Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 13/21/01. The contractual start date was in October 2014. The draft report began editorial review in June 2017 and was accepted for publication in November 2017. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Steve Goodacre is the chairperson of the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Health Technology Assessment (HTA) programme Clinical Evaluation and Trials Board and a member of the HTA Funding Boards Policy Group. Fiona Lecky is a member of the NIHR HTA Emergency and Hospital Care Panel. Catherine Nelson-Piercy has received personal fees from Leo Pharma (Leo Pharma A/S, Copenhagen, Denmark) and personal fees from Sanofi-Aventis (Sanofi SA, Paris, France) outside the submitted work.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2018. This work was produced by Goodacre et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2018 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Introduction

Background and rationale

Pregnant and postpartum women are at an increased risk of developing venous thromboembolism (VTE), which may involve deep-vein thrombosis (DVT) (a blood clot in the veins of a limb, which may be clinically silent or cause limb pain and/or swelling) or a pulmonary embolism (PE) (a blood clot in the artery of the lungs, causing respiratory symptoms such as shortness of breath and chest pain).

Pulmonary embolism is a leading cause of death in pregnancy and post partum, affecting women who would otherwise expect to have a long life expectancy in full health. The outcome for the fetus is dependent on the outcome for the mother, so maternal mortality, which is currently estimated at 0.85 [95% confidence interval (CI) 0.52 to 1.32] per 100,000 maternities,1 and morbidity associated with PE has inevitable consequences for fetal mortality and morbidity. Women with an appropriately diagnosed and treated PE are at a low risk of experiencing adverse outcomes, so accurate diagnosis can result in substantial benefits. However, the investigations used to diagnose PE [diagnostic imaging with ventilation–perfusion (VQ) scanning or computerised tomography (CT) pulmonary angiography (CTPA)] carry risks of radiation exposure, risk of reaction to contrast media and false-positive diagnoses, are inconvenient for patients and incur costs for health services. Clinicians investigating suspected PE in pregnant and postpartum women therefore need to choose between risking the potentially catastrophic consequences of a missed diagnosis if imaging is withheld and risking iatrogenic harm to women without PE if imaging is overused.

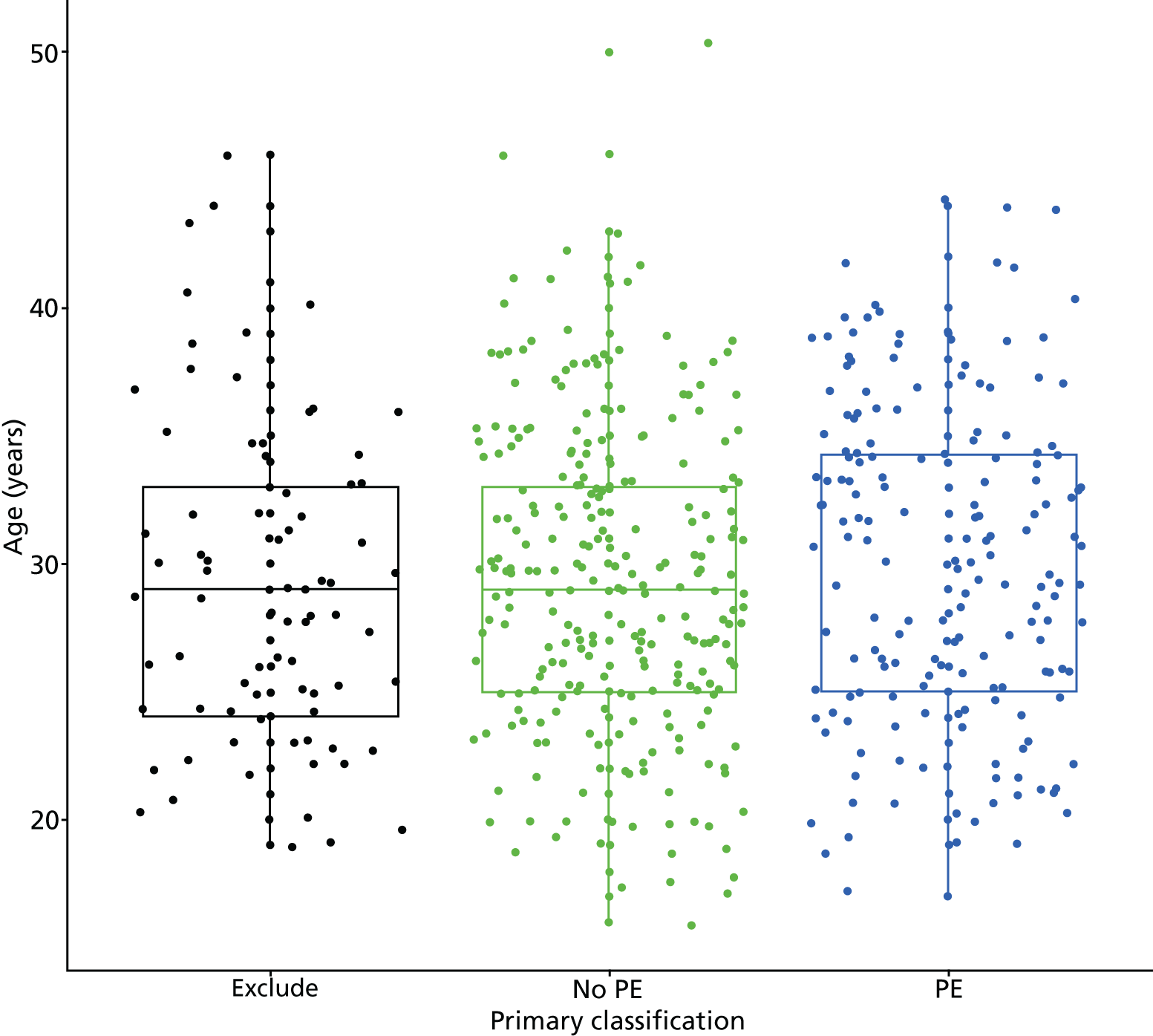

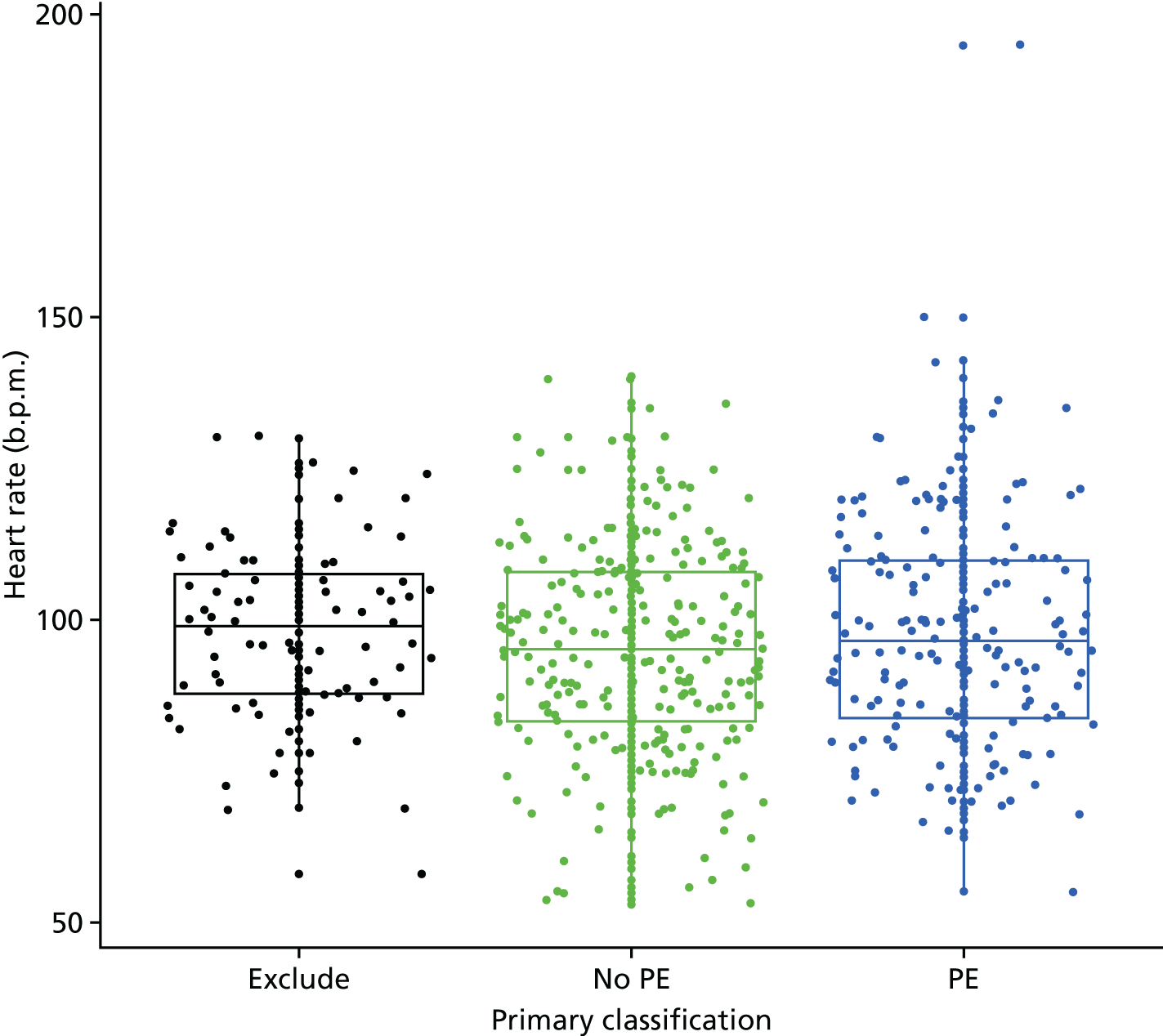

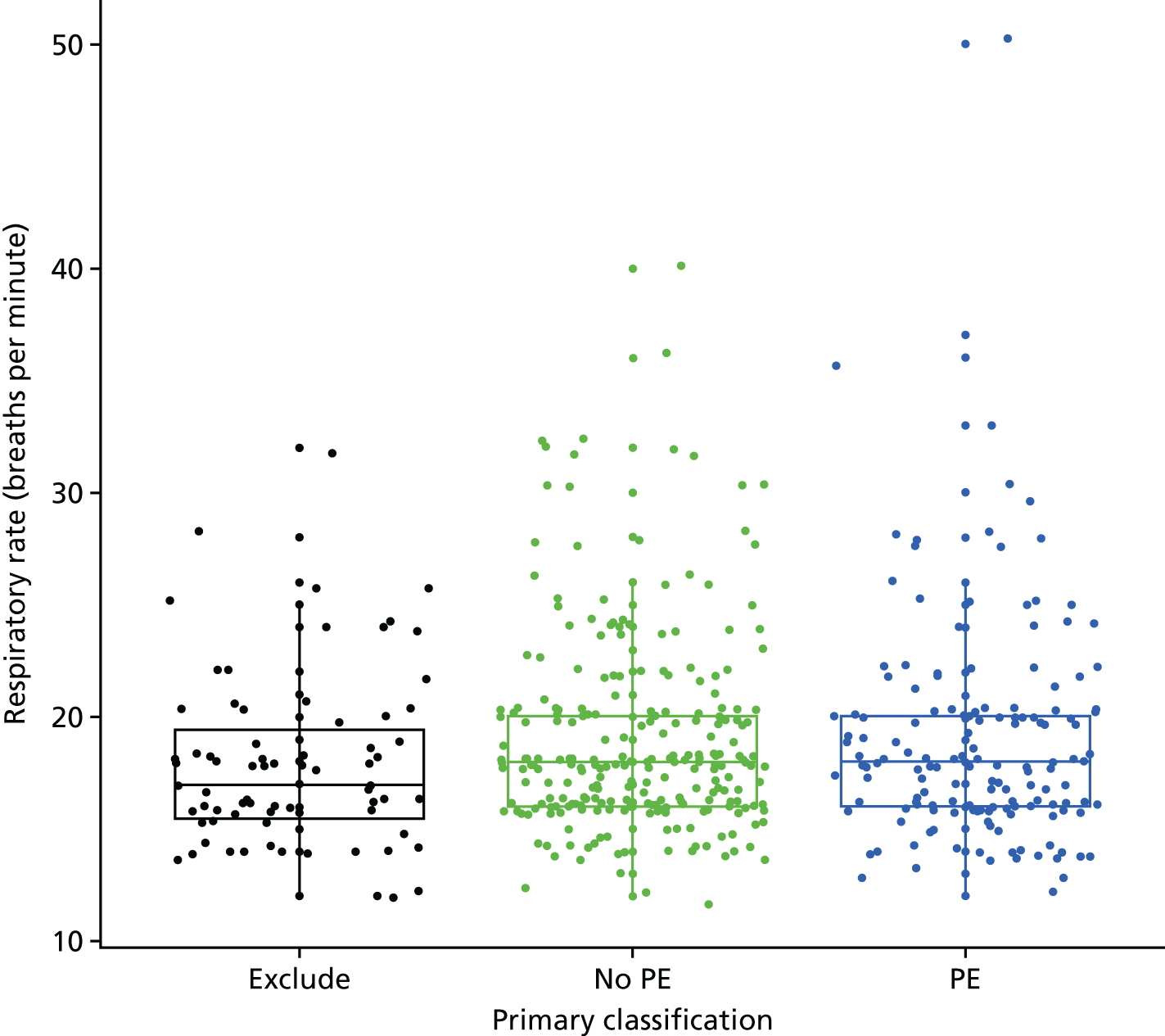

Pregnant and postpartum women with symptoms suggesting PE could be selected for diagnostic imaging on the basis of clinical features or blood tests (biomarkers). A previous history or family history of VTE, immobilisation, surgery and a number of medical and obstetric complications are known to be associated with an increased risk of VTE. 2 Abnormal observations, such as a rapid heart rate, rapid respiratory rate or reduced peripheral oxygen saturation, may be caused by PE, although these may be caused by other pathologies or a normal physiological response to pregnancy.

Individual clinical features are unlikely to have sufficient accuracy to select women for diagnostic imaging, but could be combined to form a clinical decision rule (CDR). This uses a number of clinical features in a structured manner to generate an estimate of the clinical risk of PE or a rule to determine whether or not PE should be investigated. In the general (non-pregnant) population with suspected PE, Wells’s score3 and revised Geneva score4 have been developed to estimate the risk of developing PE, whereas the PE rule-out criteria (PERC) rule5 has been developed to select patients for investigation (details of the scores and the rule are provided in Chapter 3). These scores and the rule have been extensively validated in the general population with a suspected PE, but the differences between the pregnant and non-pregnant populations mean that findings cannot be automatically extrapolated to the pregnant or postpartum population.

A number of biomarkers have been suggested for use in the PE diagnosis but, to date, only the D-dimer measurement has been used in routine clinical practice. Plasma D-dimers are specific cross-linked fibrin derivatives produced when fibrin is degraded by plasmin, with elevated levels indicating thrombolysis. They are elevated in VTE but also in other conditions such as pregnancy, pre-eclampsia, infections, malignancy and surgery. The D-dimer threshold for positivity is usually set to optimise sensitivity (> 95%) at the expense of specificity. In the general population with a suspected PE, the D-dimer measurement has been recommended alongside a clinical risk score (such as Wells’s score) as a way of ruling out PE in low-risk patients without the need for diagnostic imaging. The lack of specificity in the pregnant and postpartum population means that separate validation in this population is required, perhaps using a pregnancy-specific threshold for positivity. There is some evidence that using a higher threshold for positivity can improve the D-dimer specificity in pregnancy without compromising sensitivity. 6

In summary, although clinical features (structured as a CDR) and the D-dimer measurement are widely used to select patients with a suspected PE for diagnostic imaging in the general population with a suspected PE, evidence of their performance in the relevant population is required before they can be advocated for use in pregnant or postpartum women with a suspected PE.

Literature review

Diagnostic studies of pregnant or postpartum women undergoing imaging for a suspected PE could provide evidence to support the use of clinical features, decision rules or biomarkers to select women for imaging if they compare these index tests to an imaging reference standard. They could also provide estimates of the prevalence of PE in the investigated population to inform the design of future studies.

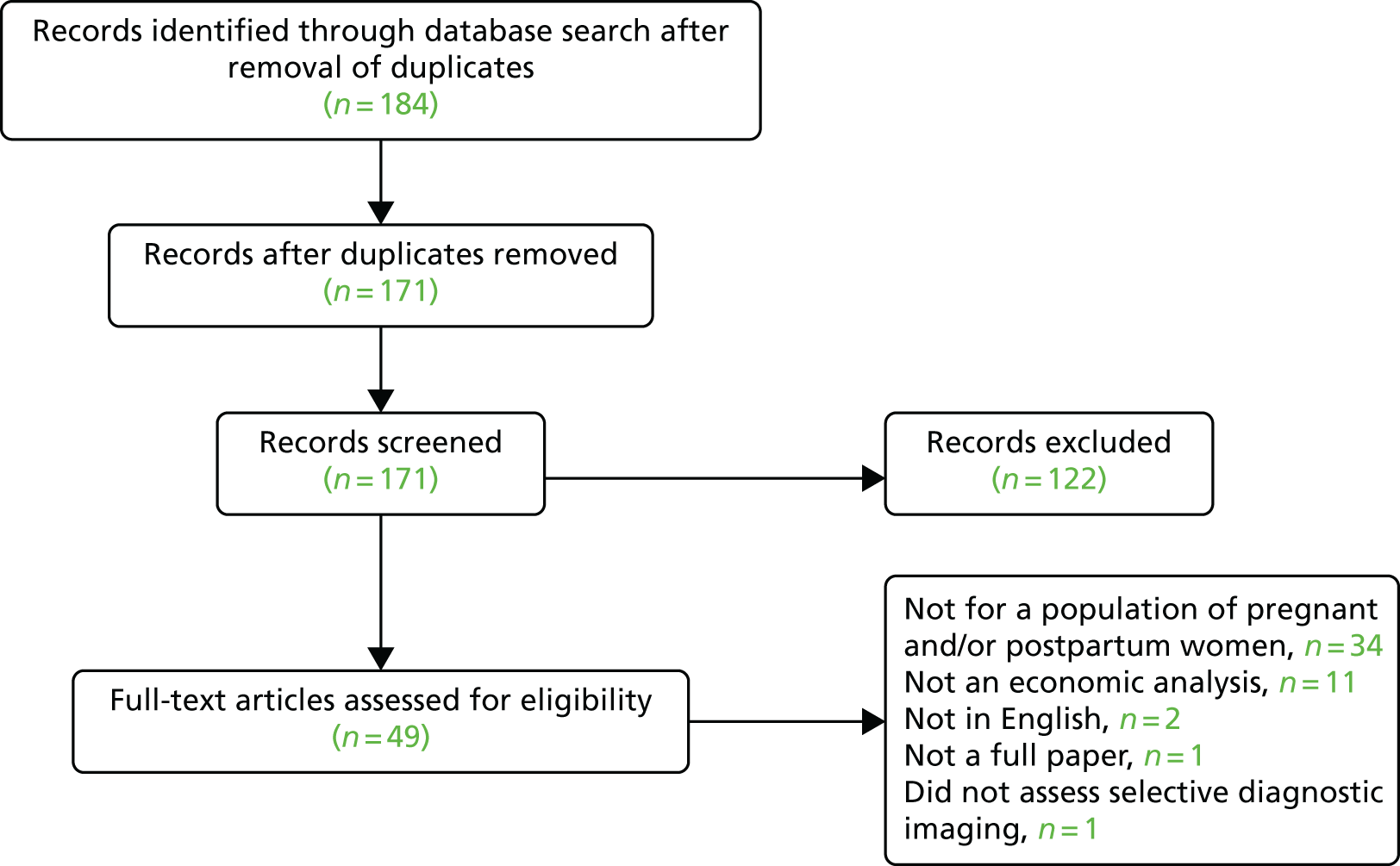

In January 2014, we systematically searched electronic databases for diagnostic studies of pregnant or postpartum women undergoing imaging for a suspected PE7 and identified 11 relevant articles, along with a conference abstract and a paper in press. We have since updated the literature searches and have identified an additional four papers, along with the published version of the paper in press. 8 These are outlined in Table 1.

| Study (year of publication) | Country | Population | Index tests | Reference standard | Main findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Balan et al. (1997)9 | UK | 82 pregnant women, one hospital, 5 years | None | VQ scan | VQ scan: 31 (38%) normal, 19 (23%) low probability, 14 (17%) intermediate, 18 (22%) high probability |

| Chan et al. (2002)10 | Canada | 113 pregnant women, two hospitals, 4 and 10 years | None | VQ scan | VQ scan: 83 (73.5%) normal, 28 (24.8%) non-diagnostic, two (1.8%) high probability |

| Scarsbrook et al. (2007)11 | UK | 94 pregnant women, one hospital, 5 years | None | VQ scan | VQ scan: 89 (92%) normal, seven (7%) non-diagnostic, one (1%) high probability |

| Cahill et al. (2009)12 | USA | 304 pregnant or postpartum women, one hospital, 5 years | Clinical featuresa | 108 CTPA and 196 VQ scan |

CTPA: 18 (5.9%) diagnosed PE Clinical features: low oxygen saturation and chest pain predicted PE, other features did not |

| Damodaram et al. (2009)13 | UK | 37 pregnant women, one hospital, 4 years | D-dimer | VQ scan |

VQ scan: 13 (35%) low probability, 24 (65%) intermediate or high probability D-dimer: 73% sensitivity, 15% specificity |

| Shahir et al. (2010)14 | USA | 199 pregnant women, one hospital, 8 years | None | 106 CTPA and 99 VQ scan |

CTPA: 4/106 (3.7%) PE VQ scans: zero high probability, two (2%) intermediate probability, 19 (19%) low probability, 14 (14%) very low probability, 63 (64%) normal, one (1%) inconclusive |

| Deutsch et al. (2010)15 | USA | 102 pregnant or postpartum women, one hospital, 7 years | Clinical featuresb | CTPA |

CTPA: 13/102 (13%) PE Clinical features: only chest pain predicted PE |

| Hassanin et al. (2011)16 | Egypt | 60 postpartum women, one hospital, years not reported | D-dimer | CTPA |

CTPA: four (6.6%) PE D-dimer: positive in all patients |

| O’Connor et al. (2011)17 | Ireland | 125 pregnant or postpartum women, one hospital, 5 years |

Modified Wells’s score D-dimer Arterial blood gas measurement with PE ECG |

CTPA |

CTPA: 5/103 (5%) PE Modified Wells’s score: 100% sensitivity, 90% specificity D-dimer: 0% sensitivity, 74% specificity |

| Bourjeily et al. (2012)18 | USA | 343 pregnant women, one hospital, 5 years | Clinical featuresc | CTPA |

CTPA: eight (2.3%) PE Clinical features: no association found between clinical features and PE |

| Abele and Sunner (2013)19 | Canada | 74 pregnant women, three hospitals, 1.5 years | None | Perfusion scan and CTPA if abnormal | Perfusion scan: 61 (82.4%) normal perfusion, 13 (17.6%) abnormal – one (1.4%) PE on CTPA |

| Nijkeuter [(2013) abstract]20 | The Netherlands | 149 pregnant women, three hospitals, 9 years | None | CTPA | CTPA: six (4.2%) PE, eight (5.6%) inconclusive, 129 (90.2%) normal |

| Cutts et al. (2014)8 | UK and Australia | 183 pregnant women, two hospitals, 4 years |

Modified Wells’s score D-dimer |

VQ scan |

VQ scan: four (2%) high probability, six (3%) non-diagnostic, 173 (95%) normal D-dimer: 48/51 positive Modified Wells’s score predicted PE |

| Browne et al. (2014)21 | Ireland | 124 pregnant and postpartum women, one hospital, 3 years | None | CTPA | CTPA: 1/70 (1.4%) PE in pregnant women, 5/54 (9.3%) PE in postpartum women |

| Bajc et al. (2015)22 | Sweden | 127 pregnant women, one hospital, 5 years | None | VQ SPECT | VQ SPECT: 11/127 (9%) PE |

| Jordan et al. (2015)23 | USA | 50 pregnant or postpartum women, one hospital, 4 years | None | CTPA | CTPA: 1/50 (2%) PE |

| Ramsay et al. (2015)24 | UK | 127 pregnant women, one hospital, 3 years | None | VQ scan | VQ scan: 2/127 (1.6%) PE |

In addition to these studies of pregnant and postpartum women with a suspected PE, Kline et al. 25 undertook a systematic review of studies of people with suspected PE, which included pregnant and postpartum women. The authors identified 17 studies including 25,399 patients, of whom 506 (2%) were pregnant, with a 4.1% (95% CI 2.6% to 6.0%) prevalence of PE.

The analysis reported by Kline et al. 25 and 10 of the studies identified by our review reported the overall prevalence of PE, which was generally found to be low when compared with the non-pregnant population, but did not examine the diagnostic accuracy of clinical features, CDRs or the D-dimer measurement. The remaining seven studies were mostly small and had a low prevalence of PE, and thus had limited power to estimate diagnostic accuracy (especially sensitivity) or detect an association with a reference standard diagnosis of PE.

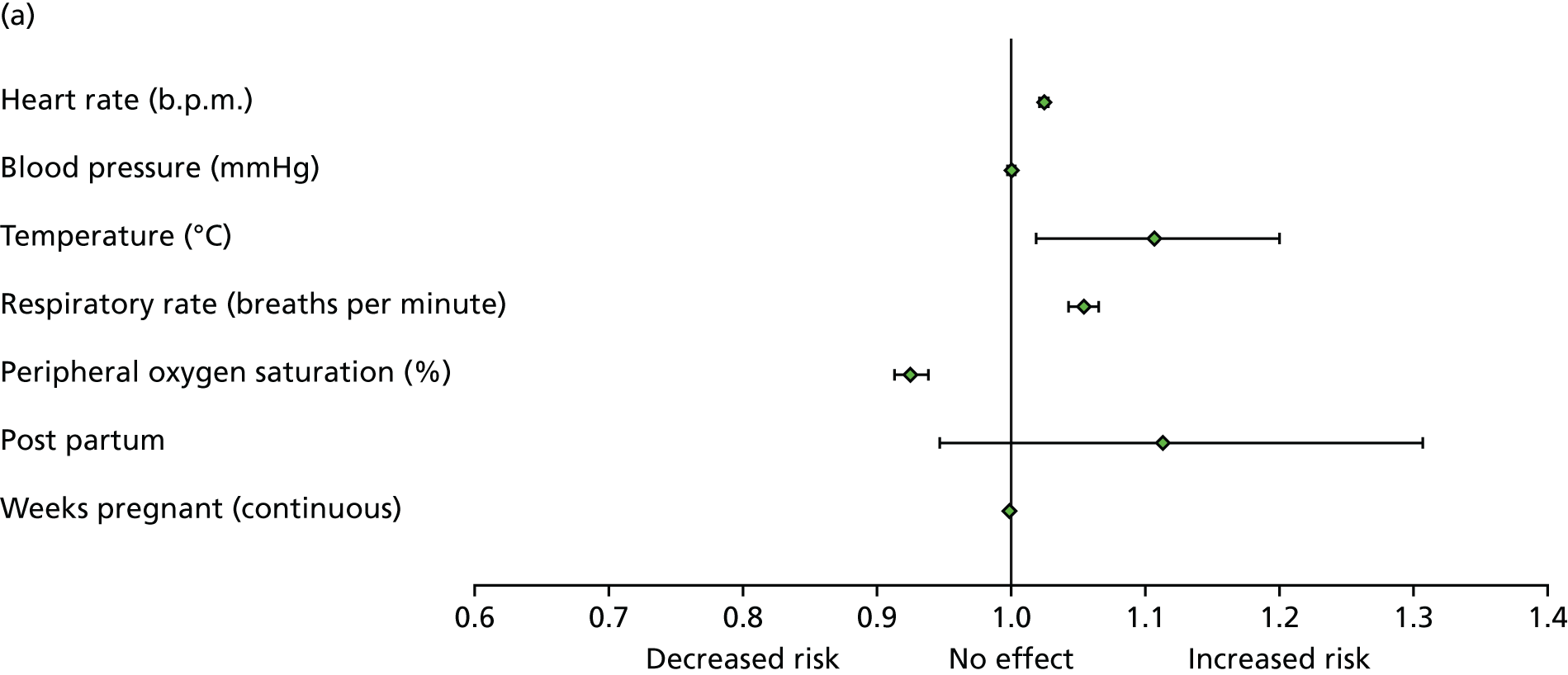

Cahill et al. 12 found that chest pain and low oxygen saturation were associated with a diagnosis of PE, but other features [dyspnoea, tachycardia, Alveolar–arterial (A–a) gradient] showed no evidence of association. Deutsch et al. 15 also found that chest pain showed some association with a diagnosis of PE, while other features (dyspnoea, heart rate, respiratory rate, blood pressure, oxygen saturation, A–a gradient) did not. Bourjeily et al. 18 found no association between dyspnoea, chest pain, pleuritic chest pain, haemoptysis, cough, DVT signs, wheeze, pleural rub, heart rate, respiratory rate or systolic blood pressure and a diagnosis of PE.

Two studies have suggested that the modified Wells’s score may be useful in pregnant or postpartum women. O’Connor et al. 17 reported that a modified Wells’s score of ≥ 6 units (meaning that PE is likely) has a sensitivity of 100% and a specificity of 90% for PE, whereas Cutts et al. 8 reported a sensitivity of 100% (95% CI 40% to 100%) and a specificity of 60% (52% to 67%). The wide CIs for sensitivity mean that further research is required. Other CDRs, such as the Geneva score and the PERC rule, have not yet been tested in pregnant or postpartum women with a suspected PE.

Studies of the D-dimer measurement in pregnant and postpartum women8,13,16,17 suggest that high levels of positivity at conventional thresholds limit the diagnostic value of this test. However, indirect evidence from studies of the D-dimer measurement for suspected DVT in pregnancy suggests potential diagnostic value. Chan et al. 26 reported 100% sensitivity (95% CI 77% to 100%) and 60% specificity (95% CI 52% to 68%) for the qualitative SimpliRED (Agen Biomedical, Brisbane, QLD, Australia) D-dimer in suspected DVT and, although another study of five commercially available assays6 reported specificities ranging from 6% to 23%, further analysis suggested that using a higher threshold for positivity could improve sensitivity without compromising specificity.

In summary, diagnostic studies of pregnant and postpartum women with a suspected PE currently provide insufficient evidence to support their use as a way of selecting women for diagnostic imaging.

Risk factors for pulmonary embolism in pregnancy and post partum

Stronger evidence exists relating to predicting the risk of a pregnant or postpartum woman developing PE (as opposed to diagnosing PE in a pregnant or postpartum woman with suspected PE). Epidemiological studies have compared women who developed PE in pregnancy or post partum with a control group without PE to identify the risk factors for developing PE in pregnancy. Knight et al. 27 compared women with antenatal PE identified through the UK Obstetric Surveillance System (UKOSS) research platform with pregnant control group participants and showed that multiparity and body mass index (BMI) were independent predictors of developing PE. Kane et al. 28 used patients identified by the Scottish Morbidity Record 2 to show that women aged > 35 years, with previous VTE, pre-eclampsia, antenatal haemorrhage or postnatal haemorrhage were more likely to develop PE than those without these characteristics. Henriksson et al. 29 showed that VTE is associated with pregnancy following in vitro fertilisation. Sultan et al. 30 linked primary (Clinical Practice Research Datalink) and secondary (Hospital Episode Statistics) care records to show that BMI, complications of pregnancy (pre-eclampsia, antenatal or postnatal haemorrhage, diabetes mellitus, hyperemesis), comorbidities (varicose veins, cardiac disease, hypertension) and recent hospital admission were associated with an increased risk of developing PE. A similar analysis in postpartum women30 showed that smoking, varicose veins, comorbidities, pre-eclampsia/eclampsia, diabetes mellitus, parity, postpartum haemorrhage, caesarean section, stillbirth, postpartum infection, maternal age, BMI and infant birthweight were predictors of VTE included in a clinical prediction model.

These risk factors for developing PE in pregnancy and post partum could be used to select women with suspected PE for imaging. However, there are two reasons why risk factors may not be diagnostically useful. First, guidelines2 recommend using thromboprophylaxis in pregnancy and post partum to attenuate the thromboembolic risk associated with recognised risk factors. Second, public and professional awareness of risk factors may prompt a lower threshold for presentation and referral to diagnostic services when risk factors are present. The use of risk factors to select women for imaging therefore needs evaluation in a population with suspected PE.

Current practice

Guidelines from the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (RCOG)2 recommend that pregnant or postpartum women with a suspected PE should receive diagnostic imaging with VQ scan or CTPA. The guidelines recommend against the use of D-dimer testing and highlight the lack of evidence to support the use of clinical probability assessment in pregnancy. Guidelines from the American Thoracic Society31 also recommend the non-selective use of diagnostic imaging, whereas guidelines from the European Society of Cardiology32 suggest a possible role for D-dimer in selecting patients.

These recommendations for pregnant and postpartum women contrast with guidelines from the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE)33 and the American College of Chest Physicians34 for the general (non-pregnant) population with a suspected PE, for whom diagnostic imaging is selectively used based upon structured clinical assessment and D-dimer measurement.

The differences in thresholds for investigation are reflected in the differences in the prevalence of PE in the investigated populations. In a review of studies of patients investigated for a suspected PE, Kline et al. 25 reported a prevalence of 4.1% for pregnant patients compared with 12.4% for non-pregnant patients. Most of the studies in our review reported a prevalence of PE below 10%.

Need for further research

Existing research suggests that clinical assessment, CDRs and/or D-dimer measurement could be used to select women for imaging, but more precise estimates of diagnostic value are needed before a selective strategy can be recommended. Furthermore, the appropriate use of clinical assessment or biomarkers to select women for imaging can be determined only by explicitly weighing the risks, costs and benefits of different strategies.

Research is required to improve our estimates of the diagnostic accuracy of clinical assessment and biomarkers. A prospective cohort study is in theory the best method for measuring accuracy and developing and validating a CDR, but it would be severely limited by the low incidence of PE in pregnancy and the low prevalence of PE in women presenting with a suspected PE. The incidence of VTE (DVT and PE combined) is cited to be 1 in 1000 pregnancies. 2 A recent meta-analysis35 supports this estimate and reports a pooled incidence of PE of 0.4 per 1000 pregnancies, with individual study estimates35 ranging from 0.1 to 0.67 per 1000 pregnancies. Estimates from UK studies are at the lower end of this range, with data from UKOSS27 suggesting an incidence of 0.13 antenatal PE per 1000 pregnancies and data from the Scottish Morbidity Record 228 suggesting 0.2 antenatal and postnatal PE per 1000 pregnancies. Meanwhile, most of the studies in our literature review reported a rate of one or two patients with PE per hospital per year.

