Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 14/212/02. The contractual start date was in February 2016. The draft report began editorial review in July 2017 and was accepted for publication in October 2017. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Bryony Beresford and Megan Thomas were authors of primary studies that are included in this review. Catriona McDaid is a member of the National Institute for Health Research Health Technology Assessment (HTA) and Efficacy and Mechanism Evaluation Editorial Board. Catherine Hewitt is a member of the HTA Commissioning Board.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2018. This work was produced by Beresford et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2018 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Background

Introduction

This project was undertaken in response to a commissioning brief from the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Health Technology Assessment (HTA) programme. The call was for a systematic review to address the question of which interventions – pharmacological and non-pharmacological – are clinically effective for non-respiratory sleep disturbances in children with neurodisabilities (NDs) and which have generalisable, as opposed to disorder-specific, effects. The brief requested a broad systematic review to ‘take stock’ of the current evidence that is available on what works and for whom and to identify promising interventions for future primary research. The following two sections describe the definitions used to identify the scope of the review; we then move on to discuss, specifically, the issue of sleep disturbance in children with NDs.

Sleep disturbance

Sleep has been described as an active ‘restorative process’1 and is essential for optimal physical and mental functioning and well-being. It is a complex process: the timing, duration and quality of sleep is the outcome of the interplay of biological processes, socioenvironmental influences and behaviours. As a result, there is a wide range of reasons why an individual’s sleep may be affected in some way and, for children with NDs, the cause may be multifactorial. 2–9

The International Classification of Sleep Disorders – Third Edition (ICSD-3)10 lists the current diagnostic categorisation of sleep disorders as follows: insomnia, sleep-related breathing disorders, central disorders of hypersomnolence (e.g. narcolepsy), circadian rhythm sleep–wake disorders, parasomnias, sleep-related movement disorders and ‘other sleep disorders’.

The extent to which sleep is disturbed, or interrupted, is a diagnostic criterion for insomnias and circadian rhythm sleep–wake disorders. That said, it is accepted that there needs to be room for clinical judgement regarding the clinical significance of the extent of sleep disturbance. 11

However, although the ICSD-3 provides a classification and diagnostic framework, it is important to note that, in paediatric research at least, very few studies actually use the ICSD-3 criteria to define or screen research participants. 12,13 Instead, in both the clinical and research literature, a number of different phrases are used to describe the manifestations of a sleep disorder in terms of the impact that it has on an individual’s sleep: sleep disturbance, sleep problems and sleep difficulties. 2 Such terms have all been used for issues related to falling asleep (i.e. sleep initiation) and staying asleep, as opposed to night wakings or very early waking (i.e. sleep maintenance). The scope of this review was guided by the commissioning brief, which made two clear specifications: it should be concerned with ‘non-respiratory sleep disturbance’ and sleep disturbance (experienced by the child and/or parent) should be a feature of the presenting problem. The ICSD-3 classification was use to specify sleep disorders that were relevant, or not, to the review. Three types of sleep disorder were not relevant because disturbed sleep is not a diagnostic feature, namely sleep-related breathing disorders, central disorders of hypersomnolence (e.g. narcolepsy) and sleep-related movement disorders. Interventions that addressed sleep disturbances that aligned with the diagnostic features of insomnias or circadian sleep–wake cycle disorders were included. In addition, we included parasomnias because of the potential impact that they could have on parental sleep. However, for reasons noted above, we did not require studies to use the ICSD-3 to define or screen participants. We briefly set out the ICSD-3 definitions of these disorders in the following sections.

Insomnia disorders

The ICSD-3 definition of insomnia is as follows: a persistent difficulty with sleep initiation, duration, consolidation or quality, which occurs despite adequate opportunity and circumstances for sleep and results in some form of daytime impairment. It comprises three subcategories: (1) chronic insomnia disorder, (2) short-term insomnia disorder and (3) other insomnia disorders. In children, chronic insomnia also includes behavioural insomnia disorders, the aetiology of which is located in the practices of parents around bedtime/settling and responding to night/early-morning wakings. 12 Behavioural insomnias are common in childhood, with an even higher prevalence among children with NDs. 14

Circadian rhythm sleep–wake disorders

Circadian rhythm sleep–wake disorders are characterised by abnormalities in the length, timing and/or regularity of the sleep–wake cycle relative to the day–night cycle. It is caused by genetic, neurological or visual pathway damage/disorders affecting circadian rhythms, including melatonin release. 14,15

Parasomnias

Parasomnias were included in the review because of the impact that they have on parents’ sleep. The ICSD-3 defines parasomnias as sleep-related occurrences that represent undesirable physical or cognitive experiences (e.g. sleep terrors, sleep walking) occurring out of sleep, during the transition from sleep to the awake state or from the awake state to sleep. They are more common in children than in adults. 16

Childhood neurodisability

A consensus definition offered by Morris et al. 17 defines NDs as:

. . . congenital or acquired long-term conditions that are attributed to impairment of the brain and/or neuromuscular system and create functional limitations.

A wide range of conditions fall under this definition, including cerebral palsy, autism spectrum disorder (ASD), Down syndrome and other chromosome disorders, epilepsy, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), neurometabolic degenerative conditions (e.g. Batten disease), genetic disorders (e.g. Rett syndrome), as well as non-specific diagnoses such as ‘learning/intellectual disability’ and ‘developmental delay’. The involvement of the brain and/or neuromuscular system means that children can experience a range of impairments (e.g. sensory, learning, physical/motor function and speech and language) and health complications or clinical needs (e.g. respiratory, orthopaedic, gastroenterological and pain management). The severity of impairment can range from mild to profound. The fact that it is not uncommon for some conditions to co-occur adds to the complexity and severity of impairment. It is not surprising, therefore, that many children with NDs are frequent users of the health service at all levels: community, primary care inpatient and outpatient settings. 18

In terms of epidemiology, some NDs are quite common (e.g. autism affects ≈1 in 100 children, cerebral palsies affect ≈1 in 400 children and severe intellectual disabilities affect ≈3 in 1000 children). However, also within this ‘cluster’ of conditions are very rare syndromes [e.g. tuberous sclerosis (incidence of < 1 in 100,000) and ataxia telangiectasia (incidence of < 1 in 40,000)]. 19 Estimates of the overall prevalence of ND among the child population in England vary depending on the measure/indicator used and all are flawed in some way. However, it is generally accepted that ≈4 in 100 children have a ND and that children with NDs constitute the largest group of disabled children. 19

Sleep disturbances in children with neurodisabilities

Sleep disturbances in children with NDs are more common and more severe than in children with typical development. 14,15 However, non-respiratory sleep disturbance is very rarely a diagnostic criterion. Indeed, this is the case only with respect to four conditions: Rett syndrome, Angelman syndrome, Smith–Magenis syndrome and Williams syndrome. 20

The impacts of sleep disturbance

Sleep disturbance can have an impact on all members of the family: the child and their parents and siblings. Indeed, often it is the parents’ own sleep deprivation or poor sleep quality that precipitates them to seek help with their child’s sleep. 9,21 Child sleep problems are associated with poor outcomes for parents, such as heightened levels of parental stress and irritability,22,23 and for children, including poorer educational progress and daytime behaviour problems. 24 These outcomes in themselves increase demands on statutory services, as well as creating further additional support needs, such as respite care. 25,26 The wider association between sleep quality and economic consequences has also been described. 27,28 Parents consistently highlight the need for support with their child’s sleep problems,29,30 although, historically, little time has been allocated to training the relevant professionals to provide this kind of support. 31 Parents, practitioners and other stakeholders agree that research on sleep management interventions is a priority with respect to children with NDs. 32

Interventions for non-respiratory sleep disturbance

Interventions to address sleep disturbance among children with NDs examine both pharmacological and non-pharmacological approaches.

Pharmacological interventions act on an aspect of the physiological processes of sleep and/or the timing of the sleep–wake cycle; the most frequently used interventions are melatonin (a hormone playing a key role in the timing of the sleep–wake cycle), clonidine (which inhibits noradrenaline activity and hence has a soporific effect) and antihistamines [which inhibit neurotransmitters (histamines) that are involved in wakefulness/alertness]. 33–35 All are prescribed ‘off-label’. Other pharmacological interventions are used in relation to children’s sleep, such as medications to manage seizures and pain; however, these are outside the scope of this review because the primary purpose of the intervention is not sleep disturbance.

Non-pharmacological interventions address other causes of disturbances in sleep initiation, maintenance and/or scheduling and are wide-ranging in approach. Interventions that are available within and/or outside the NHS include:

-

behavioural and cognitive behavioural interventions – addressing behavioural aspects of sleep including parents’ management of sleep behaviours and routines

-

chronotherapy – intervening in the timing of sleep within the 24-hour cycle

-

phototherapy (or ‘bright light therapy’) – using light exposure to effect changes in the circadian rhythm

-

dietary interventions – removing stimulants and restricting to hypoallergenic food

-

sensory interventions, including weighted blankets36 and ‘safe space’ bed tents37

-

cranial osteopathy38

-

changing the bedroom environment, for example by removing any televisions or other stimulatory materials and adjusting heating and/or lighting.

Current guidance on the management of sleep disturbance in children advocates that once clinical (e.g. pain or seizures) or respiratory reasons for sleep disturbance are excluded, behavioural approaches that seek to change parents’ responses to sleep-related problems should be the ‘first port of call’ for any child,33,39–41 with pharmacological intervention (and to date, this is typically melatonin) suggested in cases in which such approaches prove ineffective, which should be used alongside behavioural parent-directed approaches. 2,42

The justification for this is that, in common with children with typical development, the origins of sleep difficulties for many disabled children are behavioural, located in the way in which parents address and manage their child’s sleep. 4,43,44 The intensity of behavioural intervention depends on the complexity of the sleep problem and/or child/family-centred factors. Sleep problems that cannot be resolved through low-intensity approaches (e.g. simple information leaflets, verbal information/guidance during a routine appointment, one-off ‘sleep management workshops’) may require a more tailored and sustained approach involving a detailed assessment of the sleep problem, the creation of a bespoke sleep management strategy (based on behaviour modification principles) and time-limited (typically face-to-face) support as parents implement the strategy. In recent years, there has also been an increasing interest in using groups, as opposed to a series of one-to-one sessions, to deliver behavioural sleep support to parents. 45 Furthermore, online ‘self-directed’ sleep management interventions for adults are now available (e.g. Sleepio.com), and the management of sleep disturbance also appears within the curricula of newly available online parenting interventions for parents of children with typical development and disabilities (e.g. Stepping Stones Triple P). Constrained resources and wider changes in the way in which health care is delivered mean that it is likely that these newer modes of delivering behavioural sleep management intervention, such as groups and self-management, will increasingly be considered and used by clinicians and parents. 46 It was important, therefore, that this review examined evidence of the impact that the mode of delivery has on outcomes.

The availability of sleep interventions and the organisation of sleep disturbance services

A number of different services deliver a sleep management intervention to children with NDs. They include community paediatric teams, general practitioners, health visitors, specialist paediatric neurology/autism/ADHD services, child and adolescent mental health services and tertiary sleep services. Within the UK, third-sector organisations (e.g. Sleep Scotland, Scope, the Children’s Sleep Charity) are also highly active in this area. Such organisations offer education/training to parents and professionals on sleep and behavioural approaches to managing sleep difficulties, as well as sleep intervention services. Some NHS trusts are commissioning services of this kind from third-sector organisations such as these.

