Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 10/104/34. The contractual start date was in January 2013. The draft report began editorial review in March 2017 and was accepted for publication in March 2018. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Christopher Williams reports personal fees from Taylor and Francis (Abingdon, UK) and from Five Areas Ltd (Clydebank, UK) outside the submitted work and is president of the British Association for Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapies (BABCP). Sally-Ann Cooper reports grants from the National Institute for Health Research Health Technology Assessment programme during the conduct of the study.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2018. This work was produced by Jahoda et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2018 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Introduction

Depression and learning disabilities

Depression is common and places a significant burden on health services. For example, in 2011/12 the cost of prescribed antidepressant medication alone was £31.4M in Scotland1 and in 2015 it was £284.7M in England. 2 From 2008–12, of all psychiatric hospital discharges, mood disorders were the most common discharge diagnosis in women. 3 Depression is clearly a major public health challenge: it is the third leading contributor to the global burden of disease, and is expected to rise; the World Health Organization predicts that it will be the second leading contributor to the global burden of disease by 2020. 4

The term ‘learning disability’ refers to people who have significant impairments of both intellectual and functional ability, with age at onset occurring before adulthood. A significant proportion of the UK population has learning disabilities. Approximately 2% of adults and 3.5% of children have an intelligence quotient (IQ) of < 70. 5,6 Individuals with learning disabilities have higher levels of mental ill health than the general population, with a point prevalence of 40% for adults. 7

Depression is at least as common in adults with learning disabilities as in the general population, with a point prevalence of ≈5%. 8,9 Indeed, depression is the most common type of mental ill health experienced by adults with learning disabilities;7 anxiety disorders are also common, with a point prevalence of ≈4%. 10 Depression is more enduring than for the general population,11 suggesting that it is either a more severe condition, or more poorly managed. For example, a study with a British cohort found that adults with learning disabilities were four times more likely than the population without a learning disability to meet criteria for chronic depression over a 28-year period. 12 The US 2000 incident cohort with learning disabilities has been calculated to have lifetime costs (in excess of costs for people without learning disabilities) of US$44.1B. 13 Poorly addressed depression makes a clear contribution to these costs. Hence, as well as the human suffering that depression brings to people with learning disabilities, their families, local communities and society more widely, inadequately managed depression is a financial burden.

Psychological therapies for depression

In recent years there have been important innovations in the treatment of depression. A number of high-intensity psychosocial interventions are as effective as, and longer lasting than, medications in the treatment of non-psychotic depression. 14 This was confirmed in a recent individual patient-level meta-analysis with over 1700 patients treated in randomised controlled trials (RCTs). 15 The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) recommends cognitive–behavioural therapy (CBT) to treat mild to moderate depression,16 and high-intensity forms of CBT delivered by mental health experts are recommended to treat moderate and severe levels of depression. 17 There is now an increasing emphasis on low-intensity delivery, as used in the Improving Access to Psychological Therapies (IAPT) programme in England. These include written self-help books, computerised CBT and self-help groups. 18–22 The evidence base for these approaches continues to grow, given the attraction of therapies that are less resource intensive.

In behavioural activation, the focus is on behaviour more than on cognition, emphasising engagement with potential environmental reinforcers. Behavioural activation also takes account of valued activities,23 emphasising the importance of purposeful routine activities such as household chores and self-care, as well as achievement, pleasure and closeness to others. Avoidance is a key target for change, with the aim of breaking the vicious cycle linked to mood and activity, whereby reduced activity lowers mood. In turn, the worse people feel, the more withdrawn they become. Behavioural activation has been shown to be at least as effective as antidepressant medications, and superior or non-inferior to CBT, placebo pills and treatment as usual (TAU) among patients with more severe depression,24–27 with effects as lasting as CBT following treatment termination. 28 Behavioural activation appears to be less complicated to learn than CBT, it is possible to train non-specialist nurses to deliver it26 and it can be delivered as a high-intensity or low-intensity therapy. 29,30

Psychological therapies for depression in adults with learning disabilities

Although psychological therapies have become established first-line interventions for depression in the general population, this has not been the case for adults with learning disabilities, owing to the additional complexities involved in making these interventions accessible to adults with cognitive and verbal communication impairments. Arguably, psychological therapies are more advisable than pharmacotherapy for adults with learning disabilities than for the general population, as limitations in verbal communication skills reduce their ability to report and describe adverse effects of drugs, which can be further disabling or potentially have serious health effects. Perhaps more importantly, people with learning disabilities should have the opportunity to access effective psychological therapies just like anyone else. Awareness of the inequity in provision of psychological therapies has grown, but there remain considerable limitations in the existing evidence base, and in its implementation. This was recently synthesised by the NICE guideline31 on mental health problems in people with learning disabilities. A key point is the need for modifications to the treatment interventions, depending on the type and extent of need of each adult with learning disabilities. 32

In 2016, NICE identified that the only available evidence on psychological interventions for depression in people with learning disabilities was for CBT, adapted for people with learning disabilities. Only three RCTs (total participants, n = 130)33–35 and three controlled before-and-after studies (total participants, n = 130)36–38 were identified that explored the use of CBT for the treatment, or prevention, of depression in adults with learning disabilities. These included only participants with mild, or mild and moderate, learning disabilities. Only two studies reported outcomes beyond the immediate end of treatment. 35,36 Although the trials had variations in the adaptations made to the intervention – and suffered from inadequate power as a result of the small size (being feasibility or pilot studies), leading to imprecise estimates – NICE concluded that CBT may result in a clinically meaningful reduction in depressive symptoms over TAU at 38 weeks’ follow-up. However, the combined evidence was assessed, using the Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) approach, as being of very low quality. One feasibility RCT with 32 participants also evaluated the cost-effectiveness (from the perspective of the NHS and social care services) of individual CBT constituting 16 weekly 1-hour sessions. 35 The cost difference between the two arms was £5650 but given the small size of the study, it is unclear whether or not CBT is a cost-effective option for people with mild to moderate learning disabilities. NICE recommended adapted CBT for depression be considered for adults with mild/moderate learning disabilities, but were not confident enough in the evidence to make a strong recommendation.

There are possible advantages to considering the use of behavioural activation for people with learning disabilities, given that it is less complicated to learn than CBT and can be delivered by non-specialists. However, the only study on behavioural activation with people with learning disabilities and depression was the feasibility study we undertook to inform the design of the study reported here. It was a pre–post trial with 22 participants recruited over a 12-month period, at one site. 39 Outcomes showed evidence of positive change on depressive symptoms for those able to self-report on the Glasgow Depression Scale40 pre- and post-intervention, and at 3 months’ follow-up after end of treatment. We therefore used this study to inform the design of the trial reported here.

Trial objectives

Primary objective

To measure the clinical effectiveness of BeatIt, a behavioural activation intervention adapted for adults with learning disabilities and depression, compared with a guided self-help intervention (StepUp), in reducing self-reported depressive symptoms.

Secondary objectives

-

Does BeatIt lead to a greater reduction in carer-reported depressive symptoms than StepUp?

-

Does BeatIt lead to a greater reduction in self-reported anxiety symptoms than StepUp?

-

Does BeatIt lead to a greater reduction in carer-reported aggressiveness than StepUp?

-

Does BeatIt lead to more significant and sustainable changes in participants’ activity levels than StepUp?

-

Does BeatIt lead to a significantly greater improvement in participants’ quality of life (QoL) than StepUp?

-

Does BeatIt improve carers’ sense of self-efficacy in supporting adults with learning disabilities who are depressed, compared with StepUp?

-

Is BeatIt a cost-effective intervention for the management of depression experienced by adults with learning disabilities, compared with StepUp?

-

Does BeatIt improve carers’ reported relationships with the adults with learning disabilities and depression that they support, compared with StepUp?

In addition, qualitative methods were used to address process issues, which could help to inform the future uptake of BeatIt or StepUp in practice. We explored the perspectives of:

-

participants receiving BeatIt and StepUp

-

carers supporting participants receiving BeatIt and StepUp

-

therapists delivering BeatIt and StepUp.

Chapter 2 Trial design and methods

Study design

This was the first large-scale RCT of an adapted individual psychological therapy for people with learning disabilities and a mental health problem. The design was a multicentre, single-blind RCT of adapted behavioural activation compared with an adapted, guided self-help intervention. The behavioural activation intervention was referred to as ‘BeatIt’, and the guided self-help intervention was called ‘StepUp’.

To ensure that it would be possible to recruit to the study, there was an internal pilot phase. Consequently, there were two phases of data collection:

-

Phase 1 – there was an initial 7-month internal pilot phase in Scotland, in which the criterion for success was to recruit a minimum of 20 participants (approximately three per month).

-

Phase 2 – following the successful completion of the internal pilot phase, the study sites in England and Wales were opened and recruitment continued at all three sites for an additional 11 months.

The trial was supplemented with an economic evaluation to consider the cost-effectiveness of providing the intervention compared with the attention control (see Chapter 6). There was also a qualitative study to explore the views and experiences of participants, their supporters and therapists who took part in the trial (see Chapter 7). The trial protocol has been published. 41 A description of all approved changes to the original protocol that were submitted are shown in Table 1.

| Version | Changes made to the protocol |

|---|---|

| From version 1 to 2 | The SSQ3 was added to the self-report measures |

| The Guernsey Community and Leisure Participation Assessment was removed | |

| Proxy-reported measures of aggression (BPI-S) and of selected aspects of adaptive behaviour (ABS-RC2) were added | |

| An 8-month follow-up call to the carer was added, to collect data on service and medication use | |

| A procedure and questionnaire for screening suicidal participants was added and suicidal intent was added to the exclusion criteria | |

| The separate consent forms for participation in the main study and participation in the qualitative interviews were combined into one form | |

| The Depression Carer Self-Efficacy Scale was removed and replaced with the EDSE scale | |

| Activity data were to be collected from the participant and carer jointly, rather than from the carer alone | |

| From version 2 to 3 | The timing of the qualitative interviews was changed from 12 months post randomisation to between 4 and 8 months post randomisation, to allow better recall |

| Decision to accept self-referrals | |

| Originally, it was specified that the supporter had to have known/worked with the participant for a minimum of 6 months. This was changed to 6 months OR is able to obtain information for the 4 months before randomisation | |

| Exclusion criteria: factors that prevent the participant from interacting with the carer and therapist or retaining information from the therapy – changed ‘dementia’ to ‘late-stage dementia’ | |

| To carry out inter-rater reliability checks on the fidelity ratings | |

| The need to communicate any potential risks to researchers and therapists was added to the protocol: Risk information regarding visiting participants at home will be communicated to researchers and therapists by the referring individual/organisation. The participant should be informed of this. If the allocated participant is not previously known to services, the therapist should follow their service’s standard procedure for seeing new clients safely | |

| The period of time for follow-up interviews was amended to ‘between 2 weeks before and 4 weeks after the due date’ |

Ethics approval and research governance

Multicentre approval was granted by the West of Scotland Research Ethics Committee 3. Research and development approval was granted in all study sites: Cumbria Partnership NHS Foundation Trust, Lancashire Care NHS Foundation Trust, Betsi Cadwaladr University Health Board, South Staffordshire and Shropshire Healthcare NHS Foundation Trust, NHS Lanarkshire, NHS Ayrshire and Arran, and NHS Greater Glasgow and Clyde. The International Standard Randomised Controlled Trial Number (ISRCTN) reference for the study is ISRCTN09753005.

