Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 12/167/95. The contractual start date was in June 2014. The draft report began editorial review in April 2017 and was accepted for publication in August 2017. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

The institutions of most of the authors have received funding from the National Institute for Health Research Health Technology Assessment programme for other studies. Christian Gold received funding from the Research Council of Norway during the conduct of the study. Christian Gold, Claire Grant, Helen Odell-Miller, Sarah Faber, Karin Antonia Mössler, Stephan Sandford, Anna Maratos and Monika Geretsegger are clinically trained music therapists.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2017. This work was produced by Crawford et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2017 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Introduction

Autism spectrum disorder and impact of autism on health

Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) are lifelong developmental disabilities that affect > 600,000 people in the UK. 1 People with ASD may have severe problems communicating with others, and this can lead to difficulties in relationships and impaired social functioning. 2 These disabilities can give rise to emotional distress and behavioural problems and increased levels of contact with health and social care services. 3–5 It is estimated that > £3B a year is spent on supporting children and adults with ASD in the UK. 3 Caring for a child with ASD can be challenging, and parents of children with ASD are more likely to experience difficulties, such as emotional distress and financial hardship. 5

Problems in social interaction and communication among children with ASD normally become apparent during the first 2 years of life. 6 The average age of diagnosis of ASD is 4 years. 7 The prognosis of ASD is very varied, but the majority of people diagnosed with this condition in childhood go on to need long-term input from services as adults. 8 If successful, interventions and treatments delivered to people with ASD during childhood have the potential to have a long-term impact on mental health, social functioning and costs of care of people with this condition.

Interventions and treatments for autism spectrum disorder

There is no known cure for ASD and there are no effective pharmacological interventions for the core symptoms of the condition. Although some psychotropic medications have been shown to help reduce the extent of challenging behaviours,9 current guidance from the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence states that psychotropic medication should not be used to manage the core features of ASD, because the balance of risks and benefits do not favour their use. 10 In recent years, a variety of parent-mediated interventions that aim to help family carers to develop and implement successful strategies for supporting young children’s communication and managing behaviour have shown promising results. 11 However, the authors of a 2014 Cochrane review noted that most studies to date have not reported statistically significant evidence of changes in primary outcomes and that their impact on children’s adaptive skills and parental stress is unclear. 12

Music therapy is a form of psychosocial intervention that aims to harness the power of music to provide an alternative means to learn about and develop communication skills and relationships. A number of small-scale studies have generated promising results that suggest that ‘improvisational music therapy’ (IMT) for children with ASD can help to improve social communication and reduce symptoms of ASD. 13–15 In IMT, the child and the therapist spontaneously co-create music using singing, musical instruments and movement. IMT has been described as a developmental, child-centred approach in which a trained music therapist follows the child’s focus of attention, behaviours and interests to facilitate growth in the child’s social communicative skills and promote development in other areas. 16 A Cochrane systematic review in 2014 identified 10 small randomised controlled trials (RCTs) of music therapy (involving 165 participants) and found evidence of improvements in social interaction and communication skills. 12 On the basis of these findings, the authors concluded that music therapy may help children with ASD. However, they highlighted differences in the approach to delivering music therapy in these trials compared with normal clinical practice. Most children receiving music therapy in clinical practice receive weekly sessions, but most trials tested therapy that was delivered more frequently than this. Another limitation of previous trials is that they examined the impact of music therapy only as it was being delivered. To our knowledge, no trials to date have examined whether or not any benefits associated with therapy persist once treatment stops.

The TIME-A study

The TIME-A study is an international multicentre RCT of IMT for children with ASD that was funded by the Research Council of Norway (ISRCTN78923965). 17 The study set out to test the impact of 5 months of IMT on children with ASD aged between 4 and 7 years. The study aimed to recruit a minimum of 300 children and follow them up over 1 year to compare the social affect and social responsiveness of those offered music therapy with those offered enhanced standard care (ESC). Standard care was enhanced by offering all parents of children in the trial three 60-minute sessions of advice and support.

Over the course of the first year of the trial, recruitment successfully started in six countries, but the rate of recruitment was lower than required. In collaboration with the chief investigator of the international trial (CG), we applied for additional funding from the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Health Technology Assessment (HTA) programme to set up an English arm of the study, with the aim of helping to ensure that the international trial succeeded in achieving the required sample size and increasing the generalisability of findings to children and parents in contact with NHS services in the UK.

The NIHR-funded arm of the trial was designed in keeping with the protocol for the international TIME-A study, with three exceptions. First, feedback from parents in England who helped us to design the protocol led us to include an assessment of parental stress and parental mental well-being; therefore, questionnaires assessing these outcomes were added to the study. Second, the international trial outcomes were assessed 2, 5 (primary end point) and 12 months after randomisation. However, in the NIHR-funded arm of the trial we dropped the 2-month assessment in order to maximise the rate of recruitment into the study. Third, the international study also set out to collect some service use data in order to explore the cost-effectiveness of music therapy for children with ASD. We were asked to drop this component of the study and have therefore not included any data on service utilisation or cost-effectiveness in this report. Results of the trial have also been published in Bieleninik et al. 18

Rationale for the study

Improvisational music therapy has the potential to improve social interaction and the communication skills of children with ASD and, therefore, have an impact on the long-term prognosis of the condition. Previous trials of this intervention have been too small to provide a precise estimate of any treatment effect and have not examined whether or not any benefits associated with this intervention persist once treatment has stopped. The international multicentre TIME-A trial was designed to test the clinical effectiveness of IMT over a 1-year period. The NIHR-funded arm of the trial was designed to help ensure that the international trial met its recruitment target and to make it easier to generalise the results of the international study to children in contact with NHS services in the UK. In this report, we will present the methods used in the international trial and minor differences in the design of the NIHR-funded arm of the trial, followed by the main results of the international trial and those of participants recruited in the NIHR-funded arm of the study.

Aim and objectives

The aim of the international TIME-A study was to assess the clinical effectiveness of music therapy for children with ASD.

The objectives were to:

-

examine whether or not adding IMT to ESC for children with ASD improves their social communicative skills assessed by masked researchers

-

examine whether or not adding music therapy to ESC for children with ASD improves their social responsiveness as reported by parents

-

to explore whether or not any response to music therapy varies with how often treatment is delivered (once-weekly therapy compared with three times per week).

In addition, in the NIHR-funded arm of the trial we explored whether or not adding IMT to ESC of children with ASD was superior to ESC alone in reducing stress and improving the mental well-being of the parents of children in the study.

Chapter 2 Methods

Design

The TIME-A study is a three-arm, parallel-group, researcher-masked, international multicentre RCT. All parents of children in the trial were offered ESC, which comprised usual treatment plus the offer of three sessions of advice and support. In addition, half the study sample were randomly allocated to high-frequency (three times per week) or low-frequency (once per week) IMT delivered over a 5-month period.

The primary outcome measure was the severity of symptoms of ASD assessed 5 months after randomisation, using the social affect algorithm of the Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule (ADOS). 19,20

Study setting

The setting for the international trial was state-funded, voluntary and private sector-funded health, educational and social care services in Australia, Austria, Brazil, Israel, Italy, Korea, Norway and the USA. Participants for the NIHR-funded arm of the study were recruited from schools and NHS clinics in Bedfordshire, Cambridgeshire, Essex and London.

Participants

Children aged between 4 and 7 years who had a clinical diagnosis of ASD and their parents. To maximise the generalisability of the study findings, we used broad inclusion criteria and limited the exclusion criteria to essential features that were not compatible with using the intervention or participating in the trial.

Inclusion criteria

Families were considered for inclusion if:

Exclusion criteria

Families were excluded if:

-

the child had received music therapy in the last year

-

the child had severe sensory disorder (we excluded children with severe visual or hearing impairment, as this would have prevented them from being able to make full use of the music therapy)

-

the parent of the child was unable or unwilling to provide written informed consent to take part in the trial.

Recruitment

Methods of recruitment varied between countries in the international trial, but generally involved publicising the study at specialist centres for the assessment and treatment of children with ASD. In the NIHR-funded arm of the trial, we initially contacted clinicians working in health-care services and child development centres, and outpatient child and adolescent mental health services. Members of the research team presented plans for the study at local academic and clinical meetings and asked staff to seek verbal consent from parents of children who might be eligible to take part in the study. It quickly became evident that it would be difficult for children to attend music therapy sessions if they were delivered anywhere other than at the school they attended. Therefore, we changed our approach to recruitment and focused on schools that specialised in catering for the educational needs of children with ASD and other developmental disorders. Initially, staff at schools contacted parents of children who might be eligible and researchers organised meetings at schools for parents of children with ASD so that they could find out about the study.

Parents who agreed to meet a member of the study team were provided with written and verbal information about the study, including a copy of a parent information sheet. Before any trial-specific procedures were performed, the parent was asked to sign and date an informed consent form. Following this, the researcher assessed eligibility and collected baseline clinical and demographic data. Those who were ineligible were thanked for their time and informed of the reason(s) why they were ineligible.

Randomisation

Researchers at each site entered data from the baseline assessment onto a web-based case report form. Remote web-based randomisation was undertaken through a fully automated service operated by Uni Research (Norway) (OpenClinica, version 3.3; Open Clinica, LLC, Waltham, MA, USA). The allocation ratio for the study was 1 : 1 : 2, such that equal numbers of participants were allocated to IMT and to ESC and, among those allocated to music therapy, equal numbers were allocated to high- and low-frequency treatment. Randomisation was stratified by site and made in blocks, with block size randomly assigned to either four or eight. A project co-ordinator based in Norway (ŁB), who had had no contact with participants, checked eligibility and baseline data before randomisation via an online system. Following randomisation, parents and therapists were given information about allocation status, and arrangements were made for delivering parent advice and support sessions. For those in one of the two experimental arms of the trial, arrangements were also made for delivering music therapy sessions.

Study researchers were based in separate departments from those involved in organising treatment, helping to ensure that they remained masked to the allocation status of participants. Parents were given written information about the importance of researchers not finding out whether or not their child was receiving music therapy and researchers began every contact with a parent, clinician or teachers with a reminder of the importance of their remaining masked to the allocation status of the child.