Although there has been no systematic analysis of the way that sleep disturbance in children with NDs is managed by the NHS, a recent survey of paediatricians by the British Paediatric Respiratory Society led to the conclusion that services for sleep disorders in children were ‘chaotic and unplanned . . . often unfunded and frequently perceived as inadequate for local needs’. 47 Current practice in prescribing medicines such as melatonin has been described as haphazard48 and access to behavioural interventions as patchy. 49

There are a number of reasons for this current state of affairs, including the apparent absence of education on sleep disorders and sleep management in medical school education,50 a lack of recognition of the importance of assessing/checking for sleep disturbance, lack of knowledge/skills or resources to deliver non-pharmacological interventions, parental expectations regarding their child’s sleep, the complexity and range of conditions falling under the umbrella of NDs and the complexity of sleep disturbance and its potential causes. In addition, although there have been some attempts to develop sleep management pathways within paediatrics, these have been restricted to particular types of sleep disturbance and/or sleep intervention and/or diagnostic groups, for which the evidence is more plentiful and/or of higher quality. 47,51,52

Informing the development of a robust evidence base

A robust evidence base is clearly required to inform the development of a paediatric ND sleep management pathway for non-respiratory disturbance that integrates pharmacological and non-pharmacological interventions. A first step towards this, as noted in the commissioning brief, is to ‘take stock’ of the existing evidence base. Our preliminary scoping found that previous systematic reviews have mainly focused on either individual NDs51,53–57 and/or single interventions or pharmacological interventions only. 7,53,56,57 Three reviews that included pharmacological and non-pharmacological interventions were restricted by type of population: children with ASDs,51 children aged 0–12 years with cerebral palsy or traumatic brain injury58 and children with ADHD. 54 One review with a wide population of chronic health conditions in patients aged up to 19 years (including NDs) investigated non-pharmacological interventions (behavioural and non-behavioural);1 another review of behavioural interventions focused on disabled children aged up to 8 years. 59 The search end dates for the previous reviews we identified ranged from 2004 to 2013. None of the previous reviews addressed the research question in the commissioning brief and a new review was considered appropriate.

Given the complexity of sleep disturbance in children with ND, and in contrast to previous reviews, it was essential that our review evaluated pharmacological and non-pharmacological interventions, as much as existing evidence allows, across the range of NDs and age groups. This allows identification of evidence gaps, as well as the accumulation of knowledge on which sleep disturbance interventions work (solely or in combination with other interventions) and for whom they work within the diverse population of children with NDs.

Aims and objectives

There were two overarching aims of this review: (1) to identify the implications for practice for non-respiratory sleep disturbance in children with NDs, evidence permitting, and (2) to inform the focus and priorities of a future call by NIHR for primary research in this area. Unlike previous systematic reviews, we have sought to be holistic in terms of both the population (all children with a ND) and the types of intervention (i.e. pharmacological and non-pharmacological). The objectives were to:

-

evaluate and compare the clinical effectiveness of different intervention approaches to sleep disturbances for children with NDs and, when possible, to:

-

examine whether or not intervention clinical effectiveness differs for different types of ND, different causes of sleep disturbance and different types of sleep disturbance (i.e. sleep initiation, sleep maintenance and sleep scheduling)

-

review and evaluate evidence regarding the use of more than one intervention approach, sequentially or in combination, to manage a specific cause of sleep disturbance

-

review and evaluate evidence regarding the impact that the setting and/or skills/qualifications of practitioners have on intervention clinical effectiveness

-

-

describe and compare evidence regarding the acceptability and feasibility of sleep disturbance interventions

-

describe the settings in which sleep disturbance interventions are being delivered, and by whom

-

make recommendations, when appropriate, with respect to the management of sleep disturbance among children with ND generally and/or with respect to particular NDs

-

identify and describe interventions that look promising and are of relevance to and/or feasible for the NHS but that have not been robustly evaluated

-

make recommendations regarding priorities for future primary research on this topic

-

disseminate the findings in a timely and effective way.

Chapter 2 Methods

This systematic review was undertaken in accordance with Systematic Reviews: CRD’s Guidance for Undertaking Reviews in Health Care60 and reported in line with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses. 61

The review protocol was published prospectively and was registered with PROSPERO as CRD42016034067 (see www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO/display_record.php?RecordID=34067??).

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Studies were assessed for eligibility based on the criteria detailed in the following sections.

Population

Studies of children and young people with NDs who were experiencing non-respiratory sleep disturbances were eligible for inclusion in the review.

-

Children and young people aged from 0 to 18 years were eligible. We did not expect to find many studies targeted at very young infants. Some previous reviews have used a lower age cut-off point of 3 months and others have not. Given the comprehensive nature of the review, we did not use a lower age cut-off point. ND was defined in accordance with the consensus definition developed by Morris et al. :17

. . . congenital or acquired long-term conditions that are attributed to impairment of the brain and/or neuromuscular system and create functional limitations.

-

Non-respiratory sleep disturbances, of any duration, related to the initiation, maintenance or scheduling of sleep, diagnosed by a health-care professional based on parental/carer or child report or sleep observation were eligible.

-

Excluded non-respiratory sleep disorders were central disorders of hypersomnolence (in which daytime sleepiness is not caused by nocturnal sleep disturbance or misaligned circadian rhythms) and sleep-related movement disorders.

We excluded studies of respiratory-related sleep disturbances. However, NDs are complex conditions and sleep disturbances may have multifactorial causes. Therefore, we included studies in which the respiratory-related component was being controlled and the focus of the intervention was another cause of sleep disturbance. We also excluded studies in which the main focus of the intervention was not treatment of the sleep disturbance (e.g. interventions to control seizures when sleep outcomes were also reported) and studies of mixed populations of children with and without a ND, unless the results were reported separately for the two groups or the sample was predominantly (> 90%) children with a ND.

Intervention

NHS-relevant pharmacological and non-pharmacological interventions targeted at improving sleep initiation, maintenance, scheduling or sleep quality in any setting were eligible for inclusion. For pharmacological studies, ‘NHS relevant’ was defined as relating to drugs that are licensed for use for this indication in children or that are currently used for this purpose in the NHS. For non-pharmacological studies, ‘NHS relevant’ was defined as those interventions meeting current practice standards; for example, behavioural interventions that used punishment were excluded. Multicomponent interventions were eligible.

The NHS-relevant pharmacological interventions were melatonin, clonidine and antihistamines.

The NHS-relevant non-pharmacological interventions included (but were not restricted to):

-

behavioural interventions delivered in a range of settings such as primary, secondary and tertiary or community, outpatient or inpatient that were delivered in groups or to individual children/families by health-care professionals

-

self-help booklets, web-based packages and other online support

-

behavioural/cognitive–behavioural interventions addressing behavioural aspects of sleep, including parents’ management of sleep behaviours and routines

-

chronotherapy – intervening in the timing of sleep within the 24-hour cycle

-

phototherapy (or ‘bright light therapy’) – using light exposure to effect changes in the circadian rhythm

-

dietary interventions – removing stimulants, restricting to hypoallergenic food

-

sensory interventions, including weighted blankets and ‘safe space’ bed tents

-

cranial osteopathy

-

changing the bedroom environment, for example by removing any televisions or other stimulatory materials and adjusting heating and/or lighting.

Comparator

Studies using no intervention, waiting list control, placebo or another NHS-relevant intervention were eligible for inclusion.

Outcomes

The following outcomes were assessed.

Primary outcomes:

-

child’s sleep-related outcomes – parent-/carer- and child-reported outcomes relating to the initiation, maintenance, scheduling or quality of sleep (using measures such as sleep diaries, standardised scales, e.g. the Composite Sleep Disturbance Index or Epworth Sleepiness Scale) and objective measures such as actigraphy (used to calculate outcomes such as total sleep duration, time taken to fall asleep or sleep efficiency)

-

parent sleep-related outcomes – quality of sleep

-

measures of perceived parenting confidence and/or efficacy and/or understanding of sleep/sleep management (which are particularly relevant for parent training/behavioural interventions that seek to change the way that parents manage sleep disturbance).

Secondary outcomes:

-

child-related quality of life, daytime behaviour and cognition

-

parent/carer quality of life and well-being, including global quality of life (e.g. Short Form questionnaire – 36 items) and more specific outcomes such as physical well-being, mental well-being, and mental health (e.g. stress, depression)

-

family functioning

-

adverse events, including side effects from medication.

Data on uptake of the intervention, retention and intervention adherence were used as indicators of the acceptability and feasibility of the intervention. Quantitative or qualitative data on parents’/children’s experiences of receiving a sleep disturbance intervention included:

-

the acceptability and feasibility of the intervention

-

other experiences of receiving the intervention

-

satisfaction with intervention outcomes and ‘fit’ with their priorities with regard to their child’s sleep disturbances; views/perspectives on the mechanisms by which outcomes were achieved.

Study design

Randomised controlled trials (RCTs) and non-randomised controlled studies, such as controlled before-and-after studies and cohort studies with a control group, were included. Both parallel and crossover RCTs were eligible for inclusion. Concerns have been expressed by others that a crossover design may be inappropriate owing to uncertainty about the duration of the effect of interventions on sleep patterns and circadian rhythm and, therefore, on the most appropriate duration for the washout period. 48 We agree with these concerns. However, given that the aim was to undertake a broad review and, as there were few RCTs likely to be available, we included crossover studies.

In order to achieve the second objective of the review, studies without a control group were included in the absence of controlled studies, that is, cohort studies and before-and-after studies. This was because they could include potentially promising interventions that were at an early stage of evaluation. Case studies were not eligible for inclusion.

Qualitative and quantitative studies were included if they reported data on parents’ or children’s experiences of receiving a sleep disturbance intervention (including intervention acceptability), such as the process of receiving the sleep intervention, satisfaction with intervention outcomes and ‘fit’ with their priorities with regard to their child’s sleep disturbances, and views/perspectives on the mechanisms by which outcomes were achieved. Data could be collected as part of studies of clinical effectiveness or studies that only sought to examine research questions on experiences and satisfaction.

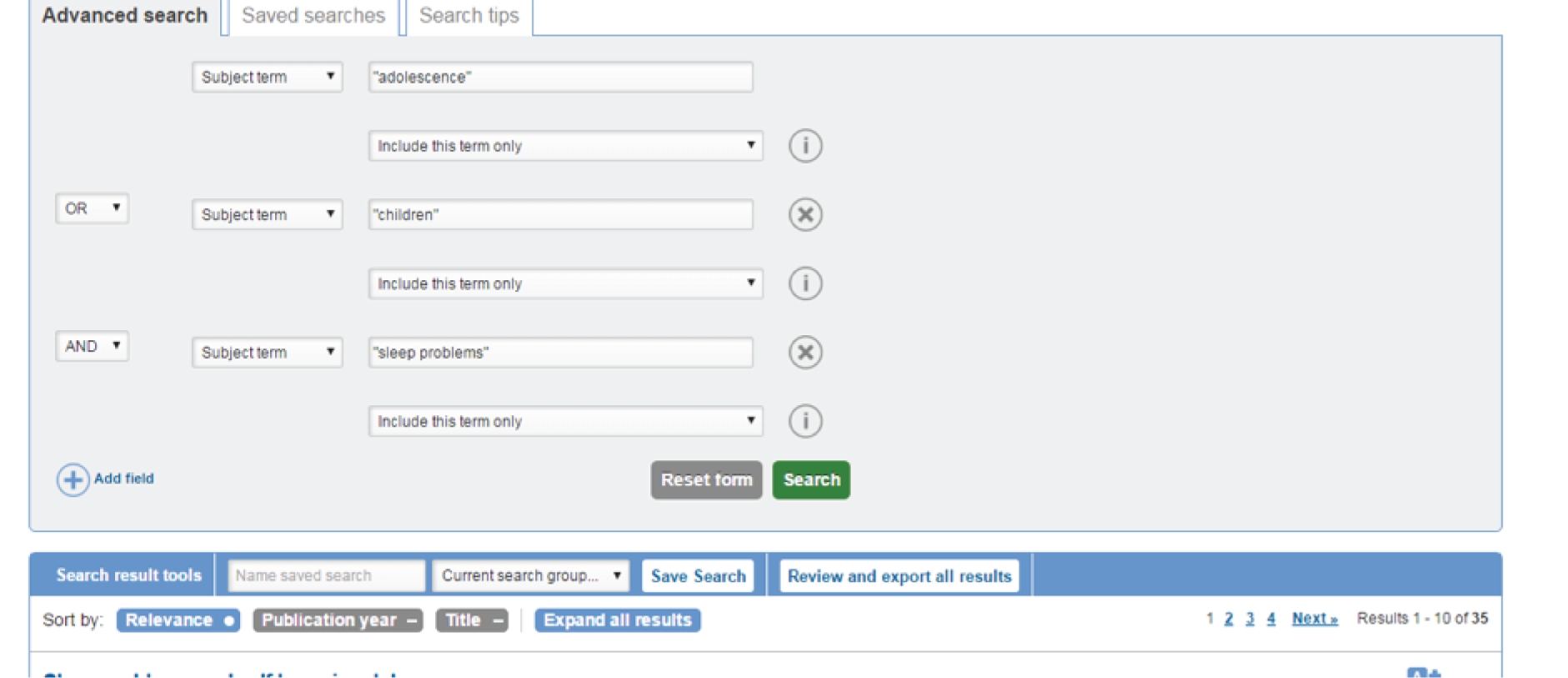

Literature searches

The available evidence was identified by carrying out systematic searches of electronic databases, and reference checking of relevant reviews and included studies. The list of included studies identified from the electronic searches was shared with clinicians in the team to establish if there were any relevant studies that were missing. The searches were undertaken by an experienced information specialist and the search strategy was peer reviewed by a second information specialist.

