Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 10/104/25. The contractual start date was in July 2012. The draft report began editorial review in November 2017 and was accepted for publication in July 2018. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Alexander Szubert reports grants from National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) and the Medical Research Council (MRC) during the conduct of the study. Robert Tilley reports personal fees from NIHR Clinical Research Network outside the submitted work. Peter Wilson reports personal fees from 3M Advisory Panel, Roche Drug Safety Monitoring Board and Merck Sharp & Dohme Corp. (MSD; Hoddesdon, UK) outside the submitted work. Achyut Guleri reports receiving fees from Novartis as a member of advisory boards and speaker panels, and consultancy fees from Astellas (Chertsey, UK), AstraZeneca (Cambridge, UK), MSD and Schering-Plough (Hoddesdon, UK); he also received support to attend scientific conferences, including accommodation and travel payments from Becton Dickinson (Winnersh Triangle, UK), Carefusion UK (Winnersh Triangle, UK), Janssen-Cilag (High Wycombe, UK) and MSD. Paul R Chadwick reports non-financial support from Novartis (Frimley, UK), and grants and personal fees from NIHR outside the submitted work. Bernadette Young reports grants from the Wellcome Trust outside the submitted work. M Estee Török reports grants from Academy of Medical Sciences/The Health Foundation, grants from Medical Research Council (MRC), grants from NIHR Cambridge Biomedical Research Centre, grants from MRC/Department of Biotechnology Partnership Grant, and personal fees from Oxford University Press outside the submitted work. Martin J Llewelyn reports personal fees from Pfizer (Walton Oaks, UK) outside the submitted work and is a member of the panel that develops the European Society of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases/Infectious Diseases Society of America clinical practice guideline on Staphylococcus aureus bacteraemia.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2018. This work was produced by Thwaites et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2018 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Introduction

This chapter includes material that has been adapted from the trial protocol published in Thwaites et al. 1 © Thwaites et al. ; licensee BioMed Central Ltd. 2012. This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Background

Staphylococcus aureus bacteraemia is one of the most common and serious bacterial infections worldwide. There were over 12,000 cases of S. aureus bacteraemia in the UK in 2016/17, and around 25% of patients died. 2,3 Current treatment guidelines recommend that S. aureus bacteraemia should be treated with ≥ 14 days of an intravenous (i.v.) beta-lactam antibiotic, or a glycopeptide if the bacterium is meticillin resistant. Combination antimicrobial therapy is generally not recommended, except in severe meticillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) infections (e.g. endocarditis) or in the presence of prosthetic joint infections. 4–7 Most of the recommendations are based on uncontrolled observational studies and clinical experience, and views of how to manage S. aureus bacteraemia differ widely. 8,9

How might adjunctive rifampicin improve outcomes from S. aureus bacteraemia?

Three properties make rifampicin an attractive, if unproven, antibiotic for S. aureus bacteraemia treatment. First, it has good oral bioavailability. 10 Second, it penetrates cells, tissues and biofilms better than beta-lactam and glycopeptide antibiotics (the current mainstays of S. aureus bacteraemia treatment) and, therefore, in combination with these agents, may resolve serious S. aureus infections faster and more effectively. 11 Third, it is cheap: a daily 600 mg dose costs £0.73 by mouth and £7.67 intravenously. 12

The best clinical predictor of complications and death from S. aureus bacteraemia is the persistence of bacteria in blood 48–96 hours after the start of active antimicrobial therapy. 13–15 Persistent bacteraemia (> 48 hours) occurs in around 40% of patients, despite prompt removal of any infected foci and effective antimicrobial therapy,13,14 and increases the patient’s risk of metastatic complications and death nearly fivefold. 13 Why S. aureus persists in blood despite treatment with antibiotics with good in vitro activity is uncertain, but is probably explained by the failure of currently recommended first-line antibiotics (beta-lactams and glycopeptides) to kill the bacteria associated with pus (dead or dying neutrophils), viable cells or biofilms. The well-documented survival of S. aureus within each of these ecological niches may lead to persistent bacterial seeding of the bloodstream and recurrent–recalcitrant infection. In addition, it has been proposed that bloodstream neutrophils may act as ‘Trojan horses’ for S. aureus dissemination, providing bacteria with further protection from first-line antibiotics with poor intracellular activity, such as the recommended beta-lactams and glycopeptides. 16

Rifampicin, clindamycin, the tetracyclines and the fluoroquinolones are all concentrated within cells, but, with the exception of rifampicin, their activity is reduced in the acidic environments found within intracellular phagolysosomes. 17,18 Rifampicin has been repeatedly shown to be highly effective against S. aureus within cells18,19 and against bacteria associated with biofilms and prostheses. 11,20 Beta-lactams and glycopeptides do not pass easily into eukaryotic cells or biofilms, and do not kill S. aureus associated with these niches as effectively as free, extracellular bacteria. 21,22 Data from animal models of severe S. aureus infections have generally shown rifampicin-containing antibiotic combinations to be superior with respect to reduced bacteria counts, sterilisation and cure rates, independent of the model used. 11 Yet, despite the breadth of these experimental findings, the potential advantages of adjunctive rifampicin for the treatment of severe S. aureus infections in humans remain theoretical. There are insufficient data from only 246 patients randomised between rifampicin- and non-rifampicin-containing regimens in controlled trials to confirm or refute a beneficial effect.

What are the potential problems of using adjunctive rifampicin for S. aureus bacteraemia?

There are three important potential problems with using rifampicin for the treatment of S. aureus bacteraemia: the development of rifampicin-resistant bacteria, interactions with other drugs and hepatic toxicity. Resistance can be acquired rapidly when rifampicin is used alone in treatment, resulting from mutations in the drug binding site [the β-subunit of the bacterial deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA)-dependent ribonucleic acid (RNA) polymerase]. Interactions with other drugs are mediated by the ability of rifampicin to increase its metabolism through the potent induction of the hepatic cytochrome P450 system. Lastly, rifampicin can cause hepatic toxicity, although the enormous worldwide experience of using rifampicin for the prevention and 6-month treatment of tuberculosis confirms that the drug is extremely well-tolerated and causes clinically significant hepatitis in < 1% of patients. 23

The frequency with which rifampicin resistance develops during the combination therapy of S. aureus bacteraemia and the factors associated with its development are difficult to assess from the published literature. New resistance was not reported in any of the 433 patients treated with adjunctive rifampicin in three non-randomised clinical studies of S. aureus bacteraemia and other serious S. aureus infections,24–26 giving an observed incidence of 0% with upper 97.5% confidence limit of 0.8%. However, other clinical series have reported the emergence of rifampicin resistance in 20–40% of patients after a median of 9–12 days of treatment (range 5–58 days). 27–29 One of these studies, a retrospective description of 42 rifampicin-treated patients with native valve S. aureus endocarditis, reported that those who developed resistance (21%) were more likely to have prolonged bacteraemia than a selected control group who were not given rifampicin, although the control group had a significantly less severe form of the disease at the start of treatment. 27 The investigators also reported that rifampicin had clinically important interactions with other drugs in 52% of patients, but a high proportion of patients were coinfected with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) (18%) and/or hepatitis C (48%) and required methadone (which interacts with rifampicin) for opiate addiction (57%). This population were also at a high risk of having rifampicin-related hepatic toxicity, but hepatic dysfunction occurred in only nine patients; all patients were infected with hepatitis C and had abnormal liver function tests before starting rifampicin.

In summary, there are insufficient clinical data to determine the true incidence of rifampicin resistance, drug interactions and hepatic toxicity. Only one large, randomised controlled trial (RCT) will provide these data and allow the potential risks of adjunctive rifampicin to be properly balanced against the potential benefits.

Adjunctive rifampicin for S. aureus bacteraemia: current clinical evidence, guidelines and practice

Four RCTs, involving 246 patients in total, have examined the effectiveness of adjunctive rifampicin for serious S. aureus infections, including patients with bacteraemia. 30–33 The first two trials, published > 25 years ago, enrolled adults with any serious S. aureus infection, of whom 47 out of 121 (39%) were bacteraemic at randomisation. 30,31 The third trial enrolled 42 adults, all of whom had S. aureus bacteraemia and endocarditis,32 and the fourth enrolled 83 adults who were admitted to intensive care with MRSA pneumonia, but only 9 out of 83 (11%) were bacteraemic. 33 A stratified meta-analysis of the results from these trials was performed; subgroup analysis of bacteraemic adults was possible for all but the fourth trial, which did not provide sufficient data. Overall, adjunctive rifampicin reduced infection-related deaths by 55% (p = 0.02) and bacteriological failure by 58% (p = 0.004), with similar (54%, 77%) but non-significant (p = 0.22, p = 0.17) reductions in the bacteraemic subgroup (n = 89).

The daily dose of rifampicin in these studies varied from 600 mg to 1200 mg. Significant drug interactions were not reported in any of the studies, and details concerning hepatic toxicity were not provided in the first three trials. 30–32 The most recent trial reported that 6 out of 41 (15%) patients treated with rifampicin developed hyperbilirubinaemia (vs. one control patient) but the impact on treatment was not described. 33 This trial was also the only one to report rifampicin resistance developing on treatment: new resistance was found in 14 out of 41 (34%) rifampicin-treated patients, although it did not appear to have a significant impact on clinical cure rates. 33

There are limited data from uncontrolled, observational studies supporting the use of adjunctive rifampicin, although, given the potential for confounding by indication, their results must be interpreted cautiously. A prospective study of 381 adults with S. aureus bacteraemia found that the mortality of those with severe disease was halved in those who received adjunctive rifampicin (mortality 38% vs. 17%; p < 0.001), without an increased incidence of rifampicin resistance. 25 A retrospective analysis of patients with staphylococcal sternal wound infections, 35% of whom had S. aureus bacteraemia, reported that adjunctive rifampicin was independently associated with a reduced risk of treatment failure [hazard ratio (HR) 0.26, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.10 to 0.64; p = 0.004]. 26 A recent observational study of 964 patients with S. aureus bacteraemia reported that 512 (53%) patients received combination therapy and the majority (301/512, 59%) received rifampicin. 34 Combination therapy was not associated with reduced mortality in all patients, but was associated with reduced deaths and infection-related complications in those suffering from device-related infections.

The current observational study found that 17% of NHS patients with S. aureus bacteraemia were treated with rifampicin, but with large variations in use across the six centres (range 1–75% of patients). 35 Rifampicin was used to treat 21% of MRSA bacteraemia and 15% of meticillin-susceptible bacteraemia, and was not reserved for severe, complex disease as the guidelines suggest;4–7 13% of uncomplicated i.v. catheter-related bacteraemia were treated with rifampicin. However, rifampicin was given more often to patients with MRSA bacteraemia resulting from foci other than i.v. catheters – although even in this indication only 24% received it. An unadjusted comparison of inpatient mortality showed that 23% of patients not treated with rifampicin died compared with 13% given rifampicin (p = 0.03). The impact on survival appeared to be more marked in those with a non-removable focus of infection (whose inpatient mortality was higher), although there was no statistical evidence supporting smaller relative effects of adjunctive rifampicin in those with removable foci (p = 0.39).

Rationale

The results of the meta-analysis, together with data from observational studies indicate, that adjunctive rifampicin may have a surprising and substantial impact on survival from S. aureus bacteraemia. They do not, however, constitute evidence of sufficient rigour to influence current treatment guidelines, clinical practice, or indeed the equipoise of clinicians recruiting patients into the proposed trial – even clinicians in centres using rifampicin in a greater proportion of patients have indicated their willingness to randomise, as they recognise the lack of evidence supporting their practice. In particular, although statistically significant, the results from the trial meta-analysis are not convincing, as they are based on a small number of patients in a small number of trials over a wide period of time. In addition, the potential negative impact of rifampicin toxicity, interactions and resistance cannot reliably be assessed in these studies. Current guidelines recommend adjunctive rifampicin only for the treatment of severe MRSA infections, specifically endocarditis, bone and joint infections, and infections involving prostheses (category II evidence). 5,7 But with weak support for these recommendations it is unsurprising that few physicians follow them in practice. The ARREST (Adjunctive Rifampicin to Reduce Early mortality from STaphylococcus aureus bacteraemia) trial was designed to provide a definitive answer to the role of adjuvant rifampicin therapy in the treatment of S. aureus.

Objectives

The hypothesis addressed by the ARREST trial is that adjunctive rifampicin will enhance the killing of S. aureus early in the course of antibiotic treatment, sterilise infected foci and blood faster, and thereby reduce the risk of dissemination, metastatic infection and death. Therefore, the primary objective of the trial was to investigate the impact of adjunctive rifampicin on bacteriologically confirmed failure/recurrence or death through 12 weeks from randomisation. Secondary objectives included evaluating the impact of rifampicin on all-cause mortality up to 14 days from randomisation, or clinically defined failure/recurrence or death, toxicity [serious and grade 3/4 adverse events (AEs), any modification of treatment as a result of drug interactions], emergence of resistance and duration of bacteraemia, and assessing the cost-effectiveness of adjunctive rifampicin for S. aureus bacteraemia in the NHS.

Substudies

There were three ancillary studies to the main trial. First, with assistance from the trial public and patient representative, Jennifer Bostock, the process of obtaining consent to enter the trial was examined. Patients/legal representatives who did not consent to participation in the trial were offered the opportunity to complete a questionnaire exploring reasons for this; participants/legal representatives at one trial centre who did consent were offered the opportunity to be interviewed by the ARREST trial patient and public representative to explore their experiences of trial participation.

Samples were collected for two further ancillary studies for which funding will be sought separately. Participants enrolled at Guy’s and St Thomas’ NHS Foundation Trust, Cambridge University Hospitals NHS Trust, Oxford University Hospitals NHS Trust, The Royal Liverpool and Broadgreen University Hospitals NHS Trust, and Brighton and Sussex University Hospitals NHS Trust were approached for additional consent for a pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic (PK/PD) substudy – a population PK/PD study of rifampicin, flucloxacillin and vancomycin for the treatment of S. aureus. The aim of the substudy is to determine the pharmacological parameters of rifampicin that best predict treatment success and provide a rational basis from which optimal dose, frequency and route of administration can be modelled statistically and/or explored in future studies.

All participants were also approached for additional consent for the host DNA/RNA substudy to investigate the influence of host and bacterial genetics on disease severity and outcome from S. aureus. The aim is to identify host and bacterial genetic factors that influence disease severity (e.g. the development of metastatic complications) and poor outcomes from S. aureus bacteraemia.

The samples for the PK/PD and DNA/RNA substudies have been archived at the King’s College London Biobank until funding has been secured.

Chapter 2 Methods

This chapter includes material that has been adapted from the trial protocol published in Thwaites et al. 1 © Thwaites et al. ; licensee BioMed Central Ltd. 2012. This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Trial setting

Patients were recruited from 29 large UK NHS Hospital Trusts:

-

Guy’s and St Thomas’ NHS Foundation Trust

-

Oxford University Hospitals NHS Trust

-

University College London (UCL) Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust

-

Royal Free London NHS Foundation Trust

-

King’s College Hospital NHS Foundation Trust

-

Brighton and Sussex University Hospitals NHS Trust

-

The Royal Liverpool and Broadgreen University Hospitals NHS Trust

-

Sheffield Teaching Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust

-

Cambridge University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust

-

Royal United Hospital Bath NHS Trust

-

Royal Devon and Exeter NHS Foundation Trust

-

Plymouth Hospitals NHS Trust

-

Hull and East Yorkshire Hospitals NHS Trust

-

South Tees Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust

-

Heart of England NHS Foundation Trust

-

St George’s Healthcare NHS Trust

-

Portsmouth Hospitals NHS Trust

-

University Hospital Southampton NHS Foundation Trust

-

Blackpool Teaching Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust

-

The Leeds Teaching Hospital NHS Trust

-

Aintree University Hospital NHS Foundation Trust

-

Bradford Teaching Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust

-

County Durham and Darlington NHS Foundation Trust

-

Dartford and Gravesham NHS Trust

-

North Cumbria University Hospitals

-

University Hospitals of Leicester NHS Trust

-

Wirral University Teaching Hospital NHS Foundation Trust

-

The Newcastle Upon Tyne Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust

-

Salford Royal NHS Foundation Trust.

The main criteria for selecting participating hospitals were that they had an existing S. aureus bacteraemia ward consultation service and sufficient numbers of S. aureus bacteraemias to be able to recruit patients (potential to recruit a minimum of one patient per month), as well as the necessary research infrastructure to conduct the trial.

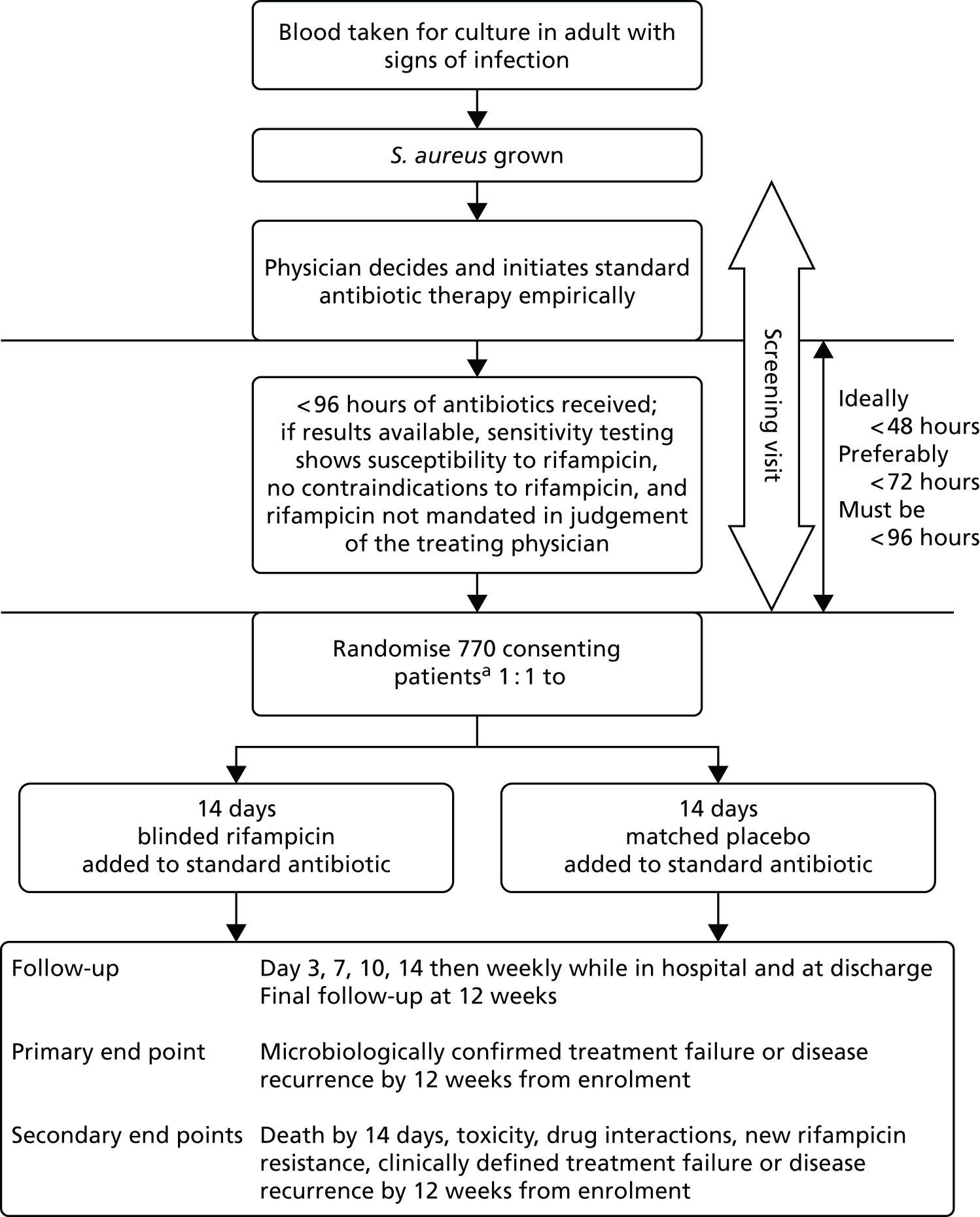

The overall trial design is summarised in Figure 1.

