Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was commissioned and funded by the HTA programme on behalf of NICE as project number 12/75/01. The protocol was agreed in January 2013. The assessment report began editorial review in July 2013 and was accepted for publication in November 2013. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

none

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2014. This work was produced by Westwood et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

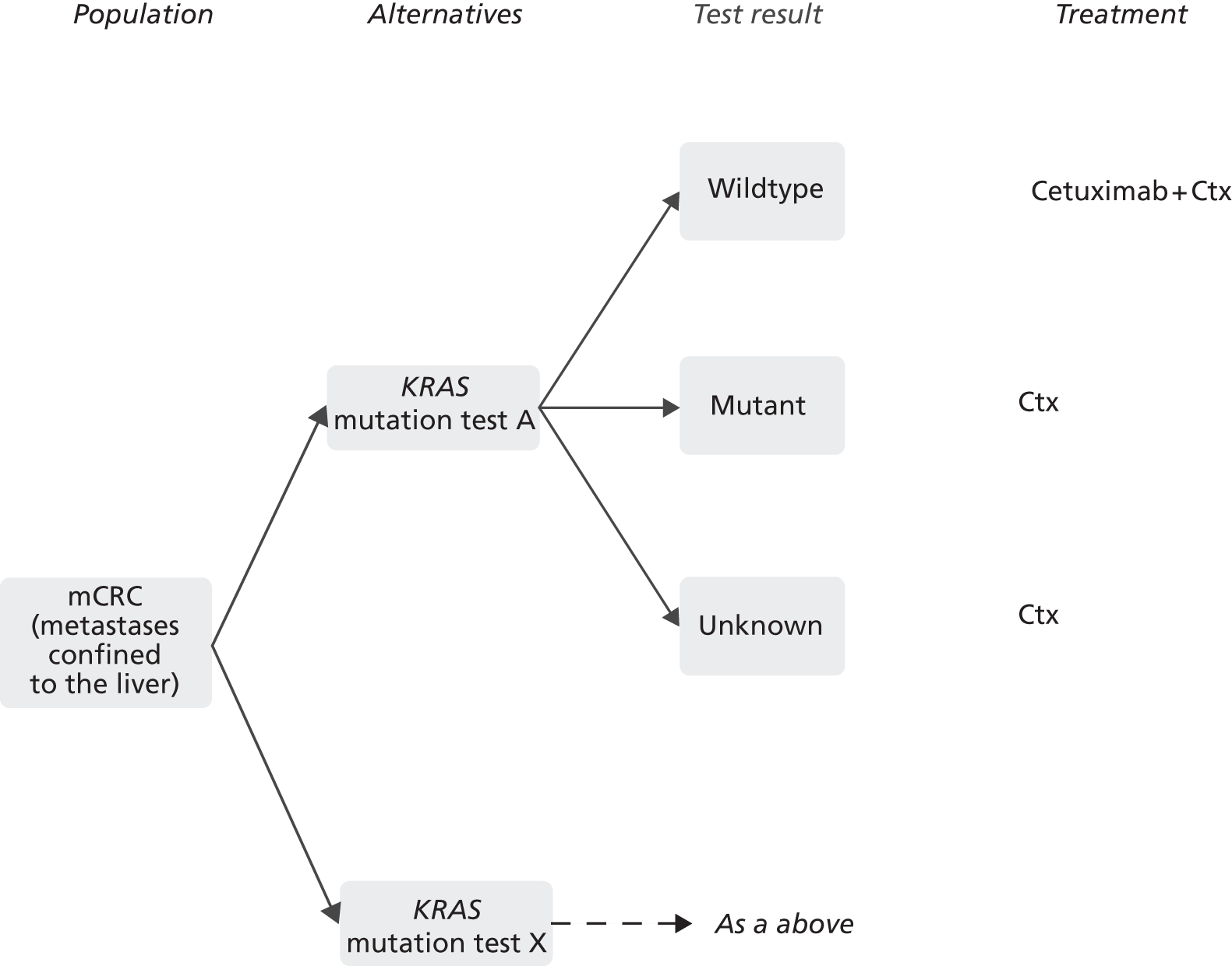

Chapter 1 Objective

The overall objective of this project was to summarise the evidence on the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of Kirsten rat sarcoma viral oncogene (KRAS) mutation tests (commercial or in-house) for the differentiation of adults with metastatic colorectal cancer (mCRC) whose metastases are confined to the liver and are unresectable and who may benefit from first-line treatment with cetuximab in combination with standard chemotherapy from those who should receive standard chemotherapy alone, as recommended in the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) technology appraisal TA176. 1 To address clinical effectiveness, data on the clinical validity of the different KRAS mutation tests (sensitivity/specificity for detection of mutations known to be linked to insensitivity to cetuximab) are required. Because methods of testing KRAS mutation status differ in terms of both the mutations targeted and the limit of detection (the lowest proportion of tumour cells with a mutation that can be detected), the definitions of KRAS mutant and KRAS wild type vary according to which test is used. All testing methods are essentially reference standard methods for classifying mutation status, as defined by the specific test characteristics, and it is therefore not useful to select any particular test as the reference standard. In addition, the relationship between insensitivity to cetuximab and the presence of specific mutations or combinations of mutations, as well as the relationship between insensitivity to cetuximab and the level of mutation present, are uncertain. Therefore, the following research questions were formulated to address the review objectives:

-

What is the technical performance of the different KRAS mutation tests {e.g. proportion of tumour cells needed, limit of detection [minimum percentage mutation detectable against a background of wild-type deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA)], failures, costs, turnaround time}?

-

What is the accuracy (clinical validity) of KRAS mutation testing, using any test, for predicting response to treatment with cetuximab in combination with standard chemotherapy?

-

How do clinical outcomes from treatment with cetuximab in combination with standard chemotherapy and, when reported, from treatment with standard chemotherapy alone vary according to which test is used to select patients for treatment?

-

What is the cost-effectiveness of the use of the different KRAS mutation tests to decide between standard chemotherapy or cetuximab in combination with standard chemotherapy?

First-line chemotherapy of unresectable colorectal liver metastases seeks to achieve a tumour response such that the tumour is judged to be resectable. For this reason, resection rate is considered the ideal reference standard for question 2 and the optimal outcome measure for question 3.

Chapter 2 Background and definition of the decision problem

Population

The indication for this assessment is the detection of mutations in the KRAS oncogene in adults with mCRC, in whom metastases are confined to the liver and are unresectable. The presence or absence of KRAS mutations can affect the choice of first-line chemotherapy in these patients and mutation testing is used to direct the treatment pathway. 1

The 2010 cancer registration data from the Office for National Statistics2 showed that colorectal cancer (CRC) was the third most common cancer in both men and women, accounting for approximately 13% of all new cancer cases. The 2010 age-standardised incidence rate for CRC in England was 56.5 per 100,000 in men and 36.1 per 100,000 in women and this has remained constant for both sexes over the last 10 years. 2 In 2009 there were approximately 36,000 new cases of CRC recorded in England and Wales,3 and in 2010 there were 14,691 recorded deaths from CRC in England and Wales, accounting for around 10% of all cancer deaths. 4 Age-standardised 5-year survival rates for CRC in England (2005–9) were 54.2% for men and 55.6% for women. 5 Approximately two-thirds of CRC cases (64% in 2009) are cancers of the colon and one-third (36%) are rectal (including the anus). Most (60%) rectal cancer cases occur in men and colon cancer cases are evenly distributed between the sexes. 3 CRC incidence is strongly related to age, with incidence rates increasing from age 50 years and peaking in the over 80s; in the UK (2007–9), 72% of new cases were diagnosed in people aged > 65 years. 3 There is some evidence in UK men of an association between incidence of CRC and deprivation; 2000–4 data show incidence rates approximately 11% higher for men living in more deprived areas than for men living in the least deprived areas. 6 National Bowel Cancer Audit data for 2011 included 28,260 new cases in England and Wales of which 21,306 (75.4%) were surgically treated; 3425 (16.1%) of these had confirmed liver metastases. 7 Reported estimates of the prevalence of KRAS mutations in codons 12 and 13 in the tumours of patients with mCRC range from 35% to 42%8–10 and are similar (approximately 36%) when samples taken from metastases are considered separately. 8,9 The three most common mutations, G12D, G12V and G13D, account for approximately 75% of all KRAS mutations. 8 Because not all patients whose tumours are wild type for KRAS codons 12 and 13 respond to treatment with epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR)-inhibiting monoclonal antibodies, the potential effects of mutations in codons 61 and 146 of KRAS have also been investigated. A US study,11 which found KRAS codon 12 or 13 mutations in 900/2121 (42.4%) CRC patients, conducted further analysis of the 513 wild-type samples and found 19 additional mutations in KRAS codon 61 and 17 in KRAS codon 146; these additional mutations represent < 2% of the total study population.

Intervention technologies

There are a variety of tests available for KRAS mutation testing (Table 1) in NHS reference laboratories currently providing testing [laboratories participating in the UK National External Quality Assurance Scheme (NEQAS)]. The tests used can be broadly divided into two subgroups: mutation screening and targeted mutation detection. Mutation screening tests screen samples for all KRAS mutations (known and novel) whereas targeted tests analyse samples for specific known mutations. Successful mutation analysis is dependent on adequate sample quality and a sufficient quantity of tumour tissue in the sample. The sample requirements vary between test methods, with some (e.g. Sanger sequencing) requiring up to 25% tumour cells. The limit of detection (the percentage of mutation detectable in a tumour sample against a background of wild-type DNA) may also vary between different test methods, with some studies reporting mutation detection at as little as 1% against a background of wild-type DNA (see Table 1). This is an important issue as it is unclear whether detecting diminishingly small proportions of mutation is clinically useful – should patients with very low proportions of mutation be treated as mutant or wild type? There is some evidence that the results of KRAS mutation testing in plasma samples correlate well with those obtained from tumour tissue. 13,14 However, tissue samples remain the gold standard. Clinical opinion, provided by specialist advisors during scoping, suggested that plasma testing is currently a ‘research only’ application that should not be included in this assessment.

| Sequencing method | Targeted (mutations targeted)/screening test | Limits of detection (% mutation) | Number of laboratories using the method | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NEQAS reporta | Laboratory contactb | |||

| Commercial tests | ||||

| Therascreen® KRAS RGQ PCR Kit (QIAGEN, Hilden, Germany) | Targeted (7 mutations: six codon 12 and one codon 13) | 0.77–6.43% | 3 | 1 |

| Therascreen® KRAS Pyro Kit (QIAGEN) | Targeted (12 mutations: six codon 12, one codon 13 and five codon 61) | 1.0–3.5% | 2 | |

| cobas® KRAS Mutation Test (Roche Molecular Systems, Branchburg, NJ, USA) | Targeted (19 mutations: six codon 12, six codon 13 and seven codon 61) | 1.6–6.3% depending on mutation | 4 | 4 |

| KRAS LightMix® kit (TIB MOLBIOL, Berlin, Germany) | Targeted (9 mutations: seven codon 12 and two codon 13) | Unclear | 0 | 0 |

| KRAS StripAssay® (ViennaLab, Vienna, Austria) | Targeted (13 mutations: eight codon 12, two codon 13 and three codon 61) | Unclear | 0 | 0 |

| In-house tests | ||||

| Sanger sequencing | All mutations within specific codons of the KRAS gene | Unclear | 6 | 1 |

| Pyrosequencing | All mutations within specific codons of the KRAS gene | 5–10%b | 15 | 8 |

| Real-time PCR | Targeted (details unclear) | Unclear | 2 | 0 |

| High-resolution melt analysis | All mutations within specific codons of the KRAS gene | ∼5%b | 2 | 2 |

| Next-generation sequencing | All mutations within specific codons of the KRAS gene | ∼5%b | 0 | 0 |

| MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry | All mutations within selected codons in the KRAS oncogene | ∼10% | 1 | 0 |

A Provisional Clinical Opinion (PCO) from the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO), published in 2009,15 recommended universal KRAS mutation testing in patients with mCRC in whom treatment with EGFR inhibitors is being considered. The recommendation also stated that testing should be carried out in an accredited laboratory and that patients whose tumours have KRAS mutations in codons 12 or 13 should not be treated with EGFR inhibitors. At the time that this guidance was published there were no US Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved tests for KRAS mutations. The ASCO PCO specified that samples should be selected by a pathologist to include predominantly tumour cells without significant necrosis or inflammation; be freshly extracted or stored in an appropriate preservation solution or rapidly frozen; be neutral-buffered formalin fixed and paraffin embedded and the area of interest selected by the pathologist. 15 Acceptable assay types were listed as real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR) using probes specific for the most common mutations in codons 12 and 13; direct sequencing of exon 1 in the KRAS gene; and the Therascreen commercial kit (at that time manufactured by DxS, Manchester, UK). 15 Subsequently, the QIAGEN Therascreen KRAS Rotar-Gene Q (RGQ) PCR Kit has been approved by the FDA when used with the QIAGEN QIAamp® DSP DNA FFPE (formalin fixed paraffin embedded) Tissue Kit and the QIAGEN Rotor-Gene® Q MDx (software version 2.1.0) and KRAS Assay Package. 16

Targeted mutation detection tests

All targeted tests are commercial kits and these look for different numbers of mutations within specific codons of the KRAS gene and have differing limits of detection. They may therefore differ in their ability to accurately differentiate patients who are likely to benefit from treatment with cetuximab in combination with standard chemotherapy from those who should receive standard chemotherapy alone.

