Notes

Article history

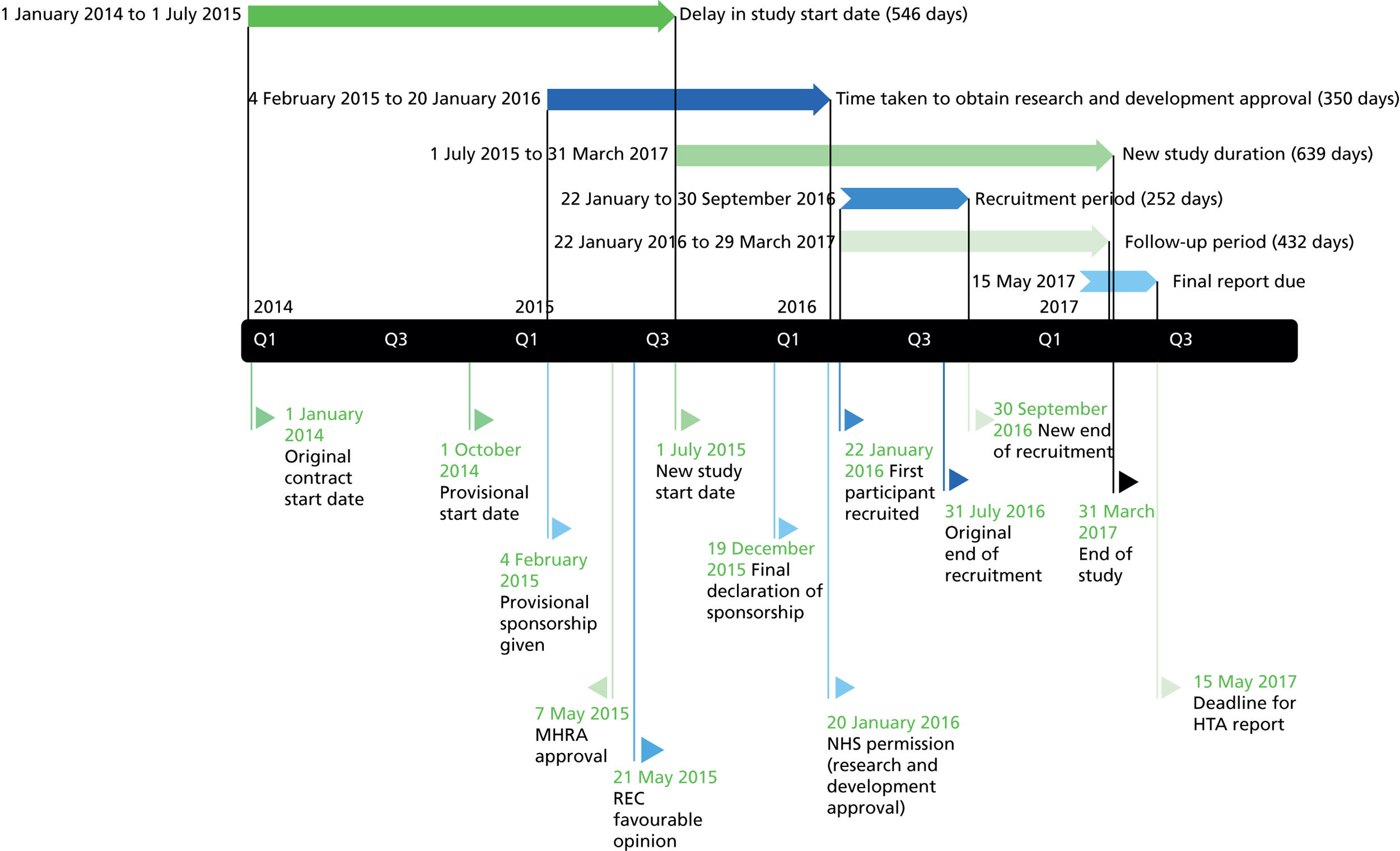

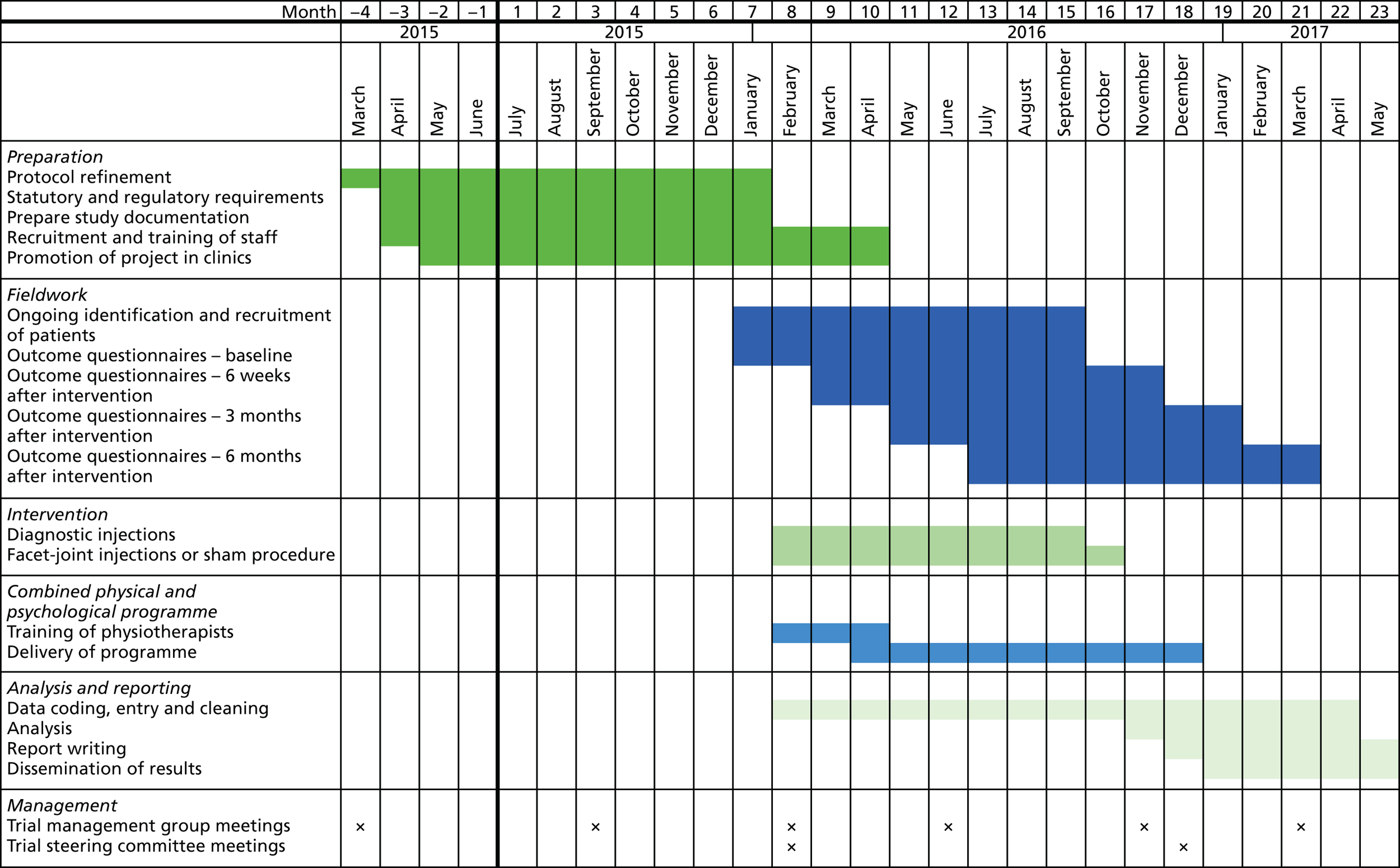

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 11/31/02. The contractual start date was in July 2015. The draft report began editorial review in May 2017 and was accepted for publication in September 2017. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Rod S Taylor is the chairperson of the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Health Services and Delivery Research programme researcher-led panel and is a current member of the NIHR Priority Research Advisory Methodology Group (PRAMG). He was a member of the NIHR Health Technology Assessment General Board between 2014 and June 2017. Funding from BioQ Pharma has been awarded to the Swansea Centre for Health Economics to conduct a pilot study of the use of OneDose ReadyfusOR in the postoperative delivery of pain relief. Deborah Fitzsimmons is not involved in this study but is the Academic Director of the research centre that has received the grant. Stephanie Poulton reports personal fees from the Neuro Orthopaedic Institute (NOI) and personal fees from Pain and Performance, outside the submitted work. Pain and Performance is a private organisation that teaches and runs seminars about pain for professionals and treats people in pain (see www.painandperformance.com)

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2017. This work was produced by Snidvongs et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2017 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Introduction

Funding history

The FACET (Feasibility of Assessing the Clinical- and cost-Effectiveness of Therapeutic lumbar facet-joint injections) feasibility study was a commissioned proposal funded by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Health Technology Assessment (HTA) programme (reference number HTA 11/31/02); the funding contract was agreed in July 2013. A favourable ethical opinion was given on 21 May 2015 and NHS permission was granted on 20 January 2016, with the first participant recruited to the study on 22 January 2016. Following an extension agreement with the funder, recruitment ended on 30 September 2016 and the study closed on 31 March 2017.

Structure of this report

In this chapter, the existing evidence for therapeutic intra-articular lumbar facet-joint injections (FJIs) for non-specific low back pain (LBP) is reviewed and the need for a pilot trial is presented. In Chapter 2 the feasibility study procedure and associated methodological work are described, with the results of this work being presented in Chapter 3. The implications of our findings are discussed in Chapter 4 and the conclusions drawn with regard to a full trial are presented in Chapter 5.

Background

Low back pain causes more global disability than any other condition, and has a lifetime prevalence of up to 85%. 1 Non-specific LBP, in which symptoms are experienced without any recognisable pathology,2 is thought to affect around 90% of all LBP sufferers, with between 1% and 5% of patients presenting with LBP having a serious spinal pathology such as vertebral fracture, malignancy, infection and inflammatory disease. 3

The economic costs of LBP have been reported to be £12.3B per annum in the UK alone. 4 Chronic LBP, with a prevalence of 3–10%,5 is associated with depression, anxiety, deactivation, inability to work and substantial societal costs. 1,6

Common contributors to LBP in adults are thought to include lumbar facet-joints. 7 These are paired synovial joints between the superior and inferior articular processes of consecutive lumbar vertebrae and between the fifth lumbar vertebra and the sacrum. Encapsulated nerve endings have been demonstrated in these facet-joints, supplied by medial branches of the dorsal rami nerves (‘medial branch nerves’). Facet-joint contributions to LBP may arise from any structure that is part of the facet-joints, including the fibrous capsule, synovial membrane, hyaline cartilage and bone.

Low back pain with a likely facet-joint component can be treated with interventions targeting the facet-joints, including intra-articular (within the joint itself) FJIs, periarticular medial branch nerve blocks or radiofrequency denervation of the medial branch nerves innervating the joints. The technique of FJI is not standardised and may be carried out with or without radiological guidance to confirm needle placement. 8 Lumbar FJIs involve the injection of an active substance, typically steroids with or without a local anaesthetic, intra-articularly or next to the joint (periarticular injections). They are commonly carried out under radiological or fluoroscopic guidance, although they can be performed under ultrasound or computerised tomography scanning guidance. 9

The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidelines for managing LBP were recently updated [NICE guideline (NG59)10]. These guidelines propose a care pathway in which all those aged ≥ 16 years with LBP with or without sciatica should be provided with advice and information, tailored to their needs and capabilities, to help them self-manage at all steps of the treatment pathway, including education on the nature of LBP and sciatica and encouragement to return to work and pursue normal activities of daily living. 11 Those with a specific episode or flare-up of LBP should consider a group exercise programme, manual treatment or a psychological therapy package. If these therapies fail, pharmacological options and combined physical and psychological (CPP) programmes should be offered, followed by radiofrequency denervation or surgical approaches such as fusion. The guidelines make specific ‘do not use’ recommendations for a range of groups of treatments including acupuncture and electrotherapy; traction, braces and corsets; disc replacement; and spinal injections (including FJIs). The NICE guidelines omit intra-articular FJIs on the grounds of there being insufficient high-quality evidence to support their use and recommend instead targeting the facet-joints’ nerve supply (medial branch nerves) as the predominant pain generator source. However, intra-articular FJIs remain in common use. 12

