Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 12/145/04. The contractual start date was in June 2014. The draft report began editorial review in January 2017 and was accepted for publication in October 2017. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Laura Jones reports personal fees from Quit51 Bionical outside the submitted work. Jonathan Mathers reports personal fees from Health Education England outside the submitted work. Melanie Calvert reports personal fees from Astellas Pharma Inc. and Ferring Pharmaceuticals outside the submitted work. Jonathan Deeks was a member of the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Health Technology Assessment Commissioning Board and the NIHR Efficient Study Designs Board.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2018. This work was produced by Moiemen et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2018 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Introduction and background

Burn injury is the fourth most common type of trauma after road traffic accidents, falls and interpersonal intentional injury. 1 In 2004, it was estimated that 11 million people of all ages suffered a fire-related burn injury worldwide, that is, more than the number of people diagnosed with a human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection and tuberculosis combined. 2,3 Burns cause 265,000 deaths annually and are one of the leading causes of disability-adjusted life-years lost. 2 Seventy-one per cent of patients who survive suffer significant scarring. 4 Burn care during the last 30 years has seen a steep change in survival. 5 Fortunately, the increased survival has been paralleled by improved acute care and durable wound cover resulting in less deformity and scarring. However, there is still a great, and increasing, need for post-burn scar management. In a systematic review, Lawrence et al. 6 identified the need for further research to address the lack of a consistent definition of scarring, poor assessment methodology and the need for comprehensive scar outcome measures. In a comprehensive review of 703 burn survivors’ records, Gangemi et al. 4 identified the risk factors for post-burn hypertrophic scarring. These factors included being a young person, being female, having dark skin, sustaining a severe burn, the number of surgical procedures performed to achieve wound cover, the site on the body where the burn occurred (neck and upper limb in this study) and the time to the wound healing.

Post-burn hypertrophic scarring is typically treated non-invasively with the use of moisturiser, massage,7 pressure garments8,9 or silicone,10–13 or these modalities in various combinations. A survey of 19 paediatric NHS burn services in the UK showed that 18 services routinely use pressure garments for the prevention of hypertrophic scarring following burn injury. 14

History of hypertrophic scarring and pressure garment therapy

The first historical mention of keloid scarring dates back to the time of the ancient Egyptians, who recognised the condition and even realised at the time that treatment is difficult and that doing nothing is a wise strategy. The Edwin Smith Surgical Papyrus from 1700 BC, which predates Hippocrates by almost 1000 years, is thought to have been authored by an architect, a high priest and a physician of the Old Kingdom of ancient Egypt. The papyrus is a 4.88-metre scroll, with a detailed description of 84 case studies. It is considered to be a trauma manual of different parts of the body that is aimed at battle injuries. 15,16 In one case, there is a description of a growth on the chest of one of the patients and the author wisely recommended not to excise.

Although scarring was recognised in ancient times, the clear understanding and definition of the hypertrophic scar occurred much more recently. In 1962, Mancini and Quaife17 made the distinction between keloid and hypertrophic scarring in the way that we understand it today. In 1973, Madden and Peacock18 provided the first histological understanding of keloid and hypertrophic scarring.

In the sixteenth century, Ambroise Paré, a French barber surgeon who pioneered battlefield medicine, described pressure therapy for scarring. 19 In 1649, Thomas Johnson translated the original book The Work of that Famous Ambroise Paré20 that was first published by Paré in 1545. Paré recommended using pressure onto scars to improve their quality by applying a lead plate that is rubbed against mercury onto the scars. 21

It was not until the middle of the twentieth century that elasticated conforming garments were first used to improve surgical wound scars on the neck. In 1960, Fujumori et al. 22 published their experience of applying an adhesive foam mould to neck hypertrophic scars. At a similar time, Cronin23 and Gottlieb24 separately reported using cervical splints after the release of neck contractures and reconstruction with split-thickness skin grafts. Dr Duane Larson, the chief of staff of Shriners Hospitals for Children, and his team were the first to introduce the modern elasticated custom-made pressure garment, as we know it today, for burns. Several publications from their centre in the late 1960s and early 1970s publicised the technique in the USA and Canada and then worldwide. 20

Evidence of the effectiveness and efficacy of pressure garment therapy

Pressure garment therapy (PGT) for the prevention and treatment of hypertrophic scarring has become the standard of care in almost all burn centres globally. In spite of the widespread use, randomised controlled trials (RCTs) on PGT were not published until the 1990s, when Kealey et al. 25 reported a RCT of 110 patients comparing Tubigrip™ (Mölnlycke Health Care Ltd, Dunstable, UK; a cotton elastic garment) with elastic nylon pressure garments. The clinical outcome of the two groups was comparable, with significantly greater adherence and lower cost in the Tubigrip arm of the trial. In 1995, Chang et al. 26 randomised 122 patients, who required either skin grafting or their wounds to be healed over a period > 2 weeks, to either PGT or no PGT. The two groups were matched for age, percentage of total body surface area (TBSA) burned and length of hospital stay. Patients were followed up until their scars matured. The median time to scar maturation was 266 days in the PGT arm and 273 in the no-PGT arm, with no statistical difference between the two groups as assessed by the Vancouver Scar Scale (VSS).

In 2000, Groce et al. 27 and Moore et al. 28 independently presented two RCTs at the annual conference of the American Burn Association. Groce et al. 27 randomised 46 children from Galveston, TX, USA, who had a mean TBSA burn percentage of 11.2%, to receive PGT or no PGT. 27 The authors reported improvement of scar height at 6 months, but no significant difference in vascularity, pigmentation or pliability between the two arms of the trial. This work was presented as a preliminary study with only 6 months’ follow-up. In a separate publication, Groce et al. 29 presented the 18-month follow-up of the same cohort. They could not demonstrate any clinical improvement when they compared low- and high-pressure therapy after 18 months’ follow-up. Moore et al. 28 included 23 patients from Seattle, WA, USA, with forearm burns in a RCT. For each patient, half of their scar received pressure and the other half did not. The authors followed the patients every 3 months, until the scars matured, and objectively measured scar colour, softness and thickness. The authors reported improved scar softness, as measured by a durometer, at 6 months but the difference in improvement between PGT and no PGT disappeared at 12 months. Scar thickness, as measured by ultrasound, did not show any significant difference between the two groups at any time point. When three physicians assessed the scars, they incorrectly identified the part of the scar that had pressure therapy in 70%, 75% and 80% of the cases. The authors concluded that pressure garments did not alter the ultimate appearance of burn scars following skin grafting.

In 2005, Van den Kerckhove et al. 30 published a RCT of 60 patients with 3 months’ follow-up. They compared two types of pressure: 15 and 10 mmHg. Scarring was objectively assessed monthly for a total follow-up of 3 months, which is a very short follow-up period for the assessment of scar maturation. The authors found significant improvement of scar thickness and erythema when using a pressure of 15 mmHg compared with 10 mmHg.

In 2009, Anzarut et al. 31 conducted a systematic review of the available evidence for the use of PGT and assessed the quality of this available evidence. In the same article, the authors also conducted a meta-analysis to quantify the clinical effectiveness of PGT. The authors identified six studies in their review, one of which was unpublished [Tredget EE, Shankowsky HA, Mathey S and Anzarut A (editor), Edmonton, AB, Canada; 2004]26–30 which included a total of 316 patients. These six studies were considered to be of high methodological quality. The meta-analysis for global scar assessment did not show a difference between PGT and no PGT. However, scar height showed a small but statistically significant improvement when PGT was used. Other secondary outcome measures, including vascularity pliability and colour, failed to demonstrate a difference between the two therapies. The authors concluded that methodologically rigorous and adequately powered studies were required and called for a definitive trial of the clinical effectiveness of PGT for the prevention of abnormal scarring after burn injury.

