed in order to provide uniform family material required for international collaborative research studies. In 1999, these criteria were revised to include extracolonic tumours. 1 However, with the development of techniques to investigate tumours, such as MSI and MMR immunohistochemistry (IHC), in 1997 the Bethesda guidelines were developed to aid selection of tumours for testing and subsequently identifying individuals with LS. These guidelines were revised in 2004. It should be noted that all AC must be met whereas only one Bethesda criterion is necessary.

| AC II | Revised Bethesda guidelines |

|---|---|

| At least three separate relatives with CRC or a LS-associated cancer | CRC diagnosed in a patient aged < 50 years |

| One relative must be a FDR of the other two | Presence of synchronous, metachronous colorectal or other LS-related tumours, regardless of age |

| At least two successive generations affected | CRC with MSI-H phenotype diagnosed in a patient aged < 60 years |

| At least one tumour should be diagnosed before the age of 50 years | Patient with CRC and a FDR with a LS-related tumour, with one of the cancers diagnosed at age < 50 years |

| FAP excluded in CRC case(s) | Patient with CRC with two or more FDRs or SDRs with a LS-related tumour, regardless of age |

| Tumours pathologically verified |

The Bethesda criteria include MSI-high (MSI-H). This refers to MSI testing where the National Cancer Institute (NCI) has recommended a panel of five markers, known as Bethesda (or NCI) markers, which include two mononucleotides (BAT25 and BAT26) and three dinucleotide repeats (D2S123, D5S346 and D17S250). Tumours with no instability in any of the markers are considered to be microsatellite stable (MSS). When one reference marker is mutated, a tumour is considered to be MSI-low (MSI-L), and if two or more markers are altered, it is considered to be MSI-H. 12 In some cases an additional panel of five markers is used; if 3 out of 10 show instability then it is classified as MSI-H, and if two or fewer, MSI-L.

Unfortunately, there are limitations to MSI testing due to MLH1 silencing commonly occurring in non-hereditary cancers. Thus, MSI is found in approximately 15% of sporadic CRC cases (i.e. CRC with no apparent hereditary component),1 and according to Umar and colleagues, as many as 50% of suspected cases of LS are not confirmed by a genetic defect (that is, mutation in one of the known MMR genes). 12 Hence, the Bethesda criteria have been criticised as being insensitive and non-specific, because strictly applied they would result in approximately 25% of all CRC being tested. In turn, this has stimulated the development of additional tests for the diagnosis of LS, as presented in Table 3.

| Test | Description |

|---|---|

| MSI | Preliminary test performed on tumour tissue. Those with high instability proceed to either DNA analysis or IHC. However, the presence of MSI in the tumour alone is not sufficient to diagnose LS as sporadic CRC may exhibit MSI |

| IHC | Preliminary test performed on tumour tissue to identify one of four MMR proteins (MLH1, MSH2, MSH6 and PMS2). Those with negative staining proceed to DNA analysis of the gene/genes indicated IHC testing helps to identify the MMR gene that most likely harbours a constitutional (‘germline’) mutation, as abnormal expression of a MMR protein points to a mutation in that gene |

| Methylation of MLH1 and/or BRAF V600E testing of tumour tissue | Preliminary molecular genetic test performed on tumour tissue of patients with negative staining for MLH1 on IHC The presence of BRAF V600E mutation or hypermethylation of MLH1 make LS unlikely |

| DNA analysis of MMR genes (MLH1, MSH2, MSH6, PMS2) | Diagnostic test, typically performed on blood. DNA analysis (gene sequencing, deletion/duplication testing) of MLH1, MSH2, MSH6, PMS2 |

Current evidence supports genetic testing for LS to include:13

-

evaluation of tumour tissue for MSI through molecular MSI testing and/or IHC of the four MMR proteins (MLH1, MSH2, MSH6 and PMS2)

-

molecular genetic testing of the tumour for MLH1 gene methylation and/or somatic BRAF V600E mutation to help identify those tumours more likely to be sporadic than hereditary, as the presence of a BRAF V600E mutation makes LS very unlikely1

-

molecular genetic testing of the MMR genes to identify a constitutional (germline) mutation when findings are consistent with LS.

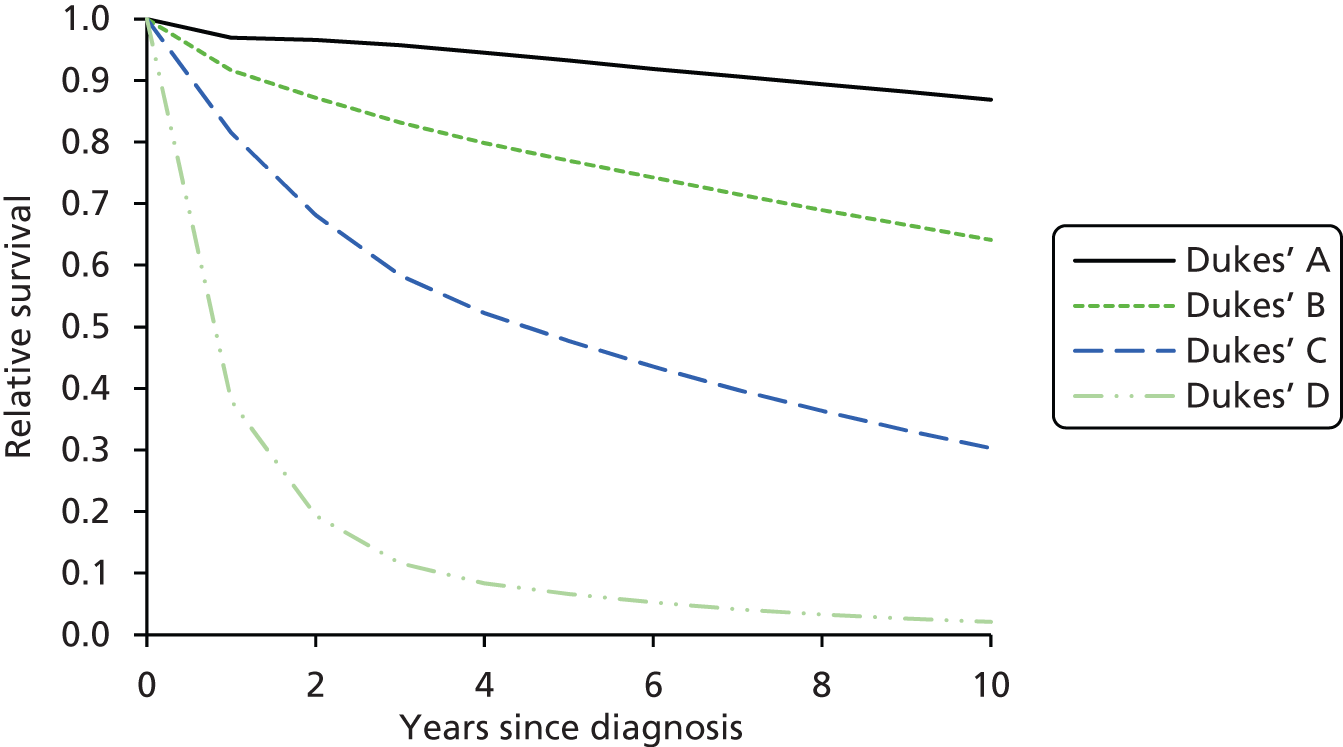

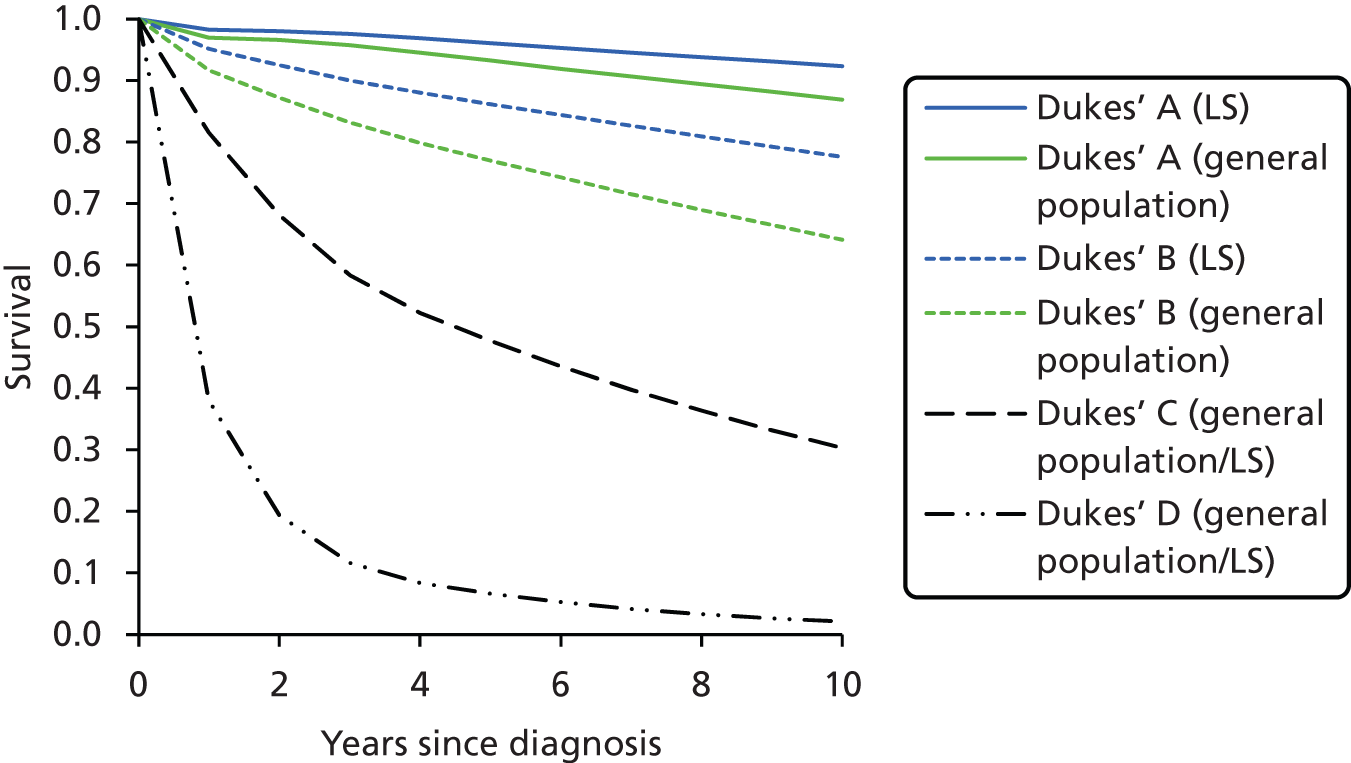

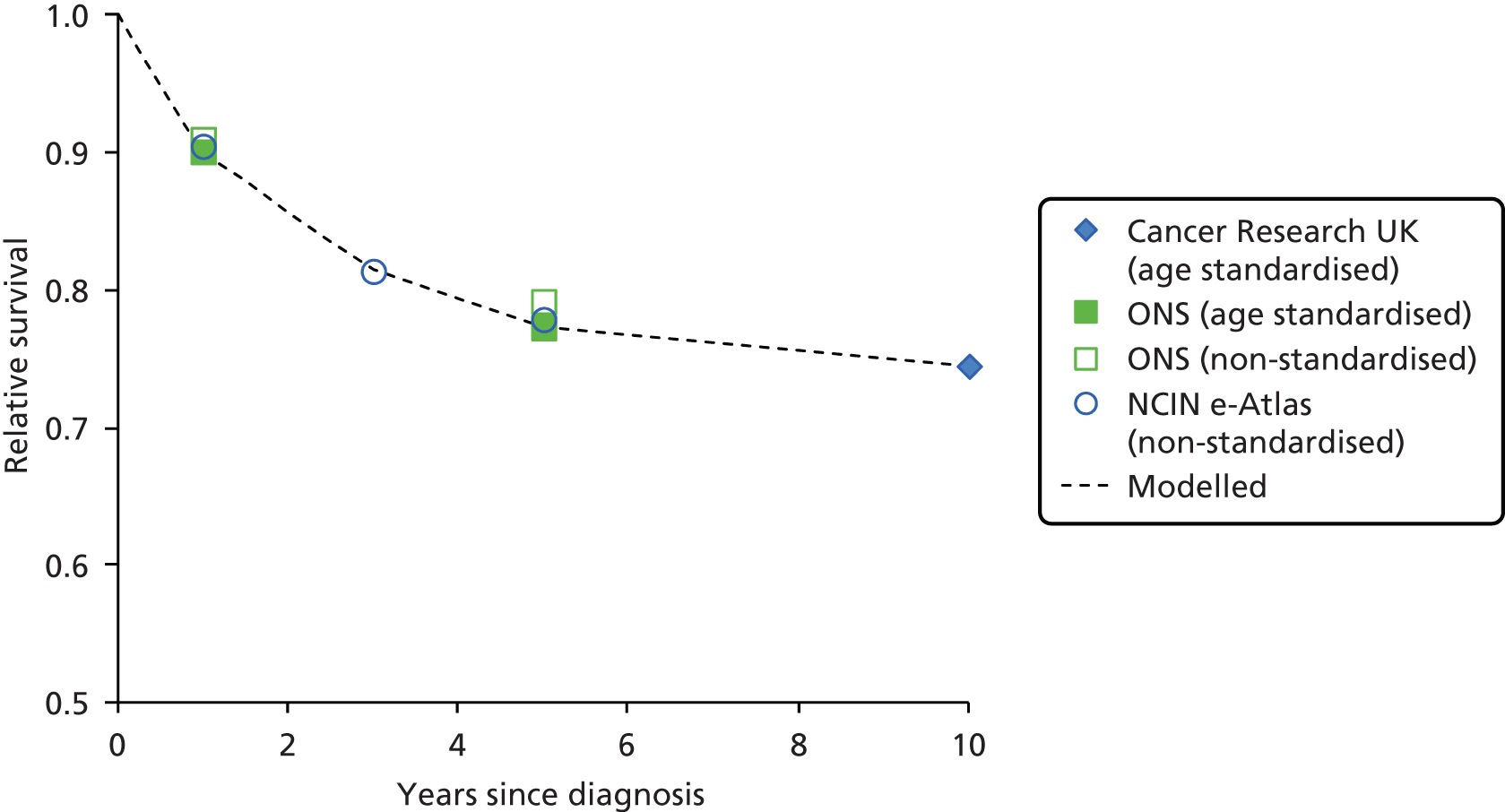

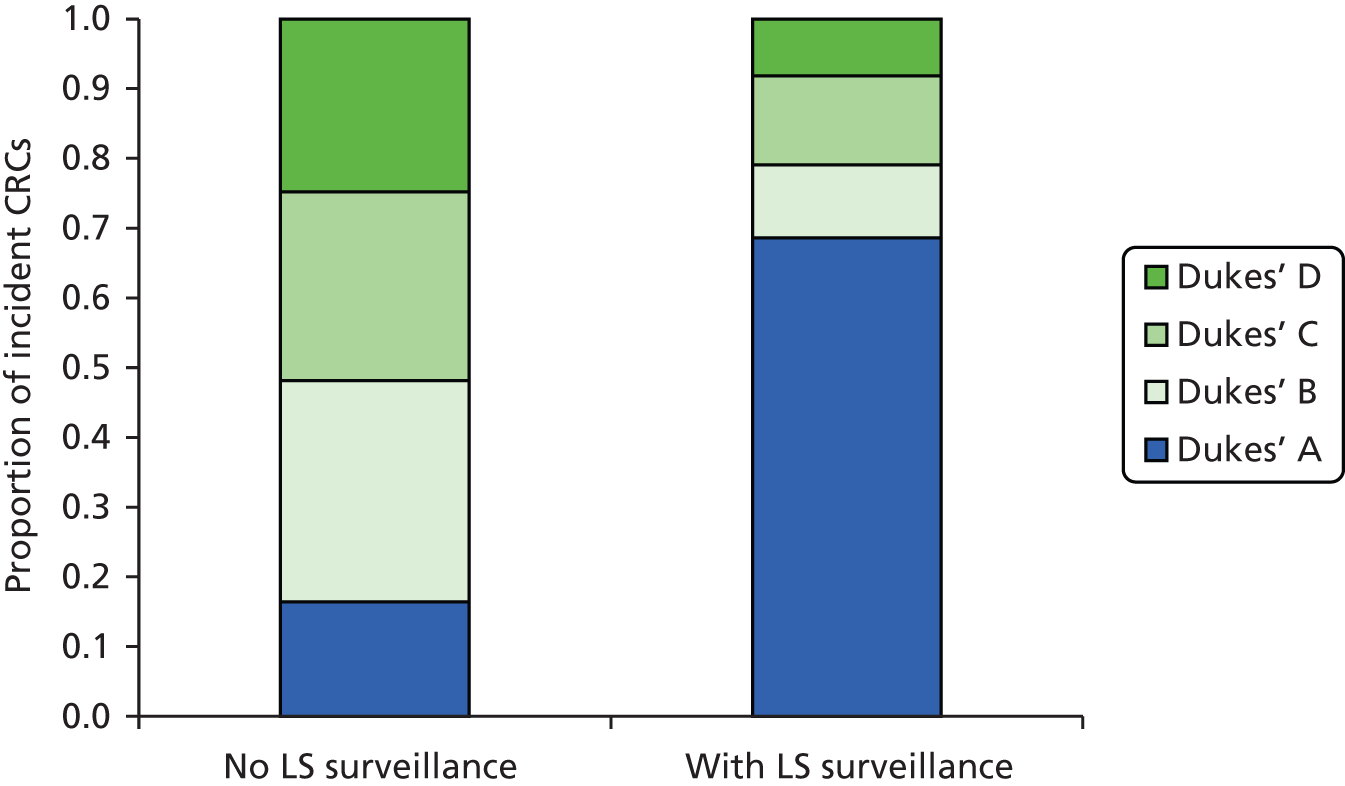

Prognosis

Colorectal tumours in LS appear to evolve through the adenoma–carcinoma sequence. However, this progression is accelerated compared with CRC in sporadic and other familial settings, i.e. 2–3 years as opposed to 8–10 years. 12,14 Furthermore, adenomas in LS often occur in younger individuals and tend to be larger and more severely dysplastic than in sporadic cases. 14 That said, recent studies have confirmed early suspicions that patients with CRC from LS families survive longer than sporadic CRC patients with same-stage tumours. 15 The reasons for the favourable survival rate with CRC in this syndrome remain unclear, but are likely related to a reduced propensity to metastasise. Explanations include that immunological host defence mechanisms may be more active in tumours of the MSI Pathology Research International 3 phenotype, and that the relatively high mutational load that occurs in tumours with defective DNA repair systems is detrimental to their survival. 14

Furthermore, there is definite evidence for a genotype–phenotype correlation in LS; for example, one study found that MSH6 mutation carriers had markedly lower cancer risks overall than MLH1 or MSH2 mutation carriers. 2 Carriers of a MMR gene mutation have a very high risk of developing CRC (25–70%) and endometrial cancer (EC) (30–70%) and an increased risk of developing other tumours. 5

Management of disease

Surveillance

As LS is a hereditary condition, identification of family members carrying a MMR gene defect is desirable, as colonoscopic surveillance, and possibly prophylactic and/or altered surgical management, may be offered to high-risk individuals.

Given that screening for a mutation is time-consuming and expensive – largely because four genes may have to be analysed and their mutational spectra are wide (Vasen 20071) – the British Society of Gastroenterology (BSG) and the Association of Coloproctology of Great Britain and Ireland (ACPGBI)9 recommend that individuals with a substantially elevated personal risk of gastrointestinal malignancy be offered surveillance on the basis of one or more of the following criteria:

-

a family history (FH) consistent with an autosomal dominant cancer syndrome

-

pathognomonic features of a characterised polyposis syndrome personally or in a close relative

-

the presence of a constitutional (‘germline’) pathogenic mutation in a CRC susceptibility gene

-

molecular features of a familial syndrome in a CRC arising in a first-degree relative (FDR).

Individuals fulfilling at least one of the above criteria should be referred to a NHS regional genetics centre for assessment, genetic counselling and mutation analysis of relevant genes, where appropriate.

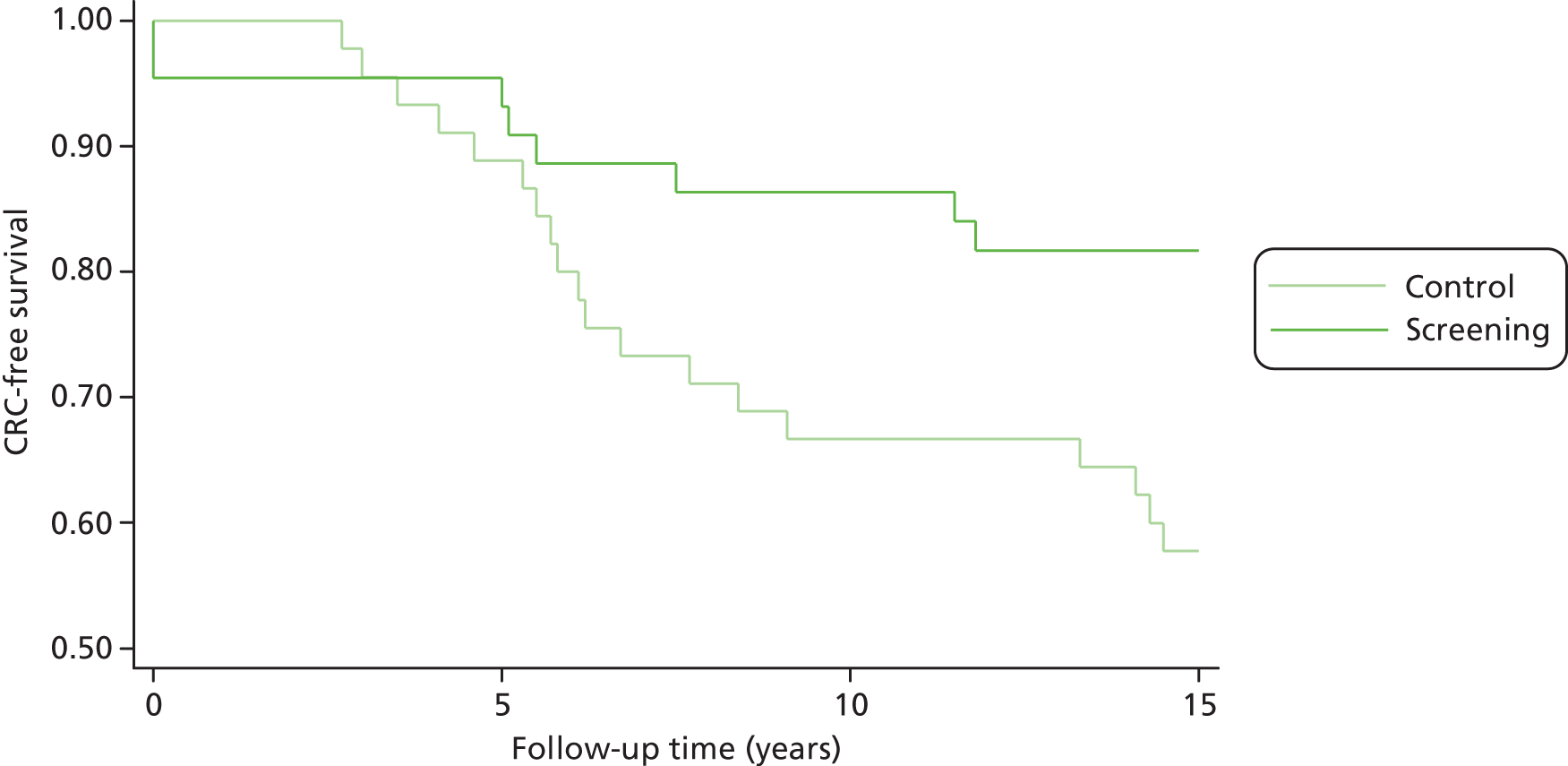

Vasen and colleagues (2007)1 highlight a study in which 10-year surveillance of 22 LS families reduced the development of CRC by 60% and also decreased mortality. 10,16 Appropriately targeted surveillance also means that those without a gene defect may be spared intensified surveillance, which is costly and carries not insignificant risks of morbidity and mortality. 1

If LS has been identified, large bowel surveillance is recommended by the BSG and ACPGBI for probands and family members as follows:9

Total colonic surveillance (at least biennial) should commence at age 25 years. Surveillance colonoscopy every 18 months may be appropriate because of the occurrence of interval cancers in some series. Surveillance should continue to age 70–75 years or until co-morbidity makes it clinically inappropriate. If a causative mutation is identified in a relative and the consultand is a non-carrier, surveillance should cease and measures to counter general population risk should be applied.

Reproduced from Gut, Cairns SR, Scholefield JH, Steele RJ, Dunlop MG, Thomas HJ, Evans GD, et al. , Volume 59, pp. 666–89, 2010 with permission from BMJ Publishing Group Ltd.

-

Families fulfilling Amsterdam criteria, but without evidence of DNA mismatch repair gene defects (following negative analysis of constitutional DNA and negative tumour analysis by microsatellite instability testing/immunohistochemistry), require less frequent colonoscopic surveillance.

-

Gastrointestinal surveillance should cease for people tested negative by an accredited genetics laboratory for a characterised pathogenic germ-line mutation shown to be present in the family, unless there was a significant, coincidental finding on prior colonoscopy.

-

Reproduced from Gut, Cairns SR, Scholefield JH, Steele RJ, Dunlop MG, Thomas HJ, Evans GD, et al. , Volume 59, pp. 666–89, 2010 with permission from BMJ Publishing Group Ltd.

The evidence for upper gastrointestinal surveillance in all of these disorders is weak, but limited evidence suggests it may be beneficial.

Debate continues regarding the appropriate age for and frequency of surveillance, but the above criteria are in agreement with further published data. 1 However, the situation becomes more complex when the proband does not have a detectable DNA alteration associated with LS, or when an alteration with an unclear significance is identified. 4 Vasen and colleagues (2007)1 suggest that this is the case for approximately 30% of families meeting the AC I, for whom a less intensive surveillance protocol may be recommended (i.e. colonoscopy at 3–5 year intervals, starting 5–10 years before the first diagnosis of CRC or at > 45 years).

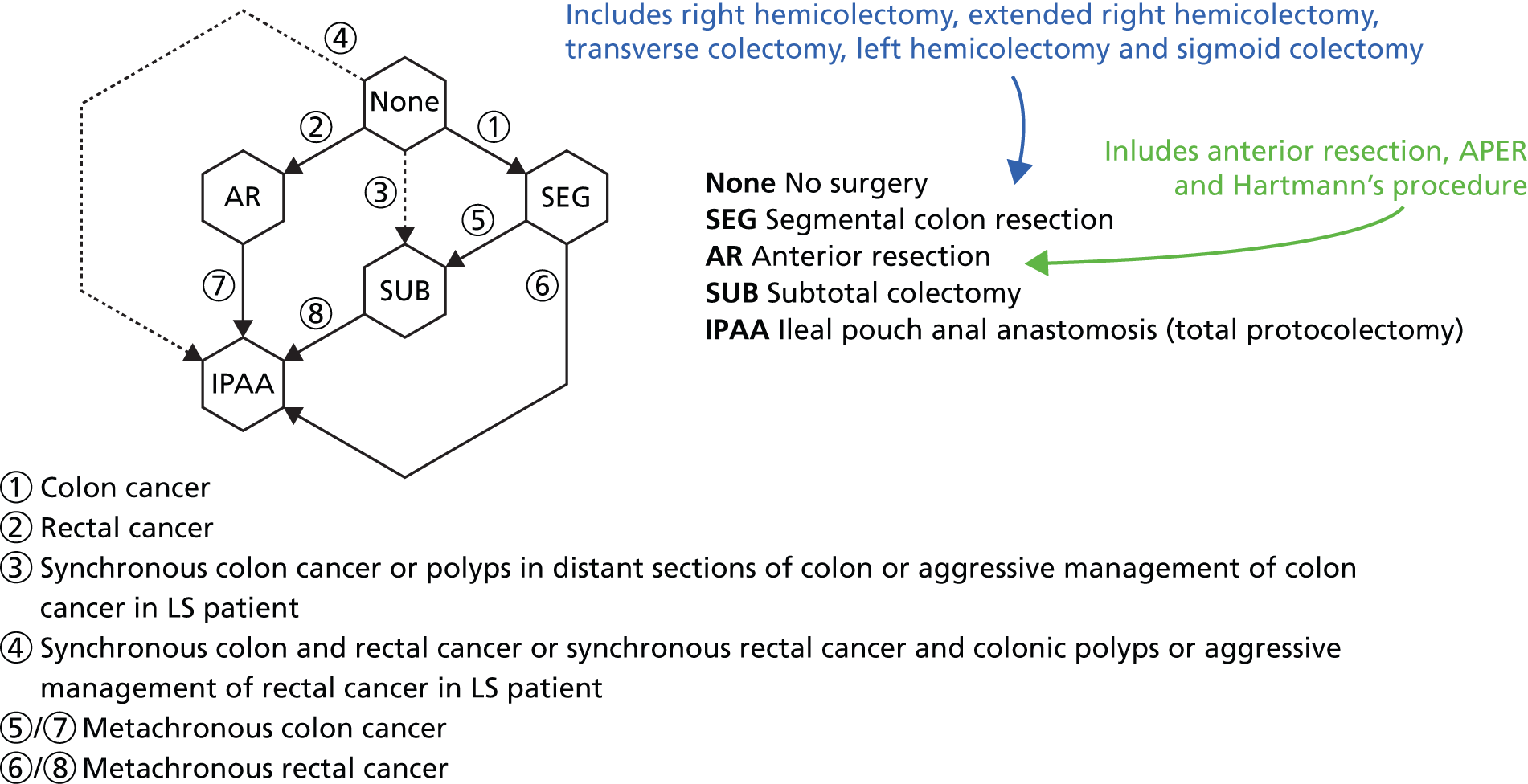

Surgical management

Several studies have shown that patients with LS have an increased risk of developing multiple (synchronous and metachronous) CRCs. 1 The type of surgery received, i.e. total or subtotal colectomy, depends on the location of the tumour and the stage of the cancer. Studies have shown that adenomas in patients with LS are located mainly in the proximal colon (ascending and transverse);14 therefore, a subtotal colectomy is favoured, which involves removal of most of the colon, leaving a small amount to be reattached to the rectum. Clinicians may also discuss prophylactic colectomy as a reasonable option in mutation carriers for whom colonoscopy is painful or difficult, or for a patient with adenomas that cannot be removed easily; however, this remains controversial.

