Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 06/38/01. The contractual start date was in September 2009. The draft report began editorial review in September 2016 and was accepted for publication in June 2017. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Keith Greene is the founder and shareholder of K2 Medical Systems (Plymouth, UK) and Clinical Director for the development of the INFANT system. Christopher Mabey is employed by, and is a shareholder of, K2 Medical Systems, the technology provider for the study. Edmund Juszczak reports grants from the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Health Technology Assessment (HTA) and Efficacy and Mechanism Evaluation programmes during the conduct of the study, and is a member of the NIHR HTA Commissioning Board. Peter Brocklehurst reports grants and personal fees from the Medical Research Council and grants from the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, NIHR Health Services and Delivery Research, NIHR HTA and Wellcome Trust, outside the submitted work, and is chairperson of the NIHR HTA Women and Children’s Health panel and is a member of the HTA Prioritisation Group. Sara Kenyon is a member of the NIHR HTA Women and Children’s Health panel and received NIHR funding to undertake the HOLDS (High Or Low Dose Syntocinon® for delay in labour) trial, and was part funded by the NIHR Collaboration for Leadership in Applied Health Research and Care West Midlands.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2018. This work was produced by Brocklehurst et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2018 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Introduction

The justification for the trial, the supporting literature and the methods of the trial were published as a trial protocol in BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth. Sections of this chapter are reproduced from Brocklehurst. 1 This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited. The text below includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original text.

Continuous electronic fetal monitoring (EFM) in labour is widely used throughout the developed world. However, its potential for improving fetal and neonatal outcomes has not been realised. The reasons for this are probably complex, but are likely to include difficulty of interpreting the fetal heart rate trace correctly during labour, when the birth attendant has many competing tasks. For intrapartum monitoring to improve fetal and neonatal outcomes, the interpretation of the fetal heart rate has to be substantially and consistently improved. This standard has to be sustained and be independent of any health professional’s individual ability. Computerised interpretation of the fetal heart rate and intelligent decision support has the potential to deliver this improvement in care. The aim of EFM is to detect abnormalities of the fetal heart rate pattern during labour that are associated with asphyxia so that action can be taken to expedite delivery and prevent stillbirth and the development of neonatal encephalopathy (NNE). Therefore, the potential benefits of EFM are immense. Prevention of even a modest proportion of perinatal asphyxia will improve the health and well-being of thousands of children and their families throughout the world each year. In addition, the cost to the NHS Litigation Authority (NHSLA) for obstetrics is very large and rising. EFM could contribute to a substantial reduction. Furthermore, if this technology can work in the complex process of labour, it also has the potential to improve patient safety in a wide range of health-care settings.

The problem of perinatal asphyxia

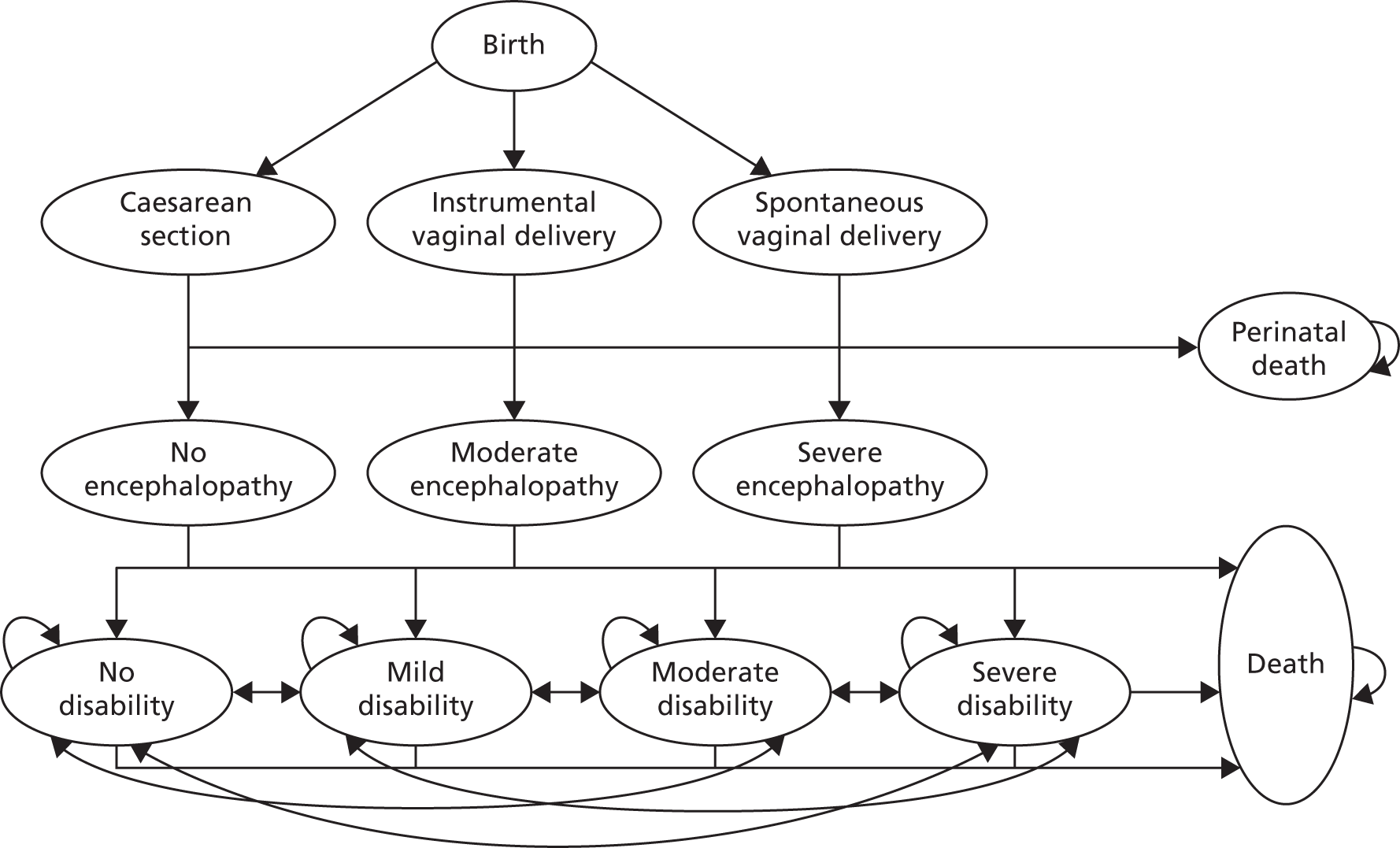

Perinatal asphyxia, if severe, can result in intrapartum stillbirth. If less severe, it results in the development of an encephalopathic state in the newborn. This is characterised by a decreased level of consciousness, altered reflexes, abnormal tone and ultimately permanent damage to the brain. Moderate or severe NNE occurs in approximately 2 out of 1000 births. 2 With more severe asphyxial encephalopathy there is an increased risk of death or neurodevelopmental abnormalities: 25% of infants who have moderate asphyxial encephalopathy will develop cerebral palsy and around 80% of infants who have severe encephalopathy and survive will develop cerebral palsy. 3 Perinatal asphyxia may account for up to 30% of all cases of cerebral palsy4 and it is a very significant health-care and financial burden on the NHS. A reduction in the number of babies born with perinatal asphyxia would reduce the associated mortality and, among survivors, the burden of ill health and incapacity. It could also result in substantial savings in litigation costs in the UK.

Efficacy of continuous electronic fetal monitoring

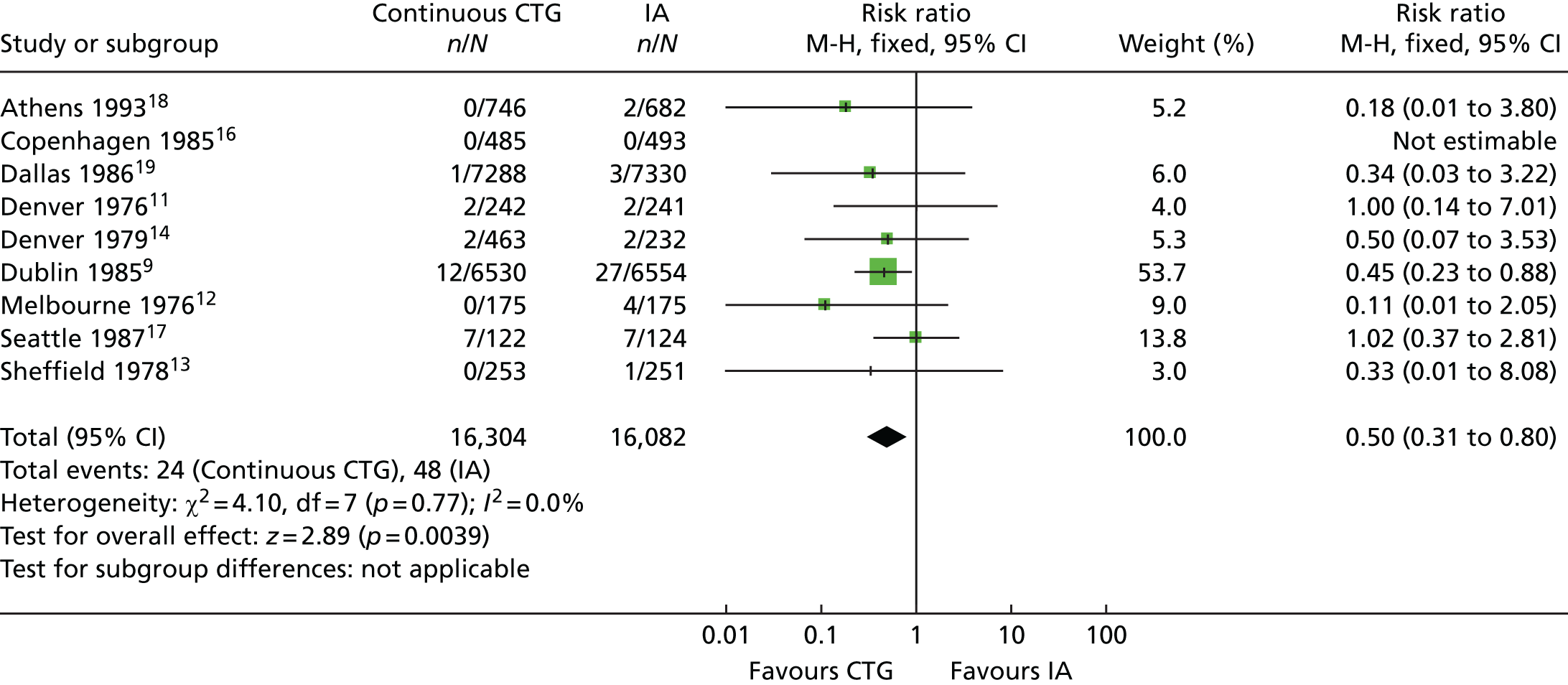

Continuous electronic fetal monitoring was invented in the 1960s. 5,6 The recorder displays the fetal heart rate and maternal uterine activity on a continuous line graph, called the cardiotocograph (CTG) tracing. EFM was widely introduced in the 1970s7 and it became controversial in the 1980s when it was shown to poorly predict Apgar scores and fetal acid–base status at delivery. 8 The largest randomised controlled trial (RCT) (the Dublin trial) showed no reduction in perinatal mortality or in cerebral palsy using EFM. 9 However, systematic reviews and meta-analyses of all trials indicated some benefits of EFM: for example, a 58% reduction in odds of deaths attributable to intrapartum hypoxia [95% confidence interval (CI) 2% to 83%]10 (Table 1) and a 50% reduction in risk of neonatal seizures (95% CI 20% to 69%) (Figure 1). 20 EFM is widely used on many women during labour in the UK. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidelines for fetal monitoring in the NHS detail explicit criteria for implementing EFM; as a result, EFM is carried out in capproximately 60% of all women in labour. 21 EFM has been shown to be associated with an increase in caesarean sections and instrumental vaginal births. In a review of 11 trials involving a total of 18,961 women, there was a 63% increase in the odds of a caesarean section (95% CI 1.29 to 2.07), and in 10 trials involving a total of 18,615 women there was a 15% increase in the odds of an instrumental vaginal birth (95% CI 1.01 to 1.33). 20

| Study and year of publication | Patients in the (n) | Perinatal deaths (n) | Perinatal deaths as a result of fetal hypoxia (n) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EFM group | IA group | EFM | IA | EFM | IA | |

| Haverkamp et al., 197611 | 242 | 241 | 2 (FD 0, ND 2) | 1 (FD 0, ND 1) | 0 | 0 |

| Renou et al., 197612 | 175 | 175 | 1 (FD 0, ND 1) | 1 (FD 1, ND 0) | 0 | 1 (FD) |

| Kelso et al.,197813 | 253 | 251 | 0 | 1 (FD 0, ND 1) | 0 | 1 (ND) |

| Haverkamp et al., 197914 |

230 229 |

231 | 3 (FD 0, ND 3) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Wood et al., 198115 | 445 | 482 | 1 (FD 0, ND 1) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| MacDonald et al., 19859 | 6474 | 6490 | 14 (FD 3, ND 11) | 14 (FD 2, ND 12) | 7 (FD 3, ND 4) | 7 (FD 2, ND 5) |

| Neldam et al., 198616 | 482 | 487 | 0 | 1 (FD 1, ND 0) | 0 | 1 (FD) |

| Luthy et al., 198717 | 122 | 124 | 17 (FD 1, ND 16) | 18 (FD 1, ND 17) | 0 | 1 (FD) |

| Vintzileos et al., 199318 | 746 | 682 | 2 (FD 0, ND 2) | 9 (FD 2, ND 7) | 0 | 6 (FD 2, ND 4) |

| Total | 9398 | 9163 | 40 (4.2/1000) | 45 (4.9/1000) | 7 (0.7/1000)a | 17 (1.8/1000)a |

FIGURE 1.

The effect of EFM vs. intermittent auscultation on the incidence of neonatal seizures. Review: continuous cardiotocography as a form of EFM for fetal assessment during labour; comparison: continuous cardiotocography vs. intermittent auscultation; outcome: 26 neonatal seizures. CTG, cardiotocography; df, degrees of freedom; FBS, fetal blood sample; IA, intermittent auscultation; M-H, Mantel–Haenszel.

Human error and systems failure

In the late 1980s it became apparent that a human element might be a factor in the failure of EFM to deliver improved outcomes. In one case–control study, the intrapartum management of 38 babies severely asphyxiated at birth was compared with that of 120 controls. 22 Cardiotography was abnormal in 29% of babies in the control group, but in only 9% was the abnormality severe. In contrast, 87% of the babies asphyxiated at birth had an abnormal CTG and in 61% of cases the abnormality was severe. However, the most striking finding was the length of time required for the staff to recognise the CTG abnormality. With moderate abnormalities, the mean time until recognition was 91 minutes [standard deviation (SD) 61 minutes]; paradoxically, with severe abnormalities it was 128 minutes (SD 100 minutes). The authors could give no plausible reason for the standard of CTG interpretation being so poor. However, it was clear from this study that, if the quality of interpretation of the intrapartum CTG had been higher, the benefits from EFM would almost certainly have been significantly and substantially enhanced.

In 1990, Ennis and Vincent published the results of their study of 64 cases of poor perinatal outcome from the archives of the Medical Protection Society. 23 In 11 cases, EFM was not performed, despite being indicated, and in six cases the technical quality of the tracing was inadequate. In 19 cases the CTG trace was missing, and in 14 cases a significant abnormality in the CTG trace either was unnoticed or did not result in any action being taken; in only 14 cases was appropriate monitoring performed and action taken. In only 16 cases was a consultant involved to aid in the interpretation of the CTG. In a further case–control study based in Oxford, published in 1994, intrapartum care was assessed in 141 cases of cerebral palsy and in 62 perinatal deaths with a probable intrapartum cause. 24 The authors found that, compared with control babies, abnormal fetal heart rate patterns were 2.3 times as common in babies who went on to develop cerebral palsy and 6.7 times as common in fetuses that died in the perinatal period. In addition, the authors found that clinicians failed to respond to these clear signs of abnormality in 26% of cerebral palsy cases and 50% of perinatal deaths, compared with 7% of control cases. On the basis of these figures, it can be estimated that approximately one case of cerebral palsy and one perinatal death can possibly be prevented in every 4500 deliveries. If one assumes 700,000 births per annum in the UK, 174 cases of cerebral palsy and 158 perinatal deaths could be prevented each year. Stewart et al. 25 reported that perinatal mortality in the UK is twice as high at night as during the day, and twice as high in July and August as in the rest of the year. They suggested that excess deaths may be because of over-reliance on inexperienced staff at night and a shortage of staff during the peak summer holiday months; they also suggested that the excess might be related to physical and mental fatigue of the caregivers. In 1999, the Confidential Enquiry into Stillbirths and Deaths in Infancy (CESDI) studied the proportion of 567 cases for which there was evidence of suboptimal care in labour. CESDI then looked at whether or not improved care could possibly or probably have prevented the adverse outcome. 26 Suboptimal care was identified in 71% of cases; a better outcome could possibly (in 28% of cases) or probably (in 22% of cases) have been anticipated, if care had been adequate. The report authors noted that interpretation of the CTG remained the most frequent problem identified as a cause of suboptimal care.

Does improving training solve the problem?

In a study of the efficacy of intrapartum intervention, Young et al. 27 found evidence of substandard care in labour in 74% of babies with low Apgar scores. Following the introduction of regular audit of low Apgar scores, with intensive feedback to clinical staff, this proportion fell to 23%, but then increased to 32% over the following year. However, following the introduction of compulsory training in CTG interpretation for all staff, the proportion of low Apgar score cases associated with substandard care fell back once again to only 9%. It is clear from this study that improved interpretation of CTGs during labour can bring about a striking increase in the quality of care, with measurable impacts on neonatal condition. However, intensive education is not sustainable in most clinical settings. With recent changes in the training of junior medical and midwifery staff, it is clear that there is a need to develop other systems that are less reliant on individual motivation and training. These systems need to work equally well, regardless of the time of day, day of the week, month of the year, and the level of staffing on the labour ward.

Litigation and the costs to families and society

Maternity services are associated with far higher litigation costs than other services. This is reflected in the various arrangements for the development of risk management standards across the UK (Clinical Negligence Scheme for Trusts in England; Welsh Risk Pool; Clinical Negligence and Other Risks Indemnity Schemes and NHS Quality Improvement Scotland in Scotland).