Since the Anzarut et al. 31 systematic review and meta-analysis, there have been only a few RCTs of the use of PGT. 32–34 In 2010, Candy et al. 32 included a total of 53 patients in their trials, who had a mixture of post-burn, trauma and surgical wound scars that developed for 3–9 months before inclusion into the trial. 32 Participants were randomised into two trial arms of two pressures: 20–25 and 10–15 mmHg. The trial showed improvement in the redness and thickness, but no improvement in the pliability or colour of the scars of patients treated with the high-pressure garments. A four-arm RCT was published in same year from the same centre but had a different cohort of 104 Chinese patients, who had scars at variable stages of maturation that were caused by a mixture of burns, trauma or surgery. Patients were randomised to groups that used pressure garments, silicone gel sheets or a combination of pressure garments and silicone gel sheets, or a single-blinded control group. The treatment was given for 6 months. The results suggested that there was a benefit regarding scar thickness for both the pressure garment and the combined groups. 33

In 2010, Engrav et al. 34 published a follow-on trial from Seattle, WA, USA, from the Moore et al. 28 trial in 2000. As in the original study design, scars were divided into proximal or distal parts. A ‘treatment’ pressure of 17–24 mmHg was applied to one half of the scar and a ‘control’ pressure of < 5 mmHg was applied to the other half, enabling a ‘within-wound study’. The authors reported the results of 67 consecutive patients who were enrolled over the 12-year period with 12 months’ follow-up. They objectively measured scar hardness, colour and thickness, and the clinical appearance of the scars was also assessed by a panel of experts. Twenty-three patients from the Moore et al. trial from 2000 were included in this study. The authors stated that wounds treated with normal compression (> 15 mmHg) were significantly softer and thinner and had improved clinical appearance. They also concluded that these findings were evident only with moderate to severe scars and recommended the use of PGT for children. As the authors mentioned, there were changes in staffing, garment manufacturing and the hardware and software used to assess scars during the 12 years of the study. As an example, 11 of the 25 patients who received treatment between 2000 and 2007 received a pressure of ≥ 15 mmHg instead of < 5 mmHg as a control pressure. Regarding the recommendation for using PGT in children and for moderate and severe burns, there was no stratification of data by age or scar severity to justify this. The data that were presented came from only three children aged < 15 years. Eleven experts assessed the clinical appearance of the scars. The experts could identify the treatment zone in only 3 of the 41 patient photographs. Unfortunately, this trial was rated as having a high risk of bias.

Complications and adherence with pressure garment therapy

None of the clinical trials discussed in the previous section reported the adverse effects that may be associated with using PGT or the costs of the custom-made garments. Only one trial reported the problem of adherence in the use of the garment. 25 It is usually recommended that pressure garments are worn 23–24 hours a day from the time of the burn wound healing until scar maturation. Wearing the garment can be uncomfortable, especially in warm climates, and can cause overheating, wound breakdown or itching or appear unattractive. The garment can also cause skeletal and facial growth delay during the use of pressure garments for facial burns in children; however, this growth delay recovers after the therapy is discontinued. 35

In 2000, Hubbard et al. 36 reported two cases of children who received PGT for facial and upper trunk scars and developed obstructive sleep apnoea.

Pressure garment therapy is a high-demand treatment for burn survivors who may have very complex recovery and rehabilitation programmes. It is not surprising that adherence with PGT is a significant problem. 37,38 In 1994, Johnston et al. 39 conducted a structured adherence survey of 145 adult burn survivors. In total, 101 patients returned the questionnaire. The overall adherence rate was 41%. Adherence was better in men, in those with higher income (i.e. > US$30,000) and in those with burns of < 8% TBSA. The qualitative study conducted by Ripper et al. ,40 in 2009, gave an excellent insight into patients’ experience of PGT. Ninety-five per cent of respondents reported functional or physical problems in using the pressure garment, in the form of sweating, overheating, pain or itch, and 67% reported that additional effort is needed to manage the garment.

Evidence emerging during the time period of the PEGASUS study

During 2015–16, both a RCT protocol41 and a Cochrane review protocol42 were published. The RCT was designed to examine the effectiveness of low pressure (4–6 mmHg) on skin graft donor site scarring using Tubigrip, a low-cost elasticated cotton garment that is gentle to apply to fragile wounds. The Cochrane review protocol (which has recently been withdrawn) emphasised the need to clear the uncertainty that still exists regarding the clinical effectiveness of PGT, the use of which is advocated but has never been scientifically proven. Since the commissioning brief for this study was released, there has been little new evidence to support or discourage the use of PGT.

Rationale for the PEGASUS study

Although PGT is an established clinical treatment for post-burn hypertrophic scarring in almost all NHS burns service providers in the UK, there is limited evidence of PGT’s efficacy, clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness. There is also some evidence of poor adherence with the treatment, inconvenience and occasional complications. Although there appears to be adequate uncertainty of the value and effectiveness of PGT to consider the need to conduct a well-designed definitive trial,31 health-care professionals (HCPs) have been actively engaged or advocating this therapy for decades and a lack of clinical and personal equipoise may be a barrier to recruiting to an ethically acceptable RCT. In addition, patients, parents or their carers may have an expectation of receiving PGT for scar management, and these expectations may represent a barrier to their willingness to participate in a RCT. Identifying the barriers to, and the facilitators of, conducting a full-scale trial, or indeed if such a trial is feasible at all, is the main objective of the PEGASUS (A mixed-methods feasibility study including a randomised trial of PrEssure Garment therApy for the prevention of abnormal Scarring after bUrn injury in adultS and children) study.

The PEGASUS pilot feasibility trial will also inform the design of the full-scale trial. Burn survivors experience multifactorial problems related to scarring, function, psychological and social difficulties and reduced quality of life (QoL). Identifying core scar outcome domains is important to select patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs) that are specific, and unique, to both the patients’ and the HCPs’ experiences of post-burn scarring. A validated burn-specific measure for post-burn hypertrophic scarring should be considered as the primary outcome measure for a full-scale trial of PGT.

The PEGASUS study consists of a series of studies organised in two phases. In phase 1 (P1), national staff surveys and interviews with HCPs, patients and carers were conducted to assess the feasibility and acceptability of the trial in principle and to identify the suitability of potential outcome and economic assessments. A novel element of the study was the exploration of the feasibility of capturing costs and resource use from both NHS and societal perspectives and the feasibility of using contingent valuation (willingness to pay; WTP) to value outcomes and process utility from a patient perspective.

In phase 2 (P2), a pilot RCT tested the feasibility of running a RCT in practice and, particularly, whether or not it would be possible to recruit patients in sufficient numbers for a full-scale trial of PGT. Integrated qualitative research examines, in detail, the experiences of patients and clinicians of participating in, and delivering, the pilot trial. This research was designed to provide an opportunity to reflect upon trial participation and processes (e.g. recruitment and outcome assessment) and to understand how practice is influenced by staff and patients’ attitudes to PGT, as seen in P1.

Chapter 2 Aims and objectives of the PEGASUS study

Objectives of the different phases of the study

The aim of the PEGASUS study was to assess the feasibility of a full-scale RCT on the clinical effectiveness and the cost-effectiveness of PGT. If such a trial was feasible, the outcome of the PEGASUS study would inform the design of the full trial.

The PEGASUS study was organised in two phases: P1 and P2. In the following sections, we list the objectives addressed in each phase and briefly indicate the study method used. Full details of methods are included in each chapter.

Phase 1

Phase 1 consisted of a series of surveys and interviews with patients and health-care providers. The following objectives were assessed:

-

The current UK practice of PGT, including the number of patients receiving treatment, how garments are manufactured, costs of the garments to each NHS burns service and an estimate of the total costs to the NHS – data were collected by a web-based survey that was sent to all UK NHS burns units and data of the duration of PGT across the burn care providers were also collected. (Details and results are reported in Chapter 3.)

-

The number of children and adults eligible to be included in a PGT clinical trial in UK NHS burns units – data were collected by the same web-based survey used in objective 1. (Details and results are reported in Chapter 3.)

-

The views of HCPs [including consultants, nurses, physiotherapists and occupational therapists (OTs)] on conducting a RCT to compare PGT and no PGT, including attitudes to participation, perceived equipoise and barriers to, and facilitators of, undertaking and participating in a full-scale RCT of PGT – data were collected through a second web-based questionnaire, which was sent to individual HCPs, and in-depth interviews. (Results are reported in Chapter 4.)

-

The experience of patients and carers of PGT and their willingness to be randomised between PGT and no PGT – the impact of PGT on psychological and social functioning, body image and self-esteem and the psychological protection that some patients feel that PGT provides were explored. PGT treatment burden, perceived benefits and compliance (adherence to the treatment) were also assessed. Qualitative interviews were undertaken with patients who previously received PGT and/or their carers, either as face-to-face interviews or telephone interviews. (Details and results are reported in Chapter 5.)

-

Patient-centred outcomes that specifically measure post-burn scarring and appropriate methods of evaluating these outcomes – specific domains that are important to the patients, carers and HCPs were established in order to select the most suitable primary outcome for the full-scale trial. Data from the staff attitudes survey (objective 3) and from qualitative interviews with patients and carers (objective 4) and clinicians and HCPs were used. (Details and results are reported in Chapter 5.)

-

Appropriate methods for evaluating outcomes for the health economic analysis and resource use. (Details and results are reported in Chapter 6.)