Chemotherapy

At least three chemotherapeutic agents have been proven to be effective in the treatment of CRC – 5-FU (also known as fluorouracil) with or without leucovorin (also known as folinic acid), oxaliplatin and irinotecan – although experimental and clinical studies suggest that MSI-H tumours are resistant to 5-FU-based chemotherapy. Therefore, according to Vasen and colleagues (2007),1 prospective clinical trials are needed before definitive recommendations can be given.

Epidemiological studies have demonstrated that non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (e.g. aspirin) reduce the risk of CRC. 14 A recent study showed that a daily dose of aspirin reduced the incidence of CRC in carriers of LS after 56 months’ follow-up. 17 The mechanisms by which aspirin prevents the development of cancer are unknown, though some have suggested that aspirin may be proapoptotic in the early stages of CRC development. Importantly, the Colorectal Adenoma/Carcinoma Prevention Programme 2 (CAPP2) trial of aspirin prophylaxis in LS has demonstrated that aspirin treatment for up to 3 years reduces, a decade later, the overall incidence of LS-associated cancers, including CRC, by 63%. 17 A further dosage determination trial (CAPP3) is therefore planned in LS patients worldwide (www.capp3.org) and highlights the importance of identifying individuals and families with LS.

Description of technologies under assessment

The major laboratory tests used in the evaluation of patients suspected of having LS include testing of tumour tissue using IHC, MSI testing and constitutional testing for MMR mutations (generally from peripheral blood mononuclear cells). Family members undergo predictive genetic testing for the pathogenic mutation identified in the proband (unless they have also developed a relevant cancer). 4 Other tests which may be carried out on tumours include BRAF V600E and methylation of MLH1.

Immunohistochemistry

In families with an increased probability of a MMR gene mutation, IHC analysis for MMR proteins MSH2, MLH1 and MSH6 in tumour tissue may be used as the first step to confirm the presence of MMR deficiency. Pathogenic mutations in MMR proteins frequently lead to the absence of a detectable gene product, or expression of the protein in an abnormal location, for example in the cytoplasm rather than the cell nucleus. Therefore, when tumour tissue from patients suspected of having LS is stained for MMR proteins, a negative or less intense nuclear staining may be visible as compared with the surrounding normal colonic tissue used as a positive control. 4,18

The advantage of IHC, as opposed to MSI, is that abnormal staining of a specific MMR protein is related to the underlying gene defect and can therefore direct further genetic mutation analysis. 1 IHC is a well-established technique widely available in cell pathology laboratories; however, when used to analyse MMR proteins in the setting of LS diagnosis, it must be performed to an adequate standard. Hence, at a workshop in 2006 it was decided that MMR IHC should only be available within the NHS via a laboratory accredited to Clinical Pathology Accreditation standards, obliged to participate in the UK National External Quality Assessment Scheme Immunocytochemistry (NEQAS ICC) for MMR proteins. 19 This workshop made a number of recommendations, including that MMR IHC should be performed for all four main MMR proteins, in part to address the issue of tissue fixation artefact. Care must also be taken in histopathological interpretation of MMR IHC that an adequate and representative tissue sample has been analysed.

Although MMR IHC can give useful and informative results, its sensitivity is limited by a number of factors, for example tissue fixation, the variety and different performance characteristics of primary antibodies and the fact that some pathogenic mutations may result in catalytically inactive but antigenically intact proteins. 15,20–23 Hence, there is a place for MSI analysis in cases with a high prior probability of LS, but with apparently normal expression of the MMR proteins. 1

A particular issue with IHC is that approximately 15% of sporadic colon cancers lose expression of MLH1 because of somatic hypermethylation of the gene’s promoter. Therefore, whereas abnormal expression of MSH2, MSH6 or PMS2 is in itself reasonably good evidence that a tumour was due to LS, loss of MLH1 in itself is not. Other evidence must be used in interpretation in these circumstances, and thus testing for BRAF V600E and/or MLH1 promoter methylation may also be performed. The presence of the BRAF V600E mutation indicates a sporadic rather than LS-associated CRC, but the absence of BRAF V600E does not distinguish between sporadic tumours and those caused by LS. Similarly, MLH1 promoter methylation is highly correlated with a sporadic origin for a tumour, but is not absolutely conclusive, because individuals and families are described with constitutional MLH1 promoter methylation defects. 24

Microsatellite instability testing

Microsatellite instability refers to the variety of patterns of microsatellite repeats observed when DNA is amplified from a tumour with defective MMR compared with DNA amplified from surrounding normal colonic tissue. Repetitive mono- or dinucleotide DNA sequences (microsatellites) are particularly vulnerable to defective MMR. 4 MSI is prevalent in tumours from patients with MMR mutations, and in patients meeting either AC. 4 Therefore, microsatellite analysis is commonly used as the first diagnostic screening test for LS. 18

Microsatellite instability testing involves amplification of a standardised panel of DNA markers (Bethesda/National Institutes of Health markers), although laboratories may use 10 or more markers and, more recently, a commercially available kit based on five mononucleotide markers has become popular as mononucleotide microsatellites may be the most sensitive markers for use in detecting MSI. 4 The process involves microdissection of tumour tissue, followed by extraction of DNA which is then amplified and run on a DNA fragment length analyser. Using such microsatellite markers, additional peaks in tumour tissue DNA in comparison with normal tissue DNA indicate MSI. 25 Instability in 30% or more of the markers is considered MSI-H, less than 30% MSI-L and no shifts or additional peaks MSS. However, if instability is observed at any mononucleotide markers, MSI may be diagnosed. For this reason, MSI testing is moving to a smaller panel of mononucleotide markers, making the process more efficient and cheaper.

As for any molecular pathological analysis, tissue to be selected for MSI analysis must be first assessed by a histopathologist, prior to some degree of microdissection, which aids in maximising sensitivity. There is debate regarding the relative costs of MMR IHC and MSI testing, but NHS service laboratory costings indicate there is little to choose between the two. MSI may be more reproducible and can be performed with smaller amounts of tissue. 26 As there is not yet a UK NEQAS scheme for MSI, the reproducibility of MSI compared with IHC is not established.

BRAF V600E and methylation testing

The presence of MSI in the tumour by itself is not sufficient to diagnose LS because 10–15% of sporadic CRCs exhibit MSI. 25 MSI in non-LS tumours is usually caused by hypermethylation of the MLH1 gene. This acquired epigenetic inactivation of MLH1 is typically associated with mutations in the BRAF gene (specifically the V600E mutation), which has been described in ≈ 35% of sporadic MSI-H CRCs. 25 Therefore, identification of hypermethylation of MLH1 and/or BRAF V600E is an indication that a patient does not have the LS germline mutation.

Ideally, tests would be performed together as the presence of the BRAF V600E mutation theoretically reduces the chance of LS as the cause of that tumour; however, because any test has a finite false negative (FN) rate, it is still a possibility. Additionally, if MLH1 promoter methylation is present but the BRAF V600E mutation is not, this would highlight the small possibility that the patient may have LS due to a constitutional MLH1 methylation defect. It is also possible that he or she could have an inherited MLH1 genetic mutation and could have acquired MLH1 promoter methylation as the ‘second hit’ in the tumour. In these cases, loss of heterozygosity of chromosome 3p (where MLH1 is located) is observed. 25

Constitutional genetic testing

Multiple methods have been used for constitutional genetic testing (tests for mutations that affect all cells in the body and have been there since conception) in LS, in order to find inherited or, if de novo, potentially inheritable MMR gene mutations. The method(s) used should ideally be able to detect any possible mutation associated with LS, for example nonsense, missense and frameshift mutations, genomic deletions, duplications and rearrangements, as explained in Tables 4 and 5. 4

| Mutation | Description |

|---|---|

| Missense | A change in one DNA base pair that results in the substitution of one amino acid for another in the protein made by a gene |

| Nonsense | A change in one DNA base pair that results in a premature signal to stop building a protein. This type of mutation results in a shortened protein that may function improperly or not at all |

| Insertion | Changes the number of DNA bases in a gene by adding a piece of DNA. As a result, the protein made by the gene may not function properly |

| Deletion | Changes the number of DNA bases by removing a piece of DNA. Small deletions may remove one or a few base pairs within a gene, while larger deletions can remove an entire gene or several neighbouring genes. The deleted DNA may alter the function of the resulting protein(s) |

| Duplication | Consists of a piece of DNA that is abnormally copied one or more times. This type of mutation may alter the function of the resulting protein |

| Frameshift mutation | Occurs when the addition or loss of DNA bases changes a gene’s reading frame. A reading frame consists of groups of three bases that each code for one amino acid. A frameshift mutation shifts the grouping of these bases and changes the code for amino acids. The resulting protein is usually nonfunctional. Insertions, deletions and duplications can all be frameshift mutations |

| Splice site | Causes abnormal mRNA processing, generally leading to in-frame deletions of whole exons or out-of-frame mRNA mutations leading to nonsense-mediated decay of mRNA. Mutations may be located deep in intronic sequences |

| Promoter | Mutations in the controlling region of a gene leading to its non-expression. Epigenetic mutations, i.e. abnormal methylation of CpG sites may give rise to the same effect |

| Test | Description | Comments |

|---|---|---|

| High-output screening techniques | SSCP CSGE DGGE DHPLC |

These methods all take advantage of the observation that alteration of DNA confers chemical properties that allow it to be differentiated from normal DNA (now considered obsolescent/obsolete in the UK) |

| DNA sequencing | This can be used following a high-output screening technique or as a primary approach when IHC patterns allow for targeting of a MMR gene | The main method used in the UK for detecting most MMR gene mutations. However, it does not reliably allow for detection of deletions or rearrangements, which are also important in LS. DNA sequencing has become automated in recent years, greatly reducing the required time, costs and expertise4 |

| Methods to detect large structural DNA abnormalities | MLPA is the preferred technique in the UK | Large structural DNA abnormalities are an important cause of LS (5–25% of cases, depending on the gene) but are not generally detected by high-output screening techniques or DNA sequencing. There are several methods for detecting these defects. MLPA, which involves measurement of the relative copy number of DNA sequences, has evolved to become a standard approach for analysing MMR genes for deletions4 |

| Conversion analysis | Only a single allele is analysed at a time. This can increase the yield of genetic testing but is technically complicated, expensive and not widely available |

Measuring the accuracy of diagnostic tests for Lynch syndrome

One aspect of the evaluation of new tests is measuring their accuracy by calculating their sensitivity and specificity. This requires specification of the best available method of identifying the target condition of interest, known as the reference standard. Most mutations causing LS are point mutations or small insertions or deletions, suitably detected by DNA sequencing. However, some LS-associated mutations are deletions/duplications of exons in MLH1 and MSH2. These are more difficult to detect and, currently, the most appropriate technology available is multiplex ligation-dependent probe amplification (MLPA), which is a multiplex polymerase chain reaction (PCR) method able to simultaneously detect copy number changes across multiple DNA sequences within one sample. Therefore, the ideal reference standard is considered to be sequencing plus MLPA.

Chapter 2 Definition of the decision problem and review question

The question addressed by this health technology assessment (HTA) is as set out in the final scope published by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR), and is reproduced here for reader convenience.

A protocol was developed a priori by the authors to address the decision problem.

The methods used to address specific aspects of the decision problem are detailed at the beginning of each of the relevant chapters which follow.

Test accuracy review question

What is the accuracy of tumour-based tests for LS in all newly diagnosed persons with CRC under 50 years of age, and those considered according to clinical criteria to be at high risk?

Population

-

All newly diagnosed patients under the age of 50 years with CRC.

-

Participants considered to be at high risk of LS, i.e. those fulfilling AC II or Bethesda criteria.

-

Individuals with personal cancer history or FH indicators.

Intervention

Tumour-based tests for evidence of mutations in the genes encoding the MLH1, MSH2, MSH6 and PMS2 DNA MMR enzymes. These tests include MSI, IHC, BRAF and methylation.

Comparators

Genetic testing by sequencing followed by MLPA is considered the gold standard.

Design

An evidence synthesis by systematic review to determine the accuracy of tumour-based tests.

Health-care setting

Primary and secondary care settings.

Test outcomes

The outcomes of interest include measures of:

-

diagnostic test accuracy

-

test failure rate

-

discordant test results.

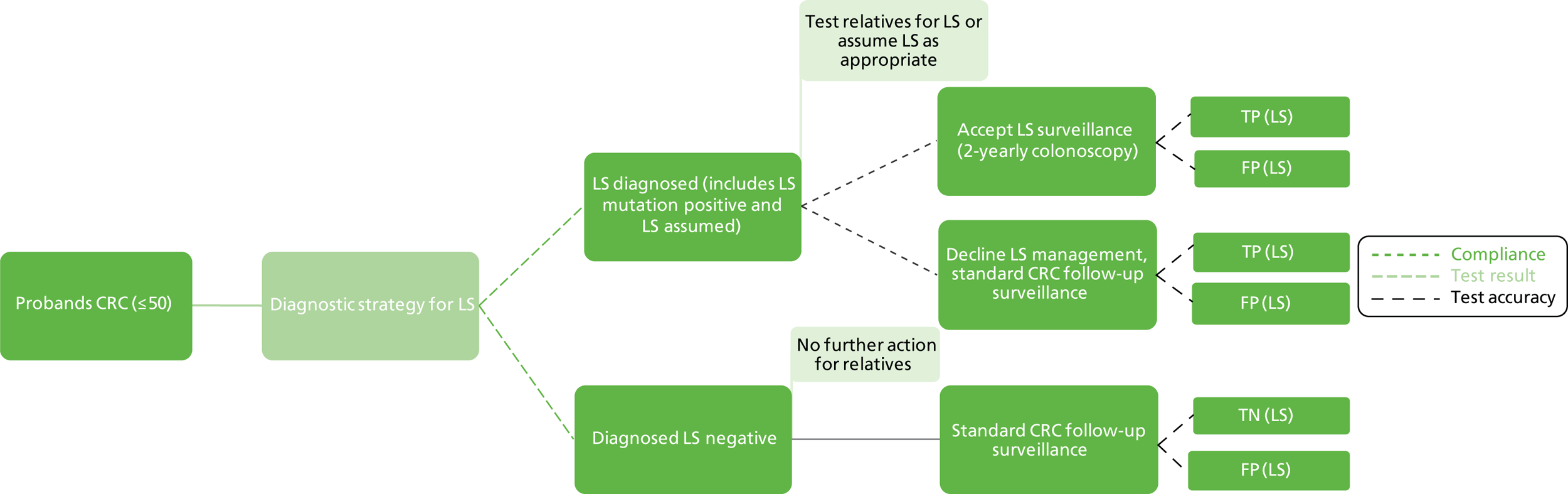

Decision problem

We will compare genetic testing of all identifiable close relatives with no genetic testing (extreme case analysis) and with a level of genetic testing similar to that carried out in the local health-care setting, which we believe is reasonably typical of current practice across the NHS.

For clarity we would restate and define the suggested specific outcomes contributing to the general aim of assessing effectiveness, cost-effectiveness and cost–utility, as follows:

-

diagnostic accuracy of identifying LS in those presenting with CRC < 50 years of age

-

patient outcome, considering both quantity and quality of life, in those presenting with CRC < 50 years of age

-

diagnostic accuracy of identifying LS in close family members of those presenting with CRC < 50 years of age

-

patient outcome, considering both quantity and quality of life, in close family members of those presenting with CRC < 50 years of age

-

contributing to patient outcome, the number of cancers, particularly CRCs detected, their severity and their age at onset

-

cost of alternative strategies

-

contributing to cost (and patient outcome), the number of surveillance investigations, particularly check colonoscopies, undertaken.

Outcomes of interest are the cost-effectiveness and cost–utility of different strategies for testing probands and their close relatives, the diagnostic accuracy and yield of different strategies for high-risk subjects, and cases of surveillance avoided. Data on these outcomes are likely to be used along with clinical utility scores to estimate quality-adjusted life-years (QALYs).

Modelling will be employed to identify the cost-effectiveness of strategies for the investigation of all new cases of CRC in individuals < 50 years of age for markers of HNPCC. The models will explore the yield of individuals at high risk of HNPCC among the close relatives of probands and identify to what extent unnecessary surveillance (by colonoscopy or other methods) can be avoided. The analysis will also briefly examine whether or not it could be more cost-effective to undertake genetic testing alone without IHC or MSI.

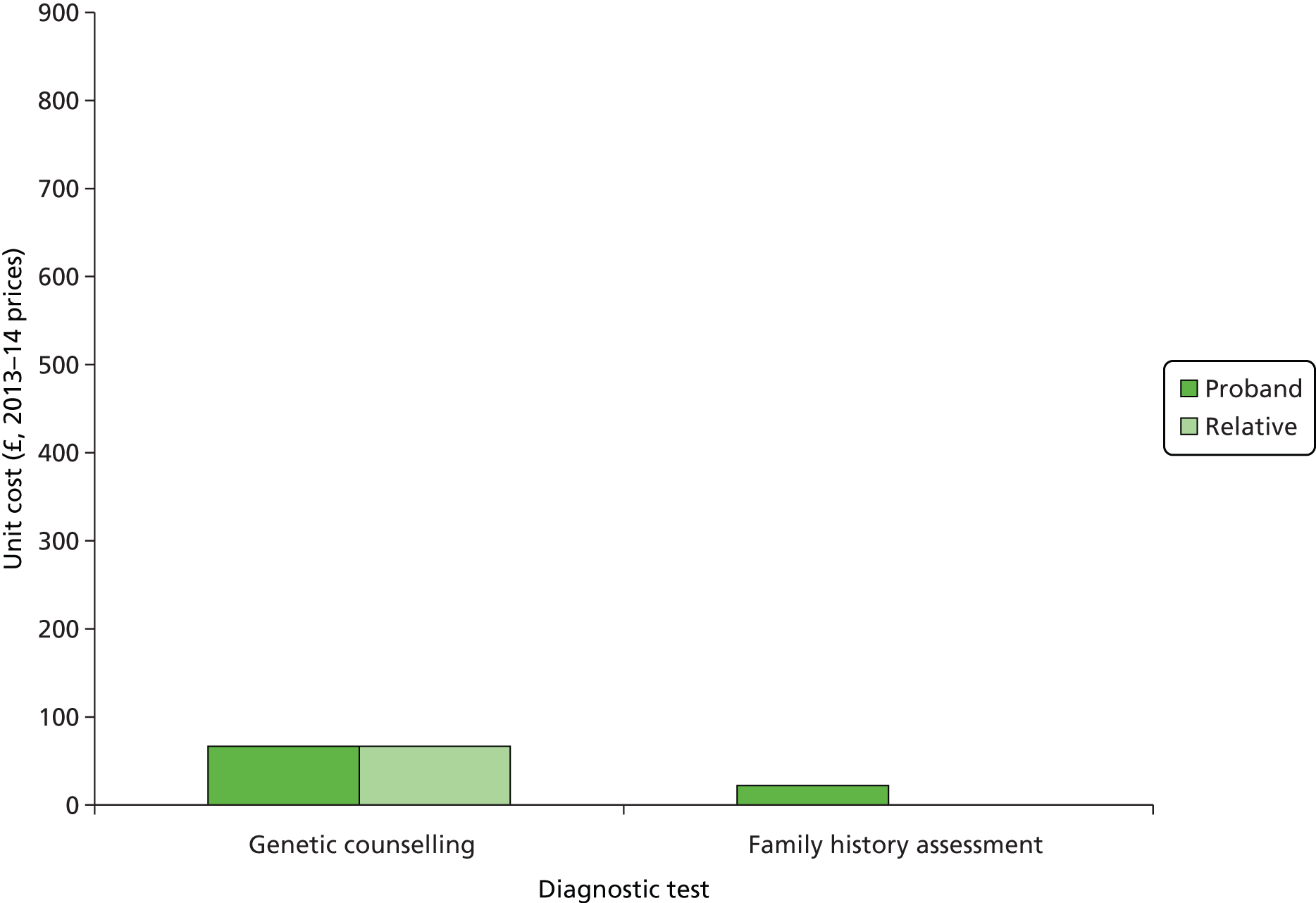

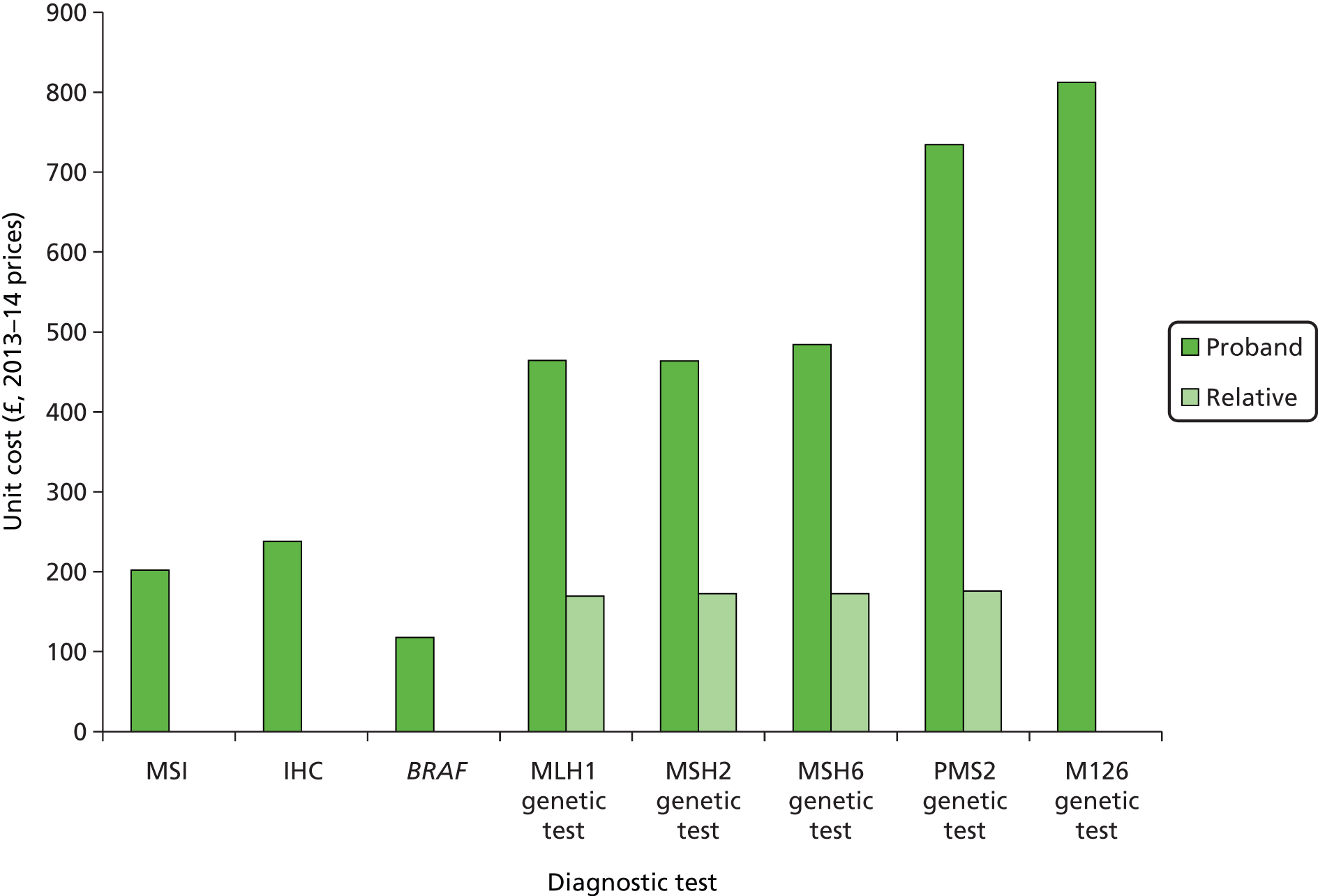

Cost considerations

The cost analysis will be based on the UK NHS setting and will be from an NHS and Personal Social Services (PSS) perspective.

The costs for consideration include:

-

cost of equipment, any additional tests (pre screening), reagents and consumables, participation in NEQAS

-

staff and training of staff

-

maintenance of equipment

-

costs associated with surgeon time and the management of operating theatre time

-

medical costs arising from ongoing care following test results, including those associated with clinical genetics, surgery, time spent in hospital and treatment of cancer.

Chapter 3 Assessment of test accuracy

Methods for reviewing test accuracy

The diagnostic accuracy of the tests IHC and MSI was assessed by a systematic review of research evidence. The review was undertaken following the principles published by the NHS Centre for Reviews and Dissemination. 28

Identification of studies

The search used clusters for LS and HNPCC, joined together using the Boolean connector OR for sensitivity. The following databases were searched: MEDLINE, MEDLINE In-Process & Other Non-Indexed Citations, EMBASE, PsycINFO, Health Management Information Consortium (HMIC) (all via Ovid), The Cochrane Library (all), Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL) (via EBSCOhost), Applied Social Sciences Index and Abstracts (ASSIA) [via Cambridge Scientific Abstracts (CSA)] and Web of Science [via Institute for Scientific Information (ISI)]. The search was limited to human-only populations and to the English language, but did not use any methodological search filters. The National Research Register (NRR), Current Controlled Trials, ClinicalTrials.gov, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) website, the European Medicines Agency (EMEA) website and Google were also searched. The search is recorded in Appendix 1.

Searches were deduplicated and managed using EndNote X5 (Thomson Reuters, CA, USA). Relevant studies were then identified in two stages. Titles and abstracts returned by the search strategy were examined independently by two researchers (TJH and HC) and screened for possible inclusion. Disagreements were resolved by discussion. Full texts of the studies which could not be excluded were obtained. Two researchers (TJH and HC) examined these independently for inclusion or exclusion, and disagreements were again resolved by discussion.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Population

Persons at risk of LS according to any of the following clinical or FH indicators:

-

age < 50 years at diagnosis

-

clinical criteria (e.g. AC II or Bethesda criteria)

-

FH indicators

-

personal cancer history indicators

-

combinations of the above.

In the case of two-gate diagnostic accuracy studies, the population could be persons with any CRC, but must have included a subsample with a known mutation in the genes encoding the MLH1, MSH2, MSH6 and PMS2 DNA MMR enzymes.

Interventions and comparators

The use of tumour-based tests, such as MSI and IHC, to look for evidence of mutations in the genes encoding the MLH1, MSH2, MSH6 and PMS2 DNA MMR enzymes.

The assessment of test accuracy assumed a genetic definition of LS. The reference standard for test accuracy studies was, therefore, genetic testing by sequencing.

Outcomes

Studies were included if outcomes were relevant to diagnostic test accuracy, i.e. if data were available to populate a 2 × 2 table and/or sensitivities and specificities were provided. Additionally, data on test failure rates were included in the review.

Study design

For the review of test accuracy, the protocol allowed inclusion of all study designs, unless evidence on the intervention and outcome of interest was already available from more rigorous study designs (as judged with reference to standard hierarchies of evidence).

Systematic reviews were used as a source for finding further studies and to compare with our systematic review. For the purpose of this review, a systematic review was defined as one that has:

-

a focused research question

-

explicit search criteria that are available to review, either in the document or on application

-

explicit inclusion/exclusion criteria, defining the population(s), intervention(s), comparator(s) and outcome(s) of interest

-

a critical appraisal of included studies, including consideration of internal and external validity of the research

-

a synthesis of the included evidence, whether narrative or quantitative.

Studies were excluded if they did not match the inclusion criteria, and in particular if they were:

-

pre-clinical or in animals

-

reviews, editorials and opinion pieces

-

case reports

-

studies with < 10 participants.

Data extraction strategy

Data were extracted by one reviewer (TJH) using a standardised data extraction form and checked by a second reviewer (HC). Disagreements were resolved by discussion, with involvement of a third reviewer if necessary. Appendix 2 shows the blank data extraction forms used.

Critical appraisal strategy

The methodological quality of the studies was assessed according to criteria specified by the Quality Assessment of Diagnostic Accuracy Studies-2 (QUADAS-2) tool for test accuracy studies. 29

Quality was assessed by one reviewer and judgements were checked by a second. Any disagreement was resolved by discussion, with involvement of a third reviewer as necessary. The two instruments are summarised below. Results were tabulated and the relevant aspects described in the data extraction forms.

Internal validity

The QUADAS-2 quality appraisal tool sought to assess the following considerations:

-

Description of patient selection.

-

Was a consecutive or random sample of patients enrolled?

-

Was a case–control design avoided?

-

Did the study avoid inappropriate exclusions?

-

Could the selection of patients have introduced bias?

-

Are there concerns that the included patients do not match the review question?

-

Description of index and reference tests.

-

Was the index test assessor blind to the results of the reference standard and vice versa?

-

Was a threshold pre-specified?

-

Could the conduct or interpretation of the index test or reference standard have introduced bias?