The total cost of claims reported to the NHSLA over the period 1996–2006 was £3.8B [Great British pounds (GBP)]. The annual figures for the value of maternity claims paid out (Table 2) demonstrate an increase of almost sixfold over the last 13 years and the rate of increase shows no signs of slowing. In response to a parliamentary question on 29 January 2007, it was stated that the total NHS compensation payout in 2006 was £593M, with £68M resulting from just 10 cases, all of which were related to pregnancy and childbirth. By 2015/16, the total payout had risen to £1.488B, with £578M being attributable to maternity cases alone. 28 In 2007, the BBC reported a settlement of £6M for a child with cerebral palsy after doctors were alleged to have mismanaged the birth. 29 By 2015, the cost of a single case of cerebral palsy had risen to over £10M. 30 Even successful defence can cost up to £0.5M. In 2016, the NHSLA reported that the annual value of submitted claims related to pregnancy-related cerebral palsy had risen from £354M in 2004/5 to £989.7M in 2015/16. 28 In 2000, the British Medical Journal highlighted the importance of ‘system errors’ in medical disasters31 and analogies were drawn with errors in aviation. It suggested that some techniques used in this industry could be applied effectively to medical care, such as safety drills, revalidation, ‘nearmiss’ reporting and a ‘no blame’ culture. The role of expert systems and ‘intelligent alarms’ was highlighted.

| Year maternity claims paid out | Total cost in millions (GBP) |

|---|---|

| 2003/4 | 96 |

| 2004/5 | 121 |

| 2005/6 | 144 |

| 2006/7 | 171 |

| 2007/8 | 162 |

| 2008/9 | 222 |

| 2009/10 | 197 |

| 2010/11 | 234 |

| 2011/12 | 422 |

| 2012/13 | 508 |

| 2013/14 | 458 |

| 2014/15 | 501 |

| 2015/16 | 578 |

The potential solution: development of the intelligent decision support software

A group in Plymouth has been working on the problem of resolving human error in the management of labour for many years [Medical Research Council (MRC) funded for 10 years] and has developed intelligent computer systems as decision aids to support clinicians. The group was funded by the MRC for development and clinical validation of a decision support tool for the management of labour using the CTG. It comprises feature extraction of all relevant data from the CTG and clinical history which have been found to influence clinicians’ decision-making, and then an analysis of these within a rule-based expert system. The specific piece of decision support software to be evaluated in INFANT has been designed by K2 Medical Systems (Plymouth, UK) (a spin-off company from the University of Plymouth) to run on the K2 Medical Systems data collection system (Guardian®). Guardian is a system for managing information from labour monitoring.

The data collection system (Guardian)

The Guardian system consists of a medical-grade personal computer (PC) platform (Figure 2) that meets the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency standards for a class IIa device. The design has been informed by user preference studies and ethnographic and audio-visual observations of clinical care and decision-making. 32,33 It has a touch-screen user interface (Figure 3) and is connected to a conventional CTG recorder at the woman’s bedside.

FIGURE 2.

Guardian system: example of hardware.

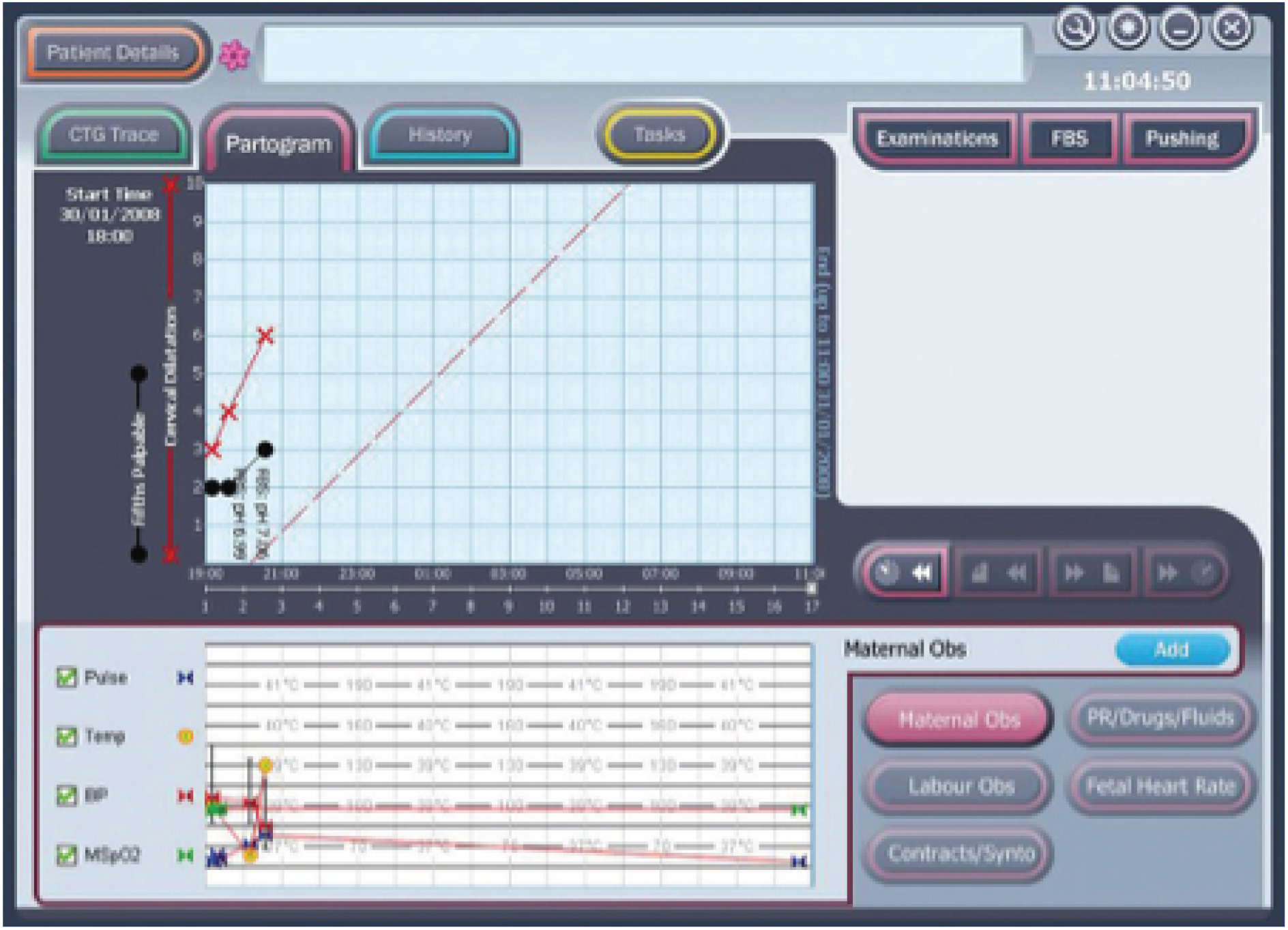

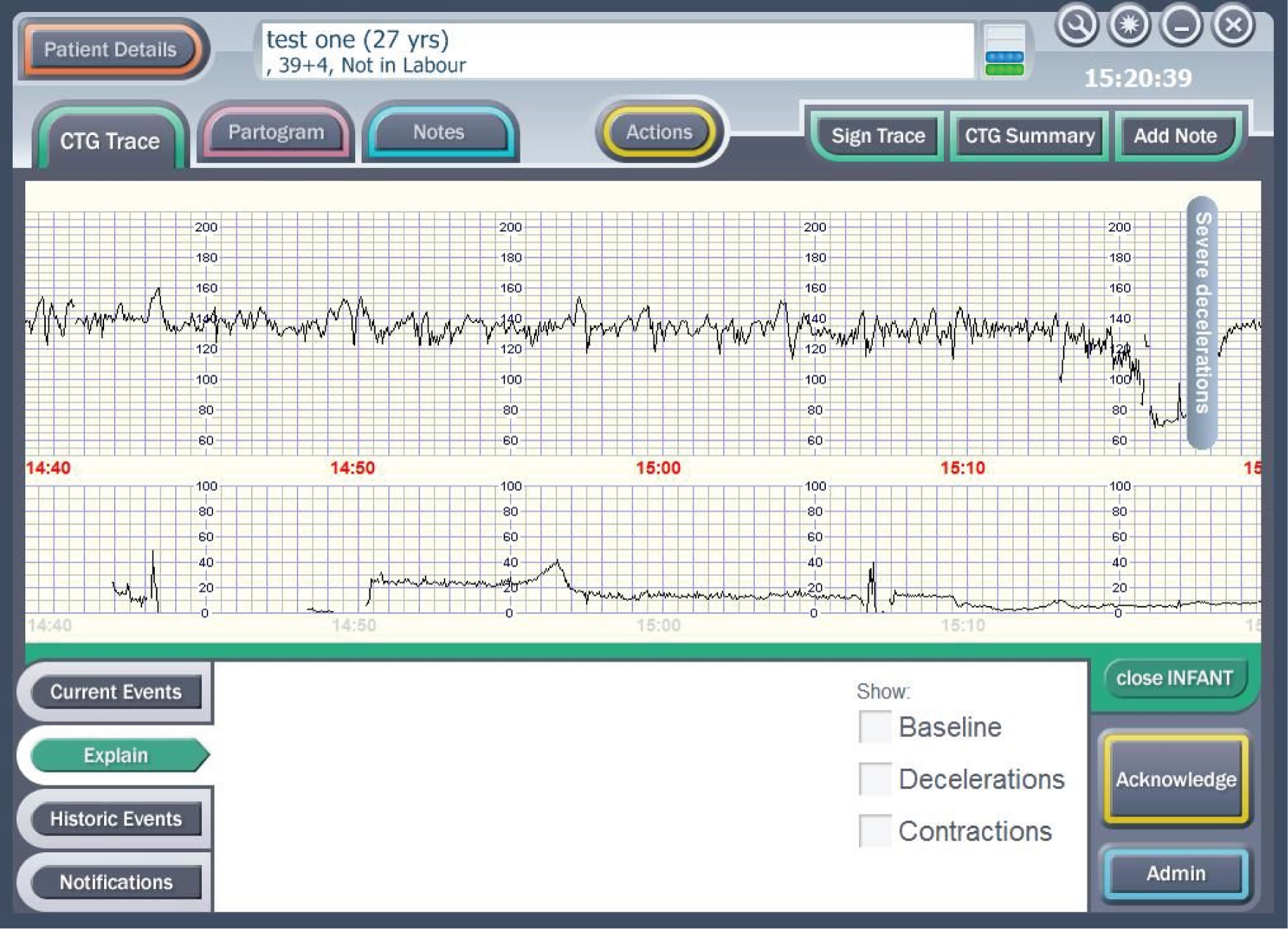

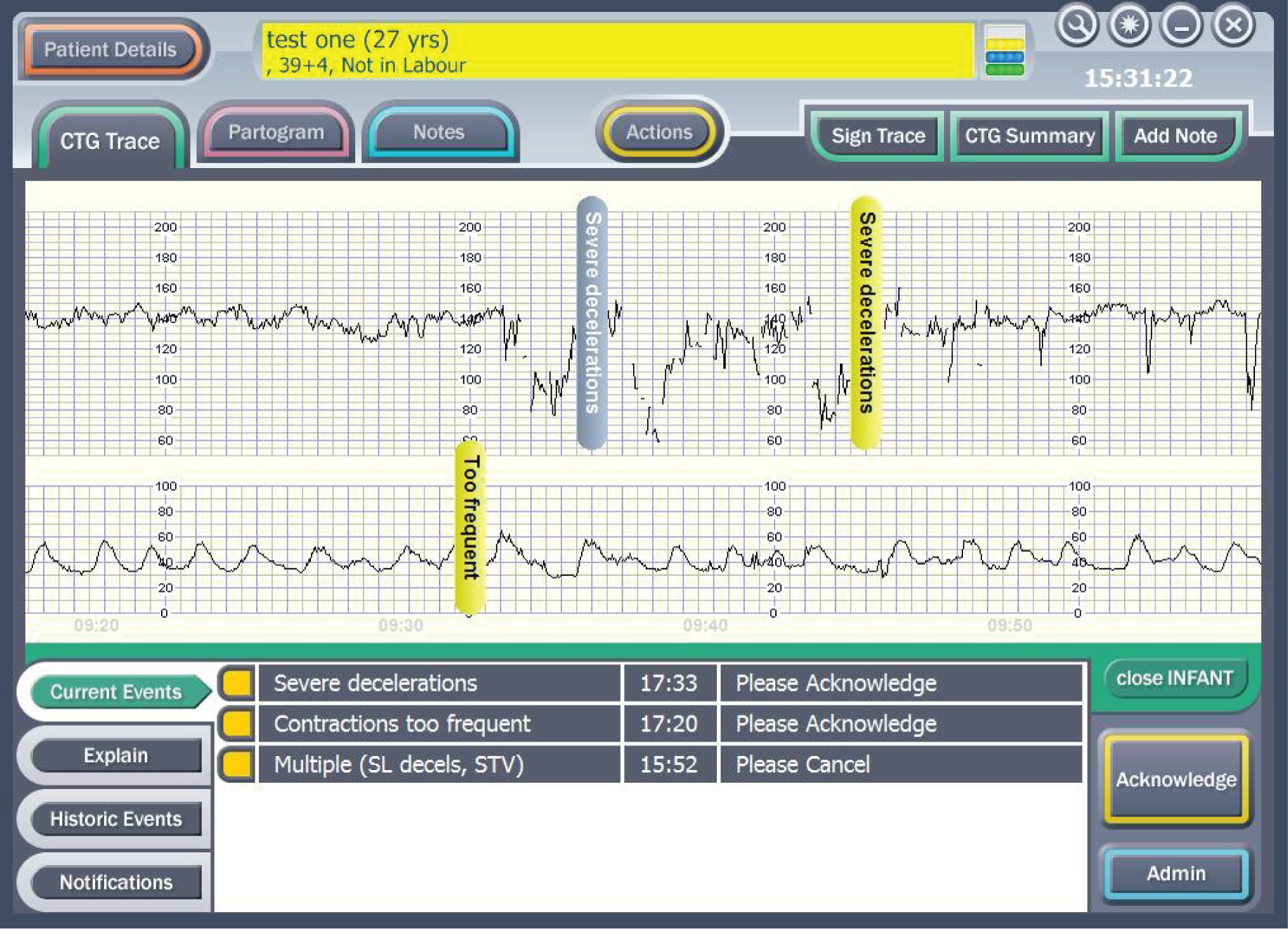

FIGURE 3.

Guardian system: example of screen.

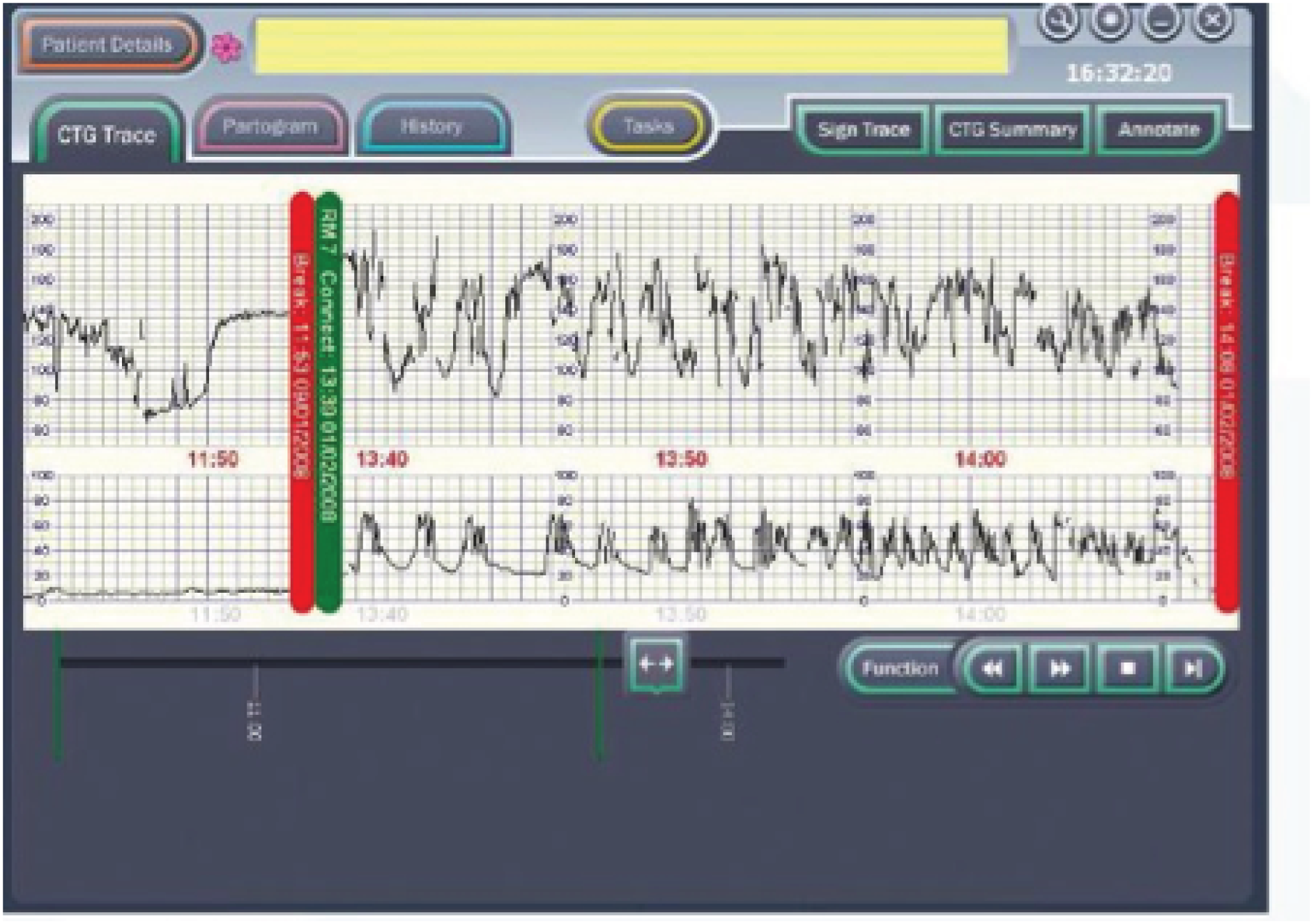

The PC uses the Microsoft Windows® (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA) operating system and runs the decision support software developed by the Plymouth group. The clinician enters clinical information (antenatal risk factors, vaginal examination data, fetal blood sample results, etc.) via the touch-screen. This information is displayed as a partogram (Figure 4). It displays the CTG on a computer screen alongside other clinical data [e.g. the partogram, maternal vital signs (including Modified Early Warnings Systems charts) and details of maternal anaesthesia and analgesia] that are collected as part of routine clinical care. Guardian does not interpret any of the data being collected, but acts as an interface to collect and display data at the bedside, centrally on the labour ward, in consultants’ offices or remotely. The system requires little or no training to use and has been used for routine clinical care by a number of hospitals throughout the UK. 34 If CTG is performed by ultrasound or electrocardiography (ECG) clip, the PC system automatically collects these data from the RS 232 digital data port of any CTG recorder. The system displays the CTG data on the screen (Figure 5).

FIGURE 4.

Guardian system: example of partogram on screen.

FIGURE 5.

Guardian system: example of decision support on screen.

The decision support software

The decision support software is a specific piece of software that has been developed to run on the Guardian system. It extracts the important features of baseline heart rate, heart rate variability, accelerations, type and timing of decelerations, the quality of the signal and the contraction pattern from the CTG. The decision support software then analyses these data along with the quality of the signals. The system’s assessment of the CTG is presented as a series of colour-coded alerts depending on the severity of the abnormality detected (Figures 6–8). The system can therefore be viewed as an intelligent prompt, but by recording the chronology of events it also offers the opportunity to later audit the actual clinical decision-making process in a similar way to an aircraft’s black box.

FIGURE 6.

Example of a ‘blue level of concern’.

