Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 11/01/26. The contractual start date was in March 2013. The draft report began editorial review in October 2017 and was accepted for publication in April 2018. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Christopher C Butler is a National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) senior investigator. Kerenza Hood and Amanda Roberts are members of the NIHR Health Technology Assessment General Board. Kerenza Hood is a member of the NIHR Clinical Trials Unit Standing Committee.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2018. This work was produced by Francis et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2018 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Introduction

Importance of the problem

Otitis media with effusion (OME) is the commonest cause of hearing loss in children in the UK, and up to 80% of children are affected by OME by 4 years of age. 1 Overall, the prognosis for OME is good, with over 50% of OME episodes resolving spontaneously within 3 months and 95% resolving within 1 year. However, 30–40% of children have recurrent OME episodes, and 5% of preschool children (aged < 5 years) have persistent (> 3 months) bilateral hearing loss associated with OME. 2

Hearing loss from OME can have an important impact on children’s mood, communication, concentration, learning, socialisation and language development. This may affect other family members and family function. OME in early childhood can affect intelligence quotient (IQ), behaviour and reading into teenage years. 3

The UK’s National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) 2008 guideline for OME management recommends a ‘watchful waiting’ period of 3 months, with referral to an ear, nose and throat (ENT) department if hearing is significantly affected, if OME persists for > 3 months or if there is suspected language or developmental delay. 4 Similar recommendations come from the American Academy of Pediatrics and the American Academy of Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery. 5,6 Treatment options for these children are limited to hearing aids or surgical insertion of ventilation tubes (grommets or tympanostomy tubes) through the tympanic membrane. Hearing aids are an effective treatment, but this intervention is not problem free; children often find them uncomfortable, may feel self-conscious and may become a target for bullying. 7

Although the diagnosis of OME in primary care has increased over the last decade, the number of grommet operations performed in England fell from 43,300 in 1994–95 to 25,442 in 2009–10, primarily as a result of the watchful waiting strategy. 8 However, OME remains the commonest reason for childhood surgery in the UK and comprises a considerable workload for hospital ENT departments. Furthermore, there is wide variation in the rate of grommet surgery between regions that is unlikely to be explained by variation in disease. In Wales, there is sixfold variation in the European age-standardised rates of grommet surgery between the highest and the lowest local authorities. 9

Both hearing aids and surgery require referral to secondary care with risks and major cost consequences. The Department of Health and Social Care-commissioned ‘McKinsey’ report10 stated that the NHS could save £21M per year by reducing grommet insertion, a procedure that was assessed as being ‘relatively ineffective’, by a further 90%. This position has been challenged. Deafness Research UK11 and ENT UK’s 2009 OME (Glue Ear) Adenoid and Grommet Position Paper12 conclude that reducing access to grommets will disadvantage thousands of children who are in genuine need of treatment.

Rationale for the current trial

Antibiotics, topical intranasal steroids, decongestants, antihistamines and mucolytics are all ineffective treatments for OME. 13–15 A rigorous evaluation of anti-inflammatory treatment for OME has been a priority for many years. 16 Cochrane systematic reviews have found insufficient evidence for the effectiveness of both oral steroids and autoinflation (AI) devices in resolving OME in children to recommend implementation, but sufficient evidence to recommend further research. 14

A recent trial of an AI device in children aged 4–11 years with OME has found a modest effect for some children. 17 However, 80% of children are affected by OME before the age of 4 years, at a time when language development is most rapid and hearing loss has its greatest effect on language development. 3 Alternative management options to hearing aids or surgery for children aged < 4 years (who are unable to use an AI device) are required.

Williamson et al. 18 evaluated topical intranasal steroids for children with OME in general practice and found that they are unlikely to be clinically effective for OME. This may be because topical steroids applied through the nose are unlikely to reach the middle ear. However, systemic steroids do reach the middle ear epithelium and modulate OME in animal models. 19

The evidence from in vitro and animal models suggests that steroids reduce middle ear effusions and middle ear pressure. 20–23 Various mechanisms have been proposed for a role for steroids in resolving middle ear effusions, including (1) reducing arachidonic acid and associated inflammatory mediators, (2) shrinking perieustachian tube lymphoid tissue, (3) enhancing secretion of eustachian tube surfactant with a resultant improvement in tubal function and (4) reducing middle ear fluid viscosity by its action on mucoproteins. 24

The latest update of the Cochrane review on oral or topical steroids for OME (last search conducted in August 2010) found no benefit from intranasal steroids. 14 However, the review did identify evidence of a statistically significant benefit from oral steroids plus antibiotics versus antibiotics alone for OME (five studies, 409 participants; 23% in the intervention group and 47% in the control group with persistent OME at follow-up) and a trend toward a significant benefit for oral steroids versus placebo in the short term (three studies, 108 participants). Oral antibiotics alone are not effective. The only study to assess the effect of oral steroids on hearing as an outcome was underpowered.

Studies included in the systematic review were short term, underpowered, often had poorly described inclusion criteria and/or did not assess hearing at the time of inclusion, used ears rather than children as the unit of analysis and used intermediate outcome measures, such as tympanometry results, rather than improved hearing. No cost-effectiveness studies of oral steroids for OME were found. Therefore, there is insufficient evidence to recommend oral steroids as a treatment for persistent OME because of inadequate evidence about the short-term effects on hearing and cost-effectiveness, and the absence of evidence about the longer-term effects.

Potential harms from oral steroids

No significant adverse effects from steroids were reported by the studies included in the Cochrane review. However, the numbers of participants were too small to rule out that possibility. Short courses of prednisolone are widely used in treating children with acute asthma and adverse events are extremely rare; when adverse events do occur, they are largely limited to behavioural disturbances and dyspepsia and resolve on withdrawal of the steroid drug. The safety of multiple short courses of oral steroid therapy has been evaluated. 25 Short courses of oral steroids, such as prednisolone, do not have lasting negative effects on bone metabolism, bone density, adrenal gland function, or weight or height, even if used on several occasions over the course of 1 year. 26

Summary

There is an important evidence gap regarding the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of short courses of oral steroid treatment for OME. Identifying an effective, safe, cost-effective, acceptable non-surgical intervention for OME in children (including those in the first 4 years of life) for use in primary care remains an important research priority.

The Oral STeroids for the Resolution of otitis media with effusion In CHildren (OSTRICH) trial aimed to determine the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of a 7-day course of oral prednisolone (steroid) in improving hearing over the short term in children with bilateral OME, as diagnosed at an ENT outpatient or paediatric audiology/audiovestibular medicine (AVM) clinic, who have had symptoms attributable to OME present for at least 3 months and currently have significant hearing loss (as demonstrated by audiometry). 27

Chapter 2 Methods

Summary of the trial design

The OSTRICH trial was a double-blind, individually randomised, placebo-controlled trial involving children with persistent OME and significant hearing loss, which aimed to determine the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of a 7-day course of oral steroids in improving hearing in children with bilateral OME. The trial was based in secondary care, primarily in ENT outpatient clinics, but also included paediatric audiology and AVM clinics. Participating sites were asked to identify children (aged between 2 and 8 years) with persistent bilateral OME and significant hearing loss. Eligible, consented children were randomly assigned to one of the two treatment groups: oral steroids or matched oral placebo.

At the baseline visit, participants’ hearing was assessed and parents reported on quality of life (QoL), the impact of OME on the family and health status, using established assessment tools. Children aged > 5 years were also asked about their QoL. Parents were asked to complete a diary for the first 5 weeks following enrolment to record daily symptom severity, use of medication and health-care consultations. Participants were followed up at 5 weeks, 6 months and 12 months after the day of randomisation.

The main analysis compared hearing resolution at week 5 in the active treatment group (oral steroids) and the placebo group.

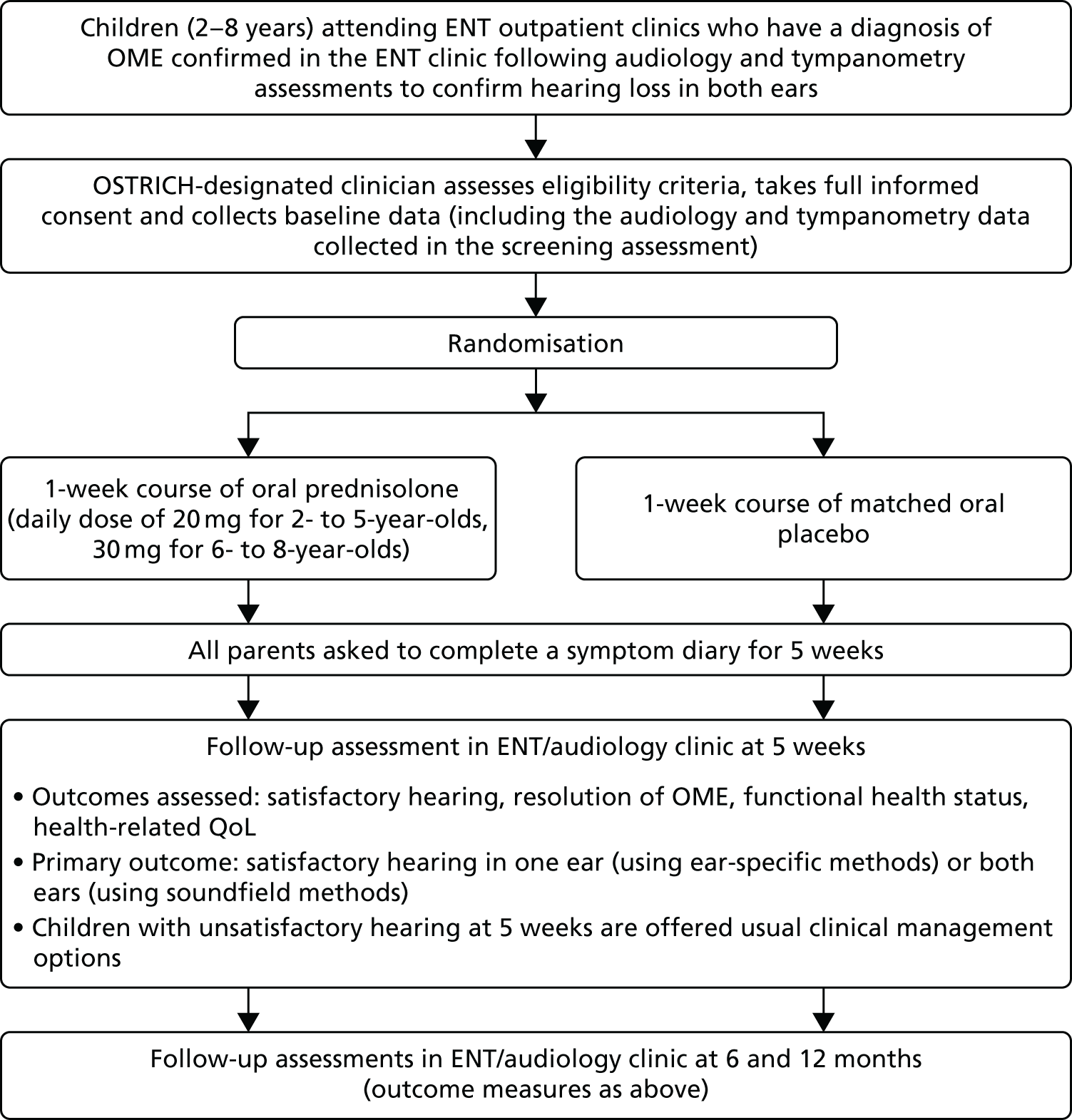

The schedule of events and participant flow for the trial is summarised in Figure 1.

FIGURE 1.

Trial schema and participant flow.

Clinical effectiveness objectives

Primary objective

The primary objective was to determine the clinical effectiveness of a 7-day course of oral steroids in improving hearing at 5 weeks from randomisation in children with bilateral OME, who have had symptoms attributable to OME present for at least 3 months, and currently have significant hearing loss (as demonstrated by audiometry). Oral steroids are likely to take effect within the first few weeks, and most of the existing evidence is for an effect at 4–6 weeks. This is, therefore, the time point at which the maximum effect is expected.

Secondary objectives

To assess the longer-term (up to 12 months) effect of the intervention on:

-

hearing

-

resolution of OME

-

insertion of ventilation tubes (grommet surgery) rates

-

symptoms

-

adverse effects

-

functional health status

-

QoL.

Setting

Participants were recruited from ENT outpatient or paediatric audiology and AVM clinics across Wales and England.

Site recruitment

The trial was open to participant recruitment from 19 March 2014 until 31 March 2016. A principal investigator led each site.

Ear, nose and throat outpatient clinics and paediatric audiology/AVM clinics were considered to be sites for the purpose of the trial. The Clinical Research Network (CRN) in England and the Health and Care Research Wales Workforce in Wales supported site recruitment.

Clinics were invited to take part in the trial by e-mail or newsletter from the CRN. Interested practices were initially contacted by e-mail and asked to provide further information about their feasibility for conducting the trial. This was followed up by telephone from the trial team to discuss the trial in more detail.

Each site involved had a research nurse/co-ordinator and a local site pharmacy.

Participant selection

Children were eligible to join the trial if they attended a participating NHS site for their routine care, met the following inclusion criteria and did not meet any of the exclusion criteria.

Inclusion criteria

-

Aged 2–8 years (e.g. reached second birthday and not yet reached ninth birthday).

-

Symptoms of hearing loss attributable to OME for at least 3 months (or had audiometry-proven hearing loss for at least 3 months).

-

Diagnosis of bilateral OME made in an ENT or paediatric audiology and AVM clinic on the day of recruitment or during the preceding week.

-

Audiometry-confirmed hearing loss of > 20 decibels hearing level (dBHL) averaged within the frequencies of 0.5, 1, 2 and 4 kHz in both ears by pure-tone audiometry (PTA) ear-specific insert, visual reinforcement audiometry (VRA) or ear-specific play audiometry, or hearing loss of > 25 dBHL averaged within the frequencies of 0.5, 1, 2 and 4 kHz by soundfield VRA or soundfield performance/play audiometry in the better-hearing ear, on the day of recruitment or within the preceding 14 days.

-

First time in the OSTRICH trial.

-

Parent/legal guardian able to understand and give full informed consent.

Exclusion criteria

Children who met one or more of the following criteria were not eligible for inclusion:

-

was currently involved in another clinical trial of an investigational medicinal product (CTIMP) or participated in a CTIMP during the last 4 months

-

had a current systemic infection or ear infection

-

had a cleft palate, Down syndrome, diabetes mellitus, Kartagener syndrome or primary ciliary dyskinesia, renal failure, hypertension or congestive heart failure

-

had confirmed, major developmental difficulties (e.g. was tube fed, had chromosomal abnormalities)

-

existing known sensory hearing loss

-

had taken oral steroids in the preceding 4 weeks

-

had a live vaccine in the preceding 4 weeks if aged < 3 years

-

had a condition that increases the risk of adverse effects from oral steroids (i.e. on treatment likely to modify the immune system or be immunocompromised, for example undergoing cancer treatment)

-

had been in close contact with someone known or suspected to have varicella (chickenpox) or active herpes zoster (shingles) during the 3 weeks prior to recruitment and had no prior history of varicella infection or immunisation

-

already had ventilation tubes (grommets)

-

was on a waiting list for grommet surgery and anticipated having surgery within 5 weeks, and was unwilling to delay it.

Participant recruitment

Participating clinicians (in ENT or paediatric audiology/AVM) were asked to identify eligible patients with bilateral hearing loss and a diagnosis of OME during routine outpatient consultations, from current grommet surgery waiting lists or hearing aid review lists. In addition, potentially eligible children were identified in audiology, AVM, paediatric audiology and community audiology clinics and interested parents/legal guardians were directed to the participating OSTRICH trial clinician.

Informing parents of potentially eligible children about the trial

Participating sites were asked to identify all children between the ages of 2 and 8 years who had been referred to the ENT clinic for probable OME and to write to their parent/legal guardian(s) (hereafter referred to as parent) to inform them about the trial.

Identification of potentially eligible children

Participating clinicians identified potentially eligible children who were attending routine clinics with bilateral hearing loss or a diagnosis of OME. Parents of children were approached about the trial by an ENT/audiovestibular clinician (doctor, nurse or audiologist). Each child had an audiometry assessment and a clinical assessment (both routine procedures for those attending these clinics) before they were assessed for eligibility to enter the trial.

The participating clinician assessed eligibility and interested parents of eligible children were invited to speak with a designated clinical member of the OSTRICH trial team. This individual explained the trial to the child’s parent and provided them with a written patient information sheet (PIS). If the parent had already received the PIS with their clinic invitation, then the designated individual went through this with the parent. Age-appropriate pictorial information sheets were also provided for children who were old enough to use them.

Informed consent

Parents were asked to provide informed consent. The clinician taking consent also assessed the child’s capacity to understand the nature of the trial and, when appropriate, the views of children capable of expressing an opinion were taken into account; children deemed to have sufficient understanding were asked to sign an age-appropriate assent form.

Parents were informed that they had the right to withdraw consent from participation in the OSTRICH trial at any time and that the clinical care of their child would not be affected by declining to participate or withdrawing from the trial.

All participating sites were asked to keep an anonymous screening log of all ineligible and eligible but not consented/not approached patients. This was used to assess potential selection bias.

Randomisation, blinding and unblinding

Randomisation

Randomisation was co-ordinated centrally by the South East Wales Trials Unit, Centre for Trials Research. The randomisation schedule was prepared by the trial statistician (TS) and comprised random permuted blocks that were stratified by site and child’s age. The investigational medicinal product (IMP) manufacturer (Piramal Healthcare UK Limited, Grangemouth, UK) was provided with a list of random allocation numbers linking to either the oral steroid or the placebo. Whether the allocations related to the oral steroid or placebo was determined by an independent statistician to ensure that the TS remained blinded. The allocation numbers were used to label the trial medication packs. Each trial medication pack had a unique identification number (trial pack number).

As children were recruited, they were assigned the next vacant participant identification number. Trial medication packs were released only once informed consent had been obtained and a consent form was signed. Participants were randomised to receive either the oral steroid or the matching placebo by receiving the next sequentially numbered trial pack allocated to the participant by the site pharmacy. A designated member of the OSTRICH trial site team (when possible), or the participant’s parent, collected the pack from the pharmacy on behalf of the participant. Participant randomisation was considered to have occurred once a consent form was signed and the trial pack was received. The trial pack number was then entered onto the participant’s case report form (CRF) by the research nurse.

Blinding

The placebo was matched for consistency, colour and solubility, as well as visually, in identical packaging to the active treatment. Participants, parents, all clinic staff and members of the OSTRICH trial team remained blinded to treatment allocation.

Unblinding

The active treatment used in this trial was a licensed product (or placebo) used outside its licensed indication. Parents were provided with information about the medication that their child was prescribed, which included instructions for use and information on unblinding.

Withdrawal and loss to follow-up

Parents were informed that they had the right to withdraw consent for their child’s participation in any aspect of the trial at any time. If a parent indicated that they wished to withdraw their child from the trial they were asked to give a reason for withdrawal.

Parents who wished to withdraw their child from the trial were asked to decide if they wished to withdraw their child from:

-

further treatment, but allow the child to participate in all further data collection

-

active follow-up, but allow existing data and their child’s medical records to be used

-

all aspects of the trial, as well as requiring all data collected to date to be excluded from the analysis.

To minimise loss to follow-up, parents who had given permission to be contacted by short message service (SMS) text messaging were sent a reminder of their scheduled appointment, when possible, a few days before the appointment.

Trial interventions

Participants were randomised to the active treatment group [oral soluble prednisolone (oral steroid)] or control group (matched oral soluble placebo). Clinicians were blinded to allocation and so prescribed the trial intervention (either prednisolone or placebo); this was dispensed by the site pharmacy.

Oral soluble prednisolone (oral steroid)

Participants in the active treatment group received a 7-day course of oral soluble prednisolone. The soluble prednisolone tablets (5 mg) used in this trial were manufactured by Waymade PLC trading as Sovereign Medical (Basildon, Essex, UK). The marketing authorisation is PL06464/0914.

Piramal Healthcare UK Limited, which has a Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA) manufacturing authorisation (MIA IMP 29595), repackaged and supplied the soluble prednisolone tablets.

Placebo

The placebo used in this trial was matched for consistency, colour and solubility, as well as visually and in its packaging. The placebo was manufactured, packaged and supplied by Piramal Healthcare UK Limited.

Dosage

Oral steroid or placebo

-

For children aged 2–5 years: a single daily dose of four tablets (20 mg of prednisolone) for 7 days.

-

For children aged > 5 years: a single daily dose of six tablets (30 mg of prednisolone) for 7 days.

The daily dose stated was the most commonly used dose in previous studies of OME, and is similar to the standard dose for the treatment of other conditions with inflammatory components (such as asthma).

All IMP products were manufactured and reconciled into sealed and labelled ‘trial packs’ by Piramal Healthcare UK Limited in accordance with good manufacturing practice and in compliance with clinical trial regulations. 28 Trial materials were stored under the conditions specified by the manufacturer (or in the summary of product characteristics) and stored in designated temperature-monitored areas at site pharmacies.

Trial procedures

Training

All staff involved in the trial, including clinicians, research nurses/co-ordinators and pharmacists at sites were provided with written standard operating procedures and received trial-specific training in trial procedures and good clinical practice prior to commencing the trial.

