Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 13/87/08. The contractual start date was in January 2015. The draft report began editorial review in December 2016 and was accepted for publication in June 2017. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Catriona McDaid is a member of the National Institute for Health Research Health Technology Assessment and Efficacy and Mechanism Evaluation Editorial Board. Christine Moffatt has received grant funding from 3M UK PLC and Smith and Nephew, two health science-based technology companies, outside the submitted work.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2018. This work was produced by Tilbrook et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2018 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Background

Chronic venous leg ulcers

Chronic venous leg ulcers (VLUs) are wounds of the lower limb caused by a diseased venous system, which results in swollen legs and damage to the tissues, usually around the ankles. VLUs are most commonly the result of severe varicose veins, a previous deep-vein thrombosis, trauma or failure of the calf muscle pump, all of which result in impaired venous return. Obesity and immobility are additional important factors contributing to venous dysfunction. 1

The VLUs may take many months to heal (with approximately 25% failing to heal completely), during which time they result in significant suffering and reduction in quality of life for patients. 2 VLUs have a tendency to become recurrent, with rates of recurrence estimated at between 18% and 28%. 3 As a result, the management of VLUs represents a substantial cost to the NHS, the majority of which is attributed to nurse time. Estimated lifetime prevalence of VLUs is between 1% and 3% of the elderly population in the USA and Europe. 4 It is estimated that 1% of the adult population will suffer from leg ulcers at some point in their life. 5 Furthermore, incidence and prevalence of ulceration is predicted to increase as a result of the increasing age and obesity of the population in the USA and Europe. A recent cohort study conducted in the UK estimated that 278,000 VLUs per year are managed by the NHS. 6 Furthermore, the annual cost to the NHS of this management was estimated to be £941M, with substantially more cost associated with unhealed wounds. 7

Current treatment strategies

Current treatment strategies for VLUs focus on efforts to reduce venous hypertension. At present, compression is the main treatment for venous ulceration and few additional therapies have robust evidence to suggest they improve healing rates.

Compression therapy

The mainstay of treatment of leg ulcers is graded compression therapy (target pressure of 40 mmHg) and this is the recommended first-line treatment in UK guidelines. 2 The aim of compression therapy is the reduction of venous hypertension, improvement in calf muscle function and the creation of a wound environment conducive to wound healing. Compression therapy in the form of bandages and hosiery has been shown to be effective in many randomised controlled trials (RCTs). 8 However, despite this treatment, patients take many months to heal (with median healing times of approximately 12 weeks in previous trials)3 and for some patients compression therapy does not result in resolution of their leg ulcers. The use of compression (as well as dressings, largely to manage the wound exudate) can be expensive as nurse time is required to change bandages, which can be required weekly or more frequently.

In addition, effective treatment of VLU requires adherence to compression therapy which, for many patients, is uncomfortable and sometimes painful and inconvenient for everyday life (compression is bulky and dressings have to be changed several times weekly). In addition, the use of thicker bandaging systems, such as four-layer bandaging, may restrict movement of the ankle and cause difficulty in wearing shoes. 9

Topical therapies

The most frequently used topical antimicrobials in wound care practice are chlorhexidine, iodine, silver-containing products, mupriocin (Bactroban®, GlaxoSmithKline, Brentford, UK) and fucidic acid. Historically, agents such as acetic acid, honey, hydrogen peroxide, sodium hypochlorite, potassium permanganate and proflavine have all been used. 10 There is currently a lack of reliable evidence to support an association between topical agents and reduction in time to healing in VLUs. 11

Adjunctive drug therapies

A recent Cochrane review has shown pentoxifylline to be an effective adjunct to compression therapy and possibly more effective than placebo or no treatment in the absence of compression. 12 However, pentoxifylline is not commonly prescribed in the NHS13 and has common and intolerable side effects, some of which have the potential to be life-threatening. 14 Other adjunctive drugs, including venoactive drugs, are not recommended owing to insufficient evidence regarding their use and unclear mechanism of action. 15

Surgery

Surgery to treat superficial varicose veins has been shown to prevent recurrence of ulcers once they have healed but does not improve time to healing of existing ulcers. 16 An ongoing RCT is further investigating surgery as a treatment for chronic ulceration, comparing early versus delayed endovenous treatment of superficial venous reflux. 17 This study is due to publish in November 2018. 17

Other therapies

Research into the use of novel cell-based therapies, such as allogenic cells and growth factors, is currently in progress. 18–20 Owing to their cost and associated side effects, it is thought that such therapies are unlikely to be made widely available. 18 If other treatments were able to reduce the time to healing, this would be a significant breakthrough.

Potential role of aspirin as a treatment for venous leg ulcers

Aspirin (also known as acetylsalicylic acid) has been widely used as a medication for > 100 years and is inexpensive, readily available and generally safe to use. Aspirin is a cyclo-oxygenase inhibitor that irreversibly reduces prostaglandin 2 and thromboxane A2. 21 At low doses, it is used very widely to reduce cardiovascular events in those at high risk. 22

The exact mechanism by which aspirin may improve time to healing of VLUs is unclear but it is potentially associated with both the inhibition of platelet activation and the reduction of inflammation. 23

Possible adverse events (AEs) associated with the use of aspirin include gastric ulceration and other gastrointestinal effects. Other effects include liver and renal toxicity, exacerbation of asthma and dermatological reactions. Antiplatelet drugs, when administered in combination with anticoagulants, are associated with a higher risk of gastrointestinal bleeding than that associated with each drug class used alone. 24

Existing evidence on aspirin in the treatment of venous leg ulcers

To date, there have been two small RCTs that have investigated the use of aspirin (300 mg/day) in patients with VLUs of ≥ 2 cm2 in area. The first, a UK-based study in 20 participants, reported healing of 38% of ulcers in the intervention group (aspirin in combination with compression therapy), compared with 0% in the control group (placebo in combination with compression therapy), over a study period of 4 months. The average time to healing was not reported. 25 del Río Solá et al. 26 reported a study of 51 participants to whom aspirin was given in combination with compression therapy (n = 23) compared with compression therapy alone (n = 28). The researchers reported the average time to healing as 12 weeks in the aspirin group compared with 22 weeks in the control group, but that there was no significant difference between groups in the proportion of patients with ulcers healed (74% in the aspirin group and 75% in the control group). These two studies were the only RCTs identified in a recently conducted Cochrane systematic review23 and, owing to variations and limitations in the data, a meta-analysis was not undertaken. Application of GRADE (Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development and Evaluations)27 to the data highlighted that the evidence was of low to very low quality.

Explanation of rationale

The Aspirin for Venous leg Ulcers Randomised Trial (AVURT) was undertaken to address the primary question of whether or not the addition of 300 mg of daily aspirin to standard evidence-based therapies demonstrates evidence of a reduction in time to healing of VLUs. This pilot trial was developed to explore this question as well as assessing the feasibility (especially in terms of participant recruitment and treatment compliance) and safety (in terms of aspirin-related AEs) of conducting a larger-scale pragmatic study, powered to investigate the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of aspirin for VLU healing.

This research is important because leg ulcers are common and costly and result in significant patient suffering. 2 If aspirin, which is commonly used in many patients, was able to reduce the time to healing of VLU with limited risk of treatment-related harm, then this would result in a potentially important reduction in resource use and an improvement in patients’ health-related quality of life. Because aspirin is generally safe, cheap, well tolerated (for most patients) and widely available, the potential impact on this population is large.

Two previously conducted RCTs have been performed on the use of aspirin in the treatment of VLUs. 25,26 The findings of both trials suggested that there may be benefit in patients with VLUs taking aspirin: one reported that a greater proportion of patients healed with 300 mg of aspirin together with standard compression bandaging25 and one reported a shorter time to healing with 300 mg of aspirin in conjunction with gradual compression therapy. 26 However, both trials have been assessed as being at a risk of bias. 23 The authors of the Cochrane review23 concluded that the low-quality and insufficient evidence from the two included trials meant that they were unable to make definitive claims on the benefits and potential harm of oral aspirin, as an adjunct to compression therapy, on the recurrence and healing of VLUs. The Cochrane review23 recommended that further high-quality studies were needed.

A RCT is required to assess the potential effectiveness and safety profile of aspirin in this population. However, it would be premature to conduct a full trial initially, not least as it is not clear how many people with VLUs currently take aspirin or other antiplatelet medications and the potential impact of this on the design and feasibility of any future study.

During the registration of AVURT, we identified two other RCTs investigating aspirin for VLUs. ASPiVLU (ASPirin in Venous Leg Ulcer Healing)28 was a trial being conducted in Australia that was planning to randomise patients with VLU to receive either 300 mg of aspirin or placebo. The primary end point of that study was time to complete healing of reference ulcer at or before 12 weeks post randomisation. Aspirin4VLU (Low Dose Aspirin for Venous Leg Ulcers) was a trial being conducted in New Zealand that was planning to randomise VLU patients to either 150 mg of aspirin or placebo in addition to standard care. The primary end point was time to complete healing of reference/largest ulcer. A secondary outcome of this study is change in estimated reference ulcer area from baseline to 24 weeks. 29

Research objectives

To assess the efficacy of aspirin on time to healing of VLUs, to examine safety issues in this cohort of patients and to assess the feasibility of proceeding from a Phase II trial to a Phase III trial of clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness.

Primary objective

To compare the effects of 300 mg of aspirin plus standard care with placebo plus standard care on time to healing of the reference chronic VLU (largest eligible venous ulcer).

Secondary objectives

To assess the safety of aspirin in patients with VLUs and feasibility of leading directly from the pilot Phase II trial into a larger pragmatic study (Phase III) of effectiveness and efficiency, and check, in accordance with the Acceptance Checklist for Clinical Effectiveness Pilot Trials (ACCEPT) criteria,30 whether or not the pilot study fulfilled four criteria:

-

confirming that the effect sizes in the British and Spanish RCTs were too large, but

-

confirming that smaller effect sizes were still plausible, while

-

confirming that the intervention does not lead to unacceptably high rates of serious adverse events (SAEs), and

-

confirming that we can recruit at the planned rate.

Additional objective

To perform an individual patient-level meta-analysis using the data from AVURT and other published25,26,31 and unpublished studies [e.g. A Carolina Weller Barker, I Darby, T Haines, M Underwood, S Ward, P Aldons, E Dapiran, JJ Madan, P Loveland, A Sinha, M Vicaretti, R Wolfe, M Woodward, J McNeiJ (ASPiVLU). School of Public Health and Preventative Medicine, Monash University, Melbourne, VIC, Australia, 2015]. The objective of performing this meta-analysis is to assess the clinical effectiveness on time to healing of VLUs and safety of aspirin use. This will take place following completion of the other trials, which are still recruiting patients28,29 at the time of writing.

Chapter 2 Methods

This chapter reports the methods used to conduct AVURT. It describes the study design and protocol from recruitment of participants to completion in the study, data analysis procedures, quality assurance and governance. The trial protocol has been published. 32

Design

A multicentred, pilot, Phase II randomised double-blind, parallel-group, placebo-controlled efficacy trial.

Setting

Patients presenting at community leg ulcer clinics/hospital outpatients’ clinics, or registered with a leg ulcer clinic but receiving care at home, were recruited. Some sites could use patient identification centres (PICs) to identify patients to take part. Participants were recruited from 10 centres in England, Wales and Scotland (see Appendix 1) from leg ulcer hospital outpatient clinics (n = 5), community leg ulcer clinics or community caseloads (n = 3), a wounds clinic in a university (n = 1) and a primary care leg ulcer clinic (n = 1). At each of the nurse-led community centres (n = 3), a doctor was identified to work with the centre to review and confirm the patient’s eligibility for the trial, to prescribe the investigational medicinal product (IMP) and to review changes to concomitant medication.