FIGURE 7.

Example of a ‘yellow level of concern’.

FIGURE 8.

Example of a ‘red level of concern’.

Studies using the intelligent support software

Three studies conducted by the Plymouth group35–37 demonstrated that the software, when used ‘offline’, performed as well as expert obstetricians in interpreting the CTG and managing labour subsequently, and that the system performed better than routine clinical practice. The system identified more cases that went on to have a poor outcome and anticipated clinical decision-making. In one of these studies involving labours that had resulted in a stillbirth, the system ‘intervened’ (i.e. recognised the abnormality which would have prompted delivery) more than 6 hours earlier than happened in actual clinical practice and more than 2 hours before the experts. If this translated into clinical practice, it would be reasonable to expect that a number of such deaths might have been prevented if the software had been in use at the time. In all other poor-outcome groups the system ‘intervened’ much earlier than had happened in routine clinical practice and at a similar time as the experts. The system failed to predict one perinatal death, whereas the experts in the ‘offline’ study, and those functioning in routine clinical practice, failed to predict several deaths. These extensive ‘offline’ validation studies have shown that the system matches the performance of an expert obstetrician in interpreting the CTG and performed considerably better than routine clinical practice. Furthermore, the system is not overinterventional. From these data it seems reasonable to hypothesise that the clinical use of this computer-based decision support software would decrease the incidence of perinatal mortality and morbidity.

Current practice

Continuous electronic fetal monitoring is widely used for the majority of women during labour and birth in the UK. NICE guidelines for fetal monitoring detail explicit criteria indicating which women should be offered EFM during labour; approximately 60% of all women in labour meet these criteria. 21 This study did not aim to influence the number of women who received EFM.

Research objectives

Our hypotheses were that:

-

a substantial proportion of substandard care results from a failure to correctly identify abnormal fetal heart rate patterns

-

improved recognition of abnormality would reduce substandard care and poor outcomes

-

improved recognition of normality would reduce unnecessary intervention.

These led to the objectives of the study, to:

-

determine whether or not intelligent decision support can improve interpretation of the intrapartum CTG and, therefore, improve the management of labour for women who are judged to require EFM. Specifically, will the system, compared with current clinical practice:

-

identify more clinically significant heart rate abnormalities?

-

result in more prompts and timely action on clinically significant heart rate abnormalities?

-

result in fewer poor neonatal outcomes?

-

change the incidence of operative interventions?

-

-

assess whether or not the use of intelligent decision support improved the quality of routine care received by women undergoing EFM during labour. This information was important for evaluating whether or not the decision support software decreases the risk of suboptimal care in labour; it was also useful to explore the effect that such an intervention may have on litigation costs for obstetrics

-

determine whether or not the use of the decision support software was cost-effective in terms of the incremental cost per poor perinatal outcome prevented

-

determine whether or not use of the decision support software had any effect on the longer-term neurodevelopment of children born to women participating in the INFANT study.

Chapter 2 Methods

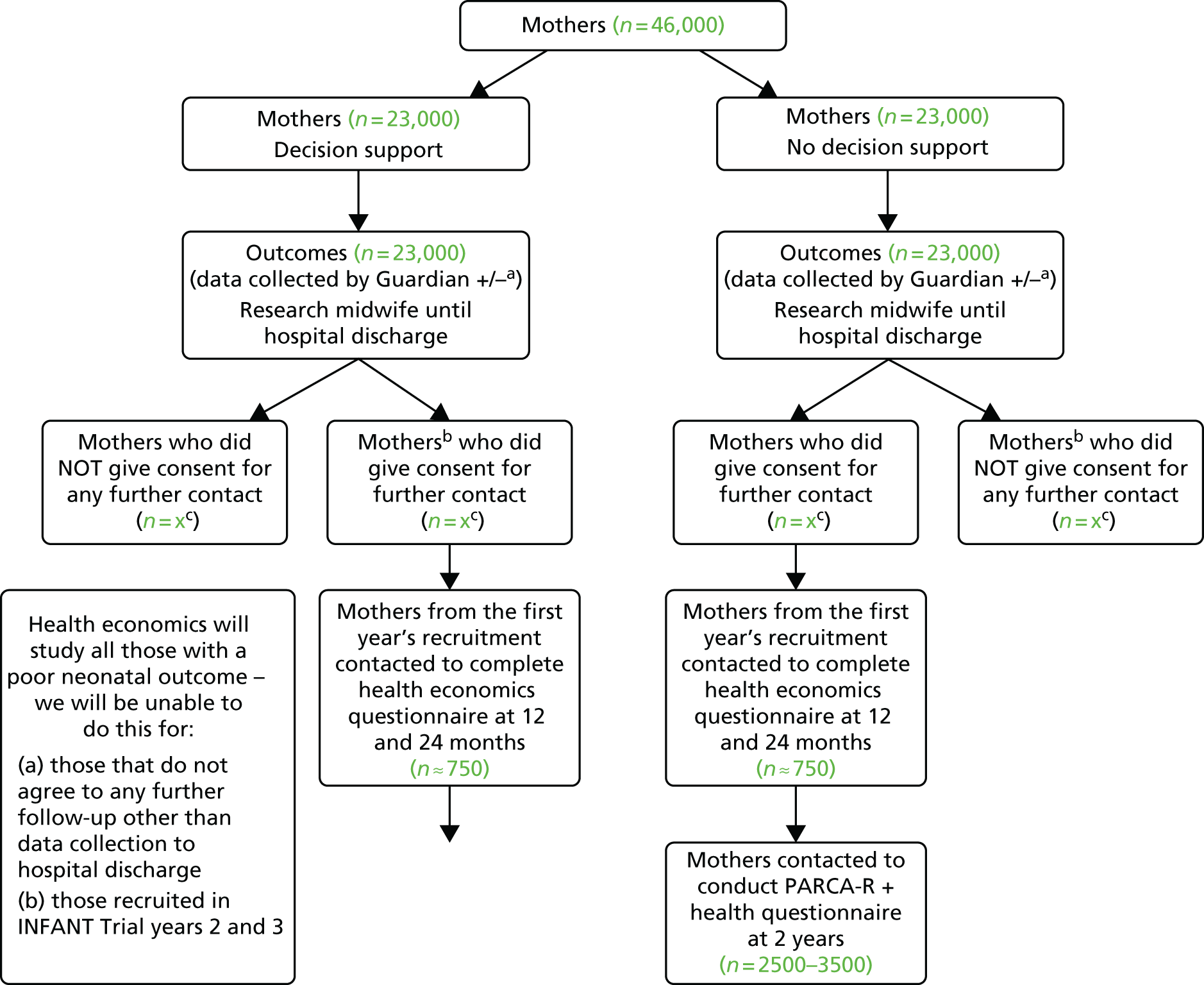

The INFANT study was an individually randomised controlled trial of 46,000 women who were judged to require EFM in labour. Follow-up was completed at 2 years for a sample of 7000 surviving children born to women participating in the INFANT study.

Trial eligibility and randomisation

Inclusion criteria

Women admitted to a participating labour ward who fulfilled all of the following criteria were eligible to be recruited and randomised.

-

Women were judged to require EFM by the local clinical team based on existing guidelines, and the woman consented to have EFM, and EFM was possible.

-

Note that EFM is defined as the active decision of the health-care professional and the woman to initiate EFM for the purpose of fetal monitoring, usually because of perceived risk factor(s) that increase the likelihood of fetal compromise occurring in labour.

-

The decision to initiate EFM can occur at any time during labour. Some women with known factors that place them at higher risk of fetal compromise during labour would already know that EFM throughout labour was planned. Others started labour with intermittent monitoring and then were judged to require EFM at some point during the labour. Women were eligible to participate at any stage of labour.

-

-

Women were pregnant with a single fetus or twins.

-

Gestational stage was ≥ 35 weeks (≥ 245 days).

-

There was no known gross fetal abnormality, including any known fetal heart arrhythmia such as heart block.

-

Women were aged ≥ 16 years.

-

Women were able to give consent to participate in the trial as judged by the attending clinicians.

Exclusion criteria

-

Triplet or higher-order pregnancy.

-

Criteria for EFM not met, including elective caesarean section prior to the onset of labour.

Information for women and obtaining informed consent

Information about the trial was provided to women during the antenatal period (see Appendix 1), after their booking appointment. This process was individualised for each participating centre depending on their routine practices. For example, in some centres, women were provided with information about the trial at their routine ultrasound scan appointment (18–22 weeks). All women had the opportunity to ask questions.

When a woman presented in early labour to the labour ward in a participating centre, she was given a copy of the participant information leaflet (see Appendix 2) and a verbal explanation of the INFANT trial. She was then asked whether or not she would like to participate in the study and, if she agreed, she was asked to sign an INFANT trial consent form. Then, if at any point EFM was commenced during labour, the midwife responsible for the woman’s care checked her eligibility to participate in the trial and that she was still happy to take part. This was documented, and then the woman was randomised by the Guardian system to either the decision support (intervention) arm or the no decision support (control) arm.

All women in labour admitted to the participating centres were expected to have their labour information recorded in the Guardian system, in accordance with the current practice in each centre. This did not change the way health professionals managed labour; it merely changed the way they managed the information generated by the process of monitoring labour and how they recorded this information. It was clearly stated that women were free to withdraw from the study at any time for any reason without prejudice to future care, and with no obligation to give the reason for withdrawal.

Written informed consent was obtained by means of a dated signature from the woman and the signature of the person who obtained informed consent (see Appendix 3); this would be the principal investigator (or a qualified health-care professional with delegated authority). A copy of the signed informed consent document was given to the woman. A further copy was retained in the woman’s medical notes, a copy was retained by the principal investigator and a final copy was sent to the trial co-ordinating centre.

A senior investigator was available at all times to discuss concerns raised by women or clinicians during the course of the trial.

Randomisation

The Guardian system prompted the health professional providing care to consider whether or not the woman was eligible for the INFANT trial when EFM had been used for > 5 minutes. Intermittent use of EFM for durations of up to 5 minutes could be employed for intermittent monitoring, but when used for longer periods of time this would indicate that a decision had been made to initiate EFM, in which case the woman may have been eligible to participate in the trial. If the health-care professional indicated that the woman was not yet eligible because an active decision had not been made to initiate EFM, then the Guardian system prompted the health-care professional again, if the CTG continued to be recorded for longer than 5 minutes in that or any subsequent episode of monitoring.

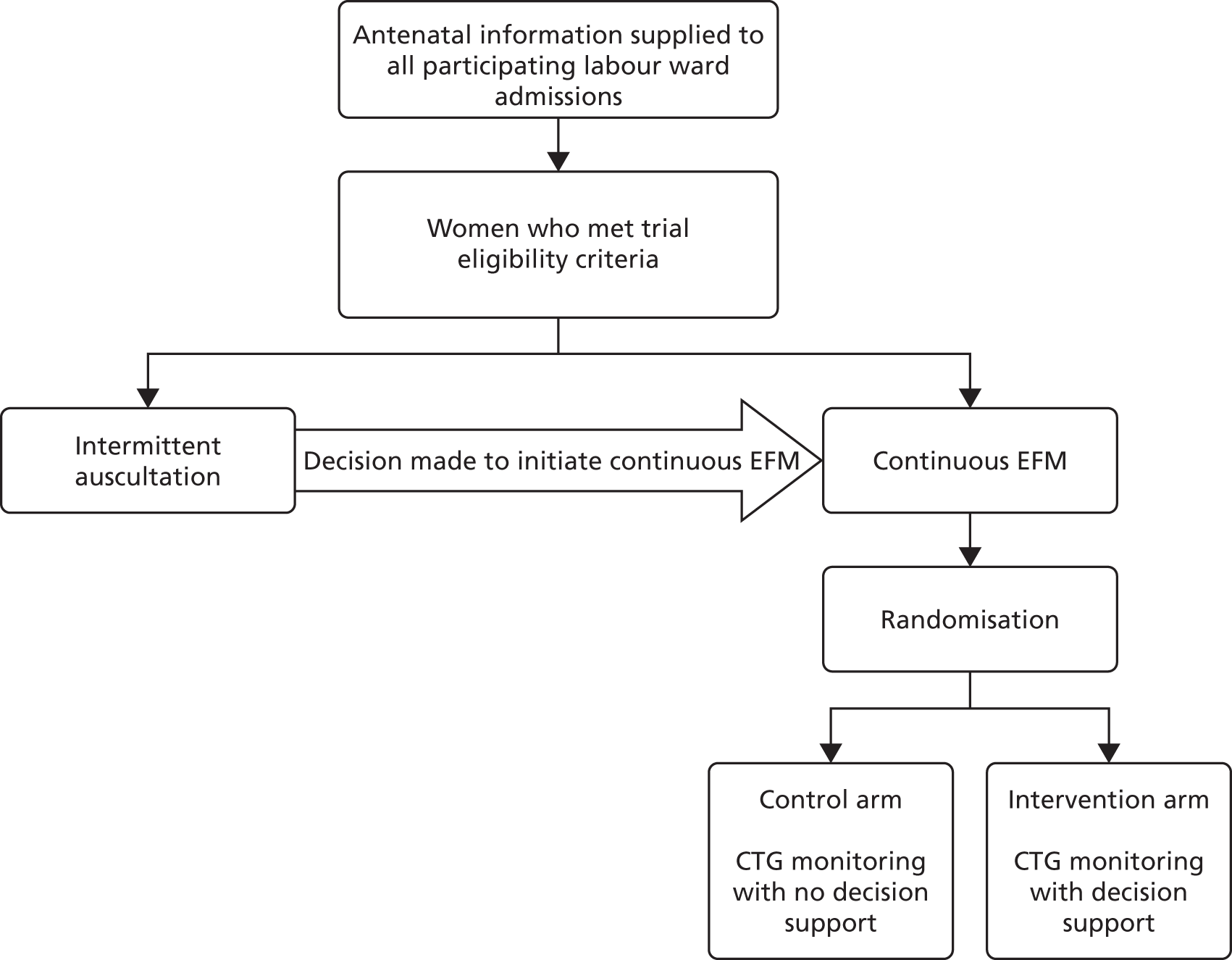

When the health-care professional indicated that a woman was eligible to participate, the Guardian system clarified that the necessary eligibility criteria for trial entry had been met (i.e. that the health professional gave the required answers to a number of questions posed by the Guardian system, and then the Guardian system randomly allocated the women in the ratio 1 : 1 to either ‘CTG with no decision support’ or ‘CTG with decision support’) (Figure 9). The allocations were computer generated in Stata® version 10 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA) using stratified block randomisation employing variable block sizes to balance between the two trial arms by singleton or twin pregnancy, and within each participating centre. The procedures for randomisation were fully documented, reviewed and signed off prior to the start of the trial and monitored by the co-ordinating centre during the trial.

FIGURE 9.

Flow diagram.

Planned interventions

The intervention was the use of decision support software. In order to accurately reflect any potential impact of the decision support software in contemporary NHS practice, such as changes in midwifery presence during labour consequent upon knowledge of the allocation, it was desirable that clinicians were not masked to allocation.

Clinical management

The Guardian system was developed to be used with all women in labour in the participating centres. It was only the decision support software that runs on this system that was being tested in this trial.

Clinicians in all participating centres were initially trained in the use of the decision support software by staff from the trial co-ordinating centre (see Appendix 4). This process included developing a ‘training team’ at each site which was responsible for cascading training among the local clinicians. The clinical management of women in the trial was not altered by their participation; however, staff caring for women in the decision support arm received a series of graded alerts or alarms when abnormalities of the CTG were detected by the system, which increased in urgency with the severity of the abnormality as judged by the system. No additional training was provided to clinical staff in how to respond to fetal heart rate abnormalities as part of their participation in the trial because, in the UK and Republic of Ireland, staff supervising labour and delivery are expected to have had such training, for example by completing computer-based training packages every 6–12 months, attending annual lectures and attending regular CTG review meetings.

Primary outcome measures

Primary short-term outcome

The primary short-term outcome was a composite of poor neonatal outcome including deaths [intrapartum stillbirths plus neonatal deaths (i.e. deaths up to 28 days after birth) except deaths as a result of congenital anomalies], significant morbidity (moderate or severe NNE, defined as the use of whole-body cooling) and admissions to a neonatal unit within 48 hours of birth for ≥ 48 hours (with evidence of feeding difficulties or respiratory illness and when there was evidence of compromise at birth suggesting that the condition was the result of mild asphyxia and/or mild encephalopathy).

Note: we recognised that the signs of mild encephalopathy can be subtle and hence a number of babies identified as having this condition were likely to have a range of non-specific signs such as respiratory difficulty and poor feeding rather than features more specifically associated with encephalopathy. 38 Therefore, we included ‘admission to the neonatal unit within 48 hours of birth for ≥ 48 hours where there is evidence of compromise at birth’. Since this was a mature group of babies (born ≥ 35 weeks), any difference in the incidence of these admissions was felt likely to result from differences in perinatal asphyxia.

Primary long-term outcome

The primary long-term outcome was the Parent Report of Children’s Abilities-Revised (PARCA-R) composite score39,40 at the age of 2 years for a subset of 7000 infants.

Note: neurodevelopmental delay and cerebral palsy are the most important long-term adverse outcomes associated with perinatal asphyxia. However, the incidence of moderate or severe cerebral palsy is around 1.5–2.5 per 1000 live births, depending on the definition and the method of ascertainment. There is also uncertainty about the proportion of these cases that results from intrapartum asphyxia in mature infants; however, 30% appears to be a reasonable estimate. 4 Therefore, given the rarity of this outcome, it was unlikely that a clear difference could be demonstrated between the two groups in a trial of 46,000 births. In order to have reassurance that any benefits of the intervention, with respect to short-term outcomes, had not occurred at the expense of later neurodevelopmental delay, we measured neurodevelopment in a proportion of the surviving children at the age of 2 years.

Secondary outcome measures

Secondary short-term outcomes

Neonatal

-

Intrapartum stillbirth (excluding deaths as a result of congenital anomalies).

-

Neonatal deaths up to 28 days after birth (excluding deaths as a result of congenital anomalies).

-

Moderate or severe encephalopathy.

-

Admission to neonatal unit within 48 hours of birth for ≥ 48 hours with evidence of feeding difficulties, respiratory illness or encephalopathy (when there was evidence of compromise at birth).

-

Admission to a higher level of care.

-

An Apgar score of < 4 at 5 minutes after birth.