Data collection

The schedules for timing, frequency and method of collection of all trial data are summarised in Table 1. Assessments were performed as close as possible to the required time point (e.g. 5 weeks’ follow-up at 4 weeks post intervention treatment, with a window of + 2 weeks, and 6 and 12 months follow-up with a window of ± 2 weeks).

| Data type | Time point | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline evaluation | Follow-up period | |||

| 5 weeks | 6 months | 12 months | ||

| Clinic visit | Clinic visit/parent diary | Clinic visit/questionnaire | Clinic visit/questionnaire | |

| 1. Demographics | ✗ | |||

| 2. Medical history | ✗ | |||

| 3. Audiometry | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ |

| 4. Tympanometry | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ |

| 5. Otoscopy | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ |

| 6. Medication use | ✗ | |||

| 7. Insertion of ventilation tubes | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | |

| 8. Daily symptoms | ✗ | |||

| 9. Adverse effects | ✗ | |||

| 10. Resource use | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | |

| 11. Functional health status (OM8-3029) | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ |

| 12. HRQoL (HUI330 and PedsQL31) | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ |

| 13. SAEs | |↔| | |||

| 14. Withdrawals | |↔| | |||

Baseline assessments

Once informed consent had been obtained, the OSTRICH trial nurse:

-

registered the participant and their parent to the trial (this included collecting the names and addresses of the participants and their parents)

-

completed the medical history and baseline CRFs (which included recording audiology, tympanometry and otoscopy assessments)

-

provided the parent with the trial medication (when possible) or the prescription for the parent to take to the pharmacy, and provided the medication guidance and instructions-for-use leaflet of the trial medication

-

provided the questionnaire booklet to the parent and completed this with the participant (if appropriate)

-

gave the parent a 5-week symptom diary and provided them with instructions on diary completion

-

arranged the next clinic appointment (at week 5) for the participant to attend with their parent (and instructed them to bring any unused medication with them).

Follow-up assessments

Follow-up assessments for all participants were conducted at week 5 (4 weeks post intervention treatment, + 2-week window) and at 6 and 12 months (± 2-week window). At the 5-week follow-up appointment, any unused trial medication was collected and returned to the pharmacy for disposal.

Diary

Parents were asked to complete a diary for the first 5 weeks. In week 1, this was completed daily to record treatment adherence. Thereafter, it was completed weekly for 4 weeks to record symptoms, adverse events, health-care consultations, additional medication taken, time off school/nursery and parental time off work.

Clinical assessments

The hearing assessments described in Table 2 were measured at 5 weeks post randomisation (4 weeks post treatment) and at 6 and 12 months.

| Measurement | Outcome |

|---|---|

| Audiometry | Hearing in each ear assessed by PTA, ear-specific insert VRA or ear-specific play audiometry, or in both ears together by soundfield VRA or soundfield performance/play audiometry |

| Tympanometry (using calibrated standardised tympanometers and modified Jerger classification types B and C were considered abnormal)32 | Presence of middle ear effusion in each ear |

| Otoscopy | Appearance of tympanic membrane |

In current practice, the recommended standard methods to assess hearing thresholds are ear-specific PTA at 0.5, 1, 2 and 4 kHz in children aged ≥ 3 years and soundfield VRA in children aged < 3 years. However, equally, those under 3 years of age may comply with PTA. Therefore, it was recommended that the audiologist or clinician use their judgement on the most appropriate method of assessment for the child and, when possible, maintain that method for the subsequent follow-ups.

Ear-specific VRA through the use of insert earphones is considered the ‘gold standard’ practice, but it was believed that soundfield VRA provided a reasonable assessment of the child’s level of hearing and ensured the feasibility of the trial in a range of research sites.

Although the follow-up of participants was continued for 12 months, after the 5-week assessment, all participants resumed to ‘usual care’ and all treatment decisions were made by their parents in consultation with their clinician.

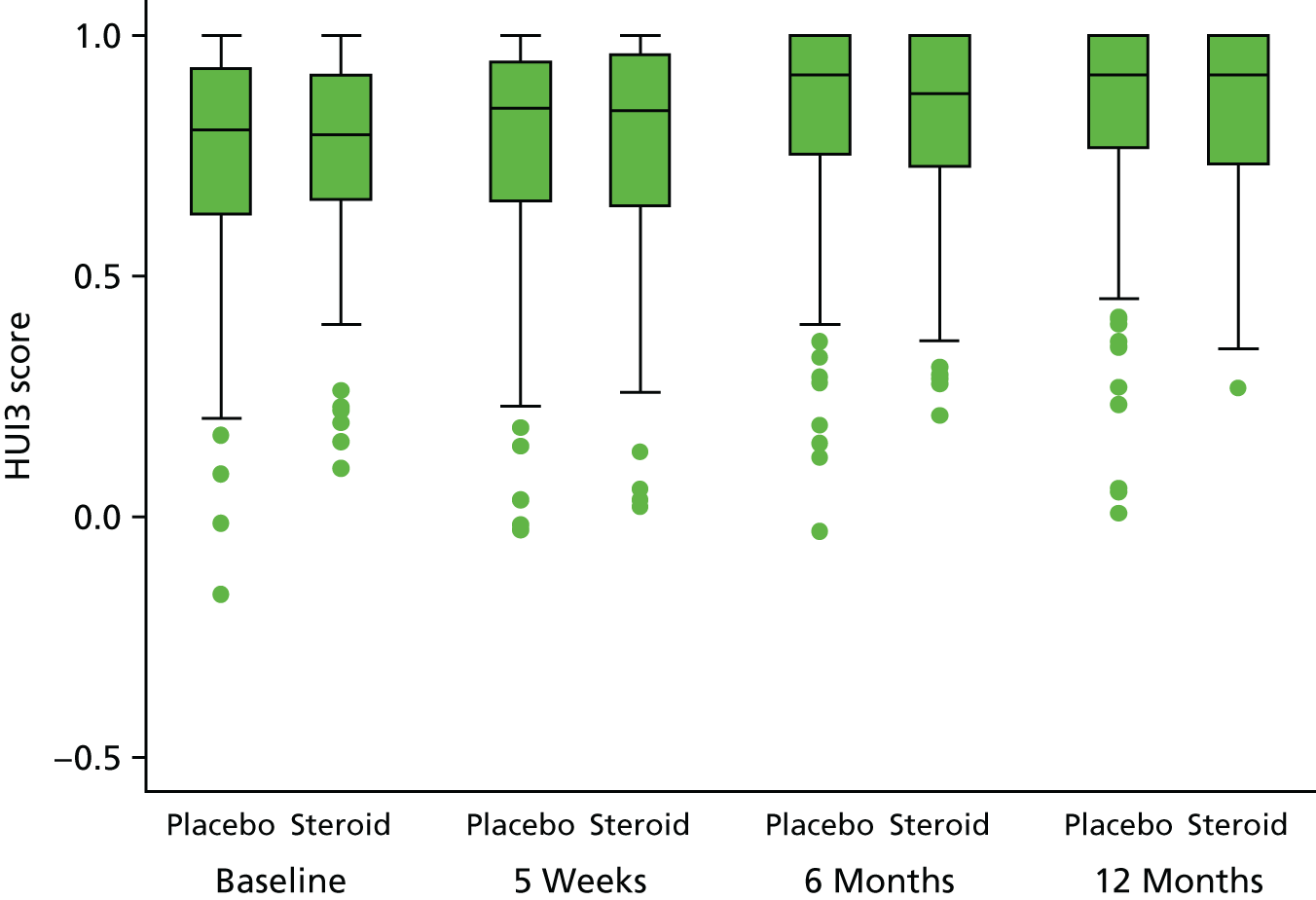

Functional health status and quality of life

Functional health status [assessed via the OM8-30 (Otitis Media Questionnaire)]29 and health-related quality of life (HRQoL) [assessed via the Paediatric Quality of Life Inventory (PedsQL)31 and the Health Utilities Index, version 3 (HUI3)]30 were assessed at the end of week 5 and at 6 and 12 months, through parent-completed questionnaires. Additional questionnaires comprising the child version of the PedsQL were given to children aged ≥ 5 years. There were two age-specific versions for children aged 5–7 years and for those aged ≥ 8 years. Scoring for the three and nine OM8-30 facets was provided by Professor Mark Haggard. A further description of how these measures were used and interpreted within the economic analysis is provided in Chapter 4, Outcomes used in the economic analysis.

Safety monitoring

Parents were asked to record non-serious adverse reactions or events or possible side effects and rate their severity in the parent diary up to the end of the fifth week of trial participation.

Data management and monitoring

Data quality

Data monitoring was conducted throughout the trial across all of the recruiting sites; this included a 10% quality control of all data sets. Further monitoring was triggered if an error rate of > 1% was detected.

Data cleaning

The OSTRICH trial database was built with internal validations and ranges; queries arising during data entry were referred back to the site research nurses. When data collected on paper CRFs conflicted with those collected via the web-based database, the value on the paper CRF was deemed to be the true value, unless the paper CRF had already been appropriately annotated with a correction. Self-evident correction rules were developed during the course of the trial, in response to common errors of CRF completion.

Research governance

This trial had clinical trial authorisation from the UK Competent Authority (MHRA reference number 21323/0039/001-0001) and was reviewed as risk category type B. Ethics approval was granted from the NHS Research Ethics Committee (REC), recognised by the United Kingdom Ethics Committee Authority. The initial approval was granted by the National Research Ethics Service REC for Wales on 28 February 2013 (reference number 13/WA/0004). NHS research and development (R&D) approval was sought from the respective NHS-relevant organisations in Wales and England.

The trial was assigned a European Union Drug Regulating Authorities Clinical Trials (EudraCT) number (2012-005123-32) and an International Standard Randomised Controlled Trial Number (ISRCTN 49798431; registered on 7 December 2012).

Patient and public involvement

The study had a patient and public involvement (PPI) representative who has a child who had long-standing OME. She joined the trial as a member of the trial management group. Our Trial Steering Committee (TSC) and Independent Data Monitoring Committee (IDMC) also had PPI representatives who had personal experience of children with OME. Our PPI representatives made important contributions to reviewing parent and child information sheets, providing feedback on the trial protocol and providing guidance on strategies for successful recruitment. One of our PPI representatives was also interviewed for a case study on the BBC (British Broadcasting Corporation) Wales News. 33 The trial has also benefited from our PPI representatives’ contribution during the analysis and dissemination of study results and they will continue to contribute to dissemination activities.

Outcome measures

Primary outcome measure

The primary outcome was an assessment of acceptable hearing at 5 weeks from randomisation (4 weeks after conclusion of treatment), whereby acceptable hearing is defined as ≤ 20 dBHL averaged within the frequencies of 0.5, 1, 2 and 4 kHz in at least one ear in children assessed by PTA, ear-specific insert VRA or ear-specific play audiometry, and ≤ 25 dBHL averaged within the frequencies of 0.5, 1, 2 and 4 kHz in children assessed by soundfield VRA or soundfield performance/play audiometry. These thresholds are based on national guidelines. 34

Secondary outcome measures

The secondary outcomes assessed the longer-term (up to 12 months) effects of the intervention on:

-

acceptable hearing at 6 and 12 months (as defined in Primary outcome measure)

-

tympanometry (using calibrated standardised tympanometers and modified Jerger classification types A, B and C)32

-

otoscopic findings

-

health-care consultations related to OME and other resource use

-

insertion of ventilation tubes (grommet surgery) at 6 and 12 months

-

adverse effects

-

symptoms (reported by parent and child, if appropriate)

-

functional health status

-

HRQoL.

Clinical effectiveness statistical considerations

Sample size calculation

The sample size calculation was based on demonstrating a change in the rate of resolution of hearing loss at 5 weeks post randomisation (i.e. 4 weeks post completion of treatment), from 20% in the control group to 35% in the intervention group. OME resolves spontaneously in a high proportion of children, and some studies have found a significantly higher rate of spontaneous resolution. For example, Williamson et al. 18 found a resolution rate in their control group of 47%. However, we anticipated a lower spontaneous rate of resolution both because we only included children who had been symptomatic for at least 3 months and because we were recruiting children in a secondary care setting, in which a more severe spectrum of illness was anticipated. The Cochrane review of oral steroids for OME reported a ratio of proportions for resolution of OME at 2 weeks of 3.80 [95% confidence interval (CI) 0.93 to 15.52]. 14 In the five studies in the Cochrane review of oral steroids versus placebo, overall there was a 23% recovery rate in the placebo plus antibiotic group and a 47% recovery rate in the oral steroid plus antibiotic group, with a 24% difference (antibiotics on their own are ineffective). 14 The OSTRICH study selected a conservative estimate of 1.75 for its effect size (ratio of proportions) because it was believed that a 15% absolute increase in the rate of resolution at 5 weeks would represent a clinically meaningful benefit that could result in a meaningful reduction in unnecessary operations and a related saving in costs for the NHS. In order to demonstrate a difference between 20% and 35% with an alpha of 0.05 and 80% power, the study needed 302 participants (nQuery software version 4.0; Statistical Solutions Ltd, Cork, Ireland). The study sample size was 380 to allow for a 20% loss to follow-up at 12 months. Although the primary outcome data were gathered at 5 weeks, it was believed that it was important to be able to assess long-term outcomes and, therefore, the study wanted to ensure that it would have sufficient power for longer-term follow-up assessments.

Statistical analysis

A detailed statistical analysis plan (SAP) was developed and signed off by the chief investigators and the TS, and approved by the IDMC, before the study trial database was locked and any data were examined. Data analysis was conducted in IBM SPSS Statistics version 20.0 (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA) and Stata® version 13.1 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA).

Definitions of populations

Screened population

The screened population comprises all children assessed for eligibility at the initial appointment.

Intention-to-treat population

The intention-to-treat (ITT) population comprises all randomised children and was analysed in the groups to which the children were randomised (regardless of the treatment they received and compliance with the treatment).

Per-protocol population

The per-protocol (PP) population comprises those children randomised who satisfied the study eligibility criteria, received and adhered to their allocated intervention for the 7 days and did not receive any surgery for grommets 5 weeks from randomisation. Children who presented > 14 days before or after the scheduled 5-week visit date were considered not to have complied with the trial protocol and were excluded from the PP population.

Analysis

All of the clinical effectiveness analyses were by ITT without imputation, with outcome values compared between groups using mixed-effect two-level regression models to adjust for site and age of child (2–5 years and 6–8 years) as stratification variables.

Primary analyses

The primary analyses employed a logistic regression model to investigate differences in the proportion of children with acceptable hearing at the 5-week post-randomisation follow-up appointment between the two treatment groups. In addition to age and site, models were adjusted for days from randomisation to the 5-week follow up. Results are presented as the absolute difference in proportions, the adjusted odds ratio (OR) (comparing the odds of an event in the oral steroid group with the placebo group), 95% CI and p-value. For comparison with other studies, the relative risk (RR) was also presented. Sensitivity analyses were performed using the PP population and using allocation-respecting methods, such as complier average causal effect (CACE) modelling to investigate the effect of adherence to treatment using instrumental variable regression. This was carried out by fitting a structural mean model (i.e. White;35 White et al. 36). Adherence was defined as taking all 7 days of oral steroids versus partial adherence (taking < 7 days of oral steroids and taking some/none over the 7 days). Imputation was not necessary because of the low numbers of children missing primary outcome data.

Two effect modifiers were originally identified as a basis for subgroup analyses: age of child and history of atopy (presence of eczema, asthma or hay fever). The following further-identified confounders were defined in advance of any analysis based on best available evidence:

-

the season the child was randomised

-

whether or not the child received antibiotics for an ear infection in the last month

-

number of previous episodes

-

duration of ear symptoms

-

number of previous OME episodes (first vs. more than one)

-

household smoke present

-

deprivation score

-

previous tonsillectomy or adenoidectomy.

Relevant interaction terms were entered into the primary regression analyses for each of the outcomes in order to conduct prespecified subgroup analyses. As the trial was powered to detect overall differences between the groups rather than interactions of this kind, the results of these exploratory analyses are presented using CIs as well as p-values.

One secondary analysis of the primary outcome was proposed using weighted (to account for the number of frequencies recorded) average decibel at the 5-week follow-up as a continuous outcome. As the majority of children had their ears tested at all four frequencies, the weighted results were very similar to the unweighted results, so these were dropped from the analysis. This outcome was modelled in two ways:

-

as a child-level analysis, to explore using the average, best or worst hearing levels from children assessed via PTA, ear-specific insert VRA or ear-specific play audiometry

-

as an ear-level analysis to account for both ears being tested using the ear-specific VRA.

Both approaches used multilevel linear regression modelling [(1) child nested within site and (2) ears nested within child nested within site] adjusting for baseline decibel, child’s age at recruitment and time of the 5-week follow-up (in days). Results were presented as the difference in adjusted means (oral steroid minus placebo), alongside 95% CIs and p-values.

Secondary outcomes

Secondary outcomes with a binary outcome (present/absent), such as satisfactory hearing (as assessed by audiology/tympanometry), otoscopy outcomes (presence of perforation, effusion, bubbles) and insertion of ventilation tubes, were analysed using repeated measures logistic regression to investigate the differences between the treatment groups and time (at 5 weeks’ and at 6 and 12 months’ follow-up). Time was nested within participants nested within site and included an interaction term for time and treatment group to investigate any divergent or convergent pattern in outcomes. The global interaction effect was tested. In addition to the aforementioned covariates, baseline measures of outcome were also adjusted for when possible.

An adjusted multilevel Cox (shared frailty) regression model examined the time (days) since recruitment to insertion of ventilation tubes between treatment groups, the effect was reported as an adjusted hazard ratio (HR) alongside 95% CIs.

For continuous secondary outcomes, such as the HUI3, PedsQL (overall and five domains) and OM8-30 scores (total and the three facets), repeated measures linear regression models were used to investigate differences between the treatment groups and over time (5 weeks and 6 and 12 months), adjusting for baseline scores. Transformations (squared and cubed) to the raw scores were performed, as necessary, to improve residuals and model fit. If no transformations were suitable, the raw scores were dichotomised and a repeated measures logistic regression model was used. The use and interpretation of these measures for the economic analysis are described in Chapter 4, Health outcome measures.

