Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 11/129/76. The contractual start date was in April 2013. The draft report began editorial review in May 2017 and was accepted for publication in October 2017. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Simon Gilbody is deputy chairperson of the Health Technology Assessment programme Commissioning Board. Tim J Peters chaired the Medical Research Council–National Institute for Health Research Methodology Research Programme panel from 2007 to 2014. Ian Anderson has received personal fees from the following: Alkermes plc, Lundbeck Ltd, Otsuka Pharmaceutical Ltd, Janssen Ltd and Takeda Pharmaceutical Company Ltd.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2018. This work was produced by Kessler et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2018 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Introduction

Background

Depression is ranked among the top five contributors to the global burden of disease and by 2030 is predicted to be the leading cause of disability in high-income countries. 1 In the UK, people with depression are usually managed in primary care and antidepressants are often the first-line treatment. The number of prescriptions for antidepressants has risen dramatically in recent years, increasing by 6.8% (3.9 million items) between 2014 and 2015. Indeed, antidepressants have shown a greater increase in the volume of prescribing in recent years than drugs for any other therapeutic area, with over 61 million prescriptions being issued in England in 2015, at a cost of £2685M. 2

However, the largest study of sequenced treatment for depression, the STAR*D (Sequenced Treatment Alternatives to Relieve Depression) study,3 found that half of those treated did not experience a reduction of ≥ 50% in depressive symptoms following 12–14 weeks of treatment with a single antidepressant. The reasons for non-response include non-adherence to medication, which may be a result of intolerance. However, a substantial proportion of those who take their antidepressants in an adequate dose and for an adequate period do not experience a clinically meaningful improvement in their depressive symptoms. This can be termed treatment-resistant depression (TRD).

When first-line antidepressant treatments do not work, general practitioners (GPs) can be unsure of what to offer next. The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) now advises GPs to reconsider the treatment options if there has been no response after 4–6 weeks of treatment with antidepressant medication. 4 However, there is currently limited evidence to guide management.

Existing evidence on the pharmacological management of treatment-resistant depression

The current NICE guideline4 describes the following pharmacological strategies for sequencing treatments after inadequate response to the initial treatment: switching antidepressants, augmenting medication by adding a drug that is not an antidepressant and combining antidepressants. The guideline4 comments that the evidence for the benefit of switching, either within or between classes, is weak.

Connolly and Thase5 comment that switching antidepressants after an inadequate response is not ‘unequivocally supported by the data, although switching from a SSRI [selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor] to venlafaxine or mirtazapine may offer greater benefits’. Similarly, there is very little evidence on combining two antidepressants.

The evidence for the effectiveness of augmentation with a non-antidepressant is likewise of variable quality. There is some evidence for augmentation with lithium or a thyroid hormone, but mainly in combination with tricyclic antidepressants, which are not prescribed as often today. The use of the atypical antipsychotics to augment the newer antidepressants is better supported by research,6,7 with quetiapine (Seroquel; AstraZeneca plc, Cambridge, UK) and aripiprazole (Abilify®; Otsuka Pharmaceutical Co. Ltd, Tokyo, Japan) the most promising. 8 However, this combination has not, to date, been adopted with any enthusiasm in UK primary care. This may be because of a lack of experience in prescribing them for this indication as they are usually initiated in secondary care. There are also concerns about their adverse events (AEs), including sedation, metabolic syndrome and central obesity and extrapyramidal effects. 9 Indeed, the current NICE guidance recommends that antidepressants should not be combined or augmented without the advice of a consultant psychiatrist. 4

It is possible that GPs would consider adding a second antidepressant, rather than an atypical antipsychotic or lithium, as part of the management of TRD. They are more familiar with these drugs and their starting routines; in addition, there is less concern about their AEs and less need for monitoring. In general, stepwise combination of drug treatments is a standard part of the management of chronic diseases such as asthma and hypertension in primary care and has led to improved clinical outcomes. GPs are comfortable with this model of care and would probably readily adopt this strategy if it were found to be effective. We think that there may be an opportunity to substantially improve the treatment of people with depression in primary care by using antidepressants in combination. However, one of the reasons that this strategy has not been adopted is the lack of convincing evidence for its effectiveness, especially in the primary care setting.

There is a pharmacological rationale for adding a second antidepressant to selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) or serotonin–noradrenaline reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs) with a different and complementary mode of action. Mirtazapine, an alpha2-adrenoreceptor antagonist, increases central noradrenergic and serotonergic neurotransmission by inhibiting negative feedback from synaptic noradrenaline (NA) acting on presynaptic alpha2 autoreceptors on noradrenergic neurones and alpha2 heteroreceptors on 5-hydroxytryptaminergic (5-HT) neurones. Its mechanism of action is, therefore, different from that of both SSRIs and SNRIs, which inhibit synaptic neurotransmitter reuptake after release. Thus, treatment with mirtazapine in combination with either a SSRI or a SNRI may produce a sustained increase in both 5-HT and NA synaptic availability in terminal fields. A further property of mirtazapine not shared by SSRIs and SNRIs is its affinity for the 5-HT2C receptor, where it acts as an inverse agonist. This mechanism has been linked to specific therapeutic effects. Overall, there is the potential for a synergistic action that could enhance the clinical response compared with the response of those patients receiving only monotherapy. Mirtazapine is now off patent and relatively inexpensive.

Because of its different mechanism of action, there is an argument that switching to mirtazapine alone after SSRI treatment failure might be an effective strategy, rather than subjecting patients to the potential AE burden of a second medication. The STAR*D study compared mirtazapine with nortriptyline in a group of patients who had not responded to two consecutive antidepressant monotherapy regimes. 10 The rates of remission were low for both drugs, suggesting that switching to mirtazapine monotherapy is not the most useful strategy.

In spite of the potential benefit of combining mirtazapine with a SSRI, there is relatively little trial evidence to support this strategy. Carpenter et al. 11 compared the addition of mirtazapine to a SSRI with placebo in a group of 26 patients who had not responded to at least 4 weeks of monotherapy. Although the sample size was very small, the results in terms of effectiveness and tolerability are encouraging,11 but more definitive evidence is required before widespread adoption of this strategy. In patients who have not failed previous treatment, Blier et al. 12,13 reported that mirtazapine in combination with a SSRI gave a greater improvement than monotherapy12 and that it was well tolerated with either a SSRI or a SNRI (venlafaxine),13 with both combinations providing significantly higher remission rates than a SSRI alone. In contrast, a larger study found no benefit from combining antidepressants, including mirtazapine and venlafaxine, over SSRI monotherapy with escitalopram (Cipralex®; Lundbeck, Copenhagen, Denmark), although combined treatment had a higher side-effect burden. 14

Mirtazapine treatment is, however, associated with more weight gain than SSRIs15 and, therefore, as well as assessing the efficacy of its combination with SSRIs, it is important to determine its AE burden, especially when used long term.

Defining treatment-resistant depression

Many definitions of TRD have been proposed. These definitions cover a broad spectrum, ranging from failure to respond to at least 4 weeks of antidepressant medication given at an adequate dose16 to more stringent criteria based on non-response to multiple courses of treatment. 5 A number of staging systems have been proposed, including, most recently, the three-stage model suggested by Conway et al. 17 However, as the authors acknowledge, although the various models may provide guidance in defining TRD, they lack empirical support.

In this study we used a more inclusive definition of TRD, that is, patients who still met the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, Tenth Revision (ICD-10),18 criteria for depression after taking a SSRI or a SNRI antidepressant at an adequate dose [based on the British National Formulary (BNF)19 and advice from psychopharmacology experts] for a minimum of 6 weeks. This definition corresponds to stage I TRD as described by Thase and Rush. 20 It is directly relevant to UK primary care, given the large numbers of non-responders in primary care and the current uncertainty about what course of action to recommend for this group of patients.

Although this 6-week criterion seems a relatively short period to define treatment resistance, many of the patients who satisfy this criterion of ‘non-response’ are suffering from moderate to severe chronic depression. The baseline measures for a recent study of the effectiveness of cognitive–behavioural therapy (CBT) for TRD in primary care, CoBalT (Cognitive behavioural therapy as an adjunct to pharmacotherapy for primary care patients with treatment resistant depression: a randomised controlled trial),21 found that 59% of those recruited had been depressed for > 2 years, 70% had been prescribed their current antidepressant for > 12 months and 28% satisfied the ICD-10 criteria18 for severe depression. These data on chronicity and severity illustrate the extent of the unmet need in this population. 22

It is, therefore, important to undertake a study to investigate the effectiveness of the addition of mirtazapine to SSRIs or to SNRIs in primary care. In the UK, most depression is diagnosed and treated in primary care; this is where most antidepressants are prescribed and where most treatment resistance is encountered. The rise in antidepressant prescribing has continued at a steady rate in the UK despite the introduction of the government initiative Improving Access to Psychological Services (IAPT). Failure to adequately respond to treatment is a substantial problem and there is a need to develop the evidence base for the rational prescribing of antidepressants in primary care. An effective intervention has the potential to have a substantial impact on the health and economic burden associated with this patient group.

Aims and objectives

This trial investigated whether or not combining mirtazapine with SNRI or SSRI antidepressants results in better patient outcomes and more efficient NHS care than SNRI or SSRI therapy alone in TRD. All patients who entered the trial were recruited from primary care and had TRD, defined as meeting ICD-1018 criteria for depression after at least 6 weeks of treatment with either a SSRI or a SNRI antidepressant at an adequate dose.

Our specific aims were to:

-

determine the effectiveness of the addition of the antidepressant mirtazapine to a SSRI or a SNRI in reducing depressive symptoms and improving quality of life (QoL) at 12 and 24 weeks and 12 months (compared with the addition of a placebo)

-

determine the cost-effectiveness of this intervention over 12 months

-

qualitatively explore patients’ views and experiences of taking either two antidepressant medications or an antidepressant and a placebo and identify patients’ reasons for completing or not completing the study, including reasons for withdrawal from the study medication

-

qualitatively explore GPs’ views on prescribing combined antidepressant therapy in this patient group.

