Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 11/136/04. The contractual start date was in March 2013. The draft report began editorial review in March 2017 and was accepted for publication in November 2017. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Matthew L Costa is a member of the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Health Technology Assessment (HTA) General Board and reports grants from the trauma industry (Stryker Corporation, X-Bolt Orthopaedics, Onbone, Smith & Nephew plc, Heraeus Holding GmbH and DePuy Synthes Companies); grants from the AO Foundation; and grants from NIHR and the European Union outside the submitted work. Sarah E Lamb was a member of the NIHR HTA Additional Capacity Funding Board, NIHR HTA End of Life Care and Add-on Studies, NIHR HTA Prioritisation Group and NIHR HTA Trauma Board during this study.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2018. This work was produced by Costa et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2018 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Introduction

Adapted with permission from Achten et al. 1 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

Background

The tibia is the most commonly broken major bone in the leg. In younger patients, fractures of the tibia typically occur during sporting activity or road traffic accidents, but in older patients they can happen during simple falls. Injuries usually require hospital admission and surgery, resulting in prolonged periods (months) away from work and social activities.

The treatment of displaced, extra-articular fractures of the distal tibia (lower third) remains controversial. These injuries are difficult to manage because of the limited soft-tissue cover, poor vascularity of the area and proximity of the fracture to the ankle joint. Infections, non-union and malunion are well-recognised complications.

Non-operative treatment is one option and avoids the risks associated with surgery. Sarmiento et al. ,2 in 2003, reviewed 450 closed fractures of the distal tibia following functional bracing: 13.1% developed a malunion (defined as > 7° of angulation or 12 mm of shortening). Another study,3 using a more robust definition of 10 mm of shortening and 5° of angulation, found a higher rate of malunion (26.4%). In this study, Böstman et al. 3 treated patients using a long leg cast, and failure to maintain reduction led to surgical treatment with an intramedullary (IM) nail. Thirty-two out of 103 cases required nailing at a mean of 9 days following injury. Two patients in this group, and three in the non-operative group, went on to have a non-union. 3 Union rates were faster with IM nailing than with conservative treatment and median values were 12.5 and 14.5 weeks, respectively (p < 0.001). 3 Digby et al. 4 also found that non-operative treatment for tibial fractures in the metaphyseal region leads to unacceptable deformity and ankle stiffness. Therefore, operative treatment is now the treatment of choice for the majority of patients with a fracture of the distal tibia.

Surgical treatment options are expanding and include locked IM nails, plate and screw fixation, as well as external fixator systems, including the Ilizarov frame and hybrid fixators. External fixators may be beneficial in selected cases, particularly those involving severe soft-tissue injuries, but, in the UK, the IM nail and ‘locking’ plate options are most commonly used for extra-articular fractures. Mid-shaft fractures of the tibia are generally successfully treated with locked IM nails. However, in the more distal metaphyseal region of the tibia, the fixation may be less stable. 5 The bolts or screws that are inserted into the nail may break,6 malalignment may occur7 and there is a risk that the nail will penetrate into the ankle joint. 8,9

The development of locking plates, in which a thread on the head of the screws locks into the holes in the plate to create a ‘fixed-angle’ construct, has led to a recent increase in the use of locking plate fixation. However, locking plates are not without risks and they require greater soft tissue dissection, which carries a risk of infection, wound breakdown and damage to the surrounding structures. 10

In a retrospective study11 of 111 patients with extra-articular fractures of the distal tibia (4 to 11 cm proximal to the plafond), a comparison was made between IM nail and locking plate fixation. Seventy-six fractures were treated with an IM nail and 37 were treated with a medial plate. 11 Nine patients (12%) had a delayed union or non-union in the IM nail fixation group and one patient (2.7%) had a non-union after locking plate fixation (p = 0.10). Angular malalignment of ≥ 5° occurred in 22 patients with IM nails (29%) and two with locking plates (5.4%; p = 0.003). The authors concluded that fractures of the distal tibia may be treated successfully with locking plates or IM nails, but that delayed union, malunion and secondary procedures were more frequent after IM nailing. Janssen et al. 12 found similar results: delayed union was higher in the IM nail fixation group (25%) than in the locking plate fixation group (16.7%) and rotational malalignment was also higher in the IM nail fixation group (16.7%) than in the locking plate group (0%). However, this was not a randomised controlled trial (RCT) and the results do need to be interpreted with some caution. Randomised prospective assessment are necessary to further clarify these issues and provide information about costs associated with these fractures. 11

Only two prospective RCTs had been published when this trial began. 13,14 In the first,13 64 patients were randomised to either IM nail or plate fixation for the treatment of a closed extra-articular fracture. The time to union was found to be similar for the two groups and there was no difference in terms of Olerud–Molander Ankle Score (OMAS) at 2 years. However, a significant difference was observed in the number of wound complications: one in the IM nail fixation group versus seven in the plate group. This paper concluded that IM nailing is the treatment of choice for this injury. However, the method of randomisation was poorly described and so bias in group assignment may have occurred. The study used traditional (non-locking plates) rather than the newer fixed-angle devices. Furthermore, the study included patients with Tschene classification C2 soft-tissue injuries, which may have influenced the results. The second trial14 randomised 111 patients to either IM nail fixation or ‘locking’ plate fixation. This trial also showed no difference in the time to union but, 1 year after the injury, there was some evidence of improved American Orthopaedic Foot and Ankle Society functional scores in the IM nail fixation group. However, this was a single-centre investigation and > 20% of the patients in the trial were lost to follow-up.

In a meta-analysis, Zelle et al. 15 reviewed 1125 extra-articular fractures of the distal tibia. They reported that non-union, malunion and infection rates were similar for patients undergoing IM nailing and locking plate fixation. It must be noted that none of the studies in the review was a RCT.

Pre-pilot trial

We performed a pilot study involving 24 patients with extra-articular fractures of the distal tibia that were closed or Gustilo and Anderson grade 1. 16 The study was a RCT with clinical assessment, functional outcomes and radiological images performed at baseline and at 6 weeks, and 3, 6 and 12 months post surgery. The study was performed to obtain an estimate of the potential effect size to inform the sample size calculation for a larger definitive trial and to assess recruitment rates and study feasibility.

The study had 12 patients in each group. There was no statistically significant difference between the groups 6 months after the injury but there was a 10-point difference [standard deviation (SD) 20 points] in the Disability Rating Index (DRI)17 in favour of the IM nail group. More secondary procedures were required in the ‘locking’ plate fixation group. There was also a difference in the cost of the implants.

This pilot study, combined with the literature review, provided compelling evidence to support the development of a definitive RCT in multiple centres.

Null hypothesis

There was no difference in the DRI score between adults with a displaced fracture of the distal tibia treated with locking plate fixation versus IM nail fixation.

Objectives

The primary objective was to estimate the difference in the DRI scores between the trial treatment groups at 6 months after injury.

The secondary objectives were to:

-

estimate the difference in early functional status at 3 months and later functional status at 12 months

-

estimate the difference in health-related quality of life between the trial treatment groups in the first year after injury

-

determine the complication rate of IM nail fixation versus locking plate fixation in the first year after injury, including radiological complications – non-union and malunion

-

investigate, using appropriate statistical and economic analytical methods, the resource use, costs and comparative cost-effectiveness of IM nail fixation versus locking plate fixation.

Chapter 2 Methods

Adapted with permission from Achten et al. 1 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

Trial design

We conducted this project as a two-phased study. Phase 1 (internal pilot) determined the expected rate of recruitment in a large-scale multicentre RCT in this complicated area of trauma research. Phase 2 (main phase) was a RCT in 28 acute trauma centres across the UK.

Internal pilot summary

The pilot took place in six centres over a period of 6 months. Screening logs were kept at each site to determine the number of patients assessed for eligibility and reasons for any exclusion. In addition, the number of eligible and recruited patients, and the number of patients who declined consent/withdrew, were recorded.

Main randomised controlled trial summary

All adult patients presenting at the trial centres with an acute fracture of the distal tibia were potentially eligible to take part in the trial. The broad eligibility criteria ensured that the results of the study could readily be generalised to the wider patient population. A computer-generated randomisation sequence, stratified by centre and age, was produced and administered independently by a secure web-based service, Warwick Clinical Trials Unit (WCTU). Randomisation was on a 1 : 1 basis to either IM nail fixation or locking plate fixation. Both of these operations are widely used within the NHS and all of the surgeons in the chosen centres were familiar with both techniques.

Baseline demographic data, radiographs and pre-injury functional data using the DRI and the OMAS questionnaire were collected. The patients were also asked to fill out the EuroQol-5 Dimensions (EQ-5D) health-related quality-of-life questionnaire twice at baseline; once to indicate their typical pre-injury health status and a second time to indicate their current post-injury status.

In conjunction with the clinical team, a research associate performed a clinical assessment and recorded any early complications at 6 weeks, and a radiograph was taken. A further clinical assessment and radiograph was also taken at 12 months postoperatively to detect late complications. Functional outcome, health-related quality of life and resource use questionnaires were collected at 3, 6 and 12 months postoperatively.

Participants

Inclusion criteria

The inclusion criteria for this trial were that the patient:

-

was aged ≥ 16 years

-

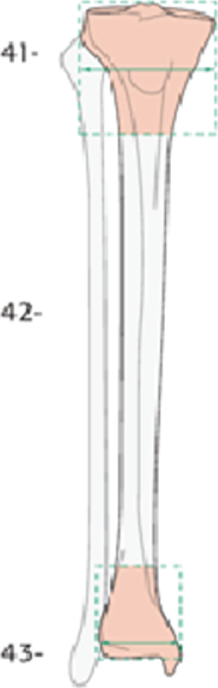

had any fracture that involves the distal tibial metaphysis, which was defined as a fracture extending within 2 Müller squares of the ankle joint18 (a Müller square is shown in Figure 1)

-

had a closed fracture

-

would, in the opinion of the attending surgeon, benefit from internal fixation of the fracture.

FIGURE 1.

Müller square. 18 Reproduced with permission. Copyright by AO Foundation, Biel, Switzerland.

Exclusion criteria

The exclusion criteria for this trial were that:

-

there is, in the opinion of the attending surgeon, a contraindication to IM nailing – the presence of total knee replacement OR the medullary canal is too narrow OR there is a pre-injury deformity of the medullary canal OR it is not possible to achieve fixation of four cortices with screws distal to the fracture

-

the fracture is open

-

there is a contraindication to anaesthesia

-

there is evidence that the patient would be unable to adhere to trial procedures or complete questionnaires

-

the fracture extends into the ankle joint (i.e. intra-articular fracture).

Screening and recruitment

All of the centres involved in the trial were UK NHS acute trauma centres. All of the centres provided definitive surgical fixation of this type of fracture in their hospital as part of routine clinical practice.

The internal pilot informed, and tested, the recruitment rate for the main trial. 16 Recruitment took place in six trial centres over a period of 6 months. The expected rate of recruitment was based on the pre-pilot study performed at the lead centre. The average recruitment rate for the pre-pilot study, during which 24 patients were recruited, was 1.3 patients per month. The other centres involved in the trial were all regional trauma units with similar catchment areas to the lead centre. However, a conservative recruitment rate of 0.75 patient per centre per month (pcpm) was estimated for the full trial based on our previous experience of multicentre trials, in which we found that recruitment outside the lead centre was at a lower rate. Our plan was to progress to the main phase if this recruitment rate could be achieved at the end of the internal pilot. Our intention was to recruit 320 participants, from a minimum of 18 centres in total (including the lead centre), over a 30-month period.

Screening logs were collected throughout the trial to assess the main reasons for patient exclusion as well as the number of patients unwilling to take part. Patients were screened by the research associates in the emergency department and trauma unit at the trial centres. The trial was carried out in accordance with the Mental Capacity Act 200519 and the procedures for undertaking trials in ‘emergency settings’ were followed as described in detail in Consent. The consent procedures were reviewed at the end of the pilot period.

Consent

Patients with a fracture of the distal tibia are admitted to hospital, through the emergency department, to a trauma ward. Patients are in pain and often treated with opiate-based painkillers during the initial treatment of their injury, so mental capacity may be impaired. However, although surgical treatment for a closed fracture of the tibia is urgent, it is not a time-critical intervention. In fact, traditionally, surgeons have deliberately waited a day or more before operating in order to let soft-tissue swelling settle. Once the leg is immobilised in a plaster cast, the pain is much better controlled, so mental capacity usually returns quite quickly following admission to the trauma ward.

During the internal pilot phase of the trial, we monitored the number of patients with impaired capacity and reviewed these data in conjunction with the Trial Steering Committee (TSC). In the context of this injury, by the time the patient was due to have surgery, none of the potentially eligible patients was judged to have reduced capacity according to the clinical team responsible for patient care. Therefore, informed consent from the patient was obtained by the local research associate before surgery. Patients were provided with verbal and written information about the study.

For those patients who withdraw from the trial after written consent had been obtained, data obtained up to the point of withdrawal have been included in the final analysis.

Randomisation

Following informed consent, the method of fixation was allocated using a secure, centralised, web-based randomisation service, delivered by an accredited clinical trials unit (WCTU). The randomisation service was available 24 hours each day to facilitate the inclusion of all eligible patients. The allocated treatment was reported to the research associate, who informed the treating surgeon. The surgeon then arranged the allocated surgery on the next available trauma operating list, as per standard practice at that institution; this ensured the integrity of the randomisation process. Allocation was implemented using a minimisation algorithm (sometimes referred to as adaptive randomisation) that attempts, at recruitment of each new patient, to balance the marginal totals for each level of the stratification factors. Experience indicates that, for studies in which some centres recruit only a relative small number of patients, this method tends to perform better than conventional stratification methods and may provide potential gains in efficiency. 20

Stratification by centre helped to ensure that any clustering effect related to the centre itself was equally distributed in the trial arms. The catchment area (the local population served by the hospital) was similar for all of the hospitals, each hospital being a trauma unit dealing with these fractures on a daily basis. Although it could have been possible that the surgeons at one centre may have been more expert in one or the other treatment than those at another centre, all of the recruiting hospitals were chosen on the basis that both techniques were routinely available at the centre, that is, theatre staff and surgeons were equally familiar with both forms of fixation. This did not eliminate the surgeon-specific effect of an individual at any one centre. 21 However, fixation of a fracture of the tibia is not an uncommon procedure and many surgeons will be involved in the management of this group of patients: between 10 and 30 surgeons at each centre, including consultants and trainees. Therefore, we expected that each individual surgeon would operate on only two or three patients enrolled in the trial – and indeed this was the case – greatly reducing the risk of a surgeon-specific effect on the outcome at any one centre.

Stratification on the basis of age was used to discriminate between younger patients with normal bone quality sustaining high-energy fractures and older patients with low-energy (fragility) fractures related to osteoporosis. The stratification would have helped to identify any effect related to the quality of the patients’ bone. The use of dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry is widely regarded as the gold standard for the assessment of bone density. However, such an investigation may be expensive and would not have been routinely available at all centres.

Therefore, we used age as a surrogate for bone density. In a large study in Norway, involving 7600 participants, it was demonstrated that bone mineral density remains stable up until the age of 50 years. After the age of 50 years, bone mineral density decreased steadily in males, while in females there was an initial decline between the ages of 50 and 65 years, with a further decline in both age groups thereafter. 22 Over 1000 patients with a fracture were recently assessed in a study by Court-Brown et al. 23 This study confirmed that there is a clear bimodal distribution according to the age of the patient. The crossover of the two peaks of incidence was around 50 years of age. These studies provide strong evidence that patients > 50 years of age become increasingly vulnerable to fragility fractures. Therefore, we chose an age of 50 years as the stratification cut-off point for this trial.

Sequence generation

A minimisation algorithm was used to allocate participants, so no random sequences were generated before the study. This is standard practice for trials conducted at WCTU.

Blinding

The type of fixation determines the site of clearly visible surgical scars. Specifically, the insertion of an IM tibial nail requires a surgical incision at the knee. Therefore, the patients could not be blind to their allocated treatment. In addition, the treating surgeons were also not blind to the treatment, but did not take part in the postoperative assessment of the patients. The functional outcome data were collected and entered into the trial central database via questionnaire administered by a research assistant/data clerk in the trial central office. The radiographs collected were reviewed by an independent assessor who was not involved in any other data collection or analysis.

Post-randomisation withdrawals

Participants could decline to continue to take part in the trial at any time and without prejudice. The participants were made aware that a decision to decline consent or withdraw would not affect the standard of care that they would receive.

Participants had two options for withdrawal:

-

Participants could withdraw from completing any further questionnaires but allow the trial team to continue to view and record any relevant hospital data that were recorded as part of normal standard of care, including radiographs and further surgery information.

-

Participants could withdrawal wholly from the study and only data obtained up to the point of withdrawal would be included in the final analysis of the study; thereafter, no further data were collected for that participant.

Once withdrawn, the patient continued under the care of their surgical team, as per normal clinical practice.

Interventions

All the hospitals involved in this trial used both methods of fixation as part of routine clinical care. Consultant orthopaedic trauma surgeons supervised the surgery, all of whom were familiar with both techniques. Operative fixation of fractures of the distal tibia usually takes place under a general anaesthetic, but this decision was made by the attending anaesthetist as per their usual clinical practice.

Each patient had the allocated surgery according to the preferred technique of the operating surgeon. Although the basic principles of IM nailing and locking plate fixation are inherent in the technique (see Intramedullary nail fixation and Locking plate fixation), there are several different implant systems and several different options for the positioning of the screws. Similarly, each surgeon would have made minor modifications to their surgical technique according to preference and the specific pattern of each fracture. In this trial, the details of the surgery were left entirely to the discretion of the surgeon, to ensure that the results of the trial could be generalised to as wide a group of patients as possible. A copy of the ‘operating record’ formed part of the trial data set.

Although all of the surgeons in the trial were familiar with both techniques, it is possible that an individual surgeon may have had more experience with one technique than the other. In general, the proficiency of an individual surgeon to perform the procedure may change over time, as the surgeon gains experience and expertise. The term ‘learning curve’ is often used to describe this process. It was important to be aware of this effect within the trial. Therefore, the operating time was recorded from the operative record for each surgery, as a proxy to measure the task ‘efficiency’ of the surgeons (quality assurance of the clinical process), and the number of complications (e.g. infections) at 6 weeks after surgery was also recorded as a patient-based outcome related to surgeon ‘expertise’. However, as there were a large number of centres and a large number of surgeons at each of these centres, no individual surgeon was expected to perform more than a handful of the procedures. Therefore, the effect of the surgeon and their learning curve would be minimal in this particular trial.