Diagnostic sensitivity is the key determinant of the acceptability of any strategy to select women for diagnostic imaging. Patients and clinicians need to know that sensitivity has been estimated with sufficient precision to ensure that women with a negative diagnostic assessment have a low risk of developing PE. The precision of estimates of sensitivity depends on the number of patients recruited with PE. Using a cohort design to accrue sufficient numbers of participants with PE to estimate sensitivity with sufficient precision would be prohibitively expensive and difficult to deliver.

A case–control design offers an alternative when the low prevalence of disease makes a cohort design unfeasible or unacceptably inefficient. The identification of women with the diagnosis of interest (PE in pregnancy or post partum) allows us to recruit sufficient numbers with PE to make reasonably precise estimates of sensitivity. The case–control design carries an increased risk of bias compared with that of the cohort design,36 but this can be reduced by ensuring that the control group is a representative sample of women with suspected PE who have negative imaging and that the patients are a representative sample of women presenting with a suspected PE who are diagnosed and treated for PE.

Existing decision rules may not be appropriate to the pregnant and postpartum population, but can be tested in a case–control or cohort study. A decision rule for the pregnant and postpartum population could be derived from a case–control or cohort study, but would need validation in a new study. Expert consensus provides a relatively quick and cheap method for deriving a CDR that could then be validated in a case–control or cohort study.

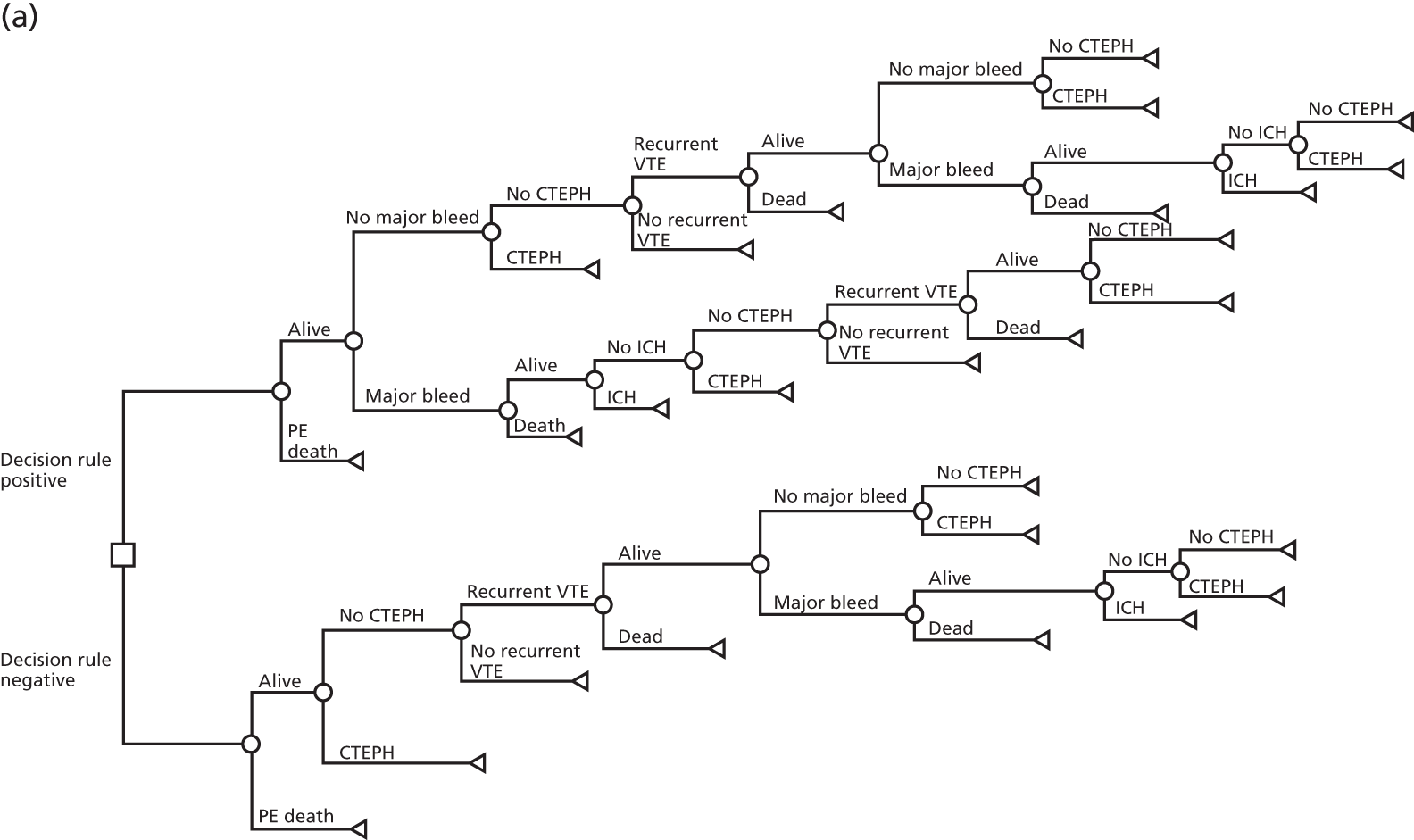

Secondary research in the form of decision-analysis modelling is required to explicitly weigh the costs, risks and benefits of different strategies for selecting women for diagnostic imaging. This allows us to estimate how diagnostic tests lead to differences in clinically meaningful outcomes. Decision-analysis modelling is particularly important in this situation, when the best method of estimating diagnostic parameters (a cohort study) may not be feasible. Decision-analysis modelling allows us to explore the potential impact of uncertainty on our findings. A value-of-information analysis can then be undertaken to determine whether or not further research would be worthwhile to obtain more accurate or precise estimates of diagnostic accuracy.

Aims and objectives

We aimed to estimate the diagnostic accuracy, effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of strategies (including CDRs) for selecting pregnant or postpartum women with a suspected PE for imaging, and to determine the feasibility and value of information of further prospective research.

Our specific objectives were to:

-

use expert consensus to derive three new CDRs (with different trade-offs between sensitivity and specificity) for pregnant and postpartum women with a suspected PE

-

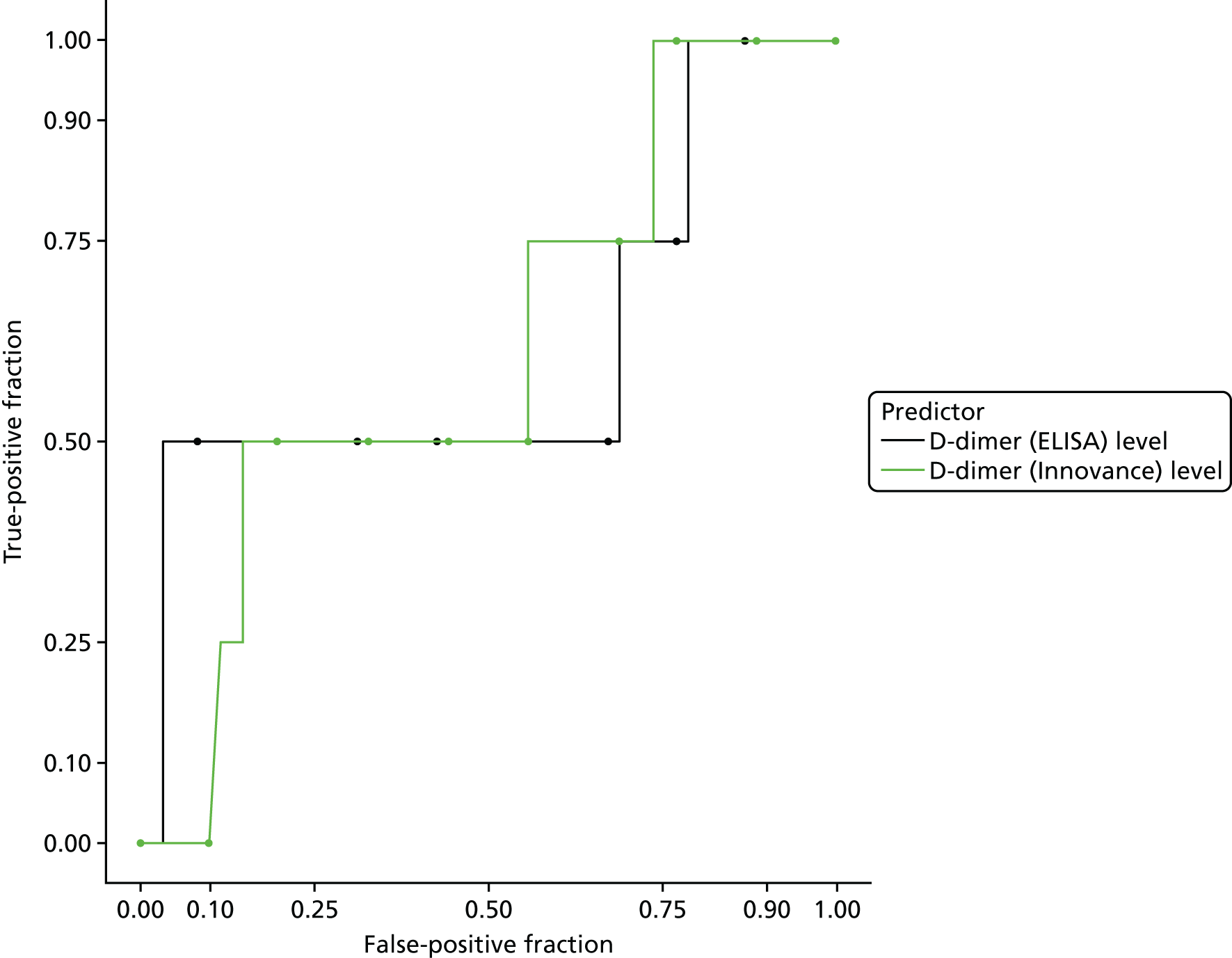

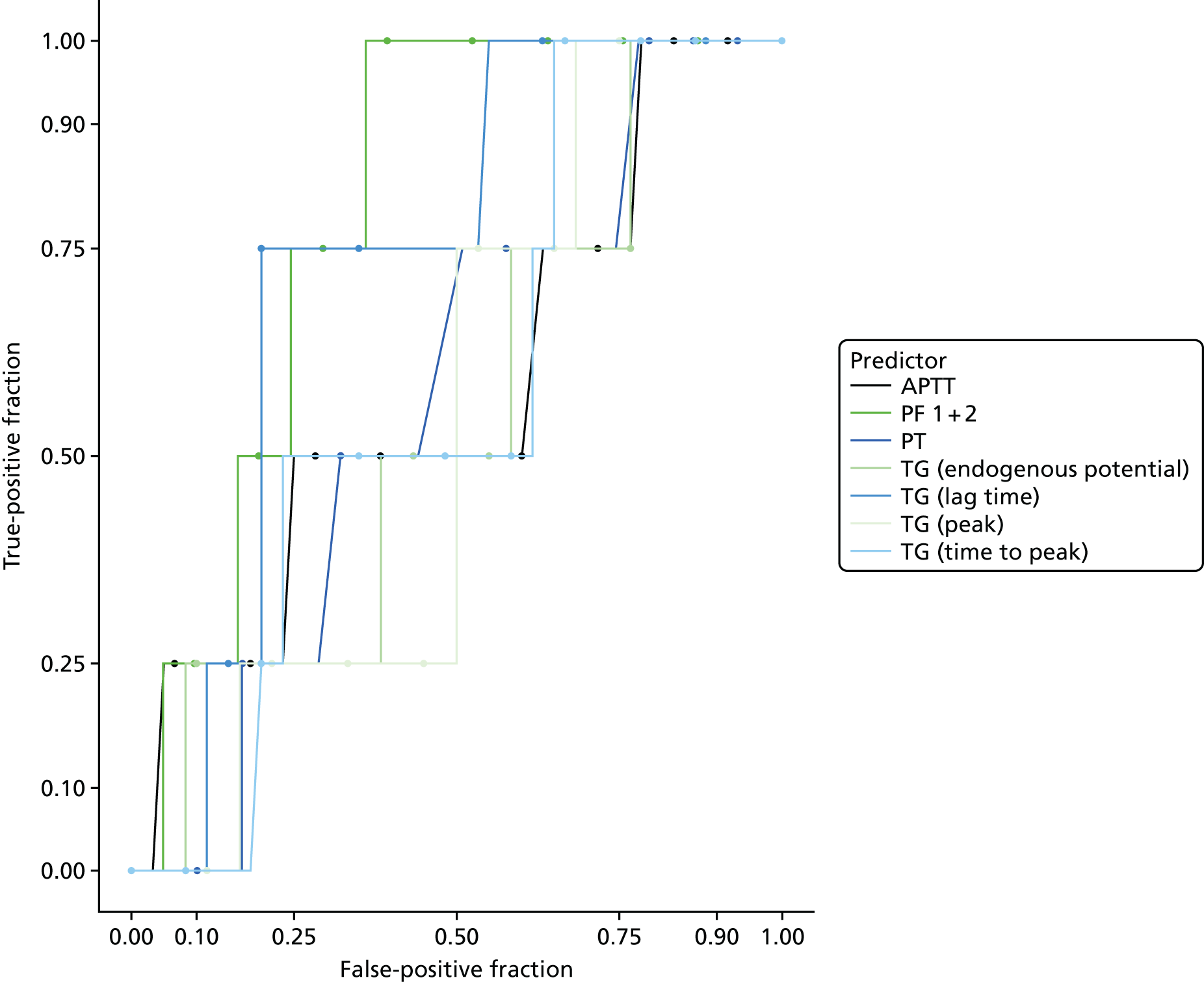

estimate the diagnostic accuracy of clinical variables, our expert-derived CDRs, existing CDRs (Wells’s score, Geneva score and PERC score) and D-dimer in pregnant and postpartum women with a suspected PE

-

use a statistical analysis of women with a diagnosed or suspected PE to derive a new CDR for pregnant and postpartum women with a suspected PE

-

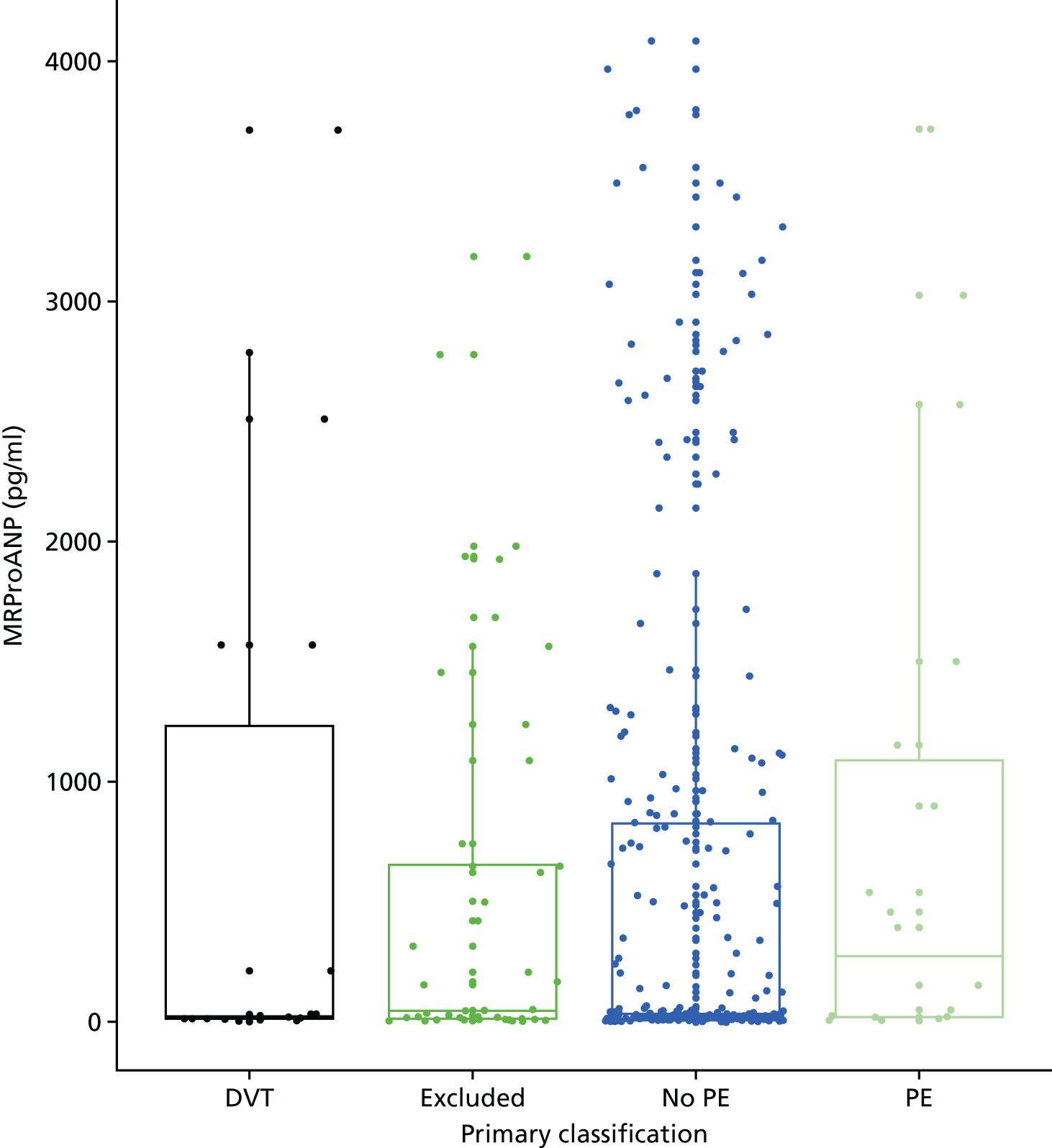

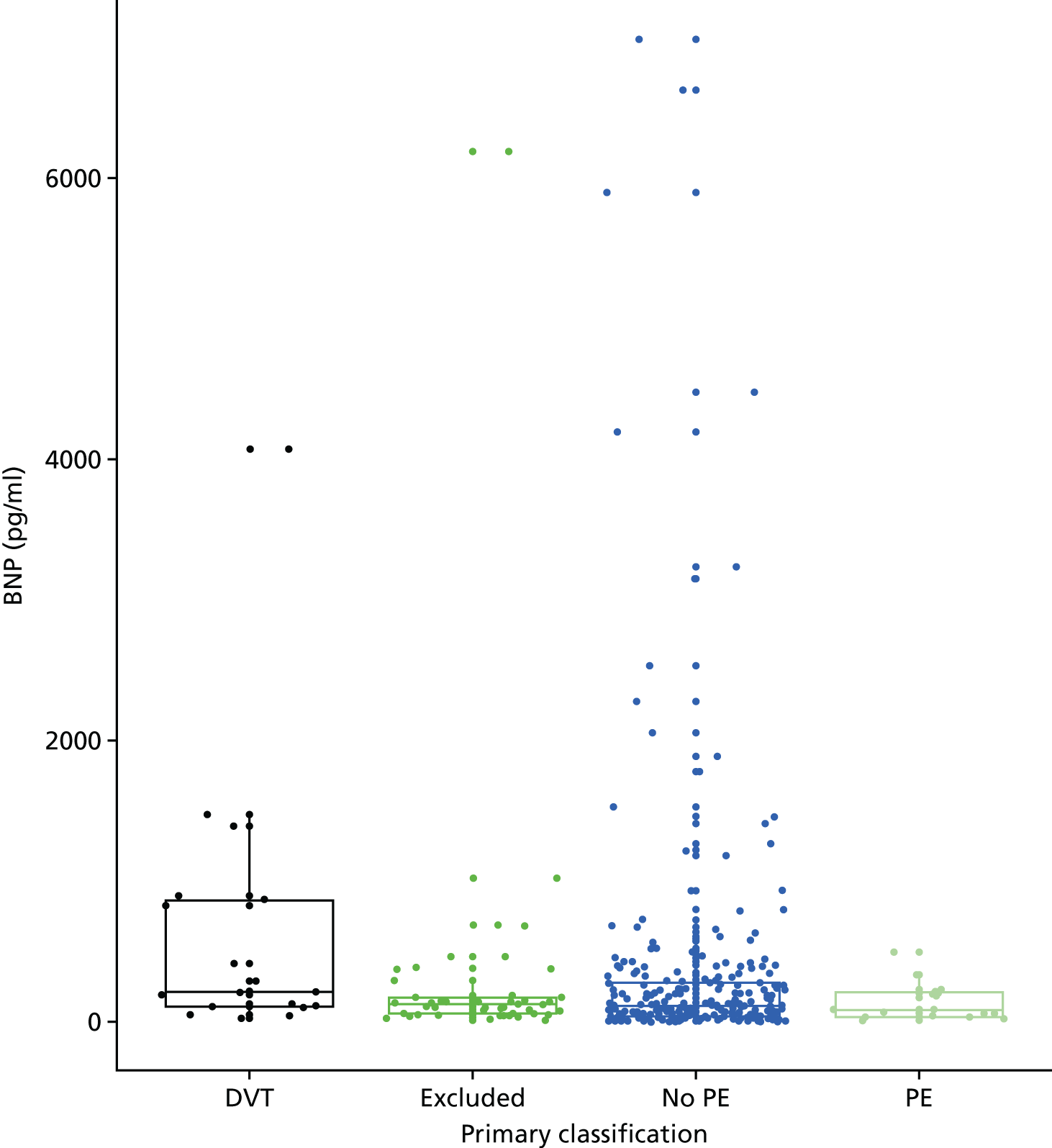

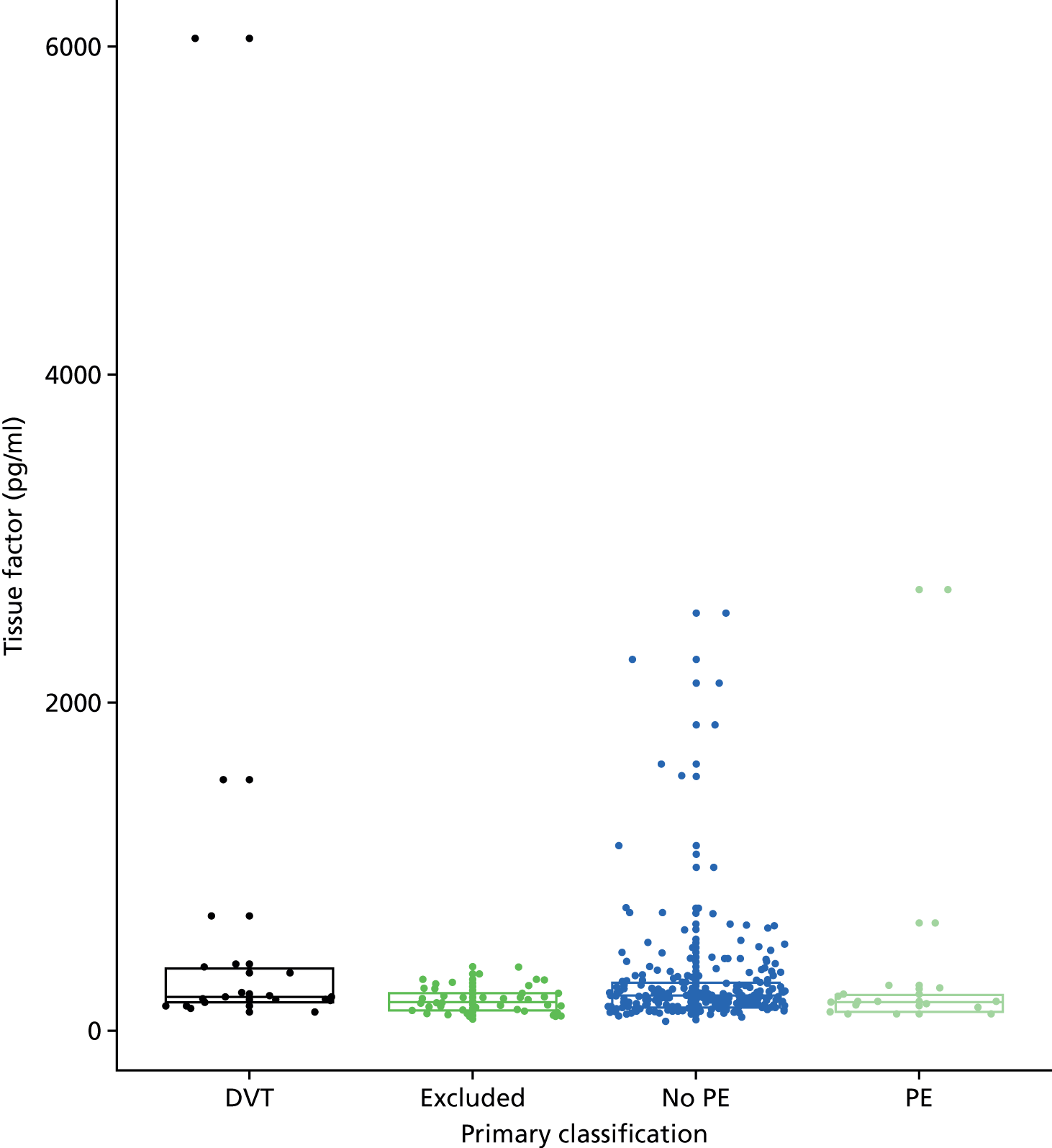

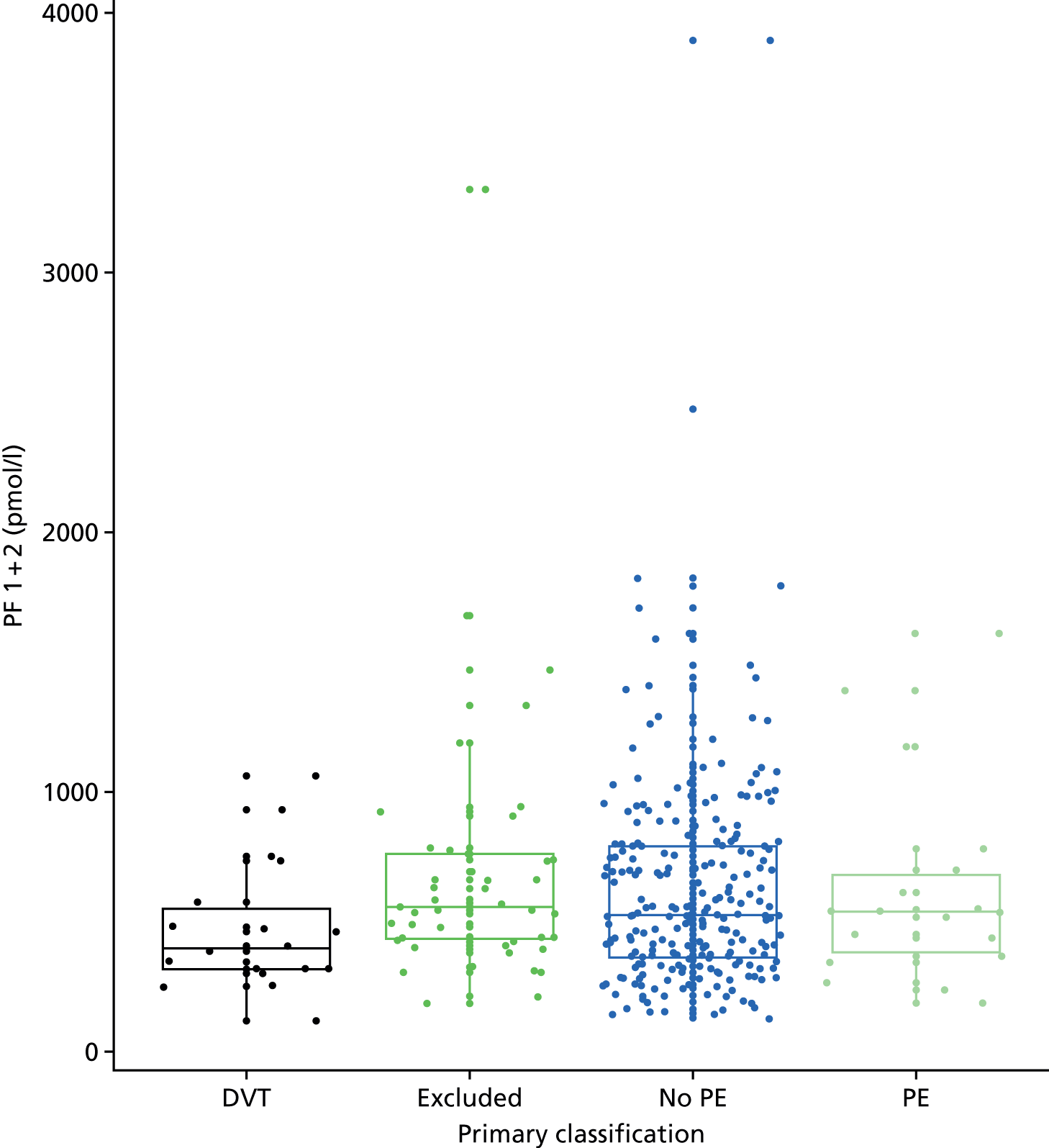

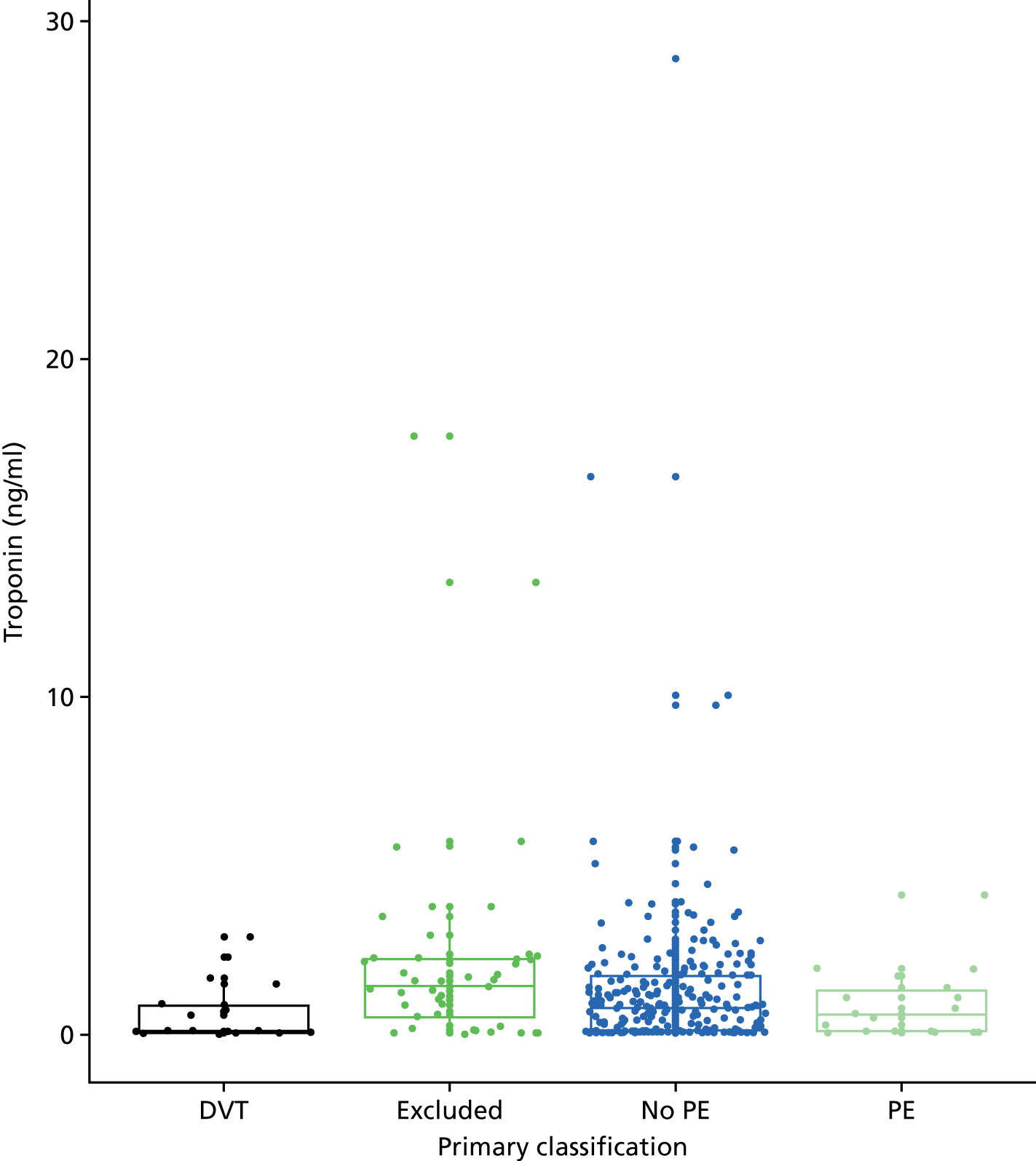

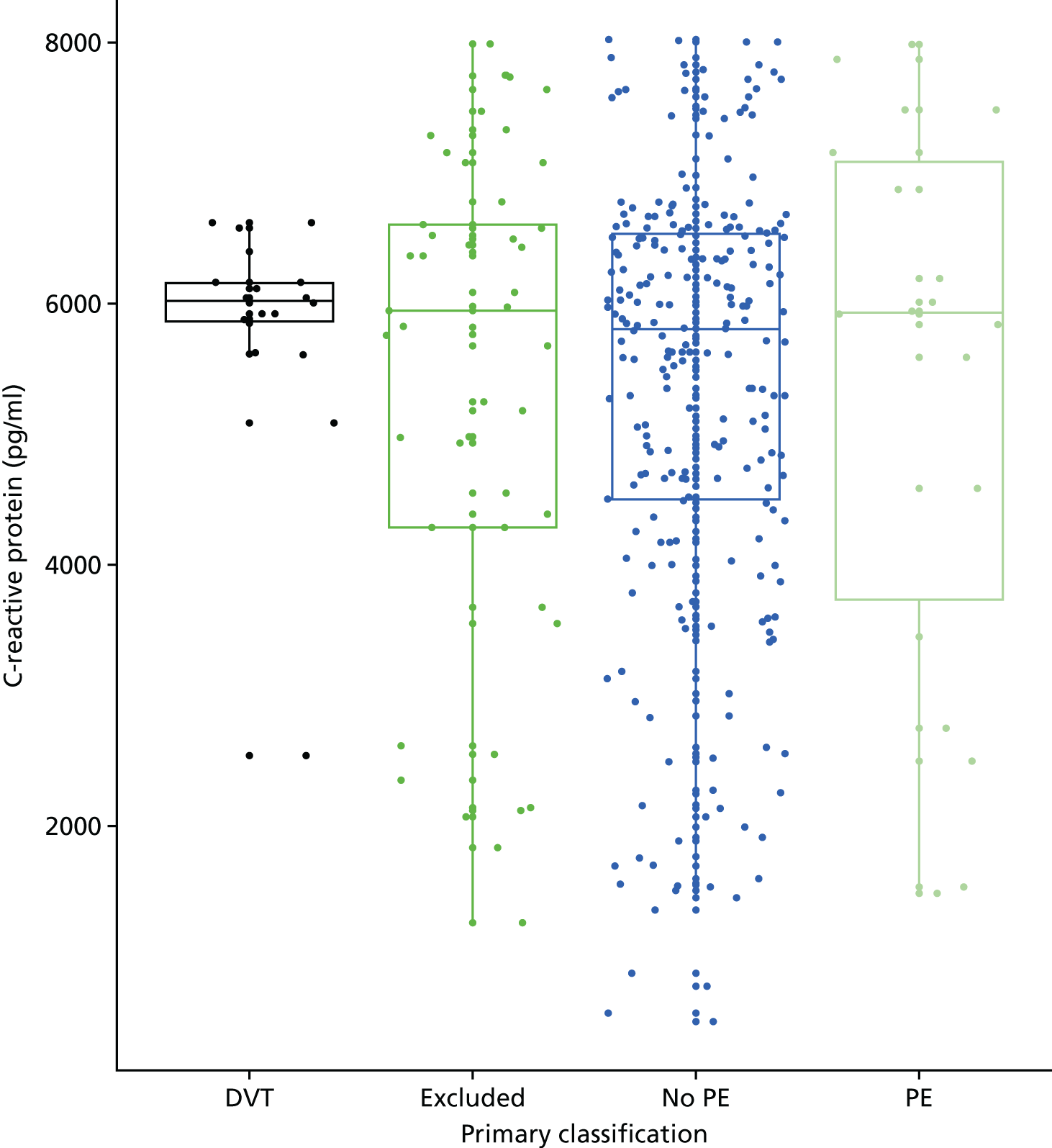

explore the potential diagnostic value of biomarkers for PE in pregnant and postpartum women

-

determine the feasibility of using a prospective cohort design to validate a new CDR or biomarker

-

estimate the effectiveness, in terms of adverse outcomes from VTE, bleeding and radiation exposure, and the cost-effectiveness, measured as the incremental cost per quality-adjusted life-year (QALY), of different strategies

-

estimate the value of information associated with further research.