-

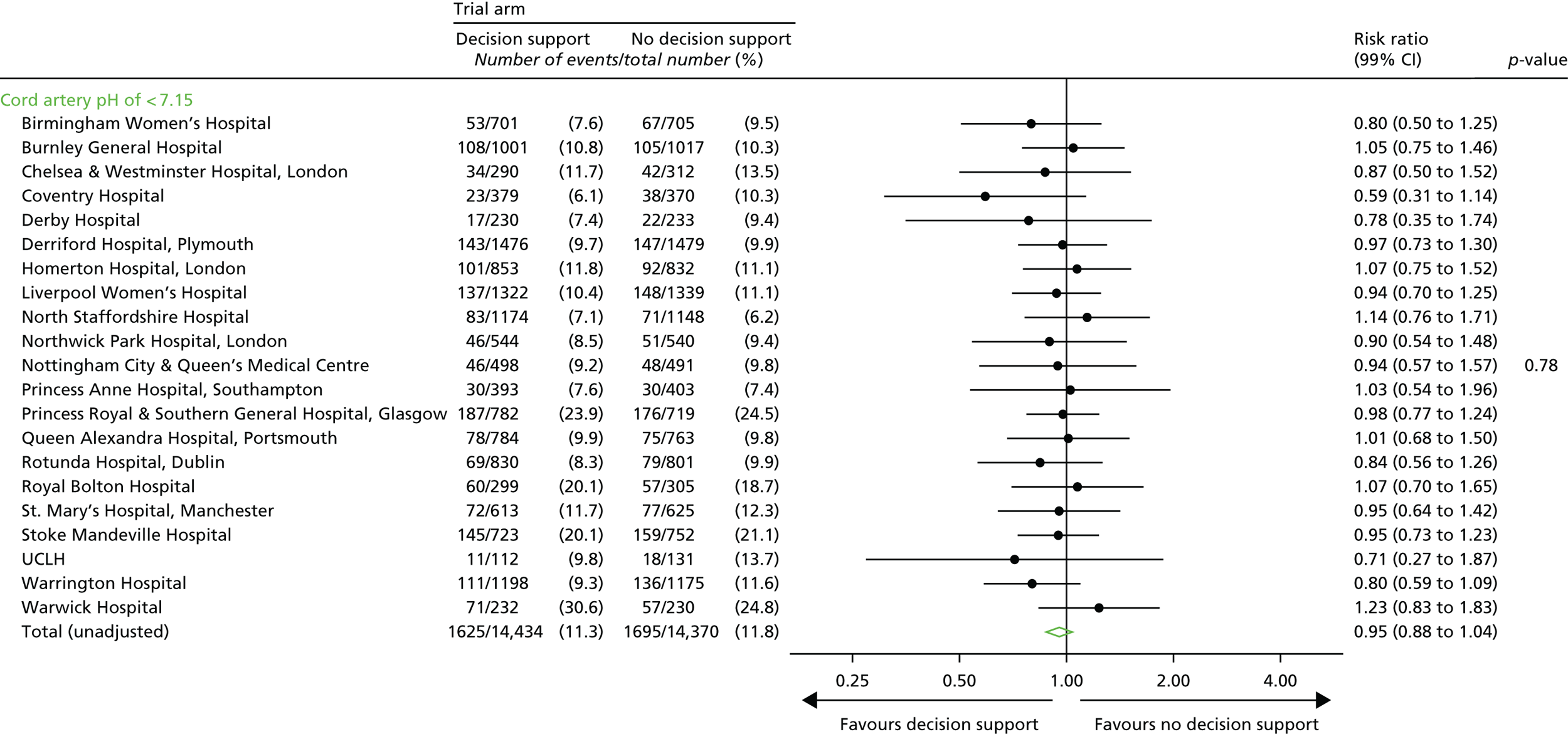

The distribution of cord blood gas data for cord artery pH.

-

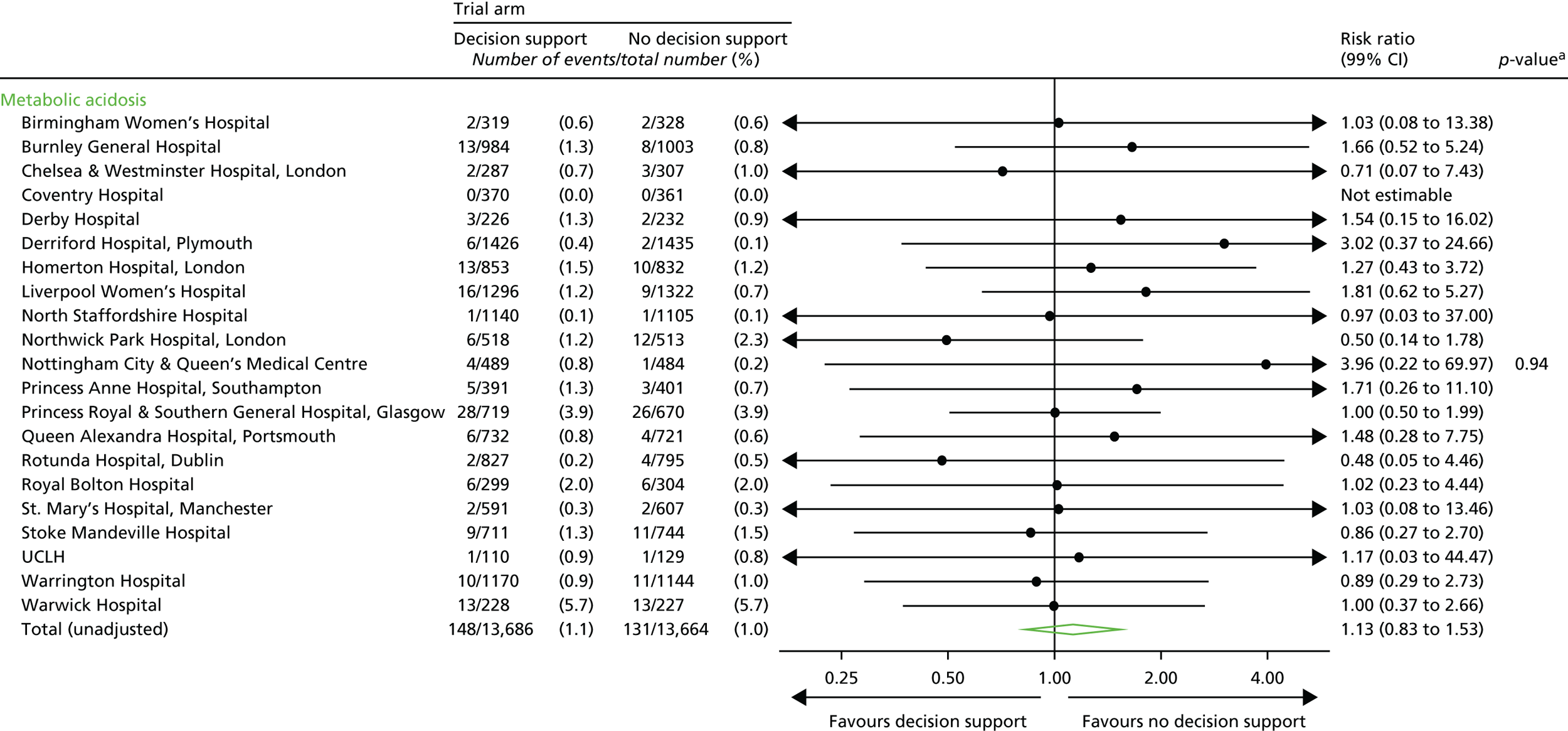

Metabolic acidosis (defined as a cord artery pH of < 7.05 and a base deficit in extracellular fluid of ≥ 12 mmol/l).

-

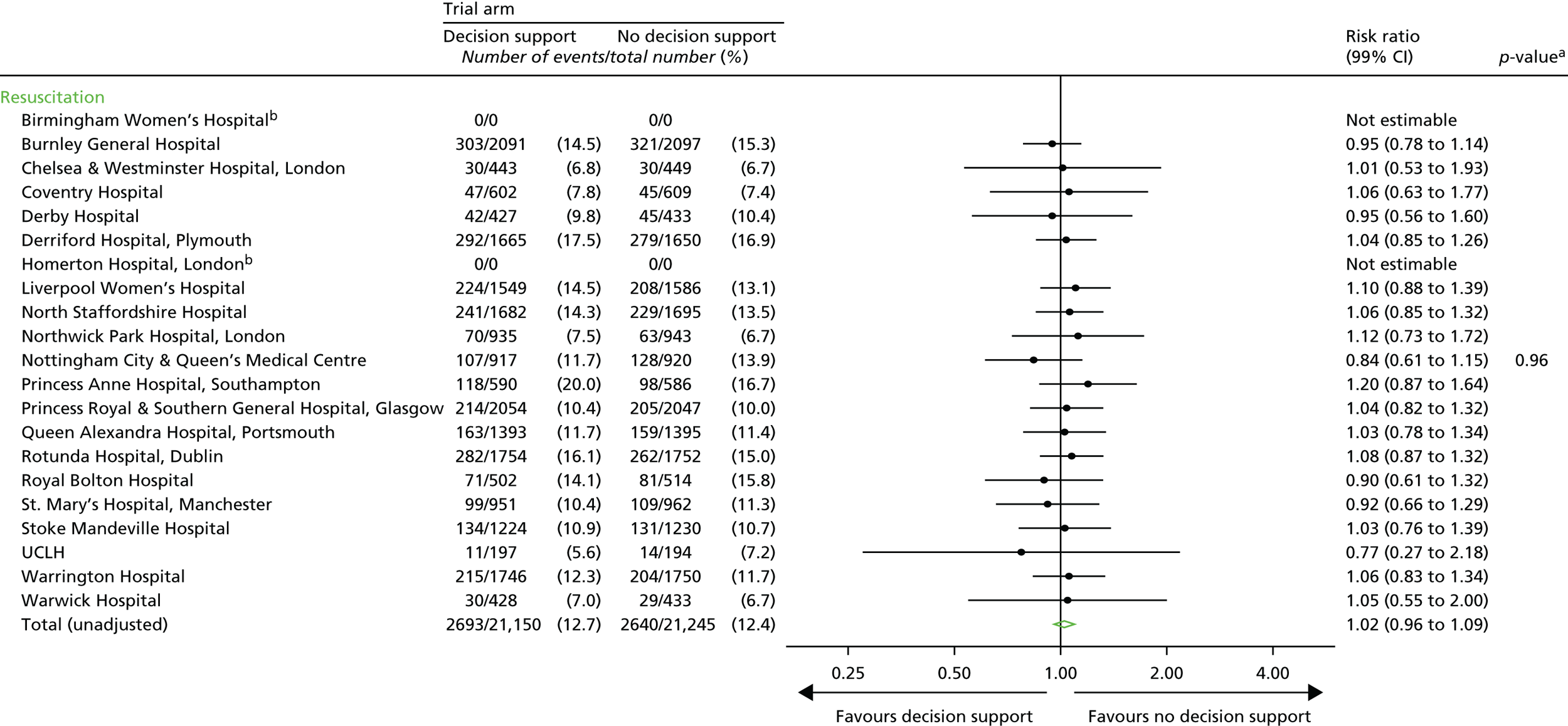

Resuscitation interventions.

-

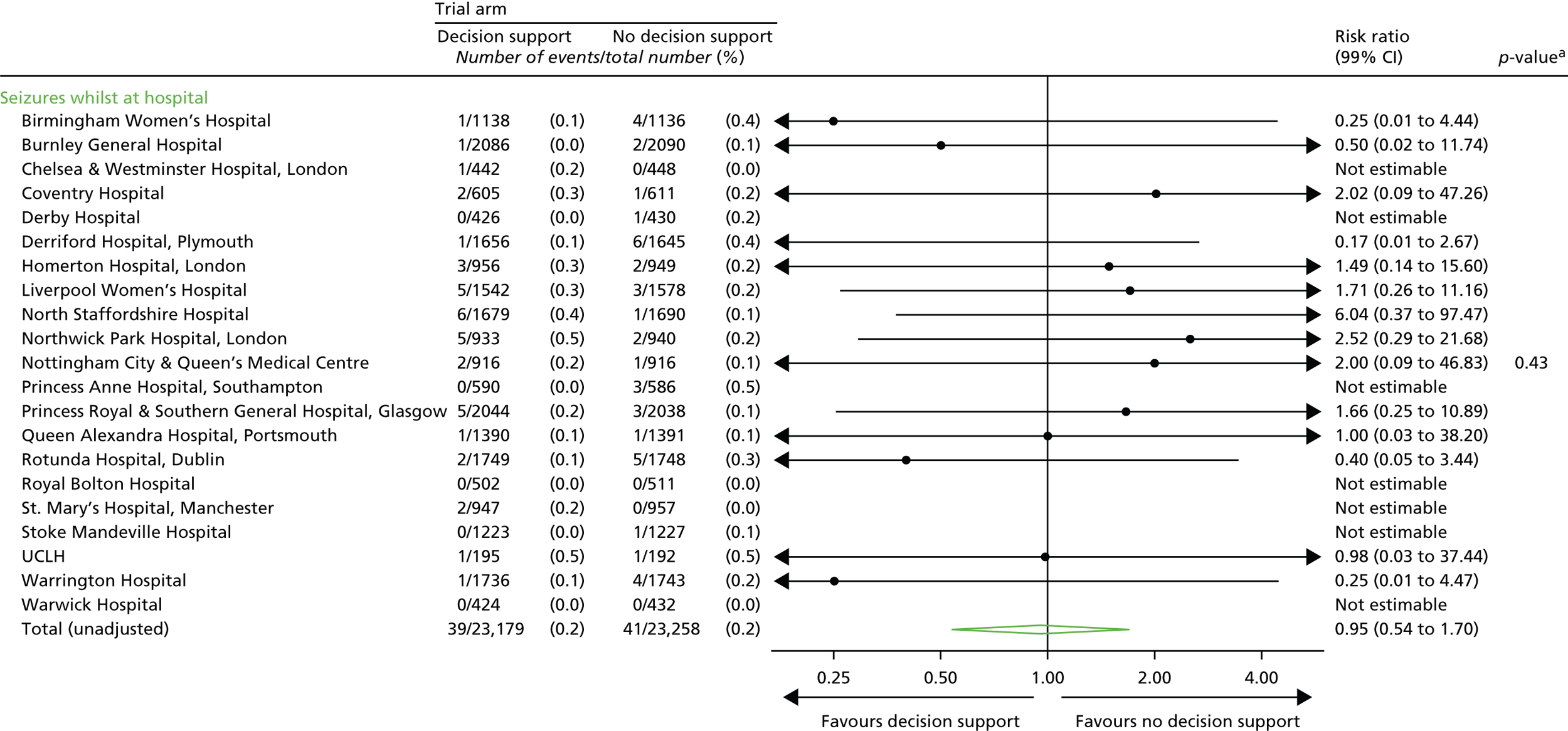

Seizures.

-

Destination immediately after birth.

-

Length of hospital stay.

Maternal

-

Mode of delivery.

-

Operative intervention (caesarean section or instrumental delivery) for:

-

fetal indication or

-

failure to progress or

-

a combination of fetal distress and failure to progress or

-

other reason.

-

-

Grade of caesarean section.

-

Episiotomy.

-

Any episode of fetal blood sampling.

-

Length of:

-

first stage of labour from trial entry

-

second stage of labour from trial entry

-

labour from trial entry (total).

-

-

Destination immediately after birth.

-

Admission to a higher level of care.

Secondary long-term outcomes (infant)

Health and development outcomes at 24 months

-

Non-verbal cognition scale (PARCA-R).

-

Vocabulary subscale (PARCA-R).

-

Sentence complexity subscale (PARCA-R).

-

Late deaths up to 24 months (after the neonatal period).

-

Diagnosed with cerebral palsy.

-

Non-major disability.

-

Major disability.

-

Breastfeeding (collected at 12 and 24 months).

Quality-of-care outcomes

-

Adverse outcome (trial composite primary outcome plus metabolic acidosis) when it is judged that suboptimal care has occurred in labour: levels 1 to 3 separately and combined.

-

Level 1: suboptimal care, but different management would have made no difference to outcome.

-

Level 2: suboptimal care, and different management might have made a difference to outcome.

-

Level 3: suboptimal care, and different management would reasonably be expected to have made a difference to the outcome.

Note: in all cases of adverse outcome (trial primary outcome plus a cord artery pH of < 7.05 with a base deficit of ≥ 12 mmol/l) and all neonatal deaths and intrapartum stillbirths care in labour was assessed, to determine if it was suboptimal, by panel review similar to that undertaken by the Confidential Enquiry into Maternal and Child Health (CEMACH). 26 Intrapartum notes were copied and anonymised, and all references to trial allocation removed. The notes were then examined by a panel of an experienced obstetrician, midwife and neonatologist to identify if there was suboptimal care, particularly in relation to interpretation of the CTG and actions that flowed from any identification of CTG abnormalities.

Process outcomes (after trial entry)

