Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 10/32/02. The contractual start date was in March 2012. The draft report began editorial review in June 2017 and was accepted for publication in November 2017. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

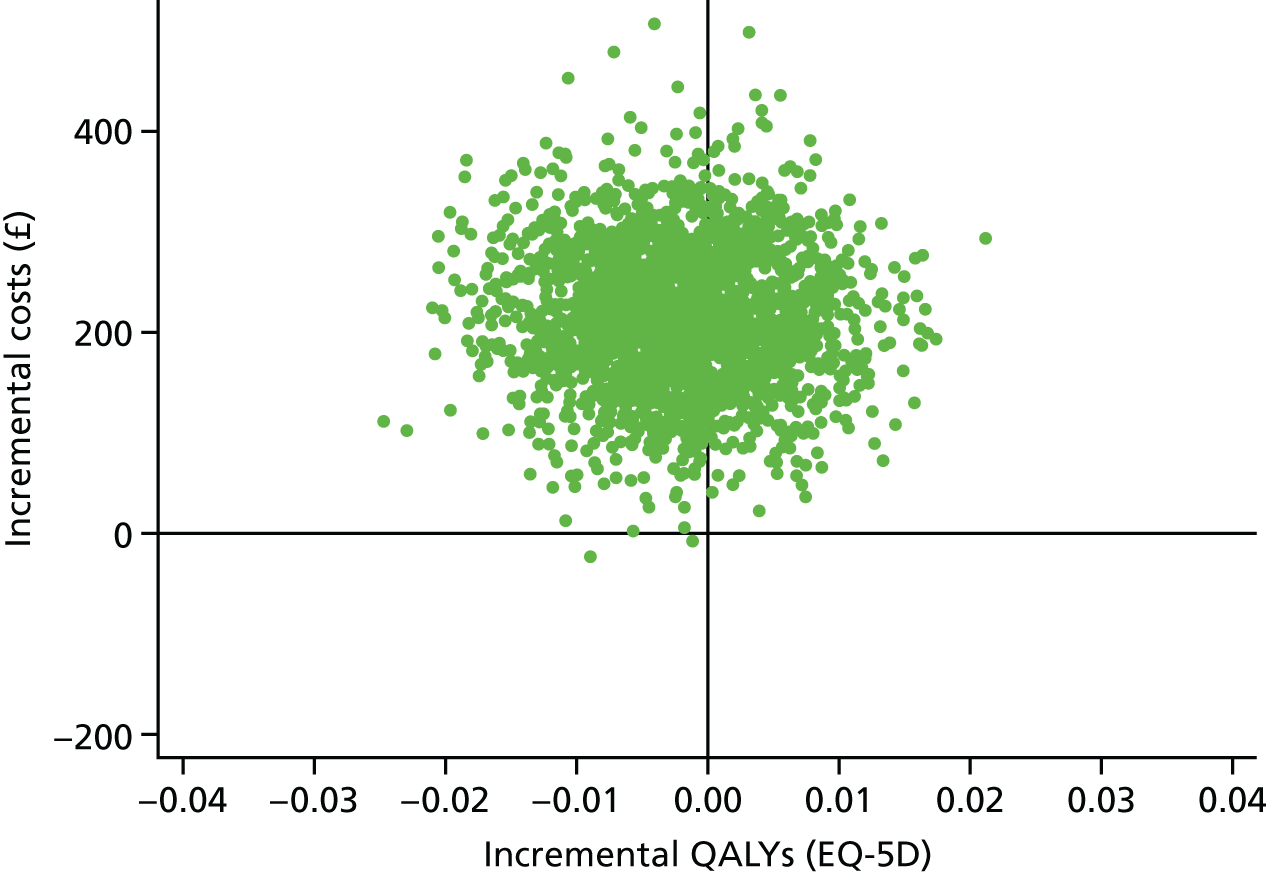

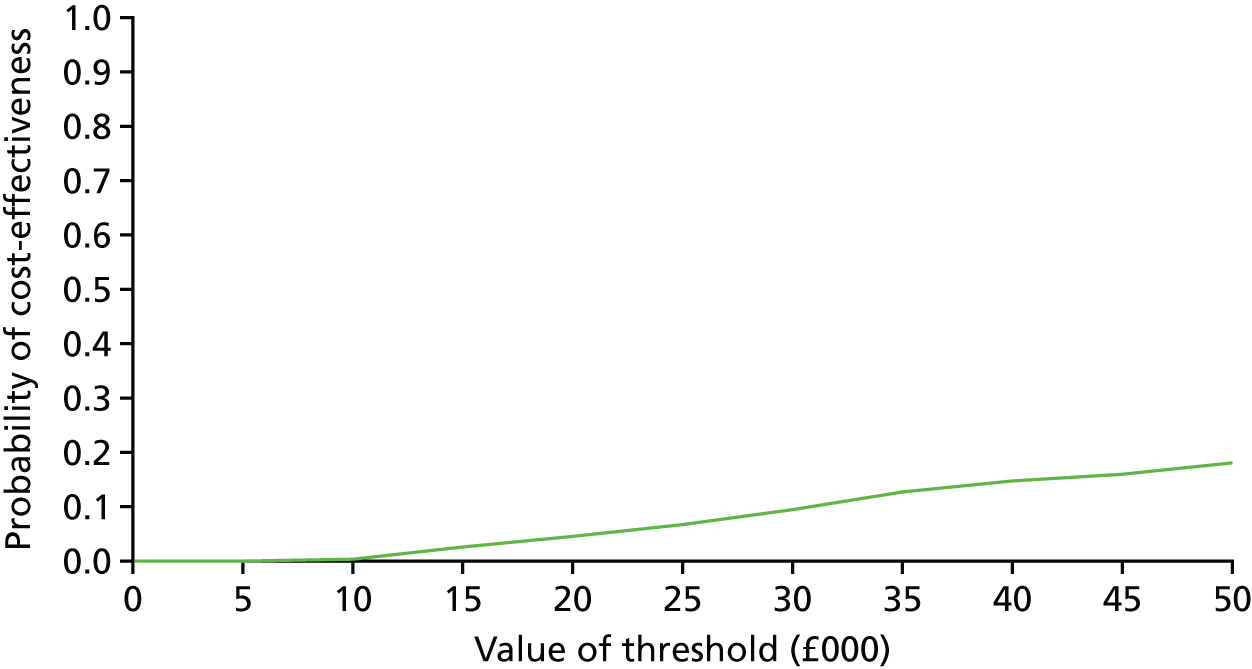

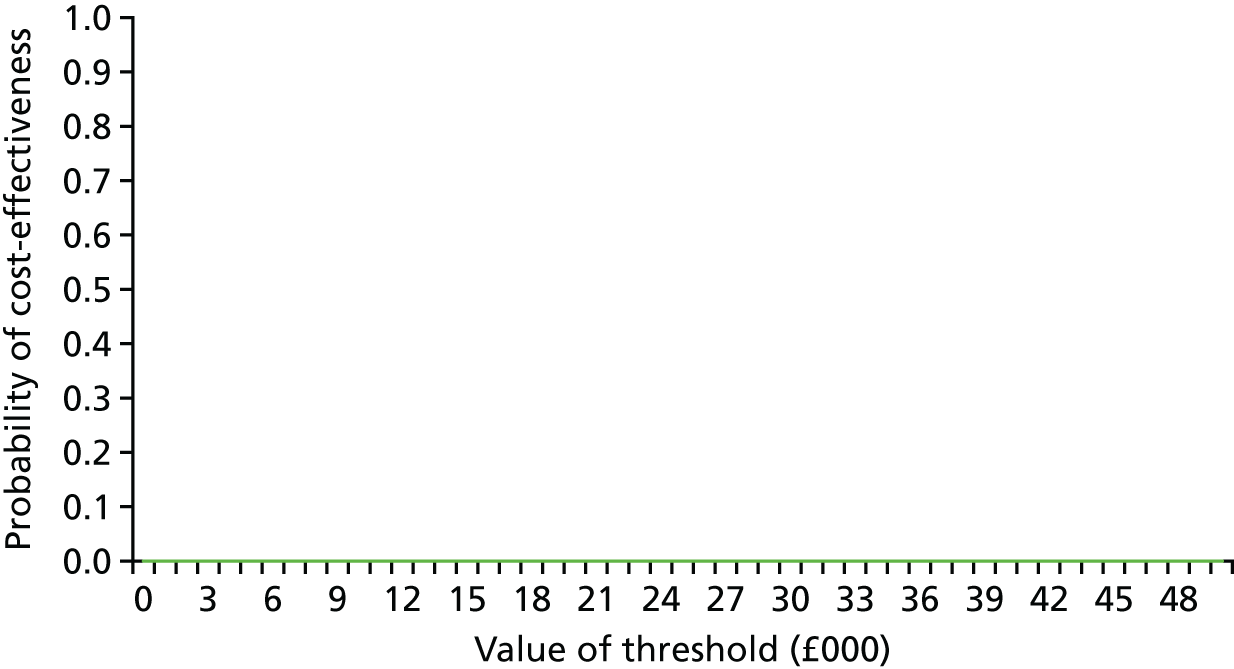

Lee David is the director of 10 Minute CBT. She helped to develop Pedometer And Consultation Evaluation-UP (PACE-UP) patient resources and training for the PACE-UP nurses and received personal fees from 10 Minute CBT during the conduct of this study. Tess Harris is a member of the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Health Technology Assessment Primary Care and Community Preventative Interventions panel. Julia Fox-Rushby reports grants from the NIHR and membership of the Public Health Research Research Funding Board during the conduct of the study. Katy Morgan’s salary was funded through a NIHR research methods fellowship (reference number MET-12-16), during the conduct of the study.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2018. This work was produced by Harris et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2018 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Introduction: why this study was needed

Benefits and risks of physical activity and current physical activity guidelines

What are the benefits of physical activity for adults and older adults?

Physical activity (PA) leads to reduced mortality, a reduced risk of > 20 diseases and conditions, and improved function, quality of life and emotional well-being. 1 Physical inactivity is the fourth leading risk factor for global mortality;2 in 2008, it was estimated to have caused 9% of premature mortality and 5.3 million deaths worldwide. 3 Physical inactivity is also a major cost burden on health services. 1,4,5

What are the current physical activity guidelines and who is achieving them?

Adults and older adults are advised to be active daily and, for health benefits, should achieve at least 150 minutes (2.5 hours) weekly of at least moderate-intensity activity [moderate to vigorous PA (MVPA)] or 75 minutes of vigorous-intensity PA, or an equivalent combination, achieved in bouts of at least 10 minutes’ duration. 1,2 Muscle-strengthening activities are also recommended on at least 2 days weekly,1,2 but are not part of our intervention, which is focused on increasing walking. One effective way to achieve the aerobic PA recommendations is by undertaking 30 minutes of moderate-intensity PA on at least 5 days weekly. 1,6,7 Regular walking is the most common PA of adults and older adults, and walking at a moderate pace (3 miles or 5 km per hour) qualifies as moderate-intensity PA. 8 Time spent being sedentary for extended periods should also be minimised, as this is an independent disease risk factor,1 which increases steeply with age from 45 years. 9 There is an increasing awareness that as a dose–response relationship exists for PA and health benefits, getting inactive people to do a little more PA is also important, rather than just relying on trying to achieve PA recommendations. 10,11 Emphasising that the 30 minutes can be built up from 10-minute bouts is an important message for older adults and those with disabilities, enabling them to increase their MVPA gradually. Among adults in England aged ≥ 19 years, 66% of men and 56% of women self-reported meeting the recommended PA levels, whereas only 58% of men and 52% of women aged 60–74 years did so. 12 Lower socioeconomic groups9 and Indian, Pakistani, Bangladeshi and Chinese ethnic groups are significantly less likely to report meeting the recommended PA levels, whereas the activity levels of other ethnic groups (black Caribbean, black African and Irish) are similar to that of the general population. 13 Over one-third of adults worldwide are insufficiently active, but there is large geographical variation. 10,14 However, PA, including walking, is very unreliably recalled, so surveys overestimate PA levels. 15 Objective accelerometry found that only 5% of men and 4% of women aged 35–64 years and 5% of men and 0% of women aged ≥ 65 years achieved the recommended PA levels, which is a fraction of those who self-report achieving them. 9

What are the risks from increasing physical activity?

The risks from a sedentary lifestyle far exceed the risks from regular PA. 6,16,17 Moderate-intensity PA carries a low injury risk,18 mainly musculoskeletal injury or falls. 19 Walking is very low risk, ‘a near perfect exercise’. 8 Screening participants for contraindications before participating in light- to moderate-intensity PA programmes is no longer advocated. 6,20 An important safety feature of our study is that individualised goals can be set from the participant’s own baseline, in line with the advice that older adults in particular should start with low-intensity PA and increase the intensity gradually: the ‘start low and go slow’ approach. 16,17 This worked well with our previous PA trial in older adults, which employed a similar approach and showed no increase in adverse events (AEs). 21

Strategies for increasing physical activity

How can adults and older adults increase their physical activity levels?

A systematic review of PA interventions reported moderately positive short-term effects, but the findings were limited by mainly unreliable self-report measures in motivated volunteers. 22 This review has recently been updated by three complementary Cochrane reviews assessing (1) face-to-face PA interventions,23 (2) remote (including postal and telephone) and web 2.0 interventions24 and (3) a direct comparison of these two approaches. 23 Evidence supports the effectiveness of both face-to-face interventions and remote or web 2.0 interventions for promoting PA. However, the reviewers called for future studies to provide greater detail of the components of face-to-face interventions and to assess the impact on quality of life, AEs and economic data,23 and to include participants from varying socioeconomic and ethnic groups. 24 Only one study25 met the review criteria to compare face-to-face interventions with remote or web 2.0 interventions (many trials were excluded as a result of having less than 1 year’s follow-up data or an inadequate control group); this study showed no effect on cardiorespiratory fitness25 and there were no reported data for PA, quality of life or cost-effectiveness. 23 The review concluded that there was insufficient evidence to assess whether face-to-face interventions or remote and web 2.0 approaches are more effective at promoting PA, and called for more high-quality comparative studies. 23 None of the studies included in the reviews provided objective PA measurement. 23,24 Other studies have concluded that exercise programmes in diverse populations can promote short- to medium-term increases in PA when interventions are based on health behaviour theoretical constructs, individually tailored with personalised activity goals and using behavioural strategies. 26,27 A critical review and a best-practice statement on older people’s PA interventions advised home-based rather than gym-based programmes, and behavioural strategies (e.g. goal-setting, self-monitoring, self-efficacy, support, relapse prevention training), rather than health education alone. 17,27 National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE)’s guidance concluded that no particular behaviour change model was superior and that training should focus on generic competencies and skills, rather than on specific models. 28 More recent complementary NICE guidance specifically recommended that goals, planning, feedback and monitoring techniques should be included in behaviour change interventions. 29 Starting low, but gradually increasing to moderate intensity is promoted as best practice, with advice to incorporate interventions into the daily routine (e.g. walking). 17 A recent systematic review of walking interventions concluded that interventions tailored to people’s needs, targeted at the most sedentary people and delivered at the level of the individual or household, can be effective, although evidence directly comparing interventions targeted at individuals, couples or households was lacking. 30

Are pedometers helpful?

Pedometers are small, cheap devices, worn at the hip, providing direct step count feedback. A systematic review (of 26 studies) found that pedometers increased steps per day by 2491 steps [95% confidence interval (CI) 1098 to 3885 steps] and PA levels by 27%, with significant reductions in body mass index (BMI) and blood pressure. 31 A second review (of 32 studies) found an average increase of 2000 steps per day. 32 Step count goals and diaries were key factors. 31,32 Several limitations were recognised: study sizes were small and long-term effects were undetermined; many studies included several components (e.g. pedometer and support), so independent effects were difficult to establish; and the inclusion of older people and men was limited. 31,32 Recent studies have addressed some of these limitations. A pedometer plus behaviour change intervention increased PA at 3 months, but not at 6 months, in 210 older women, with pedometers providing no additional benefit. 33 Two trials in high-risk groups showed sustained step count increases at 12 months. 34,35 A recent study of 298 older adults found a significant increase in both step counts and time in MVPA at 3 months and 12 months from a practice nurse-delivered pedometer-based walking intervention, but did not separate out pedometer- and nurse support-related effects. 21 NICE recently updated its advice from advising the use of pedometers only as part of research36 to advising their use as part of packages, including support to set realistic goals, monitoring and feedback. 37

How do step count goals relate to physical activity recommendations?

Step count goals lead to more effective interventions, but no specific approach to goal-setting is favoured. 28 Goals are based on a fixed target (e.g. 10,000 steps per day)38,39 or on advising incremental increases from the baseline as a percentage (5% per week,40 10% biweekly41 or 20% monthly33) or on a fixed number of extra steps. Those advocating a fixed number of extra daily steps have developed step-based guidelines to fit with existing evidence-based guidelines with an emphasis on 30 minutes of MVPA on ≥ 5 days weekly. 42 Despite individual variation, moderate-intensity walking appears to be approximately equal to at least 100 steps per minute. 42,43 Multiplied by 30 minutes, this produces a minimum of 3000 steps per day, to be done over and above habitual activity, which is the ‘3000 in 30’ message. 43 Several studies have advocated adding in 3000 steps per day on most days weekly, either from the beginning34 or by increasing incrementally (initially an extra 1500 steps per day and increasing),44,45 or by increasing by 500 steps per day biweekly. 35 Studies that advised adding 3000 steps per day from the baseline produced significant improvements in step counts at 3 months and two measured outcomes at 12 months, and showed sustained improvements in step counts,34,35 waist circumference34 and fasting glucose levels,35 but no sustained improvements to date in MVPA levels. Although there is no evidence at present to inform a moderate-intensity cadence (steps per minute) in older adults, Tudor-Locke et al. 46 advocate using the adult cadence of 100 steps per minute in older adults (while recognising that this may be unobtainable for some individuals) and advising that the 30 minutes can be broken down into bouts of at least 10 minutes. This model was used in a primary care walking intervention in 41 older people, which found significant step count increases from baseline to week 12, which were maintained at week 24. 47,48

Could accelerometers be useful in a pedometer-based walking intervention?

Accelerometers are small activity monitors worn like pedometers, but are more expensive; however, they are able to provide a time-stamped record of PA frequency (step counts) and intensity (activity counts). They require computer analysis, function as blinded pedometers in objectively measuring baseline and outcome data, and provide objective data on time spent in different PA intensities, including time spent in MVPA and time spent being sedentary, two important public health outcomes. Pedometer studies without accelerometers have relied on self-reported measures of these outcomes. Accelerometers are valid and acceptable to adults9,49 and older adults. 9,21,50–53 Although both instruments measure step count and are highly correlated,50 pedometers usually record lower step counts, and accelerometers cannot reliably be substituted for pedometers at an individual level. 54 Thus, although we used the accelerometer to measure outcomes, including step count, MVPA and sedentary time, we used the blinded pedometer, worn simultaneously at baseline, to set individual step count targets.

Are pedometers cost-effective?

There is limited knowledge on the cost-effectiveness of pedometer-based interventions in the UK. Recent systematic reviews that considered the economic outcomes of pedometer-based interventions found no evidence,55,56 partly because of an insufficient number of data. 57 However, a recent study assessed the cost-effectiveness of giving an individualised walking programme and pedometer with or without a PA consultation alongside a community-based trial of 79 people. 58 The incremental cost-effectiveness ratios (ICERs) per persons achieving an additional 15,000 steps per week were £591 and £92 with and without the consultation, respectively. However, even with this highly selected sample, no data on quality of life were collected, and the impacts on long-term outcomes were not estimated.