Chapter 2 Methods

Study design

The MIR trial was a two-parallel-group, multicentre, pragmatic, placebo-controlled randomised trial with allocation at the level of the individual. Patients were recruited from general practices in England in the areas surrounding our four recruiting centres: (1) Bristol, (2) Exeter, (3) Hull/York and (4) Manchester/Keele. The primary outcome was measured at 12 weeks. The double-blinded randomised allocation was maintained for a period of 12 months, although participants could be unblinded at their request or at the request of their GP after measurement of the primary outcome at 12 weeks; outcomes were also measured at 24 weeks and 12 months.

An economic evaluation was conducted alongside the randomised controlled trial (RCT) to evaluate the cost-effectiveness of the intervention at 12 months (see Chapter 4). A nested qualitative study was conducted to explore patients’ and GPs’ views of the use of an additional antidepressant (see Chapter 5). The trial protocol has been published. 23

Ethics approval and research governance

Ethics approval for the study was given by South East Wales Research Ethics Committee (REC) Panel C (reference: 12/WA/0353). Bristol Clinical Commissioning Group (CCG) and other relevant CCGs provided research governance assurance. Clinical trial authorisation was provided by the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA). The trial sponsor was the University of Bristol. The trial was registered as EudraCT number 2012-000090-23 (January 2012) and ISRCTN06653773 (September 2012). A summary of the changes made to the original protocol is given in Table 1.

| Description | Submitted | Approved |

|---|---|---|

| Original submission (v8.3) | 8 November 2012 | N/A |

| Amendment 1 (protocol v8.4) | 23 January 2013 | 25 January 2013 |

| Revised submission | ||

| Not setting an upper age limit | ||

| Clarification of DMEC to review data | ||

| Defining an adequate dose of a SSRI/SNRI | ||

| Unblinding option at 12 weeks | ||

| Dementia included in exclusion criteria | ||

| Clarification of GP changes to drug regime because of failure to respond | ||

| Amendment 2 (protocol v8.5) | 3 April 2013 | N/A |

| Changes requested by REC | ||

| Addition of PCT sites | ||

| Clarification of minimisation criteria and of issue of medicine to unblinded participants | ||

| GP information sheet revised | ||

| PIS | ||

| Amendment 3 (protocol v8.6) | 16 April 2013 | 23 April 2013 |

| Response to REC-suggested changes | ||

| Change wording from ‘tablet’ to ‘capsule’ | ||

| Amendment 4 (protocol v8.7) | 4 October 2013 | 4 October 2013 |

| Dates for project milestones revised | ||

| Appendix 3: UHB’s AE SOP replaced with MIR trial-specific AE SOP | ||

| Amendment 5 (protocol v8.8) | 3 July 2015 | 11 September 2015 |

| Section 13.3 Expected Adverse Events and Reactions updated to reflect a revised SMPC | ||

| Immediate implementation because of urgent safety measures |

Participants

The trial sought to recruit participants from primary care who had depression that had not responded to at least 6 weeks of treatment with SSRI or SNRI antidepressants, prescribed at an adequate dose. We planned to recruit 470 participants over 18 months from 96 practices in four centres.

Inclusion criteria (all must apply)

Eligible patients were those who met all of the following criteria.

-

Aged ≥ 18 years and in primary care.

-

Treated for depression for at least 6 weeks with any one of the following SSRI or SNRI antidepressants at recommended BNF doses – fluoxetine, sertraline, citalopram, escitalopram, fluvoxamine, paroxetine, duloxetine or venlafaxine (see Appendix 1, Table 25 for the adequate dose table).

-

Adhered to their medication. Adherence to medication is difficult to measure. To operationalise our definition of treatment resistance, we used the Morisky four-item self-report measure of compliance,24 as adapted for CoBalT. 25 The Morisky measure has previously been validated against electronic monitoring bottles, with a score of zero (range 0–4) indicating at least 80% compliance. 18,26 Given the relatively long half-life of antidepressant medication, individuals who have forgotten to take one or two tablets were not excluded.

-

Scored ≥ 14 points on the Beck Depression Inventory-II (BDI-II). 27

-

An ICD-10 diagnosis of depression [assessed using the Clinical Interview Schedule – Revised (CIS-R)]. 28

Exclusion criteria (presence of any warrants exclusion)

General practitioners were asked to exclude patients who fulfilled any of the following exclusion criteria at the time of the record search:

-

patients currently taking combined or augmented antidepressant treatment

-

patients having their medication managed by a psychiatrist

-

patients with dementia (formal diagnosis), bipolar disorder, psychosis or alcohol or substance abuse/dependence

-

women who were pregnant, planning a pregnancy or breastfeeding

-

patients who were unable to complete the study questionnaires

-

patients who had had a previous adverse reaction to mirtazapine

-

patients currently being treated with a monoamine oxidase inhibitor (MAOI), including moclobemide, or with other medical contraindications to mirtazapine.

Recruitment of participants

We used two methods of recruitment: record search and in-consultation recruitment.

Method 1: search of general practice computerised records to identify patients being treated for depression

The search of general practice computerised records identified all patients in the appropriate age range who had been prescribed SSRI or SNRI antidepressants for ≥ 6 weeks and who were currently being prescribed an antidepressant medication at an adequate dose for depression, as recommended in the BNF. 19

The GPs then screened this list of patients and excluded those patients who fulfilled any of the exclusion criteria listed above. A letter of invitation and a brief information leaflet about the study were sent by the general practice to the remaining potential participants. This letter sought permission for the research team to contact potential participants and to send a questionnaire asking about their depressive symptoms and adherence to antidepressant medication. Potential participants replied directly to the study team indicating whether or not they agreed to be contacted. One reminder was sent to those who did not respond to the initial letter of invitation.

On the reply slip, those who did not wish to participate were asked to indicate their age, sex and reason for non-participation. In addition, non-participants were asked to indicate their willingness to take part in a brief telephone interview to discuss their reasons for non-participation.

Anonymised data on the age and sex of those patients who were mailed an invitation to participate but who did not respond (or who refused to participate when invited during the consultation) were collected to assess the generalisability of the study findings.

Method 2: in-consultation recruitment

The GPs could also invite patients to take part in the study during a consultation. In such cases, they provided patients with an information leaflet about the study and obtained permission to pass their contact details to the research team. The research team then mailed a questionnaire to potential participants asking them about their depressive symptoms and adherence to antidepressant medication.

Postal screening: assessment of depressive symptoms and adherence to antidepressants

All those who agreed to be contacted by the research team (in response to either the postal invitation or a direct invitation from their GP during a consultation) were sent a postal questionnaire. This questionnaire collected data on the following:

-

severity of depressive symptoms, using the BDI-II

-

duration of antidepressant treatment, dose of medication and adherence to medication, using the Morisky measure of compliance

-

sociodemographic variables (age, sex, marital status, ethnicity, educational qualifications, employment status, home ownership and financial difficulties).

One reminder was sent to those individuals who did not return a completed postal questionnaire within 2 weeks.

The GPs were then asked to review all of the patients who appeared to be eligible on the postal screening and to sign a form to confirm that these patients were suitable to be prescribed mirtazapine. Once GP approval was received, patients were contacted by a researcher by telephone and invited to attend a face-to-face appointment with a researcher to discuss participation in the trial and to assess their eligibility. The date, time and location of the baseline appointment were confirmed by letter. A detailed patient information sheet (PIS) and a detailed leaflet about mirtazapine were also enclosed; patients were asked to read both prior to attending the baseline appointment.

Patients who completed the screening process but were not eligible to participate received a letter informing them of this and thanking them for taking part. The letter explained that their GP had also been informed and would continue to care for them as usual. The GP received a letter which explained that the patient was ineligible as he or she had not met one or more of the eligibility criteria, but that the GP could refer the patient back to the trial if these factors changed. If the patient had given permission in the postal questionnaire, the GP also received a report that gave more detail about the inclusion criteria that were not satisfied, as well as the individual’s score on the BDI-II.

Baseline assessment

The baseline assessment was conducted in the patient’s home or at the GP’s surgery or on university premises. The researcher explained the study in detail and obtained written informed consent for the baseline assessment. If the potential participant agreed to the assessment, they completed the following questionnaires:

-

BDI-II

-

Morisky questionnaire (adherence to medication)

-

Patient Health Questionnaire-9 items (PHQ-9),29 a brief measure of depression

-

CIS-R, an in-depth psychiatric questionnaire that gives an ICD-10 diagnosis.

Patients were also asked for details of their prescribed medication, prior use of antidepressants and whether or not they were currently in receipt of psychological therapy. In addition, sociodemographic details were recorded (age, sex, ethnicity, marital status), together with information on a number of socioeconomic markers (employment status, housing situation).

Potential participants who scored ≥ 14 points on the BDI-II and who had an ICD-10 primary diagnosis of depression using the CIS-R, were told that they were potentially eligible to enter the trial [pending confirmation by the principal investigator (PI)] and were asked to provide further written consent for trial participation and indicate whether or not they were willing to be contacted about future research projects.

These potentially eligible participants were also asked to complete some further questionnaires including the:

-

General Anxiety Disorder-7 (GAD-7) questionnaire30

-

EuroQoL-5 Dimensions, five-level version (EQ-5D-5L),31 a brief measure of health-related QoL

-

Short Form questionnaire-12 items (SF-12), a brief measure of mental and physical functioning32

-

Antidepressant Side-Effect Checklist (ASEC), a measure of antidepressant side effects. 33

They were asked further questions about their history of depression, whether or not they had ever been referred to a psychiatrist and the strength of their preference for active treatment over placebo (as this could potentially affect medication adherence and outcomes). Additional information was collected on life events, financial stress, social support and use of alcohol. 34

Once the baseline assessment was complete, the local research clinician (PI) reviewed the baseline information and confirmed whether or not the patient was eligible for the MIR trial.

Informed consent

Prior to the start of the baseline assessment, patients were asked to provide written informed consent for the storage and processing of the data collected at the time of the assessment. This covered the data collected from both those who were found to be ineligible to participate in the trial as well as those who were eligible, thus, enabling the trial to be reported in line with the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) guidelines. 35 Those patients who were identified as eligible to participate in the trial were asked to provide additional written informed consent for this purpose. The original signed and dated consent forms were held securely as part of the trial site file, with copies given to both the participants and their GPs for their records.