Review of the literature: a review of systematic reviews and meta-analyses

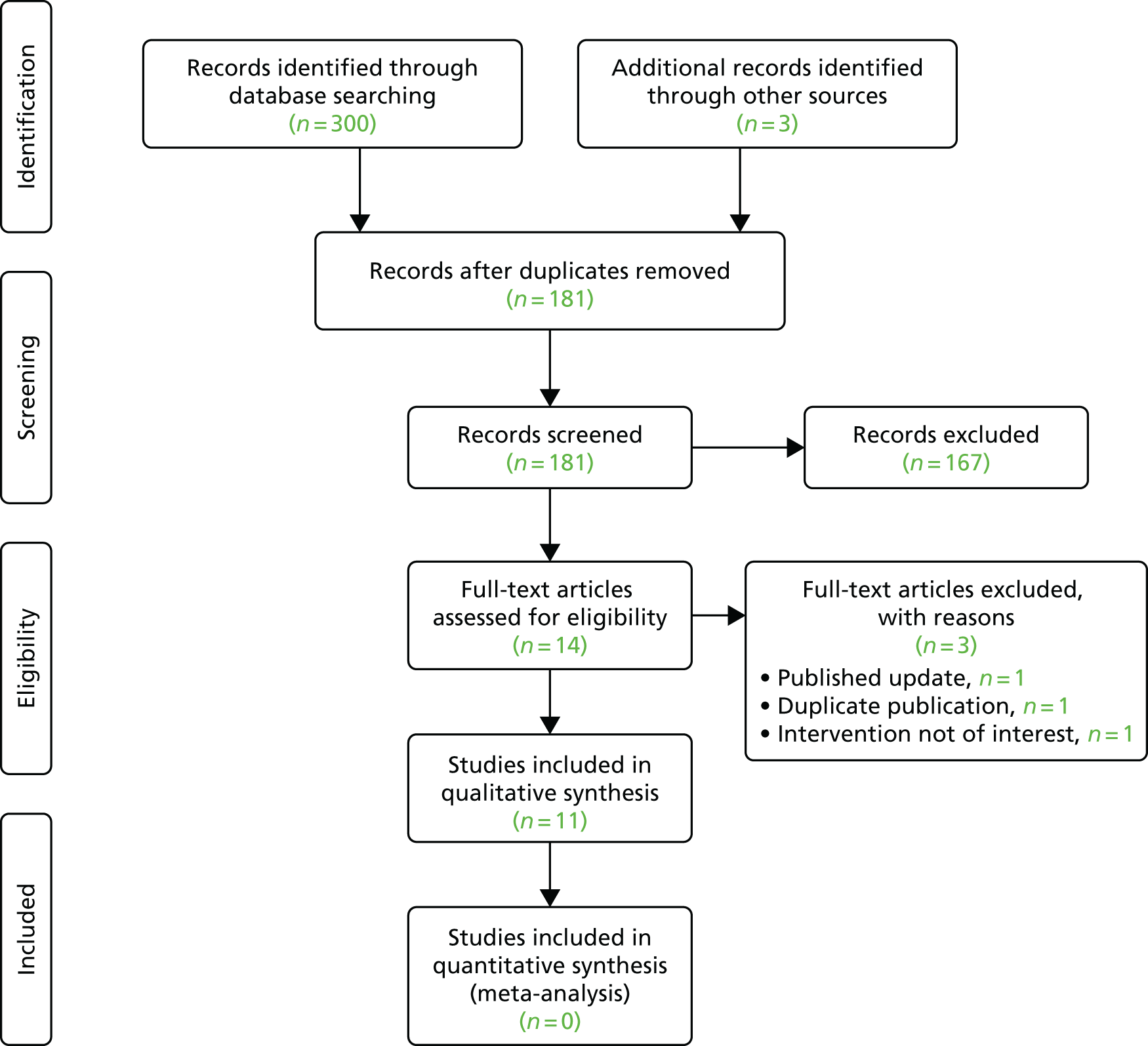

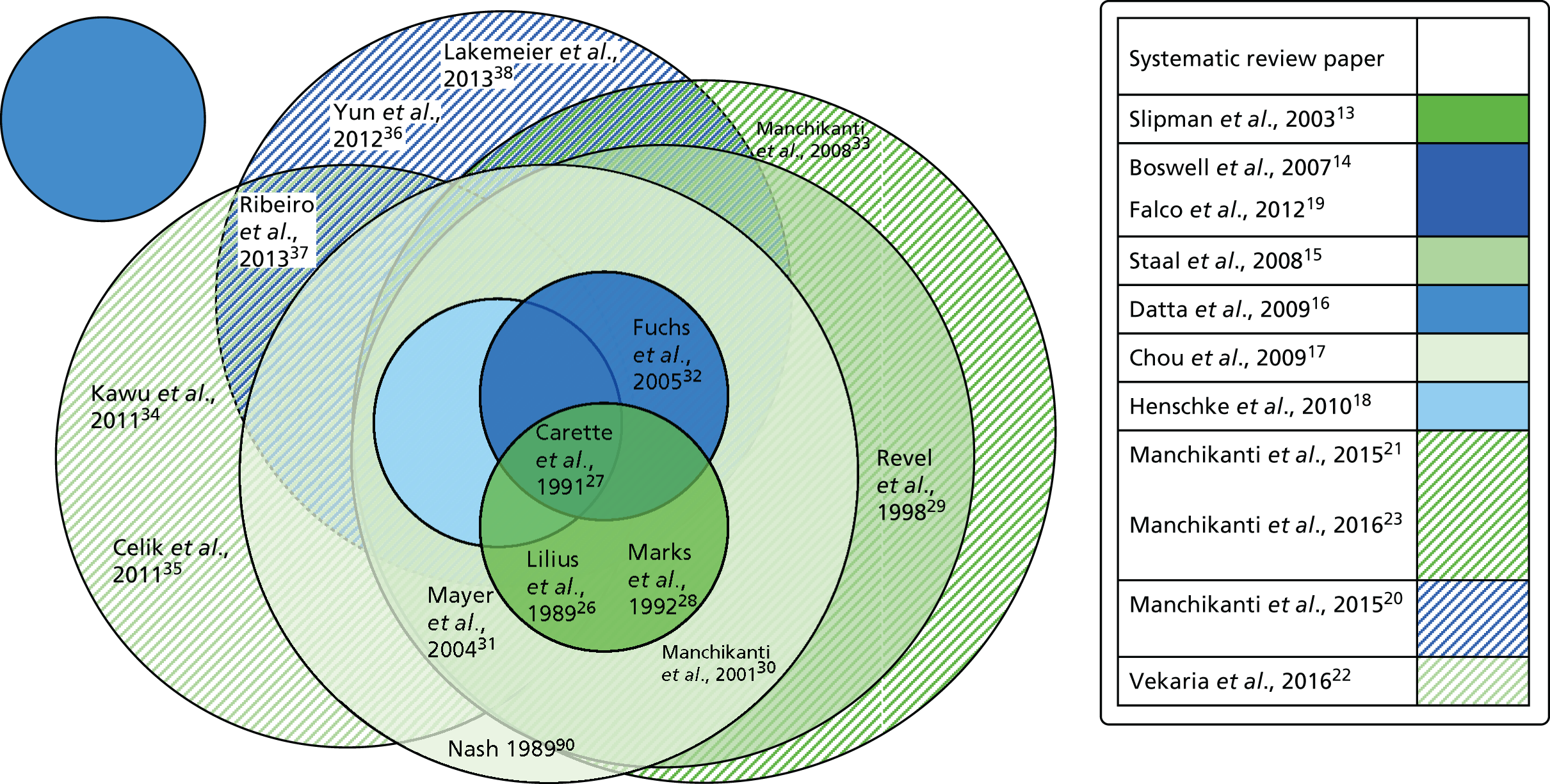

We undertook a literature search to identify systematic reviews and meta-analyses of randomised controlled trials of intra-articular lumbar FJIs for chronic LBP. We searched MEDLINE, EMBASE and the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials from 1966 to February 2017; the search strategies used are detailed in Appendix 1. Two reviewers (Saowarat Snidvongs and Fausto Morell-Ducos) independently screened and assessed full-text articles for eligibility. The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) flow diagram is illustrated in Figure 1. Eleven systematic reviews14–24 met the inclusion criteria; the sources of the reviews are summarised in Appendix 2. The Assessment of Multiple Systematic Reviews (AMSTAR) checklist,25 applied by two independent reviewers to assess the methodological quality of the systematic reviews, demonstrated significant variations between the reviews, with AMSTAR scores ranging between 2 and 10 out of a maximum of 11 points, as shown in Appendix 3 (a low score is associated with a higher risk of bias).

FIGURE 1.

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) flow diagram for the systematic review search. Adapted from Moher et al. 13 © 2009 Moher et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

In total, 14 randomised controlled trials were identified across these 11 reviews; 13 were obtained as full-text articles and their findings are summarised in Table 1. Appendix 4 illustrates that, given the variation in dates when the reviews were undertaken and their precise inclusion/exclusion criteria, no one review included all of these trials. The authors of these systematic reviews concluded that the level of clinical heterogeneity across the included randomised controlled trials – different injection procedures, substances and comparators – precluded any meta-analyses.

| First author, year (country, n randomised) | Population | Intervention | Comparator | Primary outcome | Follow-up (months) | Key findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lilius, 198926 (Finland, n = 109) | Unilateral LBP for > 3 months, failed analgesics and physiotherapy, no diagnostic blocks | (1) Radiologically guided intra-articular lumbar FJIs with bupivacaine and methylprednisolone; (2) radiologically guided pericapsular injections with bupivacaine and methylprednisolone | Sham (radiologically guided intra-articular lumbar FJIs with physiological saline) | Not stated – assessed pain, disability and return to work | 3 months | No difference in outcomes at follow-up between the two active groups and the sham group. Improvement in pain, disability and work attendance in all groups |

| Carette, 199127 (Canada, n = 101) | LBP for > 6 months, normal neurological examination, > 50% pain reduction after single intra-articular diagnostic injection with lidocaine | Fluoroscopy-guided intra-articular lumbar FJIs with methylprednisolone and isotonic saline | Sham (fluoroscopy-guided intra-articular lumbar FJIs with isotonic saline) | Not stated – assessed pain severity, back mobility and limitation of function | 6 months | No differences in outcomes at 1 and 3 months between the two groups. At 6 months, patients in the intervention group reported greater self-rated improvement, lower pain intensity and less physical disability than patients in the sham group |

| Marks, 199228 (Scotland, UK, n = 86) | LBP for > 6 months, failed non-narcotic analgesics and physiotherapy, no diagnostic blocks | Radiologically guided intra-articular lumbar FJIs with lidocaine and methylprednisolone | Radiologically guided lumbar facet-joint medial branch nerve blocks with lidocaine and methylprednisolone | Pain intensity | 3 months | Marginally longer duration of response in the intervention group after 1 month, otherwise no difference in outcomes at other time points between the two groups. Some short-term pain relief seen in both groups |

| Revel, 199829 (France, n = 80) | LBP for > 3 months, failed analgesics and physical therapy, no diagnostic blocks | Fluoroscopy-guided intra-articular lumbar FJIs with lidocaine plus periarticular corticosteroid steroid injection (not evaluated) | Fluoroscopy-guided intra-articular lumbar FJIs with saline plus periarticular corticosteroid steroid injection (not evaluated) | Pain intensity using VAS | 30 minutes after injections | Significantly reduced pain scores in the intervention group compared with the comparator group |

| Manchikanti, 200130 (USA, n = 84) | LBP for > 6 months, failed conservative management, positive response following controlled comparative diagnostic blocks with lidocaine and bupivacaine | Lumbar facet medial branch nerve blocks with lidocaine or bupivacaine, Sarapin® (High Chemical Company, Levittown, PA, USA) and methylprednisolone | Lumbar facet medial branch nerve blocks with lidocaine or bupivacaine and Sarapin | Not stated – assessed pain characteristics, physical health, mental health, functional status, return to work and narcotic intake | Up to 2.5 years | No difference in outcomes at follow-up between the groups; improvement in pain and functional outcomes in groups I (IA and IB) and II (IIA and IIB) |

| Mayer, 200431 (USA, n = 70) | ‘Chronic disabling work related lumbar spinal disorder’ for > 6–12 months, ‘lumbar segmental rigidity’ on clinical examination, no diagnostic blocks | Fluoroscopy-guided bilateral intra-articular lumbar FJIs with lidocaine, bupivacaine and depot corticosteroid and home stretching exercise programme | Home stretching exercise programme only | Range of motion, pain and disability | Not specified – after completing the home stretching exercise programme | No difference in pain and disability reported at follow-up between the two groups, but greater improvement in range of motion in the intervention group |

| Fuchs, 200532 (Germany, n = 60) | LBP for > 3 months, facet-joint osteoarthritis on imaging | Computerised tomography-guided intra-articular lumbar FJIs with triamcinolone | Computerised tomography-guided intra-articular FJIs with sodium hyaluronate | Pain intensity, functioning and quality of life | 180 days | No difference in outcomes at follow-up between the two active groups; improvement in pain and functional outcomes in both groups |

| Manchikanti, 200833 (USA, n = 120) | LBP for > 6 months, failed conservative management, 80% pain relief following controlled comparative diagnostic blocks with lidocaine and bupivacaine | IA: lumbar facet-joint medial branch nerve blocks with bupivacaine; IB: lumbar facet-joint medial branch nerve blocks with bupivacaine and Sarapin | IIA: lumbar facet-joint medial branch nerve blocks with bupivacaine and steroid; and IIB: lumbar facet-joint medial branch nerve blocks with bupivacaine, steroid and Sarapin | Not stated – assessed pain relief, work status, opioid intake and functional status | 1 year | No difference in outcomes at follow-up between the groups; improvement in pain and functional outcomes in both groups |