-

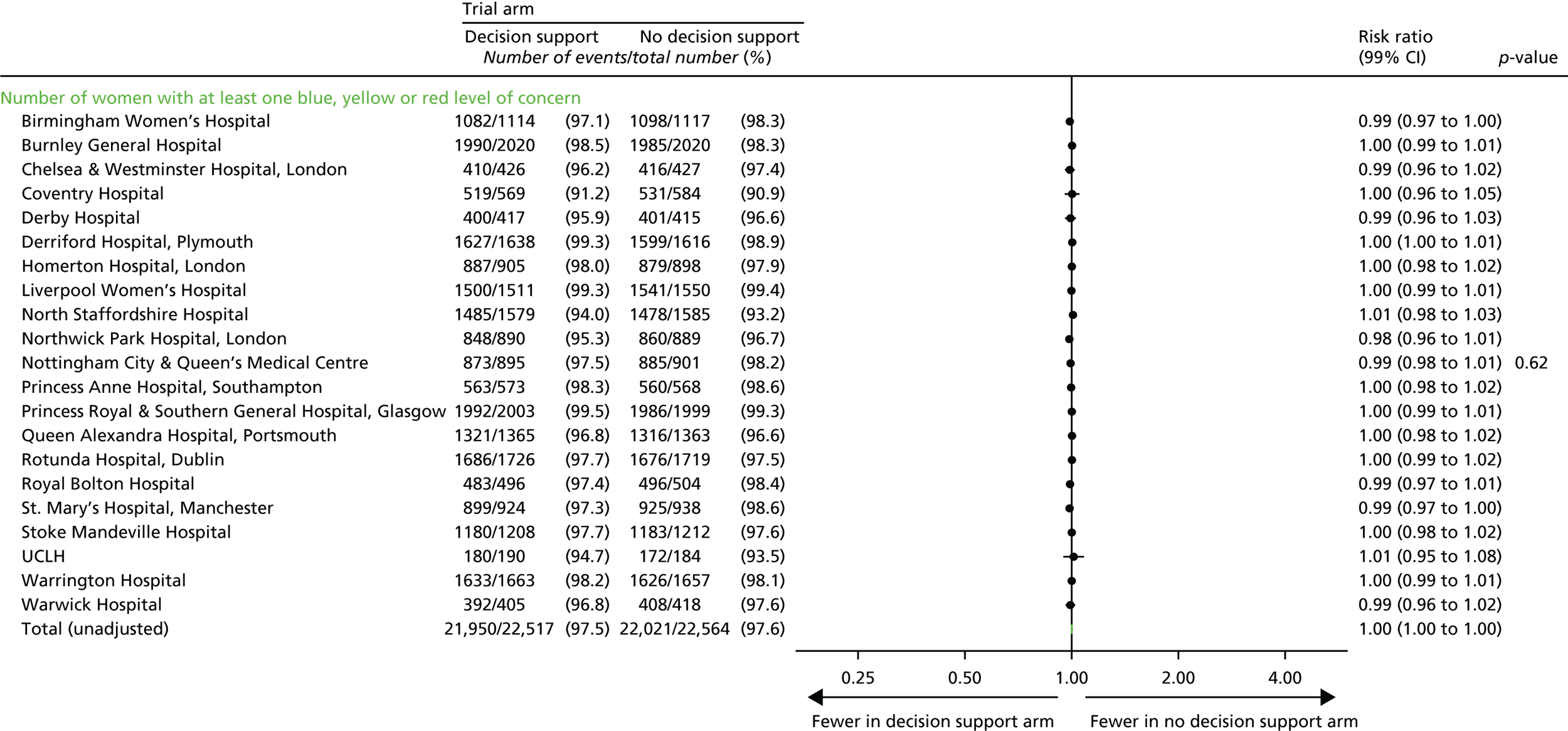

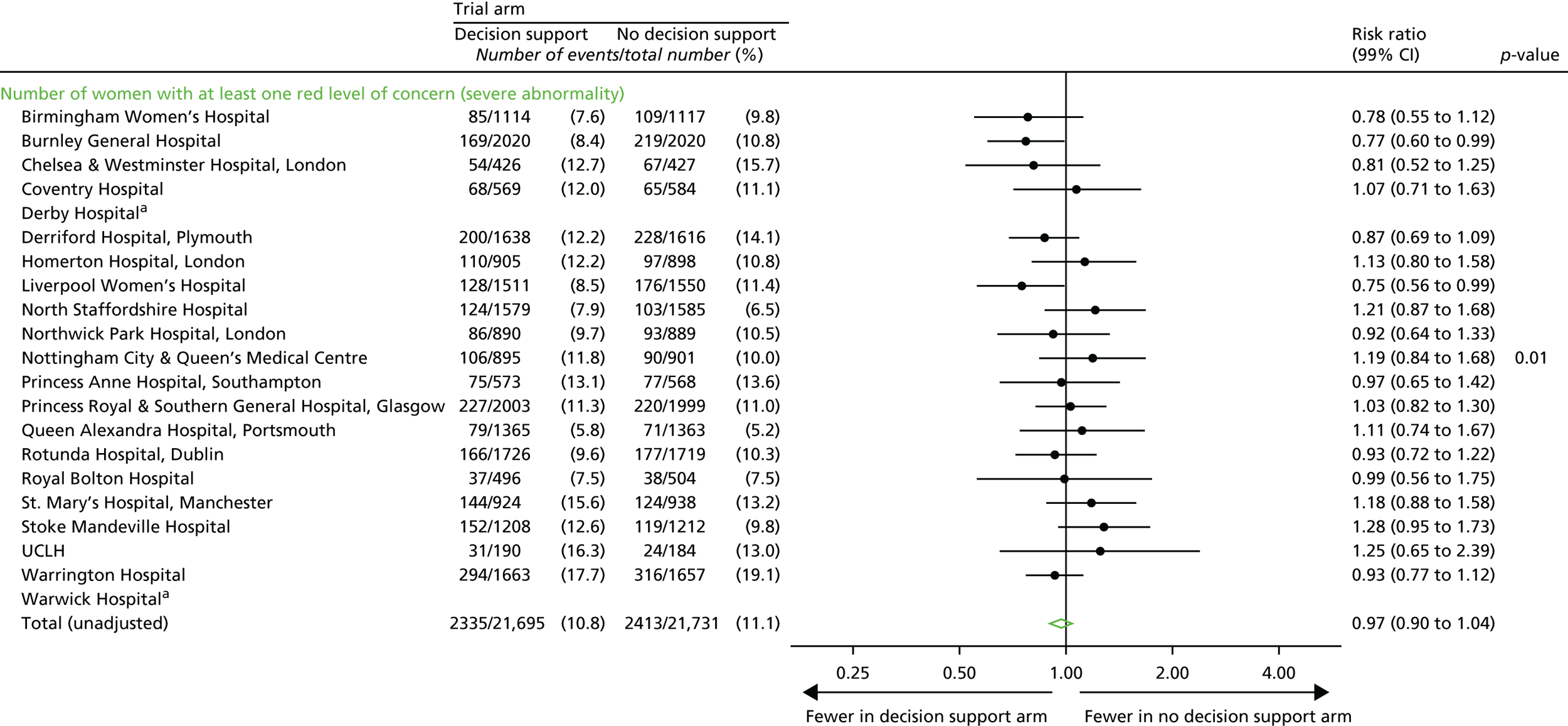

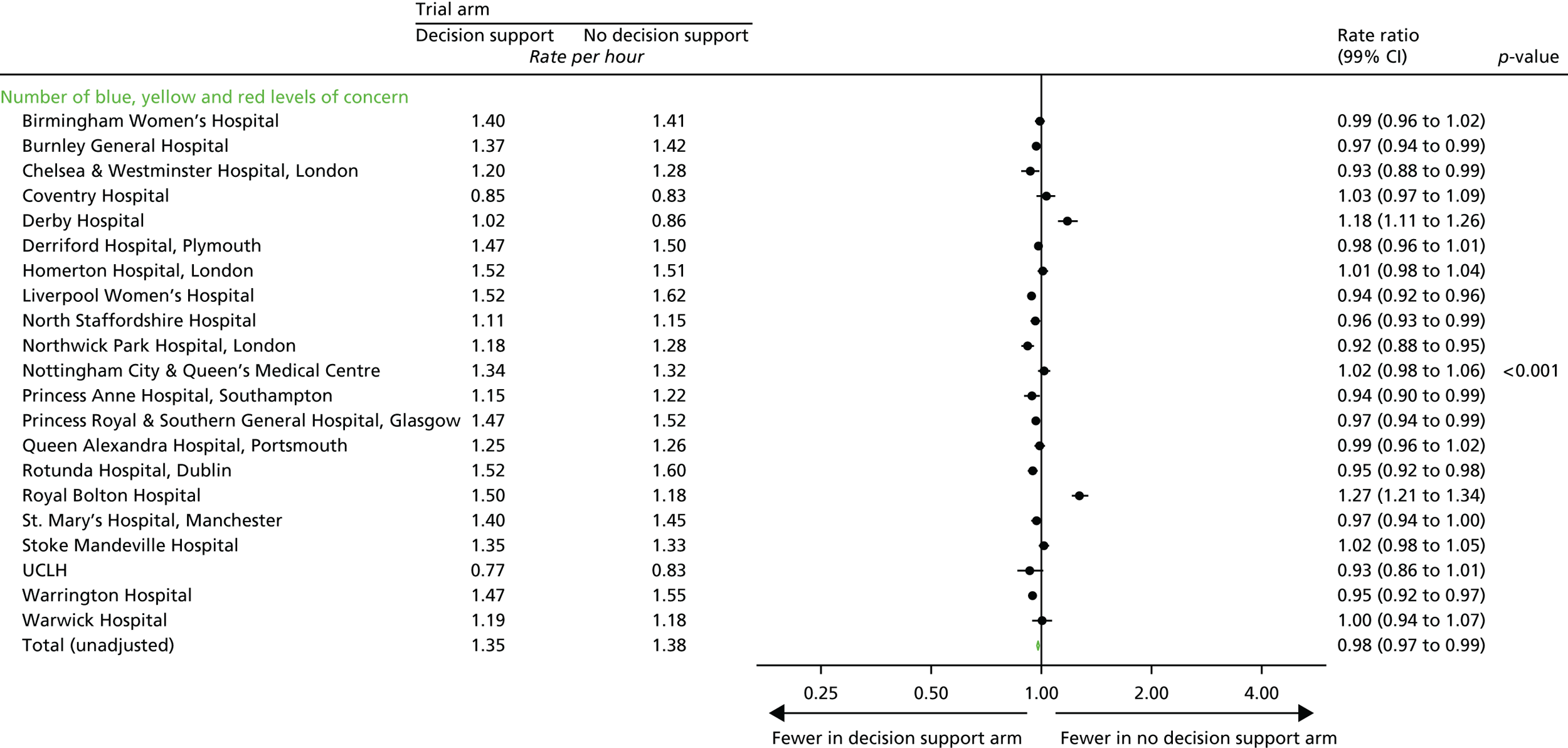

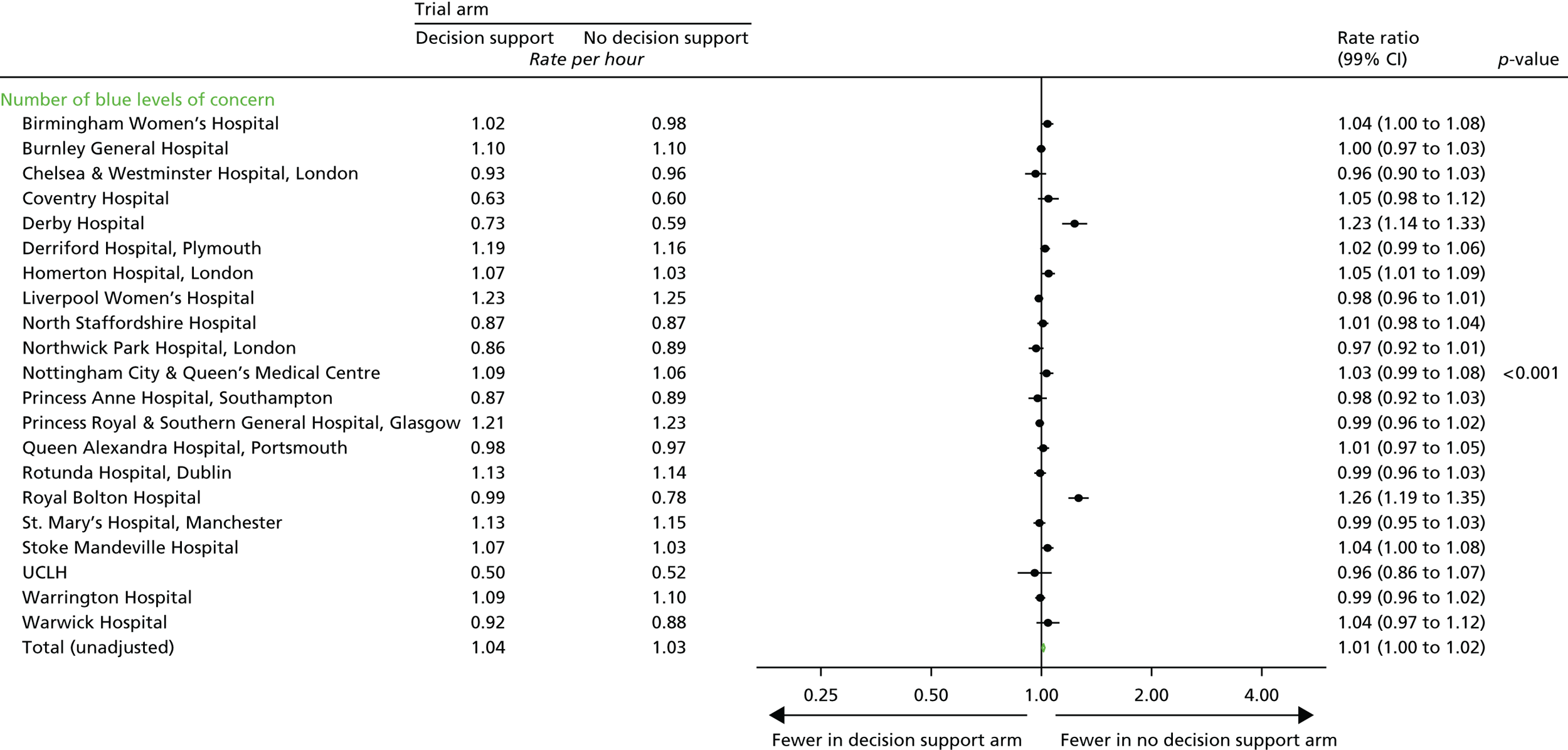

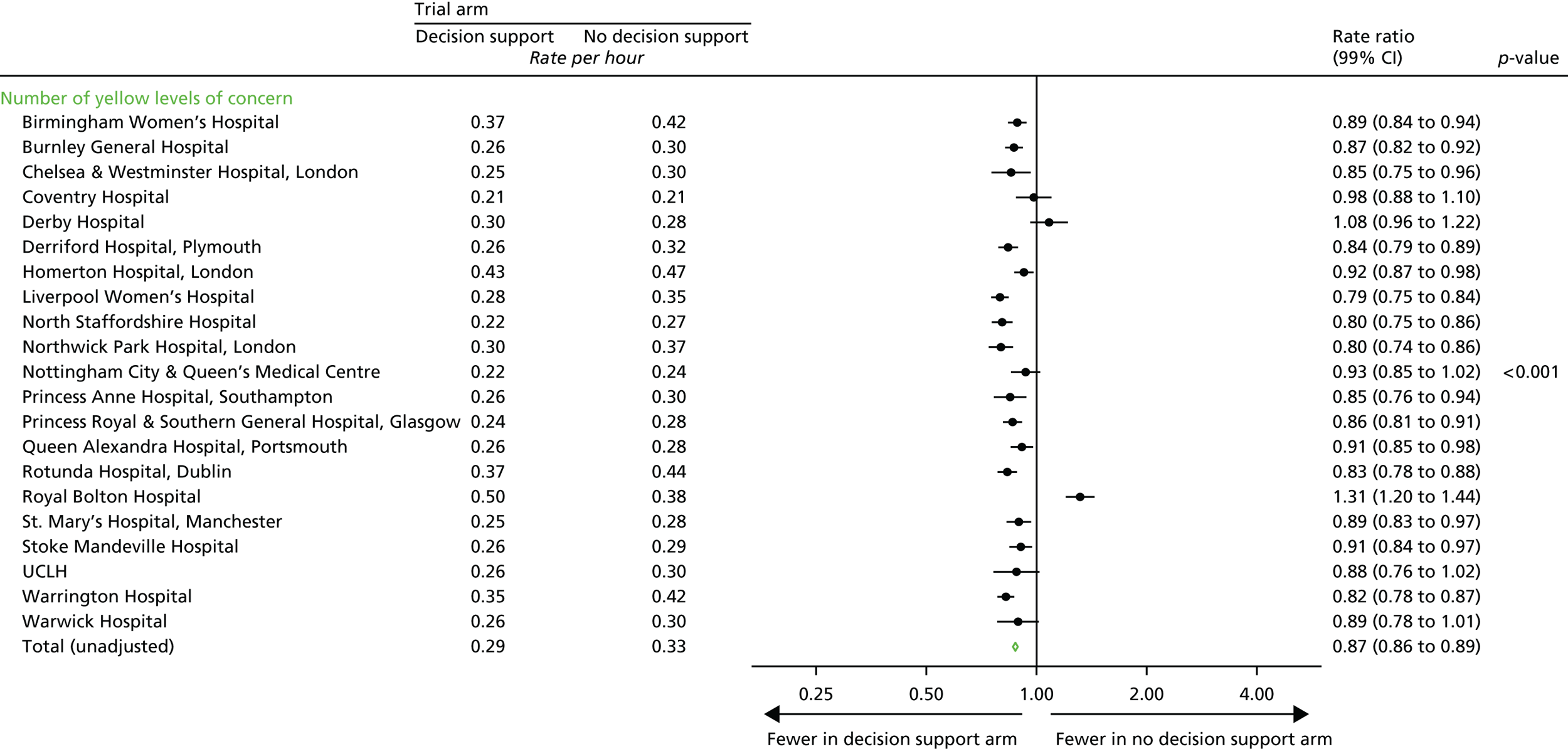

Total number of CTG abnormalities (blue, yellow and red levels of concern) detected by the decision support software.

-

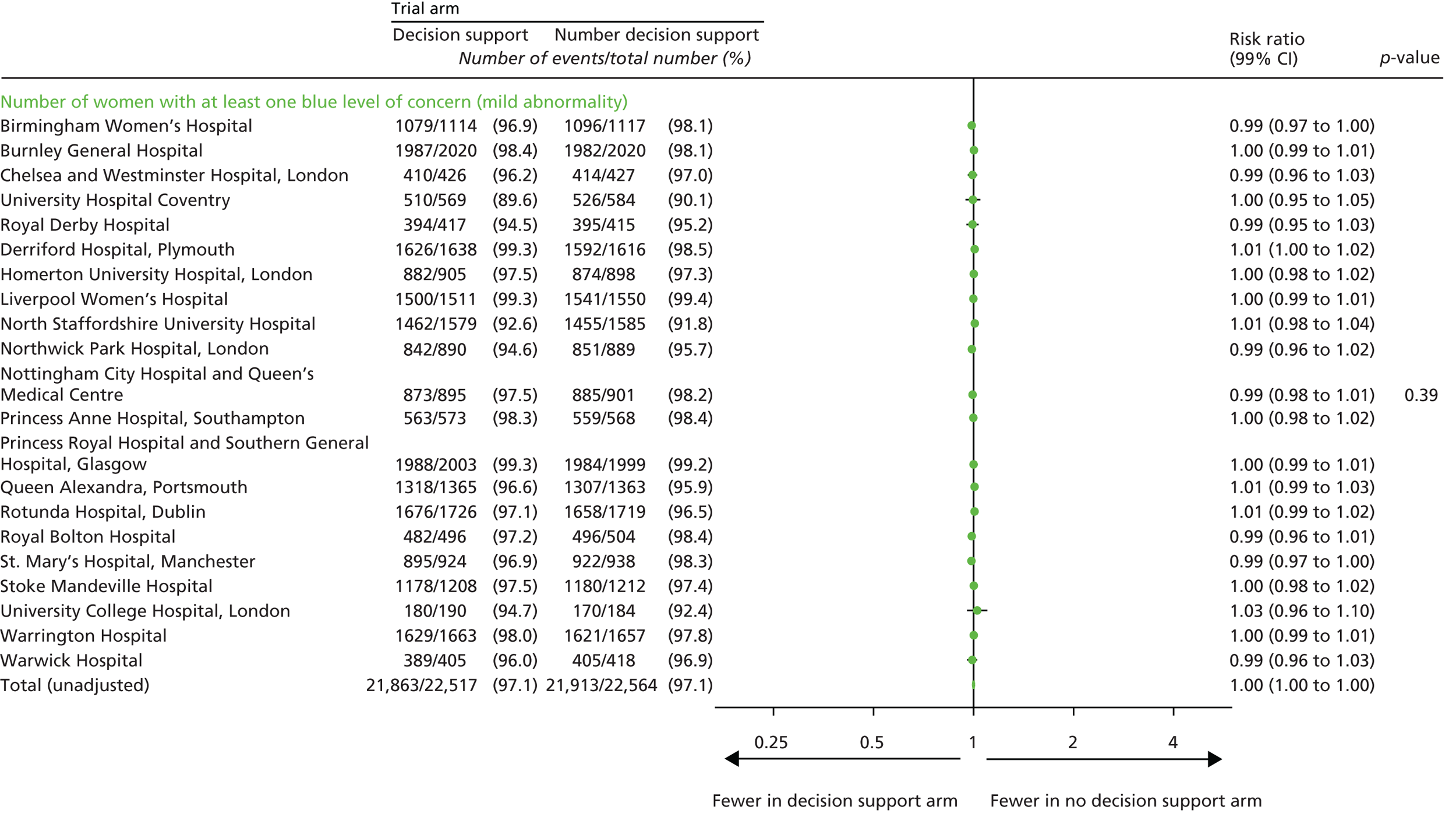

Number of blue levels of concern on the decision support software, indicating a mild abnormality on the CTG.