Phase 2

Phase 2 was a multicentre pilot RCT that was conducted in four paediatric and six adult recruiting centres across England and Wales. This trial was an open two-arm trial with 12 months’ follow-up. Participants were randomised to PGT or no PGT, with both groups receiving other modalities of scar management, such as massage, moisturisation or silicone treatment.

The following objectives were assessed in the pilot RCT:

-

Recruitment rates and willingness to randomise between PGT and no PGT in multiple sites within the pilot RCT. (Details and results are reported in Chapter 7.)

-

Adherence with randomised allocation and PGT therapy. (Details and results are reported in Chapter 7.)

-

Possible processes for achieving blinded assessment of outcomes. (Details and results are reported in Chapter 7.)

-

Outcome distributions to inform a sample size calculation for a future trial. (Details and results are reported in Chapter 7.)

-

The perspectives, and experiences, of the patients, carers and HCPs who participated in the trial on trial participation and processes by qualitative process evaluation. (Details and results are reported in Chapter 8.)

-

The feasibility and success of the economic assessment to inform the assessment of cost-effectiveness in a future trial. (Details and results are reported in Chapter 9.)

The original study plan involved running P1 and P2 sequentially to allow findings from the qualitative work and surveys to influence the design of the pilot trial. However, the study duration was reduced on the request of the funding board and the two phases were run concurrently, which reduced the opportunity of findings from P1 to influence the design of the pilot trial in P2.

Chapter 3 UK survey of current practice of pressure garment therapy

Relevant objectives

The following objectives are assessed in this chapter:

-

to detail the manufacturers of pressure garments, the types of garments and the length of time that PGT is used, by patient group

-

to assess the number of children and adults eligible to be included in a trial of PGT.

Background

Pressure garments are designed to deliver a recommended pressure using an elastic fabric that contains Lycra® (INVISTA, Wichita, KS, USA). Scar management therapists are offered a choice of different fabrics and make their choice based on the functional requirements and comfort of the patient. Current recommendations, issued by suppliers of pressure garments, recommend regular wear time but do not stipulate a prescribed amount of time for the pressure garment to be effective. There is consensus, within the literature, for the length of time that patients should wear the pressure garment for, namely 23 hours a day. Following this guidance, scar management therapists recommend that their patients wear PGT for this length of time, removing garments to facilitate hygiene needs and for moisturisation and hydration of the burns scars.

Within the literature, the recommended number of months that patients should wear the pressure garment for, to achieve an optimally treated scar, ranges from 6 to 24 months. 31,43,44 The survey was designed to establish current practice concerning the length of time PGT is used and the rationale behind the recommendations.

Methodology

A web-based survey was sent to the lead OTs or physiotherapists at each of the UK NHS burns services across the UK.

The survey consisted of eight questions.

-

Who provides your burns pressure garments? (In-house/external.)

-

Approximately what is your monthly spend/cost of pressure garments for burns patients?

-

Do the general practitioners (GPs) fund the burns pressure garments?

-

How many new burns patients go into garments per month or year?

-

How many of these new patients are adults?

-

How many of these new patients are children?

-

Approximately how long do your burns patients wear garments for? (For example, 6–18 months.)

-

What guides you to select a particular garment?

The aim of the survey was to establish who provides the pressure garments for the burns patients throughout the UK, the current practice with regard to the length of time pressure garments are worn and the number of eligible patients that each NHS burns service could potentially recruit per month. In tallying the results, we have separated services for adults from services for children to enable separate enumeration of patient numbers and costs by age group. Across the existing 30 NHS burns services, 26 provide services for adults and 25 for children.

A total of 30 responses to the web-based survey were received from 15 services for adults and 15 services for children. Each of the remaining services was contacted again, via telephone and follow-up e-mails, but we were unable to obtain the required data. In calculating the total number of patients, we extrapolated the results obtained from the survey, stratifying by children and adults and by burns service type. Predicted annual NHS costs were computed assuming, on average, that children require 12 garments and adults require eight garments per year, with the average cost of an in-house garment being £50 and an externally sourced garment £81.

We were able to identify which of the NHS burns services manufacture in-house garments and which externally source them by reviewing the minutes from the Pressure Garment Meeting April 2016. We also contacted the external manufacturers by telephone to confirm which NHS burns services they currently supply and were able to identify from this the provider of pressure garments across the sites.

Results

Responses

A total of 26 NHS burns services were identified that provided care to adults and 25 that provided care to children. Responses were received from 15 of the adult services (58%) and 15 (60%) of the child services (Table 1).

| Burns unit’s tier level | Number of units in NHS | Results from survey of units | Extrapolation to NHS | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of units responding | Number of adults per year | Number of children per year | Garment spend per year (£) | Total number of adults per year | Total number of children per year | Total spend per year (£) | ||

| Children only | ||||||||

| Burns facility | 7 | 2 | 0 | 12 | 11,664 | 0 | 60 | 58,320 |

| Burns unit | 8 | 7 | 0 | 540 | 395,424 | 0 | 588 | 442,080 |

| Burns centre | 10 | 6 | 0 | 552 | 536,544 | 0 | 828 | 804,816 |

| Adults only | ||||||||

| Burns facility | 8 | 3 | 27 | 0 | 16,752 | 78 | 0 | 49,056 |

| Burns unit | 8 | 5 | 312 | 0 | 202,953 | 499 | 0 | 324,725 |

| Burns centre | 12 | 7 | 540 | 0 | 290,472 | 792 | 0 | 391,272 |

| Total | 53 | 30 | 879 | 1104 | 1,453,809 | 1369 | 1476 | 2,070,269 |

Numbers of patients receiving pressure garment therapy

Currently, within the UK, patients are treated for their burns injury within one of the three following NHS burns services:

-

burns facility – treatment of burns with a TBSA of < 10%

-

burns unit – treatment of burns with a TBSA of < 30% for adults and < 20% for children

-

burns centre – treatment of any size burn and all complex burns.

The number of eligible patients for PGT varied across each of the NHS burns services. From the 30 NHS burns services that responded to the survey, five (three for adults and two for children) are burn facilities (for a TBSA of < 10%), twelve (five for adults and seven for children) are burns units (for a TBSA of < 30% for adults and < 20% for children) and thirteen (seven for adults and six for children) are burns centres (for all percentages of TBSA).

Survey responses indicated that the number of eligible patients from the burn facilities ranged from 0 to 1 patients per month, burns units had 1–15 patients per month and burn centres had 2–18 patients per month. The services that responded to the survey estimated that, in total, 879 adults and 1104 children are treated each year, 55% in burns centres and 43% in burns units. Assuming similar patient numbers in facilities, units and centres that did not respond, we estimate that there are 1369 adults and 1476 children treated across the UK in burns services each year.

Source and cost of pressure garments

Information on garment source was available for all 26 services for adults and 25 of the services for children. Thirty-seven (72%) NHS burns services, the majority, choose to externally source pressure garments; of these services, 35 use the manufacturer Jobskin Ltd (Nottingham, UK), one DM Orthotics Ltd (Redruth, UK) and one Gottfried Medical, Inc. (Toledo, OH, USA). The remaining 14 (28%) NHS burns services provide an in-house service, which is mostly provided by the OT department, although one NHS burns service used their orthotics department.

Of the adult services, 31% produce pressure garments in-house; of the child services, 26% produce them in-house. The 30 services that completed the web-based survey consisted of eight with in-house pressure garment services and 22 with externally sourced pressure garment services, which were equally split between paediatric and adult services.

The approximate cost for the in-house garments per NHS burns service was £3237.50 per month, giving a yearly spend of £38,850 per service. The approximate cost for the external garments per NHS burns service was £4329.58 per month, giving a yearly spend of £51,995. We noted variation in the monthly spends per burns service, with a range of £300–5420 and a mean of £2986.

Extrapolating to all UK units based on the predicted patient numbers and standardised costs and garment numbers, and accounting for the split between internal and external provision, we estimate that the total NHS annual spend on pressure garments is £765,053 for adult services and £1,305,216 for paediatric services.

Funding for the provision of pressure garments varies depending on the burns unit and the hospital trust. The majority of the burns units obtain funding for pressure garments from the hospital budget, which is allocated to the following departments:

-

occupational therapy department

-

therapy department

-

burns and plastics

-

emergency budget.

Only three of the respondents received the pressure garment funding through their general practice.

Duration of pressure garment therapy

It is advised by the manufacturer and by the therapist that the patient wears the garment for 23 hours a day until the scars are fully mature. ‘Fully mature’ is a term that is used when the scars are no longer responding to pressure, appear pale in appearance when looking at vascularity, and do not alter in height when the garments are removed. When asking the question in regard to wear time, it was found that the time to scar maturity varied across the units and between patients. The length of time that patients are expected to wear pressure garments ranged across the burns centres from 3 months to 2 years, with the majority of burns centres recommending patients wear pressure garments for 12–18 months and with no difference noted between adult and paediatric recommendations.

