Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 15/141/04. The contractual start date was in December 2012. The draft report began editorial review in October 2016 and was accepted for publication in May 2017. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Michael J Sweeting reports grants from the National Institute for Health Research during the conduct of the study. Jessica K Barrett reports grants from the Medical Research Council during the conduct of the study. Roger M Greenhalgh serves as a salaried director of BIBA Medical and has an equity interest in the company, and also serves as an expert witness on behalf of patients with vascular disease.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2018. This work was produced by Patel et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2018 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Introduction

Scientific background

Abdominal aortic aneurysm

Abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA) is defined as a localised enlargement of the abdominal aorta, such that the diameter is > 3 cm or > 50% larger than the normal diameter. 1–3 It was recognised if an aneurysm is found in one site, there is an increased chance of one being found elsewhere in the arterial tree. The commonest by far is AAA and patients with it have increased chance of thoracic aortic aneurysm and also popliteal aneurysm. It was soon recognised that all of the arteries of patients with aneurysms are wider and the term ‘dilating’ arterial disease was used. 4 In addition, it was described as ‘arteriomegaly’. 5 To support the concept that there were other causative factors of dilatation, diabetes mellitus was found in only 1% of ‘dilating disease patients’. 4

Epidemiology and risk factors

Abdominal aortic aneurysm is a common condition affecting particularly men aged > 60 years. In the second half of the twentieth century, there was a steady increase in mortality from aortic aneurysm in England and Wales. 6–8 According to population screening studies using ultrasonography, the prevalence of aortic aneurysm among 65-year-old men is 4%. 9 In the 65–74 years age group, the prevalence increases to 5% in men and to about one-third in women. 10 Following these reports, aneurysm screening programmes, usually of men aged 65 years, were implemented in several countries. These programmes have now reported a much lower prevalence of 1.9% in England and 1.7% in Sweden, respectively. 11,12 As well as the decline in incidence of clinically relevant aneurysms in men in England, Wales and Scotland, the age at which these aneurysms present has increased by 5–10 years. 13 Reports from other countries also show that aneurysm-related mortality is no longer increasing. 14–16

Increasing age and male gender are known to be the strongest associated risk factors. Other risk factors associated with AAAs include smoking and ethnicity. The wall weakens as a result of loss of elastin and collagen17 or fibrillin18 and the dilating process associated with more inflammation. 19

Age, sex and ethnicity

The risk of aneurysm increases dramatically after 60 years of age. Clinically relevant aneurysms (> 4 cm in diameter) are present in approximately 1% of men aged between 55 and 64 years, and the prevalence increases by 2–4% per decade thereafter. 20,21 In the UK, the rate of aneurysm in Caucasian men aged > 65 years is about 4.7%. Rupture of the aneurysm occurs in 1–3% of men aged ≥ 65 years, with a mortality rate of 70–95%. This equates to around 3000 deaths from rupture each year in men aged ≥ 65 years in England and Wales. Aneurysms are much less common in individuals of Asian and African descent. However, when adjusted for age, the rate of aneurysm-related mortality is higher among African Americans than in Caucasians. 22 Other studies have shown that the Asian population (men and women), who tend to be of smaller stature, are disadvantaged when being considered for endovascular aneurysm repair (EVAR), as the presence of smaller vessels is not conducive to easy deployment or long-term durability of the grafts. 23,24

Abdominal aortic aneurysms are four to six times more common in men than in women. 25 In addition, aneurysms develop in women approximately a decade later than in men. However, there is evidence that for women the risk of rupture, growth rates and operative mortality are all higher. 25–30

Smoking

Smoking has been found to be the principal risk factor for aneurysm formation, growth and rupture. 31,32 It is a much stronger risk factor than for coronary artery disease. The duration of exposure rather than the level of exposure appears to determine the risk of the development of an aneurysm in men aged > 50 years. The slow decline of risk after the cessation of smoking and the higher relative risk for small compared with large aneurysms suggests that smoking is a direct causative factor. 32

Other risk factors

Patients with aneurysms frequently have atherosclerosis, and numerous studies show an association with coronary heart disease and peripheral atherosclerosis. 33,34 A host of other risk factors, such as poor lung function,35 hypertension and high cholesterol levels,36,37 have been suggested to increase the risk of aneurysmal development, although there are conflicting reports in the current literature. A positive family history, especially in male first-degree relatives, is also associated with increased risk of aneurysm. 38,39 Studies suggest lower prevalence of diabetes for dilating (aneurysmal) disease, stenosing arterial disease and a protective role for diabetes on the development of aneurysms. 4 Diabetes has also been associated with slower aneurysm growth rates. 37,40,41

To obtain insight into the pathological processes associated with the vascular remodelling that accompanies aortic dilatation, early work in our group compared the histological features and the activity of matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) in aneurysm biopsies. 19 The histological feature most clearly associated with enlarging aneurysm diameter was a higher density of inflammatory cells in the adventitia. This inflammation was non-specific. We also identified gelatinase A (MMP-2) as the principal metallogelatinase in small aneurysms and an increasing activity of gelatinase B (MMP-9) in large aneurysms. This early work identified that the recruitment of inflammatory cells into the adventitia, with subsequent elaboration of metalloproteinases, including gelatinase B, may contribute to the rapid growth and rupture of larger aneurysms.

We also found that a strong interaction occurs between fibrillin genotype and blood pressure and that this contributes to the development of aneurysmal disease. 18 Marfan syndrome is a congenital disorder of connective tissue that is associated with various systemic complications, and the defective gene has been mapped to the fibrillin-1 (FBN1) gene on chromosome 15. 42

Our group was also involved with early work exploring genetic variants of collagen III and AAA. Variations in collagen structure were recognised in Ehlers–Danlos syndrome type IV and could also be associated with a predisposition to aortic aneurysm. We reported, in 1991, that genetic variants of type III collagen may influence the extensile properties of the aortic wall and that mutations in the type III collagen gene may be associated with aortic aneurysms. 17 More specifically, variation at the haptoglobin locus could have a direct effect on the degradation of elastin in atherosclerotic aorta, whereas variation at the cholesteryl ester transfer protein locus could affect lipid metabolism and promote atherosclerosis. These results indicated that a gene on chromosome 16 was associated with aortic aneurysm.

Around the same time, Irizarry et al. 43 demonstrated the presence of interstitial collagenase [now known as matrix metalloproteinase 1 (MMP-1)] in specimens of AAAs and Curci et al. 44 reported that, because elastin represents a critical component of aortic wall structure and a matrix substrate for metalloelastases, human macrophage elastase may have a direct and singular role in the pathogenesis of aortic aneurysms.

Aneurysms result from chronic weakening of the arterial wall, and approximately 80% occur between the renal arteries and aortic bifurcation. Aneurysmal expansion can also be found in the suprarenal segment and can sometimes extend upwards into the thoracic segment of the aorta above the diaphragm or downwards beyond the aortic bifurcation into the common iliac arteries. When the aneurysm becomes large, it may be diagnosed by examining the abdomen of the supine patient and feeling for a large pulsatile mass. Large aneurysms in thin people are easy to detect, but the accuracy of the clinical examination is much reduced by obese body habitus and small aneurysm size. 45 There is also large variability in the interobserver sensitivity for detection of aneurysms, and even an experienced clinician may miss palpating an aneurysm in the presence of central obesity or abdominal distension. 46

The majority of aneurysms are asymptomatic and, if undetected, the aortic dilatation can continue for many years. It can lead to catastrophic rupture, which is fatal in > 80% of cases. If left untreated, aneurysms have been known to grow to very large sizes, up to ≥ 15 cm, and, in rare cases, have ruptured at more modest diameters as small as 3–4 cm. Large and life-threatening aneurysms are preceded by a long period of subclinical growth in the diameter of the aneurysm (about 1.6 mm/year on average). Although diagnosis is usually incidental, expansion may become painful and lead to pulsating sensations in the abdomen or pain in the chest, lower back or groin.

The treatment options for asymptomatic aneurysms are conservative management, surveillance with a view to eventual repair and immediate repair. Repair is indicated if the aneurysm is > 5.5 cm, grows > 1 cm per year or is symptomatic (tender). 47,48 The successful management of the condition depends on the clinician finding the correct balance between careful surveillance of the aneurysm diameter until it enlarges to a point at which the risk of rupture is deemed to exceed the risk of death from elective surgery.

Detection and treatment of abdominal aortic aneurysm

Detection and screening

Owing to the asymptomatic nature of the disease, a considerable number of cases present as an emergency following a rupture, which has only a 10–20% survival rate. 49 The in-hospital survival rate for treating a ruptured aneurysm is just above 50%, but many patients never have the opportunity to undergo surgical intervention. 21

As the condition is not always found early, population screening programmes have been set up. The basis for such programmes is the known increased risk of rupture for aneurysms > 5.5 cm, whereas neither open surgery50,51 nor endovascular repair52 is of benefit for aneurysms of 4.0–5.4 cm. Both of these aneurysms being more common in men, the number of women affected is much lower and, therefore, the real threshold of intervention could be lower in women, though trial data do not show this. 53

The method of population screening is based on ultrasound. Duplex ultrasound scanning of the abdomen is safe, inexpensive and non-invasive. Ultrasound-based assessments quantify the maximal anterior–posterior and transverse diameter of the aorta. Among asymptomatic patients, ultrasound detects the presence of aneurysms accurately and reproducibly. Sensitivity and specificity are both close to 100% when compared with operative findings, making ultrasound an ideal test for mass screening. 54,55

Ellis et al. 56 showed that variability can be 8 mm if a different operator or system is used, but 4 mm for the same operator and ultrasound system. In the UK Small Aneurysm Trial,57 trained nurses had a reproducibility of 2 mm. The UK Small Aneurysm Trial57 and Aneurysm Detection And Management (ADAM)51 trial criterion of 5.5 cm was based on an outer-to-outer front-to-back ultrasound measurement. Scott et al. ,58 for UK screening, chose inner to inner.

However, when assessing aneurysm size, ultrasound is less precise than computed tomography (CT). Reproducible measurement of aneurysm size is important because it is the single component of prognosis and also because it provides a baseline to determine the aneurysm growth rate. An aneurysm growth rate of > 1 cm/year has been suggested as a threshold for surgery irrespective of size,59 even though there is no evidence to suggest that the growth rate influences rupture risk independently of aneurysm size.

The efficiency of ultrasound-based screening in men aged ≥ 65 years has been very well demonstrated in population-based randomised controlled trials (RCTs) and subsequent meta-analyses. 60–67 The aneurysm-associated mortality rate, the number of ruptured aneurysms and the number of emergency operations can be reduced significantly by a single ultrasound examination in men over the age of 65 years. At the same time, there is a two- to threefold increase in the number of elective aneurysm operations. In the UK, The NHS Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm Screening Programme68 was introduced after research and analysis of data from a number of randomised trials and existing local screening programmes in England that showed a reduction in aneurysm-related mortality when men aged ≥ 65 years were offered ultrasound screening. The evidence was assessed by the UK National Screening Committee against a set of internationally recognised criteria that confirmed that screening all men aged ≥ 65 years saves lives. The programme is aimed at reducing deaths from ruptured aneurysms through early detection, appropriate monitoring and treatment. The introduction of aneurysm screening to men aged 65 years is estimated to reduce premature death from ruptured aneurysms by up to 50% over 10 years. The prevalence of aneurysms in men is three times higher than in women and, currently, there is no good evidence to support aneurysm screening in older women.

Investigation of abdominal aortic aneurysm for possible intervention

In the EVAR trials, CT was used to investigate the suitability of aneurysms for intervention. Initially, three-dimensional scanning was not well advanced, but the technique greatly improved with time, and with it the interpretation of the findings and sizing of the infrarenal aorta.

Follow-up after aneurysm repair

At the beginning of the EVAR trials, routine follow-up of AAAs, even annually, was not usual and patients with open repair (OR) were frequently discharged to primary care. Ultrasound gathered favour with relation to population screening and detection.

Intervention for aortic aneurysm

Intervention for aortic aneurysm depends on the size or diameter of the aneurysm and is a balance between the risk of rupture and the operative mortality for aneurysm repair. Appropriate patient selection and timing of repair for the aneurysm is based on identifying individuals at the greatest risk of aneurysm rupture. Patients undergoing surgical intervention have immediate perioperative risks that must be weighed against the low likelihood of rupture before death from other causes. 69

Frequency of screening

Most people with aneurysms in the diameter range 3.0–5.5 cm are kept under review in surveillance programmes. There is consensus that very small aneurysms (3.0–3.9 cm) have a very small risk of rupture and, therefore, do not require surgical intervention. Most aneurysms initially measuring < 40 mm are very unlikely to expand to a size necessitating repair within 5 years,70 and patients with aneurysms of this size should receive ultrasound surveillance at regular intervals. Over the last two decades longitudinal studies of patients with smaller aneurysms have provided insights into the ideal timing of repair and the need for, and frequency of, ultrasound surveillance if an expectant management strategy is followed. A Cochrane review summarising the results from four trials to date demonstrated no advantage to early repair (via open or endovascular surgery) for small aneurysms in the range 4.0–5.5 cm. A policy of ultrasound surveillance is also advised as the ‘best care’ for patients with asymptomatic aneurysms of this size. 48 Once the aneurysm reaches 5.5 cm (measured by duplex ultrasound in males) or the aneurysm growth rate exceeds 1 cm per year, it is recommended that a vascular surgeon review the patient immediately (or within 2 weeks) to prevent interval rupture. If fit enough for surgery the patients should be considered for elective surgical repair at this juncture. For females, a maximum aortic diameter of 5.0 cm, as measured by duplex ultrasound, is considered to be the point at which a referral to a vascular surgeon is mandated.

Treatment of abdominal aortic aneurysm once detected

Medical therapy

Patients diagnosed with AAA who do not meet the criteria for intervention at the time of the initial diagnosis should be managed conservatively based on the results of randomised trials. The criteria for intervention are an aneurysm diameter of < 5.5 cm, a growth rate of > 1 cm per year or a tender aneurysm. 50 However, the natural history of aneurysms is one of progressive expansion necessitating regular clinical evaluation and surveillance of aneurysm diameter to identify aneurysms that satisfy the criteria for justified intervention.

Medical therapies focus on the management of modifiable risk factors for aneurysm and cardiovascular disease with the goals of reducing the need for intervention as a result of aneurysm expansion or rupture, reducing morbidity and mortality associated with repair, and reducing cardiovascular morbidity and mortality. 71 Although many pharmacological therapies aimed at limiting aneurysm expansion and preventing rupture have been investigated, currently there is no proven focused therapy that reduces aneurysm growth. A systematic review and meta-analysis investigating the impact of a range of pharmaceutical agents (including beta-blockers, other antihypertensive therapies, antibiotics and anti-inflammatory agents including statins) demonstrated little evidence of reduction in aneurysm growth rates. 72 Among the factors associated with aneurysm expansion and rupture, smoking is the most important modifiable risk factor and smoking cessation is recommended for all patients with aneurysms. 73 Although reduced aneurysm expansion and rupture risk have not been clearly demonstrated among those who have stopped smoking, smoking cessation has other benefits. In addition, because aneurysm is regarded as a coronary risk equivalent, most guidelines recommend aspirin, statins and antiplatelet therapy for patients with aneurysms to reduce the risk of a future cardiovascular event. Other medical conditions, such as hypertension, should be treated as appropriate. In general, there is surprisingly little high-quality evidence on medical treatment for small aneurysms, especially in relation to the use of newer beta-blockers, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors and statins. 74

Open surgical repair

For patients whose AAA satisfies criteria for intervention, OR was regarded as the gold standard before these UK trials. It involves an incision of the abdomen to directly visualise the aortic aneurysm. Dubost et al. described how the technique involves access either through a transabdominal route or via a retroperitoneal approach. 75 During OR the aneurysmal portion of the aorta is replaced with a graft, usually made of DACRON® (Invista™, Wichita, KA, USA) or polytetrafluoroethylene. 76 The graft is sutured within the aorta. The DACRON is anastomosed to the aortic neck and either to the aortic bifurcation below (tube graft) or to the two iliac arteries (bifurcation device).

Recovery after OR is substantial and, in the UK, operative mortality has been reported to be 5.6%. 47 Immediately following surgery, patients can expect to spend 1–3 days in the intensive care unit (ICU), followed by 4–10 days on the hospital ward. After discharge, patients will take 3–6 months to fully recover their energy and return to their preoperative daily activities.

Advent of endovascular aortic repair

Before the advent of EVAR, OR was the only surgical treatment available for aortic aneurysms. In the spring of 1990, word came of a novel endovascular technique which was later reported in 1991 by Parodi et al. in Argentina. 77 However, it later transpired that Volodos et al. in the Ukraine (at the time of the Soviet Union), a student of Dotter, had already done such a procedure, unknown to the Western world. 78

By 1996 it was evident that commercial EVAR devices would become available shortly. The urge was to learn the new device method, but it would require comparison with OR for those patients medically fit for OR, although Parodi et al. 77 had championed the method for those patients not fit enough for OR.

The EVAR trials [EVAR trial 1 (EVAR-1) and EVAR trial 2 (EVAR-2)] were set up to meet the above need and funded by the Health Technology Assessment (HTA) programme under the then director, Sir Miles Irving.

Even though a registry of devices was also introduced at about the same time,79 this lacked the RCT discipline of comparison with the then alternative. Sir Miles Irving called for, and delivered, device funding by NHS subventions such that the only way to achieve funding was as part of the EVAR trials. The shorthand for the procedure was taken from these world-first trials: ‘EVAR’.

A feature of the trials was for complete endorsement by the Vascular Surgical Society of Great Britain and Ireland and the British Society of Interventional Radiology. Together these societies recommended collaboration of both disciplines for the trial and together the societies founded the EVAR trial centres.

Endovascular aneurysm repair was seen as a minimally invasive option which involves the insertion of a stent graft into the lumen, effectively excluding the aneurysm from blood flow and minimising the risk of rupture. The concept of endograft is to deploy inside the aneurysm through femoral access to exclude the aneurysm sac from circulation. EVAR requires adequate aortic and iliac fixation sites for effective sealing and fixation. The first devices were assembled in the sterile operating room and deployed. There was inevitable delay before commercial higher-quality devices became available. The earliest systems used handmade stent grafts that allowed a repair to lie entirely within the abdominal aorta (aortoaortic graft). Subsequently, it was shown that the aortoaortic endovascular grafts were suitable for < 10% of patients and bifurcation systems were developed; these allowed a greater proportion of aneurysms to be managed by an endovascular method. 80 In-house systems were introduced in the UK that employed an aorto-uniiliac stent graft system made with the second side being occluded using a DACRON sac and stent and the procedure completed with a femoro–femoral crossover graft. 81,82 This left patients with two small incisions in the groin and minimum pain. These in-house systems were soon superseded as commerical higher-quality devices became available.

The imagined advantages of EVAR over OR included reduced operative time, avoidance of general anaesthesia, less trauma and postoperative pain, reduced hospital length of stay and use of intensive care facilities, reduced blood loss and reduced immediate postoperative mortality.

Post-surgical surveillance

The European Society for Vascular Surgery, in agreement with the EVAR protocol, recommends that all EVAR patients should undergo CT 30 days post procedure. If there is any endoleak, then further CT at 6 and 12 months is recommended. In patients with no early endoleak and stable or shrinking aneurysm, annual duplex ultrasound scanning is recommended. Any subsequent new endoleak or increase in aneurysm sac size should prompt more detailed imaging with CT. 83 Many clinicians now follow patients almost exclusively by ultrasound to measure maximum aneurysm diameter and obtain further imaging only if the sac fails to shrink or expands > 5 mm.

Currently, the European Society for Vascular Surgery recommends colour duplex ultrasound imaging at least once every 5 years following OR. 83 Imaging protocols following EVAR are controversial and currently the topic of much debate.

Endoleaks

The inability to obtain or maintain a secure seal between a vessel wall and a transluminally implanted intra-aneurysmal graft was a complication unique to the evolving technique of endovascular aneurysm exclusion. As the term ‘leak’ had long been associated with aneurysm rupture, the term ‘endoleak’ was proposed as a more definitive description of this phenomenon. White et al. 84 first proposed standardisation of the terminology describing this important sequela to endovascular aneurysm exclusion. This was important to facilitate uniform reporting of clinical trial data vital to the evaluation of this emerging technique.

Endoleaks represent the most common complication of EVAR and occur in 20–25% of patients. 85,86 They are frequently identified in late imaging follow-up and used to justify lifelong follow-up of these patients. If left untreated, endoleaks can lead to fatal ruptures. 87 There are five different types of endoleaks, all of which are characterised by persistent blood flow within the aneurysm sac but outside the stent graft. 88 The classification is determined by the source of vessels that causes the inflow into the sac. Type I endoleaks are leaks at the proximal aorta and stent graft (type IA) or leaks at the distal iliac and stent graft limb (type IB). Type II endoleaks are caused by retrograde flow through collateral vessels into the aneurysm sac. Type III endoleaks are holes, defects or separations in the stent graft material. Type IV endoleaks represent porous graft walls. Type V endoleaks have been described as being as result of endotension with an enlarging aneurysm sac without a visible endoleak. 89 Other complications that can occur after EVAR include device migration90–92 and postoperative stent graft kinking. 93 CT angiography has been the most commonly used modality for follow-up after EVAR and is currently the best method for detecting endoleaks.

Clinical trials comparing endovascular aneurysm repair and open repair

We searched MEDLINE and EMBASE for all articles published from 1 January 2000 to 31 May 2016 using search terms ‘15 year follow-up of EVAR for intact abdominal aortic aneurysm’, ‘long-term elective repair’, ‘abdominal aortic aneurysm’, ‘minimally invasive surgery’, ‘vascular surgical procedures’, ‘endovascular surgery’ and ‘open surgery’.

