Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 11/95/03. The contractual start date was in November 2012. The draft report began editorial review in August 2014 and was accepted for publication in June 2015. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

none

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2016. This work was produced by Morrell et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Background

This chapter details the background to the report and presents an overview of postnatal depression (PND): the size and importance of the problem, the need for prevention, current service provision and the approaches to interventions to prevent the condition.

Description of health problem

Depression is a leading cause of life lived with disability. PND, also termed postpartum depression, is defined using standardised diagnostic criteria as a major depressive disorder in the year following childbirth. 1 PND has a wide range of symptoms measured in clinical practice and in research using symptom self-reports as a proxy for clinical assessment. 1 It is distinguished from the more transient ‘baby blues’ and the rarer and more acute puerperal psychosis. Severe PND is associated with suicide and infanticide, especially when the woman has psychotic symptoms. 2

The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders-Fifth Edition (DSM-V)3 does not recognise PND as a separate diagnosis, so, to be diagnosed, women must meet the criteria for depression. The specifier is ‘with peripartum onset’ (the most recent episode occurring during pregnancy and in the 4 weeks following delivery). 4 The following symptoms must be present for at least 2 weeks to fulfil the criteria for major depression: a depressed mood or a loss of interest or pleasure in daily activities which represents a change from normal mood; and a clinically significant distress or impairment in social, occupational, educational or other important areas of functioning. Five or more of the symptoms in Box 1 must also be present for a major depressive episode to be determined.

-

Depressed mood most of the day, almost every day, indicated by subjective report or others’ observations.

-

Reduced interest or pleasure in all (or nearly all) activities for most of the day, almost every day.

-

Significant weight loss or weight gain or decrease or increase in appetite almost every day.

-

Insomnia or hypersomnia almost every day.

-

Psychomotor agitation or retardation almost every day.

-

Fatigue or loss of energy almost every day.

-

Feelings of worthlessness or excessive or inappropriate guilt almost every day.

-

Diminished ability to think or concentrate, or indecisiveness, almost every day.

-

Recurrent thoughts of death, recurrent thoughts of suicide without a plan, a plan for committing suicide or a suicide attempt.

In contrast, the World Health Organization’s International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Edition (ICD-10) diagnosis code F53, is for mental disorders associated with the puerperium, that is postnatal or postpartum depression commencing within 6 weeks of delivery, that do not meet the criteria for disorders classified elsewhere. 5 ICD-10 also requires several symptoms to be endorsed for a diagnosis of depression and most cases of PND will meet criteria for disorders classified elsewhere. ICD-10 uses key symptoms of persistent sadness or low mood and/or loss of interest or pleasure, fatigue or low energy; at least one of these symptoms, most days, most of the time for at least 2 weeks. If any of these are present, associated symptoms such as disturbed sleep, poor concentration or indecisiveness, low self-confidence, poor or increased appetite, suicidal thoughts or acts, agitation or slowing of movements and guilt or self-blame define the degree of depression.

Prevalence

Postnatal depression is a public health problem4,6 which occurs in most cultures. 6–8 The prevalence of both major or minor depression during the first postnatal year is 7–13%. 9 Among a sample of more than 8000 women in England, 13% scored 13 or more (the threshold to identify women with probable major depression)2 on the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS)10 on at least one postnatal assessment. 11

Some women recover by the time their infant is 6 months old, but in 50% of women depression can last for more than 6 months. 12 Although PND is defined as depression within the 12 months after the birth of an infant, a significant number of women remain depressed for over 1 year,13 and some women remain depressed for 4 years. 12

Although depression postnatally may not be different from depression occurring in non-pregnant women, some women become depressed for the first time postnatally, some experience postnatal recurrence of previous depression13 and, for others, depression begins antenatally and continues postnatally. 14–16 Antenatal depression is the strongest predictor of PND,14 being as common as PND, with 18.4% of women having depressive symptoms throughout pregnancy. 17 Antenatal anxiety is commonly comorbid with antenatal depression and also increases the likelihood of PND. 14,15,18

Additional factors have consistently been associated with PND. Some PND may be biologically mediated and specifically linked to childbirth. 1 Some women with PND may be genetically more reactive to the environmental trigger for depression. 19 In other women, who have a general vulnerability to depression, PND may occur because childbirth is a stressor. 1 The strongest predictors of PND are antenatal anxiety and antenatal depression,14 lack of social support, a history of depression, neuroticism, low self-esteem, stressful life events during pregnancy, poor marital relationship and domestic violence. 1,20,21 Women themselves have reported that the causes of their PND were lack of support, pressure to do things right, their personality (prone to mental health problems), pressure (work or money), hormonal changes and resurfaced memories. 22 As the aetiology is diverse, it is difficult to predict accurately which women will develop PND.

Impact of health problem

The burden of PND can extend, in its most severe form, to suicide and, less frequently, infanticide. 23 The impact of PND on mothers is compounded by impairments to the mother–infant interaction24 and impairments to the infant’s longer-term emotional, cognitive, behavioural and social development. 25,26 The impact of withdrawn behaviour24 and vocally communicated sadness27 appears to be worsened when women live in poorer socioeconomic circumstances, and is worse if the infant is a boy28,29 or if depression becomes a chronic problem. 30,31 Additional later risks for infants are mediated through the effect of chronic depression on the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis functioning in offspring, into adolescence. 25,32,33

Depressed pregnant women have a greater risk of delivering a low-birthweight infant. 34 Antenatal depression is a risk factor for infant mood33,35 and for depression in offspring at 18 years of age, with higher risk among offspring whose mothers are less educated. 16,36 There is a potential impact on fathers, around 10% of whom are at risk of depression, particularly during the 3–6 months after the infant is born. 37 This depression is moderately positively correlated with maternal depression, but it is unclear if there is an association or a causal influence, and the direction of the influence, if any, is unknown. 37 Furthermore, postnatal paternal depression is associated with depression in offspring. 16

Current service provision

Variation in service and uncertainty about best practice

Free maternity care in the UK, delivered predominantly by midwives and obstetricians, provides opportunities for women to have contact with health-care services. The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) provides evidence-based guidelines for antenatal, intrapartum and postnatal care, and for antenatal and postnatal mental health. 38 Among those at low obstetric and medical risk, nine antenatal consultations are recommended for women expecting their first baby and seven consultations for those expecting a subsequent child. 39 Most women give birth in hospital maternity units, or in free-standing or alongside midwifery units and stay in for less than 2 days; fewer than 3% give birth at home. 40

Traditionally in the UK, hospital midwives have provided care in hospital for antenatal, labouring and postnatal women. Community midwifery teams have provided antenatal care in the community, and postnatal care during visits to the woman’s home, community health centres and children’s centres for up to 28 days after birth. Care is usually transferred on postnatal day 10 to the health visiting service and is provided by health visitors; specially trained public health nurses. Most health visitors now offer antenatal visits.

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence guidance38 recommends that primary health-care professionals should routinely enquire about past and current mental illness, and family history of perinatal mental illness, at a woman’s first appointment in early pregnancy, and postnatally (4–6 weeks and 3 or 4 months) to identify predictive risk factors. NICE guidance38 also recommends that midwives enquire within the first 24 hours after birth about a woman’s experience of her labour. In some locations, midwife-provided services have developed to provide an opportunity for women to discuss their birth experiences, but these do not always include access to formal psychological support.

The community midwife’s role includes an increased focus on improving public health and current pre-registration midwifery education covers the identification of potential mental health issues for childbearing women. The Maternal Mental Health Pathway41 guidance focuses on the health visitor’s role in maternal mental health and wellbeing during pregnancy and postnatally, recognising the contribution of midwives, mental health practitioners and general practitioners (GPs).

Other maternity support roles include maternity support workers and volunteers, such as breastfeeding peer supporters, counsellors and doula support (women who provide support to other women), during pregnancy, labour and birth and the early postnatal period.

Infrequently in the UK, and more commonly in the USA and a small number of other countries, CenteringPregnancy® (Centering Healthcare Institute, Boston, MA, USA) is available. 42,43 The CenteringPregnancy44 approach provides group care to women at similar stages of pregnancy by means of a health assessment and provision of education and peer support. Health-care professionals help women to participate in their own care and to learn from each other about pregnancy and care of the new infant.

Identification of postnatal and antenatal depression

There has been a lack of consistency in the routine approach to the identification of PND9,45,46 by primary health-care professionals. 47 NICE advocates a case-finding approach for depressive symptoms,38 based on two questions, the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ)-2, from the PHQ-9, as follows:48,49 ‘Over the last 2 weeks, how often have you been bothered by any of the following problems?’ (1) ‘Little interest or pleasure in doing things’ and (2) ‘Feeling, down, depressed, or hopeless’. 49 The EPDS,10 the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS)50 and the full PHQ-9 are to be used as follow-up tools as part of a fuller assessment process. The EPDS is frequently used as it performs well for major and minor depression,45 and is acceptable to women and health-care professionals. 51 The EPDS is not used systematically throughout the UK to identify depressive symptoms during pregnancy or postnatally partly because it ‘does not satisfy the National Screening Committee’s criteria for the adoption of a screening strategy as part of national health policy’. 52

Current service costs

Apart from the distress for women and the potential long-term consequences for infants, there are additional public health, social and economic consequences of maternal depression. 4 The cost of PND to the UK government is estimated as £45M53 to £61M per year. 4 For each exposed child, the estimated cumulative economic costs of adverse child development linked to a mother’s depression is £8190. 54 The health-care costs associated with postnatal paternal depression have been estimated for fathers with depression as £11,041, for fathers at high risk of developing depression as £1075 and for fathers without depression as £945 at 2008 prices. 55 In New Zealand, the potential value for money of implementation of a PND screening programme was assessed and the programme was found to be cost-effective. 56 In contrast, following a cost-effectiveness analysis, a system to identify PND in the UK was reported not to represent value for money based on the assumed cost of false positives. 57 Little is known about the economic consequences of PND or the cost-effectiveness of interventions aiming to prevent or alleviate PND symptoms. 58 Substantial economic returns have been estimated for investment in the prevention of mental health problems, with potential long-term pay-offs continuing into adulthood. 59

Despite the ‘case-finding’ approach to identify women at greater risk of PND, mainly based on earlier experience of mental health problems, little attention is paid to the prevention of PND, and no specific instruments are available to reliably predict PND among asymptomatic women. Some health visitors in the UK use the EPDS, but this practice varies nationally. It is likely that even less attention is paid to identifying depression and anxiety antenatally than postnatally.

Description of technology under assessment

Preventive interventions for postnatal depression

This section provides an overview of the rationale for the prevention of PND and a description of approaches that have been explored to prevent PND. There is evidence of the effectiveness of pharmacological60 and psychological interventions61–63 to treat PND within four main approaches: general counselling, interpersonal psychotherapy (IPT), cognitive–behavioural therapy (CBT) and psychodynamic therapy. 1 Prevention of a major depressive episode implies reducing the intensity, duration and frequency of depressive symptoms. 64

NHS England has provided a £1.8M budget for public health responsibilities, covering screening, immunisation and health-visiting services. 65 Less than 5% of NHS funding in England is spent on prevention, of all conditions. 65 The Marmot et al. 66 review aims to strengthen the role and impact of ill-health prevention, prioritising prevention and early detection of mental health conditions and early intervention. Traditionally primary, secondary and tertiary prevention activities are designed, respectively, to reduce the risk of developing health problems, to identify and manage pre-symptomatic ill health and to reduce the impact of the disease.

Three levels of preventive intervention are relevant to the prevention of PND:67

-

Universal preventive interventions are available to all women in a defined population not identified on the basis of increased risk for PND.

-

Selective preventive interventions are offered to women or subgroups of the population whose risk of developing PND are significantly higher than average, because they have one or more social risk factors.

-

Indicated preventive interventions are offered to women at high risk of developing PND on the basis of psychological risk factors, above-average scores on psychological measures or other indications of a predisposition to PND but who do not meet diagnostic criteria for PND at that time.

Universal preventive approaches may be less stigmatising than selective preventive interventions, but little attention has been paid to universal prevention in pregnant women, partly because the cost of a universal programme is likely to be high63 compared with a selective approach to identify higher-risk women. For example, 81% of women do not have an EPDS score 13 or more during pregnancy. 14 However, there is a rationale for providing a preventive intervention to women with subthreshold symptoms of depression who may otherwise go on to develop depression. 18,64

The outcomes for a selective intervention depend on how the population and risks are identified and defined. 63 Although indicated preventive interventions for PND could be regarded as addressing prodromal symptoms and therefore are not actually preventive, they could be regarded as early intervention. 68

The rationale for antenatal prevention of PND is based on data from the Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children study14 showing that 43.7% of women with an EPDS score 13 or more at 32 weeks of pregnancy experienced elevated symptoms postnatally. Aiming to prevent, identify and treat antenatal depression presupposes that this will lead to a reduction in antenatal maternal morbidity and severity, deleterious effects on the developing infant, postnatal maternal morbidity and severity and other adverse outcomes in the offspring. 16,69 Hence, investment during pregnancy and postnatally may yield future benefits and financial savings in different areas of health and social care.

Evidence of preventive interventions

A wide range of support and treatment approaches have been explored because of the diverse aetiology of PND (physiological, social or psychological) with the aim of changing the mechanisms leading to PND. 68 Several interventions to prevent PND have been developed as modifications of promising interventions to treat PND. These are classified as psychotherapeutic, biological, pharmacological, educational or social support. Cochrane and other systematic reviews have provided some contradictory findings about the potential to prevent PND. Not enough is known about the effectiveness of these preventive interventions.

Psychological approaches to the prevention and treatment of depression

The psychological literature attests to the large effort expended on research into differing psychological approaches to the prevention70 and treatment of depression. 71–75 Although depression has often been the initial target condition for testing psychological approaches, it has equally often proved to be a more challenging condition when attempting to establish mechanisms of change that are specific to particular models of therapeutic interventions. A review of 101 randomised controlled trials (RCTs) on the treatment of major depression concluded that IPT, CBT and behaviour therapy are effective, while brief dynamic therapy and emotion-focused therapy are possibly effective. 72

A different body of literature suggests relatively small differences between the outcomes of different psychological interventions for depression. An earlier review which controlled for researcher allegiance (belief in the superiority of a treatment) found small effect sizes from comparisons between specific therapies. 73 This finding has been broadly supported in a meta-analysis of 58 outcome studies for depression which made direct comparisons between specific therapies, which yielded similarly small effect sizes. 74 However, arguments suggesting that researcher allegiance bias is related to treatment effects have been both supported76 and challenged. 77

A wide-ranging review of the efficacy and effectiveness of psychological therapies in general concluded that they were broadly effective for depression with little difference between theoretically diverse interventions. 78 Estimates of the proportion of outcome variance attributable to components of therapy comprised the following: extra-therapeutic factors, 40% (e.g. delivered individually or in a group or the number of sessions); relationship, 30%; placebo/expectancy effects, 15%; and specific techniques, 15%. 78,79 A subsequent meta-analysis in which common factor control groups were employed supported these estimates. 80

Extensive efforts have been afforded in relation to the development of measures81 and the measurement of outcomes82 in psychotherapeutic interventions, and the role of non-specific (common) factors, such as congruence, positive regard and empathy, has long been recognised. 83,84 The account of broadly similar outcomes despite diverse therapeutic interventions (termed the equivalence paradox)85 has yielded sophisticated accounts to explain this phenomenon, with the existence of common factors persisting as one major explanatory source. 85 However, others have argued that there is no clear evidence supporting a causal link between common factors and therapeutic outcomes. 86 The debate is not so much focused on the validity of the concept but rather on the absence of experimental manipulation as a route to determining which common factors, if any, impact on therapeutic change. The concepts of hope and expectancy, among others, have been posited as common factors, but the main focus for research has been on the concept of the therapeutic relationship or alliance.

Educational interventions

Attention has been paid to developing preventive strategies or interventions that focus on couple communication or parenting skills to ease the transition to parenthood. 87 Antenatal preparation for parenthood has traditionally focused on aspects of the woman’s pregnancy and on preparation for childbirth, with less attention paid to what to expect when the infant arrives or to couple communication or parenting. 88,89 Dyadic relationship quality is adversely affected90 in 67% of new mothers91 and 45% of new fathers92 during the first year of parenthood. Despite the central role of partner support in maternal mood,93 new parent couples have reported being shocked by and unprepared for adverse changes in their relationship, feeling sad and bemused that no one had talked to them about the changes they would experience in their relationships. 94

Some preventive educational interventions have been delivered universally to all expectant parents, making use of the opportunities to access this population through established antenatal care pathways, thereby reaching couples who may not otherwise seek such support. 95 These, and more targeted, approaches cover a variety of levels of intensity and format and timings.

Social support

Social support is a multidimensional concept that incorporates appraisal, companionship, informational, motivational and instrumental support; that is ‘. . . information leading the subject to believe that they are cared for and loved, esteemed and a member of a network of mutual obligations’. 96 Social support involves both social relationships that are embedded, such as relationships with family members or friends, and those that are created. 97

There are several pathways through which social relationships and social support can affect mental health. Social support can operate to promote health directly by enhancing feelings of well-being or by buffering the negative influences of stressful events. Integration in a social network might also directly produce positive psychological states, including sense of purpose, belonging and recognition of self-worth. 98 These positive states, in turn, might benefit mental health because of an increased motivation for self-care, as well as the modulation of the neuroendocrine response to stress. 98 Being part of a social network enhances the likelihood of accessing various forms of social support, which in turn protects against distress. 99 Members of a social network can exert a salutary influence on mental health by role modelling health-relevant behaviours. 100

Several different psychosocial mechanisms link aspects of social relationships to physical and emotional well-being: social influence/social comparison, social control, role-based purpose and meaning (mattering), self-esteem, sense of control, belonging and companionship and perceived support availability. 101 Given the importance of social support on mental health outcomes, enhancing social support has been used as a strategy for both the prevention and treatment of PND.

Pharmacological interventions or supplements

Some of the earliest interventions for the treatment and prevention of PND were hormonal. Uncontrolled studies used progesterone,102–104 but no controlled studies have been conducted of progesterone or oestradiol, as either a treatment or prevention.

Compared with the results of trials supporting antidepressant treatment for major depression, there is relatively little evidence to guide the clinician in treating or preventing PND. The mainstay of treatment has been antidepressant medication but women are reluctant to take antidepressants,60 as they are concerned about their safety when breastfeeding and the potential for side effects to disturb their interaction with their infant. 105

It has been reported that fish consumption and omega-3 status after childbirth are not associated with PND,106 but there is still interest in exploring the role of omega-3 fatty acids in PND, alone or combined with supportive psychotherapy. 107

Complementary and alternative medicine

This review adopts a generic definition of complementary and alternative medicine (CAM): ‘A group of diverse medical and health-care systems, practices and products that are not presently considered to be part of conventional medicine’. 108 Although this definition meets with problems in many areas of medical practice, in that what were once regarded as CAM are now provided as part of conventional medical service, it works reasonably well in perinatal depression, as CAMs are not generally provided in perinatal services.

Complementary and alternative medicine is widely used by pregnant women in the Western world, particularly those who are highly educated and have high incomes,109 often to reduce stress and improve mood; however, their use remains controversial. 110 Controversy extends beyond the definition of CAM, to the nature of the effects of CAM and to the quality of CAM research. CAM is also widely used by the general public, particularly women,111,112 many of whom do not report its use to their doctors. It is often used to promote wellness in the positive holistic sense as well as in the management of symptoms and disease. CAM has been offered to women with the aim of treating both antenatal depression63,113–115 and PND,63,116 alone or in combination.

The CAM interventions most commonly explored in these studies include aromatherapy, massage, hypnosis and other forms of relaxation therapy, herbal medicine, mindfulness and meditation, acupuncture and general traditional Chinese medicine, Ayurvedic medicine and homeopathy. Acupuncture is a popular form of treatment for depression outside the perinatal period, and there is evidence that its effectiveness is equivalent to that of antidepressants117 and that side effects are rare. Acupuncture in the context of antenatal depression was examined by a Cochrane review118 that reported inconclusive evidence.

Mind–body therapies have also been used to treat depression in general and in the perinatal period specifically,116,119 and for many there is some evidence of effectiveness. 120 Mindfulness has received specific attention in the context of perinatal depression121 and is supported by an evidence base showing that it is effective in depression in general. 122

Yoga and tai chi/qi gong are practised both alone and as a component of Ayurvedic and traditional Chinese medicine and are used by pregnant women to improve their health. 110,119 The health effects of these traditional medical approaches are held to extend beyond physical fitness, suppleness and strength, and they overlap with those of simple physical activity, which has also been investigated as an intervention to reduce depressive symptoms in pregnant women. 123

Summary

In summary, the prevention of PND is an important and somewhat neglected area in the UK in terms of the potential impact on women and their infants and families. Within the NHS, effort is currently directed towards treating identified depression in perinatal women, particularly postnatally. A range of psychological, educational, pharmacological social support and CAM interventions have been explored to minimise the development of and the intensity, duration, and frequency of depressive symptoms. The next chapter defines the decision problem.

Chapter 2 Definition of the decision problem

Decision problem

The focus of this report is the prevention of PND and optimisation of the mental health of pregnant and postnatal women, and consequently the health of their infants.

The population comprised all pregnant women (universal), pregnant women or subgroups whose risk of developing PND was significantly higher than average because they had one or more social risk factor (selective), and pregnant women at high risk of developing PND on the basis of psychological risk factors, above-average scores on psychological measures or other indications of a predisposition to PND or diagnosed depression (indicated). The population also included all postnatal women in their first 6 postnatal weeks (universal), postnatal women or subgroups whose risk of developing PND was significantly higher than average because they had one or more social risk factor (selective), and postnatal women at high risk of developing PND on the basis of psychological risk factors, above-average scores on psychological measures or other indications of a predisposition to PND (indicated), but not postnatal women diagnosed with depression.

All interventions suitable for pregnant women and women in the first 6 postnatal weeks were included. All usual care and enhanced usual-care control and active comparisons were considered. In the review of both the quantitative and the qualitative research literature, all outcomes were considered.

Overall aim and objectives of assessment

The overall aim of the report was to evaluate the clinical effectiveness, cost-effectiveness, acceptability and safety of antenatal and postnatal interventions to prevent PND. The purpose of the study was to apply rigorous methods of systematic reviewing of quantitative and qualitative studies, evidence synthesis and decision-analytic modelling to evaluate the preventive impact on women and their infants and families.

The objectives of the review were as follows:

-

to determine the clinical effectiveness of antenatal interventions and postnatal interventions to prevent PND (systematic review of quantitative research)

-

a. to identify moderators and mediators of the effectiveness of preventive interventions

-

b. to undertake a meta-analysis of available evidence [including a network meta-analysis (NMA) as appropriate]

-

-

to provide a detailed service user and service provider perspective on the uptake, acceptability and potential harms of antenatal and postnatal interventions (systematic review of qualitative research)

-

a. to examine the main service models for prevention of PND in relation to the underlying programme theory and mechanisms, with a focus on group- and individual-based approaches (realist synthesis)

-

-

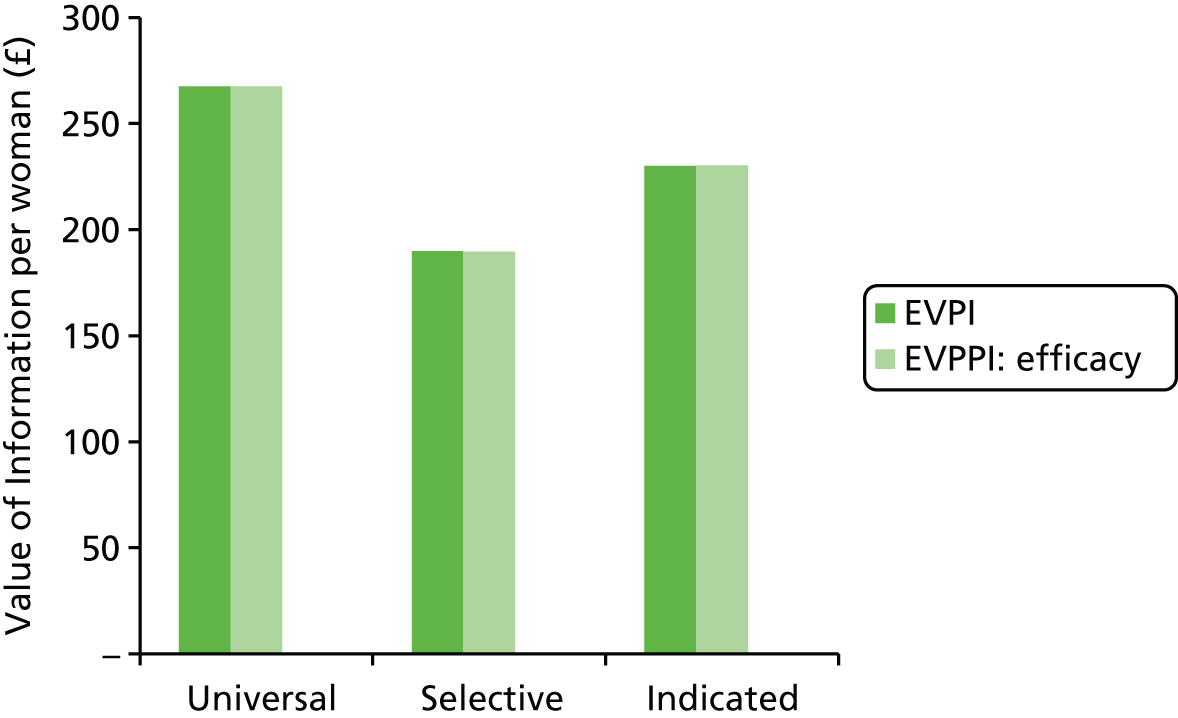

to undertake an economic analysis, including a systematic review of economic evaluations and the identification of other evidence needed to populate an economic model

-

to determine the potential value of collecting further information on all or some of the input parameters (expected value of information analysis).

Service user involvement

The Nottingham Expert Patient (EP) committee is a group of women who have experienced the distressing effects of severe PND. Three of the women in the group were admitted to a mother and baby unit and all received community psychiatric care. The EP committee, established in 2009, has acted as the patients’ ‘voice’, advising the East Midlands Perinatal Mental Health Clinical Network Board on how to develop local services to meet the needs of women who experience mental health problems in pregnancy and after childbirth. The EP committee has joined the newly formed National Perinatal Mental Health Clinical Reference Group to ensure that the experiences and views of patients inform and influence the planning and delivery of the specialised service.

The EP committee were pleased to be invited to contribute to this review, to be involved in the development of the research proposal and to provide patient and public involvement (PPI) advice throughout the research. The EP committee reviewed the draft research proposal and provided detailed feedback to the principal investigator. The EP committee has maintained involvement through contact with the principal investigator (JM), ad-hoc meetings, having an EP committee member sit on the Expert Clinical/Methodological Group and providing input into this report.

Service user feedback on the draft proposal

The EP committee was initially somewhat sceptical that interventions could prevent PND. Early detection and treatment of PND was considered more of a priority than prevention. The importance of educating health professionals in the detection of and impact of PND was also highlighted. Further discussion and consideration led to collective acknowledgement that all members of the EP committee had experienced the most severe PND, which may not have been preventable. It was agreed that prevention, or at least a reduction in severity of moderate or mild PND, may be possible and worth investigating.

Service user feedback on the proposal and ongoing review

The EP committee questioned the meaning of PND, especially with regard to the term ‘depression’, as for many of the women anxiety was the major symptom. The research team decided to include maternal anxiety or stress as a secondary outcome, with depression as the primary outcome.

It was suggested that both infanticide (although rare) and the decision to terminate a pregnancy (if PND had been experienced in a previous pregnancy) should be considered as outcomes. Maternal suicide (no longer the most common cause of maternal death)23 was another potentially preventable outcome. It was agreed to cover these outcomes in the background section of this report. Family outcomes were also emphasised, as the entire EP committee reported the impact of their PND on their children and family members. Of particular note was the impact of their PND on partners, who also may become depressed or anxious.

The group discussed the distinction between prevention and treatment. The question was posed, ‘When is an intervention considered treatment and when is it prevention?’ One EP committee member had been on antidepressant medication before conceiving (although symptom free) because she experienced PND with her first child. This medication was increased at the end of the first trimester when she developed symptoms of anxiety. This also calls into question the term postnatal depression, as many women also become ill in the antenatal period. There was some debate around EPDS scores in the literature and the cut-off point for including studies as prevention studies. It was decided that trials in which included women had a raised EPDS but no diagnosis of PND would be classed as prevention studies.

Service user feedback on acceptability of interventions to prevent postnatal depression

Given their relatively extreme experiences of PND, the EP committee’s view on potential interventions to prevent PND was very open. When faced with a life-changing and potentially life-threatening illness, they felt the choice of intervention was likely to be focused on proven effectiveness.

Medication during pregnancy was perceived to be acceptable to women who have experienced PND in a previous pregnancy, especially severe PND. However, they felt that preventive medication was probably undesirable for those women in their first pregnancy who are asymptomatic but deemed ‘at risk’. Other non-pharmacological interventions, such as those being investigated in this review, were considered more likely to be acceptable to the majority of pregnant women.

Overall, the acceptability of interventions to prevent PND was perceived to be influenced by many factors, not least whether or not a woman has a history of PND. The potential for prevention or lessening the severity of PND was viewed by the EP committee as a very encouraging and exciting prospect.

Chapter 3 Review methods

Overview of review methods

This chapter details the methods used to identify RCTs, systematic and other reviews and qualitative studies suitable for inclusion in the review. Figure 1 illustrates the four phases of the review, including the data extraction, analysis and interpretation phases.

FIGURE 1.

Overview of review methods. Key: IPI, indicated preventive intervention; QALY, quality-adjusted life-year; SPI, selective preventive intervention; TIDieR, template for intervention description and replication; UPI, universal preventive intervention. This is an Open Access article124 distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 3.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non- commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/.

Methods for reviewing and assessing clinical effectiveness

Search strategies for identification of studies

The review of effectiveness of interventions to prevent PND constituted the central platform for this report. The objectives of the individual RCTs and the data available from them determined what NMAs were feasible. The analysis of effectiveness determined the subsequent qualitative synthesis and economic analyses. The leading candidate interventions, demonstrated in terms of potential effectiveness, became the focus for the realist synthesis. This filtered approach recognised that it would not be feasible to conduct rich interpretive explorations across the wide heterogeneity of possible interventions and, therefore, interpretive resources were focused where they were most likely to yield insights on current and future interventions.

Search strategy for randomised controlled trials and systematic reviews

Search activities were as follows:

-

searches of electronic databases

-

searches of the internet

-

searches of specific websites

-

citation searches

-

reference lists of relevant studies

-

hand searches of relevant journals

-

scrutiny of references listed in reviews of the prevention of PND

-

suggestions from experts and those working in the field.

Searches of electronic databases

A comprehensive search of 12 electronic bibliographic databases was undertaken to identify systematically clinical effectiveness literature comparing different interventions to prevent PND. The literature search strategy is presented in Appendix 1. The list of electronic bibliographic databases searched for published and unpublished clinical effectiveness research evidence is presented here:

-

The Cochrane Library including the Cochrane Systematic Reviews Database, Cochrane Controlled Trials Register, Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects (DARE), Health Technology Assessment (HTA) and NHS Economic Evaluation Database (NHS EED) 1991; searched on 28 November 2012

-

MEDLINE (via Ovid) 1946–week 3 November 2012; searched on 30 November 2012

-

PreMEDLINE (via Ovid) 4 December 2012; searched on 5 December 2012

-

EMBASE (via Ovid) 1974–4 December 2012; searched on 5 December 2012

-

Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL; via EBSCOhost) 1982; searched on 11 December 2012

-

PsycINFO (via Ovid) 1806–week 4 November 2012; searched on 5 December 2012

-

Science Citation Index (via ISI Web of Science) 1899; searched on 5 December 2012

-

Social Science Citation Index (via ISI Web of Science) 1956; searched on 5 December 2012

-

Applied Social Sciences Index and Abstracts (ASSIA) (via ProQuest) 1987; searched on 19 December 2012

-

Allied and Complementary Medicine Database (AMED) (via Ovid) 1985–December 2012; searched on 5 December 2012

-

Conference Proceedings Citation Index–Science (CPCI-S) (via ISI Web of Science) 1990; searched on 5 December 2012

-

Midwives Information and Resource Service (MIDIRS) Reference Database 1991; searched on 24 July 2013.