Pressure garment selection

Pressure garment selection is routinely done by an experienced burns therapist who will consider many external factors (including physical and psychological factors) when selecting whether or not the patient is appropriate for PGT and the design of the garment. A wide range of designs are available both externally and internally, with bespoke garments often being designed and altered by the in-house technician or external manufacturer to ensure that the scar area is covered and the appropriate pressure is applied.

Within the survey we asked the NHS burns services ‘What guides you to select a particular garment?’. In 16 of the responses, the following criteria were listed as being important when selecting a particular garment:

-

burn location

-

burn size

-

patient’s age

-

functional ability

-

dexterity.

In addition to these factors, one site mentioned that all patients who have suffered a burn injury are prescribed PGT regardless of factors such as scar size and location. A blanket referral into pressure garments is unusual, as the therapist will usually complete a subjective assessment as part of their initial assessment that will determine the scar therapy requirements of the individual patient.

Factors for selecting a particular garment did vary between adults and paediatrics; one NHS burns service stated that it would consider the patient’s type of work and whether or not certain pressure garments would be suitable in some environments.

Two of the paediatric sites considered factors relating to children and their age, such as the need for current or future toilet training, when selecting particular pressure garments.

Local protocols for scar management using PGT vary across the service but are transferable within networks and the wider scar management service throughout the UK. The British Burn Association’s Burn Therapists’ Special Interest Group allows scar management therapists to meet annually to discuss current practice and benchmark their service to ensure that a gold standard of practice is available and delivered. Scar management guidelines are used by each of the networks for therapists to read and follow as their service allows; many different scar modalities are available but finance and staffing has an impact on whether or not these are available in each of the UK burns services. It is important to note that, as a result of staffing levels, three of the burns services that responded to the web-based survey only partially completed the survey.

Summary

-

Thirty out of 51 services in England, Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland responded to the survey, representing 15 adult and 15 paediatric burns services. Missing data were obtained from conference reports and manufacturers.

-

We estimate that NHS burns services treat 2845 eligible patients over a 12-month period: 1476 who are aged < 16 years and 1369 aged ≥ 16 years.

-

Routinely, pressure garments are used for between 6 and 18 months and are either manufactured in-house or sourced externally (from three different companies). The majority of burns centres recommend that patients wear pressure garments for 12–18 months, with no difference noted between adult and paediatric recommendations.

-

Few UK trusts employ in-house technicians to manufacture pressure garments, with only between one-quarter and one-third choosing to provide an in-house service and the majority choosing to externally source. In-house garments are generally less expensive than externally sourced garments. Many of the individual services stated that they are aware of the difference in cost but are unable to apply for additional staff funding to employ pressure garment technicians, and so they continue to use external companies.

-

The funding streams of the pressure garment services varied across the UK, with many services not being able to provide their monthly garment costs initially because funding for the service was part of a much larger budget. Many services are still reliant on the ‘therapy budget’ or ‘plastics budget’ to fund the pressure garments, with others managing to get their general practice or health board to fund them. It is estimated that the cost of pressure garments to the NHS for burns patients is £2,171,184 per annum.

Chapter 4 National burns staff attitude survey and interviews

Relevant objective

The following objective is assessed in this chapter:

-

to understand the willingness of clinicians and therapists to randomise children and adults between PGT and no PGT, and to identify perceived barriers to participation in a RCT.

Methods

Online survey and analysis

A staff attitude survey was developed by the PEGASUS team in-house, given the lack of appropriate validated questionnaires in the literature (see Appendix 1). We sought input from our patient and public involvement (PPI) group during development, and pilot tested the survey with local burns staff, making revisions to language and ordering when necessary. The questionnaire, via fixed (e.g. yes/no, Likert scaling) and free-text responses, covered the following areas: (1) respondent demographics, (2) experience with PGT, (3) views on PGT for children and young people, and adults, (4) views on a full-scale RCT of PGT, (5) participation in a full-scale RCT of PGT, (6) patients’ (children and young people, parents, and adults) willingness to participate in a RCT and (7) clinical and non-clinical outcomes. Fixed-response data were analysed using simple descriptive statistics. Free-text responses were analysed using a simple content analysis (thematic) approach.

Survey sampling

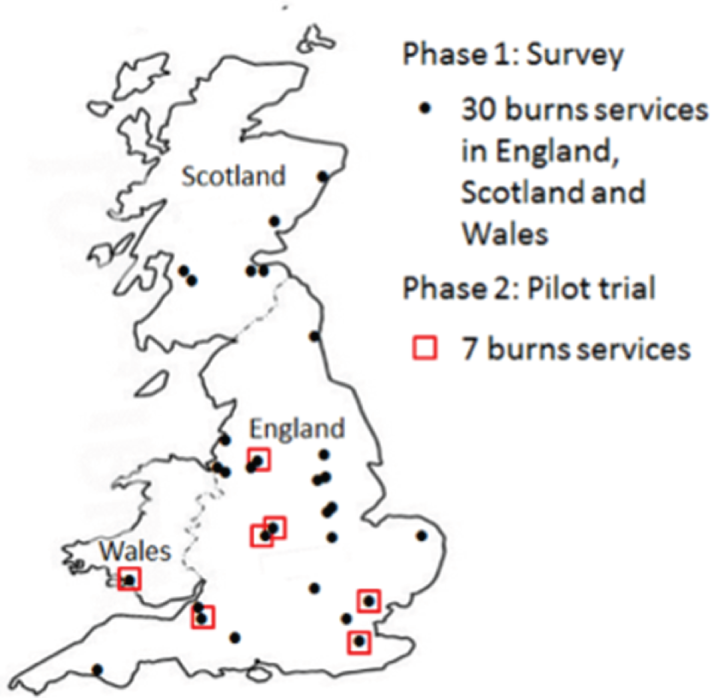

Between October 2014 and March 2015, 30 burns services across England, Wales and Scotland were approached to participate in the survey (Figure 1). The survey link was sent out to all staff involved in PGT or scar management by the lead therapist in each service. Reminder e-mails were sent out up to three times, with all staff actively encouraged to participate within the data collection window.

FIGURE 1.

Map of PEGASUS P1 and P2 burns services in England, Scotland and Wales.

Qualitative telephone interviews and analysis

At the end of the online survey, participants were invited to provide their details to give permission for the PEGASUS research team to contact them to explore their survey responses in more detail. Respondents who left their details were then purposively sampled based on the following variables: (1) profession, (2) yes versus no response to a RCT for PGT and (3) agreement versus disagreement with attitudinal survey questions. A semistructured discussion guide was developed (see Appendix 2) based on the survey questions, the literature, discussions with our PPI group and the wider PEGASUS research team. Interviews were undertaken by telephone, audio-recorded, transcribed clean verbatim and analysed using a thematic approach. 45 Quotations in Results are identified using the participant’s unique identifier code and indicate whether the quotation was from an adult patient, a parent of a paediatric or adolescent patient or a member of NHS burns service staff. Staff quotations indicate profession and, when required, whether or not the quotation was from a survey free-text response.

Results

Sample characteristics and response rates of survey and interview participants

Responses were received from 245 burns service staff from 28 out of 30 NHS burns services in England, Scotland and Wales that were approached to participate. Following cleaning of the data, 223 surveys were usable for analysis. It was not possible to accurately calculate the number of staff who were approached to participate within each service to calculate the response rate for the survey, but the mean number of respondents from each service was eight (range 1–24). Fifteen survey respondents from 13 burns services also participated in a semistructured telephone interview (average interview length was 32 minutes, range 19–41 minutes). Table 2 provides a summary of respondent sample characteristics for the survey and interview participants. Participants were predominantly female, nurses or therapists and caring for both adults and children.