Randomisation, concealment of allocation and blinding

Following the baseline assessment, eligible and consenting participants were randomised using the automated randomisation service provided by the Bristol Randomised Trials Collaboration (BRTC). Randomisation was carried out by means of a computer-generated code to ensure concealment of allocation.

Randomisation was stratified by centre (n = 4) to ensure balance in terms of local differences. Minimisation was used to ensure balance in important prognostic indicators, that is, baseline BDI-II score (using approximate tertiles derived from CoBalT baseline scores: < 26 points; 26–34 points; ≥ 35 points), sex and whether or not the patient was currently receiving a psychological therapy (yes/no). We used minimisation with a probability weighing of 0.8 to reduce predictability. 36

Once this had been completed, the University Hospitals Bristol NHS Foundation Trust (UHB) pharmacy, which was the central trial pharmacy, was notified. A participant pack containing an initial 8-week supply of medication was sent by registered post from the UHB pharmacy either to participants’ GP surgery or, in exceptional circumstances, to their home.

Treatment group allocation

Participants were randomly assigned to one of two treatments: (1) one × 15-mg encapsulated mirtazapine tablet daily for 2 weeks followed by two × 15-mg encapsulated mirtazapine tablets for up to 50 weeks or (2) identical placebo tablets. Participants were free to withdraw from the medication at any time. Participants, clinicians, outcome assessors and the research team were blinded to allocation. All participants continued with their GP care and usual antidepressants as agreed by their GP. Clinicians were not restricted in their use of psychological services.

Unblinding was available through the trial pharmacy at all times in case of a medical emergency (‘emergency unblinding’). After the 12-week primary outcome had been completed, the code could also be broken at the request of a participant or his or her GP (‘elective unblinding’). Those who had not requested emergency or elective unblinding were unblinded at the end of the follow-up period or on withdrawal from the study. The trial team did not provide further supplies of the trial medication once participants had been unblinded.

Follow-up

Follow-up data collection took place at five time points: 2, 6, 12 and 24 weeks and 12 months post randomisation. Measurement of the primary outcome took place at the 12-week follow-up. The 12-month follow-up was designed to enable the investigation of any longer-term effects on study outcomes.

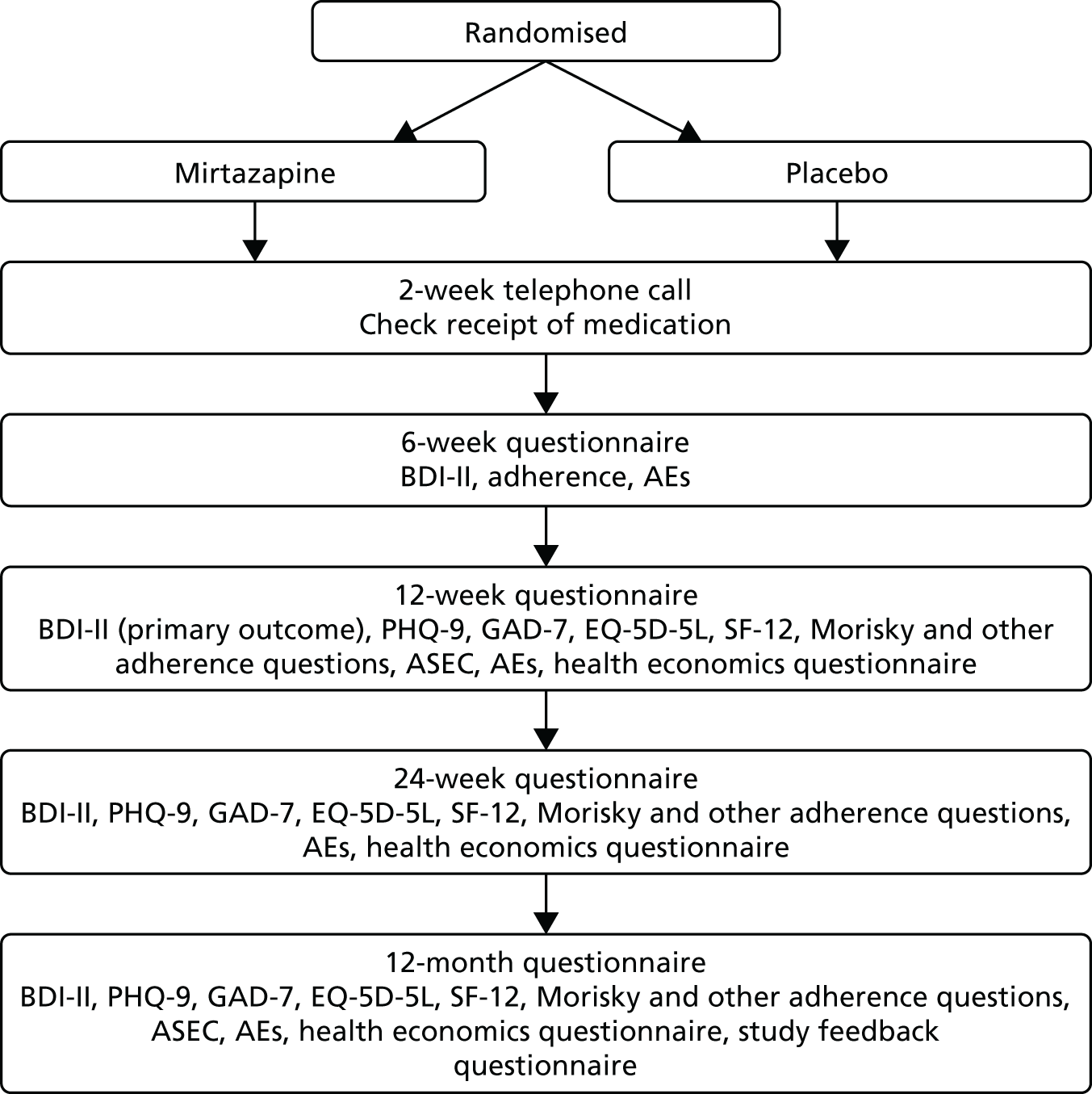

At 2 weeks post baseline, researchers contacted participants briefly by telephone to check that they had received and started their trial medication. At 6, 12 and 24 weeks and at 12 months, participants were asked to complete self-report outcome questionnaires. The follow-up schedule is summarised in the flow chart presented in Figure 1. Follow-up questionnaires could be completed face to face with the researcher, by telephone or by post. If a postal questionnaire was not returned, a reminder was sent.

FIGURE 1.

Follow-up schedule.

Throughout the follow-up process participants were asked about possible AEs and were advised to consult their GP about these if appropriate. Participants were sent a £5 gift voucher with the 12- and 24-week and the 12-month questionnaires, to thank them for their participation.

At the end of the 12-month follow-up period (or on withdrawal from the study), participants were advised to return to their GP to discuss their continued care.

Withdrawal of trial participants

Participants could withdraw from the trial at any time, for any reason, without their medical care being affected. When possible, data already collected would continue to be used in the trial; participants who withdrew from the trial were asked if they were still willing to provide follow-up data. If a patient withdrew, the reason for, and type of, withdrawal was documented on the case report form (CRF).

Principal investigators had the right to withdraw participants from the trial medication in the event of intercurrent illness, AEs, serious adverse events (SAEs), suspected unexpected serious adverse reactions (SUSARs) or protocol violations or for administrative reasons or other reasons; this was documented on the CRF.

Although there is no evidence that the medication is teratogenic, if a participant discovered that she was pregnant during the trial, she was instructed to stop her trial medication immediately, although she was still able to continue to participate in completion of the trial outcome measures if she wished. A longer monitoring period was put in place to establish the safe delivery of a healthy infant, at which point follow-up would stop.

Data collection and management

To standardise processes across the four centres and maximise data quality, researchers were trained to use detailed standard operating procedures (SOPs) for each stage of data collection. A number of cross-checks were routinely performed as a means of ensuring that any data inconsistencies arising from either the baseline assessment or a follow-up were identified and resolved. Trial data were entered into an OpenClinica version 3.1.4 (Waltham, MA, USA) database at each centre. A range of data validation checks were carried out in both Microsoft Access® 2013 (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA) and Stata® 14 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA) to minimise erroneous or missing data.

The trial sponsor took primary responsibility for ensuring that the design of the study met appropriate standards and that arrangements were in place to ensure appropriate conduct and reporting. The trial was run in accordance with Good Clinical Practice (GCP)37 and current regulatory guidance.

We employed standard strategies to ensure the quality of the data; for example, a random sample of 10% of CRFs was checked by the trial research team against entries within the database. Consistency checks on key variables were also conducted to identify unlikely or inconsistent responses. These were checked by the research team against hard-copy questionnaires and the database was updated accordingly.

Outcome measures

Primary outcome

The primary outcome was change in the BDI-II score at 12 weeks post randomisation, measured as a continuous variable.

The BDI-II is a 21-item self-report instrument used to measure the severity of depressive symptoms occurring over the previous 2 weeks; it has been widely used in depression trials and extensively validated. 27 The 21 items are rated on a four-point severity scale (0–3) and are summed to give a total score (range 0–63 points). A higher score on the BDI-II denotes more severe depression.

Secondary outcomes

The BDI-II was also completed at 24 weeks and at 12 months to assess the longer-term effect of the intervention. Other outcome measures included at the 12- and 24-week and the 12-month follow-up assessments are listed below:

-

treatment response, measured as an improvement of ≥ 50% in BDI-II score at 12 weeks compared with baseline

-

the rate of remission of symptoms, defined as a BDI-II score of < 10 points at 12 weeks

-

depression, as measured using the PHQ-9

-

change in anxiety symptoms (measured using the GAD-7) at 12 weeks

-

all of the above outcomes at 24 weeks and 12 months

-

antidepressant use and adherence (using the Morisky questionnaire and additional questions)

-

QoL (measured using the EQ-5D-5L)

-

social and physical functioning (measured using the SF-12) at 12 and 24 weeks and 12 months

-

AEs, including any new symptoms or worsening of existing symptoms, consultations for a documented deterioration in illness and SAEs (self-reported or from a review of primary care notes) and side effects (measured using the ASEC) at 12 weeks and 12 months

-

cost-effectiveness from the perspectives of the NHS, patients and society (using self-report questionnaires at 12 and 24 weeks and at 12 months and using primary care practice data on consultations, services and prescriptions over the 12-month trial period).

