Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 09/104/16. The contractual start date was in September 2011. The draft report began editorial review in September 2014 and was accepted for publication in April 2015. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

P Ronan O’Connell reports a contract research agreement with Medtronic to study neuromodulation in an animal model of faecal incontinence. Sandra Eldridge reports grants from Queen Mary University of London during the conduct of the study.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2015. This work was produced by Horrocks et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Introduction

Background

Faecal incontinence (FI) poses a significant UK public health problem. Its prevalence is difficult to accurately assess, although the best studies estimate this at 11–15% in the adult population1 and as high as 50% in care homes. 2,3 As prevalence and severity increase with age,4 FI is expected to become a greater problem in an increasingly aged population. It is known to be an under-reported problem, with many symptomatic patients suffering in silence. 5–8 FI has a significant impact on quality of life, causing social and psychological disability,9,10 and often leads to people suffering from stigmatisation and social exclusion. 5,11,12 The attendant socioeconomic burden of FI is high not only because of the cost of health-care utilisation, but also because of job absenteeism. 13,14

Management of faecal incontinence

Management of FI is challenging because of a widespread lack of expertise, high prevalence and multiple aetiologies. Initial management involves a tailored stepwise approach, beginning with more conservative strategies (diet, toilet training and medications) and moving on to appropriate nurse-led bowel retraining programmes and psychosocial support. Combinations of these treatments often prove effective;15,16 however, many patients suffer refractory symptoms, for which the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence recommends moving to more invasive measures. 17 Depending on local expertise, surgery – for example sphincter repair, artificial sphincter, dynamic graciloplasty or a permanent stoma – may be the only option for these patients. Surgical procedures are invasive and have, at best, variable success rates with significant risk of morbidity. 18–21

Neuromodulation is a relatively new treatment modality for FI which is bridging the gap between conservative strategies and invasive surgery in centres where expertise exists. It is based on recruitment of residual anorectal neuromuscular function pertinent to continence by electrical stimulation of the peripheral nerve supply, without the need for surgery to the anus itself.

Sacral nerve stimulation (SNS) employs direct electrical stimulation to the sacral nerve roots (mainly the S3 nerve root) and is a safe, effective treatment for FI, with short-, medium- and long-term median success rates reported as 63% (range 33–66%), 58% (range 52–81%) and 54% (range 50–58%) respectively. 22–28 SNS has become the first-line surgical treatment option for FI. 17 Despite largely favourable data, SNS requires two operations and is not without risk of morbidity. 29 Although it is cost-effective compared with other surgical options,30 SNS does have high associated costs, recently estimated as £20,484 for the first 10 years of a patient’s treatment,31,32 because of the combination of equipment, hospital admission and ongoing care.

Tibial nerve stimulation in faecal incontinence

Tibial nerve stimulation is a minimally invasive neuromodulatory modality. The tibial nerve contains afferent and efferent fibres originating from the fourth and fifth lumbar and first, second and third sacral nerves. Thus, stimulation of the tibial nerve is thought to lead to similar changes in anorectal neuromuscular function as observed with SNS (owing to shared sacral root effects) but without the need for a permanent surgically implanted device. Tibial nerve stimulation (TNS) is an outpatient treatment, which can be delivered by any trained health-care professional, and is consequently much cheaper than SNS. Initially described for urinary incontinence,33 TNS was first used for FI in 2003. 34 Since then, there have been several publications regarding the use of TNS to treat FI. Two main delivery methods are described:

-

Percutaneous tibial nerve stimulation (PTNS) involves electrical stimulation via a needle placed adjacent to the tibial nerve just above the ankle. This is delivered via the Urgent® PC neuromodulation system (Uroplasty Limited, Manchester, UK). Treatment is typically delivered as 12 30-minute treatments, given either weekly for 12 weeks or twice-weekly for 6 weeks.

-

Transcutaneous tibial nerve stimulation (TTNS) involves electrical stimulation which is delivered via two-pad electrodes placed over the tibial nerve just above the ankle. This is usually delivered via a transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS) machine. Treatment regimens vary considerably, although administration is usually in 20- to 30-minute sessions over a period of weeks or months.

The main advantage of PTNS over TTNS is the proximity of the needle to the tibial nerve, enabling higher treatment amplitude to be delivered while avoiding the painful skin sensations associated with transcutaneous treatment.

Evidence for percutaneous tibial nerve stimulation in faecal incontinence

Published studies of PTNS include nine case series34–42 (one study34 included a ‘control’ group for comparison), one small single-centre randomised single-blind trial (PTNS vs. TTNS vs. sham),43 one comparative case-matched study (PTNS vs. SNS)44 and one prospective clinical audit with a ‘pseudo’ case–control model (PTNS vs. SNS). 31 A recent review by the authors summarises the results. 45 Five publications are from the same institution and report results from an accumulating database. Interpretation and comparison of these studies is hampered by a lack of standardised and universally accepted outcome measures, observer and patient blinding, performance and interpretation bias and attrition bias.

When considering data from bowel diaries to assess treatment success (the most universally accepted method in the SNS literature), two studies39,43 reported that 63% and 82% of patients had a ≥ 50% reduction in the weekly number of faecal incontinence episodes (FIEs) immediately after treatment. Two studies reported longer-term follow-up, with 59% of patients experiencing treatment success after 1 year39 and 53% at a median of 22 months,42 based on the same outcome measure. When considering FIEs as a count, six studies1–3,6,8,9 reported this outcome, with a median reduction from five episodes to one per week immediately following treatment (a statistically significant reduction in three of these studies36,38,42) and a median reduction from six episodes to one in the two studies that reported this outcome in the longer term (at 1 year39 and at a median of 29 months42), which led to a statistically significant reduction in both.

The randomised single-centre study of PTNS versus TTNS versus sham treatment in 30 patients43 reported that 82% of patients in the PTNS group, 45% of patients in the TTNS group and 13% of those in the sham group had ≥ 50% reduction in the weekly number of FIEs immediately after treatment. This was statistically significant across all groups (p = 0.035).

In summary, the observational studies of PTNS showed improvements in most outcome measures (bowel diary, Cleveland Clinic Incontinence Score and quality-of-life measures) after treatment compared with baseline. A small three-arm RCT of PTNS versus TTNS versus sham showed effects of both treatments over sham, with PTNS appearing superior. 45

It seems that PTNS may offer a low-cost (estimated at £5916 for the first 10 years based on 6-monthly ‘top-up’ sessions)31 minimally invasive outpatient technique with almost no associated morbidity. 46 If this is true, and PTNS offers similar efficacy to SNS, PTNS may be considered as a genuinely new option in the pathway between conservative management and the more invasive surgical procedure of SNS.

Limitations of the current published evidence for percutaneous tibial nerve stimulation in faecal incontinence

To our knowledge, no double-blind placebo-controlled trial of PTNS in patients with FI has been performed. Thus, notably, the effect of PTNS in FI, over and above that of meetings with a nurse specialist alone, remains unknown. This is important because:

-

PTNS is available in several centres in the UK and, although much cheaper than SNS, there is still a cost associated with its use. Increasing numbers of centres are using it, but many are doing so with speculation that it is little more than an expensive form of acupuncture.

-

The possible placebo effect of PTNS should not be underestimated:

-

High placebo responses are almost universally observed in trials of therapy for functional47,48 and organic48,49 colorectal diseases.

-

Therapeutic responses have been achieved by acupuncture alone in FI,50 noting that the medial ankle is an established acupuncture site for the viscera (‘sanyinjiao’ or ‘spleen 6’).

-

Regular meetings with a specialist nurse may confer some benefit even without formal bowel retraining. 51

-

-

The influence of unblinded observers, especially when interpreting bowel diary data, is also a potential source of bias.

Study aims

We aimed to assess the clinical effect of PTNS, compared with sham electrical stimulation, in the treatment of patients with significant FI in whom conservative management strategies have already failed.

We also planned to test the effect of PTNS versus sham electrical stimulation on:

-

improvements in validated incontinence scores

-

patient-centred FI-related symptoms

-

disease-specific and generic quality-of-life measures.

Hypothesis

A 12-week course of PTNS results in a clinical response rate of 55% compared with a sham response rate of 35%, with clinical response defined as a reduction in the weekly number of FIEs of ≥ 50%.

Chapter 2 Methods

Overview: study design

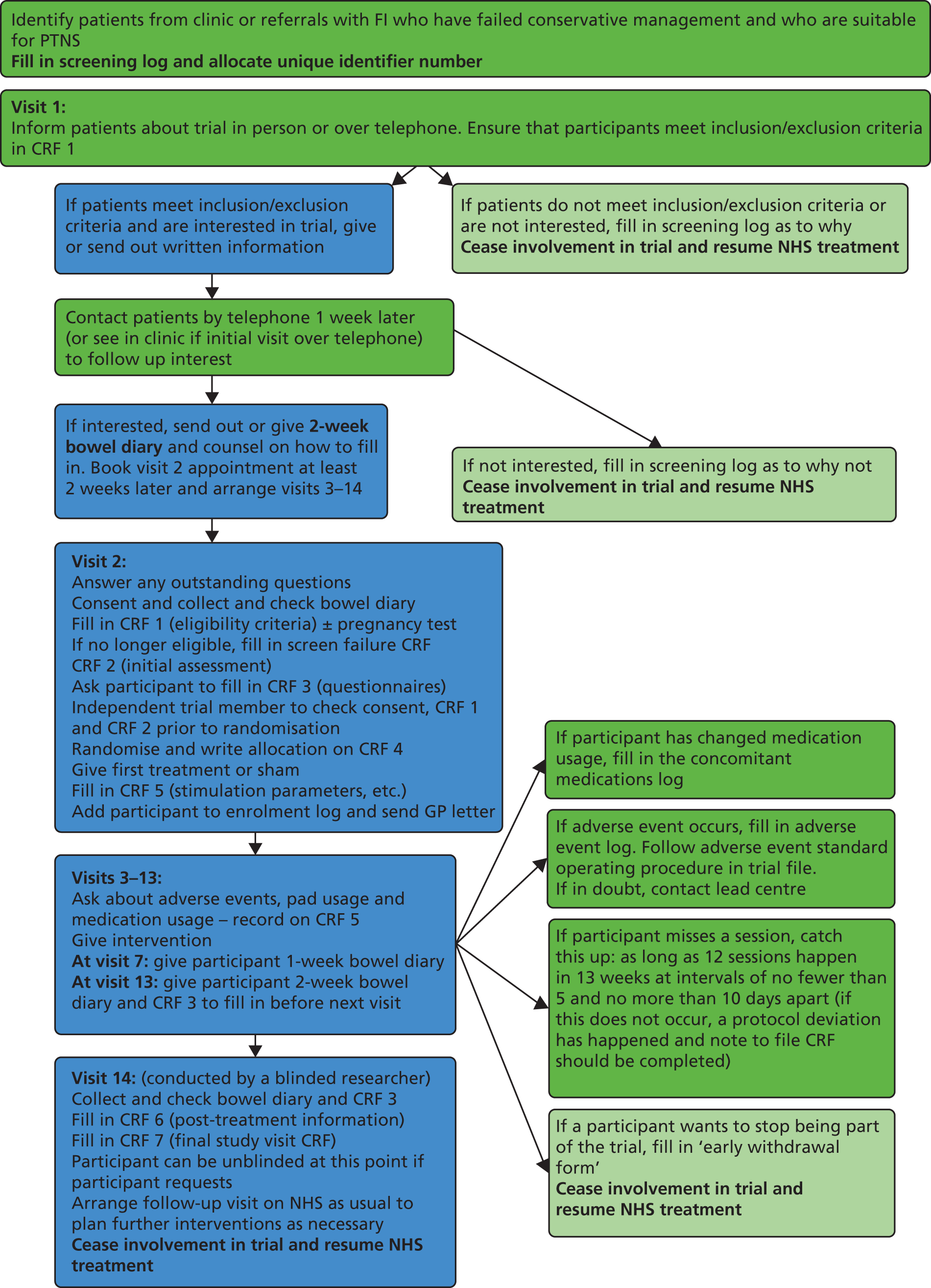

The CONFIDeNT (CONtrol of Faecal Incontinence using Distal NeuromodulaTion) study was a UK-based multicentre, pragmatic, parallel-arm, double-blind, randomised controlled trial comparing PTNS with sham electrical stimulation, with equal allocation, stratified by sex and centre, in the treatment of FI, and assessing outcomes following a standard 12-week treatment schedule. The detailed trial protocol is available to view online (www.nets.nihr.ac.uk). The study method is summarised in a flow diagram (see Appendix 1). Events occurring at each visit are detailed in Appendix 2. All case report forms used can be seen in Appendix 3.

Study outcomes

Clinical outcomes

These were assessed at baseline (prior to therapy) and 2 weeks following completion of a 12-week course of treatment. Clinical outcomes were derived from 2-week bowel diaries and a series of validated, investigator-administered questionnaires.

Primary

Responder versus non-responder: responder defined as a patient achieving ≥ 50% reduction in total FIEs per week, as recorded on a 2-week self-completed bowel diary.

Secondary

-

Percentage change in FIEs per week (i.e. patients achieving ≥ 25%, ≥ 75% or 100% reduction in weekly FIEs).

-

Change in FIEs per week as a continuous measure.

-

Change in symptom severity score: St Mark’s Continence Score (SMCS). A score from 0 (best) to 24 (worst) with > 5 indicating significant symptoms. 52

-

Change in disease-specific quality-of-life scores:

-

Change in general quality-of-life measures: Short Form Questionnaire-36 items (SF-36). 55 A score with eight domains with scores given as percentages.

-

Change in patients’ health status and overall health using European Quality of Life-5 Dimensions (EQ-5D)56 questionnaire.

-

Change in patient-centred outcomes questionnaire. A derivative of the International Consultation on Incontinence Modular Questionnaire – Bowel57 with a score from 1 (best) to 80 (worst).

-

Likert scale of patients’ global impression of success (scale of 0–10).

-

Qualitative data:

-

patient-perceived impression of change in use of incontinence pads and constipating medications

-

patient-perceived impression of change in urinary symptoms

-

patient impression of the treatment in general

-

patient-perceived allocation (PTNS or sham).

-

Other outcomes recorded at each visit:

-

stimulation parameters

-

adverse events and concomitant medications.

In addition to this, patients completed a bowel diary after six treatments and this formed a further secondary outcome.

Clinical centres

Centres with specialist expertise in FI, including nurse-led (or equivalent) incontinence services, were invited to participate in the study. Centres had to demonstrate experience with PTNS, having previously completed a full set of 12 treatments in a minimum of three patients. Each centre also required a minimum of two staff members to run the trial and ensure satisfactory blinding.

