Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 10/65/02. The contractual start date was in September 2012. The draft report began editorial review in September 2016 and was accepted for publication in March 2017. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Edward Lamb reports that he was a member of the development groups for both the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence chronic kidney disease and Kidney Disease Improving Global Outcomes clinical guidelines, which have considered the relative accuracies of proteinuria and albuminuria testing.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2017. This work was produced by Waugh et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2017 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Introduction

Clinical background

Pre-eclampsia (PE) is a multisystem disorder of pregnancy associated with raised blood pressure (BP) and proteinuria. 1 Hypertensive disorders in pregnancy (HDP) remain the second leading cause of direct maternal deaths in the UK and account for 20% of all stillbirths. 2,3 One in five women with hypertension is diagnosed with PE, resulting in complex treatment and substantial health-care costs. 1 Women with the severest forms of PE require high-dependency care,1 although definitions of severe disease are not consistent. PE is also responsible for significant infant morbidity related to fetal growth restriction and prematurity resulting in prolonged neonatal intensive care treatment and lifelong handicaps; the additional NHS costs to care for a preterm baby born before 33 and 28 weeks’ gestation are £61,509 and £94,190, respectively. 1 Extra costs of £939M for the care of preterm babies per year in the NHS are linked to neonatal care. 1

Proteinuria measurement has been a key component of the screening and diagnostic strategies for modern antenatal care. Normal ranges have been defined,4 but the optimal method of detection remains uncertain. 5,6 Furthermore, the diagnosis of PE does not always imply that serious maternal or perinatal morbidity will occur. None of the diagnostic features of PE is predictive of severe adverse outcome. 7

The potential impact of early and accurate assessment of PE is enormous. The reliable diagnosis of significant proteinuria is critical in women with hypertension in pregnancy because it distinguishes those with PE from those with isolated hypertension; this distinction determines future monitoring and management. 1 Furthermore, the determination of the most appropriate threshold for abnormal proteinuria that predicts clinical outcome helps to better focus resource on high-risk women and reduce unnecessary intervention. Currently, women with suspected PE undergo 24-hour proteinuria testing, mainly as inpatients, to evaluate the severity of the condition. The cost associated with 24-hour protein measurement and additional testing needs to be evaluated against identifying women with PE and avoiding the mortality, morbidity and costs associated with undiagnosed PE.

The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) acknowledges the paucity of evidence relating to the diagnosis of significant proteinuria and the unclear prognostic value of various urinary protein thresholds. 1 They have highlighted the need for ‘large, high-quality prospective studies comparing the various methods of measuring proteinuria (automated reagent-strip reading devices, urinary protein–creatinine ratio, urinary albumin–creatinine ratio, and 24-hour urine collection) in women with new-onset hypertensive disorders during pregnancy’. 1

Our proposed study aims to address this shortfall in evidence by determining which method of measurement is most accurate in predicting not only PE but, more importantly, clinically significant outcomes. This will help to inform decisions regarding clinical management of gestational hypertensive disorders during pregnancy.

Description of technology

Comparative test

Measurement of 24-hour urine protein is currently the gold standard for the assessment of proteinuria in pregnancy. However, this test is associated with significant costs related to hospital admission, as often women are admitted as an inpatient for up to 48 hours until the results become available. Furthermore, the measurement is subject to errors (in as many as 20% of patients) as a result of incomplete collection. Diagnosis of proteinuria in HDP also varies with the type of laboratory assay used. These errors are compounded for other point-of-care (POC) technologies. 8

Index tests

Proteinuria estimation by a urinary spot protein–creatinine ratio (SPCR) test or a urinary spot albumin–creatinine ratio (SACR) test in women with suspected PE is available as a laboratory test performed on a random ‘spot’ sample of urine.

A reliable, accurate and cost-effective SPCR or SACR test, that is equivalent or better than 24-hour protein estimation at predicting adverse maternal and fetal outcomes, could be employed as the primary test in the assessment of women with suspected PE. Furthermore, given the rising costs of inpatient care, the use of a SPCR test or a SACR test has the potential to deliver significant cost improvements. A clearer understanding of the threshold of proteinuria (by any measurement) that predicts increased risks of adverse maternal and fetal outcomes will allow the concentration of scarce NHS resource onto the more intensive monitoring of fewer women.

Summary of current evidence

Current recommendations for assessment of proteinuria vary. Recently published NICE guidelines1 in the UK suggest the use of an automated reagent strip reading device to detect proteinuria. In women with a result of 1+ or more, the use of SPCR or 24-hour urine collection is recommended to quantify proteinuria. Significant proteinuria is defined as a SPCR greater than 30 mg/mmol or a validated 24-hour urine collection of > 300 mg/24 hours. When 24-hour urine collection is used to quantify proteinuria, a recognised method of evaluating completeness of the sample is recommended. 1 The Society of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists of Canada9 suggests using urinary dipstick testing to screen for proteinuria, with the definition of significant proteinuria similar to the NICE guidelines. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists10 consider 24-hour urine protein estimation of > 300 mg as significant proteinuria for a diagnosis of PE.

Work leading to the trial

Diagnostic accuracy of spot protein–creatinine ratio/spot albumin–creatinine ratio in assessing proteinuria in women with hypertensive disorders in pregnancy

Price et al. ,11 in 2005, and Cote et al. ,12 in 2008, performed systematic reviews of 1214 women with gestational hypertension. The SPCR test, with a cut-off point of 30 mg/mmol, had a pooled sensitivity of 83.6% [95% confidence interval (CI) 77.5% to 89.7%], a specificity of 76.3% (95% CI 72.6% to 80.0%), a positive likelihood ratio (LR+) of 3.53 (95% CI 2.83 to 4.49) and a negative likelihood ratio (LR–) of 0.21 (95% CI 0.13 to 0.31). Both groups of authors concluded that the SPCR test was a reasonable ‘rule-out’ test for proteinuria of ≥ 300 mg/day in HDP. However, laboratory assays in the primary studies were not well described. This led to the recommendation for future studies on using the SACR test to predict significant proteinuria and clinical outcomes.

Evaluation of proteinuria thresholds and assays in predicting adverse clinical outcomes

The authors have assessed the use of different laboratory assays to measure 24-hour proteinuria in pregnancy. 13 The prevalence of proteinuria of > 300 mg/24 hours and, hence, the prevalence of PE differed between the two assays studied [24.9% for the Bradford assay and 70.1% for the benzethonium chloride (BZC) assay]. The threshold of 300 mg/24 hours performed poorly as a predictor of adverse outcomes. 13 At the threshold of 500 mg/24 hours, the BZC assay predicted severe hypertension with a LR+ of 1.51 (95% CI 0.99 to 2.28) and small for gestational age with a LR+ of 1.72 (95% CI 1.11 to 2.66). However, at the threshold of 500 mg/24 hours, the LR+ for the Bradford assay for severe hypertension was 2.15 (95% CI 1.07 to 4.34), for birthweight of less than the 10th centile was 2.79 (95% CI 1.40 to 5.54) and for biochemical disease was 2.47 (95% CI 1.22 to 5.01). These data support the recommendation from NICE1 for prospective studies to explore the relationship between individual assays for proteinuria and clinical outcome.

Point-of-care measurement of proteinuria

The authors have also investigated POC testing for proteinuria and albuminuria in pregnancy and PE. 14–16 The SACR dipstick test and the fully quantitative SACR test were compared with 24-hour proteinuria. The SACR dipstick testing did not improve detection rates whether automated or visual. Fully quantitative measurement of SACR was a better predictor than any dipstick technique (LR+ 14.60, 95% CI 6.74 to 31.80; LR– 0.069, 95% CI 0.030 to 0.160). 16

In a systematic review of six studies of visual dipstick analysis, Waugh et al. 17 reported a pooled LR+ of 3.48 (95% CI 1.66 to 7.27) and a pooled LR– of 0.60 (95% CI 0.45 to 0.80) for predicting proteinuria at a level of 300 mg/24 hours at the 1+ or greater threshold. They concluded that the accuracy of dipstick urinalysis with a 1+ threshold in the prediction of significant proteinuria is poor and, therefore, of limited clinical value.

Our study comparing semiquantitative and fully quantitative POC tests for albuminuria and proteinuria found automated dipstick urinalysis to have better predictive values for significant proteinuria (LR+ 4.27, 95% CI 2.78 to 6.56; LR– 0.225, 95% CI 0.14 to 0.37) compared with conventional visual dipstick urinalysis (LR+ 2.27, 95% CI 1.47 to 3.51; LR– 0.635, 95% CI 0.49 to 0.82). Dipstick microalbumin–creatinine ratio testing did not improve overall detection rates with automated or visual testing. The fully quantitative POC test of SACR was better than any dipstick technique (LR+ 14.6, 95% CI 6.74 to 31.8; LR– 0.069, 95% CI 0.030 to 0.16). 16 These studies have informed the development of NICE clinical guideline (CG) number 107. 1

Systematic review of tests that predict onset of pre-eclampsia

The authors have evaluated the accuracy of tests in predicting the onset of PE by a systematic review of the literature. 18 This study concluded that no current tests employed in screening for PE were sufficiently accurate or effective to become part of routine care. One of the recommendations from that project was to evaluate prognostic or predictive features, such as proteinuria, that are associated with maternal and fetal complications once PE has started.

Systematic reviews on the accuracy of tests to predict complications in pre-eclampsia: TIPPS study

We have conducted systematic literature reviews to assess the predictive value of five of the commonly performed tests in PE. We analysed more than 25,000 citations and reviewed 60 relevant studies. Although we conducted good-quality reviews, including one on proteinuria, it was hard to provide recommendations on the value of tests because of the deficiencies in the primary studies. However, the data collated give face validity of the choice of tests that have been chosen for use in the study. 19

Development and validation of the PREP study

We have recently been funded by the Health Technology Assessment (HTA) programme to undertake the first prognostic study to develop a prediction rule for adverse outcomes in early-onset PE that will provide personalised estimates of maternal and fetal risks. The Prediction model for Risk of complications in Early-onset Pre-eclampsia (PREP) study will achieve this by validating the model in two prospective external data sets in the Netherlands and Canada. The data from the PREP study will complement the current project in evaluating the association between proteinuria and adverse outcomes. Furthermore, the study will also provide valuable data on outcomes of women with severe PE to further populate the decision-analytic model for an economic evaluation.

Chapter 2 Methods and design

Aims and objectives

The aim of this study was to evaluate the measurement of proteinuria in women with suspected PE. This includes women with new hypertension of ≥ 140/90 mmHg and a trace or greater of proteinuria using an automated dipstick analysis. By determining the most appropriate method and threshold for measuring proteinuria that predicts PE and its severity, it may be possible to reduce unnecessary intervention in women without PE.

Primary objective

To evaluate the accuracy of quantitative assessments of SPCR and SACR at different thresholds in predicting severe PE compared with a 24-hour urine protein measurement in pregnant women with hypertension and suspected proteinuria.

Secondary objectives

The secondary objectives of this study were to:

-

assess the accuracy of POC assessments of SPCR and SACR at different thresholds in diagnosing PE compared with a 24-hour urine protein measurement

-

identify the laboratory assay method of 24-hour proteinuria that is most accurate in the assessment of PE

-

estimate the accuracy of quantitative assessments of SPCR and SACR at different thresholds in predicting adverse fetal outcomes

-

estimate the diagnostic utility of a SPCR test or a SACR test as a potential replacement for 24-hour protein estimation by developing a decision-analytic model

-

assess the cost-effectiveness using incremental cost per quality-adjusted life-year (QALY) gained by the mother and baby in each test compared with standard practice.

For the statistical analysis plan, these have been amended to:

-

evaluate the accuracy of POC assessments of SPCR and SACR at different thresholds in predicting severe PE compared with a 24-hour urine protein measurement

-

investigate differences between laboratory assay methods for 24-hour proteinuria

-

evaluate the accuracy of both quantitative and POC assessments of SPCR and SACR at different thresholds in predicting adverse perinatal outcomes.

Study design

This was a prospective cohort study to evaluate diagnostic accuracy, which also undertook a decision-analytic modelling and cost-effectiveness analysis. The study was open to recruitment for a total of 33 months. Research Ethics Service Committee A favourable opinion from the Research Ethics Committee was sought and granted for the original study (reference number 12/NE/0301) from the National Research Ethics Service Committee North East – County Durham & Tees Valley. This became the National Research Ethics Service Committee North East – Newcastle and North Tyneside 2 for subsequent amendments.

Setting

The study was conducted in a total of 36 obstetric units in England. The last day of study recruitment was on 30 November 2015. Data were collected prospectively; participants were sampled consecutively until the target sample size was reached.

Inclusion criteria

Pregnant women aged ≥ 16 years who were at > 20 weeks’ gestation with confirmed gestational hypertension (systolic BP of ≥ 140 mmHg and/or diastolic BP of ≥ 90 mmHg) and trace or greater of proteinuria on an automated dipstick urinalysis, who are able to given written informed consent.

Exclusion criteria

Women aged < 16 years or women with new hypertension but no proteinuria on automated dipstick urinalysis, proteinuria before 20 weeks’ gestation, pre-existing renal disease, pre-gestational diabetes and chronic hypertension. Women who were unable to provide written informed consent could not take part.

Identification and screening

Potential participants were identified from women during admission to the hospital in the maternity assessment unit, delivery suite or outpatient department, subject to meeting the study inclusion and exclusion criteria.

All eligible women were given a patient information sheet at their time of booking for antenatal care to read and consider. The information sheets were made available in Urdu and Polish, as these were two of the most commonly spoken languages in the participating sites.

During pregnancy, as part of routine care, women have their BP monitored and midwives checked protein in collected urine samples using a urine dipstick. Women with high BP and trace proteinuria (who had suspected PE) were referred to a day assessment unit for regular check-ups. During a regular check-up, BP was measured and urine protein was assessed from another urine sample (POC sample) using a dipstick and an automated urinalysis machine. Women with confirmed hypertension and a trace or more of protein in this sample were eligible for the study and invited to participate by a research midwife.

Recruitment and consent

All women had the opportunity to ask questions about the study. Study discussions were undertaken by the research midwives or research nurses as per the site delegation log. If willing, written informed consent was obtained from the woman by a delegation member of the study team. The original signed consent form was held in the investigator site file, with a copy of it placed in the medical notes and a copy given to the participant.

It was clearly stated that the woman had the right to withdraw her participation at any point in the study without having to give a reason.

Reference standards and other outcomes

Severe pre-eclampsia (National Institute for Health and Care Excellence definition)

Following the 2010 NICE definition,1 severe PE was defined as either (1) severe hypertension (systolic BP of ≥ 160 mmHg or diastolic BP of ≥ 110 mmHg) and proteinuria (see Proteinuria), or (2) mild or moderate hypertension (systolic BP of ≥ 140 mmHg and/or diastolic BP of ≥ 90 mmHg) and proteinuria with one or more of the following: severe headache, visual disturbances, problems with vision, severe pain just below the ribs or vomiting, papilloedema, signs of clonus (three or more beats), liver tenderness, HELLP (Haemolysis, Elevated Liver enzymes, Low Platelets) syndrome, platelet levels below 100 × 109/l or abnormal liver enzyme levels [alanine aminotransferase (ALT) or aspartate aminotransferase (AST) levels of > 70 U/l].

Proteinuria

Proteinuria was defined as ≥ 300 mg of protein from a 24-hour urine collection using the central laboratory’s (Kent) BZC assay.

Severe pre-eclampsia (clinician diagnosis)

A clinician diagnosis of severe PE was defined as when a woman was treated with magnesium sulphate or put on a severe PE protocol.

Adverse perinatal outcome

A composite adverse perinatal outcome was identified by a Delphi survey of clinicians. This comprises one or more of the following: perinatal or infant mortality, bronchopulmonary dysplasia, necrotising enterocolitis or grade III or IV intraventricular haemorrhage. The definition used for bronchopulmonary dysplasia was oxygen dependence at 36 weeks’ postmenstrual age (gestational age at delivery plus chronological age of baby).

Sample size

The sample size for the study was chosen to allow for a demonstration that a quantitative assessment of SPCR or SACR at a given cut-off point could safely rule out the possibility of severe PE. In diagnostic testing terms, this means a test with a LR– of ≤ 0.1 and a sensitivity of at least 90% with high specificity. Previous studies have suggested that SPCR or SACR testing (when fully quantitative) may achieve this. 16

To demonstrate with 80% power that sensitivity is at least 90% within 95% confidence limits, assuming that sensitivity is actually 95%, requires 240 women with severe PE, as determined using the power one proportion command in Stata version 13 (Stata Corporation, College Station, TX, USA). The original sample size calculation assumed that 5% of recruited women would develop severe PE, with a negligible number of missing outcome data, and the recruitment target was, therefore, set at 3000 women with new hypertension and suspected PE.

Following indications in interim reports that the prevalence of PE may be higher than expected, the Trial Steering Committee recommended that the proportion of women with severe PE should be estimated from the first 500 participants to be recruited and that the target sample size should be re-estimated on this basis. Because the laboratory assessments needed to determine severe PE, as defined in the protocol, were not available for all participants (namely liver function results and platelet counts), it was necessary to use a surrogate definition of PE that was agreed with the Trial Steering Committee. In total, 419 participants out of the first 500 women had sufficient data to determine this surrogate outcome, and prevalence was estimated to be 78 out of 500 (15.6%). With the additional assumption that 14% of participants would have missing data on the primary outcome in the final analysis (also based on an interim analysis), the recruitment target was revised to 1790 women with new hypertension and suspected PE.

Data collection

Urine samples

A small amount of urine (five 1-ml aliquots) was taken from each participant’s POC sample, frozen and stored at –80 °C for secondary analysis. The remainder of the POC sample was sent to the local laboratory to obtain quantitative assessments of SPCR.

Participants were then asked to collect urine for 24 hours in a collection container provided by the research midwife. The research midwife gave detailed instructions on when the collection should start and finish. The start of 24-hour urine collection could be up to 24 hours after the POC test. When a woman returned her 24-hour urine sample, a small amount (five 1-ml aliquots) was frozen and stored at –80 °C. If clinically indicated from the initial recruitment urine sample, the remainder of the 24-hour urine sample was sent to the local biochemical laboratory to determine the 24-hour measurement of proteinuria.

Participants were asked for a third, and final, urine sample immediately before delivery and, again, five 1-ml aliquots were stored at –80 °C (delivery urine).

The aliquots of urine were sent from each of the participating sites to a central laboratory, East Kent Hospitals Trust, for analysis using standardised methods. All data were entered into a clinical data management software package supplied by MedSciNet (Stockholm, Sweden) that was configured to allow web-based entry from each of the 36 clinical sites as well as the Kent laboratory.

Clinical information and POC test results were not available to the central laboratory that conducted assessments of 24-hour proteinuria.

Medical notes

Demographic characteristics, medical history and other characteristics measured at baseline (including referral to the day assessment unit) were obtained from participants’ medical notes.

Information, other than proteinuria, that was needed to determine a diagnosis of severe PE was obtained from participants’ medical notes.

Information to determine adverse perinatal outcome was collected at birth and discharge from hospital from the hospital case notes. Neonatal outcome data for the small number of babies admitted to the neonatal unit were obtained by the midwives employed in each unit. When a mother or baby was transferred to another neonatal unit, data were collected (when possible) from all the hospitals that provided their care.

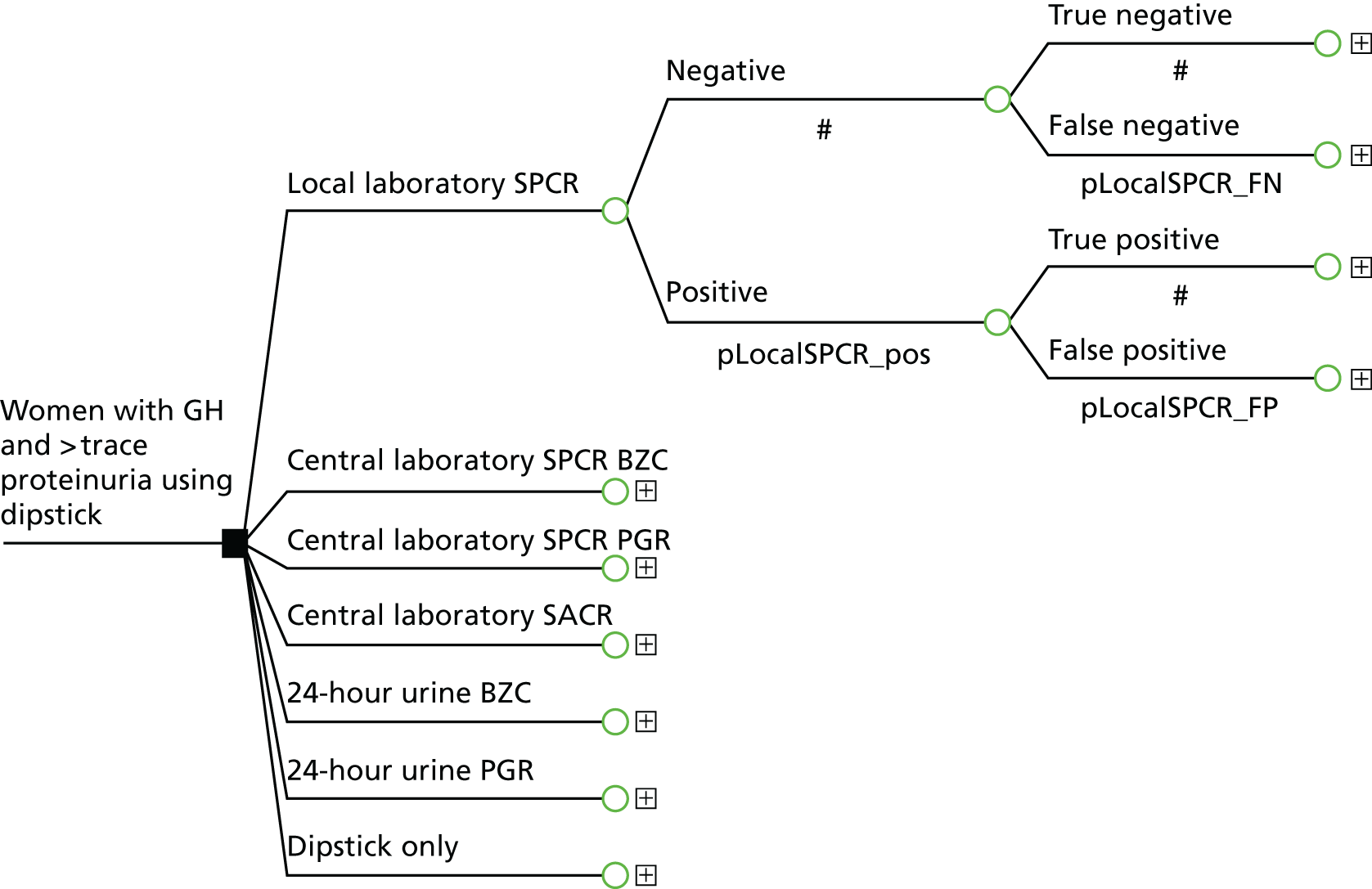

Primary analysis

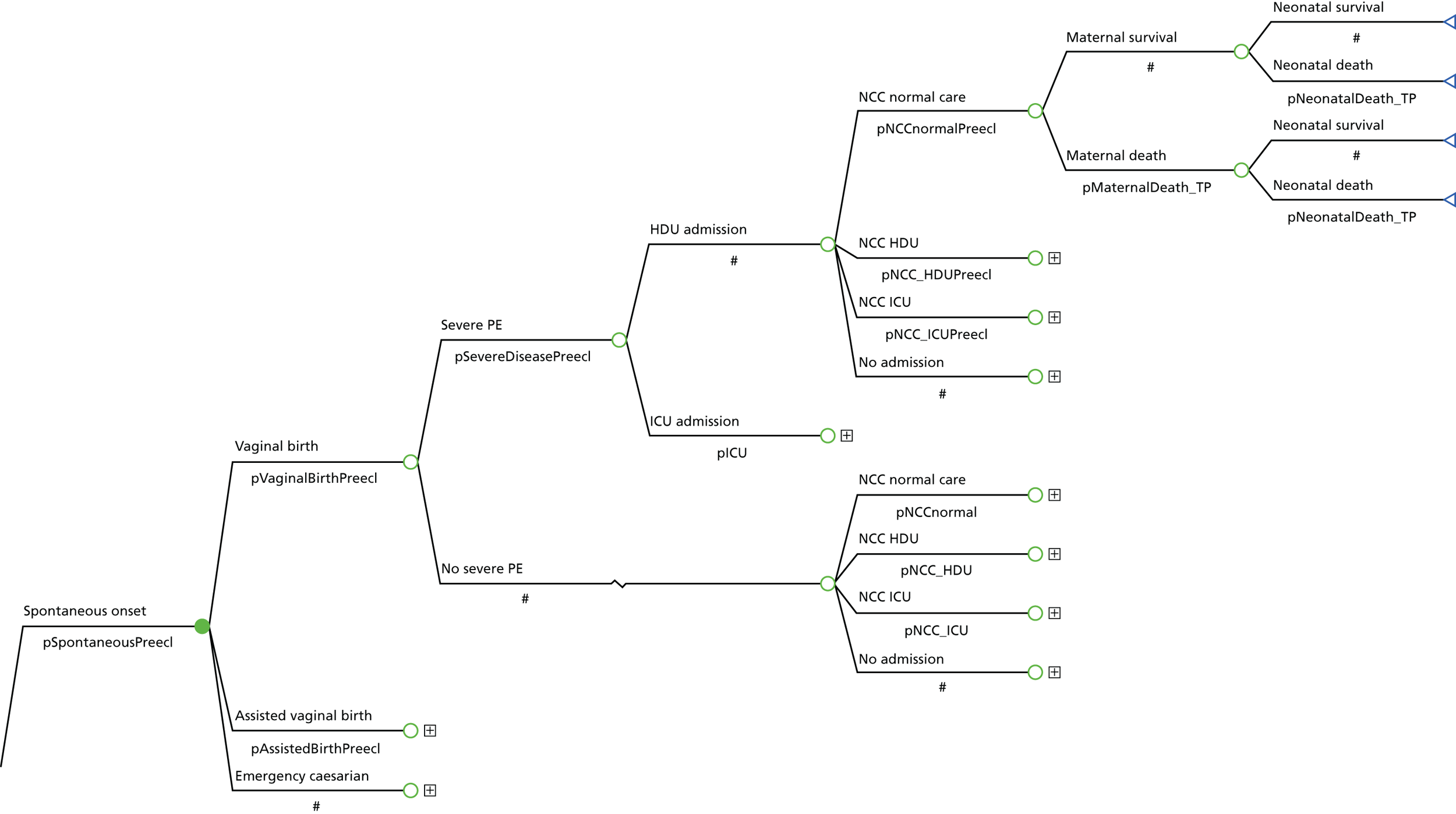

Using quantitative assessments of SPCR and SACR as index tests and the NICE definition of severe PE as the reference standard, non-parametric receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves were plotted, showing diagnostic performance at different cut-off points. 20