Participants

Participant eligibility for the trial was assessed according to the criteria below.

Inclusion criteria

To be eligible for the study, it was necessary for participants to meet all of the following criteria.

-

Having at least one chronic VLU, when chronic venous leg ulceration was defined as any break in the skin that had either (1) been present for > 6 weeks or (2) occurred in a person with a history of venous leg ulceration. Ulcers were considered purely venous if clinically no other aetiology was suspected. The ulcer was required to be venous in appearance (i.e. moist, shallow, of an irregular shape) and lie wholly or partially within the gaiter region of the leg. If the patient had more than one ulcer we chose the largest as the ‘index’ or reference ulcer for purposes of the analysis.

-

Having an ulcer with an area of > 1 cm2.

-

Having had an ankle–brachial pressure index (ABPI) of ≥ 0.8 taken within the previous 3 months or, when the ABPI is incompressible, other accepted forms of assessment included peripheral pulse examination/toe pressure/Duplex ultrasonography in combination with clinical judgement to be used to exclude peripheral arterial disease (PAD).

-

Being aged ≥ 18 years (there was no upper age limit).

-

Being able and willing to give informed consent.

Exclusion criteria

Potential participants were excluded if they fulfilled any of the following criteria.

-

Being unable or unwilling to provide consent.

-

Having a foot (below the ankle) ulcer.

-

Having a leg ulcer of non-venous aetiology (i.e. arterial).

-

Having an ABPI of < 0.8.

-

Using (self-administered or prescribed) regular concomitant aspirin.

-

Having a previous intolerance of aspirin/contraindication to aspirin (decision made according to the prescribers’ clinical judgement).

-

Taking contraindicated medication: probenecid, oral anticoagulants including coumarins (warfarin and acenocoumarol) and phenindione, dabigatran, rivaroxaban, apixiban, heparin, clopidogrel, dipyridamole, sulfinpyrazone and iloprost.

-

Having known lactose intolerance.

-

Being a pregnant or lactating/breastfeeding woman.

-

Being male or a pre-menopausal female of child-bearing potential unwilling to use an effective method of birth control [i.e. either hormonal in the form of the contraceptive pill; barrier method of birth control accompanied by the use of a proprietary spermicidal foam/gel or film; or agreement of true abstinence (withdrawal, calendar, ovulation, symptothermal and post ovulation were not acceptable methods)] from the time consent was signed until 6 weeks after the last dose of IMP. Participants were only considered not of child-bearing potential if they were surgically sterile (i.e. they had undergone a hysterectomy, bilateral tubal ligation, or bilateral oophorectomy) or they were postmenopausal.

-

Currently participating in another study evaluating leg ulcer therapies.

-

Having another reason that excluded them from participating within this trial (decision made according to the nurses’ or prescribers’ clinical judgement).

-

Having previously been recruited to this trial.

Recruitment

Patients were pre-screened on the basis of three criteria (concomitant aspirin, wound size and ulcer duration or history of venous ulceration) by study research nurses to determine those potentially eligible for the study. The reason(s) for ineligibility or not approaching patients were recorded on pre-screening logs (see Appendix 2). Two pre-screening logs were issued. Completion of the first log (version 1.0) was non-mandatory as stipulated by the trial sponsor (based on the sponsor’s belief that the clinics received a heterogeneous referral pattern of mixed aetiology ulcers not thought to be truly representative of the total population of patients with chronic VLUs). Following a recommendation by the Data Monitoring Committee (DMC), the sponsor permitted a new pre-screening log that was made mandatory (version 2.0). Patients attending clinics as part of their routine care and who satisfied the pre-screening criteria were approached by study research nurses or designated health-care professionals and provided with both verbal and written information about the trial in a face-to-face meeting (see Appendix 3). Patients were given a minimum of 24 hours to consider participation in the trial. Study research nurses then obtained voluntary full written consent from those patients who wanted to enter the trial (see Appendix 4). After they gave consent, patients were screened against the study’s full eligibility criteria by the study research nurses or designated health-care professionals using the screening case report form (CRF) (see Appendix 5). The reason(s) for a patient’s ineligibility were recorded. Patients were informed that their eligibility would be subject to confirmation by a medical practitioner and in all cases a medical practitioner determined and confirmed patient eligibility following screening. If a potential participant was not known to the medical practitioner, provision was made for the participant to be contacted by telephone by the medic to check for any possible contraindications. When the medic was satisfied of patient eligibility, they would sign off the prescription for the IMP (see Appendix 6).

Randomisation

Patients were randomly allocated in a 1 : 1 ratio to either aspirin or placebo by the Research Pharmacy (St George’s University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust, London, UK). Randomisation was stratified according to ulcer size (≤ 5 cm2 or > 5 cm2) as this is the strongest known predictor of outcome. 4

Sequence generation

The aspirin and placebo manufacturer, Sharp Clinical Services (UK) Limited (registered office in Ashby-de-la-zouch, UK), generated the randomisation schedule in advance. They provided one randomisation list to the Research Pharmacy and a copy to the senior trial statistician in the York Trials Unit (YTU; University of York). To facilitate participant allocation according to stratification, the allocation sequence on the randomisation list was mirrored top to bottom bottom to top, and each allocation was referenced 1 to 120 for participant identifier (ID). Where the participant was placed on the randomisation list (top or bottom) depended on the stratification of ulcer size (≤ 5 cm2 or > 5 cm2).

Allocation

After participant consent was taken and baseline data were recorded, the research site faxed the AVURT prescription directly to the Research Pharmacy. The AVURT prescription also indicated ulcer size. On receipt of the original signed prescription by post, the Research Pharmacy allocated the next available randomisation ID. The randomisation ID corresponded to IMP bottle number for allocation (top or bottom), in accordance with the ulcer size stratification as indicated on the prescription. IMP was dispensed by St George’s and sent by courier under temperature-controlled conditions directly to all participants. The date of randomisation, a unique patient ID and a unique screening ID were recorded by the Research Pharmacy on a Microsoft Excel® (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA) spreadsheet, which was sent to the YTU each week or when a participant was randomised.

Blinding

Participants, investigators, research and treating nurses and other attending clinicians were unaware of the trial drug allocation throughout the trial. There was a 24-hour emergency code break facility at the Research Pharmacy for health professionals to contact if they needed to determine whether or not patients were receiving aspirin or placebo for onward clinical management. However, in practical terms, it was expected that most clinicians would treat participants with AEs on the assumption that they had been randomised to receive aspirin.

Interventions

Intervention group

Intervention: 300 mg of daily oral aspirin for 24 weeks (four × 75-mg tablets were encapsulated in size 00 capsules with added lactose and magnesium stearate blend as filler).

Control group

Placebo: daily oral placebo for 24 weeks. Size 00 capsules with lactose and magnesium stearate blend as filler, which were identical in weight, colour and size to the aspirin capsules.

The full course of capsules (190 doses/capsules for 24 weeks’ treatment) were packaged into child-resistant tamper-evident bottles. Participants were advised to take the capsules whole (not crushed or chewed), once a day for 24 weeks or, if the reference ulcer was confirmed as healed before the end of 24 weeks, a member of the medical team would advise them to stop taking the medication. The time of day for taking the trial medication was not specified.

Participants were expected to receive and start their allocated trial treatment from 2 to 7 days after randomisation.

All participants were offered an evidence-based standardised approach to the management of their leg ulcers in accordance with Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN) guidance. 33 This consisted of multicomponent compression therapy aiming to deliver 40 mmHg of pressure at the ankle, when possible. The type of dressing used was at the discretion of the health-care professionals managing the participants.

Investigational medicinal product supply

The sponsor had responsibility for the order and purchase of trial medication and for arranging labelling of medication for the trial with St George’s University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust.

Manufacture, packaging and labelling

Active (aspirin) tablets were manufactured by Intrapharm Laboratories Limited, Maidenhead, UK. Overencapsulation of the 75-mg tablets and production of the matching placebo capsules was performed by Sharp Clinical Services (UK) Limited (MA IMP licence number 10284). Sharp Clinical Services (UK) Limited performed all manufacturing and packaging operations in accordance with good manufacturing practices derived from the rules governing Medicinal Products in the European Community and Good Manufacturing Practice for Medicinal Products. 34–36

The AVURT IMP was assigned an expiry date of 31 May 2016. Following the extension to participant recruitment, the sponsor arranged for stability testing of the IMP with Sharp Clinical Services (UK) Limited. The testing was conducted and the expiry date was extended to 31 January 2017.

The supplies of aspirin and placebo capsules were delivered to the Research Pharmacy, where they were stored and dispatched to all participants.

Outcomes

Primary outcome

Time to healing of the reference ulcer (the largest eligible ulcer).

Secondary outcomes

-

Ulcer size (area) measured in cm2 by specialist software and grid tracings.

-

Following healing of the reference ulcer, recurrence of ulcer on the reference leg (defined as a new ulcer on the reference leg).

-

Adverse events.

-

Ulcer-related pain using a visual analogue scale (VAS).

-

Treatment compliance (capsule count and nurse assessment of compression concordance).

-

Resource use: number of visits to clinic and/or home visits and types of dressings used.

Baseline assessment

Following confirmation of a participant’s eligibility, and before randomisation, a baseline assessment was conducted by the study or research nurse using the baseline CRF (see Appendix 7).

Participant details

Data on ethnicity were collected at baseline. Participants’ date of birth, gender and smoking status were collected at screening. Participants’ contact details (name, address, telephone numbers and e-mail address) and general practitioner (GP) details (name of GP, name of surgery and address) were recorded at the recruiting site only.

Ulcer history and assessment

The last ABPI measurement of the reference leg (leg with the largest eligible ulcer) and date it was taken were recorded, or it was noted that the ABPI was unable to be taken. When ABPI was incompressible, other assessments to exclude PAD were permitted, including peripheral pulse examination/toe pressure/Duplex ultrasonography in combination with clinical judgement, but these forms of assessments were not recorded on the CRF.

Other items recorded were number of ulcers on the reference leg, approximate duration of reference ulcer (years, months and weeks), how long ago since patient developed their first leg ulcer (years, months and weeks), and total number of ulcer episodes on reference leg (leg with largest eligible ulcer) including the reference ulcer (largest eligible ulcer). All ulcers on both legs were drawn onto a leg diagram and the reference ulcer indicated.

Digital photographs and tracings

To measure ulcer area, a photograph and tracing of the reference ulcer were taken at baseline. Photographs were taken with a Nikon Coolpix L3 (Nikon Corporation, Tokyo, Japan), in accordance with trial procedure (see Appendix 8). Anonymised digital photographs were sent to the YTU using a secure electronic method. Sites unable to use this method were able to send anonymised photographs on a memory card via a courier service to the YTU or a collection could be made by one of the trial co-ordinators.

Tracings were taken using a fine-nibbed marker pen on a wound measurement grid composed of 1-cm2 squares (P12v2, ConvaTec, Uxbridge, Middlesex, UK). The wound area was calculated by the treating or research nurse by totalling the number of squares and/or partial squares on the grid contained within the traced ulcer area.

Participant mobility, anthropometry and diabetic status

The level of a participant’s mobility (walking and ankle mobility), their height (feet/inches or centimetres) and weight (stones/pounds or kilograms) were recorded. If both metric and imperial measurements were given, a check was conducted by the YTU to determine if they were equivalent. Any differences were queried with the site. Body mass index [BMI (kg/m2)] was calculated using the formula: weight (kg) divided by height squared (m2). The presence of type of diabetes mellitus (type 1 or 2) was recorded.