See Appendix 1, Table 26 for a full schedule of the questionnaires used.

Handling missing items

For the BDI-II, PHQ-9 and GAD-7, the research team dealt with any missing data at an individual item level by adopting the following rule: if ≥ 10% of the items were incomplete, the data collected on that measure for that participant were disregarded. However, if < 10% of the items on a particular measure were missing, missing item(s) were imputed using the mean of the remaining items (rounded to an integer). Therefore, when an individual had completed 19 or 20 items for the primary outcome measure (BDI-II), the remaining one or two items were imputed. For all other measures (PHQ-9 and GAD-7), the 10% rule meant that only a single item would be imputed. Data were complete for the majority of the sample. The scoring manuals for the SF-12 and EQ-5D-5L, which require the application of complex scoring algorithms, indicated that, if any item was missing, the scale score should not be calculated.

A number of sensitivity analyses were conducted to assess the impact of missing primary outcome data on the main findings.

Trial medication

The active trial drug was mirtazapine: one × 15-mg oral capsule per day for 2 weeks, followed by 2 × 15-mg oral capsules per day for up to 12 months. The mirtazapine was encapsulated and the placebo was an identical capsule filled with an inert excipient. The placebo capsule exactly matched the encapsulated mirtazapine in dimensions and appearance, so that allocation concealment and blinding of the trial were maintained.

Packaging, labelling and dispensing

The labelling of medication packs was MHRA approved and conformed to Annexe 13 of good manufacturing practice standards and Article 13.3 of Directive 2001/20/EC. 38 Each medication pack had a medicine identification number, randomly generated to ensure that mirtazapine and placebo medicine packs were indistinguishable and, thus, maintain allocation concealment. The random numbers were generated by the BRTC and provided to the manufacturer, who used them to form the identifiers.

Sharp Clinical Services (UK) Ltd (Crickhowell, UK) provided qualified person services and distribution and project management. It shipped labelled and numbered packages to the central trial pharmacy (UHB Clinical Trials Pharmacy), where the trial medication was stored under controlled conditions. Storage was secure and there were delegation logs for access, for which the trial pharmacy took responsibility. The trial pharmacy dispensed individual participant packs and oversaw the packaging and posting of those packs. Participant packs contained no more than an 8-week supply of the trial medication and were posted by recorded delivery. All deliveries were logged to ensure drug accountability. The trial medication was shipped and stored in conditions in line with the manufacturer’s stability data.

Concomitant medication

Pharmacodynamic interactions

Mirtazapine should not be administered concomitantly with MAOIs or within 2 weeks after discontinuation of MAOI therapy. Likewise, about 2 weeks should pass before patients treated with mirtazapine are treated with MAOIs. Participants in this study were not treated with MAOIs and GPs were advised to wait at least 2 weeks after stopping the trial medication before starting a MAOI.

Co-administration with other serotonergic active substances [L-tryptophan, triptans, tramadol, linezolid (Zyvox®; Pfizer, New York, NY, USA), lithium and St John’s wort (Hypericum perforatum) preparations] may lead to serotonin-associated effects; therefore, participants were advised to use these medications with caution. Mirtazapine may increase the sedating properties of benzodiazepines and other sedatives (notably most antipsychotic drugs, antihistamine H1 antagonists and opioids). Caution should be exercised when these medicinal products are prescribed together with mirtazapine.

Mirtazapine may increase the central nervous system depressant effect of alcohol. Participants were, therefore, advised to be cautious in their intake of alcohol while taking mirtazapine.

Other concomitant care (including switching, discontinuing or changing the dose of SSRI/SNRI medication and receipt of psychological therapies) was not prohibited.

Trial-stopping rules

The trial could be prematurely discontinued by the sponsor, chief investigator, regulatory authority or funder on the basis of new safety information or for other reasons given by the Data Monitoring and Ethics Committee (DMEC) or Trial Steering Committee (TSC).

The trial could be prematurely discontinued because of a lack of recruitment or on advice from the TSC. If the trial was to be prematurely discontinued, active participants would have to be informed and no further participant data would have been collected.

Justification of sample size

Original sample size calculation

The primary outcome was BDI-II score, reported as a continuous variable. It is difficult to estimate a clinically important difference in BDI-II score, although the NICE guideline panel for the first depression guideline39 suggests that this corresponds to about 3 points [standard deviation (SD) 0.35 points] on the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HDRS)40 for non-treatment-resistant patients and 2 points for those who are treatment resistant. The equivalent difference to 3 HDRS points for the BDI-II total score would be 3–4 points (SD 10–12 points in CoBalT), which is also a clinically important difference from the patient perspective. 41 With 200 participants in each group, we would have 91% power to detect a difference of 0.33 SDs at the 5% level. Allowing for a 15% loss to follow-up at 12 weeks, we wanted to recruit 472 patients.

For our secondary outcome, response rate, defined as a 50% reduction in symptoms using the BDI-II score, 200 patients in each group would yield 90% power to detect a difference of between 30% and 46% in response, or an odds ratio (OR) of 2, at a two-sided 5% significance level. We therefore aimed to recruit 120 patients from 24 general practices at each of the four recruiting centres.

Blinding

Participants, GPs and investigators were blinded to treatment. The effectiveness of blinding was assessed by a brief questionnaire asking participants to which arm they believed they had been allocated at the 12-week follow-up.

Statistical analysis

Baseline data analyses

Baseline sociodemographic and clinical characteristics were described by treatment group to ascertain any marked imbalances and inform any additional adjustment of the primary and secondary analyses as appropriate. Continuous variables were summarised using the mean and SD [or median and interquartile range (IQR) if the distribution was skewed] and categorical data were summarised as frequencies and proportions. All antidepressant medication use at baseline was reported by class, name, dose and duration of treatment.

Stratification, minimisation and sociodemographic variables and measures of depression and treatment preference, assessed at baseline, were explored for associations with ‘missingness’ of the primary outcome measure at 12 and 24 weeks and 12 months. Comparisons were made using chi-squared tests for categorical variables and t-tests and Mann–Whitney U-tests for continuous variables.

Primary analysis

Analysis and reporting were in line with CONSORT guidelines,35 with the primary analyses being conducted on an intention-to-treat (ITT) basis. The primary analysis was the BDI-II score at 12 weeks post randomisation, measured as a continuous variable. Linear regression modelling was used to compare the randomised groups, adjusting for stratification and minimisation baseline variables and baseline BDI-II score.

Analyses of secondary outcomes were conducted by adjusting for the baseline measure of the outcome variable and stratification and minimisation variables. Linear regression was used for continuous outcomes and logistic regression models were used for binary outcomes.

Secondary analyses

Secondary analyses of the primary and all secondary outcomes included additional adjustment for variables demonstrating a marked imbalance at baseline (ascertained using descriptive statistics).

In all analyses, we have presented regression coefficients (or ORs for binary outcomes), with 95% CIs and p-values.

Subgroup analyses

We conducted a number of prespecified analyses to investigate any differential effects in subgroups defined by a number of factors. These were carried out by introducing appropriate interaction terms in the regression models. We carried out these analyses by baseline depression severity (BDI-II) and a multilevel measure of degree of treatment resistance based on duration of symptoms and prior treatment with antidepressants.

Sensitivity analyses

In all tables, missing data are indicated in the footnotes. For our analysis of the primary outcome, we investigated the influence of missing data using sensitivity analyses that made different assumptions: ‘best’- and ‘worst’-case scenarios and multiple imputation by chained equation (MICE) to impute missing data. 42,43 When using MICE, 25 data sets were generated and 10 switching procedures undertaken. The imputation model included all variables predictive of missingness, together with all of the variables used in the primary analysis. Results from the ITT analyses of complete cases are presented alongside these analyses.

Per-protocol analyses were conducted at 12 weeks and at 12 months for the primary outcome. As these are likely to be biased, we also adopted a complier-average causal effect (CACE)44 approach.

A further sensitivity analysis using CACE methods was conducted at 24 weeks and 12 months. If we define ‘compliers’ as those who had continued taking their trial medication up until 12 weeks, we could then estimate the effect of completing a 12-week course of mirtazapine on depression outcomes at the later follow-up points (24 weeks and 12 months).

Safety reporting and disclosure

Definitions

Adverse event

Adverse events were defined as any untoward medical occurrence in a clinical trial participant. An AE did not necessarily have to have a causal relationship with the trial treatment. An AE could, therefore, be any unfavourable and unintended sign (including an abnormal finding), symptom or disease temporally associated with the use of a medicinal (investigational) product, whether or not related to the medicinal (investigational) product [International Conference on Harmonisation (ICH) definition]. 45 This included any occurrence that was new in onset or aggravated in severity or frequency from the baseline condition, or abnormal results of diagnostic procedures, including laboratory test abnormalities. All AEs were recorded on the CRF for the duration of participants’ direct involvement in the trial (12 months).

Serious adverse event

A SAE was defined by the ICH45 as any untoward medical occurrence that, at any dose of the trial medication, meets any of the following conditions:

-

Resulted in the death of the participant.

-

Was life-threatening. The term ‘life-threatening’ referred to an event in which the participant was at risk of death at the time of the event; it did not refer to an event that hypothetically might have caused death if it were more severe.

-

Required inpatient hospitalisation or prolongation of existing hospitalisation. For any events that were not immediately life-threatening or did not result in death or hospitalisation, but that could jeopardise the participant or required intervention to prevent one of these outcomes, the chief investigator would exercise his/her scientific and medical judgement to decide whether or not such an event required expedited reporting to UHB (who acted on behalf of the sponsor in these instances).

