Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 09/110/01. The contractual start date was in March 2012. The draft report began editorial review in April 2017 and was accepted for publication in October 2017. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

All contributors participated in this trial, to which GlaxoSmithKline plc donated free patches. Paul Aveyard is funded by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Oxford Biomedical Research Centre and CLAHRC. Peter Hajek and Hayden J McRobbie have provided research and consultancy to several manufacturers of smoking cessation treatments and have been paid for doing so. Tim Coleman is a member of the NIHR Health Technology Assessment Clinical Evaluation and Trials Board. Sarah Lewis is a member of the NIHR Health Services and Delivery Research funding board. Peter Hajek reports a research grant to Queen Mary University of London from Pfizer and personal consultancy fees from Pfizer. Andy McEwen reports grants from Pfizer and hospitality from North 51. Hayden J McRobbie reports a grant and honorarium from Pfizer for speaking at education meetings and an honorarium from Johnson & Johnson for speaking at education meetings and an advisory board meeting.

Disclaimer

Authors are listed in alphabetical order by centre. The list does not reflect relative contribution.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2018. This work was produced by Aveyard et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2018 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Introduction

Smoking cessation and cessation medication

Most people who try to stop smoking fail within the first few weeks of the attempt. 1 This is because they experience urges to smoke that drive them to return to smoking. The aim of smoking cessation treatment, which typically starts just before or on the quit day, is to reduce the intensity of urges so that more people can overcome the difficult first few weeks. 2,3 Over time, the urges to smoke reduce in frequency and intensity and treatment can stop. 4

There are three medications for smoking cessation that are licensed widely around the world: (1) nicotine replacement therapy (NRT), (2) bupropion and (3) varenicline (Champix®; Pfizer Inc., New York, NY, USA). All three have strong evidence of effectiveness and are safe, although bupropion has rather more contraindications to its use and results in more severe adverse effects than the other two medications. 5 In the UK, bupropion fell out of favour because of unjustified concerns about its safety and is now rarely used. Thus, when people who smoke use medication to assist them, they typically use either varenicline or NRT.

Conventionally, people stopping smoking commence NRT on quit day. However, people stopping smoking with the aid of either bupropion or varenicline begin to take the medication about 1 week prior to quit day. This allows the dose to be escalated in order to reduce the number of adverse events (AEs) that can occur with rapid escalation of the dose of either medication. Thus, the original aim of this period serves simply to ensure that people are comfortable and are taking the full dose of the medication by the time of quit day.

The most effective medication for supporting smoking cessation is varenicline. 6 One trial7 examined the mechanisms of action of smoking cessation medications, comparing varenicline, bupropion and placebo. Varenicline reduced the intensity of urges and reduced the satisfaction obtained from a lapse (temporary smoking episode during a quit attempt) to a greater extent than bupropion. Most other mood symptoms occurred with a similar intensity. This suggests that reducing urge intensity and reducing satisfaction with smoking are key mechanisms of action. Varenicline is usually started 1 week before quit day and it could be that its use prior to quit day undermines the rewarding value of cigarettes and underlies its greater effectiveness. This raises the possibility that NRT, which is usually started on the quit day, may be effective if used in this way, as it too reduces satisfaction from smoking when used concurrently with cigarettes. 8 Using nicotine in this way is termed ‘nicotine preloading’. The reason that this may help achieve smoking cessation is because nicotine from NRT desensitises the nicotinic receptors and blocks the effects of further nicotine from cigarettes. This, in turn, undermines the learnt association between smoking and brain reward, making extinction of the reinforced behaviour more likely. 9

Nicotine preloading effectiveness

Two previous reviews10,11 have examined the effectiveness of nicotine preloading and provided evidence that it approximately doubles the chance of achieving abstinence. However, our own review12 showed no strong evidence that preloading was effective, principally because some larger trials showing no benefit had been published since the earlier reviews were conducted. The relative risk (RR) for short-term abstinence was 1.05 [95% confidence interval (CI) 0.92 to 1.19; p = 0.49], with a high level of heterogeneity (I2 = 69%; p = 0.002). The RR for long-term abstinence was 1.16 (95% CI 0.97 to 1.38), with a lower level of heterogeneity (I2 = 36%; p = 0.14). The principal aim of this review was to pool all forms of NRT, although we hypothesised that nicotine patches may be more effective in the context of preloading. There is a plausible reason why patches may be more effective for preloading than other forms of NRT. Smoking while using a short-acting NRT tends not to raise the concentration of nicotine in the blood, whereas smoking and using a patch does. 8 It may be this higher concentration of nicotine that undermines the reward from cigarettes. Indeed, there was some evidence of this, with patches having a RR of 1.26 (95% CI 1.03 to 1.55) for longer-term abstinence.

Mechanisms of action of preloading

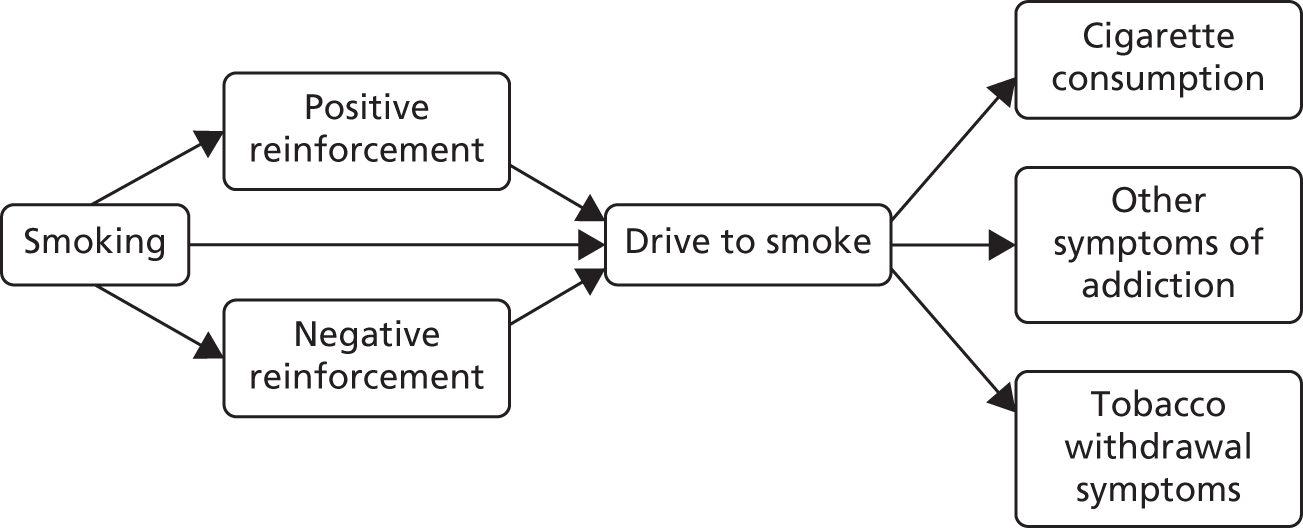

We can understand the potential mechanism of preloading by understanding the development of tobacco addiction (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

Development of tobacco addiction.

Tobacco smoking creates a positive reward, such as feelings of pleasure, which leads to the reinforcement of subsequent smoking. After a period of regular smoking, neuroadaptation to regular doses of nicotine means that people who smoke experience negative moods when nicotine concentrations in the brain drop; these feelings are relieved by smoking and, thus, smoking is negatively reinforced. Independently of any reward that people may experience, mechanisms in the nucleus accumbens set up associative learning that results in the drive to smoke. These mechanisms create an acquired drive to smoke and tobacco dependence, manifested by the regular consumption of cigarettes, the occurrence of tobacco withdrawal symptoms when unable to smoke and difficulty in stopping smoking if a person were to choose to do so.

Preloading may reduce the drive to smoke and both positive and negative reinforcement. By keeping the concentration of nicotine in the blood high, the nicotine patch can mitigate the need for nicotine and also reduce the impact of further exogenous nicotine from cigarettes, thus reducing the positive reinforcement of smoking. Likewise, if the need for nicotine is low, this may lower any impact of smoking on reducing withdrawal discomfort (negative reinforcement). All three actions, especially the reduced drive to smoke, would reduce smoke intake during the pre-quit period. The net effect of the changes in the drive to smoke mean that a person will not smoke when he or she normally would, usually when cued by the environment to do so. Not smoking when cued to smoke will begin to extinguish the learnt association between the action of smoking a cigarette and reinforcement in the brain. Alternatively, smoking when cued to smoke but receiving no reinforcement from the nicotine may also undermine the drive to smoke by weakening the association. Consequently, after cessation, urges to smoke should be lower and this makes cessation more likely to be successful. 13

Aside from this addiction-based mechanism, three other mediational hypotheses have been advanced for the mechanism of action of preloading. The first relates to medication adherence, which some evidence suggests is poor in smoking cessation. 14 The hypothesis here is that preloading enables the person to become used to using medication at a time when failure to use it does not undermine the success of the quit attempt. After quit day, when failure to use medication does undermine abstinence,15 adherence will be superior in people using preloading than in people who did not use preloading.

The second hypothesis is that the reduced level of smoking that occurs when people preload increases a person’s confidence that they can abstain from smoking after quit day; the confidence that one can achieve abstinence is associated with achieving abstinence. 16

A third hypothesis was developed from a recent trial17 in which participants were interviewed about their experiences using preloading. A large proportion reported feeling nauseous and having an aversion to cigarettes during preloading. Aversive smoking is a process in which people smoke excessively to the point of nausea and vomiting. Although it is rarely used as a treatment to enhance cessation, it is effective at increasing the rate of cessation. 18 It is, therefore, plausible that nausea and aversion to smoking mediate the effect of preloading, and we tested this in the Preloading trial.

In our review,12 we examined the putative mechanisms of action of preloading to find evidence to support or refute these possibilities. We examined the effects on both positive and negative reward, urge intensity and markers of consumption and addiction. There was scanty and mixed evidence on whether or not preloading reduced the positive reward from smoking. There was more evidence that preloading did not reduce the negative rewarding effects of smoking, that is, preloading did not appear to remove the ability of smoking to relieve tobacco withdrawal symptoms. Overall, four studies examined the effect on pre-quit urge intensity and two showed evidence of a modest reduction. There was clear evidence that preloading reduced cigarette consumption without instruction to do so. The mechanism of reduced intensity of urges suggests that we might expect reduced tobacco withdrawal symptoms after quit day, but there was reasonable evidence that this does not occur.

Cost-effectiveness

Interventions are approved by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) for use in the NHS only if they are cost-effective, defined as achieving a cost per quality-adjusted life-year (QALY) of < £20,000. Interventions for smoking cessation are typically highly cost-effective. This is because smoking is particularly harmful to health and cessation is remarkably effective at ameliorating the effects of many years of smoking. 19 In fact, West20 calculates that increments of as little as 1% in 6-month prolonged abstinence rates are highly likely to be cost-effective according to the NICE standard.

Arguably, the most reasonable way to plan a trial is to define a limit at which the intervention is cost-effective enough to change the decision on an intervention from non-use to use. In this case, the question would be: what increment in 6-month prolonged abstinence would produce a cost per QALY of < £20,000? The answer, argued by West,20 is around a 1% increment. The problem with using this to calculate a trial sample size is that it is impractically small. Any trial that would detect an effect of this size would be one or two orders of magnitude larger than most ‘large’ smoking cessation trials today. Such a trial would never be funded and would not be able to recruit to target. Therefore, cost-effectiveness, although providing a logical rationale for calculating a sample size, is not useful in this regard.

One compelling rationale for the cost-effectiveness analysis in this trial is the political realities of the health economy today. The NHS is under severe financial pressure. Preloading will inevitably cost more than the comparator, usual care, which, at this point in a quit attempt, provides no intervention. In the current NHS, additional investment in a treatment such as smoking cessation therapy is likely to be made only if the intervention is cost saving. As there are no data on the cost-effectiveness from previous trials of preloading, we set out to assess the cost-effectiveness of preloading in this trial.

Aims of the trial

It is clear, therefore, that an adequately powered trial of nicotine preloading is required to address the uncertainty about the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of treatment and could usefully explore potential mechanisms of action, which could be practically as well as theoretically useful. A trial of varenicline preloading showed that people who spontaneously suppressed their smoking in response to varenicline were much more likely to achieve abstinence than those who did not. 21 Other trials have reported similar associations with NRT. 21–24 In clinical use, therefore, one could suggest stopping preloading in those who do not suppress their smoking and bringing forward the quit day. However, subsequent planned replication found evidence that the effect was much less strongly predictive of the ability to quit smoking during nicotine preloading. 25 We, therefore, planned to examine the effectiveness of preloading in a trial powered to detect modest effects on long-term abstinence and investigate potential mediators that could allow therapists to judge whether to continue or abandon preloading. The objectives were to:

-

examine the relative efficacy of a nicotine patch worn for 4 weeks prior to quitting plus standard NHS care post quit compared with standard NHS care only in smokers undergoing NHS treatment for tobacco dependence (addressed in Chapter 3)

-

examine the adverse effects and safety of nicotine preloading (addressed in Chapter 3)

-

examine the incremental cost-effectiveness of nicotine preloading (addressed in Chapters 6 and 7)

-

examine possible mediating pathways between nicotine preloading and outcomes (addressed in Chapter 4)

-

examine moderators of the effects of preloading, including the use of varenicline and baseline levels of dependence (addressed in this chapter and in Chapter 4)

-

investigate opinions of the preloading intervention (addressed in Chapter 5)

-

assess adherence to preloading treatment and subsequent standard smoking cessation pharmacotherapy (addressed in Chapter 3).

Chapter 2 Methods

Design

This was an open-label, multicentre, pragmatic superiority trial in which participants were randomised 1 : 1 to non-use or use of a nicotine patch for 4 weeks prior to quit day. Participants used standard pharmacotherapy and behavioural support for stopping smoking thereafter. The primary outcome was prolonged biochemically validated abstinence, measured 6 months after quitting. The protocol was published26 and implemented with one change, which related to participants who had moved from the area during follow-up and were not available to attend in person for carbon monoxide (CO) measurement to confirm abstinence. We, therefore, asked such participants to provide a saliva sample and measured cotinine or anabasine concentrations to confirm abstinence from smoking. Anabasine is a tobacco-specific alkaloid that will indicate smoking abstinence in a person who is using NRT or e-cigarettes. Cotinine is a metabolite of nicotine with a much longer half-life, making it a good indicator of nicotine consumption within the last week, and will be in low concentrations in people who do not smoke or use nicotine.

In the original proposal to the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR), we did not suggest collecting genetic samples or assessing the impact of quitting on weight gain. However, these additional non-trial-related hypotheses were added to the published protocol. 26 In the event, it turned out to be impractical to collect genetic samples and this ambition was abandoned. The observational analyses of the impact of quitting and failed quit attempts on weight gain will be reported separately.

Participants and settings

In three recruitment centres, Birmingham, Bristol and Nottingham, general practitioners (GPs) spoke to, wrote to, e-mailed or texted patients listed as smokers on the electronic health record. GPs encouraged their patients who wished to quit smoking with the help of pharmacotherapy and behavioural support to enrol in the trial. The final centre, London, was an existing NHS smoking cessation clinic, which asked participants seeking treatment if they would also like to take part in the trial. Thus, in all centres, patients were recruited from those who sought treatment at their own instigation, by referral from their GP or by advertising in various online and print media.

Potential participants telephoned the research team to learn more about the trial and were screened for eligibility and entered into our online trial database. If a potential participant appeared to be eligible and wanted to participate, we made an appointment and sent out the participant information sheet. At this initial appointment, we again described the trial and obtained witnessed consent with a signature and confirmed eligibility. The researcher, typically a research nurse, saw participants at their own general practice or at the London centre. We included people who were:

-

regular smokers of cigarettes, cigars and/or roll-up tobacco cigarettes, with or without marijuana, aged ≥ 18 years

-

suitable for preloading in the judgement of the researcher (see below)

-

seeking support to stop smoking from the NHS Stop Smoking Service

-

willing to set a quit day in 4 weeks

-

able to understand and willing to adhere to study procedures.

We excluded:

-

pregnant or breastfeeding women

-

people with extensive dermatitis or another skin disorder that precluded patch use

-

people who had acute coronary syndrome or who had had a stroke in the past 3 weeks

-

people with an active phaeochromocytoma or uncontrolled hyperthyroidism that would increase the risk of arrhythmias from the nicotine patch.

We judged if people would be suitable for preloading by assessing whether or not they were addicted to smoking. This was based on a clinical judgement of the following factors, with no specific cut-off points used:

-

time to first cigarette in the morning, with earlier use reflecting a higher level of addiction

-

number of cigarettes smoked per day, with a greater number reflecting a higher level of addiction

-

higher levels of exhaled CO, which reflect a higher level of addiction

-

failure of previous quit attempts despite use of appropriate pharmacotherapy.