Current treatments received

Participants’ medications at baseline were recorded by the study research nurse in a medication diary (see Appendix 9). The medication diaries were then given to participants for recording changes to non-trial medication. The participants were asked to bring their diary along to each clinic assessment for review by the study research nurse and site medical practitioner to check that participants were safe to continue with the IMP. Medication data were not collected for analysis.

Participants’ current treatment(s) for their VLU were recorded (type of compression bandaging), as was the level of ankle pressure compression being aimed for (mmHg) and the primary dressing in contact with the ulcer.

Ulcer-related pain

Participants were asked to rate the intensity of any leg ulcer-related pain over the previous 24 hours using the 21-point Box Scale (BS-21). 37 The BS-21 is a VAS that is divided into units of five and ranges from a value of 0 (no pain) to 100 (worst pain imaginable).

Resource use

The treating or research nurse recorded resource use on the CRFs. They initially recorded the type of dressing administered and level of compression aimed for and subsequently, during follow-up, only recorded a change in the type of dressing administered and/or level of compression.

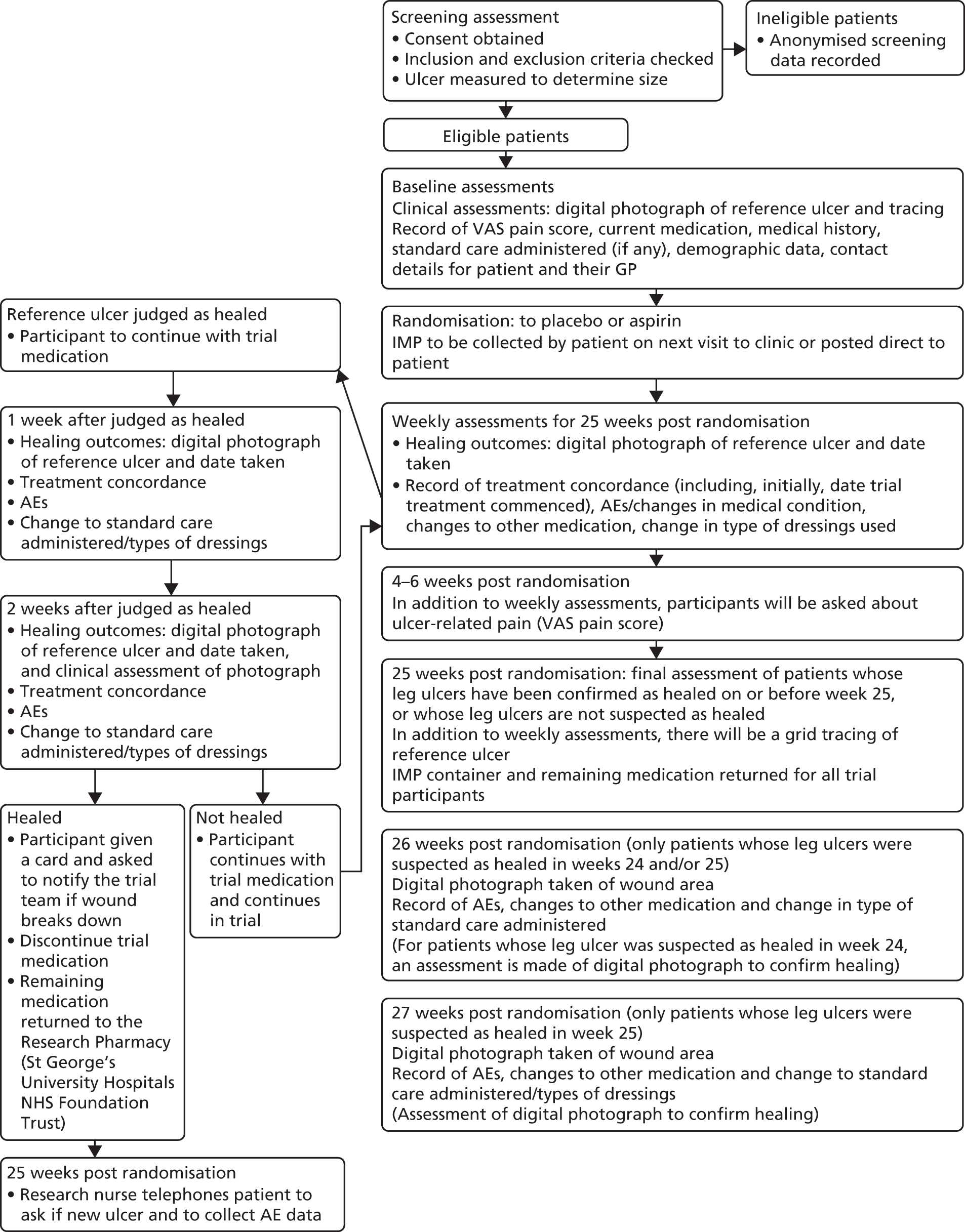

Outcome assessments

Participants were followed up weekly or fortnightly, depending on their usual pattern of attendance at clinic, for a minimum of 25 weeks post randomisation. Participants were not asked to make any additional visits for the purposes of the trial. The participant weekly data collection file, made up of CRFs and forms, was completed during follow-ups by research nurses or treating nurses (see Appendix 10). In addition, recorded in the file were the weeks in which participants missed or did not have an appointment, the randomisation date, the date that the first IMP dose was taken and the time of day that the IMP was generally taken. A summary flow chart of participant follow-up is shown at Appendix 11.

Planned participant follow-up was for 25 weeks post randomisation, but participants who had a wound initially judged as healed in week 24 or 25 were followed up for 2 further weeks (26 and 27 weeks post randomisation, respectively) to confirm healing. Table 1 summarises the schedule of assessments. All anonymised completed CRFs were faxed or sent via the University of York’s secure electronic system to the YTU.

| Study procedures | Screening | Baseline | During treatment (weekly for 25 weeks post randomisation) | Post treatment (only participants whose reference leg ulcer was judged as healed in weeks 24 and 25) | Post treatment (only participants whose reference leg ulcer was judged as healed in week 25) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Week 1 | Weeks 2–3 | Weeks 4–6 | Weeks 7–24 | Week 25 | Week 26 | Week 27 | |||

| Informed consent | ✓ | ||||||||

| Inclusion/exclusion criteria | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||

| Demographics | ✓ | ||||||||

| Dispensing of IMP | ✓ | ||||||||

| Medical history | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||

| Concomitant medication | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓a | ✓ | ✓ |

| AEs/side effects/change to health status | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Ulcer photographb | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓a | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Tracing of ulcer | ✓ | ✓ | ✓a | ||||||

| Resource use: change to type of usual care/compression bandage administered | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓a | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Compliance | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓a | ||||

| Pain score | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||

| Ulcer reccurrence (only patients whose leg ulcer was confirmed as healed before week 25) | ✓ | ||||||||

Measurement and verification of primary outcome measure

Time to healing of the reference ulcer

The treating or research nurse identified and monitored the reference ulcer. Healing was defined as complete epithelial cover in the absence of a scab (eschar) with no dressing required. Healing was determined by the treating nurse or research nurse and a digital photograph was taken of the wound area. Healing was reported by the treating site on Form D (see Appendix 10) which was submitted to the YTU. Time to healing was measured in days from the date of randomisation to the date that the ulcer was first assessed as healed. After the treating or research nurse initially judged the ulcer to be healed, participants were followed up for a further 2 weeks, in accordance with the Food and Drug Administration guidelines,38 to confirm healing.

Measurement of secondary outcomes

Ulcer size

The reference ulcer was measured using wound grid tracings at screening, baseline and at final follow-up and at other follow-up visits when a photograph could not be taken. Treating nurses calculated the ulcer size by totalling the number of squares and/or partial squares on the grid contained within the traced ulcer area size and reported the measurement in the CRFs.

Anonymised digital photographs were taken at baseline and at all weekly or fortnightly follow-up visits. All digital images were checked and the ulcer size calculated using SigmaScan® software (Sigma Scan Pro version 5.0, SigmaScan, Systat Software Inc., San Jose, CA, USA) by one researcher, Rachael Forsythe (Specialist Registrar in Vascular Surgery, St George’s Hospital, London, UK) who was blinded to treatment allocation.

Ulcer recurrence

Weekly follow-up CRFs were not completed for participants after their reference ulcer had been confirmed as healed. To collect ulcer recurrence data, participants were given a card with contact details for their recruiting site (see Appendix 12) and were asked to phone the clinic if they developed a new ulcer on their reference leg. In addition, at week 25 post randomisation, the research nurse phoned participants whose reference ulcer had healed, to collect data on leg ulcer recurrence. The date of recurrence of a new venous ulcer on the reference leg was recorded (see Appendix 10, Form E).

Ulcer pain

Participants were asked to rate the intensity of any leg ulcer-related pain over the previous 24 hours using the BS-21. Ulcer-related pain was collected at baseline and at weeks 4, 5 and 6 after randomisation. It was thought that aspirin might have a positive effect on pain. We required one pain score at follow-up but took measurements at three follow-up time points to allow for participants not being seen every week.

Participant compliance with treatment

To monitor treatment concordance with the IMP and compression, the treating nurses recorded in the weekly CRFs (see Appendix 10) how often a participant was taking the capsules and, when applicable, reasons for not taking them every day. Treating nurses also recorded whether or not a participant had fully, had partially, or had not complied with compression therapy, with reason(s) for non-compliance captured when possible.

At the end of the study, the remaining IMP or, in cases when participants had taken all the trial medication, the empty container, was returned to the Research Pharmacy, which undertook a pill count. This information was then forwarded to the YTU for inclusion in the analysis.

Resource use

At follow-up visits (weekly or fortnightly depending on a participant’s usual pattern of care), changes to the level of compression therapy were recorded (see Appendix 10, Form A) and changes to the type of primary dressing or bandaging (see Appendix 10, Form B). The number of times participants had other wound consultations in the previous week was also recorded.

Patient safety

Each participant was regularly reviewed by their treating nurse and/or physician working closely with the AVURT research team and was continually assessed for any increased dyspepsia, other gastrointestinal symptoms, skin rashes and any other possibly linked AEs that could be attributable to the IMP.

Known side effects

Common side effects of aspirin as listed on the summary of product characteristics, which was supplied by the IMP manufacturer (Intrapharm Laboratories Limited), included increased bleeding tendencies and dyspepsia.

Adverse events: definitions

The following definitions were applied in the study.

Adverse event

-

Any untoward medical occurrence in a patient or clinical trial participant who is administered an IMP and which does not necessarily have a causal relationship with this treatment, and which may include an exacerbation of a pre-existing illness.

-

Increase in frequency or severity of pre-existing episodic condition.

-

A condition (regardless of whether or not it was present prior to the start of the trial) that is detected after trial drug administration (this does not include pre-existing conditions recorded as such at baseline, continuous persistent disease or a symptom present at baseline).

Adverse reaction

-

Any untoward and unintended responses to an IMP related to any dose administered.

Serious adverse event or serious adverse reaction

-

Any AE or reaction that, at any dose, results in death.

-

Any AE or reaction that, at any dose, is life-threatening (places the subject, in the view of the investigator, at immediate risk of death).

-

Any AE or reaction that, at any dose, requires hospitalisation or prolongation of existing hospitalisation [hospitalisation is defined as an inpatient admission, regardless of length of stay, even if it is a precautionary measure for observation (including hospitalisation for an elective procedure and for a pre-existing condition)].

-

Any AE or reaction that, at any dose, results in persistent or significant disability or incapacity (substantial disruption of one’s ability to conduct normal life functions).