-

Resulted in persistent or significant disability/incapacity. This means any event that seriously disrupted the ability of the participant to lead a normal life; in other words, one that led to a persistent or permanent significant change, deterioration, injury or perturbation of the participant’s body functions or structure, physical activity and/or QoL.

-

Was a congenital anomaly/birth defect. This related to exposure to the trial drug before conception (in men or women) or during pregnancy that resulted in an adverse outcome in the child.

-

Other medical events. This related to medical events that could jeopardise the subject or required an intervention to prevent a characteristic or consequence of a SAE. Such events were referred to as ‘important medical events’ and were also considered as ‘serious’ in accordance with the definition of a SAE.

Adverse event associated with the use of the drug

An AE was considered to be associated with the use of the drug if the attribution was possible, probable or very likely, as in the following definitions:

-

Not related – an AE that was not related to the use of the drug.

-

Doubtful – an AE for which an alternative explanation was more likely, for example concomitant drug(s), concomitant disease(s) or the relationship in time suggesting that a causal relationship was unlikely.

-

Possible – an AE that might be because of the use of the drug and for which an alternative explanation, for example concomitant drug(s) or concomitant disease(s), was inconclusive. The relationship in time was reasonable and, therefore, the causal relationship could not be excluded.

-

Probable – an AE that might be the result of the use of the drug. The relationship in time was suggestive (e.g. confirmed by withdrawal from trial medication). An alternative explanation was less likely, for example concomitant drug(s) or concomitant disease(s).

-

Very likely – an AE that was listed as a possible adverse reaction and could not be reasonably explained by an alternative explanation, for example concomitant drug(s) or concomitant disease(s). The relationship in time was very suggestive (e.g. it was confirmed by withdrawal from trial medication and reintroduction).

Procedure for reporting

All AE reporting was in accordance with the MIR trial SOP for AE reporting (see Appendix 1).

All adverse events

All AEs were reported by the chief investigator from the time that a signed and dated informed consent form was obtained until completion of the last trial-related procedure (collection of follow-up data 12 months after randomisation). Those occurrences meeting the definition of SAEs were reported using the SAE form (see Appendix 1), including SAEs spontaneously reported to the investigator within 30 days after the participant had completed the trial (including post-trial follow-up). UHB, on behalf of the sponsor, would evaluate any safety information that was spontaneously reported by a chief investigator beyond the time frame specified in the protocol. All AEs, regardless of seriousness, severity or presumed relationship to the trial drug, were recorded in the source document and the CRF, together with any measures taken. All PIs recorded in the CRF their opinion concerning the relationship of the AE to the trial therapy. UHB, on behalf of the sponsor, assumed responsibility for appropriate reporting of AEs to the regulatory authorities.

Serious adverse events

All SAEs were reported to UHB (who monitored SAEs on behalf of the sponsor) and the relevant PI by a delegated member of the research team within 24 hours of their knowledge of the event. The chief investigator and trial manager were also informed. All SAEs that were not resolved by the end of the trial (i.e. by the end of the primary care notes review follow-up period), or that were not resolved on discontinuation of the participant’s participation in the trial, were followed until (1) the event resolved/stabilised/returned to baseline, (2) the event could be attributed to other factors unrelated to the trial or (3) it became unlikely that additional information could be obtained.

The death of a participant was considered a SAE, as was any event requiring hospitalisation (or prolongation of hospitalisation) that occurred during the course of a participant’s participation. Exceptions to this were hospitalisations for:

-

social reasons, in the absence of an AE

-

in-clinic protocol measures

-

surgery or procedure planned before entry into the trial (this was documented on the CRF).

Suspected unexpected serious adverse reaction

All relevant information about a SUSAR that occurred during the course of the trial was reported to the MHRA and the relevant ethics committee by UHB, on behalf of the sponsor, as soon as possible (fatal or life-threatening SUSARs were reported within 7 days; those that were not fatal or life-threatening were reported within 15 days).

The expectedness of an AE was determined by whether or not it was listed in the Summary of Medicinal Product Characteristics (SMPC), the BNF and/or the study protocol.

Expected AEs and adverse reactions are presented in Appendix 1, Box 2.

Quality assurance

Good Clinical Practice37 is an international ethical and scientific quality standard for designing, conducting, recording and reporting studies that involve the participation of human subjects. Compliance with this standard provides public assurance that the rights, safety and well-being of trial subjects are protected, consistent with the principles that originated in the Declaration of Helsinki,46 and that the clinical trial data are credible. This research trial ran in accordance with GCP.

Direct access to source data/documents

The PIs and trial site teams allowed monitors (from UHB, on behalf of the sponsor), persons responsible for the audit, representatives of the REC and representatives of the regulatory authorities to have direct access to source data/documents. This was reflected in the PIS. Trial monitoring was undertaken on behalf of the sponsor by UHB using their monitoring SOP.

Trial monitoring

Before the trial

The PIs and trial sites allowed the monitors to visit the sites and facilities where the trial took place to ensure compliance with the protocol requirements. The University of Bristol’s Green Light procedure was implemented in each of the other collaborating centres in order to document preparedness to conduct recruitment locally. A monitoring plan was agreed prior to commencement of the trial.

During the trial

The PIs allowed the monitors and/or the sponsor to:

-

inspect the sites, the facilities and the material used for the trial

-

meet all members of their team involved in the trial

-

consult all of the documents relevant to the trial

-

check that the CRFs had been filled out correctly

-

directly access source documents to compare data therein with the data in the CRFs

-

verify that the trial was carried out in compliance with the protocol and local regulatory requirements

-

carry out trial monitoring at regular intervals, depending on the recruitment rate and arranged between the chief investigator and monitor.

All information dealt with during these visits was treated as strictly confidential.

Quality assurance during the trial

We employed standard strategies to ensure the quality of the data; for example, a random sample of 20% of the CRFs was checked by the trial research team against entries in the database. Recruiting sites were asked to perform a self-audit on all entries and provide a report to the Bristol trial centre (who would report to the trial sponsor). A 10% sample audit was conducted by the UHB monitoring team.

The content of the database was validated at two stages, as follows:

-

At the data-entry stage, validation rules were set to run on submission of data in order to direct researchers to fields that required completion, should any essential fields be missed, and to flag up anomalous or incomplete entries so that researchers could correct data prior to final submission of the electronic CRF.

-

Management information regarding data quality and completeness at centre, site and patient level was generated from data within the trial database and used by the trial manager to inform the implementation and monitoring of the trial.

Standard operating procedures were developed to address each aspect of quality control and the quality assurance procedures.

Data handling

The database and randomisation system were designed to protect patient information and maintain anonymity. Data were stored securely in line with the Data Protection Act 1998. 47 The chief investigator was the custodian of the data. Access to the final data set was restricted to the MIR trial team in the first instance. The team were open to requests by other investigators to access anonymised data.

Other methodological issues

Extension to the trial in 2015

We were obliged to request additional funding for the trial to meet the recruitment target set out in the trial protocol. At the end of September 2014, we had recruited and randomised 200 participants. The recruitment period as set out in the original application was to have ended on 28 February 2015. The final target was 470 participants and it was not likely that we would achieve this within the designated time frame. Recruitment rates during the study had been good and to target. However, there were delays in set-up and in obtaining the necessary permissions from regulatory bodies and finalising contracts with the supplier of the trial medication. An extension of 7 months was awarded and we recruited 480 participants in the revised timescale.

Elective unblinding after the primary outcome at 12 weeks

In the initial study design we proposed that participants would remain blind to allocation for 52 weeks. However, we were advised by the REC that this was not ethically acceptable and that we should offer elective unblinding after the 12-week primary outcome. Therefore, after the 12-week follow-up and data collection (the primary outcome), participants who wished to continue in the study had the following two options:

-

to continue with the trial medication, blind to allocation, with the understanding that they could be unblinded at any time if they wished

-

to be unblinded to their allocation, which would mean that they would no longer receive the trial medication but would remain in the study.

The randomised blinded design was, therefore, preserved intact up until the primary outcome at 12 weeks. However, after that point, participants could discover whether they had been taking placebo or the active treatment. Those who were unblinded then had the option to discontinue their treatment or to consult their GP and request treatment with mirtazapine. Therefore, in addition to the two blinded groups who continued to receive the trial medication, there were now four unblinded groups, as follows, all of whom were included in the remaining follow-ups:

-

those who had been taking placebo up to 12 weeks and who decided to request mirtazapine from their GP

-

those who had been taking placebo up to 12 weeks and who did not request mirtazapine

-

those who had been taking mirtazapine up to 12 weeks and who decided to continue with the drug, now supplied by their GP

-

those who had been taking mirtazapine up to 12 weeks and who decided not to continue with this drug.