-

Are there concerns that the conduct or interpretation of the question have introduced bias for the index test or reference standard?

-

Is the reference standard likely to classify the target condition?

-

Description of patient flow and timing.

-

Did all patients receive a reference standard and was it the same test for each?

-

Were all patients included in the analysis?

-

Could the patient flow have introduced bias?

External validity

External validity was judged according to the ability of a reader to consider the applicability of findings to a particular patient group and service setting. Study findings can only be generalisable if they provide enough information to consider whether or not a cohort is representative of the affected population at large. Therefore, studies that appeared to be typical of the UK CRC population with regard to these considerations were judged to be externally valid.

Methods of data synthesis

Details of the extracted data and quality assessment for each individual study are presented in structured tables and as a narrative description. Any possible effects of study quality on the effectiveness data are discussed. Data on test accuracy are presented as sensitivity and specificity, where available.

In most of the studies, the accuracy of the interventions has been evaluated against the reference (gold) standard of constitutional genetic testing and thus, for the purpose of this assessment of test accuracy, a genetic definition of LS is assumed. The results are generally reported as follows:

-

Sensitivity: true positive (TP)/(TP + FN). This is the probability of detecting LS in someone with LS.

-

Specificity: true negative (TN)/[false positive (FP) + TN). This is the probability of not detecting LS in someone without LS.

-

Positive predictive value (PPV): TP/(TP + FP). This is the probability of someone with a positive result actually having LS.

-

Negative predictive value (NPV): TN/(TN + FN). This is the probability of someone with a negative test result actually not having LS.

-

Accuracy or concordance with reference standard: (TP + TN)/(TP + TN + FP + FN). This is the percentage of test results correctly identified by the test, i.e. the rate of agreement with the reference standard.

-

Discordance: cases of disagreement between the reference and index test.

Results

The results of the assessment of test accuracy will be presented as follows:

-

an overview of the quantity and quality of available evidence together with a table summarising all included trials (see Table 9), a table of patient characteristics (see Table 10) and a summary table of key quality indicators (see Table 11)

-

a critical review of the available evidence, covering:

-

the quantity and quality of available evidence

-

a summary table of the study characteristics

-

a summary table of the population characteristics

-

study results in terms of sensitivity and specificity analysis, presented in narrative and tabular form

-

quantity and quality of research available.

-

Number of studies identified

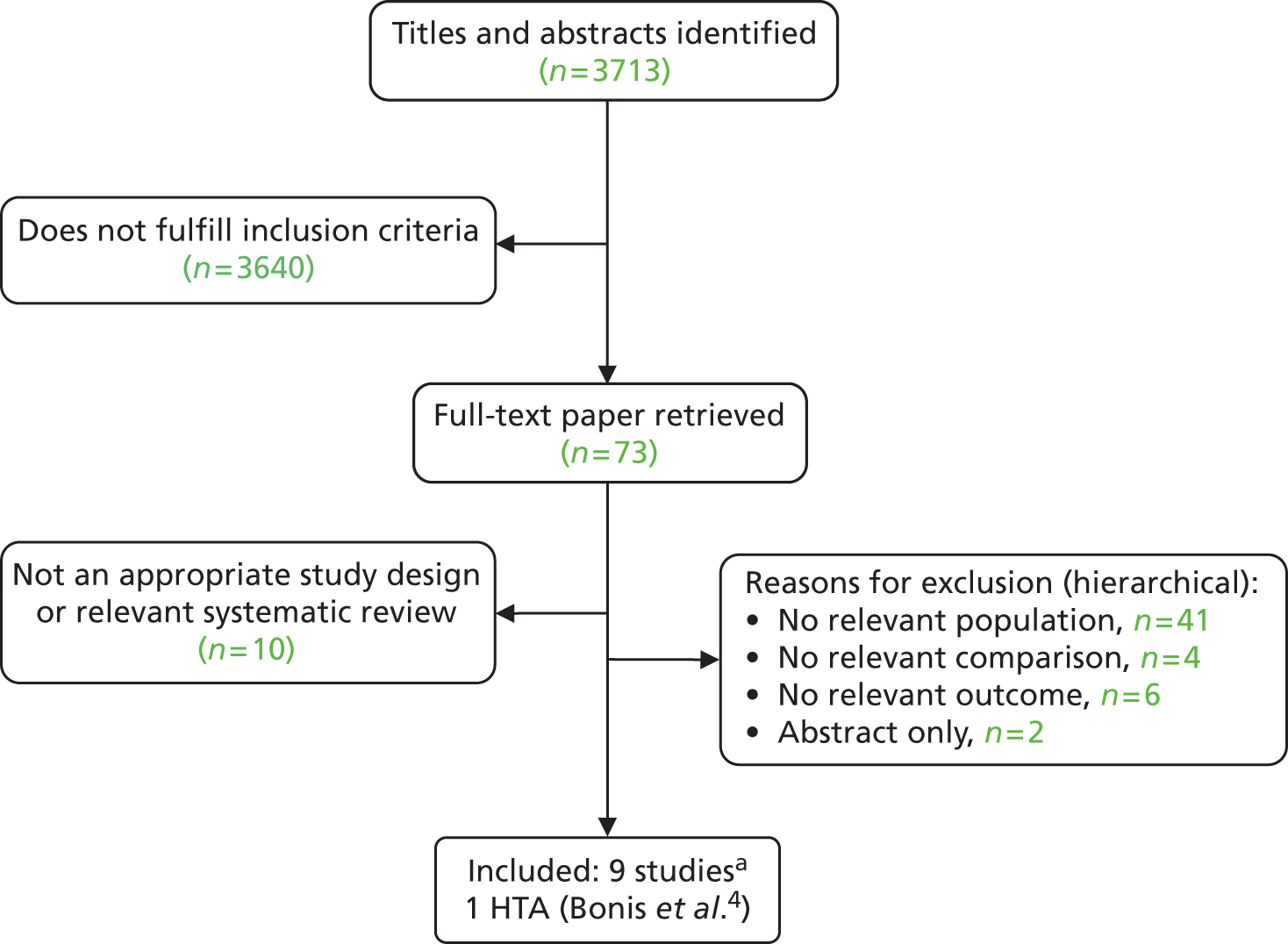

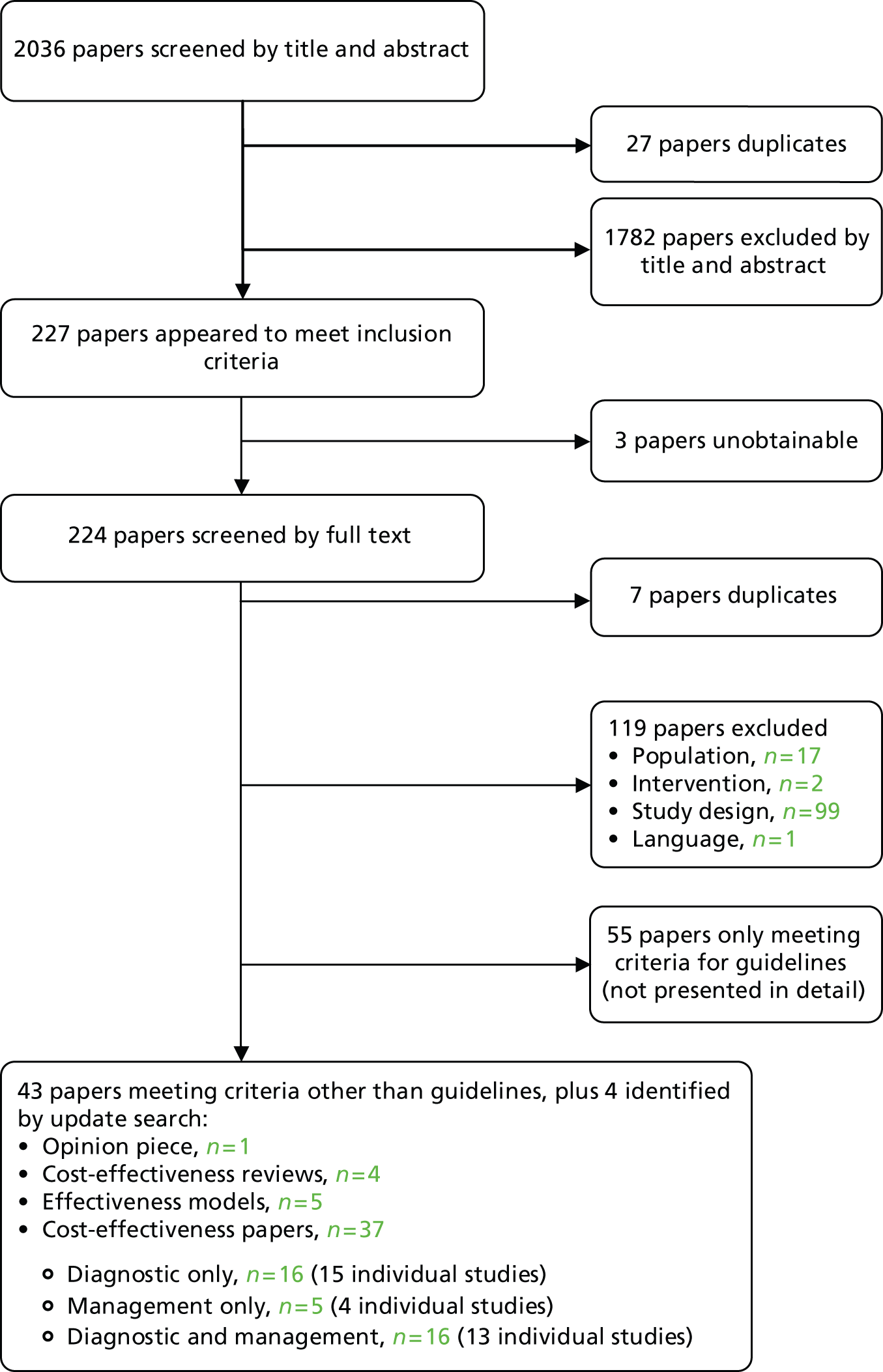

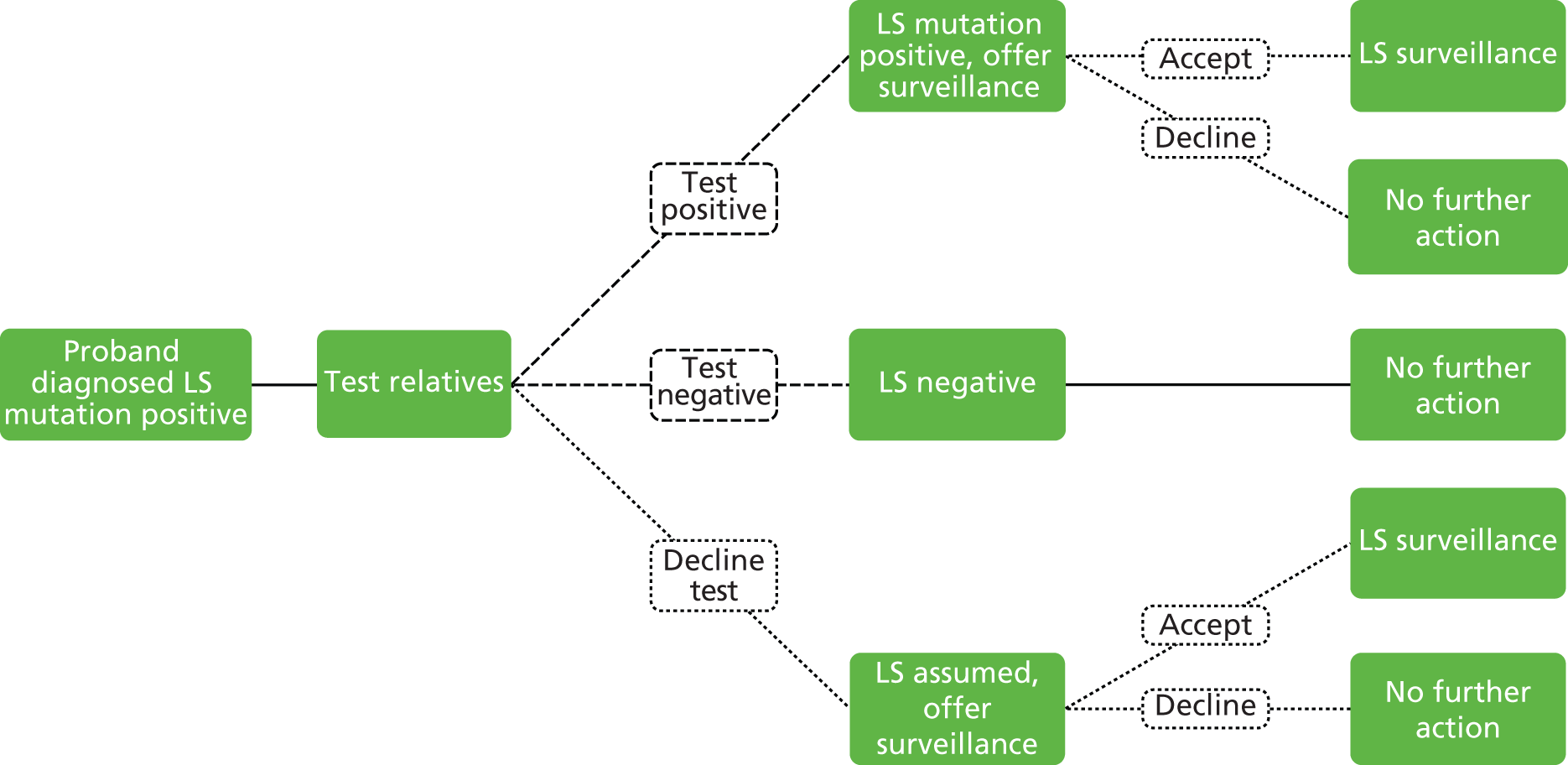

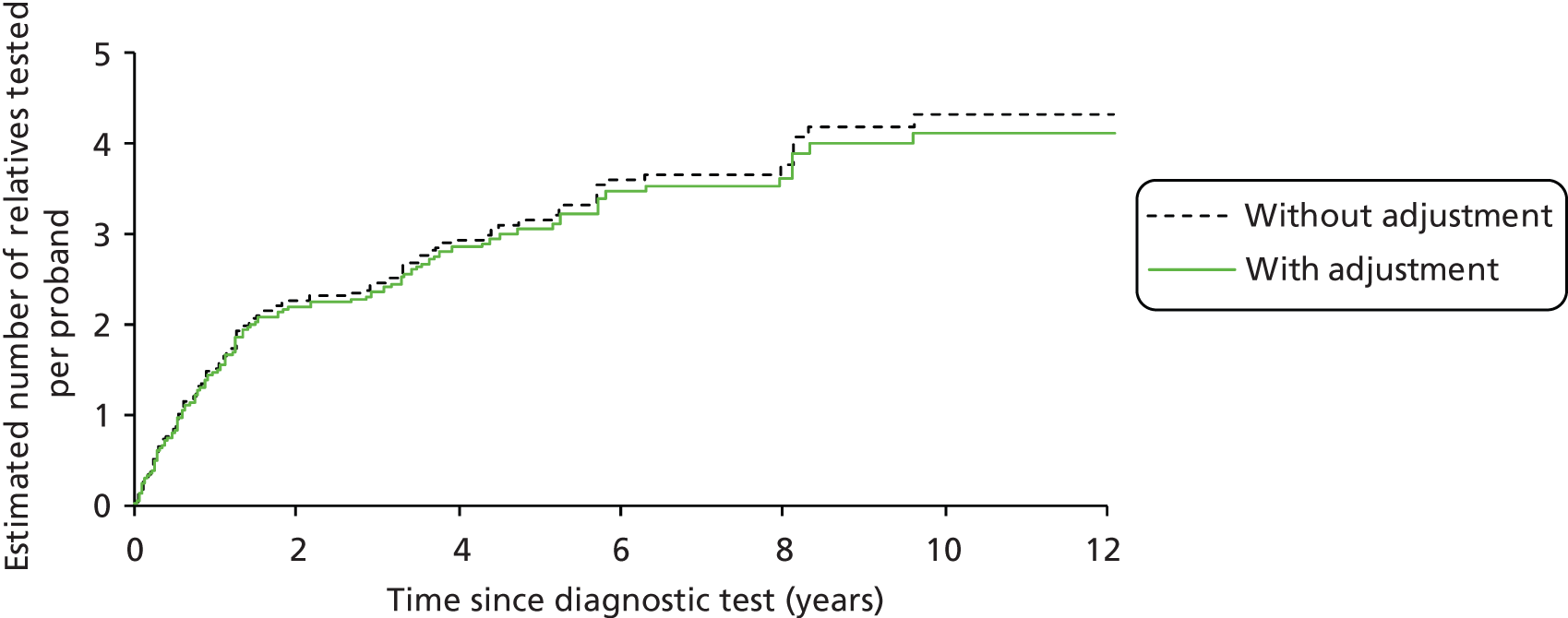

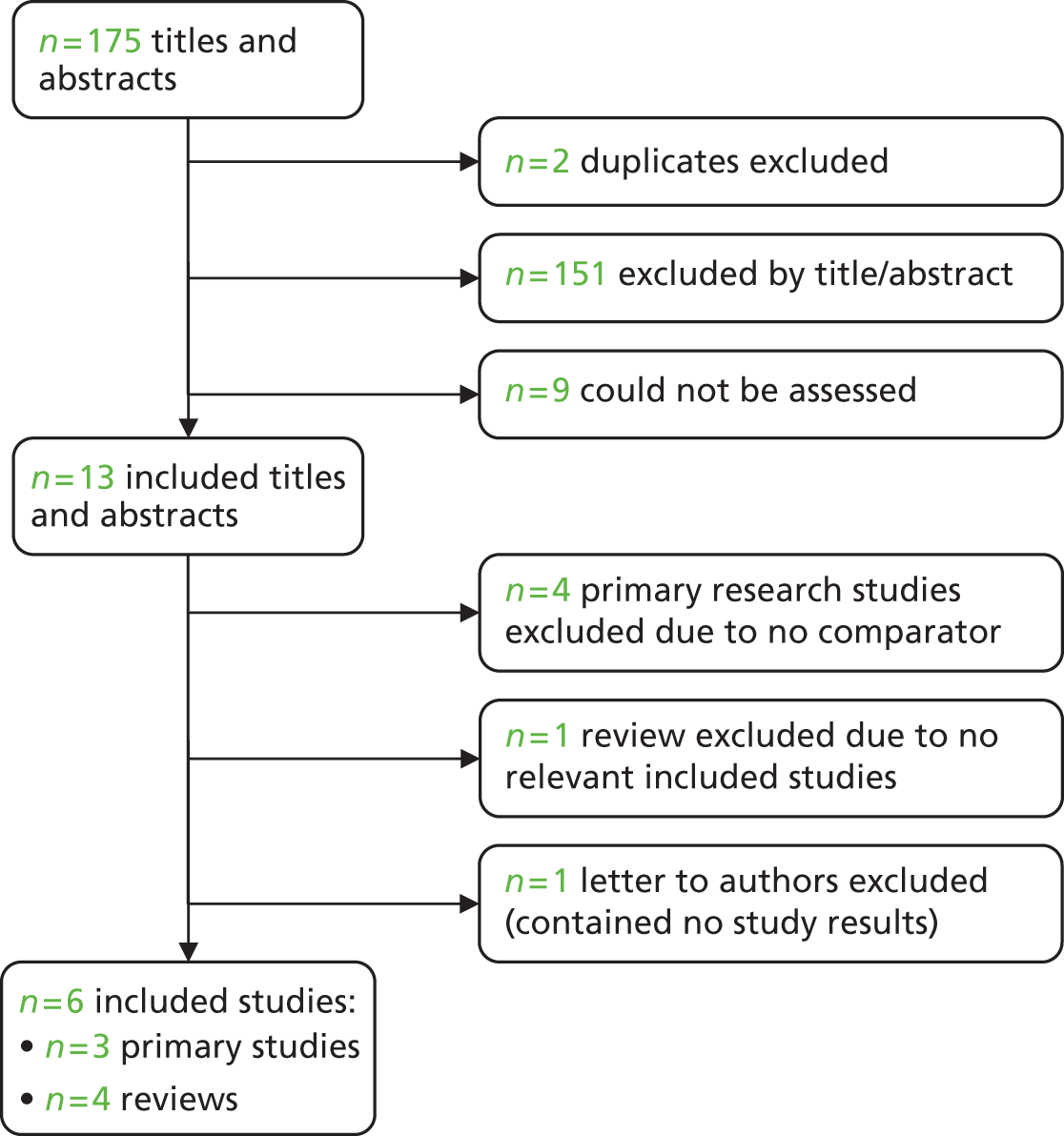

The electronic searches retrieved a total of 3713 titles and abstracts. A total of 3640 papers were excluded, based on screening of title and abstract. As a relevant technology assessment (TA) was retrieved in the search [Bonis and colleagues (2007)4], rather than duplicate effort, we included studies dated from 2005 onwards, and provide a summary of findings by the previous TA. Full text of the remaining 73 papers was requested for more in-depth screening, to give a total of 10 published papers included in the review. The process of study selection is shown in Figure 1.

FIGURE 1.

Summary of study selection. a, It is unclear whether or not two of the included studies are from the same population.

Number of excluded studies

Papers were excluded for at least one of the following reasons: duplicate publication; narrative review; and publication (systematic review or individual primary study) not considering the relevant intervention, population, comparison or outcomes. The bibliographic details of the 73 studies retrieved as full papers and subsequently excluded, along with the reasons for their exclusion, are detailed in Appendix 3.

Number and description of included studies

Bonis and colleagues (2007)

This review continues from a well-presented and thorough systematic review produced by Bonis and colleagues (2007), which is a TA commissioned by the US Department of Health and Human Services. 4 As such, an overview of the findings is discussed. The assessment of multiple systematic reviews (AMSTAR) quality assessment criteria for systematic reviews are displayed below (Table 6). 30 The one concern regarding the quality of the Bonis and colleagues (2007) TA is that MEDLINE was the only database searched. However, other sources included clinical experts and bibliographies of reviews.

| AMSTAR criterion | Response | |

|---|---|---|

| Was an ‘a priori’ design provided? | Yes | ✓ |

| No | ||

| Cannot answer | ||

| Not applicable | ||

| Was there duplicate study selection and data extraction? | Yes | ✓ |

| No | ||

| Cannot answer | ||

| Not applicable | ||

| Was a comprehensive literature search performed? | Yes | |

| No | ✓a | |

| Cannot answer | ||

| Not applicable | ||

| Was the status of publication (i.e. grey literature) used as an inclusion criterion? | Yes | |

| No | ✓ | |

| Cannot answer | ||

| Not applicable | ||

| Was a list of studies (included and excluded) provided? | Yes | ✓ |

| No | ||

| Cannot answer | ||

| Not applicable | ||

| Were the characteristics of the included studies provided? | Yes | ✓ |

| No | ||

| Cannot answer | ||

| Not applicable | ||

| Was the scientific quality of the included studies assessed and documented? | Yes | ✓ |

| No | ||

| Cannot answer | ||

| Not applicable | ||

| Was the scientific quality of the included studies used appropriately in formulating conclusions? | Yes | ✓ |

| No | ||

| Cannot answer | ||

| Not applicable | ||

| Were the methods used to combine the findings of studies appropriate? | Yes | ✓ |

| No | ||

| Cannot answer | ||

| Not applicable | ||

| Was the likelihood of publication bias assessed? | Yes | |

| No | ✓ | |

| Cannot answer | ||

| Not applicable | ||

| Was the conflict of interest stated? | Yes | ✓ |

| No | ||

| Cannot answer | ||

| Not applicable | ||

The characteristics of the studies relevant to this review which were included in Bonis and colleagues (2007) are presented in Table 7.

| Author and location | Population | Analysis |

|---|---|---|

| Calistri 200031 Italy Multicentre |

45 unrelated patients with CRC either fulfilling AC; from families meeting 2/3 AC; diagnosed with CRC at age < 50 years but with no FH; having at least one FDR with CRC; or having multiple neoplasms | Tissue samples from cancer analysed for MSI. DNA from peripheral blood samples analysed for MSH2 and MLH2 |

| Christensen 200232 and Katballe 200233 Denmark Single centre |

42 patients with CRC selected based upon clinical and FH meeting either AC I (n = 11) or a suggestive FH | MSH2 and MLH1 genes sequenced in 31 patients. MSI obtained in 35 patients; IHC performed in 40 patients. Compared sensitivity/specificity of these tests against sequencing as the reference standard |

| Debniak 200034 Poland Single centre |

168 consecutive patients with CRC in whom FAP was excluded Group A: 43/143 patients apparently sporadic, i.e. late onset (age > 40 years), no FH of LS-related tumours and no synchronous or metachronous cancer Group B: 25 were LS based on age ≤ 40 years, familial LS-related cancer or synchronous or metachronous cancer. The remainder were apparently sporadic |

IHC performed in all patients. MSI examined in all. Sequencing performed in all from group B and those from group A who showed abnormal IHC or MSI |

| Dieumegard 200035 France Multicentre |

34 patients with CRC who represented one of three groups: (1) AC I, (2) incomplete AC I (missing at least one criterion but strong FH), (3) age < 50 years and absence of LS-related cancers in family | All patients tested for MSI. Patients with MSI-H and nine MSS cases underwent germline testing for MMR. IHC was performed in all but four patients |

| Durno 200536 Canada Multicentre |

Patients with CRC at age ≤ 24 years (selected from a total of 1382 patients in a cancer registry) | Tumours analysed for MSI, IHC and blood for MMR |

| Farrington 199837 Scotland Multicentre |

50 unrelated patients with CRC at age < 30 years. Identified retrospectively from cancer registrations since 1970 compared with 26 age-matched volunteers without cancer | Detailed FH obtained from cases, paraffin-embedded archival tumour material obtained along with matched normal tissue from 42 patients. Tumour and normal tissue analysed for MSI. Genomic sequencing done on all patients and controls using peripheral blood |

| Peel 200038 USA Multicentre |

Referral of LS-case families (AC). These were from the ICG HNPCC group database (but they give MSI-HL vs. MSS which is not covered in the other papers) | MSI testing was performed in 10 families; diagnostic mutation testing of MSH2 and MLH1 was performed in 11 families |

| Shia 200511 USA Single centre |

A group of 112 colorectal adenocarcinomas (n = 83) or adenomas (n = 29) obtained from 110 patients treated at the cancer centre. These cases had a FH that fulfilled one of the following criteria: (1) AC I or II, (2) a set of relaxed AC that we referred to as ‘HNPCC-like’ and (3) Bethesda criteria | All patients started with MSI testing, followed by mutation analysis |

| Southey 200539 Australia Single centre |

Men and women from the Victorian Colorectal Cancer Family Study who were younger than age 45 years when diagnosed with a histologically confirmed, first primary adenocarcinoma of the colon or rectum. A random selection of 222 patients were asked to participate | Patients answered a risk factor questionnaire, and received IHC and MSI screening. Germline MMR mutation testing was conducted for all patients with one or more of the following characteristics: a FH that fulfilled the AC for LS; a tumour that was MSI-H, MSI-L, or that lacked expression of at least one MMR protein; and presence in a random sample of 23 patients selected from those who had tumours that were MSS and did not lack expression of any MMR protein |

| Terdiman 200140 USA Single centre |

Eligible families had to have two or more FDRs with CRC at any age, an individual with CRC diagnosed before 50 years of age or a single individual with synchronous or metachronous CRCs. Probands were selected based on convenience and age at cancer diagnosis. When multiple family members were available for molecular testing, the individual with cancer diagnosed at the youngest age was selected as proband | Paraffin-embedded tumour samples were obtained from all probands for MSI analysis and MSH2/MLH1 immunostaining. Subjects found to have tumours demonstrating MSI-H (n = 47) were invited for germline genetic testing of MSH2 and MLH1. Gene testing was carried out in 32 of the 47 eligible families. Eight probands refused testing for fear of insurance discrimination. In seven instances, the proband was deceased (n = 4) or could not be recontacted (n = 3) |

| Wahlberg 200241 USA Single centre |

Families were identified by self- or health-care provider referral and were enrolled on the basis of multiple cases of CRC, early age of CRC diagnosis or the familial association of CRC with other LS-associated tumours | Sequencing and MSI analysis of tumour samples from 48 families. IHC analysis of 24 tumour samples (subset of 48 for MSI analysis) of sufficient quality for IHC |

In terms of test accuracy results, Bonis and colleagues (2007)4 found very little published information related to the analytic validity of laboratory testing for LS and there was some concern that there may be variability between testing facilities. They found that genomic rearrangements and large deletions were missed when only sequencing and gene screening was performed, with limited evidence to suggest that approximately one-quarter to one-third of the identified MMR mutations were large genomic deletions/rearrangements. Most studies identified cases from cancer registries or used other selection strategies to target patients at risk of LS. Although this is a valid recruitment technique from a clinically relevant population, the definition of high risk differs from study to study (among the selected populations) and this may or may not reflect the criteria used to refer for testing in clinical practice.