Baseline assessment

At baseline, trained researchers used the ADOS19 and the ADI-R21 to check eligibility. In order to minimise inconvenience for parents and children, the results of any recent ADOS assessment were used in lieu of baseline data (so long as this had been completed within 6 weeks prior to their entry into the study). To take part in the study, potential participants needed to meet the criteria for ASD on the ADOS and on two of the three domains of the ADI-R. This combination of data from direct observation and interviews with parents has been used to establish eligibility in previous high-quality trials of interventions for children with ASD. 22,23

Researchers also collected baseline data on age and gender of the child and socioeconomic status of the child’s parent. Finally, researchers collected information about the child’s level of cognitive ability from medical and school records. When this information was not available, they collected information from the parent about developmental milestones and presented this to an experienced clinician who used it to estimate whether the child had no, mild, moderate or severe mental retardation, using the World Health Organization (International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Edition)’s criteria. 24

Outcome measures

The primary outcome measure was the severity of symptoms of ASD using the social affect algorithm derived from the ADOS,19,20 assessed by a trained researcher masked to the allocation status of the child. We selected this measure because of its strong psychometric properties and because it has been widely used in other RCTs of children with ASD. 22,23,25 Higher scores on the ADOS and the social affect algorithm indicate higher levels of impairment.

The secondary outcome was the Social Responsiveness Scale (SRS)26 – a carer-based assessment of the severity of ASD symptoms that has high inter-rater and test–retest reliability. 27,28

In the NIHR-funded arm of the trial, we added two additional secondary outcomes:

-

Parenting Stress Index – Short Form (PSI-SF): a widely used measure of parental stress that has been validated among parents of children with ASD. The questionnaire generates three subscores (parental distress, which indicates the extent to which the respondent is experiencing stress in their role as a parent; dysfunctional interaction, which indicates the extent to which a parent experiences interactions with their child as satisfying; and a ‘difficult child’ score, which indicates how easy the respondent finds it to parent their child). Higher scores on the PSI-SF indicate higher levels of stress.

-

Warwick–Edinburgh Mental Well-Being Scale (WEMWBS): a short validated measure of mental well-being. 29 Higher scores on the WEMWBS indicate higher levels of mental well-being.

All outcome measures were assessed at baseline and at 5 and 12 months.

Interventions

Improvisational music therapy

Improvisational music therapy is a form of music therapy for children with ASD that was originally developed in Britain in the 1950s by Paul Nordoff and Clive Robbins and was subsequently refined by Juliette Alvin, and Wigram and Gold. 13 It is a child-centred treatment approach that utilises the potential that making music has to enhance social engagement and the expression of emotions. 13 During sessions of IMT, music played or sung by the therapist generally attunes to the child’s musical or other behaviours, and aims to engage the child and establish a connection with them. To this end, the ‘musical’ features of the child’s expression, such as rhythm, melodic patterns and timbre, are expressed through the child playing tuned and untuned percussion instruments (including wind instruments, such as the recorder and the kazoo, the keyboard and singing). These musical expressions by the child may be mirrored, reinforced or complemented by the therapist, who uses the first instrument, such as the keyboard, guitar, clarinet, flute or other orchestral instrument, thus allowing for moments of synchronisation between the child and the therapist and giving the child’s expressions a pragmatic meaning within the context of the session. The therapist uses skills in creating suspense, direction and musical form to draw the child into a musical relationship. While engaging in joint musical activities, the child is offered adult and child versions of musical instruments and given opportunities to develop and enhance communication skills through imitation, joint attention, turn-taking and affect sharing, all of which are associated with development in language and social competency. 30,31

Music therapy sessions in the TIME-A trial lasted for 30 minutes and were delivered over a 5-month period in local schools or NHS facilities.

All music therapists in the trial had previous experience of working with children with ASD. IMT was conducted in accordance with a consensus treatment guide of IMT developed for this study16 and the study protocol. 17

Treatment frequency

The TIME-A trial involved two active treatment groups in which music therapy sessions were offered at two different levels of frequency: once per week (low frequency) or three times per week (high frequency). Over the 5-month treatment period, those in the low-frequency treatment arm were offered up to 20 sessions and those in the high-frequency treatment arm were offered up to 60 sessions.

Enhanced standard care

All parents of study participants were offered ESC in addition to usual care from primary and secondary services; parents were offered three advice and support sessions delivered over a 5-month period. These sessions were delivered by experienced clinicians who received regular supervision and comprised psychoeducation, information about support organisations and support in coping with current problems. This type of support is recommended for parents of children with ASD,10 and helped to ensure that all study participants received a basic level of support across all study centres.

Treatment fidelity

To determine whether or not treatment was delivered as intended, music therapists were asked to videotape all sessions. Video recordings were used during monthly supervision sessions, and extracts from a random sample of recordings were rated by three independent raters across the full international trial, in accordance with prepublished criteria. 16 An average of two independent raters rated 606 randomly selected therapy sessions on eight main principles of treatment. For each item, scores could range from 0 (not used at all) to 5 (used frequently and with mastery). Scores of ≥ 3 indicated that there was evidence in accordance with the prepublished criteria. 16

Follow-up

Five months after randomisation, parents were contacted by the researcher to make arrangements for their first follow-up assessment. A parent or teaching assistant was present with the child during assessments. Follow-up assessments took place at a time that was convenient for the parent and their child. This was usually at a school or NHS clinic, but occasionally took place in the family’s home. A final follow-up interview was conducted 12 months after randomisation.

Follow-up assessments were carried out through face-to-face interviews. As well as reimbursing any travel costs or other reasonable expenses incurred by parents, they were also given a £20 honorarium following completion of the 12-month follow-up interview.

Sample size

The study had a group sequential design and a planned first interim analysis with around 300 participants randomised. At a 5% level of statistical significance, and assuming 20% dropout, 300 participants provided 93% power to detect a mean difference of 2.5 on the social affect score of the ADOS at 5 months, but only 20% for a mean difference of 1.0.

At the point when we applied for NIHR funding, 74 children had been recruited to the international trial and we estimated that it would achieve 200 recruits by the end of the proposed recruitment period. Therefore, we set out to recruit 100 children to help ensure that the international trial reached its minimum target of 300 participants.

Data analysis

The main statistical analysis was an intention-to-treat (ITT) analysis of mean change, using longitudinal models and including all participants who had data of at least one follow-up time point. The primary analysis compared changes in the social affect score of the ADOS between the two active arms of the trial and those randomised to ESC at 5 months. We calculated linear mixed-effects models with maximum likelihood estimation, both unadjusted and adjusted for site as a random effect, and both for the primary two-arm comparison and for the three-arm comparison, including frequency of IMT. In the sensitivity analysis for the primary outcome and comparison, we conducted t-tests with multiple imputation for missing data, imputing 50 data sets and using diagnosis, age and site for the imputation. In a second sensitivity analysis, we included the music therapist as a random effect nested within site.

As an exploratory analysis, we also analysed the proportion of participants who had any reduction in the ADOS social affect score, as in a previous study. 32 In this binary ITT analysis, we included all participants randomised improved on the primary outcome, as in a previous study. 32 We included all participants randomised, assuming no improvements for missing data; this was supplemented with an available case analysis. We calculated risk ratios with two-sided 95% confidence intervals (CIs) using Wald’s unconditional maximum likelihood estimation. All statistical analyses were conducted using R, version 3.3.1 (The R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria). 33 Differences in parental stress and mental well-being were compared between the two arms of the trial after adjusting for baseline differences using linear regression.

Parent involvement

Initial plans for this study were presented at a meeting of 15 parents of children with ASD from Hillingdon Child Development Centre. Parents supported the overall design of the study, but raised concerns about how their children would be taken to and from music therapy sessions. They also asked that outcomes for parents, as well as children, be assessed. Following this feedback, we began to explore options for delivering music therapy sessions in schools and added two parent-rated outcome measures (the PSI-SF and the short version of the WEMWBS) to our secondary outcomes.

During the course of the study, we continued to meet parents of children with ASD (four meetings in London and four between East Anglia and Essex). At these meetings, we updated people on the study progress and sought their advice on logistical issues. One of the main topics discussed at these meetings was access to music therapy for children of families who were randomised to the control arm of the trial. This resulted in an agreement that music therapists would provide workshops for parents at the end of the study on how they might use music in the interactions with their children.

Parents of children with ASD were also represented on the Project Management Group and the Trial Steering Committee (TSC). Dr Morag Maskey, who is both a researcher and a parent of a child with ASD, commented on draft versions of the parent information sheet and a summary of the results of the study, which was sent to all parents whose children took part in the trial and this report.

Ethics approval and governance

The study was conducted in accordance with the recommendations for physicians involved in research on human subjects adopted by the 18th World Medical Assembly, Helsinki 1964 and later revisions. 34

Ethics approval was obtained by the relevant ethics committees in each of the countries where the study took place. We obtained approval for the NIHR-funded arm of the study from the National Research Ethics Service (NRES) Committee West Midlands – The Black Country (Research Ethics Committee reference number 14/WM/1047). All parents were provided with written and verbal information about the study prior to deciding whether or not they and their child would take part. Freely given, written informed consent was obtained from parents prior to the start of data collection. An independent data monitoring committee in Norway monitored safety and examined interim efficacy results. In addition, study progress and safety were reviewed by a separate independent TSC and an independent data monitoring and ethics committee.

Changes to the study protocol

-

At the start of the study we intended to exclude all those children who had ever received music therapy. This exclusion was subsequently limited to those who had received music therapy in the 12 months prior to recruitment.

-

In the study protocol we stated that music therapy would not be offered to those in the control arm of the trial. However, following feedback from parents, some centres provided some music therapy to children in the control arm of the trial after collection of all 12-month follow-up data had been completed.

-

In the protocol we referred to the primary outcome as ADOS social communication at 5 months. However, in this report we use the term ‘social affect’ to reflect the algorithm items now used for this domain of the ADOS.

-

Early in the study it became apparent that delivery of the high-frequency music therapy (three times a week) would be possible only if children received treatment in school. It was not possible to arrange transport for children from schools to NHS facilities during the day, and this would also have resulted in children being taken away from schools. In consultation with teachers and parents, we therefore arranged for music therapy sessions to be delivered in schools.