EVAR trial 1, the first and largest randomised trial of endovascular aortic repair compared with OR of aortic aneurysms, began in 1999, alongside its sister trial EVAR-2, to evaluate the efficacy of endovascular repair in patients too frail to be considered for OR and compared best medical therapy with endovascular aortic repair. 94–96 A number of trials have now been undertaken to compare endovascular with OR, but EVAR-2 remains unique in addressing the question of whether or not endovascular repair is justified in patients in whom OR is not an option, usually on the grounds of poor anaesthetic fitness. Other randomised clinical trials with protocols like that of EVAR-1, comparing open and endovascular repair, followed in the Netherlands [the Dutch Randomised Endovascular Aneurysm Management (DREAM) trial],97 USA [Open Versus Endovascular Repair (OVER) trial]98 and France (Anévrysme de l’aorte abdominale, Chirurgie versus Endoprothése; ACE). 99

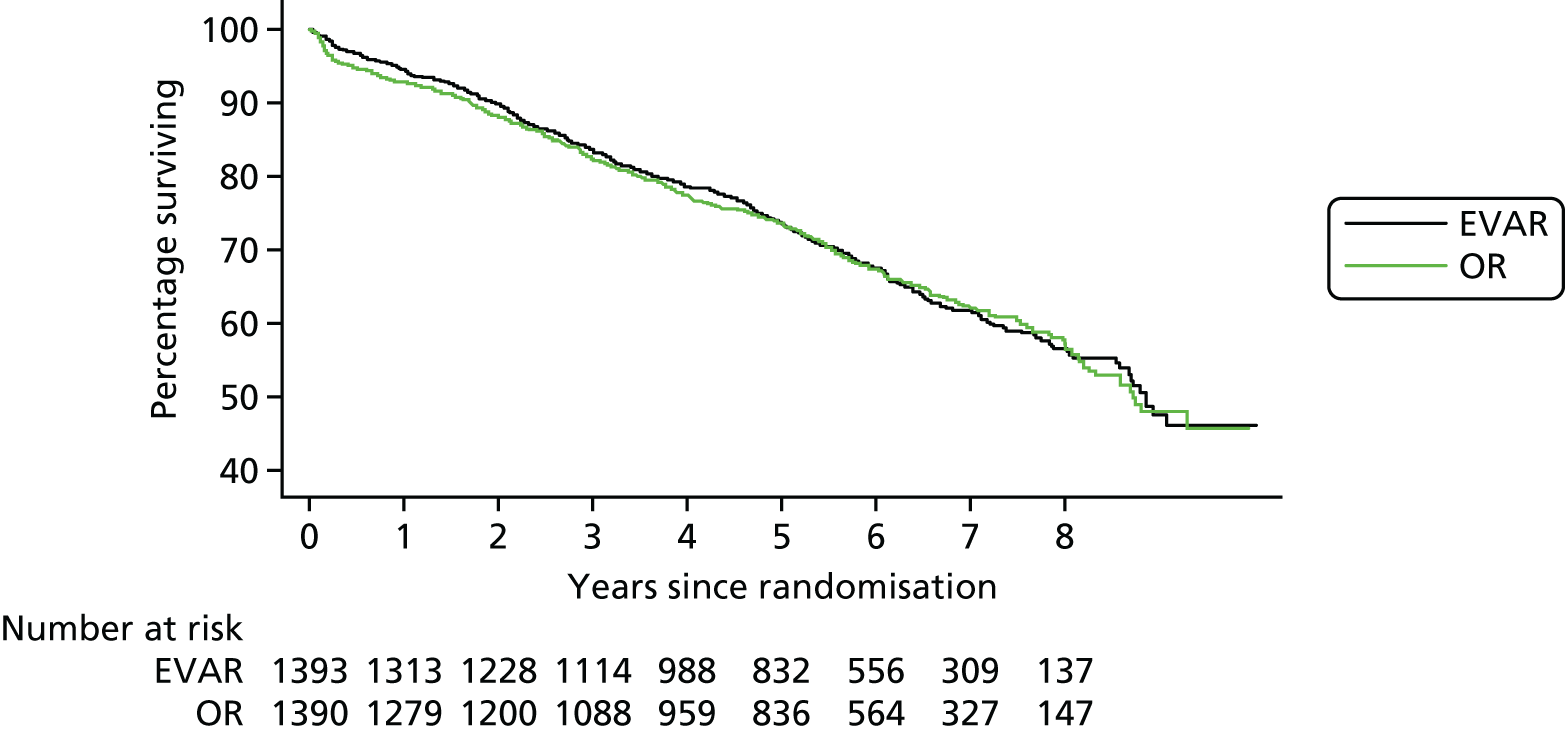

EVAR trial 1

Before the current report of late follow-up to 15 years, EVAR-1 offered the longest follow-up of any of the RCTs comparing EVAR with OR up to 10 years. Early 30-day results were reported in 2004,100 mid-term results in 2005101 and long-term follow-up over 8 years (median 6 years) in 2010. 94 Baseline characteristics were not significantly different between treatment groups. The perioperative (30-day) mortality was significantly lower for EVAR (1.8% vs. 4.3%). During 6904 person-years of follow-up, 524 deaths occurred, 76 of which were aneurysm related. Kaplan–Meier survival curves for all-cause mortality among the two cohorts converged at 2 years, demonstrating that the survival advantage favouring EVAR is lost. With regard to aneurysm-related mortality, Kaplan–Meier curves converged at 6 years because of endograft failure leading to late rupture-related mortality, increasing substantially in the EVAR group. Secondary outcomes including graft complications, reinterventions and costs favoured OR over the long term. Although there was a health-related quality of life (HRQoL) benefit with EVAR at 3 months, this benefit was lost at 1 year. Based on these findings, the EVAR-1 investigators concluded that, although EVAR offered lower operative mortality, there was no difference in total or aneurysm mortality. Furthermore, EVAR was associated with increased rates of complications, reinterventions and costs.

The Dutch Randomised Endovascular Aneurysm Management trial

One year after the start of EVAR-1, the DREAM trial, which used a similar protocol to EVAR-1, began enrolling patients from 26 centres in the Netherlands and four centres in Belgium. Three hundred and fifty-one patients whose maximum aneurysm diameter was > 5.0 cm and who were deemed to have acceptable risk for both procedures were randomised to undergo either open or endovascular repair. Operative mortality was reported in 2004, 2-year follow-up in 2005 and long-term follow-up in 2010. 97,102–104 The primary study outcomes were rates of death from any cause and reinterventions. The 30-day postoperative mortality was 1.2% after EVAR and 4.6% after OR. At 2 years post procedure, the cumulative rates of aneurysm-related death remained lower for EVAR than for OR (2.1% vs. 5.7%), a difference that was entirely attributable to the initial perioperative outcomes. 104 Survival curves for all-cause mortality converged at 1 year and, by the end of follow-up, all-cause mortality was equivalent between groups. As with the EVAR-1, the rates of graft-related complications and reinterventions were higher after EVAR.

The Open Versus Endovascular Repair trial

The OVER trial was the first RCT in the USA and enrolled patients between 2002 and 2008 from 42 Veterans Affairs Medical Centres. Again, trial design was based on that of EVAR-1 but only men were recruited. Eight hundred and eighty-one patients with an aneurysm of maximum diameter > 5.0 cm, an iliac aneurysm of diameter > 3.0 cm or an aneurysm of diameter > 4.5 cm and rapid enlargement (> 0.5 mm in 6 months), were randomised to undergo either open or endovascular repair. Interim data analysis was reported in 2009 and long-term results in 2012. 98,105 The primary study outcomes were procedure failure, secondary therapeutic procedures, length of stay, quality of life, erectile dysfunction, major morbidity and death. The 30-day mortality was 0.5% after EVAR and 3.0% after OR. Survival curves converged at 2 years and over 9 years of follow-up, mortality rates were not significantly different between groups (7.0% EVAR vs. 9.8% OR). There were no differences between the two groups in major morbidity, procedure failure, secondary therapeutic procedures, aneurysm-related hospitalisations, HRQoL or erectile dysfunction. In this trial, incisional hernia was included as an OR-related complication. As a result, the rates of secondary intervention were found to be similar between groups (13.7% EVAR vs. 12.5% OR), with the majority of secondary procedures in the EVAR group as a result of endovascular revisions compared with repair of incisional hernia in the OR group.

The Anévrysme de l’aorte abdominale, Chirurgie versus Endoprothése trial

The fourth RCT, with a similar design to EVAR-1, was the ACE trial, which randomly assigned 316 patients with an aneurysm > 5.0 cm to EVAR or OR surgery. 99 As with the trials above, there were no significant differences in the cumulative survival or major adverse events rates at the 1 year’ follow-up and at 3 years’ follow-up. In contrast to the other three trials, operative mortality was also not significantly different (0.6% EVAR vs. 1.3% OR). The need for reintervention was higher in the EVAR group than in the OR group (16% vs. 2.4%).

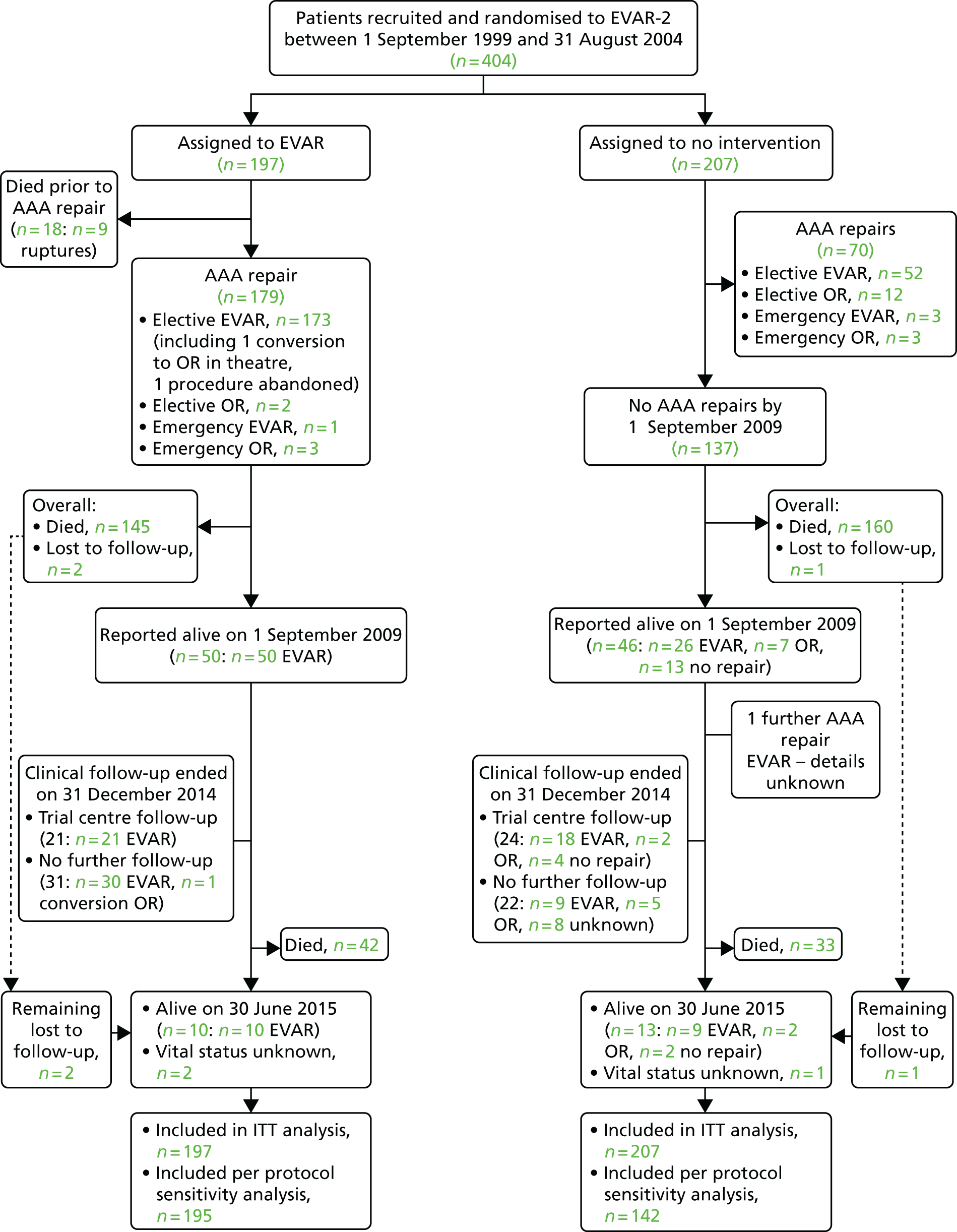

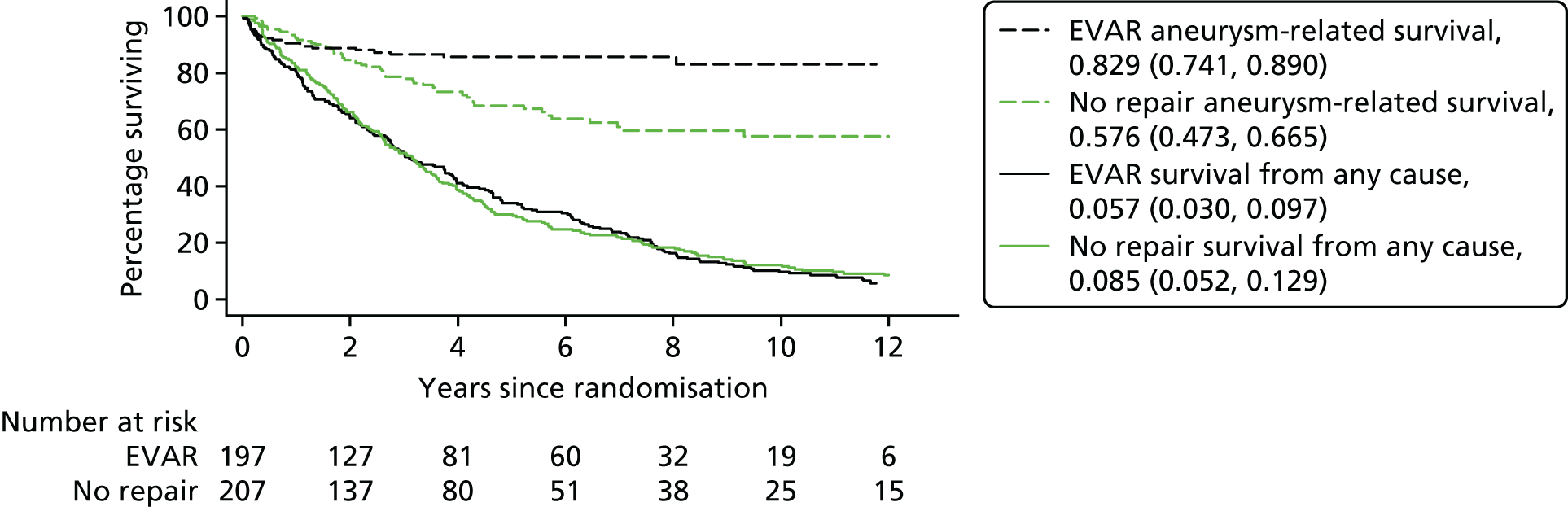

EVAR trial 2

Unlike EVAR-1, EVAR-2 remains unique and its publication altered global practice. Endovascular repair of AAA was originally developed for patients who were considered to be physically ineligible for open surgical repair. Whereas the four previously described major RCTs enrolled patients who were physically fit enough to undergo either EVAR or OR, EVAR-2 enrolled patients who were too high risk for open surgical repair, randomising such unfit patients to EVAR or observation. The enrolment protocol and data collection methods were identical to those of EVAR-1. 106 Three hundred and thirty-eight patients were enrolled and randomised between September 1999 and December 2003. 107 After mid-term analysis on this cohort, an additional 66 patients were recruited for long-term follow-up, giving a total of 404 patients. 95 A total of 197 patients were randomised to EVAR while 207 were assigned to have no intervention. However, of the 207 patients in the observation arm, 70 eventually underwent some form of aneurysm repair attributable to rupture, rapid growth, symptomatic aneurysm or patient preference. Patients were followed for rates of death, graft-related complications and reinterventions, and costs up to the end of 2009. The 30-day operative mortality was 7.3% in the EVAR group. The overall rate of aneurysm rupture in the no-intervention group was 12.4 per 100 person-years. Aneurysm-related mortality was lower in the EVAR group, but this advantage did not result in any benefit in terms of total mortality. A total of 48% of patients who survived endovascular repair had graft-related complications, and 27% required reintervention within the first 6 years. During 8 years of follow-up, endovascular repair was considerably more expensive than no repair (cost difference £9826).

After the 10-year results of EVAR-2, the funding and enthusiasm for EVAR use in situation dropped as these HTA-funded trials had shown that no operation was not only giving false hope, unnecessary cost and no change in the expected date of death. The per-protocol analysis hinted at some benefit in patients who actually underwent EVAR.

Evidence outside the trials

Outside the evidence from these trials, Schermerhorn et al. 108 recently assessed perioperative and long-term survival, reinterventions and complications after EVAR compared with OR of AAA in propensity score-matched cohorts of Medicare beneficiaries who underwent repair during the period 2001–8 and were followed until 2009. The authors found that endovascular repair, compared with OR, was associated with early survival advantage that gradually decreased over time, with catch-up of mortality after 3 years. The rate of rupture after aneurysm repair was significantly higher under EVAR than OR.

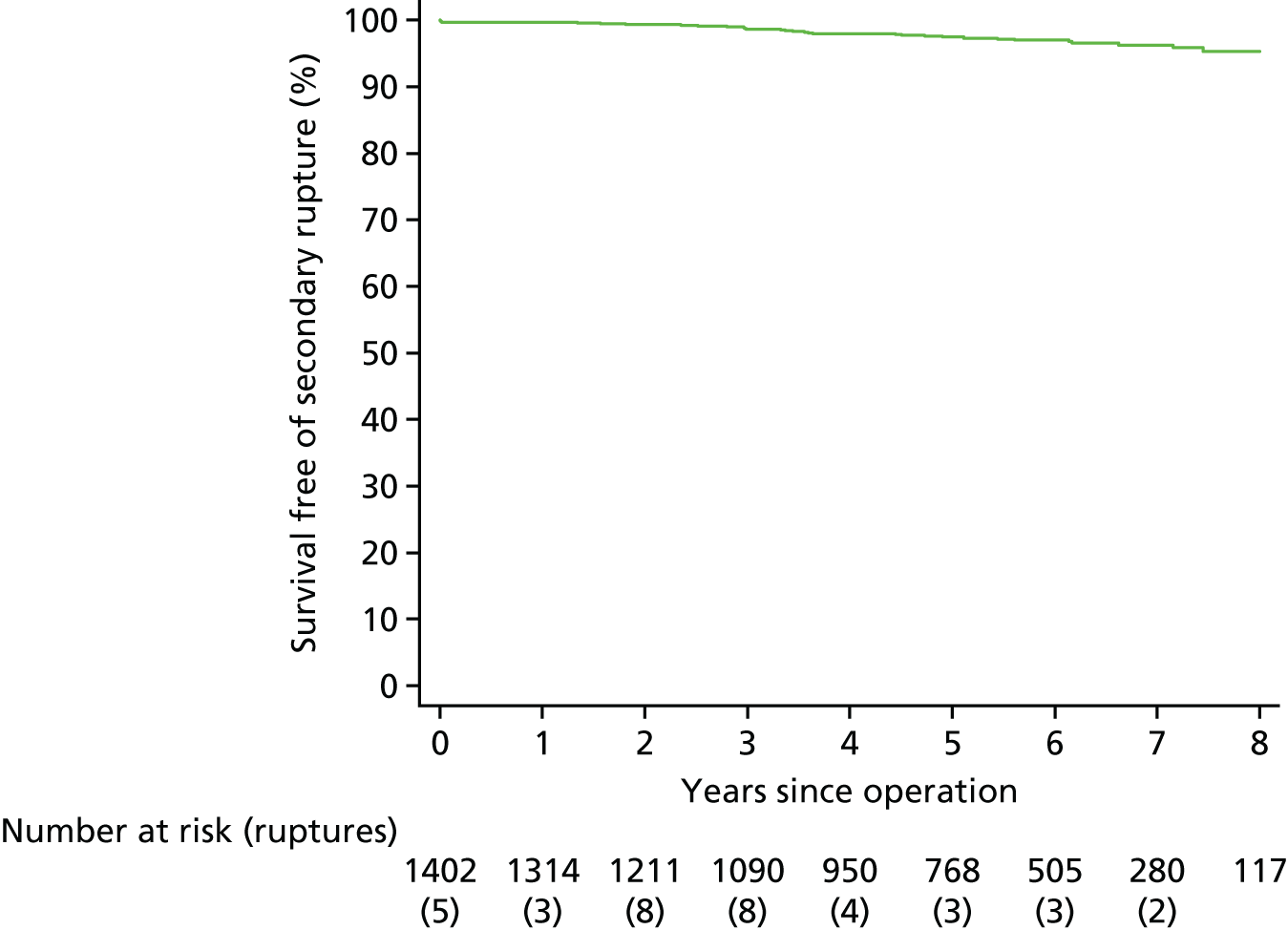

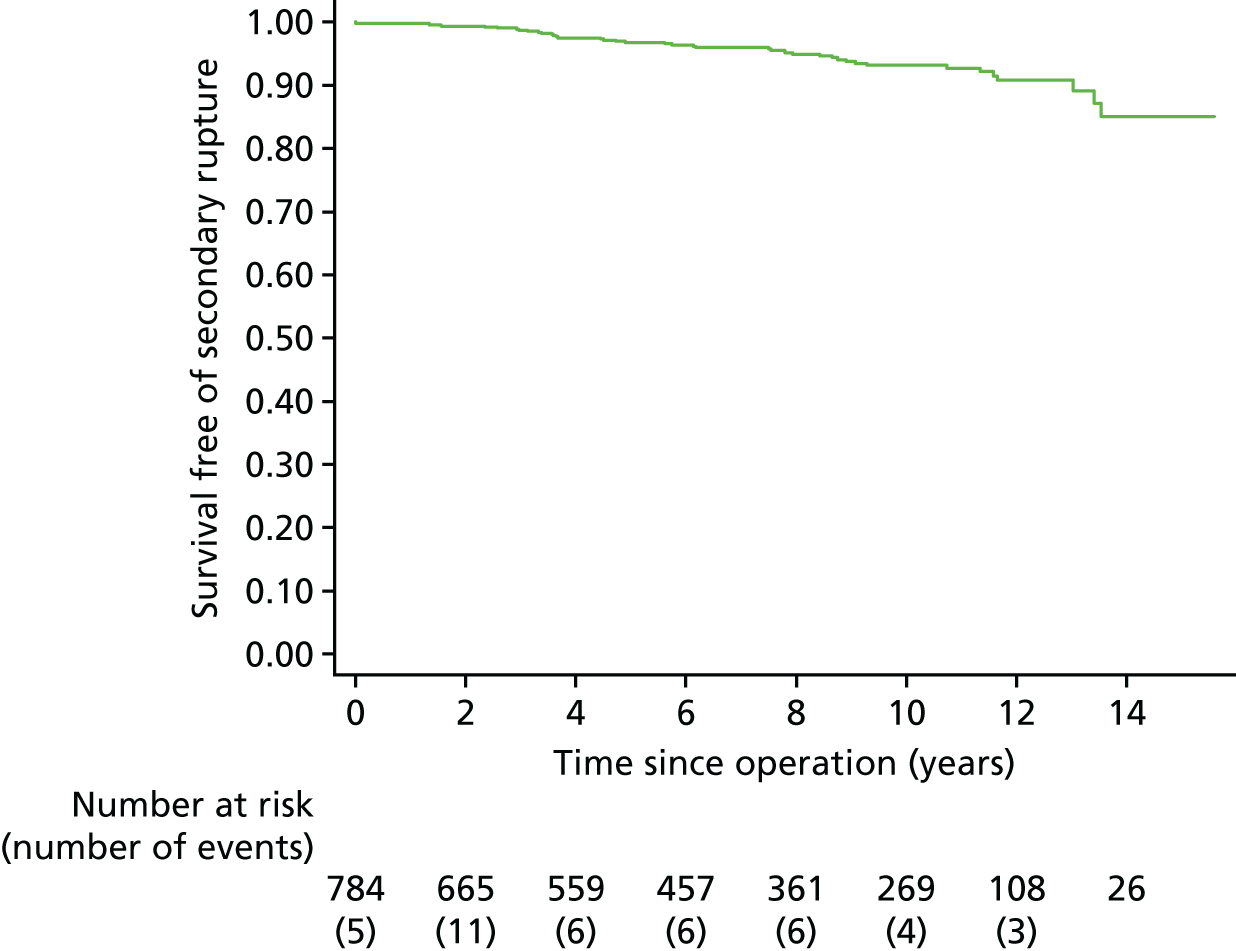

A recent observational study from a single institution in Queensland, Australia,109 reported no differences in 5-, 10- and 15-year survival rates between OR (n = 982, median follow-up 6.5 years) and EVAR (n = 358, median follow-up 4.0 years), but suffered from incomplete patient reporting. The EUROpean collaborators on Stent-graft Techniques for abdominal aortic Aneurysm Repair (EUROSTAR) database has reported that rate of secondary sac rupture after EVAR is low for the first 4 years, but after this time the rate appears to increase, particularly in those with known sac expansion. 110 A previous report from the EVAR trials defined a ‘cluster’ of findings (type I endoleak, type III endoleak, type II endoleak with sac expansion, kinking and migration), which was associated with secondary sac rupture with 67% risk of death. 111

There has been no previous comprehensive report of very long-term follow-up of EVAR or OR beyond 10 years. EVAR-1 reported follow-up for aneurysm-related and total mortality for a period of 8 years,94 at which point there was no difference between endovascular and open abdominal aneurysm repair and the problem of secondary sac rupture after EVAR, associated with 67% mortality, was just becoming apparent. 111 The original trial protocol stated that if concerns became apparent about the durability of EVAR, the trial should be extended to address this issue. In this report we present long-term results up to 15 years, of EVAR-1 in terms of aneurysm-related and total mortality, cause of death, aneurysm-related reinterventions and cost-effectiveness. We also report results up to 15 years for EVAR-2 in terms of overall mortality.