Participants

A multipoint recruitment strategy was adopted with the aim of recruiting participants with mild to moderate learning disabilities and clinical depression across three study sites: (1) Scotland (Greater Glasgow and Clyde, Lanarkshire and Ayrshire), (2) England (Cumbria and Lancashire) and (3) North Wales (Betsi Cadwaladr University Health Board). Participants were also recruited from Shropshire and Staffordshire specialist learning disability services. For pragmatic reasons, Shropshire and Staffordshire were administered by the North Wales site. The recruitment sites comprised both rural and urban areas.

Potential participants were screened by research assistants and considered eligible for recruitment if they met all of the following inclusion criteria and did not meet any of the exclusion criteria.

Inclusion criteria

-

Had mild/moderate learning disabilities as assessed using the Wechsler Abbreviated Scale of Intelligence™ (WASI™)42 and a modified version of the Adaptive Behavior Scale – Residential and Community: Second Edition (ABS-RC2)43 to assess adaptive behaviour skills.

-

Aged ≥ 18 years.

-

Had clinically significant unipolar depression as determined using the Diagnostic Criteria for Psychiatric Disorders for use with Adults with Learning Disabilities (DC-LD),44 which was assessed by research assistants at screening who were trained in the use of the diagnostic assessment.

-

Gave informed consent to participate.

-

Had a level of expressive and receptive communication skills in English to allow for participation in treatment (reading skills were not required).

-

Had a family member, paid carer or other support person who could complete screening and baseline visits and had supported them ideally for a minimum of 6 months OR who was able to obtain information for the 4 months before randomisation.

-

Had a carer or other named individual who could accompany the participant to weekly or fortnightly treatment sessions with the therapist and who was providing them with a minimum of 2 hours support per week.

Exclusion criteria

-

Was suicidal as assessed during the screening process.

-

Had a measured IQ of > 75.

-

Experienced difficulties that prevented them from interacting with the carer and therapist or retaining information from the therapy (e.g. late-stage dementia, significant agitation, withdrawal arising from psychosis).

-

Did not consent to have their general practitioner (GP) contacted about their participation in the study.

Additional participants

As stated in the inclusion criteria above, a support person who had known the participant for at least 4 months was also recruited to take part in the trial as an informant for each individual participant.

Recruitment procedure

Although a multipoint recruitment strategy was adopted, most participants were recruited through specialist community health teams for people with learning disabilities. A smaller number of participants were recruited through social work colleagues, third sector organisations working alongside the community teams and IAPT services in Lancashire, which are open to anyone with mental health problems.

The approach to recruitment was for members of the research team to meet with members of the community teams or other organisations and provide an explanation about the study and suitable participants. This was a critical task, as few people with learning disabilities self-refer or are given psychological help for depression. Most receive help because their difficulties have become a problem for someone else. Referrals to health services are often for behavioural difficulties such as anger management problems or anxiety disorders that are proving disruptive or difficult for others to manage or support. Therefore, when describing who might be suitable participants, members of the research team highlighted that it would be important to bear in mind individuals whose depressive symptoms might be overshadowed by other presenting problems. Members of the community teams or other organisations were then able to identify potential participants, provide them with a brief explanation of the study and give them an information pack. These packs contained a letter, information sheets and a Freepost envelope that they could return if they were interested in finding out more about the study. It was suggested to participants that they might find it useful to discuss the study information with a friend or supporter.

Adults with learning disabilities are often supported by several people. For example, they may have multiple paid carers working in shifts or different supporters in their home and day-centre environments. This means that the potential participant may not have known who they could discuss the study with. This could have created a situation in which information sheets went missing before potential participants were able to discuss the study with supporters and make an informed decision about whether or not they wanted to participate. To take account of this, as in previous studies, the member of staff who gave out the information sheet was asked to notify a NHS secretary in the learning disabilities team (who was independent of the research study) that an information sheet had been handed out. After 2 weeks, if no tear off reply slip had been received, the NHS secretary contacted the individual once, by telephone, to check that they still had the information pack. If the information pack had gone missing, a second information pack was sent out.

On receiving a reply slip, a member of the research team arranged to meet the potential participant at their home or another convenient location for them. The participant was also asked if they would like someone to support them when they met to discuss the research project. When the member of the research team met with the participant, they talked through the information sheet and invited questions. If the participant was satisfied with the responses obtained, they would then be invited to participate in the study.

Advice about the information sheets and the approach taken to recruitment was provided by the Trial Steering Committee. The views of the Committee members with intellectual disabilities and a family member proved particularly helpful.

Informed consent

Individuals who chose to take part in the study were asked to complete a written consent form by members of the research team. The consent form was read to the individual with learning disabilities, they were asked to sign it, and this was witnessed by a carer or another individual who was independent of the study. Those who did not have the capacity to consent to participate were excluded from the study. The researchers all received training on assessing capacity to consent in adults with learning disabilities based on the relevant UK legislation45,46 and established best practice.

Randomisation, concealment and blinding

Participants who provided informed consent were screened and provided baseline data before being randomised. The flow diagram for the study is shown in Figure 1. Individuals were allocated to the BeatIt arm or the StepUp arm in a 1 : 1 ratio, using a blocked randomisation within each study centre. Mixed block sizes of length four and six were used at random. The randomisation was stratified by study centre and the use of antidepressants. At the design stage, several potential stratification variables were considered but ultimately not used, including the use by participants of other drugs that may have some mood-stabilising properties and are commonly prescribed in this population. For example, an estimated 25% of the population have comorbid epilepsy and may be taking carbamazepine, sodium valproate, lamotrigine or pindolol. Changes in the prescription of antidepressants and other mood-stabilising drugs were monitored over the duration of the study.

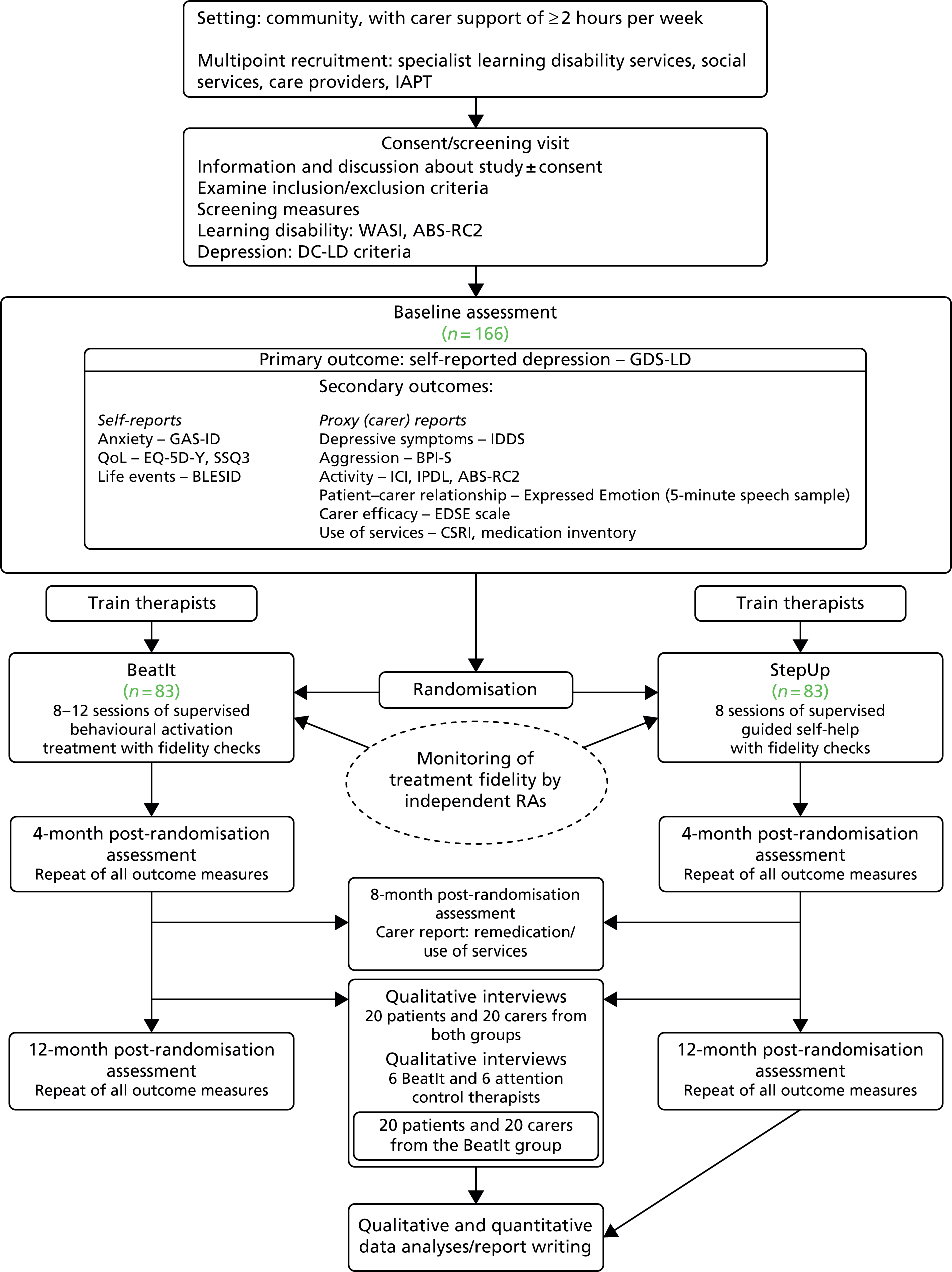

FIGURE 1.

