Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 09/22/50. The contractual start date was in October 2011. The draft report began editorial review in August 2016 and was accepted for publication in November 2017. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Elizabeth Ball declares UK travel reimbursement from Shire Medical (Lexington, MA, USA) outside the submitted work. Jonathan J Deeks was Deputy Chairperson of the National Institute for Health Research Health Technology Assessment (HTA) Commissioning Board (2011–16) and the HTA Efficient Study Designs Board (2016).

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2018. This work was produced by Khan et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2018 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Introduction

Background

Definition and prevalence of chronic pelvic pain

Chronic pelvic pain (CPP) may be defined as pain in the pelvic and lower abdominal region that lasts for 6 months or longer. 1 Idiopathic CPP is defined as CPP with an uncertain or unknown structural cause, that is, CPP that is unrelated to gynaecological organs, after the exclusion of other recognisable gynaecological pathology. 2 Symptoms include dysmenorrhoea (painful periods), dyspareunia (pain during sexual intercourse), dyschesia (painful bowel motions), dysuria (painful micturition) and constant or intermittent pelvic pain, which may or may not be related to the menstrual cycle. 3

In primary care, the annual prevalence of CPP is 38 out of 1000 in women aged 15–73 years,4 a rate comparable with that of asthma (37/1000) and chronic back pain (41/1000). 5,6 Unusually, no effective management policy exists for CPP. Only 20–25% of women respond to conservative treatment. 7 CPP remains the single most common indication for referral to a gynaecology clinic, accounting for 20% of all outpatient appointments. 8

Personal and societal costs of chronic pelvic pain

Chronic pelvic pain can have a substantial negative effect on a woman’s quality of life (QoL). Women with CPP tend to report reduced general physical health scores than those without pain. 9,10 Women with CPP describe loss, social isolation and effects on relationships. They have a high incidence of comorbidity, sleep disturbance and fatigue. 3 They tend to cope outside the health system and usually do not see a health-care provider. 8 Pain affects daily activities; around 18% of employed women in the UK take at least 1 day off work each year because of such pain. 9 The annual direct cost of health care for women with CPP was estimated to be £158M, with a further £24M in indirect costs, in 1992. 11 More recent data for endometriosis estimated that the total annual societal burden of endometriosis-related symptoms was approximately £8.2B, with 1.5 million women affected. 12

Pathogenesis of chronic pelvic pain

The pathogenesis of CPP is poorly understood. CPP may be a symptom of a single or multiple coexisting structural pathologies. The source of the pain can be either visceral (including the reproductive, urinary and gastrointestinal tracts) or somatic (including the pelvic bones, ligaments, muscles and fascia). The most recent taxonomy of pain from the International Society for the Study of Pain (ISSP) lists conditions such as endometriosis, fibroids, adenomyosis, cystic ovaries and pelvic inflammatory disease (PID) as pathological causes of CPP. 13 Adhesions, frequently associated with endometriosis and pelvic congestion syndrome, are not defined within the ISSP taxonomy and, indeed, the relationship between CPP and pelvic vein insufficiency is controversial. 14 The severity of pain may not be related to the severity of the underlying pathology, as illustrated by endometriosis, when the stage of disease is poorly correlated with reported pain. 15 Pelvic pain may not be gynaecological in origin, however. Musculoskeletal dysfunction can include muscle laxity, manifesting as pelvic organ prolapse, muscle spasms (which can potentially lead to nerve entrapment) and trigger points (hyperirritable regions within skeletal muscle). Finally, pelvic pain may have origins in the bowel or the bladder. Irrespective of the underlying cause, women with CPP are more likely to have structural and functional changes to the central nervous system, and an increased risk of psychological distress and dysfunctional stress responses, than pain-free control women. 16

A significant proportion of women with CPP appear to have no obvious underlying pathology identified during laparoscopy. 17 Differences in the clinical thresholds for performing laparoscopy may vary over time or location, but data from the UK-based LUNA (Laparoscopic Uterosacral Nerve Ablation) trial17 showed that clinicians did not identify any condition at laparoscopy in 54% of participants. In these cases, the CPP may have had an unknown cause that was not related to gynaecological organs and could be referred to as ‘idiopathic’. The ISSP and European Association of Urology (EAU) define a subgroup of CPP, in which no obvious disease is found, to be CPP syndrome. 13,18 Endometriosis-associated pain, vulval pain, bladder pain, primary dysmenorrhea and CPP with cyclical exacerbations are differentiated as subtypes of CPP syndromes by the ISSP. The EAU notes that, when pain is localised to a single organ, some specialists designate the pain accordingly, for example bladder pain syndrome, but when pain is localised to more than one site, the term ‘CPP syndrome’ should be used. Categorisation of the symptoms of idiopathic CPP syndrome into functional and psychological categories may then be appropriate. In a proportion of women, there may be a psychosomatic component, and psychological symptoms may be both causative and associative.

For this study, we used a working definition of idiopathic CPP with an uncertain or unknown structural cause after the exclusion of any other recognisable gynaecological pathology. This was derived by a nominal group method using an expert independent panel (EIP). A diagnosis of idiopathic CPP was arrived at once all other organic causes of pain were excluded by various diagnostic technologies or empirical treatment. 2

Variation in the presentation of chronic pelvic pain

Symptoms experienced in CPP are variable and non-specific, so establishing a differential diagnosis can be hard. With this chronic condition, women present repeatedly over several years. 19 It is possible in these cases that a previously diagnosed condition (e.g. endometriosis) has recurred or a new condition has developed (e.g. depression in a woman previously diagnosed with endometriosis). At present, there is wide variation in clinical practice concerning the diagnosis and management of CPP. 20 Women go from pillar to post, seeing several health professionals before eventually having their underlying condition identified. This wastes both the patient’s time and NHS resources. The diagnosis of endometriosis may be delayed by over 8 years after first presentation with CPP symptoms,19,21,22 potentially demoralising the patient and missing the opportunity to improve their QoL and fertility through early effective treatment.

Diagnosis of the cause of chronic pelvic pain

A troublesome clinical issue is the lack of accurate tools to efficiently diagnose and direct cases of women. 23 The Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (RCOG) guidelines on the management of CPP provide a number of suggested initial investigations, including history, microbiological screening and vaginal examination, all with weak evidence (levels B or C) for recommendations. 20 If no cause of pain is found, the first port of call is often to perform a diagnostic laparoscopy.

Clinical assessment and ultrasound

The order of tests in current practice can vary between clinicians and according to presentation, but the RCOG’s clinical guidelines20 suggest that a clinical history is taken and a vaginal examination is performed. When there is suspicion of PID or a potential need, screening for chlamydia and gonorrhoea in women aged < 25 years may be performed. A transvaginal ultrasound may be performed,24 followed by a laparoscopy under general anaesthetic.

Laparoscopy

Diagnostic laparoscopy is a surgical procedure that allows a clinician to view the contents of the abdomen or pelvis to inform a diagnosis of CPP. A therapeutic laparoscopy is a surgical procedure used by a clinician to treat various conditions that may cause CPP. Endometriosis, pelvic adhesions, chronic PID and ovarian cysts are often observed via laparoscopy in women with CPP. 8 In a cohort of 487 women recruited into a trial of neuroablation for CPP, 54% of women had no identifiable pathology at laparoscopy, whereas 31% had endometriosis, 5% had PID and 17% had adhesions. 17 Approximately 11% had more than one finding. Those women with moderate to significant pathology were excluded from this trial. This is in broad agreement with other surveys. 8

The role of laparoscopy in the differential diagnosis of chronic pelvic pain

There is evidence to suggest that deep-infiltrating endometriosis, bladder pain syndrome/interstitial cystitis25 and irritable bowel syndrome26,27 are causally related to CPP, whereas, for adhesions, there is fair evidence. The associations between severe endometriosis and pelvic pain, and between endometriosis in general and infertility, are confirmed. However, there is little or no association between minimal endometriosis, pelvic adhesions or dilated pelvic veins and pain. 28 Debate remains over the relation between observed superficial peritoneal endometriosis and the extent of the laparoscopic finding,29 or with the degree of reported pain. 28

A combination of the non-invasive tests for the diagnosis of endometriosis can sometimes provide insufficient or poor-quality evidence. 30 However, of all conditions associated with CPP, many are not amenable to either laparoscopic diagnosis or treatment. Of those conditions for which laparoscopy has a role, most are managed by gynaecologists, and this probably explains the common use of laparoscopy for evaluating women with CPP. Over 40% of laparoscopies are performed solely as a diagnostic test to identify the causes of CPP. 31 The decision to perform a laparoscopy should be based on the history, physical examination and ultrasound scans suggesting a visceral origin.

The accuracy of laparoscopy in the diagnosis of chronic pelvic pain

The value of laparoscopy as a diagnostic tool for CPP has been considered in several papers,8,31,32 including a review of published reports of laparoscopically diagnosable conditions, in which an average of 61% of women undergoing laparoscopy for CPP had an identifiable pathology, compared with pathology in 28% of those without CPP. 8 However, invisible (occult) endometriosis can be present in a seemingly normal peritoneum. 33 A ‘negative’ laparoscopy for some women may lead to them feeling disappointed that no diagnosis has been made34 and disengage them from the care pathway. 35

However, a visual diagnosis of endometriosis during laparoscopy has been demonstrated to be unreliable. Only 54–67% of suspected endometriotic lesions are confirmed histologically, and 18% of women clinically suspected to have endometriosis have no evidence of endometriosis in biopsy samples. 36 A meta-analysis found that a positive finding through the use of laparoscopy will not be verified by histology in half of the cases (assuming a prevalence of 20%), although a negative laparoscopy is highly accurate for excluding endometriosis. 37 Other conditions identifiable through laparoscopy are listed in Table 1.

| Target conditions | Diagnostic criteria | Diagnosis by | |

|---|---|---|---|

| MRI | Laparoscopy | ||

| Endometriosis | Visualisation of endometriotic lesions with histological confirmation of biopsies from lesions37 |

Uncertain. MRI had a sensitivity of 85% and a specificity of 89% for detecting biopsy-proven endometriosis38 MRI had a sensitivity and a specificity for diagnosis of rectovaginal deep-infiltrating endometriosis of 55% and 99%, respectively. Sensitivity for other locations was considerably higher, for example, on uterosacral ligaments it was 85%39 |

Negative laparoscopy was accurate for excluding endometriosis (pooled LR –0.06, 95% CI 0.01 to 0.47) compared with biopsy, but positive findings were not as accurate (pooled LR 4.30, 95% CI 2.45 to 7.55)37 |

| Adhesions | Visualisation, directly or by absence of movement between adjacent organs | Evidence from a single trial: sensitivity of 88% and specificity of 93%40 | Gold standard |

| Chronic PID | Laparoscopic visualisation or histology from fimbrial mini biopsy | Ultrasonography represents preferable initial non-invasive diagnostic method. MRI sensitive for tubal, ovarian and pelvic abscesses41 | Can confirm tubo-ovarian abscesses and the presence of Fitz-Hugh–Curtis syndrome, but may fail to detect early disease or those with endosalpingitis only42,43 |

| Adenomyosis | Presence of diffuse endometrial tissue in myometrium at post-hysterectomy biopsy | MRI had a pooled sensitivity of 77% and a specificity of 89% against histological diagnosis44 | Uncertain. May observe bulky uterus |

Magnetic resonance imaging in the diagnosis of chronic pelvic pain

Advances in imaging techniques suggest that magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) may be a useful non-invasive tool for diagnosing some conditions that cause CPP, such as adenomyosis44 and deep-infiltrating endometriosis. 45 MRI has an established role in the diagnosis of adenomyosis and is currently the most accurate available non-invasive test in use. 46 The role of MRI in diagnosing small deposits of endometriosis20 is less established. A Cochrane review reported that no imaging techniques met the criteria for a replacement or triage test for detecting superficial pelvic endometriosis. 30 Several factors contribute to this poor accuracy of MRI: non-pigmented lesions will not be hyperintense on T1 scans, small focal lesions may have variable signal intensity, plaque-like lesions are hard to delineate and adhesions cannot be directly identified, but are implied when the normal anatomy is distorted. Other conditions, such as fibroids and congenital uterine anomalies, may co-exist and are accurately diagnosed with MRI. 47

Magnetic resonance imaging is currently not recommended in guidelines nor used in routine practice for the investigation of CPP; the important question is whether or not a normal MRI scan has a high enough negative predictive value to replace and avoid laparoscopy. In CPP women, MRI may potentially have an important role in eliminating the need for surgery.

There are currently no agreed standardised protocols for MRI of the pelvis in the evaluation of pelvic pain. Radiologists determine the protocol used based on the clinical information and the suspected pathology, as well as personal preference and experience. Various bodies, such as the European Society of Urogenital Radiology (ESUR), have recommended protocols for pelvic assessment for various conditions,48 but none specifically addresses CPP.

Treatment of chronic pelvic pain

As diagnoses emerge through careful history and examination and directed investigation, so may treatment strategies. These should be tailored to the needs of individual women, whatever the cause. A multidisciplinary approach is considered ideal for achieving this. Chronic symptoms need long-term management and a multimodal approach.

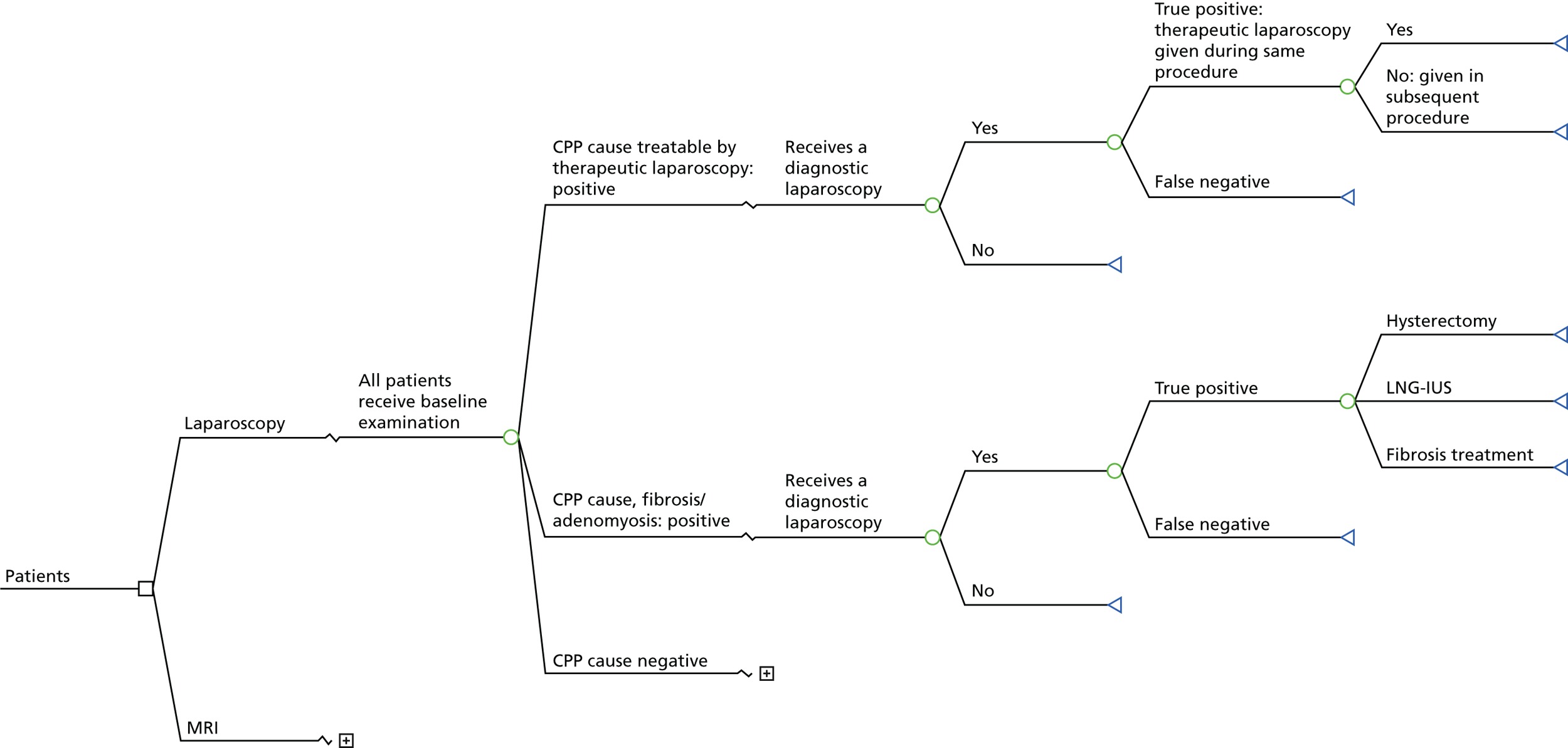

Some clinicians prefer that a diagnostic and therapeutic investigation is performed as part of a single procedure – sometimes referred to as ‘see-and-treat’ laparoscopy. 49,50 For example, adhesiolysis may be performed in what started as a diagnostic procedure. 51 Depending on the severity and corresponding patient consent, endometriosis may be treated at the time of diagnosis by either electrocoagulation, laser vaporisation or excision. 52 Endometrioma and benign ovarian cysts are usually excised. 53 The type of treatment offered may depend on the extent of the disease and surgical expertise. Surgical removal of deep-infiltrating endometriosis is highly specialised and, in the UK, undertaken in accredited specialist centres. Preoperative MRI scans can aid the planning of this complex surgery.

Other conditions observed at laparoscopy are not amenable to immediate laparoscopic treatment, for example myomectomy for subserosal fibroids. 54 Few surgeons attempt uterine-sparing surgery for adenomyosis, as a result of it frequently being diffused throughout the myometrium.

A diagnostic laparoscopy may also provide the opportunity to undertake other investigations, such as a cystoscopy, if symptoms are suggestive of bladder or intrauterine conditions. Some gynaecologists may also use the cover of a general anaesthetic to perform investigations capable of being performed as an outpatient procedure, such as hysteroscopy or insertion of a levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system.