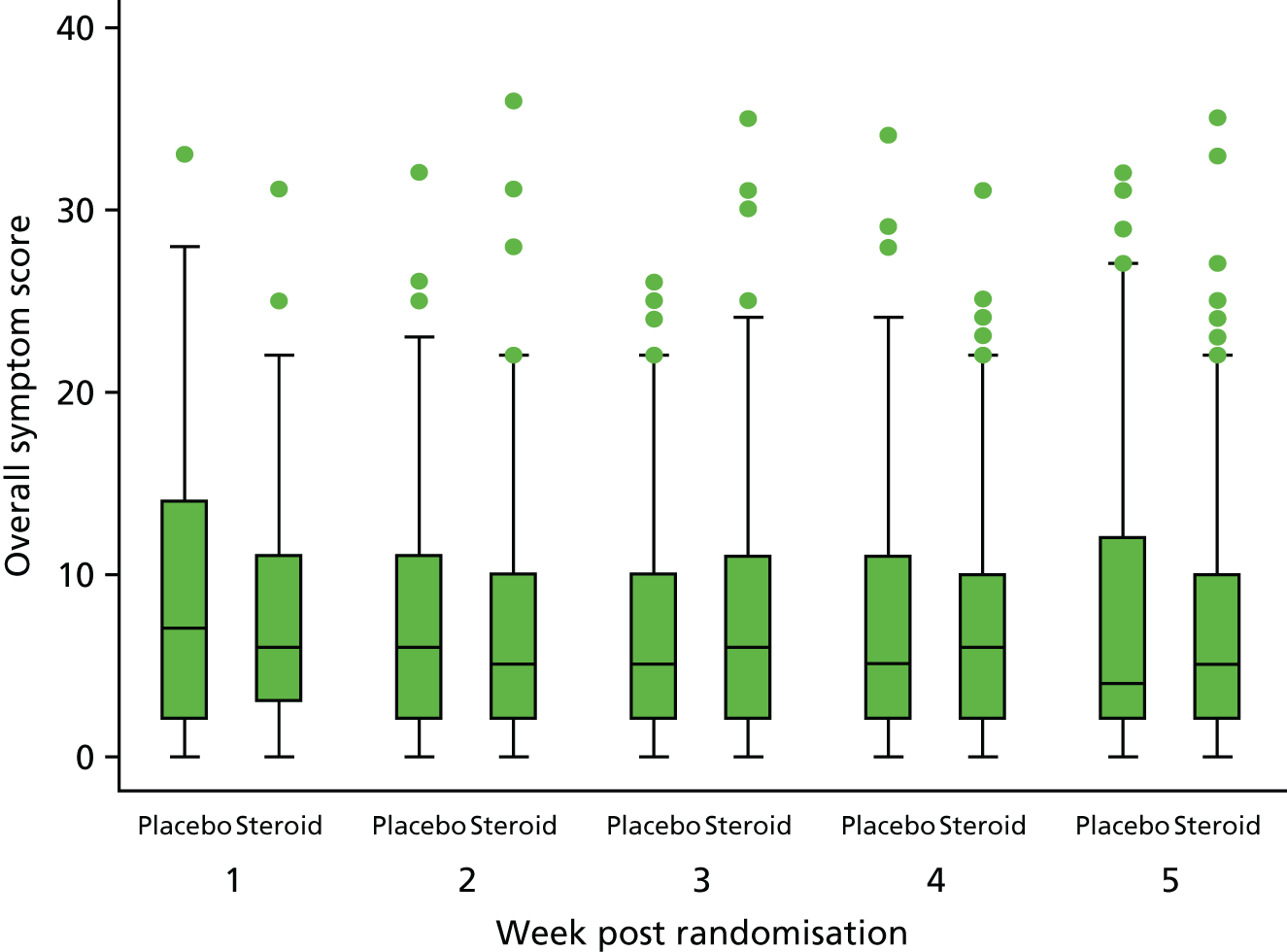

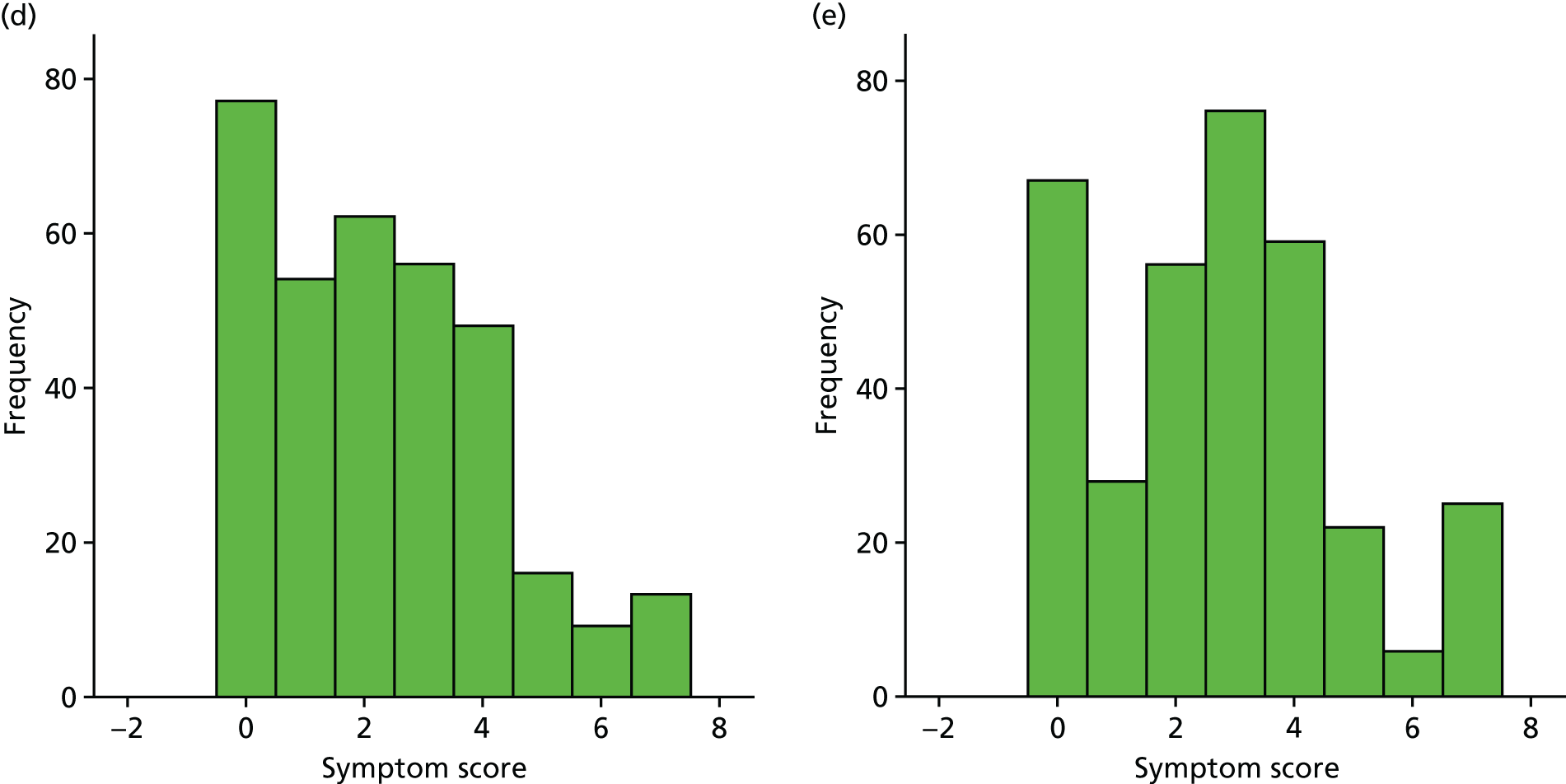

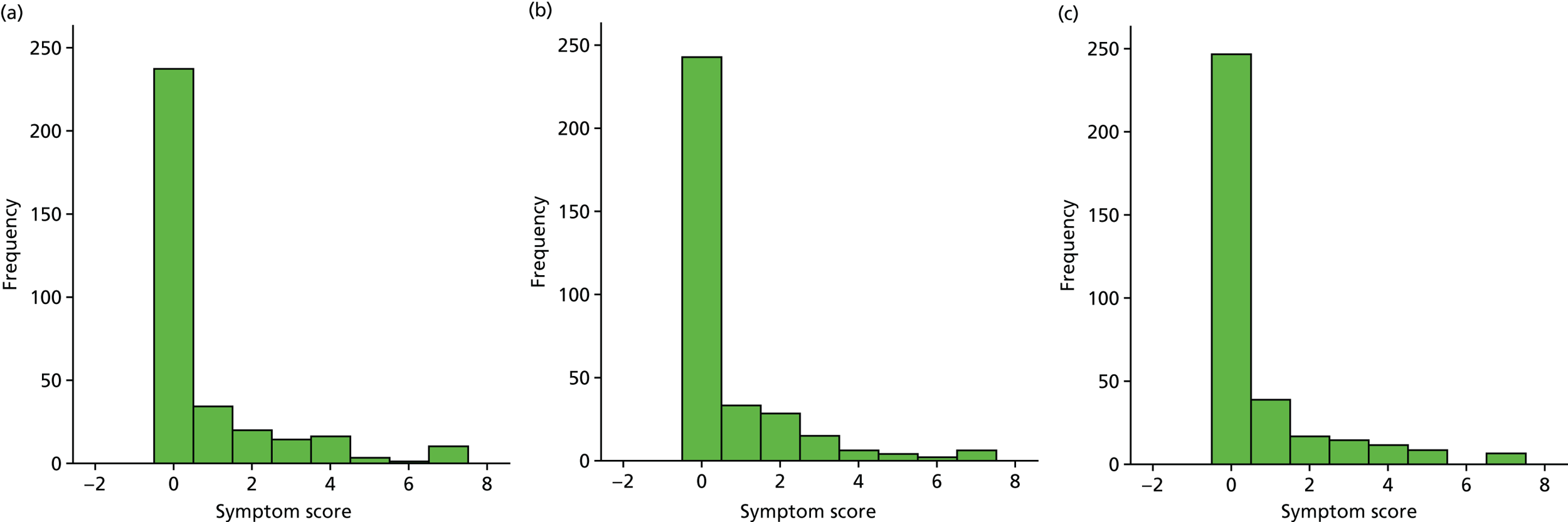

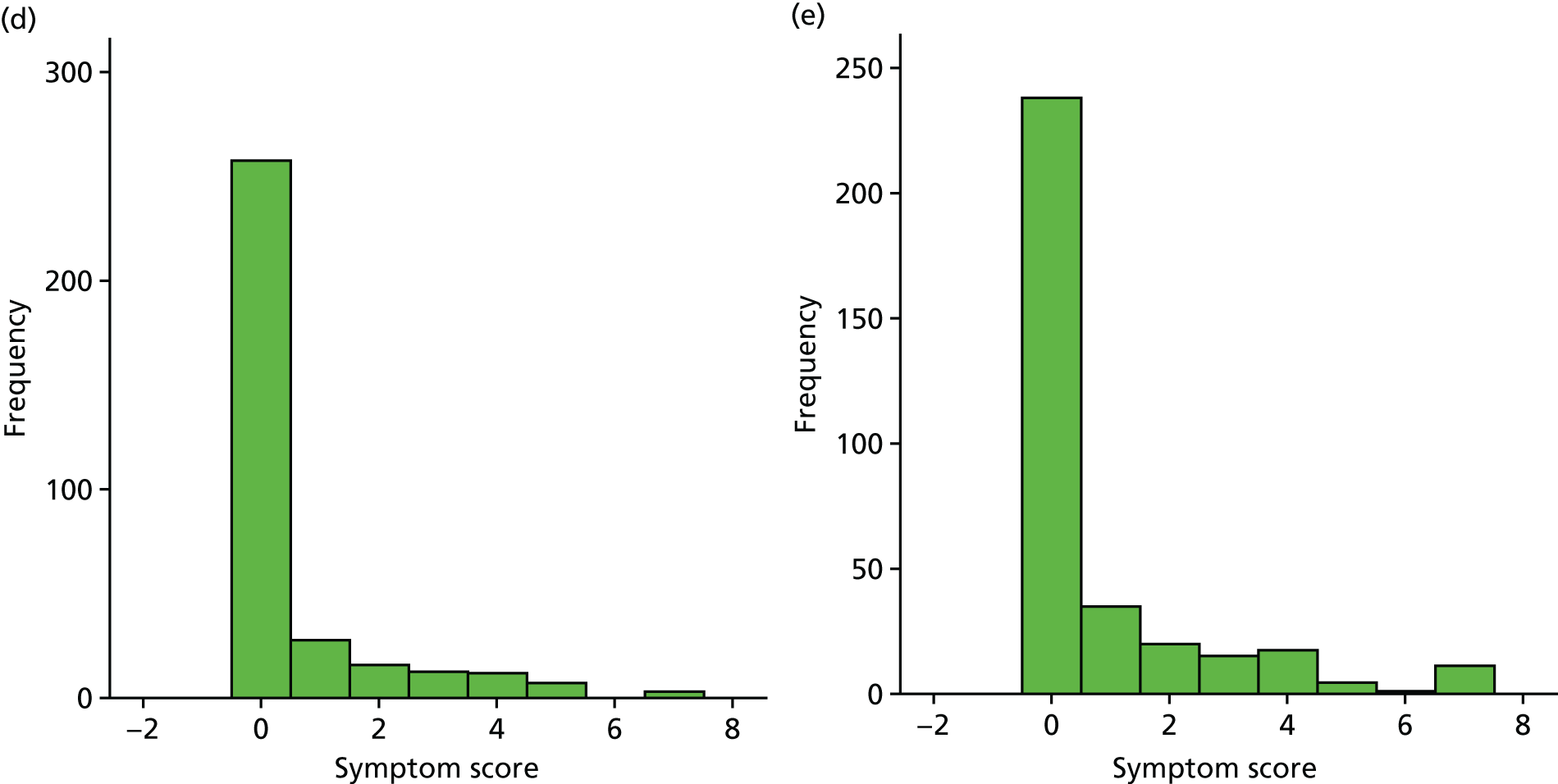

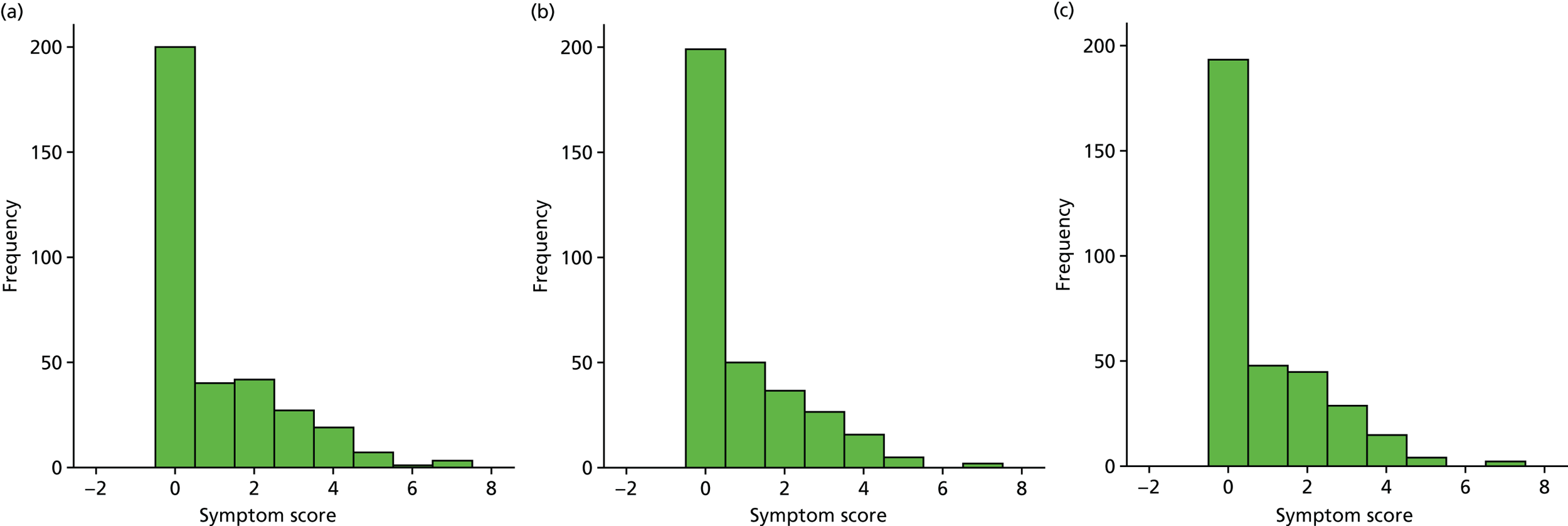

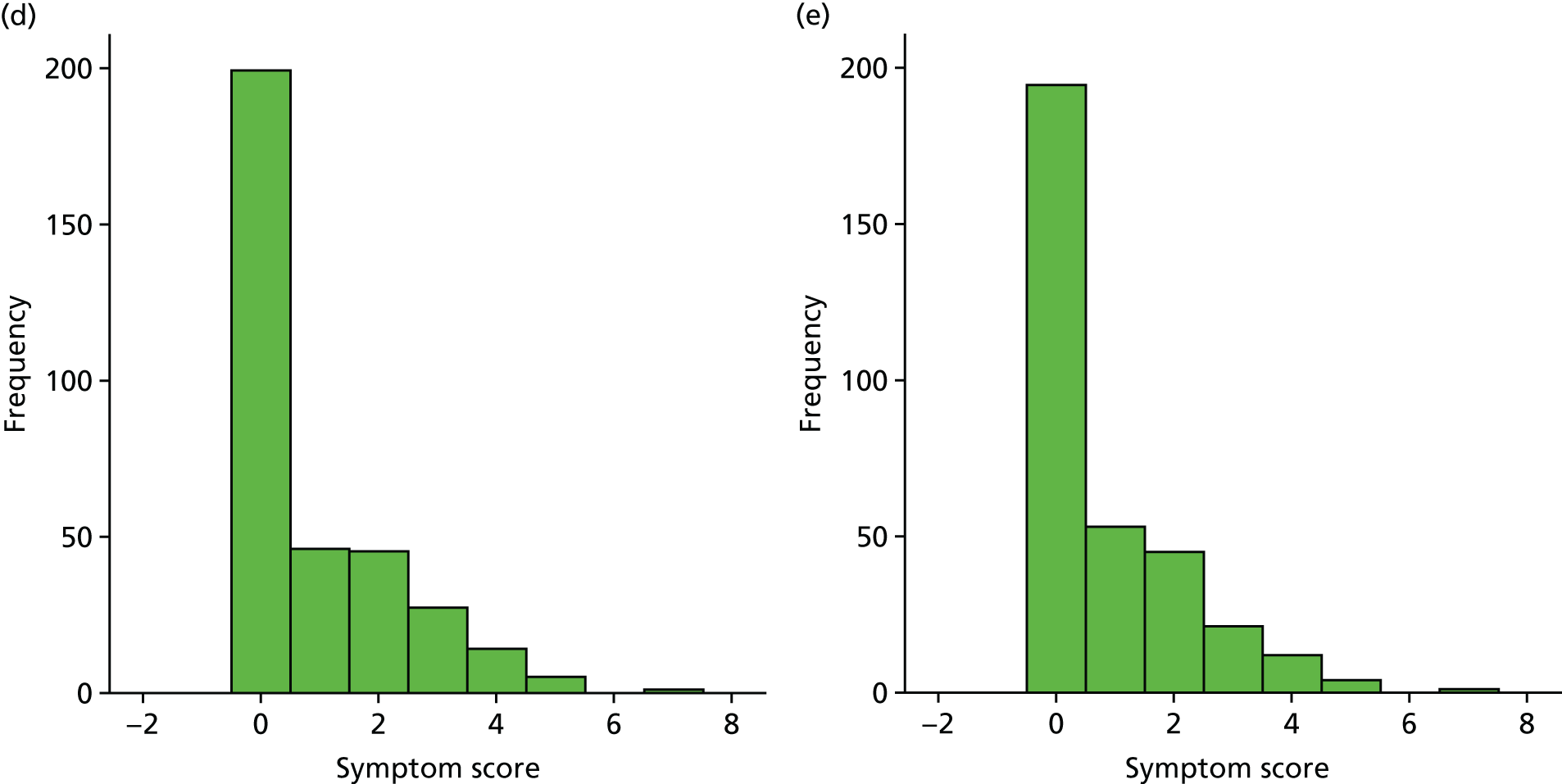

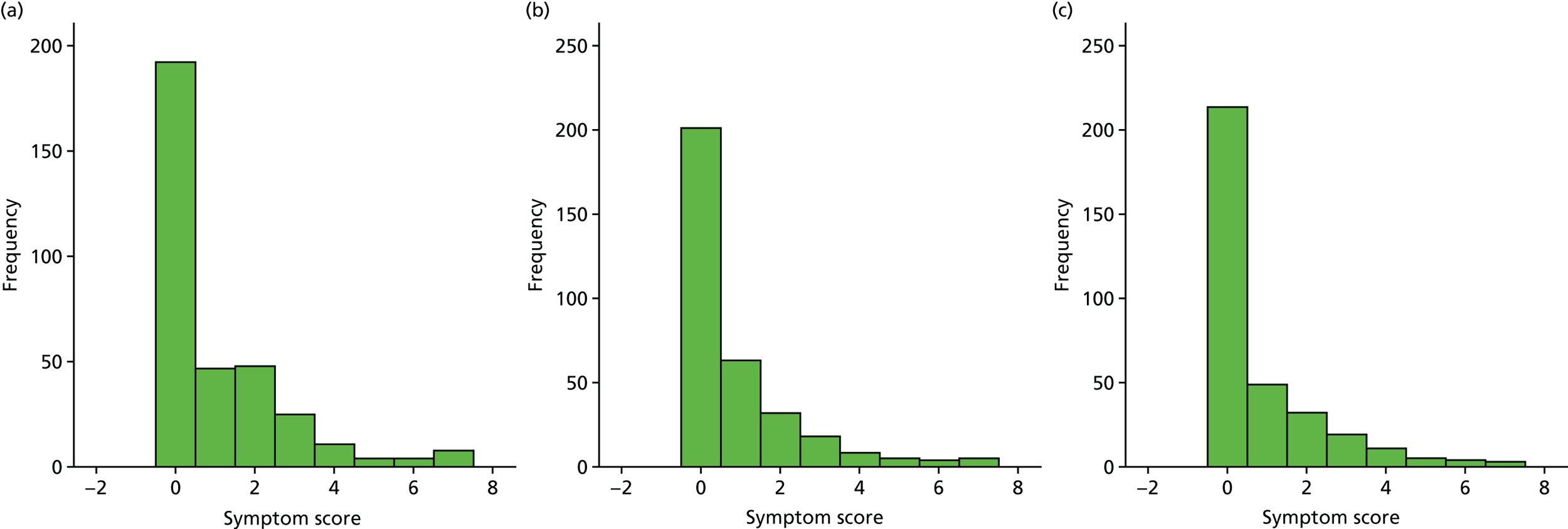

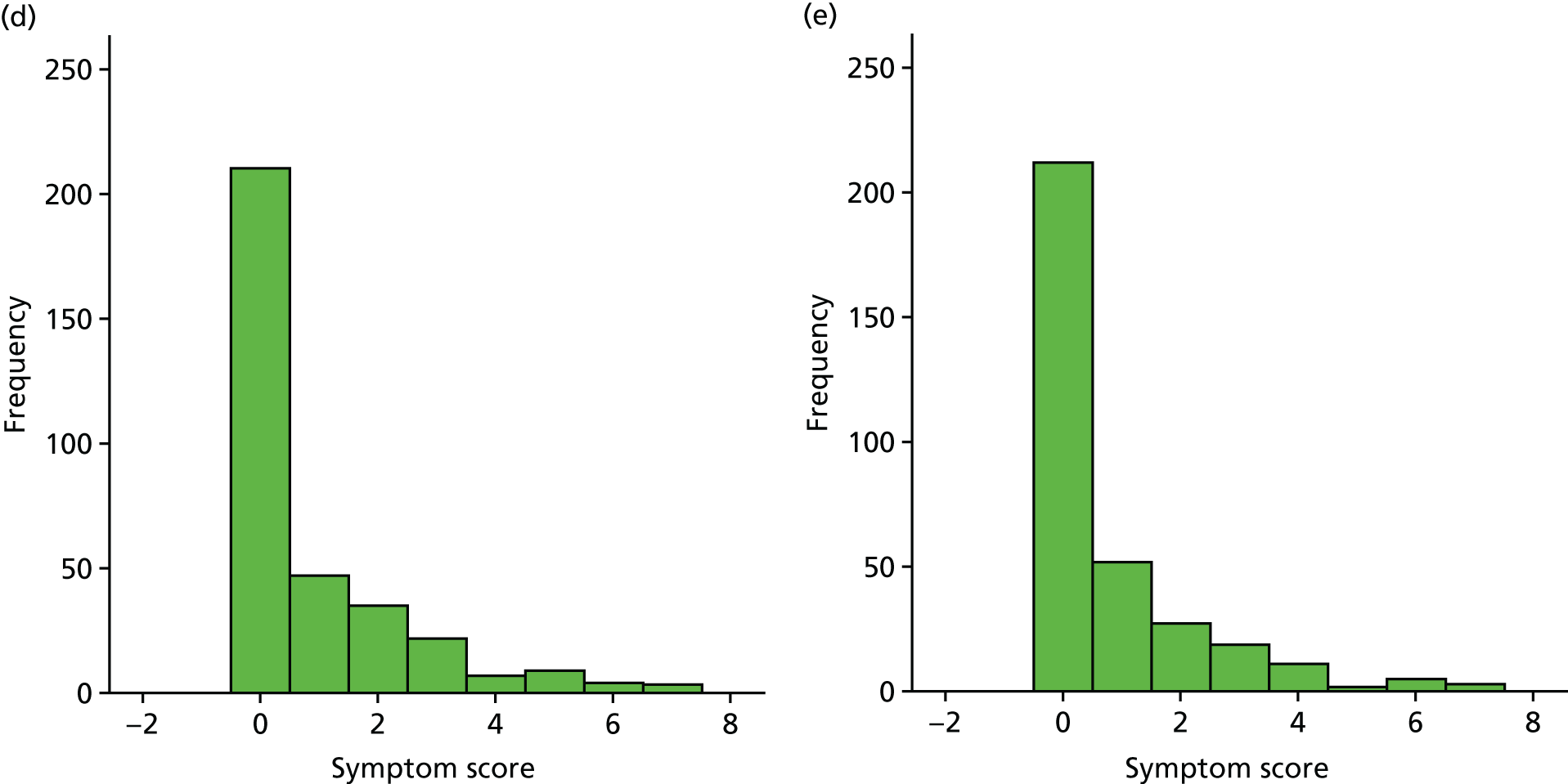

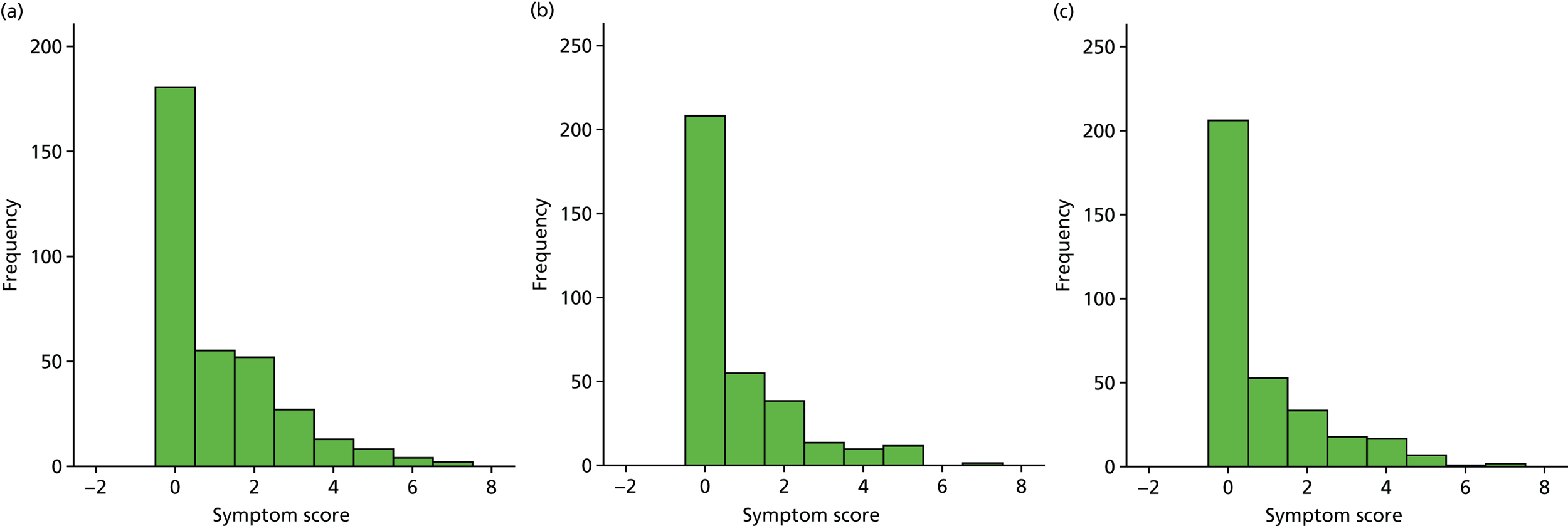

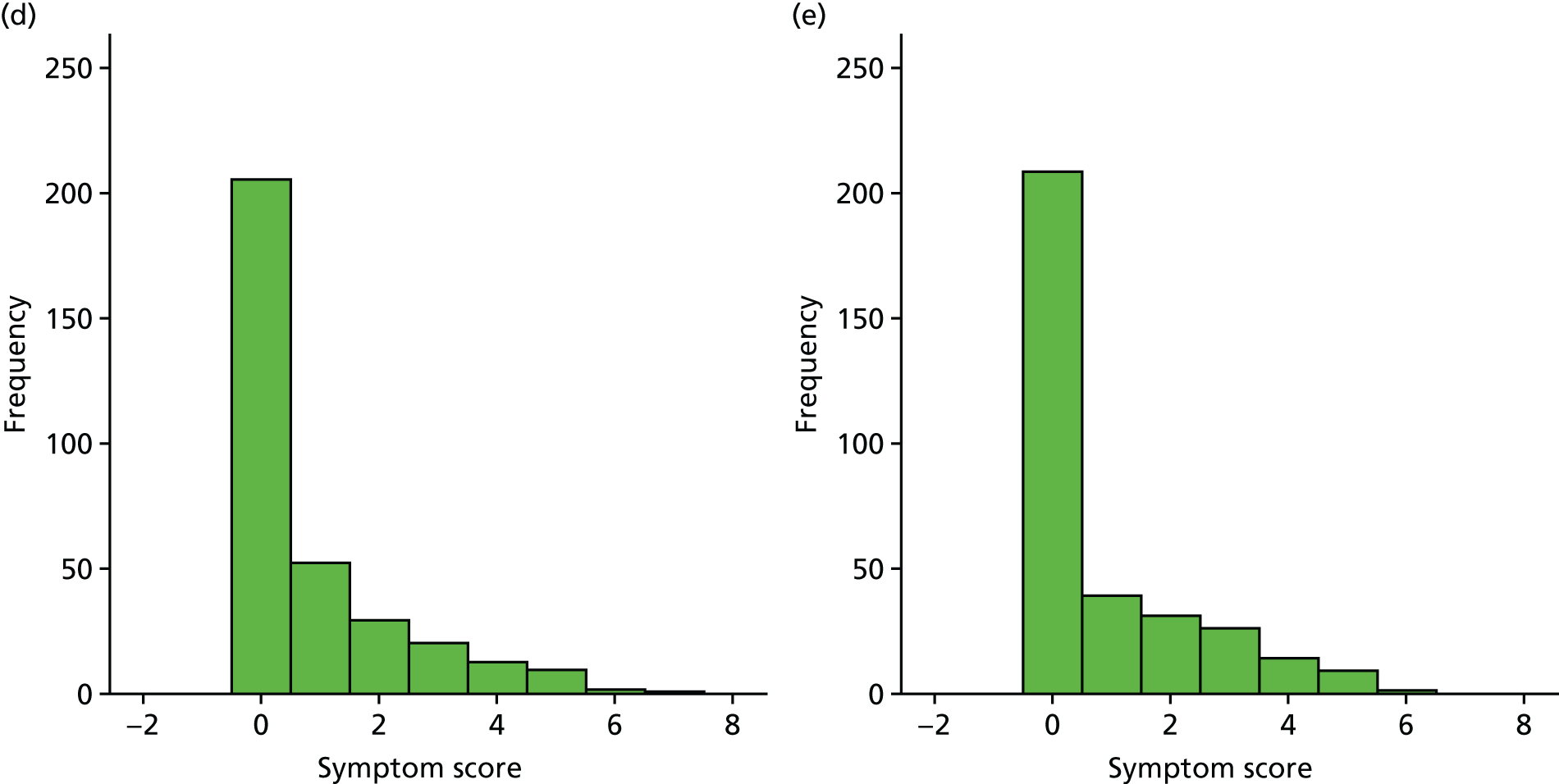

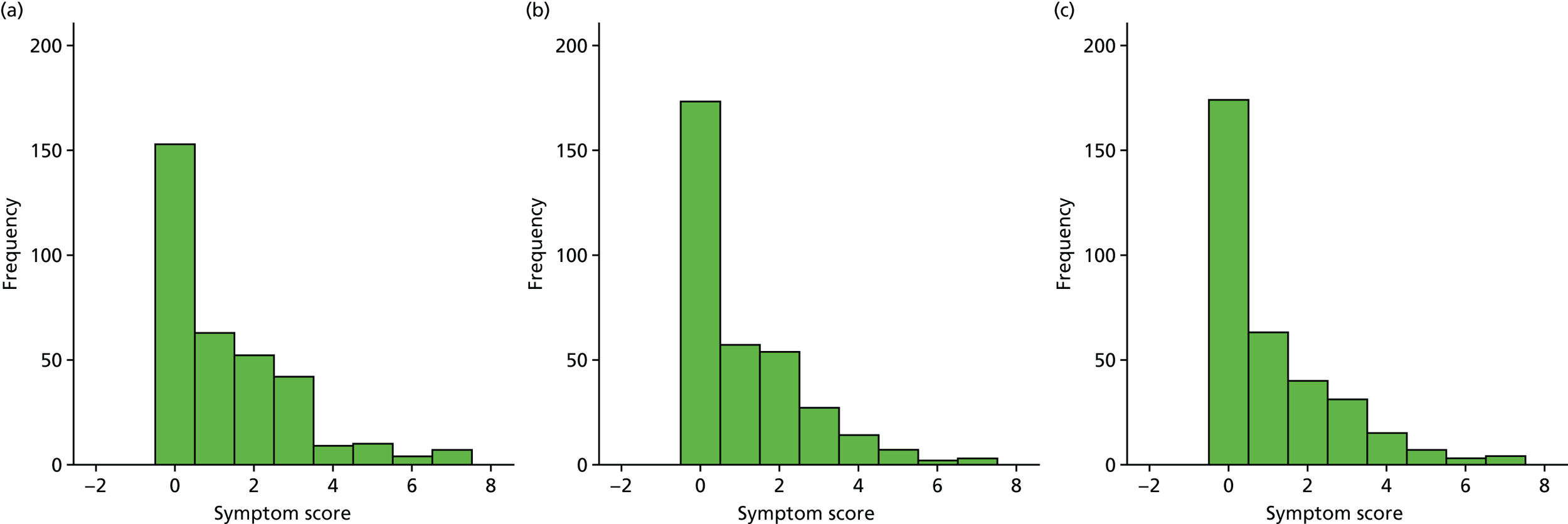

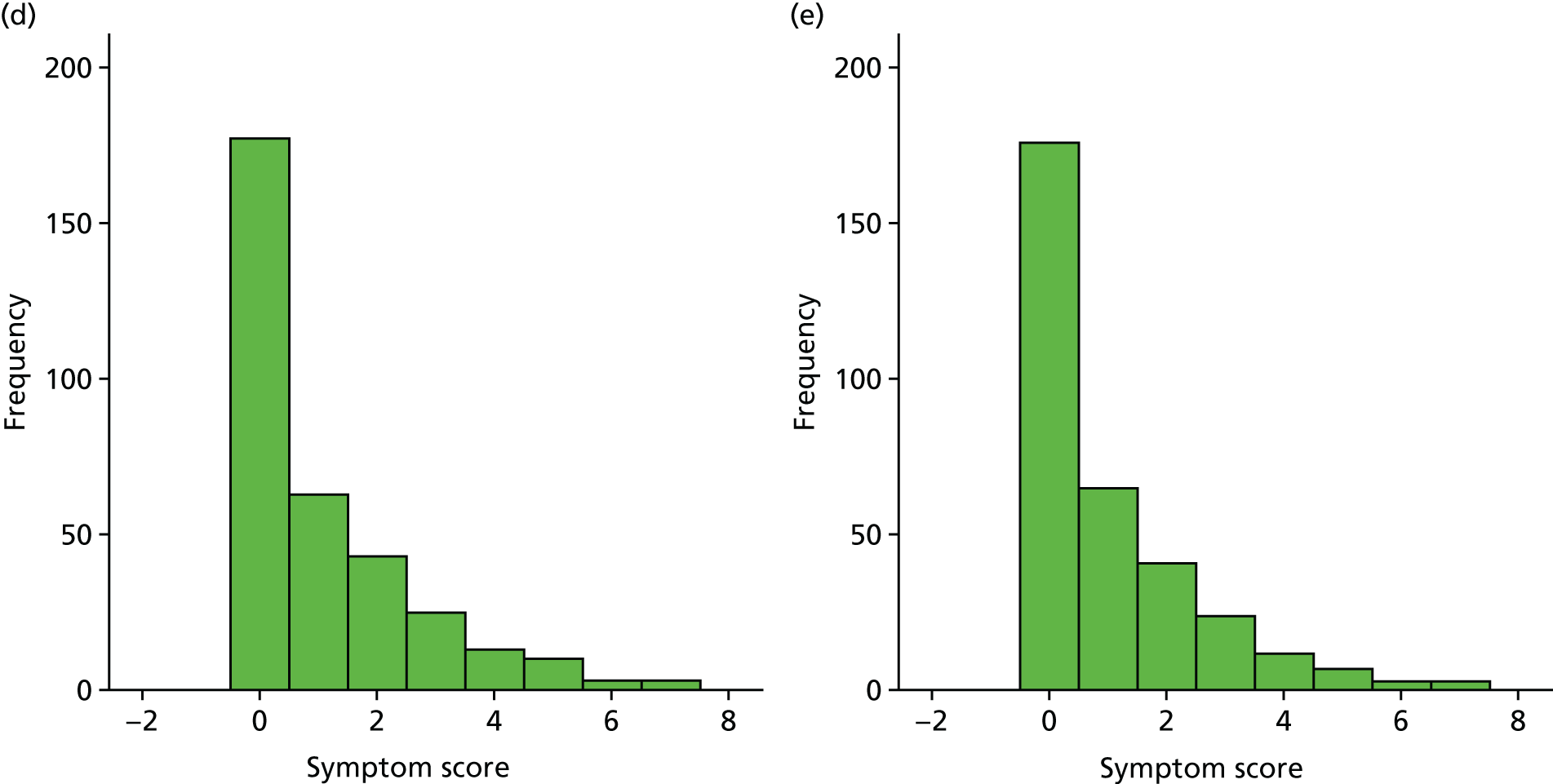

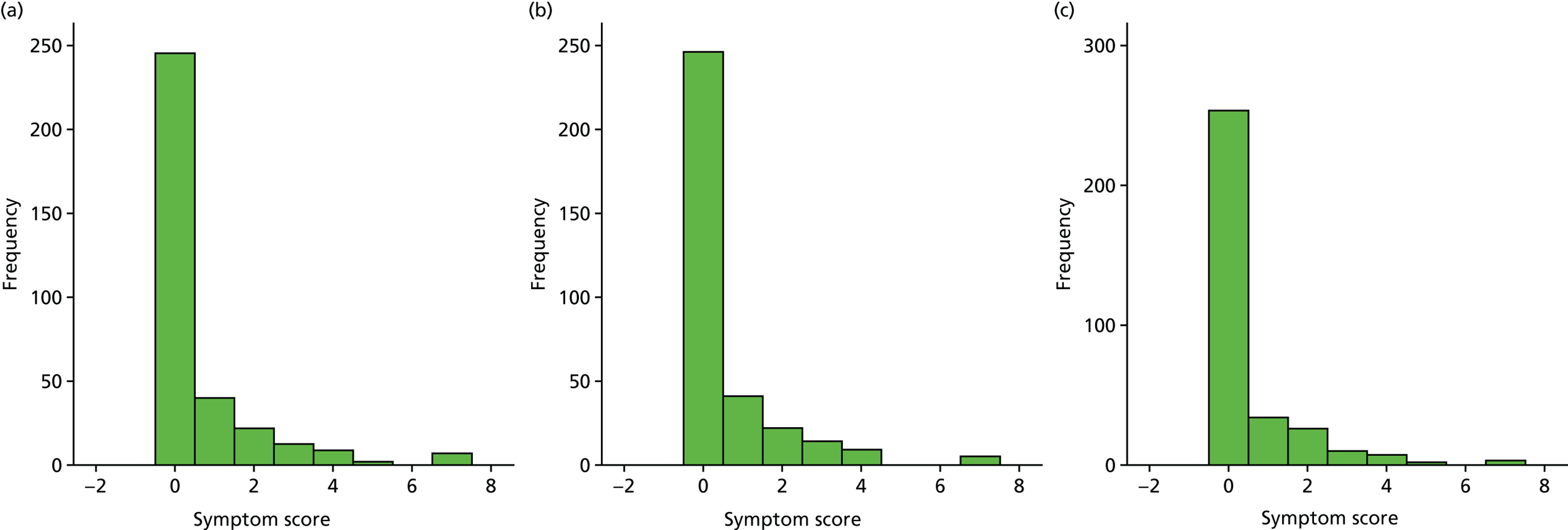

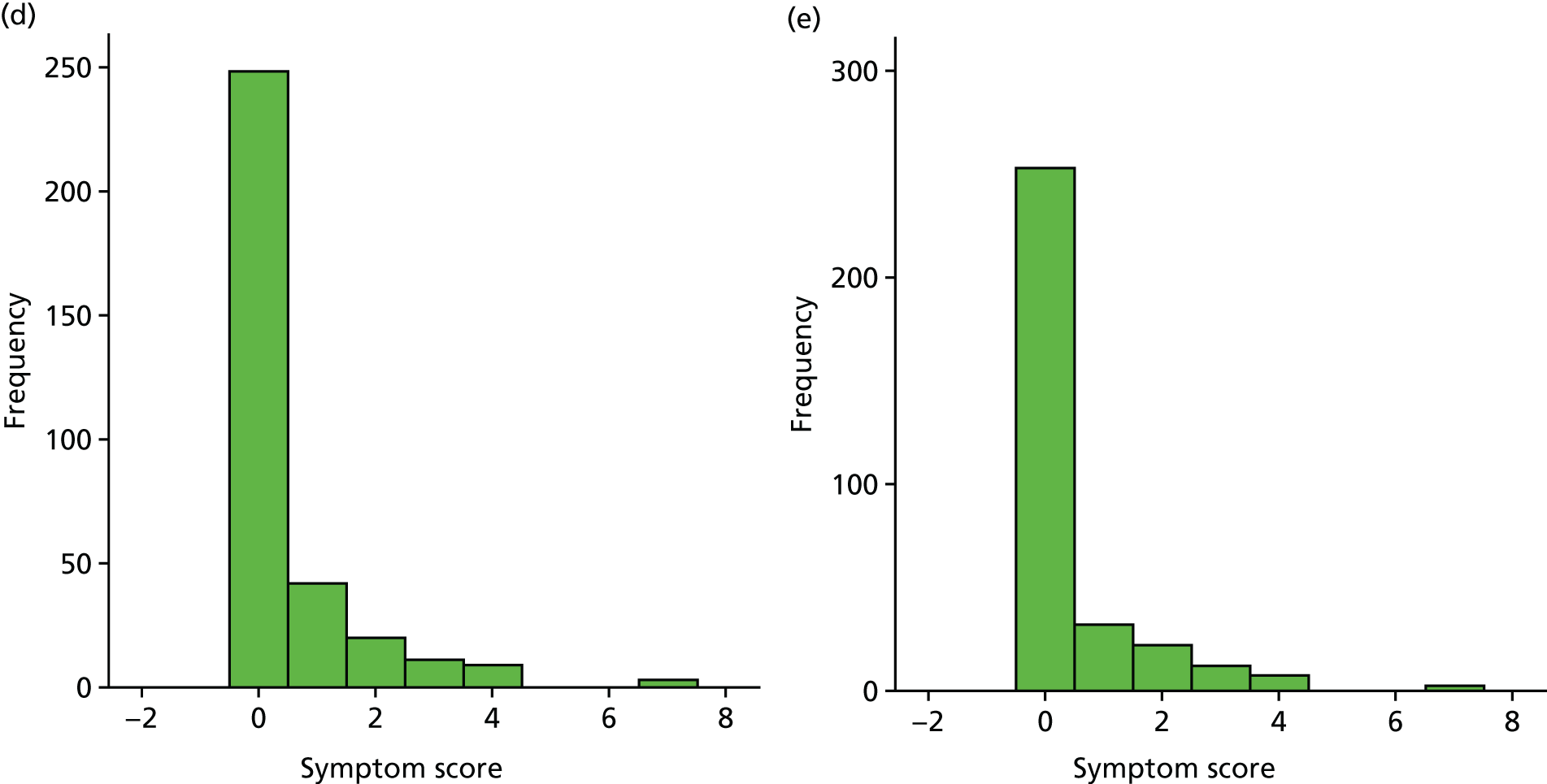

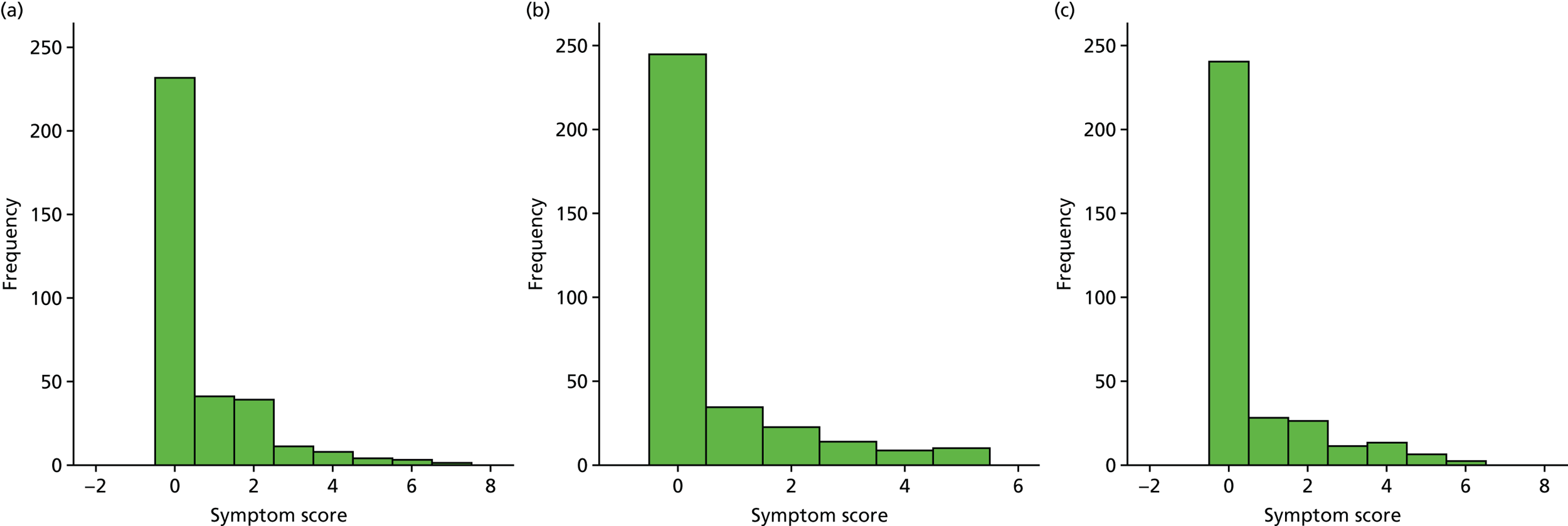

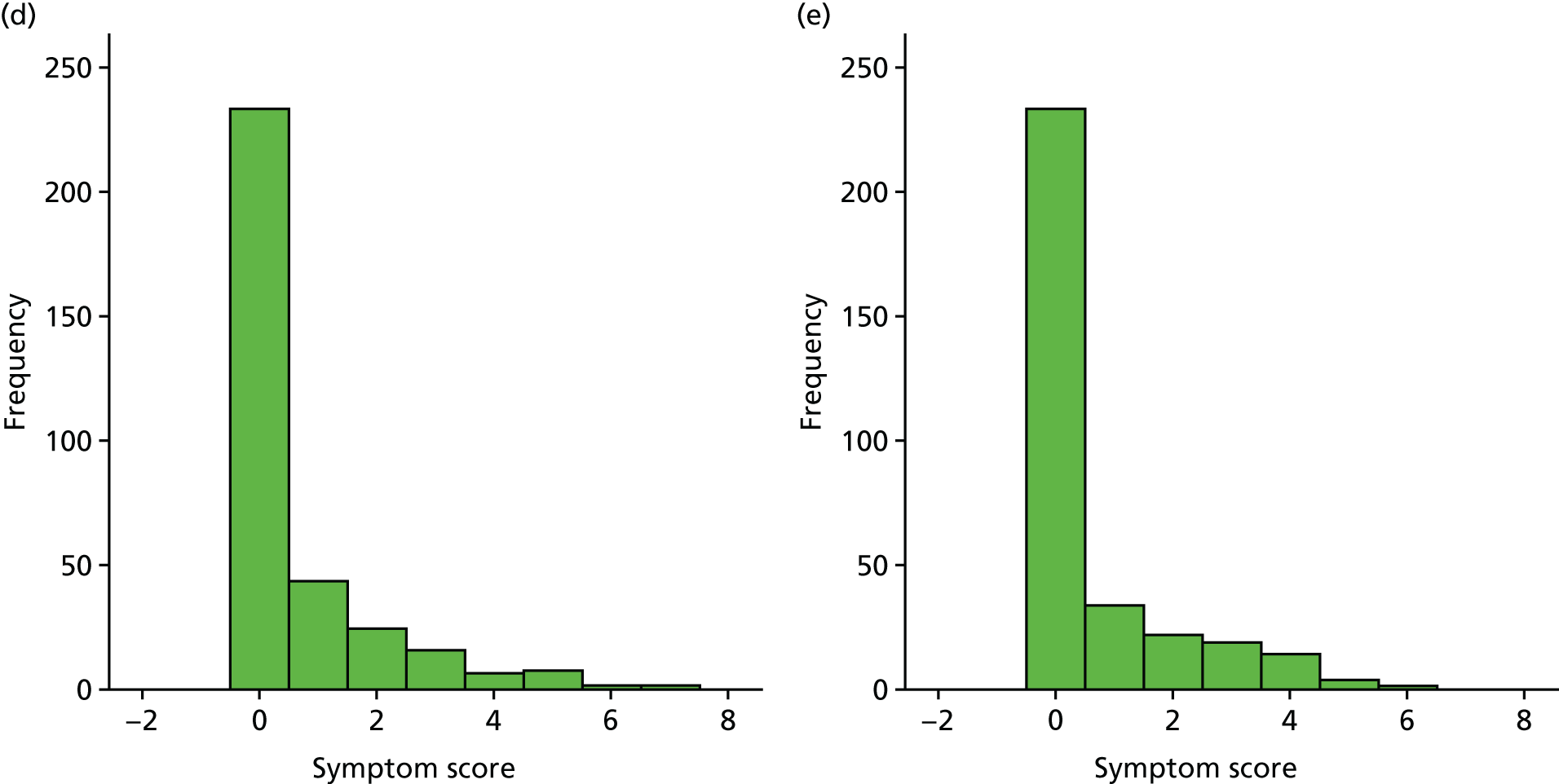

A number of outcomes were calculated from the parents’ diary for the first 5 weeks, such as parent-reported symptoms, total days off school/nursery and work for ear and non-ear problems, and the number of OME-related health-care consultations. Weekly scores were reported on the child’s symptoms on a scale of 0 to 6 (not present to as bad as it could be) for eight symptoms (any problems with hearing, ear pain, speech, energy levels, sleep, attention span, balance, being generally unwell). The protocol stated that the duration between the start and the resolution of symptoms would be examined and modelled using a Cox regression model. Given the limited number of weeks of follow-up, this analysis was not possible and the following analysis proposal was written into the SAP and signed off in advance of the sight of any data.

The correlation between symptom scores in the symptom diary was examined via Cronbach’s alpha and a factor analysis was used to determine whether or not the eight symptoms could be combined in an overall score. This was carried out for symptoms at each week to demonstrate the validity of using the total symptom score to measure child illness. For the overall score, a multilevel linear repeated measures model (adjusting for age of child and site) was used. Changes in nausea and in behaviour and mood over time were examined separately. The effect of oral steroids is reported as the adjusted difference in means score alongside 95% CIs.

For days off school/nursery and work, and OME-related health-care consultations, these were analysed first using a Poisson multilevel model; however, a negative binomial model was found to be a better-fitting model, according to the Akaike information criterion (AIC). The results were presented as the adjusted incidence rate ratio (IRR) (in the oral steroid group compared with the placebo group) alongside 95% CIs.

Changes to statistical methods from the protocol

The following changes were added to the SAP following publication of the protocol paper and approved by the IDMC:

-

For the primary outcome, in addition to adjusting for child’s age at recruitment, site and time to follow-up were also deemed to be important to adjust for.

-

A negative binomial model was used instead of the intended Poisson model, as a result of overdispersion.

-

For the symptoms scores, a component was added to combine each individual symptom score into an overall score so that the issue of multiple outcomes was overcome.

The following changes were omitted from the SAP following publication of the protocol paper:

-

Given the limited number of weeks of follow-up, the duration between the start and resolution of symptoms was not examined and modelled using a time-to-event (Cox regression) model. Instead, the analysis proposed in point 3 above was included.

Additional exploratory analysis

Additional exploratory analysis was conducted as part of a student research project assessing the association between baseline hearing threshold and HRQoL (including both overall HRQoL and scores for each domain). Pearson’s correlation coefficient (assuming that the distributions were sufficiently normally distributed) was used and 95% CIs and p-values were presented. Pearson’s correlation coefficient (r) was used to investigate the strength of any correlations.