FIGURE 1.

Trial schema. a, Incapacitated adults would be eligible, provided that they had an appropriate legal representative.

Patient selection

As S. aureus bacteraemia is a serious infection for which the standard treatment requires i.v. antibiotics, all eligible patients were hospital inpatients at the time of recruitment. Patients were identified via the clinical microbiology laboratory and the infectious diseases/microbiology consult service at each centre. When possible, patients were screened for eligibility on the day that their blood cultures were flagged positive with S. aureus. Written informed consent was obtained from patients. Incapacitated adults were eligible provided that they had an appropriate legal representative to provide consent. The principal investigator (PI) or another experienced independent physician was required to follow the Mental Capacity Act 200536 to formally assess the capacity of the individual to make an informed decision to participate in the trial. If incapacity was confirmed, then written informed consent was sought from either a personal (e.g. a relative) or a nominated (e.g. consultant intensivist caring for the patient, but not involved in the trial) legal representative.

Inclusion criteria

The trial enrolled adults aged ≥ 18 years who had S. aureus (meticillin susceptible or resistant) grown from at least one blood culture, who had received < 96 hours of active antibiotic therapy for the current infection (not including rifampicin, and excluding any stat doses), and the patient or legal representative had provided written informed consent for participation in the trial.

Although the formal inclusion criteria stated that patients must have received < 96 hours of active antibiotic therapy for the current infection, the best clinical predictor of complications and death from S. aureus bacteraemia is the persistence of bacteria in blood 48–96 hours after the start of active antimicrobial therapy. 13–15 Therefore, patients were included in the trial as soon after initiation of active antibiotic therapy as possible, within 48 hours whenever possible and ideally within 72 hours.

Exclusion criteria

Patients were excluded from the trial if they had an infection not caused by S. aureus alone in the opinion of the infection specialist (e.g. S. aureus was considered a blood culture contaminant, or polymicrobial culture with another organism was likely to be contributing clinically to the current infection); if sensitivity results were already available and demonstrated rifampicin-resistant S. aureus [defined by British Society for Antimicrobial Chemotherapy in vitro disc susceptibility testing or by Vitek® (bioMérieux, Marcy l’Etoile, France) testing]; if the infection specialist, in consultation with the treating physician, considered rifampicin to be contraindicated for any reason; if the infection specialist, in consultation with the treating physician, considered rifampicin treatment to be mandatory for any reason; if the infection specialist suspected active infection with Mycobacterium tuberculosis; or if the patient had been previously been randomised in the ARREST trial for a prior episode of S. aureus bacteraemia.

As the underlying hypothesis was that rifampicin may improve outcomes by increasing the rate of early bacterial killing, results of in vitro sensitivity testing were not required before randomisation, as it was important to initiate rifampicin as soon as S. aureus was identified. This also ensures that results are generalisable to empiric treatment of S. aureus bacteraemia in the future. However, if for any reason in vitro susceptibility results were already available at the point when randomisation would be considered, and demonstrated rifampicin resistance, then the patient was not eligible.

Randomisation

Eligibility was confirmed by the ARREST trial site investigators (PI, co-PI or research nurse) via the online ARREST trial database, and patients were randomised into two parallel groups in a 1 : 1 ratio, to standard i.v. antibiotic therapy plus 14 days of placebo, or standard i.v. antibiotic therapy plus 14 days of rifampicin. The choice and duration of the standard antibiotic therapy was left to the attending physician. Randomisation was stratified by clinical centre, as blinded drug (in fully made-up and labelled treatment packs) was pre-shipped to local pharmacies. A computer-generated sequential randomisation list using variably sized permuted blocks was prepared by the trial statistician and incorporated securely into the online trial database. The list was concealed until allocation, after eligibility was confirmed by researchers at the local hospitals, who then performed the randomisation. A 24-hour web-based randomisation service was provided via the online ARREST trial database.

Trial intervention

Rifampicin/placebo was given by oral or i.v. route, depending on the attending physician’s preference and the patient’s status. Providing that a patient could swallow safely, the preference was to use rifampicin orally. Intravenous administration was permitted for patients who were not able to swallow or absorb tablets. Rifampicin is a well-established, widely used drug, and was not used outside its licensed indication during the course of the trial.

The oral investigational medicinal product (IMP) was prepared by a Clinical Trials Supplier (Sharp Clinical Services, Crickhowell, UK). It was supplied as 300 mg of rifampicin capsules (Sanofi-Aventis, Guildford, UK) [summary of product characteristics (SPC); www.medicines.org.uk/emc/medicine/21223/SPC/Rifadin±300mg±Capsules/ (accessed 4 June 2018)] or placebo oral 300-mg capsules containing cellulose. The rifampicin capsules were over-encapsulated so that they were identical in appearance to the placebo capsules. The capsules were supplied to trial centres as individual participant-blinded treatment packs so that they were dosed and dispensed in the same way.

The i.v. IMP was provided via standard hospital stock and consisted of either rifampicin for i.v. infusion [600 mg of rifampicin for i.v. injection (Sanofi-Aventis) SPC www.medicines.org.uk/emc/medicine/6435 (accessed 4 June 2018)] or standard saline as the placebo. Participants receiving i.v. infusions in the intensive care unit (ICU) could have their infusion volume altered in accordance with standard local practice and the SPC. The trial pharmacist at each hospital had access to a copy of the randomised allocations for each ARREST trial number for their centre in order to prescribe i.v. rifampicin if required.

Dose

The dose of rifampicin/placebo was prescribed on the basis of the patient’s weight:

-

those < 60 kg received 600 mg every 24 hours

-

those ≥ 60 kg received 900 mg every 24 hours.

Oral doses could be given once or twice daily depending on clinician and patient preference, and subgroup analysis was prespecified according to initial oral dosing frequency (elicited at randomisation). If taken twice daily, 900 mg daily (three capsules) was taken as unequal divided doses (600 mg in the morning and 300 mg in the afternoon). As rifampicin can also be taken once daily, this provided adequate exposure.

Where i.v. was prescribed, it was administered to the patient over 2–3 hours.

Blinding and masking

Rifampicin for i.v. infusion is supplied as a vial of red powder that requires reconstitution with 10 ml of water for infusion with saline. The resulting fluid for i.v. infusion is orange. It was impossible to safely and reliably produce a red-powder placebo that produced an identical orange infusion. Therefore, the ward nurse making up the i.v. drug for the infusion was not blind to the treatment, nor was the hospital pharmacist dispensing either rifampicin or saline for i.v. administration. The ward nurses were instructed not to divulge the colour of the drug to the physicians caring for the patient. In addition, the infusion was covered by an opaque bag to disguise the treatment. As far as possible, the trial physicians, research nurses and other physicians caring for the patient remained blinded, as were all trial and data management staff except for statisticians.

Rifampicin can turn urine (and tears/sweat) reddish-orange. It is impossible to safely replicate this effect with a placebo; therefore, urine discolouration was a potential source of unblinding, particularly for the participant. There is, however, considerable inter- and intra-individual variability in the effect of rifampicin on urine colour. In addition, the opportunity for physicians to examine the urine at the bedside occurred only in participants with urinary catheters. Catheters were not required by all participants and were removed at the earliest opportunity. The opportunity for physicians to inspect urine was also limited by ensuring that the catheter bags were emptied regularly and urine was not allowed to accumulate in large volumes. The success of blinding was assessed at the final 12-week visit, when physicians and participants were asked which treatment they believed they had received.

Dose modifications, interruptions and discontinuations

Toxicity was managed in both randomised groups according to standard clinical practice. In some situations, changes in the patient’s condition meant that the dose of rifampicin needed to be reduced or stopped altogether. Whenever possible, this was done without unblinding. Unblinding was performed only when knowledge of the allocated treatment had a direct bearing on clinical management. Patients were not put at any additional risk by trial randomisation, as any patient who developed a suspected adverse reaction to a study drug was managed as if they were receiving rifampicin, and the study drug was discontinued.

The most important rifampicin toxicity is liver impairment, although serious hepatic toxicity is rare (< 1% of patients). The study drug (rifampicin/placebo) was withdrawn without unblinding if significant liver toxicity was observed [blood aspartate aminotransferase (AST)/alanine transaminase (ALT) of > 5× upper limit of normal (ULN)] without other probable causes, and was withdrawn for grade 4 liver toxicity (blood AST/ALT of > 10× ULN) regardless of probable cause. The dose of the study drug was reduced if less severe liver dysfunction occurred according to the judgement of the treating physician. Other medications (including other antibiotics) were continued at the discretion of the treating physician. Rifampicin-related hepatic toxicity requires no specific treatment other than its withdrawal and, therefore, knowledge of whether the patient was receiving rifampicin or placebo was not mandated for patient management.

Rifampicin has a number of other uncommon side effects, which include anorexia, nausea, vomiting and diarrhoea, headache and drowsiness, haemolytic anaemia, thrombocytopenic purpura, disseminated intravascular coagulation and leucopenia, flushing, urticaria and rashes, and a flu-like syndrome with fever (although this is usually associated with administration twice or three times per week).

Rifampicin/placebo was discontinued before 14 days in two specific situations:

-

When other antibiotics being used to treat S. aureus bacteraemia were stopped before 14 days after randomisation. This was to prevent rifampicin being given as monotherapy, which could theoretically increase the risk of resistance.

-

When results from S. aureus susceptibility testing became available after the patient had been randomised and initiated on rifampicin/placebo and indicated resistance to rifampicin. This was to prevent any toxicity from an additional but ineffective drug being used. Primary rifampicin resistance was expected in < 1% enrolled patients based on observational study data. 35

Other antibiotics

Infection specialist consultation, with advice on management to non-specialists caring for the trial participants, followed normal clinical practice in all sites. Attending physicians could change ‘backbone’ antibiotics on the basis of clinical need and infection specialist advice and use open-label rifampicin after 14 days. When judged clinically necessary, the attending physicians could stop the blinded trial drug before 14 days to use open-label rifampicin, with participants continuing follow-up ‘off study drug, on study’.

Assessments and follow-up

Trial assessment schedule

All participants were followed by the centre trial teams for 12 weeks for evaluation of all-cause mortality, morbidity and toxicity. To assess the outcome measures, patients were visited on the ward by the centre PI, one of their clinical team (e.g. a specialist registrar) or a research nurse. The schedule for timing, frequency and method of collection of all study data is summarised subsequently. Assessments were performed as close as possible to the required time point.

Screening and randomisation visits

Patients were identified through the clinical microbiology laboratory and the infectious diseases/microbiology consult service of each centre. All the trial centres ran a clinical consult service for all cases of S. aureus bacteraemia and identified such patients as soon as their blood cultures become positive. The screening visit took place as soon as possible after a potential patient had been identified by the microbiology laboratory. The trial’s central hypothesis was that early intervention with rifampicin enhances bacterial killing and improves clinical outcome. Therefore, it was essential that patients were randomised as early as possible in their treatment and by the limit defined by the inclusion criteria of < 96 hours of active antibiotic therapy for the current infection. For this reason, patient consent to recruitment was requested within 2 hours of the screening assessment whenever possible, and ideally within 4 hours.

Written informed consent to enter into the trial and be randomised was obtained from patients or a person with responsibility (a legal representative, such as a legal authority).

After consent was obtained from the patient or their legal representative, clinical information including medical history and examination as well as weight were recorded. C-reactive protein (CRP) and liver function tests are routine investigations for patients with suspected S. aureus bacteraemia and results were also recorded.

Randomisation took place as soon as possible after eligibility was confirmed and consent was signed.

Follow-up

At each main clinical assessment (days 0, 3, 7, 10, 14, weekly until discharge, week 12 final visit), the following was undertaken:

-

Assessment of new or ongoing foci of infection together with arrangements to identify, remove or drain the foci if necessary.

-

Assessment of clinical treatment response, including whether or not the patient was febrile (> 37.5 °C) in the previous 24 hours.

-

All grade 3 or 4 AEs, all serious adverse events (SAEs) and all AEs of any grade leading to modification of rifampicin/placebo dose or its interruption/early discontinuation were recorded. With the exception of events leading to modification/interruption/discontinuation of the study drug, the severity and likely relationship of these AEs to rifampicin/placebo was documented by a physician. Any drug interactions leading to dose modification of any drug (including concomitant medications) were also recorded.

-

Assessment of adherence to rifampicin/placebo (missed pills).

-

Assessment of resource utilisation (medications, procedures, laboratory tests and other relevant resource use categories).

Blood cultures were repeated on days 0, 3 and 7 to assess duration of bacteraemia in all patients as persistent bacteraemia is strongly predictive of worse outcomes. Blood cultures could be taken at any other time points necessary for clinical management, but were additionally taken if potential treatment failure was suspected (e.g. in patients who still had a positive blood culture on day 7 and in whom transoesophageal echocardiography was being considered) or when S. aureus bacteraemia recurrence was suspected. CRP levels were measured on days 0, 3, 10 and 14 to assess treatment response. Levels of ALT, bilirubin and alkaline phosphatase were assessed on days 3 and 10 to evaluate liver toxicity. Full blood count was measured at baseline in all patients as total white blood cell count/total neutrophils may be important baseline prognostic determinants. The ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid plasma (2.5 ml of blood) and PAXgene blood RNA tube (2.5 ml of blood) were taken from patients on day 0 and stored for later DNA/RNA extraction when consent had been provided for this. If a patient had already been discharged from hospital before day 7, 10, or 14, these additional investigations requiring a blood draw (culture, CRP, ALT, alkaline phosphatase, bilirubin, serum storage) were not required, so patients were not asked to attend ARREST trial-specific outpatient appointments on these days, but returned at 12 weeks only.

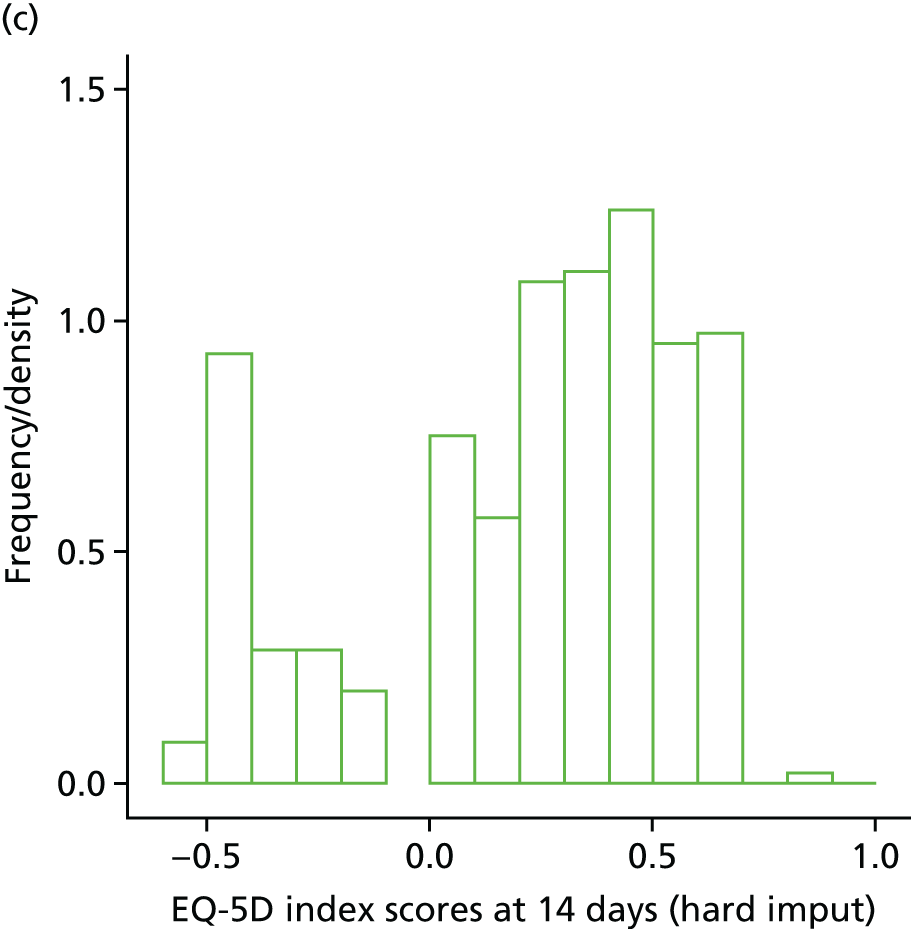

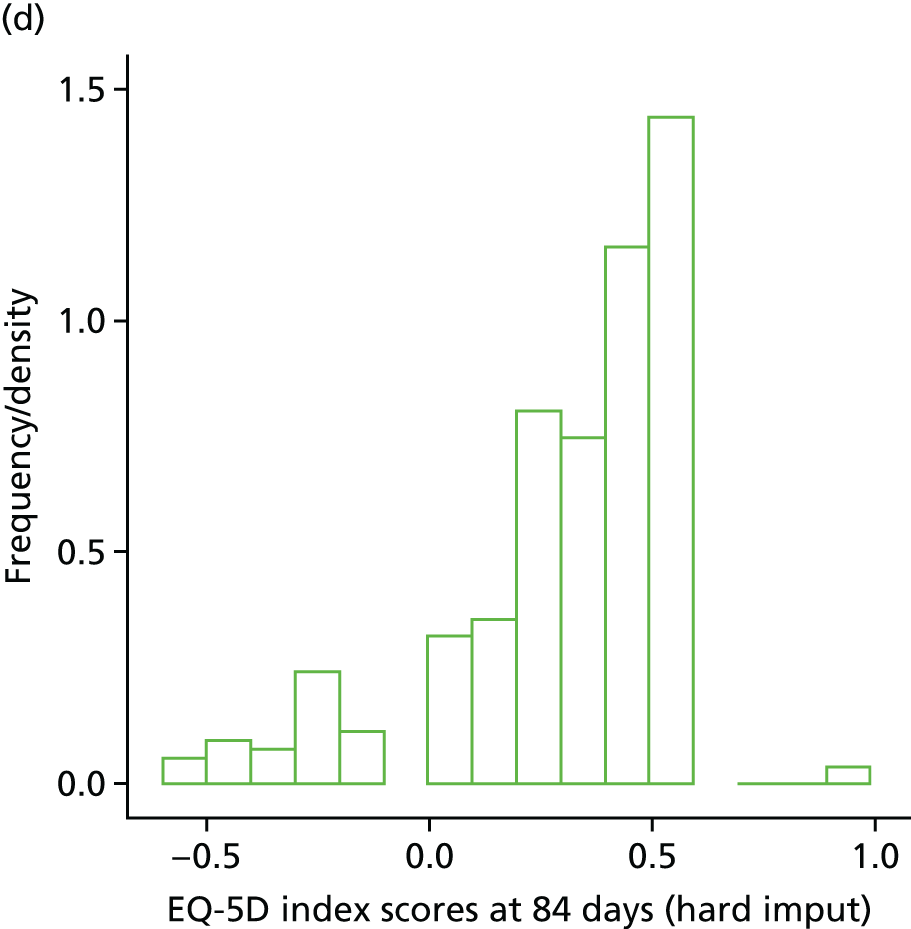

The EuroQol-5 Dimensions (EQ-5D) for quality-of-life assessment was administered on days 0, 7, 14 and at the final visit.

