Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 12/127/12. The contractual start date was in July 2014. The draft report began editorial review in July 2017 and was accepted for publication in March 2018. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Maureen Coggrave reports personal fees from Hollister Incorporated (Libertyville, IL, USA) and Wellspect HealthCare (Weybridge, UK), both outside this study. John Norrie was a member of the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Commissioning Board from 2010 to 2016, is currently an editor on the NIHR Journals Editorial Board and is Deputy Chairperson of the NIHR Health Technology Assessment General Board. Peter Donnan reports grants from Shire plc (Dublin, Ireland), Novo Nordisk A/S (Bagsværd, Denmark), GlaxoSmithKline plc (London, UK), AstraZeneca plc (Cambridge, UK) and Gilead Sciences Inc. (Foster City, CA, USA), outside this study. He is also a member of the New Drugs Committee of the Scottish Medicines Consortium.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2018. This work was produced by McClurg et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2018 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Introduction

Scientific background

The prevalence of multiple sclerosis (MS) is increasing in the UK, and MS is the most common neurological condition in young adults (the average age at onset is 34 years), affecting > 100,000 people at present. 1 It is estimated that 60% of people with multiple sclerosis (PwMS) have problematic neurogenic bowel dysfunction (NBD);2 increased life-expectancy rates, as a result of advances in health care, present additional challenges of the ageing bowel. 3 NBD is rated as one of the most distressing scenarios affecting these patients and includes the symptoms of constipation and faecal incontinence (FI). 4 Constipation can lead to the individual becoming housebound, spending hours trying to empty their bowels and limiting their ability to work; whereas FI is often described as the most devastating event imaginable, leading to social and emotional issues. 5 A MS Trust report6 published in April 2017 revealed that emergency admissions (many of which are thought to be preventable) to hospital for PwMS have increased by 12.7% over the 2 years 2015/16, with overall admissions for bladder- and bowel-related issues, for example impaction, costing £10.4M in 2015/16.

Aetiology of neurogenic bowel dysfunction

Aetiology of NBD in PwMS is multifactorial; reduced mobility and polypharmacy may have a contributory causative role. Coincidental pelvic nerve lesion, occurring during childbirth, could also contribute to FI in women with MS. 7 Spinal cord lesions appear to be most important in the pathogenesis of NBD symptoms in MS. 8 The pathways of neural control of defecation are not fully defined; however, cortical and pontine centres may play a pivotal role in the regulation of sacral segments. 8,9

Conduction times of central motor pathways to sphincteric sacral neurons and pelvic floor striated muscle have been shown to be prolonged in MS. 10 Impaired anorectal sensation may also contribute to the symptoms; somatosensory-evoked potentials were delayed in PwMS compared with controls in one study. 11 Loss of central modulation on spinal cord segments may lead to sympathovagal imbalance, which, in turn, can lead to constipation, characterised by lengthened colon transit time. 12 Constipation has thus been attributed to rectal outlet obstruction, absent or incomplete puborectalis, anal canal and sphincter musculature relaxation, and prolonged colonic transit time. 10,13 Regarding FI, studies have described reduced sensation of rectal filling, reduced rectal compliance, low anal sphincter pressures and hyper-reactivity of the rectal wall. The coexistence of FI and constipation can be explained by inco-ordinated action of the external/internal anal sphincter during expulsion; poor pelvic musculature relaxation may cause incomplete emptying of the rectum, which precipitates FI when anal sphincter weakness and anorectal hyposensitivity are present. 14,15

Current treatment/management options

Management of NBD in PwMS has been little explored and lacks supporting evidence. 16 It is costly both in terms of patient time and to the NHS (e.g. PwMS have two to three times more admissions to hospital for bowel complications than non-MS patients). 17 It also has an impact on the families and carers of PwMS. 18 PwMS use laxatives, suppositories, prolonged digital rectal stimulation and/or rectal irrigation, but often these interventions have inconsistent results. For example, one patient in our previous study would take laxatives two evenings per week, but then could not leave the house the next day as he had no control over when he would pass stool. 5

Evidence for the clinical effectiveness of abdominal massage for constipation

A Cochrane systematic review19 has been undertaken to determine the effects of abdominal massage for the relief of symptoms of chronic constipation in comparison with no treatment or other treatment options. Nine randomised controlled trials (RCTs) (12 randomised comparisons) involving 427 participants were included in the review. 19 The study populations were small (with a maximum of 32 participants per group), heterogeneous and all were rated as having a moderate or high risk of bias. Findings from two trials suggested that abdominal massage compared with advice from a physician provided significant additional relief of symptoms from constipation in the short term. Two trials found no significant differences between groups. One trial, which had the three groups (aroma massage, plain massage and control), reported that both the aroma massage group and the plain massage group had an improved quality of life. The review concluded that there were insufficient data to allow reliable conclusions to be drawn on the effects of abdominal massage in the management of constipation. There was some evidence to suggest that there might be a therapeutic effect; however, larger, more rigorous trials are required to provide evidence of both the clinical effectiveness and the cost-effectiveness of abdominal massage.

How the intervention might work

There is some evidence to suggest that abdominal massage will reduce colonic transit time and enable predictable complete evacuation; however, the possible mechanism of action is not yet fully understood. 20,21 The function of the gastrointestinal tract is influenced by, among other things, activity in the parasympathetic division in the autonomic nervous system. Stimulation of the parasympathetic division increases the motility of the muscles, increases the digestive secretions and relaxes sphincters in the gastrointestinal canal. 22–24 Massage is thought to stimulate peristalsis in the gut by producing rectal muscular waves that stimulate the somatoautomatic reflex and initiate bowel sensation, thereby reducing colonic transit time. 25 Furthermore, the active massaging action may result in a softening of stool consistency, allowing the stool to be passed more easily. 26

Development of the intervention

The abdominal massage intervention used within this trial was based on massage as formally taught in physiotherapy training within the UK and used by an expert in the area in earlier studies. 27–29 This expert was involved in the development of the training materials and in the training of the clinicians undertaking the massage. All clinicians involved with teaching the massage to participants underwent 1 half day of training in the massage technique, as well as presentations on NBD and good bowel care. Information provided to participants on bowel care was based on the MS Society’s handbook on bowel management. A description of the intervention has previously been published. 30 A copy of the training materials is available in Appendix 1.

Who delivers the intervention

In previous studies, the massage was delivered by a health-care professional (HCP) with experience in massage, a family carer or by the patient themselves. It was discovered, however, that the amount of training and support received by participants is poorly described. In this trial, the massage was designed and taught to be either self-massage or undertaken by a ‘carer’. Likewise, the training of the ‘trainers’ (HCPs involved in seeing the patient and teaching the massage) was such that it was delivered in one half-day session, but also required individuals to undertake further practice, to consolidate their training. If this limited training plus support materials for HCPs and patients were to prove effective, then the abdominal massage could potentially be implemented in many settings to patient populations who experience constipation.

Hypothesis

A 6-week intervention of abdominal massage and bowel management advice (intervention group) will improve symptoms and quality of life in PwMS who have NBD compared with advice alone (control group).

Chapter 2 Trial design and methods design

The Abdominal Massage for Bowel Dysfunction Effectiveness Research (AMBER) trial was designed to evaluate whether or not abdominal massage is an effective treatment in reducing the symptoms of NBD, particularly constipation, in PwMS. This trial was a multicentre, patient-randomised, superiority trial comparing the following in PwMS who have stated that their constipation is ‘bothersome’: an intervention of optimised bowel care with once-daily abdominal massage for 6 weeks with the control of optimised bowel care without massage. A description of the trial protocol has already been published. 30

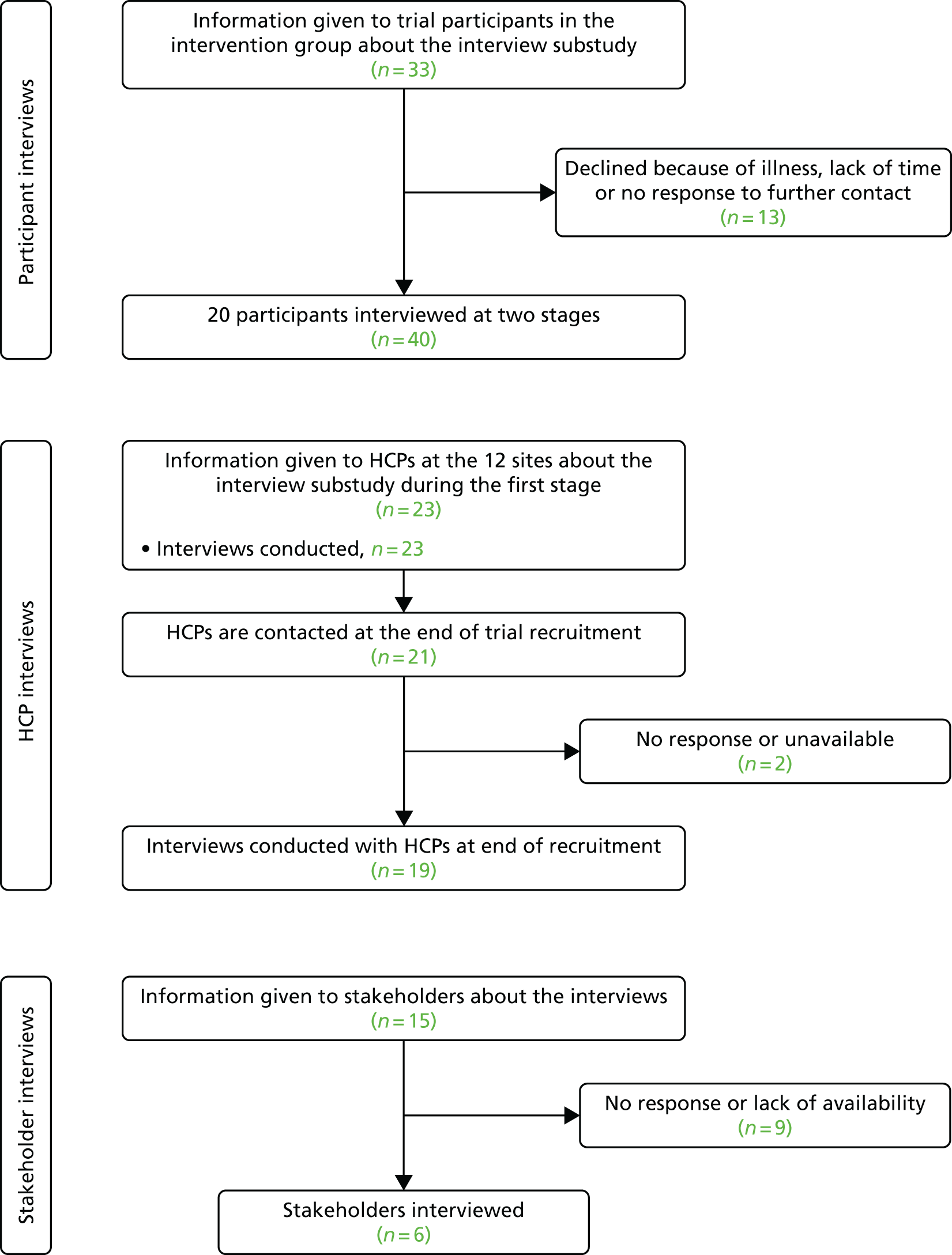

The main trial was supported by a process evaluation to explore the possible mediating factors that may affect the clinical effectiveness of the intervention, how these mediating factors influence clinical effectiveness, and whether or not the factors differ between the randomised groups. Trial processes were evaluated to provide evidence of potential importance in the future implementation of the intervention (see Chapter 5).

The main study objectives were to:

-

establish if an optimised bowel care programme (i.e. provision of advice/information on bowel management) with abdominal massage, compared with an optimised bowel care programme alone, is more clinically effective and cost-effective in reducing the symptoms of NBD at week 24 in PwMS

-

identify and investigate, via a process evaluation, the possible mediating factors that affect the clinical effectiveness of the intervention (including intervention fidelity), how these mediating factors influence clinical effectiveness and whether or not the factors differ between the randomised groups (see Chapter 5)

-

undertake a formal economic evaluation of the interventions from a NHS and a patient perspective (see Chapter 4)

-

undertake a feasibility study relating to the mechanisms of action using anal manometry and colonic transit tests at one tertiary bowel centre where these tests are routinely undertaken

-

record data to validate the responsiveness of a questionnaire to change in quality of life following an intervention.