Information sources

A range of databases were searched in February and March 2016 and updated in February 2017 to ensure coverage from the fields of health, nursing and allied health, and social care. We searched Applied Social Sciences Index and Abstracts (ASSIA), The Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, Conference Proceedings Citation Index, Cumulative Index to Nursing & Allied Health, Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects, EMBASE, Health Management Information Consortium, MEDLINE, MEDLINE In-Process & Other Non-indexed Citations, PsycINFO, Science Citation Index, Social Care Online and Social Policy & Practice.

The Social Care Online, Social Policy & Practice, Health Management Information Consortium, Conference Proceedings Citation Index and PsycINFO all provide some coverage of reports and other unpublished documents; therefore, the available grey literature are represented in the search results.

In addition, ClinicalTrials.gov, the World Health Organization (WHO) International Clinical Trials Registry Platform and the UK Clinical Trials Gateway were searched for trials, both ongoing and completed. No limits on date, language or study design were applied in the searches. Full details of search strategies used and numbers of records retrieved are given for each database in Appendix 1.

While the search results were being scanned, some additional search terms that had not been included in the original search strategies were identified. Consequently, we carried out some further searches of each of the databases that incorporated these new terms alongside the original search strategy. Details of these additional search strategies can be found in Appendix 2.

The reference lists of relevant systematic reviews and included studies were also scanned.

Screening and study selection

The database search results were all loaded into EndNote bibliographic software [version 17.0.2.7390, Clarivate Analytics (formerly Thomson Reuters), Philadelphia, PA, USA] and deduplicated.

There was a three-stage screening process to manage the large number of records. First, the titles of the records were screened for relevance. Two researchers did this jointly for 10% of the titles, and the remainder were screened independently by a single researcher. Records that were identified as potentially relevant based on their title were screened independently by two researchers. When there was no consensus, a third member of the team was consulted. The full texts of potentially relevant papers were ordered. Finally, full papers were independently screened against the eligibility criteria by two researchers. Disagreements were resolved by consensus or by consultation with a third team member if necessary.

Data extraction

A data extraction form for study details was developed and piloted. A Microsoft Excel 2010® spreadsheet (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA) was used to extract the outcome data. Owing to the various ways in which adverse events were described in papers, data for this outcome were extracted separately into a table using Microsoft Word 2010® (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA). All data were extracted by one researcher and checked by a second. Details of the data items extracted are available in Appendix 3. For the purposes of this review, we extracted follow-up data relating to the assessment time point closest to the end of the intervention.

Assessment of risk of bias

The Cochrane risk of bias tool62 was used to assess the quality of RCTs and the newly developed tool, A Cochrane Risk Of Bias Assessment Tool: for Non-Randomized Studies of Interventions (ACROBAT-NRSI), was used to assess the non-randomised controlled before-and-after studies. 63 Uncontrolled before-and-after studies were assessed using questions adapted from ACROBAT-NRSI, as used in another HTA review. 64 Risk of bias was independently assessed by two researchers. Disagreements were resolved through consensus and through discussion with a third researcher if necessary. In addition, for crossover trials, we assessed whether or not an appropriate analysis using paired data was conducted and whether or not there was a treatment by period interaction, as undertaken in a previous systematic review including crossover studies. 65

A summary risk-of-bias score was calculated following guidance. 62 This score was calculated as follows: any study that had one or more of the domains on the risk-of-bias tool classified as ‘no’ was considered to be rated as having a high risk of bias. Any study that had one or more domains classified as ‘unclear’ on the risk-of-bias tool was considered to be rated as having an unclear risk of bias. To be considered to have a rating of a low risk of bias, a study needed to meet the criteria on all domains on the risk-of-bias tool and classify them as ‘yes’.

For studies containing qualitative and quantitative data on parents’ and/or children’s satisfaction with the intervention, take-up, retention and adherence to the intervention and experiences of the intervention, the quality of the study was assessed and reported using the quality appraisal checklist of Hawker et al. 66

It was not possible to blind the types of non-pharmacological interventions and comparators used in the studies under consideration. In addition, owing to the nature of the outcomes measured, robust, blinded outcome assessment was difficult. Although actigraphy-based child sleep outcomes are more objective than parent-reported measures, we did not consider these to be true objective outcomes, with non-blinding unlikely to introduce bias. Therefore, all of the measures were regarded as having the capacity to be influenced by lack of blinding.

Analysis

The synthesis aimed to:

-

Assess the clinical effectiveness of the interventions for sleep disturbance, in particular interventions that may work across conditions.

-

Inform future research by identifying gaps in the evidence and identifying interventions that are the most promising front runners to be considered for future primary research.

First, narrative and tabular summaries of key study characteristics were undertaken. This allowed a mapping of which interventions have been investigated for which ND and for which type of sleep disturbance (e.g. sleep initiation) in order to identify interventions that have been investigated across conditions. We also mapped information on the feasibility and acceptability of each of the interventions.

Synthesis involved paired meta-analyses and narrative synthesis.

Meta-analyses

Pharmacological intervention studies

When sufficient data for our primary and secondary outcomes were available, they were pooled in quantitative synthesis using a random-effects model (for continuous outcomes). As data sets often included both parallel and crossover trials, or just crossover trials, data were pooled using the generic inverse variance method in RevMan version 5 (The Cochrane Collaboration, The Nordic Cochrane Centre, Copenhagen, Denmark). 67 Only crossover trials with a washout period were included in meta-analyses, for which data from both treatment periods were used. For trials without a washout period, we considered using data from the first period only; however, in the event, this was not possible, as data summaries were not provided by treatment period for these trials.

The recommendations provided in the Cochrane handbook were followed as closely as possible. 68 The mean difference (MD) between melatonin (M) and placebo (P) at the end point was either taken as reported in the article or calculated as the difference in means for each group/period:

When a 95% confidence interval (CI) for the group means was presented instead of a standard deviation (SD) (e.g. Garstang and Wallis69), the SD was calculated using the formula:

where the t-value was obtained by entering = tinv(1–0.95, N-1) in a cell in a Microsoft Excel spreadsheet.

For the crossover trials, when only means and SDs for the measurements of the intervention (melatonin) and the control (placebo) were available, the SD of within-participant differences between M and P measurements was estimated using the formula:

The correlation coefficient ρ was estimated from other studies reporting all three SDs for the same outcome or by using 0.5 when no other studies were available to use.

The standard error (SE) of the MD was calculated using:

where N is the sample size, or by dividing the MD by the t-statistic when this was presented for a two-sample t-test of the period differences (e.g. Weiss et al. 70).

To transform the parallel-group trial data for entry into the generic inverse variance facility, a two-sample t-test was conducted to calculate the unadjusted difference (and SE of the MD) between the groups at follow-up (post intervention) using raw group summary data (N, mean and SD).

Statistical heterogeneity between trials was assessed using the I2 statistic. 71 Two sources of potential clinical and methodological heterogeneity were identified for the pharmacological intervention trials, and subgroup analyses were conducted based on these, when appropriate:

-

type of neurological disorder – population primarily with ASD

-

receipt of prior intervention – whether or not participants were offered an additional intervention prior to the start of the study.

The risk of publication bias was not formally assessed.

When data could not be pooled, summaries of the findings for each trial and outcome are presented with a (estimated unadjusted) MD and 95% CI between melatonin and control at follow-up.

Adverse event data are summarised narratively.

Non-pharmacological intervention studies

Non-pharmacological intervention studies included parallel-group RCTs and before-and-after studies. Owing to insufficient data for each outcome and/or significant heterogeneity in study design and intervention, data were not pooled in meta-analyses. Narrative and quantitative summaries of the findings for each trial and outcome are presented. For continuous data in the RCTs, the preferred choice was difference in end-point data; however, when a (estimated unadjusted) MD between intervention and control at follow-up could not be calculated, the difference in change scores from baseline to follow-up was presented instead.

We had planned to undertake a mixed-treatment comparison of the multiple treatment options;72 however, this was not possible owing to the paucity of RCTs for interventions other than melatonin. Adverse event data are summarised narratively.

Narrative synthesis

Although we planned to undertake separate quantitative and qualitative syntheses, this was to a large extent not possible, as few studies could be pooled. With the exception of the melatonin trials, there was a large degree of variability between studies evaluating different classes of interventions. For example, for behavioural interventions, there was wide variability in aspects of the interventions such as mode of delivery, duration and intensity of interventions, as well as in the comparators used. There was also variability in the conditions being studied, outcomes reported and the measures used to assess individual outcomes, follow-up times and types of data reported. Consequently, there were few instances in which it became appropriate to pool the data. Thus, it became necessary to adopt a principally narrative synthesis to report the findings. We present a narrative synthesis as our main analysis, with comparisons made for melatonin versus placebo, which were the only interventions that we judged could be appropriately compared.

Narrative synthesis was undertaken when quantitative synthesis was not appropriate or there were insufficient data, and applied mainly to the non-pharmacological interventions. When possible, we display outcomes in a forest plot, even when studies are not statistically pooled, to aid exploration of study results. When feasible, we investigated the subgroup characteristics outlined previously. Non-pharmacological studies were grouped by type of intervention (i.e. comprehensive parent-directed tailored, comprehensive parent-directed non-tailored or non-comprehensive) and comparator if heterogeneous. We explored outcomes by type of sleep disturbance with the aim of identifying effects that may be transferable to other NDs. Results are discussed in the context of ratings of risk of bias in the individual studies.

In terms of the qualitative data analysis, the topic areas that were subject to review were well defined; we therefore adopted a thematic approach to data extraction, analysis and synthesis. 60,73 To start, studies were grouped into pharmacological, behavioural and other non-pharmacological studies. For each, a descriptive report of relevant studies, and topic areas covered, was produced. The tabulated data were then scrutinised and analytical notes were made that summarised findings across studies with respect to the topic areas. Part of this process involved testing for contradictions in the evidence. 74

The synthesis interrogated such data, when available, to assist in identifying interventions that could be generalisable across conditions and those that are condition specific. 75,76 Factors taken into consideration in identifying promising interventions included feasibility of delivery of the intervention in a NHS setting, acceptability to children and families, evidence of clinical effectiveness or in the direction of clinical effectiveness based on CIs (taking into consideration the clinical significance of the estimates).

