Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 08/24/02. The contractual start date was in September 2016. The draft report began editorial review in October 2016 and was accepted for publication in April 2017. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Jonathan Cook reports membership of the Health Technology Assessment (HTA) Efficient Study Designs Board outside the submitted work; Malcolm Loudon states that between 2002 and 2004 his research fellowship was sponsored by Ethicon Inc. to carry out a randomised controlled trial evaluating rubber band ligation against stapled haemorrhoidopexy; he received no direct financial support. John Norrie reports membership of the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Journals Library Editorial Group; non-financial support from the HTA commissioning board; and is a member of the NIHR HTA Editorial Board.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2017. This work was produced by Watson et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2017 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Introduction

Small amounts of text in this report have been adapted from Watson et al. 1 © Watson et al. ; licensee BioMed Central Ltd. 2014. This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly credited.

The eTHoS study: either Traditional Haemorrhoidectomy or Stapled haemorrhoidopexy for haemorrhoidal disease

In 2010, the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Health Technology Assessment (HTA) programme funded the eTHoS (either Traditional Haemorrhoidectomy or Stapled haemorrhoidopexy for haemorrhoidal disease) study. The study evolved in response to a HTA programme-commissioned call issued in 2008 inviting proposals for a study. The call itself arose after completion of a HTA-commissioned and -funded evidence synthesis written by Burch et al. 2 One of the key recommendations was the need for a well-designed, multicentre, prospective randomised controlled trial (RCT) to inform the evidence for the management of haemorrhoidal disease. This report describes the research.

The eTHoS study was a major multicentre UK-based RCT investigating the clinical effectiveness (including safety) and cost-effectiveness of stapled haemorrhoidopexy (SH) and traditional excisional haemorrhoidectomy (TH) for adult patients with grade II, III or IV haemorrhoids.

This chapter reflects clinical practice, particularly within the NHS, and the evidence available at the time of study inception, and discusses changes in NHS practice and any relevant literature published since 2009.

Background

The burden of the problem

Haemorrhoidal disease is common in all age groups from the mid-teens onwards; however, the direct causes are unclear. Haemorrhoids, or ‘piles’ as they are most commonly known, are defined as enlarged areas of vascular tissue at the top of the anal canal. Symptoms from haemorrhoids include bleeding, pain, itch and prolapse, and these can have an impact on a person’s quality of life. For significantly enlarged and protruding haemorrhoids, surgery is often advised as an effective way to control the symptoms. 3

The most commonly used clinical grading system for haemorrhoids is the one created by Goligher,4 who described four stages of haemorrhoids: grade I – protrusion of piles into anal canal; grade II – prolapse of haemorrhoids externally on defaecation, but return into the anal canal spontaneously; grade III – prolapse of haemorrhoids on defaecation and remain prolapsed until they are manually replaced into the anus; and grade IV – prolapsed and irreducible haemorrhoids.

The treatment of patients with haemorrhoidal disease continues to have considerable workload and cost implications for the NHS. Approximately 25,000 haemorrhoidal procedures were performed as hospital day-case or inpatient admissions in England over the period of 2006–7. 5 The treatment of haemorrhoidal disease is directed at relieving its related symptoms and this remains the current surgical philosophy.

Management of disease

The management of haemorrhoids is initially community-based. For early-grade haemorrhoids (grades I and II) patients are advised to avoid straining at stool and asked to increase the proportion of fruit and fibre in their diets. There is a large range of proprietary treatments that are available ‘over the counter’. These include topical creams and suppositories. Their efficacy is poor. Patients with refractory symptoms, or who have symptoms that cross over with those of bowel cancer and inflammatory bowel disease, are referred to a surgical outpatient clinic for investigation and treatment. Once inflammatory bowel disease and cancer have been excluded, the first line of treatment for grades II–III haemorrhoids is rubber band ligation (RBL). RBL is often offered as a ‘course’ of repeated treatments in the outpatient setting. RBL is successful in treating symptoms around 40% of the time and those patients who remain symptomatic after treatment are offered surgery. There are three main surgical techniques for haemorrhoids. These include excisional (or traditional) haemorrhoidectomy, SH and haemorrhoidal artery ligation (HAL).

In 2009, there were two main standard surgical treatments for haemorrhoids: traditional (or excisional) surgery and SH. A third operation, HAL, had been introduced but was not then in widespread use.

Traditional surgical haemorrhoidectomy

Traditional haemorrhoidectomy involves excision of the haemorrhoidal cushions and has generally been advocated for larger symptomatic haemorrhoids (grades III and IV). The technique involves the excision of haemorrhoid tissue. This is most commonly done by electrocautery, but occasionally sharp dissection with scissors is used. Other energy devices, the Harmonic® scalpel (Ethicon Endo-Surgery, Cincinnati, OH, USA) and the LigaSure™ device (Valleylab, Boulder, CO, USA) can also be used. The resulting wounds can either be sewn up (closed haemorrhoidectomy or Ferguson technique) or left open (open haemorrhoidectomy or Milligan–Morgan technique). This traditional approach, while effective, is nonetheless associated with severe immediate postoperative pain. Improved understanding of the pathogenesis of haemorrhoids6 and of the complications associated with excisional haemorrhoidectomy led to the invention of newer surgical procedures, including SH.

Stapled haemorrhoidopexy

Stapled haemorrhoidopexy was first developed by Longo at the end of the last millennium. 7 Its potential advantages over traditional surgery included a reduction of operating time, length of hospital stay, time to return to work and postoperative pain. 8 These features, compared with traditional haemorrhoid surgery, made SH attractive to patients and health-care providers at the time. However, uncertainties remained concerning complication rates, recurrence of symptoms and costs, which impeded its extensive use in the NHS. The stapling devices used for the procedure have evolved over the last two decades (1997–2017). The design has been refined to reduce the chance of postoperative bleeding and for the gun to be more effectively used in male patients (who have a narrower pelvis). Other manufacturers have also entered the market and produced guns that are significantly cheaper (Chex CPH 32 staple gun; Frankenman, Sheung Wan, Hong Kong) than the leading product, the PPH03 staple gun (Johnson & Johnson, New Brunswick, NJ, USA).

A newer technique, HAL was beginning to be adopted but was not being used across the NHS to any great degree. This surgical technique is also performed under general anaesthetic and involves the identification and ligation of the haemorrhoid arteries that feed haemorrhoids. The procedure is often combined with a suture that ‘pexies’ the prolapsing tissue back into the upper anal canal.

Evidence leading to the inception of the eTHoS study

Multiple RCTs comparing SH with TH and/or other conventional surgeries were analysed in four systematic reviews and a HTA journal publication. 2,9–12 The HTA publication included a review of the clinical effectiveness data from 27 RCTs (n = 2279). When comparing SH with TH, the studies showed equivalent complication and pain rates at day 21 post surgery. However, SH patients had less pain in the immediate postoperative period (first week) than those who received TH. Over the longer term, there was a significantly increased rate of residual prolapse requiring re-intervention with SH; however, there was no evidence of a difference in the number of patients experiencing pain or bleeding between the SH arm and the TH arm. The economic evaluations of the two interventions found that TH dominated SH, but it should be noted that SH and TH had very similar costs and quality-adjusted life-years (QALYs). 2 The additional cost of the stapling instrument was largely, but not completely, offset by savings in the length of operating time and hospital stay. In terms of QALYs, the improvements in quality of life as a result of lower pain levels in the early postoperative period with SH were offset by losses in quality of life as a result of the higher rate of symptoms over the follow-up period. SH thus appeared to be associated with less pain in the immediate postoperative period, but a higher rate of recurrence in the longer term and an increased need for further surgery. 13 These findings were based on data from small trials, all with methodological flaws, and provided only limited data on quality of life (or, with respect to an economic interpretation, health-state utilities) in the early postoperative period.

At the inception of the eTHoS study there was a reasonable volume of work on grade III and IV haemorrhoids; however, there were limited clinical and economic data regarding SH or TH for grade II haemorrhoids. 14 Members of our group had conducted a small single-centre RCT comparing RBL with SH for grade II haemorrhoids using both clinical and economic outcomes. 15 This had shown a superior clinical effect of SH compared with RBL in terms of recurrence of haemorrhoid symptoms. However, from a health economic standpoint, SH compared with RBL could not be justified, even with a 2-year follow-up. The trend over a longer period, however, suggested that the greater failure rate for RBL may eventually reach a level that justified the increased cost of SH. More robust data on the outcome of RBL have since come from the HubBLe (haemorrhoidal artery ligation versus rubber band ligation for the management of symptomatic second-degree and third-degree haemorrhoids) study16 comparing HAL with RBL, which shows that RBL, when given as a course of two or three treatments, is as clinically effective as HAL.

There was, therefore, a need for an adequately powered, high-quality multicentre RCT comparing the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of SH with that of TH in the NHS setting.

Evidence since the inception of the eTHoS study

Since the start of the eTHoS study there have been very few well-designed, prospective large-scale RCTs comparing SH with TH. 17–19 There were no new trials that included quality-of-life outcomes or looked at the health economics of interventions. These trials included a direct comparison between SH and TH. 20–22 HAL has become more widely used over the course of the eTHoS study and this is reflected in the number of RCTs examining its clinical effectiveness and utility. Results published in 2016 from the HubBle study suggest that HAL is no better than repeat RBL, which challenges the place of HAL in the modern surgical management of haemorrhoid disease. 16

A recent network meta-analysis of 98 RCTs, which included 7827 patients and 11 surgical treatments for grade III and IV haemorrhoids, compared a number of surgical and clinical outcomes23 (Table 1). Patients who had received TH had significantly more postoperative complications than those who had received HAL, LigaSure device and Harmonic scalpel haemorrhoidectomies. Patients who received SH had less pain and resumed normal activities more quickly than those who received TH, but there was a significantly higher chance of recurrent symptoms. The study, however, did not assess patient-reported symptoms nor quality of life.

| Outcome | Ranking | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1st | 2nd | 3rd | 4th | 5th | 6th | 7th | 8th | 9th | 10th | 11th | |

| Post-operative complications | Harmonic;p = 0.447 | Harmonic;p = 0.351 | LigaSure; p = 0.291 | LigaSure; p = 0.344 | Stapled; p = 0.263 | Stapled; p = 0.365 | Open; p = 0.377 | Open; p = 0.295 | Closed; p = 0.321 | Closed; p = 0.352 | Radiofrequency; p = 0.484 |

| Post-operative bleeding | Submucosal; p = 0.405 | THD; p = 0.334 | THD; p = 0.332 | Harmonic;p = 0.186 | LigaSure; p = 0.254 | LigaSure; p = 0.240 | Open; p = 0.216 | Open; p = 0.297 | Stapled; p = 0.293 | Radiofrequency; p = 0.259 | Radiofrequency; p = 0.498 |

| Reoperation | THD; p = 0.710 | Laser; p = 0.312 | Harmonic;p = 0.300 | Stapled; p = 0.334 | Open; p = 0.257 | Open; p = 0.355 | Closed; p = 0.390 | Radiofrequency; p = 0.594 | n/a* | n/a | n/a |

| Duration of surgery | Radiofrequency; p = 0.539 | Harmonic; p = 0.381 | Harmonic; p = 0.276 | Stapled; p = 0.293 | Stapled; p = 0.314 | THD; p = 0.293 | THD; p = 0.537 | Open; p = 0.887 | Closed; p = 0.498 | Closed; p = 0.490 | Laser; p = 0.909 |

| Operative blood loss | Bipolar scissors; p = 0.707 | LigaSure; p = 0.280 | LigaSure; p = 0.380 | Stapled; p = 0.300 | Stapled; p = 0.313 | Laser; p = 0.752 | THD; p = 0.335 | Closed; p = 0.481 | Open; p = 0.423 | n/a† | n/a |

| Length of hospital stay | Radiofrequency; p = 0.620 | Submucosal; p = 0.376 | THD; p = 0.308 | Stapled; p = 0.392 | LigaSure; p = 0.228 | LigaSure; p = 0.363 | Open; p = 0.296 | Open; p = 0.308 | Closed; p = 0.220 | Closed; p = 0.428 | Laser; p = 0.392 |

| Time to first bowel movement (days) | THD; p = 0.853 | LigaSure; p = 0.533 | Harmonic;p = 0.470 | Stapled; p = 0.566 | Open; p = 0.596 | Open; p = 0.263 | Bipolar scissors; p = 0.569 | n/a‡ | n/a | n/a | n/a |

| Time to normal activities (days) | THD; p = 0.478 | Stapled; p = 0.370 | Stapled; p = 0.333 | LigaSure; p = 0.262 | LigaSure; p = 0.310 | LigaSure; p = 0.198 | Open; p = 0.183 | Open; p = 0.339 | Open; p = 0.284 | Closed; p = 0.322 | Radiofrequency; p = 0.315 |

| Pain on day 1 | THD; p = 0.584 | Starion; p = 0.269 | Stapled; p = 0.292 | Stapled; p = 0.255 | LigaSure; p = 0.292 | LigaSure; p = 0.277 | Radiofrequency; p = 0.254 | Closed; p = 0.427 | Open; p = 0.422 | Submucosal; p = 0.480 | n/a§ |

| Pain on day 7 | THD; p = 0.295 | Stapled; p = 0.342 | Stapled; p = 0.230 | LigaSure; p = 0.222 | LigaSure; p = 0.194 | Closed; p = 0.231 | Open; p = 0.242 | Open; p = 0.285 | Submucosal; p = 0.382 | n/a¶ | n/a |

| Recurrence of haemorrhoids | Submucosal; p = 0.381 | Radiofrequency; p = 0.358 | LigaSure; p = 0.277 | LigaSure; p = 0.315 | Closed; p = 0.273 | Open; p = 0.383 | Stapled; p = 0.287 | Stapled; p = 0.649 | THD; p = 0.785 | n/a¶ | n/a |

| Recurrent haemorrhoidal symptoms | Laser; p = 0.530 | LigaSure; p = 0.333 | Closed; p = 0.296 | THD; p = 0.282 | Open; p = 0.448 | Stapled; p = 0.482 | Harmonic;p = 0.467 | n/a# | n/a | n/a | n/a |

The aim of the eTHoS study was to assess whether or not SH was more clinically effective and cost-effective than TH for patients with grades II, III and IV haemorrhoids.

The primary objective was to compare patient-reported overall health-related quality of life measured using the EuroQol-5 Dimensions, three-level version (EQ-5D-3L) responses over a period of 24 months.

The secondary objective was to compare subdomains of health [Short Form questionnaire-36 items (SF-36) scores, pain and symptoms], disease recurrence, complication rates, direct and indirect costs to the NHS and cost-effectiveness (measured in terms of incremental cost per QALY, when QALYs are derived from responses to the EQ-5D-3L and the SF-36).

Chapter 2 Study design

The eTHoS study was a large multicentre UK pragmatic RCT to assess whether or not SH is more clinically effective and cost-effective than TH for people presenting with haemorrhoids (grades II, III and IV). 1

Participants

Potential participants were adults referred to NHS hospitals for consideration of surgical treatment and identified according to the inclusion and exclusion criteria specified below. Participants could have previously had RBL or HAL, but not undergone any other form of haemorrhoid surgery.

Inclusion criteria

-

Patients with circumferential haemorrhoids of grades II, III or IV.

-

Patients aged ≥ 18 years.

-

Written informed consent obtained.

Exclusion criteria

-

Previous surgery for haemorrhoids (traditional or stapled, except RBL or HAL).

-

Previous surgical treatment for anal sphincter injury repair or symptomatic incontinence or perianal sepsis.

-

Known inflammatory bowel disease.

-

Malignant gastrointestinal disease, within the last 5 years.

-

Medically unfit for surgery or for completion of the study.

-

Pregnant women.

Participants were randomised to one of the two study groups on a 1 : 1 basis. The randomisation minimisation algorithm used centre, grade of haemorrhoidal disease (II, III or IV), baseline EQ-5D-3L score (categorised as < 0.6, 0.6 to < 0.8 and 0.8 to 1.0) and sex. A remote telephone interactive voice response randomisation application, hosted by the Centre for Healthcare Randomised Trials (CHaRT), Health Services Research Unit (HSRU) at the University of Aberdeen, was used to perform the randomisation.

The main criterion for selection of NHS hospital sites across the UK where participant recruitment could take place was that each hospital centre had at least two members of staff to occupy two key research roles. One was that of the research role – a (co-investigating) colorectal consultant; the other was that of a local recruitment officer, for example a nurse or junior doctor. In exceptional circumstances the colorectal consultant performed both roles. At each centre there may have been more than one colorectal consultant (co-investigator) who was fully eTHoS trained and actively screening potential patients (for eligibility) and for subsequent recruitment onto the study. At each centre one of these consultants assumed the leading role of local lead colorectal surgeon for the eTHoS trial. A total of 32 UK NHS sites took part in the study. These were NHS Highland and Islands, Inverness; NHS Grampian, Aberdeen; North Tees and Hartlepool Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust, Stockton-on-Tees; Sheffield Teaching Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust, Sheffield; County Durham and Darlington NHS Foundation Trust, Durham; Leeds Teaching Hospitals NHS Trust, Leeds; Norfolk and Norwich University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust, Norwich; Central Manchester University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust, Manchester; Chelsea and Westminster Hospital NHS Foundation Trust, London; NHS Greater Glasgow and Clyde, Glasgow; Betsi Cadwaladr University Health Board, Rhyl; Oxford University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust, Oxford; Aintree University Hospital NHS Foundation Trust, Liverpool; Dr Gray’s Hospital, Elgin; Brighton and Sussex University Hospitals NHS Trust, Brighton; South Tees Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust, Middlesbrough; Calderdale and Huddersfield NHS Foundation Trust, Huddersfield; Wirral University Teaching Hospital, Upton, Wirral; Croydon Health Services NHS Trust, Croydon; Royal Free London NHS Foundation Trust, London; The Mid Yorkshire Hospitals NHS Trust, Wakefield; Royal Cornwall Hospitals NHS Trust, Truro; The Hillingdon Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust, London; Bwrdd Iechyd Aneurin Bevan Health Board, Wales; Weston Area Health NHS Trust, Somerset; Derby Teaching Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust, Derby; NHS Forth Valley, Stirling; Gateshead Health NHS Foundation Trust, Gateshead; Colchester Hospital University NHS Foundation Trust, Colchester; Basildon and Thurrock University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust, Basildon; United Lincolnshire Hospitals NHS Trust, Lincoln; and University Hospital of South Manchester NHS Foundation Trust, Manchester.

Study interventions

Eligible participants who consented were placed on the appropriate waiting list by the treating colorectal surgeon or his/her designated team member. Participants received the allocated intervention to which they were randomised:

-

stapled haemorrhoidopexy

-

traditional excisional haemorrhoidectomy.

Each centre’s participating surgeons had undergone appropriate recognised training for both SH and TH surgery. Surgery was performed by surgeons in training: either independently, if signed off by their supervising consultant, or under the direct supervision of their consultant. Pre- and postoperative care followed the respective surgeon’s and/or centre’s standard policies.

Outcome measures

Primary outcome measures

Patient reported

The primary outcome was quality of life gained over the follow-up period [area under the curve (AUC) derived from EQ-5D-3L measurements taken from patient questionnaires distributed at baseline, 1 week, 3 weeks, 6 weeks (postoperatively), 12 months, (EQ-5D-3L only at 18 months if not completed at 12 months) and 24 months post randomisation].