Flow chart showing BeatIt study design and participant follow-up. BLESID, Bangor Life Events Schedule for Intellectual Disabilities; BPI-S, Behavior Problems Inventory for Individuals with Intellectual Disabilities – Short Form; CSRI, Client Service Receipt Inventory; EDSE, Emotional Difficulties Self-Efficacy; EQ-5D-Y, EuroQol-5 Dimensions – youth version; GAS-ID, Glasgow Anxiety Scale for people with an Intellectual Disability; GDS-LD, Glasgow Depression Scale for People with Learning Disabilities; ICI, Index of Community Involvement; IDDS, Intellectual Disabilities Depression Scale; IPDL, Index of Participation in Domestic Life; RA, research assistant; SSQ3, Social Support Questionnaire – three questions.

To conceal the allocation of participants from the research team, researchers randomised each participant to a treatment arm using an automated system run by the Robertson Centre for Biostatistics (RCB). The system did not reveal the random allocation to the researcher but notified the study coordinator, who then contacted the clinicians to arrange subsequent treatment visits. Thus, the researchers collecting outcome data remained unaware of the study arm to which participants had been assigned.

Interventions

Therapists

To avoid contamination, there were separate therapists for the behavioural activation (BeatIt) and the guided self-help intervention (StepUp). BeatIt and StepUp therapists were recruited from specialist community teams for people with a learning disability and, in Lancashire, they were also recruited from mainstream mental health IAPT services. Hence, the therapists were assistant and trainee psychologists, community nurses and occupational therapists who all had prior training and experience of working with people who have learning disabilities and mental health problems. The IAPT therapists who worked on the trial were low-intensity workers, who were trained to deliver brief, manualised psychological interventions for depression and anxiety disorders but did not necessarily have experience of working with adults with learning disabilities.

The therapists received 1–2 days of training about the delivery of the intervention and were given a manual and packs of materials for use in each treatment session. The training was delivered separately for BeatIt and StepUp therapists. All trainers completed an initial training course in collaboration with the curriculum developer (AJ) before training independently. The training provided (1) a background to the interventions and the underpinning theory, (2) an overview of the content and structure of the interventions, (3) an introduction to each of the exercises and self-report materials, and training and practice in their delivery and use, (4) how to deal with potential barriers to progress and (5) how to work alongside both clients with learning disabilities and their carers.

Supervisors

The supervisors were clinical psychologists with experience of delivering psychological therapies to people with learning disabilities. They all received 2 days of training in the intervention they supervised. The training followed the same format as the therapists’ training but included further guidance about supervision of participants. Time was spent highlighting issues that could cause confusion or may need particular support from the supervisor (e.g. producing the BeatIt formulation; delivery of the problem-solving StepUp booklet). Finally, care was taken to emphasise the limits of each intervention to avoid contamination and ensure that the core ingredients of BeatIt and StepUp remained distinct. For example, the StepUp therapy did not include homework tasks, with the exception of the problem-solving booklet. Hence, the therapists needed to be reminded to avoid following up on plans discussed in previous sessions.

Supporters

Table 2 shows the relationship of the supporters to the participants. Of the 161 participants at the outset, both residential (n = 49) and non-residential (n = 33) support workers featured most commonly, while parents were the next largest group (n = 34). The friends were other individuals with learning disabilities. When possible, participants chose who they wanted to support them in therapy sessions but some individuals had very limited formal or informal support, and in certain instances a visiting professional offered to help.

| Relationship | Site (n) | All (n) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Scotland | England | Wales and SSSFT | ||

| Parent | 15 | 13 | 6 | 34 |

| Sibling | 6 | 1 | 1 | 8 |

| Other family member | 2 | 1 | 1 | 4 |

| Support worker (residential) | 22 | 8 | 19 | 49 |

| Visiting social care assistant | 3 | 0 | 1 | 4 |

| Visiting professional (community nurse) | 7 | 5 | 2 | 14 |

| Spouse or partner | 3 | 2 | 2 | 7 |

| Support worker (non-residential) | 13 | 13 | 7 | 33 |

| Grandparent | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Advocate | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Social worker | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Housing officer | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Friend | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| Supervisor | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Total | 74 | 46 | 41 | 161 |

Behavioural activation (BeatIt)

BeatIt was adapted from Lejeuz et al. ’s47 behavioural activation intervention. The underpinning theory of behavioural activation is that a negative cycle of withdrawal and avoidance of activity plays a key role in the development and maintenance of depression and low mood. Consequently, the main goal of the intervention was to break this negative cycle and bring the individual into contact with positive environmental contingencies that produce a corresponding improvement in mood. The focus was not on pleasurable activity but rather on regular activities that were purposeful, sustainable and consistent with life goals. For example, volunteering for a charity might provide someone with a reason to get up in the morning and take care of their personal appearance, as well as bringing them into contact with others and providing them with a valued social role.

BeatIt was delivered on an outreach basis, face to face at the participant’s home, except when participants chose to meet elsewhere or their living circumstances made it impossible to deliver the intervention at home. Sessions were scheduled to last for between 1 and 2 hours and were delivered on a weekly to fortnightly basis, to help build rapport and ensure continuity across sessions. When it was anticipated that sessions would last > 1 hour, a break was scheduled. The sessions were delivered to the participant alongside someone who provided regular support in their life. The participants were asked to choose who they would like to join them during sessions. A meeting was held with the supporter before starting therapy proper, to help them understand what the therapy involved and what their role in the sessions would be.

The overarching aim in the BeatIt intervention was to foster a collaborative approach, with an agenda agreed by the client and the supporter at the beginning of each session. The repetition and structure was designed to aid memory and understanding, helping the client to anticipate what was going to happen both within and across sessions and to play a more active role in therapy.

Adaptations to BeatIt

A number of adaptations was made to ensure that the behavioural activation intervention was both accessible to clients with a learning disability and sensitive to their life circumstances. There was careful piloting of the intervention and the views of people with learning disabilities and their families played a crucial role in determining the adaptations.

Supporter involvement

One of the main changes to the existing intervention was to involve a significant other in the client’s life in therapy sessions. People with learning disabilities are likely to rely on others for support in their everyday lives, including engagement in activity. They may lack the agency or the ability to recall and follow through with plans for activity without support. Involving a significant other in the therapy sessions helps to ensure ecological validity (i.e. that the intervention makes sense in the context of their wider lives).

Adapting materials and exercises

Adapting materials and therapeutic activities was designed to ensure that they were accessible and engaging. All exercises and forms were carefully developed and piloted before use. Using visual materials, such as photographs of activities, allowed participants to make active choices and helped to scaffold the therapeutic dialogue.

Assessing level and salience of activity

Care was required when examining a participant’s pattern of activity to avoid making assumptions about what level of activity was satisfactory. For example, a participant attending a college course several afternoons a week and going to a drama group on a weekly basis might have only 6 hours of regular purposeful daytime activity per week. However, this may be regarded as a relatively substantial package of support compared with that of other people with intellectual disabilities. Therefore, therapists were encouraged to carefully chart a participant’s ratio of activity and inactivity. Another issue the therapists were asked to consider was a participant’s level of control and engagement with the activities in which they took part. Being present at an activity does not necessarily mean that someone takes part or interacts with others who are there.

Formulation

A formulation was presented to the participant and their supporter using a behavioural activation framework to explain the participant’s difficulties and provide a shared ‘story’ or common frame of reference for joint work with the participant and supporter.

Barriers

Few participants presented with depression alone and most had other emotional, interpersonal and practical difficulties that needed to be addressed to allow people to increase their purposeful activity. Thus, another adaptation of the intervention was to tackle other barriers to change; the manual included guidance about how to deal with the most common barriers that were identified when the intervention was piloted.

These common barriers included (1) anxiety, (2) self-confidence and negative self-perceptions related to having a learning disability, (3) anger management/interpersonal difficulties, (4) chronic pain, (5) needing to learn or re-learn skills and (6) organisational barriers, such as a lack of support or inflexible support, which prevented participants from carrying out planned activities.

The manual made clear that this was not an exhaustive list of barriers and that this aspect of the intervention needed to be tailored to the individual concerned.

Ending therapy and final booklet

Twelve weeks of therapy were not considered to be sufficient to solve all clients’ difficulties, which it was thought would fluctuate in relation to the ongoing challenges they faced in their lives. Therefore, steps were taken to help maintain or build on therapeutic change. First, care was taken to avoid an abrupt end to therapy. Second, the participant and supporter were given a final booklet at the end of therapy, detailing the progress made, how this had been achieved and how progress could be maintained. Third, the presence of the supporter meant that there would be continuing support when the therapist input ended.

BeatIt materials

A comprehensive set of materials was provided to facilitate therapy session activities, including pictures and post boxes for an initial activity to gain insight into the participant’s pattern of activity, worksheets for a life-goals task and forms to chart a hierarchy of activities to work on. There were also mood and activity diaries for participants to complete between sessions with the help of supporters and activity sheets to be used to plan and schedule activities to be carried out between sessions. Templates were also provided for the formulation and final booklets to be produced for participants and supporters.

BeatIt: the therapy sessions

The manual describes 12 sessions, which can be divided into three main phases: (1) assessment and formulation, (2) working towards change and (3) finishing therapy. There was sufficient flexibility within the manual to allow the intervention to be tailored to the individual’s particular difficulties and life circumstances. The therapist could also make telephone contact between sessions to prompt participants about planned activities between sessions.

The first phase consisted of five sessions and involved socialising the client into the approach, identifying key areas to work on in relation to increasing activity/overcoming avoidance, and developing an individual formulation. The first three sessions involved key exercises: (1) to develop an understanding of the person’s activities, in the past and present, and what they would like to do in the future, (2) to help identify their main life goals and (3) to develop a hierarchy of potential activities in the areas of purposeful daytime, domestic and social activities, along with a plan of how these could be accessed.

In this first phase, the therapist also introduced mood and activity diaries, which the clients were asked to complete with the assistance of their supporter between sessions. Activity scheduling was also gradually introduced. Self-monitoring and scheduled activities were core features of the intervention.

Information gleaned from the first three therapy sessions furnished the therapist with material to develop an outline formulation. Session 4 was used to review what had been covered in the first three sessions and to check whether or not ideas for the formulation resonated with the participant and supporter. This feedback helped to finalise the illustrated formulation booklet, which was delivered in session 5. The formulation included the agreed plan to increase the participant’s activity or engagement through scheduled activity in three life domains: (1) domestic tasks, (2) purposeful daytime activity and (3) social/recreational activity. The plans may have included (1) recovering lost skills and interests, (2) graded exposure to reduce avoidant behaviours and (3) targeting inherently reinforcing activity and activity likely to increase access to other positive reinforcers through a programme of scheduled activity.