-

Feedback from parents attending advisory group meetings in the NIHR study was that, although they valued the ESC they received, they felt that it was better to describe these sessions as ‘advice and support’ rather than counselling sessions – the name used in the international trial. The name of the sessions was duly changed. Further details of the methods of the study have been published in Bieleninik et al. 18

Chapter 3 Results

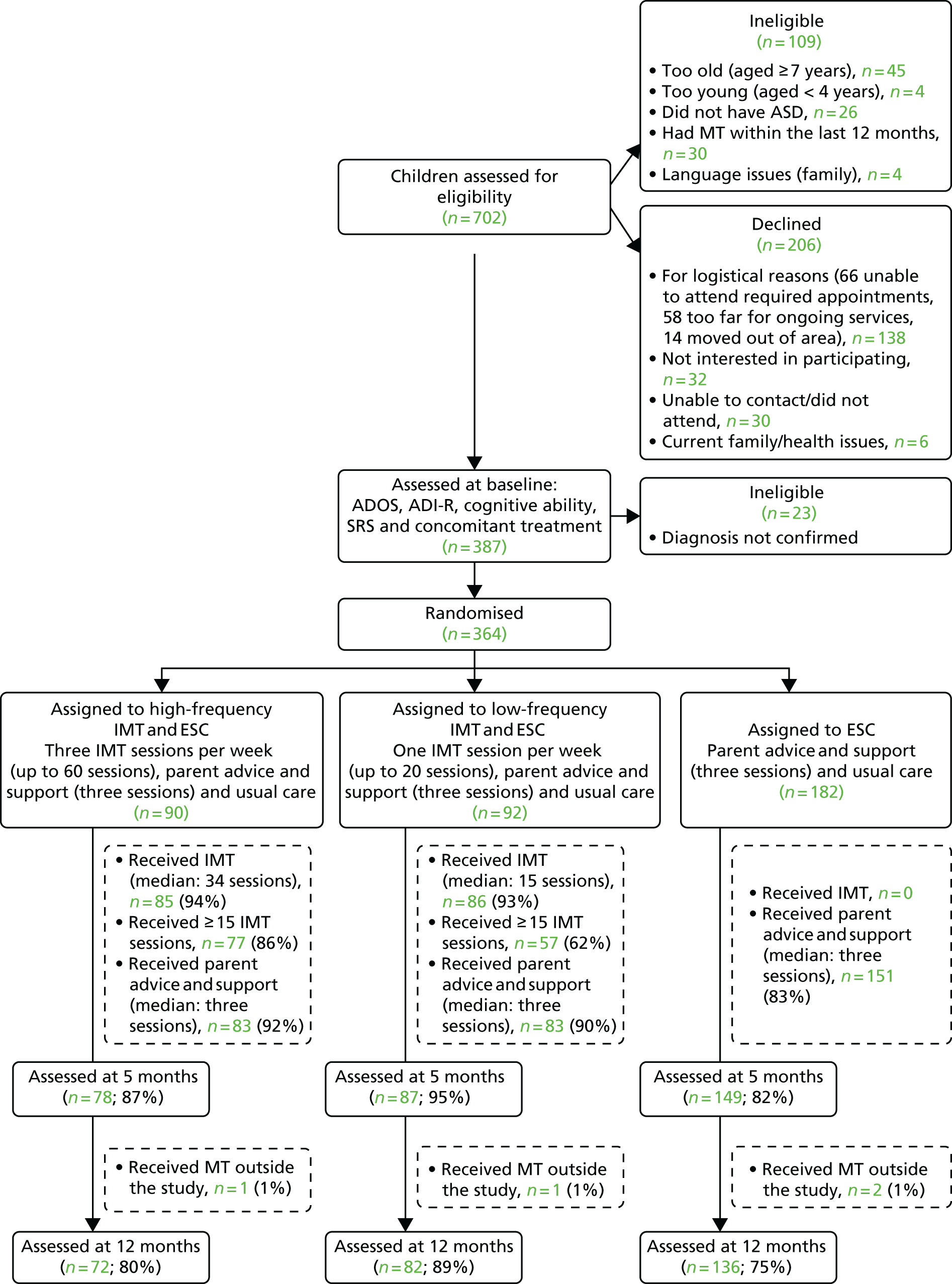

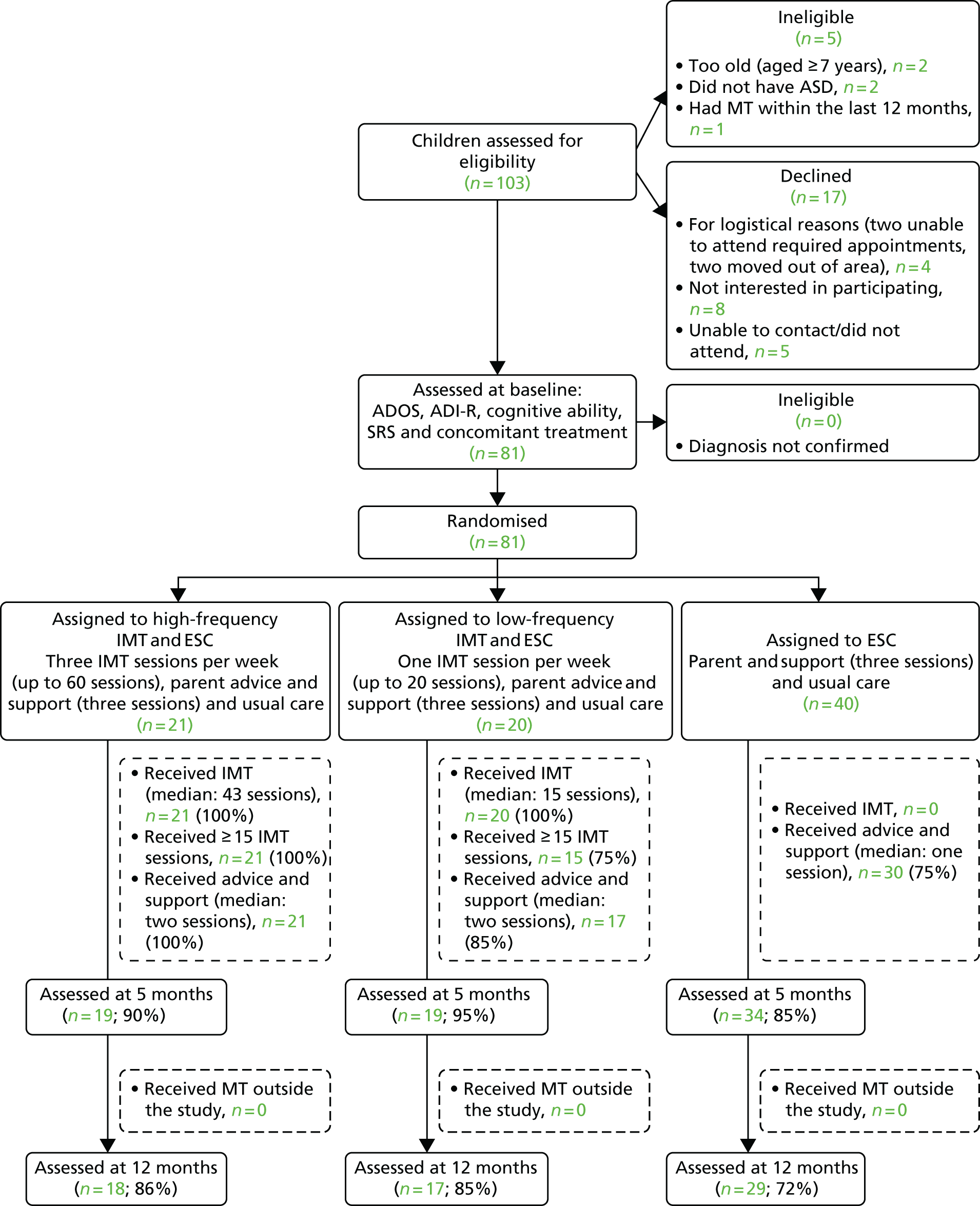

Recruitment to the international study took place between November 2011 and November 2015, and recruitment to the NIHR-funded arm of the trial was between November 2014 and November 2015. A total of 702 children were assessed for eligibility in the international trial, of whom 109 were ineligible, 206 declined prior to baseline assessment and another 23 were found ineligible at baseline (Figure 1). In the NIHR-funded arm of the trial, 103 were assessed for eligibility in the international trial, of whom five were ineligible and 17 declined prior to baseline assessment (Figure 2).

FIGURE 1.

Study flow chart for 702 children assessed for the international trial. MT, music therapy.

FIGURE 2.

Study flow chart for 103 children assessed for the NIHR-funded arm of the trial. MT, music therapy.

In the international trial, a total of 364 participants were randomised: 182 to IMT plus ESC, and 182 to ESC alone. Of the 182 children randomised to receive IMT, 90 were randomised to high-frequency IMT and 92 to low-frequency IMT.

In the NIHR-funded arm of the trial, 81 participants were randomised, with 41 randomised to IMT (21 high-frequency and 20 low-frequency treatment). The Norwegian data monitoring committee examined the first interim efficacy analysis in September 2015. Although the formal criterion for early stopping was not met, a decision was made to stop further recruitment as a result of the limited funding.