Participants had the opportunity to complete the questionnaires on a secure portal on the eTHoS trial website using log-in details provided by the study team. In the event that the postal questionnaires were not returned or completed via the website, for the 1- and 3-week questionnaires, participants were telephoned to obtain the missing data. Postal reminders were issued if there was no response to the 6-week, 12-month and 24-month questionnaires. A final reminder followed if there was no response to the subsequent reminder. This reminder was shortened to include only the EQ-5D-3L questionnaire.

Health economic

Incremental cost per QALY gained, with QALYs based on the responses to the EQ-5D-3L at 24 months, was measured. QALYs were calculated from participant responses to the EQ-5D-3L completed at baseline, 1 week, 3 weeks and 6 weeks post surgery, and 12 (or 18) and 24 months post randomisation. Costs were collected at baseline, 6 weeks, and 12 and 24 months after randomisation. Participants also provided information about their use of health services via the health-care utilisation questions within the eTHoS trial patient questionnaires (see Appendix 1).

Secondary

Patient reported

Patient-reported secondary outcomes were:

-

generic health profile as measured by the SF-36 and the EQ-5D-3L

-

visual analogue scale (VAS) pain score

-

Cleveland Incontinence Score (CIS)

-

Haemorrhoid Symptom Score (HSS)

-

postoperative analgesia consumption

-

recurrence of haemorrhoids

-

tenesmus.

Clinical

The clinical secondary outcomes were intra-operative and postoperative complications, including:

-

haemorrhage

-

requirement for blood transfusion

-

anal stenosis

-

anal fissure

-

urinary retention (which requires catheterisation)

-

residual anal skin tags

-

difficult defaecation

-

wound discharge

-

pelvic sepsis

-

pruritus

-

recurrence of haemorrhoids.

Economic

The economic secondary outcomes were:

-

costs based on NHS resource use data

-

length of hospital stay

-

use of health services for haemorrhoid-related events or treatments

-

patient costs (treatments, travel to health services, sick leave)

-

need for alternative management for haemorrhoids (e.g. surgery, drugs)

-

other use of health services, such as:

-

visits to general practitioner (GP)

-

visits to practice nurse

-

visits to colorectal surgeon

-

-

QALYs estimated from the EQ-5D-3L at 24 months

-

cost-effectiveness analysis (incremental cost per case of SH and TH excision avoided).

Chapter 3 Methods

Research ethics and regulatory approvals

The eTHoS study was given favourable ethics approval by the North of Scotland Research Ethics Committee (REC) on 18 June 2010 subject to receiving individual research approvals from each host organisation prior to the commencement of the study at site (reference number 10/20802/17). The study was co-sponsored by NHS Highland and the University of Aberdeen. The study was registered and was given an International Standard RCT Number (ISRCTN80061723).

Project management group

The study was supervised by a project management group (PMG). This consisted of the grant holders and representatives from the study office, who provided day-to-day support for the study. Observers were invited to attend at the discretion of the PMG. The PMG met every 6 months, on average, during the course of the study.

Study oversight committees

The study Data Monitoring Committee (DMC) comprised three independent individuals who met initially at the beginning of the study when terms of reference and other committee procedures were agreed. The committee then met an additional four times during the course of the study to monitor unblinded baseline and outcome data provided by the study statistician and details of serious adverse events (SAEs). The DMC reported any recommendations to the chairperson of the Trial Steering Committee (TSC). The TSC comprised four independent individuals who oversaw the study. At the invitation of the chairperson, grant holders and observers/members of the host university (University of Aberdeen) and the funder (HTA programme) could also attend. Terms of reference for the TSC were agreed at the commencement of the study and the group met annually throughout the duration of the study. The terms of reference for the DMC and TSC can be accessed on request from the eTHoS study office.

Patient and public involvement

An independent patient and public involvement representative was a member of the TSC. A patient representative was also involved in the grant application and throughout the study as a grant holder. Patient and public involvement was sought in the development of the participant newsletter. Both members reviewed the paperwork and provided constructive feedback in its development.

Participants

Study flow

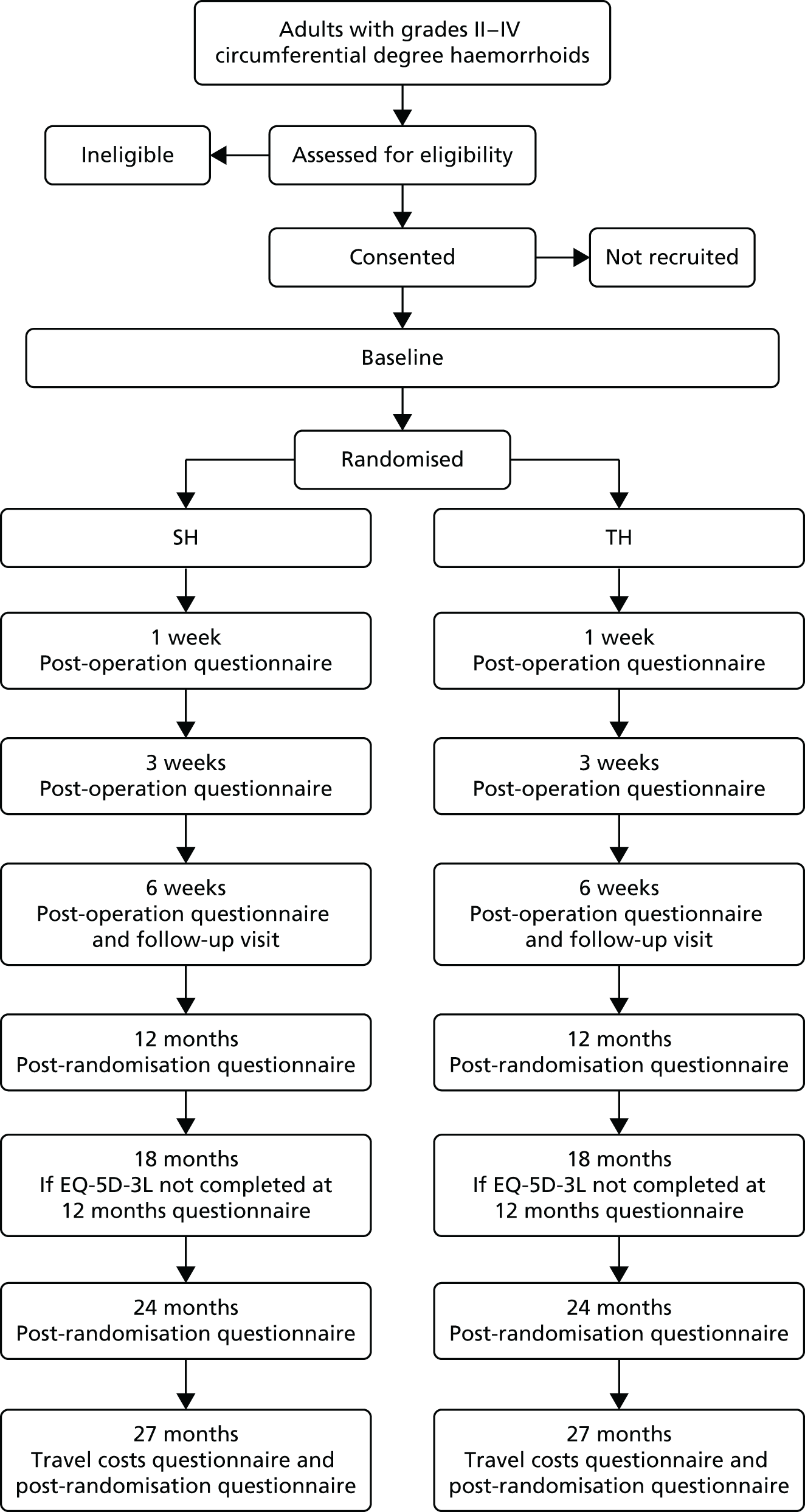

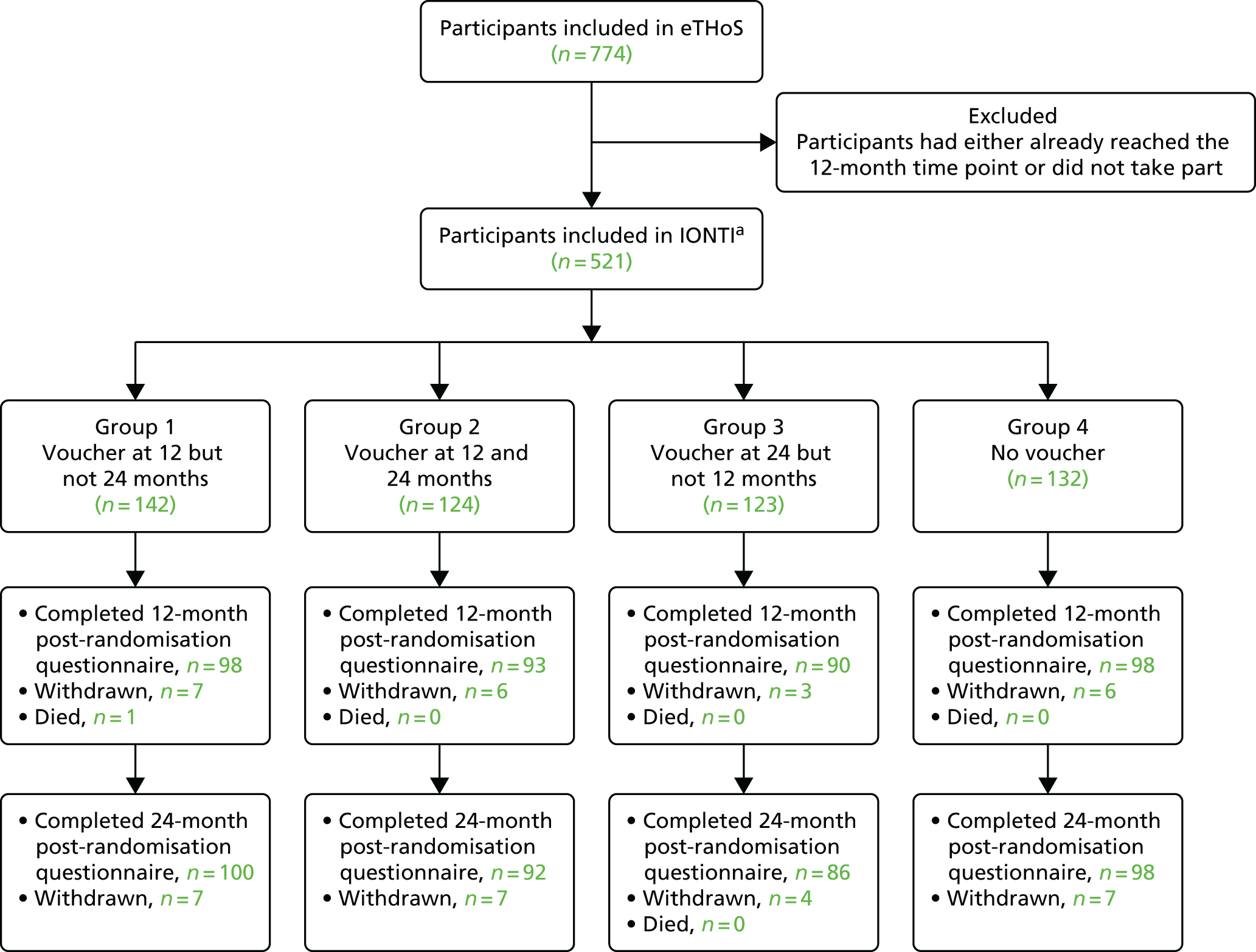

The flow of participants through the study is detailed in Figure 1.

FIGURE 1.

Participant study flow.

Identification of patients and recruitment

Patients were identified by colorectal clinicians in participating sites, and were supported by local clinical research teams.

Colorectal clinicians assessed the eligibility of the participants for surgery according to standard practice. At the initial consultation, the colorectal clinician discussed the various treatment options available and provided information regarding the eTHoS study. Risks and benefits of all treatments were also discussed as part of standard clinical practice. Patients who had undergone RBL or HAL but still had symptoms were eligible for the study. Patients who had received any other form of haemorrhoid surgery were excluded from the study. Participants who expressed a strong preference for one of the interventions were also excluded. Identified eligible patients were then given a patient information leaflet (PIL; see Appendix 2), which contained details of the study and context. The clinician, or a trained member of the local clinical team, was able to answer any questions/discuss the study with the potential participants. Patients were encouraged to take time to read through the PIL and to take it home if they should wish. If the patient agreed to be contacted at home, then a member of the local research team would call to discuss the study. Patients who gave verbal agreement to take part in the study were then requested to complete documents [consent form and baseline questionnaire, which collected data on the EQ-5D-3L, the SF-36, the CIS and the HSS, and patient preference for surgery outcomes (see Appendices 2 and 3)] and return these by post to the local study team at their treating hospital or bring them when they returned to hospital for preoperative assessment or at the time of the operation. The consent form was then countersigned on receipt by the local study team member.

Patients who were able to make a decision to join the study while they were at the initial consultation were provided with the eTHoS study participant baseline questionnaire. This was completed only once a patient was eligible and happy to take part in the study and had signed the consent form. Contact details for both the local and central team were provided on the PIL. Further checking against eligibility criteria was performed by local research staff. Current clinical status was also captured on the baseline case report form (CRF) (see Appendix 3).

Following full written consent and baseline data completion, patients were randomised as near to their surgery date as possible. For those patients who did not consent to participate, an ‘Ineligible/Declined’ form (see Appendix 3) was completed by a local study team member, detailing non-personal data, including the reason(s) for the participant declining (if provided), or the ineligibility criterion. These data were recorded on the study database to inform the consort.

Randomisation

Participants were randomised to one of the two study groups on a 1 : 1 basis. The minimisation algorithm used centre, grade of haemorrhoidal disease (II, III or IV), baseline EQ-5D-3L score and sex. A remote telephone interactive voice response randomisation application hosted by CHaRT, HSRU at the University of Aberdeen was used to perform randomisation. The first participant was randomised on 13 January 2011 and the final participants were randomised on 1 August 2014 when the randomisation system was closed.

Study interventions

Eligible participants who consented were placed on the appropriate waiting list by the treating colorectal surgeon or his/her designated team member. Most participants received the allocated intervention, which was either SH or TH. Some received alternative treatment or did not receive treatment; however, participants were followed up regardless of the intent-to-treat analysis. Treatment data were captured on the hospital and surgery CRF (see Appendix 3). Each centre’s participating surgeons had to have undergone appropriate recognised training for both SH and TH. Surgeries were performed by surgeons in training; either independently, if signed off by their supervising consultant, or under the direct supervision of their consultant. Pre-operative and postoperative care followed the respective surgeon’s and centre’s standard care policies. Although the two procedures being compared are offered as routine care, not all sites provided postoperative information (what to expect after the haemorrhoid treatment) to participants. Therefore, we prepared a participant postoperative leaflet that sites could make available to participants if they wanted to (see Appendix 2).

Data collection

Follow-up consisted of clinical follow-up at 6 weeks after treatment. Postal questionnaires were distributed at 1 week, 3 weeks and 6 weeks after treatment, and 12 months (or 18 months if EQ-5D-3L not completed at 12 months) and 24 months after randomisation (Table 2). The main outcome assessment was planned at 24 months’ (from the date of randomisation) follow-up.

| Outcome | Time point | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | Surgical form | 1 week post treatment | 3 weeks post treatment | 6 weeks post treatment | 12 months post randomisation | 24 months post randomisation | 27 months post randomisation | |

| Clinical status | ✓ | |||||||

| Surgical details | ✓ | |||||||

| Patient preference | ✓ | |||||||

| 6 weeks’ clinical follow-up | ✓ | |||||||

| EQ-5D-3La | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| SF-36 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| Pain VAS | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||

| HSS | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| CIS | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| Health-care Utilisation questions | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||

| Travel costs questionnaire | ✓ | |||||||

| Recurrence | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||

| Analgesia question | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||

| DCE | ✓ | |||||||

| Hospital Statistics for further surgery | ✓ | |||||||

Consent was sought from all participants recruited to the study to be flagged for notification of haemorrhoidal recurrence. To evaluate long-term safety, the participants who had further haemorrhoidal surgery were identified via registry databases: Hospital Episode Statistics (HES) in England, Patient Episode Database Wales (PEDW) in Wales and Information Services Division (ISD) data in Scotland, when all participants had reached 12 months post randomisation.

Safety reporting

We reported SAEs in accordance with the guidance from the National Research Ethics Service, which is a subdivision of the National Patient Safety Agency. As such, non-SAEs were not collected or reported. All SAEs were recorded on the SAE report form (see Appendix 3). In addition, SAE forms recorded all deaths during the course of the study whether or not these were related to the research procedures. The following occurrences were potentially expected: intraoperative occurrences associated with the intervention, including anaesthetic-related problems, intraoperative instrument failure, damage to adjacent organs and bleeding. Possible (expected) occurrences associated with either type of surgery occurring at any time during the study included haemorrhage, requirement for blood transfusion, anal stenosis, anal fissure, pain, urinary retention, residual anal skin tags, anal fistula, prolapse, difficult defaecation, faecal urgency, wound discharge, pelvic sepsis, systemic complications and pruritus.

The details of any of the occurrences listed above were recorded on the CRFs and on participant-completed questionnaires and reported to the DMC in annual reports, but were not recorded as a SAE unless defined as an event occurring to a research participant that was related (resulted from administration of any of the research procedures) and was expected or unexpected, which caused death, was life-threatening, required hospitalisation, resulted in significant incapacity/disability or was otherwise considered medically significant by the investigators. Expected and unexpected SAEs were recorded.

Change of status/withdrawal

Participants remained on the study unless they chose to withdraw consent or if the principal investigator, chief investigator or study office felt that it was no longer appropriate for the participant to continue (i.e. the participant became unable to complete the study documentation). Reasons for participant withdrawal from the study were recorded on the ‘withdrawal/change of status’ form (see Appendix 3). Participants could withdraw from treatment but remain in the study for follow-up questionnaires and/or to have relevant outcome data collected from NHS records if consent remained for this.

Data management

Clinical data were collected at the individual hospital centres using hospital-based records and hard-copy CRFs (see Appendix 3). Clinical data were then input onto the eTHoS study database by local researchers using an electronic web-based data capture system [in addition relevant clinical data being collected from registry databases (HES, PEDW and ISD)]. Extensive range and consistency checks enhanced the quality of the data. Staff in the study office provided periodic data queries to local research staff to ensure that the data were as complete and accurate as possible. Questionnaires returned by post to the study office were entered onto the database by data-trained members of the central research team.

Data collected during the course of the research were kept strictly confidential and accessed only by members of the study team. Participants’ details were stored on a secure password-protected and user-specific database under the guidelines of the 1998 Data Protection Act,24 including encryption of any identifiable data. Participants were allocated an individual-specific study number and all data, other than personal data, were identified only by this unique study number.

The content of approximately 10% of CRFs and participant questionnaires entered at sites were checked to ensure accuracy. To ensure that sites had understood the data-entry processes and that they were efficiently entering the data, a sample from the first CRFs entered by each site were selected. Further paper CRFs and questionnaires were selected at random. This was completed at the study office (a copy of the paper forms were sent/faxed from the individual sites to the University of Aberdeen to facilitate this). An error rate of < 5% required no further action; however, if the error rate was > 5%, a 100% check of all forms from that site was undertaken.

Some questionnaires were returned directly to the University of Aberdeen. A 10% random sample of questionnaires returned to the study office were checked by a different data co-ordinator/clerk than the person responsible for the initial data entry, and the action on identified error rate was identical to that described above.

