Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 12/28/05. The contractual start date was in October 2013. The draft report began editorial review in October 2017 and was accepted for publication in February 2018. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Richard IG Holt received fees for lecturing, consultancy work and attendance at conferences from the following companies: Boehringer Ingelheim (Ingelheim am Rhein, Germany), Eli Lilly and Company (Indianapolis, IN, USA), Janssen Pharmaceutica (Beerse, Belgium), Lundbeck (Copenhagen, Denmark), Novo Nordisk (Bagsværd, Denmark), Novartis (Basel, Switzerland), Otsuka Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd (Tokyo, Japan), Sanofi-Aventis (Paris, France) and Sunovion Pharmaceuticals, Inc. (Marlborough, MA, USA). Paul French is a member of the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Health Technology Assessment Mental, Psychological and Occupational Health funding panel. Melanie J Davies and Kamlesh Khunti are members of a NIHR Clinical Trials Unit. Melanie J Davies reports personal fees from Novo Nordisk, Sanofi-Aventis, Eli Lilly and Company, Merck Sharp & Dohme (Kenilworth, NJ, USA), Boehringer Ingelheim, AstraZeneca (Cambridge, UK), Janssen Pharmaceutica, Servier Laboratories (Neuilly-sur-Seine, France), Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma Corporation (Tokyo, Japan) and Takeda Pharmaceuticals International Inc. (Canton of Zürich, Switzerland) and grants from Novo Nordisk, Sanofi-Aventis, Eli Lilly and Company, Boehringer Ingelheim and Janssen Pharmaceutica. Kamlesh Khunti has received fees for consultancy and being a speaker for Novartis, Novo Nordisk, Sanofi-Aventis, Eli Lilly and Company, Servier Laboratories and Merck Sharp & Dohme. He has received grants in support of investigator and investigator-initiated trials from Novartis, Novo Nordisk, Sanofi-Aventis, Eli Lilly and Company, Pfizer (New York, NY, USA), Boehringer Ingelheim and Merck Sharp & Dohme. Kamlesh Khunti has also received funds for research and honoraria for speaking at meetings, and has served on advisory boards for Eli Lilly and Company, Sanofi-Aventis, Merck Sharp & Dohme and Novo Nordisk. David Shiers is an expert advisor to the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) centre for guidelines, a board member of the National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health (NCCMH) and a clinical advisor (on a paid consultancy basis) to the National Clinical Audit of Psychosis (NCAP); any views given in this report are personal and not those of NICE, NCCMH or NCAP. David Shiers reports personal fees from the Wiley-Blackwell publication Promoting Recovery in Early Psychosis, 2010 (ISBN 978-1-4051-4894-8), as he is a joint editor in receipt of royalties. John Pendelbury received personal fees for involvement in the study from a NIHR grant; he reports personal fees from the Greater Manchester Mental Health NHS foundation trust outside the submitted work and has published papers in the area of weight management and physical health related to mental health. Marian E Carey and Yvonne Doherty report being employed by the Leicester Diabetes Centre, an organisation (employer) jointly hosted by a NHS hospital trust and the University of Leicester and which is the holder (through the University of Leicester) of the copyright of the STEPWISE programme and of the Diabetes Education and Self-Management for Ongoing and Newly Diagnosed (DESMOND) suite of programmes, training and intervention fidelity framework that were used in this study. Fiona Gaughran reports personal fees from Otsuka and Lundbeck and personal fees and non-financial support from Sunovion, outside the submitted work, and has a family member with professional links to Eli Lilly and Company and GlaxoSmithKline (Brentford, UK), including shares.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2018. This work was produced by Holt et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2018 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Introduction

Obesity and weight gain in people with schizophrenia

Schizophrenia, a psychotic illness, affects ≈1% of the population. Mortality rates in people with schizophrenia are increased twofold to fourfold, with life expectancy reduced by 10–20 years. 1–3 Around 75% of people with schizophrenia die from physical illness, most commonly cardiovascular disease. Weight gain is a key contributor to excess morbidity and mortality, with obesity being two or three times more prevalent in people with schizophrenia than in the general population. 4 The rates of obesity have increased substantially and have risen faster than in the general population over the past three decades. 5

The cause of the increase in obesity is multifactorial and includes environmental factors (such as poverty, urbanisation, poor diet6,7 and physical inactivity), disease effects (such as altered neuroendocrine functioning, altered reward perception) and treatment effects; antipsychotics cause weight gain in 15–72% of patients. 8 Weight gain is observed early in treatment; between 37% and 86% of people with a first episode of psychosis gain > 7% of their body weight over 12 months. 9 Much of this weight gain occurs within 12 weeks of treatment initiation10 but continues in the longer term, albeit at a slower rate. 11

Interventions to control or reduce antipsychotic-related weight gain

The British Association of Psychopharmacology has reviewed interventions designed to promote weight loss or attenuate weight gain in people taking antipsychotics. Given the underlying mechanisms associated with weight gain, these have taken three, usually exclusive, approaches: (1) lifestyle interventions to improve diet and physical activity, (2) adjustment of antipsychotic medication to minimise the use of drugs associated with the greatest weight change and (3) the use of adjunctive medications that may attenuate the antipsychotic effect. The STructured lifestyle Education for People WIth SchizophrEnia, schizoaffective disorder and first episode psychosis programme (STEPWISE) intervention was intended to promote weight loss through lifestyle modification. However, when the intervention was designed, the developers also considered the effect of the illness and treatment and how these could interact with lifestyle modification.

Prior to the STEPWISE project, a systematic review of randomised controlled trials (RCTs) reported that non-pharmacological interventions lead to a mean 3.12-kg weight reduction over a period of 8–24 weeks in people with schizophrenia, with commensurate change in other cardiovascular risk factors. 12 Programmes offered benefits regardless of treatment duration, modality (individual vs. group setting), behaviour change versus educational content or whether they aimed to prevent weight gain or promote weight loss. Most interventions contained cognitive behavioural elements as well as diet or exercise-based content. The sample size of RCTs was generally small (median 53, range 15–110) and most participants were not followed up beyond 12 weeks. Of the few studies with long-term follow-up, not all sustained long-term weight control. 13 The systematic review team called for larger trials with long-term follow-up and a focus on weight maintenance following initial intervention.

The 2014 National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidance on psychosis and schizophrenia in adults14 expanded this review to 24 studies with similar conclusions. Several of these studies included significant numbers of individuals with other types of mental illness, for whom the strategies needed to promote weight loss may be different. Consistent with the earlier systematic review, few studies examined weight change beyond 6 months, and only six studies included > 100 participants. No study was undertaken in the UK, most were rated as being at moderate risk of bias and there was substantial heterogeneity of effect size. NICE concluded that lifestyle interventions were effective in reducing and maintaining body weight in the short term, but, without longer-term data, the effects beyond 6 months were unknown.

The most recent systematic review published in August 2017 included 17 studies and 1968 participants. 15 Sixty-six per cent of participants had schizophrenia spectrum disorders. Consistent with previous publications, the 10 studies reporting short-term interventions of < 6 months’ duration showed greater weight loss than usual care [standardised mean difference (SMD) –0.20, 95% confidence interval (CI) –0.34 to –0.05], but with significant heterogeneity in response. The six studies that reported interventions lasting longer than 1 year showed a more consistent weight reduction (SMD −0.24, 95% CI −0.36 to −0.12). However, within this group, only two of the six studies achieved a statistically significant weight loss, both of which included people with other severe mental illnesses.

Although some weight loss programmes have promoted behaviour change through intensive one-to-one counselling strategies, resource scarcity in many health services makes the sustainability of such programmes challenging. 16 An alternative is structured education, which encompasses patient-centred, group educational programmes with a clear philosophy, a written curriculum and a basis in behaviour change theory and empirical data and is delivered by trained, quality-assessed educators. 17 The NICE diabetes mellitus prevention guidance advocates structured education as a potentially cost-effective method for the promotion of self-management and behaviour change in people with chronic disease. 18

The Leicester Diabetes Centre structured education approach

The STEPWISE intervention was developed by the Leicester Diabetes Centre (LDC), using the same process used in developing the Diabetes Education and Self-Management for Ongoing and Newly Diagnosed (DESMOND) programme. 19 The DESMOND programme and other adaptations have effectively promoted lifestyle change and induced weight loss in multicentre RCTs. The curricula promote physical activity, a healthy diet and weight loss by encouraging self-regulation through self-monitoring (feedback), relapse prevention (identifying and addressing barriers to change) and goal-setting strategies. It incorporates standardised educator training and a quality assurance programme.

Rationale and objectives

Rationale

Pragmatic interventions that offer long-term weight control or reduction in people with schizophrenia or first episode psychosis are needed. The STEPWISE trial aimed to evaluate if a structured lifestyle education programme, delivered in a community mental health setting, supported weight loss at 1 year in adults with schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder or first episode psychosis.

Objectives

-

To develop a group-based, structured self-management lifestyle education programme for people with schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder and first episode psychosis.

-

To conduct a multicentre RCT to investigate if the intervention leads to a clinically important difference in weight change, as well as physical activity and diet, compared with usual care.

-

To conduct a mixed-methods process evaluation to explore intervention delivery, participant and facilitator experiences and explain discrepancies between expected and observed outcomes.

-

To conduct an economic evaluation of the intervention.

-

To assess the fidelity of intervention delivery when undertaken at 10 different sites.

Chapter 2 Intervention development

The aim of the intervention development phase was to develop a sustainable evidence-based programme to support people with schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder or first episode psychosis with their weight management in a way that is acceptable and feasible to deliver within NHS settings and available resources. The intervention was developed by a team from the LDC, together with expert colleagues, patients and public involvement.

Literature review

The meta-analysis of non-pharmacological interventions designed to address antipsychotic-associated weight gain by Caemmerer and colleagues12 was updated by re-running the search strategy across the PsycINFO, MEDLINE, PubMed, Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL) and Cochrane Library databases using the original search terms, and only one further paper was identified. 20

The literature review reported the benefits of non-pharmacological interventions, but the effectiveness did not differ between modalities or intervention duration, or between interventions that employed group-based versus individual approaches. The only difference was the benefit of outpatient over inpatient interventions. Some studies suggested that nutritional interventions were more effective than cognitive–behavioural therapy, but there was considerable overlap between interventions, making these distinctions difficult to determine. Most interventions ran as 12–24 weekly sessions, delivered either in groups or individually. Some interventions provided specific cardiovascular exercise training. Common dietary themes included:

-

reading food labels

-

switching drinks from full sugar to low calorie

-

eating healthy snacks

-

eating more slowly and deliberately

-

recognising satiety.

Several used ‘psychoeducation’, but further details were not specified, and a theoretical basis was reported in only one study that employed social cognition theory. 21

Development of a theoretical framework

As the theoretical basis of the interventions was specified in only one paper, despite this being widely considered to be good practice,22 we used the wider behaviour change and weight management literature to inform our approach. We considered three key areas that are core to weight management interventions in people with schizophrenia:

-

behaviour change theory, specifically with a focus on food and physical activity

-

the psychological processes underlying weight management

-

the challenges of living with psychosis and the impact on eating and weight.