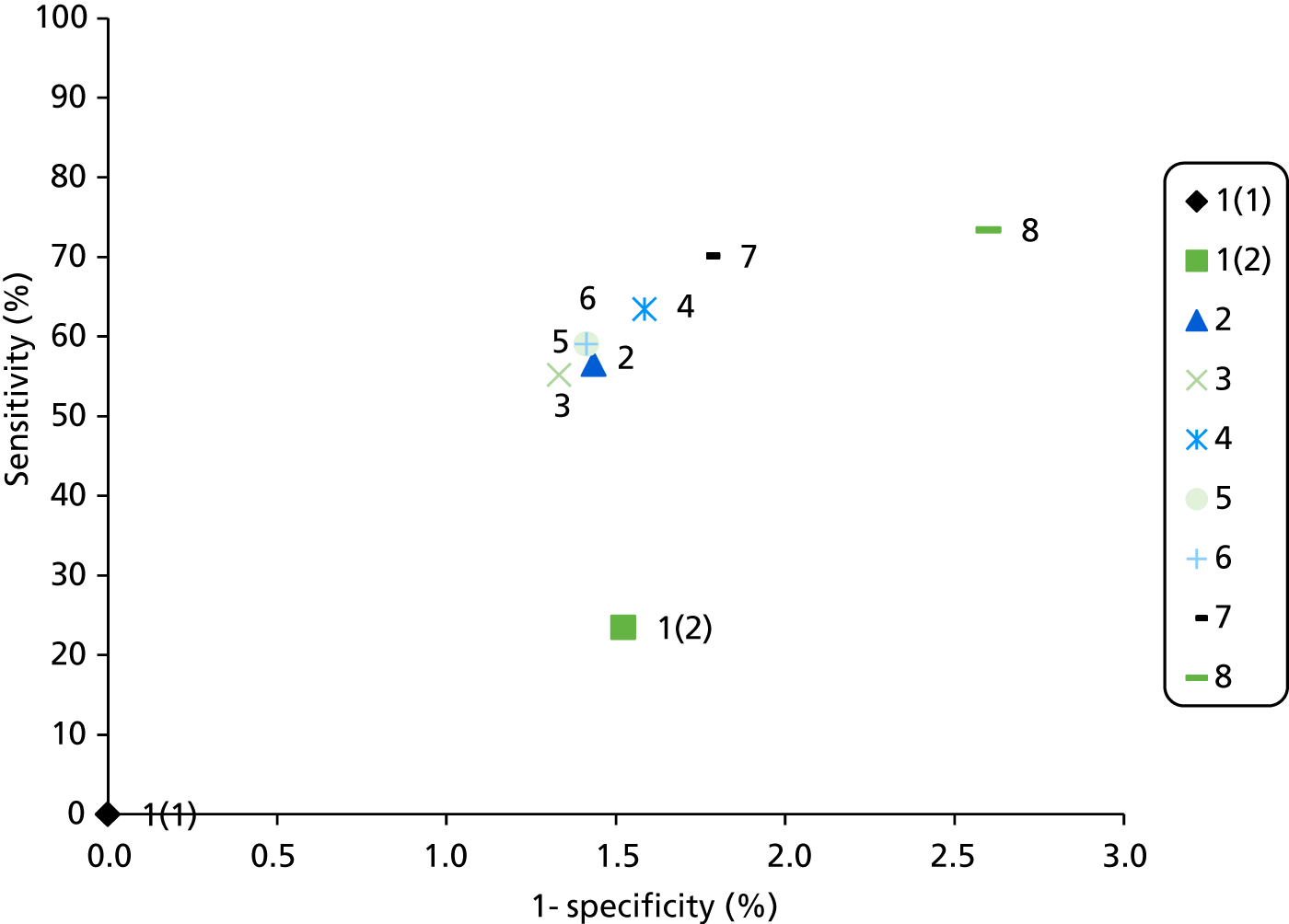

A summary of the relevant test accuracy results from Bonis and colleagues (2007)4 is presented in Table 8. The sample sizes of the studies were generally small. Sensitivity and specificity for both MSI and IHC appear variable with very broad confidence intervals (CIs).

| Author and location | Reference test | Index test | n | Sensitivity, % (95% CI, %) | Specificity, % (95% CI, %) | Risk of bias according to Bonis and colleagues | Qualitya |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Calistri 200031 Italy Multicentre |

PCR → SSCP | MSI | 56 | 100 (59 to 100)b | 44 (14 to 79)b | Comment: Study sample assembled with unclear selection process Verification bias: No |

C |

| Christensen 200232 and Katballe 200233 Denmark Single centre |

PCR → SSCP and HD → sequencing of abnormal patterns | IHC | 42 | 69 (39 to 91)c | 83 (59 to 96)c | Comment: Selection from a population of 1514 incident CRCs Verification bias: No |

B |

| 11 | 50 (7 to 93)d | 100 (48 to 100)d | |||||

| MSI | 45 | 100 (69 to 100)b | 87 (66 to 97)b | ||||

| Debniak 200034 Poland Single centree |

PCR → sequencing | IHC | 168 | 18 (2 to 51)c | 100 (94 to 100)c | Comment: Sampled from consecutive CRCs, selection process not transparent Verification bias: Yes; only 43/143 apparently sporadic CRCs were tested, but it is unclear how they were selected |

C |

| MSI | 168 | 83 (36 to 100)b | 87 (76 to 94)b | ||||

| Dieumegard 200035 France Multicentre |

PCR → SSCP → sequencing of abnormal patterns | IHC | 34 | 57 (18 to 90)c | 64 (35 to 87)c | Comment: Sampled with unclear selection process Verification bias: Yes; only seven sporadic CRCs underwent genetic testing |

B |

| 10 | 50 (7 to 93)d | 50 (7 to 93)d | |||||

| MSI | 34 | 100 (66 to 100)b | 60 (32 to 84)b | ||||

| 10 | 100 (54 to 100)f | 25 (0 to 81)f | |||||

| Durno 200536 Canada Multicentre |

PTT and sequencing | IHC | 16 | 75 (19 to 99)c | 75 (19 to 99)c | Comment: Retrospective cohort of CRC patients aged < 24 years at diagnosis who were still alive (since 1970) Verification bias: No |

C |

| MSI | 16 | 100 (48 to 100)b | 25 (0 to 81)b | ||||

| Farrington 199837 Scotland Single centre |

PCR → IVSP → sequencing PCR → sequencing |

MSI | 50 | 86 (57 to 98)b | 73 (52 to 88)b | Comment: Retrospective cohort of CRC patients aged < 30 years at diagnosis who were still alive (since 1970) Verification bias: No |

B |

| Peel 200038 USA Multicentre |

PCR → sequencing | MSI | 11 | 100 (29 to 100)b | 83 (36 to 100)b | Comment: Referral HNPCC cases, other than the 1134 CRC probands who were also included but were not assessed with laboratory tests Verification bias: No |

C |

| 100 (29 to 100)f | 83 (36 to 100)f | ||||||

| Terdiman 200140 USA Single centre |

MSI → PCR → DGGE → sequencing | IHC | 114 | 94 (71 to 100)g | 13 (4 to 30)g | Comment: Retrospective cohort of CRC probands with ≥ 2 CRCs in FDRs, age < 50 years at diagnosis or multiple tumours in same patient Verification bias: Yes; only patients with MSI-H were assessed |

B |

| Wahlberg 200241 USA Single centre |

PCR → sequencing | IHC | 70 | 55 (23 to 83)c | 88 (69 to 97)c | Comment: Selection among referrals to a specialised centre Verification bias: No |

B |

| MSI | 70 | 100 (77 to 100)b | 59 (41 to 75)b |

Included primary research studies

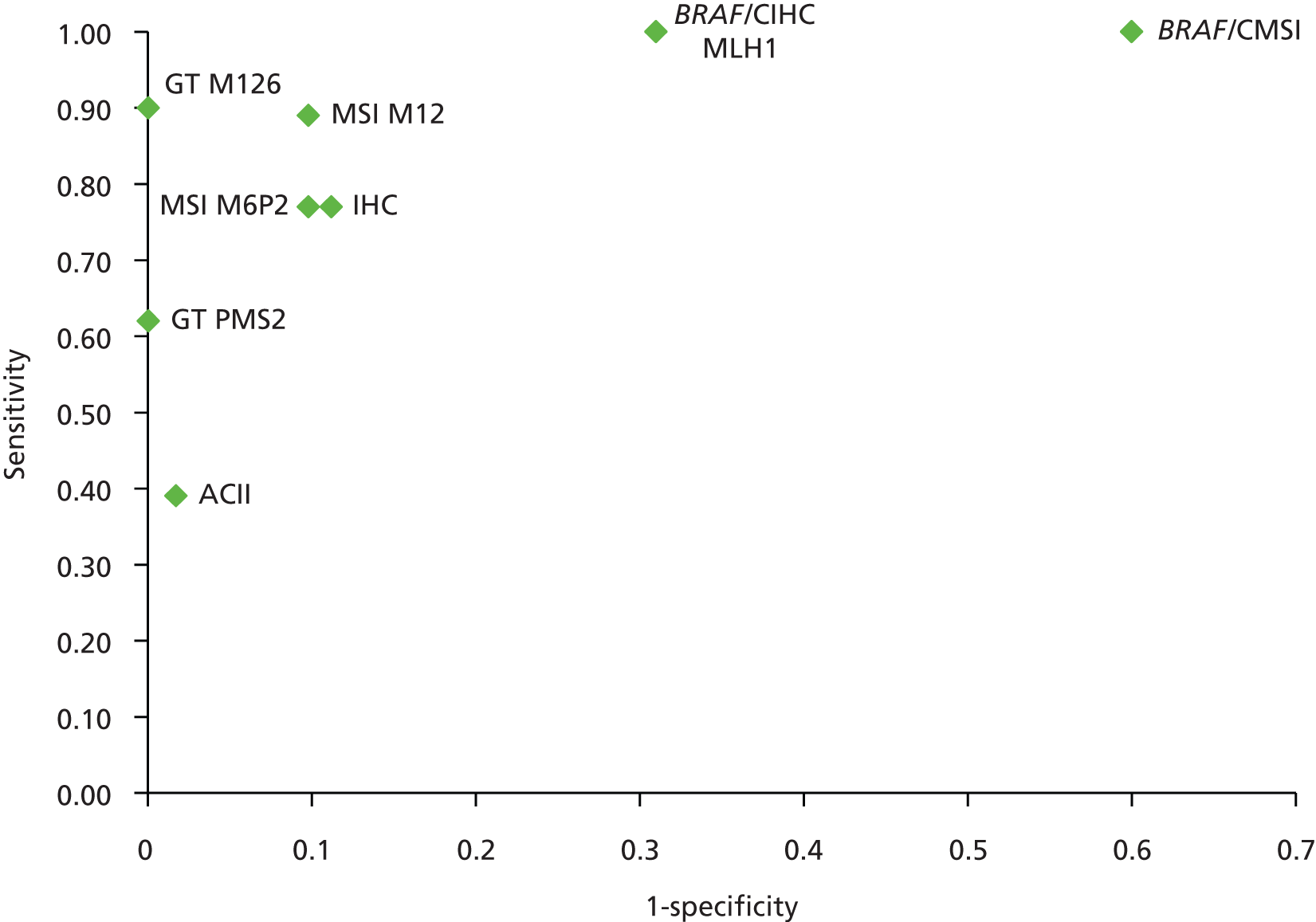

Nine test accuracy papers were included, five investigating IHC as the index test, one MSI and three studying both IHC and MSI. No papers were identified on tests for BRAF V600E and methylation of MLH1. All included citations are summarised in Table 9.

| Author and year | Patients (n) | Test | Centre and country | Design | Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| aBarrow 201120 | Sample, 36 Control, 6 |

IHC | Single centre, UK | Two-gate Sample patients retrospectively identified with mutation Control patients consecutively recruited Supported in part by grants from the Bowel Disease Research Foundation and Central Manchester and Manchester Children’s University Hospitals NHS Trust research grant scheme. This study group is supported by the NIHR Manchester Biomedical Research Centre |

ROC curves, sensitivity and specificity at optimum cut-offs |

| aBarrow 201042 | Sample, 51 Control, 17 |

IHC | Single centre, UK | Two-gate Sample patients retrospectively identified with mutation Control patients consecutively recruited Supported by MAHSC and the NIHR Manchester Biomedical Research Centre and by a grant from the Bowel Disease Research Foundation |

ROC curves, sensitivity and specificity at optimum cut-offs |

| Becouarn 200543 | 197 | IHC | Unclear, France | Single-gate Recruitment not described Funded by PHRC from the Délégation Régionale à la Recherche Clinique d’Aquitaine |

Sensitivity, specificity |

| Limburg 201144 | 195 | IHC | Unclear, USA/Canada/Australia | Single-gate Recruitment described as random, but no further details Funded by Myriad Genetic Laboratories, Salt Lake City, UT. The Colon Cancer Family Registry is supported by NIH National Cancer Institute grants |

Sensitivity, specificity, NPV, PPV |

| Niessen 201221 | 281 | IHC and MSI | Unclear, the Netherlands | Single-gate Recruitment not described Funded by the Dutch Cancer Society |

Sensitivity, specificity, NPV, PPV |

| Shia 200511 | 110 | IHC and MSI | Single centre, USA | Single-gate Recruitment not described Funded in part by the Kleber Foundation, the Sloan Kettering Institute, the Byrne Foundation and the Tavel-Reznik Fund for Colon Cancer Research |

Sensitivity, specificity |

| Southey 200539 | 131 | IHC and MSI | Single centre, Australia | Single-gate Random recruitment Funded by grants from the National Health and Medical Research Council (Australia) and the Victorian Health Promotion Foundation |

Sensitivity, specificity, NPV, PPV |

| Stomorken 200545 | 250b | IHC | Single centre, Norway | Single-gate Consecutive recruitment Funded by the Norwegian Cancer Society |

Sensitivity, specificity |

| Wolf 200646 | 81 | MSI | Single centre, Austria | Single-gate Recruitment not described Funded by the Medical Scientific Fund of the University of Vienna Medical School and the Medical Scientific Fund of the Mayor of Vienna |

Sensitivity, specificity |

Study characteristics

The majority of included studies employed a single-gate design where one sample of individuals was assessed by both the index test and reference standard. Only Barrow and colleagues (2010 and 2011) used a two-gate design, where the index test was performed on a group of participants with a known (positive) mutation status and a smaller group of controls with no applicable mutation status. 20,42 However, despite most studies being of a single-gate design, not all participants received the reference standard. Many studies cited cost as a reason for not performing genetic testing on participants who appeared to be MSS (i.e. those with no evidence of abnormal patterns of microsatellite repeats). This often led to confusing patient numbers and apparent missing data. In general, sample sizes were relatively small with poor reporting of patient characteristics. Details on robustness of testing were often lacking (e.g. results being checked by a second assessor), particularly for IHC, which may be prone to interobserver variability.

Barrow and colleagues (2010)42 present a two-gate, single-centre UK study investigating the semi-quantitative assessment of IHC for MMR proteins in LS. Patients with LS which had already been confirmed by germline mutation in one of the MMR genes – MLH1, MSH2 or MSH6 – and previous histologically proven CRC were identified through the North West Regional Genetics Lynch Syndrome Database. The control cases were consecutive unselected patients aged > 60 years with histologically proven left-sided colonic or rectal cancer (i.e. considered to be sporadic CRC as opposed to LS). A relatively small LS sample (n = 51) was recruited, with an even smaller control group (n = 17). IHC methods were described in detail; sections of tumour tissue were incubated with antibodies against the MMR proteins or antigens MLH1, MSH2, PMS2 and MSH6. The intensity of immunoreactivity (a measure of the reaction between the antibody and antigens of the tumour cells) was measured on a 0–3 scale, based on comparison of intensity of reactivity of the tumour cells with the positive control cells. A score of 0 = no tumour cell immunopositivity; 1 = 1–10% positive tumour cells; 2 = 11–50% positive tumour cells; 3 = 51–80% positive tumour cells; and 4 = ≥ 80% positive tumour cells. Information on the reference standard was not provided. Outcomes were receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves and sensitivity and specificity at optimum cut-offs (the cut-off score which demonstrates the best trade-off between sensitivity and specificity). However, raw data were not provided to populate a 2 × 2 table of positive and negative results.

The second paper by Barrow and colleagues (2011)20 appears to use the same pool of participants as the previous study, although with lower numbers. In this instance, the aim was to compare two novel methodologies: quantitative 3,3′-diaminobenzidine IHC (DAB-IHC) and quantitative quantum dot IHC (QD-IHC) in the identification of MMR mutation carriers. Also a two-gate design, this study had an LS sample size of 36, and a control group of only six. As per the previous study, participants had already received germline mutation testing, although details were not provided.

With regard to the DAB-IHC, sections were incubated with antibodies against the MMR proteins MLH1, MSH2, MSH6 and PMS2. With control positive tissue (normal colon), the protocol was optimised to a level that maximised specific nuclear immunoreactivity, while minimising non-specific background reactivity. For the QD-IHC, only staining for MLH1 and MSH2 was performed.

Again, relevant outcomes include ROC curves, and sensitivity and specificity at optimum cut-off, yet the raw data were not provided to populate a 2 × 2 table of positive and negative results.

A French study presented by Becouarn and colleagues (2005)43 examines a strategy to detect LS in patients by combining clinical selection (patient age at onset of cancer < 50 years or FH of HNPCC tumours) and MSI testing plus IHC, leading to MMR germline mutation analysis. It should be noted that only IHC was considered to be the index test, with MSI the prior test.

It is not clear how many centres were involved; however, the sample size was reported to be 197. Recruited participants were diagnosed with CRC between 1998 and 2001, and deemed high risk for LS owing to young age at onset or FH. Patient flow throughout the study is somewhat unclear and complex. It appears that testing by MSI took place in order to group participants according to MSI-H, MSI-L and MSS. Only patients who were MSI-H and MSI-L and those with valid IHC results for MLH1 and MSH2 received germline testing.

For IHC, the search for MMR proteins MLH1 and MSH2 was conducted on fixed tissue embedded in paraffin. Loss of MLH1 or MSH2 expression was defined as the absence of nuclear staining in tumour cells, in the presence of positive controls; preservation of protein expression was defined as the presence of nuclear staining in tumour cells and internal controls; non-interpretable staining was defined as the absence of staining in tumour cells and internal controls or slice detachment. For the reference standard, the search for mutations of the MSH2 and MLH1 genes was performed in MSI-H and MSI-L tumour tissues. The search for germline mutations and their characterisation was based on denaturing high-performance liquid chromatography (DHPLC) screening and/or direct sequencing using an automatic sequencer. The search for large MSH2 and MLH1 gene rearrangements was performed in certain patients when point mutations were not identified. For IHC, data were provided to populate a 2 × 2 table, therefore sensitivity and specificity could be calculated.

Limburg and colleagues (2011)44 present a study examining the prevalence of mutations in MLH1, MSH2 and MSH6 via IHC in a population-based sample of patients with young-onset (age at onset < 50 years) CRC. Employing six centres across Canada, the USA and Australia, a random sample of 195 CRC cases were recruited during phase 1 of the Colon Cancer Family Registry collaboration (1997–2002). No prior testing was performed and no preselection based on FH, so high risk for LS was based on age criterion alone. Minimal details are given for the index test, with MMR protein expression reported as present, absent or inconclusive.

The reference standard uses extracted DNA samples from peripheral blood for full mutation analyses of MLH1, MSH2 and MSH6. DNA was amplified by PCR and then directly sequenced. Large rearrangement testing for MLH1 and MSH2 was performed by Southern blot analysis in conjunction with MLPA. Germline alterations were categorised as deleterious/suspected deleterious, likely neutral or variant of uncertain significance. Reported outcomes were sensitivity, specificity, NPV and PPV, with raw data available to populate a 2 × 2 table.

The study by Niessen and colleagues (2006)21 investigated the sensitivity and specificity of IHC and MSI, the aim being to analyse the value of FH, MSI analysis and MMR protein staining in the tumour to predict the presence of a MMR gene mutation in such patients. Performed in the Netherlands (although it is unclear how many centres were involved), 281 individuals with CRC, who were high risk for LS according to young onset or personal cancer history, were recruited.

Microsatellite instability markers included two mononucleotide repeats (BAT25 and BAT26) and three dinucleotide repeats (D2S123, D5S346 and D17S250). For MSI analysis, control DNA was obtained from normal tissue or from peripheral blood lymphocytes from the same patient. Cancers were classified as MSI-H when two or more markers showed MSI and as MSI-L when no more than one marker showed MSI. The authors state that as a limited number of markers were analysed, the classification MSS was not used. IHC for the MLH1, MSH2 and MSH6 proteins was also carried out. The sections were scored as either negative (i.e. absence of detectable nuclear staining of cancer cells) or positive for MLH1, MSH2 and MSH6 staining. Protein expression in normal tissue adjacent to the cancer served as an internal positive control.

Mutation analysis of the MLH1, MSH2 and MSH6 genes was carried out on DNA isolated from peripheral blood lymphocytes by denaturing gradient gel electrophoresis, followed by direct sequencing. For the detection of large deletions (exonic deletions or deletions of a complete gene) and duplications, MLH1/MSH2 exon deletion MLPA was used. Cases that had deletions of more than one exon in the MLH1 or MSH2 gene were confirmed by Southern blot analysis. Sensitivity, specificity, PPV and NPV were reported along with data to populate a 2 × 2 table.

Shia and colleagues (2005)11 report a single-centre study performed in the USA with 110 participants. The study objective is not clearly described. Participants were recruited from 1995 to 2003 by a FH questionnaire administered in gastrointestinal endoscopy and oncology clinics, by personal interview of persons undergoing surgery for CRC or by referrals to the clinical genetics service. In order to be included, participants had to have a FH that fulfilled one of the following criteria: (1) AC I or II, (2) a set of relaxed AC (three or more CRCs among first- and second-degree relatives of a family) or (3) Bethesda criteria.

The study started with MSI testing, followed by germline analysis of MLH1 and MSH2 in all cases that exhibited MSI and cases with carcinoma that did not exhibit MSI. Cases that showed no mutation in MLH1 or MSH2 were tested for mutation in MSH6.

Microsatellite instability testing was performed on microdissected DNA from paraffin-embedded tissue blocks using a standard PCR method. All tissue was tested with seven markers: four mononucleotide markers (BAT25, BAT26, BAT40, PAX6); two dinucleotide markers (D2S123, D17S250); and one mixed dinucleotide and trinucleotide marker (MYCLI). IHC was performed using antibodies against MLH1, MSH2 and MSH6. Normal colon mucosa were used as a positive control and MSI tumours known to lack MLH1 or MSH2 protein expression were used as a negative control. Tumours displaying a total absence of nuclear staining while adjacent normal mucosa or stromal/lymphoid cells showed presence of nuclear staining were scored ‘negative’ for expression of protein. Tumours were scored according to staining intensity:

-

weak if < 10% of the tumour was stained and the intensity was weak

-

heterogeneous if two or more of the following staining patterns were identified, each present in at least 20% of the tumour: (1) no nuclear staining, (2) weak nuclear staining, (3) moderate nuclear staining and (4) strong nuclear staining.

Mutation analysis was performed using DHPLC and direct sequencing. Cases with tumours that exhibited MSI but in which a point mutation in MLH1, MSH2 or MSH6 was not detected were analysed for large deletions in MLH1 and MSH2. Mutations were determined to be disease-causing based on sequencing results, segregation analysis and published data and mutation databases. Outcomes include sensitivity and specificity with raw data available.

An investigation into the relationship between MMR protein expression, MSI, FH and germline MMR status was performed by Southey and colleagues (2005). 39 The study took place in a single centre in Australia. One hundred and thirty-one patients with young-onset CRC were randomly recruited, i.e. patients who were younger than 45 years when diagnosed with a histologically confirmed, first primary adenocarcinoma of the colon or rectum. Sensitivity and specificity results for both IHC and MSI were reported.

For IHC, the expression of MLH1, MSH2, MSH6 and PMS2 was assessed on paraffin-embedded sections using antibodies MLH1, MSH2, MSH6 and PMS2. Normal colonic epithelium adjacent to tumour and lymphocytes served as positive controls. A gastrointestinal pathologist scored the tumours as positive when nuclear staining in tumour tissue was present, or negative when staining was absent.

Microsatellite instability testing was performed on invasive tumour cells microdissected from 5-µm sections of paraffin-embedded archival tumour tissue. DNA extracted from histologically normal cells microdissected from colonic or lymph node tissue, or DNA extracted from peripheral-blood lymphocytes, was used as a negative control. Ten microsatellite markers were assessed: three dinucleotide repeats (D5S346, D17S250 and D2S123) and seven mononucleotide repeats (BAT25, BAT26, BAT40, MYB, TGFβRII, IGFIIR and BAX). The degree of instability in each tumour was scored as MSS, MSI-L and MSI-H when zero to one, two to five and six to 10 markers, respectively, were identified as unstable.

For the reference standard, MLH1, MSH2, MSH6 and PMS2 genes were screened for germline mutations using sequencing approaches, except for exon 4 of MSH6, which was screened in eight overlapping fragments using DHPLC. Putative mutations were confirmed via direct automated sequencing. Variants were defined as deleterious if they could be predicted to produce a shortened or truncated protein product, or if they were missense mutations that have been reported previously to be deleterious. The MLPA assay to detect large genomic alterations in MLH1 and MSH2 was performed on samples from 10 patients who had tumours lacking at least one MMR protein expression and for which no previous mutation had been identified by sequencing. Mutation testing was conducted on participants with one or more of the following characteristics: a FH that fulfilled the AC for HNPCC; a tumour that was MSI-H, MSI-L or that lacked expression of at least one MMR protein; and a random sample of 23 patients selected from those who had tumours that were MSS.

Stomorken and colleagues (2005)45 report on a single-centre study based in Norway. Two hundred and fifty families were consecutively recruited according to their FH of CRC and other cancers. Inclusion criteria consisted of AC I or II, aggregation of four or more LS-related cancers on one side of the family, patients with ‘very early onset’ CRC and those with multiple primaries including colorectal or endometrial cancers. It should be noted that the participants with CRC provided a subsample of 105 families. The aim of the study was to validate the sensitivity, specificity and predictive value of IHC, compared with various clinical criteria, to select LS relatives for mutation testing.

Immunohistochemistry of all tumours for the presence of MLH1, MSH2 and MSH6 MMR proteins was performed using a formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissue block containing tumour tissue and normal adjacent mucosa. Staining of tumours was evaluated using normal epithelial cells, stromal cells or lymphocytes in the same slide as controls. The percentage of nuclear staining was graded as follows: complete absence of detectable nuclear staining (0); positive staining in < 30% of the tumour cells (1+); positive staining in 30–60% of the tumour cells (2+); or positive staining in > 60% of the tumour cells (3+).

MLH1 and MLH2 genes were sequenced by Myriad Genetics Inc. (Salt Lake City, UT). All index persons without a mutation demonstrated by sequencing and with a lack of MMR protein expression were subjected to analyses for large rearrangements in the MLH1 and MSH2 genes. The remaining individuals who were lacking gene products of MSH2 and/or MSH6 genes were subjected to mutation analysis of the MSH6 gene by sequencing. Large rearrangements in MSH6 were not tested for. Data were available to populate a 2 × 2 table, although sensitivity and specificity were not reported.

Wolf and colleagues (2006)46 report an Austrian study where participants were selected retrospectively from among individuals with suspected hereditary CRC from 2000 to 2003. The sample size was 81, with all tumours obtained by surgical resection. The aim of the study was to evaluate the revised AC and Bethesda guidelines (therefore the index test under scrutiny was MSI).

Nuclear DNA was isolated from paraffin-embedded tissue after histological verification by an experienced pathologist, prior to PCR amplification. DNA was also taken from blood samples.

For MSI, two groups of five markers each were selected: group 1 consisted of D5S346, HSCAP53L, D2S123, BAT26 and D18S34, while group 2 consisted of D5S82, D2S134, D13S175, D11S904 and BAT25. In the event of instability, additional smaller fragments were identified in the tumour sample compared with the corresponding normal tissue. If only one of the markers in the first group showed instability, five further markers (group 2) were used. The degree of instability was evaluated according to the percentage of markers showing band shifts. MSI-H was considered to exist when at least 30% of the analysed markers were unstable; any lower degree of instability, or no instability, was interpreted as MSS.

The exons of MLH1 and MSH2 as well as the promoter regions of each gene underwent sequence analysis. If DNA from tumour tissue was available, analysis of DNA from corresponding normal tissue or peripheral blood was performed on fragments containing a mutation. If no mutation was found in the tumour, sequence analysis was performed with DNA from normal tissue or peripheral blood.

Appropriate outcomes for this review were sensitivity and specificity, with raw data provided.