What is the role of primary care in promoting physical activity?

Primary care centres (general practices) in the UK provide health care and health promotion, free at the point of access, to a registered list of local patients (for many of whom PA will be of benefit), using disease registers to provide annual or more frequent chronic disease reviews via a multidisciplinary health-care team providing continuity of care. NICE guidance found that brief interventions in primary care are cost-effective, and it therefore recommends that all primary care practitioners should take the opportunity to identify inactive adults and provide advice on increasing PA levels. 36 New 5-yearly NHS health checks include adults aged 40–74 years and incorporate advice on increasing PA, often from primary care nurses. 59 Primary care nurses are effective at increasing PA, particularly walking, in this age group. 60 Not only can PA advice through consultation with health professionals be individually tailored61 and have more impact than other PA advice,62 but this is particularly the case for older adults,63 especially given the uncertainty about the effectiveness of exercise referral schemes from primary care. 64 Exercise-prescribing guidance in primary care reinforces the importance of follow-up to chart progress, set goals, solve problems, and identify and use social support;65 this will be an important feature of the nurse PA consultations in this trial. Evaluation of the UK Step-O-Metre programme, delivering pedometers through primary care, showed self-reported PA increases, but advised investigation with a randomised controlled trial (RCT) design. 44 Two trials, both in older primary care patients, have assessed the effectiveness of pedometers plus primary care PA consultations; one small trial (n = 41) showed a significant effect on step counts at 3 months, which was maintained at 6 months,47,48 and the other was our recent Pedometer Accelerometer Evaluation-LIFT (PACE-LIFT) trial21 (n = 298), which showed differences in both step counts and time in MVPA in bouts of at least 10 minutes, at 3 and 12 months for the nurse intervention compared with the control group. Neither trial separated out pedometer effects from the support provided. 21,47,48

Theoretical base, piloting and preparatory work to develop the intervention

The pedometer-based intervention is based on work cited above,31,32 showing that pedometers can increase step counts and PA intensity. 31,32 It extends current understanding by also including older adults and men, having a 12-month follow-up and ensuring that the pedometer and support components could be evaluated separately. The patient handbook, diary (both available on the journals library website: www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/programmes/hta/103202/#/) and practice nurse PA consultations use behaviour change techniques (BCTs; e.g. goal-setting, self-monitoring, feedback, boosting motivation, encouraging social support, addressing barriers or relapse anticipation). These techniques have been successfully used by non-specialists in primary care after brief training,66 and are emphasised in the Improving Health: Changing Behaviour: NHS Health Trainer Handbook,67 based on evidence from a range of psychological methods and intended for NHS behaviour change programmes, with local adaptation. 67 They also include techniques specifically recommended to be included in more recent NICE guidance (goals, planning, feedback and monitoring). 29 We adapted the Improving Health: Changing Behaviour: NHS Health Trainer Handbook67 for use in this trial into Pedometer And Consultation Evaluation-UP (PACE-UP) nurse and patient handbooks, to focus specifically on PA using pedometers. The BCTs were classified in accordance with the refined taxonomy of BCTs for PA interventions by Michie et al. 68 Diary recording of pedometer step counts provides clear material for PA goal-setting, self-monitoring and feedback, and should fit well with this approach. We have adopted the approach used by others44,45 of advocating adding in 3000 steps per day to an individual’s baseline on most days weekly in an incremental manner, and of advising on gradually increasing PA intensity to achieve more time in MVPA, with the message that 3000 steps in 30 minutes will help people to achieve PA guidelines. 43 Relevant pilot and preparatory work includes observational work using pedometers and accelerometers in primary care53 and a successful trial with older primary care patients developing the PA consultations and pedometer-based walking intervention (the PACE-LIFT trial; ISRCTN4212256121,69). The PACE-LIFT trial demonstrated that tailored support from practice nurse PA consultations combined with a pedometer-based walking programme (plus accelerometer feedback on PA intensity) led to an increase in both step counts and time in MVPA compared with the control group at both 3 and 12 months in 60- to 75-year-old primary care patients. The trial was limited in terms of both ethnic and socioeconomic diversity, has not yet published on sedentary time or cost-effectiveness and, as mentioned, was unable to separate out the effects of the pedometer (and accelerometer feedback) from the effects of nurse support. 21

Rationale for research

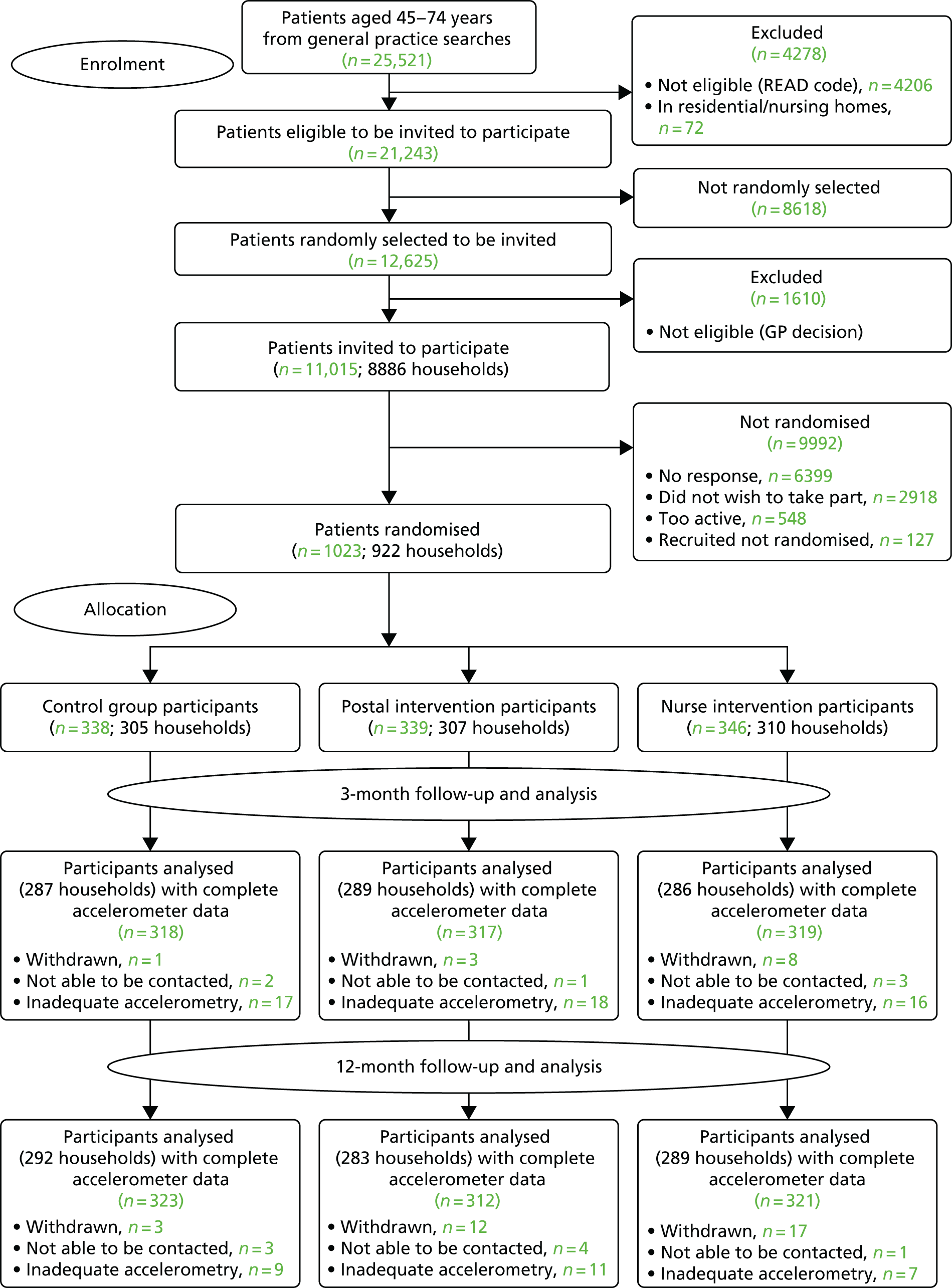

The PACE-UP trial aimed to fill the gaps in the current evidence base by evaluating the effect of a pedometer-based walking intervention, with and without additional nurse PA consultations in a population-based, primary care sample of inactive adults and older adults. The initial trial included follow-up to 1 year and aimed to ensure that adequate numbers of men, older adults and individuals from diverse socioeconomic and ethnic backgrounds were included. It also enabled the effectiveness of taking part as an individual or as a couple to be estimated. The intervention used step goals and diaries, and the PA consultations and patient handbook were based on BCTs, such as those used in the Improving Health: Changing Behaviour: NHS Health Trainer Handbook. 67 To objectively test the effectiveness of the intervention on important public health outcomes, such as time spent in MVPA and time spent being sedentary, PA outcomes were assessed by accelerometry. Anonymised practice demographic data were available for all those invited to participate, enabling the investigation of inequalities in trial participation. Qualitative evaluations were also needed to explore the reasons for trial non-participation, the acceptability of the intervention to both participants and practice nurses and the barriers to, and facilitators of, the intervention. An economic evaluation was performed alongside the trial and was also used to inform long-term cost-effectiveness.

Chapter 2 Methods

This chapter is a summary of the full study protocol for the trial as originally funded, except for the paragraph which describes changes to the published protocol. Some of the material, including the tables, has already appeared in publication,70 and is reproduced here under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article,70 unless otherwise stated. Further funding was later awarded by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Health Technology Assessment programme for a 3-year follow-up of the trial cohort, the methods and results of which are described in Chapter 8.

Study design

The PACE-UP walking intervention trial was a pragmatic, three-arm parallel-cluster trial (randomised by household to allow individuals and couples to participate). It was based in primary care with 45- to 75-year-old inactive adults, with a 12-month follow-up period, and compared the following three groups: control (usual PA); pedometer and written instructions by post (pedometer by post); and pedometer, written instructions and practice nurse individually tailored PA consultations (pedometer plus nurse support).

Study aims and objectives

Study aims

The main hypotheses to be addressed were as follows:

-

Does a 3-month postal pedometer-based walking intervention increase PA in inactive 45- to 75-year-olds at the 12-month follow-up point?

-

Does providing practice nurse support through dedicated PA consultations provide additional benefit?

The study also aimed to assess the cost-effectiveness of both interventions, whether or not any factors modified the intervention effects and the effect of the interventions on patient-reported outcomes, anthropometric measures and primary care-recorded AEs.

Primary objectives (relating to the primary outcome of step counts)

In inactive adults aged 45–75 years, the primary objectives were to:

-

confirm that tailored support from practice nurse PA consultations combined with a pedometer-based walking programme can promote an increase in step counts compared with the control group at 12 months (pedometer plus nurse support vs. control)

-

determine whether or not the simple provision by post of pedometers plus written instructions for a pedometer-based walking programme can promote an increase in step counts compared with the control group at 12 months (pedometer by post vs. control)

-

estimate the effect of tailored support from practice nurse PA consultations combined with a pedometer-based walking programme compared with the postal pedometer-based walking programme, on step counts at 12 months (pedometer plus nurse support vs. pedometer by post).

Secondary objectives (relating to secondary outcomes of time in moderate to vigorous physical activity in bouts, sedentary time and cost-effectiveness)

In inactive adults aged 45–75 years, the secondary objectives were to:

-

confirm that tailored support from practice nurse PA consultations combined with a pedometer-based walking programme can promote an increase in steps counts at 3 months and time spent in MVPA in ≥ 10-minute bouts at 3 and 12 months, and a decrease in sedentary time at 3 and 12 months compared with control (pedometer plus nurse support vs. control)

-

determine whether or not the simple provision by post of pedometers plus written instructions for a pedometer-based walking programme can promote an increase in step counts at 3 months, an increase in time spent in MVPA in ≥ 10-minute bouts at 3 and 12 months and a decrease in sedentary time at 3 and 12 months compared with the control group (pedometer by post vs. control)

-

estimate the effect of tailored support from practice nurse PA consultations in addition to the pedometer-based walking programme alone on step counts at 3 months, and time spent in MVPA in ≥ 10-minute bouts and sedentary time at 3 and 12 months (pedometer plus nurse support vs. pedometer by post)

-

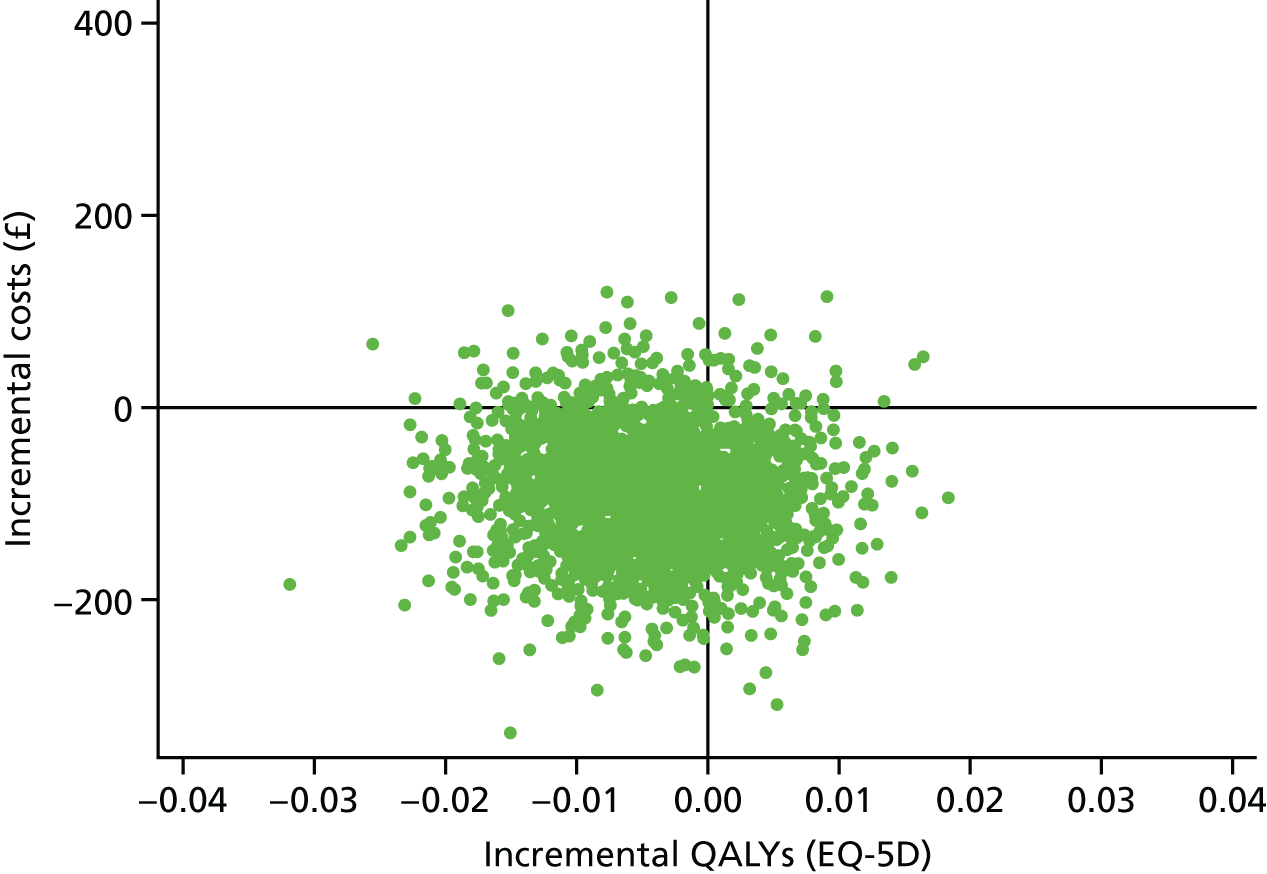

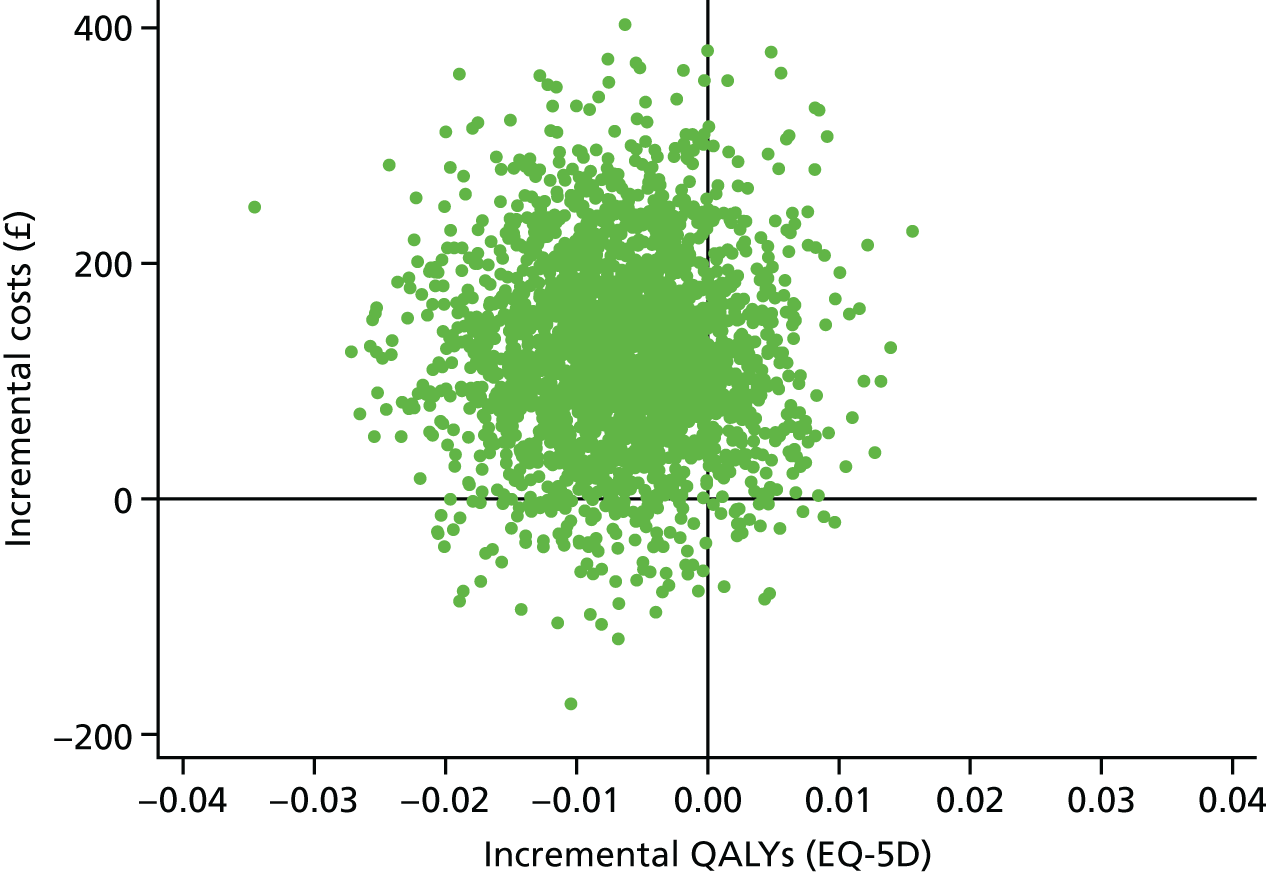

determine the cost-effectiveness of these alternative approaches to increasing PA levels at both 12 months and from a lifetime perspective from the viewpoint of the NHS and participants (see Chapter 4).