Further searches for grey literature were conducted from January to March 2013 on additional resources. A list of the additional resources is presented in Appendix 1.

Search strategy search terms

The search strategy was developed using an iterative approach. The search used a combination of thesaurus and free-text terms for postnatal and antenatal depression combined with terms for prevention or risk factors or generic terms for interventions. The search comprised four facets:

-

Facet 1 comprised terms for the population (pregnant and postnatal women).

-

Facet 2 comprised terms for prevention.

-

Facet 3 comprised terms for known risk factors for PND.

-

Facet 4 comprised generic terms for interventions.

Facet 1 was combined separately with facets 2, 3 and 4. The major search refinement was to reduce the number of search terms in facet 1, then extra terms were added for facets 2, 3 and 4. In addition, the searches were combined with search filters for specific study designs when appropriate. All searches were performed by an information specialist (AC) from November to December 2012. Copies of The Cochrane Library and all the other search strategies are presented in Appendix 1.

The search strategy was used to search the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) and then to search other databases not indexed by Clinical Trials. CENTRAL runs sensitive strategies on MEDLINE and EMBASE to identify relevant published RCTs; therefore, MEDLINE and EMBASE were not searched retrospectively. Records were retrieved through planned manual searching of a journal or conference proceedings to identify all reports of RCTs and controlled clinical trials. 125 The search was run with a systematic reviews filter to find Cochrane and other systematic reviews. The number of RCT and systematic review results obtained for the various databases searched is presented in Appendix 2.

Citation searches, reference lists, relevant journals and clinical experts

Reference tracking of all included and relevant studies was performed and reference lists of relevant reviews and systematic reviews were scrutinised to identify additional, relevant studies not retrieved by the electronic search to identify further potentially eligible RCTs. Searching of key journals, selected following consultation with clinical experts, was conducted using electronic table of contents alerts from January to July 2013 for 33 journals, presented in Appendix 3. Clinical advisors were also contacted about further potentially relevant RCTs.

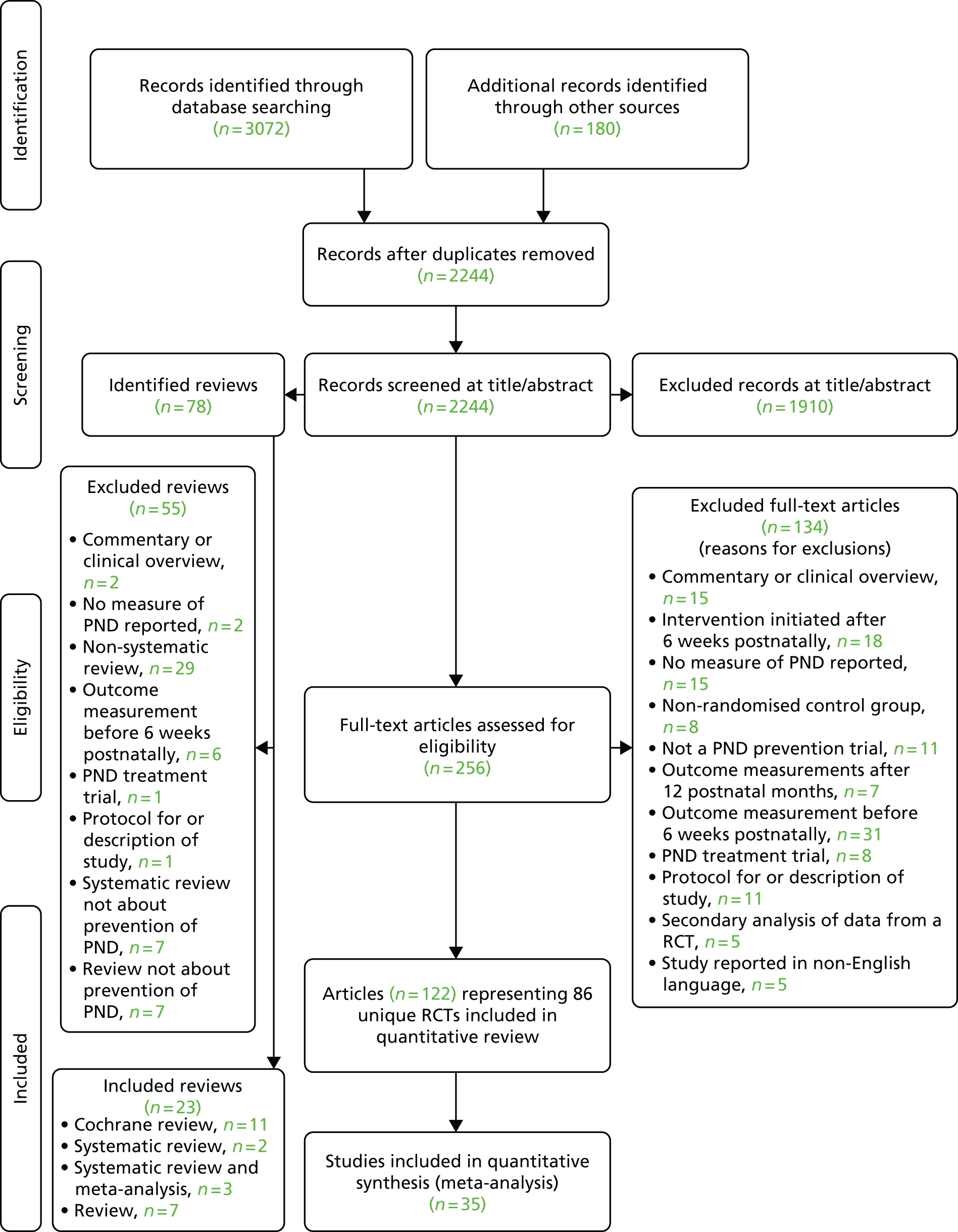

Search outcome summary for the randomised controlled trials

Search result citations were imported and merged into Reference Manager, version 12126 (Thomson ResearchSoft, San Francisco, CA, USA), and duplicates were removed by Reference Manager or deleted manually (by JM and AC).

Review protocol

The population, intervention, comparators, outcomes, study designs (PICOS) process was used to break down the research question into concepts and search terms. Recognising that systems of care differ internationally, rather than concentrating solely on UK-based RCTs, we were deliberately inclusive in our search to capture RCTs of all interventions, irrespective of their health-care context. The research protocol is registered on PROSPERO (registration number CRD42012003273).

Inclusion and exclusion criteria for quantitative studies

Population

The population included women of all ages who were either pregnant or had given birth in the previous 6 weeks. The population was separated according to level of risk of PND into three levels, universal, selective or indicated, as follows:

-

Universal: all women in a defined population not identified on the basis of increased risk of PND.

-

Selective: women or subgroups of the population whose risk of developing PND was significantly higher than average because they had one or more social risk factors such as general vulnerability, aged less than 18 years, at risk of violence, ethnic minority, human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) positive, living in deprivation or financial hardship or poverty, or single, socially disadvantaged or unsupported.

-

Indicated: women at high risk of developing PND on the basis of psychological risk factors, above-average scores on psychological measures or other indications of a predisposition to PND but who did not meet diagnostic criteria for PND at that time, such as antenatal depression, a raised symptom depression score and a history of PND or history of major depression.

The population dimension for the PICOS framework is presented in Box 2.

Pregnant women (universal).

Postnatal women with a live baby born within the previous 6 weeks (universal).

Vulnerable pregnant or postnatal women who were aged less than 18 years; at risk of violence; an ethnic minority; HIV positive; living in deprivation, financial hardship or poverty; or single, socially disadvantaged or unsupported (selective).

Pregnant or postnatal women with a raised score on the antenatal risk questionnaire, Beck Depression Inventory, Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression scale, the Cooper predictive index, depression symptom checklist, EPDS, HADS, Hamilton Depression Rating Scale, Health during pregnancy questionnaire; a past history of PND or major depression (indicated).

Pregnant women with a diagnosis of depression using Research Diagnostic Criteria or DSM-IV criteria (indicated).

ExcludedPostnatal women with a diagnosis of PND.

Pregnant women with comorbid psychiatric disorders.

Postnatal women with major medical problems.

DSM-IV, Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders-Fourth Edition.

Interventions

The preventive interventions were also separated into three levels of preventive intervention according to the population for which the intervention was intended:

-

Universal preventive interventions: interventions available for all women in a defined population not identified on the basis of increased risk of PND.

-

Selective preventive interventions: interventions offered to women or subgroups of the population whose risk of developing PND was significantly higher than average because they had one or more social risk factors.

-

Indicated preventive interventions: interventions offered to women at high risk of developing PND on the basis of psychological risk factors, above-average scores on psychological measures or other indications of a predisposition to PND but who did not meet diagnostic criteria for PND at that time.

Seven main classes of interventions were also categorised as presented in Box 3.

Pharmacological agents or supplements: prescribed antidepressants, calcium, dietary supplements, hormone therapy, thyroid therapy.

Psychological: the breadth of psychological interventions and approaches which comprise components of a psychotherapeutic approach.

Social support: home visits, telephone-based peer support, doula support, social support.

Educational: educational information booklets and classes.

Organisation of maternity care: alternative forms of contact with care providers, primary care strategies.

CAM or other: music, acupuncture, tai chi, yoga, pregnancy massage, aromatherapy, exercise and herbal medicine.

Midwifery-led interventions: different approaches to antenatal care, CenteringPregnancy, team midwife care, caseload midwifery.

ExcludedTreatment trials for women with PND.

Interventions initiated preconceptually.

Interventions initiated more than 6 weeks postnatally.

Comparators

All comparison arms for all eligible studies in all countries were included, whether usual care, enhanced usual care, or an active comparison group.

Outcomes

The main outcome was a validated measure of symptoms of maternal depression or a diagnostic measure of depression from 6 weeks to 12 months postnatally. Other maternal outcomes of anxiety and well-being were included. Binary, categorical or continuous outcomes were included, whether as a single measure or assessed at more than one postbaseline treatment time point. The outcomes dimension is presented in Box 4.

Depression symptoms measured on a validated self-completed instrument.

Depression diagnosis.

Anxiety symptoms.

Diagnostic measure of anxiety.

Birth outcomes.

Infant outcomes.

Family outcomes.

ExcludedNo measure of PND reported in the results.

Outcome measurements more than 12 months postnatally.

Outcome measurements less than 6 weeks postnatally.

Physiological measurement.

Unvalidated measures of depression.

Study designs

The study designs dimension is presented in Box 5.

RCTs.

Economic evaluations alongside RCTs.

Systematic reviews of the prevention of PND.

ExcludedBefore-and-after studies.

Case–control studies.

Cohort studies.

Commentary or clinical overviews.

Cross-sectional surveys.

Description of a study.

Non-randomised control groups.

Non-systematic reviews.

Not a PND prevention trial.

Ongoing RCTs.

Protocols for a RCT.

Reviews not about prevention of PND.

Secondary analysis of data from a RCT.

Studies reported in non-English language.

Systematic reviews not about prevention of PND.

Search strategy and outcome summary for the qualitative studies

Electronic databases

The search for the clinical effectiveness evidence was run with a qualitative filter to identify qualitative studies. The list of electronic bibliographic databases searched is presented in Appendix 1. The search was run again with a mixed-methods filter (devised with AB) to find papers that used quantitative and qualitative methodology. The numbers of qualitative studies and mixed-methods studies retrieved for the various databases searched are presented in Appendix 4.

Study selection

Study selection criteria and procedures for the quantitative review

Two reviewers (JM and PS) independently screened the titles and abstracts to identify papers for possible inclusion. If no abstract was available, the full paper was retrieved for scrutiny. Full papers for RCTs were obtained if the abstract showed that the study fulfilled the inclusion criteria or it was unclear from the abstract whether or not the inclusion criteria were fulfilled. All full papers retrieved were independently reviewed by two reviewers. Papers were not excluded on quality at this selection stage. The full papers had to fulfil the inclusion criteria presented in Tables 2–5. Where there was no consensus following discussion about inclusion at the full-paper stage, a third reviewer or clinical expert (CLD, HS or SS-B) was consulted. The reasons for exclusion are presented in Appendix 5.

Study quality assessment checklists and procedures for the randomised controlled trials

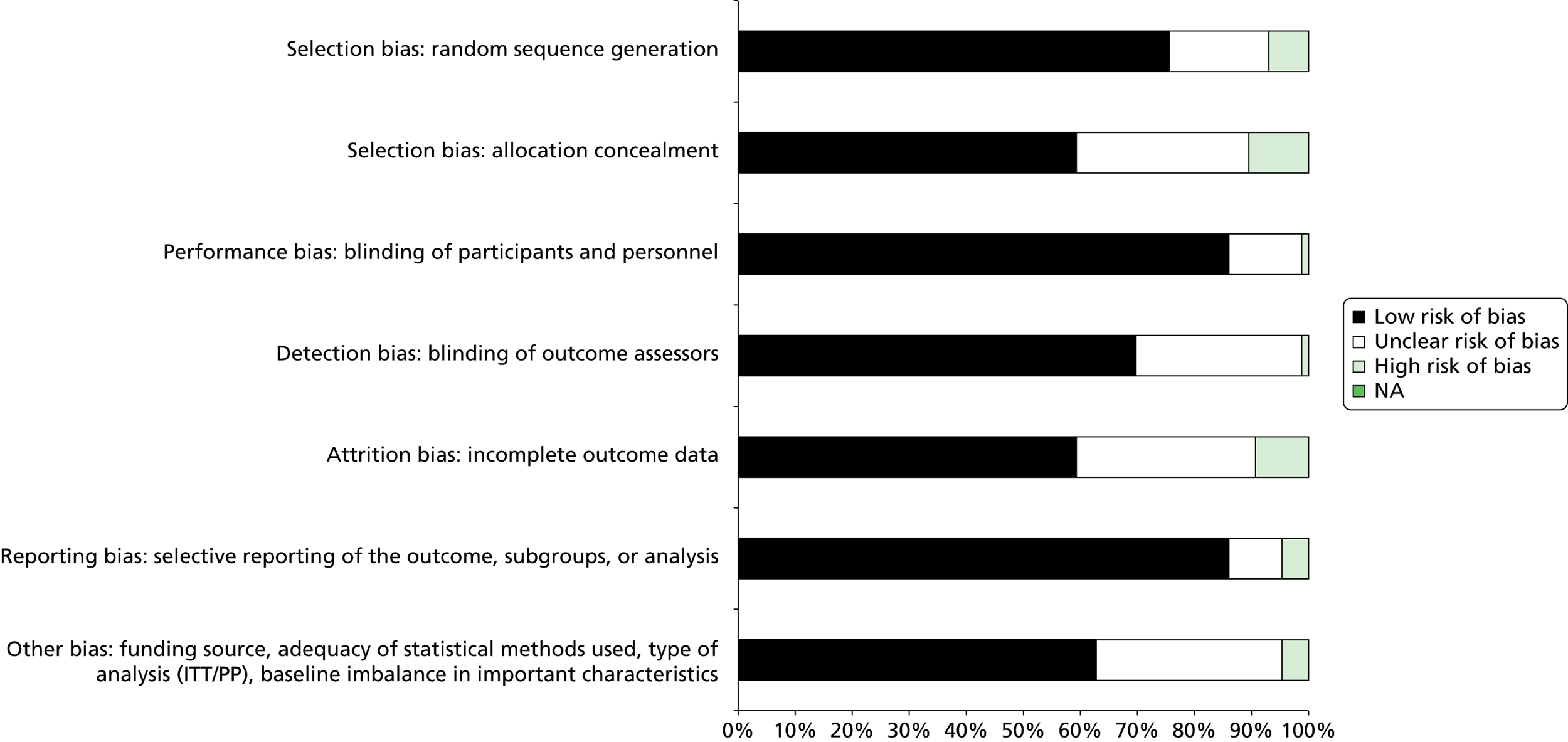

Risk-of-bias assessment

The quality of each paper was assessed independently by two reviewers (JM and PS) using the Cochrane Collaboration’s tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. 126 Any disagreements about risk of bias were resolved by a third reviewer. The risks assessed were:

-

risk of selection bias (random sequence generation and allocation concealment)

-

risk of performance bias (blinding of participants and personnel)

-

risk of detection bias (blinding of outcome assessors)

-

risk of attrition bias (incomplete outcome data)

-

risk of reporting bias (selective reporting of the outcome, subgroups or analysis)

-

risk of other sources of bias (any important concerns about other possible sources of bias such as funding source, adequacy of statistical methods used, type of analysis, baseline between-group imbalance in important prognostic factors).

The risks were assessed as low risk of bias, high risk of bias or unclear risk of bias. For each assessed risk, the reviewers provided a statement, description or direct quotation to support their judgement. A summary assessment of risk was made across all the risks, to inform the interpretation of plausible bias and summary risk of bias is presented in Chapter 4, the overview of results for quantitative and qualitative studies.

Data extraction for randomised controlled trials

Data from the full papers were entered on to a specially designed, pre-piloted and tailored data extraction form, to summarise the intervention. The primary aim of the study was documented (PND prevention, antenatal well-being, birth outcomes, general health, general psychological well-being, infant outcomes or family outcomes). The intervention and comparison arms were described. The data extraction form indicating the main RCT characteristics is presented in Appendix 6.

Outcomes were recorded as maternal, neonatal and family outcomes, using mean [standard deviation (SD)] values when available and numbers and proportions of participants in specific outcome categories. The quality of the extracted data was checked (JM and PS).

Potential moderators

Potential moderators are variables describing population characteristics, for which the intervention may have a different effect for different values of the moderator variable. 127 These were documented when there was some basis for believing that the maternal population characteristics might have a moderating effect on the outcomes, for example maternal age, parity, being a sole parent, history of mental health problems and history of PND. Baseline depression scores were recorded to estimate the population mean depression score for women who entered the studies.

Potential mediators

Potential mediators are variables that could help explain the process by which an intervention was effective. 127 These were documented, such as the timing of the intervention, the provider, the number of sessions offered and whether the intervention was individual based or group based.

Data synthesis of randomised controlled trials

A large number of RCTs and systematic reviews were eligible for inclusion according to our broad inclusion characteristics. We conducted a narrative description of the studies according to the level of preventive intervention (universal, selective or indicated), class of intervention and the context within which the RCTs were undertaken.

Meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials

Methods of evidence synthesis

The extracted data and quality assessment variables were presented, for each study, in structured tables and as a narrative description. Both conventional RCTs, in which individual women were randomised to interventions, and cluster RCTs (CRCTs) were eligible for inclusion. Estimates of treatment effect and standard error of treatment effects from CRCTs were included in the analyses after allowing for the cluster design.

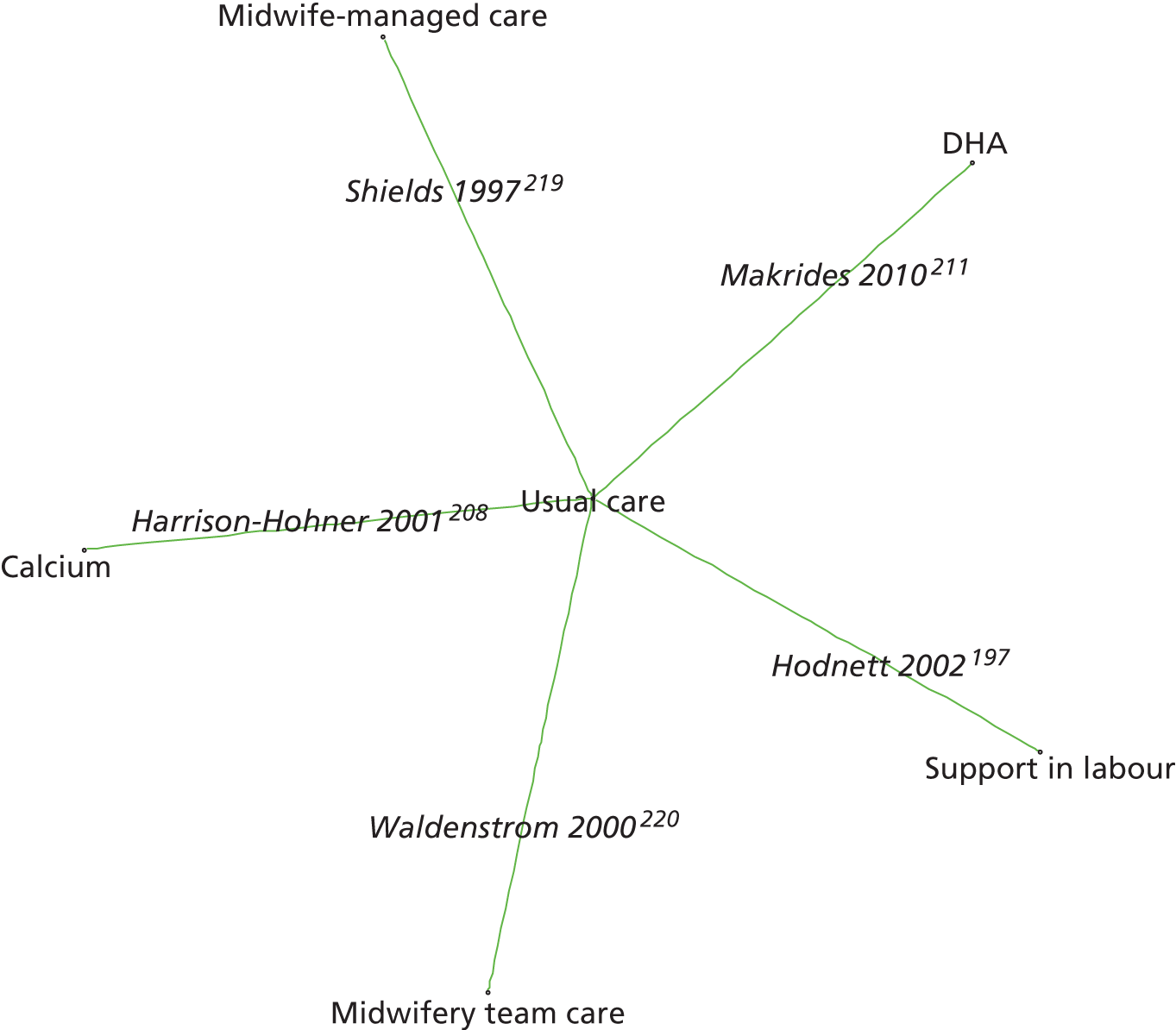

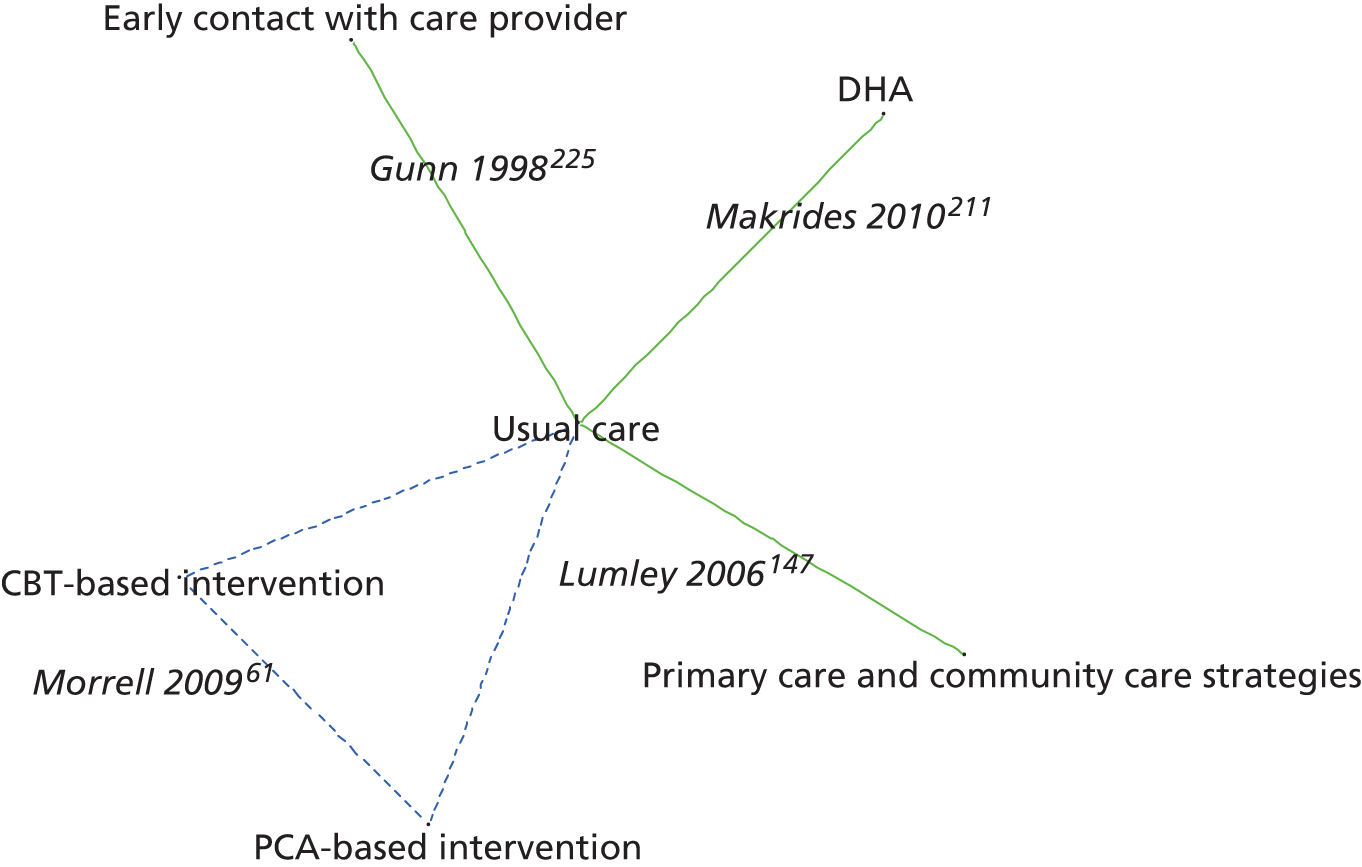

The reference treatment, for comparative purposes and for estimating intervention effects, was defined as usual care. Usual care in the UK, Australia, Canada, France, Norway and the USA was assumed to be sufficiently similar to be interchangeable and was collectively defined as ‘usual care’ for the purpose of the analysis.