-

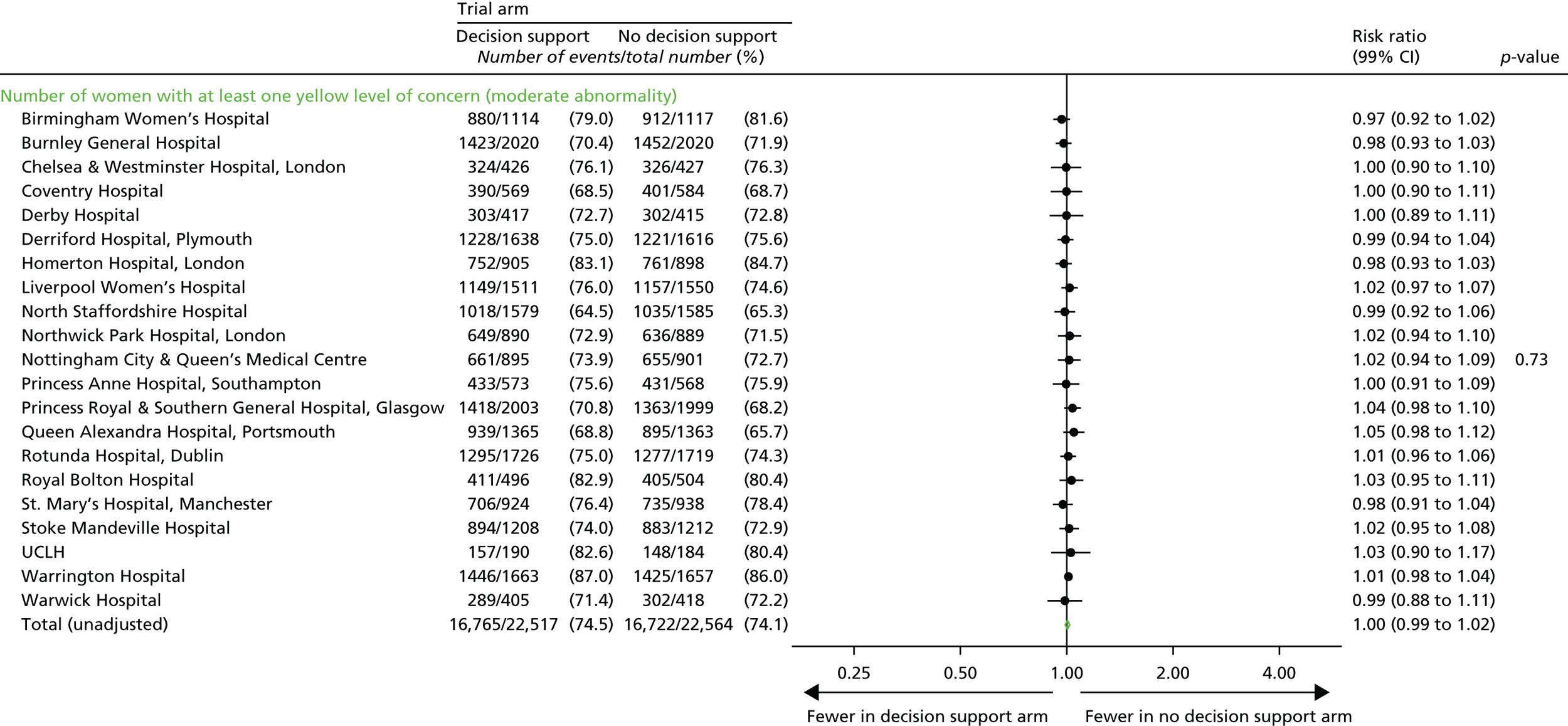

Number of yellow levels of concern on the decision support software, indicating a moderate abnormality on the CTG.

-

Number of red levels of concern on the decision support software, indicating a severe abnormality on the CTG.

-

Number of women with at least one yellow level of concern on the decision support software, indicating an abnormality on the CTG.

-

Number of women with at least one red level of concern on the decision support software, indicating a severe abnormality on the CTG.

-

Time from first red level of concern to birth.

Note that it was important to collect and analyse process outcomes in the trial, as a failure to detect differences in clinical or quality-of-care outcomes between the two randomised groups may be because of poor adherence with the alerts of the system, rather than the system not correctly identifying abnormalities with the CTG. In addition, as the trial allocation was not masked, it was important to measure any change that resulted from clinicians being aware of whether or not the decision support system was in operation.

-

Number of thumb entries per hour from time of trial entry to first yellow level of concern or until fully dilated (10 cm) if no abnormality detected or first yellow level of concern occurred prior to trial entry.

-

Number of vaginal examinations.

-

Epidural analgesia.

-

Labour augmentation.

-

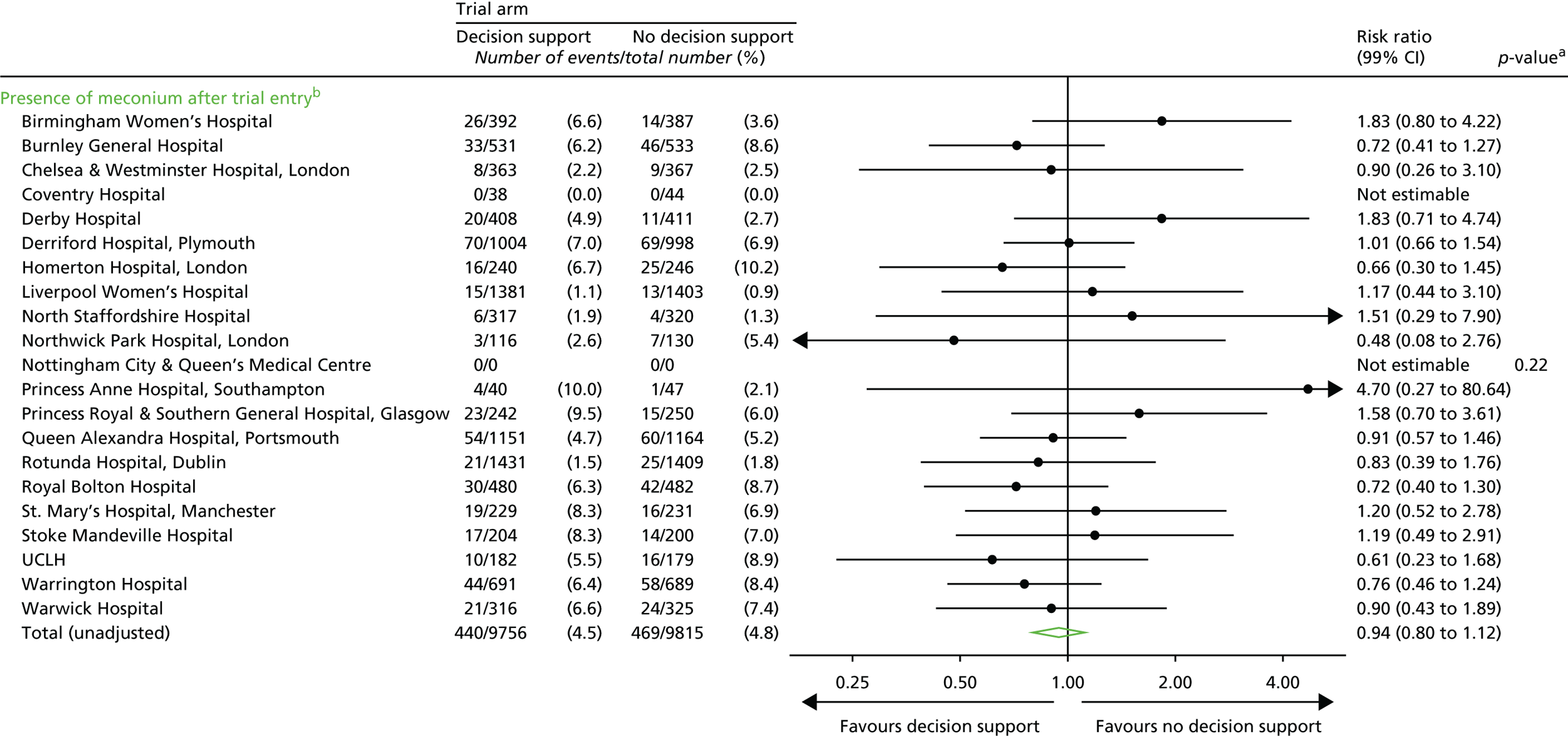

Presence of meconium.

Note: some of these later process outcomes (e.g. the number of thumb entries per hour) were proxy measures to determine the presence of a health professional in the delivery room during the labour, which allowed us to quantify any differences between the groups with respect to support offered to women during labour. Although unlikely, knowledge of the trial allocation could have resulted in less frequent contact with the woman allocated decision support in labour. Less frequent contact would have resulted in a lower number of these process measures.

Data collection

For all participating women and babies, labour variables and outcomes were stored automatically and contemporaneously on the Guardian system. Data collected via the system were sent electronically to the trial co-ordinating centre. Data were extracted from the notes of babies admitted to the neonatal unit and for all neonatal deaths (see Appendices 5–7), as well as for mothers admitted for a higher level of care (see Appendix 8). Not all data fields were collected at every centre. However, when an item was collected, these data were sent to the clinical trials unit. The trial did not collect the reason why EFM was being used, as this was not recorded. All children surviving to be discharged home from hospital following their birth were ‘flagged’ at the NHS Information Centre for those born in England, and for those born in Scotland comparable systems were used. All deaths occurring after discharge home from hospital were notified to the trial co-ordinating centre. At 2 years after trial entry a sample of 7000 surviving children (3500 in each group) were followed up. The family was sent a two-part parent-completed questionnaire to assess the child’s health, development and well-being (see Appendix 9). The first part of the questionnaire comprised the PARCA-R, which had been previously validated as a means of assessing neurodevelopment in a trial setting. 39,40 The second part focused on general health issues, and had also been used previously.

Calculation of proposed sample size

The proposed total sample size was 46,000 births.

The following data sources and assumptions were used in the calculation of the trial sample size.

Incidence of intrapartum stillbirth

This was estimated as 0.35 per 1000 births. This estimate was derived from the following incidence data: 0.51 per 1000 births for women of all gestation periods (England, Wales and Northern Ireland, 2004)41 and 0.27 per 1000 births for women at ≥ 37 weeks’ gestation (Trent Region, 2005). 42 This trial restricted eligibility to women at ≥ 35 weeks’ gestation; therefore, the incidence was expected to be lower than in women at all gestational ages, which includes those who deliver preterm. However, it was also expected to be higher than for all women at term. As the women being recruited were all judged to require EFM and it was assumed that women in this ‘risk group’ would be at increased risk of adverse outcomes, the incidence was likely to be higher. In addition, these estimates used a denominator of all modes of births and so they included women having elective caesarean sections, who are not at risk of intrapartum stillbirth as there is no intrapartum period. Approximately 7% of women have elective caesarean sections, and removal of these women would increase the incidence further. Therefore, an estimate of an incidence of 0.35 per 1000 births appeared reasonable.

Incidence of neonatal death

This was estimated as 0.7 per 1000 births. This estimate was derived from the following data: 3.4 per 1000 births for women of all gestation periods (England, Wales and Northern Ireland, 2004)41 and 0.89 per 1000 births in those women at ≥ 37 weeks’ gestation (Trent Region, 2005). 42 This trial restricted eligibility to women at ≥ 35 weeks’ gestation; therefore, the incidence would be expected to be lower than among women of all gestational ages, which includes those who deliver preterm. However, it would be higher than for all women at term. A reasonable estimate of neonatal death for babies at 35 weeks’ gestation or more was therefore considered to be 1.0 per 1000 births. Using data from the Trent Survey 200542, 30% of neonatal deaths were as a result of congenital anomalies. Therefore, this rate was reduced to 0.7 per 1000 births. As the women being recruited were all judged to require EFM and it was assumed that women in this ‘risk group’ would be at increased risk of adverse outcomes, the incidence may have been higher. Therefore, an estimate of an incidence of 0.7 per 1000 births appeared reasonable.

Incidence of severe and moderate neonatal encephalopathy

The most appropriate estimate of the incidence of NNE in babies born at ≥ 35 weeks’ gestation was 1.3 per 1000 births (Trent & Northern Region, 2002). 43 However, as above, women being recruited to this trial were all judged to require EFM, which means that they may have been at increased risk of adverse outcomes; therefore, the incidence may have been higher.

Combined outcomes

Data were available on some combined outcomes. For example, the incidence of intrapartum stillbirths plus deaths on the labour ward assumed to be as a result of intrapartum asphyxia (the incidence of which is much lower than neonatal mortality) plus severe and moderate NNE was 1.7 per 1000 births (95% CI 1.5 to 1.9; range 0.8–2.3) (18 hospitals, Trent, 2003–4) and 1.9 per 1000 births (95% CI 1.6 to 2.3; range 0.6–2.3) (12 hospitals, Yorkshire Neonatal Network, 2004–5). 43 These data are for babies born at ≥ 35 weeks’ gestation, with the incidence of these outcomes being higher in the larger hospitals, which attract women with more complicated pregnancies.

Incidence of primary outcome for INFANT

We assumed an incidence of the primary outcome of 3 per 1000 births. This was calculated by summing the rate of intrapartum stillbirth, neonatal death, and moderate and severe encephalopathy, which gave an incidence of 2.35 per 1000 births. However, added to this figure was mild encephalopathy, which was reported to occur in 1.25 per 1000 births, and other significant morbidity [other admissions to the neonatal unit within 48 hours of birth for ≥ 48 hours (e.g. with feeding difficulties, respiratory symptoms or seizures)], for which there were no good estimates of incidence. The estimate of 3 per 1000 births erred on the side of caution and an increased incidence of this outcome in the trial would either (a) increase the power of the trial to demonstrate the same effect size or (b) allow detection of a smaller effect size with the same trial size or (c) necessitate a smaller trial if the postulated effect size (or larger) was detected.

Effect size

The effect size that can be detected with 46,000 women (23,000 in each group), assuming a 5% level of significance and 90% power, was a 50% reduction in poor neonatal outcome rate from 3 to 1.5 per 1000 births. We approximated the number of women recruited with the number of infants born, even though women with a twin pregnancy were eligible to join the trial. Approximately 1 in 80 pregnancies are twin pregnancies; however, a proportion of these births will occur at < 35 weeks’ gestation and a large proportion of the term births would be by elective caesarean section. Therefore, we estimated that < 1% of all births in the study would be twins. In a study of 164 preterm infants,40 the mean PARCA-R composite score at 2 years was 80 points (SD 33 points) and the mean Mental Development Index (Bayley Scales of Infant Development II) score was approximately half a SD below the standardised mean of 100. We assumed that a normal group of term-born infants would have a PARCA-R composite score half a SD above this sample of preterm infants, so we estimated a mean 2-year score of 96 points (SD 33 points). Based on this estimate, a follow-up sample of 7000 children (3500 per arm) in the INFANT study would have over 90% power to detect a difference of 3 points in the PARCA-R composite score with a two-sided 5% significance level. The incidence of severe metabolic acidosis (a cord artery pH of < 7.05) has been reported as 10 per 1000 births. 44–47 The proposed sample size was therefore able to detect a 28% relative risk reduction in this incidence with > 80% power in those babies who had their cord artery pH measured.

Assumptions

Variations in some of the assumptions of incidence produced marked variations in the required sample size as the anticipated overall incidence was so low. For example, Table 3 illustrates the impact on the required sample size of varying the incidence of the primary outcome, assuming a 5% level of significance and 90% power for the same effect size (a 50% relative risk reduction).

| Incidence of primary outcome in (per 1000 births) | Relative risk | Total sample size required | |

|---|---|---|---|

| No decision support group | Decision support group | ||

| 3.0 | 1.5 | 0.5 | 46,000 |

| 4.0 | 2.0 | 0.5 | 34,000 |

| 5.0 | 2.5 | 0.5 | 27,000 |

| 6.0 | 3.0 | 0.5 | 22,000 |

Table 4 illustrates the variation on the effect size that could be detected with a sample size of approximately 46,000 women with variations in incidence.

| Total sample size | Relative risk | Incidence of primary outcome in (per 1000 births) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| No decision support group | Decision support group | ||

| 46,000 | 0.50 | 3.00 | 1.50 |

| 46,000 | 0.56 | 4.00 | 2.25 |

| 46,000 | 0.61 | 5.00 | 3.05 |

| 46,000 | 0.64 | 6.00 | 3.85 |

Loss to follow-up

It was assumed that loss to follow-up for the short-term primary outcome would be negligible, as most of this information would be collected before the woman left the delivery room in which she had been recruited. For neonatal outcomes, a small number of babies were admitted to a neonatal unit separate from where they were born or planned to be born, in which case data were collected from these sites through the research midwives employed by the study in the participating centres. At the time of entry to the study all women were asked for permission for their contact details to be downloaded to the trial co-ordinating centre along with their clinical details from the Guardian system. The families selected for follow-up at 2 years were contacted by post 8 weeks after birth and informed that they had been selected for the follow-up study. Contact with families who agreed to take part was maintained during the period between birth and the follow-up assessment by sending a birthday card each year along with a FREEPOST change-of-address card to facilitate communication with University College London (UCL) Comprehensive Clinical Trials Unit about updated contact details.

Trial management

Research governance

The sponsor of the trial was initially the University of Oxford (January 2009 to May 2012), but changed to UCL when the trial moved (May 2012 to June 2016). The trial was run on a day-to-day basis by the project management group. This group reported to the Trial Steering Committee (TSC), which was responsible to the research sponsor. At each participating centre, local principal investigators reported to the project management group via the project-funded staff based at the UCL Comprehensive Clinical Trials Unit.

Insurance

NHS indemnity operated in respect of the clinical treatment being provided. In addition, the sponsor had appropriate insurance-related arrangements in place.

Trial Steering Committee

The trial was supervised by an independent TSC. The precise terms of reference for the TSC were agreed at its first meeting. A TSC charter similar to that used by the Data Monitoring Committee (DMC) (see Data Monitoring Committee) was completed.

Data Monitoring Committee

An independent DMC was established for the trial. This was independent of the trial organisers. The terms of reference for the DMC were agreed at the first meeting. A DMC charter was completed following the recommendations of the DAMOCLES (DAta MOnitoring Committees: Lessons, Ethics, Statistics) study. 48

During the period of recruitment to the trial, interim analyses were supplied, in strict confidence, to the DMC, together with any other analyses the DMC requested. In the light of interim data, and other evidence from relevant studies, the DMC would inform the TSC if, in its view, there was proof beyond reasonable doubt that the data indicated that any part of the protocol under investigation was either clearly indicated or contraindicated, either for all women or for a particular subgroup of trial participants. A decision to inform the TSC would in part be based on statistical considerations. Appropriate criteria for proof beyond reasonable doubt could not be specified precisely. A difference of at least three standard errors (SEs) in the interim analysis of a major endpoint may have been needed to justify halting, or modifying, the study prematurely. This criterion had the practical advantage that the exact number of interim analyses would be of little importance, and so no fixed schedule was proposed. 49 Unless modification or cessation of the protocol was recommended by the DMC, the TSC, collaborators and administrative staff (except those who supply the confidential information) would remain masked to the results of the interim analysis. Collaborators and all others associated with the study were able to write, through the trial office, to the DMC, to draw attention to any concerns they may have about the possibility of harm arising from the treatment under study, or about any other matters that may have been relevant.