Medical treatments are also options for CPP, irrespective of surgical intervention. The combined oral contraceptive pill is used post laparoscopy for prevention of the recurrence of endometriosis, as are long-acting reversible contraceptives. 55–57 Gabapentin is used for women with no identifiable cause of pain, although evidence for its efficacy is limited. 58

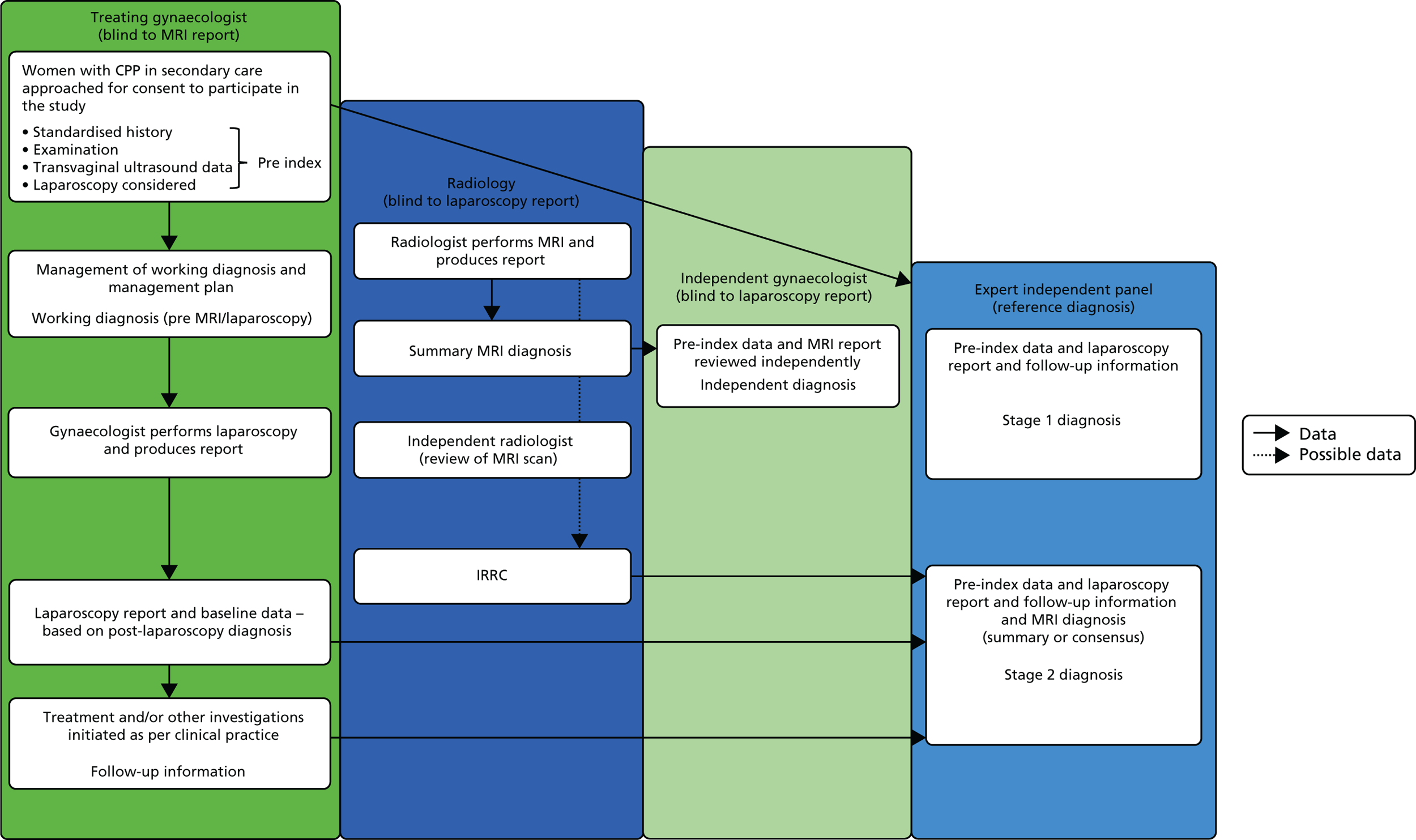

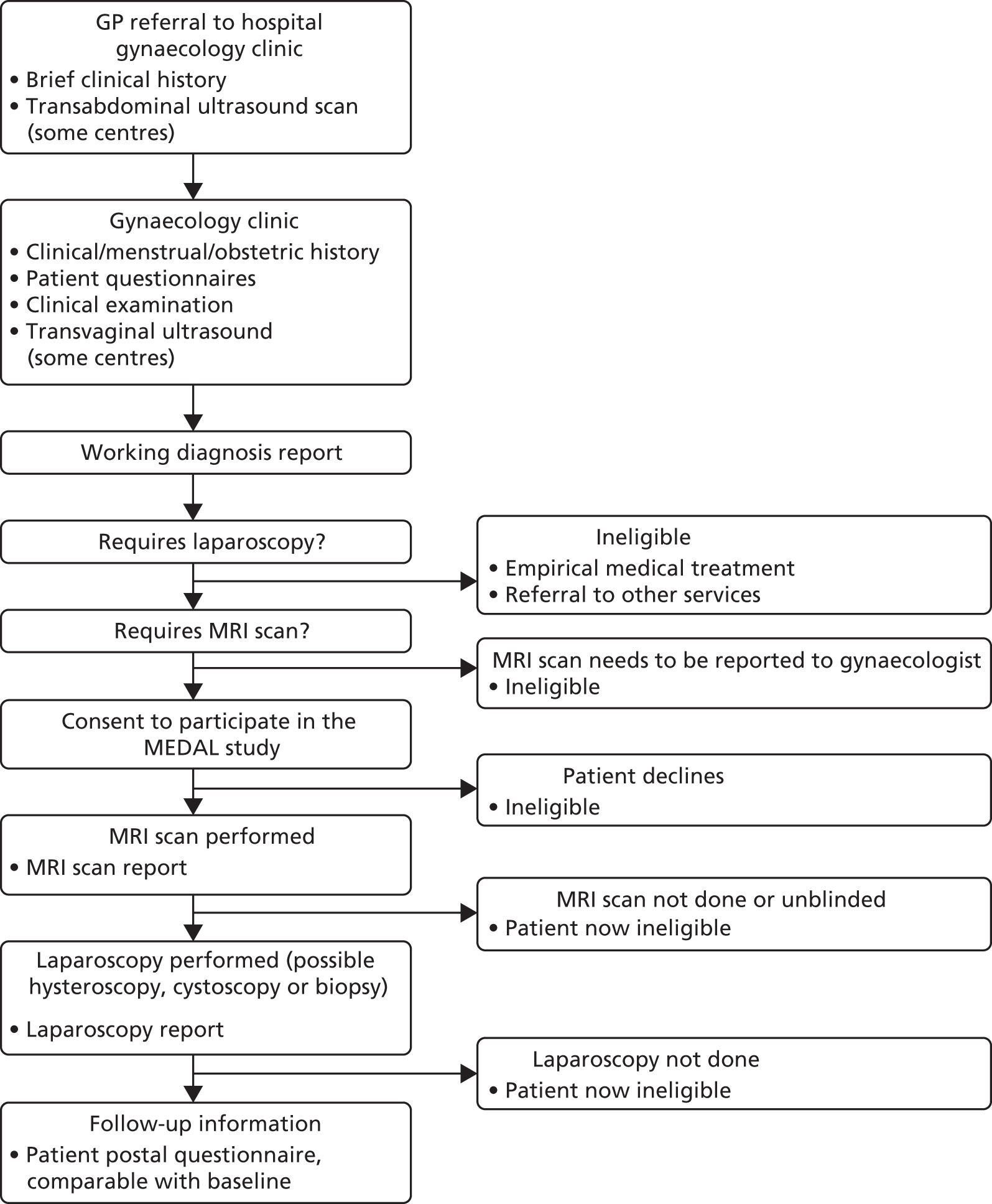

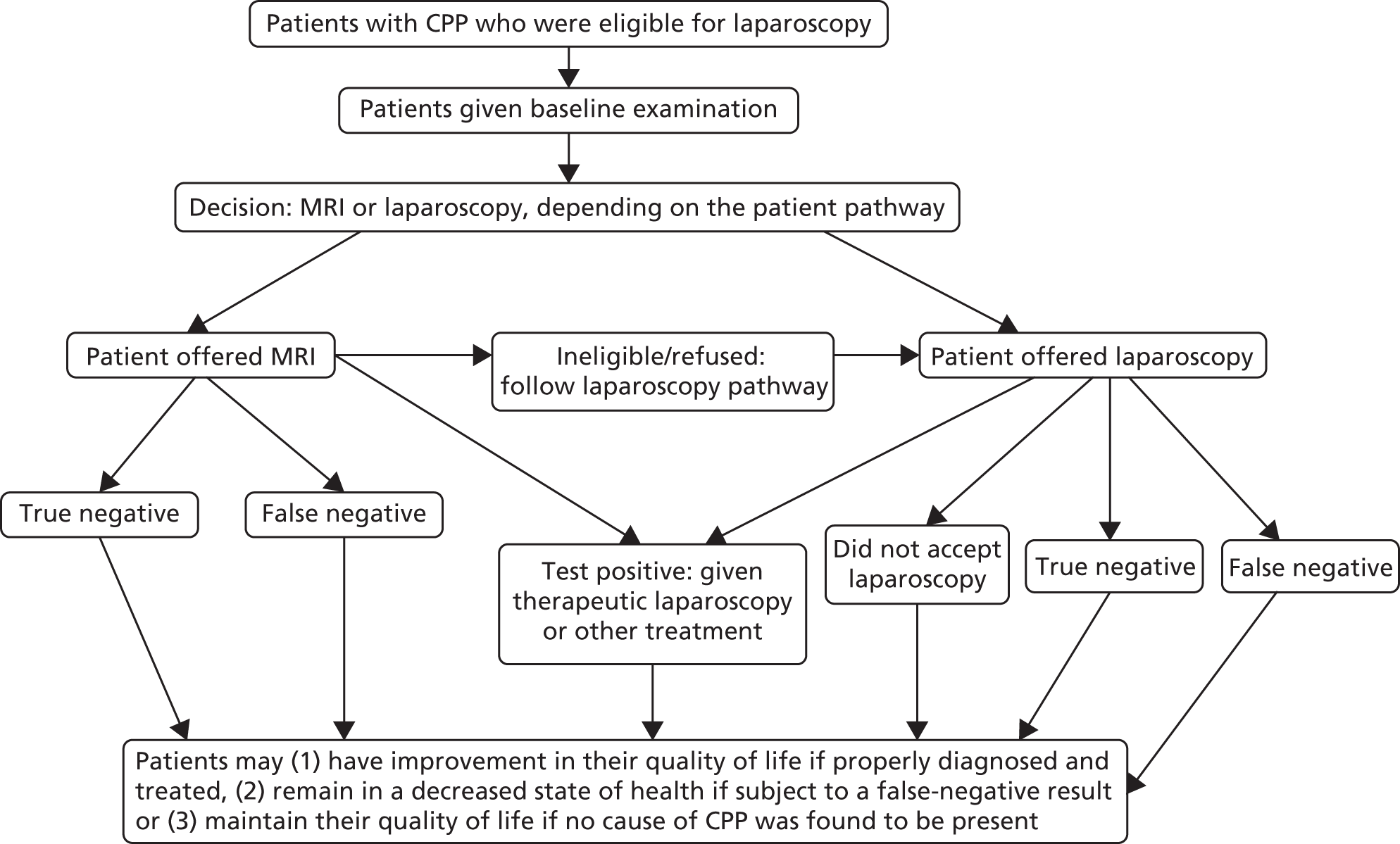

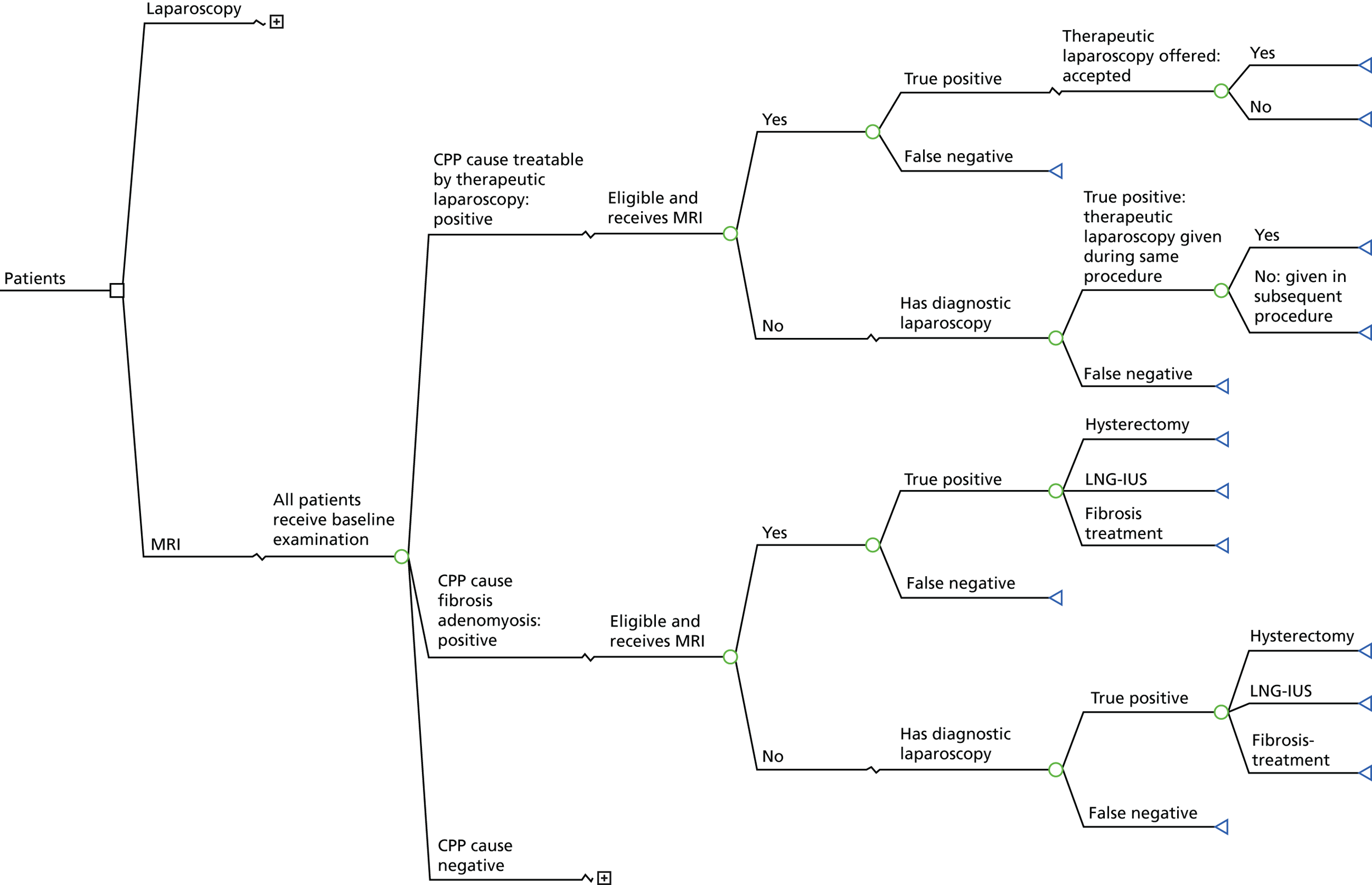

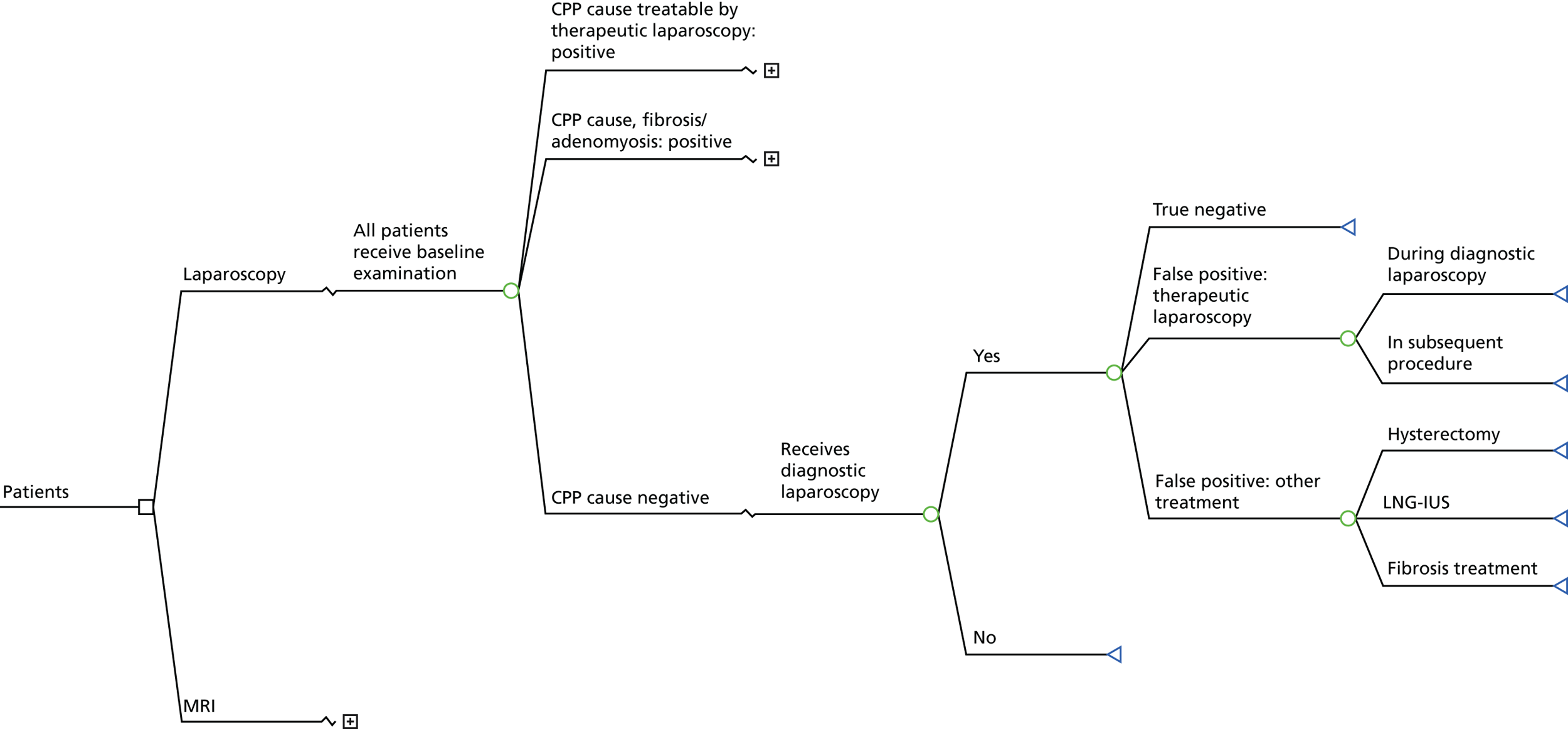

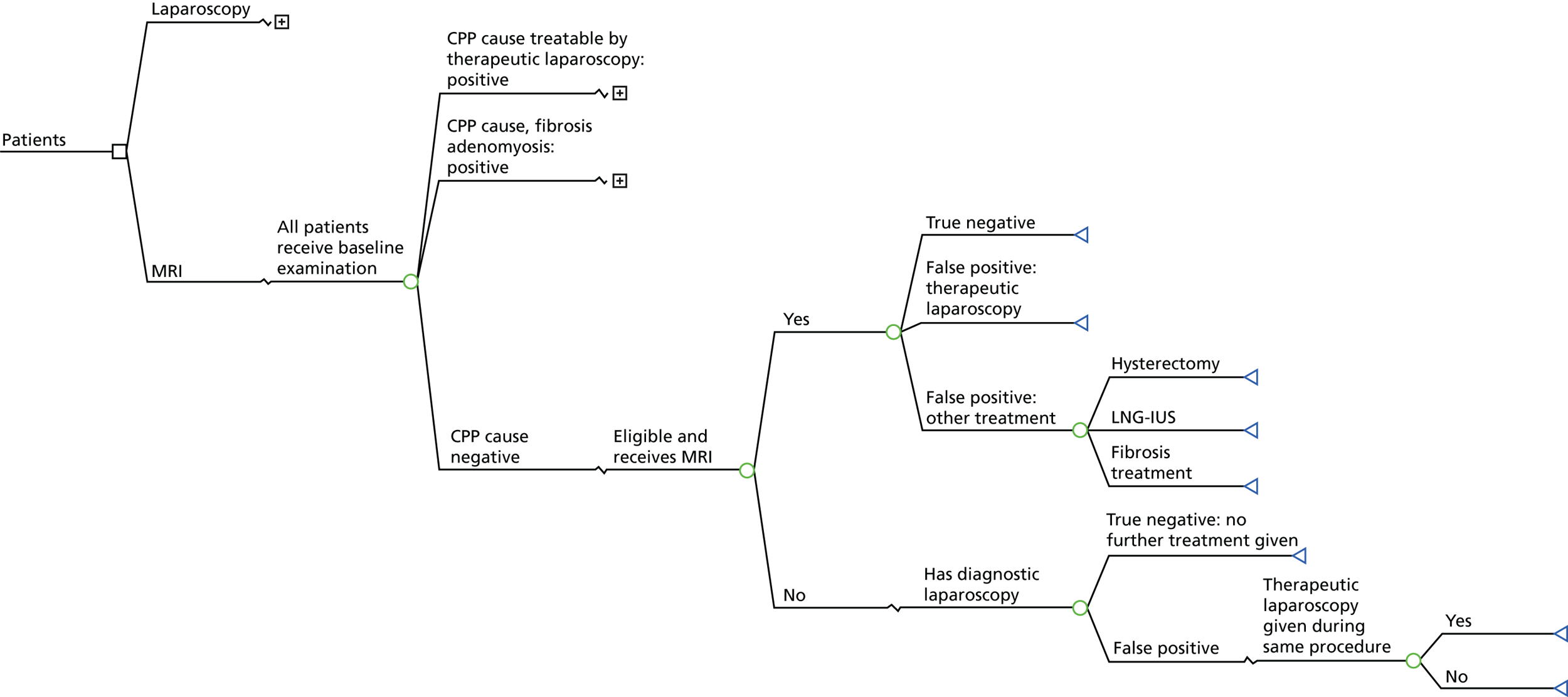

Overview of the Magnetic resonance imaging for Establishing Diagnosis Against Laparoscopy study

The MRI for Establishing Diagnosis Against Laparoscopy (MEDAL) study recruited women from 26 UK hospitals (as listed in Appendix 1, Table 29). An outline of the test-accuracy study design is shown in Figure 1. MRI was undertaken before laparoscopy, but the resulting report and images were not to be provided to the gynaecologist, unless there was a critical finding, such