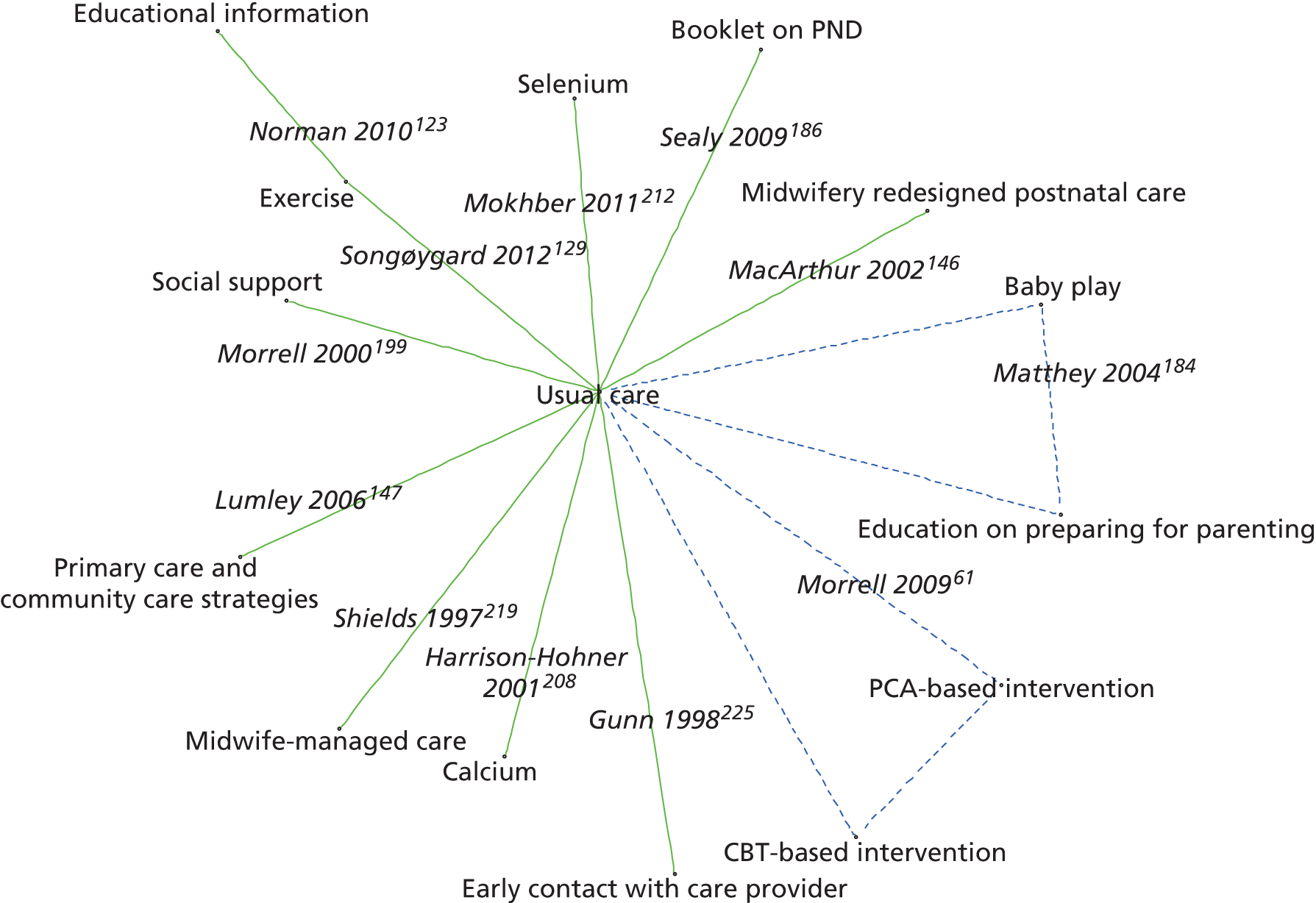

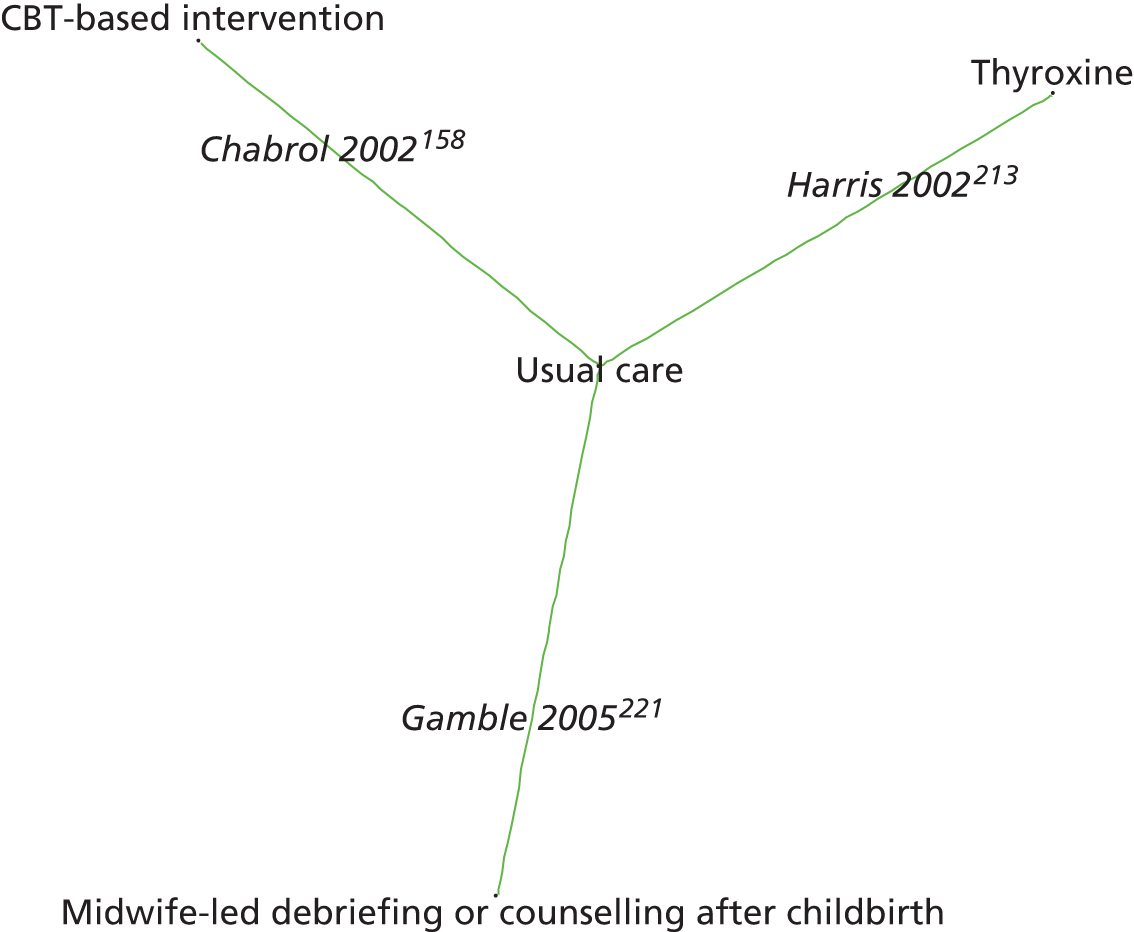

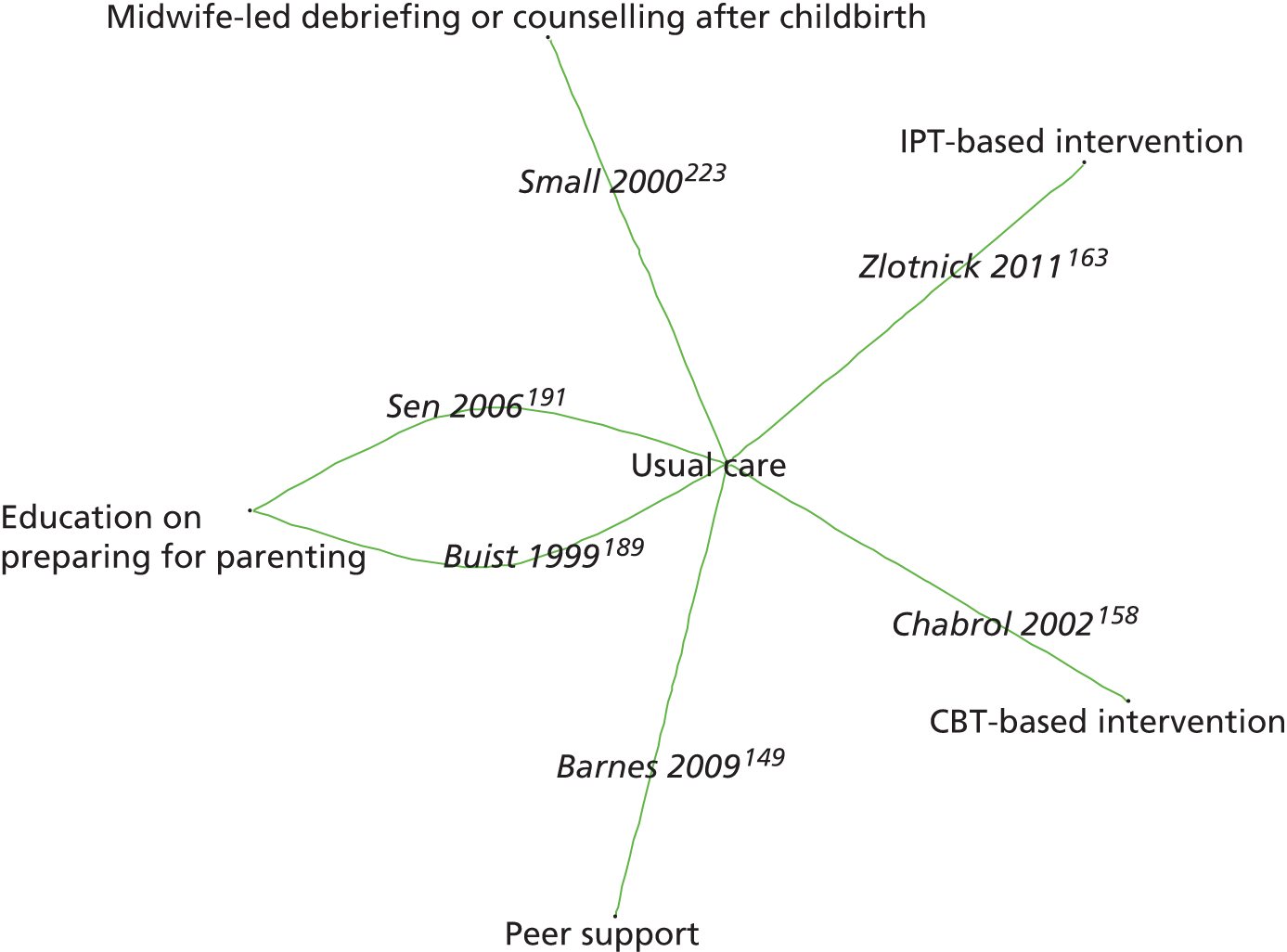

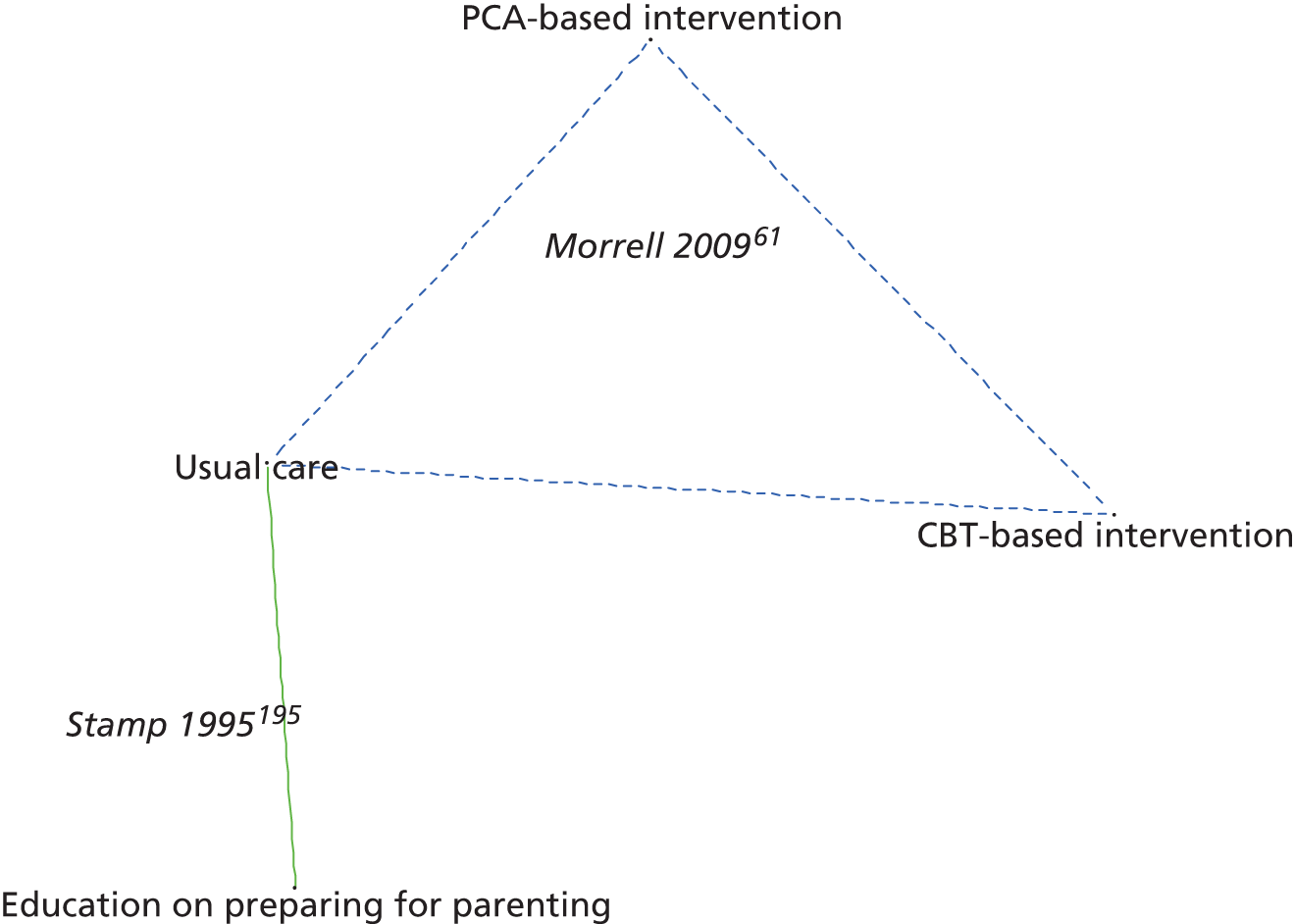

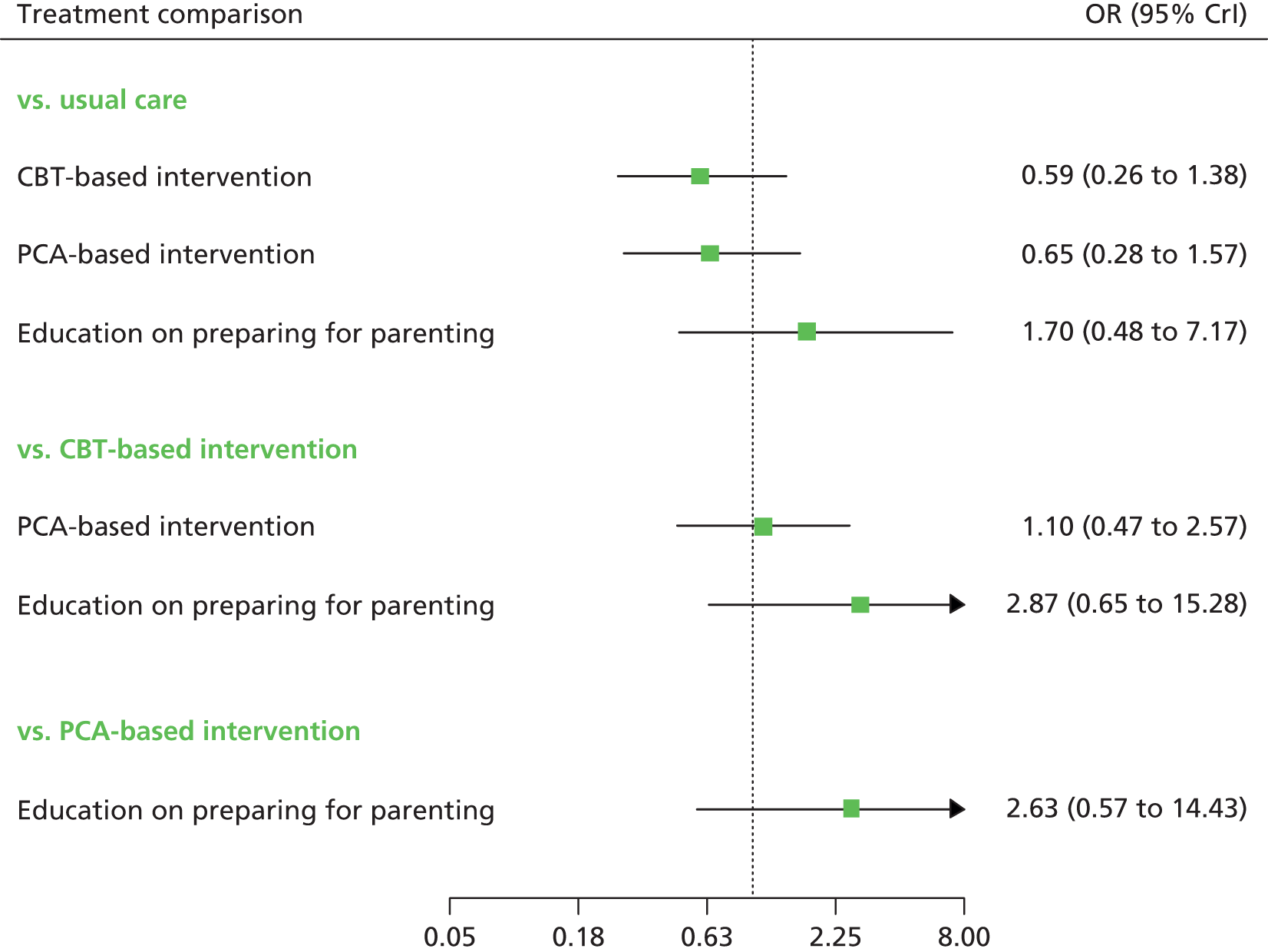

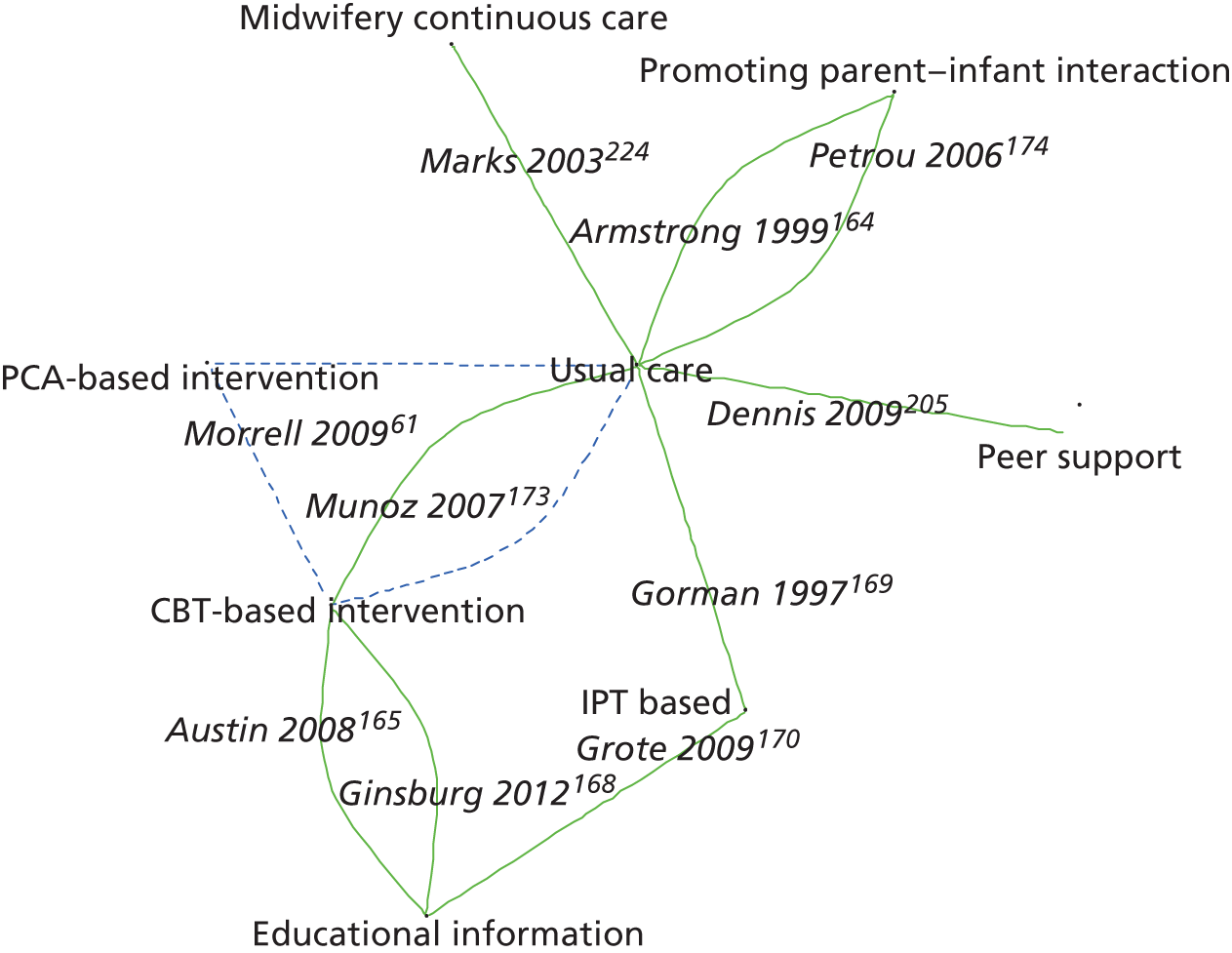

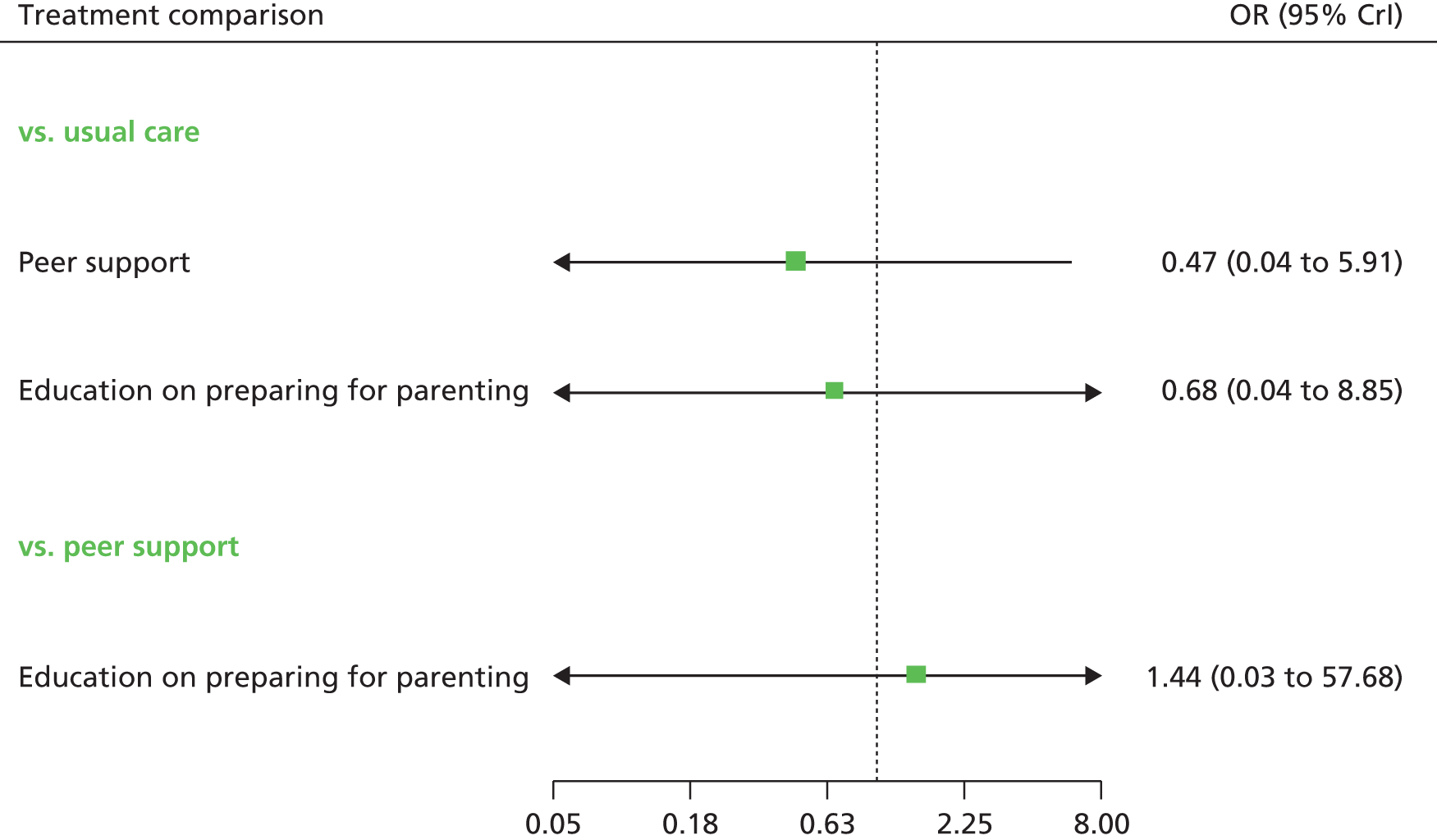

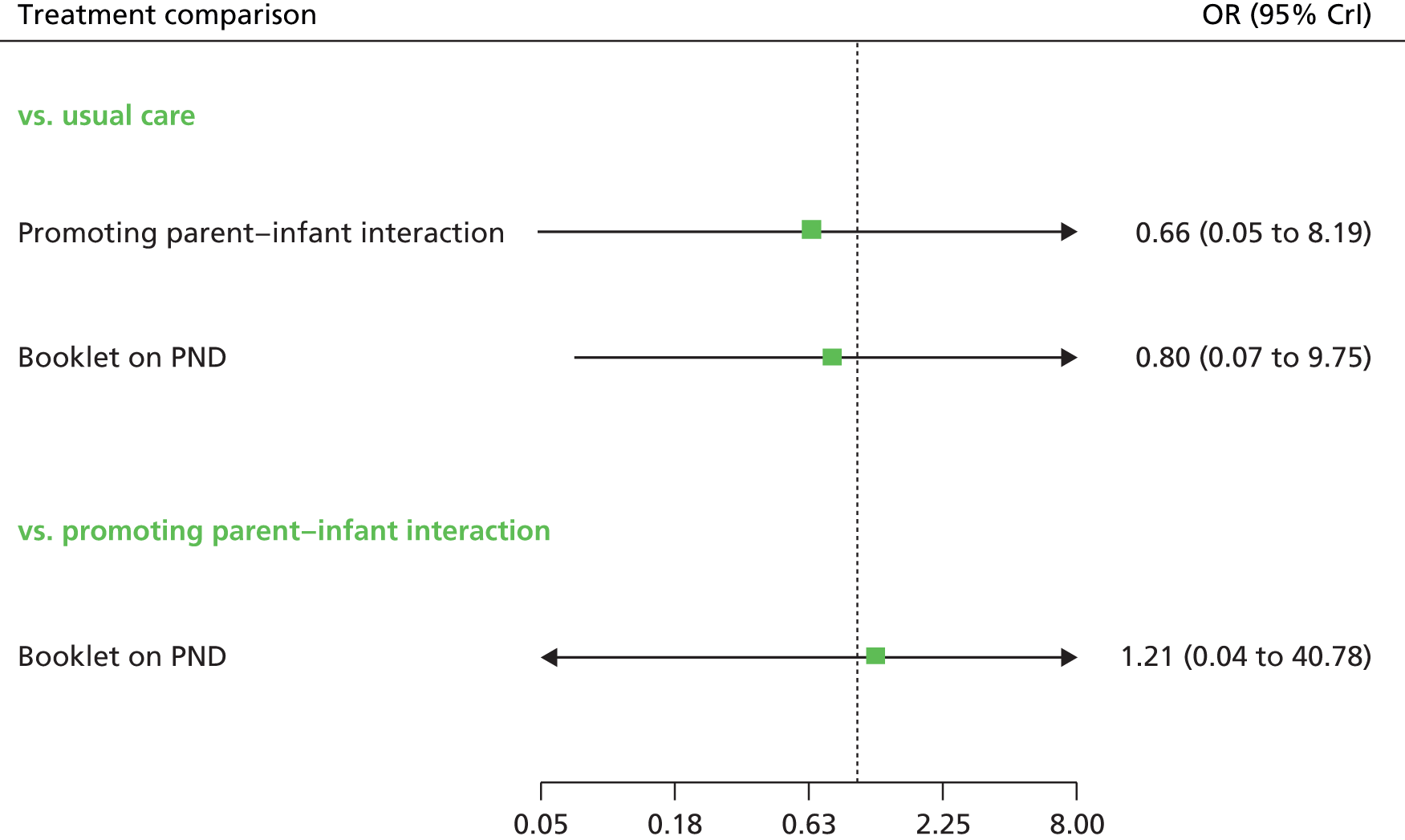

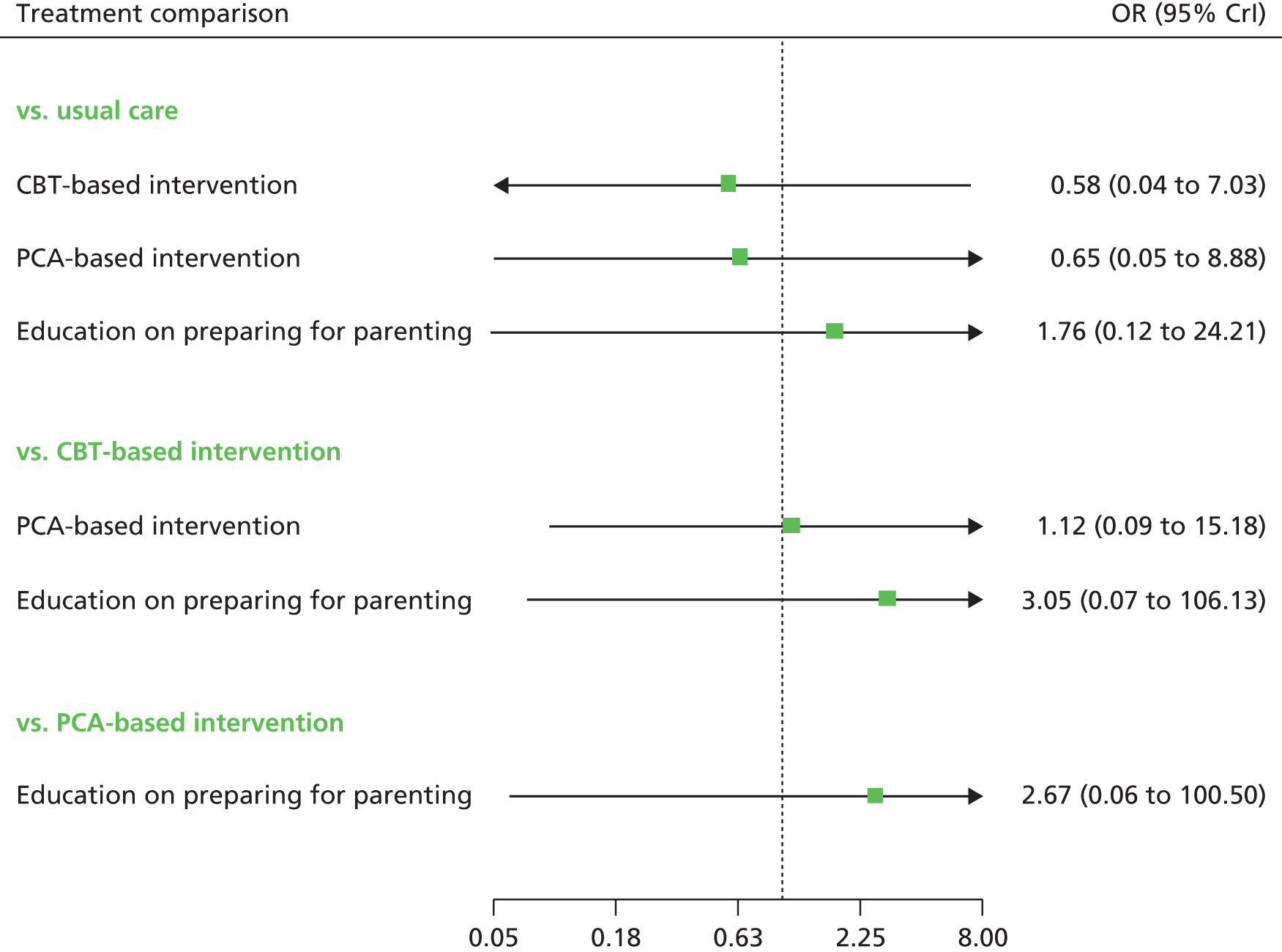

The evidence was synthesised using a NMA. 128 A NMA (also known as a mixed-treatment comparison or a multiple treatment comparison) is an extension of a standard (pairwise) meta-analysis. It allows evidence from RCTs comparing different interventions to be combined to provide an internally consistent set of intervention effects while respecting the randomisation used in individual studies. The NMA enables a simultaneous comparison of all evaluated interventions in a single coherent analysis; thus, all interventions can be compared with one another, including comparisons not evaluated within individual studies. The only requirement is that each study must be linked to at least one other study through having at least one intervention in common. The analysis preserves the within-study randomised treatment comparison of each study and assumes that there is consistency across evidence. As with standard pairwise meta-analyses, treatment effects are assumed to be exchangeable across studies. In addition, it is assumed that treatment effects are transitive such that if the effect of intervention 2 relative to intervention 1 is d21 and the effect of intervention 3 relative to intervention 1 is d31, then the effect of intervention 3 relative to intervention 2 is d32 = d31 – d21; this allows a synthesis of direct and indirect evidence about intervention effects and a simultaneous comparison between interventions. Evidence from RCTs presenting data at any assessment time up to 12 months were considered relevant to the decision problem.

Methods for the estimation of efficacy

Statistical model for Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale threshold score

The number of women who had an EPDS score greater than a specified threshold was available from several studies at four different postnatal stages depending on the study (i.e. 6 weeks, 3 months, 6 months and 12 months). Most studies used one threshold, although the thresholds varied across studies (i.e. threshold score of 10, 11, 12 and 13). One study129 reported the number of women who had an EPDS score at two thresholds (i.e. 10 and 13).

The EPDS threshold scores were regarded as being ordered categorical data with categories 0–9, 10, 11, 12, 13 and 14 or more. We assumed an underlying proportional odds model such that:

where αj is the cumulative log-odds for the control intervention (x = 0) and β is the log-odds ratio for the experimental intervention (x = 1) relative to the control intervention. The model assumes that the cumulative log-odds ratios are independent of the threshold so that the effect of treatment does not depend on the threshold. Although this may be a strong assumption, it cannot be assessed in studies that use only one threshold, which are all but one study.

Studies were classified as follows:

-

RCTs randomising women to interventions and reporting data using one threshold

-

RCTs randomising women to interventions and reporting data using two thresholds

-

CRCTs.

Randomised controlled trials randomising women to interventions and reporting data using one threshold

For RCTs, randomising women to interventions and reporting data using one threshold, we let rik be the number of women with a response greater than the threshold for each arm out of nik women for arm k in study i. We assumed that the data follow a binomial likelihood such that:

where pik is the probability that a women has a response greater than the threshold in arm k of study i. The pik values are transformed to the real line using a logit link function such that:

where

µi is the study-specific baseline log-odds of having a response greater than the threshold in the control intervention of the study and δi,bk is the study-specific log-odds ratios of having a response greater than the threshold in the intervention group compared with the control intervention, b.

Randomised controlled trials randomising women to interventions and reporting data using two thresholds

For RCTs randomising women to interventions and reporting data using two thresholds, we fitted a proportional odds model using the freely available software package R (The R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria) using the ‘polr’ function within the MASS package and obtained the sample estimate of the log-odds ratio, yi,bk, and its standard error, Vi,bk, for intervention k relative to intervention b in study i. We assumed that the sample log-odds ratios arose from a normal likelihood such that:

Cluster randomised controlled trials

For two-arm CRCTs (which reported data using one threshold), the sample estimate of the log-odds ratio, yi,bk, and its adjusted standard error, Vi,bk, for intervention k relative to intervention b in study i were extracted and assumed to have arisen from a normal likelihood such that:

For three-arm CRCTs (which reported data using one threshold), the two intervention effects are correlated because they are both estimated relative to the same control. The likelihood function for study i was defined to be bivariate normal such that:

where yi,bk and Vi,bk are as defined before, and se2i,1 is the variance of the control intervention log-odds.

The population standard errors of the log-odds ratios and the population standard error of the control intervention in a three-arm cluster randomised trial were assumed to be known and equal to the sample estimates.

For a random (intervention)-effects model, we assumed that the study-specific log-odds ratios arose from a common population distribution such that:

where d1k is the population log-odds ratios for intervention k relative to the reference intervention (i.e. usual care) and τ is the between-study SD. We assumed a homogenous variance model in which the between-study SD was assumed to be common to all treatment effects. For multiarm trials, these univariate normal distributions are replaced by a multivariate normal distribution to account for correlation between treatment effects within a multiarm study.

Parameters were estimated using Markov chain Monte Carlo simulation conducted using the freely available software package WinBUGS 1.4.3. (MRC Biostatistics Unit, Cambridge, UK). 130

The model was completed by giving the parameters prior distributions:

-

Vague prior distributions for the trial-specific baselines, µi ∼ N(0,1000).

-

Vague prior distributions for the treatment effects relative to reference treatment, d1t ∼ N(0,1000).

Weakly informative prior distribution for the between-study SD of treatment effects, τ ∼ HN(0, 0.322) [in addition, as a sensitivity analysis, the model was also run using the conventional vague prior distribution τ ∼ U(0,2)].