Ethics approval and research governance

Ethics approval for the trial was granted by the West of Scotland Research Ethics Committee (REC) 4 on 11 June 2014 (reference number 14/WS/0111). NHS approval was granted for 10 different trusts/foundation trusts in England, and two local health boards granted approval for the two sites in Scotland. The trial sponsor was Glasgow Caledonian University (GCU) and the AMBER trial office was based in the Nursing, Midwifery and Allied Health Professions Research Unit (NMAHP RU) at GCU. The AMBER trial was registered with the International Standard Randomised Controlled Trial Number (ISRCTN) registry (ISRCTN85007023) and on ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT03166007).

Participants

The trial recruited PwMS who reported that they were ‘bothered’ (in their own judgement) by their NBD symptoms at 12 sites across UK (n = 2 in Scotland and n = 10 in England).

Inclusion criteria

People were eligible for the trial if they met the following inclusion criteria:

-

bothered by their NBD

-

aged ≥ 18 years

-

diagnosis of MS (in a stable phase, i.e. no MS relapse in the previous 3 months)

-

no major change of medication in the previous 1 month [e.g. introduction of disease-modifying treatments (DMTs)]

-

not used abdominal massage in the previous 2 months.

Exclusion criteria

-

Being unable to undertake the massage themselves and did not have a carer willing to do it.

-

Being unable to understand the trial processes in order to give informed consent.

-

Contraindications to abdominal massage, which included the following: history of abdominal/pelvic cancer, hiatus, inguinal or umbilical hernia, rectal prolapse, inflammatory bowel disease, volvulus and pregnancy.

-

Abdominal scars, abdominal wounds or skin disorders that may make abdominal massage uncomfortable.

If a potential participant reported recent sudden and severe changes in bowel habits or rectal bleeding, these symptoms were first discussed with the consultant at the relevant site to determine suitability.

Recruitment procedure

The research team at each trial site were responsible for identifying potential participants. Following identification of potentially eligible individuals, a letter of introduction and an ‘expression of interest’ form was either posted or given to patients at their routine clinic appointment. Each patient approached about the trial was allocated a unique participant identifier number. This consisted of six characters: three letters that were an abbreviation of the site name followed by three numbers that were allocated on a consecutive basis (e.g. 001 for first participant). This unique identifier was used throughout the trial and was added to all participant paperwork. Once a completed ‘expression of interest’ form was returned, a member of the research team telephoned the individual to provide further information and assess eligibility. If eligible and willing to take part, the individual was sent a baseline appointment letter along with a 7-day bowel diary for completion. The participant completed the bowel diary the week before the baseline appointment. Participants were also asked to bring someone who was willing to do the massage to this appointment, if required.

Informed consent

Informed, written consent was obtained for all participants at the baseline appointment and included consent to any site-specific tests. The REC agreed to the completion of bowel diaries before the baseline appointment, as the participants’ consent was implied by them willingly completing the diary. There was no use of these data until participants had provided written informed consent; this method aided recruitment to the trial because it meant that there was only one clinic visit required. Participants were made aware that the treatment was allocated at random, regardless of any personal preference they had. They had the right to withdraw from the trial at any time and for any reason; all participants were also made aware that withdrawal would not affect their routine care.

The consent form also had the option for the participant to be contacted if they were interested in taking part in the process evaluation interviews. Chapter 5 explains the consent method followed for this part of the study. The general practitioners (GPs) of all those who took part in the trial were informed of their involvement.

Randomisation, concealment and blinding

Participants who provided written informed consent were randomly allocated to one of two treatment groups during their baseline appointment: (1) advice to optimise bowel care (control group) or (2) advice to optimise bowel care and abdominal massage (intervention group). The web-based randomisation service was provided by the Tayside Clinical Trials Unit (CTU), a UK Clinical Research Collaboration (UKCRC)-registered trials unit, and research staff at sites carried out the randomisation. In a few instances, the AMBER trial central office would assist with the randomisation remotely. This took place when there may have been issues for the staff when connecting to the web-based randomisation system (room allocation with no computer or web connectivity issues). Group allocation was relayed by telephone to the site and copies of the relevant randomisation paperwork were sent to all of those involved. Owing to the nature of the intervention, it was not possible to blind the participants or site staff to the allocation. Participant group allocation was unknown to the data analysis team. Randomisation was stratified by site and minimised on level of disability (walking unaided, aided or wheelchair bound).

Treatment group allocation

Both trial groups

Participants in both the intervention and the control group received a 6-week intervention consisting of one face-to-face consultation (baseline appointment) followed by weekly telephone calls to review adherence and any changes/difficulties with their bowel management. This meant that both groups had the same number of contacts with a HCP. Both groups received advice to optimise bowel care, as described in the following section.

Control group (advice to optimise bowel care)

During the baseline appointment, the participants’ existing routine bowel care was reviewed and discussed with them by a member of the site research team. Dietary and fluid advice was provided, and participants were encouraged to be more active and to use a correct defaecation position, which was described to them. Participants were given a copy of the bowel care advice leaflet of the MS Society that reinforced this advice [see project web page URL: www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/programmes/hta/1212712/#/ (accessed 30 October 2017)].

Intervention group (abdominal massage and advice to optimise bowel care)

In addition to optimised bowel care as described for the control group, staff delivering the intervention (local HCPs all fully trained in the massage technique) taught the participant and/or his or her carer how to deliver the abdominal massage. This teaching included the following:

-

Viewing a short trial-specific digital versatile disc (DVD) that demonstrated the massage techniques for carer and self-massage (Figure 1 shows a picture captured from the training DVD).

-

Provision of a study-specific abdominal massage training booklet.

-

A demonstration of the massage technique on the participant.

-

Practice of the various strokes by the carer or participant.

-

An opportunity for the participant and carer to ask questions. Possible adaptations to accommodate a participant’s disability were also discussed. A daily massage of 10 minutes duration was recommended.

FIGURE 1.

A picture from the AMBER trial training DVD, which demonstrates the massage strokes to be used.

Participants in this group were given an information pack that consisted of the following:

-

the MS Society’s bowel care advice booklet

-

the massage DVD

-

patient abdominal massage training information leaflets.

In order to standardise the intervention delivery across all sites, training for all site staff delivering the intervention was provided by one individual with clinical expertise in the area. Staff attended a trial training day and/or they were trained during the site initiation visits. Each staff member had to perform practical demonstrations and be deemed proficient in the technique before being signed off as fully competent. Sites were contacted after the baseline appointment of their first participant from the intervention group to discuss how staff found delivering the massage and to answer any questions. Further training was available at this point, but all sites felt confident in the delivery of the intervention. Any questions/feedback from the individual sites were shared with all research site staff via monthly update teleconferences. The weekly telephone calls to participants were done either by the staff member who delivered the massage training, or by another member of staff on the delegation log.

Participants randomised to the control group were informed that they would be given access to the massage training materials at the end of their follow-up (week 24). In addition, some of the sites offered to hold training sessions with the control group participants after they had completed the study.

A description of how to perform the massage technique can be found in Appendix 1, along with the training material given to participants as an aide memoire.

Mechanistic evaluation

One of the sites in the AMBER trial [University College Hospital (UCH), London] is a regional NBD centre where standard anorectal physiology and colonic transit tests are routinely undertaken. AMBER trial participants recruited at this site underwent the following tests before the intervention, and then again at 24 weeks:

-

Anorectal pressure test – this test involves the insertion of a small probe into the rectum to measure the strength of the anal muscles.

-

Anal and rectal sensation and capacity was measured by using a tiny amount of current and inflating a small balloon within the rectum (a balloon was inserted via a tube, and sensory thresholds to progressive distension were established. The initial tube was then removed and a different catheter with a bipolar electrode inserted; the sensory threshold to 1 mA of current was then determined).

-

Transit tests – three sets of radiopaque capsules were posted to the participant, who ingested them in the order specified in the instructions on 3 consecutive days. Participants then attended for an abdominal radiography 2 days after the last capsule to determine total colonic transit time (not segmental transit).

This was a small substudy in the AMBER trial to look at possible mechanisms involved in NBD in PwMS and to look at the feasibility of undertaking such tests within this population and their compliance with attending the repeat tests.

Data collection and management

Data were collected and recorded on study-specific paper-based case report forms (CRFs) by either site staff or the participants (bowel diaries and patient-reported outcomes during weeks 1–6 and week 24). Sites were trained on completion of all the paperwork before recruitment commenced and a monthly teleconference, with all sites jointly, allowed any data issues/inconsistencies to be discussed and resolved. The AMBER trial central office entered all data into the OpenClinica database (OpenClinica, LLC, Waltham, MA, USA). This was set up and managed by Tayside CTU. A range of data validation checks was used to minimise erroneous and missing data.

Baseline assessment

Demographic data and information on participants’ MS, medical history and bowel symptoms were collected at the baseline assessment. Participants also completed a questionnaire booklet which contained five different questionnaires (including the primary and secondary outcome measures – see Outcome measures and Appendices 2 and 3). Information on current medication was recorded, including any laxative use. Participants were given the bowel diaries and questionnaires, which were to be completed during the 6-week intervention phase, at the baseline assessment, with an instruction sheet detailing how they should be completed. Baseline anorectal physiology and colonic transit time data were collected from the London participants using an anorectal physiology CRF.

Baseline assessments were conducted between 22 January 2015 and 19 July 2016.

Participant follow-up

The duration of follow-up was 24 weeks from the date of randomisation.

Outcomes were collected through the following documents, which were completed by participants:

-

a questionnaire booklet at weeks 6 and 24 (the same as the baseline questionnaire)

-

a 7-day bowel diary (control group) or bowel and massage diary (intervention group) at weeks 1 to 6 and during week 23

-

patient resource-use questionnaires at weeks 1–6, and weeks 12, 18 and 24.

All information completed by the participants was returned to the AMBER trial central office by reply-paid envelopes that were provided.

Anorectal physiology and colonic transit time data were collected at week 24 in UCH participants only.

Site research staff telephoned all participants weekly during weeks 1 to 6 and again at week 24 to collect additional information on any potential issues, changes in diet/exercise/fluid, adverse events (AEs) and any changes in medication. Any potential issues with bowel management or the massage were discussed and fed back to the AMBER trial central office if deemed necessary.

All AMBER trial follow-ups were completed by 19 January 2017.

Table 1 shows the AMBER trial matrix and data collected at each time point.

| Item | Time point | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Screen | Week –1 | Baseline appointment | Telephone call | Post | Telephone call and post | Withdrawal of data collection | |||||||

| Week 1 | Week 2 | Week 3 | Week 4 | Week 5 | Week 6 | Week 12 | Week 18 | Week 24 | |||||

| Informed consent | 7 | ||||||||||||

| Inclusion/exclusion | 7 | ||||||||||||

| Medical history | 7 | ||||||||||||

| Current medications | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | ||||

| Randomisation | 7 | ||||||||||||

| 7-day bowel diary | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | |||

| Process evaluation/interviewsa | 7 | 7 | |||||||||||

| 7-day bowel and massage diarya | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | ||||

| Trial questionnairesb | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | |||||||||

| Physiology formsc | 7 | 7 | Visit | 7 | |||||||||

| Patient resource questionnaire | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | ||||

| AEs | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | |||||

Outcome measures

Primary outcome: Neurogenic Bowel Dysfunction Score

The Neurogenic Bowel Dysfunction Score (NBDS)31 is a 10-item questionnaire covering frequency of bowel movements (0–6 points); headache, perspiration or discomfort during defaecation (0–2 points); medication for constipation or faecal incontinence (0–4 points each); time spent on defaecation (0–7 points); frequency of digital stimulation or evacuation (0–6 points); frequency of faecal incontinence (0–13 points); flatus (0–2 points); and perianal skin problems (0–3 points). The maximum score is 47 points; the higher the score, the more severe the symptoms, with a score of ≥ 14 points rated as severe. In the AMBER trial, the primary outcome measure was the change in the NBDS from baseline to week 24.