Study population

All adult patients attending the specialist continence or pelvic floor clinics at each of the centres were considered for participation in the study. This included patients with FI symptoms sufficiently severe to warrant intervention and in whom appropriate conservative therapies, such as diet, pelvic floor exercises, biofeedback and loperamide, had failed. Specialist investigations including structural and functional anorectal assessment were not mandatory, and anal sphincter injury was not a contraindication.

Inclusion criteria

-

Faecal incontinence sufficiently severe to warrant intervention (as recommended by the principal investigator at each site).

-

Failure of appropriate conservative therapies.

-

Age ≥ 18 years.

Exclusion criteria

-

Inability to provide informed consent for the research study.

-

Inability to fill in the detailed bowel diaries required for outcome assessments (this will exclude participants who do not speak/read English).

-

Neurological diseases, such as diabetic neuropathy, multiple sclerosis and Parkinson’s disease (including any participant with painful peripheral neuropathy).

-

Anatomical limitations that would prevent successful placement of needle electrode.

-

Other medical conditions precluding stimulation, for example bleeding disorders, certain cardiac pacemakers, peripheral vascular disease or ulcer, lower leg cellulitis.

-

Congenital anorectal anomalies or absence of native rectum as a result of surgery.

-

A cloacal defect.

-

Present evidence of external full-thickness rectal prolapse.

-

Previous rectal surgery (rectopexy/resection) done < 12 months prior to the study (24 months for cancer).

-

Stoma in situ.

-

Chronic bowel diseases such as inflammatory bowel disease leading to chronic uncontrolled diarrhoea.

-

Pregnancy or intention to become pregnant.

-

Previous experience of SNS or PTNS.

Following in-depth discussion with the research ethics committee, it was decided that, as some of the outcome questionnaires had not been validated in languages other than English, we should exclude people who do not understand written or spoken English from the study.

Data collection

We planned that each patient should attend for 14 visits and the events that occurred at each visit were as follows.

Visit 1: interest – eligibility

At this appointment, or over the telephone, a local researcher trained in good clinical practice determined eligibility by interview on the basis of defined inclusion and exclusion criteria listed on case report form (CRF) 1. The participants’ details were recorded on the screening log, and each participant was allocated a unique participant identifier number (see below). These data were used to complete the Consolidated Standard of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) flow chart and to generate reports on non-recruited patients for discussion at management group meetings.

Eligible subjects were provided with adequate explanation of the aims, methods, expected benefits and risks of participating in the study and given a patient information sheet containing this information. Participants were allowed 1 week to consider their participation (in accordance with good clinical practice). Participants who remained interested were provided with a bowel diary to complete over the next 2 weeks. Each participant was counselled on how to fill this diary in. Appointments were then booked for visits 2–14, with visit 2 being at least 2 weeks later to allow time for diary completion.

Unique participant identifier codes

Once a participant was registered on the screening log, he or she was allocated a unique participant identifier code. This consisted of six characters: three letters followed by three numbers. The letters denoted the study centre code, and the number was allocated on a consecutive basis, for example 001 for the first participant, and so on.

Visit 2: consent – confirm eligibility – baseline assessment – randomisation – first intervention

At this appointment, a member of the local team (trained in informed consent) answered any further questions and then asked the participant to sign the study consent form (also countersigned by the local researcher). All prospective participants were reminded of the need to be logistically able to complete the full protocol of 12 sessions at weekly intervals. Once the consent form was signed, the local investigator confirmed eligibility by recording data on CRF 1. If the participant was a female of childbearing potential, a urine pregnancy test was performed at this point.

The researcher then recorded all baseline data of FI history, past medical history and medication usage (using CRF 2 – initial assessment). The participant was asked to fill in the questionnaires (CRF 3) and to hand in the completed bowel diary, which was checked for completeness. Prior to randomisation the consent form, eligibility criteria (CRF 1) and initial assessment (CRF 2) were verified by another member of the research team.

Participants who failed to complete the bowel diary properly were given another 2-week bowel diary to complete and returned 2 weeks later for the trial to commence. If they failed a second attempt, they became a screen failure, and were withdrawn. Another participant was recruited in their place.

The researcher performed the randomisation, recorded this information on CRF 4 and (now unblinded) delivered the first 30-minute intervention (real PTNS or sham). Parameters of stimulation were recorded (CRF 5). The participant’s details were entered on the enrolment log, and a general practitioner (GP) letter, informing the GP of the participant’s involvement in the trial, was sent out.

Visits 3–13: intervention – interim information

At appointments 3–13, an unblinded researcher (who might be the same person as in visit 2) delivered the 30-minute intervention, having checked CRF 4 to confirm randomisation allocation. They enquired about adverse events, concomitant medication usage and pad usage, and recorded these on CRF 5.

At visit 7, participants were given a 1-week interim bowel diary to complete between visits 7 and 8. This bowel diary was collected and checked at visit 8.

At visit 13, participants were given a 2-week bowel diary to complete prior to attending visit 14, 2 weeks later.

Visit 14: final study visit

The final study visit was performed by a blinded member of the research team (i.e. somebody who was not present at visits 2–13). At this appointment, the bowel diary was collected and checked for completeness. The participant was then asked to complete the questionnaire document (CRF 3) and the post-treatment questionnaire (CRF 6).

The researcher then ensured that all documents were present and filled in correctly, prior to the principal investigator completing and signing off CRF 7. The participant was then unblinded as to treatment allocation and further follow-up was arranged as necessary.

Participants who failed to complete the interim bowel diary between visits 7 and 8 attempted this again the following week, and this was recorded as a protocol deviation. Participants who failed to complete the final bowel diary were again asked to complete this after visit 14, and they returned for another final study visit 2 weeks later. This was also a protocol deviation.

After completion of trial

After visit 14, participants who received ‘sham’ stimulation were offered PTNS on an open-label basis. Participants who received real PTNS and who derived significant benefit were offered ‘top-up’ sessions as per local departmental protocols. Participants who received real PTNS but derived no significant benefit were offered further treatments on an ‘open-label’ basis, following local departmental protocols.

Study procedures: delivery of percutaneous tibial nerve stimulation or sham

Participants received PTNS or sham using the recommended standard of 12 weekly 30-minute outpatient stimulations. Appendix 4 details exactly how PTNS and sham electrical stimulation were administered. Treatments were tailored to participants’ needs but protocol tolerance stipulated a minimum of 10 treatments, no fewer than 5 days or greater than 10 days apart, to be completed in 13 weeks. Treatments given outside these windows were classed as a protocol deviation.

Percutaneous tibial nerve stimulation was delivered via the Urgent® PC neuromodulation system, a reusable external pulse generator that provides visual and auditory feedback. It has an adjustable current setting from 0 to 9 mA in pre-set 0.5-mA increments, a fixed-pulse frequency of 20 Hz and a pulse width of 200 microseconds.

Transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation was used for the delivery of sham electrical stimulation (Biostim M7 TENS unit, Biomedical Life Systems, Vista, CA, USA). The sham treatment was a modification of that used and validated in the pivotal level I trial of Peters et al. 58 in overactive bladder (OAB) syndrome. 59 However, this was improved upon by inserting (at the same site) the Urgent® PC needle in all subjects. In the Peters study, the Urgent PC® needle was used in the PTNS arm, but the sham arm employed an acupuncture technique using a Streitberger needle, which does not puncture the skin.

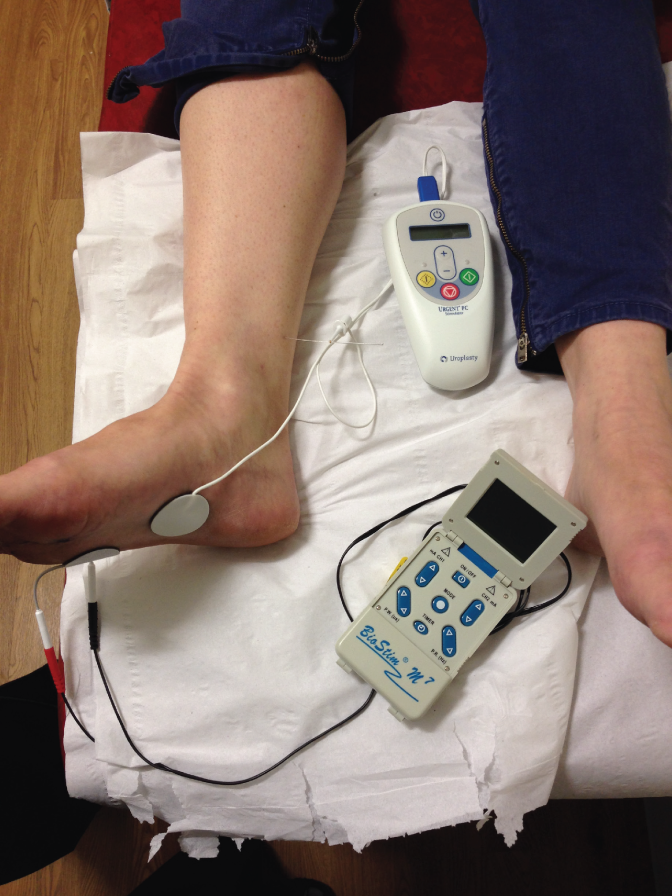

Treatments were always given in individual treatment rooms, with participants lying supine on a clinical couch. They were asked to remove clothing and shoes so as to bare legs from the knees downwards. A ‘gardener’s kneeling stool’ was placed over both legs, just below the knees, and a sheet draped over this to hide the participant’s feet from their view (Figure 1). Once the participant was comfortable, but prior to equipment set-up, each researcher read a standardised paragraph to the participant, informing them of what to expect. This read:

I am now going to start the nerve stimulation treatment. I will be inserting a small electrode needle, like an acupuncture needle, into your leg and putting sticky electrodes onto your foot. When I turn the machine on you will be asked when you can first feel an electrical sensation in your ankle or foot. I will carry on increasing the intensity of this until it is slightly uncomfortable, then I will turn it down a little if necessary. Occasionally you may also feel numbness or slight movement of your toes. This is normal. I will set the machine up and leave it running for 30 minutes. You may or may not continue to feel the stimulation during this time – this is normal also. After 30 minutes have elapsed I will remove the needle and sticky electrodes (the machine automatically turns off at this time). If the treatment becomes uncomfortable at any point please let me know and I will turn it down or stop the machine.

FIGURE 1.

Photographs of equipment set-up.

All participants then had an Urgent® PC machine and a TENS machine set up on their right foot, unless there was a reason why the right foot could not be used, under which circumstances the left foot was used. In the true PTNS arm, the Urgent® PC was used as normal, and the TENS machine left turned off. In the sham arm, the TENS machine was used to provide the electrical stimulation and the Urgent® PC was turned on only to provide the auditory stimulus. Following satisfactory treatment commencement, the sheet was draped fully over the participant’s feet, ensuring that accidental unblinding could not take place. The researcher then filled in the paperwork for this visit and left the room, returning after 30 minutes to remove the equipment.

Treatment arm

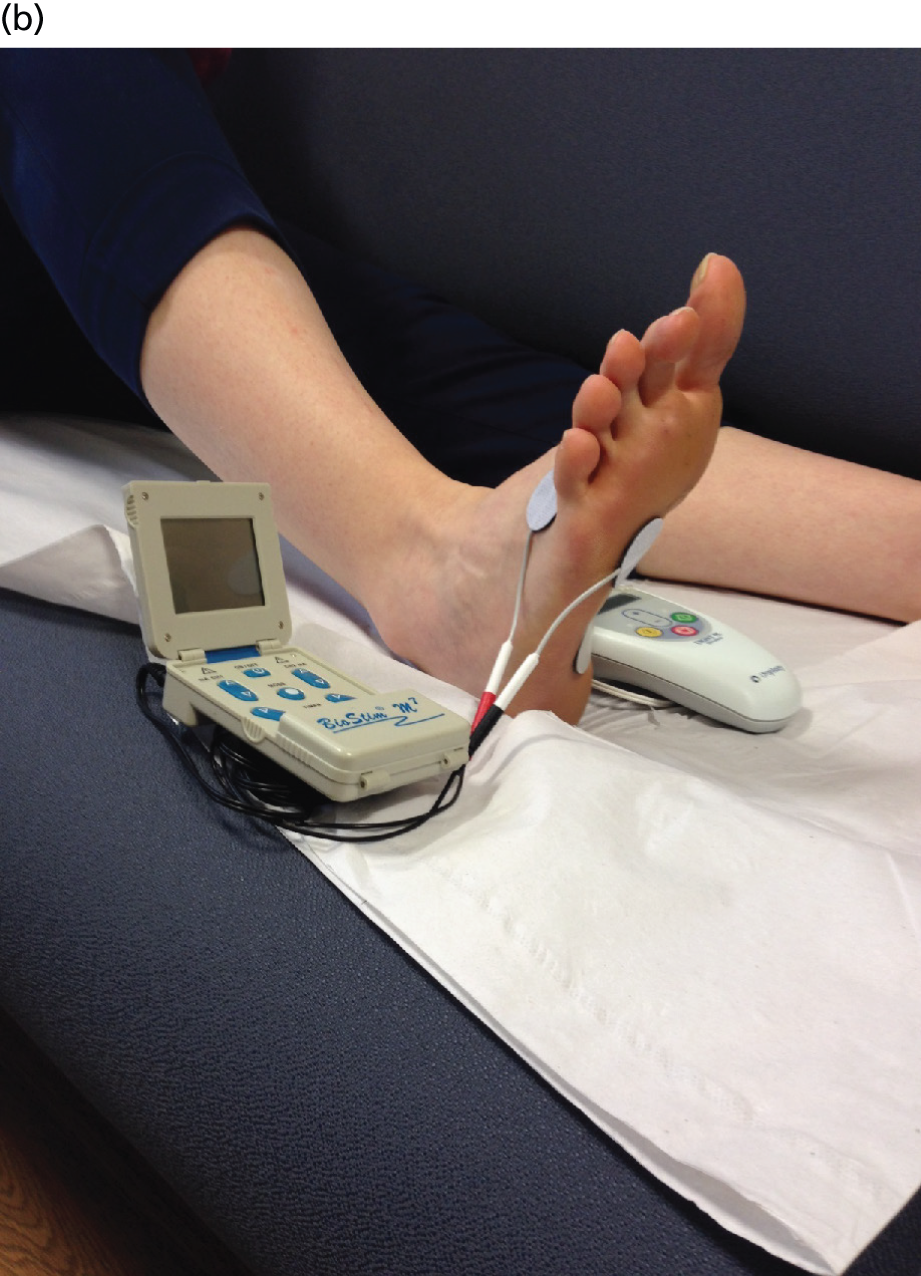

After checking equipment, which should have included the Urgent® PC machine, lead wire, alcohol wipe and electrode needle with tube assembly, the site of needle insertion was identified on the lower inner aspect of the right leg approximately three finger breadths (5 cm) cephalad to the medial malleolus and approximately one finger breadth (2 cm) posterior to the tibia. The area was cleaned with ethanol and the needle electrode–guide tube assembly placed over the identified insertion site at a 60° angle between electrode and ankle. The 34-gauge needle electrode was gently tapped to pierce the skin and thence advanced using a rotating motion approximately 2 cm. The lead wire was then connected to the stimulator and to the ipsilateral calcaneal reference electrode (Figure 2a). The lead wire was then taped to the participant’s leg so that the PTNS participant experienced the same sensations as the sham participant. The TENS machine was connected to two electrodes, one placed under the little toe and one on top of the foot (Figure 2b). The TENS machine was not turned on. The setting for PTNS therapy was determined by increasing the current slowly while observing the participant’s sensory response (appropriate response being in great toe or sole of foot) or motor response (plantar flexion of foot or great toe). Current was then reduced by one level for therapy, and continued for 30 minutes, at which point the electrode was removed.