Other objectives

-

To determine the effect of the interventions on anthropometric measures (BMI, waist circumference and body fat) at 12 months.

-

To determine the effect of the interventions on patient-reported outcomes (self-reported PA levels, anxiety and depression score, exercise self-efficacy, quality of life, pain, AEs) and on primary care-recorded AEs at 3 months and 12 months.

-

To determine whether or not age groups (< 60 years vs. ≥ 60 years), sex, taking part as a couple, socioeconomic group, disability, pain, BMI and exercise self-efficacy modify the effect of the intervention on increasing step count at 3 months and 12 months (ethnic group was originally intended to be included as an effect modifier, but there was inadequate power for this analysis because of the low number of non-white participants; see Changes from the published protocol).

-

To compare the age, sex, socioeconomic group and ethnicity of those taking part in the trial with those invited but not participating, and to explore the reasons for not participating (see Chapter 5).

-

To assess the fidelity and quality of the intervention implementation over time, by the evaluation of patient diary step count goals and recorded step counts for both intervention groups at the 3-month assessment, and the number and timing of recorded practice nurse contacts for the nurse support group (see Chapter 6).

-

To explore the intervention’s acceptability to practice nurses and inactive adults, the reasons for dropout and the durability of effects, by qualitative interviews with participants after the 12-month follow-up, and a focus group with the nurses on study completion (see Chapter 7).

Practice and participant inclusion/exclusion criteria

Practice inclusion criteria

General practices were recruited through the Primary Care Research Network – Greater London. Practices were required to be in the south-west London cluster, have a practice list size of > 9000, give a commitment to participate over the duration of the study, have a practice nurse interested and with time to carry out the PA interventions and trial procedures, and have the availability of a room for the research assistant to recruit participants and carry out baseline and follow-up assessments.

Participant inclusion criteria

Participants were patients aged 45–75 years, who were registered with one of the recruited south-west London general practices, were able to walk outside the home and had no contraindications to increasing their MVPA levels.

Participant exclusion criteria

-

Physical activity based (by screening question on invitation letter). In order to maximise the benefits of the intervention to individuals and the NHS, the trial focused on less-active adults, using a single-item validated questionnaire measure of self-reported PA as a screening question to identify them. 60 Those who reported achieving a minimum of 150 minutes of MVPA weekly1 on their response letter were excluded (participants who, on subsequent baseline accelerometer assessment, were found to be above this PA level were not excluded, as they would be included if this intervention were to be rolled out in primary care).

-

Health based [either by the Read code from primary care records or by general practitioner (GP)/practice nurse opinion, or from the telephone or face-to-face baseline assessment with the research assistant] for the following reasons:

-

housebound or living in a residential or nursing home

-

three or more falls in the previous year, or one or more falls in the previous year requiring medical attention

-

terminal illness

-

dementia or significant cognitive impairment

-

registered blind

-

new-onset chest pain, myocardial infarction, a coronary artery bypass graft or an angioplasty within the last 3 months

-

a medical or psychiatric condition that the GP (or practice nurse) considered to exclude the patient (e.g. acute systemic illness such as pneumonia, acute rheumatoid arthritis, unstable/acute heart failure, significant neurological disease/impairment, unable to move about independently, psychotic illness)

-

pregnancy.

-

Recruitment of practices and participants: informed consent

Practice recruitment

The Primary Care Research Network – Greater London identified practices that fitted the above practice inclusion criteria. Practice recruitment was challenging for a number of reasons, including difficulties in finding practices with sufficient space to accommodate a research assistant on a regular basis, finding practices with nurses willing and with sufficient time to be engaged in delivering the intervention and finding practices that were prepared to provide administrative support. The Primary Care Research Network – Greater London provided us with strong support to recruit practices. Initially, six practices were recruited, with an additional practice added half-way through to boost recruitment. This was necessary, as recruitment at that point was running at just below 10% and we were concerned that we would not achieve the target recruitment from the original six practices within 12 months. The practices were selected to include a range of sociodemographic factors and geographical circumstances based on the practice postcode Index of Multiple Deprivation71 (IMD) scores (at least one practice from each quintile).

Participant recruitment

Practice staff identified patients aged 45–74 years on their primary care electronic patient record system, and, using Read codes and local care home knowledge, excluded ineligible patients (patients were aged 45–74 years when selected, but some were aged 75 years by the time of recruitment or randomisation). A list of potentially eligible patients was produced and ordered by household, with a unique household identifier number. An anonymised list was then used by the research team to create at least four random samples of 400 individuals at each practice. A maximum of two people per household were selected (we were aiming to select couples). If a household had two individuals, one was selected at random, and if the second individual had an age difference of ≤ 15 years, they were also selected; if they fell outside this age range, they were not included. If a household had more than two individuals, one was selected at random, and if there was a second individual aged within ≤ 15 years they were also selected; if there was not a second individual aged within ≤ 15 years, this became an individual household. Each sample list was examined by practice nurses or GPs to ensure trial suitability prior to invitation (see Participant exclusion criteria). Participants were recruited between September 2012 and October 2013, and follow-up was completed by October 2014.

Non-responders and non-participants

See Chapter 5 for more details.

Informed consent

Patients were sent an invitation letter from their own practice, along with a participant information sheet and a screening question on self-reported PA. A reminder invitation was sent if no reply was received after 6 weeks. A log was kept of the response rates from each practice. The decision regarding participation in the study was entirely voluntary. Those interested in participating returned the reply slip, including a response to a single screening question about their usual PA levels. If the participant self-reported as not achieving the PA guidelines,1 the research assistant arranged a baseline appointment for them and ran through the participant information sheet, and handled any questions or concerns that they had. If they were happy to proceed, they signed the study consent form; this form included consent to be contacted for qualitative interviews and consent for their general practice records for the year of the trial to be downloaded after trial follow-up was completed. Participants who had difficulty understanding, speaking or reading English were accompanied by a family member or friend during the research assistant appointment. Participants within a couple could attend together or separately.

Changes from the published protocol

We planned to recruit from six general practices, but to enable target recruitment, a seventh practice was added in December 2012. Changes from protocol-planned analyses70 were approved by the Trial Steering Committee (TSC), prior to analysis. We report MVPA in ≥ 10-minute bouts, as this relates more closely to PA guidelines. 1,2 Only 20% of participants were non-white; ethnic group was therefore excluded from the subgroup analyses, as a result of low power.