Secondary outcomes

Bowel symptoms

The Constipation Scoring System (CSS)32 was completed at baseline and at weeks 6 and 24 to assess constipation symptoms. The CSS is an eight-item questionnaire with items on frequency of bowel movement, difficulty with evacuation, feeling of incomplete evacuation, pain, length of time for evacuation, assistance with evacuation, number of failed attempts and the duration of constipation. The maximum score is 30 points, with higher scores indicating greater severity. A 7-day bowel diary (designed for use in the AMBER trial) was used to record information on bowel symptoms, such as frequency of bowel movement, time spent defaecating, stool type (Bristol stool chart33), laxative use, additional interventions (such as digital stimulation) and if there were any episodes of bowel incontinence. The diary was completed prior to baseline, during weeks 1–6 and at week 23. In the intervention group, a 7-day massage diary was used to record daily information on massage compliance and duration and was completed prior to baseline, during weeks 1–6 and at week 23.

Bladder dysfunction

Bladder function was measured using the SF-Qualiveen, consisting of an eight-item questionnaire assessing bladder dysfunction, such as leakage and signs of incomplete voiding. 34 Often, if patients with MS are suffering from constipation, they report that their bladder symptoms are worse, especially urgency and frequency, which can lead to an increase in urinary incontinence. This outcome measure allowed the effect of the change in bowel function on the bladder to be assessed at baseline and at weeks 6 and 24. A higher score indicates a poorer quality of life.

Quality-of-life outcomes

To determine health status, the EuroQol-5 Dimensions, five-level version (EQ-5D-5L), generic questionnaire was used. 35 Participants completed the EQ-5D 5L at baseline and at weeks 6 and 24.

A neurogenic bowel impact score (NBIS) questionnaire was completed at baseline and at weeks 6 and 24. This score was developed by one of the collaborators on the AMBER trial as part of a National Institute for Health Research (NIHR)-funded postdoctoral fellowship. The questionnaire has three subscores [(1) quality of life, (2) faecal incontinence and (3) symptoms] and includes four stand-alone items. It is intended for use with individuals with a range of conditions that result in NBD. The measure’s reliability and criterion validity were to be evaluated.

Economic outcomes

The cost and use of NHS services were collected via a patient resource questionnaire [see project web page URL: www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/programmes/hta/1212712/#/ (accessed 30 October 2017)] during weeks 1–6 and at weeks 12, 18 and 24. From this information (along with the EQ-5D-5L data) the costs and quality-adjusted life-years (QALYs) were calculated for each group. A cost–utility analysis was conducted to calculate the incremental cost per QALY of abdominal massage compared with optimised bowel care; this is described in detail in Chapter 4.

Change of medication

Changes of medication were recorded using a current medication form. Any changes to a participant’s medications during their involvement in the trial were recorded. Also recorded were any reductions or stoppage of laxatives between baseline and week 24.

Radiopaque marker transit tests

Different parameters were collected on an anorectal CRF (see Report Supplementary Material 1) for the physiology and transit tests. The total number of markers remaining in the gut at abdominal radiography was analysed to determine any differences between baseline and week 24, and all other data were summarised.

Adverse events

Expected AEs arising from the treatments in the AMBER trial are noted below. These are common in individuals with constipation and thus were not collected as AEs but noted in the weekly follow-up data collection:

-

increased flatulence

-

abdominal cramps

-

stomach rumblings/noises

-

loose stool, which in some instances may lead to faecal incontinence.

All AEs (for which a participant sought intervention from a HCP) and SAEs (including death, life-threatening conditions, inpatient hospitalisation or prolongation of existing hospitalisation and persistent or significant disability or incapacity) were assessed for causality, severity and expectedness, and were reported to the relevant regulatory bodies. If a site was in doubt about whether or not an event was an AE, this was reported and discussed before data lock. Any AE that was deemed as ongoing at the end of the trial was reviewed and further clarification from the site was sought. If the AE was still ongoing after this (owing to the nature of the event, but not related to the intervention), this was when the follow-up ended.

Adverse events (including SAEs) were coded with the Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities (MedDRA)36 16.1 and reported by primary System Organ Class (SOC) and preferred term (PT). Participants were counted only once when calculating the incidence of AEs. An overview table was created counting the number of AEs by SOC and PT.

Sample size

The sample size for the RCT was based on the NBDS, using data from a pilot study37 that provided the only published data available on abdominal massage in this group of patients. That study37 found a difference of 4.21 points in the NBDS between those receiving the intervention {mean score of 6.86 points [standard deviation (SD) 3.8 points] at 8 weeks} and the comparison group [mean score of 11.07 points (SD 7.02 points) at 8 weeks]. Other outcomes in that study changed in favour of the intervention and participants anecdotally reported that the massage was relaxing and that they were keen to do it themselves. Using these data, we selected a minimum clinically important difference (MCID) of 4.21 points and selected the higher SD of 7.02 points, found in the comparison group, as the basis for our sample size calculation.

Using these data, 60 participants per group was calculated as the necessary number of participants to detect a difference between groups of 4.21 points (SD 7.02 points) at a 5% level of significance with 90% power. Thus, for a fully powered study, the total sample size, allowing for a 20% dropout rate, was 150. However, in response to suggestions from the funding body, the sample size was increased to 200 participants (100 per group), which allowed for greater attrition.

Statistical analyses

Statistical methods for analysis of the main primary and secondary outcomes are detailed in the following sections. This document was drawn up by the trial statisticians, reviewed by the Project Management Group and formally signed off by the chief investigator and trial statistician before analysis commenced.

Analysis populations

Analysis was performed for the intention-to-treat population and is reported in accordance with Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT). 38

Subgroups

Subgroup analyses were carried out by first testing for a subgroup factor by intervention interaction. If this was significant at the 5% level, results were estimated separately by the different subgroups. This included a secondary analysis comparing those who undertook the massage themselves with those who had a carer massage them.

Missing data

The extent of missing data was explored in the outcomes, especially the primary outcome. Patterns of missing data were explored and predictors of missingness examined, especially if these varied by intervention. A table was constructed to assess differences in characteristics of those with complete data and those with missing data for the primary analysis. Multiple imputation (MI) was implemented for the primary outcome, assuming data were missing at random.

Summary of trial data

All continuous variables were summarised using the following descriptive statistics: non-missing sample size, number of missing records, mean, SD, median, maximum and minimum. The frequency and percentages (based on the non-missing sample size) of observed levels were reported for all categorical measures. In general, all data were listed, sorted by subject and treatment and, when appropriate, by visit number within subject.

All summary tables were structured with a column for each treatment group and an additional column for the total population relevant to that table/treatment, including any missing observations.

Demographic and baseline variables

The baseline characteristics of participants that were recorded comprised age, sex, body mass index (BMI), type of MS, site, number of years since diagnosis, cognitive symptoms of MS and level of mobility (walking unaided, aided or wheelchair bound).

Prior and current medications

Prior medications were all medications that were being taken by a participant before the trial started. Concomitant medications were all medications commenced during the trial and all changes to the dosing of prior medications. Prior medications were listed but not analysed. Concomitant medications were analysed by number of medications taken.

Treatment adherence

Treatment adherence was calculated from the weekly bowel diaries. The number of times the bowel massage was done per week was used in the main analysis. For the control group, this number was set to 0.

Efficacy analyses

Data for continuous outcome measures (both primary and secondary) were assessed for normality before analysis. Transformations of the outcome variables were used when necessary, if these were not normally distributed.

If data were normally distributed, outcome measures were assessed by multiple linear mixed-model regression. The primary analysis consisted of comparisons between treatment groups (bowel massage vs. no massage) at the final visit (week 24), adjusted for site, minimisation variable level of mobility (walking unaided, aided or wheelchair bound), as well as baseline measure of the outcome and sex.

In a secondary analysis of the primary outcome, additional baseline variables (age, sex, BMI, type of MS, number of years since diagnosis and cognitive symptoms of MS) were included in the model.

When data were not normally distributed and could not be transformed into a normal distribution, they were analysed using non-parametric methods in addition to multiple linear regression.

In addition to the comparison of baseline with week 24, a repeated measures mixed-model analysis was performed on the outcomes using all available visits.

Data for categorical outcome measures were assessed by logistic regression in the same way as described for continuous outcome measures.

Primary efficacy analysis

The primary outcome measure was the between-group difference in the change of NBDS at week 24 with the analysis adjusted, as described above.

Secondary efficacy analyses

Bowel outcomes

-

Between-group difference in change in constipation symptoms. Analysis variable is the total constipation score.

-

Bowel symptoms (7-day bowel diary). The percentage of normal stools per week was calculated and used for analysis. In addition, the number of days that a stool was passed and time spent passing stools was analysed.

-

Radiopaque marker transit tests. The number of total markers was used for the analysis.

-

Adherence to massage schedule (massage diary). As this is only available for the intervention treatment group, data are summarised in the descriptive statistics. No formal testing was done.

Urinary outcomes

-

Between-group difference in change in total score of bladder function (SF-Qualiveen).

Quality-of-life outcomes

-

Between-group difference in change in health-related quality of life, measured by the EQ- 5D-5L using both the EuroQol Visual Analogue Scale (EQ-VAS) and the index score.

-

Between-group difference in change of patient-reported quality of life. This consists of four scores derived from the NBD patient-reported outcomes tool.

-

Between-group difference in change in medication, analysed as all patients who stopped using laxatives at week 24. This was determined from the concomitant medication page.

-

Between-group difference in change in medication, analysed as the number of changes in usual laxative use at week 24. This was taken from the bowel diary as the number of changes from usual laxative use to use of fewer laxatives at week 24.

-

Between-group changes in the regular use of medications to counter constipation were assessed at weeks 6 and 24.

Reporting conventions

Values of ≥ 0.001 are reported to three decimal places; p-values of < 0.001 are reported as < 0.001. The mean, SD and any other statistics, other than quantiles, are reported to one decimal place greater than the original data. Quantiles, such as median or minimum and maximum, use the same number of decimal places as the original data. Estimated parameters not on the same scale as raw observations (e.g. regression coefficients) are reported to three significant figures.

All analyses were performed using SAS® 9.3 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA. SAS and all other SAS Institute Inc. product or service names are registered trademarks or trademarks of SAS Institute Inc. in the USA and other countries. ® indicates USA registration.) All data, analysis programs and output were kept on the Mackenzie Server and backed up according to the internal Tayside Clinical Trials Unit (TCTU) information technology standard operating procedures.

Analysis programs were required to run without errors or warnings. The analysis programs for outcomes were reviewed by a second statistician and any irregularities in the programs were investigated and fixed, and the date of finalised analysis programs was signed and recorded.

Economic analysis

The cost of abdominal massage and optimised bowel care relative to optimised bowel care alone in PwMS who have NBD was considered from NHS and patient perspectives. Health-care resource use by patients in both trial groups was collected at each of the follow-up time periods (weeks 1–6, 12, 18 and 24). This included contact with health professionals and medications prescribed. These were costed using NHS pay and prices or, when appropriate, other (e.g. market-based) sources. The economic analysis (including the methods used) is detailed in Chapter 4.

Important changes to protocol after trial commencement

All sites used protocol version 2, dated 18 November 2014, throughout the trial duration. The London site used an additional patient information leaflet (PIL) to describe the additional tests carried out at this site. After original approval of the PIL, one of the tests was no longer completed routinely at the London site, so this information was removed and the amended PIL was approved by all relevant regulatory bodies. This change was carried out before any patients were recruited at the site.

Another substantial amendment was to incorporate a substudy, entitled SWAT (study within a trial) 24, in the AMBER trial. Participants were randomised to receive either the original cover letter or an enhanced cover letter (sent with the questionnaire at week 24) to evaluate whether or not the wording used would increase return rates of the questionnaires.

Data from the substudy will contribute to the Trial Forge39 initiative to improve trial efficiency and to the Cochrane review of strategies to improve trial retention. 40

The results of the Trial Forge39 project will help to increase the evidence base on the retention of participants to trials. The only change to the AMBER trial was the way that the cover letter sent with questionnaires was written (no protocol change).