Interventions

Intervention group

In the intervention group, participants wore a 21-mg nicotine patch daily for an intended 4 weeks prior to quit day. The intention was that this would be worn for 24 hours per day. However, any participants who had experienced previous AEs at night from 24-hour patch use were advised to wear the patch during waking hours only.

We asked participants to smoke as normal and not reduce nicotine consumption. Reducing consumption would probably lower the nicotine concentration in the blood, which could have resulted in cigarettes being more rewarding and, thus, have undermined the supposed benefits of preloading. 27

We referred patients to the NHS Stop Smoking Service to set a quit day, obtain behavioural support and receive a prescription of pharmacotherapy to support cessation. Although we aimed for this quit day to be 4 weeks from the start of preloading, in keeping with the pragmatic design, we asked participants and NHS clinics to set this date within a window from 3 to 5 weeks after starting preloading. Preloading was allowed to continue for up to 8 weeks in exceptional circumstances. Preloading was also allowed to restart once, if necessary, for example if this was interrupted because a participant was admitted to hospital. In such cases, participants aimed to complete 3–5 weeks of preloading from the date of recommencement. We dispensed NRT in two lots, one of 2 weeks and a second, 1 week later, of 3 weeks. We made arrangements to dispense additional lots of NRT if preloading was extended.

The researchers explained the rationale of preloading and prompted action planning to maximise adherence to the patches, that is, they talked through participants’ daily routine and assisted them to use it and environmental cues to minimise the chance of forgetting to use the patches. They provided reassurance about concerns that participants may have about side effects and how to manage them. A booklet containing this information was supplied to participants. We aimed to see participants 1 week after commencing preloading. At this visit, we asked participants about their experiences and their understanding of the necessity of preloading and again addressed these beliefs as well as concerns about preloading.

We offered participants lower-strength patches from the beginning if they reported experiencing adverse reactions to the 21-mg patch or if, during the treatment course, they experienced symptoms of nicotine overdose such as nausea, salivation and/or pounding heartbeat or other symptoms that they believed were due to the patch strength. We stopped preloading if a participant requested it, if it was not possible to alleviate AEs by reducing the dose or if an intervening health state or contraindication to preloading emerged.

Control group

The research team were keen to offer participants in the control group a placebo, but the NIHR Health Technology Assessment (HTA) Board would not allow this. We were concerned that offering no treatment would lead to disengagement and, to counteract this, we developed a behavioural intervention that could seem plausible to participants but had no evidence that it would increase abstinence. We asked participants to consider their smoking pattern and the triggers for particular cigarettes (e.g. the first cigarette of the day, the first after dinner) and to plan ways to reduce these cues. Such a process is standard in smoking cessation support, so participants in the intervention group were likely to engage in this after preloading and in preparation for quitting. The control group received a booklet outlining this process, which was designed to be comparable to the booklet supplied to the intervention group. As in the intervention group, participants in the control group were referred to the NHS Stop Smoking Service to commence a quit attempt between 3 and 5 weeks after enrolment.

Standard smoking cessation treatment common to both arms

In both arms, at the first and second contacts, we facilitated contact between participants and the local NHS Stop Smoking Service and wrote a referral letter to encourage the NHS Stop Smoking Service to work with us on encouraging participants to continue preloading. In particular, we asked the NHS Stop Smoking Service advisors to ignore the presence or absence of preloading when discussing and recommending the use of pharmacotherapy to support the quit attempt. We especially asked advisors to feel free to use varenicline, which starts prior to quit day and, hence, would be used concurrently with nicotine preloading. This is because we were keen that the treatment provided by the NHS Stop Smoking Services did not differ between trial arms. NICE guidance has specifically recommended against this combination of NRT and varenicline,28 which advisors wrongly assumed was because of safety concerns about concurrent use. We therefore addressed this in the referral letter, by telephone and in face-to-face discussions with the NHS Stop Smoking Service.

The NHS trains Stop Smoking Service advisors to give weekly behavioural support starting 1–2 weeks prior to quit day and continuing until at least 4 weeks after quit day. This support addresses issues such as planning for the quit day, the ‘not a puff’ rule and how to deal with difficult situations, such as others smoking around the person who has quit. It also provides monitoring of behaviour and validation of abstinence through CO testing. The support is largely withdrawal-orientated therapy. 29

Our protocol26 allowed all other medication to be used concurrently with preloading.

Outcomes

We followed up participants on five occasions for outcome assessment. These were named in relation to quit day and are shown in Table 1.

| Visit name | Timing in relation to baseline | Main purpose |

|---|---|---|

| –3 weeks | 1 week after baseline |

AE assessment Data on mediators Data on adherence |

| +1 week | ≈5 weeks after baseline |

AE assessment Data on mediators Data on adherence |

| +4 weeks | ≈9 weeks after baseline | Data from NHS Stop Smoking Service on abstinence |

| +6 months | ≈7 months after baseline | Abstinence |

| +12 months | ≈13 months after baseline | Abstinence |

The first follow-up appointment was a face-to-face appointment, when possible, and occurred 1 week after baseline and 3 weeks before quit day. One week after quit day we telephoned participants to collect data on AEs, adherence to preloading and use of, and adherence to, other smoking cessation pharmacotherapy. We obtained data on smoking cessation from the NHS Stop Smoking Service at 4 weeks or, failing this, from a telephone call to the participant. At 6 and 12 months, we telephoned participants to obtain data on smoking status and health service use. We invited participants who claimed to be abstinent for at least 1 week to a meeting where we asked them to provide an exhaled CO concentration reading. Participants were compensated £15 for their time for attending this meeting. Therefore, if they attended a meeting at both 6 and 12 months’ follow-up, participants were compensated a total of £30.

Primary outcome

The primary outcome was 6-month prolonged abstinence, defined according to the Russell Standard criteria. 30 This allows a grace period of 2 weeks following quit day when lapses do not count against abstinence. Thereafter, we counted a person as abstinent if they smoked fewer than five cigarettes or cigars up to the 6-month assessment and were biochemically confirmed abstinent by an exhaled CO concentration of < 10 parts per million (p.p.m.).

Secondary outcomes

The secondary outcomes were 12-month Russell Standard abstinence and biochemically confirmed 7-day point prevalence abstinence at 4 weeks, 6 months and 12 months.

Adverse events

We defined AEs as those that occurred after baseline and until 1 week after quit day, thereby covering the period of preloading and an additional week for AEs to emerge. This excluded planned events, such as scheduled surgery. In the protocol,26 we deemed that we would report only AEs of moderate severity or above, that is, those events that hindered or prevented the person going about their normal activities. This is because these events matter more to patients and because NRT has been used for many years and so many common minor AEs are known already.

We assessed the AEs arising from preloading in two ways. First, we elicited AEs from participants in both arms at the contacts at –3 weeks (1 week after baseline) and +1 week (5 weeks after baseline and 1 week after quit day). Spontaneously occurring AEs were coded at the level of preferred term and system organ class using the MedDRA (Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities) coding system. 31 However, spontaneously occurring reports may introduce bias. It seemed illogical to participants in the control group and to treating staff to discuss AEs when the participant was taking no medication at all. Therefore, second, at 1 week after baseline we also gave all participants a questionnaire concerning symptoms of nicotine overdose in the previous 24 hours (such as nausea and excessive salivation).

We defined serious adverse events (SAEs) as those leading to hospitalisation, death, permanent disability or congenital abnormality and reported these separately. We obtained the medical history of participants experiencing SAEs and these were classified by an independent assessment panel blinded to allocation as unrelated or unlikely to be, possibly, probably or definitely related to the use of nicotine patches.

Sample size

We determined the sample size from plausible estimates of 6-month abstinence. We estimated that 15% of participants in the control group would attain 6-month abstinence based on data from similar trials. 17,32,33 We felt that a RR of 1.4 was plausible based on our meta-analysis12 and would make preloading valuable to NHS Stop Smoking Service commissioners. 12 This gave us a sample size of 893 per group, or 1786 in total, to achieve 90% power (Table 2).

| Prolonged abstinence in control group, % | Prolonged abstinence in intervention group, % | Trial with 80% power, number per group | Trial with 90% power, number per group |

|---|---|---|---|

| RR = 1.3 | |||

| 14 | 18.2 | 1249 | 1655 |

| 15 | 19.5 | 1150 | 1524 |

| 16 | 20.8 | 1064 | 1409 |

| 20 | 26.0 | 805 | 1065 |

| RR = 1.4 | |||

| 14 | 19.6 | 734 | 970 |

| 15 | 21.0 | 676 | 893 |

| 16 | 22.4 | 625 | 825 |

| 20 | 28.0 | 471 | 622 |

| RR = 1.5 | |||

| 14 | 21.0 | 490 | 646 |

| 15 | 22.5 | 451 | 594 |

| 16 | 24.0 | 416 | 549 |

| 20 | 30.0 | 313 | 412 |

Randomisation

The research team randomised participants at the baseline visit following consent, assessment of eligibility and enrolment. An independent statistician used Stata® 14.2 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA) to generate a randomisation list, stratified by treatment centre and using randomly permuted blocks of varying sizes, using a 1 : 1 ratio. This sequence was incorporated into an online database and the sequence remained concealed from all research staff.

Blinding

This was an open-label trial so participants, research staff and NHS Stop Smoking Service personnel knew to which group participants were assigned. Blinded follow-up was impossible as all staff had been involved in recruitment.

Statistical analysis

The analysis of all cessation outcomes was performed using the intention-to-treat (ITT) principle as outlined in the Russell Standard. 30 Thus, everyone was included in the denominator and presumed to be smoking if this information remained unknown. This presumption was shown to be true in one trial that went to extraordinary lengths to establish the true status of those who did not respond to standard follow-up. 30 For the primary analysis, we calculated adjusted odds ratios (ORs) using multivariable logistic regression in Stata 14.2. We also calculated the percentage achieving abstinence, the risk difference (RD), RRs and 95% CIs using the post-estimation adjrr procedure in Stata 14.2. As the randomisation was stratified by centre, we adjusted for this covariate in the analysis and this was considered the primary analysis. In sensitivity analyses, we adjusted for two well-known predictors of abstinence to improve precision: the longest previous abstinence and the degree of addiction measured by the strength of urges to smoke at baseline. 34–36 Finally, because we envisaged that the use of NRT would deter NHS Stop Smoking advisors from prescribing varenicline, which is more effective than other pharmacotherapy,6 we also adjusted for varenicline use.

We had pre-planned subgroup analyses that were assessed by including multiplicative interaction terms in the calculations described in the previous paragraph. The presumed mechanism of action of preloading suggests that preloading could be more effective in people who are more addicted to nicotine. This was assessed by investigating whether or not outcomes varied with baseline Fagerström Test for Cigarette Dependence (FTCD) score or exhaled CO concentration readings and is reported in Chapter 3. In another analysis, we examined whether or not the effect of preloading was less pronounced in people who used varenicline in the pre-quit period. This is because varenicline includes a period of use of at least 1 week prior to quit day and this appears to have similar effects to preloading. 21

The population in whom we analysed the occurrence of AEs was all those who provided data on such events. The analysis of spontaneously elicited AEs was confined to events of moderate severity and above. We anticipated that most minor AEs would relate to well-established adverse reactions to nicotine patches; confining the analysis to AEs of moderate severity and above may identify novel adverse reactions to preloading specifically that were of more concern to patients. The analysis used analogous statistical models to those applied for the primary and secondary outcomes.

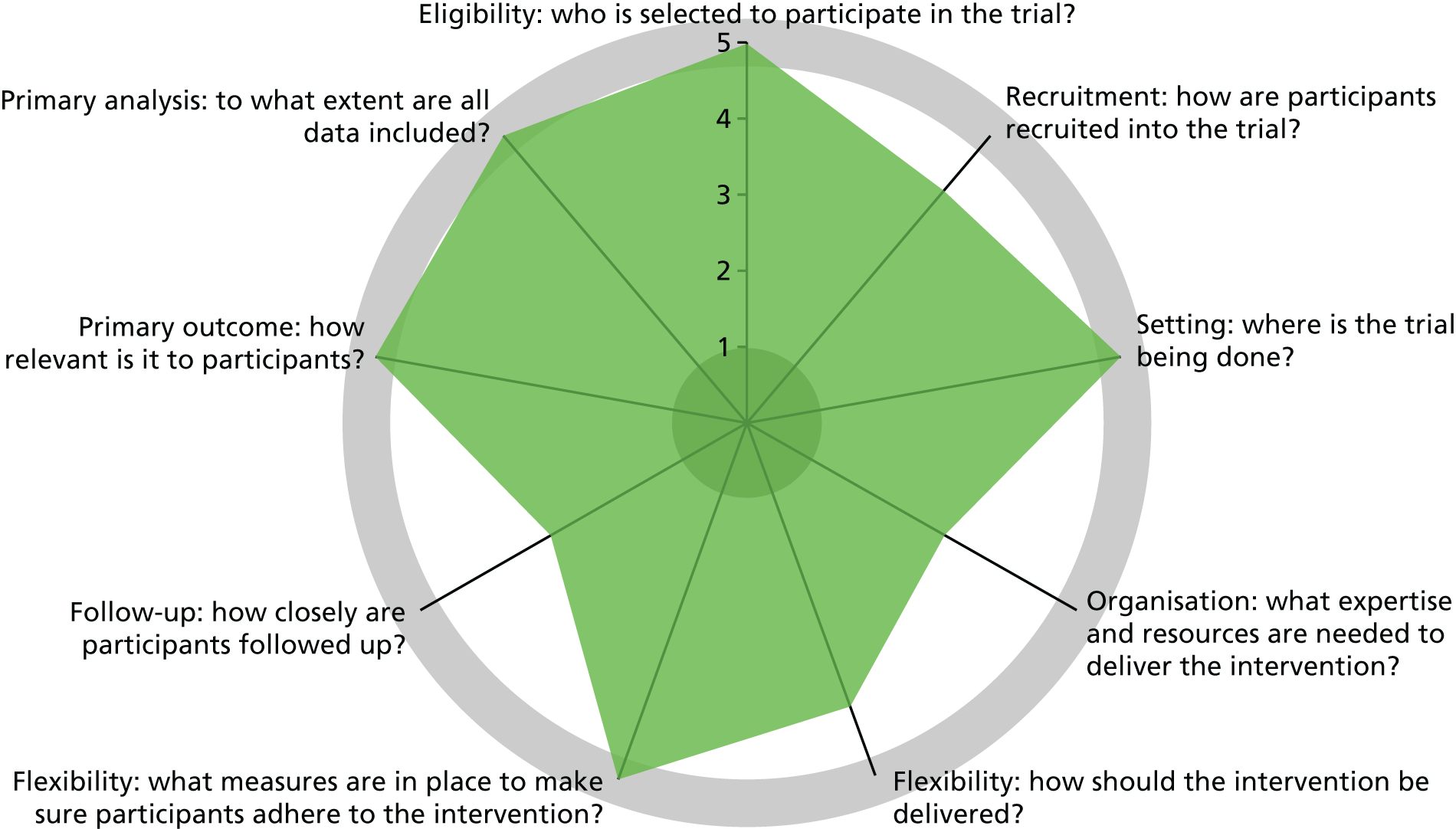

Design features classified by PRECIS-2

Trials vary on an explanatory to pragmatic continuum; this can be assessed and represented by a tool called PRECIS-2 (PRagmatic Explanatory Continuum Indicator Summary). 37 The aim of this trial was to examine the effectiveness of preloading in everyday clinical practice. In the UK, this was in the context of the NHS Stop Smoking Service. However, the aim was also to examine AEs and safety, which meant that these were assessed by researchers trained to assess these outcomes appropriately. Furthermore, NHS Stop Smoking Services do not routinely follow up people who try to stop smoking beyond 4 weeks, which meant that we instituted special follow-up measures to assess smoking abstinence. It was because of these aims that the trial design scored less than the maximum for pragmatic design features on the PRECIS-2 wheel (Figure 2).