The Therascreen KRAS RGQ PCR Kit is a CE-marked real-time PCR assay for the qualitative detection of seven mutations in codons 12 and 13 of the KRAS gene. It has been approved by the US FDA for the application covered by this assessment, that is, the selection of patients with mCRC for treatment with cetuximab. The Therascreen KRAS RGQ PCR Kit uses two technologies for the detection of mutations: ARMS (amplification-refractory mutation system) for mutation-specific DNA amplification and Scorpions for detection of amplified regions. Scorpions are bifunctional molecules containing a PCR primer covalently linked to a fluorescently labelled probe. A real-time PCR instrument [Rotor-Gene Q 5-Plex HRM (high-resolution melt) for consistency with CE marking] is used to perform the amplification and to measure fluorescence. 17 There is an earlier version of the Therascreen KRAS PCR Kit that also uses ARMS and Scorpions for the detection of KRAS mutations and is designed to detect the same KRAS mutations as the current, reformulated and revalidated version. Evidence for both versions will be included in this assessment.

The Therascreen KRAS Pyro Kit is a CE-marked test for the quantitative measurement of 12 mutations in codons 12, 13 and 61 of the KRAS gene. The kit is based on pyrosequencing technology and consists of two assays, one for detecting mutations in codons 12 and 13 and a second for detecting mutations in codon 61. The two regions are amplified separately by PCR and then amplified DNA is immobilised on streptavidin sepharose high-performance beads. Single-stranded DNA is prepared and sequencing primers added. The samples are then analysed using the PyroMark® Q24 System (QIAGEN). The KRAS Plug-in Report is recommended by the manufacturer for the analysis of the results; however, the analysis tool within the pyrosequencer can also be used. 18

The cobas KRAS Mutation Test from Roche Molecular Systems is a CE-marked TaqMelt™ real-time PCR assay intended for the detection of 19 mutations in codons 12, 13 and 61 of the KRAS gene. The assay uses DNA extracted from FFPE tissue and is validated for use with the cobas® 4800 System.

The KRAS LightMix Kit from TIB MOLBIOL is a CE-marked test designed for the detection and identification of mutations in codons 12 and 13 of the KRAS gene. The first part of the test involves PCR amplification of the KRAS gene. To reduce amplification of the wild-type KRAS gene and therefore enrich the mutant KRAS gene, a wild type-specific competitor molecule is added to the reaction mix. This is called clamped mutation analysis. The second part of the test procedure involves melting curve analysis with hybridisation probes. The melting temperature is dependent on the number of mismatches between the amplification product and the probe and allows the detection and identification of a mutation within the sample. The test is run on the LightCycler® instrument (Roche). 19

The KRAS StripAssay from ViennaLab is a CE-marked test for the detection of mutations in the KRAS gene. The test procedure involves three steps: the DNA is first isolated from the specimen; PCR amplification is then performed; and the amplification product is then hybridised to a test strip containing allele-specific probes immobilised as an array of parallel lines. Colour substrates are used to detect bound sequences, which can then be identified with the naked eye or by using a scanner and software. 20 There are two versions of the KRAS StripAssay: one is designed to detect 10 mutations in codons 12 and 13 of the KRAS gene and the other is designed to detect the same 10 mutations in codons 12 and 13 plus three mutations in codon 61.

Mutation screening tests

‘In-house’ laboratory-based tests are designed to detect all mutations within specific codons of the KRAS gene.

Pyrosequencing assays are the most commonly used method of KRAS mutation testing in UK laboratories (see Table 1). The process involves first extracting DNA from the sample and amplifying it using PCR. The PCR product is then cleaned up before the pyrosequencing reaction. The reaction involves the sequential addition of nucleotides to the mixture. A series of enzymes incorporate nucleotides into the complementary DNA strand, generate light proportional to the number of nucleotides added and degrade unincorporated nucleotides. The DNA sequence is determined from the resulting pyrogram trace. 21

Sanger sequencing is also a commonly used method (see Table 1); however, there is much variation in the detail of how the method is carried out. In general, after DNA is extracted from the sample it is amplified using PCR. The PCR product is then cleaned up and sequenced in both forward and reverse directions. The sequencing reaction uses dideoxynucleotides labelled with coloured dyes that randomly terminate DNA synthesis, creating DNA fragments of various lengths. The sequencing reaction product is then cleaned up and analysed using capillary electrophoresis. The raw data are analysed using analysis software to generate the DNA sequence. All steps are performed at least in duplicate to increase confidence that an identified mutation is real. It should be noted that sequencing works well only when viable tumour cells constitute at least 25% or more of the sample. 22

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence contact with laboratories (October/November 2012) suggested that several laboratories were planning to convert to next-generation sequencing in the coming year. As with Sanger sequencing, there is much variation in the methodology used to perform next-generation sequencing. The concept is similar to Sanger sequencing; however, the sample DNA is first fragmented into a library of small segments that can be sequenced in parallel reactions. 23

High-resolution melt analysis assays are also commonly used by laboratories participating in the UK NEQAS scheme (see Table 1). For this technique the DNA is first extracted from the sample and amplified using PCR. The HRM reaction is then performed. This involves a precise warming of the DNA during which the two strands of DNA ‘melt’ apart. Fluorescent dye that binds only to double-stranded DNA is used to monitor the process. A region of DNA with a mutation will ‘melt’ at a different temperature to the same region of DNA without a mutation. These changes are documented as melt curves and the presence or absence of a mutation can be reported. 24

Matrix-assisted laser desorption ionisation time-of-flight (MALDI-TOF) mass spectrometry is currently used by one laboratory participating in the UK NEQAS scheme. This technique involves extracting DNA and amplifying it using PCR. The PCR products are then cleaved and fragments separated based on mass by the MALDI-TOF mass spectrometer. This generates a ‘fingerprint’ of the DNA with each fragment represented as a peak with a certain mass. The ‘fingerprint’ of the test sample is compared with the ‘fingerprint’ of the wild-type DNA. A mutation would appear as a peak shift due to a change in the mass of a fragment caused by a base change. 25 MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry can be used to identify all mutations within selected codons in the KRAS oncogene and has a limit of detection of approximately 10% tumour DNA in a background of wild-type DNA. 26

Subgroup analyses of patients tested for KRAS mutation status from randomised controlled trials (RCTs) have shown that treatment with the EGFR-inhibiting monoclonal antibody cetuximab in combination with standard chemotherapy can increase progression-free survival (PFS) and tumour response in patients with KRAS wild-type tumours compared with standard chemotherapy alone. 27,28 In contrast, patients whose tumours were positive for KRAS mutations had reduced PFS and tumour response when treated with cetuximab in combination with standard chemotherapy compared with standard chemotherapy alone. 27,28 These two trials formed the basis of NICE technology appraisal 176,1 which recommends cetuximab in combination with standard chemotherapy for the first-line treatment of mCRC in patients whose tumours are KRAS wild type and whose metastases are confined to the liver and are unresectable. However, both of these trials used a pre-CE-marked version of the LightMix KRAS Kit (TIB MOLBIOL), which is not currently in use by any laboratory participating in the UK NEQAS scheme.

Care pathway

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence guidance on the diagnosis and management of CRC was updated in 2011. 29

Diagnosis of colorectal cancer

This guideline states that patients referred to secondary care for suspected CRC should be assessed using colonoscopy, flexible sigmoidoscopy followed by barium enema or computed tomography (CT), dependent on comorbidities and local expertise and test availability. When a lesion suspicious of cancer is detected a biopsy should be performed to confirm the diagnosis. 29

All patients with histologically confirmed CRC should be offered contrast-enhanced CT of the chest, abdomen and pelvis to estimate the stage of the disease. Further imaging [e.g. contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) or positron emission tomography/computed tomography (PET/CT)] may be considered if the CT scan shows metastatic disease only in the liver. 29 The aim of further imaging is to identify those patients who have resectable metastases, or metastases that may become resectable following response to chemotherapy. For the second group of patients, European Society for Medical Oncology (ESMO) 2010 clinical practice guidelines for the treatment of advanced CRC30 recommend establishing KRAS mutation status to determine the best treatment regimen. These guidelines do not stipulate which specific mutations should be analysed or which test method should be used. The KRAS status of a patient’s tumour is identified through analysis of a biopsy sample or, more frequently, a section of resected tumour tissue. The tissue is fixed in formalin and embedded in a block of paraffin for storage by the pathologist, who also examines the histology and evaluates the tumour content of the sample. Macro dissection may be performed before DNA is extracted and mutation analysis is carried out to determine the KRAS status of the tumour.

To minimise turnaround time, guidance from the Royal College of Pathologists31 recommends that mutation testing should be ordered by the pathologist reporting on the cellular make-up of the tumour. However, this is not currently universal practice and often the decision to perform a KRAS mutation test is often taken at the multidisciplinary team (MDT) meeting. If a sample is stored as a FFPE specimen for a long time this can lead to DNA degradation, which can result in a higher chance of failure when testing for KRAS mutations. The timing of the KRAS test varies between patients, with some clinicians preferring to test at diagnosis, potentially before the disease becomes metastatic, and other clinicians waiting until the cancer has progressed to metastatic disease. If the KRAS status is tested early, then the result is then referred to if metastatic disease develops. It has been suggested that analysing multiple resection or biopsy samples from the same patient increases the chances of identifying a KRAS mutation because of potential heterogeneity between tumour sites. The evidence on this is conflicting, with studies reporting that testing a single site only will potentially misclassify between 2% and 10% of tumours as KRAS wild type. 32,33

Treatment of colorectal cancer

In patients with unresectable liver metastases whose primary tumour has been resected or is potentially operable and who are fit enough to undergo liver surgery, the aim of chemotherapy is to induce tumour response such that resection becomes possible. The KRAS mutation status of a patient’s tumour is used to determine the optimal chemotherapy regimen for this purpose. Evidence suggests that patients with KRAS wild-type tumours are more likely to benefit from treatment with an EGFR-inhibiting monoclonal antibody (cetuximab) in combination with standard chemotherapy. However, patients whose tumours are positive for KRAS mutations are more likely to benefit from standard chemotherapy alone. In addition, the overall health and the preferences of the patient should be taken into consideration when selecting treatment.

The choice of standard chemotherapy is covered by NICE clinical guideline 131,29 which recommends that one of the following sequences of chemotherapy is considered:

-

oxaliplatin in combination with infusional fluorouracil plus folinic acid (FOLFOX) as first-line treatment and then single-agent irinotecan as second-line treatment

-

FOLFOX as first-line treatment and then irinotecan in combination with infusional fluorouracil plus folinic acid (FOLFIRI) as second-line treatment

-

oxaliplatin and capecitabine (XELOX) as first-line treatment and then FOLFIRI as second-line treatment.

The guideline further states that raltitrexed should be considered only for patients who are intolerant to fluorouracil and folinic acid or for patients for whom these drugs are not suitable. 29 NICE technology appraisal 6134 suggests that oral therapy with either capecitabine or tegafur with uracil (in combination with folinic acid) can also be considered as an option for the first-line treatment of mCRC.

With respect to the use of biological agents (EGFR inhibitors), NICE technology appraisal 1761 recommends cetuximab in combination with FOLFOX or FOLFIRI, within its licensed indication, for the first-line treatment of mCRC:

-

in patients in whom the primary colorectal tumour has been resected or is potentially operable

-

in patients in whom the metastatic disease is confined to the liver and is unresectable

-

when the patient is fit enough to undergo surgery to resect the primary colorectal tumour and to undergo liver surgery if the metastases become resectable after treatment with cetuximab.

The European Medicines Agency marketing authorisation for cetuximab states that it is ‘indicated for the treatment of patients with EGFR-expressing, KRAS wild-type metastatic colorectal cancer’. 35 Therefore, KRAS mutation testing is an important component of the care pathway. Cetuximab (monotherapy or combination therapy) and bevacizumab (in combination with non-oxaliplatin chemotherapy) for the treatment of mCRC after first-line chemotherapy are not recommended in NICE technology appraisal 242. 36 However, these treatments may be given to some patients through the Cancer Drugs Fund. If cetuximab is considered in the third-line setting, KRAS status is often not retested but a decision will be made based on the result of the KRAS test performed earlier in the care pathway. No other biological agents are currently recommended by NICE for the first-line treatment of patients with unresectable liver metastases from CRC.

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence clinical guideline 13129 stipulates that all patients with primary CRC undergoing treatment with curative intent should be followed up at a clinic visit 4–6 weeks after the potentially curative treatment. They should then have regular surveillance including:

-

a minimum of two CT scans of the chest, abdomen and pelvis in the first 3 years and

-

regular serum carcinoembryonic antigen tests (at least every 6 months in the first 3 years).

They should also have a surveillance colonoscopy at 1 year after initial treatment and, if the result is normal, further colonoscopic follow-up after 5 years and thereafter as determined by cancer networks.