Intramedullary nail fixation

The IM nail is inserted at the proximal end of the tibia and passed down the hollow centre (medullary canal) of the bone in order to hold the fracture in the correct (anatomical) position. The reduction technique, the surgical approach, the type and size of the nail, the configuration of the proximal and distal interlocking screws and any supplementary device or technique were left at the discretion of the surgeon, as per standard clinical practice.

Locking plate fixation

A locking plate is inserted at the distal end of the tibia and passed under the skin onto the surface of the bone. Again, the details of the reduction technique, the surgical approach, the type and position of the plate, the number and configuration of fixed-angle screws and any supplementary device or technique were left to the discretion of the surgeon. The only stipulation was that fixed-angle screws must be used in at least some of the distal screw holes – this is standard practice with all distal tibia locking plates.

Rehabilitation

All patients randomised into the two groups received the same standardised, written physiotherapy advice detailing the exercises they needed to perform for rehabilitation following their injury. All of the patients in both groups were advised to move their toes, ankle and knee joints fully within the limits of their comfort. Weight-bearing status was recommended by the treating surgeon. In this pragmatic trial, any other rehabilitation input beyond the written physiotherapy advice (including a formal referral to physiotherapy) was left to the discretion of the treating clinicians. However, a record of any additional rehabilitation input (type of input and number of additional appointments) together with a record of any other investigations/interventions were requested as part of the 3-month, 6-month and 12-month follow-ups, which formed part of the trial data set.

Outcomes

The primary outcome measure for this study was the DRI. 17 The DRI is a validated questionnaire that is self-reported (i.e. filled out by the patient). 24 It consists of 12 items specifically related to function of the lower limb and provides an overall score from 0 to 100 points, in which 0 points represents no disability and 100 points represents complete disability. These data were collected at baseline, 3, 6 and 12 months postoperatively (Table 1). The DRI has been proven to be a robust and practical clinical and research instrument, with good responsiveness and acceptability for assessment of disability caused by impairment in the lower limb.

| Time point | Data collection |

|---|---|

| Baseline | DRI, OMAS questionnaire, pre-injury and current EQ-5D and radiographs |

| 6 weeks | DRI, OMAS questionnaire, EQ-5D, record of complications or other interventions and resource use questionnaire |

| 3 months | DRI, OMAS questionnaire, EQ-5D, record of complications or other interventions and resource use questionnaire |

| 6 months | DRI, OMAS questionnaire, EQ-5D, record of complications or other interventions and resource use questionnaire |

| 12 months | DRI, OMAS questionnaire, EQ-5D, radiographs, record of complications or other interventions and resource use questionnaire |

Existing guidance for the calculation of DRI scores is unclear as regards the appropriate way to calculate overall scores in the presence of missing items; the most common approach is to take an average of available item scores. Owing to the low number of missing items, all analyses presented used complete cases only, that is, 12 complete item responses out of 12.

The secondary outcome measures in this trial were as follows:

The OMAS questionnaire is a self-administered patient questionnaire designed to assess ankle pain and function. It is a good outcome tool for assessing symptoms after a fracture around the ankle joint. 25 The score is based on nine different items: (1) pain, (2) stiffness, (3) swelling, (4) stair climbing, (5) running, (6) jumping, (7) squatting, (8) supports and (9) work/activities of daily living. 16 The scoring system correlates well with parameters considered to summarise the results after this type of injury and, therefore, is recommended for use in scientific investigations.

The EQ-5D is a validated, generic health-related quality-of-life measure consisting of five questions regarding five dimensions of health. The answers can be converted into a health utility score. 26 It has good test–retest reliability, is simple for patients to use and gives a single preference-based index value for health status that can be used for broader cost-effectiveness comparative purposes.

All complications were recorded, including malunion, non-union, infection, wound complications, vascular and neurological injury and venous thromboembolism. A record was also kept of any other surgery required in relation to the index fracture, including removal of any surgical implant. The adverse events have been broken down into ‘local complications related to the fracture or its treatment’, ‘systemic complications potentially related to the fracture or its treatment’ and ‘unrelated adverse events’ during the 12 months after the injury.

For the radiographic evaluation of complications, standard anteroposterior and lateral radiographs of the tibia and fibula were taken at baseline, at 6 weeks and at 12 months after the injury, as described in Outcomes. The radiographs were viewed using OsiriX software version 7.5 (Pixmeo, Berne, Switzerland). The radiographs were reviewed by an independent trauma surgeon from University Hospitals Coventry & Warwickshire NHS Trust. An assessment was made on the alignment of the tibia in both the coronal (lateral) and sagittal (anteroposterior) views of the tibia, and there was also an assessment of any shortening present.

Threshold values were used to define ‘malunion’ as follows:3

-

coronal angulation of the distal tibia fixation of > 5°

-

sagittal angulation of the distal tibia fixation of > 10°

-

shortening of > 10 mm.

Threshold values have been shown to be more reliable than absolute measurements of deformity in the distal tibia (Thomas Wood, Department of Trauma and Orthopaedics, University Hospitals Coventry and Warwickshire NHS Trust, 2016, unpublished data).

We used techniques common in long-term cohort studies to ensure minimum loss to follow-up, such as collection of multiple contact addresses and telephone numbers, mobile phone numbers and e-mail addresses. Considerable efforts were made, by the trial team, to keep in touch with patients throughout the trial by means of newsletters, and so on.

Follow-up

Baseline, standardised radiographs were copied from the hospital picture archiving and communication system. Copies of the baseline clinical report forms and images were sent to the trial co-ordinating centre.

As part of routine clinical practice, patients were seen in the outpatient fracture clinic on a regular basis after this injury. For this trial, the sample size was based on the primary outcome measure at 6 months, when patients with an uncomplicated fracture may be expected to return to normal activities; but to ensure that all complications and secondary procedures were captured, we continued follow-up for 1 year. 14

The research associate performed a clinical assessment and made a record of any early complications at the 6-week routine follow-up appointment. Radiographs were taken at 6 weeks and 12 months (or before 12 months if the surgeon felt that the fracture was united). An uncomplicated fracture of the distal tibia would be expected to be clinically united at 6 months after the injury. However, radiographic union may lag behind the clinical picture. Therefore, the 12-month radiographs were used to assess if there are long-term complications, such as non-union and arthritis of the ankle joint.

The outcome and resource use data were collected using questionnaires at 3, 6 and 12 months postoperatively. Patients were asked to complete their 6-month and 12-month postoperative questionnaire during their routine follow-up appointments if they had one or to return them by post if they did not have an appointment at these time points. Text messages were sent to patients to inform them that a questionnaire was due or was on its way. Text messages were only sent to those patients who had given their prior consent to this by initialling the corresponding box on the consent form.

Adverse event management

Adverse events are defined as any untoward medical occurrences in a clinical trial participant that do not necessarily have a causal relationship with the treatment.

Serious adverse events (SAEs) are defined as any untoward and unexpected medical occurrence that:

-

results in death

-

is life-threatening

-

requires hospitalisation or prolongation of existing inpatients’ hospitalisation

-

results in persistent or significant disability or incapacity

-

is a congenital anomaly or birth defect

-

is any other important medical condition that, although not included in the above, may require medical or surgical intervention to prevent one of the outcomes listed.

All SAEs were entered onto the SAE reporting form and faxed to a dedicated fax machine at WCTU within 24 hours of the investigator becoming aware of them. Once received, causality and expectedness, as determined by the principal investigator at each centre, were confirmed by the chief investigator. SAEs that were deemed to be unexpected and related to the trial were notified to the Research Ethics Committee (REC) and sponsor within 15 days. All such events were reported to the TSC and Data Monitoring Committee (DMC) at their subsequent meetings.

Serious adverse events that may have been expected as part of the surgical interventions, and that did not need to be reported to the main REC, were complications of anaesthesia or surgery (e.g. wound complications, infection, damage to a nerve or blood vessel and thromboembolic events) and secondary operations for or to prevent infection, malunion or non-union or for symptoms related to the metalwork. All participants experiencing SAEs were followed up until the end of the trial, as described in the protocol.

Risks and benefits

The risks associated with this study were predominantly those associated with the surgery: infection, bleeding and damage to the adjacent structures such as nerves, blood vessels and tendons. Participants in both groups had surgery and were potentially at risk from any/all of these complications. We believed that the overall risk profile was similar for the two interventions, but assessment of the number of complications in each group was a secondary objective of this trial.

Statistical analysis

Sample size

The minimum clinically important difference (MCID) is 8 points on the primary outcome (DRI) measurement scale. The DRI is a 12-question, patient-reported, functional outcome measure (physical exercise or sports, running, heavy physical work, heavy lifting, carrying a bag, leaning over a wash-stand, making a bed, moderate physical work, walks, mounting stairs, sitting still more than briefly and dressing or undressing) converted to a 100-point scale in which 0 points represents normal function and 100 points represents complete disability. At an individual patient level, a difference of 8 points represents the ability to climb stairs or run, with ‘some difficulty’ versus with ‘great difficulty’. At a population level, 8 points represents the difference between a ‘healthy patient’ and a ‘patient with a minor disability’. In addition, 8 points corresponds approximately to the clinically worthwhile benefit identified in other studies24 and is slightly lower than the 10-point difference between treatment group means in our pre-pilot study.

The SD of DRI score in our pilot study was approximately 20 points; the sample size was also estimated for a larger and smaller SDs to obtain an indication of the sensitivity to changes in this parameter. Assuming the distribution of DRI score in the study populations to be approximately normal, which is consistent with assumptions made for other reported trials using DRI as the primary outcome measure, Table 2 shows the total trial sample size with two-sided significance set at 5% for various scenarios of power and sample SD.

| SD (points) | Power, sample size (n) | |

|---|---|---|

| 80% | 90% | |

| 15 | 112 | 150 |

| 20 | 198 | 264 |

| 25 | 308 | 412 |

In Table 2, the number of 264 patients, represented in bold, represented the most likely scenario, based on our current knowledge, for 90% power to detect the selected MCID. Allowing a margin of 20% loss during follow-up, this gives a value of 320 patients in total. Therefore, 160 patients randomised to each group would provide 90% power to detect a difference of 8 points in the DRI score at 6 months, with 90% power at the 5% significance level.

Standard statistical summaries (e.g. medians and ranges or means and variances, dependent on the assumed distribution of the outcome) and graphical plots are presented for the primary outcome measure and all secondary outcome measures. Baseline data are summarised to check comparability between treatment arms and to highlight any characteristic differences between those individuals in the study, those who were ineligible and those who were eligible but withheld consent.

Analysis plan

The detailed statistical analysis plan was created by the trial statisticians and agreed by the DMC at the start of the study, in line with standard operating procedures at WCTU. Any subsequent amendments to this initial statistical analysis plan were clearly stated and justified to the DMC.

Software

All routine data reporting and final analysis was conducted using Stata® version 14 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA). 27

Data validation

Prior to formal analysis, data were checked for outliers, missing values and validated using the defined score ranges for all outcome measures. Queries were reported to the trial co-ordinator and investigated with the relevant recruiting centre if appropriate. Any subsequent changes to the database were recorded in accordance with the relevant WCTU standard operating practice and the UK Fixation of Distal Tibia Fractures (FixDT) trial data management plan.

Missing data

Data may not be available as a result of withdrawal of patients, lack of completion of individual data items or loss to follow-up. Reasons for data ‘missingness’ were ascertained and reported as far as possible. Any patterns of missingness were carefully considered, including, in particular, whether or not data could be treated as missing completely at random. No formal statistical testing was planned to assess missingness, but model assumptions were checked and patterns of missingness explored. If judged appropriate, missing data in the primary outcome (DRI score) was imputed using the ice (imputation by chain equation) procedure in Stata version 14. Any imputed data were on an individual-item level, as opposed to an overall score level. Reasons for ineligibility, non-compliance, withdrawal or other protocol violations are stated and any patterns are summarised.

Interim analyses

There were no planned interim analyses for the UK FixDT study.

Final statistical analyses

Null hypothesis

The null hypothesis for the UK FixDT study was that there is no difference in the DRI score between adult patients with a fracture of the distal tibia treated with IM nail fixation versus locking plate fixation.

Multilevel model

The main analysis plan was to investigate differences in the primary outcome measure, the DRI score at 6 months after surgery, between the two treatment groups on an intention-to-treat basis. In addition, early functional status was also assessed and reported at 3 months and later functional status at 12 months. The unadjusted differences between treatment groups were assessed using a Student t-test, based on a normal approximation for the DRI score at 6 months, and at other occasions. Tests were two-sided and considered to provide evidence for a significant difference if p-values are < 0.05 (5% significance level). Estimates of treatment effects are presented with 95% confidence intervals (CIs).

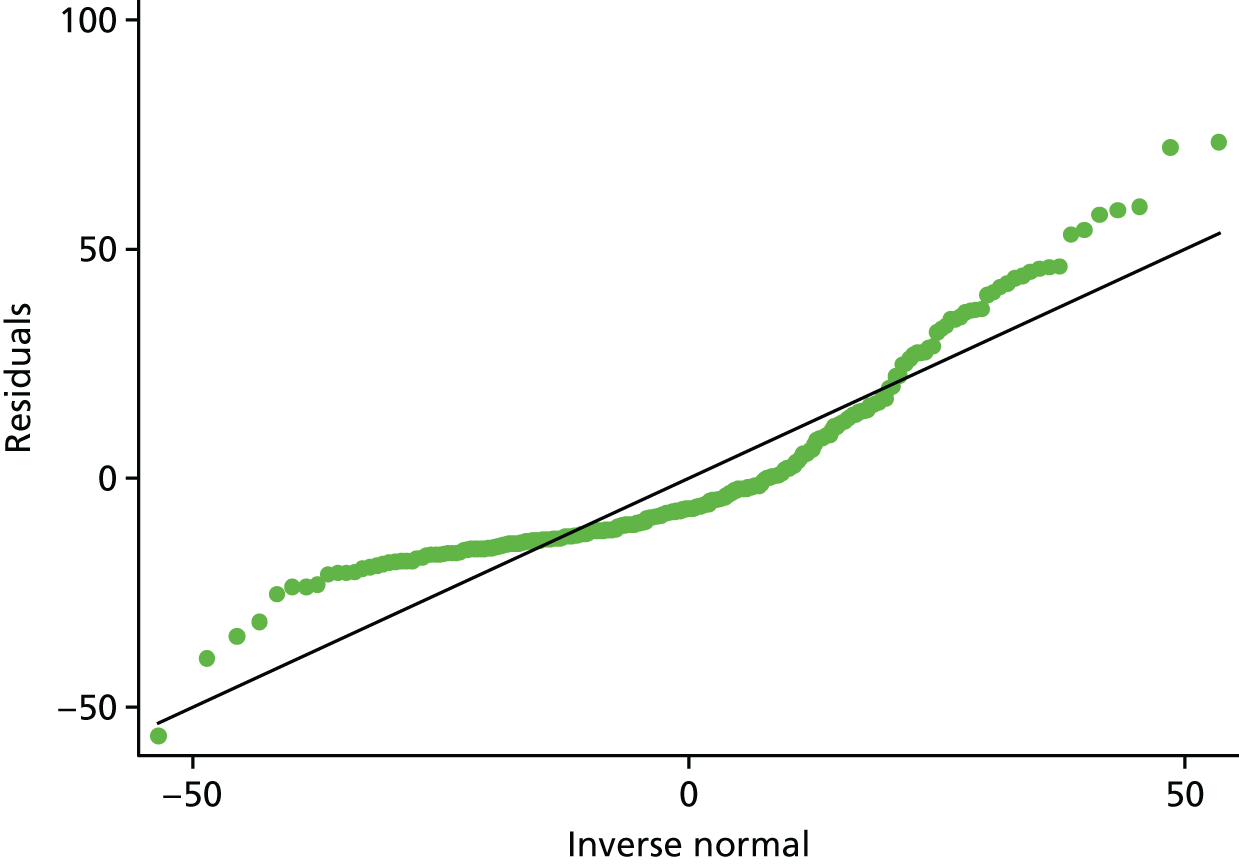

In addition to the unadjusted analysis (t-tests), we planned to undertake regression analyses to adjust for any imbalance between test treatments groups in patient age group, baseline pre-injury score and sex. The fixed-effects analysis (linear regression model) was also generalised by adding a random effect for recruiting centre to allow for possible heterogeneity in patient outcomes because of, more generally, the recruiting centre. Outcome data were assumed to be normally distributed during modelling, but subsidiary analyses were also undertaken after appropriate variance-stabilising transformations. The primary focus was the comparison of the two treatment groups of patients and this was reflected in the analysis, which was conducted together with appropriate diagnostic plots to check the underlying model assumptions. Treatment effects are presented for both the unadjusted and adjusted analyses, with 95% CIs as appropriate.

Any interactions between age group or sex and the main treatment effect were not expected to be considerable, and the sample size calculations were not conducted with these potential analyses in mind. Analyses were, however, undertaken for each of these variables. Formal interaction tests were conducted and reported with appropriate 95% CIs.

Complications

The number of events were compared between treatment groups on an intention-to-treat basis, in line with the main outcome analyses. Complications profiles are presented in three sections: (1) local complications related to the fracture or its treatment, (2) systemic complications potentially related to the fracture or its treatment and (3) unrelated adverse events within the 12-month time frame of the trial. These include information from the 6-week follow-up appointment with the research associate, in conjunction with data from patient-reported questionnaires at 3, 6 and 12 months post randomisation, and any other reports of SAEs. The data were cross-referenced between multiple data sources and clinical judgement was used to classify events in to the presented categories.

Exploratory analysis

To complement the preplanned analysis, a post hoc exploratory analysis using DRI score at all four time points was conducted. This analysis simplified longitudinal data collected at four time points to a single value, namely the area under the curve (AUC), and facilitated comparisons of the AUCs between treatment groups. It is advisable, in the presence of missing data, to use summary statistics generated by mixed models, as estimates will not be biased under the assumption that data are missing at random or are missing completely at random. 28 Therefore, we fitted a repeated measures mixed model, with the same fixed-effect structure as used in the primary analyses (adjusted for sex and age group), but with a three-level random-effects structure, in which observations (time points) were nested within participants and participants nested within recruitment site. The mixed and margins commands in Stata version 14 were used to obtain parameter estimates and standard errors (SEs) and the lincom command used to calculate AUC for each group. 27 AUCs associated with the two treatment groups were tested using a t-test.

Health economic analysis plan

The following sections summarise the health economics analysis plan, with full details provided in Chapter 4.

Objectives

The economic evaluation was designed to estimate the costs of resource inputs and quality-adjusted life-year (QALY) profiles of each trial participant over the 12-month time horizon of the trial, allowing mean differences in costs and QALYs to be compared between the two arms of the trial. The primary objective was to evaluate the incremental cost-effectiveness of extra-articular distal tibia fractures treated with IM nail fixation versus locking plate fixation and to provide an estimate of the incremental net benefit.