Rationale for follow-up from 10 years up to 15 years

In July 1999, the UK EVAR-1 and EVAR-2 trials were commissioned by the NHS research and development (R&D) HTA programme [now known as the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) HTA programme]. The trials were funded for 4 years (from July 1999 to 2003), followed by a 2-year extension, which was granted to ensure that recruitment targets were met. Subsequently, long-term follow-up support was awarded for a further 5 years of follow-up until July 2010 (up to 10 years of follow-up). The trial objectives were to assess the safety and efficacy of EVAR against the established open surgical treatment in the management of large aneurysms of at least 5.5 cm diameter as measured using CT. Two trials were instigated: EVAR-1 would compare EVAR against OR in patients who were considered fit and suitable for both procedures and EVAR-2 would compare EVAR against no intervention for patients who were considered suitable for EVAR but unfit for OR. The primary outcome for both trials was mortality, with secondary outcomes of complications, reinterventions, HRQoL, adverse events, costs and cost-effectiveness.

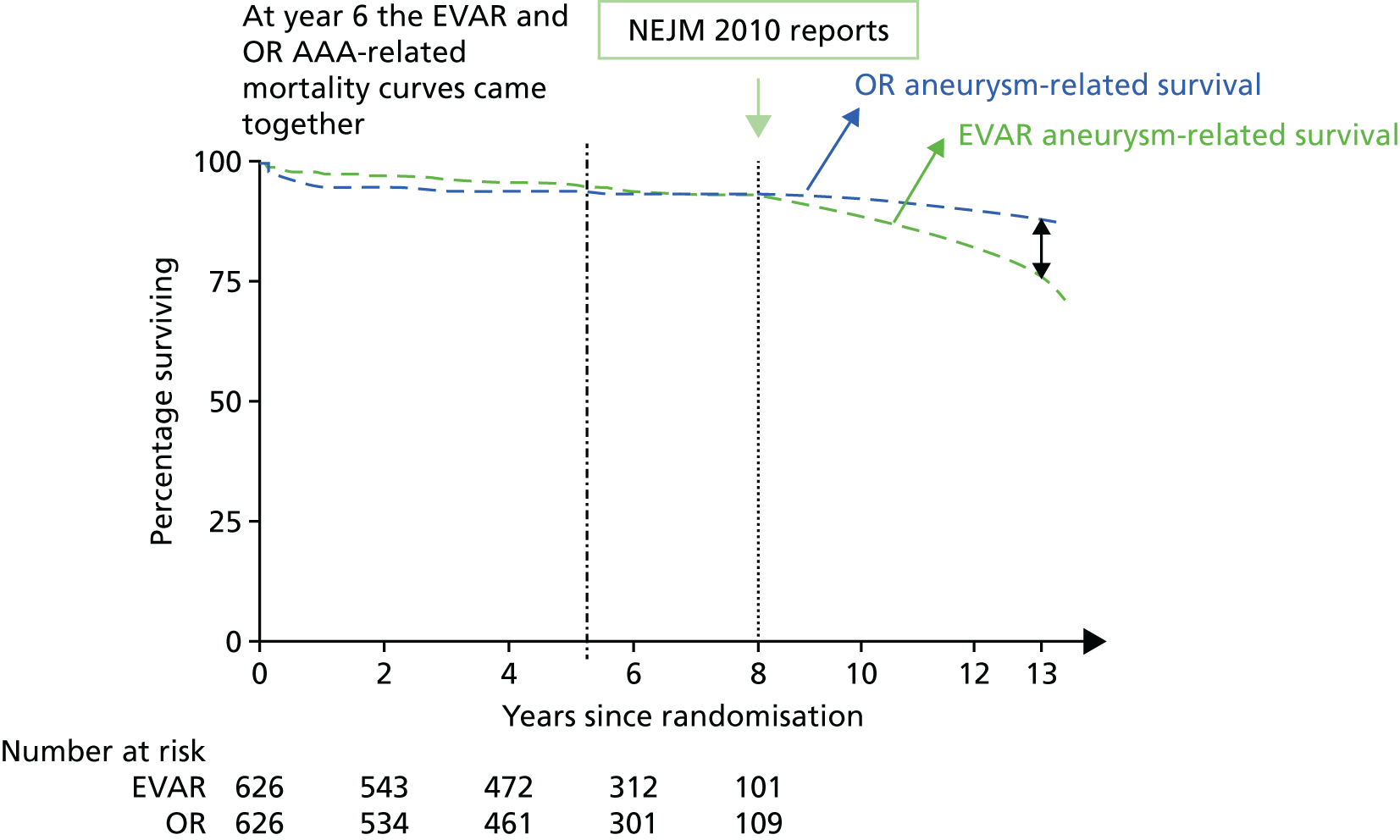

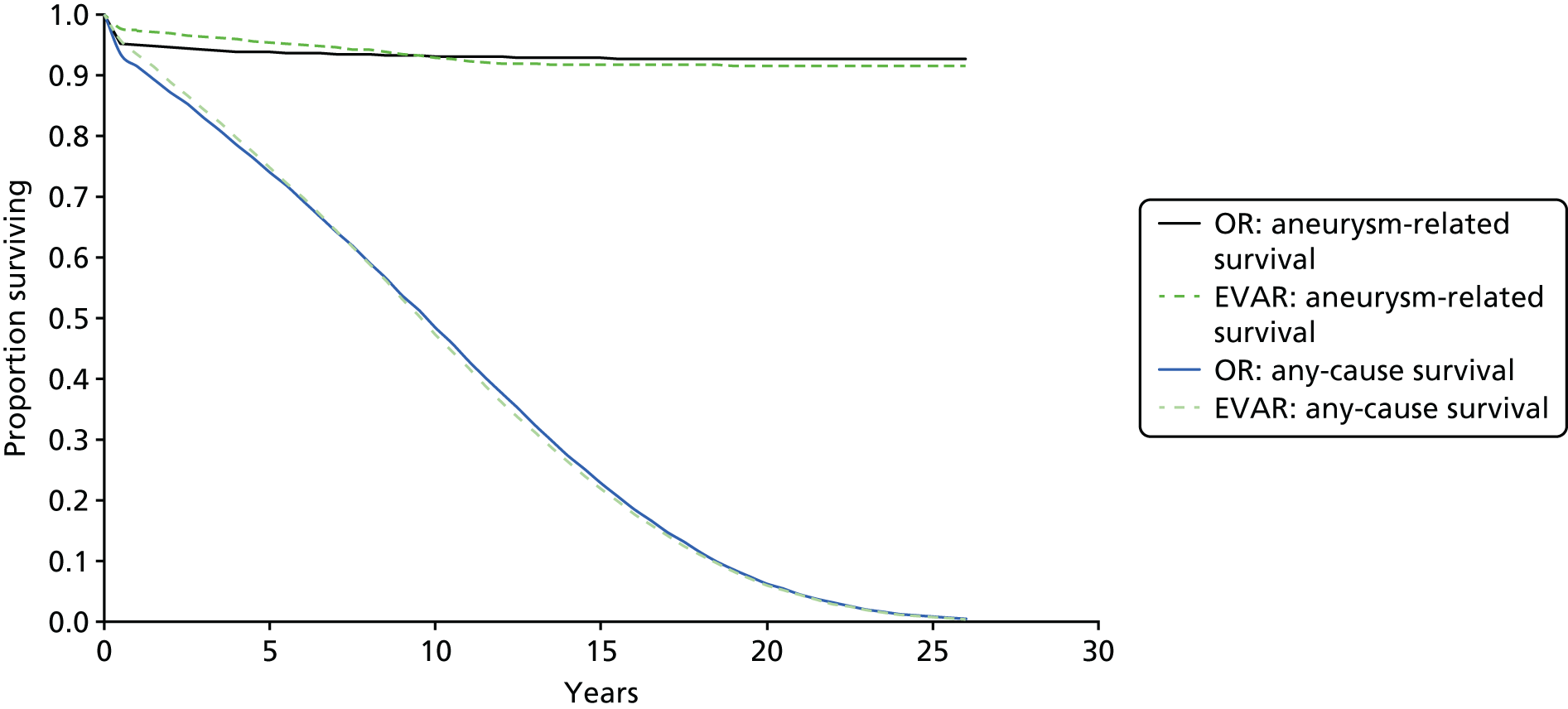

In follow-up until December 2009, 27 sac ruptures had occurred after EVAR, carrying a 67% mortality rate. Type I endoleak, type III and type II with sac expansion, kinking and migration were identified as the ‘cluster’ of complications associated with these late EVAR secondary sac ruptures. 111 It is possible that the early aneurysm-related mortality benefit of EVAR is lost as a result of these late sac ruptures and death. If this trend were to continue, after 15 years, OR would have a lower aneurysm-related mortality than endovascular repair, even with every attempt made to intervene to correct known causes of sac expansion to reduce the risk of secondary rupture in EVAR patients. The possible future projection is shown graphically for EVAR-1 in Figure 1. The rationale for continuing follow-up to 15 years in EVAR-1 was to test this hypothesis. The primary outcome measure for the 15-year follow-up was aneurysm-related mortality and total mortality.

FIGURE 1.

Projected aneurysm-related survival after 8 years of follow-up in EVAR-1 based on observed trends. NEJM, New England Journal of Medicine.

Our secondary outcomes included reinterventions (time to first reintervention, to first reintervention for a life-threatening problem and to first serious reintervention).

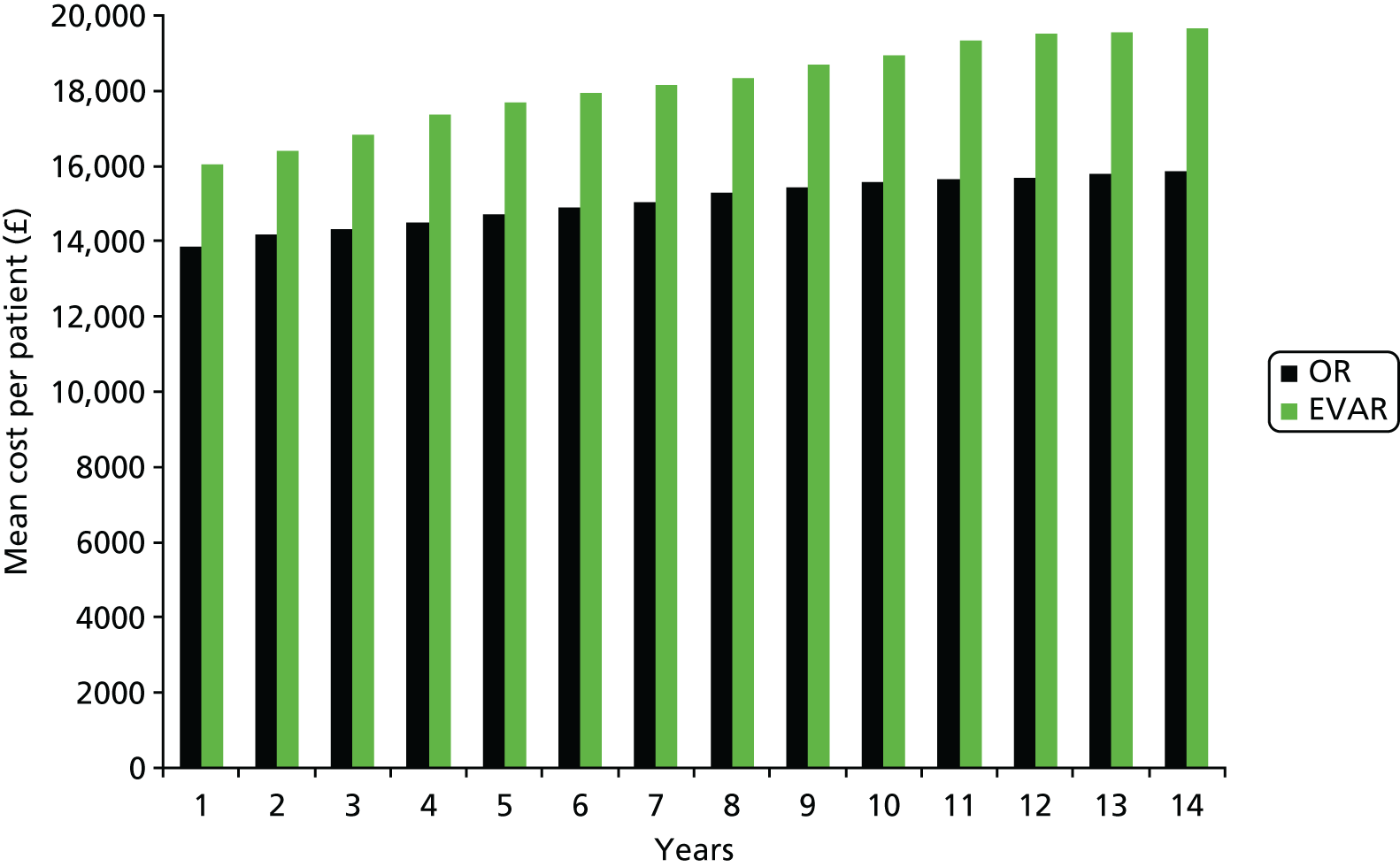

Other secondary outcomes included complications, cost and cost-effectiveness. The evaluation of cost-effectiveness of OR and EVAR after a 15-year time period is particularly pertinent because EVAR-related complications continue to occur many years after the original procedure. This objective required knowledge of continuing graft-related complications and use of hospital resources to the end of 2014.