Protocol changes

During the course of the review, we identified numerous RCTs for the melatonin studies. We therefore decided to include only RCTs for this intervention. For all other interventions, we have included any design except case studies, as per the original protocol. Some studies reported multiple case studies that were not eligible for inclusion in the review. We made the decision to exclude uncontrolled studies with fewer than 10 participants.

Patient and public involvement

Three parents of children with NDs (two mothers, one father) acted as project advisors. They were recruited from a permanent parent consultation group of the chief investigator’s research unit. These parents were invited to the project team meetings, which were held three times over the course of study and were attended by the research team and all co-applicants. Each parent attended at least one meeting. They were also consulted, via e-mail, regarding the implications of the findings of the review. The children’s diagnoses included autism and rare, genetic conditions. At the first meeting, an early item on the agenda was a presentation of an overview of systematic reviews as a research method. Throughout the meetings, the parents were encouraged to share their experiences and opinions, and their contributions provided useful contextual information.

Chapter 3 Results

Study selection

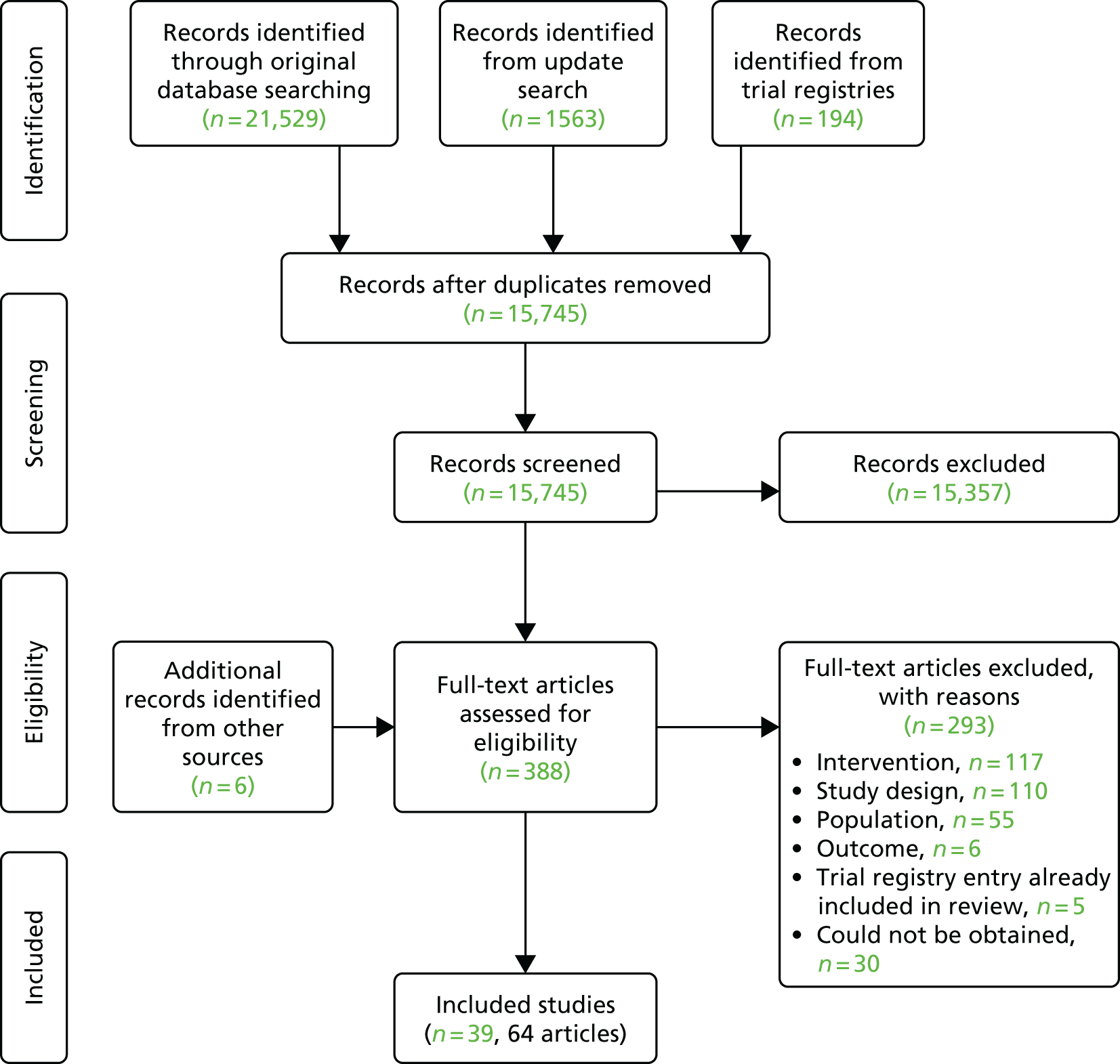

The searches identified 23,292 records: 21,529 records were identified from the original searches undertaken in February and March 2016, 1563 were identified from the updated searches undertaken in February 2017, 194 were identified from trial registries and 6 were identified from subsequent reference checking (Figure 1). After removing duplicate references, 15,745 titles were screened. On the basis of titles, 14,420 titles were excluded; a further 937 were excluded on reading the abstract.

FIGURE 1.

Flow chart of the study selection process.

Full-text articles were sought for the remaining 388 records. We could not obtain full-text articles for 30 of the records. Of these, 11 were conference abstracts that were not available in full text22,77–86 and five were trial registry entries that were recorded as ‘complete’ but had no study results available. 87–91 We contacted the authors to check whether or not there were any publications from the trials and received one response that the authors did not intend to publish the results as fewer than 10 participants had been recruited into the study. 91 Two trials were registered as ‘terminated’ with no published results (one owing to poor recruitment,92 and the other for unknown reasons 93 and our attempt to contact authors did not elicit a response). One trial was registered as ‘study status unknown’94 with no published results; we contacted the authors but received no response. Five trials were eligible but ongoing so were excluded from the review as results were not yet available. 95–99 A further six articles could not be obtained from the British Library. 100–105

A total of 358 full-text articles were, therefore, assessed, including two non-English language papers that required translation. Of these, 117 articles (33%) were excluded because the intervention was out of scope or sleep disturbance was not the target of the intervention, 110 (31%) were excluded based on study design, 55 (15%) were excluded owing to the population, 6 (2%) were excluded based on the outcomes evaluated and 5 trials (1%) identified from trial registries were related to studies that had been completed and had already been identified through the searches and included in the review. 36,48,49,106,107 Appendix 4 lists all studies excluded at full-text screening and reasons for exclusions.

Overview of included studies

There were 39 included studies reported in 64 articles. Although we sought to include studies published in any language, all the studies meeting the eligibility criteria were published in English. The included studies were from the UK (n = 13, 33%), the USA (n = 10, 26%), Australia (n = 6, 15%), Canada (n = 5, 13%), the People’s Republic of China (n = 1, 2.6%), the Netherlands (n = 1, 2.6%), Hong Kong (n = 1, 2.6%), Italy (n = 1, 2.6%) and Israel (n = 1, 2.6%).

Thirteen RCTs investigated a pharmacological intervention, which in all cases was oral melatonin (Table 1). We did not identify any eligible pharmacological studies investigating clonidine or antihistamines. Twenty-six studies investigated non-pharmacological interventions, of which 12 were RCTs. Of these, nine (35%) evaluated parent-directed tailored interventions; eight (31%) evaluated parent-directed non-tailored interventions; two (8%) evaluated non-comprehensive parent-directed interventions; and seven (27%) evaluated other non-pharmacological interventions – dietary interventions (n = 2, 5%), alternative medicine (n = 1, 3%), exercise-based intervention (n = 1, 3%), faded bedtime with response costs (n = 1, 3%), weighted blankets (n = 1, 3%) and a light therapy plus a behavioural programme (n = 1, 3%). Thirteen studies explored feasibility and/or acceptability and/or parent/clinician views of sleep disturbance interventions. 36,49,106,107,122–130

| Study details and design | Participants randomised (total N and by group) | Trial treatments | Sleep disturbance | Mean age (SD) | ND disorder | Previous sleep hygiene/behavioural interventions | Risk of bias (low, unclear, high) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Melatonin vs. placebo: parallel-group RCTs | |||||||

| Appleton et al. (2012)48 | |||||||

|

Associated publications: Gringras et al. (2012),108 Appleton et al. (2011),109 Appleton et al. (2012)48 UK |

N = 146 (melatonin, n = 70; placebo, n = 76) |

Melatonin: 0.5 mg, 45 minutes before bedtime for 12 weeks Placebo: matching capsule, 0.5 mg for 12 weeks Melatonin and placebo dose could be raised to 2 mg, 6 mg to 12 mg in first 4 weeks then maintained |

Problems with sleep initiation and sleep maintenance |

Melatonin: 106.0 months (34.8 months) Placebo: 100.7 months (37.4 months) |

DD alone, and DD + other | Yes | Low |

| Cortesi et al. (2012)110 | |||||||

| Italy | N = 160 (melatonin, n = 40; melatonin and CBT, n = 40; CBT, n = 40; placebo, n = 40) |

Melatonin: controlled release, 3 mg at 21.00 hours for 12 weeks CBT: four, weekly individual sessions Melatonin and CBT: as above Placebo: identical tablet, 3 mg at 21.00 hours for 12 weeks |

Problems with sleep initiation and sleep maintenance |

Melatonin: 6.8 years (0.9 years) Melatonin and CBT: 6.4 years (1.1 years) CBT: 7.1 years (0.7 years) Placebo: 6.3 years (1.2 years) |

ASD | None stated | High |

| Van der Heijden et al. (2007)111 | |||||||

|

Associated publications: Hoebert et al. (2009)112 The Netherlands |

N = 107 (melatonin, n = 54; placebo, n = 53) |

Melatonin: fast release, 3 mg (if < 40 kg), 6 mg (if > 40 kg) at 19.00 hours for 4 weeks Placebo: identical appearing placebo at 19.00 hours for 4 weeks |

Problems with sleep initiation |

Melatonin: 9.1 years (2.3 years) Placebo: 9.3 years (1.8 years) |

ADHD | None stated | Unclear |

| Crossover trials | |||||||

| Camfield et al. (1996)113 | |||||||

|

Individualised ‘N of 1 crossover trials’ Canada |

N = 6 |

Melatonin: 0.5 mg for three cases, 1.0 mg for three cases, taken at 18.00 hours Placebo: identical capsule Ten-week trial. For each of the five 2-week intervals, participants were randomised to receive placebo or melatonin for 1 week with the alternate agent given in the second week |

Problems with sleep initiation and sleep maintenance | 7.3 years (4.6 years) | Mixed | Yes | High |

| Dodge and Wilson (2001)114 | |||||||

|

Associated publications: Hoebert et al. (2009)112 USA |

N = 36 |

Melatonin: 5 mg at 20.00 hours for 2 weeks Placebo: capsule and filler packaged to be identical to the melatonin, 5 mg at 20.00 hours for 2 weeks Washout period: 1 week |

‘Chronic sleep problems’ | 89 months (NR) | Mixed (mainly cerebral palsy) | Yes | Unclear |

| Garstang and Wallis (2006)69 | |||||||

| UK | N = 11 |

Melatonin: 5 mg for 4 weeks Placebo: dose NR, for 4 weeks Washout period: 1 week |

Problems with sleep initiation and sleep maintenance | 8.6 years (3.1 years) | ASD only, and ASD + learning disability | Yes | High |

| Jain et al.115 (2015) | |||||||

|

Associated Publications: Jain et al. (2014)116 USA |

N = 11 |

Melatonin: sustained release, 9 mg 30 minutes before bedtime for 4 weeks Placebo: identical appearance to melatonin tablets, dose NR Washout period: 1 week |