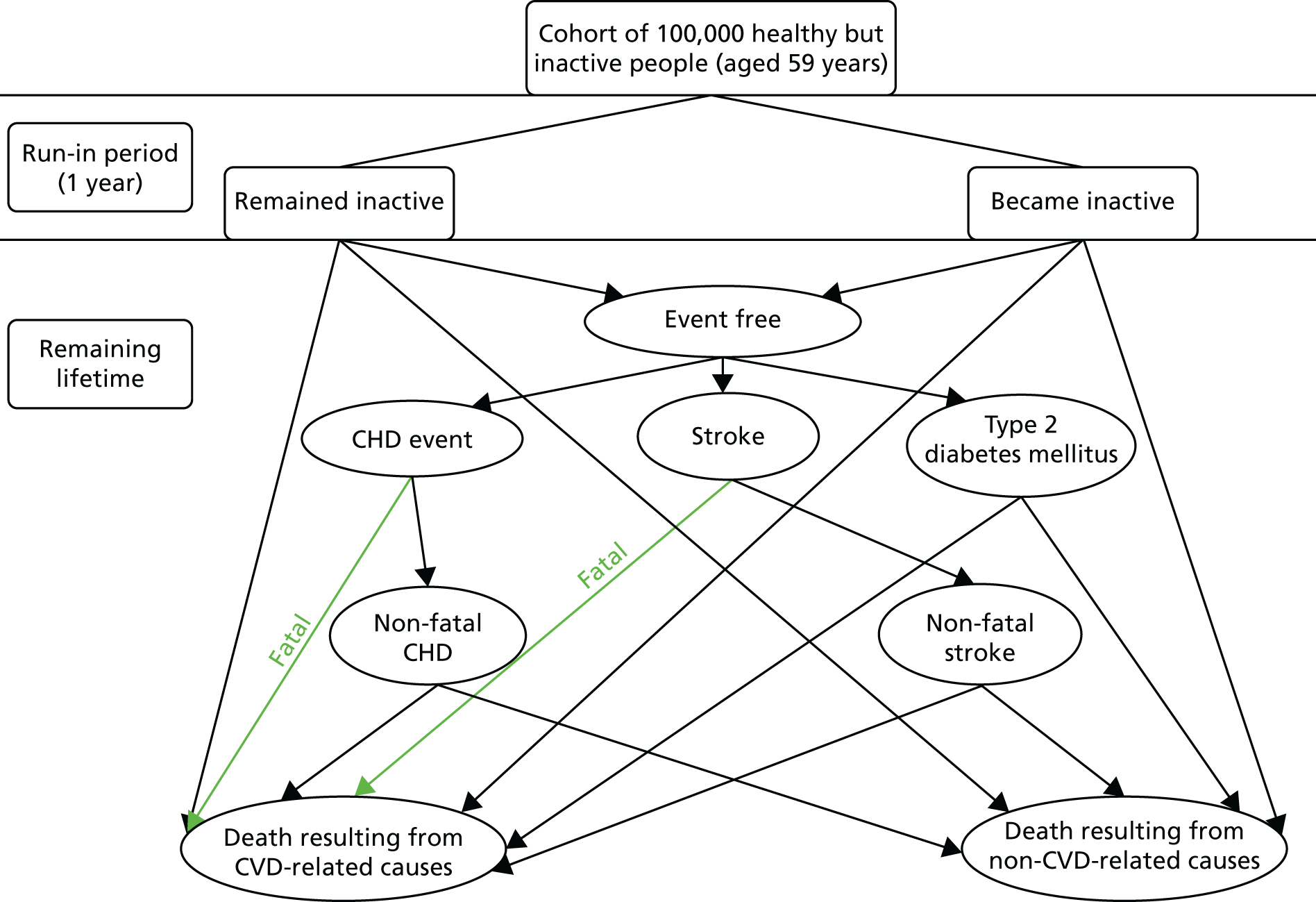

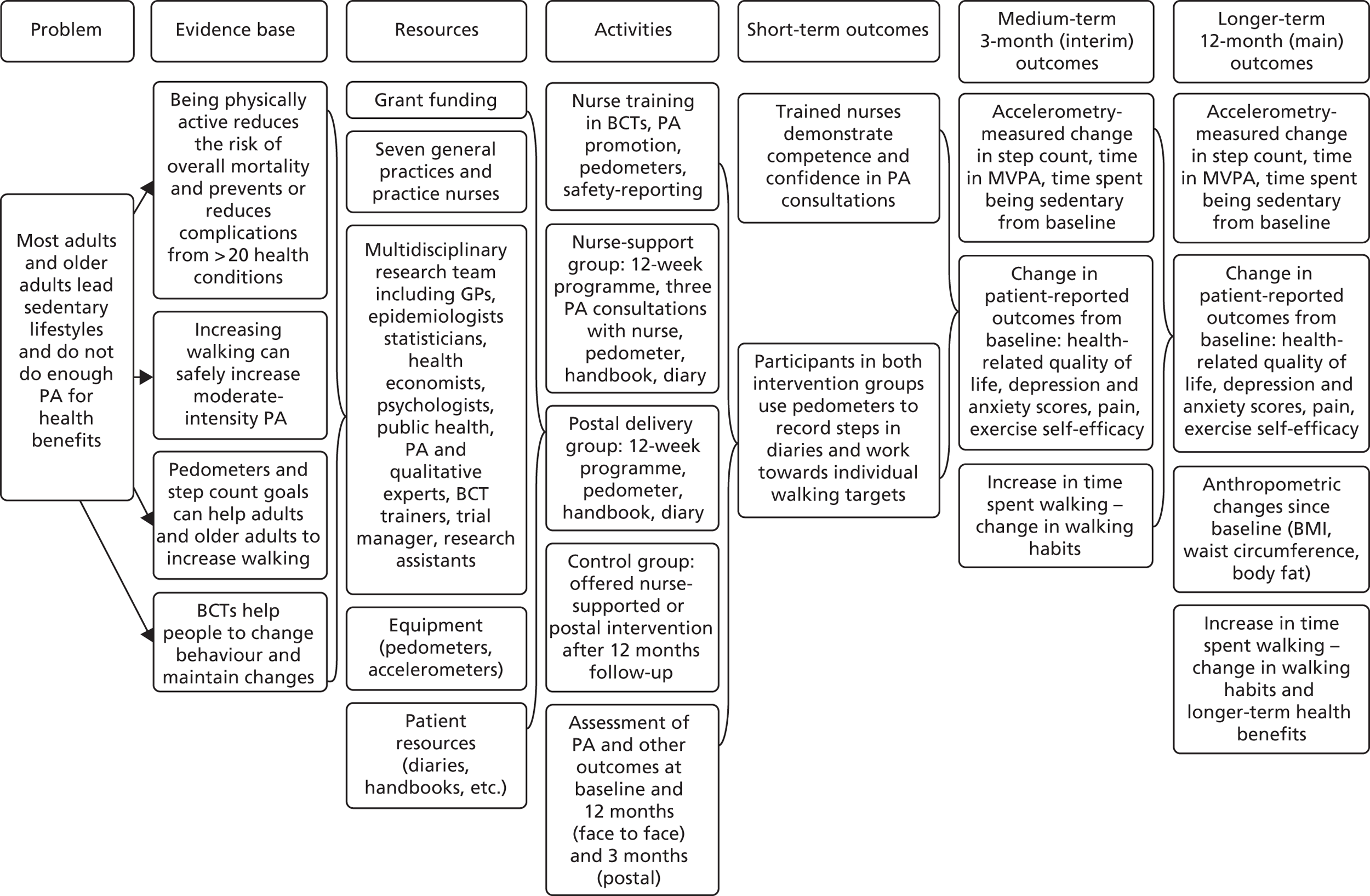

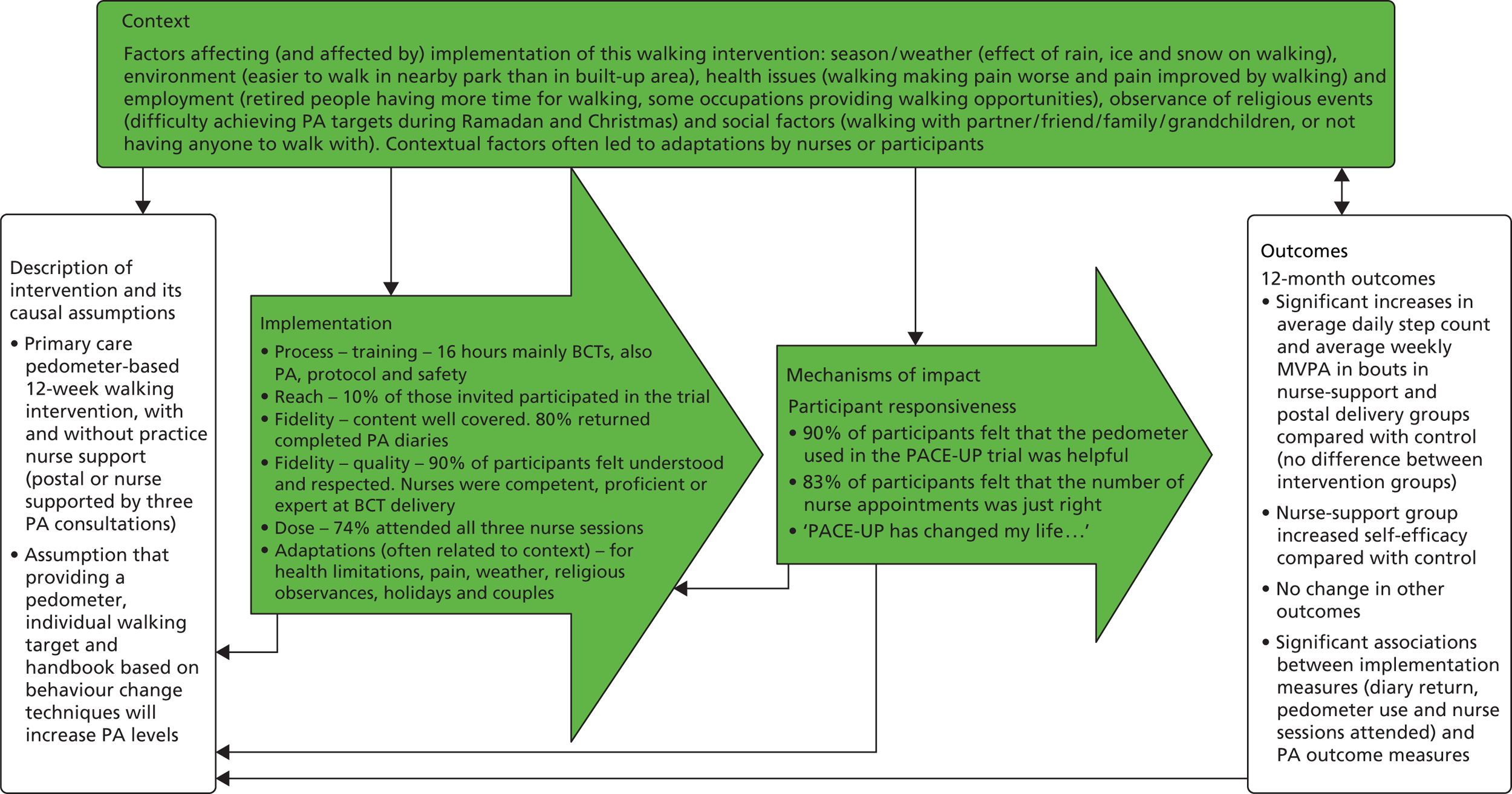

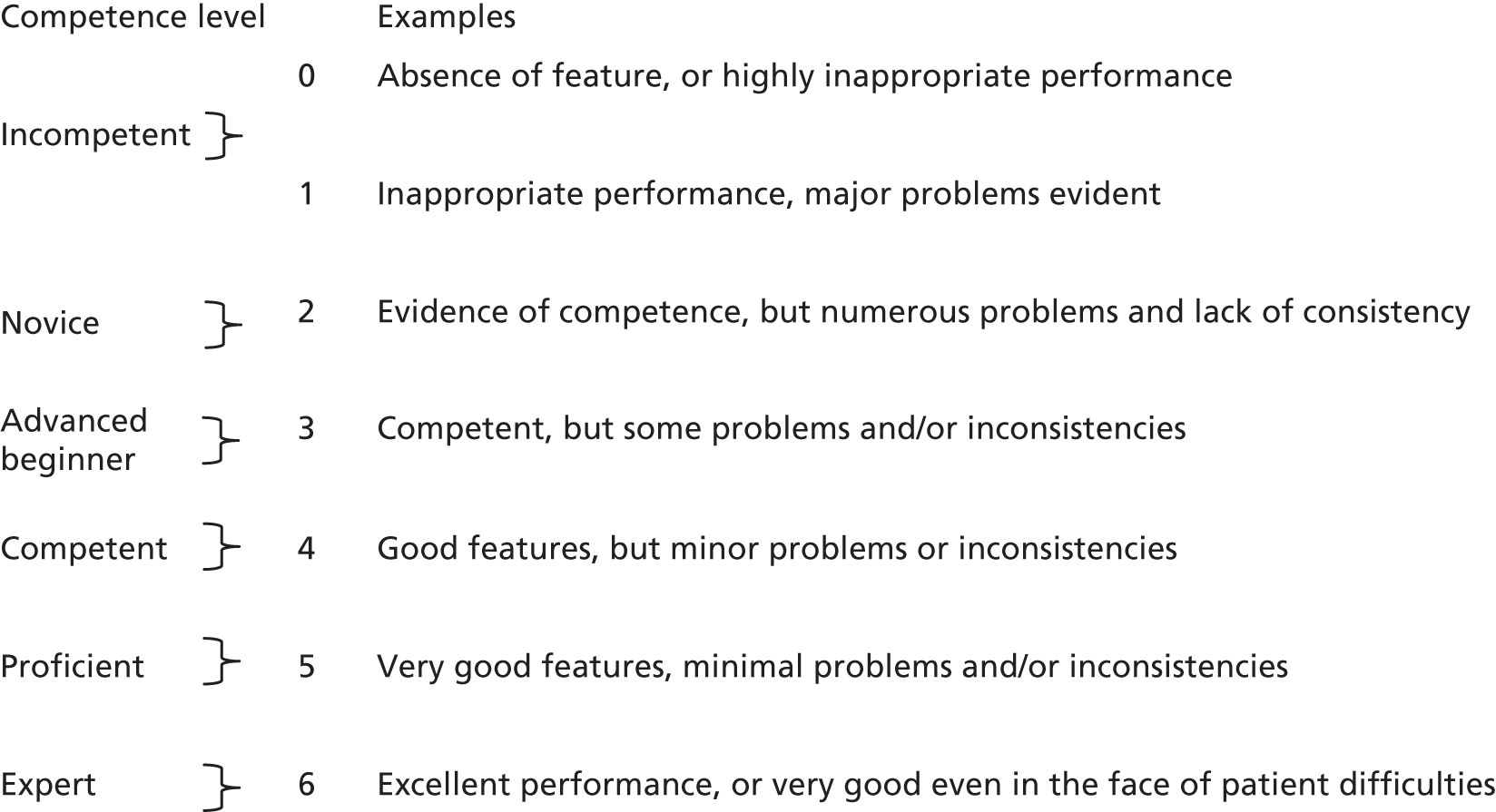

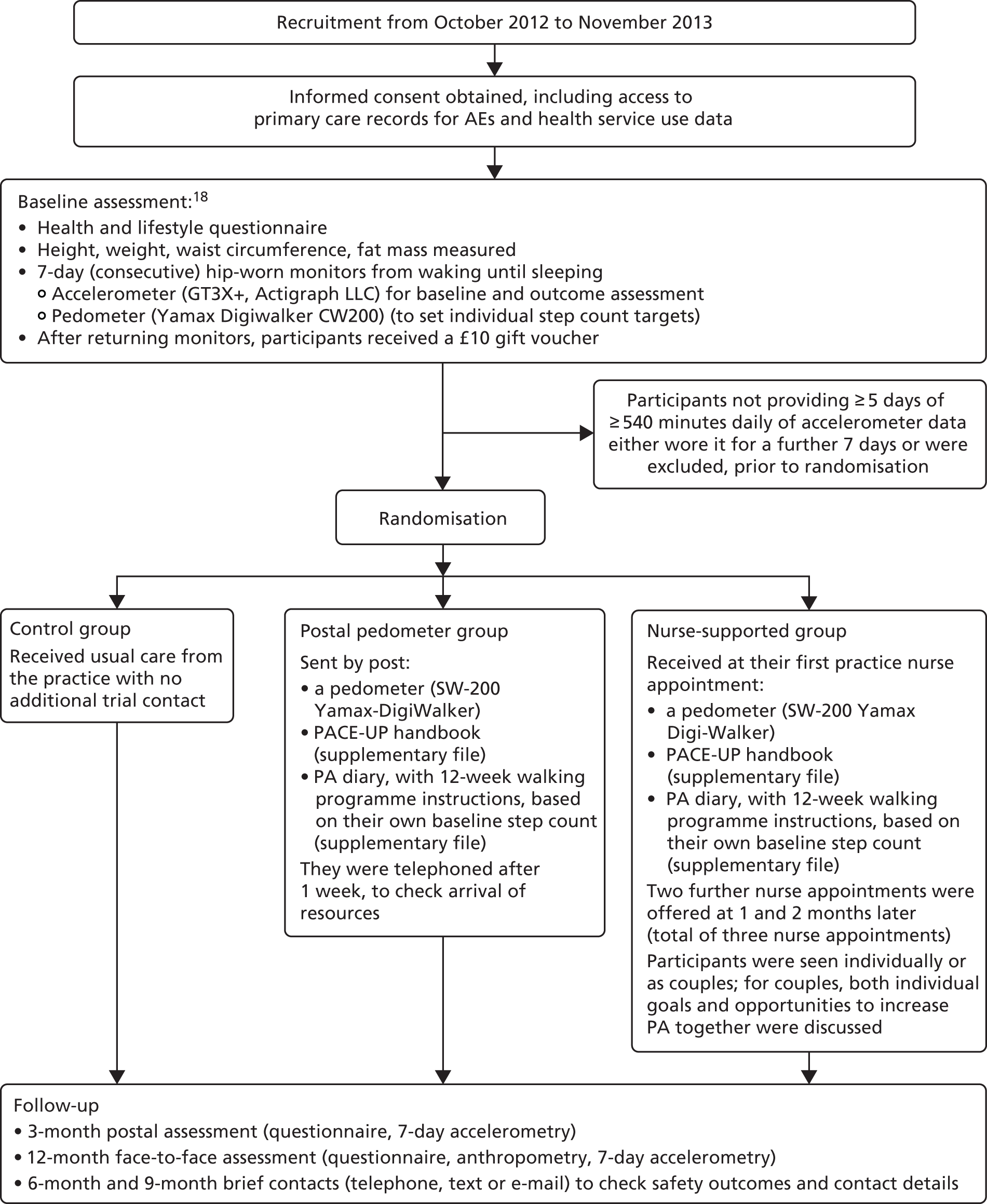

Interventions

Table 1 shows the components of the intervention provided to the postal and nurse groups. Table 2 shows the content of the patient handbook and the patient diary and the BCTs that were included in each of them, rated according to Michie et al. ’s CALO-RE taxonomy. 68 Table 3 shows the timing and session content for the three dedicated nurse PA consultations and the BCTs intended to be covered in each session. Figure 1 provides a summary of the 12-week walking programme in terms of steps per day or time spent walking, to be added to each individual’s baseline average daily steps. The training received by the practice nurses in order to deliver the interventions is described in Chapter 6. A figure summarising the trial procedures and complex intervention components is shown in Appendix 1, Figure 17.

| Component | What was provided | Trial arm receiving | Additional details on components |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pedometer | Yamax Digi-Walker (Yamasa Tokei Keiki Co., Ltd, Tokyo, Japan), SW-200 model |

|

Provided direct step count to participants. Required daily manual recording and resetting |

| PACE-UP handbook, 12-week walking plan and step count diarya | Handbook to support the 12-week walking programme. Individualised walking plan (see Figure 1). Diary to record weekly step count and walks for 12 weeks |

|

Baseline average daily step counts (from the blinded pedometer assessment) were used to create individual targets. The 12-week walking programme gradually increased targets to achieve an additional 3000 steps per day (approximately 30 minutes of brisk walking) on ≥ 5 days weekly. Daily step counts and target achievement were recorded in the diary. Table 2 lists BCTs in the PACE-UP handbook and diary |

| Practice nurse-dedicated PA consultations | Three individually tailored consultations. Participants could be seen individually or as a couple | Nurse-support group only | Session timings, content and planned BCTs are shown in Table 3. Sessions reinforced the intervention defined in the diary and the handbook. The nurse consultation allowed some additional BCTs to be used and provided an opportunity to individually tailor the intervention to participants’ needs |

| Component | Guide to content | aBCTs68 |

|---|---|---|

| Patient handbook |

|

1 and 2 4 7, 9 and 16 19 21 4 16, 1, 2, 26, 29 and 35 |

| Patient diary |

|

16 and 21 7, 9, 19 and 26 10, 12 and 13 20 and 29 20 2, 20 and 35 12, 13 and 29 12, 16 and 29 8 38, 17 and 11 9, 21 and 35 16, 29 and 36 8 and 35 1, 2, 7 and 23 16, 20 and 29 11, 16 and 17 1, 16 and 29 |

| Sessions | Guide to session content | aBCTs68 |

|---|---|---|

| Session1: week 1, first steps (30 minutes) |

|

1 and 2 2 4 and 21 19 21 and 26 20 7, 9 and 16 12 and 13 37 |

| Session 2: week 5, continuing the changes (20 minutes) |

|

10 and 19 12 and 13 8 7, 9 and 16 8 and 29 9 and 35 18, 29 and 36 37 |

| Session 3: week 9, building lasting habits (20 minutes) |

|

10 and 19 11 and 17 12 and 13 35 7, 23, 29 and 35 7, 9, 16 and 26 37 |

FIGURE 1.

A summary of the PACE-UP walking programme. Adapted from Harris et al. 70 This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

Procedure for the postal intervention group

The participants received (by post) a pedometer (Yamax Digi-Walker, SW-200 model; Yamasa Tokei Keiki Co., Ltd, Tokyo, Japan), instructions and a 12-week step count diary for the 12-week walking intervention (see Figure 1). The research assistant contacted the participant to check that the pedometer had been received and to resolve any difficulties with the equipment. At the end of the 12-month follow-up period, the postal group were offered a single practice nurse PA appointment, if they wanted it.

Procedure for the nurse intervention group

Three dedicated PA consultations (week 1, week 5 and week 9) were arranged with the practice nurse, to individually tailor and support the 12-week pedometer-based walking programme (see Figure 1). At their first appointment, participants were given the same pedometer, diary and handbook that the postal group received. Participants were asked to wear a pedometer and keep a diary record of daily steps for 4 weeks between appointments, in order to review targets and goals at their next appointment. Participants were seen individually or as a couple.

Procedure for the control group

The participants were advised to continue their usual activity levels and were not offered the 12-week walking intervention, but were free to participate in any other PA, just as they would if they were not enrolled in the trial. At the end of the 12-month follow-up period, the control group was offered to receive a pedometer and the PACE-UP 12-week walking programme handbook and diary, either by post or as part of a single PA practice nurse appointment, as preferred.

Outcome measures

Primary and secondary outcome measures

These were selected to reflect the needs of the target population, helping adults and older adults to increase their PA, particularly through walking, and to inform UK public health policy. The primary outcome was the change in average daily step count, measured over 7 days, between baseline and 12 months, assessed objectively by accelerometry (GT3X+; ActiGraph LLC, Pensacola, FL, USA). Secondary outcomes were as follows: changes in step counts between baseline and 3 months; changes in time spent weekly in MVPA in ≥ 10-minute bouts between baseline and 3 months, and between baseline and 12 months; and time spent sedentary between baseline and 3 months, and between baseline and 12 months. All of these secondary outcomes were also assessed objectively by accelerometry. Cost-effectiveness was also a secondary outcome in our protocol [incremental cost per change in step count and per quality-adjusted life-year (QALY)]; this is presented in Chapter 4.

Ancillary outcomes

-

Change in self-reported PA, measured over the same 7 days as accelerometry using the short International Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ)72 and the General Practice Physical Activity Questionnaire [(GPPAQ)73 as part of the 7-day PA questionnaire; see Appendix 1].

-

Change in other patient-reported outcomes (from the health and lifestyle questionnaires at baseline, 3 months and 12 months; see Appendix 1): confidence in ability to do PA, as measured by exercise self-efficacy;74 anxiety and depression, as measured by the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS);75 perceived health status (health-related quality of life), as measured by the EuroQol-5 Dimensions, five-level version (EQ-5D-5L);76 and self-reported pain, measured by two items from the Medical Outcomes Study 36-item short-form health survey. 77

-

Change in anthropometric measurements (weight, BMI, waist circumference, body fat; see Ascertainment of outcomes, Anthropometry, for measurement details).

-

Adverse outcomes [falls, fractures, injuries, exacerbation of pre-existing conditions, major cardiovascular events and deaths from serious AEs (SAEs)] were collected as part of safety monitoring for the trial, by questionnaire self-report items designed by us at 3 and 12 months, and from primary care records after the 12-month follow-up period, for those giving consent.

-

Health service use for those giving consent to primary care record access for the 12-month trial period, numbers of the following occurrences were collected for health economic evaluations (see Chapter 4): primary care consultations, accident and emergency (A&E) attendances, emergency and elective hospital admissions and outpatient referrals.

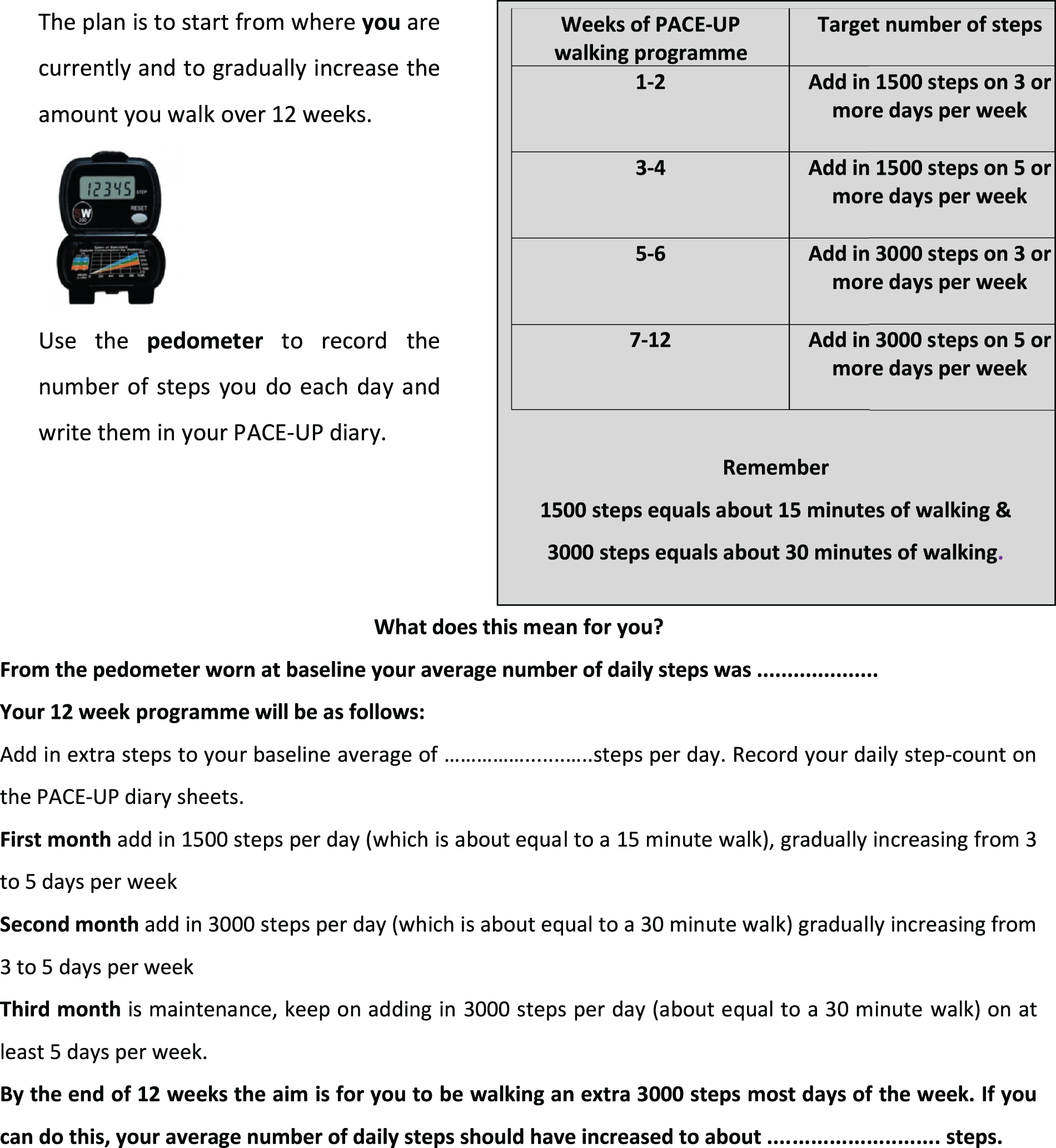

Ascertainment of outcomes

See Figure 2 for the schedule for outcome assessments and measures.

Accelerometry

Participants were asked to carry on with their usual PA levels and to wear an accelerometer (GT3X+, ActiGraph LLC) on a belt over one hip, during waking hours (from rising until going to bed) for 7 days, only removing it for bathing, at baseline, 3 months and 12 months. Participants were offered the option of text messaging to remind them to wear the accelerometer each day and to return it after the 7 days. A diary was provided to record what activities were done and for how long. The monitor, belt and diary were posted back on completion. Once returned, the participants received a £10 gift voucher.

Anthropometry

At the baseline and 12-month face-to-face assessments, the following measurements were taken: height (measured in bare feet to the nearest 0.5 cm using a stadiometer), weight (measured to the nearest 0.1 kg), body fat, bioimpedence [using the Tanita body composition analyser BC-418 MA (Tanita Corporation, Tokyo, Japan)] and waist and hip circumference (using a standard technique and tape measure with a clear plastic slider).

Questionnaire measures

Questionnaire measures were collected using validated tools (detailed under Outcome measures, Ancillary outcomes), as part of self-completed questionnaires at 3 months and 12 months.

In terms of the self-reported PA in the previous week, for the IPAQ72 we used the measure of MVPA (total minutes of vigorous and moderate PA weekly) and the measure of walking (total minutes of walking weekly). The GPPAQ73 provides a PA index (PAI), which is calculated from a combination of PA from both work and leisure activities. Active individuals are those who self-report ≥ 3 hours of MVPA per week on the PAI. However, walking is not included in the calculation of the PAI, although it is asked about in the questionnaire. Analysis of similar GPPAQ data compared with objective accelerometry in our earlier PACE-LIFT trial21 demonstrated that a modified PAI, which also included walking at a brisk pace for at least 3 hours per week, improved validity and repeatability compared with the standard GPPAQ. 78 A modified index, GPPAQ-Walk, was therefore generated.

In addition, the following were also recorded at baseline: demographic information, based on 2011 census questions79 (e.g. marital status, ethnic group, occupation, employment, household composition, home ownership); a list of common self-reported chronic conditions (e.g. heart disease, lung disease, arthritis, stroke, diabetes mellitus, depression); disability, as measured by the Townsend score;80 limiting long-standing illness;79 current medications; smoking; and alcohol consumption.

Several other questionnaire variables were collected at all three time periods, but were not considered to be ancillary trial outcomes in the trial protocol:70 loneliness, measured by a single item;81 risk of falls, measured using the Falls Risk Assessment Tool,82 was assessed using a combination of both self-reported items and direct observation of the ability to rise from a chair without using arms; and self-reported usual PA, as measured by the modified Zutphen Physical Activity Questionnaire. 83 Data from these variables are not presented in this report.