Decisions about exploratory health economic analyses would be assessed following a review of the subgroup analyses, as described in Primary analyses.

Summary of changes to the trial

The main changes to the protocol that occurred during the conduct of the trial are summarised below.

A number of changes were made to the protocol to make it easier for sites to recruit children and schedule the follow-up appointments. For example, the study extended the site coverage into England, the eligibility criteria for audiometry-confirmed hearing loss was extended to 14 days preceding recruitment, follow-up visits were conducted in ENT or audiology outpatient clinics, and the time-frame windows for follow-up were extended to + 2 weeks for the 5-week follow-up and ± 2 weeks for the 6- and 12-month follow-ups. Paediatric audiology and AVM clinics were included as sites, and audiovestibular physicians were included as designated OSTRICH trial clinicians.

Additions were made to the exclusion criteria, such as ear infections, Kartagener syndrome or primary ciliary dyskinesia, existing known sensory hearing loss, undergoing cancer treatment, on a waiting list for grommet surgery and anticipated to have surgery within 5 weeks and unwilling to delay it, and live vaccines 4 weeks prior to recruitment if aged < 3 years.

A number of changes to the planned trial procedures were made because of time constraints resulting from the longer than anticipated recruitment period; for example, the removal of medical notes search and data linkage used to identify health-care consultations during the 12-month follow-up period in primary and secondary care. As a result of this, a specific assessment of resource use at baseline could not be collected.

Finally, a number of further amendments were made to the protocol, such as sending reminders for follow-up appointments, contacting parents regarding missed appointments and exploratory analysis to assess the association between baseline hearing threshold and QoL. In addition, the study undertook a qualitative substudy to explore parents’ understanding of the treatment options available to them, their views on shared decision-making in the context of managing glue ear (OME) and their views on the use of oral steroids for glue ear (OME). Further changes were made to the proposed longer-term modelling to be conducted as part of the health economic analysis as a result of the trial results, which are explained in detail in Appendix 1.

Chapter 3 Results

Site recruitment

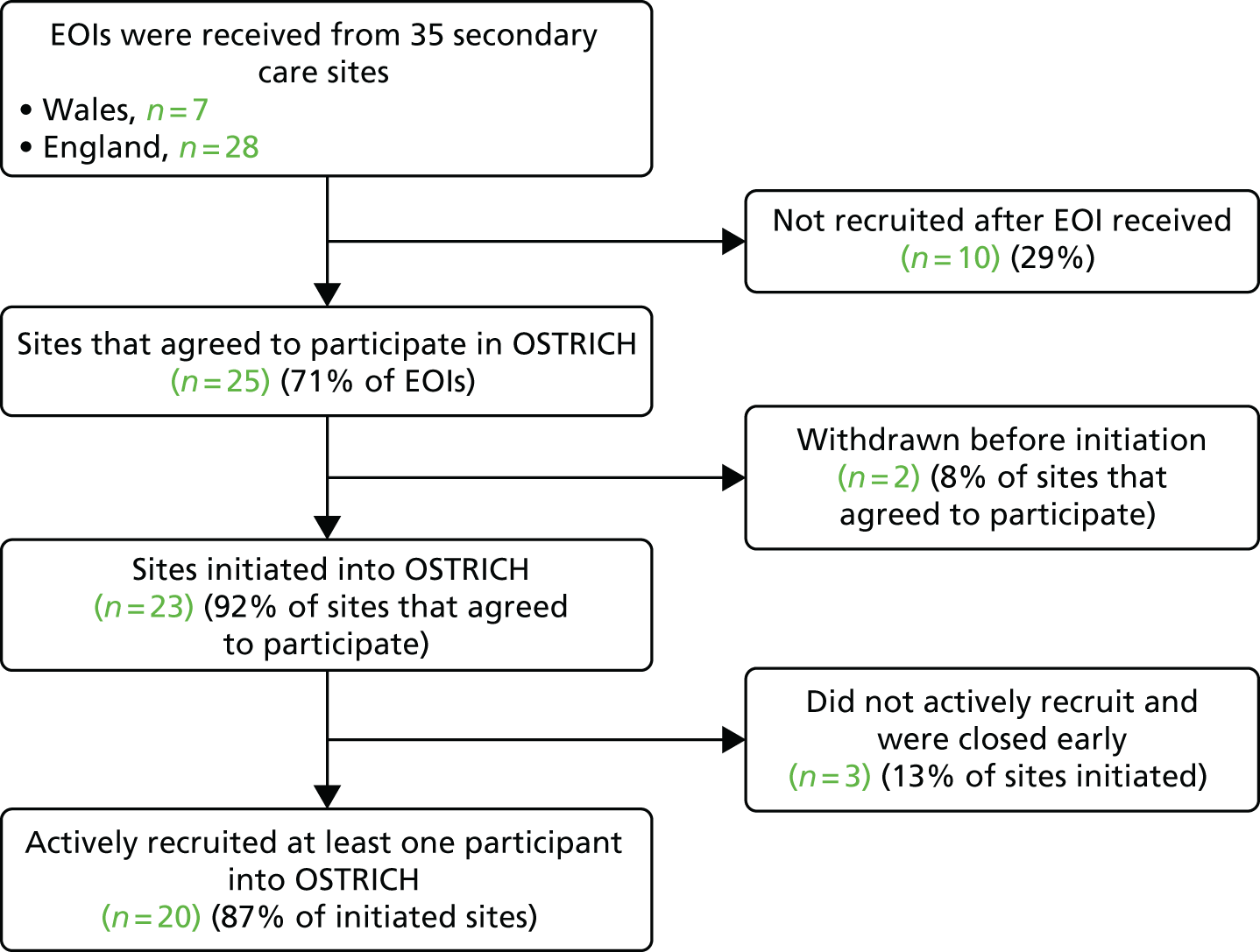

The study initially planned to recruit participants from seven secondary care sites in Wales; however, it became apparent that it would not be possible to recruit all 380 children in the allotted time from Wales only, recruitment was therefore extended to sites in England. In total, 35 expressions of interest were received; 13 were from enquiries made by Comprehensive Local Research Network research leads and a further 15 resulted from a call from the Medicines for Children CRN and National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) ENT Specialty Group. Ten sites did not progress any further, as they felt unable to commit to the recruitment target or were no longer looking to take on new studies. The process of obtaining local R&D approval was started for two sites but was not progressed, as a result of the lengthy time taken for initial discussions and approvals. A breakdown of the number of sites that expressed an interest in participating, agreed to participate and were actively recruited is presented in Figure 2.

FIGURE 2.

Site recruitment flow. EOI, expression of interest.

Participant recruitment and trial flow profile

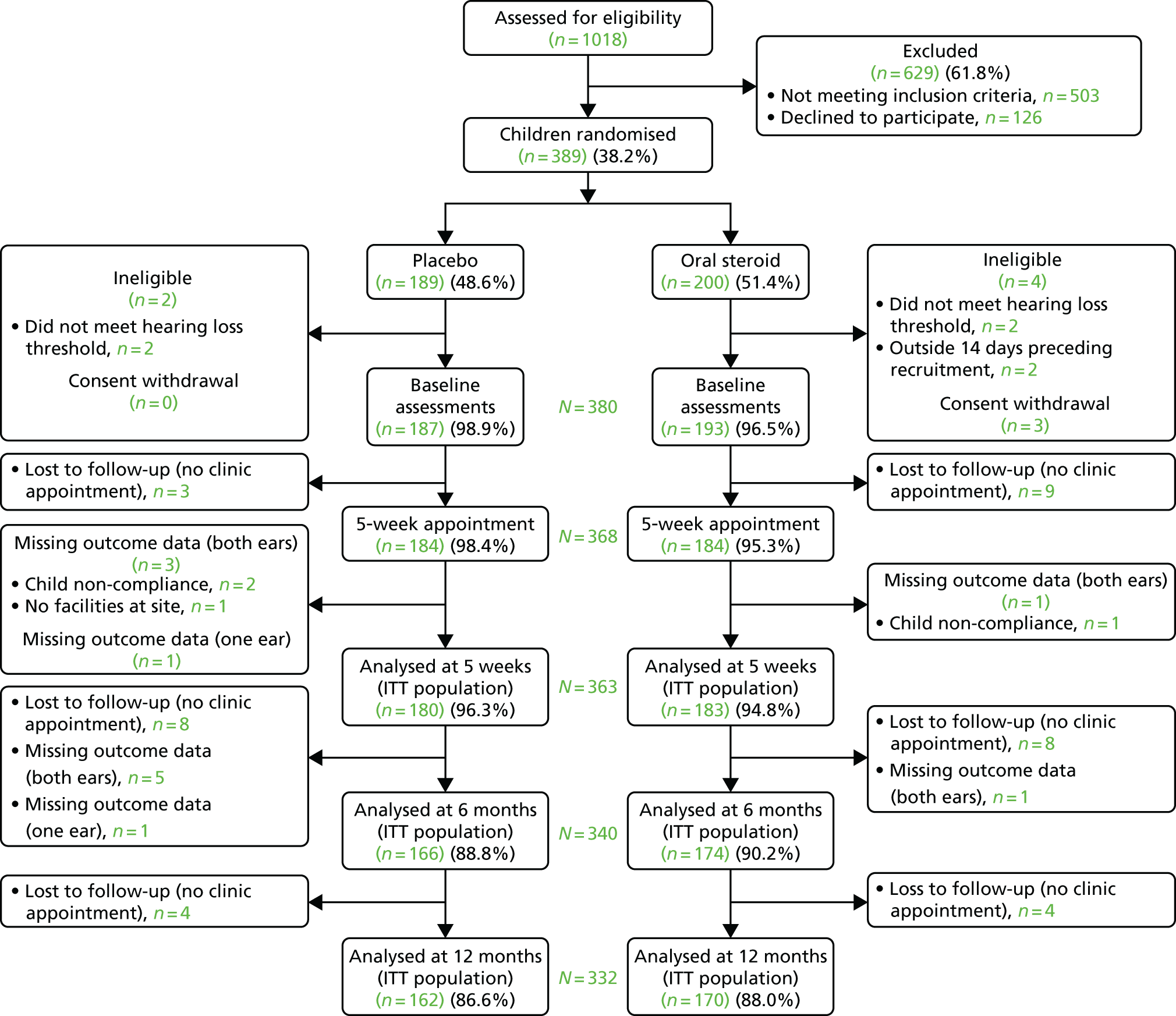