A score of > 30 on the Sleep Behaviour Questionnaire | 8.4 years (1.3 years) | Epilepsy | None stated | High |

| Wasdell et al. (2008)117 | |||||||

|

Associated publications: Carr et al. (2007)118 Canada |

N = 51 |

Melatonin: controlled release, 5 mg, 20–30 minutes before bedtime for 10 days Placebo: identical to melatonin, 5 mg, 20–30 minutes before bedtime for 10 days ‘Placebo washout’: 3–5 days |

Problems with sleep initiation and sleep maintenance | 7.4 years (NR) | Mixed | Yes | Unclear |

| Weiss et al. (2006)70 | |||||||

| Canada | N = 23 |

Melatonin: short-acting, 5 mg, 20 minutes before bedtime for 10 days Placebo: for 10 days ‘Placebo washout’: 5 days |

Problems with sleep initiation | 10.3 years (NR) | ADHD | Yes | Unclear |

| Wirojanan et al. (2009)119 | |||||||

| USA | N = 18 |

Melatonin: 3 mg, 30 minutes before bedtime for 2 weeks Placebo: 3 mg, 30 minutes before bedtime for 2 weeks No washout period |

‘Sleep problem’ | 5.5 years (3.6 years) | Mixed (fragile X Syndrome/ASD) | None stated | Unclear |

| Wright et al. (2011)106 | |||||||

| UK | N = 20 |

Melatonin: standard release, 2 mg, 30–40 minutes before bedtime for 3 months Placebo: identical to melatonin, 2 mg, 30–40 minutes before bedtime for 3 months Melatonin and placebo dose increased by 2 mg every 3 nights to a maximum of 10 mg. Taken for 3 months Washout period: 1 month |

Problems with sleep initiation and sleep maintenance | 9.0 years (2.9 years) | Mixed (autism and Asperger syndrome) | Yes | Unclear |

| Melatonin vs. melatonin-crossover trials | |||||||

| Hancock et al. (2005)120 | |||||||

| UK | N = 8 (≤ 18 years, n = 5) |

Melatonin: 1 × 5 mg plus 1 × 5-mg placebo, 30 minutes before bedtime for 2 weeks Melatonin: 2 × 5 mg of melatonin (10 mg in total), 30 minutes before bedtime for 2 weeks Washout period: 2 weeks |

Quine sleep index score of at least 6 |

All: 12.1 years (10.0 years) ≤ 18 years: 6.9 years (4.0 years) |

Tuberous sclerosis | None stated | High |

| Jan et al. (2000)121 | |||||||

| Canada | N = 16 (≤ 18 years, n = 15) |

Melatonin: sustained release, variable doses from 2 mg to 10 mg, 30 minutes before bedtime for 11 days Control: fast-release melatonin, variable doses from 2 mg to 10 mg for 11 days No washout period |

‘Chronic sleep wake disorders’ |

All: 10.1 years (4.9 years) ≤ 18 years: 9.3 years (4.1 years) |

Mixed | None stated | High |

The mean age of the children included in the studies ranged from 2 to 12 years. In 16 studies (41%), participants were described in terms of a single ND diagnosis as follows: ADHD (n = 5), autism spectrum condition (ASC) (n = 3), ASD (n = 3), epilepsy (n = 1), tuberous sclerosis (n = 1), ‘mental retardations’ (we have replaced this term with ‘learning disability’; this is interchangeable with the term ‘intellectual disability’) (n = 2) and severe ND (n = 1). In 22 studies (56%), participants were reported to have two or more NDs. One study did not report participants’ NDs. There was also a range of sleep disturbance represented in the eligible studies. Owing to the different terminology used to describe sleep disturbances in the eligible studies, we have classified sleep disturbance under the following headings: sleep initiation (n = 30, 77%) (e.g. sleep latency, sleep association, settling, bedtime resistance and insomnia); sleep maintenance (n = 26, 67%) (e.g. night waking, waking time, parasomnia, co-sleeping and sleep fragmentations) and sleep scheduling (n = 1, 2.5%) (e.g. daytime sleepiness). Three studies (7%) reported that parents completed sleep questionnaires or assessment tools to determine their child’s eligibility, including the Sleep Behaviour Questionnaire,131 Quine sleep index132 and the Children’s Sleep Habits Questionnaire (CSHQ). 133 Five studies (13%) did not specify the types of sleep disturbance eligible for inclusion. Children often had multiple sleep disturbances.

Melatonin

Study characteristics

Table 1 is a summary of the characteristics of the melatonin studies, and Appendix 5 provides further details. Of the 13 RCTs evaluating oral melatonin, which were undertaken in Canada, Italy, the Netherlands, the UK and the USA, 10 compared melatonin with placebo only; one compared melatonin, cognitive–behavioural therapy and a combination of the two with placebo; and two compared two regimens of melatonin (5 mg vs. 10 mg, and fast release vs. sustained release). Ten were crossover trials and three were parallel-group RCTs. Observed sample sizes ranged from 6 to 160 participants.

Assessment of risk of bias

A summary assessment of risk of bias for each RCT is provided in Table 1 and the full risk-of-bias assessment involving each bias domain is provided in Appendix 6 and Report Supplementary Material 1. One trial was rated as having a low risk of bias. 48 The ratings of risk of bias in the remaining RCTs were high or unclear; therefore, the findings from these studies may not be robust.

We could not locate a registered protocol for nine trials69,70,106,110,113–115,117,119 and one trial protocol was registered retrospectively,111 making it unclear whether or not the studies were free of selective reporting. Seven studies provided no, or little, detail regarding sequence generation;70,106,111,113,114,117,119 and four studies provided little or no detail regarding allocation concealment. 110,113,114,119 For three studies, how blinding was undertaken was unclear. 69,70,113 In three studies, the analysis of incomplete outcome data was not considered69,110 or was unclear. 114

Melatonin versus placebo

Eleven trials (n = 589 randomised participants) compared melatonin with placebo: eight crossover trials,69,70,106,113–115,117,119 two two-armed parallel-group trials,48,111 and one four-armed trial of oral melatonin, cognitive–behavioural therapy, oral melatonin plus cognitive–behavioural therapy and placebo. 110

The washout period used by the crossover trials varied. One had no washout period,119 one had a 1-month washout period106 and the remaining five trials had a washout period of between 3 and 7 days. 69,70,114,115,117 Camfield et al. 113 reported six ‘N of 1’ crossover trials with no washout period.

Six of the trials varied drug dosages depending on the child’s age and/or weight and tolerance of dosage (see Table 1). The dose ranges were 0.5–1 mg,113 0.5–12 mg,48 3–6 mg111 and 2–10 mg. 106 Fixed dosages were 3 mg (n = 2),110,119 5 mg (n = 4)69,70,114,117 and 9 mg. 115 Matched placebos were used except for in one trial,70 in which the placebo was not explicitly described, although in this trial the authors reported that each patient received a blister card of 30 days’ supply of medication.

The length of time that melatonin was prescribed for varied between studies: 10 days,70,117 2 weeks,114,119 4 weeks,69,111,115 5 weeks113 and 12 weeks. 48,106,110

The age of participants included in these trials ranged from 1 to 18 years, although the mean age across studies was broadly similar, ranging from 5.5 to 10.3 years (see Table 1). The ND that was represented varied. Four trials included children with a mixed range of neurodevelopmental disabilities,48,113,114,117 three trials included only children with ASC,69,106,110 two trials included children with ADHD,70,111 one trial included children with ASD and/or fragile X syndrome119 and one trial included children with epilepsy. 115

The type of sleep disturbances reported in the participants also varied. Most trials had more than one criterion for inclusion in the trial and included children with a mix of sleep disturbances (see Table 1) relating to sleep initiation48,69,70,106,110,111,113,117 and sleep maintenance. 48,69,106,110,113,117 However, two trials focused on a single sleep problem (‘sleep onset insomnia’111 and ‘initial insomnia’70) and one trial required a score of > 30 in the Sleep Behaviour Questionnaire. 115 Two studies did not specify the type of sleep problems eligible for inclusion. 114,119

Seven trials specified in their inclusion criteria that a preceding psychoeducational or behavioural sleep management intervention had to have been ineffective. 48,69,70,106,113,114,117 In five of these trials, guidance on sleep was provided as part of the trial in the form of a behaviour therapy advice booklet,48 tailored sleep hygiene advice,117 a sleep hygiene intervention,70 a sleep hygiene advice leaflet69 and behaviour management and parenting support. 106 In four of these trials, only children who continued to experience sleep problems were randomised. 48,70,106,117

Across these 11 trials, 19 sleep-related outcomes were measured (see Appendix 7). The most commonly measured outcomes were total sleep time (TST) (n = 11), sleep onset latency (SOL) (n = 10), number of night wakings (n = 6) and sleep efficiency (n = 5). Additional outcomes included arousals, bedtime, CSHQ, difficulty falling asleep, sleep onset, time from drug to sleep, longest sleep episode, the Sleep Behaviour Questionnaire, percentage of sleep stages, wake after sleep onset (WASO), nights without awakening, wake-up time, naptime, moving time, ‘interdaily stability’, ‘interdaily variability’ and ‘L5’ (average activity during the least active 5 hours). Definitions of outcome measures can be found in Appendix 7.

All trials had follow-up periods that commenced immediately following the completion of the intervention: 10 days,70,117 2 weeks,114,119 4 weeks,69,111,115 10 weeks113 or 12 weeks. 48,106,110

Global measures and composite scores

Total sleep time

All 11 trials48,69,70,106,110,111,113–115,117,119 (n = 589 randomised participants) assessed TST (see Appendix 7); four measured this using parent-reported sleep diaries only,69,106,113,114 whereas the remaining seven48,70,110,111,115,117,119 used both actigraphy and sleep diaries. However, of these, three report only actigraphy-measured TST data,110,111,119 as the sleep diaries were used purely to inform, or verify, actigraphy data. This follows existing guidance on the interpretation of actigraphy data. 134 The remaining four trials48,70,115,117 reported TST derived from both parent-completed sleep diaries and actigraphy data.