as suspected malignancy. This blinding was necessary in order not to distort clinical practice and avoid verification bias arising from knowledge of this index test. A diagnostic laparoscopy was performed and, together with information from the history, examination and ultrasound, produced a post-laparoscopy diagnosis (Figure 2). Information was collected from those who were not eligible for the test-accuracy study. Follow-up information was elicited directly from participants at 6 months.

FIGURE 1.

The MEDAL study flow chart. IRRC, Independent Radiology Review Committee.

FIGURE 2.

Patient pathway and data points through the MEDAL study. GP, general practitioner.

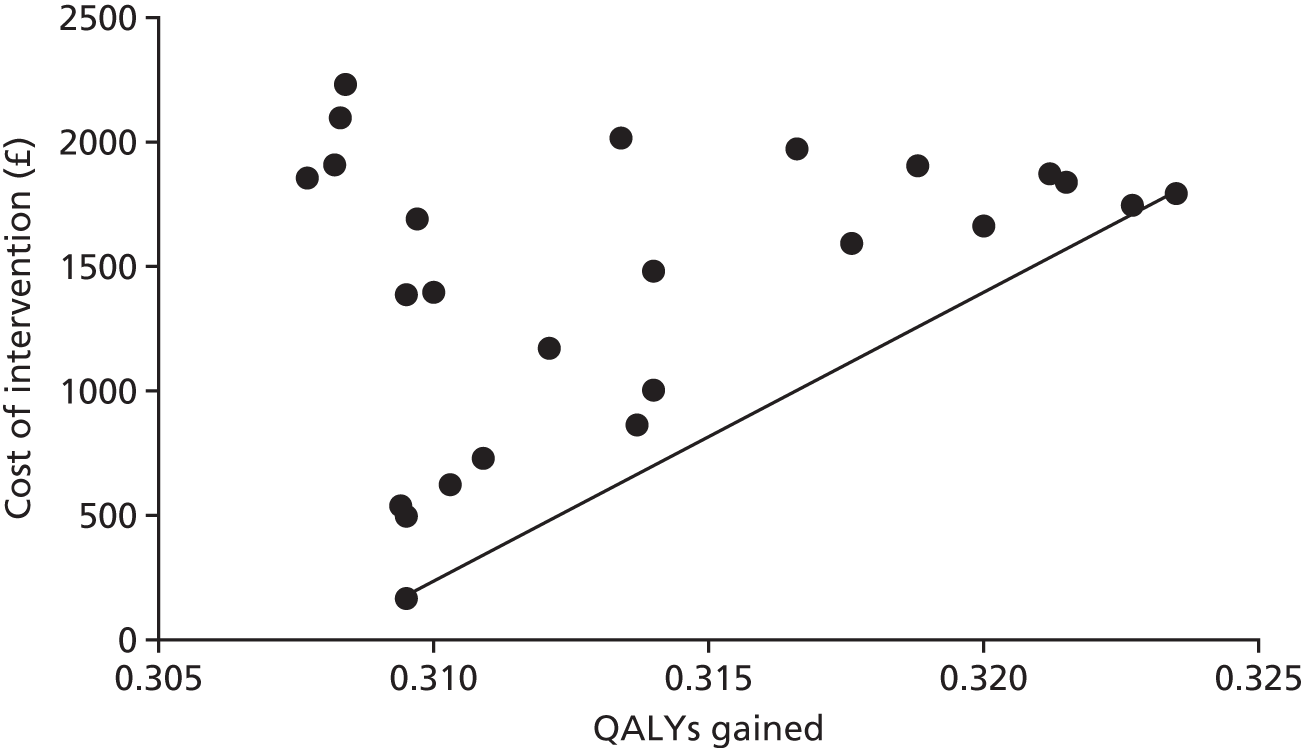

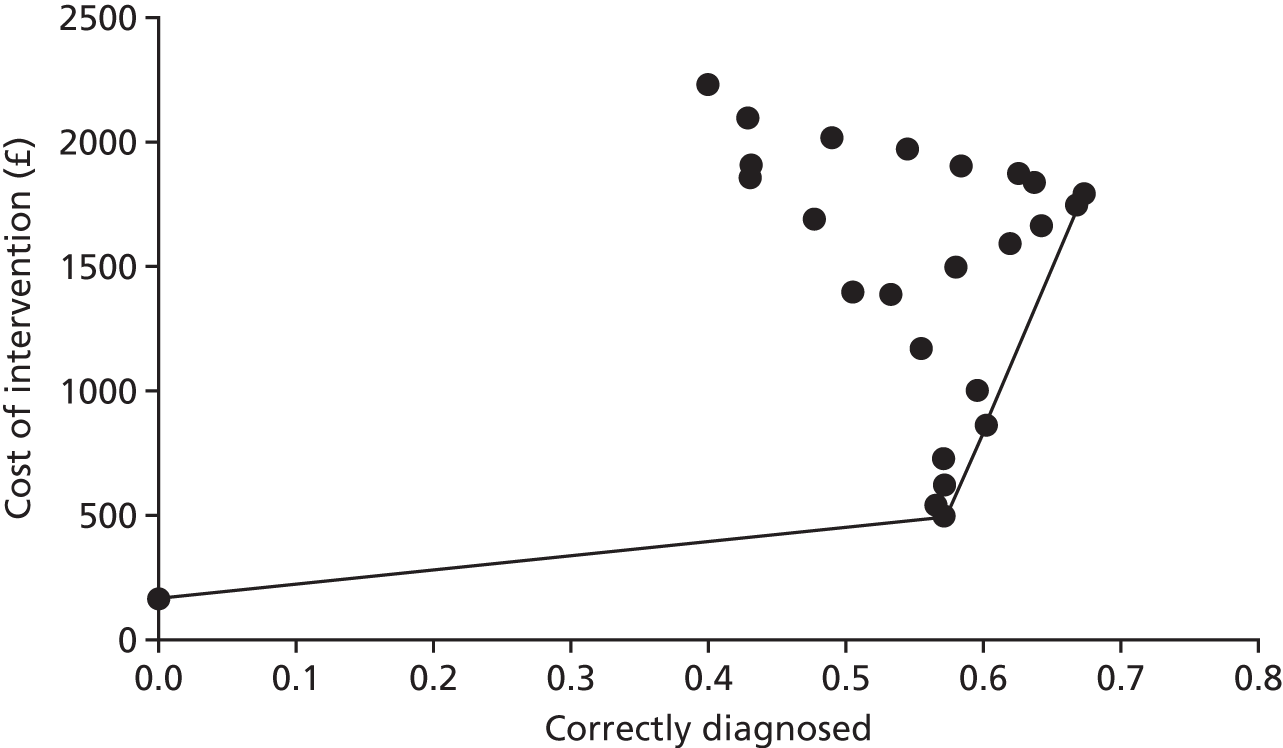

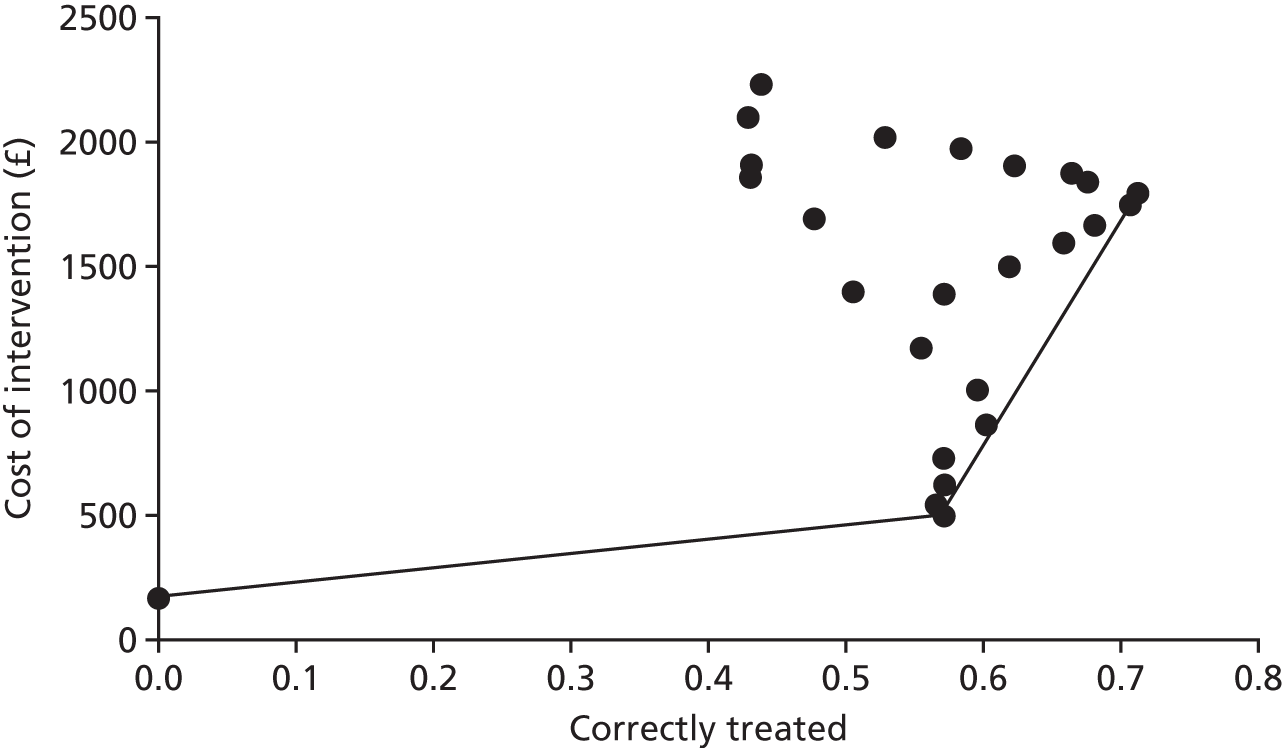

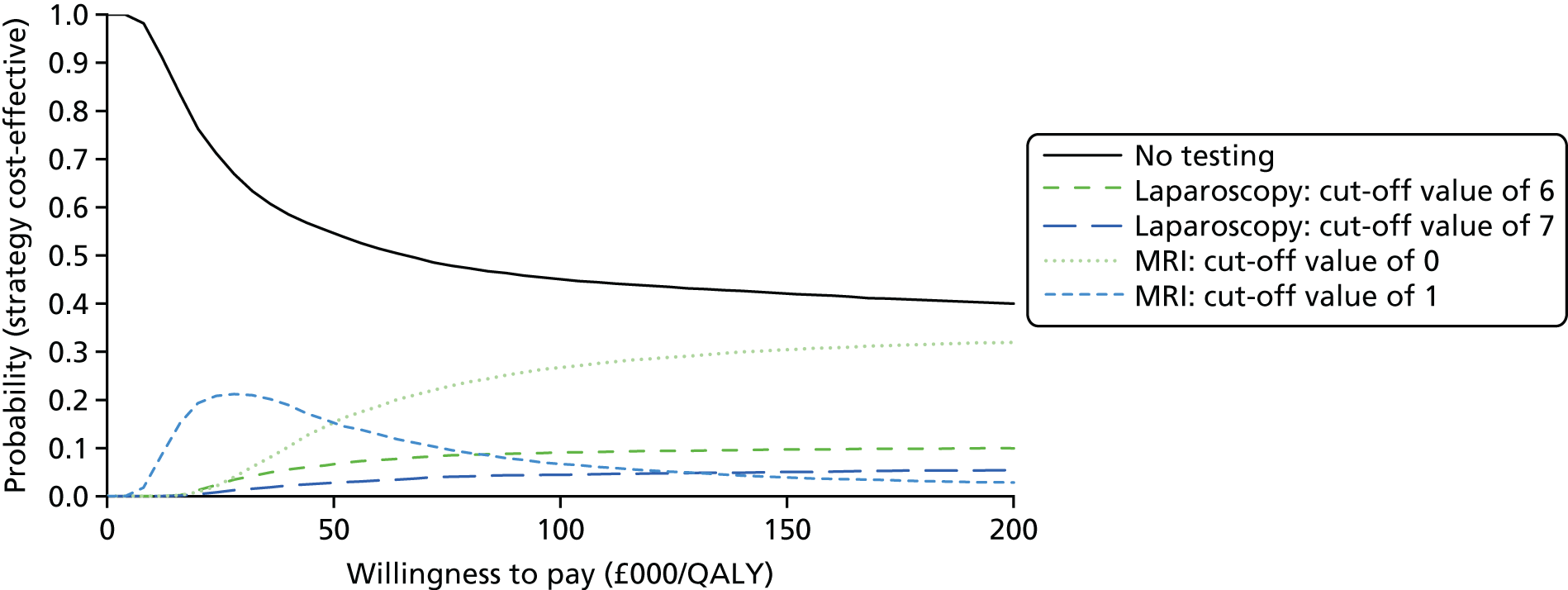

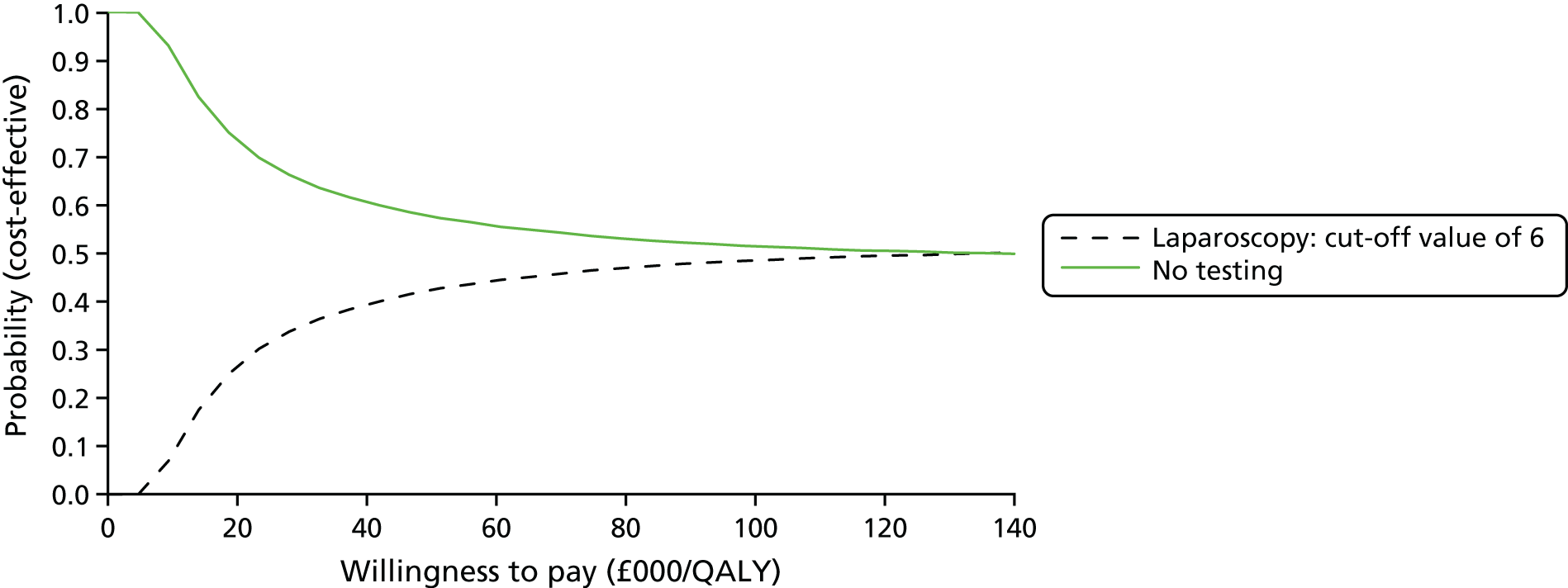

An economic evaluation was performed to establish the cost-effectiveness of MRI as an alternative to laparoscopy for the sensitivity and specificity values of the various target conditions.