| Characteristics | Methodology, n (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Survey (N = 223) | Interview (N = 15) | |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 29 (13.0) | 3 (20.0) |

| Female | 192 (86.1) | 12 (80.0) |

| Not stated | 2 (0.9) | 0 (0.0) |

| Profession | ||

| Doctors | 29 (13.0) | 3 (20.0) |

| Nurse/charge nurse | 89 (39.9) | 4 (26.7) |

| OT | 43 (19.3) | 5 (33.3) |

| Physiotherapist | 32 (14.3) | 2 (13.3) |

| Other | 30 (13.5) | 1 (6.7) |

| Patient group | ||

| Adults (aged ≥ 16 years) | 67 (30.0) | 4 (26.7) |

| Children (aged ≤ 15 years) | 56 (25.1) | 3 (20.0) |

| Adults and children | 100 (44.8) | 8 (53.3) |

| Pilot site | ||

| Yes | 88 (39.5) | 3 (20.0) |

| No | 127 (57.0) | 12 (80.0) |

| Missing | 8 (3.6) | 0 (0.0) |

Perspectives on pressure garments as part of scar management therapy

One hundred and sixty-seven of the survey respondents reported that they provided care either to adults only (n = 67) or to adults and children (n = 100). Table 3 provides a summary of staff perspectives on the use of PGT for scar management in adult patients. Staff reported that they agreed with the statements that PGT is one of the most important treatments (n = 123/167; 74%) and that it is beneficial to patients (n = 150/167; 90%), and just over half (n = 93/167; 56%) thought that it should remain the standard scar management treatment. However, 58% of staff (n = 97/167) were unsure about whether or not there was research evidence on the clinical effectiveness of PGT and some (n = 43/167; 26%) were uncertain of the benefits of PGT.

| Survey statements | Patients, n (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Adults (N = 167) | Children (N = 156) | |

| PGT is one of the most important treatments | ||

| Strongly agree or agree | 123 (73.6) | 115 (73.7) |

| Neither agree nor disagree | 35 (20.9) | 34 (21.8) |

| Disagree or strongly disagree | 7 (4.2) | 6 (3.8) |

| Missing | 2 (1.2) | 1 (0.6) |

| PGT is a beneficial treatment | ||

| Strongly agree or agree | 150 (89.8) | 145 (92.9) |

| Neither agree nor disagree | 14 (8.4) | 7 (4.5) |

| Disagree or strongly disagree | 1 (0.6) | 1 (0.6) |

| Missing | 2 (1.2) | 3 (1.9) |

| There is research evidence that PGT is an effective treatment | ||

| Strongly agree or agree | 68 (40.7) | 62 (39.8) |

| Neither agree nor disagree | 67 (40.1) | 67 (42.9) |

| Disagree or strongly disagree | 30 (18.0) | 25 (17.0) |

| Missing | 2 (1.2) | 2 (1.3) |

| PGT should remain the standard treatment | ||

| Strongly agree or agree | 93 (55.7) | 77 (50.6) |

| Neither agree nor disagree | 65 (38.9) | 71 (45.5) |

| Disagree or strongly disagree | 7 (4.2) | 5 (3.2) |

| Missing | 2 (1.2) | 1 (0.6) |

| I am uncertain that PGT is a beneficial treatment | ||

| Strongly agree or agree | 43 (25.7) | 45 (28.8) |

| Neither agree nor disagree | 29 (17.4) | 38 (24.4) |

| Disagree or strongly disagree | 93 (55.7) | 57 (36.5) |

| Missing | 2 (1.2) | 16 (10.2) |

One hundred and fifty-six of the survey respondents reported that they provided care either to children only (n = 56) or to adults and children (n = 100). Table 3 provides a summary of staff perspectives of the use of PGT for scar management in paediatric patients. In a similar pattern to responses to the adult data, staff reported that they agreed with the statements that PGT is one of the most important treatments (n = 115/156; 74%) and that it is beneficial to patients (n = 145/156; 93%) and half (n = 77/156; 51%) thought that it should remain the standard scar management treatment. However, 60% of the staff (n = 92/156) were unsure about whether or not there was research evidence on the clinical effectiveness of PGT and some (n = 45/156; 29%) were uncertain of the benefits of PGT.

The majority of staff reported that they perceived pressure garments to be important and of benefit to patients, even though they were unsure whether or not there was research evidence of clinical effectiveness. Staff, often based on their own clinical experience, reported that pressure garments were important because of the benefits to scar management and the fact that PGT was better than other treatments, such as the use of silicone and massage. Reported benefits included (1) improving scar appearance, (2) helping to control symptoms such as itch, (3) helping functionality, (4) reducing the time it takes for the scar to mature and (5) providing physical (e.g. protection) and psychological (e.g. confidence and security) benefits:

It makes the scar paler, it makes it softer, it can help minimise itching, it can . . . where there are bands forming that make contractures it can hold those tightly against the body and minimise those, softens, flattens, pales, less lumpy, more pliable. So it’s about the colour, the texture and the height.

TLR05 OT

There were, however, some interviewees who articulated that they did not perceive any benefit of using pressure garments. Rather, they believed that the patients perceived a benefit as a result of the ‘scenario’ in clinical practice, in which patients are influenced by the treatment plan specified by the clinician and have an expectation of pressure garments:

Well, I don’t know whether they are benefits actually, I don’t think they are benefits. I think we have created a scenario where patients feel bad without them. So in other words if I gave them joss sticks and said if you use these three times a day and massage with some lavender and it’s really important you do that, and if you do that for 3 months non-stop they might get the same benefit, we don’t know. It’s that whole scenario about it. Even before the patient’s fully healed people start talking about we’ll measure you up for the pressure garments, and so it’s almost a done deal.

TEG15 consultant

A small number of interviewees expressed some uncertainty about the benefits of PGT. For example, benefits were reported as being dependent on the location of the scar, the type of scar and the characteristics of the patient. Some interviewees stated that the benefits were only apparent if the pressure garments were well fitted and the patients were compliant with treatment but for some patients, even if they were compliant, scar outcomes could be poor. There was discussion of the facts that scars ‘settle’ over time anyway, irrespective of the treatment, but that pressure garments, although perhaps not better than other treatments, were better than no treatment at all:

I think in some cases some patients do comply really well, and they still get some quite bad scarring and they are wearing a pressure garment. But you have no comparison to say well would that scarring have been a lot worse if they hadn’t worn the garment. There are some individual things I think does influence it, and I do think there are some quirks, so I think some children that absolutely comply to their pressure garment can still get a bad scar.

TSC06 OT

There was a split decision, to some extent, within the survey respondents about whether or not PGT should remain the standard treatment for scar management. Interviewees highlighted that they perceived there to be a role for pressure garments in scar management but that the decision to use pressure garments was dependent on clinical judgement and experience. This ‘judgement’ was also linked to the perceived benefits of PGT based on characteristics of the scar and the patient. The role of PGT in scar management and perceived benefits were particularly apparent for those working with children:

I think it’s a clinical judgement on what that scar is doing, how it’s behaving. But I definitely feel there’s a clear role for the use of pressure garments, and that for some, particularly I think the tricky more aggressive scars, I think pressure garments work better than some of the other options out there.

TSC06 OT, children only

Some interviewees also reflected that PGT should be part of a ‘toolkit’ of treatment options and that the pressure garments should only be used when required, based on clinical experience, rather than as standard care in which all patients are expected and expect to receive them:

I think it is [PGT] definitely a very important treatment modality to have in my toolkit, and I do use it.

TSA11 OT

When explored in further detail during the interviews, there was a range of knowledge about the research evidence on the clinical effectiveness of PGT. Some participants were fully aware that there is currently little evidence to show that PGT is clinically effective; however, others stated that the survey had prompted them to look at the evidence and led to the realisation that they had made an assumption about the existence of good evidence of clinical effectiveness. In addition, for some, they found in their own anecdotal experience that PGT was effective:

. . . this is proper research evidence as in . . . so this is the group I think in Canada that did a very good comprehensive review of pressure garment use a long time ago.

TEG15 consultant

This is very interesting, and I own this, this was a complete assumption that there was evidence, because everybody does it, and it was only after I had filled out your survey and then was having a conversation with one of my therapy colleagues who said actually that isn’t necessarily the case. So I was erroneously confident in my knowledge [laughs].

TCW12 clinical psychologist

Attitudes to a full-scale randomised controlled trial for pressure garment therapy

In response to the question ‘Do we need a full-scale RCT of PGT?’, 67% of staff participants (n = 149/223) answered yes, 8% (n = 17/223) answered no, and 26% (n = 57/223) were undecided. Table 4 shows the breakdown of responses to this question by professional group and pilot versus non-pilot site. Nearly all doctors (n = 26/29; 90%) and the majority of therapists (OT, n = 32/43, 75%; and physiotherapists, n = 24/32, 75%) identified a need for a trial; however, there was less certainty for nurses (n = 52/89; 58%) and other professional groups (n = 15/30; 50%). There was a similar proportion of pilot site (n = 61/88; 69%) and non-pilot site (n = 83/127; 65%) respondents reporting the need for a full-scale RCT of PGT. Although only 8% (n = 17/223) of survey respondents overall said that there was no need for a full-scale RCT, further exploration of these responses as part of the free-text survey and the interview data highlighted the complexity of the underpinning rationale. The rationale for responding yes to this question was centred, in the main, around providing evidence to support current PGT practice:

Yes, and what I really would like to see is a good trial that supports it, because my feeling is that if we run a good trial with enough numbers then we’ll give ourselves the evidence. So if we can get a NICE [National Institute for Health and Care Excellence] recommendation to use pressure garments on burns then we won’t face a situation in the future where the people holding the purse strings say well actually that’s not a proven technique to improve scar maturation so we’ll not pay for it. I am worried about the implications on our care in the future if we don’t get the evidence for doing it.