Population characteristics

In general, patient characteristics were poorly reported, as were inclusion and exclusion criteria, although patients were often filtered by prior testing. Comparable characteristics are presented in Table 10.

| Characteristic | Becouarn 200543 | Limburg 201144 | Niessen 200621 | Shia 200511 | Stomorken 200545 | Wolf 200646 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of patients | 197 | 195 | 281 | 110 | 105a (50)b | 81 |

| Description | Patient age at onset of cancer < 50 years or FH of HNPCC tumours | Population-based sample of patients with young-onset (age < 50 years) CRC | Individuals with CRC who were high risk for LS according to young onset or personal cancer history were recruited | Participants recruited from 1995 to 2003 by a FH questionnaire, by personal interview prior to surgery for CRC, or by referrals to the clinical genetics service | Families recruited according to FH of CRC and other cancers. Inclusion criteria consisted of AC I or II, four or more LS-related cancers on one side of the family, early-onset CRC, multiple primaries including CRC or EC | Participants selected retrospectively from individuals with suspected hereditary CRC |

| Age, years | ||||||

| 0–30, n | 13 | |||||

| 31–40, n | 40 | |||||

| 41–50, n | 111 | |||||

| ≥ 51, n | 33 | |||||

| < 50, n | 224 | |||||

| Mean age, years (SD) | 42.9 (6.1) | 45 (11)c | 50.5d | |||

| Sex | ||||||

| Male, n (%) | 115 (58) | 128 (46) | 48 (44) | 39 (48) | ||

| Female, n (%) | 82 (42) | 104 (53.3) | 153 (54) | 62 (56) | 42 (52) | |

| Cancer location | ||||||

| Rectum, n | 41 | |||||

| Left colon, n (%) | 75 | 130 (74.7) | ||||