Vague prior distributions were used for trial-specific baseline and treatment effect parameters. However, a weakly informative prior distribution was used for the between-study SD because there were insufficient studies with which to estimate it from the sample data alone; this prior distribution was chosen to ensure that, a priori, 95% of the study-specific odds ratios were within a factor of 2 from the median odds ratio for each treatment comparison.

Convergence of the Markov chains to their stationary distributions was assessed using the Gelman–Rubin statistic. 131 The chains converged within 25,000 iterations; a burn-in of 30,000 iterations was used. We retained a further 10,000 iterations of the Markov chain with which to estimate parameters.

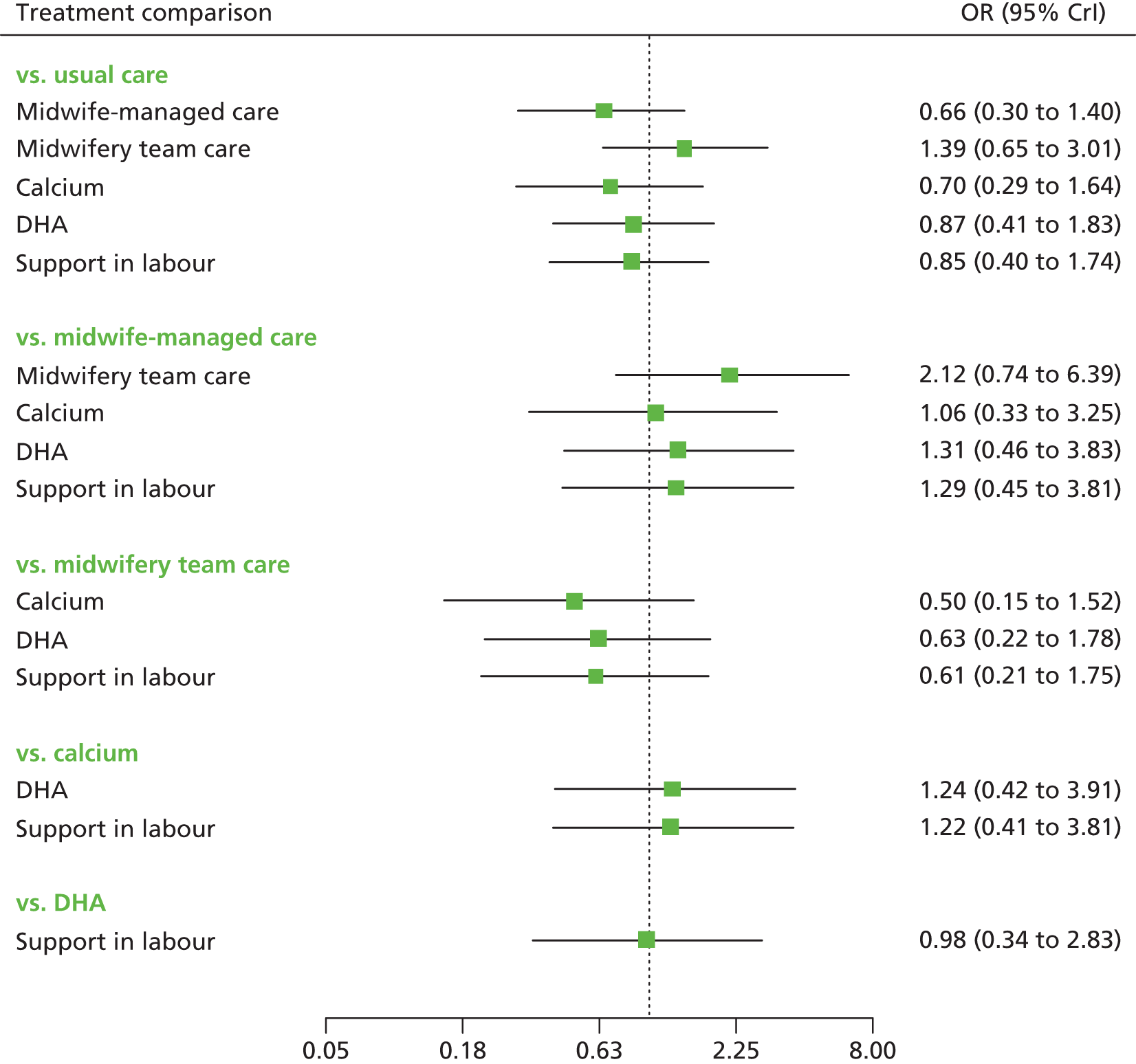

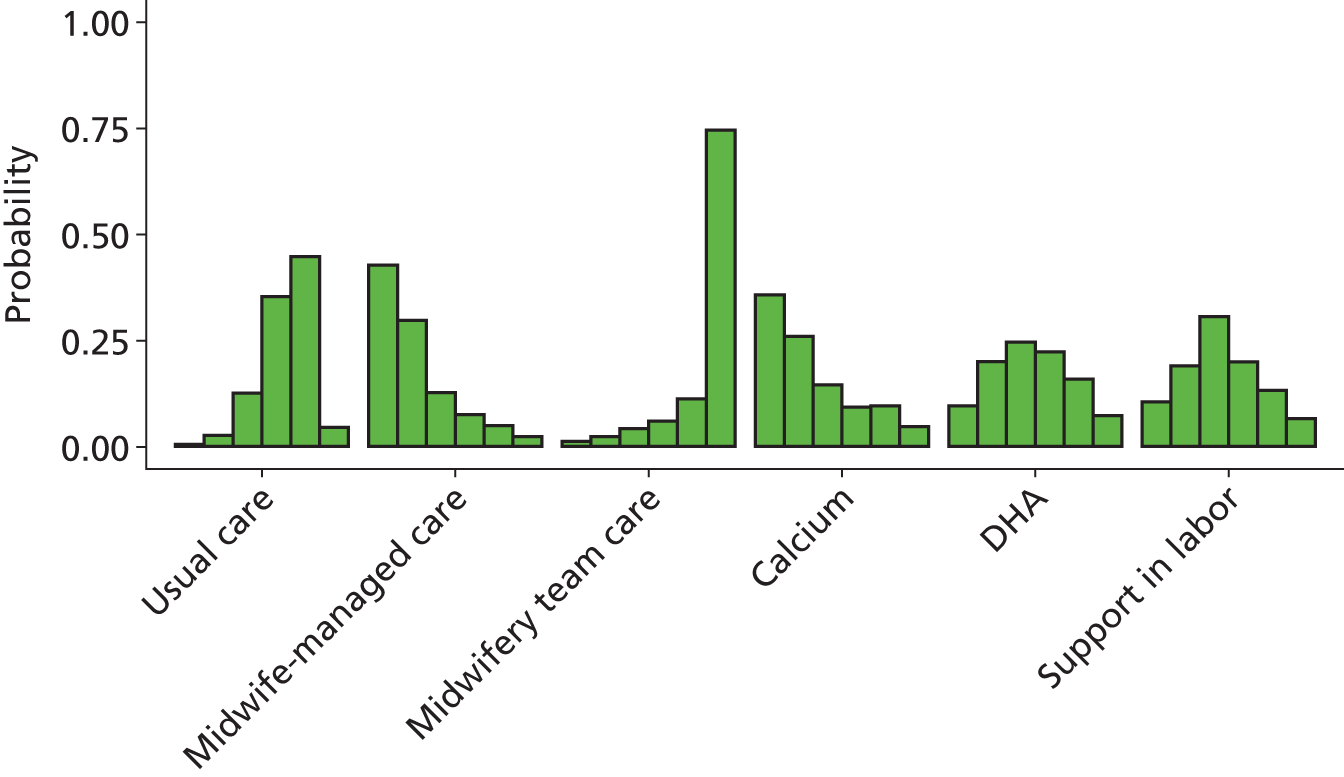

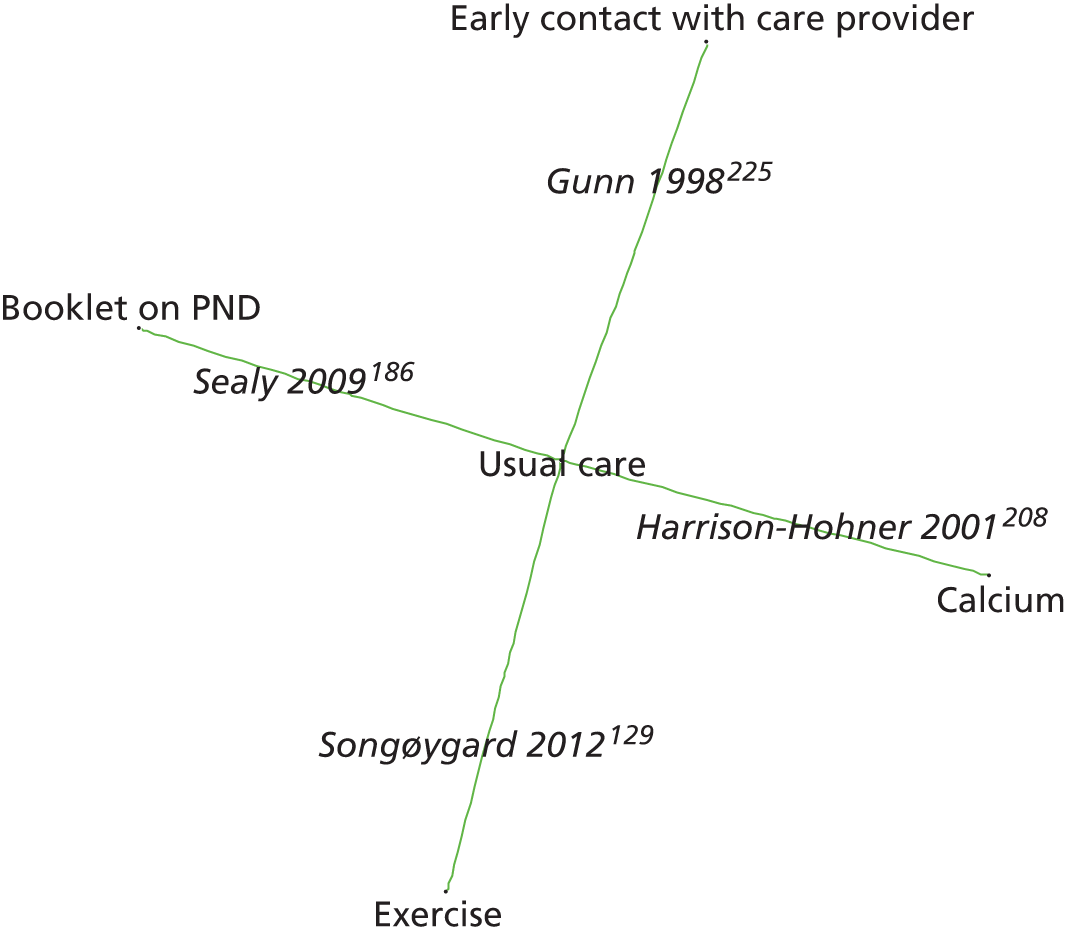

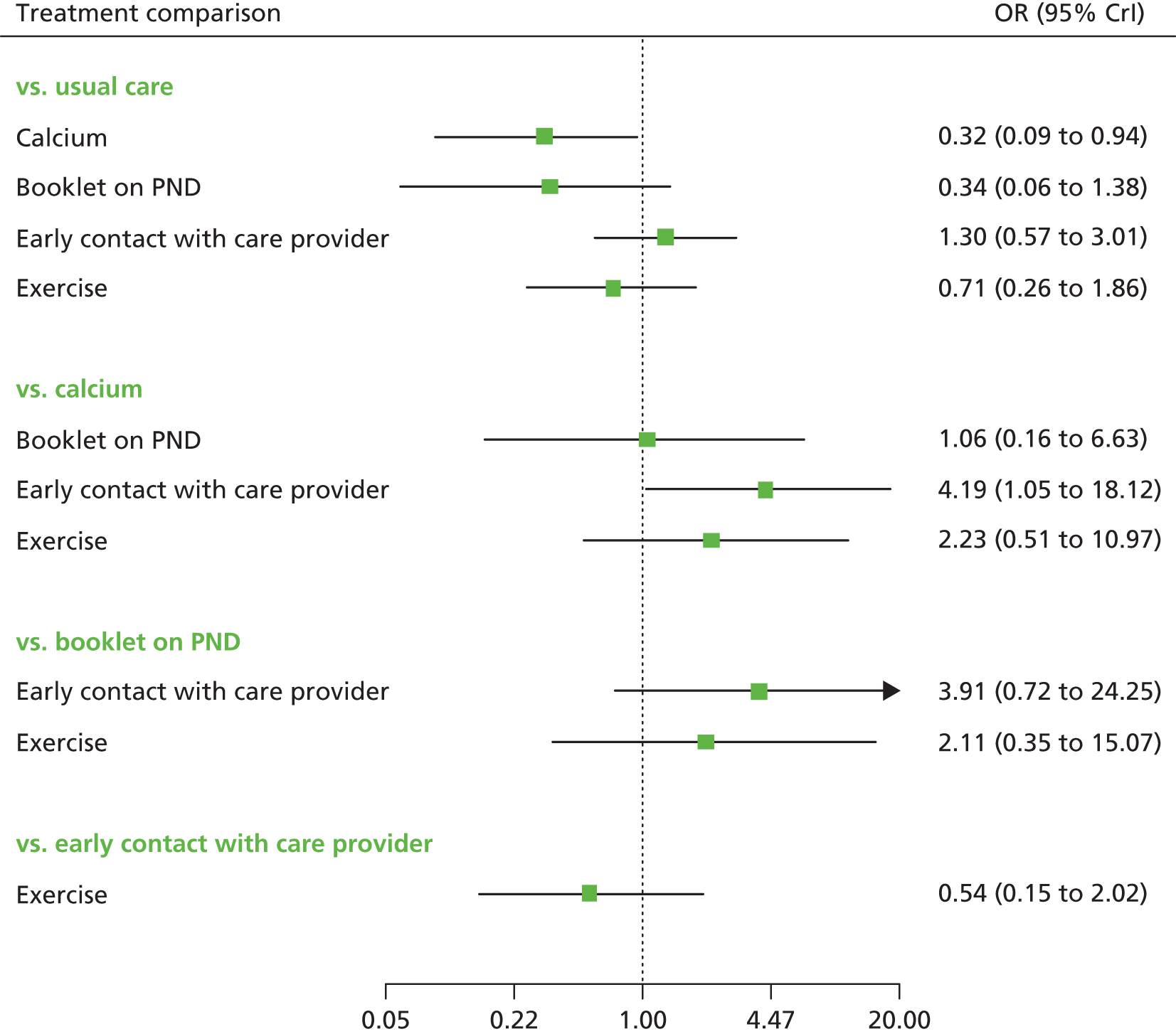

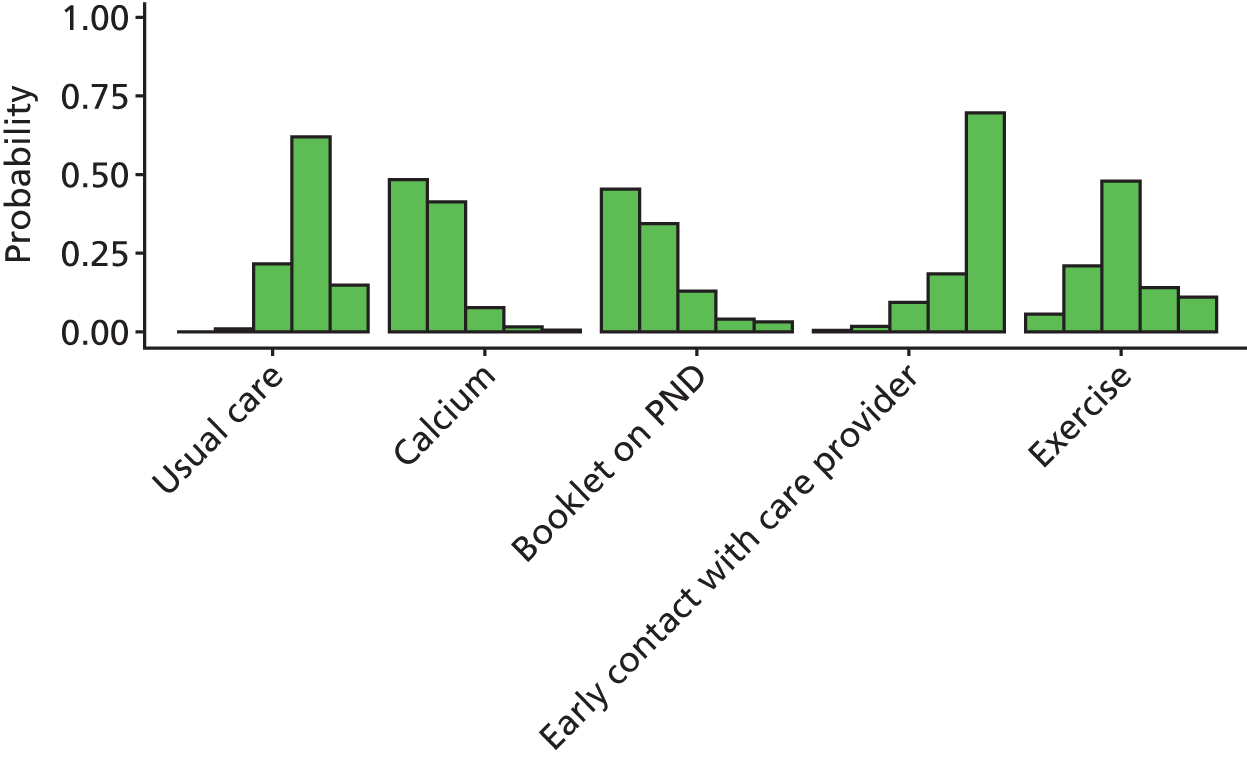

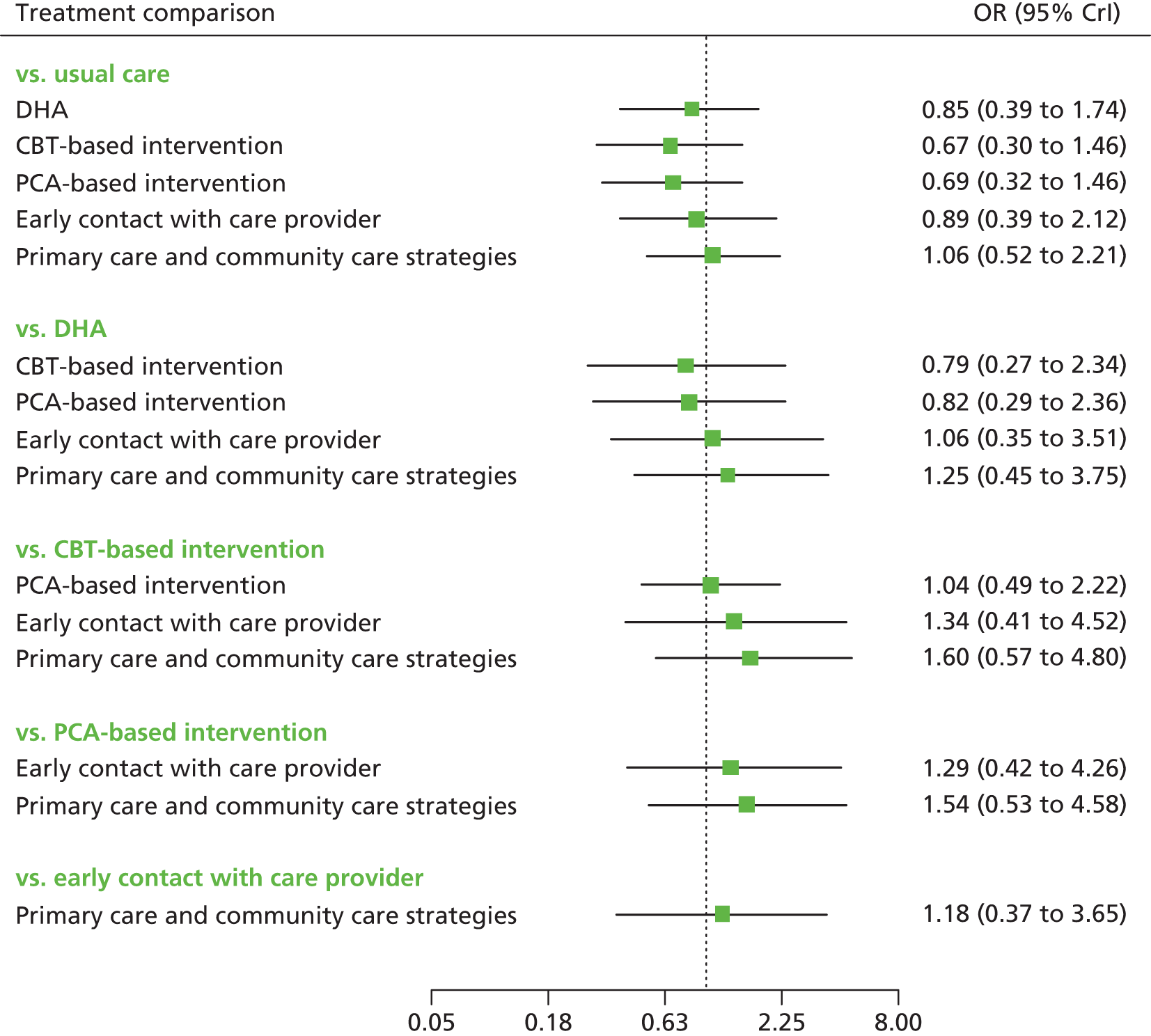

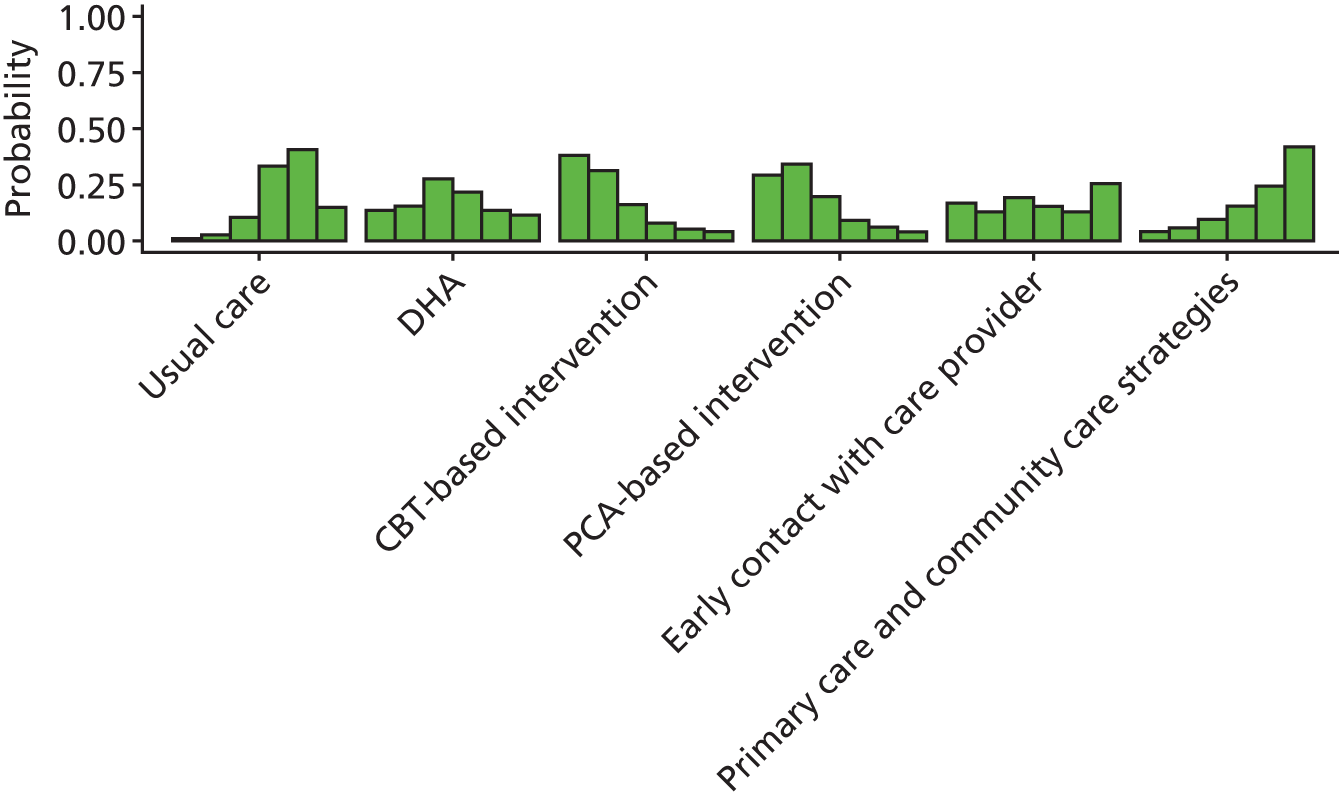

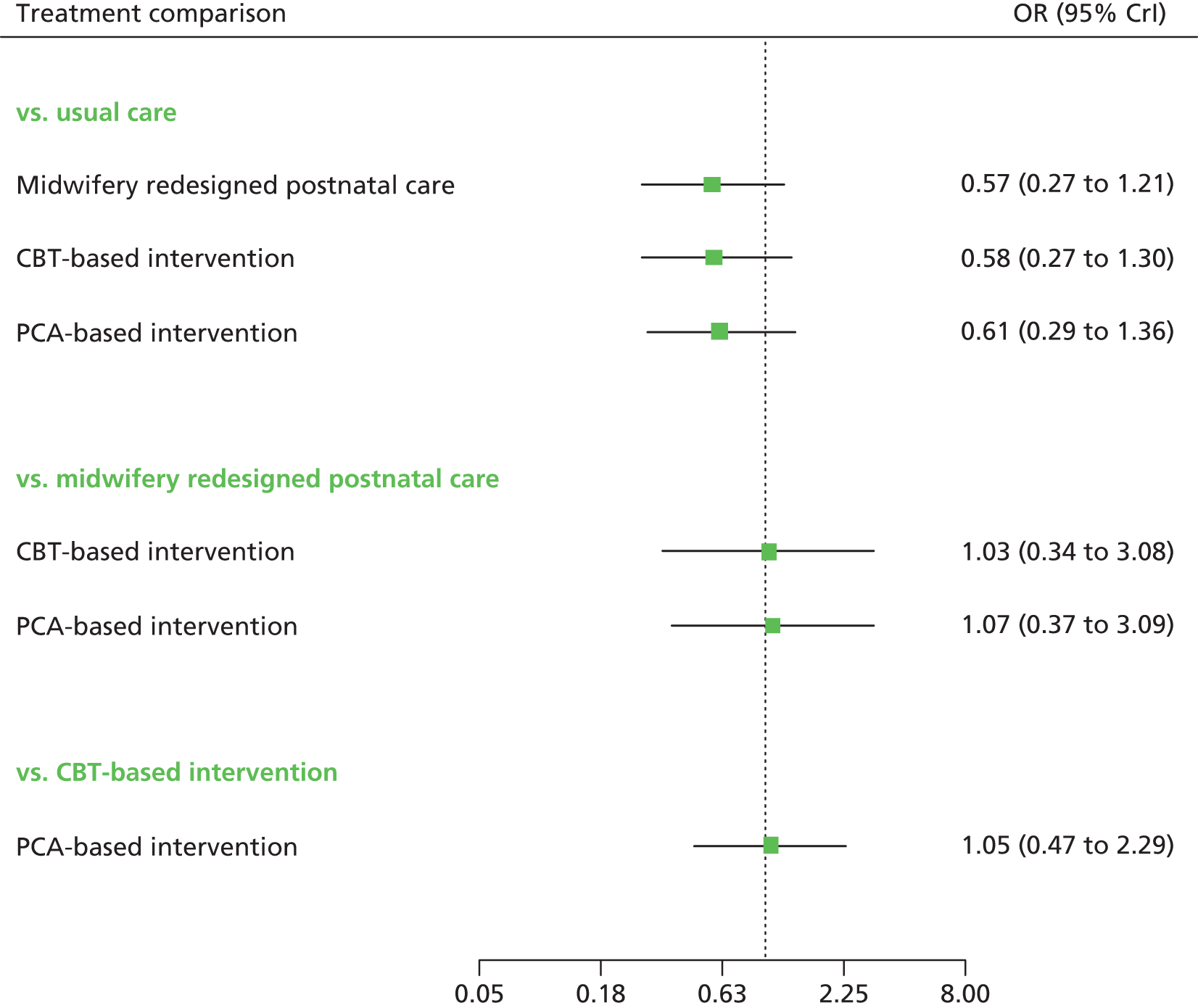

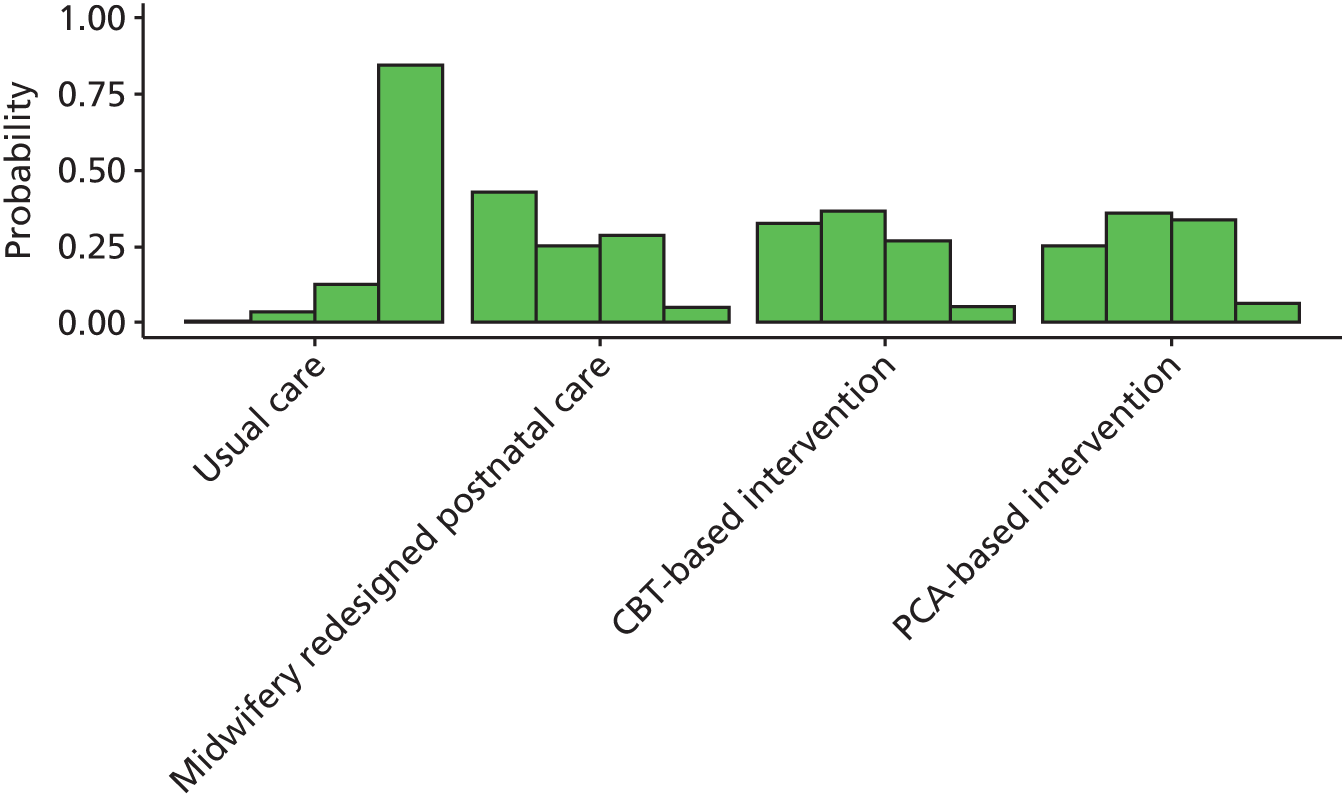

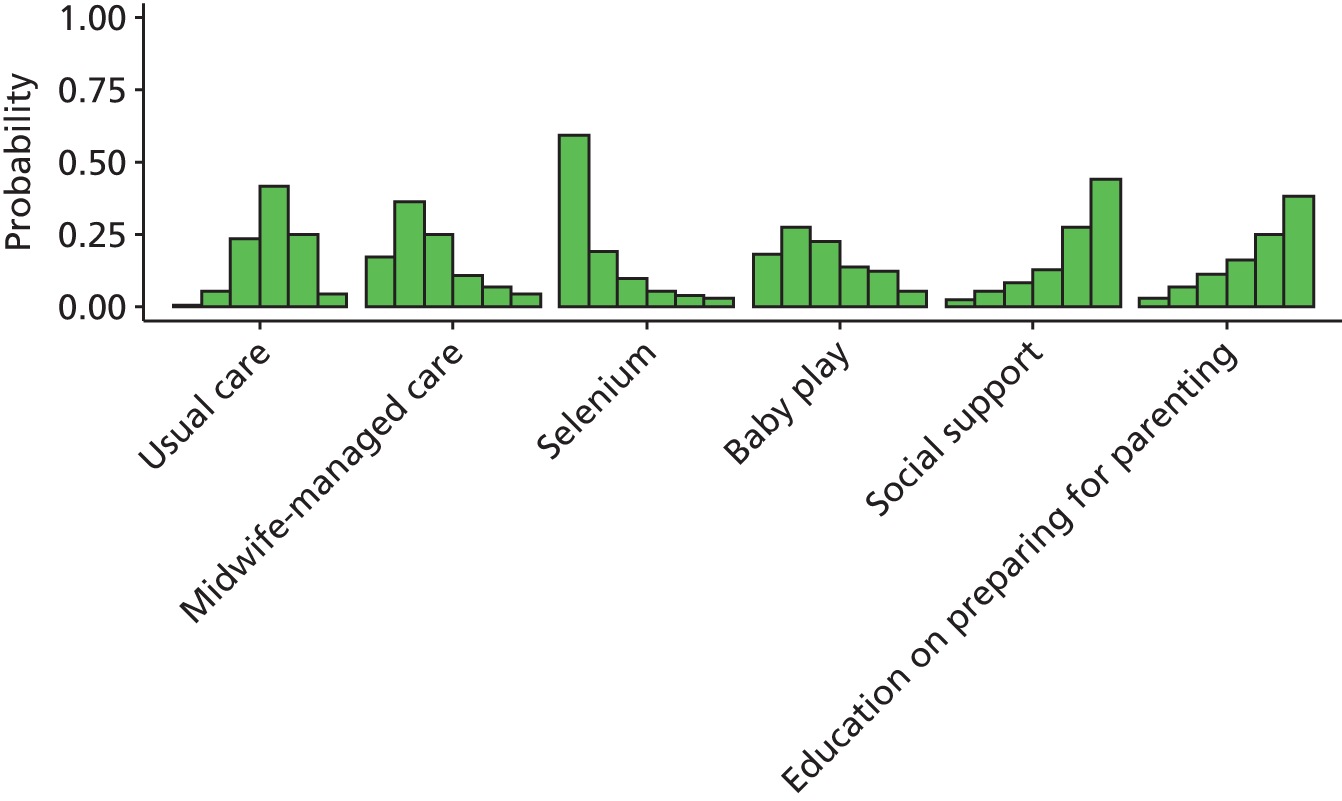

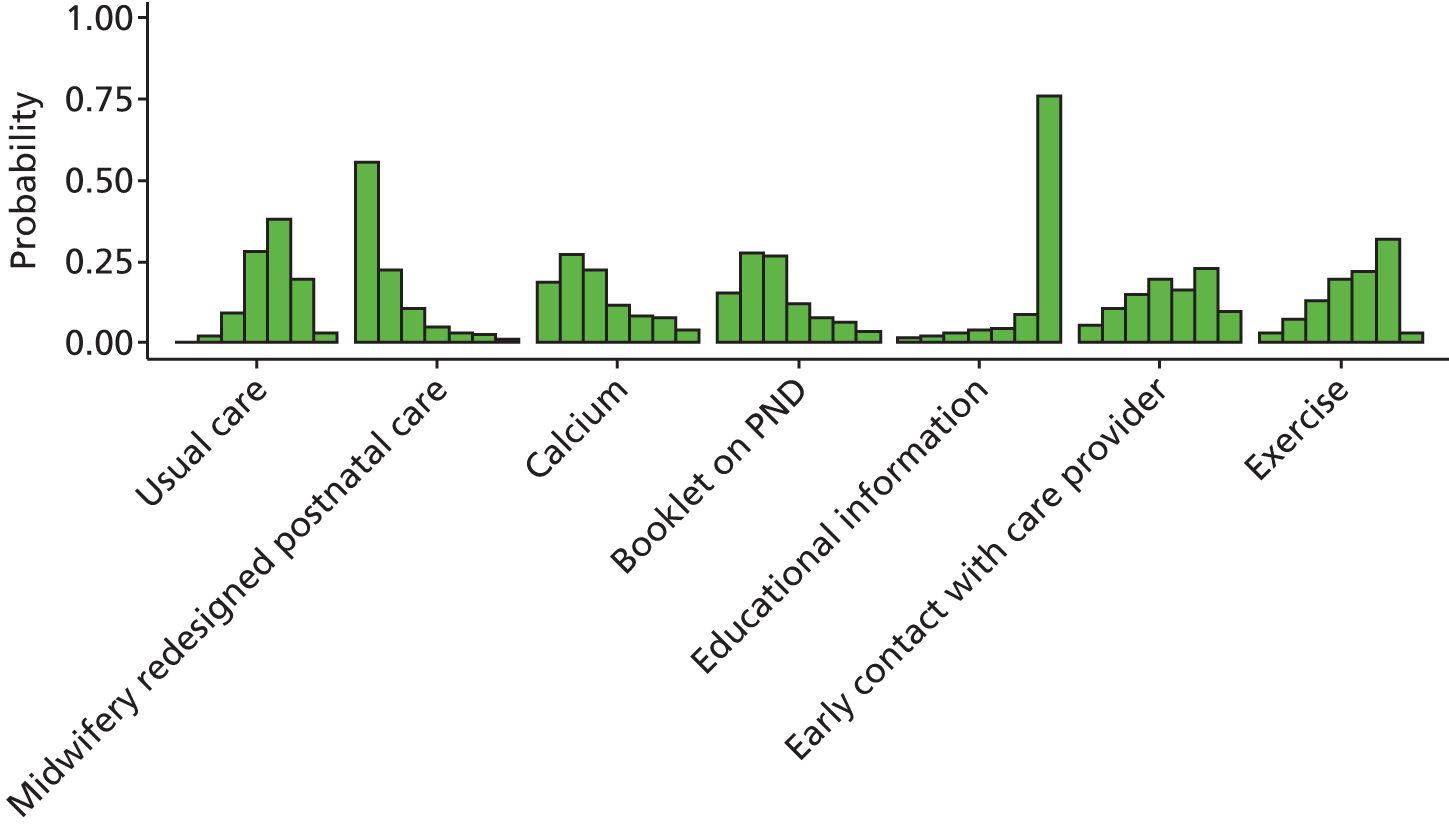

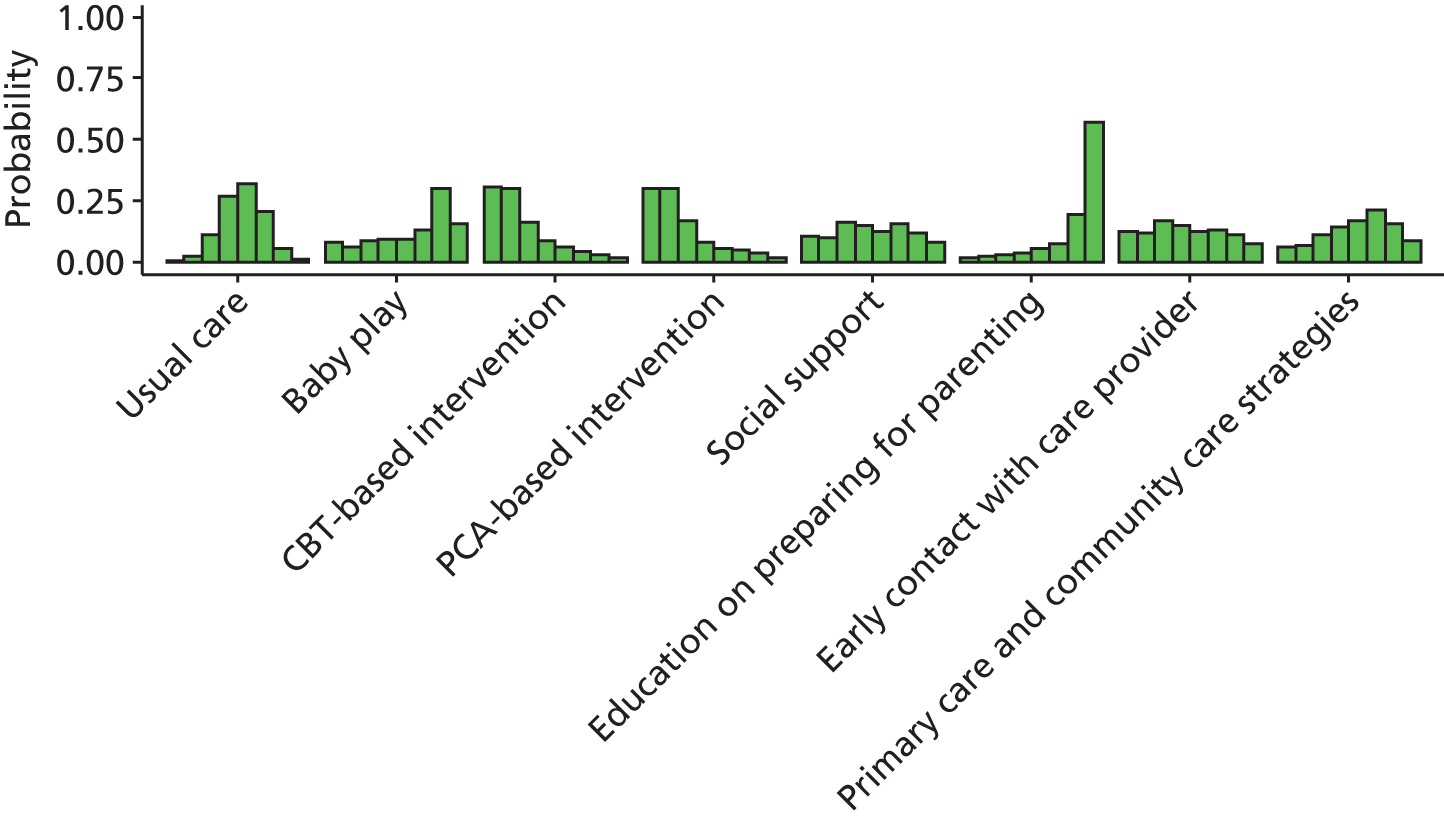

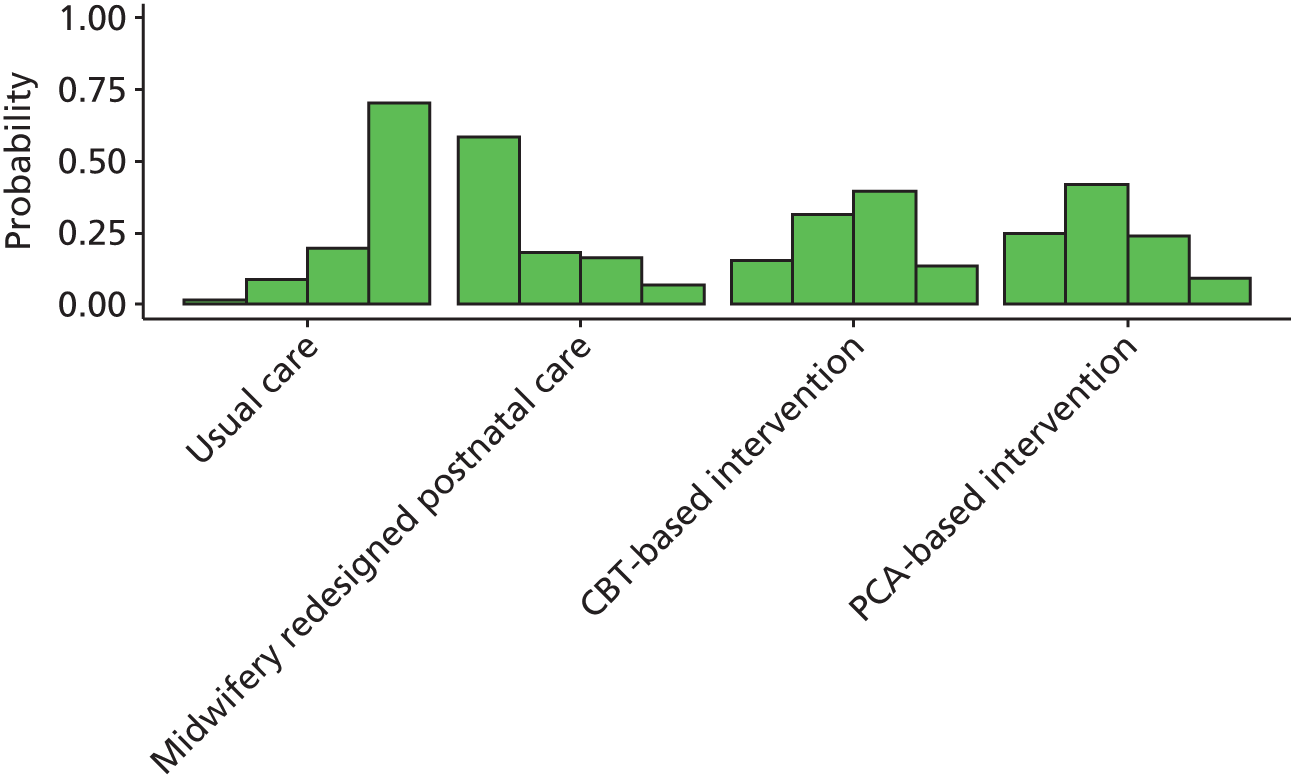

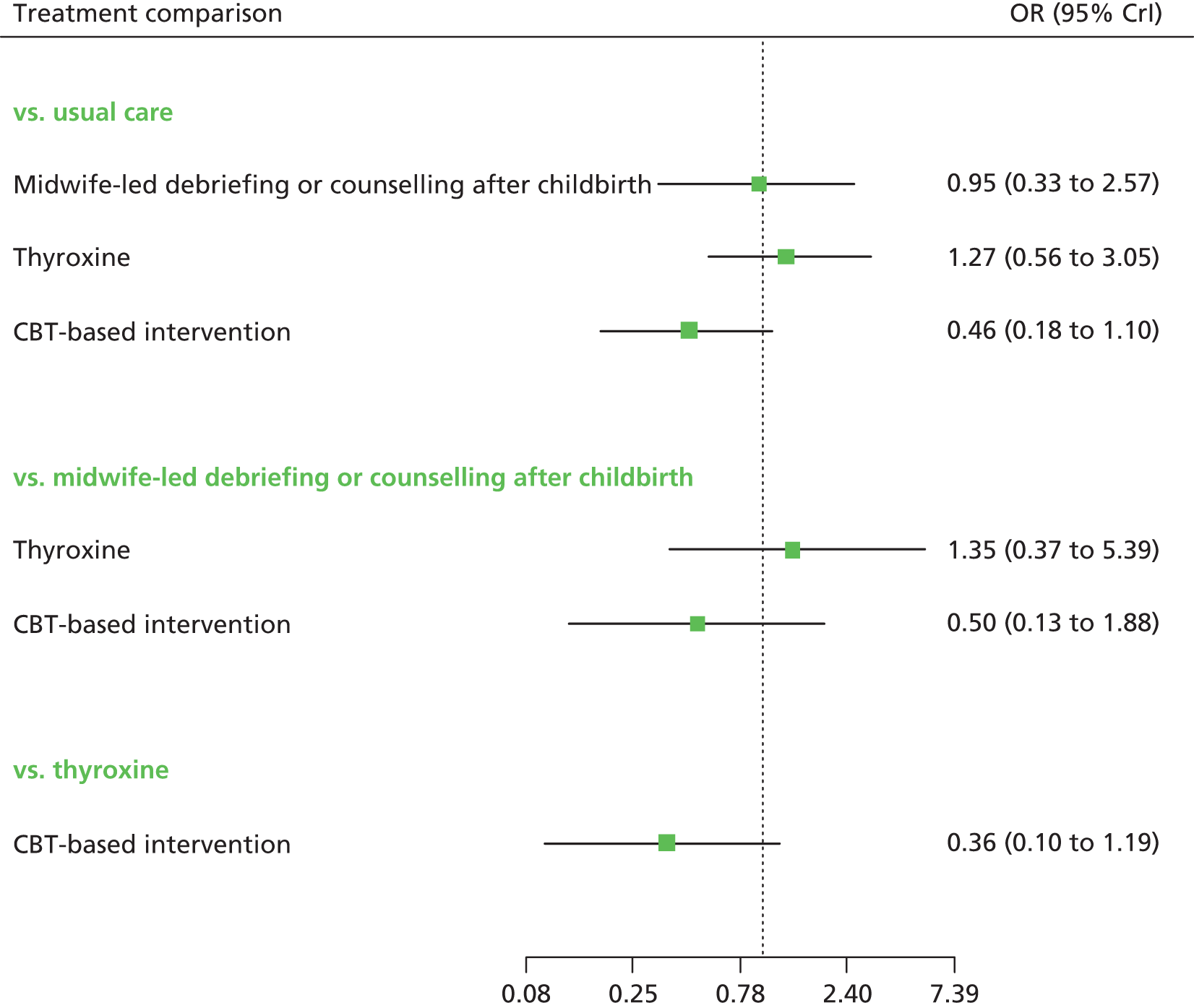

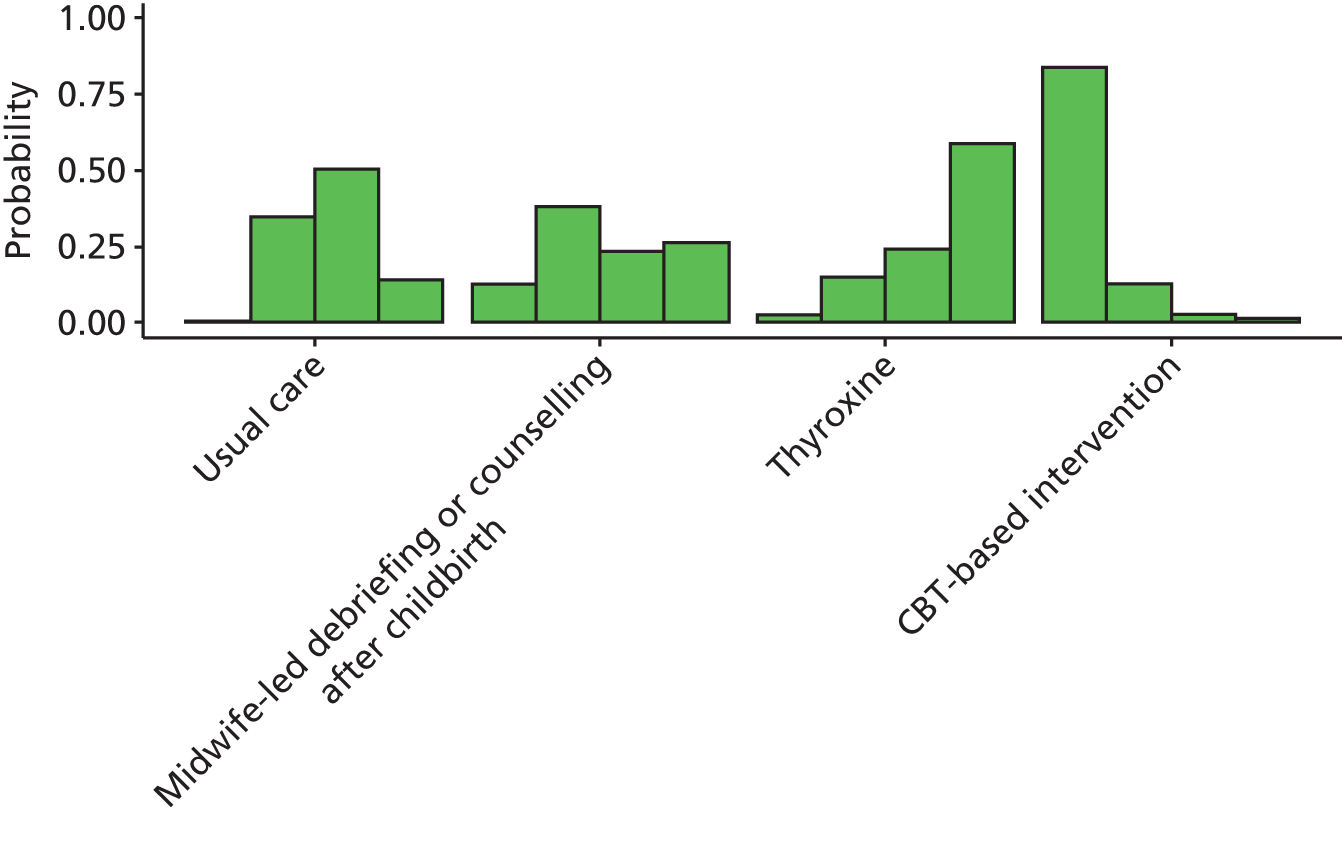

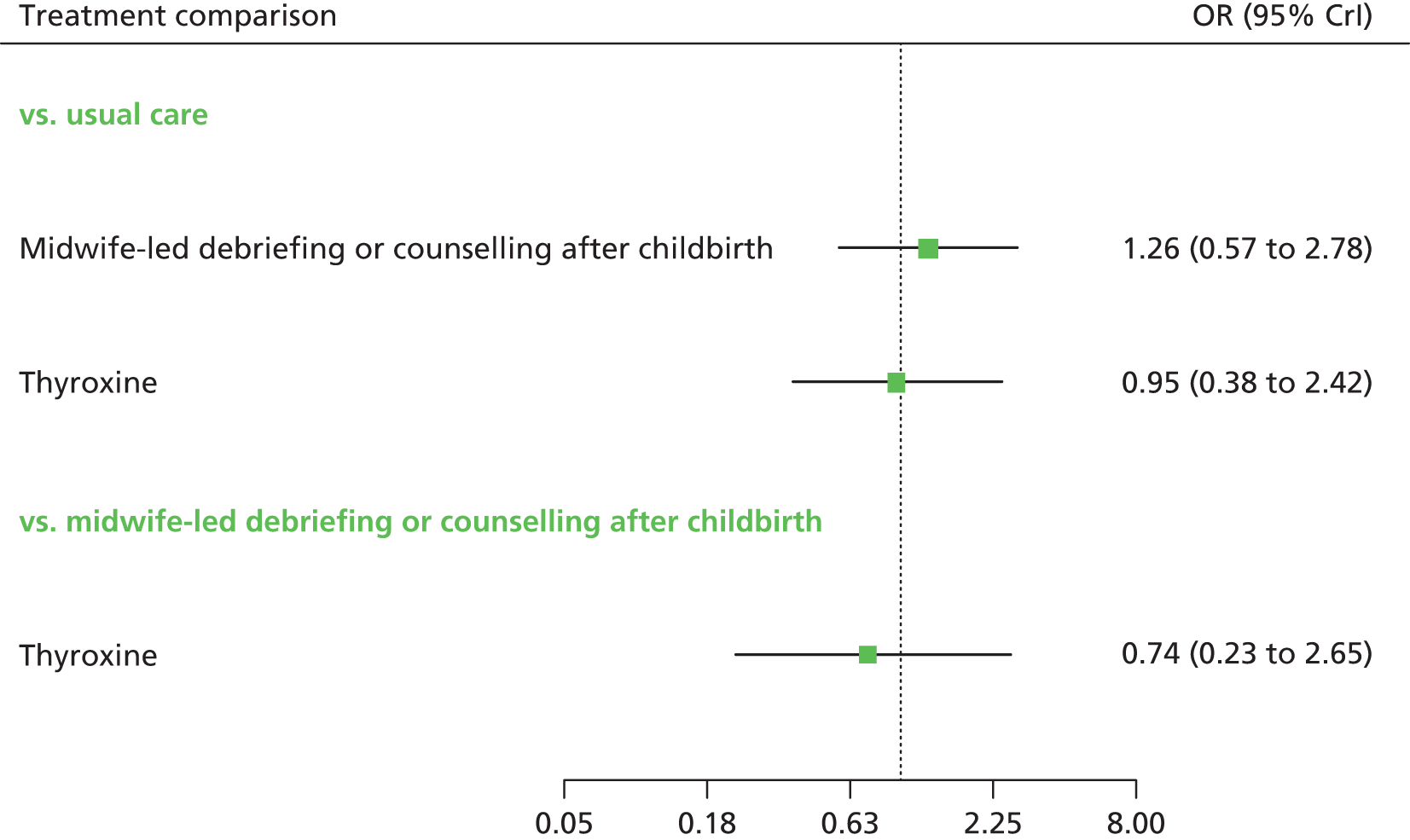

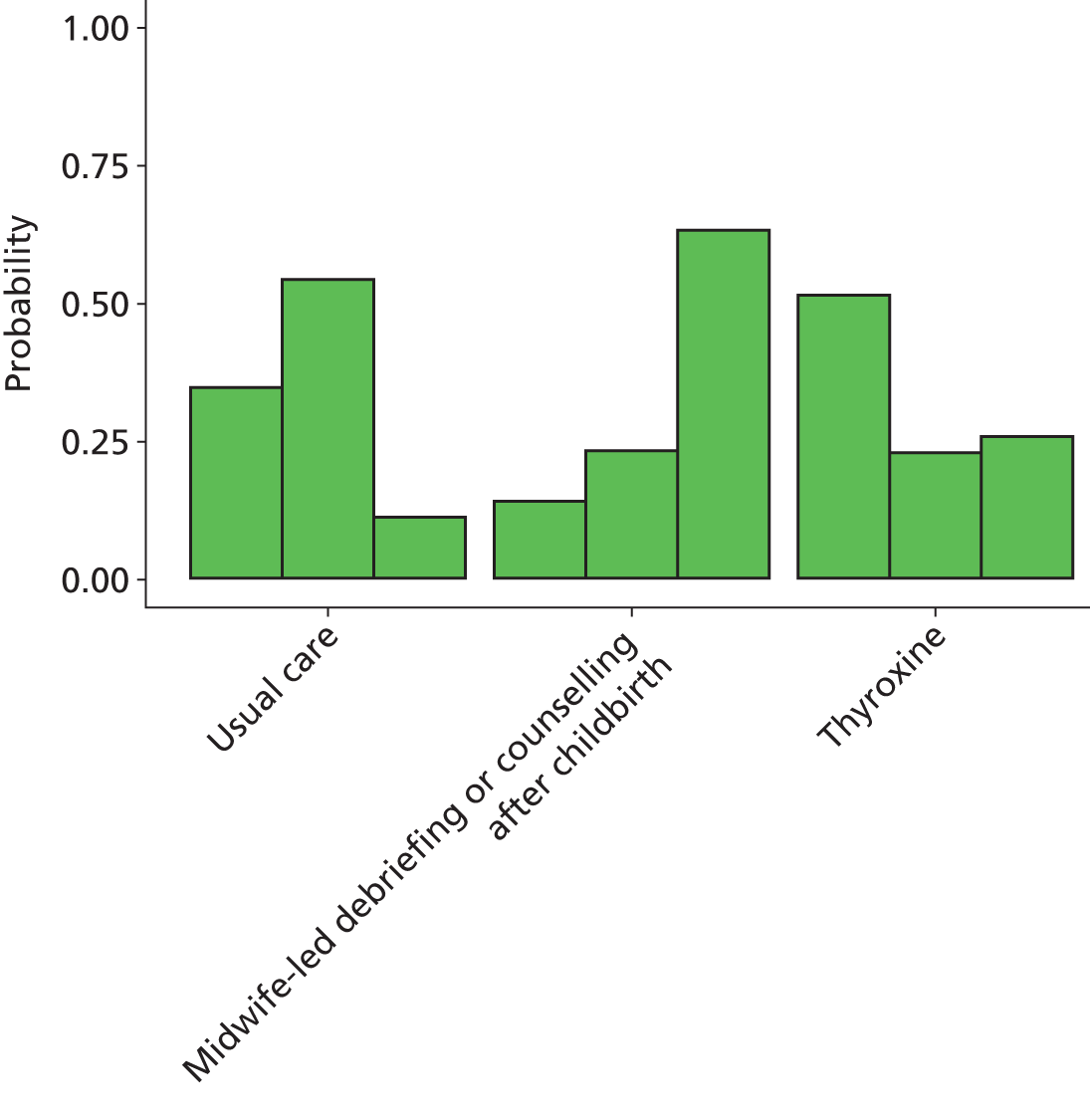

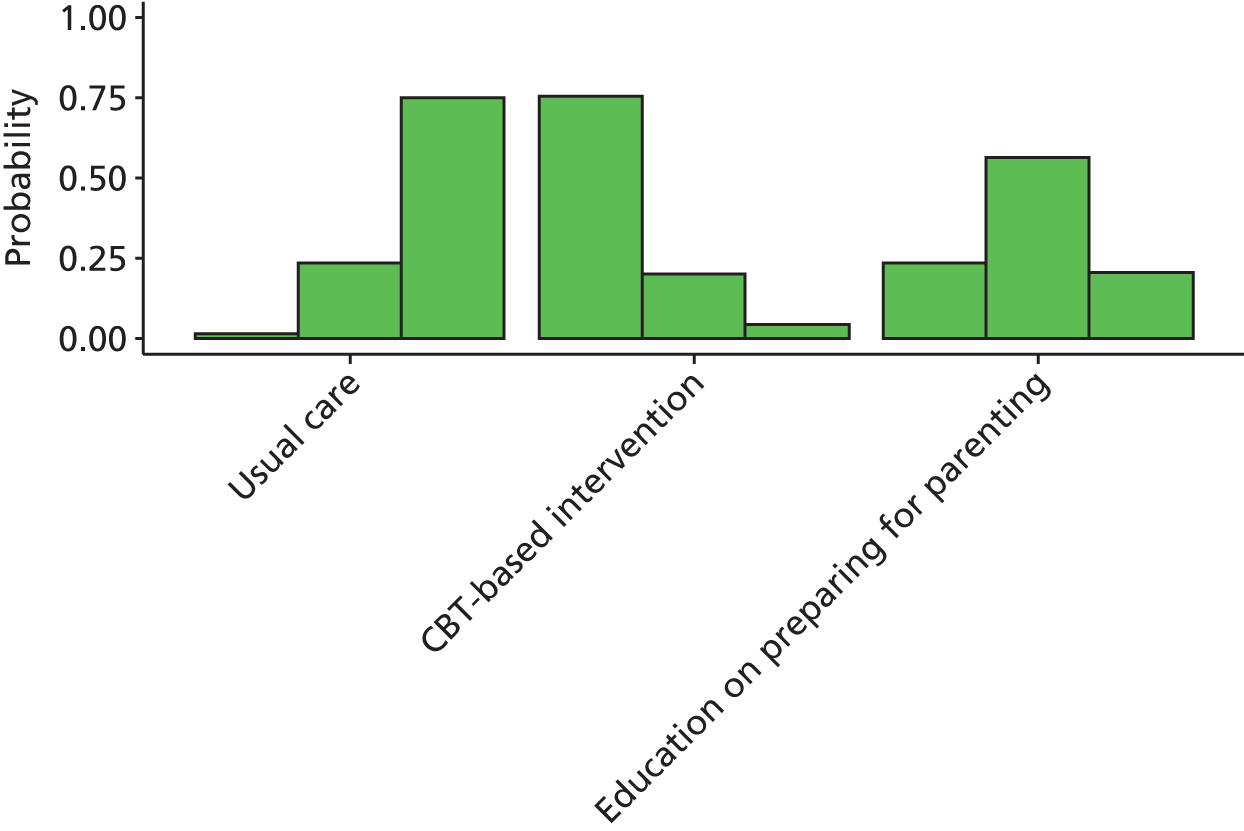

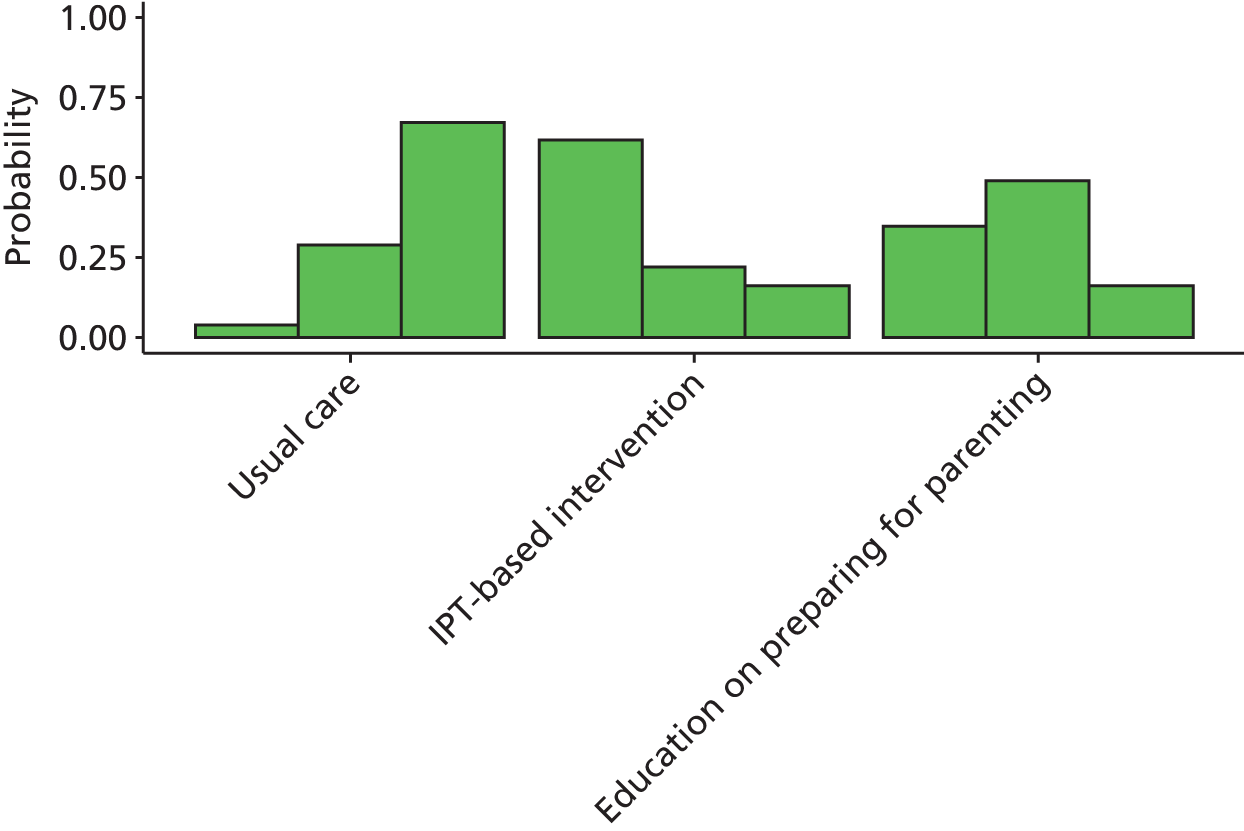

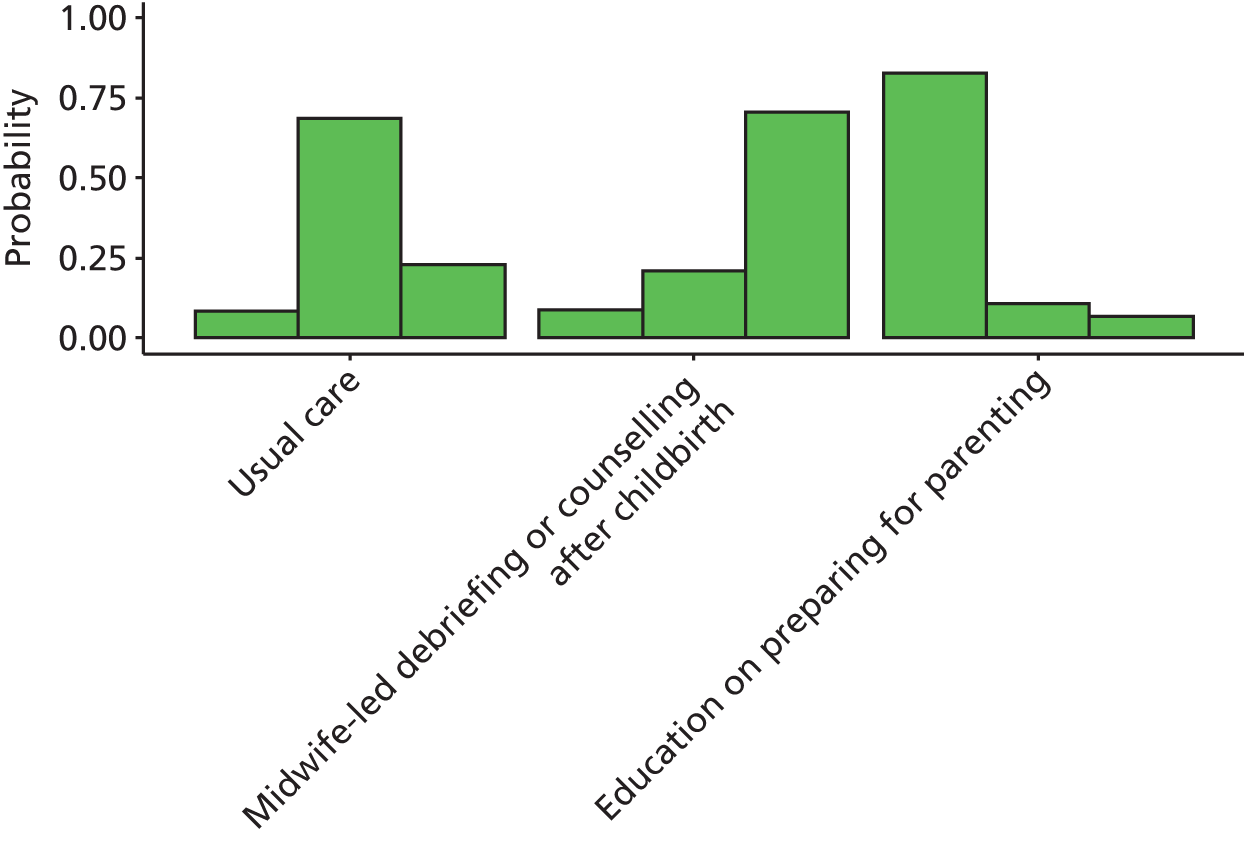

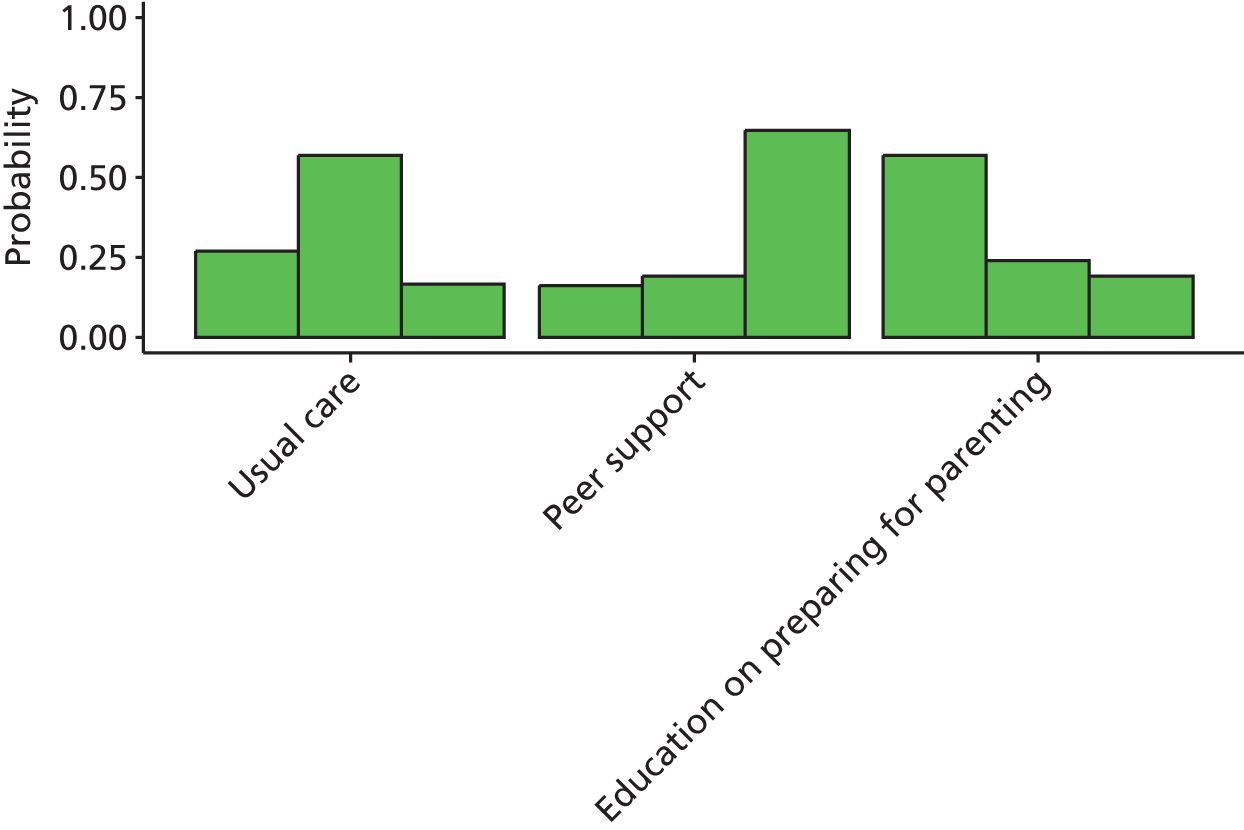

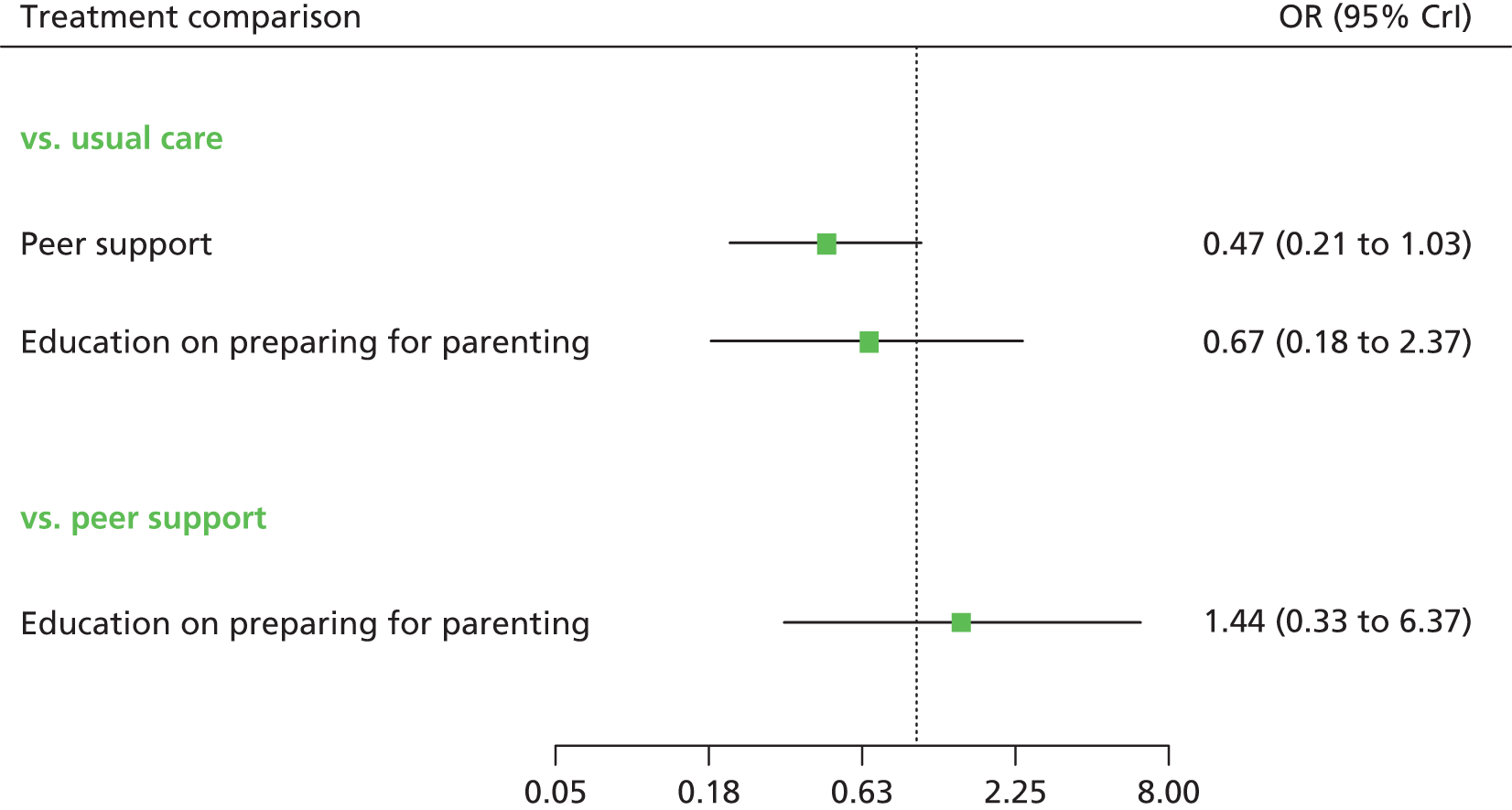

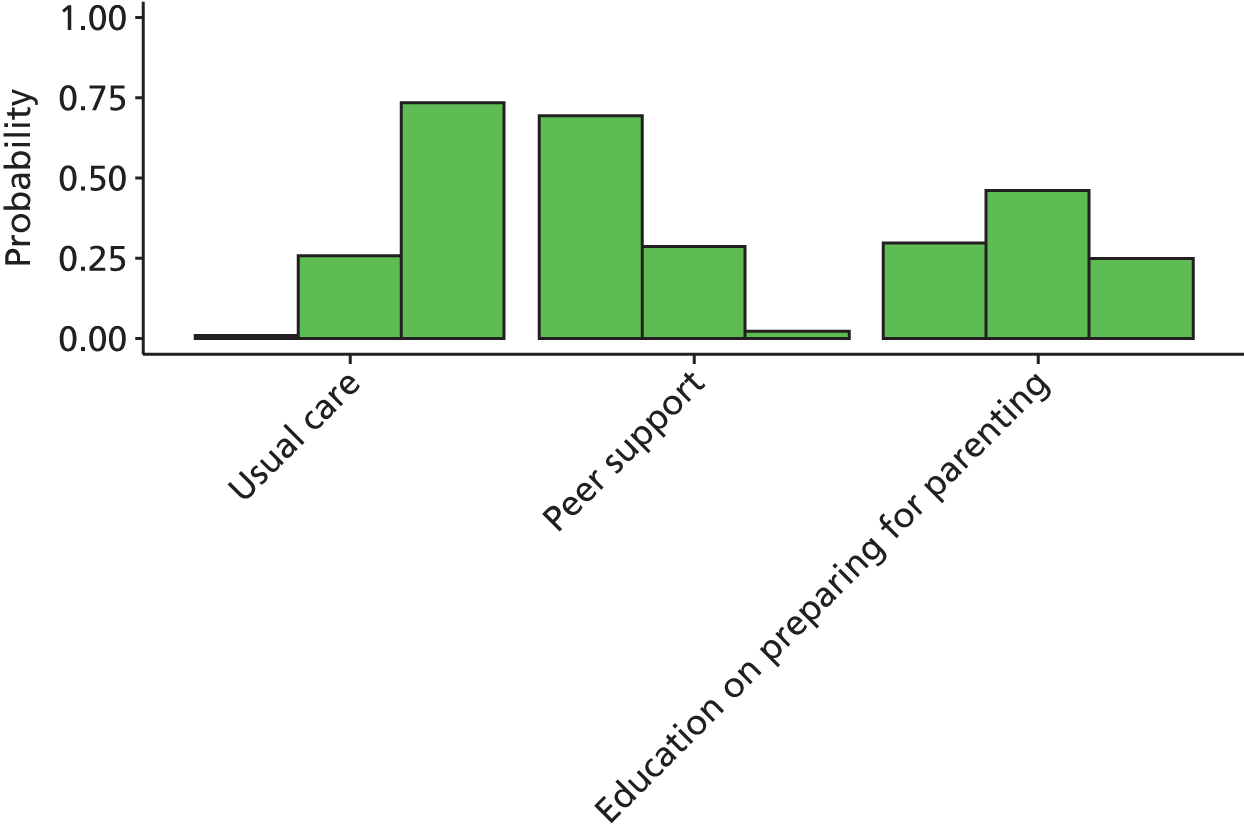

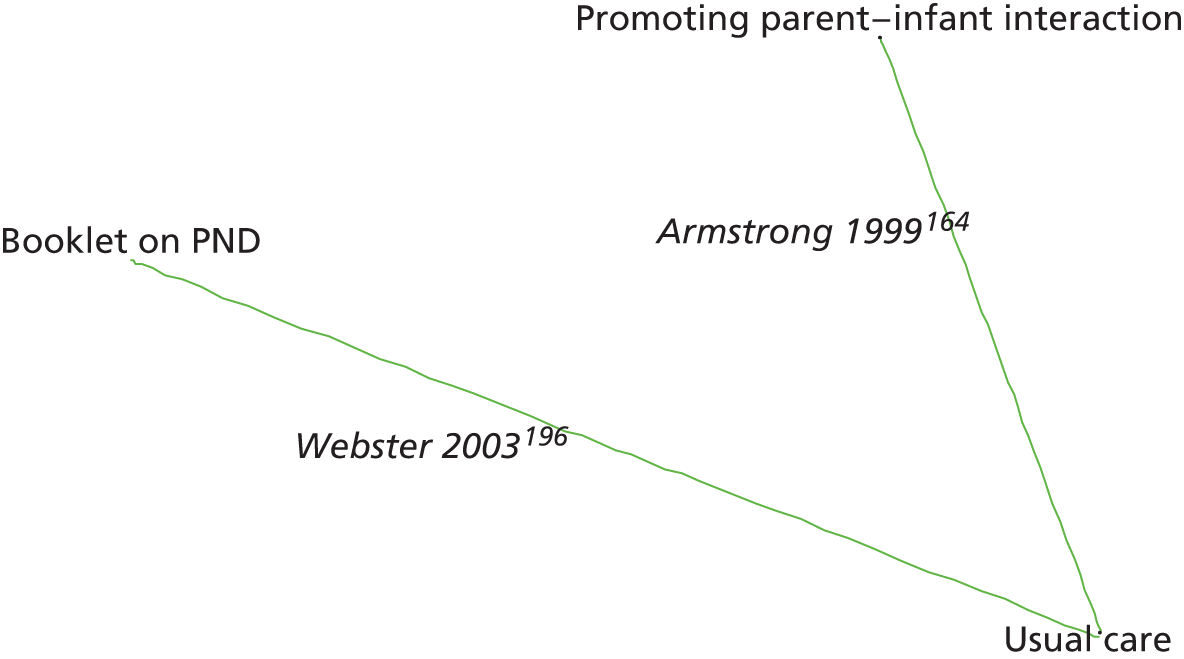

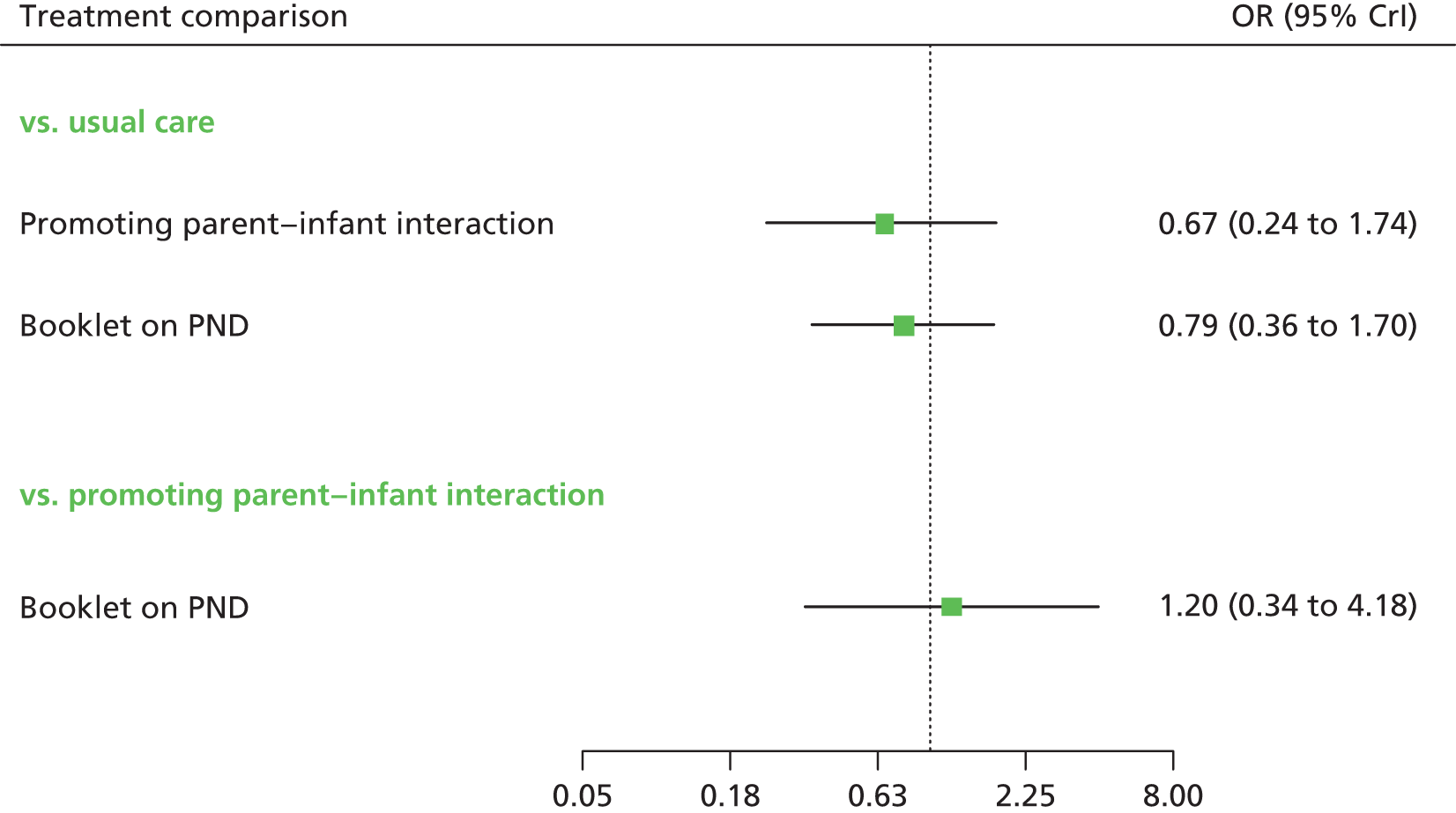

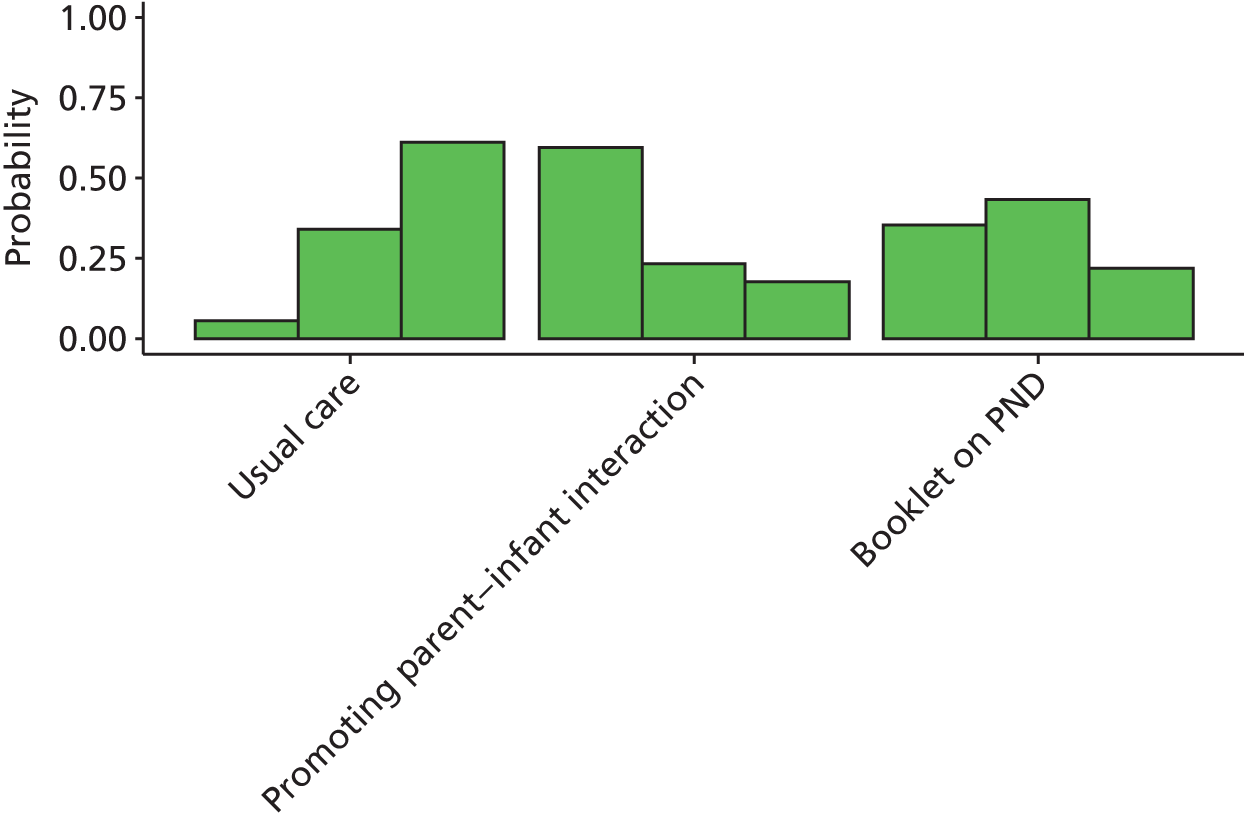

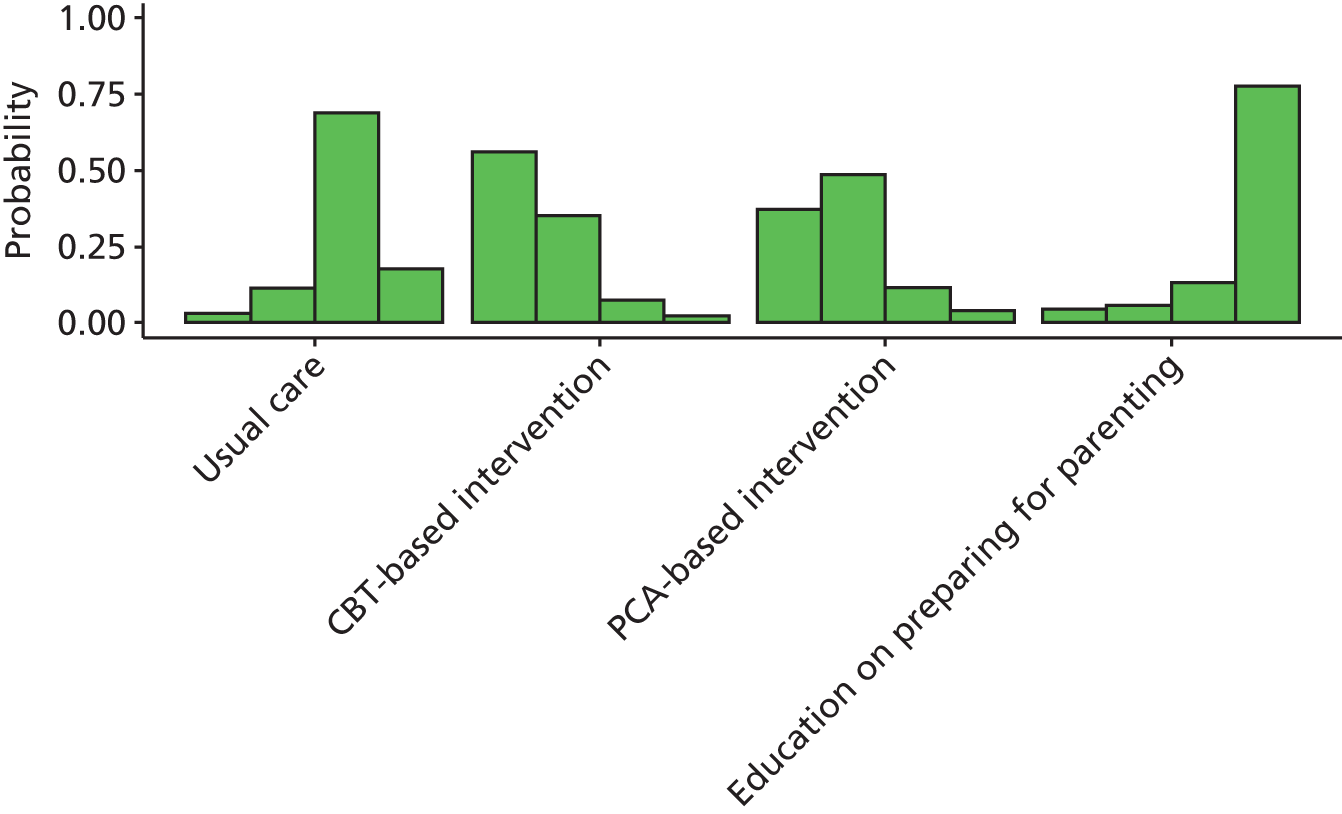

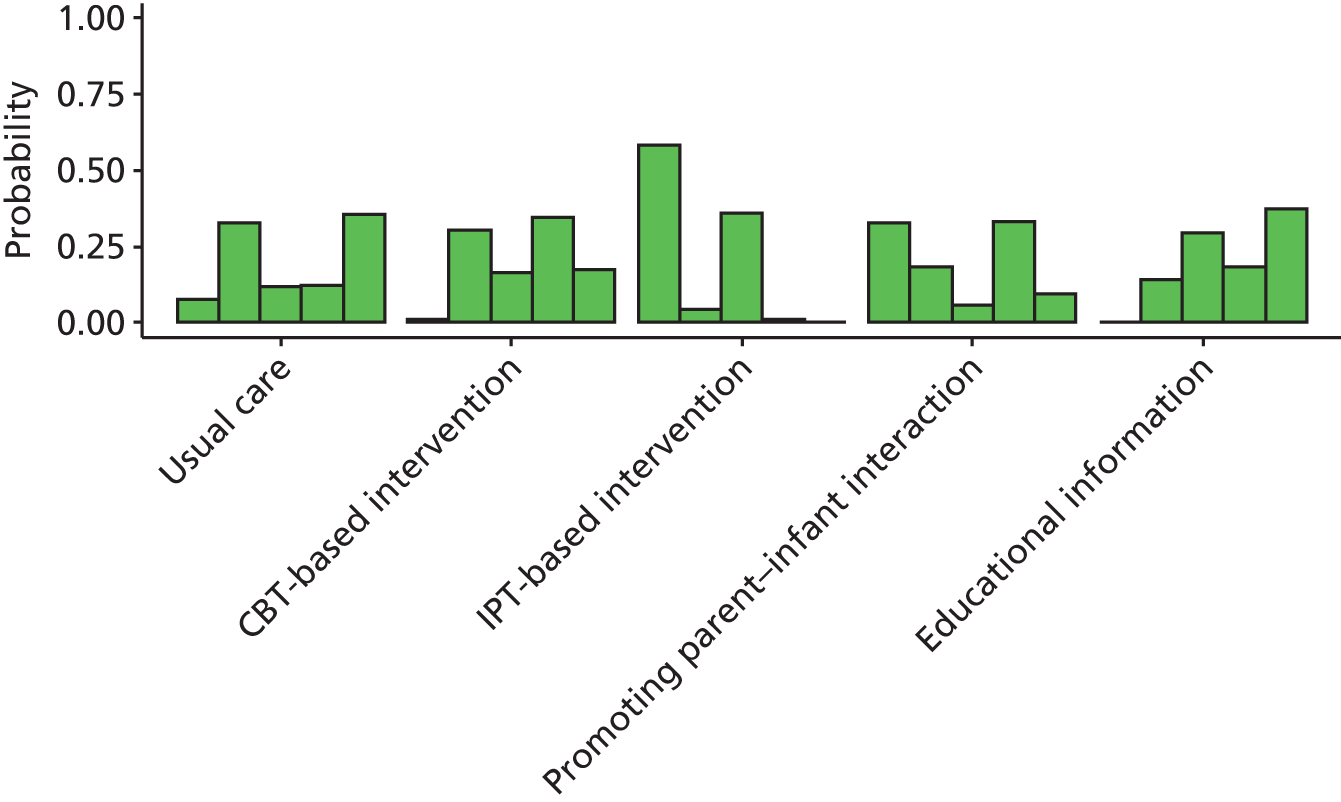

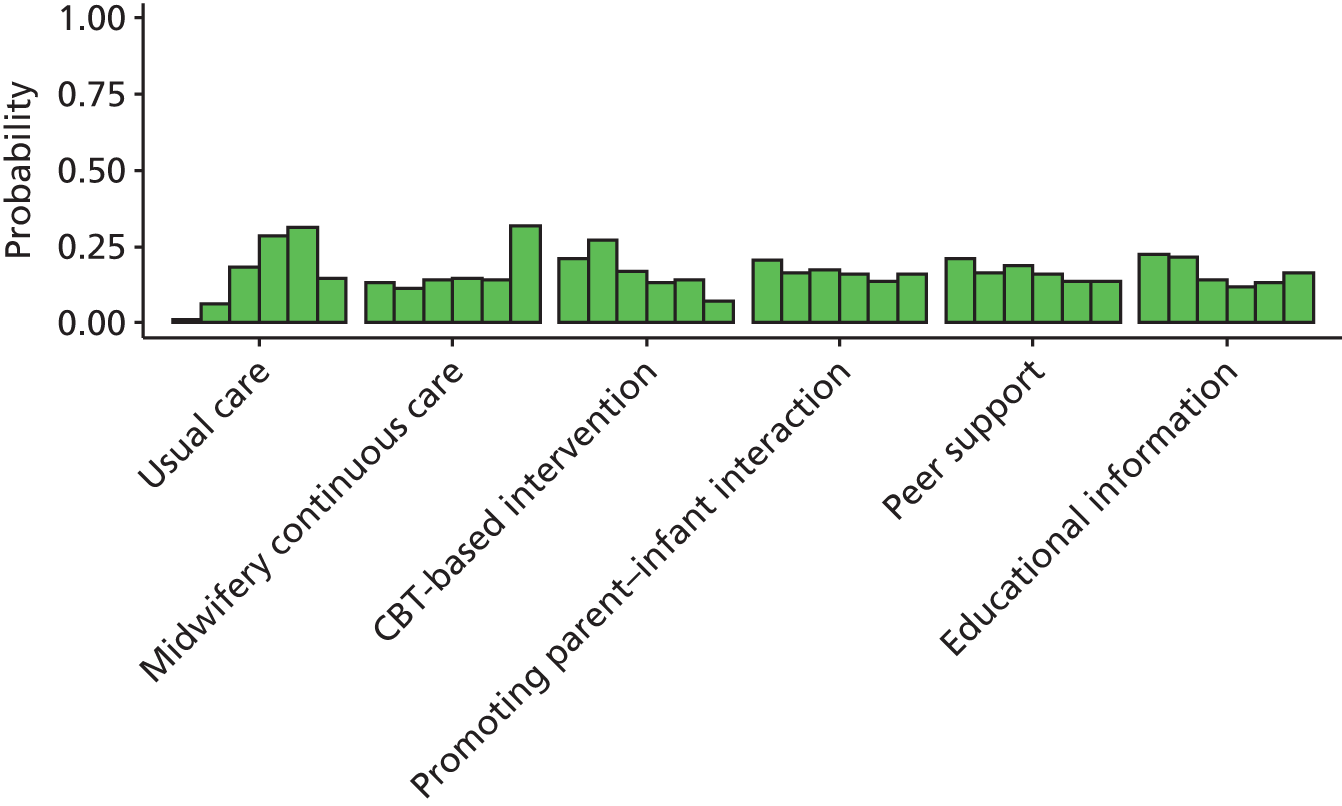

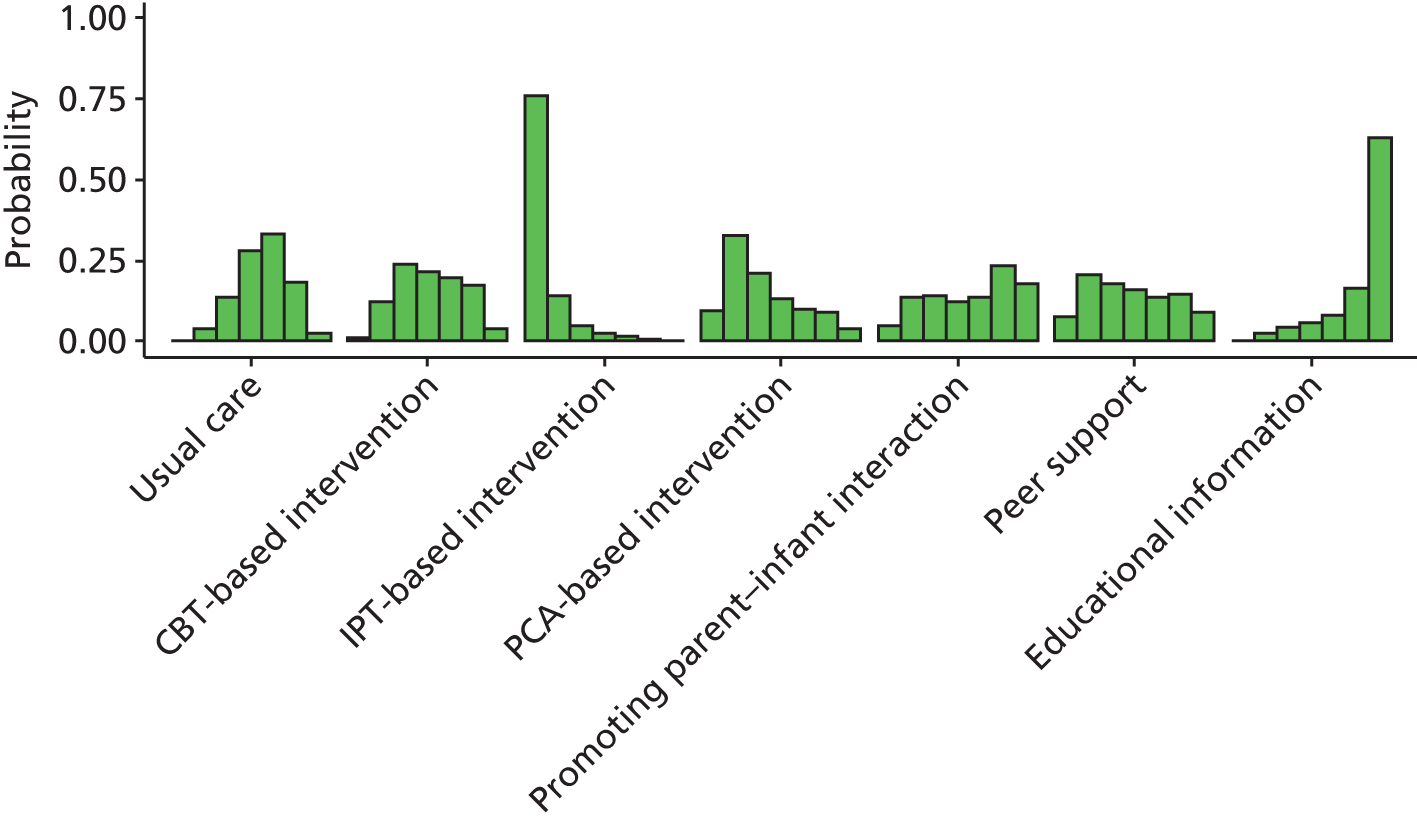

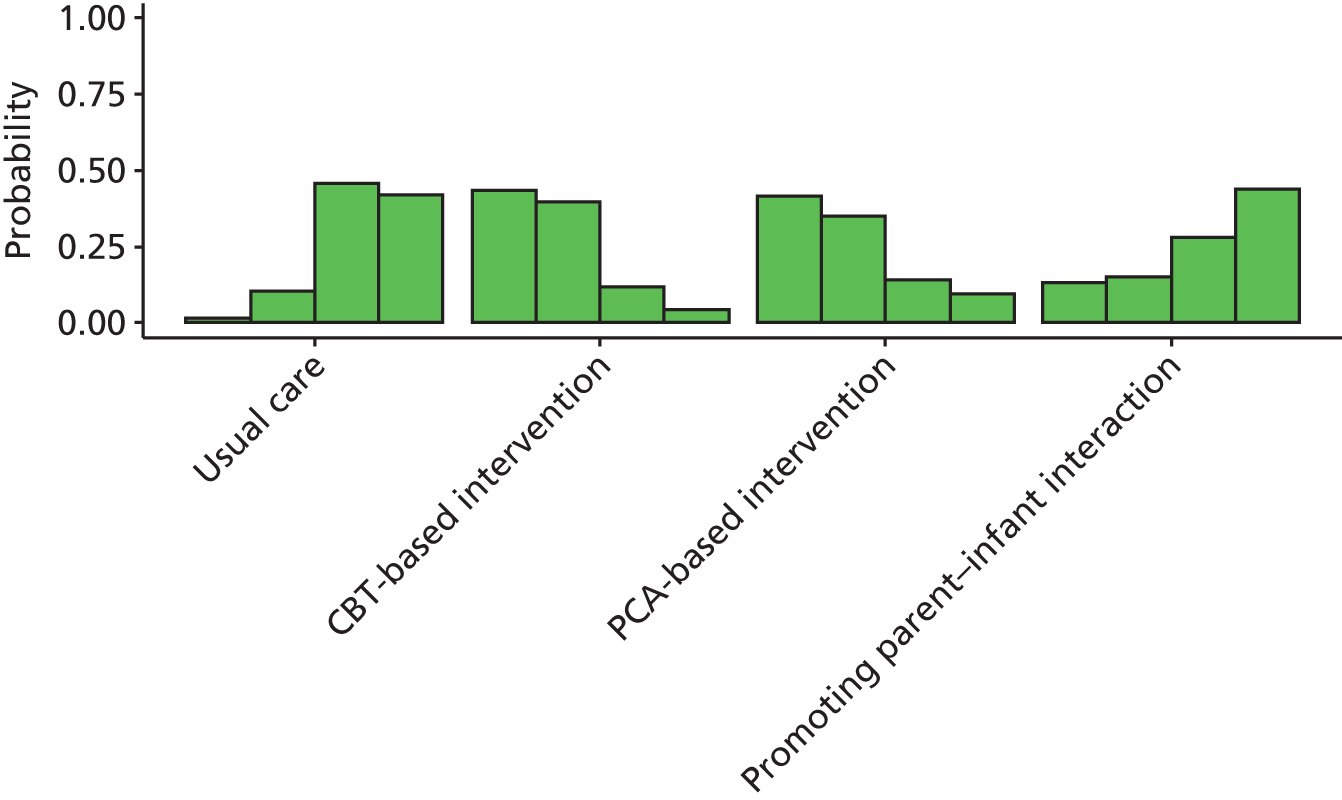