TCW01 consultant

| Survey question | Survey responses, n (%) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample | Professional group | Site (missing n = 8) | |||||||

| Total (n = 223) | Interview (n = 15) | Doctors (n = 29) | Nurse/charge nurse (n = 89) | OT (n = 43) | Physiotherapist (n = 32) | Other (n = 30) | Pilot (n = 88) | Non-pilot (n = 127) | |

| Is a full-scale RCT of PGT needed? | |||||||||

| Yes | 149 (66.8) | 8 (53.3) | 26 (89.7) | 52 (58.4) | 32 (74.4) | 24 (75.0) | 15 (50.0) | 61 (69.3) | 83 (65.4) |

| No | 17 (7.6) | 2 (13.3) | 1 (3.4) | 8 (9.0) | 3 (7.0) | 0 (0.0) | 5 (16.7) | 5 (5.7) | 11 (8.7) |

| Undecided | 57 (25.6) | 5 (33.3) | 2 (6.9) | 29 (32.6) | 8 (18.6) | 8 (25.0) | 10 (33.3) | 22 (25.0) | 33 (26.0) |

| Staff willingness to participate in a full-scale RCT of PGT | |||||||||

| Yes | 143 (64.1) | 9 (60.0) | 23 (79.3) | 60 (67.4) | 26 (60.5) | 18 (56.3) | 16(53.3) | 73 (83.0) | 68 (53.5) |

| No | 15 (6.7) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (6.9) | 4 (4.5) | 4 (9.3) | 2 (6.3) | 3 (10.0) | 3 (3.4) | 11 (8.7) |

| Do not know | 65 (29.1) | 6 (40.0) | 4 (13.8) | 25 (28.1) | 13 (30.2) | 12 (37.5) | 11 (36.7) | 12 (13.6) | 48 (37.8) |

| Service willingness to participate in a full-scale RCT of PGT | |||||||||

| Yes | 144 (64.6) | 10 (66.7) | 21 (72.4) | 61 (68.5) | 25 (58.1) | 21 (65.6) | 16 (53.3) | 73 (83.0) | 67 (52.8) |

| No | 4 (1.8) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (3.4) | 1 (1.1) | 1 (2.3) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (3.3) | 1 (1.1) | 3 (2.4) |

| Do not know | 75 (33.6) | 5 (33.3) | 7 (24.1) | 27 (30.3) | 17 (39.5) | 11 (34.4) | 13 (43.3) | 14 (15.9) | 57 (44.9) |

Staff did, however, acknowledge that there was a need to challenge embedded practice that was not evidence based, particularly given the cost and treatment burden of PGT:

I think that it would be very helpful for everyone if we had objective evidence that pressure garments worked, because as time goes on, funding, etc., is going to be more and more dependent on evidence-based treatment, and I think that having strong evidence to support the pressure garments and the use of pressure garments, and therapy time to make garments or to measure, etc., and carry out the treatments, it’s always easier to justify if we’ve got some hard evidence.

TSC07 consultant

One consultant reflected that, even though they did not see the benefits of PGT, they were engaged in the study because they were concerned about the potential impact of changes to burns scar management on staffing and morale within the team:

. . . we wouldn’t be doing this project if I wasn’t, but generally to some extent it’s a problem [lack of PGT evidence] because I could take a very authoritarian view in my department and just stop using pressure garments. That puts one person out of a job, possibly two, and it would in one single act turn all of the burns therapists against me, because they have been taught, fed, aligned that these are effective, and they have categorical anecdotal proof. So I tread a careful line, and I’ve taken a view that I will stop people from wearing them once I review them in my clinic. But it’s an awful expense as well, because if you think about the number of clinical attendances, and the number of times the patient is seen by highly specialised staff, the garments that are worn, then actually it’s a serious cost and we could use that on something else.

TEG15 consultant

It was perceived that having ‘hard’ evidence might help to placate burn service management, give a definitive answer whether or not PGT should be used and would also to help to boost staff confidence in talking to patients about treatment options:

I am confident in the way I explain the things [pressure garments] to patients, and to advise them as to how these things work, and what I’ve seen from my experience about the other members of the team. But to actually have that hard evidence would just I suppose give us another backup to say if that is the case that we can show that to patients.

TWY10 physiotherapist

There were two main reasons why participants said that there was not a need for a RCT of PGT: first, they had limited awareness of any lack of clinical effectiveness evidence; and, second, they were happy with PGT as a treatment and were concerned, from an ethical point of view, that there would be a no-pressure-garment arm in a trial:

I guess it was interesting because I hadn’t even thought about people not being offered pressure therapy, and perhaps that was my ignorance, is that I had assumed that it was something that was a treatment that had been researched and proved to be something that it was clinically effective and that we should be using. So I was very much, I’ll own it, I was coming from a position of ignorance that hadn’t actually realised that wasn’t necessarily the case . . . Yes, because I was ignorant before [when responded no to a RCT in survey], I thought we had one, why would you do it again?

TCW12 clinical psychologist

Those staff who were undecided about a RCT reflected that their reasoning centred around staffing and ethical concerns. The latter may highlight a lack of equipoise. Participants raised concerns about not having enough staff to participate in a RCT and around the specific design of the RCT (see Chapter 8 for further discussion). The ethical concerns were similar to those who said no to a RCT for PGT. Staff, in particular nurses, struggled to reconcile the fact that by undertaking a RCT there was a chance that patients, who they believed should be in pressure garments, might not receive them, that is, ‘withholding’ the best treatment. This was particularly true for patients with certain scar characteristics, such as very large or ‘severe’ scars. Furthermore, the staff were concerned that patients would want the ‘best treatment’, which in their view is PGT:

Yes, mine was mainly from an ethical background of if it is seen, and I don’t know if it is or not, as the gold standard treatment now, how the study would take place, some people not having pressure garments, some people having pressure garments, I don’t really . . . because obviously with a study you need to provide the treatment that’s at least as good as the treatment you . . . or think is as good as the treatment you’ve got now, so I couldn’t get my head around, I couldn’t understand what could be as good as having pressure garments, because otherwise you’re disadvantaging perhaps some patients who wouldn’t have pressure garments to measure against.

TSW14 nurse

Attitudes to undertaking and participating in a full-scale randomised controlled trial for pressure garment therapy

Table 4 shows the proportion of staff and perceived proportion of burns services who would or would not be willing to participate in a full-scale RCT of PGT, split by profession and pilot versus non-pilot site. Overall, two-thirds of respondents (n = 143/223, 64%) reported that they and their NHS burns service (n = 144/223, 65%) would be willing to participate in a full-scale of RCT for PGT; however, nearly one-third did not know (staff, n = 65/223, 29%; NHS burns services, n = 75/223, 33%). When split by professional group, doctors (n = 23/29, 79%) and nurses (n = 60/89, 67%) were more likely to say yes to participating than other professional groups, for example physiotherapists (n = 18/32, 56%). Respondents from pilot sites were also more likely to say that they would participate than those from non-pilot sites (pilot site, n = 73/88, 83%; non-pilot site, n = 68/127, 54%). When asked whether or not their NHS burns services would be willing to participate, doctors (n = 21/29, 72%), nurses (n = 61/89, 69%) and physiotherapists (n = 21/32, 66%) were more likely to say yes than other groups. Similar to staff participation, respondents from pilot sites were more likely to state that their NHS burns service would take part than those from non-pilot sites (pilot site, n = 73/88, 83%; non-pilot site, n = 68/127, 55%).