| Right colon, n (%) | 68 | 44 (25.3) | ||||

| Transverse colon, n | 13 | |||||

| Number meeting AC II (%) | 10 (5.1) | 50 | 38 | 43.2 | ||

| Number meeting Bethesda criteria | 12 | 43 | 72 | |||

| Number HNPCC-like | 40 | |||||

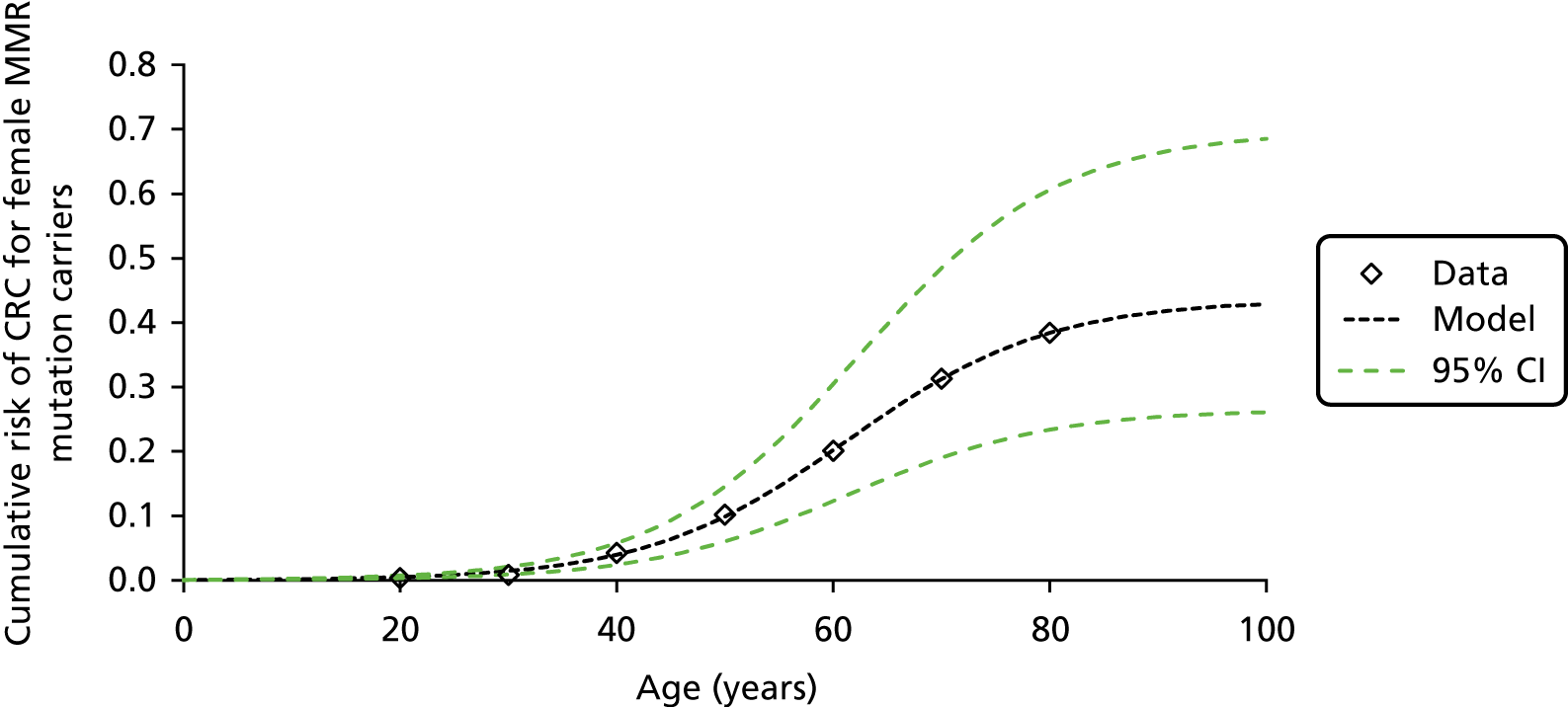

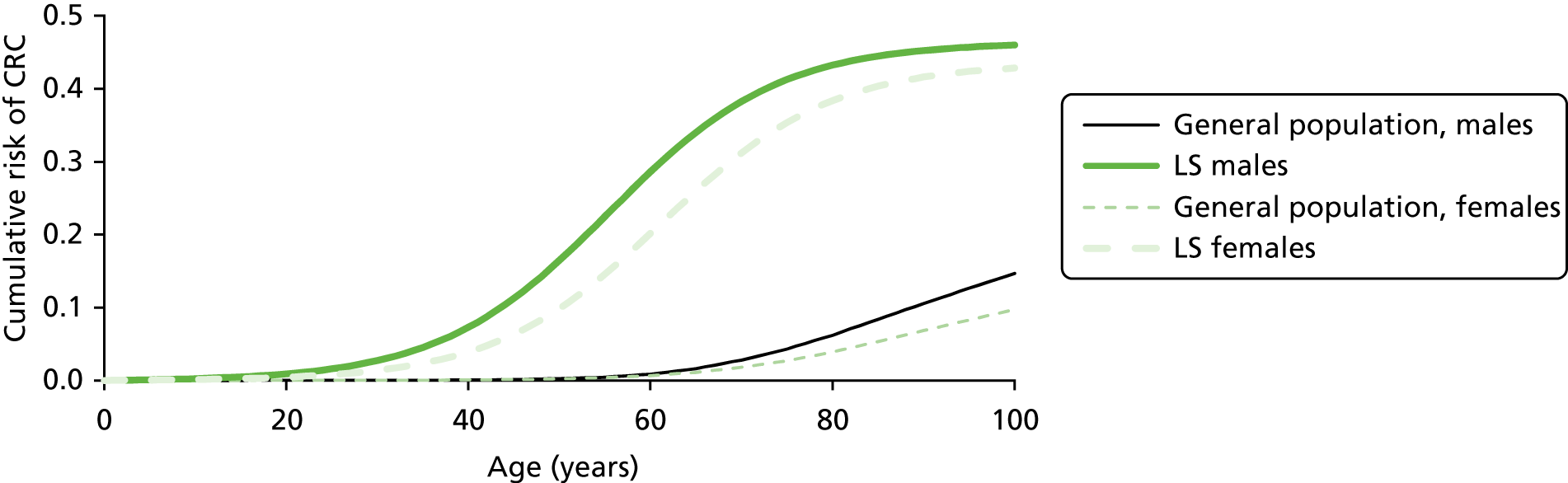

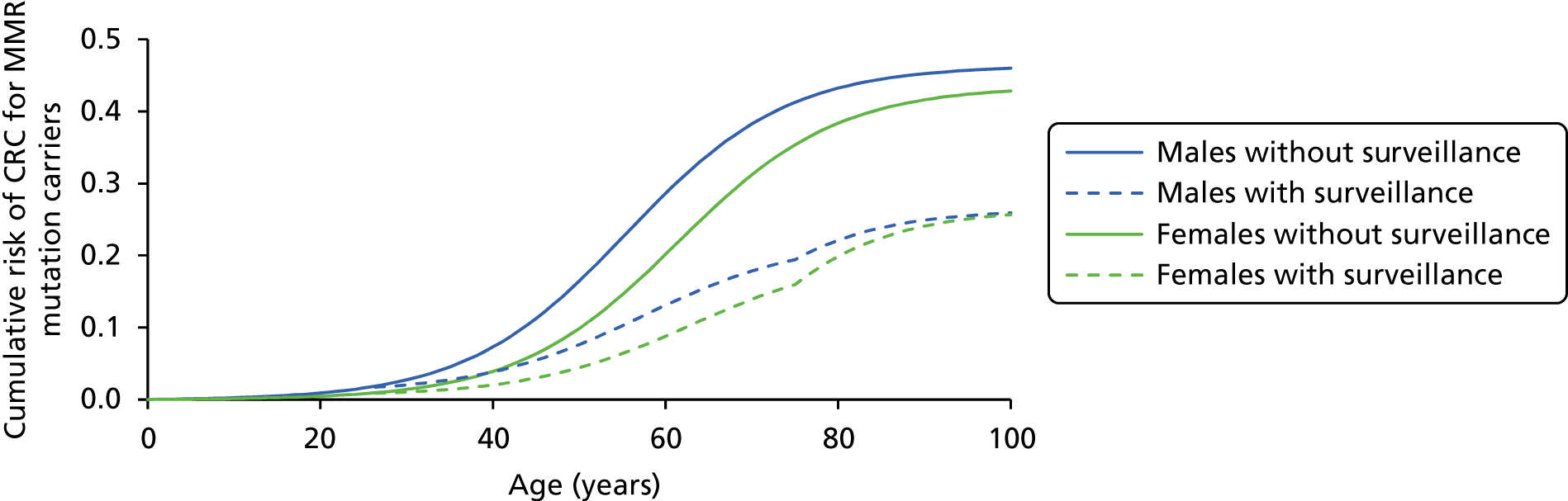

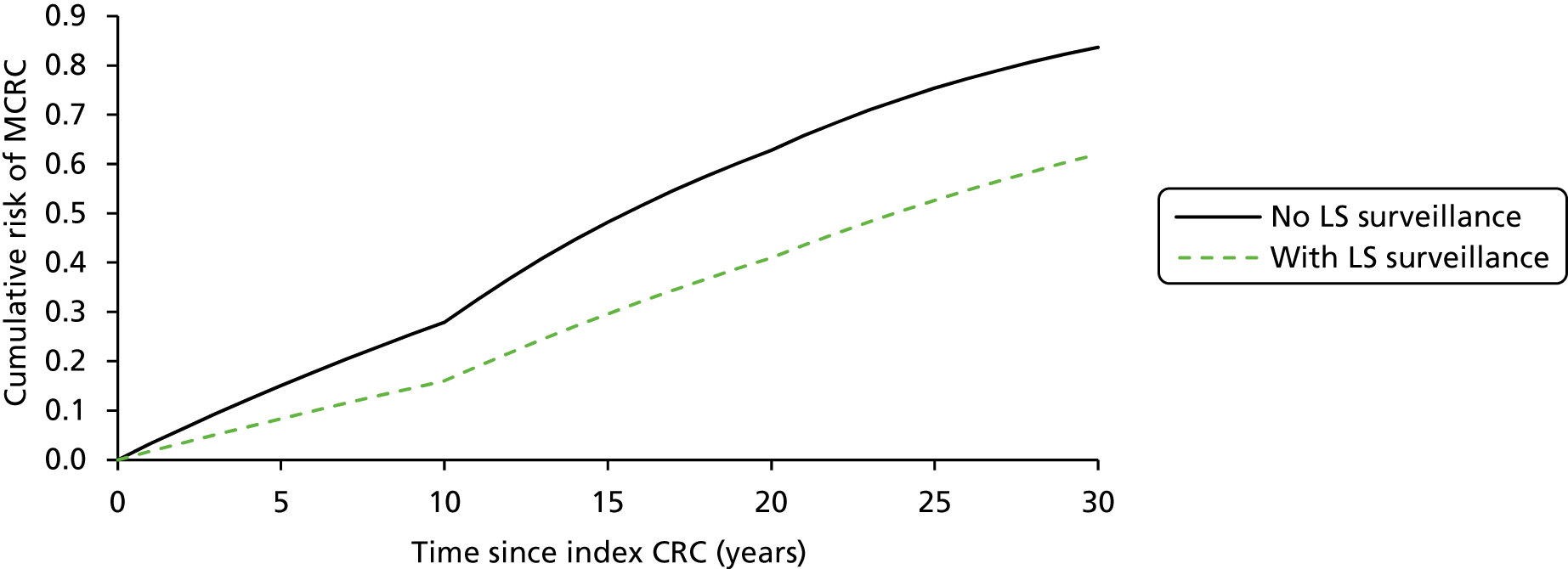

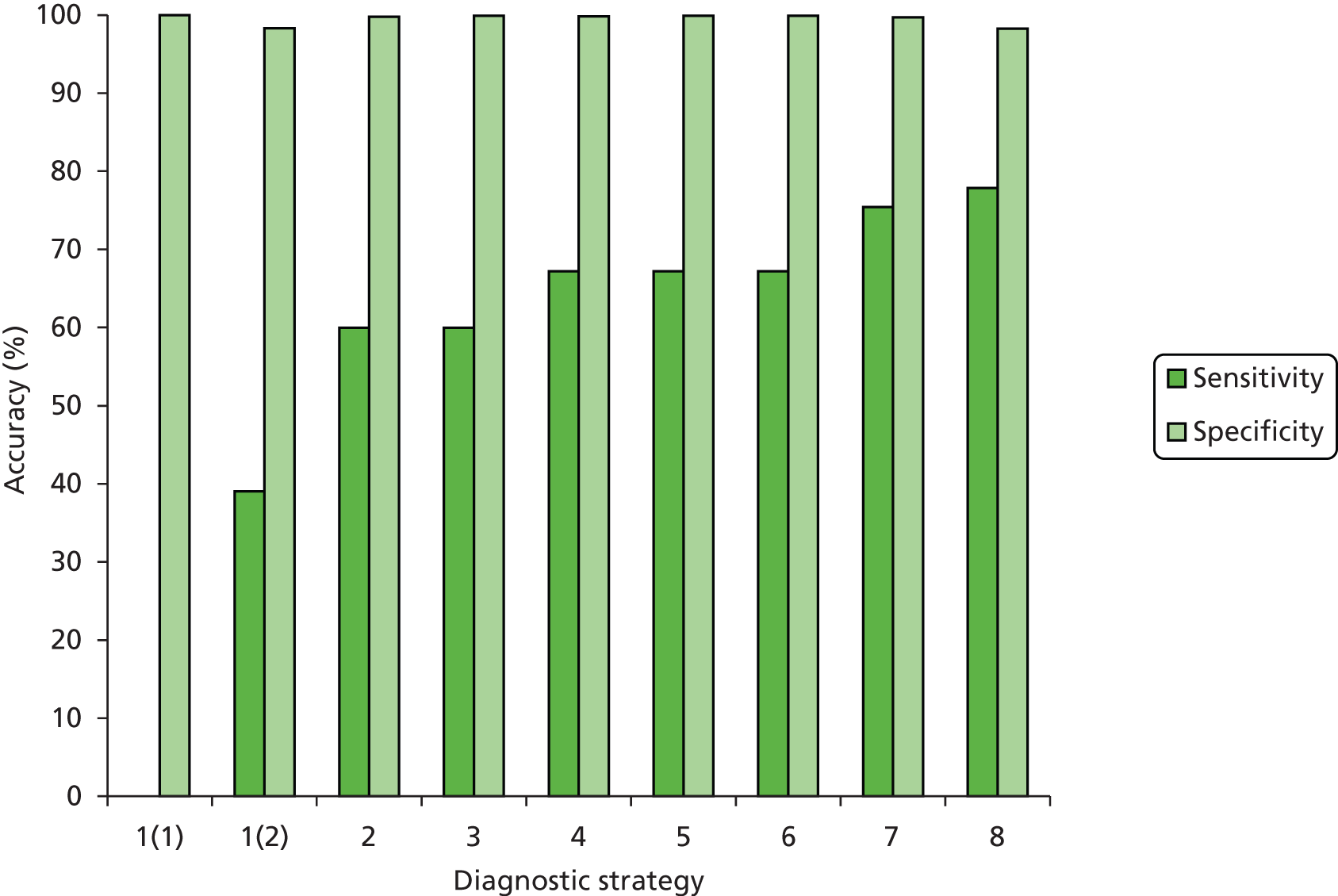

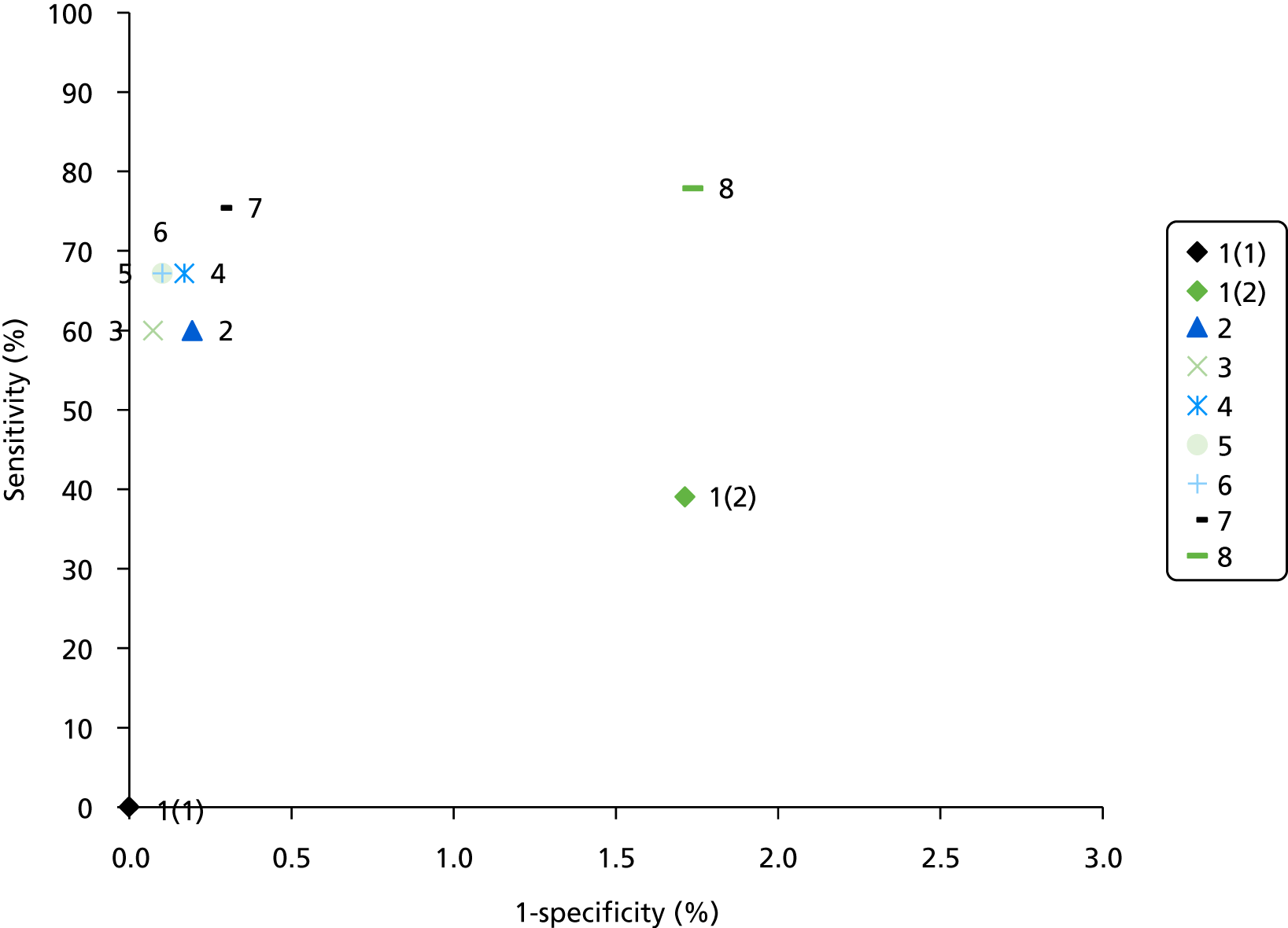

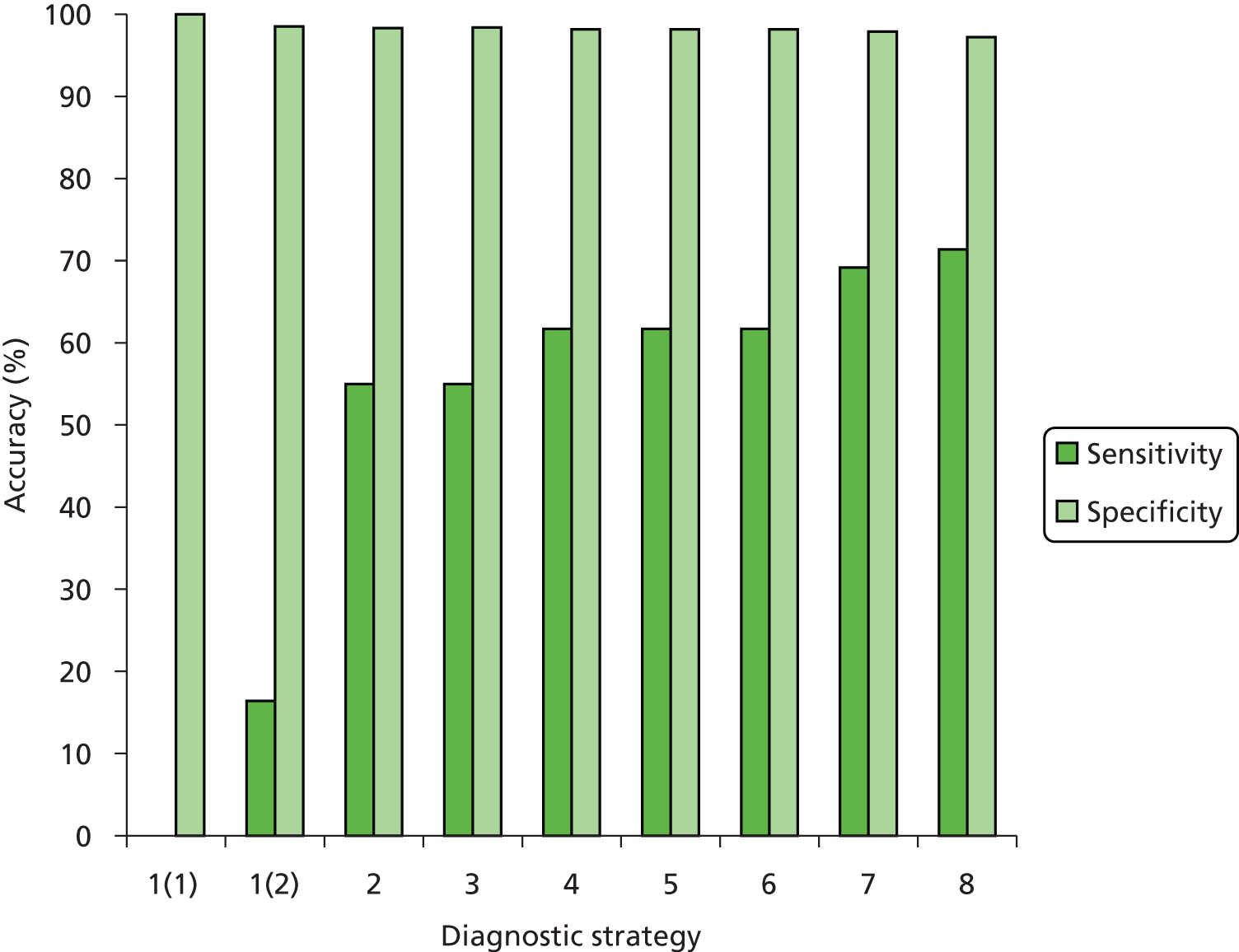

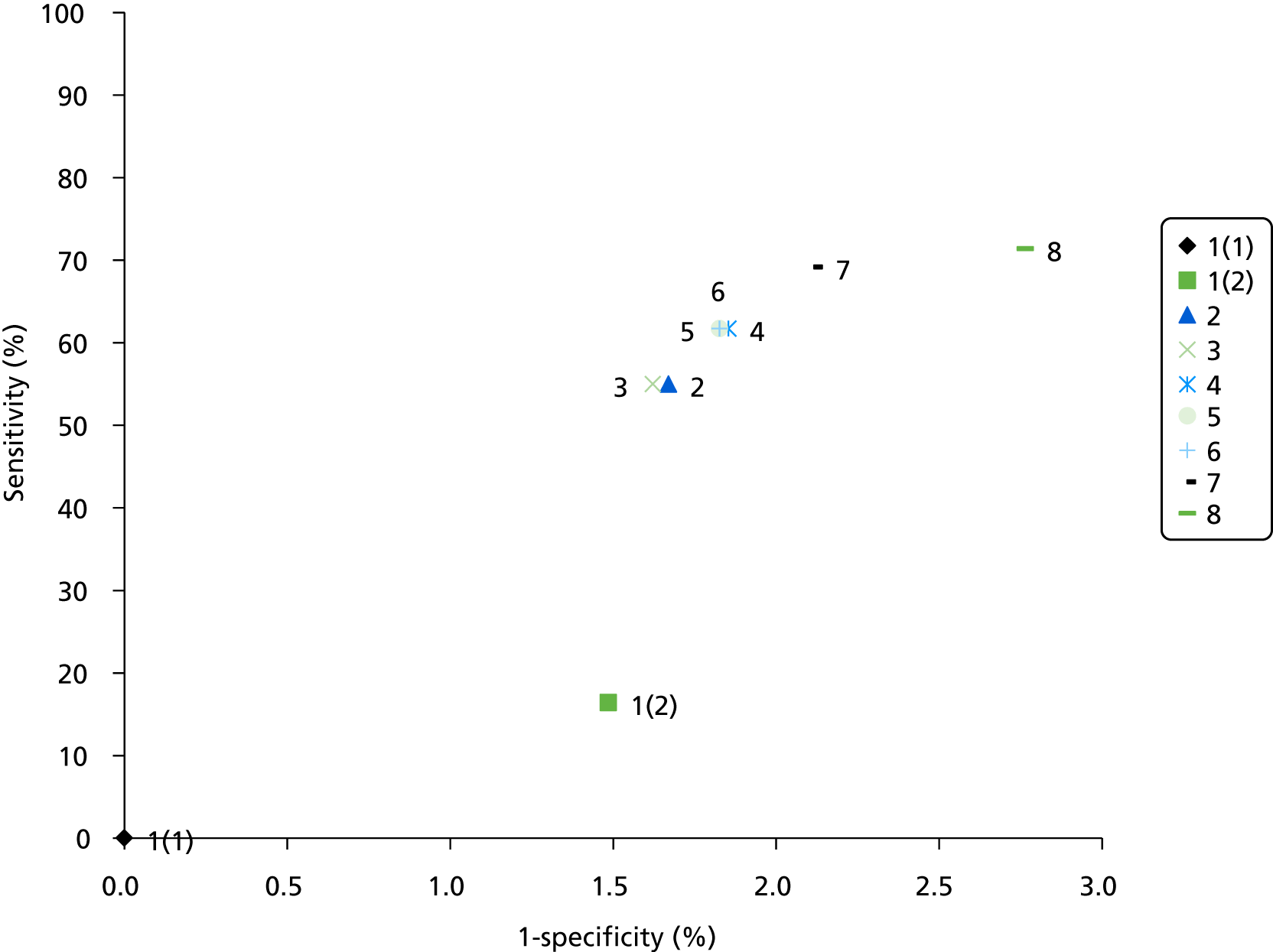

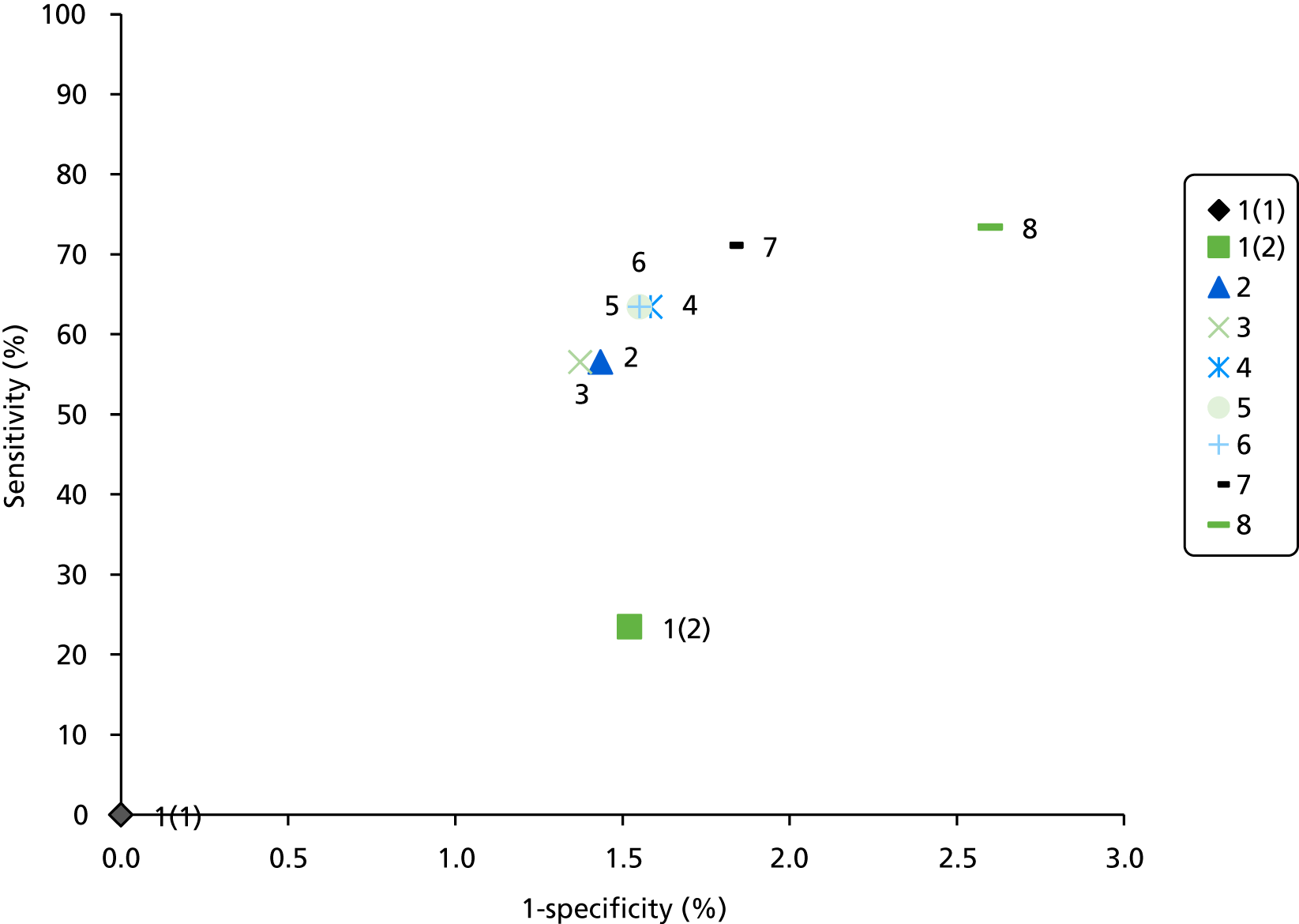

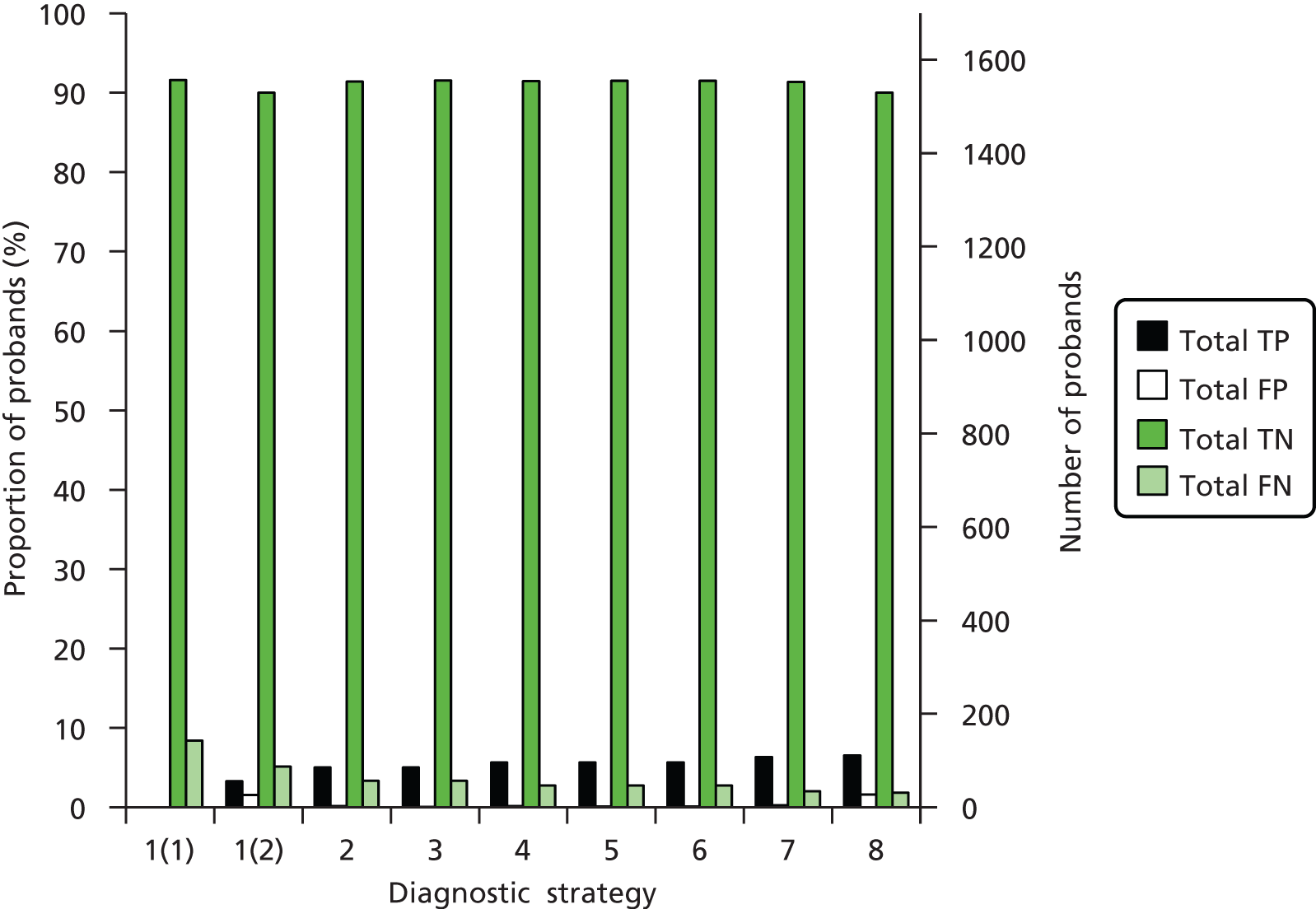

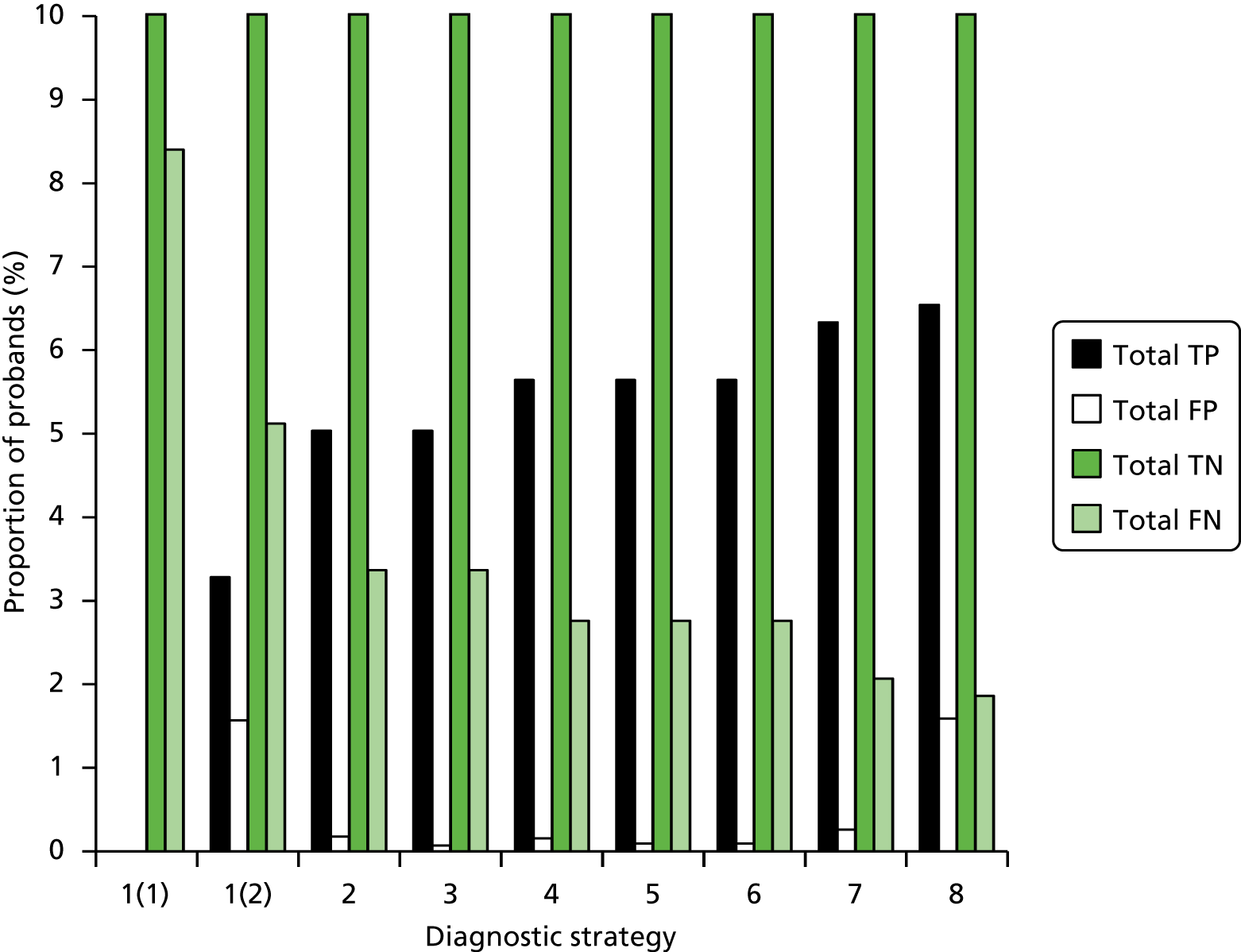

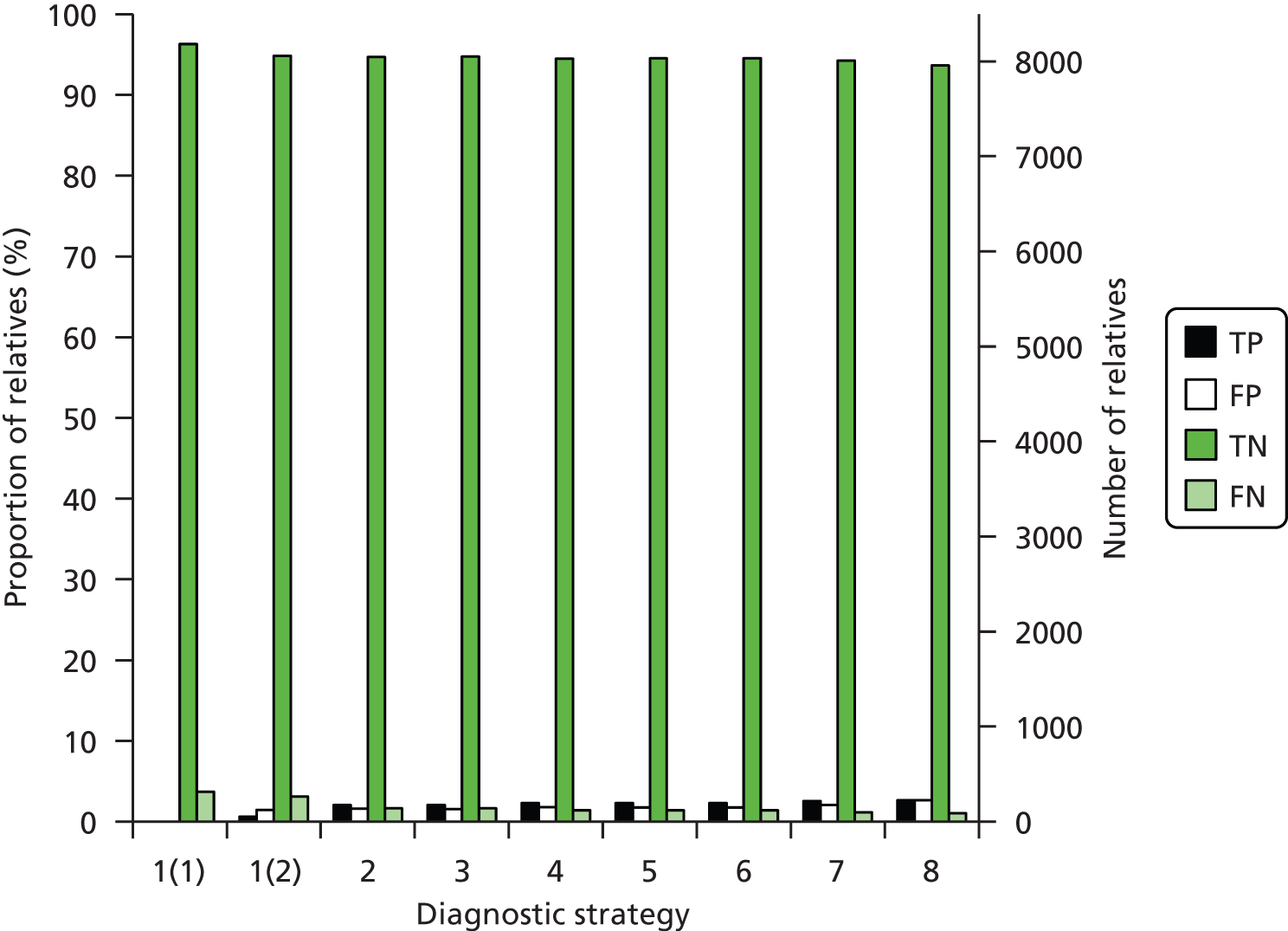

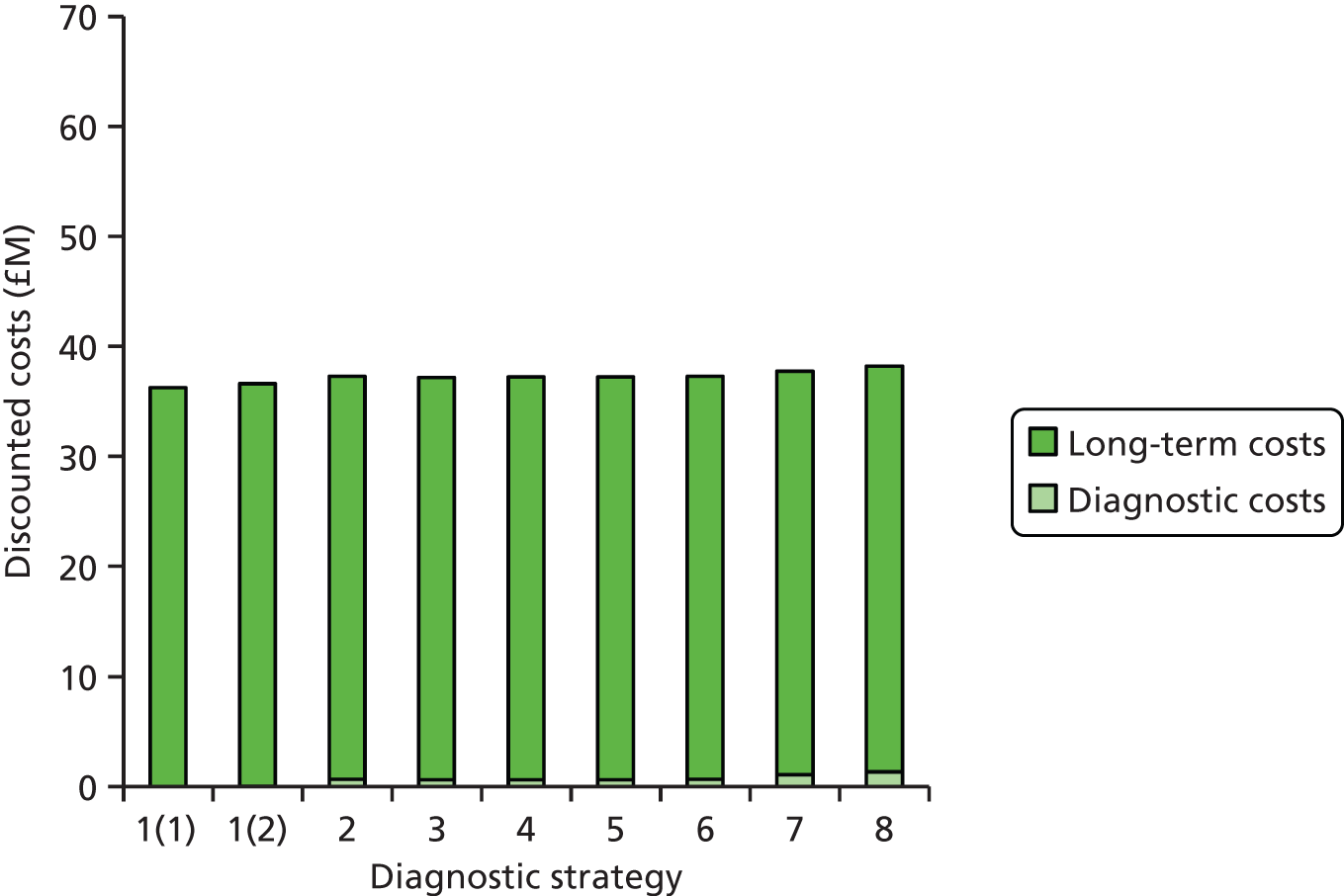

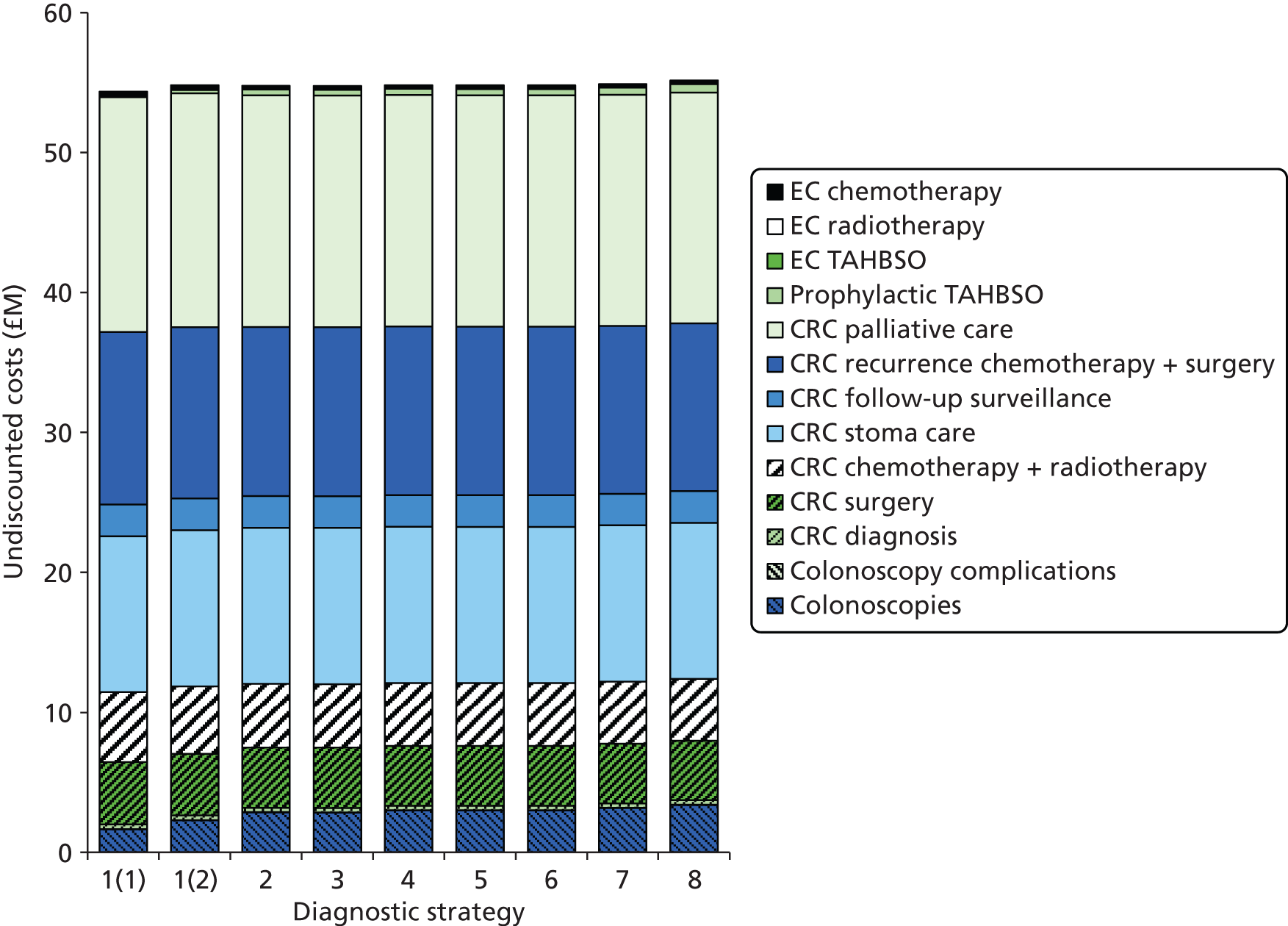