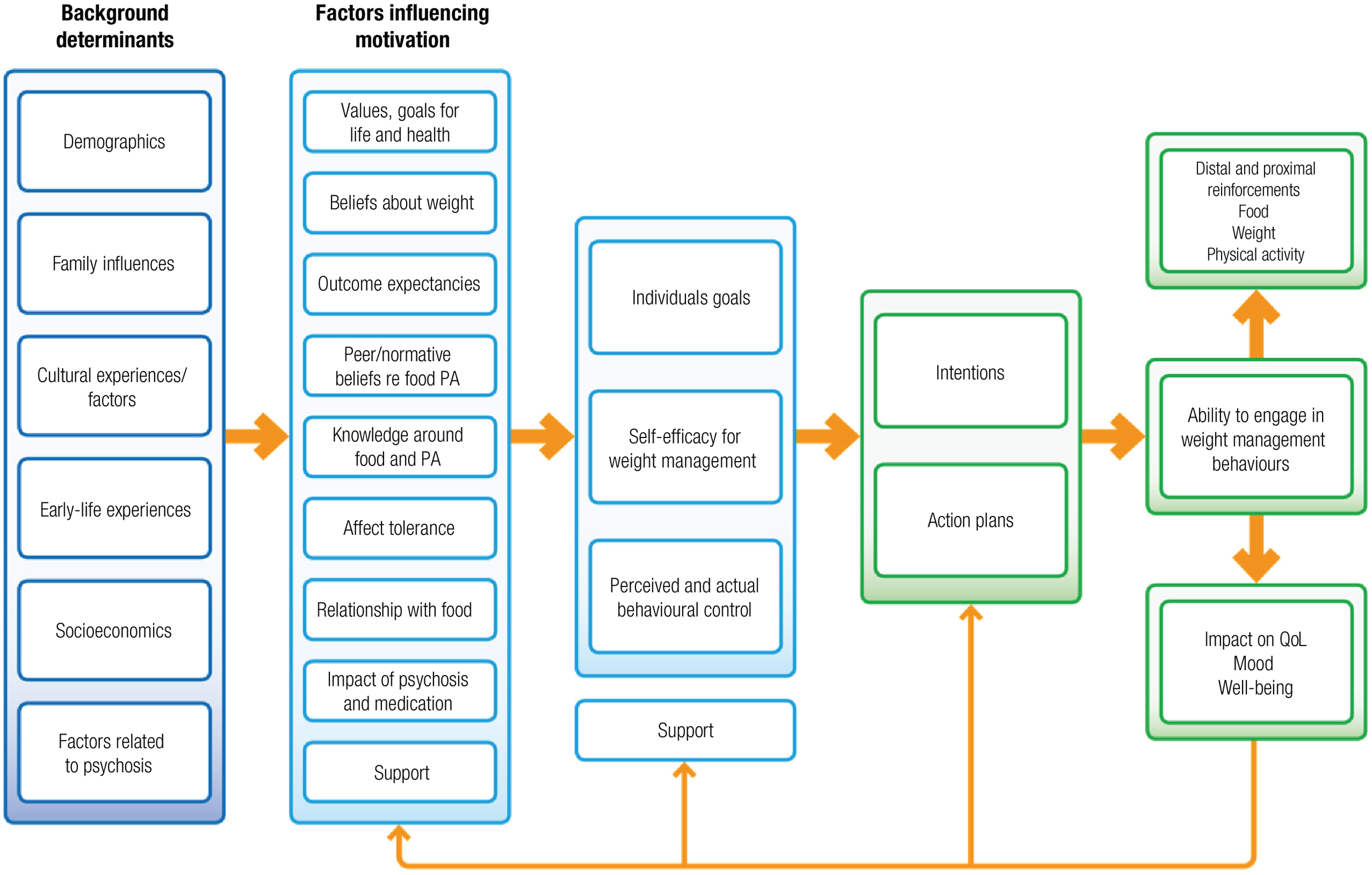

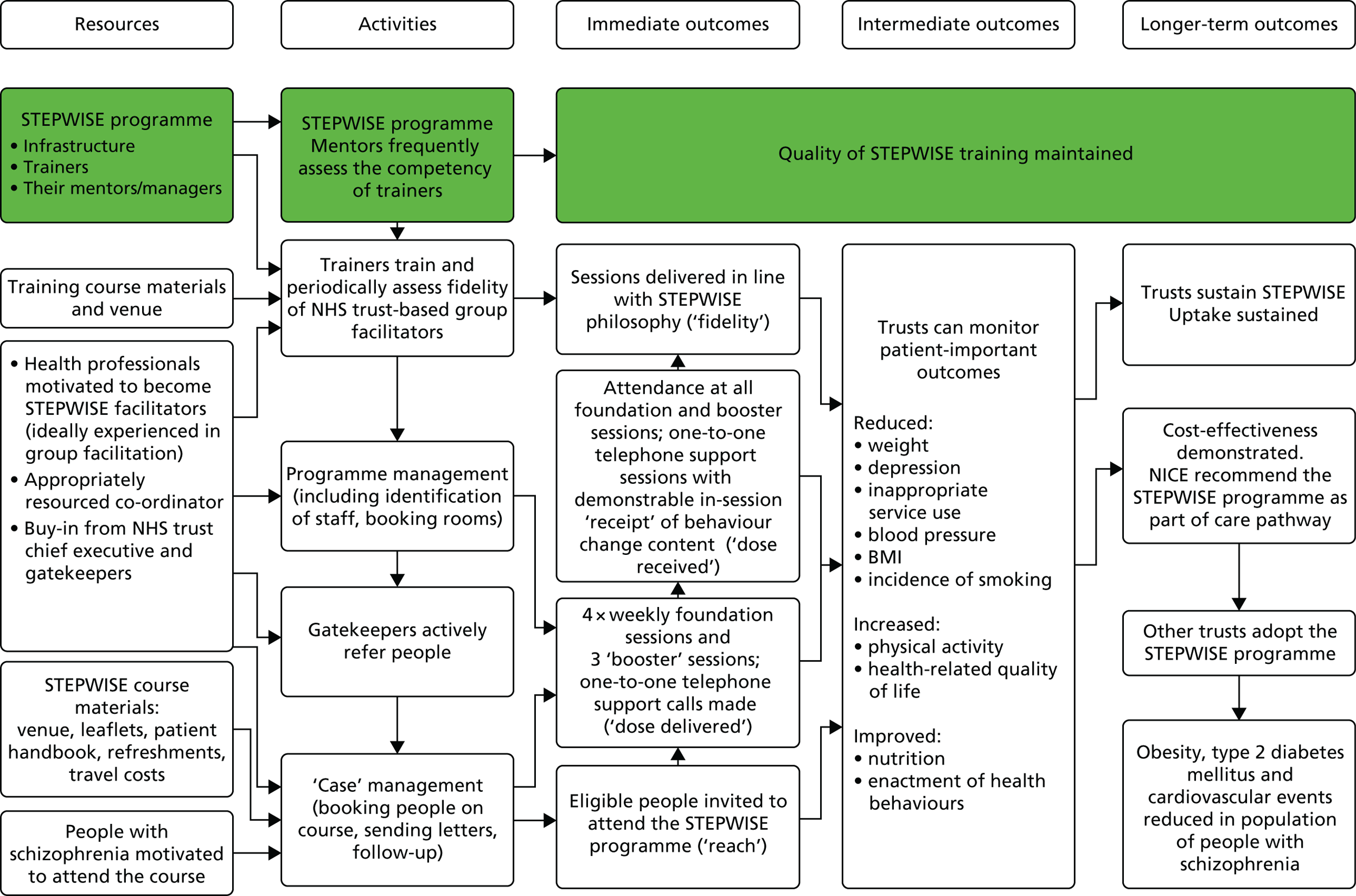

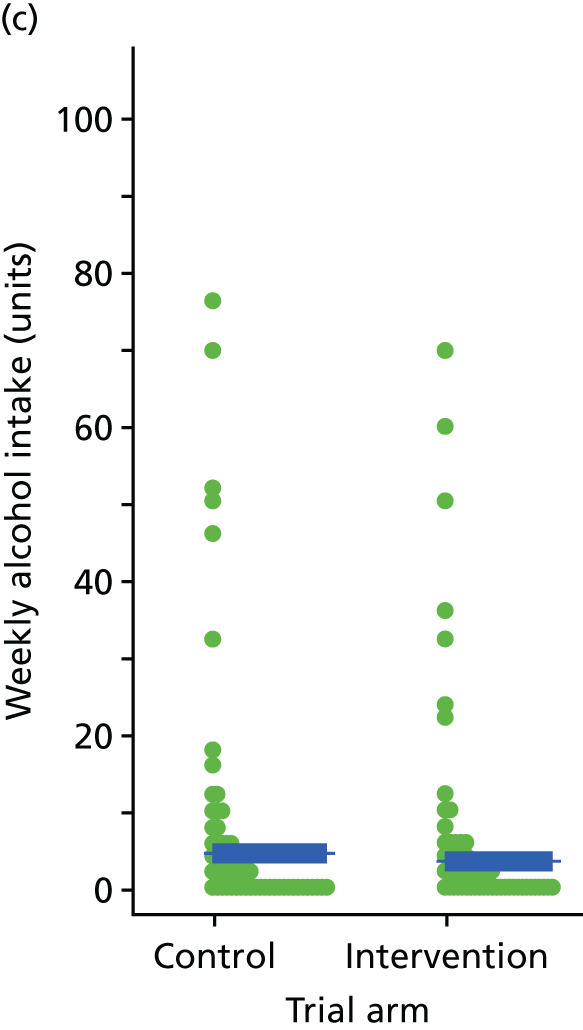

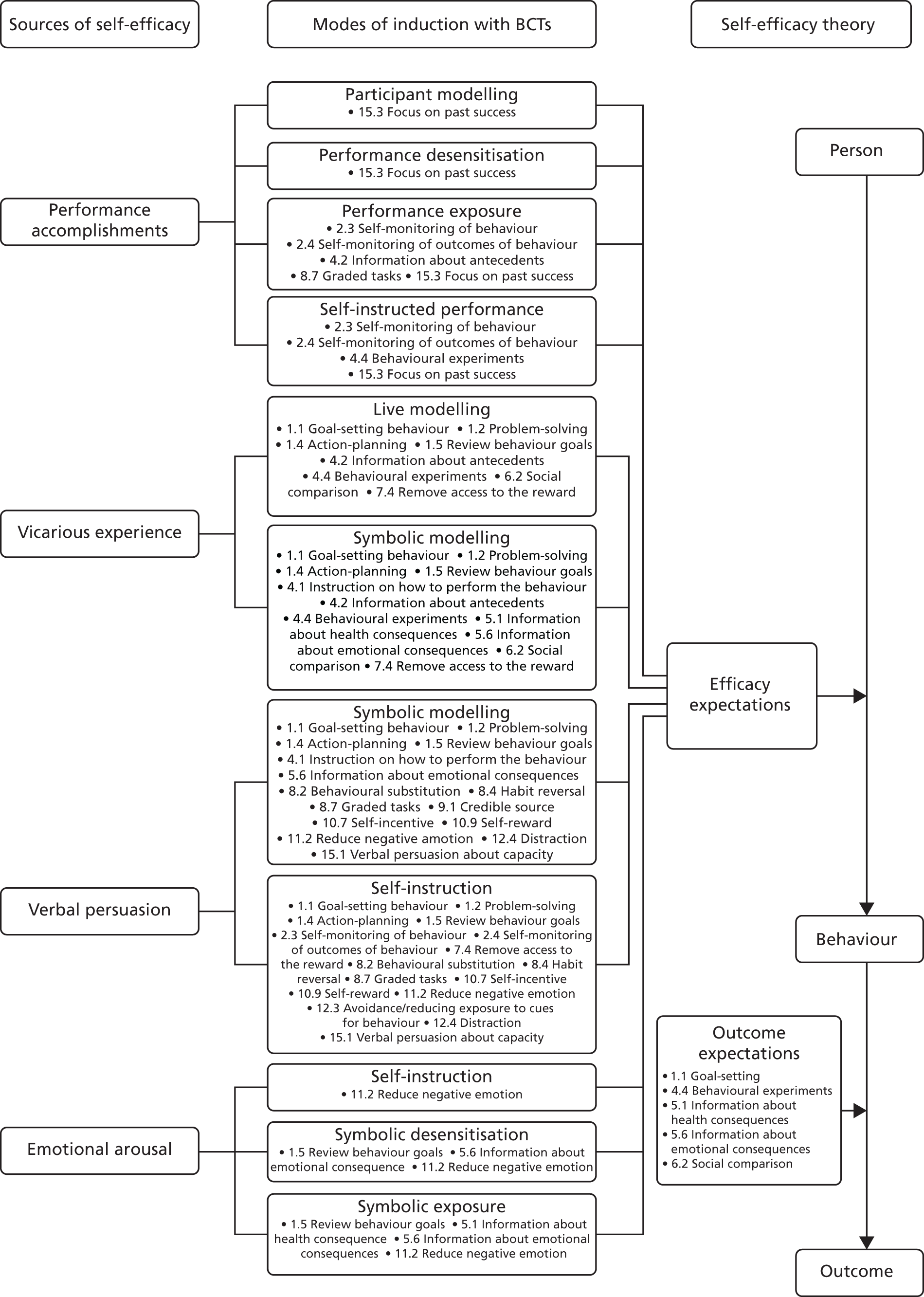

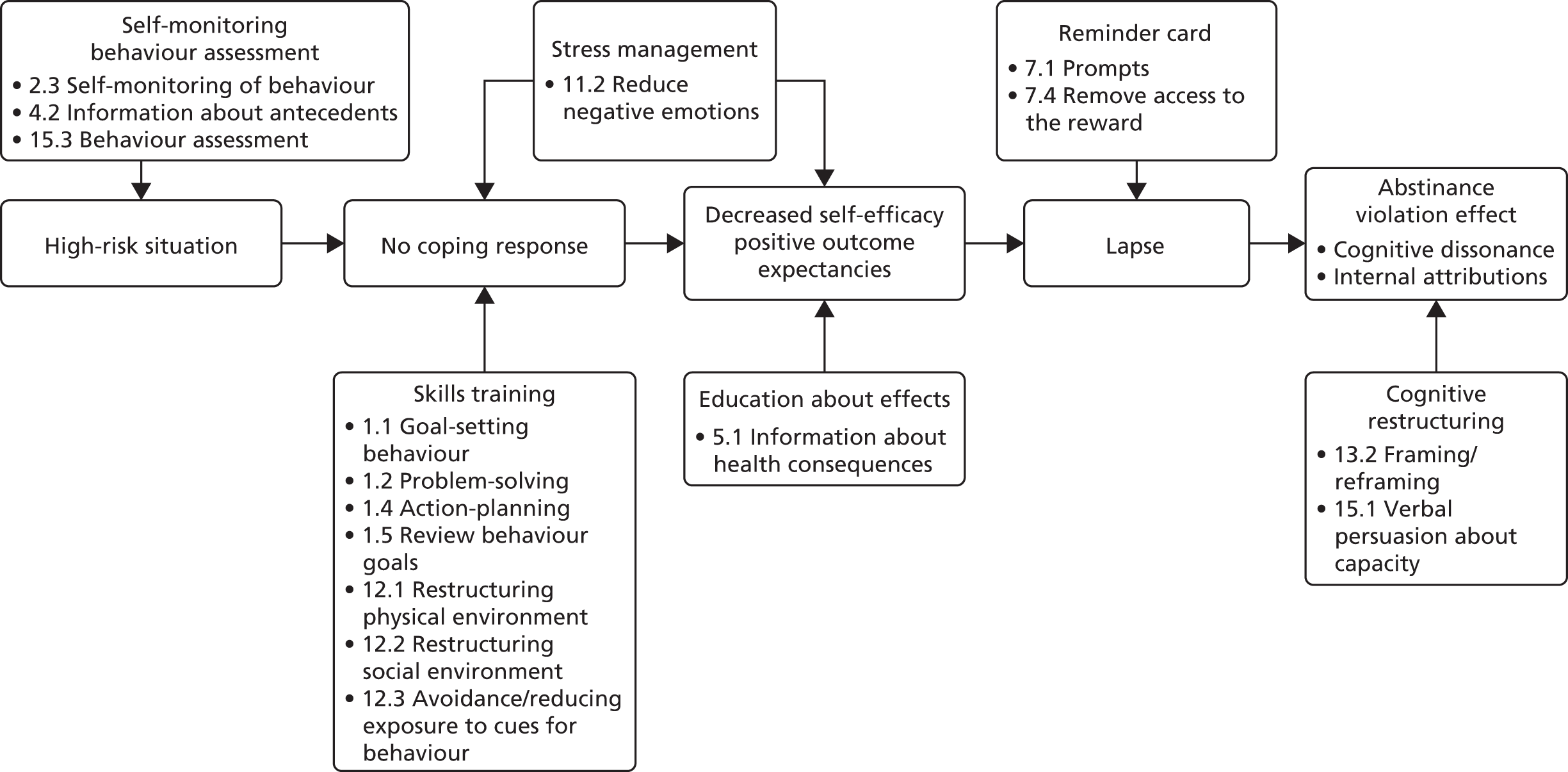

These core factors determined the draft theoretical framework that guided the overall intervention development (Figure 1). We thus ensured a focus on key hypothesised problem behaviours, were clear about the receipt of the intervention by participants24 and thus applied appropriate behaviour change techniques. 25,26 The intervention was inspired by a number of theories, but systematically employed three (Table 1), and intervention components were coded using the behaviour change taxonomy. 25

FIGURE 1.

Theoretical framework of the STEPWISE intervention. Reproduced from Holt et al. 23 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The figure includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original text.

| Identified target behaviour/problem | Theory | Participant receipt and potential behavioural outcome | Intervention on the STEPWISE course | Mapping to behavioural taxonomy |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Belief about weight problems (e.g. because of their medication, they can have no impact on their weight) | Self-regulation theory – specifically, illness representations around weight management

|

To have identified their own potential erroneous beliefs and questioned these in order to directly influence their decisions around weight management |

‘Your story’ session: elicit participants’ beliefs about what caused their weight problem, what ‘treatment’ would help to manage it, the consequences for them and their health Topic sessions: information sessions throughout the course, specifically the impact of medication on their weight and the strategies that they can employ to manage their weight |

Not completely specified, but included in:

|

| Low levels of confidence around being able to engage in successful weight management, possibly related to multiple unsuccessful attempts at sustained weight loss | Self-efficacy

|

Increased belief in their ability to engage successfully in weight management. Identified strategies to increase their self-efficacy and engage in behaviour change |