-

Any AE or reaction that, at any dose, results in a congenital anomaly or birth defect (in offspring of subjects or their parents taking the IMP regardless of time of diagnosis).

-

Any AE or reaction that is related to another important medical condition.

Important medical events that may not be immediately life-threatening or result in death or hospitalisation but may jeopardise the subject or may require intervention to prevent one of the outcomes listed in Serious adverse event or serious adverse reaction was also considered serious.

Suspected unexpected serious adverse reaction

A suspected unexpected serious adverse reaction (SUSAR) is an adverse reaction (AR) that is classed in nature as both serious and unexpected.

An unexpected AR is when both the nature and the severity of the event are not consistent with the reference safety information (RSI) available for the IMP in question.

Assessments

At each follow-up appointment, the treating nurses asked participants if they had experienced any changes in their health and indicated their response in the CRFs. Participants whose reference leg ulcer had healed, and, therefore, were no longer receiving follow-up appointments, were contacted at week 25 post randomisation by a research nurse who collected information on AEs that the participant had experienced since the last data collection point (see Appendix 10, Form E).

Details of the AEs/ARs were recorded in clinic notes and on AE logs held at the recruiting sites. The causality, severity and expectedness assessment was conducted by medically qualified doctors at the sites who were blind to treatment allocation in accordance with the following descriptions.

Causality assessment

-

Definitely: there is clear evidence to suggest a causal relationship, and other possible contributing factors can be ruled out.

-

Probably: there is evidence to suggest a causal relationship, and the influence of other factors is unlikely.

-

Possibly: there is some evidence to suggest a causal relationship (e.g. the event occurred within a reasonable time after administration of the trial medication). However, the influence of other factors may have contributed to the event (i.e. the patient’s clinical condition, other concomitant events).

-

Unlikely: there is little evidence to suggest that there is a causal relationship (e.g. the event did not occur within a reasonable time after administration of the trial medication). There is another reasonable explanation for the event (e.g. the participant’s clinical condition, or other concomitant treatments).

-

Unrelated: there is no evidence of any causal relationship.

-

Not assessable: note – if this description was used, then the sponsor assumed that the event was related to the IMP until follow-up information was received from the investigator to confirm a definitive causality assessment.

Any SUSAR assessed as related to the IMP was required to be reported to the sponsor, irrespective of how long after IMP administration the reaction had occurred.

Expectedness assessment

Assessment was based solely on the available RSI for the IMP and was described using following categories.

-

Expected: an AE that is classed in nature as serious and that is consistent with the information about the IMP listed in the RSI or clearly defined in the study protocol.

-

Unexpected: an AE that is classed in nature as serious and that is not consistent with the information about the IMP listed in the RSI.

All assessments were reviewed by the chief investigator using specific guidance notes from the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) clinical trials tool kit. 39

Reporting

Non-serious and serious AEs were reported by the sites to the trial manager at the YTU on the sponsor’s AE log. SAEs were recorded on the sponsor’s SAE form and reported directly to the sponsor (St George’s University Hospital) within 24 hours of the local investigators becoming aware. The sponsor followed up SAEs to their resolution and was responsible for reporting the events to Research Ethics Committee (REC), the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA) and the trial manager at the YTU.

All AEs, ARs, SAEs and serious ARs were reviewed by the sponsor and chief investigator and subsequently the DMC (blinded to allocation), which made the final decision regarding the severity and causality and relationship between the event and treatment.

Withdrawal

Participants were deemed to have exited the trial when they:

-

withdrew consent

-

were lost to follow-up

-

died

-

had completed follow-up (i.e. 25 weeks post randomisation or, for patients whose leg ulcer was first assessed as healed in weeks 24 and 25, weeks 26 and 27, respectively).

If a participant chose to withdraw from the trial then reasonable effort was made to establish the reason for this withdrawal. For participants leaving the trial before final follow-up, nurses completed a change to study status form (see Appendix 10, Form F), giving the main reason for the participant’s exit. No further follow-up data were collected. Participants withdrawing from the study were given the option for their data not to be used.

Participants stopped treatment for any one of the following reasons, but continued with follow-up:

-

Unacceptable treatment toxicity that, in the investigator’s opinion, is attributable to the IMP or a SAE.

-

Intercurrent illness that prevents further protocol treatment.

-

Any change in a participant’s condition that, in the investigator’s opinion, justified the discontinuation of treatment.

-

If a participant became pregnant or suspected that they were pregnant.

-

Reference ulcer confirmed as healed.

-

A participant chose to discontinue treatment.

Participants whose leg ulcer was initially assessed as healed were encouraged to take the IMP during the 2-week observation period. If healing was confirmed after 2 weeks, the participant stopped taking the trial medication and follow-up was suspended until a final follow-up in week 25.

Sample size

The target sample size was 100 participants. This sample size is sufficient to test the feasibility of study procedures, such as recruitment and retention, and is large enough to demonstrate whether or not there is evidence for efficacy in line with two previous trials of aspirin for leg ulcers. 25,26

The primary outcome was time to healing of the largest eligible leg ulcer (reference ulcer). Ulcer area and duration of ulcer are known prognostic factors for healing. In a previous leg ulcer study, Venous leg Ulcer Study IV (VenUS IV), after adjustment for log-area of ulcer and log-duration of ulcer, the standard error for the time to healing estimate was 0.105, with data on 448 participants. 3 Applying this to a smaller sample of 100 participants implies that the standard error of such a sample would be increased to 0.22 [obtained from 0.105 × √(448/100)]. A 95% confidence interval (CI) for the log-hazard ratio (HR) would thus be the estimate of the log (HR) ± 1.96 × 0.222 = log(HR) ± 0.435. The antilog of this is 1.54 and the 95% CI for the HR would be the observed value divided or multiplied by this. Hence, if our HR were the same as that suggested by the existing studies (i.e. about 1.5), then our CI would be 0.97 to 2.31, which just includes 1.00. It would be unlikely that, if the HR is as these two previous smaller studies suggest, we would observe an overall HR of < 1.00. Compliance and follow-up were measured as part of the study and so there is no formal inflation of the recruitment target for drop out.

A secondary outcome was change in wound area. Using data from the Venous leg Ulcer Study I (VenUS I) of compression bandaging,40 ulcer area was measured for 245 participants who were measured within 60 days of recruitment. Ulcer area has a highly skewed distribution, so we calculated a difference in log-area at follow-up, after adjustment for log-ulcer area at baseline and time elapsed until follow-up. The residual standard deviation (SD) was 1.09. Two groups of 50 participants would give us 80% power to detect a difference of 0.62 on the natural-log scale, corresponding to a reduction of 46% in ulcer area at follow-up. In the current study, we had multiple measurements of wound area and so predicted that we should be able to detect smaller differences.

Statistical methods

The statistical methods for the analysis of the trial data were prespecified and detailed in a statistical analysis plan (SAP) before the completion of data collection. The SAP was prepared by the trial statisticians and reviewed by members of the Trial Management Group (TMG) and DMC. However, given that the final number of participants randomised was much lower than the 100 planned (n = 27), many of the pre-planned analyses were infeasible or inappropriate. In this section, we describe the analyses as performed, highlighting any deviations from the SAP.

Pre-screening, screening and eligibility data

The flow of participants through the trial is presented in a Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) diagram. 41 The number of patients who were pre-screened, were approached and consented is reported. Reasons for ineligibility at the pre-screening phase and reasons for not consenting are summarised.

Baseline data

Participant characteristics and clinical baseline measurements are summarised descriptively overall and by trial arm. These measures include age, gender, BMI, diagnosis of diabetes mellitus, ethnicity, participant’s level of mobility and ankle mobility, reference ulcer size and corresponding stratification (≤ 5 cm2 or > 5 cm2), time since first ulcer, duration of reference ulcer (actually referring to the duration of the ulcer up to but not beyond randomisation), left/right reference leg, total ulcers on reference leg, ABPI of the reference ulcer, levels of pain from the reference ulcer, current compression and dressing treatments. Continuous measures were summarised using mean, SD, median, minimum, maximum and interquartile range (IQR). Categorical measures were reported as counts and percentages. No formal statistical comparisons of baseline factors by trial arm were undertaken.

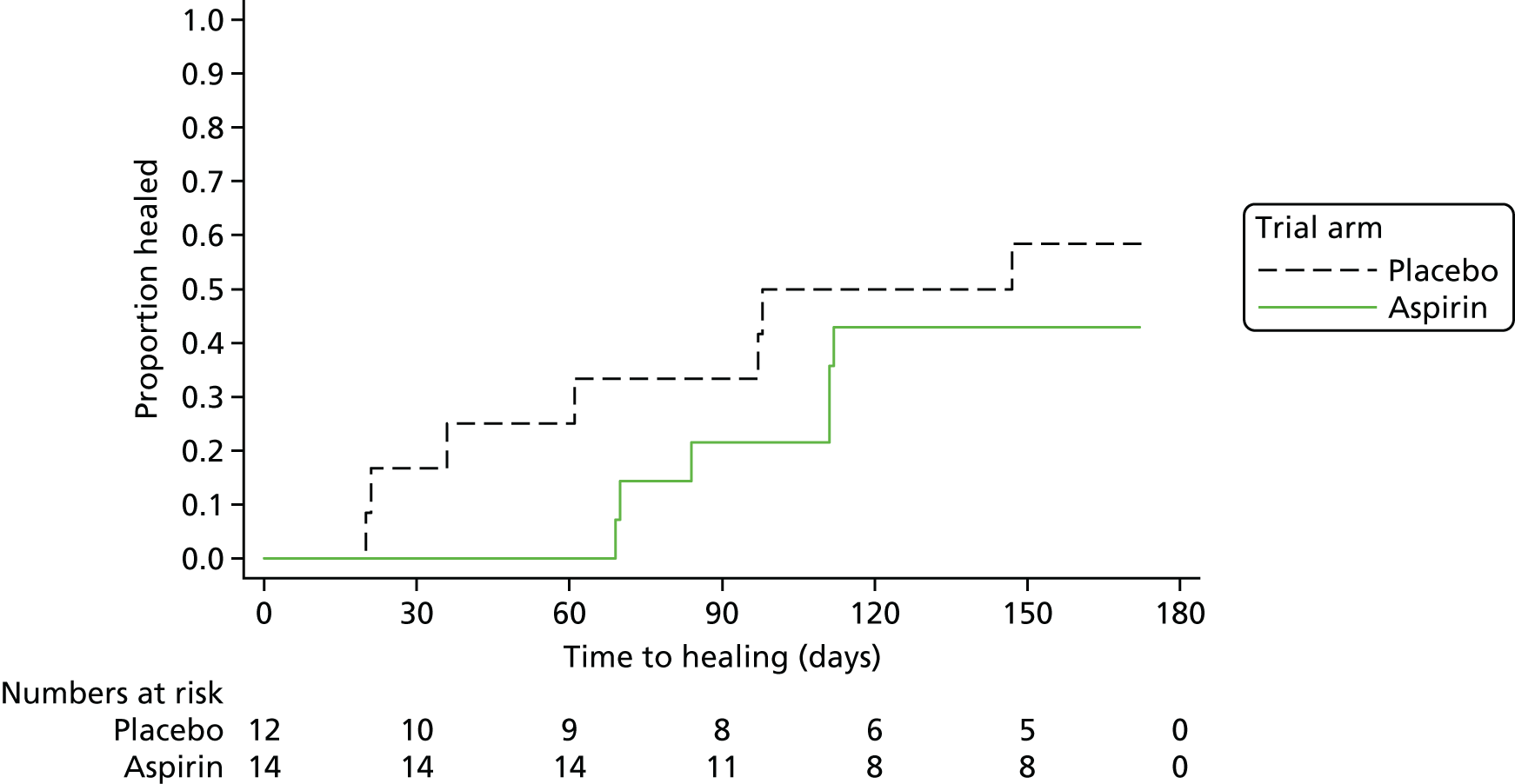

Primary outcome

The primary analysis investigated the difference in time to healing by trial arm using Cox’s proportional hazards regression adjusted for ulcer area (cm2) and ulcer duration (days) at baseline, both logarithmically transformed. Ulcer area and ulcer duration tend to have a skewed distribution and, therefore, a logarithmic transformation is used to obtain a distribution that is closer to the normal. It was initially planned to subsequently test for the inclusion of shared centre frailty effects; however, the final distribution of participants across centres (see Table 2) made the frailty model an impractical choice for this analysis. Therefore, only the Kaplan–Meier survival curve, the log-rank test and the Cox’s regression model, both unadjusted and adjusted for the logarithm of the area and of the ulcer duration, were undertaken. HRs, corresponding 95% CIs and p-values for the model covariates are presented.