Measuring response to treatment

In 1979 the World Health Organization (WHO) and the International Union Against Cancer introduced criteria for the classification of the response of solid tumours to treatment. 37 These criteria were an early attempt to standardise reporting of response outcomes and were widely adopted; however, some problems with their use have subsequently developed. There has been variation in the methods used for incorporating into response assessments the change in size of measurable lesions, as defined by WHO; the minimum lesion size and number of lesions to be recorded have also varied; the definitions of progressive disease (PD) have sometimes been related to change in a single lesion and sometimes to change in overall tumour load (sum of the measurements of all lesions); and there has been confusion around how to use three-dimensional measures from new technologies such as CT and MRI in the context of the WHO criteria. 38 The Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumours (RECIST) Group is a collaborative initiative that was instigated to review the WHO criteria. The RECIST criteria use the same categories as the WHO criteria [complete response (CR), partial response (PR), stable disease (SD) and PD]. 38 RECIST guidance recommends CT and MRI for measuring target lesions in response assessment and that imaging-based evaluation is generally preferable to clinical examination. It is suggested that follow-up assessments every 6–8 weeks is a ‘reasonable norm’. 38 Taking into account the longest diameter only for all target lesions, the RECIST criteria, as they are applicable to this assessment, can be summarised as follows:38

-

CR – disappearance of all target lesions and no new lesions

-

PR – at least a 30% decrease in the sum of the longest diameters of target lesions, taking the sum of the baseline diameters as the reference, and no new lesions

-

PD – at least a 20% increase in the sum of the longest diameters of target lesions, taking the smallest sum of the longest diameters recorded since treatment started as the reference, or the appearance of one or more new lesions

-

SD – neither sufficient shrinkage to be classified as PR or sufficient increase to be classified as PD, taking the smallest sum of the longest diameters recorded since treatment started as the reference, and no new lesions.

Best overall response is defined as the best response recorded from the start of treatment to disease progression. 38

First-line chemotherapy of unresectable colorectal liver metastases seeks to achieve a tumour response such that the tumour is judged to be resectable. For this reason, resection rate is considered the ideal reference standard for research question 2 and the optimal outcome measure for research question 3 (see Chapter 1). Objective response rate (ORR), defined as best overall response = CR + PR, is also of interest as there is some evidence that ORR correlates well with resection rate. 39 Tumour status following treatment/resection is defined by the residual tumour (R) classification, in which R0 = no residual tumour, R1 = microscopic residual tumour and R2 = macroscopic residual tumour.

This assessment compares the performance and cost-effectiveness of KRAS mutation testing options, currently available in the UK NHS, for the differentiation of adults with mCRC whose metastases are confined to the liver and are unresectable and who may benefit from first-line treatment with cetuximab in combination with standard chemotherapy from those who should receive standard chemotherapy alone.

Chapter 3 Assessment of clinical effectiveness

A systematic review was conducted to summarise the evidence on the clinical effectiveness of the different KRAS mutation testing options, currently available in the UK NHS, for differentiating adults with mCRC whose metastases are confined to the liver and are unresectable and who may benefit from first-line treatment with cetuximab in combination with standard chemotherapy from those who should receive standard chemotherapy alone. Systematic review methods followed the principles outlined in the Centre for Reviews and Dissemination (CRD) guidance for undertaking reviews in health care40 and the NICE Diagnostic Assessment Programme manual. 41 In addition to the effectiveness review, additional data were obtained from an online survey of laboratories participating in the UK NEQAS pilot scheme for KRAS mutation testing.

Systematic review methods

Search strategy

Search strategies were based on target condition and intervention, as recommended in the CRD guidance for undertaking reviews in health care40 and the Cochrane Handbook for DTA Reviews. 42

Candidate search terms were identified from target references, browsing database thesauri [e.g. MEDLINE medical subject headings (MeSH) and EMBASE Emtree], existing reviews identified during the rapid appraisal process and initial scoping searches. These scoping searches were used to generate test sets of target references, which informed text mining analysis of high-frequency subject indexing terms using EndNote X5 reference management software (Thomson Reuters, CA, USA). Strategy development involved an iterative approach testing candidate text and indexing terms across a sample of bibliographic databases and aimed to reach a satisfactory balance of sensitivity and specificity.

The following databases were searched for relevant studies from 2000 to January 2013:

-

MEDLINE (OvidSP) (2000 to Week 2 January 2013)

-

MEDLINE In-Process and Other Non-Indexed Citations and Daily Update (OvidSP) (up to 21 January 2013)

-

EMBASE (OvidSP) (2000 to Week 3 2013)

-

Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (CDSR) (Wiley) (The Cochrane Library 2000 to Issue 12, 2012)

-

Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) (Wiley) (The Cochrane Library 2000 to Issue 12, 2012)

-

Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects (DARE) (Wiley) (The Cochrane Library 2000 to Issue 4, 2012)

-

Health Technology Assessment (HTA) database (Wiley) (The Cochrane Library 2000 to Issue 4, 2012)

-

Science Citation Index (SCI-EXPANDED) (Web of Knowledge) (2000 to 22 January 2013)

-

Conference Proceedings Citation Index (CPCI-S) (Web of Knowledge) (2000 to 22 January 2013)

-

Latin American and Caribbean Health Sciences Literature (LILACS) (Internet) (up to 24 January 2013), http://regional.bvsalud.org/php/index.php?lang=en

-

BIOSIS Previews (Web of Knowledge) (2000 to 22 January 2013)

-

National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) HTA programme (Internet) (up to 25 January 2013)

-

International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO) (Internet) (up to 25 January 2013), www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/.

Completed and ongoing trials were identified by searches of the following resources:

-

National Institutes of Health ClinicalTrials.gov (Internet) (2000 to 23 January 2013), www.clinicaltrials.gov/

-

Current Controlled Trials (Internet) (2000 to 29 January 2013), www.controlled-trials.com/

-

WHO International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (ICTRP) (Internet) (2000 to 25 January 2013), www.who.int/ictrp/en/.

Searches were undertaken to identify studies of KRAS testing for mCRC. The main EMBASE strategy for each set of searches was independently peer reviewed by a second information specialist using the Peer Review of Electronic Search Strategies Evidence-Based Checklist (PRESS-EBC). 43 Search strategies were developed specifically for each database and the keywords associated with CRC were adapted according to the configuration of each database. Searches took into account generic and other product names for the intervention. No restrictions on language or publication status were applied. Full search strategies are reported in Appendix 1.

Electronic searches were undertaken for the following conference abstracts:

-

ASCO conference proceedings (Internet) (2007–13), www.asco.org/ASCOv2/Meetings/Abstracts

-

ESMO conference proceedings (Internet) (2007–13), www.esmo.org/education-research/abstracts-virtual-meetings-and-meeting-reports.html

-

American Association for Cancer Research conference proceedings (Internet) (2007–13), www.aacrmeetingabstracts.org/search.dtl

-

Association for Molecular Pathology conference proceedings (Internet) (2007–13), www.amp.org/meetings/past_meetings.cfm.

Identified references were downloaded into EndNote X4 software for further assessment and handling.

References in retrieved articles were checked for additional studies. The final list of included papers was also checked on PubMed for retractions, errata and related citations. 44–46

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Separate inclusion criteria were developed for each of the three clinical effectiveness questions; these are summarised in Table 2.

| What is the technical performance of the different KRAS mutation tests? | What is the accuracy of KRAS mutation testing, using any test, for predicting response to treatment with cetuximab in combination with standard chemotherapy? | How do outcomes from treatment with cetuximab in combination with standard chemotherapy and, when reported, from treatment with standard chemotherapy vary according to which test is used to select patients for treatment? | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Participants | Adult patients (≥ 18 years) with mCRC and a resected or resectable primary tumour whose metastases are confined to the liver and are unresectable but may become resectable after response to chemotherapy | Adult patients (≥ 18 years) with mCRC and a resected or resectable primary tumour whose metastases are confined to the liver and are unresectable but may become resectable after response to chemotherapy | Adult patients (≥ 18 years) with mCRC and a resected or resectable primary tumour whose metastases are confined to the liver and are unresectable but may become resectable after response to chemotherapy Patients who have been tested for KRAS mutation status |

| Setting | Secondary or tertiary care | ||

| Interventions (index test) | Any commercial or in-house KRAS mutation test listed in Table 1 | Any commercial or in-house KRAS mutation test listed in Table 1 | First-line chemotherapy with cetuximab in combination with standard chemotherapya |

| Comparators | Not applicable | Not applicable | Standard chemotherapya |

| Reference standard | Not applicable | Response to treatment with cetuximab in combination with standard chemotherapy (e.g. PFS, ORR, disease control rate) | Not applicable |

| Outcomes | Proportion of tumour cells needed, failures, limit of detection, turnaround time, costs, expertise/logistics of test | Overall survival or PFS in patients whose tumours are KRAS mutant vs. overall survival or PFS in patients whose tumours are KRAS wild type. Test accuracy – the numbers of true positives, false negatives, false positives and true negatives | PFS, overall survival, ORR, disease control rate |

| Study design | To be addressed by survey (see Survey of laboratories providing KRAS mutation testing); publications from UK laboratories | RCTs (CCTs and cohort studies will be considered if no RCTs are identified) | RCTs (CCTs will be considered if no RCTs are identified) |

Inclusion screening and data extraction

Two reviewers (MW and PW) independently screened the titles and abstracts of all reports identified by searches and any discrepancies were discussed and resolved by consensus. Full copies of all studies deemed potentially relevant were obtained and the same two reviewers independently assessed these for inclusion; any disagreements were resolved by consensus. Details of studies excluded at the full paper screening stage are presented in Appendix 5.

Studies cited in materials provided by the manufacturers of the Therascreen KRAS RGQ PCR Kit and Therascreen KRAS Pyro Kit (QIAGEN), the cobas KRAS Mutation Test Kit (Roche Molecular Systems), the KRAS LightMix Kit (TIB MOLBIOL) and the KRAS StripAssay (ViennaLab) were first checked against the project reference database, in EndNote X4; any studies not already identified by our searches were screened for inclusion following the process described above.

Data were extracted on the following: study design/details, participant details (e.g. inclusion/exclusion criteria, age, liver metastases details, criteria for unresectability, performance status, previous treatments), KRAS mutation test(s) and mutations targeted, intervention details, clinical outcomes, test performance outcome measures (against treatment response as reference standard), details of specific mutations identified by outcome measure (when reported), test failure rates and limits of detection. Data were extracted by one reviewer, using a piloted standard data extraction form, and checked by a second (MW and PW); any disagreements were resolved by consensus. Full data extraction tables are provided in Appendix 2.

Quality assessment

The risk of bias in included RCTs was assessed using the Cochrane Collaboration’s tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. 47 Studies used to derive accuracy data, for the ability of KRAS mutation tests to predict treatment response, were assessed using the QUADAS-2 tool. 48 Risk of bias assessments were undertaken by one reviewer and checked by a second reviewer (MW and PW) and any disagreements were resolved by consensus.

The results of the risk of bias assessments were summarised and are presented in tables and graphs in the results section of this chapter and in full, by study, in Appendix 3.

Survey of laboratories providing KRAS mutation testing

We conducted a web-based survey to gather data on the technical performance characteristics of KRAS mutation tests. We sent an e-mail invitation via NEQAS to laboratories participating in the UK NEQAS pilot scheme for KRAS mutation testing. We used SurveyMonkey online software to run the survey. We structured the survey into sections on:

-

laboratory details

-

KRAS testing methods

-

logistics

-

technical methods

-

costs.

When possible we used multiple choice options with tick boxes to make the survey quick and easy to complete. A copy of the survey is provided in Appendix 4.

Methods of analysis/synthesis

The results of studies included in this review were summarised by research question (see Chapter 1), that is, studies providing technical information on KRAS mutation testing in NHS laboratories in the UK (see What are the technical performance characteristics of the different KRAS mutation tests?), studies providing information on the accuracy of KRAS mutation tests for predicting response to treatment (see What is the accuracy of KRAS mutation testing for predicting response to treatment with cetuximab plus standard chemotherapy and subsequent resection rates?) and studies reporting information on how clinical outcomes may vary according to which test is used to select patients for treatment (see How do outcomes from treatment with cetuximab plus standard chemotherapy vary according to which test is used to select patients for treatment?). We planned to use a bivariate/hierarchical summary receiver operating characteristic (HSROC) random-effects model to generate summary estimates and a summary receiver operating characteristic (SROC) curve for test accuracy data49–51 and a DerSimonian and Laird random-effects model to generate summary estimates of treatment effects. However, because the review identified a small number of studies with between-study variation in participant characteristics, methods used to test for KRAS mutations and mutations targeted, we did not consider meta-analysis to be appropriate and have provided a structured narrative synthesis.