Results are presented as odds ratios [and 95% credible intervals (CrIs)], the between-study SD (and its 95% CrI) and rankograms (i.e. the probability of treatment rankings). CrIs provide an x% interval such that there is a x% probability that the true parameter lies within the interval. Rankograms provide the probabilities of each treatment being ranked as the best, second best, and so on through to the lowest-ranked treatment. The between-study SD provides a measure of heterogeneity in treatment effects between studies; on the log-odds scale, a between-study SD less than 0.5 is indicative of mild heterogeneity, of between 0.5 and 1 is indicative of moderate heterogeneity and of greater than 1 is indicative of extreme heterogeneity.

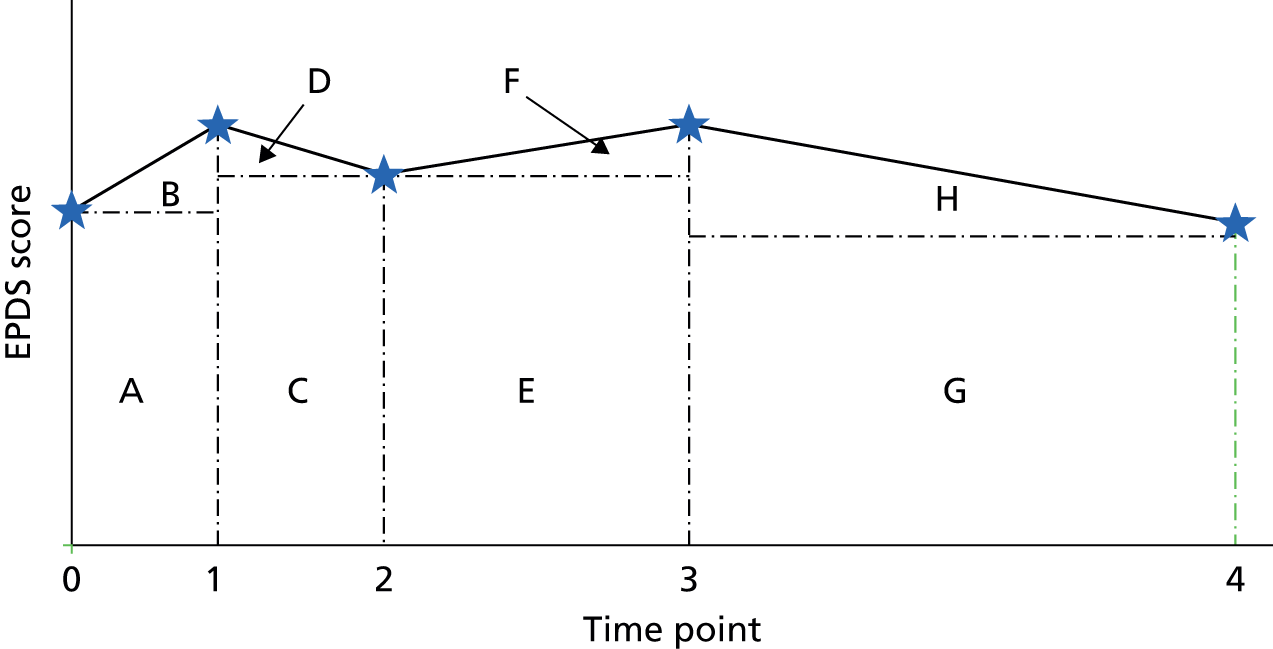

Statistical model for Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale mean scores

The analysis of the EPDS score data was conducted in two stages: (1) a treatment-effects model in which the effect of each intervention was estimated relative to usual care and (2) a baseline (i.e. usual-care) model in which the absolute response to usual care was estimated. The treatment-effects model provides estimates of relative treatment effects which are used to make inferences about the relative effects of interventions. The estimates of treatment effects relative to usual care were combined with the baseline model to provide estimates of absolute responses for each intervention; these estimates were used as inputs to the economic model.

Treatment-effects model

In general, each study provided data for each intervention in each study at baseline and at least one on-treatment assessment time. We excluded the baseline data from the treatment-effects model; the remaining data are longitudinal (i.e. repeated measures) and are correlated between times.

We began by supposing that we have observations, yij = (xij, Sij), for i = 1, 2, . . ., I and j = 1, 2, . . ., J for women in study i receiving intervention j, that is we suppose that the sample mean EPDS scores for women in study i receiving treatment j at times t can be denoted by the vector xij = (xij1, . . ., xijT)T, and that the sample mean variance–covariance matrix, Sij, is:

where the diagonal elements are the variances of the sample means at each time, the off-diagonal elements are the covariances between sample means at different times and the rijSi are the sample estimates of the within-study correlation coefficients, which depend on study si.