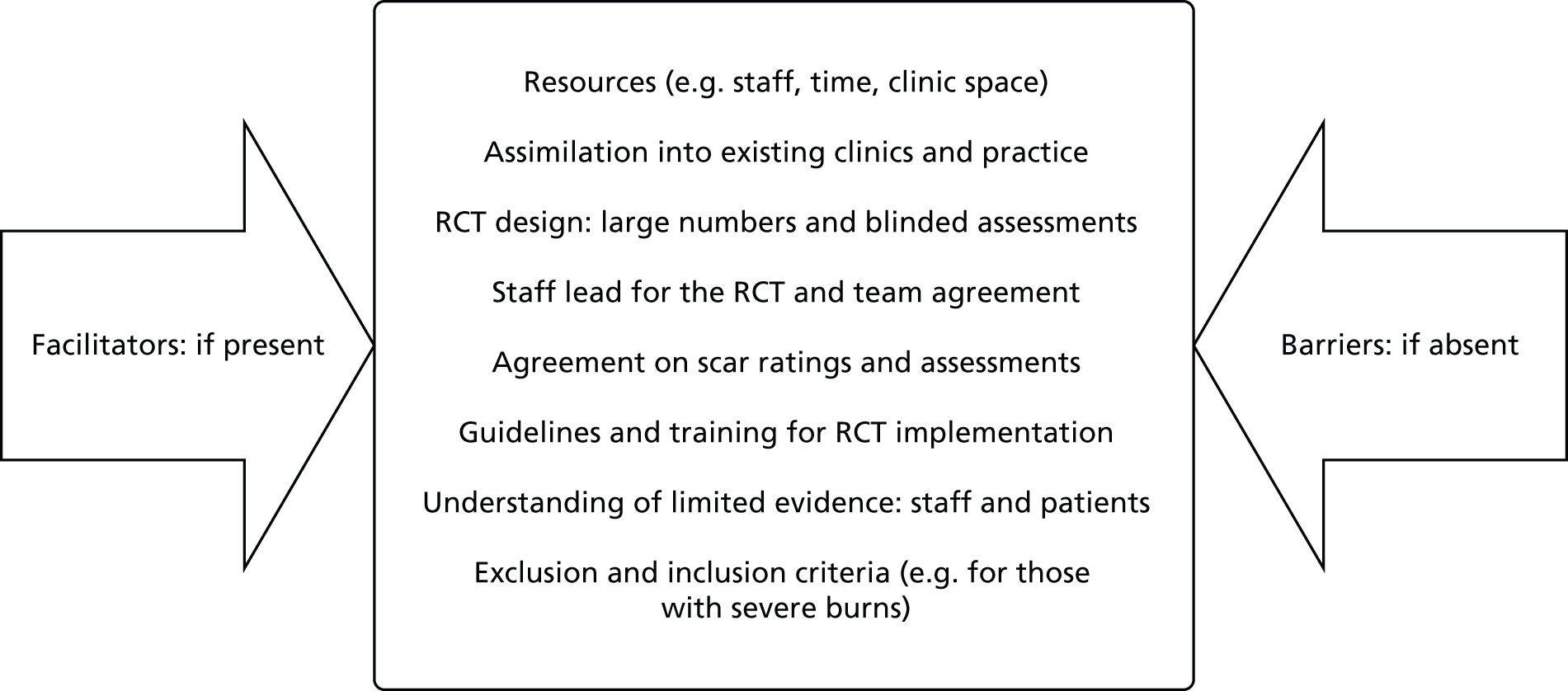

As part of the interviews, the barriers to, and facilitators of, staff and service participation in a full-scale RCT of PGT were explored (Figure 2). Many of the factors identified, for example appropriate resourcing for staff, worked in both directions; if they were present they acted as a facilitator of participation and if they were absent they acted as a barrier. Linking with the concerns given in Attitudes to a full-scale randomised controlled trial for pressure garment therapy concerning the need for a full-scale RCT, staff reported their general willingness to be part of a future RCT, although there were some reservations, particularly around what involvement would actually entail, as well as the feasibility and practicability of undertaking this type of clinical effectiveness study for an embedded clinical treatment:

FIGURE 2.

Barriers to, and facilitators of, NHS burns staff and service participation in a full-scale RCT of PGT.

I was a bit unsure in what my role would . . . say we were to participate exactly what my role would be. Would I be the therapist that then does the assessment and then sends that off somewhere for it all to be compiled together? Because there would need to be training to make sure that we’re all rating the scars in the same way to show that they are improving or not improving, and I think at the moment people use different scales, people do things slightly differently. So I think it would be training and then support throughout the process.

TSC06 OT, children only

Yes, I think that’s reasonable, because I think at the moment the staffing levels that we have are very . . . we are struggling to meet the need. Obviously by the time the trial comes round it would depend on staffing levels and the situation of the service at the time, the changes that we’re looking to making we’re looking to . . . there may be an investment needed there as well from what we’re just trying to do within the department let alone adding to that. But I know that there is a lot of support for research and development, and if that was the case perhaps that would be something that the trust would consider.

TSA11 OT

I think it’s a very tricky thing to do [run a RCT of PGT], I don’t know how. Again just with it being such an emotive thing with children, to see . . . every parent wants the best for their child. I would be . . . I think we need to do something like this.

TRH04 physiotherapist, children only

Key barriers included ethical concerns over the ‘usual-care’ treatment group, patient characteristics and burn type, whether or not patients would agree to participate and, for those who did consent, would they comply with treatment and trial processes:

I would have a problem with that, because if they are consented . . . if they know that if they do this they will get this benefit, and if they don’t do it they won’t get that benefit I don’t think people who are fully understanding are going to consent to be in it. I think you will probably only get people who don’t quite understand what they are signing up to . . . I would much rather the study design assessed patients who did not comply with the treatment in the first place and look retrospectively at their outcome, and the assessors not knowing whether they have pressure garments or not.

TLR05 OT

I think, I thought I can see where it’s coming from, my brain . . . I can’t see how you can get across all the practicalities of or the barriers that might come up to actually prove it, because I would have thought across different centres you’re going to have to make sure that how you’re going to rate the scar. There’s so many questions about how scarring is assessed anyway and what scales to use, I just don’t . . . Well we’d have to be very clear that didn’t, because otherwise it would bias the study. That would just be one of my questions, is whether it would be better just to do this study with adults rather than including children.

TSC06 OT, children only

Summary

-

The national survey and related interviews have allowed us to describe and explore the acceptability of a trial of PGT, in principle, across a broad sample of UK NHS burns services and staff.

-

The majority of staff reported that they perceived a need for a full-scale RCT of PGT; however, the rationale underpinning this was complex. The core issue was an apparent lack of clinical equipoise around the research question and PGT as a treatment.

-

A large proportion of staff stated that they want a full-scale RCT of PGT, not necessarily to provide evidence of the best treatment for patients, but rather to support current practice and the continued use of PGT for burns scar management.

-

In general, staff and services were receptive to the idea of a UK trial and stated that they would likely participate, demonstrating ‘buy-in’. However, it was clear that the strong views about the use of PGT have the potential to influence the conduct of a full-scale RCT, if those views are not recognised and taken into account as part of the trial design.

-

The exploration of the perceived barriers to, and facilitators of, a full-scale RCT of PGT highlighted that a future trial must take into account the following issues: the recruitment of parents and children, the definition of appropriate outcome measures and scar assessments and the scope and definition of eligibility criteria for severity of burns.

Chapter 5 Identification of patient-, parent- and clinician-reported outcomes

Relevant objectives

The following objectives are addressed in this chapter:

-

to assess the experience of patients and parents of PGT and assess willingness to be randomised between PGT and no PGT

-

to identify and select patient-centred outcomes.

Methods

Data sources

Data for this analysis of willingness to participate in a trial, patient-centred outcomes and subsequent outcome domains were drawn from three different sources: (1) the free-text responses in the staff attitude survey (n = 223; 28/30 NHS burns services), (2) semistructured telephone interviews with a sample of the staff survey respondents (n = 15; 13 NHS burns services) and (3) semistructured interviews with adult patients and parents (n = 40, 24 adults and 16 parents; four NHS burns services). Please see Chapter 3 for a detailed description of the methods used for data sources (1) and (2).

Sampling and recruitment for adult and parent interviews

To be eligible to participate in an interview, patients or parents of paediatric (aged 0–8 years) and adolescent (aged 9–15 years) patients had to have ≥ 6 months’ experience of PGT and have finished PGT no more than 2 years prior to the interview. We attempted to include a range of patients according to sex, age, ethnicity and type and severity of burn to facilitate a maximum variation sample. Participants were recruited by OTs and/or research nurses (RNs) working at four of the PEGASUS pilot trial sites in England: Queen Elizabeth Hospital, Birmingham (adults only); Birmingham Children’s Hospital (BCH) (parents only); St Andrews Centre for Plastic Surgery and Burns, Broomfield Hospital, Essex (adults only); and Queen Victoria Hospital, East Grinstead (adults and parents). Clinical staff provided information sheets to potential interviewees and took written consent to pass contact details on to the PEGASUS qualitative research team. A member of the qualitative research team then contacted potential interviewees, provided further information and answered questions as necessary, and then arranged a suitable time, date and venue for the interview. Interviews were mainly conducted in the patient’s home, which was the preferred venue; however, a small number took place on university and hospital premises or via telephone. Written informed consent was taken prior to the start of interview data collection.