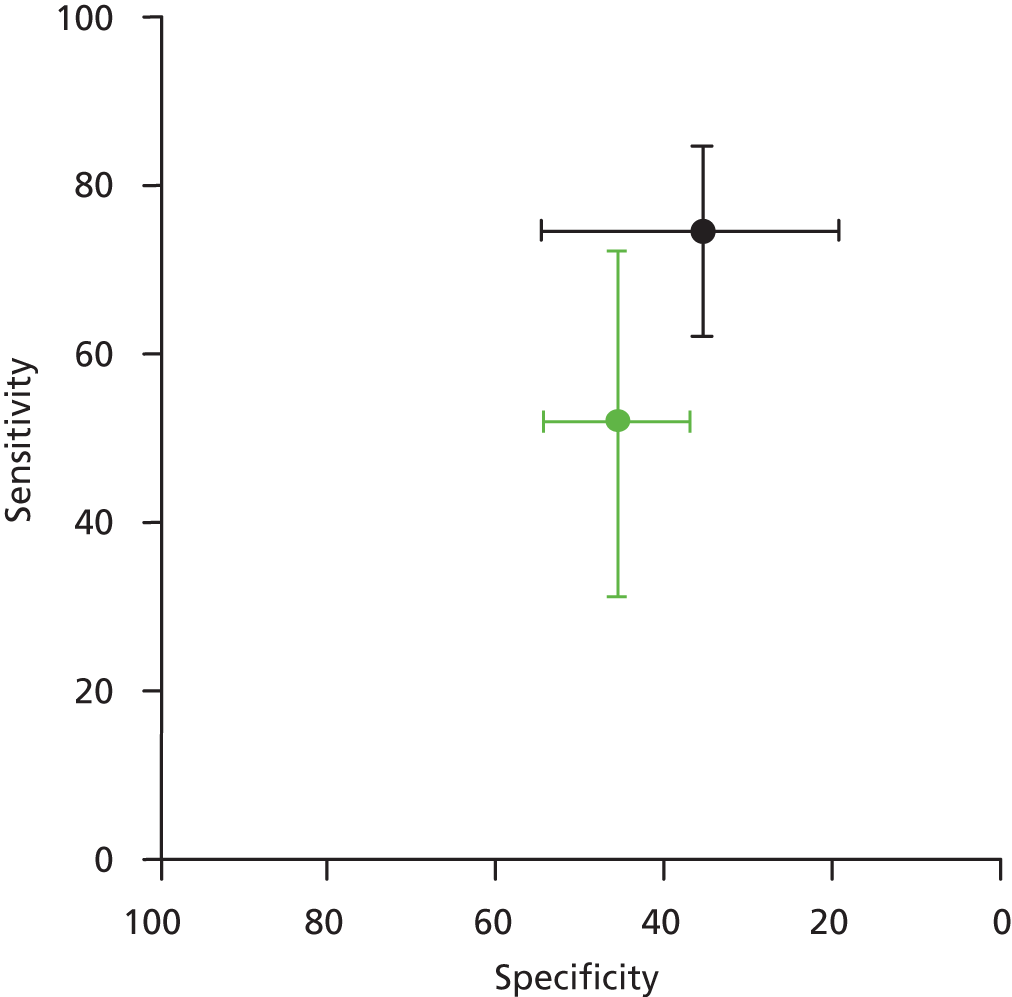

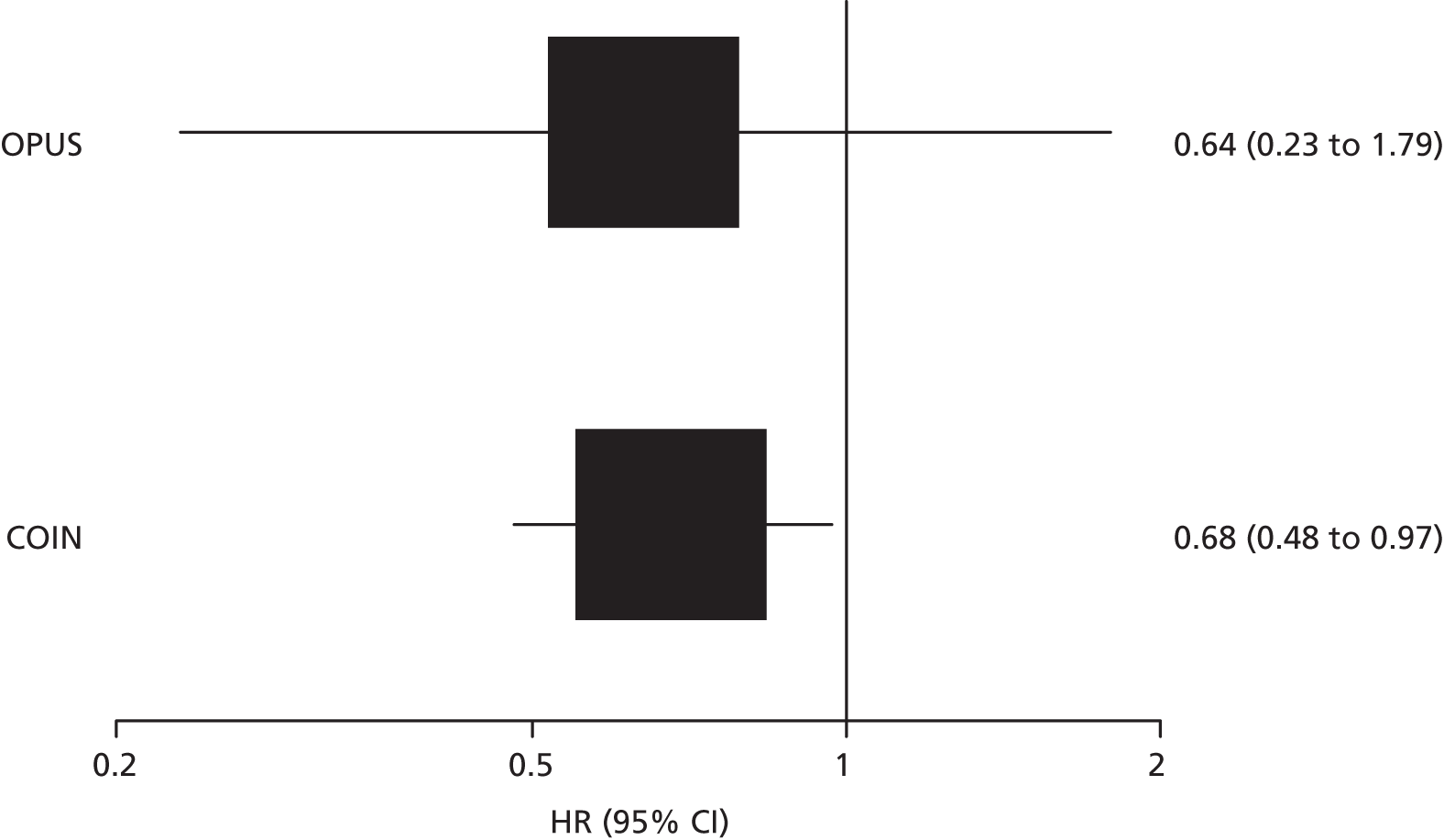

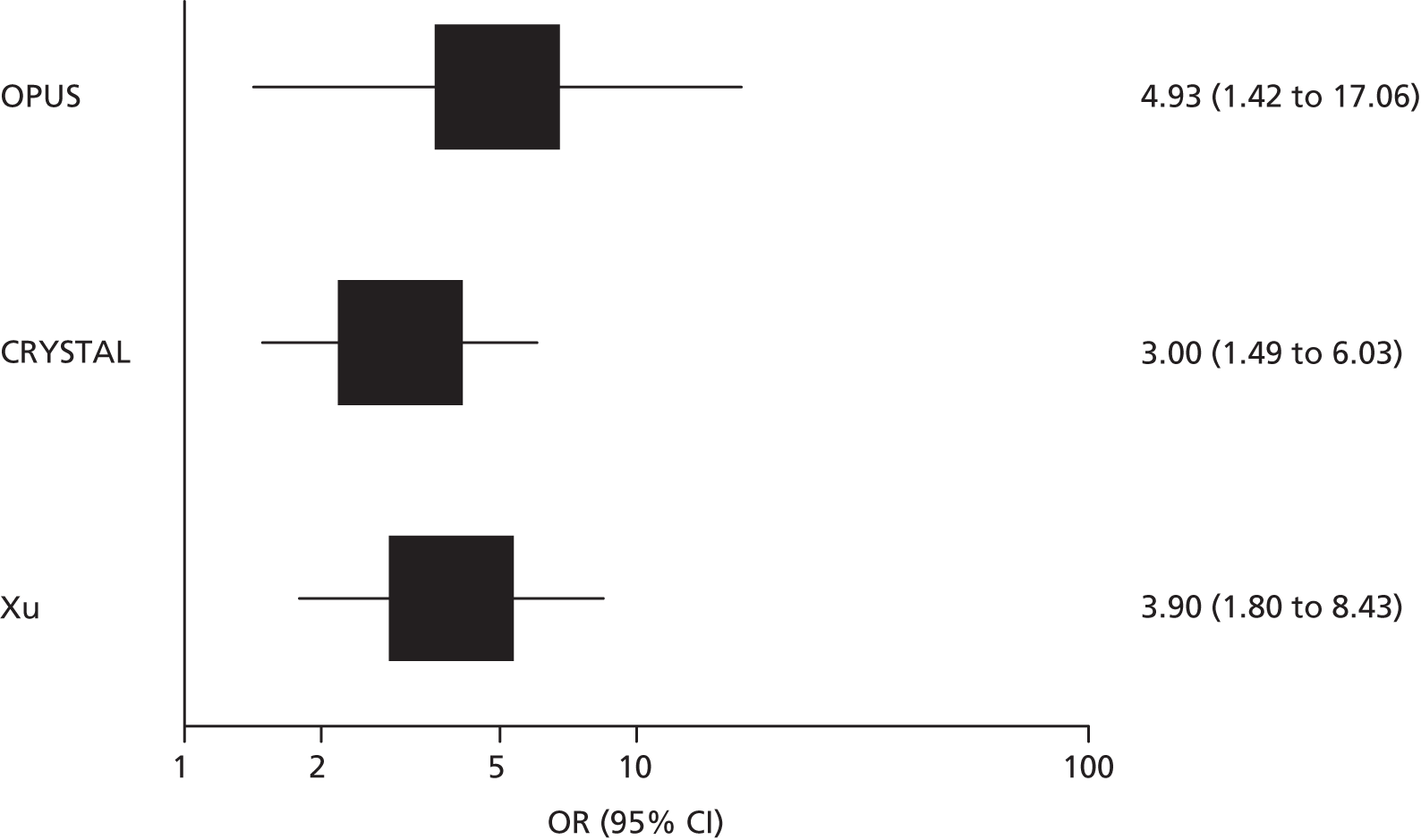

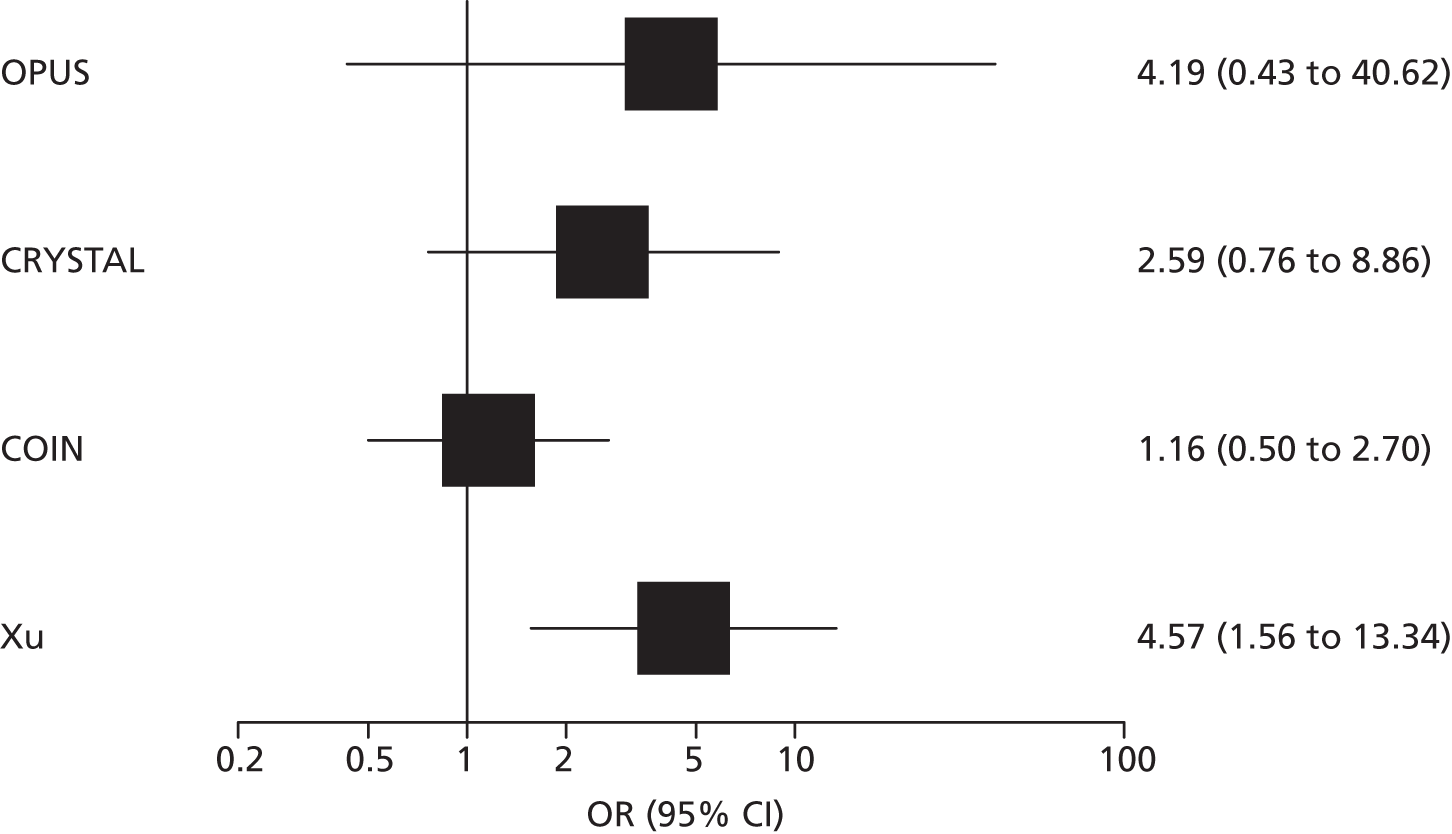

For all studies that provided data on accuracy for the prediction of response to treatment with cetuximab in combination with standard chemotherapy, the absolute numbers of true-positive (TP), false-negative (FN), false-positive (FP) and true-negative (TN) test results, as well as sensitivity and specificity values with 95% confidence intervals (CIs), are presented in results tables, for each reference standard response (e.g. ORR or resection rate) reported. When reported, data on the numbers of failed KRAS mutation tests and reasons for failure were also included in the results tables. The results of individual studies were plotted in the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) plane to illustrate the trade-off between sensitivity and specificity and for ease of comparison between test methods; separate plots were provided for each reference standard response. For RCTs providing information on how clinical outcomes may vary according to which test is used to select patients for treatment with cetuximab in combination with standard chemotherapy, hazard ratios (HRs) with 95% CIs were provided for PFS and odds ratios (ORs) with 95% CIs were reported for tumour response outcomes (ORR and resection rate). The results of individual studies were illustrated in forest plots. Between-study clinical heterogeneity was assessed qualitatively. There were insufficient studies to assess heterogeneity statistically using the chi-squared test or I2 statistic.