Those patients discharged before 12 weeks were managed and followed up through each centre’s infectious diseases outpatient clinic. Final follow-up at 12 weeks was either by a ward visit (if the patient was still admitted to hospital) or by a clinic visit with interview and clinical assessment. In the event that the patient was unable to attend clinic, the follow-up visit could take place over the telephone. If failure or S. aureus bacteraemia recurrence was suspected then repeat blood cultures were performed together with a clinical assessment and EQ-5D.

The trial end was defined as the final 12-week visit of the last patient to be randomised. At the end of the trial, the vital status of all participants was ascertained from electronic NHS records, and consent was sought for this.

Procedures for assessing efficacy

The primary outcome was:

-

time to death or bacteriologically confirmed failure/disease recurrence up to 12 weeks from randomisation.

This outcome measure was assessed by visiting the patient on days 3, 7, 10 and 14, and weekly thereafter until discharge from hospital, and the final clinical assessment 12 weeks after recruitment [either by a ward visit (if the patient was still admitted to hospital) or by a clinic visit or telephone call]. Consent to contact the patient’s general practitioner (GP) was also obtained.

The definition of bacteriologically confirmed failure was:

-

symptoms and signs of infection ongoing for > 14 days from randomisation

-

the isolation of same strain of S. aureus (confirmed by genotyping) from either blood or another sterile site (e.g. joint fluid, pus from tissue) indicating blood-borne dissemination of the bacteria.

The definition of bacteriologically confirmed disease recurrence was:

-

the isolation of the same strain of S. aureus from a sterile site after > 7 days of apparent clinical improvement.

As defined, failure reflected both the speed of killing of S. aureus and sterilisation of infected foci/blood, and both failure and recurrence reflected the risk of dissemination and metastatic infection. Outcome measures included S. aureus infection of sterile sites other than just blood, because such disseminated infection can be the consequence of failure to treat initial infections adequately. Asymptomatic bacteraemia without any sign or symptom of infection was not considered failure. Additional blood cultures were requested as soon as the PI/study physician suspected failure or recurrence. All bacterial isolates (initial and all subsequent) from patients randomised in the trial were originally intended to be genotyped by multilocus sequence and spa-typing and tested for susceptibility to rifampicin.

A substantial proportion of bacteriological failure/recurrences did not have both baseline and failure/recurrence isolates stored [17 (61%) of 28 failures/recurrences where S. aureus was isolated from a sterile site]. In order to avoid excluding a substantial proportion of potential primary end points, the statistical analysis plan specified that the primary analysis would include all bacteriologically confirmed failures and recurrences (i.e. without restricting to the same strain).

In the 11 pairs of baseline and failure/recurrence isolates that were stored, same strain was defined by whole-genome sequencing using Illumina technology (San Diego, CA, USA) on the basis of 40 single nucleotide variants between baseline and failure/recurrence isolates. All failure/recurrence isolates were within 12 single nucleotide variants of the baseline isolate {median 1 [interquartile range (IQR) 1–6; range 0–12] single nucleotide variant}.

The secondary efficacy outcome measures were:

-

time to all-cause mortality up to 14 days

-

time to clinically defined failure/recurrence/death by 12 weeks

-

duration of bacteraemia

-

AEs (grade 3/4 AEs, SAEs, AEs of any grade leading to modification of rifampicin/placebo dose or interruption/early discontinuation) (all AEs reported, primary comparisons based on time to first event)

-

the proportion modifying any treatment (including concomitant medications) as a result of drug interactions

-

the proportion developing rifampicin-resistant S. aureus

-

cost-effectiveness of rifampicin.

Mortality was reported on the ARREST trial database on a SAE electronic case report form (eCRF). Clinically defined failure/recurrence was assessed clinically in the same manner as bacteriologically confirmed failure or recurrence; however, microbiological confirmation was not required (e.g. patients who failed clinically but for whom blood cultures were not taken). Clinically defined failure/recurrence was primarily determined by radiological evidence for an ongoing or new active infection focus by 12 weeks and the requirement for ongoing or new antibiotic therapy.

The PIs were required to report all potential failures/recurrences and these were adjudicated as trial end points by an independent end-point committee. The blinded independent review committee consisted of two infectious disease physicians with experience in acute/general medicine (Professor Tim Peto, Oxford University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust, Oxford, UK; Dr Graham Cooke, Imperial College Healthcare NHS Trust, London, UK; see Acknowledgements). Potential failures/recurrences were also identified through questions regarding signs and symptoms of ongoing or new S. aureus infections on routine case report forms, and S. aureus isolated from any microbiological specimen. For all such potential failures/recurrences a structured clinical narrative was completed by the site physician and approved by the site PI. All reported failures, recurrences and deaths were then adjudicated using standardised proformas by the committee without knowledge of randomised allocation.

Blood cultures were taken on days 3 and 7 following randomisation to assess duration of bacteraemia. Sensitivity to rifampicin was repeated on the day 3 and 7 blood cultures and in all subsequent S. aureus isolates grown at scheduled time points or at failure/recurrence in order to assess the secondary end point: development of rifampicin-resistant S. aureus.

The levels of CRP were measured longitudinally as a continuous measure of response to infection.

Procedures for assessing safety

Hepatitis is the most important side effect of rifampicin. Liver function tests were performed twice while on rifampicin/placebo (days 3 and 10) to assess laboratory safety parameters. Additional safety blood tests or investigations were performed to investigate symptoms or monitor emergent laboratory test abnormalities as clinically indicated.

Grade 3 and 4 AEs and SAEs were elicited at the regular clinical assessments, through consultation with the patient, their medical team or their medical records. All such AEs were reported on eCRFs, together with AEs of any grade leading to modification of rifampicin/placebo dose or its interruption/early discontinuation. All AEs (clinical and laboratory) were graded using the Common Toxicity Criteria grading scale v3.0. The SAEs were defined following the International Conference on Harmonisation of Technical Requirements for Registration of Pharmaceuticals for Human Use37 as events that led to death, were life-threatening, caused or prolonged hospitalisation (excluding elective procedures), caused permanent disability, or were other important medical conditions or with a real, not hypothetical risk of one of the previous categories. The SAEs were reported to the Medical Research Council (MRC) Clinical Trial Unit (CTU) at UCL according to standard timelines. All SAEs were reported on study eCRFs, unless they were specifically related to the S. aureus bacteraemia episode for which the patient was originally admitted (in which case they were reported as infection-related events). The protocol specifically exempted events related to S. aureus bacteraemia from AE reporting, unless the event was fatal, to avoid double-counting. The severity and likely relationship of any AEs to rifampicin/placebo were documented by a physician. All reported AEs were coded centrally at the MRC CTU at UCL using the Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities (MedDRA).

All modifications to rifampicin/placebo dose or administration were recorded, as were all significant drug interactions requiring modification of study and non-study medication.

Procedures for assessing health-related costs of S. aureus and quality of life

Health-care-related costs of S. aureus bacteraemia in the NHS and the evaluation of health-related quality of life (HRQoL) were evaluated using the EQ-5D. These assessments were used further to inform the cost-effectiveness of adjunctive rifampicin and relevant antibiotic regimens for S. aureus bacteraemia (see Chapter 5). Information on health-care-related costs of patients in the trial was collected, starting from when the first positive blood culture was taken and continuing for the duration of follow-up. Information on hospitalisation costs (including procedures, laboratory tests and concomitant medications) was collected at the regular clinical assessments, and data on other health-care resource utilisation (post-discharge outpatient visits, medications and procedures) were collected at the 12-week visit.

Within-trial assessments of HRQoL (using the EQ-5D) were also used in the economic analysis. The EQ-5D scores were used to weight lifetime lived by its quality; the EQ-5D tariff developed for the UK was used to derive the scores from the participants’ responses to the EQ-5D descriptive system. The cost-effectiveness analysis thus used quality-adjusted life-years (QALYs) as the outcome measure.

Sample size

The trial was originally designed with two coprimary outcomes: all-cause mortality by 14 days and bacteriological failure/recurrence or death by 12 weeks. Assuming 80% power, a two-sided alpha of 0.025 (to adjust for multiple testing given two coprimary outcomes) and a 10% loss to follow-up by 12 weeks, 920 participants were needed to detect a 30% relative reduction in bacteriological failure/death from 35% to 25%, an absolute difference of 10% corresponding to an number needed to treat (NNT) of 10 participants. Assuming 80% power, a two-sided alpha of 0.025 and a lower 4% loss to follow-up by 14 days (as most participants remained in hospital over this time scale), 940 participants were needed to detect a 45% relative reduction in mortality from 16% to 9%, an absolute 7% difference and a NNT of 14 participants. The total sample size was originally therefore 940 participants.

Recruitment to the trial was slower than anticipated. To facilitate successful completion of the trial and at the request of the trial funder, after 3 years of recruitment 14-day mortality was moved from a coprimary to a secondary outcome. Therefore, 12-week bacteriological failure/recurrence or death became the sole primary outcome with consequent decrease in sample size [as a result of the increase in the two-sided alpha (type I error) from 0.025 (two coprimary outcomes) to 0.05 (one primary outcome)]. With 12-week bacteriological failure/recurrence or death as the sole primary outcome, the total sample size became 770 participants (alpha = 0.05, other assumptions as above).

The protocol and statistical analysis plan specified that the primary outcome (bacteriologically confirmed failure/recurrence or death) would be analysed using time-to-event methods as described in Statistical methods. The sample size calculation treated this outcome as binary, in order to produce a conservative estimate of sample size given uncertainties in the underlying assumptions, and because all patients were to be followed for a fixed 12-week period (i.e. no additional power was gained from longer follow-up in some patients).

Statistical methods

Randomised groups were compared following the principle of intention to treat, including all follow-up regardless of changes to treatment. The statistical analysis plan prespecified that any patient who was randomised in error (defined as realising that the patient should not have been randomised before taking blinded study drug and not ever taking study drug and, hence, not followed up) would be excluded. The blinding means that there was no possibility that knowledge of randomised allocation affected this judgement about what was an error. Any participants who were randomised in good faith (i.e. not by mistake) but never took study drug were included in all analyses.

The time-to-event analyses measured time from randomisation. Analyses of clinical outcomes censored at the earliest of 12 weeks from randomisation and the last clinical information. Analyses of mortality censored at the earliest of the time scale being considered (2 weeks, 12 weeks) or last vital status information (including that ascertained at trial closure through the NHS records).

The primary analyses were unstratified because the randomisation stratification factor (centre) was expected to have some small strata and participants in these strata might then not contribute to comparisons. Results from secondary stratified analyses (stratified log-rank test and stratified Cox regression) were very similar (data not shown). Lost to follow-up was defined as not having been assessed in person or by telephone at the 12-week final visit (within a window of 1 week before to 8 weeks after week 12) by a trial clinician and not having information on whether or not signs/symptoms of S. aureus were present (e.g. from the patient’s GP).

Primary analysis of the primary end point included all randomised participants other than those considered randomised in error (following the statistical analysis plan): secondary analysis of the primary end point was to exclude those (expected < 1%) who were subsequently identified as having had a rifampicin-resistant S. aureus bacteraemia on susceptibility testing. As no patients were identified after randomisation as having had a rifampicin-resistant S. aureus bacteraemia at enrolment, this analysis was identical to the primary analysis. In the statistical analysis plan (but not the protocol), a per-protocol analysis was also specified for the primary end point, including all participants in the primary intention-to-treat analysis who received active/placebo for ≥ 80% of days from the start of trial drug to earliest of 14 days subsequently/death/discontinuation of active antibiotics (not including trial drug).

Safety analyses included all data between randomisation and 12 weeks post randomisation (inclusive). Non-fatal events related to S. aureus bacteraemia were not considered AEs/SAEs in the protocol.

When composite outcomes did not include all-cause mortality as part of the composite, competing risks analysis methods were used. Analogous to a Kaplan–Meier estimate, competing risk methods use cumulative incidence functions to estimate the probability of the event. The effect of randomised group on the subdistribution hazard that corresponds to this cumulative incidence function was estimated. Stratification is not possible with the estimating equation approach used to estimate these subdistribution hazards and so these analyses were conducted unstratified.

The CRP and liver function test results were compared between randomised groups over time using generalised estimating equations (normal distribution, independent correlation structure) with randomised group, adjusting for the stratification factor, baseline values and scheduled visit week as categorical independent variables and interaction between baseline values and scheduled visit week. The closest measurement to each scheduled visit date within equally spaced windows was used as the measurement at each scheduled visit. The midpoint between two scheduled assessment days was taken as belonging to the latter window (e.g. a measurement taken on day 12, midpoint between day 10 and day 14, would be considered as day 14 in the analysis). When there were two values within one of these equally spaced windows, but both equidistant from the nominal assessment day, the later value was used. Analyses were based on observed data. To account for CRP values above the limit of quantification in one centre (i.e. CRP levels only reported as > 156 mg/l if above this threshold), mean CRP level was estimated using normal interval regression. For analyses of change from baseline, these values were assumed equal to the limit of quantification.

For blood cultures, baseline (used to define baseline resistance/susceptibility) was defined as the closest up to and including day 0, and up to 1 day post randomisation providing this was on or before date of start of the trial drug. Cultures prior to randomisation were used in preference to cultures the same number of days after randomisation, but on or before the date of start of trial drug. As eligibility was based on the screening of positive blood cultures, and because the intention was to characterise persisting bacteraemia, baseline bacteraemia included cultures on day 1 when a culture on the day of or on the day prior to randomisation was not available. For duration of bacteraemia, baseline was defined as the closest up to and including day 0 within the preceding day, and up to 1 day post randomisation.

For laboratory measurements (e.g. CRP levels), baseline was defined as the closest up to and including day 0 within the preceding 4 days, and up to 1 day post randomisation providing this was on or before date of start of trial drug. Measurements prior to randomisation were used in preference to measurements the same number of days after randomisation, but on or before the date of start of trial drug.

A deep infection focus was defined as infection of implanted vascular device, native/prosthetic heart value, native/prosthetic bone/joint, or deep tissue infection/abscess (including vertebral bone/disc or other bone infection, epidural or intraspinal empyema, infected intravascular thrombus, brain infection).

Information on all antibiotics received through 12 weeks was collected, but not according to specific indication. Primary antibiotic treatment, and its duration, was therefore defined by complete cessation of all antibiotics for 2 days, with the exception of vancomycin when intermittent dosing up to 1 week was allowed. The cessation of vancomycin was defined by adding the number of days between the last two doses to the date of the final dose.

Subgroup analyses

Subgroup analyses were conducted to assess consistency of effects across different participant characteristics. The primary method of assessing subgroup effects was an interaction test within a Cox proportional hazards regression. For the continuous factors, both categorisation and natural cubic splines were used [five knots at the 10th, 25th, 50th, 75th and 90th centiles; four knots at the 10th, 33rd, 67th and 90th centiles for Charlson Comorbidity Index score (as 10th and 25th centiles identical)] to test for interactions. Subgroup analyses were conducted unstratified to avoid losing information from small strata with no events in one randomised group. No formal adjustment for multiple testing was made for subgroup analyses.

Twelve subgroup analyses were prespecified in the protocol for the primary end point, namely time from initiation of antibiotics to initiation of randomised treatment, time from randomisation to initiation of randomised treatment, initial oral randomised treatment frequency (once vs. twice daily), initial treatment with oral trial drug only or regimen containing i.v. trial drug, class of primary antibiotic treatment, other antibiotic adjuncts (e.g. gentamicin), MRSA/meticillin-sensitive Staphylococcus aureus (MSSA), i.v. catheter-associated infection/other, deep focus/no deep focus, endocarditis/no endocarditis, age, and CRP levels (terciles).

The statistical analysis plan included six additional subgroup analyses, but prioritised the subgroup analyses into three priority groups as follows (with all analyses in each group being given equal priority) (* = in protocol).

1. *Time from initiation of first active antibiotic treatment to initiation of randomised treatment (0–24, > 24–48, > 48–72, > 72 hours).

1. *Class of initial antibiotic treatment, and according to individual drugs when these are used by > 10% of the trial population.

1. *MRSA/MSSA.

1. *i.v. catheter (central/peripheral venous line)/implanted vascular device-associated infection versus other (based on portal of entry).

1. *Deep focus (implanted vascular device, native/prosthetic heart valve, native/prosthetic joint, deep tissue infection/abscess)/no deep focus (based on foci of infection).

1. *Endocarditis (main focus/foci of infection at time first positive blood culture taken = native heart valve/prosthetic heart valve)/no endocarditis.

1. *Foci of infection known/not known.

1. *Age (terciles).

2. *Initial oral randomised treatment frequency (once vs. twice daily).

2. *Initial treatment with oral trial drug only or regimen containing i.v. trial drug.

2. *Whether or not gentamicin was administered between first positive blood culture and 48 hours post randomisation, regardless of activity.

2. Whether or not any active antibiotic other than that first administered (excluding trial drug), trial drug and gentamicin was administered between first positive blood culture and 48 hours post randomisation (yes vs. no).

2. *Baseline CRP (terciles).

2. Charlson Comorbidity Index score (0, 1–2, 3–4, ≥ 5).

3. Time from randomisation to initiation of randomised treatment (0–4, > 4–12, > 12–24, > 24 hours).

3. Community, health-care associated and nosocomial acquisition.

3. Calendar year of randomisation.

3. Baseline neutrophils (terciles).

Additional exploratory subgroups defined by initial total daily dose (600 vs. 900 mg) were also considered, as well as whether or not the patient was bacteraemic at randomisation, leading to 20 subgroups in total.

Data collection and handling

Data were entered by staff at each NHS trust hospital on to eCRFs on the online ARREST trial database. Staff with data entry responsibilities were required to complete database training before they were granted access to the database. Data were exported into Stata® (v15.1) (StataCorp LLC, College Station, TX, USA) for analysis.

Interim analyses

The trial was reviewed by the ARREST trial’s Data Monitoring Committee (DMC). It met four times in strict confidence over the course of the trial: 14 November 2013, 31 October 2014, 26 May 2015 and 24 February 2016. DMC recommendations were communicated through a letter to the Trial Steering Committee (TSC) following each meeting.

Clinical site monitoring

Trial monitoring was carried out in accordance with the protocol. Trial centres agreed to provide access to source data and consent was gained from patients for direct access to patient notes. All centres that had a minimum of four patients who had completed follow-up (week 12 visit or death) were monitored on site at least once during the trial. The following data were validated from source documents:

-

eligibility and signed consent

-

trial drug and antibiotic management

-

safety events

-

any data concerns raised by central monitoring.

Patient and public involvement

The ARREST trial was developed with the Healthcare Associated Infection Service Users Research Forum (SURF) [www.hcaisurf.org (accessed 4 June 2018)], in particular, Jennifer Bostock, who was the patient and public involvement (PPI) representative on the ARREST Trial Steering Committee. Jennifer Bostock advised on the inclusion of incapacitated adults, the application of the Mental Capacity Act 200536 and the information provided to patients. SURF is no longer active, but Ms Bostock is helping to disseminate the trial results beyond the academic and health-care professional community to other patient groups that she works with, including MRSA Action UK.

In particular, given recruitment challenges, Ms Bostock developed and led the substudy investigating patients’ and carers’ reasons for, and for not, participating in the trial. This is reported in full in Chapter 4.

Protocol changes

The trial was approved by the London (Westminster) Research Ethics Committee (reference number 12/LO/0637). See Appendix 1 for changes to the protocol.