Overview of the study design

We undertook an expert consensus study to address objective 1. A Delphi study was used to identify and select potential clinical predictors and a consensus group was used to create the CDRs.

We undertook a case–control study to address objectives 2 and 3. The design should strictly be described as a prospective cohort study of pregnant or postpartum women with a suspected PE augmented with a retrospective cohort of pregnant or postpartum women with a diagnosed PE. However, for the purposes of brevity and to avoid concerns that using the term ‘cohort study’ may under-represent the risk of bias associated with the design, we will use the term ‘case–control study’ throughout this report.

Women with a suspected PE were identified through a prospective study of pregnant or postpartum women presenting to hospital with a suspected PE. Women with a diagnosed PE were retrospectively identified through UKOSS, a UK-wide obstetric surveillance system that has been set up to conduct research on uncommon disorders of pregnancy. Details of the UKOSS methods are available at www.npeu.ox.ac.uk/ukoss/methodology. The cases involved women with a diagnosed PE and a small number of women with a suspected PE who ultimately had a diagnosed PE, whereas the control participants were women with a suspected PE who had PE ruled out.

We undertook a biomarker study to address objective 4. The women with a suspected PE from the case–control study and any pregnant or postpartum woman diagnosed with DVT at the participating hospitals were asked to provide blood samples for analysis. The inclusion of women with diagnosed DVT was planned as an efficient way of increasing the number in the cohort with VTE. There are good pathophysiological reasons for expecting candidate biomarkers to have similar sensitivity for DVT and PE, and studies of D-dimer measurement in the non-pregnant population have shown similar sensitivity and specificity for DVT and PE. 37

We addressed objective 5 by determining recruitment rates in the prospective study of women with a suspected PE and determining the prevalence of PE in this population. This would allow us to estimate the potential size and duration of a cohort study powered to estimate the sensitivity of a CDR or biomarker with adequate precision.

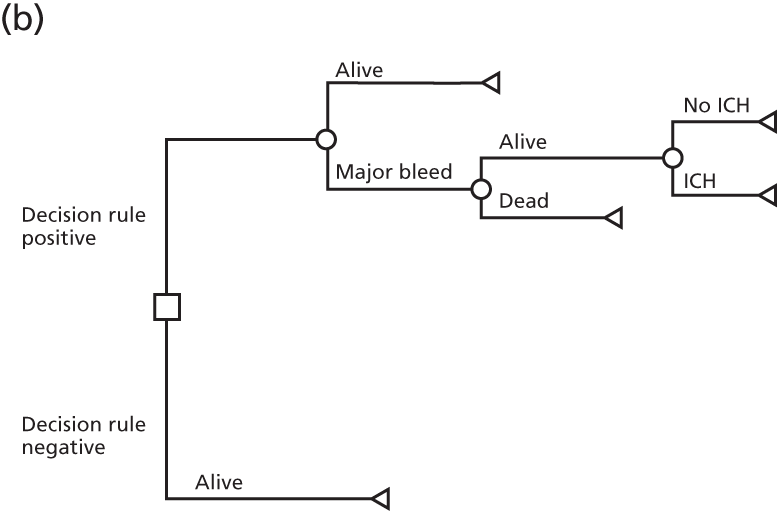

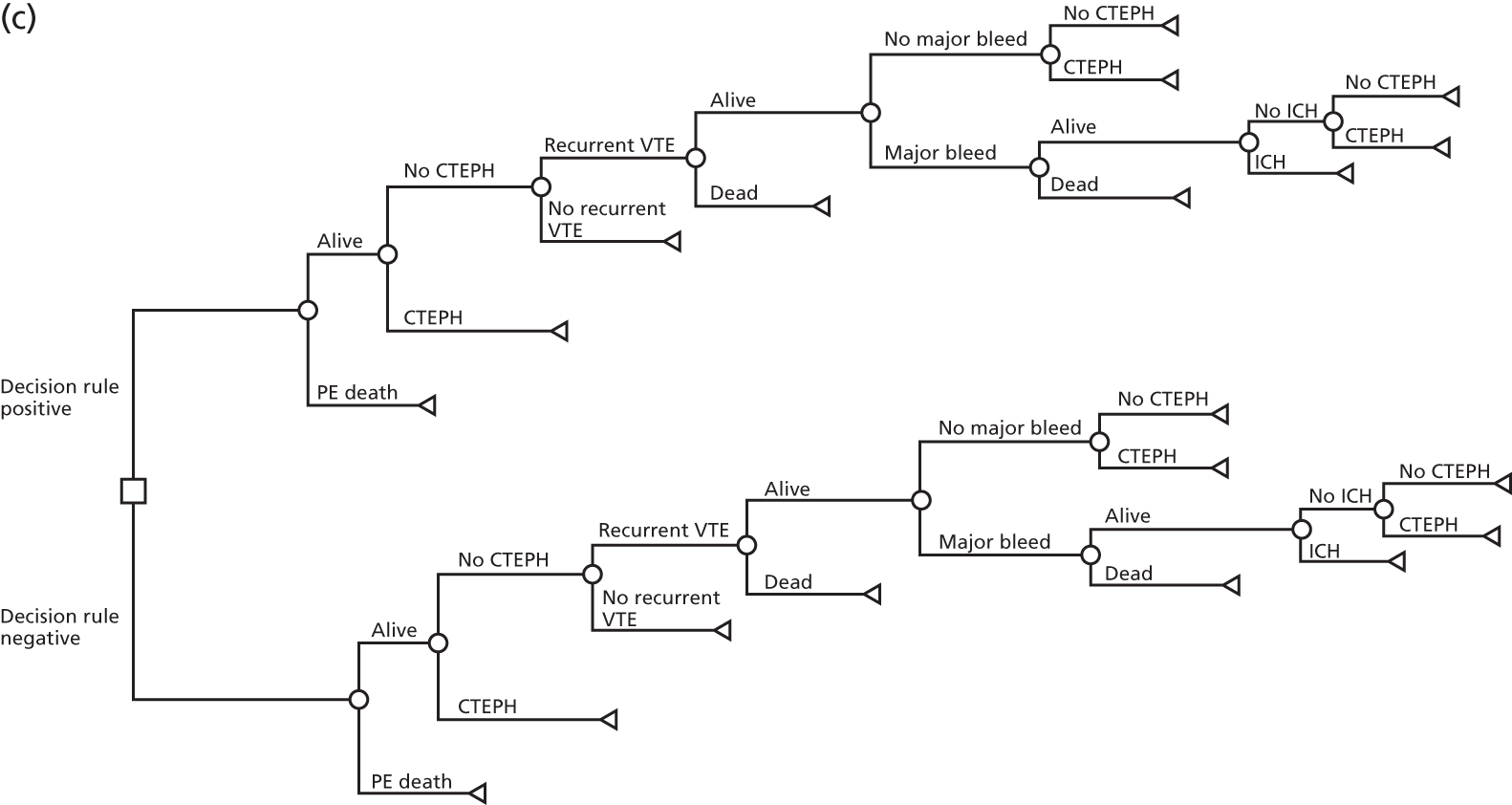

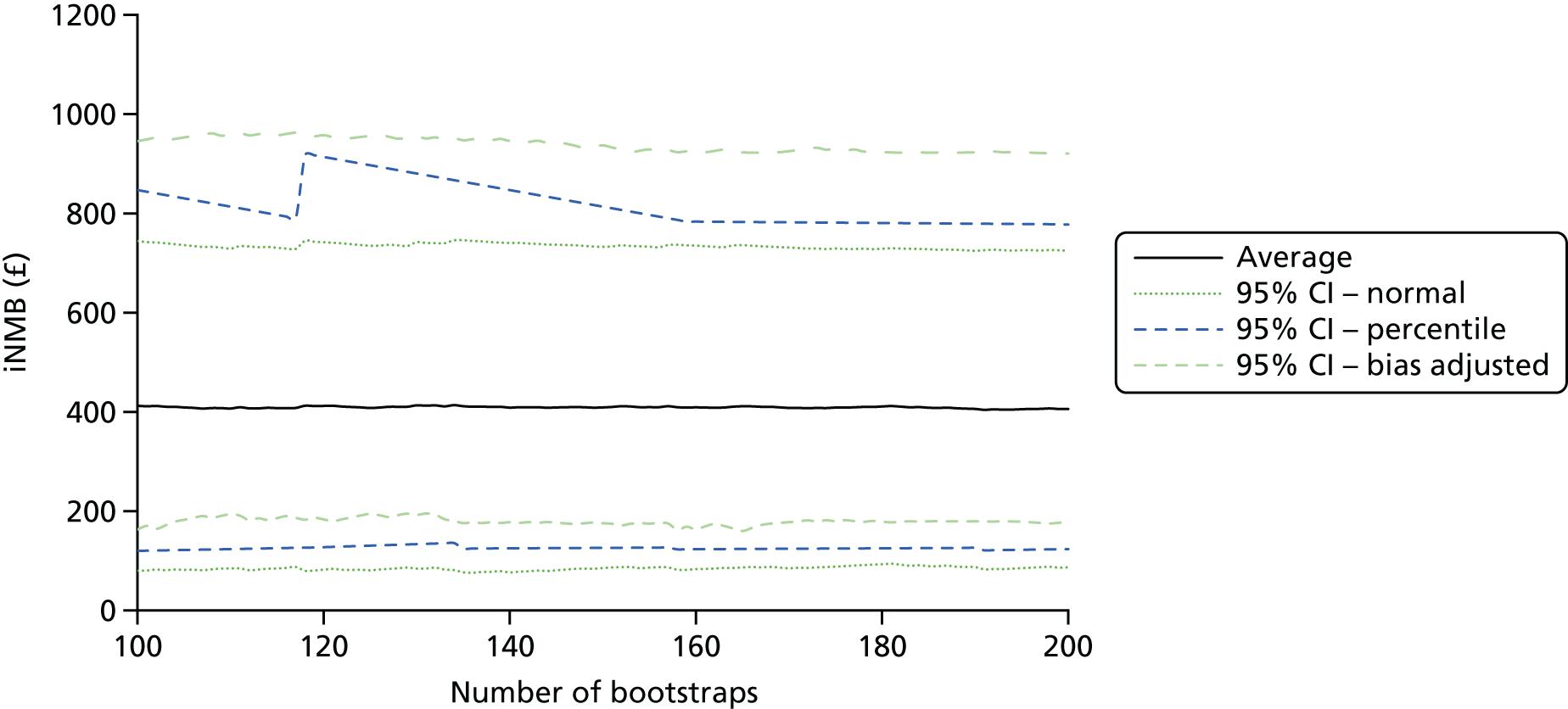

We developed a decision-analysis model to address objectives 6 and 7. It was designed to estimate the costs incurred and the expected outcomes from thromboembolism, bleeding and radiation exposure if a hypothetical cohort of pregnant or postpartum women were investigated for a suspected PE using different strategies with a range of sensitivities and specificities, varying from no testing/treatment to imaging for all. The diagnostic accuracy of the strategies was estimated from the case–control study and other parameters were estimated from the systematic literature reviews. Clinical outcomes were modelled to estimate the costs and QALYs accrued by each strategy. We then estimated the value of information associated with further prospective research.

Health technologies being assessed

The focus of our evaluation was any health technology that can be used to select pregnant or post partum women with a suspected PE for diagnostic imaging, including clinical features, risk factors and biomarkers, either alone or combined to form a CDR. An initial literature review undertaken during proposal development identified a number of potential clinical features, risk factors, biomarkers and CDRs that could be used to select women for diagnostic imaging. These formed the basis for data collection and analysis. We specifically ensured that we included the constituent elements of CDRs validated for use in the non-pregnant population with a suspected PE (Wells’s score, Geneva score, PERC score and D-dimer).

We also used expert opinion in the project team to identify potential clinical predictors that were not identified by our literature review, including other symptoms (chest pain, dyspnoea, syncope, palpitations), other risk factors (gestational age, smoking status, family history, thrombophilia, varicose veins, intravenous recreational drug use), examination findings (respiratory rate, blood pressure, temperature) and routine investigations [electrocardiogram (ECG), chest radiograph].

We used the following methods to structure clinical variables into a CDR:

-

existing CDRs (PERC rule, Wells’s score, Geneva score) modified to be appropriate to the pregnant and postpartum population

-

expert opinion to create up to three CDRs with varying trade-off between sensitivity and specificity that could be tested in the case–control study population

-

statistical derivation of a CDR using the case–control study population.