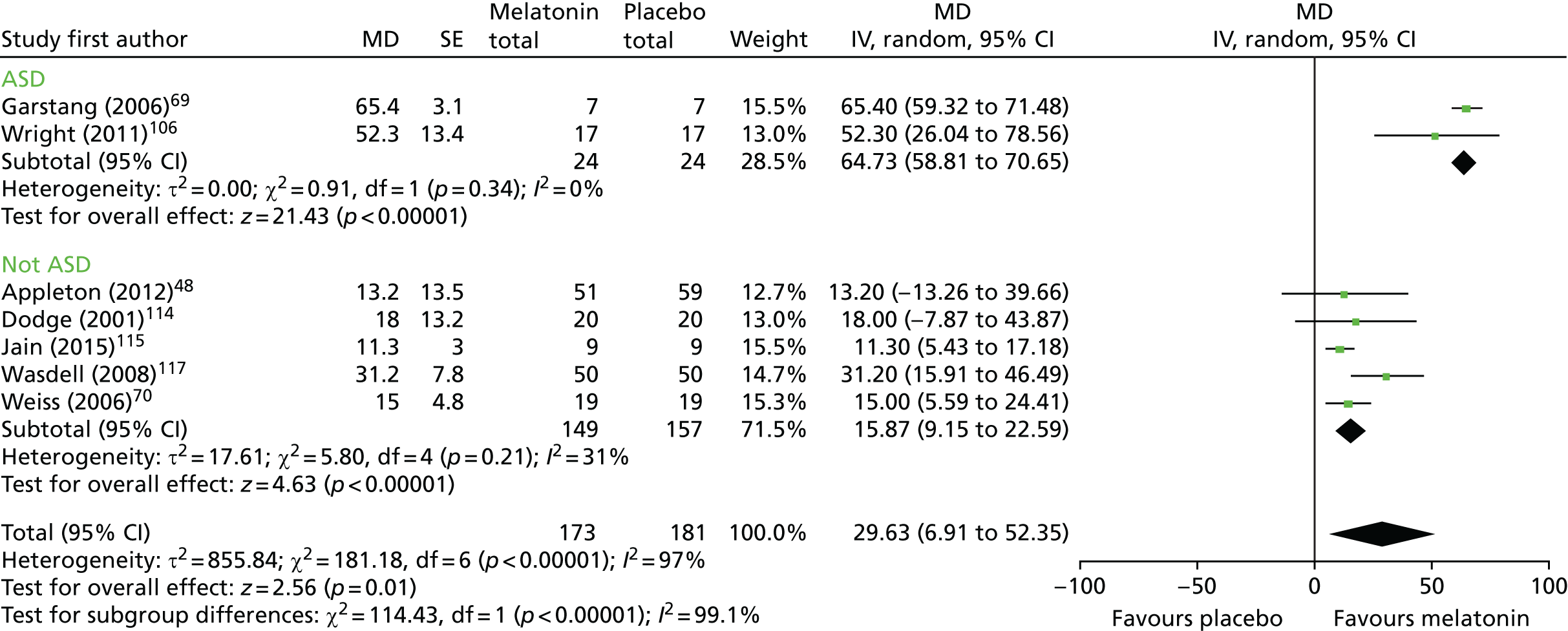

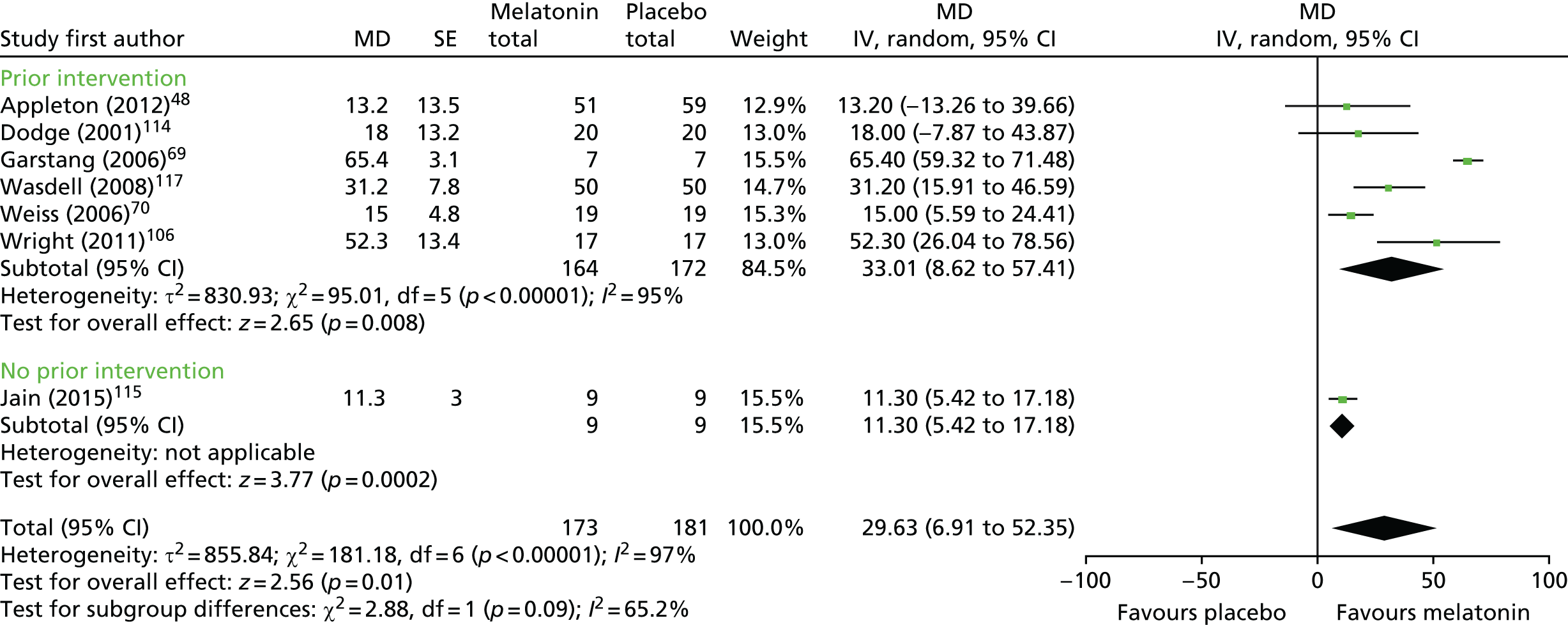

Data from seven trials using sleep diary-reported TST were pooled: six crossover trials with a washout period (n = 122 analysed participants),69,70,106,114,115,117 and one parallel-group trial (n = 110). 48 Note that in the forest plot (Figure 2), the sample sizes presented count participants in crossover trials twice (as being in the melatonin and placebo groups), so the figures reported in the text and shown in the figures may not match for this reason. There was a statistically significant increase in sleep diary-reported TST with melatonin compared with placebo (pooled MD 29.6 minutes, 95% CI 6.9 to 52.4 minutes; p = 0.01; see Figures 2 and 3). Statistical heterogeneity was high (I2 = 97%) and this treatment effect is unlikely to be generalisable, although the effect estimates were all in the direction of benefit with melatonin. Heterogeneity was reduced when studies were stratified based on whether or not the study population was exclusively ASD or not (test for subgroup differences: p < 0.001; I2 = 99%); there was a pooled MD of 64.7 minutes (95% CI 58.8 to 70.7 minutes, I2 = 0%) for the studies of ASD (n = 24), and a smaller pooled MD of 15.9 minutes (95% CI 9.2 to 22.6 minutes, I2 = 31%) for the studies of mixed or other populations (n = 208). There was only a single study (n = 9) in which participants had no prior sleep hygiene or behavioural intervention limiting the usefulness of this subgroup analysis; the overall results did not substantially change with removal of this study (pooled MD 33.0 minutes, 95% CI 8.6 to 57.4 minutes, n = 223; Figure 3). When the single trial rated as having a low risk of bias is considered alone, the increase in sleep time with melatonin was 13.2 minutes (95% CI –13.3 to 39.7 minutes). 48

FIGURE 2.

Sleep diary-reported TST: melatonin vs. placebo and ASD subgroup analysis. df, degrees of freedom; IV, instrumental variable.

FIGURE 3.

Sleep diary-reported TST: melatonin vs. placebo and prior intervention subgroup analysis. df, degrees of freedom; IV, instrumental variable.

The study of six ‘N of 1’ trials in six participants also reported sleep diary TST but, owing to the unusual trial design, could not be included in the meta-analysis. 113 The authors reported no ‘notable difference in sleep pattern or daytime behaviour between melatonin and placebo weeks’113 and provided raw data for each participant. From this, we calculated the MD between melatonin and placebo for parent-reported TST to be 13.9 minutes in favour of the melatonin group (95% CI –6.8 to 34.6 minutes; p = 0.14).

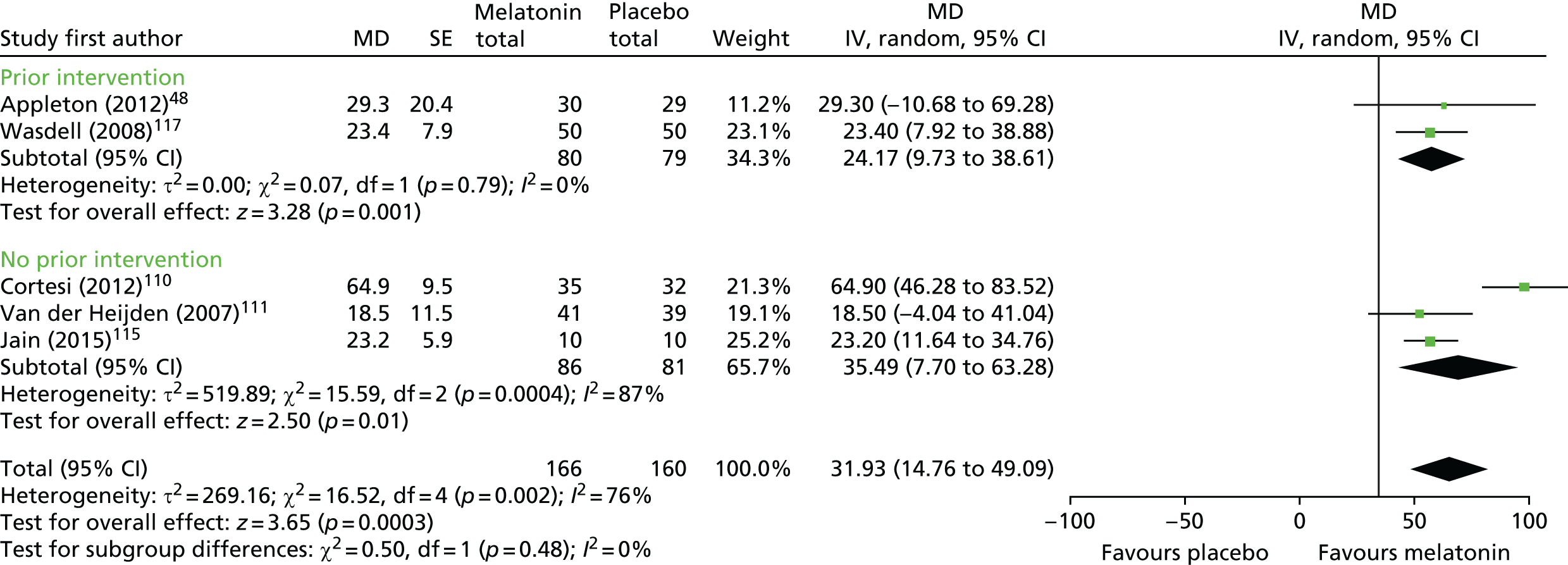

Five trials48,110,111,115,117 (n = 266 analysed participants) were pooled for actigraphy-measured TST, comprising two crossover trials with a washout period (n = 60)115,117 and three parallel-group trials (n = 206). 48,110,111 Weiss et al. 70 used actigraphy to measure TST post intervention and reported that there was no significant difference between melatonin and placebo, but the study did not provide data on this outcome to allow it to be included in the meta-analysis.

There was a statistically significant increase in actigraphy-measured TST with melatonin compared with placebo (pooled MD 31.9 minutes, 95% CI 14.8 to 49.1 minutes; p < 0.001) (Figure 4). Heterogeneity was high (I2 = 76%) and this treatment effect is unlikely to be generalisable, although the effect estimates were all in the direction of benefit with melatonin. There was no statistically significant difference in effect between the studies in which participants received or did not receive a prior intervention (test for subgroup differences, p = 0.48; I2 = 0%). Subgroup analysis by type of ND was not possible.

FIGURE 4.

Actigraphy-measured TST: melatonin vs. placebo. df, degrees of freedom; IV, instrumental variable.

One study without a washout period119 (n = 12 analysed participants) reported a MD in actigraphy-measured TST post intervention of 21 minutes between melatonin and placebo, favouring melatonin. Using non-parametric analysis methods, the authors report p-values of 0.0019 and 0.02 for this outcome, based on data sets produced using two different approaches for dealing with missing data (complete case and last observation carried forward). This outcome was also analysed using a paired t-test, giving a p-value of 0.057. We have estimated the 95% CI for the MD of 21 minutes as –0.7 to 42.7 minutes.

For TST based on polysomnography at 4 weeks immediately post intervention,115 there was no significant difference between melatonin and placebo, with a reported MD of 39.3 minutes (favouring placebo, 95% CI –34.7 to 113.3 minutes, n = 10).

Sleep efficiency

Five trials48,110,111,115,117 (n = 475 randomised participants) reported sleep efficiency (i.e. the ratio of TST to total time in bed): one trial used both actigraphy and parent report,117 three used actigraphy data only48,110,111 and one trial used polysomnography. 115

Cortesi et al. 110 also measured the percentage of children who achieved a sleep efficiency in the normative level of > 85% at the 12-week assessment.