Secondary outcomes

Adverse events

Adverse events were reported overall and by trial arm in terms of number of participants with at least one event and total number of events. Serious and non-serious events were presented separately and according to whether or not they were thought to be related or unrelated to treatment. For SAEs, reasons for the serious nature of the events were reported. Differences in total number of events by trial arm were compared using negative binomial regression adjusted for size and duration of ulcer (both log transformed).

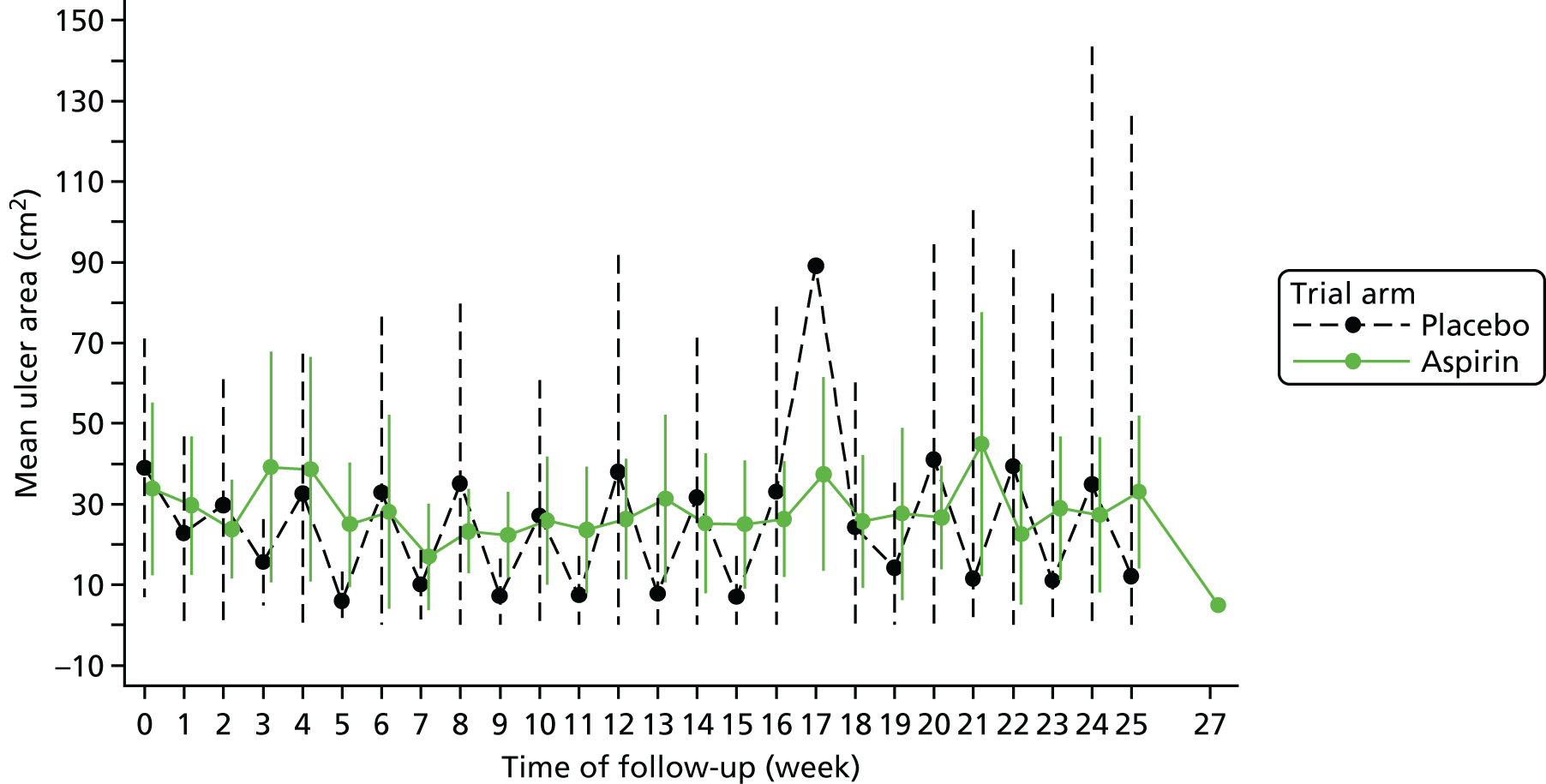

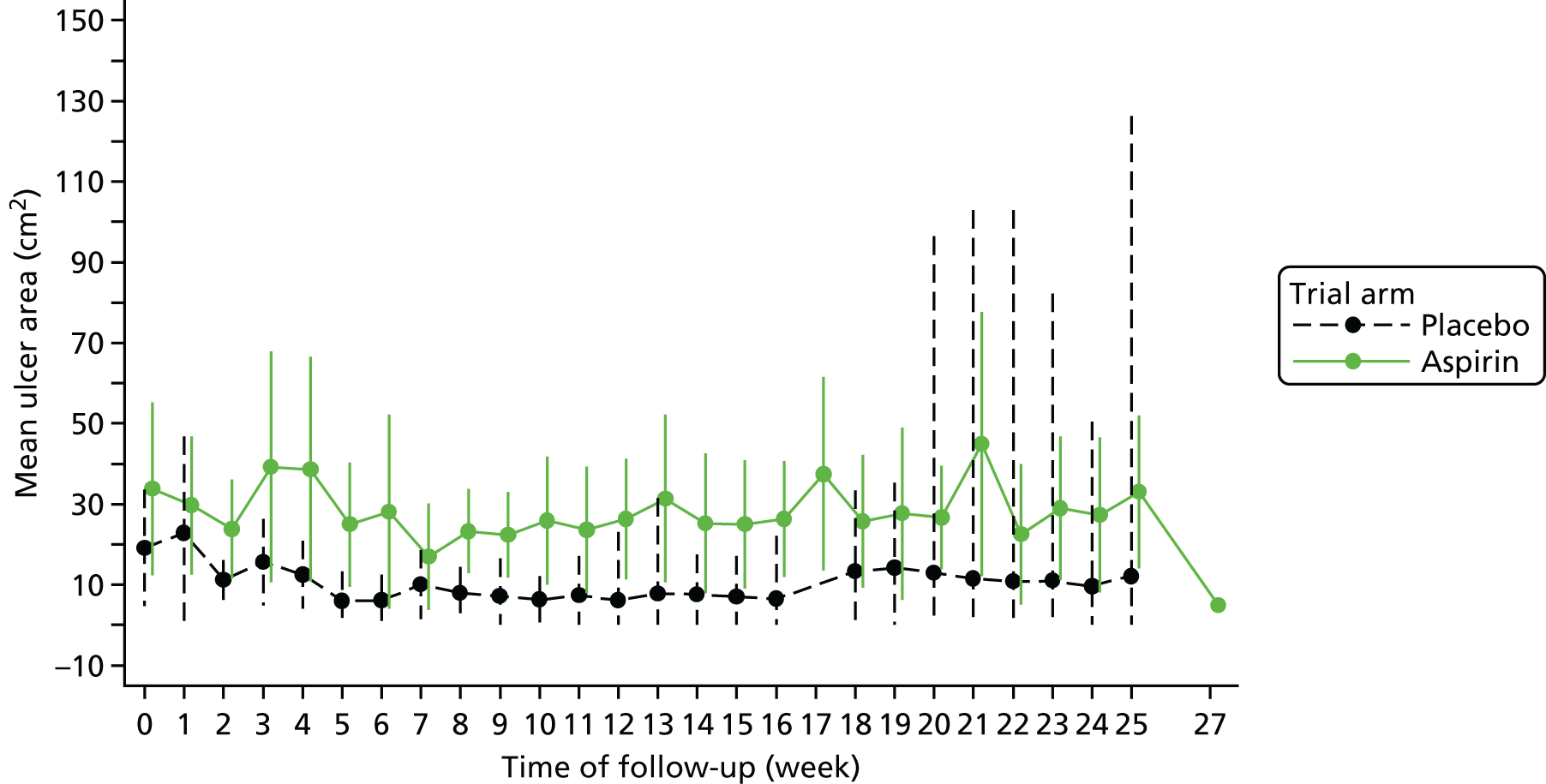

Ulcer size

The area resulting from the analysis with the SigmaScan was used in statistical analysis whenever available. In the case when a photograph could not be taken, the measure of the ulcer area was obtained by using the tracing of the ulcer, if available. The area at baseline and at each assessment is summarised using descriptive statistics (mean and SD) for each trial arm and overall. A plot containing means and 95% CIs for both trial arms was also produced with lower confidence limits truncated at zero, as wound area can only be positive.

It was planned a priori that the logarithm of the ulcer area would be investigated via a repeated measures mixed model to see if there were any differences by trial arm; however, owing to the low number of participants and the high number of time points, this model was not judged to be appropriate for the final analysis.

Ulcer recurrence

As a recurrence of the reference ulcer was reported for only two participants, the Cox proportional hazards regression initially planned was not performed. For both participants the number of days from healing to recurrence is presented.

Time to first investigational medicinal product dose

The median time in days from randomisation to date the first IMP dose was taken was presented alongside 95% CI by trial arm and overall.

Time of day

The number of participants who reported taking their study drug in the morning, afternoon and evening is summarised using counts and percentages.