Results of the assessment of clinical effectiveness

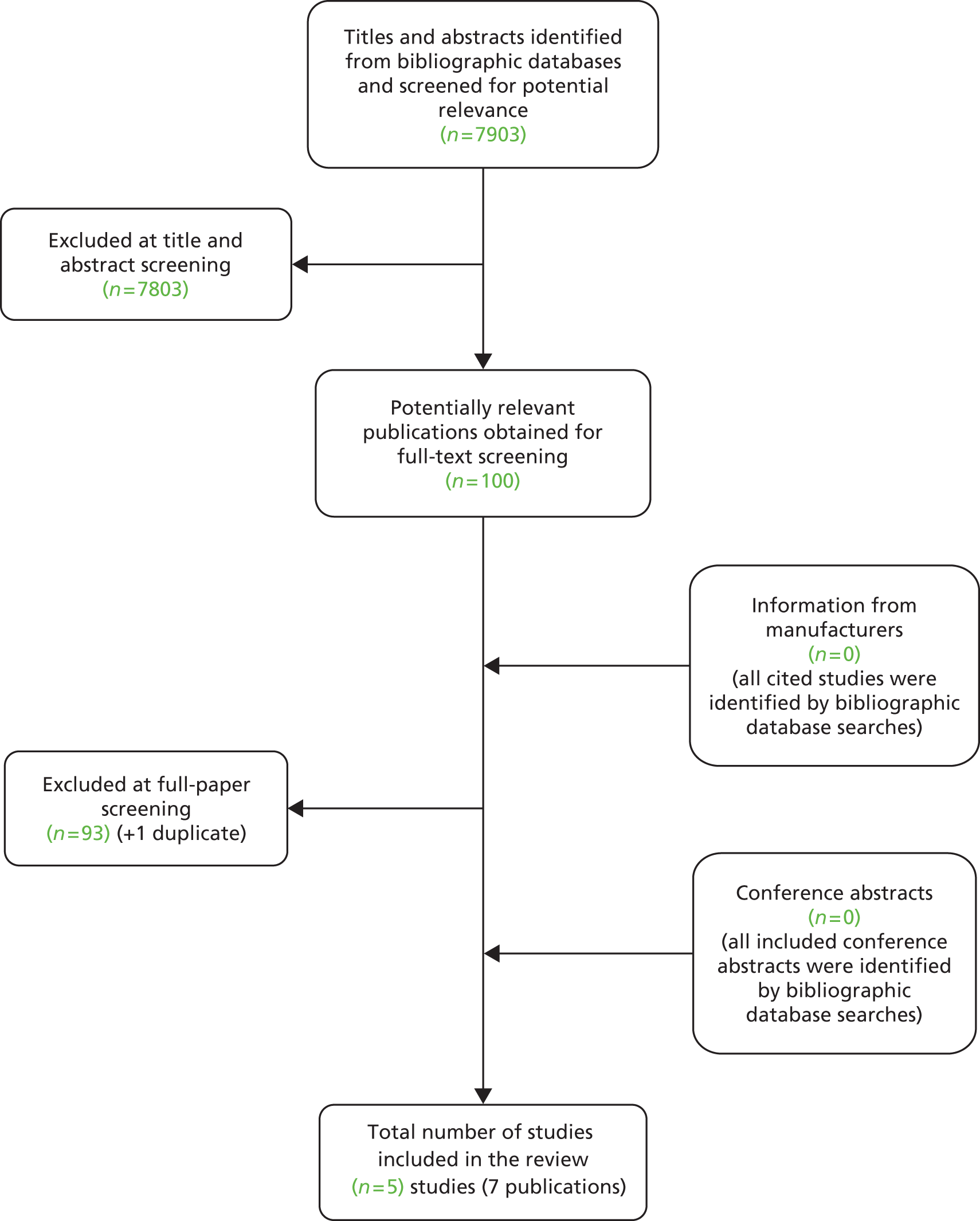

The literature searches of bibliographic databases identified 7903 references. After initial screening of titles and abstracts, 100 were considered to be potentially relevant and were ordered for full paper screening. No additional papers were ordered based on screening of papers provided by test manufacturers; all studies cited in documents supplied by the test manufacturers had already been identified by the bibliographic database searches. No additional studies were identified from searches of clinical trials registries or from hand searching of conference abstracts. Figure 1 shows the flow of studies through the review process and Appendix 5 provides details, with reasons for exclusions, of all publications excluded at the full paper screening stage.

FIGURE 1.

Flow of studies through the review process.

Based on the searches and inclusion screening described earlier, seven publications of five studies were included in the review. 27,28,52–56 Because data for participants with colorectal metastases and no extrahepatic metastases were frequently reported as subgroup analyses of larger trials, the authors of two additional potentially relevant trials in patients with mCRC were contacted to request subgroup data. The author of the Central European Cooperative Oncology Group (CECOG) trial57 reported that only 23 (15%) participants had metastases that were limited to the liver and that no subgroup data were available for these participants. The authors of the NORDIC-VII trial58 did not respond to our request.

No studies conducted in UK NHS laboratories were identified that reported information on the technical performance characteristics of KRAS mutation tests. One study52 reported data on tumour response following treatment with cetuximab plus FOLFOX6 or cetuximab plus FOLFIRI in a group of patients with unresectable colorectal liver metastases who were tested for tumour KRAS mutation status. This study provided information on the accuracy of the Therascreen KRAS PCR test for the prediction of response to treatment. Additional data, supplied by the COIN trial investigators, allowed calculation of accuracy for prediction of resection of liver metastases following treatment with cetuximab plus FOLFOX or XELOX, in which a combination of pyrosequencing and MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry was used to asses KRAS mutation status [D Fisher, Medical Research Council (MRC) Clinical Trials Unit, London, 19 April 2013, personal communication]. Four RCTs, reported in six publications,27,28,53–56 compared the effectiveness of cetuximab plus standard chemotherapy with that of standard chemotherapy alone in patients whose tumours were KRAS wild type. Because the method used to determine mutation status varied between trials, these RCTs provide some information on how clinical outcomes may vary according to which test is used to select patients for treatment.

All included studies were published in 2009 or later. The study providing information on test accuracy was a multicentre European study funded by Merck Serono, Sanofi Aventis and Pfizer. 52 Two of the four RCTs were multicentre European studies funded by Merck Serono,27,28,53,56 one was a multicentre study conducted in the UK and the Republic of Ireland and funded by the UK MRC54 and one was a single-centre study conducted in China and published as an abstract only (no funding details reported). 55

Full details of the characteristics of the study participants, study inclusion and exclusion criteria, KRAS mutation test used and mutations targeted, and treatment groups are reported in the data extraction tables presented in Appendix 2. For studies providing test accuracy data, full details of the KRAS mutation testing process are reported as part of the QUADAS-2 risk of bias assessment in Appendix 3.

What are the technical performance characteristics of the different KRAS mutation tests?

Literature review

No studies reporting the technical performance of KRAS mutation tests on clinical samples in UK laboratories were identified. Data on the technical performance characteristics of KRAS mutation tests, as experienced by UK laboratories, were therefore derived solely from the results of the online survey.

Laboratory survey results

A total of 31 laboratories participated in the 2012–13 UK NEQAS pilot scheme for KRAS mutation testing. The survey was completed by 21 laboratories; however, five of these were based outside the UK (Norway, Belgium, Switzerland, Italy and Ireland) and one was excluded as KRAS mutation testing was carried out for haematological malignancies only. Therefore, survey results were analysed for 15 laboratories (response rate 50%).