Measurement of outcomes

Health-related quality of life was estimated using responses from the EQ-5D. This instrument facilitates the generation of a utility score from a person’s health-related quality of life. A health utility score refers to the preference that individuals have for any particular set of health outcomes. Patients completed the EQ-5D questionnaire at baseline and at 3, 6 and 12 months after randomisation, thus providing values of their health status at the time of questionnaire completion. Patients self-completed an additional EQ-5D at baseline, which assessed their pre-injury health-related quality of life. The standard UK (York A1) tariff values were applied to these responses at each time point to obtain utility scores. 29 The York A1 tariff set was derived from a survey of the UK general population (n = 3337), which used the time trade-off valuation method to estimate utility scores for a subset of 45 EQ-5D health states, with the remainder of the EQ-5D health states subsequently valued through the estimation of a multivariate model. 29 Resulting utility scores ranged from –0.59 to 1.0, with 0 representing death and 1.0 representing full health; values below 0 indicate health states worse than death. The second measurement component of the EQ-5D consists of a 20-cm vertical visual analogue scale (VAS) ranging from 100 (best imaginable health state) to 0 (worst imaginable health state), which provides an indication of the participant’s own assessment of their health status on the day of the survey. QALYs, which formed the main outcome of the economic analysis, were calculated using the AUC approach, assuming liner interpolation between the utility measurements. A five-level version of the EQ-5D (EuroQol-5 Dimensions, five-level version; EQ-5D-5L) was newly available at the start of the trial, but a UK tariff set for this version of the measure had not yet been published. Consequently, on advice from the TSC, it was decided to measure health-related quality-of-life outcomes using the EQ-5D.

Measurement of costs

Total costs for the two intervention arms were estimated by combining (1) resources used during the operation (implants and consumables), (2) total costs for the inpatient hospital stay and (3) patient-reported data on resource usage at 3, 6 and 12 months post randomisation. For the 3-month data, the recall period covered the period following hospital discharge; however, the recall period at subsequent time points covered the period since the last questionnaire was due to be completed. The trial participant questionnaires provided information on broader NHS and Personal Social Services (PSS) resource use as a result of the fracture. Specifically, the questionnaires captured the frequency of use of community-based health and social care services, number and duration of admissions to inpatient wards [classified as orthopaedics (your leg), orthopaedics (any bones), rehabilitation unit], number of diagnostic tests, use of outpatient services (classified as orthopaedics, physiotherapy, emergency department), medication use, and use of aids and adaptations. PSS included number of weeks of frozen/hot Meals on Wheels, laundry services and number of visits of carers and social workers. Total costs of resource usage were estimated by combining the unit cost data for each service with the resource usage data. In addition, the questionnaires captured private costs incurred by the patient as a result of the fracture, such as private physiotherapy. Productivity losses and lost income were also captured.

Cost-effectiveness analytical methods

An incremental cost-effectiveness analysis was performed, expressed in terms of incremental cost per QALY gained. Multiple imputation methods were used to impute missing data and avoid biases associated with complete-case analysis. The results of the economic evaluation were expressed in terms of incremental cost per QALY gained. A series of sensitivity analyses was undertaken to explore the implications of uncertainty on the incremental cost-effectiveness ratios (ICERs). Heterogeneity of cost-effectiveness results was addressed through the use of subgroup analysis. Further details are provided in Chapter 4.

Reporting

The reporting of the health economic evaluation is consistent with the Consolidated Health Economic Evaluation Reporting Standard statement. 30

Ethics approval and monitoring

Standard NHS cover for negligent harm was in place. There was no cover for non-negligent harm.

Ethics committee approval

The UK FixDT trial was approved by the Coventry and Warwickshire REC on 6 November 2012 (REC reference number 12/WM/0340) and by the research and development department of each participating centre. The final, approved, study protocol has been published. 1

Trial Management Group

The day-to-day management of the trial was the responsibility of the trial co-ordinator, who was based at WCTU and supported by the administrative staff. This management was overseen by the Trial Management Group (TMG), which met monthly to assess progress. It was also the responsibility of the trial co-ordinator to undertake training of the research associates at each of the trial centres. The trial statistician and health economist were closely involved in the setting up of data-capture systems and the design of databases and clinical reporting forms.

Trial Steering Committee

A TSC was responsible for monitoring and supervising the progress of the UK FixDT trial. The TSC consisted of independent experts, a lay member and the chief investigator on behalf of the TMG. Membership of the TSC is given in Acknowledgements.

Data Monitoring Committee

The DMC was independent of the trial and was tasked with monitoring ethics, safety and data integrity. The trial statistician provided the data and analyses requested by the DMC at each of the meetings. Membership of the DMC is given in Acknowledgements.

Patient and public involvement

Before the pilot study that led to the UK FixDT trial, an informal survey was conducted at a large university hospital trust to establish the opinion of patients and their carers with regard to research in orthopaedic trauma. We established that patients place great importance on research comparing different types of interventions in the area of trauma surgery. Furthermore, patients have demonstrated that they are willing to take part in such trials.

The opinions of patients regarding the interventions and the trial procedures were reviewed during the pilot study16 and informed the design of the UK FixDT trial and, specifically, the patient-facing materials.

Independent lay representation was present on the TSC. Members of the trauma patient and public involvement group also reviewed the progress of the UK FixDT trial at the annual National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) trauma trials meetings.

Chapter 3 Results

Screening and recruitment

Screening

Screening for potential participants began in April 2013. In total, 2118 patients with a tibial fracture were screened over 36 months. Screening data are presented to help assess the generalisability of the results to the overall population. Screening data are presented for all sites, with the exception of the Edinburgh site, which was closed to recruitment early in the main phase of the study.

There were significant differences in the total number of potential participants who were assessed between recruiting sites because of the varying practice at each site; for example, some sites screened children aged < 16 years but other sites were adult-only trauma centres. The wide variation in totals by centre indicates that some sites screened extensively and recorded any patient with a fracture involving the tibia; however, others appear to have only recorded fractures of the distal tibia on the screening logs.

The reasons why screened patients were not eligible (n = 1581) are detailed in Table 27, Appendix 1.

The most common reasons for participant ineligibility were that the fracture did not extend to within 2 Müller squares of the ankle joint (375/1581; 24%), the fracture was open (369/1581; 23%) and the fracture extended into the ankle joint (329/1581; 21%).

The total number of potentially eligible patients for the study was 537. The reasons why potentially eligible patients were not randomised (n = 216) are given in Table 28, Appendix 1.

Of the 537 eligible potential participants identified on screening logs, 40% (216/537) were not randomised. The conversion rate of eligible potential participants to randomised participants was therefore 60%. The most common reasons for non-participation were that there were no research staff available to consent the patient (n = 53; 25%) or that the surgeon had a preference to use an IM nail (n = 54; 25%). The other common reason was that the patient did not want to be part of a research study (n = 25; 12%). There were 18 potential participants for whom the reason for non-participation was ‘other’; these reasons included skin around ankle precluded plate fixation (n = 4), primary amputation (n = 3) and hind foot nail used (n = 2). The complete table of reasons why eligible potential participants were not randomised, by site, is given in Table 28, Appendix 1.

Data on sex and age were available for almost all of the patients screened (2003/2118; 95%). The largest subgroup of screened patients were men aged < 50 years, who accounted for 41% (819/2003) of the screened population.

Table 3 shows the age and sex of potentially eligible participants by randomised status (randomised or not randomised). The ages of both groups were similar and a t-test comparing the means of both groups showed no evidence of a difference in age (mean difference –0.9 years, 95% CI –4.1 to 2.3 years). Likewise, a two-sample test of proportions showed no evidence of a difference in sex distribution between the two groups (p = 0.818).

| Characteristics | Randomisation status | |

|---|---|---|

| Randomised | Not randomised | |

| Age (years) | ||

| n | 321 | 216 |

| Mean (SD) | 45.1 (16.3) | 46.0 (18.5) |

| Median (IQR) | 43.4 (31.6–57.5) | 44.8 (30.2–57.5) |

| Sex, n (%) | ||

| Female | 124 (39) | 80 (37) |

| Male | 197 (61) | 130 (60) |

| Missing | 0 (0) | 6 (3) |

Recruitment

The trial planned to recruit 320 participants in total. Formal recruitment began in April 2013, with the first participant being randomised on 22 April 2013 at the lead site, University Hospitals Coventry and Warwickshire NHS Trust. Recruitment was undertaken at 28 sites over 36 months, with the final participant being randomised on 3 May 2016. For reporting purposes, the final participant has been included in the April 2016 recruitment month for ease of presentation. Details of site names and their opening dates are listed in Table 4.

| Number | Full name | Opening date |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | University Hospitals Coventry & Warwickshire | 8 April 2013 |

| 2 | Addenbrookes Hospital | 2 May 2013 |

| 3 | Frenchay Hospital | 12 June 2013 |

| 4 | University Hospitals of Leicester | 16 July 2013 |

| 5 | Nottingham University Hospitals | 25 July 2013 |

| 6 | James Cook Hospital | 5 September 2013 |

| 7 | John Radcliffe Hospital | 20 December 2013 |

| 8 | Aberdeen Royal Infirmary | 14 January 2014 |

| 9 | Derriford Hospital | 15 January 2014 |

| 10 | Royal Stoke University Hospital | 31 January 2014 |

| 11 | Royal Sussex County Hospital | 30 January 2014 |

| 12 | Royal Infirmary of Edinburgh | 16 January 2014 |

| 13 | Royal Victoria Infirmary | 6 February 2014 |

| 14 | Glasgow Royal Infirmary | 11 March 2014 |

| 15 | Royal Berkshire Hospital | 8 May 2014 |

| 16 | Poole Hospital | 13 May 2014 |

| 17 | Queen Alexandra Hospital | 29 May 2014 |

| 18 | King’s College Hospital | 10 June 2014 |

| 19 | Aintree University Hospital | 15 July 2014 |

| 20 | Southampton General Hospital | 4 August 2014 |

| 21 | University Hospitals of Birmingham | 5 August 2014 |

| 22 | Leeds Teaching Hospital | 12 August 2014 |

| 23 | St George’s Hospital | 11 September 2014 |

| 24 | Hull Royal Infirmary | 13 October 2014 |

| 25 | North Tyneside General Hospital & Wansbeck General | 20 November 2014 |

| 26 | Heartlands Hospital | 3 February 2015 |

| 27 | Sunderland Royal Hospital | 26 February 2015 |

| 28 | Basingstoke & North Hampshire Hospital | 10 June 2015 |

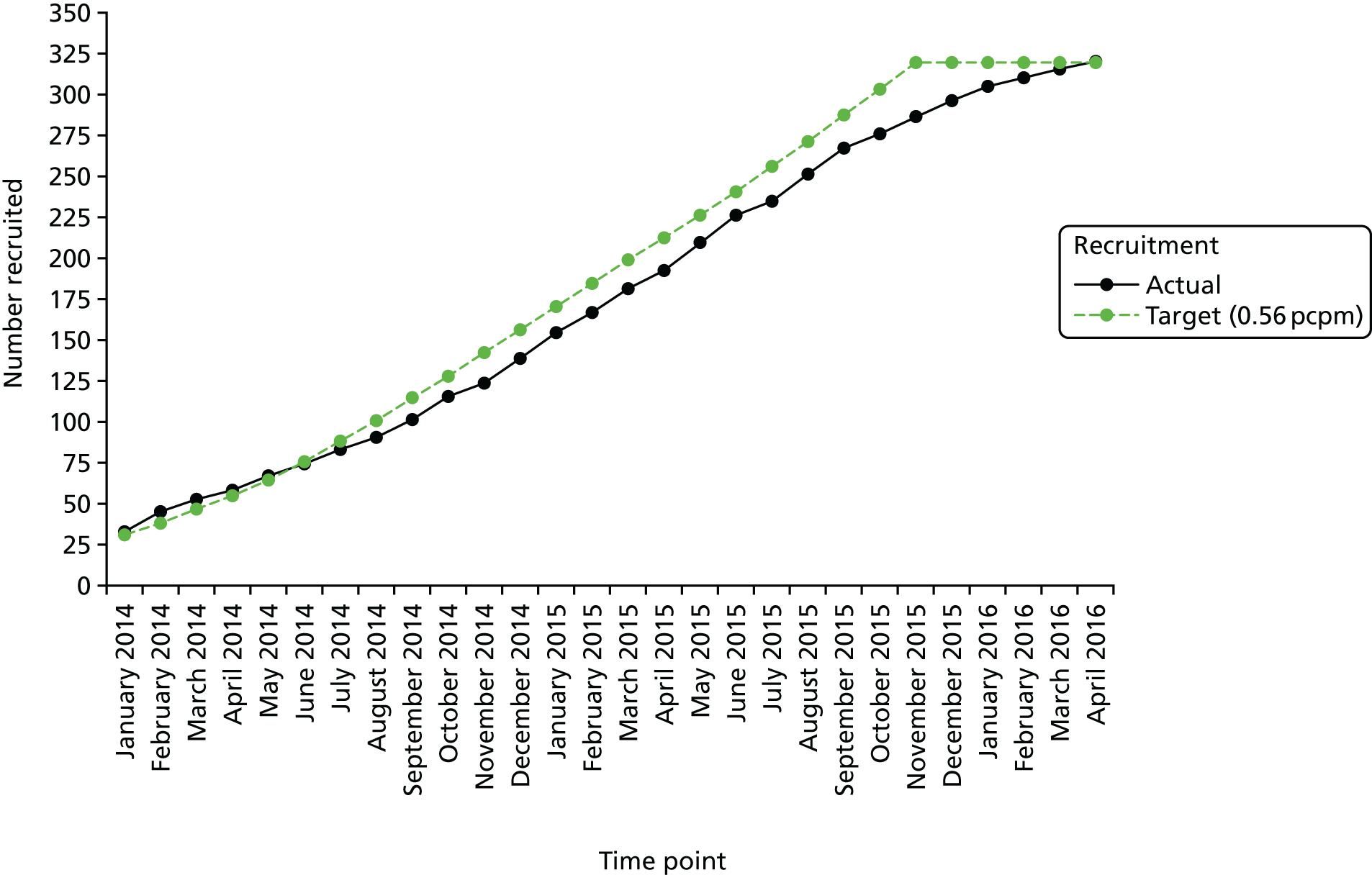

The pilot phase was completed at the end of November 2013, with six sites open to recruitment. The planned recruitment rate was 0.75 participants pcpm. The recruitment rate averaged 0.6 participants pcpm during this phase, so the TSC recommended that the number of sites was increased from 18 to at least 24 to enable the trial to meet the target recruitment of 320 participants within the 30-month recruitment window. This resulted in a revised target of 0.6 participants pcpm.

Actual recruitment rates, by site, are shown in Table 29, Appendix 1. The overall observed recruitment rate for the main phase of the trial was 0.47 participants pcpm. This was somewhat lower than the revised target and so the number of trial sites was further increased to 28. One site was closed after just one patient was recruited, and screening data are not presented for this site.

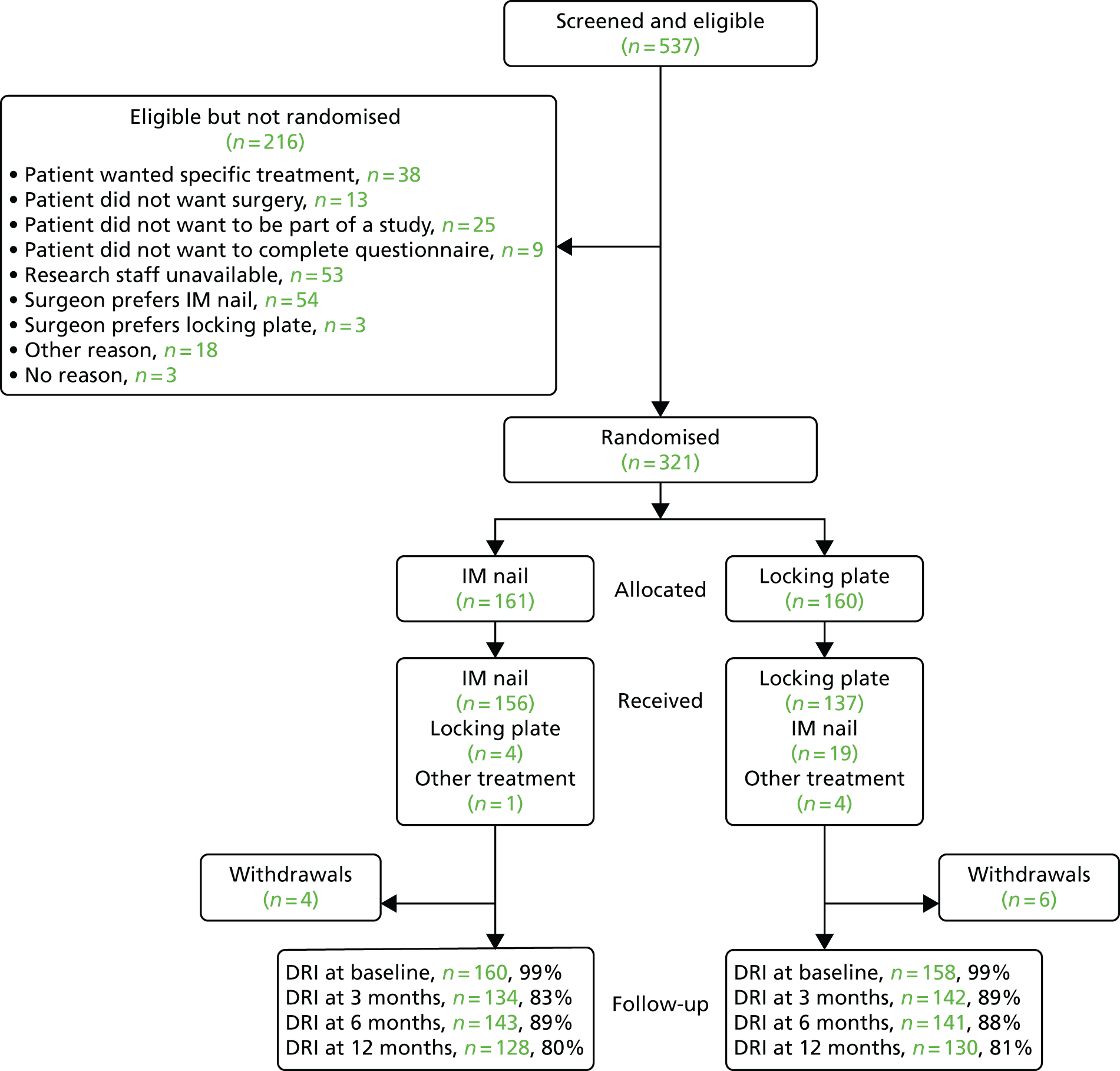

Figure 2 illustrates the progression of recruitment over time, towards the required sample size target of 320. Recruitment slowed towards the end of the planned recruitment phase, so the recruitment window was extended, although this was still within the original timeline of the trial. Figure 3 shows the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) flow diagram for the UK FixDT trial.