The first child was randomised on 20 March 2014 and the last on 5 April 2016. The flow of children through the trial is represented in the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) trial profile diagram in Figure 3.

FIGURE 3.

The main trial CONSORT flow diagram. ITT, intention to treat.

A total of 1018 children were assessed for eligibility, with 389 children (38%) randomised into the trial over a period of 25 months. A total of 535 reasons for exclusion were given for 503 children. The main reasons for exclusion were insufficient hearing loss (49.3%) and having no diagnosis of OME on the day of recruitment or the preceding week (16.1%). The parents of 126 children (12.3%) declined participation, and a small number were unable to be consented at site. The majority (50%) gave no reason for declining. The most common reasons given were ‘having grommets fitted’ (12%) and ‘carer not wishing the child to have steroids’ (9%). After randomisation, a further six children were found to be ineligible and three withdrew from the trial (and declined the use of their data), leaving 380 children (193 in the oral steroid group and 187 in the placebo group). There was slight differential loss to follow-up for the 5-week clinic appointment (nine in the oral steroid group vs. three in the placebo group), but over 95% of the population were retained for the analysis of the primary outcome at 5 weeks.

Randomisation was remote and online, and was stratified by site and age of the child at recruitment (2–5 years and 6–8 years). For the majority of the recruiting sites and children aged 2–5 years, treatment allocation was well balanced (Table 3). There was, however, a slight imbalance of treatment allocation in the 6- to 8-years stratum and in a few sites. The explanation for this imbalance is that there were 53 incomplete blocks of allocations (29 in age stratum 2–5 years and 24 in age stratum 6–8 years). In one site, allocations were stopped mid-block as a result of the IMP expiring and requiring disposal or the study recruitment period ending mid-block.

| Site identifier | Number of participants randomised | Treatment group (number of participants) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Placebo | Oral steroid | ||

| 1 | 76 | 38 | 38 |

| 2 | 28 | 12 | 16 |

| 3 | 7 | 3 | 4 |

| 4 | 41 | 20 | 21 |

| 5 | 7 | 4 | 3 |

| 6 | 13 | 7 | 6 |

| 7 | 3 | 1 | 2 |

| 8 | 64 | 30 | 34 |

| 9 | 26 | 14 | 12 |

| 10 | 30 | 14 | 16 |

| 11 | 18 | 9 | 9 |

| 12 | 3 | 1 | 2 |

| 13 | 22 | 12 | 10 |

| 14 | 6 | 2 | 4 |

| 15 | 5 | 0 | 5 |

| 16 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| 17 | 13 | 7 | 6 |

| 18 | 14 | 7 | 7 |

| 19 | 8 | 5 | 3 |

| 20 | 4 | 2 | 2 |

| Age category, n (%) | |||

| 2- to 5-year-olds | 270 | 134 (49.6) | 136 (50.4) |

| 6- to 8-year-olds | 119 | 55 (46.2) | 64 (53.8) |

| Total | 389 | 189 (48.6) | 200 (51.4) |

Baseline characteristics

The baseline demographics of the randomised children were similar in the two groups (Table 4). Slightly more boys were randomised, and the majority were from a white ethnic background. Over 60% of children were randomised in the winter or spring. For over two-thirds of children, this was their first episode of OME, although around 10% in each group had had six or more episodes. Over 60% of children had had their current problem for > 12 months (see Table 4). Comparable numbers of children had previously had a tonsillectomy/adenoidectomy, and a marginally higher proportion in the placebo group had received surgery for the insertion of ventilation tubes or had been fitted with a hearing aid. Just under 30% of children were on a waiting list for ventilation tubes. Of those with a sibling, one-quarter either currently had or previously had OME. Around 65–70% of children did not have asthma, eczema, or hay fever and 15% were on long-term medications. Fewer than 10% in each treatment group had received antibiotics for an ear infection in the past month.