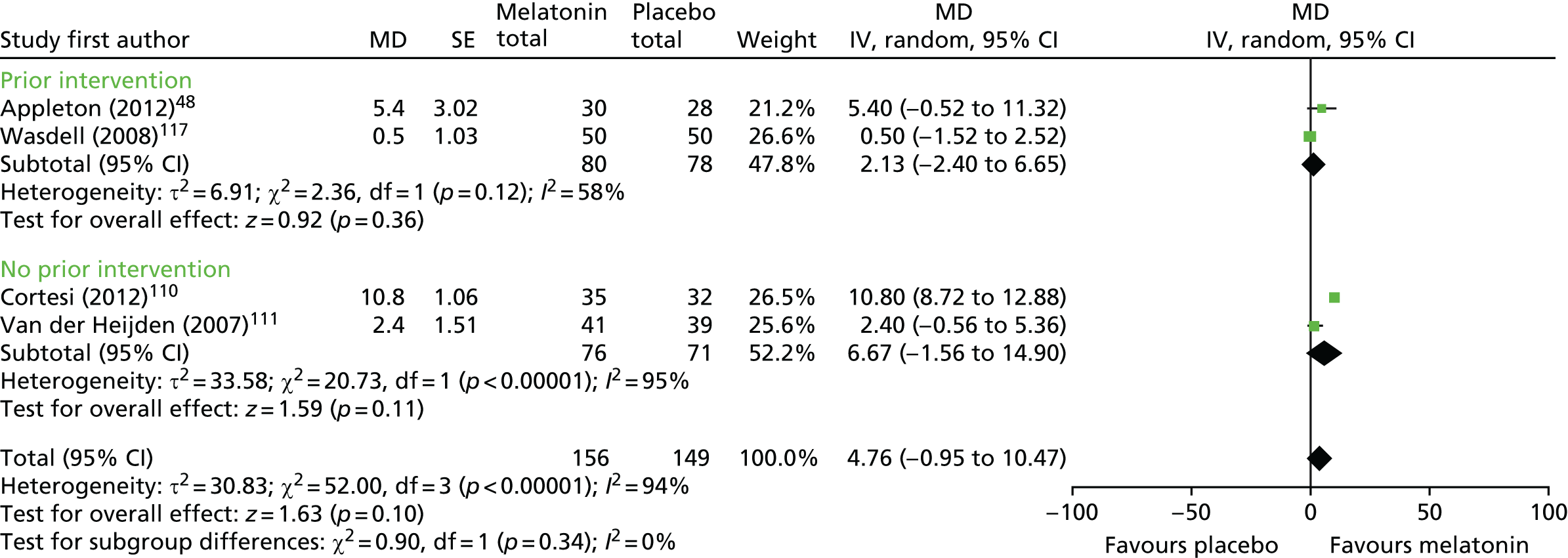

Four trials48,110,117,135 (n = 255 analysed participants) for actigraphy-measured sleep efficiency were pooled, comprising three parallel trials (n = 205) and one crossover trial with a washout period (n = 50). There was no statistically significant difference in sleep efficiency with melatonin compared with placebo (pooled MD 4.76% favouring melatonin, 95% CI –0.95% to 10.47%; p = 0.10; Figure 5). Heterogeneity was high (I2 = 94%) and this treatment effect is unlikely to be generalisable; although the trials did consistently report very small differences between groups in the proportion of time spent in bed asleep, these are unlikely to be clinically meaningful.

FIGURE 5.

Actigraphy-measured sleep efficiency: melatonin vs. placebo. df, degrees of freedom; IV, instrumental variable.

For the single trial117 reporting parent-reported sleep efficiency (n = 50 analysed participants), there was no statistically significant difference between groups (MD 0.30% favouring melatonin, 95% CI –0.90% to 1.49%; p = 0.62).

Cortesi et al. 110 reported the percentage of children who achieved a sleep efficiency in the normative range (> 85%) as 46.43% of the melatonin group compared with none of the placebo group.

Jain et al. 115 reported no difference in polysomnography-measured sleep efficiency (MD 3.8% favouring melatonin, 95% CI –2.5% to 10.1%, n = 10).

Sleep initiation

Sleep onset latency

Ten trials48,69,70,106,110,111,114,117,119 (n = 583 randomised participants) measured SOL, the time from bedtime to sleep onset time (see Appendix 7): three trials reported parent-reported SOL data only;69,106,114 two reported actigraphy-measured SOL data only;110,119 four reported both actigraphy-measured and parent-reported SOL data;48,70,111,117 and one used polysomnography- and actigraphy-measured data, but reported only the results of the polysomnography. 115 As with TST, trials reporting actigraphy data stated that it was informed, or verified, by parent-reported sleep diaries.

Cortesi et al. 110 also calculated the percentage of children who met either a standard sleep criterion for SOL of ≤ 30 minutes or a reduction of SOL by 50%. Wright et al. 106 used an additional measure of SOL defined as the duration of time between taking the medication and falling asleep.

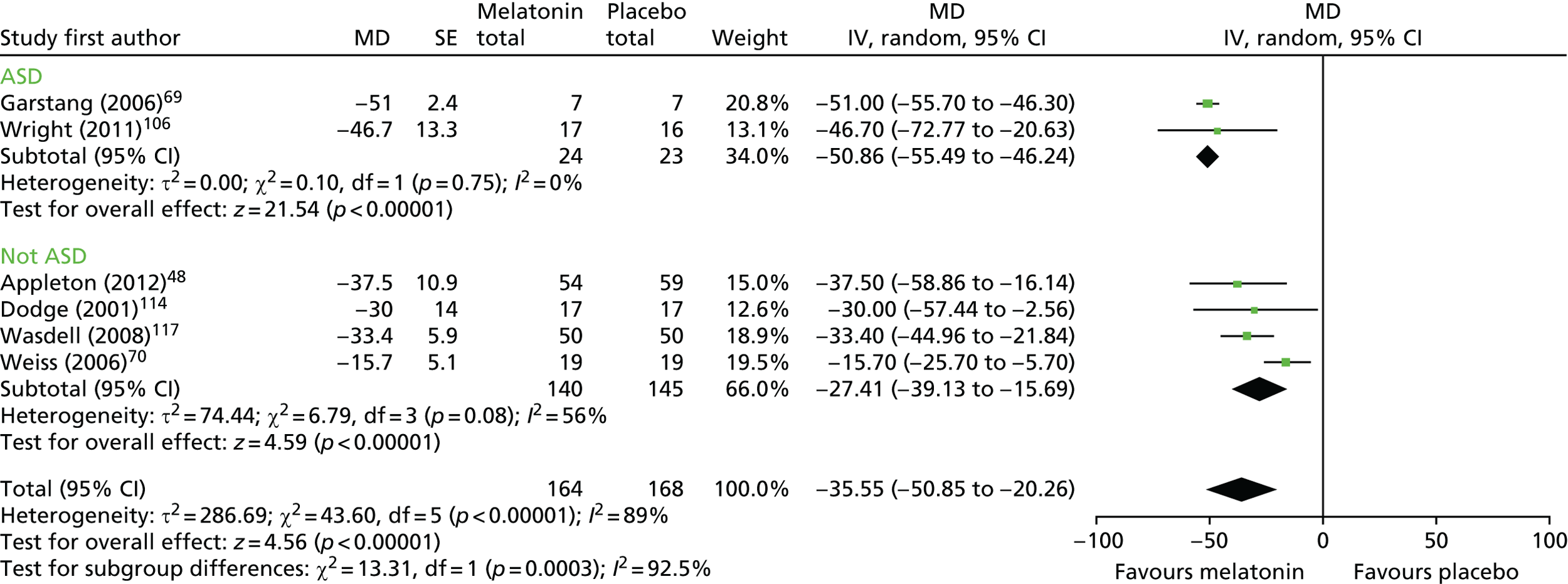

For parent-reported/sleep diary SOL, six trials48,69,70,106,114,117 (n = 223 analysed participants) were pooled, comprising five crossover trials with a washout period (n = 110)69,70,106,114,117 and one parallel-group trial (n = 113). 48 There was a statistically significant decrease (favouring melatonin) in SOL for melatonin compared with placebo (pooled MD –35.6 minutes, 95% CI –50.9 to –20.3 minutes; p < 0.001; Figure 6). Heterogeneity was high (I2 = 89%) and the treatment effect is unlikely to be generalisable, although the effect estimates were all in the direction of benefit with melatonin. There was a statistically significant difference in effect between the studies of children with ASD and those with mixed and other populations (test for subgroup differences, p < 0.001; I2 = 93%). There was a larger difference in the ASD group between melatonin and placebo, with a mean reduction in favour of melatonin of 50.9 minutes (95% CI –55.5 to –46.2 minutes) compared with 27.41 minutes (95% CI –39.1 to –15.7 minutes) in the other group. Subgroup analysis by whether or not participants had received a prior intervention was not possible.

FIGURE 6.

Sleep diary-measured SOL: melatonin vs. placebo. df, degrees of freedom; IV, instrumental variable.

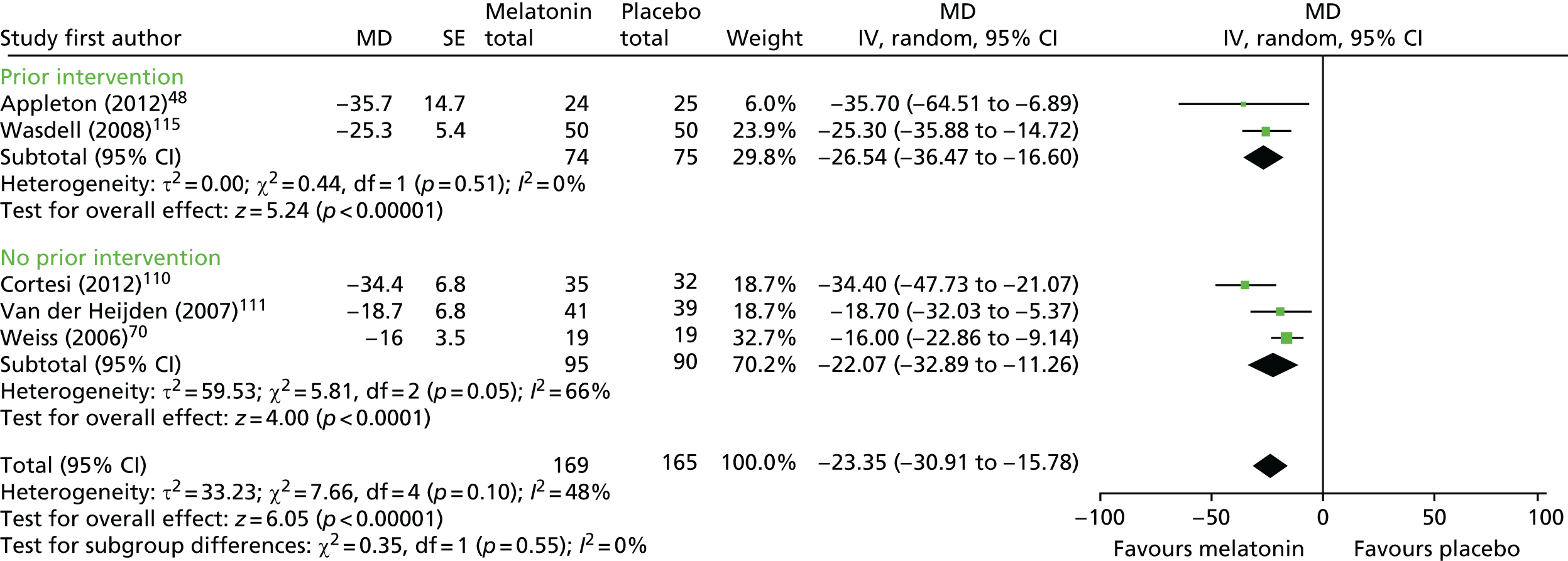

For actigraphy-measured SOL, five trials48,70,110,111,117 (n = 265 analysed participants) were pooled, comprising three parallel trials (n = 196)48,110,111 and two crossover trials with a washout period (n = 69). 70,117 There was a statistically significant decrease (favouring melatonin) in actigraphy-reported SOL (pooled MD –23.4 points, 95% CI –30.9 to –15.8 points; p < 0.001; Figure 7). There was moderate heterogeneity (I2 = 48%). Based on the subgroup analysis, there was no statistically significant difference in effect between studies in which participants had or did not have a prior intervention (test for subgroup differences, p = 0.55; I2 = 0%). A subgroup analysis based on neurodevelopmental condition was not possible.