Rationale for the Magnetic resonance imaging for Establishing Diagnosis Against Laparoscopy study

There is a perception that diagnostic laparoscopy, an invasive, expensive and potentially risky procedure, is used far too frequently in the NHS, as a significant proportion of women have no pathology identified. 59 The procedure is associated with an approximate 3% risk of minor complications (e.g. nausea and vomiting, shoulder-tip pain) and a 0.24% risk of unanticipated injury causing major complications (e.g. bowel perforation), resulting in two-thirds of women requiring laparotomy. 59–61 There is an estimated risk of death of 3.3 to 8 per 100,000 women,59,61 and payments in medical negligence cases totalled £24.3M in one survey published in 2000. 62

Magnetic resonance imaging is easily accessible, less invasive and cheaper than surgery. In some circumstances, MRI may add a diagnostic benefit over laparoscopy, such as in the cases of severe deep-infiltrating endometriosis and adenomyosis. MRI may also be used to triage cases, so that therapeutic laparoscopy could be better planned. The aim of the MEDAL study was to determine the proportion of women for whom MRI could remove the need for a laparoscopy or, in other words, for whom MRI could be a replacement for laparoscopy.

For MRI to be used in routine clinical practice for the evaluation of CPP, imaging protocols and reporting need to be standardised to allow homogeneous MRI performance between centres and to limit acquisition and interobserver variability. Currently, there are no routinely used standardised reporting guidelines for CPP in the UK. 63 Guided by the MEDAL study, members of the study panel have proposed a template for the standardised reporting of CPP. 63

Following various treatment options, such as the oral contraceptive pill or hormone treatment, some women will undergo laparoscopy resulting in 50% of women having a negative laparoscopy with no pathological cause of pain identified. 8 Although a negative laparoscopy may fail to identify the pathology, it may have a reassuring effect on the patient. A laparoscopy may also have the potential to be a ‘see-and-treat’ laparoscopy if superficial peritoneal endometriosis is observed; MRI would add no benefit in that case.

The choice of study design

Test-accuracy studies are designed to generate measures of accuracy by comparison of the index test with a reference standard, a test that confirms or refutes the presence or absence of disease beyond reasonable doubt. Classical test-accuracy studies require that the target condition is independently verified by the reference test, which must provide a definitive diagnosis, be applicable in all cases and preferably be performed alongside the index test. Complete verification of the presence or absence of a target condition is essential to reduce bias and to maximise the statistical power of the study. By comparing the index test with the reference standard, the result of the index test can be categorised as a true positive, a false positive, a true negative or a false negative. Measures of index test accuracy, including sensitivity, specificity, positive and negative likelihood ratios, and diagnostic odds ratios, can be computed. 64

Verification of the reference standard is frequently dichotomised as disease present/disease absent. In the MEDAL study, we aimed to determine the accuracy of MRI in the differential diagnosis of the causes of CPP. There is a range of potential target conditions and, correspondingly, of reference diagnoses. MRI will visualise the various conditions with different degrees of accuracy (Table 2). To determine the sensitivity of MRI for each pathology would require a large number of participants, to accommodate the low prevalence of some conditions. Furthermore, some pathologies are not independent of each other and could frequently be concurrently observed; for example, endometriosis can give rise to adhesions from fibrotic tissue. Therefore, the principal research question is how frequently does a MRI scan correctly predict the reference diagnosis, thereby removing the need for a laparoscopy or, conversely, what diagnoses cannot be accurately ruled out by a MRI scan and require laparoscopic investigation?

| Radiological feature | Criteria used in analysis to indicate the presence of a target condition | Reference or justification |

|---|---|---|

| Anatomy of uterus, ovaries, adnexal structure, bladder and bowel | Not used for analysis | |

| Uterine size, appearance, JZ thickness, adjacent myometrial thickness, endometrial thickness | Adenomyosis is diagnosed in two ways:

|

|

| Presence of fibroids, location, number and maximum size | Presence of fibroids reported, irrespective of location, number or size | Fibroids are seen on the MRI scan |

| Ovarian size, ovarian cysts, and, if present, their size and signal intensity | Endometrioma of the ovary is diagnosed if the ovary had a cystic area or deposit with:

|

|

| Presence and location of other masses |

|

Bazot et al.,39 Bazot et al.65 and Chamié et al.66 |

| Presence of free or loculated fluid | Diagnosis of PID if either free fluid or tubal masses are seen, with low or intermediate signal intensity on T1, T2 and T1-FS images | |

| Adhesions | Diagnosis of adhesions if reported as:

|

|

| Bladder status, including wall thickness if abnormal | Not used for analysis | |

| Presence of small bowel in pelvis, location and description | Not used for analysis | |

| Other observations; for example, lumbar spine abnormalities | Not used for analysis |

In the context of the MEDAL study, there were a number of target conditions to be considered, not all of which had a perfect reference standard of identification against which to make a differential diagnosis. There was a risk of partial or differential verification of the underlying causes, with their inherent biases. There are several proposed study designs that overcome the problems of an imperfect reference diagnosis. 67 In the absence of a single ‘gold standard’ test, the results of several imperfect tests or observations can be combined to create a composite reference standard. These can be combined according to a predefined algorithm or a consensus diagnosis obtained from considering all the information.

We employed a panel (consensus) diagnosis in which a group of experts determined the presence or absence of the target condition based on several sources of information captured along the patient pathway. This was an acceptable way of addressing the problem of achieving a diagnosis from multiple sources of information and of subjective assessment of that information, as a diagnosis is achieved by consensus. 68 A final diagnosis can be obtained for all women and the panel method reflects the clinical reality, in which several items of information are synthesised by the clinician. The results of this methodology can be viewed as being generalisable to clinical practice.

To establish whether or not MRI can replace laparoscopy, a paired design was employed, in which both tests were compared with the reference standard. As sensitivity and specificity can vary across subgroups, the two tests and the reference standard are best performed in the same population. 68 It is feasible to perform MRI and laparoscopy in women with CPP and, although MRI does not interfere with laparoscopy, the paired design is preferable to a randomised trial. 69 As MRI would precede laparoscopy, it can also be viewed as a triage test, directing only women with a specific condition towards a laparoscopic confirmation or operative laparoscopic procedure. A fully paired study design is also appropriate for this type of diagnostic situation.

The certainty with which gynaecologists have made their diagnoses will be measured and compared as a secondary measure of diagnostic efficacy. In order to be clinically effective, tests should contribute to the diagnostician’s decision-making,70 for example, by changing a differential diagnosis, strengthening an existing hypothesis or simply reassuring the clinician. Although accuracy is the chief concern, the extent to which clinicians make use of test results also relies on their confidence that the test has contributed usefully to a diagnosis. The MEDAL study therefore evaluated the diagnostic impact of MRI and of laparoscopy by conducting a:

-

before-and-after comparison of diagnostic certainty for having diagnosed the cause of CPP

-

before-and-after comparison of diagnostic certainty for the leading diagnosis

-

before-and-after comparison of the number of differential diagnoses considered per patient

-

retrospective survey of the test’s perceived usefulness.

On the basis of clinical history, examination and ultrasound findings only, treating gynaecologists were asked to state whether or not a pathological cause for CPP was identified, and to express their certainty regarding this decision. They were also asked to list their differential diagnoses, to state whether each was thought to be a cause of CPP and to express their certainty regarding these opinions. After the laparoscopy was performed, clinicians were asked for a revised differential diagnosis and associated certainty using identical questions. A comparison between pre- and post-laparoscopy diagnostic certainty was made, primarily to determine the utility of laparoscopy for identifying a pathological cause of CPP, and secondarily to compare changes in the certainty surrounding the leading differential diagnosis. The number of differential diagnoses considered before laparoscopy was also compared directly with the number considered after the test results were known.

An identical process was followed with independent non-treating gynaecologists (who were blind to the laparoscopic findings) who used MRI to arrive at a diagnosis. Pre-MRI diagnoses and associated certainty based on the same clinical history, examination and ultrasound findings were compared with post-MRI revised diagnoses and certainties. Independent gynaecologists were also asked whether or not they believed that the patient required a laparoscopy.

The gynaecologist’s subjective assessment of the usefulness of MRI or laparoscopy was evaluated after disclosure of the relevant test results, by asking clinicians to select one of four statements that best reflected their perception of the contribution of the test to each case. These statements were initially drafted with reference to those used in published before-and-after diagnostic confidence studies,71–73 and modified for their relevance to a CPP diagnosis following consultation with eight practising gynaecologists.

Aim and objectives

Aim

The aim was to assess if MRI could add value to the decision to perform a laparoscopy in women presenting with CPP. In doing so, we wanted to determine the number of women for whom MRI is sufficiently accurate to avoid the need for a laparoscopy in the investigation of CPP, following evaluation of the presenting characteristics with a detailed history, clinical examination and ultrasound.

Objectives

-

To estimate the accuracy of post-MRI diagnoses with respect to:

-

the absence of any observed condition or cause, that is, idiopathic CPP

-

the main gynaecological conditions or causes of CPP as target conditions, using post-laparoscopy diagnoses and EIP consensus (with and without incorporating MRI findings) as reference standards.

-

-

To determine the added value of MRI in a care pathway involving baseline history, clinical examination and ultrasound before performing laparoscopy.

-

To quantify the impact that a pre-laparoscopy MRI scan can have on decision-making with respect to triaging for therapeutic laparoscopy.

-

To determine the cost-effectiveness of MRI compared with laparoscopy.

Chapter 2 Methods

Introduction

We conducted a test-accuracy study in a prospective cohort of women with CPP symptoms, subjected them to thorough investigations, including our index tests (MRI scan and laparoscopy), and sought expert panel consensus to establish a reference diagnosis. We performed a comparative test-accuracy study with panel consensus for determining the reference standard.

Oversight

The study was conducted in accordance with the protocol, which received a favourable ethics opinion from East Midlands (Nottingham 1) Research Ethics Committee (reference number 11/EM/0281). NHS trust research governance approval was obtained from 26 recruiting hospitals in the UK. The study sponsor was the Queen Mary University of London. Independent oversight for the MEDAL study was requested by the funding body; however, how this oversight should be arranged or what it should entail were unclear, as the study was not considered to be distinct from that of randomised controlled trials. For the MEDAL study, the Data Monitoring Committee was defined as a subgroup of the Study Steering Committee (SSC). All members were independent of the MEDAL study management group. The chairperson of the SSC (along with the lay member) was not included in the Data Monitoring Committee.

Study oversight was provided by an independent steering committee and an independent data monitoring committee (see Acknowledgements for membership).

Study participants and setting

Any woman aged ≥ 16 years, who had been referred to a gynaecologist with CPP of at least 6 months’ duration, was potentially eligible. Women were assessed by a gynaecologist, which involved a standardised assessment and a clinical examination. If clinically indicated, women were referred for an ultrasound scan. If a laparoscopy was indicated and the patient wished to proceed with the laparoscopy, and was prepared to have a MRI scan, eligibility to participate in the study was confirmed. Women were excluded if they had had a hysterectomy, were pregnant or were unable to give written informed consent, or if they definitely had a clinical indication for a MRI scan, based on examination, history or ultrasound. Women were also excluded if they had an identifiable cause of CPP for which treatment could be initiated without a laparoscopy. Eligible women who provided written informed consent were committed to the study by telephone registration service at Birmingham Clinical Trials Unit (University of Birmingham, Birmingham, UK).

Pre-index tests

History and patient-completed questionnaires

A structured assessment template for use by all gynaecologists was provided, which first collected data from the participant and then allowed the clinician to create a clinical record. The assessment incorporated (1) demographic details; (2) menstrual, contraceptive and obstetric history; (3) tobacco and alcohol use; and (4) previous investigations and treatments for pelvic pain. Visual analogue scales were used to elicit scores (from 0 to 10) for pain symptoms of (1) dysmenorrhea (including pain occurring pre menses, during menstruation, post menses and mid-cycle); (2) dyspareunia (at the point of penetration, deep pain, burning pain, post-coital pain); (3) dysuria (full bladder, micturition); (4) muscle/joint pain in the pelvis; and (5) backache and migraine. A body map to illustrate the location of pain was also provided. The assessment also included standardised patient-completed questionnaires, previously validated in either women with pelvic pain or other clinical symptom groups. The domains captured by the questionnaire components of the assessment were:

-

neuropathic pain symptoms, measured using the short-form McGill Pain Questionnaire74

-

bowel symptoms, measured using the Rome III diagnostic criteria75

-

urinary problems, measured using the Pelvic Pain and Urgency/Frequency (PUF) Patient Symptom Scale76

-

sexual activity, measured using the Sexual Activity Questionnaire77

-

personality characteristic, measured using the Big Five Inventory scale78

-

psychological coping strategies, measured using the Pain Catastrophizing Scale79

-

endometriosis-related pain, measured using the Short Form Endometriosis Health Profile Questionnaire (EHP-5)80

-

risk of depression, measured using the Patient Health Questionnaire depression module (PHQ-2)81

-

sexual and physical abuse history, measured using the Sexual and Physical Abuse History questionnaire82

-

QoL and well-being, measured using the EuroQol-5 Dimensions, three-level version (EQ-5D-3L) instrument and the Investigating Choice Experiments CAPability (ICECAP)-A measure. 83,84

Clinical examination and ultrasound

Each woman underwent a clinical examination by the recruiting gynaecologist. A data collection form helped to direct the examination, which aimed to describe the location of any abdominal tenderness, and any tenderness, erythema, discharge or lesions on the external genitalia. A bimanual examination aimed to identify vaginismus, bladder wall or uterosacral ligament tenderness, cervical excitation, uterine size, position, contour, consistency and mobility, ovarian tenderness, mobility and presence of masses. A speculum examination of the vagina was used to identify prolapse, vaginal atrophy, polyps and cervicitis, and also allowed swabs to be taken if indicated and if the woman consented. A urine sample was provided to perform a dipstick test to detect urinary tract infection.

The intention was for all women to have a detailed ultrasound scan, in accordance with the study protocol, scanning by both the transabdominal route on a full bladder and then the transvaginal approach on an empty bladder. However, in some centres, the ultrasound was scheduled with a sonographer prior to the first appointment with the gynaecologist. In these cases, it was not possible to repeat the ultrasound, and an incomplete data set for the study was extracted from the report. The intention was to describe the uterine size by both approaches, and also to examine the uterine position, myometrial appearance and endometrial width, as well as ovarian size, location and presence of ovarian cysts and, finally, bladder wall thickness, all by transvaginal ultrasound. Further information sought included the presence of free or loculated fluid and organ- or site-specific tenderness or restricted mobility.

Index tests

Magnetic resonance imaging scan

Women were asked to fast for 2–4 hours prior to the scan and not to empty their bladder immediately prior to the scan. Antiperistaltic agents were contraindicated, but antispasmodic drugs were acceptable.

The MRI standard protocol comprised T1 and T2 axial, T2 sagittal, T2 coronal and T1-fast-spin (FS) axial, sagittal and coronal sequences, using standardised anatomical landmarks, slice thicknesses and field of view. If unexpected abnormalities were detected, additional sequences, potentially using the contrast media gadolinium, could be added to the scanning protocol to enable further clarification and assessment.

To ensure blinding of assessments, a MRI scan was performed before diagnostic laparoscopy, and treating gynaecologists and investigators were kept blind to the MRI reports and images. To identify radiological parameters for inclusion in the MRI report, a two-generational Delphi survey with an expert panel of 28 radiologists specialising in gynaecological MRI from across the UK was undertaken. 63 The MRI report collected data described in Table 2.

The radiologists’ assessments of the quality of the scan were captured, and they were asked to summarise the observations and provide a radiological diagnosis in free-text form.

The MRI scan was also independently reported by a second radiologist who was blinded to the initial MRI report. This would be a radiologist involved in reviewing scans for the study, but based at a different site from the initial reporting radiologist. Where the local and independent radiologists agreed on the summary diagnosis, the findings were accepted as a consensus and provided the ‘post-MRI diagnosis’ data for analysis. Lack of agreement between local and independent radiologists prompted a review by the Independent Radiology Review Committee (IRRC), made up of three experienced radiologists who were not involved in imaging participants in the study. The IRRC agreed a consensus MRI report. The finalised report was provided to the independent gynaecologist for determining the post-MRI diagnosis, and to the EIP for the second stage in the reference diagnosis.