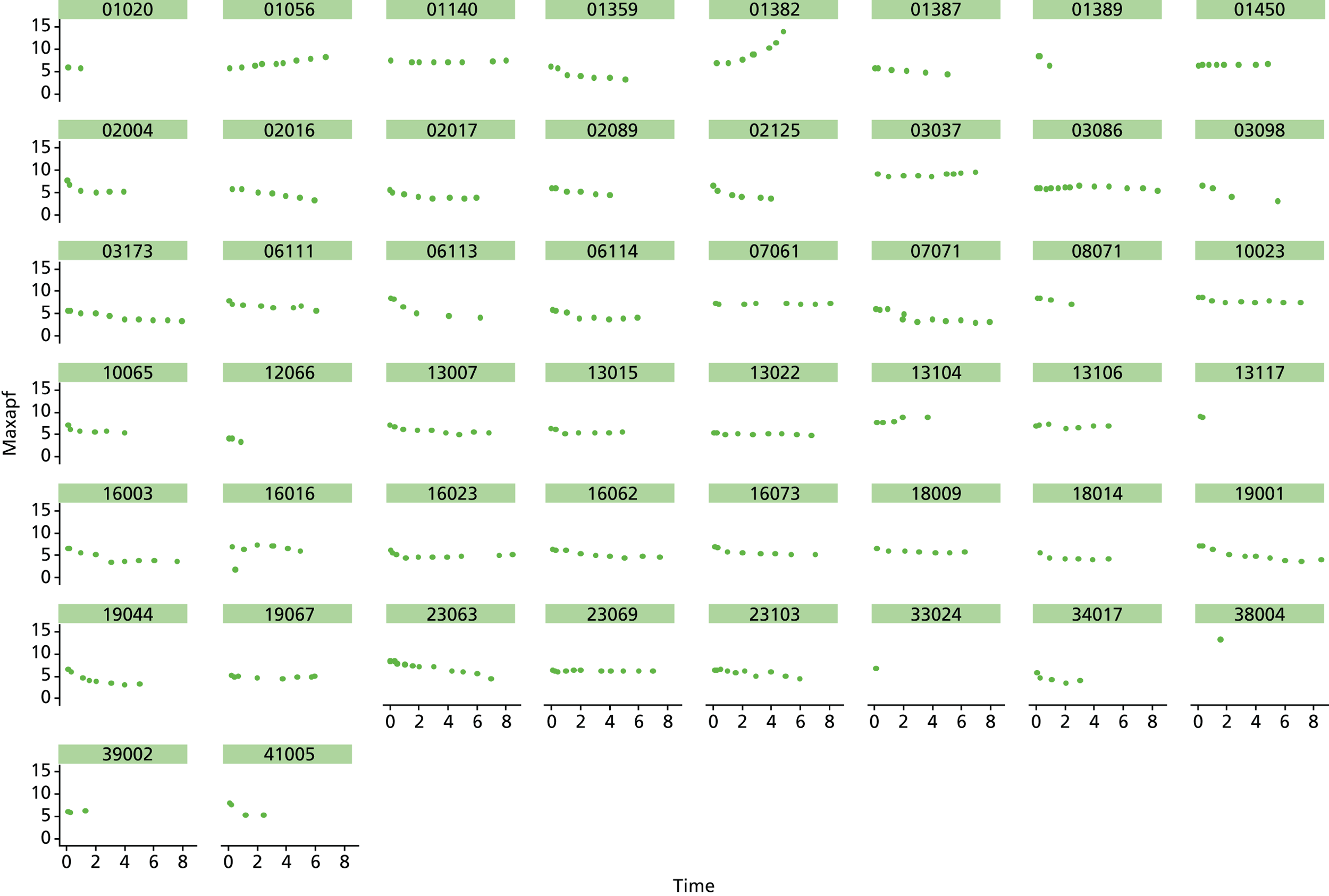

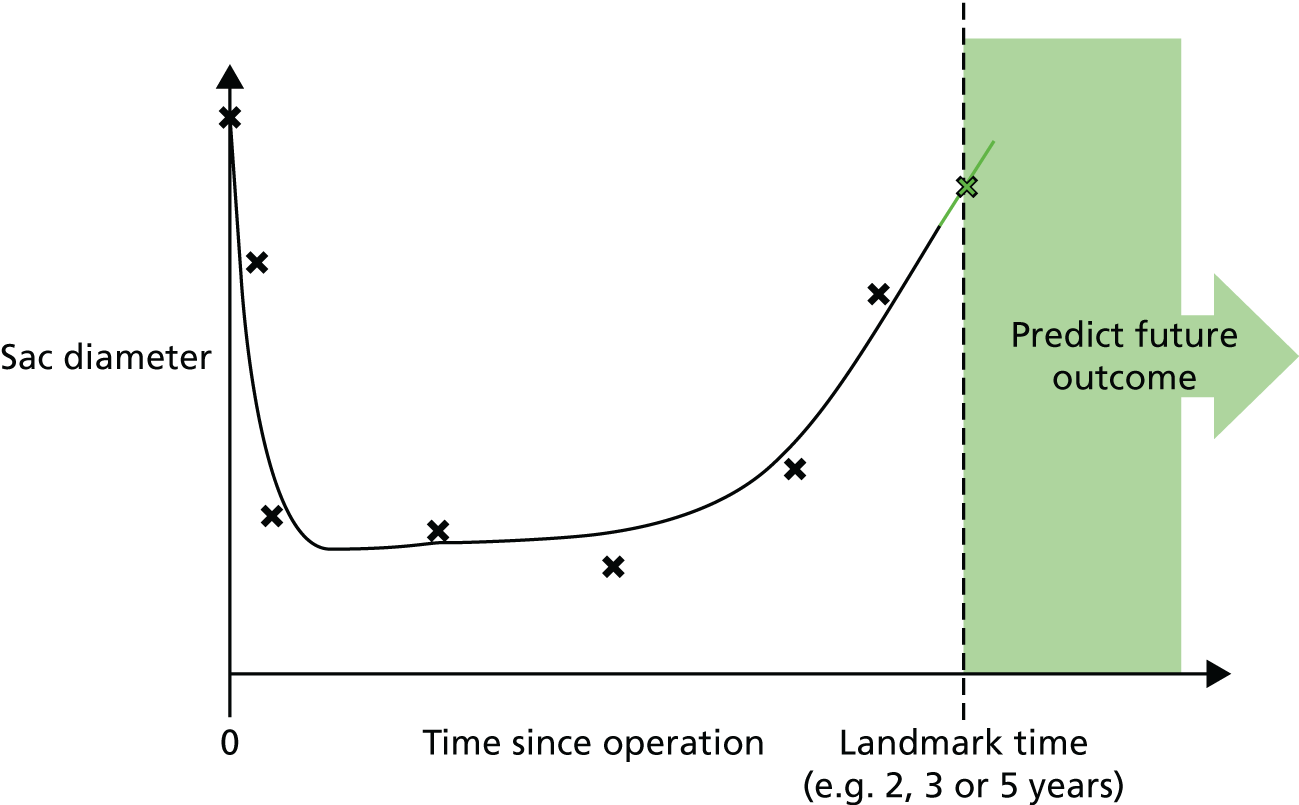

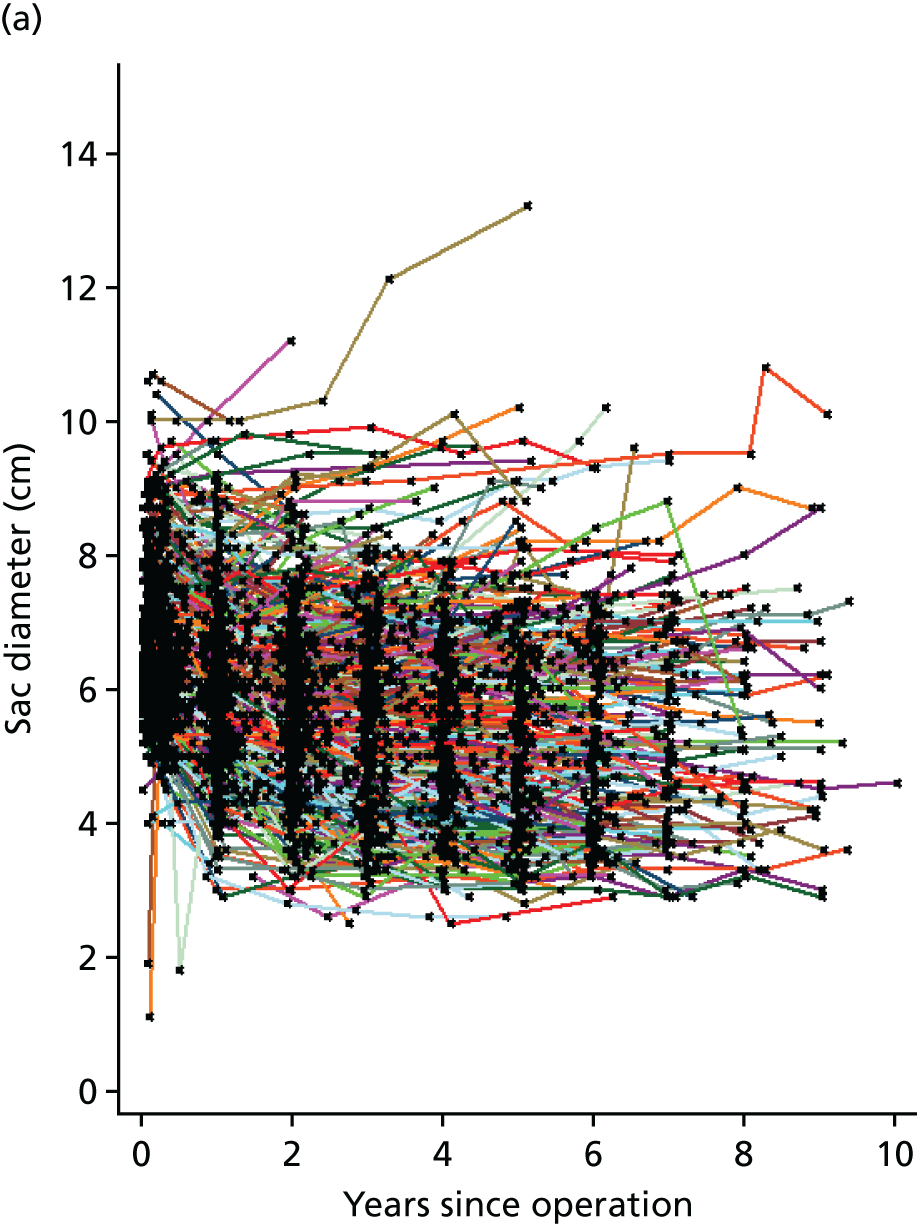

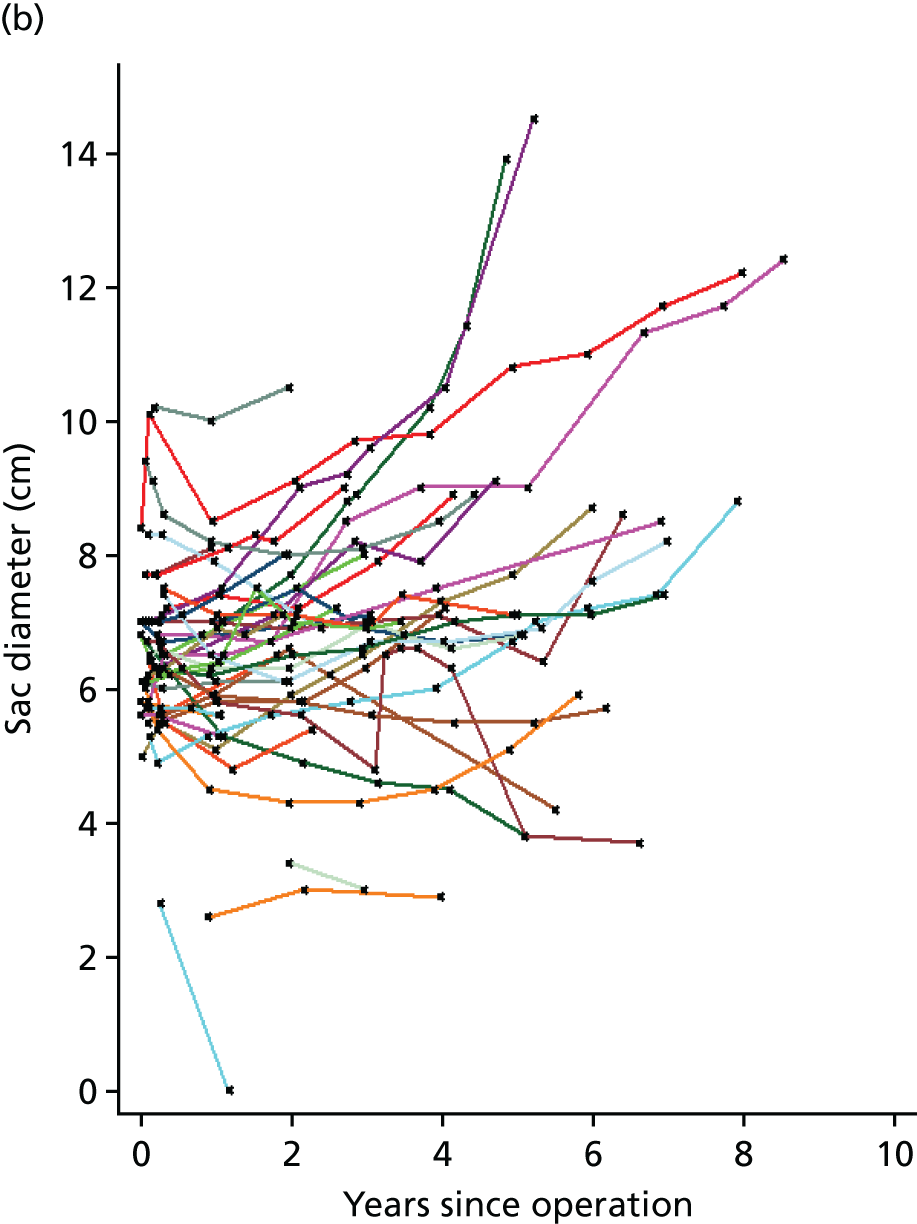

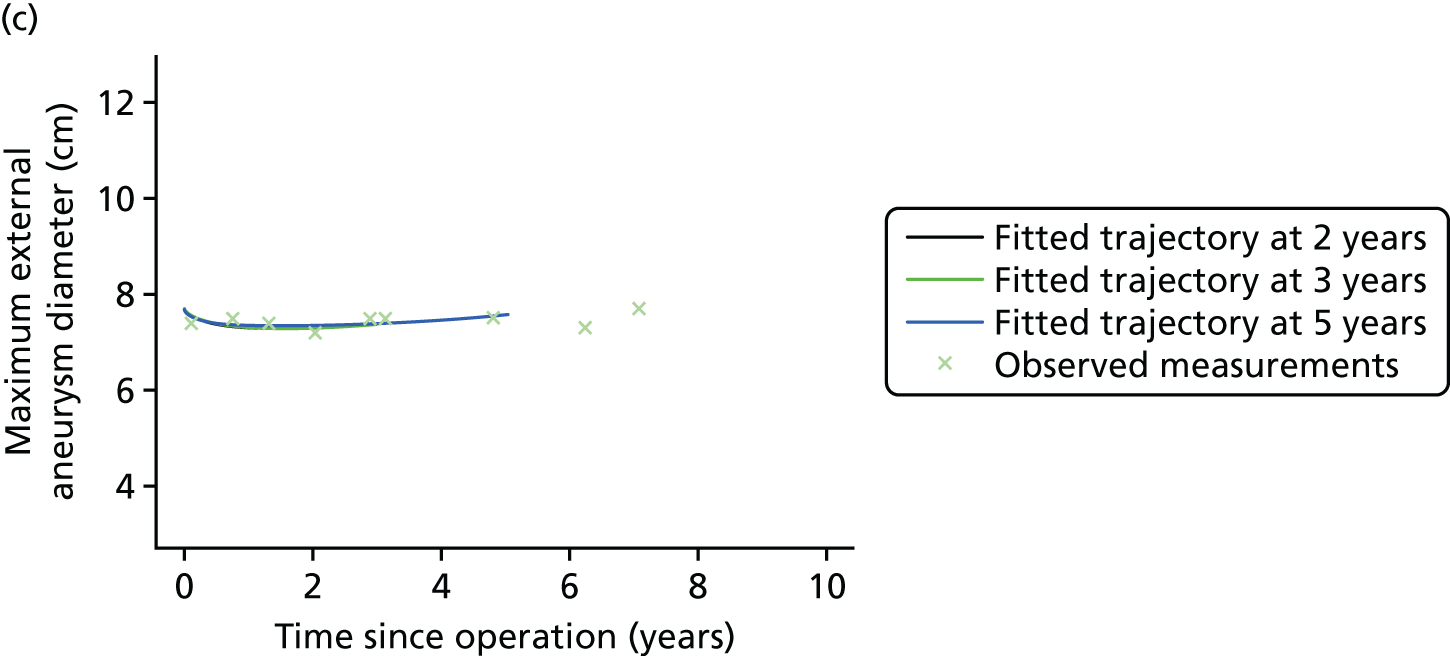

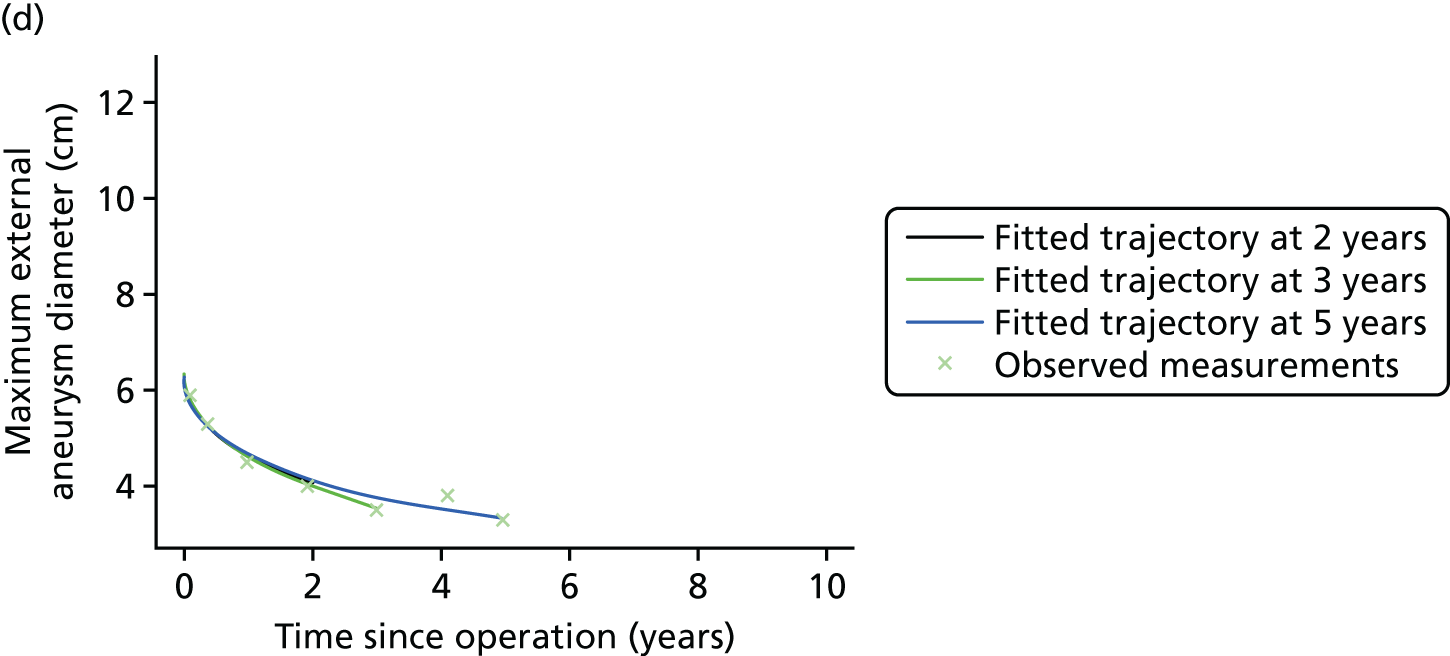

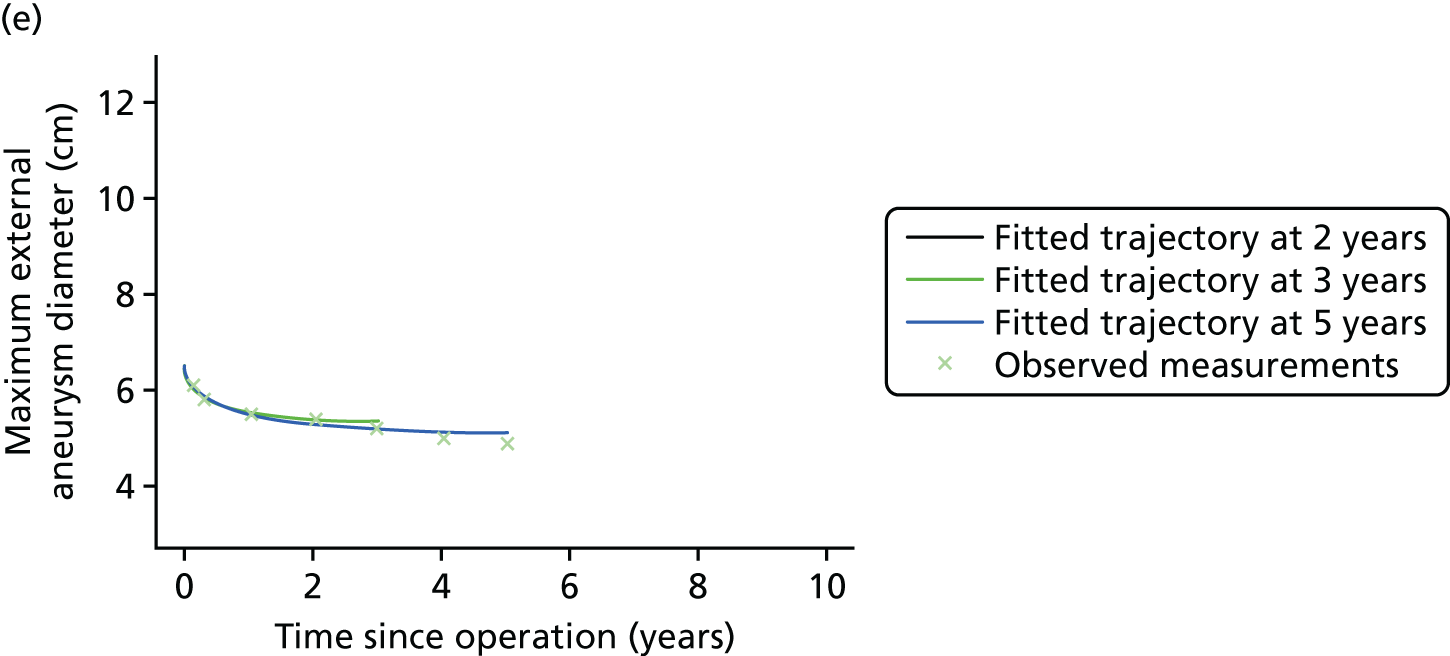

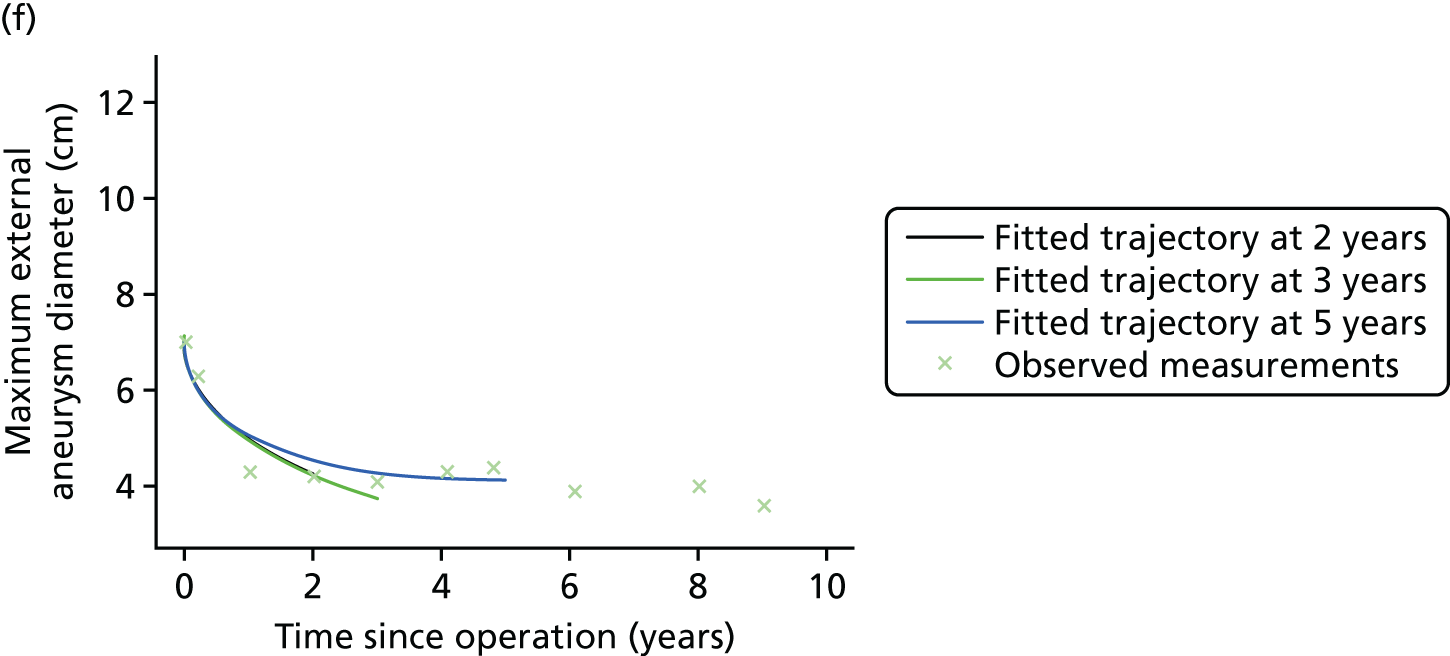

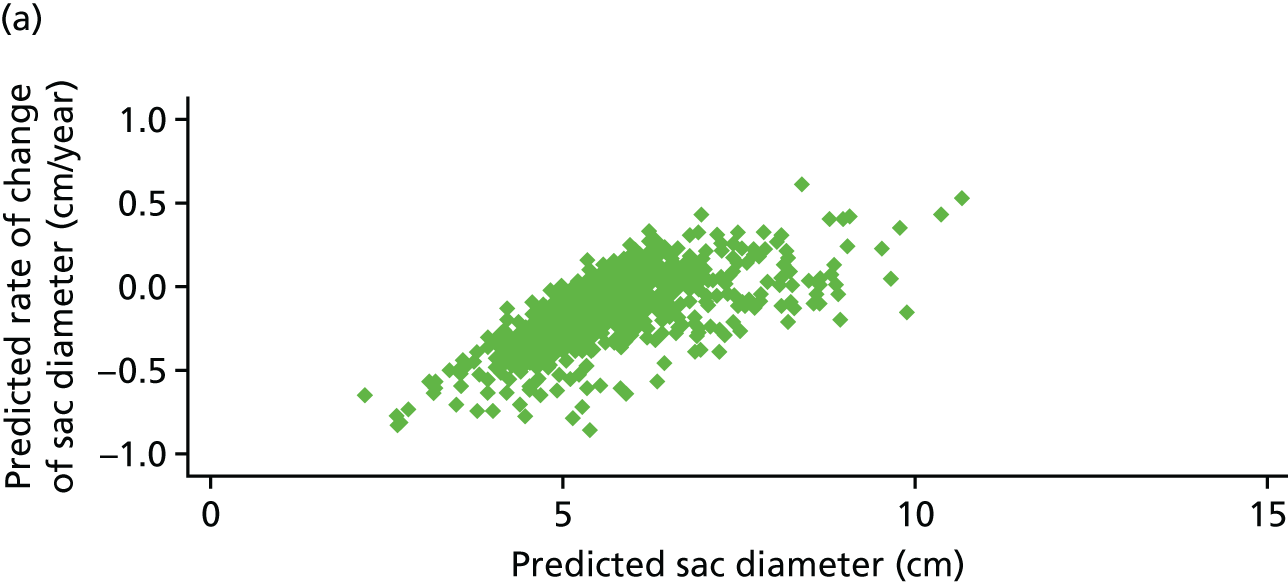

Based on the 27 sac ruptures reported by Wyss et al. ,111 in 2010, it was hypothesised that sac growth after EVAR is associated with an increased risk of rupture and the presence of a significant complication or endoleak. It was therefore assumed that patterns of sac growth might predict the need for reintervention, even in the absence of a defined endoleak. A further outcome was therefore to investigate any association between sac growth (Figure 2) and secondary rupture, complication, endoleak and reintervention correction.

FIGURE 2.

Change in sac diameter of a random selection of 50 patients (post-EVAR measurements only, preoperative measurements excluded). Graphs by ID.

In 2012, there was a call with vignette (NIHR Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre – HTA) for addressing the question ‘What is the optimal management strategy for type II endoleaks?’ The then Director of the HTA programme, Professor Tom Walley, questioned whether or not the HTA-funded EVAR trials would produce data that could answer this question. The authors of the EVAR trials considered the Director’s question and considered that an individual patient data (IPD) meta-analysis of EVAR-1, the DREAM trial, the OVER trial and ACE would produce much useful information and among it some on type II endoleaks. We informed the HTA programme that we would be able to address the question ‘What is the optimal management strategy for type II endoleaks?’ without requiring further data collection.