Chapter 3 Results

Practice details

Across four centres, 106 general practices agreed to collaborate in the MIR trial; record searches were conducted and mailings sent out. A summary of the practice characteristics of the participating general practices is presented in Table 2. The median number of patients invited to participate in the study per general practice was similar in all four centres.

| Practice details | Centre | Total | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bristol | Exeter | Manchester/Keele | Hull/York | ||

| Number of practices | 33 | 22 | 31 | 20 | 106 |

| Practice size (number of patients), median (IQR) | 10,100 (8442–14,019) | 9890 (4802–13,695) | 6021 (3926–9292) | 11,862 (6056–14,800) | 9200 (5869–13,353) |

| Number of full-time GPs per practice, mean (SD) | 6 (2.2) | 6 (3.9) | 5 (3.1) | 6 (2.5) | 6 (3.0) |

| Number of patients per practice | |||||

| Invited, median (IQR) | 158 (77–215) | 150 (86–261) | 118 (73–248) | 261 (143–405) | 153 (80–262) |

| Completed screening questionnaire, median (IQR) | 22 (8–28) | 23 (14–31) | 12 (6–34) | 29 (16–42) | 21 (9–32) |

| Randomised, median (IQR) | 5 (2–9) | 4 (3–8) | 2 (1–3) | 6 (4–9) | 4 (2–7) |

| Percentage of patients completing screening questionnaire who were randomised | 26 | 24 | 13 | 20 | 21 |

Flow of participants into the trial

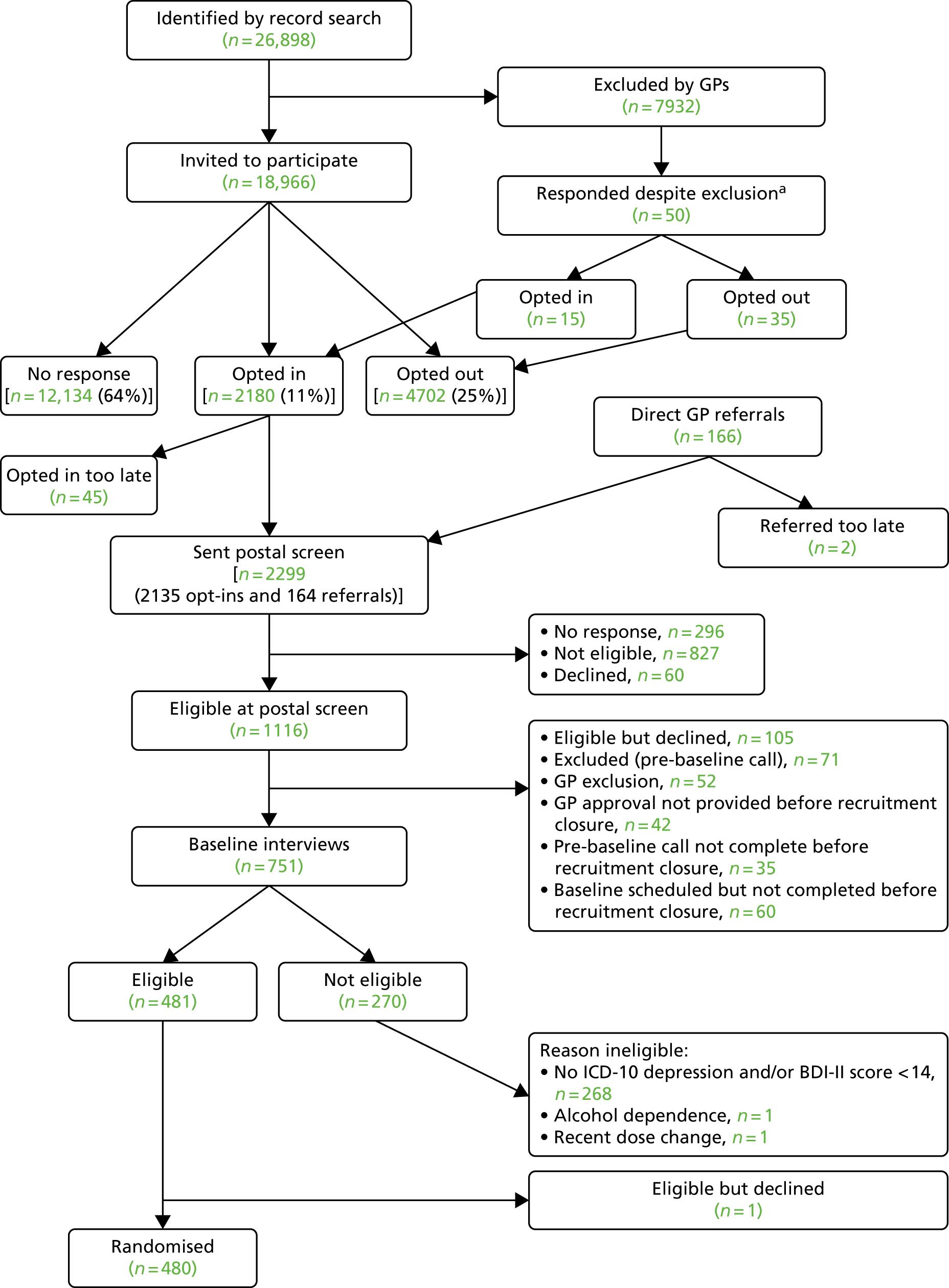

A screening process was designed first to identify those patients being treated for depression and then to assess their depressive symptoms and adherence to antidepressant medication to identify the target population who were potentially eligible to participate in the MIR trial. Potential participants were then invited to a baseline assessment with a researcher to establish their eligibility. The flow of participants through these three stages is outlined in Figure 2. The screening process commenced in August 2013 and the final patient was randomised to the trial on 6 October 2015. All follow-up data were collected between August 2015 and 31 October 2016.

FIGURE 2.

Flow of participants: recruitment pathway. a, Invited by practice despite GP exclusion. Of these, 15 patients opted in (of whom 3 were randomised). Note: Some patients may be ineligible for more than one reason.

Search of general practice computerised records to identify patients being treated for depression

There were 26,898 patients aged ≥ 18 years who were currently being prescribed antidepressants for ≥ 6 weeks at an adequate dose identified through searches of the general practice computerised records. A further 166 individuals were referred to the study directly by their GP. GPs excluded 7932 individuals who were ineligible. Fifty patients were invited as a result of an administrative error and responded, of whom 15 opted in to participate in the trial.

In total, 19,016 patients were mailed a letter of invitation to participate in the study, asking for their permission for the research team to contact them (although 50 of these were invited in error having been excluded by their GPs). GPs invited 166 patients to take part during consultation. Of these, 2180 patients (11%) responded to the letter of invitation and opted in, 4702 (25%) responded and opted out and 12,134 (64%) did not respond to the invitation (see Figure 2).

When available, information on age and sex were recorded from GP records and are summarised in Appendix 2, Tables 28 and 29.

Assessment of depressive symptoms and adherence to antidepressant medication

A screening questionnaire was mailed to 2299 potential participants, of whom 296 individuals did not complete the assessment screen and 60 declined. Of those who returned their questionnaire, 827 were not eligible; mostly this was because their BDI-II score was below the threshold of 14 points, they were not adhering to their antidepressant medication or they did not meet the criteria for an adequate dose/duration of treatment. Other reasons for ineligibility at this stage were pregnancy, breastfeeding, treatment with mirtazapine or amitriptyline and being part of another Clinical Trial of an Investigational Medicinal Product (CTIMP). In total, 1116 patients were eligible at the postal screen stage. However, 105 decided not to participate, 71 were excluded at the pre-baseline check and 52 were excluded by their GP as not suitable. A total of 137 were excluded because their checks were not completed before the closure of recruitment.

When available, information on age and sex were recorded from GP records and are summarised in Appendix 2, Table 30.

Baseline assessment of eligibility to participate in the randomised controlled trial

A total of 751 potential participants attended a face-to-face baseline appointment with a researcher to establish their eligibility to participate in the MIR trial and obtain written informed consent. In total, 270 individuals were ineligible to participate. The majority (n = 268) were ineligible because they did not meet the ICD-10 criteria for depression or failed to meet the BDI-II threshold. In total, 480 individuals were eligible to participate, gave written informed consent and were randomised.

The available information on age, sex and socioeconomic status for those who did and did not attend a baseline assessment is summarised in Table 3.

| Sociodemographic characteristics | Attendance | |

|---|---|---|

| Did not attend (N = 365) | Attended (N = 751) | |

| Age (years) | ||

| Number with available data | 365 | 751 |

| Mean (SD) | 50.22 (14.6) | 51.20 (13.4) |

| Sex | ||

| Number with available data | 365 | 751 |

| Female, n (%) | 260 (71.2) | 513 (68.3) |

| Employment status | ||

| Number with available data | 363 | 746 |

| In paid employment, n (%) | 198 (54.6) | 390 (52.3) |

| Not in employment, n (%) | 165 (45.5) | 356 (47.7) |

| Educational attainment | ||

| Number with available data | 363 | 750 |

| A level, Higher or above, n (%) | 146 (40.2) | 360 (48.0) |

| GCSE, Standard Grade or above, n (%) | 129 (35.5) | 247 (32.9) |

| No formal qualifications, n (%) | 88 (24.2) | 143 (19.1) |

| Housing | ||

| Number with available data | 364 | 750 |

| Home owner, n (%) | 208 (57.1) | 432 (57.6) |

| Tenant or living with relative/friend, n (%) | 150 (41.2) | 314 (41.9) |

| Hostel/care home, homeless or other, n (%) | 6 (1.7) | 4 (0.5) |

Summary of recruitment by centre

There were 480 participants recruited to the study from the four study centres. Bristol recruited the most participants (n = 177), Exeter recruited 122 participants, Hull/York recruited 99 participants and Manchester/Keele recruited 82 participants. A summary of recruitment by centre is presented in Appendix 2, Table 31.