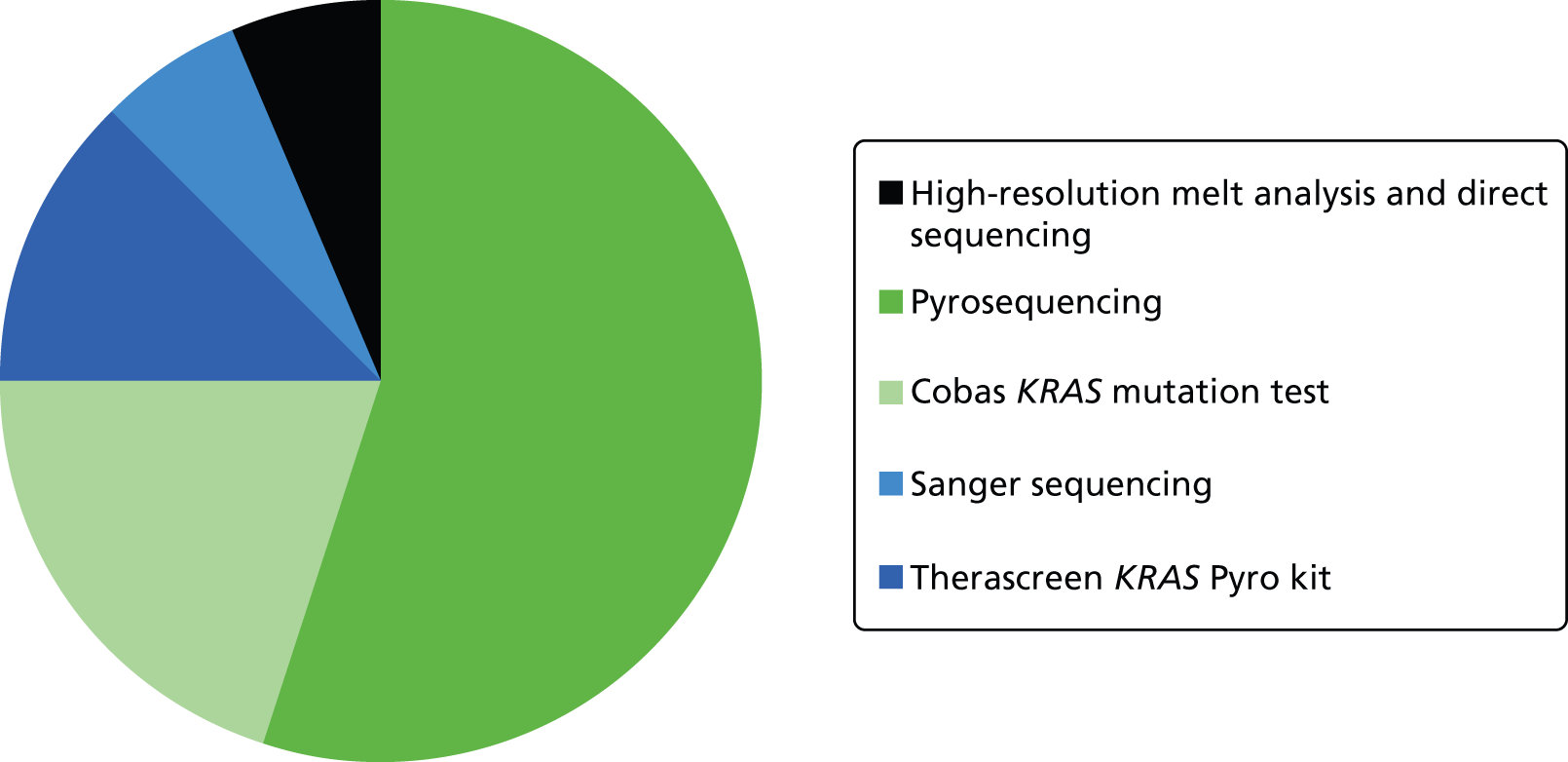

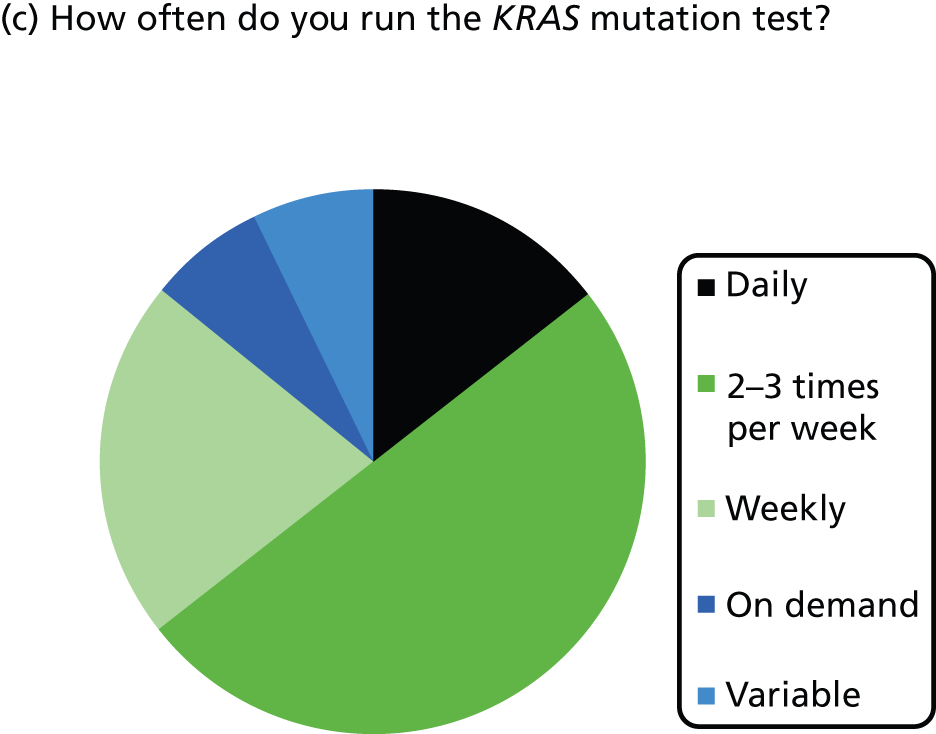

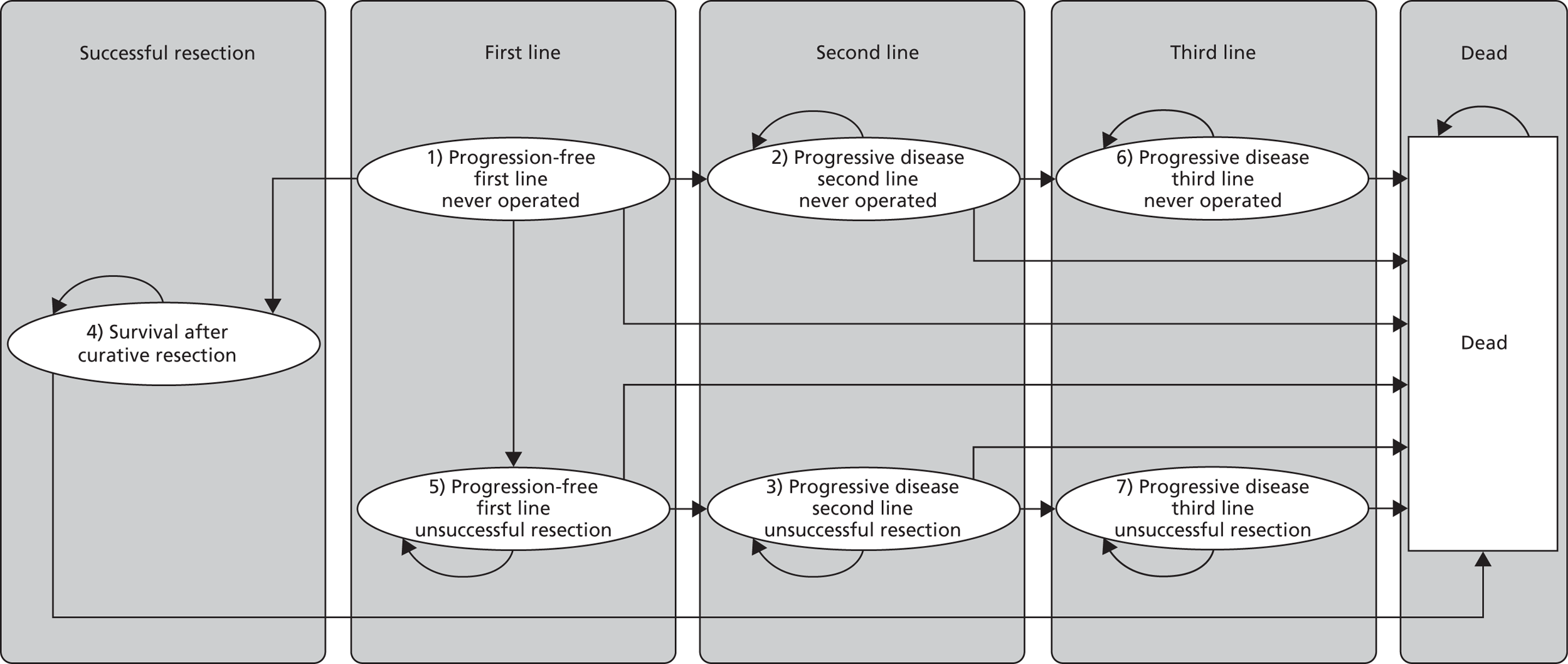

KRAS mutation test methods (Figure 2)

Fifteen laboratories stated that they used one method of KRAS mutation testing; one of these stated that they sometimes use a single KRAS mutation testing method and sometimes multiple methods (e.g. to confirm mutations).

FIGURE 2.

KRAS mutation tests used in NHS laboratories in the UK participating in the UK NEQAS pilot scheme for KRAS mutation testing.

Pyrosequencing, using in-house methods, was the most commonly used KRAS mutation test with nine laboratories using this approach, although one of the laboratories using pyrosequencing stated that it was in the process of switching to HRM analysis because of its quicker turnaround time. The cobas KRAS Mutation Test was used by three laboratories, Sanger sequencing was used by two laboratories and only a single laboratory used the Therascreen KRAS Pyro Kit. The final laboratory, which had initially reported using only a single method of KRAS mutation testing, stated that it used HRM analysis and direct sequencing. The laboratory that reported sometimes using multiple methods reported details for only one testing method (Sanger sequencing); however, this laboratory did state that it used Sanger sequencing in the event of an unusual pyrosequencing result. It also stated that its reason for using more than one testing method was the ability to fully characterise detected mutations. This suggests that its first choice method was in fact pyrosequencing not Sanger sequencing. This laboratory is therefore included in both methods in Figure 2 and the numbers above. All other laboratories stated that they used the reported KRAS mutation testing method for 100% of the samples.

Nine laboratories reported that samples were referred to their laboratory for testing on demand (one specified that this was MDT meetings, via pathologist, or oncologist), two reported mixed referral (some centres on demand, some all CRC samples), one laboratory reported that all resected primary CRC samples were sent for testing, one reported that samples were sent through clinical trials, one reported that all resected primary CRC plus metastatic samples were sent for testing and one laboratory did not answer this question.

The main reasons cited for choice of KRAS mutation testing method were mutation coverage (n = 13, 87%), ease of use (n = 12, 80%) and cost (n = 11, 73%). Nine laboratories (60%) also selected sensitivity (proportion of tumour cells required) and seven (47%) selected turnaround time. One laboratory did not answer this question. There was no apparent association between test method and reason for choice.

Of the eight laboratories that completed the questionnaire for pyrosequencing, all reported that they targeted mutations in codons 12, 13 and 61. Two of these laboratories reported that all mutations were targeted, one using commercial primers and one using self-designed primers. Two laboratories reported that they targeted specific mutations using self-designed primers. The others all used self-designed primers but did not state whether they targeted all or specific mutations; one laboratory stated that it also targeted mutations in codon 146. Two laboratories used Sanger sequencing. One stated that it targeted specific mutations but did not provide any further details. The other stated that it targeted mutations in codons 12, 13 and 61 using self-designed primers. One laboratory stated that it used a single testing method only, HRM analysis, and subsequently stated that it used HRM analysis and direct sequencing; mutations in codons 12, 13 and 61 and all mutations in exons 2 and 3 were targeted. Details on primers were not reported. The other four laboratories used commercial KRAS mutation testing kits.