Statistical methods and study analysis

Ground rules for the statistical analysis

Study analyses followed the statistical analysis plan agreed in advance by the TSC. The main statistical analyses were based on all randomised participants, irrespective of subsequent compliance with the treatment allocation. Statistical significance was at the two-sided 5% level with corresponding confidence intervals (CIs) derived.

Sample size

Data on the 24-month AUC (QALYs) for the EQ-5D-3L scores in this patient group were sparse, but an effect size of 0.25 standard deviations (SD) was considered a worthwhile difference in quality-of-life measures. A sample size of 338 per group was required to provide a 90% power to detect a difference in the mean area under the quality-of-life AUC curve with a significance level of 5% (two-sided alpha). To allow for 15% non-response in the outcome, we required 400 participants in each treatment group. This sample size would also give 90% power to assess differences in the secondary outcome of recurrence between the two interventions from around 10% to around 4%. This difference is supported by a recent systematic review,9 which showed a non-statistical trend of higher recurrence in the SH group than in the TH group.

Primary/secondary outcome analysis

The primary outcome, AUC (measured by the EQ-5D-3L), was generated for each participant using the trapezoidal rule and analysed using linear regression. The analysis was adjusted for the minimisation variables, centre was accounted for by using cluster robust standard errors while the others were fixed effects. To be included in the primary analysis, participants had to have at least one short-term measure (1 week, 3 weeks or 6 weeks post surgery) and at least one long-term measure (12, 18 or 24 months post randomisation). In the sensitivity analysis, missing EQ-5D-3L data were estimated using a multiple imputation (MI) by chained equations using the ‘ice’ Stata® version 14 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA) command. It also included assessment of the robustness of the treatment effect estimates by altering the minimum number of EQ-5D-3L values needed for each participant and also compliance (using a per-protocol analysis that comprised those participants who received their allocated intervention). Secondary analyses for the primary outcome included the EQ-5D-3L AUC over 6 weeks and 12 months.

Secondary outcomes (SF-36, CIS and HSS) were analysed using linear mixed models with adjustment for minimisation variables. Tenesmus was analysed with the chi-squared test for trend and further surgical intervention was analysed with the chi-squared test. All other secondary outcomes were analysed using either logistic or linear regression. Continuous variables were summarised with mean (SD) or median [interquartile range (IQR)], whereas discrete variables were number and percentages. All analyses were assessed at the two-sided 5% significance level and done using Stata software.

Planned subgroup analyses

Subgroup analyses explored the possible treatment effect modification of clinically important factors (haemorrhoidal grade and sex) through the use of treatment-by-factor interaction, all using a stricter two-sided 1% level of statistical significance.

Patient preference analyses

Baseline data were summarised by treatment preference based on surgical outcome scenarios and the primary and secondary outcomes were analysed using linear regression adjusted for patient preference and minimisation variables. Presence of a treatment-by-preference interaction was assessed. In addition, associations between preference and drop-out were analysed. The patient preference analysis is reported in Chapter 9.

Timing and frequency of analyses

A single principal analysis was carried out when the final participant reached the 24-month time point.

Economics methods

Introduction

Although a de novo economic model was planned to assess the long-term cost-effectiveness (assessed in terms of incremental cost per QALY) and net benefits of SH and TH, the results of the study-based economic evaluation in conjunction with the clinical findings rendered the planned modelling unnecessary. Therefore, the following section describes the methods for the study-based economic evaluation. The question to be addressed by the economic evaluation was ‘what are the relative cost-effectiveness (assessed in terms of incremental cost per QALY) and net benefits of SH and TH?’. The cost-effectiveness analysis follows the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE)’s reference case25 and the International Society for Pharmacoeconomics and Outcomes Research’s recommendations on conducting economic evaluations alongside clinical trials. 26 A secondary analysis also assessed cost to participants. The methods and analysis for the within-trial analysis are described below. The perspective of study was that of the health service provider (the NHS) and the costs are expressed in pounds sterling for the financial year 2014–15. 27 Costs and benefits incurred in the second year were discounted at a rate of 3.5% per annum. 25 The follow-up period for the economic analysis was 24 months.

Within-trial analysis

Health service use was recorded prospectively, and retrospectively, for each participant. Intervention resource use was collected prospectively for every participant in the study using questionnaires at baseline and CRFs, and follow-up resource use was collected retrospectively at 6 weeks, and 12 and 24 months (see Appendix 1). The underlying aim was to keep economic data collection as parsimonious as possible in order to minimise the burden on the participants and the effect on response rates. A postal questionnaire of all participants was used to ascribe participant costs to typical episodes of health service use, and was initially sent at 18 months post randomisation (see Appendix 1), but this was changed during the course of the study to 27 months post randomisation. This was to allow a shortened third reminder to be issued at 18 months for the 12-month questionnaire.

The areas of resource use considered comprised four broad areas:

-

intervention resource use

-

secondary care resource use

-

primary care resource use

-

resource use directly incurred by the participants.

Intervention resource use

The intervention resource use was recorded on a per-patient participant basis. The resources used to provide surgery were established by consulting with relevant staff at participating centres (surgeons, theatre nurses, business managers) and members of the study team to elicit information on:

-

equipment, such as the type of stapler used

-

frequency of use of said equipment

-

consumables used during surgery, such a surgical trays

-

staff mix of the surgical team (e.g. grade of the operating surgeon, grade of the anaesthetist, grade and number of nurses).

In addition to this, the operative information was collected on the CRFs and provided details of the grade of staff involved and the duration of procedure. Length-of-stay information was elicited for each participant through the CRFs by collecting the date of admission and discharge. For the initial intervention, data cost estimation focused on those resources that differed between the two interventions, that is, it was assumed that there would be no difference in time in recovery or time on the ward following the procedure (for those managed as day cases).

Other secondary care resource use

The use of subsequent care, such as inpatient stay (duration of stay), reoperation or other surgical interventions (SH or TH) and outpatient visits over the study follow-up period, was obtained from the CRFs (6 weeks) and patient questionnaire (12 and 24 months).

Primary care resource use

All primary care resource use, such as general practice doctor and nurse contacts and medications prescribed to treat haemorrhoids, was obtained from the participant questionnaire administered at 12 and 24 months.

Derivation of costs

The costs of the health service utilisation were estimated by combining resource use data with unit costs of resource use. Unit costs were based on study-specific estimates in combination with data from standard sources. Unit costs for the equipment used in stapling were obtained from the manufacturers of the products through personal communication with sites using the equipment or from published price lists. Table 3 details the unit costs used, the source of the estimate and any assumptions used to derive them.

| Resource item | Unit cost (£) | Comments | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Stapler | |||

| Ethicon PPH03 (Johnson & Johnson, New Brunswick, NJ, USA) | 442.01 | Box of three – £1105.04 excluding VAT | NHS Scotland and NHS England Hub prices (Ewan McDonald, NHS Grampian, 2016, personal communication) |

| Chex CPH 32 | 276.00 | Box of three – £690 excluding VAT | NHS Scotland and NHS England Hub prices |

| EEA™ Staplers with DST™ Series technology (Covidien Ltd, Dublin, Ireland) | 269.62 | Box of three – £674.06 excluding VAT | NHS Scotland and NHS England Hub prices |

| Surgeon and anaesthetist | |||

| Consultant | 2.30 per minute | £138 per hour | PSSRU (2015)28 |

| Specialty doctors and associate specialists | 2.13 per minute | £128 per hour | PSSRU (2015)28 |

| Surgical trainee | 1.20 per minute | £72 per hour | PSSRU (2015)28 |

| Fellow | 0.85 per minute | £51 per hour | PSSRU (2015)28 |

| Nurses | |||

| Band 5 | 0.72 per minute | £43 per hour | PSSRU (2015)28 |

| Band 6 | 0.85 per minute | £51 per hour | PSSRU (2015)28 |

| Anaesthetic drug cost | |||

| General | 14.31 | Various drugs (propofol) | BNF (2016)29 |

| General and block | 15.17 | Various drugs (bupivacaine hydrochloride) | BNF (2016)29 |

| Spinal | 2.25 | Various drugs (lidocaine, etc.) | BNF (2016)29 |

| Interventions at 6 weeks | |||

| Outpatient appointment | 122.5 | Average colorectal specialty | NHS Reference Costs 2014 to 2015 27 |

| Re-admissions after interventiona | 201 | Admitted VB07Z emergency medicine, category 2 | NHS Reference Costs 2014 to 2015 27 |

| Emergency outpatient visitsb | 162 | Emergency medicine, category 2 investigation with category 2 treatment | NHS Reference Costs 2014 to 2015 27 |

| Further interventions at 6 weeks, for example haemorrhoidectomy | 1106 | Day case FZ22E intermediate anal procedures, aged ≥ 19 years, with complications score of 0 | NHS Reference Costs 2014 to 2015 27 |

| Proctoscopy | 10.99 | – | – |

| Medicines, for example Movicol® (Norgine, Pharmaceuticals Ltd, Uxbridge, UK) | Various | Based on patient report | BNF (2015)30 |

| Glyceryl trinitrate paste | 39.30 | Price per 30-g tube | BNF (2015)30 |

| Diltiazem paste | 78.83 | Price for 2% diltiazem cream per 30-g tube | BNF (2015)30 |

| Repeat SH and TH further interventions | |||

| Day case | 751 | FZ23A minor anal procedures, aged ≥ 19 years | NHS Reference Costs 2014 to 2015 27 |

| Day case | 1118 | Day case FZ22D intermediate anal procedures, aged ≥ 19 years, with complications score of 1 or 2 | NHS Reference Costs 2014 to 2015 27 |

| Post discharge events | |||

| Doctor visits | 44 | Per 11.7-minute consultation, including qualification costs | PSSRU (2015)28 |

| Nurse visits | 11 | Per 15.5-minute consultation, including qualification costs | PSSRU (2015)28 |

| Medications | |||

| Analgesic | Various | As reported by participants | BNF (2016)29 |

| Laxative | Various | As reported by participants | BNF (2016)29 |

| Antibiotics | Various | As reported by participants | BNF (2016)29 |

| RBL | 181 | FZ23A minor anal procedures, aged ≥ 19 years, procedures in outpatients | NHS Reference Costs 2014 to 2015 27 |

Unit costs for outpatient visits were obtained from the NHS reference costs for the period of 2014–15. 27 Unit costs for GP visits were obtained from the Personal Social Services Research Unit28 unit costs of social care. The unit costs of anaesthetic drugs, such as propofol used in the operation and post surgery, were derived from the British National Formulary. 29 For each participant the number of visits was multiplied by the appropriate unit cost. These costs were summed to produce a total cost per patient. The unit cost of the type of stapler used in the intervention was based on the cost of the stapler specified for each patient.

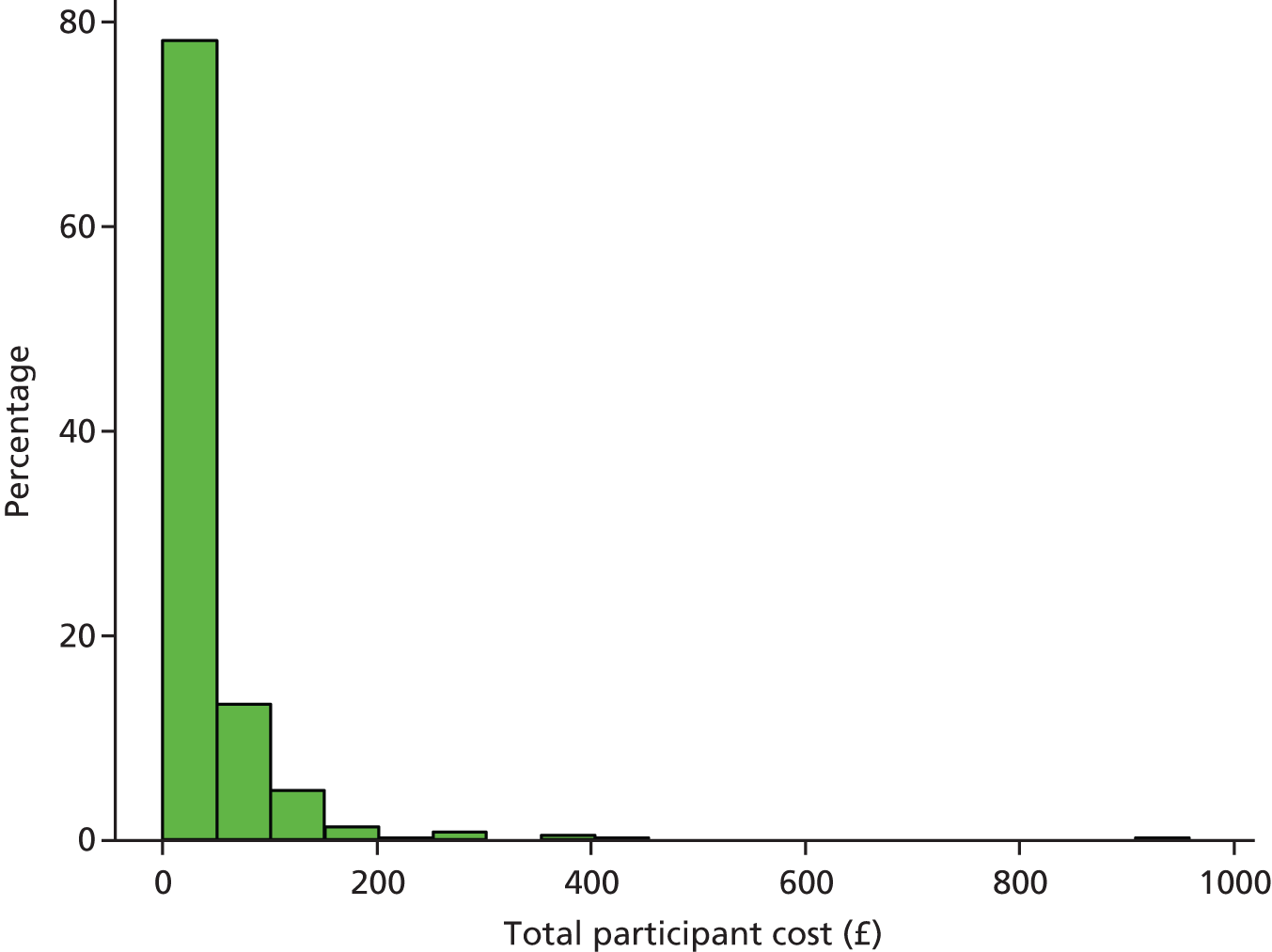

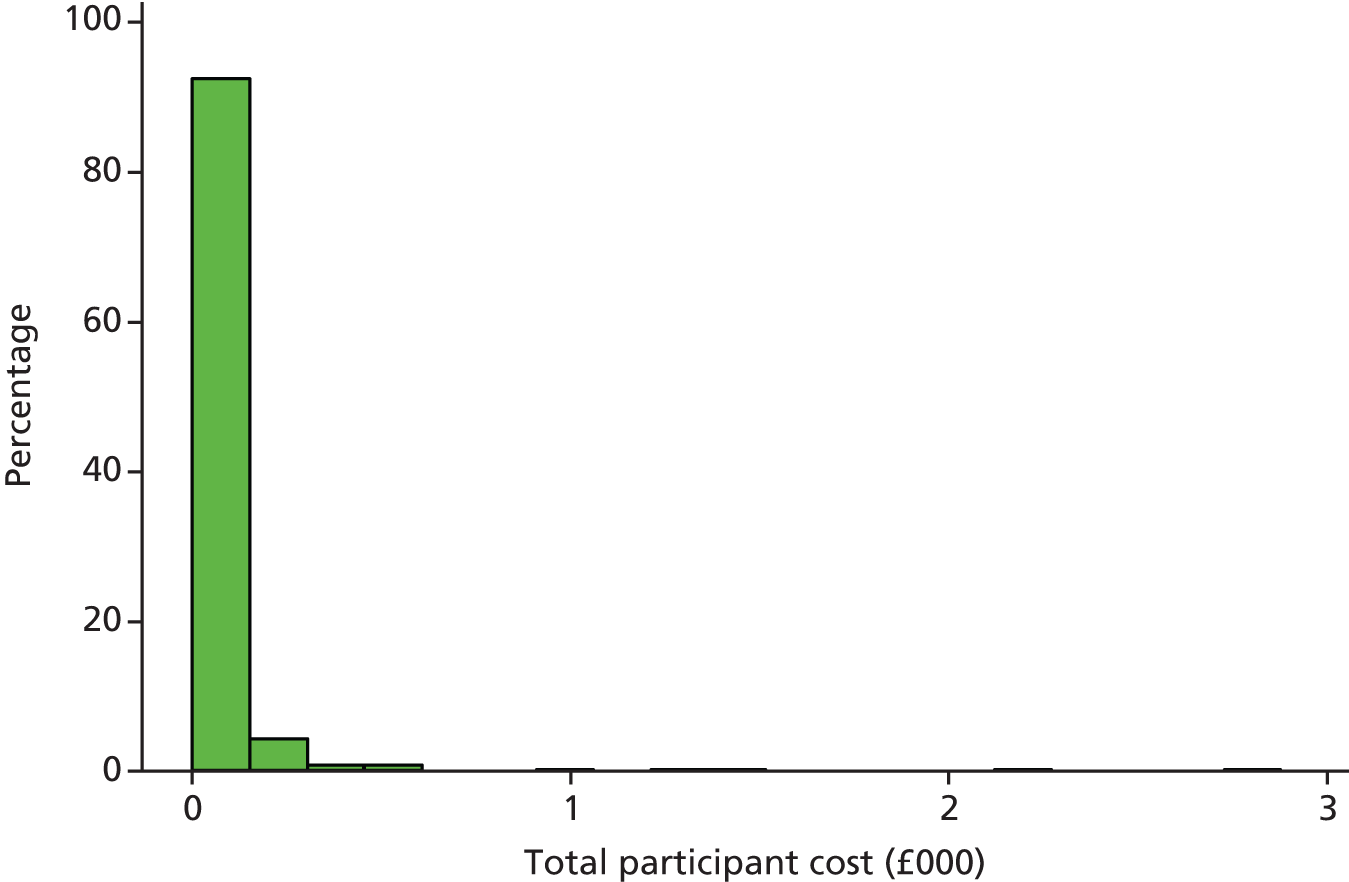

Measurement of resource utilisation for participants’ management of haemorrhoids

Participant resource use comprised three main elements: self-purchased health care; travel costs for making return visit(s) to NHS health care; and time costs of travelling and attending NHS health care.

-

Self-purchased health care is likely to include items such as prescription costs and over-the-counter medications. Information about these was collected through the health-care utilisation questions.

-

Estimation of travel costs requires information from participants about the number of visits to, for example, their GP or consultant (estimated from the health-care utilisation questions) and the cost to the participant of making the return journey to each type of health-care provider. The latter was collected using the participant cost questionnaire (see Appendix 1).