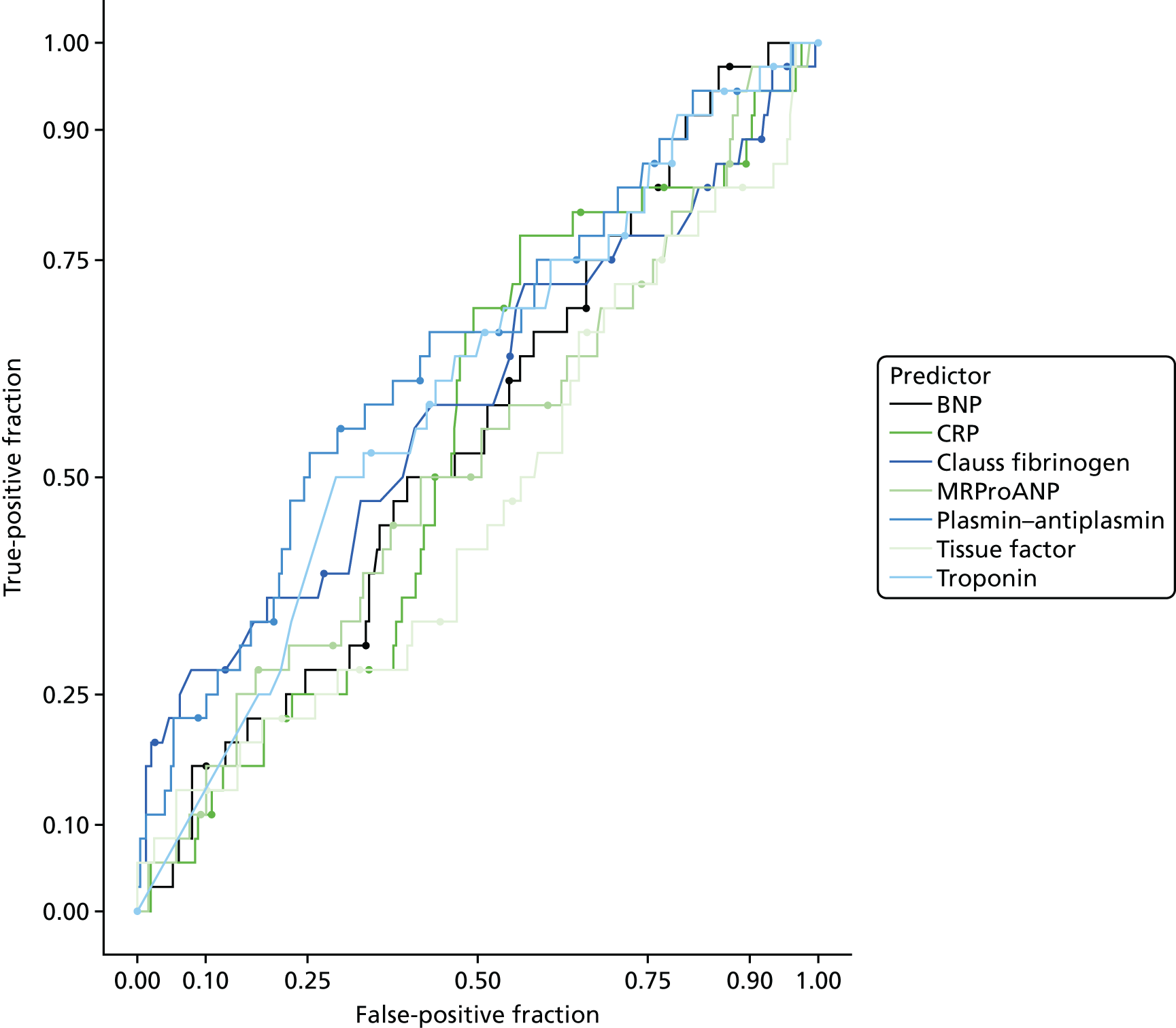

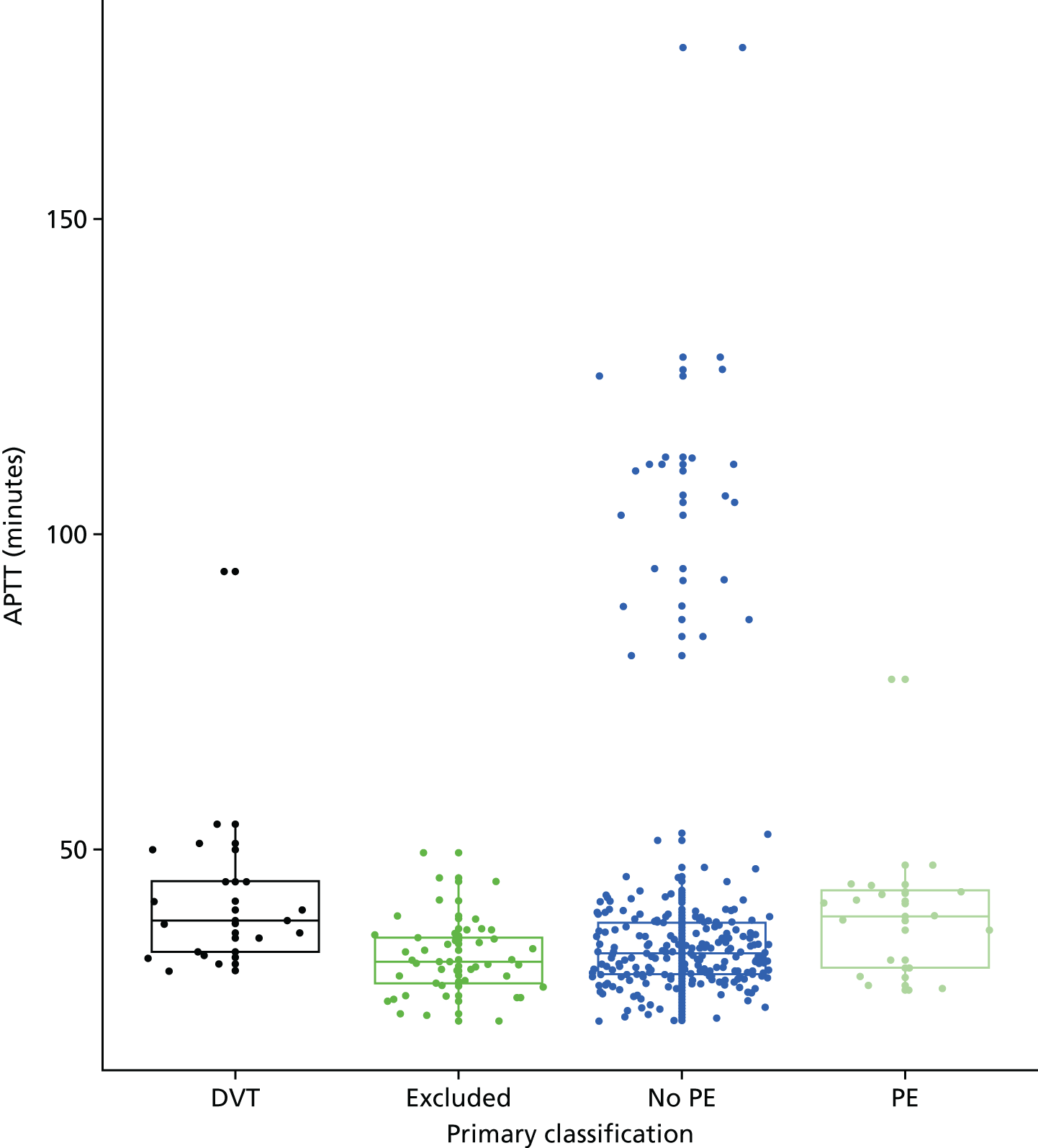

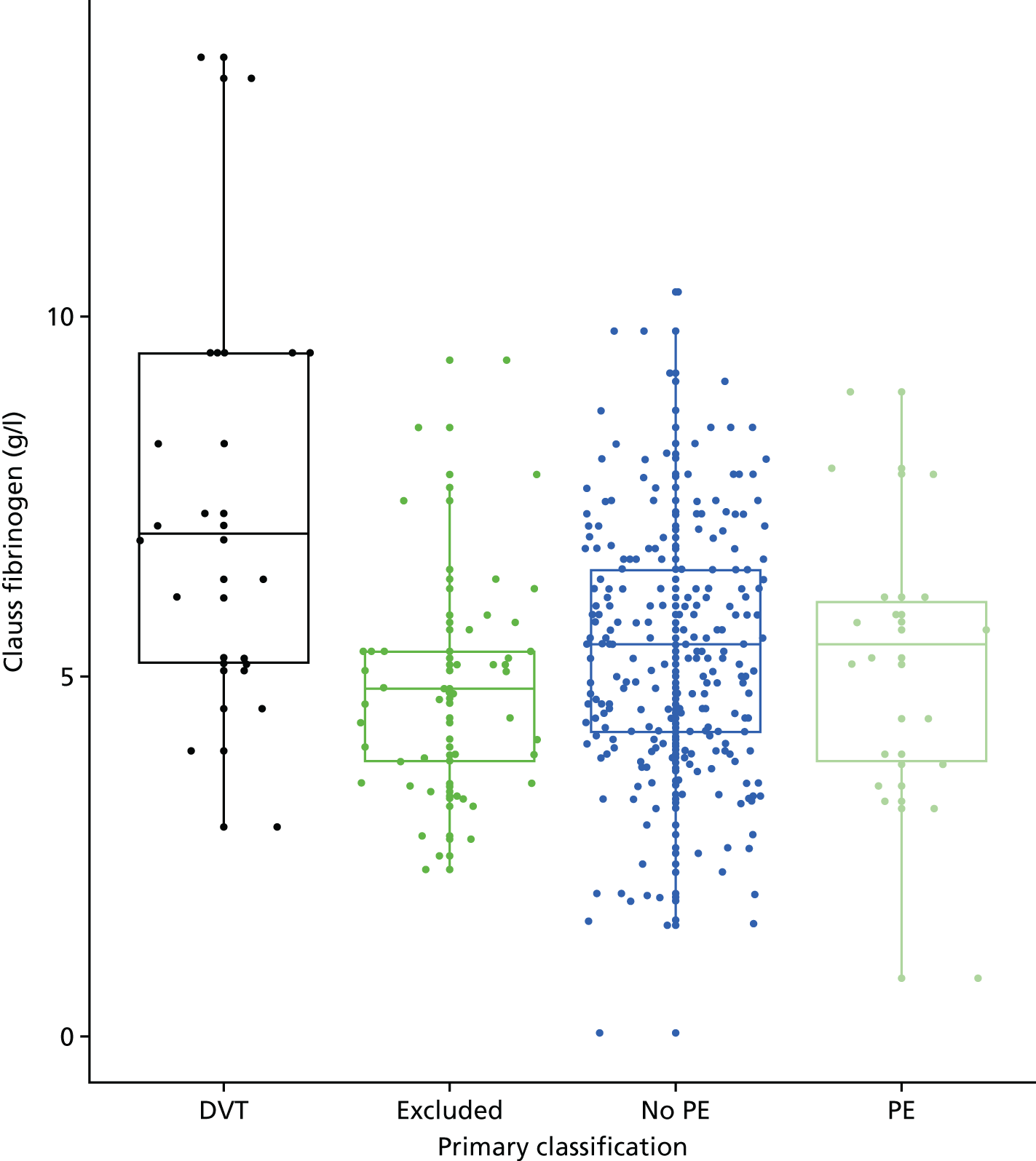

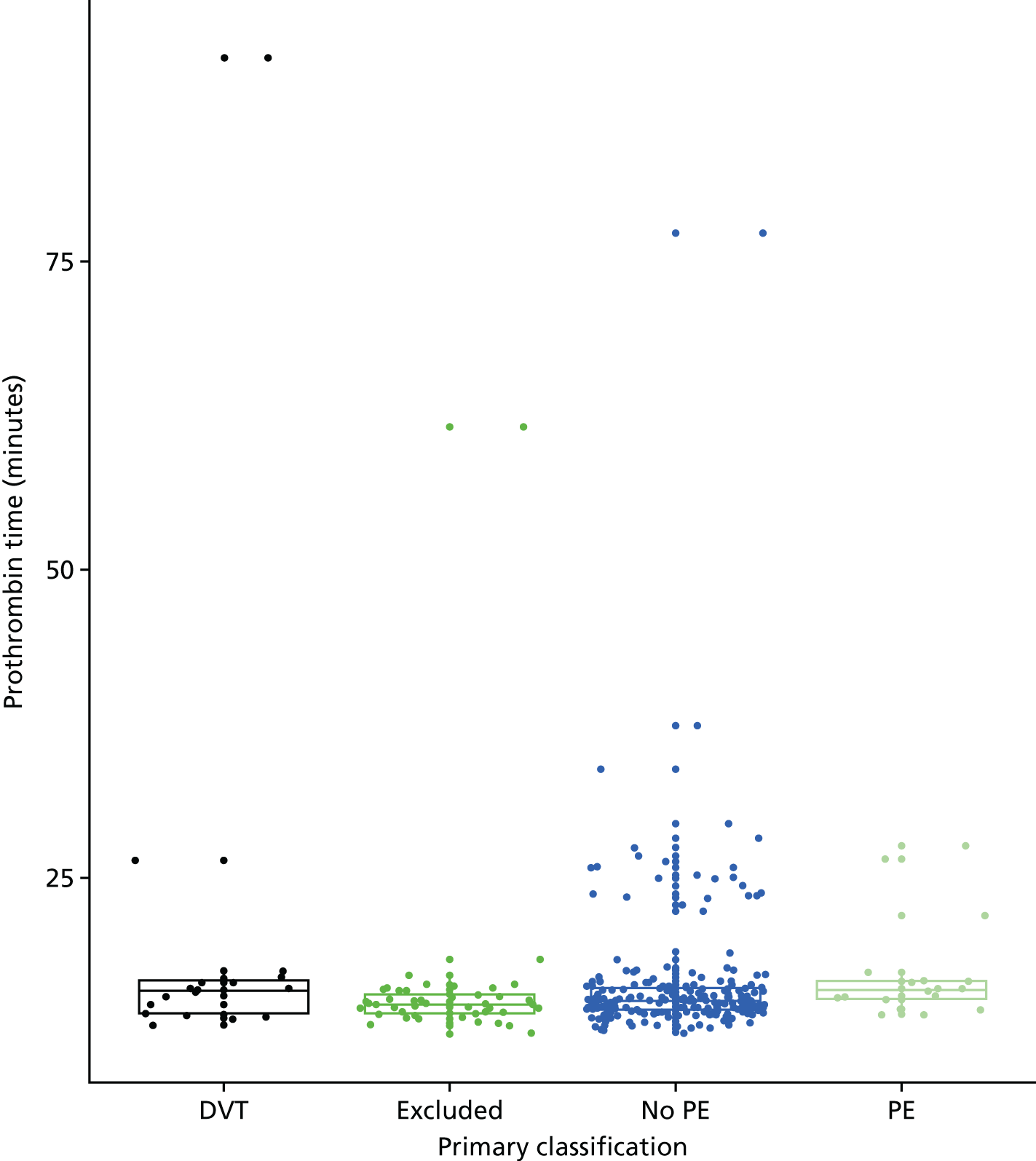

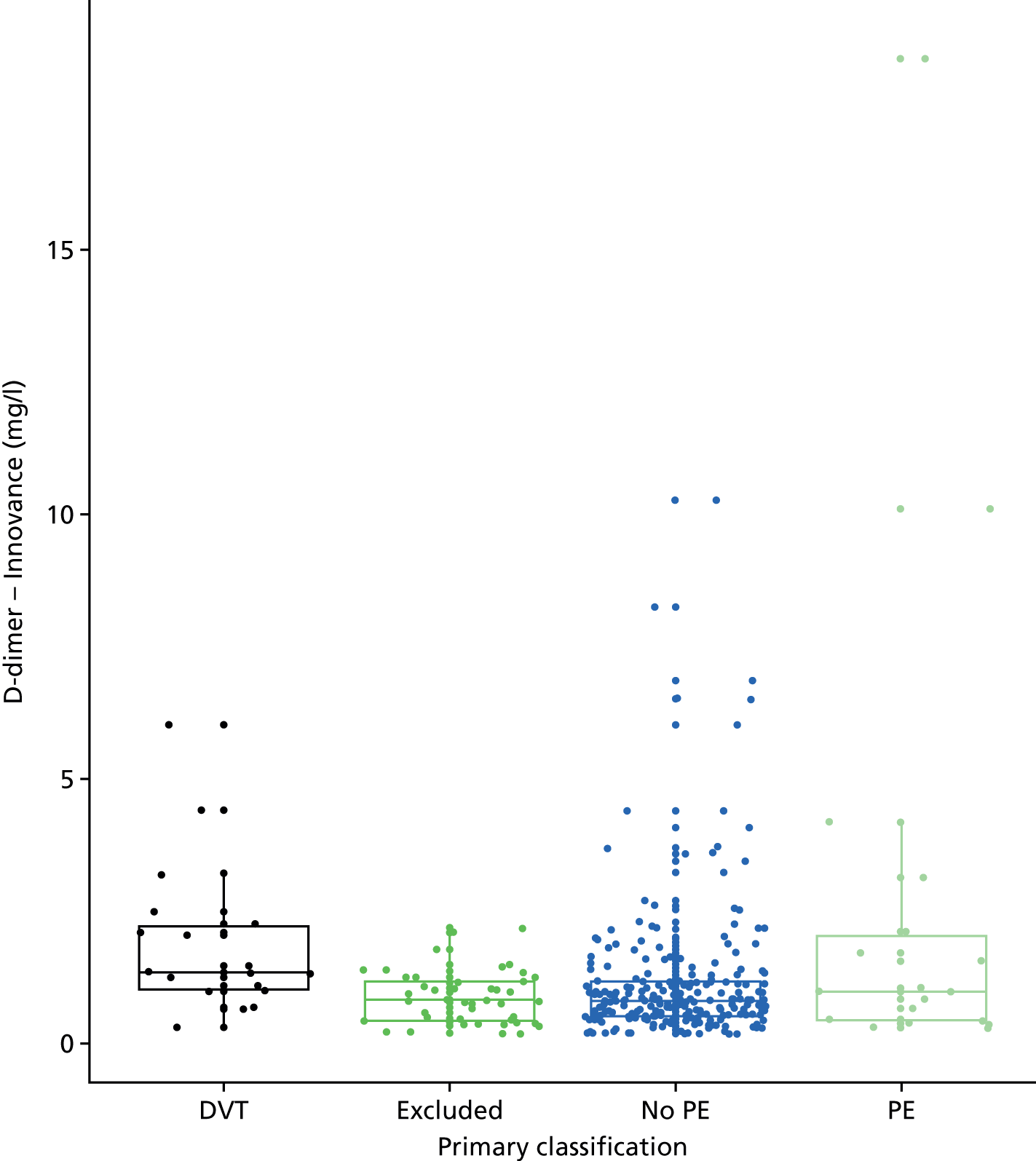

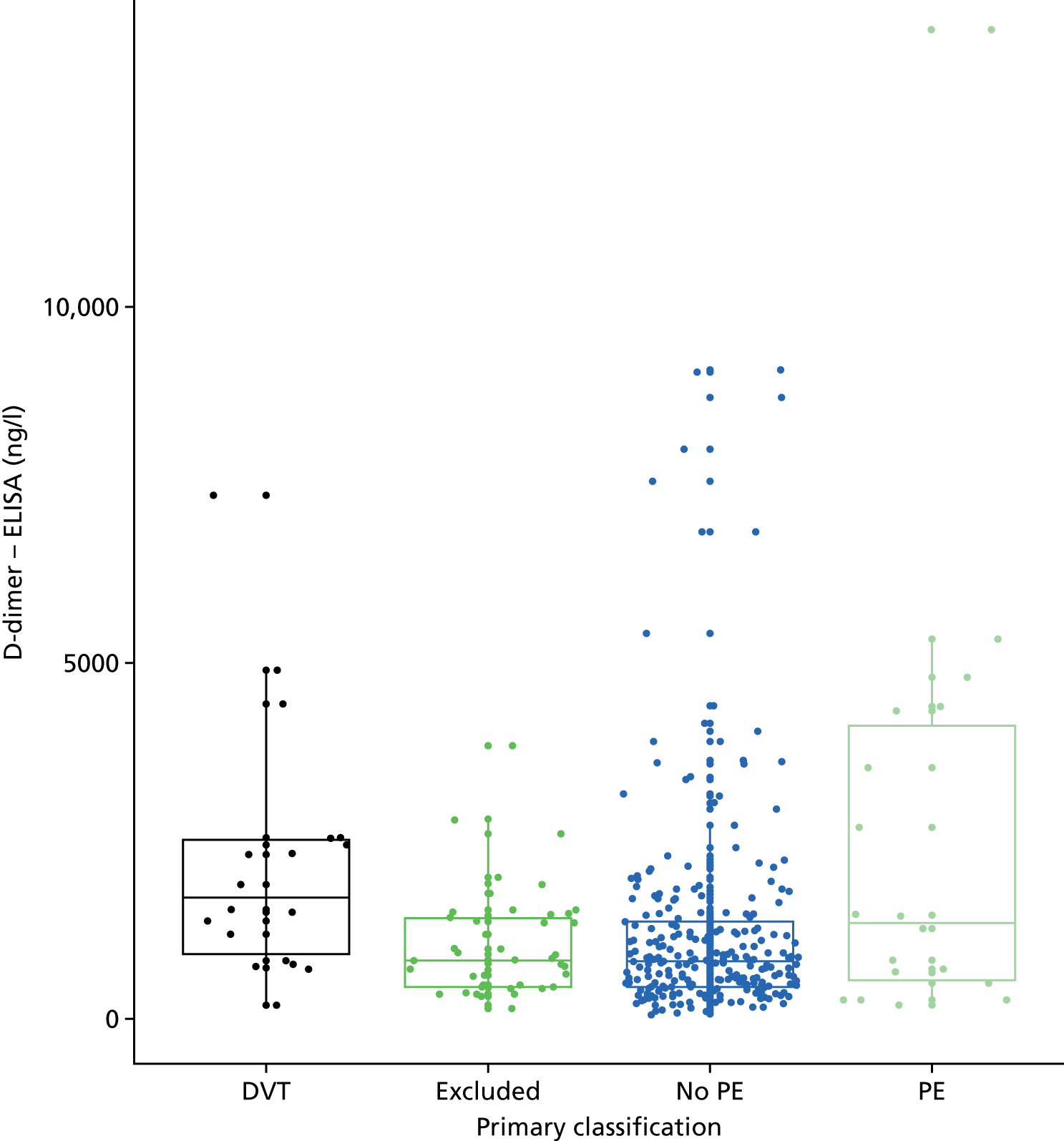

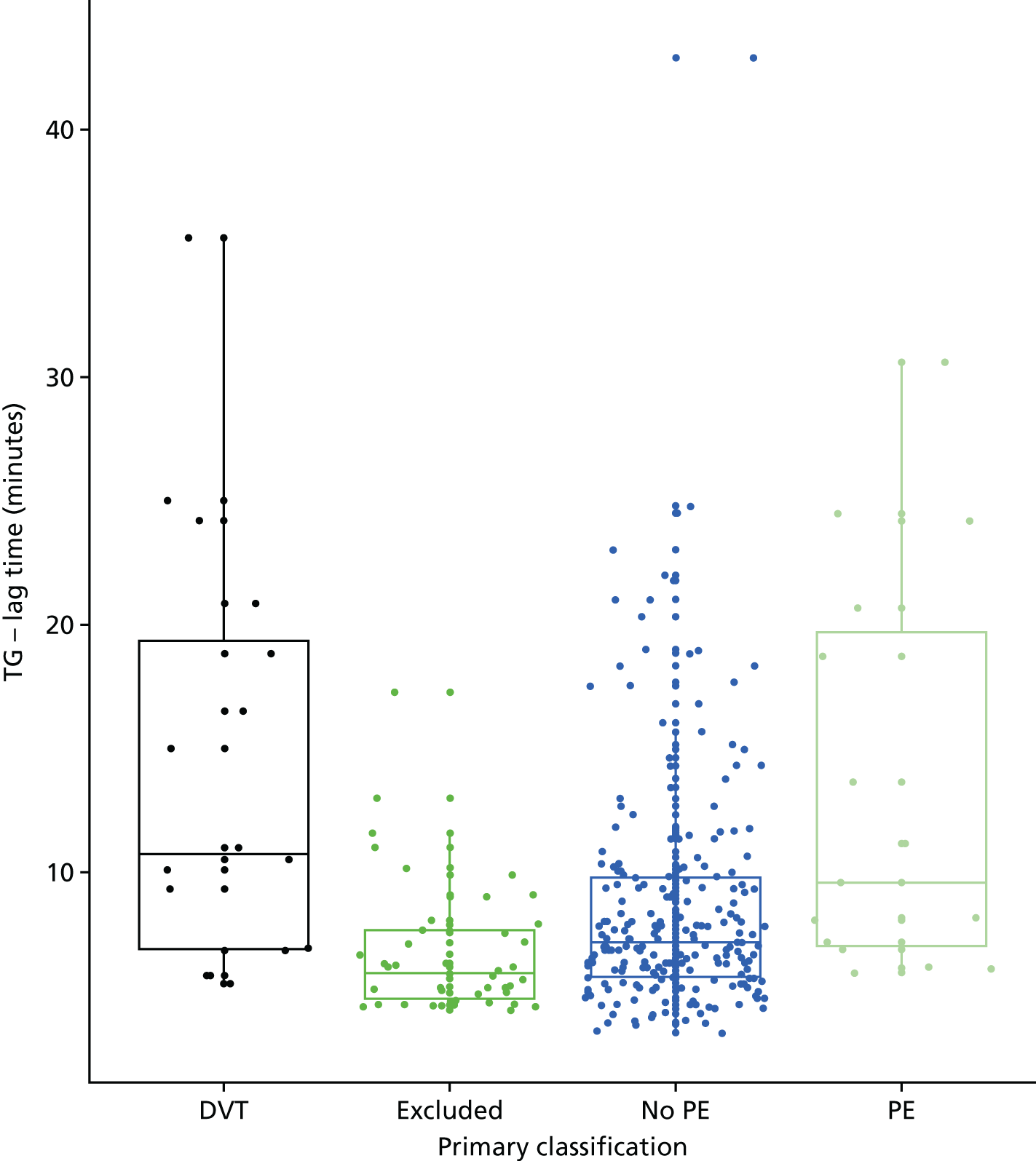

In terms of biomarkers, D-dimer is the only biomarker currently used in routine practice to select patients for VTE imaging, but it is unlikely to have adequate specificity in pregnancy at conventional thresholds for positivity. We therefore planned to examine the accuracy of D-dimer [enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) and Innovance (Siemens Healthcare Diagnostics Products GmbH, distributed by Sysmex UK Ltd, Milton Keynes, UK)] with a higher (pregnancy-specific) threshold for positivity. We also planned to evaluate the following biomarkers: cardiac troponin I, B-type natriuretic peptide (BNP), prothrombin fragment 1 + 2 (PF 1 + 2), plasmin–antiplasmin complexes, prothrombin time (PT), activated partial thromboplastin time (APTT), Clauss fibrinogen levels, thrombin generation, soluble tissue factor, C-reactive protein (CRP), and mid-regional pro-atrial natriuretic peptide (MRProANP).

Chapter 2 Expert consensus clinical decision rule study

Introduction

Clinical decision rules combine a number of symptoms, signs and simple investigation findings into assessment tools to guide therapeutic or diagnostic decisions at a patient’s bedside. Effective CDRs have the potential to standardise care, improve outcomes and increase efficiency. Consensus methodological guidelines38 recommend that the variables in CDRs are initially determined statistically using data from a representative sample of relevant patients. Identified variables, which appear to provide satisfactory diagnostic accuracy for the target condition, are then tested in external samples during validation studies to confirm their performance. Finally, the impact of CDRs on patient outcomes is evaluated in impact studies. 39 Although many statistically derived CDRs have shown excellent results, there are examples of when clinician gestalt or CDRs based on expert clinical opinion have demonstrated equivalent or superior accuracy.

Aims and objectives

We undertook an expert consensus study to derive three CDRs to select pregnant or postpartum women with suspected PE to receive diagnostic imaging. We intended that one rule would be developed with what we anticipated would be an optimal balance of sensitivity and specificity (the primary rule), another would optimise sensitivity at the expense of specificity (the sensitive rule) and another would optimise specificity at the expense of sensitivity (the specific rule). The consequences of the rule being false negative (failure to diagnose PE) are clearly more serious than the consequences of the rule being false positive (unnecessary imaging), so we anticipated that the optimal balance of sensitivity and specificity in the primary rule would be high sensitivity with modest specificity. The sensitive rule would therefore aim to further reduce the risk of false-negative assessments, whereas the specific rule would be specific only relative to the primary rule.

Methods

A two-stage consensus process, guided by best-practice guidelines, was conducted to reduce biases arising from the subjectivity of expert views, and to maximise content and face validity. 40–42

In the first stage, a modified Delphi survey was conducted to identify candidate predictors of PE. Purposive sampling was used to recruit a heterogeneous group of subjects encompassing the full spectrum of expertise relevant to UK PE management in pregnancy. A sample size of 20 panel members was chosen in accordance with guidelines from the Research And Development (RAND) Corporation. 43 Self-completed questionnaires were subsequently administered using a pre-piloted web-hosted questionnaire. The survey was conducted between January and October 2016.

The classical Delphi approach was modified slightly with the replacement of an open first round with a systematic literature review to identify possible PE predictors. 7 Participants were asked to rate the predictive value of each variable on a 1 (not predictive) to 5 (very strongly predictive) Likert scale and to justify their opinion in free text. A mixed-methods approach was taken to summarise each round’s findings. In subsequent Delphi iterations, participants were provided with quantitative (percentage results and frequency histograms) and qualitative (free-text answers grouped by theme) results of the previous round and a summary of their previous opinions.

Up to four Delphi rounds were planned, dependent on when group agreement or stability of opinion was achieved on at least 80% of variables. Judgements on the consensus and stability of opinion on each variable were guided by quantitative measures of agreement (> 70% agreement for weak/strong prediction) and changes in responses between rounds. Patient and public representatives commented on the patient acceptability of each predictor variable generated through Delphi consultation.

Similarly, a series of four face-to-face consensus meetings of clinical Diagnosis of Pulmonary Embolism in Pregnancy (DiPEP) co-investigators were planned. In the initial meeting, the nominal group technique (NGT) was used to formulate the content of the three expert CDRs. This meeting was facilitated by an independent researcher experienced in the NGT, which followed recommended principles for best practice in developing consensus,41,42 consisting of the following steps:

-

presentation of a summary of Delphi survey results

-

facilitated group discussion of individual candidate variables

-

initial rating round for inclusion of each variable

-

facilitated discussion of rating results

-

further rating and discussion rounds

-

confirmation of variables with group consensus for inclusion in CDRs.

Online surveys were designed and implemented using the SmartSurvey web application (SmartSurvey Ltd, Tewkesbury, UK). Data analysis was performed in Microsoft Excel® 2013 (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA). Diagnostic accuracy metrics were calculated using R, version 3.3.2 (The R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria). Ethics approval was obtained from the University of Sheffield. No financial incentives were offered and participants remained anonymous throughout the Delphi survey.

Results

The systematic literature review identified 45 potential variables for evaluation in the Delphi Survey, comprising demographic, obstetric and medical characteristics; symptoms; clinical signs; and bedside investigations.

All 20 experts invited to participate in the Delphi survey completed the first-round questionnaire. At this stage, consensus was adjudged to have been reached on 12 out of the initial 45 variables (27%). Of these, 17 experts also participated in second and third rounds, during which consensus was obtained on a further 26 variables. At this stage, it was apparent that opinions diverged widely on the remaining seven variables and had not been significantly influenced by feedback between rounds. Free-text responses indicated that further convergence of opinion with additional rounds of surveying was unlikely to occur. It was considered that further sampling would lead to declining response rates rather than more relevant findings and the Delphi study was therefore terminated after round 3. Table 2 summarises the results of the Delphi survey.

| Consensus for strong prediction of PE | Consensus for moderate prediction of PE | Consensus for weak prediction of PE | No consensus reached |

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

Twenty-four variables that were felt to be moderately or strongly predictive of PE were carried forward for consideration in the consensus meetings. Two further variables from the Delphi survey were additionally considered after the initial presentation of results at the request of the DiPEP clinical investigators: pleuritic chest pain (rated as weakly predictive) and active medical comorbidity (no consensus). During the initial NGT meeting, consensus was subsequently achieved for the inclusion of 13 predictors in the final CDRs. Variable weightings and the CDR cut-off point for each CDR (balanced, sensitive, specific) were agreed in two subsequent facilitated roundtable meetings. The scope of the CDRs, in terms of which patients these could be applied to, was also confirmed. The final CDRs developed are presented in Table 3.

| Included variables | Variable weightinga | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary CDR | Sensitive CDR | Specific CDR | |

| Haemoptysis | 3 | 1 | 4 |

| Pleuritic chest pain | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Previous VTE | 3 | 1 | 4 |

| Family history of VTE in first-degree relative | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Hospital admission, surgery or significant injury within 90 days (excluding NVD or caesarean section) | 2 | 1 | 1 |

| Obstetric complicationb | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Active medical comorbiditiesc | 2 | 1 | 1 |

| Post partum or third trimester | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Raised BMI of ≥ 30 kg/m2 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Clinical symptoms or signs of DVTd | 3 | 1 | 4 |

| Oxygen saturation of < 94% on room air | 3 | 1 | 3 |

| Tachycardia of > 100 b.p.m. (in the first or second trimester, or post partum)/tachycardia of > 110 b.p.m. (in third trimester) | 2 | 1 | 2 |

| Increased respiratory rate of > 24 breaths per minute | 2 | 1 | 2 |

| CDR cut-off point | 3 | 1 | 4 |

Discussion

We have used expert consensus to develop three CDRs for the purpose of selecting pregnant or postpartum women with a suspected PE for imaging. The primary rule is intended to achieve an appropriate balance between sensitivity and specificity, whereas the sensitive and specific rules prioritise sensitivity and specificity, respectively. These rules have been developed for testing in the DiPEP study and are not ready for clinical use.

To our knowledge, there have been no other CDRs developed specifically for this purpose. Wells’s PE criteria, the Geneva score and the PERC rule were developed to assess the clinical probability of PE in the general population with a suspected PE, but were not developed for pregnant or postpartum women. Our consensus-derived rules share a number of criteria with these rules (haemoptysis, previous VTE, clinical symptoms or signs of DVT, recent injury or surgery) and have adapted others by using pregnancy-specific thresholds (heart rate, oxygen saturation). Our expert consensus group drew on pre-existing rules for the general population, but adapted and added criteria to make the rules relevant to the pregnant population.

Consensus development provides a relatively quick and efficient way of developing a CDR, but has some inevitable limitations. Experts should base their judgements on empirical data, but, as Chapter 1 has highlighted, there are very limited data relating to the clinical prediction of PE in pregnancy. In the absence of empirical evidence, experts may base their judgements on personal experience, which is known to be subject to cognitive biases, such as the availability heuristic and the Dunning–Kruger effect. These may lead to overestimation of the importance of atypical but memorable observations, as well as overestimation of diagnostic certainty.

The consensus methods used are intended to reduce the risk of domination by a single expert opinion, but can have the opposite risk of discouraging legitimate questioning of commonly held beliefs. We deliberately restricted the number of experts involved in the final phase of developing the rules to ensure that this process was manageable. This carries the risk of supressing dissenting views in the interests of achieving a practical output.

Conclusion

We have developed three CDRs through expert consensus that need to be tested to determine their ability to discriminate between pregnant or postpartum women with and without PE.

Chapter 3 Case–control study

Aims and objectives

The case–control study was intended to compare participants with PE with control participants without PE to allow for the estimation of the diagnostic accuracy of clinical features, CDRs and biomarkers, and statistical derivation of a new CDR. To minimise bias, we tried to ensure that the case participants and control participants were selected in a similar way (i.e. that case participants presented to hospital with suspected PE were investigated accordingly). The postpartum period was defined as the 6 weeks (42 days) at the end of a pregnancy beyond the first trimester. As noted in Chapter 1, the design could more accurately be described as a prospective cohort study of women with a suspected PE augmented with a retrospective cohort of women with a diagnosed PE, but, for the reasons previously outlined, we will use the term case–control study.

Methods

Study population

Diagnosed PE: the UKOSS research platform was used to identify a sample of pregnant or postpartum women who were diagnosed with PE in the UK after presentation with a suspected PE. We identified and collected data from any woman diagnosed with PE at a hospital participating in the UKOSS platform between 1 March 2015 and 30 September 2016.

Suspected PE: we recruited a sample of pregnant or postpartum women investigated for a suspected PE across 11 participating sites. We anticipated that 98% of women in the sample would have no confirmed diagnosis of PE and would constitute the control group. Those with a diagnosis of PE confirmed would be analysed with the patients with PE.

Inclusion/exclusion criteria

Diagnosed PE: we included women with PE if they met any of the following definitions:

-

pulmonary embolism confirmed using imaging (angiography, CT, magnetic resonance imaging or VQ scan showing a high probability of PE)

-

pulmonary embolism confirmed at surgery or post mortem

-

clinical diagnosis of PE resulting in a course of anticoagulation therapy for > 1 week.

Women meeting criterion 1 or 2 were included as patients with PE in the primary analysis. Women with a clinical diagnosis of PE (criterion 3) were excluded from the primary analysis, but were included as patients with PE in the secondary analysis. This was because of the risk of incorporation bias if the clinical reference standard diagnosis of PE was based on the clinical variables or biomarkers being used as index tests.

We excluded women who did not present with a suspected PE prior to diagnosis (i.e. with PE identified as an incidental finding). We collected data from women who required life support at presentation (chest compressions or assisted ventilation) to allow for the estimation of the incidence of PE in pregnancy, but did not include these women in the analyses in this study.

Suspected PE: we included any pregnant or postpartum woman presenting to the participating hospitals who was considered to require diagnostic imaging for a suspected PE. Women were recruited once the clinician had decided that imaging would be required. However, not all women received lung imaging; in a proportion of patients, the decision that imaging was required was reversed by a more senior clinician, and some women received imaging only for DVT (e.g. venous ultrasound). Women who had PE ruled out clinically (i.e. without diagnostic imaging of the lungs for PE) were excluded from the primary analysis, but included in the secondary analysis. This was because of the risk of bias if the PE was missed as a result of a lack of adequate imaging and the decision not to undertake imaging was based on the clinical variables or biomarkers that constituted the index tests.

We excluded women who needed life support on presentation to hospital (chest compressions or assisted ventilation), women who had been diagnosed with PE earlier in the current pregnancy, women who were unable or unwilling to provide informed consent, women aged < 16 years and women previously recruited to the study. The form used for screening is shown in Report Supplementary Material 1 (the suspected PE screening form).

Setting/context

Diagnosed PE

UKOSS collects data from all UK hospitals with a consultant-led maternity unit. Patients for this study presented through a variety of routes, depending on local practice, but were ultimately the responsibility of the obstetric services, and thus women who had PE at any stage in gestation were identified, provided that their pregnancy was ongoing. Postpartum women were identified if they were still under obstetric care, but inevitably this meant that patient identification became less reliable towards the end of the postpartum period.

Suspected PE

Pregnant and postpartum women with a suspected PE are investigated in secondary care, but may follow a variety of different pathways, depending on local practice. At each hospital, patient recruitment was targeted at the location at which the decision to undertake diagnostic imaging was made – this included the emergency department, the maternity unit or both.

Sampling

Diagnosed PE

Nominated clinicians in each consultant-led maternity unit in the UK were sent a card each month and asked to report all patients with antenatal or postnatal PE, thus covering the entire cohort of UK births. In addition, the ascertainment of any maternal deaths from PE occurring during the study period was checked through MBRRACE-UK (Mothers and Babies: Reducing Risk through Audits and Confidential Enquiries across the UK), the collaboration responsible for the UK Confidential Enquiries into Maternal Death. When a patient was identified, the UKOSS clinician was contacted and asked to complete a data collection form if appropriate.

It was not practical to obtain consent for data collection from individual women with a diagnosed PE. The Confidentiality Advisory Group of the Health Research Authority and equivalent bodies in the devolved nations consider that organisations seeking to use NHS information for research purposes without consent should seek anonymised or pseudonymised data only, and not any personally identifiable information. Accordingly, names, addresses, postcodes, dates of birth and NHS or hospital numbers were not collected in the UKOSS research platform.

Suspected PE

Clinicians in the participating hospitals prospectively identified pregnant or postpartum women with a suspected PE considered to require diagnostic imaging. They contacted the research nurse/midwife or recruiting clinician, who provided women with information about the study, and checked the eligibility criteria. Informed consent to participate was sought prior to discharge, which at some hospitals included consenting women who returned for outpatient appointments for diagnostic imaging.

Data collection and follow-up

Diagnosed PE

UKOSS clinicians who reported a patient were asked to complete a data collection form detailing the clinical variables, diagnostic test results, management and outcomes (see Report Supplementary Material 2, the diagnosed PE data collection form). Up to five reminders were sent if completed forms were not returned. On receipt of the data collection forms, patients were checked to confirm that they met the patient definition (see Inclusion/exclusion criteria). Duplicate reports were identified by comparing the woman’s year of birth, hospital, the date of a suspected PE and the expected date of delivery, or the date of birth for postpartum women.

Suspected PE

The research nurse/midwife completed a data collection form incorporating clinical variables, diagnostic test results and management, using information from patient records (see Report Supplementary Material 3, the suspected PE data collection form). Participants provided a blood sample and underwent diagnostic imaging in accordance with local protocols. Ideally, the research nurse/midwife would collect clinical data prior to diagnostic imaging being performed and would thus be blinded to the results of the diagnostic imaging. However, some patients were recruited after diagnostic imaging had been performed. For these patients, we asked the research nurse/midwife to record whether or not they were aware of the results of the diagnostic imaging when they collected clinical data.

At 30 days after recruitment, the research nurse/midwife reviewed hospital records and recorded details of any adverse events and the results of any additional diagnostic investigations for PE. When the research nurse/midwife was aware of follow-up care outside the hospital NHS trust, attempts were made to complete follow-up data using hospital records from the relevant location. All participants who provided contact details, except for those who had died or withdrawn from the study, were sent a questionnaire by mail, e-mail or telephone to record any additional adverse events, details of the health care received, health utility and standardised quality of life using the EuroQol-5 Dimensions, five-level version [(EQ-5D-5L), www.euroqol.org/, accessed 13 June 2017]. Participants received up to three reminders to complete the 30-day questionnaire. One of the two reminders used an alternative method of contact in accordance with their stated preference (e.g. telephone or e-mail if there was no response to posted mail). When insufficient information or no information was obtained on the data collection form, the research nurse/midwife follow-up or the patient follow-up questionnaire, the woman’s general practitioner (GP) was contacted to rule out serious adverse events of additional diagnostic investigations for PE using primary care records.

Women recruited with a suspected PE who were subsequently diagnosed with PE were cross-checked with the UKOSS patients to avoid duplication. If duplication was found, data collected by the research nurse/midwife were used.

Non-recruited women with suspected PE: women presenting to the participating hospitals with suspected PE who were eligible but not approached to request participation, were retrospectively identified from hospital systems, radiology records and communication between clinicians (see Report Supplementary Material 4, non-recruited suspected PE screening form). The research nurse/midwife then extracted anonymised data from the hospital records. The anonymised data included, when possible, the clinical variables and the imaging, treatment, and follow-up data used to diagnose PE (see Report Supplementary Material 5, non-recruited suspected PE data collection form). No blood sample was taken and no follow-up questionnaire was administered, and any data not available in the case notes were recorded as missing. These data were used to explore whether or not the recruited sample was representative.

Sample size

The sample size for the UKOSS data were inevitably determined by the incidence of PE during the data collection period. Based on a previous similar study,27 we anticipated that we would identify 150 patients with diagnosed PE over the 18 months of the study. We aimed to recruit 250 women with suspected PE over the same time period, resulting in around 155 women with PE, and 245 women without PE in the control group, assuming that the prevalence of PE is 2% in those with a suspected PE. This would allow for the estimation of sensitivity or specificity of 90% with a SE of around 2.5% and 2.0%, respectively. Assuming that the ratio of women with PE to women without PE in the control group would be around 0.4, this sample size would be sufficient to identify an odds ratio of a clinical predictor of around 2, with 90% power and 5% two-sided significance. 44

With a limited sample size, the complexity of any statistical model was limited in terms of the number of predictor variables that could be included. This was addressed by selecting only those variables that were felt to be clinically important in the model and by aiming for maximum parsimony in the final model. The statistical analysis outlined in the study proposal stipulated modelling outcomes by splitting the cohort into a training data set and a validation data set. This effectively reduces power, so, in developing the statistical analysis plan, an alternative approach of leave-one-out cross-validation was planned instead.

Data management

Diagnosed PE data and suspected PE data were collected on study-specific case report forms (CRFs) and entered onto a secure electronic data capture system at UKOSS and the Clinical Trials Research Unit (CTRU) at the University of Sheffield. The prospective data were managed via the CTRU Prospect system (epiGenesys, University of Sheffield, Sheffield, UK), which used inbuilt validation to promote high-quality data and security management features to ensure data confidentiality. On completion of the study, pseudonymised UKOSS data were encrypted and uploaded to the Prospect system. Physical data were stored in accordance with good clinical practice and local standard operating procedures.

Ethics and research and development approvals

Ethics approval for the study was obtained from the London Brent Research Ethics Committee (reference 14/LO/1695). A feasibility assessment for each participating site was undertaken by the research team and in accordance with local research governance procedures. Permission to undertake the research study was granted and reviewed in response to project amendments.

Patient and public involvement

Four members of the public, representing interests in obstetric care and emergency medicine, were actively involved in the oversight of the study via membership of the Study Steering Committee. Patient and public involvement (PPI) representatives influenced the development of study documents and data collection, shaped the dissemination strategy and commented on outputs. PPI representatives also engaged with external organisations such as the Sheffield Emergency Care Forum and Thrombosis UK.

Analysis populations

The primary analysis population consisted of women recruited with a suspected PE and women identified through UKOSS with a diagnosed PE. Women who presented to hospital needing life support were excluded from the suspected PE sample and were used in the UKOSS sample only to estimate the overall PE incidence. They were therefore excluded from all analyses reported in this study. We also excluded any women from the UKOSS sample if it was not recorded whether or not they presented to hospital needing life support, unless presenting physiological data showed that life support would not have been needed.

We planned a priori that the primary analysis should be limited to participants with diagnostic imaging, surgery or post-mortem confirmation of PE or in whom PE had been ruled out by diagnostic imaging, and thus included only patients without diagnostic imaging, surgery or post-mortem confirmation in the secondary analyses. We also planned a priori to undertake the secondary analysis excluding isolated subsegmental PE, as the identification of subsegmental PE on imaging may be unreliable and the need for treatment may be uncertain.

We identified any duplicates between the UKOSS data set and the women with a suspected PE. If the woman was recruited with a suspected PE, then the corresponding UKOSS data were removed from the overall data set. If the woman was identified but not recruited with a suspected PE, then the UKOSS data were retained. The anonymised data relating to women’s presentation with a suspected PE were used in a descriptive analysis of the non-recruited patients.

Reference standard classification

We planned that the classification of participants as having PE (PE present) or not having PE (PE absent) should be based on the results of imaging, thromboembolic events and the evidence of treatment for PE, regardless of whether or not participants were recruited with a suspected PE or identified as having a diagnosed PE through UKOSS. Two independent assessors (SG and CNP), who were blind to the clinical predictors and the blood results, used a structured process to classify the diagnostic imaging results, the details of adverse events and the details of treatments given, and thus to classify all participants and non-recruited participants as PE present (women with PE) or PE absent (control group participants). Details of the structured process are provided in Appendix 1. Disagreements were resolved through adjudication by a third assessor (FL). This process also classified how participants would be handled in the primary and secondary analysis.

We structured the process of classification for primary and secondary analysis around the following principles:

Primary analysis –

-

Pulmonary embolism was present if lung imaging was reported as showing PE or if venous imaging showed DVT in the presence of symptoms indicating suspected PE (i.e. if the patient met the eligibility criteria), if surgery or a post-mortem examination revealed PE or if the 30-day follow-up identified a subsequent diagnosis of PE.

-

Pulmonary embolism was absent if lung imaging was reported as negative for PE, unless the 30-day follow-up identified subsequent PE.

-

Pulmonary embolism was absent if lung imaging was non-diagnostic, no treatment was given for PE (defined as therapeutic anticoagulation for at least 1 week) and no subsequent PE was identified on follow-up.

-

Women with clinically diagnosed PE were excluded (i.e. if lung imaging was non-diagnostic, but treatment was given for PE).

-

Women with clinically ruled-out PE were excluded (i.e. if lung imaging was not done).

The secondary analyses examined the following reclassifications –

-

the inclusion of women with clinically diagnosed PE as PE present (i.e. women with no lung imaging or non-diagnostic lung imaging who received treatment for PE)

-

the inclusion of women with clinically ruled out PE as PE absent (i.e. women with no lung imaging who did not receive treatment for PE)

-

the exclusion of women with isolated subsegmental PE.

Clinical variable classification

Clinical variables that could be diagnostically useful were classified on the basis of a priori categorisation as to whether the variable was present or absent. For most patients, this was on the basis of an expected association between a variable and the presence or absence of PE. If the variable was present, then it was expected that PE would be more likely to be present. Continuous variables were determined from the expert opinion of DiPEP co-investigators, existing criteria used in the relevant decision tools,2 or widely acknowledged physiological definitions (e.g. tachycardia) to give clinically meaningful classifications. Table 4 outlines the classification.

| Clinical variables | Present | Absent |

|---|---|---|

| Aged > 35 years | > 35 years | ≤ 35 years |

| BMI of ≥ 30 kg/m2 | ≥ 30 kg/m2 | < 30 kg/m2 |

| Ex-smoker (prior) | Gave up smoking before pregnancy | No |

| Ex-smoker (during) | Gave up smoking during pregnancy | No |

| Current smoker | Current smoker | No |

| Previous pregnancy of < 24 weeks’ gestation | One or more | None |

| Previous pregnancy of > 24 weeks’ gestation | One or more | None |

| Previous pregnancy problems | Any from list 1a | None from list 1a |

| History of VTE in first-degree relatives | Yes | No |

| History of varicose veins | Yes | No |

| History of i.v. drug use | Yes | No |

| Known history of thrombophilia | Yes | No |

| Surgery in the previous 4 weeks | Yes | No |

| Significant injury in the previous 4 weeks | Yes | No |

| Previous VTE | Yes | No |

| Other previous medical problem | Any from list 2b | None from list 2b |

| Other previous medical problem with risk of VTE | Any from list 3c | None from list 3c |

| Pregnant vs. post partum | Post partum | Pregnant |

| Trimester | Second | First |

| Trimester | Third | First |

| Multiple pregnancy | Yes | No |

| History of long-haul travel during this pregnancy | Any within 1 month | None within 1 month |

| Period of immobility/bed rest during this pregnancy | Any within 1 month | None within 1 month |

| Prior thrombotic event in this pregnancy | Yes | No |

| Other problem in current pregnancy | Any from list 1a | None from list 1a |

| Other problem in current pregnancy with risk of VTE | Any from list 4d | None from list 4d |

| Pleuritic chest pain | Yes | No |

| Other (non-pleuritic) chest pain | Yes | No |

| SOB on exertion | Yes | No |

| SOB at rest | Yes | No |

| Haemoptysis | Yes | No |

| Other productive cough | Yes | No |

| Syncope | Yes | No |

| Palpitations | Yes | No |

| Other symptoms | Yes | No |

| Tachycardia | Heart rate of > 100 b.p.m. (in first or second trimester, or post partum) or > 110 b.p.m. (in third trimester) | Other or not recorded |

| Tachypnoea | Respiratory rate of > 24 breaths per minute | Other or not recorded |

| Hypoxia | SaO2 on room air of < 94% | Other or not recorded |

| Low systolic BP | Systolic BP of < 90 mmHg | Other or not recorded |

| Low diastolic BP | Diastolic BP of < 50 mmHg | Other or not recorded |

| Fever | Temperature of > 37.5 °C | Other or not recorded |

| Clinical signs of DVT | Yes | No or not recorded |

| PE-related ECG abnormality | Yes | Other |

| PE-related chest radiograph abnormality | Yes | Other |

| Other chest radiograph abnormality | Yes | Other |

| Diagnostic impression | PE at least as likely as any other diagnosis | Other |

| D-dimer | Above the gestational age-specific threshold (see Clinical variable classification) | Below gestational age-specific threshold |

Other previous medical problems and other problems in the current pregnancy were analysed in two ways using the lists above. First, they were analysed using any other previous medical problem or problems with the current pregnancy as the predictor of PE (lists 1 and 2). Then, they were limited to other previous medical problems and problems in the current pregnancy that were known to be associated with an increased risk of VTE, based on the outcome of developing the expert consensus-derived CDRs. Problems specifically tested as a separate predictor (e.g. previous thrombotic event) were not included.

The following ECG abnormalities were classified as being PE related: SI QIII TIII pattern, complete or incomplete right bundle branch block, right axis deviation, simultaneous T-wave inversions in the inferior (II, III, aVF) and right precordial leads (V1–3), right atrial enlargement (peaked P wave in lead II of > 2 mm in height), clockwise rotation (shift of the R/S transition point towards V6, persistent S wave in V6) or atrial tachyarrhythmia (atrial fibrillation, flutter or tachycardia).

Chest radiographs were classified by reviewing the radiology report produced as part of clinical care. If the report mentioned the PE or pulmonary infarction in describing radiographic changes or identified potentially PE-related findings (such as atelectasis) without providing an alternative explanation for the finding, then we classified it as referring to a PE-related abnormality. All other abnormal radiographs were classified as having other abnormality.

The diagnostic impression was reviewed by one of the investigators (SG) and classified by whether or not PE was at least as likely as any other diagnosis, based on with the criterion used in Wells’s PE score. 3 This was done at two levels: (1) a strict judgement in which only diagnostic impressions that clearly stated that PE was at least as likely as any other diagnosis were included and (2) a permissive judgement in which any diagnostic impression that suggested that PE was as least as likely as any other diagnosis was included.

D-dimer measurements were recorded as part of routine care in a proportion of women with suspected PE and women with diagnosed PE in the UKOSS cohort. The biochemical analysis was undertaken in many different hospitals, using different assays with different diagnostic thresholds. Furthermore, we expected specificity to decline with gestational age. We therefore planned to test a threshold for positivity for D-dimer that varied with gestational age and was defined in relation to the threshold used for that assay at the relevant hospital rather than as an absolute value. We used the standard threshold during the first trimester, 1.5 times the standard threshold for the second trimester and two times the standard threshold for the third trimester and post partum. This was based on data showing how D-dimer levels increase during pregnancy45 and evidence that a higher threshold may improve specificity for diagnosing VTE in pregnancy without sacrificing sensitivity. 6

Missing data

The process for classifying the reference standard (PE present or absent) described above outlines how data relating to imaging, follow-up and treatment are handled. In general, if data were missing, it was assumed that imaging was not performed, treatment was not given or follow-up was negative. However, all data were presented to the independent assessors so that they could take the presence or absence of data into account when making their judgement.

For the clinical variables, there was scope for missing data if the attending clinician failed to measure or record the data, or if the UKOSS clinician or research nurse/midwife was unable to access the necessary hospital records. Analyses involving multiple clinical variables (i.e. multivariable regression and analysis of decision rules) have to either impute missing variables or exclude every patient with a missing variable. In these analyses, we included patients with small numbers of missing data, with missing variables imputed as being normal or negative, and excluded patients with large numbers of missing data (i.e. if any of the following criteria were met):

-

more than one of heart rate, respiratory rate and oxygen saturation were missing

-

more than half of the variables relating to previous medical history were missing

-

more than half of the variables relating to the current pregnancy were missing.