FIGURE 2.

Overall recruitment progression and target recruitment during the main phase (January 2014–April 2016) of the UK FixDT trial.

FIGURE 3.

The Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) flow diagram.

Table 5 describes the follow-up rates achieved during the trial. The expected follow-up rate used for sample size adjustment at 6 months was 80%. This was surpassed at the 6-month time point, with 88% of DRI assessments completed. Similar completion rates of 86% and 80% were achieved at the 3- and 12-month time points, respectively.

| Follow-up status | Time point, n (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | 3 months | 6 months | 12 months | |

| Returned questionnaire | 318 (99) | 276 (86) | 284 (88) | 258 (80) |

| Missed questionnaire | 3 (1) | 41 (13) | 29 (9) | 49 (15) |

| Consent withdrawn before time point | 0 (0) | 3 (1) | 6 (2) | 8 (3) |

| Died before time point | 0 (0) | 1 (< 1) | 2 (1) | 6 (2) |

Tables 30 and 31, Appendix 1 demonstrate recruitment by stratification variables, namely age group and centre. There is good balance with respect to each factor, indicating that the minimisation procedure used to allocate treatment was implemented successfully.

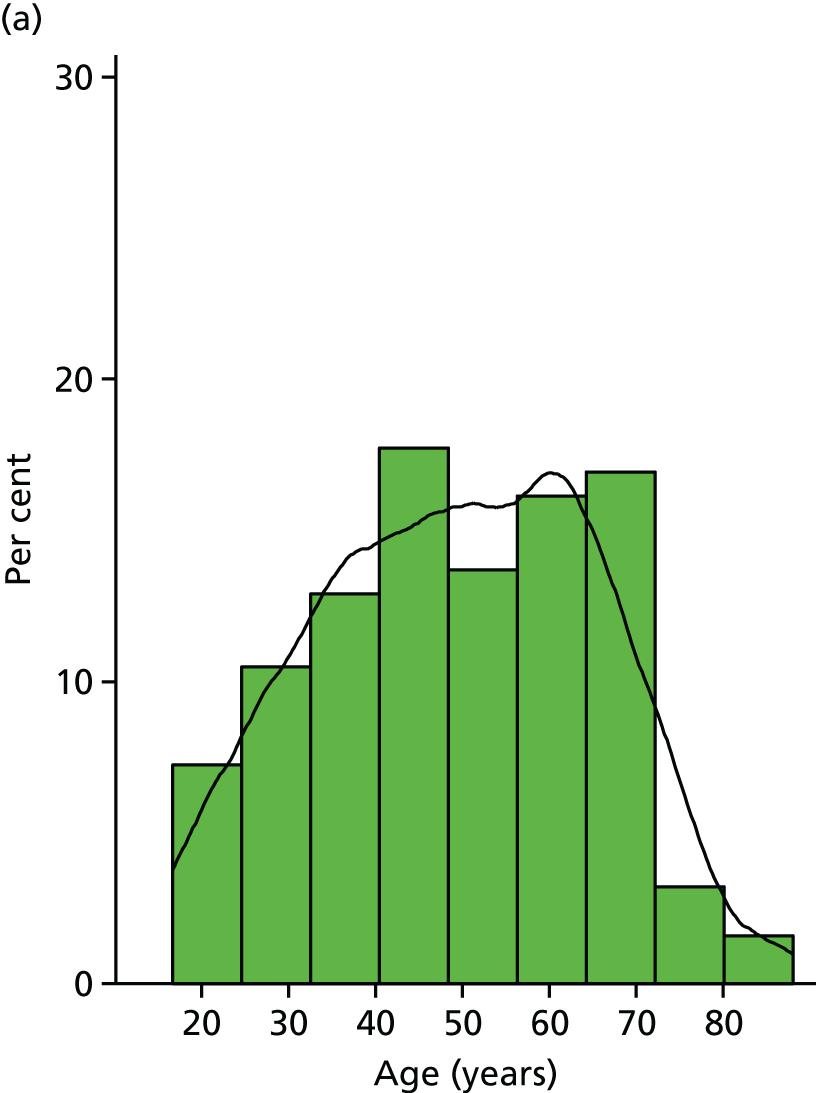

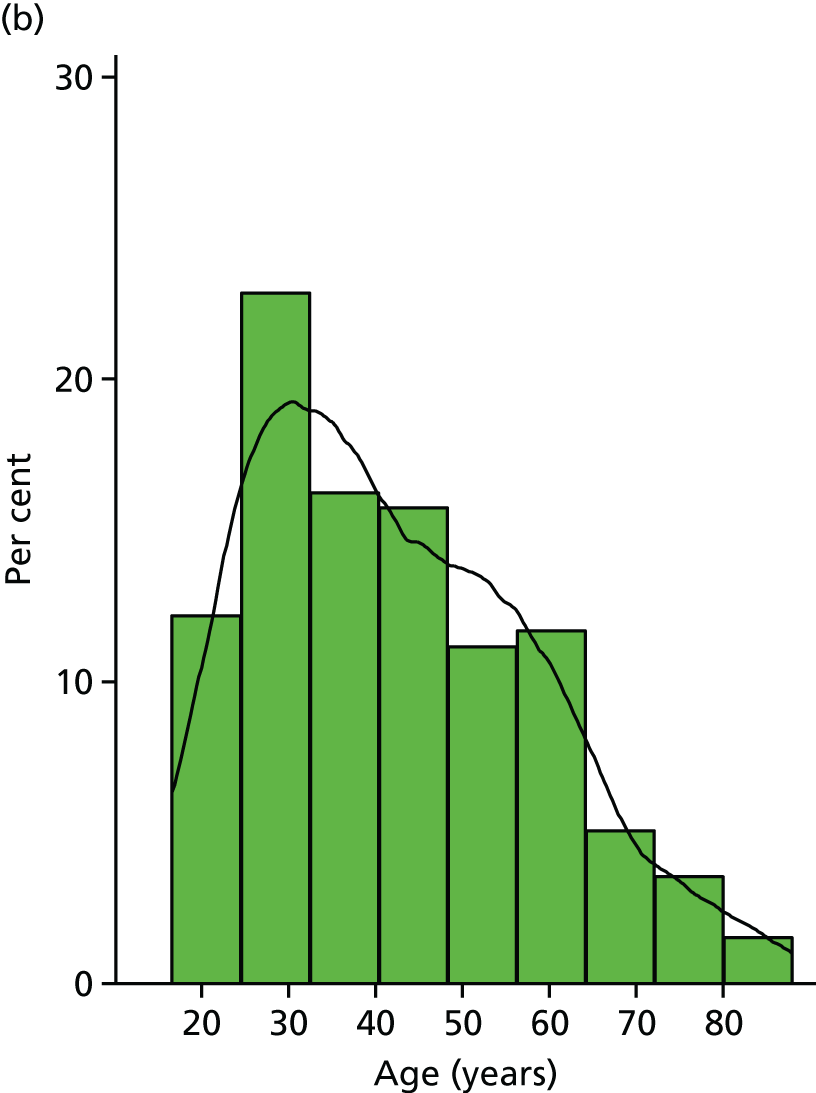

The histograms in Figure 4 show the distribution of age in years, separately by sex. The overlaid kernel density estimator (the kdensity option of the histogram function in Stata version 14) shows the smoothed distribution and highlights the differences between sexes, with a noticeable but expected peak in the number of young male patients randomised. The mean difference in age between men and women was 6.8 years, 95% CI 3.2 to 10.4 years.

FIGURE 4.

Age distribution of randomised participants by sex. (a) Female; and (b) male.

Participant characteristics

The baseline demographic and clinical data were collected directly from the participant at site as part of the baseline participant’s questionnaire. The baseline demographic and clinical characteristics of both treatment groups are well balanced, as shown by allocated treatment group in Table 6. Baseline patient-reported outcome measures also showed good balance with similar mean scores being seen across all four outcomes measures, as expected.

| Demographic and clinical characteristic | Treatment groupa | |

|---|---|---|

| IM nail fixation (N = 161) | Locking plate (N = 160) | |

| Age (years) | ||

| Mean (SD) | 44.3 (16.3) | 45.8 (16.3) |

| Median (IQR) | 41.3 (30–57) | 45.6 (32–58) |

| Sex, n (%) | ||

| Female | 65 (40) | 59 (37) |

| Male | 96 (60) | 101 (63) |

| Side of fracture, n (%) | ||

| Left | 67 (42) | 75 (47) |

| Right | 93 (58) | 84 (53) |

| Missing | 1 (1) | 1 (1) |

| Previous problems on the injured side, n (%) | ||

| Yes | 40 (25) | 36 (23) |

| No | 120 (74) | 123 (77) |

| Mechanism of injury, n (%) | ||

| Low-energy fall | 85 (53) | 87 (54) |

| High-energy fall | 27 (17) | 24 (15) |

| Road traffic accident | 15 (9) | 22 (14) |

| Crush injury | 8 (5) | 3 (2) |

| Contact sports injury | 14 (9) | 11 (7) |

| Other | 11 (7) | 12 (8) |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | ||

| Mean (SD) | 27.7 (6.2) | 27.7 (6.9) |

| Median (IQR) | 26.5 (23–31) | 26.7 (23–30) |

| Current smoking status | ||

| Yes, n (%) | 53 (33) | 50 (31) |

| No, n (%) | 107 (66) | 108 (68) |

| If yes, for how many years smoking | ||

| n | 48 | 40 |

| Mean (SD) | 19 (12) | 26 (14) |

| Median (IQR) | 18 (10–28) | 28 (15–37) |

| Alcohol consumption (units per week), n (%) | ||

| 0–7 | 86 (53) | 87 (54) |

| 8–14 | 28 (17) | 24 (15) |

| 15–21 | 28 (17) | 22 (14) |

| > 21 | 18 (11) | 22 (14) |

| Diabetes, n (%) | ||

| Yes | 6 (4) | 7 (4) |

| No | 154 (95) | 152 (95) |

| DRI (pre-injury) | ||

| Mean (SD) | 9.9 (19.0) | 10.0 (18.4) |

| Median (IQR) | 1.1 (0–10.6) | 1.6 (0–11.5) |

| OMAS (pre-injury) | ||

| Mean (SD) | 91.4 (19.0) | 94.2 (14.0) |

| Median (IQR) | 100 (95–100) | 100 (95–100) |

| EQ-5D index score (pre-injury) | ||

| Mean (SD) | 0.860 (0.23) | 0.888 (0.21) |

| Median (IQR) | 1 (0.80–1.00) | 1 (0.85–1.00) |

| EQ-5D VAS score (pre-injury) | ||

| Mean (SD) | 81.5 (17.7) | 80.9 (17.5) |

| Median (IQR) | 85 (70–95) | 90 (74–90) |

At the baseline assessment, participants were also asked whether or not they had a strong treatment preference and, if so, for which treatment: 70% (222/321) had no preference; 16% (52/321) preferred IM nail fixation and 13% (43/321) locking plate fixation, with 1% (4/321) of participants not giving a response.

Interventions

Table 7 provides information on the surgical procedures performed. Table 8 provides further detail specific to those participants who received an IM nail or locking plate, respectively. Unless otherwise stated, all further analyses and tables in the remainder of the report will be described on an intention-to-treat basis.

| Operation details | Treatment groupa | |

|---|---|---|

| IM nail fixation (N = 161) | Locking plate (N = 160) | |

| Intraoperative problems, n (%) | ||

| Yes | 3 (2) | 3 (2) |

| No | 157 (98) | 156 (98) |

| Missing | 1 (1) | 1 (1) |

| If yes, what was the problem? (n) | ||

| Nerve injury | 0 | 0 |

| Vascular injury | 0 | 1 |

| Tendon injury | 0 | 0 |

| Extension of fracture | 3 | 2 |

| Intra-articular extension of the fracture, n (%) | ||

| Yes | 7 (4) | 3 (2) |

| No | 127 (79) | 128 (80) |

| Missing | 27 (17) | 29 (18) |

| Fixation of the fibula, n (%) | ||

| Yes | 10 (6) | 12 (8) |

| No | 150 (93) | 146 (91) |

| Missing | 1 (1) | 2 (1) |

| Any other surgery for additional injuries, n (%) | ||

| Yes | 8 (5) | 3 (2) |

| No | 152 (94) | 156 (97) |

| Missing | 1 (1) | 1 (1) |

| Lead surgeon grade, n (%) | ||

| Consultant | 90 (56) | 99 (62) |

| Staff grade/associate specialist | 13 (8) | 15 (9) |

| Specialist trainee | 50 (31) | 41 (26) |

| Other | 7 (4) | 4 (3) |

| Missing | 1 (1) | 1 (1) |

| Total number of surgeons present in theatre | ||

| Mean | 2.5 | 2.4 |

| n | 159 | 159 |

| Median | 2 | 2 |

| Missing | 2 | 1 |

| Operation total duration (minutes) | ||

| n | 158 | 158 |

| Mean (SD) | 124 (43) | 124 (44) |

| Median (IQR) | 120 (90–145) | 120 (96–151) |

| Treatment-specific operation detail | n (%) |

|---|---|

| IM nail fixation (n = 174) | |

| Number of bolts used in coronal plane | |

| 0 | 16 (9) |

| 1 | 50 (29) |

| 2 | 108 (62) |

| Missing | 0 (0) |

| Number of bolts used in sagittal plane | |

| 0 | 67 (39) |

| 1 | 82 (47) |

| 2 | 25 (14) |

| Missing | 0 (0) |

| Number of bolts used in oblique plane | |

| 0 | 144 (83) |

| 1 | 27 (16) |

| 2 | 2 (1) |

| Missing | 1 (1) |

| Number of blocking screws used | |

| 0 | 138 (79) |

| 1 | 31 (18) |

| 2 | 3 (2) |

| 3 | 2 (1) |

| 4 | 0 (0) |

| Missing | 0 (0) |

| Reduction technique used | |

| Open | 12 (7) |

| Closed | 106 (61) |

| Skeletal traction | 20 (11) |

| No traction | 34 (20) |

| Missing | 2 (1) |

| Surgical approach used | |

| Medial parapatella | 69 (40) |

| Lateral parapatella | 0 (0) |

| Tendon splitting | 102 (58) |

| Suprapatella approach | 2 (1) |

| Missing | 1 (1) |

| Locking plate (n = 142) | |

| Number of locking screws used distal to fracture | |

| 1 | 0 (0) |

| 2 | 8 (6) |

| 3 | 24 (17) |

| 4 | 53 (37) |

| 5 | 36 (25) |

| 6 | 16 (11) |

| > 6 | 4 (3) |

| Missing | 1 (1) |

| Number of locking screws used proximal to fracture | |

| 0 | 36 (25) |

| 1 | 4 (3) |

| 2 | 16 (11) |

| 3 | 46 (32) |

| 4 | 33 (23) |

| 5 | 7 (5) |

| > 5 | 0 (0) |

| Missing | 0 (0) |

| Number of non-locking screws used distal to fracture | |

| 1 | 60 (42) |

| 2 | 50 (35) |

| 3 | 21 (15) |

| 4 | 6 (4) |

| 5 | 2 (1) |

| 6 | 2 (1) |

| > 6 | 1 (1) |

| Missing | 0 (0) |

| Number of non-locking screws used proximal to fracture | |

| 0 | 43 (30) |

| 1 | 38 (27) |

| 2 | 17 (12) |

| 3 | 19 (13) |

| 4 | 21 (15) |

| 5 | 4 (3) |

| > 5 | 0 (0) |

| Missing | 0 (0) |

| Reduction technique used | |

| Open | 73 (51) |

| Closed | 53 (37) |

| Skeletal traction | 11 (8) |

| No traction | 5 (4) |

| Missing | 0 (0) |

| Surgical approach used | |

| Longitudinal over medial malleolus | 93 (65) |

| Other | 49 (35) |

| Missing | 0 (0) |

It was of note that the mean duration of the operations was the same for both treatment groups.

Treatment allocation

A total of 91% (293/321) of participants received their allocated treatment (Table 9). Among those participants allocated to the IM nail fixation group, 97% of whom received their allocated treatment and in those allocated to the locking plate group, 86% of whom received their allocated treatment. There were two participant withdrawals before any intervention was undertaken, two were treated with external fixation only and one was treated with manipulation under anaesthetic only.

| Received | Allocated (n) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| IM nail fixation | Locking plate | Total | |

| IM nail fixation | 156 | 19 | 175 |

| Locking plate | 4 | 137 | 141 |

| Other | 1 | 4 | 5 |

| Total | 161 | 160 | 321 |

In total, there were 28 participants who received a treatment that was not their allocated treatment; more participants deviated from their allocated treatment in the locking plate group (n = 23) than in the IM nail fixation group (n = 5). The most common reasons why participants did not receive their allocated treatment was because of either surgeon choice (n = 10, 36%) or a clinical decision intraoperatively (n = 13, 46%) (Table 10).

| Reason | Allocated (n) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| IM nail fixation | Locking plate | Total | |

| Surgeon choice | 3 | 7 | 10 |

| Clinical decision intraoperatively | 1 | 12 | 13 |

| Lack of equipment | 0 | 2 | 2 |

| Patient choice | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Withdrawal from trial before treatment | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| Total | 5 | 23 | 28 |

The baseline demographics of patients receiving their allocated treatment were broadly similar to those not receiving allocated treatment, with mean age 45 versus 47 years, although patients who did not receive their allocated treatment were more likely to be male (75%).