In the second phase of therapy (sessions 6–10), the participant, therapist and supporter worked to follow through with their plans, although these could be altered in light of new information or changing circumstances. For cases in which progress was limited, care was taken to highlight whatever achievements had been made, and activities and goals could be renegotiated to make them more achievable. The advantage of having the supporters present in sessions was that the scheduled activities were negotiated with both the supporters and participants, thereby helping to avoid making plans that the participant was not motivated to carry through or the supporter was unwilling or unable to support.

As stated above, the challenge of the approach was to overcome the barriers to change; the main issues faced by participants were tackled in the second phase of the therapy. These barriers included gaps in skills or lost skills, tackling emotional or interpersonal problems such as anxiety or anger difficulties, low self-esteem and chronic pain. Of course, the barriers were not all to do with the participants themselves and work also had to be carried out with supporters and organisations to ensure that people received the sensitive and flexible support that they required. For example, in some settings participants were not even allowed to engage in domestic tasks such as cooking or making themselves a snack.

If rapid progress was made, the number of sessions in this middle phase could be reduced.

The third and final phase (sessions 11 and 12) concerned the end of therapy. The first of these sessions involved recapping on the work that had been completed and highlighting progress made. At the final session, a booklet was given to the participant and supporter, describing their achievements and including a plan for maintenance and continued improvement.

Guided self-help (StepUp)

Guided self-help (StepUp) was chosen as an active control intervention because it is comparable to BeatIt in terms of receipt of some therapist attention, the use of a structured approach and the presence of a supporter in all therapy sessions. StepUp also offered an ethical alternative in the absence of any other evidence-based psychological therapies for people with learning disabilities and depression and a lack of information about the outcomes of usual care. Guided self-help is a psychoeducational approach, providing new knowledge and skills to help participants deal with common difficulties associated with depression to help lift their mood.

Once again, this intervention was delivered on an outreach basis, face to face at the participant’s home, unless they asked to meet elsewhere or their living circumstances made it impossible to deliver the intervention at home. Sessions were scheduled to last for 1 to 1.5 hours, with a break scheduled for sessions that continued beyond 1 hour. The sessions were delivered on a weekly to fortnightly basis to help build rapport and ensure continuity across sessions.

StepUp adaptations

Accessibility

The self-help booklets were developed in Glasgow with the assistance of people with learning disabilities from Enable, a third-sector organisation in Scotland. The resources were designed to be used by people with learning disabilities alongside a supporter. Most study participants had few, if any, literacy skills. Care was taken to ensure that the topics covered, the language used and the format, including the use of case examples, helped to make the booklets comprehensible for individuals with learning disabilities.

Relevance

The involvement of people with learning disabilities from Enable also helped to ensure that the content of the booklets and the examples used would be familiar and relevant to individuals with a learning disability.

As this was a manualised approach, the therapist went through all of the booklets in the same order with each participant and supporter. The drawback was that the different booklets were perceived to be more or less salient to different participants. Hence, when someone stated that they slept well, the booklet on sleep was delivered in light of this and reframed as reviewing the participant’s strengths and as a way of keeping well.

StepUp materials

This was a manualised approach, and the main accompanying materials were the four booklets concerning (1) feeling down, (2) sleep, (3) exercise and (4) problem-solving. There were also worksheets for the therapists to record the main points that the client and supporter had taken from the sessions, and worksheets to plan and review a problem-solving exercise to be used with the final self-help booklet. Paperwork was provided for the final two sessions, to draw together key points from across the different booklets and to produce a plan for the continued use of the booklets.

StepUp: the therapy sessions

Therapists attempted to promote a spirit of collaboration with the participant and supporter, and an agenda was agreed at the beginning of each session.

Setting the scene

The therapy started (session 1) with an initial meeting with the participant and carer to build rapport, explain the materials and provide coaching in the use of the materials.

Going through the booklets

In the subsequent five meetings (sessions 2–6), the therapist went through the booklets with the clients and supporters. The first three booklets were read within one session each, starting with ‘feeling down’, which provided an explanation of depression and depressive symptoms. The next two booklets concerned ‘sleep’ and ‘exercise’, describing how they are linked to depression and how improving sleep and increasing exercise can help to lift someone’s mood. The final booklet dealt with the more complicated topic of problem-solving and how such skills can help in overcoming depression. Owing to the complexity of this final topic, the problem-solving booklet was delivered over two sessions.

The booklets were designed to be made personally relevant to individuals. Characters were introduced to illustrate particular points and participants were asked how their experiences compared with those of the characters. The booklets also prompted discussion about whether or not the suggested changes or plans could be helpful for the participants and supporters. However, with the exception of the problem-solving booklet, in which the participant was asked to complete an exercise between sessions, a clear instruction was given to therapists to avoid returning to any particular plans or ideas that were discussed in previous sessions. It was important for therapists to avoid creating any expectation that clients and supporters were being set specific tasks to carry out between sessions.

Ending therapy

The two final sessions (7 and 8) helped to avoid an abrupt ending to therapy and gave time to consider the continued use of the booklets moving forward. The aim of the penultimate session was to review key messages from each booklet for participants, before going on to consider how the booklets could complement each other. For example, doing more exercise could help with sleep. In the same vein, better problem-solving abilities could help someone to manage their finances better, leaving sufficient funds to get out on a more regular basis.

At the final session, plans were made with the patient and supporter for the continued use of the booklets.

To clarify areas of overlap and difference between the behavioural activation and guided self-help interventions used in the study, an overview of the two interventions is shown in Table 3.

| Characteristic | Trial arm | |

|---|---|---|

| BeatIt | StepUp | |

| Type of intervention | Behavioural activation | Guided self-help |

| Number of sessions | 12 | 8 |

| Supporter present during sessions | Yes | Yes |

| Manualised | Yes | Yes |

| Review progress made between sessions | Yes | No |

| Address barriers to change | Yes | No |

| Intervention-specific materials | Mood and activity diaries to be completed between sessions; worksheets and identifying meaningful activities (post boxes and pictures); worksheets for identifying life goals and values; worksheets for planning and reviewing activities between sessions; individualised formulation booklet; list of common barriers to change with suggested materials for addressing them; final end-of-therapy booklet |

Four self-help booklets about In addition, summary sheets to identify key messages from each booklet and worksheets for problem-solving booklet homework task; and worksheets for making plans for continued use of booklets |

| Homework between sessions | Homework activities planned each session from session 3 to 11 and reviewed at following session | One homework task set during session 5 after reading through problem-solving booklet |

Fidelity to the intervention

Development of the fidelity measure

The first part of the fidelity measure concerned the presence of techniques and elements that were essential components of the described interventions. Each session for the two interventions had a different structure and content, with a greater variation in content for BeatIt than for StepUp. A simple descriptive rating of three core key activities specific to each session was developed for both interventions. For example, the core items for session 3 of BeatIt were: ‘Review of first homework activities and consider strategies for increasing motivation’, ‘Collaboratively draw up hierarchy of activities that include each target life domain’ and ‘Use a pictorial or other prompt that successfully engages the client’, with each item scored as simply present or absent. For StepUp, items for sessions 2, 3 and 4 were ‘The therapist asks the client and supporter what they can remember from the last session and reviews and discusses the topic’, ’The booklet for the current session is read through together with the client and supporter’ and ‘The client and supporter are asked what they think are the most important messages from the booklet that has been read’. For BeatIt there were additional items regarding homework and the use of diaries, which were unique aspects of this intervention.

The second part of the fidelity assessment concerned the ‘quality’ of therapy delivery. This was designed as a quality and non-specific therapy process measure for structured and manualised therapies. The structure of the measure was based on fidelity scales such as those described by Hepner et al. 48 and reported in Hunter et al. ,49 themselves based on the Cognitive Therapy Scale50 which is a precursor of the Cognitive Therapy Scale – Revised (CTS-R). 51 The 10 items in the current measure assessed whether or not the therapist:

-

creates an agenda and agrees what will be covered in the session

-

maintains a focus and clear structure to the session

-

avoids offering therapy outside the remit of the intervention

-

asks for feedback from the previous session

-

asks for feedback and reaction to the current session

-

conveys understanding by checking and rephrasing

-

adjusts content and style of own communication

-

communicates clearly without hesitations and with good pace

-

shows empathy

-

shows warmth and respect.

The rating of these was accompanied by an extended description of the factor addressed by the item, with the addition of clear operationalisation as part of the manual for the measure. For example, the descriptor for item 7, ‘adjusts content and style of own communication’ was as follows:

A core skill in working with people with learning disabilities is the ability to adjust how the therapist communicates to ensure that the client understands the communication. This is a complex skill and requires the therapist to be very aware of the client’s responses as clients may not communicate a lack of understanding in an obvious manner; this item may involve therapists using shorter sentences, breaking information into smaller chunks, using pictures and drawings.

The operationalisation aid was as follows:

There is a difficulty in judging adjustment, as many clients seem to follow the interaction well, and on that basis it could be argued that the therapist is adjusting the interaction to meet the client’s needs. To rate this, we should be listening for clear signs of the therapist using a different language, shorter statements and more pauses and that this might vary at key points in the interaction when new information or a more complex part of the process is introduced. Some therapists have difficulty doing this and use very complex language. In cases of very high complexity, speed or very long passages of speech by the therapist, it should be safe to assume that adjustment is not happening (all people with learning disability will struggle with multiple complex concepts without the opportunity to adjust and repeat). An additional complexity is that the therapist may be speaking to the carer in a different manner than they do to the client. This will demonstrate adaptation of delivery; however, it may be seen as excluding the client from parts of the therapy. This item will be judged on the complexity of delivery (some delivery may be so complex that it will not be possible for any person with a learning disability to understand even if they appear to do so) and evidence of rephrasing and adjusting language to explain and repeat a point.

The scale was rated on a four-point anchored scale, specific to each item. Thus, for item 7 the anchors were as follows:

-

The therapist does not adjust their communication style and communicates in a way that seems to be too complex for the client (and carer) or overcompensates and communicates in a way that seems condescending.

-

The therapist makes some adjustment to their communication style at some points in the session, but this is not based on how the client and carer respond and is not consistent throughout the session.

-

The therapist adjusts their communication style throughout most of the session and this appears to be well matched to the level of understanding of the client (and carer).

-

The therapist adjusts their communication style throughout the session and clearly reflects the client’s understanding in their adjustments in a way that shows accommodation to the client’s needs in each part and activity of the session.

The fidelity measures were then piloted by Dave Dagnan and Andrew Jahoda to assess six recorded sessions (three BeatIt and three StepUp). Each recording was separately rated by Dave Dagnan or Andrew Jahoda and then discussed to identify challenges in the wording of the items, their descriptors and operationalisation information. These processes enabled the further development of operationalisation information. A consensus rating of these recordings was agreed and used to develop criteria for training raters.