Our rationale for this approach was that if large numbers of data were missing, then any assumption about the pattern of missing data would be speculative and it would be best to exclude the patient, whereas, if only a few variables were missing, it would be more likely that these were not recorded because they were expected to be normal or negative. Imputing missing data as normal or negative would tend to overestimate specificity and underestimate sensitivity. We felt that this represented a conservative assumption that would accord with clinician willingness to accept a degree of overinvestigation and unwillingness to accept the risk of missed PE. We felt that imputing abnormal or positive values when variables were missing, especially in validating CDRs, would be met with scepticism by the clinical users of our findings and would undermine the clinical credibility of these findings.

Planned analyses

Demographic and baseline characteristics were presented descriptively for the cohorts with diagnosed PE and suspected PE, and the eligible but non-recruited patients with suspected PE. Demographics, baseline characteristics and prevalence of PE diagnosis were then compared between the recruited women and the non-recruited women with suspected PE to explore whether or not those recruited were a representative cohort.

The cohort with diagnosed PE and the recruited cohort with suspected PE were then combined to form the main data set for analysis. The primary analysis was limited to women with PE confirmed or ruled out by imaging, surgery or post-mortem examination. Secondary analyses examined the effect of (1) including women with clinically diagnosed PE, (2) including women with clinically ruled-out PE and (3) excluding women with subsegmental PE as outlined above.

Clinical variables were compared between women with PE and those without PE. Univariable logistic regression was then used to determine the association between each variable and the presence or absence of PE.

Summaries of the responses to the assessment questionnaires were tabulated for each time point.

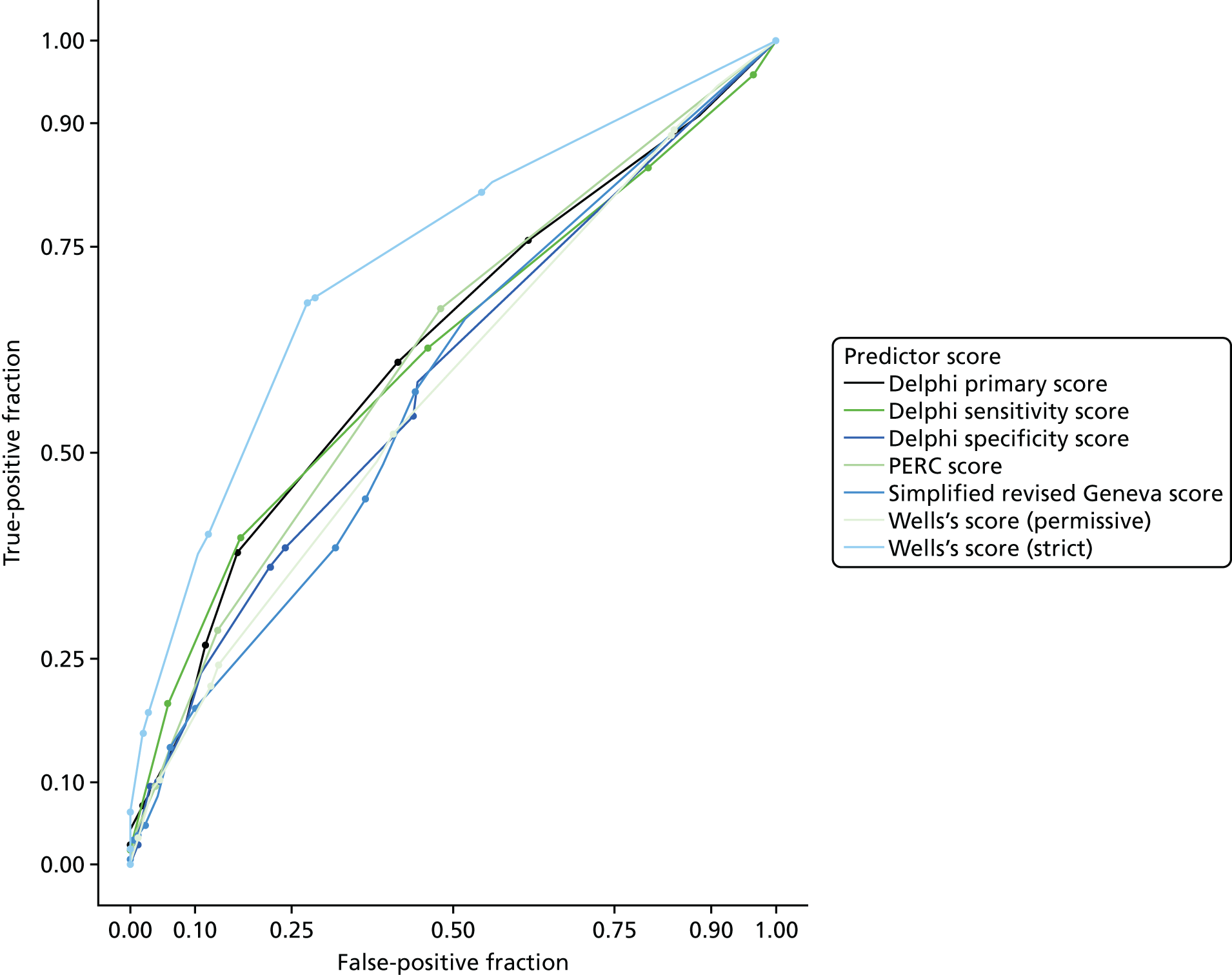

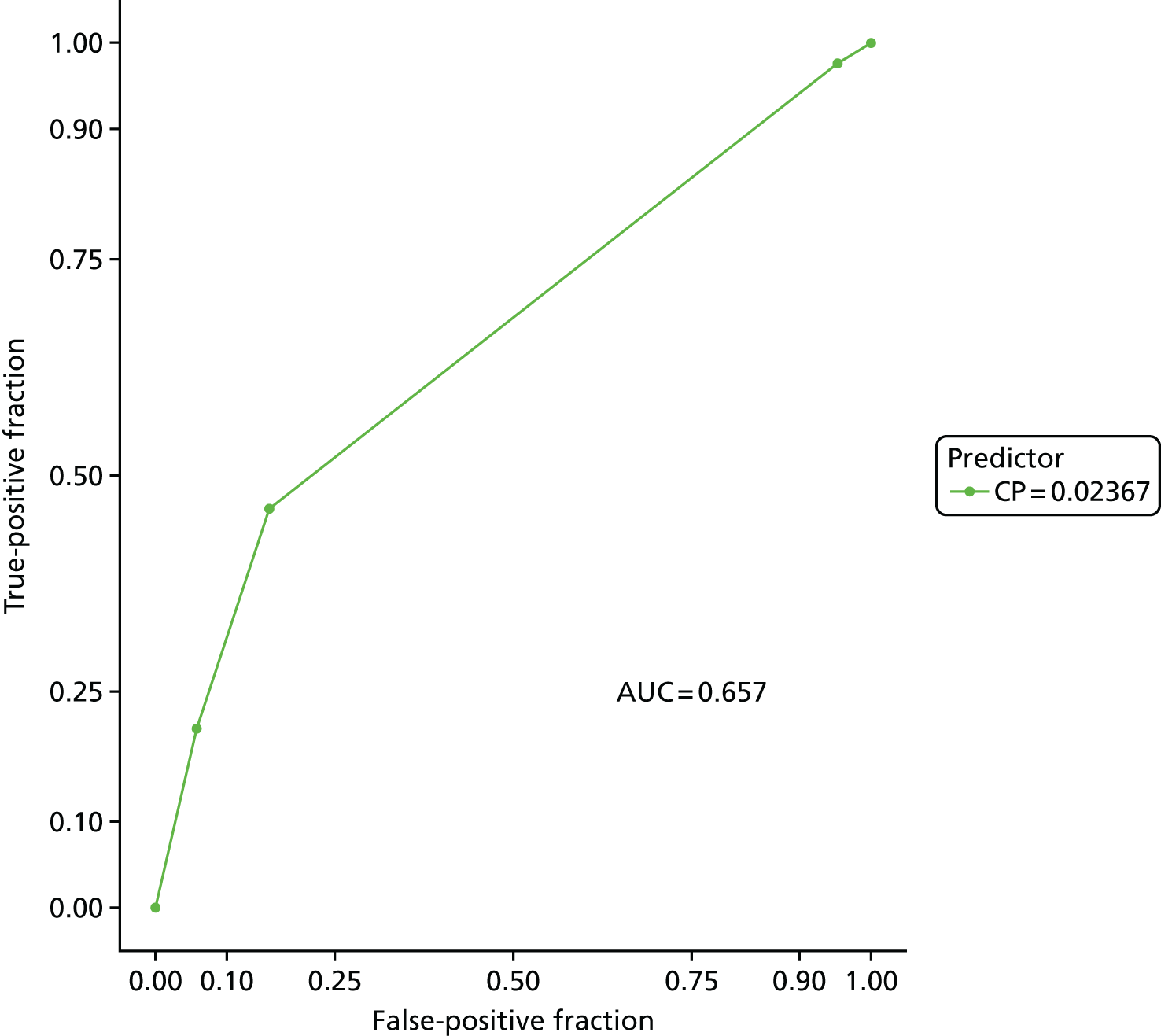

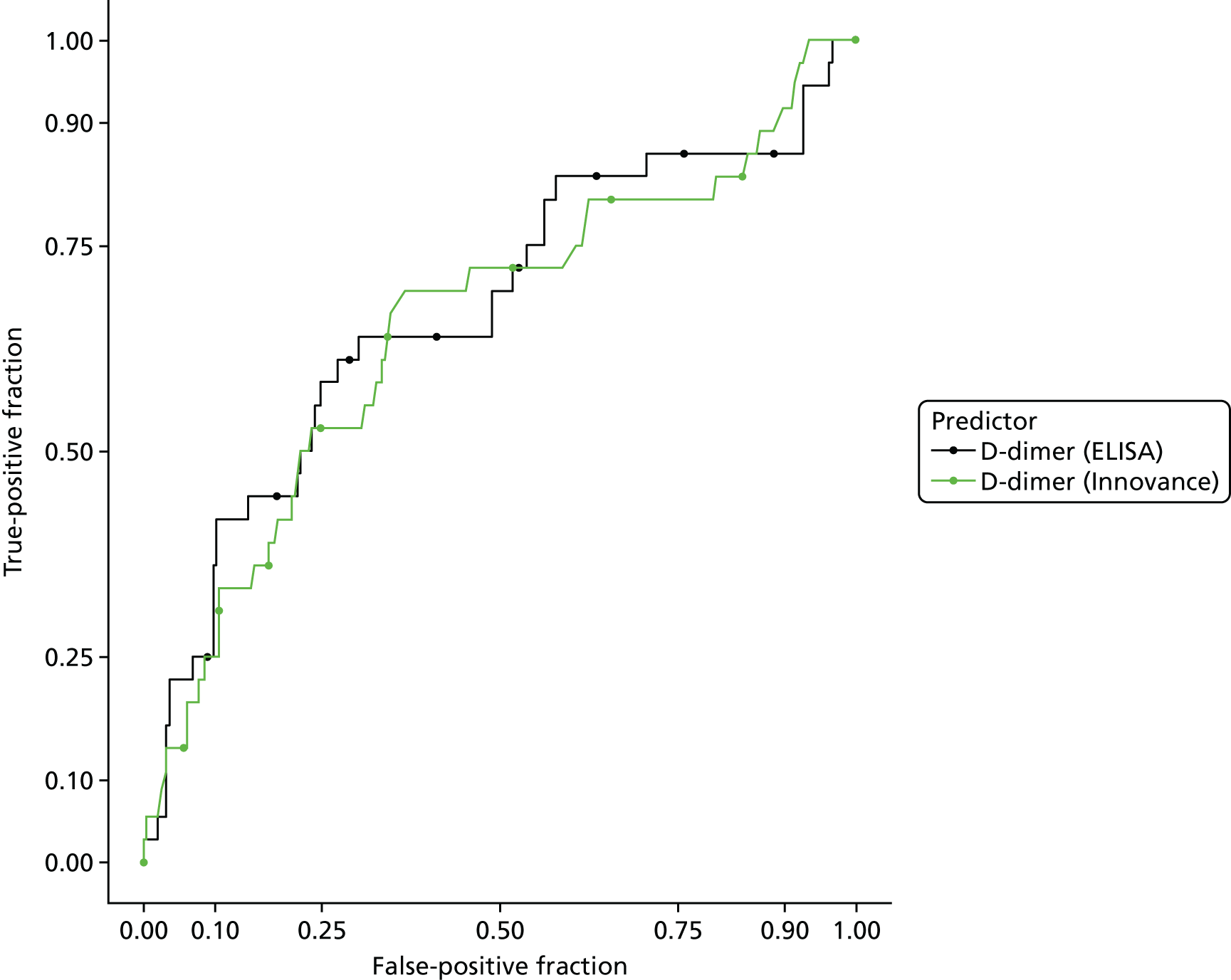

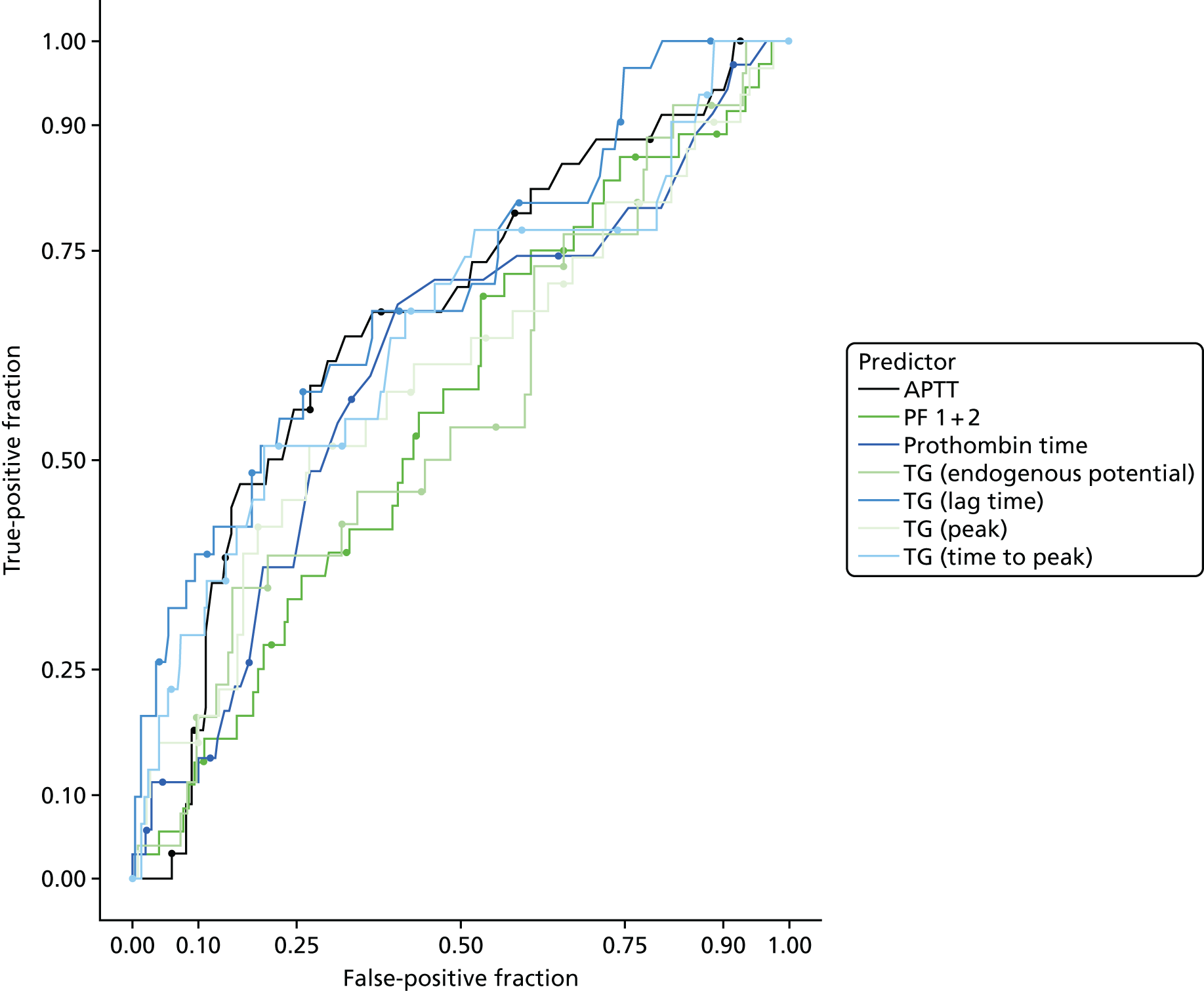

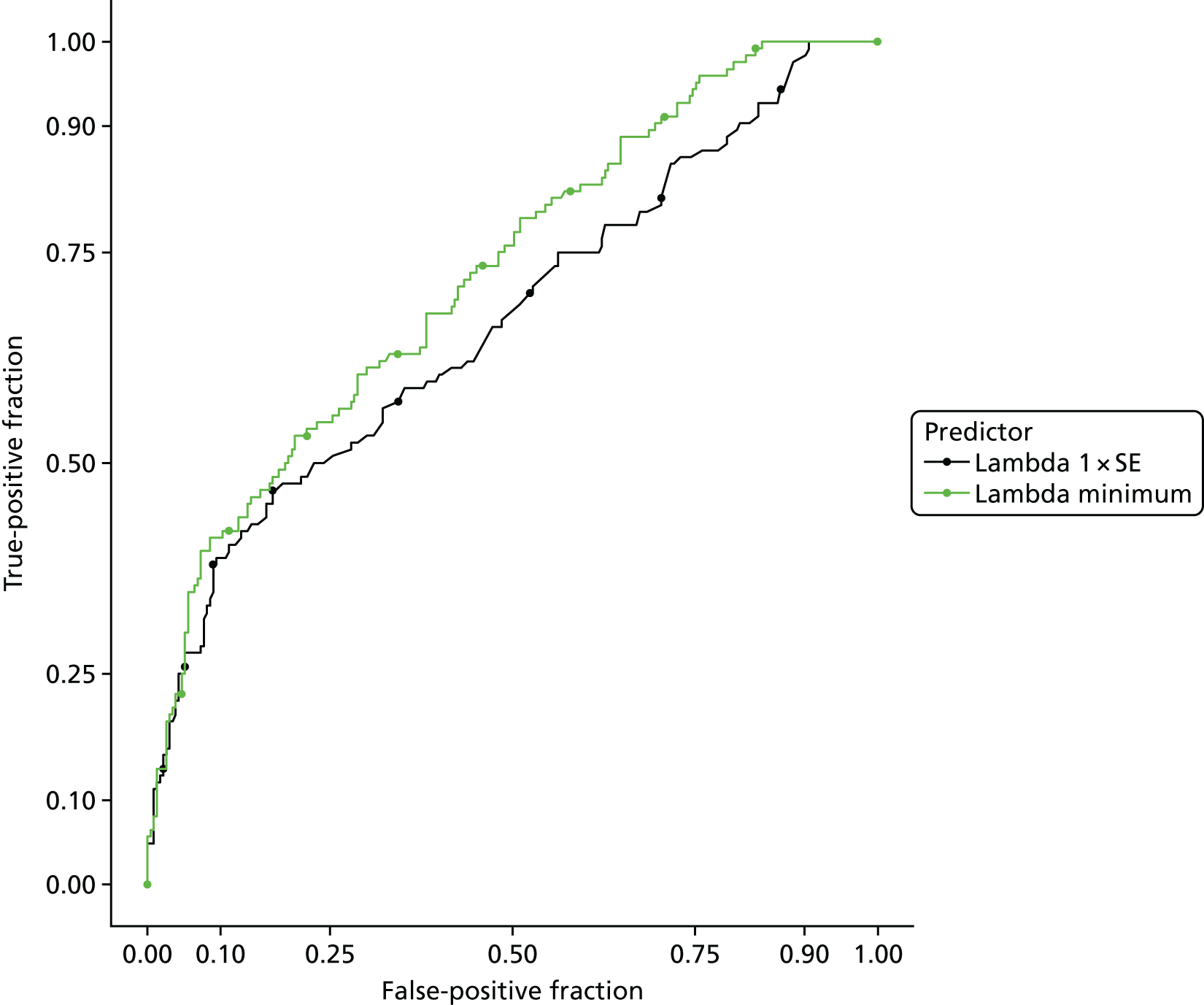

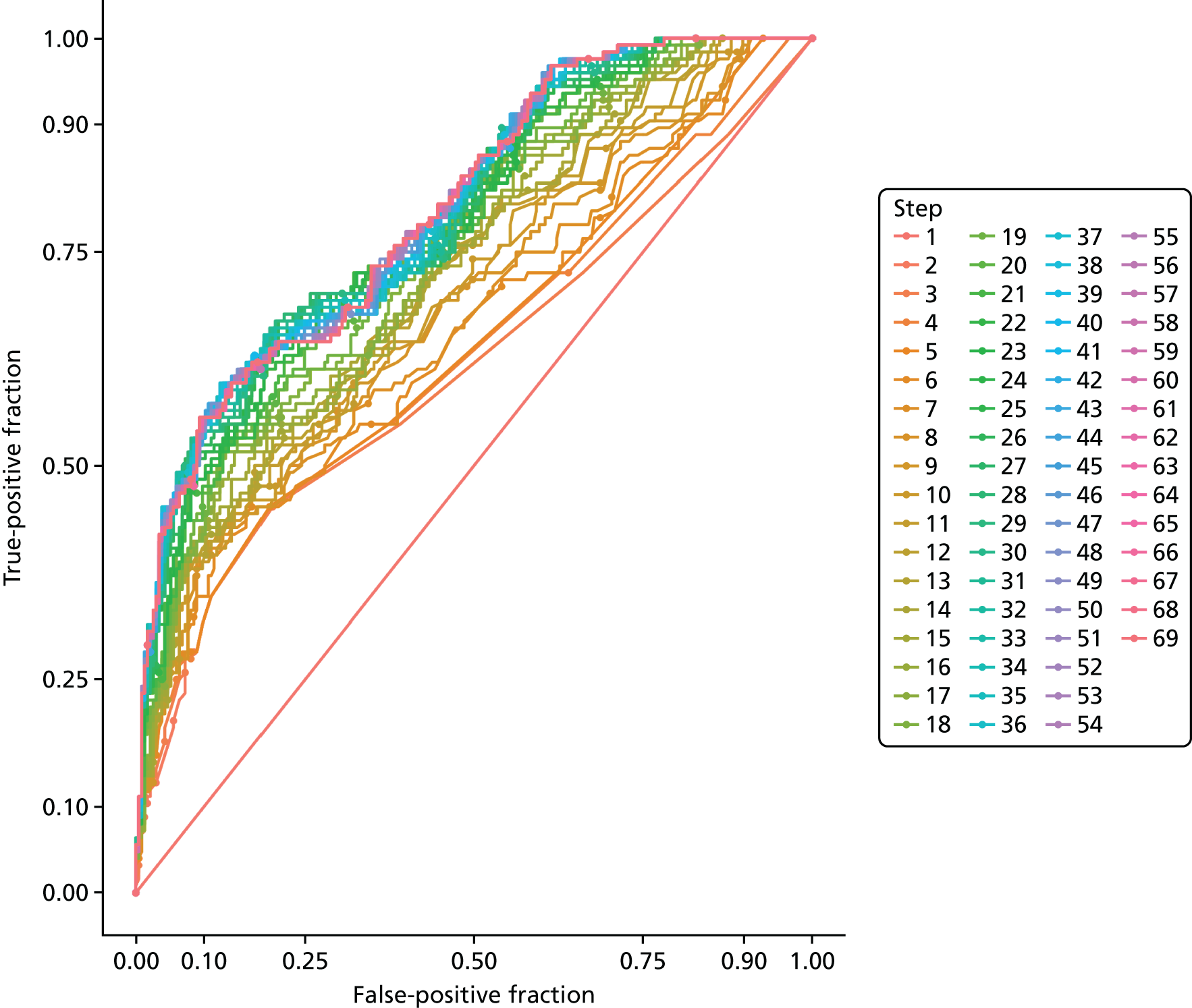

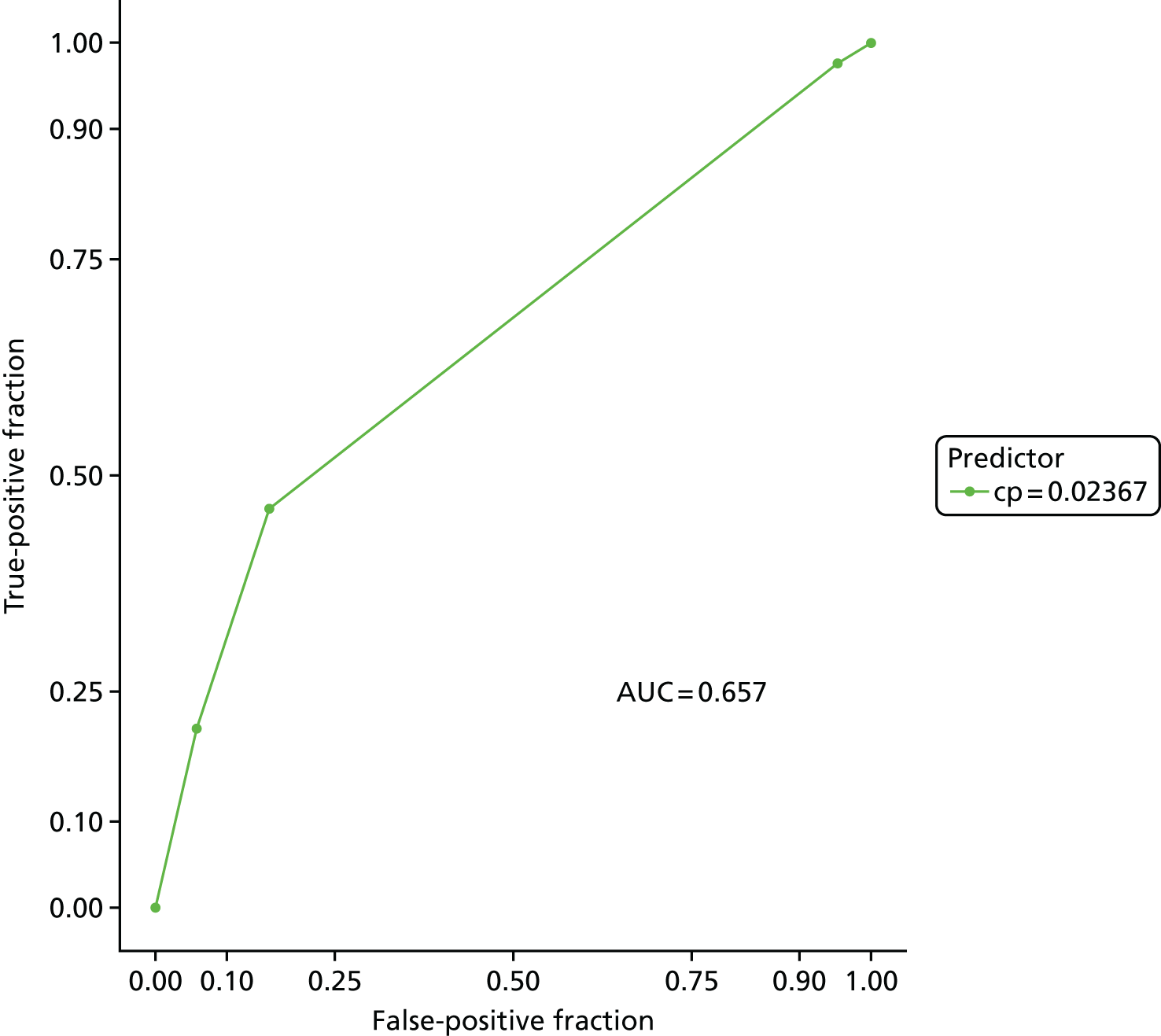

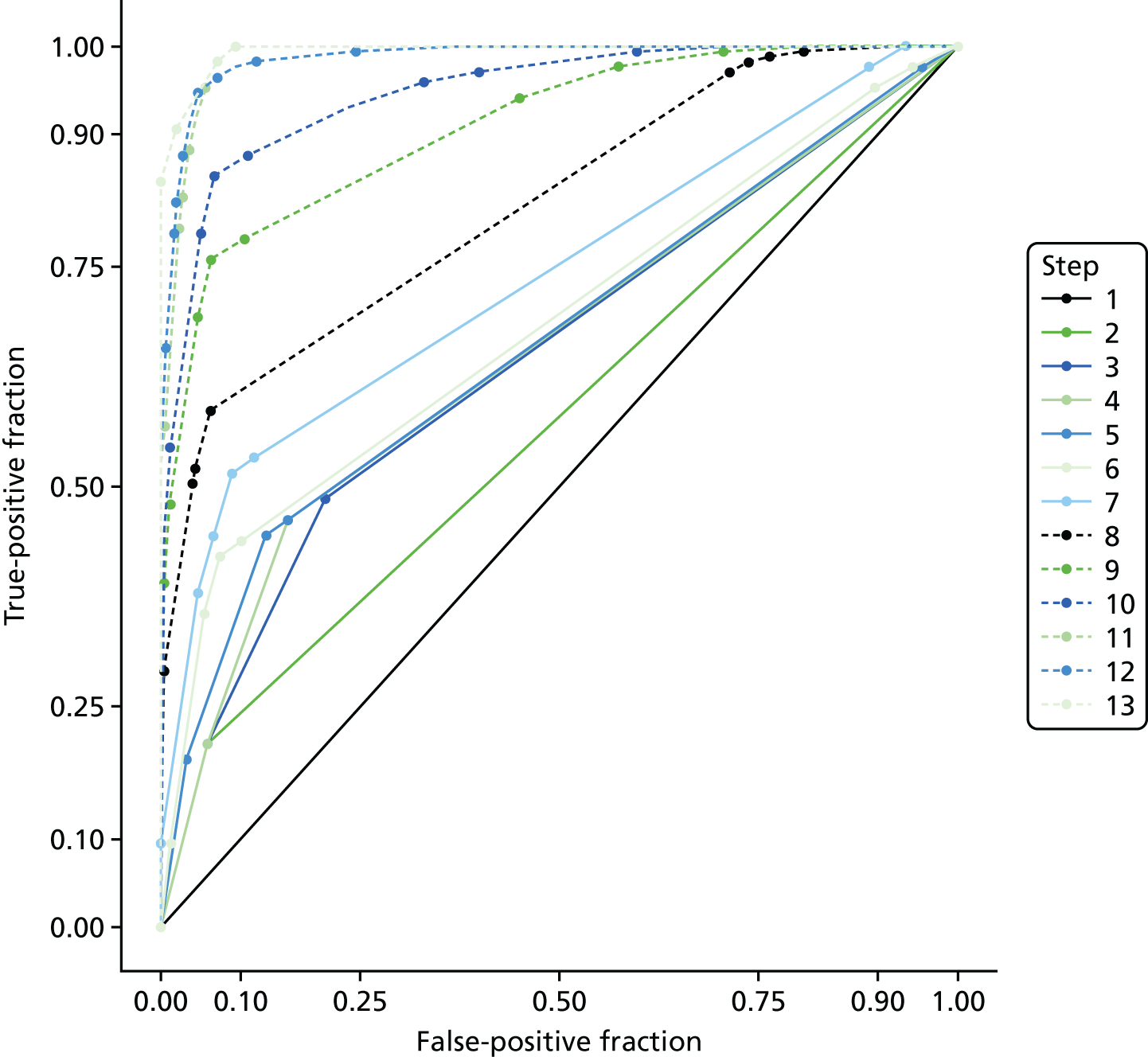

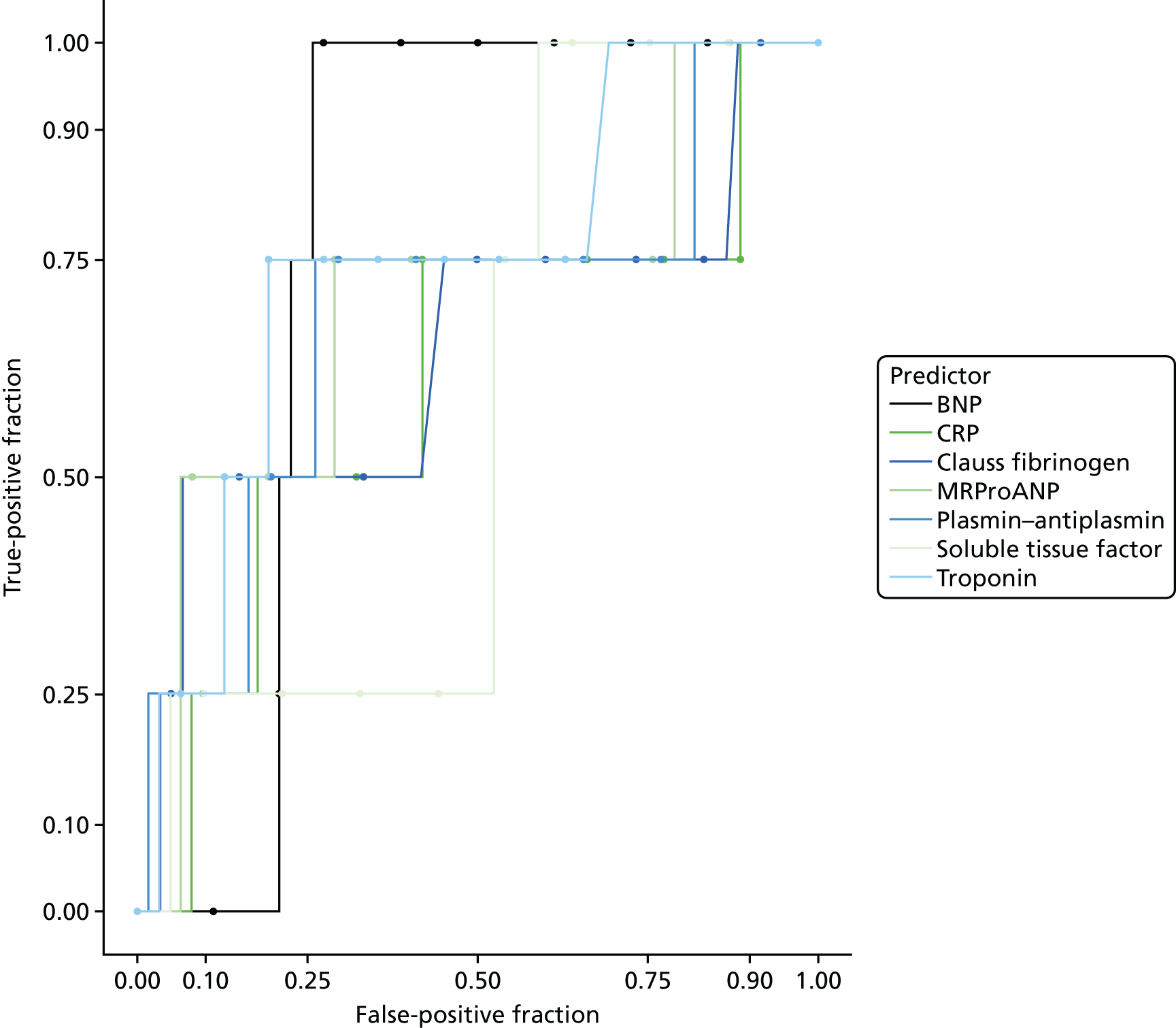

The accuracy of each index test was assessed by reporting and comparing the sensitivity and specificity. The combined sensitivity and specificity was assessed by plotting receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves and quantified by the area under the curve (AUC). By virtue of the case–control design oversampling the proportion of patients with PE, no attempt was made to estimate the positive and negative predictive values.