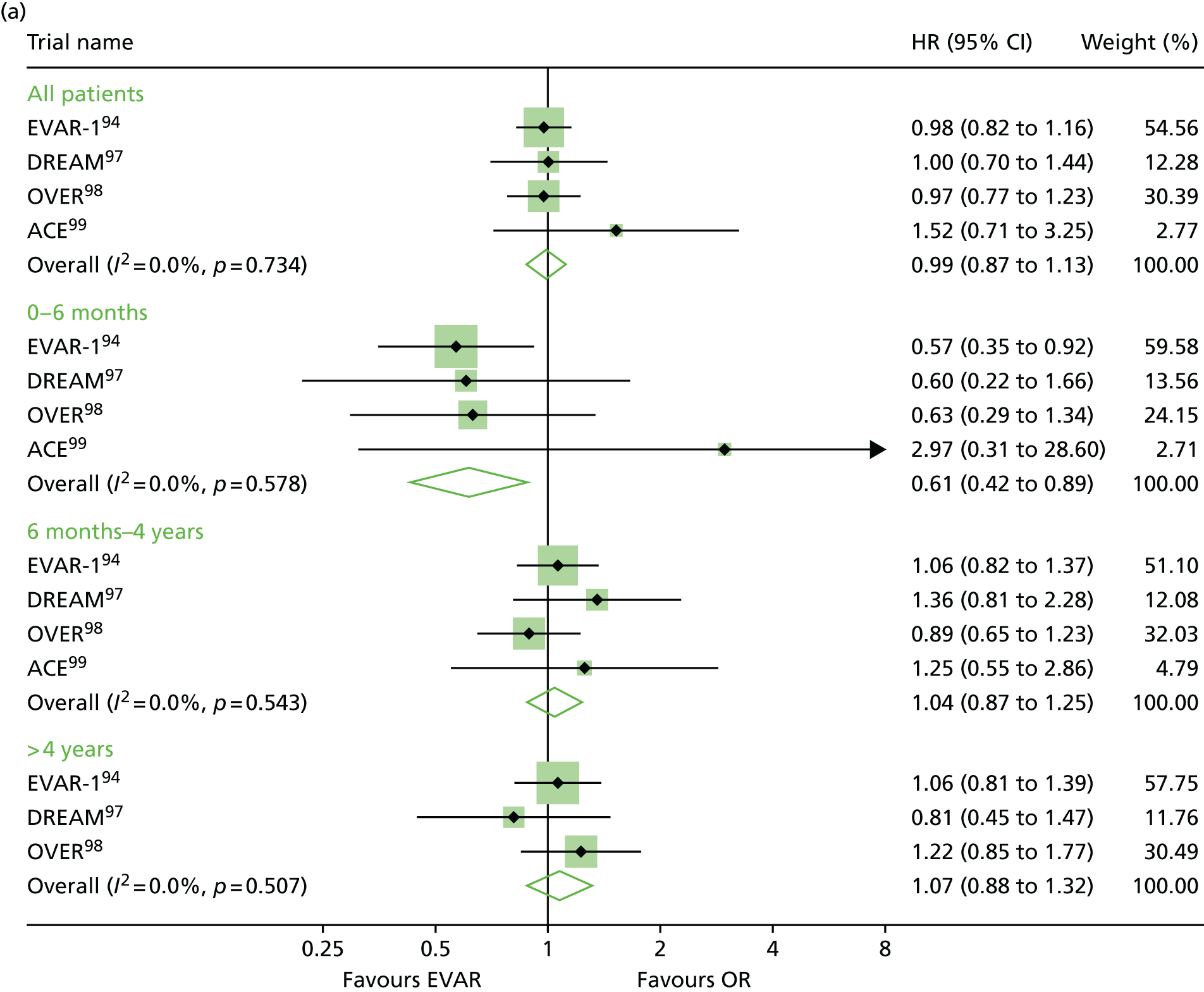

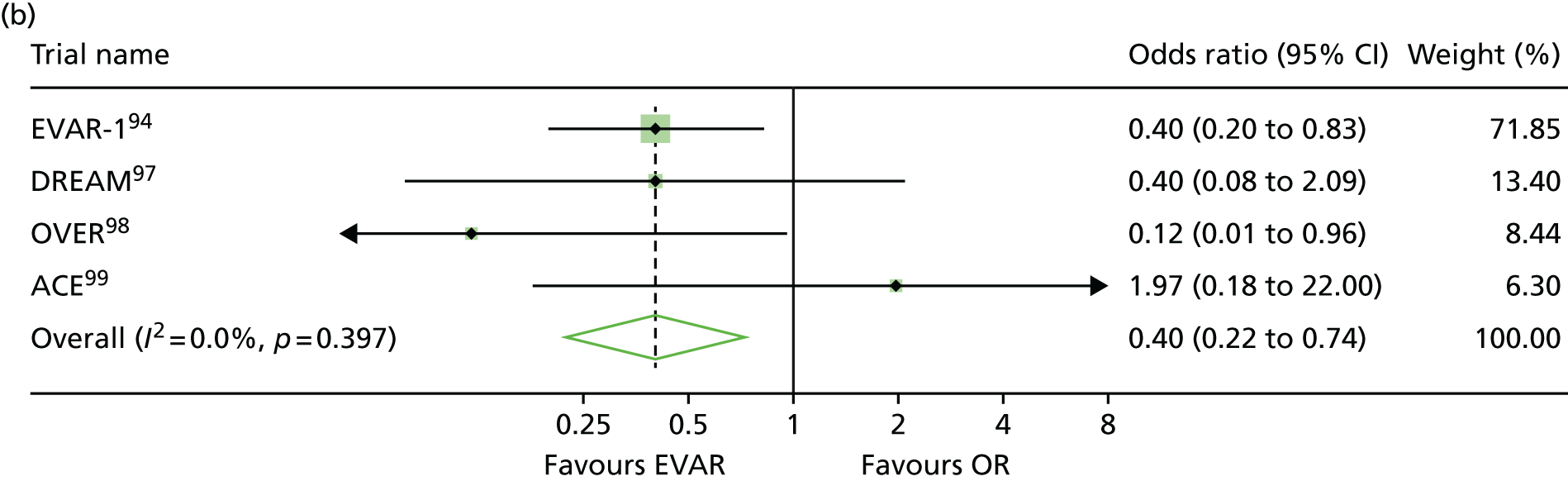

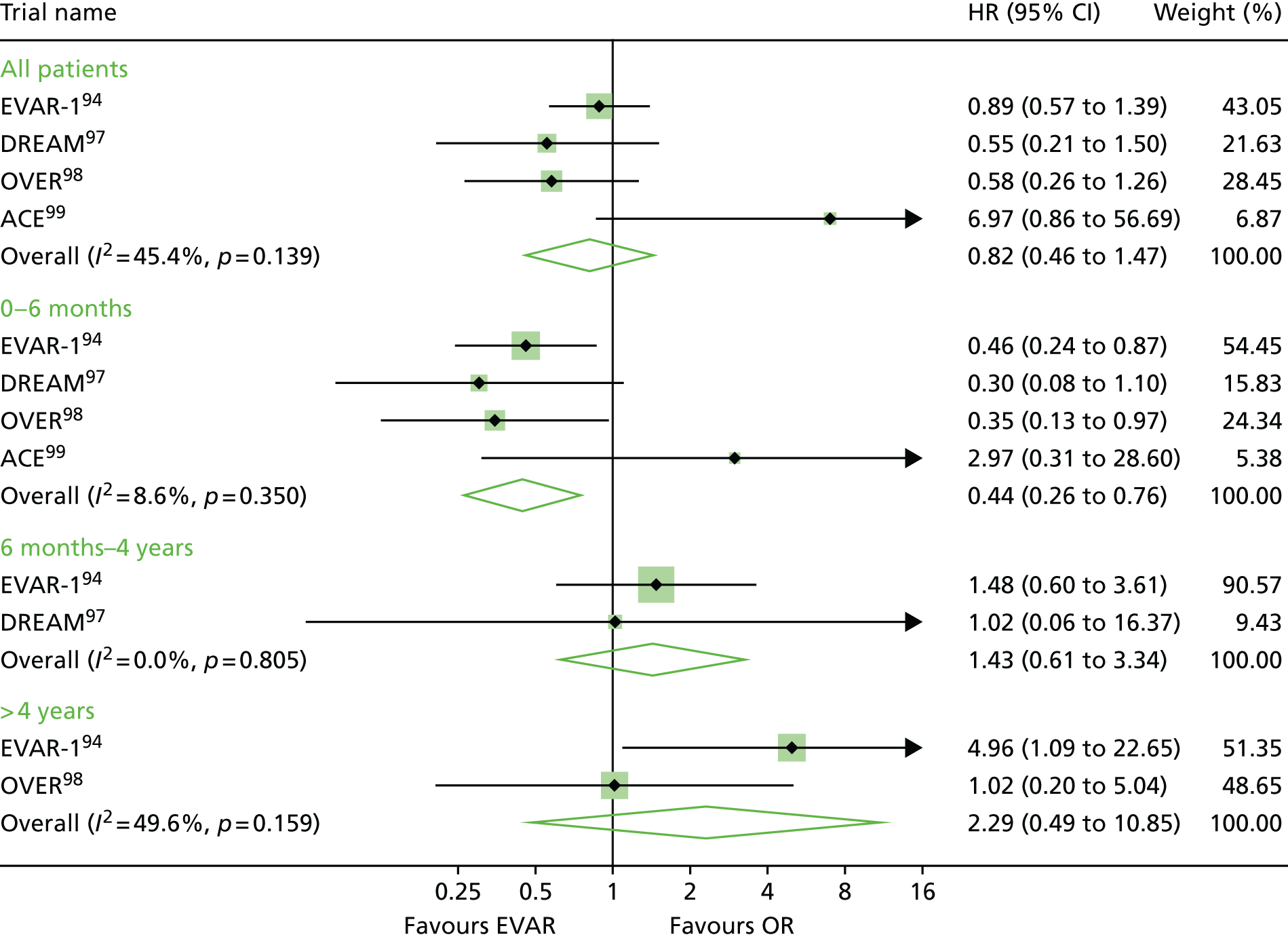

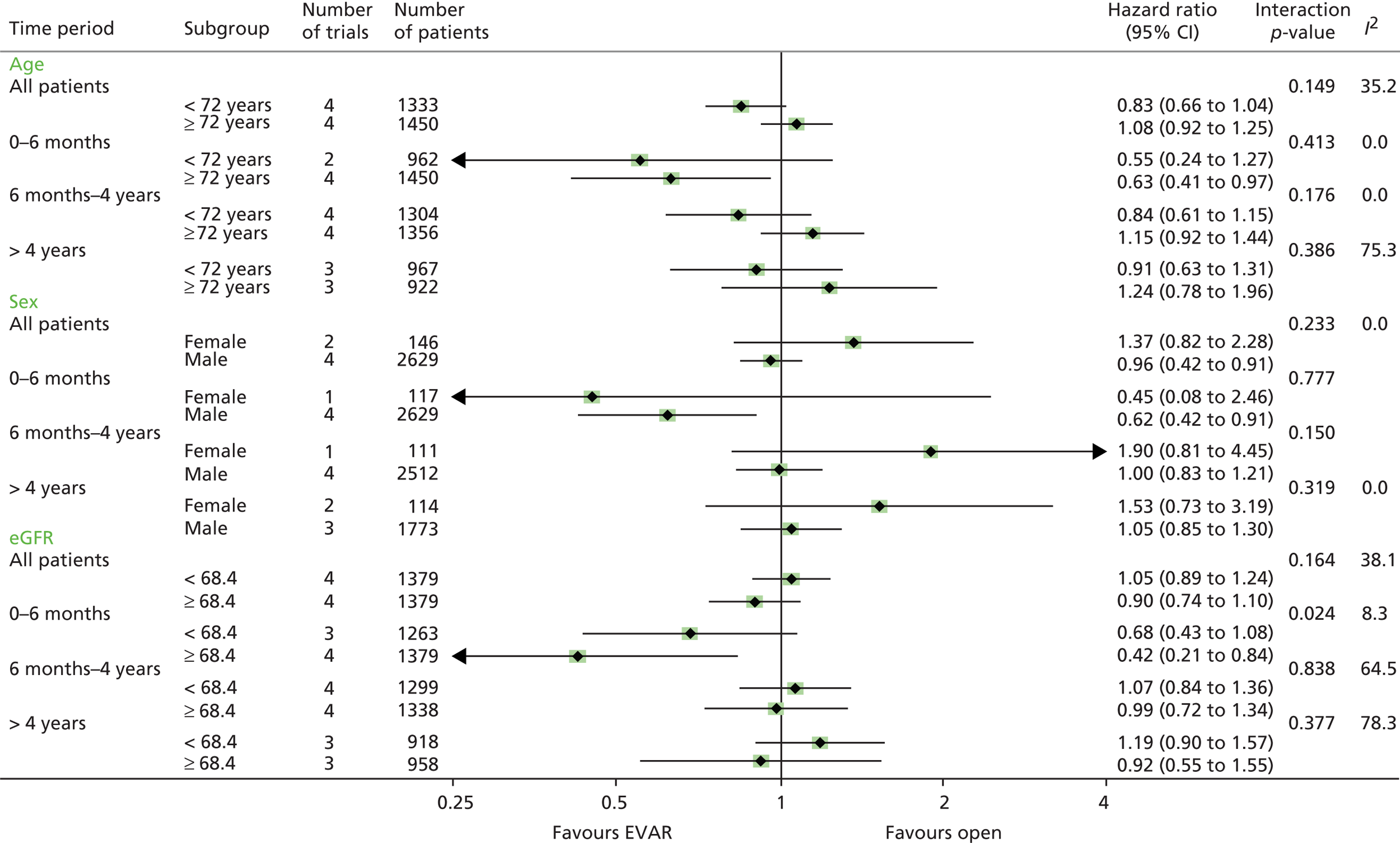

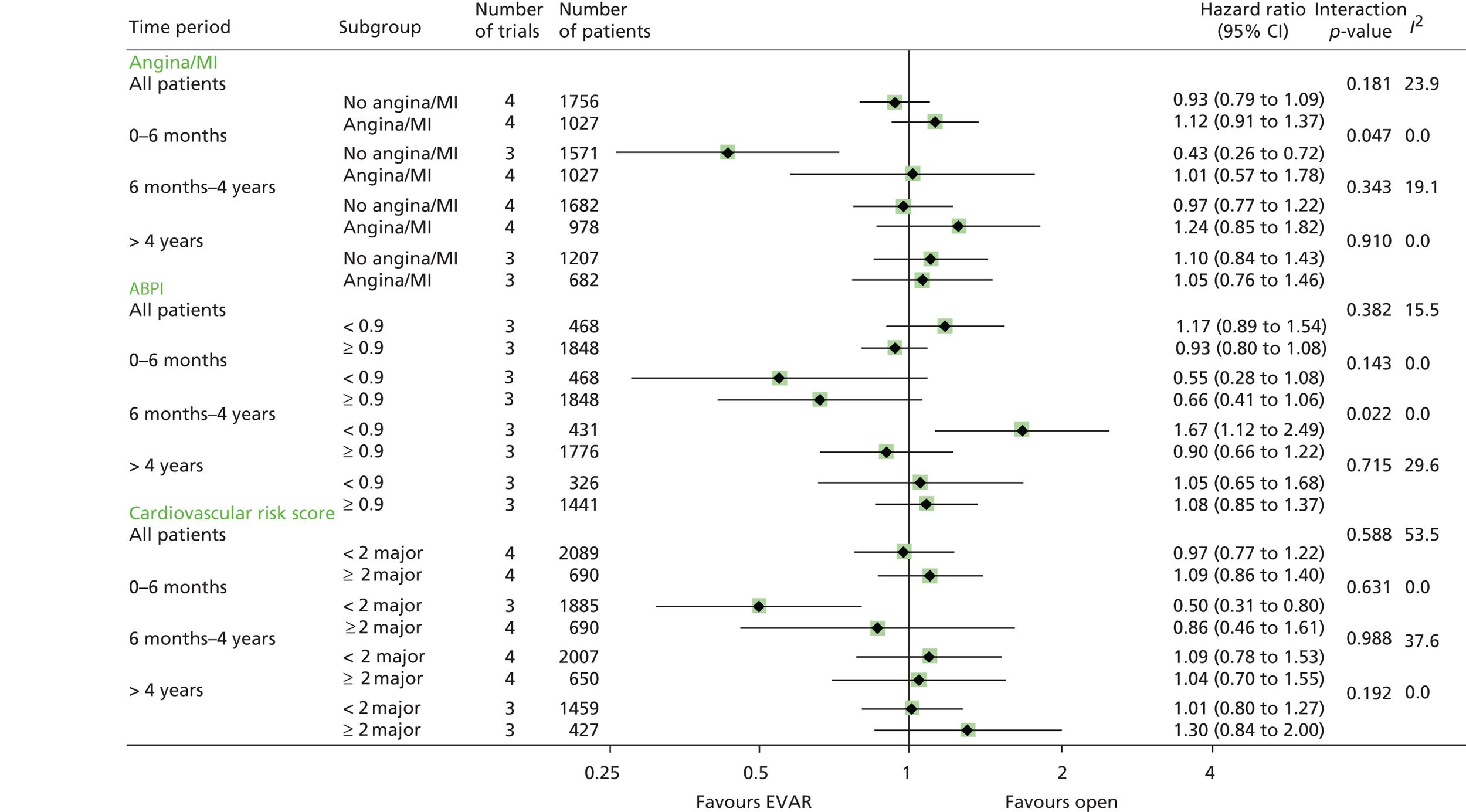

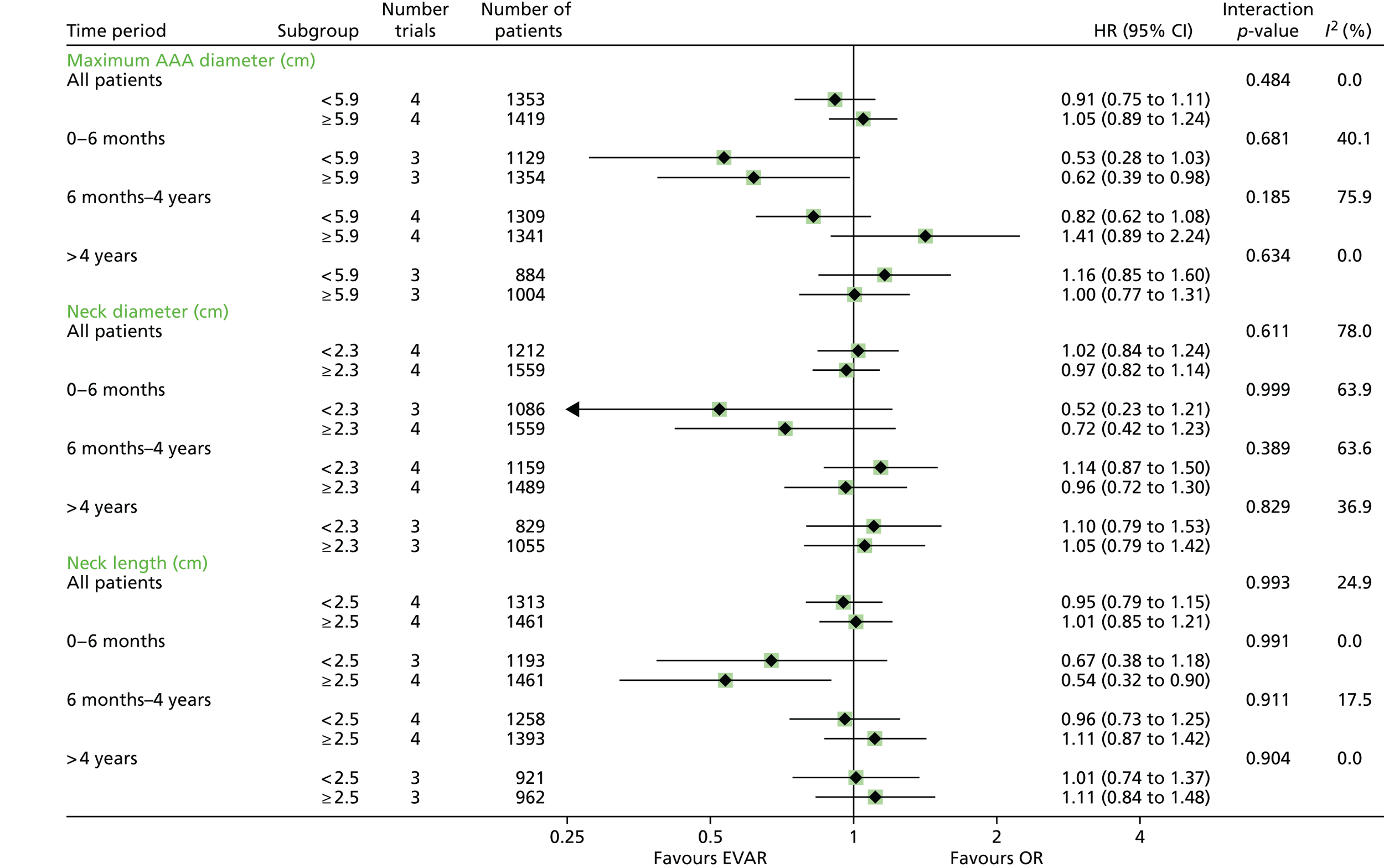

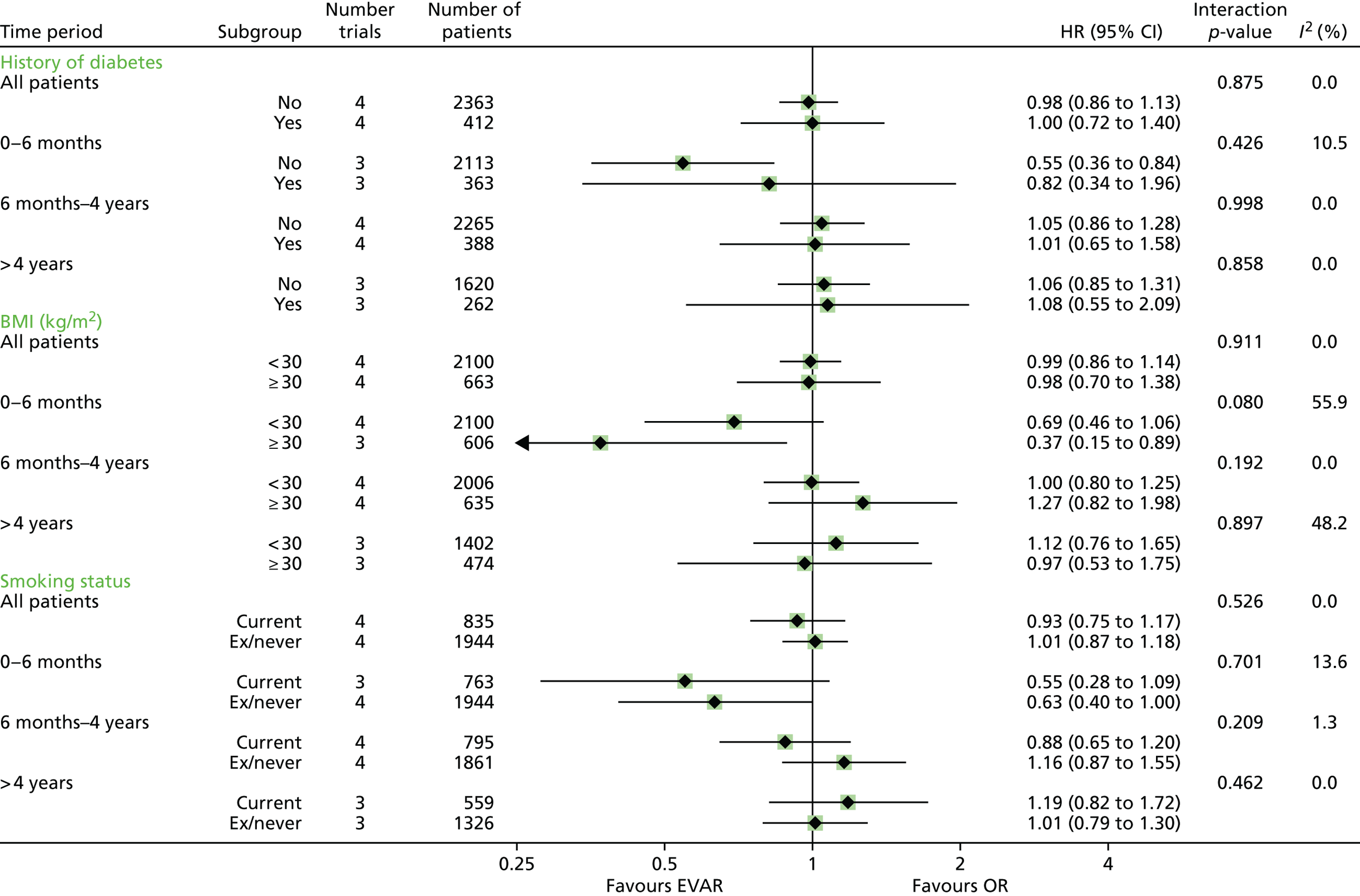

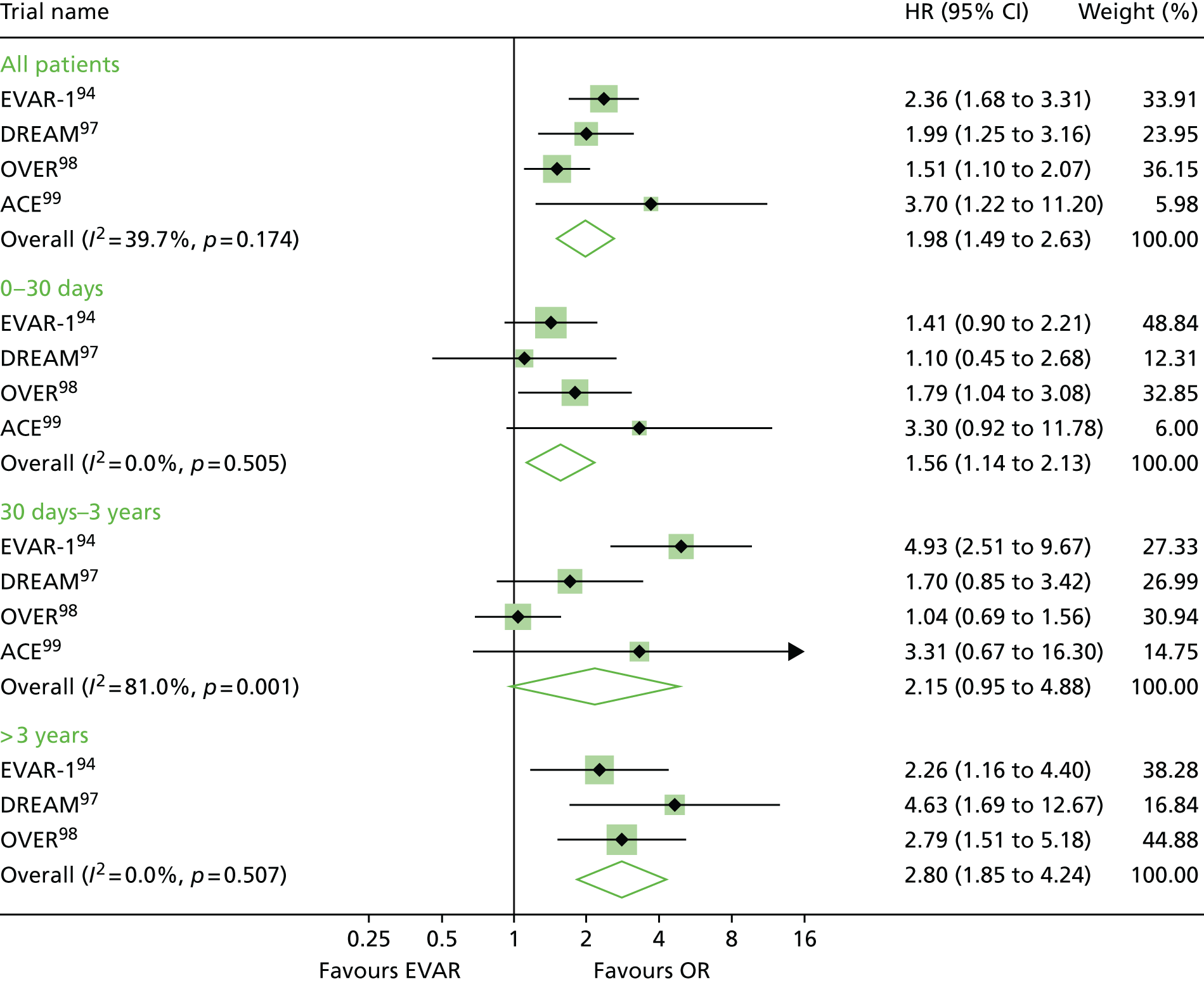

An IPD meta-analysis of four multicentre randomised trials of EVAR compared with OR was conducted to a prespecified analysis plan, reporting on mortality, aneurysm-related mortality and reinterventions.