FIGURE 2.

Equipment set-up. (a) PTNS needle and calcaneal electrode and (b) TENS surface electrode placements.

Sham arm

The same protocol was followed as for the treatment arm. The only difference was that the needle was inserted only 2 mm into the skin and subcutaneous tissue, that is just in far enough not to fall out and not deep enough to be close to the tibial nerve. The lead was then taped to the participant’s leg near to, but not touching, the needle. The purpose of this was to prevent unblinding in the event of the participant inadvertently seeing the equipment. The PTNS surface electrode (see Figure 2a) on the calcaneus was also attached. The two active TENS surface electrodes were employed as shown in Figure 2b, with one placed under the little toe and one on top of the foot. Once all equipment was set up, the practitioner picked up both the Urgent® PC machine and the TENS machine, one in each hand. Both machines were turned on. The TENS machine was set to a pulse frequency of 10 Hz and a pulse width of 200 microseconds. Then, after pressing buttons simultaneously on the Urgent® PC machine and the TENS machine, the practitioner increased the adjustable current setting (which ranged from 0 to 10 mA in pre-set 1-mA increments on the TENS machine). The setting for therapy was determined in the usual way by observing the participant’s sensory reactions or their foot for toe/ankle extensor motor responses, and if necessary the current was reduced by one level for therapy. The reason both machines were used together was so that the audible sounds produced by the Urgent® PC stimulator were the same in both the PTNS and the sham arms, to decrease auditory variation between the study arms.

This sham treatment was shown in a departmental pilot to be both more acceptable and more realistic than that described by Peters et al. ,58 which involved the placement of a Streitberger needle. We also confirmed that this sham, using TENS to deliver the electrical stimulation, does not stimulate the posterior tibial nerve (proven in a neurophysiological pilot by the consultant neurophysiologist).

Treatment quality control

The importance of quality control and standardisation of technique between individuals and centres was recognised. In order to keep the quality high, each researcher was taught and certified to give PTNS by a uroplasty-approved trainer. Each researcher also underwent a personal training session at the site initiation visit by the trial research fellow (EH) on how to deliver PTNS and sham according to the CONFIDeNT protocol. Each researcher was then observed delivering both treatments. Six-monthly site visits throughout the duration of the trial involved assessment of technique. Retraining was undertaken where necessary.

Withdrawal criteria

Participants were withdrawn from the treatment or the trial if they fulfilled any of the criteria below at any point following delivery of the first treatment.

Withdrawn from treatment only (follow-up data still collected)

-

Participant no longer wished to be involved in trial treatments.

-

Participant developed a medical condition listed in the exclusion criteria.

-

Participant became pregnant or intended to become pregnant.

-

Unblinding occurred.

-

Participant had an intercurrent illness.

Withdrawn from the trial (no follow-up data collected)

-

Participant was lost to follow-up (could not be contacted by telephone or other means).

-

Participant no longer wished to be involved in the trial.

-

Death.

Early withdrawal was documented carefully and all participants were followed up in the NHS in the usual way. In the case of each participant who withdrew, permission was sought to use the data that had already been collected.

Randomisation

Participants were randomised, with allocation concealment, using a bespoke web-based computer program held at Nottingham Clinical Trials Unit. Each centre randomised its own participants to receive either PTNS or sham following baseline data collection and immediately prior to delivery of the first treatment. The computer program required the researcher to input the unique participant identifier code, sex and date of birth, and immediate on-screen randomisation occurred. Allocation was on an equal basis with initial stratification by sex and then stratification of females by centre. Stratification by sex was used to reduce the potential confounding effects of variation in outcomes between male and female participants. As males represent only 10% of patients and only one or two male participants were expected from each centre (owing to differing pathophysiologies60), randomisation stratified on centre would increase the probability that all the males were allocated to PTNS or sham by chance. To avoid this situation, only females were stratified by centre, achieving a near balance of PTNS and sham arms and allowing comparability by centre.

Blinding

Blinding of participants

Participants were blinded to allocation, but had knowledge of the 50% chance of receiving sham treatment. For both PTNS and sham interventions (1) a standardised description of the technique was read from a card prior to each treatment, which described what the patient should expect – an electrical sensation variably in the ankle or foot with or without motor responses in the foot (note: there is significant variability in conscious sensation and motor responses even between participants undergoing only PTNS); (2) the lower extremity was draped from view, ensuring participants had no knowledge of equipment set-up; and (3) the audible sounds present during PTNS and sham treatments were identical.

Performance bias considerations

In order to avoid either arm receiving more advice or reassurance, the interaction of the administering researcher was standardised and limited to a general welcome, addressing any concerns (while recording adverse events) and answering questions regarding loperamide dosages and incontinence pad use (both recorded in outcome variables). The standardised description of the technique (as stated above) was read to the participant, the equipment set up and fully covered and then participant left to receive the 30-minute treatment.

Blinding of trial staff

At least two researchers were available at each site to run the study, one of whom performed the randomisation and all treatments, and was necessarily unblinded, while the other remained blinded and carried out the final data collection. Blinding and unblinding procedures are detailed in Appendix 5.

Sample size calculation

Data published at the time of sample size calculation35,39,46,61 and our own data36 on 50 patients suggested a 60% success rate for PTNS based on our chosen primary outcome measure. There were no RCT data for PTNS in FI; however, the pivotal level I SumiT trial of PTNS in OAB symptoms,58 which used a similar global response assessment of urinary incontinence and intention-to-treat analysis, observed a moderate or marked improvement in symptoms in 55% in the PTNS arm and only 21% in the sham arm. On the basis that placebo responses are frequently higher for bowel than for bladder symptoms,47–49 we selected a sham response rate of 35% while keeping the more conservative estimate of treatment response of 55% (the difference of 20% we believe remains clinically important in relation to other therapies such as SNS). In total, 212 participants were required to detect this difference with 80% power at the 5% significance level. We expected to screen 235 participants at baseline to allow for a 10% failure to attend for randomisation, baseline data collection and first treatment.

Statistical methods

Statistical methods are detailed in the statistical analysis plan (see Appendix 6). This document was drawn up by the trial statisticians and reviewed by the Trial Steering Committee (TSC) and Data and Safety Monitoring Committee (DSMC), and received formal sign-off from both committees prior to unblinding and analysis.

The analysis was carried out using Stata version 12.1 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA), interfacing with Realcom Impute (2007, Centre for Multilevel Modelling, University of Bristol, Bristol, UK), which was used to multiply impute missing outcome and baseline covariate data. 62

All patients randomised who received the first treatment were included in the intention-to-treat analysis of the primary end point. Those in whom post-treatment data were unavailable at 14 weeks for any reason (loss to follow-up or failure to complete treatment) had their outcome multiply imputed under the assumption of data missing at random using variables prognostic of outcome, such as measure of outcome made at baseline, and others predictive of ‘missingness’ (i.e. the reason it is missing) such as mean number of FIEs per week at baseline, age, sex and, where available, mid-study bowel diary data. The numbers of variables included in each imputation model were limited by the relatively small number of study centres. Multilevel multiple imputation was performed using the multivariate normal distribution in Realcom Impute, using treatment allocation, patient sex and allocation as auxiliary variables. After a burn-in of 1000 runs of the Monte Carlo Markov chain sampler, missing values were filled every 500th run to create a total of 10 completed data sets for analysis. The data were analysed in Stata and the results pooled by Rubin’s rules. 62

The final analysis was adjusted for variables that were selected prior to data extraction. A decision was made to fit fixed effects for sex, randomisation and baseline level of outcome and to fit a random effect for study centre. In order to handle potential clustering effects of patients within centre, the intracluster correlation coefficients (ICCs) and their 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for the outcomes by centre were estimated using the user-contributed Stata command sea_obi, which allows the ICC to be negative. 63 Random-effects models were fitted by restricted maximum likelihood estimation (e.g. xtmixed. . ., reml). For outcomes with a negative ICC, linear regression models were fitted (without clustering) using the regress command.

For binary outcomes, logistic mixed-effects models were used, adjusting for baseline mean number of FIEs per week and sex and with a random effect for study centre. Estimates from these models are presented as adjusted odds ratios with 95% CIs. For continuous outcomes, linear mixed-effects models were used, adjusting for baseline measure of outcome and sex, and with a random effect for study centre. Estimates from these models are presented as adjusted difference in means.

Per-protocol analysis was carried out for all outcome measures to include those patients who received a full course of treatment as per the protocol, that is at least 10 treatments in 13 weeks that were no fewer than 5 and no more than 10 days apart. Sensitivity analyses were performed for all outcome measures, excluding any patients who had reported no episodes of FI in their 14-day baseline bowel diary, and excluding those centres that had randomised fewer than five patients.

Subgroup analyses for the primary outcome, fitting an interaction term between the categorical variable defining the subgroups and the randomisation variable, were performed, as follows:

-

males versus females

-

severity of FI (those with ≥ 7 weekly FIEs vs. those with < 7 weekly FIEs)

-

age (< 40 years, 40–60 years and > 60 years)

-

type of FI (both urge and passive, urge only or passive only).

Ethical arrangements and research governance

This trial was granted ethical approval in June 2010 (Research Ethics Committee reference 10/H0703/25).

The trial was conducted in compliance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki (1996),64 and in accordance with all applicable regulatory requirements including but not limited to the Research Governance Framework for Health and Social Care,65 trust and research office policies and procedures, and any subsequent amendments. The trial was compliant with the approved protocol and research ethics committee conditions of approval, and in line with good clinical practice guidelines. 66

Information regarding study participants was kept confidential and managed by each study site in accordance with the Data Protection Act,67 NHS Caldicott Guardian Agreements,68 The Research Governance Framework for Health and Social Care65 and research ethics committee approval.

Important changes to protocol after study commencement

Following study commencement, two amendments were made to the protocol, one major and one minor, but with no change to the study intervention. The following were amended:

-

The post-treatment information questionnaire (CRF 6) was amended following recommendation by the TSC. It suggested that the recording of week-by-week incontinence pad and loperamide usage was neither satisfactory nor accurate, and that this information would be better captured by questionnaire at the end. Thus, two extra questions were added to the final questionnaire.

-

Cleveland Clinic Incontinence Score was updated to the SMCS. This was used throughout but misnamed in the original protocol.

-

Clarification was added to the protocol to include details of the per-protocol analysis criteria.

-

Statistical analysis section was updated:

-

Multiple imputation method for handling missing outcome data rather than the last value carried forward method was included on recommendation from the Health Technology Assessment, as this is the widely accepted standard.

-

Regression models fitted to estimate treatment effect were changed from fixed centre effects to random centre effects. 69

-

-

Centre eligibility criteria were updated to remove the absolute requirement of a minimum of five participants recruited, following discussion with the TSC that this was an arbitrary and unnecessary requirement.

Trial oversight

The trial was under the auspices of the chief investigator and the pragmatic clinical trials unit at Barts and The London School of Medicine and Dentistry. The project was overseen by a TSC.

The TSC had an independent chairperson, and met every 6 months throughout to provide overall supervision and ensure the trial was conducted to the rigorous standards set out in the Medical Research Council’s guidelines for good clinical practice. 66 Specifically, the TSC’s role was to ensure:

-

that the views of users and carers were always taken into consideration

-

the scientific rigour of the study and adherence to protocol

-

that project milestones were met

-

that expertise/advice was provided to the Trial Management Group (TMG).

Membership of the TSC was:

-

senior statistician – Sandra Eldridge

-

independent chairperson – Professor Christine Norton, Professor of Nursing (King’s College London)

-

independent external member – Professor Ronan O’Connell, clinical and research expertise in lower gastrointestinal neuromodulation (University College Dublin)

-

patient and public involvement representative – Deborah Gilbert, chief executive (Bowel & Cancer Research charity).

The TMG was responsible for day-to-day project delivery in each participating centre. It met monthly and was answerable to the TSC. The group was responsible for overseeing and managing:

-

trial recruitment and retention rates

-

site initiation, training, monitoring, compliance and correction/preventative actions

-

data management (collection, quality control, entry and query management)

-

adverse and serious adverse event (SAE) reporting

-

study milestones

-

study reporting

-

budget expenditure and accruals.

The TMG comprised:

-

chief investigator – Charles Knowles

-

academic clinical fellow – Emma Horrocks

-

trial manager – Natasha Stevens

-

trial statistician – Stephen Bremner.

A DSMC was appointed to monitor unblinded comparative data and make recommendations to the TSC. The DSMC initially met together with the TSC, and subsequently 2 weeks prior to the TSC to enable any findings/recommendations to be submitted to the TSC. DMSC meeting timings and conclusions can be seen in Appendix 7. A DAMOCLES DSMC charter70 was adopted (see Appendix 8), and an independent pragmatic clinical trials unit statistician provided the DSMC with an unblinded comprehensive report prior to each meeting.

The DSMC comprised:

-

independent lead – Professor Dion Morton, Professor of Surgery, University of Birmingham

-

independent member – Professor Elaine Denny, Professor of Health Sociology, University of Birmingham

-

independent statistician – Dr Daniel Altmann, Senior Lecturer in Medical Statistics, London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine, University of London.

Patient and public involvement

Patient and public involvement was considered at all stages of this trial from conception to dissemination. This is described in detail in Appendix 9.