Outcomes

Primary outcome

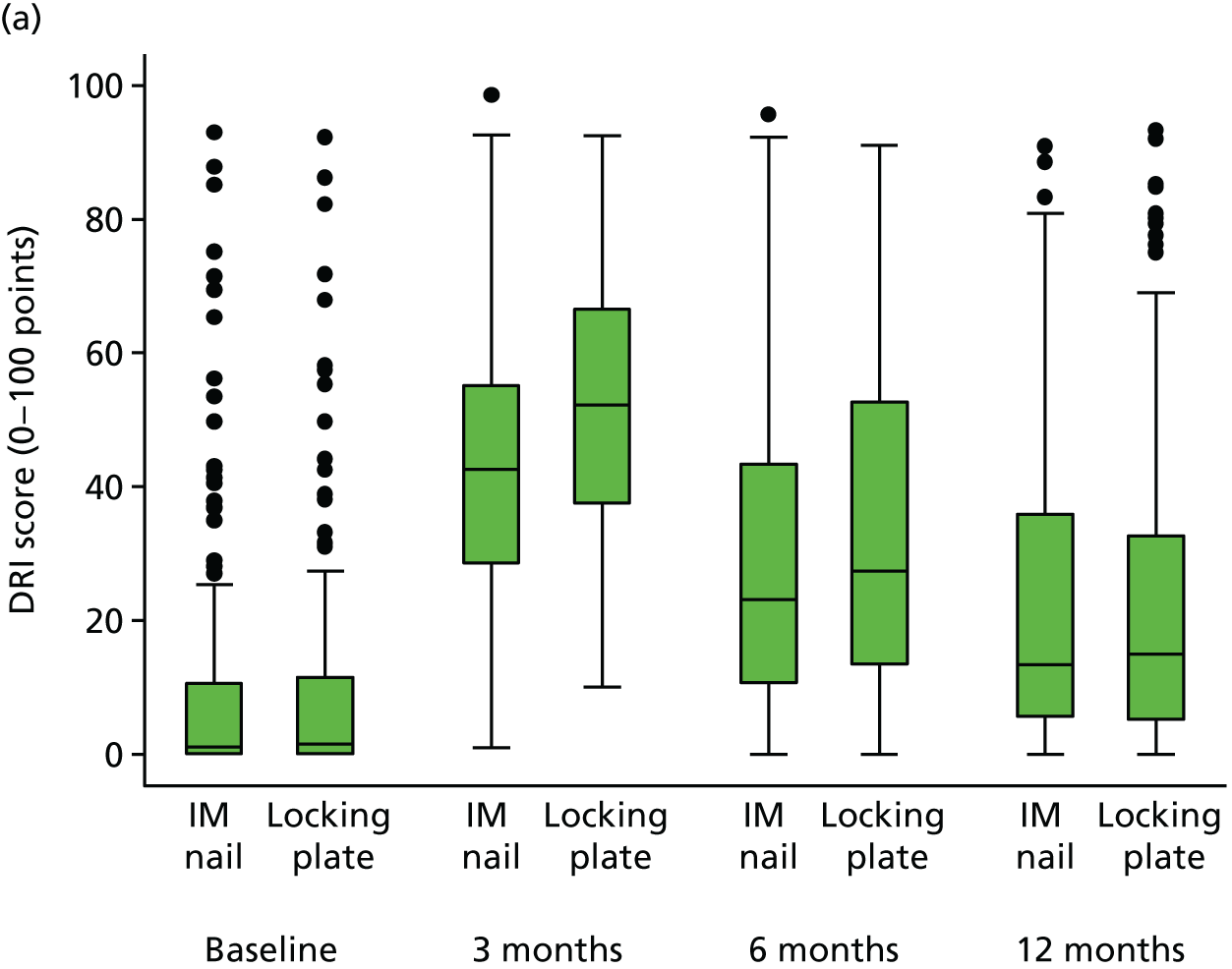

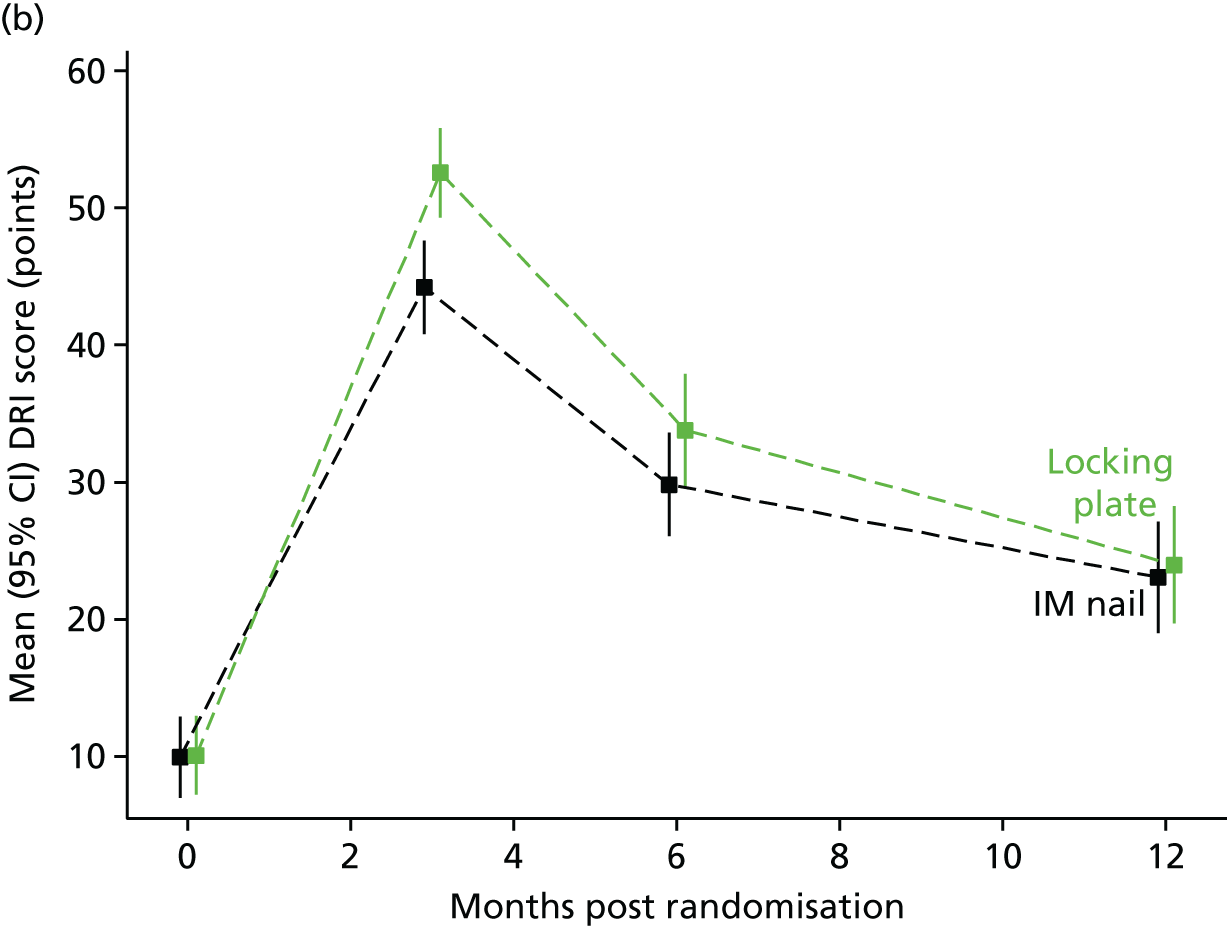

Figure 5a shows the trend in group DRI score means over the trial. Figure 5b shows the distribution of the DRI score at each time point, in which the middle bar is the median, the box represents the interquartile range and the whiskers extend to 1.5 times the interquartile range, with observations outside this range presented individually. Figure 5b demonstrates there is a treatment group difference in favour of the IM nail fixation group at 3 months, but this is reduced and not statistically significant at the 6-month time point and decreases further at the 12-month time point. Model assumptions were checked and appeared to be appropriate.

FIGURE 5.

The DRI. (a) Box plots of baseline and follow-up scores; and (b) overall trend in means and 95% CIs.

Table 11 shows the treatment estimates modelled using mixed-effects linear regression model, as previously described. The adjusted estimate of the treatment effect for the DRI score, at the 6-month post randomisation time point based on an intention-to-treat analysis, is 4.0 points (95% CI –1.0 to 9.0 points) in favour of the IM nail fixation group compared with the locking plate group. The p-value of 0.114 indicates that there is no evidence for a statistically significant difference in the DRI score between the two treatment groups at the 6-month post-randomisation time point. The prespecified MCID for the DRI is 8 points; therefore, at the 6-month time point we conclude that if there is a difference in the disability outcomes of the two groups, it is likely to be appropriately small as to be clinically unimportant. However, the 95% CI does include the prespecified MCID.

| Time point (months) | Treatment group | Difference (95% CI) | p-value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IM nail fixation | Locking plate | ||||||

| Mean (SD) | n | Mean (SD) | n | Raw | Adjusteda | ||

| 3 | 44.2 (19.9) | 132 | 52.6 (19.9) | 141 | 8.4 | 8.8 (4.3 to 13.2) | < 0.001 |

| 6 | 29.8 (23.1) | 142 | 33.8 (24.7) | 140 | 4.0 | 4.0 (–1.0 to 9.0) | 0.114 |

| 12 | 23.1 (23.3) | 125 | 24.0 (24.6) | 129 | 0.9 | 1.9 (–3.2 to 6.9) | 0.468 |

The adjusted estimate of the treatment effect at 3 months is 8.8 (95% CI 4.3 to 13.2) in favour of the IM nail fixation group compared with the locking plate group. The p-value of < 0.001 indicates that there is strong evidence for a statistically significant difference in treatment group means at 3 months. The estimated treatment effect is larger than the prespecified MCID for the DRI of 8 points, so this difference is likely to be clinically important to patients. At the 12-month time point, the p-value of 0.468 indicates that there is no evidence for a statistically significant difference in the DRI score between the two treatment groups at the 12-month post-randomisation time point, and the adjusted treatment difference is 1.9 points (95% CI 3.2 to 6.9 points) in favour of the IM nail fixation group compared with the locking plate group.

Secondary outcomes

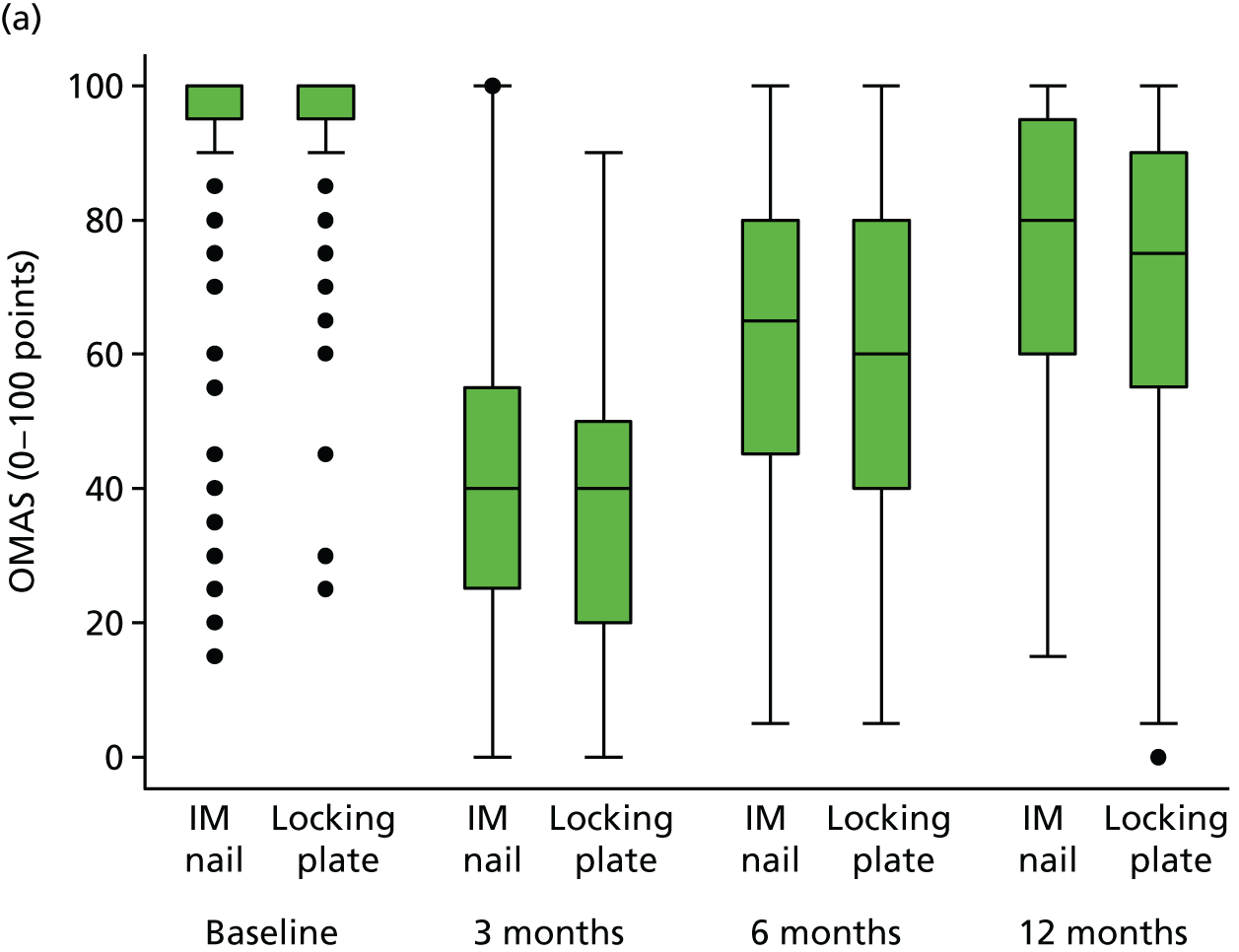

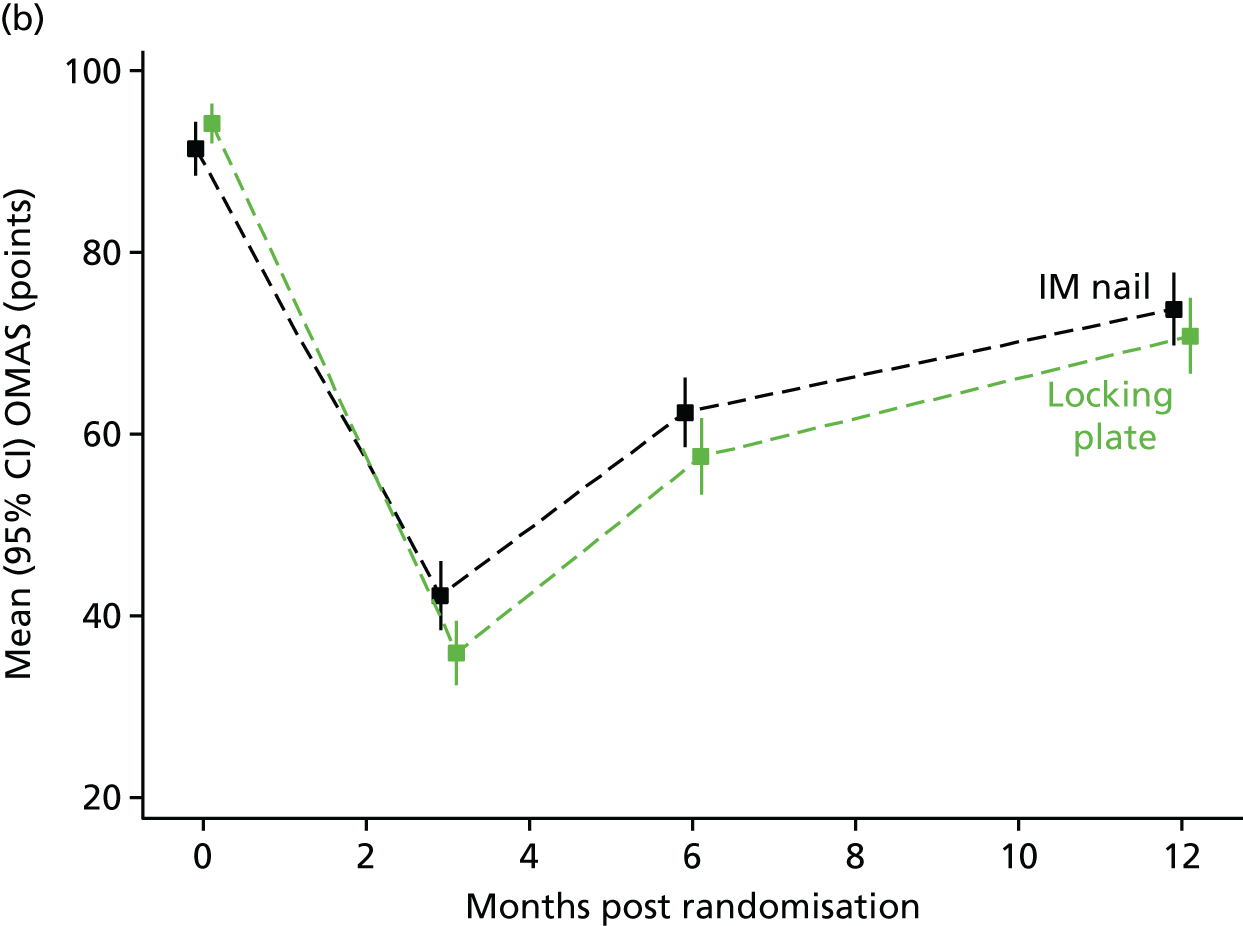

Olerud–Molander Ankle Score questionnaire

The adjusted estimate of the treatment effect for the OMAS, at the 6-month post-randomisation time point based on an intention-to-treat analysis, is –6.0 points (95% CI –11.2 to –0.7 points) in favour of the IM nail fixation group compared with the locking plate group (Figure 6 and Table 12). The p-value of 0.026 indicates that there is evidence for a statistically significant difference in the OMAS between the two treatment groups at the 6-month time point.

FIGURE 6.