| Variables | Treatment group | |

|---|---|---|

| Placebo (N = 187) | Oral steroid (N = 193) | |

| Child demographics | ||

| Age (years) at recruitment, mean (SD) | 5.08 (1.60) | 5.30 (1.60) |

| 2–5 years, n (%) | 133 (71.1) | 131 (67.9) |

| 6–8 years, n (%) | 54 (28.9) | 62 (32.1) |

| Male gender, n (%) | 102 (54.5) | 109 (56.5) |

| Townsend deprivation quintile, n (%) | ||

| 1 – least deprived | 32 (17.1) | 25 (13.0) |

| 2 | 16 (8.6) | 23 (11.9) |

| 3 | 48 (25.7) | 45 (23.3) |

| 4 | 46 (24.6) | 48 (24.9) |

| 5 – most deprived | 45 (24.1) | 52 (26.9) |

| Ethnicity, n (%) | ||

| White | 134 (82.7) | 143 (82.2) |

| Mixed/multiple ethnic | 10 (6.2) | 10 (5.2) |

| Asian/Asian British | 13 (8.0) | 18 (10.3) |

| Black/African/Caribbean/black British | 3 (1.9) | 3 (1.7) |

| Other ethnic | 2 (1.2) | 0 (0.0) |

| Missing | 25 (0.0) | 19 (0.0) |

| Season randomised, n (%) | ||

| Spring (March–May) | 64 (34.2) | 70 (36.3) |

| Summer (June–August) | 32 (17.1) | 33 (17.1) |

| Autumn (September–November) | 31 (16.6) | 34 (17.6) |

| Winter (December–February) | 60 (32.1) | 56 (29.0) |

| Height measured, n (%) | 62 (33.2) | 74 (38.3) |

| Height (cm), mean (SD) | 112.22 (11.34) | 115.08 (10.59) |

| Weight measured, n (%) | 70 (37.4) | 75 (38.9) |

| Weight (kg), mean (SD) | 20.24 (5.49) | 21.77 (5.95) |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | ||

| Centile, n (%) | 60 (32.1) | 69 (35.8) |

| Median (25th–75th centiles) | 18.5 (16.4 to 23.1) | 21.0 (18.7 to 24.6) |

| Relation of carer to child, n (%) | ||

| Mother | 159 (85.5) | 171 (88.6) |

| Father | 24 (12.9) | 20 (10.4) |

| Other | 3 (1.6) | 2 (1.0) |

| Missing | 1 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Medical history of children | ||

| First episode of OME, n (% yes) | 135 (72.2) | 128 (66.3) |

| Length of time had problems attributable to this episode of OME, n (%) | ||

| < 6 months | 26 (13.9) | 19 (9.9) |

| 6 to < 9 months | 28 (15.0) | 22 (11.5) |

| 9 to < 12 months | 18 (9.6) | 20 (10.4) |

| ≥ 12 months | 115 (61.5) | 131 (68.2) |

| Missing | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.0) |

| Previous ventilation tubes (grommet surgery), n (% yes) | 19 (10.2) | 14 (7.3) |

| On waiting list for ventilation tubes, n (% yes) | 52 (27.8) | 55 (28.6) |

| Fitted with hearing aids, n (% yes) | 31 (16.6) | 27 (14.0) |

| If yes, frequency of use | ||

| Not at all | 5 (16.1) | 2 (7.4) |

| Occasionally | 2 (6.5) | 2 (7.4) |

| Most of the time | 8 (25.8) | 15 (55.6) |

| All of the time | 16 (51.6) | 8 (29.6) |

| Previous tonsillectomy, n (% yes) | 8 (4.3) | 9 (4.7) |

| Previous adenoidectomy, n (% yes) | 8 (4.3) | 8 (4.1) |

| Family history of OME | ||

| Has a brother or sister?, n (% yes) | 147 (78.6) | 156 (80.8) |

| If yes, at least one currently has or has had OME | 34 (23.3) | 44 (28.4) |

| Missing | 1 (0.0) | 1 (0.0) |

| Atopy, n (%) | ||

| None | 131 (70.1) | 125 (64.8) |

| At least one | 56 (29.9) | 68 (35.2) |

| Asthma | 22 (11.9) | 21 (11.2) |

| Eczema | 41 (22.2) | 41 (21.6) |

| Hay fever | 16 (8.7) | 21 (11.1) |

| Missing | 0 (0.0) | 3 (0.0) |

| Medications | ||

| Presently using medication regularly for longer than 1 week, n (% yes) | 25 (13.4) | 32 (16.7) |

| Asthma (β-agonist or corticosteroid inhaler, corticosteroid inhaler in combination) | 20 | 23 |

| Leukotriene receptor antagonists | 1 | 2 |

| Antihistamine | 4 | 2 |

| Nasal steroids | 3 | 1 |

| Antibiotics | 0 | 0 |

| Pain relief (ibuprofen, paracetamol) | 2 | 2 |

| Other | 8 | 17 |

| Antibiotics for an ear infection in the last month, n (% yes) | 13 (7.0) | 19 (9.9) |

| Missing | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.0) |

| Smoking in house (> 5 hours a week), n (% yes) | 56 (29.9) | 51 (26.4) |

Ear-specific PTA was the favoured hearing assessment in the older age group (i.e. 6–8 years) and is the recommended standard method in children aged 3 years or older. The remainder of 6- to 8-year-olds had ear-specific VRA or play audiometry. Soundfield VRA or soundfield performance/play audiometry was used in only 19.3% of children aged 2–5 years. The method of audiometry was balanced across treatment groups (Table 5). Over 85% of ears were tested using ear-specific methods over all four frequencies (0.5, 1, 2 and 4 kHz), with slightly lower numbers (around 80%) using the soundfield VRA or soundfield performance/play audiometry. Hearing loss was slightly worse in the oral steroid group, with most children having mild to moderate hearing loss. Tympanometry and otoscopy were performed in almost all children, with the majority having type B tympanograms, and a small proportion having type C tympanograms. The tympanic membrane could be visualised in most ears and the appearance suggested the presence of middle ear infusion. QoL was high and comparable between treatment groups (Table 6).

| Hearing assessment | Treatment group | |

|---|---|---|

| Placebo (N = 187) | Oral steroid (N = 193) | |

| Audiometry | ||

| Method of audiometry, n (%) | ||

| PTA | 94 (50.3) | 108 (56.0) |

| Ear-specific VRA | 3 (1.6) | 2 (1.0) |

| Ear-specific play audiometry | 61 (32.6) | 61 (31.6) |

| Soundfield VRA | 17 (9.1) | 16 (8.3) |

| Soundfield performance/play audiometry | 12 (6.4) | 6 (3.1) |

| Average decibel (dBHL) that is audible, mean (SD) | ||

| PTA, ear-specific VRA/play audiometry | (N = 158) | (N = 171) |

| Right ear | 37.07 (7.49) | 35.94 (8.59) |

| Left ear | 37.39 (8.00) | 35.89 (8.83) |

| Best-hearing ear | 34.24 (7.21) | 32.69 (8.21) |

| Worst-hearing ear | 40.22 (7.10) | 39.25 (7.94) |

| Average of the two ears | 37.23 (6.53) | 35.97 (7.51) |

| Soundfield average decibel (dBHL) | (N = 29) | (N = 22) |

| Mean (SD) | 41.13 (8.12) | 38.35 (9.30) |

| Overall, n (%) | ||

| Average of the two ears and soundfield | 37.83 (6.93) | 36.25 (7.74) |

| Degree of hearing loss (dBHL range), n (%) (based on overall dBHL) | ||

| Slight (16–25) | 8 (4.3) | 13 (6.7) |

| Mild (26–40) | 116 (62.0) | 134 (69.4) |

| Moderate (41–55) | 63 (33.7) | 44 (22.8) |

| Moderately severe (56–70) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (1.0) |

| Severe (71–90) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Profound (> 90) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Tympanometry | ||

| Tympanometry performed, n (% yes) | 187 (100.0) | 192 (99.5) |

| Type: right ear, n (% yes) | ||

| B (flat) | 181 (96.8) | 184 (96.8) |

| C (retracted/negative) | 6 (3.2) | 6 (3.2) |

| Missing | 0 (0.0) | 3 (0.0) |

| Type: left ear, n (% yes) | ||

| B (flat) | 181 (97.8) | 182 (95.8) |

| C (retracted/negative) | 4 (2.2) | 8 (4.2) |

| Missing | 1 (0.0) | 1 (0.0) |

| No type B ears | 1 (0.5) | 3 (1.6) |

| One type B ear | 8 (4.3) | 10 (5.2) |

| Two type B ears | 177 (95.2) | 178 (93.2) |

| Otoscopy | ||

| Visualise the tympanic membrane, n (%) | ||

| Right ear | 180 (96.3) | 192 (99.5) |

| If yes | ||

| Perforation present | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Appearance suggests presence of middle ear effusion | 180 (100.0) | 190 (99.0) |

| Bubbles behind the ear drum | 20 (11.1) | 22 (11.6) |

| Visualise the tympanic membrane, n (%) | ||

| Left ear | 178 (95.2) | 189 (97.9) |

| If yes | ||

| Perforation present | 2 (1.1) | 2 (1.1) |

| Appearance suggests presence of middle ear effusion | 177 (99.4) | 187 (98.9) |

| Bubbles behind the ear drum | 20 (11.2) | 19 (10.1) |

| Measure | Treatment group | |

|---|---|---|

| Placebo (N = 187) | Oral steroid (N = 193) | |

| HUI3,a median score (25th–75th centiles) | 0.80 (0.63–0.93) | 0.79 (0.66–0.92) |

| Range (min. to max.) | –0.16 to 1.00 | 0.10 to 1.00 |

| Missing | 28.0 | 29.0 |

| PedsQL,b median score (25th–75th centiles) | 187.0 | 189.0 |

| Physical functioning | 90.6 (78.1–100.0) | 90.6 (79.7–98.4) |

| Emotional functioning | 70.0 (60.0–85.0) | 75.0 (55.0–85.0) |

| Social functioning | 90.0 (75.0–100.0) | 90.0 (72.5–100.0) |

| Psychosocial health summary | 78.8 (63.54–87.5) | 78.3 (63.4–87.1) |

| Total summary | 82.1 (69.0–90.5) | 82.6 (68.0–90.7) |

| Missing | 0.0 | 4.0 |

| School functioning | 75.0 (58.3–90.0) | 70.0 (58.3–85.0) |

| Missing | 8.0 | 10.0 |

| OM8-30,c mean score (SD) | 187 | 190 |

| Infection-related physical health factor | –0.31 (1.03) | –0.17 (0.99) |

| General development impact factor | 0.52 (1.24) | 0.48 (1.20) |

| Reported hearing difficulties factor | 0.74 (0.78) | 0.87 (0.82) |

| Total summary score | 0.47 (1.04) | 0.60 (1.03) |

| Parent-reported overall child’s health, n (%) | ||

| Poor | 4 (2.2) | 6 (3.2) |

| Fair | 28 (15.1) | 29 (15.5) |

| Good | 61 (33.0) | 54 (28.9) |

| Very good | 56 (30.3) | 55 (29.4) |

| Excellent | 36 (19.5) | 43 (23.0) |

| Missing | 2 (0.0) | 6 (0.0) |

Time of follow-up assessments

Follow-up assessments were scheduled at 5 weeks (35 days), 6 months (182 days) and 12 months (365 days) after randomisation. Parents were encouraged to return for assessment as close as possible to the scheduled date. Table 7 shows that the range of timings for the follow-up assessments were comparable between treatment groups. A total of 316 children attended all three assessments, 14 attended the 5-week follow-up assessment only, four attended only the 6- and 12-month follow-up assessments, 38 attended two of the three and four children missed their 5-week assessment, but returned for the 6- and 12-month assessments. The proportion of responders attending the clinic within the specified window (± 14 days) was high at 5 weeks (≈90% in each group) but then decreased over the next two time points. A greater proportion of children randomised to receive oral steroids attended their appointments within the window (71% in the placebo group vs. 79% in the oral steroid group at 6 months, and 65% vs. 75%, respectively, at 12 months).

| Treatment group | Follow-up time point | Number of participants | Attending within window (± 14 days), n (%) | Days between recruitment and clinic assessment | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) | Median (25th–75th centile) | Min. | Max. | ||||

| Placebo | 5 weeks | 184 | 165 (89.7) | 40.46 (9.14) | 37.5 (35.0–42.0) | 28 | 96 |

| 6 months | 172 | 133 (71.0) | 187.72 (21.49) | 183.0 (178.25–194.0) | 96 | 275 | |

| 12 months | 162 | 115 (64.8) | 371.38 (25.55) | 364.0 (357.0–374.75) | 310 | 512 | |

| Oral steroid | 5 weeks | 184 | 171 (92.9) | 39.52 (6.63) | 37.0 (35.0–42.0) | 27 | 71 |

| 6 months | 175 | 139 (79.4) | 187.37 (20.73) | 183.0 (179.0–193.0) | 119 | 276 | |

| 12 months | 170 | 127 (74.7) | 371.06 (30.93) | 366.0 (358.75–373.0) | 294 | 665 | |

Medication adherence

A 7-day course of oral steroids or matched placebo was given as a single daily dose of 20 mg for children aged 2–5 years or 30 mg for 6- to 8-year-olds. Over 90% of diaries were returned, in which over 98% of responders reported that they started medication and, hence, initiated treatment (Table 8). In total, 31 diaries were not returned, but all medication had been received according to pharmacy records and 79% had reported taking all medication for 7 days. One participant had not completed the adherence data, but had provided dates to enable a verification that medication had been taken for the 7 days. Of those initiating treatment, the majority initiated treatment the day after recruitment as instructed. More parents reported that the child did not find the oral steroid as palatable (did not like the taste or spat it out) as the placebo (21 vs. 10 children). Minimal numbers of children vomited after medication.

| Medication adherence outcome | Treatment group | |

|---|---|---|

| Placebo (N = 187) | Oral steroid (N = 193) | |

| Medication received, n (%) | 187 (100.0) | 193 (100.0) |

| Diary returned, n (%) | 170 (90.1) | 179 (92.7) |

| Initiated treatment, n (%) | 167 (98.2) | 176 (98.3) |

| Implementation in those who initiated, n (%) | ||

| Fully compliant for 7 days (all taken for 7 consecutive days) | 134 (80.7) | 138 (78.4) |

| Partial compliance | 32 (19.1) | 38 (21.6) |

| Compliance unknown | 1 (0.6) | 0 (0.0) |

| All 7 days taken (all/some medication reported) | 147 (88.0) | 157 (89.2) |

| < 7 days taken (1–6 days) | 19 (11.3) | 19 (10.8) |

| Persistence, n (%) | ||

| Medication reported as not stopped | 147 (88.0) | 157 (89.2) |

| Medication stopped at days 5–7 | 8 (5.4) | 10 (5.7) |

| Medication stopped at days 1–4 | 11 (6.6) | 9 (5.2) |

| Days between recruitment and treatment start | ||

| 0 (same day as recruitment), n (%) | 4 (2.4) | 6 (3.4) |

| 1 (day after recruitment as instructed), n (%) | 134 (80.7) | 148 (85.1) |

| ≥ 2, n (%) | 28 (16.9) | 20 (11.5) |

| Median (min., max.) (days) | 1 (0, 20) | 1 (0, 14) |

Main trial results

Primary outcome

Proportion of children with acceptable hearing between trial groups at 5 weeks post randomisation

The ITT population (i.e. children analysed as randomised with primary outcome data) comprised 363 children (placebo group, n = 180; oral steroid group, n = 183). Of these, 59 children (33%) in the placebo group and 73 children (40%) in the oral steroid group had acceptable hearing at 5 weeks, resulting in a 7.1% (95% CI –2.8% to 16.8%) difference between treatment groups and a number needed to treat to benefit of 14.1 [95% CI number needed to treat to harm of 35.7 to ∞ to number needed to treat to benefit of 6.0 (Table 9)].

| Type of analysis | Treatment group, n (%) | Adjusteda OR (95% CI) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Placebo | Oral steroid | |||

| ITT population | (N = 187) | (N = 193) | ||

| Acceptable hearing | ||||

| No | 121 (67.2) | 110 (60.1) | Reference | |

| Yes | 59 (32.8) | 73 (39.9) | 1.36 (0.88 to 2.11) | 0.164 |

| PP population | (N = 116) | (N = 127) | ||

| Acceptable hearing | ||||

| No | 76 (65.5) | 75 (59.1) | Reference | |

| Yes | 40 (34.5) | 52 (40.9) | 1.27 (0.75 to 2.17) | 0.378 |

| CACE | ||||

| Primary analysis | 0.07b (–0.02 to 0.16) | 0.109 | ||

| Full adherence to oral steroid (vs. none/some) | 0.08b (–0.03 to 0.20) | 0.103 | ||

The point estimate for the treatment effect suggests that the odds of having acceptable hearing at 5 weeks were 36% higher for children randomised to receive oral steroids than children randomised to receive a placebo (see Table 9). However, this difference is not statistically significant. There was a small effect of clustering of outcome within site (intracluster correlation coefficient 0.02, 95% CI 0.003 to 0.20). The adjusted RR drew a similar conclusion of no significant treatment effect at 1.21 (95% CI 0.92 to 1.60; p = 0.169).

The sensitivity analyses showed similar results and no significant difference between treatment groups in both the PP population and when adjusting for adherence in a CACE analysis. The latter showed a small increase of 1% in acceptable hearing for children whose parents stated that they had fully adhered for all 7 days of the oral steroid course (see Table 9). Multiple imputation (MI) was also prespecified in the SAP, but as the proportion missing the primary outcome in each treatment group was minimal [only 17 (5%) of all children], imputation was not carried out and a complete-case analysis was appropriate.

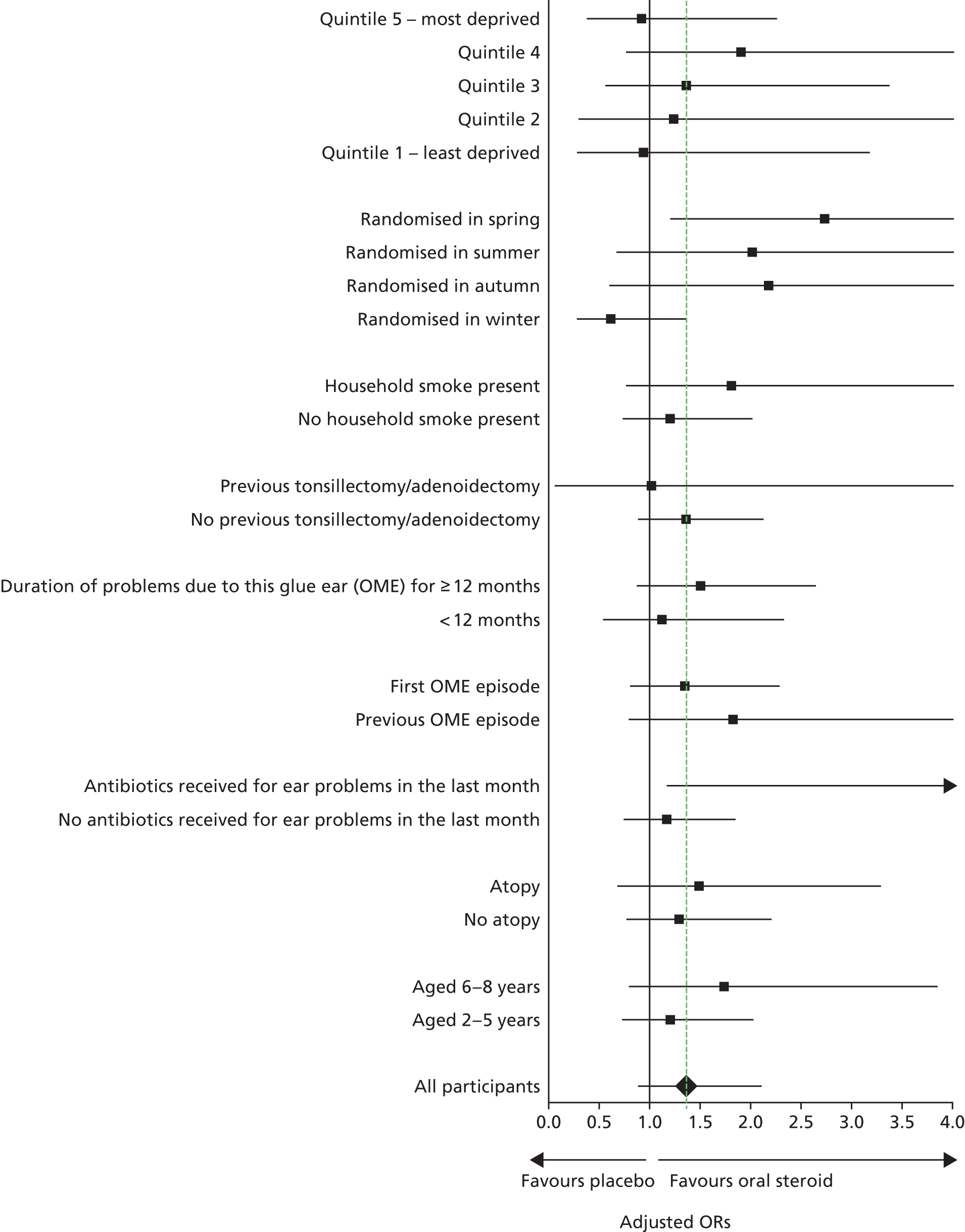

Subgroup analyses

No differences in treatment effects between subgroups were found (Figure 4), and the p-values for the interaction term (treatment group by subgroup) in the model ranged from 0.04 to 0.74 (see Appendix 2).

FIGURE 4.

Forest plot of subgroup analyses.

Secondary analysis of the primary outcome

Two secondary analyses of the primary outcome were proposed in the SAP at 5 weeks, using the outcome as a continuous measure. This enabled an examination of any improvements or deterioration in dBHL over time. This outcome was modelled in two ways:

-

as a child-level analysis using the average, best or worst hearing levels from children assessed via PTA (whereby two ears were assessed) and the only assessment of hearing in those using ear-specific insert VRA or ear-specific play audiometry

-

as an ear-level analysis to account for both ears being tested using the ear-specific VRA.