Chapter 3 Results

Participant flow

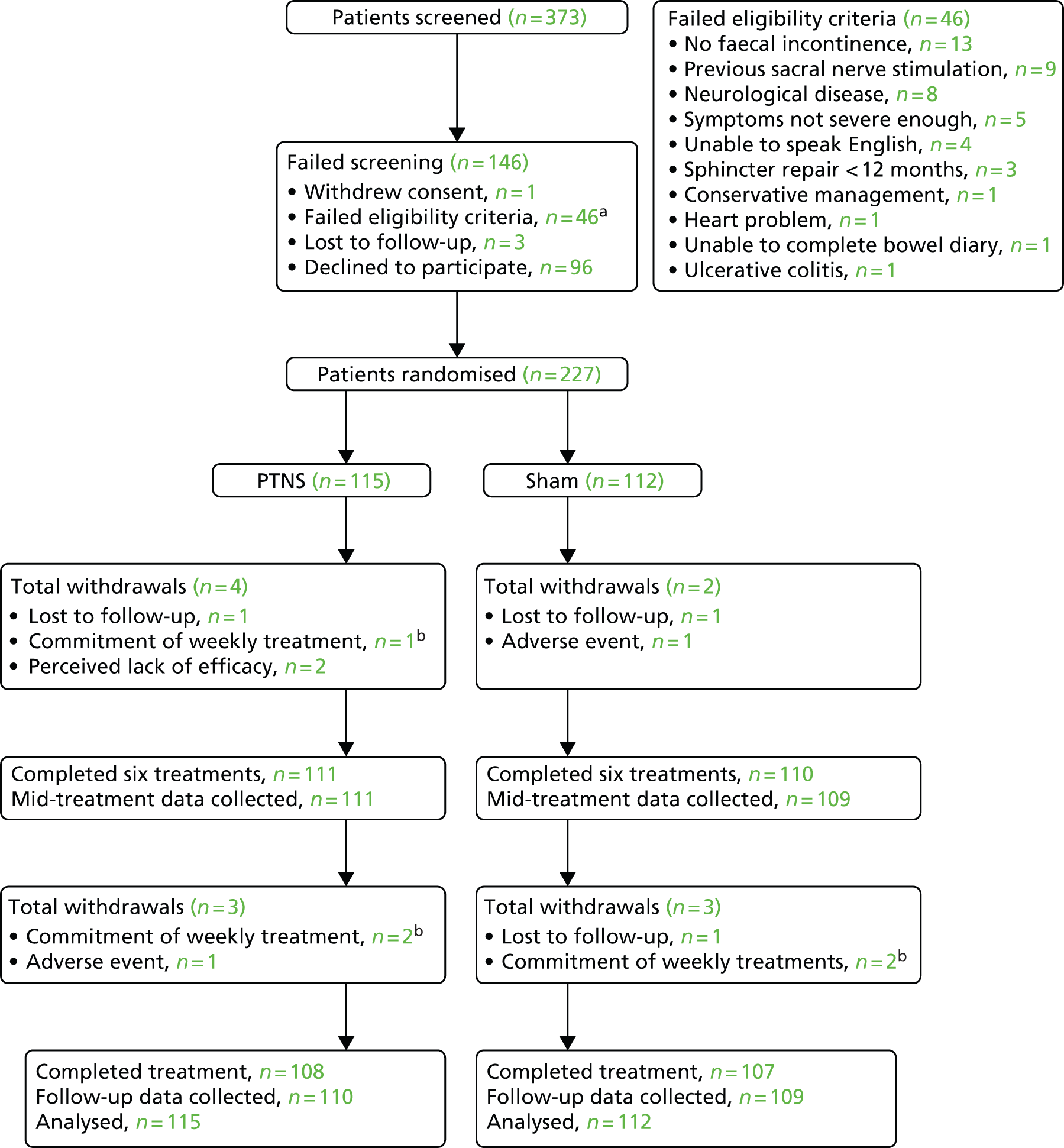

The CONSORT diagram shows the flow of participants through the trial (Figure 3). Non-completing participants either withdrew from treatment (and remained in the trial) or withdrew from the trial (in which case no further data were collected from them). Permission was, however, sought to use the data that had already been collected.

FIGURE 3.

Flow of patients through the study. a, See eligibility criteria box; b, withdrawal from treatment only.

Trial recruitment

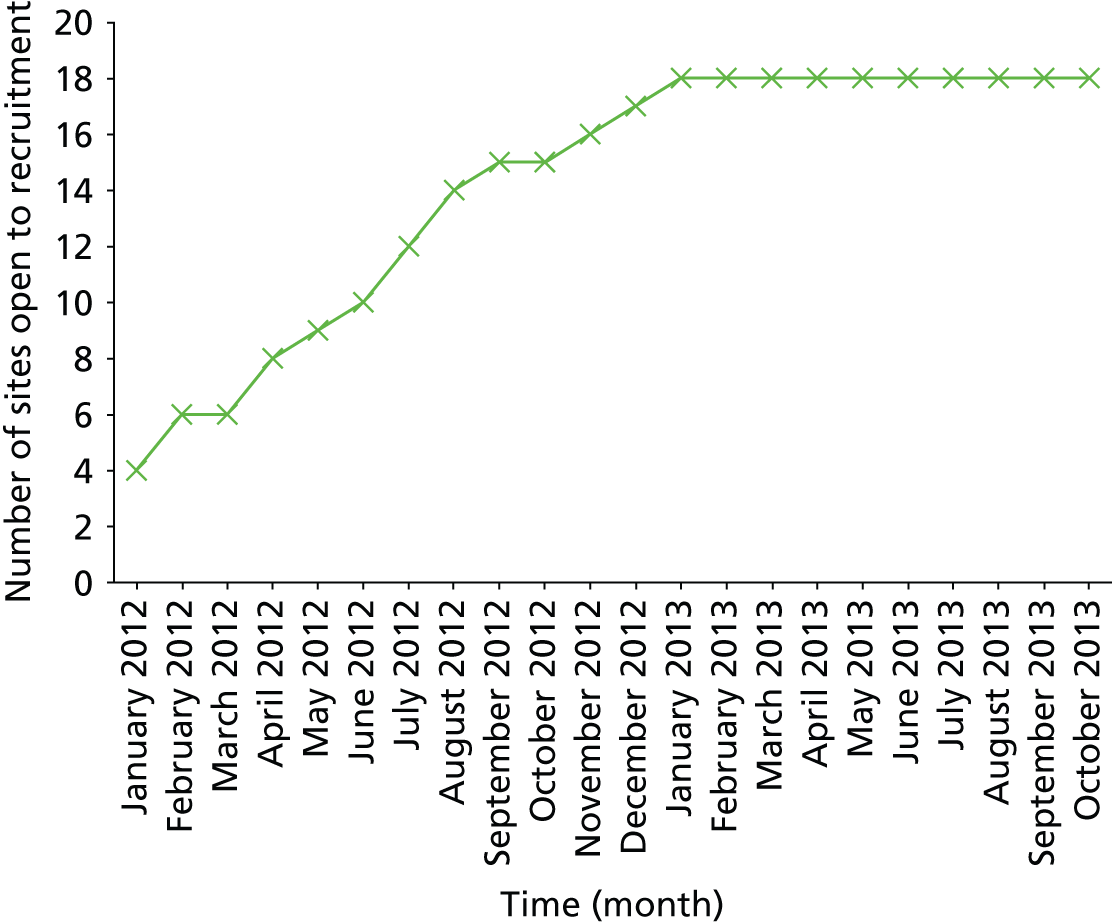

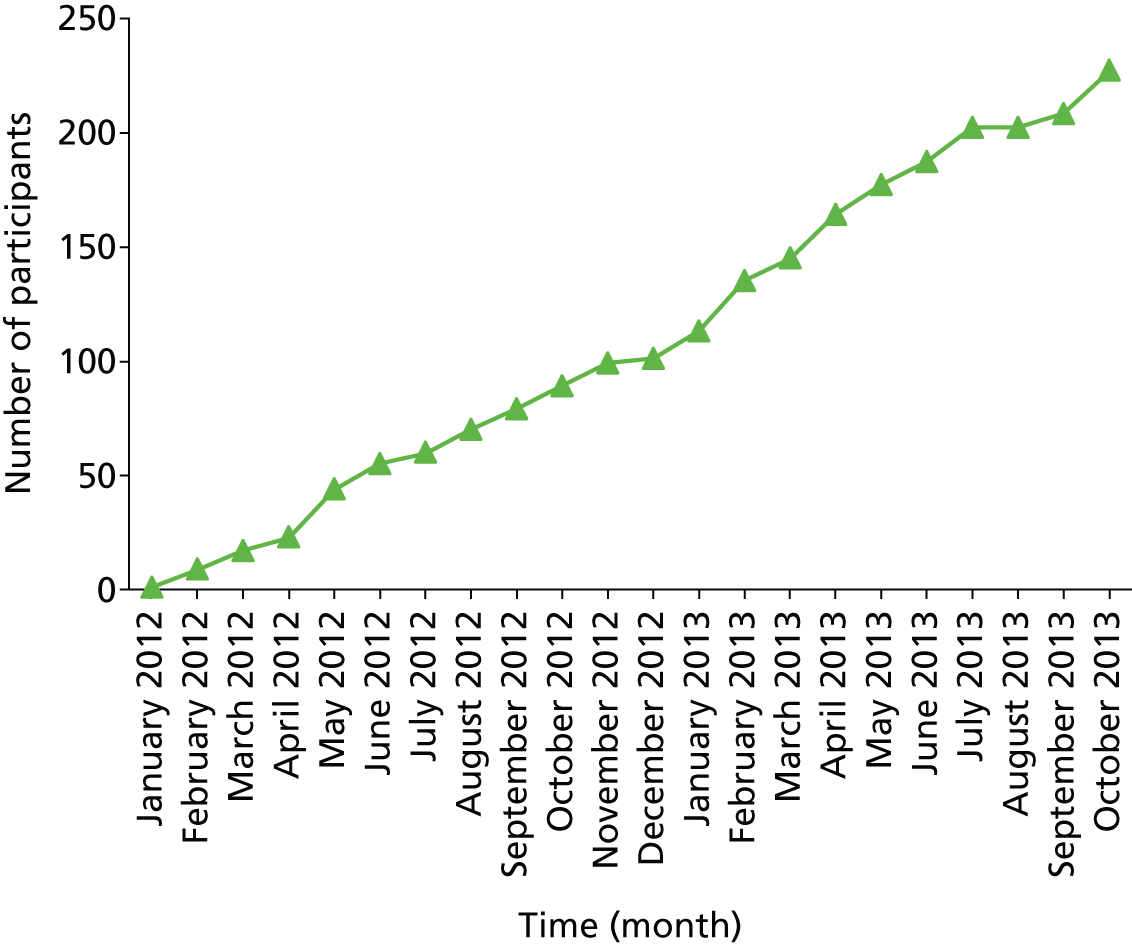

Seventeen of the 18 UK centres recruited participants for the trial between 23 January 2012 and 31 October 2013. The remaining centre was unable to participate because of staff shortages. Trial centres were Barts Health NHS Trust, London; Aintree University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust, Liverpool; University Hospital Southampton NHS Foundation Trust, Southampton; Sandwell and West Birmingham NHS Trust, Birmingham; Sheffield Teaching Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust, Sheffield; The Community Specialist Colorectal Clinic, Ching Way Medical Centre, London; Leicester General Infirmary, Leicester; Queen’s Medical Centre, Nottingham; Castle Hill Hospital, Hull; University College Hospital, London; Bristol Royal Infirmary, Bristol; St Mark’s Hospital, London; Guy’s and St Thomas’ Hospital, London; Poole Hospital NHS Foundation Trust, Poole; Leeds Royal Infirmary, Leeds; Pilgrim Hospital, Boston, Lincolnshire; and University Hospital of South Manchester, Wythenshawe. Centre recruitment rate is shown in Figure 4.

FIGURE 4.

Recruitment of sites.

In total, 373 participants were screened and, of these, 227 (61%) were randomised. The overall recruitment rate is shown in Figure 5. The number of participants per site ranged from 1 to 45. There were 12 participant withdrawals: seven from the trial and five from treatment (see Figure 3).

FIGURE 5.

Participant recruitment.

Data quality

Data return was generally very high and quality was very good. Data from bowel diaries were 97.7% complete. This was probably a consequence of bowel diary training for each patient prior to completing the diary and the vigilant checking of bowel diaries on return. Questionnaire completion was also very good (mean 90.4%, range 77.6–100%). For all data, percentages were calculated from the corrected denominator; however, as data return was so high, individual values for number of patients for each outcome have not been recorded in the tables. These are available in Appendix 10.

Baseline data

In total, 227 participants were randomised: 115 to receive PTNS and 112 to receive sham electrical stimulation.