The OMAS questionnaire. (a) Box plots of baseline and follow-up scores; and (b) overall trend in means and 95% CIs.

| Outcome measure, time point | Treatment group | Difference (95% CI) | p-value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IM nail fixation | Locking plate | ||||||

| Mean (SD) | n | Mean (SD) | n | Raw | Adjusteda | ||

| OMAS (points) | |||||||

| 3 months | 42.3 (22.1) | 130 | 36.0 (21.3) | 139 | –6.3 | –7.0 (–12.0 to –2.0) | 0.006 |

| 6 months | 62.4 (23.1) | 139 | 57.6 (24.9) | 135 | –4.9 | –6.0 (–11.2 to –0.7) | 0.026 |

| 12 months | 73.8 (22.5) | 20 | 70.8 (24.2) | 29 | –3.0 | –3.6 (–9.1 to 1.9) | 0.195 |

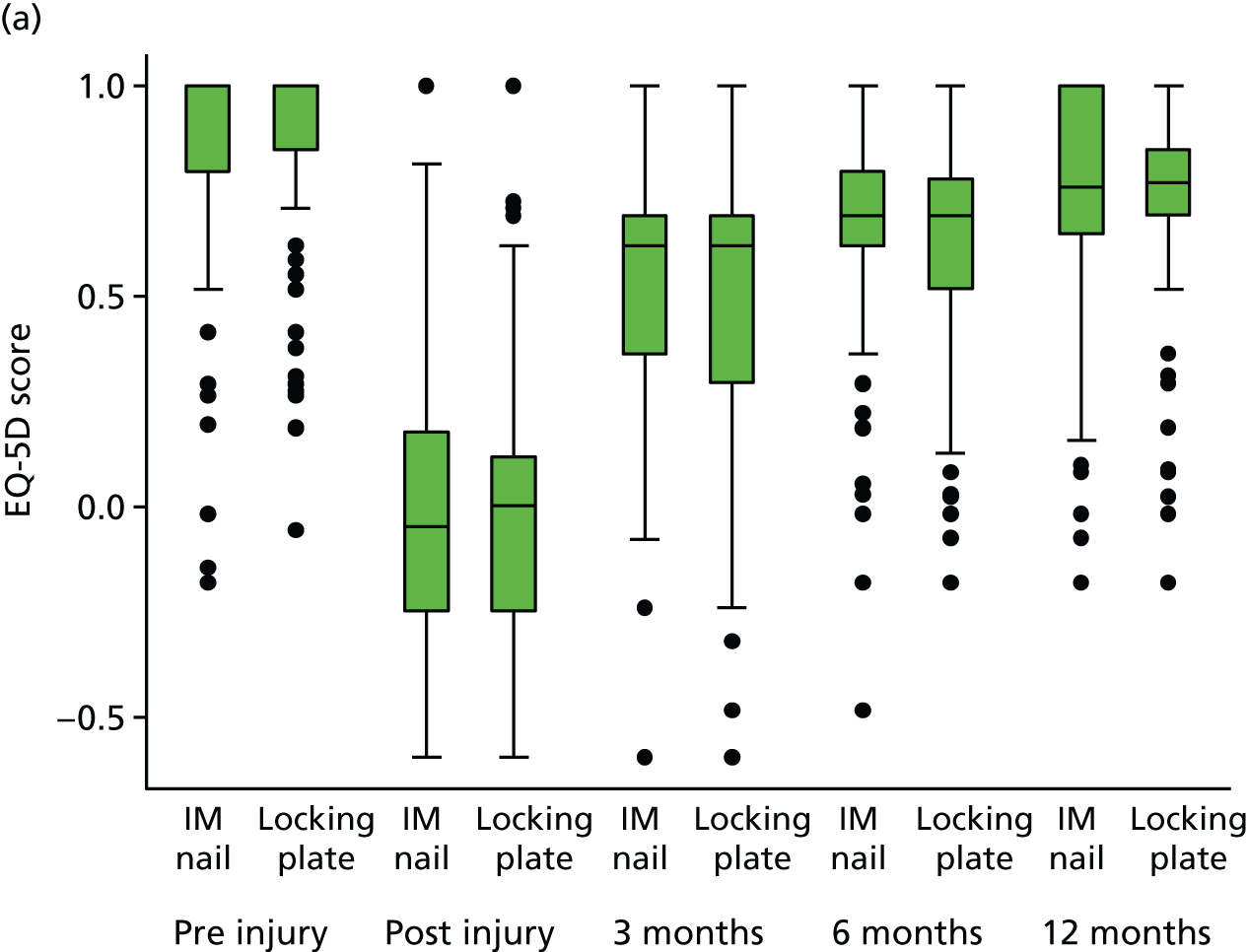

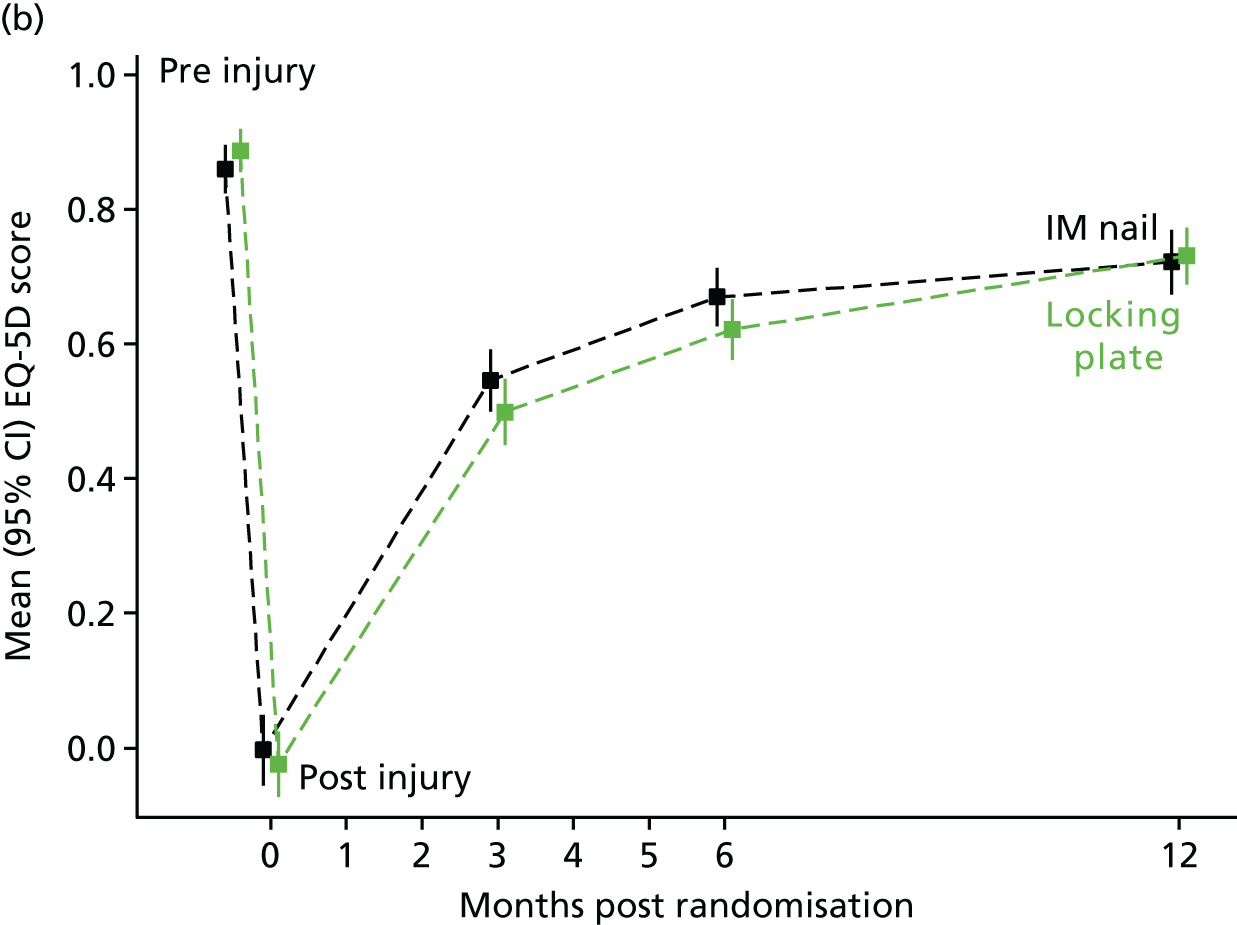

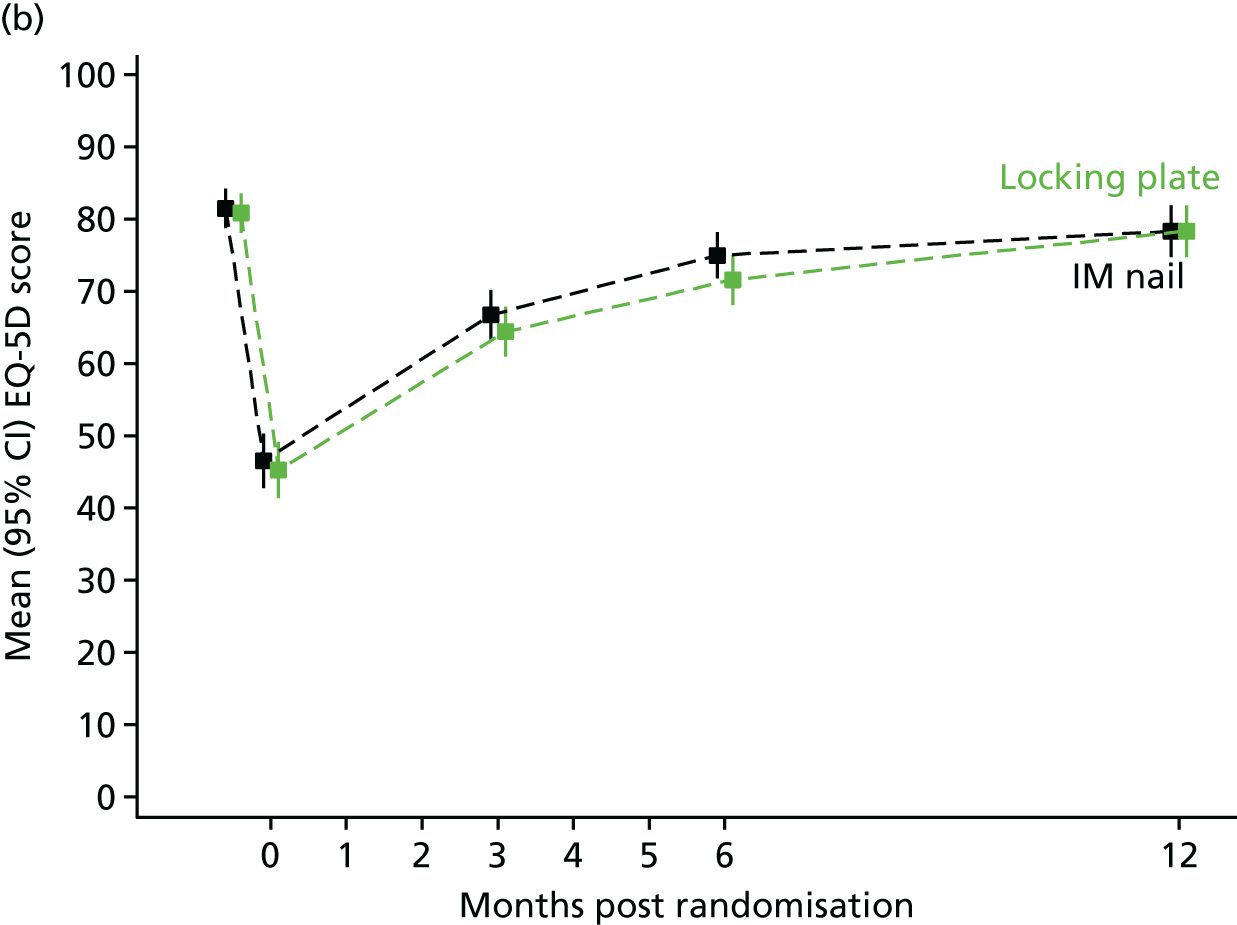

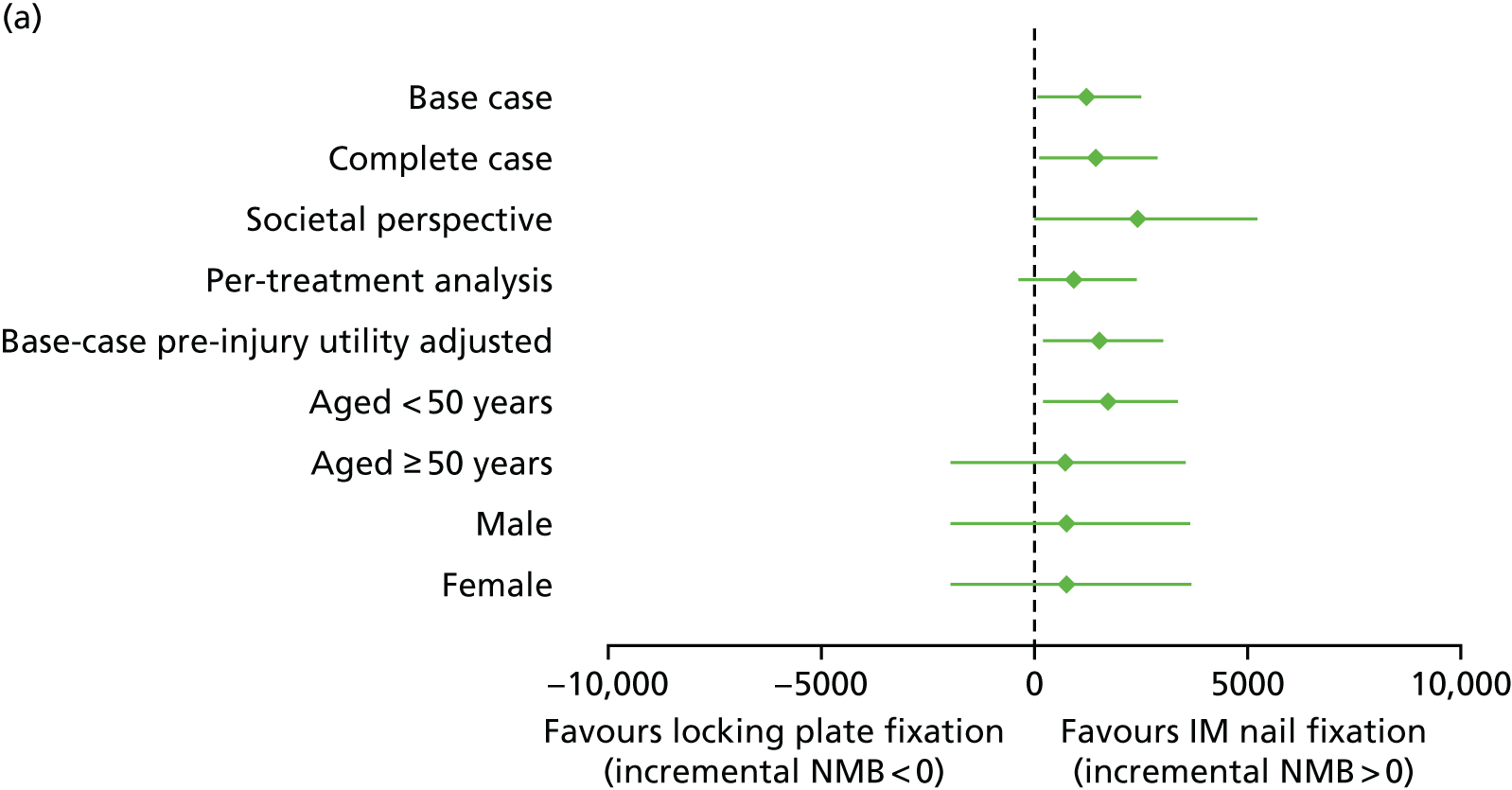

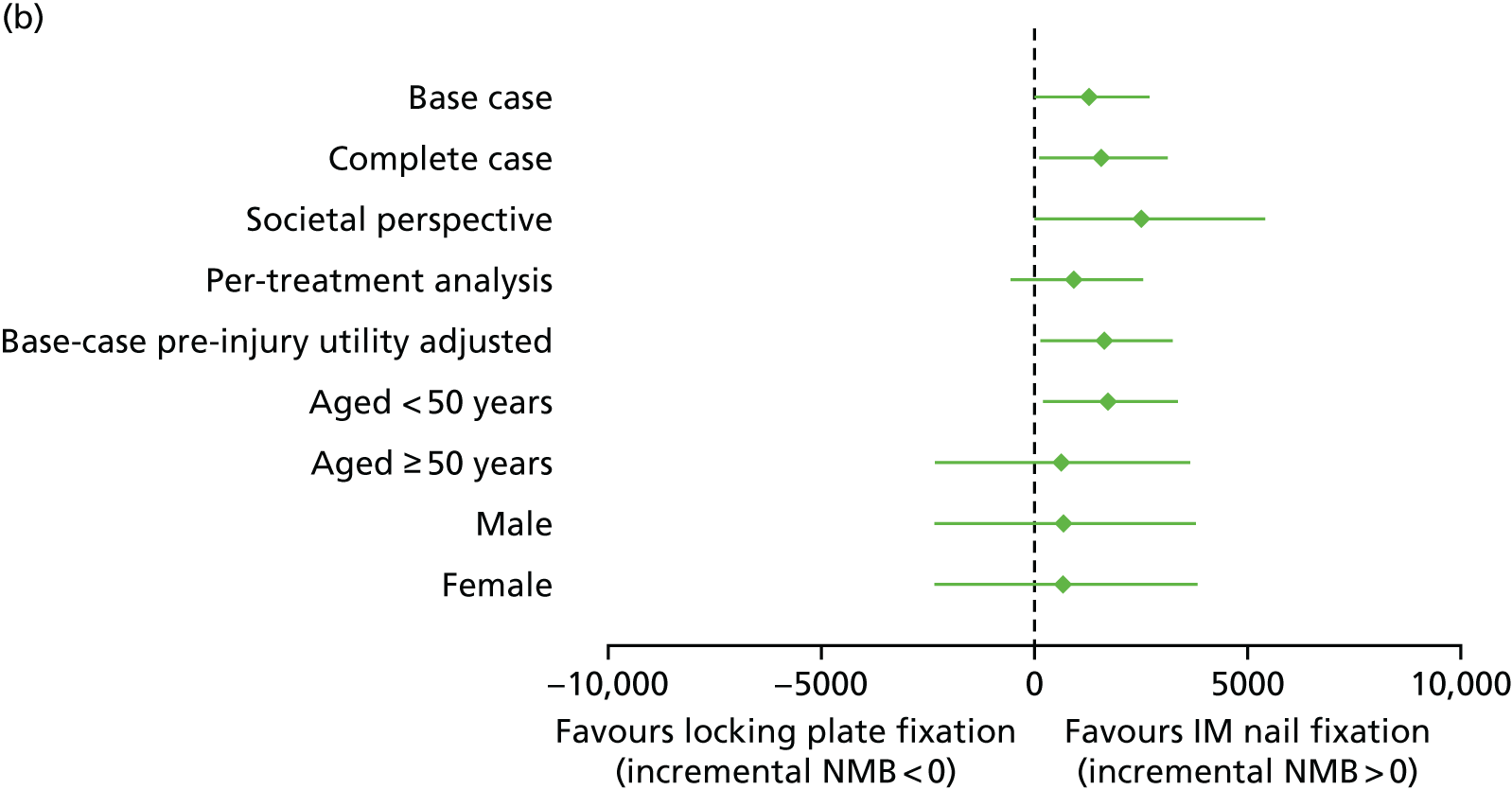

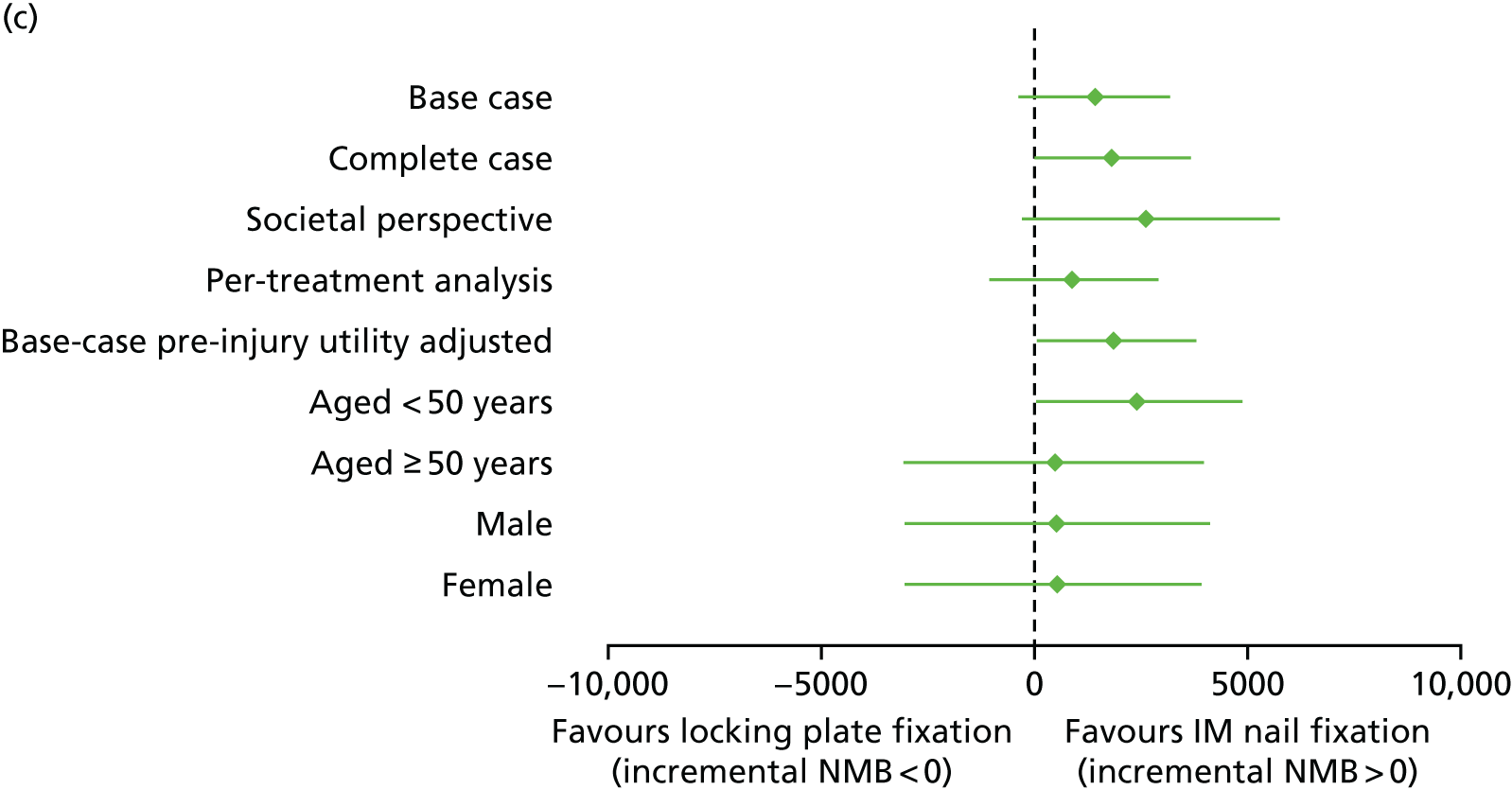

| EQ-5D index score | |||||||

| Post injury | –0.003 (0.334) | 158 | –0.024 (0.311) | 156 | –0.021 | –0.030 (–0.09 to 0.03) | 0.331 |

| 3 months | 0.546 (0.273) | 134 | 0.499 (0.302) | 142 | –0.047 | –0.058 (–0.12 to 0.00) | 0.067 |

| 6 months | 0.670 (0.265) | 143 | 0.622 (0.275) | 141 | –0.048 | –0.064 (–0.12 to –0.01) | 0.029 |

| 12 months | 0.722 (0.278) | 128 | 0.731 (0.246) | 130 | 0.009 | –0.018 (–0.07 to 0.05) | 0.525 |

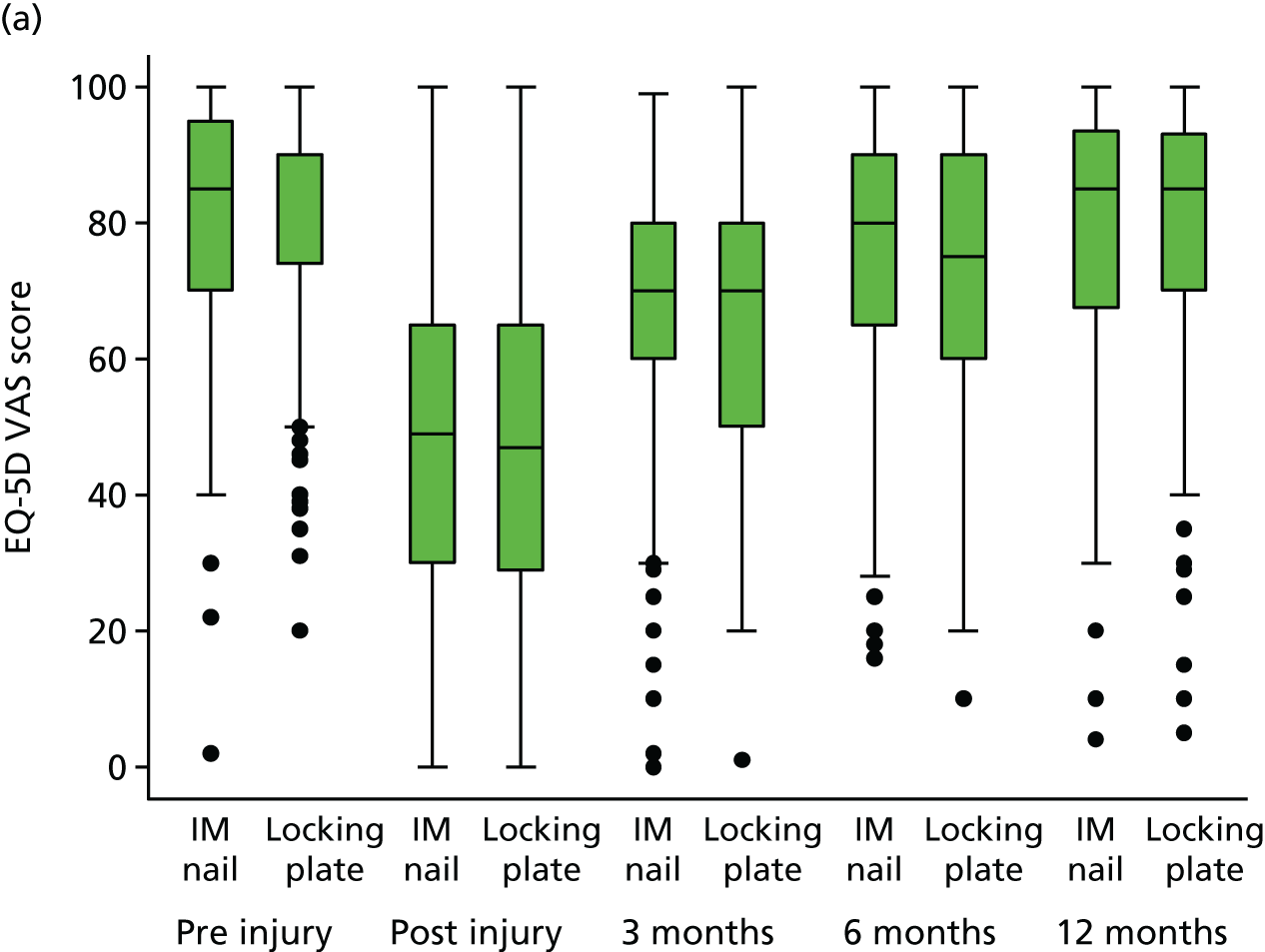

| EQ-5D VAS score | |||||||

| Post injury | 46.6 (24.5) | 158 | 45.3 (24.8) | 157 | –1.3 | –0.8 (–5.7 to 4.0) | 0.735 |

| 3 months | 66.7 (20.5) | 134 | 64.4 (21.1) | 142 | –2.3 | –1.9 (–6.4 to 2.6) | 0.418 |

| 6 months | 75.0 (19.6) | 143 | 71.6 (21.2) | 141 | –3.4 | –2.5 (–6.8 to 1.8) | 0.247 |

| 12 months | 78.3 (20.5) | 128 | 78.4 (20.8) | 129 | 0.1 | –0.2 (–4.6 to 4.2) | 0.935 |

EuroQol-5 Dimensions index score

The adjusted estimate of the treatment effect for the EQ-5D index score, at the 6-month post-randomisation time point based on an intention-to-treat analysis, is –0.063 points (95% CI –0.12 to –0.01 points) in favour of the IM nail fixation group compared with the locking plate group (Figure 7 and see Table 12). The p-value of 0.033 indicates that there is evidence for a statistically significant difference in the EQ-5D score between the two treatment groups at the 6-month time point.