All study groups were asked about falls, injuries, fractures, exacerbation of any pre-existing conditions and the costs of any treatments in the 3- and 12-month questionnaires. Questions on the financial costs of participating in walking and other PAs were asked in the 3- and 12-month questionnaires.

Primary care computerised record measures

For participants who gave written consent, the following data were collected from their electronic primary care records, for the 12-month duration of the trial, after the 12-month follow-up:

-

adverse events potentially relating to trial participation [Read codes relating to falls, fractures, injuries, cardiovascular events (myocardial infarction, coronary artery bypass graft, coronary angioplasty, transient ischaemic attack, stroke) and death]

-

health service use – GP consultations, practice nurse consultations (excluding those for the trial), A&E attendances, emergency and elective hospital admissions and outpatient referrals.

These data were downloaded and pseudoanonymised before removal from the practice.

Baseline and follow-up data collection

Baseline data collection

At baseline, a face-to-face assessment with the research assistant occurred at the participant’s general practice, and questionnaire and anthropometric data were collected (see Ascertainment of outcomes). Participants were then given a belt with an accelerometer (GT3X+, ActiGraph LLC) and a blinded pedometer (Yamax Digiwalker CW200) on it, and asked to wear this for 7 days. The CW200 pedometer model was used to enable the baseline target-setting of the pedometer step count, because of its 7-day memory of consecutive daily steps. However, it is bulky to wear and complicated to use, so this model was not used for the intervention.

Follow-up data collection

Follow-up data collection was conducted in the same way for all trial groups (Figure 2): (1) 3 months (postal) after randomisation (questionnaires and accelerometry) and (2) 12 months (face to face) after the baseline assessment (questionnaires, accelerometry and anthropometry). Participants were also contacted by the research assistant at 6 and 9 months after randomisation by telephone or e-mail to check on falls for trial safety reporting and contact details. For those in the intervention groups, a replacement pedometer or batteries were offered at each contact point, if required. The intervention groups were asked to return their 12-week step count diary following the intervention at 3 months. This was then photocopied and sent back to participants.

FIGURE 2.

Schedule of outcome assessment measures used in the PACE-UP trial.

Accelerometer data reduction

The accelerometer measured vertical accelerations in magnitudes from 0.05 to 2.0 g sampled at 30 Hz, then summed over a 5-second epoch time period. ActiGraph data were reduced using Actilife software (v 6.6.0; ActiGraph LLC, Pensacola, FL, USA), ignoring runs of ≥ 60 minutes of zero counts. 70 Vertical counts were used, as these are the basis of the validated step count and MVPA algorithms. The analysis summary variables used were step counts, accelerometer wear time, time spent in MVPA (≥ 1952 counts per minute, equivalent to ≥ 3 metabolic equivalents),84 time spent in ≥ 10-minute MVPA bouts and time spent being sedentary (≤ 100 counts per minute, equivalent to ≤ 1.5 metabolic equivalents). 85

Adverse events and serious adverse events

An AE was defined as any unfavourable and unintended sign, symptom, syndrome or illness that developed or worsened during the observation period of the trial. This included:

-

exacerbation of a pre-existing illness

-

an increase in frequency or intensity of a pre-existing condition

-

a condition detected or diagnosed after the trial started (but which might have been present at baseline)

-

a persistent disease or symptoms present at baseline that worsened following the start of the trial.

A SAE was defined as any AE occurring during the trial for any of the three groups that resulted in any of the following outcomes:

-

death

-

a life-threatening AE

-

inpatient hospitalisation or prolongation of existing hospitalisation

-

a new disability/incapacity.

All AEs were assessed for seriousness, expectedness and causality. All AEs were recorded and closely monitored until resolution or stabilisation, or until it had been shown that the study intervention was not the cause. Participants were asked to contact the trial site immediately in the event of any SAE. The chief investigator was informed immediately and determined seriousness and causality in conjunction with two other medically trained trial investigators. A SAE that was determined to be directly or possibly trial related was reported, within agreed time frames, to the TSC and the ethics committee. All SAEs were reported annually to the TSC, ethics committee and the trial sponsor.

Although it was important to record AEs contemporaneously for trial safety monitoring during the trial, there was a risk of bias in their reporting, with those having nurse contact having more opportunities for reporting falls, injuries and illnesses. For analyses and reporting, we therefore concentrated on measures for which there were fewer risks of bias between groups: (1) spontaneously reported SAEs, (2) falls, fractures and injuries from questionnaire self-report at 3 and 12 months and (3) falls, fractures, injuries, cardiovascular events (new episode of any of the following: myocardial infarction, angioplasty, coronary artery bypass, stroke, transient ischaemic attack, new-onset angina, ischaemic heart disease) and deaths from primary care records after the 12-month follow-up point.

Sample size

A total of 217 patients in each of the three trial arms would allow a difference of 1000 steps per day to be detected between any two arms of the trial, with 90% power at the 1% significance level. However, we planned to randomise households. Assuming an intracluster correlation of 0.5 and an average household size of 1.6 eligible patients, we needed to analyse 282 patients per trial arm. Allowing for approximately 15% attrition, we needed to randomise a total of 993 patients (331 control participants, 331 participants receiving a pedometer by post and 331 participants receiving a pedometer plus nurse support). We initially planned on six practices to each recruit approximately 166 patients (approximately 55 participants to each of the three groups), but to enable target recruitment, a seventh practice was added.

We anticipated a 20% recruitment rate among eligible participants, based on other PA interventions (including with pedometers) among middle-aged and older adults in primary care, where the recruitment rate was between 17% and 35%. 21,33,86–89 We estimated that, even if our recruitment rate was as low as 10%, we would have enough eligible participants at practices. In fact, the recruitment rate dipped to below 10%, so a seventh practice was added.

Randomisation, concealment of allocation, contamination and treatment masking

Randomisation and concealment of allocation

Following completion of the baseline assessment (including providing accelerometry data on ≥ 5 complete days of ≥ 9 hours/540 minutes), each participant was allocated to a trial group using the King’s College London clinical trials unit internet randomisation service, to ensure independence of the allocation. If participants were unable to provide at least 5 days of ≥ 540 minutes wear time on accelerometry, they were asked to wear the accelerometer for a further 7 days, or they were excluded if this was not possible. Randomisation was at a household level. Randomisation of a group household took place only after both members of the household had completed the baseline assessment. Block randomisation was used within the practice with randomly sized blocks (2, 4 or 6) to ensure balance in the groups and an even nurse workload. Participants were informed by telephone which group they had been allocated to.

Contamination

Contamination could occur between partners in a household; we minimised this by ensuring that, if two household members were recruited, they were allocated to the same group (i.e. randomisation was at a household level). Contamination would have occurred if the control group used a pedometer to increase their walking during the 12-month trial follow-up. We tried to discourage participants in the control group from buying a pedometer, by ensuring that they knew that they would receive one at the end of follow-up. A question was included in the 12-month questionnaire to ask if they had used a pedometer during the course of the trial.

Treatment masking

Participants were randomised only after the successful return of accelerometers with 5 days’ recording. It was not possible to mask participants to their intervention group. The research assistants who carried out follow-up assessments were not masked to group allocation for pragmatic reasons alone: the study was funded to support only enough researchers to carry out recruitment and follow-up simultaneously. However, the main outcome was assessed objectively through accelerometry, and the assessment of the quality of the outcome data was done blind to intervention group: days with < 9 hours of data were excluded. Weight and body fat were also assessed objectively using the Tanita scales, which provided electronic printouts of results, and other outcomes were assessed using standardised measures (e.g. patient-reported outcomes from questionnaires). The statistician carrying out the primary analyses was masked to group allocation as far as possible.

Withdrawals, losses to follow-up and missing data

Withdrawals and losses to follow-up

Participants could withdraw from the trial at any point. Participants who withdrew following informed consent, and prior to randomisation, were replaced with another participant. Participants who withdrew after randomisation were not replaced and were asked if they were prepared to contribute to further data collection on outcomes at 3 and 12 months. Participants were made aware that withdrawal from the trial would not affect future care and that information on those who withdrew or were lost to follow-up that had already been collected would still be used, unless consent for this was withdrawn.

Procedure for accounting for missing data

Only days with at least 540 minutes of registered time on an accelerometer on a given day were used, which was consistent with previous work (the PACE-LIFT trial,21 Trost et al. 90 and Miller et al. 91). Participants were randomised only if they provided at least 5 such days of accelerometer data at baseline. A multilevel linear regression model was used, taking account of repeated days within individuals to estimate the baseline average daily step count for each subject, adjusted for the day of the week and the day order of wearing the accelerometer. The same approach was used to estimate the average daily step count at 3 months and 12 months. The main covariates – age, sex, practice, month of baseline accelerometry and whether or not participants were taking part as a couple – were known for all participants, and most patients had complete data for other measures. To lessen attrition bias, the primary analysis included all participants with at least 1 satisfactory day of accelerometry recording at 12 months (i.e. a wear time of ≥ 540 minutes). The main analysis assumed that, depending on the model covariates, outcome data were missing at random. This was likely to be true for missing data as a result of accelerometer failure, and was plausible for missing days and participants who did not return accelerometers. However, an alternative plausible assumption is that participants who failed to provide outcome data were less active. Multiple imputation was used to impute values for those with no accelerometer data at 12 months (see Statistical methods, Sensitivity analyses). Further sensitivity analyses examined the impact of assuming that missing step counts at 12 months in the control group were equal to their baseline values and, in the two intervention groups, varied between 1500 steps lower and 1500 steps higher than their baseline values.

Statistical methods

The analysis and reporting was in line with the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) guidelines, with the primary analysis on an intention-to-treat basis. That is, all participants with outcome data were included, regardless of their adherence to the interventions. All participants were included in the primary analysis if they had at least 1 satisfactory day of accelerometer recording (≥ 540 minutes) of registered time during a day, out of 7 days, at 12 months. The adequacy of the randomisation process to achieve balanced groups was checked by comparing participant characteristics in the three arms (e.g. sex, age, socioeconomic group, baseline PA level or BMI). Stata®, version 12 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA) was used for all analyses.

Primary analysis

The primary outcome measure was change in average daily step count from baseline to the 12-month follow-up point measured over 7 days. However, to overcome Lord’s paradox,92 the analytic approach regressed 12-month outcomes on baseline measures, thus allowing for regression to the mean. Eligibility was defined on the basis of ≥ 5 days with ≥ 540 minutes’ activity at baseline. If the participant was asked to wear the accelerometer for a second time, the second 7 days was used in the analysis. If there were > 7 days’ wear on the accelerometer, then the first 7 days were used and later readings were discarded. The primary analysis used all participants providing at least 1 day of ≥ 540 minutes accelerometry wear time at 12 months (i.e. a complete-case analysis).

All analyses were carried out using Stata, version 12. The xtmixed procedure was used for regression models. A two-stage process was used for accelerometry data. Stage 1 estimated the average daily step count at both baseline and 12 months, using a multilevel model in which daily step counts were regressed on day of the week and day order of wearing the accelerometer (from day 1 to day 7) as fixed effects, and with day within individual as the random effect (i.e. level 1 was the day within individual and level 2 was individual). In stage 2, average daily step count at 12 months was regressed on baseline average daily step count, sex, age, general practice, month of baseline accelerometry and treatment group as fixed effects, and household as the random effect, to allow for clustering at a household level (i.e. level 1 was individual and level 2 was household). This method effectively measured the change in step count from baseline to 12 months, minimising bias and maintaining power. Adjusting for baseline steps controlled for many factors that predict the number of steps in cross-sectional analyses (e.g. BMI, socioeconomic group, health status). The reference group for the intervention group comparisons was the control group. The post-estimation command pwcompare was used to obtain the estimates of change with 95% CIs and p-values for the difference in change in steps for the postal group versus the control group, the nurse-support group versus the control group and the nurse-support group versus the postal group. This last comparison provided information on whether or not the nurse intervention promoted a worthwhile increase in activity compared with a pedometer alone. It should be noted that, although this estimate can be obtained from the difference of the first two estimates, pwcompare also provided 95% CIs for this comparison. Checks were carried out to confirm that the distribution of residuals from the regression model for change in steps was normally distributed.

Secondary and ancillary outcome analyses

Secondary PA outcome measures from accelerometry were total weekly minutes of MVPA in ≥ 10-minute bouts, average daily sedentary time at 12 months and steps, MVPA in bouts and sedentary time at 3 months. These data were processed and analysed in the same way as described for the step counts (see Primary analysis). MVPA was highly positively correlated with step counts and sedentary time was negatively correlated with step counts.

Other ancillary outcomes were changes in exercise self-efficacy, anxiety, depression, perceived health status (health-related quality of life, as measured using the EQ-5D-5L), self-reported pain, anthropometric measures (weight, BMI, waist circumference, body fat) and self-reported PA from the IPPAQ and GPAQ questionnaires. Changes in these outcomes from baseline to 3 and 12 months were analysed using identical models to stage 2, as described in Primary analysis (i.e. level 1 was individual and level 2 was household).

Adverse event analyses

The number of participants who suffered an AE between 0 and 3 months or between 0 and 12 months (a spontaneously reported SAE or a systematically reported SAE from the 3- or 12-month questionnaire, or a SAE collected from the primary care record data) was compared between groups using exact tests for categorical tables.

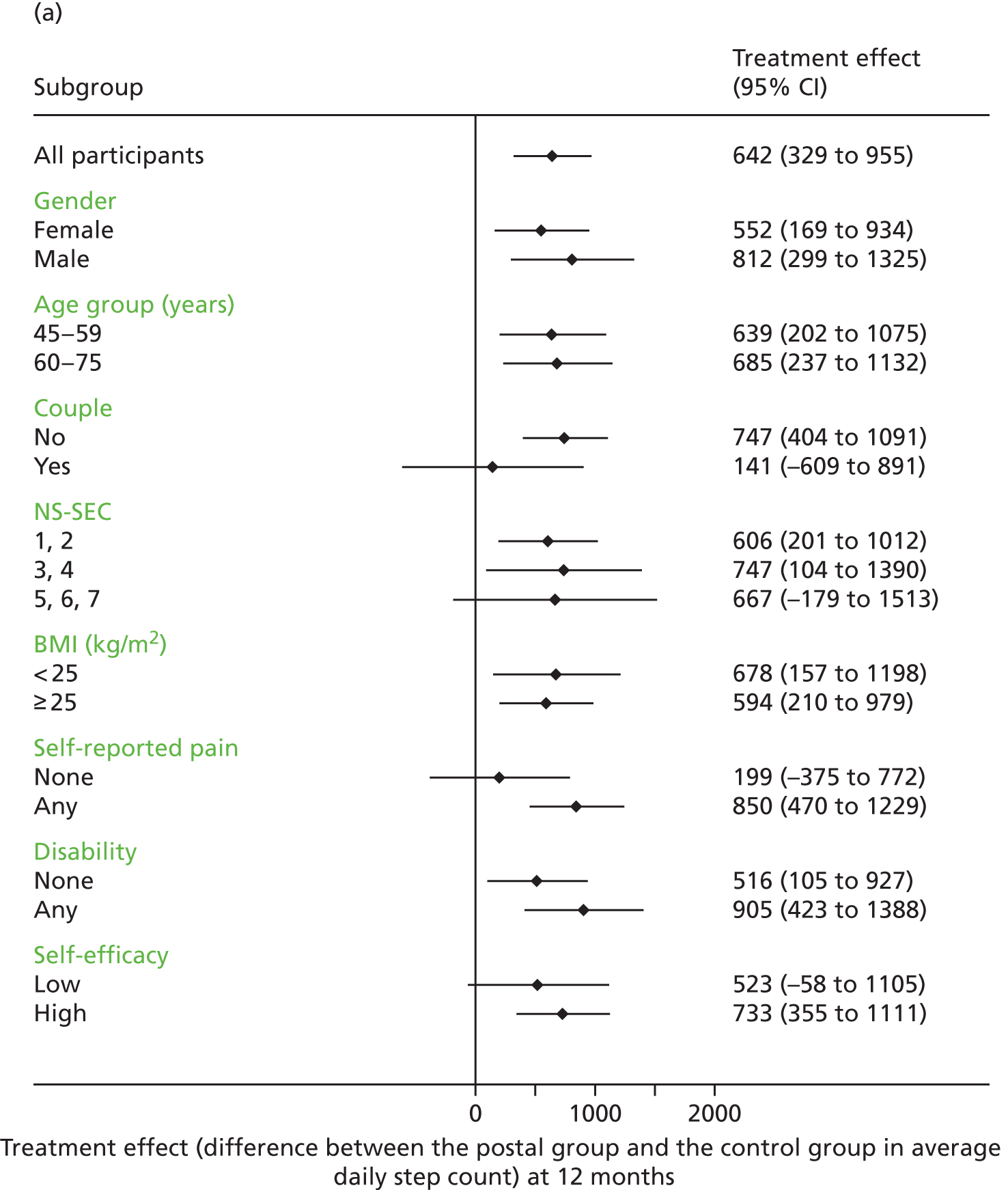

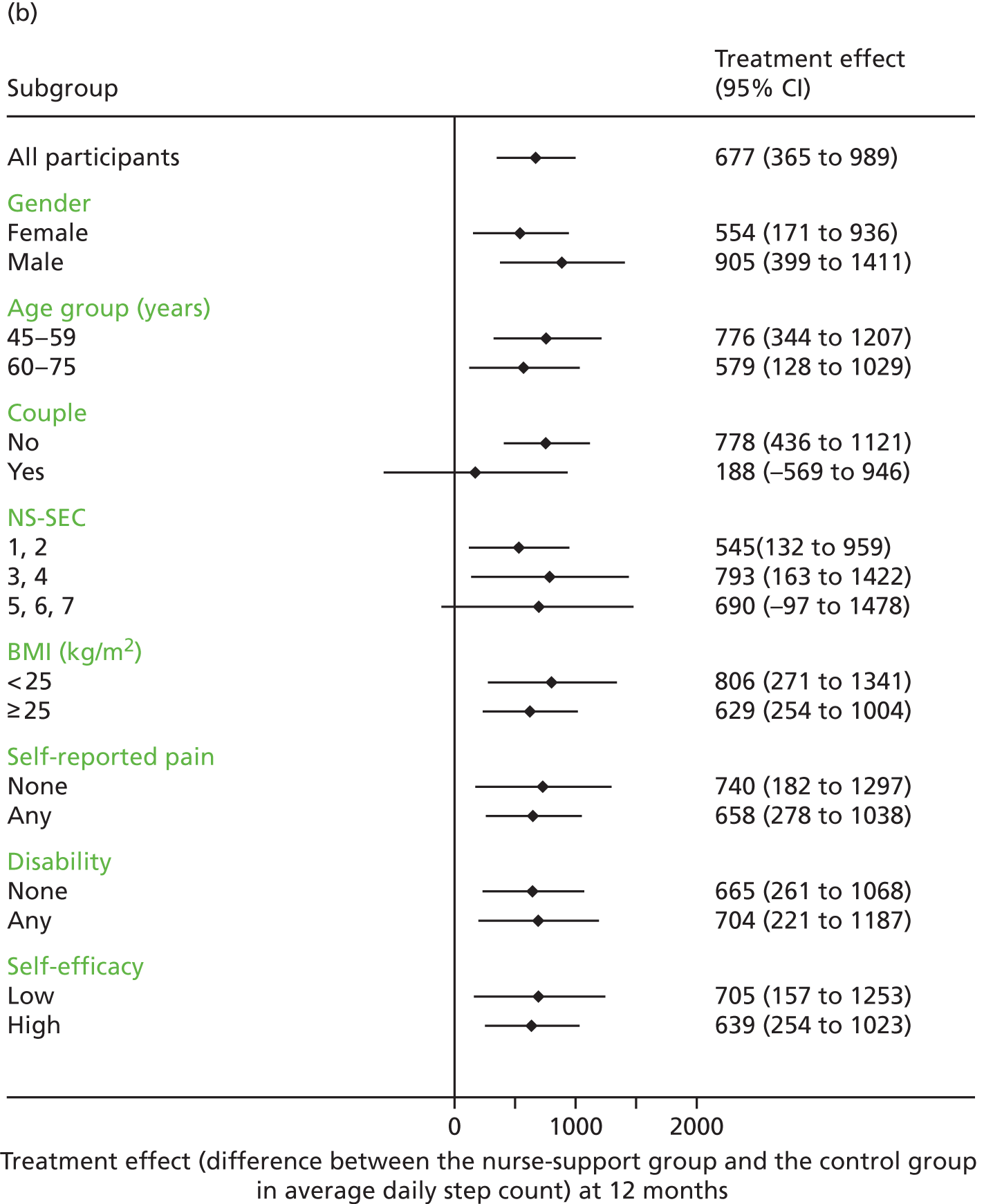

Subgroup analyses

Sex, age groups (< 60 years or ≥ 60 years), taking part as a couple, socioeconomic subgroups, BMI, disability, pain and exercise self-efficacy were examined as potential effect modifiers by adding interaction terms to the regression model for the primary outcome, which was changes in step counts at 12 months.