When each participant was allocated to a therapist, the therapist was instructed to record two particular sessions for fidelity purposes. These were selected to ensure that an early and a later session were recorded and that exemplars from every session would be equally available across both arms of the study. The recordings were returned to the research centre and uploaded. To avoid unblinding, researchers from one centre were allocated recordings from a different centre to rate for fidelity. Training for fidelity raters was delivered as follows:

-

Each researcher rated each of the six criterion recordings. After each recording was rated, a discussion was held with Dave Dagnan in which the reasoning behind each rating was discussed. Criteria for satisfactory agreement was set as full agreement on the technical presence or absence of treatment components and disagreement by no more than one point on four or fewer items in the 10-item therapy quality scale. A minimum of four recordings were rated in the training. If a researcher achieved criterion in less than four recordings, further recordings were rated and discussed until four recordings had been rated. Six raters were trained, although only four contributed to the final data set, with one rater carrying out ratings for inter-rater reliability; all achieved criterion between three and six recordings.

-

To ensure consistency and prevent drift throughout the fidelity rating process, a further recording was jointly rated by Dave Dagnan and the researcher every 20 fidelity ratings; the same criteria for agreement was applied as in the original training.

-

Inter-rater reliability data were generated by a further rater who rated 48 recordings with a balanced number of ratings from each site in each arm of the study. This rater was trained using the same procedure as the primary fidelity raters with the same consistency rating every 20 ratings.

Supervision

To help ensure that the therapy was delivered with fidelity to the manual, therapists received supervision from a clinical psychologist experienced in delivering psychological therapies to people with a learning disability on a weekly or fortnightly basis, with face-to-face supervision meetings at least once a month. In some locations, supervision was given to small groups of therapists (two to four). A supervision agreement was made with each of the therapists at the outset. The therapists brought therapy logs to supervision that they had completed after meeting with clients. The therapist used the logs to record (1) what tasks had been carried out in the session, (2) what had been carried out successfully, (3) barriers faced and (4) their plan for the next session. There was also a space for any other notes or thoughts to be recorded and an additional section for the BeatIt participants about any homework set for the participant to complete between sessions. The logs provided a structure for the supervision and notes were kept to provide a record of each supervision meeting and signed by both supervisor and therapist.

Data management

The trial was conducted in accordance with the principles of Good Clinical Practice (GCP) to ensure quality of data and protection of participants. These matters were carefully discussed with members of the Trial Steering Committee; members of the Committee with learning disabilities requested to run through the measures with the researchers in Scotland. When doing so, the Committee members offered helpful advice about ensuring that the process of data collection was engaging and accessible for participants. Data were collected by trained researchers and health professionals, using detailed standard operating procedures. Any inconsistencies were investigated and resolved in a timely manner. Careful quality checks were made before data were submitted to RCB. Once data had been submitted, further independent quality checks were performed by RCB before database lock. After database lock, the final statistical analyses were carried out.

Data collection and blinding

As shown in Figure 1, data were collected at three time points:

-

baseline

-

time 1 – 4 months post randomisation (post intervention)

-

time 2 – 12 months post randomisation (follow-up/maintenance).

The data were collected on an outreach basis, face to face, and this ordinarily occurred at a participant’s home, unless another location that offered privacy was preferable. As data were also collected from carers, arrangements were made to have separate meetings with both carers and participants when the researcher visited. There was one additional data collection point at 8 months via telephone with the carer alone, to chart any changes in the participant’s medication use and receipt of services.

Both treatments were of similar duration and included a support person. Moreover, both groups of participants were told that they were joining the BeatIt trial, rather than being told that they were being allocated to the BeatIt or StepUp intervention. These key similarities helped prevent research assistants from becoming unblinded if participants made reference to their therapy sessions during follow-up meetings. In addition, none of the researchers conducted qualitative interviews or was involved in the fidelity checks for participants from whom they collected outcome data. Qualitative interviews and therapy fidelity ratings were carried out by a researcher other than the researcher who gathered the outcome data from the participant concerned.

Measures

Primary outcome measure

The primary outcome was the Glasgow Depression Scale for people with a Learning Disability (GDS-LD),40 a self-reported measure of depressive symptoms. The GDS-LD is a 20-item scale that asks participants to indicate how often they have experienced particular depressive symptoms over the previous week using a three-point scale (never/sometimes/always).

Secondary outcome measures

Measures of depression and anxiety

Depressive symptoms (carer rating)

Carers completed the Intellectual Disabilities Depression Scale (IDDS)52 to provide an informant view of participants’ depressive symptoms. This is a 38-item behavioural checklist designed to measure the frequency of observable depressive behaviours within a 4-week period.

Anxiety symptoms (self-rating)

Self-reported anxiety symptoms were measured using the Glasgow Anxiety Scale for people with an Intellectual Disability (GAS-ID). 53 This scale has three sections dealing with worries, specific fears and physiological symptoms that the respondent may have experienced over the previous week and grades them using a three-point scale (never/sometimes/always).

Level of aggressive behaviour

The aggressive/destructive behaviour subscale of the Behavior Problems Inventory for Individuals with Intellectual Disabilities – Short Form (BPI-S)54 was completed by carers and used to examine the frequency with which the participants displayed different aggressive behaviours.

Quality of life

Quality of life (self-report)

The EuroQol-5 Dimensions – Youth version (EQ-5D-Y)55 was used to measure QoL outcomes. This version was developed for young people aged ≥ 8 years. Although the language is not childish, it is more straightforward and comprehensible. 56 The five questions are accompanied by a 100-point visual analogue scale [EuroQol Visual Analogue Scale (EQ-VAS)], on which participants are asked to rate how good or bad their health is on that day.

Community involvement

The Index of Community Involvement (ICI)57 recorded the frequency of participation in social, community-based and domestic and leisure activities over a 4-week period.

Domestic activity

The Index of Participation in Domestic Life (IPDL)58 was designed to record changes to participation in 13 household tasks during the previous 4 weeks.

Perceived social support

The Social Support Questionnaire – three questions (SSQ3)59 is a three-item questionnaire that examines perceived social support (PSS). It recorded both the size of participants’ social networks and their satisfaction with the levels of support that they received.

Adaptive behaviour

Four subscales of part 1 of the ABS-RC2,43 concerning the motivation to engage in tasks and to take responsibility, were used as a proxy measure of activity avoidance. These subscales were (1) domestic activity (six items), (2) self-direction (five items), (3) responsibility (three items) and (4) socialisation (seven items).

Carer self-efficacy and carer–patient relationship

Carer self-efficacy

The carers’ perceptions of their ability to provide support to adults with a learning disability was examined using the Emotional Difficulties Self-Efficacy (EDSE) scale. 60,61 This is a four-item questionnaire that asks carers to rate their confidence in supporting the emotional difficulties of the person with a learning disability.

Carer–patient relationship

The Expressed Emotion: Five-Minute Speech sample (FMSS)62 was used to assess the relationships between carers and participants by asking carers to speak about their thoughts and feelings towards the people whom they support, uninterrupted for 5 minutes, and rating their responses.

Life events

Finally, the Bangor Life Events Schedule for Intellectual Disabilities (BLESID)63 self-report version was used to record participants’ recent life events. This questionnaire was used to record the important life events that had taken place in participants’ lives over the previous 12 months and the impact that these events had on their lives. This allowed for the analysis of potential changes in the reactions to life events over time, such as a reduction in the negative impact experienced in response to new events that occurred during the course of the study. Because BLESID records events experienced over a period of 12 months, it was used only at baseline and the 12-month follow-up.

Health economics

Resource use

The Client Service Receipt Inventory (CSRI)64 is a validated tool to measure total package resource use and has been used in evaluations involving service users with psychiatric problems and service users with learning disabilities. It records items such as contacts with community-based primary care, other health or social services, educational services, and outpatient and inpatient attendances. Unit costs for most of these are available.

Medication inventory

Both prescription and over-the-counter (OTC) medication use was recorded. Any changes in the use of medication over the course of the intervention and during follow-up were noted to determine if there were treatment differences between the two arms of the study. In combination with the CSRI, medication use was costed.

Expectations of therapy

Participants’ expectations of the potential of therapy to be successful were assessed before starting the intervention using two questions rated on a four-point scale. The questions were taken from the Therapy Expectation Measure,65 developed for use with people who have learning disabilities.

Sample items from the primary outcome measure and selected secondary outcome measures can be found in Appendix 1.

Sample size

In the first 18 months of an earlier pre–post trial of BeatIt, the mean reduction in GDS-LD39 scores at 3 months’ follow-up was 8.50 points [standard deviation (SD) 5.24 points].

The present study was powered to detect a mean between-group difference of 0.6 SD units, or 3.14 points on the GDS-LD.

If the BeatIt group in this study could achieve an 8.5-point improvement in GDS-LD scores at 12 months, then this allows for the StepUp group showing 5.36-point improvement over the same time period (i.e. 63% of the improvement in the BeatIt group).

Alternatively, this allows for a small improvement in the StepUp group, in conjunction with a large short-term improvement in the BeatIt group, followed by some regression. For example, if the BeatIt group show an improvement from baseline to 12 months of 6 points, then the study would be powered to detect a difference if the mean improvement in the StepUp group was 2.86 points.

To have 90% power to detect this difference, the study required 60 participants in each arm to provide outcome data at 12 months post randomisation. The primary analysis was to be an analysis of covariance, adjusting for baseline GDS-LD score, which would have the power to detect smaller intervention effects, depending on the level of correlation in scores over time.

There were no data to inform the effect of clustering of outcomes for participants with learning disabilities seen by each therapist. The assumption was made that each therapist would work with an average of nine participants (i.e. several part-time therapists at each site) and an intraclass correlation of 0.025 was assumed, resulting in the sample size being increased by 20% to 72 per group, or 144 in total. A recruitment target of 166 participants allowed for a loss to follow-up of ≤ 13.3%. A meta-analysis of research with the general population66 found a post-intervention effect size on self-reported depression symptoms of behavioural activation therapy versus supportive therapy of 0.75. These designs were similar to our own attention control design. However, they did not report data regarding long-term follow-up in comparison with supportive therapy. The effects relative to brief psychotherapy were 0.56 post intervention and 0.50 after an average follow-up of 4 months, suggesting that the effects of behavioural activation therapy might persist for some time. Our follow-up at 12 months post randomisation was approximately 9 months post intervention, so we would be able to detect differences between groups only if they persisted over a longer time frame than usually studied. Therefore, we believed that an effect size for sample size estimation purposes of 0.60 was realistic given the results of this meta-analysis for behavioural activation versus supportive therapy, and this would also be considered to be of ‘moderate’ size and thus meaningful from a clinical perspective for an individual therapeutic intervention.