Chapter 3 Results

Participant flow diagram

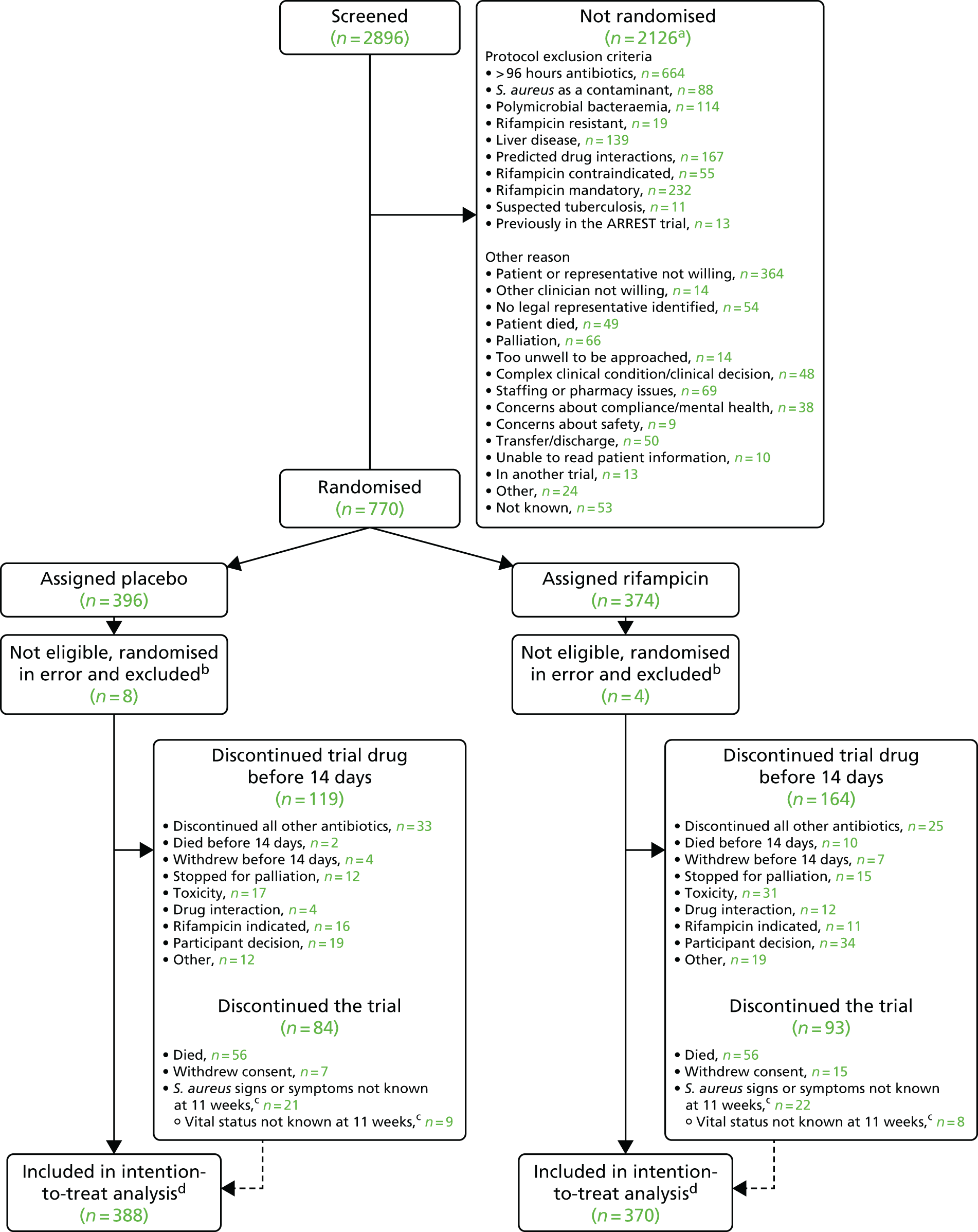

Between 10 December 2012 and 25 October 2016, 770 participants from 29 UK hospital groups were randomised to add placebo (n = 396) or rifampicin (n = 374) to their ‘backbone’ antibiotic treatment (Figure 2). A total of 2896 participants were screened for entry to the trial. The most common reason for not randomising a potentially eligible participant was that they had already received > 96 hours of antibiotics (n = 664). In 364 cases, the participant was not willing. Rifampicin was considered mandatory in 232 cases. Known rifampicin resistance occurred in only 19 cases; however, 139 cases were not eligible because of pre-existing liver disease raising concerns about rifampicin treatment and 167 cases because of predicted drug interactions.

FIGURE 2.

Participant flow diagram. a, Reasons are not mutually exclusive and, therefore, total is more than the number of participants not randomised. b, Seven participants with predicted drug interaction, two misdiagnosed (S. aureus not grown from blood but only other samples), rifampicin considered mandatory in one, a clinician considered one participant should not have been randomised because of acute kidney injury, a clinician considered one participant should not have been randomised as they were in another study (not of an IMP). c, Final 12-week visit could occur any time from 11 weeks onwards in accordance with the protocol. Consent withdrawals not included in these numbers. d, Time-to-event analyses included all time at risk from randomisation to the earliest of the event or last clinical follow-up if the event had not occurred. © The Author(s). Published by Elsevier Ltd. This is an open access article published under the CC BY 4.0 licence.

A total of 12 participants (placebo, n = 8; rifampicin, n = 4) were randomised in error (the participant should not have been randomised and never received trial drug) and were excluded following the statistical analysis plan. Of these 12 participants, seven participants had predicted drug interactions, two were misdiagnosed (S. aureus was not grown from blood), rifampicin was considered mandatory in one patient, a clinician considered that one participant should not have been randomised owing to acute kidney injury, and a clinician considered that one participant should not have been randomised as they were in another study (not of an IMP, allowed according to the protocol).

Thus, 758 (placebo, n = 388; rifampicin, n = 370) participants were included in the analyses. The median number of patients recruited per centre was 11 (IQR 4–30 patients, range 1–163 patients). A total of 415 (54.7%) participants were recruited from five centres (Oxford, n = 163; Guy’s and St Thomas’, n = 99; Liverpool, n = 62; Plymouth, n = 48; and Sheffield, n = 43). The large number of centres recruiting small numbers of participants, together with the relatively large block size (6–8), led to a small imbalance in the numbers included randomised to the placebo (n = 388) and rifampicin groups (n = 370).

Baseline characteristics

Baseline characteristics were well-balanced between randomised groups (Tables 1 and 2).

| Factor | Treatment group | Total (N = 758)a | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Placebo (N = 388) | Rifampicin (N = 370)a | ||

| Male, n (%) | 246 (63.4) | 249 (67.3) | 495 (65.3) |

| Age at last birthday (years), median (IQR) | 66 (51–76) | 64 (49–76) | 65 (50–76) |

| Charlson Comorbidity Index score,a median (IQR) | 2 (0–3) | 1 (0–3) | 2 (0–3) |

| Cancer (N = 756), n (%) | 60 (15.5) | 66 (17.8) | 126 (16.6) |

| Chronic lung disease (N = 756), n (%) | 42 (10.8) | 48 (13.0) | 90 (11.9) |

| Congestive heart disease (N = 756), n (%) | 40 (10.3) | 42 (11.4) | 82 (10.8) |

| Moderate or severe liver disease (N = 755), n (%) | 5 (1.3) | 5 (1.4) | 10 (1.3) |

| Moderate or severe renal disease (N = 755), n (%) | 80 (20.6) | 58 (15.7) | 138 (18.2) |

| Diabetes,a n (%) | 119 (30.7) | 109 (29.5) | 228 (30.1) |

| Active injecting drug use (N = 751), n (%) | 41 (10.6) | 42 (11.4) | 83 (10.9) |

| Weight (kg) (N = 755), median (IQR) | 76.0 (65.0–90.0) | 76.0 (64.0–89.0) | 76.0 (64.0–90.0) |

| Admitted to ICU,a n (%) | 36 (9.3) | 34 (9.2) | 70 (9.2) |

| CRP level (mg/l) (N = 755),b mean (SE) | 163 (5.2) | 166 (5.3) | 164 (3.7) |

| White blood cell count (× 109/l) (N = 752), median (IQR) | 9.5 (6.7–13.4) | 9.5 (7.1–13.1) | 9.5 (6.9–13.2) |

| Neutrophil count (× 109/l) (N = 752), median (IQR) | 7.3 (4.7–11.0) | 7.4 (4.9–10.7) | 7.3 (4.8–10.9) |

| Lymphocyte count (× 109/l) (N = 751), median (IQR) | 1.0 (0.7–1.5) | 1.0 (0.7–1.5) | 1.0 (0.7–1.5) |

| SOFA score (points),a median (IQR) | 2 (1–4) | 2 (1–4) | 2 (1–4) |

| Vascular catheter in situ (N = 744), n (%) | 102 (26.8) | 89 (24.5) | 191 (25.7) |

| Surgery in the last 30 days (N = 756), n (%) | 53 (13.7) | 37 (10.1) | 90 (11.9) |

| Days between first new symptom caused by S. aureus and randomisation,a median (IQR) | 4 (3–6) | 4 (3–6) | 4 (3–6) |

| Days between drawing of first positive blood culture and randomisation,a median (IQR) | 3 (2–3) | 3 (2–4) | 3 (2–3) |

| Hours of active antibiotic therapy before randomisation, median (IQR) | 63 (42–75) | 60 (41–76) | 62 (42–75) |

| Blood culture positive at randomisation, n (%) | 69/326 (21.2) | 88/316 (27.8) | 157/642 (24.5) |

| Factor | Treatment group, n (%) | Total (N = 758),a n (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Placebo (N = 388) | Rifampicin (N = 370)a | ||

| Mode of acquisition of infectiona | |||

| Community acquired | 240 (61.9) | 245 (66.2) | 485 (64.0) |

| Nosocomial infection (onset ≥ 48 hours after admission) | 76 (19.6) | 56 (15.1) | 132 (17.4) |

| Health-care associated (all other) | 72 (18.6) | 68 (18.4) | 140 (18.5) |

| MRSA | 21 (5.4) | 26 (7.0) | 47 (6.2) |

| Rifampicin-resistant infection at randomisation (N = 750)b | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Main focus/foci of infectiona,c | |||

| Native heart valve | 16 (4.1) | 17 (4.6) | 33 (4.4) |

| Native joint | 34 (8.8) | 29 (7.8) | 63 (8.3) |

| Prosthetic heart valve/jointd | 5 (1.3) | 9 (2.4) | 14 (1.8) |

| Implanted vascular device (other than i.v. catheter) | 23 (5.9) | 13 (3.5) | 36 (4.7) |

| Deep tissue infection/abscess | 94 (24.2) | 82 (22.2) | 176 (23.2) |

| Central or peripheral i.v. catheter | 67 (17.3) | 63 (17.0) | 130 (17.2) |

| Skin/soft tissue (excluding wounds) | 66 (17.0) | 72 (19.5) | 138 (18.2) |

| Surgical wound | 15 (3.9) | 10 (2.7) | 25 (3.3) |

| Pneumonia or urinary tract infection | 30 (7.7) | 30 (8.1) | 60 (7.9) |

| Not established | 67 (17.3) | 72 (19.5) | 139 (18.3) |

| Any deep-seated focuse | 159 (41.0) | 142 (38.4) | 301 (39.7) |

| Likely portal of entry of S. aureus into the bloodstreamc | |||

| Clinically apparent skin or soft tissue infection unrelated to a surgical intervention | 131 (33.8) | 124 (33.5) | 255 (33.6) |

| Infected surgical wound within last 3 months, with or without associated prosthesis | 19 (4.9) | 19 (5.1) | 38 (5.0) |

| Peripheral vascular catheter (including arterial line) | 23 (5.9) | 26 (7.0) | 49 (6.5) |

| Central vascular catheter (including PICC line) | 50 (12.9) | 42 (11.4) | 92 (12.1) |

| Other implanted vascular device (e.g. pacemaker, stent, graft) | 15 (3.9) | 12 (3.2) | 27 (3.6) |

| Respiratory | 16 (4.1) | 13 (3.5) | 29 (3.8) |

| Per-urethral or suprapubic urinary catheter | 7 (1.8) | 8 (2.2) | 15 (2.0) |

| Recent (within 1 week of bacteraemia) urological surgery | 1 (0.3) | 3 (0.8) | 4 (0.5) |

| Not known (absence of any of the above) | 110 (28.4) | 108 (29.2) | 218 (28.8) |

| Injecting drug user | 8 (2.1) | 9 (2.4) | 17 (2.2) |

| Corticosteroid injection into joint | 4 (1.0) | 2 (0.5) | 6 (0.8) |

| Other | 2 (0.5) | 3 (0.8) | 5 (0.7) |

| Not completed (missing data) | 2 (0.5) | 1 (0.3) | 3 (0.4) |

A total of 495 (65.3%) participants were men (see Table 1). The median age was 65 years (IQR 50–76 years), median weight was 76.0 kg (IQR 64.0–90.0 kg) and the median Charlson Comorbidity Index score was 2 (IQR 0–3). Diabetes (30.1%), renal disease (18.2%), cancer (16.6%) and chronic lung disease (11.9%) were all common comorbidities. A total of 83 (10.9%) participants were active injecting drug users, 70 (9.2%) participants were in an ICU, 90 (11.9%) participants had undergone surgery in the past 30 days, and 127 (16.8%) participants had consent provided by a legal representative because of incapacity. Reflecting disease severity, mean CRP level was 164 mg/l [standard error (SE) 3.7 mg/l] and a median Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA) score was 2 points (IQR 1–4 points).

At randomisation, participants had already received a median of 62 hours (IQR 42–75 hours) of active antibiotics, with their first blood culture taken a median of 3 days (IQR 2–3 days) previously and their first symptoms occurring a median of 4 days (IQR 3–6 days) previously. A total of 157 out of 642 (24.5%) participants still had a positive blood culture on the day of randomisation.

A total of 485 (64.0%) infections were community acquired, with only 132 (17.4%) infections being nosocomial; 47 (6.2%) were caused by MRSA. No patients were known to have rifampicin-resistant S. aureus bacteraemia at randomisation.

The initial focus was deep in 301 (39.7%) patients, including 33 (4.4%) with endocarditis and 14 (1.8%) with infected prostheses. A total of 130 (17.2%) infections were due to infected central/peripheral lines, and 138 (18.2%) were associated with skin/soft tissue infections. Another type of focus was identified in 49 (6.5%) participants and not established in 139 (18.3%) participants.

In 255 (33.6%) participants, the most likely portal of entry of S. aureus into the bloodstream was a clinically apparent skin or soft tissue infection unrelated to a surgical intervention. Central or peripheral lines were the most likely portal of entry in 141 (18.6%) participants, although 191 (25.7%) had a vascular catheter in situ at randomisation. For 218 (18.6%) participants, the portal of entry was unknown.

Follow-up and treatment received

Overall, completeness of scheduled visits was high up to 14 days. Excluding visits after death or discharge, day 3 visits were missed in 10 out of 372 (2.7%) participants in the placebo group versus 12 out of 350 (3.4%) participants in the rifampicin group, day 7 visits were missed in 15 out of 337 (4.5%) participants in the placebo group versus 16 out of 311 (5.1%) participants in the rifampicin group, day 10 visits were missed in 22 out of 293 (7.5%) participants in the placebo group versus 26 out of 262 (9.9%) participants in the rifampicin group, and day 14 visits were missed in 9 out of 230 (3.9%) participants in the placebo group versus 13 out of 204 (6.4%) participants in the rifampicin group. Completeness dropped after 14 days when patients started to be discharged, for example visits were missed in 21 out of 149 (14.1%) participants in the placebo group versus 19 out of 134 (14.2%) participants in the rifampicin group at day 21, 23 out of 115 (20.0%) participants in the placebo group versus 23 out of 93 (24.7%) participants in the rifampicin group at day 28, and 25 out of 89 (28.1%) participants in the placebo group versus 19 out of 58 (32.8%) participants in the rifampicin group at day 35.

A total of 22 (2.9%) participants withdrew consent. At the 12-week visit, only 39 (5.1%) participants had unknown vital status and 65 (8.6%) were not assessed for signs/symptoms of S. aureus infection (including consent withdrawals).

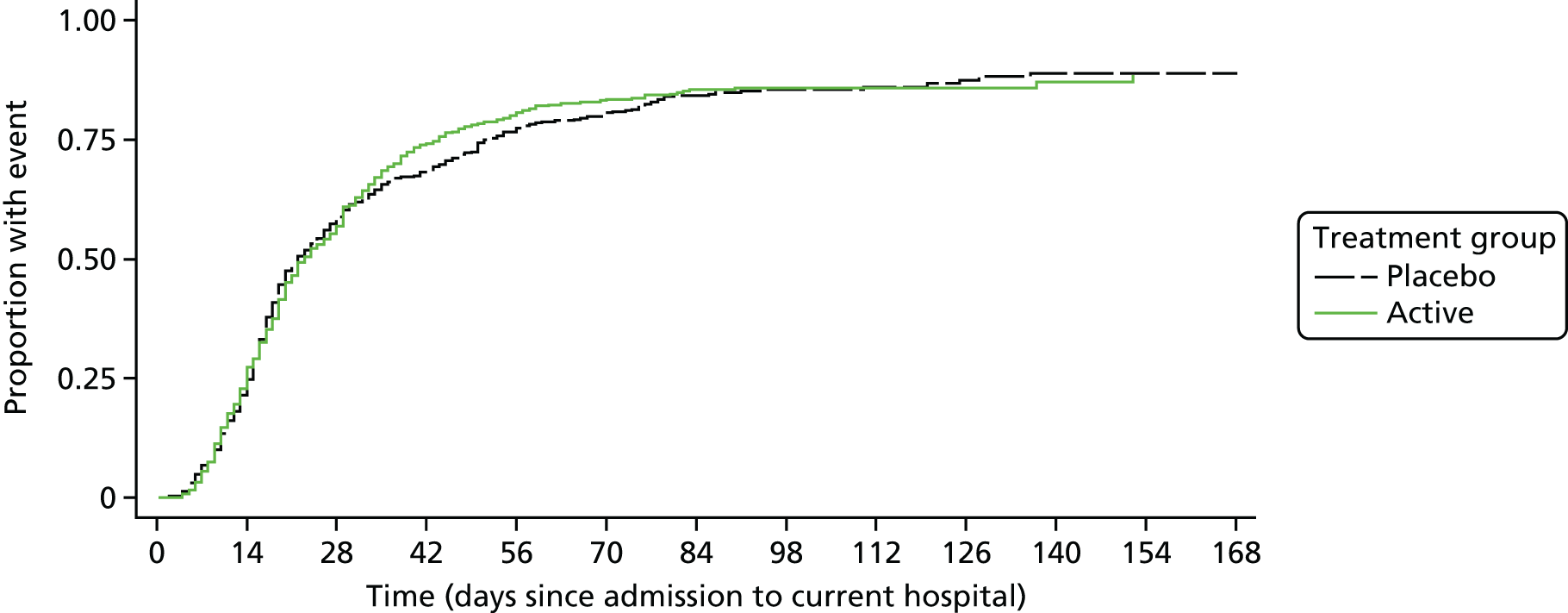

A total of 23 (3.0%) participants were still in hospital at 12 weeks [15 (3.9%) participants in the placebo group vs. 8 (2.2%) participants in the rifampicin group; p = 0.17). The median initial hospitalisation duration was 21 days (IQR 14–50 days) versus 22 days (IQR 13–43 days) in placebo and rifampicin groups, respectively (p = 0.80) (Figure 3). A total of 132 (39.8%) participants in the placebo group versus 138 (44.8%) participants in the rifampicin group were discharged on outpatient parental antibiotic therapy (p = 0.35). A total of 94 (24.2%) participants in the placebo group versus 83 (22.4%) participants in the rifampicin group were readmitted post discharge and before 12 weeks (p = 0.56), spending a median of 9 nights (IQR 4–20 nights) and 10 nights (IQR 3–20 nights) in hospital post original discharge, respectively. Any admission was considered relating to S. aureus bacteraemia in 16 (4.1%) participants in the placebo group and 9 (2.4%) participants in the rifampicin group (p = 0.19).