‘Sharing stories’ session: eliciting what has gone well in terms of behaviour change, problem-solving around challenges and observing and learning from others’ successes and problem-solving. Discussing feelings as activators of, and barriers to, change Next steps: action-planning, identifying barriers, problem-solving and setting small graded tasks |

|

| Maintenance of behaviour change, particularly as there are strong cues to previous behaviours and thus high likelihood of relapse | Relapse prevention model:

|

Reviewed the situations that would most likely result in relapse. Developed plans of how to manage these when they occur View relapse as a natural part of the change process and as an opportunity to learn rather than berate themselves and reinforce a potential negative self-perception |

Keeping it going: visual tools and interactive exercises to explore potential sources of relapse and develop plans to overcome this when it occurs |

|

Intervention development

Initially, we planned to adapt the STEPWISE programme from the DESMOND ‘Let’s Prevent Type 2 Diabetes programme’ intervention, which seeks to promote lifestyle changes in people who are at an increased risk of developing type 2 diabetes mellitus, and results in modest benefits in biomedical and lifestyle outcomes. Although significant weight change was not achieved, progression to diabetes mellitus in those who were at risk of developing it decreased. 27 However, it rapidly became apparent from the literature review, early meetings with stakeholders and the expert opinions of health-care professionals actively providing local weight management interventions in mental health settings that, although the underlying principles of the Let’s Prevent Type 2 Diabetes programme were relevant, the programme itself was not suitable for people with schizophrenia.

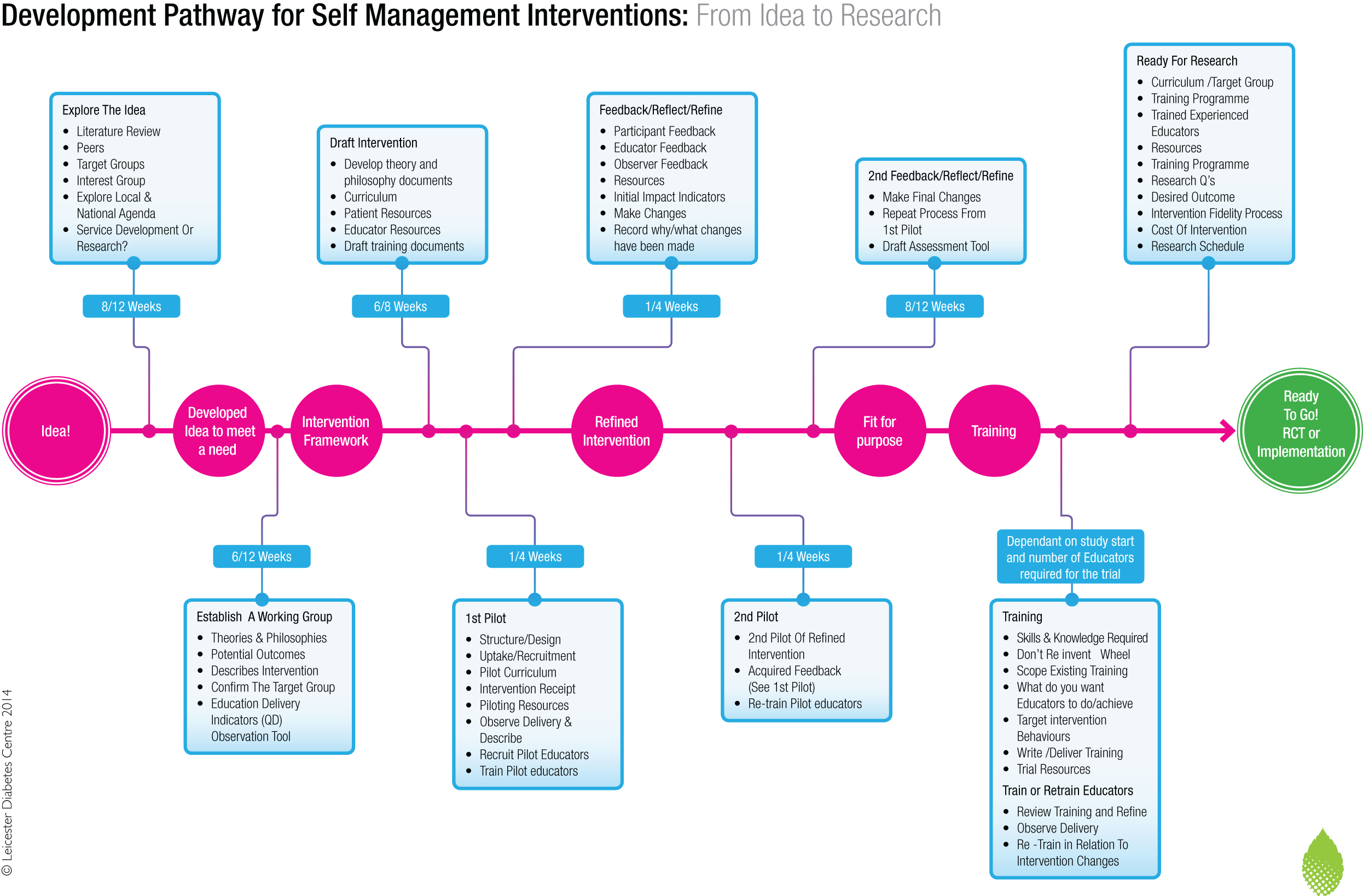

The STEPWISE intervention was therefore developed from first principles, using an established pathway and robust framework28 (Figure 2). The prototype STEPWISE intervention aimed to promote autonomous problem-solving around dietary and physical activity choices, with a specific focus on relapse prevention and weight improvement.

FIGURE 2.