Other non-substantial changes included the:

-

addition of new sites as the trial progressed (original target was 10 sites but final total was 12 sites)

-

set-up of two patient-identifying centres to assist two sites with recruitment

-

sites collecting the NBDS during the telephone call with participants at week 24 to maximise the primary outcome data in the study.

Trial oversight

The trial was led by the chief investigator who, along with the trial management team members (consisting of a trial manager, a data co-ordinator and a process evaluation researcher), were employed by NMAHP RU.

The trial was overseen by a Project Management Group (PMG), a Trial Steering Committee (TSC) and a Data Monitoring and Ethics Committee (DMEC).

The PMG had a teleconference approximately every 4–6 weeks during the recruitment period and then bimonthly after this. The group’s role was to support any decision-making that the trial management team needed further advice on.

The TSC had both an independent chairperson and members but also consisted of the trial collaborators. The TSC had four meetings over the course of the trial, with additional updates on recruitment when requested. The TSC commended the team on recruiting to target and on time.

An independent DMEC, chaired by a statistician, had three meetings over the course of the study, and additional updates were provided when requested. All statistical reports to the DMEC were prepared by a statistician from the TCTU. The DMEC had no issues with the trial continuing at any time point and commended the team on the recruitment and management of the study. The DMEC charter can be reviewed in Appendix 2.

Patient and public involvement

The AMBER trial has had active participation with a group of PwMS (hereafter referred to as the MS focus group). Some of the MS focus group were involved with the development of the grant application, providing feedback on the lay summary, trial design and appropriate outcome measures and questionnaires. Several additional PwMS became involved during the very early stages of the trial and throughout implementation and dissemination of results. The MS focus group included males and females, with various levels of disability and of various ages, some with and some without NBD. Approximately 10 members of the MS focus group attended each of the meetings. Material to review was sent electronically before the meetings and was available in hard copy at the meetings; very helpful feedback and discussions took place. One of the members of the MS focus group has also attended each TSC meeting as a lay representative and has actively engaged in the conversations and discussions at each meeting. Before recruiting any participants to the trial, the MS focus group reviewed the massage training DVD and the massage training material that would be given to the participant to take home with them, and their input to this was extremely influential. The group’s opinion of the initial version of the training DVD was that the visual was excellent but the language used was ‘too clinical’. This was overcome by the chief investigator of the trial doing a voice-over on the DVD; the group reviewed this again and it was deemed much more acceptable and user friendly. Many of the trial participants subsequently commented that they thought the video was extremely useful and easy to follow.

We initially had two different training documents and we asked the group which would be better used as an aide memoire. The MS focus group had very mixed opinions on their preferences, and discussed the style, language and diagrams used. It was therefore concluded that both of these additional training materials would be provided to all participants in the intervention arm and they could decide which material they felt was better for them. However, there is the possibility of combining the information into one single training document if the intervention is rolled out to clinical care.

Participants in the AMBER trial were given quite a lot of information to take away with them at the baseline appointment, in the form of a ‘follow-up pack’. This pack included all the questionnaires and bowel diaries and study instructions on what they had to complete over the 6-week intervention period, and also the massage training DVD and reading materials (only if the participant was in the intervention group). The MS focus group reviewed this pack and thought that it was logical and clear and some further feedback from site staff implied that the participants ‘liked’ having this pack to take away with them.

We kept in touch with the MS focus group throughout the study, giving updates on recruitment, and there were discussions on dissemination plans. A dissemination day was held on 23 January 2018 in Glasgow Caledonian University, to which all the research staff involved in the study, and local participants, were invited. Representatives of the MS focus group also attended.

Throughout the active recruitment of the study, local and national MS charities were aware of our research and promoted the study where regulations allowed.

Chapter 3 Results

Trial recruitment

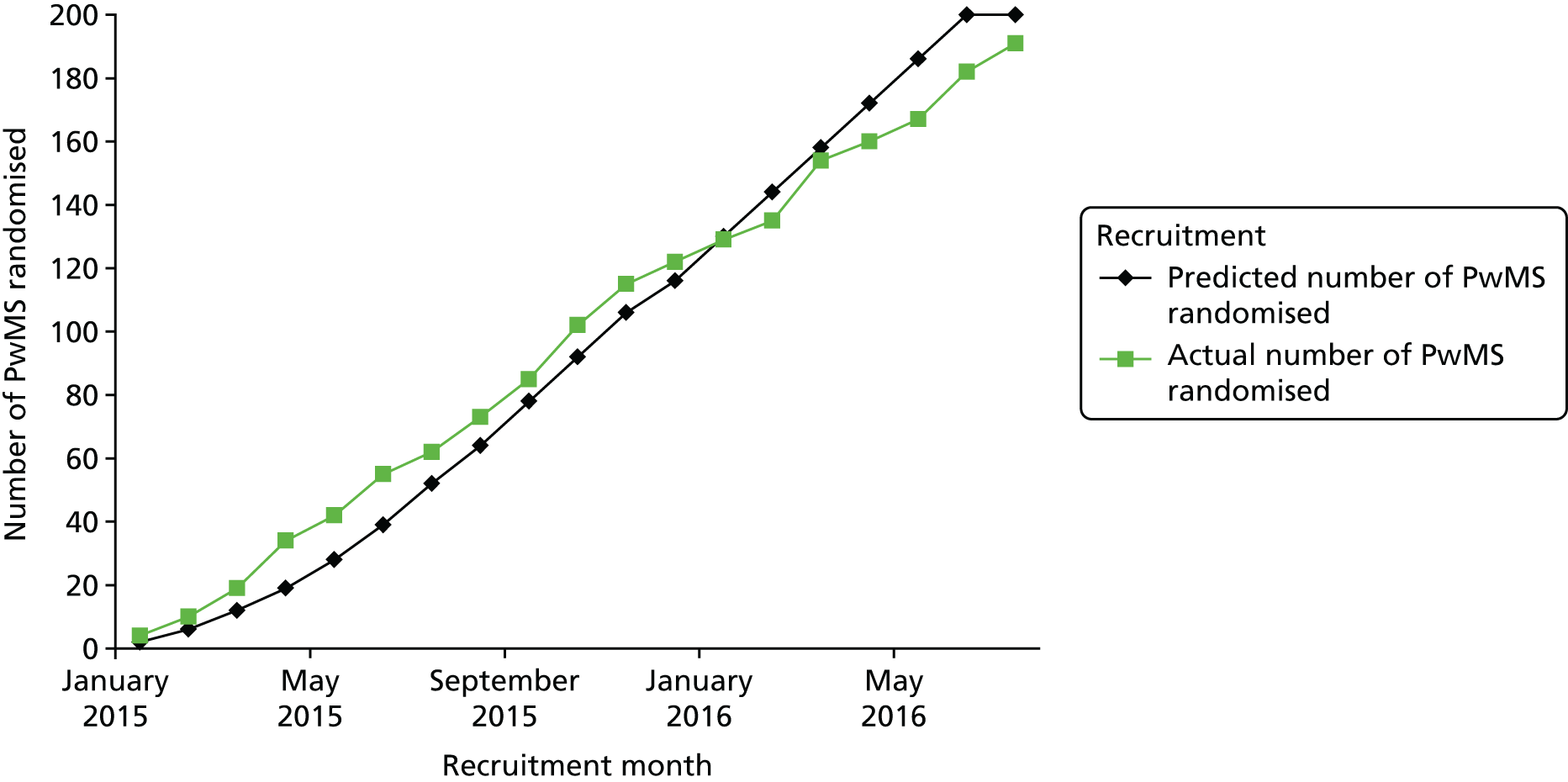

Recruitment overall was considered very successful; Figure 2 shows how well the actual recruitment met the expected monthly targets over the 18 months of active recruitment. The trial oversight committees agreed to stop recruitment on time at 191 participants after reviewing attrition information. Twelve sites recruited participants from 22 January 2015 to 19 July 2016 and each site recruited between 9 and 26 participants (see Appendix 3).

FIGURE 2.

Predicted recruitment vs. actual recruitment.

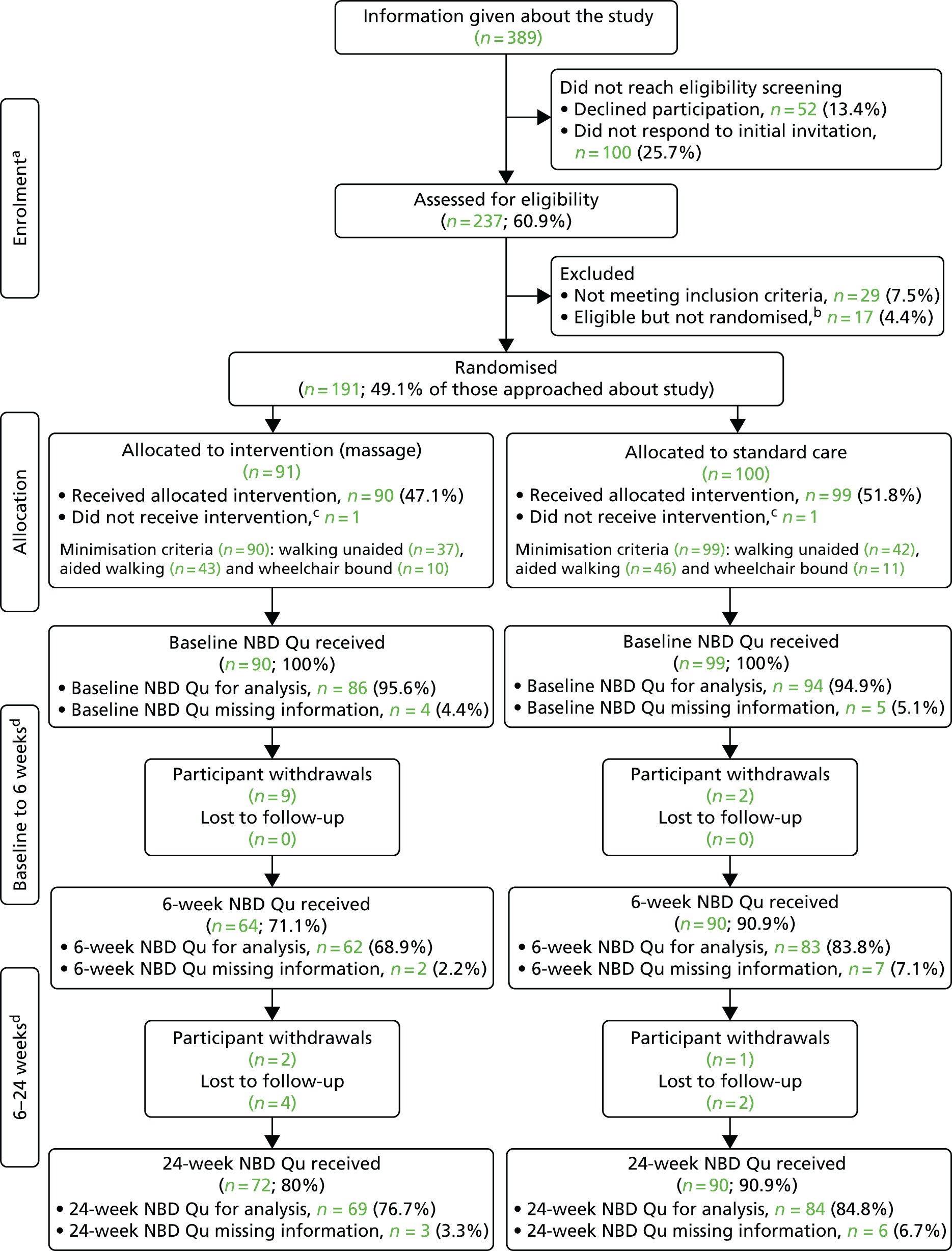

The CONSORT flow diagram (Figure 3) shows the movement of participants through the AMBER trial. There were 237 PwMS and possible bowel problems screened (≈61% of the 389 PwMS approached by the research staff) and 191 PwMS (81% of those screened; 49% of those approached) were randomised. The near 50% uptake on those approached versus those randomised was in accordance with the estimate of uptake stated in the protocol.