| Kawu, 201134 (Nigeria, n = 18) | LBP for > 3 months, failed analgesics, MRI features of facet-joint arthropathy, no diagnostic blocks | Radiologically guided lumbar FJIs with bupivacaine and methylprednisolone | Physiotherapy (McKenzie regimen) | Not stated – assessed pain relief and satisfaction with treatment | 6 months | Greater decreases in pain and higher levels of satisfaction in the intervention group than in the comparator group |

| Celik, 201135 (Turkey, n = 80) | LBP for < 4 months, no diagnostic blocks | Fluoroscopy-guided lumbar FJIs with bupivacaine and methylprednisolone | Diclofenac, thiocolchicoside and bed rest for 4 days | Not stated – assessed LBP disability and pain intensity | 6 months | Greater decreases in pain and disability in the intervention group than in the comparator group; improvement in pain and functional outcomes in both groups |

| Yun, 201236 (Korea, n = 57) | LBP (no duration specified), clinical indicators of facet syndrome, no diagnostic blocks | Fluoroscopy-guided lumbar FJIs with lidocaine and triamcinolone | Ultrasound-guided lumbar FJIs with lidocaine and triamcinolone | Pain and activities of daily living | 3 months | No difference in outcomes at follow-up between the two active groups; improvement in pain and functional outcomes in both groups |

| Ribeiro, 201337 (Brazil, n = 60) | LBP for > 3 months, clinical diagnosis of lumbar facet-joint syndrome, no diagnostic blocks | Fluoroscopy-guided intra-articular lumbar FJIs with lidocaine and triamcinolone | Intramuscular paravertebral injections with lidocaine and triamcinolone | Not stated – assessed quality of life, functional capacity, pain on back extension, percentage improvement scale, analgesic usage | 24 weeks | ‘Slightly superior’ results in the intervention group than in the comparator group; improvement in pain and functional outcomes in both groups |

| Lakemeier, 201338 (Germany, n = 56) | LBP for > 24 months, > 50% pain reduction after single intra-articular diagnostic injection with bupivacaine | Fluoroscopy-guided intra-articular lumbar FJIs with bupivacaine and betamethasone | Radiofrequency denervation of the lumbar facet-joint medial branch nerves | LBP-related disability using the Rowland Morris Disability Questionnaire | 6 months | No difference in outcomes at follow-up between the two active groups; improvement in pain and functional outcomes in both groups |

The conclusions drawn from the systematic reviews were generally equivocal. Although there was some trial evidence demonstrating the effectiveness of therapeutic lumbar FJIs in the management of chronic LBP, the limited to moderate quality of this evidence was insufficient to support their use in practice. The current evidence base for FJI is neatly summed up by a recent and high-quality systematic review by Vekaria et al. ,23 which concluded that ‘The studies found here were clinically diverse and precluded any meta-analysis. A number of methodological issues were identified. The positive results, whilst interpreted with caution, do suggest that there is a need for further high-quality work in this area.’23

Rationale for a feasibility study

To provide further high-quality research in this area, the NIHR HTA programme issued a commissioning brief in 2011 to answer the research question, ‘Is a definitive study to assess the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of facet-joint injections compared with best non-invasive care for people with persistent non-specific low back pain feasible?’ [see www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/programmes/hta/113102/#/ (accessed 31 October 2017)].

Two research teams were funded by the NIHR in response to this commissioned call: (1) the Facet Feasibility study (the addition of intra-articular facet-joint injections to best usual non-invasive care) (reference HTA 11/31/01) led by Professor Martin Underwood, University of Warwick [see www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/programmes/hta/113101/#/ (accessed 31 October 2017)] and (2) this project, the FACET feasibility study (a multicentre double-blind randomised controlled trial comparing intra-articular lumbar facet-joint injections with a sham procedure, followed by a combined physical and psychological programme) (reference HTA 11/31/02) [see www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/programmes/hta/113102/#/ (accessed 31 October 2017)] led by Professor Richard Langford, Barts Health NHS Trust.

Study aims and research questions

The aim of the FACET feasibility study was to assess the feasibility of conducting a definitive study to evaluate the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of FJIs compared with a sham procedure in patients with non-specific LBP of > 3 months’ duration.

To inform a full trial, a number of questions first need to be assessed by a feasibility study:

-

Given the multiple sites with the potential to generate back pain, can patient selection criteria be optimised, using clinical and investigative diagnostic methods?

-

Can the method of injection be standardised and an appropriate sham procedure be established?

-

Can justification for further studies to evaluate treatment methods to target and attenuate the source of chronic LBP of facet-joint origin be delivered?

-

Is a sham-controlled trial design acceptable to patients and clinicians?

-

Can a sufficient number of patients be recruited and retained?

Study objectives

-

To assess the eligibility criteria and recruitment and retention of patients in the two treatment arms (FJIs vs. sham procedure) by assessing the feasibility of recruitment in the three centres, reviewing the number of completed patient data sets, auditing the quality of data entry at the centres and assessing and analysing any protocol violations (such as failure to deliver the CPP programme – recommended therapy at the time of the establishing this study39), side effects and other adverse outcomes.

-

To assess the feasibility and acceptability of the two treatment arms from the point of view of patients and their pain teams.

-

To assess the feasibility of the proposed definitive study design, including:

-

testing of the randomisation and blinding procedures

-

development of appropriate active and sham procedures for FJIs

-

assessment of the consistency of the trial sites in terms of delivering the CPP programme

-

assessment of the ability to collect the outcomes proposed for the main trial (pain, functioning, health-related quality of life, anxiety and depression, health-care resource utilisation, complications and adverse events).

-

-

To estimate outcome standard deviations (SDs) to inform the power calculation for a definitive study.

-

To finalise the protocol design, statistical plan, number of centres required and study duration for the definitive study.

Chapter 2 Methods

Study design

This feasibility study utilised a blinded parallel two-arm pilot randomised controlled trial design. Following a positive diagnostic medial branch nerve block, participants with non-specific LBP were individually randomised in a 1 : 1 ratio to receive either the FJI (intervention group) or a sham (placebo injection) procedure (control group). Both the intervention group and the control group received a CPP programme after their active or sham injections.

Participants

The study sought patients with non-specific LBP based on the following inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Inclusion criteria

-

Patients aged 18–70 years attending pain clinics identified during routine clinical assessment of non-specific LBP. Clinical indicators of pain of facet-joint origin included tenderness over the facet-joints, referred leg pain above the knees and worsening pain on extension, flexion and rotation of the lumbar spine.

-

Low back pain of ≥ 3 months’ duration.

-

An average pain intensity score of ≥ 4 out of 10 in the 7 days preceding recruitment despite NICE-recommended treatment. NICE clinical guideline CG887 recommended providing patients with advice and information to promote self-management of their LBP and offering one of the following treatments, taking into account patient preference: an exercise programme, a course of manual therapy or a course of acupuncture.

-

Dominantly paraspinal (not midline) tenderness at two bilateral lumbar levels.

-

At least two components of NICE-recommended best non-invasive care completed, including education and one of a physical exercise programme, acupuncture or manual therapy. 7

-

Patients are suitable for the FJIs.

Exclusion criteria

-

Patient refusal to consent.

-

More than four painful lumbar facet-joints. No more than four facet-joints were to be injected to limit the total dose of intra-articular steroids.

-

Patient has not completed at least two components of NICE-recommended best non-invasive care, including education and one of a physical exercise programme, acupuncture or manual therapy. 7

-

‘Red flag’ signs. These are possible indicators of serious spinal pathology and include thoracic pain, fever, unexplained weight loss, bladder or bowel dysfunction, progressive neurological deficit and saddle anaesthesia. 40

-

Known hypersensitivity to study medications.

-

Dominantly midline tenderness over the lumbar spine, any other dominant pain or radicular pain.

-

Any major systemic disease or mental health illness that may affect the patient’s pain, disability and/or their ability to exercise and rehabilitate, as judged by the Principal Investigators.

-

Any active neoplastic disease, including primary or secondary neoplasm.

-

Pregnant or breastfeeding patients (verbal confirmation obtained at screening; prior to each interventional procedure involving radiography, local hospital procedures will be followed to confirm that female participants are not pregnant).

-

Any evidence of previous lumbar FJIs, previous lumbar spinal surgery or any major trauma or infection to the lumbar spine.

-

Patients with morbid obesity (body mass index of ≥ 35 kg/m2).

-

Participation in another clinical trial of an investigational medicinal product or disease-related intervention in the past 30 days.

-

Patients unable to commit to the 6-month study duration.

-

Patients involved in legal actions or employment or benefit tribunals related to their LBP.

-

Patients with a known history of substance abuse.

Recruitment procedures

It was originally planned to recruit patients from pain clinics at the three participating NHS centres and their associated community based pain clinics. However, because of the early termination of the study by the funder, recruitment was undertaken at only one centre, Barts Health NHS Trust. Recruitment took place over 9 months. The first participant was recruited in January 2016 and the last participant was recruited in September 2016.

Patients were referred by their general practitioner (GP) as a standard clinical referral with LBP requiring further specialist assessment, for reasons such as uncertain diagnosis, failure of conservative treatment and expectation of therapeutic interventions. Potentially eligible patients were identified by a pain clinician based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Participants were free to withdraw from the study at any time without giving a reason; the participant information sheet stated that ‘a decision to withdraw from the study at any time will not affect the standard of care that you receive now or in the future’ (see Appendix 5). Participants who withdrew from the study received a routine follow-up appointment in their pain clinic for continuing assessment and management by their pain physician.

Informed consent

Potential participants were given a copy of the information sheet (see Appendix 5) and a verbal explanation of its contents, including information on the nature of the study, the implications and constraints of the study protocol and any known side effects and risks involved in taking part in the study. A medically qualified investigator on the delegation log obtained written informed consent.

Sample size calculation

At the outset of the study it was expected that a total of 60 patients would be recruited, to be able to estimate the precision of an assumed 20% attrition rate with an error of ±5% at the 95% confidence level. Assuming that 24 full data sets per arm were completed at the end of the study, this would give a reasonable estimate of variance of the outcomes. 41

Diagnostic test

Following screening and consent, all participants underwent a diagnostic medial branch nerve block. Those who achieved a positive response were randomised to the intervention group or the control (sham) group.

The diagnostic medial branch nerve injections were carried out at each painful lumbar level under radiological guidance. With the patient lying in the prone position on a radiolucent table, the investigator examined the patient’s back to elicit paraspinal tenderness and confirmed appropriate landmarks and facet-joints to be injected using radiological image intensification. The C-arm of the image intensifier was obliquely rotated as required to facilitate visualisation of the target for injection. The spinal needle was used to inject 0.5 ml of 1% lidocaine per level, with six levels injected. A positive response was defined as a ≥ 50% pain reduction lasting for > 30 minutes, that is, the duration of action of lidocaine, measured using a pain intensity numerical rating scale (NRS) and assessed in the standing position.

Interventions

The FJIs, sham procedure and diagnostic tests were carried out by the Principal Investigator at Barts Health NHS Trust, a Fellow of the Faculty of Pain Medicine of the Royal College of Anaesthetists in the UK. During all of the interventional procedures strict aseptic conditions were adhered to and local theatre protocols were followed with regard to admission and discharge criteria, including the use of the World Health Organization (WHO) Surgical Safety Checklist42 to identify the correct patient prior to starting the procedure. The investigator carrying out the injections was not blinded to randomisation group.

Active injection

Before undertaking this feasibility study, a web-based survey of 250 UK pain specialists was carried out utilising the Delphi method to agree on the choice of needle, injectate and volume of injection, as well as the choice of steroid, dose and volume and maximum dose of steroid (see Appendix 6).

In the intervention group, each participant received four FJIs at two bilateral lumbar levels, with 0.5 ml of 0.5% bupivacaine (Marcain Polyamp Steripack 0.5%, Aspen Pharma Trading Limited, Dublin, Ireland) and 20 mg of methylprednisolone (Depo-Medrone 40 mg/ml, Pfizer, Kent, UK) injected per joint. No more than four facet-joints were to be injected to avoid any potential confounding effect attributable to the systematic action of exceeding 80 mg of methylprednisolone. The volume of injectate did not exceed 1 ml per joint as it would be possible to rupture the intra-articular capsule with greater volumes, spreading the local anaesthetic and steroid to other potentially pain-generating structures.

Paraspinal tenderness was elicited as described previously. The skin was anaesthetised with 1% lidocaine (Lidocaine Hydrochloride Injection BP 1% w/v, Hameln Pharmaceuticals Ltd, Gloucester, UK) and a 22G 90-mm Quincke spinal needle was advanced through the skin, subcutaneous tissue and paraspinal muscle towards the facet-joint under radiological guidance. Entry of the needle was confirmed by visualisation of the needle position within the joint space and local anaesthetic and steroid were injected into the joint.