Baseline findings

Ninety per cent of participants were female, with a mean age of 57 years (range 20–85 years). Mean symptom duration was 8 years (range 5 months to 50 years). Baseline demographics and clinical data are summarised in Table 1. Previous treatments and relevant past medical history are summarised in Tables 2 and 3 respectively. Complete lists of past medical history and regular medications are presented in Appendices 11 and 12. Demographics of the two arms were evenly matched for age and sex as per stratification. Of note, approximately 40% of participants appeared to have concomitant symptoms of FI and evacuatory difficulties (39% in PTNS arm and 44% in sham arm), and approximately 60% had concomitant urinary symptoms (61% in PTNS arm and 64% in sham arm).

| Outcome | PTNS | Sham |

|---|---|---|

| Sex (female), n (%) | 104 (90) | 101 (90) |

| Age (years), median (IQR) | 58 (50–67) | 58 (48–65) |

| Duration of symptoms (months), median (IQR) | 60 (24–168) | 48 (24–108) |

| Obstetric history,a n (%) | 95 (91) | 96 (95) |

| Vaginal deliveries only,a n (%) | 90 (95) | 96 (100) |

| C-sections only,a n (%) | 5 (5) | 0 (0) |

| Episiotomies or tears,a n (%) | 78 (87) | 82 (85) |

| Passive FI, n (%) | 88 (77) | 86 (77) |

| Urge FI, n (%) | 94 (82) | 93 (83) |

| Flatus incontinence, n (%) | 74 (64) | 83 (74) |

| Evacuatory difficulties, n (%) | 44 (39) | 49 (44) |

| Straining, n (%) | 34 (30) | 37 (33) |

| Digitation, n (%) | 12 (10) | 15 (13) |

| Urinary symptoms, n (%) | 70 (61) | 72 (64) |

| Urinary urgency, n (%) | 50 (43) | 49 (44) |

| Urinary urge incontinence, n (%) | 39 (34) | 42 (38) |

| Treatment | PTNS | Sham |

|---|---|---|

| Antidiarrhoeal medications, n (%) | 77 (67) | 67 (60) |

| Biofeedback, n (%) | 56 (49) | 59 (53) |

| Pelvic floor exercises, n (%) | 37 (32) | 36 (32) |

| Fibre supplementation, n (%) | 18 (16) | 30 (27) |

| Laxatives/suppositories/irrigation, n (%) | 20 (17) | 16 (14) |

| Anal sphincter repair, n (%) | 4 (3) | 4 (4) |

| Other anal surgery, n (%) | 11 (10) | 8 (7) |

| Defecatory advice, n (%) | 9 (8) | 7 (6) |

| Other, n (%) | 5 (4) | 8 (7) |

| Outcome | PTNS | Sham |

|---|---|---|

| Hysterectomy,a n (%) | 30 (29) | 24 (24) |

| Vaginal operation,a n (%) | 3 (3) | 2 (2) |

| Pelvic operation,a n (%) | 19 (18) | 16 (16) |

| Abdominal operation, n (%) | 28 (24) | 30 (27) |

| Anal operation, n (%) | 6 (5) | 9 (8) |

| Neck or back pain, n (%) | 15 (13) | 21 (19) |

| OAB, n (%) | 15 (13) | 7 (6) |

| Diverticular disease, n (%) | 4 (3) | 6 (5) |

| Irritable bowel syndrome, n (%) | 1 (1) | 4 (4) |

Bowel diary data at baseline

Baseline bowel diaries demonstrated a median of 6.0 FIEs per week in PTNS patients, comprising a median of 3.0 urge faecal incontinent episodes and a median of 2.0 passive episodes. In the sham arm there was a median of 6.9 FIEs per week, but with a slightly higher rate of passive FI (median 3.0 episodes) than urge episodes (median 2.5 episodes) (Table 4).

| Outcome | PTNS | Sham |

|---|---|---|

| FIEs per week | ||

| Median (IQR) | 6.0 (2.0–14.0) | 6.9 (2.5–16.0) |

| Mean (SD) | 9.9 (11.2) | 10.4 (10.9) |

| Urge FIEs per week | ||

| Median (IQR) | 3.0 (0.9–8.0) | 2.5 (0.5–7.0) |

| Mean (SD) | 5.3 (7.2) | 4.8 (5.9) |

| Passive FIEs per week | ||

| Median (IQR) | 2.0 (0.0–7.5) | 3.0 (0.0–8.0) |

| Mean (SD) | 4.6 (6.0) | 5.7 (7.6) |

Other baseline outcome measures

Baseline SMCSs were similar between the arms, with a mean score of 14.4 (standard deviation 3.7) in the PTNS arm and of 15.4 (standard deviation 4.1) in the sham arm. All 211 patients who completed their SMCS had significant FI on the basis of their score being > 5 (Table 5).

| Outcome | PTNS | Sham |

|---|---|---|

| SMCSa | ||

| Median (IQR) | 14.0 (12.0–17.0) | 16.0 (13.0–18.0) |

| Mean (SD) | 14.4 (3.7) | 15.4 (4.1) |

| SMCS > 5, n (%) | 110 (100) | 101 (100) |

| FIQoL scores | ||

| Lifestyleb | ||

| Median (IQR) | 2.7 (1.8–3.4) | 2.5 (1.7–3.6) |

| Mean (SD) | 2.6 (0.9) | 2.6 (1.0) |

| Coping and behaviourb | ||

| Median (IQR) | 1.7 (1.2–2.3) | 1.6 (1.1–2.6) |

| Mean (SD) | 1.9 (0.7) | 1.9 (0.9) |

| Depression and self-perceptionb | ||

| Median (IQR) | 3.1 (2.0–3.4) | 2.6 (2.0–3.7) |

| Mean (SD) | 2.8 (0.9) | 2.7 (0.9) |

| Embarrassmentc | ||

| Median (IQR) | 2.0 (1.7–2.7) | 2.0 (1.3–2.7) |

| Mean (SD) | 2.2 (0.8) | 2.1 (0.8) |

| Patient-centred outcomesd | ||

| Median (IQR) | 8.9 (7.8–9.8) | 9.2 (8.3–10.0) |

| Mean (SD) | 8.5 (1.6) | 8.7 (1.7) |

| GIQoLe | ||

| Median (IQR) | 130.0 (113.0–141.0) | 126.5 (109.0–139.0) |

| Mean (SD) | 126.7 (18.8) | 123.8 (20.2) |

| SF-36 scores (%) | ||

| Physical functioning | ||

| Median (IQR) | 70.0 (45.0–90.0) | 65.0 (40.0–85.0) |

| Mean (SD) | 65.7 (27.4) | 61.4 (28.4) |

| Role-physical | ||

| Median (IQR) | 50.0 (0.0–100.0) | 25.0 (0.0–75.0) |

| Mean (SD) | 46.4 (42.1) | 36.4 (41.4) |

| Bodily pain | ||

| Median (IQR) | 60.0 (40.0–90.0) | 57.5 (32.5–90.0) |

| Mean (SD) | 61.3 (30.0) | 58.2 (31.5) |

| General health | ||

| Median (IQR) | 50.0 (35.0–70.0) | 50.0 (30.0–70.0) |

| Mean (SD) | 51.2 (23.4) | 50.3 (23.8) |

| Vitality | ||

| Median (IQR) | 45.0 (30.0–57.5) | 50.0 (30.0–60.0) |

| Mean (SD) | 43.9 (22.1) | 42.7 (22.8) |

| Social functioning | ||

| Median (IQR) | 62.5 (37.5–75.0) | 62.5 (37.5–87.5) |

| Mean (SD) | 58.4 (28.8) | 59.3 (31.6) |

| Role-emotional function | ||

| Median (IQR) | 66.7 (0.0–100.0) | 33.3 (0.0–100.0) |

| Mean (SD) | 58.4 (28.8) | 59.3 (31.6) |

| Mental health | ||

| Median (IQR) | 60.0 (44.0–76.0) | 64.0 (48.0–76.0) |

| Mean (SD) | 60.3 (21.0) | 60.8 (21.6) |

| EQ-5D index scoref | ||

| Median (IQR) | 0.73 (0.62–0.85) | 0.73 (0.62–0.85) |

| Mean (SD) | 0.69 (0.27) | 0.63 (0.34) |

Primary outcome

The percentage of patients achieving a ≥ 50% reduction in weekly FIEs was similar in both arms at 38% (39 out of 103) for PTNS and 31% (32 out of 102) for sham treatment (unadjusted odds ratio 1.333; adjusted odds ratio 1.283, 95% CI 0.722 to 2.281; p = 0.396) (Tables 6 and 7).

| Outcome | Odds ratio | 95% CI | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| ≥ 50% reduction FIEs (primary outcome) | 1.283 | 0.722 to 2.281 | 0.396 |

| ≥ 25% reduction in FIEs | 1.264 | 0.730 to 2.190 | 0.404 |

| ≥ 75% reduction in FIEs | 1.615 | 0.770 to 3.388 | 0.205 |

| 100% reduction in FIEs | 1.635 | 0.592 to 4.514 | 0.344 |

| Difference in means | |||

| Change in FIEs | –2.262 | –4.185 to –0.339 | 0.021 |

| Change in urge FIEs | –1.456 | –2.693 to –0.219 | 0.021 |

| Change in passive FIEs | –0.635 | –1.668 to 0.397 | 0.228 |

| FIQoL embarrassment | 0.036 | –0.151 to 0.223 | 0.706 |

| FIQoL coping | 0.013 | –0.171 to 0.197 | 0.889 |

| FIQoL lifestyle | 0.086 | –0.075 to 0.248 | 0.290 |

| FIQoL depression | 0.014 | –0.297 to 0.324 | 0.927 |

| SF-36 physical functioning | –1.854 | –6.992 to 3.284 | 0.479 |

| SF-36 role-physical | 1.113 | –8.866 to 11.092 | 0.826 |

| SF-36 bodily pain | –1.026 | –6.815 to 4.764 | 0.728 |

| SF-36 general health | –0.158 | –4.749 to 4.433 | 0.946 |

| SF-36 vitality | –3.142 | –8.129 to 1.845 | 0.215 |

| SF-36 social functioning | 5.209 | –0.740 to 11.157 | 0.087 |

| SF-36 role emotional | –4.815 | 14.802 to 5.171 | 0.343 |

| SF-36 mental health | –0.509 | –4.831 to 3.814 | 0.817 |

| SMCS | –0.047 | –1.033 to 0.939 | 0.925 |

| Patient-centred outcomes | –0.545 | –1.081 to –0.008 | 0.047 |

| EQ-5D index score | –0.017 | –0.078 to 0.044 | 0.583 |

| GIQoL | –1.300 | –5.168 to 2.568 | 0.506 |

| Likert scale of success | 0.808 | –0.055 to 1.672 | 0.068 |

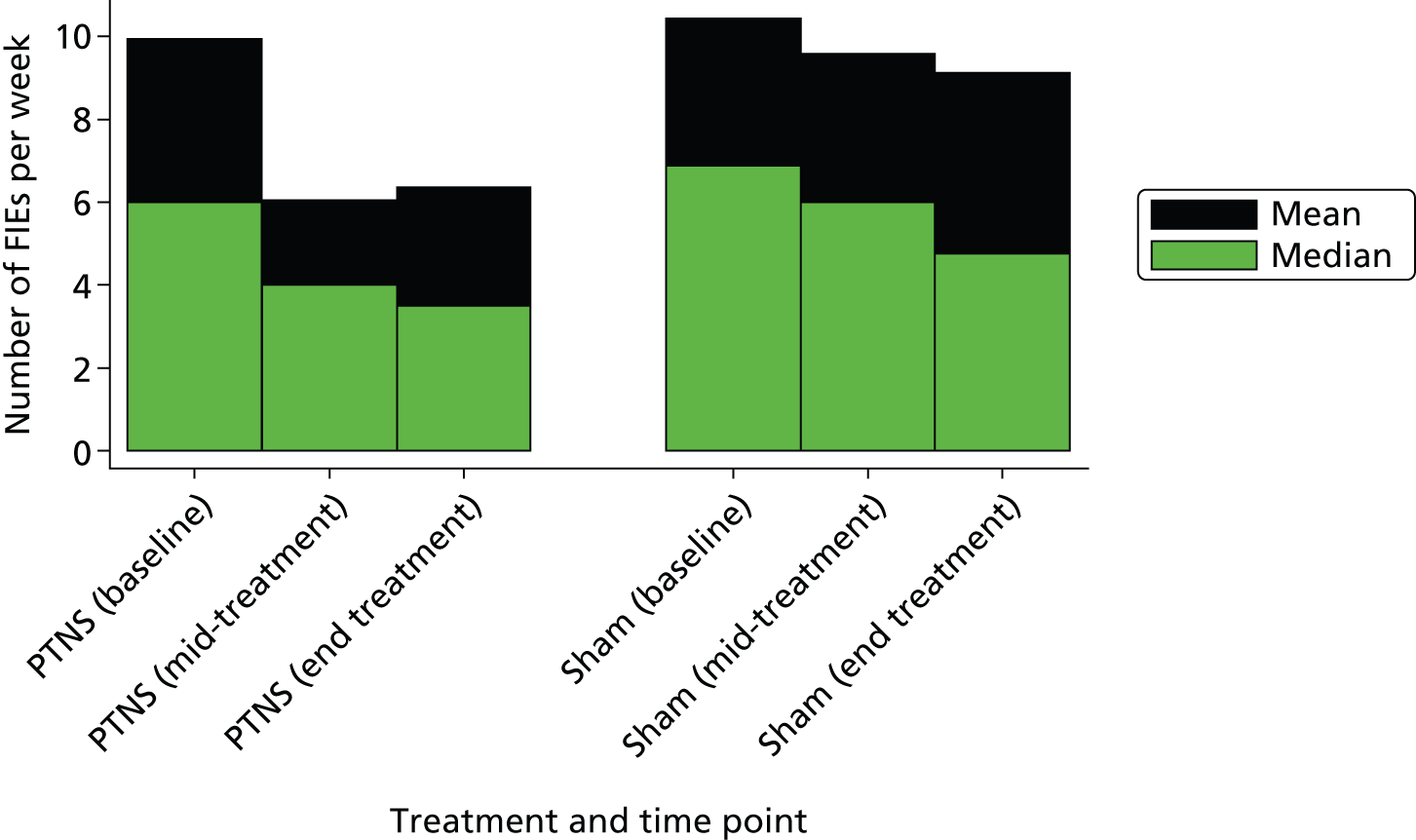

| Outcome | Baseline | End of treatment | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PTNS | Sham | PTNS | Sham | |

| FIEs per week | ||||

| Median (IQR) | 6.0 (2.0–14.0) | 6.9 (2.5–16.0) | 3.5 (1.0–10.0) | 4.8 (1.5–12.8) |