-

The cost of participant time was estimated in a similar manner. The participant was asked, in the participant cost questionnaire, how long they spent travelling to, and attending, their last visit to each type of health-care provider. Participants were also asked what activity they would have been undertaking (e.g. paid work, leisure, housework) had they not attended the health-care provider. Time away from displaced activities was measured in hours and also costed using standard economic conventions, for example the Department of Transport estimates for the value of leisure time. The unit costs used in the estimation of patient time and travel costs are all summarised in Table 4.

| Activity | Unit costs (£) | Assumptions | Source of data |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cost per mile travelled by car | 0.45 per mile | HMRC-approved mileage rate | HMRC31 |

| Car parking charges | Various | As stated by participant | Participant questionnaire |

| Cost of public transport (fares) | Various | As stated by participant | Participant questionnaire |

| Cost of non-emergency patient transport (ambulance) | 44.50 per journey | – | NHS Reference Costs 2014 to 2015 27 |

| Cost related to participant and companion time | |||

| Paid work | 13.47 per hour | Based on average economic wage per week of £528 assuming 39.2 hours per working week | ONS’s Average Weekly Earning Time Series Dataset (2015)32 |

| Housework | 10.66 per hour | Cost of housework in the NHS (assumed annual salary of £21,000 gross) | NHS Pay Review Body (2015)33 |

| Child care | 13.47 per hour | As paid work | ONS’s Average Weekly Earning Time Series Dataset (2015)32 |

| Caring for family/friend | 13.47 per hour | As paid work | ONS’s Average Weekly Earning Time Series Dataset (2015)32 |

| Voluntary work | 13.47 per hour | As paid work | ONS’s Average Weekly Earning Time Series Dataset (2015)32 |

| Leisure activities | 6.62 per hour | Value for non-working time (2010 prices inflated to 2015) | WebTAG: TAG Data Book, December 2015 34 |

| Retired | 6.62 per hour | Value for non-working time (2010 prices inflated to 2015) | WebTAG: TAG Data Book, December 2015 34 |

| Unemployed | 6.62 per hour | Value for non-working time (2010 prices inflated to 2015) | WebTAG: TAG Data Book, December 2015 34 |

| Disabled (long-term unrelated to haemorrhoids) | 6.62 per hour | Value for non-working time (2010 prices inflated to 2015) | WebTAG: TAG Data Book, December 2015 34 |

| Incontinence day pads | 1.57 | Mean monthly cost of nappies (the least expensive) £47.10 (three per day) | Fader et al., 200835 |

| Incontinence day pads | 0.66 | Mean monthly cost of nappies (the least expensive) £19.80 (one per night) | Fader et al., 200835 |

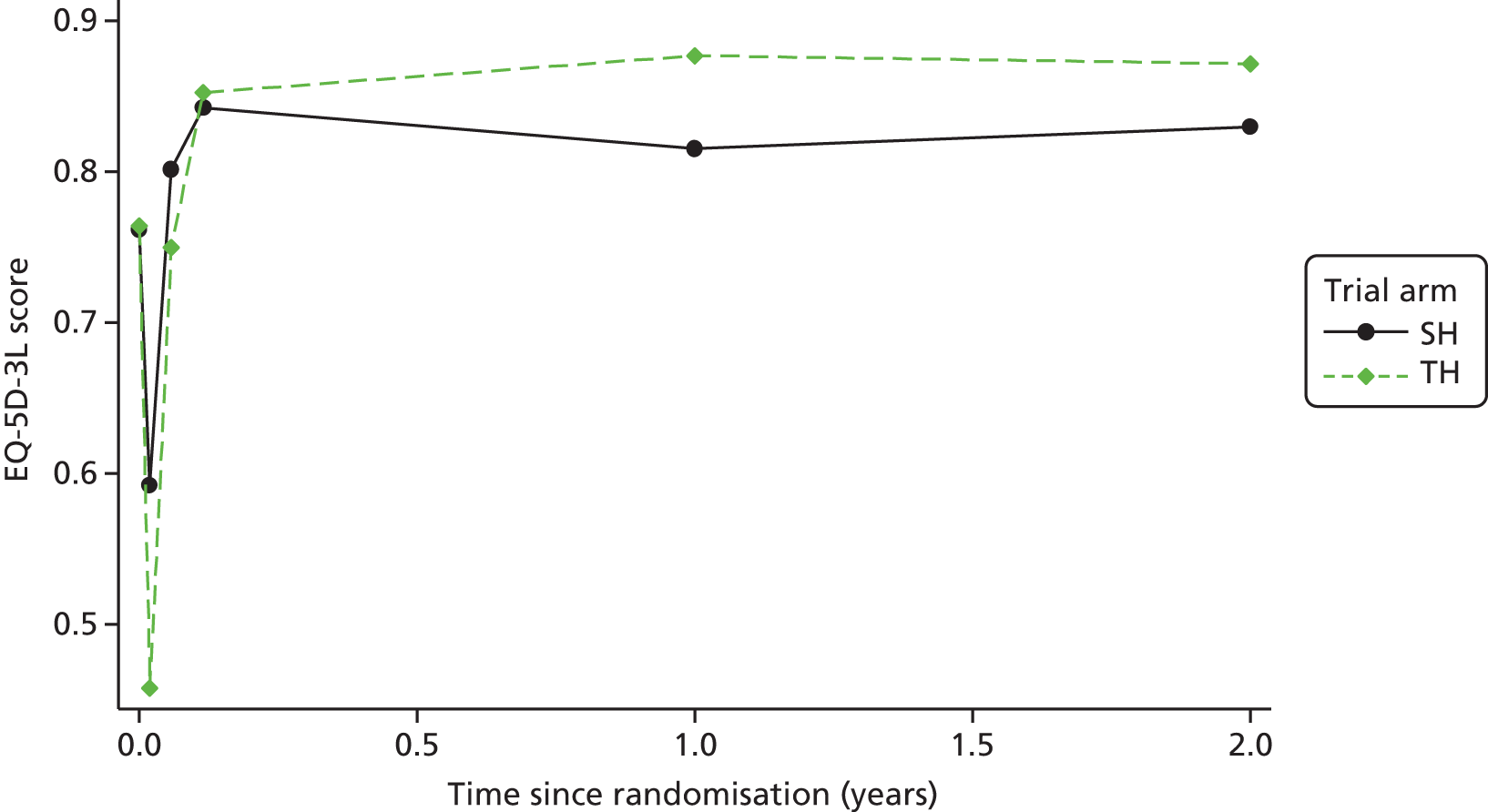

Quality of life

Clinical effectiveness in the economic analysis was measured in terms of QALYs. The EQ-5D-3L36 generic quality-of-life instrument was administered to all study participants at baseline, at 1 week, 3 weeks and 6 weeks, and at 12 months and 24 months. The EQ-5D-3L measure divides health status into five dimensions (mobility, self-care, usual activities, pain/discomfort and anxiety/depression).

Responses to the EQ-5D-3L are presented in graphical format, illustrating percentage of respondents with any or severe problems on each health domain, split by randomised arms of the study. Results are presented in accordance with EuroQoL guidelines. 37

Responses to the EQ-5D-3L questionnaires were valued using UK general population tariffs,38 based on the time trade-off technique to generate a utility score for every participant within the study. Quality-of-life data derived from the EQ-5D-3L were combined with mortality data from the study, using the standard assumption that all participants who died during the study will have a utility value of zero from the date of death to the end of follow-up. QALYs were then calculated on the basis of these assumptions using an AUC approach, assuming linear extrapolation of utility between time points.

Quality-of-life data were also collected using the SF-36 questionnaire for comparison. SF-36 data were collected at baseline, 6 weeks, and at 12 and 24 months. The SF-36 is a generic measure obtained from a multipurpose, short-form health survey with 36 items. 39 It yields an eight-scale profile of functional health and well-being scores along with psychometrically based physical and mental health summary domains and a preference-based health utility index. These data were converted into a Short Form questionnaire-6 Dimensions (SF-6D) utility index using a published algorithm. 40 As described above for the EQ-5D-3L, QALYs were also derived from these data and a secondary analysis was used.

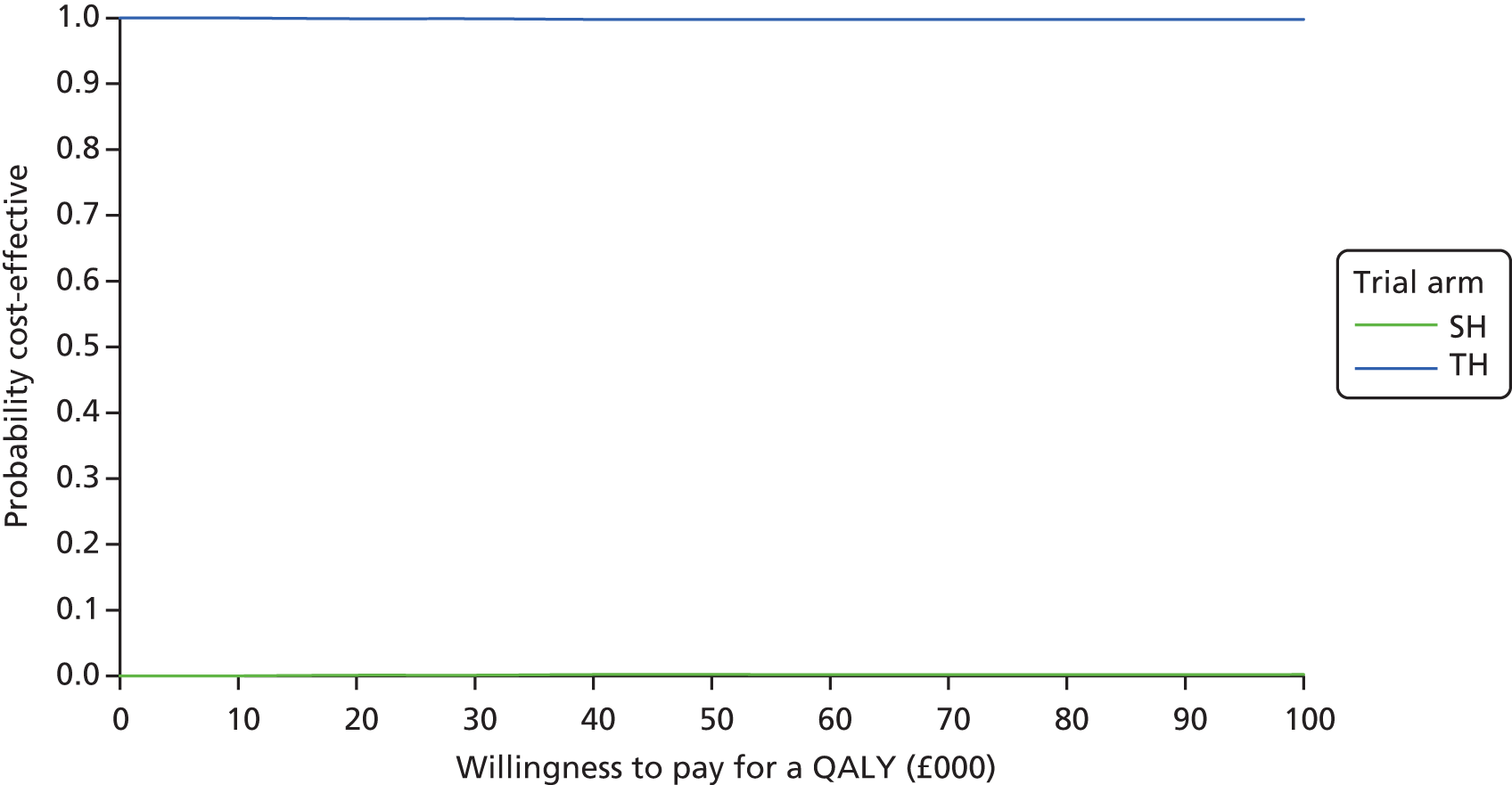

Cost-effectiveness analysis methods

Economic analyses were consistent with the methods described for the main statistical analyses (primary outcome). All data analyses were conducted using Stata software. The primary economic analysis was based on the imputed data of all participants as randomised, irrespective of the treatment allocation. There was a substantial number of missing data and this posed problems for data analysis, especially surrounding data reported using participant-completed questionnaires. Therefore, statistical MI of missing data was undertaken. The imputation analysis was performed using Stata’s MI procedure. 41 Missing component costs (e.g. cost of primary care, outpatient care) and utility values were imputed at each questionnaire time point (12 and 24 months). The cost–utility analysis was conducted using the MI data. Briggs et al. 42 concluded that imputing the missing data is preferable to a complete or available case analysis.

Components of cost data were imputed based on linear regression models adjusted for minimisation variables, baseline utility and treatment allocation group. Missing utility values were imputed using predictive mean-matching, accounting for the five closest estimates. Chained equations were used for the imputations. The imputation procedure predicted 10 plausible alternative imputed data sets, which was found to be sufficient to provide stable estimates. Analysis of incremental costs and outcomes was undertaken across the 10 imputed data sets and combined to generate one imputed estimate of incremental costs and QALYs. All imputed data sets were plotted on cost-effectiveness acceptability curves (CEACs) using similar methods to the main analyses. Sensitivity analysis was applied in order to assess robustness of the results to realistic variations in the levels of the underlying data and also alternative assumptions, for example QALYs derived from the SF-36.

Data are presented descriptively, and the primary outcome measure was analysed using linear regression with adjustment for the minimisation variables. The minimisation variables are centre, grade of haemorrhoidal disease (II, III or IV), baseline EQ-5D-3L score and sex.

The primary economic analysis presents estimates of the incremental cost per QALY of SH versus TH. The incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER) can be compared with the benchmark willingness-to-pay (WTP) thresholds for cost-effectiveness in the NHS context of £20,000 to £30,000 per QALY gained, as applied by NICE. 43 Regression-based methods (as above) were used to estimate difference in costs for care between SH and TH, over the 24-month study period. CIs (95%) were estimated using parametric methods. To facilitate interpretation of the study results, the within-trial economic analysis is also presented in the form of a balance sheet in which differences in terms of benefits and costs of the two study interventions are presented in their natural or clinical units. Item-level costs are presented descriptively, consistent with the data presentation in the effectiveness analyses.

To explore the skewness of data, a generalised linear model was used; this model allows for heteroscedasticity by selecting an appropriate distributional family for the data. 44 The family offers alternative specifications to reflect the relationship between the mean and the variance of the estimates under considerations. The most appropriate distributional family was selected by (1) performing a modified Parks test, which identified two potentially viable distributional families for costs, namely Gaussian or Gamma; and (2) consulting the Akaike information criterion, which identified a Gaussian model with an identity link as having the lowest Akaike information criterion score and the most appropriate model fit. Regression models applied to cost components (such as ‘other treatments’ and ‘hospital costs’) in the analyses above are also assumed to follow the same distributional assumptions as the total cost data. A standard ordinary least squares model was also identified as the most appropriate model and applied to the analysis of incremental QALY gains. All analyses were conducted using heteroscedastic robust standard errors.