Publication policy

The chief investigator was responsible for co-ordinating the dissemination of data from this study. All publications using data from the study to undertake original analyses were submitted to the TSC for review before release. To safeguard the scientific integrity of the trial, it was agreed that data from the study would not be presented in public before the main results were published, without the prior consent of the TSC. The success of the trial depended on a large number of midwives and obstetricians. For this reason, chief credit for the results would be given not to the committees or central organisers, but to all who collaborated and participated in the study. It was agreed that authorship at the head of the primary results paper would take the form ‘The INFANT Collaborative Group’, to avoid giving undue prominence to any individual.

Chapter 3 Substudy of maternal anxiety in labour during recruitment to the pilot phase of the INFANT trial

During the process of application to the Research Ethics Committee (REC) for approval to undertake the INFANT trial, the committee was concerned that the use of the decision support technology during labour may increase anxiety among the women taking part. The committee asked the trial team to provide some reassurance that participating in the trial would not result in unacceptable anxiety for the women taking part.

We developed the study described below to address this. Sections of this chapter have been reproduced with permission from Barber et al. 50 Copyright © 2013, MA Healthcare Limited. Quotations from participants in this qualitative study have been reproduced verbatim from this publication with permission from the journal.

Introduction

Anxiety is common in pregnancy51 and EFM can lead to increased anxiety. 52 A study in Australia reported interviews with 100 women shortly after a straightforward birth and found that only 15% reported no anxiety during labour and birth. 53

Confidential enquiries into perinatal deaths have repeatedly demonstrated that most poor infant outcomes arise during labour. EFM was introduced into clinical practice to try to prevent these poor outcomes; however, we know that poor interpretation of fetal heart rate patterns occurs. Improvements in CTG interpretation have to be sustainable and ideally be independent of clinicians’ abilities. Computerised interpretation and decision support have the potential to improve care.

If women are aware of an effective method of interpreting their baby’s heart rate during labour, and understand that this is safer than an individual clinician’s interpretation, this may result in reduced anxiety.

The INFANT decision support software assesses the CTG and provides a colour-coded ‘ladder of concern’, which appears on the CTG screen (see Chapter 1 for more detail).

The aim of this study was to explore whether or not the use of EFM during labour increases or reduces anxiety levels among women and whether or not the addition of the INFANT decision support software has a positive or negative effect on these anxiety levels. We initially used a survey to measure anxiety in women randomised to each arm of the INFANT trial. We then used qualitative interviews in a smaller number of women to explore their feelings of anxiety associated with the use of monitoring in labour and the decision support system.

Methods

Survey

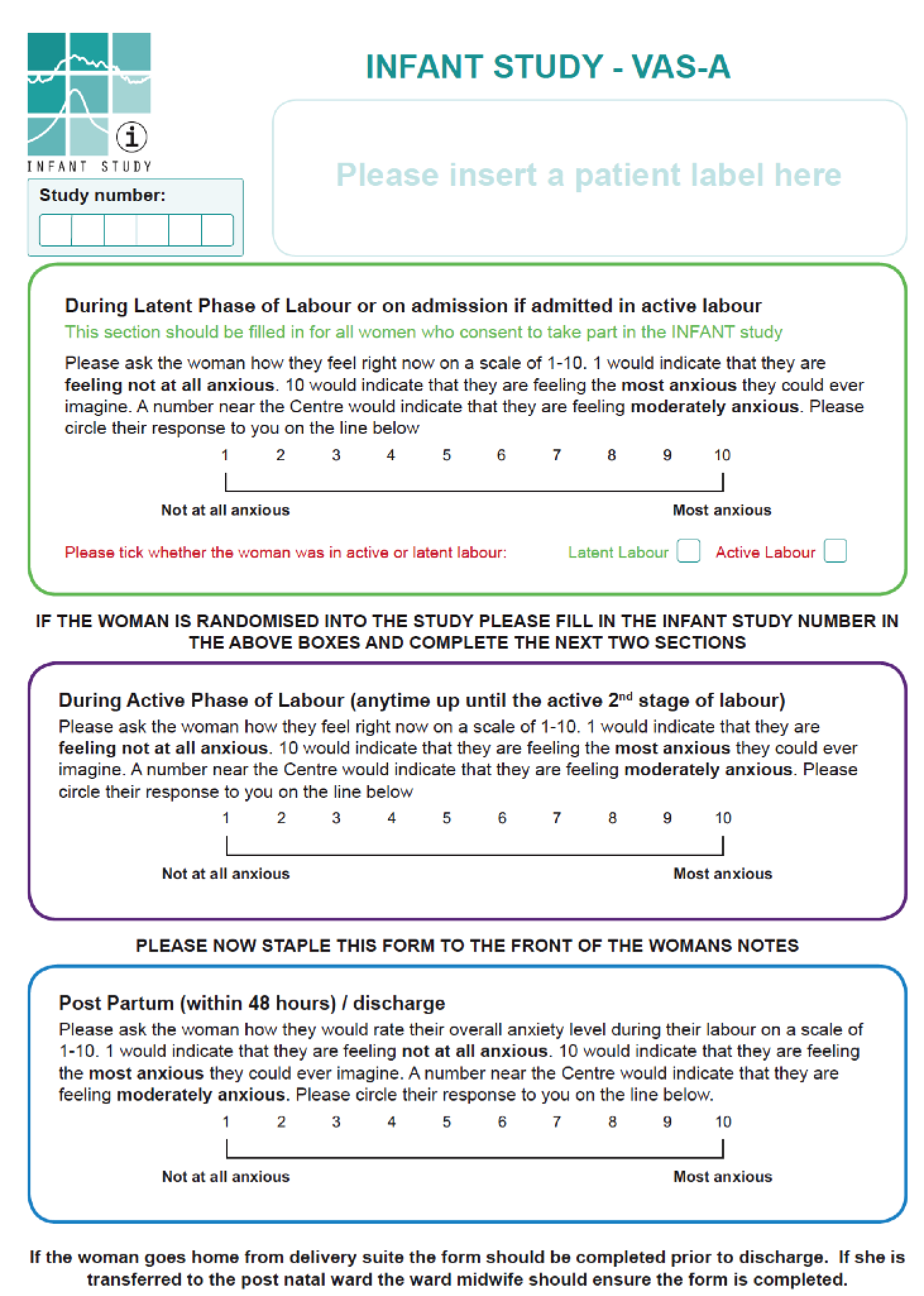

From 5 January 2010 to 18 July 2010, 469 women were recruited to the pilot phase of the INFANT trial from the Royal Blackburn Hospital. A total of 234 women were recruited to the CTG monitoring only (control) group and 235 were recruited to the CTG monitoring plus decision support (intervention) group. The eligibility criteria and process of recruitment are described in Chapter 2. In a subset of women approached to participate in the INFANT trial, we measured anxiety in the latent phase of labour when cervical dilatation was ≤ 3 cm with an effaced cervix. If the woman was recruited into the trial, we measured anxiety at a further two time points: during the active phase of labour when the cervical dilatation was 4–7 cm, and within 48 hours post partum. At each time point, the midwife asked women to rate their anxiety using a visual analogue scale – anxiety (VAS-A) from 1 (not at all) to 10 (very much so). Their responses were recorded on the VAS-A study form (Figure 10).

FIGURE 10.

The INFANT study visual analogue scale form.

Statistical analysis

The change in VAS-A scores in the two groups (control and intervention) (1) from the latent to the active phase of labour and (2) from the latent phase to the postpartum period was analysed using repeated measures analysis of covariance (ANCOVA). This enabled us to include all women in the analysis, even those with data at only one time point. The correlation between scores between phases was calculated using the Pearson correlation coefficient. Two-sided significance tests were used, taking a p-value of 0.05 as significant. The analysis was conducted using statistical software Stata version 11.1.

Qualitative study

Women from two of the study sites in the INFANT trial (Warrington Hospital and University Hospital of North Staffordshire) were approached to be interviewed about their experiences of birth and fetal monitoring by a single trained qualitative researcher. Women were approached after giving birth and before hospital discharge. A purposive sampling approach was used to ensure that equal numbers of women from the two arms of the trial were recruited, and that the number and severity of alerts was wide-ranging and well balanced between the two groups. The trial’s statistician identified potential women to be included and informed the qualitative researcher of their study number. The interviewer was masked to the women’s trial allocation and pattern of alerts until after the interviews were complete.

The interviews collected views of the whole birth experience but included semistructured prompting to explore women’s feelings about monitoring and their understanding of the INFANT trial. The interviewer and another senior qualitative researcher undertook the analysis jointly. An initial thematic analysis was undertaken using NVivo (QSR International, Warrington, UK) software to support the coding process. This was followed by a framework analysis, summarising the experiences and attitudes of each woman and mapping these against the woman’s characteristics (hospital of birth, study allocation, maternal age, gestation at trial entry and number of yellow and red alerts).

Results

Quantitative study

The VAS-A score sheets were completed by 275 out of 469 (59%) women [CTG monitoring only: 142 out of 234 (61%); CTG monitoring plus decision support: 133 out of 235 (57%)]. In the control group, data were available for 128 (55%) women from the latent phase, 104 (44%) for the active phase and 81 (35%) for the postpartum period. In the intervention group, data were available for 124 (53%) women for the latent phase, 106 (45%) for the active phase and 81 (34%) for the postpartum period.

The VAS-A scores are shown in Table 5. The scores were approximately normally distributed. In each group, anxiety levels increased from a score of around 5 points in the latent phase to around 6 points in the active phase, then dropped below 5 points in the postpartum period. There was no difference between groups in the change in anxiety from the latent to the active phase (p = 0.84) or from the latent phase to the postpartum period (p = 0.88). The scores were positively correlated: 0.48 between latent and active phase, 0.41 between the latent phase and the postpartum period, and 0.44 between the active phase and the postpartum period.

| Phase | VAS-A scores | Between-group difference in mean change (95% CI) | p-value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CTG monitoring only | CTG monitoring plus decision support | |||||

| n | Mean (SD) | n | Mean (SD) | |||

| Latent | 128 | 5.0 (2.7) | 124 | 4.8 (2.6) | ||

| Active | 104 | 5.7 (2.7) | 106 | 5.5 (2.9) | –0.08 (–0.93 to 0.76) | 0.84 |

| Postpartum | 81 | 4.5 (2.4) | 81 | 4.4 (2.4) | –0.06 (–0.84 to 0.71) | 0.88 |

Qualitative study

A total of 18 women were interviewed, including six with their birthing partner, who was either their partner or mother. Table 6 provides a list of the women interviewed with details of their hospital of birth, trial group, age, gestation at trial entry and number of alerts. Four women had no alerts, seven had at least one yellow but no red alerts and seven had at least one red alert. The number of red and yellow alerts were evenly distributed across the trial groups.

| Interview IDa | Hospital | Trial arm | Maternal age (years) | Gestation at randomisation (weeks) | Number of yellow alerts | Number of red alerts |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 01 | Warrington | Control | 30 | 41 | 2 | 2 |

| 02 | Warrington | Control | 23 | 39 | 3 | 0 |

| 08 | Warrington | Control | 30 | 40 | 1 | 0 |

| 14 | Warrington | Control | 23 | 26 | 4 | 1 |

| 21 | Warrington | Control | 29 | 40 | 5 | 1 |

| 22 | Warrington | Control | 36 | 38 twins | 13 | 2 |

| 07 | Warrington | Decision support | 49 | 41 | 5 | 0 |

| 15 | Warrington | Decision support | 28 | 39 | 0 | 0 |

| 18 | Warrington | Decision support | 26 | 41 | 1 | 0 |

| 19 | Warrington | Decision support | 38 | 37 | 4 | 2 |

| 20 | Warrington | Decision support | 36 | 38 | 3 | 0 |

| 04 | North Staffs | Control | 37 | 39 | 0 | 0 |

| 05 | North Staffs | Control | 31 | 37 | 0 | 0 |

| 11 | North Staffs | Control | 39 | 42 | 3 | 0 |

| 03 | North Staffs | Decision support | 27 | 40 | 0 | 0 |

| 09 | North Staffs | Decision support | 28 | 41 | 8 | 2 |

| 10 | North Staffs | Decision support | 21 | 41 | 6 | 1 |

| 16 | North Staffs | Decision support | 31 | 38 | 4 | 0 |

Levels of understanding

Among participants, there was a patchy understanding of what the trial was about, beyond a general view that it was seeking to understand people’s experiences in labour and improve care for other women in the future. This is a finding that is widely reflected in the literature. 54–56 Women were frequently unclear about what is ‘normal’ monitoring of the baby in labour and what is part of the trial, and whether or not they would have been monitored anyway:

It was nothing, you know, that was intervening with anything, so I hadn’t minded at all. I just hadn’t been totally aware that I’d be hooked up to a machine the whole time. I just thought it was if you needed to be on the machine, they’d then monitor it through the computer . . . I wasn’t sure whether I had to be on the machine for the sake, you know, for the baby’s sake and whatnot or whether it was because I was, because of the study. I wasn’t too sure what it was that I had to actually be on it for.

Participant 02, control arm

My understanding at the time of it was really just that it would be somebody maybe 1 or 2 years after the birth would be following up with a questionnaire and maybe a phone call or something just to see what my experience was . . . I don’t recall the monitoring being part of the study but a huge deal wasn’t made of it anyway, but as I say it wouldn’t have been a problem if it was, but I was going to be monitored anyway with being induced.

Participant 05, control arm

Participant 05 (control arm) also said, ‘I didn’t remember them saying which group I was in. Is there different groups?’. Similarly, participant 14 (control group) said, ‘I don’t remember anything to do with groups’. Furthermore, she did not clearly recall any monitoring at all. This participant had a vague recollection of ‘bands’ being used for monitoring her baby’s heart, and that the baby’s heartbeat had dropped at one stage, but said, ‘I definitely don’t remember anything being put round me’ other than her transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation machine. Similarly, a woman in the intervention arm (participant 18) said, ‘Groups? They might have mentioned it but I don’t remember it’.

One couple (04, control arm) knew they had been allocated to a group but were unaware of how and why they had been selected for participation. The male partner had spent quite a lot of time trying to work out for himself what the monitor readings meant:

It would be nice to know.

You know, why your specific case was chosen. Was it just it was randomly chosen or was it because they wanted to, to look at it for a certain reason?

Or is it just that we were placed in this particular bracket, you know?

Well, was it just random that our, you know, results were picked out? Or was it because, like we think, [female] had a rapid delivery? Or, you know, or something come up on the results why they decide?

However, other participants in both groups were aware that there were different arms and demonstrated an awareness of which arm they were in as well as how they were allocated to a group:

Basically what they told us, well it says in the leaflet as well, that you might not be selected for the trial on a computer. Basically she tapped in some information on the screen and then it come up whether you’d be selected for it. And she typed it in and she said we weren’t selected for it.

Participant 01, control arm

It was frequently suggested by participants that being given information about the trial towards the end of pregnancy rather than during the labour episode may improve understanding, as it was difficult for people to absorb the information or give it any priority during labour. This approach of providing information during pregnancy should have been happening in the centres, and a few women did recall discussing it at antenatal appointments or seeing posters about it in previous visits, but others did not. Women also mentioned feeling ‘vague’ or ‘confused’ about the information provided during labour because of the pain relief medication they had taken.

There was little evidence that feeling underinformed had led women to regret taking part. This was because EFM was commonly seen as routine care and not particularly invasive. Even women who disliked not being able to mobilise because of the monitoring failed to express major concerns about the information and consent process.

One exception to this was a woman in the decision support arm who said that she felt ‘mithered’ by having to answer all the questions needed to take part in the trial:

I didn’t want to be asked; I just wanted to be left alone to get on with going through the labour . . . I just wanted to be left alone and that took like 15, 20 minutes to do all that so like she was asking me questions and I was contracting as well . . . I signed it because I thought – and I said this to my mum this morning – the only reason that I signed it was because I thought if the midwife thinks that we’re co-operating with this then she’ll give us some drugs [laughter]. She’ll give me some more drugs, that’s what I thought . . . It was something that was so shoved in my face and I didn’t really have a choice basically . . . because I wanted to keep my midwife nice and sweet.

Participant 15, decision support arm

She complained that she ‘hated’ being monitored because it restricted her movements. It did not make her feel more anxious, but she regretted taking part because she felt that it spoilt her otherwise good experience of a spontaneous vaginal birth. She was so bothered by the restrictions on movement that she requested that the monitoring be stopped. It is clear from her interview that she did not understand that she would have had monitoring anyway and that it was not a consequence of taking part in the trial. She said that monitoring should be used ‘only if it’s an emergency for the baby’ and did not understand that the purpose of monitoring was to detect concerns before they become emergencies. When this was discussed during the interview she commented:

So in that case it does change my views differently then, then yes, if I would have known it was something to do with protecting the baby then yes I would have had it on in labour.

Participant 15, decision support arm

Monitoring and reassurance

Women in both groups of the trial reported finding monitoring reassuring. There was no difference in the pattern of responses between the two groups, or between women with few alerts and those with many.

For example, one woman said:

That showed what the heartbeat was doing, you know, ranging from sort of whatever it was, 100 to 150. And there was a guide next to it to say what’s acceptable and what’s, you know, risky. [um] So that was quite reassuring, wasn’t it?

Participant 04, control arm, no alerts

Oh, I thought it was brill, to be honest, because as I say a lot of the time I felt a little bit out of the loop. From where I was sitting I could see all the screens and what was going on so I found that, you know, sort of quite comforting.

Participant 03, decision support arm, no alerts

Being able to monitor what was happening with [baby 1] and sort of midway through what was happening with [baby 2] with their heart rates and things made me very reassured.

Participant 22, control arm, 13 yellow and two red alerts

I did quite enjoy having the monitors on actually. . . . you can just see, see sort of their heartbeat and how strong your contractions were, whereas normally you couldn’t, you haven’t got that.

Participant 09, decision support arm, eight yellow and two red alerts

Several women (or their partners) said that the monitor also helped reassure the partner. This generated a sense of involvement because they could observe a contraction and support their partner appropriately. Participant 19 (decision support arm) said that her partner ‘kept checking the paper. I think he was fascinated by it’.

Monitoring and restriction of movement

On those occasions when objections were raised about monitoring, this was most usually because of the restrictions it placed on movement. Some women said that they did not find the monitor restrictive or uncomfortable, including participant 19 (decision support arm). When asked if she could move around she said:

Yes, I was on my side for most of it, they said that’s the most comfortable position for me so I just stayed on my side.

Did you mind being monitored at all?

No, no anything that helps really.

When you say helps, in what way?

I mean, well like just in case there’s any complications, I’d rather be monitored and have them spot them, so.

You found it sort of reassuring?

Yes, yes extra reassurance.