Although the woman-specific EPDS scores are discrete in the range 0–30, and the underlying distribution of EPDS scores is unlikely to be normal, we appeal to the central limit theorem which states that as the sample size approaches infinity for any underlying distribution with finite mean and variance, then the distribution of the sample mean is normal. Therefore, we assume that the likelihood for the samples means for women in study i, receiving treatment j is:

where vij = (vij1, . . ., vijT)T represents the study-specific population mean vector of EPDS scores for treatment j in study i.

Published papers provided no information on the correlation between sample means at different times. Therefore, we began by assuming that the rijSi is zero. We also assumed that the population standard errors, σijtnijt were known and equal to the sample standard errors, sijt, where σijt are the population SDs of an individual observation for women in study i, receiving treatment j at time t.

The model for the treatment effects follows that for a NMA of repeated measures as presented by Dakin et al. 132 We estimate the treatment effects separately for each time such that:

where µit is the population mean EPDS score for the baseline treatment (which is allowed to vary between studies) in study i at time t and δijt is the population mean effect of treatment j in study i at time t.

We used an unconstrained baseline model in which the effect of the baseline treatment in each study is fixed at each time, thereby preserving the randomisation within each study. We assumed that the effects of treatment j in study i at time t arose from a normal distribution such that:

where ai,k indicates the treatment used in the kth arm of study i. We assumed a homogeneous variance model in which the between-study SD was assumed to be common to all treatment effects and also across times. For multiarm trials, these univariate normal distributions are replaced by a multivariate normal distribution to account for correlation between treatment effects within a multiarm study.

Parameters were estimated using Markov chain Monte Carlo simulation conduction using WinBUGS 1.4.3. 130

The model was completed by giving the parameters prior distributions:

-

Vague prior distributions for the trial-specific baselines, μi ∼ N(0,1000).

-

Vague prior distributions for the treatment effects relative to reference treatment, d1t ∼ N(0,1000).

-

A weakly informative prior distribution for the between-study SD of treatment effects, τ ∼ HN(0,2).

Vague prior distributions were used for trial-specific baseline and treatment effect parameters. However, a weakly informative prior distribution was used for the between-study SD because there were insufficient studies with which to estimate it from the sample data alone; this prior distribution has median 0.95 (95% CrI 0.04 to 3.17) and was chosen to ensure that, a priori, 95% of the study-specific differences between interventions in mean EPDS scores were within a range ± 3.1 for each treatment comparison.

Convergence of the Markov chains to their stationary distributions was assessed using the Gelman–Rubin statistic. 131 The chains converged within 25,000 iterations; therefore, a burn-in of 30,000 iterations was used. We retained a further 10,000 iterations of the Markov chain to estimate parameters.

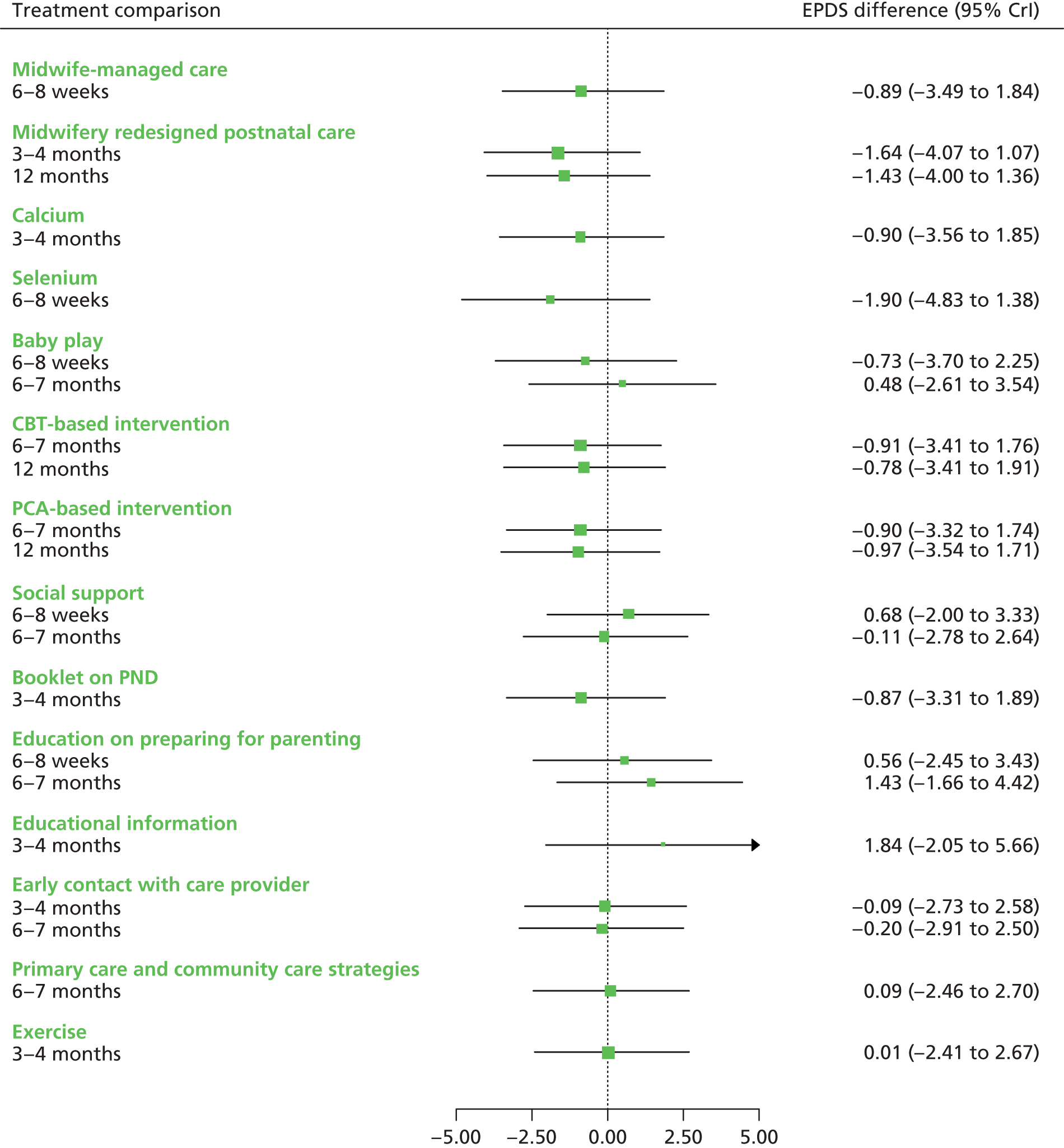

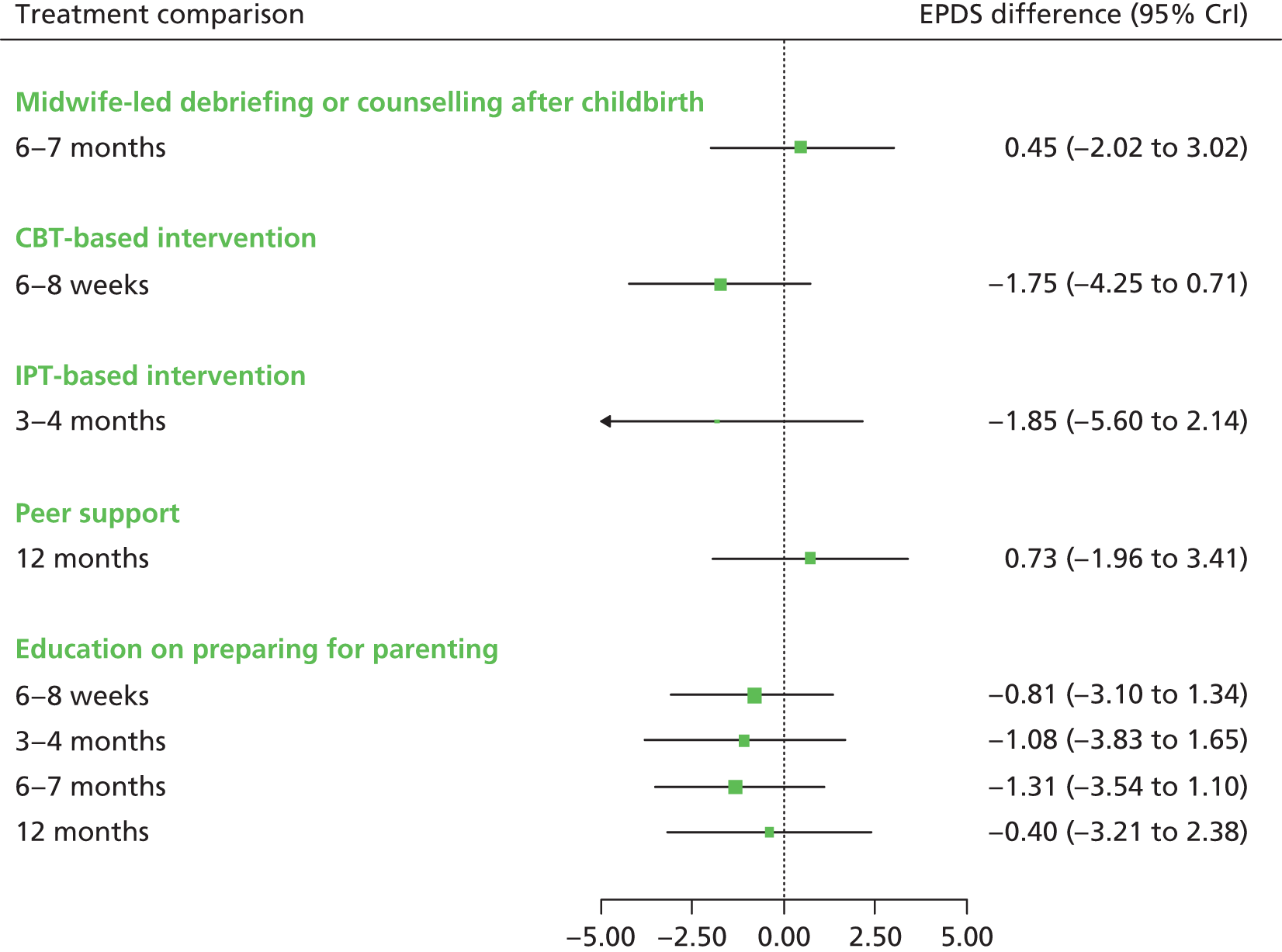

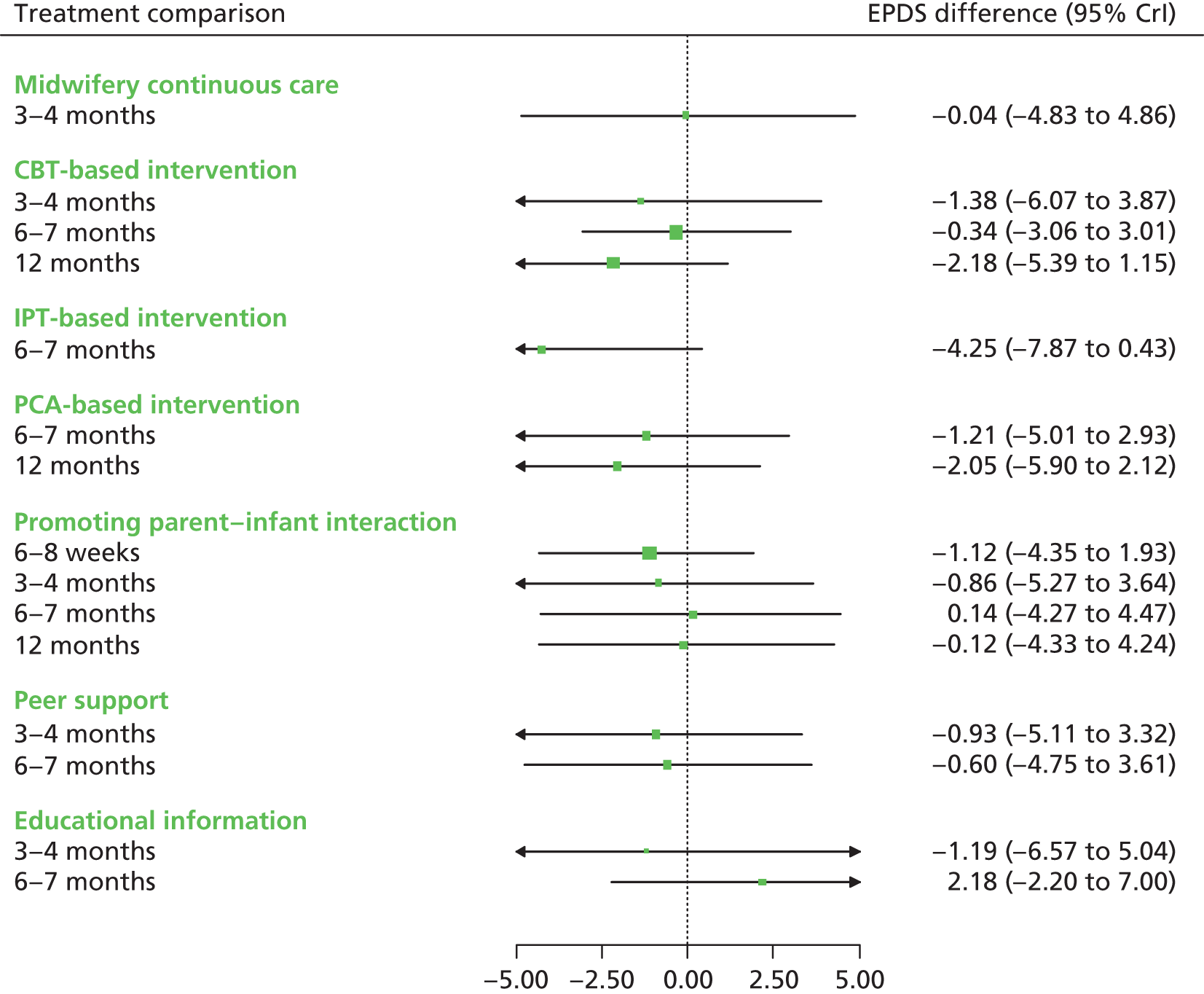

Results are presented as differences between intervention in mean EPDS scores and 95% CrIs, the between-study SD (and its 95% CrI) and rankograms (i.e. the probability of treatment rankings) at each time. Crls provide an x% interval such that there is a x% probability that the true parameter lies within the interval. Rankograms provide the probabilities of each treatment being ranked the best, second best, through to the lowest-ranked treatment. The between-study SD provides a measure of heterogeneity in treatment effects between studies; for continuous outcome measures the extent to which the between-study SD indicates mild, moderate or extreme heterogeneity depends on the scale of measurement and the variation within study.

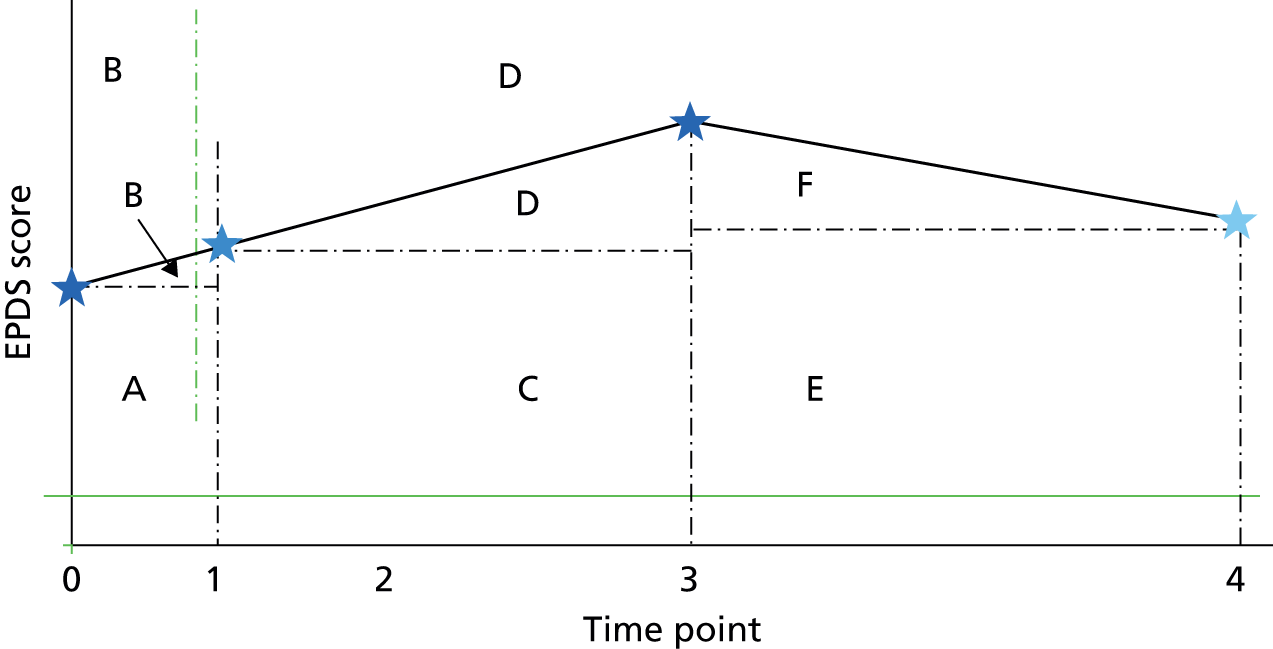

Baseline model

In general, studies in which the control intervention was usual care provided data at baseline and at least one on-treatment assessment time. Therefore, the data are longitudinal (i.e. repeated measures) and are correlated between times.