Sham procedure

The control group received four injections of 0.5 ml of normal saline (0.9% sodium chloride) at two bilateral lumbar levels. A low volume was chosen to avoid irritation of any structure that is part of the facet-joints, including the fibrous capsule, synovial membrane, hyaline cartilage and bone. The sham group would not receive systematic steroid administration as it has been shown that the addition of parenteral steroid does not contribute to the pain relief achieved by targeted injections. 43

Paraspinal tenderness was elicited as described previously. The skin was anaesthetised with 1% lidocaine and a 22G 90-mm Quincke spinal needle was advanced through the skin, subcutaneous tissue and paraspinal muscle towards the periarticular space under radiological guidance. Placement of the needle in the periarticular space was confirmed by visualisation of the needle position next to the joint space and normal saline was injected at this site.

Combined physical and psychological programme

Both the intervention group and the control group underwent a CPP programme delivered by trained physiotherapists. Research on CPP management of LBP has demonstrated that equally effective management can be achieved with far fewer than the 100 hours prescribed in the 2009 NICE guidance. 7 The study therefore proposed to deliver a programme drawing on the methods and evidence from the Back Skills Training (BeST) trial. 44

Physiotherapists on the delegation log were trained to deliver the Back Skills Training programme by the lead physiotherapist. Individual physiotherapists undertook approximately 10 hours of online training at www.backskillstraining.co.uk (accessed 11 November 2017) and received a certificate of completion and a trainer manual to support CPP programme delivery. The lead physiotherapist organised face-to-face meetings with each physiotherapist to ensure competency and standardised delivery.

Each participant attended an initial one-to-one hour-long assessment with a trained physiotherapist at which information was gathered, including the impact of pain on their activity and their thoughts and beliefs regarding LBP. Individualised goals were identified with one specific to physical activity. Participants then selected and practised an individualised exercise programme.

Six weekly 1.5-hour sessions of a group-based CPP programme were scheduled for each participant. Completion of the CPP programme was defined as having completed a minimum of four out of six sessions. The session contents are detailed on the website www.backskillstraining.co.uk and address the following:

-

understanding pain

-

pain fluctuations

-

unhelpful thoughts and feelings

-

restarting activities or hobbies

-

when pain worries us

-

coping with flare-ups.

One session per programme was observed by the lead physiotherapist to assess consistency of delivery and to provide feedback and support for the physiotherapists running the course. Two research physiotherapists in total, including the lead physiotherapist, delivered the programme to the study participants at Barts Health NHS Trust.

Each participant received a Back Skills Training Patient Workbook, which provided a summary of each week’s content for their reference at home. It was expected that participants would be in groups of fewer than 10 people; four to five groups of four to five participants per site were anticipated.

Regulatory approvals

The study was conducted in compliance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki (1996)45 and the principles of Good Clinical Practice46 and in accord with all applicable regulatory requirements including but not limited to the Research Governance Framework47 and the Medicines for Human Use (Clinical Trials) Regulations 2004,48 as amended in 2006 and 2008, the sponsor’s policies and procedures and any subsequent amendments.

The required regulatory approvals were obtained in the UK. The study received ethics approval from the National Research Ethics Service (NRES) Committee London – City & East (reference 15/LO/0500) and clinical trial authorisation from the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA) (reference 14620/0046/001–0001). The trial protocol was reviewed by the MHRA’s clinical trials team and the trial was considered to be a type A Clinical Trial of an Investigational Medicinal Product (CTIMP), that is, the risks are no higher than those of standard medical care. The Summary of Product Characteristics (SmPCs) for each investigational medical product (bupivacaine and methylprednisolone acetate) are available to view on the Electronic Medicines Compendium. 49,50 Health Research Authority (HRA) approval was obtained and the study was given permission by the sponsor’s Joint Research Management Office (JRMO) to recruit patients at Barts Health NHS Trust.

Imaging authorisation was given by the sponsor’s clinical radiation expert and medical physics expert, as all of the participants would receive ionising radiation in the form of X-rays for the diagnostic injections, FJIs and sham procedure.

Randomisation and blinding

Participants were allocated to either the intervention group or the control group in a 1 : 1 ratio, with stratification by centre and minimisation on baseline pain scores (categories). To ensure concealment, the allocation sequence was computer generated and provided through a password-protected web-based portal developed and maintained by the Peninsula Clinical Trials Unit (PenCTU).

It was not possible to blind the operator (Principal Investigator) as the injections were intentionally given at different sites (intra-articular vs. periarticular) and the injections looked different (methylprednisolone is provided as a cloudy suspension, whereas the sham injection was clear). However, study participants and the remainder of the research team, including the Chief Investigator, research nurses conducting the outcome assessments and data analysts, were blinded for the duration of the study. Unblinding took place at the end of the study once data analysis had been completed. A standard operating procedure was in place for emergency unblinding, in accordance with the sponsor guidelines.

Outcomes

The outcome questionnaire visits took place in research nurse-led clinics at baseline (pre randomisation) and at 6 weeks, 3 months and 6 months post randomisation. A sample case report form is shown in Appendix 7 and the schedule of outcome assessment is shown in Table 2. The outcome questionnaire covered a range of pain- and disability-related issues and was in accord with the Initiative on Methods, Measurement, and Pain Assessment in Clinical Trials (IMMPACT)-recommended core outcome measures for chronic pain trials. 51 The following assessment tools were used in the study.

-

Pain intensity and characteristics – Brief Pain Inventory (BPI) (Short Form) Modified,52 with its 11-point NRS, and short-form McGill Pain Questionnaire version 2 (SF-MPQ-2). 53 As movement could potentially influence the intervention (lumbar FJIs or sham procedure), all numerical rating scores were assessed in the standing position.

-

Use of co-analgesics in the previous week – participant self-report.

-

Lack of efficacy of pain relief, or, for side effects, early withdrawal from the study.

-

Expectation of benefit (asked at baseline only) – measured on a scale from 0 to 6, ranging from ‘expect no improvement’ to ‘expect total improvement’.

-

Health-related quality of life – EuroQol-5 Dimensions five-level version (EQ-5D-5L)54 and Short Form questionnaire-12 items (SF-12). 55

-

Functional impairment – Oswestry Low Back Pain Disability Questionnaire56 and Pain Self-Efficacy Questionnaire (PSEQ). 57

-

Satisfaction with treatment (after treatment given) – NRS from 0 to 10, with 0 = ‘extremely dissatisfied’ and 10 = ‘extremely satisfied’.

-

Complications and adverse events – these were the subject of enquiry at visits and following procedures, as well as being spontaneously reported at any time. They were acted on as necessary and for the patients’ benefit and were fully documented on case report forms and medical notes.

-

Co-psychological well-being – Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS),58 Pain Catastrophizing Scale (PCS),59 SF-12 and BPI.

-

Health-care utilisation and costs and impact on productivity –Stanford Presenteeism Scale (SPS) 6,60 self-reported measures of sickness absence over the previous 3 months and health-care utilisation in the form of hospital visits, treatments and medications. These data were collected at each outcome visit on the case report form.

| Assessment | Prescreening | Visit | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 (6 weeks after injections ± 2 weeks) | 5 (3 months after injections ± 2 weeks) | 6 (6 months after injections ± 2 weeks) | ||

| Informed consent | ✗ | ||||||

| Targeted physical examination | ✗ | ✗ | |||||

| Inclusion/exclusion criteria fulfilled | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | |

| Medical history recorded | ✗ | ||||||

| Demographic data recorded | ✗ | ||||||

| Drug history recorded | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | |

| Breakthrough analgesia recorded | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | |||

| Adverse events | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ||

| Outcome questionnaires | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | |||

| Expectation of benefit scale | ✗ | ||||||

| BPI (Short Form) | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | |||

| SF-MPQ-2 | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | |||

| EQ-5D-5L | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | |||

| SF-12 | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | |||

| Oswestry Low Back Pain Disability Questionnaire | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | |||

| PSEQ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | |||

| HADS | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | |||

| Pain Catastrophizing Scale | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | |||

| SPS 6 | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | |||

| Satisfaction with treatment scale | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ||||

Adverse events

Adverse events were assessed by a blinded subinvestigator at each visit and an adverse event form was completed as necessary (see Appendix 8). Adverse events are defined as any untoward medical occurrence in a subject to whom a medicinal product has been administered; an adverse reaction is an untoward and unintended response in a subject to an investigational medicinal product (IMP) that is related to any dose administered to that subject. A serious adverse event or reaction results in death, is life-threatening, requires inpatient hospitalisation or prolongation of an existing hospitalisation, results in persistent or significant disability or incapacity or is a congenital anomaly or birth defect. A suspected unexpected serious adverse reaction is any serious adverse event that is both suspected to be related to the IMP and unexpected.

Adverse events not already identified locally were recorded at each trial visit and managed in accordance with the sponsor’s requirements. Serious adverse events were reported to the JRMO by the investigators within 24 hours of the research team becoming aware of them and causality and expectedness were confirmed by the Chief Investigator, as the sponsor’s medical representative.

Study management and committees

The Trial Management Group (TMG) was responsible for the overall management of the project and included all co-applicants and members of the study research team. A Trial Steering Committee (TSC) provided independent advice and support to the study and aimed to report to the funder on study progress. It was chaired by an independent clinician with experience of pain trials. A Data Monitoring Committee (DMC) had access to unblinded data and made recommendations to the TSC on whether there were any ethical or safety reasons why the trial should not continue. It included independent members who were all experts in pain medicine.

Patient and public involvement

Patients with personal experience of LBP collaborated in the early stages of study design, for example advising on the acceptability of study visits and the outcome questionnaires. The questionnaires were tested on patients presenting to the multidisciplinary pain clinics and were deemed to be acceptable. Patient representatives were invited to attend the TSC meetings; however, there was no patient or public involvement in the management or running of the trial beyond the initial set-up stage.

Statistical analysis

Analyses were conducted in accordance with the International Conference on Harmonisation (ICH) statistical guidelines for clinical trials61 and the Consolidated Standards for Reporting Trials (CONSORT) reporting checklist for trials. 62 As this was a feasibility study, it was not planned to formally inferentially test differences in outcomes or costs between or within the groups. Mean recruitment and attrition rates were calculated with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). Means and SDs for all outcomes for the two groups at baseline and at the follow-up visits were reported. A detailed statistical analysis plan was prepared by the study statistician (RST) prior to any data analysis. Analyses were performed blinded to group allocation using Stata® 14.2 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA).

Health economics analysis

A health economics analysis plan was developed in collaboration with the study’s health economist and statistician. A formal economic analysis was not proposed (as this was a feasibility study). Any outcomes from this feasibility study would be used in the design of the definitive study. In particular, the health economics analysis looked at the ability to collect the outcomes proposed for the main trial and to inform a robust framework to assess the cost-effectiveness of lumbar FJIs for persistent non-specific LBP for a future definitive randomised controlled trial.

The resources used in the delivery of the intervention and sham procedure were calculated from the case report forms and in consultation with the trial team. Health-care resource use was captured through administration of specific questions to trial participants at each assessment, with responses recorded on case report forms, with a focus on collecting data on the most relevant and important drivers of health resource use and costs. Published national costs were used to calculate the costs of delivering each treatment arm. A summary of the costing methods employed are presented in Appendix 9. In addition, a literature review was conducted to review the scope and quality of the current economic evidence base for the use of FJIs in patients with non-specific LBP (see Appendix 9).

Descriptive analyses of the outcomes were used to report utilities based on the relevant tariff for each of the health-related quality-of-life outcomes. Economic outcomes were measured using the EQ-5D-5L (the preferred approach of the study team and for NICE decision-making) and the Short Form questionnaire-6 Dimensions (SF-6D63), used as a means of calculating utilities from the SF-12. A descriptive analysis of the health-related quality of life outcomes was summarised and was to provide estimates of quality-adjusted life-years (QALYs) gained as a result of receiving the intervention within the study period.

Summary of changes to the study protocol

The minor and major amendments made to the protocol over the duration of the study are detailed in Appendix 10.

Chapter 3 Results

Screening and recruitment

It was originally planned to screen and recruit participants across three centres; however, given the delays in study set-up, the funder directed that screening and recruitment take place at one centre only. The timelines of the study and the reasons for the delays are presented at the end of this chapter.