FIGURE 3.

Days from admission to current hospital to original post-randomisation discharge. p = 0.80 subhazard regression. Note: death treated as competing risk.

A total of 744 (98.2%) participants initiated blinded trial drug a median of 4.3 hours (IQR 2.3–7.8 hours) after randomisation. Reasons for not initiating blinded trial drug were patient decision (n = 7), increasing liver enzyme levels (n = 2), starting on open-label rifampicin (n = 2), withdrawn for palliation (n = 1), incorrectly believing that the bacteraemia was rifampicin resistant (n = 1) and unable to access i.v. trial drug from trials pharmacy at weekend (n = 1).

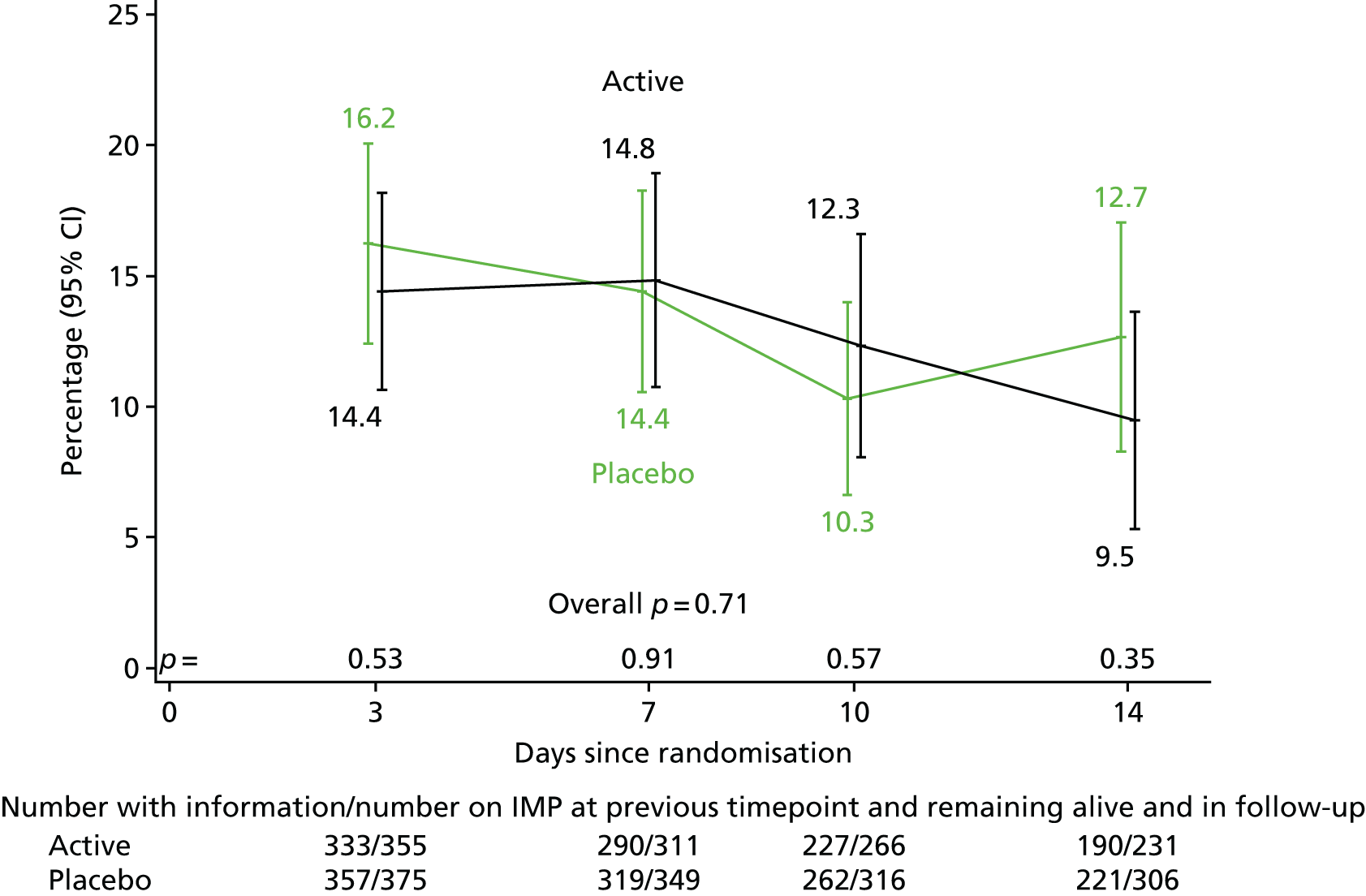

A total of 96 (12.7%) participants initiated i.v. trial drug rather than oral trial drug (Table 3). A total of 595 (78.5%) participants initiated 900 mg daily rather than 600 mg daily and 362 (52.2%) participants twice daily rather than once daily. The median dose was 11.1 mg/kg (IQR 10.0–12.9 mg/kg). The trial drug was initiated a median of 68 hours (IQR 48–85 hours) after starting active antibiotics for the current infection. The trial drug was continued for a median of 12.6 days (IQR 6.0–13.2 days) for participants in the rifampicin group versus 13.0 days (IQR 11.3–13.5 days) in participants in the placebo group (p < 0.0001; discontinuations primarily because of antibiotic-modifying AEs and drug–drug interactions, see Safety). A total of 60 (15.5%) participants in the placebo group versus 51 (15.6%) participants in the rifampicin group received the i.v. trial drug. Percentages reporting missing any doses of trial drug ranged from 9.5% to 16.2% but did not differ between randomised groups (Figure 4; global p = 0.71).

| Factor | Treatment group | Total (N = 758) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Placebo (N = 388) | Rifampicin (N = 370) | ||

| Never initiated trial drug, n (%) | 8 (2.1) | 6 (1.6) | 14 (1.8) |

| Initiated i.v. trial drug, n (%) | 51 (13.1) | 45 (12.2) | 96 (12.7) |

| Initiated oral trial drug, n (%) | 329 (84.8) | 319 (86.2) | 648 (85.5) |

| Initiated trial drug once daily, n (%) | 175 (45.1) | 173 (46.8) | 348 (45.9) |

| Initiated trial drug twice daily, n (%) | 205 (52.8) | 191 (51.6) | 396 (52.2) |

| Initiated 600 mg of trial drug daily, n (%) | 74 (19.1) | 75 (20.3) | 149 (19.7) |

| Initiated 900 mg of trial drug daily, n (%) | 306 (78.9) | 289 (78.1) | 595 (78.5) |

| Initial total daily dose (mg/kg) (N = 741), median (IQR) | 11.2 (9.9–12.9) | 11.0 (10.0–12.7) | 11.1 (10.0–12.9) |