We retrospectively applied each of the decision rules derived by expert consensus (see Chapter 2) and the following existing decision rules to the data to estimate diagnostic performance:

These rules were not developed for use in the pregnant population, so we removed criteria that were not relevant to the pregnant population and adapted criteria when appropriate to be relevant to the pregnant population. We therefore removed exogenous oestrogen from the PERC rule and used the thresholds developed for our analysis of clinical variables to dichotomise age, oxygen saturation and heart rate (see Table 4). The need to design a CRF that would be usable for both prospective and retrospective data collection and that would address the multiple study objectives meant that criteria used in each rule did not always map precisely onto variables in the CRF. Furthermore, data for some of the variables were missing. Appendix 2 outlines how the criteria in each rule were applied to the study data.

The diagnostic performance of CDRs is normally presented as the proportion in each risk stratum with the outcome of interest (in this case PE). This is similar to reporting positive and negative predictive values for a diagnostic test. This approach would be misleading in the DiPEP analysis, because the prevalence of PE in the analysis cohort has been deliberately inflated using the UKOSS data to increase the precision of estimates of sensitivity. Positive and negative predictive values are dependent on sensitivity, so the proportion of PE in each stratum would be much higher than if the rule was used in a typical clinical cohort with low prevalence. We therefore assessed the accuracy of each index test by calculating sensitivity and specificity at the usual or recommended decision-making threshold, plotting ROC curves and quantifying the AUC. The consensus-derived rules each specified a threshold for the rule being positive or negative. The PERC score was considered positive if any criterion was positive. The Wells’s criteria score was considered to be positive if the score was ≥ 4 points (PE likely). The simplified revised Geneva score was considered to be positive if the score was ≥ 4 points (moderate or high risk).

D-dimer (as measured in the hospital laboratory and recorded in the clinical notes) was analysed as a separate index diagnostic test, rather than as one of the clinical variables, and was not included in the CDRs, multivariable analysis or recursive partitioning. The diagnostic accuracy was assessed by calculating the sensitivity and specificity at the hospital laboratory threshold and the pregnancy-specific thresholds outlined previously. We did not use ROC analysis for D-dimer because of the complexity of having to use different thresholds for different assays across the multiple hospitals contributing data to the study.

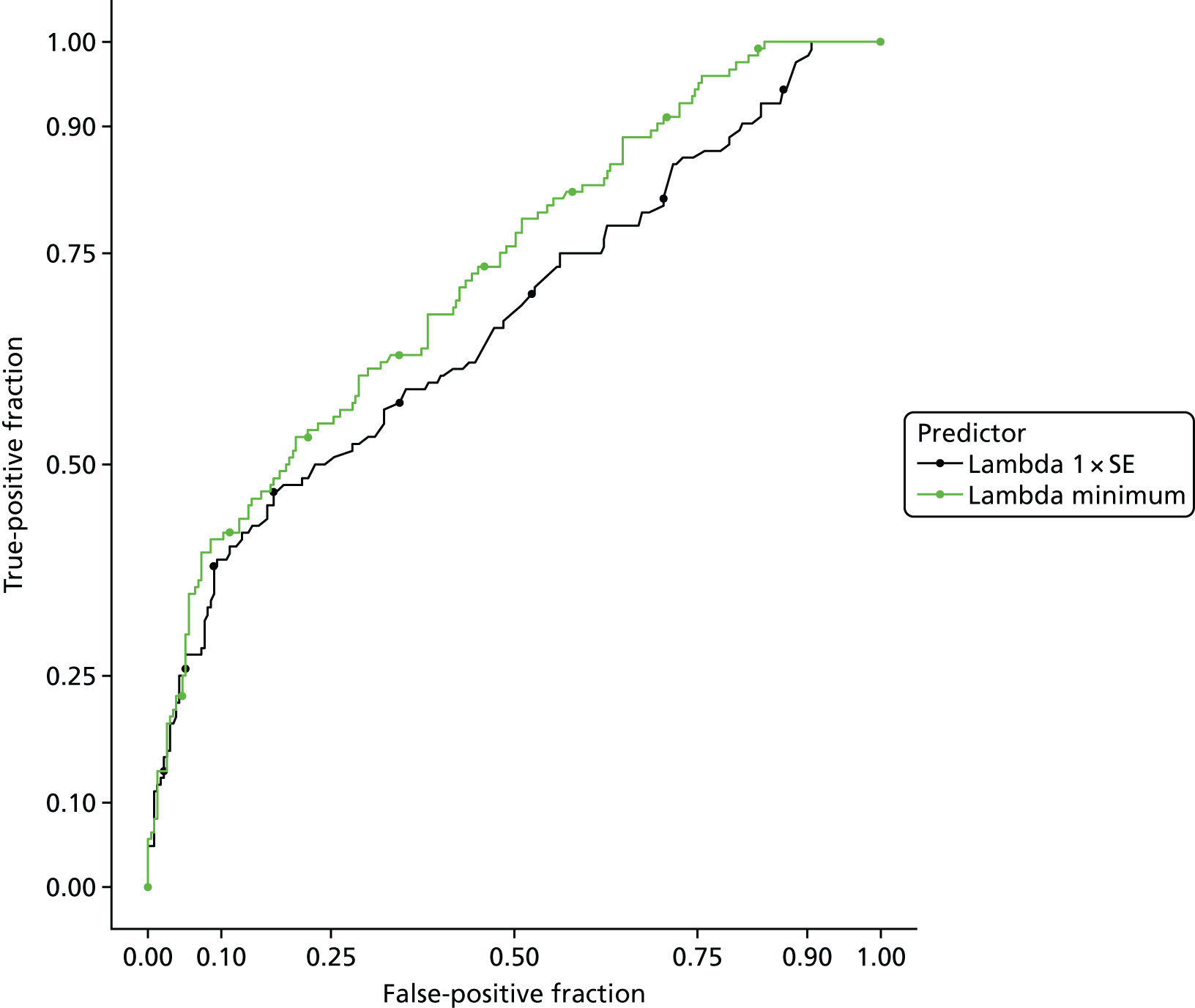

Methods of statistical modelling

Three statistical modelling approaches were used in the development of new decision rules:

-

Logistic regression.

Univariable logistic regression analyses were undertaken to identify associations between clinical features and diagnosis of PE.

-

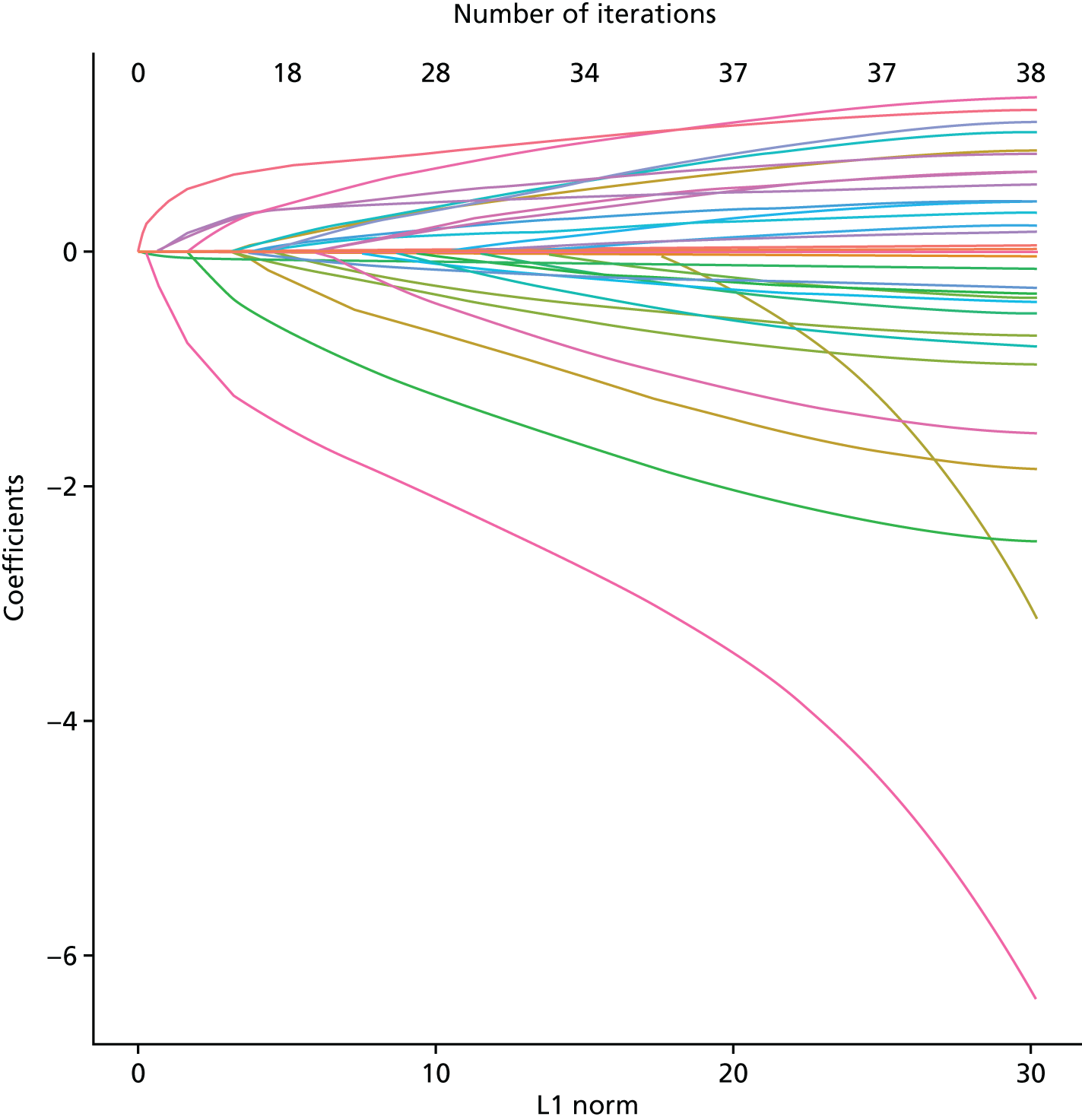

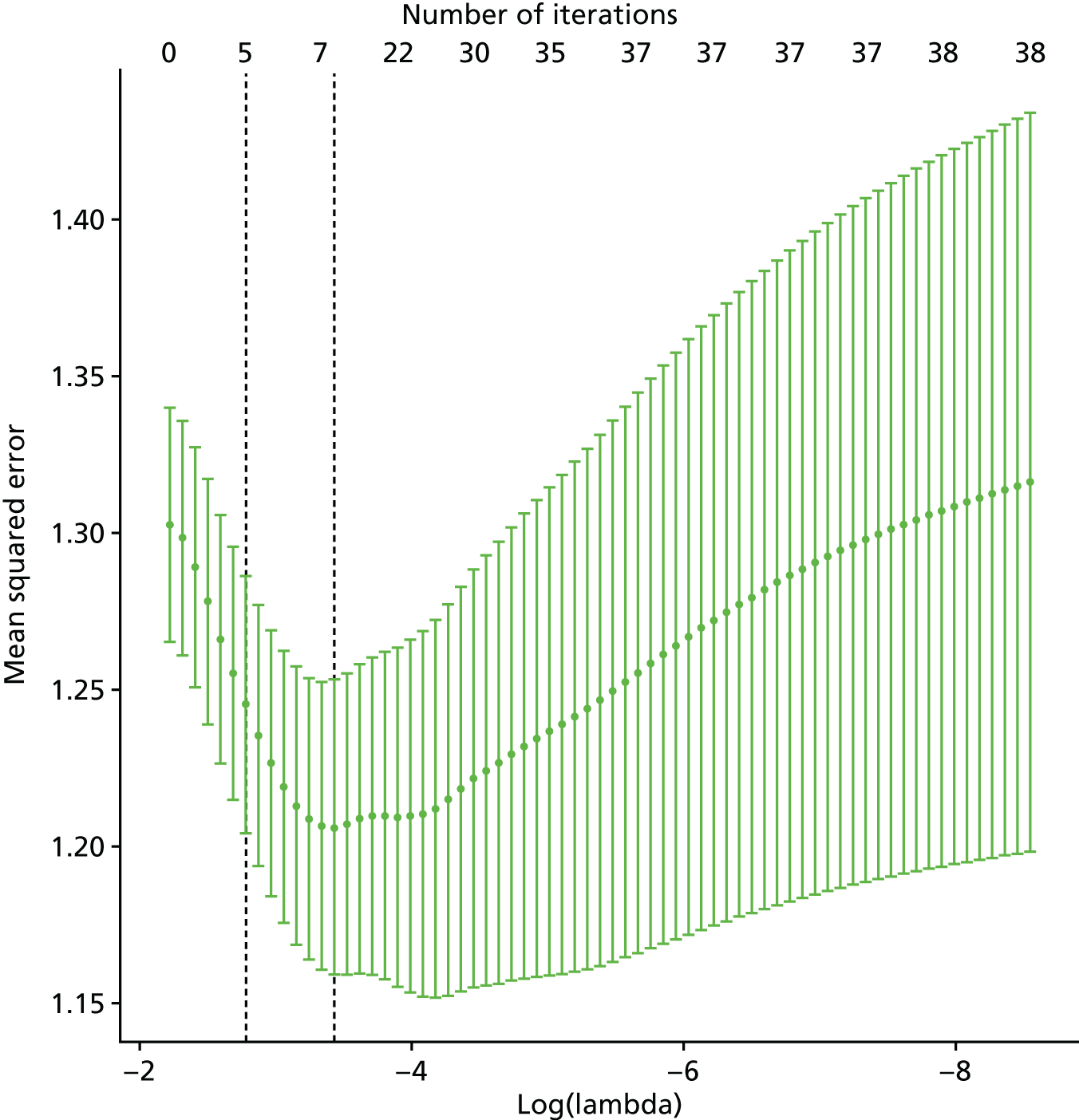

The least absolute shrinkage and selection operator (LASSO).

The LASSO regression modelling approach was used to assess the predictor variables and estimate the effect of each variable on the outcome. 46–48 This method is also based on multivariable logistic regression modelling, but addresses some of the problems of overfitting in the presence of multiple correlated covariates. The LASSO adaptation of logistic regression applies a penalisation against higher-dimension models, thereby helping to protect against coefficients being spuriously inflated. 49 We included all clinical variables in the analysis, regardless of their univariable association, but did not include receipt of thromboprophylaxis as a clinical variable. Thromboprophylaxis is targeted at women who are at risk of VTE and is intended to prevent PE. It is therefore likely to have a complex and inconsistent association with PE.

-

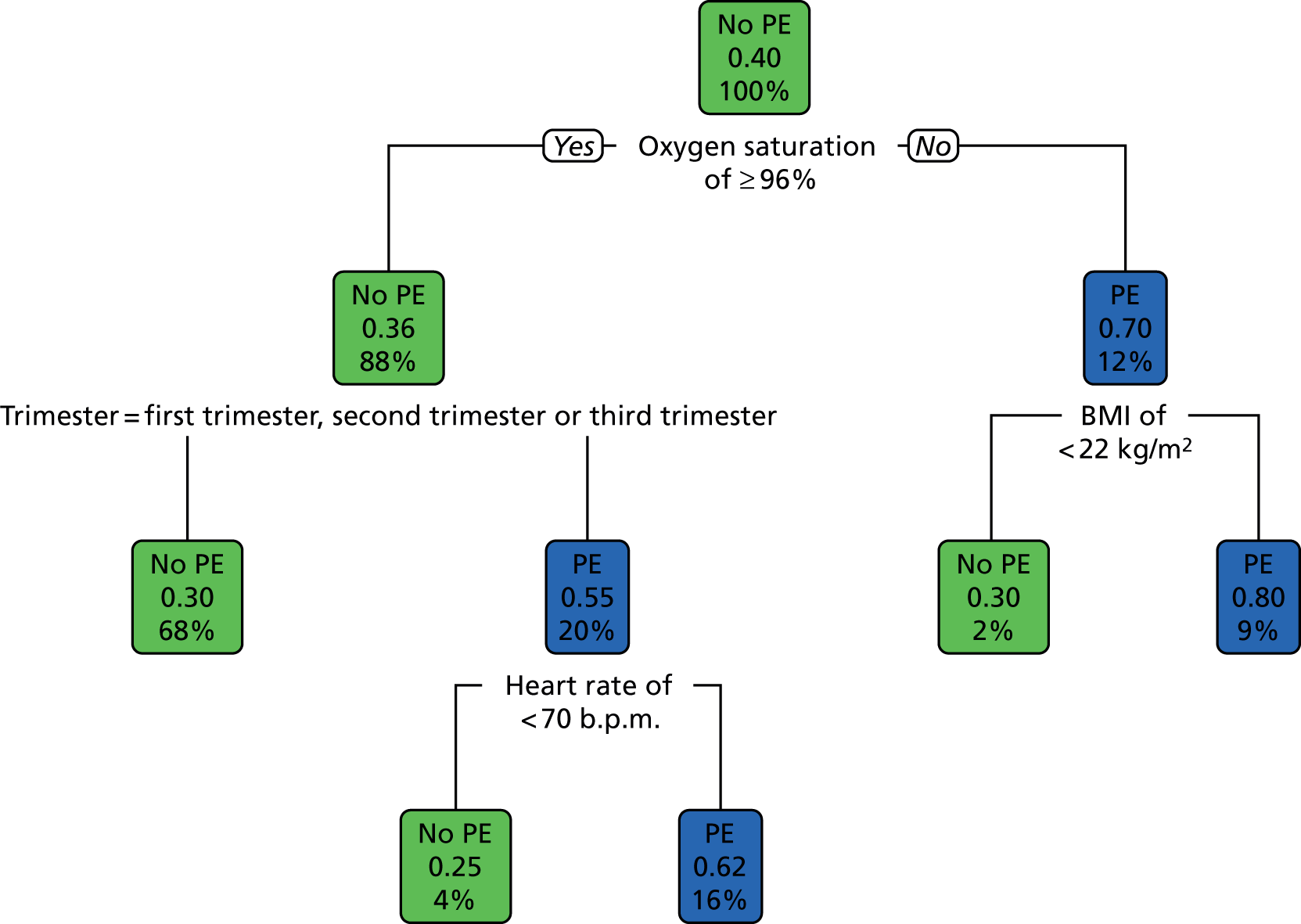

Recursive partitioning.

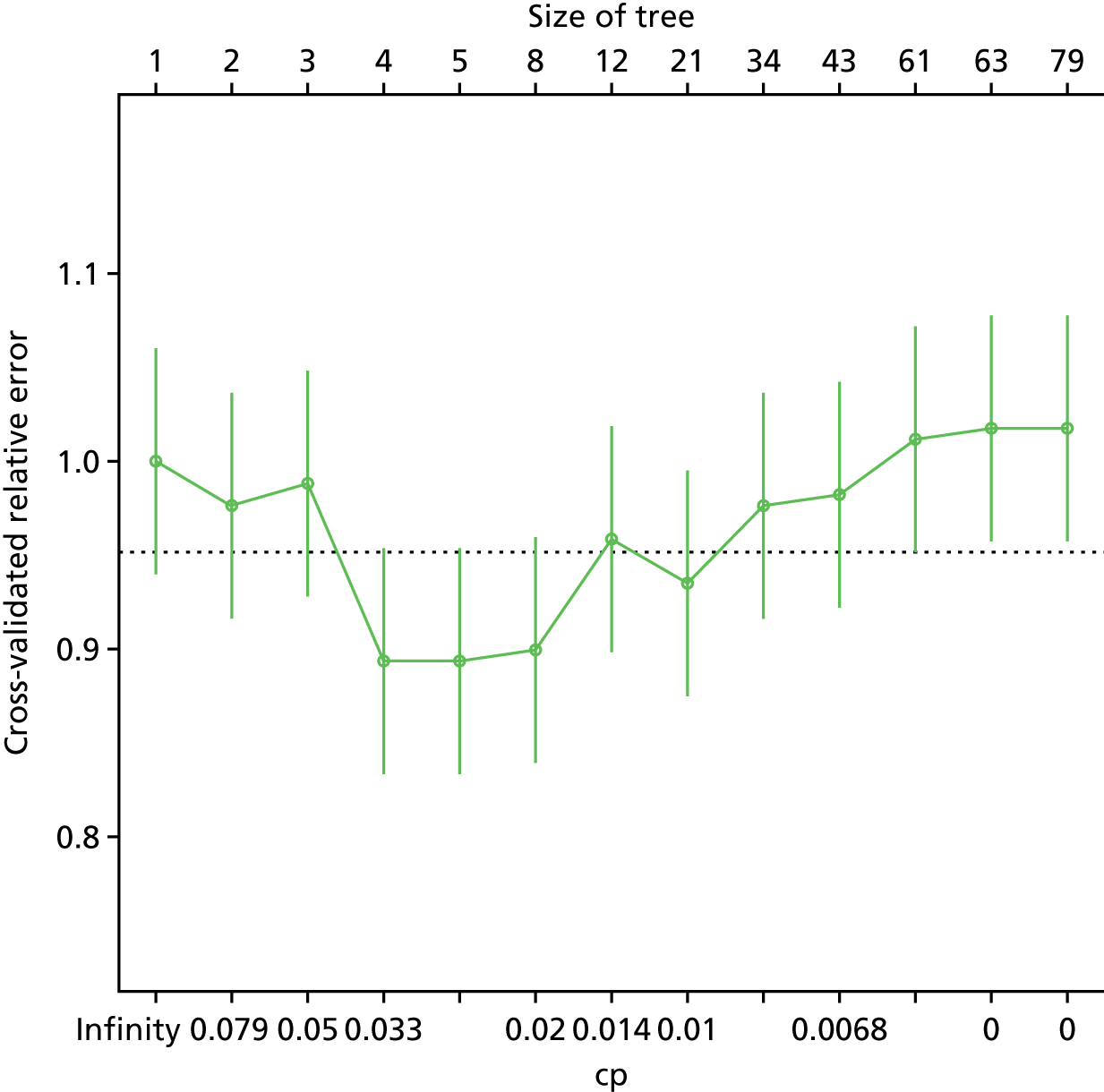

Recursive partitioning50 is a different approach which is used to create decision tree models. Rather than estimating a formula linking outcome to a combination of covariates, recursive partitioning attempts to identify subgroups with higher incidences of PE based on their characteristics, the aim being to derive a rule with optimal sensitivity (ideally of > 95%). This had the advantage that continuous variables did not need to be dichotomised beforehand, as the partitioning algorithm not only determines which subset of variables provides the optimal classification, but also the cut-off points within predictor variables. As is standard practice when performing recursive partitioning, cross-validation is employed at each partition to ensure that fully fitted trees were pruned based on a function of the complexity parameter that minimises the cross-validation error in order to avoid overfitting.

We intended that clinicians would review the derived models to ensure clinical credibility. We planned to purge variables that were considered to be inappropriate (e.g. if it was something that could not in practice be assessed) and then refit the models and recalculate the coefficients of the remaining covariates. Clinical opinion would then be sought to weight/round the coefficients into simple decision rules and decide upon a threshold for decision-making.

In accordance with the principles of reproducible research, all analyses were performed using a literate programming approach, which allowed the recreation of tables and figures at will by anyone experienced in using the software. The scripts were version controlled using the Git version 2.13 [(2017) Github Inc., San Francisco, CA, USA] control system and self-documenting. The statistical programming language R was used to undertake the statistical analysis.

Results

Women with diagnosed pulmonary embolism

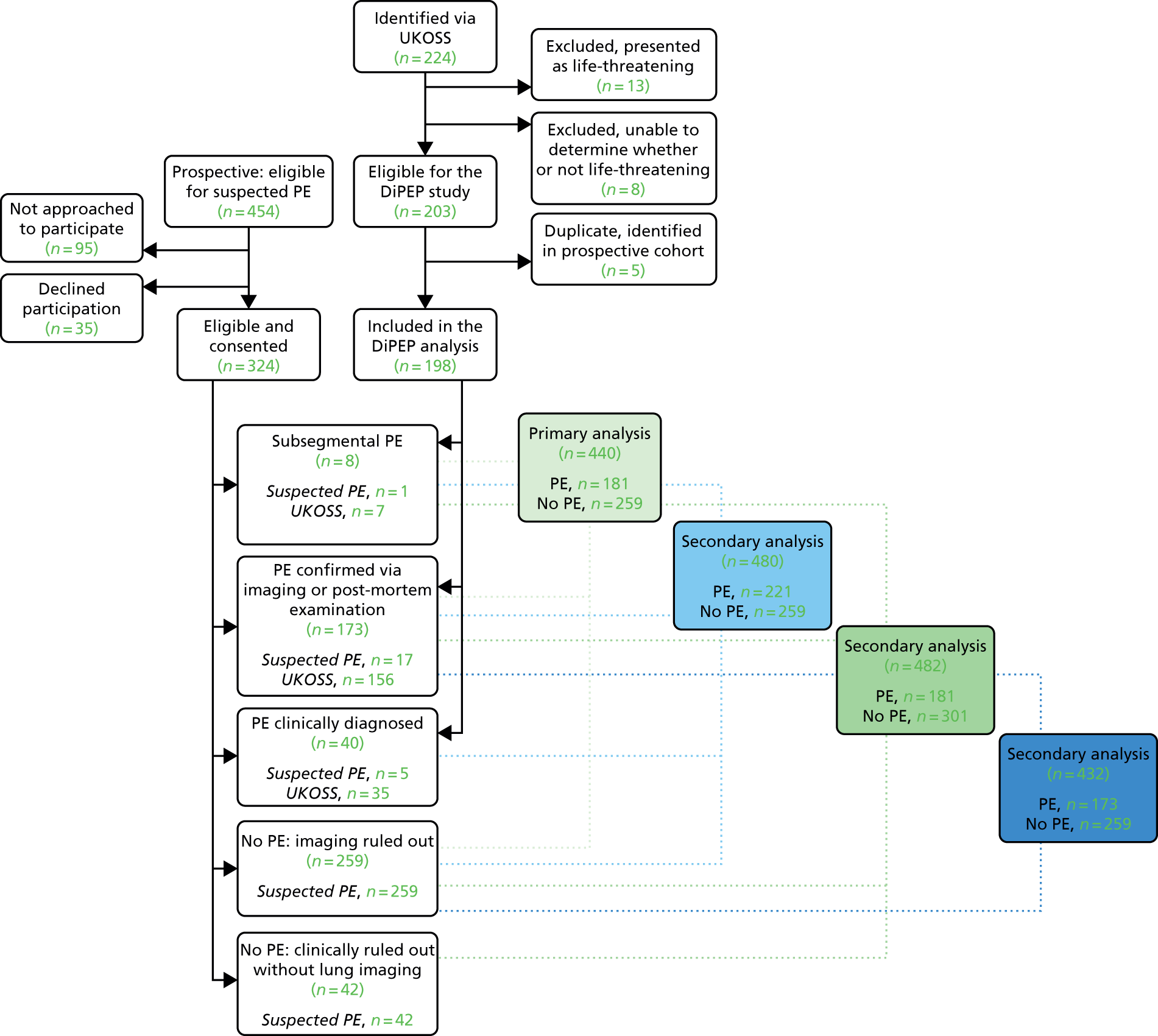

A total of 224 women were identified through the UKOSS between 1 March 2015 and 30 September 2016. We excluded 13 women because they were recorded as presenting with life-threatening features and a further eight women because presentation with life-threatening features was not recorded and the absence of life-threatening features could not be inferred from physiological data. We identified five women who had also been recruited with suspected PE (their data were removed from the UKOSS data set) and three whose characteristics matched women in the eligible but non-recruited data set (their data were retained in the UKOSS data set). Thus, we included data from 198 women with diagnosed PE in the study analysis.

Women with suspected pulmonary embolism

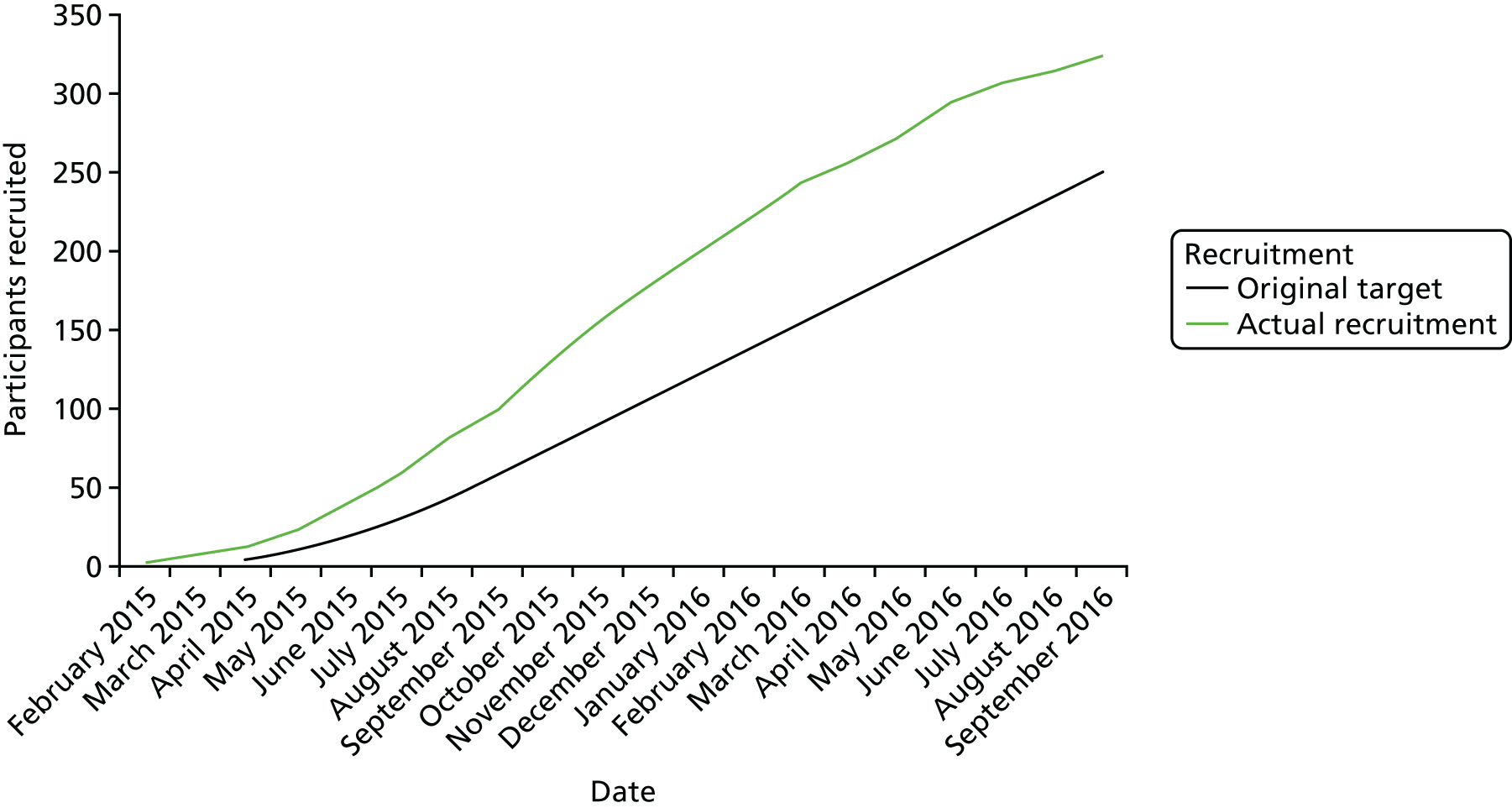

We originally planned to recruit across eight sites over 18 months at a rate of two per site per month to achieve a sample size of 250 women. However, we realised after developing the detailed statistical analysis plan and examining initial data that the exclusion of those with clinically diagnosed or clinically ruled-out PE from the primary analysis would potentially leave the primary analysis underpowered. We therefore increased the number of participating sites to 11 to ensure that the planned sample size of 250 women would be achieved for the primary analysis.

A total of 324 women were recruited across 11 participating sites between 15 February 2015 and 31 August 2016. The result of diagnostic imaging for PE was known by the research nurse/midwife at the time of consent for 46 out of 324 women (14%). A further 35 were eligible for recruitment but declined to participate and 95 were not asked to participate despite being eligible, usually because of the lack of availability of an appropriate person to undertake recruitment. Non-identifiable data were collected from this latter group of women, who formed the cohort of eligible but non-recruited women. Appendix 3 provides details of the recruitment process and the flow of participants through the study. The mean monthly recruitment rate per site was 1.7 women per month per site across the study.