| Mean (SD) | 9.9 (11.2) | 10.4 (10.9) | 6.4 (7.6) | 9.1 (10.7) |

| Urge FIEs per week | ||||

| Median (IQR) | 3.0 (0.9–8.0) | 2.5 (0.5–7.0) | 1.5 (0.0–4.5) | 1.5 (0.5–5.5) |

| Mean (SD) | 5.3 (7.2) | 4.8 (5.9) | 3.0 (4.2) | 4.4 (6.5) |

| Passive FIEs per week | ||||

| Median (IQR) | 2.0 (0.0–7.5) | 3.0 (0.0–8.0) | 1.5 (0.0–5.0) | 1.5 (0.0–6.5) |

| Mean (SD) | 4.6 (6.0) | 5.7 (7.6) | 3.4 (4.6) | 4.7 (6.6) |

Secondary outcomes

Percentage change in faecal incontinence episodes

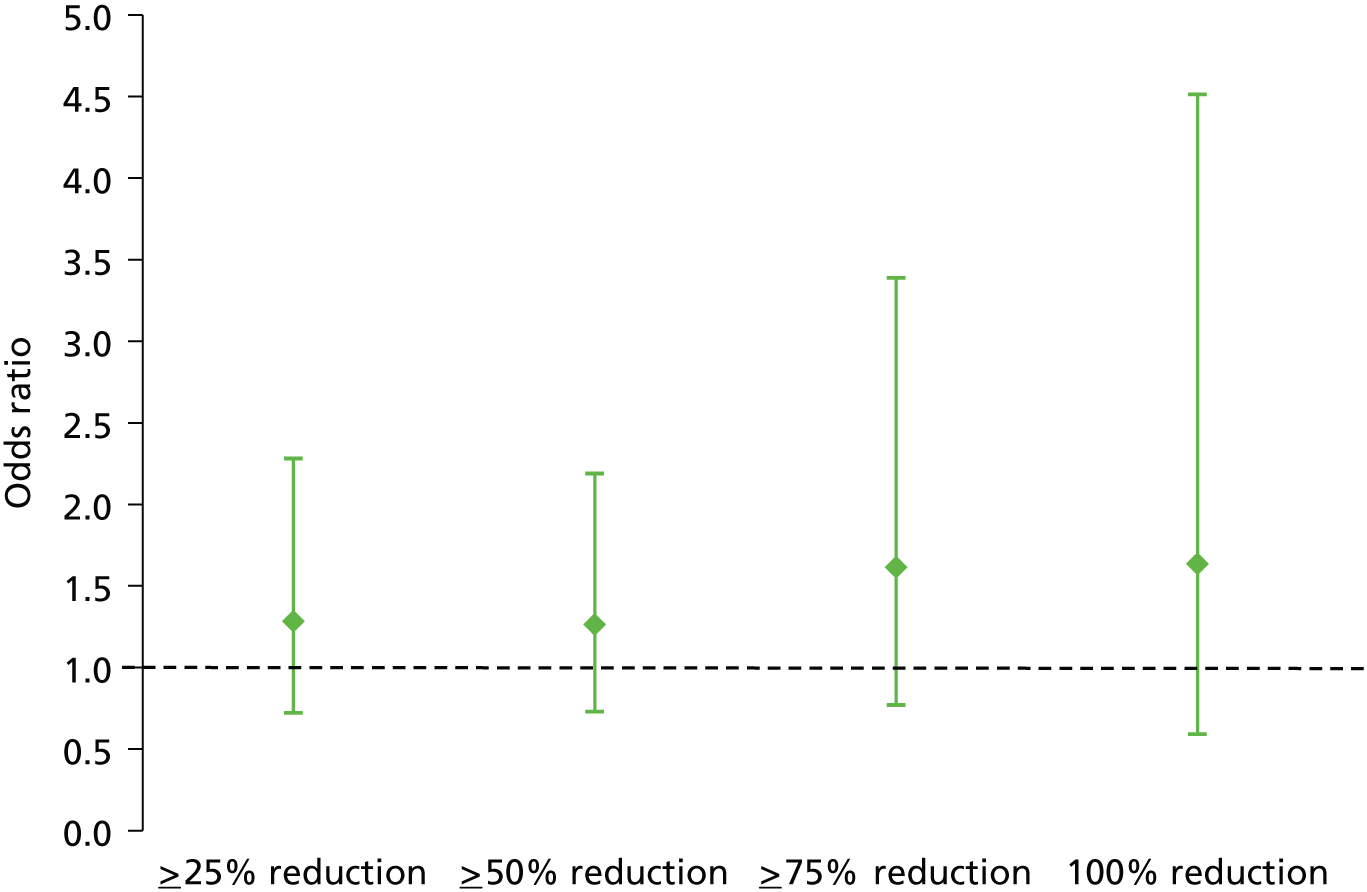

No significant difference was observed between the PTNS and sham arms in the number of participants achieving > 25%, > 75% and 100% reductions in weekly FIEs (see Table 6 and Figure 6).

FIGURE 6.

Adjusted odds ratios and 95% CIs of percentage reduction in FIEs: PTNS vs. sham.

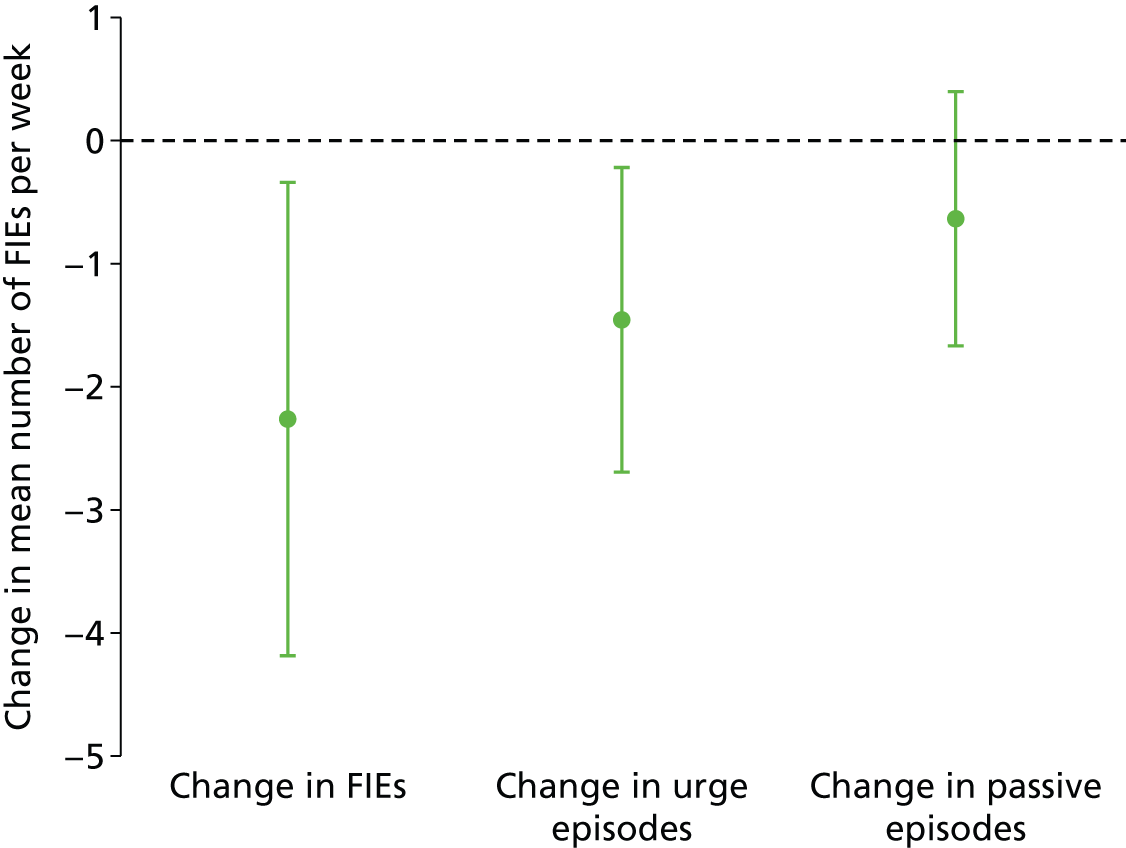

Change in faecal incontinence episodes as a continuous measure

There was a greater decrease in total number of FIEs per week in the PTNS than the sham arm (difference in means –2.3, 95% CI –4.2 to –0.3) episodes per week, and this difference was significant (p = 0.02). This comprised a reduction in urge FIEs (–1.5, 95% CI –2.7 to –0.2; p = 0.02) but not in passive FIEs (–0.64, 95% CI –1.67 to 0.40; p = 0.23) per week (see Table 6 and Figures 7 and 8). There was very little continued improvement from mid-treatment to end of treatment (indicating that those who are likely to respond to treatment will have done this by week 6).

FIGURE 7.

Adjusted difference in mean (95% CI) number of FIEs per week: PTNS vs. sham.

FIGURE 8.

Faecal incontinence episodes per week by treatment arm and time point.

Change in symptom severity score: St Mark’s Continence Score

No significant difference in SMCS was observed between the PTNS and sham arms following treatment (difference in means –0.047, 95% CI –1.033 to 0.939; p = 0.93) (Table 8 and see Table 6).

| Outcome | Baseline | End of treatment | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PTNS | Sham | PTNS | Sham | |

| SMCS | ||||

| Median (IQR) | 14.0 (12.0–17.0) | 16.0 (13.0–18.0) | 14.0 (11.0–17.0) | 15.0 (11.0–18.0) |

| Mean (SD) | 14.4 (3.7) | 15.4 (4.1) | 13.9 (4.3) | 14.6 (4.6) |

| SMCS > 5 | ||||

| n (%) | 110 (100) | 101 (100) | 104 (100) | 101 (100) |

Change in quality-of-life measures

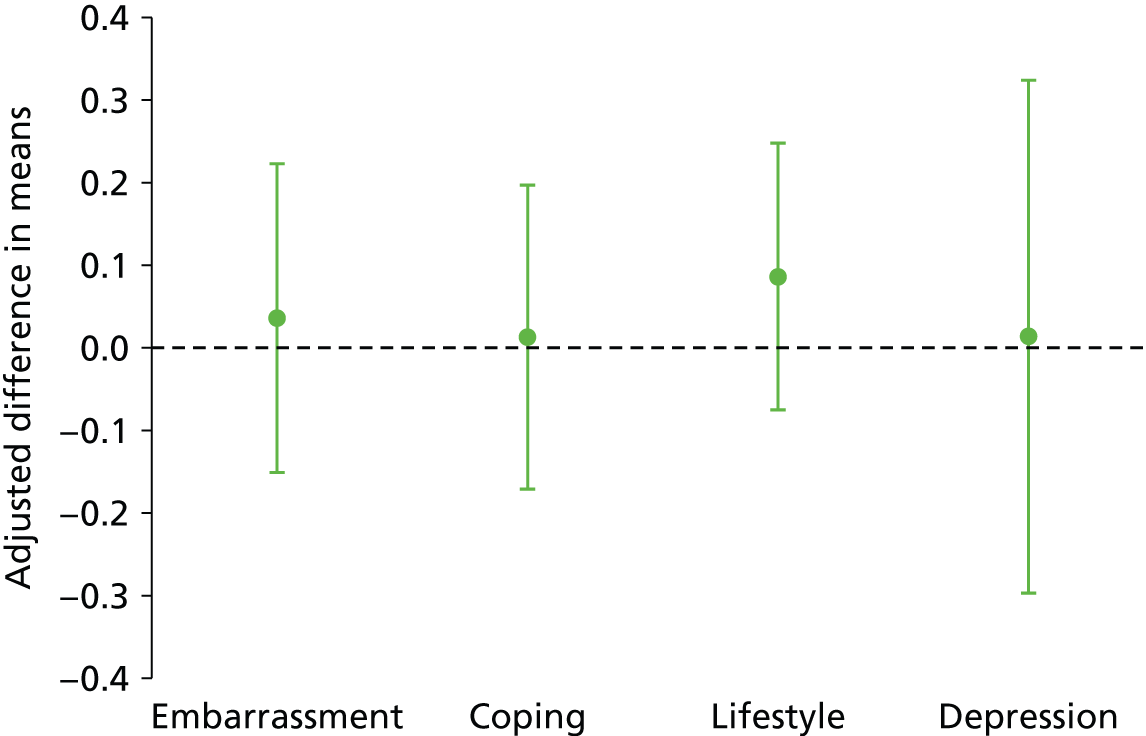

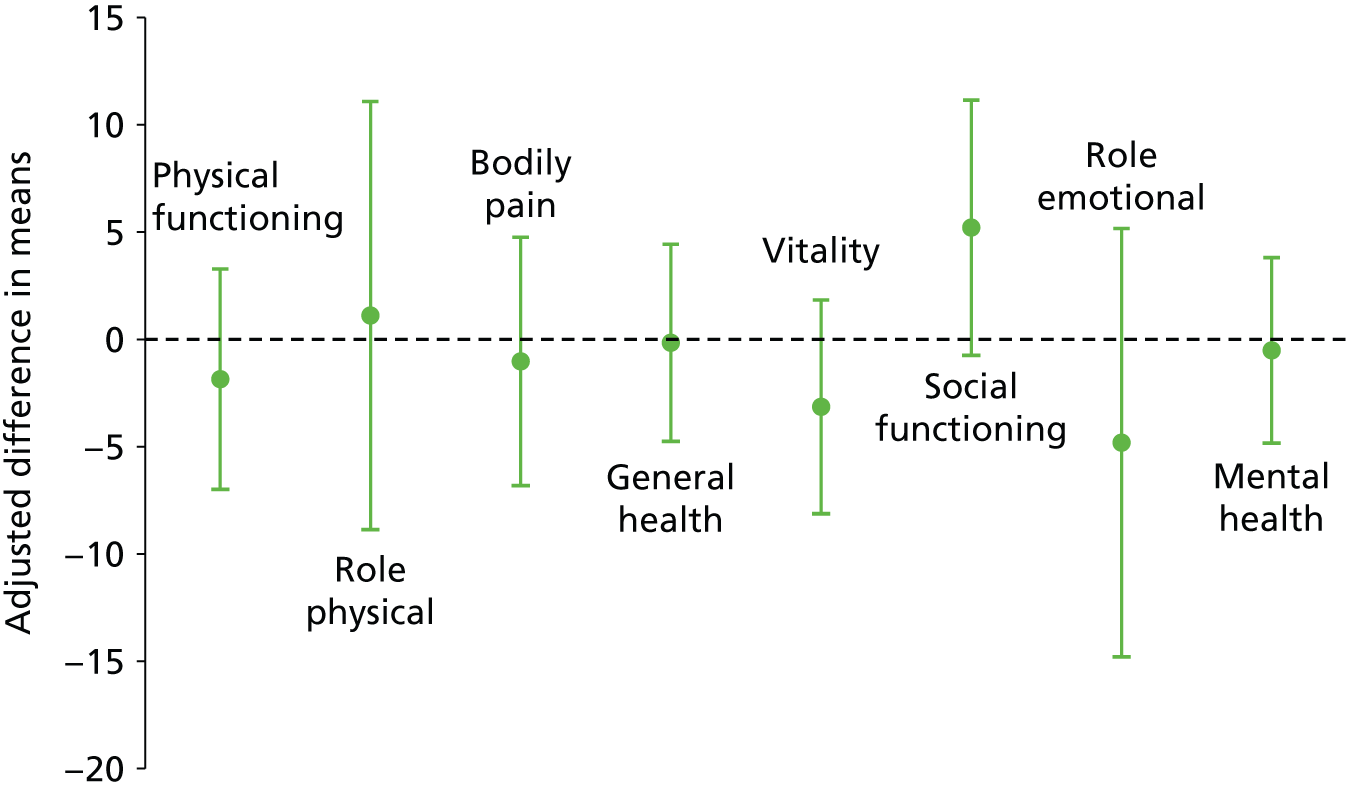

No significant differences were seen in the disease-specific (FIQoL and GIQoL) or generic (SF-36) quality-of-life measures between the PTNS and sham arms following treatment (Table 9 and Figures 9 and 10; see also Table 6).