The diagnostic criteria used for the analysis of the accuracy of MRI are given in Table 2. These were defined by the lead radiological investigator and confirmed by a second radiologist otherwise not involved in the study. There were potential variations in diagnosis, for example in relation to whether an intermediate signal from a T1 and T1-FS image of a bowel mass was indicative of deep-infiltrating endometriosis; therefore, the different diagnostic criteria were considered in alternative or sensitivity analyses.

The MRI reports were not provided to the gynaecologist unless unexpected significant findings were identified by the local reporting radiologist. We prespecified the circumstances in which this may happen, such as identification of an unexpected cancer, abscess or non-gynaecological abnormality requiring immediate attention. In the case of unblinding, the participant was excluded from the diagnostic accuracy study and managed appropriately.

Laparoscopy

The diagnostic laparoscopy was performed under general anaesthetic in accordance with the gynaecologist’s standard practice. After a pneumoperitonium was established, a laparoscope was introduced to visualise the abdominal and pelvic structures, and any pathology. Laparoscopy was performed by an experienced gynaecologist who was capable of identifying all potential target conditions. Surgical findings were reported using a standardised proforma, which collected the information described in Table 3.

| Laparoscopic feature | Criteria used in analysis to define the observation of the target condition |

|---|---|

| Presence, location and severity of endometriosis | Presence of endometriosis in any location, categorised as either superficial or deep. Biopsies may have been taken for histological confirmation, but the results were not considered for the criteria. AFS grading was used85 |

| Presence, location and appearance (filmy, dense/vascular or an absent plane) of adhesions | Presence of adhesions in any location, irrespective of appearance |

| Presence of adenomyosis | Presence of adenomyosis observed. It is acknowledged that adenomyosis cannot be directly observed, but other features might be suggestive |

| Presence, location, type (simple, dermoid, cancerous, other) and size of ovarian cysts | Presence of any ovarian cysts, regardless of type |

| Presence, location and maximum size of fibroids | Presence of any fibroids, regardless of location. It is acknowledged that submucosal and small intramural fibroids cannot be directly observed, but other features may be suggestive or they may have been observed by hysteroscopy |

| Presence of PID | Presence of features indicative of PID |

| Pelvic congestion syndrome | Observation of dilated pelvic veins |

When clinically indicated, additional procedures were performed at the time of surgery. Information was collected on procedures, including ablation or excision of superficial endometriosis, ovarian cystectomy, adhesiolysis, hysteroscopy (noting the presence of fibroids or the insertion of the levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system), endometrial biopsies and histological confirmation of pathology and cystoscopy. If bladder biopsies were collected, the histological confirmation of pathology was recorded.

Follow-up

Some of the target conditions may respond well to treatment; therefore, information was collected at 6 months following laparoscopy, using a postal questionnaire. The questionnaire contained all of the elements of the initial patient questionnaire, including the visual analogue scales, validated questionnaires and questions regarding further tests and treatments, but omitted the demographic and history questions, as the answers to these questions would not have changed. Women were sent reminders if they failed to respond to the initial questionnaire. The information gained from follow-up was considered by the EIP when assigning the reference standard.

Assigning the cause of pain

At several stages in the study path for each patient, the treating gynaecologist and the independent gynaecologist reviewed the diagnostic evidence available. To establish a possible diagnosis for each target condition (including idiopathic CPP), they indicated their level of certainty that the condition was causing the pelvic pain on a numerical rating scale, ranking from 10 being certain (expressed as a 99 in 100 chance), through 5 being a fairly good possibility (a 5 in 10 chance) to 0, considered to be no chance or less than a 1 in 100 chance.

The first condition was the absence of structural cause, defined as idiopathic or unknown. There then followed seven structural gynaecological causes (superficial peritoneal endometriosis, deep-infiltrating endometriosis, endometrioma of the ovary, adhesions, ovarian cysts, adenomyosis, fibroids), together with the option to specify another gynaecological cause. The non-gynaecological causes offered were psychological or psychosexual, gastrointestinal, urinary, musculoskeletal, neurological or another pathological cause, with the requirement to specify the diagnosis further. Definitions for idiopathic CPP, superficial peritoneal and deep-infiltrating endometriosis, adhesions and pelvic congestion syndrome were provided.

Determining the role of magnetic resonance imaging by independent assessment

The treating gynaecologists were kept blind to the MRI scan report so that they could make an unbiased assessment of the laparoscopic findings. If MRI was found to be useful in the MEDAL study, an MRI scan would precede laparoscopy in the investigative pathway in the future. In order to model the impact of using the MRI scan report, an independent gynaecologist reviewed each case. This gynaecologist was randomly selected from another hospital recruiting to the MEDAL study, so was familiar with the study aims, processes and data collection. The independent gynaecologist was provided with all the data collection forms for the pre-index tests and clinical history, together with the laparoscopy report. The information was anonymised. The independent gynaecologists were asked to complete the certainty scales for each condition, which constituted the pre-MRI independent diagnosis and should be highly correlated with the recruiting gynaecologists’ diagnoses post laparoscopy, being derived from the same information. The independent gynaecologists were then asked to read the MRI scan report and repeat the process, completing the certainty scales. There were three extra hypothetical questions at this second post-MRI stage: if the gynaecologist was treating that particular patient, would they have scheduled a laparoscopy (having reviewed the MRI scan report), if they would have scheduled a therapeutic laparoscopy and, if so, would they anticipate that the diagnostic and therapeutic elements would be performed as part of a single procedure?

Reference standard

The analysis considers two sets of reference standard. The first identified was to assess the accuracy of the MRI scan for observing a condition, and the second was to assess the accuracy of the MRI scan for identifying the condition(s) causing pelvic pain. The first set used findings from laparoscopy for the reference standard, and the second used consensus from an EIP. It was expected that not all women who were observed to have each condition would have it categorised as being the source of pelvic pain.

Piloting the expert independent panel

There is little evidence on how panels should be convened or how information should be presented. Given the amount of information to be considered by the panel and the associated review time, the study management group, in conjunction with the EIP chairperson, considered the use of a summary report. To ensure that the diagnosis based on the summary report was the same as the diagnosis based on all of the data collection forms (initial patient assessment, including patient questionnaire, clinical examination, ultrasound, post-laparoscopy report and, finally, the MRI scan report), a pilot EIP panel was convened to pilot and review the process. The pilot EIP panel consisted of three clinicians not involved in the study recruitment.

Ten cases were presented to the three members. For the first five cases, two of the three members used the summary report and the third member used the data forms. For the last five cases, two members, who had previously used the summary report, used the data collection forms. For each case, the members defined a single or multiple diagnosis. Results from the meeting indicated that the summary report and data collection forms allowed the members to produce the same diagnosis. Data collection forms were preferred, or used in conjunction with the summary report, when cases were considered to be complex (e.g. when a patient had multiple conditions and various confounding factors).

To elicit a diagnosis, a form with a list of the target conditions was provided. This was comparable to the form used by the treating and independent gynaecologist, except that the certainty scale was not used and simple yes/no answers were allowed. During the pilot EIP meeting, members were allowed to record multiple causes. This was considered unsatisfactory as a reference standard, as they would complicate accuracy assessments, so the initial guidance regarding the first eight cases presented to the main EIP members was to diagnose what they believed to be the single main cause of pain. The process was performed in two stages: once with all of the data, except those from the MRI report, and then a second time, including the data from the MRI report. The first-stage diagnosis avoided incorporation bias from knowledge of the MRI scan results, whereas the second-stage diagnosis provided information to determine the added value of the MRI scan. Two further yes/no questions were posed to the panel: (1) does the laparoscopy add anything to your diagnosis that was not available from other investigations and (2) could this laparoscopy have a therapeutic purpose?

Feedback from these eight cases suggested that, in some instances, it was necessary to select more than one condition, given that two or more conditions could equally be the cause of pain. The criteria and guidance were changed so that EIP members could select any clinically appropriate conditions they believed to be the cause of pain, provided that they were at least 50% certain. The diagnosis form still allowed only yes/no answers, but multiple reasons could be given. The first eight cases were reviewed again at a later meeting using the revised criteria.

Expert panel membership and meeting format

The panel membership consisted of 15 consultant gynaecologists who were not involved in the study recruitment. Each face-to-face meeting was made up of three members who provided the reference diagnosis for each case presented based on the summary report of the data, with the individual data forms available if required.

The first-stage reference diagnosis was based on patient history and reported symptoms, clinical examination, ultrasound, laparoscopy and follow-up. For the second-stage reference diagnosis, the MRI scan report was provided. For both stages, each EIP member individually recorded the conditions that they were more than 50% certain were the cause of pain, and addressed the two questions regarding the potential gain from the laparoscopy, prior to a group discussion. The meeting chairperson documented the discussion and how agreement was reached, and the final consensus diagnosis constituted the reference standard.

Sample size

A sample size of 250 women was chosen a priori to address the primary research question of determining the proportion of women for whom MRI is sufficiently accurate to replace laparoscopy in the investigation of CPP, following evaluation of the presenting characteristics. With this sample size, the study was anticipated to have > 90% power (at p = 0.05) to detect a reduction of 10% in the number of laparoscopies needed (i.e. from 100% down to 90%). This difference would be cost-effective if laparoscopy was at least 10 times more expensive than MRI. Estimates used at the start of the study placed laparoscopy at being 7.4 times more expensive than MRI (£1274 vs. £173); however, these NHS tariffs may not necessarily reflect the true cost of the total investigative pathway, which will be estimated through primary data collection as part of this study.

Having 250 women as the sample size was also expected to provide a reasonable number of cases of each of the more common target conditions from which to estimate the sensitivity of MRI for diagnosis. We anticipated a high sensitivity of MRI for detecting common pathological causes of CPP; therefore, we based our calculations on an anticipated sensitivity of 80% for any particular condition (a sensitivity of 90% has also been provided for comparison; Table 4). We then computed the 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for these sensitivities for a range of prevalences of any particular condition (see Table 4). These figures could equally apply to specificity. For a target condition with a prevalence of 30% or more, we expected to be able to reliably rule out a sensitivity or specificity of < 70% if the ‘true’ sensitivity or specificity was > 80%.

| Assumed sample size of 250 women | Assumed sensitivity (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Prevalence (%) | Number of cases | 80 | 90 |

| 50 | 125 | 72–87 | 84–95 |

| 40 | 100 | 71–87 | 82–95 |

| 30 | 75 | 69–88 | 82–96 |

| 20 | 50 | 66–90 | 78–97 |

In May 2013, when the target sample size had already been slightly exceeded (269 women), the trial team, together with the input of the independent oversight committees, decided to extend recruitment until the end of September 2013, with a revised target of 340 women, and the protocol was amended accordingly. At this stage, the study was recruiting faster than was originally planned. The aim of extending recruitment was to improve the statistical precision of the accuracy estimates for the less prevalent gynaecological causes, and this revised plan was ratified by the external Trial Steering Committee. For example, a sensitivity of 90% would have a lower 95% CI boundary of 80% for conditions occurring in 30% of women in a sample size of 250, and in conditions occurring in 20% of women in a sample size of 340. However, between May 2013 and September 2013, recruitment to the study unexpectedly started to slow and this revised target was not met, with a final sample size of 291 participants at the start of the diagnostic study.

Data analysis

Reliability estimates

Agreement between the three individual members of the EIP in their diagnosis (for ‘any gynaecological cause’ and each gynaecological cause separately) was analysed using the methodology proposed by Fleiss,72 which is a generalisation of the Cohen’s kappa statistic to the measurement of agreement among multiple raters. In addition, the agreement between the consensus panel diagnosis, made with and without the MRI findings, was analysed using the Cohen’s kappa agreement statistic. In both cases, the kappa value was presented alongside its 95% CI. We also reported the number of cases in which disagreements occurred.

Accuracy estimates

By comparing the index test with the reference standard, the results of the index test were categorised as a true positive, a false positive, a true negative or a false negative. The sensitivity of each test was computed as the proportion of all positive results on the reference standard that were true positives, and the specificity was computed as the proportion of all negative results on the reference standard that were true negatives.

The prevalence of all gynaecological and non-gynaecological conditions in relation to whether or not they were believed to be causing pain (as determined by the reference standard established by the consensus of the EIP) was calculated, along with the 95% CIs, using binomial exact methods. 86 For gynaecological conditions, estimates of prevalence for whether or not the condition was also observed at laparoscopy were also produced.

The initial analysis looked at the diagnostic accuracy of MRI in being able to detect if a condition actually existed (regardless of whether or not it was judged to be the cause of pain), using the laparoscopy report as the reference standard; MRI data were taken directly from the MRI scan report using the set of rules described in Table 2. Accuracy estimates for this additional analysis (sensitivity and specificity, along with 95% CIs) were calculated, and Fisher’s exact test was used to explore if MRI and laparoscopy detected the same women with a presence of each target condition.