Chapter 3 Results of the trial

Participant flow

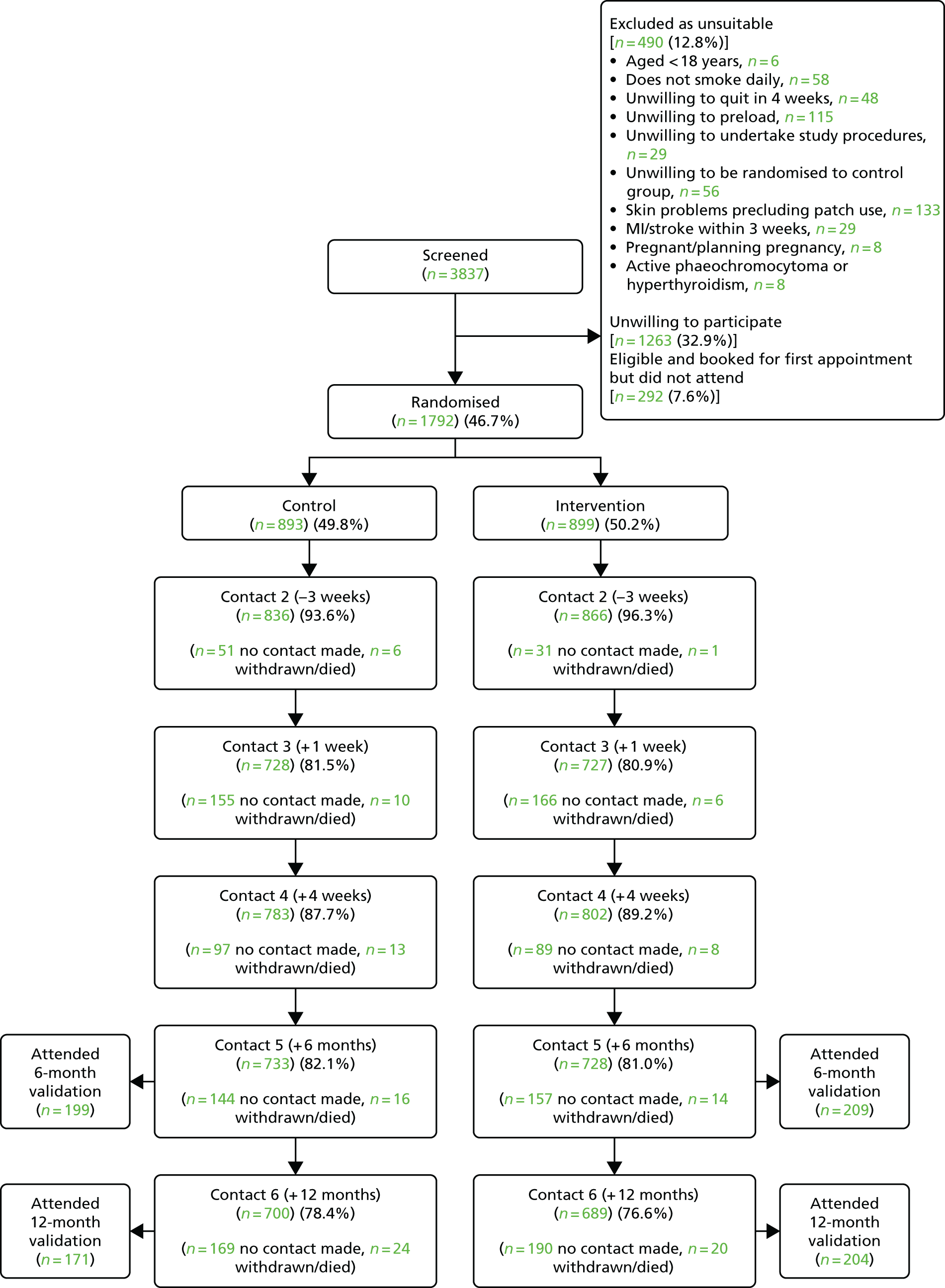

Between 13 August 2012 and 10 March 2015, 3837 people telephoned about enrolment. Of these, 1805 (47.0%) attended the initial appointment and 1792 (99.3%) of those were eligible and were enrolled in the study. Overall, 490 (12.8%) people who had telephoned were ineligible; the most common reasons for ineligibility were skin problems and an objection to using preloading patches (Figure 3).

FIGURE 3.

Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) flow diagram. MI, myocardial infarction. Adapted from the Preloading Investigators. 39 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

One week after baseline, we followed up 1702 (95.0%) participants; and 5 weeks after baseline, 1 week after quit day, we obtained data from 1456 (81.3%) participants. These assessments provided data on AEs.

In total, 312 (17.4%) participants never made a quit attempt, 157 (17.5%) in the intervention group and 155 (17.4%) in the control group. We obtained data on 1585 (88.5%) participants at 4 weeks, 1461 (81.5%) at 6 months and 1389 (77.5%) at 12 months after quit day. The proportion successfully followed was similar in each group. Although 331 (18.5%) participants did not provide data at 6 months, we knew that 97 of these participants were smoking at 4 weeks post quit day and could not, therefore, be classified as abstinent at 6 months and that 54 of these participants never made a quit attempt and likewise could not be classified as abstinent at 6 months. Thus, altogether, we were certain of the primary outcome in 1612 (90.0%) participants.

Baseline characteristics

The baseline characteristics were well balanced between the trial arms (Table 3). The mean age of participants was 48.9 [standard deviation (SD) 13.4] years. Men constituted 52.6% of the participants and 75.6% identified as white British. The proportion of participants with an advanced level of education was lower than the UK average. 40 Fifty-two per cent were in employment. Participants smoked a mean of 18.9 (SD 9.3) cigarettes per day at baseline, had a mean nicotine dependence score of 5.2 (SD 2.2), indicating moderate addiction, and a mean exhaled CO concentration of 23.7 (SD 12.5) p.p.m. One-third (32.5%) had used behavioural support or pharmacotherapy to try to quit in the previous 6 months.

| Characteristic | Trial group | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Control (N = 893) | Intervention (N = 899) | Total (N = 1792) | |

| Age (years), mean (SD) | 48.8 (13.4) | 49.1 (13.3) | 48.9 (13.4) |

| Gender, n (%) | |||

| Male | 469 (52.6) | 473 (52.6) | 942 (52.6) |

| Female | 422 (47.3) | 426 (47.4) | 848 (47.4) |

| Ethnicity, n (%) | |||

| White: British | 675 (75.6) | 680 (75.6) | 1355 (75.6) |

| White: Irish | 36 (4.0) | 25 (2.8) | 61 (3.4) |

| White: other | 57 (6.4) | 55 (6.1) | 112 (6.3) |

| White and black Caribbean | 17(1.9) | 15 (1.7) | 32 (1.8) |

| White and black African | 3 (0.3) | 5 (0.6) | 8 (0.5) |

| White and Asian | 8 (0.9) | 6 (0.7) | 14 (0.8) |

| Mixed other | 7 (0.8) | 8 (0.9) | 15 (1.8) |

| Indian | 11 (1.2) | 10 (1.1) | 21 (1.2) |

| Pakistani | 9 (1.0) | 6 (0.7) | 15 (0.8) |

| Bangladeshi | 2 (0.2) | 13 (1.5) | 15 (0.8) |

| Asian: other | 3 (0.3) | 3 (0.3) | 6 (0.3) |

| Black: Caribbean | 29 (3.3) | 34 (3.8) | 63 (3.5) |

| Black: African | 8 (0.9) | 13 (1.5) | 21 (1.2) |

| Black: other | 4 (0.5) | 3 (0.3) | 7 (0.4) |

| Chinese | 3 (0.3) | 2 (0.2) | 5 (0.3) |

| Other | 12 (1.3) | 14 (1.6) | 26 (1.5) |

| More than one option | 0 | 4 (0.4) | 4 (0.2) |

| Missing | 9 (1.0) | 7 (0.8) | 16 (0.9) |

| Educational qualifications, n (%) | |||

| Degree or equivalent and above | 201 (22.5) | 218 (24.3) | 419 (23.4) |

| A levels or vocational level 3 and above | 198 (22.2) | 207 (23.0) | 405 (22.6) |

| Other qualifications below A level or vocational level 3 | 230 (25.8) | 212 (23.6) | 442 (24.7) |

| Other qualifications (e.g. foreign) | 52 (5.8) | 52 (5.8) | 104 (5.8) |

| No formal qualifications | 204 (22.8) | 199 (22.1) | 403 (22.5) |

| Missing | 8 (0.9) | 11 (1.2) | 19 (1.06) |

| Occupation, n (%) | |||

| Employed | 467 (52.3) | 468 (52.1) | 935 (52.3) |

| Unemployed | 126 (14.1) | 116 (12.9) | 242 (13.5) |

| Looking after home and family | 33 (3.7) | 44 (4.9) | 77 (4.3) |

| Student | 17 (1.9) | 22 (2.5) | 39 (2.2) |

| Retired | 153 (17.1) | 152 (16.9) | 305 (17.1) |

| Long-term sick or disabled | 26 (2.9) | 26 (2.9) | 52 (2.9) |

| Missing | 4 (0.5) | 8 (0.9) | 12 (0.7) |

| Smoking history | |||

| Type of cigarette smoked, n (%) | |||

| Manufactured cigarettes | 615 (68.9) | 607 (67.5) | 1222 (68.2) |

| Tobacco roll-ups | 272 (30.5) | 284 (31.6) | 556 (31.0) |

| Cigars | 6 (0.7) | 8 (0.9) | 14 (0.8) |

| Cigarettes per day (continuous) | |||

| Mean (SD) | 18.7 (9.0) | 19.1 (9.6) | 18.9 (9.3) |

| Median | 19 | 18 | 18 |

| Range | 0–60 | 0–80 | 0–80 |

| IQR | 12–30 | 14–20 | 13–20 |

| Dependence (FTCD), mean (SD) | 5.2 (2.2) | 5.2 (2.2) | 5.2 (2.2) |

| CO concentration reading (contact 1) | |||

| Mean (SD) | 23.8 (12.8) | 23.5 (12.3) | 23.7 (12.5) |

| Median | 21 | 21 | 21 |

| Range | 0–100 | 0–100 | 0–100 |

| IQR | 15–30 | 15–30 | 15–30 |

| Longest previous abstinence (continuous, days) | |||

| Mean | 358.4 | 442.3 | 400.3 |

| SD | 750.7 | 993.7 | 881.4 |

| Median | 90 | 90 | 90 |

| IQR | 21–330 | 14–365.3 | 21–330 |

| Smoking cessation support in last 6 months, n (%) | |||

| Yes | 304 (34.0) | 279 (31.0) | 583 (32.5) |

| No | 588 (65.9) | 619 (68.9) | 1207 (67.4) |

| Missing | 1 (0.1) | 1 (0.1) | 2 (0.1) |

Medication adherence

One week after baseline, nearly three-quarters of participants in the active group reported using the patch daily; in the subsequent 3 weeks of preloading, > 80% of participants in the active group reported using the patch daily (Table 4). In total, 49 (5.5%) participants discontinued preloading prematurely. The majority who ceased preloading did so during the first week of treatment.

| Variable, n | Number (%a) of participants |

|---|---|

| Week –3 (N = 866) | |

| How many days was the patch worn over the last week? | |

| 0 (0%) | 5 (0.6) |

| 1–3 | 34 (3.9) |

| 4–6 | 177 (20.4) |

| 7 (100%) | 645 (74.5) |

| Missing | 5 (0.6) |

| How many patches were used over the last week? (Median 7; range 0–14) | |

| 0 | 4 (0.5) |

| 1–6 | 179 (20.7) |

| 7 | 510 (58.9) |

| > 7 | 168 (19.4) |

| Missing | 5 (0.6) |

| Week +1 (N = 727) | |

| How many days was the patch worn over the last 3 weeks? | |

| 0–7 | 41 (5.6) |

| 8–14 | 47 (6.5) |

| 15–21 | 617 (84.9) |

| Missing | 22 (3.0) |

| How many patches were used over the last 3 weeks? (Median 21; range 0–42) | |

| 0–7 | 40 (5.5) |

| 8–14 | 46 (6.3) |

| 15–21 | 513 (70.6) |

| > 21 | 102 (14.0) |

| Missing | 26 (3.6) |

Post-quit day medication in those who made a quit attempt after preloading was also assessed. At 1 week after quit day, 11.8% of the control group and 8.2% of the intervention group were not using any medication. It is possible that these participants made a quit attempt without medication or that they made a quit attempt but had abandoned the attempt, and, hence, the medication to support the attempt, by the time of the assessment at 1 week after quit day (Table 5).

| Medication used | Trial group, n (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Control (N = 738)a | Intervention (N = 742)a | Total (N = 1480)a | |

| None | 87 (11.8) | 61 (8.2) | 148 (10.0) |

| Varenicline | 218 (29.5) | 164 (22.1) | 382 (25.8) |

| Bupropion | 6 (0.8) | 12 (1.6) | 18 (1.2) |

| Nicotine patches only | 99 (13.4) | 169 (22.8) | 268 (18.1) |

| Acute nicotine onlyb | 74 (10.0) | 44 (5.9) | 118 (8.0) |

| Combined nicotine | 156 (21.1) | 170 (22.9) | 326 (22.0) |

| Missing | 113 (15.3) | 135 (18.2) | 248 (16.8) |

Primary and secondary outcomes

The primary outcome, biochemically validated 6-month abstinence, was achieved by 157 (17.5%) participants in the intervention group and 129 (14.5%) participants in the control group, a difference of 3.02 (95% CI –0.37 to 6.41).

The secondary outcomes showed similar modest differences. At 4 weeks, 319 (35.5%) participants in the intervention group achieved 7-day point prevalence abstinence, whereas 288 (32.3%) participants in the control group did so. At 12 months, 126 (14.0%) participants in the intervention group achieved validated prolonged abstinence, whereas 101 (11.3%) participants in the control group achieved it (Tables 6 and 7).

| Outcome | Analysis | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unadjusted | Adjusteda | Adjustedb | Adjustedc | |||||

| OR (95% CI) | p-value | OR (95% CI) | p-value | OR (95% CI) | p-value | OR (95% CI) | p-value | |

| Primary outcome: 6-month Russell Standard abstinence | ||||||||

| Intervention | 1.25 (0.97 to 1.62) | 0.081 | 1.25 (0.97 to 1.62) | 0.081 | 1.26 (0.97 to 1.62) | 0.081 | 1.34 (1.03 to 1.73) | 0.028 |

| Secondary outcomes | ||||||||

| 4 weeks, Russell Standard abstinence | ||||||||

| Intervention | 1.21 (1.00 to 1.48) | 0.052 | 1.21 (1.00 to 1.48) | 0.053 | 1.22 (1.00 to 1.48) | 0.051 | 1.32 (1.08 to 1.62) | 0.007 |

| 4 weeks, 7-day point prevalence abstinence | ||||||||

| Intervention | 1.16 (0.95 to 1.41) | 0.148 | 1.16 (0.95 to 1.41) | 0.149 | 1.16 (0.95 to 1.41) | 0.150 | 1.26 (1.03 to 1.54) | 0.027 |

| 6 months, 7-day point prevalence abstinence | ||||||||

| Intervention | 1.13 (0.90 to 1.41) | 0.306 | 1.13 (0.90 to 1.41) | 0.306 | 1.14 (0.90 to 1.43) | 0.275 | 1.20 (0.95 to 1.51) | 0.129 |

| 12 months, Russell Standard abstinence | ||||||||

| Intervention | 1.28 (0.97 to 1.69) | 0.085 | 1.28 (0.97 to 1.69) | 0.085 | 1.27 (0.96 to 1.69) | 0.091 | 1.36 (1.02 to 1.80) | 0.036 |

| 12 months, 7-day point prevalence abstinence | ||||||||

| Intervention | 1.22 (0.97 to 1.54) | 0.083 | 1.23 (0.97 to 1.54) | 0.082 | 1.22 (0.97 to 1.54) | 0.087 | 1.28 (1.01 to 1.62) | 0.038 |

| Outcome | Analysis | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unadjusted | Adjusteda | Adjustedb | Adjustedc | |||||

| RD/RR (95% CI) | p-value | RD/RR (95% CI) | p-value | RD/RR (95% CI) | p-value | RD/RR (95% CI) | p-value | |

| Primary outcome: 6-month Russell Standard abstinence | ||||||||

| Estimated risks | 17.5 and 14.5 | |||||||

| RR | 1.25 (0.97 to 1.62) | 0.081 | 1.21 (0.98 to 1.50) | 0.081 | 1.21 (0.98 to 1.50) | 0.082 | 1.27 (1.03 to 1.57) | 0.029 |

| RD | 3.02 (–0.37 to 6.41) | 0.081 | 3.02 (–0.37 to 6.41) | 0.081 | 3.03 (–0.37 to 6.43) | 0.080 | 3.80 (0.41 to 7.18) | 0.029 |

| Secondary outcomes | ||||||||

| 4 weeks, Russell Standard abstinence | ||||||||

| Estimated risks | 36.3 and 31.9 | |||||||

| RR | 1.14 (1.00 to 1.29) | 0.053 | 1.14 (1.00 to 1.29) | 0.053 | 1.14 (1.00 to 1.29) | 0.051 | 1.19 (1.05 to 1.35) | 0.007 |

| RD | 4.35 (–0.04 to 8.73) | 0.052 | 4.33 (–0.04 to 8.70) | 0.052 | 4.37 (–0.01 to 8.75) | 0.050 | 5.89 (1.60 to 10.19) | 0.007 |

| 4 weeks, 7-day point prevalence abstinence | ||||||||

| Estimated risks | 35.5 and 32.3 | |||||||

| RR | 1.10 (0.97 to 1.25) | 0.149 | 1.10 (0.97 to 1.25) | 0.149 | 1.10 (0.97 to 1.25) | 0.151 | 1.15 (1.02 to 1.31) | 0.027 |

| RD | 3.23 (–1.15 to 7.61) | 0.148 | 3.22 (–1.15 to 7.59) | 0.149 | 3.22 (–1.17 to 7.60) | 0.150 | 4.86 (0.58 to 9.14) | 0.026 |

| 6 months, 7-day point prevalence abstinence | ||||||||

| Estimated risks | 22.3 and 20.3 | |||||||

| RR | 1.10 (0.92 to 1.31) | 0.306 | 1.10 (0.92 to 1.31) | 0.306 | 1.10 (0.92 to 1.32) | 0.276 | 1.15 (0.96 to 1.37) | 0.129 |

| RD | 1.98 (–1.81 to 5.77) | 0.306 | 1.98 (–1.81 to 5.76) | 0.306 | 2.11 (–1.68 to 5.91) | 0.275 | 2.93 (–0.85 to 6.71) | 0.129 |

| 12 months, Russell Standard abstinence | ||||||||

| Estimated risks | 14.0 and 11.3 | |||||||

| RR | 1.24 (0.97 to 1.58) | 0.086 | 1.24 (0.97 to 1.58) | 0.086 | 1.24 (0.97 to 1.58) | 0.093 | 1.30 (1.02 to 1.66) | 0.036 |

| RD | 2.71 (–0.37 to 5.78) | 0.085 | 2.71 (–0.37 to 5.78) | 0.085 | 2.66 (–0.43 to 5.75) | 0.091 | 3.31 (0.22 to 6.39) | 0.036 |

| 12 months, 7-day point prevalence abstinence | ||||||||

| Estimated risks | 22.4 and 19.0 | |||||||

| RR | 1.17 (0.98 to 1.41) | 0.083 | 1.17 (0.98 to 1.41) | 0.083 | 1.17 (0.98 to 1.41) | 0.088 | 1.21 (1.01 to 1.45) | 0.038 |

| RD | 3.32 (–0.43 to 7.07) | 0.082 | 3.32 (–0.42 to 7.06) | 0.082 | 3.28 (–0.48 to 7.04) | 0.087 | 3.98 (0.23 to 7.73) | 0.037 |