This primary analysis used the central laboratory’s (Kent) BZC total protein assay from the 24-hour urine sample to determine PE, and was conducted for each of the following assays using the spot urine sample at recruitment:

-

a SPCR test from a local laboratory

-

a SPCR test using the BZC assay at a central laboratory (Kent)

-

a SPCR test using the pyrogallol red (PGR) assay at a central laboratory (Kent)

-

a SACR test from a central laboratory (Kent).

Diagnostic accuracy was summarised using the area under the ROC curve, as well as sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value, negative predictive value, and LR+ and LR– at prespecified cut-off points (30 mg/mmol for SPCR12 and 2 mg/mmol for SACR). 16

Areas under the ROC curves for the quantitative SPCR and SACR assays were compared using the non-parametric method of DeLong et al. 21 to give a CI and significance test for the difference in area, with SPCR testing from a local laboratory as the comparator. Sensitivity and specificity at the prespecified cut-off points were compared using McNemar tests for paired proportions.

These analyses were restricted to the subsample for which the 24-hour urine sample result and the four assays were all non-missing.

Secondary analyses

Point-of-care dipstick test

The POC test using the urine dipstick proteinuria result at recruitment was analysed to determine its diagnostic performance, using the same methods and reference standard as the primary analysis (restricted to the subsample for which the 24-hour urine sample result and dipstick test result were both non-missing), and using the standard threshold of 1+. 16

Proteinuria as reference standard

The primary analysis was repeated using proteinuria [≥ 300 mg/24 hours using the central laboratory’s (Kent) BZC assay] as the reference standard in place of severe PE (NICE definition). 1

Severe pre-eclampsia (clinician diagnosis) as reference standard

The primary analysis was repeated using clinician diagnosis of severe PE [magnesium sulphate or severe pre-eclamptic toxaemia (PET) protocol] as the reference standard in place of the NICE definition. The central laboratory’s BZC and PGR assays using the 24-hour urine sample were also included as index tests in this analysis, as they were not part of the definition of the reference standard.

The two definitions of severe PE (clinician diagnosis and NICE definition) were cross-tabulated.

Prediction of adverse perinatal outcome

The four assays of the urine sample at recruitment and two assays of the 24-hour urine sample were analysed to see how well they predicted adverse perinatal outcomes, using the same methods as the primary analysis.

Receiver operating characteristic curves were plotted separately for the following as predictors of adverse perinatal outcomes:

-

change in SPCR from recruitment to delivery spot urine samples assessed using the BZC assay at the central laboratory (Kent)

-

maximum SPCR from recruitment and delivery spot urine samples assessed using the BZC assay at the central laboratory (Kent).

These ROC curves were compared with the ROC curve for the central laboratory’s BZC assay of the recruitment sample.

No cut-off points were specified a priori for the last two, and these analyses were considered exploratory.

Subgroup analysis

The primary analysis was repeated on the subgroup of women with 1+ or higher on the POC dipstick test, that is excluding those with a ‘trace’ result only. This is the population of women who would currently be referred for further testing.

Laboratory assay method for 24-hour proteinuria

The primary analysis was repeated using the central laboratory’s (Kent) PGR assay instead of the assay in the NICE definition of severe PE.

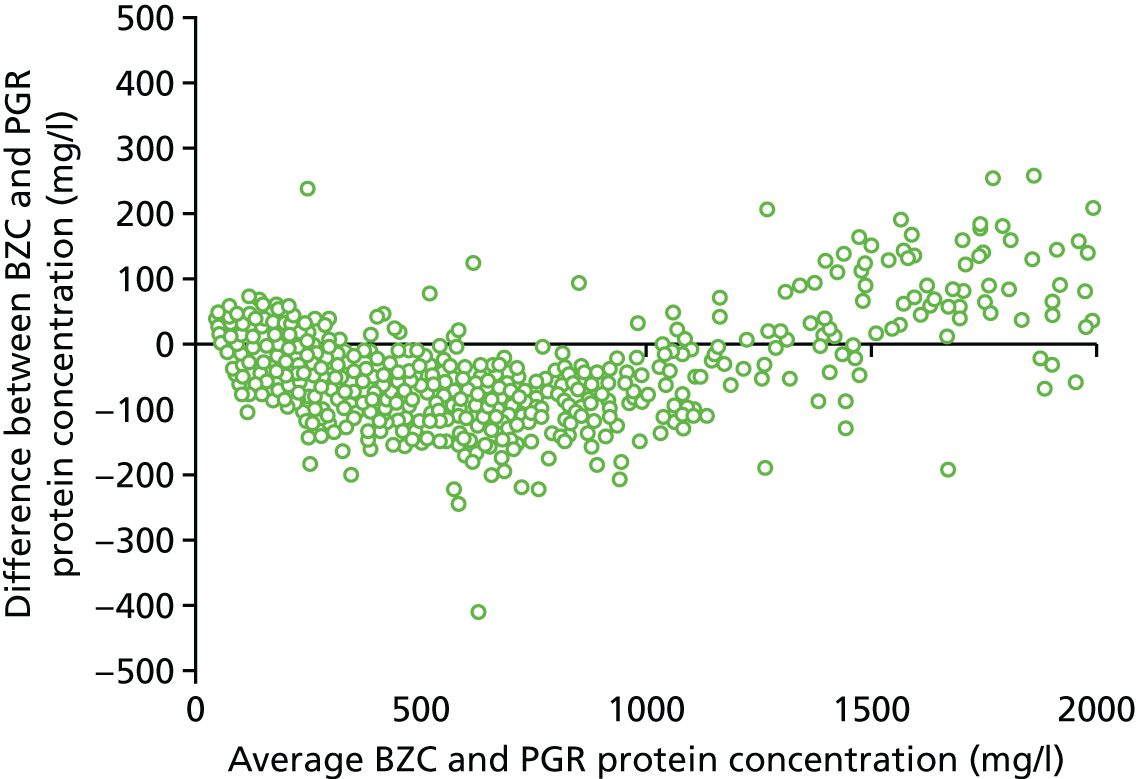

The two definitions of severe PE (using the BZC and PGR assays) were cross-tabulated. Exploratory investigation of the agreement between the central laboratory’s (Kent) BZC and PGR assays of total protein from the 24-hour urine sample was undertaken using a Bland–Altman plot. 22

Changes to the protocol

Owing to the availability of POC testing in the UK and the availability and cost of the equipment needed, the SPCR and fully quantitative SACR POC tests that were stated in the original study protocol were not undertaken. This change was covered in substantial amendment 2 , which was added in version 2.0 of the protocol, dated 7 April 2015. It is hoped that this can be completed as a separate piece of work in the future.

Chapter 3 Results

For the DAPPA (spot protein–creatinine ratio and spot albumin–creatinine ratio in the assessment of pre-eclampsia: a diagnostic accuracy study with decision-analytic model-based economic evaluation and acceptability analysis) trial timeline and key milestones see Appendix 1.

Participant flow

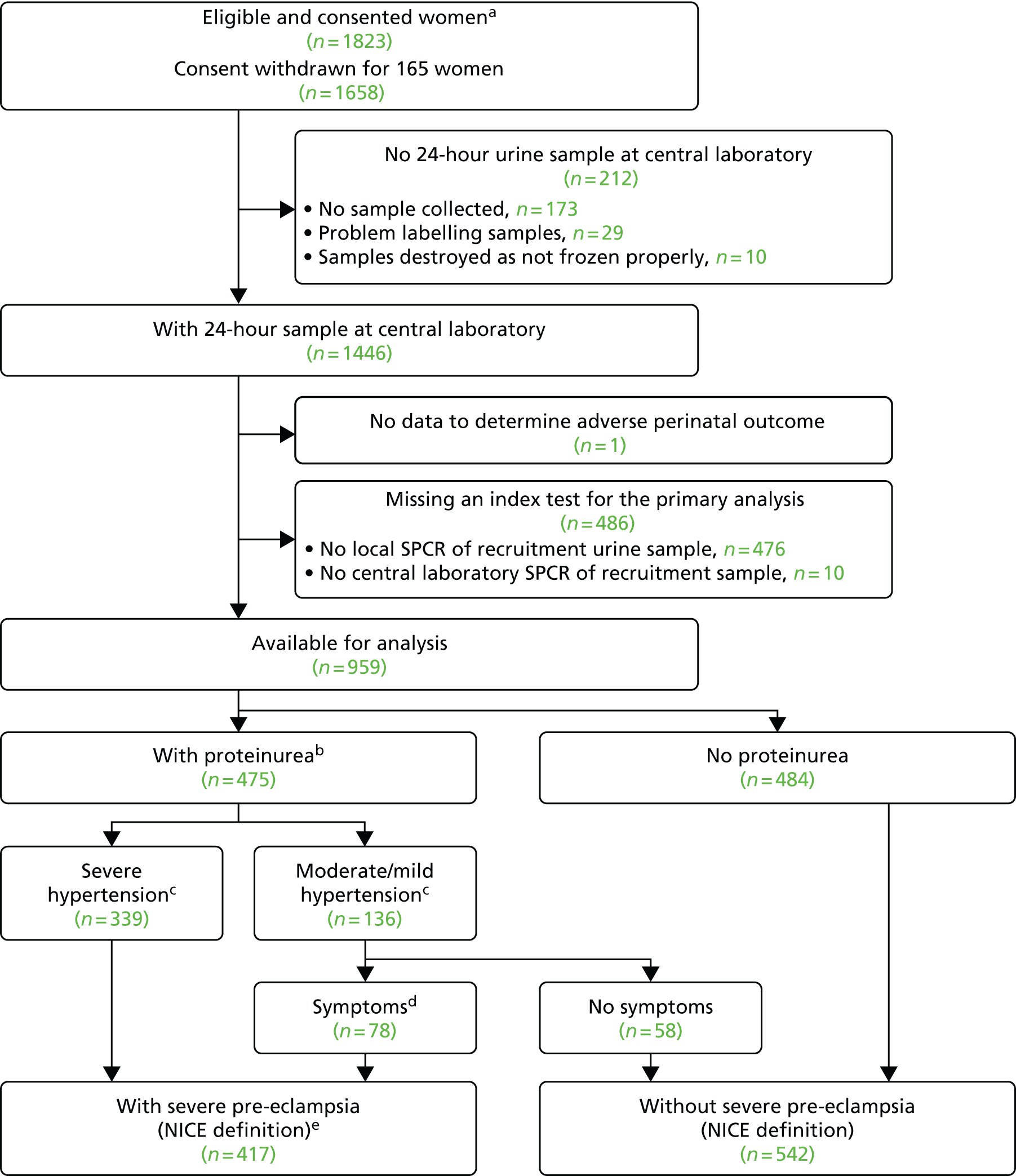

The number of eligible participants consented and recruited was 1823. In total, 165 women had to be withdrawn because they withdrew consent, refused or were unable to collect any samples after recruitment, or the samples were collected but not frozen.

There were 1658 women who had completed patient records for inclusion in the final database. However, the central laboratory’s test results for urinary protein in the 24-hour urine sample were not available for 212 women, leaving 1446 women for whom the primary outcome of severe PE could be determined (Figure 1). The prevalence of severe PE in these women was 44% (638/1446). Note that even assuming that none of the 212 women with missing test results developed severe PE, the prevalence of severe PE in the 1658 eligible and consented women would still have been 38% (638/1658).

FIGURE 1.

Participant flow chart showing the number of eligible and consented women, the number for whom a diagnosis of severe PE using the NICE definition could be determined, the number included in the primary analysis and the number with severe PE. a, > 20 weeks’ gestation with confirmed gestational hypertension (systolic BP of ≥ 140 mmHg or diastolic BP of ≥ 90 mmHg) and trace or more proteinuria on automated dipstick analysis; b, 24-hour urine sample (the central laboratory’s BZC assay) total protein concentration of ≥ 300 mg; c, severe – systolic BP of ≥ 160 mmHg or diastolic BP of ≥ 110 mmHg, mild/moderate – systolic BP of ≥ 160 mmHg or diastolic BP of ≥ 110 mmHg; d, severe headache, visual disturbances, problems with vision, severe pain just below the ribs or vomiting, papilloedema, signs of clonus (three or more beats), liver tenderness, HELLP syndrome, platelet levels below 100 × 109/l, abnormal liver enzyme levels (ALT or AST level of > 70 U/l); e, either (1) severe hypertension and proteinuria or (2) mild/moderate hypertension and proteinuria with one or more symptoms.

Unfortunately, local laboratory SPCR testing of the recruitment urine sample was not available for 476 women, and a further 10 women had missing central laboratory SPCR test data for the recruitment urine sample (see Figure 1). To compare the diagnostic accuracy of the four assays (three central laboratory and one local laboratory) on the recruitment urine sample, the analysis was restricted to those women with data for all four assays, and excluded one other woman with missing adverse perinatal outcome (n = 959). The prevalence of severe PE in this subsample was 43% (417/959), similar to the prevalence in the 1446 women with 24-hour urine protein sample data.

Characteristics of participants

The number of women by centre is shown in Table 1, for eligible and consented women, for women for whom a diagnosis of severe PE using the NICE definition could be determined, and for women included in the primary analysis. Baseline characteristics, including demographics, concurrent medication, medical history and family history, are summarised in Table 2. BP at recruitment and spot urine protein, creatinine and SPCR at recruitment are summarised in Table 3.

| Centre | Trust | Number (%) of women | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Eligible and consented (N = 1658) | Diagnosis of severe PE could be determined (N = 1446) | Included in the primary analysis (N = 959) | ||

| Royal Victoria Infirmary | The Newcastle upon Tyne Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust | 218 (13) | 175 (12) | 170 (18) |

| Whipps Cross, Newham and The Royal London | Barts Health NHS Trust | 131 (8) | 116 (8) | 103 (11) |

| St Thomas’ Hospital | Guy’s and St Thomas’ NHS Foundation Trust | 128 (8) | 120 (8) | 84 (9) |

| James Cook University Hospital | South Tees Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust | 87 (5) | 70 (5) | 42 (4) |

| North Tyneside General Hospital | Northumbria Healthcare NHS Foundation Trust | 86 (5) | 61 (4) | 42 (4) |

| Sunderland Royal Hospital | City Hosptials Sunderland NHS Foundation Trust | 77 (5) | 72 (5) | 67 (7) |

| John Radcliffe Hospital | Oxford University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust | 61 (4) | 60 (4) | 1 (< 1) |

| Warrington Hospital | Warrington and Halton Hospital NHS Foundation Trust | 61 (4) | 51 (4) | 23 (2) |

| Royal Shrewsbury Hospital | Shrewsbury and Telford Hospital NHS Trust | 58 (4) | 58 (4) | 28 (3) |

| St George’s Hospital | St George's University Hospital NHS Foundation Trust | 50 (3) | 42 (3) | 26 (3) |

| Queen’s Hospital | Burton Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust | 49 (3) | 49 (3) | 25 (3) |

| Milton Keynes Hospital | Milton Keynes University Hospital NHS Foundation Trust | 45 (3) | 40 (3) | 27 (3) |

| Royal Cornwall Hospital | Royal Cornwall Hospital NHS Trust | 44 (3) | 42 (3) | 36 (4) |

| St James’s University Hospital | The Leeds Teaching Hospitals NHS Trust | 41 (2) | 41 (3) | 21 (2) |

| Queen Alexandra Hospital | Portsmouth Hospitals NHS Trust | 41 (2) | 29 (2) | 26 (3) |

| Queen Elizabeth Hospital | Gateshead Health NHS Foundation Trust | 37 (2) | 28 (2) | 20 (2) |

| Leicester Royal Infirmary | University Hospitals of Leicester NHS Trust | 35 (2) | 23 (2) | 22 (2) |

| St Mary’s Hospital | Central Manchester University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust | 32 (2) | 32 (2) | 32 (3) |

| Southport and Ormskirk Hospital | Southport and Ormskirk Hospital NHS Trust | 31 (2) | 30 (2) | 27 (3) |

| University Hospital of North Tees | North Tees and Hospital NHS Foundation Trust | 30 (2) | 30 (2) | 15 (2) |

| Queen's Medical Centre | Nottingham University Hospitals NHS Trust | 28 (2) | 26 (2) | 10 (1) |

| St Michael’s Hospital | University Hospital Bristol NHS Foundation Trust | 27 (2) | 24 (2) | 21 (2) |

| North Manchester Hospital | The Pennine Acute Hospitals NHS Trust | 27 (2) | 24 (2) | 0 (0) |

| Royal Derby Hospital | Derby Teaching Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust | 25 (2) | 24 (2) | 15 (2) |

| Norfolk and Norwich University Hospital | Norfolk and Norwich University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust | 25 (2) | 20 (1) | 3 (< 1) |

| Queen Charlotte and Chelsea Hospital | Imperial College Healthcare NHS Trust | 24 (1) | 17 (1) | 12 (1) |

| South Tyneside District Hospital | South Tyneside NHS Foundation Trust | 23 (1) | 20 (1) | 9 (1) |

| Royal Blackburn Hospital and Burnley General Hospital | East Lancashire Hospitals NHS Trust | 21 (1) | 16 (1) | 11 (1) |

| Colchester General Hospital | Colchester Hospital University NHS Foundation Trust | 19 (1) | 18 (1) | 16 (2) |

| Derriford Hospital | Plymouth Hospitals NHS Trust | 18 (1) | 17 (1) | 0 (0) |

| Arrow Park Hospital | Wirral University Teaching Hospital NHS Foundation Trust | 15 (1) | 12 (1) | 8 (1) |

| Nottingham City Hospital | Nottingham University Hospitals NHS Trust | 14 (1) | 13 (1) | 1 (< 1) |

| Worcestershire Royal Hospital | Worcestershire Acute Hospitals NHS Trust | 13 (1) | 10 (1) | 9 (1) |

| Cumberland Infirmary | North Cumbria University Hospitals NHS Trust | 12 (1) | 12 (1) | 0 (0) |

| University Hospital of North Durham | County Durham & Darlington NHS Foundation Trust | 11 (1) | 11 (1) | 5 (1) |

| Stafford Hospital | University Hospitals of North Midlands NHS Trust (previously Mid Staffordshire) | 8 (< 1) | 8 (1) | 2 (< 1) |

| Peterborough City Hospital | North West Anglia NHS Foundation Trust | 6 (< 1) | 5 (< 1) | 0 (0) |

| Demographic criteria | Eligible, consented (not withdrawn) (N = 1658) | Diagnosis of severe PE (NICE definition) could be determined (N = 1446) | Included in primary analysis (N = 959) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | |||

| Median (quartiles) | 30 (25, 34) | 30 (25, 34) | 30 (26, 34) |

| Weight (kg) | |||

| Median (quartiles) | 76 (65, 91) | 76 (65, 91) | 76 (64, 90) |

| Height (cm) | |||

| Median (quartiles) | 164 (160, 168) | 164 (160, 168) | 164 (160, 168) |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | |||

| Median (quartiles) | 28 (24, 34) | 28 (24, 34) | 28 (24, 33) |

| Country of origin, n (%) | |||

| UK | 1219 (74) | 1059 (73) | 706 (74) |

| Africa | 93 (6) | 88 (6) | 59 (6) |

| Eastern European | 82 (5) | 71 (5) | 38 (4) |

| Other | 59 (4) | 52 (4) | 31 (3) |

| Western European | 44 (3) | 36 (2) | 19 (2) |

| Pakistan | 37 (2) | 34 (2) | 29 (3) |

| India | 36 (2) | 31 (2) | 22 (2) |

| Bangladesh | 32 (2) | 28 (2) | 20 (2) |

| Caribbean | 28 (2) | 22 (2) | 17 (2) |

| South East Asia | 14 (1) | 11 (1) | 8 (1) |

| Middle East | 8 (< 1) | 8 (1) | 6 (1) |

| China | 6 (< 1) | 6 (< 1) | 4 (< 1) |

| Family history, n (%) | |||

| PE | 266 (16) | 237 (16) | 166 (17) |

| Hypertension/cardiovascular disease | 692 (42) | 609 (42) | 408 (43) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 569 (34) | 500 (35) | 328 (34) |

| Renal disease | 37 (2) | 32 (2) | 24 (2) |

| Taking aspirin | 373 (22) | 336 (23) | 213 (22) |

| Number of previous pregnancies beyond 20 weeks’ gestation, n (%) | |||

| 0 | 1066 (64) | 937 (65) | 616 (64) |

| 1 | 344 (21) | 300 (21) | 203 (21) |

| 2 | 151 (9) | 131 (9) | 85 (9) |

| 3 | 48 (3) | 38 (3) | 29 (3) |

| 4 | 29 (2) | 26 (2) | 19 (2) |

| 5 | 10 (1) | 8 (1) | 4 (< 1) |

| ≥ 6 | 10 (1) | 6 (< 1) | 3 (< 1) |

| Number of previous pregnancies of 20 weeks’ gestation or less (including terminations), n (%) | |||

| 0 | 1163 (70) | 1002 (69) | 664 (69) |

| 1 | 337 (20) | 308 (21) | 209 (22) |

| 2 | 85 (5) | 71 (5) | 45 (5) |

| 3 | 43 (3) | 38 (3) | 24 (2) |

| 4 | 16 (1) | 13 (1) | 5 (1) |

| ≥ 5 | 14 (1) | 14 (1) | 12 (1) |

| Previous hypertension in pregnancy | 298 (18) | 264 (18) | 183 (19) |

| Symptoms at recruitment, n (%) | |||

| Headache | 666 (40) | 572 (40) | 381 (40) |

| Nausea | 222 (13) | 189 (13) | 137 (14) |

| Vomiting | 81 (5) | 71 (5) | 53 (6) |

| Epigastric pain | 176 (11) | 148 (10) | 97 (10) |

| Visual disturbance | 294 (18) | 251 (17) | 175 (18) |

| Reduced fetal movements | 123 (7) | 106 (7) | 74 (8) |

| Measurement | Median (quartiles) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Eligible and consented (n = 1658) | Diagnosis of severe PE could be determined (n = 1446) | Included in primary analysis (n = 959) | |

| Systolic BP (mmHg) | 145 (140, 152) | 145 (140, 152) | 145 (140, 152) |

| Diastolic BP (mmHg) | 94 (90, 99) | 94 (90, 99) | 94 (90, 100) |

| Urine protein concentration (mg/l)a | 510 (250, 1420) | 520 (250, 1405) | 520 (250, 1360) |

| Urine creatinine concentration (mmol/l)a | 12 (7, 18) | 12 (7, 18) | 12 (7, 18) |

| Urine protein–creatinine ratio (mg/mmol)a | 46 (22, 132) | 46 (22, 131) | 46 (22, 129) |