Sensitivity analyses

Sensitivity analyses were carried out for the primary outcome (change in step counts from baseline to 12 months). The effects of using different criteria for defining satisfactory wear at 12 months were examined as follows: (1) at least 5 days of ≥ 540 minutes’ wear time, (2) ≥ 1 day of ≥ 600 minutes’ wear time and (3) ≥ 5 days of ≥ 600 minutes’ wear time. The effect of adjusting for change in wear time between baseline and 12 months was also examined.

Additional sensitivity analyses assessed whether participants lost to follow-up or who failed to provide a single adequate day’s recording might have introduced bias. This was first done by assuming that outcome data were missing at random, depending on the model covariates, using the Stata procedure mi impute. The first model used the standard model covariates to impute missing step counts at 12 months (treatment group, baseline steps, sex, age, general practice, month of baseline accelerometry and household as a random effect) and the second model added in the National Statistics Socio-economic Classification (NS-SEC), self-reported pain and fat mass as additional covariates. Further analyses explored the possible impact of outcomes not being missing at random, using the following assumptions: among those with missing data in the control group, the change in mean steps from baseline to 12 months was 0, and among those with missing data in each of the intervention groups, the change in mean steps from baseline to 12 months was –1500, 0 or +1500.

Ethics approval and research governance

Ethics approval was granted for the trial from London, Hampstead Research Ethics Committee (reference number 12/LO/0219). The NHS Research and Development approval was granted by the Clinical Commissioning Groups in south-west London, through the Primary Care Research Network, to cover all the practice sites.

Management of the trial

The trial progress, including recruitment, safety, finance and data management, was reviewed regularly by the trial management group (TMG). This was made up of the chief investigator, two trial investigators, the trial statistician and the trial manager. The TMG met on a monthly basis. All of the trial investigators met as a group (the trial investigator group) on a biannual basis, and the TSC met prior to participant recruitment, and then annually or biannually as necessary. Minutes were kept of all TMG, trial investigator group and TSC meetings. The TSC included a patient advisor and more details of their role in terms of patient and public involvement are given in Appendix 1.

Further trial follow-up at 3 years

After the initial trial results were analysed, funding was obtained to follow up the trial cohort at 3 years. Details of the methods and results for this further follow-up are given in Chapter 8.

Chapter 3 Results

The main results from the PACE-UP trial are published,93 and are reproduced here under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided that the original author and source are credited.

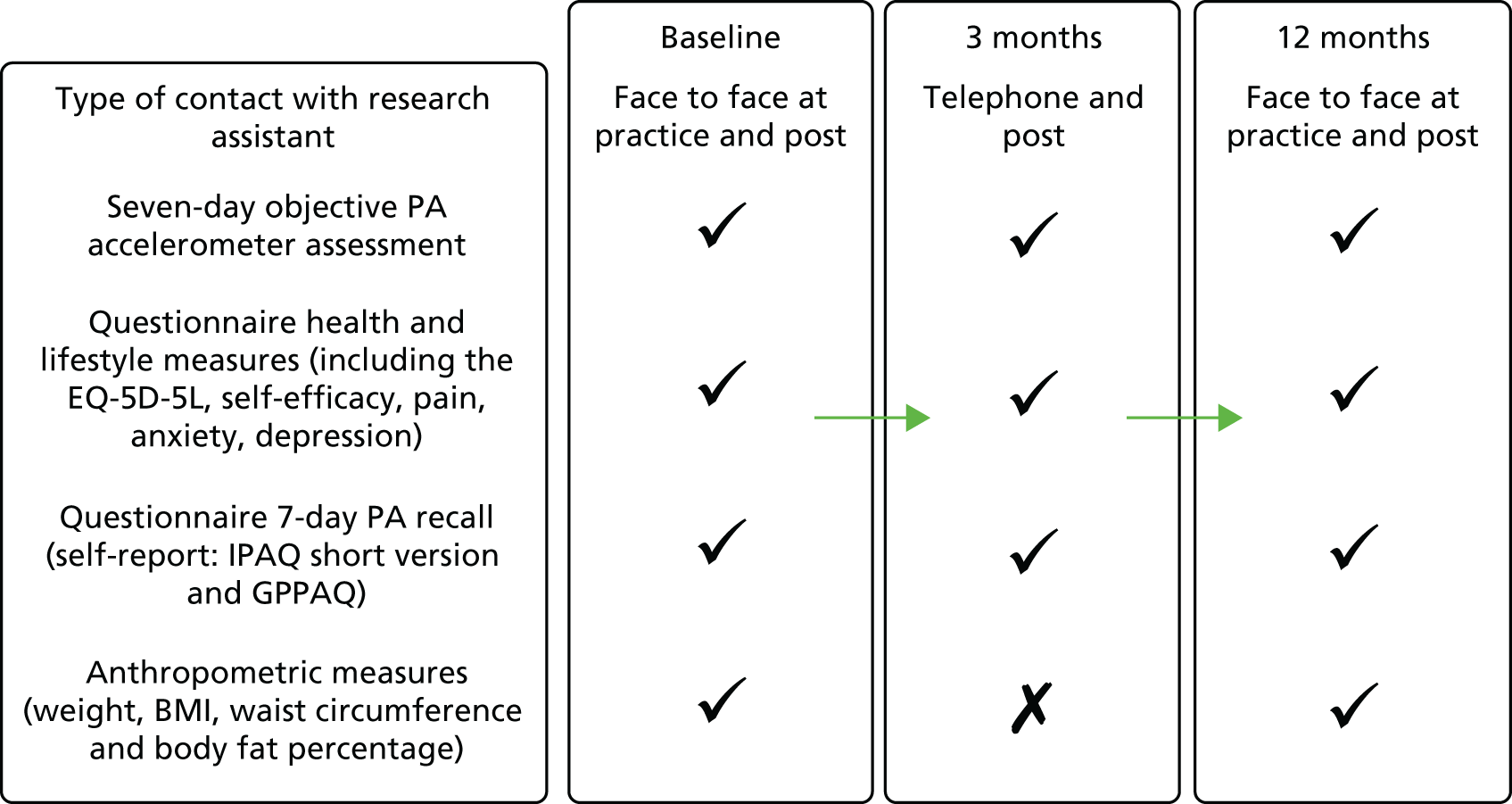

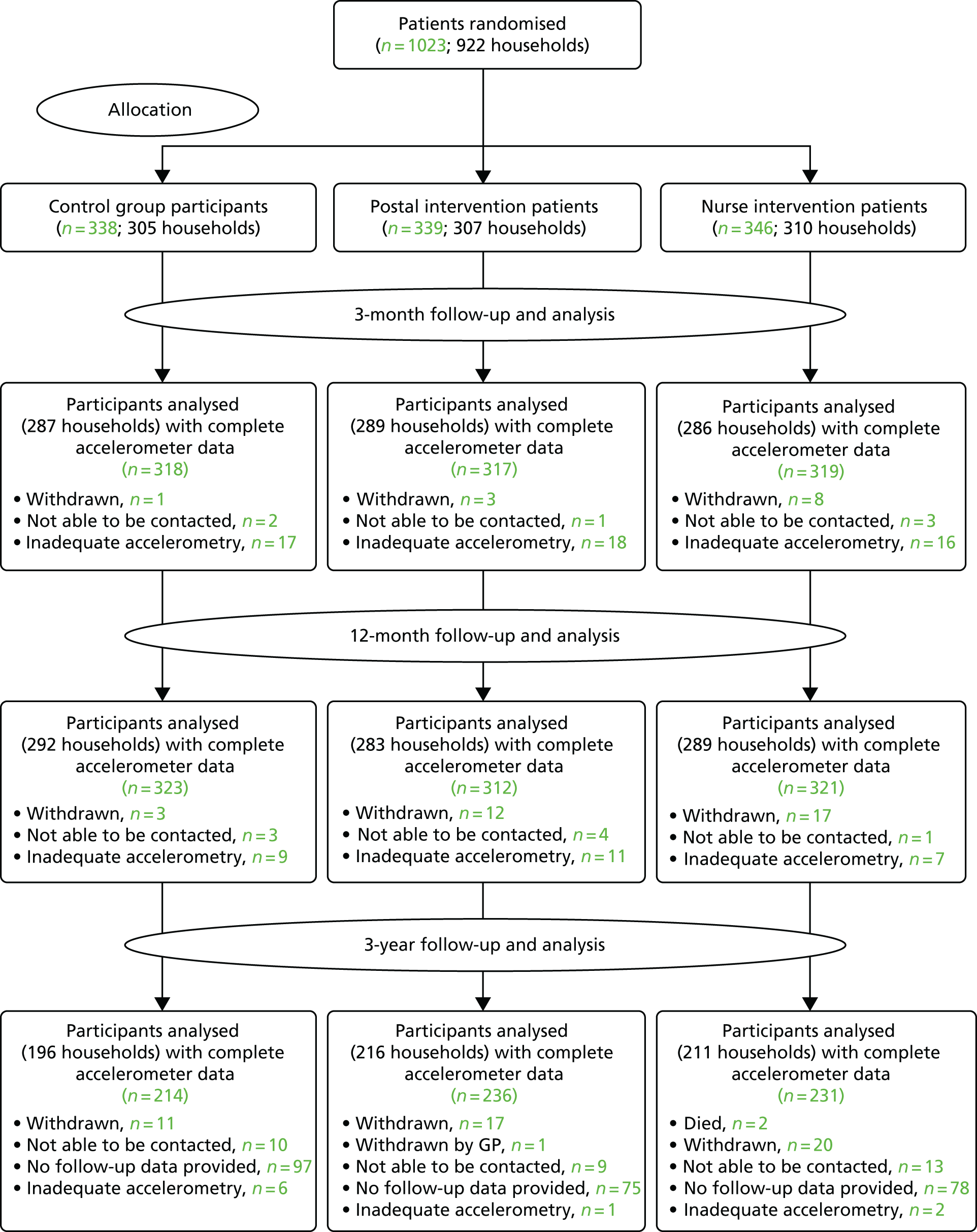

Recruitment of participants

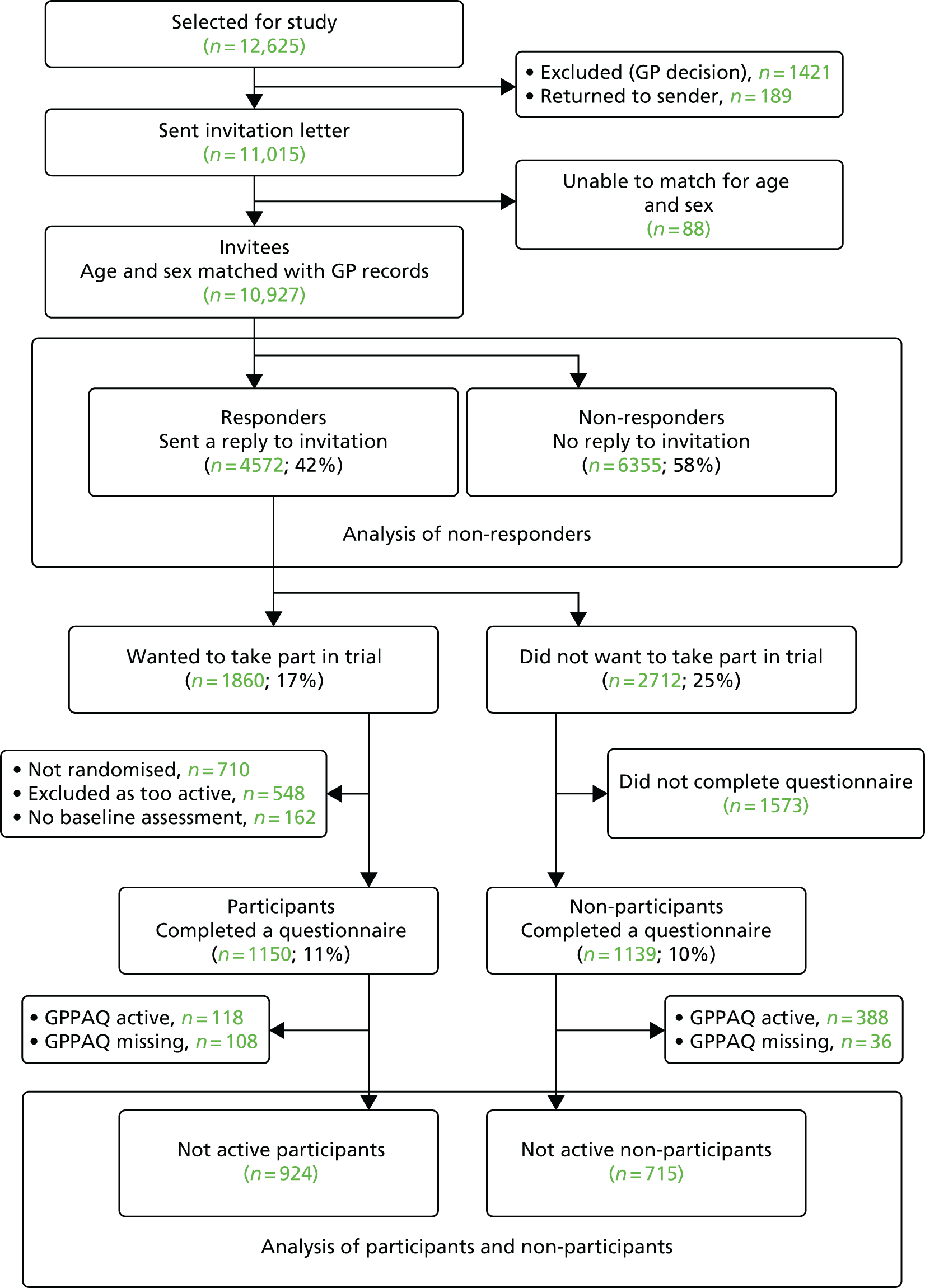

The CONSORT diagram of participant flow (Figure 3) shows that of the 11,015 people invited to participate, 6399 did not respond and 548 were excluded as a result of self-reported PA guideline achievement; therefore, 1023 out of 10,467 (10%) were randomised.

FIGURE 3.

The PACE-UP trial CONSORT flow diagram. Adapted from Harris et al. 93 This is an open access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, provided the original work is properly cited. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0.

Baseline characteristics of the study population (Table 4)

Participants recruited to the trial were evenly spread across the age groups. Just over one-third of those recruited were men, around two-thirds were married and around one-fifth took part in the trial as a couple. The majority were in full- or part-time employment, mostly in high-level manual, administrative or professional jobs, with a minority in intermediate or routine and manual occupations. About 80% of those recruited were of white ethnicity, around 10% were black/African/Caribbean or black British and approximately 7% were Asian or Asian British. In terms of health factors, just under 10% were current smokers, around 80% reported their health as being good or very good, the majority had one or more chronic disease and some self-reported pain, around 60% reported no current disability, around 10% had a high depression score, around 20% had a high anxiety score, and around two-thirds of participants were overweight or obese. Recruitment occurred throughout all four seasons, but was slightly higher in summer and slightly lower in winter. All of these factors were well balanced between the three randomised groups.