Adjustment for predictors of abstinence left the results essentially unchanged, except for adjustment for the use of post-quit day varenicline use, which changed the results noticeably. The effect of preloading was larger than in the unadjusted results and was statistically significant.

Subgroup analysis

There was no evidence that people who used varenicline as their post-cessation medication received less benefit from nicotine preloading than people using other cessation medication. For the effect of preloading compared with control for participants using varenicline, the OR was 1.42 (95% CI 0.90 to 2.26). For participants not using varenicline, the OR was 1.30 (95% CI 0.95 to 1.77; p = 0.740) for the interaction.

Adverse events

Adverse events that were moderate or severe in intensity were uncommon in both arms. Therefore, the absolute difference between arms was small with an absolute difference in the percentage of participants suffering an AE in the intervention group compared with the control group of up to 4% (Table 8).

| Event | Trial group | Percentage point difference (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Control (N = 860) | Intervention (N = 880) | ||

| Gastrointestinal disorders | 19 (2.2) | 55 (6.2) | 4.0 (2.2 to 5.9) |

| Abdominal pain | 3 (0.3) | 6 (0.7) | 0.3 (–0.3 to 1.0) |

| Diarrhoea | 3 (0.3) | 8 (0.9) | 0.6 (–0.2 to 1.3) |

| Nausea | 8 (0.9) | 30 (3.4) | 2.5 (1.1 to 3.8) |

| Vomiting | 3 (0.3) | 14 (1.6) | 1.2 (0.3 to 2.2) |

| General disorders | 11 (1.2) | 30 (3.3) | 2.1 (0.7 to 3.5) |

| Asthenia | 5 (0.6) | 10 (1.1) | 0.6 (–0.3 to 1.4) |

| Fatigue | 0 (0.0) | 6 (0.7) | 0.7 (0.1 to 1.2) |

| Injuries, poisoning and procedural complications | 8 (0.9) | 4 (0.5) | –0.5 (–1.2 to 0.3) |

| Musculoskeletal and connective disorders | 7 (0.8) | 10 (1.1) | 0.3 (–0.6 to 1.2) |

| Nervous system | 16 (1.9) | 56 (6.4) | 4.5 (2.7 to 6.4) |

| Abnormal dreams | 1 (0.1) | 9 (1.0) | 0.9 (0.2 to 1.6) |

| Dizziness | 6 (0.7) | 15 (1.7) | 1.0 (0.0 to 2.0) |

| Headache | 3 (0.3) | 14 (1.6) | 1.2 (0.3 to 2.2) |

| Poor-quality sleep | 3 (0.3) | 20 (2.3) | 1.9 (0.9 to 3.0) |

| Psychiatric | 7 (0.8) | 17 (1.9) | 1.1 (0.0 to 2.2) |

| Depressed mood | 4 (0.5) | 5 (0.6) | 0.1 (–0.6 to 0.8) |

| Respiratory | 21 (2.4) | 15 (1.7) | –0.7 (–2.1 to 0.6) |

| Chest infection | 4 (0.5) | 1 (0.1) | –0.3 (–0.8 to 0.2) |

| Influenza-like illness | 3 (0.3) | 7 (0.8) | 0.4 (–0.3 to 1.2) |

| Nasopharyngitis | 7 (0.8) | 4 (0.5) | –0.4 (–1.1 to 0.4) |

| Skin and subcutaneous tissue disorders | 4 (0.5) | 7 (0.8) | 0.3 (–0.4 to 1.1) |