Data from the IPD meta-analysis have been used to address the question of the management of type II endoleaks following EVAR.

Chapter 2 Methods

Detailed descriptions of the trial design, methodology and results after 10 years of follow-up have previously been reported, including an earlier HTA programme report which was published in February 2012. 96

Participants

Men and women aged ≥ 60 years were enrolled into EVAR-1 between 1 September 1999 and 31 August 2004 from 37 hospitals in the UK. Twelve hundred and fifty-two patients whose maximum aortic aneurysm diameter was ≥ 5.5 cm, with aortic morphology compatible with endograft placement within the manufacturer’s instructions for use (IFU) and who were deemed to have an acceptable risk of postoperative death for both procedures were randomised to undergo either OR or EVAR.

EVAR trial 2 was designed to address the question of whether or not endovascular repair reduces the rate of death among patients who were considered to be physically ineligible for OR. During the same time period, patients of both sexes who were at least 60 years of age with large aneurysms (≥ 5.5 cm in diameter) and who were deemed unfit for OR, were randomly assigned to undergo either EVAR or no repair.

Interventions

In EVAR-1, patients were randomised to undergo either OR or EVAR. In EVAR-2, patients were randomly assigned to undergo either EVAR or no repair.

Objectives

The objective was to follow up the world’s first RCT of EVAR compared with OR with up to 15 years of follow-up; to reconvene the EVAR trial centres and brief them on the uncertainty of outcome versus OR in the very long term and to inform them of the risk of secondary rupture;111 to re-establish a link via the new EVAR trial manager and identify and brief the current lead vascular surgeon and radiologist at each of the 37 trial centres; with funding for clinical trial data collection and results of CT scanning or other imaging, to identify the contacts for these purposes; and then to be in a position to achieve the 10–15 years of additional clinical follow-up for all alive patients from 1 September 2009.

Outcomes (measures)

Our primary outcome was aneurysm-related mortality and total mortality. Aneurysm-related mortality was defined as all deaths from aneurysm rupture before repair, within 30 days of the primary procedure, within 30 days of any reintervention attributable to the aneurysm, from other aneurysm-related causes (including graft infection or fistula), or from secondary aneurysm rupture after repair. Our secondary outcomes included reintervention (time to first reintervention, first reintervention for a life-threatening problem and first serious reintervention). Further secondary outcomes included complications, sac growth and risk of late complications, costs and cost-effectiveness.

For the primary mortality outcome, patients were followed up from 1 September 1999 to 30 June 2015 [using record linkage from the Office for National Statistics (ONS), with death classification based on death certificates and clinical information provided to the Endpoint Committee]. Patients were followed up for death (total and aneurysm related), dates as above, and for graft-related complications and reinterventions from 1 September 2009 to 31 March 2015. For graft-related reinterventions between 1 September 2009 and 31 March 2015, follow-up was predominantly using record linkage to administrative data for hospital readmissions and reinterventions via Hospital Episode Statistics (HES).

Reinterventions, including incisional hernia repair throughout the trial and other operative procedures preceding death, were subsequently checked with the trial centres, with 89% concordance between administrative and clinical site data. Graft-related complications and reinterventions were also directly obtained from the trial centres with a new case record form for our follow-up between 1 September 2009 and 31 March 2015. The primary analysis compared rates of total mortality and aneurysm-related mortality to 30 June 2015; aneurysm-related mortality was adjudicated and confirmed by the Endpoint Committee.

Sample size

As of 1 September 2009, there were 711 patients with an average age of 80 years reported alive and under follow-up in EVAR-1 (357 and 354 in the EVAR and OR groups, respectively), and 96 patients with an average age of 82 years reported alive and under follow-up in EVAR-2 (50 and 46 in the EVAR and no-intervention groups, respectively). This gives 80% power at the 5% significance level to detect hazard ratios (HRs) of 1.25 and 1.83 during the extended follow-up periods in EVAR-1 and EVAR-2, respectively, assuming 10% to be still alive at the end of June 2015.

Randomisation and blinding

Randomisation was conducted using computer-generated sequences of randomly permuted blocks stratified by centre at the trial hub (Charing Cross Hospital). Patients in EVAR-1 were randomly allocated (1 : 1) to undergo either OR or endovascular repair. In EVAR-2, patients were randomly allocated (1 : 1) to undergo either EVAR or to have no intervention. There was no blinding in either trial.

Statistical methods

All analyses were performed according to a predefined statistical analysis plan and were based on the intention-to-treat (ITT) principle, with outcomes assessed from the time of randomisation. Cox regression modelling was used to compare total mortality, aneurysm-related mortality and time to first graft-related reintervention. Crude regression estimates were presented as well as ones adjusted for two sets of baseline covariates: primary adjustment for age, sex, aneurysm diameter, forced expiratory volume in 1 second, log-creatinine level and statin use; secondary adjustment for the primary covariates as well as body mass index (BMI), smoking status (current, past and never), systolic blood pressure and serum cholesterol level. For the graft-related reintervention analysis, additional secondary adjustment was made for top neck aortic diameter at the level of the lowest renal artery, neck length (distance between the lowest renal artery and the start of the aneurysm) and common iliac diameter (largest of both legs). The primary and secondary adjustment results were very similar and the latter are reported. Baseline data were almost complete, with 94% and 92% of patients in EVAR-1 and EVAR-2, respectively, having a complete set of covariates for the adjusted analyses. HRs were presented as the EVAR group relative to the OR group for EVAR-1 and the EVAR group relative to the no-intervention group for EVAR-2. Owing to non-proportional hazards during the first 8 years of follow-up,94,95 data were analysed by splitting follow-up into four time periods: 0–6 months, 6 months–4 years, 4–8 years and > 8 years. HRs presented in these time periods help to explain the non-proportionality, but must be interpreted conditional on surviving up to the time point in question and are therefore dependent on how the randomised groups fared in the follow-up prior to the time period. Deviations from the proportional hazards assumption were assessed overall and within these periods by regressing scaled Schoenfeld residuals against log of time. Regression estimates are presented both unadjusted and adjusted for baseline covariates. Kaplan–Meier estimates were used to show survival probabilities up to 15 years in each group. Tests of interaction were performed for total mortality and aneurysm-related mortality between randomised group and sex, age and aneurysm diameter (the last two as continuous variables).

In EVAR-1, two sensitivity analyses were performed to allow inclusion of patients with missing covariates in the adjusted models: first, the missing indicator method112 and, second, multiple imputation using chained equations that included terms for the event outcome and the estimate of the cumulative baseline hazard. 113–117

In addition, a per-protocol analysis was performed in EVAR-1 on data from patients who had undergone their randomly assigned treatment. This analysis excluded patients who did not undergo aneurysm repair, those who underwent emergency repair, those in whom the repair was abandoned during surgery (i.e. the aorta was left unrepaired) and those who did not undergo the randomly assigned procedure.

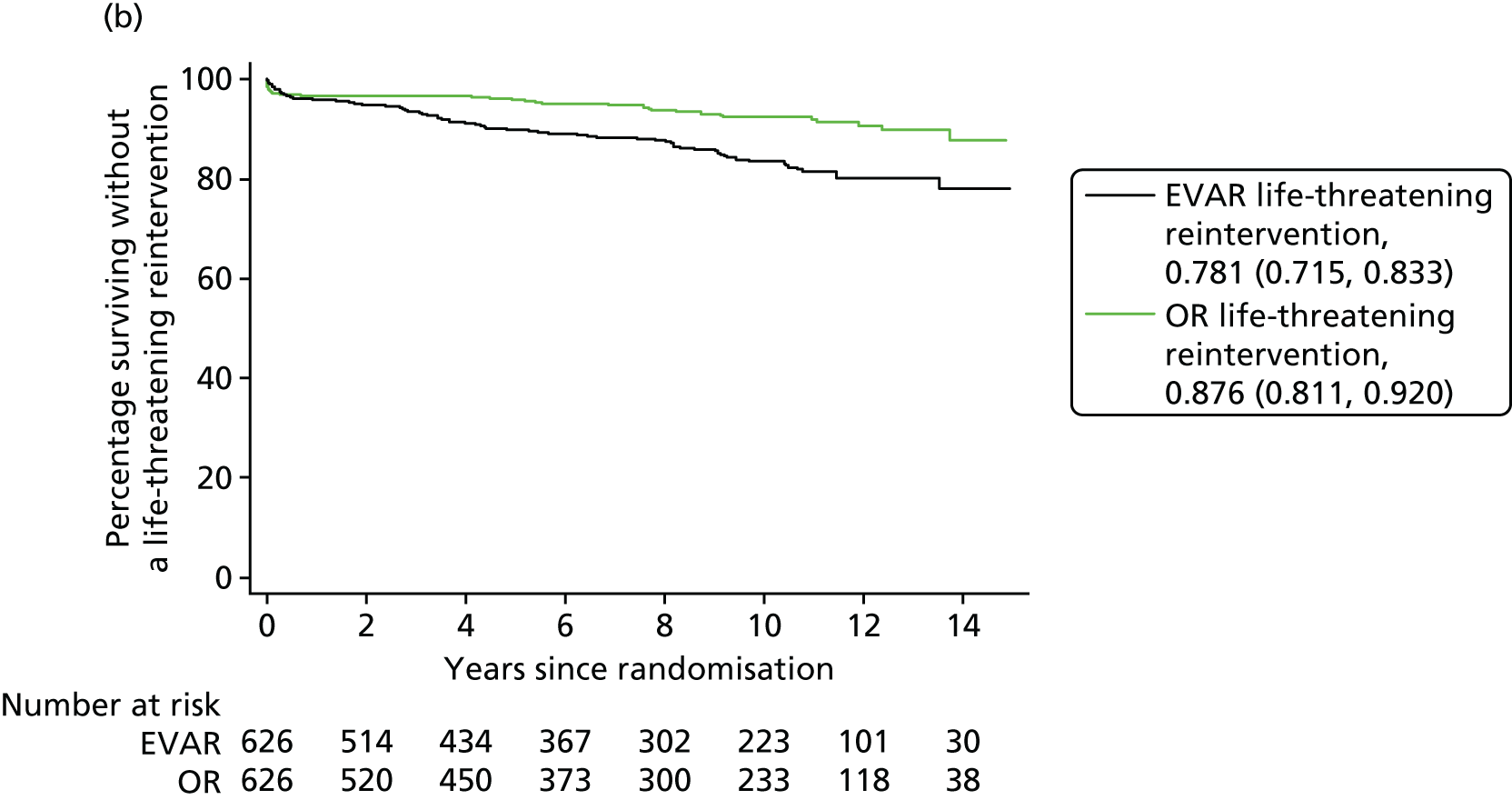

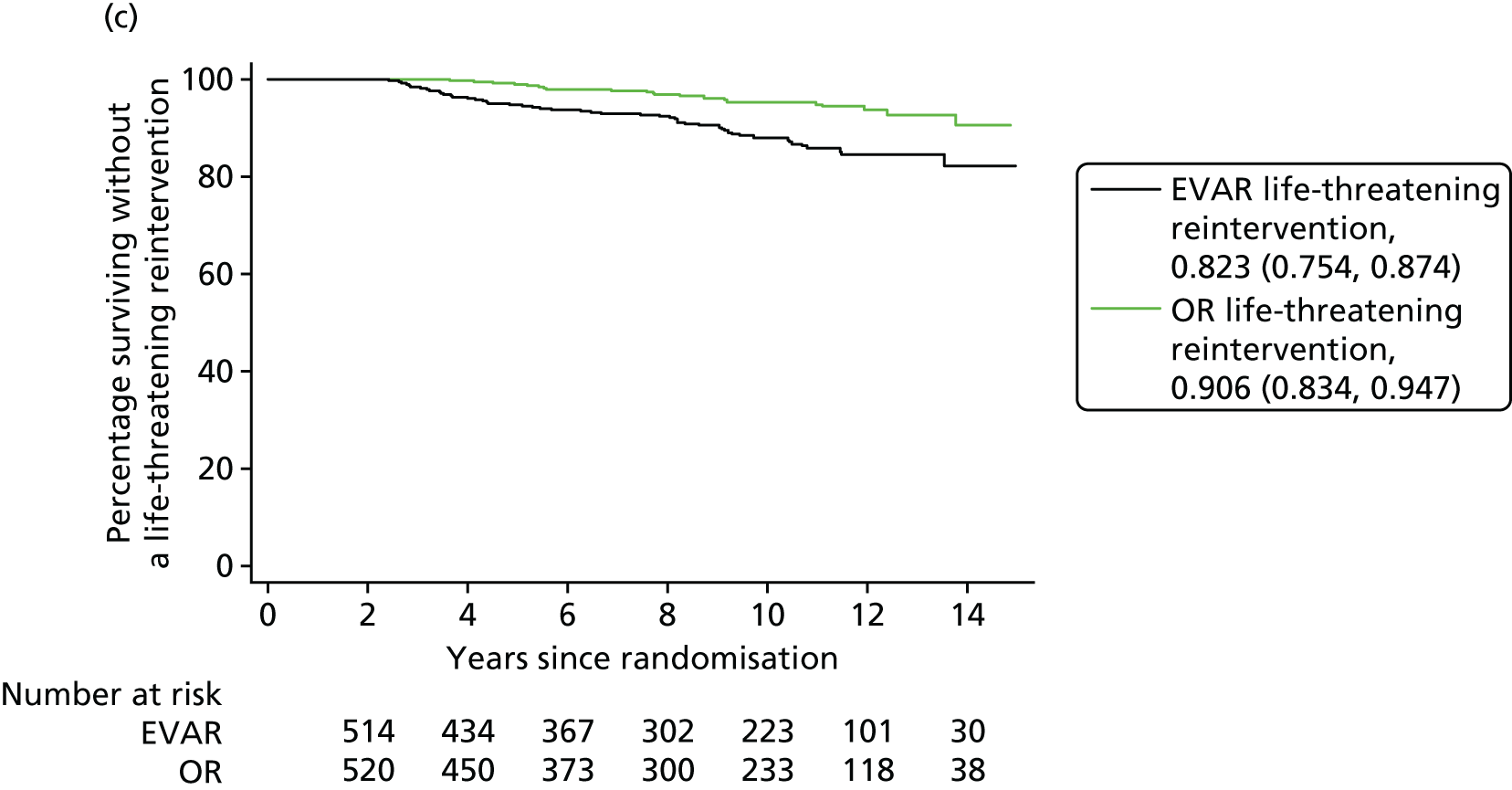

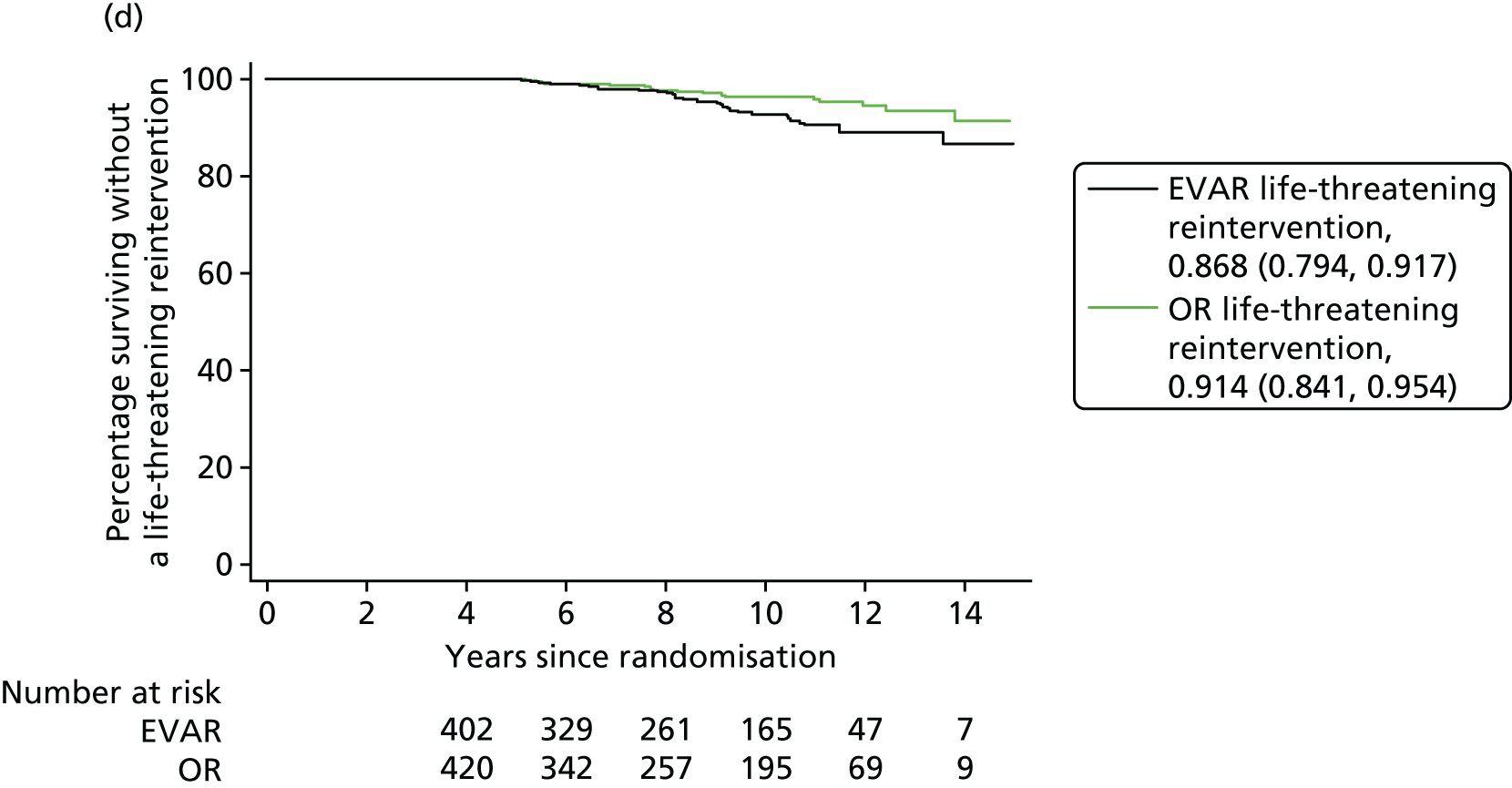

In the EVAR-1 analysis, time to first reintervention analyses were conducted separately for any graft-related reintervention, any serious reintervention (see two or three stars in Table 1) and any life-threatening condition (see four or five stars in Table 1). The criteria used to censor individuals are provided in Severity score for reinterventions. Further analyses were also undertaken in patients without any reintervention between randomisation and 2 years and without any reintervention between randomisation and 5 years.

All analyses were carried out in Stata version 13 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA). The Data Monitoring and Ethics Committee (DMEC) approved the statistical analysis plan.

Methods used for very long-term follow-up and changes to protocol

Patients in both trials were followed up comprehensively for rates of perioperative and late death, graft-related complications, reinterventions and resource use until September 2009. 94

By the end of the 10-year follow-up in September 2009, three of the participating centres had merged with other local participating centres into single NHS trusts (Leeds, Belfast and Glasgow). All the trial participants at four further centres that had recruited very small numbers of patients had died and so were also not included in late follow-up. A total of 31 centres therefore participated in late follow-up to 15 years. Ethics approval for extended patient follow-up was obtained on 16 February 2011 from the UK North West Multicentre Research Ethics Committee, which did not require patients to be reconsented for ongoing follow-up of the EVAR trials up to 15 years (reference number 98/8/26 for EVAR-1 and reference number 98/8/27 for EVAR-2). Patient consent for the ongoing audit of medical notes for follow-up was given by each patient before randomisation. The EVAR trials’ extended follow-up for both trial 1 and trial 2 was to be based on a review of hospital notes and continued flagging with the Medical Research Information Service for date and cause of death. As with the earlier follow-up, a lead clinician and a local co-ordinator were identified at each of the centres. The co-ordinator was to be remunerated for annual data extraction of clinical information from patient hospital notes relating to aneurysm-related complications and reinterventions from routine hospital visits for surveillance of the aneurysm repair for 2010–14.

Very long-term follow-up for reinterventions: October 2009 to March 2015

For the current phase of very long-term follow-up, funding was not achieved until 26 April 2012 and the trial manager was appointed on 1 December 2012. There was a delay in the signing of contracts between Imperial College London and the NIHR. The collaboration agreement was a four-way agreement that included the University of Cambridge (statistics) and the University of York (cost-effectiveness). Final contracts were not signed until 28 August 2013. In addition, local R&D approval was required from the 32 NHS trusts (30 in England, one in Scotland and one in Northern Ireland). First contact with each of the NHS trust R&D offices was made by the trial manager in December 2012. This process was not completed until 28 January 2014. A new case record form (see Appendix 1) was designed with the expectation of collecting data on complications and reinterventions retrospectively for 2010–12 from clinical notes review and then prospectively for a further 3 years. Imaging scans and reports were also gathered as well as information on adverse events such as strokes, myocardial infarctions (MIs), chronic renal failure and amputation.

Owing to the delays described above, prospective data collection did not start until late in 2013. After 1 year of data collection, it became clear that for EVAR-1 the majority of OR patients (72%) and some EVAR patients (32%) were no longer being followed up at the original trial centres and some hospital mergers had taken place leading to patients being followed up at non-trial hospitals. For EVAR-2, nearly all of the patients had died. At a meeting of the Data Management Subcommittee of the Trial Management Committee (TMC) on 4 November 2014, it was decided to obtain permission for record linkage follow-up for all English trial patients alive or lost to follow-up in September 2009, by obtaining administrative data for hospital readmissions and procedures for patients from EVAR-1 only. There were so few EVAR-2 patients surviving, that given the need to provide robust justification to obtain ethics approval for using administrative data, this option was not pursued for EVAR-2 patients.

Obtaining permission to do this was a two-stage procedure. As patients had not given consent for access to their routine hospital administrative data on enrolment during 1999–2004, we had to obtain ethics approval (section 251) from the Confidentiality Advisory Group (CAG) to enable disclosure of confidential patient information. This required a lengthy process to demonstrate our institution met the stringent information governance requirements. The application to the CAG was submitted on 23 September 2014 and approval was granted on 18 February 2015. The second part of the process involved an application for HES data, which was submitted on 19 February 2015. HES is a government data warehouse containing records of all patients, tracked by their unique NHS number, admitted to NHS hospitals in England and contains details of inpatient care, outpatient appointments and accident and emergency attendance records. HES data allowed us to obtain patient data on all hospital readmissions and procedures (with procedure coding) until 31 March 2015 for 655 of the 724 (90%) patients alive in September 2009, including 13 patients previously lost to follow-up. Only seven English patients evaded HES record linkage. All procedures identified via HES which were potentially related to the original aneurysm repair, including abdominal hernia repairs, were validated with the relevant trial centre or where possible with other non-trial hospitals. There was 89% concordance between administrative data and clinical site data.