FIGURE 3.

The CONSORT flow diagram. Qu, questionnaire. a, In the enrolment and screening information, all percentages are calculated from the number of people approached about the study (n = 389); b, reasons for those who were eligible but did not take part vary from a patient’s personal circumstances changing to baseline appointments being made for a patient but he/she not attending; c, in each group, one participant was randomised and subsequently deemed ineligible for the trial when eligibility was reassessed. No data were collected for these two participants; and d, these sections show the breakdown for the primary outcome measure (NBDS) at each stage of data collection: baseline, week 6 and week 24. All percentages calculated are from n = 90 (intervention group) and n = 99 (control group).

Of the randomised participants, 22 did not complete the study. Two of these were post-randomisation exclusions (essentially randomised in error) and data were not collected from these two participants. Thus, the analysis was based on 189 participants: 90 in the intervention group (abdominal massage plus advice on optimised bowel care) and 99 in the control group (only advice on optimised bowel care). The inequality in the number of participants per group was attributable to minimisation at site level.

For the 20 correctly randomised participants (intervention group, n = 15; control group, n = 5) who did not complete the study, baseline data were successfully collected and all participants agreed that their existing data could be used. Participants either withdrew (intervention group, n = 11; control group, n = 3) or were lost to follow-up (intervention group, n = 4; control group, n = 2). In some instances, if the data were not returned, then the week-6 and week-24 follow-up data collection was completed by the researcher during a telephone call. This explains the differing numbers for the NBDS in the CONSORT flow diagram at weeks 6 and 24 in relation to reported withdrawals or loss to follow-up.

Quality of participant-completed outcome data

Participant-completed outcomes were returned by post at weeks 6 and 24. Questionnaire and bowel diary data were checked for completeness and every effort was made to collect any missing information when acceptable to do so.

The CONSORT flow diagram (see Figure 3) shows the numbers available for the primary outcome analysis at baseline and weeks 6 and 24 (NBDS). During monitoring of the study attrition rates and primary and secondary outcome data received, it was evident that some participants were stating that they had returned their outcome measures by post but these were not received in the AMBER trial office. Thus, in order to maximise our available primary outcome data for analysis, from 22 March 2016 onwards, the research staff at each site completed the NBDS (10 questions) during the telephone call at week 24. This increased our available data for primary outcome analyses at 24 weeks, compared with 6 weeks, in both study groups (intervention group, 76.7%; control group, 84.8%).

There was a greater number of withdrawals/losses to follow-up in the intervention group (15/90) than in the control group (5/99).

For all outcome data, the numbers available for analysis and any reasons for missing data will be reported when discussing each outcome below.

Reasons for withdrawal/losses to follow-up

There were two randomisation failures and 20 participants who withdrew and were lost to follow-up (n = 14 intervention group, n = 16 control group; none withdrew consent for use of existing data). We have undertaken an analysis of the missing data (see Appendix 4) and it would seem that they do not suggest any major biases in the primary analysis. The reasons for withdrawal in the intervention group were varied and included change in diagnosis of MS, family circumstances, worsening of condition and too much paperwork. There is also the possibility that those in the control group remained in the study so that they would receive the training in the abdominal massage and had not yet experienced the potential disappointment of the intervention not working for them, which might increase the likelihood of withdrawing from the study. Interestingly, of those who took part in the interview study, none withdrew or were lost to follow-up, which may indicate that this was a more motivated group or that taking part in the interviews facilitated retention.

Missing primary outcome data

The missingness of the primary outcome data appeared to be relatively unrelated to baseline characteristics, apart from the following: trial group (more missing data in the intervention group), more missing data in those not wheelchair bound, slightly more missing data for women and for younger participants, and more missing data in some centres (see Appendix 4 and Chapter 6 for possible reasons for all of the above). However, using the characteristics at baseline to impute missing data, MI was carried out for the primary outcome and the primary analysis was repeated as a sensitivity analysis. This approach assumes that data are missing at random; this is discussed further in Chapter 6.

Baseline data

The mean age of participants was 53 years (SD 10.4 years) and 81% (154/189) were female. Mean time since diagnosis of MS was 14.3 years (SD 9.1 years). Baseline demographics and clinical data are summarised in Table 2. Demographics and symptom characteristics of the two groups were comparable at baseline.

| Characteristic | Trial group | |

|---|---|---|

| Intervention (N = 90) | Control (N = 99) | |

| Clinical characteristics | ||

| Minimisation variable: walking aids, n (%) | ||

| Walking unaided | 37 (41.1) | 42 (42.4) |

| Aided walking | 43 (47.8) | 46 (46.5) |

| Wheelchair bound | 10 (11.1) | 11 (11.1) |

| Age (years), mean (SD) | 53.5 (11.32) | 51.3 (10.32) |

| Sex, n (%) | ||

| Male | 14 (15.6) | 21 (21.2) |

| Female | 76 (84.4) | 78 (78.8) |

| BMI (kg/m2), mean (SD) | 27.4 (6.207) | 26.22 (5.525) |

| Time since diagnosis of MS (years), mean (SD) | 14.8 (9.76) | 13.9 (8.64) |

| Type of MS, n (%) | ||

| Benign | 0 (0.0) | 2 (2.0) |

| Relapsing–remitting | 45 (50.0) | 61 (61.6) |

| Secondary progressive | 36 (40.0) | 23 (23.2) |

| Primary progressive | 9 (10.0) | 13 (13.1) |

| Severity of symptoms, n (%) | ||

| Cognitive | ||

| None | 39 (43.3) | 35 (35.4) |

| Moderate | 50 (55.5) | 61 (62.6) |

| Severe | 1 (1.1) | 3 (3.0) |

| Pain | ||

| None | 41 (46.6) | 46 (46.5) |

| Moderate | 43 (47.8) | 52 (52.5) |

| Severe | 6 (7.6) | 1 (1.0) |

| Spasm | ||

| None | 33 (36.7) | 31 (31.3) |

| Moderate | 58 (64.4) | 63 (64.7) |

| Severe | 17 (12.2) | 11 (11.1) |

| Depression | ||

| None | 41 (45.6) | 52 (52.5) |

| Moderate | 45 (50.0) | 42 (43.5) |

| Severe | 4 (4.4) | 4 (4.0) |

| Fatigue | ||

| None | 8 (8.9) | 5 (5.1) |

| Moderate | 58 (64.5) | 68 (68.7) |

| Severe | 24 (26.7) | 26 (26.3) |

| Bladder | ||

| None | 12 (13.3) | 15 (15.2) |

| Moderate | 57 (63.4) | 59 (59.6) |

| Severe | 29 (32.2) | 29 (29.3) |

Bowel symptoms

To be eligible to participate in the trial, participants had to be ‘bothered’ by their constipation. Bowel symptoms had commenced > 10 years ago in 37% of participants and < 1 year ago in 4% of participants. The main bowel symptoms reported by participants at baseline were a feeling of incomplete emptying, straining to pass stool and bloating (Table 3).

| Bowel symptoms | Trial group | |

|---|---|---|

| Intervention (N = 90) | Control (N = 99) | |

| Pain: yes, n (%) | 59 (65.6) | 60 (60.6) |

| Bloating: yes, n (%) | 76 (84.4) | 86 (86.9) |

| Faecal incontinence: yes, n (%) | 39 (43.0) | 60 (60.6) |

| Successful opening of bowels 2–4 times a week, n (%) | 59 (65.6) | 53 (53.5) |

| Type of stool (Bristol stool chart) over the last week (%) | ||

| Types 1 and 2 | 21.8 | 19.4 |

| Types 3 and 4 | 20.2 | 23.6 |

| Types 5, 6 and 7 | 16.1 | 14.6 |

| No stool | 39.8 | 38.8 |

| Missing | 2.3 | 2.4 |

| Constipated (no stool + types 1 and 2) | 61.6 | 58.2 |

| Straining to pass stool: yes, ≥ 25% of the time, n (%) | 80 (88.9) | 74 (74.8) |

| Digital stimulation: yes, ≥ 25% of the time, n (%) | 28 (31.1) | 29 (29.3) |

| Feeling of incomplete emptying: yes, ≥ 25% of the time, n (%) | 83 (92.8) | 94 (94.9) |

Primary analyses

The primary analysis is the comparison between treatment groups (bowel massage vs. no massage) at the final visit (24 weeks), adjusted for site and minimisation variable level of mobility (walking unaided, walking aided, or wheelchair bound), as well as baseline measure of the outcome and sex.