Statistical analyses

The statistical analyses were specified in a statistical analysis plan (SAP) (see Appendix 2), which was approved before database lock.

The primary analysis compared GDS-LD scores at 12 months post randomisation between intervention groups, adjusting for baseline GDS-LD scores, study centre and use of antidepressants at baseline within a mixed-effects linear regression model, including therapist as a random effect. Similar methods were applied to the primary outcome measure at the immediate post-intervention assessment (4 months post randomisation) and to secondary outcome measures at each assessment point. These models were used to estimate between-group differences at each follow-up time point, and to estimate mean changes from baseline within each intervention group. Repeated measures analyses, adjusting for stratification factors, were also applied to each outcome measure. These models were used to confirm the results of analyses looking at each follow-up time point separately, as well as estimating mean changes in outcomes between 4 and 12 months. In general, analyses were carried out using the available data. However, analyses of the primary outcome were repeated using multiple imputation, to assess whether or not the results were sensitive to missing data. To impute missing values at each time point, prediction models were based on age, antidepressant use and any previous or subsequent measurements of the primary outcome; prediction models did not include randomised group. Models for the primary outcome were extended to explore the effects of baseline characteristics, including the stratification factors, chronicity of depressive symptoms, life events and history of previous psychological intervention. The moderating effects of these factors were explored by using appropriately constructed interaction terms within linear regression models. These moderation analyses were exploratory only and designed to inform future translation of the intervention into routine clinical practice. Selected analyses were repeated using a per-protocol population of participants who attended at least eight BeatIt therapy sessions or at least six StepUp sessions.

Additional exploratory analyses were outlined in the SAP as potential avenues for future investigation. These analyses have not yet been carried out and are not included in this report.

Chapter 3 Participants

This chapter describes the characteristics and circumstances of participants recruited to the trial. This includes:

-

the flow of participants into the trial, including referral sources

-

demographic characteristics and circumstances of participants across the two therapy arms

-

characteristics of carers across the two therapy arms

-

the services people were receiving in the 4 months before baseline across the two therapy arms.

Flow of participants into the trial

Figure 2 reports the flow of participants into the trial. In total, 934 information packs were sent out, from which 233 reply slips were received (four of these slips indicated that the potential participant was not interested in taking part). In total, 186 people gave their consent to take part in the study, and at that point their eligibility was assessed. Of these 186 people, 19 people were excluded, most as a result of not meeting depression criteria (eight people) or the IQ being above the threshold for inclusion in the trial (six people). An additional three people withdrew before randomisation, and three people were randomised but no therapist was available.

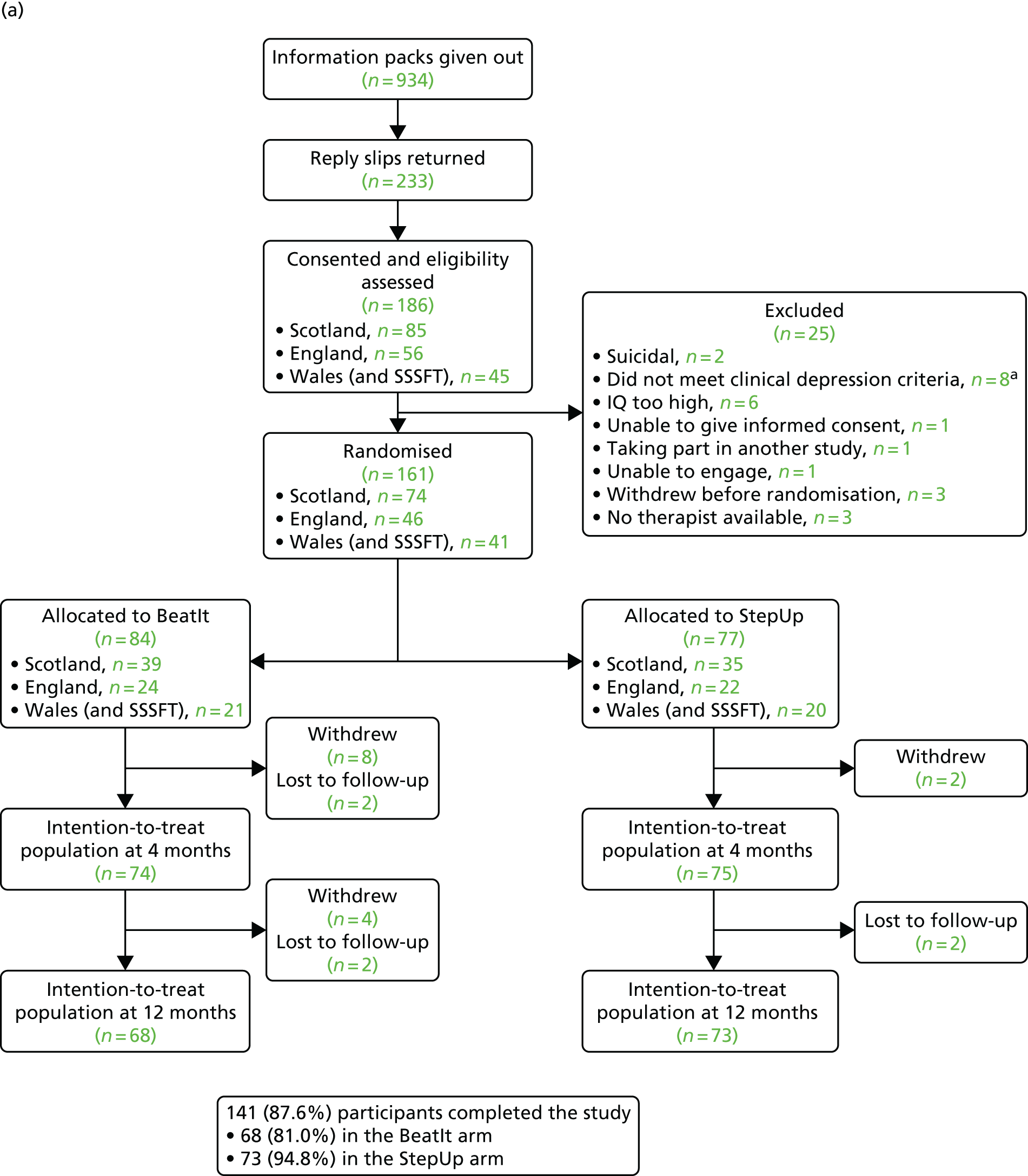

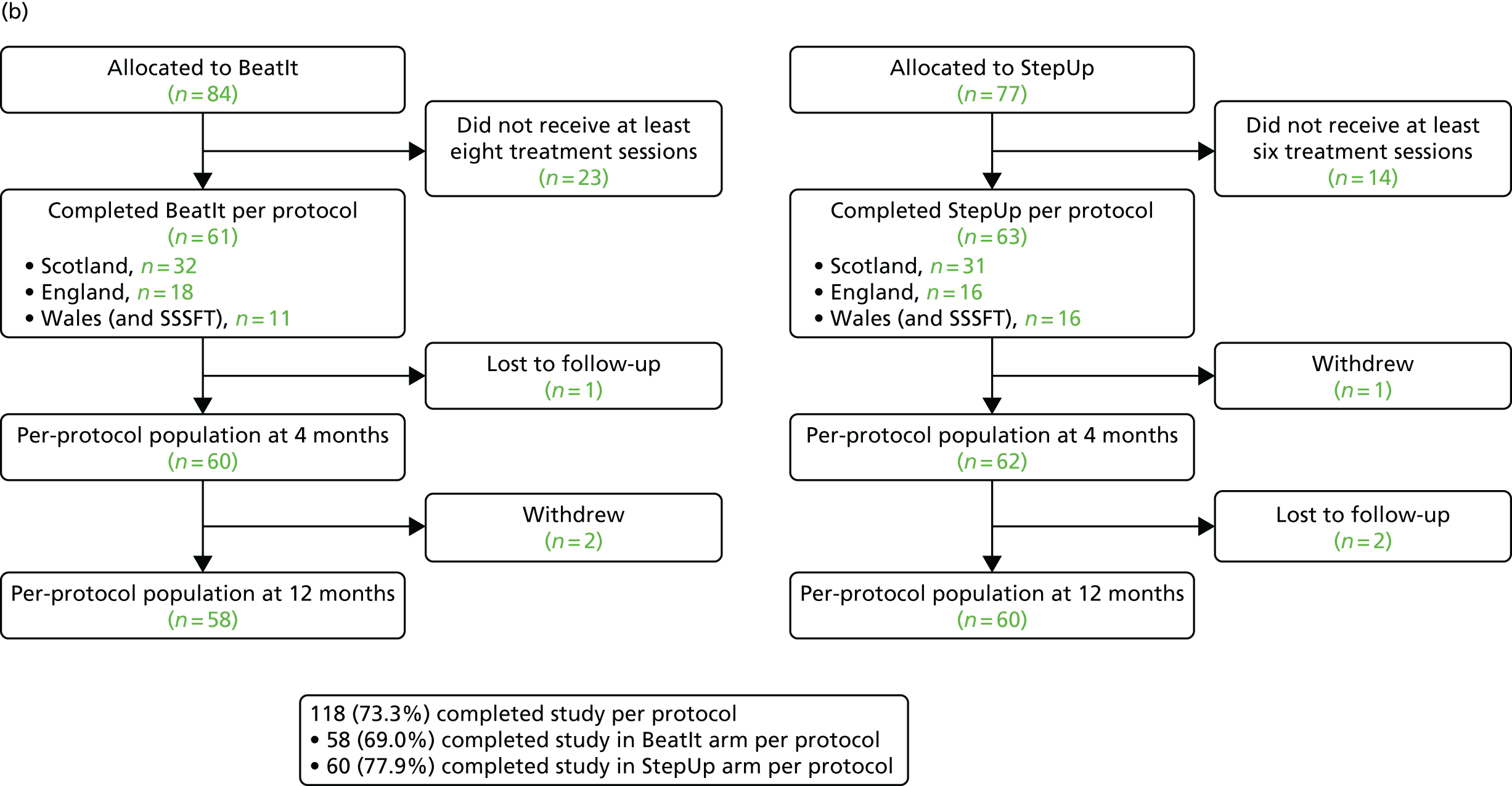

FIGURE 2.