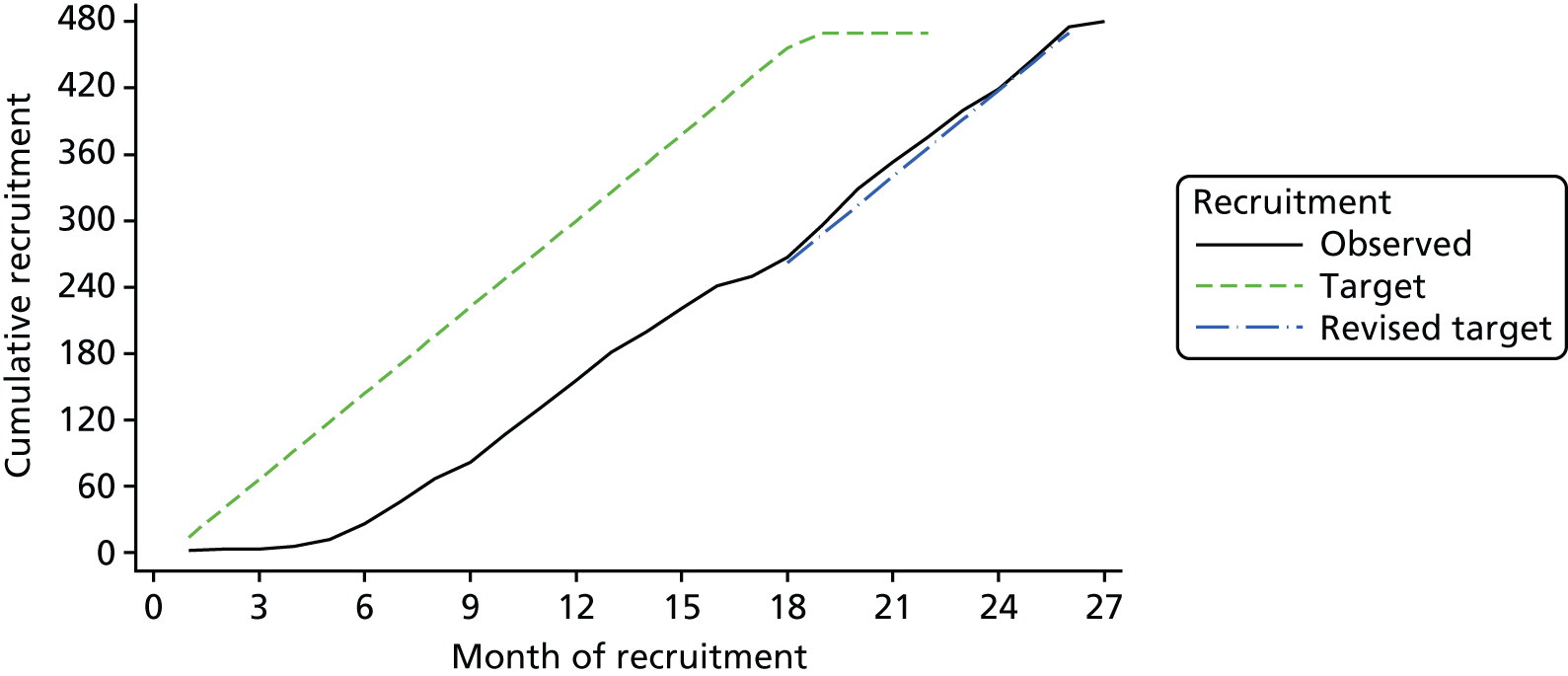

A summary of the overall predicted and actual recruitment is provided in Figure 3. Owing to delays in start-up, a 7-month extension was needed to meet the final target.

FIGURE 3.

Predicted and actual recruitment.

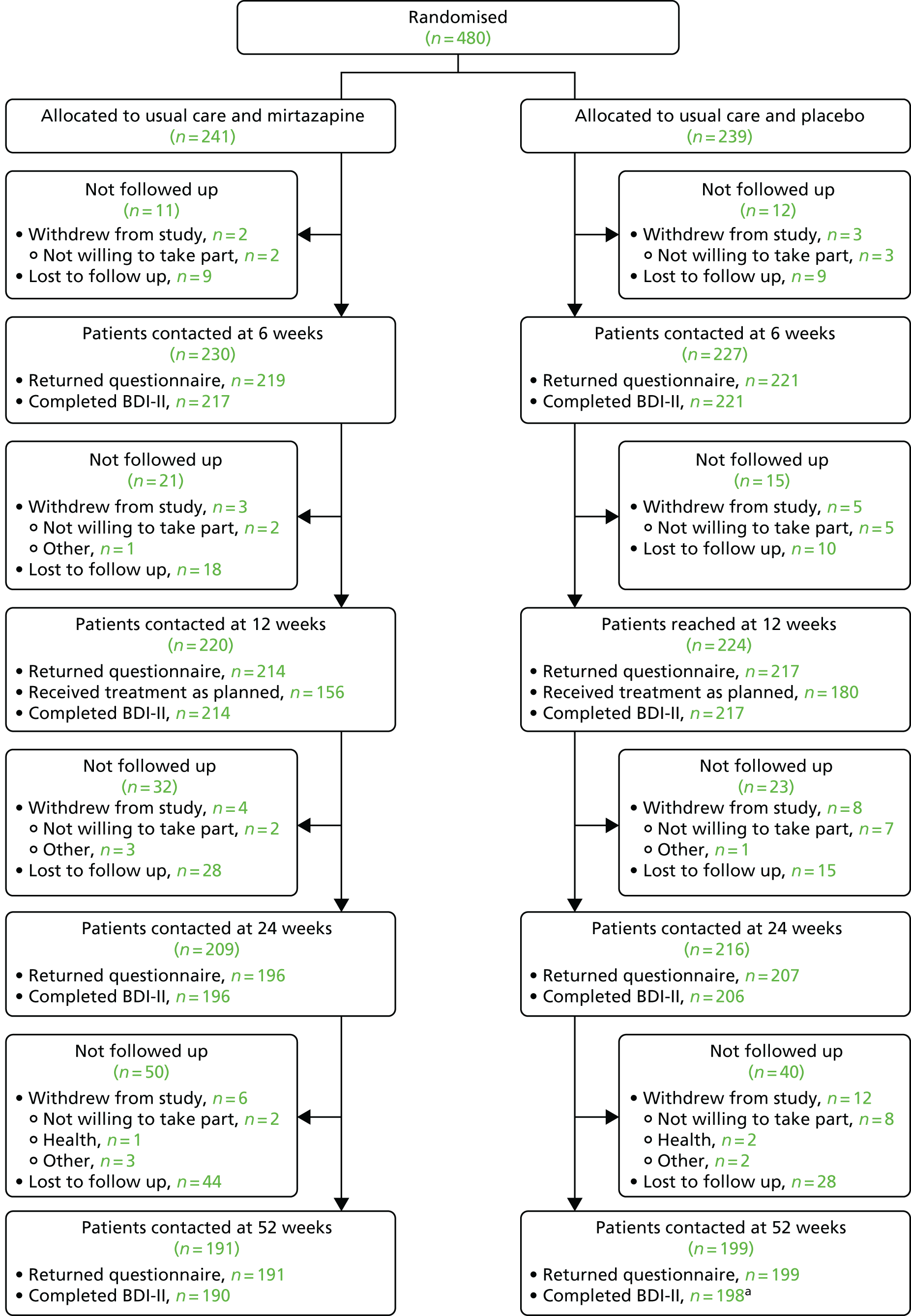

Follow-up of participants in the trial

Of the 480 participants randomised, 241 were allocated to receive usual care and mirtazapine and the remaining 239 were allocated to receive usual care and placebo. The CONSORT flow diagram for the MIR trial is presented in Figure 4. The number of participants who withdrew from the study – as well as a breakdown of the reasons for withdrawal – is presented alongside the number who were lost to follow-up at each follow-up time point.

FIGURE 4.

Flow of participants from randomisation onwards. a, One participant allocated to usual care and placebo withdrew after 12 months of follow-up.

There were six withdrawals among the participants allocated to receive usual care and mirtazapine and 12 withdrawals among those allocated to receive usual care and placebo (including one participant who withdrew after 12 months of follow-up). Withdrawals tended to occur later in follow-up and the most common reason for withdrawal in both groups was a lack of willingness to take part. The timings and reasons for withdrawals are described in Figure 4 and in Appendix 2, Tables 32 and 33.

There were 19 protocol deviations affecting 20 participants (10 among those allocated to usual care and mirtazapine and 10 among those allocated to usual care and placebo). These included one instance when a participant was given the medication of another participant (both participants were allocated to the placebo arm) and one instance when one participant allocated to the placebo arm received another participant’s mirtazapine prescription and vice versa. The most common protocol deviation was participants having difficulty receiving the medication (10 participants). In one case, this led to an emergency unblinding and, in another, the GP prescribed mirtazapine. All protocol deviations are summarised in Appendix 2, Tables 34 and 35.

Baseline characteristics of randomised participants

Table 4 provides a summary of the descriptive statistics used to assess the baseline comparability of the randomised groups. Data were collected at baseline on sociodemographic characteristics, caring responsibilities, treatment preference, severity of depression and measures of depression. A number of baseline imbalances were observed, suggesting that participants in the mirtazapine group had more severe depression. Participants randomised to this group were more likely to have had a prior history of depression and their last course of antidepressants was more recent. A higher proportion of participants in the mirtazapine group than the placebo group had suicidal thoughts at baseline.

| Variable | Allocated groups | |

|---|---|---|

| Mirtazapine + usual care (N = 241), n (%) | Placebo + usual care (N = 239), n (%) | |

| Stratification variable | ||

| Centre | ||

| Bristol | 89 (36.9) | 88 (36.8) |

| Exeter | 61 (25.3) | 61 (25.5) |

| Manchester/Keele | 41 (17.0) | 41 (17.2) |

| Hull/York | 50 (20.7) | 49 (20.5) |

| Minimisation variables | ||

| Female | 168 (69.7) | 164 (68.6) |

| Baseline BDI-II score, points | ||

| 14–25 | 77 (32.0) | 79 (33.1) |

| 26–34 | 78 (32.4) | 78 (32.6) |

| ≥ 35 | 86 (35.7) | 82 (34.3) |

| Currently receiving psychological services | 33 (13.7) | 29 (12.1) |

| Sociodemographic variables | ||

| Age (years), mean (SD) | 50.4 (13.8) | 49.9 (12.5) |

| Ethnic group | ||

| White | 233 (96.7) | 235 (98.3) |

| Mixed | 6 (2.5) | 2 (0.8) |

| Asian/British Asian | 1 (0.4) | 1 (0.4) |

| Other | 1 (0.4) | 1 (0.4) |

| Marital status | ||

| Married/cohabiting | 142 (58.9) | 135 (56.5) |

| Single | 47 (19.5) | 53 (22.2) |

| Separated | 9 (3.7) | 9 (3.8) |

| Divorced | 32 (13.3) | 27 (11.3) |

| Widowed | 11 (4.6) | 15 (6.3) |

| Employment status | ||

| Employed | 109 (45.2) | 135 (56.5) |

| Unemployed | 132 (54.8) | 104 (43.5) |

| Educational attainment | ||

| Degree or equivalent | 44 (18.3) | 51 (21.3) |

| HNC, HND, SVQ (Level 4 or 5) or RSA Higher Diploma | 17 (7.1) | 28 (11.7) |

| A level, Higher or equivalent [GNVQ/NVQ Advanced, GSVQ/SVQ (Level 3) or RSA Advanced Diploma] | 54 (22.4) | 36 (15.1) |