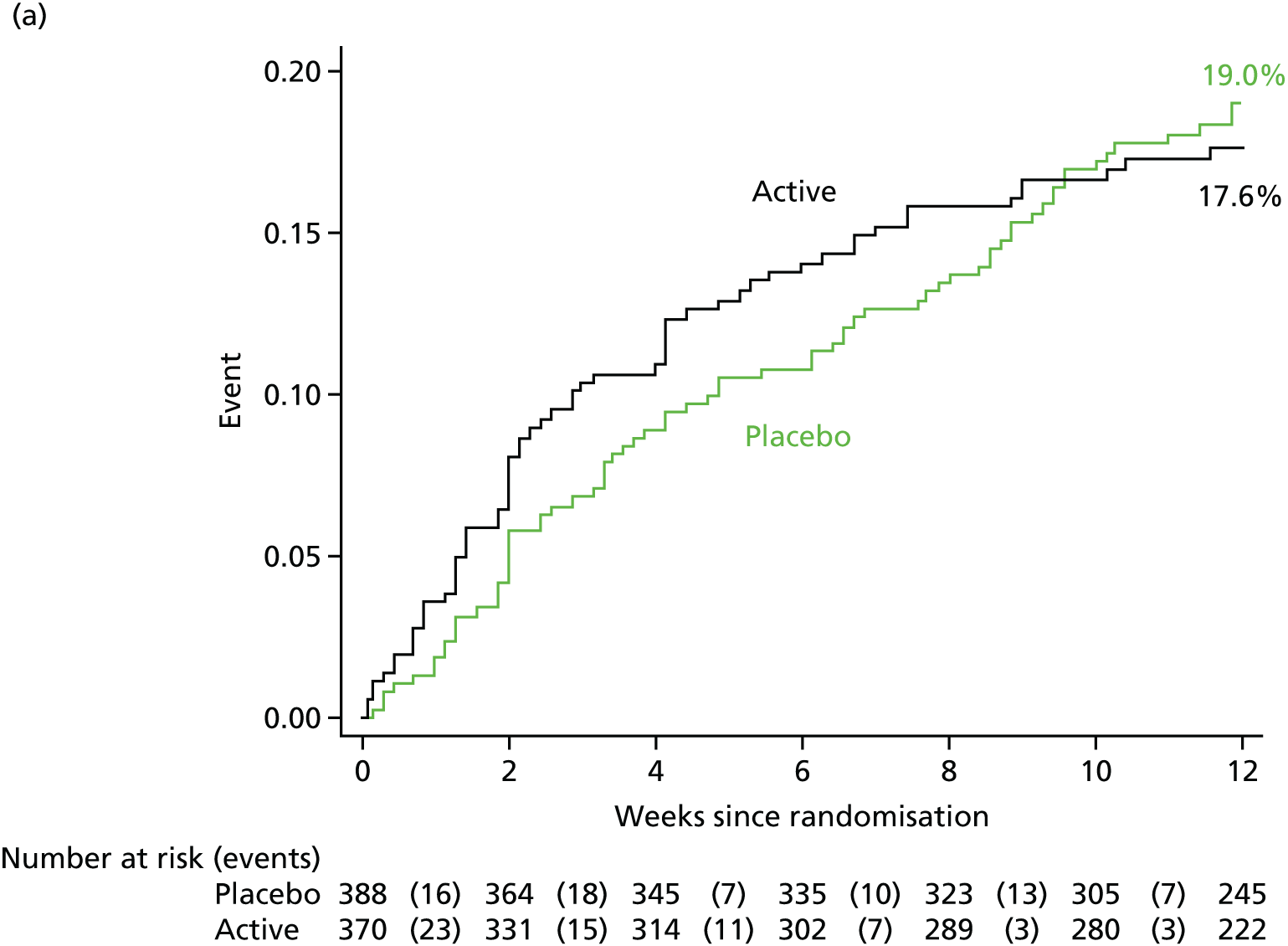

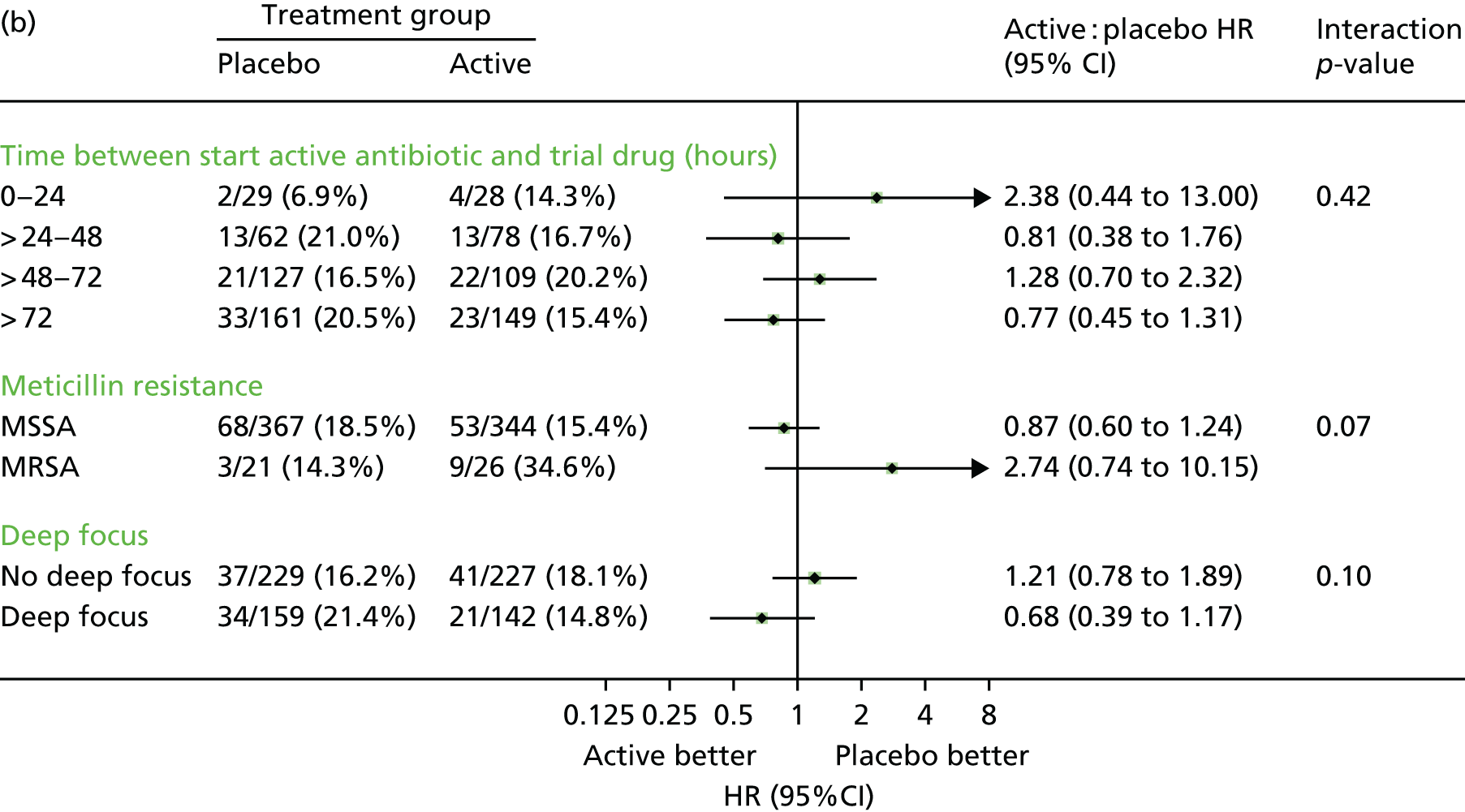

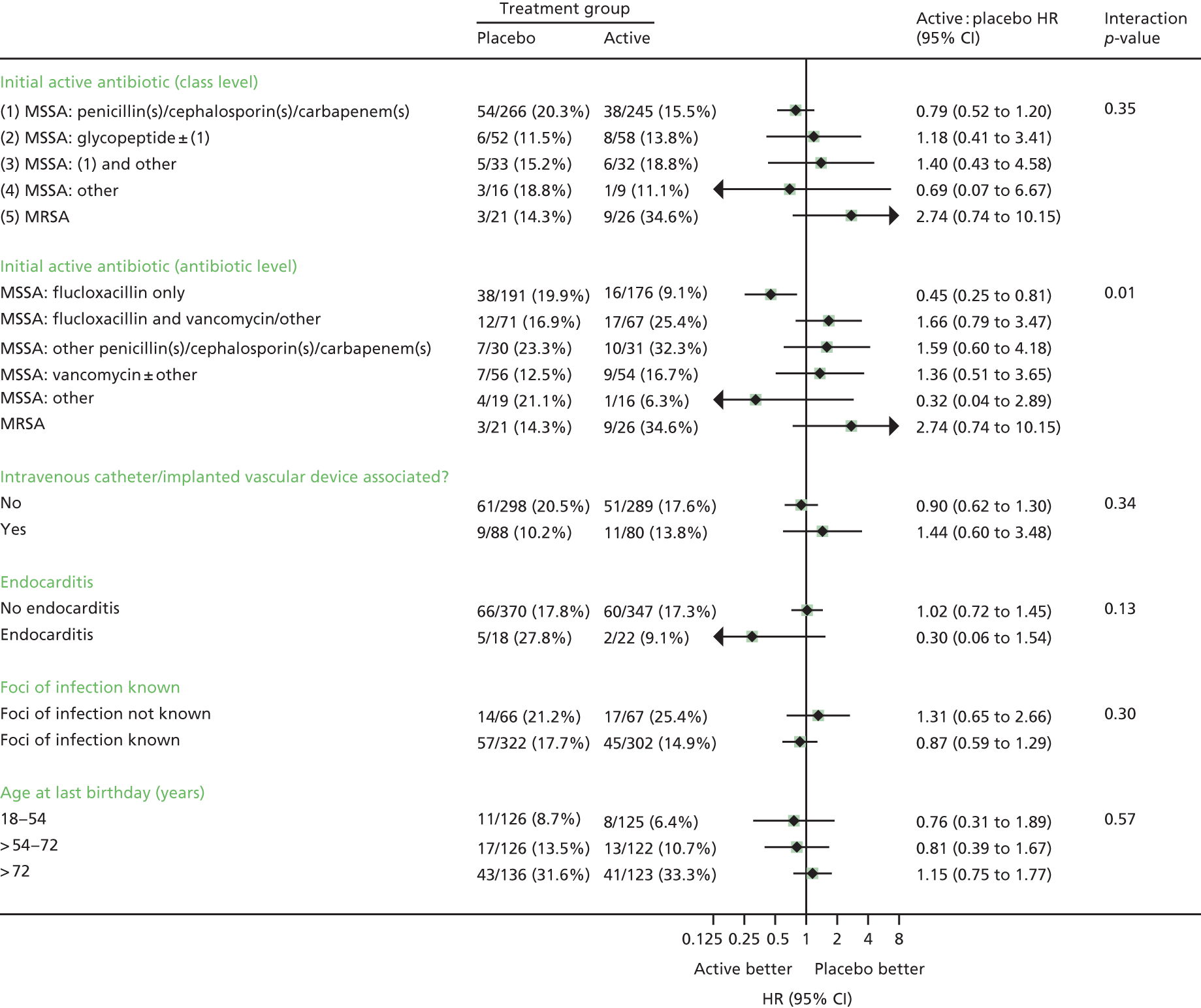

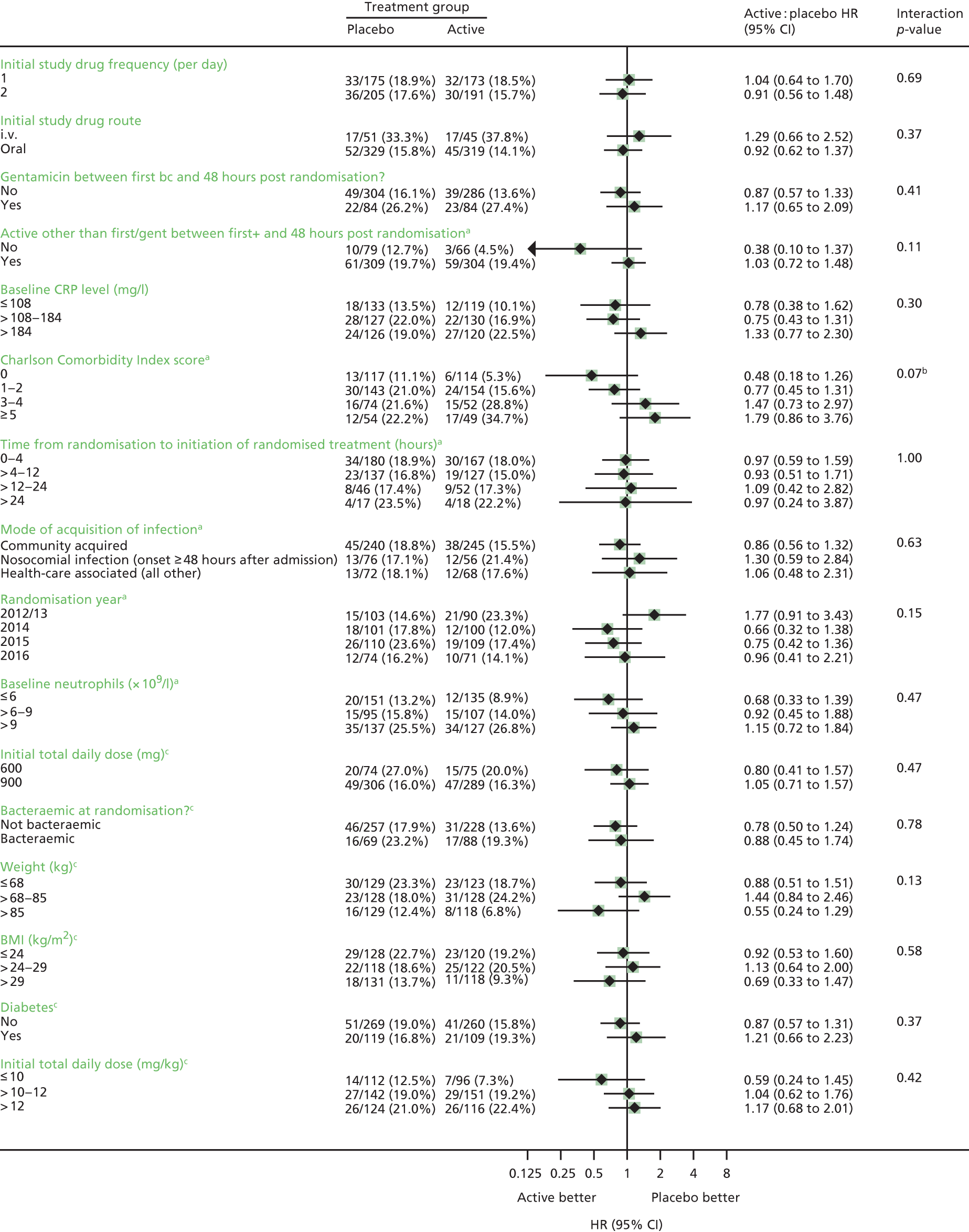

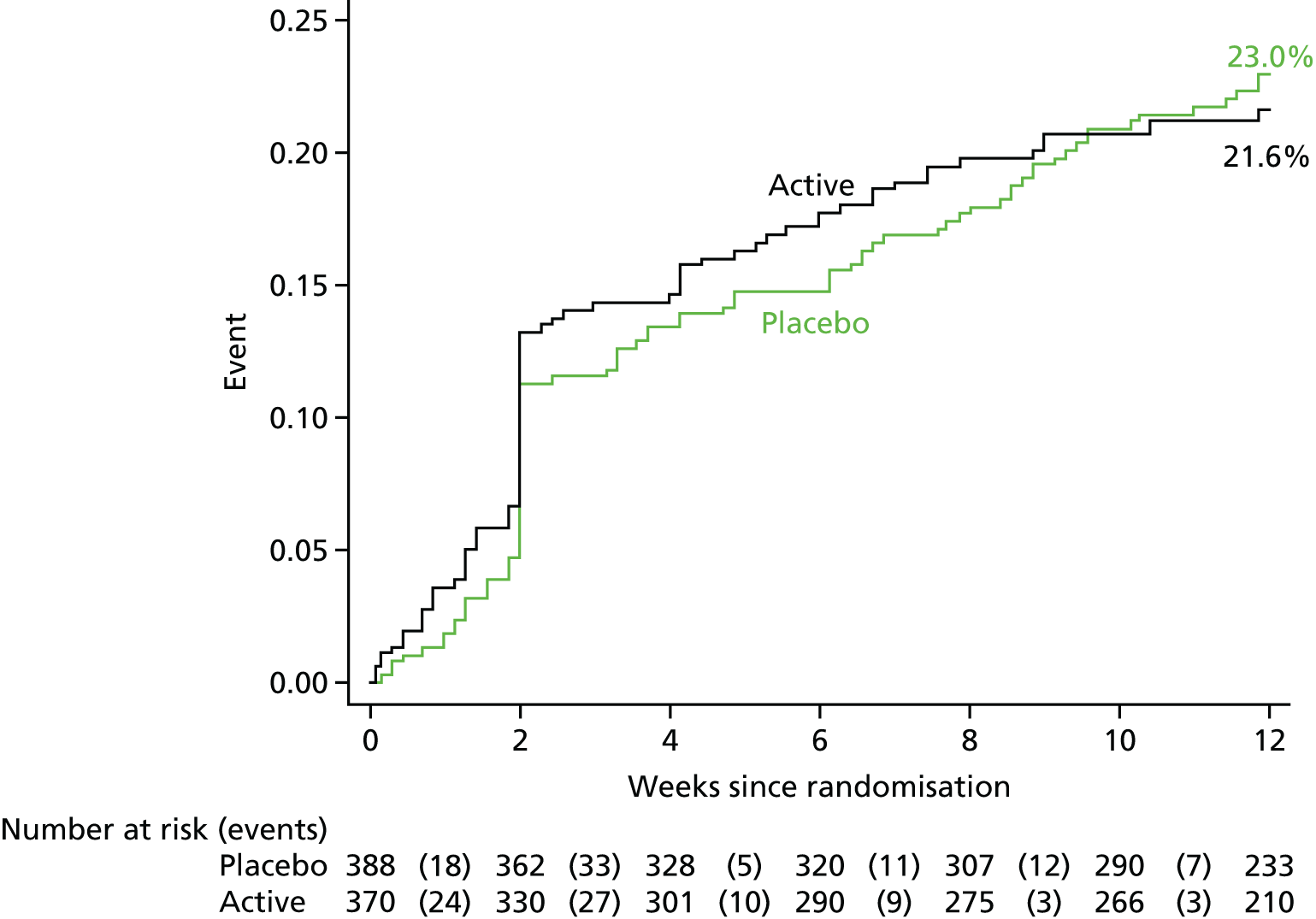

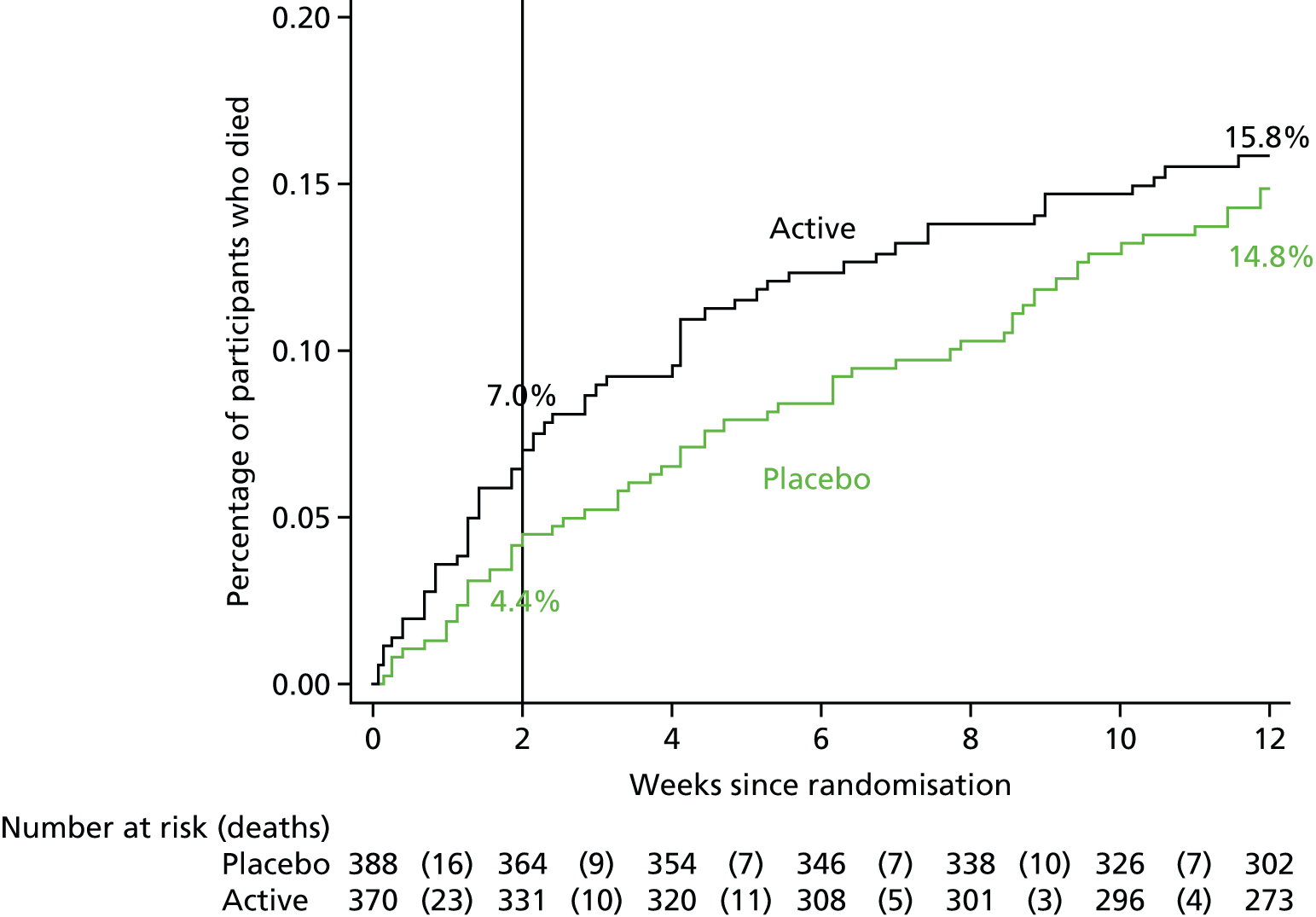

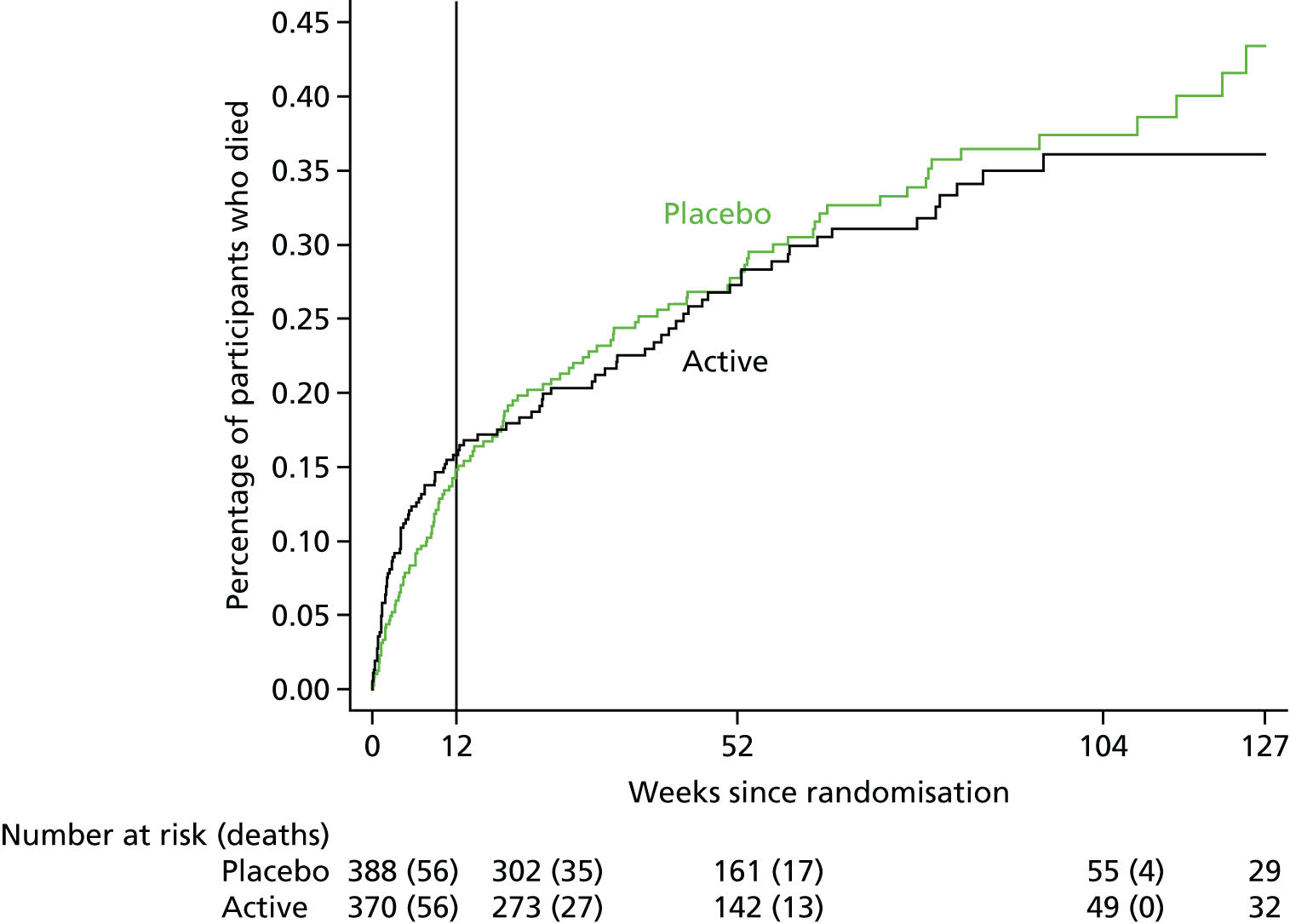

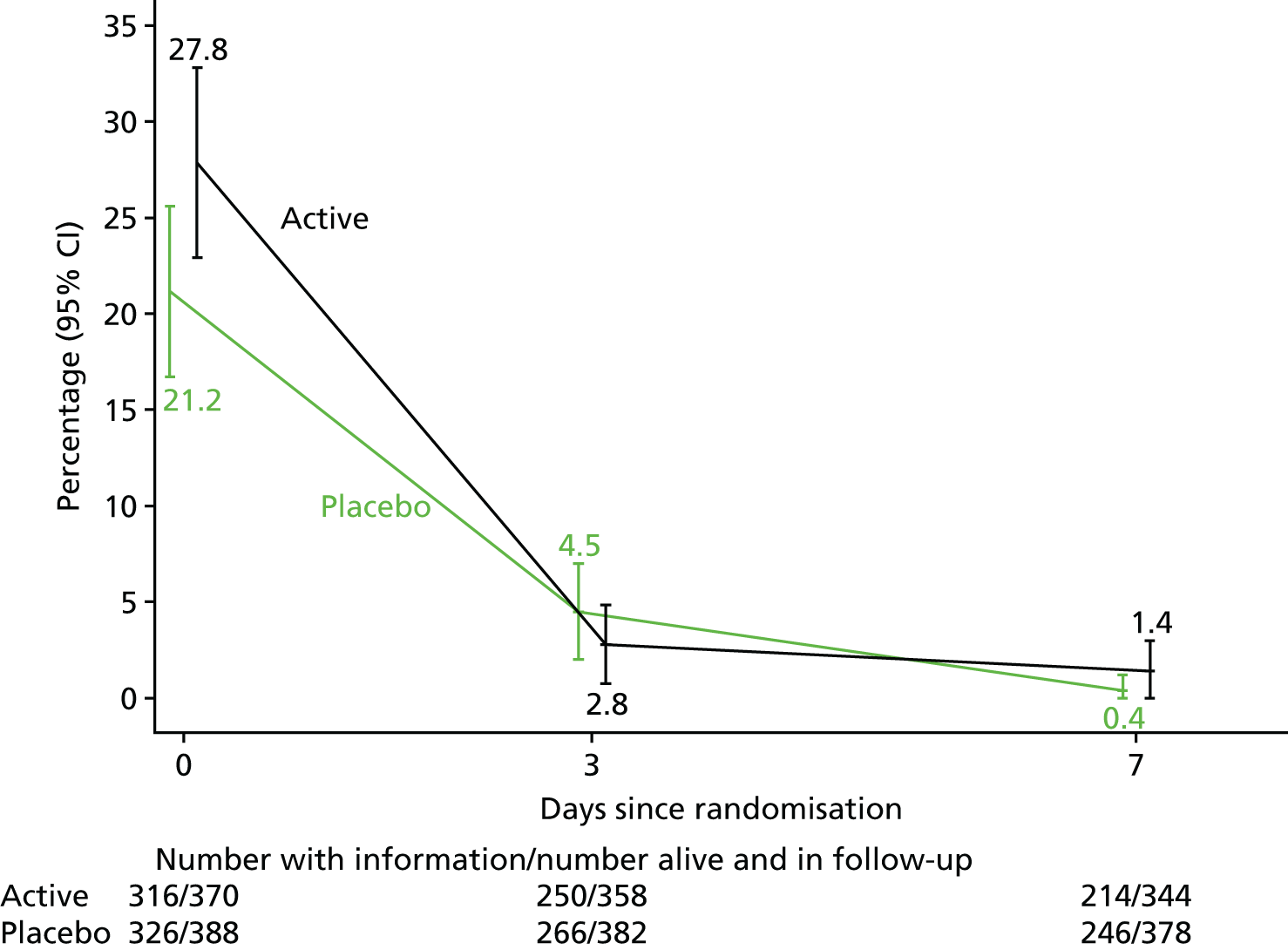