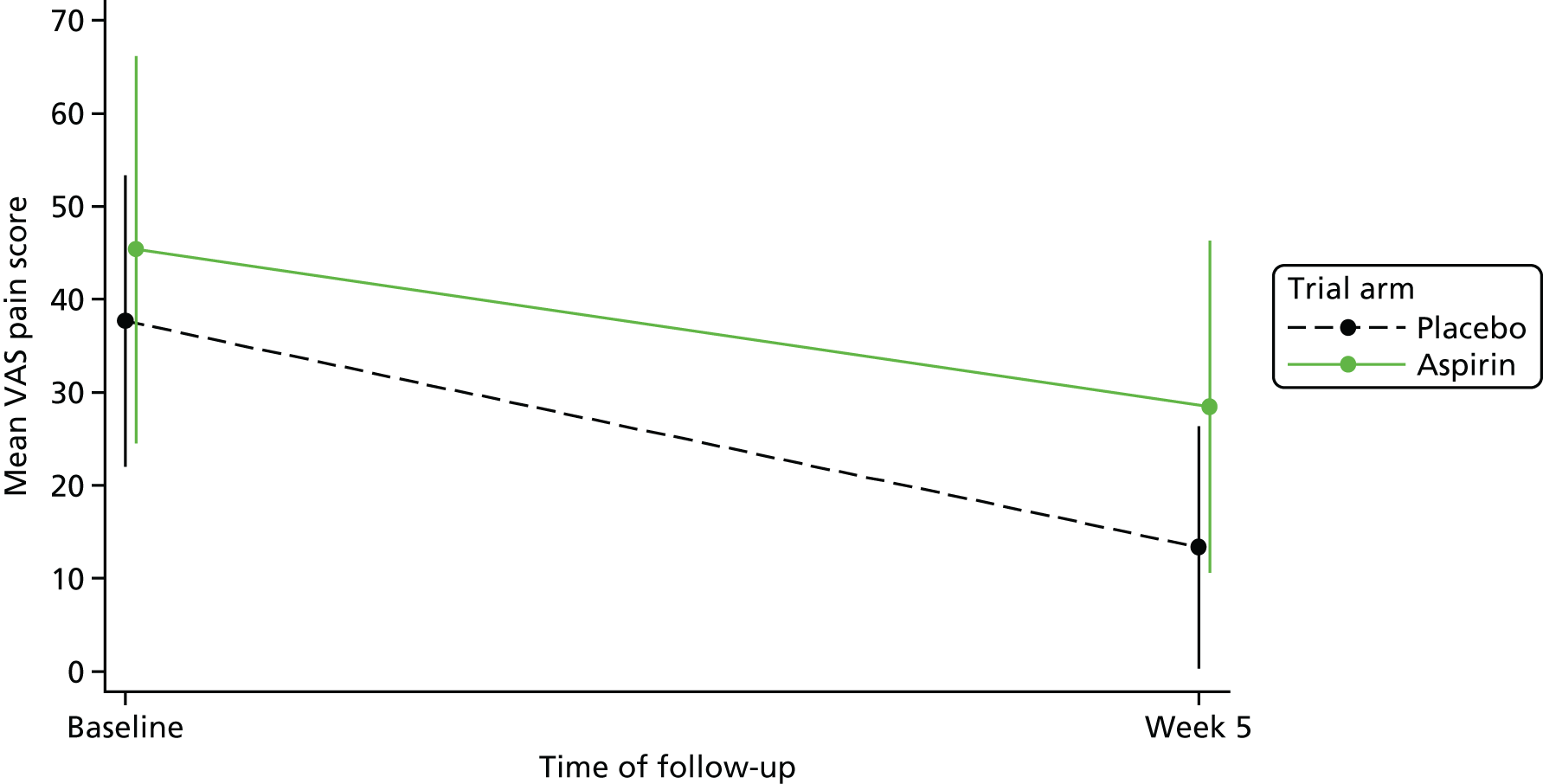

Ulcer pain

The VAS scale [from 0 (no pain) to 100 (worst pain imaginable)] to measure pain was used at baseline and at weeks 4, 5 and 6 in order to increase the likelihood of capture, as not all patients were seen weekly. Only one VAS score was used for the analysis: if the week 5 VAS score was present, this was used; if it was not and either only week 4 or only week 6 were provided, then the corresponding VAS score was used; if both week 4 and week 6 were provided but week 5 was not, then the VAS completed on the closest date to week 5 was taken; if both weeks were completed an equidistance from week 5, then week 4 was taken.

Descriptive statistics of VAS score (mean, SD, median, minimum, maximum, IQR) were calculated overall and for each trial arm at baseline and at week 5, obtained as defined above. A plot of the means and 95% CIs for both trial arms at baseline and at week 5 was produced.

The planned linear regression analysis, aimed to compare differences in pain scores between allocated groups, was not performed owing to low numbers.

Participant compliance with treatment

At each assessment visit, compliance with both the compression therapy (for those receiving this treatment) and with the study capsules was recorded. This was via the following two questions: ‘Has the participant complied with their [compression therapy] treatment’ (fully/partially/not at all), and ‘How often has the participant taken their AVURT capsules (300-mg aspirin/placebo per day) this week?’ (every day/most days/some days/not at all). The responses to both of these questions were given numerical values: fully = 1, partially = 2, and not at all = 3; and every day = 1, most days = 2, some days = 3, and not at all = 4. To calculate compliance with compression treatment, the responses across all weeks up to healing/trial exit were summed and divided by the number of visits attended to obtain the mean compliance level for each participant. This compliance level was then categorised as fully compliant if the mean value was 1, partially compliant if the value was between 1 and 3 (not inclusive), and not at all compliant if the value was equal to 3. The number and percentage of participants in each of these categories is presented.

Compliance with study capsules was analysed similarly but only considering responses in the weeks following delivery of the capsules. The compliance level was categorised as fully compliant if the mean value was 1, partially compliant if the value was between 1 and 4 (not inclusive), and not at all compliant if the value was equal to 4. Reasons for lack of full compliance are presented.

The second way that compliance with AVURT capsules was assessed was through the use of the count of the returned capsules at the end of the study. Each participant was given 190 capsules and by subtracting the number of returned pills it was possible to obtain an estimate of the number of capsules actually taken. The number of capsules that should have been taken was calculated starting from the date of first dose until 2 weeks after healing (for those who had healed) or the date of the last visit (for those who did not heal). From this, the percentage of capsules that each participant took (of those they should have taken) was calculated. The level of compliance was split into 11 categories (100%, 90–99%, 80–89%, etc.) and the count and percentage of patients falling in each category is presented (see Tables 13 and 14).

Resource use

Level of compression therapy

The number of changes to compression therapy is presented overall and by trial arm, and also stratified by time to healing (or censoring) using the categories 0–2 months, > 2 to 4 months, and > 4 months. The number and percentage of changes to low/medium/high or no compression therapy are presented overall and by trial arm.

Bandaging and hosiery

The number and percentage of changes to each bandage type are presented overall and by trial arm, as are the number and percentage of patients who received each type of bandaging at least once during the study.

Dressing

The number of changes per participant to dressing type is summarised overall and by trial arm, and stratified by time until healing (or censoring) using the categories 0–2 months, > 2 to 4 months, and > 4 months.

The number and percentage of changes to each dressing type are presented overall and by trial arm, as are the number and percentage of patients who received each type of dressing at least once during the study.

Wound consultations

For each participant, the number of wound consultations per week was calculated by summing the number of consultations the participant had in the previous week, declared on the weekly CRFs, plus the visit in which the CRF was completed and dividing it by the number of visits actually attended. The mean number of wound consultations per week is presented alongside SD, median, minimum, maximum and IQR (see Table 22).

Approvals obtained and governance

Ethics and Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency approvals

The trial was approved by Nottingham REC on 29 January 2015 (REC reference number 14/EM/1305) and by the University of York Health Science Research Governance Committee on 16 February 2015. The MHRA approved the study on 26 March 2015 (MHRA reference 16745/0221/001-001). The London Local Research Network completed their global checks on 7 May 2015 and thereafter research governance approval was obtained from each trial centre. The trial was registered with ClinicalTrials.gov and assigned the number NCT02333123, and with the European Clinical Trials Database and assigned the European Clinical Trials Database (EudraCT) number 2014-003979-39.

Trial monitoring

The AVURT was monitored by the sponsor, St George’s University of London. The trial was conducted and monitored in compliance with their standard operation procedures:42 International Conference on Harmonisation Harmonised Tripartite Guidelines For Good Clinical Practice E6 (ICH GCP) and the Medicines for Human Use (Clinical Trials) Regulations 2004 (SI 2004/03) (as amended).

The purpose of the monitoring was to ensure:

-

the safety and welfare of trial participants

-

that trial data were accurate and verified from source data when possible

-

that the trial was compliant with good clinical practice and other regulatory requirements.

Trial oversight

The trial was overseen by the TMG, the Trial Steering Committee (TSC) and the DMC.

Trial Management Group

The TMG was responsible for project oversight, directing the management of the trial and reviewing progress. The TMG was chaired by the chief investigator and comprised the trial co-ordinators, trial statisticians and the majority of the coapplicants including a patient representative.

Trial Steering Committee

The TSC provided overall supervision of the progress of the trial towards its interim and overall objectives, to ensure adherence to the protocol and patient safety. The TSC approved the trial protocol prior to participant recruitment, reviewed recruitment, protocol deviations, the trial’s results and recommendations made by the DMC.

The TSC was chaired by an independent representative (Professor Julie Brittenden) and membership consisted of three other independent members, a patient representative and members of the research team, including the chief investigator, the sponsor’s representative, the trial statistician and trial co-ordinators. The TSC met for the first time prior to participant recruitment and then three times during the course of the trial.

Data Monitoring Committee

The main role of the DMC was to ensure the safety of trial participants, to protect the validity of the trial, to advise the investigators and to make recommendations to the TSC about whether or not the trial should continue. The DMC approved the SAP and reviewed recruitment figures, protocol deviations, protocol amendments and AE data.

The DMC was chaired by an independent representative (Professor Peter Franks) and membership consisted of three other independent members and members of the research team, including the chief investigator, the sponsor’s representative, the trial statistician and trial co-ordinators.

Patient and public involvement

At the grant application stage, the views of six patients attending a leg ulcer clinic were elicited. Specifically, they were asked for their views on the likely willingness of patients to take aspirin on a daily basis, given its possible side effects, if it were shown to improve healing of leg ulcers. All responded that they would be willing to take medication if it meant that their ulcer was likely to heal more rapidly. They thought that the risks of aspirin were acceptable given that many patients already take it regularly for cardiovascular disease. In terms of a trial, they thought that they would be happy to receive a dummy tablet (placebo) if it meant that more information could be gleaned about the efficacy of aspirin in terms of healing ulcers – even though a further larger trial might be required to confirm the results. Some patients questioned the benefit about taking a high dose of aspirin. However, the feeling expressed by some was that the perceived increased risks would be worthwhile if it significantly decreased time to healing.

There were two patient coapplicants. Ellie Lindsay, president of the Leg Club Foundation, was a member of the TMG, and our other patient representative, Laurie Williams, was a member of the TSC. Both were involved in the development of the trial during the application stage and throughout the study. They were also involved in the development of the trial’s patient information resources.

Protocol amendments

Amendments to the protocol were required by REC prior to approval. Following approval, no substantial amendments were made to the protocol. Details of all ethics and MHRA amendments are detailed in Appendix 13.