Baseline characteristics were well balanced between study arms, both in the international trial as a whole (Table 1) and in the sample in the NIHR-funded arm of the study (Table 2). The median age of children in both the international trial and the NIHR-funded arm was 5.4 years [standard deviation (SD) 0.9 years]. Most children in both the international trial (n = 302, 83.0%) and the NIHR-funded arm of the trial (n = 67, 82.7%) were male. The proportion with impaired cognitive ability [intelligence quotient (IQ) of < 70] was higher in the NIHR-funded arm of the study (n = 62, 76.5%) than in the international trial as a whole (n = 165, 46.3%). Very few children had received music therapy prior to entering the trial (3.4% in the international trial and 6.2% in the NIHR-funded arm).

| Characteristics | All participants | Treatment arm | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Participants randomised to receive IMT | Participants randomised to receive ESC | |||||

| n | Value | n | Value | n | Value | |

| Age (years)a | 364 | 5.4 (0.9) | 182 | 5.5 (0.9) | 182 | 5.4 (0.9) |

| Sex (male)b | 364 | 302 (83%) | 182 | 153 (84.1%) | 182 | 149 (81.9%) |

| Diagnosisb | 364 | 182 | 182 | |||

| Childhood autism (ICD code F84.0) | 301 (82.7%) | 151 (83%) | 150 (82.4%) | |||

| Atypical autism (ICD code F84.1) | 3 (0.8%) | 3 (1.6%) | 0 (0%) | |||

| Asperger’s syndrome (ICD code F84.5) | 14 (3.8%) | 8 (4.4%) | 6 (3.3%) | |||

| PDD (ICD code F84.9)c | 46 (12.6%) | 20 (11%) | 26 (14.3%) | |||

| Previous MT (> 12 months ago)b | 356 | 12 (3.4%) | 179 | 4 (2.2%) | 177 | 8 (4.5%) |

| ADOS moduleb | 364 | 182 | 182 | |||

| Module 1 | 224 (61.5%) | 103 (56.6%) | 121 (66.5%) | |||

| Module 2 | 129 (35.4%) | 73 (40.1%) | 56 (30.8%) | |||

| Module 3 | 11 (3%) | 6 (3.3%) | 5 (2.7%) | |||

| ADOS T = totala | 363 | 17.7 (5.3) | 182 | 18 (5.4) | 181 | 17.4 (5.2) |

| ADOS social affecta | 364 | 13.8 (4.4) | 182 | 14.1 (4.5) | 182 | 13.5 (4.3) |

| Social responsiveness totala | 359 | 159.5 (28.8) | 180 | 159.3 (27.9) | 179 | 159.7 (29.8) |

| Concomitant treatmentsa | 364 | 23.7 (28.3) | 182 | 25.5 (31.4) | 182 | 21.9 (24.9) |

| IQ sourceb | 364 | 182 | 182 | |||

| K-ABC | 8 (2.2%) | 3 (1.6%) | 5 (2.7%) | |||

| Other standardised test | 210 (57.7%) | 107 (58.8%) | 103 (56.6%) | |||

| Clinical judgement | 146 (40.1%) | 72 (39.6%) | 74 (40.7%) | |||

| IQ, standardised testa | 211 | 75.4 (26.2) | 103 | 74.7 (25) | 108 | 76.1 (27.4) |

| Mental retardation (IQ of < 70)b | 356 | 165 (46.3%) | 176 | 81 (46.0%) | 180 | 84 (46.7%) |

| ADI-R Aa | 364 | 18.3 (5.8) | 182 | 18.4 (5.8) | 182 | 18.2 (5.8) |

| ADI-R Ba | 364 | 13 (4.2) | 182 | 12.9 (4.1) | 182 | 13.1 (4.3) |

| ADI-R Ca | 364 | 5.8 (2.4) | 182 | 5.8 (2.3) | 182 | 5.9 (2.5) |

| Characteristics | All participants | Treatment arm | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Participants randomised to receive IMT | Participants randomised to receive ESC | |||||

| n | Value | n | Value | n | Value | |

| Age (years)a | 81 | 5.4 (0.9) | 41 | 5.6 (0.9) | 40 | 5.2 (0.9) |

| Sex (male)b | 81 | 67 (82.7%) | 41 | 33 (80.5%) | 40 | 34 (85%) |

| Diagnosis [childhood autism (ICD code F84.0)]b | 81 | 81 (100%) | 41 | 41 (100%) | 40 | 40 (100%) |

| Previous MT (> 12 months ago)b | 81 | 5 (6.2%) | 41 | 2 (4.9%) | 40 | 3 (7.5%) |

| ADOS moduleb | 81 | 41 | 40 | |||

| Module 1 | 57 (70.4%) | 24 (58.5%) | 33 (82.5%) | |||

| Module 2 | 24 (29.6%) | 16 (39%) | 8 (20%) | |||

| ADOS totala | 81 | 19.8 (5.8) | 41 | 20.7 (5.8) | 40 | 19 (5.9) |

| ADOS social affecta | 81 | 15.3 (4.9) | 41 | 15.9 (5.1) | 40 | 14.8 (4.6) |

| ADOS language and communicationa | 81 | 3.8 (1.6) | 41 | 3.9 (1.7) | 40 | 3.8 (1.5) |

| ADOS reciprocal social interactiona | 81 | 11.5 (3.9) | 41 | 12 (3.9) | 40 | 11 (3.9) |

| ADOS restricted and repetitive behavioura | 81 | 4.5 (2.3) | 41 | 4.8 (2.2) | 40 | 4.2 (2.4) |

| Social responsiveness totala | 80 | 159.1 (28.4) | 41 | 161.5 (28.5) | 39 | 156.5 (28.5) |

| Concomitant treatmentsa | 81 | 8.3 (14.6) | 41 | 8.3 (15.7) | 40 | 8.2 (13.6) |

| IQ sourceb | 81 | 41 | 40 | |||

| Other standardised test | 1 (1.2%) | 1 (2.3%) | 0 (0%) | |||

| Clinical judgement | 80 (98.8%) | 40 (97.7%) | 401 (100%) | |||

| Mental retardation (IQ of < 70)b | 81 | 62 (76.5%) | 41 | 28 (68.3%) | 40 | 34 (85%) |

| ADI-R Aa | 81 | 20.9 (4.8) | 41 | 21.2 (4.4) | 40 | 20.5 (5.1) |

| ADI-R Ba | 81 | 13.6 (3.5) | 41 | 13.3 (3.4) | 40 | 14 (3.7) |

| ADI-R Ca | 81 | 5.5 (2.1) | 41 | 5.3 (1.6) | 40 | 5.7 (2.5) |

A total of 50 participants (14%) in the international trial and nine (11%) in the NIHR-funded arm of the trial were lost to follow-up at 5 months. The reasons for withdrawal from the study were mainly attributable to change of address, parental frustration that their child was randomised to ESC or poor physical health of the child. Baseline characteristics of those who dropped out at 5 months were largely similar to those who were followed up (Table 3).

| Characteristics | All | Participants at 5 months | p-value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Followed up | Dropped out | ||||||

| n | Value | n | Value | n | Value | ||

| Age (years)a | 364 | 5.4 (0.9) | 314 | 5.4 (0.9) | 50 | 5.3 (0.9) | 0.517 |

| Sex (male)b | 364 | 302 (83%) | 314 | 266 (84.7%) | 50 | 36 (72%) | 0.044 |

| Diagnosisb | 364 | 314 | 50 | 0.645 | |||

| Childhood autism (ICD code F84.0) | 301 (82.7%) | 257 (81.8%) | 44 (88%) | ||||

| Atypical autism (ICD code F84.1) | 3 (0.8%) | 3 (1%) | 0 (0%) | ||||

| Asperger’s syndrome (ICD code F84.5) | 14 (3.8%) | 12 (3.8%) | 2 (4%) | ||||

| PDD (ICD code F84.9)c | 46 (12.6%) | 42 (13.4%) | 4 (8%) | ||||

| Previous MT (> 12 months ago)b | 356 | 12 (3.4%) | 306 | 9 (2.9%) | 50 | 3 (6%) | 0.491 |

| ADOS moduleb | 364 | 314 | 50 | 0.864 | |||

| Module 1 | 224 (61.5%) | 192 (61.1%) | 32 (64%) | ||||

| Module 2 | 129 (35.4%) | 112 (35.7%) | 17 (34%) | ||||

| Module 3 | 11 (3%) | 10 (3.2%) | 1 (2%) | ||||

| ADOS totala | 363 | 17.7 (5.3) | 313 | 17.6 (5.3) | 50 | 18.1 (5) | 0.554 |

| ADOS social affecta | 364 | 13.8 (4.4) | 314 | 13.7 (4.4) | 50 | 14.1 (4.5) | 0.569 |

| ADOS LCa,d | 364 | 3.3 (1.5) | 314 | 3.3 (1.5) | 50 | 3.1 (1.4) | 0.318 |

| ADOS RSIa,e | 364 | 10.5 (3.6) | 314 | 10.4 (3.5) | 50 | 11 (3.7) | 0.285 |

| ADOS RRBa,f | 363 | 3.9 (2) | 313 | 3.9 (2.1) | 50 | 4 (1.6) | 0.830 |

| Social responsiveness totala | 359 | 159.5 (28.8) | 310 | 159.1 (28.5) | 49 | 162.3 (31) | 0.493 |

| Concomitant treatmentsa | 364 | 23.7 (28.3) | 314 | 23.6 (28.2) | 50 | 24.1 (29.3) | 0.919 |

| IQ sourceb | 364 | 314 | 50 | 0.161 | |||

| K-ABC | 8 (2.2%) | 7 (2.2%) | 1 (2%) | ||||

| Other standardised test | 210 (57.7%) | 175 (55.7%) | 35 (70%) | ||||

| Clinical judgement | 146 (40.1%) | 132 (42%) | 14 (28%) | ||||

| IQ, standardised testa | 211 | 75.4 (26.2) | 178 | 75.9 (26.3) | 33 | 72.8 (25.7) | 0.539 |

| Mental retardation, (IQ of < 70)b | 356 | 165 (46.3%) | 309 | 144 (46.6%) | 47 | 21 (44.7%) | 0.929 |

| ADI-R Aa | 364 | 18.3 (5.8) | 314 | 18.2 (5.8) | 50 | 18.6 (5.5) | 0.698 |

| ADI-R Ba | 364 | 13 (4.2) | 314 | 13.1 (4.2) | 50 | 12.6 (3.9) | 0.453 |

| ADI-R Ca | 364 | 5.8 (2.4) | 314 | 5.9 (2.5) | 50 | 5.3 (1.9) | 0.032 |

Masking of assessors was broken unintentionally in 20 participants (15 in the IMT group and five in the ESC group). There was no evidence of broken or subverted allocation concealment.