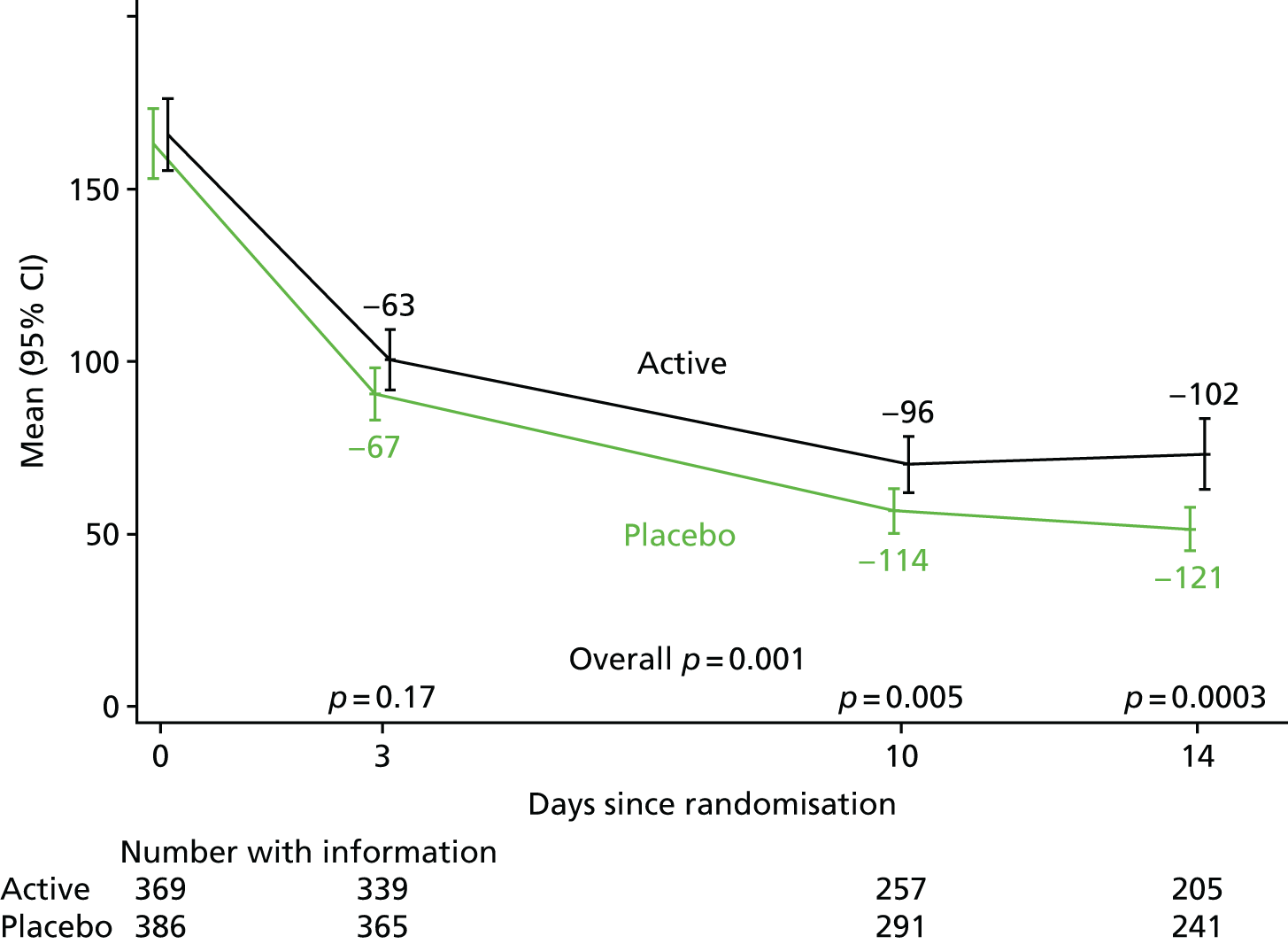

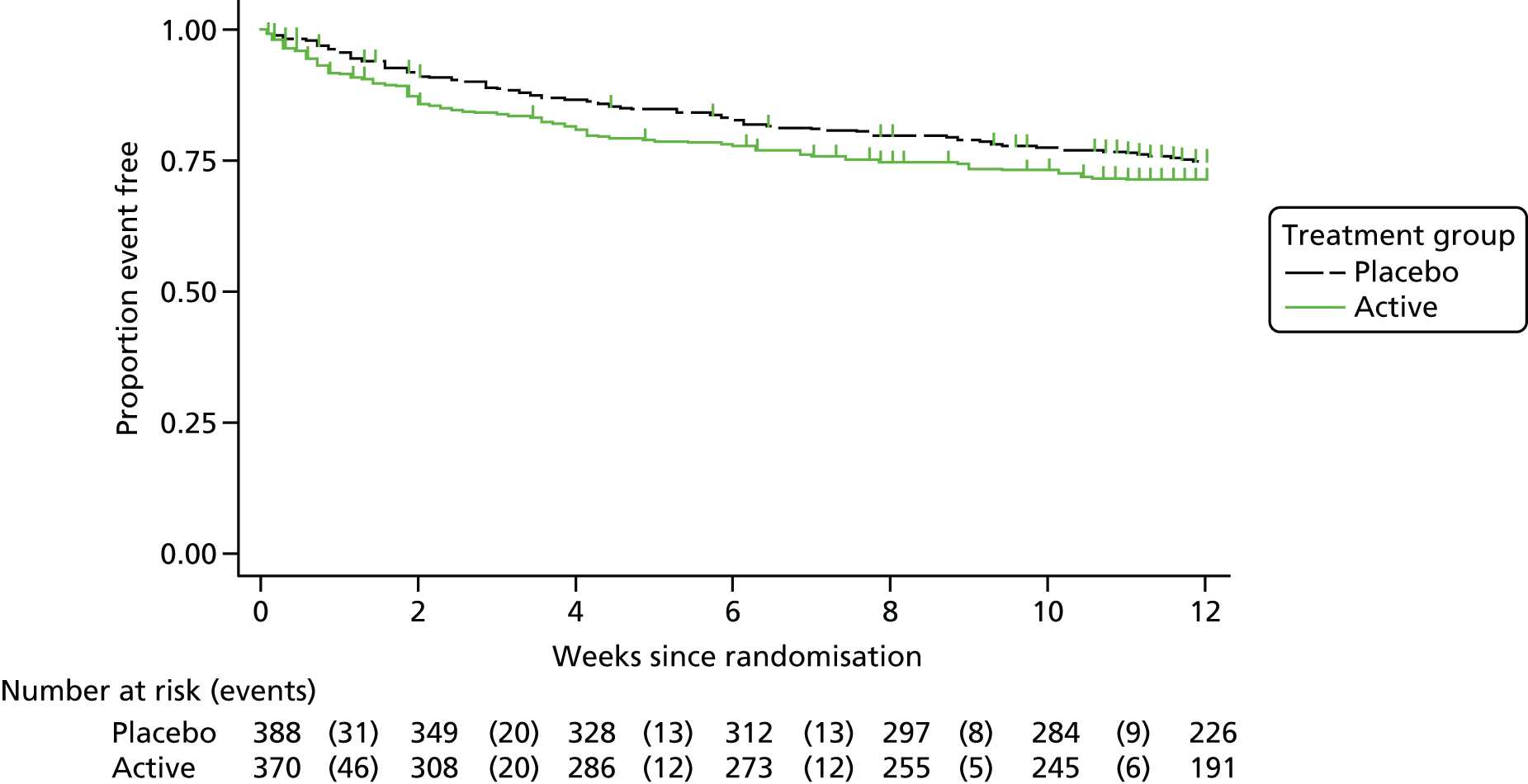

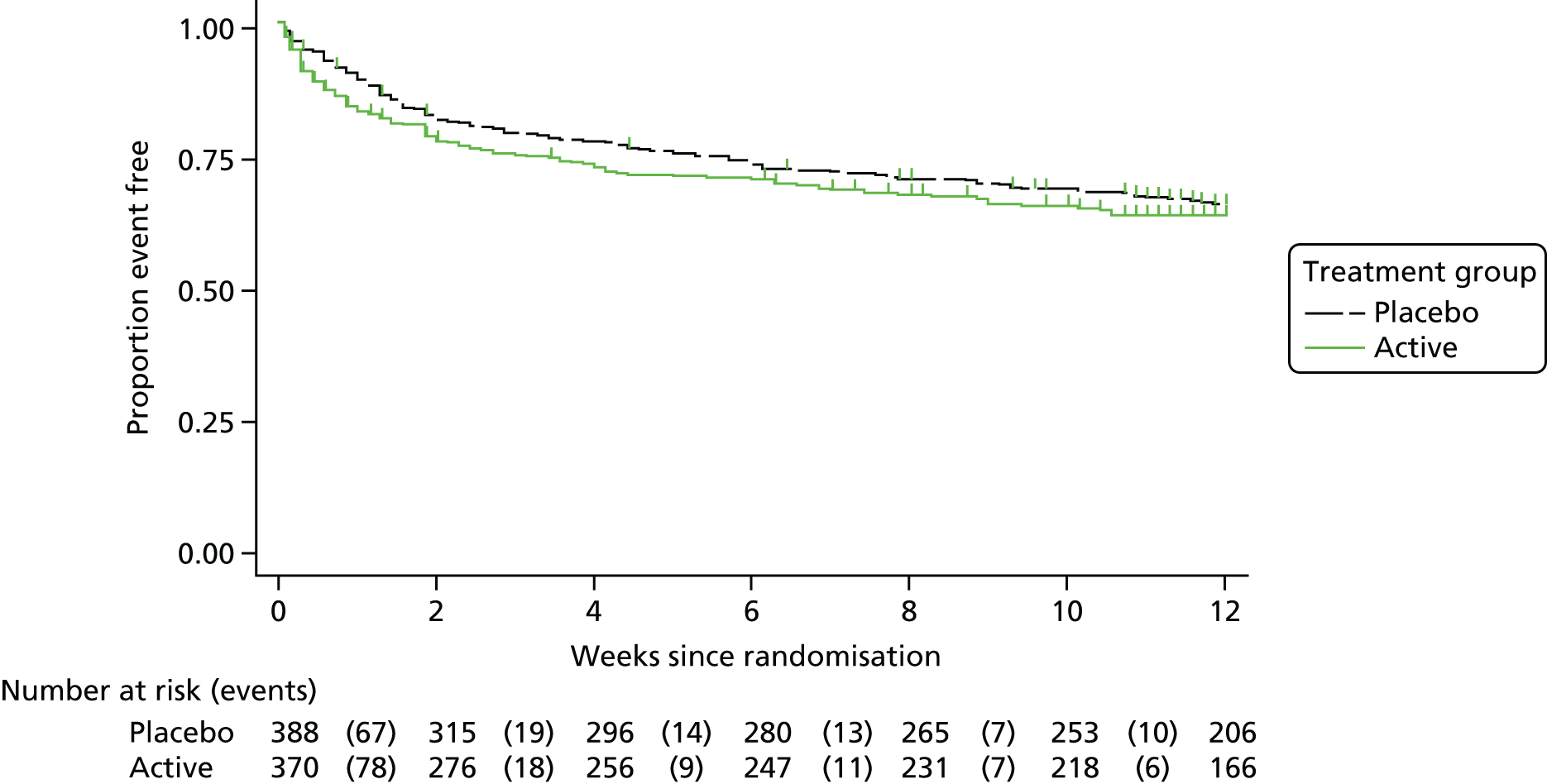

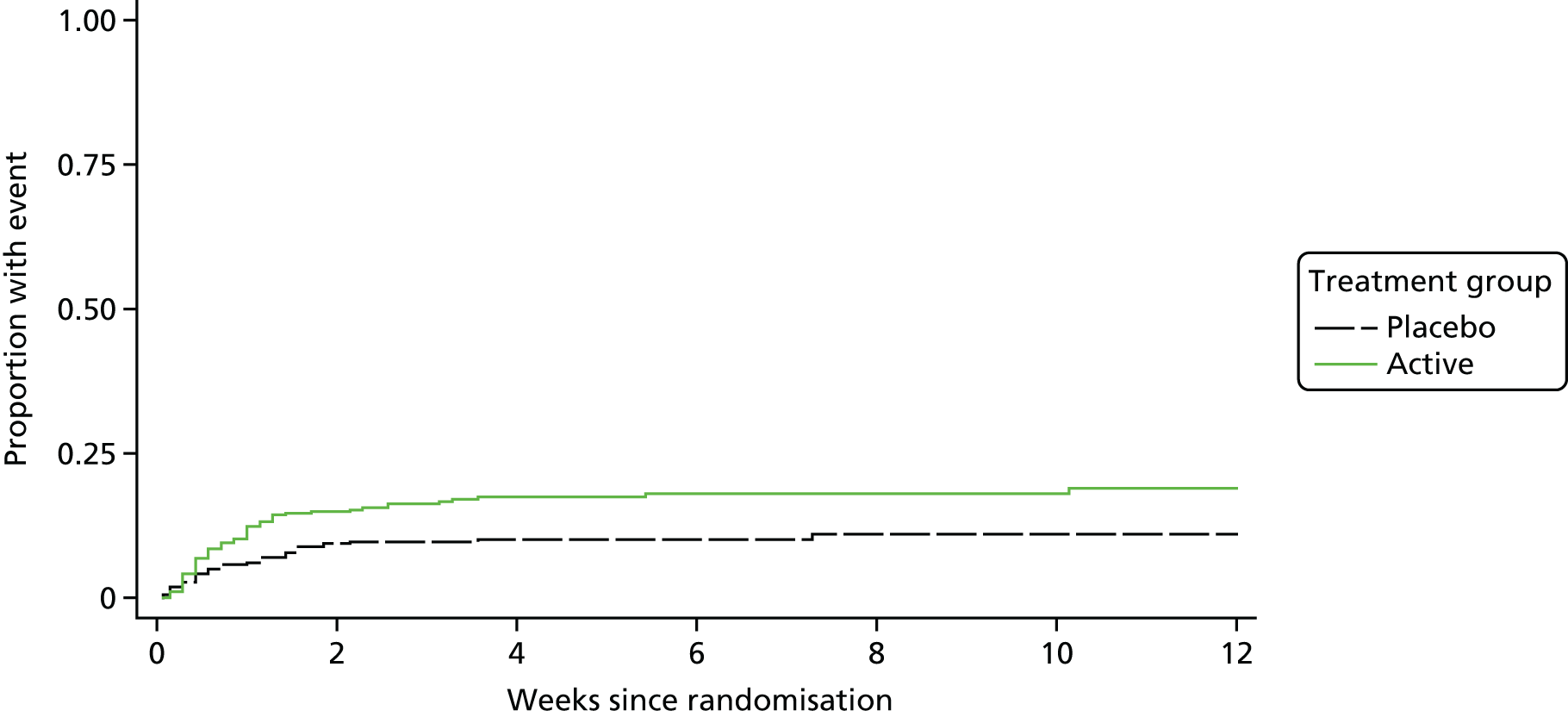

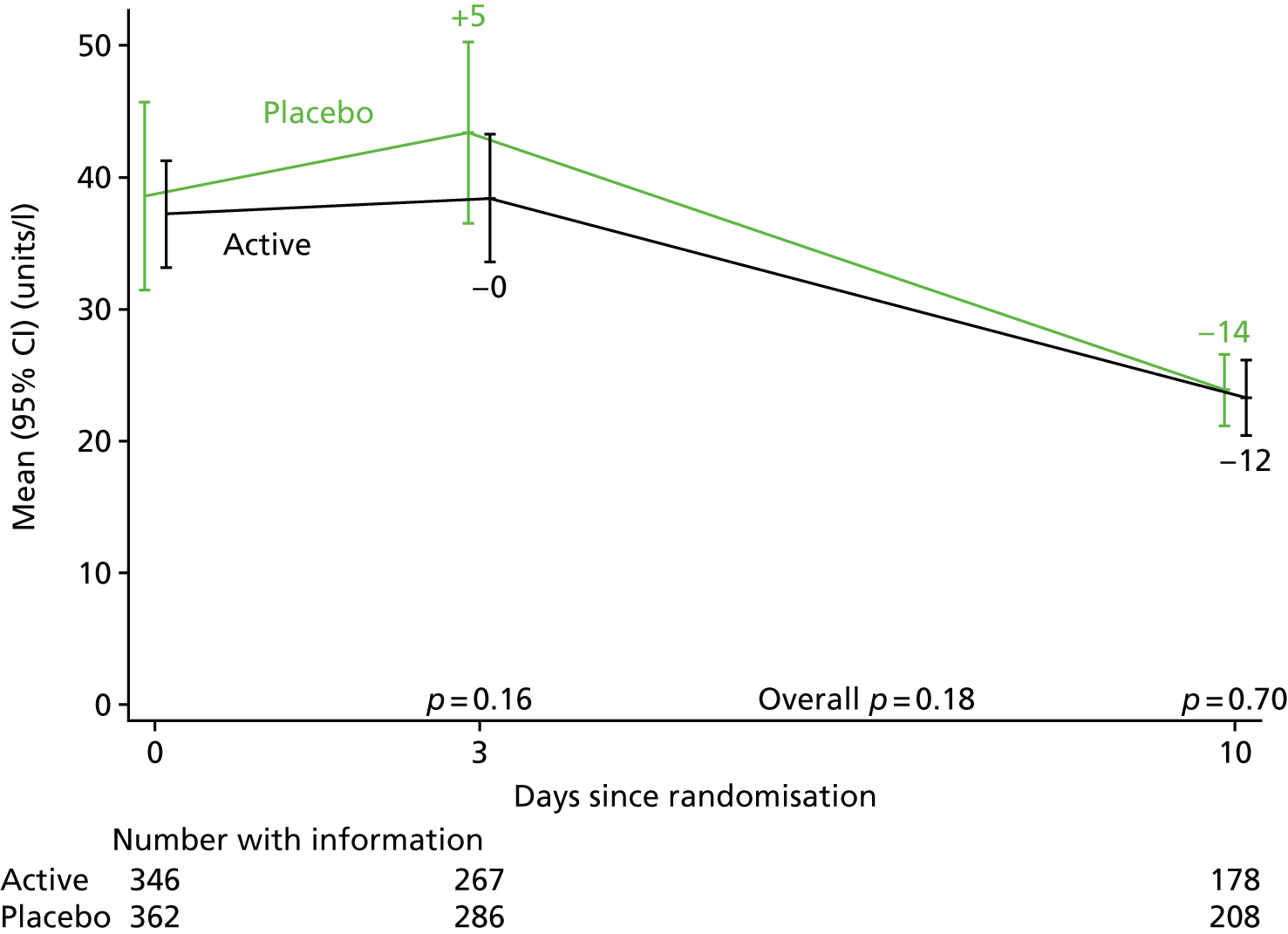

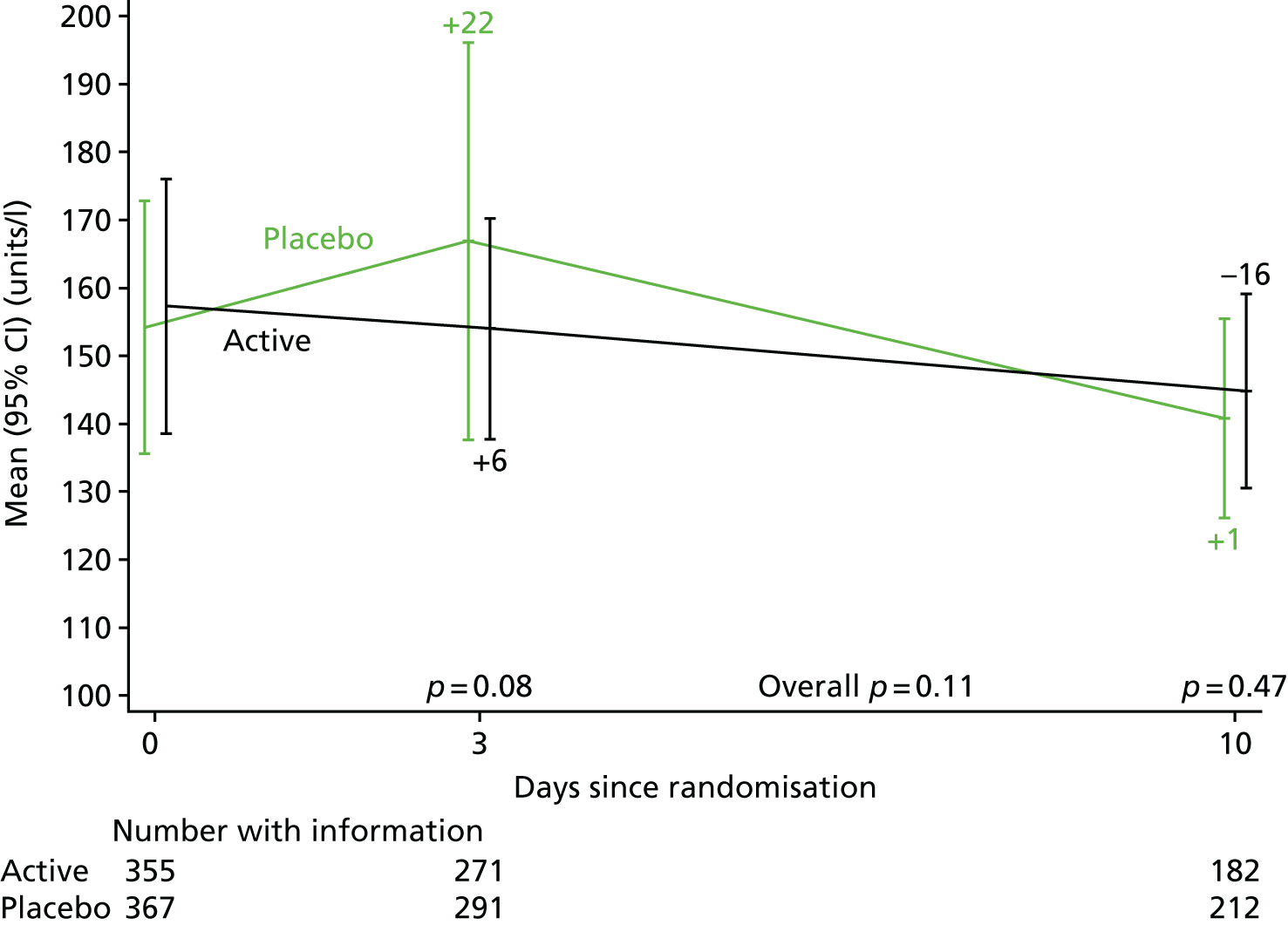

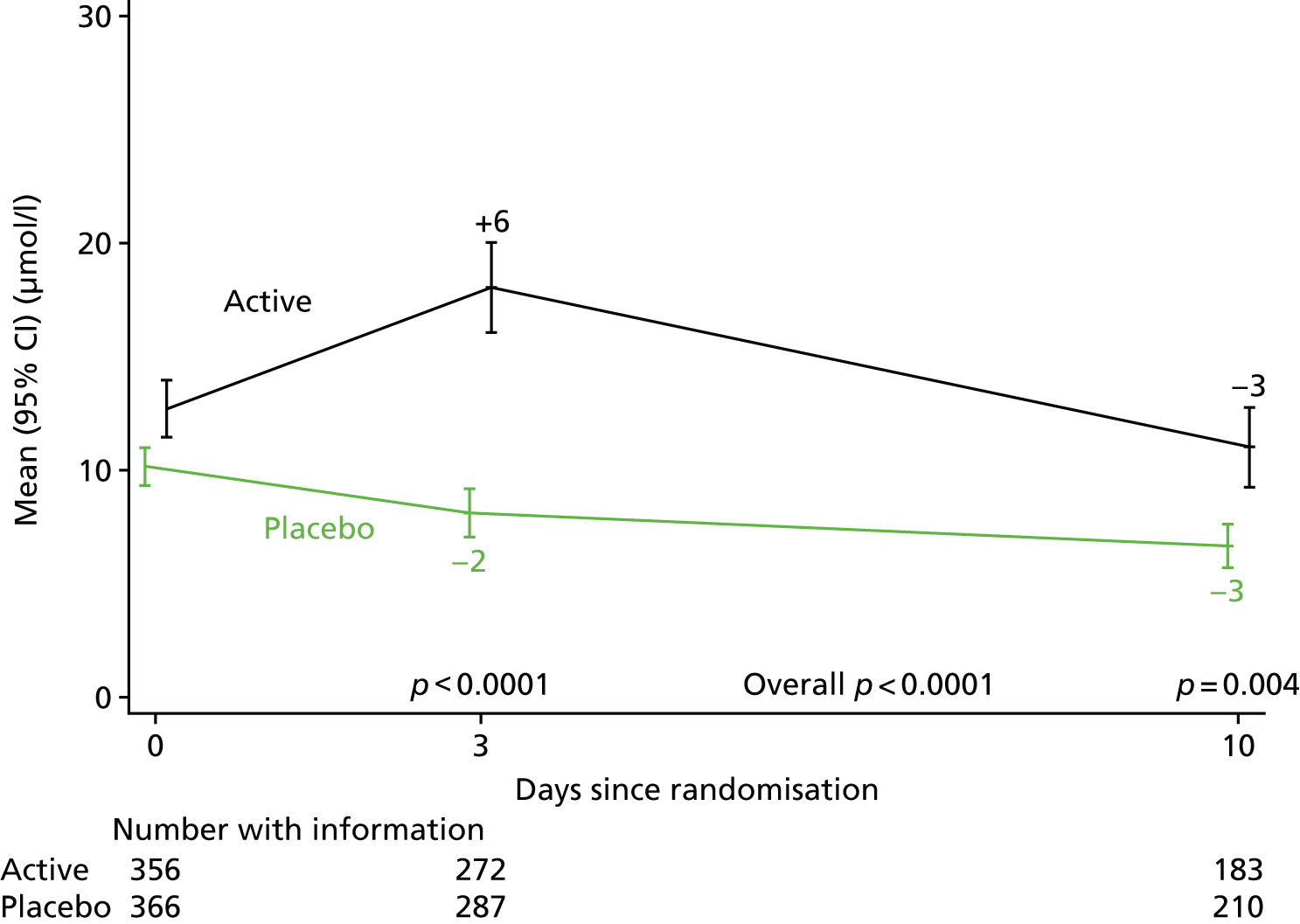