Participant flow diagram. Data were removed from analysis. (a) Intention-to-treat population; and (b) per-protocol population. SSSFT, South Staffordshire and Shropshire Healthcare NHS Foundation Trust. a, Includes one participant initially allocated to StepUp in error.

This resulted in 161 people being randomised into the trial. Six people were lost to follow-up and 14 people withdrew during the trial, resulting in a total of 141 participants who completed the trial. Sixty-nine of these 141 participants were recruited in Scotland, 38 in England and 34 in Wales.

Table 4 shows that two-thirds of the participants were referred by community nurses, psychologists and psychiatrists who worked in community teams for people with learning disabilities.

| Profession | Site (n) | Total (n) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Scotland | England | Wales | ||

| Nurse | 30 | 23 | 30 | 83 |

| Psychologist | 27 | 0 | 1 | 28 |

| Psychiatrist | 11 | 0 | 4 | 15 |

| Social worker | 4 | 0 | 4 | 8 |

| Dietitian | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| Self-referral | 0 | 6 | 0 | 6 |

| IAPT therapist | 0 | 9 | 0 | 9 |

| Clinical studies officer | 0 | 5 | 0 | 5 |

| Support worker | 0 | 3 | 0 | 3 |

| Reviewing officer | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 |

| Unknown | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Total | 74 | 46 | 41 | 161 |

Participants at baseline

Seventy-seven participants were randomised to receive StepUp and 84 participants were randomised to receive BeatIt. The imbalance of seven participants was a result of using a stratified randomisation scheme. Participants were randomised in six strata defined by recruitment site (Scotland, England, Wales) and whether or not participants were taking antidepressants at baseline (yes/no). Within these strata, participants were randomised in blocks of length four (two to each arm) and six (three to each arm), with block lengths occurring at random. Therefore, within each stratum, the imbalance between treatment groups could be at most three in either direction (if the study stopped midway through a block of six allocations, and that block had consisted of three allocations to one group by three allocations to the other group). Across the six strata, at the end of the trial, the balance of randomisations were as follows:

-

Scotland, taking antidepressants: 29 to BeatIt and 27 to StepUp; difference = +2

-

Scotland, not taking antidepressants: 10 to BeatIt and eight to StepUp; difference = +2

-

England, taking antidepressants: 12 to BeatIt and 13 to StepUp; difference = –1

-

England, not taking antidepressants: 12 to BeatIt and nine to StepUp; difference = +3

-

Wales, taking antidepressants: 12 to BeatIt and 11 to StepUp; difference = +1

-

Wales, not taking antidepressants: nine to BeatIt, and nine to StepUp; difference = 0.

Table 5 describes demographic and health characteristics of the 161 participants who began the trial at baseline, broken down across the two therapy arms. Overall, a slight majority of participants were female, with a mean age of 40 years. Most participants were white and single. The mean Full Scale IQ was 58.34 for StepUp participants and 55.44 for BeatIt participants.

| Variable | Trial arm | |

|---|---|---|

| StepUp (N = 77) | BeatIt (N = 84) | |

| Gender, n (%) | ||

| Male | 38 (49.4) | 38 (45.2) |

| Female | 39 (50.6) | 46 (54.8) |

| Age (years) | ||

| Mean (SD) | 40.1 (12.0) | 40.3 (11.7) |

| IQ, mean (SD) | ||

| Verbal | 63.14 (10.15) | 58.87 (8.67) |

| Performance | 58.45 (8.11) | 57.84 (9.18) |

| Full Scale | 58.34 (8.38) | 55.44 (8.02) |

| Ethnicity, n (%) | ||

| White | 75 (97.4) | 81 (96.4) |

| Other | 1 (1.3) | 2 (2.4) |

| Unknown | 1 (1.3) | 1 (1.2) |

| Marital status, n (%) | ||

| Married/live-in partner | 7 (9.1) | 5 (6.0) |

| Separated/divorced/widowed | 1 (1.3) | 6 (7.1) |

| Single | 67 (87.0) | 73 (86.9) |

| Unknown | 2 (2.6) | 0 (0.0) |

| Vision, n (%) | ||

| Visual impairment | 45 (58.4) | 55 (65.5) |

| No visual impairment | 32 (41.6) | 29 (34.5) |

| Hearing, n (%) | ||

| Hearing impairment | 8 (10.4) | 20 (23.8) |

| No hearing impairment | 69 (89.6) | 64 (76.2) |

| Mobility problems, n (%) | ||

| Mobility problems | 20 (26.0) | 19 (22.6) |

| No mobility problems | 57 (74.0) | 65 (77.4) |

| Antiepileptic medication, n (%) | 9 (11.7) | 4 (4.8) |

A majority of participants (58.4% of StepUp participants and 65.5% of BeatIt participants) had some degree of visual impairment, with smaller proportions (10.4% of StepUp participants; 23.8% of BeatIt participants) having some degree of hearing impairment. Approximately one-quarter of participants (26.0% of StepUp participants; 22.6% of BeatIt participants) had mobility problems.

Table 6 describes selected circumstances of the 161 participants who began the trial at baseline, broken down by therapy arm. In terms of deciles of neighbourhood deprivation (where 1 is the most deprived and 10 is the least deprived) based on participants’ postcodes, participants on average were living in slightly more deprived postcodes than the median. In terms of negative life events, participants in both therapy arms had experienced on average more than one negatively experienced life event in the 12 months before baseline (mean 1.36 events for StepUp participants; mean 1.48 events for BeatIt participants).

| Variable | Trial arm | |

|---|---|---|

| StepUp (N = 77) | BeatIt (N = 84) | |

| Deprivation decile, mean (SD) | 3.8 (2.1) | 4.5 (2.6) |

| BLESID (life events): number of life events experienced negatively, mean (SD) | 1.36 (1.60) | 1.48 (1.59) |