| Skin irritation | 2 (0.2) | 5 (0.6) | 0.3 (–0.3 to 0.9) |

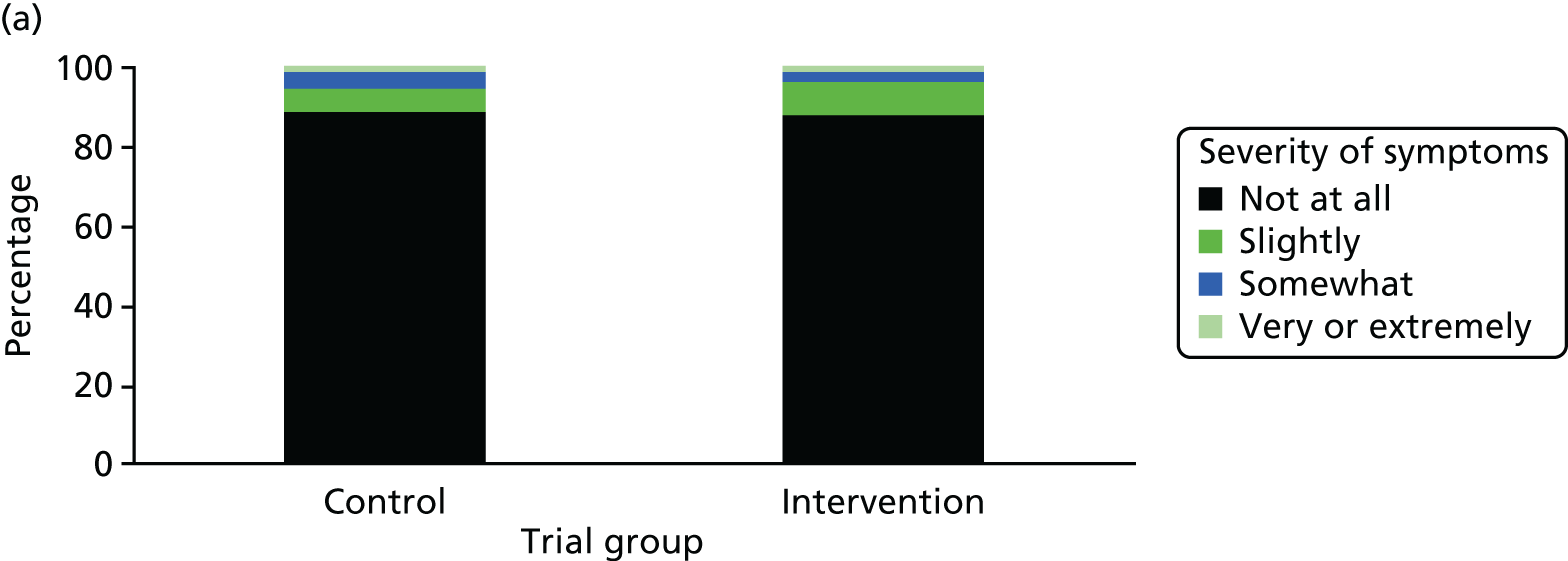

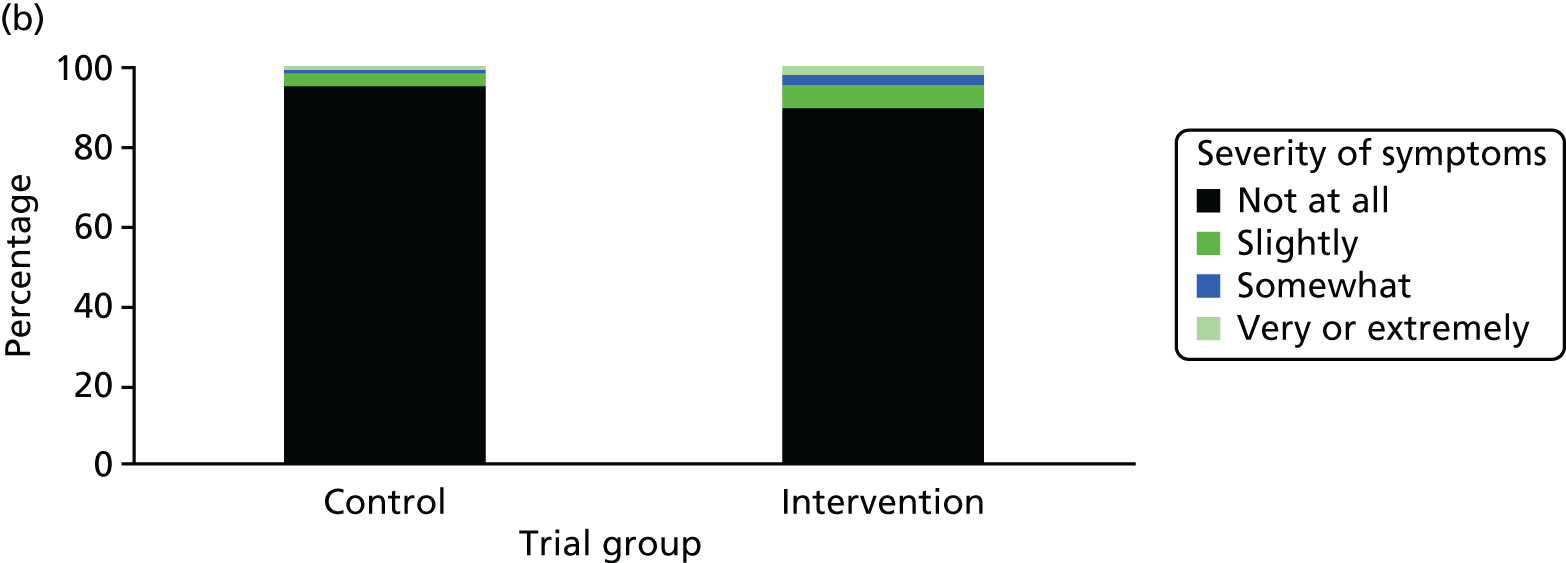

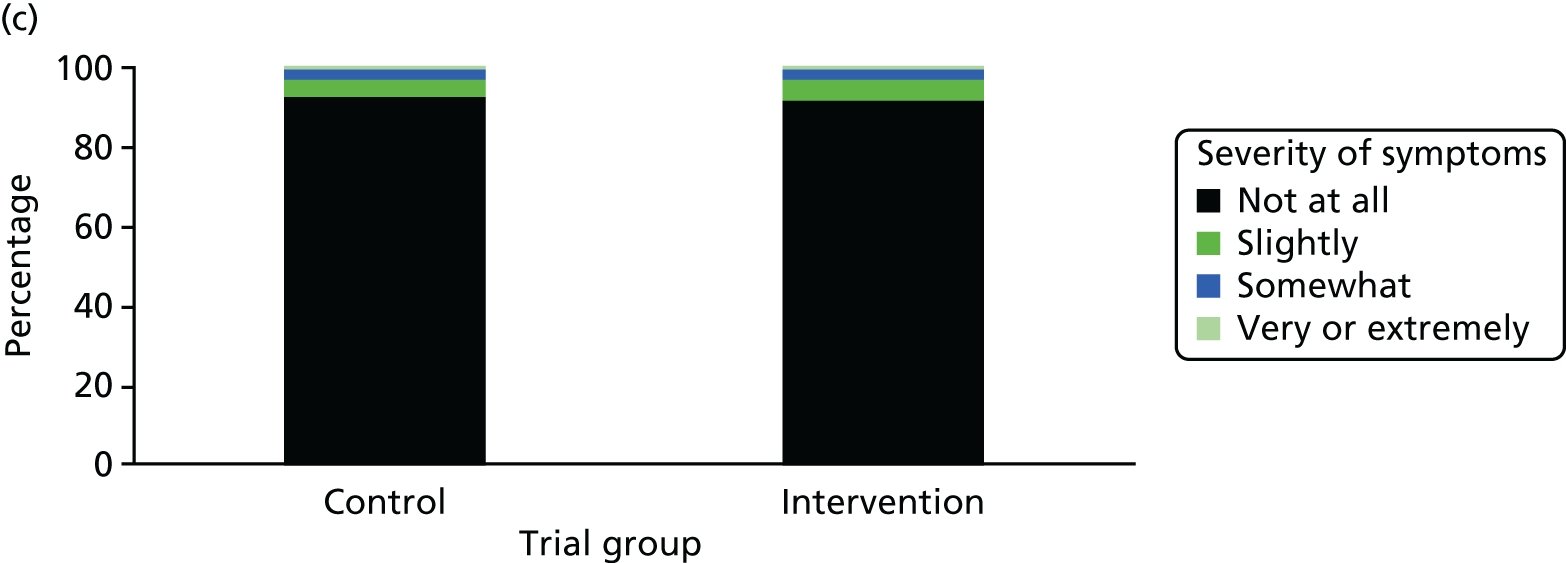

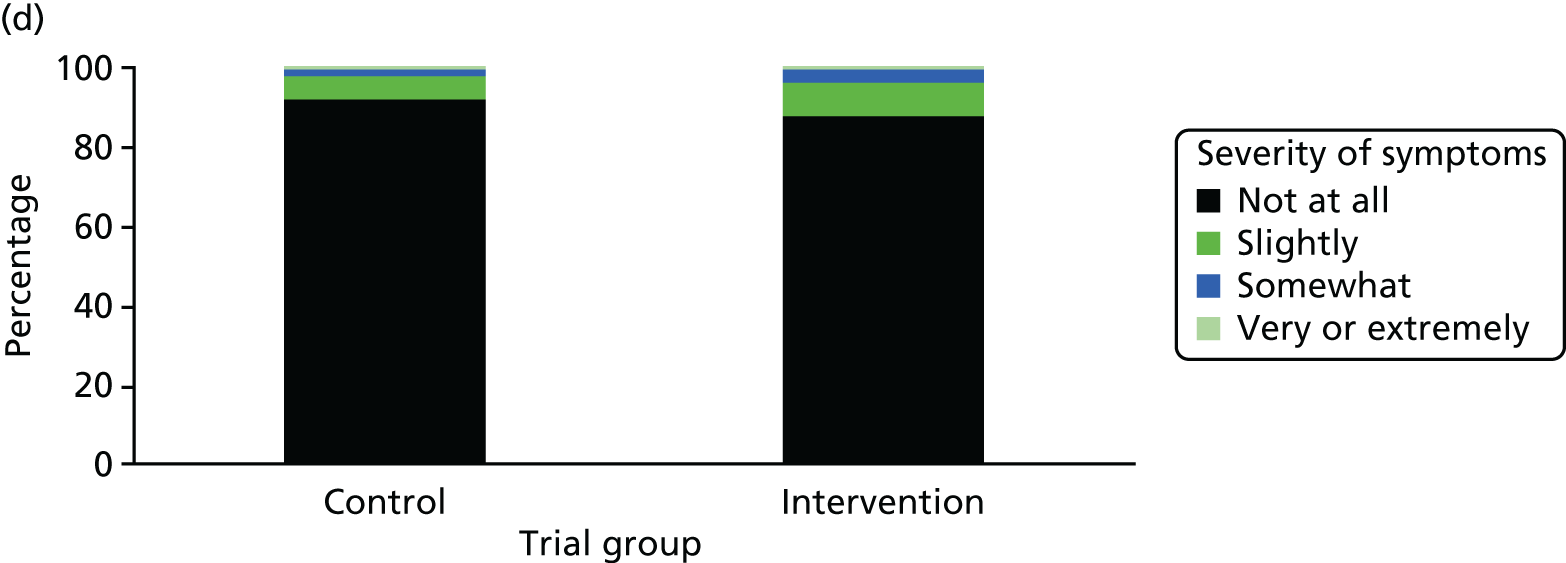

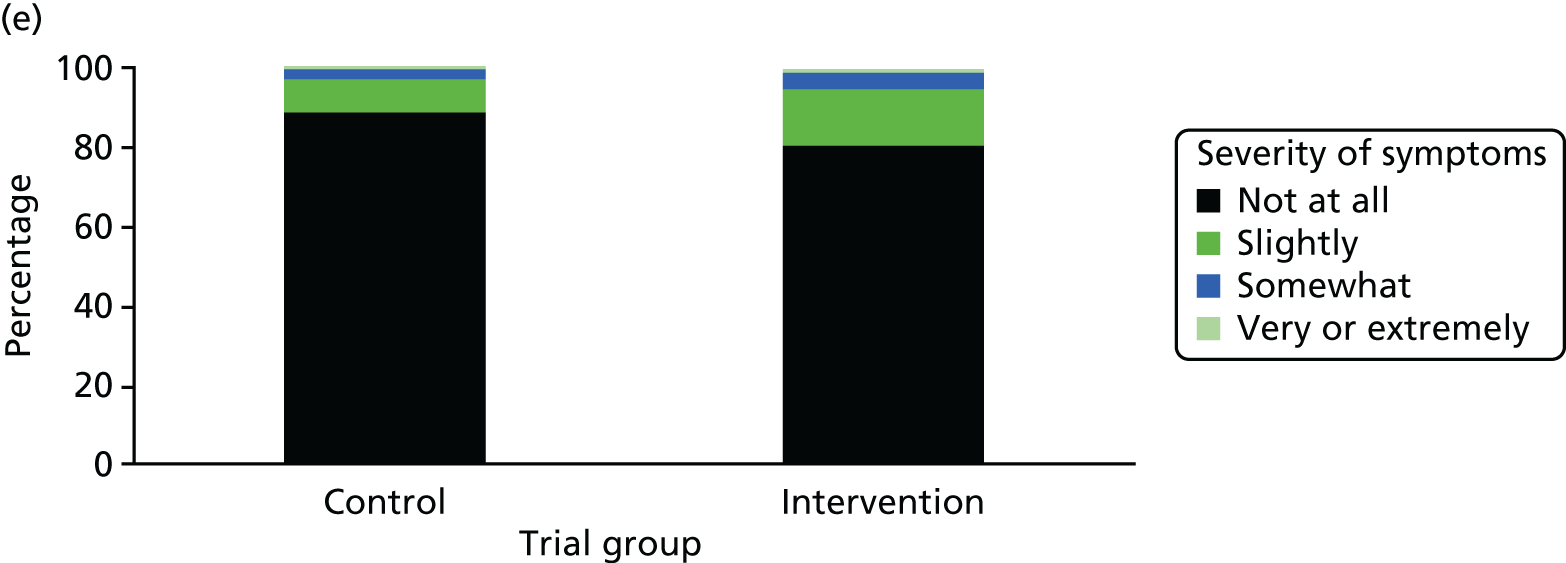

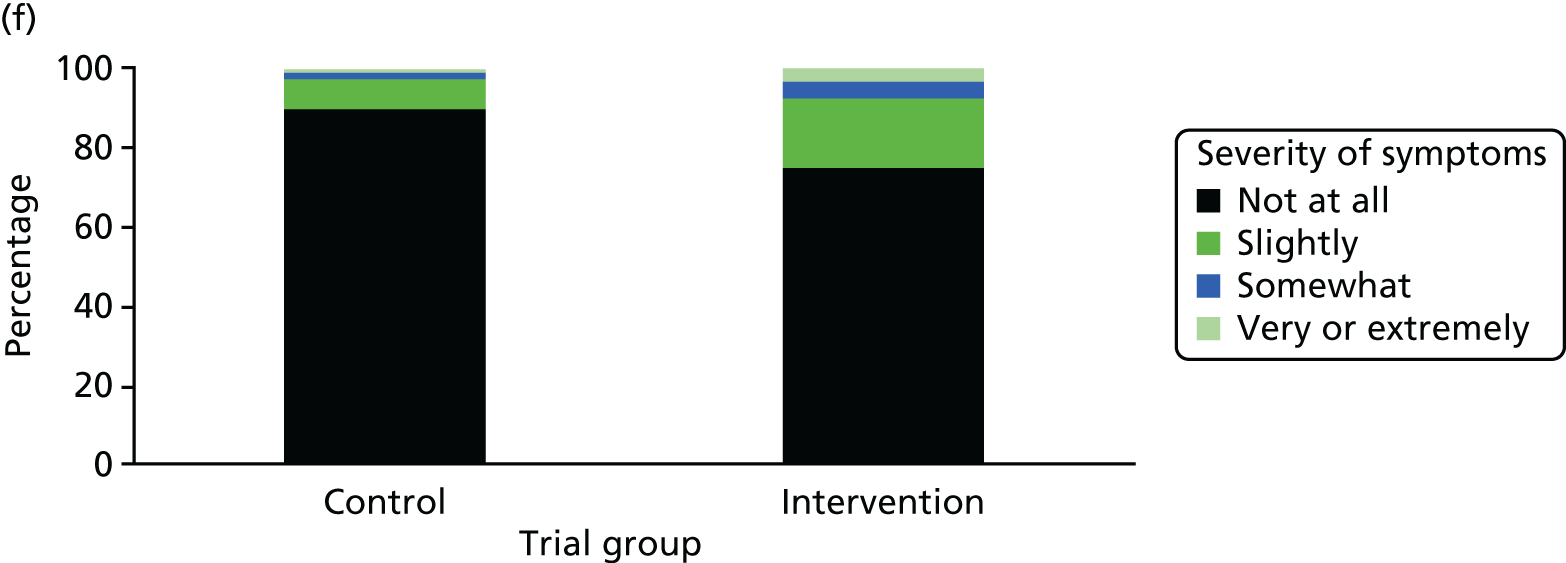

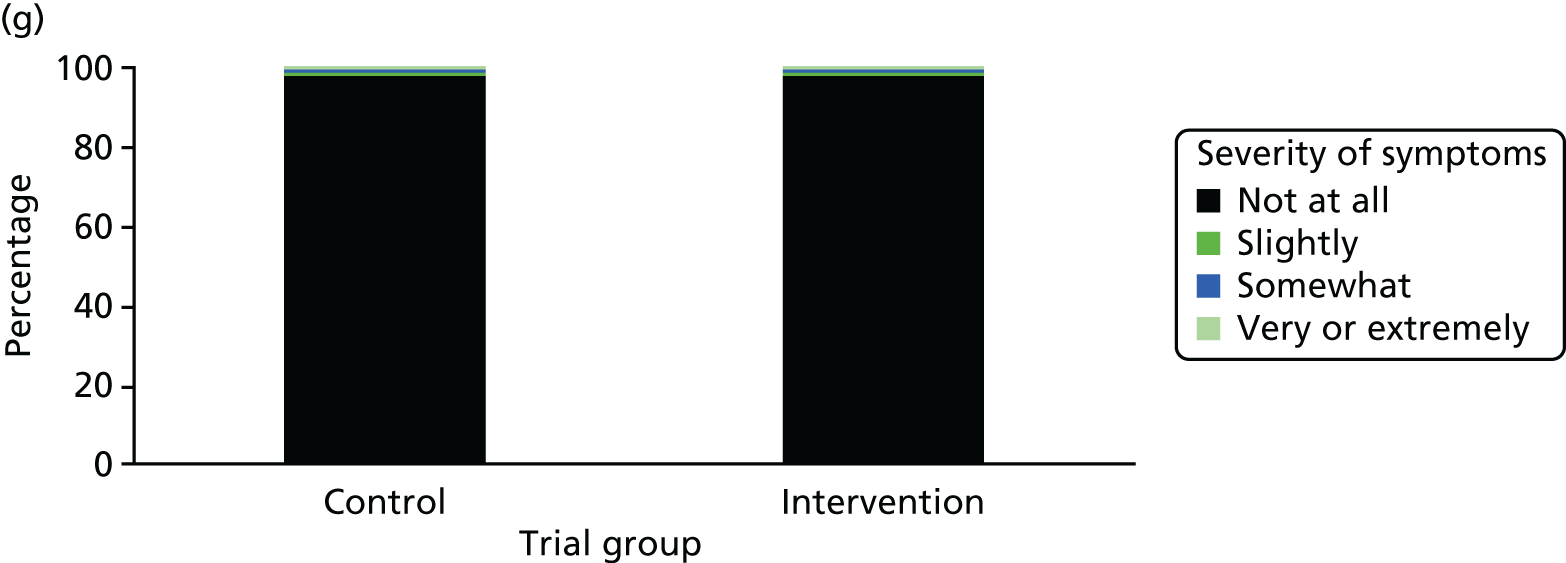

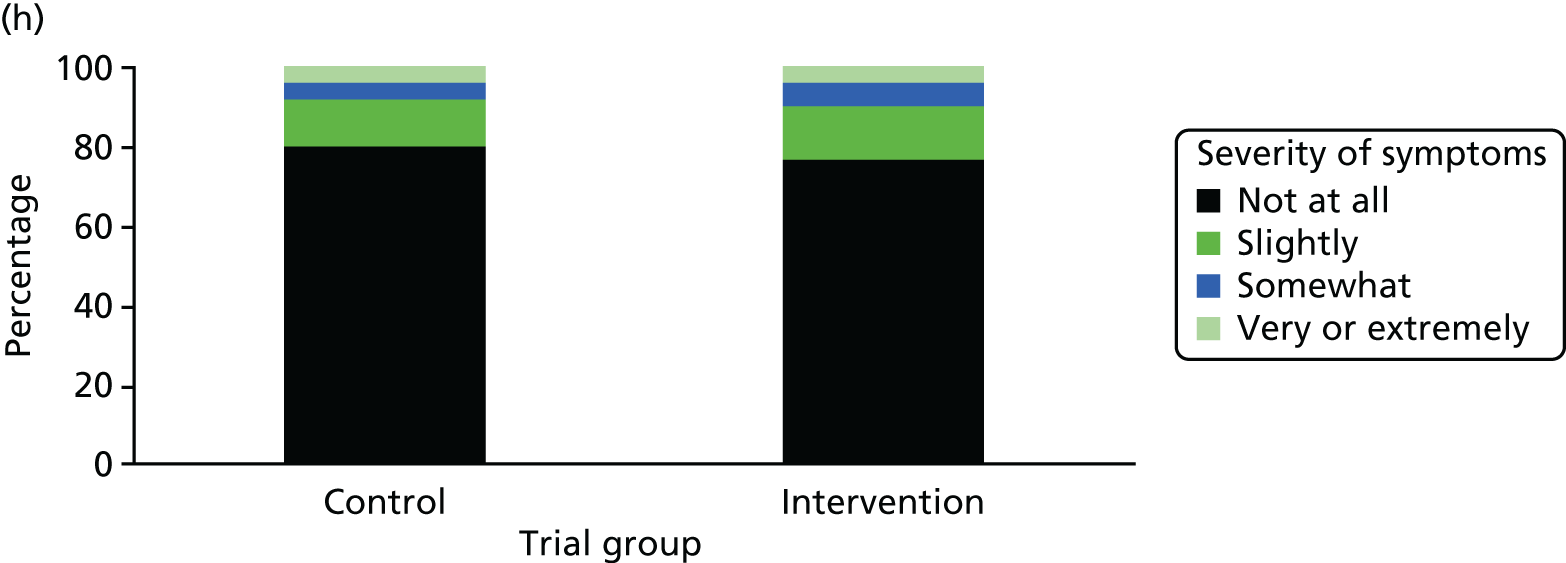

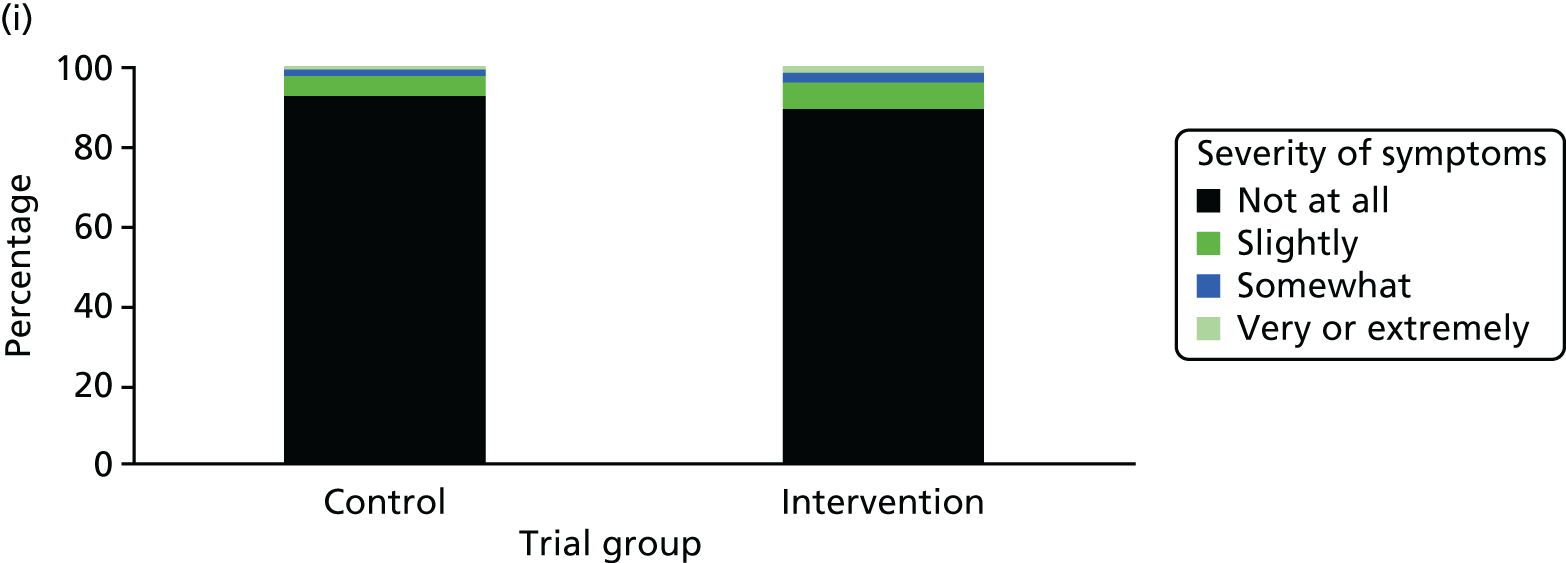

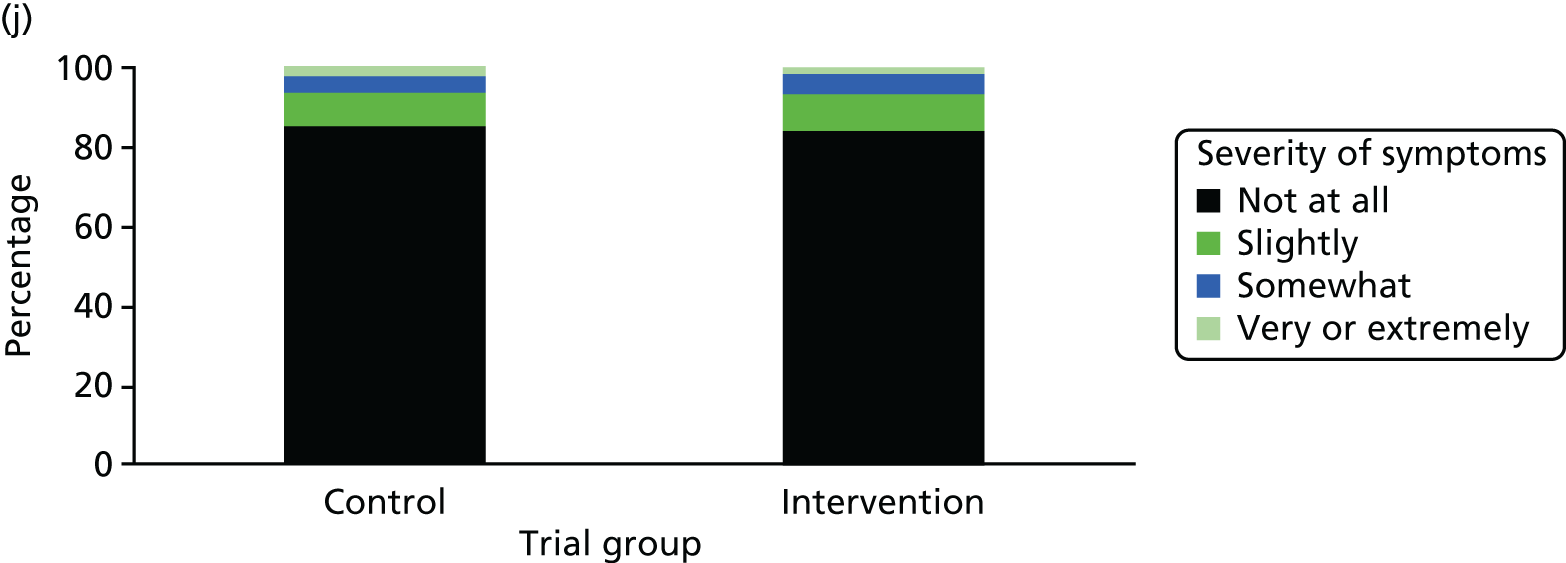

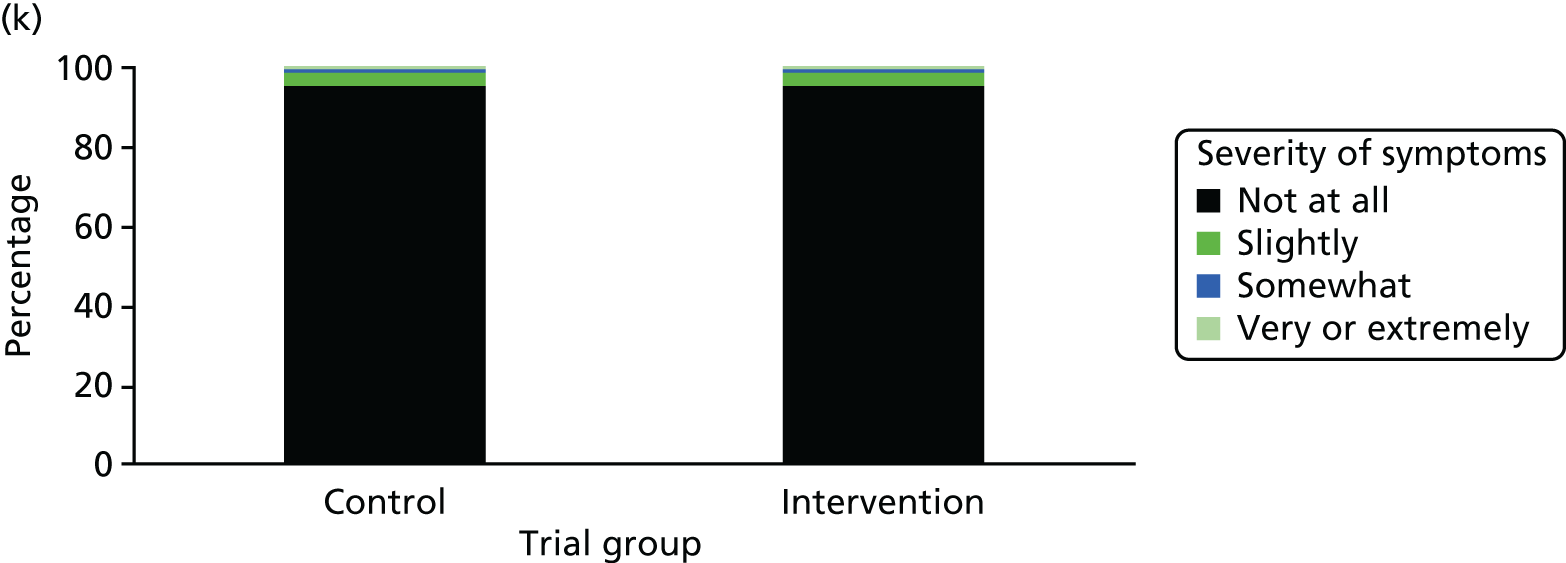

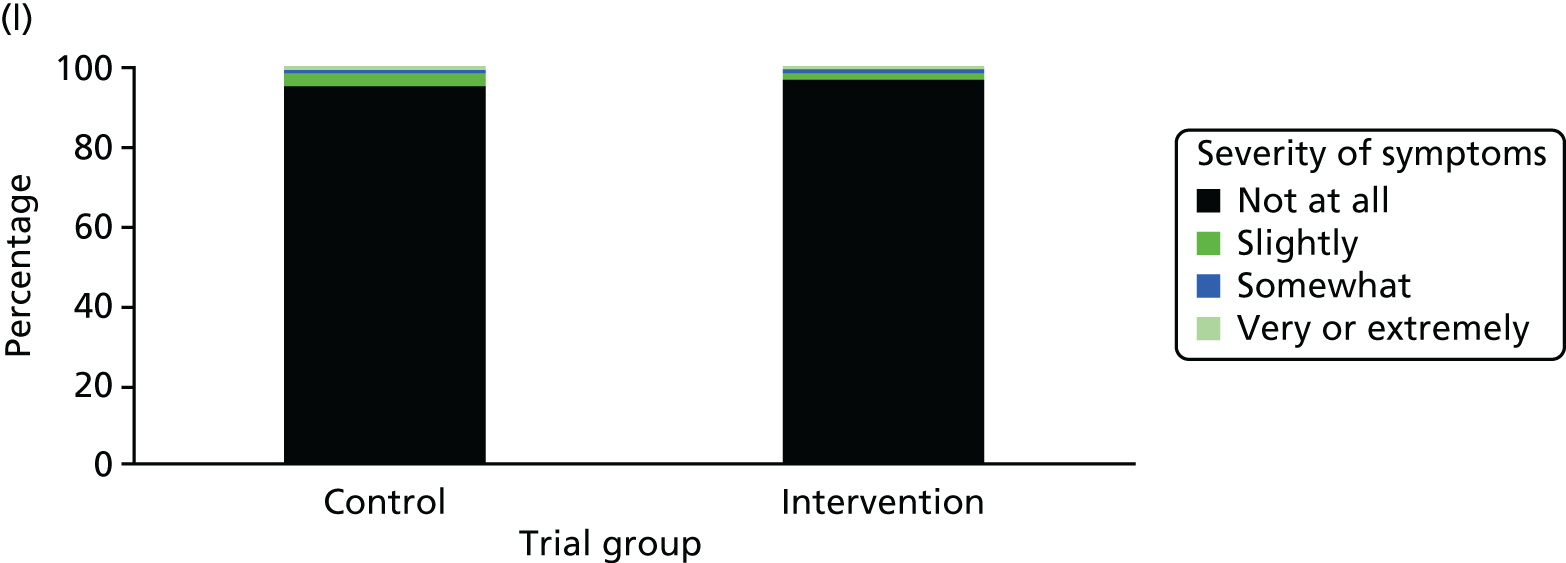

One week after baseline, 394 (45.5%) participants in the intervention group and 271 (32.4%) participants in the control group reported at least one symptom from the checklist of symptoms of nicotine excess (p < 0.001 for the difference). The only three symptoms for which there was statistically significant evidence that they were more common in the intervention group were dizziness, palpitations and nausea. Of these symptoms, 5.6% and 3.0% were somewhat or very dizzy in the intervention and control groups, 3.9% and 1.9% had palpitations and 8.1% and 3.1% experienced nausea, respectively (Figure 4).

FIGURE 4.

Prevalence and severity of symptoms experienced in the last 24 hours, reported after having been in the preloading group or control group for 1 week. (a) Stomach pain; (b) cold sweat; (c) diarrhoea; (d) palpitations; (e) dizziness; (f) nausea; (g) vomiting; (h) headaches; (i) watery mouth; (j) weakness; (k) tremor; and (l) pallor.

There were 17 SAEs during the 5-week period, nine in the intervention group and eight in the control group, giving an OR of 1.12 (95% CI 0.42 to 3.03). Of these, one was judged to be possibly caused by preloading: acute coronary syndrome in a 64-year-old woman. The SAEs reported are summarised in Table 9.

| Age and gender | Trial group | Relevant medical history | Event |

|---|---|---|---|

| 68-year-old man | Intervention | Chronic myeloid leukaemia | Hospitalised with chest infection |

| 85-year-old woman | Intervention | Osteoporosis | Hospitalised with pelvic fracture following accidental fall |

| 72-year-old woman | Intervention | None | Hospitalised for aspiration of malignant pleural effusion |

| 65-year old woman | Intervention | Cardiovascular disease, hypertension, pacemaker and history of blackouts | Hospitalised for a blackout |

| 27-year-old woman | Intervention | Psychotic illness, illicit drug use | Psychotic episode following period of illicit drug use leading to anxiety attacks |

| 64-year-old woman | Intervention | None | Acute coronary syndrome |

| 54-year-old woman | Intervention | Angina | Hospitalised with acute coronary syndrome or non-cardiac chest pain |

| 45-year-old woman | Intervention | Self-harming | Hospitalised for increased self-harming and suicidal ideation |

| 68-year-old man | Control | Reflux oesophagitis | Hospitalised with cancer of the oesophagus |

| 55-year-old woman | Control | COPD and type 2 diabetes mellitus | Death due to COPD |

| 59-year-old man | Control | Alcohol dependence | Death as a result of an accidental house fire |

| 52-year-old man | Control | Two previous hernia repairs | Hospitalised for hernia repair |

| 47-year-old woman | Control | None | Hospitalised for pyelonephritis |

| 38-year-old woman | Control | Asthma | Hospitalised with chest infection |

| 64-year-old woman | Control | COPD | Exacerbation of COPD |

| 25-year-old man | Control | None | Pneumonia |

Chapter 4 Moderators and mediators of the effect of nicotine preloading

Introduction

Chapter 3 showed no evidence that, in the primary analysis, preloading was an effective strategy for promoting smoking cessation in the current NHS setting. This is because preloading deterred the use of varenicline, the most effective smoking cessation medication, as a post-quit day medication. 6 However, when adjusted for the use of varenicline, there was evidence of an independent effect of preloading as an effective strategy for promoting smoking cessation. However, in the future, it is plausible that this deterrent effect could be overcome by changing the guidelines or the everyday customs and practices of smoking cessation therapists. Therefore, it is appropriate to understand better how preloading may work and the people for whom it may work best. This may allow us to maximise the benefit for patients and, in those who choose preloading, to monitor the effectiveness of the strategy and discontinue preloading if benefits are unlikely.