Reference standard classification

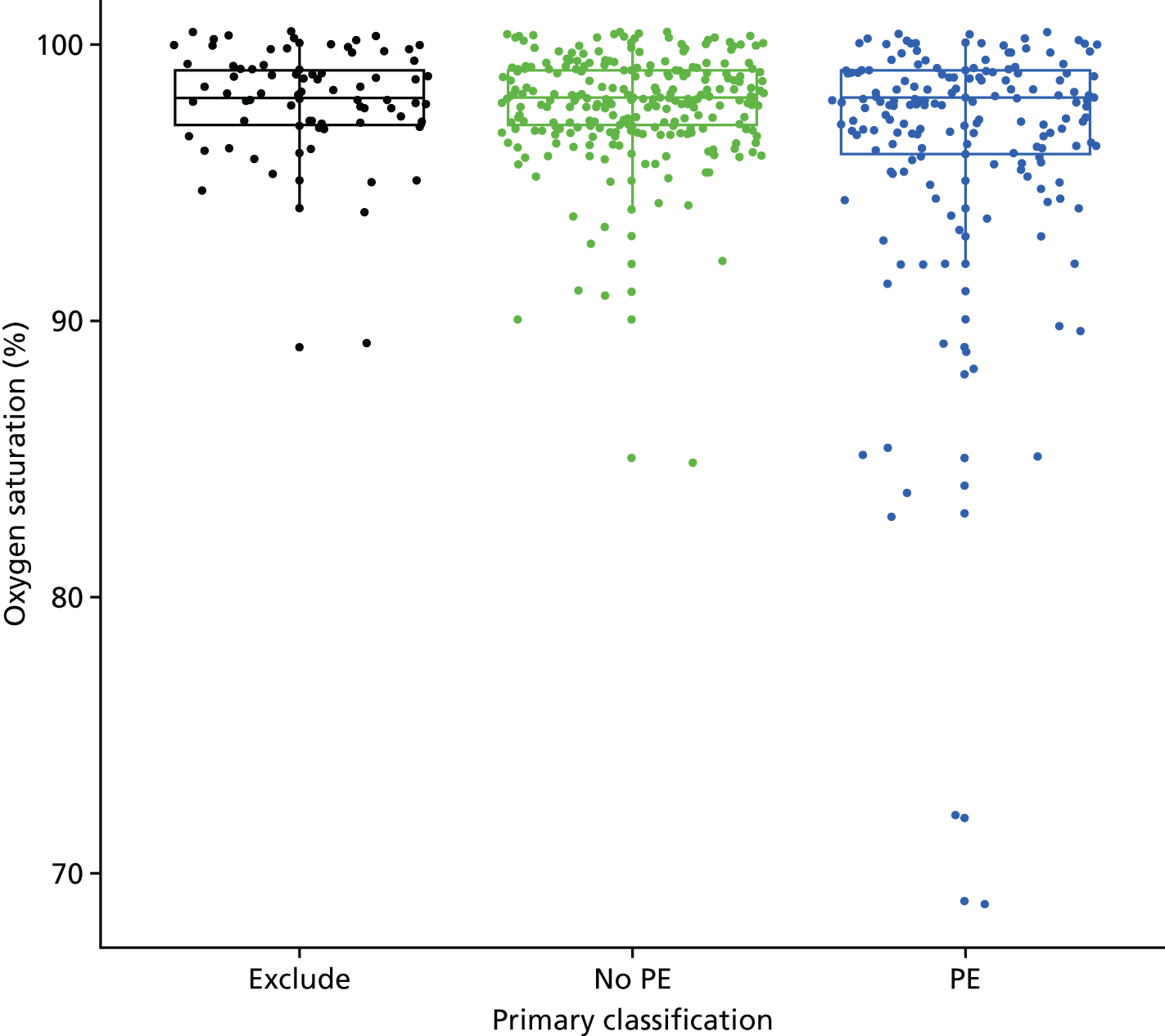

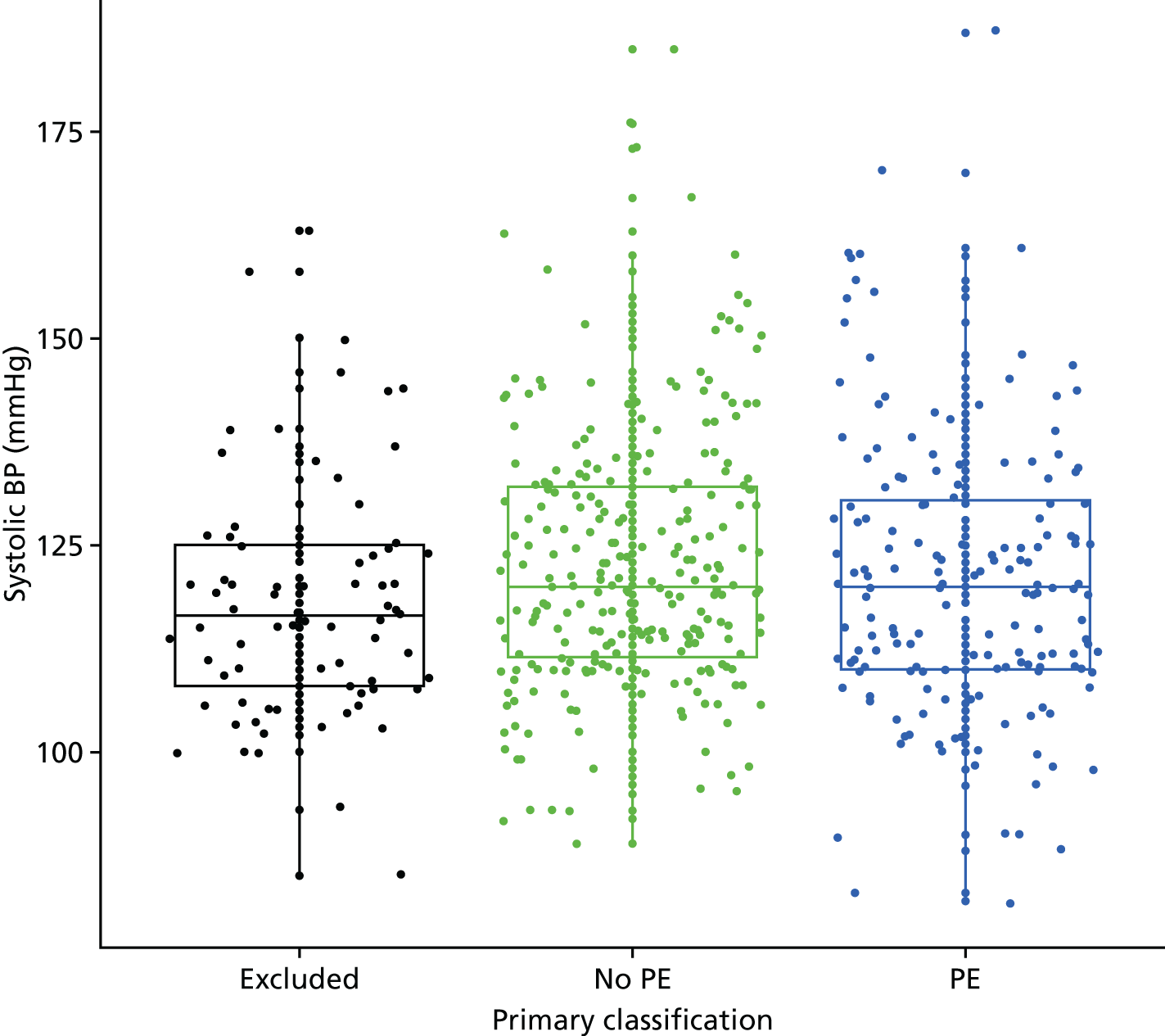

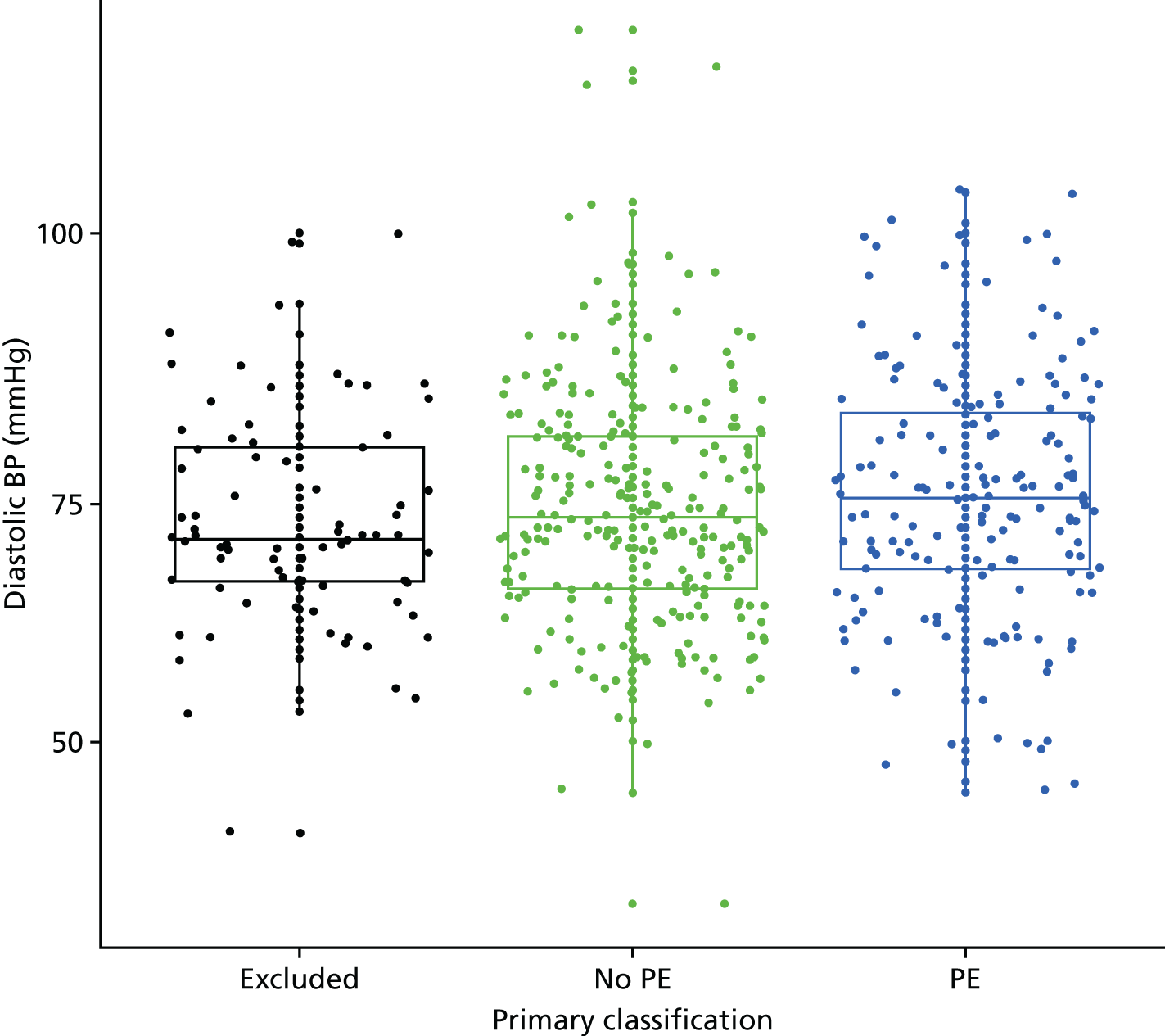

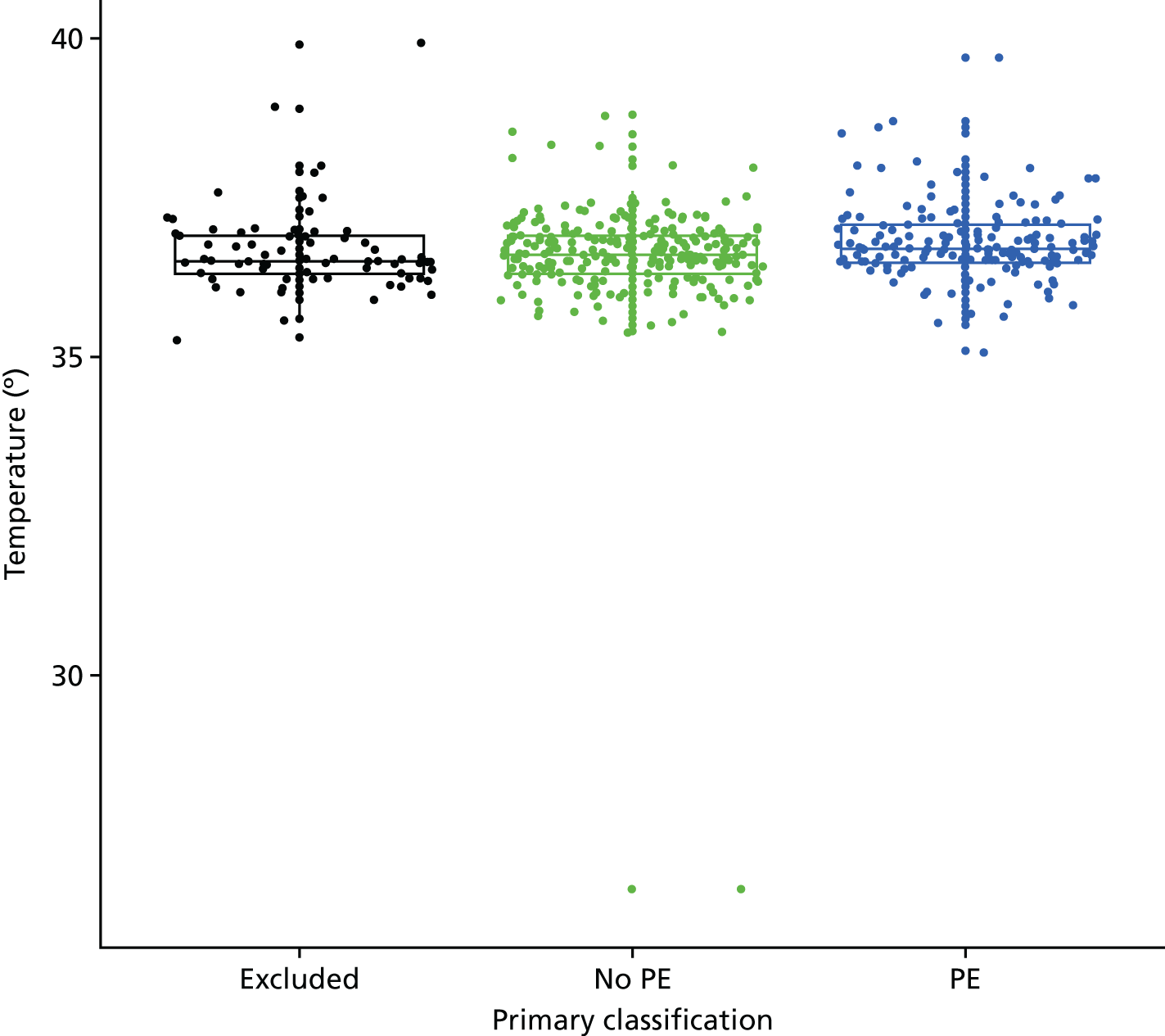

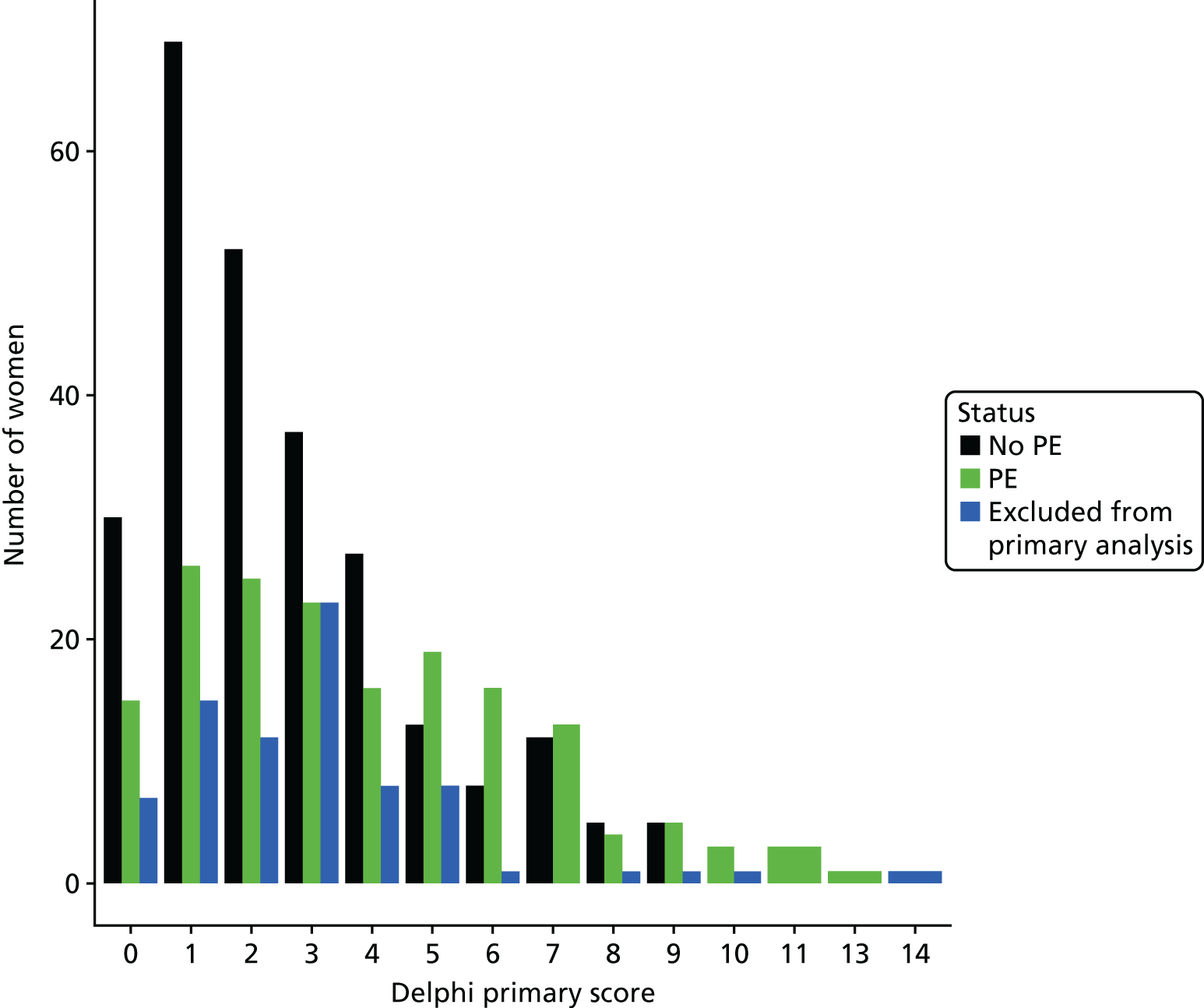

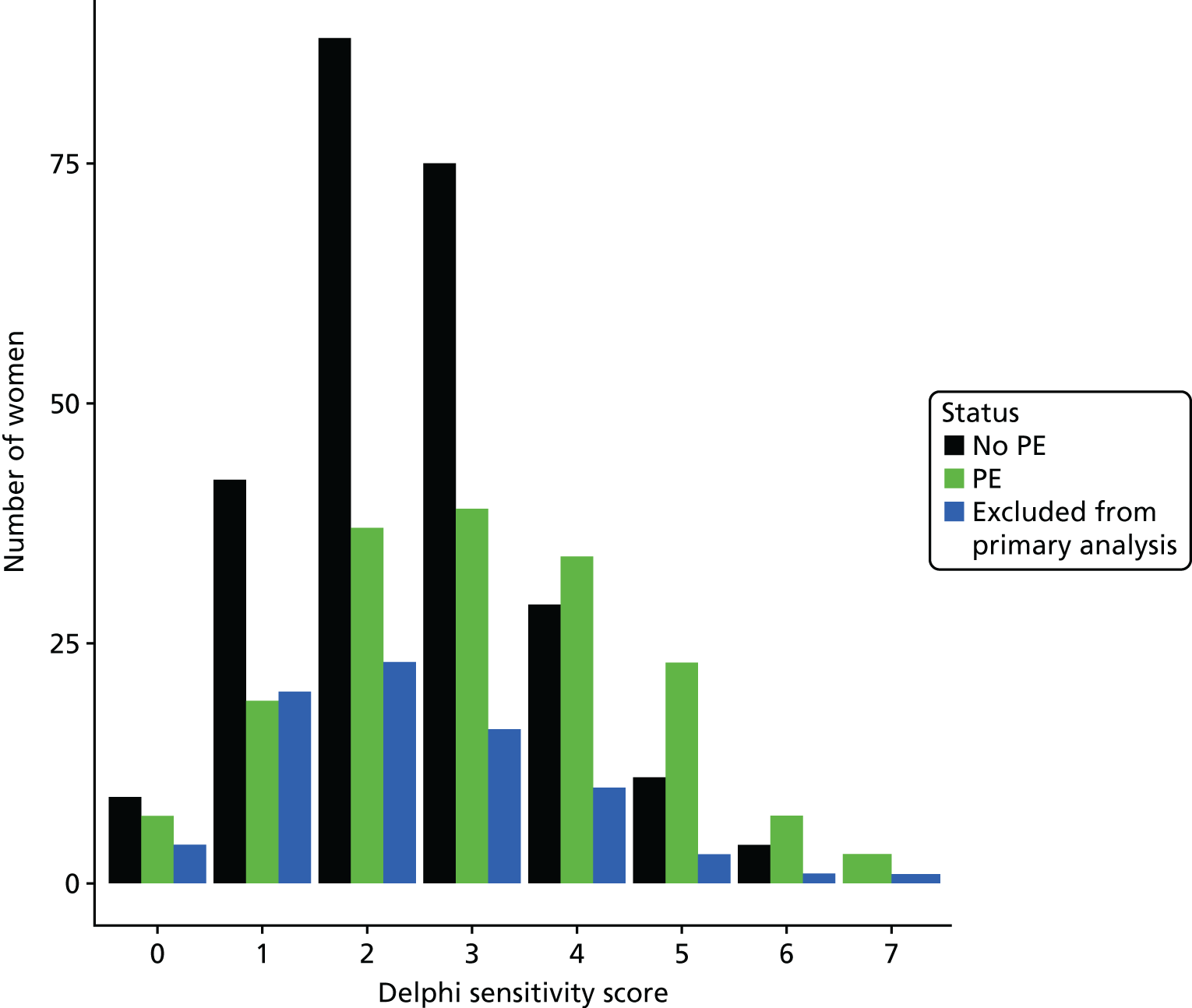

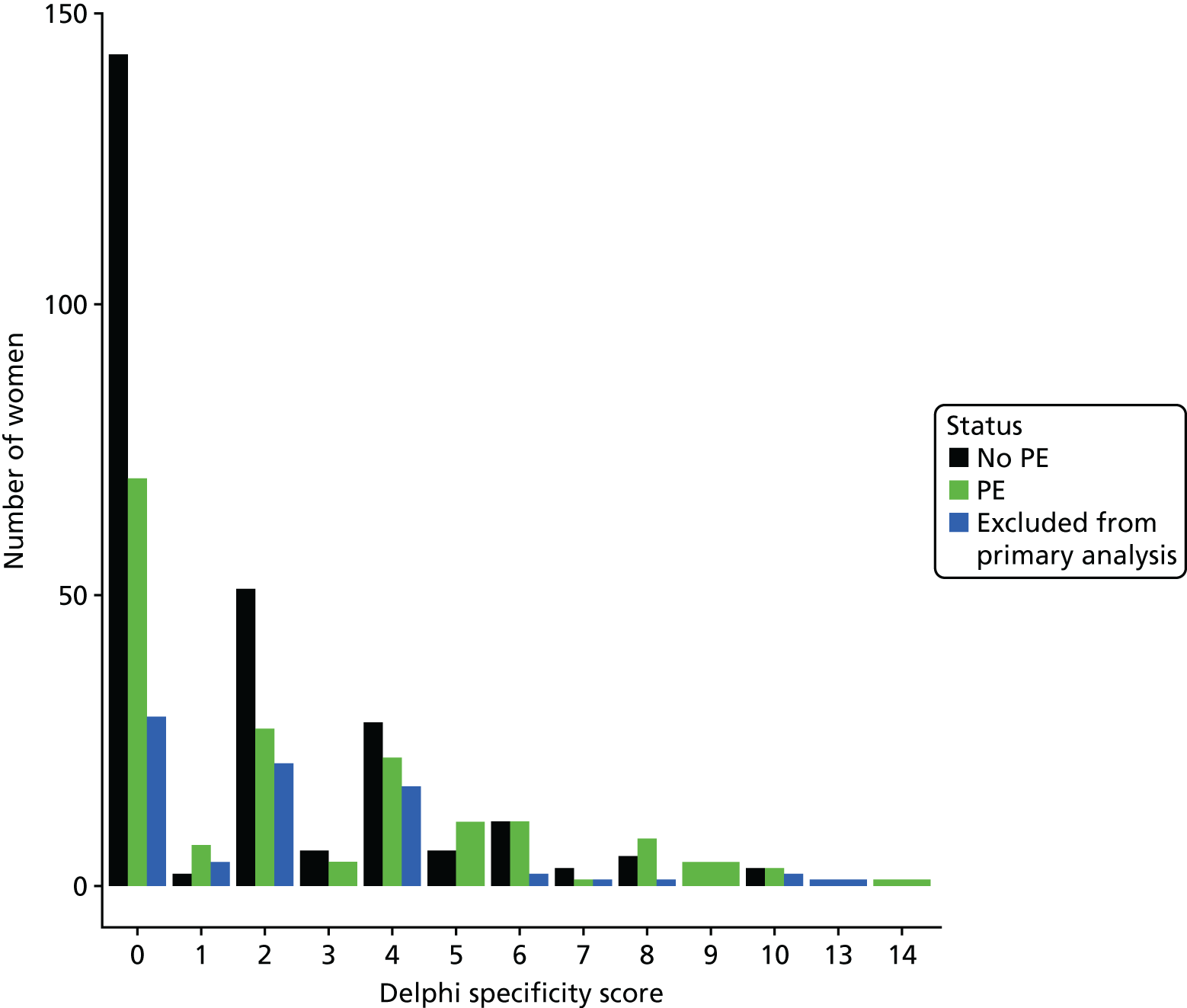

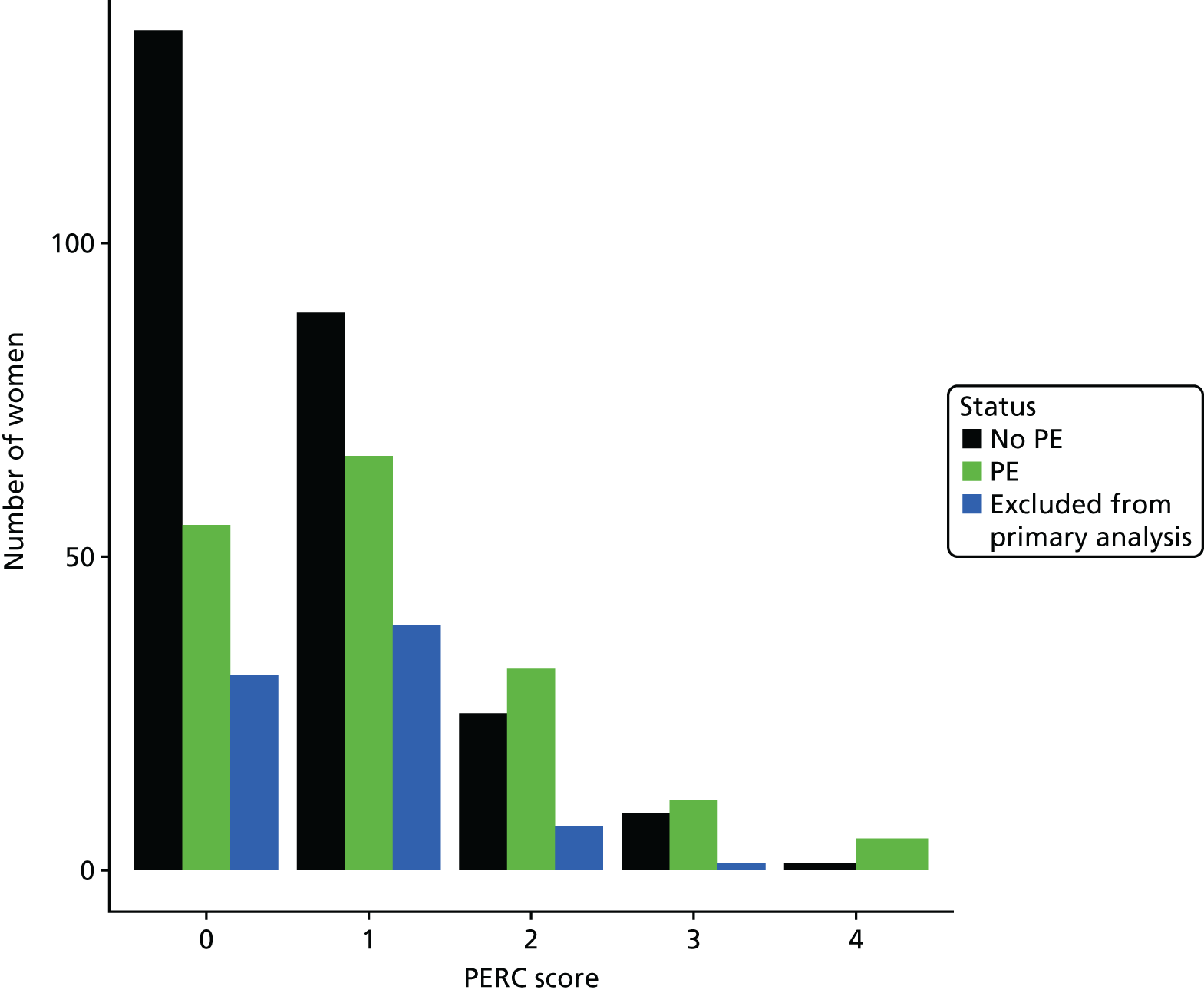

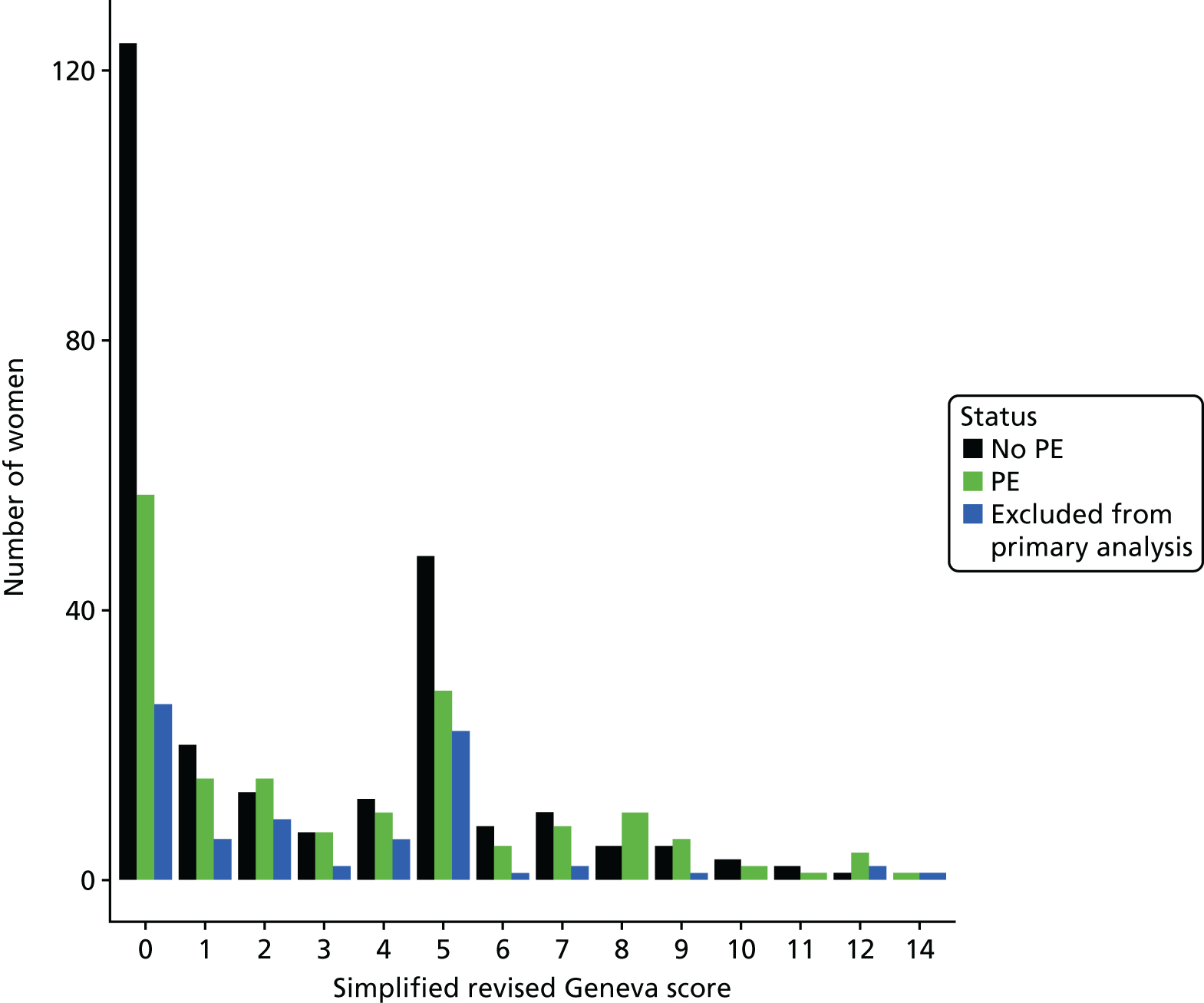

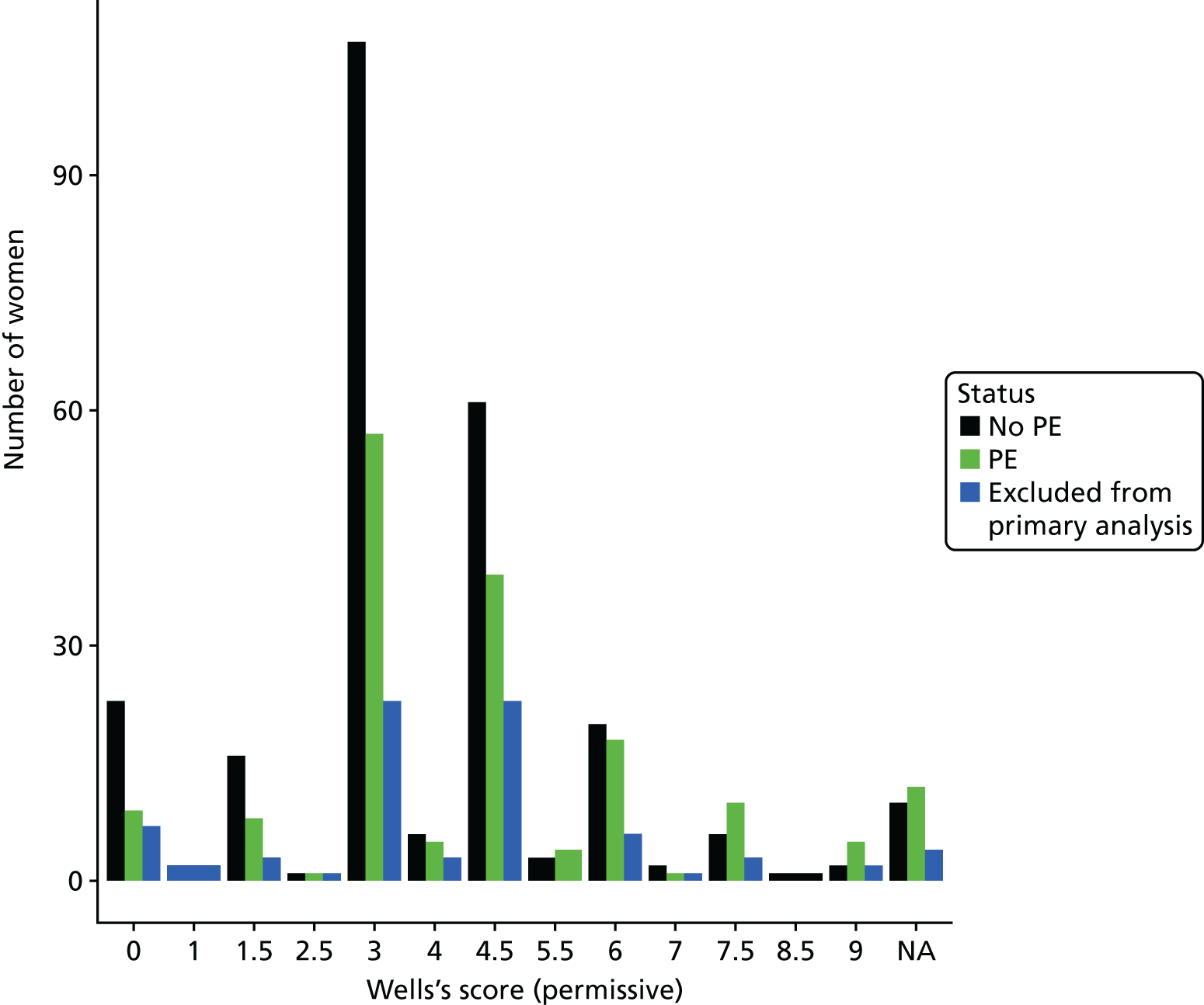

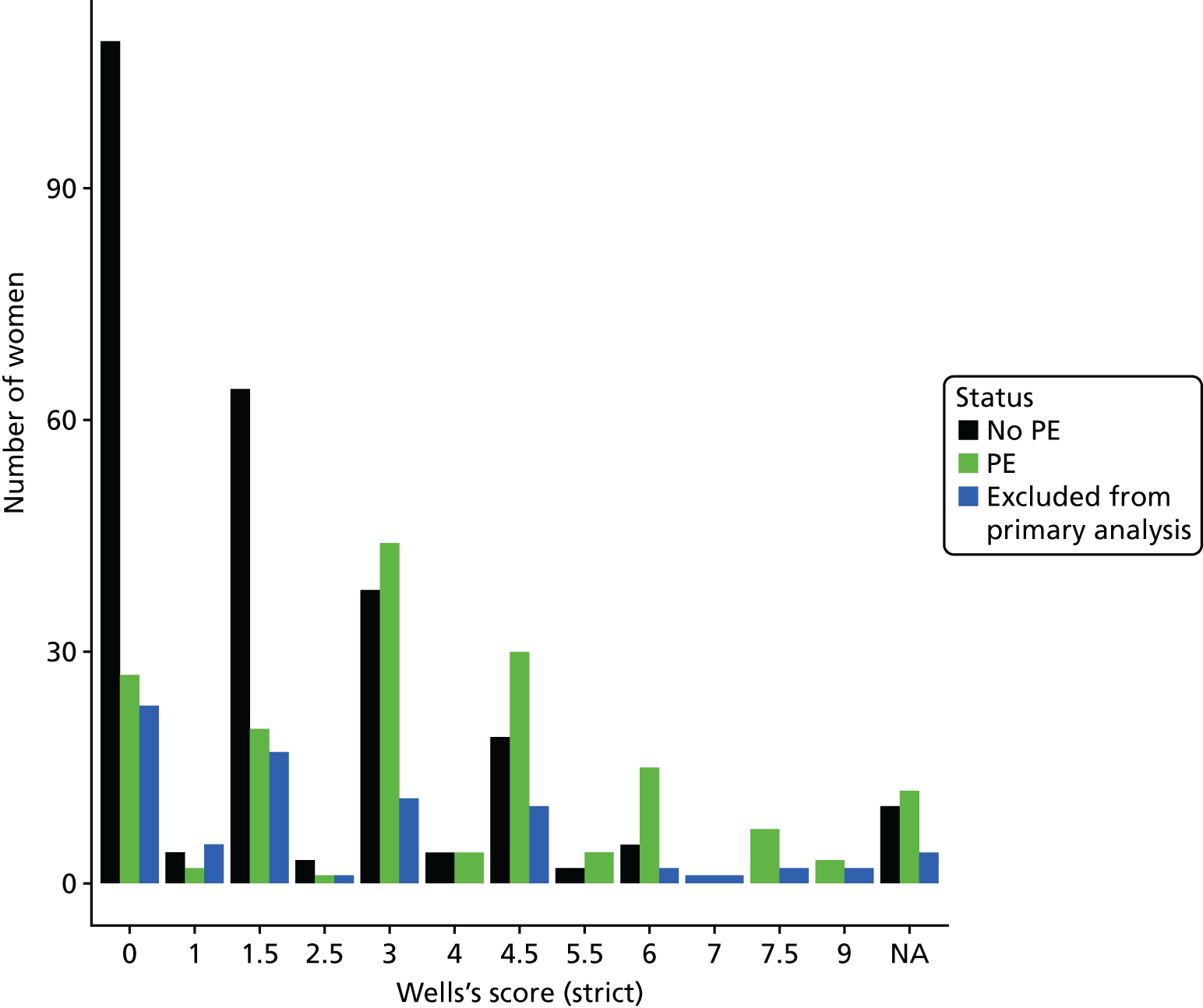

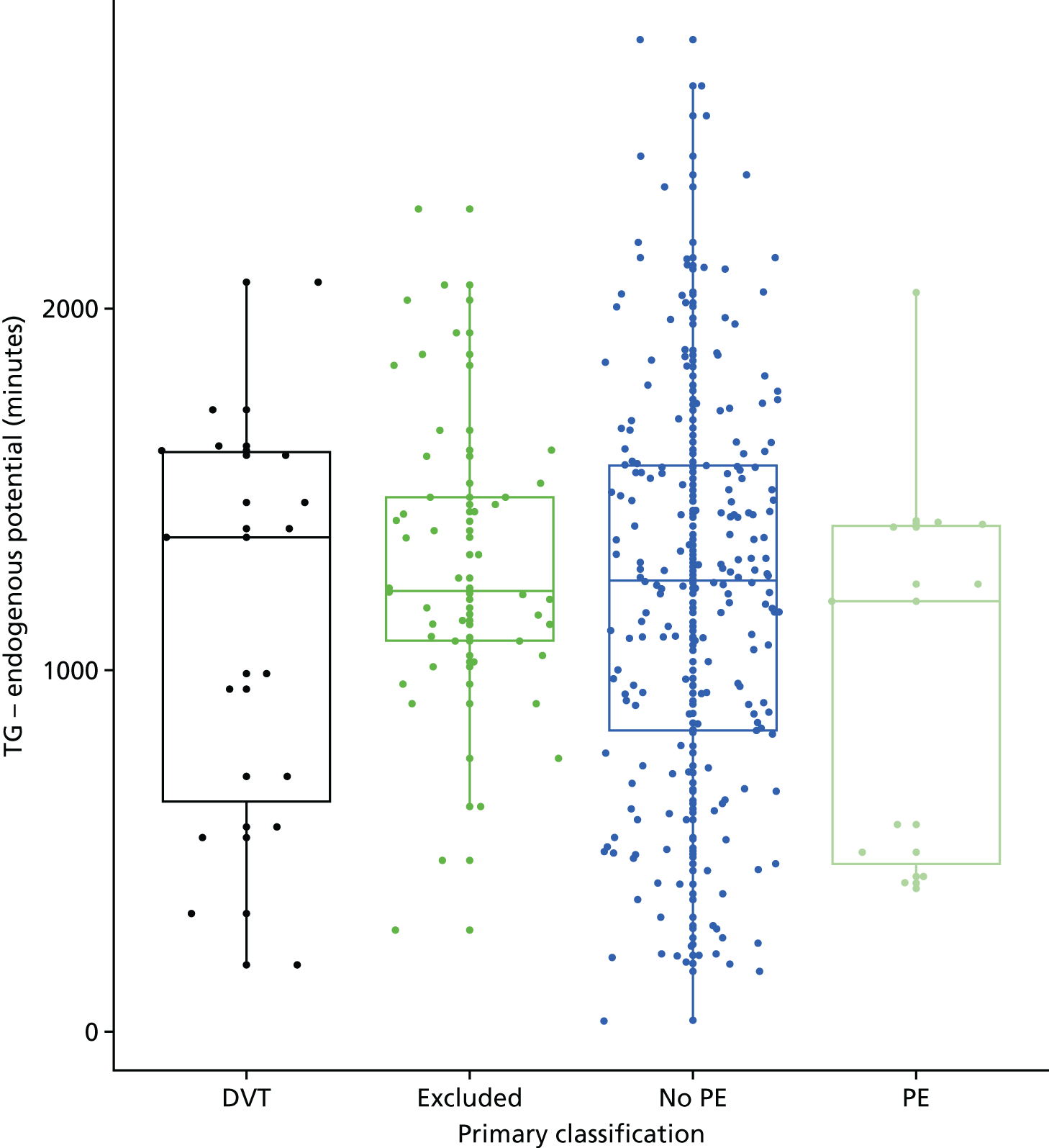

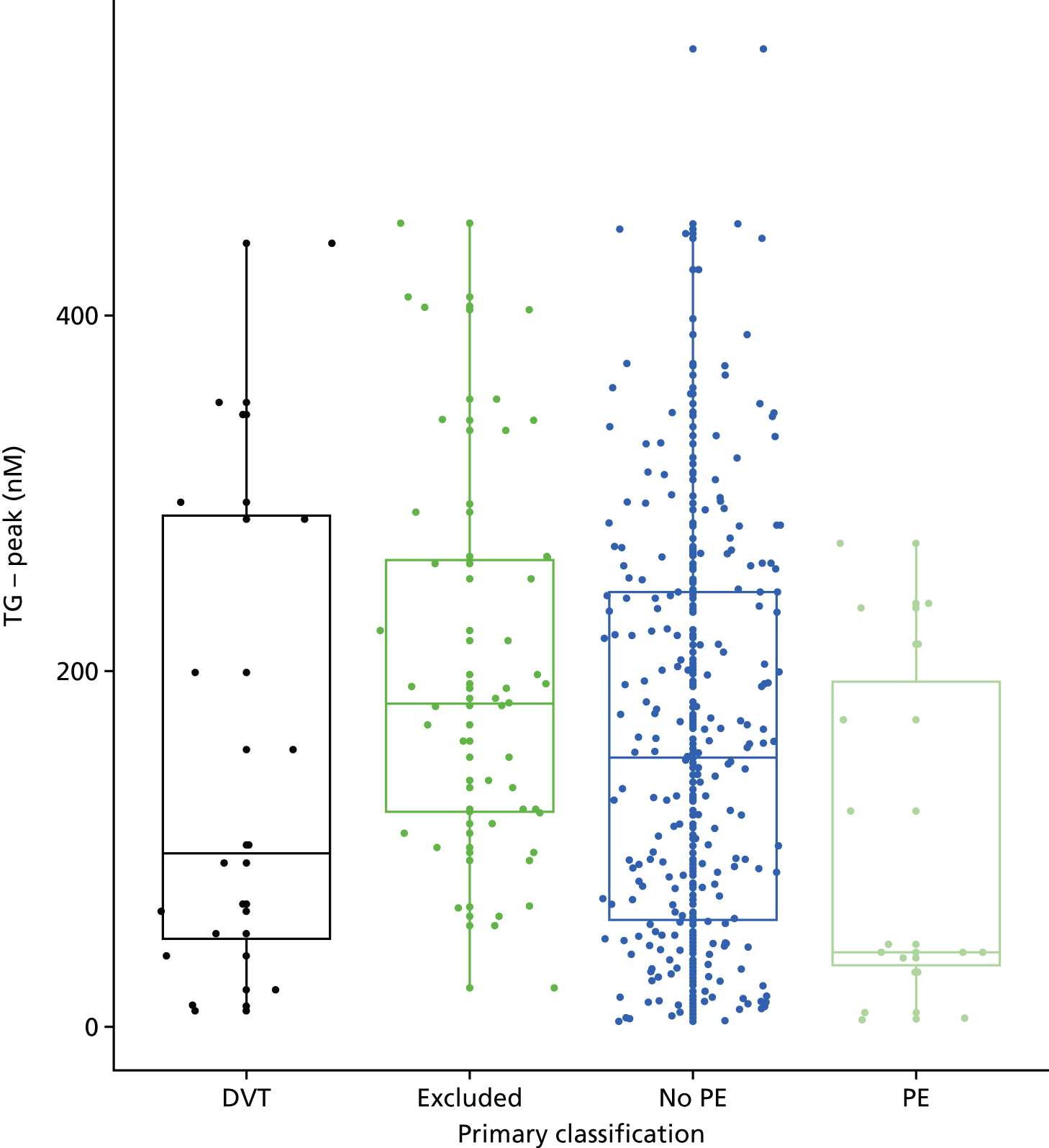

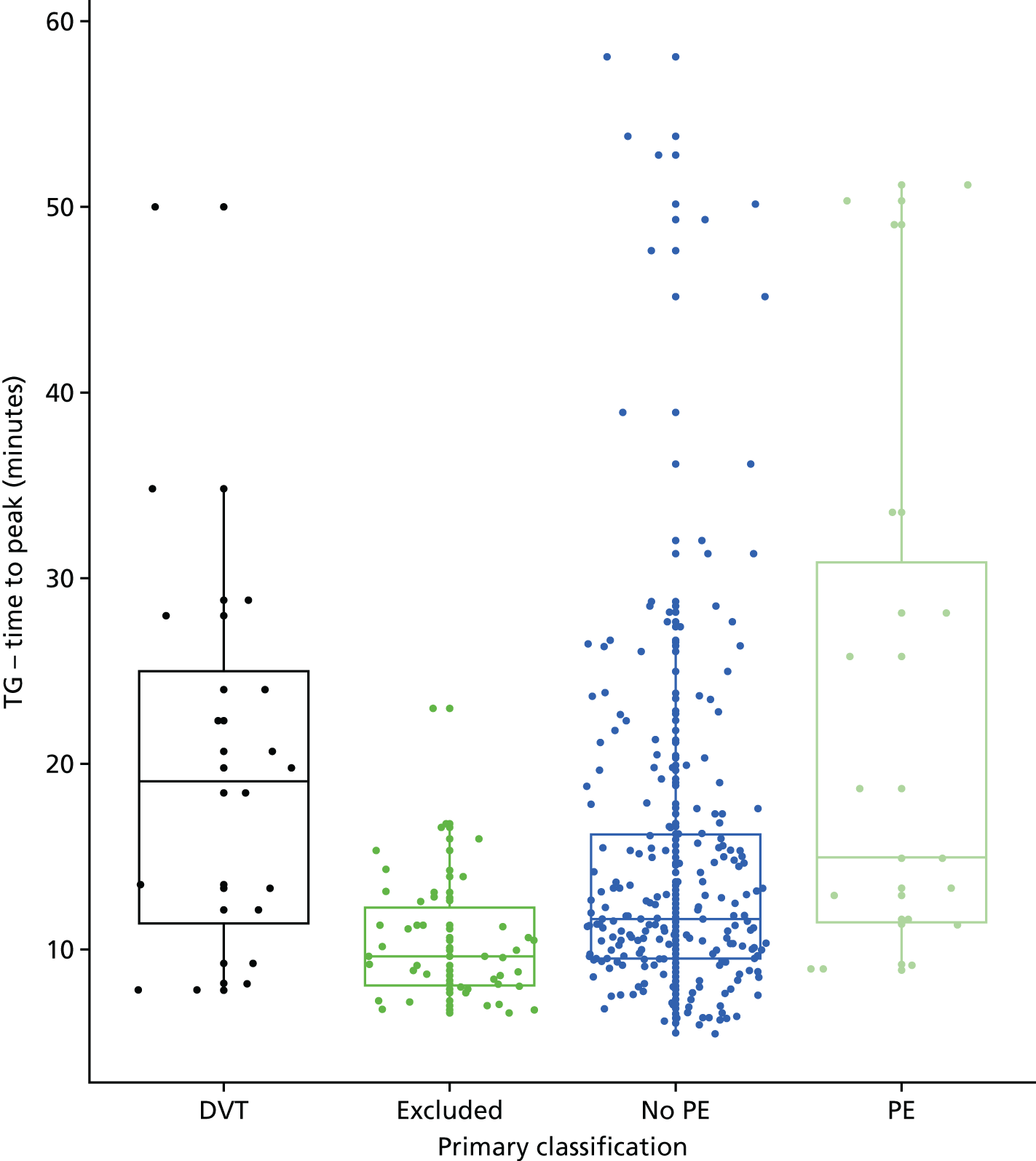

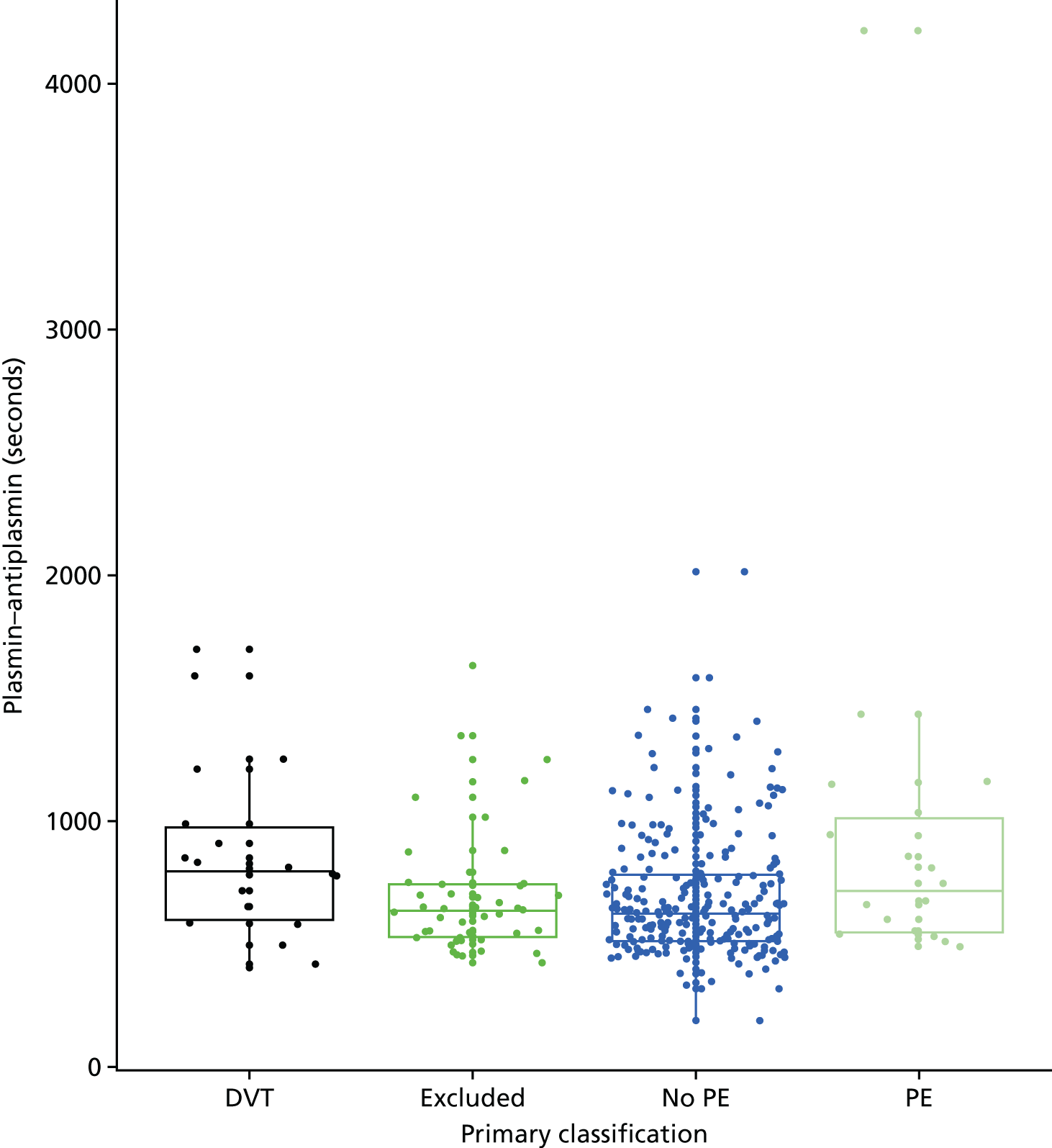

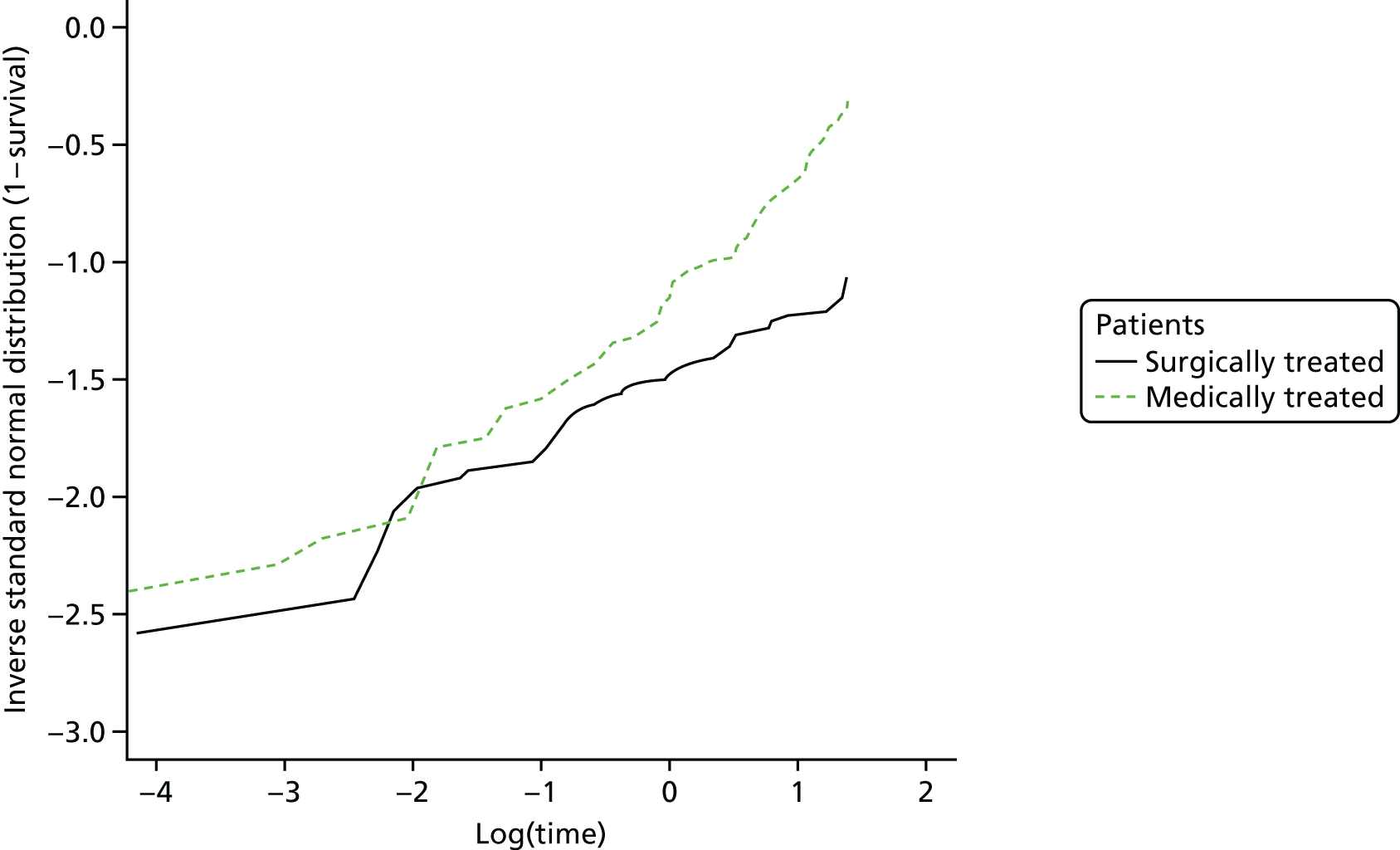

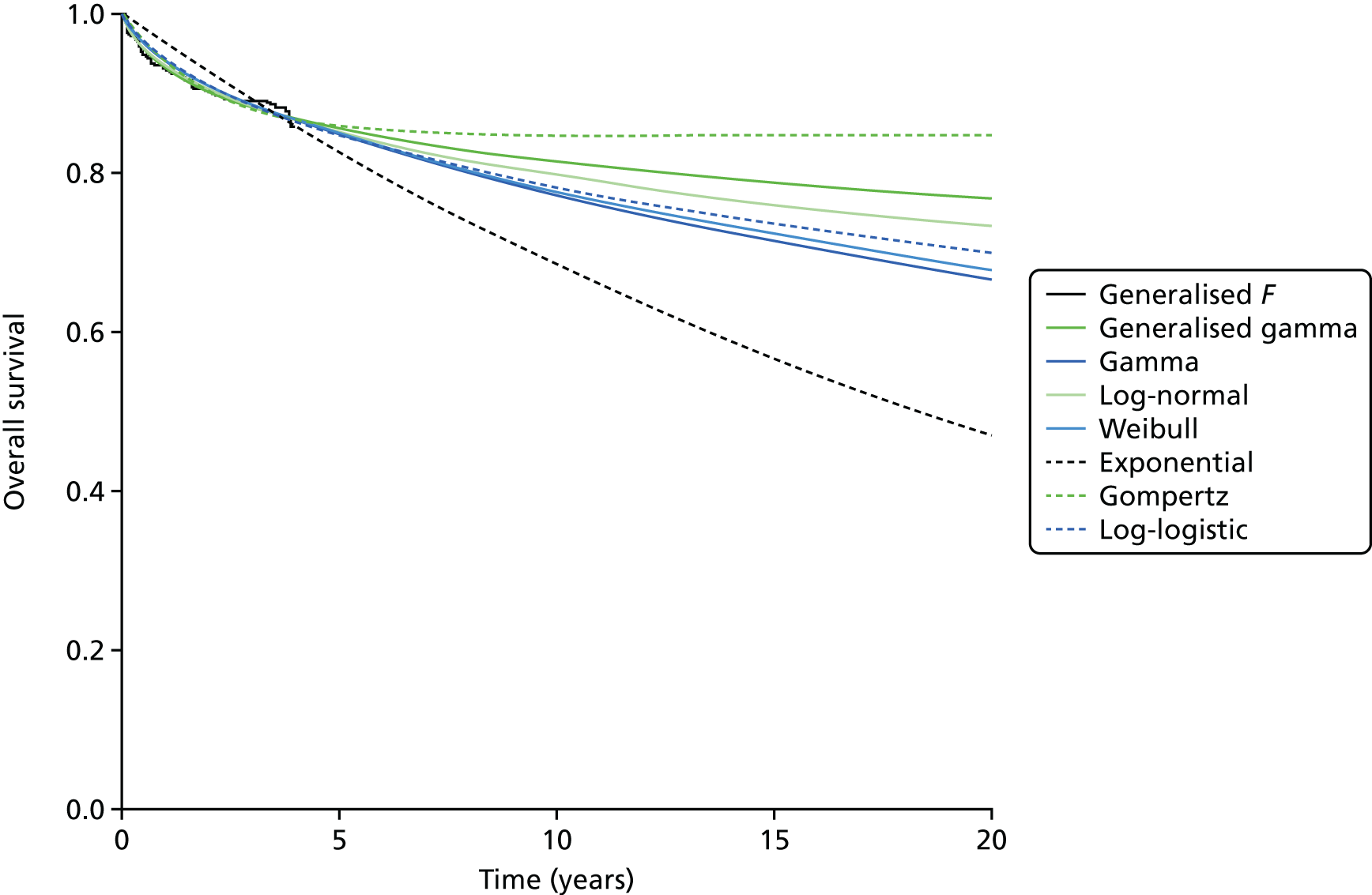