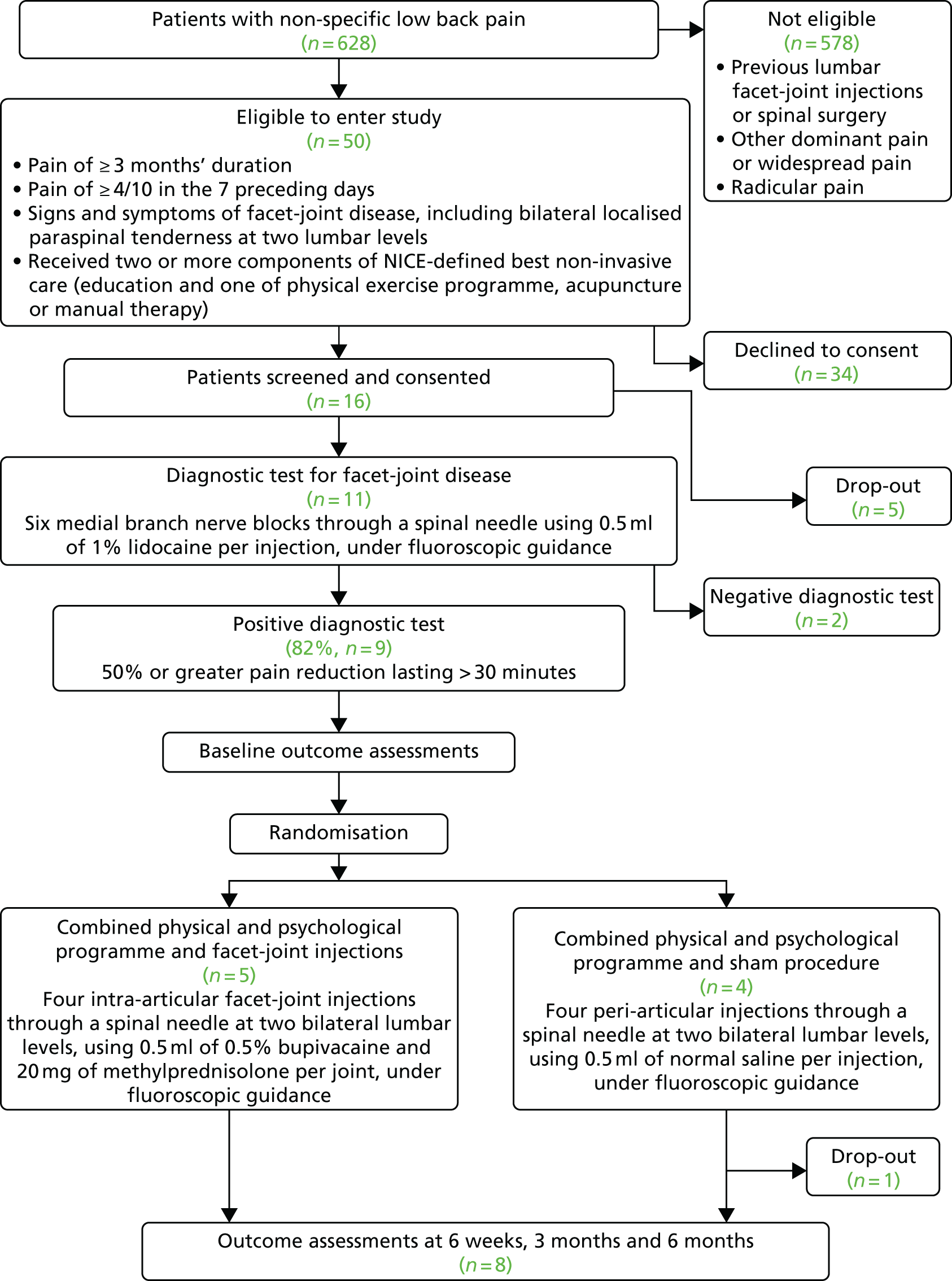

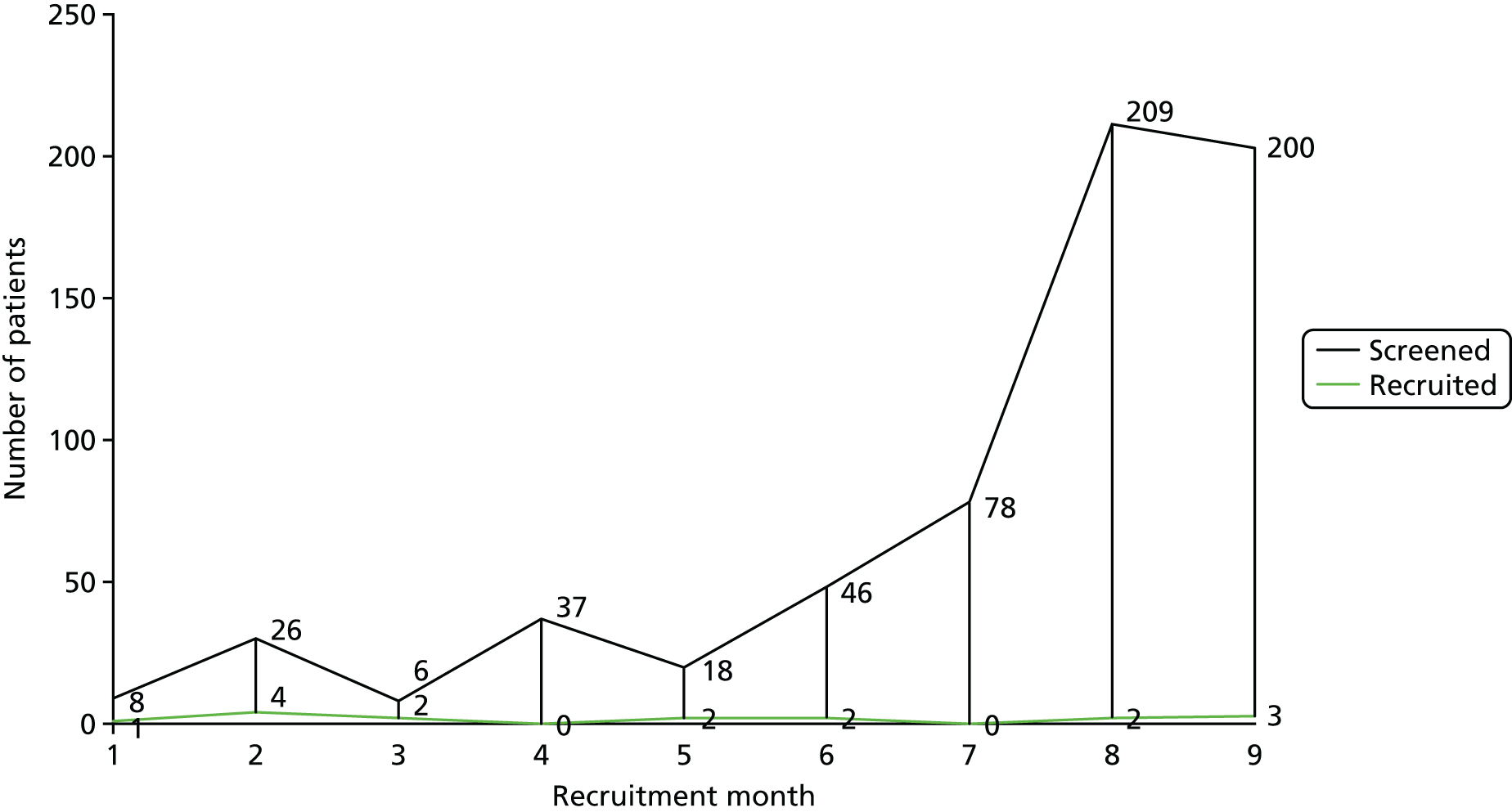

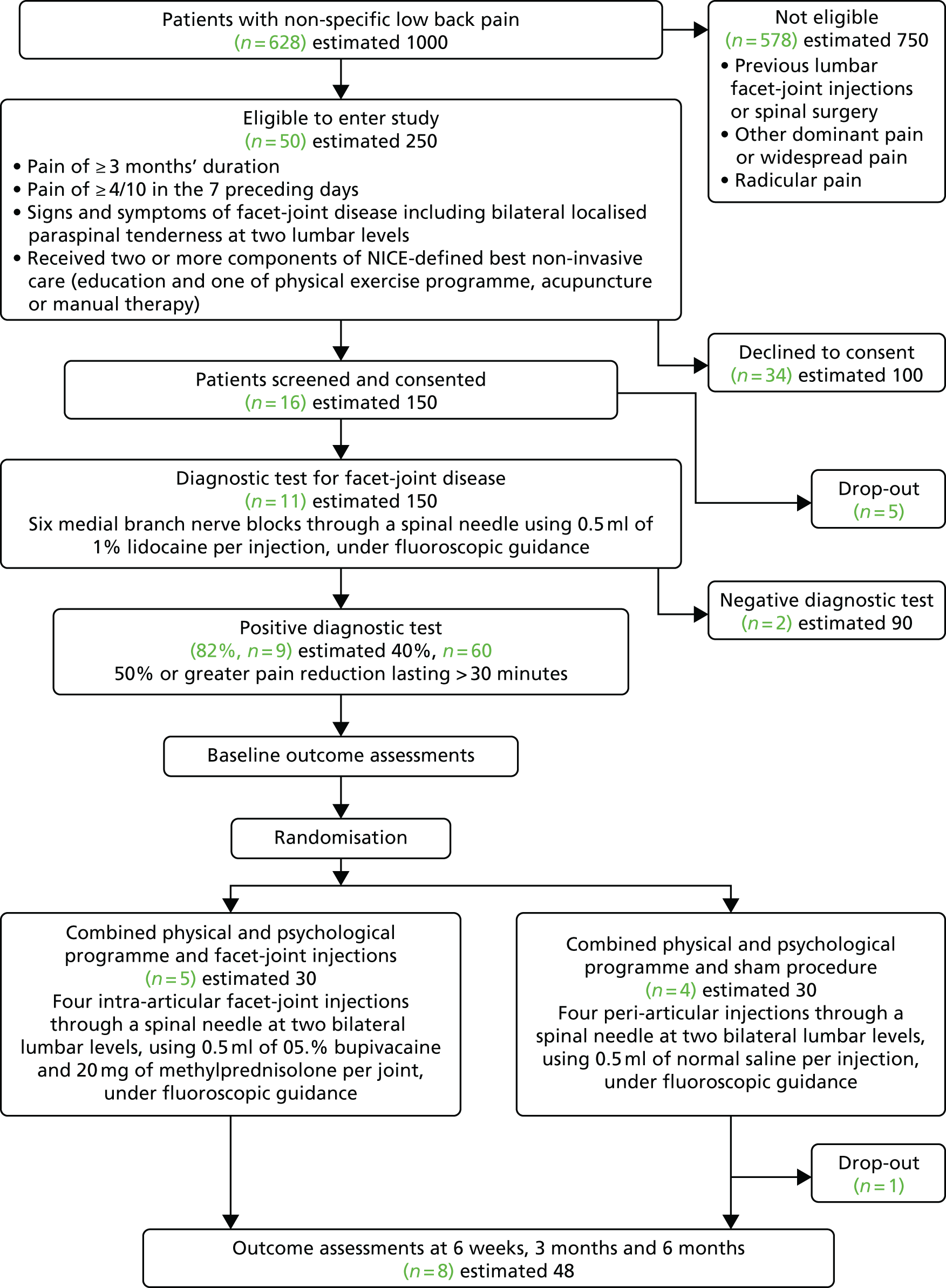

Recruitment began at Barts Health NHS Trust on 20 January 2016 and was terminated on 30 September 2016. As shown in Figure 2, during this time 628 patients referred to the recruiting clinics by their GP with non-specific LBP were screened for eligibility to enter the study. Of the 50 patients who met the inclusion criteria, 16 agreed to take part in the study and 11 received the diagnostic test for facet-joint disease. Nine participants had a positive response and were randomised to receive either lumbar FJIs with steroid or a sham procedure. The target sample size in each centre was 20 participants. The actual participant screening-to-recruitment ratio was 70 : 1 (628 : 9), which contrasts with an expected prestudy ratio of 17 : 1 (1000 : 60). The recruitment rate varied between zero and four patients per month (median two participants per month (Table 3).

FIGURE 2.