Effect modification

This chapter addresses two questions. The first examines effect modification or moderation of the possible treatment effect of preloading. It is possible that preloading was effective only for a subgroup of the population of smokers seeking help to quit. Given its proposed mechanism of action on undermining the reward from smoking and the drive to smoke, we hypothesised that preloading would be more effective for people who showed evidence of higher dependence on cigarettes. This might be evidenced by a higher cigarette consumption at baseline (shown by cigarettes per day or exhaled CO concentration at baseline) or a higher dependence score (FTCD). Understanding this may help us target preloading to the group who stand to gain a greater than average benefit from preloading, thereby maximising the cost-effectiveness of the treatment approach.

Mechanism of action of preloading

The second question addresses the question of how preloading may work.

As discussed in Chapter 1, Mechanisms of action of preloading, our review of the mechanisms of action of preloading revealed scant evidence for any of these mechanisms explaining the possible effectiveness of this strategy. This is important for clinical practice. Nicotine preloading may not help everyone who is trying to stop smoking. Therapists could monitor whether or not preloading is achieving its intermediate effects and, if not, abandon the strategy early, saving resources on behalf of the NHS. In this chapter, we examine the possible mediating pathways between nicotine preloading and outcomes.

Method

Design

The trial protocol and main outcomes are described in Chapters 2 and 3. For the moderation analysis, we followed the same analysis strategy as outlined in Chapter 2, Statistical analysis, but added multiplicative interaction terms to the equation between two markers of dependence assessed at baseline and trial group. As markers of dependence we used FTCD, the standard measure of baseline dependence, and exhaled CO concentration. The latter is a measure of smoke intake in the preceding hours; more dependent smokers draw more heavily on their cigarettes or smoke more cigarettes per day and, hence, tend to have higher CO measurements.

For the mediation analysis, we followed the regression framework described by Kenny. 41 The steps are as follows:

-

show that the preloading variable causes smoking cessation (Chapter 3)

-

show that preloading causes change in the mediator

-

show that change in the mediator is associated with smoking cessation

-

to establish complete mediation, show that controlling for change in the mediator abolishes the association between preloading and cessation.

Given that Chapter 3 showed that, on adjustment for the effect of post-cessation varenicline, there was evidence for the efficacy of preloading, this chapter deals with steps 2–4.

Outcomes

For the moderation analyses, the outcome was the primary outcome: Russell Standard 6-month abstinence.

We assessed the impact of preloading on potential mediators of effect outlined in Figure 5. These were measured 1 week after starting preloading or the control condition (3 weeks prior to quit day) and were:

-

positive reinforcement – modified Cigarette Evaluation Questionnaire (mCEQ) satisfaction subscale42 and noticing whether cigarettes were more or less enjoyable than previously

-

negative reinforcement – mCEQ reward subscale

-

drive to smoke – self-reported change in urge strength and change in frequency of the urge to smoke combined, assessed using the Mood and Physical Symptoms Scale – Craving (MPSS-C) subscale;43 smoking stereotypy taken from the Nicotine Dependence Syndrome Scale;44 the mCEQ craving question; and a question used by Hajek et al. 21 in a similar trial that asked participants to rate their urge to smoke compared with usual

-

cigarette consumption – cigarettes per day and exhaled CO concentration

-

symptoms of addiction – modified score on the FTCD,45 modified by removing cigarette consumption from the scale to ensure that symptoms of addiction were distinct from cigarette consumption.