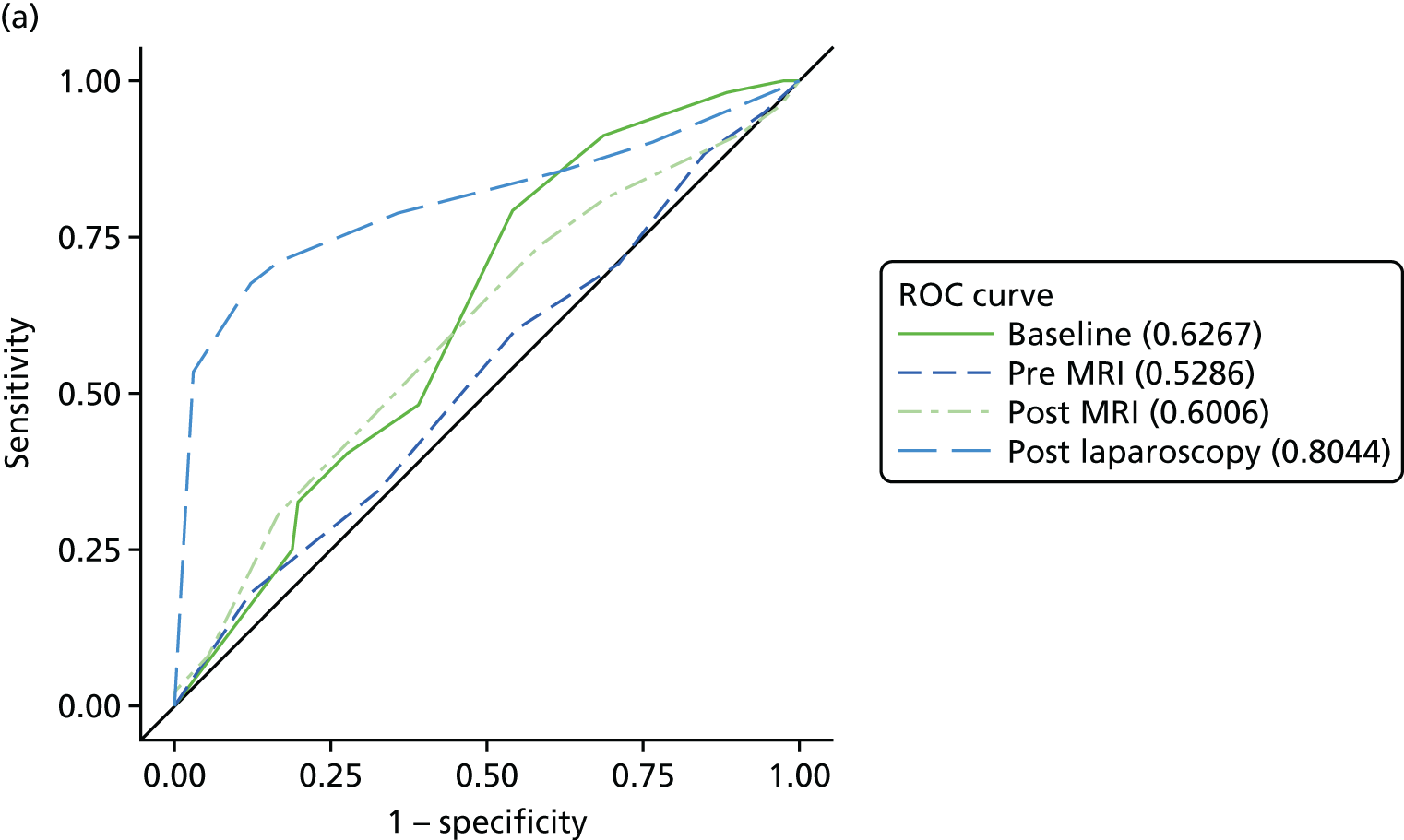

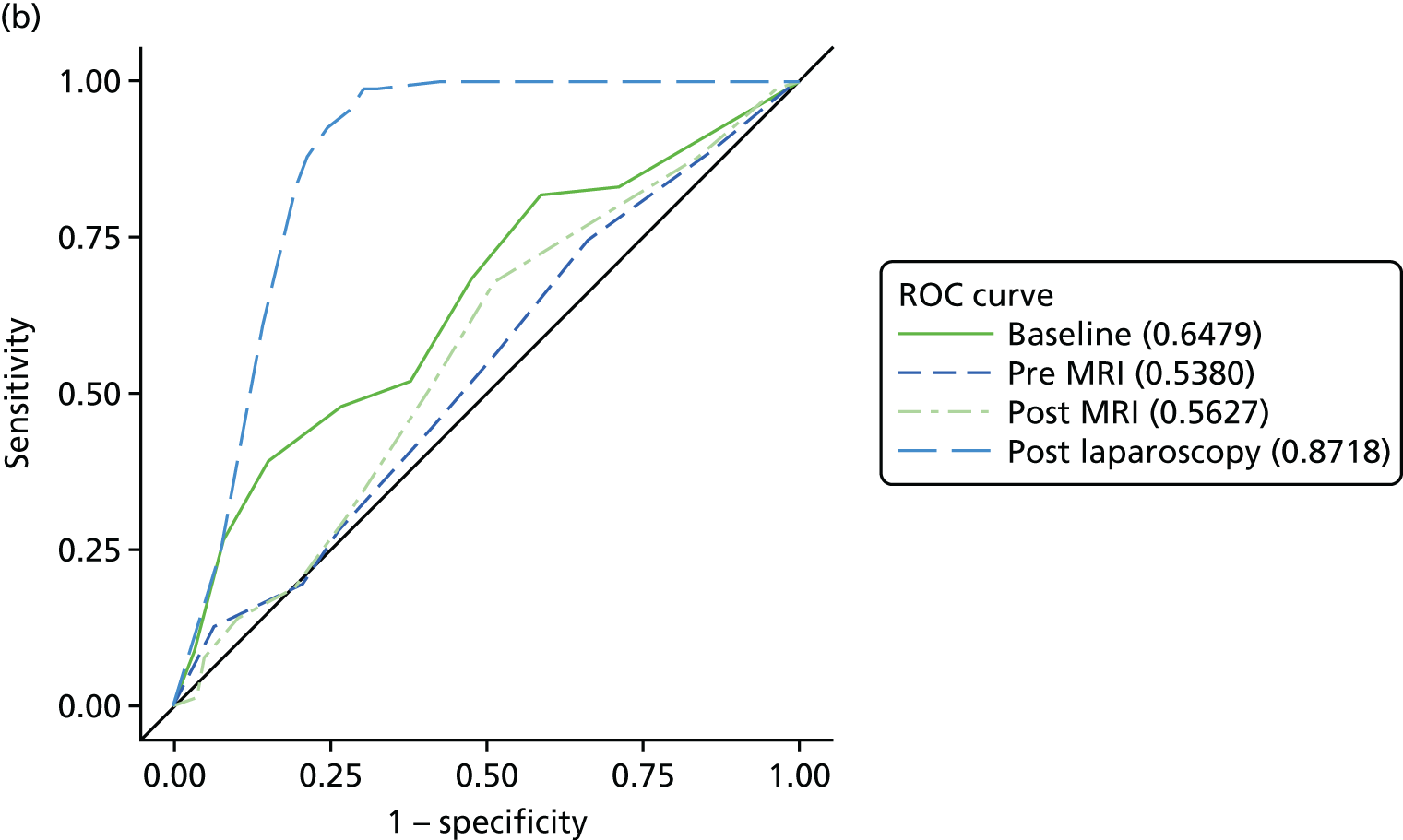

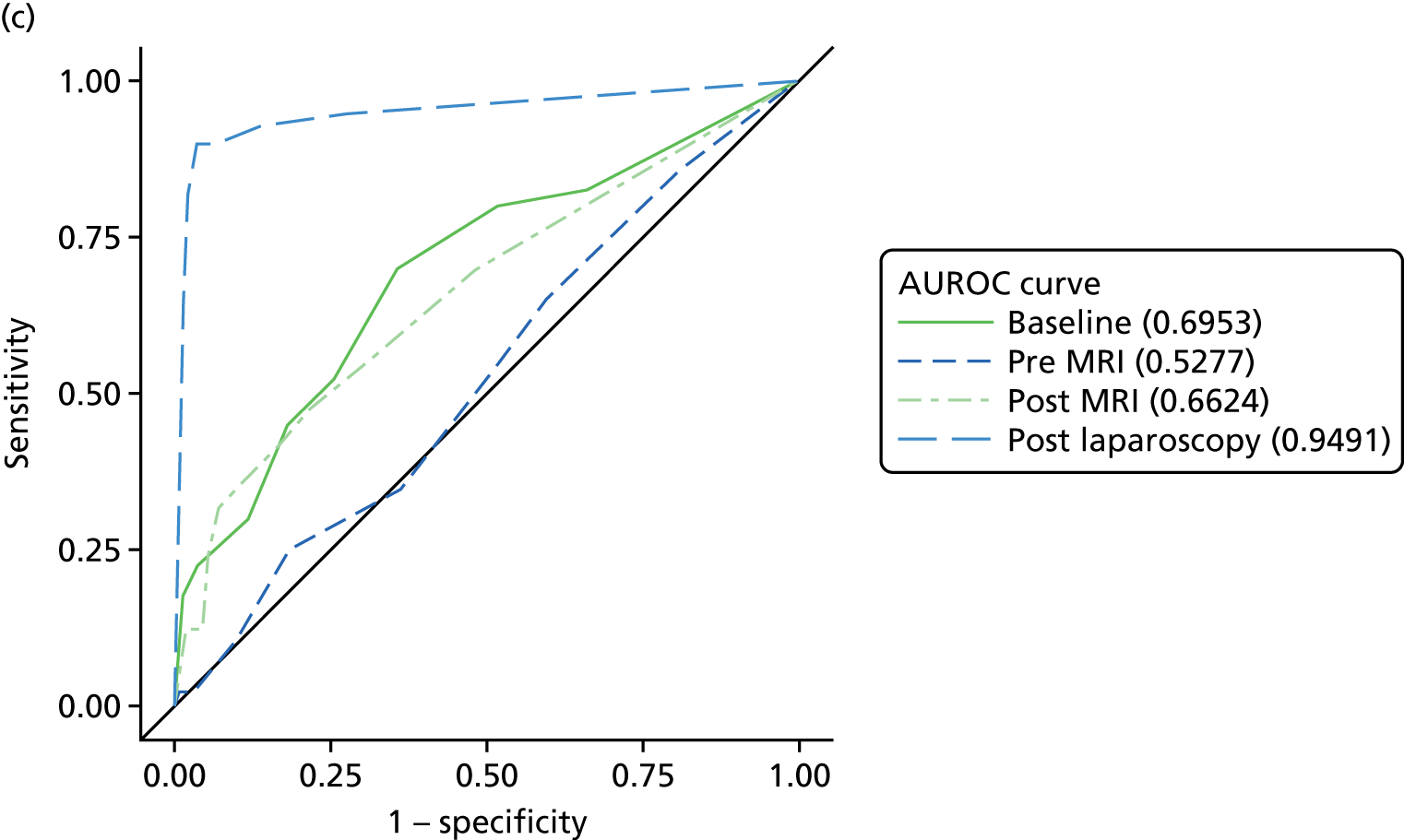

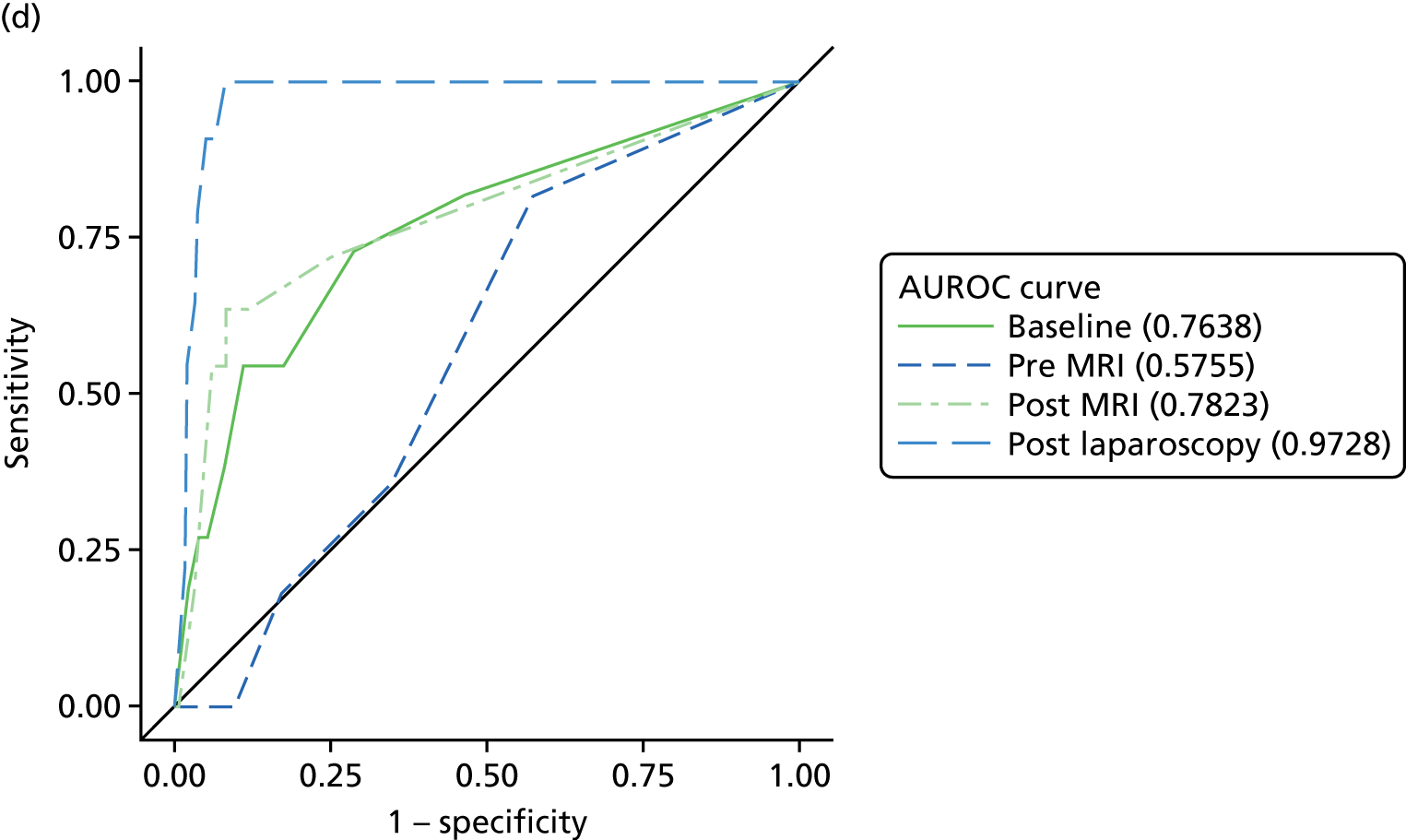

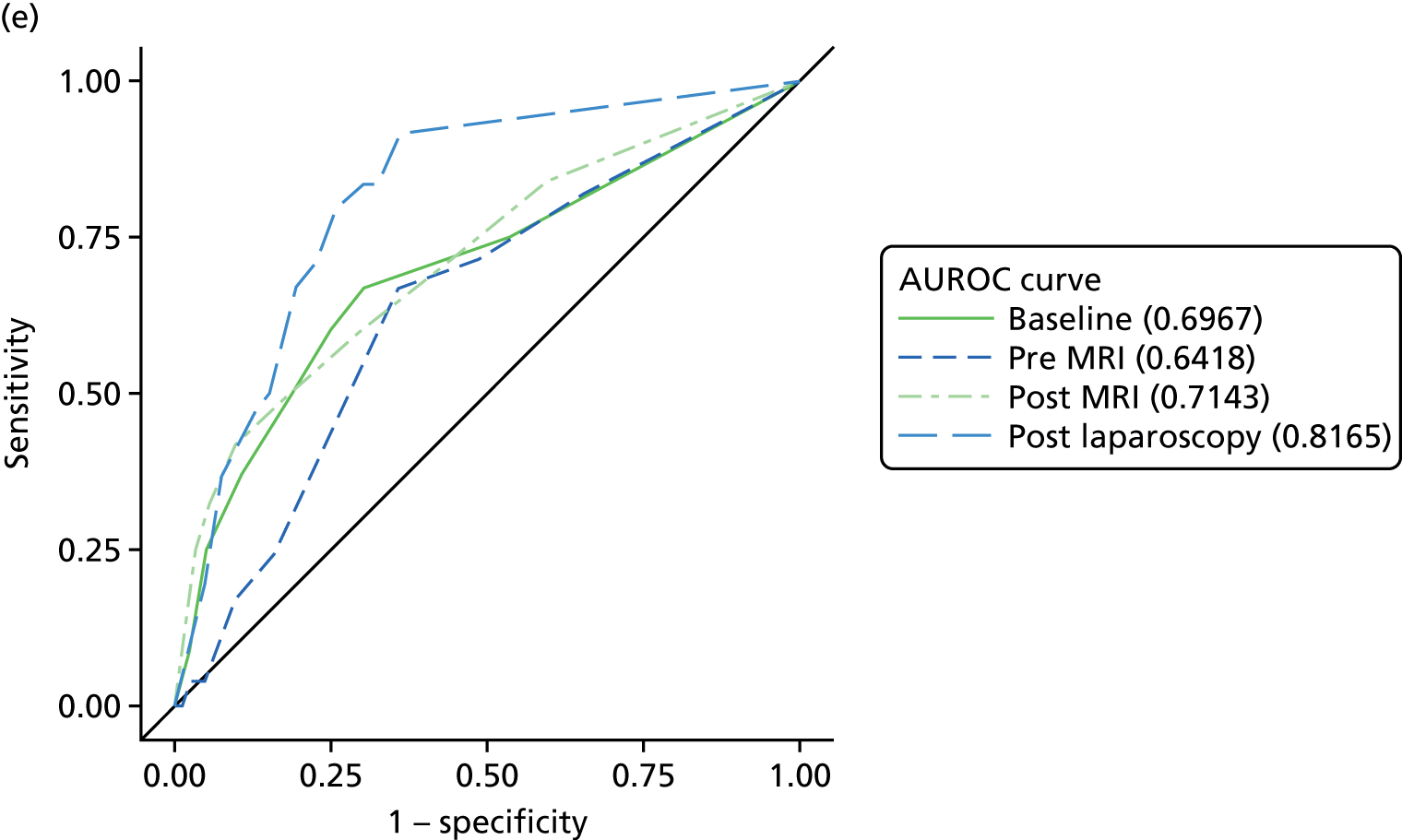

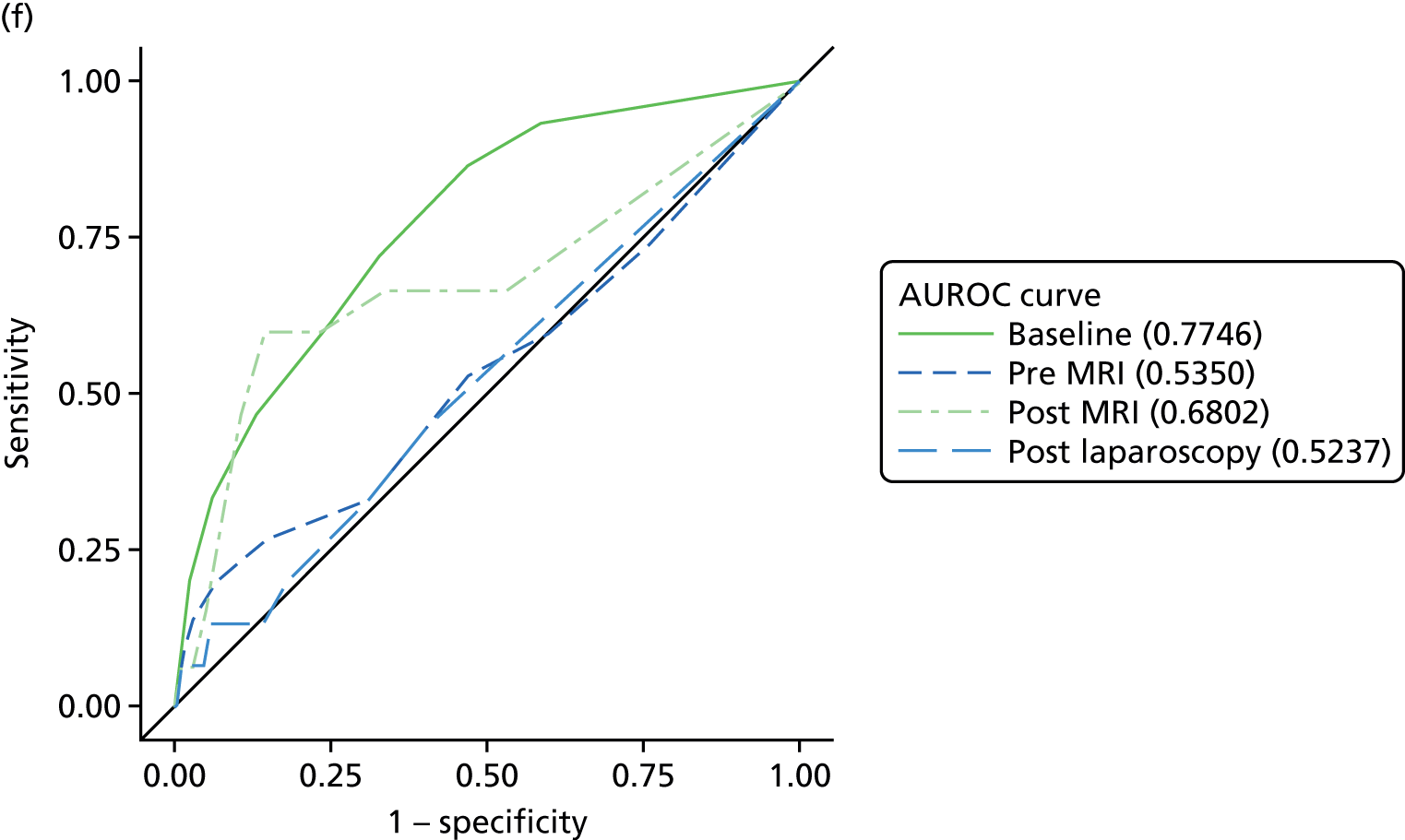

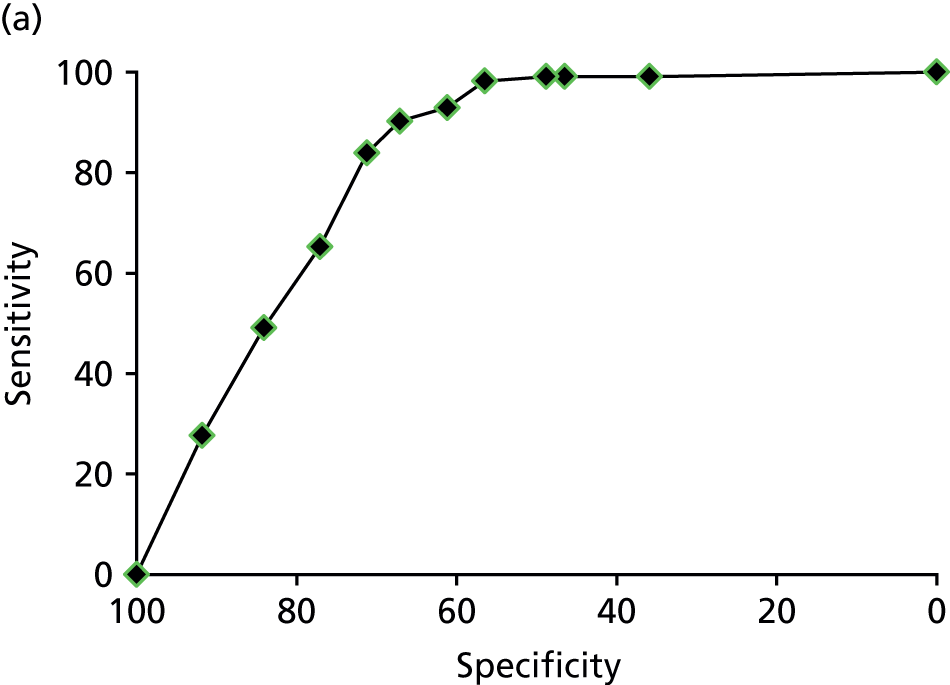

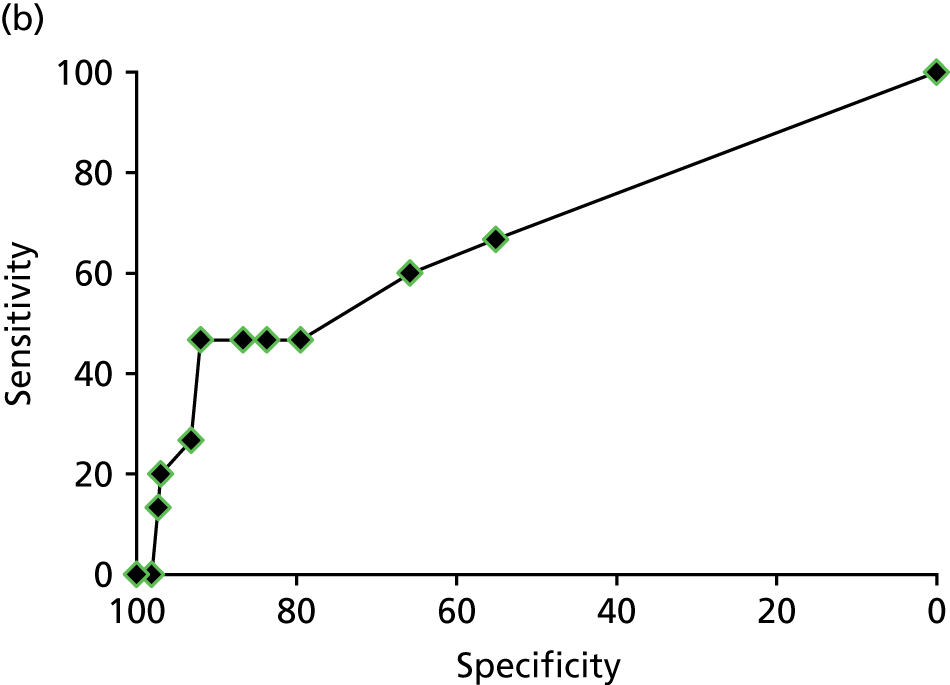

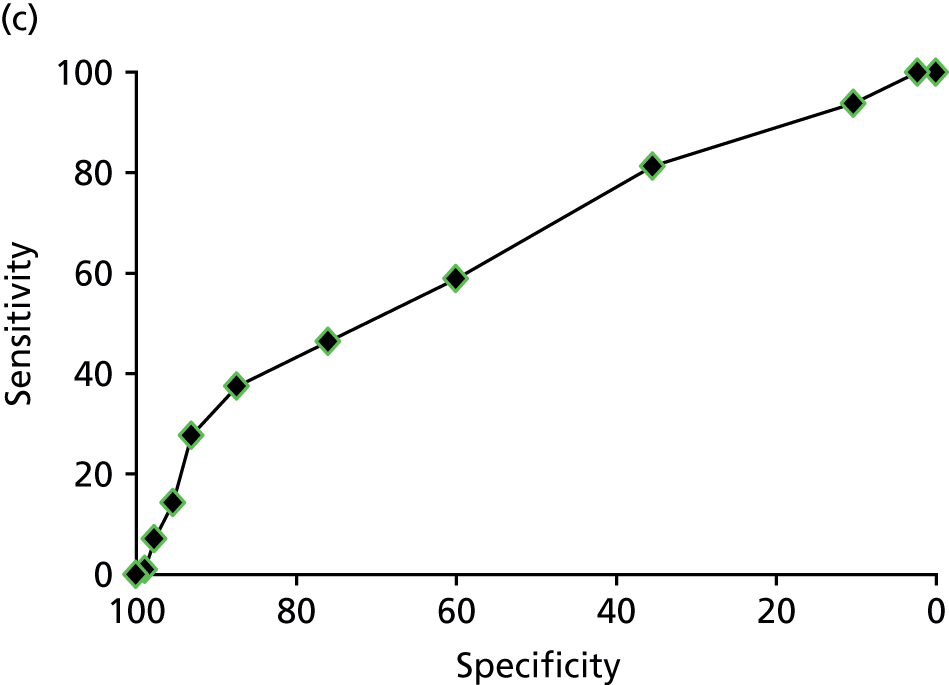

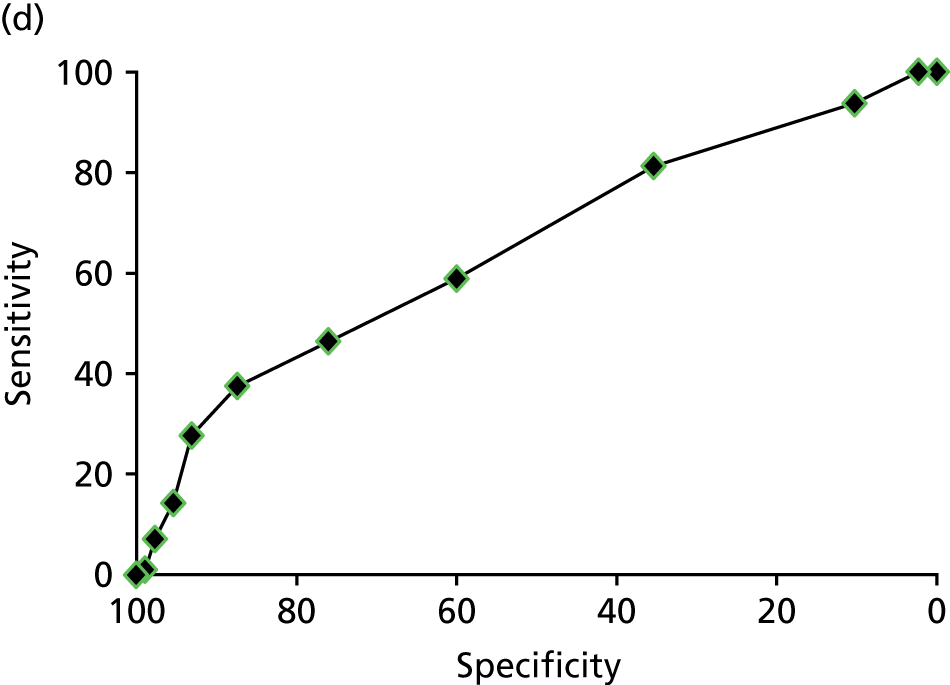

The primary analysis involved calculations of sensitivity and specificity (and the associated 95% CIs) for the presence or absence of each structural gynaecological cause of pain; data were taken from the binary yes/no responses of the reference standard before and after the MRI data were revealed. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves were also constructed for each test for each condition, using the certainty estimates (0 = ‘no chance/almost no chance’ to 10 = ‘certain, practically certain’) provided by the clinician and the binary responses of the reference standard. The area under the ROC (AUROC) curve and the 95% CI were estimated for each test. Differences between the AUROC estimates of each of the four diagnoses were then calculated using a non-parametric approach for correlated data,71 and these differences are presented along with their 95% CIs. The same analysis was done to compare the responses after the MRI data were revealed (from the independent gynaecologist) with the responses after the laparoscopy had been undertaken (from the treating gynaecologist), to compare the accuracy of MRI-based diagnoses with laparoscopy-based diagnoses. Only participants with laparoscopic, MRI and EIP diagnoses were included in the analysis.

The proportion of women for whom a diagnostic and/or therapeutic laparoscopy could be avoided was calculated by adding up the number of women needing treatment other than laparoscopy (women with adenomyosis, fibroids or PID) and the number of women not needing any treatment (as a result of the absence of any gynaecological cause), which were correctly identified from the MRI scan.

All analyses were performed using SAS, version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

Chapter 3 Diagnostic study results

Recruitment

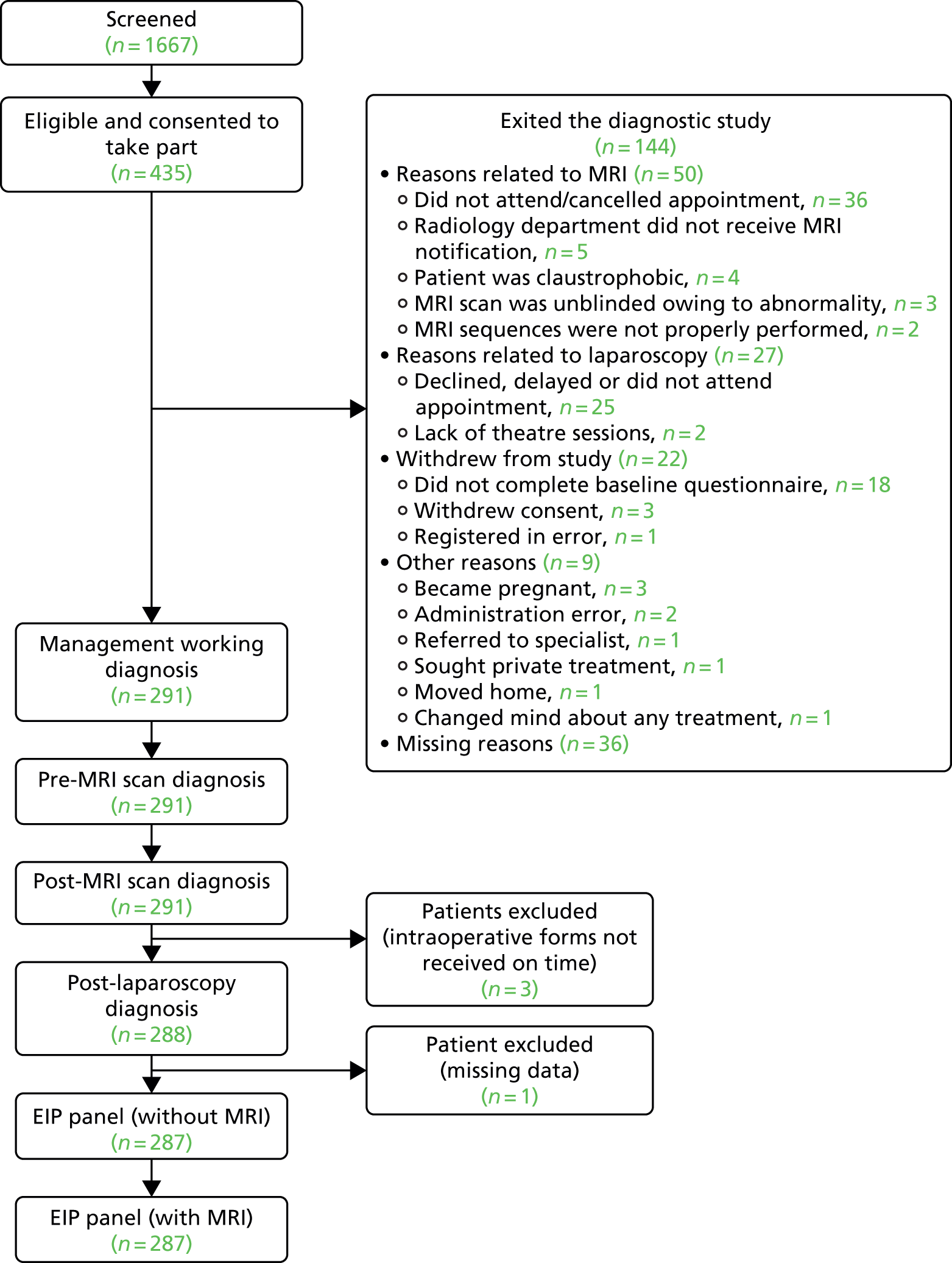

The recruitment of participants started in December 2011 and closed in September 2013. A total of 1667 women were screened. A total of 435 women, who consented to participate, were recruited into the study from 26 centres (see Appendix 1, Table 29). Ultimately, 287 women contributed to the analysis (Figure 3).

FIGURE 3.

Flow chart of participants, showing the numbers who provided data at each stage.

The original sample size of 250 participants was reached ahead of schedule, so the sample size was revised to 340 participants. The sample size was increased to improve the precision of estimates for all target conditions, but most notably for the less common target conditions.

Characteristics of participants

The mean age of the women in our sample was 31.6 years [standard deviation (SD) 8.3 years]. Of these, 197 women (68.5%) were in employment and 96 (33.5%) had received a university-level education. There were 216 white women (74.5%). The duration of pain was, on average, 4.2 years (SD 4.8 years); pain was present on at least 1 day every week in 226 women (79.5%), with a mean pain score of 7.1 points (SD 2.8 points) during menstrual periods and 6.4 points (SD 2.6 points) before menstrual periods. The average age at menarche was 12.8 years (SD 1.7 years). Heavy periods were a feature in 147 women (58.6%). Around three-quarters of women (n = 212; 73.4%) were sexually active, with pain during intercourse featuring over the last 20.3 months (SD 20.7 months). Contraceptive hormones had been prescribed for pain to 162 women (55.7%). Chlamydia testing was undertaken in 202 women (70.4%), of whom 176 (89.3%) had received negative results. Laparoscopy and MRI had been used for diagnosis in the past in 80 (27.5%) and 30 women (10.3%), respectively. Infertility was not a complaint in 206 women (85.1%). Further details of participant characteristics are shown in Table 5 and Appendix 1, Tables 30 and 31.

| Characteristic | Value |