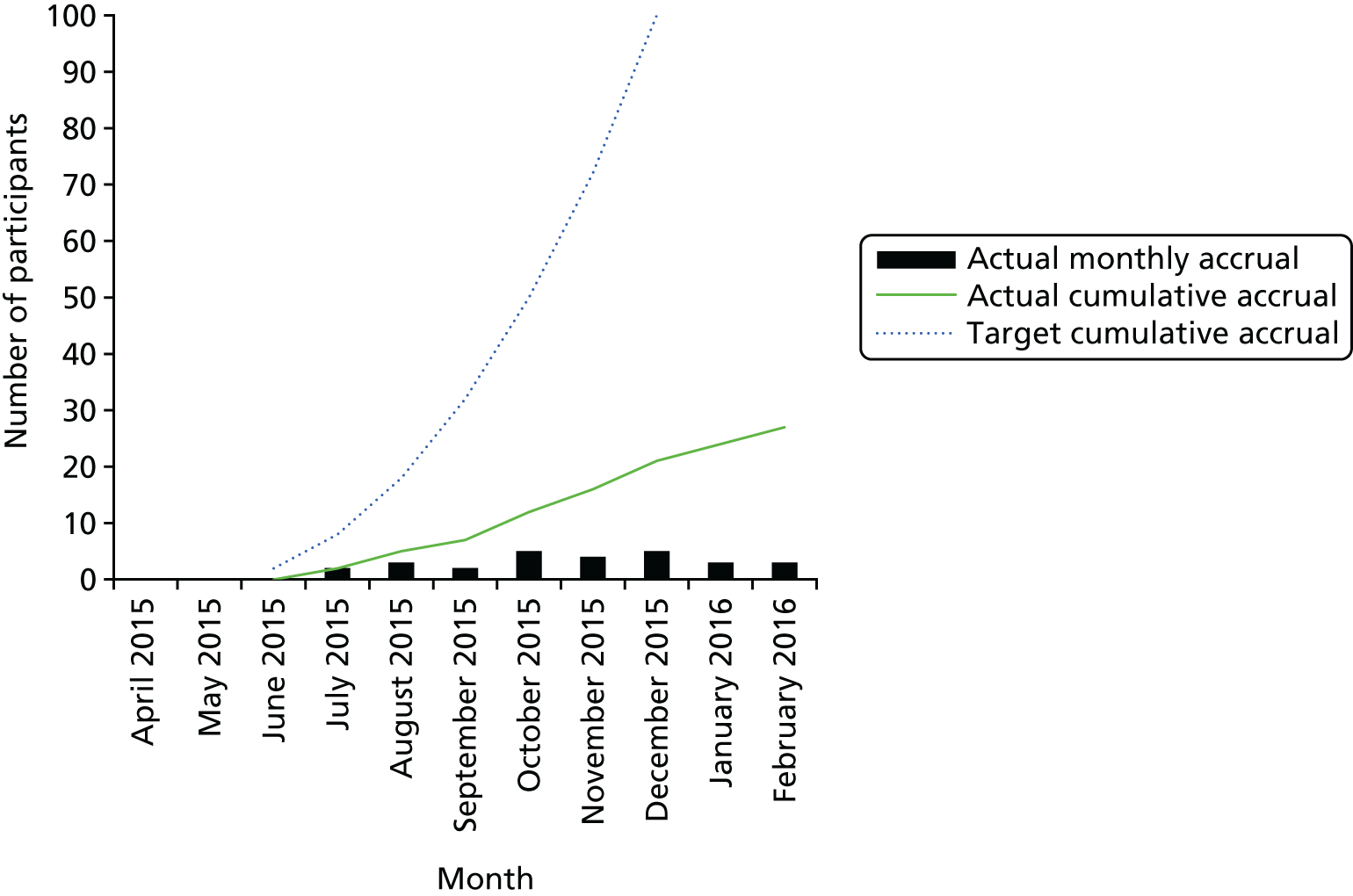

Chapter 3 Results: feasibility of recruitment

The original participant recruitment window was for 6 months and was due to finish on 30 September 2015. Owing to delays in sites opening and to allow the last few sites to open sufficient time to recruit, this was extended to an 8-month recruitment window. Consequently, to allow the full follow-up of all participants, the total duration of the trial was extended by just over 5 months to 14 December 2016 (the project was originally due to close on 30 June 2016).

Site recruitment

Ten sites opened to recruitment. Prior to recruitment, the sites indicated the approximate number of participants they could recruit (see Appendix 1). Recruitment was largely based in leg ulcer community clinics and hospital outpatient clinics. Many of the recruiting sites were chosen as they had been high recruiters to other leg ulcer studies.

Eleven sites were initially interested in participating. Nottingham University Hospitals NHS Trust subsequently declined after undertaking a complete screening review of its patient population, which consisted of 3300 patients referred with chronic oedema of all forms with many suffering from venous leg ulceration. An analysis of their patient profile indicated that they would have little access to non-complex patients. The remaining 10 sites were submitted to REC for approval:

-

St George’s Healthcare NHS Trust London

-

Bradford Teaching Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust

-

Leeds Community Healthcare NHS Trust

-

Newcastle upon Tyne Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust

-

Cardiff & Vale University with Aneurin Bevan University Health Board (Newport)

-

Hull and East Yorkshire Hospitals NHS Trust

-

Harrogate and District NHS Foundation Trust

-

Mid Yorkshire Hospitals NHS Trust (Wakefield)

-

Lancashire Care NHS Foundation Trust

-

Sussex Community NHS Trust (Brighton).

Sites were opened throughout the participant recruitment phase and, of these sites, three (Bradford, Leeds and Wakefield) did not open but were in various stages of contracts, training, site initiation visits and approvals when the trial closed to recruitment. During the recruitment phase, we received interest from three other sites that opened after they received REC and local research and development (R&D) approvals: NHS Tayside (Dundee), NHS Lanarkshire and Kent Community Health NHS Foundation Trust. We were also in discussion with Birmingham Community Healthcare NHS Trust towards the end of the recruitment phase.

Barriers to recruitment

The first site opened to recruitment on 23 June 2015, almost 3 months later than scheduled. Barriers to recruitment included a delayed start due to issues releasing the IMP. Because there was uncertainty about when the IMP would be available, we were unable to confirm a start date for recruitment. Sites were expected to recruit their first patient within 35 days of submission of their site specific information forms to their local R&D. Local checks were likely to include the availability of the IMP. Once the IMP had been released, there was a slow rate of sites opening over the summer owing to staff availability at the sites. At three sites key staff were on long-term leave or had left and were waiting for new staff to be appointed before proceeding.

Participant recruitment

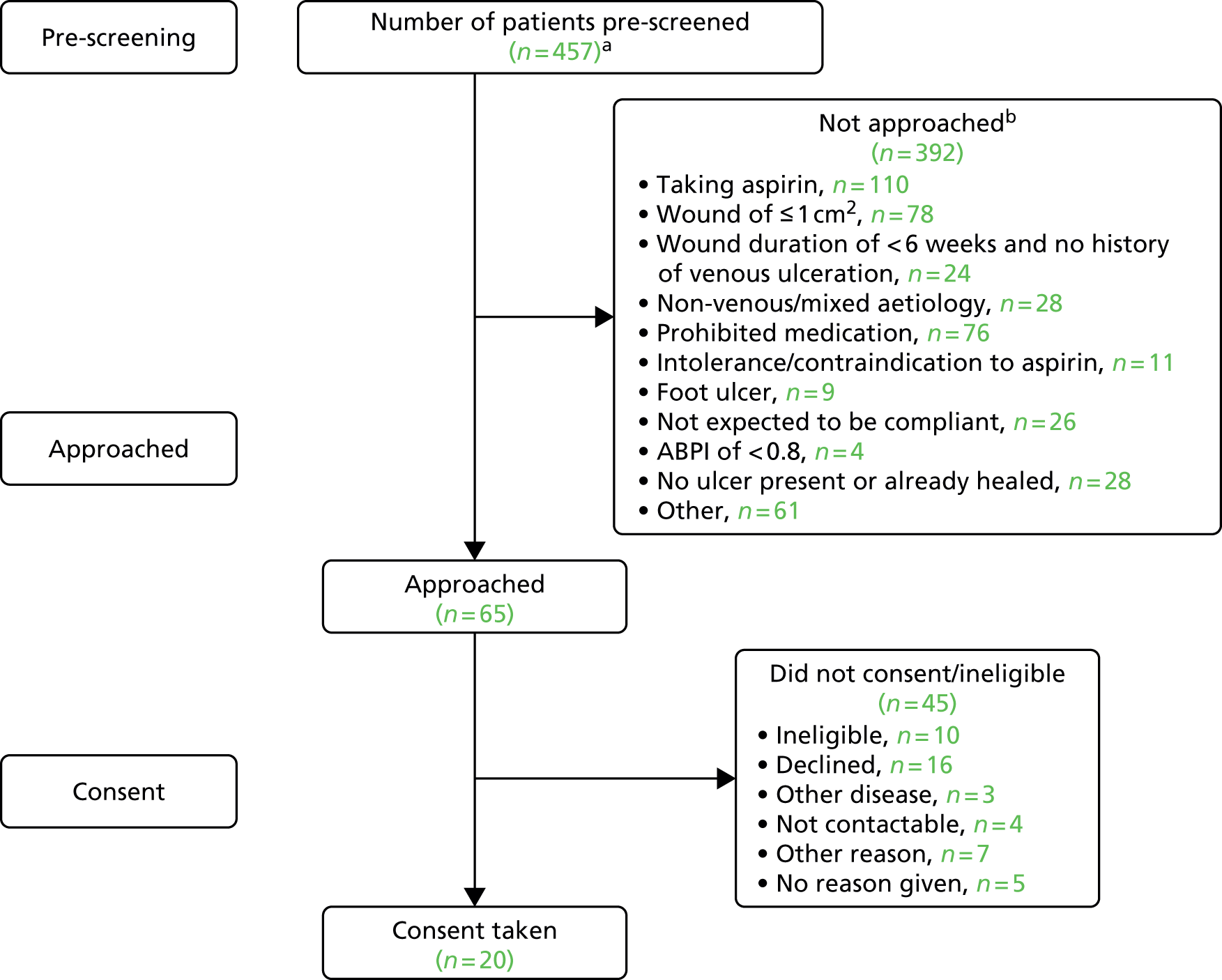

Once open to recruitment there were fewer than expected eligible patients at sites. The pre-screening data from sites indicated various and multiple reasons for patients not being approached (Figure 1). The main reasons for participant ineligibility were:

-

already taking aspirin or other prohibited medication

-

having a small or otherwise ineligible ulcer.

FIGURE 1.

The AVURT pre-screening study flow. a, The actual number of patients pre-screened was higher than 457 as the first version of the pre-screening log was not mandatory; and b, reasons not mutually exclusive.

In the last few months of recruitment, when all sites were open, the trial was recruiting three to five participants per month (see Appendix 14). It was generally thought by some sites that a large proportion of leg ulcer patients were receiving treatment in general practices (i.e. in primary care) or outside primary care in specialist clinics and by district nurses. It was therefore likely that the patients being seen by the secondary recruiting sites were older, more likely to have mixed disease and, therefore, more likely to be already taking aspirin.

Strategies to improve recruitment

Strategies to improve recruitment were explored. Modification of the eligibility criteria was assessed with reference to the pre-screening log data. The only acceptable modification to the exclusion and inclusion criteria was to include a smaller wound size. However, those with a wound area of < 1 cm2 were excluded, as these ulcers usually heal very rapidly.

In October and November 2015, the chief investigator and a trial manager contacted the recruiting sites that had been the first to open (Kent, Hull, Brighton, Harrogate and Newcastle) to discuss possible solutions to improve participant recruitment. During meetings with sites, a number of ideas were discussed, including:

-

Advertising via social media.

-

Posters to inform patients about the study.

-

Newsletter for sites.

-

Flyers for sites to remind staff to recruit to the study.

-

Radio advertising (Hull and Harrogate).

-

An amendment to protocol to allow participants to visit sites for follow-up purposes (the protocol stated that patients will not be invited to attend clinics for research purposes), and to introduce per-patient payments for visits that were not part of routine care. This was a particular problem for one site (Newcastle) that did not routinely see patients in clinic after their initial visit.

-

Allowing for more telephone follow-ups so that participants did not need to come in to clinic as regularly as once per week or once per fortnight.

-

Remove minimum ulcer size from the eligibility criteria, in line with the study being conducted in New Zealand. 29

Apart from removing the minimum ulcer size criterion, each of the options considered would have potentially benefited just one or two of the recruiting sites and, therefore, a variety of strategies would need to be implemented across the trial. The funder and REC had required for regular follow-up to monitor patient safety and, therefore, less frequent follow-up was not viewed as a feasible option by the research team.