Reference standards and other outcomes

Reference standards and perinatal outcomes are summarised in Table 4 for women included in the primary analysis.

| Standard and outcome | Number of women (%) (n = 959) |

|---|---|

| Severe PE (the NICE definition) | 417 (43) |

| Proteinuria | 475 (50) |

| Severe PE (the clinician diagnosis) | 193 (20) |

| Eclampsia | 30 (3) |

| Gestational age < 36 weeks | 223 (23) |

| Median (weeks) | 37 |

| Interquartile range (weeks) | 36–39 |

| Range (weeks) | 23–43 |

| Multiple birthsa | 53 (6) |

| Adverse perinatal outcome | 62 (6) |

| Perinatal/neonatal mortality | 18 (2) |

| Bronchopulmonary dysplasia | 27 (3) |

| Necrotising enterocolitis | 7 (1) |

| Intraventricular haemorrhage | 16 (2) |

Only 32% (134/417) of the women who met the NICE definition of severe PE had a clinician diagnosis of severe PE, and, in addition, 11% (59/542) of women who did not meet the NICE definition had a clinician diagnosis (Table 5).

| Clinical diagnoses, number of women | NICE definition, number of women | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Without severe PE | With severe PE | Total | |

| Without severe PEa | 483 | 283 | 766 |

| With severe PEa | 59 | 134 | 193 |

| Total | 542 | 417 | 959 |

The majority (149/193, 77%) of those with a clinician diagnosis of severe PE had both magnesium sulphate treatment and followed a severe PE protocol (Table 6).

| PET protocol, number of women | Treatment, number of women | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Without magnesium sulphate | With magnesium sulphate | Total | |

| Without severe | 766 | 13 | 779 |

| With severe | 31 | 149 | 180 |

| Total | 797 | 162 | 959 |

Of the 417 women with severe PE according to the NICE definition, 8% had an adverse perinatal outcome compared with 5% of women without severe PE (p = 0.033) (Table 7). Of the 193 women with a clinician diagnosis of severe PE, 15% had an adverse perinatal outcome, compared with 4% of women without a clinician diagnosis of severe PE (p < 0.001) (Table 8).

| NICE definition, number of women | Perinatal outcome, number of women | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Without adverse | With adverse | Total | |

| Without severe PE | 515 | 27 | 542 |

| With severe PE | 382 | 35 | 417 |

| Total | 897 | 62 | 959 |

| Clinician diagnosed, number of women | Perinatal outcome, number of women | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Without adverse | With adverse | Total | |

| Without severe PEa | 732 | 34 | 766 |

| With severe PEa | 165 | 28 | 193 |

| Total | 897 | 62 | 959 |

Table 9 shows the prevalence of severe PE (according to both definitions) and adverse perinatal outcomes separately for women aged < 35 years and for women aged ≥ 35 years, and also separately for women aged < 40 years and for women aged ≥ 40 years.

| Women affected by | Age (years), n (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| < 35 (N = 729) | ≥ 35 (N = 230) | < 40 (N = 907) | ≥ 40 (N = 52) | |

| Severe PE (NICE definition) | 329 (45) | 88 (38) | 399 (44) | 18 (35) |

| Severe PE (clinician diagnosis) | 147 (20) | 46 (20) | 186 (21) | 7 (13) |

| Adverse perinatal outcome | 51 (7) | 11 (5) | 62 (7) | 0 (0) |

Primary analysis

The diagnostic accuracy of the four assays using the spot urine sample at recruitment was compared using prespecified thresholds of 30 mg/mmol for SPCR and 2 mg/mmol for SACR. Tables 10–13 show index test results cross-tabulated against the reference standard (severe PE, NICE definition). Sensitivities, specificities, LR+s and LR–s are shown in Table 14. The three SPCR tests all had sensitivity in excess of 90% at the prespecified thresholds but with poor specificity. The central laboratory’s SACR test had significantly higher sensitivity (99%, 95% CI 98% to 100%) than the local laboratory’s SPCR test, but its specificity (23%, 95% CI 20% to 27%) was significantly lower. The high sensitivities and LR–s of ≤ 0.1 suggest that all of the tests could be used as rule-out tests for severe PE (NICE definition). From Tables 10–13 the negative predictive values of each of the three SPCR tests was 92–93% (98% for the SACR test), so a negative result from one of these tests brings the risk of developing severe PE down to 7–8% (2% for the SACR test), compared with the pre-test risk of 43%.

| Threshold (mg/mmol) | Number of women | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Without severe PE | With severe PE | Total | |

| < 30 | 309 | 27 | 336 |

| ≥ 30 | 233 | 390 | 623 |

| Total | 542 | 417 | 959 |

| Threshold (mg/mmol) | Number of women | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Without severe PE | With severe PE | Total | |

| < 30 | 333 | 29 | 362 |

| ≥ 30 | 209 | 388 | 597 |

| Total | 542 | 417 | 959 |

| Threshold (mg/mmol) | Number of women | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Without severe PE | With severe PE | Total | |

| < 30 | 302 | 22 | 324 |

| ≥ 30 | 240 | 395 | 635 |

| Total | 542 | 417 | 959 |

| Threshold (mg/mmol) | Number of women | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Without severe PE | With severe PE | Total | |

| < 2 | 126 | 3 | 129 |

| ≥ 2 | 416 | 414 | 830 |

| Total | 542 | 417 | 959 |

| Assay | Threshold | Sensitivity (%) (95% CI) | Specificity (%) (95% CI) | Likelihood ratios (95% CI) | p-value for comparison with the local laboratory’s SPCRa | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LR+ | LR– | Sensitivity | Specificity | ||||

| Local laboratory – SPCR | 30 mg/mmol | 94 (91 to 96) | 57 (53 to 61) | 2.18 (1.96 to 2.39) | 0.11 (0.07 to 0.16) | – | – |

| Central laboratoryb – SPCR via the BZC assay | 30 mg/mmol | 93 (90 to 95) | 61 (57 to 66) | 2.41 (2.15 to 2.68) | 0.11 (0.07 to 0.15) | 0.68 | 0.012 |

| Central laboratoryb – SPCR via the PGR assay | 30 mg/mmol | 95 (92 to 97) | 56 (51 to 60) | 2.14 (1.93 to 2.35) | 0.09 (0.06 to 0.13) | 0.30 | 0.47 |

| Central laboratoryb – SACR | 2 mg/mmol | 99 (98 to 100) | 23 (20 to 27) | 1.29 (1.23 to 1.35) | 0.03 (0.00 to 0.07) | < 0.0001 | < 0.0001 |

| POC – proteinuria dipstick test | 1+ | 98 (96 to 99) | 20 (17 to 24) | 1.22 (1.17 to 1.28) | 0.11 (0.04 to 0.18) | 0.001 | < 0.0001 |

Because we used a cut-off point for SACR of 2 mg/mmol based on published work in pregnancy,16 and we note that this is different from the cut-off point chosen in other clinical contexts, we performed a further analysis to examine whether or not a different cut-off point for SACR would have calibrated better with a cut-off point of 30 mg/mmol for SPCR, and to show how an alternative choice of cut-off point for the SPCR test would have affected sensitivity and specificity of these assays. Exploratory analyses are presented in Tables 15 and 16 for different cut-off points. These analyses suggest that a cut-off point of 8 mg/mmol for SACR achieves comparable diagnostic accuracy to a cut-off point of 30 mg/mmol for SPCR. Note that a cut-off point of 3.5 mg/mmol has been suggested in other contexts. 23

| Threshold (mg/mmol) | Assay and sample (SPCR) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Local laboratory | Central laboratorya via the BZC assay | Central laboratorya via the PGR assay | ||||

| Sensitivity (%) (95% CI) | Specificity (%) (95% CI) | Sensitivity (%) (95% CI) | Specificity (%) (95% CI) | Sensitivity (%) (95% CI) | Specificity (%) (95% CI) | |

| 10 | 100 (99 to 100) | 5 (3 to 7) | 100 (99 to 100) | 9 (7 to 12) | 100 (99 to 100) | 9 (6 to 11) |

| 20 | 97 (96 to 99) | 37 (32 to 41) | 98 (96 to 99) | 42 (38 to 46) | 99 (97 to 100) | 36 (32 to 40) |

| 30 | 94 (91 to 96) | 57 (53 to 61) | 93 (91 to 95) | 61 (57 to 66) | 95 (93 to 97) | 56 (52 to 60) |

| 40 | 88 (85 to 91) | 73 (69 to 77) | 88 (85 to 91) | 73 (69 to 77) | 90 (87 to 93) | 67 (63 to 71) |

| 50 | 82 (78 to 85) | 80 (76 to 83) | 82 (78 to 85) | 80 (76 to 83) | 85 (81 to 88) | 75 (71 to 79) |

| 60 | 77 (73 to 81) | 83 (79 to 86) | 77 (73 to 81) | 84 (81 to 87) | 79 (75 to 83) | 79 (76 to 83) |

| Threshold (mg/mmol) | Sensitivity (%) (95% CI) | Specificity (%) (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 100 (99 to 100) | 7 (5 to 9) |

| 2 | 99 (98 to 100) | 23 (20 to 27) |

| 3.5 | 99 (98 to 100) | 35 (31 to 39) |

| 8 | 96 (94 to 98) | 57 (53 to 61) |

| 16 | 89 (86 to 92) | 73 (69 to 76) |

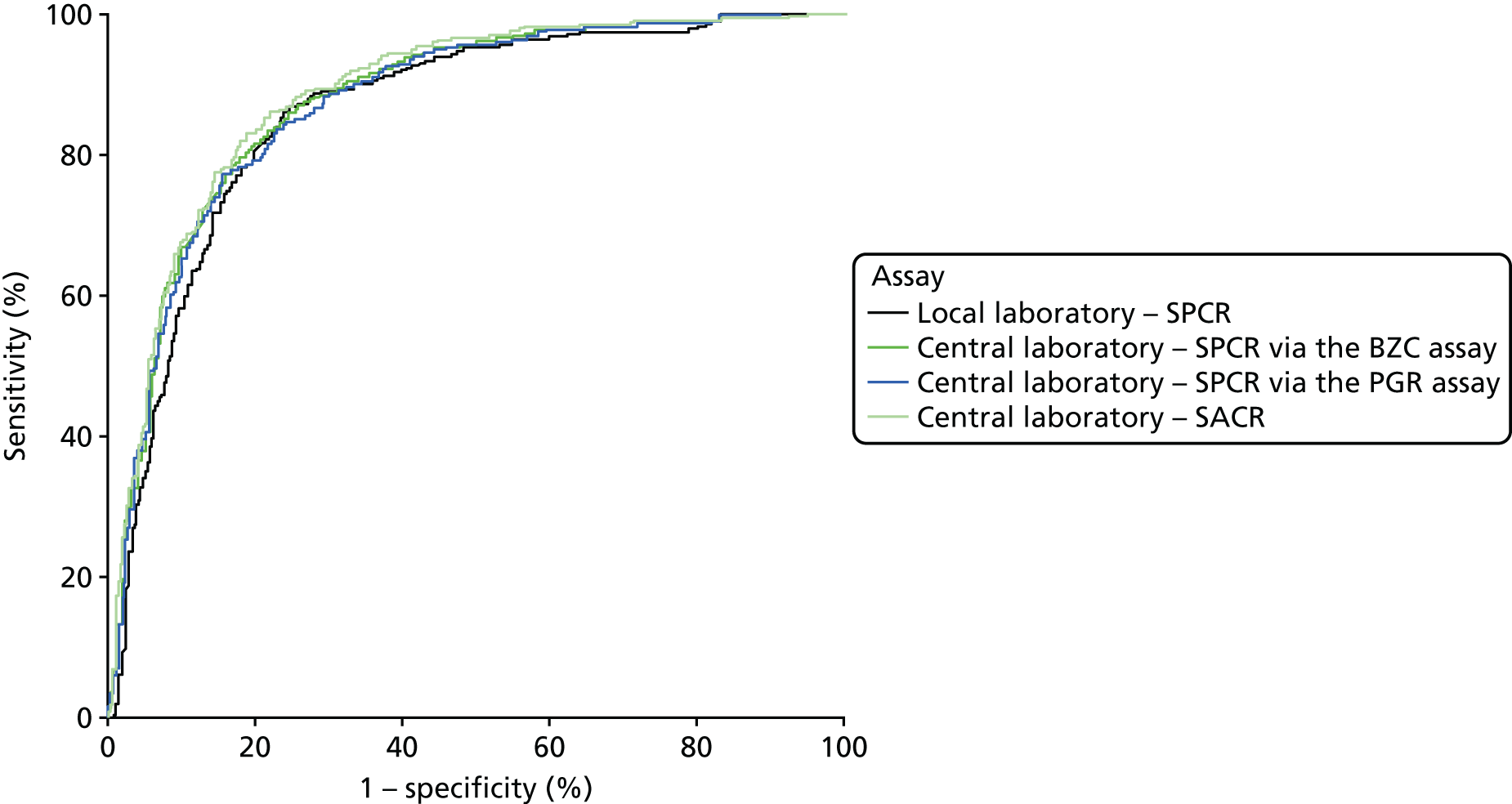

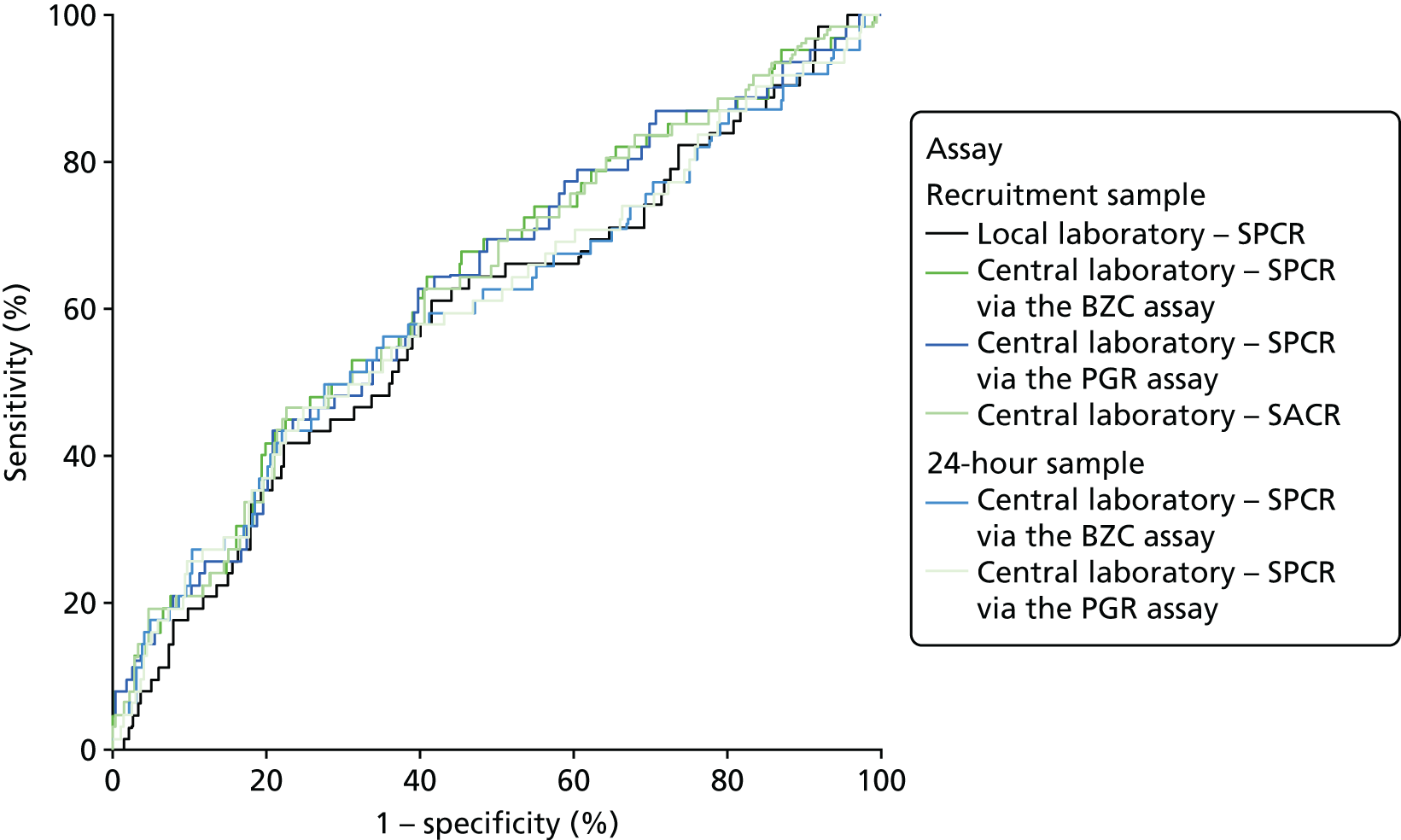

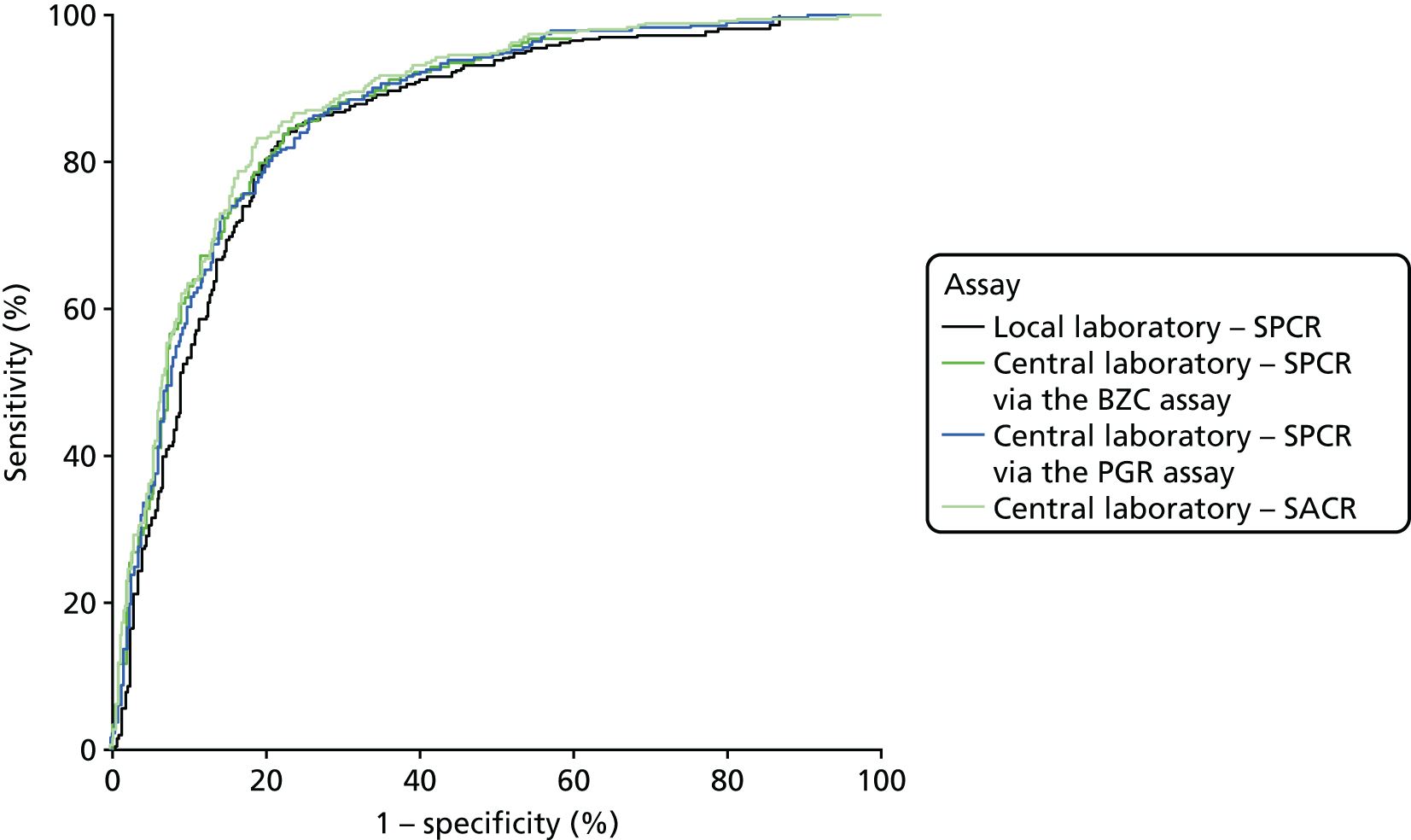

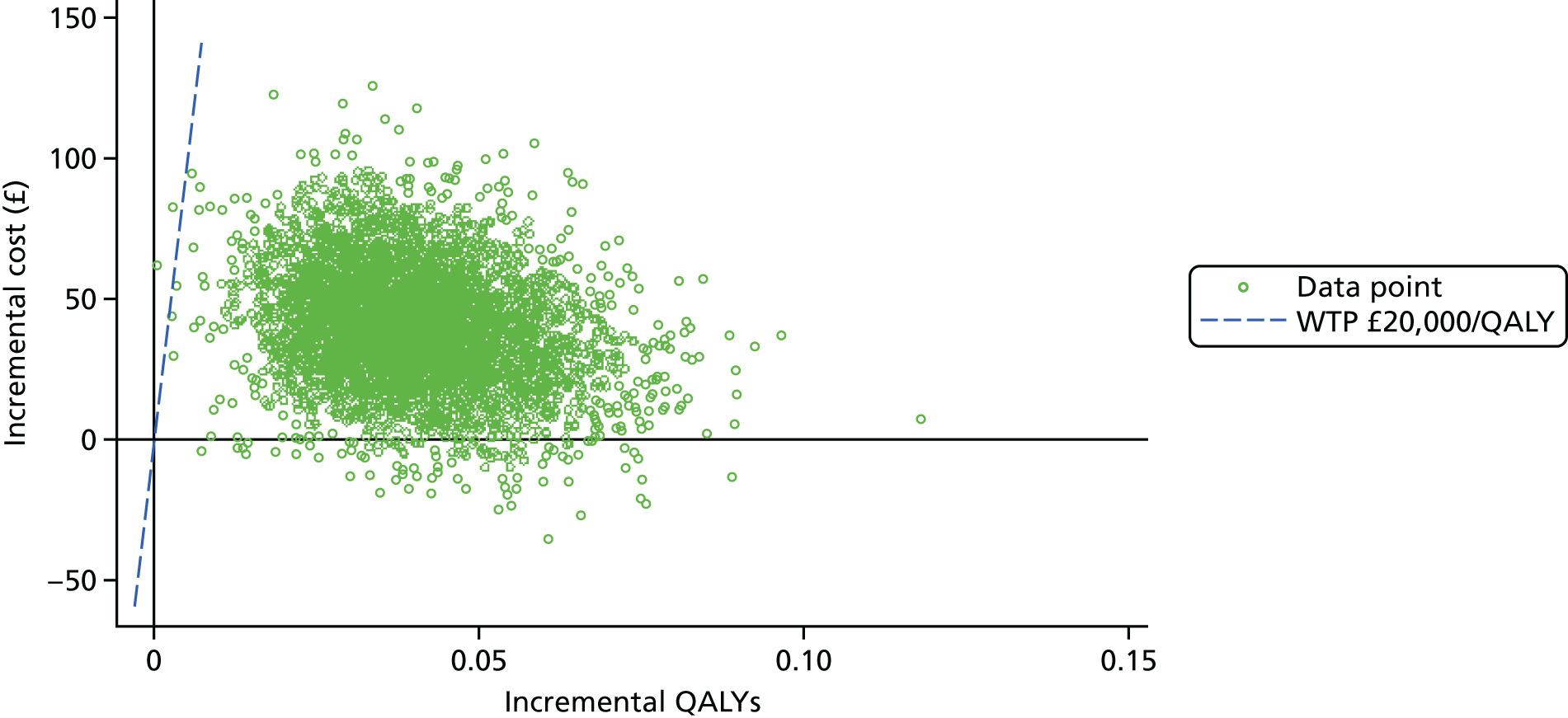

When overlain the ROC curves for the four assays were similar (Figure 2). The area under the central laboratory’s SACR assay curve was significantly greater than that for the local laboratory’s SPCR test, although the difference may not be of practical importance (0.02, 95% CI 0.01 to 0.04; p = 0.004) (Table 17).