The Leicester development pathway for self-management interventions. Reproduced with permission from Dr Sharon Spencer (Dr Sharon Spencer, University of Leicester, November 2017, personal communication).

The intervention development incorporated four stages, the first three of which are described in this section:

-

foundation of the programme

-

prototype

-

pilot of prototype and incorporation of amendments and adaptation

-

facilitator training.

The programme was developed collaboratively by a team with expertise in the development of obesity and lifestyle programmes, and mental health-care professionals and researchers with specialist knowledge of schizophrenia and psychosis. Following the literature review, we sought the opinion of service users in Sheffield and Leicester between January and September 2014. Three meetings were held in Leicester at a user-led mental health support group; these were attended by 11 people with schizophrenia or other mental health conditions, who provided input to discussions of the suggested prototype curriculum, resources and subsequent iterations. Topics and suggestions were drawn directly from the group, but the researchers also raised issues that they wished to explore with service users. In addition, other service users, carers and investigators provided input at monthly meetings and in one-to-one interviews. We sought advice from expert practitioners with experience of delivering lifestyle management groups for people with psychosis in Salford, UK, and Sydney, Australia. The principles of the constant comparative approach based on grounded theory were used to analyse these meetings. 29

Six themes emerged from the service users:

-

transportation to and from the venue

-

venue and time

-

level of concentration

-

sessions

-

incentives and motivation

-

accompanying persons.

These are described in Testing the pilot intervention and informed the design of the prototype intervention, its content, delivery and logistics.

Prototype

The user group specifically contributed to the intervention format and played an important role in refining the logistics, content and delivery. The Sheffield mental health team and research team also suggested further changes to the prototype curriculum and resources; for example, appropriate supporting tools (incentives) for participants were introduced and the curriculum terminology was adjusted to improve its acceptability.

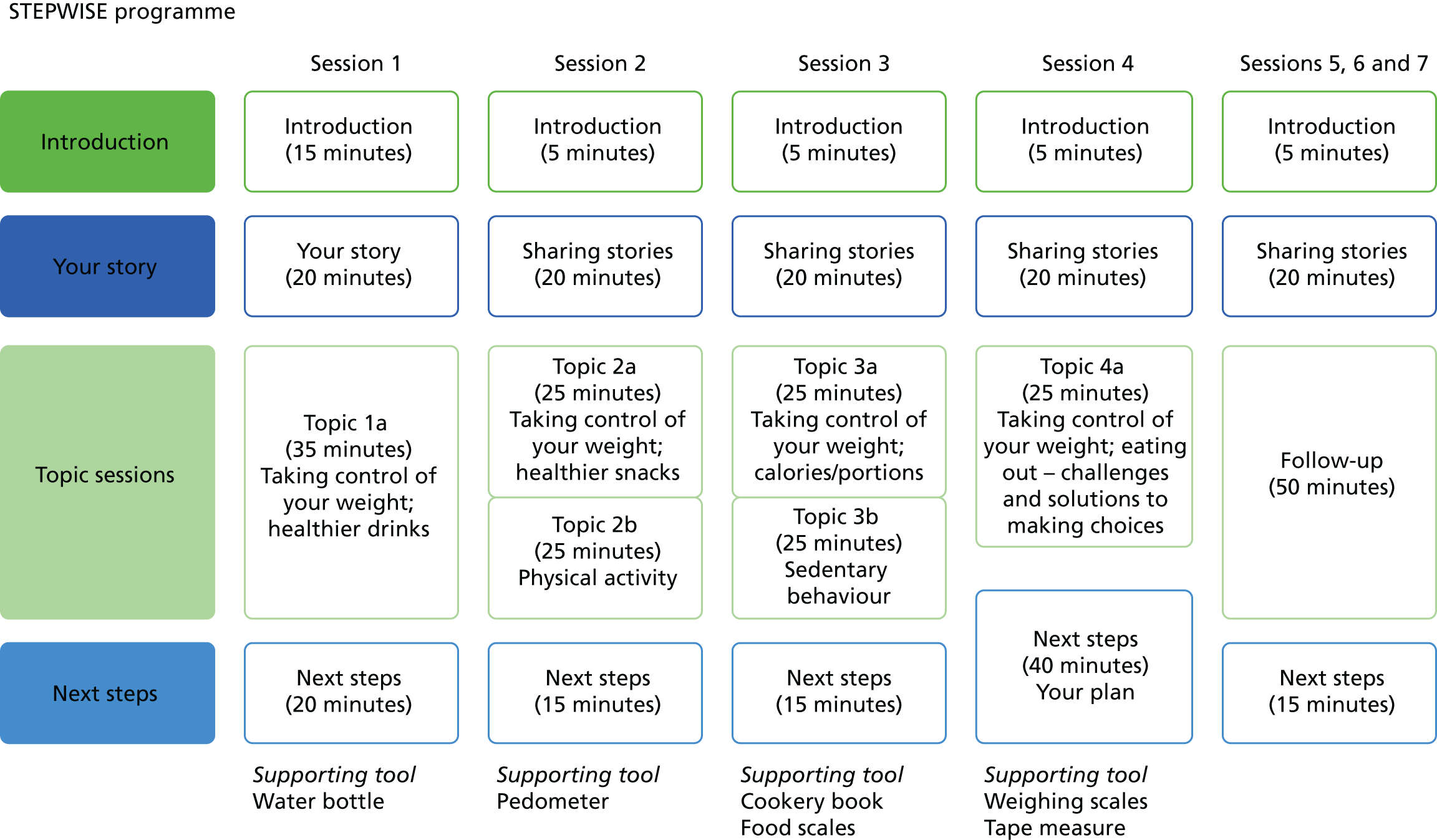

The prototype intervention comprised four 90-minute core group education sessions, delivered to small groups of six to eight participants over 4 consecutive weeks. A breakdown of each session can be found in Figure 3. The curriculum included individual personal stories, taking control of weight, healthier food and drink choices, the relationship between weight and medication, and the relationship between calories and portions and physical activity. The intervention had a written curriculum to ensure consistency and resources in line with its person-centred philosophy. Participants were not ‘taught’ in a formal way, but instead were supported to discover and work out knowledge for themselves to inform their goals and plans.

FIGURE 3.

Outline of the STEPWISE group sessions. Reproduced from Holt et al. 23 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The figure includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original text.

Although the intervention was designed to be delivered by two local trained facilitators, the prototype sessions were delivered in Sheffield by the development team and were watched by health-care professionals who had been identified as potential facilitators. Feedback from the developers and potential facilitators confirmed the appropriateness of content and resources, while challenging any assumptions made about style and content. We envisaged that at least one facilitator would be a registered mental health professional, whereas the other would have a professional background as a registered mental health professional, mental health support worker, health-care assistant or similar. Current experience of working with people with mental health issues and knowledge of antipsychotics were key facilitator attributes.

To provide ongoing support, a series of 110-minute follow-up ‘booster’ sessions were designed to occur every 3 months after the end of the core sessions. Fortnightly support telephone calls from the facilitator team were arranged and appropriate training was given to the facilitators.

Testing the pilot intervention

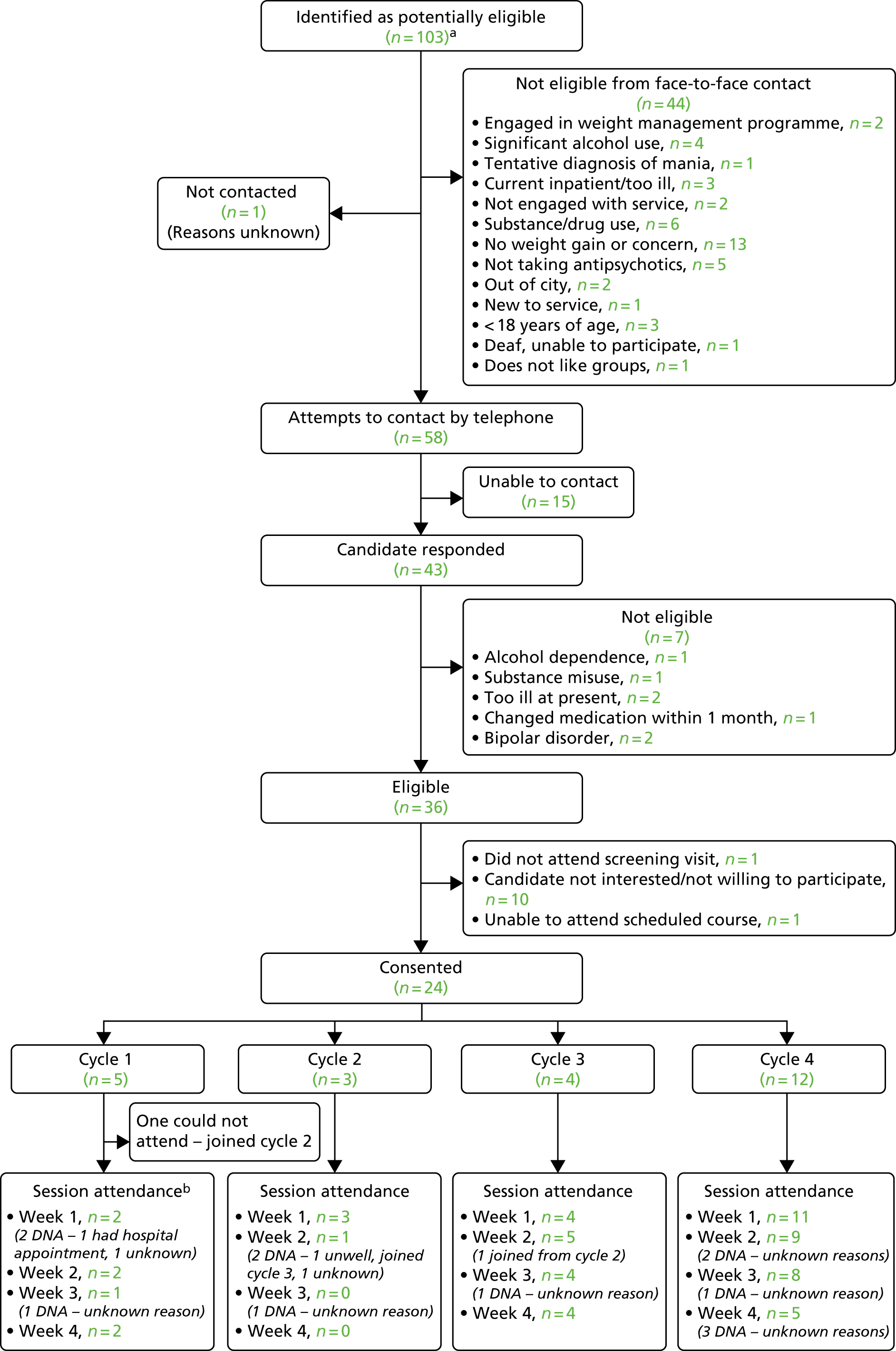

The pilot testing of the intervention was undertaken in a community setting and comprised a cycle of four cohorts between May and December 2014 (Figure 4). Biomedical and lifestyle outcomes were not collected during the pilot. The aims were to:

-

test the components of the intervention

-

assess the skills and knowledge required from facilitators and so inform the training programme content

-

understand the obstacles to, and enablers of, delivering the intervention in a real-world situation in accordance with intervention mapping, as described by Bartholomew et al. ,22 and following the Medical Research Council framework for evaluating complex interventions. 30

FIGURE 4.

Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials flow diagram for the STEPWISE Intervention Development Study. a, Sheffield Health and Social Care NHS Foundation Trust advised that approximately 100 patients (60 patients at one Community Mental Health Team, 20 at another and 20 at a third Community Mental Health Team) from care co-ordinator lists were prescreened and deemed not to meet the basic inclusion criteria. A further cohort of patients was then prescreened for cycle 4, with a further 64 identified as potentially eligible; b, two participants recruited prior to the first Intervention Development Study cycle were unable to attend but willing to take part in the second cycle; however, they did not take part in the second cycle as a result of returning to work (n = 1) and not being contactable (n = 1). DNA, did not attend.