FIGURE 7.

The EQ-5D index. (a) Box plots of baseline and follow-up scores; and (b) overall trend in means and 95% CIs.

EuroQol-5 Dimensions visual analogue scale score

The adjusted estimate of the treatment effect for the EQ-5D VAS score, at the 6-month post-randomisation time point based on an intention-to-treat analysis, is –2.5 (95% CI –6.8 to 1.8) in favour of the IM nail fixation group compared with the locking plate group (Figure 8 and see Table 12). The p-value of 0.247 indicates that there is no evidence of a statistically significant difference in the EQ-5D VAS score between the two treatment groups at the 6-month time point.

FIGURE 8.

The EQ-5D VAS. (a) Box plots of EQ-5D VAS baseline and follow-up scores; and (b) overall trend in EQ-5D VAS means and 95% CIs.

Per-treatment analysis

Table 13 shows the results of per-treatment analyses, in which participants were analysed in per-treatment groups, that is, those who received IM nails compared with those who received locking plates. The five participants who did not receive either treatment were excluded from these analyses. An adjusted per-treatment analysis of the DRI scores at 6 months gave an adjusted treatment effect of 4.2 (95% CI –0.9 to 9.2) and a p-value equal to 0.103. Adjusted analysis at 3 and 12 months also gave similar results to the intention-to-treat analysis in Primary outcome.

| Outcome measure, time point | Treatment group | Difference (95% CI) | p-value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IM nail fixation | Locking plate | ||||||

| Mean (SD) | n | Mean (SD) | n | Raw | Adjusteda | ||

| DRI score (points) | |||||||

| 3 months | 44.5 (20.8) | 148 | 53.2 (18.9) | 123 | 8.7 | 9.0 (4.5 to 13.5) | < 0.001 |

| 6 months | 29.9 (23.4) | 154 | 34.3 (24.6) | 126 | 4.5 | 4.2 (–0.9 to 9.2) | 0.103 |

| 12 months | 23.5 (23.5) | 136 | 24.0 (24.5) | 116 | 0.5 | 0.9 (–4.2 to 6.0) | 0.727 |

| OMAS (points) | |||||||

| 3 months | 42.1 (23.1) | 144 | 35.3 (19.9) | 123 | –6.8 | –7.2 (–12.3 to –2.2) | 0.005 |

| 6 months | 61.9 (23.8) | 150 | 57.5 (24.5) | 122 | –4.5 | –4.9 (–10.2 to 0.4) | 0.073 |

| 12 months | 73.2 (23.2) | 129 | 70.8 (23.7) | 118 | –2.3 | –2.4 (–7.9 to 3.1) | 0.395 |