Consolidated Standards for Reporting Trials (CONSORT) flow diagram showing the flow of participants through the trial.

| Outcome | Recruiting month | Total | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | ||

| Recruited | 1 | 4 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 3 | 16 |

| Screened | 8 | 26 | 6 | 37 | 18 | 46 | 78 | 209 | 200 | 628 |

The reasons for screening failure are detailed in Table 4. The greatest proportion of patients was screened from the pain clinics at St Bartholomew’s Hospital, with a screened/recruited fraction of 1.69% (Table 5). Although only 16 patients were screened from the community pain clinic at the Essex Lodge GP surgery in Plaistow, East London, the screened/recruited fraction was higher at 12.5%. No participants were recruited from the spinal orthopaedic clinic at The Royal London Hospital or from the pain clinics at Whipps Cross University Hospital and Mile End Hospital.

| Reasons | Number of patients |

|---|---|

| Previous lumbar FJIs | 192 |

| Previous lumbar FJIs | 163 |

| Previous lumbar FJIs and no previous physiotherapy | 3 |

| Previous lumbar FJIs and radiofrequency denervation | 18 |

| Previous lumbar FJIs or radiofrequency denervation and aged > 70 years | 8 |

| Other dominant pain or widespread pain | 92 |

| Radicular pain | 64 |

| Aged > 70 yearsa | 42 |

| Aged > 70 years | 29 |

| Previous lumbar FJIs or radiofrequency denervation and aged > 70 years | 8 |

| Aged > 70 years and has radicular pain | 12 |

| Aged > 70 years and has widespread pain | 1 |

| Other reasons for not meeting inclusion/exclusion criteria | 36 |

| Did not wish to take part | 34 |

| Previous major trauma to the lumbar spine | 29 |

| ‘Red flag’ signs | 29 |

| Previous lumbar spinal surgery | 25 |

| Study team unable to contact | 17 |

| Already taking part in another study | 12 |

| Limited or no English language | 11 |

| Active neoplastic disease | 7 |

| No previous physiotherapy | 7 |

| Morbid obesity (body mass index of ≥ 35 kg/m2) | 7 |

| Learning difficulties or known mental health illness | 5 |

| Known history of substance abuse | 2 |

| Aged < 18 years | 1 |

| Clinic location | Number of patients | Screened/recruited fraction (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Screened for eligibility | Randomised | ||

| Pain clinic, St Bartholomew’s Hospital | 413 | 7 | 1.69 |

| Spinal orthopaedic (‘fracture’) clinic, The Royal London Hospital | 180 | 0 | 0 |

| Community pain clinic, Essex Lodge GP surgery | 16 | 2 | 12.5 |

| Pain clinic, Whipps Cross Hospital | 12 | 0 | 0 |

| Tower Hamlets Persistent Pain Services, Mile End Hospital | 7 | 0 | 0 |

Nine out of the 11 enrolled participants had a positive response to the diagnostic lumbar facet medial branch nerve block (82%, 95% CI 48% to 98%).

Adherence to allocated treatment

Facet-joint active and placebo injection

All the participants received their randomised procedure as planned and no problems with the injections were reported. None of the participants received any additional interventional pain procedures during their time in the study.

Combined physical and psychological programme

All nine participants were invited to attend a CPP programme after they had received their randomised procedure. Three physiotherapy-led CPP programmes took place between study months 12 and 20, with four participants in the first group, three in the second group and two in the final group. Six of the nine (67%) participants successfully completed the CPP programme, defined in the protocol as having attended at least four out of the six sessions. The median number of CPP programme sessions attended was four. One participant attended the initial CPP programme assessment but did not attend the programme because of illness during that period and another participant was unable to attend the CPP programme for personal reasons. A third participant did not attend the CPP programme because of unplanned overseas leave.

Study dropout and attrition

Of the 16 patients recruited and who consented to take part in the study, five withdrew before they received their diagnostic injections (although all completed the baseline assessment questionnaires). One patient already had lumbar FJIs booked for a future date and two changed their mind about taking part (one for personal reasons and one for family reasons). Two were unable to attend for the injections as the study dates were not suitable for them.

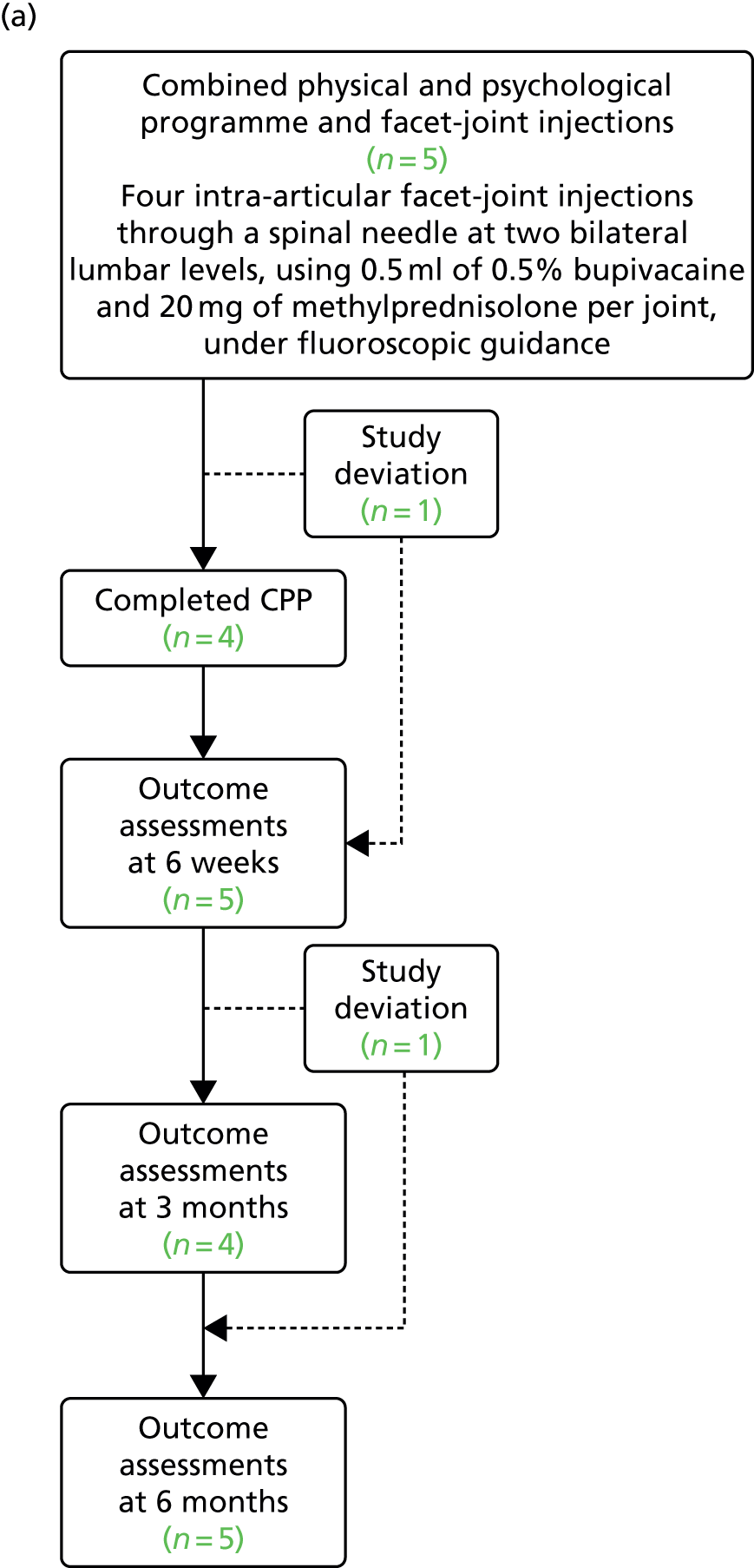

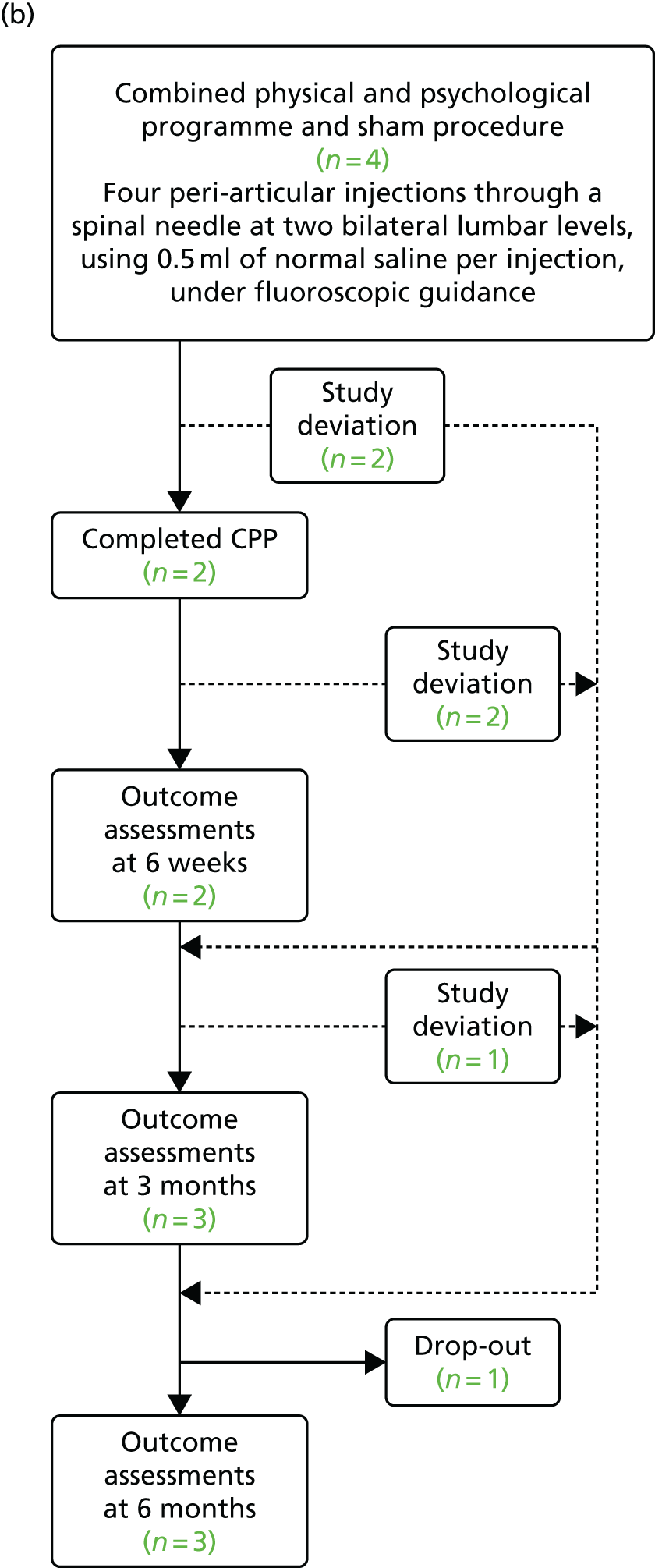

Of the nine participants who were randomised, eight completed the study (defined as having completed the final set of questionnaires 6 months after the randomised procedure), resulting in an 11% (95% CI 0.2% to 48%) attrition rate. The expected attrition rate was 20%. Six study deviations were recorded: three participants did not complete the CPP programme and three participants did not complete all of the questionnaire sets (Figure 3). A ‘study deviation’ was defined as a participant who did not attend a study visit or CPP programme session but who did not drop out of the study completely.

FIGURE 3.

Flow diagram showing the study deviations and dropouts during the study. (a) Combined physical and psychological programme and facet-joint injections; and (b) combined physical and psychological programme and sham procedure.

There were low levels of missingness of within-questionnaire data, as shown in Appendix 11. This is summarised in Table 6.

| Participant number | Questionnaires completed | Number of CPP programme sessions attended | CPP programme group | Randomisation group | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | 6 weeks | 3 months | 6 months | ||||

| 1 | Y | Y | Y | Y | 5 | 1 | Intervention |

| 2 | Y | N | N | Y | 0 | 1 | Sham |

| 3 | Y | Y | Y | Y | 6 | 1 | Sham |

| 4 | Y | Y | Y | Y | 4 | 1 | Intervention |

| 5 | Y | Y | Y | Y | 6 | 2 | Sham |

| 6 | Y | Y | N | Y | 0 | 2 | Intervention |

| 7 | Y | Y | Y | Y | 5 | 2 | Intervention |

| 8 | Y | Y | Y | N | 0 | 3 | Sham |

| 9 | Y | Y | Y | Y | 4 | 3 | Intervention |

Baseline characteristics and outcomes

The mean age of eligible participants was 45 years, with a similar proportion of males and females. Six out of 14 participants (43%) were not working at baseline (Table 7).