The participants were recruited through Sheffield Health and Social Care NHS Foundation Trust Community Mental Health Teams (CMHTs). The eligibility criteria were identical to those proposed for the future RCT (see Chapter 3, Participant selection and eligibility) to ensure that the intervention would meet the needs of potential trial participants.

Participants were identified during routine clinic appointments and case note review and given brief information about the study. A total of 103 service users with schizophrenia or first episode psychosis were approached by the mental health team, of whom 44 did not meet the eligibility criteria, 16 were non-contactable and 19 declined to participate. Twenty-four people consented to participate, and 20 attended at least one session.

The participants attended one of four pilot interventions at a local venue; these comprised the four weekly core sessions, each lasting ≈2 hours, including a refreshment break. Observation notes were taken at each session to supplement feedback from participants and facilitators in order to refine the programme content, resources and delivery as necessary in an iterative process.

Recruitment and reminders for attendance

Recruitment and retention to the first two cohorts were difficult, and novel recruitment strategies, such as the offer of transport, and text and telephone-call reminders, were needed to increase attendance. This led to improved participation in the third and fourth iterations.

Logistical considerations

Participant feedback showed that they valued the intervention and discussion mostly focused on practical ways of facilitating attendance and active engagement. Organisational issues were seen as key factors (e.g. arranging taxis helped participants to arrive in a timely manner, while reducing the anxiety of using public transport). The local mental health venue was described as a convenient and familiar place to reach. The participants reported that the number of sessions was reasonable.

Many people with schizophrenia have altered sleep patterns, which make early-morning appointments difficult, and so the time of the sessions (12.30 for a 13.00 start) was considered to be ideal. During the first cohort, participants struggled to attend on time; this was partly solved by providing taxis, but we also introduced a pre-session healthy lunch. This meant that the participants did not disrupt sessions if they arrived late, and also provided a practical demonstration of how to eat healthily on a limited budget.

Many people with schizophrenia may experience cognitive deficits and limited ability to concentrate over time. To overcome this, we incorporated sufficient and flexible breaks into the pilot intervention.

Sessions

Participants enjoyed the small-group setting, which enabled them to assimilate information more efficiently, share experiences with fellow participants and reinforce existing messages. Participants and facilitators found the resources, such as flipcharts, laminates and booklets, valuable and engaging. Participants commented on the benefit of using the same facilitators throughout the intervention. Contrary to our expectations, participants wished to attend alone and thought that they would not benefit from bringing an accompanying person to the sessions. Participants felt that undertaking the intervention was something they could accomplish on their own and that it would be easier to share information with fellow participants without the presence of people who did not have mental illness.

The use of supporting tools (e.g. samples of low-calorie drinks and snacks, kitchen scales, cookery books and pedometers) reinforced the messages provided to participants about the benefits of participation, improved internal motivation and supported engagement and attendance.

Chapter 3 Evaluation methods

Trial methods

Trial design

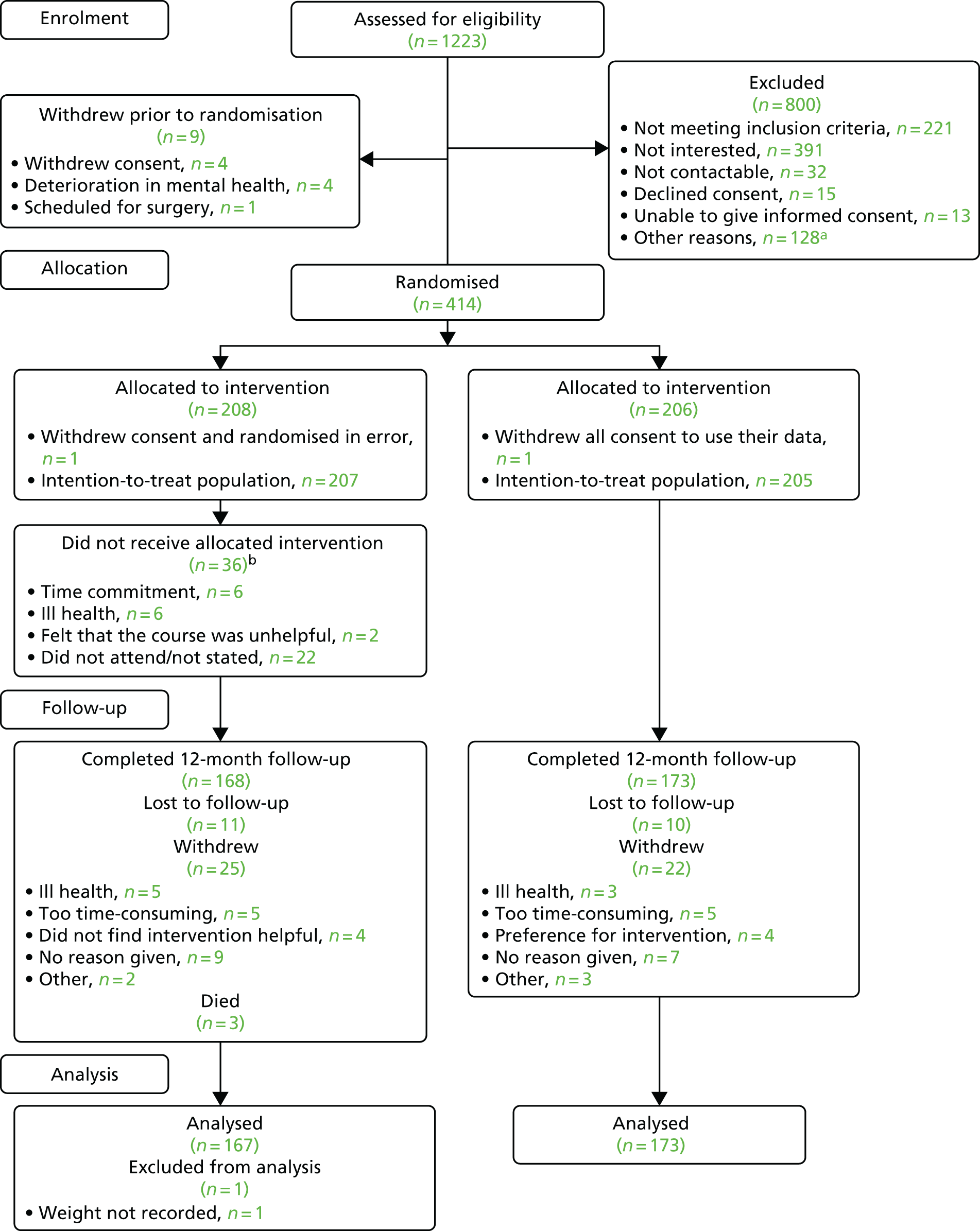

We undertook a multicentre, two-arm, parallel-group RCT of the STEPWISE structured lifestyle education programme compared with usual care plus written lifestyle advice in 10 NHS Mental Health Trusts in England. Participants were individually randomised to the STEPWISE programme or usual care. This report is concordant with the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) statement (2010). 31

Important changes to methods after trial commencement

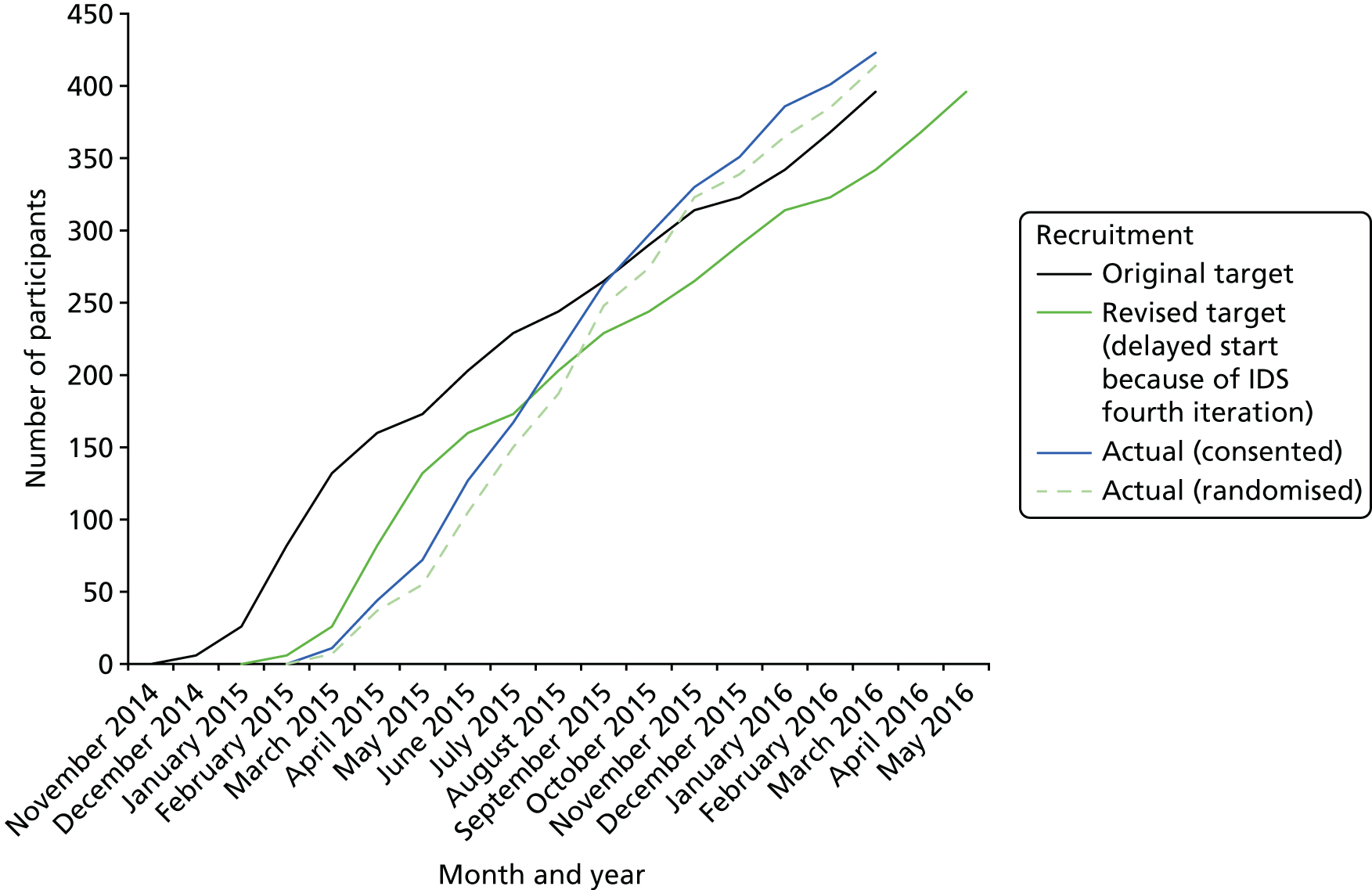

Trial recruitment commenced on 12 March 2015 (first patient, first visit) and, following this, in response to early observations and feedback from the intervention development study, a number of changes were made to the protocol. The protocol was published32 and the current version is available via the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Journals Library website. 33

Between the initial Research Ethics Committee approval and study commencement, there were two substantial amendments. These revised the sample size, clarified the eligibility criteria, described the control arm and updated the screening and consent process to ensure that recruitment could take place closer to scheduled intervention sessions.

In March 2015 (substantial amendment 3, protocol version 4.0), following feedback from the intervention development study, the option for participants in the intervention arm to bring along a friend, relative or carer to the intervention sessions was removed. This amendment also added details about referring any concerns or participant risk to the clinical care team. Amendments were made before delivery of the first foundation session (23 April 2015).