Sixty-nine patients, including 62 in either Scotland or Northern Ireland, could not be followed up via HES, of whom 48 (70%) had local follow-up at the trial centre. These 48 patients included 8 out of 15 patients in Scotland, 38 out of 47 patients in Northern Ireland and two out of seven English patients who were unmatched by HES. There were no Welsh centres. This process of using complementary sources of information from record linkage with local validation increased the completeness of patient follow-up in EVAR-1 from 51% to 97%, with only 25 patients being lost to follow-up for reinterventions by 31 March 2015.

Given the time taken for this process, the NIHR agreed to the project end date being extended until 31 August 2016.

Severity score for reinterventions

There is no recognised reporting system for reintervention or reintervention severity, to facilitate allocation of resource use. Therefore, the grading of the severity of aneurysm-related reinterventions and the associated use of high dependency or intensive care (high-dependency unit; HDU/ICU) were obtained by a questionnaire that was sent to each of the principal investigators at the 32 trial centres. Thus the EVAR trials severity score obtained is shown in Table 1.

| Reintervention category | Severity | Mean estimated days in HDU | Mean estimated days in ICU |

|---|---|---|---|

| Conversion to OR | ***** | 2.1 | 1.9 |

| Reintervention for graft infection: OR | ***** | 2.9 | 2.9 |

| Reintervention for graft infection: EVAR | ***** | 2.3 | 0.7 |

| Reoperation of OR: OR | ***** | 2.5 | 2.7 |

| Known aneurysmal extension above or below original graft: OR | ***** | 2.2 | 1.6 |

| Known aneurysmal extension above or below original graft: EVAR | ***** | 1.3 | 0.5 |

| Replacement stent graft | ***** | 1.5 | 0.6 |

| Fenestrated EVAR | ***** | 1.7 | 0.3 |

| Axillobifemoral bypass graft | ***** | 1.2 | 0.0 |

| Added stent; proximal (type Ia endoleak) or distal (type Ib endoleak) | **** | 0.4 | 0.1 |

| Staple or ligation: EVAR | *** | 0.5 | 0.0 |

| Embolisation (of endoleak) | *** | 0.1 | 0.0 |

| Sclerosis of endoleaks | *** | 0.1 | 0.0 |

| Femorofemoral crossover graft | *** | 0.2 | 0.0 |

| Distal limb procedure/revascularisation: OR | *** | 0.6 | 0.0 |

| Distal limb procedure/revascularisation: EVAR | *** | 0.1 | 0.0 |

| Amputation | *** | 0.3 | 0.0 |

| Reintervention for thrombosis of graft limb: EVAR | ** | 0.6 | 0.2 |

| Reintervention for thrombosis of graft limb: OR | ** | 0.6 | 0.2 |

| Incisional hernia: OR | ** | 0.5 | 0.0 |

| False femoral aneurysm: OR | ** | 0.1 | 0.0 |

| Minor reintervention | * | 0.0 | 0.0 |

Reinterventions recorded during follow-up included those that took place during primary admission and subsequent admissions. Also included are previously ignored reinterventions for ORs [e.g. incisional hernias (see Table 1 for full list of reinterventions recorded)]. The date of any reintervention during the primary admission was taken to be the mid-point between the date of admission and the date of discharge or in-hospital death. The censoring time for reinterventions was determined as follows:

-

For all patients from Scotland and Northern Ireland and those from England unmatched in HES with a known follow-up in 2014/15, the date of their latest follow-up was used for censoring.

-

For alive patients in Scotland and Northern Ireland and those from England unmatched in HES without a follow-up in 2014/15, the date of last follow-up or the date of audit of their notes was used for censoring.

-

For all patients in England tracked via HES, censoring was taken as 31 March 2015, unless the date of death was earlier.

-

For dead patients without a follow-up in 2014/15, the date of death was used for censoring, providing it occurred within the year after their last follow-up or date their notes were audited, otherwise these latter dates were used for censoring.

Very long-term follow-up for complications: October 2009 to March 2015

As administrative data do not report complications, only reinterventions, this meant that it would no longer be possible to conduct a comparison of complication rates by randomised group. Complication data were obtained in satisfactory numbers only for analysis of complication rate by time period in the group randomised to EVAR.

Complications were only obtained from the trial centres using the new case record form for late follow-up (see Appendix 1). The new case record form was designed to capture all information about the cluster of complications identified by Wyss et al. 111 as preceding rupture as well as all reinterventions over the whole 5-year follow-up period. Trial centres were reminded that all patients should continue in regular follow-up (the protocol specified annual follow-up including clinical, imaging and serum creatinine level assessment) and all patients, including lapsed follow-ups, should be recalled for a final clinical and imaging follow-up in 2014. As previously, the management of aneurysm-related complications was left to the discretion of the trial centre.

Very long-term follow-up for mortality: October 2009 to June 2015

Follow-up for mortality was unchanged throughout the trial and data for the date, place and cause of death from the ONS were obtained from September 2009 to June 2015. These data, together with information about reinterventions, were assessed by the Endpoint Committee, who were blinded to randomised group and trial in which the patient participated. The committee considered all events from both EVAR-1 and EVAR-2.

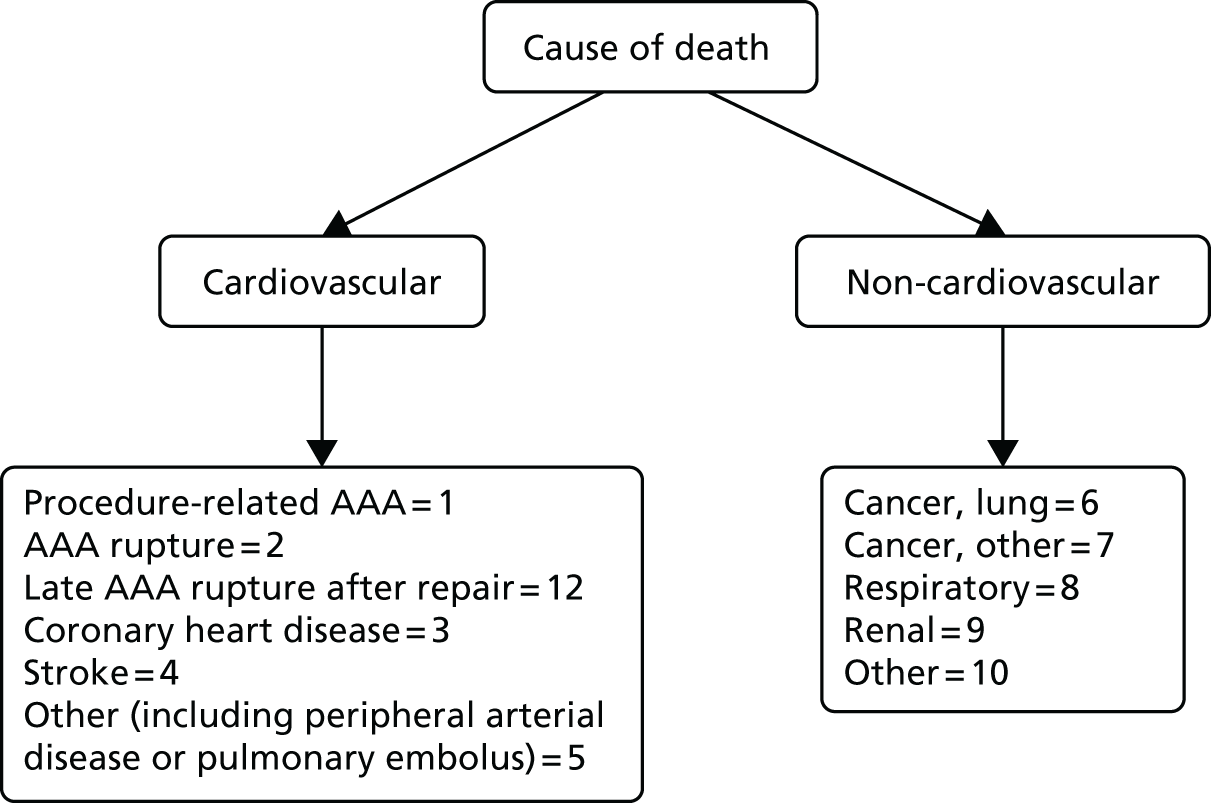

All death certificates were reviewed by an Endpoint Committee to agree cause of death (Figure 3). Aneurysm-related mortality was defined as all deaths (1) from aneurysm rupture before repair, (2) within 30 days of the primary procedure, (3) within 30 days of any reintervention attributable to the aneurysm, and (4) other aneurysm-related causes (including graft infection or fistula) or from secondary aneurysm rupture after repair. Deaths for which the underlying cause was attributed to International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Edition codes I713–719 were also classified as aneurysm related.

FIGURE 3.

Classification of death codes assigned by the Endpoint Committee.

Imaging follow-up

The original EVAR trials protocol included annual imaging via a CT scanning to record the aneurysm sac diameter in EVAR patients and anastomosis diameter in OR patients. For the late follow-up, wherever CT scanning was performed as part of routine follow-up, images were copied for transfer to the trial co-ordinating centre. After 2010, many of the centres had reverted to using duplex ultrasound and the number of CT scans available was largely curtailed. Often with duplex scans the infrarenal maximum outer-to-outer anteroposterior diameter is recorded. For EVAR, crucially, maximum sac diameter is an essential finding. Endoleaks and other complications were noted from the imaging reports reflecting the opinion of the local NHS radiologist. All CT scans that were available were examined in the trial centre core laboratory by a skilled and trained vascular fellow to note known factors associated with eventual secondary sac rupture.

Additional 231 patients not included in earlier reports

After publication of the 30-day mortality results (not the primary outcome of the trial), 26 of the 37 centres remained in equipoise and wished to continue randomising patients until the primary outcome results (mortality after minimum 1-year follow-up from randomisation) were available. The chairperson of the DMEC approved this further recruitment, provided it was undertaken as a separate study, which could report on these later cases, with more experienced clinicians responsible particularly for EVAR. Two hundred and thirty-one additional patients were therefore randomised to a separate study between 1 September 2004 and the publication of mid-term results on 15 June 2005 and are being reported for the first time. One hundred and seventy-five patients were randomised to either OR or EVAR in EVAR-1 and 56 patients to either EVAR or no intervention in EVAR-2 (total 231 patients). Patient follow-up for mortality was the same as for the main EVAR-1 and EVAR-2 patients. In EVAR-1 this included a further 175 patients who have now been included in sensitivity analyses for mortality. Of these 175 patients, 88 patients were randomised to the EVAR arm of the study, of whom 70 were alive in September 2009. Eighty-seven patients were randomised to the OR arm of the study, of whom 66 were still alive in September 2009. For EVAR-2, 28 patients were randomised to EVAR, of whom 11 were alive in September 2009 and 28 patients were assigned to the no-intervention arm, of whom eight were alive in September 2009. The delays described above made it very challenging to obtain retrospective follow-up data for these 231 patients. Evaluation of data collection for these patients by the Data Management Subcommittee of the TMC on 30 June 2014 showed follow-up information on only one-third. Where available, we therefore focused on obtaining details of the primary operation for these additional patients. This information included (1) the preoperative diameter of the aneurysm; (2) the date of operation; (3) whether the patient had an EVAR or OR; and (4) if EVAR, which device was used. All of these additional 231 patients were registered with the Medical Research Information Service for mortality reporting. This allowed the 175 EVAR-1 patients to be included in sensitivity analysis for all-cause mortality, but little else, including the impact of later generation endografts on complication and reintervention rates.

Data management

All data transferred to the co-ordinating centre at Imperial College London were entered into the trial database by the trial manager based at Charing Cross Hospital. Data were handled in a secure way according to good clinical trial practice with due consideration for patient data confidentiality. The pre-existing database and new database for late follow-up were both stored securely on a dedicated, stand-alone (non-networked) computer system that was maintained in a locked office. The system was protected by strong passwords and advanced encryption standard (14 rounds and a 256-bit key). It was accessible only to the trial manager and the data manager. The trial manager was the only person responsible for data entry. Data entry errors were assessed by carrying out double data entry on a randomly selected 10% of patients. The case record form used for late follow-up is included in Appendix 1.

The approval for obtaining HES data was granted on the condition that all data received should be stored on the Imperial College Healthcare NHS Trust system accessible to only the trial manager. The reason for this stipulation was the lack of a satisfactory information governance toolkit assessment at Imperial College London which the NHS trust had in place. The information governance toolkit is a performance tool produced by the Health and Social Care Information Centre for the Department of Health. It draws together legal rules and central guidance and presents them in one place as a set of information governance requirements. Organisations are required to carry out self-assessments of their compliance against these requirements, which include management structures and responsibilities, confidentiality and data protection and information security. A realistic time scale for completion of a satisfactory toolkit assessment is therefore in the order of several months, and in 2015 very few universities had a satisfactory assessment in place. This requirement was the reason for the delay in obtaining HES data and was satisfactorily resolved as a result of our institutions partnership with the NHS trust.

Computed tomography images that were transferred anonymously to the trial co-ordinating centre were also treated with the same level of security and confidentiality. These were subsequently transferred to the dedicated research workstation in the core laboratory at Charing Cross Hospital.

Patient and public involvement

Patient and public involvement has been a prominent aspect in the EVAR-1 and EVAR-2, and never more so than when explaining to patients the difference of the methods offered at randomisation. During follow-up we were increasingly concerned that failure to carry out clinical and imaging annual assessments could be detrimental to patient outcomes. Thus, the trial manager visited every trial centre co-ordinator who was given a copy of the Wyss paper (2010)111 to stress the need for ongoing follow-up and for this to be explained by them to patients.

In February 2015, we were granted approval to obtain confidential data on hospital admissions and procedures via HES. In June 2015, data were obtained for patients who were participants in EVAR-1 at hospitals in England and who had been lost to aneurysm-related follow-up. In order to obtain approval from the CAG we interviewed (face to face), trial patients at routine hospital visits. We explained to the patients that confidential records were held in a government database which stores information about all patient hospital visits in England. We asked them their view on access to confidential data from NHS and government records. All interviewed patients stated that they would be happy for us to access information in this way.

Organisational structure and committees

The late follow-up of the EVAR trials was managed centrally by the principal investigator (Professor Roger Greenhalgh), the trial manager (Dr Rajesh Patel) and Professor Janet Powell (co-applicant), who are based at the Charing Cross Hospital site of Imperial College London. Statistical expertise was provided by Dr Michael Sweeting (University of Cambridge) and costs and cost-effectiveness expertise were provided by Dr David Epstein who related to Professor Mark Sculpher (University of York).

Trial Management Committee

This committee was concerned with the day-to-day running of the trials and related to both the DMEC and the Trial Steering Committee. It was chaired by Professor Roger Greenhalgh and members included Professor Janet Powell (vascular biology), Dr Michael Sweeting (statistics), who related to Professor Simon Thompson, Dr David Epstein (health economics), Mr Colin Bicknell (vascular surgeon), Miss Regula Von-Allen (vascular surgeon), Mr Thomas Wyss (imaging core laboratory) and Dr Nick Burfitt (interventional radiologist). Dr Rajesh Patel (trial manager) attended all meetings to update committee members on trial progress and highlight any problematic issues.

Data Monitoring and Ethics Committee

This committee was regularly updated on trial progress and the DMEC communicated with the Trial Steering Committee. The committee was chaired by Professor Gerry Fowkes and included Dr Robert Morgan from the British Society of Interventional Radiology and Professor Bruce Campbell from the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE).

Trial Steering Committee

This committee was chaired by Professor Richard Lilford (University of Birmingham) and included Roger Greenhalgh for the applicants and TMC, as well as Michael Wyatt (Newcastle), Simon Thompson (statistics) and Mark Sculpher (health economics). The role of the committee was to liaise between the DMEC and TMC and oversee any issues relating to the progress of the trials or needs for additional funding.

Endpoint Committee

This committee was chaired by Professor Janet Powell and included an independent vascular surgeon (Professor Alison Halliday) and a consultant cardiologist (Dr Simon Gibbs). All death certificates were centrally coded at the ONS and were reviewed by this committee in relation to any aneurysm-related procedures. All available data relating to the death and a primary underlying cause of death were classified according to the groupings presented in Figure 3, where death codes 1, 2 and 12 were classified as aneurysm related. Aneurysm-related deaths were defined as all deaths occurring within 30 days of the primary aneurysm repair or any reintervention for a graft-related complication unless over-ruled by post-mortem findings or a separate procedure (unrelated to the aneurysm) that took place between the aneurysm intervention and death (code 1); all deaths from rupture of an unrepaired aneurysm (code 2); and all deaths from rupture of a repaired aneurysm, usually endograft rupture (code 12). In addition, late complications of aneurysm repair, such as aortoduodenal fistula or bowel obstruction, were recorded as procedure-related deaths (code 1).

Chapter 3 Results for EVAR trial 1

Patients

From 1 September 1999 until 31 August 2004, we recruited 1252 patients to participate in this trial, who were equally, and randomly, assigned to the two treatment groups. There were no differences in baseline characteristics between the groups, mean age 74 years, 1135 men (Table 2). 101

| Baseline characteristics by randomised group for EVAR trial 1 | ||

|---|---|---|

| Baseline characteristica | EVAR (n = 626) | OR (n = 626) |

| Age (years) | 74.1 (6.1) [0] | 74.0 (6.1) [0] |

| Number of males (%) | 565 (90) [0] | 570 (91) [0] |

| AAA diameter (cm) | 6.4 (0.9) [0] | 6.5 (1.0) [1] |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 26.5 (4.6) [1] | 26.5 (4.3) [6] |

| Diabetes (%) | 61 (10) [2] | 68 (11) [6] |

| Smoking status (%) | [1] | [1] |

| Current | 134 (21) | 136 (22) |

| Past | 419 (67) | 444 (71) |

| Never | 72 (12) | 45 (7) |

| History of cardiac diseaseb (%) | 269 (43) [0] | 261 (42) [0] |

| Systolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 148 (22) [5] | 147 (21) [2] |

| Diastolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 82 (12) [7] | 82 (13) [3] |

| ABPI (mean of both legs) | 1.01 (0.18) [13] | 1.03 (0.18) [27] |

| FEV1 (l) | 2.1 (0.7) [8] | 2.2 (0.7) [4] |

| Serum creatinine level (µmol/l)a | 102 (91–118) [1] | 102 (90–120) [4] |

| Serum cholesterol level (mmol/l) | 5.1 (1.2) [18] | 5.1 (1.1) [25] |

| Statin use (%) | 216 (35) [7] | 224 (36) [3] |

| Aspirin use (%) | 338 (54) [0] | 325 (52) [0] |

Baseline characteristics were compared between randomised groups and no differences were observed.

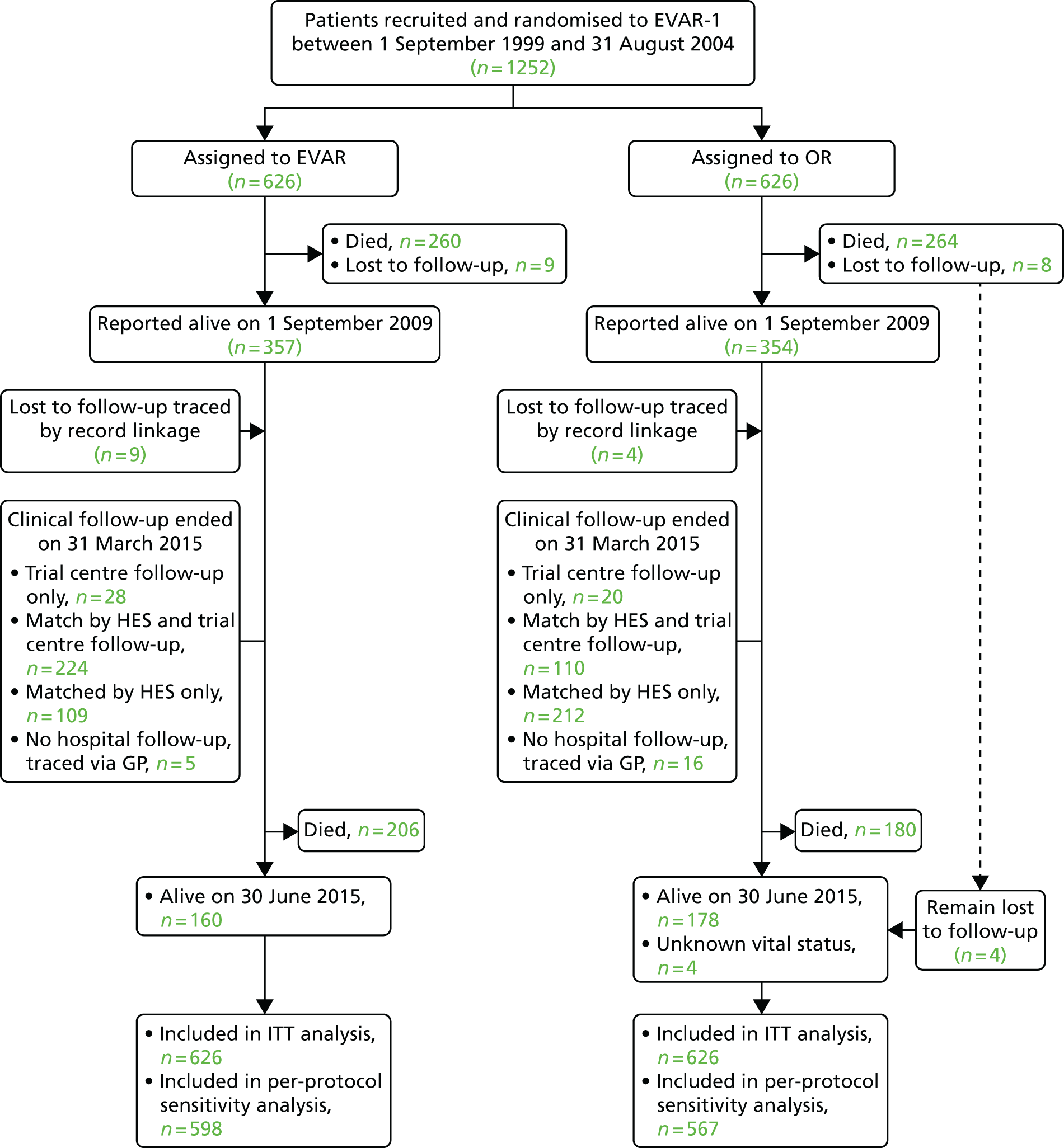

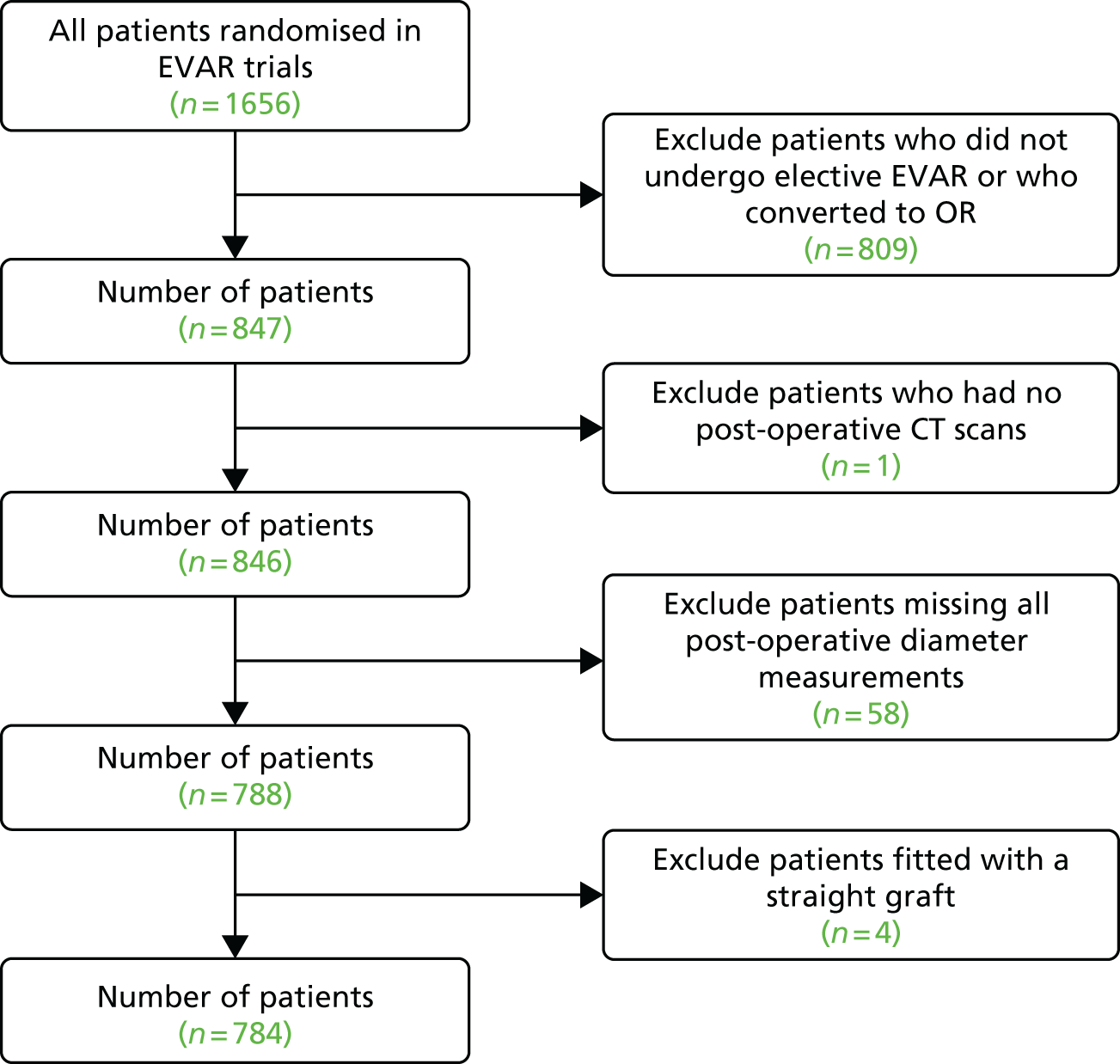

Patients were followed until 30 June 2015 (mean 12.7 years; median 12.4 years; minimum 1.8 years; maximum, 15.8 years); mean person-years observation to either death or end of the study was 8.0 years. By 30 June 2015 only four patients were lost to follow-up for mortality and 25 for reinterventions (this includes five patients in the EVAR group and 20 patients in the OR group), with data now available from record linkage for 13 of the 17 patients previously lost to mortality follow-up (Figure 4).