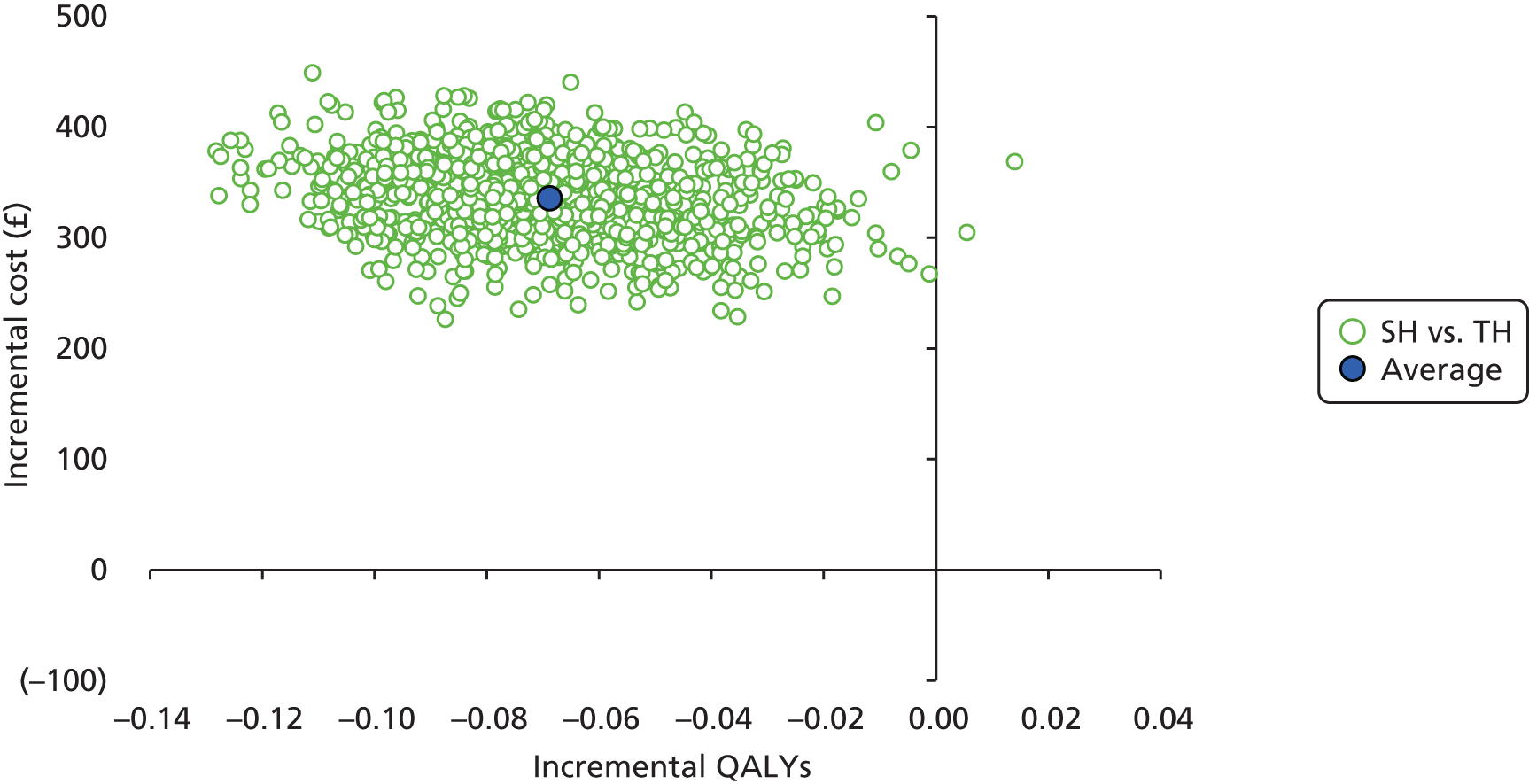

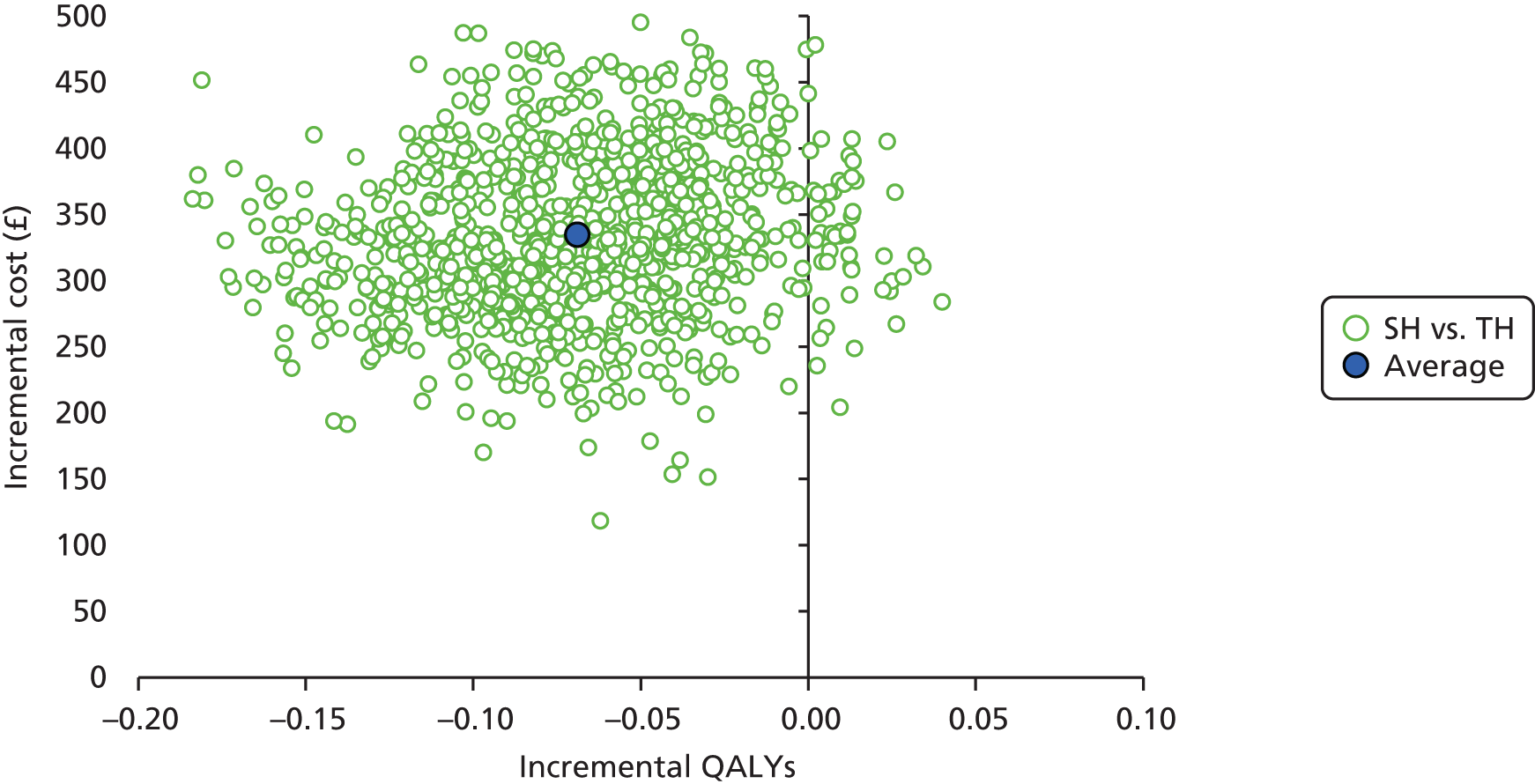

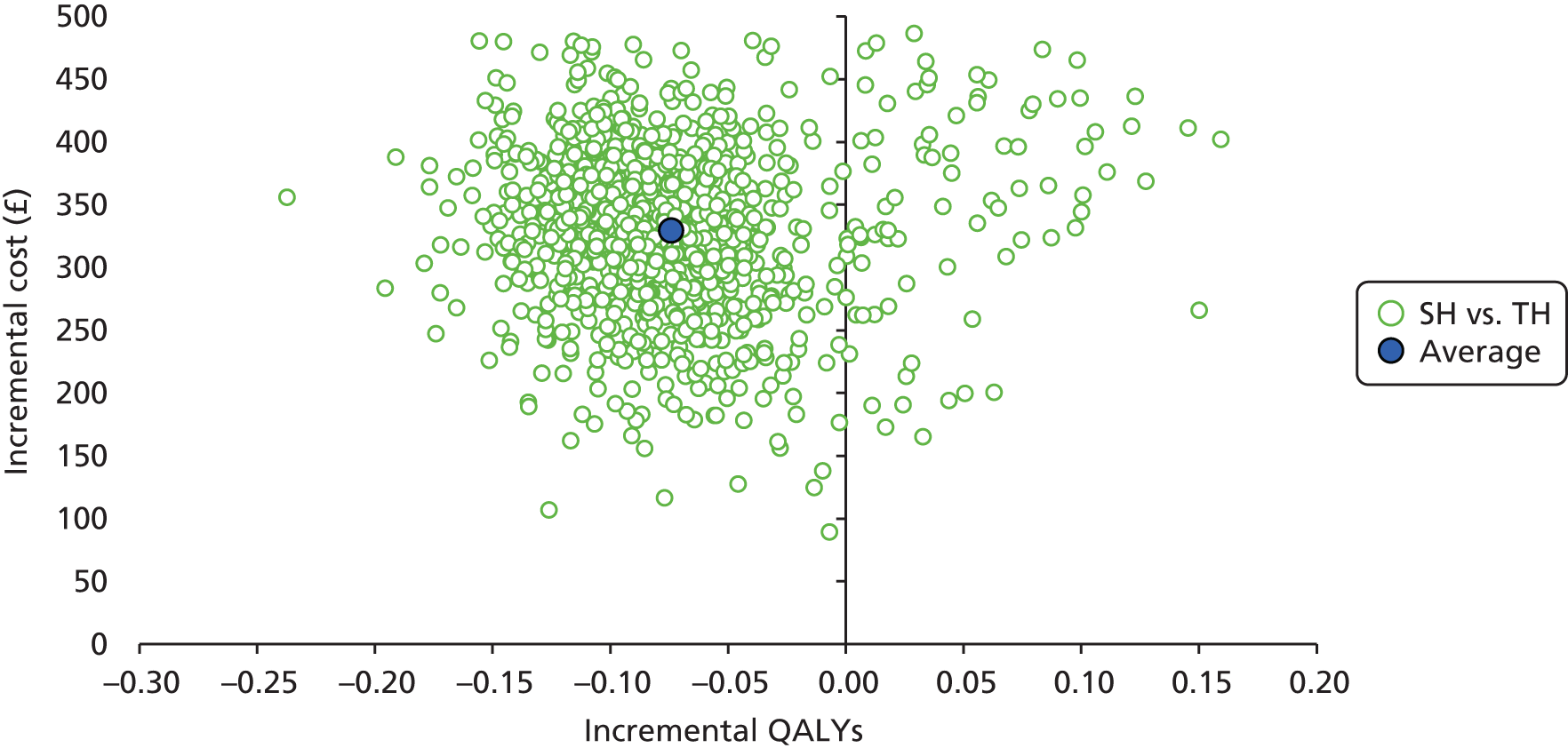

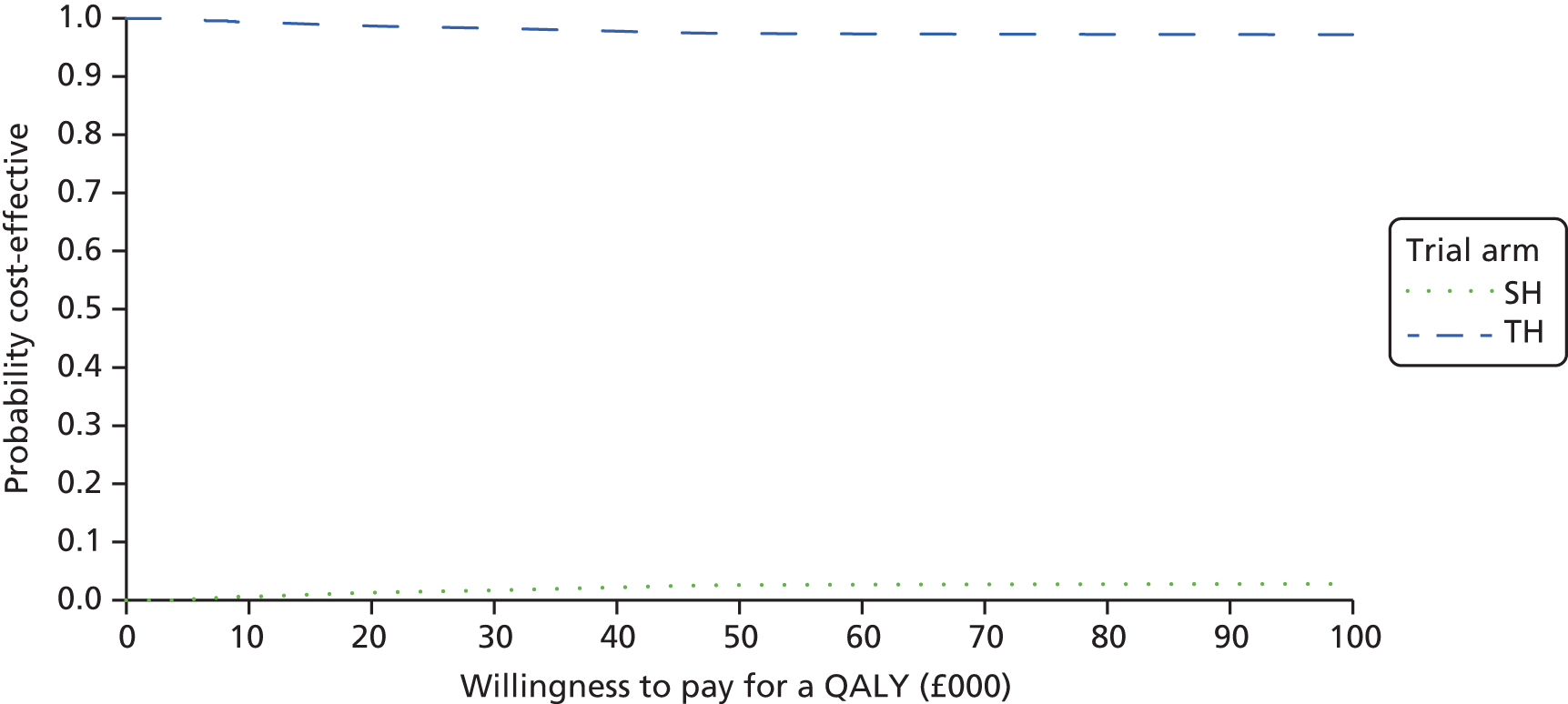

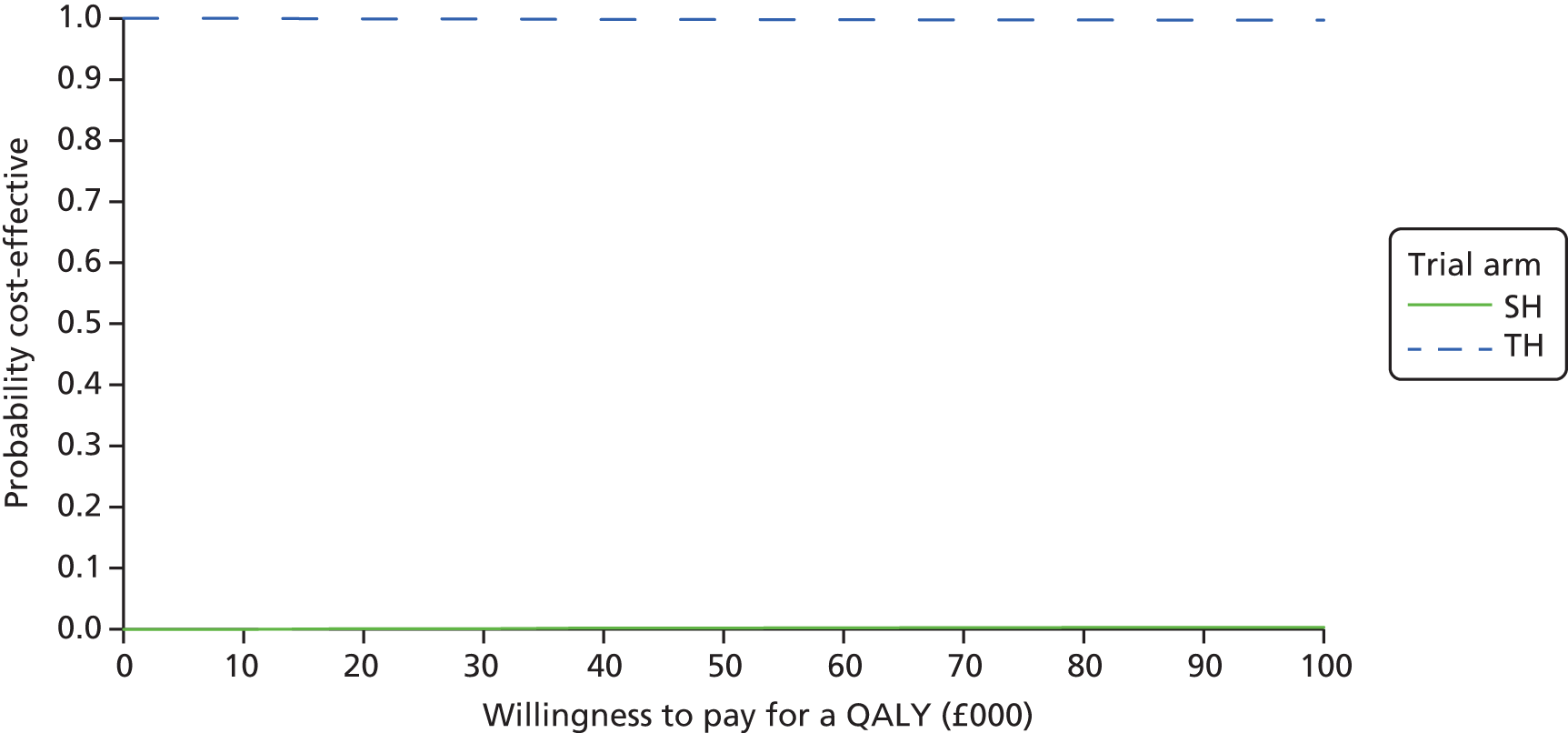

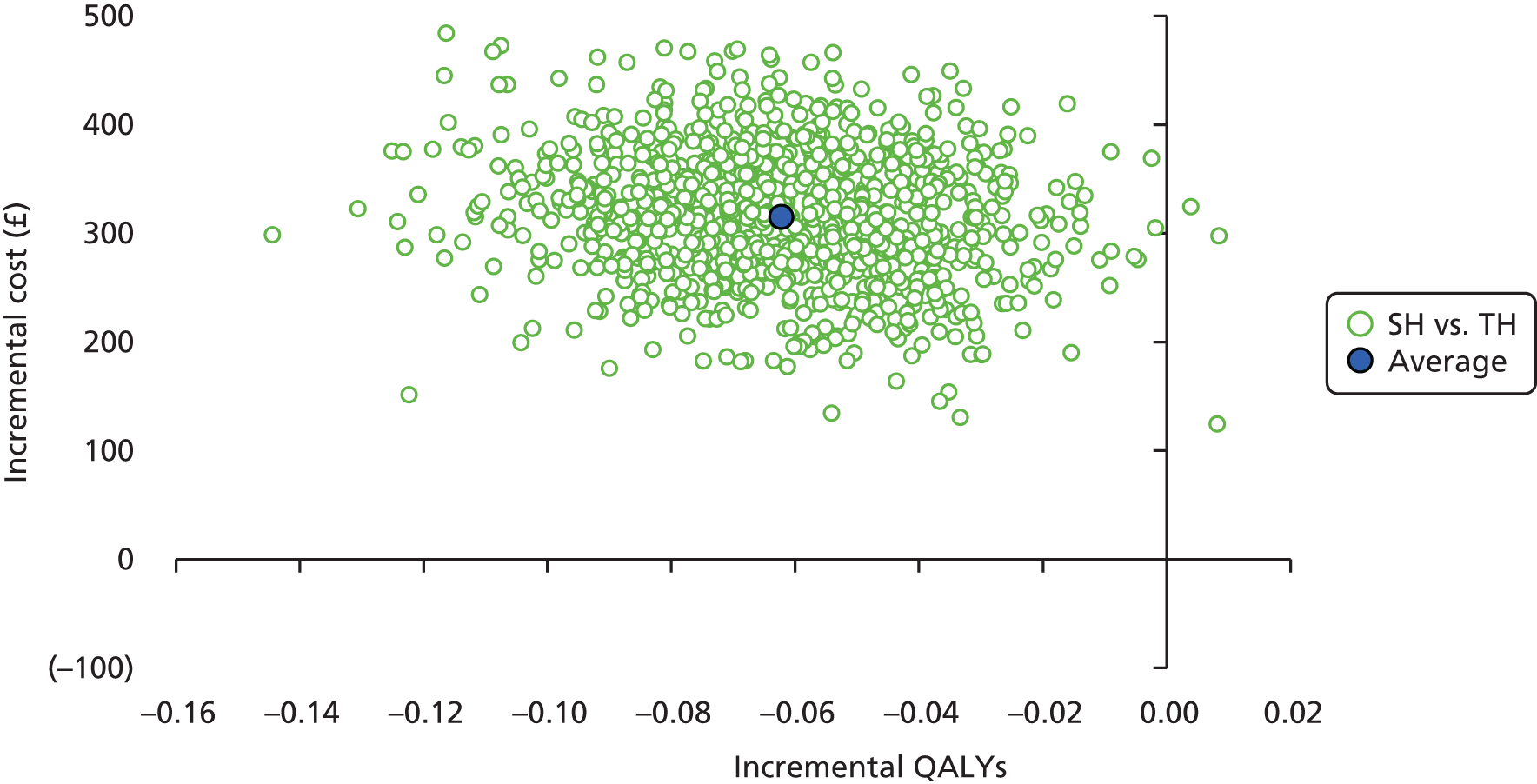

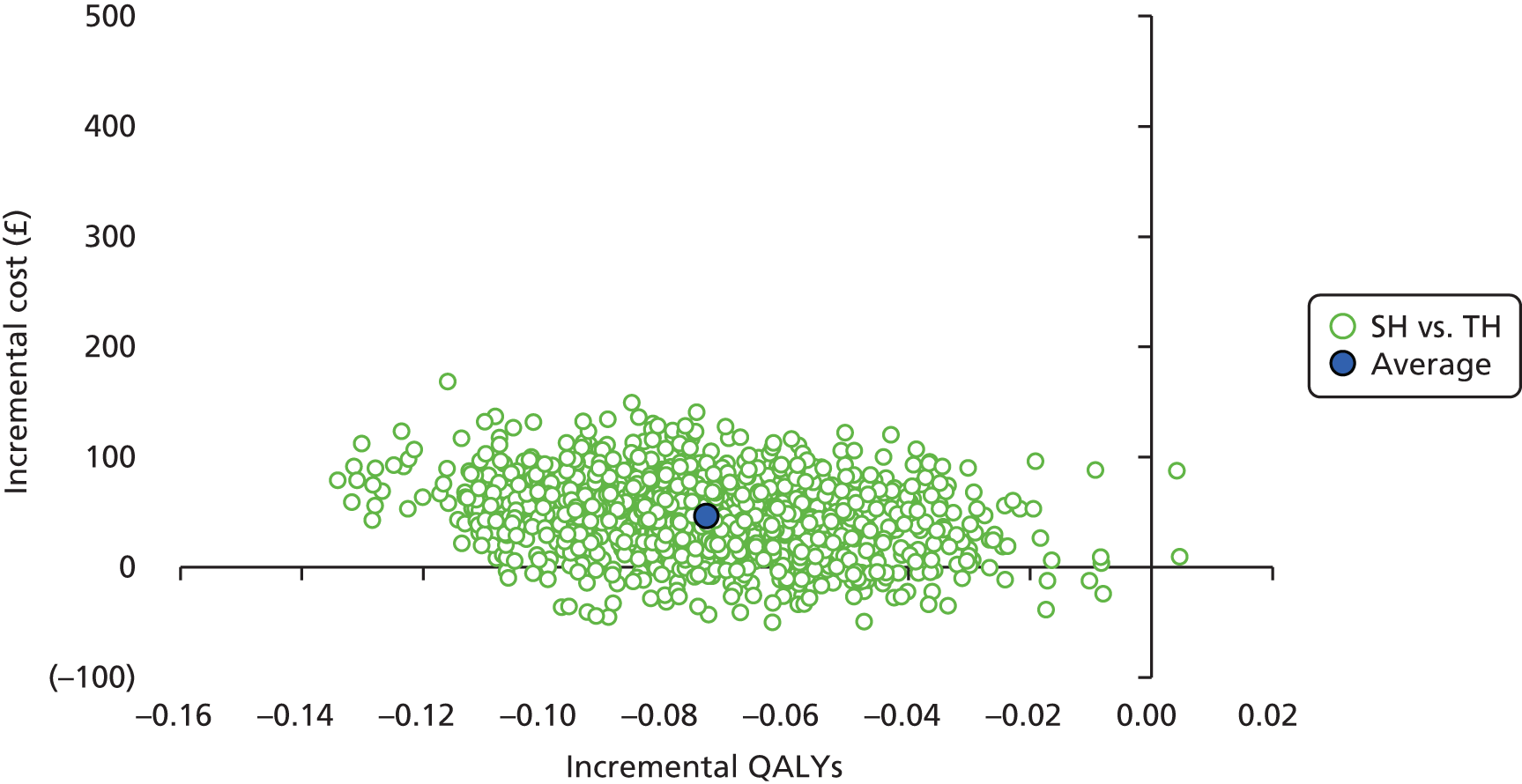

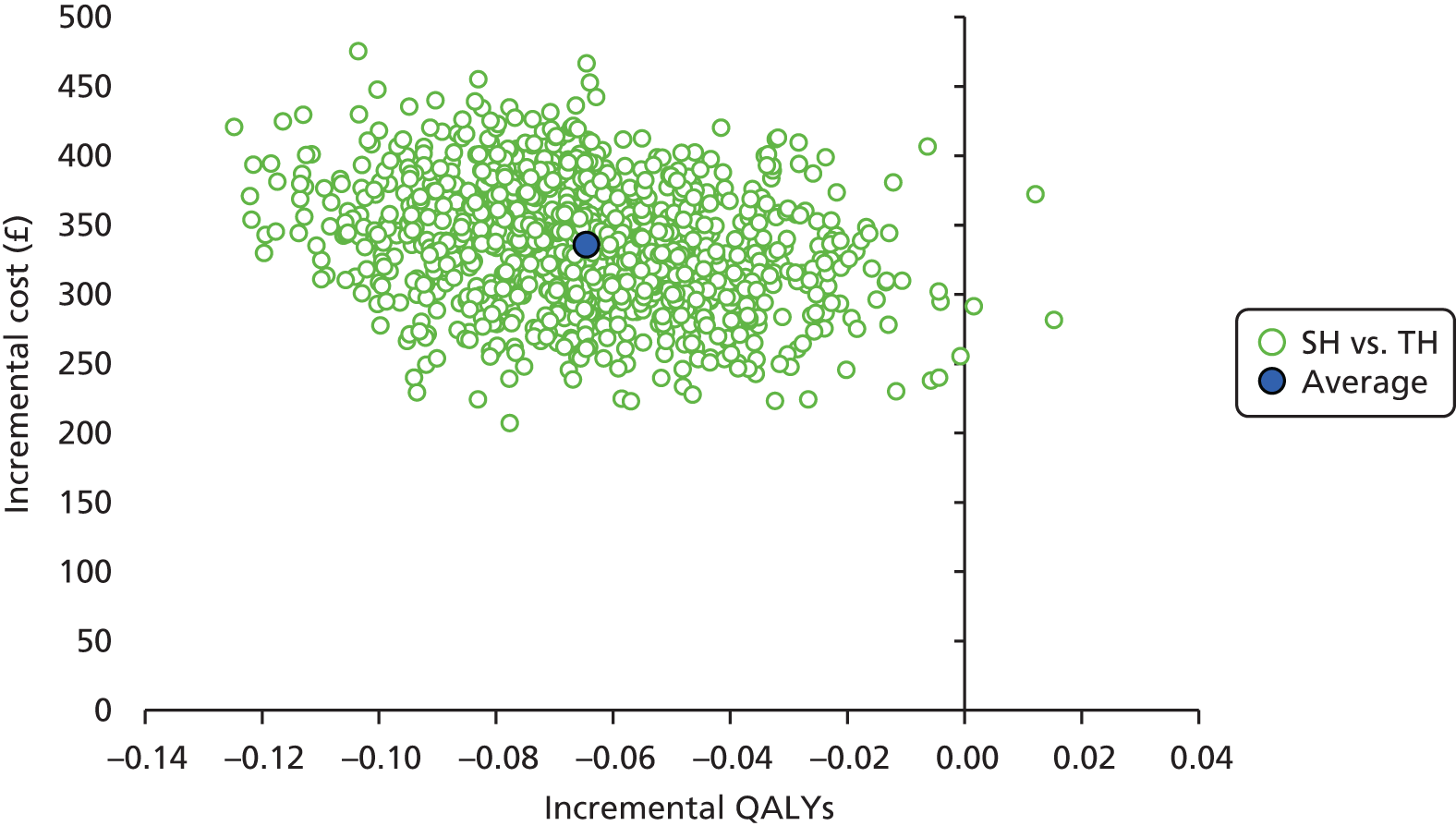

Non-parametric bootstrapping methods were used to estimate CIs to characterise uncertainty surrounding the point estimate of the ICER, using 1000 repetitions. 45 This uncertainty in the ICER is summarised using the following methods.

-

Incremental scatterplots of the 1000 replicates of joint differences in mean costs and QALYs for TH compared with SH compared with TH. 46 The incremental cost-effectiveness scatterplots allow one to see the probability of each intervention falling into each quadrant of the cost-effectiveness plane, being (1) less costly and more clinically effective; (2) more costly and less clinically effective; (3) less costly and less clinically effective; or (4) more costly and more clinically effective.

-

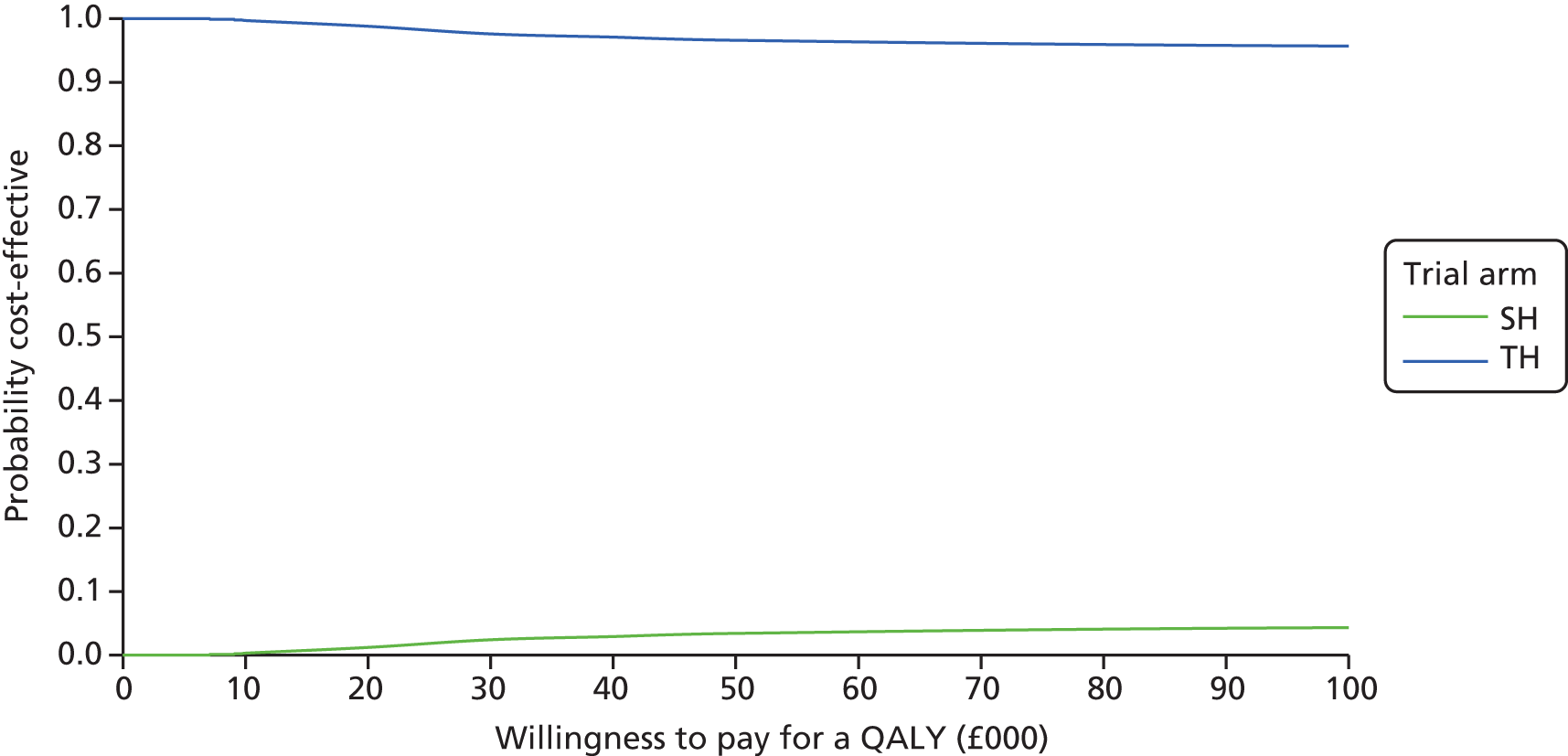

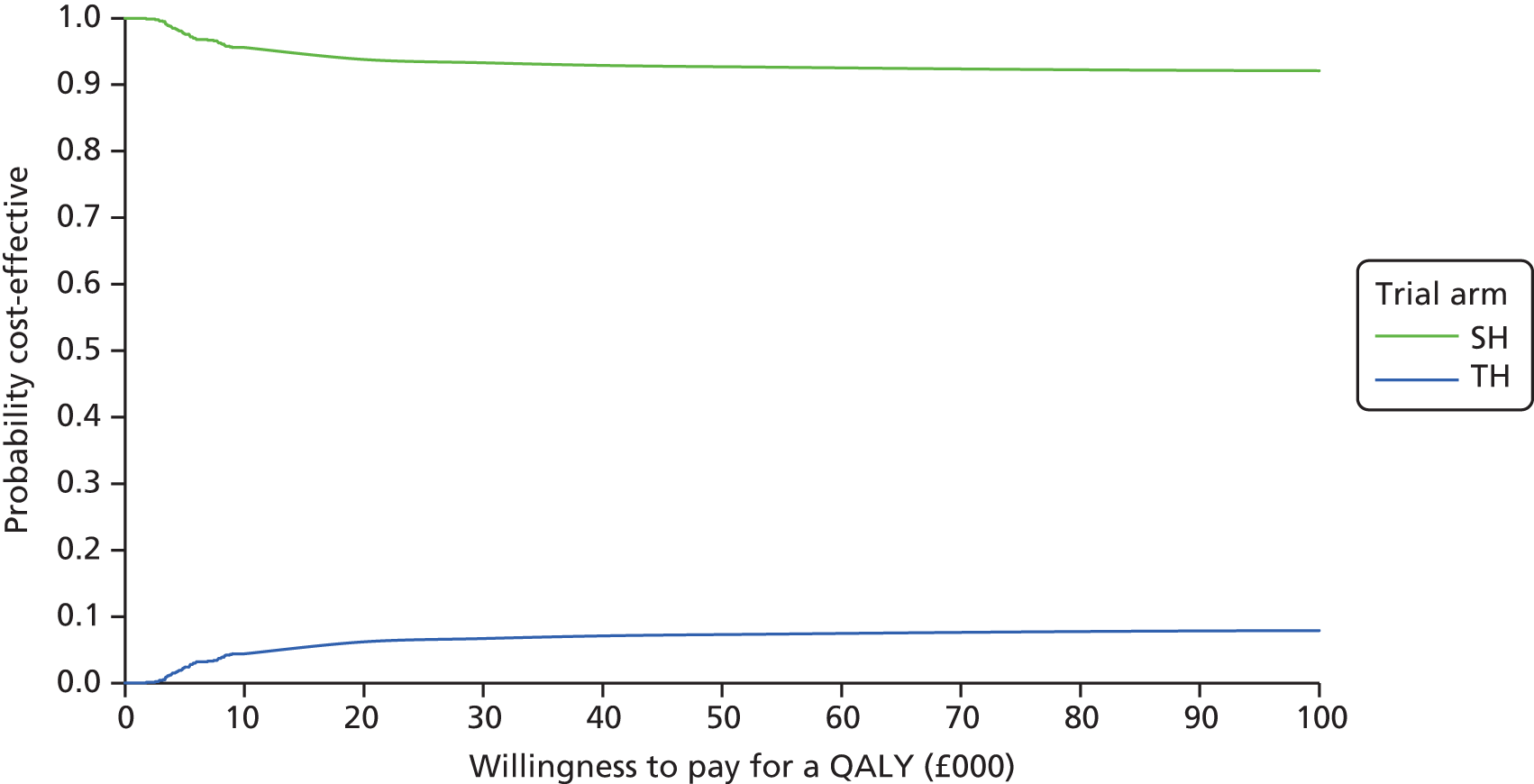

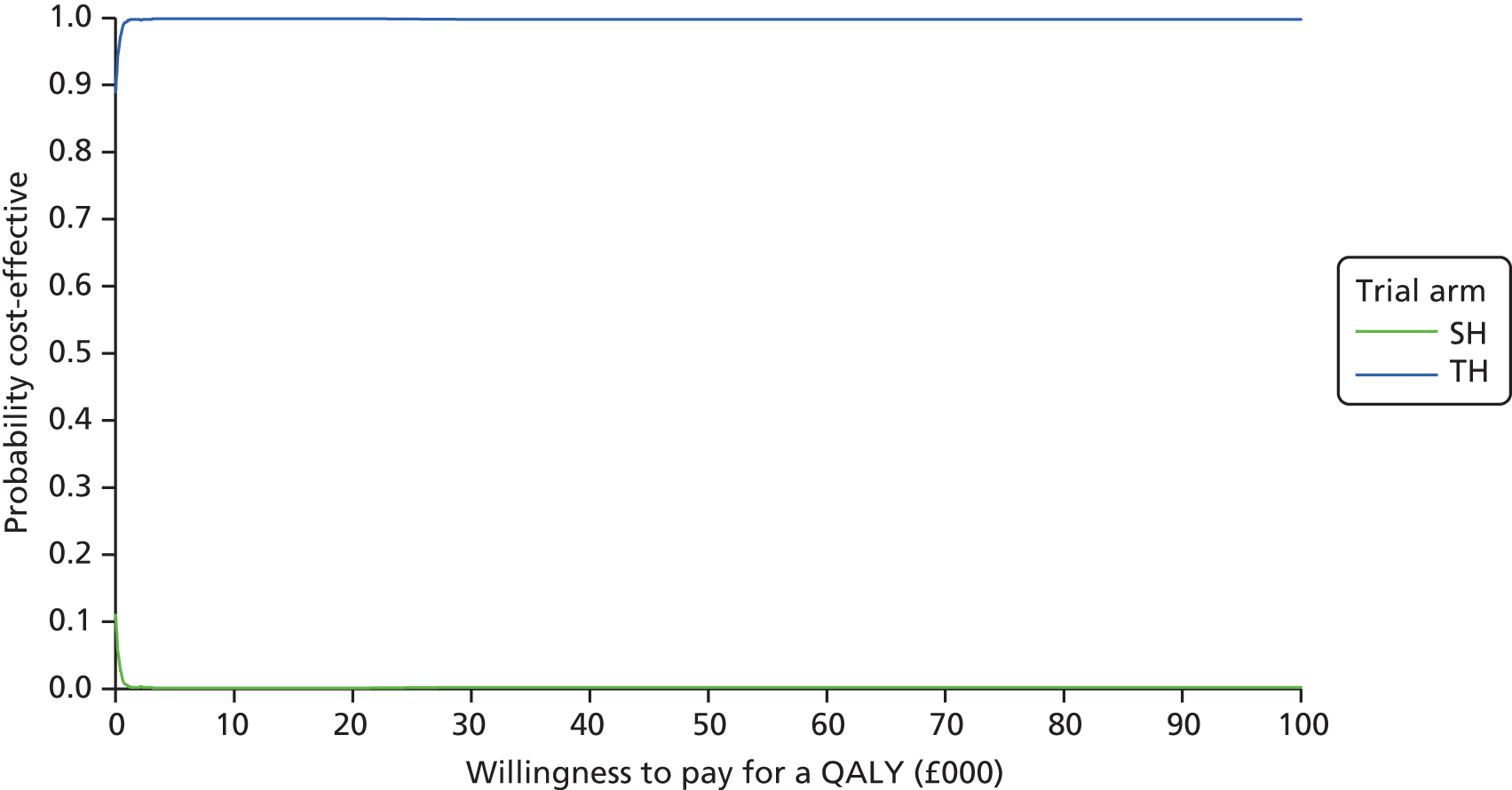

The bootstrapped estimates of joint differences in cost effects were further used to generate CEACs. CEACs were generated using estimates of net monetary benefit, generated using the bootstrapped replications, in accordance with the incremental net benefit (INB) statistic given in the following equation:

This is calculated by multiplying the incremental effects (QALYs) by the decision-makers’ WTP cost-effectiveness threshold [lambda (λ)] and subtracting the incremental cost. Although the base-case analysis INB statistic was calculated based on the upper end of the threshold set by NICE (i.e. £30,000), several cost-per-QALY thresholds ranging from £0 to £50,000 are also reported. A positive INB suggests that the intervention is cost-effective versus its comparator at the defined threshold.

Deterministic sensitivity analyses

The presentation of CEACs and scatterplots addresses some of the sampling uncertainty in the data; however, other assumptions surrounding the most appropriate discount rate and analysis models undertaken may create additional uncertainty that is not captured in the presented CEACs. The impact of using MI to impute missing data was also explored by running a complete analysis (including only participants with complete cost and QALY data).

Subgroup analyses

Like the clinical analysis subgroup, analyses explored the possible treatment effect modification of clinically important factors (haemorrhoidal grade and sex) through the use of treatment by factor interaction. We did not identify any additional subgroup analyses that were required to estimate cost-effectiveness for the within-trial analysis.