In June 2015 (substantial amendment 4, protocol version 5.0), the data collection windows for the Operational Criteria Checklist for Psychotic Illness and Affective Illness (OPCRIT+) and the outcome assessments were increased, to provide more opportunity for sites to follow up participants, allowing for missed appointments.

A further amendment in November 2015 (substantial amendment 5, protocol version 6.0) clarified the use of ‘Community Mental Health Teams’ in the eligibility criteria. This allowed potential participants within a variety of services, including those stepping down from inpatient to community services, to participate, provided that they could fully implement the learning from the intervention. This amendment also allowed 1 additional week to obtain the fasting blood sample at the 12-month follow-up.

In February 2016 (substantial amendment 6, protocol version 8.0), changes were made to the protocol to allow over-recruitment beyond the initial recruitment target, in order to allow centres to recruit in waves and run intervention groups with sufficient participants.

Participant selection and eligibility

The trial was co-ordinated from the Clinical Trials Research Unit (CTRU) in the Sheffield School of Health and Related Research (ScHARR). Delegated study staff located at participating centres identified and gained consent from potential participants. Eight of the 10 centres [and their principal investigators (PIs)] were involved at the proposal development stage, with two further centres identified through expressions of interest via the NIHR Clinical Research Network.

The trial was promoted within clinical teams and in community areas in which mental health services are delivered. Clinicians used a standardised script to ensure that potential participants received consistent information about the trial. The research team at participating sites worked with clinical teams to identify potentially eligible patients from clinic lists and other caseloads. Self-referrals were also accepted, following the use of information displayed on posters and leaflets.

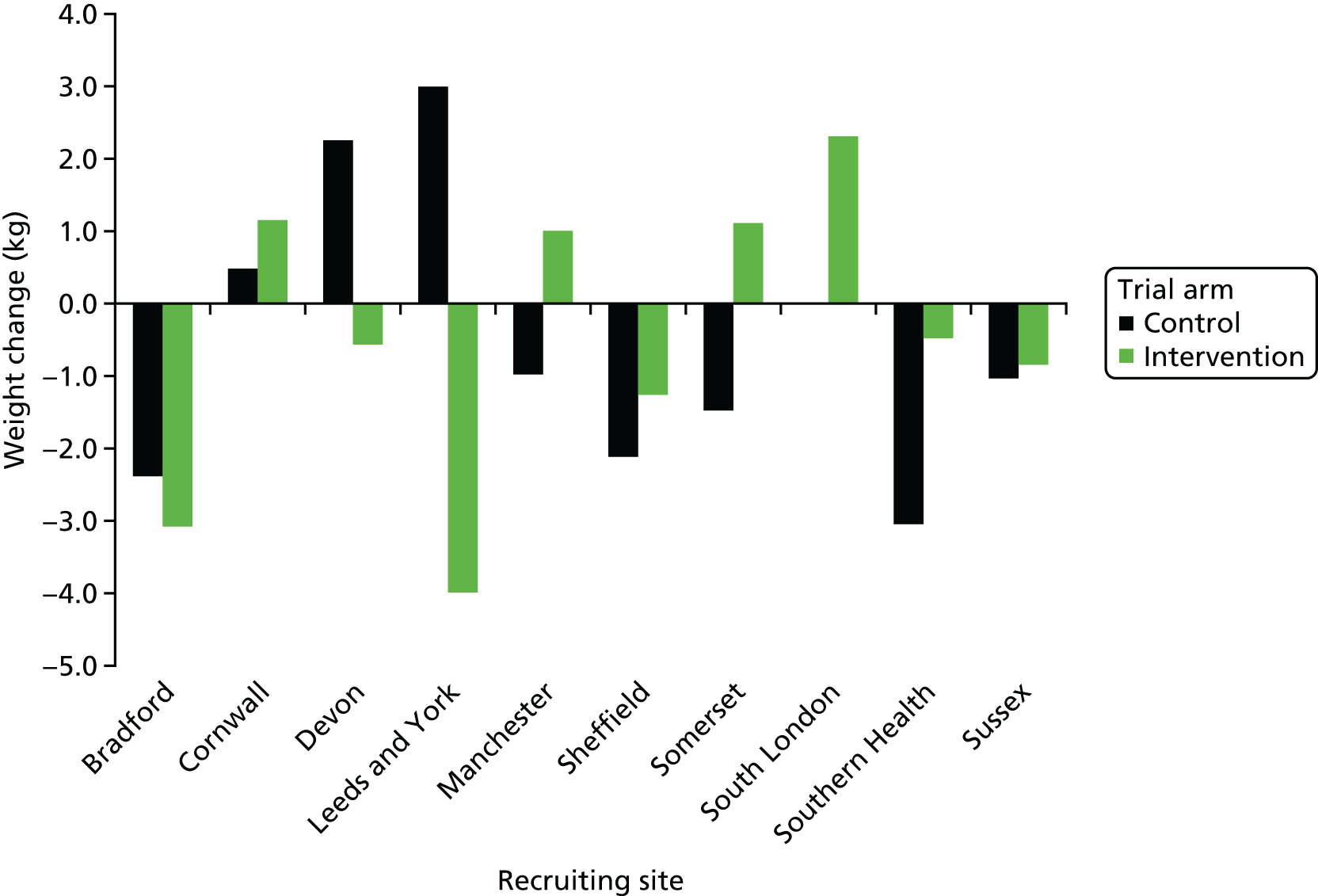

The study took place within CMHTs, including early intervention services, in 10 mental health NHS trusts in a range of locations, urban and rural, in Sheffield, Leeds, York, Bradford, Greater Manchester, South London, Sussex, Hampshire, Devon, Somerset and Cornwall.

Adults were eligible for inclusion in the study if they:

-

were aged ≥ 18 years

-

had a diagnosis of schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder [defined by the International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision (ICD-10) codes F20 and F25] or first episode psychosis (defined as < 3 years since presentation to the mental health team) using case note review

-

were being treated with an antipsychotic

-

were able to give written informed consent

-

were able and willing to attend and participate in a group education programme

-

were able to speak and read English

-

had a body mass index (BMI) of ≥ 25 kg/m2 or were concerned about their weight (in the case of participants from South Asian and Chinese backgrounds, the BMI threshold was reduced to ≥ 23 kg/m2).

People were excluded from the study if they:

-

had a physical illness that could seriously reduce their life expectancy or ability to participate in the trial

-

had a coexisting physical health problem that would, in the opinion of the PI, independently affect metabolic measures

-

had a mental illness that could seriously reduce their ability to participate in the trial

-

had a current pregnancy or were < 6 months post partum

-

had a condition associated with significant weight gain (e.g. Cushing syndrome)

-

engaged in significant alcohol or substance misuse which, in the opinion of the PI, would limit the patient’s ability to participate in the trial

-

had a diagnosis or a tentative diagnosis of psychotic depression or mania

-

had a primary diagnosis of a learning disability

-

were currently (or within the past 3 months) engaged in a systematic weight management programme, to ensure that other programmes did not have an impact on baseline measures.

During the trial, participants were not prevented from joining weight loss or physical activity programmes (intervention arm participants were encouraged to make positive behaviour change); however, any uptake of systematic programmes (other than STEPWISE) was captured at the 3- and 12-month follow-up by asking all participants if they had taken up any other weight management or physical activity programme outside the trial.

All potential participants had a minimum of 24 hours in which to decide whether or not they wished to participate, before attending a consent visit.

The CTRU co-ordinated the follow-up and data collection in collaboration with centres. Participant study data were collected and recorded on study-specific case report forms (CRFs) by site research staff and were entered onto a remote web-based data capture system at each site.

Interventions

All participants received written lifestyle advice on diet, physical activity and alcohol and smoking use before randomisation. Participants were randomised to receive either the STEPWISE education programme or usual care.

Research intervention (STEPWISE education programme)

Participants allocated to the research intervention were contacted by the session co-ordinator and provided with pre-course information, which included an introductory letter and leaflet confirming when and where the sessions would take place and what to expect.

The intervention took place over approximately a 12-month period post randomisation. Participants allocated to STEPWISE received a foundation course of four weekly 2.5-hour (including breaks) group sessions delivered by two trained facilitators. The protocol specified approximately 6–10 participants for each course, to allow for a good group size and to account for likely attrition.

The foundation course was followed by one-to-one support contact lasting for around 10 minutes, approximately every 2 weeks for the remainder of the intervention period. This contact was personalised and was mostly conducted by telephone, although it also took place in person on some occasions. The purpose of the support contact was to discuss participants’ progress towards their goals, highlight any issues and try and motivate participants to change their behaviours in line with the group-based session. When participants could not be contacted, a motivational postcard was sent to them to maintain this contact. Support contact was undertaken by a trained facilitator to support behaviour change and obtain feedback from the participant.

Participants were invited to attend 2.5-hour group-based booster education sessions at 4, 7 and 10 months post randomisation. Attendance at all intervention sessions and receipt of support contact were recorded.

Participants who attended education sessions were invited by facilitators to complete a ‘session feedback’ form at the end of each session. This was completed independently and sealed in an envelope to maintain anonymity. The envelopes were posted directly to the CTRU for data entry. Participants could choose whether or not to include their name on the feedback form, and the aim was to capture a self-report of empowerment and health belief during the intervention.

Between four and six health-care professionals or associated staff at each participating centre received facilitator training to deliver the STEPWISE intervention. This training covered the core DESMOND philosophy (3 days), specific content and delivery of the STEPWISE programme (1 day) and the content and delivery of booster sessions (1 day).

Control arm

Participants allocated to the control arm received treatment as usual (TAU), enhanced by the provision of written lifestyle advice. There is known variability in the provision of physical health care, despite NICE guidelines on the treatment and management of schizophrenia regarding healthy eating and physical health. 14 To standardise usual care in both groups as far as possible, participating centres provided printed guidance to all participants (regardless of allocation) before randomisation on the risk of weight gain and lifestyle advice, regarding diet, physical activity, smoking and alcohol use, when appropriate.

Usual care

It is appropriate in pragmatic trials for the comparison intervention to involve ‘usual practice’, offering study sites leeway in deciding what that should involve. 34 As the content of usual care can influence effect size,35 we undertook a survey of usual care at the participating centres at two time points. The methods for this exercise have been reported previously,36 but, in brief, sites were surveyed on their current practices regarding healthy eating and physical activity programmes offered to people with schizophrenia. The survey was based on current NICE guidance14 and included questions about any trust-offered healthy eating and physical activity programmes, what discussions take place with patients before antipsychotic initiation, the availability of smoking cessation support and how physical health reviews are completed, including what measures are reviewed and how often.

Measurement of outcomes

Following consent but before randomisation, research staff completed CRFs for each participant, which covered medical and psychiatric history, demographics and current medication information (Table 2). All assessments and questionnaires were undertaken either at the participant’s home or in the NHS trust. A fasting blood sample was taken, as well as measurements of vital signs and anthropometry. Baseline self-report instruments were completed, with research staff encouraged to read questions aloud to participants, with all available answer options, to ensure understanding. Participants were provided with a wrist-worn accelerometer to wear 24 hours per day for 7 days following the visit.

| Outcome measure | Time point | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-baseline | Baseline | 3 months | 12 months | |

| Eligibility criteria assessed by the clinical care team | ✗ | |||

| Medical history | ✗ | |||

| Psychiatric history | ✗ | |||

| OPCRIT+37 | ✗ | |||

| Renal function | ✗ | ✗ | ||

| Hepatic function | ✗ | ✗ | ||

| Height (to calculate BMI) | ✗ | |||

| Weight | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | |

| Waist circumference | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | |

| Physical activity [7-day wrist-worn GENEActiv (Activinsights, Kimbolton, UK) accelerometer] | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | |

| Adapted DINE questionnaire38 | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | |

| Blood pressure | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | |

| Fasting glucose | ✗ | ✗ | ||

| Lipid profile | ✗ | ✗ | ||

| Glycated haemoglobin | ✗ | ✗ | ||

| EQ-5D-5L39 | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | |

| SF-3640 | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | |

| B-IPQ41 | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | |

| BPRS42 | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | |

| Smoking status | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | |

| CSRI43 | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | |

| Changes in medication (dose and side effects) | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | |

| PHQ-944 | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | |

| Use of weight loss programmes | ✗ | ✗ | ||

| Adverse events | ✗ | ✗ | ||

| Session feedback (intervention only; each group session) | ✗ | |||

Additional information, such as medication details and details of hospital admissions, was obtained and/or verified using the patient’s medical notes. At both the 3- and the 12-month follow-up visits, research staff who were masked to treatment allocation confirmed medication information with participants, particularly doses and side effects of antipsychotic medication. They took measurements of blood pressure, weight and waist circumference (and a fasting blood sample at 12 months only) and provided the participant with a wrist accelerometer to wear for the next 7 days. Participants were asked to complete the same questionnaires as at baseline, with the addition of a form to capture the uptake of any weight loss programmes outside the STEPWISE trial. The follow-up windows at 3 and 12 months were defined as minus 2 weeks and plus 4 weeks to allow time for missed and rearranged appointments.