Primary outcome measure

Neurogenic Bowel Dysfunction Score

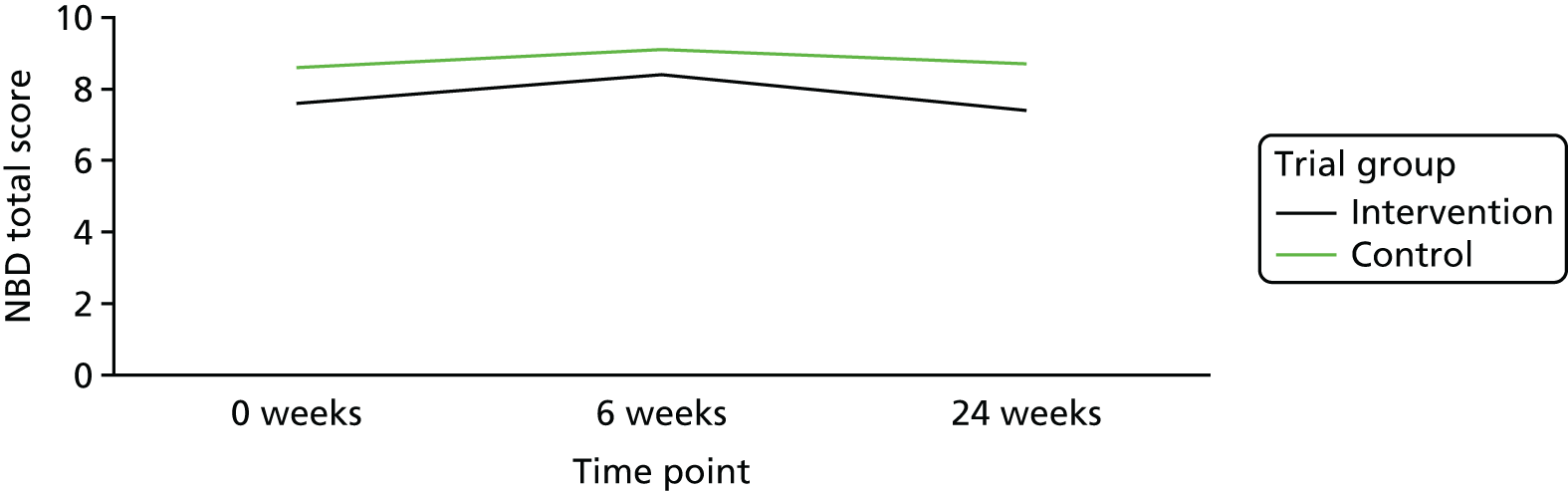

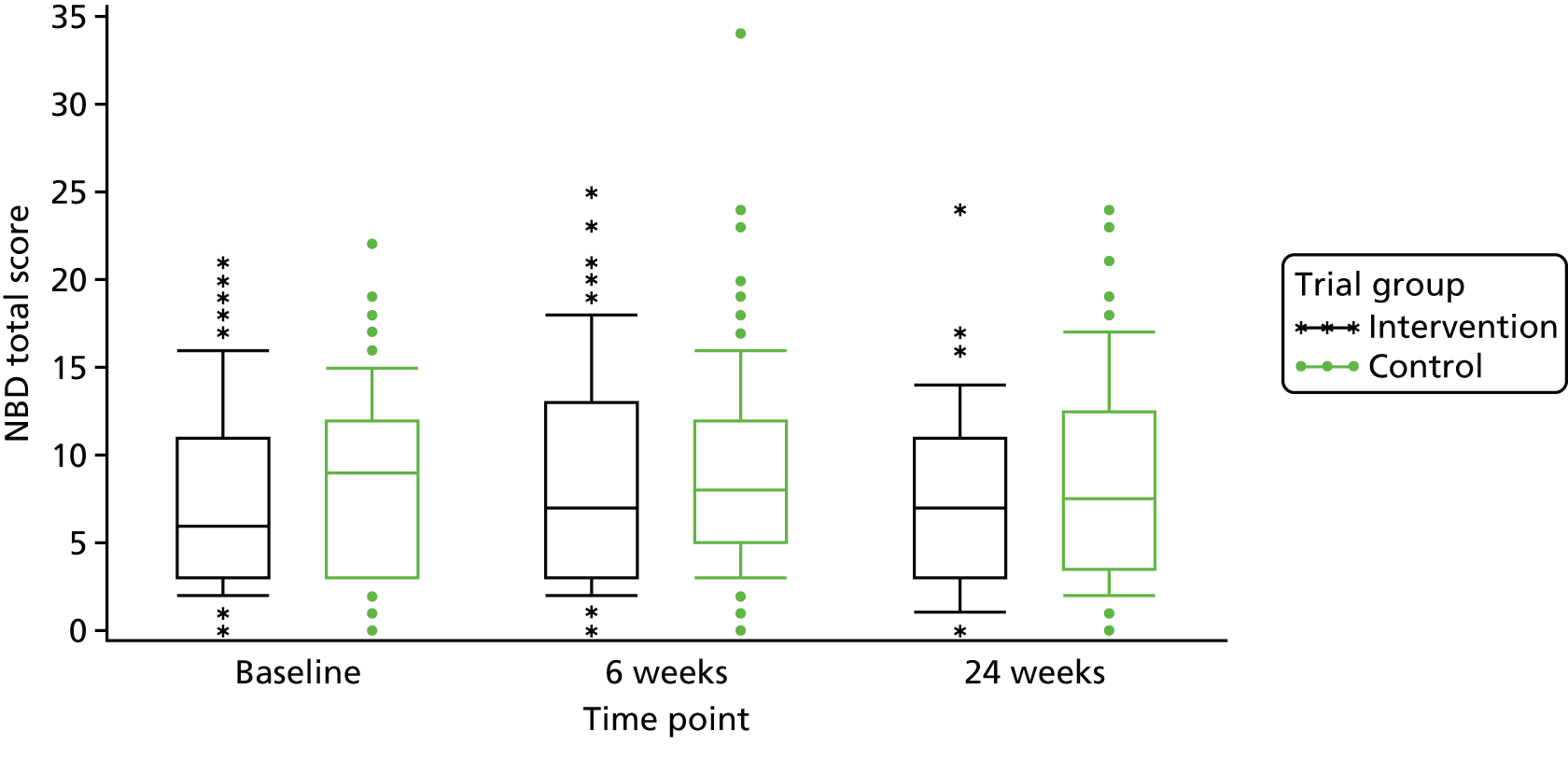

At baseline, the mean score for the intervention group was 7.6 points (SD 5.31 points) and the median was 6.0 points (range 0–21 points). For the control group at baseline, the mean NBDS was 8.6 points (SD 5.08 points) and the median was 9.0 points (range 0–22 points) (Table 4). These scores indicate that the NBD symptoms were having a minor impact on most participants. Scores of 7–11 points indicate minor impact and scores of ≥ 14 points indicate severe impact. The mean NBDS at week 24 was 7.4 points (SD 5.23 points) and the median was 7.0 points (range 0–24 points) for the intervention group; the mean NBDS was 8.7 points (SD 5.70 points) and the median was 7.5 points (range 0–24 points) for the control group at week 24. The mean adjusted difference in change between randomised groups from baseline to week 24 was not statistically significantly different [mean difference between groups (intervention – control): –1.6, 95% confidence interval (CI) –3.32 to 0.04; p = 0.0558; Table 5]. Figures 4 and 5 visually show the change over time within the two groups.

| Score | Trial group | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intervention (N = 90) | Control (N = 99) | ||||||||

| Mean (SD) | n | Median (range) | Mean (SD) | n | Median (range) | ||||

| Primary outcome measure – symptom severity | |||||||||

| NBD score (points)a | |||||||||

| Baseline | 7.6 (5.3) | 86 | 6 (0–21) | 8.6 (5.1) | 94 | 9 (0–22) | |||

| Week 6 | 8.4 (6.2) | 62 | 7 (0–25) | 9.1 (5.7) | 83 | 8 (0–34) | |||

| Week 24 | 7.4 (5.2) | 69 | 7 (0–24) | 8.7 (5.7) | 84 | 7.5 (0–24) | |||

| Secondary outcome measure – symptom severity | |||||||||

| Constipation score (points)b | |||||||||

| Baseline | 11.7 (4.1) | 88 | 12 (1–25) | 11.5 (3.8) | 97 | 11 (3–21) | |||

| Week 6 | 10.6 (4.3) | 58 | 11 (1–22) | 10.8 (4.0) | 83 | 11 (1–22) | |||

| Week 24 | 10.1 (4.1) | 57 | 10 (2–22) | 11.1 (3.9) | 81 | 11 (3–27) | |||

| Bowel diary data | |||||||||

| Time spent on toilet (minutes per week) | |||||||||

| Baseline | 75.6 (69.6) | 80 | 57.5 (3–330) | 75.8 (74.4) | 87 | 55.0 (3–370) | |||

| Week 6 | 77.9 (73.3) | 66 | 55.0 (5–315) | 85.0 (88.5) | 85 | 50.0 (2–400) | |||

| Week 24 | 78.2 (92.4) | 53 | 45.0 (3–550) | 77.0 (68.5) | 78 | 56.5 (1–295) | |||

| Number of attempts per week to empty the bowels | |||||||||

| Baseline | 10.4 (6.7) | 86 | 9 (0–35) | 8.6 (5.2) | 91 | 8 (0–32) | |||

| Week 6 | 11.3 (7.1) | 65 | 9 (2–32) | 8.9 (6.0) | 88 | 8 (1–32) | |||

| Week 24 | 10.7 (7.2) | 53 | 10 (1–43) | 8.3 (5.1) | 77 | 7 (1–23) | |||

| Number of stools passed per week | |||||||||

| Baseline | 3.9 (1.7) | 88 | 4.0 (0–7) | 4.0 (1.7) | 98 | 4 (0–7) | |||

| Week 6 | 4.3 (1.9) | 68 | 4.5 (1–7) | 3.9 (1.8) | 89 | 3 (0–7) | |||

| Week 24 | 4.3 (1.9) | 57 | 4.0 (0–7) | 3.9 (1.9) | 81 | 4 (0–7) | |||

| Bladder symptom severity | |||||||||

| SF-Qualiveen total bladder scorec | |||||||||

| Baseline | 1.8 (1.10) | 90 | 1.8 (0–4) | 2.0 (1.20) | 99 | 1.8 (0–4) | |||

| Week 6 | 1.7 (1.13) | 61 | 1.6 (0–4) | 2.1 (1.15) | 85 | 2.1 (0–4) | |||

| Week 24 | 1.7 (1.10) | 57 | 1.8 (0–4) | 2.1 (1.12) | 81 | 2.0 (0–4) | |||

| QoL | |||||||||

| EQ-5D-5L VAS scored (maximum score of 100) | |||||||||

| Baseline | 60.6 (21.1) | 89 | 60 (3–100) | 55.7 (20.6) | 98 | 60 (3–100) | |||

| Week 6 | 59.4 (24.0) | 59 | 65 (5–97) | 55.4 (20.8) | 86 | 60 (5–100) | |||

| Week 24 | 59.8 (22.6) | 58 | 62.5 (10–95) | 51.3 (20.3) | 83 | 50 (10–90) | |||

| EQ-5D-5L health index scoree (maximum score of 1) | |||||||||

| Baseline | 0.50 (0.25) | 95 | 0.6 (–0–1) | 0.50 (0.28) | 99 | 0.6 (–0–1) | |||

| Week 6 | 0.50 (0.29) | 60 | 0.6 (–0–1) | 0.50 (0.27) | 84 | 0.5 (–0–1) | |||

| Week 24 | 0.50 (0.28) | 58 | 0.6 (–0–1) | 0.50 (0.28) | 83 | 0.5 (–0–1) | |||

| New QoL measure for validation (NBIS) | |||||||||

| NBISf (total score maximum of 52) | |||||||||

| Baseline | 20.2 (8.5) | 86 | 20 (6–41) | 20.8 (7.4) | 98 | 21 (5–38) | |||

| Week 6 | 19.9 (8.2) | 56 | 19 (5–42) | 21.4 (7.0) | 82 | 21 (3–42) | |||

| Week 24 | 19.0 (8.4) | 56 | 18 (5–50) | 20.9 (7.4) | 77 | 21 (1–40) | |||

| NBIS QoL (maximum score of 24) | |||||||||

| Baseline | 9.6 (5.1) | 88 | 9 (0–22) | 10.7 (4.7) | 99 | 11 (1–22) | |||

| Week 6 | 9.9 (4.9) | 56 | 10 (0–21) | 10.7 (4.3) | 83 | 11 (1–23) | |||

| Week 24 | 9.2 (4.8) | 58 | 8.5 (2–23) | 10.7 (4.7) | 80 | 11 (0–24) | |||

| NBIS faecal incontinence score (maximum score of 12) | |||||||||

| Baseline | 3.7 (2.4) | 90 | 3 (0–10) | 3.7 (2.0) | 99 | 3 (0–9) | |||

| Week 6 | 3.6 (2.3) | 61 | 3 (0–9) | 4.1 (2.1) | 87 | 4 (0–11) | |||

| Week 24 | 3.8 (2.5) | 57 | 4 (0–12) | 4.1 (1.8) | 82 | 4 (0–9) | |||

| NBIS symptom score (maximum score of 16) | |||||||||

| Baseline | 6.9 (2.9) | 88 | 7 (0–16) | 6.4 (3.1) | 98 | 6 (1–13) | |||

| Week 6 | 6.4 (3.2) | 60 | 6 (1–14) | 6.6 (2.5) | 84 | 6 (1–14) | |||

| Week 24 | 6.0 (2.8) | 57 | 6 (1–15) | 6.2 (2.8) | 80 | 6 (0–14) | |||

| Time point | Trial group | Mean difference in change between groups (intervention–control), mixed models | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intervention (N = 90) | Control (N = 99) | |||||

| n | Mean change (95% CI) | n | Mean change (95% CI) | Adjusteda (95% CI) | p-value | |

| Baseline to week 6 | 61 | 0.6 (–0.73 to 1.98) | 80 | 0.9 (–0.5 to 2.22) | –0.58 (–2.38 to 1.22) | 0.5236 |

| Baseline to week 24 | 66 | –0.6 (–2.11 to 0.93) | 80 | 0.5 (–0.78 to 1.83) | –1.64 (–3.32 to 0.04) | 0.0558 |

FIGURE 4.

Change in NBDS over time.

FIGURE 5.

Box-and-whisker plot for NBDS.