FIGURE 2.

Receiver operating characteristic curves for the four assays of the recruitment urine sample used to diagnose severe PE (NICE definition).

| Assay | Area under ROC curve (95% CI) | Comparison with the local laboratory’s SPCR | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Difference (95% CI) | p-valuea | ||

| Local laboratory – SPCR | 0.87 (0.84 to 0.89) | – | – |

| Central laboratoryb – SPCR via the BZC assay | 0.88 (0.86 to 0.90) | 0.02 (0.00 to 0.03) | 0.057 |

| Central laboratoryb – SPCR via the PGR assay | 0.88 (0.85 to 0.90) | 0.01 (0.00 to 0.03) | 0.17 |

| Central laboratoryb – SACR | 0.89 (0.87 to 0.91) | 0.02 (0.01 to 0.04) | 0.004 |

Secondary analyses

Point-of-care dipstick test

The diagnostic accuracy of the POC urine proteinuria dipstick test at recruitment was investigated using a prespecified threshold of 1+. Table 18 shows this index test result cross-tabulated against the reference standard (NICE definition of severe PE). Sensitivity, specificity, LR+s and LR–s are shown in Table 14. As expected, the urine proteinuria dipstick at this threshold had high sensitivity (98%, 95% CI 96% to 99%) but low specificity (20%, 95% CI 17% to 24%).

| Threshold | Number of women | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Without severe PE | With severe PE | Total | |

| Trace | 108 | 9 | 117 |

| 1+ or higher | 434 | 408 | 842 |

| Total | 542 | 417 | 959 |

Proteinuria as reference standard

The diagnostic accuracy of the four assays using the spot urine sample at recruitment were compared using prespecified thresholds of 30 mg/mmol for SPCR and 2 mg/mmol for SACR. Tables 19–22 show index test results cross-tabulated against the reference standard (proteinuria). Sensitivities, specificities, LR+s and LR–s are shown in Table 23. The three SPCR tests all had sensitivity in excess of 90% at the prespecified thresholds. The central laboratory’s SACR test had significantly higher sensitivity (99%, 95% CI 98% to 100%) than the local laboratory’s SPCR test, but its specificity (26%, 95% CI 22% to 30%) was significantly lower. The high sensitivities and LR–s of ≤ 0.1 suggest that all of the tests could be used as rule-out tests for proteinuria.

| Threshold (mg/mmol) | Number of women | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Without proteinuria | With proteinuriaa | Total | |

| < 30 | 302 | 34 | 336 |

| ≥ 30 | 182 | 441 | 623 |

| Total | 484 | 475 | 959 |

| Threshold (mg/mmol) | Number of women | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Without proteinuria | With proteinuriaa | Total | |

| < 30 | 328 | 34 | 362 |

| ≥ 30 | 156 | 441 | 597 |

| Total | 484 | 475 | 959 |

| Threshold (mg/mmol) | Number of women | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Without proteinuria | With proteinuriaa | Total | |

| < 30 | 300 | 24 | 324 |

| ≥ 30 | 184 | 451 | 635 |

| Total | 484 | 475 | 959 |

| Threshold (mg/mmol) | Number of women | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Without proteinuria | With proteinuriaa | Total | |

| < 2 | 125 | 4 | 129 |

| ≥ 2 | 359 | 471 | 830 |

| Total | 484 | 475 | 959 |

| Assay | Threshold (mg/mmol) | Sensitivity (%) (95% CI) | Specificity (%) (95% CI) | Likelihood ratios (95% CI) | p-value for the comparison with the local laboratory’s SPCRa | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LR+ | LR– | Sensitivity | Specificity | ||||

| Local laboratory – SPCR | 30 | 93 (90 to 95) | 62 (58 to 67) | 2.47 (2.18 to 2.76) | 0.11 (0.08 to 0.15) | – | – |

| Central laboratoryb – SPCR via the BZC assay | 30 | 93 (90 to 95) | 68 (63 to 72) | 2.88 (2.50 to 3.26) | 0.11 (0.07 to 0.14) | 1.00 | 0.006 |

| Central laboratoryb – SPCR via the PGR assay | 30 | 95 (92 to 97) | 56 (51 to 60) | 2.14 (1.93 to 2.35) | 0.09 (0.06 to 0.13) | 0.068 | 0.83 |

| Central laboratoryb – SACR | 2 | 99 (98 to 100) | 23 (20 to 27) | 1.29 (1.23 to 1.35) | 0.03 (0.00 to 0.07) | < 0.0001 | < 0.0001 |

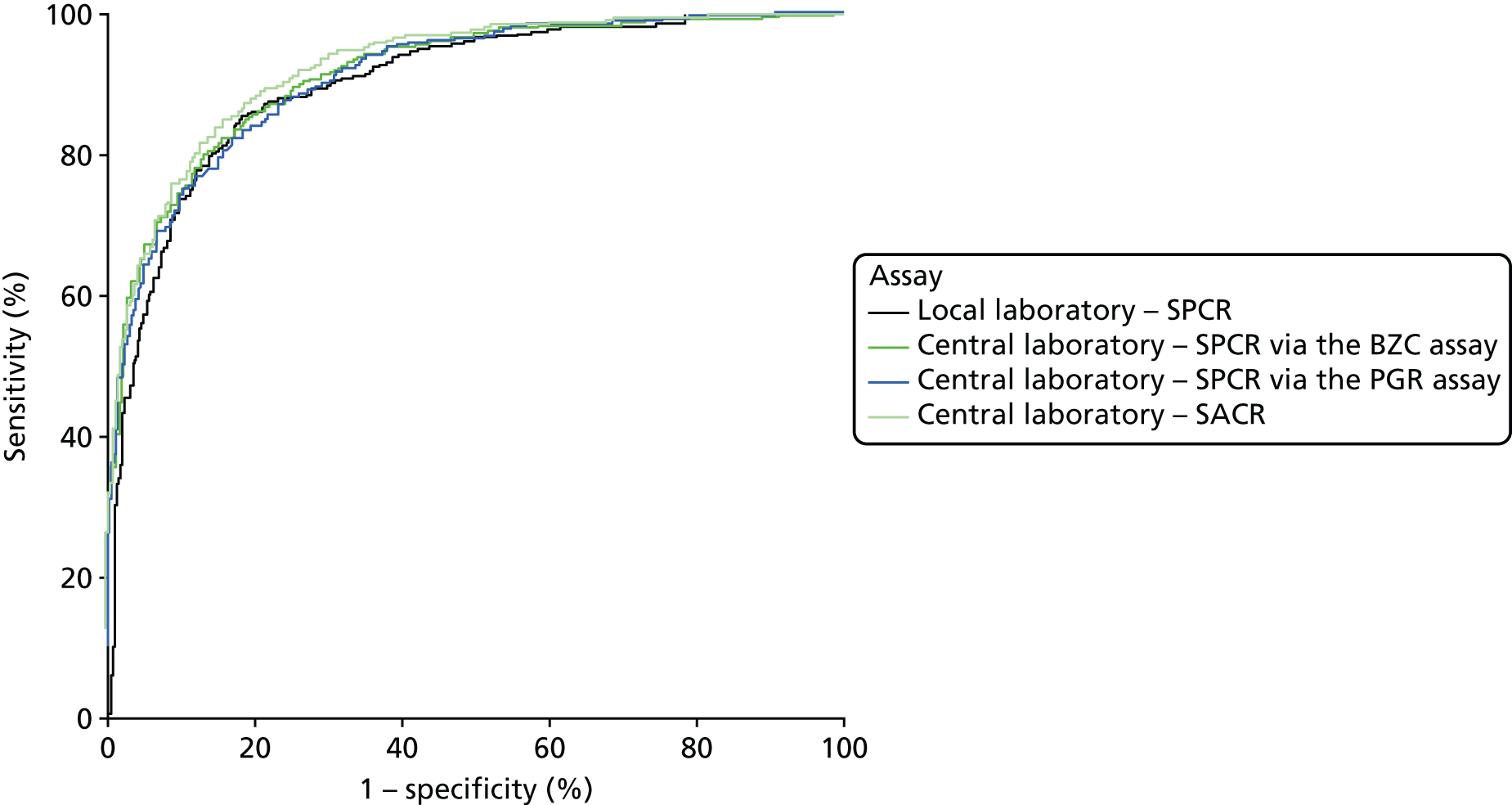

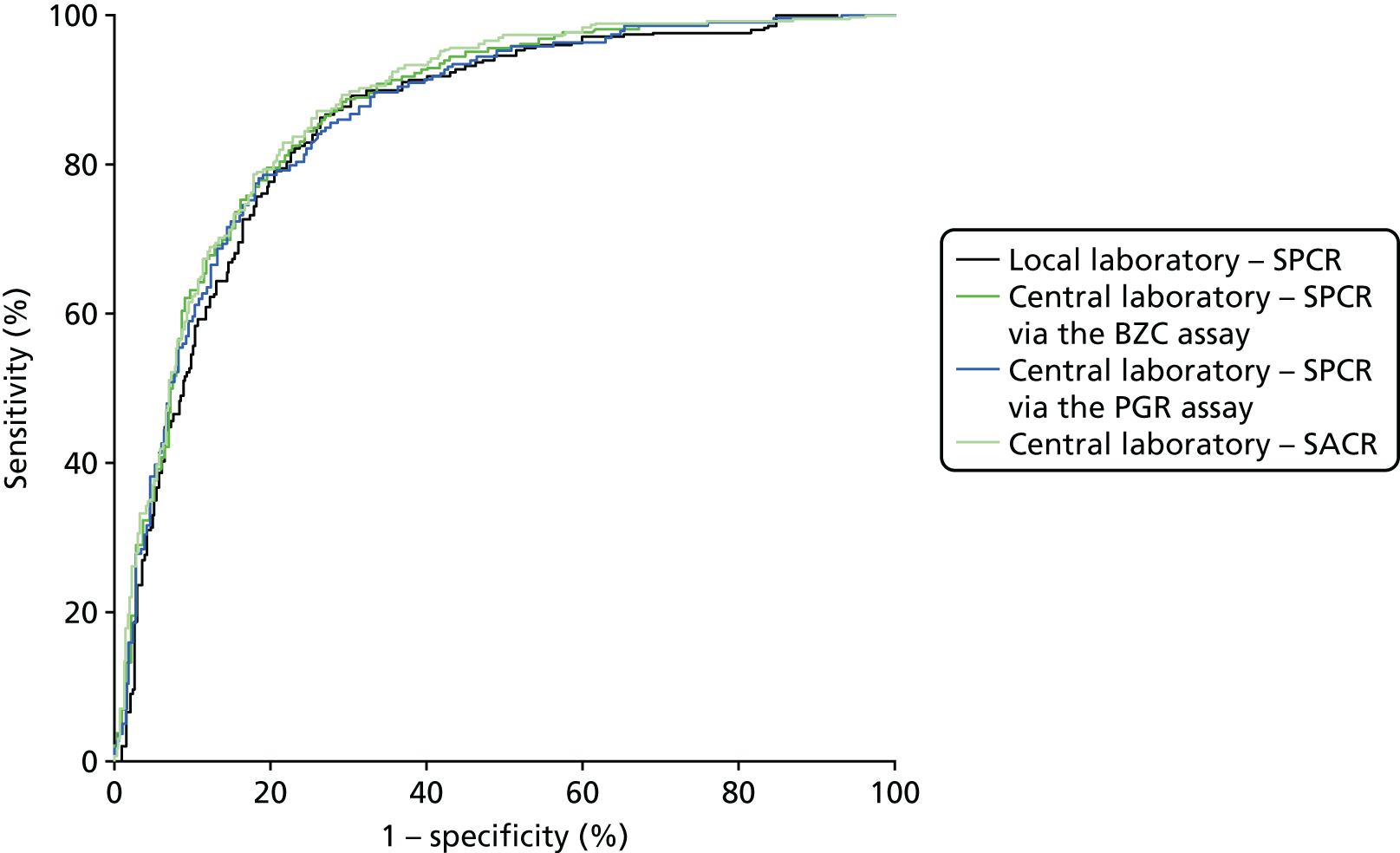

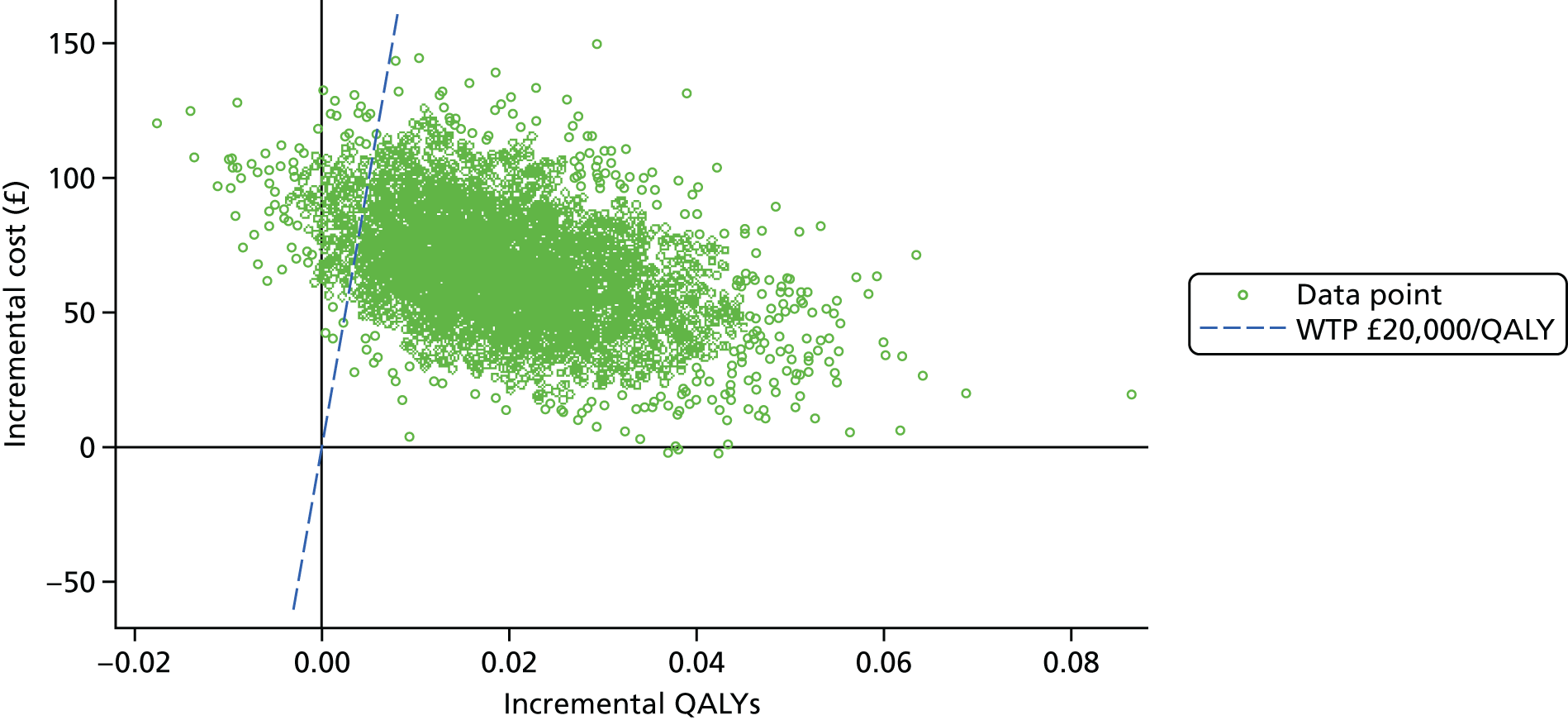

When overlain the ROC curves for the four assays were, again, similar (Figure 3). The areas under the central laboratory’s SACR curve and the central laboratory’s SPCR BZC assay curve were both significantly greater than that for the local laboratory’s SPCR curve, although the differences may not be of practical importance (Table 24).

FIGURE 3.

Receiver operating characteristic curves for the four assays of the recruitment urine sample used to diagnose proteinuria.

| Assay | Area under ROC curve (95% CI) | Comparison with the local laboratory’s SPCR | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Difference (95% CI) | p-valuea | ||

| Local laboratory – SPCR | 0.90 (0.88 to 0.92) | – | – |

| Central laboratoryb – SPCR via the BZC assay | 0.91 (0.90 to 0.93) | 0.02 (0.00 to 0.03) | 0.047 |

| Central laboratoryb – SPCR via the PGR assay | 0.91 (0.89 to 0.93) | 0.01 (0.00 to 0.03) | 0.17 |

| Central laboratoryb – SACR | 0.92 (0.91 to 0.94) | 0.02 (0.01 to 0.04) | 0.002 |

Severe pre-eclampsia (clinician diagnosis) as the reference standard

The diagnostic accuracy of the four assays using the spot urine sample at recruitment, and two assays using the 24-hour urine sample, were compared using prespecified thresholds of 30 mg/mmol for SPCR and 2 mg/mmol for SACR. Tables 25–30 show index test results cross-tabulated against the reference standard (clinician diagnosis of severe PE). Sensitivities, specificities, and LR+s and LR–s are shown in Table 31. The three SPCR tests and two SPCR tests all had sensitivity below 90% at the prespecified thresholds. The central laboratory’s SACR test from the recruitment sample had a significantly higher sensitivity (97%, 95% CI 93% to 99%) than the local laboratory’s SPCR test from the recruitment sample, but its specificity (16%, 95% CI 14% to 19%) was significantly lower.

| Threshold (mg/mmol) | Number of women | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Without severe PE | With severe PEa | Total | |

| < 30 | 308 | 28 | 336 |

| ≥ 30 | 458 | 165 | 623 |

| Total | 766 | 193 | 959 |

| Threshold (mg/mmol) | Number of women | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Without severe PE | With severe PEa | Total | |

| < 30 | 331 | 31 | 362 |

| ≥ 30 | 435 | 162 | 597 |

| Total | 766 | 193 | 959 |

| Threshold (mg/mmol) | Number of women | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Without severe PE | With severe PEa | Total | |

| < 30 | 296 | 28 | 324 |

| ≥ 30 | 470 | 165 | 635 |

| Total | 766 | 193 | 959 |

| Threshold (mg/mmol) | Number of women | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Without severe PE | With severe PEa | Total | |

| < 2 | 123 | 6 | 129 |

| ≥ 2 | 643 | 187 | 830 |

| Total | 766 | 193 | 959 |

| Threshold (mg/mmol) | Number of women | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Without severe PE | With severe PEa | Total | |

| < 30 | 338 | 32 | 370 |

| ≥ 30 | 428 | 161 | 589 |

| Total | 766 | 193 | 959 |

| Threshold (mg/mmol) | Number of women | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Without severe PE | With severe PEa | Total | |

| < 30 | 300 | 31 | 331 |

| ≥ 30 | 466 | 162 | 628 |

| Total | 766 | 193 | 959 |

| Assay and sample | Threshold | Sensitivity (%) (95% CI) | Specificity (%) (95% CI) | Likelihood ratios (95% CI) | p-value for comparison with the local laboratory’s SPCRa | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LR+ | LR– | Sensitivity | Specificity | ||||

| Recruitment sample | |||||||

| Local laboratory – SPCR | 30 mg/mmol | 85 (80 to 90) | 40 (37 to 44) | 1.43 (1.31 to 1.55) | 0.36 (0.23 to 0.49) | – | – |

| Central laboratoryb – SPCR via the BZC assay | 30 mg/mmol | 84 (78 to 89) | 43 (40 to 47) | 1.48 (1.35 to 1.61) | 0.37 (0.25 to 0.50) | 0.44 | 0.022 |

| Central laboratoryb – SPCR via the PGR assay | 30 mg/mmol | 85 (80 to 90) | 39 (35 to 42) | 1.39 (1.28 to 1.51) | 0.38 (0.24 to 0.51) | 1.00 | 0.23 |

| Central laboratoryb – SACR | 2 mg/mmol | 97 (93 to 99) | 16 (14 to 19) | 1.15 (1.11 to 1.20) | 0.19 (0.04 to 0.35) | < 0.0001 | < 0.0001 |

| 24-hour sample | |||||||

| Central laboratoryb – SPCR via the BZC assay | 30 mg/mmol | 83 (77 to 88) | 44 (41 to 48) | 1.49 (1.36 to 1.63) | 0.38 (0.25 to 0.50) | 0.37 | 0.010 |

| Central laboratoryb – SPCR via the PGR assay | 30 mg/mmol | 84 (78 to 89) | 39 (36 to 43) | 1.38 (1.26 to 1.50) | 0.41 (0.27 to 0.55) | 0.47 | 0.48 |

| POC – proteinuria dipstick test | 1+ | 92 (88 to 96) | 13 (11 to 16) | 1.06 (1.01 to 1.12) | 0.58 (0.28 to 0.89) | 0.012 | < 0.0001 |

When overlain the ROC curves for the six assays were similar and demonstrated a much poorer diagnostic accuracy compared with the NICE definition of PE as the reference standard (Figure 4). The areas under the central laboratory’s SACR (recruitment sample) curve, the central laboratory’s SPCR via the BZC assay (24-hour sample) curve and the central laboratory’s SPCR via the PGR assay (24-hour) curve were all significantly greater than that for the local laboratory’s SPCR curve, although the differences may not be of practical importance (Table 32).

FIGURE 4.