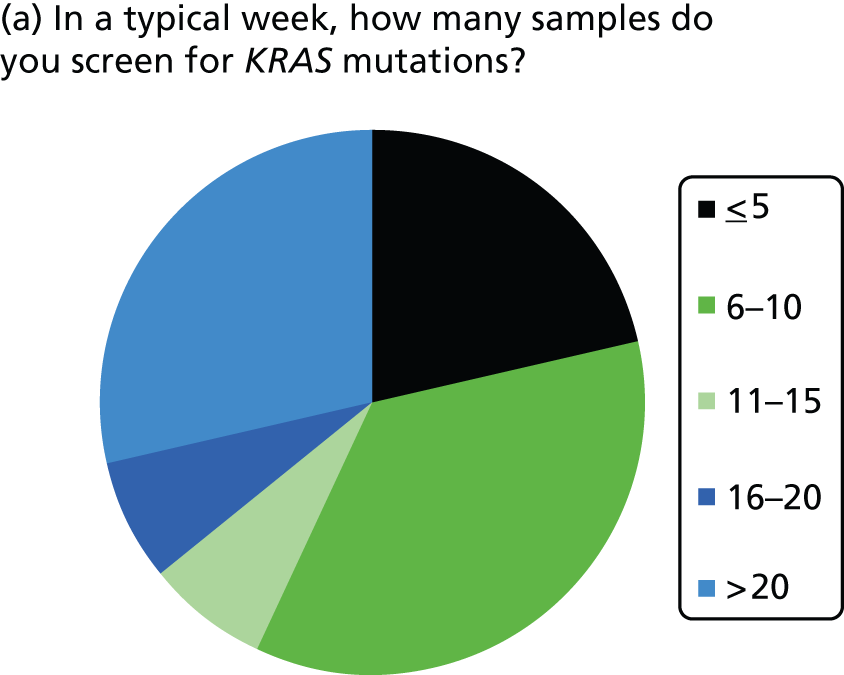

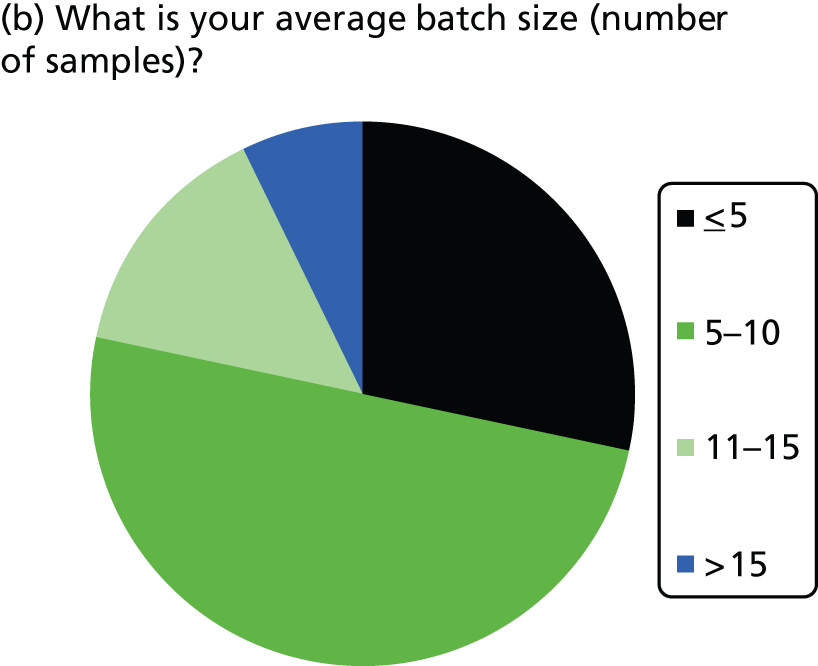

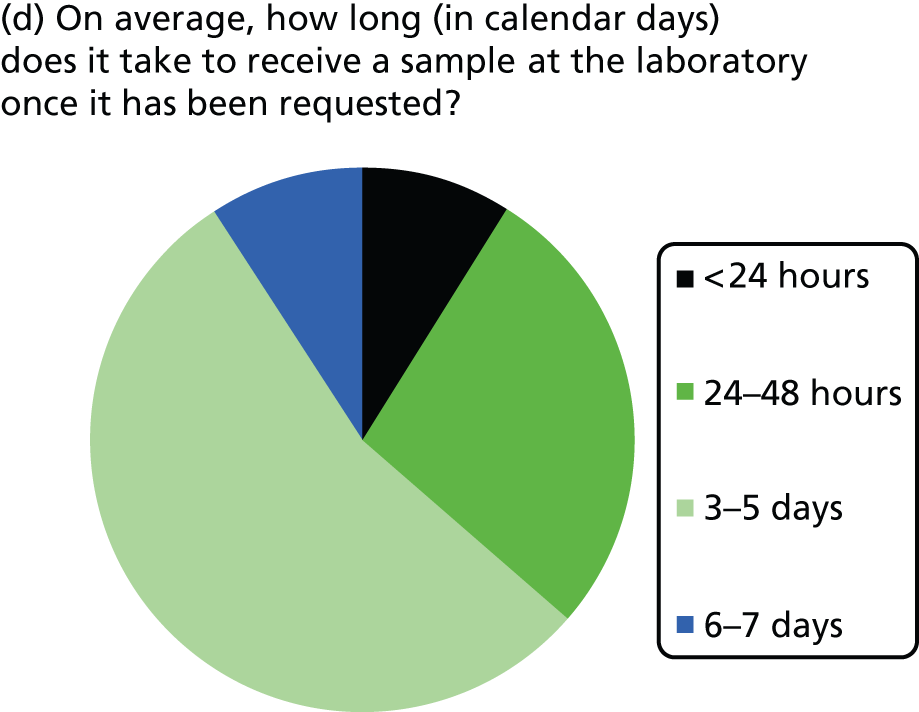

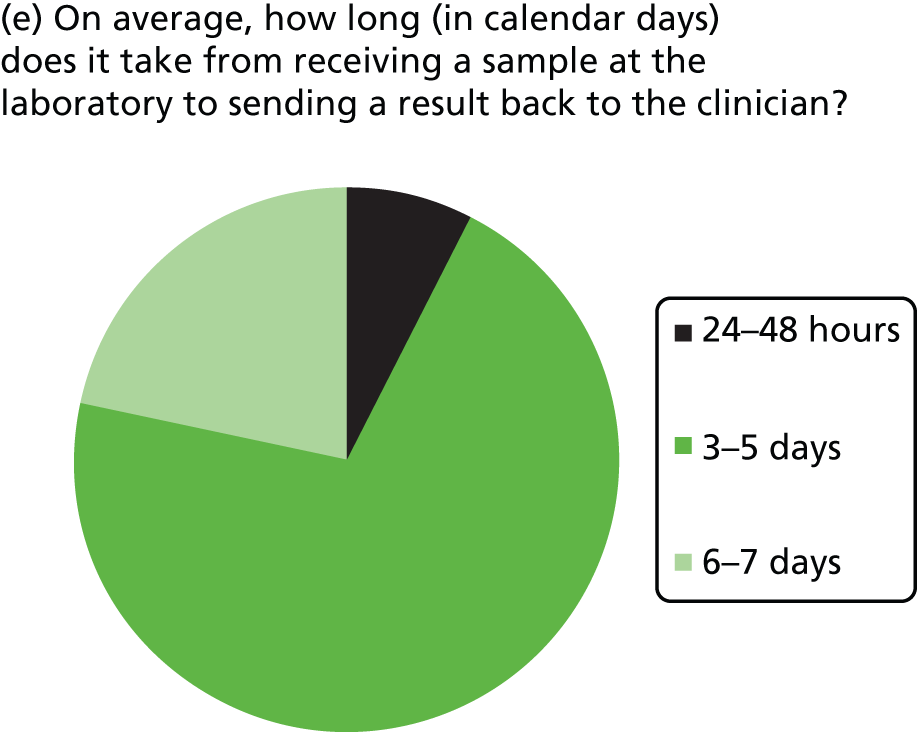

KRAS mutation test logistics (Table 3 and Figure 3)

The number of samples screened for KRAS mutations in a typical week varied by laboratory, from less than five (three laboratories) to > 20 (four laboratories). The batch size ranged from less than one to two to 15–20 samples. Only laboratories with five or less samples screened per week ran batches of three or less. Only one laboratory had a batch size of > 15 (reported as 15–20 samples per week) and this laboratory screened > 20 samples per week; most other laboratories had batch sizes between five and 10. The two laboratories using Sanger sequencing both reported screening five or less samples per week and reported batch sizes of one or two. Of the four laboratories using commercial kits, one did not report on number of samples screened or batch size, two reported screening > 20 samples per week with batch sizes of 10 and 15, and one reported screening 6–10 samples per week with a similar batch size. Only one laboratory reported that it waited until it had a certain number of samples before running the KRAS mutation test; this laboratory waited until it had 10 samples before running the test.

| KRAS mutation test | Samples per week | Batch size | Frequency of test | Wait for batch size? | Time from receiving sample to returning result to clinician |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| cobas KRAS Mutation Test Kit | 6–10 | 6–10 | Weekly | No | 6–7 days |

| > 20 | 10 | Two to three times per week | Yes, 10 | 3–5 days | |

| NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | |

| HRM analysis | 6–10 | 4 | Two to three times per week | No | 3–5 days |

| Pyrosequencing | ≤ 5 | 3 | On demand | No | 3–5 days |

| 6–10 | 6–10 | Weekly | No | 3–5 days | |

| > 20 | 15–20 | Two to three times per week | No | 3–5 days | |

| 6–10 | 8 | Weekly | No | 6–7 days | |

| 11–15 | 6–10 | Two to three times per week | No | 24–48 hours | |

| 16–20 | 10 | Two to three times per week | No | 3–5 days | |

| 6–10 | 5–10 | Two to three times per week | No | 3–5 days | |

| > 20 | 12 | Daily | No | 3–5 days | |

| Sanger sequencing | ≤ 5 | ≥ 1 | Daily | No | 3–5 days |

| ≤ 5 | 1–2 patients | Variable | No | 3–5 days | |

| Therascreen KRAS Pyro Kit | > 20 | 15 | Two to three times per week | No | 6–7 days |

FIGURE 3.

Summary of logistic information.

Most laboratories reported an average waiting time from requesting the sample for KRAS testing to receiving the sample in the laboratory of 24–48 hours (three laboratories) or 3–5 days (six laboratories), although one laboratory reported a waiting time of < 24 hours and one reported a waiting time of 6–7 days. The range in waiting times was reported by four laboratories and was 1–10 days in two and 2–30 days in one, with the fourth stating that occasionally request dates are included in referral and so the range is 1–3 weeks. Four laboratories did not report data on time to receive samples at the laboratory once the sample had been requested. The majority of laboratories had a turnaround time from receiving the sample to reporting the result to the clinician of 3–5 or 6–7 days, with only one laboratory reporting a time of 24–48 hours. The laboratory with the shortest turnaround time was one that used pyrosequencing and tested 11–15 samples per week.

KRAS mutation test technical performance (Table 4)

The minimum reported percentage of tumour cells required varied between laboratories (range < 1% to > 30%), even for those using the same KRAS mutation test. All laboratories using the cobas KRAS Mutation Test reported that the limit of detection was 1–5%; the limit of detection was reported to be either 1–5% (three laboratories) or 6–10% (five laboratories) for pyrosequencing, > 10% for Sanger sequencing and 1–5% for HRM. A variety of methods were used to determine the limit of detection. Ten laboratories reported using microdissection, with two stating that they always used this technique and others using microdissection at thresholds of < 10–50%. The laboratory that used the Therascreen KRAS Pyro Kit did not provide any data on technical performance.

| KRAS mutation test | Minimum tumour cells required (%) | Limit of detection (%) | How was limit of detection determined? | Use of microdissection? | Threshold below which microdissection used (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| cobas KRAS Mutation Test Kit | 1–5 | 1–5 | Manufacturer guidance | Yes | 10 |

| NR | 1–5 | In-house validation | No | NA | |

| 6–10 | 1–5 | Artificial blends of tumour DNA in normal DNA | Yes | 10–15 | |

| HRM analysis | 11–20 | 1–5 | Serial dilutions of control samples | No | NA |

| Pyrosequencing | >30 | 6–10 | Horizon Diagnostics reference standards | Yes | 50 |

| 11–20 | 6–10 | Spiking of wild-type DNA with mutant DNA | Yes | 20 | |

| 11–20 | 6–10 | Dilution series of known mutations at known percentage | Yes | Always | |

| 11–20 | 6–10 | Dilution series of DNA from three cell lines each with a different KRAS mutation | No | NA | |

| 6–10 | 1–5 | Cell lines with known mutations | Yes | 20; all samples that contain adenoma or when dissection would greatly improve the tumour percentage | |

| 21–30 | 1–5 | CE-marked kit, in-house validation conducted | Yes | 20 | |

| 21–30 | 6–10 | Internal quality control | Yes | Always | |

| 6–10 | 1–5 | Cell lines with set percentage tumour burden | Yes | 50 | |

| Sanger sequencing | > 30 | > 10 | Cell line with known mutation | Yes | 30 |

| ≤ 1 | > 10 | Cell line control | No | NA | |

| Therascreen KRAS Pyro Kit | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR |

KRAS mutation test failure rates (Table 5)

The proportion of samples rejected before analysis was < 2% for all 13 laboratories that provided data on rejection rates. Reasons for rejection included insufficient tumour cells/tissue, sample type unsuitable for analysis and insufficient patient identifiers. The proportion of failed tests ranged from 3% to 6% for the cobas KRAS Mutation Test Kit and from 0.2% to 10% for pyrosequencing. The one laboratory using HRM analysis reported no failed tests and of the two laboratories using Sanger sequencing one reported no failed tests and the other did not provide information on the number of failed tests. Reasons for test failure included insufficient DNA, amplification failure, DNA degradation/quality, insufficient tumour cells and poor fixation. The laboratory that used the Therascreen KRAS Pyro Kit did not provide any data on failure rates.

| KRAS mutation test | No. of samples per yeara | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Submitted, n | Rejected, n (%) | Reason for rejection | Analysed, n | Failed, n (%) | Reason for failure | |

| cobas KRAS Mutation Test Kit | NR | NR | NR | 1000 | 29 (3) | Various, most commonly DNA yield too low |

| 1358 | 7 (0.5) | Sample type unsuitable for analysis, insufficient identifiers | 1351 | 86 (6) | Insufficient extracted DNA (8%), amplification failure (92%) | |

| 1058 | 5–10 (0.7) | Insufficient tumour cells | 1058 | 28 (3) | Insufficient tumour cells, DNA degradation | |

| HRM analysis | 1000 | 0 | NA | 1000 | 0 | NA |

| Pyrosequencing | 9 | 0 | NA | 9 | 0 | NA |

| 1000 | < 10 (< 1) | Insufficient tissue left in the block | 1000 | 100 (10) | NR | |

| 1500 | 15–20 (1.5) | Insufficient tumour cells | NR | NR (1) | Assumed to be because of fixation and DNA degradation | |

| 415 | 3 (0.7) | Insufficient tumour cells | 412 | 1 (0.2) | DNA quality | |

| 374 | 0 | NA; samples preselected by laboratory | 374 | 10–20 (4) | Poor fixation | |

| 1000 | 0 | NA | 1000 | 4 (0.4) | Unknown | |

| 1000 | 10 (1) | Insufficient tumour cells, unsuitable sample type | 1000 | 50 (5) | Insufficient tumour cells, DNA degradation | |

| 1736 | ∼20 (1) | Insufficient tumour cells, insufficient tissue | 1736 | ∼30 (2) | Insufficient tumour cells, DNA degradation | |

| Sanger sequencing | 65 | 0 | NA | 65 | 0 | NA |

| 1000 | 0 | NA | 1000 | NA | Insufficient tumour cells, DNA degradation | |

| Therascreen KRAS Pyro Kit | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR |

KRAS mutation test costs (Table 6)

Only seven laboratories provided data on the cost of the KRAS mutation test. Two of these provided data on the costs of the reagents only, which were reported as £22 for Sanger sequencing and approximately £50 for pyrosequencing. A further laboratory also reported that the cost of pyrosequencing was £50. Three other laboratories reported costs for pyrosequencing, with one reporting a cost of £150, one reporting a cost of approximately £120 and the other reporting a cost of approximately £273 for a single sample, which reduced to approximately £110 per sample if running a batch of 10. The final laboratory to report cost data reported that the cost of the cobas KRAS Mutation Test Kit was £100–125. With the exception of two laboratories, all laboratories received some funding from Merck Serono. One laboratory did not provide any details on test costs or funding. The price charged to both the NHS and Merck Serono ranged from £99 to £150 per sample.

| KRAS mutation test | Cost to laboratory (£) | Funding | NHS price (£) | Merck Serono price (£) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| cobas KRAS Mutation Test Kit | NR | Merck Serono | NA | NR |

| NR | Merck Serono, private | NA | NR | |

| 100–125 | Merck Serono, private | NA | Unable to disclose | |

| HRM analysis | NR | Merck Serono | NA | NR |

| Pyrosequencing | 150 | NHS, privately funded from abroad | 150 | NA |

| NR | Merck Serono, NHS | 140 | 100 | |

| ∼120 | Merck Serono, Cancer Research UK Stratified Medicine programme | 99 | 99 | |

| NR | Merck Serono | NA | 100 | |

| ∼273 for a single sample, ∼110 if running a batch of 10 | Merck Serono | NA | 150 | |

| ∼50 (reagents only) | Merck Serono | NA | 100 | |

| 50 | Trials unit | NA | NA | |

| NR | Merck Serono, NHS, private | 120 | 120 | |

| Sanger sequencing | 22 (reagents only) | Merck Serono | NA | 100 |

| NR | Merck Serono | NR | NR | |

| Therascreen KRAS Pyro Kit | NR | NR | NR | NR |

What is the accuracy of KRAS mutation testing for predicting response to treatment with cetuximab plus standard chemotherapy and subsequent resection rates?