| Characteristic | Trial arm | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Control (N = 338) | Postal (N = 339) | Nurse (N = 346) | |

| Age (years) at randomisation, n (%) | |||

| 45–54 | 101 (30) | 118 (35) | 121 (35) |

| 55–64 | 138 (41) | 125 (37) | 124 (36) |

| 65–75 | 99 (29) | 96 (28) | 101 (29) |

| Sex (male) , n (%) | 115 (34) | 124 (37) | 128 (37) |

| Marital status (married), n (%) | 213 (64) | 215 (65) | 230 (68) |

| Randomised as a couple,a n (%) | 66 (20) | 68 (20) | 73 (21) |

| Employment status,79 n (%) | |||

| In full- or part-time employment | 190 (57) | 193 (59) | 190 (56) |

| Retired | 102 (31) | 96 (29) | 101 (30) |

| Other | 39 (12) | 39 (12) | 50 (15) |

| NS-SEC (current or previous job),79 n (%) | |||

| High-level managerial, administrative, professional | 199 (62) | 191 (60) | 184 (56) |

| Intermediate occupations | 70 (22) | 85 (27) | 95 (29) |

| Routine and manual occupations | 51 (16) | 44 (14) | 52 (16) |

| Ethnicity,79 n (%) | |||

| White | 253 (78) | 270 (83) | 267 (80) |

| Black/African/Caribbean/black British | 30 (9) | 31 (10) | 40 (12) |

| Asian/Asian British | 26 (8) | 20 (6) | 22 (7) |

| Other | 15 (5) | 4 (1) | 6 (2) |

| Current smoker, n (%) | 27 (8) | 29 (9) | 26 (8) |

| General health:79 very good or good, n (%) | 265 (80) | 277 (84) | 277 (82) |

| Chronic diseases, n (%) | |||

| None | 129 (39) | 135 (41) | 117 (35) |

| One or two | 183 (55) | 171 (51) | 188 (55) |

| ≥ 3 | 21 (6) | 27 (8) | 34 (10) |

| Presence of self-reported pain,77 n (%) | 220 (66) | 236 (71) | 234 (70) |

| Limiting long-standing illness,79 n (%) | 76 (23) | 73 (22) | 74 (22) |

| Townsend disability score,80 n (%) | |||

| None (0) | 190 (57) | 196 (59) | 210 (62) |

| Slight or some disability (1–6) | 127 (38) | 130 (39) | 124 (36) |

| Appreciable or severe disability (7–18) | 15 (5) | 8 (2) | 7 (2) |

| HADS depression score:75 borderline or high, n (%) | 36 (11) | 33 (10) | 42 (12) |

| HADS anxiety score:75 borderline or high, n (%) | 65 (19) | 64 (19) | 71 (21) |

| Low self-efficacy score,74 n (%) | 102 (31) | 96 (29) | 117 (35) |

| Month of baseline measure, n (%) | |||

| March–May | 80 (24) | 75 (22) | 76 (22) |

| June–August | 105 (31) | 106 (31) | 110 (32) |

| September–November | 88 (26) | 82 (24) | 92 (27) |

| December–February | 65 (19) | 76 (22) | 68 (20) |

| Physical characteristics | |||

| Overweight/obese: BMI of ≥ 25 kg/m2, n (%) | 227 (67) | 221 (65) | 233 (67) |

| Fat mass (kg), mean (SD) | 26 (10) | 27 (11) | 26 (11) |

| Waist circumference (cm), mean (SD) | 93 (14) | 94 (14) | 93 (13) |

| PA data | |||

| Accelerometry | |||

| Adjusted baseline step count per day, mean (SD) | 7379 (2696) | 7402 (2476) | 7653 (2826) |

| Total weekly minutes of MVPA in ≥ 10-minute bouts, mean (SD) | 84 (97) | 92 (90) | 105 (116) |

| Average daily sedentary time (minutes), mean (SD) | 613 (68) | 614 (71) | 619 (78) |

| Average daily wear time (minutes), mean (SD) | 789 (73) | 787 (78) | 797 (84) |

| 150 minutes of MVPA in ≥ 10-minute bouts (yes), n % | 61 (18) | 68 (20) | 89 (26) |

| IPAQ score72 | |||

| IPAQ MVPA score: total weekly minutes of MVPA in ≥ 10-minute bouts (N = 909), mean (SD) | 197 (314) | 147 (256) | 172 (279) |

| IPAQ walking score: total weekly minutes of walking in ≥ 10-minute bouts (N = 888), mean (SD) | 333 (333) | 330 (338) | 312 (277) |

| 150 weekly minutes of IPAQ MVPA score (N = 909): yes, n (%) | 110 (37) | 91 (30) | 109 (35) |

| 150 weekly minutes of IPAQ walking score (N = 888): yes, n (%) | 193 (65) | 190 (66) | 208 (69) |

| GPPAQ score,73 n (%) | |||

| PAI score (N = 973) | |||

| Inactive | 159 (49) | 153 (48) | 156 (47) |

| Moderately inactive | 69 (21) | 66 (21) | 83 (25) |

| Moderately active | 50 (16) | 63 (20) | 60 (18) |

| Active | 44 (14) | 36 (11) | 34 (10) |

| PAI score, including walking (GPPAQ walking score; N = 973) | |||

| Inactive | 129 (40) | 134 (42) | 133 (40) |

| Moderately inactive | 57 (18) | 56 (18) | 63 (19) |

| Moderately active | 43 (13) | 49 (15) | 47 (14) |

| Active | 93 (29) | 79 (25) | 90 (27) |

In terms of objectively measured baseline PA levels, the nurse-support group had a slightly higher baseline-adjusted average daily step count [7653 steps, standard deviation (SD) 2826 steps] and minutes spent weekly in MVPA in bouts of ≥ 10 minutes (105 minutes, SD 116 minutes) than the postal group (7402 steps, SD 2476 steps; 92 minutes, SD 90 minutes) and the control group (7379 steps, SD 2696 steps; 84 minutes, SD 97 minutes). A higher proportion of the nurse-support group participants were achieving the guidelines of ≥ 150 minutes per week of MVPA in bouts of ≥ 10 minutes (26%, 89/346) than participants in the postal group (20%, 68/339) and those in the control group (18%, 61/338). The three groups were similar in terms of average daily sedentary time, at around 10 hours per day.

In terms of self-reported PA levels the patterns were different, with the control group reporting the highest number of weekly minutes of MVPA on the IPAQ, not including walking; however, the nurse-support group reported higher levels of MVPA if walking was included. A slightly higher proportion of participants in the control group than those in the intervention groups reported being active on the GPPAQ PAI, both excluding and including walking.

Losses to follow-up

Figure 3 shows the losses to follow-up. Of the 1023 people randomised, 32 (3%) withdrew and eight (1%) were unable to be contacted at 12 months. In total, 956 out of 1023 participants (93%) provided at least 1 day of 540 minutes’ wear time accelerometer data and were included in the 12-month primary analyses.

Data completeness for accelerometry

Accelerometer wear time was similar between the groups at baseline, the 3-month follow-up point and the 12-month follow-up point (see Tables 4 and 5). Over 90% of all groups provided ≥ 5 days of ≥ 540 minutes’ wear time at 12 months (see Appendix 2, Table 23).

Effect of the intervention on accelerometer-assessed physical activity outcomes (Table 5)

Three-month (interim) outcomes

There were significant differences for the change in average daily step counts from baseline to 3 months between intervention groups and the control group: additional step counts (steps per day) were 692 steps (95% CI 363 to 1020 steps; p < 0.001) for the postal group and 1173 steps (95% CI 844 to 1501 steps; p < 0.001) for the nurse-support group, and the difference between the intervention groups was statistically significant (481 steps, 95% CI 153 to 809 steps; p = 0.004). Findings for the change in time in MVPA levels showed a similar pattern: additional MVPA in bouts of ≥ 10 minutes (minutes per week) was 43 minutes (95% CI 26 to 60 minutes; p < 0.001) for the postal group and 61 minutes (95% CI 44 to 78 minutes; p < 0.001) for the nurse-support group, and the difference between intervention groups was 18 minutes (95% CI 1 to 35 minutes; p = 0.04). There was no difference between the groups for the change in sedentary time. Summary data for the 3-month PA outcomes are shown in Appendix 2, Table 24.

| Outcome | Comparison between trial arms | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Postal vs. control | Nurse support vs. control | Nurse support vs. postal | ||||

| Effect (95% CI) | p-value | Effect (95% CI) | p-value | Effect (95% CI) | p-value | |

| Daily step count | ||||||

| 3 months | 692 (363 to 1020) | < 0.001 | 1173 (844 to 1501) | < 0.001 | 481 (153 to 809) | 0.004 |

| 12 months | 642 (329 to 955) | < 0.001 | 677 (365 to 989) | < 0.001 | 36 (–277 to 349) | 0.82 |

| Total weekly minutes of MVPA in ≥ 10-minute bouts | ||||||

| 3 months | 43 (26 to 60) | < 0.001 | 61 (44 to 78) | < 0.001 | 18 (1 to 35) | 0.04 |

| 12 months | 33 (17 to 49) | < 0.001 | 35 (19 to 51) | < 0.001 | 2 (–14 to 17) | 0.83 |

| Daily sedentary time (minutes) | ||||||

| 3 months | –2 (–12 to 7) | 0.59 | –7 (–16 to 3) | 0.16 | –4 (–13 to 5) | 0.38 |

| 12 months | 1 (–8 to 10) | 0.83 | –0.2 (–9 to 9) | 0.96 | –1 (–10 to 8) | 0.79 |

| Daily wear time (minutes) | ||||||

| 3 months | 2 (–8 to 12) | 0.69 | 4 (–6 to 14) | 0.40 | 2 (–8 to 12) | 0.65 |

| 12 months | 9 (–1 to 19) | 0.08 | 9 (–0.8 to 19) | 0.07 | 0.3 (–10 to 10) | 0.96 |

Twelve-month (main) outcomes

Both intervention groups increased their step counts between baseline and 12 months compared with the control group: additional step counts (steps per day) were 642 steps (95% CI 329 to 955 steps; p < 0.001) for the postal group and 677 steps (95% CI 365 to 989 steps; p < 0.001) for the nurse-support group, with no statistically significant difference between intervention groups (36 steps, 95% CI –277 to 349 steps; p = 0.82). Time spent in MVPA in bouts showed a similar pattern, that is, both intervention groups increased at 12 months compared with the control group: additional MVPA in bouts (minutes per week) was 33 minutes (95% CI 17 to 49 minutes; p < 0.001) for the postal group and 35 minutes (95% CI 19 to 51 minutes; p < 0.001) for the nurse-support group, with no statistically significant difference between the two intervention groups (2 minutes, 95% CI –14 to 17 minutes; p = 0.83). Again, there was no difference between the groups for the change in sedentary time. Summary data for the 12-month PA outcomes are shown in Appendix 2, Table 24.

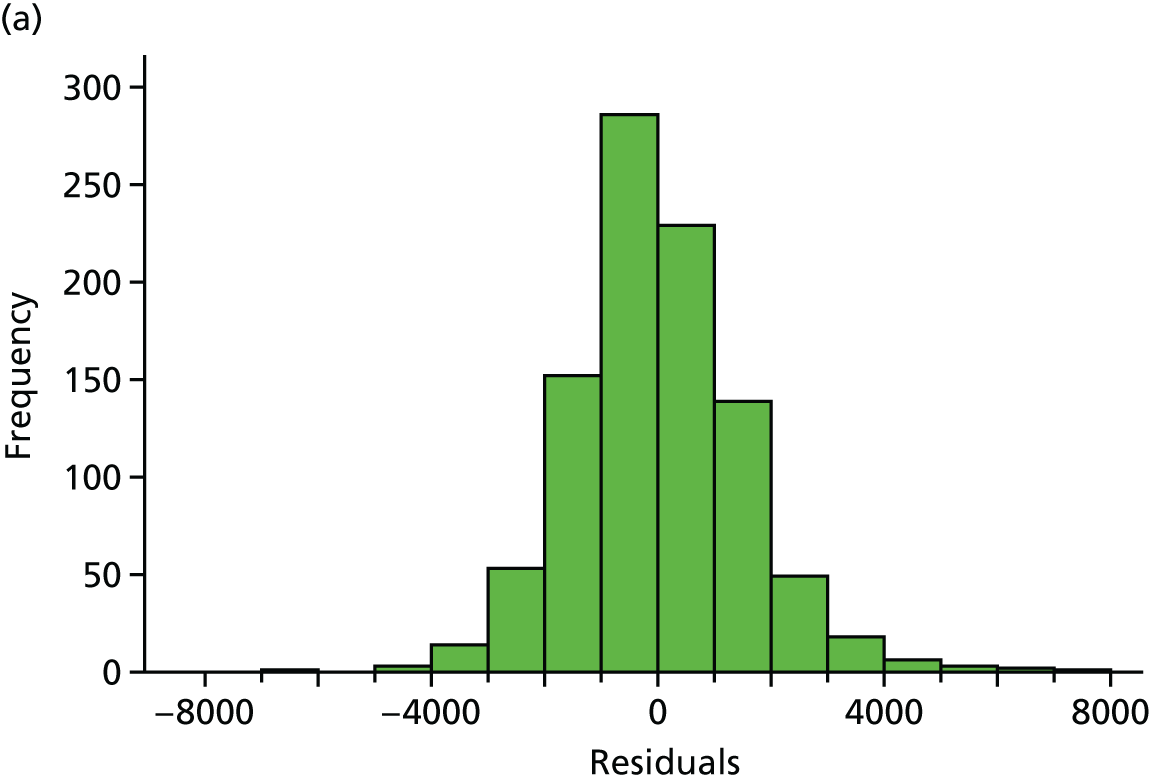

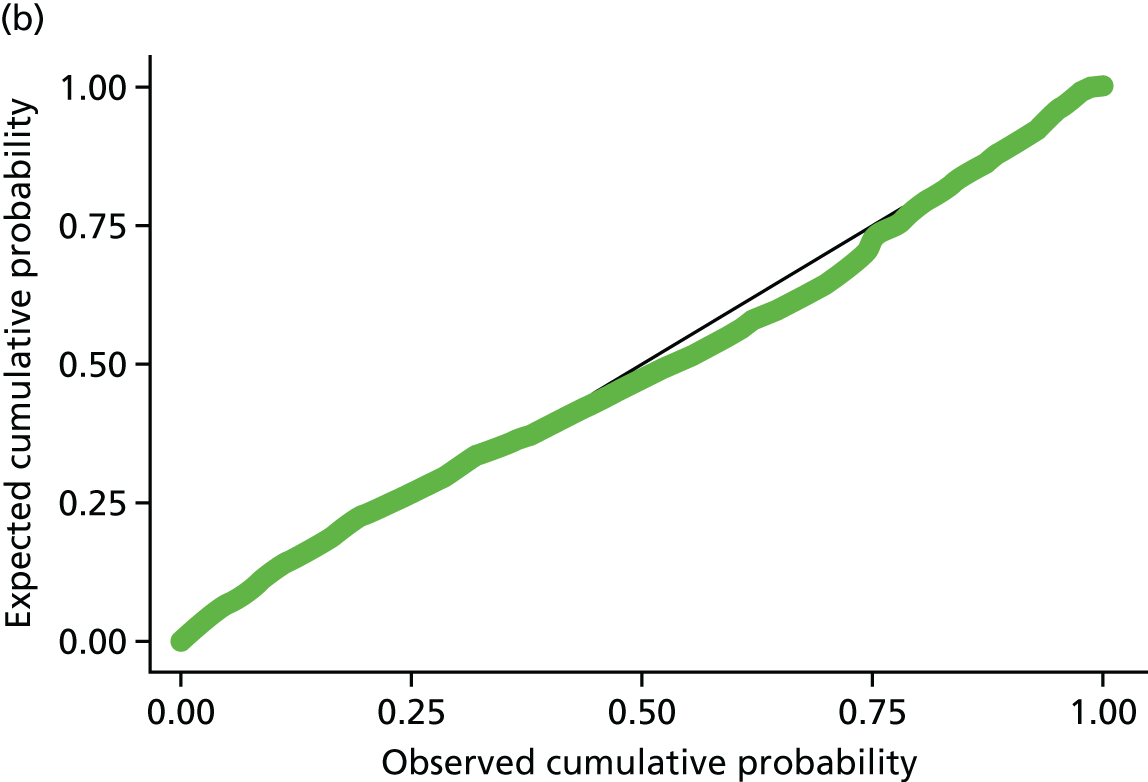

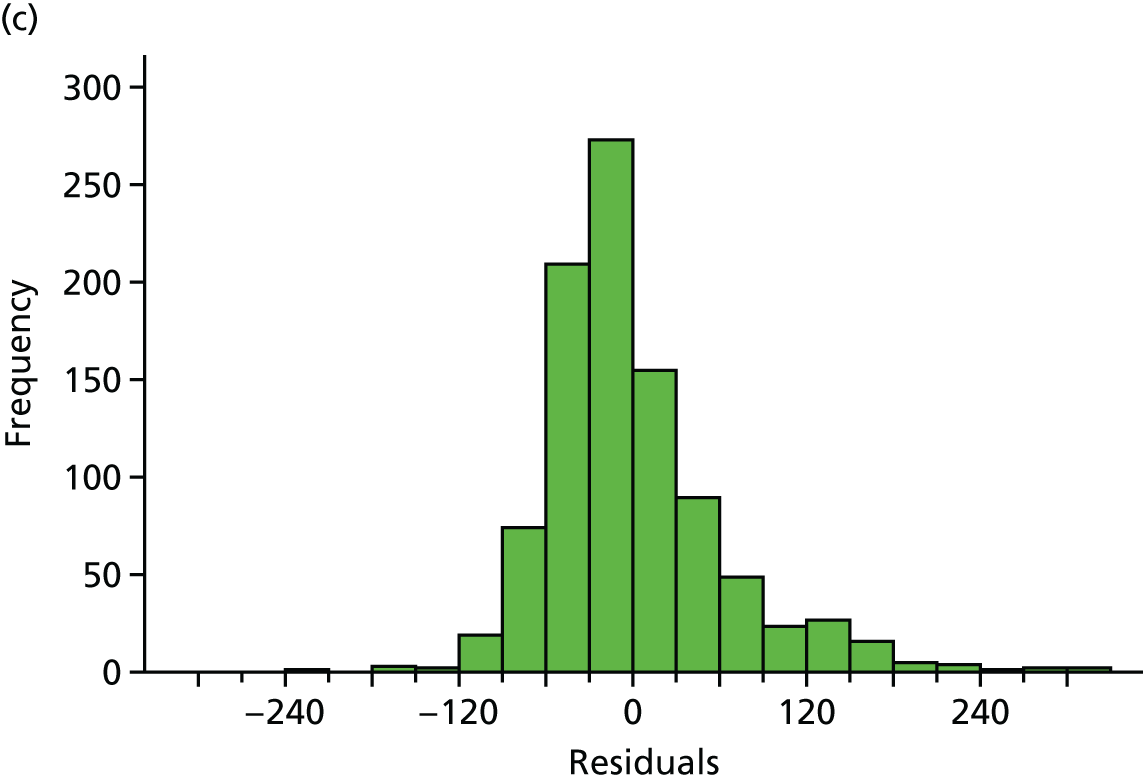

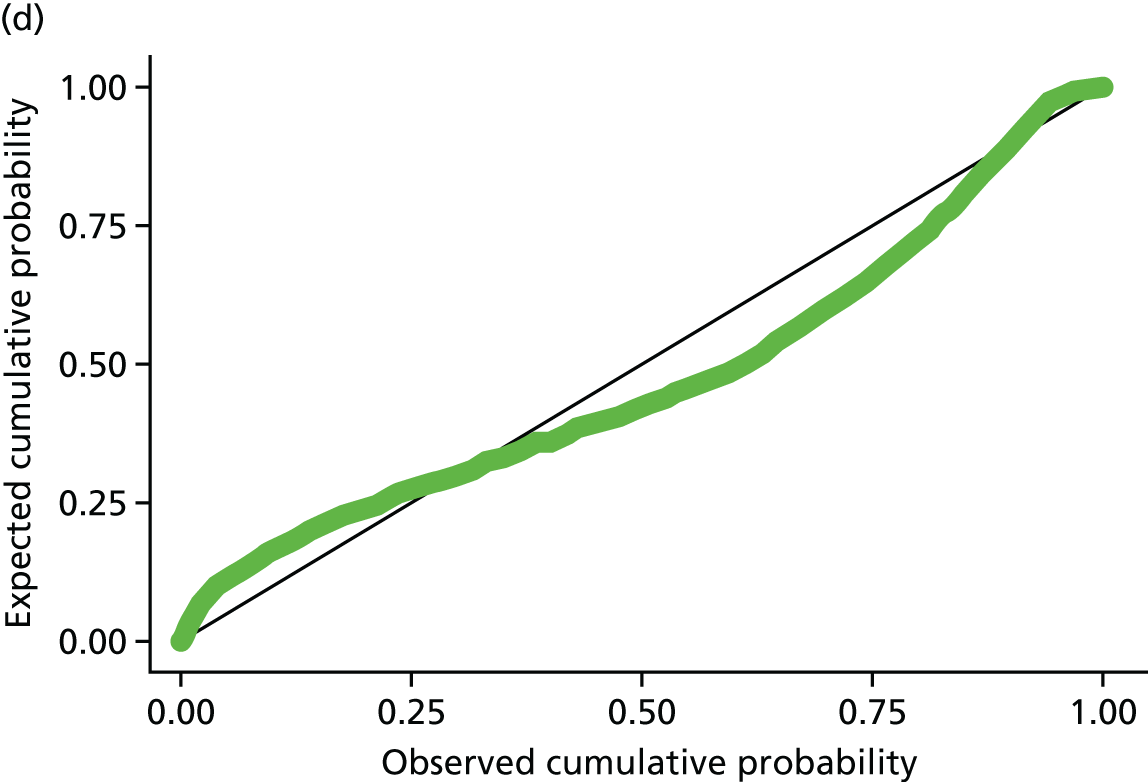

Residuals from the 12-month models for steps and weekly MVPA in ≥ 10-minute bouts were plotted, and the distribution of residuals from both models was normally distributed (see Appendix 2, Figure 18).