| Outcome | Baseline | End of treatment | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PTNS | Sham | PTNS | Sham | |

| FIQoL scores | ||||

| Lifestylea | ||||

| Median (IQR) | 2.7 (1.8–3.4) | 2.5 (1.7–3.6) | 3.0 (2.2–3.7) | 2.9 (1.9–3.7) |

| Mean (SD) | 2.6 (0.9) | 2.6 (1.0) | 2.8 (0.9) | 2.8 (1.0) |

| Coping and behavioura | ||||

| Median (IQR) | 1.7 (1.2–2.3) | 1.6 (1.1–2.6) | 1.9 (1.3–2.6) | 1.7 (1.2–2.9) |

| Mean (SD) | 1.9 (0.7) | 1.9 (0.9) | 2.0 (0.8) | 2.0 (1.0) |

| Depression and self-perceptiona | ||||

| Median (IQR) | 3.1 (2.0–3.4) | 2.6 (2.0–3.7) | 3.1 (2.2–3.7) | 2.6 (2.0–3.9) |

| Mean (SD) | 2.8 (0.9) | 2.7 (0.9) | 2.9 (1.0) | 2.8 (1.0) |

| Embarrassmentb | ||||

| Median (IQR) | 2.0 (1.7–2.7) | 2.0 (1.3–2.7) | 2.7 (1.7–3.0) | 2.3 (1.7–3.0) |

| Mean (SD) | 2.2 (0.8) | 2.1 (0.8) | 2.4 (0.8) | 2.3 (0.9) |

| GIQoL scoresc | ||||

| Median (IQR) | 130.0 (113.0–141.0) | 126.5 (109.0–139.0) | 135.0 (115.0–148.0) | 134.0 (120.0–146.0) |

| Mean (SD) | 126.7 (18.8) | 123.8 (20.2) | 132.0 (20.6) | 131.6 (20.5) |

| SF-36 scores (%) | ||||

| Physical functioning | ||||

| Median (IQR) | 70.0 (45.0–90.0) | 65.0 (40.0–85.0) | 75.0 (47.5–90.0) | 70.0 (45.0–90.0) |

| Mean (SD) | 65.7 (27.4) | 61.4 (28.4) | 67.1 (27.7) | 63.8 (29.0) |

| Role-physical | ||||

| Median (IQR) | 50.0 (0.0–100.0) | 25.0 (0.0–75.0) | 62.5 (0.0–100.0) | 25.0 (0.0–100.0) |

| Mean (SD) | 46.4 (42.1) | 36.4 (41.4) | 54.4 (44.1) | 46.2 (44.8) |

| Bodily pain | ||||

| Median (IQR) | 60.0 (40.0–90.0) | 57.5 (32.5–90.0) | 67.5 (45.0–90.0) | 67.5 (35.0–90.0) |

| Mean (SD) | 61.3 (30.0) | 58.2 (31.5) | 64.3 (28.3) | 62.1 (31.0) |

| General health | ||||

| Median (IQR) | 50.0 (35.0–70.0) | 50.0 (30.0–70.0) | 55.0 (30.0–75.0) | 50.0 (35.0–70.0) |

| Mean (SD) | 51.2 (23.4) | 50.3 (23.8) | 52.8 (24.6) | 50.6 (23.9) |

| Vitality | ||||

| Median (IQR) | 45.0 (30.0–57.5) | 50.0 (30.0–60.0) | 50.0 (25.0–60.0) | 50.0 (35.0–65.0) |

| Mean (SD) | 43.9 (22.1) | 42.7 (22.8) | 45.6 (22.2) | 46.7 (23.1) |

| Social functioning | ||||

| Median (IQR) | 62.5 (37.5–75.0) | 62.5 (37.5–87.5) | 75.0 (50.0–87.5) | 62.5 (37.5–87.5) |

| Mean (SD) | 58.4 (28.8) | 59.3 (31.6) | 66.4 (28.6) | 60.6 (31.7) |

| Role-emotional function | ||||

| Median (IQR) | 66.7 (0.0–100.0) | 33.3 (0.0–100.0) | 100.0 (0.0–100.0) | 83.3 (0.0–100.0) |

| Mean (SD) | 58.4 (28.8) | 59.3 (31.6) | 61.7 (45.3) | 60.2 (44.1) |

| Mental health | ||||

| Median (IQR) | 60.0 (44.0–76.0) | 64.0 (48.0–76.0) | 64.0 (48.0–84.0) | 64.0 (52.0–76.0) |

| Mean (SD) | 60.3 (21.0) | 60.8 (21.6) | 62.7 (25.1) | 63.0 (21.4) |

FIGURE 9.

Adjusted difference in means (95% CI) for FIQoL: PTNS vs. sham.

FIGURE 10.

Adjusted difference in means (95% CI) for SF-36: PTNS vs. sham.

Change in patient-centred outcomes score

Improvement in patient-centred outcomes (i.e. a reduction in score) was significantly greater in the PTNS arm than in the sham arm (difference in means –0.545, 95% CI –1.081 to –0.008; p = 0.047) (Table 10; see also Table 6).

| Outcome | Baseline | End of treatment | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PTNS | Sham | PTNS | Sham | |

| Median (IQR) | 8.9 (7.8–9.8) | 9.2 (8.3–10.0) | 8.4 (6.9–9.4) | 9.3 (7.6–10.0) |

| Mean (SD) | 8.5 (1.6) | 8.7 (1.7) | 7.8 (2.0) | 8.4 (2.1) |

Likert scale of patients’ global impression of success (scale 0–10)

No significant difference existed in patients’ global impression of success between the PTNS and sham arms (difference in means 0.808, 95% CI –0.055 to 1.672; p = 0.068) (Table 11; see also Table 6).

| Outcome | PTNS | Sham |

|---|---|---|

| Median (IQR) | 4.8 (0.0–6.8) | 2.1 (0.0–4.9) |

| Mean (SD) | 4.0 (3.3) | 3.2 (3.1) |

European Quality of Life-5 Dimensions analysis

There were virtually no differences between the two arms either at baseline or after treatment in respect of EQ-5D index and visual analogue scale (VAS) scores, with scores on both scales remaining unchanged over time (Table 12 and see Table 6). The full report can be viewed in Appendix 13.

| Outcome | Baseline | End of treatment | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PTNS | Sham | PTNS | Sham | |

| EQ-5D index, mean (SD) | 0.69 (0.27) | 0.63 (0.34) | 0.68 (0.28) | 0.65 (0.34) |

| EQ-5D VAS, mean (SD) | 64.50 (21.72) | 64.04 (21.24) | 64.25 (22.32) | 63.69 (23.66) |

Other outcomes

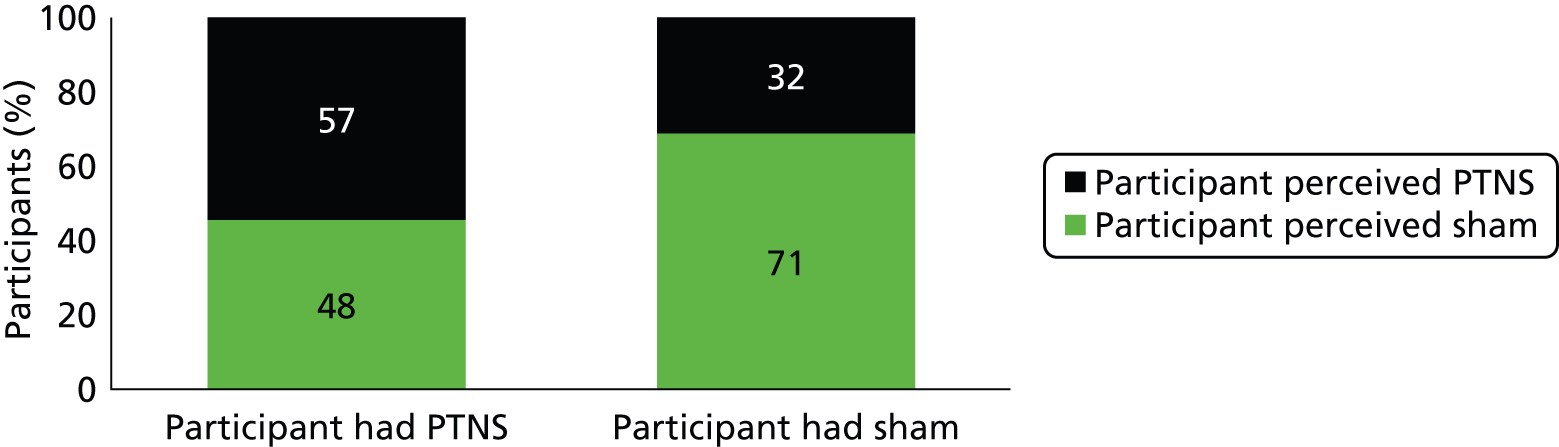

In the PTNS arm, 57 out of 107 (54%) participants thought that they had received PTNS and 48 out of 107 (46%) thought that they had received sham treatment (Figure 11). In the sham arm, 32 out of 103 (31%) participants thought that they had received PTNS and 71 out of 103 (69%) participants thought that they had received sham treatment. Overall, 208 patients answered this question, of whom 62% perceived correctly and 38% perceived incorrectly.

FIGURE 11.

Participants’ perception of treatment.

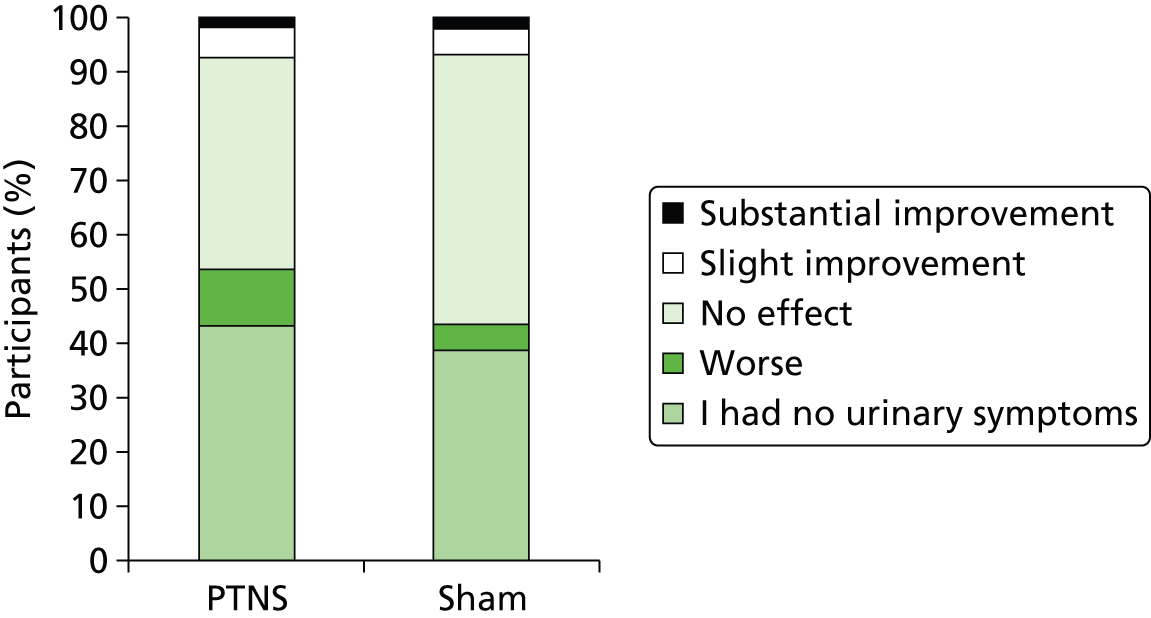

Only 13% (8 out of 61) of patients in the PTNS arm experienced slight or substantial improvement in urinary symptoms and the figure in the sham arm was similar, at 11% (7 out of 64). Most symptomatic patients reported no effect: 39% in the PTNS arm and 50% in the sham arm. Indeed, more patients in the PTNS arm than in the sham arm reported a worsening of urinary symptoms (10% vs. 5%) (Figure 12).

FIGURE 12.

Effect of treatment on urinary symptoms.

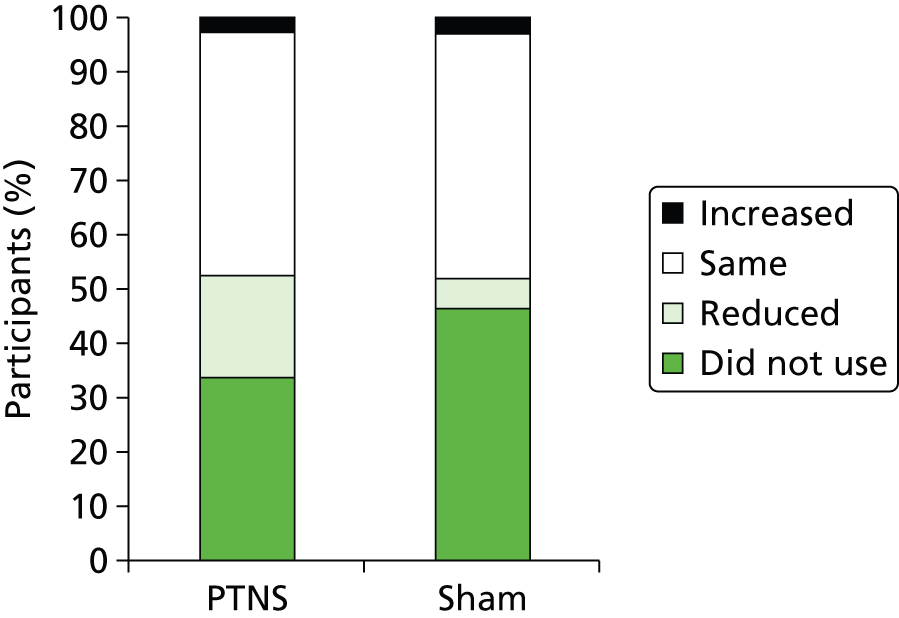

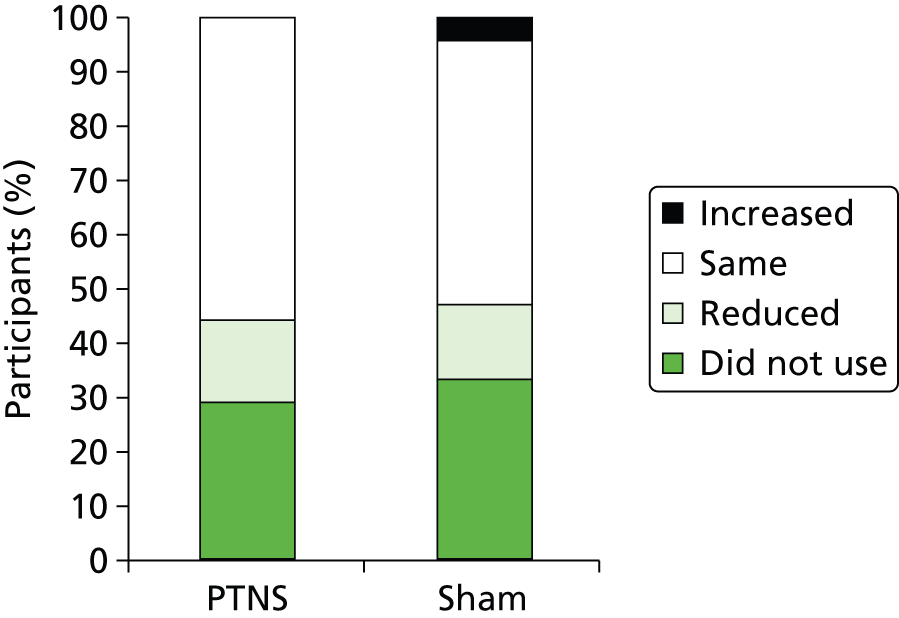

Of participants who used loperamide at baseline, the majority in both the PTNS (33 out of 49 = 67%) and sham (32 out of 38 = 84%) arms reported no change in use throughout the trial. Similar percentages in each arm (4% in PTNS vs. 5% in sham) reported increasing loperamide use. A higher percentage of patients in the PTNS arm than in the sham arm reduced their loperamide use (29% vs. 11%) (Figure 13).