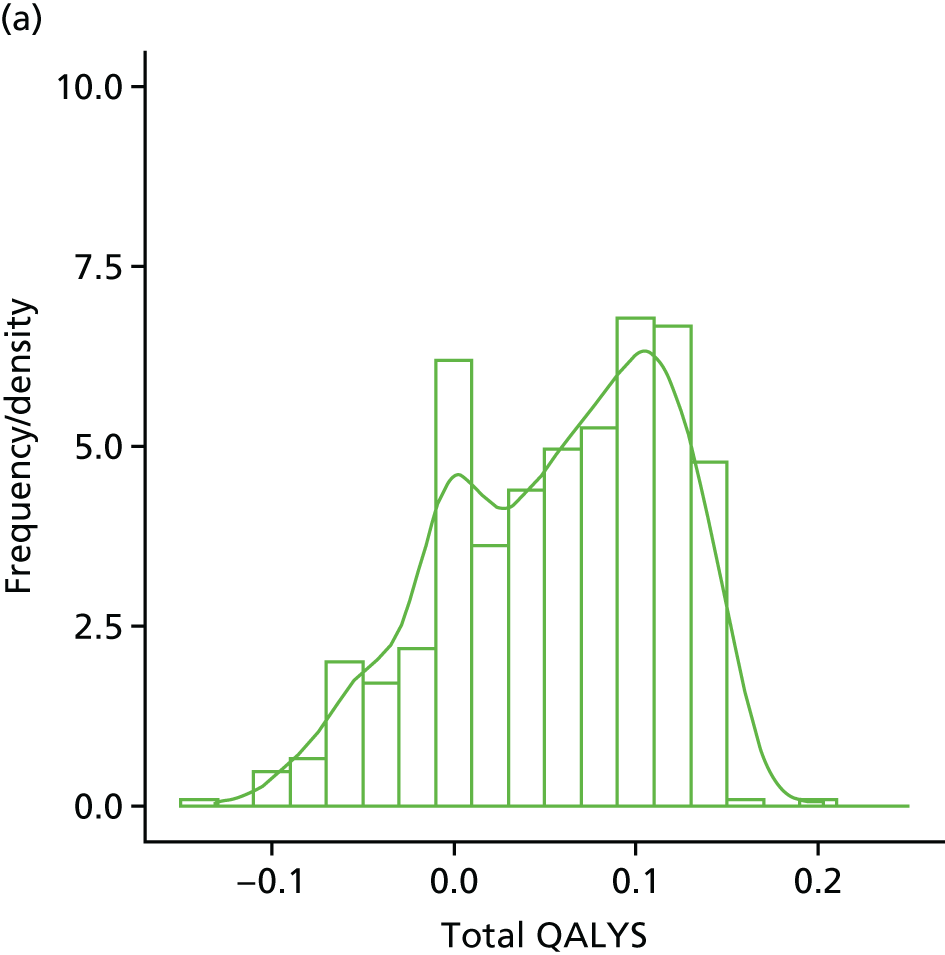

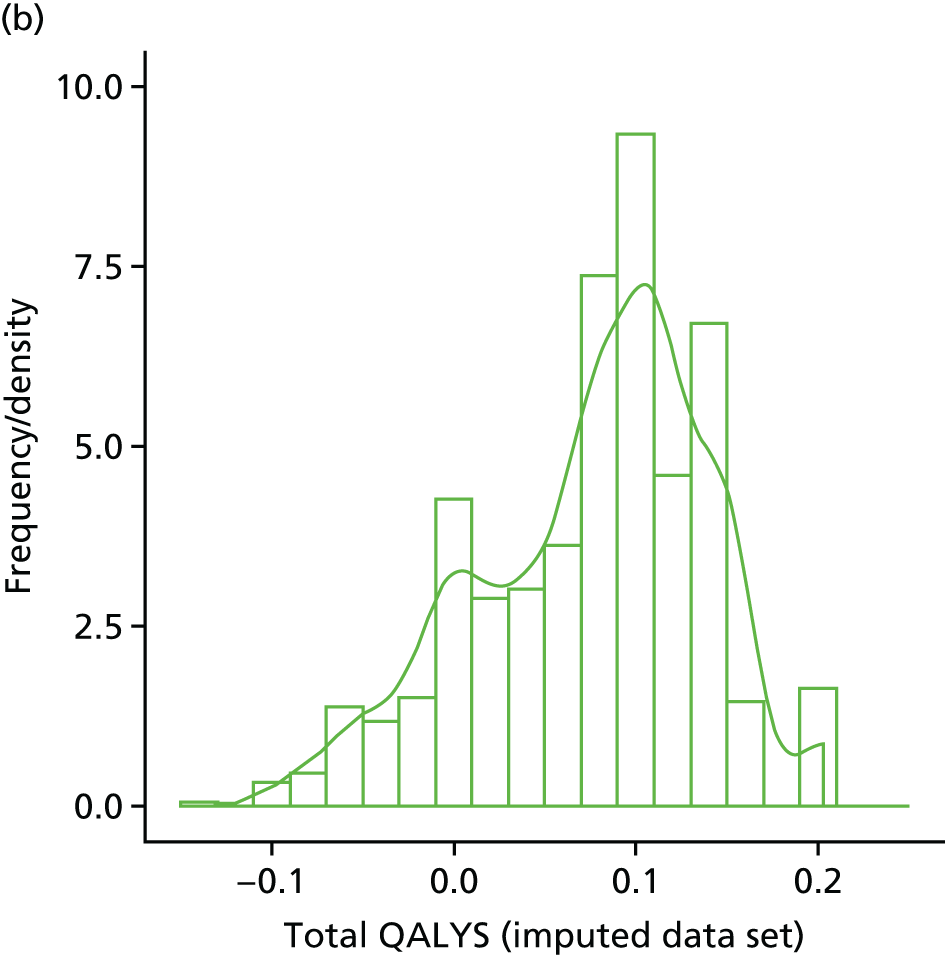

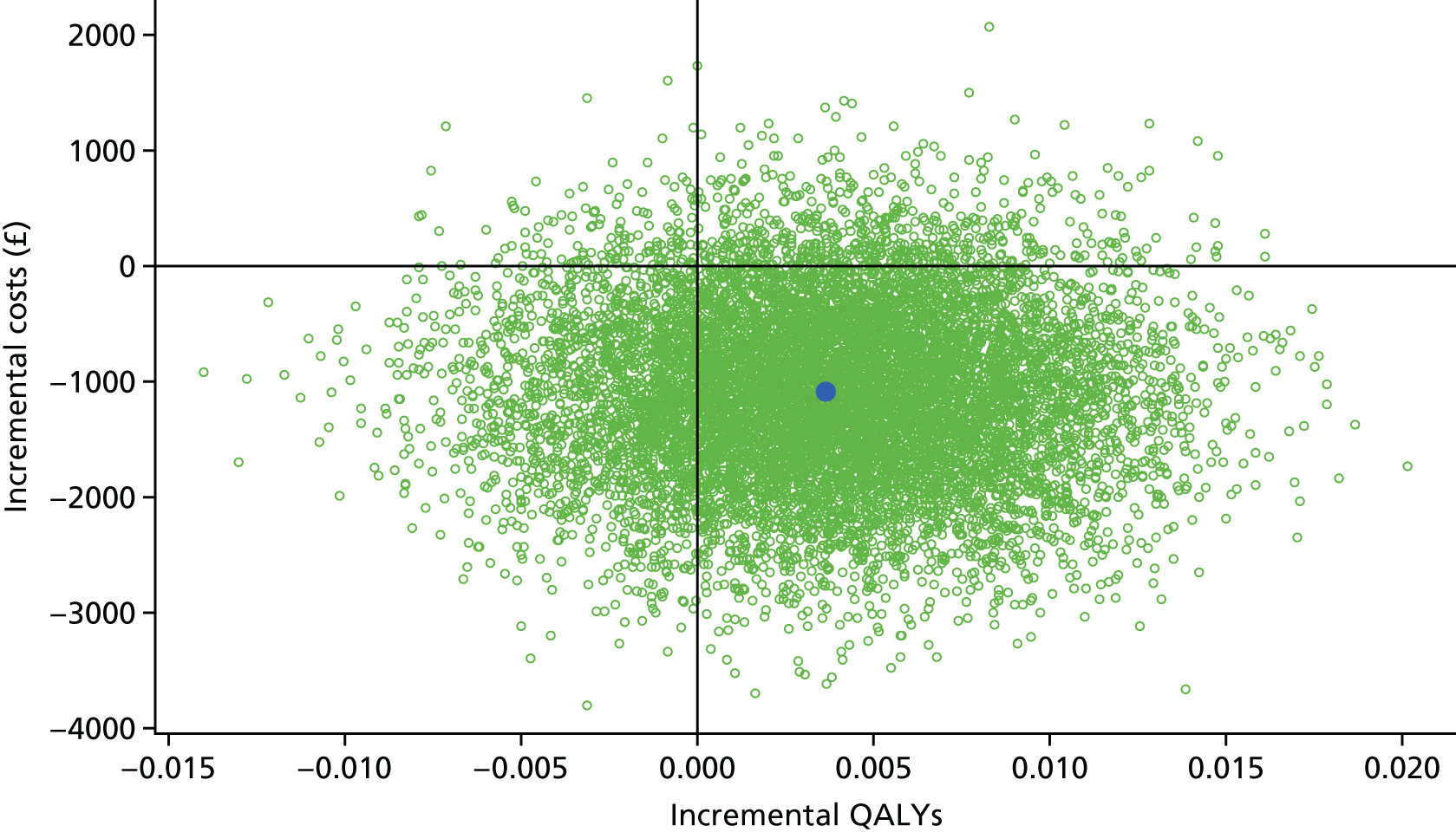

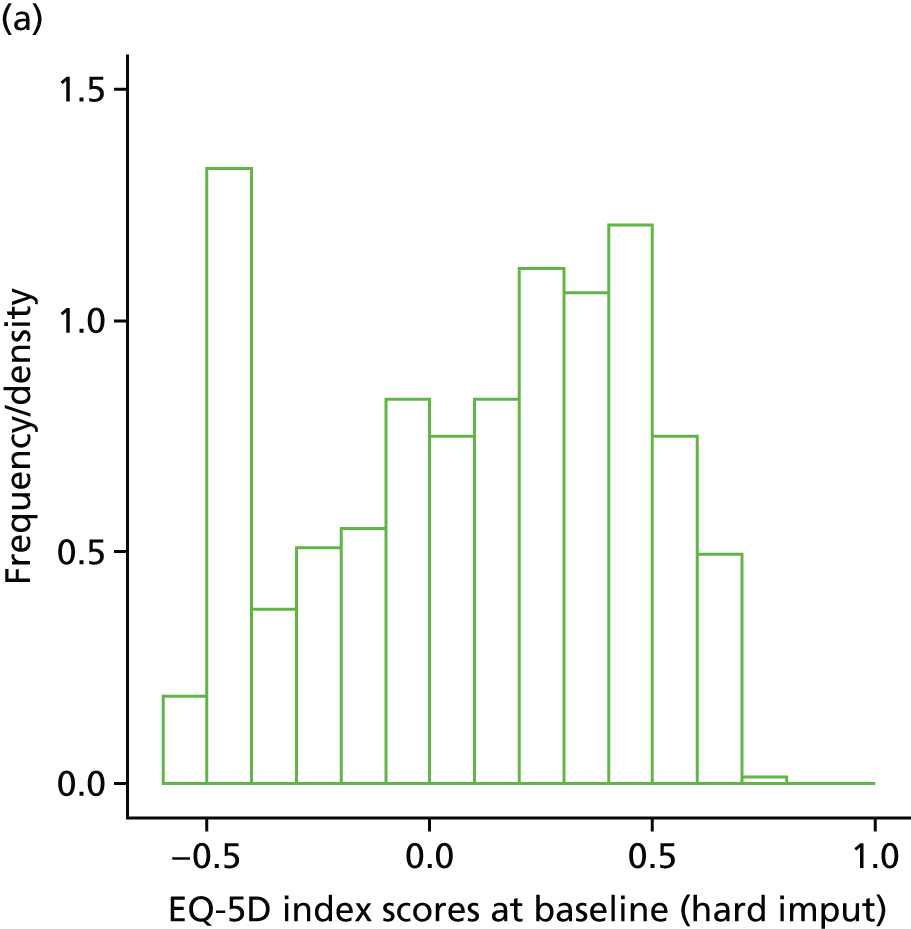

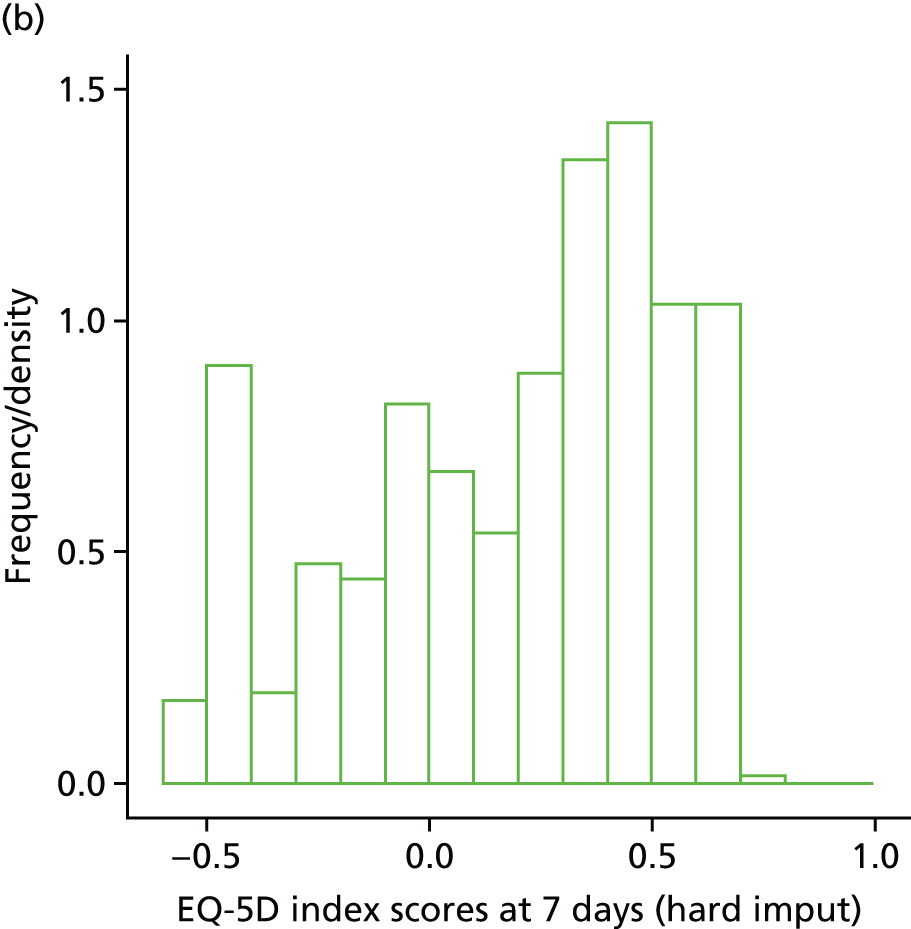

| Hours from starting active antibiotics to starting trial drug, median (IQR) | 69 (49–85) | 68 (46–85) | 68 (48–85) |