Receiver operating characteristic curves for the four assays of the recruitment urine sample and the two assays of the 24-hour urine sample used to predict severe PE (clinician diagnosis).

| Assay and sample | Area under ROC curve (95% CI) | Comparison with the local laboratory’s SPCR | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Difference (95% CI) | p-valuea | |||

| Recruitment sample | ||||

| Local laboratory – SPCR | 0.70 (0.66 to 0.74) | – | – | |

| Central laboratoryb – SPCR via the BZC assay | 0.72 (0.68 to 0.76) | 0.02 (0.00 to 0.04) | 0.11 | |

| Central laboratoryb – SPCR via the PGR assay | 0.71 (0.67 to 0.75) | 0.01 (–0.01 to 0.03) | 0.25 | |

| Central laboratoryb – SACR | 0.72 (0.68 to 0.76) | 0.02 (0.00 to 0.04) | 0.028 | |

| 24-hour sample | ||||

| Central laboratoryb – SPCR via the BZC assay | 0.74 (0.70 to 0.78) | 0.03 (0.01 to 0.06) | 0.006 | |

| Central laboratoryb – SPCR via the PGR assay | 0.73 (0.69 to 0.77) | 0.03 (0.01 to 0.05) | 0.012 | |

The diagnostic accuracy of the POC urine proteinuria dipstick test at recruitment was also investigated using a prespecified threshold of 1+. Table 33 shows this index test result cross-tabulated against the reference standard (severe PE, clinician diagnosis). Sensitivity, specificity, LR+s and LR–s are shown in Table 31. As expected, the urine proteinuria dipstick at this threshold had high sensitivity (92%, 95% CI 88% to 96%) but low specificity (13%, 95% CI 11% to 16%).

Prediction of adverse perinatal outcomes

The accuracy of the four assays using the spot urine sample at recruitment and the two assays using the 24-hour urine sample in predicting adverse perinatal outcomes were compared using prespecified thresholds of 30 mg/mmol for SPCR and 2 mg/mmol for SACR. Tables 34–39 show index test results cross-tabulated against adverse perinatal outcome. Sensitivities, specificities, LR+s and LR–s are shown in Table 40. The three SPCR tests and two SPCR tests all had sensitivity below 80% at the prespecified thresholds. The central laboratory’s SACR test from the recruitment sample had significantly higher sensitivity (94%, 95% CI 84% to 98%) than the local laboratory’s SPCR test from the recruitment sample, but its specificity (14%, 95% CI 12% to 16%) was significantly lower. The central laboratory’s SPCR test via the PGR assay also had significantly higher sensitivity (79%, 95% CI 67% to 88%) than the local laboratory’s SPCR test.

| Threshold (mg/mmol) | Number of women | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Without adverse perinatal outcome | With adverse perinatal outcome | Total | |

| < 30 | 317 | 19 | 336 |

| ≥ 30 | 580 | 43 | 623 |

| Total | 897 | 62 | 959 |

| Threshold (mg/mmol) | Number of women | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Without adverse perinatal outcome | With adverse perinatal outcome | Total | |

| < 30 | 348 | 14 | 362 |

| ≥ 30 | 549 | 48 | 597 |

| Total | 897 | 62 | 959 |

| Threshold (mg/mmol) | Number of women | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Without adverse perinatal outcome | With adverse perinatal outcome | Total | |

| < 30 | 311 | 13 | 324 |

| ≥ 30 | 586 | 49 | 635 |

| Total | 897 | 62 | 959 |

| Threshold (mg/mmol) | Number of women | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Without adverse perinatal outcome | With adverse perinatal outcome | Total | |

| < 2 | 125 | 4 | 129 |

| ≥ 2 | 772 | 58 | 830 |

| Total | 897 | 62 | 959 |

| Threshold (mg/mmol) | Number of women | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Without adverse perinatal outcome | With adverse perinatal outcome | Total | |

| < 30 | 350 | 20 | 370 |

| ≥ 30 | 547 | 42 | 589 |

| Total | 897 | 62 | 959 |

| Threshold (mg/mmol) | Number of women | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Without adverse perinatal outcome | With adverse perinatal outcome | Total | |

| < 30 | 313 | 18 | 331 |

| ≥ 30 | 584 | 44 | 628 |

| Total | 897 | 62 | 959 |

| Assay and sample | Threshold (mg/mmol) | Sensitivity (%) (95% CI) | Specificity (%) (95% CI) | Likelihood ratios (95% CI) | p-value for comparison with the local laboratory’s SPCRa | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LR+ | LR– | Sensitivity | Specificity | ||||

| Recruitment sample | |||||||

| Local laboratory – SPCR | 30 | 69 (56 to 80) | 35 (32 to 39) | 1.07 (0.89 to 1.26) | 0.87 (0.53 to 1.20) | – | – |

| Central laboratoryb – SPCR via the BZC assay | 30 | 77 (65 to 87) | 39 (36 to 42) | 1.26 (1.08 to 1.45) | 0.58 (0.31 to 0.85) | 0.059 | 0.003 |

| Central laboratoryb – SPCR via the PGR assay | 30 | 79 (67 to 88) | 35 (32 to 38) | 1.21 (1.04 to 1.38) | 0.60 (0.31 to 0.90) | 0.034 | 0.56 |

| Central laboratoryb – SACR | 2 | 94 (84 to 98) | 14 (12 to 16) | 1.09 (1.01 to 1.16) | 0.46 (0.02 to 0.91) | < 0.0001 | < 0.0001 |

| 24-hour sample | |||||||

| Central laboratoryb – SPCR via the BZC assay | 30 | 68 (55 to 79) | 39 (36 to 42) | 1.11 (0.91 to 1.31) | 0.83 (0.52 to 1.13) | 0.74 | 0.006 |

| Central laboratoryb – SPCR via the PGR assay | 30 | 71 (58 to 82) | 35 (32 to 38) | 1.09 (0.91 to 1.27) | 0.83 (0.50 to 1.16) | 0.74 | 0.73 |

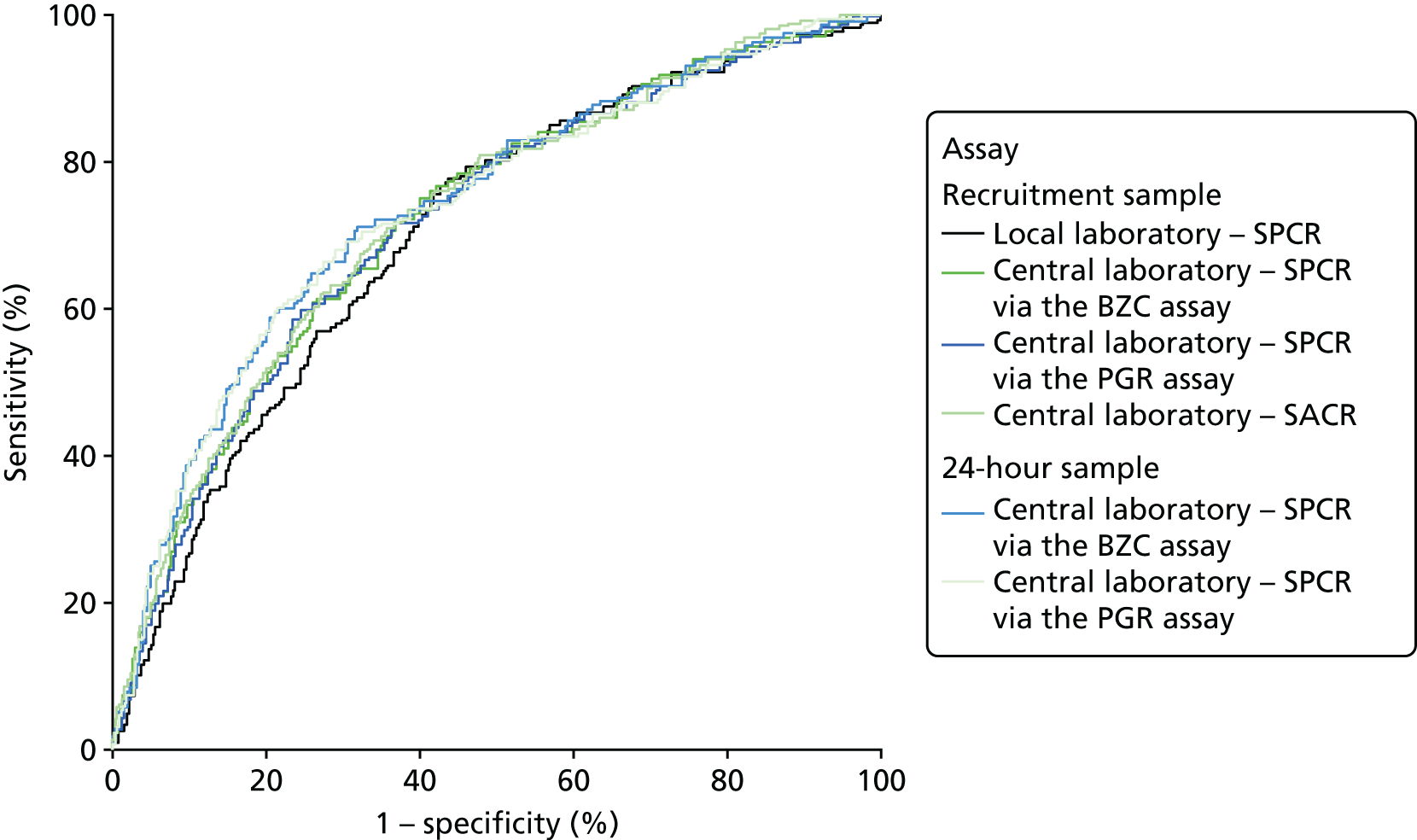

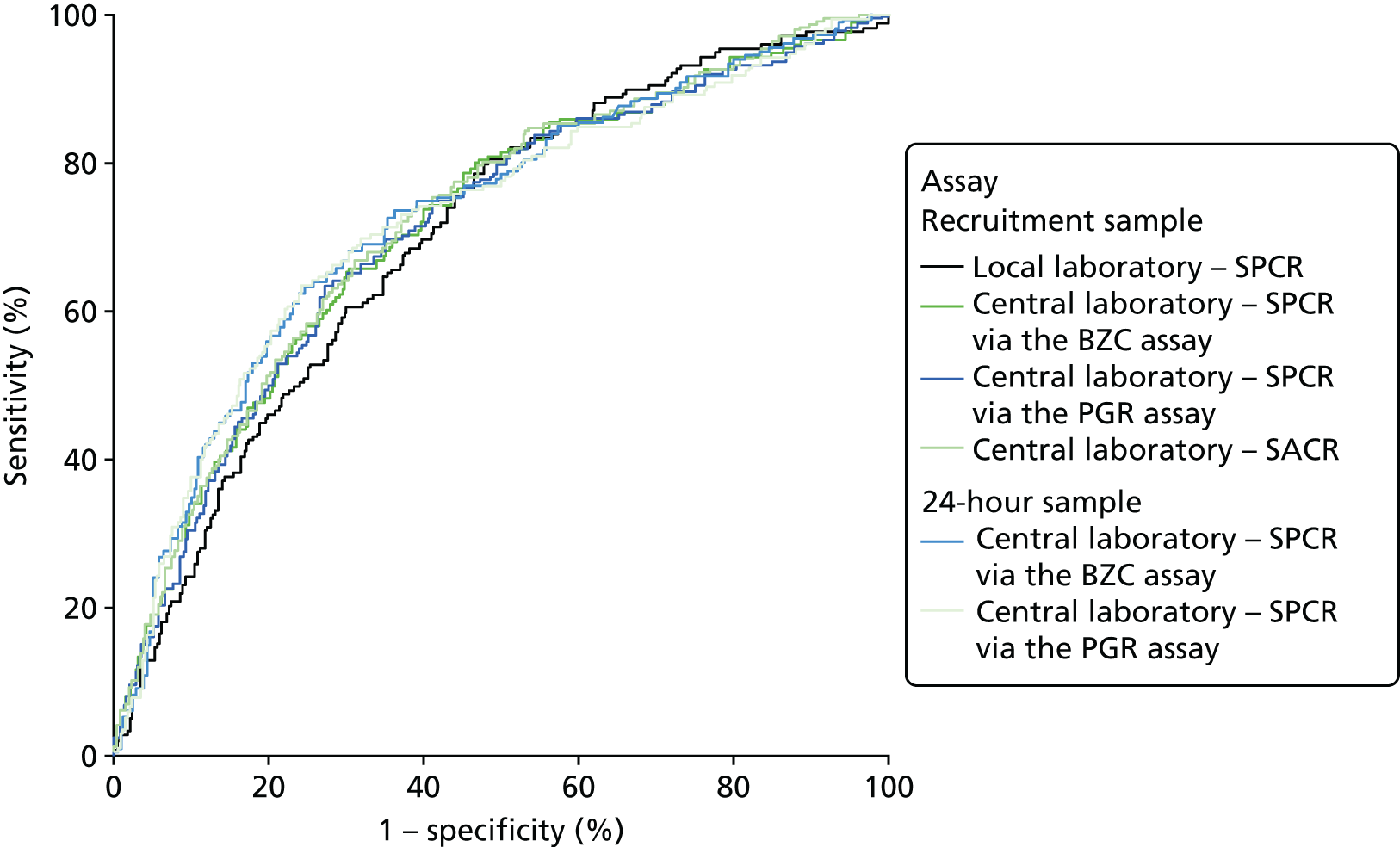

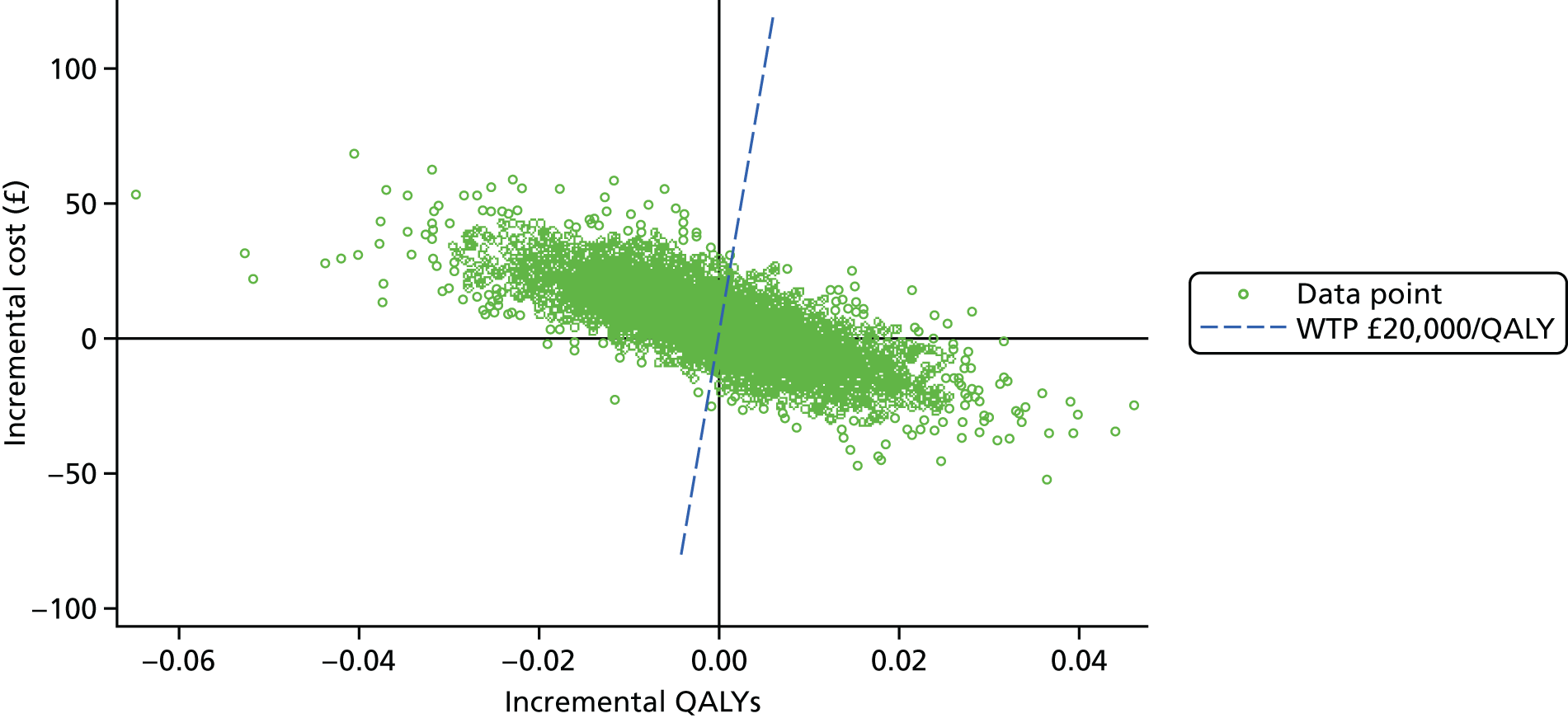

The ROC curves for all six assays demonstrated poor diagnostic accuracy (Figure 5), although the areas under the central laboratory’s SPCR via the BZC assay (recruitment sample) curve, the central laboratory’s SPCR via the PGR assay (recruitment sample) curve and the central laboratory’s SACR (recruitment sample) curve were all significantly greater than that for the local laboratory’s SPCR (recruitment sample) curve (Table 41).

FIGURE 5.

Receiver operating characteristic curves for the four assays of the recruitment urine sample and the two assays of the 24-hour urine sample used to predict adverse perinatal outcome.

| Assay and sample | Area under ROC curve (95% CI) | Comparison with the local laboratory’s SPCR | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Difference (95% CI) | p-valuea | ||

| Recruitment sample | |||

| Local laboratory – SPCR | 0.59 (0.51 to 0.67) | – | – |

| Central laboratoryb – SPCR via the BZC assay | 0.64 (0.56 to 0.71) | 0.05 (0.01 to 0.08) | 0.025 |

| Central laboratoryb – SPCR via the PGR assay | 0.63 (0.56 to 0.70) | 0.04 (0.00 to 0.08) | 0.047 |

| Central laboratoryb – SACR | 0.63 (0.56 to 0.71) | 0.04 (0.00 to 0.04) | 0.039 |

| 24-hour sample | |||

| Central laboratoryb – SPCR via the BZC assay | 0.60 (0.52 to 0.68) | 0.01 (–0.03 to 0.06) | 0.64 |

| Central laboratoryb – SPCR via the PGR assay | 0.60 (0.52 to 0.68) | 0.03 (–0.03 to 0.06) | 0.58 |

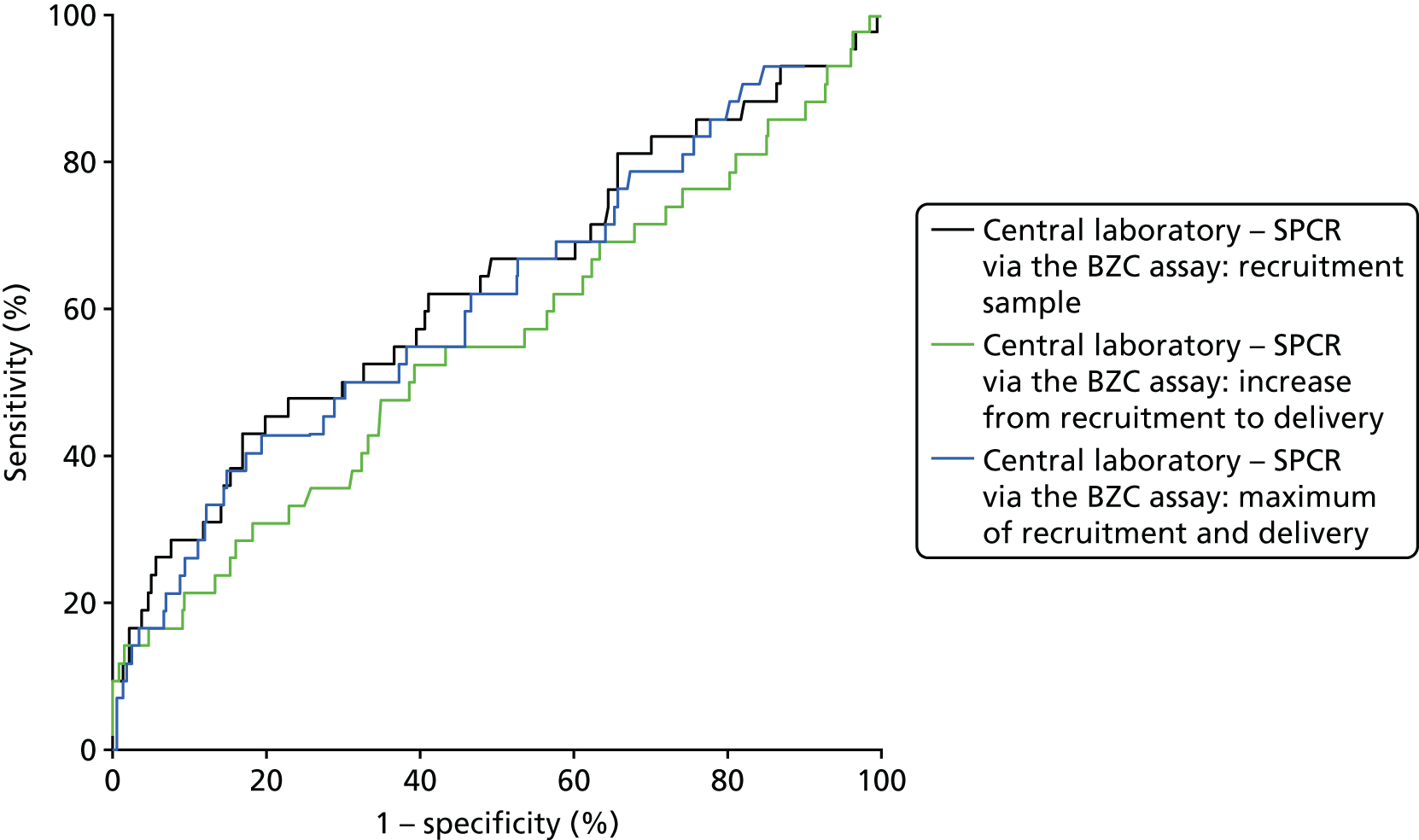

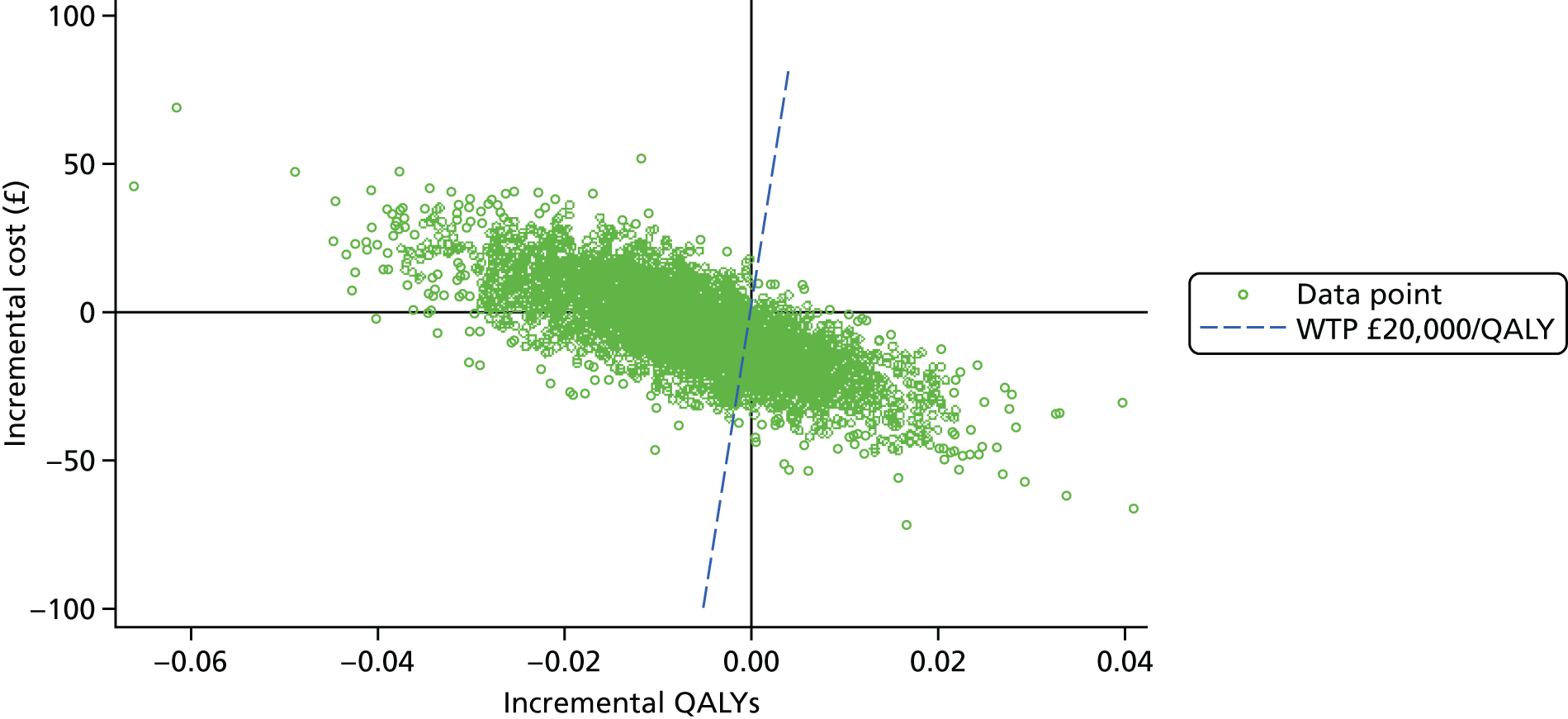

Because of missing data, only 530 women could be included in the analyses involving the central laboratory’s BZC assay of the delivery spot urine samples (i.e. the increase from recruitment to delivery and the maximum of the recruitment and delivery laboratory BZC SPCR assay). ROC curves for the prediction of adverse perinatal outcomes are shown in Figure 6, alongside that for the recruitment sample central laboratory’s SPCR test via the BZC assay for comparison. Neither the increase nor the maximum offered any improvement over the original recruitment sample in the prediction of adverse perinatal outcomes (Table 42).