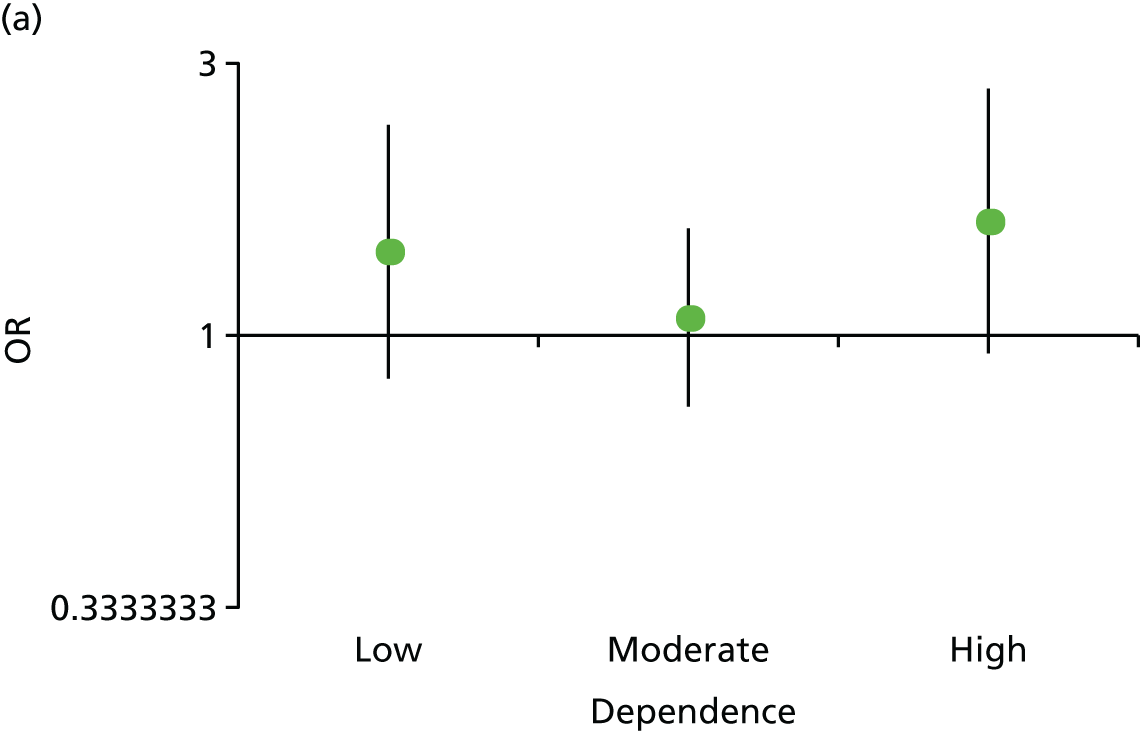

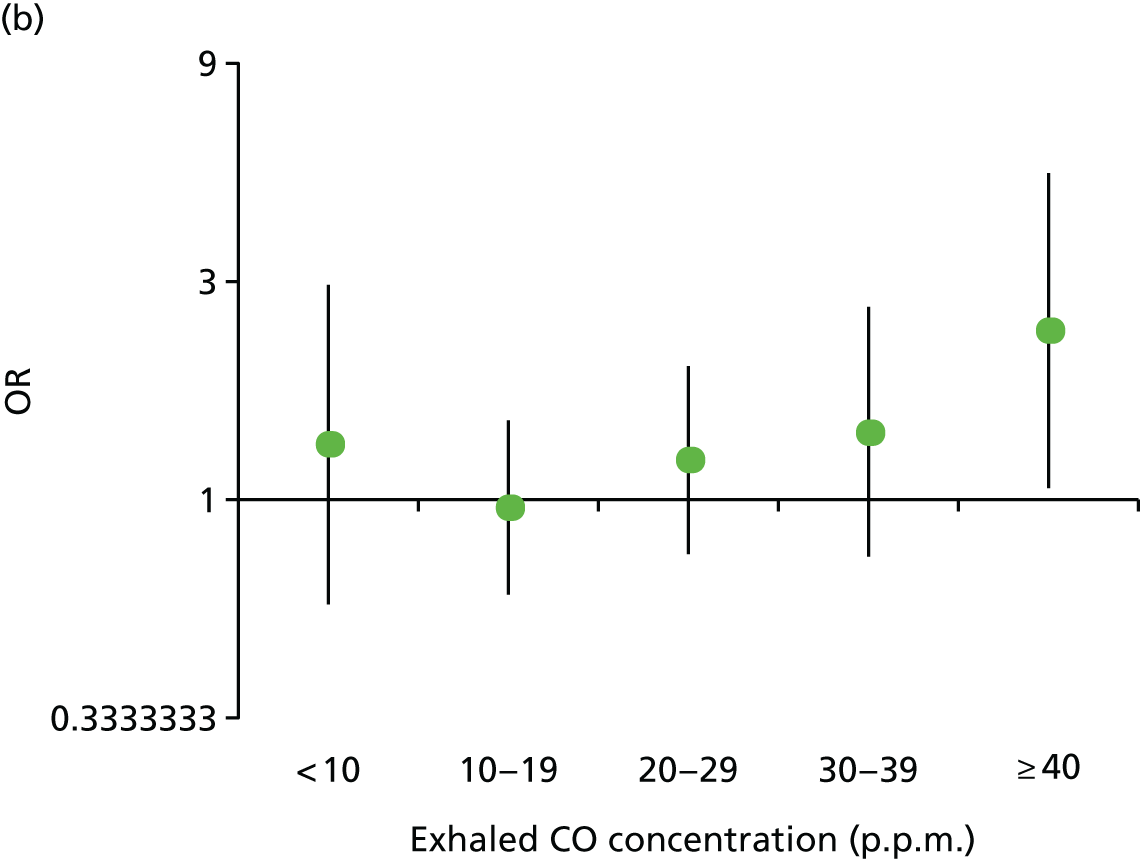

FIGURE 5.

Effect of preloading compared with control on the primary outcome, depending on baseline tobacco dependence. (a) FTCD score (0–3, 4–6 and 7–10); and (b) baseline exhaled CO concentration in p.p.m.

The hypothesis is that, by undermining the learned addiction to cigarettes during the pre-quitting period, preloading reduces the intensity of craving and withdrawal during the post-quit period. For this, we examined the effect of preloading on the intensity of urges and mood symptoms at the end of the first week of abstinence. We used the MPSS-C and the Mood and Physical Symptoms Scale – Mood (MPSS-M) subscales to measure these. The results of assessments of craving and withdrawal symptoms in those who are smoking can be hard to interpret,46 so we analysed these once in those who had been perfectly abstinent and once in those who were continuing to try to be abstinent.

For our other three mediational hypotheses, we assessed the impact of the possible mediators measured at 1 week after commencement. These were as follows:

-

Medication adherence: days of use of post-quit day medication measured at the +1-week visit.

-

Confidence question: ‘How high would you rate your chances of giving up smoking for good at this attempt?’, measured on a five-point scale (with 1 being ‘not at all’ and 5 being ‘extremely good’).

-

Nausea and aversion: we assessed nausea using the mean scores for two questions derived from themes from participant interviews in a previous trial. 47 These were ‘Over the past week how nauseous have you felt when you have seen cigarettes or lighters?’ and ‘Over the past week how nauseous have you felt when you have smelt cigarette smoke?’ and were measured on five-point scales from not at all to extremely. Aversion was measured using the aversion subscale of the mCEQ.

To maximise the sensitivity to detect mediation in the mediator analyses, our outcomes were Russell Standard 4-week and 6-month abstinence. Given that 4-week abstinence is more proximate to the mediators, it should have a stronger association with the mediators than 6-month abstinence.

Statistical analysis

The moderator analysis used the same model as for the primary analysis outlined in Chapter 2, Statistical analysis, but added, in turn, our two markers of dependence (FTCD and exhaled CO concentration) and the multiplicative term representing the baseline marker of dependence multiplied by the trial group indicator variable.

In all of the mediator analyses, we excluded people who had missing data on the mediator. In the analyses, we examined for evidence of mediation on variables assessed at –3 weeks (1 week after baseline) and at +1 week (5 weeks after baseline, 1 week after quit day).

For the second step of the mediation analysis, we assessed the effect of treatment group on mediators descriptively by comparing means between treatment groups and then by analysis of covariance, with adjustment for centre and for the baseline value of the mediator when applicable; thus, effectively examining the effect of preloading on change in the mediator. We checked the residuals to ensure that there was no marked deviation from normality.

We proceeded to the third step of mediation analysis only for those variables for which there was reasonable statistical evidence that preloading influenced the change in the mediator. We assessed the effect of mediators on abstinence outcomes at 4 weeks and 6 months using logistic regression. We looked at this first in unadjusted analysis and then with adjustment for treatment group, as advocated for mediation analysis by Kenny. 41 As previously, these analyses were adjusted for stratification by centre.

In the fourth step of mediation, we examined whether or not potential mediators (i.e. those correlated with both the treatment group and the outcome) did indeed mediate the relationship between treatment group and each outcome; this was done by adding each to a logistic regression model including the mediator and the treatment group. Given that there was strong statistical evidence for the efficacy of preloading only when adjusted for use of varenicline, we used the model adjusted for varenicline as the primary model in this analysis. We added each potential mediator singly and then all of the mediators in the same model.

Results

Modification of the effect of preloading on abstinence by baseline tobacco dependence

There was no evidence that people who were more dependent on smoking received a greater benefit from preloading. The p-values for multiplicative interaction terms for the effect of preloading in those with higher dependence scores and a higher exhaled CO concentration were 0.831 and 0.171, respectively. Per unit increase in each variable, the ORs were 1.01 (95% CI 0.90 to 1.14) and 1.01 (95% CI 0.99 to 1.04), respectively (see Figure 5).

Effect of preloading on potential mediators

Mediators measured at –3 weeks

This assessment took place 1 week after baseline and 3 weeks before quit day.

There was evidence that preloading reduced both positive and negative reward (Table 10). Preloading should reduce the drive to smoke and the reduction of reward should also reduce the drive to smoke. There was evidence that three of the four measures of drive to smoke reduced because of preloading. The exception was withdrawal mood symptoms, but measures of drive to smoke specifically all reduced. If this model is correct, then consumption of cigarettes should decrease and this was indeed observed, with a mean modest reduction of 2.6 cigarettes per day (from a baseline mean of 18.9 cigarettes per day) and a reduction in exhaled CO concentration of 3.2 p.p.m. (from a baseline mean of 23.7 p.p.m.). Likewise, perhaps reflecting a decreased drive to smoke, symptoms of addiction (FTCD, excluding daily cigarette consumption) were also shown to have decreased.

| Potential mediator | Trial group, mean (SD) | Difference between intervention and controla (95% CI) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | Intervention | |||

| At –3 weeks | ||||

| Positive reinforcement | ||||

| mCEQ satisfaction subscale | 4.132 (1.425) | 3.584 (1.351) | –0.547 (–0.651 to –0.443) | < 0.001 |

| Enjoyment more or less than usual | 2.673 (0.650) | 2.149 (0.725) | –0.524 (–0.590 to –0.459) | < 0.001 |

| Negative reinforcement | ||||

| mCEQ reward subscale | 2.945 (1.473) | 2.608 (1.338) | –0.354 (–0.459 to –0.249) | < 0.001 |

| Drive to smoke | ||||

| MPSS-C | 2.613 (0.941) | 2.141 (0.797) | –0.485 (–0.555 to –0.415) | < 0.001 |

| MPSS-M | 1.893 (0.726) | 1.904 (0.724) | 0.009 (–0.043 to 0.062) | 0.724 |

| Smoking stereotypy | 2.185 (0.761) | 2.285 (0.762) | 0.102 (0.036 to 0.168) | 0.003 |

| Urges stronger or weaker than usual | 2.911 (0.657) | 2.160 (0.722) | –0.752 (–0.818 to –0.686) | < 0.001 |

| Cigarette consumption | ||||

| Cigarettes per day | 15.7 (8.7) | 13.4 (8.3) | –2.6 (–3.2 to –2.1) | < 0.001 |

| Exhaled CO concentration | 23.58 (12.8) | 20.41 (11.7) | –3.17 (–4.0 to –2.3) | < 0.001 |

| Symptoms of addiction | ||||

| FTCD excluding cigarettes per day | 3.938 (1.789) | 3.636 (1.790) | –0.2997 (–0.403 to –0.196) | < 0.001 |

| Confidence in quitting | ||||

| How do you rate your chances? | 3.811 (0.788) | 3.853 (0.824) | 0.028 (–0.036 to 0.092) | 0.384 |

| Aversion | ||||

| Nausea | 1.334 (0.594) | 1.533 (0.736) | 0.186 (0.129 to 0.242) | < 0.001 |

| mCEQ aversion subscale | 1.339 (0.717) | 1.589 (0.954) | 0.241 (0.168 to 0.314) | < 0.001 |

| At +1 week | ||||

| Drive to smoke | ||||

| MPSS-C (in those abstinent) | 1.279 (1.046) | 1.0231 (0.958) | –0.285 (–0.438 to –0.132) | < 0.001 |

| MPSS-C (in those still trying to quit) | 1.504 (1.082) | 1.311 (1.053) | –0.214 (–0.335 to –0.093) | 0.001 |

| MPSS-M (in those abstinent) | 1.751 (0.634) | 1.719 (0.636) | –0.035 (–0.126 to 0.056) | 0.454 |

| MPSS-M (in those still trying to quit) | 1.789 (0.687) | 1.770 (0.682) | –0.007 (–0.079 to 0.065) | 0.848 |

| Confidence in quitting | ||||

| How do you rate your chances? (in those abstinent) | 4.371 (0.746) | 4.360 (0.658) | –0.010 (–0.117 to 0.097) | 0.858 |

| How do you rate your chances? (in those abstinent or still trying to quit) | 4.102 (0.916) | 4.190 (0.787) | 0.092 (–0.006 to 0.189) | 0.066 |

| Aversion (in those trying to quit) | 1.831 (1.199) | 1.976 (1.392) | 0.203 (–0.018 to 0.424) | 0.072 |

| Nausea (in those abstinent) | 0.683 (0.333) | 0.679 (0.319) | –0.011 (–0.060 to 0.038) | 0.649 |

| Nausea (in those abstinent or trying to quit) | 0.676 (0.317) | 0.695 (0.331) | 0.017 (–0.019 to 0.053) | 0.365 |

| Medication adherence | ||||

| Number of days of medication use in the last week (in those who are still trying to quit), n (%) | ||||

| 0 | 82 (14.2) | 68 (11.7) | 0.333 | |

| 1–6 | 78 (13.5) | 72 (12.3) | ||

| 7 | 419 (72.4) | 443 (76.0) | ||

Two alternative hypotheses were that preloading improves confidence in quitting and that preloading works through creating an aversion to smoking. There was no evidence that confidence in quitting improved because of preloading but there was strong evidence that both markers of aversion to smoking increased because of preloading (see Table 10). The medication adherence hypothesis could be tested only after quit day.

Mediators measured at +1 week

This assessment took place 1 week after quit day, and potentially after stopping preloading treatment, and 5 weeks after baseline.

As participants were trying to achieve abstinence and many were abstaining, we did not measure positive or negative reward from smoking cigarettes at this assessment. In the main hypothesis, reduced urges to smoke during preloading and a reduced level of smoking mean that people are experiencing cues to smoke that do not prompt smoking, thus beginning the process of extinguishing the learnt drive to smoke. This would manifest as reduced urges to smoke or craving experienced after quit day and there was evidence that this did occur, although there was no evidence that withdrawal mood symptoms were reduced. At this assessment, when participants were abstinent, it was not sensible to ask about any other potential mediators on this pathway.

As in the pre-quit period, there was no evidence that preloading increased participants’ confidence in their ability to quit smoking. Unlike in the pre-quit period, there was no evidence of a difference in aversion to cigarettes after the quit day (see Table 10).

The final mediating hypothesis is that preloading improves adherence to post-cessation medication but there was no evidence to support this (see Table 10).

Association between mediators and outcome (smoking abstinence)

We analysed the association between mediators and outcome for those variables for which there was evidence that preloading influenced the mediator (Table 11).

| Potential mediator | Abstinence | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| At 4 weeks, OR (95% CI); p-value | At 6 months, OR (95% CI); p-value | |||

| Unadjusted for treatment group | Adjusted for treatment group | Unadjusted for treatment group | Adjusted for treatment group | |

| Change from baseline at –3 weeks | ||||

| Positive reinforcement | ||||

| mCEQ satisfaction subscale | 0.974 (0.901 to 1.054); 0.521 | 0.987 (0.910 to 1.070); 0.746 | 0.915 (0.828 to 1.012); 0.083 | 0.928 (0.837 to 1.028); 0.153 |

| Enjoyment more or less than usual | 0.864 (0.761 to 0.981); 0.024 | 0.880 (0.761 to 1.017); 0.082 | 0.818 (0.695 to 0.963); 0.016 | 0.832 (0.691 to 1.003); 0.053 |

| Negative reinforcement | ||||

| mCEQ reward subscale | 0.996 (0.919 to 1.080); 0.932 | 1.006 (0.927 to 1.091); 0.885 | 1.073 (0.967 to 1.191); 0.182 | 1.089 (0.980 to 1.209); 0.112 |

| Drive to smoke | ||||

| MPSS-C | 0.959 (0.860 to 1.069); 0.445 | 0.980 (0.876 to 1.097); 0.727 | 1.060 (0.921 to 1.219); 0.416 | 1.099 (0.951 to 1.270); 0.202 |

| Smoking stereotypy | 1.021 (0.903 to 1.155); 0.741 | 1.015 (0.897 to 1.148); 0.819 | 1.080 (0.923 to 1.264); 0.338 | 1.072 (0.915 to 1.255); 0.390 |

| Urges stronger or weaker than usual | 0.864 (0.761 to 0.981); 0.024 | 0.880 (0.761 to 1.017); 0.082 | 0.818 (0.695 to 0.963); 0.016 | 0.832 (0.691 to 1.003); 0.053 |

| Cigarette consumption | ||||

| Cigarettes per day | 1.008 (0.993 to 1.023); 0.311 | 1.011 (0.995 to 1.027); 0.173 | 1.002 (0.983 to 1.022); 0.825 | 1.006 (0.986 to 1.026); 0.582 |

| CO concentration | 0.986 (0.976 to 0.996); 0.007 | 0.987 (0.977 to 0.997); 0.012 | 0.988 (0.975 to 1.001); 0.062 | 0.989 (0.976 to 1.002); 0.094 |

| Symptoms of addiction | ||||

| FTCD | 1.003 (0.918 to 1.095); 0.954 | 1.012 (0.925 to 1.106); 0.799 | 1.016 (0.907 to 1.138); 0.780 | 1.029 (0.918 to 1.153); 0.625 |

| Aversion | ||||

| Nausea | 0.888 (0.763 to 1.035); 0.128 | 0.872 (0.748 to 1.017); 0.082 | 1.072 (0.884 to 1.300); 0.481 | 1.052 (0.866 to 1.277); 0.611 |

| mCEQ aversion subscale | 1.001 (0.898 to 1.115); 0.989 | 0.990 (0.888 to 1.103); 0.856 | 1.012 (0.882 to 1.162); 0.863 | 1.000 (0.871 to 1.147); 0.992 |

| Change from baseline at +1 week | ||||

| MPSS-C | 0.750 (0.690 to 0.817); < 0.001 | 0.754 (0.692 to 0.820); < 0.001 | 0.774 (0.699 to 0.858); < 0.001 | 0.779 (0.703 to 0.863); < 0.001 |

In the analyses assessing the main hypothesis for the mechanism of action, at –3 weeks, there was no evidence of an association between change in either positive or negative reinforcement from smoking and subsequent abstinence from smoking at 4 weeks or 6 months. Although two of the three measures of drive to smoke were not associated with smoking abstinence, one of these, noticing a change in the strength of urges, was associated with abstinence. Objective reduction in consumption, measured by a reduced CO concentration over the week, was associated with later abstinence, but self-reported reduction in cigarettes smoked per day was not associated with later abstinence. There was no evidence that change in symptoms of addiction was associated with later abstinence (see Table 11). At +1 week, during the abstinence period, reduction in urge strength was associated with later abstinence.