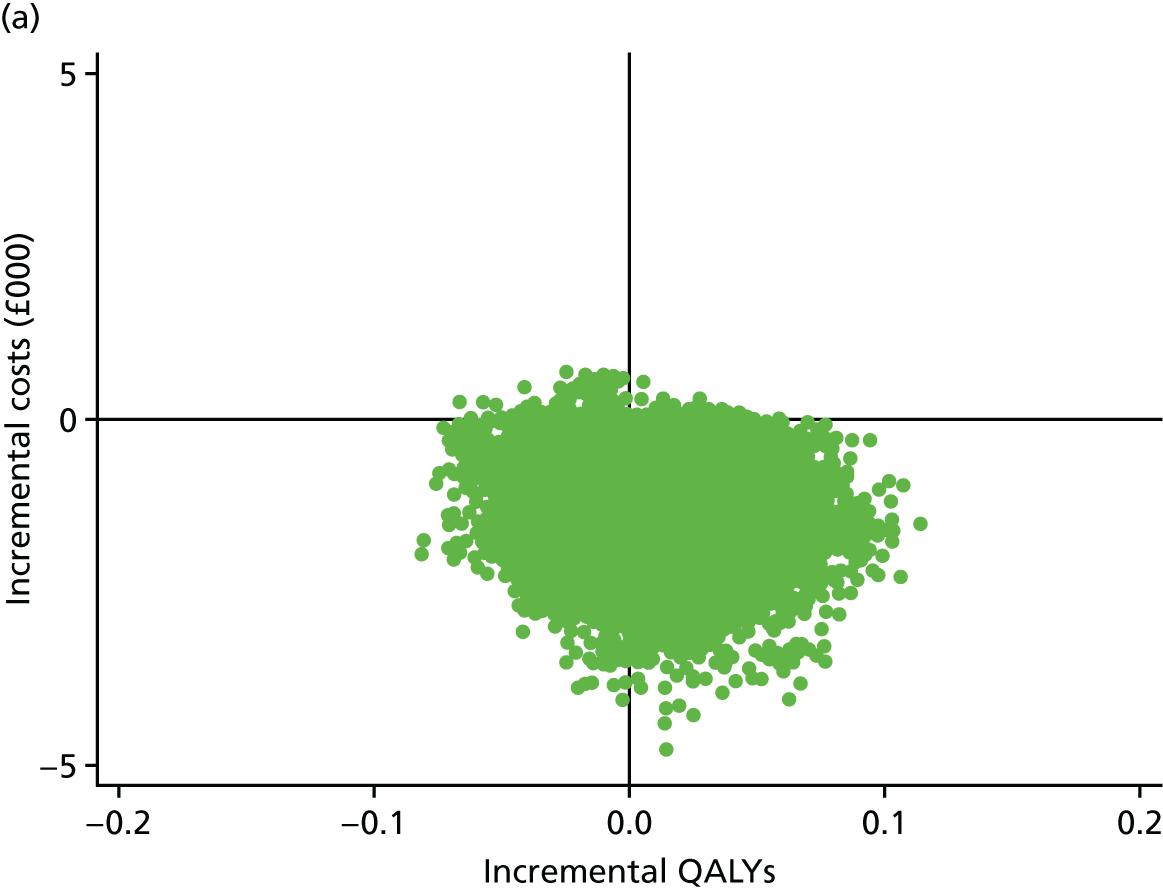

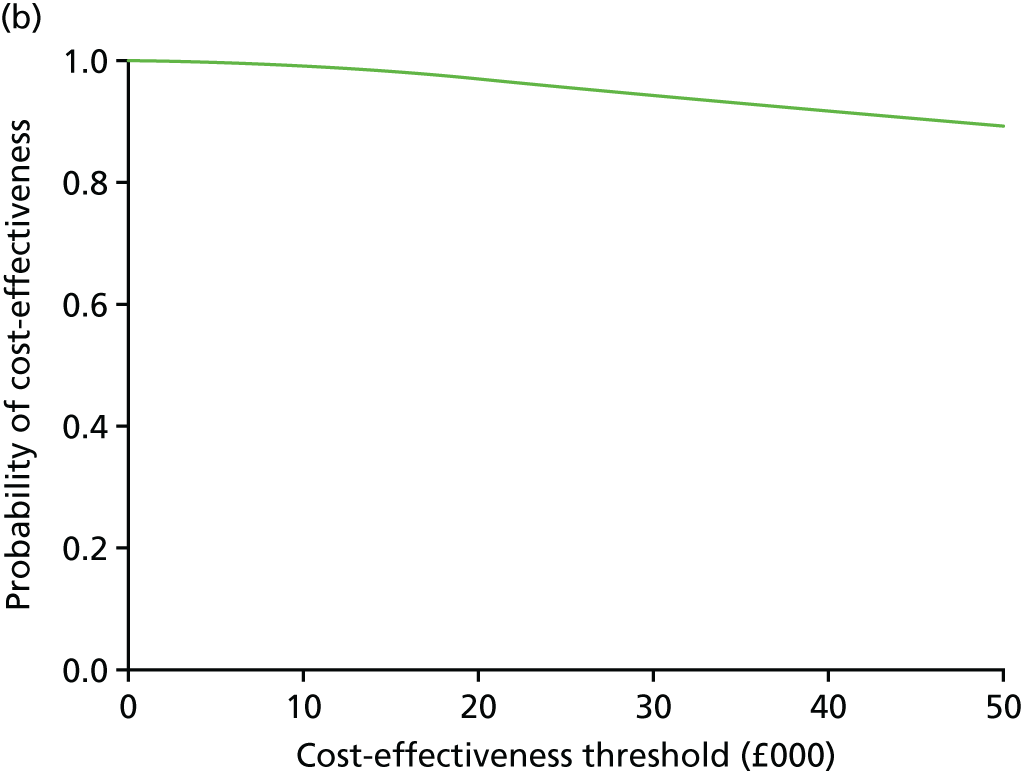

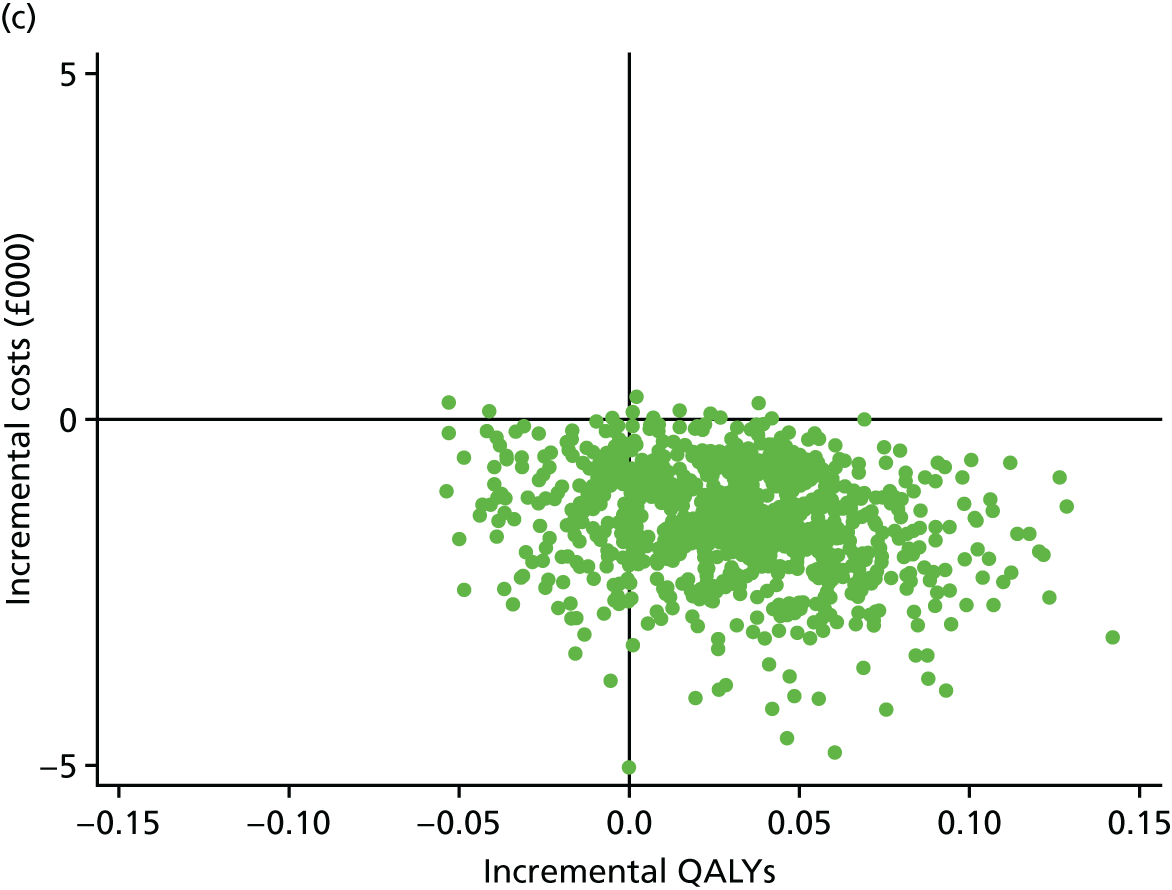

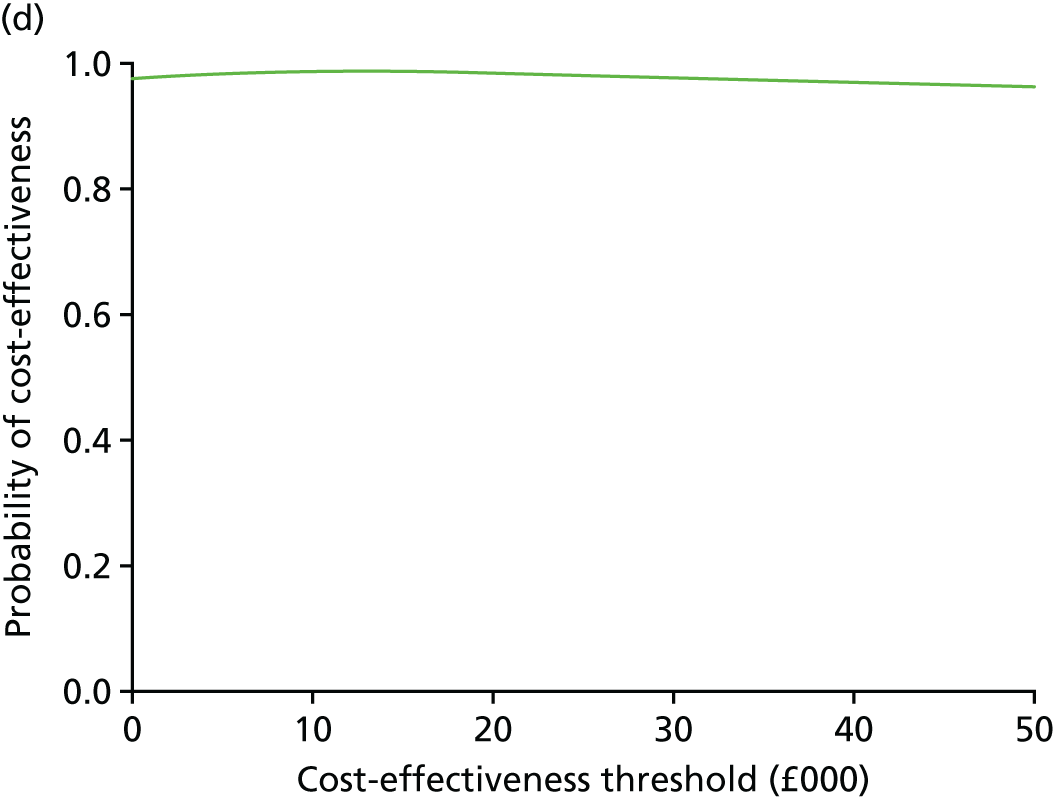

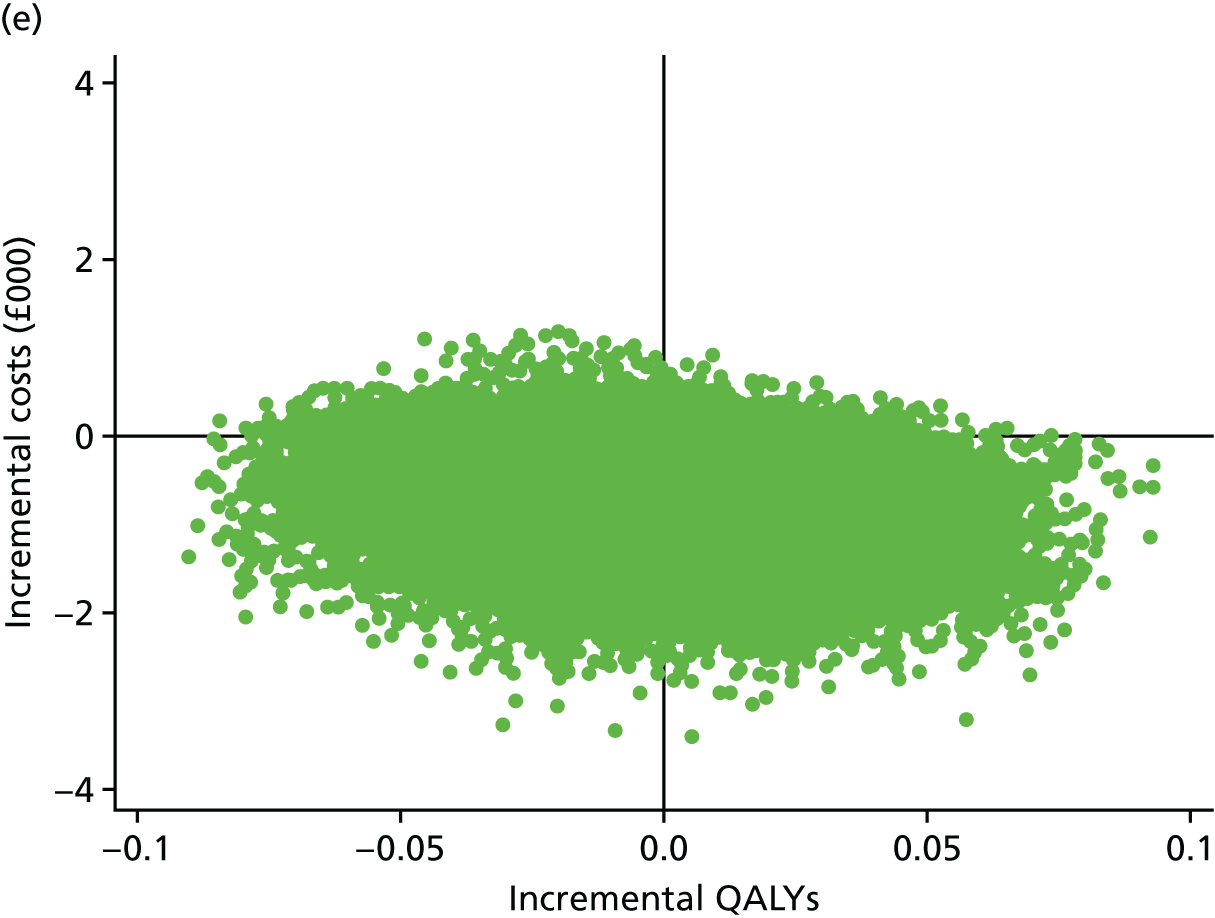

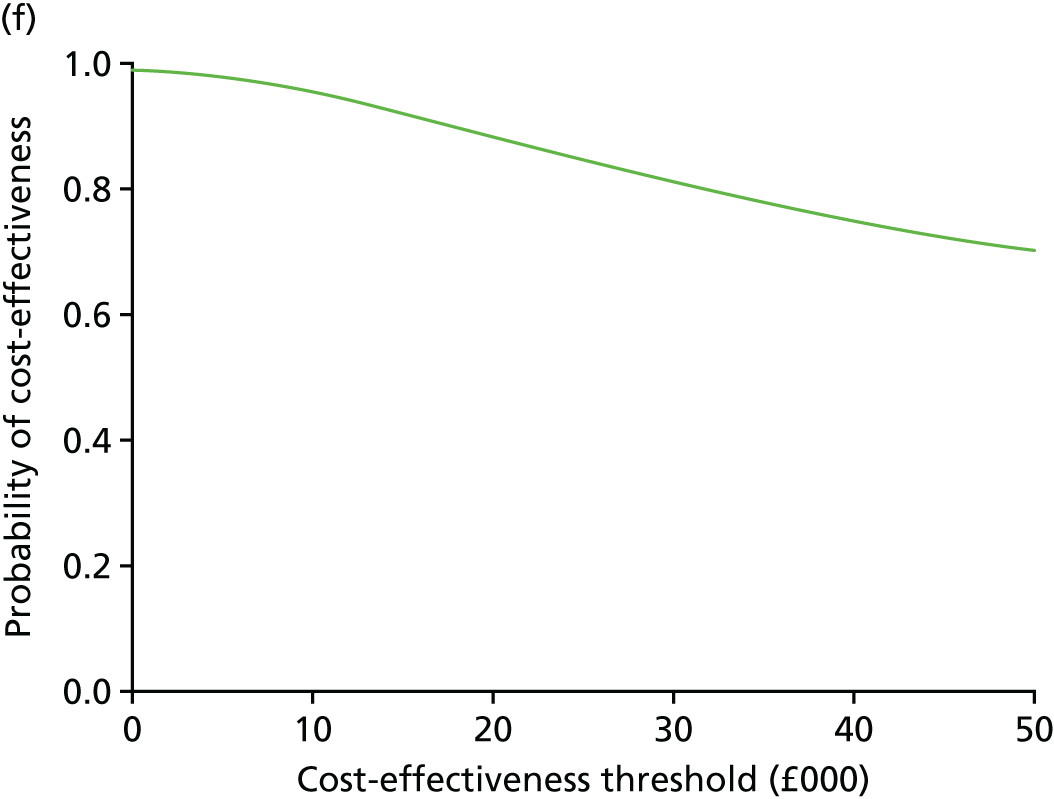

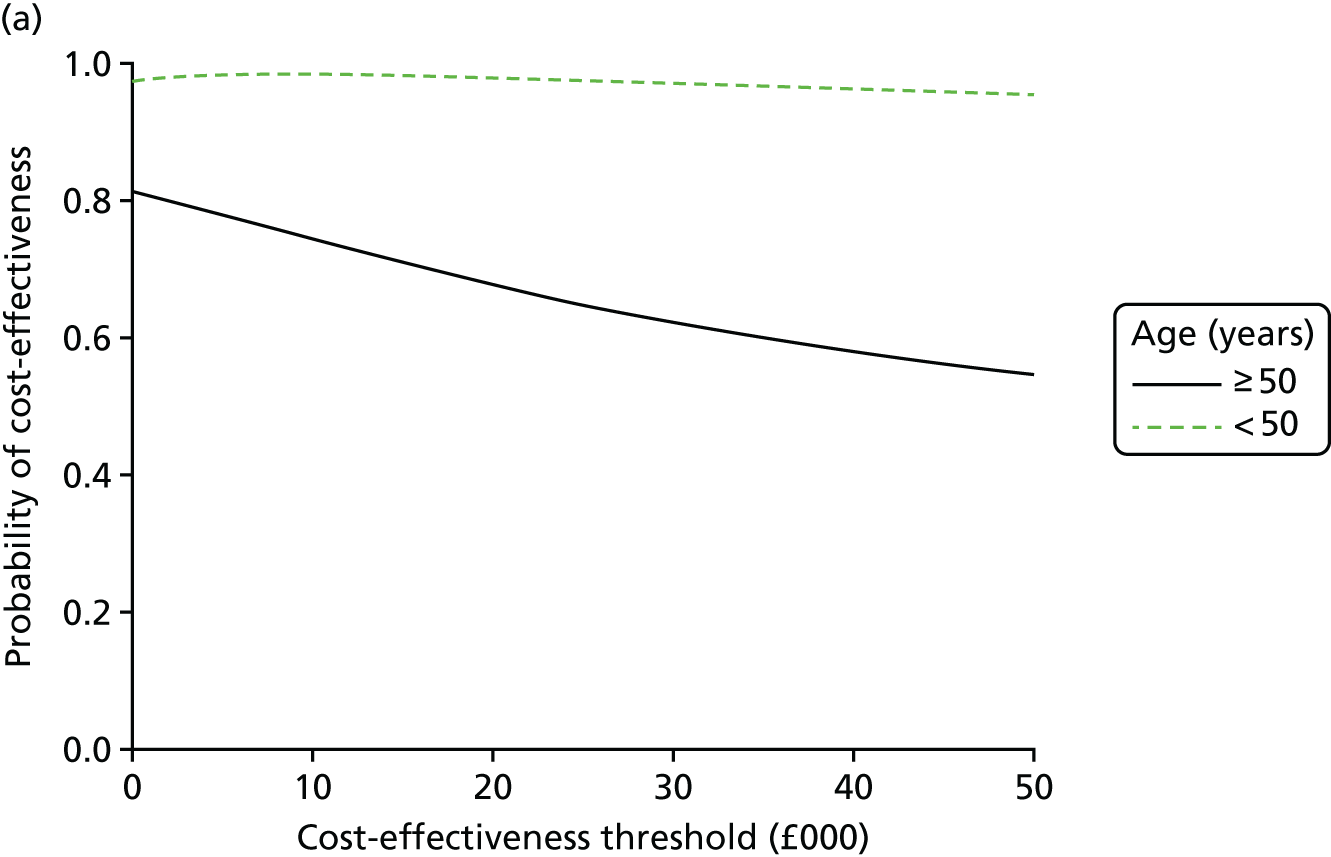

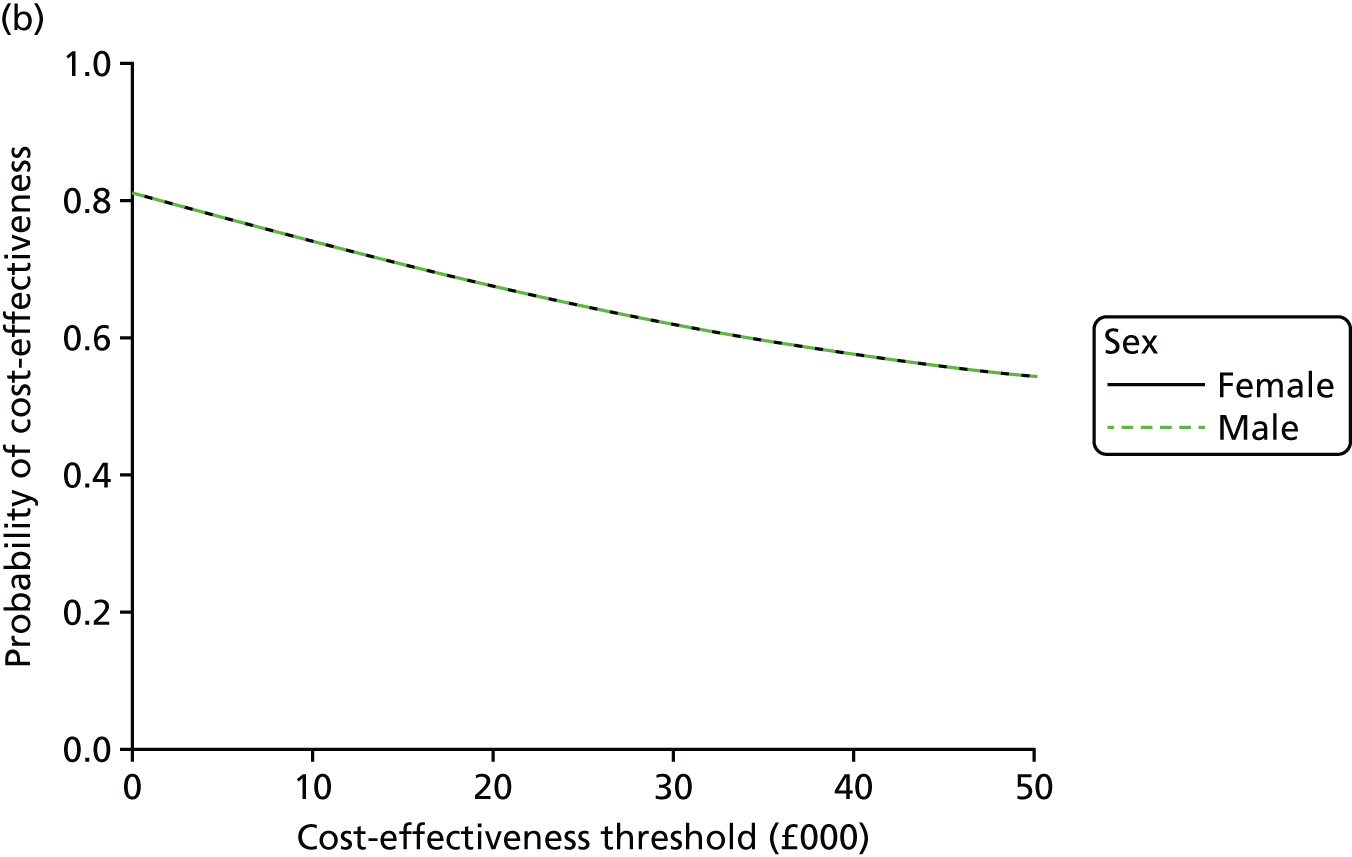

| EQ-5D index score | |||||||