| Characteristic | All eligible (N = 16a) | Not randomised (N = 7) | Randomisation group | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sham (N = 4) | Intervention (N = 5) | |||

| Age (years), mean (SD) | 44.8 (13.2) | 44.4 (14.3) | 50.5 (14.4) | 40.8 (11.5) |

| Sex (male), n (%) | 9 (56) | 2 (29) | 2 (50) | 3 (60) |

| BMI (kg/m2), mean (SD) | 27.0 (5.1) | 29.9 (5.1) | 29.6 (4.7) | 27.7 (5.6) |

| Baseline pain (0–10 VAS), mean (SD) | 8.5 (1.5) | 8.0 (1.7) | 9.5 (1.0) | 8.4 (1.5) |

| Duration of pain (months), mean (SD) | 71.9 (88.7) | 46.0 (53.6) | 51.0 (46.3) | 124.8 (135.9) |

| Location of pain, n (%) | ||||

| Bilateral | 12 (75) | 5 (71) | 3 (75) | 4 (80) |

| Unilateral | 4 (25) | 2 (29) | 1 (25) | 1 (20) |

| Aware of pain (years), mean (SD) | 6.8 (7.6) | 5.2 (4.6) | 4.2 (3.9) | 10.4 (11.3) |

| Description of health, n (%) | ||||

| Excellent | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Very good | 1 (7) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Good | 9 (64) | 3 (60) | 3 (75) | 1 (20) |

| Fair | 1 (7) | 1 (20) | 0 (0) | 3 (60) |

| Poor | 3 (21) | 1 (20) | 1 (25) | 1 (20) |

| Work status, n (%) | ||||

| Full time | 7 (50) | 1 (17) | 2 (50) | 4 (80) |

| Part time | 1 (7) | 0 (0) | 1 (25) | 0 (0) |

| Not working | 4 (29) | 3 (50) | 0 (0) | 1 (20) |

| Other | 2 (14) | 2 (33) | 1 (25) | 0 (0) |

| Illness caused participant to stop working, n (%) | ||||

| Yes | 10 (71) | 1 (20) | 3 (75) | 3 (60) |

| No | 4 (29) | 4 (80) | 1 (25) | 2 (40) |

| Missed work days, mean (SD) | 13.5 (31.1) | 0 (0) | 30.0 (52.0) | 4.5 (3.7) |

| Level of activity prior to procedure, n (%) | ||||

| Hard manual | 2 (29) | 0 (0) | 1 (33) | 1 (33) |

| Lifting | 1 (14) | 1 (100) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Walking | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Sedentary | 4 (57) | 0 (0) | 2 (66) | 2 (66) |

| Current smoker, n (%) | ||||

| Yes | 11 (79) | 2 (40) | 0 (0) | 1 (20) |

| No | 3 (21) | 3 (60) | 4 (100) | 4 (80) |

| Alcohol (units per week), mean (SD) | 0.7 (1.1) | 0.6 (1.3) | 0.5 (1.0) | 1.0 (1.2) |

| Exercise per week, n (%) | ||||

| > 5 days | 2 (14) | 0 (0) | 1 (25) | 1 (20) |

| 3–5 days | 1 (7) | 1 (20) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| 1–2 days | 5 (36) | 1 (20) | 1 (25) | 3 (60) |

| < 1 day | 6 (43) | 3 (60) | 2 (50) | 1 (20) |

Baseline patient-reported outcomes indicated a population with substantial levels of pain [mean 8.5 on a 0–10 visual analogue scale (VAS)] that was predominantly bilateral (12/16, 75%) and which had a mean duration of 72 months (see Table 7). In terms of the primary and secondary outcomes, high baseline levels of disability and mental ill health and poor overall health-related quality of life were seen (Tables 7 and 8).

| Outcome | All eligible (n = 16a) | Not randomised (n = 7) | Randomisation group, mean score (SD) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sham (n = 4) | Intervention (n = 5) | |||

| BPI (0–10) | ||||

| Worst pain | 8.5 (1.7) | 9.0 (0.9) | 9.3 (1.5) | 7.2 (2.2) |

| Least pain | 6.0 (2.7) | 6.2 (2.3) | 6.0 (2.7) | 6.0 (3.5) |

| Average pain | 7.4 (1.5) | 7.7 (1.5) | 7.5 (1.9) | 7.0 (1.6) |

| Pain now | 6.5 (2.8) | 5.2 (2.9) | 8.0 (2.3) | 6.8 (2.8) |

| Pain severity | 7.1 (1.6) | 7.0 (0.8) | 7.7 (1.7) | 6.8 (2.4) |

| General activity | 7.7 (2.5) | 7.7 (2.6) | 9.3 (1.5) | 6.6 (1.2) |

| Mood | 6.9 (2.2) | 6.7 (2.4) | 7.0 (2.4) | 7.0 (4.8) |

| Walking ability | 6.3 (2.8) | 6.2 (2.3) | 5.5 (2.0) | 7.0 (2.7) |

| Normal work | 8.1 (2.2) | 8.5 (2.1) | 8.5 (1.7) | 7.2 (2.9) |

| Relations | 6.2 (2.5) | 5.3 (3.3) | 6.5 (1.9) | 7.0 (4.8) |

| Sleep | 7.1 (3.0) | 5.8 (3.5) | 8.8 (1.9) | 7.4 (3.0) |

| Enjoyment | 7.4 (3.0) | 6.8 (3.9) | 8.3 (1.7) | 7.4 (3.0) |

| Interference | 7.1 (3.9) | 6.7 (4.7) | 7.7 (1.8) | 7.1 (2.4) |

| SF-MPQ-2 | ||||

| Continuous pain | 5.2 (2.0) | 5.6 (0.9) | 4.5 (3.0) | 5.3 (2.2) |

| Intermittent pain | 4.4 (2.5) | 4.7 (2.4) | 4.2 (2.6) | 4.3 (3.1) |

| Neuropathic pain | 2.7 (1.9) | 2.7 (2.2) | 2.1 (1.8) | 3.2 (1.7) |

| Affective descriptors | 4.0 (2.6) | 3.9 (2.8) | 2.0 (1.5) | 5.6 (2.4) |

| Total | 4.1 (1.7) | 4.2 (1.5) | 3.3 (2.0) | 4.5 (2.0) |

| Oswestry Low Back Pain Disability Questionnaire | ||||

| Total | 49.2 (17.6) | 55.8 (19.4) | 48.8 (19.9) | 43.0 (15.0) |

| PSEQ | ||||

| Total | 21.3 (12.8) | 16.5 (15.8) | 27.0 (7.7) | 22.6 (12.2) |

| SF-12 | ||||

| PCS | 33.5 (5.8) | 34.5 (5.8) | 32.7 (6.0) | 33.1 (6.7) |

| MCS | 35.7 (11.2) | 34.7 (14.7) | 43.4 (10.0) | 30.4 (4.6) |

| HADS | ||||

| Anxiety | 10.1 (4.0) | 10.3 (5.2) | 7.5 (3.4) | 12.0 (1.2) |

| Depression | 9.7 (4.1) | 11.0 (4.8) | 6.8 (3.9) | 10.4 (3.4) |

| Pain Catastrophizing Scale | ||||

| Rumination | 12.5 (3.9) | 11.7 (4.9) | 11.5 (4.0) | 14.2 (2.5) |

| Magnification | 7.1 (3.3) | 6.8 (3.3) | 6.3 (4.3) | 8.0 (3.2) |

| Helplessness | 15.7 (4.4) | 16.3 (4.8) | 11.7 (4.4) | 18.0 (4.8) |

| Total | 35.2 (11.1) | 34.8 (11.7) | 29.5 (12.3) | 40.2 (9.0) |

| EQ-5D-5L index | 0.41 (0.30) | 0.43 (0.29) | 0.40 (0.21) | 0.39 (0.35) |

| Expectation of benefit | 3.3 (1.7) | 2.7 (2.4) | 3.5 (0.6) | 3.8 (1.1) |

Given the small number of participants randomised, not unexpectedly there was evidence of imbalance in participant characteristics and patient-reported outcomes between the two groups at baseline (see Table 8).

Primary and secondary outcomes at follow-up

Given the feasibility nature of the study and the small number of participants randomised, the primary and secondary outcomes at 6 weeks’ and 3 and 6 months’ follow-up are presented descriptively, with no inferential between or within comparisons undertaken or reported (Table 9).

| Outcome | Follow-up time point, mean score (SD) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6 weeks | 3 months | 6 months | ||||

| Sham group (n = 2) | Intervention group (n = 5) | Sham group (n = 3) | Intervention group (n = 4) | Sham group (n = 3) | Intervention group (n = 5) | |

| BPI (0–10) | ||||||

| Worst pain | 5.0 (2.8) | 7.8 (1.9) | 7.3 (3.0) | 7.8 (1.7) | 6.3 (4.7) | 6.0 (3.5) |

| Least pain | 4.0 (1.4) | 5.2 (2.5) | 7.0 (3.6) | 5.3 (2.2) | 5.3 (4.5) | 5.0 (2.8) |

| Average pain | 4.5 (2.1) | 6.2 (2.5) | 6.0 (2.6) | 6.3 (2.5) | 5.3 (4.5) | 5.6 (2.6) |

| Pain now | 5.0 (2.8) | 6.6 (2.1) | 6.3 (3.0) | 5.8 (2.1) | 6.0 (4.6) | 5.2 (3.7) |

| Pain severity | 4.6 (2.3) | 6.5 (2.1) | 6.7 (3.0) | 6.3 (2.1) | 5.8 (4.5) | 5.5 (3.1) |

| General activity | 5.0 (4.2) | 6.2 (2.4) | 6.7 (2.3) | 7.3 (1.9) | 6.0 (5.3) | 5.6 (3.6) |

| Mood | 4.5 (2.1) | 7.2 (1.9) | 7.0 (3.6) | 7.8 (2.1) | 5.3 (5.0) | 5.6 (3.6) |

| Walking ability | 4.0 (1.4) | 7.2 (2.6) | 5.3 (1.5) | 6.0 (2.9) | 4.3 (4.9) | 5.0 (4.6) |

| Normal work | 5.5 (0.7) | 7.2 (2.6) | 6.0 (2.0) | 6.8 (2.8) | 5.0 (5.0) | 6.0 (4.7) |

| Relations | 3.5 (2.1) | 6.2 (3.4) | 5.7 (4.0) | 7.5 (1.9) | 4.0 (5.3) | 5.2 (3.2) |

| Sleep | 6.5 (4.9) | 8.0 (1.9) | 7.0 (2.6) | 6.3 (2.9) | 4.3 (5.1) | 6.0 (4.7) |

| Enjoyment | 4.5 (2.1) | 7.6 (2.3) | 7.7 (2.5) | 7.0 (2.2) | 4.7 (4.7) | 6.2 (3.3) |

| Interference | 4.8 (2.1) | 7.1 (1.9) | 6.5 (2.4) | 6.9 (2.2) | 4.8 (4.9) | 5.7 (3.8) |

| SF-MPQ-2 | ||||||

| Continuous pain | 3.8 (3.2) | 4.9 (3.1) | 6.3 (3.4) | 3.9 (1.4) | 4.1 (3.7) | 3.3 (2.6) |

| Intermittent pain | 4.4 (3.7) | 3.7 (2.5) | 4.9 (3.0) | 3.7 (3.5) | 3.5 (2.9) | 3.6 (3.8) |

| Neuropathic pain | 1.7 (1.8) | 4.0 (3.2) | 2.5 (1.5) | 2.0 (0.9) | 3.6 (3.4) | 3.0 (2.9) |

| Affective descriptors | 4.4 (4.8) | 4.6 (3.0) | 5.6 (4.0) | 5.4 (1.2) | 2.5 (2.5) | 3.7 (2.8) |

| Total | 3.5 (3.3) | 4.2 (2.3) | 4.8 (2.6) | 3.6 (1.5) | 3.5 (2.9) | 3.4 (2.8) |

| Oswestry Low Back Pain Disability Questionnaire | ||||||

| Total | 36.0 (17.0) | 48.4 (20.2) | 56.0 (14.4) | 39.0 (9. 9) | 42.6 (34.0) | 39.9 (26.0) |

| PSEQ | ||||||

| Total | 33.5 (10.6) | 21.2 (15.3) | 27.7 (9.6) | 31.8 (14.1) | 28.3 (21.7) | 33.2 (19.4) |

| SF-12 | ||||||

| PCS | 38.8 (10.3) | 33.7 (8.6) | 38.5 (6.8) | 40.8 (11.0) | 34.4 (12.5) | 39.5 (13.7) |

| MCS | 43.6 (15.4) | 31.3 (7.9) | 35.7 (7.8) | 37.8 (2.6) | 47.2 (22.1) | 38.1 (13.5) |

| HADS | ||||||

| Anxiety | 7.0 (1.4) | 12.8 (4.4) | 8.3 (3.8) | 11.5 (4.6) | 6.7 (5.7) | 10.0 (3.9) |

| Depression | 4.0 (4.3) | 10.8 (6.7) | 8.0 (3.5) | 9.5 (5.5) | 7.7 (8.1) | 8.4 (7.1) |

| Pain Catastrophizing Scale | ||||||

| Rumination | 11.0 (1.4) | 12.4 (4.9) | 15.0 (1.0) | 11.8 (4.8) | 15.8 (3.8) | 14.4 (5.5) |

| Magnification | 8.0 (1.4) | 6.6 (2.9) | 10.3 (0.6) | 5.0 (3.5) | 19.5 (3.5) | 13.8 (5.9) |

| Helplessness | 14.0 (2.8) | 15.0 (7.0) | 13.7 (6.5) | 15.0 (8.9) | 16.7 (6.1) | 15.5 (9.0) |

| Total | 33.0 (5.6) | 34.0 (14.0) | 19.0 (6.6) | 32.7 (17.2) | 16.7 (7.6) | 16.0 (7.4) |

| EQ-5D-5L index | 0.67 (0.30) | 0.43 (0.33) | 0.42 (0.10) | 0.62 (0.28) | 0.60 (0.50) | 0.51 (0.41) |

| Satisfaction | 6.3 (3.8) | 6.6 (0.9) | 7.3 (1.2) | 7.5 (0.6) | 9.7 (0.6) | 6.0 (2.1) |

Adverse events

Three study participants reported adverse events, with two serious events reported by one participant. All three participants reported a flare-up of their LBP, which resolved (Table 10).

| Participant number | Description of adverse event | Relationship to IMP, as judged by the Principal Investigator | Seriousness of the adverse event, as judged by the Principal Investigator | Randomisation group |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Flare-up of LBP after the randomised procedure | Expected reaction, related to the IMP | Not serious | Sham |

| 4 | Flare-up of LBP 5 months after the randomised procedure | Expected reaction, related to the IMP | Not serious | Intervention |

| 7 | Urinary incontinence | Unexpected reaction, not related to the IMP | Serious adverse event (required overnight stay in hospital) | Intervention |

| Swelling at site of injections | Expected reaction, related to the procedure but not to the IMP | Serious adverse reaction (required overnight stay in hospital) | ||

| Flare-up of LBP after the randomised procedure | Expected reaction, related to the IMP | Not serious | ||

| Flare-up of LBP 5 months after the randomised procedure | Expected reaction, related to the IMP | Not serious |

Blinding to treatment allocation

To test the fidelity of blinding, participants were asked to guess which allocation group they had been randomised to, prior to being unblinded at the end of the study. Only one out of eight participants who completed the study correctly guessed their allocation group. The blinded outcome assessor correctly guessed the allocation group for four of the nine participants.