For the child-level analysis, both treatment groups observed a similar decrease over the 5 weeks of, on average, around 7 dBHL, whichever assessment of both ears was taken [average of both, best ear, worse ear (Table 10)]. A weighted average decibel at baseline and 5 weeks was calculated to account for the number of frequencies recorded per ear/child, but as most children had their ears tested at all four frequencies, the results were very similar (see Table 10). There was no evidence of a difference between treatment groups with similar results (< 1-dBHL between-group difference). An analysis of each ear was separately conducted, and the results were similar to the main per-child analyses.

| Average, best or worse ear | Treatment group | Time point | Change (5 weeks – baseline), mean (SD) | Difference in adjusteda means (95% CI) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | 5 weeks | ||||||

| N | Mean (SD), weighted mean (SD) | N | Mean (SD), weighted mean (SD) | ||||

| Child-level analysis | |||||||

| Average hearing level | Placebo | 181 |

37.79 (6.92) 37.68 (6.93) |

181 |

30.99 (11.00) 30.84 (10.95) |

–6.80 (10.67) | –0.56 (–2.56 to 1.44) |

| Oral steroid | 183 |

36.25 (7.72) 36.18 (7.67) |

183 |

29.32 (10.38) 29.22 (10.34) |

–6.93 (9.57) | ||

| Best hearing level | Placebo | 181 |

35.24 (7.74) 35.17 (7.74) |

181 |

28.02 (11.55) 27.82 (11.46) |

–7.23 (11.59) | –0.96 (–3.07 to 1.16) |

| Oral steroid | 183 |

33.30 (8.46) 33.24 (8.43) |

183 |

25.82 (10.80) 25.71 (10.74) |

–7.48 (10.57) | ||

| Worst hearing level | Placebo | 181 |

40.33 (7.26) 40.20 (7.26) |

181 |

33.96 (11.33) 33.85 (11.29) |

–6.37 (11.12) | –0.37 (–2.52 to 1.78) |

| Oral steroid | 183 |

39.19 (8.11) 39.12 (8.03) |

183 |

32.82 (11.37) 32.72 (11.36) |

–6.37 (10.52) | ||

| Ear-level analysis | |||||||

| Placebo | 361 | 37.81 (7.91) | 361 | 31.01 (11.82) | –6.80 (11.79) | –0.78b (–2.79 to 1.23) | |

| Oral steroid | 364 | 36.20 (8.79) | 364 | 29.38 (11.54) | –6.82 (10.98) | ||

Secondary outcomes

Audiometry

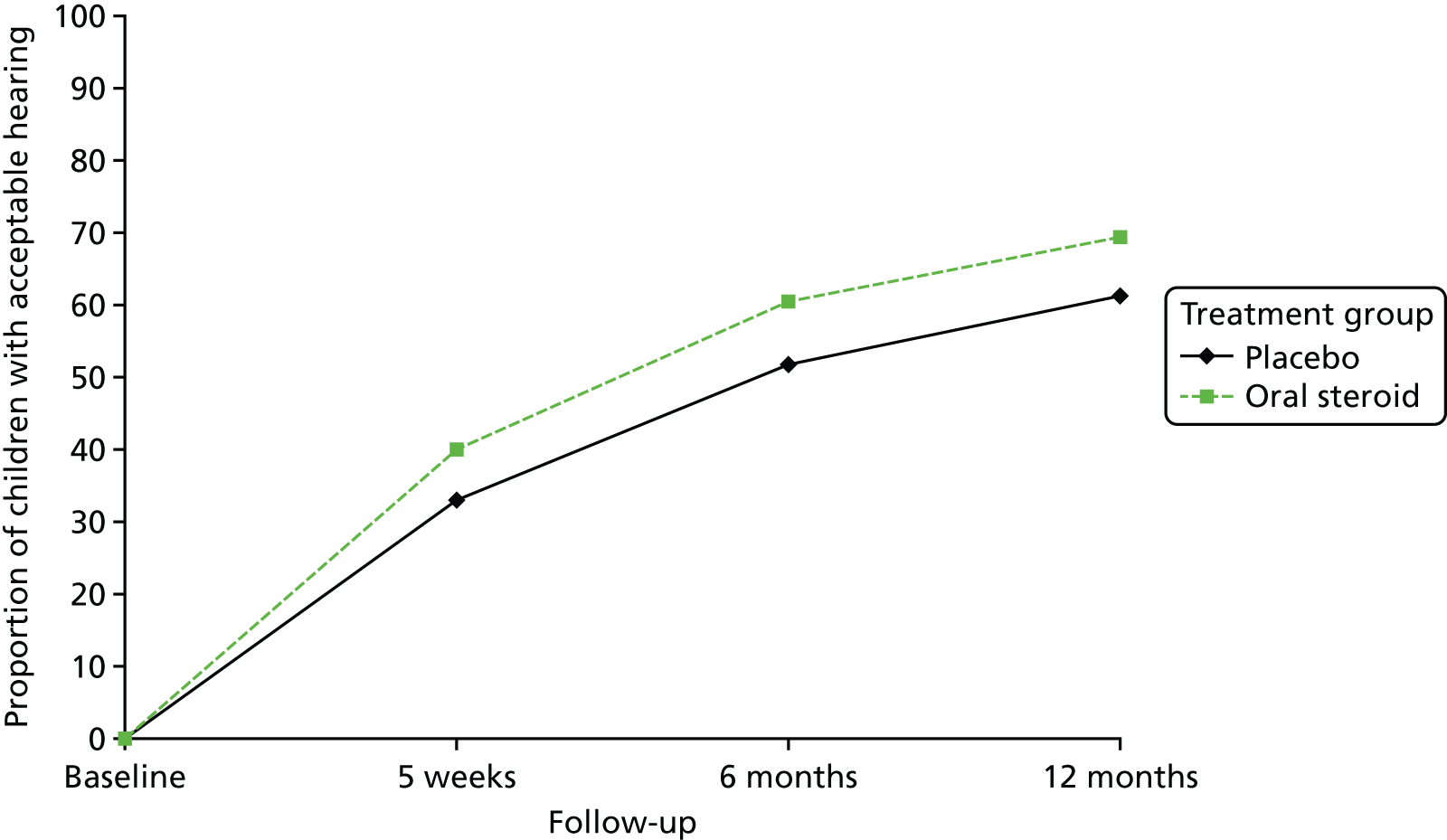

The proportion of children who attended clinic for a hearing assessment was over 95% at 5 weeks, reducing to around 86% by 12 months. Acceptable hearing using audiometry was described by examining the proportion of children with acceptable hearing between treatment groups at 5 weeks and 6 and 12 months. A total of 306 children had audiology assessments at all three time points; 19 had no follow-up at 6 months and 26 had no follow-up at 12 months. Of the 306 children, 62 had acceptable hearing at each time point [placebo group 25 (13.4%) vs. oral steroid group 37 (19.2%)]. A repeated measures multilevel logistic regression model (adjusting for site and age of child) showed that there was a significant increase in acceptable hearing from 5 weeks to the 6 and 12 months’ time points, with a constant 7–8% difference between treatment groups (Table 11 and Figure 5). There was no overall difference in acceptable hearing between groups (oral steroids compared with placebo averaged across all follow-up time points) and no differential effect of treatment over time.

| Outcome | Treatment group, n/N (%) | Effect | Treatment × time effect (p-value) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Time | Treatmenta | ||||||

| Placebo | Oral steroid | Adjustedb OR (95% CI) | p-value | Adjustedb OR (95% CI) | p-value | ||

| Acceptable hearing at audiometry | |||||||

| 5 weeks | 59/180 (32.8) | 73/183 (39.9) | Reference | 1.42 (0.91 to 2.21) | 0.121 | 0.975 | |

| 6 months | 86/166 (51.8) | 105/174 (60.3) | 2.30 (1.47 to 3.60) | < 0.001 | |||

| 12 months | 99/162 (61.1) | 118/170 (69.4) | 3.46 (2.19 to 5.46) | < 0.001 | |||

| Tympanometric resolution of OME | |||||||

| 5 weeks | 13/178 (7.3) | 7/182 (3.8) | Reference | 0.51 (0.20 to 1.30) | 0.159 | 0.007 | |

| 6 months | 17/147 (11.6) | 26/152 (17.1) | 1.69 (0.79 to 3.61) | 0.179 | |||

| 12 months | 9/144 (6.3) | 31/159 (19.5) | 0.85 (0.35 to 2.06) | 0.724 | |||

FIGURE 5.

Proportion of children with audiometric-acceptable hearing over time, by treatment group.

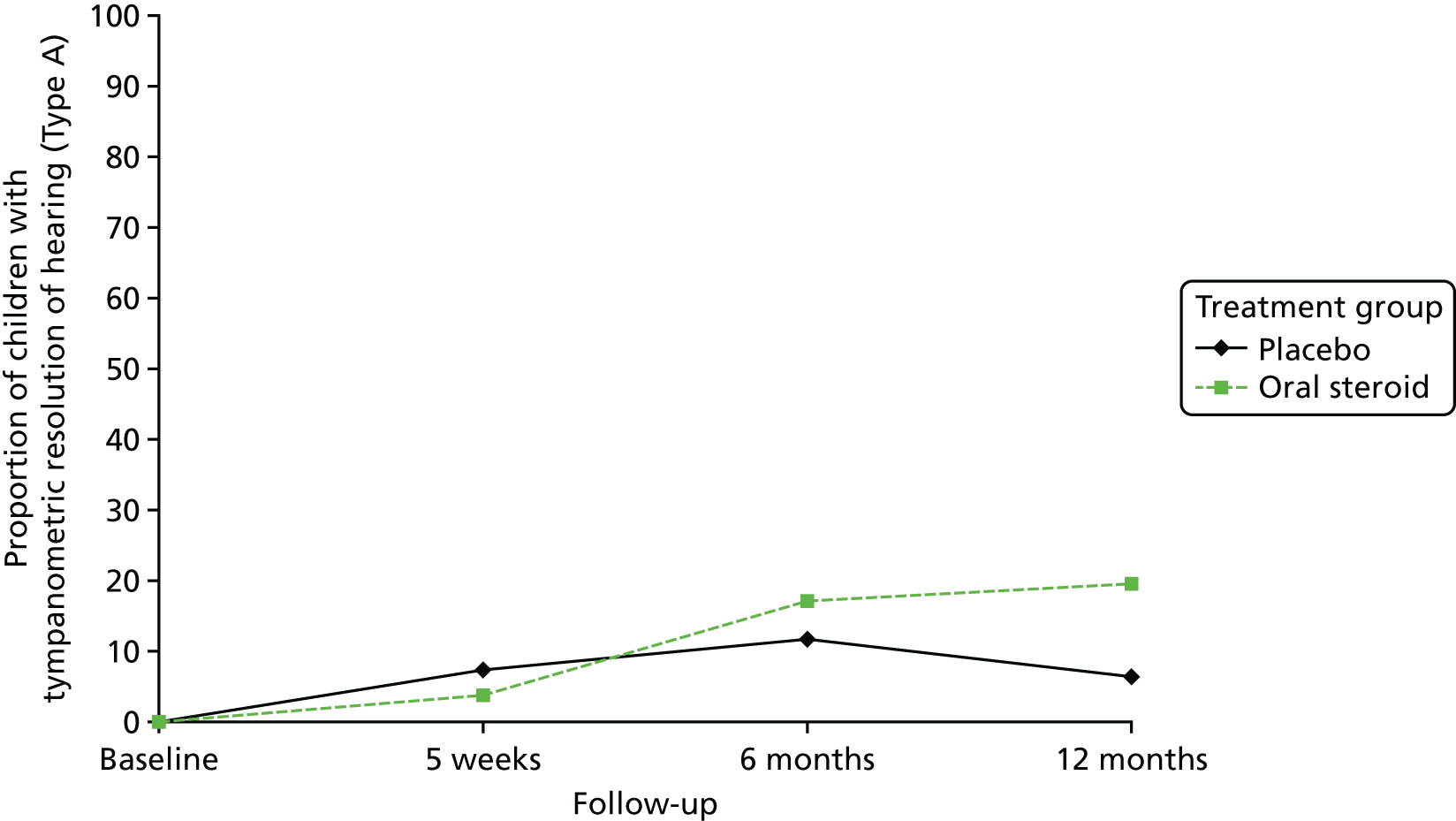

Tympanometric resolution of otitis media with effusion over time

Of those children who attended a clinic, tympanometry was performed in over 98% of children at 5 weeks, a slight decrease at 6 months to 81% and increasing to 90% at 12 months. The main reason that tympanometry was not performed was that the child had ventilation tubes in situ or was about to have surgery to place them. Evidence of tympanometric resolution of OME is defined as moving from a type B or C tympanogram at baseline to a type A tympanogram in at least one ear at the 5-week follow-up. Of the children who had tympanometry performed, a small proportion had evidence of resolution in at least one ear at 5 weeks, 6 months and 12 months (see Table 11). Although there was no overall effect between treatment groups or over time, the rate of resolution in the oral steroid and placebo groups had a different trajectory (Figure 6).

FIGURE 6.

Proportion of children with tympanometric resolution (type A) of hearing over time, by treatment group.

Otoscopy

Otoscopy was performed in over 96% of children over the three follow-up time points, and the tympanic membrane was visible for the majority of these children. Very few children had a perforation present in at least one ear with no significant difference by treatment group, but an increase was detected at 6 and 12 months when compared with perforations at 5 weeks (Table 12). There was a decrease over time in the proportion of children in whom the appearance of the tympanic membrane suggested the presence of a middle ear effusion, but there was no difference between treatment groups. There was no evidence of a difference between treatment groups in the proportion of children with bubbles present behind the ear drum, but there were significantly fewer children with bubbles present at 12 months than at 5 weeks. There was no differential effect between treatment groups in bubbles present behind the ear drum over time.

| Outcome | Treatment group, n/N (%) | Effect | Treatment × time effect (p-value) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Placebo | Oral steroid | Time | Treatmenta | ||||

| Adjustedb OR (95% CI) | p-value | Adjustedb OR (95% CI) | p-value | ||||

| Perforation present in at least one ear | |||||||

| Baseline | 2/184 (1.1) | 2/192 (1.0) | 0.78 (0.37 to 1.66) | 0.520 | 0.623 | ||

| 5 weeks | 2/169 (1.2) | 0/171 (0.0) | Reference | ||||

| 6 months | 9/152 (5.9) | 6/155 (3.9) | 12.43 (2.77 to 55.76) | 0.001 | |||

| 12 months | 7/134 (5.2) | 6/151(4.0) | 9.21 (2.00 to 42.98) | 0.004 | |||

| Presence of a middle ear effusion in at least one ear | |||||||

| Baseline | 183/184 (99.4) | 192/192 (100.0) | 0.70c (0.35 to 1.39) | 0.312 | 0.950 | ||

| 5 weeks | 152/168 (90.5) | 150/172 (87.2) | Reference | ||||

| 6 months | 96/151 (63.6) | 90/154 (58.4) | 0.18 (0.10 to 0.33) | < 0.001 | |||

| 12 months | 80/138 (58.0) | 80/151 (53.0) | 0.14 (0.08 to 0.26) | < 0.001 | |||

| Bubbles present behind the ear drum in at least one ear | |||||||

| Baseline | 23/183 (12.6) | 25/190 (13.2) | 1.57 (0.76 to 3.26) | 0.222 | 0.165 | ||

| 5 weeks | 15/164 (9.1) | 23/169 (13.6) | Reference | ||||

| 6 months | 19/147 (12.9) | 13/152 (8.6) | 1.54 (0.73 to 3.25) | 0.260 | |||

| 12 months | 4/135 (3.0) | 8/149 (5.4) | 0.30 (0.10 to 0.96) | 0.042 | |||

Insertion of ventilation tubes (grommet surgery)

Around one-fifth of children had ventilation tubes inserted between 5 weeks and 6 months (Table 13). Between 6 and 12 months, < 15% of children had new operations for ventilation tubes. There was no evidence of an overall difference between treatment group and a differential treatment effect over time. The mean time to surgery was 165.5 days (SD 104.5 days) in the placebo group and 168.0 days (SD 96.1 days) in the oral steroid group. When examined in a time-to-event model, there was no difference in the risk of operations for ventilation tubes between treatment groups (adjusted HR 0.98, 95% CI 0.69 to 1.41).

| Follow-up time point | Treatment group, n/N (%) | Effect | Treatment × time effect (p-value) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Placebo | Oral steroid | Time | Treatmenta | ||||