Biomedical measures

The biomedical outcomes were:

-

Weight outcomes – change in weight, the proportion of participants who maintained or reduced weight, percentage change in weight, waist circumference and BMI. Standard operating procedures specified how to measure body weight (e.g. light clothing, shoes off) using the Class III approved Marsden 430-C portable scales (Marsden Weighing Machine Group Limited, Rotherham, UK) to the nearest 0.1 kg; height (e.g. standing tall, feet hip-width apart and head level) using the Class I approved Marsden HM-250P stadiometer (Marsden Weighing Machine Group Limited, Rotherham, UK) to the nearest 1 cm; and waist circumference (e.g. tape lying flat and level, taut but not tight) using the Class I approved Seca 201 tape measure (Seca, Birmingham, UK) to the nearest 0.1 cm. Participants who provided 12-month weight data in accordance with the protocol received a £20 shopping voucher.

-

Vital signs and laboratory measurements:

-

blood pressure (average of three measurements) and pulse, measured by electronic sphygmomanometer in the non-dominant arm after 5 minutes’ rest

-

fasting glucose, lipid profile and glycated haemoglobin (HbA1c) at baseline and 12 months only (all blood samples were analysed by local laboratories).

-

Physical activity

Physical activity was assessed by wrist-worn accelerometer (GENEActiv, Activinsights Ltd, Kimbolton, UK). Participants were asked to wear the accelerometer on their non-dominant wrist continuously (i.e. 24 hours per day) for 7 days and data were derived using the approach reported in da Silva et al. 45 The GENEActiv.bin files were analysed with R-package GGIR, version 1.5 (Cran-R Project, the Netherlands). 28,29 Signal processing in GGIR includes the following steps:

-

autocalibration, using local gravity as a reference28

-

detection of sustained abnormally high values

-

detection of non-wear

-

calculation of the average magnitude of dynamic acceleration (i.e. the vector magnitude of acceleration corrected for gravity [Euclidean norm minus one g (ENMO)] as:

over 5-second epochs, with negative values rounded up to zero.

Files were excluded from all analyses if the post-calibration error was > 0.02 g30 or < 16 hours of wear time as recorded by either monitor during the 24-hour day of interest. Detection of non-wear has been described in detail previously. 29 In brief, non-wear is estimated based on the standard deviation (SD) and value range of each axis, calculated for 60-minute windows with 15-minute moving increments. If for at least two out of the three axes the SD is < 13 mg (milligravity) or the value range is < 50 mg, the time window is classified as non-wear.

The average magnitude of dynamic wrist acceleration (ENMO) and time accumulated in moderate or vigorous physical activity (MVPA) were calculated. The threshold for determining MVPA was ≥ 100 mg.

Four measures were taken:

-

mean acceleration calculated per day

-

MVPA based on a 5-second epoch setting (i.e. total unbouted MVPA)

-

MVPA based on a 5-second epoch setting and a bout duration of 5 minutes, inclusion criteria based on > 80%

-

MVPA based on a 5-second epoch setting and a bout duration of 10 minutes, inclusion criteria based on > 80%.

Each of the above was calculated for weekdays (provided data were available for at least 3 of the 5 days), weekends (provided data were available for at least 1 day) and all days (when data were available for at least 4 of the 7 days).