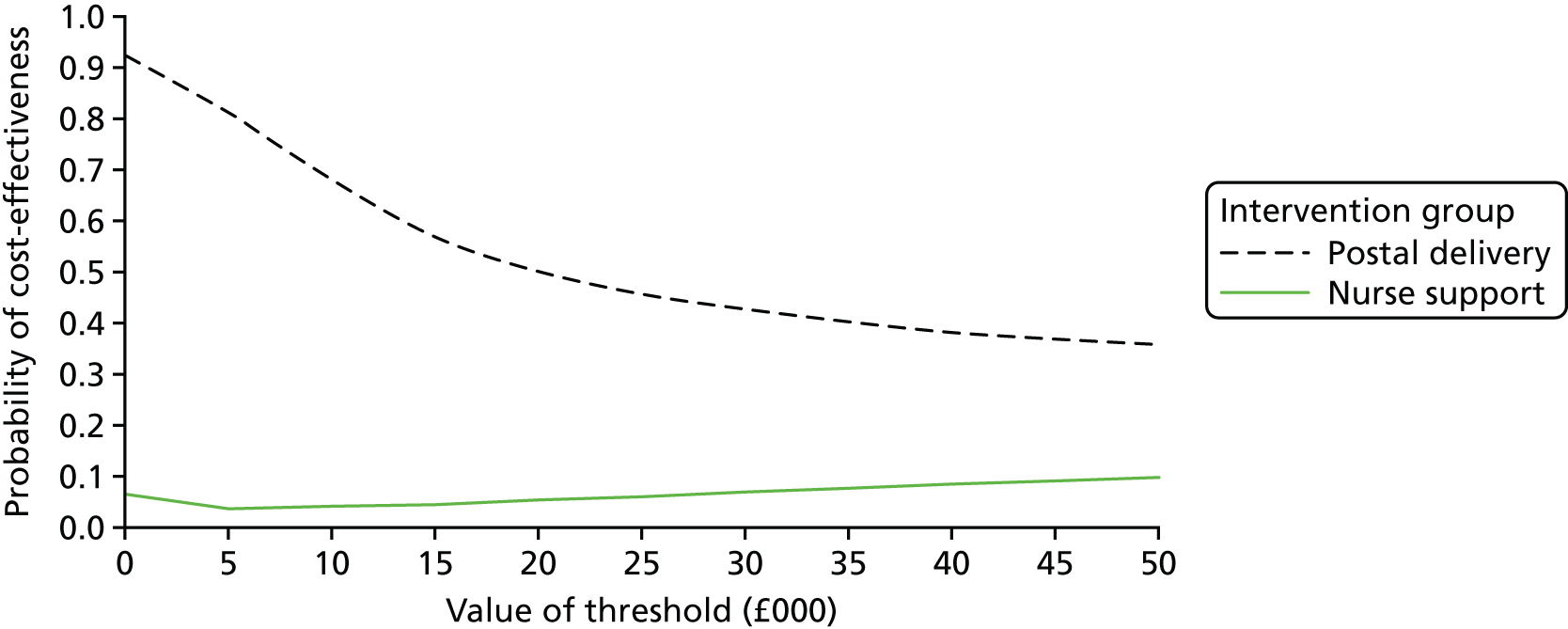

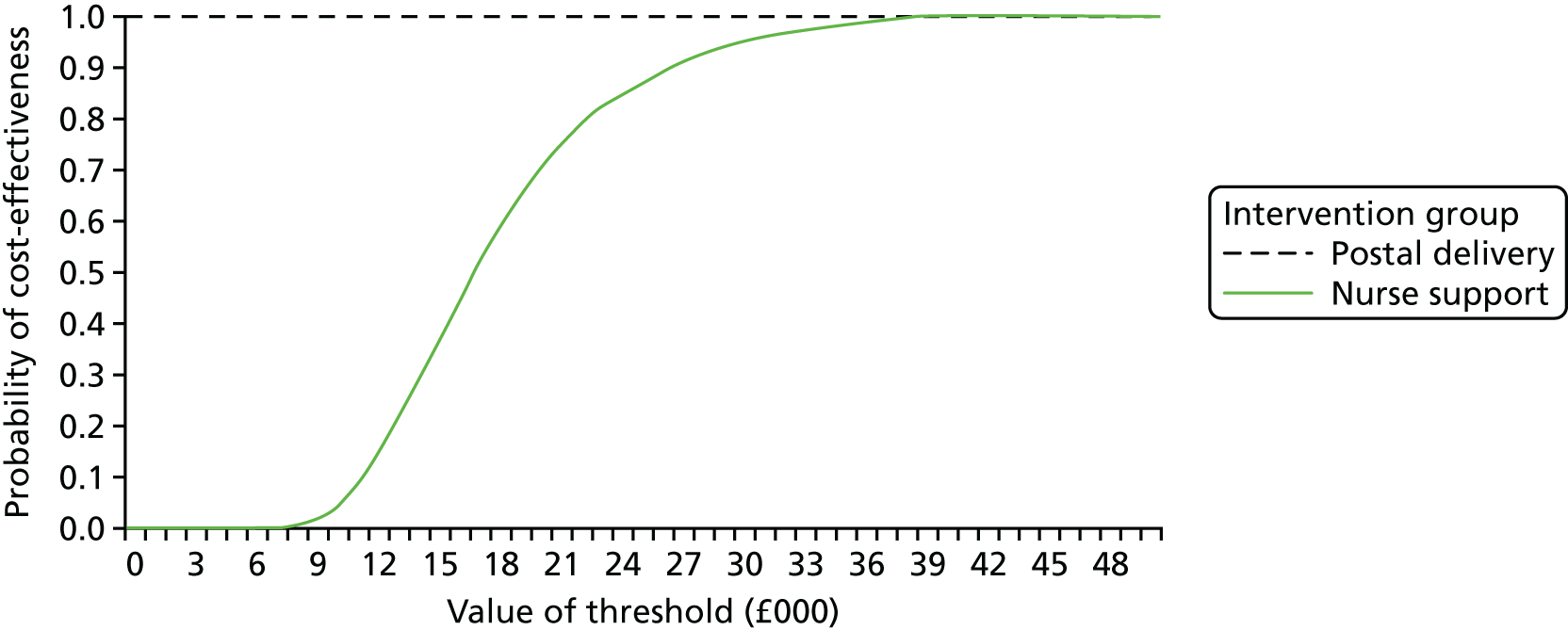

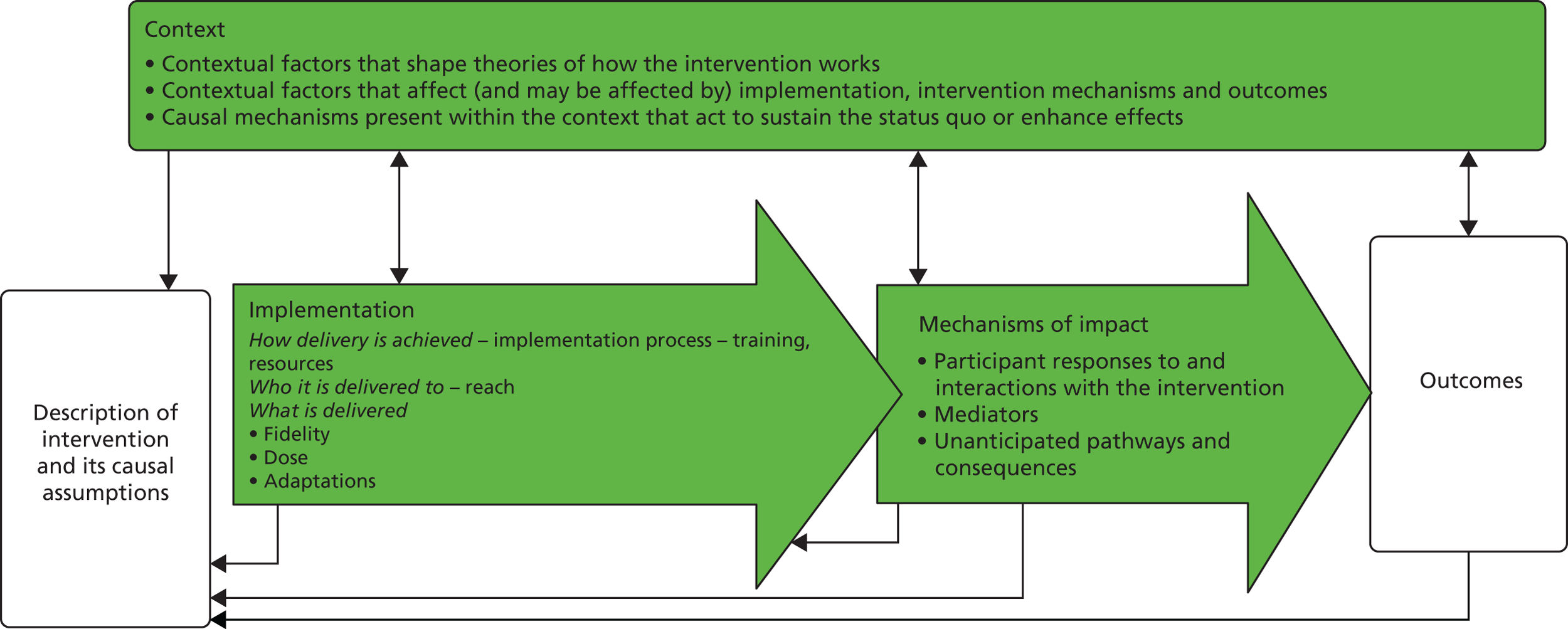

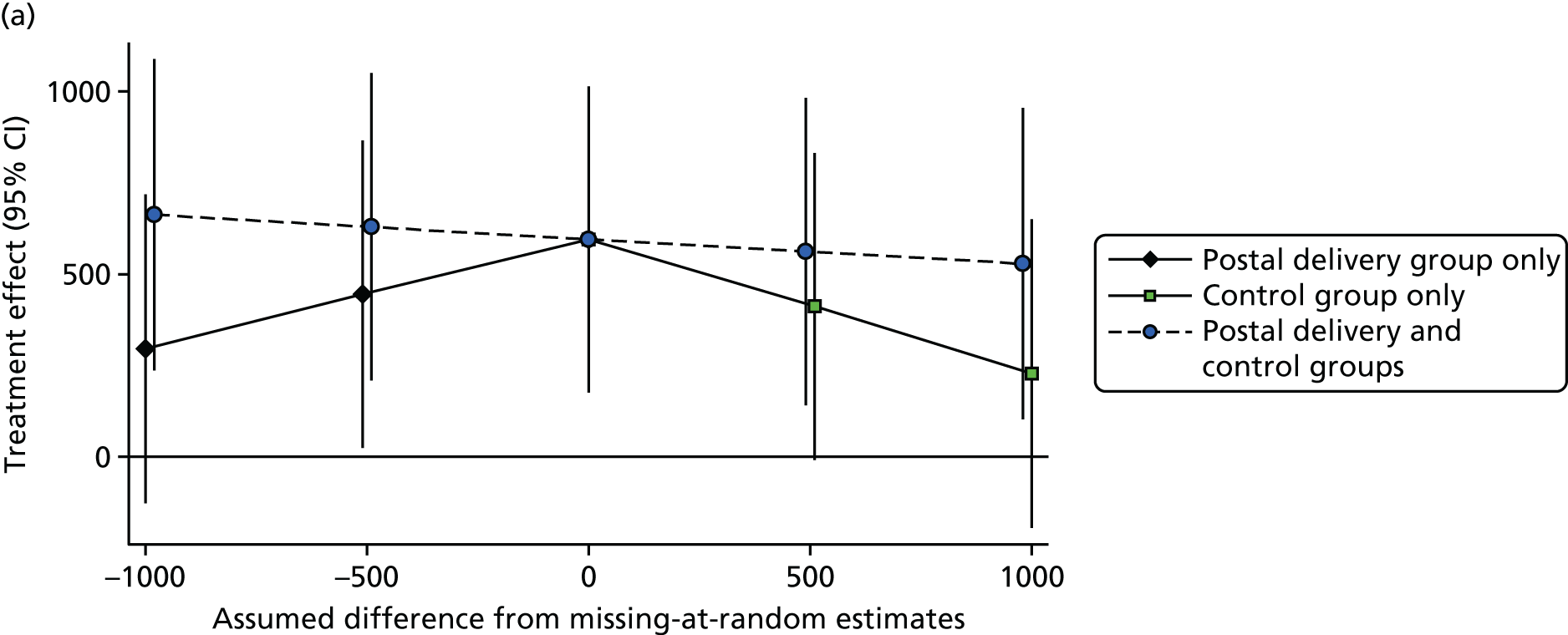

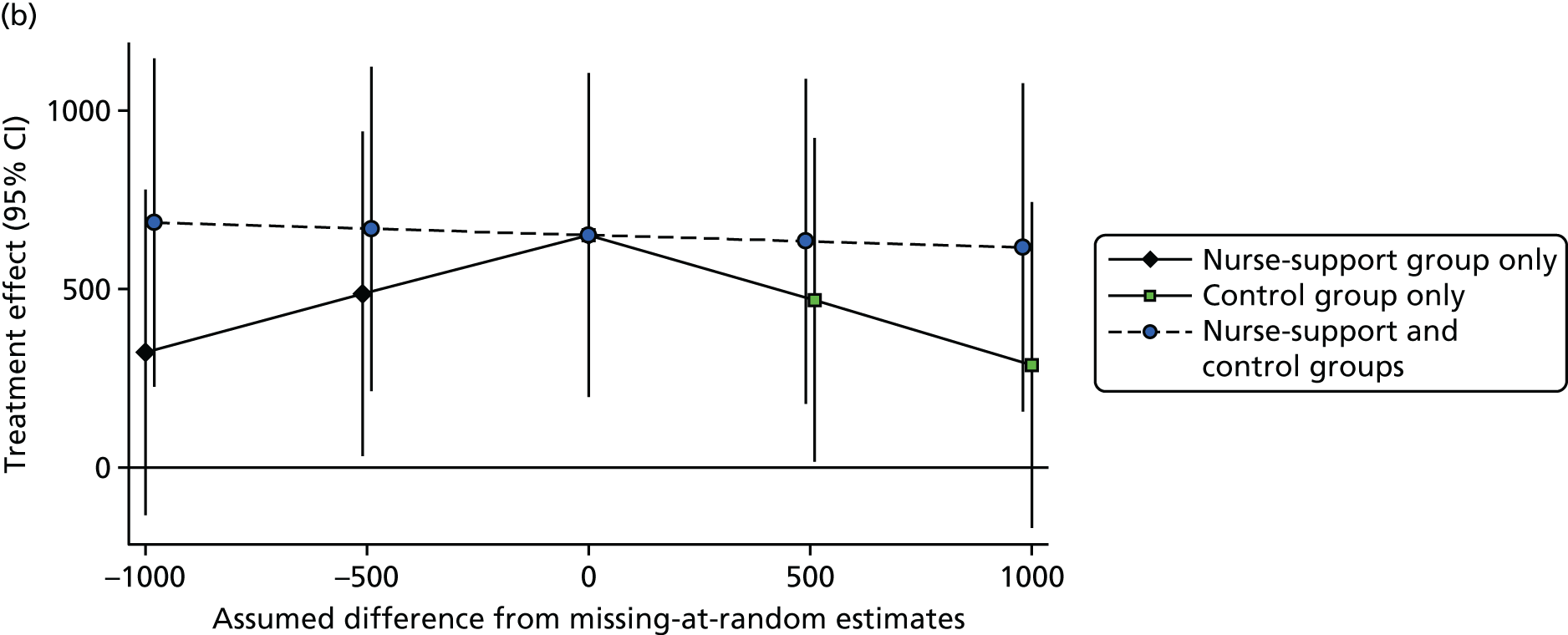

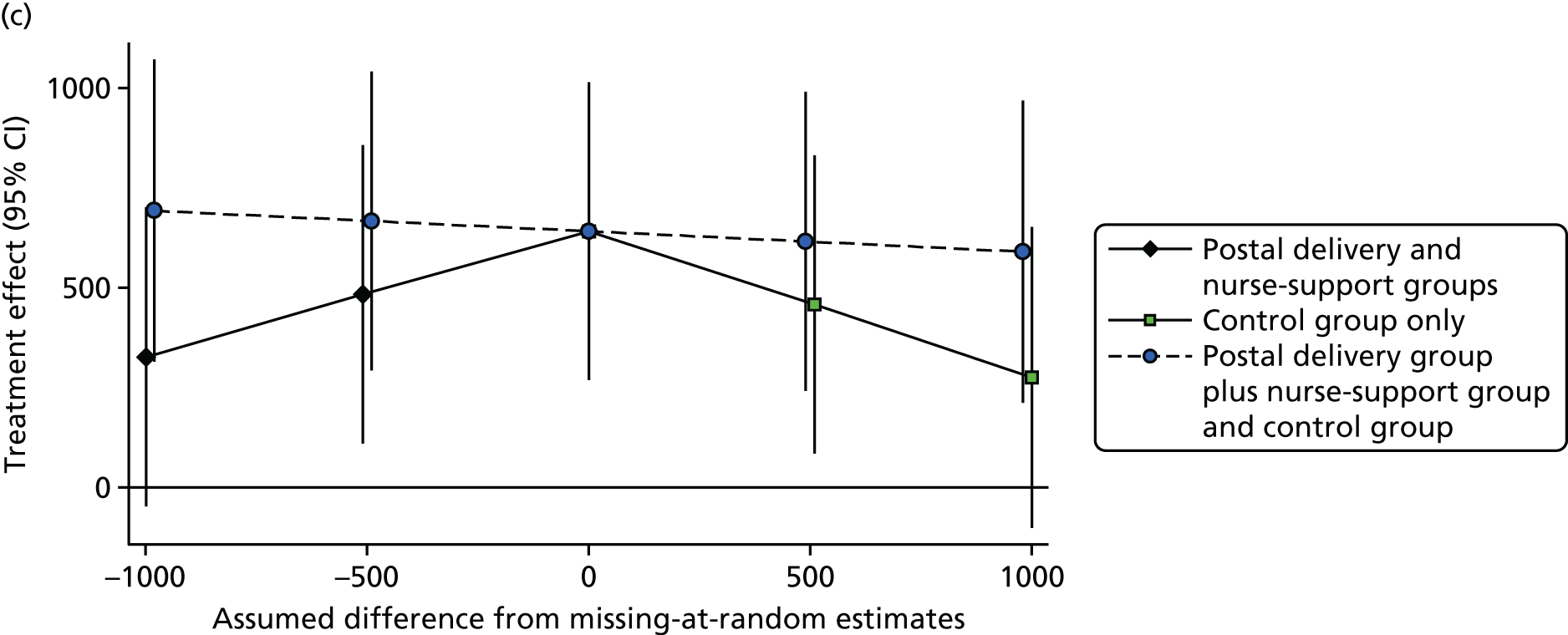

Effect of the intervention on self-reported physical activity outcomes at 12 months (Table 6)