FIGURE 13.

Effect of treatment on loperamide use.

Other potentially relevant concomitant medication usage can be seen in Appendix 14. There has been minimal concomitant medication usage and this has not been considered significant.

Of the participants who used incontinence pads, the majority [56% (44 out of 79) in PTNS arm and 49% (35 out of 72) in sham arm] reported no change in use over the period of the trial. Similar percentages of participants reduced their pad usage through the course of the trial (15% in the PTNS arm and 14% in the sham arm), while 4% participants in the sham arm had to increase their pad usage compared with none in the PTNS arm (Figure 14).

FIGURE 14.

Effect of treatment on incontinence pad usage.

Per-protocol analysis

Per-protocol analysis was carried out subsequent to the intention-to-treat analysis. To be included in these analyses, patients were required to have at least 10 treatments within 13 weeks, with 10 treatments no fewer than 5 days and no more than 10 days apart. This was to ensure that patients attended for treatments regularly and in a time frame spread evenly throughout the treatment duration.

In total, 197 of the 227 patients completed the treatment per protocol. Table 13 presents the results of the analysis of the primary outcome. The conclusion from this analysis remains unchanged and other important outcomes remain unchanged apart from the Likert scale of success, which shows that those in the PTNS arm were more likely than those in the sham arm to perceive that the treatment was successful; this difference was statistically significant.

| Outcome | Odds ratio | 95% CI | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| ≥ 50% reduction FIEs (primary outcome) | 1.269 | 0.688 to 2.341 | 0.446 |

| ≥ 25% reduction in FIEs | 1.247 | 0.698 to 2.228 | 0.456 |

| ≥ 75% reduction in FIEs | 1.631 | 0.781 to 3.409 | 0.194 |

| 100% reduction in FIEs | 1.658 | 0.590 to 4.655 | 0.338 |

| Difference in means | |||

| Change in FIEs | –2.233 | –4.275 to –0.191 | 0.032 |

| Change in urge FIEs | –1.486 | –2.778 to –0.194 | 0.024 |

| Change in passive FIEs | –0.600 | –1.663 to 0.463 | 0.268 |

| SMCS | 0.202 | –0.855 to 1.258 | 0.708 |

| GIQoL | –1.750 | –5.864 to 2.364 | 0.401 |

| FIQoL embarrassment | 0.059 | –0.141 to 0.260 | 0.563 |

| FIQoL coping | –0.007 | –0.211 to 0.196 | 0.944 |

| FIQoL lifestyle | 0.093 | –0.079 to 0.266 | 0.286 |

| FIQoL depression | 0.030 | –0.302 to 0.361 | 0.853 |

| SF-36 physical functioning | –0.601 | –5.964 to 4.761 | 0.826 |

| SF-36 role-physical | 1.562 | –9.062 to 12.186 | 0.772 |

| SF-36 bodily pain | –2.933 | –8.975 to 3.108 | 0.341 |

| SF-36 general health | 0.612 | –3.989 to 5.213 | 0.794 |

| SF-36 vitality | –2.872 | –7.967 to 2.224 | 0.268 |

| SF-36 social functioning | 5.665 | –0.518 to 11.848 | 0.074 |

| SF-36 role emotional | –6.562 | –16.988 to 3.863 | 0.216 |

| SF-36 mental health | –0.300 | –4.633 to 4.033 | 0.892 |

| Patient-centred outcomes | –0.593 | –1.141 to –0.044 | 0.034 |

| EQ-5D index score | –0.020 | –0.082 to 0.042 | 0.524 |

| Likert scale of success | 0.934 | 0.037 to 1.831 | 0.042 |

Subgroup analyses

Preplanned subgroup analyses were performed for the primary outcome only. The following subgroups were selected:

-

sex (male vs. female)

-

FI severity (> 7 episodes per week vs. < 7 episodes per week on initial bowel diary)

-

age (< 40 years, 40–60 years, > 60 years)

-

both urge and passive incontinence, only urge, only passive.

The primary outcome was negative for each of these subgroup analyses (see Appendix 15).

Sensitivity analysis

Sensitivity analysis was carried out, removing the patients who scored ‘zero’ on their initial bowel diaries (see Appendix 16). This excluded 16 patients, nine from the PTNS arm and seven from the sham arm. The primary outcome was negative for this analysis (odds ratio 1.325, 95% CI 0.736 to 2.385; p = 0.348).

Further sensitivity analysis was carried out excluding patients who were recruited from poorly recruiting centres (defined as centres recruiting fewer than five patients) (see Appendix 17). This excluded four patients from two centres, two from each arm. The primary outcome was negative for this analysis (odds ratio 1.234, 95% CI 0.693 to 2.196; p = 0.476).

Centre effect

Data were analysed to allow for a centre effect, that is, outcomes among patients being treated by the same study centre may be correlated, indicating that treatment at some centres may be more effective. The ICC was very small (< 0.001 for most outcomes), indicating no significant centre effect. The only outcomes for which the ICC was substantial were ≥ 75% reduction (ICC = 0.222) in FIEs, 100% reduction in FIEs (ICC = 0.012), change in passive FIEs (ICC = 0.106), FIQoL coping (ICC = 0.104), SF-36 social functioning (ICC = 0.012), SF-36 mental health (ICC = 0.038), EQ-5D (ICC = 0.019) and the Likert scale of success (ICC = 0.02).

Serious adverse events

There were four SAEs during the trial (Table 14). None was related to the trial treatment and all were resolved.

| SAE | Allocation | Grade | Duration (days) | Action | Relatedness | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Flexible cystoscopy for botulinum toxin type A (Botox®, Allergan) | PTNS | Moderate | 3 | H | U | R |

| Sleeve gastrectomy | Sham | Severe | 1 | H | U | R |

| Pilonidal abscess | Sham | Moderate | 26 | H | U | R |

| Shoulder manipulation | PTNS | Severe | 1 | H | U | R |

Adverse events

A total of 204 adverse events were noted in the trial, 107 in the PTNS arm and 97 in the sham arm. Table 15 reports severity by relatedness in each arm. There were seven mild related adverse events in each arm.

| Outcome | PTNS | Sham | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Related | Possibly related | Unrelated | Total | Related | Possibly related | Unrelated | Total | |

| Mild | 7 | 25 | 40 | 72 | 7 | 18 | 33 | 58 |

| Moderate | 0 | 13 | 17 | 30 | 0 | 14 | 21 | 35 |

| Severe | 0 | 4 | 1 | 5 | 0 | 1 | 3 | 4 |

Related and possibly related adverse events can be seen in Table 16. A full list of all adverse events can be seen in Appendix 18.

| Outcome | Adverse event | PTNS | Sham |

|---|---|---|---|

| Related | Pain at needle site | 4 | 3 |

| Bruising at needle site | 2 | 1 | |

| Altered sensation at needle site | 1 | 0 | |

| Bleeding at needle site | 0 | 2 | |

| Altered sensation in toe | 0 | 1 | |

| Possibly related | Pain in abdomen | 4 | 2 |

| Pain in back | 1 | 0 | |

| Pain in leg or foot | 13 | 10 | |

| Pain in perineum | 0 | 1 | |

| Altered sensation in leg or foot | 4 | 0 | |

| Altered sensation in perineum | 0 | 1 | |

| Weakness in leg | 0 | 1 | |

| Constipation | 0 | 1 | |

| Diarrhoea | 8 | 3 | |

| FI | 0 | 1 | |

| Urinary symptoms | 0 | 4 | |

| Headache/migraine | 6 | 7 | |

| Dizziness | 5 | 0 | |

| Nausea/vomiting | 0 | 1 | |

| Anxiety/depression | 1 | 1 | |

| Skin disorder | 1 | 0 |

Chapter 4 Discussion

Although PTNS and sham electrical stimulation offer some improvement in FI symptoms by reducing weekly episodes, no clinically significant benefit of PTNS over sham was demonstrated. This was demonstrated by the primary outcome, with 38% of participants in the PTNS arm and 31% in the sham arm achieving at least a 50% reduction in FIEs.

Some of the secondary outcome variables, namely reduction in mean total weekly FIEs, reduction in mean urge FIEs and improvement on the patient-centred outcomes form (a derivative of the validated International Consultation on Incontinence Modular Questionnaire – Bowel), demonstrated a significant benefit of PTNS over sham treatment. However, the margin of clinical benefit must be considered small even though statistical significance was achieved, as this improvement was based on a reduction in weekly FIEs from a median of 6.0 (IQR 2.0–14.0) to a median of 3.5 (IQR 1.0–10.0), meaning that many participants still have significant FI. It is interesting to note that, if a treatment effect was going to occur, it would have done so by six treatments.

There was no significant improvement in the SMCS in the PTNS arm compared with the sham arm. Patients in the PTNS arm of the trial showed no significant improvement in any of the quality-of-life measures, compared with patients in the sham arm.

The results of this study may seem surprising when considered in the context of other published studies of PTNS from FI. The 12 published studies on PTNS, including 10 case series, one small randomised study and one comparative case-matched study of PTNS and SNS, allude to a 63–82% response rate using the same primary outcome, which is considerably higher than the 38% reported here. The results of this study are, however, closer to a recently conducted randomised study of PTNS compared with SNS, which found that 40% of patients in the PTNS arm reported treatment success at 3 months, again significantly lower than any other previously reported data. 71 Interestingly, a double-blind placebo-controlled randomised controlled trial of TTNS for FI in the literature shows no discernible benefit of TTNS over sham treatment in the treatment of FI. 72

These findings highlight the necessity of conducting well-designed randomised controlled trials to answer clinical questions. The other previously published non-randomised studies are prone to significant bias, which may account for the difference in results.

Case series provide poor evidence and are open to significant bias. First and foremost, there is no control arm for comparison, leading to performance bias. There is no way of unpicking the effect of natural change in disease status over time or the well-recognised placebo effect of this nurse-led face-to-face intervention. Both of these issues can be ameliorated only by including a control arm. Selection bias in case series is a large problem unless subjects are truly selected consecutively. In addition to this, case series are often subject to attrition bias, as patients may be lost to follow-up or researchers may selectively report only subjects with positive findings. In case series, both the patient and the observer are often unblinded. This can introduce bias from both perspectives: patients may experience a high level of expectation, which may influence reporting; and, in addition to this, bias may be introduced from the observers’ perspective, as clinicians often have a vested interest in treatment and publication. This problem is particularly important in trials of FI that involve bowel diary data, as diaries are notoriously poorly completed and open to interpretation. 73

The only other RCTs of PTNS in the literature are those on OAB. Of these studies, two double-blinded RCTs that compare PTNS with sham electrical stimulation showed a statistically significant improvement in urinary frequency and urge urinary incontinence in the active PTNS arm compared with the sham arm (71% vs. 0% responders in the smaller study; p < 0.001;74 and 54.5% vs. 24.9% in the larger pivotal trial;58 p < 0.001). One had a significantly smaller sample size than the other (n = 35 and n = 174 respectively).

Both of these studies reported a higher treatment effect of PTNS than seen in the CONFIDeNT trial, and one that is significantly beneficial compared with sham. There could be a number of reasons for this. It could simply be a result of PTNS having efficacy in OAB but not FI. Alternatively, it could be a result of these studies selecting purely patients who had OAB, that is patients who experience bladder urgency (more akin to faecal urgency or urge FI), which may account for the CONFIDeNT trial showing no overall benefit in patients, but significant reductions in urge FIEs.

The disparity could also be a factor of primary outcome measure selection. Peters et al. 58 used a subjective primary end point involving number of patients who graded their overall bladder symptoms as moderately or markedly improved on a global response assessment. It is unclear whether or not this assessment tool has been validated. The smaller study chose an objective primary end point, equivalent to that used in the CONFIDeNT trial, of those patients who experienced a > 50% reduction in number of urge urinary incontinence episodes.

Both urological studies also reported a significantly lower treatment effect of the sham, or placebo. The placebo effect in trials of functional bowel disease is well acknowledged to be high; indeed, meta-analyses of 45 published trials estimate the placebo response rate in functional dyspepsia to be between 6% and 72%75,76 and in 50 placebo-controlled irritable bowel syndrome trials it is estimated to be between 3% and 84%. 77–79 This may indicate that the 0% placebo effect in the Finazzi-Agro et al. 74 trial is a product of a small sample size, inadequate blinding or both. The apparently lower sham response in both studies may be a result of a less effective sham.

The sham stimulation used was different in both urological studies and also different from that used in the CONFIDeNT trial. In one study, the needle was placed in the medial head of gastrocnemius muscle and electrical stimulation activated for only 30 seconds prior to the stimulator being turned off;74 in the other study, a Streitberger needle was used, which does not pierce the skin, and electrical stimulation was delivered via TENS. The sham chosen in the CONFIDeNT trial was designed to give a very similar feeling to that produced by the active treatment, by giving the sensation of the skin being pierced by the needle and by providing a constant electrical sensation.