We began by supposing that we have observations yi = (xi,Si), for i = 1, 2, . . ., I, for women in study i, that is we suppose that the sample mean EPDS scores for women in study i, receiving usual care at times t, can be denoted by the vector xi = (x1i, . . ., xiT)T, and that the sample mean variance–covariance matrix, Si, is:

where the diagonal elements are the variances of the sample means at each time, the off-diagonal elements are the covariances between sample means at different times and the rijSi are the sample estimates of the within-study correlation coefficients, which depend on study si. In practice, not all women provide data at each time and the covariances depend on the number of women who provide data at each time as well as the number of women who provide data at both times. Therefore, the covariance between sample means within a study at times t and t’ is:

Although the woman-specific EPDS scores are discrete in the range 0–30, and the underlying distribution of EPDS scores is unlikely to be normal, we appeal to the central limit theorem which states that as the sample size approaches infinity for any underlying distribution with finite mean and variance, then the distribution of the sample mean is normal. Therefore, we assume that the likelihood for the samples means for women in study i is:

where vi = (vi1, . . ., viT)T represents the study-specific population mean vector of EPDS scores for women in study i, receiving usual care at times t. Studies do not provide data at all times so that the number of times with data, Ti, in study i is such that 1 ≤ Ti ≤ T.

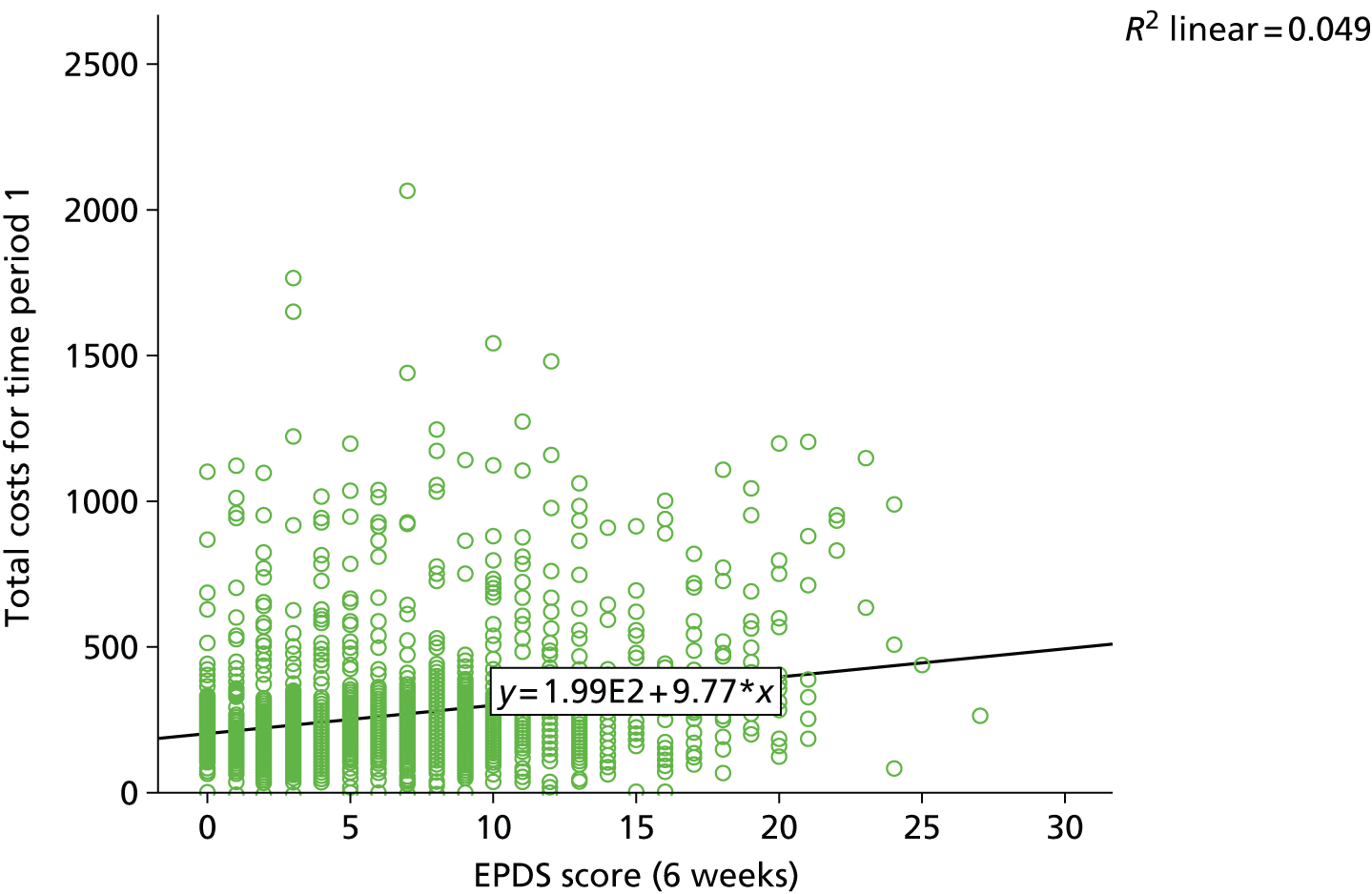

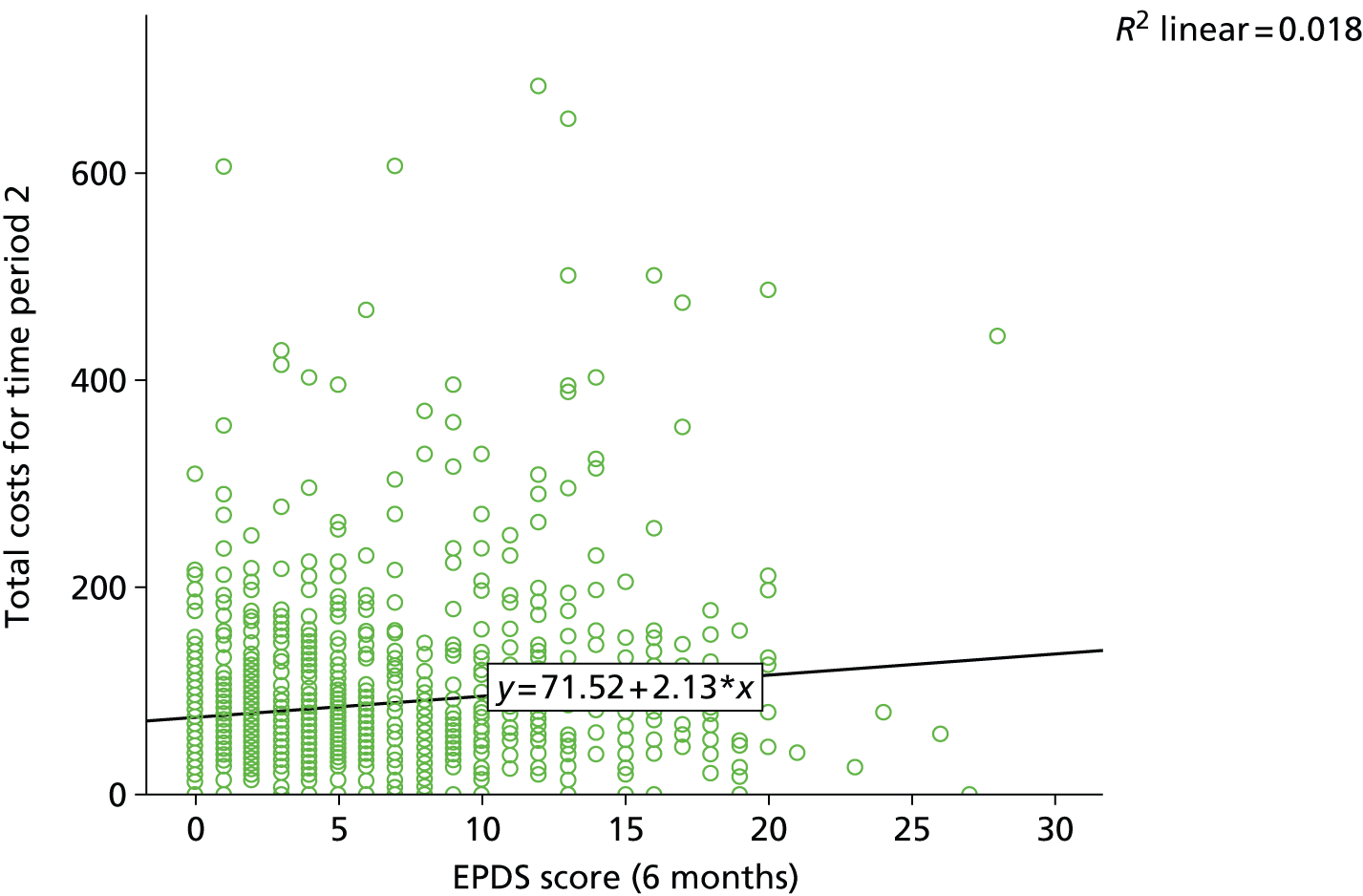

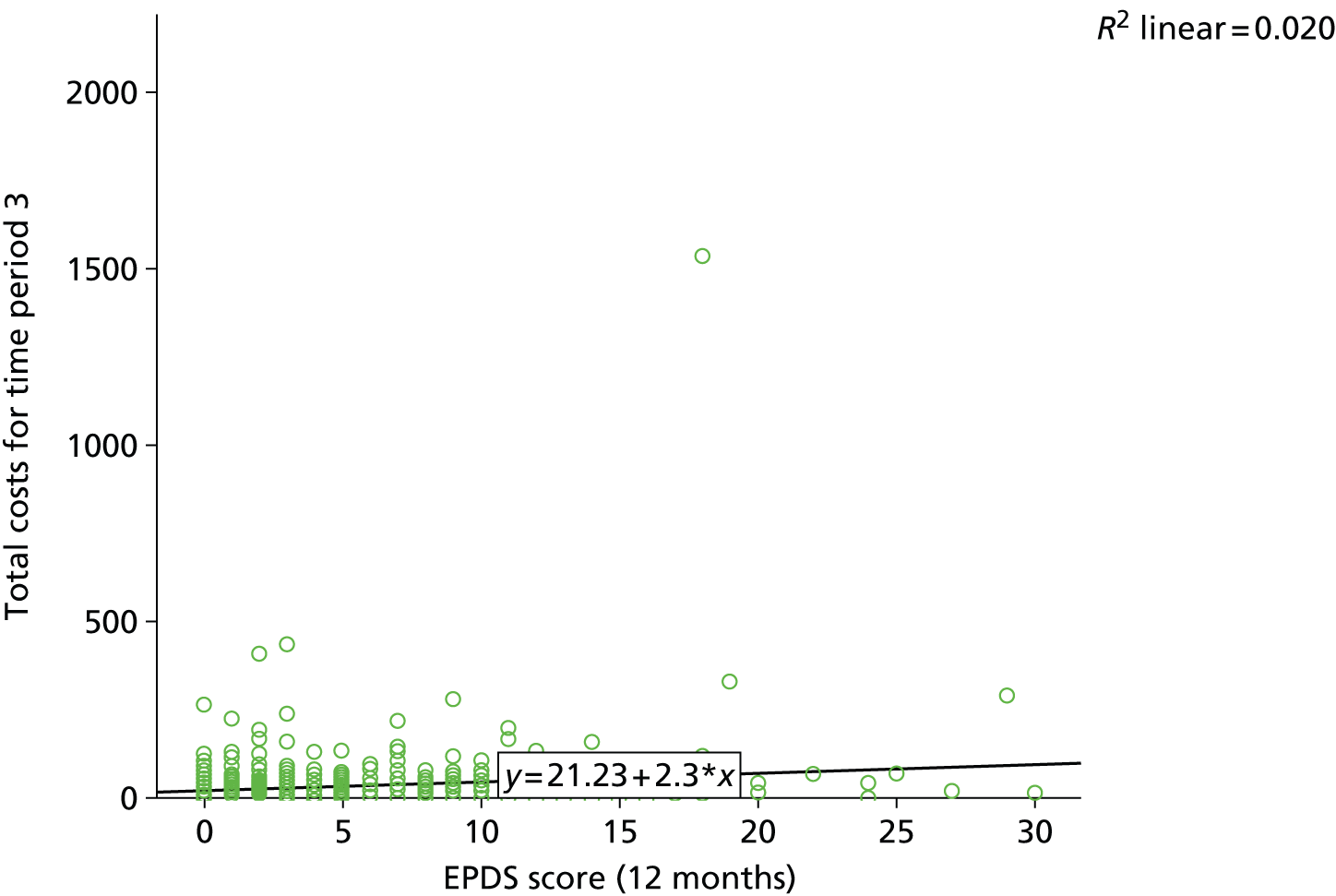

Published papers provided no information on the correlation between sample means at different times. However, using individual woman-level data from the PoNDER (PostNatal Depression Economic evaluation and Randomised controlled trial), we obtained estimates of the correlation coefficients between sample EPDS scores at baseline, 6 months and 12 months to be rb,6m = 0.345, rb,12m = 0.369 and r6m,12m = 0.721. In the absence of any additional external evidence, we made the assumptions as follows:

The model for the baseline effects follows that presented by Wei and Higgins. 133 We let υi∼MVN(Xiµ,XiΩXiT) where Xi is a Ti × T design matrix defining which of the T times are included in the study, µ is a T × 1 vector of underlying mean EPDS scores across studies, and Ω is a T × T matrix representing the between study covariance matrix for all T times. Thus, the studies are linked through the parameters that characterise the distribution of the random effects.

All analyses were conducted in WinBUGS 1.4.3. 130 The model was completed by giving the parameters prior distributions:

-

Vague prior distributions for the treatment effects relative to the reference treatment, d1t ∼ N(0,1000).

-

Weakly informative prior distributions for the between-study SD of treatment effects, τ ∼ HN(0,2).

-

Weakly informative prior distributions for the correlation coefficients U(–1,1).

Vague prior distributions were used for treatment effect parameters. However, a weakly informative prior distribution was used for the between-study SD because there were insufficient studies with which to estimate it from the sample data alone; this prior distribution has a median of 0.95 (95% CrI 0.04 to 3.17) and was chosen to ensure that, a priori, 95% of the study-specific differences in means lie within a range ± 3.1 for each treatment comparison.

Convergence of the Markov chains to their stationary distributions was assessed using the Gelman–Rubin statistic. 131 The chains converged within 10,000 iterations so a burn-in of 10,000 iterations was used. We retained a further 10,000 iterations of the Markov chain to estimate parameters after thinning the chains by retaining every 10th iteration to account for correlation between successive iterations of the Markov chain.

Results are presented as means (and 95% CrIs) and the between-study SD (and its 95% CrI) at each time.

The mean EPDS scores and the covariance matrix were extracted and were coupled with the treatment-effects model to generate absolute EPDS scores for each treatment as inputs to the economic model. Riley134 showed that, in the context of multivariate meta-analyses, ignoring the within-study correlation can have substantial impact on parameter estimates and their correlation expect when the within-study variation is small relative to the between-study variation. Morrell et al. 61 provided information about usual care, cognitive–behavioural approach (CBA)-based intervention and a person-centred approach (PCA)-based intervention at baseline, 6 months and 12 months, and was used to estimate the within-study correlation coefficients.

Methods for reviewing and assessing qualitative studies

Study selection criteria and procedures for the effectiveness review

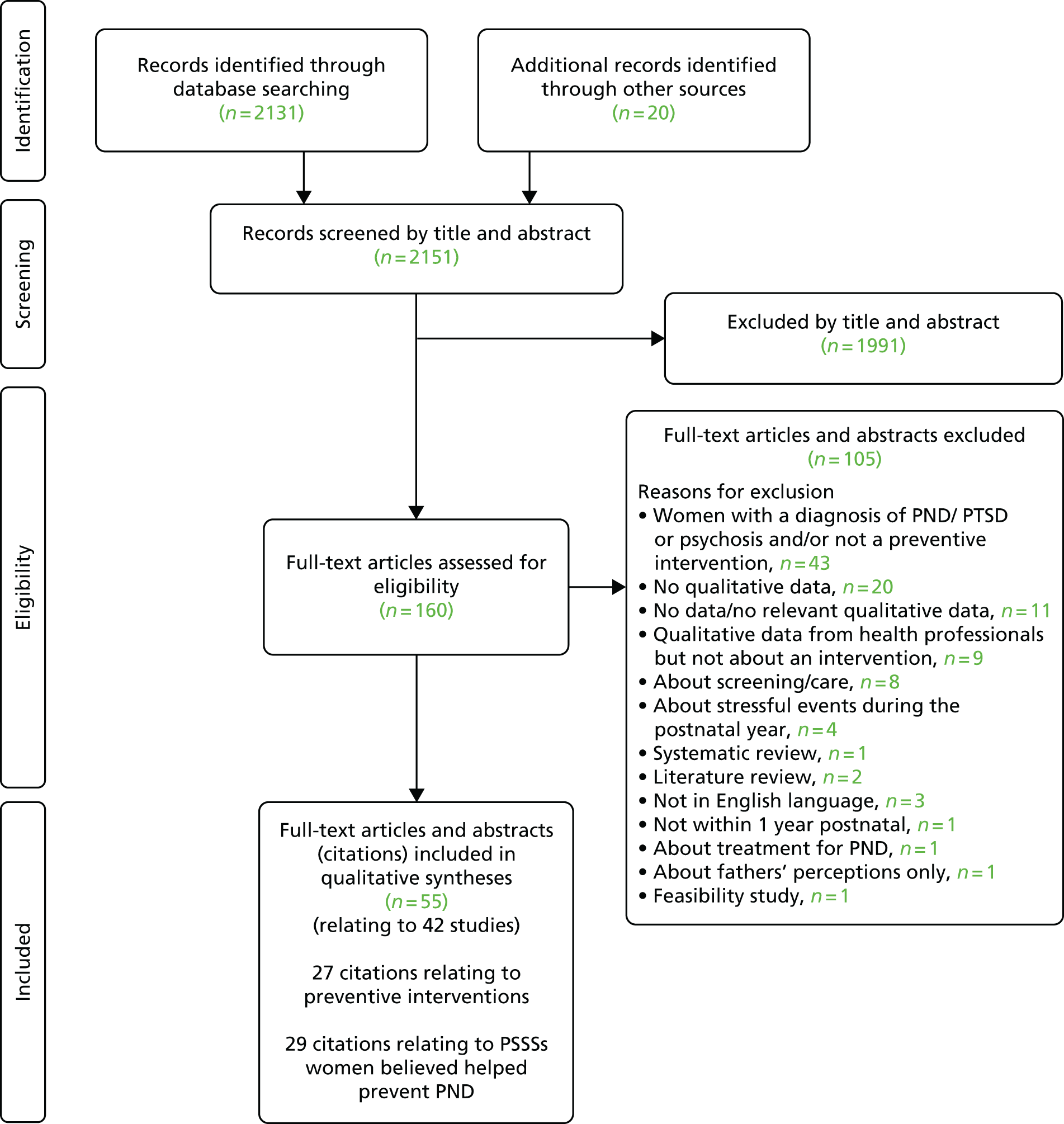

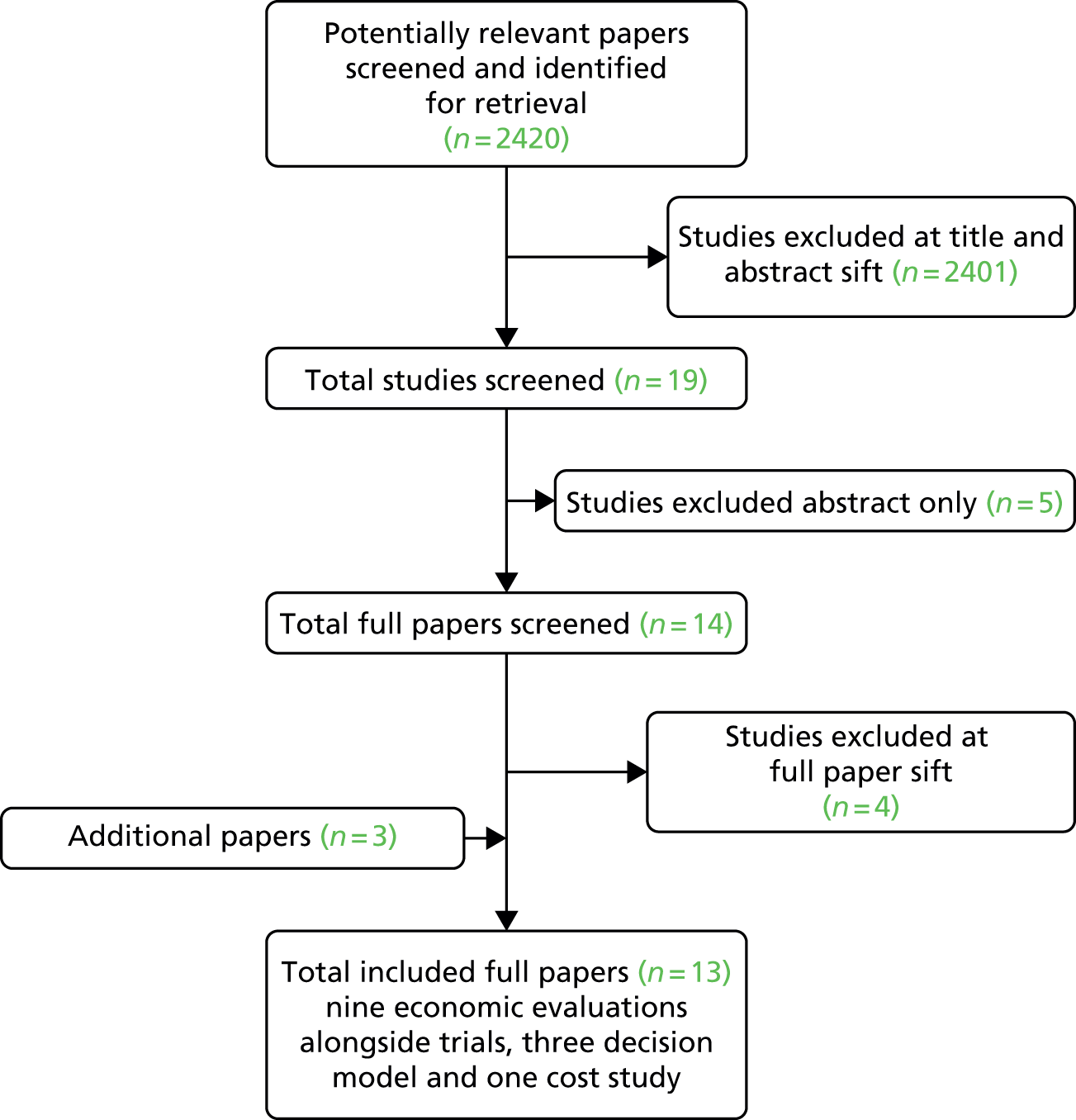

A two-stage sifting process for inclusion of studies (title and abstract then full paper sift) was undertaken. Titles and abstracts of the qualitative studies were scrutinised by one assessor (AS) using the inclusion and exclusion criteria. No papers were excluded on the basis of quality at this stage. Full papers were obtained for potentially included studies and for where the abstract provided too little information. One-fifth of the total citations identified by electronic database searching (n = 2313) were checked for inclusion or exclusion by AB (n = 427).

Inclusion and exclusion criteria for qualitative studies

The PICOS process was used to clarify the inclusion and exclusion criteria (Box 6).

Population

Studies of populations of antenatal women and postnatal women, at any point postnatally (but with qualitative data concerning the first postnatal year), and health-care practitioners involved in delivering preventive interventions for PND were relevant.

ExcludedStudies of pregnant or postnatal women with diagnosed PND or other comorbid psychiatric disorders or major medical problems.

Comparators

All comparators were considered, whether they were usual care, other controls or specific, alternative comparators.

Outcomes

All outcome measures were considered. All types of data, including case studies, interview data and observations, were considered.

Study designs

No study designs were excluded from the qualitative review (Box 7).

-

Qualitative studies concerning acceptability to pregnant women and service providers, potential harm and adverse effects were extracted.

-

Studies reporting qualitative research, qualitative data elicited via a survey or a mixed-methods study including qualitative data on the perspectives and attitudes of either: (1) those who had received preventive interventions for PND, regardless of modality, in order to examine issues of acceptability; or (2) from women who had not experienced PND, regarding PSSSs that they believed helped them to avoid the condition, in order to identify promising components of any candidate intervention.

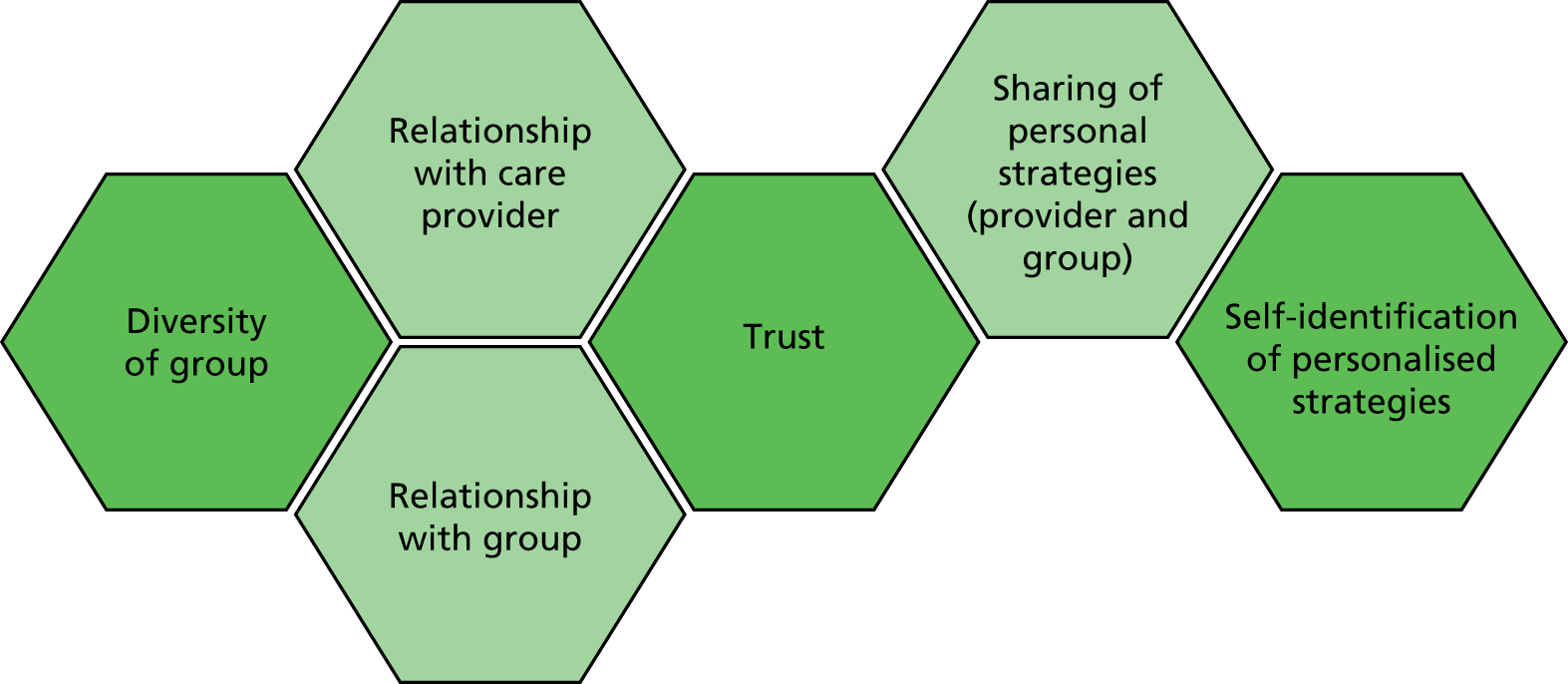

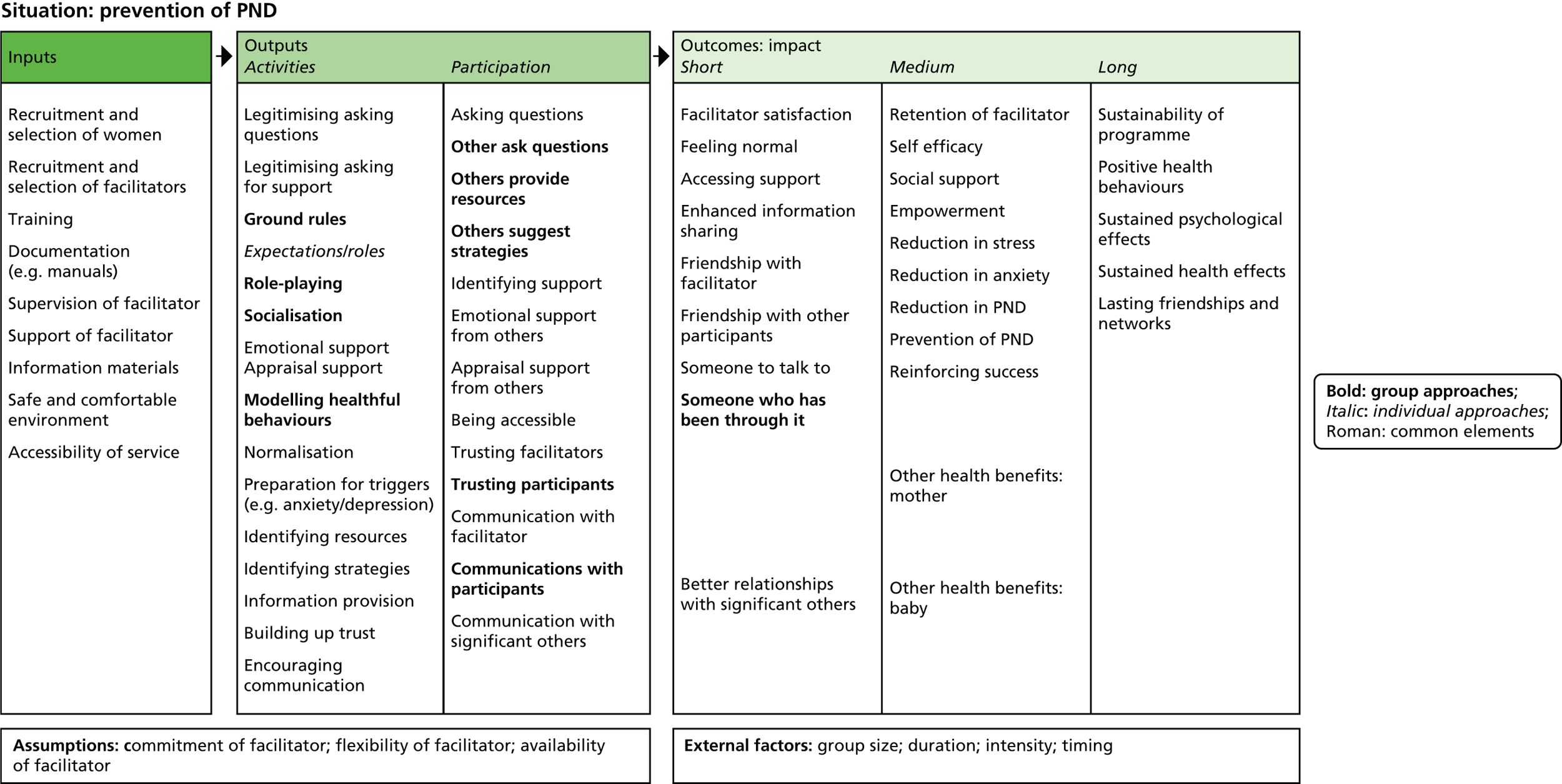

-