However, other women talked about wanting to alleviate pain by moving around or to be able to go to the toilet. The monitor restricted this movement and some women felt that the monitor straps were uncomfortable. Some women expressed a preference for a wireless monitor. One woman had heard that this was available in other hospitals. Women who disliked being monitored expressed varying degrees of resignation, assuming that they would have their movement restricted anyway (e.g. because of an epidural) or that the disadvantages of limited movement had to be balanced against the benefits for the baby and their own peace of mind:

The fact that it restricted me, that was a bit of a pain, but I don’t know whether I would have moved round that much or, you know. Because I mean I could have sat on the ball, you know, the blow up ball . . . rather than the chair, which is one of the things they recommend. But I didn’t want it. I just wanted to sit on the chair . . . No, it’s reassuring, I think because you know you don’t want your baby’s heart rate to go down. And it was quite good as well in that my husband could see when the contractions were coming on . . . I think we, it made no difference to us taking part, you know, it wasn’t detrimental, it wasn’t, I was going to be monitored anyway whether I took part in the trial or not.

Participant 20, decision support arm, three yellow alerts

And the reason I agreed, why I thought it was brilliant, was because it’s extra checks, it’s extra checks for him. And I think well he’s going to be monitored closely from now on which is amazing but, you know, because I’d do anything for him, you know, healthy baby, and if it picks up on something, fantastic, and it’s doing research for everything else, so yes . . . So it turned out that I was on this monitor for this and my heart and everything so I couldn’t move off the bed for all them hours, they wouldn’t let me move. So I couldn’t walk round, so my plan had gone way out the window. I wasn’t walking round, I’d not had my bath at all, I’m stuck on this bed, I’ve been induced. . . . The birth plan was just sit on the ball, stay upright and move as much as you can. That was basically it. And nothing happened like that and I’m saying ‘Can I get off this bed?’ ‘No, you’re being monitored for this and you’re being monitored for your heart, you’re being monitored, baby’s being monitored because of the poo because that’s dangerous, no you can’t move off this bed’. I was like ‘Ohhhh’, so I just lay down the whole day. Which was really nice and very boring.

Participant 11, control arm, three yellow alerts

Monitoring and anxiety

Women did describe anxious moments during their labour; however, these did not seem to be associated with monitoring, but were more related to the urgent comments and behaviour of staff as they responded to the monitoring results or to other clinical concerns.

There was only one clear exception to this:

So it was quite good because obviously people could see what was going on . . . because the doctor come in and said I’ve been watching you on the screen . . . Sometimes, I kept hearing her say when the heartbeat, because they kept saying she’s being naughty, they just kept saying that, and it was flashing messages up to them and I heard her say a couple of times ‘I think that heartbeat’s okay for the minute’ but that was telling her it was, so . . . They did talk about it quite a bit, they used it as a guide but said they would use their own judgement to make any decisions . . . In a way I don’t know if it’s a good thing or a bad thing, though, because right towards the end because her heartbeat had been playing up all day, we were all focused on it . . . Everyone was just focused on this monitor and the heartbeat, so I think that got a little bit stressful, because I did end up telling him [partner] ‘Stop telling me what’s happening or talking about it’ because it was making me panic . . . He says to me afterwards that he was, it was the most scared he’d ever been in his life but at the time he seemed really quite cool and took it all in his stride but obviously he was just putting a show on for me.

Participant 16, decision support arm, four yellow alerts

Nonetheless, participant 16 concluded: ‘The study didn’t really affect the birthing experience at all so that, you know, I’d do it again, that’s fine’.

This woman’s interpretation was that the staff used the decision support to justify postponing any intervention. She was glad not to have a caesarean section, but she felt that she could have had an instrumental delivery earlier: ‘I do think that because her heartbeat had been playing up so long throughout the day and things weren’t moving on for me that they should have looked at me a bit earlier and made a decision a bit earlier’. The woman’s mother, who was present during the labour and birth, and was interviewed with her, was even more convinced of the need for an early delivery:

It was about half nine and I can remember the midwife saying, ‘We’re going to leave you till eleven and if nothing’s happened by eleven we’ll get the doctor and we’ll see about taking you to theatre. But then when 11 o’clock came they had a look at you and you’d dilated quite a bit by then so they said we’ll leave you another hour, that took you to 12.00 and then again we’ll leave you another 2 hours, and that annoyed me because that’s what they kept saying. Although, you know, she was well into labour I think they should have took her for a C-section at about 11 o’clock, I do.

Mother of participant 16, decision support arm

This example suggests that CTG with decision support could lead to some cases of raised anxiety levels. There were two examples in the control group in which monitoring without decision support also caused some anxiety. Participant 08 reported that her mother had been worried at one point, although she herself was relaxed and asleep:

My mum was watching where they was monitoring me and I think I fell asleep so as I had diamorphine. And at one point, because they had one on me and one obviously for the baby’s heartbeat, and the baby must have moved so it went to zero and my mum thought it was me. She said she couldn’t see my chest rising or anything and thought I wasn’t breathing and she looked at this monitor and seen zero and she was like, ‘She’s not breathing, she’s not breathing’ and I woke up and I was like ‘What?’ [laughter].

Participant 08, control arm

The partner of participant 21 (five yellow alerts and one red alert) recalled his own fears:

Yes it was helpful, but it was also, I think, in some respects that she couldn’t see it was as well because there was quite a few scary moments.

You see, I couldn’t see that because it was . . .

Yes, I mean his heart, I could see his heartbeat going down and she couldn’t see it, so I was a bit worried there.

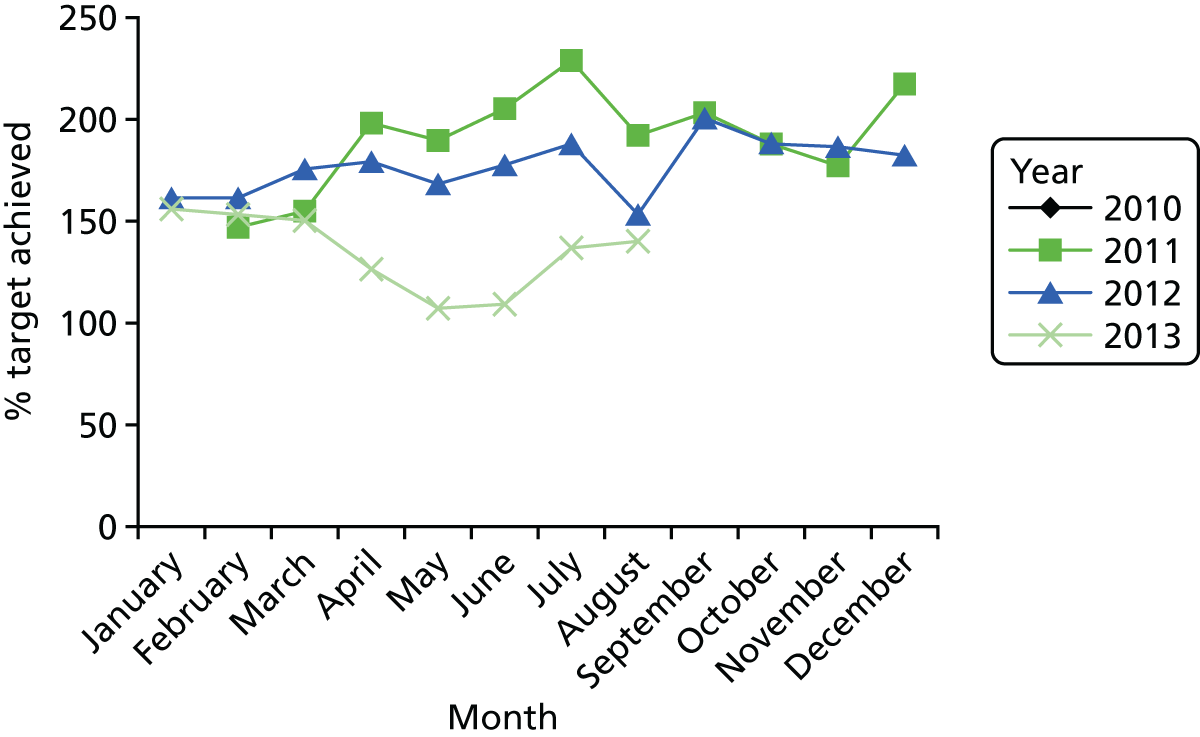

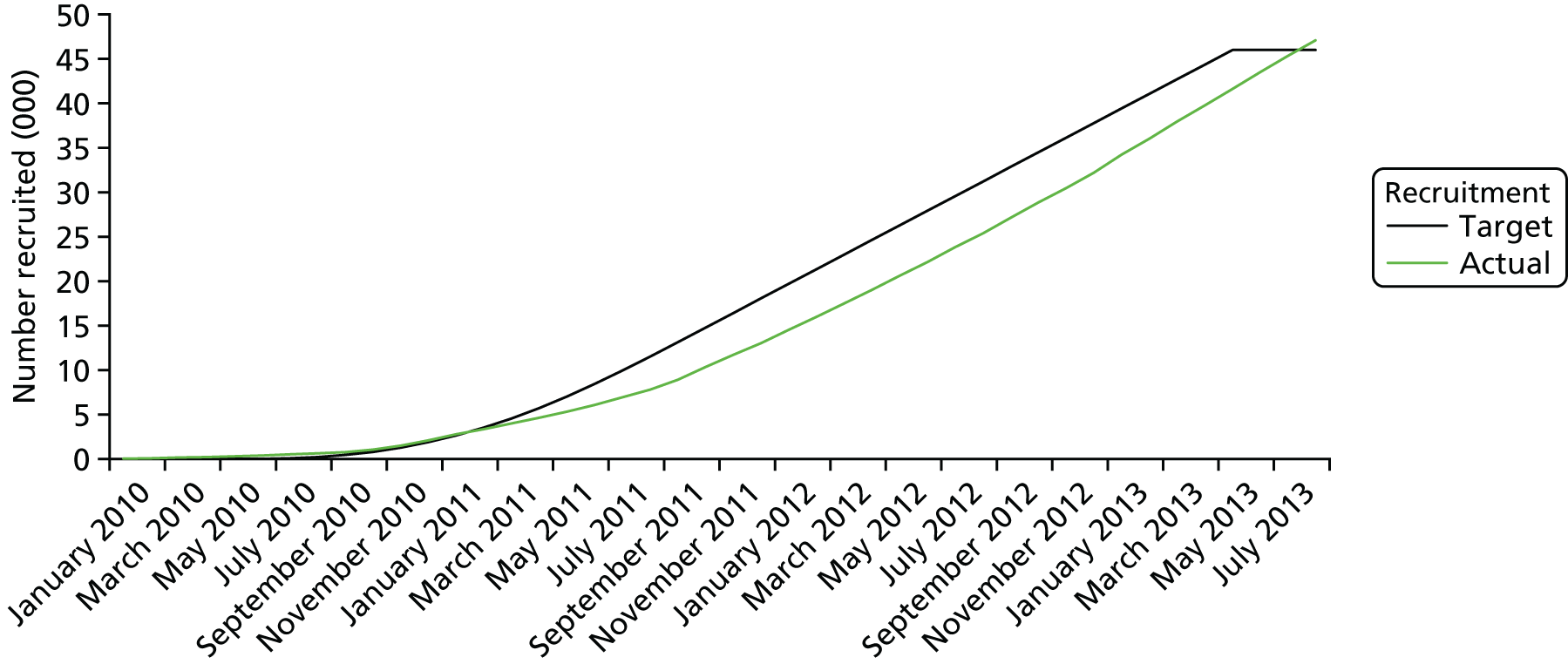

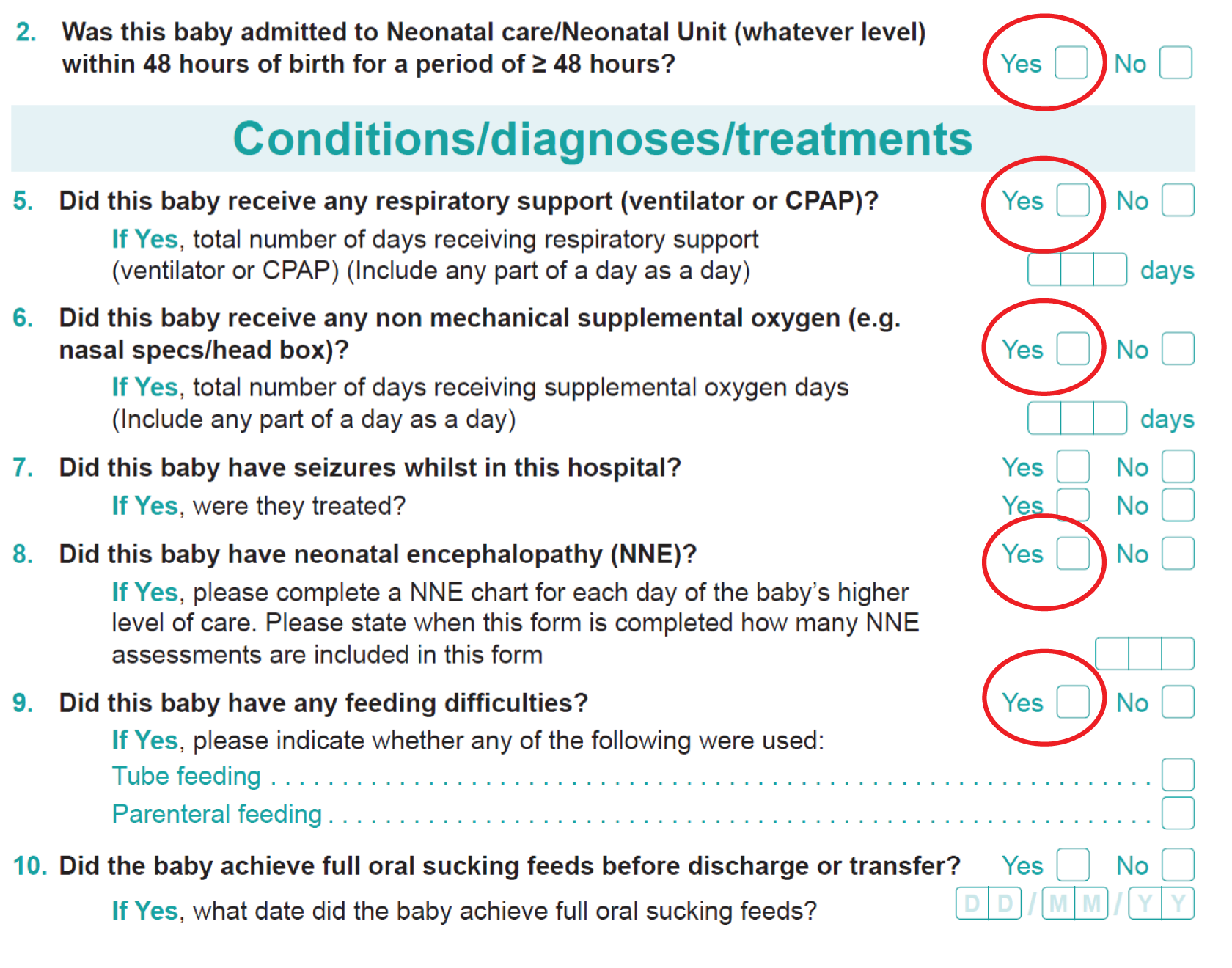

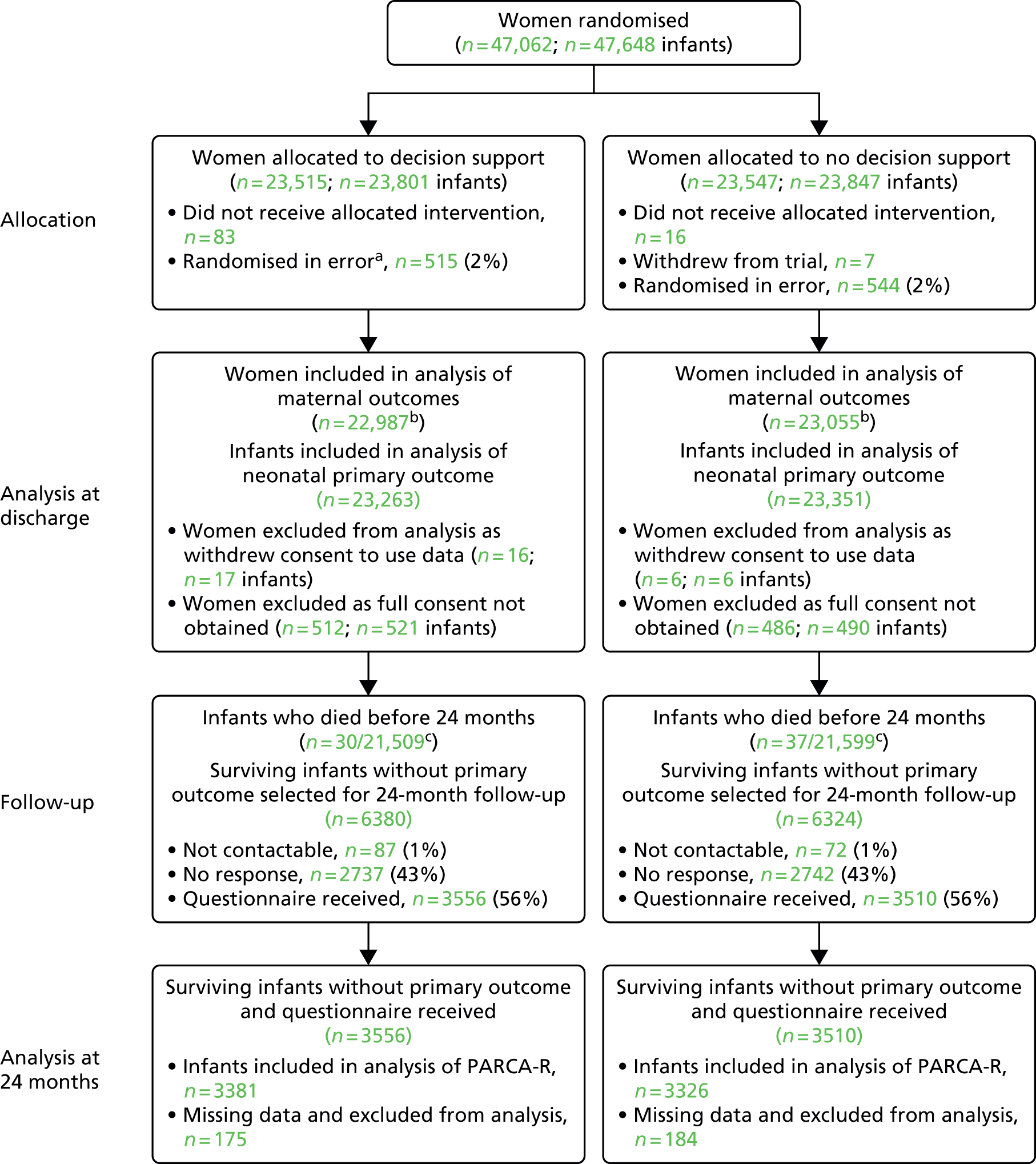

But as soon as his heartbeat started going down they all, them sitting on their desk came in to have a look.