After the second step in the mediation analysis, the only surviving competing hypothesis to our main hypothesis was that the effect of preloading was mediated by creating an aversion to smoking. However, in this third step, there was no evidence that a change in aversion (measured by nausea and the mCEQ aversion subscale at –3 weeks) predicted abstinence.

Effect of preloading on the outcome, controlled for mediators

In the final step of the mediation analysis, we considered whether or not the strength of association between use of preloading and abstinence was diminished after adding three potential mediators. These mediators, all of which showed evidence of potential mediation in the previous steps, were (1) noticing that urges were weaker than usual while still smoking, (2) reduced exhaled CO concentration while still smoking and (3) reduced urge strength after abstinence. As the clear evidence of efficacy of preloading emerged only in the analyses adjusting for post-cessation varenicline use, we used this as the primary comparison for this final stage of mediation analysis. In the data on abstinence, we included all participants in the analysis with the presumption that people who dropped out were smoking. However, where people were not followed up, the value of their mediator was not imputed and so these participants were dropped from the analysis. To ensure that the ORs were comparable across analyses, the number with valid data was used on the mediator in all analyses, including those analyses that did not include the mediator.

There was evidence that each of the mediators explained the effect of preloading to some extent (Table 12). Controlling for a reduction in urge strength reduced the effect of preloading on abstinence by 47% for 4-week abstinence and 59% for 6-month abstinence. Controlling for a reduction in exhaled CO concentration during the pre-quit period reduced the effect of preloading on abstinence by 23% for 4-week abstinence and 14% for 6-month abstinence. Controlling for a reduction in craving after quitting reduced the effect of preloading on abstinence by 28% for 4-week abstinence and 21% for 6-month abstinence. Controlling for all three potential mediators reduced the effect of preloading on abstinence by 71% for 4-week abstinence and 78% for 6-month abstinence.

| Potential mediator | OR (95% CI) for effect of treatment on smoking status at 4 weeks; p-value | OR (95% CI) for effect of treatment on smoking status at 6 months; p-value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| In model adjusted for centre and varenicline use onlya (n = 1792) | In model adjusted for centre and varenicline use only (n as available for the mediator) | In model adjusted for centre and varenicline use and mediator (n as available for the mediator) | In model adjusted for centre and varenicline use onlya (n = 1792) | In model adjusted for centre and varenicline use only (n as available for the mediator) | In model adjusted for centre and varenicline use and mediator (n as available for the mediator) | |

| Urges stronger or weaker than usual (n = 1696) | 1.32 (1.08 to 1.61); 0.007 | 1.26 (1.03 to 1.55); 0.026 | 1.13 (0.90 to 1.43); 0.303) | 1.33 (1.03 to 1.73); 0.028 | 1.29 (0.99 to 1.67) 0.056 | 1.11 (0.82 to 1.49); 0.501 |

| Change in exhaled CO concentration at –3 weeks (n = 1642) | 1.32 (1.08 to 1.61); 0.007 | 1.24 (1.01 to 1.53); 0.042 | 1.18 (0.96 to 1.46); 0.118 | 1.33 (1.03 to 1.73); 0.028 | 1.26 (0.97 to 1.64); 0.08 | 1.22 (0.93 to 1.59); 0.14 |

| Change in MPSS-C at +1 week (n = 1408) | 1.32 (1.08 to 1.61); 0.007 | 1.29, (1.03 to 1.60); 0.024 | 1.20 (0.96 to 1.50); 0.103 | 1.33 (1.03 to 1.73); 0.028 | 1.30 (0.99 to 1.70); 0.056 | 1.23 (0.94 to 1.61); 0.14 |

| All of the above (n = 1327) | 1.32 (1.08 to 1.61); 0.007 | 1.22 (0.98 to 1.53); 0.079 | 1.06 (0.82 to 1.38); 0.661 | 1.33 (1.03 to 1.73); 0.028 | 1.25 (0.95 to 1.64); 0.108 | 1.05 (0.77 to 1.44); 0.757 |

Chapter 5 People’s reactions to nicotine preloading

Introduction

It is important to understand how people feel about medical interventions, particularly in the case of behavioural issues, such as smoking cessation. People believe that they have direct insight into behavioural issues and behaviour change by virtue of their past and current experience and, therefore, need to feel that the treatment they are receiving is appropriate or they will not take it.

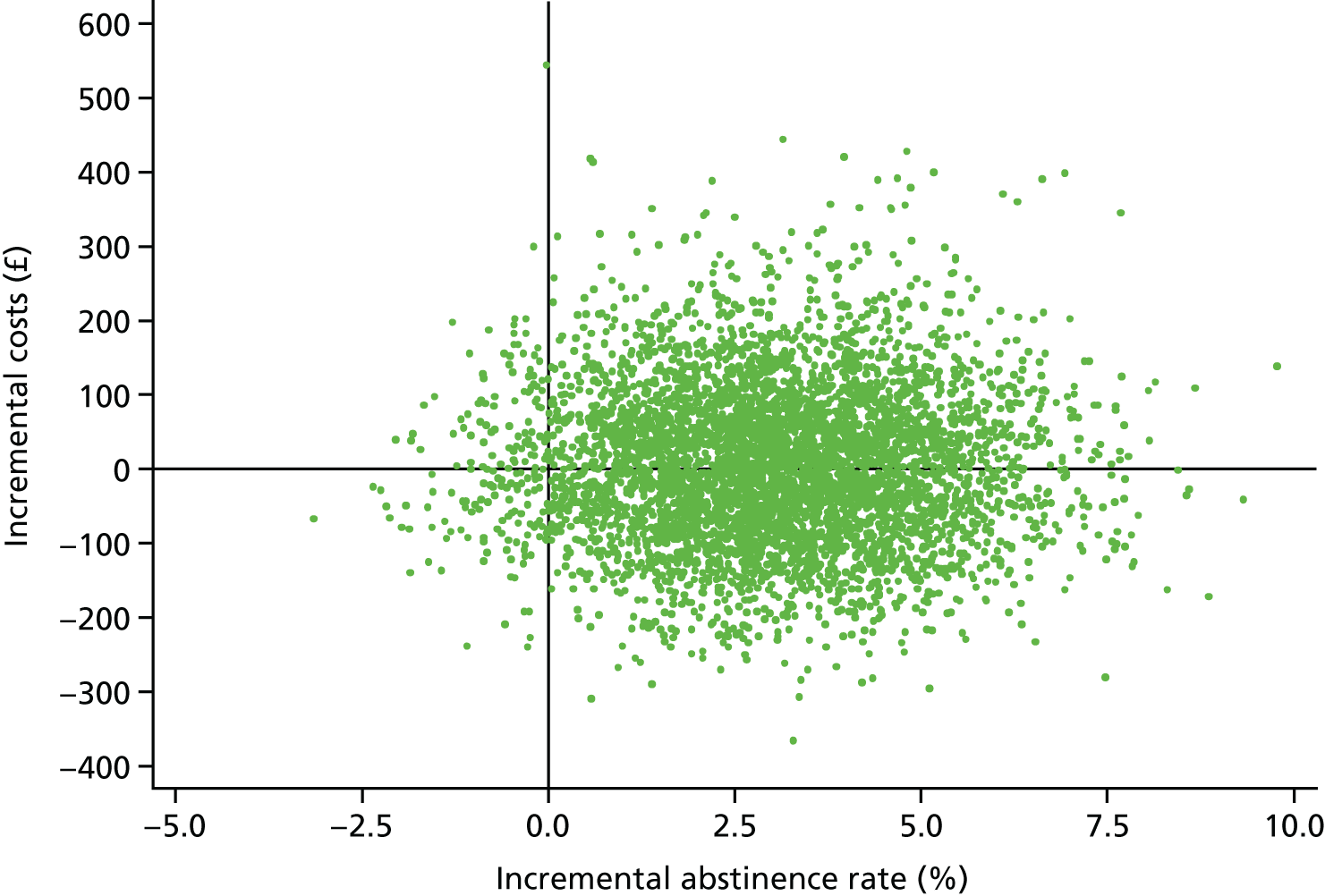

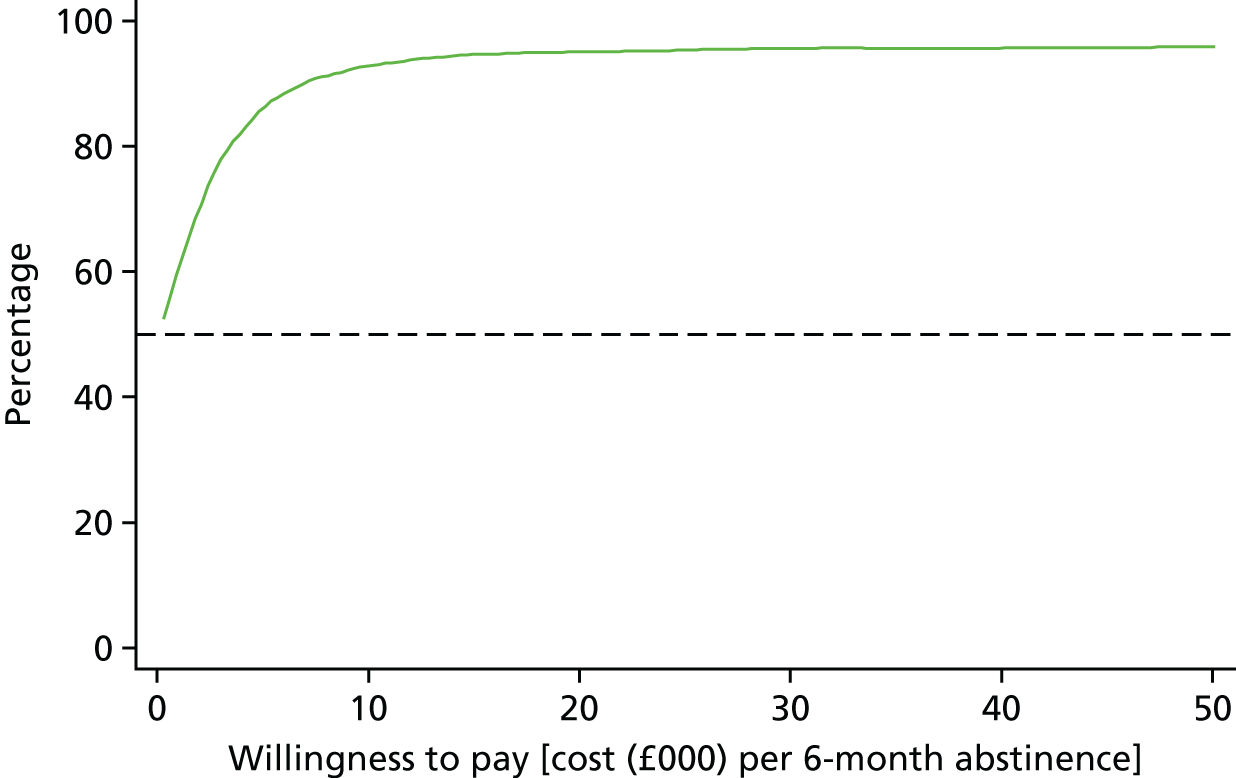

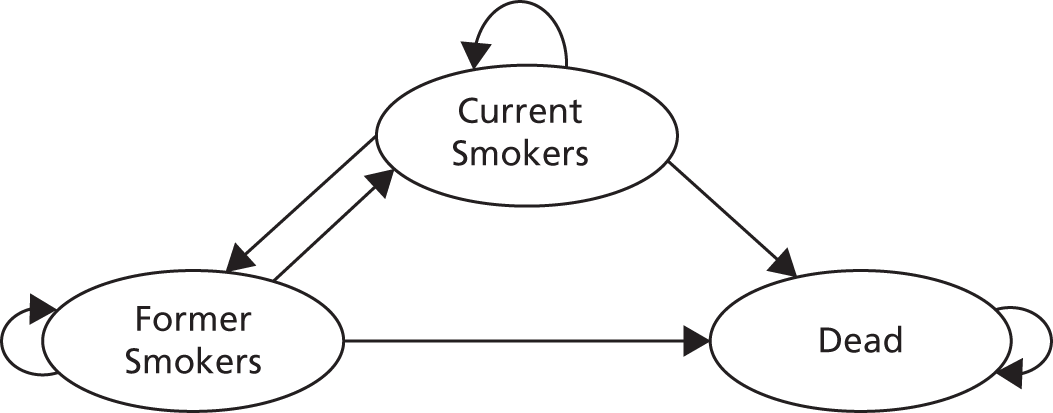

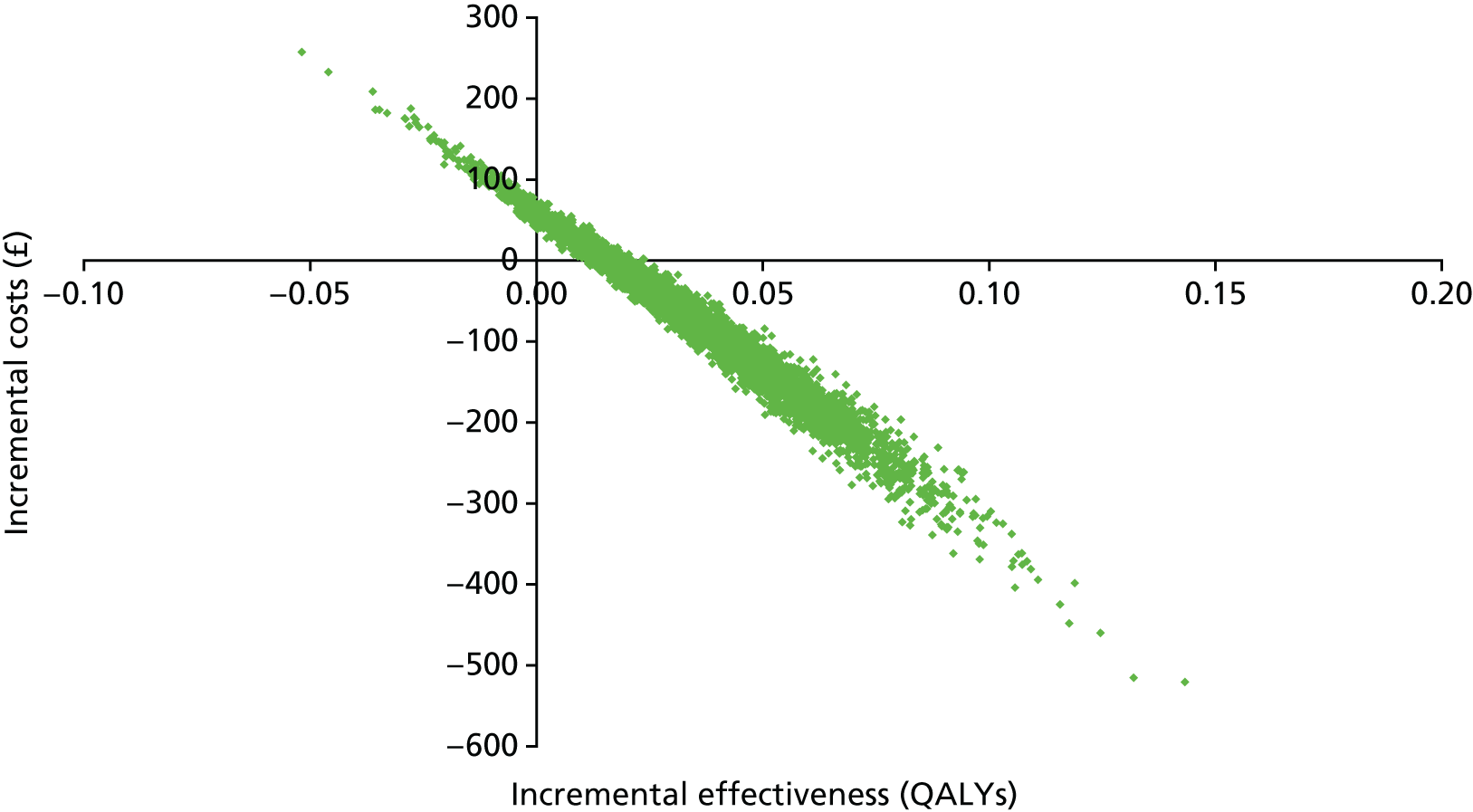

Methods