Health economics analysis

Given the importance of health economics evidence in informing decision-making, the incorporation of a health economics work package as part of a feasibility study can inform the delivery of a robust trial in the future, evaluating clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness. The main objective of the health economics analysis was to assess the feasibility of collecting data and produce an appropriate framework for a future full economic evaluation. This included a description of the main resource and cost drivers during the patient pathway in delivering the intervention and an assessment of collecting resource use information based on a resource use questionnaire devised for the feasibility study. An assessment of the performance of two preference-based health-related quality of life measures – the SF-12 (SF-6D)55 and EQ-5D-5L54 – within the feasibility study was also proposed in the original health economics analysis plan.

We intended to present both of the scores from the full EQ-5D (EuroQol-5 Dimensions) questionnaire, that is, the EQ-5D-5L descriptive system and the EQ-5D VAS, to present a comprehensive picture of patient-reported outcomes. Patients are asked to assess their health state on five dimensions – mobility, self-care, usual activities, pain/discomfort and anxiety/depression – using five levels ranging from ‘no problems’ to ‘severe problems’. A single summary index is obtained by applying a formula that attaches weights to each of the levels in each dimension. This formula is based on the valuation of EQ-5D health states from a general population sample in the UK. 64 The EQ-5D VAS is a thermometer-type vertical 20-cm scale with the end points of best imaginable health state (at the top) and worst imaginable health state (at the bottom) having numerical values of 100 and 0 respectively. This is a self-rated valuation and represents the respondents’ views of their health state and how it has affected their life on the day.

The utilities derived from the EQ-5D-5L and SF-6D were converted into QALYs to present a profile of QALY gains/losses over time.

As this was not a full trial, no inferential statistical comparisons of health-related quality of life or service use between the intervention group and the control group were planned. Instead, the focus was on reporting descriptive findings for the two groups at baseline and at the follow-up points to inform a suitable framework for a future economic evaluation if the findings from the feasibility study could be used to inform a future definitive study.

For the feasibility study, the perspective adopted was that of the UK NHS, focusing on primary and secondary resource use. However, given the impact of back pain on the patient and wider society (e.g. because of reduced/lost work productivity), a preliminary assessment of employment-related outcomes using the SPS 660 was reported as part of the trial outcomes. The economic analysis was conducted using IBM SPSS Statistics version 22 (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA).

Literature review

As part of the assessment of the feasibility of undertaking a future full economic analysis, a structured, rapid review of the literature was undertaken (see Appendix 9). This rapid review identified two partial economic evaluations (costs of FJIs)65,66 and one study that evaluated health-related quality of life. 37 We found limited economic evidence, with no cost-effectiveness studies identified of diagnostic or therapeutic FJIs. In undertaking any future trial, the feasibility of considering longer-term horizons should be fully assessed, for example whether a model-based analysis can be conducted to robustly extrapolate beyond the trial horizon, based on the suitability and quality of external literature sources.

Identification of the main resource and cost drivers associated with the delivery of facet-joint injections

A descriptive profile of resource use and costs was developed in consultation with the trial team to understand the opportunity costs associated with the delivery of the intervention. These were valued in Great British pounds in 2016 prices based on published unit costs or other literature sources. 10,67–69 The resource use reported at each of the trial visits was assessed with regard to whether it represented (1) research costs (which would be identified and excluded from any intervention costs), (2) costs attributed to routine usual NHS care or (3) opportunity costs (e.g. associated with additional staff time in managing a patient following FJIs) as a result of the intervention.

The intervention costs were considered in the following stages:

-

identification and screening of patients suitable for treatment (entry into the trial)

-

delivery of the intervention or sham procedure

-

delivery of the CPP programme

-

follow-up assessments.

The identification and screening of patients occurred during a routine consultant-led outpatient pain clinic appointment. The associated unit cost per patient was recorded as £148.03 for both groups. 67 Delivery of the intervention or sham procedure occurred at a routine day surgery unit at a cost of £691 per patient. The procedure was identified from the NHS national schedule of reference costs for 2015–1668 as an Injection of Therapeutic Substance into Joint for Pain Management (currency code AB19Z).

Delivery of the CPP programme had a mean cost of £2500 per patient. 70 However, as this programme was delivered to both groups, we excluded the CPP programme costs from the final cost analysis.

There were three follow-up assessments. Two assessments/data collection sessions were research-based, nurse-led appointments and were not included in the costs. The 6-month follow-up appointment was conducted by a consultant at an outpatient pain clinic as part of routine aftercare post procedure at a cost of £148.03 per patient for both groups. 69

Health resource use

An assessment of the feasibility of gathering appropriate resource use data from a patient sample was a major component of this evaluation. The resource use measure was developed by the clinical team based on standard clinical practice for the management of LBP and included questions on primary and secondary care resource use (e.g. hospital admissions, outpatient visits, GP surgery visits and medication use).

Feasibility of collecting resource use data

The resource use questionnaire was completed by the trial research assistant during scheduled visits to a nurse-led outpatient pain management clinic and took approximately 60 minutes per visit to complete. Although these are ‘research’ costs, the cumulative impact of collecting data will add to the costing of the time/resources for any future trial.

The focus was on collecting information on consultations with the NHS health-care professionals who would most likely be involved in the management of LBP. All costs were valued in Great British pounds using a price year of 2016. Table 23 (see Appendix 9) summarises this resource use. As the trial period was < 12 months, no discounting was applied to costs or outcomes. An additional question allowed patients to report any other resources used outside of the main categories; however, no other reported resource items were recorded.

Data on hospital contacts collected via the resource use questionnaire was compared with the data collected on adverse events and serious adverse events to ensure that there was no overlapping of data collected and, therefore, no double-counting of resource use. Prior to the analysis, appropriate decision rules were put in place for the costing of hospital admissions. If a patient was reported as having been admitted to hospital during the past 4 weeks, as a result of a serious adverse event, this was classified as an emergency hospital admission (non-elective inpatient stay). If (in an expected minority of patient cases) a hospital admission was for a condition unrelated to LBP, the reason for the unrelated hospital admission was recorded but the hospital admission was not included in the analysis.

The findings from the trial identified neither serious adverse events resulting in a hospital admission nor any other hospital admissions during the trial period. When documented adverse events were examined (n = 3 participants accounting for six health-care contacts), no additional impact on resource use was identified as one of the following: (1) already documented within the resource use questionnaire; (2) no further action or impact on resource use was documented; or (3) the adverse event was unrelated to the intervention. In two cases an adverse event was reported by the patient but no further information was available.

The resource use questionnaire collected information on current prescribed analgesics and any other medications at baseline. At the three follow-up time points, information on current analgesics and other medications was also collected along with any changes in medication during the follow-up period. The specific dates that prescriptions were issued, including the dates that any changes in medication occurred, were unknown because medications were prescribed by the patients’ GPs rather than by the trial team. Medication reported in the ‘other’ medication category that was not related to the treatment of LBP was excluded following examination of the data by the trial Chief Investigator. The costs of medication were then compiled for each time point and summated to give a total medication cost per group.

Resource use and costs

Table 11 summarises the NHS resource use for participants from baseline to 6 months’ follow-up. Overall, the total number of primary care visits was the same across the groups over the time period of the trial (seven GP visits recorded with a total cost per group of £252). 67 No emergency department admissions or hospital inpatient admissions (either elective or emergency) were recorded in either group. One outpatient appointment was recorded in the intervention group (received FJIs) at a cost of £148. 68

| Consultations for LBP | Visits | Total costs (aggregate of all follow-up time points) (£) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sham group (n = 4) | Intervention group (n = 5) | Sham group (n = 4) | Intervention group (n = 5) | |

| Total GP visits | ||||

| Number of visits/cost | 7 | 7 | 252.00 | 252.00 |

| Mean (SD) | 1.75 (1.71) | 1.4 (2.19) | 63.00 (61.48) | 50.40 (78.87) |

| Min., max. | 0, 4 | 0, 5 | 0, 44.00 | 0, 180.00 |

| Total outpatient pain clinic appointments | ||||

| Number of visits/cost | 0 | 1 | 0 | 148.03 |

| Mean (SD) | ||||

| Min., max. | ||||

| Total hospital emergency inpatient admissions | ||||

| Number of visits/cost | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Mean (SD) | ||||

| Min., max. | ||||

| Total emergency department admissions | ||||

| Number of visits/cost | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Mean (SD) | ||||

| Min., max. | ||||

| Total medication costs | ||||

| Total cost | 48.83 | 562.51 | ||

| Mean (SD) | 12.21 (11.31) | 112.50 (81.25) | ||

| Min., max. | 1.21, 29.63 | 29.63, 231.76 | ||

The main numerical differences between the two groups occurred for medication use, with a total cost of £48.83 (mean cost £12.21 per participant; SD £11.31) in the sham group and £562.51 (mean cost £112.50 per participant; SD £81.25) in the intervention group, a mean difference of £100 per participant. Further details of the medication use over each time point are provided in Table 12.

| Follow-up time period | Randomisation group | |

|---|---|---|

| Sham (n = 4) (£) | Intervention (n = 5) (£) | |

| From baseline to 6 weeks’ follow-up (visit 4) | ||

| Total | 32.05 | 35.75 |

| Mean (SD) | 8.01 (12.04) | 7.15 (12.68) |

| Min., max. | 0, 25.78 | 0, 29.27 |

| From 6 weeks’ follow-up to 3 months’ follow-up (visit 5) | ||

| Total | 4.25 | 129.63 |

| Mean (SD) | 1.06 (2.13) | 25.93 (30.94) |

| Min., max. | 0, 4.25 | 0, 77.95 |

| From 3 months’ follow-up to 6 months’ follow-up (visit 6) | ||

| Total | 12.53 | 397.13 |

| Mean (SD) | 3.12 (3.82) | 79.43 (58.95) |

| Min., max. | 0, 7.75 | 23.25, 156.12 |

| Total medication costs after treatment | ||

| Total | 48.83 | 562.51 |

| Mean (SD) | 12.21 (11.31) | 112.50 (81.25) |

| Min., max. | 1.21, 29.63 | 29.63, 231.76 |

| Difference between groups | ||

| Total cost difference | 513.68 | |

| Mean cost difference | 100.29 | |

Although there are limitations of the analysis associated with the highly skewed costs and small sample size, this suggests that a potential downstream effect of FJI is a subsequent increase in medication use and associated costs within primary care.

Table 13 provides an estimation of the total mean costs of the FJI intervention and the sham procedure. This shows that the FJI intervention was assessed as costing £118 more per patient than the sham procedure.

| Mean cost | Randomisation group, mean (SD) | Mean cost difference | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sham (n = 4) | Intervention (n = 5) | ||

| Total cost (£) | 75 (73) | 193 (219) | The intervention is £118 more expensive per patient than the sham procedure |

Outcomes

At baseline all nine patients completed the EQ-5D assessment. However, at the follow-up data collection points only six participants (two in the sham group and four in the intervention group) returned complete assessments across all three time points.

The baseline mean EQ-5D-5L and SF-6D utilities and EQ-5D VAS scores are presented in Tables 14 and 15, respectively, which compare the values for those patients who completed the assessments (complete cases) with the values for those who withdrew after completing the baseline assessments. As a point of reference, utilities from a UK population with LBP are presented. 71

| Outcome | Randomisation group | Group lost to follow-up | Utilities by disease (lower back pain)a | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sham | Intervention | |||

| EQ-5D-5L utility score | ||||

| n | 4 | 5 | 5 | 265 |

| Mean (SD) | 0.402 (0.209) | 0.387 (0.355) | 0.429 (0.362) | 0.635 (0.266) |

| Min. | 0.147 | –0.068 | –0.0004 | –0.181 |