| Adjustedb OR (95% CI) | p-value | Adjustedb OR (95% CI) | p-value | ||||

| 5 weeks | c | c | |||||

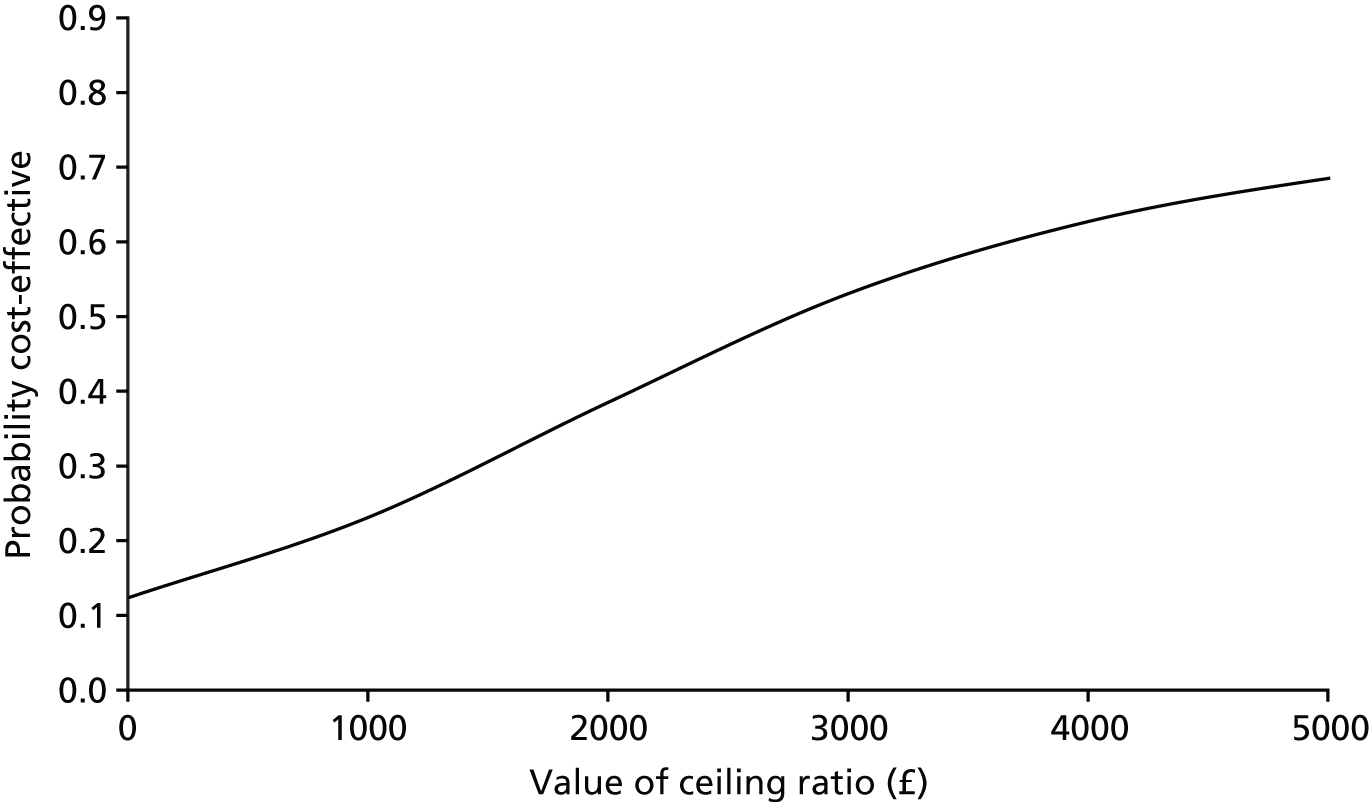

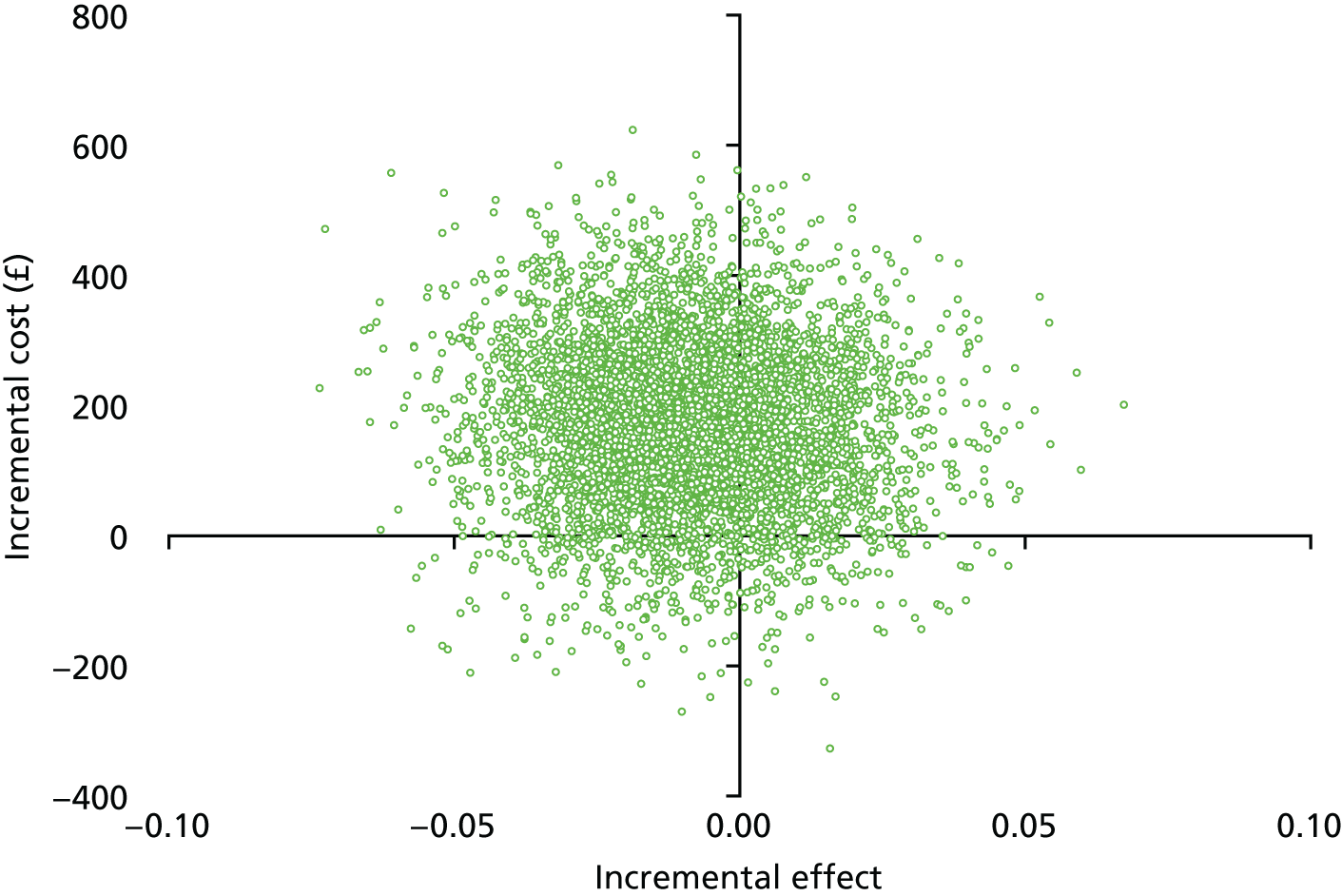

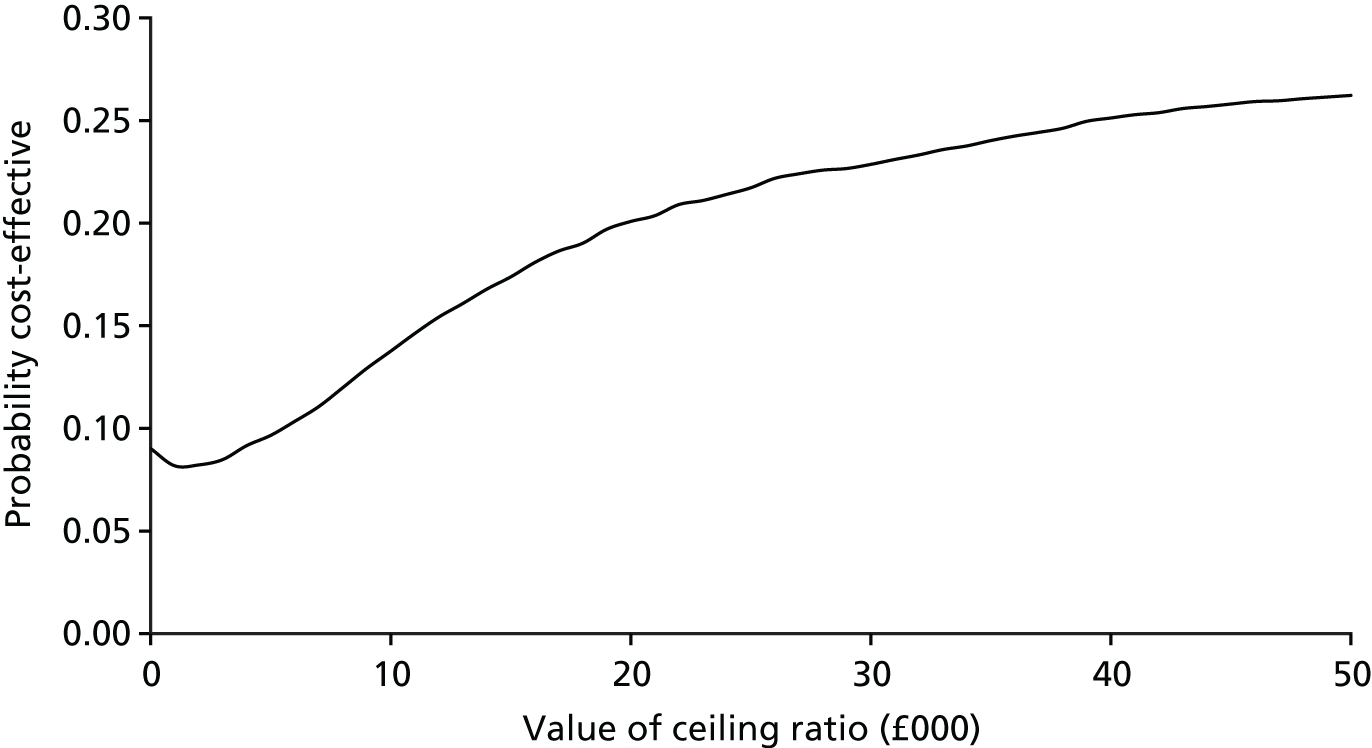

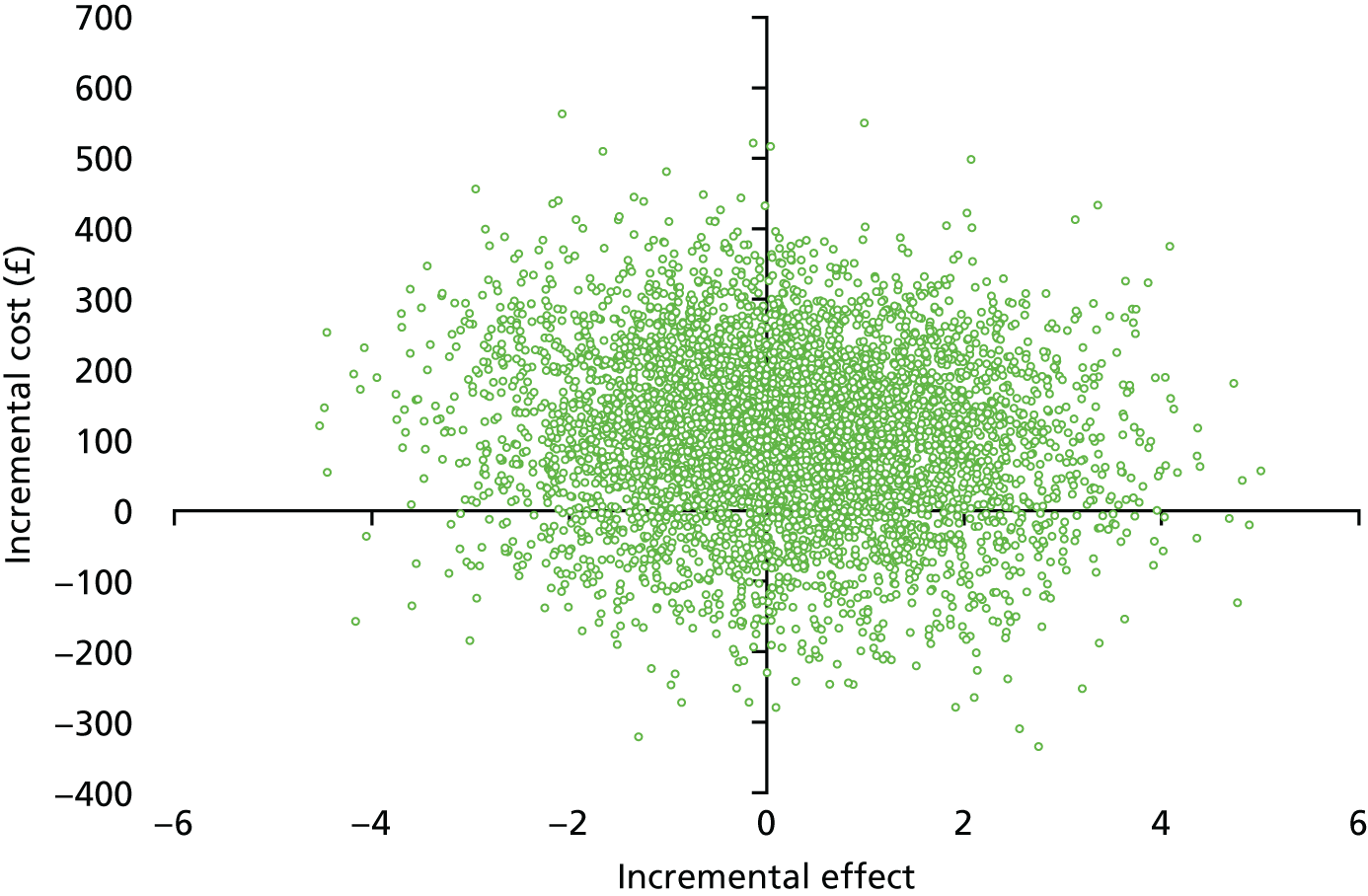

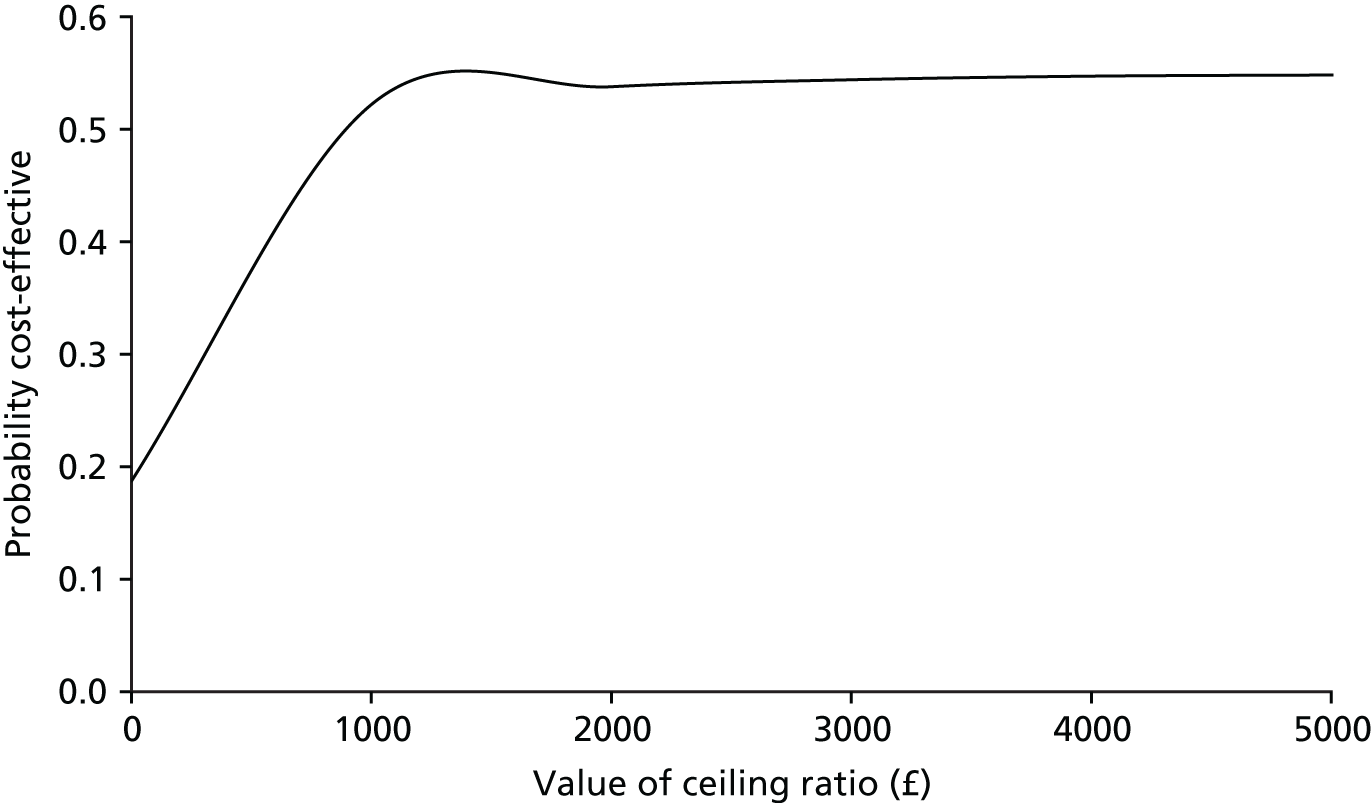

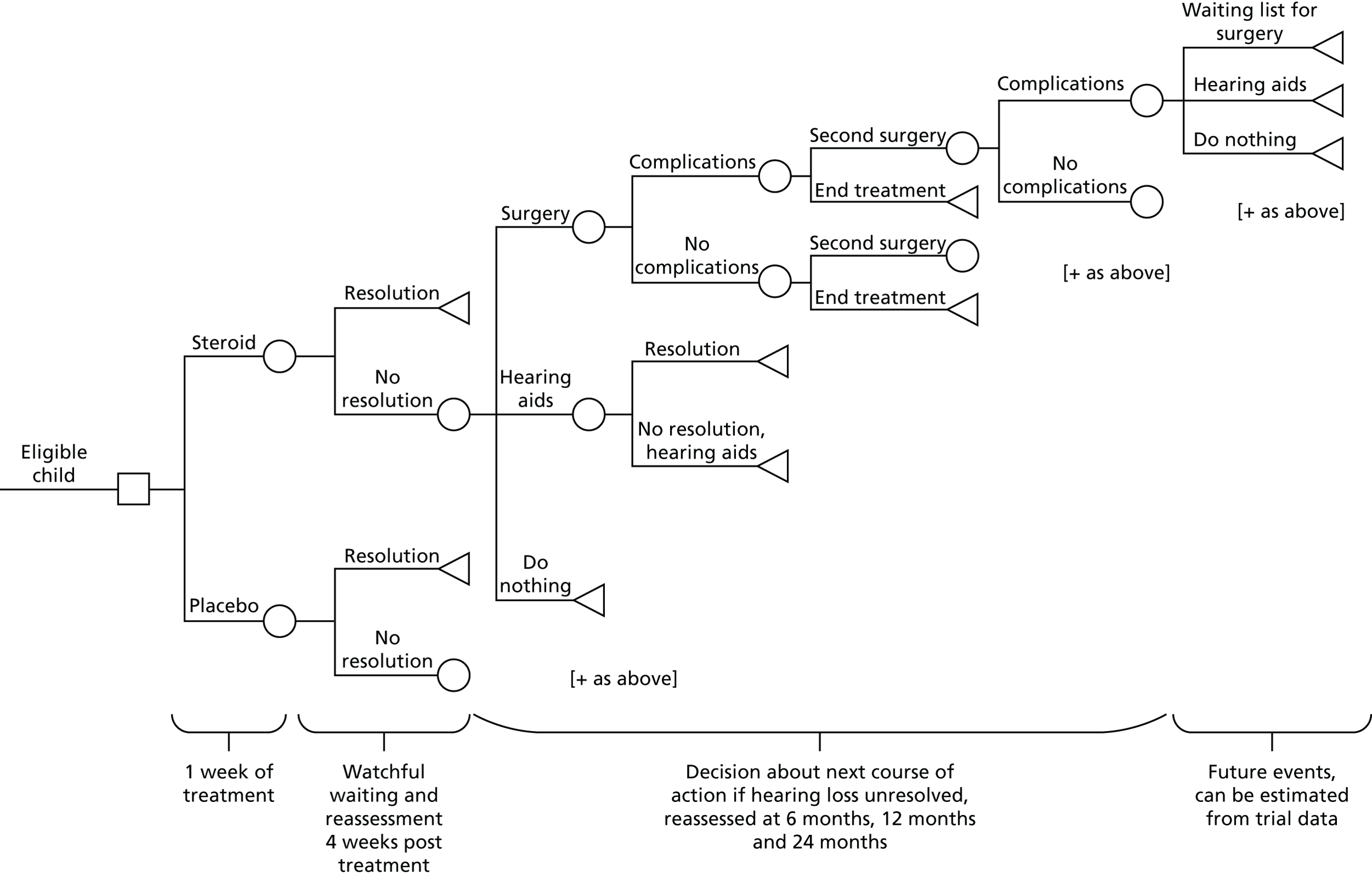

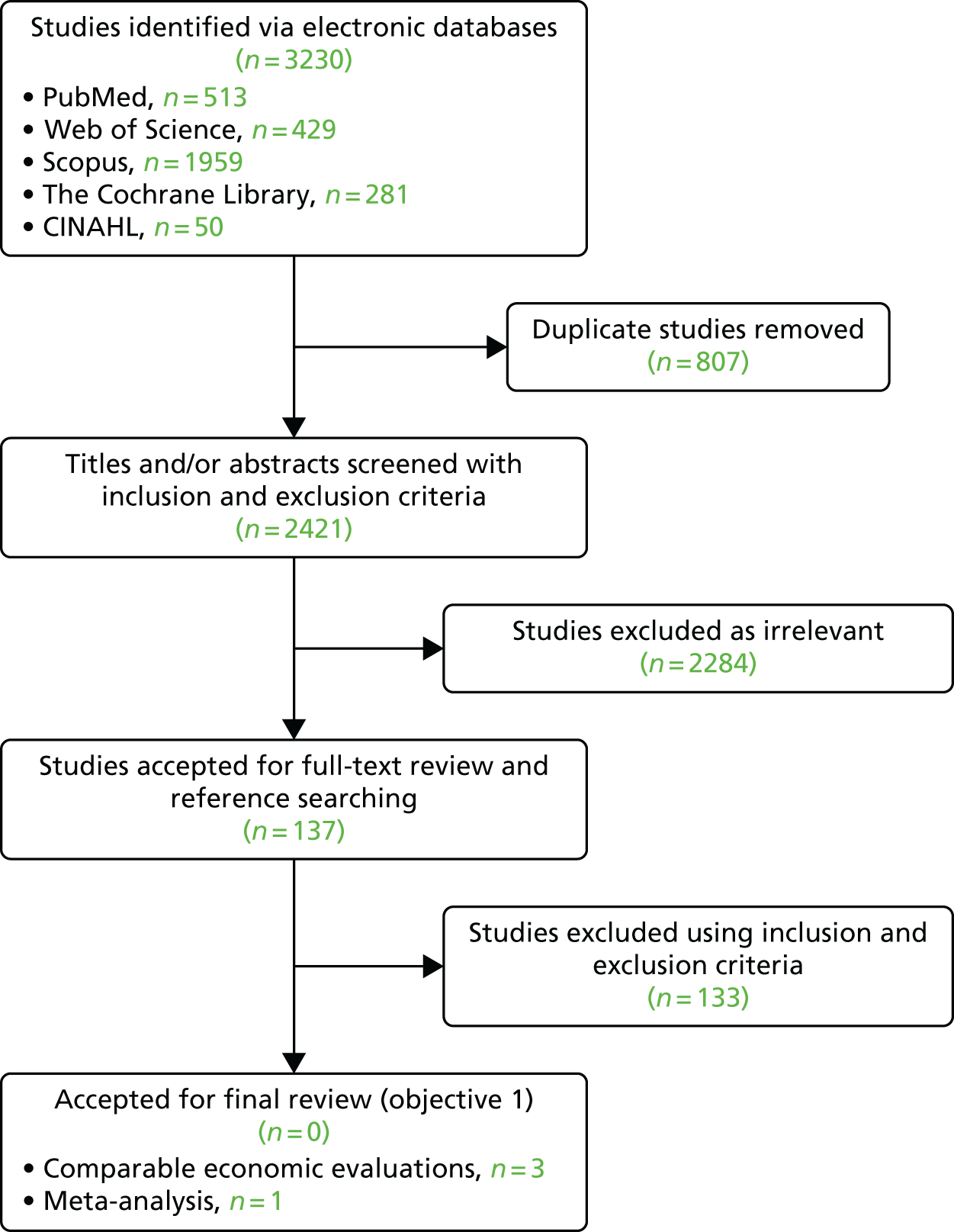

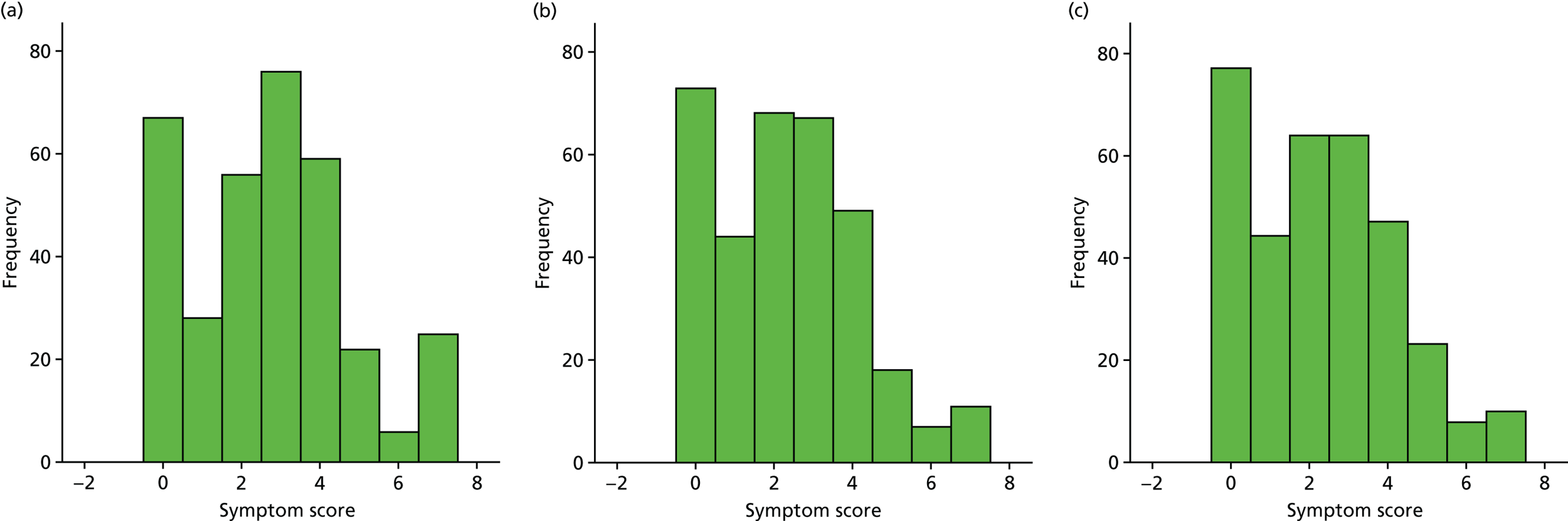

| 6 months | 38/170 (22.4) | 39/173 (22.5) | Reference | Reference | |||