|---|---|

| Age (years), mean (SD, n) | 31.6 (8.3, 291) |

| Marital status,a n (%) | |

| Single | 96 (33.2) |

| Living together | 66 (22.8) |

| Married | 110 (38.1) |

| Separated/divorced | 17 (5.9) |

| Employment,b n (%) | |

| Full-time employment | 128 (44.4) |

| Part-time employment | 50 (17.4) |

| Self-employed | 19 (6.6) |

| Caring for children | 35 (12.2) |

| Student | 22 (7.6) |

| Unemployed | 34 (11.8) |

| Highest level of education achieved,c n (%) | |

| No qualifications | 17 (5.9) |

| GCSE/O level/NVQ1–2 | 94 (32.9) |

| A level/BTEC qualification/NVQ3–4 | 79 (27.6) |

| University degree | 67 (23.4) |

| Postgraduate degree | 29 (10.1) |

| Ethnic group,d n (%) | |

| Asian/Asian British | 33 (11.3) |

| Black/black British | 18 (6.2) |

| White | 216 (74.5) |

| Mixed | 12 (4.1) |

| Any other ethnic group | 9 (3.1) |

| Do not wish to say | 2 (0.7) |

The median duration between the MRI scan and the diagnostic laparoscopy was 26 days (interquartile range of 9–54 days).

Reliability of the expert independent panel diagnoses

We investigated the reliability of the EIP reference diagnoses by looking first at the consensus ratings made with and without access to the MRI report and, second, at the agreement between individual raters in the independent expert group.

Table 6 reports the prevalence of each condition as defined by the EIP with and without access to the MRI report. We considered the primary reference standard to be the EIP consensus statement without the MRI report, as this would reduce the risk of incorporation bias in assessing the accuracy of the MRI report. However, we were interested in noting when the reference standard consensus diagnoses differed, as it was known that an MRI scan may be the only test to identify several of the conditions in some women.

| Cause of pelvic pain | Prevalence (N = 287), n (%) | Reliability | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reference diagnosis without MRI findings | Reference diagnosis with MRI findings | Assessors’ kappaa (95% CI) | Number of cases disputedb | |

| Idiopathic for gynaecological conditions | 156 (54.4) | 153 (53.3) | 0.75 (0.69 to 0.84) | 40 |

| Superficial peritoneal endometriosis | 71 (24.7) | 71 (24.7) | 0.74 (0.67 to 0.81) | 32 |

| Deep-infiltrating endometriosis | 40 (13.9) | 42 (14.6) | 0.96 (0.89 to 0.99) | 3 |

| Endometrioma of the ovary | 11 (3.8) | 13 (4.5) | 0.80 (0.73 to 0.87) | 6 |

| Adhesions | 24 (8.4) | 25 (8.7) | 0.54 (0.47 to 0.61) | 35 |

| Ovarian cysts | 1 (0.3) | 0 (0) | – | 0 |

| Adenomyosis | 11 (3.8) | 16 (5.6) |

0.32 (0.26 to 0.40) 0.60 (0.53 to 0.67)# |

24 22# |

| Fibroids | 4 (1.4) | 5 (1.7) | 0.53 (0.46 to 0.60) | 7 |

| PID | 10 (3.5) | 10 (3.5) | 0.52 (0.45 to 0.69) | 10 |

| Urinary causes | 18 (6.3) | 16 (5.6) | 0.35 (0.28 to 0.42) | 35 |

| Musculoskeletal causes | 48 (16.7) | 47 (16.4) | 0.51 (0.44 to 0.58) | 39 |

| Gastrointestinal causes | 24 (8.4) | 23 (8.0) | 0.51 (0.44 to 0.58) | 34 |

| Psychological/psychosexual causes | 78 (27.2) | 75 (26.1) | 0.53 (0.46 to 0.59) | 59 |

Table 6 shows that the difference in the number of cases detected was between zero and two for all conditions other than adenomyosis (difference of five cases detected), and cases with psychological and psychosexual causes (difference of three cases detected). Although there are clinical reasons why adenomyosis can only be detected by a MRI scan, which are likely to explain the difference, there are no reasons to explain the difference for cases with psychological and psychosexual causes. We therefore report comparisons with the second-stage MRI scan-informed EIP consensus reference diagnosis for analysis of adenomyosis, but not for any other conditions.

To assess the reliability of the EIP diagnoses, we considered the agreement between the three individual ratings made by the panel members prior to any group discussion. We computed the kappa statistic across the three raters to describe the agreement beyond that explained by chance. Kappa values above 0.80 were considered to indicate excellent agreement, whereas those between 0.60 and 0.79 indicate good agreement and those below 0.60 indicate poor or moderate agreement.