Uptake of interventions

Treatments that children received as part of standard care before and during the study are shown in Table 4. The most frequent concomitant interventions at baseline were speech and language therapy/communication training (58%) and sensory/motor therapy (including occupational therapy and physiotherapy; 41%). These numbers were similar at follow-up (see Table 4). The median number of sessions of all concomitant interventions (not including parent advice and support or IMT) over the 5-month intervention period was 45 in those allocated to ESC, compared with 36 in those allocated to IMT (high-frequency IMT, n = 31; low-frequency IMT, n = 40). Use of concomitant interventions was generally lower among participants recruited at sites funded by the NIHR, especially regarding behavioural interventions, social skills training and play therapy (Table 5).

| Intervention | Time point, n (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | 5 months | 12 months | |

| Sensory/motor therapy (including occupational therapy and physiotherapy) | 151 (41) | 109 (34) | 104 (35) |

| Speech and language therapy and communication training | 210 (58) | 163 (52) | 155 (52) |

| Play therapy or DIR/floor-time approach | 35 (10) | 28 (9) | 18 (6) |

| Behavioural/educational intervention (e.g. TEACCH or ABA) | 55 (15) | 45 (14) | 48 (16) |

| Social skills training | 31 (9) | 43 (14) | 46 (15) |

| Therapeutic leisure activities (e.g. horse riding) | 47 (13) | 55 (17) | 49 (16) |

| Other interventions | 60 (16) | 63 (20) | 67 (23) |

| No specific therapy or intervention (outside this study) | 55 (15) | 45 (14) | 37 (12) |

| Institutional stay | 12 (3) | 9 (3) | 8 (3) |

| Outpatient treatment | 38 (10) | 19 (6) | 25 (8) |

| Supplement or medication | 110 (30) | 74 (23) | 75 (25) |

| Special diet | 61 (17) | 32 (10) | 31 (10) |

| Intervention | Time point, n (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | 5 months | 12 months | |

| Sensory/motor therapy (including occupational therapy and physiotherapy) | 27 (33) | 10 (14) | 16 (25) |

| Speech and language therapy and communication training | 46 (57) | 26 (36) | 32 (50) |

| Play therapy or DIR/floor-time approach | 3 (4) | 2 (3) | 1 (2) |

| Behavioural/educational intervention (e.g. TEACCH or ABA) | 1 (1) | 2 (3) | 4 (6) |

| Social skills training | 1 (1) | 3 (4) | 6 (9) |

| Therapeutic leisure activities (e.g. horse riding) | 3 (4) | 3 (4) | 6 (9) |

| Other interventions | 6 (7) | 8 (11) | 9 (14) |

| No specific therapy or intervention (outside this study) | 14 (17) | 8 (11) | 7 (11) |

| Institutional stay | 2 (2) | 1 (1) | 2 (3) |

| Outpatient treatment | 15 (19) | 6 (8) | 8 (12) |

| Supplement or medication | 35 (43) | 12 (17) | 13 (20) |

| Special diet | 25 (31) | 9 (12) | 8 (12) |

The parents of 317 (87%) out of all participants attended at least one session of advice and support; the median number of sessions was three in all groups. Of those allocated to IMT, 171 (94%) received IMT, with a median of 34 sessions in those allocated to high-frequency IMT and 15 in those allocated to low-frequency IMT. Missed sessions were typically because of holidays or illness.

In the NIHR-funded arm of the trial, 68 (84.0%) parents offered advice and support attended at least one session (see Figure 2). The median number of sessions attended was two in the IMT arm of the trial and one in the ESC arm. All 41 (100%) children randomised to IMT received it. The median number of sessions attended was 43 in the high-frequency group and 15 in those randomised to the low-frequency group.

Of those allocated to ESC, none received IMT during the 5-month intervention period. However, two children (1.1%) in each group received music therapy outside the trial before the 12-month follow-up.

Treatment fidelity

Treatment fidelity according to the IMT manual16 was adequate in the vast majority of sessions (Table 6). Two independent raters agreed that 93% (565/606 randomly selected 3-minute segments from 63 participants) were conducted adequately (rater 1: 604/606, 99.6%; rater 2: 566/606, 93.4%; results of each principle). The mean sum score for all eight principles was 26.26 (SD 5.67); a total of 410 sessions (68%) had scores of ≥ 24.

| IMT principle | Mean fidelity score (SD) | Frequently used, number of sessions (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Musical and emotional attunement | 3.45 (0.74) | 495 (82) |

| Scaffolding interaction musically | 3.16 (0.79) | 426 (70) |

| Tapping into shared musical history | 2.98 (0.93) | 363 (60) |

| Positive therapeutic relationship | 3.67 (0.78) | 529 (87) |

| Secure environment | 3.7 (0.71) | 548 (91) |

| Following the child’s lead | 3.08 (0.87) | 408 (67) |

| Treatment goals | 3.24 (0.76) | 454 (75) |

| Enjoyment of interaction | 2.97 (0.92) | 372 (61) |

Primary outcome and secondary outcomes in the international trial

From baseline to 5 months, mean scores of ADOS social affect decreased from 14.1 to 13.3 in the music therapy group and from 13.5 to 12.4 in standard care. Unadjusted linear mixed-effects models indicate that the mean change from baseline in the ADOS social affect score at 5 months was similar among those randomised to IMT and to ESC (mean difference 0.06, 95% CI –0.70 to 0.81; p = 0.88) (Table 7). The models adjusted for site showed similar results (Table 8). Although improvements in social affect were seen at 5 and 12 months for the group as a whole, differences in mean score on the ADOS social affect scale between those randomised to IMT and to ESC were not statistically significant. From baseline to 5 months, the parent-rated social responsiveness score decreased from 96.0 to 89.2 in music therapy and from 96.1 to 93.3 in standard therapy, with no significant difference in improvement (mean difference, music therapy vs. standard care = –3.39, 95% CI –7.56 to 0.91; p = 0.13).

| Outcome | Observed values | Change from baseline | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IMT | ESC | IMT | ESC | p-valueb | |||||

| n | Mean score (95% CI) | n | Mean score (95% CI) | n | Mean score (95% CI)a | n | Mean score (95% CI)a | ||

| ADOS social affect | |||||||||

| Baseline | 182 | 14.1 (13.4 to 14.7) | 182 | 13.5 (12.9 to 14.1) | – | – | – | – | – |

| 5 months | 165 | 13.3 (12.5 to 14.0) | 149 | 12.4 (11.7 to 13.2) | 165 | –0.9 (–1.4 to –0.4) | 149 | –0.8 (–1.4 to –0.3) | 0.88 |

| 12 months | 154 | 12.6 (11.8 to 13.4) | 136 | 11.7 (10.9 to 12.5) | 154 | –1.5 (–2.0 to –1.0) | 136 | –1.6 (–2.3 to –0.9) | 0.69 |

| SRS total score | |||||||||

| Baseline | 180 | 96.0 (92.0 to 100.0) | 179 | 96.1 (91.8 to 100.4) | – | – | – | – | – |

| 5 months | 142 | 89.2 (84.6 to 93.7) | 129 | 93.3 (88.0 to 98.6) | 141 | –5.2 (–8.4 to –2.0) | 128 | –2.0 (–5.6 to 1.7) | 0.13 |

| 12 months | 132 | 86.5 (81.2 to 91.7) | 126 | 88.6 (83.4 to 93.9) | 131 | –7.4 (–11.0 to –3.8) | 124 | –5.1 (–8.9 to –1.2) | 0.26 |

| ADOS social affect score | Analysis | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unadjusted | Adjusted for site | |||||||||

| β | SE | df | t | p-value | β | SE | df | t | p-value | |

| Intercept | 13.49 | 0.34 | 868 | 39.2 | 0.000 | 13.67 | 0.58 | 868 | 23.4 | 0.000 |

| Group (IMT) | 0.59 | 0.49 | 362 | 1.2 | 0.227 | 0.45 | 0.46 | 352 | 1.0 | 0.324 |

| 5 months vs. baseline | –0.91 | 0.28 | 868 | –3.2 | 0.001 | –0.90 | 0.28 | 868 | –3.2 | 0.001 |

| 12 months vs. baseline | –1.63 | 0.29 | 868 | –5.7 | 0.000 | –1.62 | 0.29 | 868 | –5.6 | 0.000 |

| Group × (5 months vs. baseline) | 0.06 | 0.39 | 868 | 0.2 | 0.882 | 0.05 | 0.39 | 868 | 0.1 | 0.900 |

| Group × (12 months vs. baseline) | 0.16 | 0.40 | 868 | 0.4 | 0.692 | 0.14 | 0.40 | 868 | 0.4 | 0.729 |

No differences were seen in ADOS social affect score at 5 or 12 months between those randomised to high- and low-frequency IMT or between those randomised to IMT and ESC at 12 months (Table 9).

| ADOS social affect score | Analysis | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unadjusted | Adjusted for site | |||||||||

| β | SE | df | t | p-value | β | SE | df | t | p-value | |

| Intercept | 13.49 | 0.34 | 865 | 39.2 | 0.000 | 13.68 | 0.59 | 865 | 23.3 | 0.000 |

| IMT-HI (three per week) vs. ESC | 0.91 | 0.60 | 361 | 1.5 | 0.129 | 0.86 | 0.57 | 351 | 1.5 | 0.130 |

| IMT-LO (one per week) vs. ESC | 0.27 | 0.59 | 361 | 0.5 | 0.647 | 0.06 | 0.56 | 351 | 0.1 | 0.920 |

| 5 months vs. baseline | –0.91 | 0.28 | 865 | –3.2 | 0.001 | –0.90 | 0.28 | 865 | –3.2 | 0.001 |

| 12 months vs. baseline | –1.63 | 0.29 | 865 | –5.7 | 0.000 | –1.62 | 0.29 | 865 | –5.6 | 0.000 |

| [IMT-HI (three per week) vs. ESC] × (5 months vs. baseline) | –0.24 | 0.48 | 865 | –0.5 | 0.610 | –0.26 | 0.48 | 865 | –0.5 | 0.593 |

| [IMT-LO (one per week) vs. ESC] × (5 months vs. baseline) | 0.34 | 0.46 | 865 | 0.7 | 0.470 | 0.33 | 0.46 | 865 | 0.7 | 0.475 |

| [IMT-HI (three per week) vs. ESC] × (12 months vs. baseline) | 0.18 | 0.49 | 865 | 0.4 | 0.715 | 0.16 | 0.49 | 865 | 0.3 | 0.751 |

| [IMT-LO (one per week) vs. ESC] × (12 months vs. baseline) | 0.15 | 0.48 | 865 | 0.3 | 0.758 | 0.13 | 0.48 | 865 | 0.3 | 0.780 |

Statistically significant differences were also not found for total score on the SRS between those randomised to music therapy or ESC at either 5 or 12 months (Tables 10 and 11) nor in subscales of the ADOS or the SRS (see Appendix 1).