One study, the CELIM trial,52 reported sufficient data to allow calculation of the accuracy of KRAS mutation testing for predicting response to treatment in patients with colorectal liver metastases who are treated with cetuximab plus FOLFOX6 or cetuximab plus FOLFIRI. This study is potentially useful in that it could provide full information on the extent to which KRAS mutation tests are able to discriminate between patients who will have benefit from the addition of cetuximab to standard chemotherapy regimens and those who will not. The utility of the study for this assessment is limited because reporting of outcome data by mutation status was limited to objective response. Thus, we defined TPs as those patients with KRAS wild-type tumours who have a positive response to treatment with cetuximab plus FOLFOX6 or cetuximab plus FOLFIRI (best observed response = CR or PR). FPs were defined as those patients with KRAS wild-type tumours who did not have a positive response to treatment with cetuximab plus FOLFOX6 or cetuximab plus FOLFIRI (SD or PD). FNs were defined as those with KRAS mutant tumours who had a positive response to treatment with cetuximab plus FOLFOX6 or cetuximab plus FOLFIRI. TNs were defined as those with KRAS mutant tumours who did not have a positive response to treatment with cetuximab plus FOLFOX6 or cetuximab plus FOLFIRI. Full definitions of CR, PR, SD and PD are provided in Chapter 2 (see Measuring response to treatment). The publication of the results of the CELIM trial included resection rates for liver metastases; however, these data were reported for all participants and by treatment group (cetuximab plus FOLFOX6 or cetuximab plus FOLFIRI) only and not by tumour KRAS mutation status. 52 For all study participants, the R0 resection rate was 36/106 (34%, 95% CI 25% to 44%) and the R0/R1 resection and/or radiofrequency ablation rate was 49/106 (46%, 95% CI 36% to 56%). 52 (Commercial-in-confidence information has been removed.)59 All participants in the CELIM trial received treatment with cetuximab in addition to standard chemotherapy; therefore, this trial could not contribute data to question 3 on how outcomes from treatment with cetuximab plus standard chemotherapy vary according to which test is used to select patients for treatment.

Additional data, supplied by the COIN trial investigators,54 allowed calculation of the accuracy of KRAS mutation testing, using a combination of pyrosequencing and MALDI-TOF and targeting mutations in codons 12, 13 and 61, for predicting response to treatment in patients with colorectal liver metastases who are treated with cetuximab plus FOLFOX or XELOX. These data could be viewed as being of limited applicability to this assessment because the standard chemotherapy regimen used in the COIN trial does not exactly match that in our inclusion criteria (some participants received XELOX rather than FOLFOX or FOLFIRI). However, the additional data supplied did allow the calculation of accuracy with respect to prediction of the more clinically relevant outcome of potentially curative resection. In this case we defined TPs as those patients with KRAS wild-type tumours who had a potentially curative resection following treatment with cetuximab plus FOLFOX or cetuximab plus XELOX. FPs were defined as those patients with KRAS wild-type tumours who did not have a potentially curative resection following treatment with cetuximab plus FOLFOX or cetuximab plus XELOX. FNs were defined as those with KRAS mutant tumours who had a potentially curative resection following treatment with cetuximab plus FOLFOX or cetuximab plus XELOX. TNs were defined as those with KRAS mutant tumours who did not have a potentially curative resection following treatment with cetuximab plus FOLFOX or cetuximab plus XELOX.

Study details

Participants in the CELIM trial52 all had unresectable colorectal liver metastases with no extrahepatic metastases. Non-resectability was defined as five or more liver metastases or metastases that were viewed as technically non-resectable by a liver surgeon and a radiologist on the basis of inadequate future remnant, infiltration of all hepatic liver veins, infiltration of both hepatic arteries or infiltration of both portal veins. Study participants had a median age of 64 years [interquartile range (IQR) 56 to 71] and 64% were male. The primary tumour site was the colon in 61 (55%) participants and the rectum in 49 (44%) participants; the primary site was unknown in one participant. Most patients (83%) had a primary tumour of stage T3/4. The primary reason for non-resectability of liver metastases was given as ‘technically unresectable’ for 61 (55%) participants and ‘five or more metastases’ for 50 (45%) participants. Full details of the study participants are reported in Appendix 2.

KRAS mutation testing used an older version of the Therascreen KRAS RGQ PCR Kit, which is identical to the current Therascreen KRAS RGQ PCR kit in terms of mutations targeted. Both versions of the kit detected seven mutations in codons 12 and 13 (Table 7) and the two versions will be treated as equivalent for the purpose of this assessment.

| Codon | Coding DNA | Protein/amino acid, three-letter code | Protein/amino acid, one-letter code |

|---|---|---|---|

| 12 | c.34G > A | p.Gly12Ser | p.G12S |

| c.34G > C | p.Gly12Arg | p.G12R | |

| c.34G > T | p.Gly12Cys | p.G12C | |

| c.35G > A | p.Gly12Asp | p.G12D | |

| c.35G > C | p.Gly12Ala | p.G12A | |

| c.35G > T | p.Gly12Val | p.G12V | |

| 13 | c.38G > A | p.Gly13Asp | p.G13D |

Tumour response was assessed according to the RECIST criteria38 to evaluate response to EGFR inhibitor treatment; response was defined as the best response to treatment with cetuximab plus FOLFOX6 or cetuximab plus FOLFIRI observed during treatment and was assessed every four cycles (8 weeks). Post-treatment surgical review, to assess resectability, was undertaken after eight cycles of chemotherapy by senior surgeons with experience in hepatobiliary surgery; CT and MRI scans were presented by a radiologist and the surgeons were blinded to when the scans were carried out and the participants’ clinical outcome data. 52

Details of the COIN trial54 are provided in ‘How do outcomes from treatment with cetuximab plus standard chemotherapy vary according to which test is used to select patients for treatment?’

KRAS mutation test accuracy

Data from the CELIM trial52 provided estimates for the accuracy of the Therascreen KRAS RGQ PCR Kit for discriminating between patients who are likely to benefit from addition of cetuximab to standard chemotherapy regimens and those who are not. Sensitivity for the prediction of objective response was moderate (74.6%, 95% CI 62.1% to 84.7%) and specificity was poor (35.5%, 95% CI 19.2% to 54.6%) (Table 8 and Figure 4). Additional data supplied by the COIN trial investigators allowed the calculation of estimates for the accuracy of pyrosequencing and MALDI-TOF, targeting mutations in codons 12, 13 and 61, for predicting potentially curative resection following treatment with cetuximab plus FOLFOX or XELOX (D Fisher, personal communication). Sensitivity and specificity were both poor at 52.0% (95% CI 31.3% to 72.2%) and 45.6% (95% CI 37.0% to 54.3%) respectively (see Table 8 and Figure 4).

| Study | KRAS mutation test method and mutations targeted | Non-evaluable samples | Reference standard | TP | FP | FN | TN | Sensitivity (95% CI) (%) | Specificity (95% CI) (%) | Prevalence (%) | PPV (95% CI) (%) | NPV (95% CI) (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Folprecht 201052 (CELIM) | Therascreen KRAS RGQ PCR Kit | 12/111 unknown mutation status (KRAS mutation testing not carried out successfully, no reasons reported) | Objective response | 47 | 20 | 16 | 11 | 74.6 (62.1 to 84.7) | 35.5 (19.2 to 54.6) | 67 | 70.1 (58.3 to 79.8) | 40.7 (24.5 to 59.3) |

| COINa | Pyrosequencing and MALDI-TOF (codons 12, 13 and 61) | Resection rate | 13 | 74 | 12 | 62 | 52.0 (31.3 to 72.2) | 45.6 (37.0 to 54.3) | 16 | 14.9 (8.9 to 23.9) | 83.9 (73.8 to 90.5) |

FIGURE 4.

Summary receiver operating characteristic plot showing estimates of sensitivity and specificity together with 95% CIs from the CELIM trial52 (black lines) and the COIN trial (green lines) (D FIsher, personal communication).

Quality Assessment of Diagnostic Accuracy Studies assessment

A summary of the results of the QUADAS-2 assessments for the CELIM and COIN trails are presented in Table 9 and the full assessments are reported in Appendix 3. The rating of high concern regarding the applicability of the reference standard reflects the absence of data on the ability of the test (KRAS mutation status) to predict resection of liver metastases following treatment with cetuximab plus FOLFOX6 or cetuximab plus FOLFIRI for the CELIM trial, and the use of standard chemotherapy in the COIN trial that did not fully match that in the inclusion criteria for this assessment. In addition, participants in the CELIM trial were described as having technically non-resectable or five or more liver metastases from CRC and it was therefore unclear whether some participants may have had potentially resectable metastases at baseline. 52 Both studies were rated as being at high risk of bias with respect to flow and timing because approximately 15% of participants were excluded from the analyses, in most cases because they were not evaluable for response.

How do outcomes from treatment with cetuximab plus standard chemotherapy vary according to which test is used to select patients for treatment?

Four RCTs (six publications)27,28,53–56 provided data on the clinical effectiveness of cetuximab plus standard chemotherapy compared with standard chemotherapy alone in patients with colorectal liver metastases and no extrahepatic metastases whose tumours were KRAS wild type. The trials compared cetuximab in combination with standard chemotherapy (FOLFOX or FOLFIRI) with standard chemotherapy alone (see Table 11); in one trial54 standard chemotherapy could be either FOLFOX or XELOX. One trial55 included only participants with unresectable colorectal liver metastases and no extrahepatic metastases whose tumours were KRAS wild type. This trial was reported as a conference abstract only and some additional information on this trial was derived from the trial registry entry. 60 The remaining three trials, CRYSTAL,27,53 OPUS28,53,56 and COIN54 (five publications), included participants with mCRC, conducted tumour KRAS mutation testing in a subgroup of these participants and reported data for a smaller subgroup of participants whose metastases were confined to the liver; in all cases outcome data on participants whose metastases were confined to the liver were reported only for those with KRAS wild-type tumours.

Study details

Participant characteristics varied across studies. The three studies that reported subgroup data for patients with colorectal metastases confined to the liver were multicentre studies conducted in continental Europe27,28,53,56 or the UK and the Republic of Ireland. 54 The subgroup data taken from these studies represented between 11% and 14% of the total study population (see Table 11). None of the studies reported separate participant characteristics for the relevant subgroup and none reported the criteria used to define unresectable liver metastases. For the larger KRAS wild-type subgroup, study participants were similar across the three studies. The median age of study participants was 61–62 years and 54–68% of participants were male. More than 90% of participants in all three studies had an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) or a WHO performance status of 0 or 1 and two27,53,54 out of three studies included only participants with histologically confirmed adenocarcinoma. The trial that included only participants with unresectable colorectal liver metastases and no extrahepatic metastases whose tumours were KRAS wild type was reported as an abstract only and did not provide any further details of participant characteristics. 55 The trial registry entry specified histologically confirmed adenocarcinoma and ECOG performance status of 0 or 1 as inclusion criteria. 60 Full details of study participants are reported in Appendix 2.

The included trials used various methods to assess KRAS mutation status. The CRYSTAL27 and OPUS28 trials both used the LightMix k-ras Gly12 assay (TIB MOLBIOL). PCR reactions were performed on a LightCycler 2.0 system using a KRAS mutation detection-specific program. The LightMix k-ras Gly12 assay detects nine mutations in codons 12 and 13 (Table 10).

| Codon | Coding DNA | Protein/amino acid, three-letter code | Protein/amino acid, one-letter code |

|---|---|---|---|

| 12 | c.34G > A | p.Gly12Ser | p.G12S |

| c.34G > C | p.Gly12Arg | p.G12R | |

| c.34G > T | p.Gly12Cys | p.G12C | |

| c.35G > A | p.Gly12Asp | p.G12D | |

| c.35G > C | p.Gly12Ala | p.G12A | |

| c.35G > T | p.Gly12Val | p.G12V | |

| c.[34G > A; 35G > C] | p.Gly12Thr | p.G12T | |

| 13 | c.37G > T | p.Gly12Cys | p.G13C |

| c.38G > A | p.Gly13Asp | p.G13D |

The COIN trial54 used pyrosequencing of KRAS codons 12, 13 (amplification primers 5′-GGCCTGCTGAAAATGACTGA-3′ and 5′-AGAATGGTCCTGCACCAGTAATA-3′ and extension primers 5′-TGTGGTAGTTGGAGCTG-3′, 5′-TGTGGTAGTTGGAGCT-3′ and 5′-TGGTAGTTGGAGCTGGT-3′) and 61 (amplification primers 5′-CTTTGGAGCAGGAACAATGTC-3′ and 5′-CTCATGTACTGGTCCCTCATTG-3′ and extension primer 5′-ATTCTCGACACAGCAGGT-3′) together with MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry. The MALDI-TOF genotyping assay was designed using the Sequenom MassARRAY Assay Design 3.1 software (Sequenom Inc., San Diego, CA, USA) and 200 base pairs of sequence upstream and downstream of each known mutation (known mutations taken from the Catalogue of Somatic Mutations in Cancer (COSMIC) database; see www.sanger.ac.uk/genetics/CGP/cosmic). For discordant results (< 1%), Sanger sequencing of KRAS codons 12, 13 (primers 5′-AAAAGGTACTGGTGGAGTATTTGA-3′ and 5′-CATGAAAATGGTCAGAGAAACC-3′) and 61 (primers 5′-CTTTGGAGCAGGAACAATGTC-3′ and 5′-CTCATGTACTGGTCCCTCATTG-3) was undertaken. The final trial55 used pyrosequencing to identify mutations in KRAS codons 12 and 13 (information supplied in personal communication from the study author).