FIGURE 6.

Receiver operating characteristic curves for the increase from recruitment to delivery for the BZC SPCR assay, and maximum of recruitment and delivery BZC SPCR assay, in the prediction of adverse perinatal outcome.

| Assay | Area under ROC curve (95% CI) | Comparison with the recruitment sample of the central laboratory’s SPCR test via the BZC assay | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Difference (95% CI) | p-valuea | ||

| Recruitment sampleb | 0.64 (0.53 to 0.75) | – | – |

| Increase from recruitment to delivery sampleb | 0.53 (0.41 to 0.66) | –0.11 (–0.27 to 0.05) | 0.19 |

| Maximum of recruitment and delivery sampleb | 0.63 (0.52 to 0.74) | –0.01 (–0.06 to 0.04) | 0.71 |

Subgroup analysis

The primary analysis was repeated in the subset of women with 1+ or higher on the POC dipstick test. Tables 43–46 show index test results cross-tabulated against the reference standard (NICE definition of severe PE). Sensitivities, specificities, LR+s and LR–s are shown in Table 47. The three SPCR tests all had sensitivity in excess of 90% at the prespecified thresholds, but with poor specificity. The central laboratory’s SACR test had significantly higher sensitivity (99%, 95% CI 98% to 100%) than the local laboratory’s SPCR test, but its specificity (20%, 95% CI 16% to 24%) was significantly lower. The high sensitivities and LR–s of ≤ 0.1 suggest that all of the tests could be used as rule-out tests for severe PE (NICE definition) in the subgroup with 1+ or higher on the POC dipstick test.

| Threshold (mg/mmol) | Number of women | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Without severe PE | With severe PE | Total | |

| < 30 | 228 | 24 | 252 |

| ≥ 30 | 206 | 384 | 590 |

| Total | 434 | 408 | 842 |

| Threshold (mg/mmol) | Number of women | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Without severe PE | With severe PE | Total | |

| < 30 | 253 | 26 | 279 |

| ≥ 30 | 181 | 382 | 563 |

| Total | 434 | 408 | 842 |

| Threshold (mg/mmol) | Number of women | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Without severe PE | With severe PE | Total | |

| < 30 | 219 | 20 | 239 |

| ≥ 30 | 215 | 388 | 603 |

| Total | 434 | 408 | 842 |

| Threshold (mg/mmol) | Number of women | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Without severe PE | With severe PE | Total | |

| < 2 | 86 | 3 | 89 |

| ≥ 2 | 348 | 405 | 753 |

| Total | 434 | 408 | 842 |

| Assay | Threshold (mg/mmol) | Sensitivity (%) (95% CI) | Specificity (%) (95% CI) | Likelihood ratios (95% CI) | p-value for the comparison with the local laboratory’s SPCRa | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LR+ | LR– | Sensitivity | Specificity | ||||

| Local laboratory – SPCR | 30 | 94 (91 to 96) | 53 (48 to 57) | 1.98 (1.78 to 2.19) | 0.11 (0.07 to 0.16) | – | – |

| Central laboratoryb – SPCR via the BZC assay | 30 | 94 (91 to 96) | 58 (54 to 63) | 2.25 (1.99 to 2.50) | 0.11 (0.07 to 0.15) | 0.67 | 0.003 |

| Central laboratoryb – SPCR via the PGR assay | 30 | 95 (93 to 97) | 50 (46 to 55) | 1.92 (1.73 to 2.11) | 0.10 (0.05 to 0.14) | 0.39 | 0.31 |

| Central laboratoryb – SACR | 2 | 99 (98 to 100) | 20 (16 to 24) | 1.24 (1.18 to 1.30) | 0.04 (–0.01 to 0.08) | < 0.0001 | < 0.0001 |

When overlain the ROC curves for the four assays were similar (Figure 7). The area under the central laboratory’s SACR curve was significantly greater than that for the local laboratory’s SPCR curve, although the difference (0.02, 95% CI 0.00 to 0.04; p = 0.012) may not be of practical importance (Table 48).

FIGURE 7.

Receiver operating characteristic curves for the four assays of the recruitment urine sample used to diagnose severe PE (NICE definition), in the subgroup with 1+ or higher on the POC dipstick test.

| Assay | Area under ROC curve (95% CI) | Comparison with the local laboratory’s SPCR | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Difference (95% CI) | p-valuea | ||

| Local laboratory – SPCR | 0.85 (0.83 to 0.88) | – | – |

| Central laboratoryb – SPCR via the BZC assay | 0.87 (0.85 to 0.89) | 0.02 (0.00 to 0.03) | 0.074 |

| Central laboratoryb – SPCR via the PGR assay | 0.86 (0.84 to 0.89) | 0.01 (–0.01 to 0.03) | 0.31 |

| Central laboratoryb – SACR | 0.88 (0.85 to 0.90) | 0.03 (0.00 to 0.04) | 0.012 |

The same subgroup analysis (1+ or higher on the POC dipstick test) was repeated using clinician diagnosis of severe PE as the reference standard and including the two assays of the 24-hour urine sample as index tests. Tables 49–54 show index test results cross-tabulated against the reference standard. Sensitivities, specificities, LR+s and LR–s are shown in Table 55. The three SPCR tests from the recruitment urine sample and two SPCR tests from the 24-hour sample had sensitivity in excess of 80% but below 90% at the prespecified thresholds, and with poor specificity. The central laboratory’s SACR test had significantly higher sensitivity (97%, 95% CI 94% to 99%) than the local laboratory’s SPCR test, but its specificity (13%, 95% CI 10% to 15%) was significantly lower.

| Threshold (mg/mmol) | Number of women | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Without severe PE | With severe PEa | Total | |

| < 30 | 232 | 20 | 252 |

| ≥ 30 | 432 | 158 | 590 |

| Total | 664 | 178 | 842 |

| Threshold (mg/mmol) | Number of women | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Without severe PE | With severe PEa | Total | |

| < 30 | 254 | 25 | 279 |

| ≥ 30 | 410 | 153 | 563 |

| Total | 434 | 178 | 842 |

| Threshold (mg/mmol) | Number of women | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Without severe PE | With severe PEa | Total | |

| < 30 | 216 | 23 | 239 |

| ≥ 30 | 448 | 155 | 603 |

| Total | 664 | 178 | 842 |

| Threshold (mg/mmol) | Number of women | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Without severe PE | With severe PEa | Total | |

| < 2 | 84 | 5 | 89 |

| ≥ 2 | 580 | 173 | 753 |

| Total | 664 | 178 | 842 |

| Threshold (mg/mmol) | Number of women | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Without severe PE | With severe PEa | Total | |

| < 30 | 257 | 26 | 283 |

| ≥ 30 | 407 | 152 | 559 |

| Total | 664 | 178 | 842 |

| Threshold (mg/mmol) | Number of women | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Without severe PE | With severe PEa | Total | |

| < 30 | 219 | 26 | 245 |

| ≥ 30 | 445 | 152 | 597 |

| Total | 664 | 178 | 842 |

| Assay and sample | Threshold (mg/mmol) | Sensitivity (%) (95% CI) | Specificity (%)(95% CI) | Likelihood ratios (95% CI) | p-value for the comparison with local laboratory’s SPCRa | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LR+ | LR– | Sensitivity | Specificity | ||||

| Recruitment sample | |||||||

| Local laboratory – SPCR | 30 | 89 (83 to 93) | 35 (31 to 39) | 1.36 (1.26 to 1.47) | 0.32 (0.18 to 0.46) | – | – |

| Central laboratoryb – SPCR via the BZC assay | 30 | 86 (80 to 91) | 38 (35 to 42) | 1.39 (1.27 to 1.51) | 0.37 (0.23 to 0.51) | 0.13 | 0.016 |

| Central laboratoryb – SPCR via the PGR assay | 30 | 87 (81 to 92) | 33 (29 to 36) | 1.29 (1.19 to 1.39) | 0.40 (0.24 to 0.56) | 0.37 | 0.090 |

| Central laboratoryb – SACR | 2 | 97 (94 to 99) | 13 (10 to 15) | 1.11 (1.07 to 1.16) | 0.22 (0.02 to 0.42) | 0.0003 | < 0.0001 |

| 24-hour sample | |||||||

| Central laboratoryb – SPCR via the BZC assay | 30 | 85 (79 to 90) | 39 (35 to 43) | 1.39 (1.27 to 1.51) | 0.38 (0.24 to 1.52) | 0.16 | 0.024 |

| Central laboratoryb – SPCR via the PGR assay | 30 | 85 (79 to 90) | 33 (29 to 37) | 1.27 (1.17 to 1.38) | 0.44 (0.28 to 1.61) | 0.11 | 0.22 |

The ROC curves for all six assays demonstrated poor diagnostic accuracy (Figure 8), although the areas under the central laboratory’s SACR (recruitment sample) curve and the central laboratory’s SPCR test via the BZC assay (24-hour sample) curve (Figure 9) curve were both significantly greater than that for the local laboratory’s SPCR (recruitment sample) curve (Table 56).

FIGURE 8.

Receiver operating characteristic curves for the four assays of the recruitment urine sample and the two assays of the 24-hour sample used to diagnose severe PE (clinician diagnosis), in the subgroup with 1+ or higher on POC dipstick test.

FIGURE 9.

Receiver operating characteristic curves for the four assays of the recruitment urine sample used to diagnose severe PE (NICE definition, using the PGR assay).

| Assay and sample | Area under ROC curve (95% CI) | Comparison with the local laboratory’s SPCR | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Difference (95% CI) | p-valuea | ||

| Recruitment sample | |||

| Local laboratory – SPCR | 0.70 (0.66 to 0.74) | – | – |

| Central laboratoryb – SPCR via the BZC assay | 0.71 (0.67 to 0.76) | 0.01 (–0.01 to 0.03) | 0.19 |

| Central laboratoryb – SPCR via the PGR assay | 0.71 (0.67 to 0.75) | 0.01 (–0.01 to 0.03) | 0.40 |

| Central laboratoryb – SACR | 0.72 (0.68 to 0.76) | 0.02 (0.00 to 0.04) | 0.042 |

| 24-hour sample | |||

| Central laboratoryb – SPCR via the BZC assay | 0.73 (0.68 to 0.77) | 0.03 (0.00 to 0.05) | 0.040 |

| Central laboratoryb – SPCR via the PGR assay | 0.72 (0.68 to 0.77) | 0.02 (0.00 to 0.05) | 0.083 |

Laboratory assay method for 24-hour proteinuria

The percentage of women with proteinuria (≥ 300 mg/24 hours) defined using the central laboratory’s (Kent) PGR assay (55%) was greater than the percentage defined using the BZC assay (50%) (Table 57). Consequently, the percentage of women categorised as having severe PE according to the NICE definition was greater using the alternative PGR assay (48%) than using the BZC assay (43%) (Table 58).

| Threshold (mg/mmol) | Number of women | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| PGR threshold (mg/l) | Total | ||

| < 300 | ≥ 300 | – | |

| < 300 | 425 | 59 | 484 |

| ≥ 300 | 2 | 473 | 475 |

| Total | 427 | 532 | 959 |

| Severe PE defined using the BZC assaya | Severe PE defined using the PGR assay,a number of women | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Without severe PE | With severe PE | Total | |

| Without severe PE | 493 | 49 | 542 |

| With severe PE | 2 | 415 | 417 |

| Total | 495 | 464 | 959 |

The diagnostic accuracy of the four assays using the spot urine sample at recruitment were compared using prespecified thresholds of 30 mg/mmol for SPCR and 2 mg/mmol for SACR, but using the PGR assay instead of the BZC assay in the NICE definition of severe PE. Tables 59–62 show index test results cross-tabulated against this alternative reference standard. Sensitivities, specificities, LR+s and LR–s are shown in Table 63. The three SPCR tests all had sensitivity in excess of 90% at the prespecified thresholds but with poor specificity. The central laboratory’s SACR test had significantly higher sensitivity (99%, 95% CI 97% to 100%) than the local laboratory’s SPCR test, but its specificity (25%, 95% CI 21% to 29%) was significantly lower. LR–s were slightly higher than those found using the BZC assay in the proteinuria component of the definition.

| Threshold (mg/mmol) | Number of women | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Without severe PE | With severe PE | Total | |

| < 30 | 296 | 40 | 336 |

| ≥ 30 | 199 | 424 | 623 |

| Total | 495 | 464 | 959 |

| Threshold (mg/mmol) | Number of women | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Without severe PE | With severe PE | Total | |

| < 30 | 319 | 43 | 362 |

| ≥ 30 | 176 | 421 | 597 |

| Total | 495 | 464 | 959 |

| Threshold (mg/mmol) | Number of women | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Without severe PE | With severe PE | Total | |

| < 30 | 290 | 34 | 324 |

| ≥ 30 | 205 | 430 | 635 |

| Total | 495 | 464 | 959 |

| Threshold (mg/mmol) | Number of women | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Without severe PE | With severe PE | Total | |

| < 2 | 124 | 5 | 129 |

| ≥ 2 | 371 | 459 | 830 |

| Total | 495 | 464 | 959 |

| Assay | Threshold (mg/mmol) | Sensitivity (%) (95% CI) | Specificity (%) (95% CI) | Likelihood ratios (95% CI) | p-value for the comparison with the local laboratory’s SPCRa | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LR+ | LR– | Sensitivity | Specificity | ||||

| Local laboratory – SPCR | 30 | 91 (88 to 94) | 60 (55 to 64) | 2.27 (2.02 to 2.53) | 0.14 (0.07 to 0.16) | – | – |

| Central laboratoryb – SPCR via the BZC assay | 30 | 91 (88 to 93) | 64 (60 to 69) | 2.55 (2.24 to 2.86) | 0.14 (0.07 to 0.15) | 0.59 | 0.013 |

| Central laboratoryb – SPCR via the PGR assay | 30 | 93 (90 to 95) | 59 (54 to 63) | 2.24 (2.00 to 2.48) | 0.13 (0.08 to 0.17) | 0.27 | 0.52 |

| Central laboratoryb – SACR | 2 | 99 (97 to 100) | 25 (21 to 29) | 1.32 (1.25 to 1.39) | 0.04 (0.00 to 0.08) | < 0.0001 | < 0.0001 |