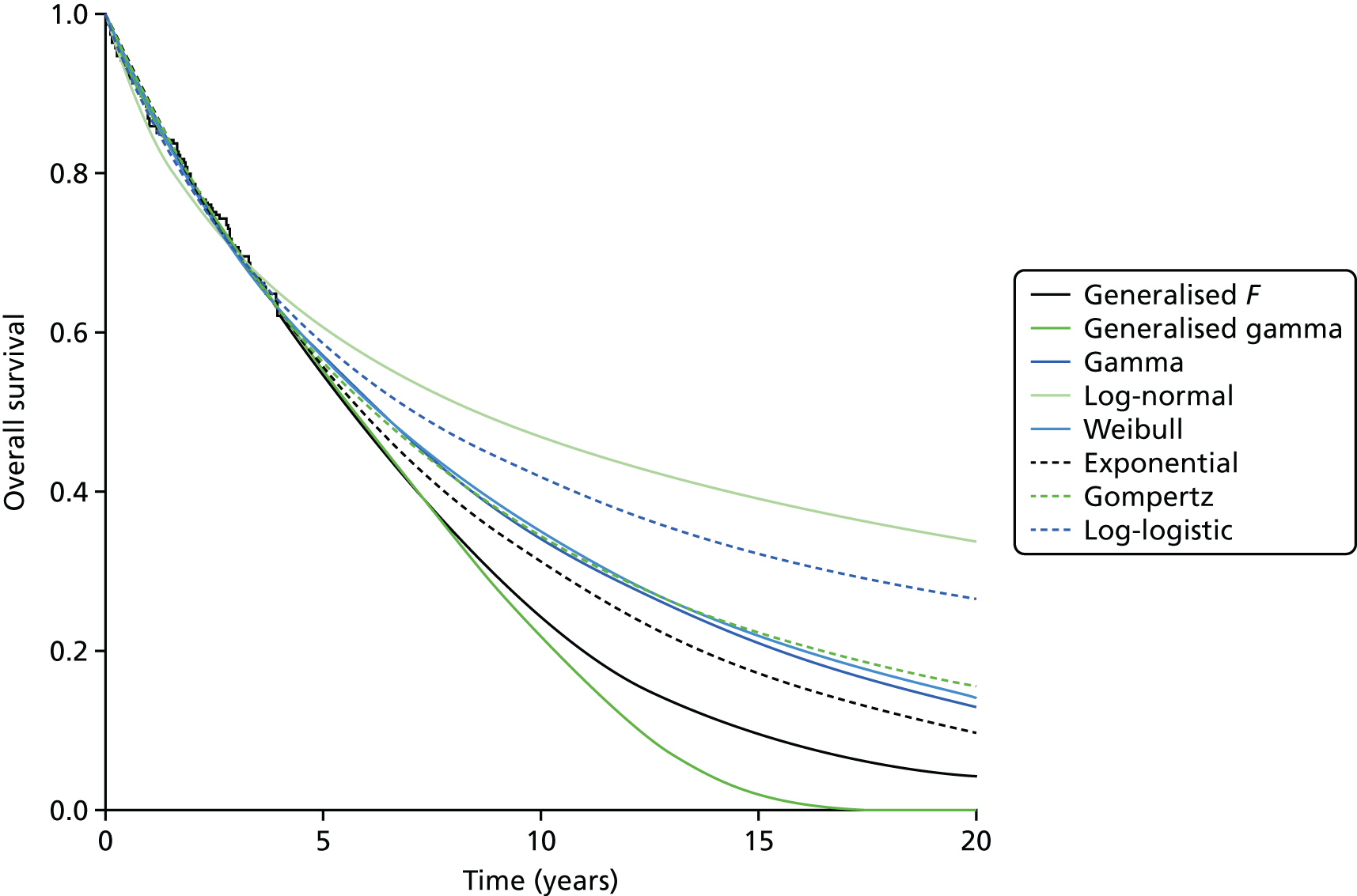

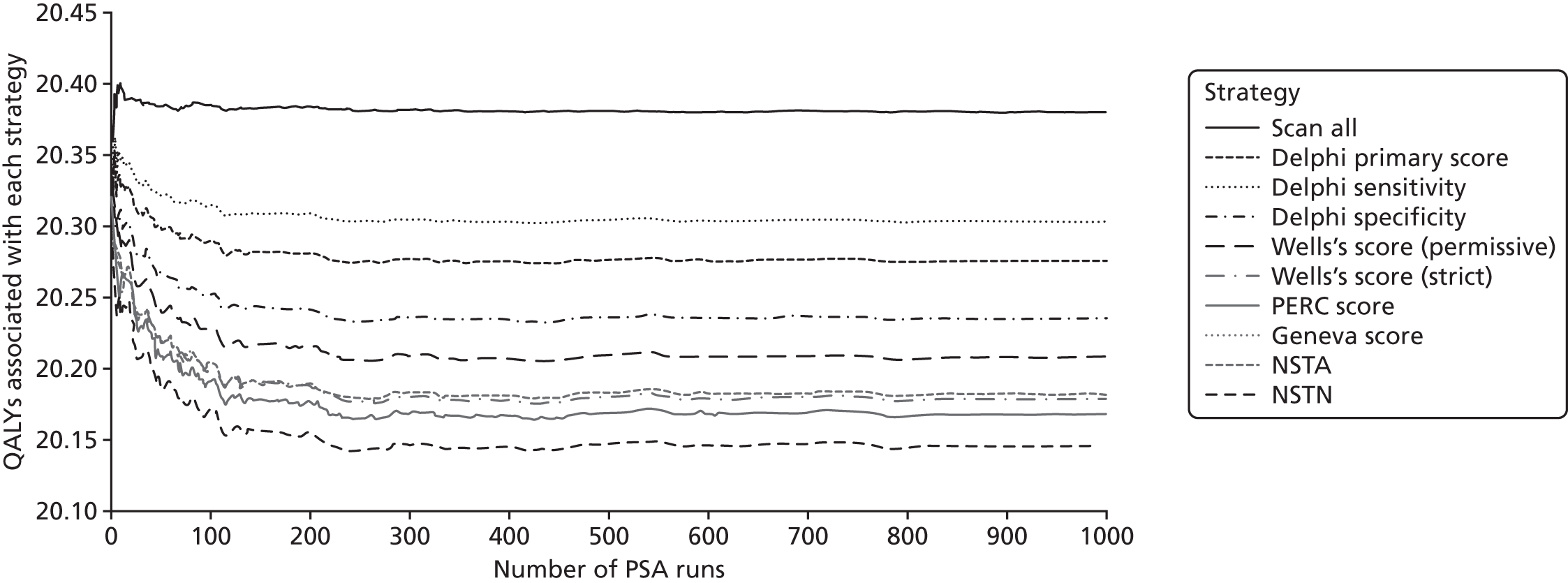

Full details of the classification process are provided in Appendix 1. The 198 patients in the UKOSS data set consisted of 163 women with PE confirmed by imaging or post-mortem examination (160 by imaging, including seven women with subsegmental PE, two by post-mortem examination alone and one by imaging and post-mortem examination) and 35 women with clinically diagnosed PE (29 with equivocal imaging and six with no imaging recorded; all treated). Thus, 163 women were included as having PE in the primary analysis, 198 women were included in the secondary analysis including those with clinically diagnosed PE, and 156 women were included in the secondary analysis excluding those with subsegmental PE.