Chapter 4 Participant baseline characteristics

Study recruitment

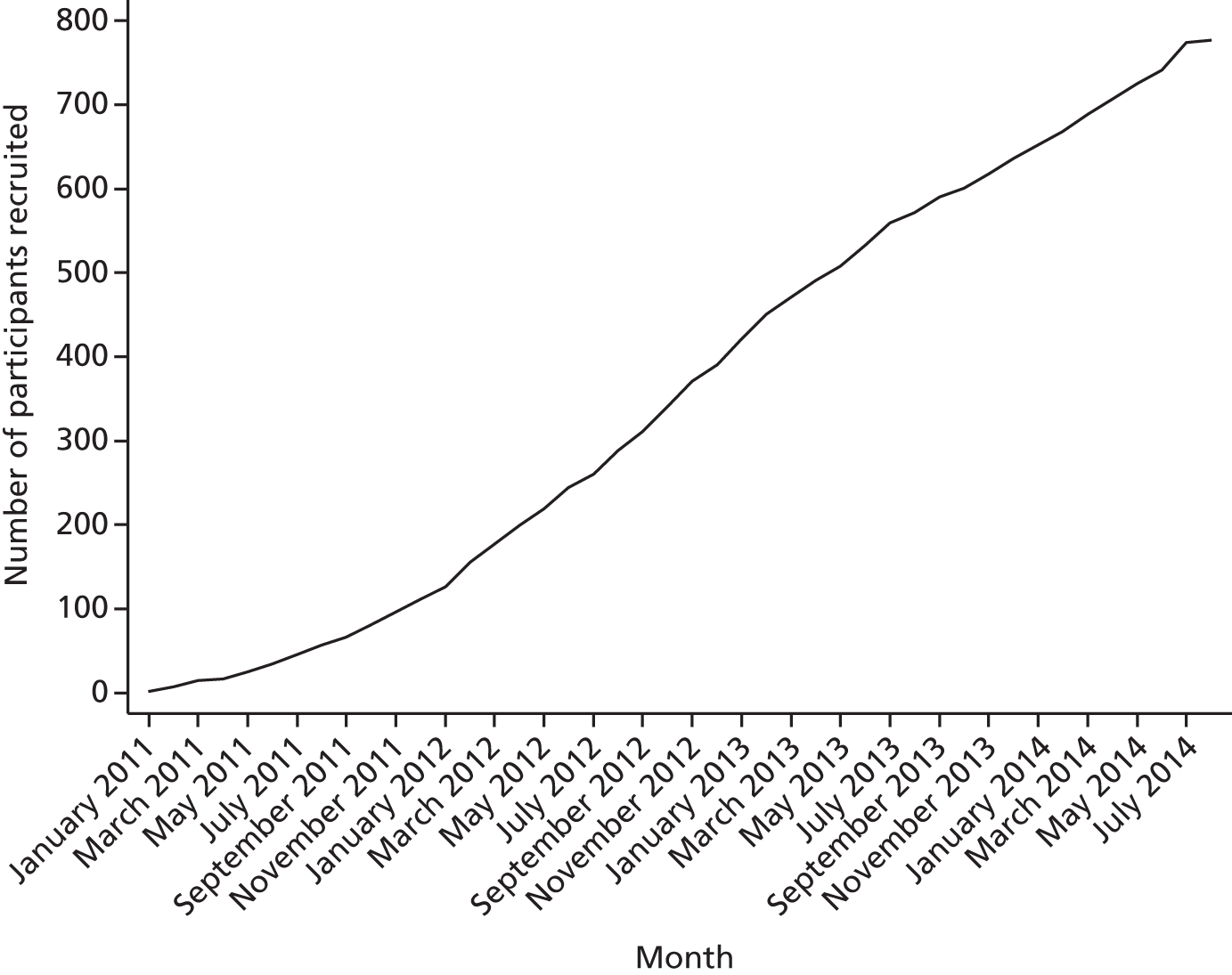

In total, 777 participants were recruited for surgical treatment from 29 out of the 32 UK-wide NHS hospitals that took part in the study (Table 5). Twenty-seven of these centres randomised 389 participants to the SH arm and 28 randomised 388 participants to the TH arm. Participants were recruited to the study between 13 January 2011 and 1 August 2014 and followed up to July 2016; however, not all the centres recruited within this period, owing to staggered introduction and early closure of centres. The trajectory of recruitment from all centres is shown in Figure 2.

| Hospital | Participants, n (%) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Eligible (N = 1056) | Excluded (N = 33) | Declined (N = 225) | Missed (N = 21) | Randomised (N = 777) | Randomised to receive | ||

| SH (N = 389) | TH (N = 388) | ||||||

| Aberdeen Royal Infirmary | 176 | 17 (7.6) | 159 (20.5) | 79 (20.3) | 80 (20.6) | ||

| Arrowe Park Hospital | 4 | 4 (0.5) | 1 (0.3) | 3 (0.8) | |||

| Barnet General Hospital | |||||||

| Basildon University Hospital | |||||||

| Chelsea and Westminster Hospital | 13 | 1(3.0) | 6 (2.7) | 6 (0.8) | 3 (0.8) | 3 (0.8) | |

| Colchester University Hospital | 16 | 13 (5.8) | 1 (4.8) | 2 (0.3) | 2 (0.5) | ||

| Croydon University Hospital | 74 | 14 (6.2) | 1 (4.8) | 59 (7.6) | 30 (7.7) | 29 (7.5) | |

| Dr Gray’s Hospital, Elgin | 6 | 1 (0.4) | 5 (0.6) | 3 (0.8) | 2 (0.5) | ||

| Forth Valley Royal Hospital | 54 | 20 (8.9) | 34 (4.4) | 18 (4.6) | 16 (4.1) | ||

| Glan Clwyd Hospital, Rhyl | 19 | 6 (2.7) | 13 (1.7) | 7 (1.8) | 6 (1.5) | ||

| Glasgow Southern General Hospital | 1 | 1 (0.4) | |||||

| Hillingdon Hospital | 49 | 12 (5.3) | 4 (19.0) | 33 (4.2) | 16 (4.1) | 17 (4.4) | |

| Huddersfield Royal Infirmary | 43 | 16 (7.1) | 3 (14.3) | 24 (3.1) | 12 (3.1) | 12 (3.1) | |

| James Cook University Hospital | 63 | 3 (1.3) | 1 (4.8) | 59 (7.6) | 30 (7.7) | 29 (7.5) | |

| John Radcliffe Hospital | 15 | 4 (1.8) | 11 (1.4) | 6 (1.5) | 5 (1.3) | ||

| Lincoln County Hospital | 12 | 1 (0.4) | 11 (1.4) | 6 (1.5) | 5 (1.3) | ||

| Manchester Royal Infirmary | 29 | 2(6.1) | 11 (4.9) | 16 (2.1) | 8 (2.1) | 8 (2.1) | |

| Nevill Hall Hospital | 6 | 1 (0.4) | 1 (4.8) | 4 (0.5) | 2 (0.5) | 2 (0.5) | |

| Norfolk and Norwich University Hospital | 19 | 12 (5.3) | 1 (4.8) | 6 (0.8) | 3 (0.8) | 3 (0.8) | |

| Northern General Hospital | 25 | 13 (5.8) | 12 (1.5) | 6 (1.5) | 6 (1.5) | ||

| Pinderfields Hospital | 23 | 3 (1.3) | 20 (2.6) | 11 (2.8) | 9 (2.3) | ||

| Queen Elizabeth Hospital | 5 | 5 (0.6) | 2 (0.5) | 3 (0.8) | |||

| Raigmore Hospital | 102 | 7 (21.2) | 8 (3.6) | 87 (11.2) | 44 (11.3) | 43 (11.1) | |

| Royal Cornwall Hospital | 32 | 17 (7.6) | 4 (19.0) | 11 (1.4) | 6 (1.5) | 5 (1.3) | |

| Royal Derby City Hospital | 35 | 35 (4.5) | 18 (4.6) | 17 (4.4) | |||

| Royal Sussex County Hospital | 66 | 66 (8.5) | 33 (8.5) | 33 (8.5) | |||

| St James’s Hospital | 3 | 2 (9.5) | 1 (0.1) | 1 (0.3) | |||

| University Hospital Aintree | 7 | 5 (2.2) | 2 (0.3) | 2 (0.5) | |||

| University Hospital of North Durham | 54 | 17 (7.6) | 37 (4.8) | 18 (4.6) | 19 (4.9) | ||

| University Hospital of North Tees | 56 | 9 (4.0) | 47 (6.0) | 23 (5.9) | 24 (6.2) | ||

| Weston Hospital | 3 | 1 (3.0) | 2 (0.3) | 1 (0.3) | 1 (0.3) | ||

| Wythenshawe Hospital | 46 | 22 (66.7) | 15 (6.7) | 3 (14.3) | 6 (0.8) | 2 (0.5) | 4 (1.0) |

FIGURE 2.

Recruitment over time.

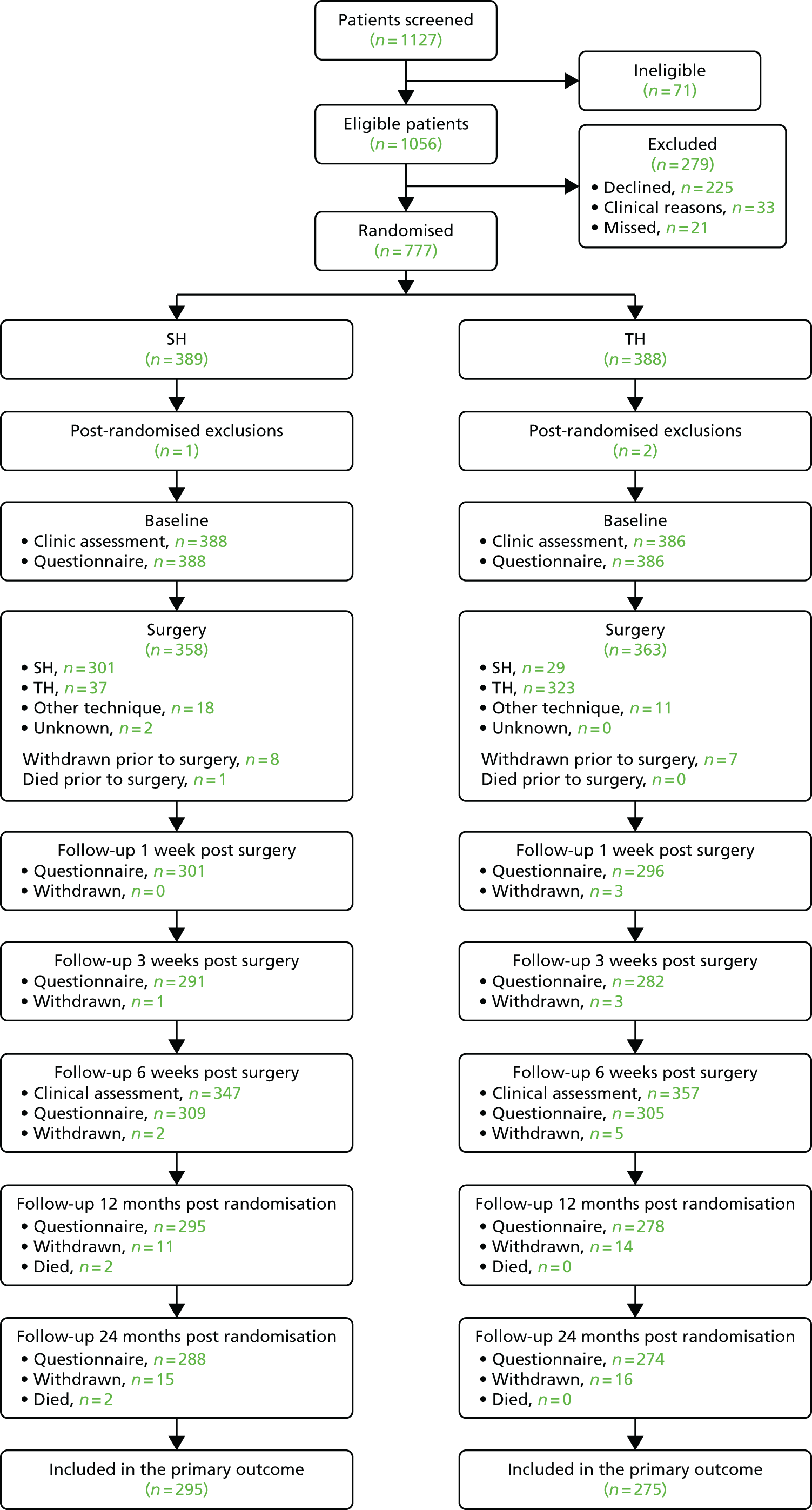

Participant flow

Figure 3 shows the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) diagram for the study. In total, 1127 participants were screened and 1056 were found to be eligible. For the 279 excluded participants, 225 declined, 33 were excluded because of clinical reasons and 21 were missed. The main reasons for ineligibility resulted from the participants having had previous surgery (26.8%) and being unable to complete study questionnaires (23.9%). The most frequent reasons for participants declining resulted from treatment preference (22.2%) and not wanting surgery (14.7%). Further details on reasons why screened participants were not randomised can be found in Table 6. Three participants were excluded post randomisation. One was under the age of 18 years and two withdrew consent within a short period following randomisation. Therefore, 774 participants were included in the study analysis and presentation of findings.

FIGURE 3.

The CONSORT flow diagram.

| Reason | Number of participants, n | % of total number of participants excluded |

|---|---|---|

| Reasons for ineligibility (n = 71) | ||

| Previous surgery | 19 | 26.8 |

| Sphincter injury | 1 | 1.4 |

| Inflammatory bowel disease | 5 | 7.0 |

| Malignant colorectal disease | 2 | 2.8 |

| Unable to complete | 17 | 23.9 |

| Other | 27 | 38.0 |

| Reasons for declining to take part (n = 225) | ||

| Participant had a preference for treatment | 50 | 22.2 |

| Participant did not want to be randomised | 16 | 7.1 |

| Participant did not want to have surgery | 33 | 14.7 |

| Participant wanted to have a particular surgeon | 5 | 2.2 |

| Participant had concerns over their health | 4 | 1.8 |

| Participant not interested or did not want to take part in the study | 4 | 1.8 |

| Participant had no time to fill in questionnaires | 3 | 1.3 |

| Participant did not want any treatment | 1 | 0.4 |

| No reason given | 109 | 48.4 |

| Clinical reasons (n = 33) | ||

| Surgeon felt that participant would benefit from a certain procedure | 11 | 33.3 |

| More than one procedure to be performed | 22 | 66.7 |

| Reasons for missing participants (n = 21) | ||

| No response from the participant | 12 | 57.1 |

| Insufficient time to approach the participant | 4 | 19.0 |

| Participant received the information too late | 2 | 9.5 |

| Other | 3 | 14.3 |

All the participants randomised attended the baseline clinical assessment and completed the baseline questionnaire. A total of 31 participants withdrew from the study; one withdrawal was caused by the surgeon’s decision, whereas the remaining were at the participants’ request. Details of the treatment received are described in Chapter 5. Six weeks post surgery, 704 participants attended clinical follow-up appointments and 614 responded to the questionnaire. At the 24-month post-randomisation follow-up, 562 participants responded; a total of 31 participants withdrew from the study by that time point. Two deaths were reported, and none was caused by a study intervention.

Baseline characteristics

The participants’ baseline characteristics are shown for the 774 participants in Table 7 (excluding the post-randomisation exclusions). Sex, grade of haemorrhoids and EQ-5D-3L score were included as minimisation variables; therefore, the balance between the two treatment groups for these covariates was ensured. The median age was 50 years old and the quality-of-life outcomes (SF-36; physical and mental component summary) were balanced between the groups. Over 60% of participants had grade-III haemorrhoids, and 35.8% of participants in the SH arm and 30.1% in the TH arm had had previous haemorrhoid treatment. The majority of participants had either no preference for the type of surgery or preferred an intervention associated with a lower risk of haemorrhoid recurrence.

| Characteristic | Trial arm | |

|---|---|---|

| SH (N = 388) | TH (N = 386) | |

| Age (years), n, median (IQR) | 388, 50 (40–60) | 386, 49 (40–59) |

| Sex (male), n (%) | 201 (51.8) | 197 (51.0) |

| BMI (kg/m2), n, mean (SD) | 372, 27.0 (5.2) | 367, 27.0 (4.9) |

| Grade of haemorrhoid, n (%) | ||

| II | 86 (22.2) | 86 (22.3) |

| III | 243 (62.6) | 240 (62.2) |

| IV | 59 (15.2) | 60 (15.5) |

| Previous haemorrhoid surgery, n (%) | 139 (35.8) | 116 (30.1) |

| Comorbidities, n (%) | 6 (1.5) | 4 (1.0) |

| Systemic medications, n (%) | ||

| Aspirin | 23 (5.9) | 16 (4.1) |

| Warfarin | 4 (1.0) | 2 (0.5) |

| Clopidogrel | 6 (1.5) | 4 (1.0) |

| Steroids | 5 (1.3) | 2 (0.5) |

| Immunosuppressants | 1 (0.3) | |

| Other | 6 (1.5) | 3 (0.8) |

| Pain (VAS), n, mean (SD) | 379, 2.8 (2.7) | 383, 2.5 (2.6) |

| Analgesia, n (%) | ||

| Yes | 139 (35.8) | 118 (30.6) |

| Missing | 7 (1.8) | 4 (1.0) |

| Number of days in a week with analgesia, n, mean (SD) | 137, 4.1 (2.2) | 117, 4.3 (2.2) |

| EQ-5D-3L, n, mean (SD) | 388, 0.764 (0.264) | 386, 0.762 (0.246) |

| SF-36, n, mean (SD) | ||

| Physical component summary | 380, 48.5 (9.4) | 377, 48.8 (9.5) |

| Mental component summary | 380, 48.8 (11.7) | 377, 49.6 (11.0) |

| CIS, n, mean (SD) | 376, 4.3 (3.9) | 376, 4.1 (4.0) |

| HSS, n, mean (SD) | 370, 10.8 (4.7) | 370, 10.4 (4.7) |

| Patient reporting tenesmus, n (%) | ||

| Always | 15 (3.9) | 9 (2.3) |

| Often | 52 (13.4) | 39 (10.1) |

| Sometimes | 93 (24.0) | 105 (27.2) |

| Rarely | 73 (18.8) | 62 (16.1) |

| Never | 150 (38.7) | 168 (43.5) |

| Missing | 5 (1.3) | 3 (0.8) |

| Patient preference, n (%) | ||

| Strongly prefer better short-term recovery | 23 (5.9) | 38 (9.8) |

| Prefer better short-term recovery | 35 (9.0) | 24 (6.2) |

| No preference | 161 (41.5) | 146 (37.8) |

| Prefer lower risk of recurrence | 95 (24.5) | 85 (22.0) |

| Strongly prefer lower risk of recurrence | 68 (17.5) | 91 (23.6) |

| Missing | 6 (1.5) | 2 (0.5) |

Table 8 summarises the level of experience of the surgeons and is broken down by surgical procedure and not randomisation group. The number of SH and TH operations performed in the previous year per surgeon are similar, whereas the number performed during a surgeon’s career differs.

| Characteristic | Trial arm | |

|---|---|---|

| SH (N = 388) | TH (N = 386) | |

| Number of operations performed during career | ||

| n, mean (SD) | 42, 102.7 (98.9) | 42, 200.1 (232.3) |

| Median (IQR) | 85 (30.0–115.0) | 100 (70.0–200.0) |

| Operations performed in previous year | ||

| n, mean (SD) | 43, 12.9 (10.3) | 40, 14.7 (12.6) |

| Median (IQR) | 10 (4.0–21.0) | 10 (4.5–23.0) |

Chapter 5 Outcomes and results

Description of sample

The surgical procedures received by each treatment group are shown in Table 9. Of the 388 participants randomised to receive SH, 358 (92.3%) had surgery and, of these, 301 (84.1%) received their allocated intervention, 37 (10.3%) received TH, 18 (5.0%) had a technique other than the study interventions and two (0.6%) are unknown as they underwent private treatment. For the 386 participants randomised to receive TH, 363 (94.0%) had surgery, 323 (89.0%) received their allocated treatment, 29 (8.0%) received SH and 11 (3.0%) received other treatments. Across both arms 53 (6.8%) participants did not receive surgery, and the reasons are shown in Table 10.