| Degree of service support, n (%) | ||

| Less than daily support | 24 (31.2) | 25 (29.8) |

| Daily support | 53 (68.8) | 59 (70.2) |

| PSS: number of family members, mean (SD) | 1.32 (1.5) | 1.98 (2.3) |

| PSS: number of non-family members, mean (SD) | 3.30 (2.6) | 2.92 (2.3) |

| Previous therapy for depression, n (%) | ||

| Yes | 14 (18.2) | 17 (20.2) |

| No | 63 (81.8) | 67 (79.8) |

| Use of antidepressants, n (%) | ||

| Yes | 51 (66.2) | 53 (63.1) |

| No | 26 (33.8) | 31 (36.9) |

| Use of mood stabilisers, n (%) | ||

| Yes | 15 (19.5) | 11 (13.1) |

| No | 62 (80.5) | 73 (86.9) |

| Antiepileptic medication, n (%) | ||

| Yes | 9 (11.7) | 4 (4.8) |

| No | 68 (88.3) | 80 (95.2) |

Service receipt in the 4 months prior to baseline

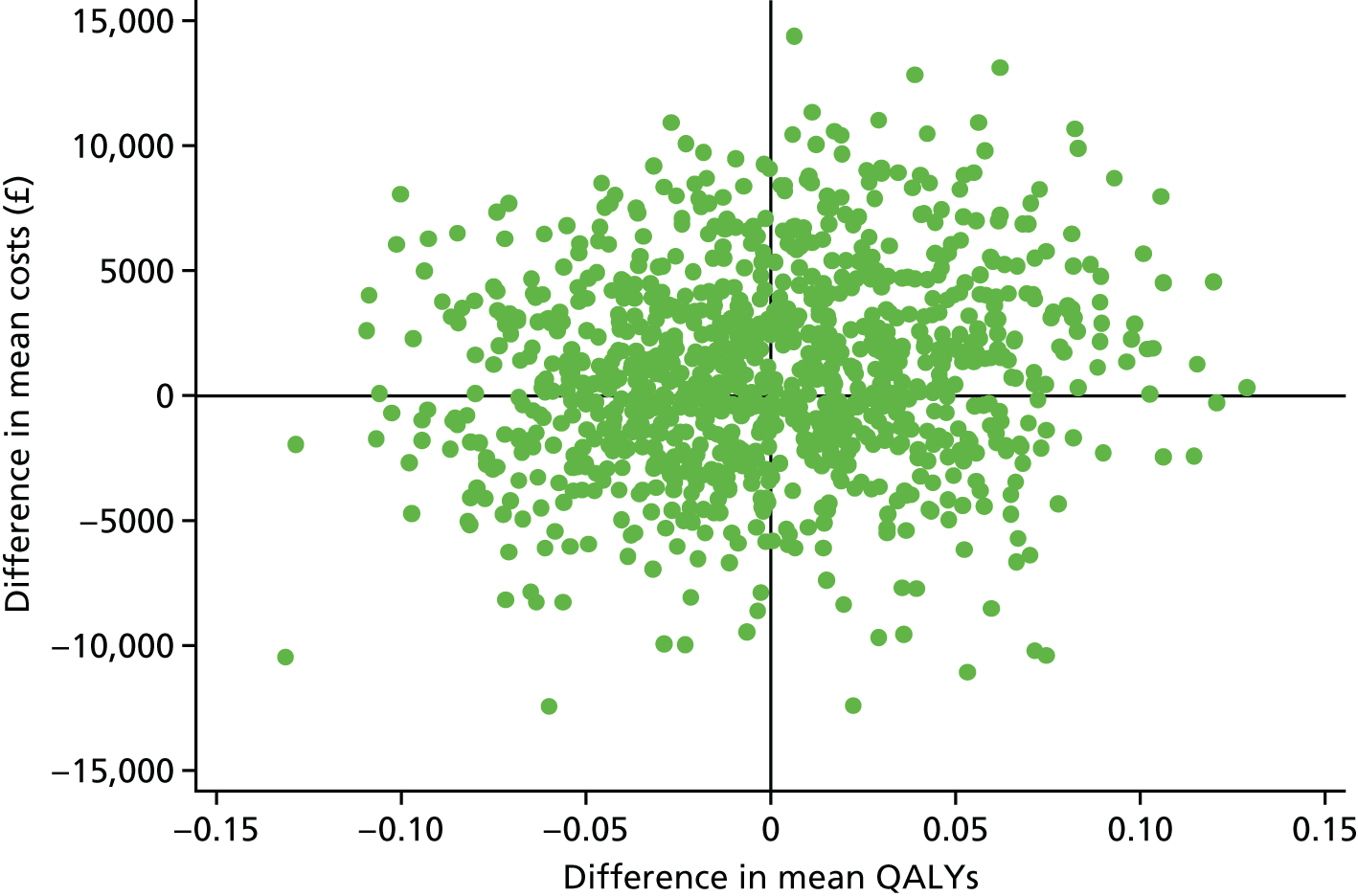

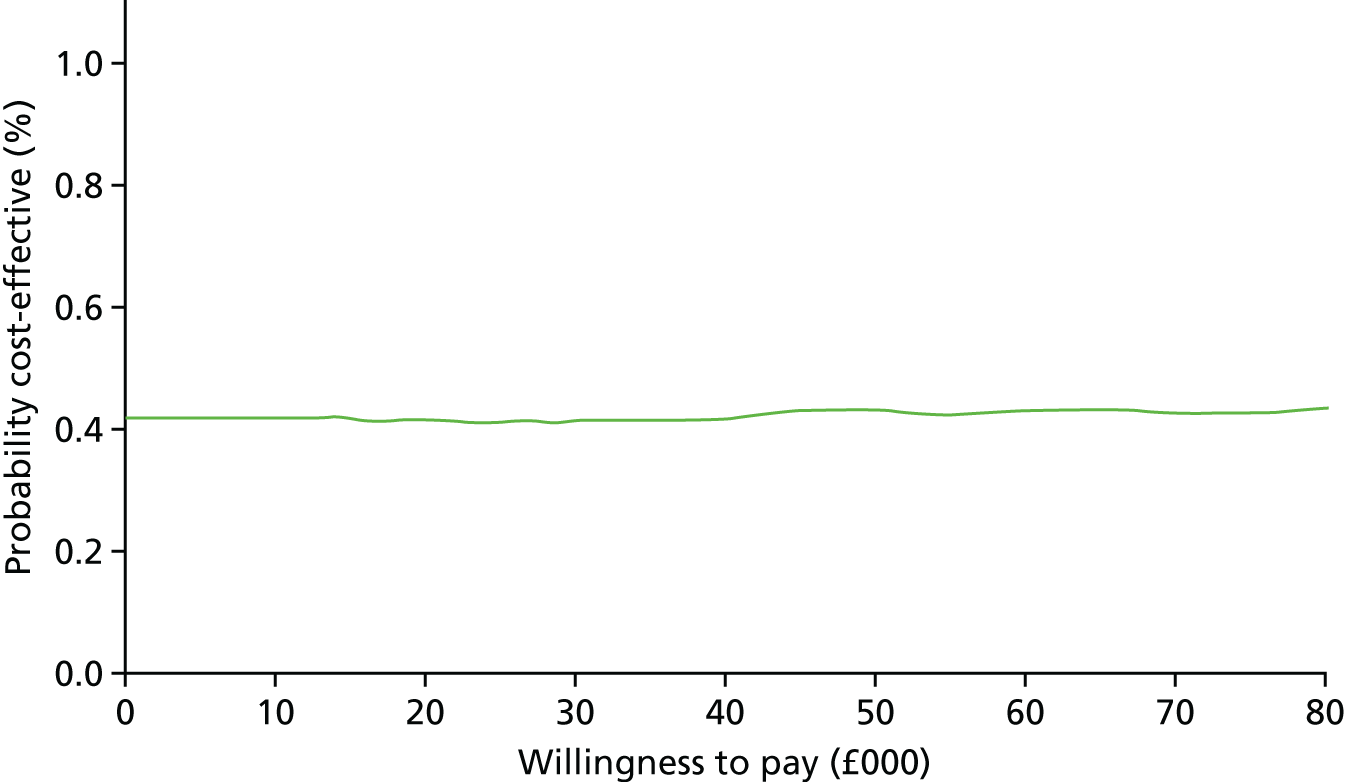

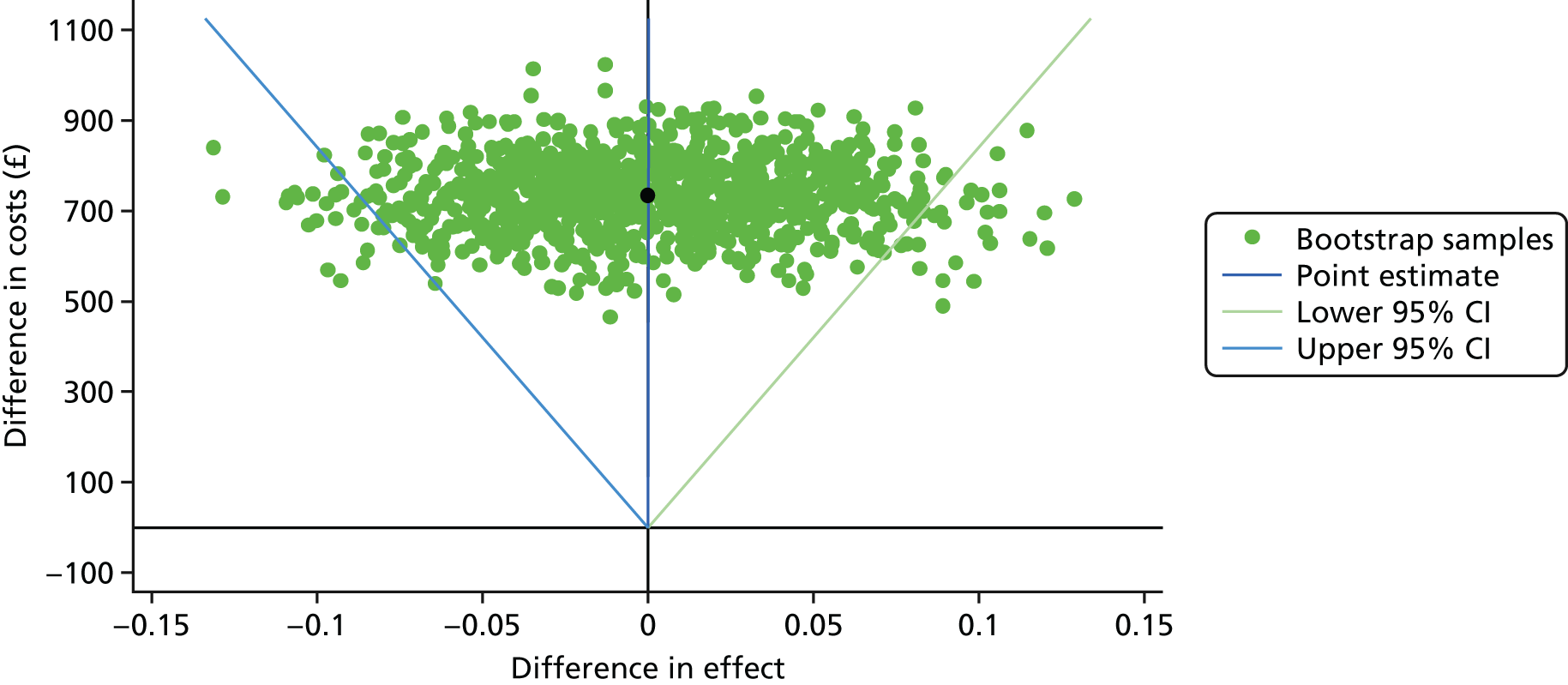

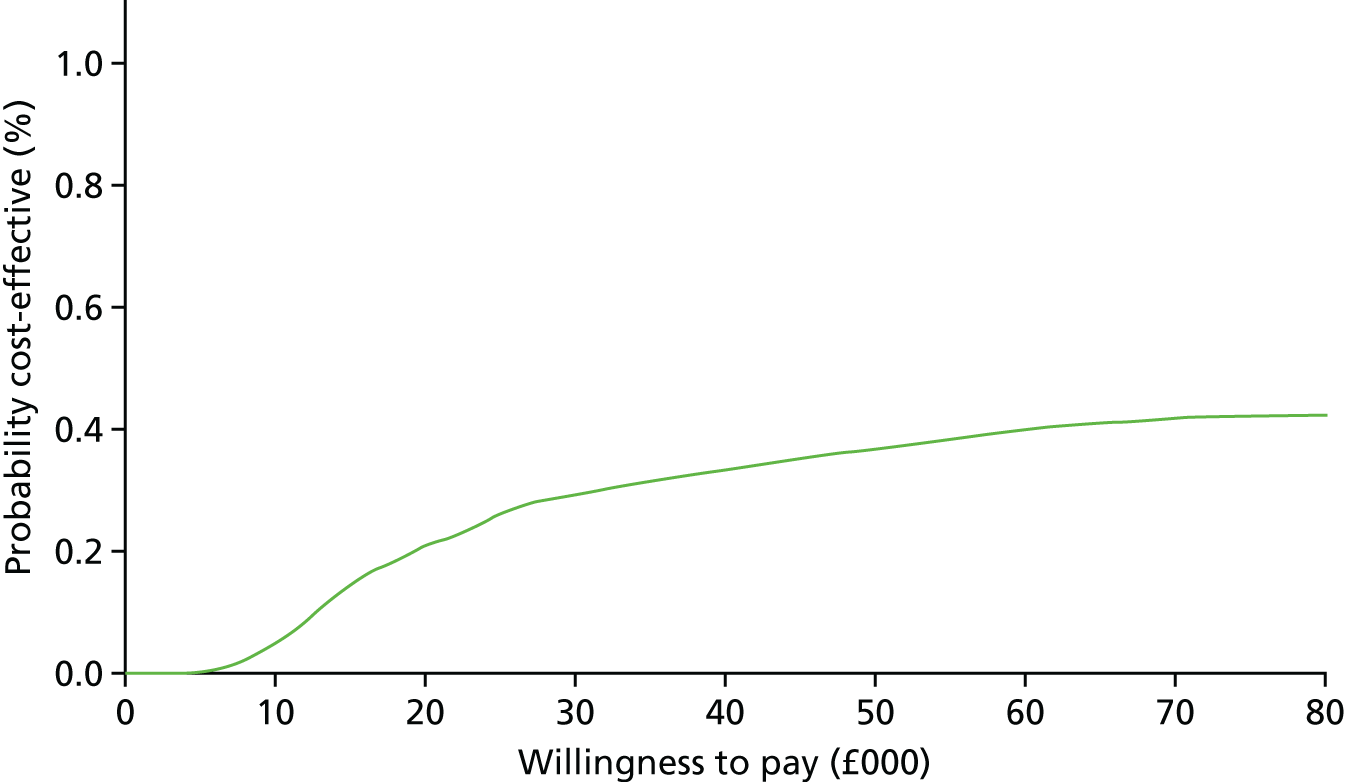

Over two-thirds of participants (68.8% of StepUp participants; 70.2% of BeatIt participants) were receiving support from services at least daily. According to the PSS scale, participants were receiving social support from an average of fewer than two family members (1.32 for StepUp participants; 1.98 for BeatIt participants) and social support from an average of approximately three non-family members (3.30 for StepUp participants; 2.92 for BeatIt participants).