The panel were in excellent agreement in identifying deep-infiltrating endometriosis and endometrioma of the ovary as causes of pelvic pain, and in good agreement in identifying superficial peritoneal endometriosis and adenomyosis when the MRI reports were used in the reference standard. Lower levels of agreement were noted for deciding that adhesions, fibroids and PID were the cause of pelvic pain. The expert panel failed to demonstrate adequate reliability in determining whether any of the non-gynaecological causes were the cause of pelvic pain for further detailed examination of these causes.

Prevalence of conditions being the cause of pelvic pain or observed on magnetic resonance imaging scans or through laparoscopy

Table 7 reports the prevalence of the causes of pelvic pain as judged by the EIP and observed through laparoscopy and MRI scans. For many conditions (superficial peritoneal endometriosis, endometrioma of the ovary, adhesions, ovarian cysts, adenomyosis and fibroids), the prevalence of observing the condition through MRI scans and/or laparoscopy was higher than the prevalence according to the judgements of the EIP, reflecting that, in many women, the conditions may be observed but not judged to be the cause of pelvic pain.

| Cause of pelvic pain | Judged as being the cause of pelvic pain, n (%) | Observation by technique, n (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reference diagnosis without MRI | Reference diagnosis with MRI | Laparoscopy (N = 287) | MRIa (N = 287) | |

| Idiopathic (no structural gynaecological cause) | 156 (54.4) | 153 (53.3) | 75 (26.1) |

49 (17.1)b 148 (51.6)c |

| Superficial peritoneal endometriosis | 71 (24.7) | 71 (24.7) | 120 (41.8) | No criteria |

| Deep-infiltrating endometriosis | 40 (13.9) | 42 (14.6) | 37 (12.9) | 3 (1.0) |

| Endometrioma of the ovary | 11 (3.8) | 13 (4.5) | 68 (23.7) | 31 (10.8) |

| Adhesions | 24 (8.4) | 25 (8.7) | 109 (39.6) | 37 (12.9) |

| Ovarian cysts | 1 (0.3) | 0 (0) | 56 (19.7) | 27 (9.4) |

| Adenomyosis | 11 (3.8) | 16 (5.6) | 21 (7.3) |

193 (67.2)b 34 (11.8)c |

| Fibroids | 4 (1.4) | 5 (1.7) | 24 (8.4) | 56 (19.5) |

| PID | 10 (3.5) | 10 (3.5) | 10 (3.5) | 15 (5.2) |

| Urinary causes | 18 (6.3) | 16 (5.6) | Not assessed | No criteria |

| Musculoskeletal causes | 48 (16.7) | 47 (16.4) | Not assessed | No criteria |

| Gastrointestinal causes | 24 (8.4) | 23 (8.0) | Not assessed | No criteria |

| Psychological/psychosexual causes | 78 (27.2) | 75 (26.1) | Not assessed | No criteria |

Superficial peritoneal endometriosis was identified as the most common gynaecological cause of pelvic pain in 25% of women, followed by deep-infiltrating endometriosis in 14%, adhesions in 8%, endometrioma of the ovary, adenomyosis and PID each in 4% and fibroids and ovarian cysts in ≤ 1%. Of the non-gynaecological causes, psychological/psychosexual causes were the most common in 27% of women, musculoskeletal causes in 17%, gastrointestinal causes in 8% and urinary causes in 6%. Fifty-four per cent of women were judged to have idiopathic pelvic pain with no structural gynaecological cause identified.

The three endometriosis conditions (superficial peritoneal, deep-infiltrating and endometrioma of the ovary) and ovarian cysts were observed twice as often with laparoscopy, and adhesions three times as often, as with MRI scans. Adenomyosis, fibroids and PID were noted more often through MRI than through laparoscopy. No MRI diagnostic criteria were available for the non-gynaecological conditions.

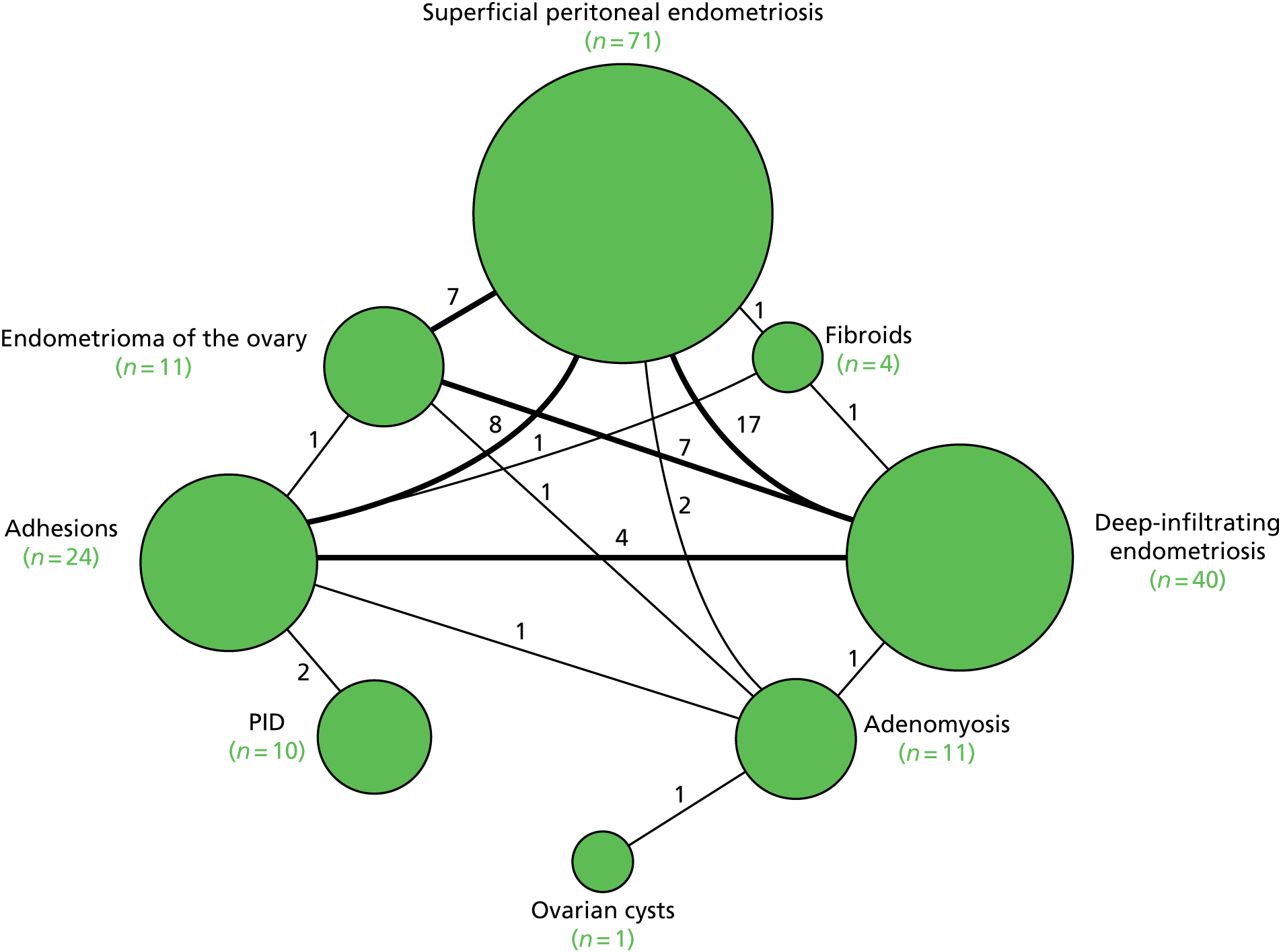

Figure 4 shows the relationships between the causes of pelvic pain based on the EIP diagnoses without the MRI report for structural gynaecological causes. Superficial peritoneal endometriosis, deep-infiltrating endometriosis and endometrioma of the ovary often occurred together: 17 out of 40 women with deep-infiltrating endometriosis also had superficial peritoneal endometriosis, 7 out of 11 women with endometrioma of the ovary also had deep-infiltrating endometriosis and 7 out of 11 women with endometrioma of the ovary also had superficial peritoneal endometriosis. Adhesions also appeared in combination with the three types of endometriosis.

FIGURE 4.

Relationships between the structural gynaecological causes.

Connecting lines indicate the number of women with both diagnoses. A total of 131 women (46%) had structural gynaecological causes and are included in Figure 4.

Comparison of observations on magnetic resonance imaging scans against a reference standard of observations made through laparoscopy

If MRI were to be useful at identifying a condition as being the cause of pelvic pain, it is a prerequisite that the condition has to be observed in the MRI image. Thus, before investigating the accuracy of MRI for identification of each condition as a cause, we assessed the accuracy of MRI for observing each condition, using a reference standard of the condition being observed through laparoscopy. Although this reference standard was thought to be suitable for identifying the three endometriosis conditions, ovarian cysts and adhesions, it was unsuitable for use as a reference standard for adenomyosis and fibroids, as it was likely to miss many cases that could not be identified from inspection of the outside of the uterus. The estimates of test accuracy for adenomyosis and fibroids should therefore be considered alongside the likelihood of misclassification of cases on the reference standard, as apparent false positives and false negatives could be caused by misclassification errors in the reference standard, as well as misclassification errors in the index test. The same concern applied to interpretation of MRI scans judged to be idiopathic, as this was defined as being the absence of all conditions, including fibroids and adenomyosis. In addition, no criteria for identifying superficial peritoneal endometriosis or the non-gynaecological conditions on MRI reports were available, and PID was excluded because few cases were detected.

Table 8 shows that MRI had poor sensitivity for detecting many conditions. MRI detected only 1 of the 36 cases of deep-infiltrating endometriosis that had been observed through laparoscopy (with a sensitivity of 3%), and picked up 20 of the 107 cases of adhesions (with a sensitivity of 19%), 11 of the 56 cases of ovarian cysts (with a sensitivity of 20%) and 22 of the 66 cases of endometrioma of the ovary (with a sensitivity of 33%). The number of false positives (reported on the MRI scan but not seen on laparoscopy) for these conditions were low, with specificities between 93% and 99%.

| Cause of pelvic pain | MRI finding | Laparoscopy finding, n | Sensitivity (95% CI) | Specificity (95% CI) | Likelihood ratio (95% CI) | Diagnostic odds ratio (95% CI) | Test of association | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | Positive | Negative | ||||||

| Idiopathica | Yes | 16 | 33 | 21.3% (12.7% to 32.3%) | 84.4% (78.8% to 89.0%) | 1.4 (0.8 to 2.3) | 0.9 (0.8 to 1.1) | 1.5 (0.8 to 2.8) | p = 0.3 |

| No | 59 | 179 | |||||||

| Idiopathicb | Yes | 55 | 93 | 73.3% (61.9% to 82.9%) | 56.1% (49.2% to 62.9%) | 1.7 (1.4 to 2.1) | 0.5 (0.3 to 0.7) | 3.5 (2.0 to 6.3) | p < 0.0001 |

| No | 20 | 119 | |||||||

| Superficial peritoneal endometriosis | Yes | 0 | 0 | 0% | 100% | – | – | – | – |

| No | 120 | 167 | |||||||

| Deep-infiltrating endometriosis | Yes | 1 | 2 | 2.8% (0.1% to 14.5%) | 99.2% (97.1% to 99.9%) | 3.5 (0.3 to 37.2) | 0.98 (0.93 to 1.04) | 3.5 (0.3 to 39.9) | p = 0.33 |

| No | 35 | 247 | |||||||

| Endometrioma of the ovary | Yes | 22 | 9 | 33.3% (22.2% to 46.0%) | 95.8% (92.2% to 98.1%) | 8.0 (3.9 to 16.5) | 0.7 (0.6 to 0.8) | 11.5 (5.0 to 26.7) | p < 0.0001 |

| No | 44 | 207 | |||||||

| Adhesions | Yes | 20 | 11 | 18.7% (11.8% to 27.4%) | 93.3% (88.4% to 96.6%) | 2.8 (1.4 to 5.6) | 0.9 (0.8 to 1.0) | 3.2 (1.5 to 6.9) | p = 0.003 |

| No | 87 | 154 | |||||||

| Ovarian cysts | Yes | 11 | 16 | 19.6% (10.2% to 32.4%) | 92.9% (88.7% to 95.9%) | 2.8 (1.4 to 5.6) | 0.9 (0.8 to 1.0) | 3.2 (2.2 to 4.5) | p = 0.009 |

| No | 45 | 208 | |||||||

| Adenomyosisa | Yes | 15 | 175 | 75.0% (51.0% to 91.0%) | 31.9% (26.0% to 38.0%) | 1.1 (0.8 to 1.4) | 0.8 (0.4 to 1.7) | 1.4 (0.5 to 4.0) | p = 0.6 |

| No | 5 | 82 | |||||||

| Adenomyosisb | Yes | 2 | 31 | 10.0% (1.2% to 31.7%) | 87.8% (83.1% to 91.5%) | 0.8 (0.2 to 3.2) | 1.0 (0.9 to 1.2) | 0.8 (0.2 to 3.6) | p = 0.9 |

| No | 18 | 222 | |||||||

| Fibroids | Yes | 21 | 35 | 87.5% (67.6% to 97.3%) | 86.4% (81.6% to 90.4%) | 6.5 (4.6 to 9.1) | 0.1 (0.05 to 0.4) | 44.6 (12.3 to 157.4) | p < 0.0001 |

| No | 3 | 223 | |||||||

We considered two different MRI definitions of adenomyosis (as defined in Table 2), the first of which was met by 193 women (69%) and the second by 34 women (12%). MRI did not show any relationship with the findings on laparoscopy for either definition of adenomyosis (p = 0.6 and p = 0.9, respectively). It was not possible to ascertain if this was attributable to the poor ability of laparoscopy or MRI to detect this condition. Observing fibroids on MRI scans was closely linked with observing fibroids on laparoscopy with a sensitivity of 88%, but 35 women had fibroids noted on MRI scans that were not observed on laparoscopy, which could be explained by the inability of laparoscopy to observe fibroids inside the uterus.

We defined an idiopathic MRI scan to be one in which no criteria for any of the above gynaecological conditions were met. As we considered two alternative MRI definitions of adenomyosis, there were two corresponding definitions of ‘idiopathic’. The first MRI definition categorised the majority of women as having adenomyosis, with only 49 women (18%) judged to have an idiopathic MRI report, and this finding showed no relationship with observing no structural gynaecological cause on laparoscopy (p = 0.3; see Appendix 2, Table 32).

Using the second definition, 148 women (52%) were categorised as having an idiopathic MRI report, of whom 93 had findings on laparoscopy. Twenty women, defined as idiopathic on laparoscopy, were noted to meet the criteria for a gynaecological condition using MRI. Overall, the idiopathic diagnoses made through laparoscopy and MRI were in agreement in only 61% of women (see Appendix 2, Table 33).

Comparison of observations made using magnetic resonance imaging against the expert panel reference standard for the cause of pelvic pain

In a further analysis, we considered whether or not MRI findings were diagnostic of the cause of pelvic pain as stated by the EIP. We compared with the EIP consensus diagnosis based on information excluding MRI for all conditions other than adenomyosis where consensus diagnoses including information from MRI was used (Table 9). Most conditions on MRI reports were less likely to be regarded as a cause of pelvic pain than conditions observed on laparoscopy; using MRI reports, superficial peritoneal endometriosis was rated as a cause of pain in 71 women, whereas it was observed in 120 women on laparoscopy; endometrioma of the ovary was noted as a cause in 11 women, but observed in 66 women; adhesions was a cause in 24 women, while noted in 107 women; ovarian cysts was a cause in only 1 woman, but noted in 56 women; adenomyosis was a cause in 16 women, but noted in 20 women; and fibroids was a cause in 4 women, while noted in 24 women. The only exceptions were deep-infiltrating endometriosis, which was regarded as a cause of pain in 39 women, but only noted in 36 women, and idiopathic (lack of a gynaecological structural cause), which was concluded in only 75 women on laparoscopy, but was the conclusion of the EIP in 156 women.

| Cause of pelvic pain | MRI finding | Expert panel consensus, n | Sensitivity (95% CI) | Specificity (95% CI) | Likelihood ratio (95% CI) | Diagnostic odds ratio (95% CI) | Test of association | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | Positive | Negative | ||||||

| Idiopathica | Yes | 26 | 23 | 16.7% (11.2% to 23.5%) | 82.4% (74.8% to 88.5%) | 0.9 (0.6 to 1.6) | 1.0 (0.9 to 1.1) | 0.9 (0.5 to 1.7) | p = 0.9 |

| No | 130 | 108 | |||||||

| Idiopathicb | Yes | 88 | 60 | 56.4% (48.3% to 64.3%) | 54.2% (45.3% to 62.9%) | 1.2 (0.9 to 1.5) | 0.8 (0.6 to 1.0) | 1.5 (0.9 to 2.4) | p = 0.08 |

| No | 68 | 71 | |||||||

| Superficial peritoneal endometriosis | Yes | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| No | 71 | 216 | |||||||

| Deep-infiltrating endometriosis | Yes | 1 | 2 | 2.6% (0.1% to 13.5%) | 99.2% (97.1% to 99.9%) | 3.15 (0.29 to 34.0) | 0.98 (0.93 to 1.03) | 3.21 (0.28 to 36.30) | p = 0.36 |

| No | 38 | 244 | |||||||

| Endometrioma of ovary | Yes | 9 | 22 | 81.8% (48.2% to 97.7%) | 91.9% (88.0% to 94.8%) | 10.1 (6.2 to 16.4) | 0.2 (0.1 to 0.7) | 50.9 (10.4 to 250.5) | p < 0.0001 |

| No | 2 | 249 | |||||||

| Adhesions | Yes | 9 | 28 | 37.5% (18.8% to 59.4%) | 89.2% (84.8% to 92.7%) | 3.5 (1.9 to 6.5) | 0.7 (0.5 to 0.9) | 5.0 (2.0 to 12.4) | p = 0.001 |

| No | 15 | 232 | |||||||

| Ovarian cysts | Yes | 0 | 27 | 0% (0% to 97.5%) | 90.4% (86.3% to 93.6%) | – | – | – | p = 0.9 |

| No | 1 | 254 | |||||||