Secondary outcomes

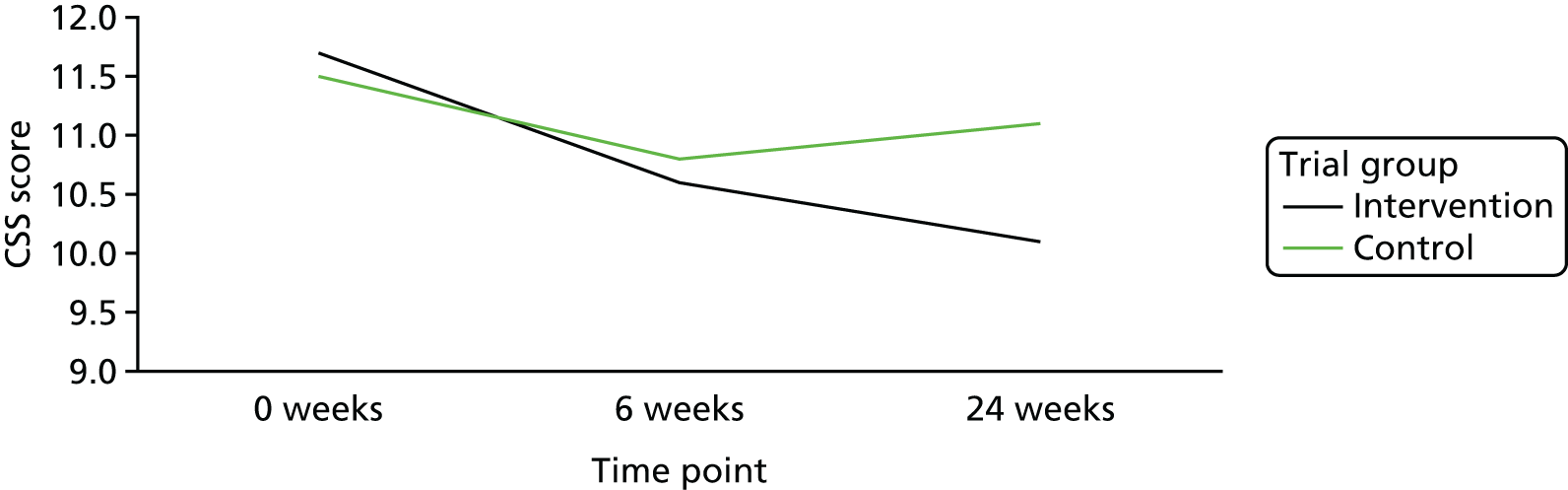

Constipation Scoring System

At baseline, the intervention group had a mean CSS score of 11.7 points (SD 4.05 points), and the control group had a mean CSS score of 11.5 points (SD 3.77 points). At week 24, the intervention group had a mean CSS score of 10.1 points (SD 4.10 points), and the control group had a mean CSS score of 11.1 points (SD 3.91 points). Figure 6 is a line graph showing the change over time in the two groups. There was no significant mean difference between the groups in change in the total CSS score between baseline and either time point (Table 6).

FIGURE 6.

Change in total CSS score over time.

| Time point | Trial group | Mean difference in change between groups, mixed models | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intervention (N = 90) | Control (N = 99) | |||||

| n | Mean change (95% CI) | n | Mean change (95% CI) | Adjusteda (95% CI) | p-value | |

| Baseline to week 6 | 57 | –1.2 (–2.11 to –0.33) | 82 | –0.3 (–1.05 to 0.48) | –0.89 (–2.03 to 0.26) | 0.1273 |

| Baseline to week 24 | 56 | –1.1 (–2.15 to –0.1) | 81 | –0.3 (–1.08 to 0.45) | –0.88 (–2.03 to 0.27) | 0.1308 |

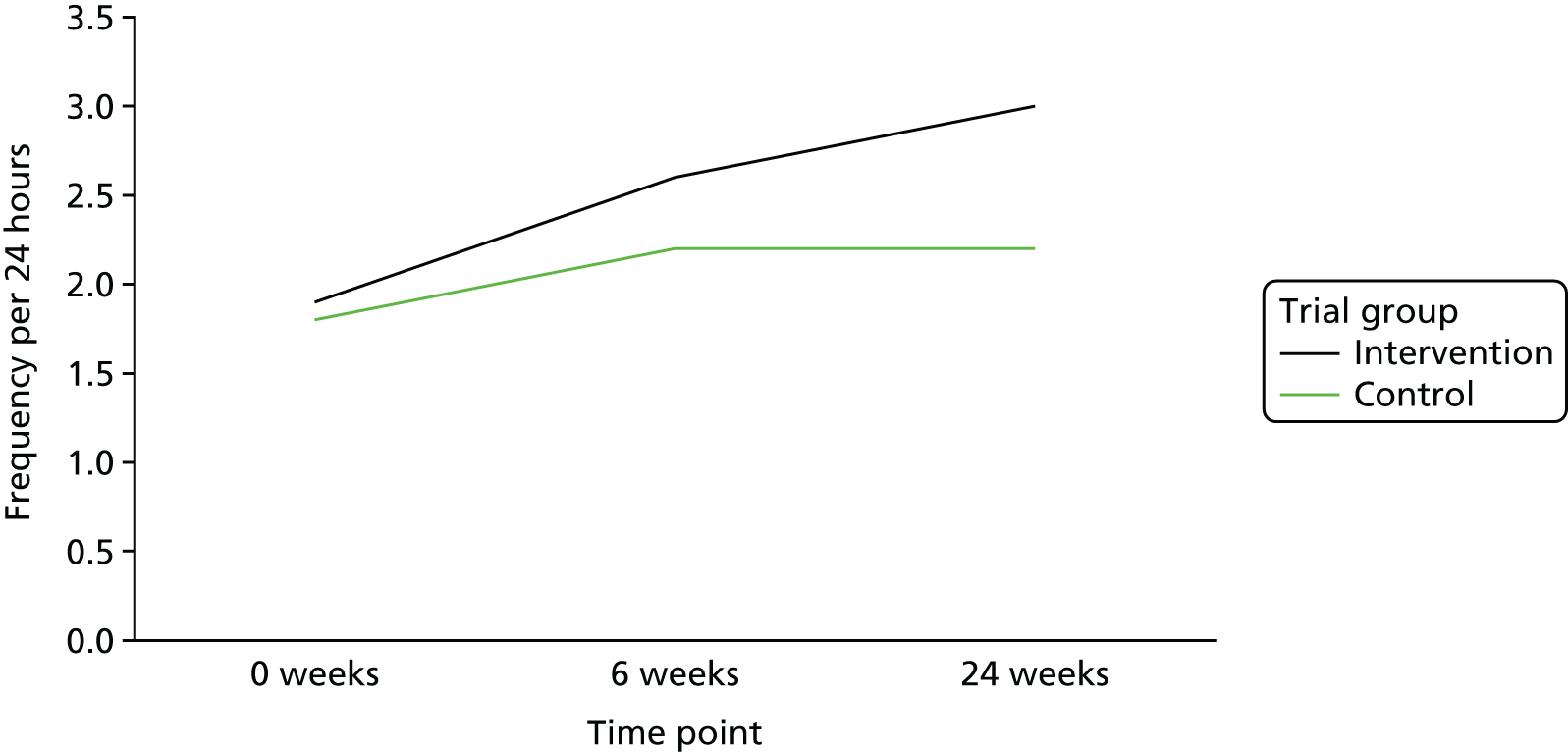

Short Form Qualiveen Bladder Questionnaire

At baseline, both groups demonstrated moderate effects of bladder dysfunction on their overall quality of life with a total SF-Qualiveen score in the intervention group of 1.8 points (SD 1.10 points) and the control group of 2.0 points (SD 1.20 points). The results in all four domains of the SF-Qualiveen, that is (1) bother with limitations, (2) frequency of limitations, (3) fears and (4) feelings related to urinary problems, were also similar in both groups There were no significant differences between groups in the change from baseline to weeks 6 or 24 in the SF-Qualiveen score (Table 7).

| Time point | Trial group | Mean difference in change between groups, mixed models | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intervention (N = 90) | Control (N = 99) | |||||

| n | Mean change (95% CI) | n | Mean change (95% CI) | Adjusteda (95% CI) | p-value | |

| Baseline to week 6 | 61 | 0.8 (–0.74 to 2.38) | 85 | 1.4 (0.26 to 2.48) | –1.09 (–2.89 to 0.70) | 0.2306 |

| Baseline to week 24 | 57 | 0.6 (–1.2 to 2.43) | 81 | 0.5 (–0.89 to 1.96) | –0.58 (–2.74 to 1.58) | 0.5968 |

EuroQol-5 Dimensions, five-level version: quality-of-life outcomes

All the results of the EQ-5D-5L are summarised in Chapter 4.

Neurogenic bowel dysfunction patient-reported outcome measure

There were no significant changes in any of the outcomes from the NBIS. All results are summarised in Table 8.

| NBIS | Trial group | Mean difference in change between groups, mixed models | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intervention (N = 90) | Control (N = 99) | |||||

| n | Mean change (95% CI) | n | Mean change (95% CI) | Adjusteda (95% CI) | p-value | |

| Total score | ||||||

| Week 6 | 53 | 0.3 (–1.34 to 1.9) | 82 | 1.0 (–0.8 to 2.01) | –1.04 (–2.72 to 0.64) | 0.2216 |

| Week 24 | 53 | –0.8 (–2.62 to 1.04) | 77 | 0.3 (–0.85 to 1.47) | –1.46 (–3.43 to 0.52) | 0.1468 |

| Quality-of-life score | ||||||

| Week 6 | 54 | 0.6 (–0.21 to 1.47) | 83 | 0.4 (–0.22 to 1.01) | 0.04 (–0.93 to 1.01) | 0.9387 |

| Week 24 | 56 | –0.2 (–1.17 to 0.81) | 80 | 0.3 (–0.45 to 0.97) | –0.70 (–1.82 to 0.43) | 0.2239 |

| Faecal incontinence score | ||||||

| Week 6 | 61 | 0.0 (–0.51 to 0.48) | 87 | 0.3 (–0.03 to 0.68) | –0.49 (–1.03 to 0.05) | 0.0768 |

| Week 24 | 57 | –0.1 (–0.69 to 0.52) | 82 | 0.4 (–0.05 to 0.78) | –0.39 (–1.01 to 0.23) | 0.2117 |

| Symptom score | ||||||

| Week 6 | 59 | –0.2 (–0.89 to 0.45) | 84 | 0.2 (–0.2 to 0.68) | –0.42 (–1.12 to 0.29) | 0.2469 |

| Week 24 | 56 | –0.4 (–1.04 to 0.22) | 80 | –0.2 (–0.66 to 0.31) | –0.26 (–0.97 to 0.46) | 0.4779 |

Bowel diary data

Within the statistical analysis plan (SAP), we identified the most important data to be analysed in the bowel diary. These were the number of days passing stools, time spent on the toilet and percentage of normal stools.

Each participant was required to complete 8 weeks of bowel diaries (at baseline, weeks 1–6 and week 24). Overall, these were well completed and compliance was high. For example, frequency of passing of stool was completed by 88 out of 90 (97.7%) participants and 98 out of 99 (98.9%) participants at baseline; by 68 out of 90 (75.5%) and 89 out of 99 (89.8%) participants at 6 weeks; and by 57 out of 90 (63%) and 81 out of 99 (81%) participants at week 24 for the intervention and control groups, respectively.