| Social responsiveness total score | Analysis | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unadjusted | Adjusted for site | |||||||||

| β | SE | df | t | p-value | β | SE | df | t | p-value | |

| Intercept | 159.45 | 2.17 | 776 | 73.5 | 0.000 | 159.21 | 3.46 | 776 | 46.0 | 0.000 |

| Group (IMT) | –0.37 | 3.06 | 361 | –0.1 | 0.904 | –0.71 | 2.89 | 351 | –0.3 | 0.806 |

| 5 months vs. baseline | –1.53 | 1.60 | 776 | –1.0 | 0.338 | –1.29 | 1.60 | 776 | –0.8 | 0.421 |

| 12 months vs. baseline | –4.17 | 1.61 | 776 | –2.6 | 0.010 | –3.92 | 1.61 | 776 | –2.4 | 0.015 |

| Group × (5 months vs. baseline) | –3.39 | 2.21 | 776 | –1.5 | 0.126 | –3.64 | 2.21 | 776 | –1.7 | 0.100 |

| Group × (12 months vs. baseline) | –2.53 | 2.25 | 776 | –1.1 | 0.262 | –2.74 | 2.25 | 776 | –1.2 | 0.223 |

| SRS total score | Analysis | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unadjusted | Adjusted for site | |||||||||

| β | SE | df | t | p-value | β | SE | df | t | p-value | |

| Intercept | 159.45 | 2.17 | 773 | 73.4 | 0.000 | 159.21 | 3.47 | 773 | 45.9 | 0.000 |

| IMT-HI (three per week) vs. ESC | –0.74 | 3.77 | 360 | –0.2 | 0.844 | –1.09 | 3.56 | 350 | –0.3 | 0.760 |

| IMT-LO (one per week) vs. ESC | –0.01 | 3.74 | 360 | 0.0 | 0.997 | –0.34 | 3.54 | 350 | –0.1 | 0.923 |

| 5 months vs. baseline | –1.53 | 1.60 | 773 | –1.0 | 0.338 | –1.29 | 1.60 | 773 | –0.8 | 0.422 |

| 12 months vs. baseline | –4.17 | 1.62 | 773 | –2.6 | 0.010 | –3.92 | 1.61 | 773 | –2.4 | 0.015 |

| [IMT-HI (three per week) vs. ESC] × (5 months vs. baseline) | –4.60 | 2.77 | 773 | –1.7 | 0.097 | –4.88 | 2.76 | 773 | –1.8 | 0.077 |

| [IMT-LO (one per week) vs. ESC] × (5 months vs. baseline) | –2.45 | 2.63 | 773 | –0.9 | 0.352 | –2.68 | 2.63 | 773 | –1.0 | 0.308 |

| [IMT-HI (three per week) vs. ESC] × (12 months vs. baseline) | –1.41 | 2.81 | 773 | –0.5 | 0.615 | –1.67 | 2.80 | 773 | –0.6 | 0.550 |

| [IMT-LO one per week) vs. ESC] × (12 months vs. baseline) | –3.49 | 2.69 | 773 | –1.3 | 0.195 | –3.68 | 2.69 | 773 | –1.4 | 0.172 |

Adverse events, hospitalisation or other institutional stays were rare at baseline (three in those randomised to ESC and nine in those randomised to IMT). During the study, there were three admissions to hospital in the ESC arm of the trial at 5 months and four at 12 months. In the IMT arm of the trial, there were six admissions to hospital at 5 months and four at 12 months. These institutional stays were typically short admissions for planned treatment of coexisting physical health conditions unrelated to the study. No other adverse events were reported.

Response rates on the Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule social affect scale at five months

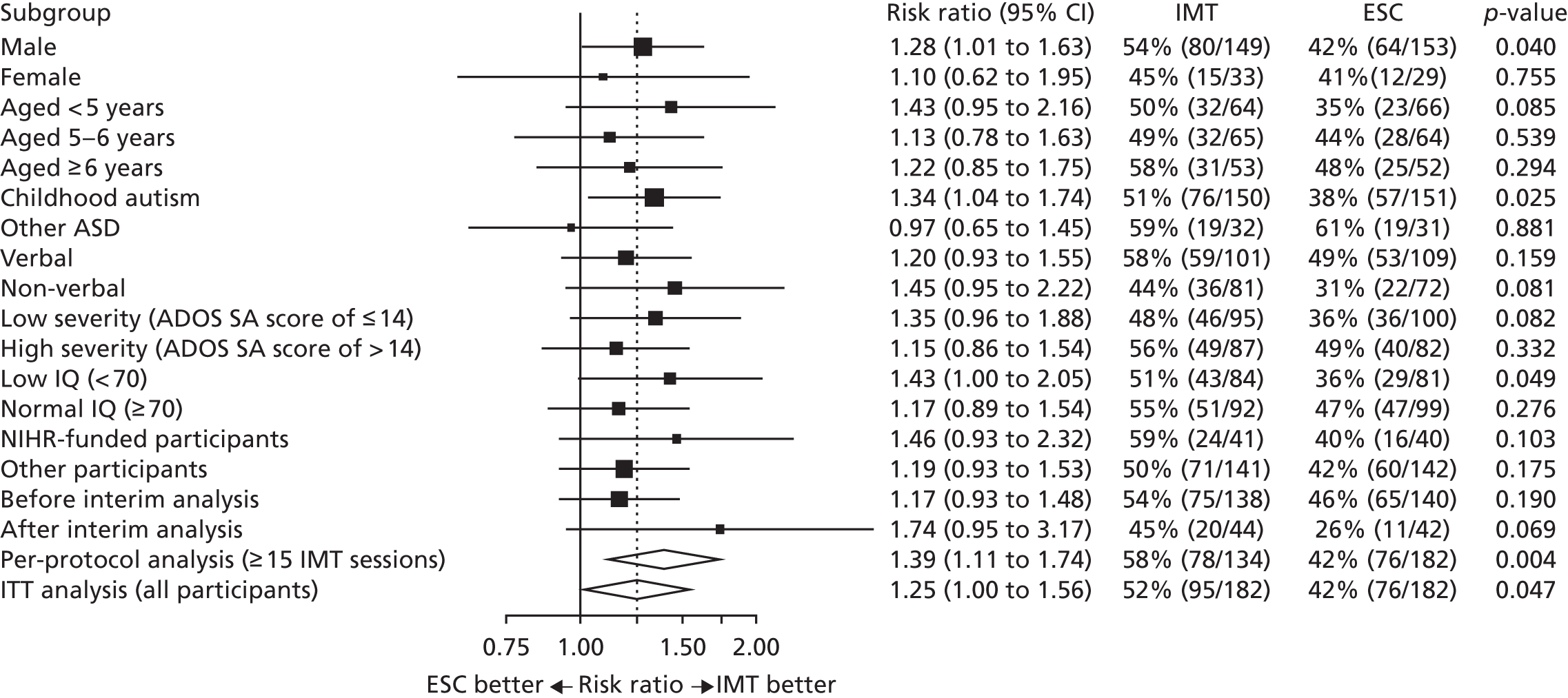

Exploratory analyses in the ITT population indicated a 25% higher proportion of improved cases in ADOS social affect score at 5 months in the IMT arm (95/182, 52%) than in the ESC arm (76/182, 42%) (risk ratio 1.25, 95% CI 1.00 to 1.56; p = 0.046). These results were similar in available case analyses and in analyses by dose group (Table 12). Subgroup analyses (Figure 3) suggested greater positive differences in response for some clinical groups, including male participants (p = 0.040), those with childhood autism (p = 0.025) or a low IQ (p = 0.049) and those who received at least 15 IMT sessions (risk ratio 1.39, 95% CI 1.11 to 1.74; p = 0.004).

| Intervention | Improved cases | |

|---|---|---|

| ITT | Available cases | |

| High-frequency IMT | 51% (46/90) | 59% (46/78) |

| Low-frequency IMT | 53% (49/92) | 56% (49/87) |

| Any IMT | 52% (95/182) | 58% (95/165) |

| ESC | 42% (76/182) | 51% (76/149) |

FIGURE 3.

Effects of IMT vs. ESC on proportion of improved cases on ADOS social affect scale at 5 months by clinical subgroup. SA, social affect.

Outcomes among people recruited in the National Institute for Health Research-funded arm of the study

The NIHR-funded arm of the trial was not sufficiently powered to detect statistically significant differences in outcomes and we did not find significant differences in ADOS social affect score (Tables 13 and 14) or social responsiveness (Table 15) between those randomised to music therapy and ESC or between those randomised to high- or low-frequency music therapy compared with those randomised to ESC in the NIHR-funded arm of the trial. Nor were differences found in subscales of the ADOS or SRS (see Appendix 2).

| Outcome | Observed values | Change from baseline | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IMT | ESC | IMT | ESC | p-valueb | |||||

| n | Mean (95% CI) | n | Mean (95% CI) | n | Mean (95% CI)a | n | Mean (95% CI)a | ||

| ADOS social affect score | |||||||||

| Baseline | 41 | 15.9 (14.3 to 17.4) | 40 | 14.8 (13.4 to 16.3) | – | – | – | ||

| 5 months | 38 | 14.3 (12.8 to 15.8) | 34 | 14.4 (12.8 to 16.1) | 38 | –1.3 (–2.5 to –0.1) | 34 | –0.8 (–2.2 to 0.6) | 0.44 |

| 12 months | 35 | 13.8 (11.8 to 15.8) | 29 | 13.7 (11.6 to 15.7) | 35 | –2.0 (–3.3 to –0.6) | 29 | –1.6 (–3.4 to 0.3) | 0.49 |

| SRS total score | |||||||||

| Baseline | 41 | 101.9 (94.0 to 109.7) | 39 | 95.3 (86.6 to 103.9) | – | – | – | ||

| 5 months | 19 | 106.7 (97.7 to 115.6) | 19 | 112.5 (101.6 to 123.4) | 19 | –0.8 (–11.0 to 9.4) | 19 | 8.1 (1.0 to 15.2) | 0.19 |

| 12 months | 20 | 111.2 (100.9 to 121.4) | 22 | 101.8 (90.6 to 112.9) | 20 | 1.1 (–9.7 to 11.9) | 21 | 3.2 (–5.6 to 12.0) | 0.97 |

| ADOS social affect score | Analysis | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unadjusted | Adjusted for site | |||||||||

| β | SE | df | t | p-value | β | SE | df | t | p-value | |

| Intercept | 14.83 | 0.80 | 152 | 18.4 | 0.000 | 15.13 | 1.25 | 152 | 12.1 | 0.000 |

| Group (IMT) | 1.03 | 1.13 | 79 | 0.9 | 0.365 | 0.87 | 1.09 | 78 | 0.8 | 0.426 |

| 5 months vs. baseline | –0.66 | 0.68 | 152 | –1.0 | 0.333 | –0.70 | 0.68 | 152 | –1.0 | 0.304 |