| Surgery details | Trial arm | |

|---|---|---|

| SH (N = 388) | TH (N = 386) | |

| Received surgery, n (%) | ||

| Yes | 358 (92.3) | 363 (94.0) |

| No | 30 (7.7) | 23 (6.0) |

| Surgical technique, n (%) | ||

| Stapling | 301 (84.1) | 29 (8.0) |

| Ethicon | 155 (51.5) | 22 (75.9) |

| Chex CPH 32 staple gun | 117 (38.9) | 6 (20.7) |

| EEA Staplers with DST Series technology | 9 (3.0) | – |

| Other | 10 (3.3) | 1 (3.4) |

| Missing | 10 (3.3) | – |

| Traditional | 37 (10.3) | 323 (89.0) |

| Open (Milligan–Morgan) | 36 (97.3) | 272 (84.2) |

| Closed (Ferguson) | 1 (2.7) | 41 (12.7) |

| Other conventional technique | – | 5 (1.5) |

| Missing | – | 5 (1.5) |

| Other technique | 18 (5.0) | 11 (3.0) |

| Surgery technique unknown | 2 (0.6) | – |

| Surgeon grade, n (%) | ||

| Consultant | 256 (71.5) | 225 (62.0) |

| Specialty doctor | 32 (8.9) | 37 (10.2) |

| Surgical trainee | 58 (16.2) | 89 (24.5) |

| Fellow | 4 (1.1) | 5 (1.4) |

| Other | 5 (1.4) | 6 (1.7) |

| Missing | 3 (0.8) | 1 (0.3) |

| Anaesthetist present, n (%) | ||

| Yes | 356 (99.4) | 363 (100.0) |

| Missing | 2 (0.6) | – |

| Anaesthetist grade, n (%) | ||

| Consultant | 287 (80.2) | 297 (81.8) |

| Specialty doctor | 45 (12.6) | 36 (9.9) |

| Fellow | – | 1 (0.3) |

| Registrar | 10 (2.8) | 21 (5.8) |

| Other | 2 (0.6) | – |

| Missing | 14 (3.9) | 8 (2.2) |

| Type of anaesthesia, n (%) | ||

| General | 236 (65.9) | 223 (61.4) |

| General and local anaesthetic block | 105 (29.3) | 127 (35.0) |

| Spinal | 15 (4.2) | 11 (3.0) |

| Other | – | 1 (0.3) |

| Missing | 2 (0.6) | 1 (0.3) |

| Duration of operation (hours), n, mean (SD) | 346, 0.4 (0.2) | 359, 0.4 (0.2) |

| Length of hospital stay (days), n, mean (SD) | 356, 0.4 (0.3) | 363, 0.4 (0.4) |

| Day cases, n (%) | 305 (85.6) | 317 (87.3) |

| Time from randomisation to surgery (days), n, mean (SD) | 358, 68.2 (78.3) | 363, 68.8 (81.1) |

| Reason | Number of participants, n (%) (N = 53) |

|---|---|

| Patient reasons | 39 (73.6) |

| Opted out of surgery | 15 |

| Cancelled surgery | 10 |

| Did not attend | 7 |

| Went private | 3 |

| Moved away | 2 |

| Withdrew prior to surgery (withdrew outcome data) | 1 |

| Withdrew consent | 1 |

| Clinical reasons | 10 (18.9) |

| Underlying health condition | 5 |

| Following preoperative consultation conservative management was decided | 1 |

| Pregnancy | 1 |

| Following preoperative consultation did not require surgery | 3 |

| Unknown | 3 (5.7) |

| Death prior to surgery | 1 (1.9) |

Surgical details

For the SH procedure, the most common staplers used were the Ethicon and the Chex staplers, used on 177 (53.6%) and 123 (37.3%) patients, respectively. For the TH procedure, the Milligan–Morgan approach was the main surgical approach, performed on 308 (85.6%) patients. The majority of participants were operated on by consultant surgeons (71.5% in the SH arm and 62.0% in the TH arm). Specialty doctors performed 8.9% of operations in the SH arm and 10.2% in the TH arm and surgical trainees performed 16.2% of the SH surgeries and 24.5% of the TH surgeries. Most procedures were performed either under general anaesthesia (65.9% in the SH arm and 61.4% in the TH arm) or with an additional local anaesthetic block in 29.3% of the SH arm and 35.0% of the TH arm. The mean duration of the operation was the same in both groups (0.4 hours), 305 (85.6%) in the SH arm and 317 (87.3%) in the TH arm were day cases and the mean number of days to surgery was similar for both groups (68.2 days in the SH arm and 68.8 days in the TH arm).

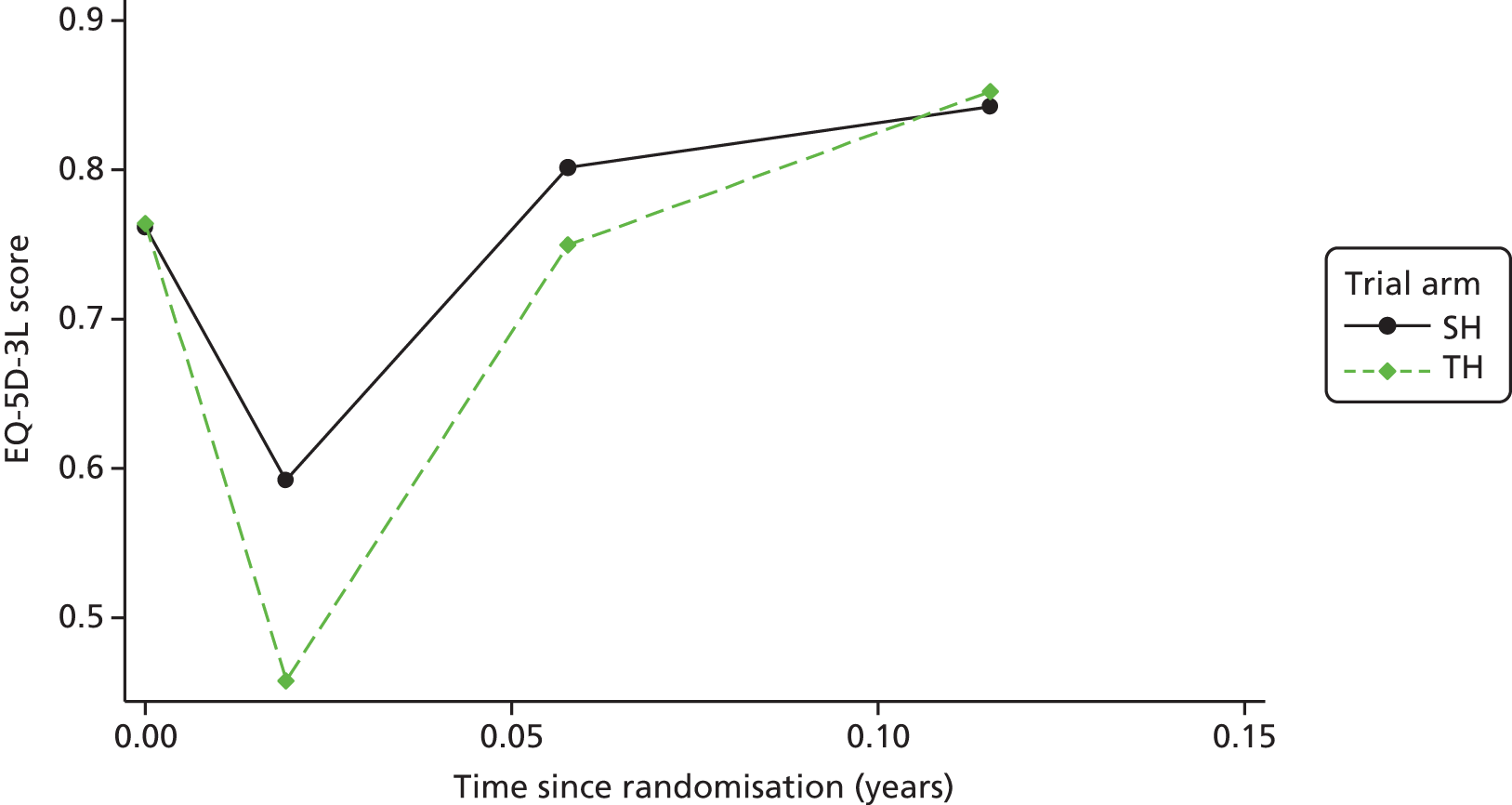

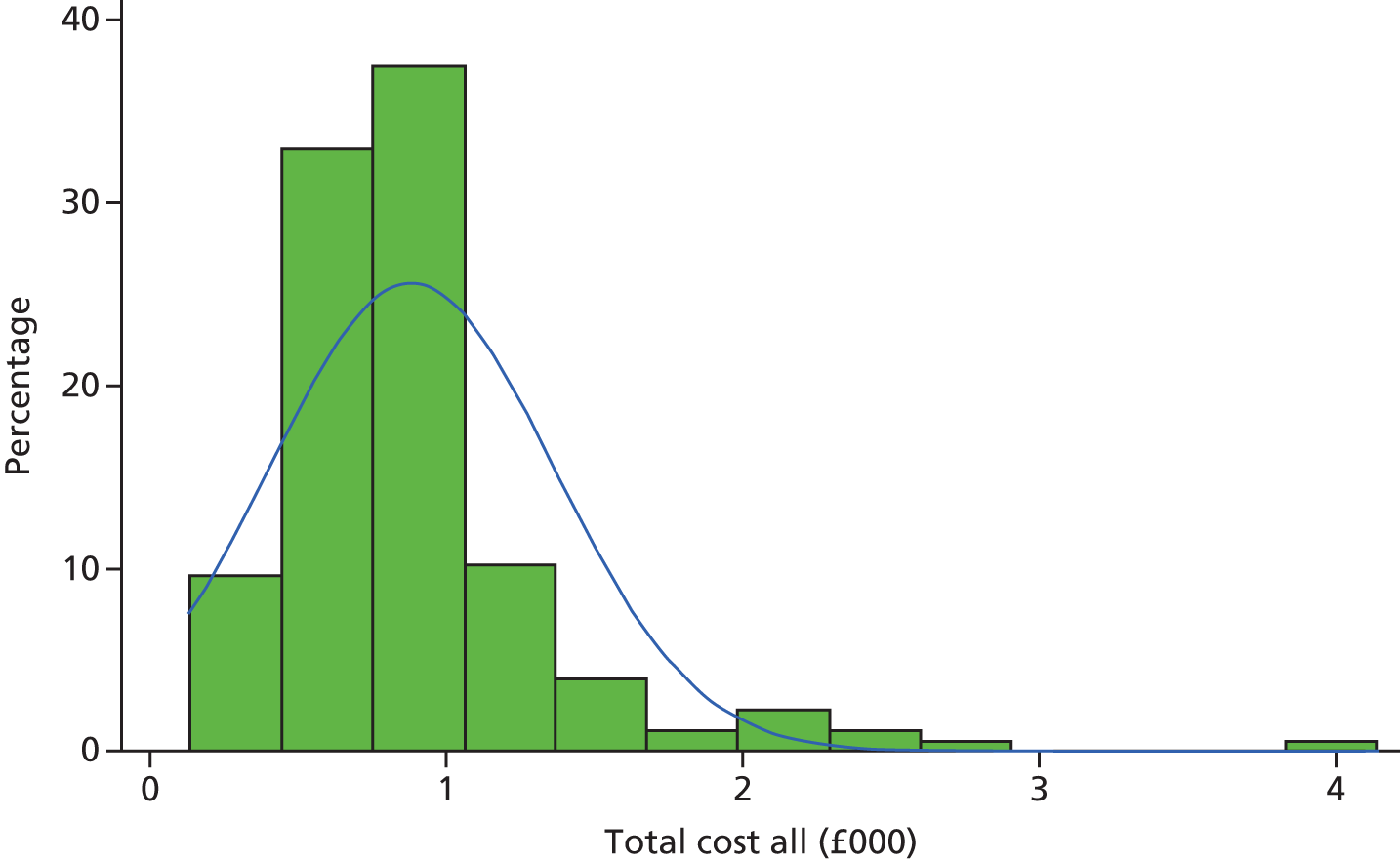

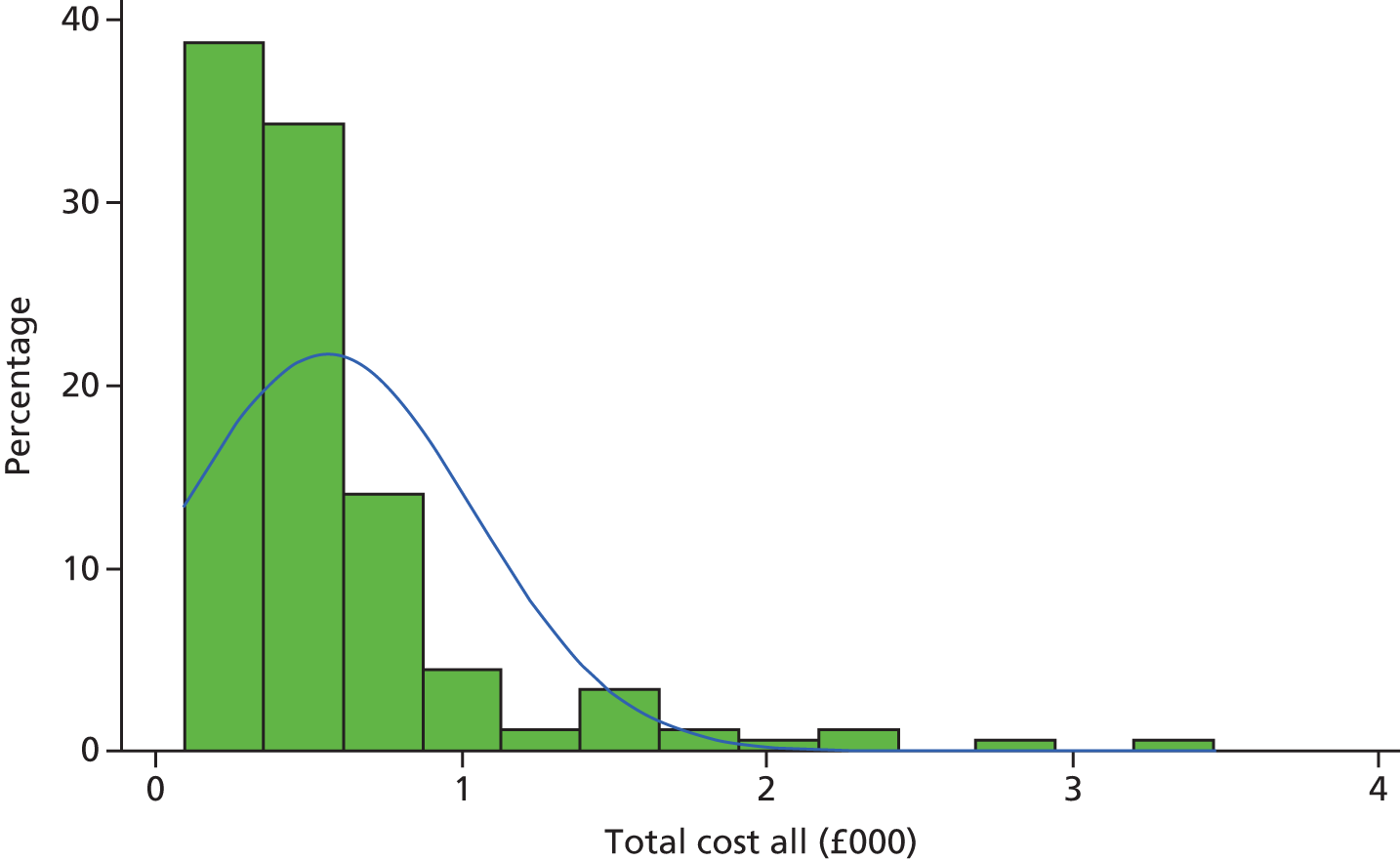

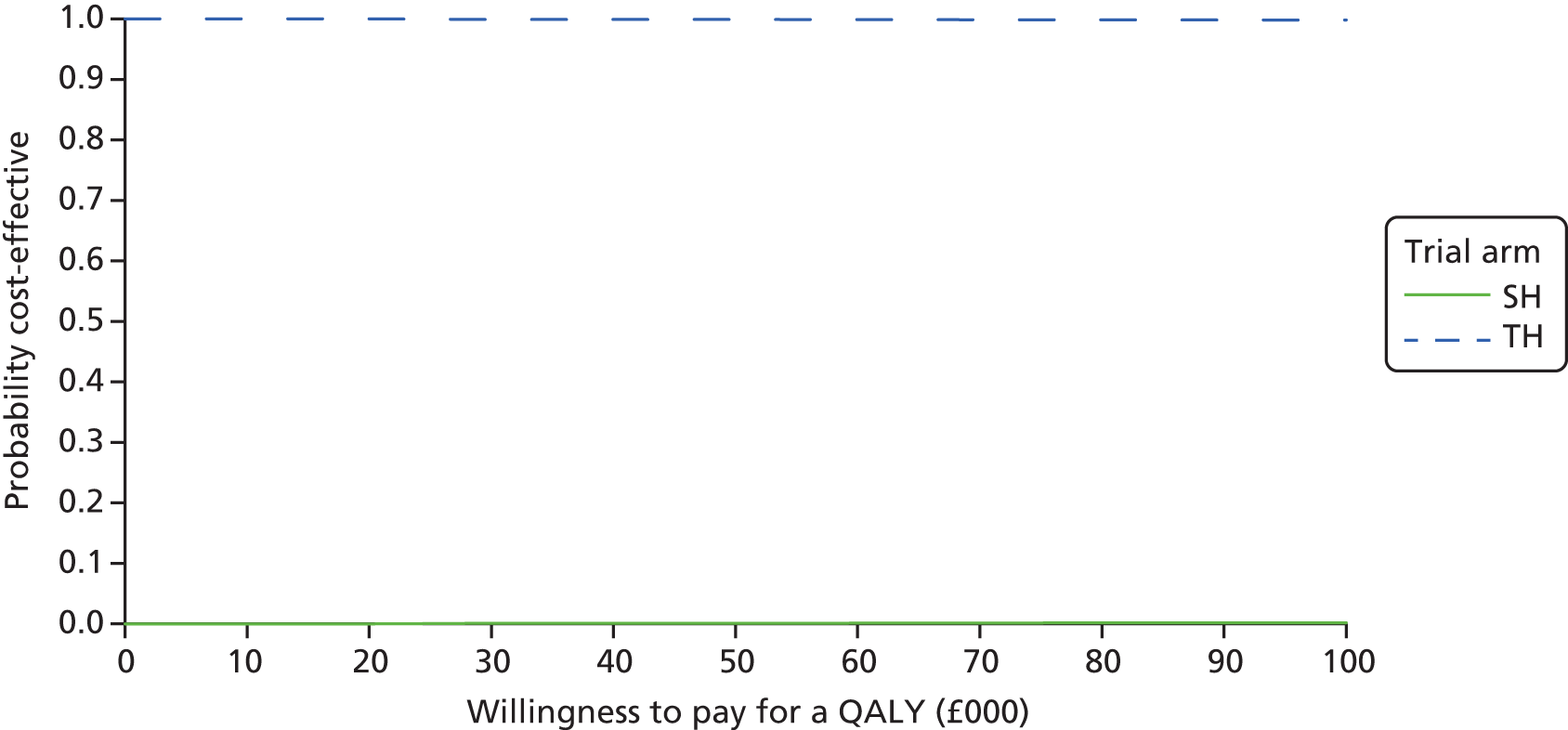

Primary outcome