FIGURE 4.

CONSORT diagram for mortality and reinterventions. GP, general practitioner.

For 13 individuals, a cause of death was established based only on a death certificate. Annual clinical follow-up with CT scanning or duplex imaging reduced steadily over the period of the trial and was consistently lower in the OR group (Table 3).

| Years since randomisation | EVAR, n/N (%) | OR, n/N (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CT | Duplexa | CT | Duplexa | |

| < 1 | 532/581 (92) | 55/566 (10)b | ||

| 1–2 | 448/543 (83) | 414/534 (78) | ||

| 2–3 | 419/503 (83) | 363/500 (73) | ||

| 3–4 | 354/474 (75) | 306/464 (66) | ||

| 4–5 | 291/443 (66) | 262/439 (60) | ||

| 5–6 | 271/409 (66) | 221/399 (55) | ||

| 6–7 | 183/370 (49) | 24/56 (43) | 144/370 (39) | 6/52 (12) |

| 7–8 | 139/339 (41) | 59/147 (40) | 97/333 (29) | 6/139 (4) |

| 8–9 | 111/297 (37) | 70/189 (37) | 58/284 (20) | 9/172 (5) |

| 9–10 | 72/263 (27) | 73/208 (35) | 26/257 (10) | 11/212 (5) |

| 10–11 | 47/220 (21) | 69/214 (32) | 8/224 (4) | 15/219 (7) |

| 11–12 | 24/135 (18) | 42/135 (31) | 6/143 (4) | 13/143 (9) |

| 12–13 | 12/74 (16) | 20/74 (27) | 1/83 (1) | 13/83 (16) |

| 13–14 | 3/41 (7) | 9/41 (22) | 2/50 (4) | 6/50 (12) |

| 14–15 | 0/9 (0) | 2/9 (22) | 0/12 (0) | 0/12 (0) |

Over the course of follow-up, CT was carried out a median of six (interquartile range 3–8) times per patient in the EVAR group and three (interquartile range 1–6) times in the OR group. Of the patients who had not had death reported by 1 September 2009, 655 of 728 (90%) patients were tracked with HES, including 13 patients previously lost to follow-up, with local follow-up reported in 48 (70%) of the remaining patients (see Figure 4). After publication of the 30-day mortality results,100 26 of the 37 trial centres remained in equipoise and continued recruitment into a separate study from 1 September 2004 until 15 June 2005, when primary outcome results were published,101 with a further 175 patients not reported previously but now used in sensitivity analyses for mortality only. Operative characteristics are shown for the 1252 patients in the EVAR-1 in Table 4a and the additional 175 patients in Table 4b.

| Baseline characteristica | EVAR (n = 626) | OR (n = 626) |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 74.1 (6.1) | 74.0 (6.1) |

| Number of males (%) | 565 (90) | 570 (91) |

| Mean AAA diameter (cm) | 6.4 (0.9) | 6.5 (1.0) |

| Procedure received | ||

| EVAR | 598 | 31 |

| OR | 16 | 571 |

| None | 12 (all died before operation) | 24 (including five who refused) |

| Unknown | 0 | 0 |

| Baseline characteristica | EVAR (n = 88) | OR (n = 87) |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 75.1 (5.9) | 75.1 (5.9) |

| Number of males (%) | 83 (94) | 81 (93) |

| Mean AAA diameter (cm) | 6.5 (1.1) | 6.4 (0.8) |

| Procedure received | ||

| EVAR | 73 | 5 |

| OR | 3 | 61 |

| None | 3 | |

| Unknown | 12 | 18 |

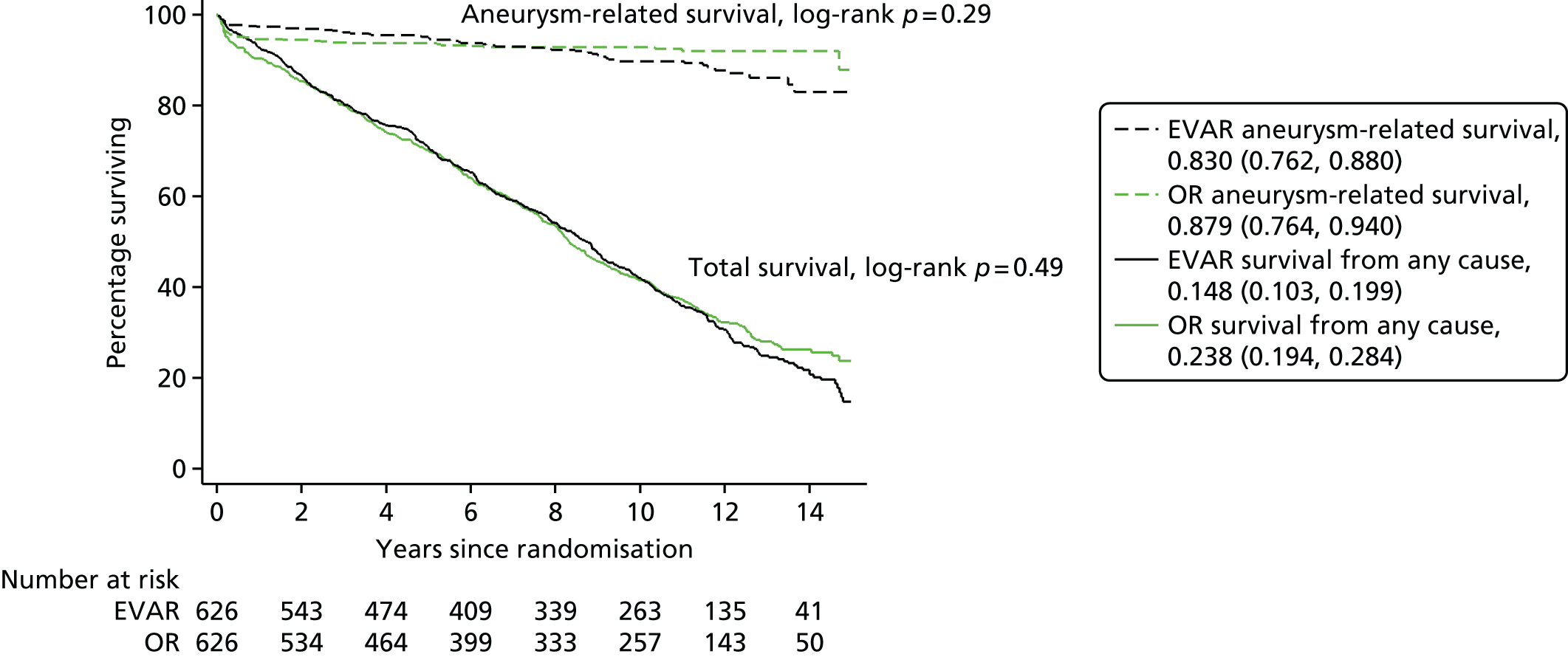

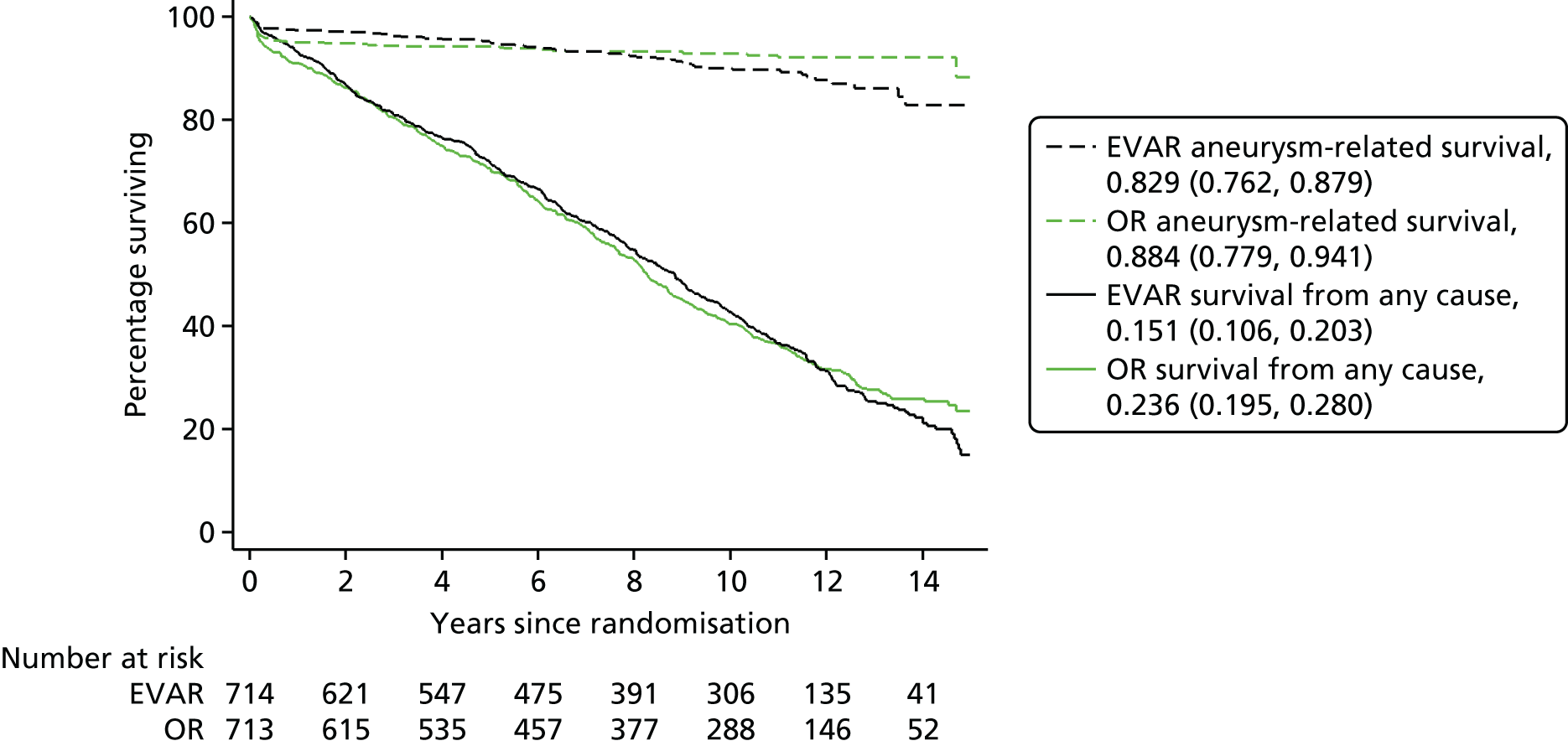

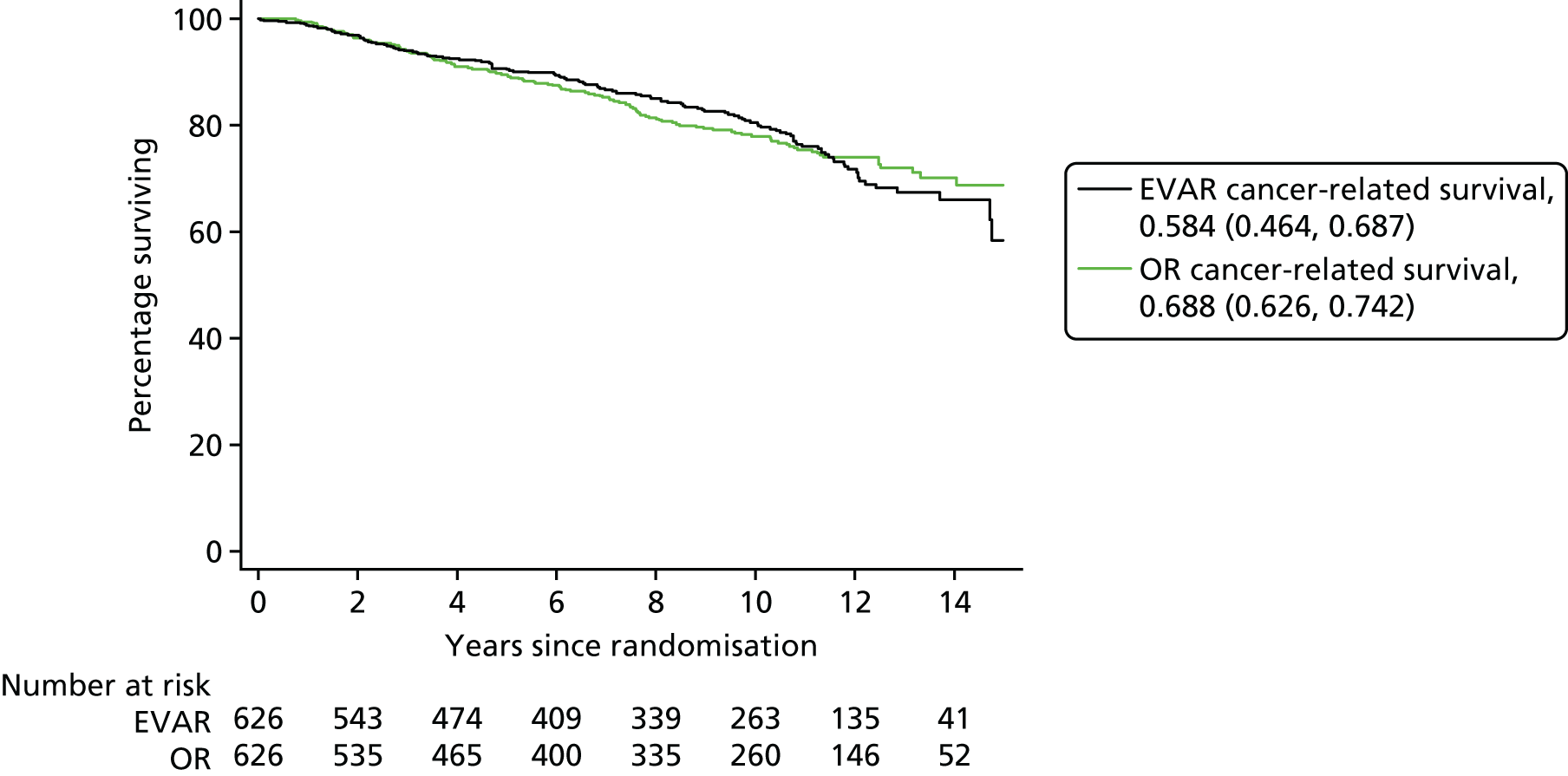

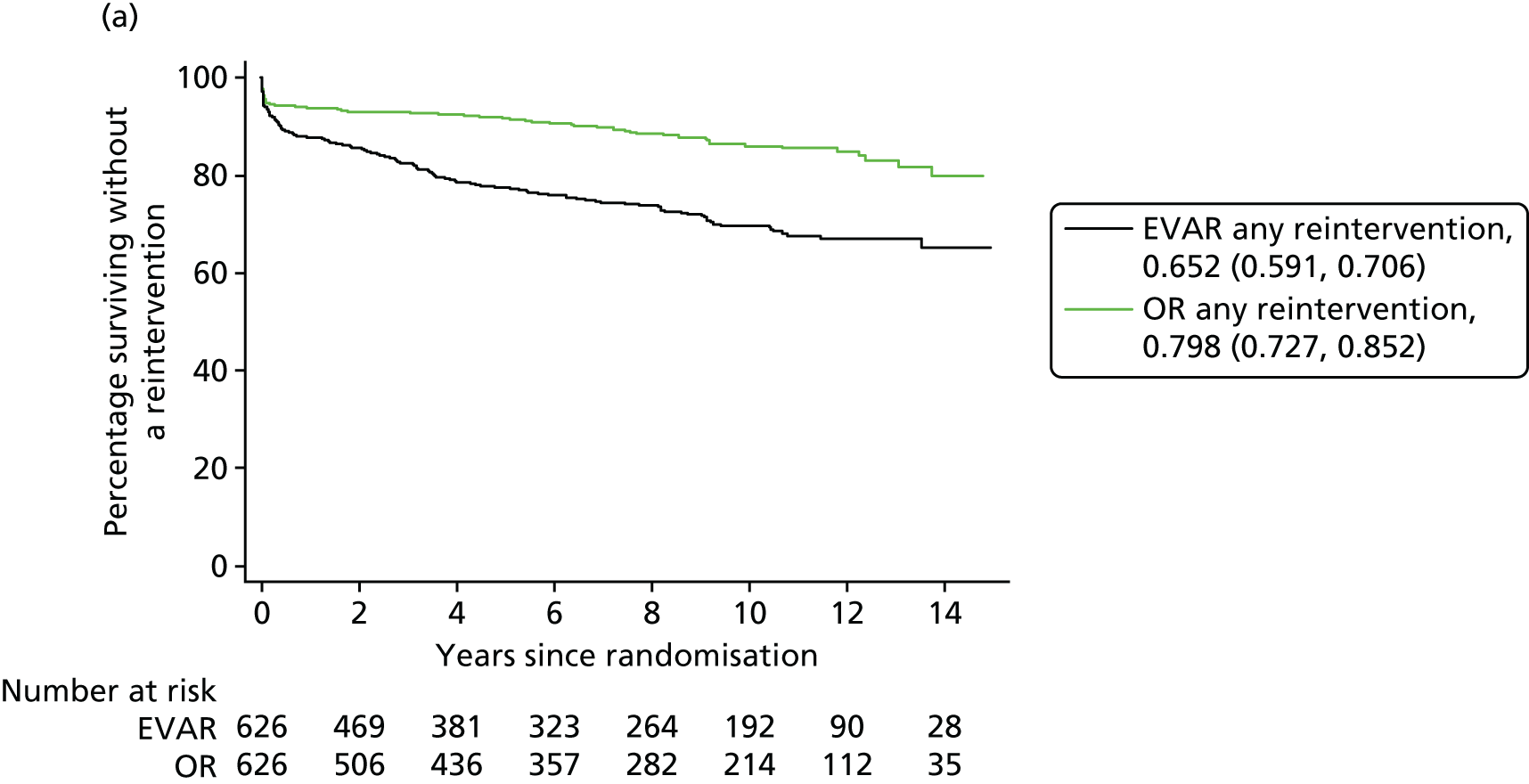

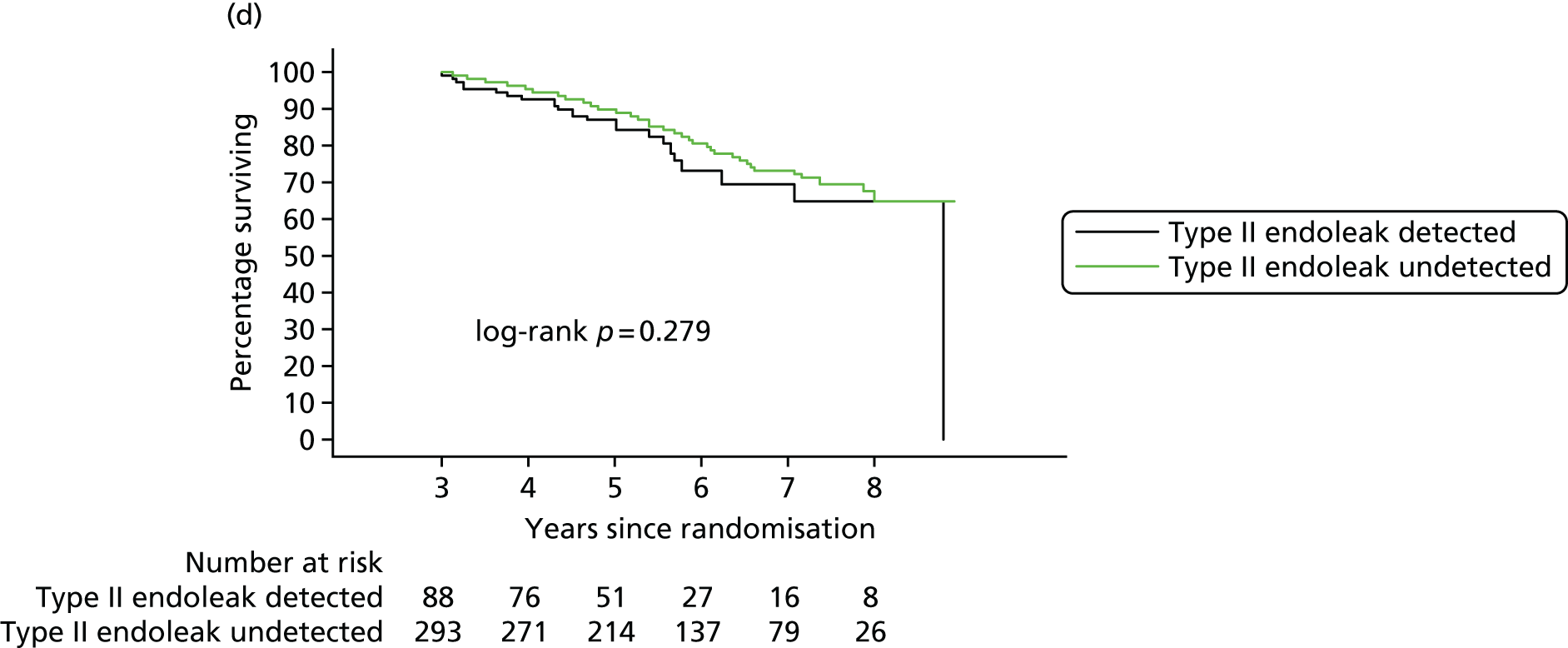

Aneurysm-related and total mortality