| 12 months vs. baseline | –1.32 | 0.72 | 152 | –1.8 | 0.070 | –1.35 | 0.72 | 152 | –1.9 | 0.063 |

| Group × (5 months vs. baseline) | –0.73 | 0.94 | 152 | –0.8 | 0.440 | –0.70 | 0.94 | 152 | –0.7 | 0.458 |

| Group × (12 months vs. baseline) | –0.68 | 0.99 | 152 | –0.7 | 0.490 | –0.65 | 0.99 | 152 | –0.7 | 0.508 |

| Social responsiveness total score | Analysis | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unadjusted | Adjusted for site | |||||||||

| β | SE | df | t | p-value | β | SE | df | t | p-value | |

| Intercept | 95.14 | 4.12 | 90 | 23.1 | 0.000 | 95.14 | 4.12 | 90 | 23.1 | 0.000 |

| Group (IMT) | 6.71 | 5.77 | 79 | 1.2 | 0.249 | 6.71 | 5.77 | 78 | 1.2 | 0.249 |

| 5 months vs. baseline | 10.01 | 4.28 | 90 | 2.3 | 0.021 | 10.01 | 4.28 | 90 | 2.3 | 0.021 |

| 12 months vs. baseline | 4.02 | 4.08 | 90 | 1.0 | 0.327 | 4.02 | 4.08 | 90 | 1.0 | 0.327 |

| Group × (5 months vs. baseline) | –8.02 | 6.02 | 90 | –1.3 | 0.186 | –8.02 | 6.02 | 90 | –1.3 | 0.186 |

| Group × (12 months vs. baseline) | –0.22 | 5.81 | 90 | 0.0 | 0.970 | –0.22 | 5.81 | 90 | 0.0 | 0.970 |

A number of parents did not provide data on mental well-being and levels of stress, with only 40 (49.4%) providing data at 5 months and 43 (53.1%) providing data at 12 months. Differences in total scores and subscales of the PSI-SF at 5 and 12 months are presented in Table 16. Differences in levels of parental distress at 12 months were significantly lower among parents of children randomised to music therapy.

| Outcome | Treatment arm, mean score (SD) | Difference at | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IMT | ESC | 5 months | 12 months | |||||||

| Baseline (n = 34) | 5 months (n = 21) | 12 months (n = 21) | Baseline (n = 40) | 5 months (n = 19) | 12 months (n = 22) | Difference (95% CI) | p-value | Difference (95% CI) | p-value | |

| PSI-SF:a parental distress | 31.85 (9.66) | 29.76 (8.04) | 31.86 (12.49) | 31.43 (9.85) | 35.16 (9.99) | 35.59 (10.60) | –0.14 (–6.06 to 0.76) | 0.12 | –0.30 (–11.17 to –1.89) | 0.007 |

| PSI-SF:a dysfunctional interaction | 32.41 (7.46) | 30.48 (5.21) | 29.14 (6.05) | 29.88 (7.07) | 32.42 (5.08) | 31.18 (7.38) | –0.07 (–3.33 to 2.00) | 0.617 | –0.19 (–5.95 to 0.81) | 0.13 |

| PSI-SF:a difficult child | 36.41 (8.86) | 35.10 (6.77) | 36.14 (8.85) | 33.78 (8.60) | 38.89 (7.41) | 35.73 (8.41) | –0.19 (–6.26 to 1.17) | 0.17 | –0.04 (–5.62 to 4.00) | 0.76 |

| Total score on PSI-SFa | 100.68 (22.90) | 95.33 (15.71) | 97.14 (24.05) | 95.08 (21.22) | 106.47 (18.23) | 102.50 (24.26) | –0.19 (–13.94 to 1.62) | 0.12 | –0.22 (–20.66 to 0.15) | 0.05 |

| Total score on WEMWBSb | 22.51 (3.81) | 22.66 (4.60) | 23.15 (2.72) | 21.22 (4.19) | 19.78 (4.36) | 20.80 (4.31) | 0.144 (–0.95 to 3.64) | 0.24 | 0.24 (–0.35 to 4.02) | 0.10 |

Chapter 4 Discussion

The results of this international multicentre trial do not provide good evidence that IMT delivered over 5 months leads to changes in social affect or social responsiveness in children aged 4–7 years with ASD. Children across the study centres engaged well with the music therapy and we did not find evidence of harms. Secondary analysis of data found that the proportion of children who had some improvement in social affect were, to a greater extent, among those randomised to IMT and among subgroups of those offered music therapy, including males, those with childhood autism, those with coexisting intellectual disability and those who received more than 15 sessions of therapy.

Results of the study among children who were recruited to the trial at NIHR-funded centres were similar to those in other international centres with high rates of uptake, and there were no statistically significant differences in study outcomes. Data from parents of children in the NIHR-funded arm of the study suggested that levels of stress were lower at 12 months among parents of children who were offered music therapy.

Strengths and weaknesses of the study design

The TIME-A study is the first large-scale trial of music therapy for children with ASD and also the largest trial of any intervention for children with ASD completed to date. The study tested the effects of the intervention in a broad range of different countries and settings and used validated measures of social affect and responsiveness that are at the core of the difficulties experienced by children with ASD. Other strengths of the study were that the efforts to maintain masking of study researchers were largely successful and there was a limited number of missing data, which was achieved by successfully following up 87% of children at 5 months.

One of the main weaknesses of the study was the limited selection of outcome measures that we used. At the time that the study was designed, there was a lack of validated measures of the core problems of social affect and communication experienced by children with ASD that were sensitive to change. 35,36 The ADOS was originally developed as a diagnostic tool to assess whether or not children have impairments and unusual behaviours that would indicate ASD. Although some previous studies have used the ADOS to assess the clinical effectiveness of interventions,22,37,38 concerns have been raised about the suitability of the ADOS to assess changes in the adaptive functioning of children with ASD. 39 Similar limitations apply to the SRS as an outcome measure for measurement of skill development in young children. A systematic review of outcome measures used to assess the impact of interventions for young children with ASD concluded that there is an urgent need for validated assessments that are sensitive to change. 35 Following this, the Brief Observation of Social Communication Change was developed specifically to assess changes in social communication skills of children with ASD. 40 Longitudinal data from children with ASD suggest that the Brief Observation of Social Communication Change may be more sensitive to change than the ADOS,40 and we cannot rule out the possibility that music therapy brought about changes in social affect that were not detected using the ADOS.

The international trial group deliberately restricted the number of outcome measures used to reduce the burden of follow-up assessments for children and their parents. Feedback from some parents of children who received music therapy suggested that potential future parent-reported outcomes may include broader improvements, such as the child’s functioning or anxiety, and those that we did not assess in this study.

Although the study was sufficiently powered to detect clinically important effects, it was not large enough to detect small differences in social affect and responsiveness that may still be valued by children and their families. The results of our secondary analysis of response rates provide some evidence that such changes may be associated with the intervention tested in this trial.

Although children in the study were followed up for longer than in any previous study of music therapy for children with ASD, the final follow-up was 12 months after randomisation. Recent findings from a trial of parent-mediated communication-focused therapy failed to find clear evidence of effectiveness at 1 year,22 but did so at 5 years. 37 We cannot rule out the possibility that there could have been differences in outcomes for children over a longer period. However, a further difference from that study is that the involvement of parents allows for generalisation across situations, and the music therapy as delivered in this trial did not consistently involve parents in a way that transferred skills.

Finally, although the rate of follow-up in the study was high, only half of the parents in the NIHR-funded arm of the trial completed the assessment of stress and mental well-being. We believe that this resulted from asking parents to complete and return these measures at their convenience rather than integrating them into the main, face-to-face assessment.

The National Institute for Health Research-funded arm of the trial

The NIHR-funded arm of the trial aimed to help ensure that the international study achieved its minimum recruitment target of 300 children and families, and to assess whether or not the outcomes of the trial were similar in England compared with other centres. At the point at which recruitment to the international trial ceased (on 1 November 2015), we had randomised 81 out of the 100 children and families we set out to recruit. The NIHR-funded arm of the trial is the largest of any of the arms of the study and successfully helped to ensure that the minimum recruitment target was reached.

Feedback from parents who attended the project advisory group was that it would be difficult to make arrangements for children to attend a treatment that might be delivered three times per week unless it was integrated into the school day. This led us to make arrangements to deliver most music therapy sessions in specialist schools working with children with ASD and other special needs. When music therapy sessions were delivered at the child’s school, attendance rates were high and we believe that is the main reason why levels of attendance among those allocated to high-frequency treatment were higher in the NIHR-funded arm of the trial (median n = 43) than at other study centres (median n = 34) where treatment was usually delivered in clinics. In contrast, attendance at parent advice and support sessions was lower in the NIHR-funded arm of the trial than at other centres. This may be because these sessions were generally organised at NHS clinics rather than at the child’s school.

In terms of demographic and clinical characteristics, children recruited to the study in the NIHR-funded arm of the trial were broadly similar to those recruited at other centres, with the exception of levels of coexisting intellectual disability. Although less than half (46.3%) of the children in the trial as a whole were judged to have coexisting intellectual disability, 62 out of the 81 children (76.5%) recruited in the NIHR-funded arm of the trial were judged to have an IQ of < 70. We believe that this resulted from our focus on recruiting children who were attending specialist schools.

With regard to outcomes of music therapy, we did not find evidence of differences in social affect or social responsiveness among children randomised to music therapy or ESC in either the international trial or the NIHR-funded arm of the study.

Our ability to assess whether or not the parents of children randomised to music therapy experienced different levels of stress or mental well-being in the following year was limited by the poor follow-up rate. However, the data we were able to collect showed that it is possible that IMT for children with ASD was associated with lower levels of parental distress and we believe that this is an area that merits further examination in future studies.

Comparison with results of previous trials

In contrast with the results of the TIME-A study, previous trials of music therapy for children with ASD have reported improvements in social affect and communication;12 however, the methodological quality of previous trials has been moderate or low and, in some, researchers were not masked to allocation status. Previous studies have also tended to focus on outcomes assessed within therapy. A methodological strength of the TIME-A study is that it assessed whether or not any such effects could be seen outside of therapy sessions and with an unfamiliar adult. The relative absence of information about the generalised effects of music therapy was highlighted in a previous systematic review,12 and the results of this trial directly address whether or not changes that appear to take place during therapy sessions can be seen outside the treatment context.