FIGURE 7.

Actigraphy-measured SOL: melatonin vs. placebo. df, degrees of freedom; IV, instrumental variable.

For both sleep diary-measured and actigraphy-measured SOL, the single study rated as having a low risk of bias48 reported a statistically significant improvement with melatonin compared with placebo (see Figures 6 and 7).

The crossover study without a washout period119 (n = 12 analysed participants) reported a statistically significant decrease in mean SOL for the melatonin period, compared with the placebo period, using a non-parametric analysis (complete-case analysis, p = 0.02; last observation carried forward, p = 0.0001), but this difference is not significant when tested using a paired t-test (MD –28.08 minutes; p = 0.10; estimated 95% CI –2.5 to 58.7 minutes).

Cortesi et al. 110 used an additional indicator of SOL (the percentage of children who met a criterion of SOL of ≤ 30 minutes or a reduction of SOL by 50% post intervention) and reported that 39% of the melatonin group versus 0% of the placebo group achieved these changes (n = 66 analysed participants). Jain et al. 115 (n = 10), using polysomnography, reported that melatonin significantly reduced the mean SOL compared with placebo, with a reported MD of –11.4 minutes (95% CI –17.2 to –5.6 minutes).

Wright et al. 106 (n = 17) reported a significant decrease in SOL with melatonin compared with placebo [MD 51.7 minutes (SD 71.9 minutes; p = 0.012; estimated 95% CI 16.5 to 86.9 minutes)].

Sleep maintenance

Number of night wakings

Six trials69,106,113,114,117,119 (n = 142 randomised participants) reported the number of night wakings.

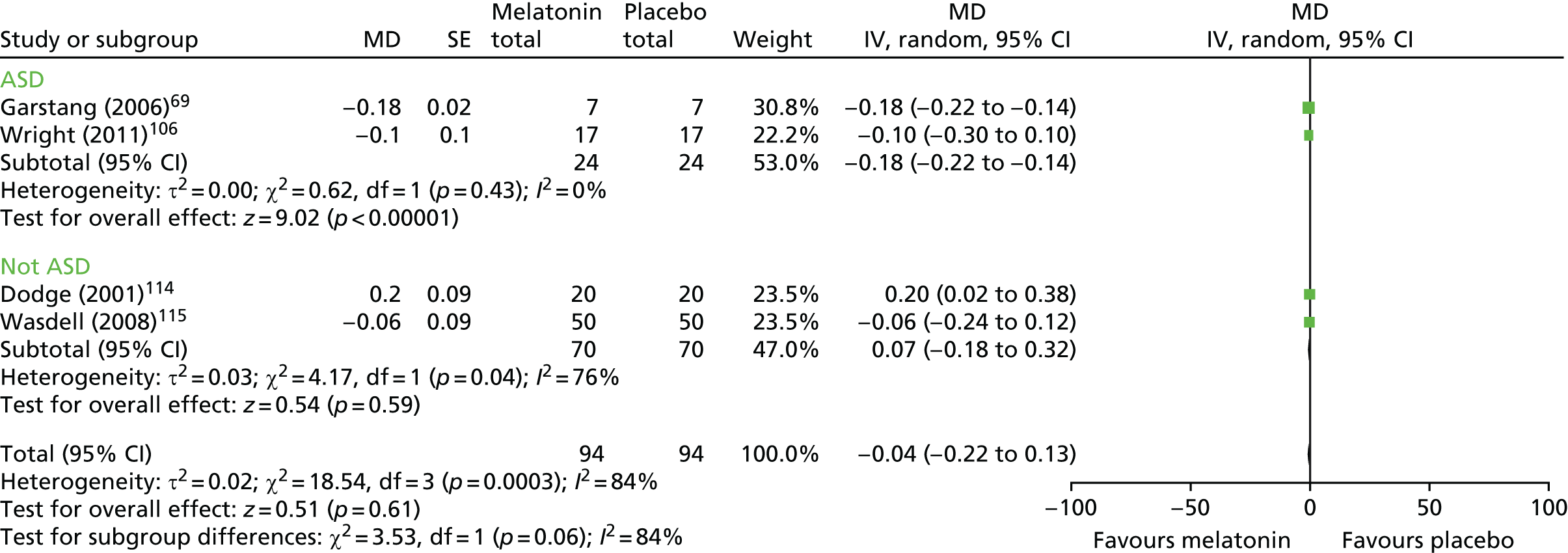

Four crossover trials with a washout period were pooled (n = 94 analysed participants). 69,106,114,117 There was no difference in the mean number of night wakings with melatonin compared with placebo (pooled MD –0.04 points, 95% CI –0.22 to 0.13 points; p = 0.61; Figure 8). Heterogeneity was high (I2 = 84%), although the results were fairly consistent, with the exception of those of Dodge and Wilson. 114 Based on the subgroup analysis, there was no statistically significant difference in effect between studies based on ND (test for subgroup differences, p = 0.06; I2 = 71%).

FIGURE 8.

Parent-reported number of night wakings: melatonin vs. placebo. df, degrees of freedom; IV, instrumental variable.

The crossover study without a washout period119 reported no significant difference for the melatonin period compared with the placebo period by either the non-parametric analyses or the paired t-test [MD by paired t-test –0.07 points (favours melatonin, p = 0.73; estimated 95% CI –0.44 to 0.30 points)]. Wasdell et al. 117 reported no statistically significant treatment difference (p = 0.48) for melatonin compared with placebo (estimated MD –0.41 points favouring melatonin, 95% CI –1.47 to 0.66 points).

Other outcomes

Six out of the 11 trials reported other outcomes of interest,110,111,113,115,117,119 although, with the exception of WASO (night waking duration and/or frequency after the child falls asleep), which was reported by two studies,110,115 each outcome measure was reported by only a single study. These data are summarised in Table 2.

| Study | Outcome | Time point, mean (SD) | MD between melatonin and placebo (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | Follow-up | |||

| Global measures and composite scores | ||||

| Cortesi et al. (2012)110 | CSHQ (total points) |

Melatonin: 66.67 (8.55) Placebo: 64.20 (4.85) |

Melatonin only: 54.78 (6.22) Placebo: 64.80 (4.52) |

–10.02 (–12.71 to –7.33) |

| WASO (minutes) |

Melatonin: 73.71 (45.00) Placebo: 69.75 (45.21) |

Melatonin: 42.21 (22.35) Placebo: 70.15 (42.76) |

–27.94 (–44.58 to –11.30) | |

| Jain et al. (2015)115 | Sleep Behaviour Questionnaire (total points) | Overall: 59.2 (10.5 ) |

Melatonin: 52.4 (5.4) Placebo: 48.3 (7.4) |

3.4 (–2.2 to 9.0) |

| WASO (minutes) | Overall: 60.6 (24.0) |

Melatonin: 42.3 (30.3) Placebo: 57.3 (31.6) |

–22.2 (–34.1 to –10.3) | |

| Wasdell et al. (2008)117 | Somnolog longest sleep episode (minutes) | Overall: 415.41 (106.23) |

Melatonin: 453.30 (118.41) Placebo: 434.26 (109.09) |

18.3 (–5.0 to 41.6) |

| Actigraph longest sleep episode (minutes) | Overall: 185.17 (102.63) |

Melatonin: 199.37 (100.46) Placebo: 189.25 (99.98) |

7.9 (–16.6 to 32.4) | |

| Sleep initiation | ||||

| Cortesi et al. (2011)7 | Bedtime (units unclear) |

Melatonin: 23.45 (1.15) Placebo: 23.41 (1.19) |

Melatonin: 22.30 (1.10) Placebo: 23.51 (1.12) |

–1.21 (–1.76 to –0.66) |

| Van der Heijden et al. (2007)111 | Sleep onset (hour : minutes) |

Melatonin: 21:40 (0.59 minutes) Placebo: 21:38 (0.47 minutes) |

Melatonin: 21:13 (0:58) Placebo: 21:48 (0:48) |

–35 minutes (–59 to –11 minutes) |

| Difficulty falling asleepa (points) |

Melatonin: 3.4 (0.9) Placebo: 3.2 points (0.7 points) |

Melatonin: 2.2 (0.9) Placebo: 3.1 points (1.0 points) |

–0.9 (–1.3 to –0.5) | |

| Jain et al. (2015)115 | Bedtime (hour : minutes) | Overall: 21:44 (0.75 minutes) |

Melatonin: 21:57 (0.91 minutes) Placebo: 21:49 (0.72 minutes) |

6.8 minutes (–23.3 to 9.7 minutes) |

| Wirojanan et al. (2009)119 | Sleep onset time (hour : minutes) | NR |

Melatonin: 20:43 (1.39 minutes) Placebo: 21:25 (2.00 minutes) |

–42 minutes (–74.8 to –9.2 minutes) |

| Sleep maintenance | ||||

| Camfield et al. (1996)113 | Nights without awakening | NR |

Raw data for nights without awakening between 22:00 and 07:00 hours per day/the number of days of complete data: Melatonin: 2/25 (8%); 0/21 (0%); 7/35 (20%); 10/29 (34%); 4/33 (12%); 26/35 (74%) Placebo: 2/28 (7%); 0/25 (0%); 1/31 (3%); 4/30 (13%); 1/31 (3%); 24/35 (69%) |

8.9 (–0.1 to 17.9) |

| Van der Heijden et al. (2007)111 | Wake up timeb (hour : minutes) |

Melatonin: 07:25 (0.39) Placebo: 07:25 (0.34) |

Melatonin: 07:21 (0.40 minutes) Placebo: 07:33 (0.26 minutes) |

–12.0 minutes (–27.1 to 3.1 minutes) |

| Moving timeb (%) |

Melatonin: 11.95 (4.38) Placebo: 10.43 (3.69) |

Melatonin: 12.79 (8.20) Placebo: 12.30 (3.88) |

0.5 (2.4 to 3.4) | |

| Jain et al. (2015)115 | Wake time (hour : minutes) | Overall: 7:09 (1:04) |

Melatonin: 7:31 (1.09 minutes) Placebo: 7:11 (1.09 minutes) |

–18.1 minutes (–0.2 to –36.0 minutes) |

| Sleep scheduling | ||||

| Cortesi et al. (2012)110 | Naptime (units unclear) |

Melatonin: 33.57 (56.63) Placebo: 37.33 (56.19) |

Melatonin: 17.00 (33.11) Placebo: 36.10 (33.28) |

–19.10 (–35.43 to –2.77) |

| Other outcomes | ||||

| Van der Heijden et al. (2007)111 | Interdaily stabilityb,c (points) |

Melatonin: 0.65 (0.13) Placebo: 0.64 (0.15) |

Melatonin: 0.66 (0.16) Placebo: 0.68 (0.11) |

–0.02 (–0.08 to 0.04) |

| Intradaily variabilityb,d (points) |

Melatonin: 0.65 (0.18) Placebo: 0.67 (0.15) |

Melatonin: 0.69 (0.23) Placebo: 0.63 (0.14) |