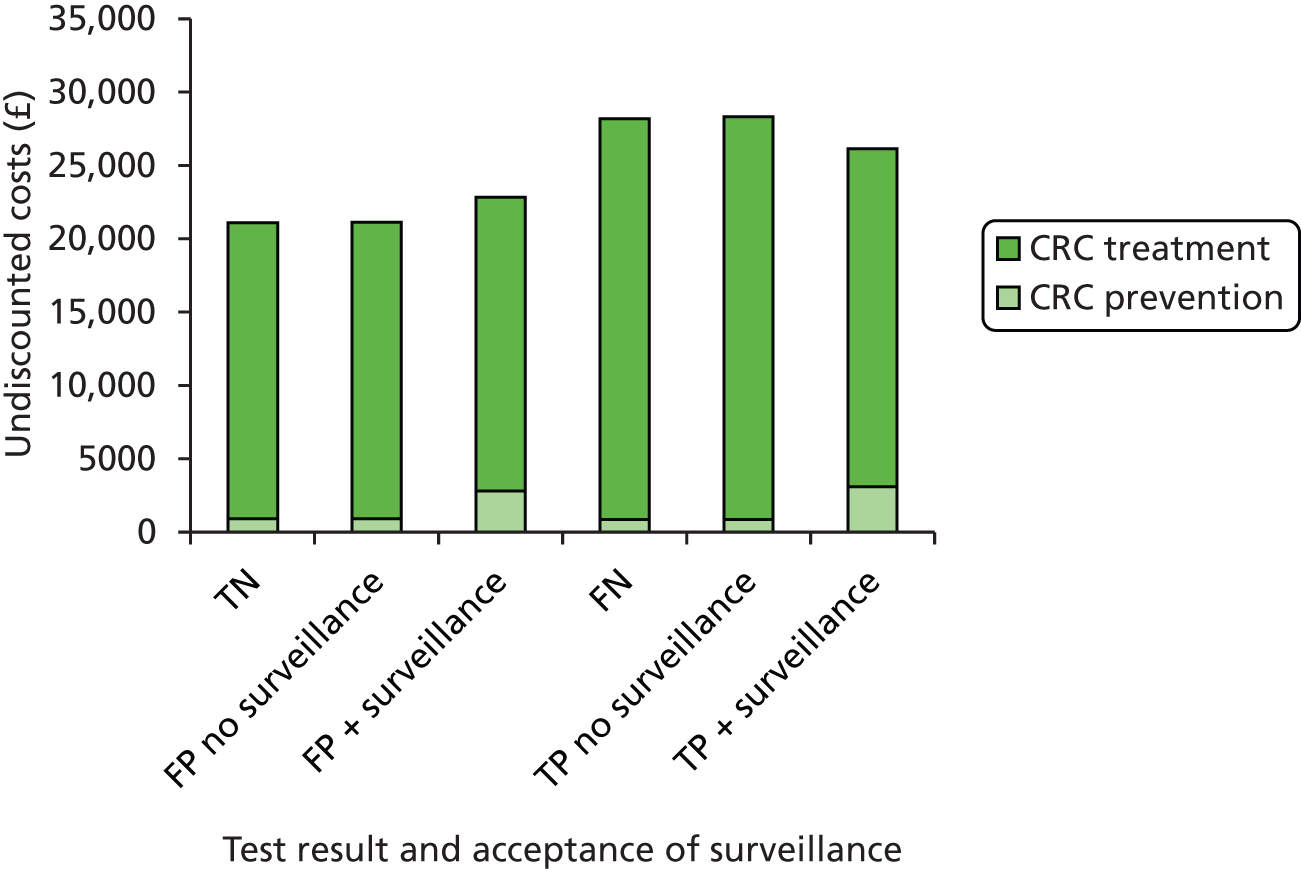

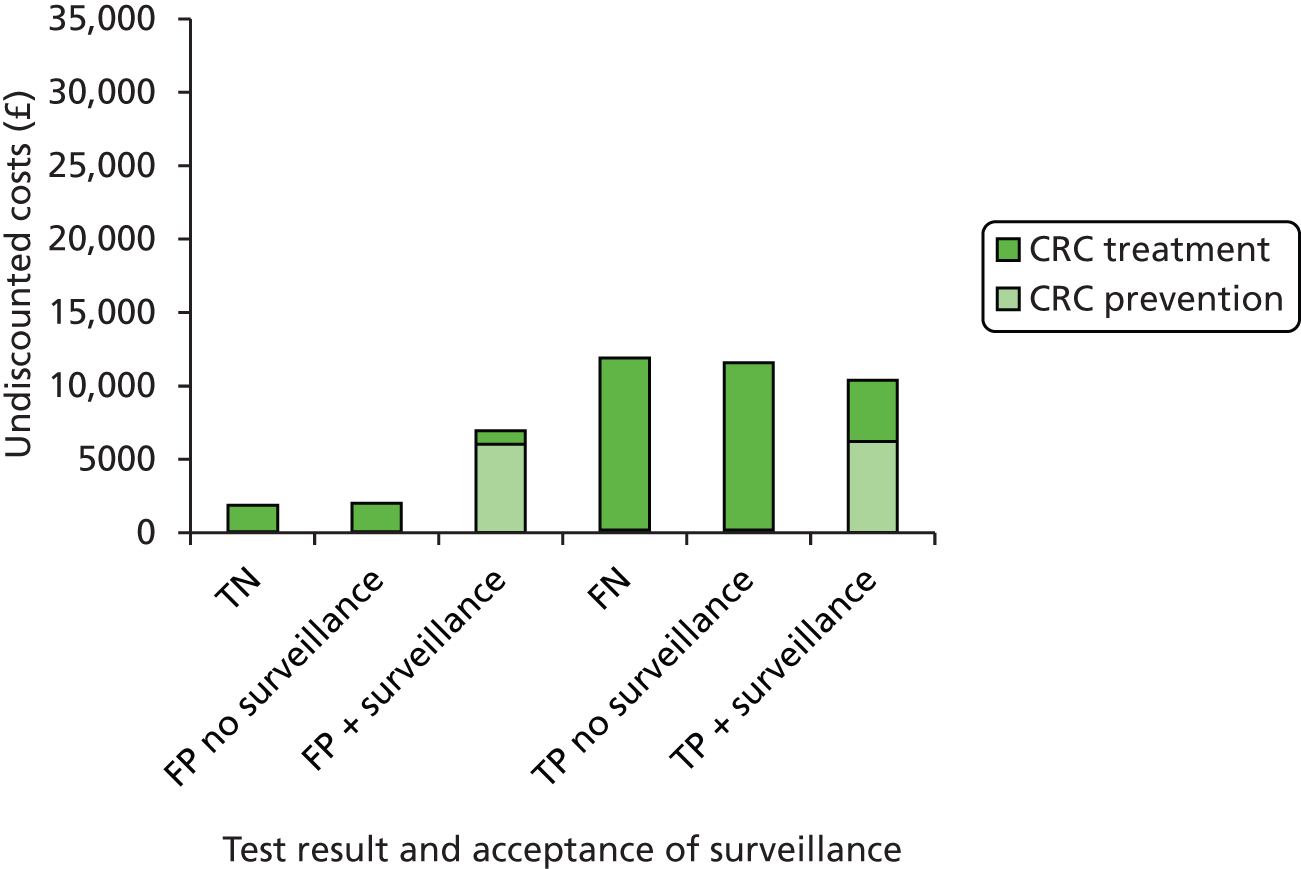

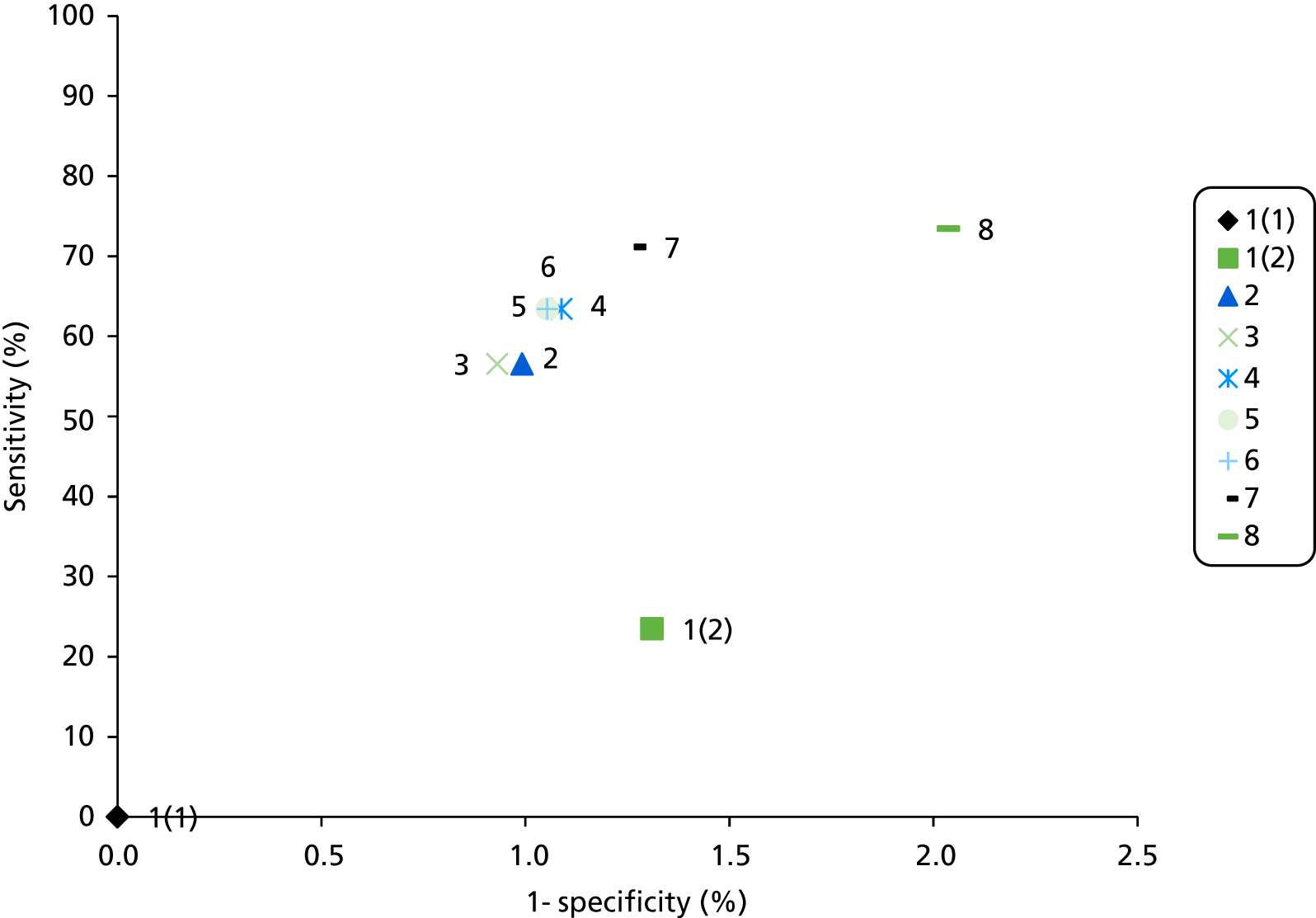

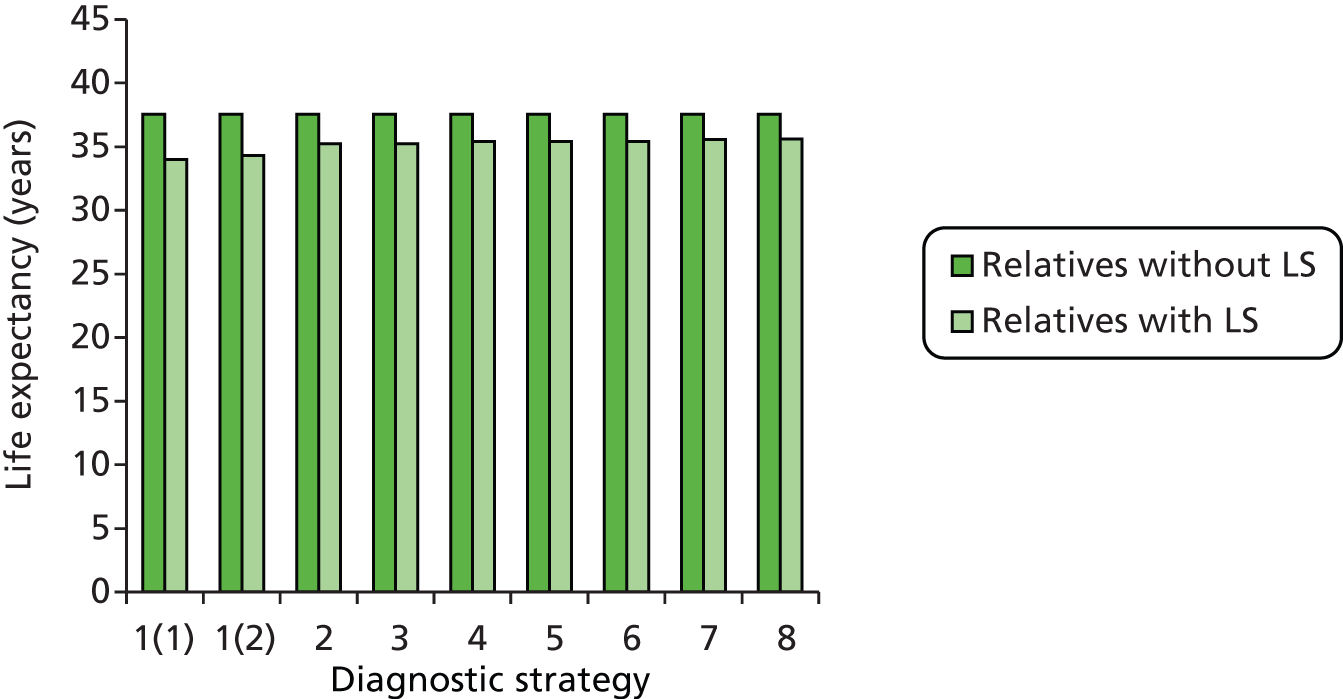

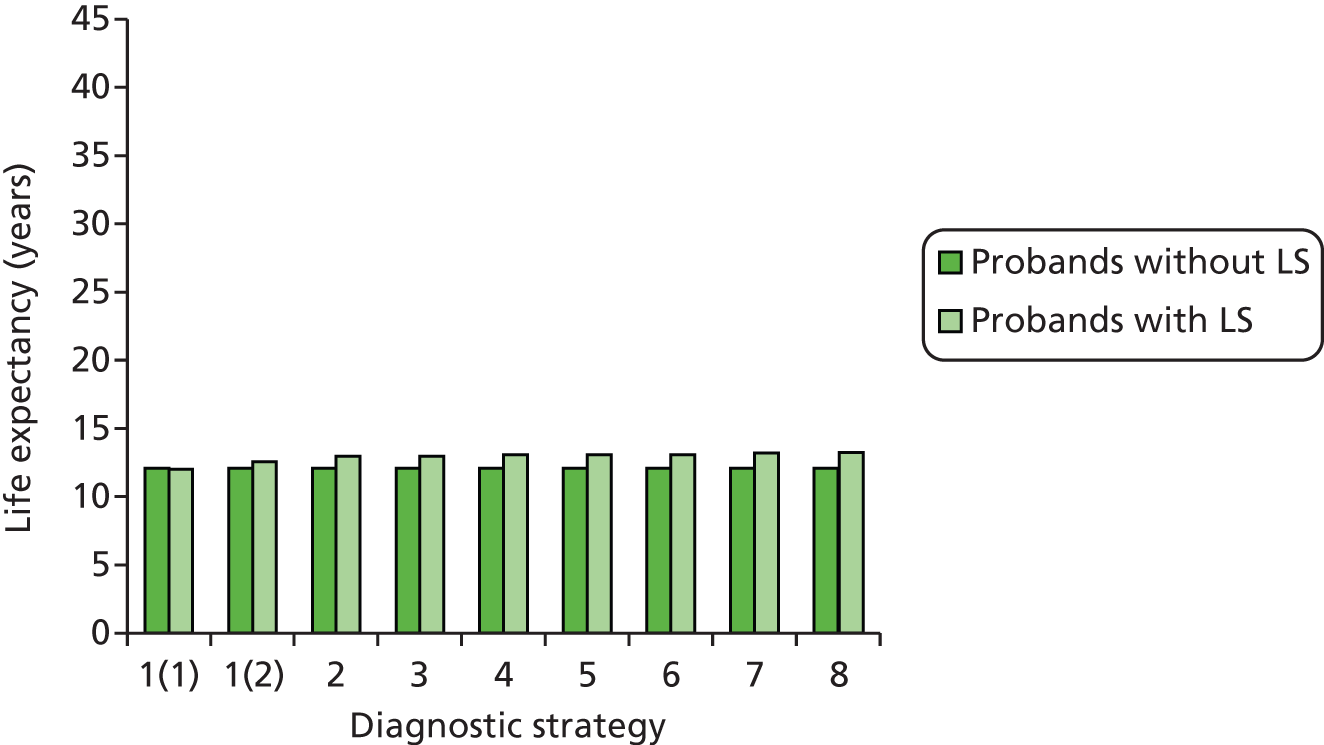

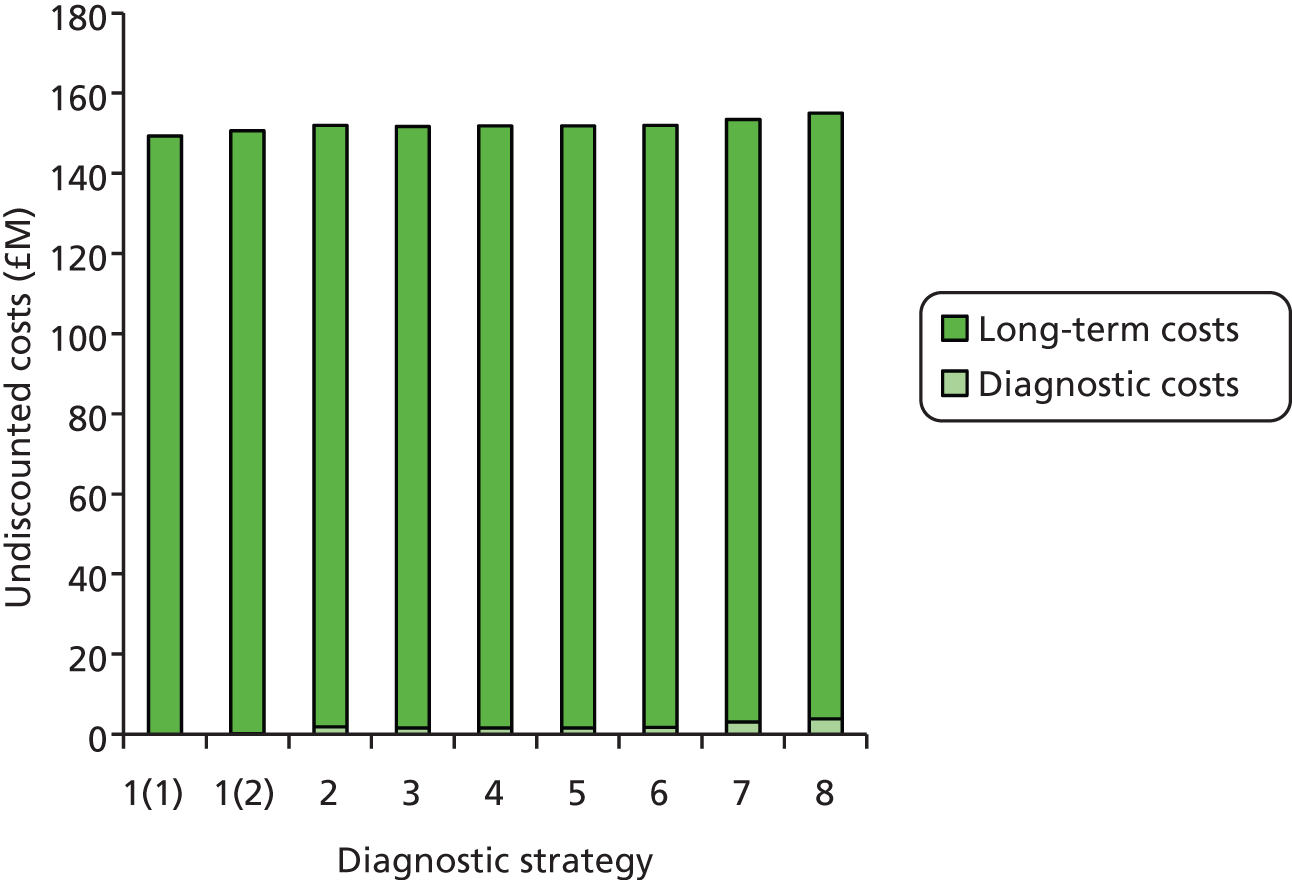

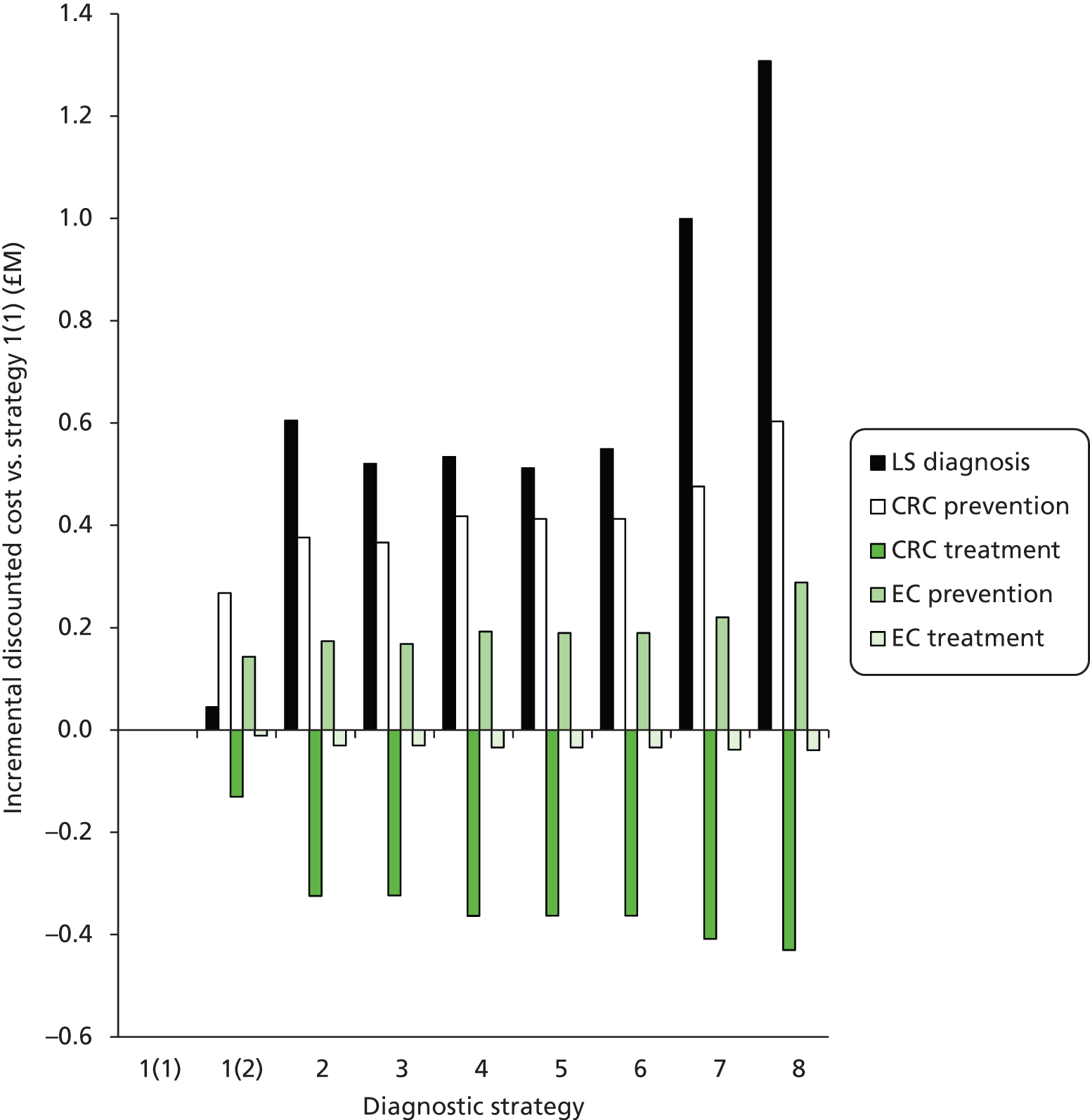

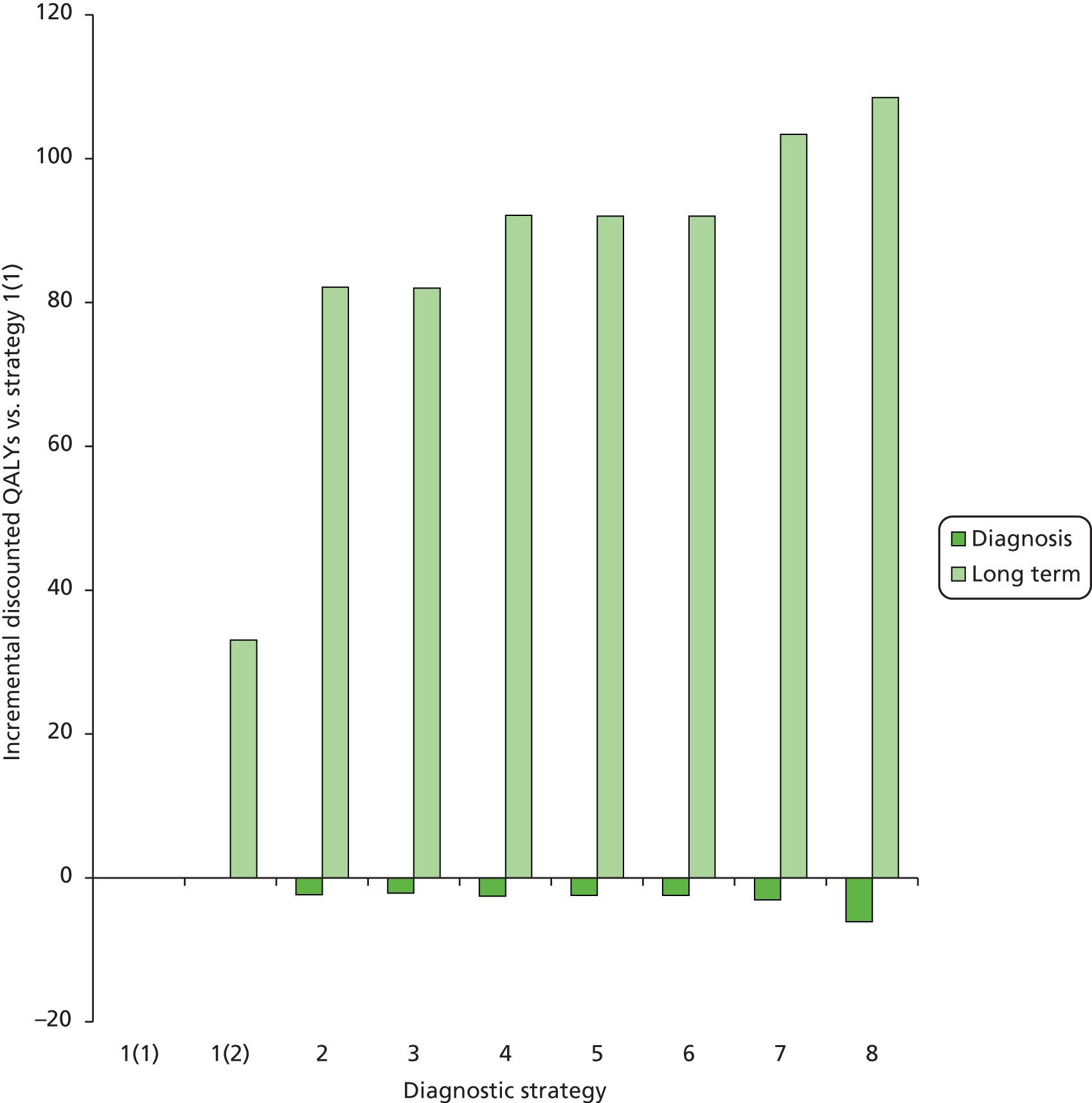

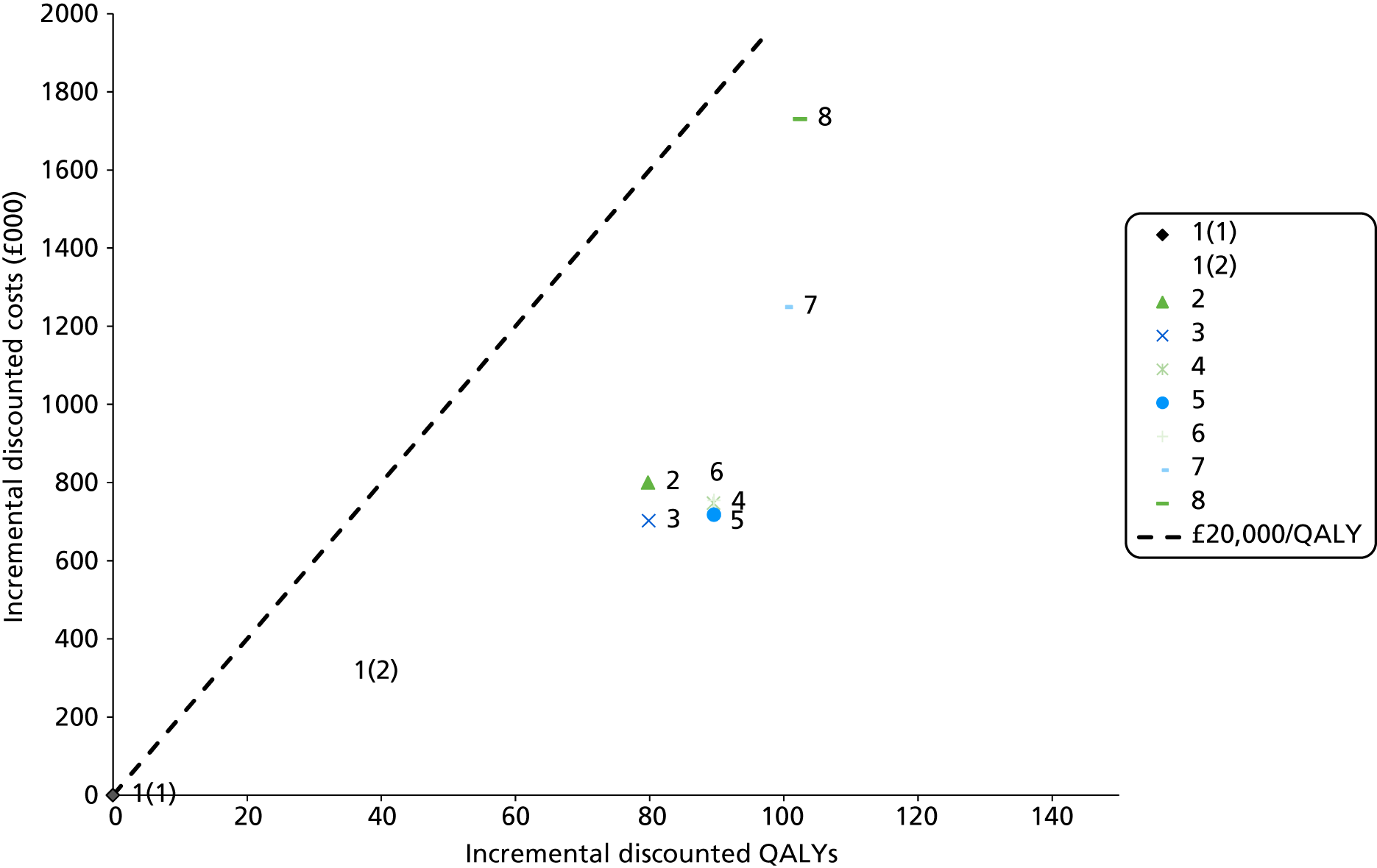

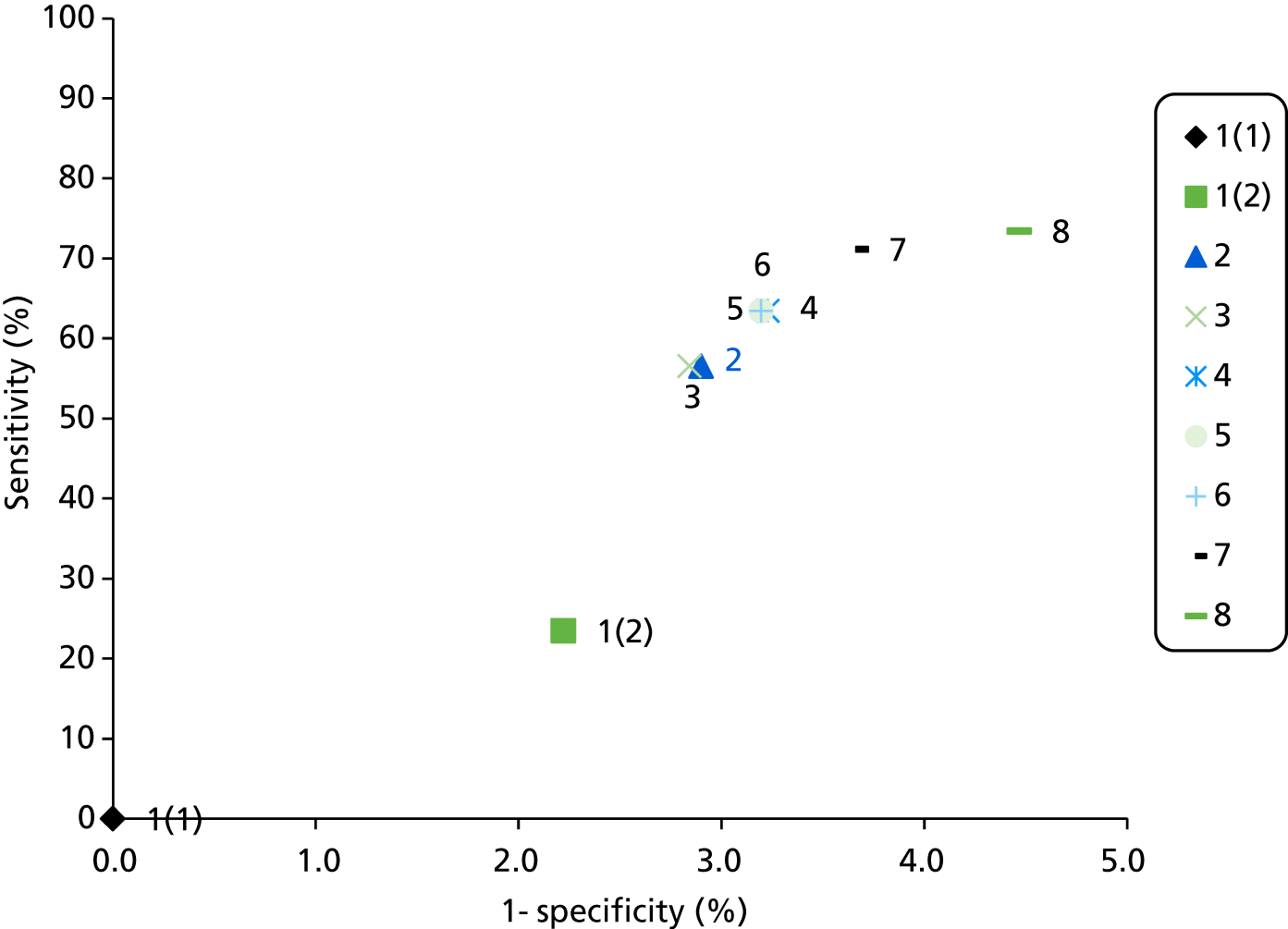

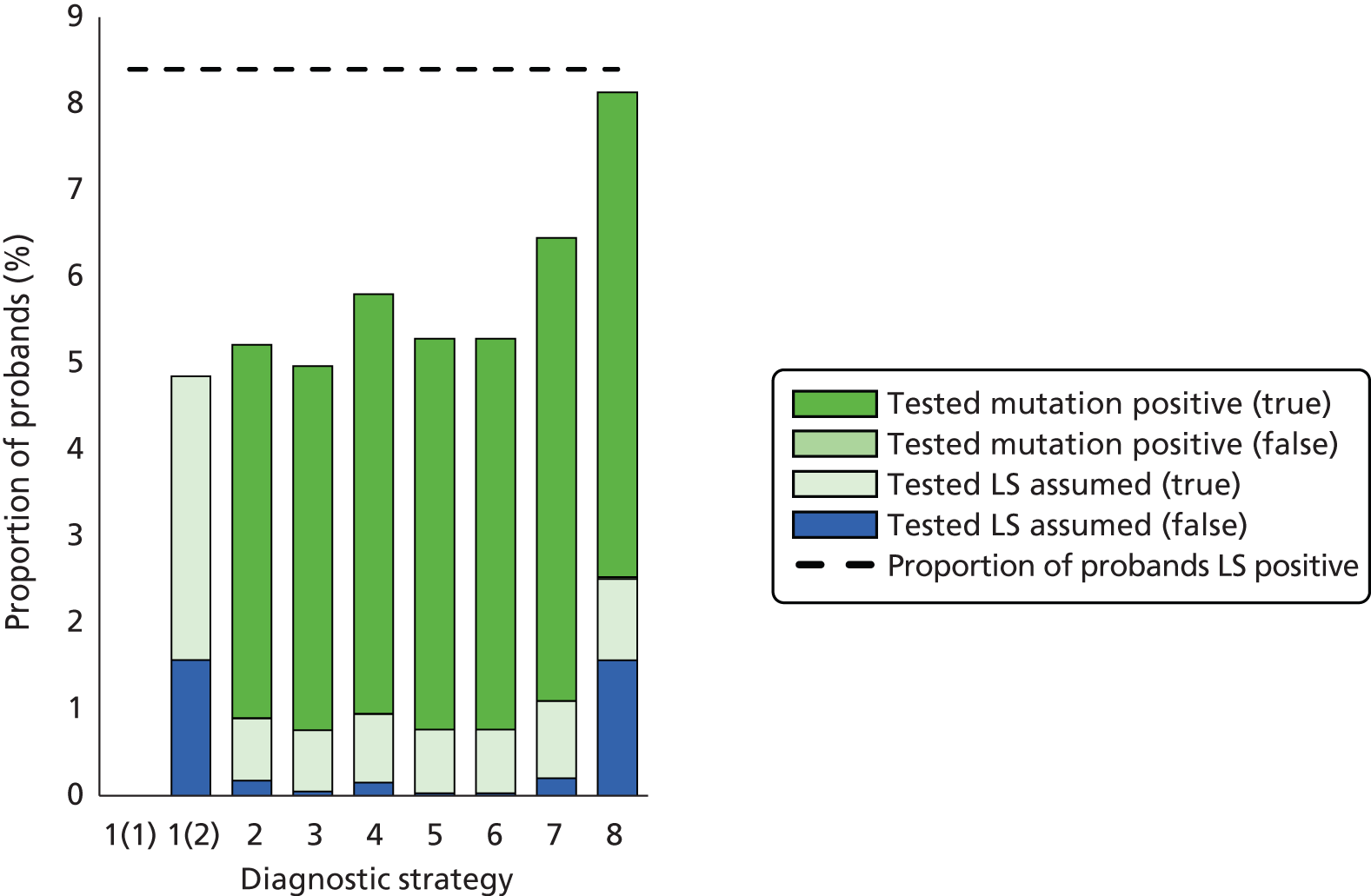

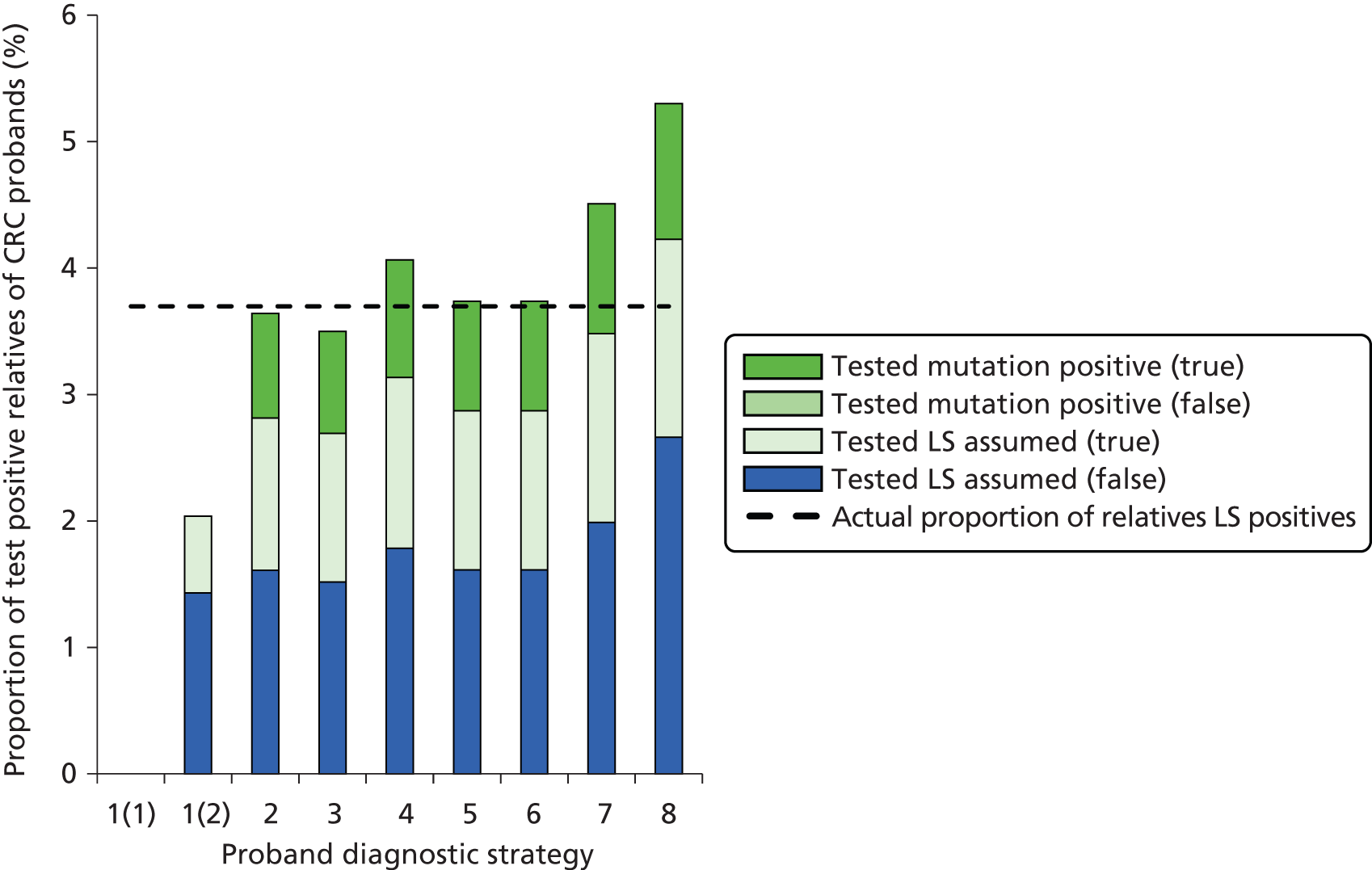

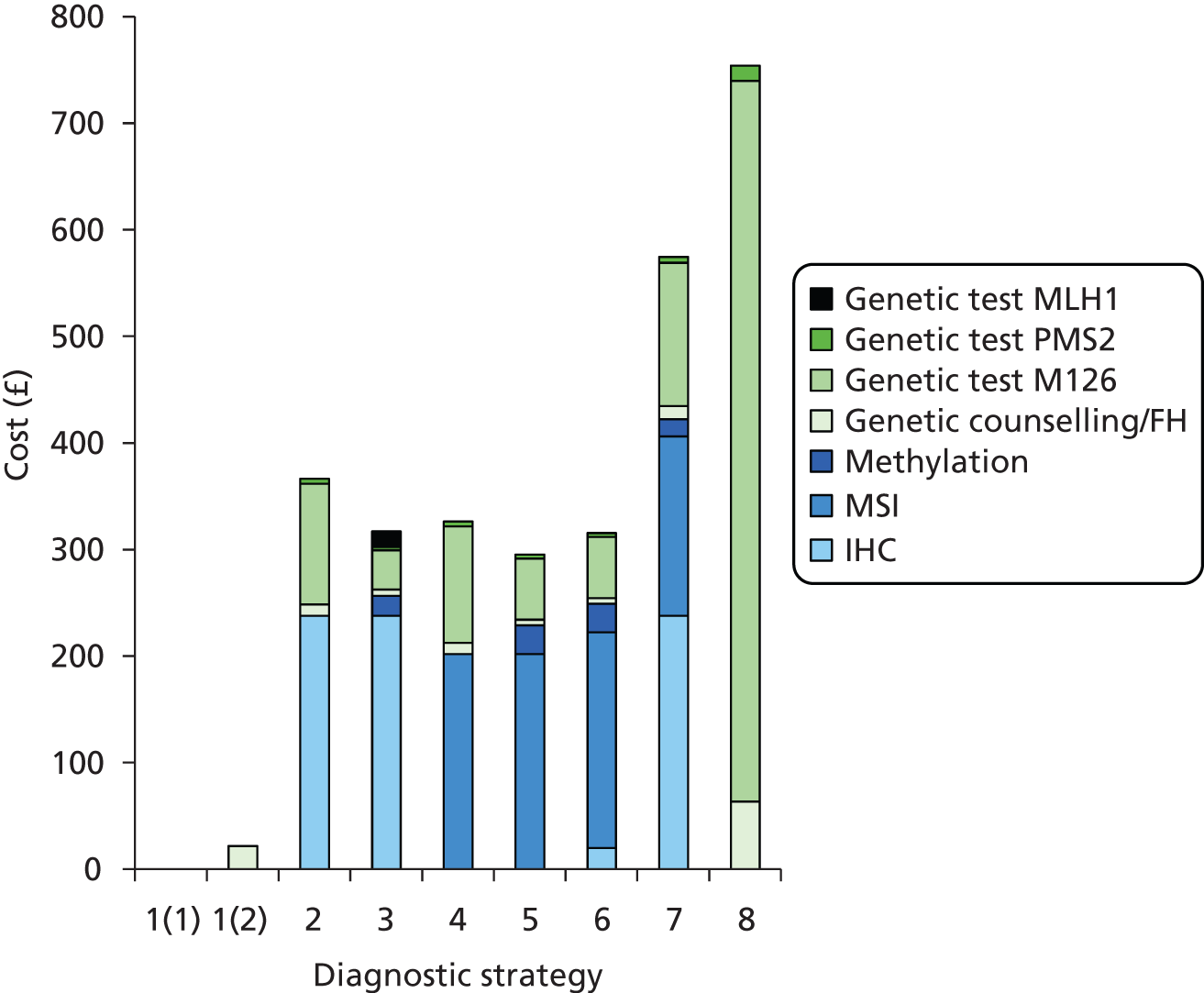

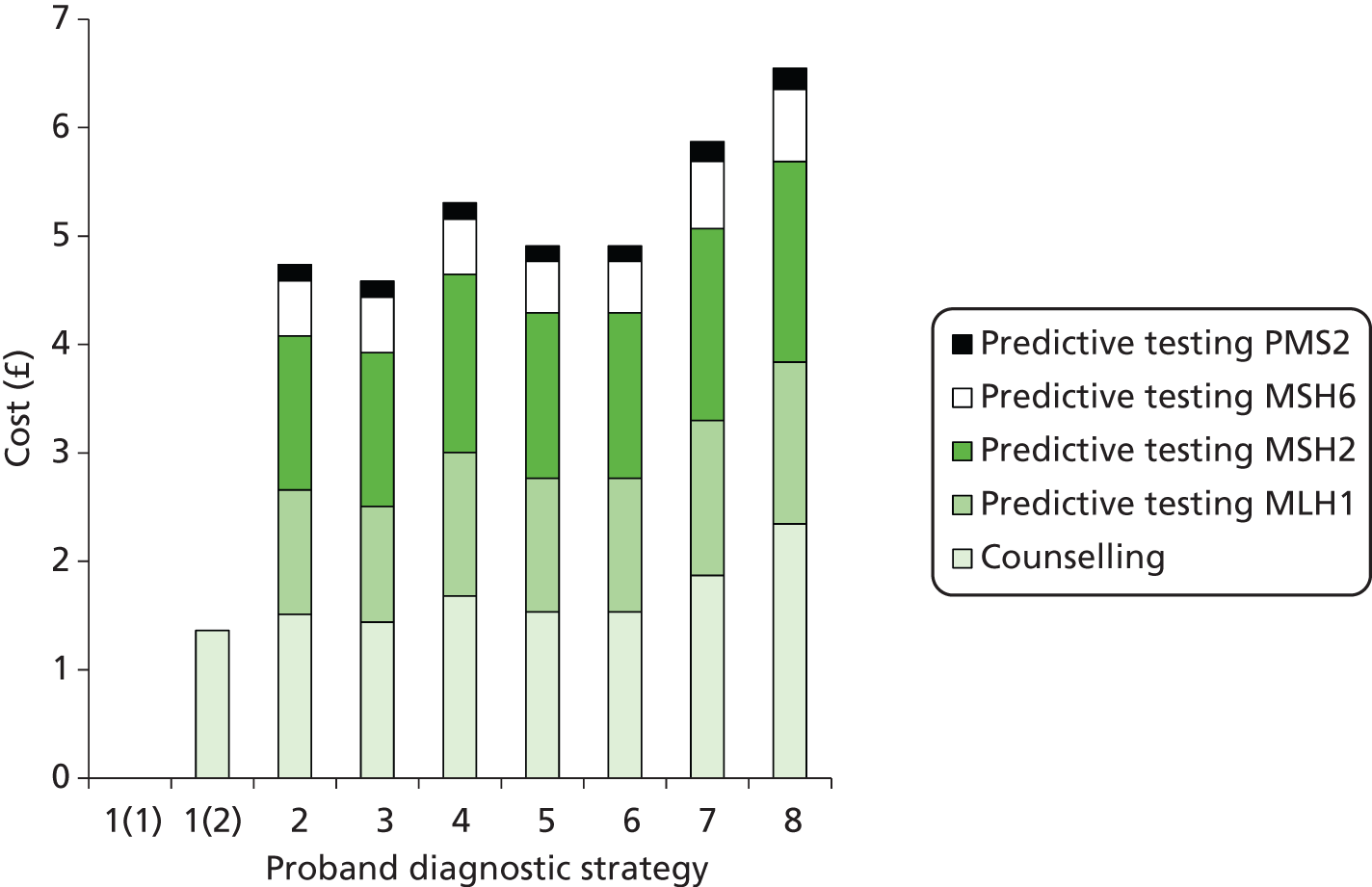

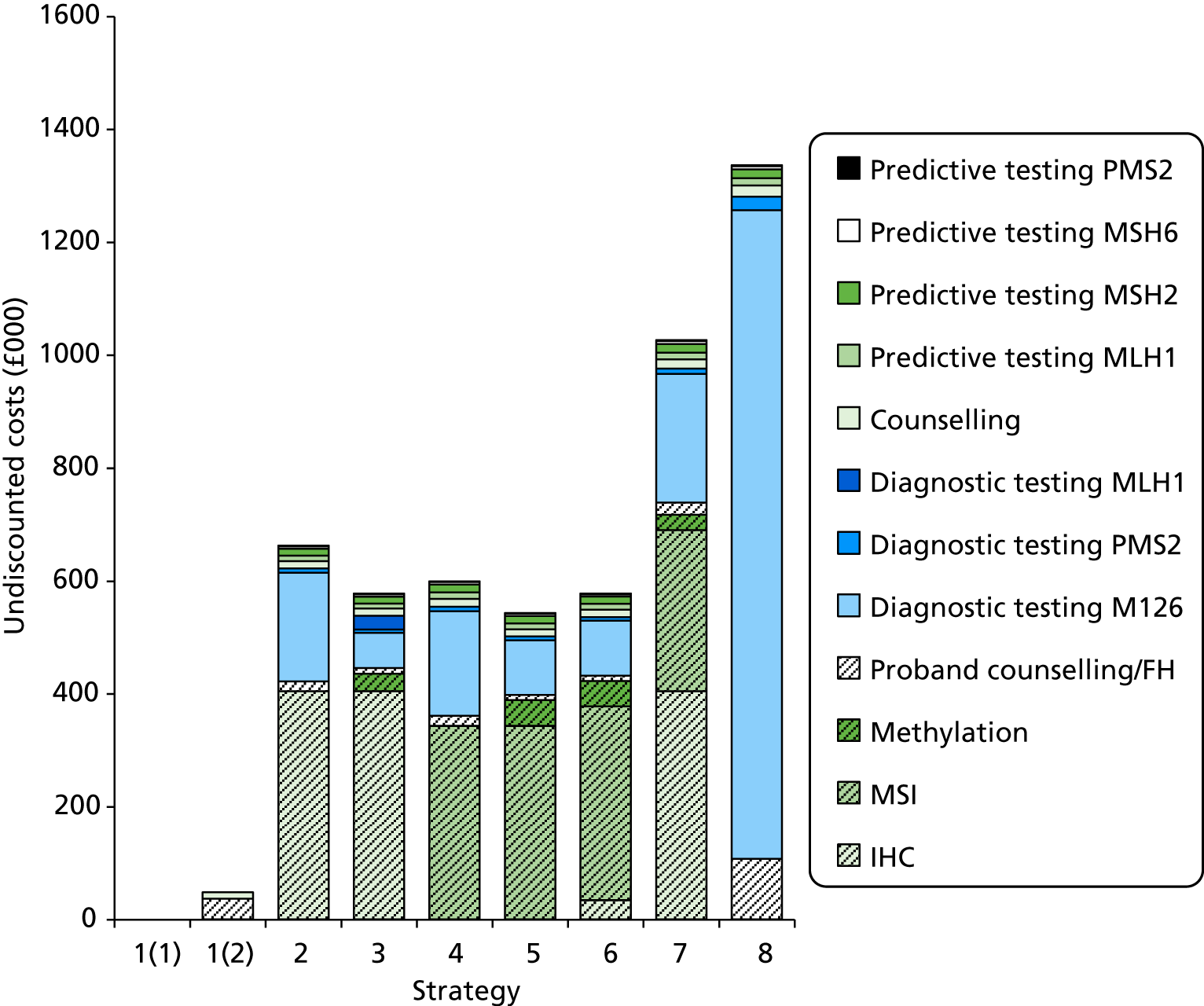

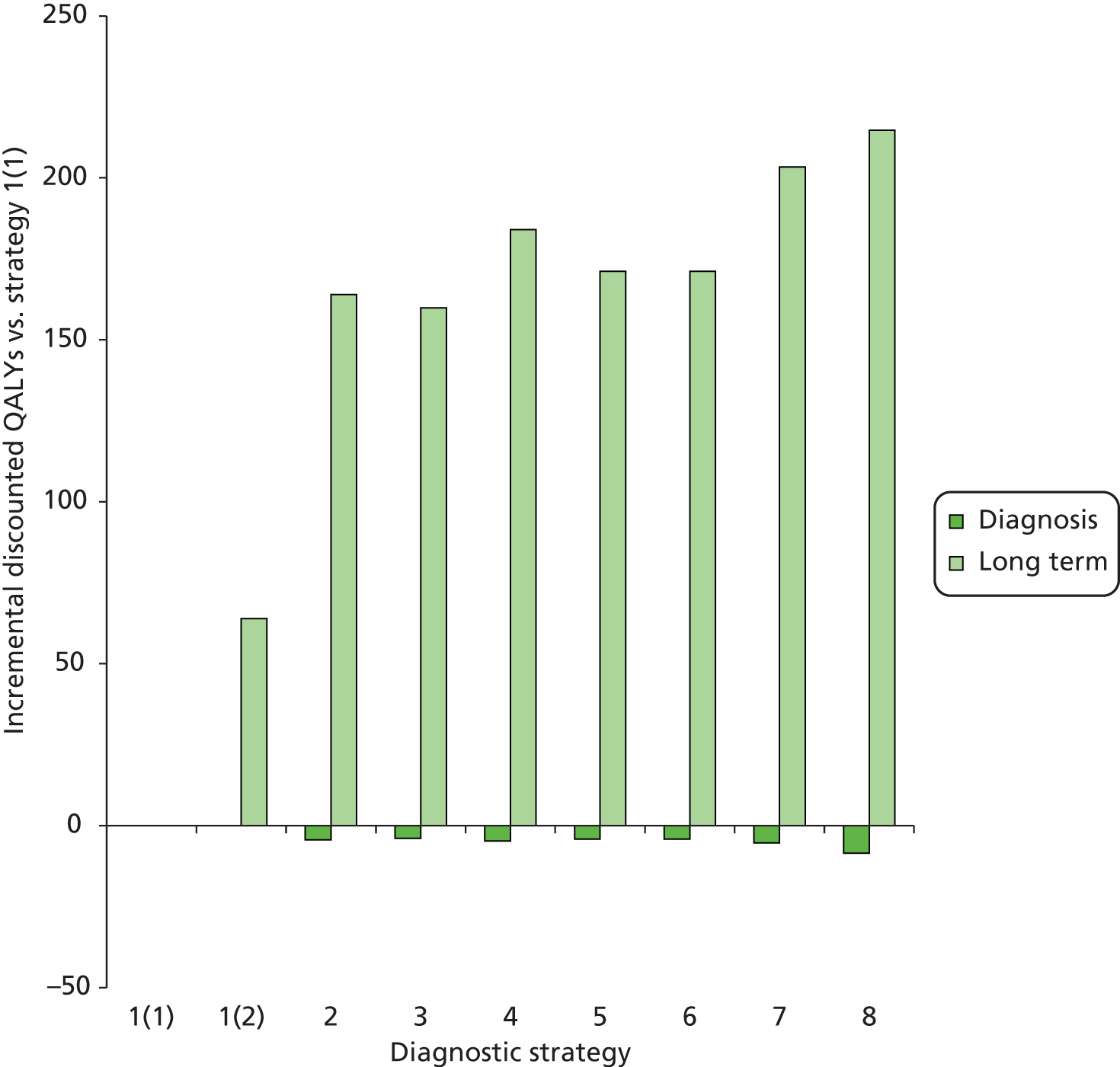

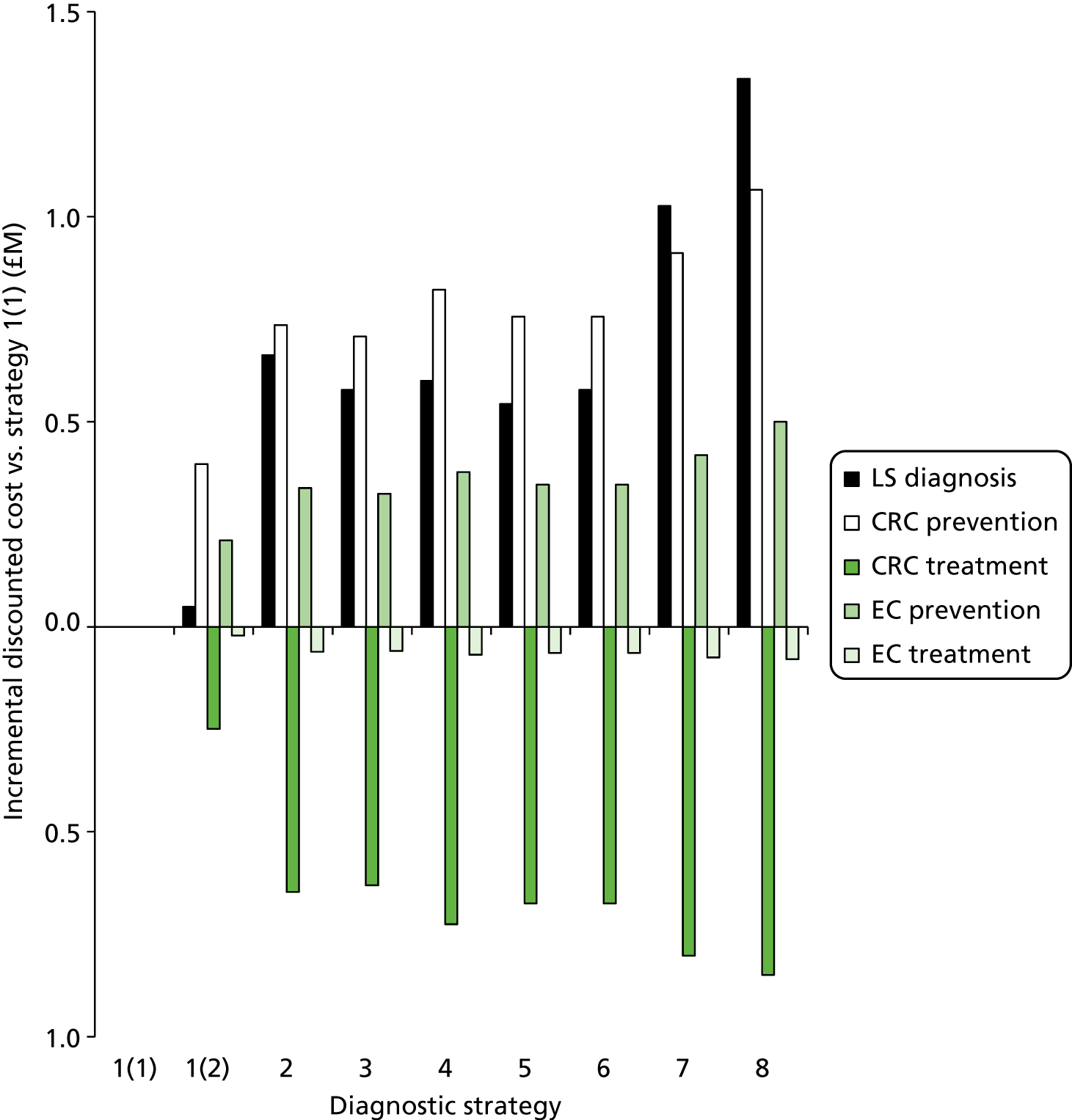

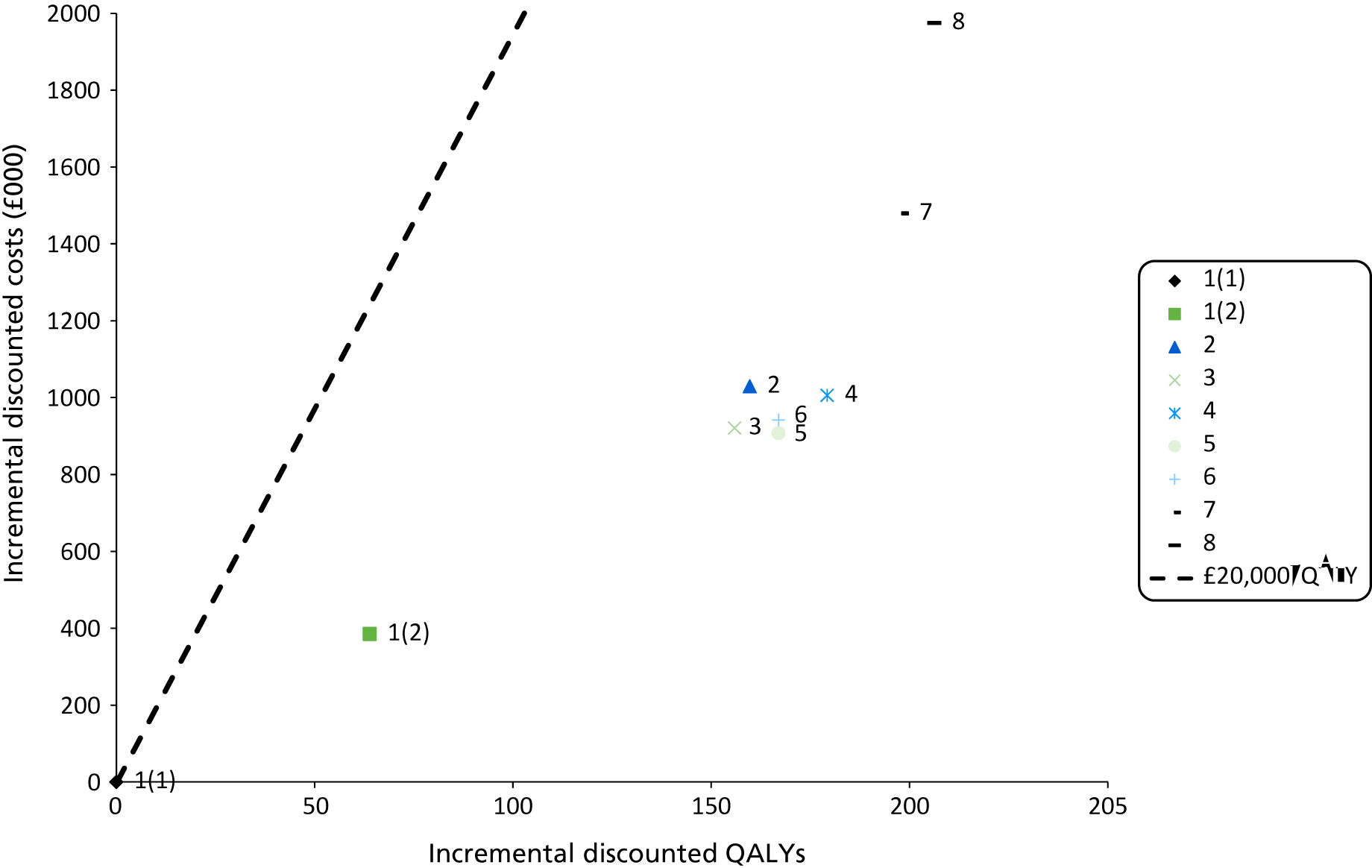

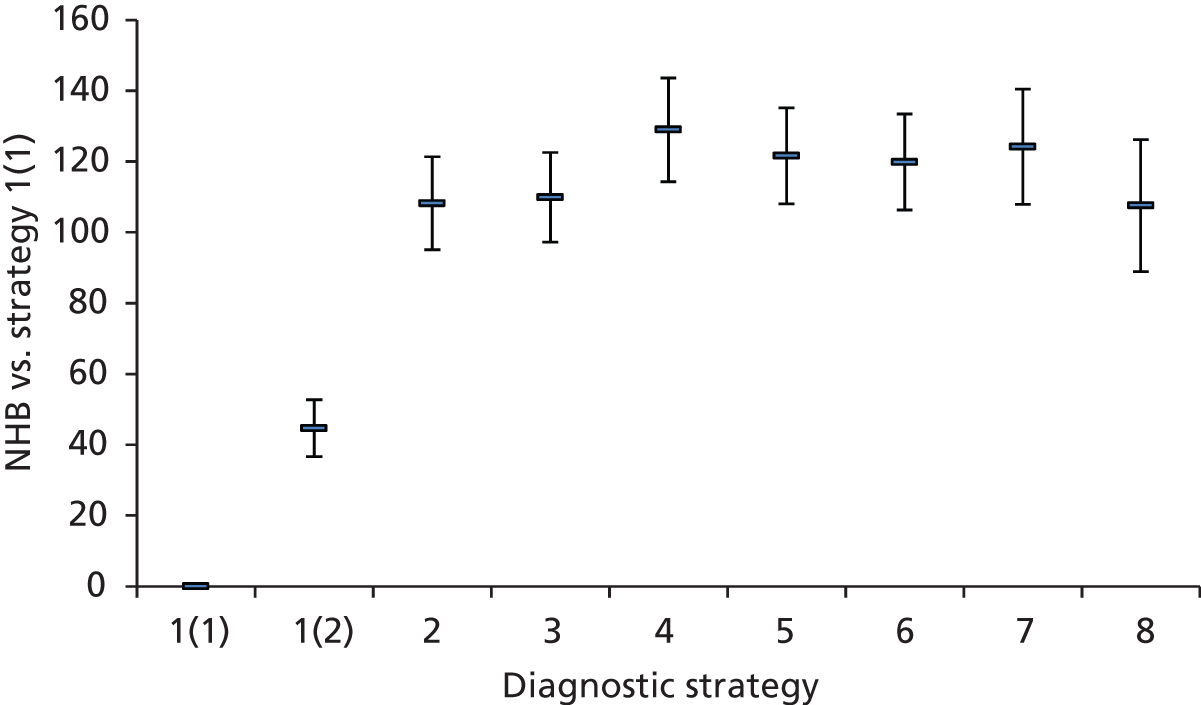

| Number with ≥ 2 LS cancers | 79 |