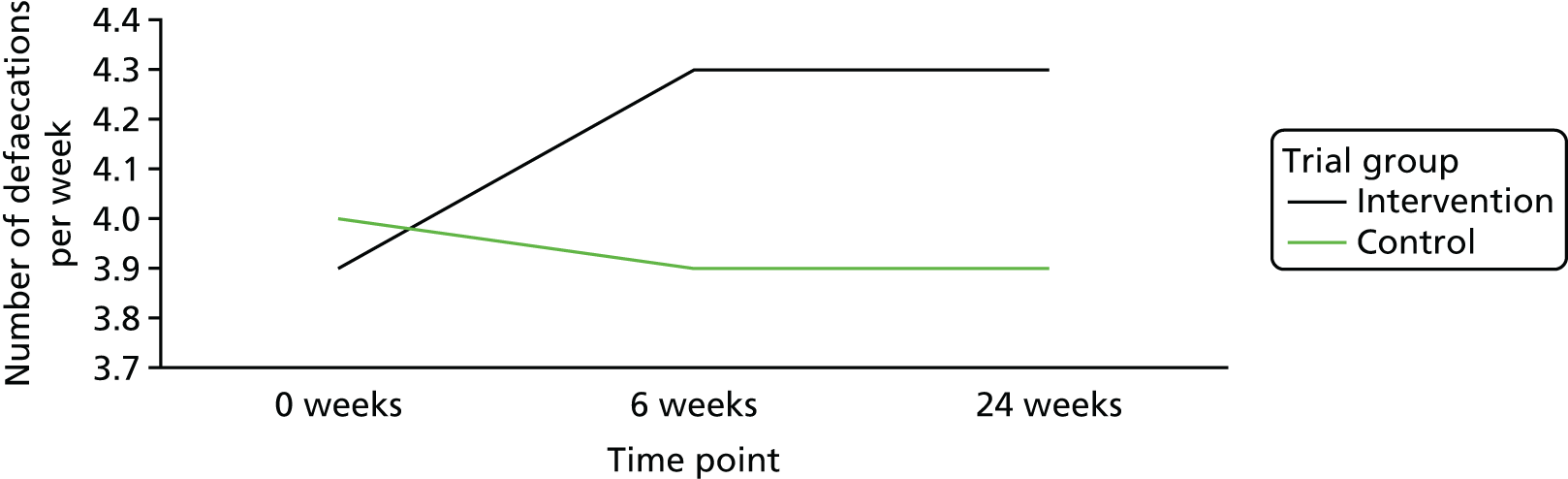

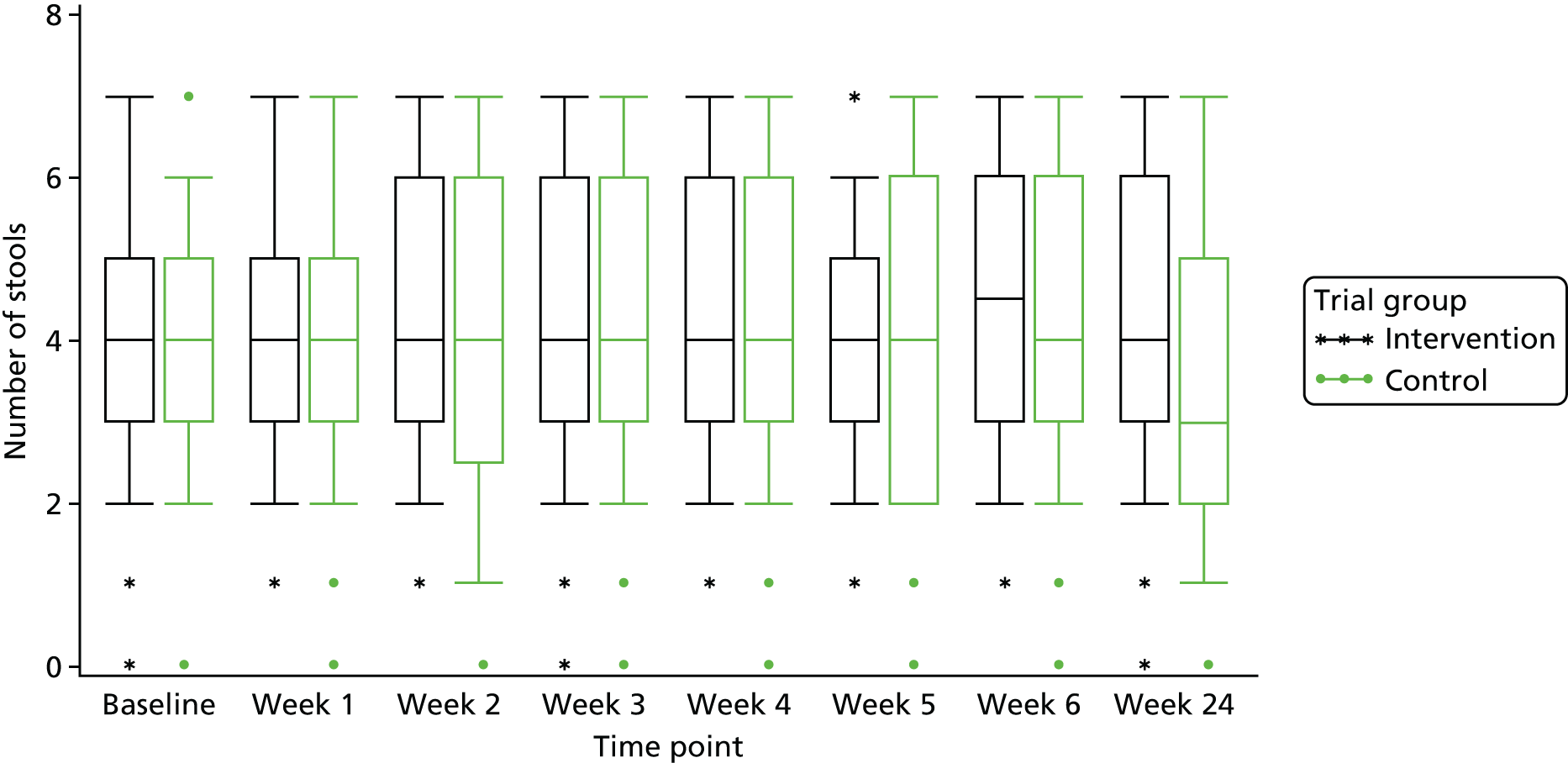

Stools passed per week

The mean frequency of stools passed per week at baseline was 3.9 (SD 1.68 stools passed per week) in the intervention group and 4.0 (SD 1.74 stools passed per week) in the control group. At week 6, this increased to 4.3 stools passed per week (SD 1.87) in the intervention group and decreased to 3.9 stools passed per week (SD 1.81) in the control group; at week 24, there was no change from week 6 in either group [i.e. mean frequency of stools passed per week was 4.3 (SD 1.88) in the intervention group and 3.9 (SD 1.89) in the control group]. Figure 7 is a line graph visually showing the change over time within the two groups.

FIGURE 7.

Change in the mean number of stools passed per week.

There was a statistically significant difference between trial groups in the change in number of stools passed from baseline to week 24 (Table 9). The difference between the trial groups was 0.62 (95% CI 0.03 to 1.21; p = 0.039). As there was some inconsistency in completion of the diaries, the analyses of change values were derived from a combination of two questions [(1) how often did you pass a stool? and (2) type of stool] to give one answer on frequency. If one or the other question was answered, this was taken as having passed a stool; if neither question was answered, this was taken as no stool passed. Figure 8 highlights very little change in the first 5 weeks.

| Time point | Trial group | Mean difference in change between groups, mixed models | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intervention (N = 90) | Control (N = 99) | |||||

| n | Mean change (95% CI) | n | Mean change (95% CI) | Adjusteda (95% CI) | p-value | |

| Stools passed per week (adjusted to combine number and type of stool if data inconsistent) | ||||||

| Baseline to week 6 | 67 | 0.4 (0.07 to 0.68) | 88 | 0.0 (–0.34 to 0.39) | 0.38 (–0.08 to 0.85) | 0.1036 |

| Baseline to week 24 | 56 | 0.1 (–0.34 to 0.51) | 80 | –0.5 (–0.88 to 0.02) | 0.62 (0.03 to 1.21) | 0.039 |

FIGURE 8.

Box-and-whisker plot of number of stools passed per week.

Time spent on the toilet

At baseline, those in the intervention group spent a mean of 75.6 minutes (SD 69.60 minutes) per week on the toilet and those in the control group spent a mean of 75.8 minutes (SD 74.36 minutes) per week on the toilet. At week 6, this time was 77.9 minutes (SD 73.26 minutes) per week for the intervention group and 85.0 minutes (SD 88.52 minutes) per week for the control group. At week 24, these times were 78.2 minutes (SD 92.43 minutes) and 77.0 minutes (SD 68.51 minutes) per week for the intervention and control groups, respectively. There was no statistically significant difference between groups in the mean change in time spent going to the toilet between baseline and either time point (Table 10).

| Time point | Trial group | Mean difference in change between groups, mixed models | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intervention (N = 90) | Control (N = 99) | |||||

| n | Mean change from baseline (95% CI) | n | Mean change from baseline (95% CI) | Adjusteda (95% CI) | p-value | |

| Time spent on the toilet (minutes per week) | ||||||

| Baseline to week 6 | 60 | –0.7 (–15.7 to 14.39) | 80 | 9.8 (–5.28 to 24.95) | –7.92 (–29.0 to 13.17) | 0.4588 |

| Baseline to week 24 | 50 | –6.5 (–21.86 to 8.78) | 71 | –3.8 (–19.71 to 12.17) | –3.35 (–23.1 to 16.4) | 0.7377 |

Type of stool

For each stool passed, participants were asked to indicate the type of the stool, as per the Bristol stool chart. 33 Using types 3 and 4 as normal, and types 1 and 2 and no stool per week as constipated, there was a reduction in the percentage of participants who were constipated in the intervention group (from 61.6% at baseline to 55.4% at week 24) and in the control group (from 59.0% to 58.9% at week 24). The percentage passing normal stools (types 3 and 4) was 20.2% in the intervention group and 17.5% in the control group at baseline; at week 24 this percentage was 23.9% in the intervention group and 22.8% in the control group (see Appendix 5).

Medications used in the AMBER trial for bowel management (information from medication form)

At baseline, 67 (74%) participants in the intervention group and 80 (80%) participants in the control group were on at least one medication, with numbers of medications ranging from 1 to 35. The number of participants on medication for management of their bowel symptoms was 44 (i.e. 44/67; 66%) in the intervention group and 54 (i.e. 54/80; 68%) in the control group. Laxido Orange (Almac Pharma Services Ltd, Craigavon, UK), Movicol (Norgrine Ltd, Hengoed, UK) and docusate sodium appeared to be the most popular medications used in both groups, with suppositories being used by approximately only 9% of participants in each group.

At the start of the trial, 44 participants were on zero medications (24 participants in the intervention group and 20 in the control group).

During the course of the study, 32 participants in the intervention group and 44 participants in the control group started new medications, with nearly twice as many new medication entries recorded in the control group compared with the intervention group (69 vs. 135). Thirteen participants in the intervention group had taken at least one additional medication for bowel management, with 19 different entries recorded in total (e.g. one participant had five entries for four different laxatives). In the control group, 12 participants started new medications for their bowels, with 33 different entries (several participants reported three or four additional bowel medications; one had 12 entries, eight for different bowel medications and four for glycerine suppositories).

At the end of the study, 15 participants in the intervention group (18 entries in total) and 13 participants in the control group (35 entries) had stopped taking some of their bowel management medications. There were still 38 participants who were not on any form of medication (intervention group, n = 20; control group, n = 18) at the end of the study.

Anorectal physiology and transit test results

University College Hospital, London, was the only site in the AMBER trial to recruit participants to a pilot substudy, to determine if any information about the mechanism of action of abdominal massage could be gleaned through anorectal physiology and colonic transit tests, which are routinely undertaken at this site. Participants had a test at baseline and a repeat test at week 24. All participants from UCH took part in the substudy.

A total of 26 participants were randomised at UCH; however, two post-randomisation exclusions occurred. All baseline outcomes for the main study were completed by 24 participants. Of these, 23 participants underwent baseline transit tests; the 23 participants comprised two male (8.7%) and 21 female (91.3%) participants, 11 from the intervention group and 12 from the control group, with a mean age of 53.5 years (SD 12.59 years). There were no baseline transit test data for one of the 24 participants. Three participants withdrew from the study during the 6 weeks of intervention and a further participant was lost to follow-up (could not be contacted for the week-24 follow-up and did not return any patient-reported outcomes). A further eight participants withdrew from having the repeat tests at week 24, leaving 12 participants with week-24 transit and physiology results. One of these participants had no baseline transit data; thus, 11 sets of baseline and week 24 transit test data were available for analysis.

There was no difference between the groups with respect to changes in the duration of bowel symptoms, faecal incontinence, infrequent emptying, pain or bloating (see Report Supplementary Material 1). The baseline data indicated that 65.2% (15/23) of the participants who underwent the transit test had slow transit, six (54.5%) in the intervention group and nine (75%) in the control group.

Table 11 shows that there was no significant difference in the change in the number of total markers between the groups; although there was a possibility that the groups were not well matched at baseline with a median number of markers of 17 (range 0–54) in the intervention group, while in the control group the median number of markers was 47 (range 0–60). The CI is wide because of the small number of participants. The markers in the rectosigmoid were relatively well matched at baseline, median 10 (range 0–46) in the intervention group and a median 12.5 (range 0–35) in the control group.

| Time point | Trial group | Mean difference in change between groups, mixed models | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intervention | Control | |||||

| n | Mean change from baseline in the number of markers (95% CI) | n | Mean change from baseline in the number of markers (95% CI) | Adjusteda (95% CI) | p-value | |

| 24 weeks | 5 | 13.2 (–20.04 to 46.44) | 6 | –7.8 (–20.29 to 4.63) | 15.7 (–37.69 to 69.01) | 0.4846 |