A flyer was produced and sent to sites to remind clinic staff to recruit to the trial (December 2015) and three electronic newsletters were sent to sites (two during recruitment, in October 2015 and December 2015) to update on participant recruitment in the trial (the third newsletter was sent in June 2016 after recruitment had closed). The flyer and newsletters were relatively cheap to produce and did not require ethics approval and so could be sent out swiftly. During training, sites were reminded to identify potential participants before opening so that the participants could be approached as soon as the sites were given the green light to recruit.

Recruitment from primary care

We explored recruitment from primary care, which was supported by the trial’s DMC. Two options were considered: to use general practices to identify patients and refer them to the secondary care sites already participating in the study (PICs) or to use general practices as recruitment and treatment centres.

The chief investigator approached the NIHR National Speciality Lead for Primary Care in December 2015 to explore how they might be able to support the study and to request some initial pre-screening to see how many patients could be identified in primary care. The NIHR Clinical Research Network, South London, UK, contacted a number of general practices on our behalf with the trial protocol including the inclusion and exclusion criteria and received three responses:

-

One Clinical Commissioning Group provided comments on the difficulty of identifying potential patients using a database search as many of the eligibility criteria, for example size of ulcer and duration of ulcer, are not coded. We were also advised that many patients were taking aspirin over the counter and that this may not currently be recorded in some patients’ records.

-

Two general practices identified a total of three potential participants in total.

We also approached Clinical Research Network Yorkshire and Humber who ran the trial’s inclusion and exclusion criteria through FARSITE (version 0.9.12.2; NorthWest EHealth Limited, Manchester, UK; https://nweh.co.uk/how-we-do-it/our-technology), a web-based anonymous search of patient records. They identified four suitable patients from 12 general practices.

We were unable to obtain details of practice list sizes, Read codes or criteria used in the searches conducted. However, the results indicated that recruitment from primary care was not a viable option using database searches. In addition, two of the recruiting sites (Lanarkshire and Sussex) advised that they would be unable to support referrals from primary care, which at one site was owing to waiting lists already for the service.

Recruitment using general practices as treatment centres was not investigated. Time constraints and budget constraints for implementing this strategy meant that this was option was not explored.

Summary

There were external factors outside the control of the research team that meant that sites were slow to open. Nine out of the 10 recruiting sites were based in secondary care and, once open, there were fewer than anticipated eligible participants. As this was a Clinical Trial of an Investigational Medicinal Product (CTIMP) study, it required more input from a doctor where nurses would otherwise often take the lead. The site make up was very different from other wound trials in which almost all sites were community based with tissue viability nurses acting as principal investigator, which was not possible here. A range of options were considered and explored to improve recruitment, including recruitment from primary care. Preliminary searches of records in primary care also indicated very few potentially eligible participants. In addition, the trial’s short recruitment window and budget constraints meant that many of the options considered to improve recruitment were not viable without a funded extension.

Chapter 4 Results

Analyses were conducted following the principles of intention to treat with all events analysed according to the participant’s original treatment allocation. Analyses were performed using Stata® version 14 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA). The trial opened to recruitment on 23 June 2015 and closed to recruitment on 29 February 2016. Participant follow-up was completed on 18 August 2016.

Participant flow

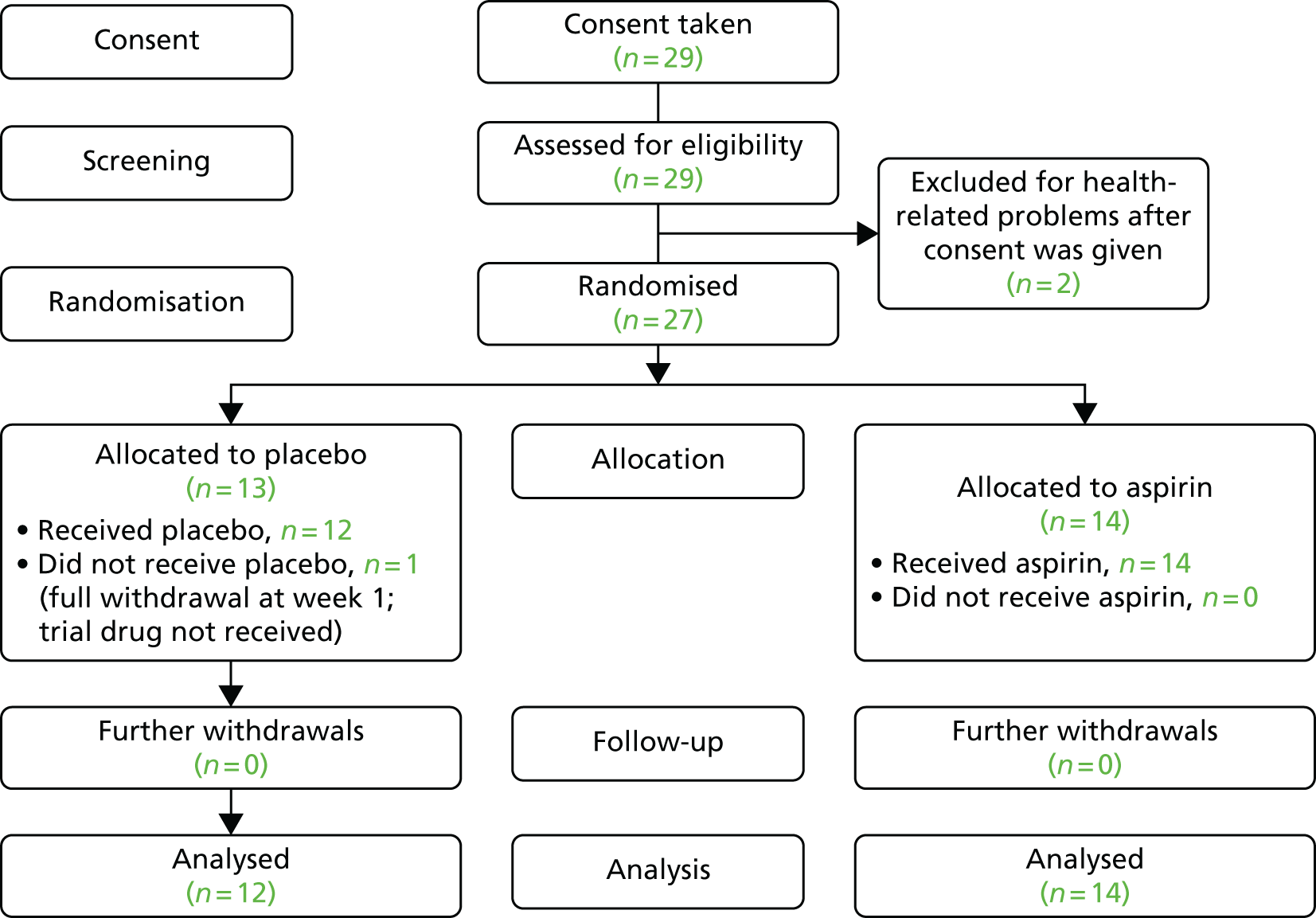

The CONSORT diagrams in Figures 1 and 2 show the flow of participants pre-screened and the flow of eligible participants during the trial. Figure 1 illustrates the number of patients pre-screened (n = 457) and the number of those who consented (n = 20). Pre-screening data were unavailable for the nine remaining patients who consented. Pre-screening was under-reported because some sites did not complete the first pre-screening log. The flow of participants in the trial is illustrated in Figure 2, which shows that 29 patients consented. The number of patients randomised by treatment group, receiving the intended treatment, completing the study protocol, and analysed for the primary outcome is presented. Two patients were excluded after they gave consent: one patient developed potential gastric problems and the other patient, affected by multiple comorbidities, was admitted to hospital.

FIGURE 2.

The AVURT CONSORT diagram.

Recruitment

Recruitment took place over 8 months, 2 months longer than originally scheduled. The trial opened on 23 June 2015 and the first participant was recruited on 13 July 2015. Recruitment closed on 29 February 2016. In total, 10 sites were opened and eight randomised a total of 27 patients (Table 2). The sites in Cardiff and Dundee did not recruit any participants. For accumulative recruitment over time see Appendix 14.

| Centre | Participants, n (%) |

|---|---|

| London, St George’s | 7 (25.9) |

| Hull and East Yorkshire | 6 (22.2) |

| Newcastle | 3 (11.1) |

| Lancashire | 3 (11.1) |

| Kent | 3 (11.1) |

| Harrogate | 2 (7.4) |

| Brighton | 2 (7.4) |

| Lanarkshire | 1 (3.7) |

| Cardiff | 0 (0) |

| Dundee/Tayside | 0 (0) |

| Total | 27 (100.0) |

Baseline data

The baseline participant and ulcer-related characteristics, as well as the baseline treatments, are shown in Tables 3–5. The average age of the 27 randomised participants was 62 years (SD 13 years) and two-thirds were male (n = 18). Participants had had their reference ulcer for a median of 15 months and the median size of ulcer was 17.1 cm2. All participants were receiving compression therapy at baseline.

| Participant characteristic | Group | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Placebo (N = 13) | Aspirin (N = 14) | Overall (N = 27) | |

| Age (years) | |||

| Mean (SD) | 62.1 (15.2) | 62.7 (11.6) | 62.4 (13.2) |

| Median (minimum, maximum) | 66.6 (38.9, 80.8) | 59.2 (47.9, 78.9) | 62.0 (38.9, 80.8) |

| IQR (25%, 75%) | (50.2, 73.4) | (54.0, 74.4) | (50.4, 74.4) |

| Missing, n (%) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Gender, n (%) | |||

| Male | 7 (53.9) | 11 (78.6) | 18 (66.7) |

| Female | 6 (46.2) | 3 (21.4) | 9 (33.3) |

| Missing | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| BMI (kg/m2) | |||

| Mean (SD) | 32.1 (8.6) | 36.6 (15.0) | 34.4 (12.3) |

| Median (minimum, maximum) | 28.4 (19.9, 44.1) | 31.6 (20.9, 70.2) | 31.5 (19.9, 70.2) |

| IQR (25%, 75%) | (25.3, 40.6) | (25.9, 40.2) | (25.3, 40.6) |

| Missing, n (%) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Mobility, n (%) | |||

| Patient walks freely | 10 (76.9) | 8 (57.1) | 18 (66.7) |

| Patient walks with difficulty | 3 (23.1) | 6 (42.9) | 9 (33.3) |

| Patient is immobile | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Missing | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Ankle mobility of reference leg, n (%) | |||

| Patient has full range of motion | 7 (53.9) | 11 (78.6) | 18 (66.7) |

| Reduced range of ankle motion | 6 (46.2) | 3 (21.4) | 9 (33.3) |

| Patient’s ankle is fixed | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Missing | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Diabetic, n (%) | |||

| Yesa | 2 (15.4) | 3 (21.4) | 5 (18.5) |

| No | 11 (84.6) | 11 (78.6) | 22 (81.5) |

| Missing | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Ethnicity, n (%)b | |||

| White British | 11 (84.6) | 12 (85.7) | 23 (85.2) |

| White Irish | 1 (7.7) | 0 (0) | 1 (3.7) |

| Indian | 0 (0) | 1 (7.1) | 1 (3.7) |

| Black African | 1 (7.7) | 1 (7.1) | 2 (7.4) |

| Missing | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Ulcer-related characteristic | Group | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Placebo (N = 13) | Aspirin (N = 14) | Overall (N = 27) | |

| Size of ulcer (cm2) | |||

| ≤ 5 cm2, n (%) | 3 (23.1) | 3 (21.4) | 6 (22.2) |

| > 5 cm2, n (%) | 10 (76.9) | 11 (78.6) | 21 (77.8) |

| Mean (SD) | 40.7 (55.1) | 43.1 (47.6) | 42.0 (50.3) |