Originally, we had planned to also conduct two discussion groups with older children aged 9–16 years. After initial delays with ethics and governance approvals and site initiation, and considering the logistics and time needed to arrange these discussion groups, it was decided to conduct a small number of further interviews with parents of older children instead. This decision was taken with the input of the Trial Management Group (TMG) and Trial Steering Committee.

Interview format and content

A semistructured discussion guide was developed (see Appendix 3) based on the literature, discussions with our PPI group and the wider PEGASUS research team. Interviews were conducted in a participant-focused manner, allowing issues and perspectives that were important to participants to emerge naturally. The topic guide and interview process was refined after reflection on a small sample of early interviews. Topics discussed included:

-

accounts of the accident and injury (when interviewees were happy to talk about these in order to provide context for the remainder of the data)

-

accounts of subsequent treatment

-

the experience of PGT and other scar management techniques

-

hopes and expectations for treatment, recovery and scar management

-

perspectives on a trial of PGT (e.g. would the interviewee have considered participating in a trial?)

-

patient-centred outcomes.

Analysis

Interviews were undertaken either face to face or via telephone, audio-recorded, transcribed clean verbatim and analysed using a thematic approach. 45 Early analytic findings were discussed among the members of the TMG and shared for discussion and feedback at PEGASUS investigator meetings, at which clinical staff delivering the pilot trial and at least one patient representative were present. Following agreement of the final themes, example quotations were identified from each data source. Quotations in Results are identified using the participant’s unique identifier code, and indicate whether the quotation was from an adult patient, a parent of a paediatric or adolescent patient or a member of NHS burns service staff. Staff quotations indicate profession and, when required, whether or not the quotation was from a survey free-text response.

Results

Sample characteristics

Table 5 describes and summarises respondent sample characteristics for the P1 adult patient and parents of paediatric or adolescent patient interviews. A total of 40 interviews with adults (n = 24) and parents (n = 16) were undertaken across four NHS burns services. Interviews lasted, on average, 51 minutes (range 19–108 minutes), with 33 conducted face to face and seven via telephone. Table 5 is supplemented with information about the burn injury, sex and age of the adult patients and the paediatric and adolescent patients whose parents were interviewed. The sample was approximately evenly split between males (52.5%) and females, across a range of ages. Most participants were white (77.5%), with the type of burn predominantly reported as flame (45.0% of total; 54.2% for adults and 31.3% for paediatric and adolescent patients) or scald (37.5% of total; 29.2% for adults and 50.0% for paediatric or adolescent patients).

| Adult and parent interviewee sample characteristicsa | Sample, n (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Total (n = 40)a | Adult patients (n = 24) | Parents of paediatric or adolescent patients (n = 16) | |

| Sex of adult patient or parent | |||

| Male | 21 (52.5) | 18 (75.0) | 3 (18.8) |

| Female | 19 (47.5) | 6 (25.0) | 13 (81.2) |

| Sex of paediatric or adolescent patient | |||

| Male | N/A | N/A | 11 (68.8) |

| Female | N/A | N/A | 5 (31.3) |

| Age of adult patient or parent (years) | |||

| < 21 | 1 (2.5) | 1 (4.2) | 0 (0.0) |

| 21–30 | 9 (22.5) | 4 (16.7) | 5 (31.3) |

| 31–40 | 9 (22.5) | 1 (4.2) | 8 (50.0) |

| 41–50 | 8 (20.0) | 6 (25.0) | 2 (12.5) |

| 51–60 | 7 (17.5) | 6 (25.0) | 1 (6.3) |

| > 60 | 6 (15.0) | 6 (25.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Age of paediatric or adolescent patient (years) | |||

| < 1 | N/A | N/A | 0 (0.0) |

| 1–5 | N/A | N/A | 8 (50.0) |

| 6–9 | N/A | N/A | 5 (31.3) |

| 10–14 | N/A | N/A | 0 (0.0) |

| > 14 | N/A | N/A | 3 (18.8) |

| Site | |||

| Queen Elizabeth Hospital, Birmingham | 8 (20.0) | 8 (33.3) | 0 |

| BCH, Birmingham | 10 (25.0) | 0 | 10 (62.5) |

| Broomfield Hospital, Essex | 8 (20.0) | 8 (33.3) | 0 |

| Queen Victoria Hospital, East Grinstead | 14 (35.0) | 8 (33.3) | 6 (37.5) |

| Ethnicity | |||

| White | 31 (77.5) | 20 (83.3) | 11 (68.8) |

| Black African/Caribbean/black British | 3 (7.5) | 2 (8.3) | 1 (6.3) |

| Asian/Pakistani | 4 (10.0) | 2 (8.3) | 2 (12.5) |

| Unknown | 2 (5.0) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (12.5) |

| Type of burn | |||

| Flame | 18 (45.0) | 13 (54.2) | 5 (31.3) |

| Scald | 15 (37.5) | 7 (29.2) | 8 (50.0) |

| Contact | 4 (10.0) | 2 (8.3) | 2 (12.5) |

| Friction | 2 (5.0) | 1 (4.2) | 1 (6.3) |

| Electrical | 1 (2.5) | 1 (4.2) | 0 (0.0) |

| TBSA of burn (%) | |||

| < 10 | 11 (27.5) | 6 (25.0) | 5 (31.3) |

| 10–20 | 5 (12.5) | 0 (0.0) | 5 (31.3) |

| 21–30 | 8 (20.0) | 4 (16.7) | 4 (25.0) |

| 31–40 | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| 41–50 | 2 (5.0) | 2 (8.3) | 0 (0.0) |

| > 50 | 4 (10.0) | 4 (16.7) | 0 (0.0) |

| Do not know | 10 (25.0) | 8 (33.3) | 2 (12.5) |

Perspectives on a trial of pressure garment therapy

During interviews with adult patients and parents of paediatric or adolescent patients who had already experienced PGT, we discussed whether or not, in principle, they would have agreed to take part in a RCT had they been approached to do so following their initial acute treatment. Many of the participants stated that they believed that they would have agreed to take part, citing reasons that were similar to those later observed during the qualitative process evaluation of our pilot trial (see Chapter 8), for example altruism towards clinical staff and a desire to help generate knowledge that would benefit future patients. This was the case for most of the adult interviewees and approximately half of the parents that we spoke to:

I would have said yes, I would take part in it. I think because being in such a strange situation I think if it helps somebody else, and it’s going to do good whatever happens, so basically I see myself as lucky, because my scars are covered virtually. Seeing me without looking just about there you can’t really tell, so I’m a lucky person, that’s how I put myself down as. But if you have got on your face, or you have got somewhere that really stands out you need as much help as you can possibly get. If by doing a trial helps somebody with something facial or whatever well brilliant.

How would you have felt having this 50/50 chance?

Yes, fine, I would have taken that, I would yes, I would have said yes whatever.

CA04, adult patient

However, when considering this during interviews, several parents felt that they would have been reluctant to take part or would have definitely refused to do so. The reasons given reflect our observations later during the qualitative process evaluation of our pilot trial (see Chapter 8), and centre upon the need for parents to feel that their children were receiving the best treatment available. Interestingly, this parent reflected on the potential for differences in attitudes towards the trial concerning the participation of adults and children:

I would have said no.

That’s fine, I need to know.

I don’t like 50/50 chances [laughs].

So you’d have said no and you would have taken . . .

I think that idea is more better for adults, and then you would say well we’ve tried it on adults, we would like to try it on children, because for a child to do a 50/50 . . . I wouldn’t risk my child like that, I would be like you do what’s best for my child. I wouldn’t be thinking if that could have worked, and I didn’t use it I feel like I would regret it. So I wouldn’t want to make that decision for my child. I’d do it [take part in the trial] for probably me . . .

BC02, parent of paediatric patient

A small number of participants were unsure as to how exactly they would have reacted to a request to consider taking part in a trial.

General outcome measure and domain identification

A large number of burn scar-specific outcomes were reported by, and perceived to be important to, patients, parents and clinicians:

I feel all outcomes are important and valid and should include clinical observations and patient-reported outcomes. I think it is very important to look at scar appearance, pain and itch but also include function, body image and impact on life as using pressure garments affects all these aspects.

ID25, survey free-text response, physiotherapist

I think from the doctors themselves they measure the size of the scar, how deep it is, how firm it is, the colouring, and they go from that, and how he is, is he scratching it, is he pulling at the vest, is he doing . . . they ask all sorts of questions, so probably everything that they have asked is going to be asked in the trial. There’s nothing that I can think of on top of that.

EC03, parent of paediatric patient