| GSCE, Standard Grade, O level or equivalent | 72 (29.9) | 78 (32.6) |

| No formal qualification | 54 (22.4) | 46 (19.2) |

| Housing | ||

| Home owner | 129 (53.5) | 134 (56.1) |

| Tenant | 96 (39.8) | 88 (36.8) |

| Living with relative or friend | 16 (6.6) | 16 (6.7) |

| Other | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.4) |

| Financial well-being | ||

| Comfortable/OK | 111 (46.1) | 113 (47.3) |

| Just about getting by or worse | 130 (53.9) | 126 (52.7) |

| Alcohol consumption (units), median (IQR) | 2.0 (1.0–4.0) | 2.0 (1.0–4.0) |

| Number of life events in the past 6 months, mean (SD) | 1.0 (1.0) | 1.1 (1.0) |

| Social support score, mean (SD) | 12.2 (4.1) | 12.8 (4.0) |

| Caring responsibilities | ||

| Providing care for someone who is disabled | 30 (12.4) | 37 (15.5) |

| How many children aged < 5 years live with you? | ||

| None | 213 (88.4) | 219 (91.6) |

| 1 or 2 | 27 (11.2) | 18 (7.5) |

| ≥ 3 | 1 (0.4) | 2 (0.8) |

| Treatment preference | ||

| Do you have a preference for either group? | ||

| Prefer to receive mirtazapine | 143 (59.3) | 146 (61.1) |

| Prefer to receive placebo | 2 (0.8) | 0 (0.0) |

| Do not mind either way | 96 (39.8) | 93 (38.9) |

| If you were to be allocated to the other group, how disappointed would you be?a | ||

| Very | 16 (11.0) | 25 (17.1) |

| Moderately | 54 (37.2) | 39 (26.7) |

| A little bit | 45 (31.0) | 44 (30.1) |

| Not really | 30 (20.7) | 38 (26.0) |

| Measures of depression | ||

| Suffered from depression in the past | 206 (85.5) | 190 (79.5) |

| Previous referral to a psychiatrist for depressionb | 71 (34.5) | 60 (31.6) |

| Number of prior episodes of depressionc | ||

| None | 3 (1.5) | 5 (2.6) |

| 1 | 14 (6.8) | 8 (4.2) |

| 2–4 | 82 (39.8) | 79 (41.6) |

| ≥ 5 | 107 (51.9) | 98 (51.6) |

| Duration of current course of antidepressants | ||

| < 6 months | 26 (10.8) | 20 (8.4) |

| ≥ 6 months | 215 (89.2) | 219 (91.6) |

| ICD-10 primary diagnosis | ||

| Mild | 38 (15.8) | 44 (18.4) |

| Moderate | 138 (57.3) | 144 (60.3) |

| Severe | 65 (27.0) | 51 (21.3) |

| Secondary psychiatric diagnosis according to the CIS-R | ||

| No diagnosis identified | 2 (0.8) | 5 (2.1) |

| Mixed anxiety and depressive disorder (mild) | 26 (10.8) | 31 (13.0) |

| Generalised anxiety disorder (mild) | 2 (0.8) | 3 (1.3) |

| Mixed anxiety and depressive disorder | 62 (25.7) | 52 (21.8) |

| Specific (isolated) phobia | 13 (5.4) | 12 (5.0) |

| Social phobia | 7 (2.9) | 15 (6.3) |

| Agoraphobia | 12 (5.0) | 9 (3.8) |

| Generalised anxiety disorder | 87 (36.1) | 97 (40.6) |

| Panic disorder | 30 (12.4) | 15 (6.3) |

| BDI-II score (points), mean (SD) | 31.5 (10.2) | 30.6 (9.6) |

| GAD-7 score (points), mean (SD)d | 11.3 (4.8) | 10.7 (4.8) |

| PHQ-9 score (points), mean (SD) | 16.7 (5.5) | 16.0 (5.5) |

| EQ-5D-5L score (points), mean (SD)e | 0.7 (0.3) | 0.7 (0.2) |

| SF-12 aggregate physical functioning score (points), mean (SD) | 45.7 (13.8) | 46.4 (13.1) |

| SF-12 aggregate mental functioning score (points), mean (SD) | 27.9 (9.6) | 29.2 (9.7) |

| CIS-R score, mean (SD) | 28.3 (8.2) | 27.0 (8.3) |

| Suicidal ideation (CIS-R thoughts/plans) | ||

| No suicidal thoughts | 81 (33.6) | 119 (49.8) |

| Patient feels life is not worth living | 59 (24.5) | 44 (18.4) |

| Suicidal thoughts | 101 (41.9) | 76 (31.8) |

All patients were taking a SSRI or SNRI at baseline; the most commonly prescribed treatments were citalopram (41.7%) and fluoxetine (24.6%) at doses of 20–60 mg (see Appendix 2, Table 36). There was little difference between the two groups in this respect: 40.7% of participants allocated to usual care and mirtazapine and 42.7% of participants allocated to usual care and placebo received citalopram at baseline, and 23.2% and 24.6%, respectively, were taking fluoxetine. In the mirtazapine group, 10.4% were taking a SNRI and in the placebo group 9.6% were taking a SNRI.

Losses to follow-up

Follow-up rates were slightly higher in the group allocated to usual treatment and placebo and the difference increased after 12 weeks (see Figure 4). At 12 weeks, 88.8% of participants allocated to usual care and mirtazapine and 90.8% of participants allocated to usual care and placebo were contacted for follow-up. By 24 weeks, 81.3% of participants allocated to usual care and mirtazapine were contacted compared with 86.6% of participants allocated to usual care and placebo. At 52 weeks, these proportions were 79.3% and 83.3%, respectively.

Missing data

The pattern of missing data was explored by identifying variables recorded at baseline that were associated with ‘missingness’ of the primary outcome at 12 weeks’ follow-up. Table 5 presents the frequency and proportion of missing data by baseline characteristic.

| Variable | Data, n (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Present (N = 431) | Missing (N = 49) | p-value | |

| Stratification variable | |||

| Centre | |||

| Bristol | 164 (38.1) | 13 (26.5) | 0.231 |

| Exeter | 110 (25.5) | 12 (24.5) | |

| Manchester/Keele | 73 (16.9) | 9 (18.4) | |

| Hull/York | 84 (19.5) | 15 (30.6) | |

| Minimisation variables | |||

| Female | 291 (67.5) | 41 (83.7) | 0.02 |

| Baseline BDI-II score (points) | |||

| 14–25 | 147 (34.1) | 9 (18.4) | 0.083 |

| 26–34 | 137 (31.8) | 19 (38.8) | |

| ≥ 35 | 147 (34.1) | 21 (42.9) | |

| Currently receiving psychological services | 54 (12.5) | 8 (16.3) | 0.453 |

| Sociodemographic variables | |||

| Age (years), mean (SD) | 50.7 (13.0) | 45.4 (13.8) | 0.008 |

| Ethnic group | |||

| White | 419 (97.2) | 49 (100.0) | 0.706 |

| Mixed | 8 (1.9) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Asian/British Asian | 2 (0.5) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Other | 2 (0.5) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Marital status | |||

| Married/cohabiting | 252 (58.5) | 25 (51.0) | 0.333 |

| Single | 89 (20.6) | 11 (22.4) | |

| Separated | 16 (3.7) | 2 (4.1) | |

| Divorced | 49 (11.4) | 10 (20.4) | |

| Widowed | 25 (5.8) | 1 (2.0) | |

| Employment status | |||

| Employed | 217 (50.3) | 27 (55.1) | 0.528 |

| Unemployed | 214 (49.7) | 22 (44.9) | |

| Educational attainment | |||

| Degree or equivalent | 87 (20.2) | 8 (16.3) | 0.429 |

| HNC, HND, SVQ (Level 4 or 5) or RSA Higher Diploma | 38 (8.8) | 7 (14.3) | |

| A level, Higher or equivalent [GNVQ/NVQ Advanced, GSVQ/SVQ (Level 3) or RSA Advanced Diploma] | 79 (18.3) | 11 (22.4) | |

| GSCE, Standard Grade, O level or equivalent | 139 (32.3) | 11 (22.4) | |

| No formal qualification | 88 (20.4) | 12 (24.5) | |

| Housing | |||

| Home owner | 242 (56.1) | 21 (42.9) | 0.160 |

| Tenant | 158 (36.7) | 26 (53.1) | |

| Living with relative or friend | 30 (7.0) | 2 (4.1) | |

| Other | 1 (0.2) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Financial well-being | |||

| Comfortable/OK | 208 (48.3) | 16 (32.7) | 0.038 |

| Just about getting by or worse | 223 (51.7) | 33 (67.3) | |

| Alcohol consumption, median (IQR) | 2.0 (1.0–4.0) | 2.0 (1.0–4.0) | 0.934 |

| Number of life events in the past 6 months, mean (SD) | 1.0 (1.0) | 1.3 (1.3) | 0.125 |

| Social support score, mean (SD) | 12.5 (4.1) | 12.7 (4.4) | 0.596 |

| Providing care for someone who is disabled | 60 (13.9) | 7 (14.3) | 0.944 |

| How many children aged < 5 years live with you? | |||

| None | 388 (90.0) | 44 (89.8) | 0.826 |

| 1 or 2 | 40 (9.3) | 5 (10.2) | |

| ≥ 3 | 3 (0.7) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Treatment preference | |||

| Do you have a preference for either group? | |||

| Prefer to receive mirtazapine | 255 (59.2) | 34 (69.4) | 0.358 |

| Prefer to receive placebo | 2 (0.5) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Do not mind either way | 174 (40.4) | 15 (30.6) | |

| If you were to be allocated to the other group, how disappointed would you be? | |||

| Very | 36 (14.0) | 5 (14.7) | 0.743 |

| Moderately | 82 (31.9) | 11 (32.4) | |

| A little bit | 81 (31.5) | 8 (23.5) | |

| Not really | 58 (22.6) | 10 (29.4) | |

| Measures of depression | |||

| Suffered from depression in the past | 351 (81.4) | 45 (91.8) | 0.069 |

| Family history of depression | 227 (64.7) | 36 (80.0) | 0.04 |