Implications for services and future research

We did not find clear evidence that individual IMT improves social affect and social responsiveness of children with ASD aged 4–7 years, as tested in this trial. However, our finding that music therapy may be more likely to influence social affect of children with childhood autism (as opposed to other ASD) and those with coexisting intellectual disability suggests that further assessment of the role of IMT in treating these children is warranted. Such research should include validated measures of social communication that are more sensitive to change, such as the Brief Observation of Social Communication Change. 40 Following feedback from parents about their experience of seeing changes in broader aspects of child mental health, such as anxiety, we believe that such studies should also include these important aspects of mental health. Assessing the impact of interventions for children with autism on anxiety is particularly important given the associations between anxiety and social functioning. 41

Feedback from parents who took part in the TIME-A study was that they valued contact with music therapists in order to get a better understanding of the intervention and how they might use music to try to enhance their communication with their children. 42 In recent years, parent- and family-centred approaches to music therapy have begun to be developed. 43 This approach involves music therapists working with parents and other family members, to support the whole family and try to embed a positive therapeutic culture in the family dynamic. Such an approach also has the potential to increase the exposure of children to music-based interventions beyond that which can be achieved in traditional music therapy sessions. A recent pilot RCT of family-centred music therapy found evidence of increased social interaction, and this approach to delivering music therapy to children with ASD44 is worthy of further investigation.

Conclusions

Adding IMT to services received by children with ASD in this trial did not result in improvements in social affect or responsiveness.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the NIHR HTA programme. Funding for the international TIME-A trial was provided by the Research Council of Norway, programmes Clinical Research and Mental Health (Research Council of Norway project number 213982). Additional support was provided to the study through the Imperial National Institute for Health Research Biomedical Research Centre and Anglia Ruskin University.

We thank all the parents and children who took part in the study, and clinical staff at Central and North West London NHS Foundation Trust, Chelsea and Westminster NHS Foundation Trust, and Cambridge and Peterborough NHS Foundation Trust for their help with completing the study. We also thank teachers and other staff at Bushmead Primary School, Columbus School and College, Hedgewood School, Northway School, Oakleigh School, Spring Common School, Queensmill School and Thorndown Primary School for their help with the study. We are grateful to Anglia Ruskin University, and to Cambridge and Peterborough Foundation Trust, for part-funding the music therapy delivered during the trial.

We thank the Clinical Research Network for help with publicising the study. We also thank members of the trial co-ordinating team, including Amy Claringbold, Verity Leeson and Kavi Gakhal, for overseeing the administration of the trial.

We are grateful to all members of the TSC [Crispin Day (chairperson), Richard Ashcroft, Elena Garralda, Nicky Seers, Vicky Slonims and Jennie Small] and the Data Monitoring and Ethics Committee [Anne O’Hare (chairperson), Paul Bassett, Annette Darbyshire and Sarah Hadley] for their support and guidance.

We are grateful to members of the Parent Advisory Group for their input to the project as experts by experience, for advising on study logistics and for helping us to interpret and communicate the study findings.

We would like to particularly thank the music therapists who delivered and supervised the music therapy (Amelia Oldfield, Alexandra Georgaki, Belinda Lydon, Pavlina Papadopoulou and Grace Watts) and the clinicians who delivered parent advice sessions at each site (Arshad Faridi, Rania Nagi, Adewale Adeoye, Alexandra Georgaki and Belinda Lydon).

Contributions of authors

Mike J Crawford was the chief investigator on the NIHR-funded arm of the study.

Christian Gold was the principal investigator of the international trial.

Helen Odell-Miller was principal investigator for the east of England recruitment sites and, together with Mike J Crawford, Christian Gold, Helen Odell-Miler and Anna Maratos, designed the NIHR-funded arm of the study.

Lavanya Thana and Sarah Faber recruited participants, collected study data and commented on a draft of this report.

Jörg Assmus analysed study data.

Łucja Bieleninik, Monika Geretsegger and Karin Antonia Mössler co-ordinated the international trial and commented on a draft of this report.

Claire Grant, Anna Maratos and Stephan Sandford also helped to oversee the running and reporting of the project. In addition, Stephan Sandford supervised music therapists in the study, and Claire Grant, Anna Maratos and Stephan Sandford helped to co-ordinate the delivery of music therapy.

Amy Claringbold co-ordinated the NIHR-funded arm of the trial and commented on a draft of this report.

Anna Maratos, Helen McConachie, Morag Maskey, Paul Ramchandani and Angela Hassiotis contributed to the development of the protocol for the NIHR-funded arm of the trial, helped to oversee the running of the project and commented on a draft of this report.

Morag Maskey contributed to the running of the study and the preparation of this report and, together with Claire Grant, helped to oversee carer involvement in the study.

Publication

Bieleninik L, Geretsegger M, Mössler K, Assmus J, Thompson G, Gattino G, et al. Effects of improvisational music therapy vs enhanced standard care on symptom severity among children with autism spectrum disorder: the TIME-A randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2017;318:525–35.

Data sharing statement

Data can be obtained from the corresponding author. All confidential data have been removed.

Disclaimers

This report presents independent research funded by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR). The views and opinions expressed by authors in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the NHS, the NIHR, NETSCC, the HTA programme or the Department of Health. If there are verbatim quotations included in this publication the views and opinions expressed by the interviewees are those of the interviewees and do not necessarily reflect those of the authors, those of the NHS, the NIHR, NETSCC, the HTA programme or the Department of Health.

References

- Baird G, Simonoff E, Pickles A, Chandler S, Loucas T, Meldrum D, et al. Prevalence of disorders of the autism spectrum in a population cohort of children in South Thames: the Special Needs and Autism Project (SNAP). Lancet 2006;368:210-15. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69041-7.

- Howlin P, Goode S, Hutton J, Rutter M. Adult outcome for children with autism. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 2004;45:212-29. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7610.2004.00215.x.

- Knapp M, Romeo R, Beecham J. Economic cost of autism in the UK. Autism 2009;13:317-36. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362361309104246.

- Croen L, Najjar D, Ray T, Lotspeich L, Bernal P. A comparison of health care utilization and costs of children with and without autism spectrum disorders in a large group-model health plan. Pediatrics 2006;118:1203-11. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2006-0127.

- Lecavalier L, Leone S, Wiltz J. The impact of behaviour problems on caregiver stress in young people with autism spectrum disorders. J Intellect Disabil Res 2006;50:172-83. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2788.2005.00732.x.

- Cox A, Klein K, Charman T, Baird G, Baron-Cohen S, Swettenham J, et al. Autism spectrum disorders at 20 and 42 months of age: stability of clinical and ADI-R diagnosis. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 1999;40:719-32. https://doi.org/10.1111/1469-7610.00488.

- Mandell DS, Novak MM, Zubritsky CD. Factors associated with age of diagnosis among children with autism spectrum disorders. Pediatrics 2005;116:1480-6. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2005-0185.

- Billstedt E, Gillberg IC, Gillberg C, Gillberg C. Autism after adolescence: population-based 13- to 22-year follow-up study of 120 individuals with autism diagnosed in childhood. J Autism Dev Disord 2005;35:351-60. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-005-3302-5.

- McPheeters ML, Warren Z, Sathe N, Bruzek JL, Krishnaswami S, Jerome RN, et al. A systematic review of medical treatments for children with autism spectrum disorders. Pediatrics 2011;127:e1312-21. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2011–0427.

- Autism: Management and Support of Children and Young People on the Autism Spectrum. Clinical Guideline 170. London: National Institute for Health and Care Excellence; 2013.

- Oono IP, Honey EJ, McConachie H. Parent-mediated early intervention for young children with autism spectrum disorders (ASD). Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2013;4.

- Geretsegger M, Elefant C, Mössler KA, Gold C. Music therapy for people with autism spectrum disorder. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2014;6. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD004381.pub3.

- Wigram T, Gold C. Music therapy in the assessment and treatment of autistic spectrum disorder: clinical application and research evidence. Child Care Health Dev 2006;32:535-42. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2214.2006.00615.x.

- Kim J, Wigram T, Gold C. The effects of improvisational music therapy on joint attention behaviors in autistic children: a randomized controlled study. J Autism Dev Disord 2008;38:1758-66. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803–008–0566–6.

- Gattino GS, Riesgo RDS, Longo D, Leite JCL, Faccini LS. Effects of relational music therapy on communication of children with autism: a randomized controlled study. Nord J Music Ther 2011;20:142-54. https://doi.org/10.1080/08098131.2011.566933.

- Geretsegger M, Holck U, Carpente JA, Elefant C, Kim J, Gold C. Common characteristics of improvisational approaches in music therapy for children with autism spectrum disorder: developing treatment guidelines. J Music Ther 2015;52:258-81. https://doi.org/10.1093/jmt/thv005.

- Geretsegger M, Holck U, Gold C. Randomised controlled trial of improvisational music therapy’s effectiveness for children with autism spectrum disorders (TIME-A): study protocol. BMC Pediatr 2012;12.

- Bieleninik L, Geretsegger M, Mössler K, Assmus J, Thompson G, Gattino G, et al. Effects of improvisational music therapy versus enhanced standard care on symptom severity among children with autism spectrum disorder: the TIME-A randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2017;318:523-4. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2017.9478.

- Lord C, Rutter M, DiLavore PC, Risi S, Gotham K, Bishop S. Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule (ADOS). Los Angeles, CA: Western Psychological Services; 2001.

- Gotham K, Risi S, Pickles A, Lord C. The Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule: revised algorithms for improved diagnostic validity. J Autism Dev Disord 2007;37:613-27. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803–006–0280–1.

- Lord C, Rutter M, Le Couteur A. Autism Diagnostic Interview-Revised: a revised version of a diagnostic interview for caregivers of individuals with possible pervasive developmental disorders. J Autism Dev Disord 1994;24:659-85. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02172145.

- Green J, Charman T, McConachie H, Aldred C, Slonims V, Howlin P, et al. Parent-mediated communication-focused treatment in children with autism (PACT): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2010;375:2152-60. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140–6736(10)60587–9.

- Owley T, McMahon W, Cook EH, Laulhere T, South M, Mays LZ, et al. Multisite, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of porcine secretin in autism. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2001;40:1293-9. https://doi.org/10.1097/00004583-200111000-00009.

- International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision (ICD-10). Geneva: World Health Organization; 1992.