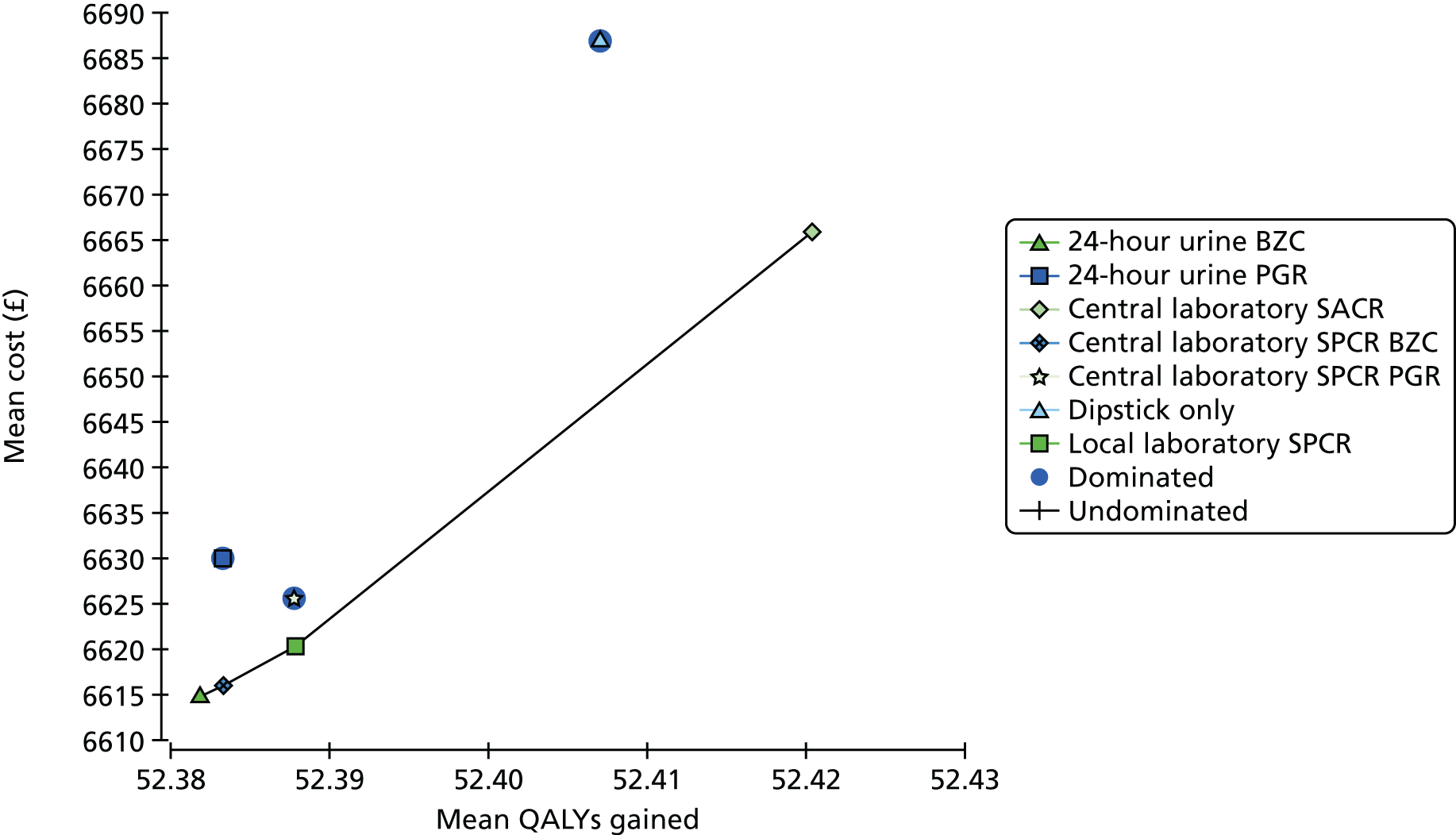

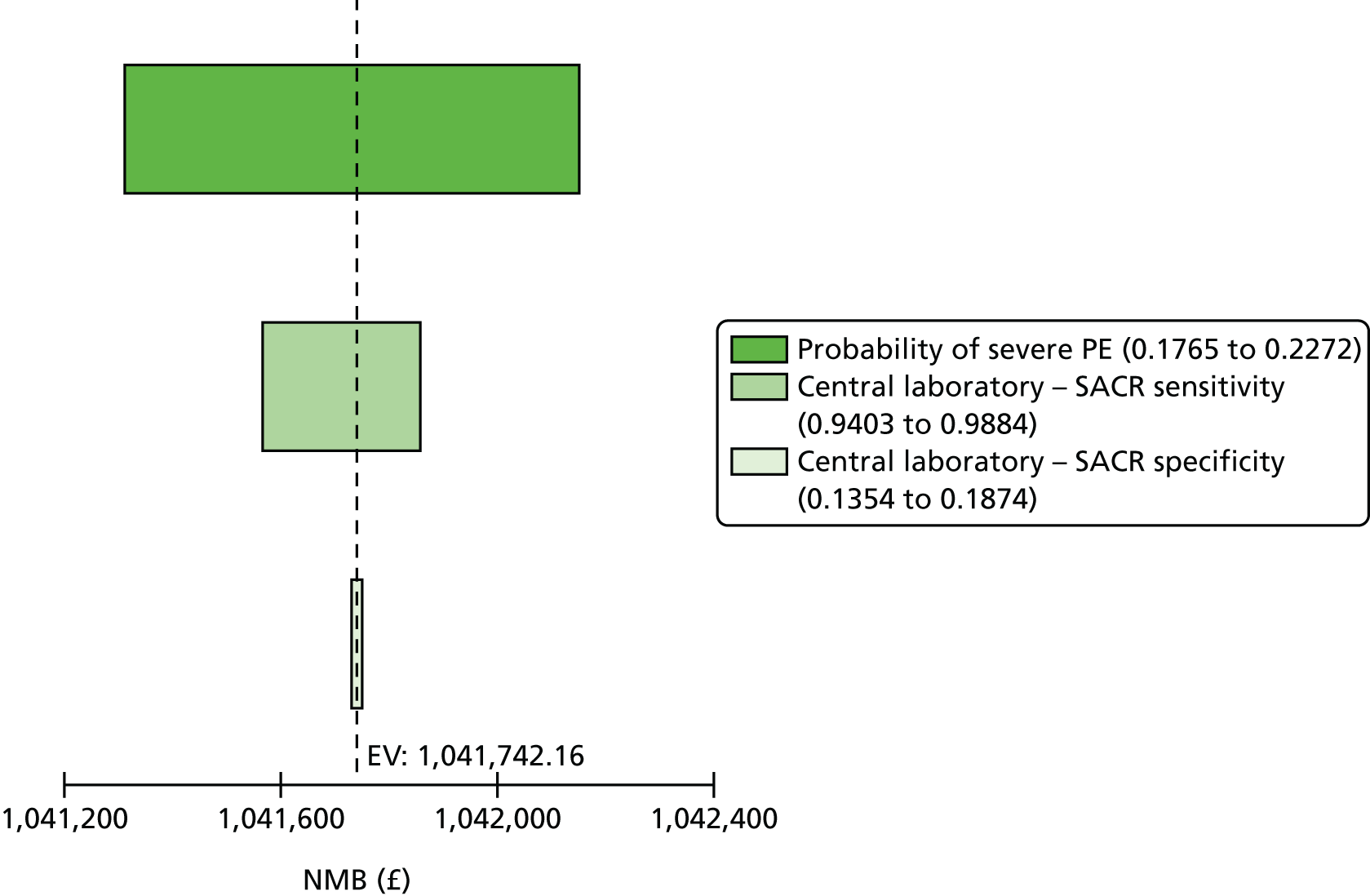

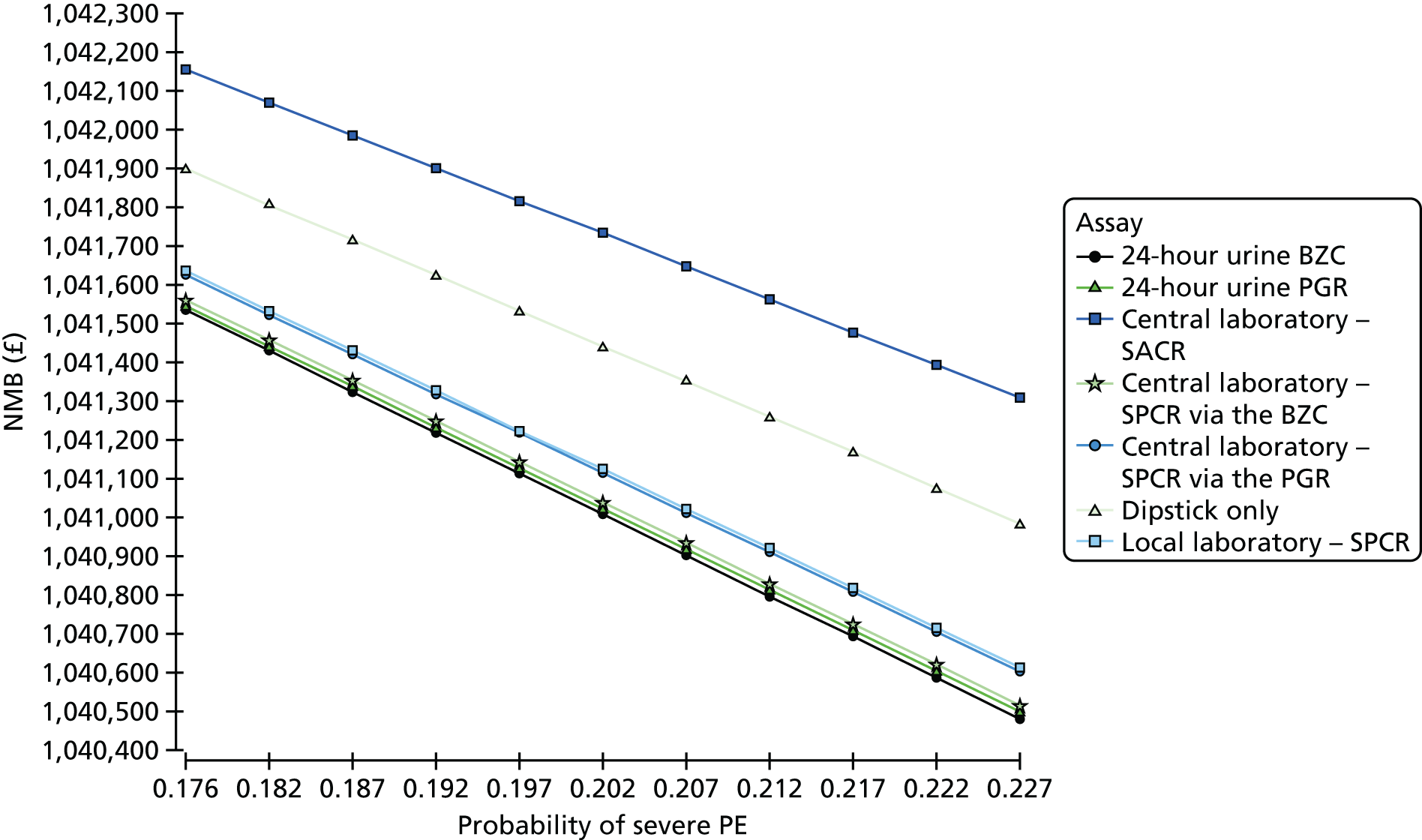

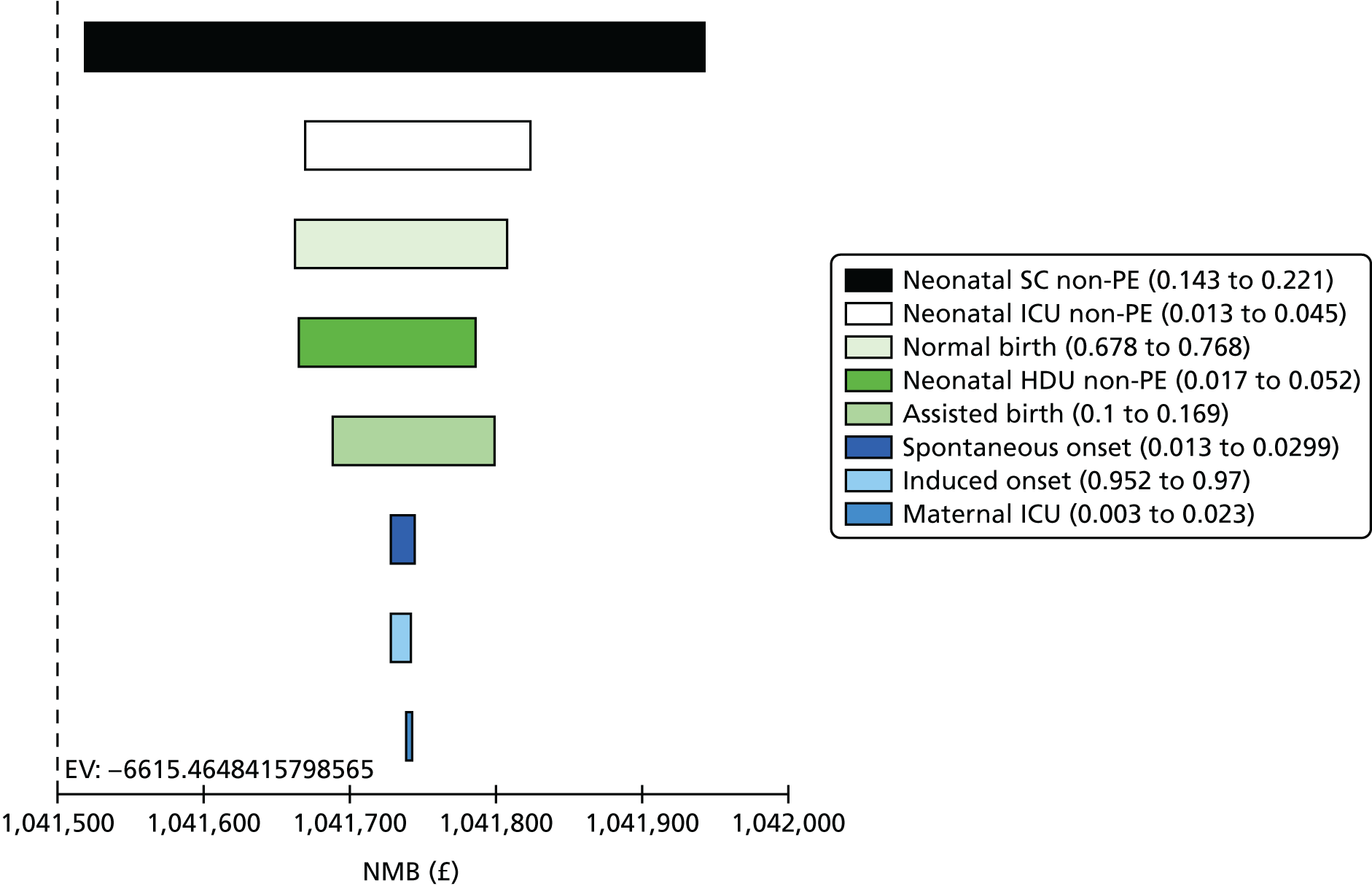

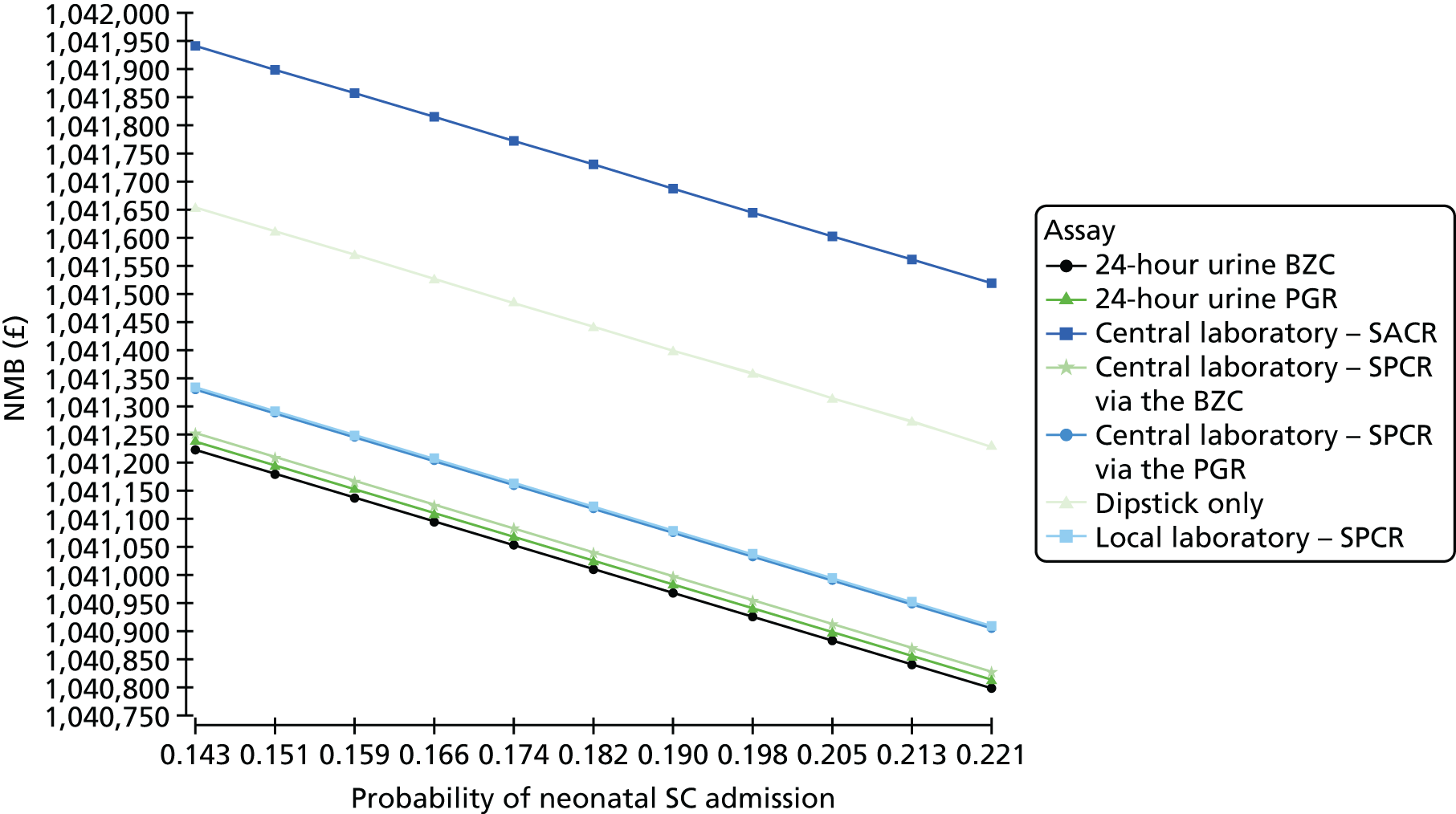

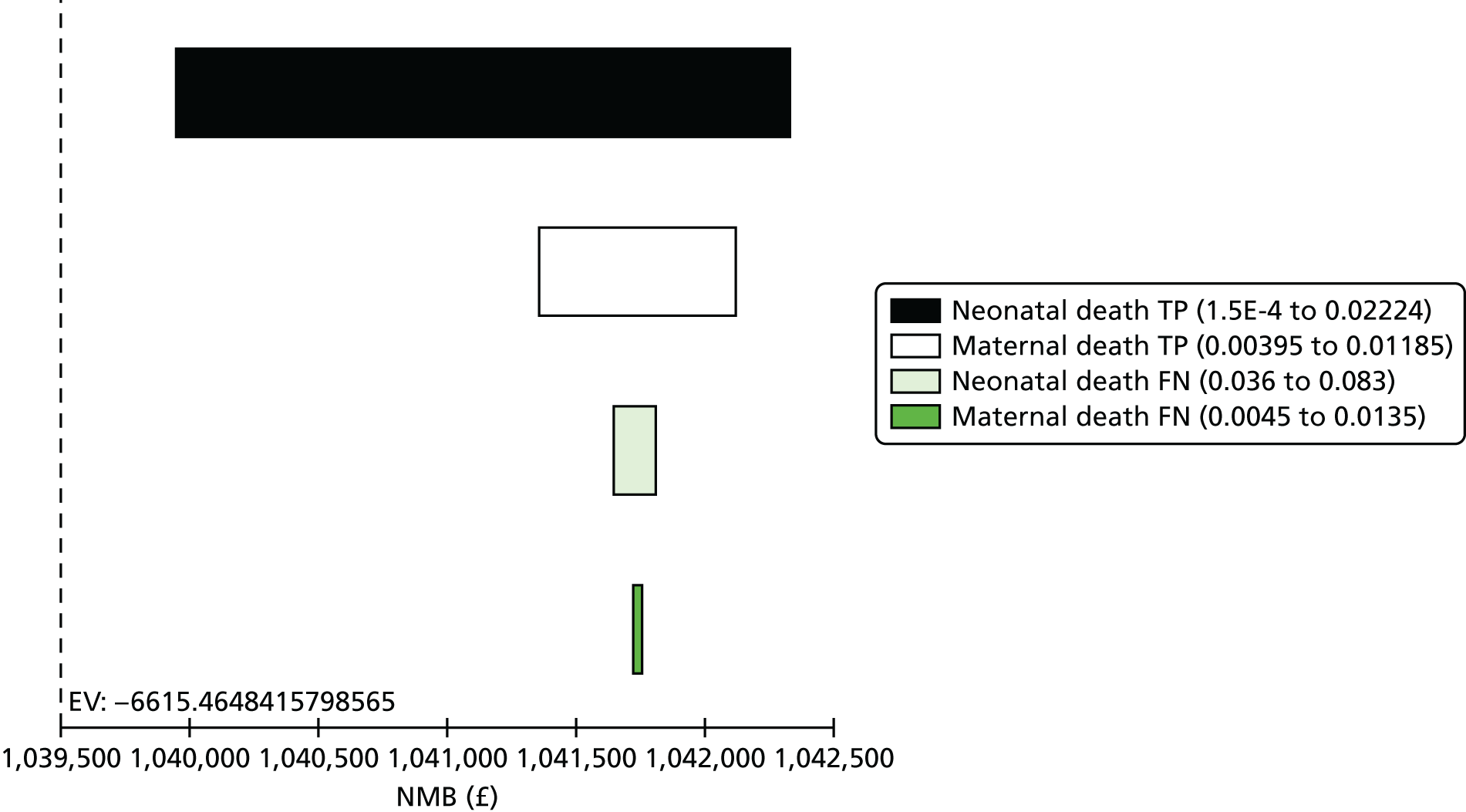

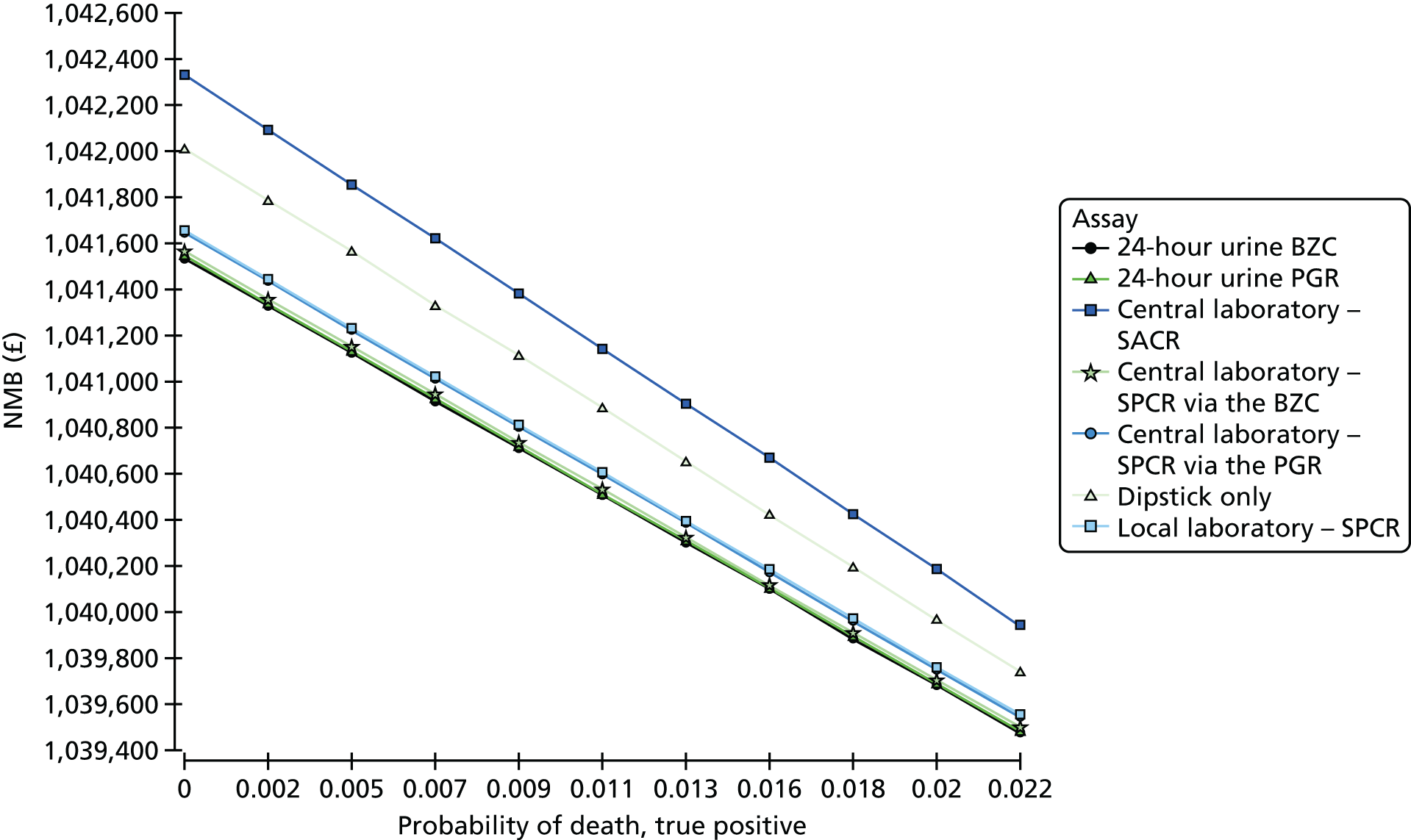

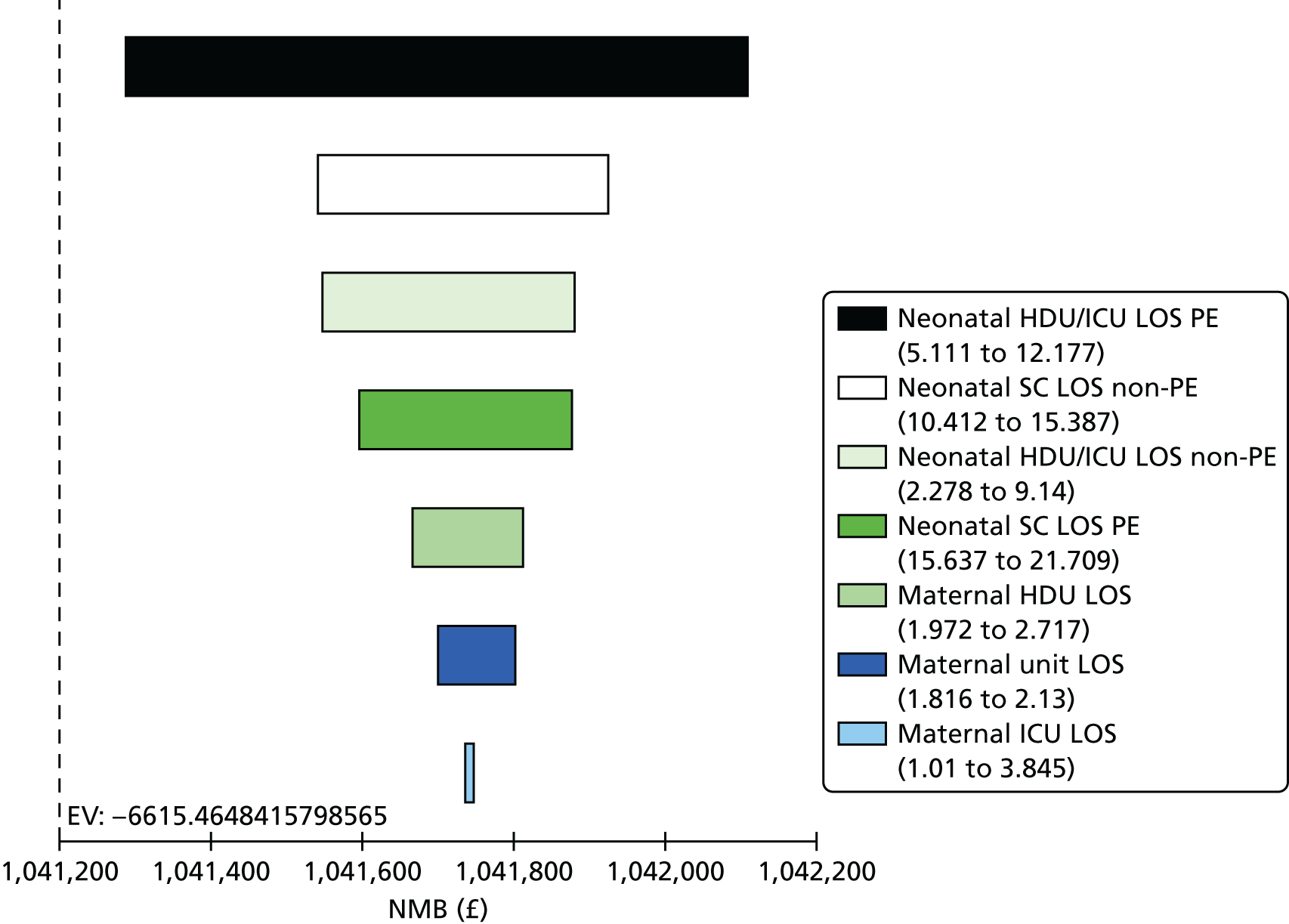

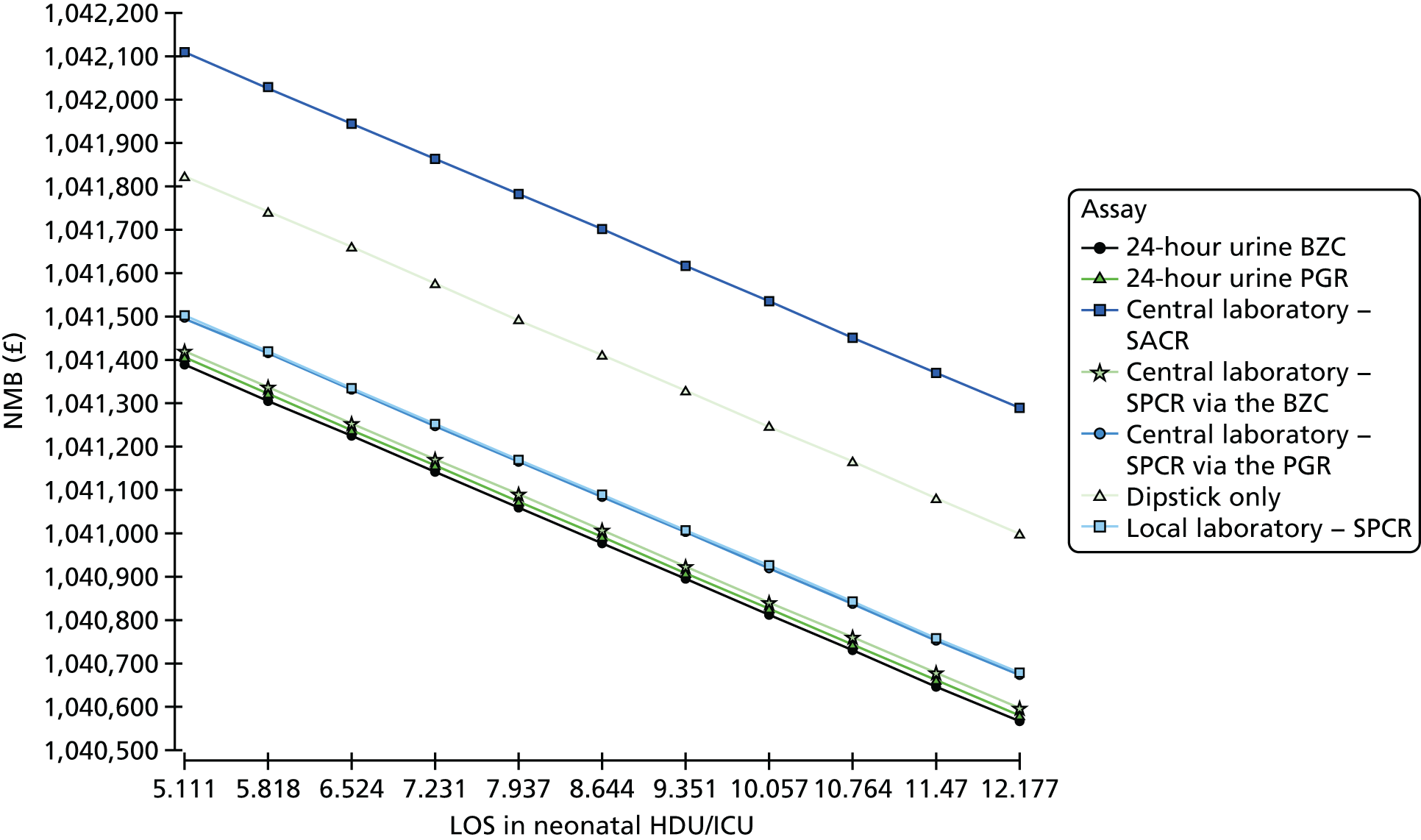

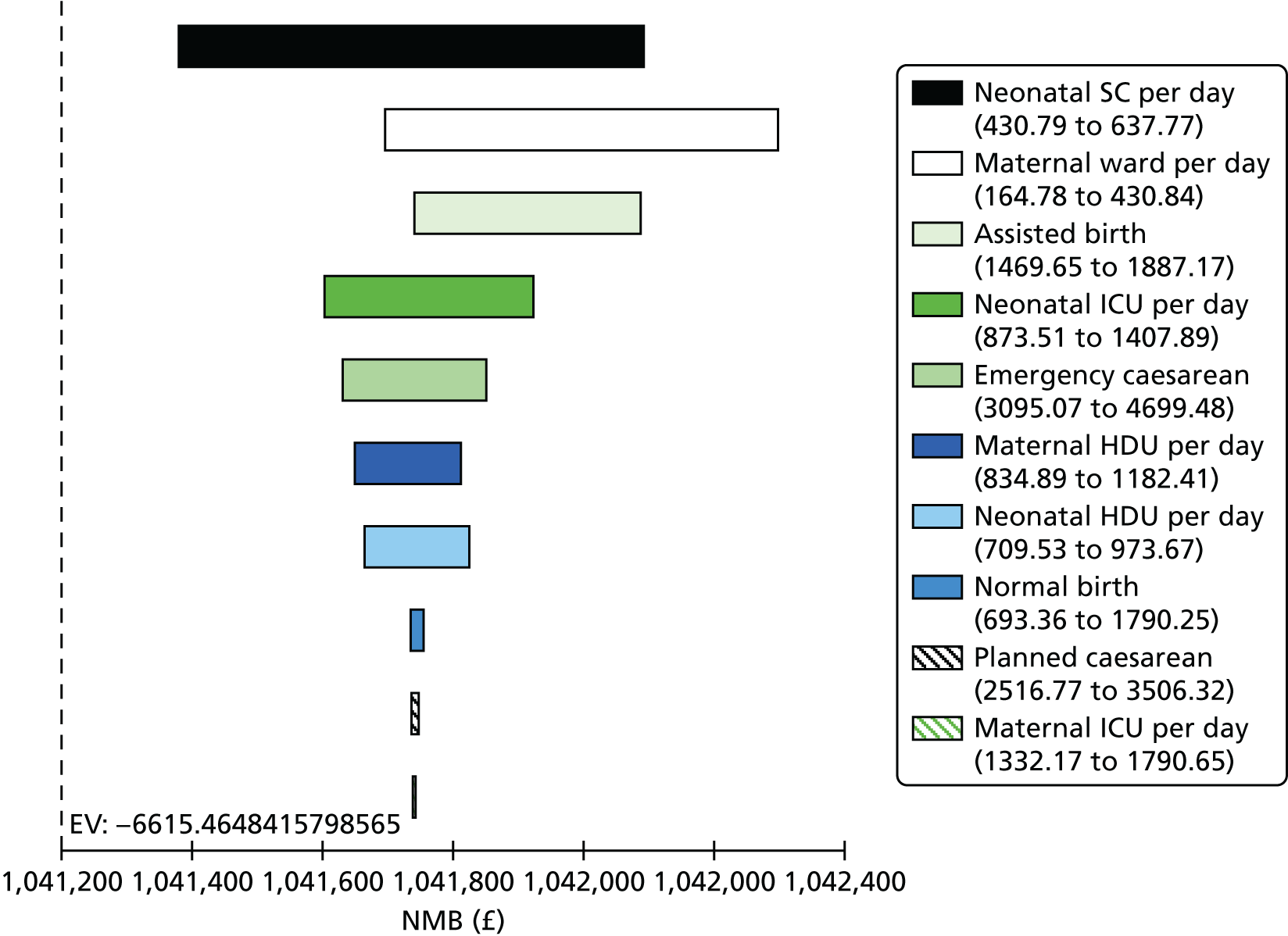

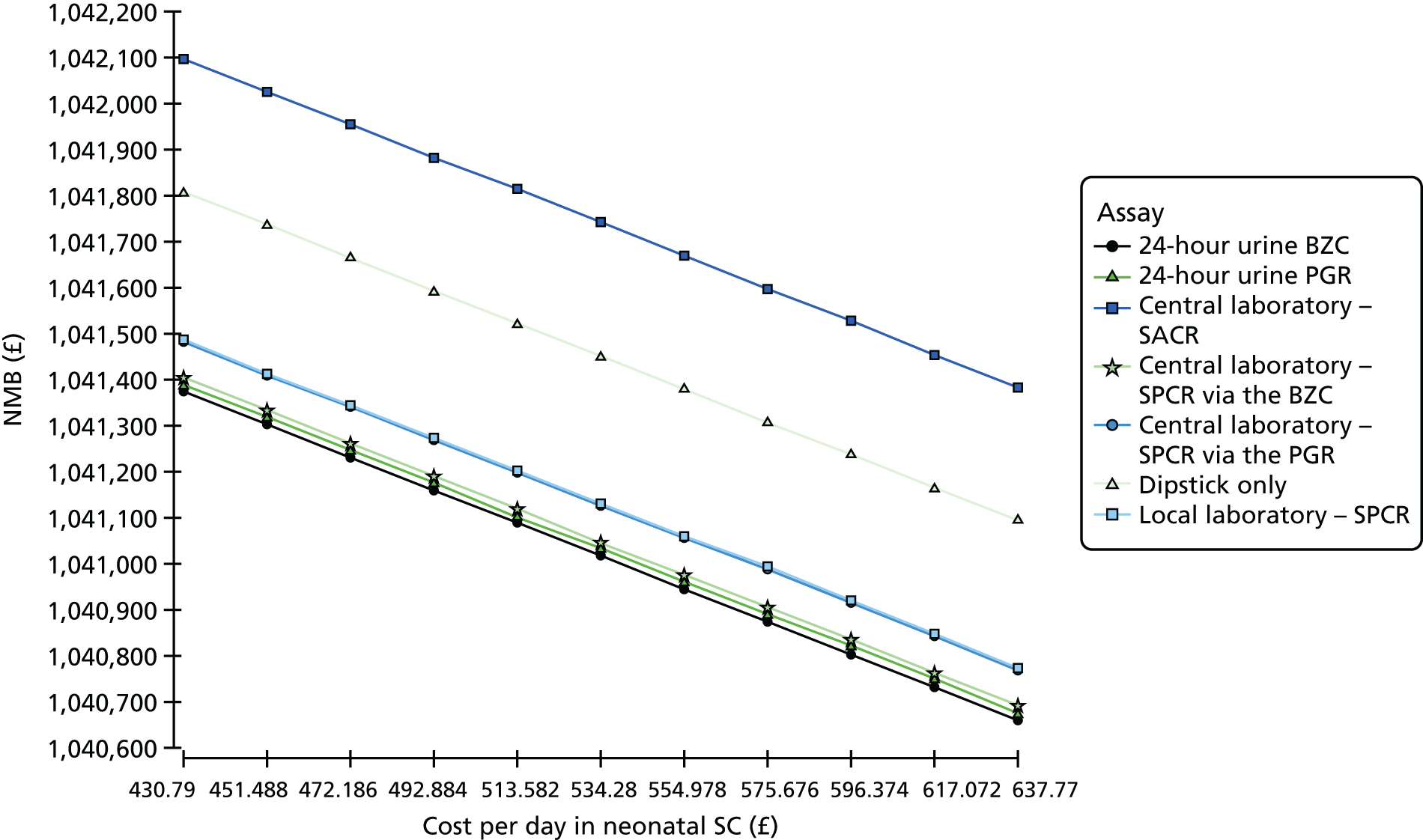

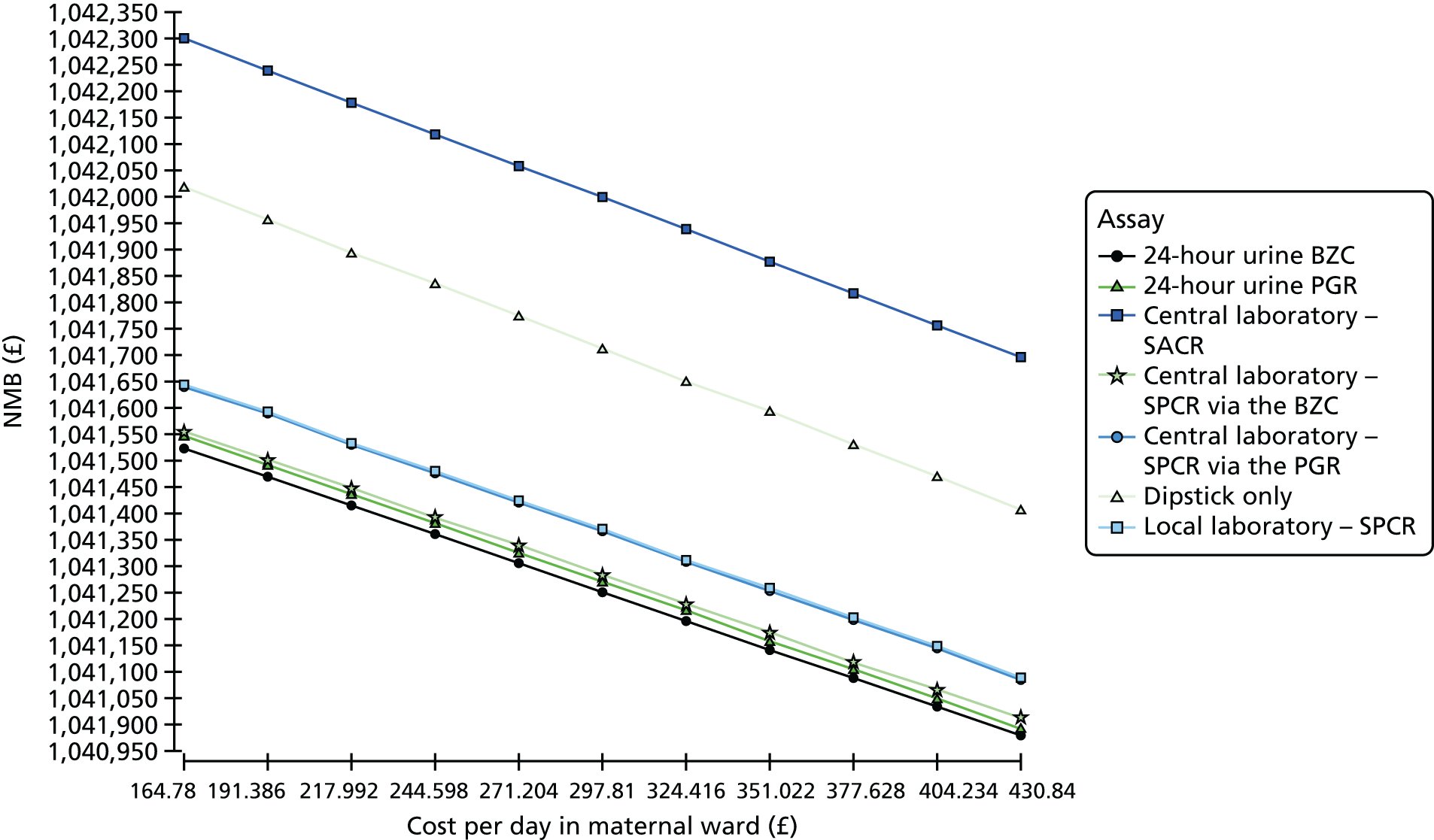

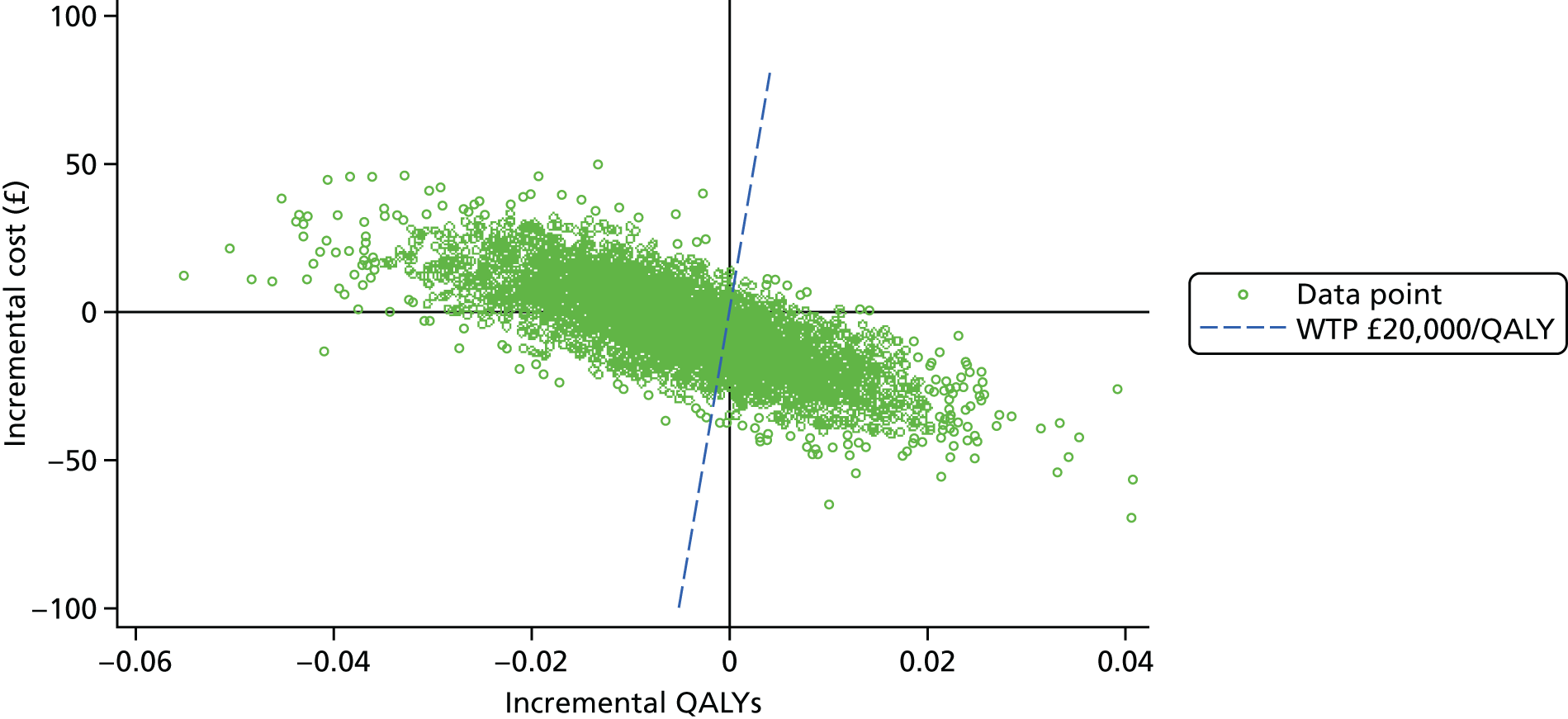

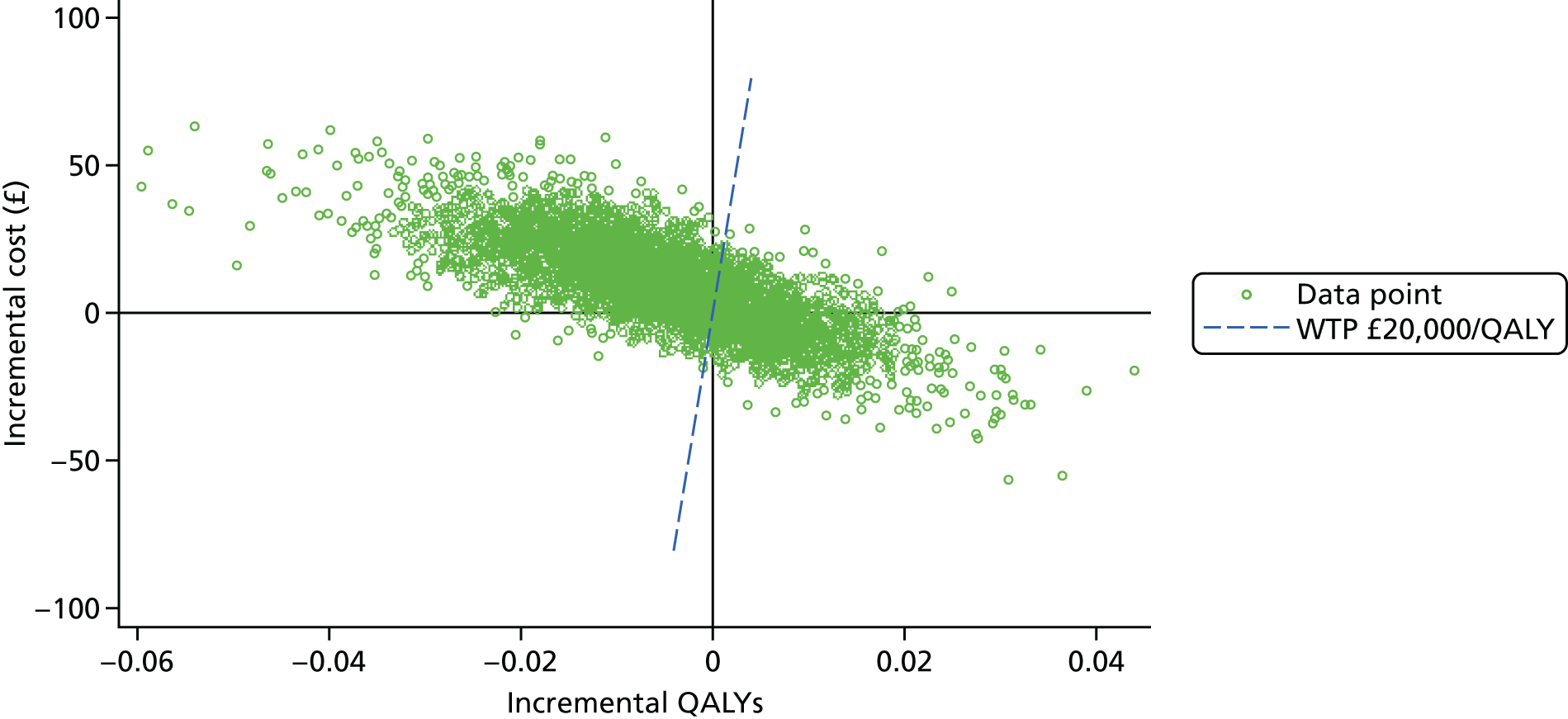

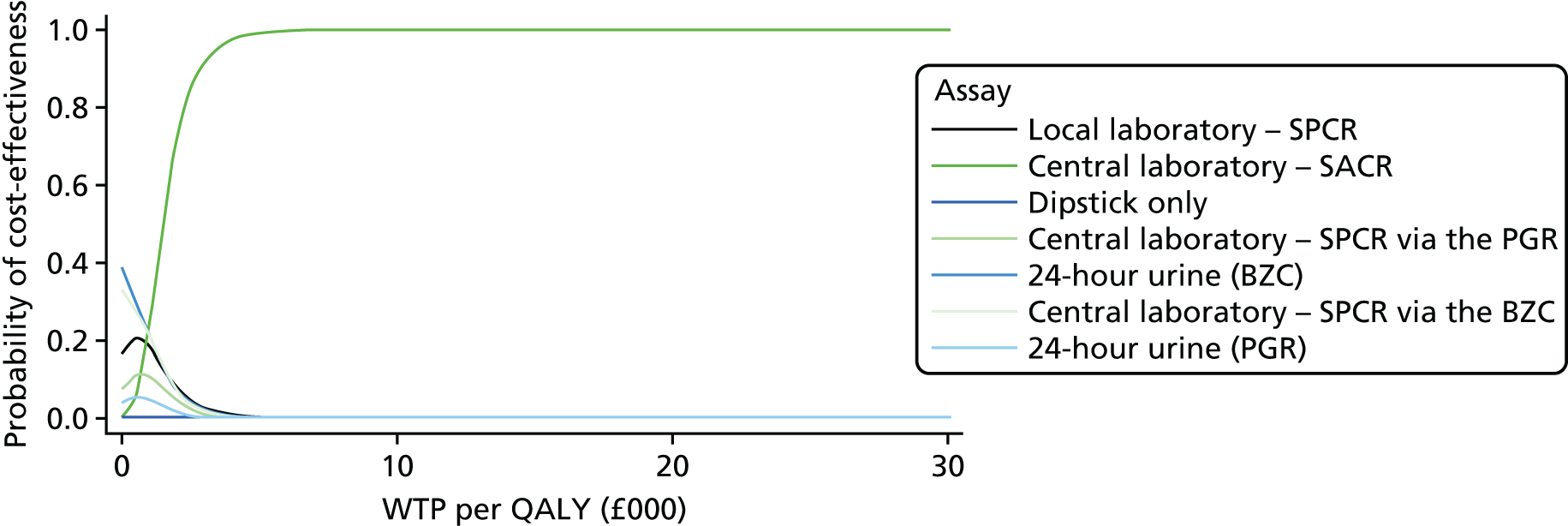

When overlain, the ROC curves for the four assays were similar (see Figure 9). The areas under the curve for all three laboratory assays were significantly greater than that for the local laboratory’s SPCR curve, although the differences may not be of practical importance (Table 64).