Lifestyle factors

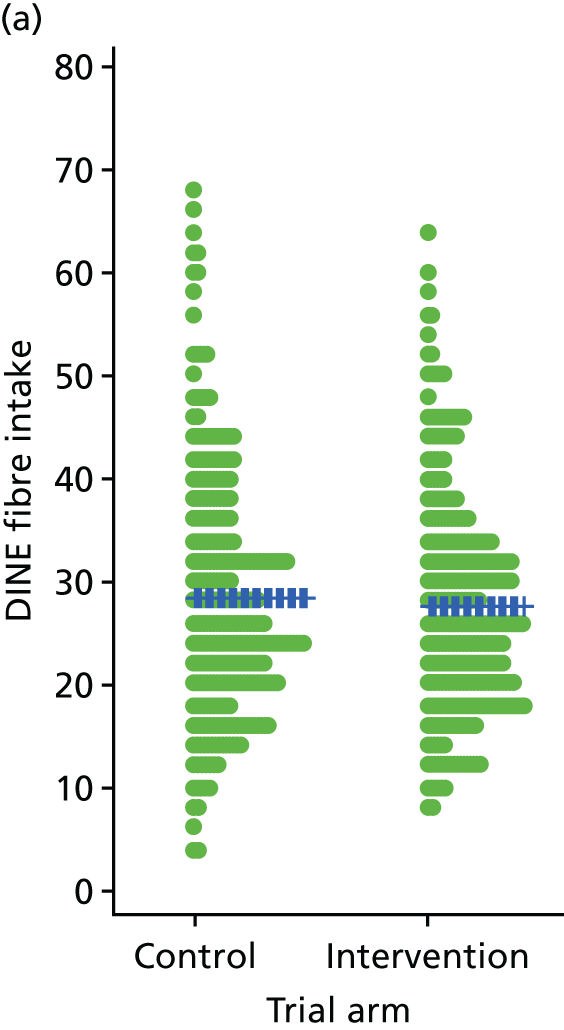

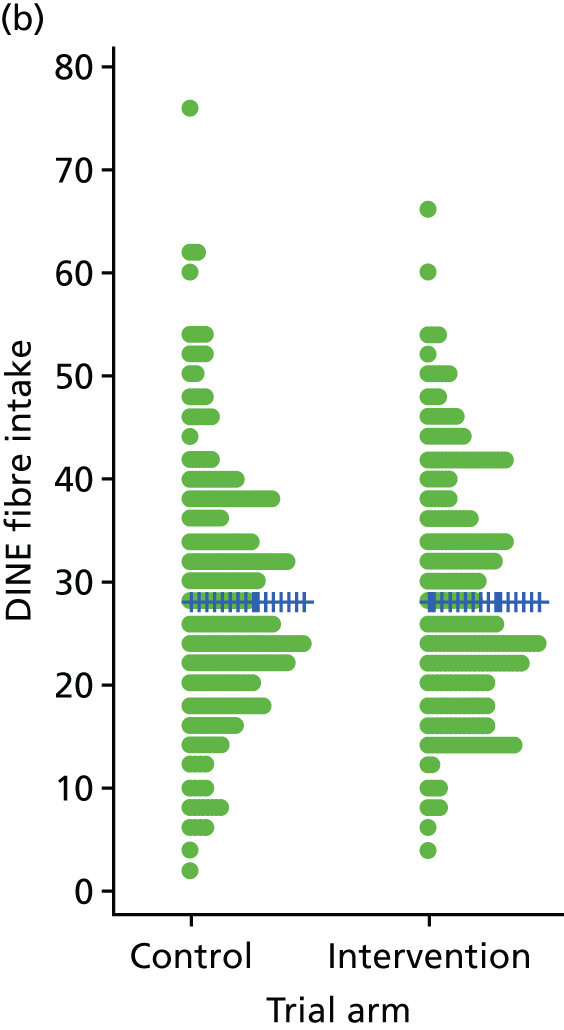

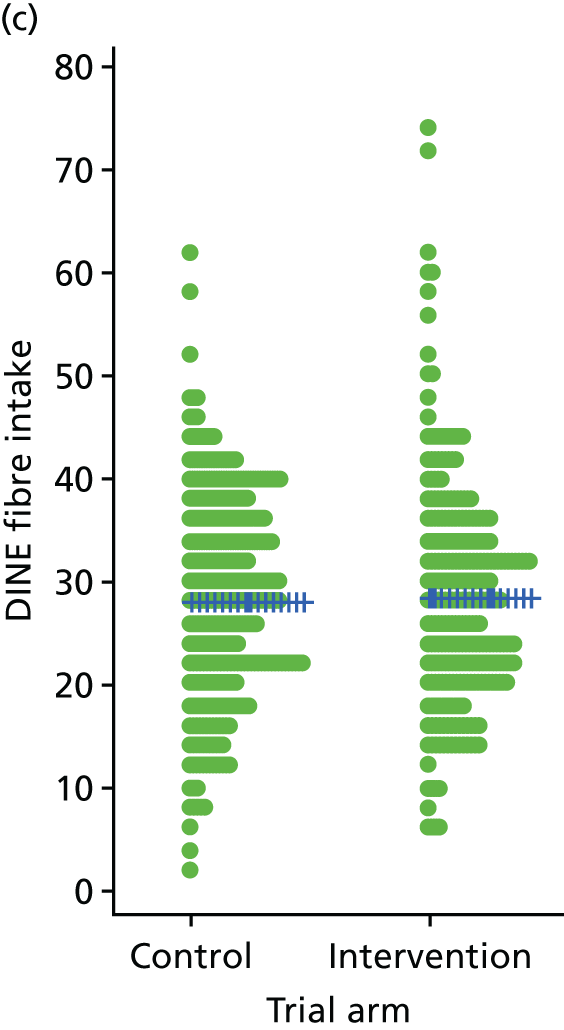

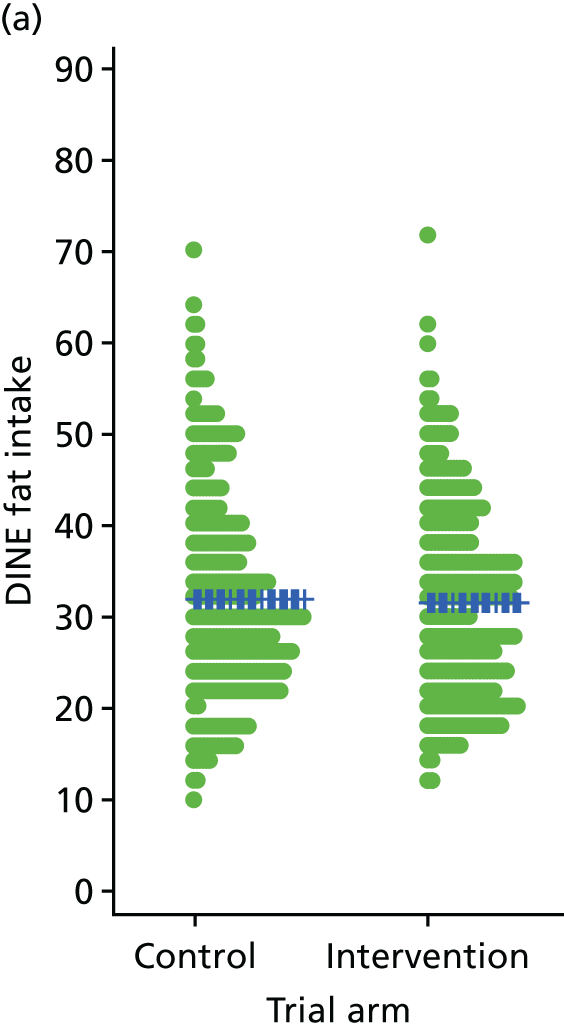

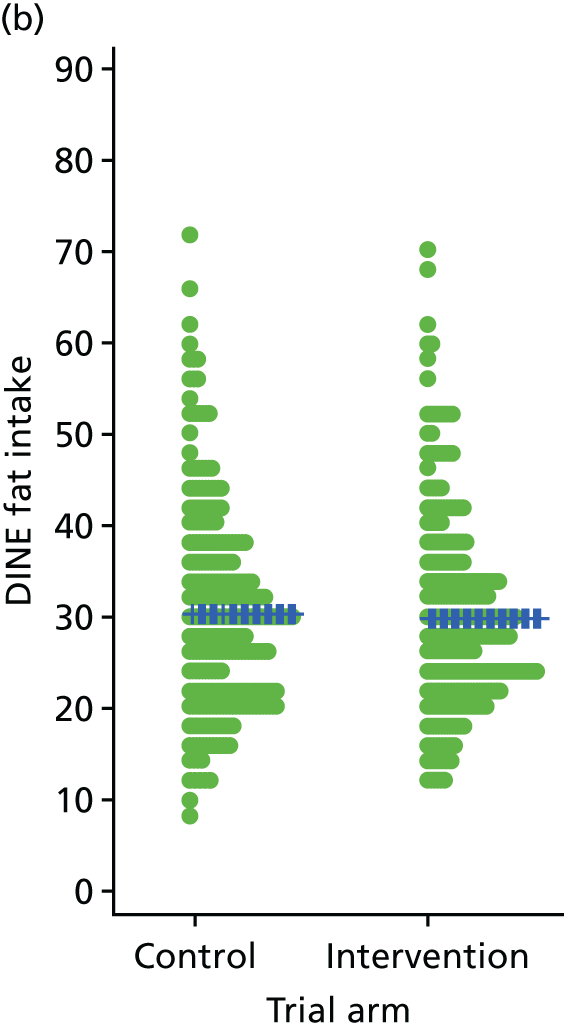

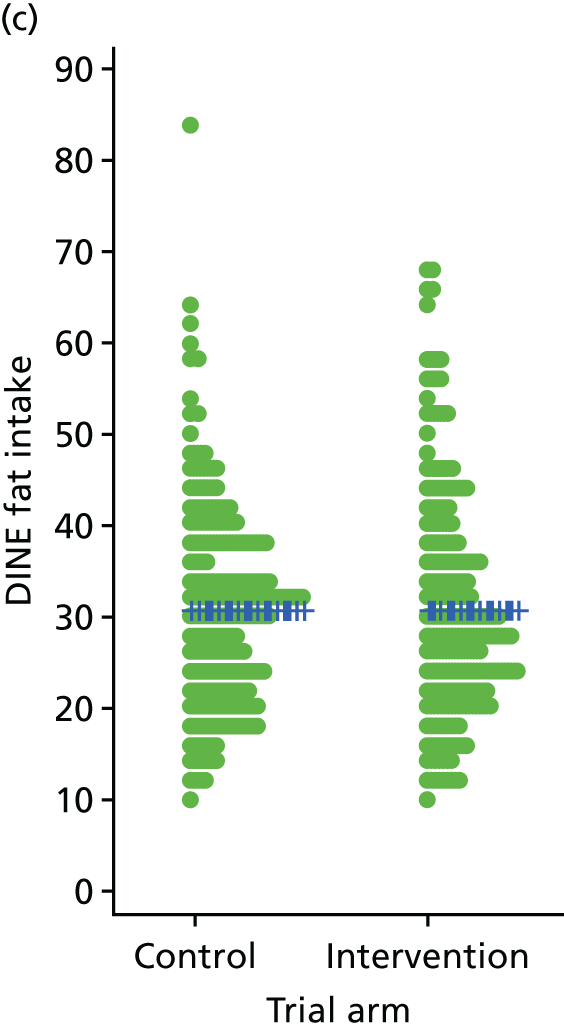

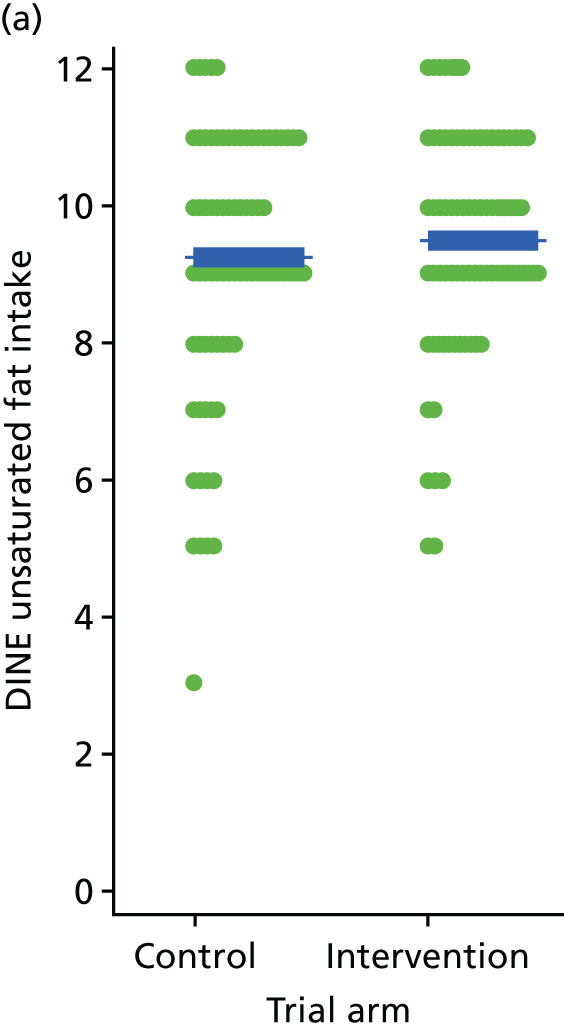

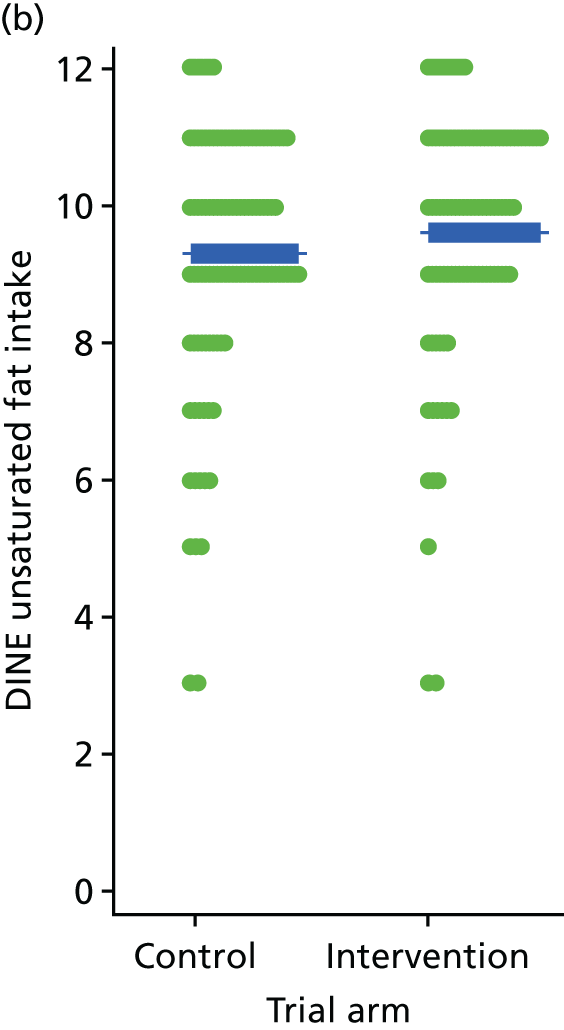

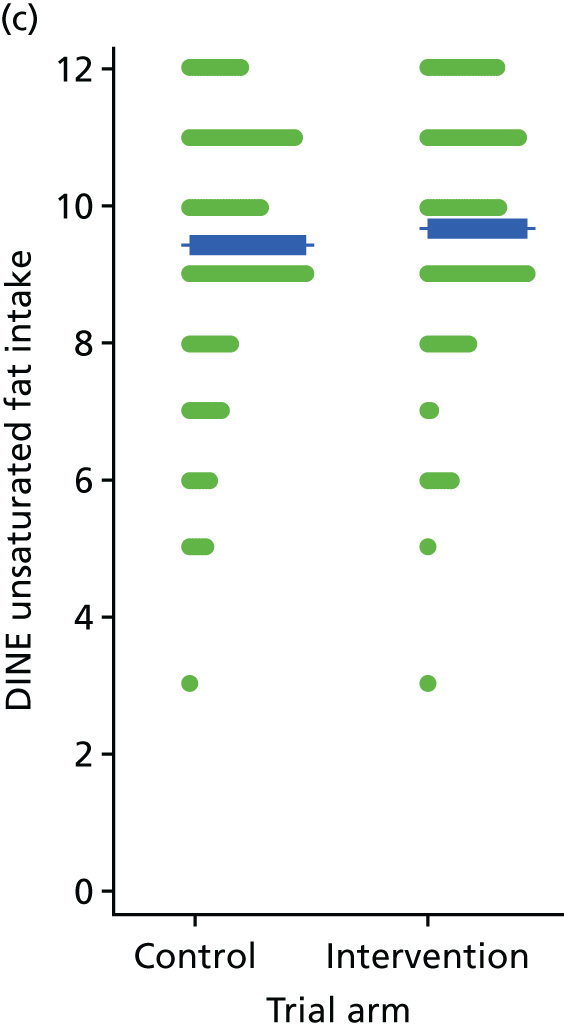

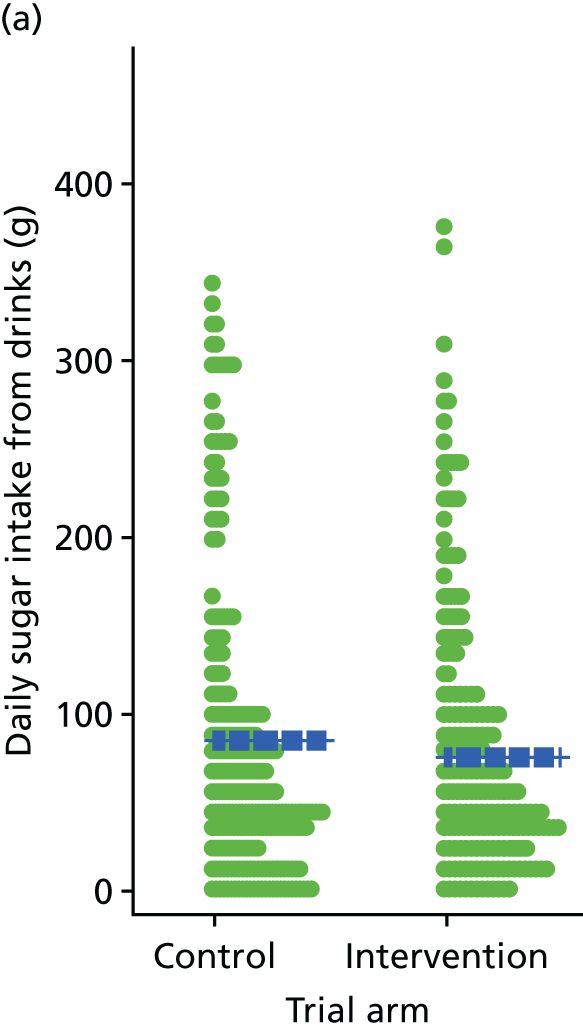

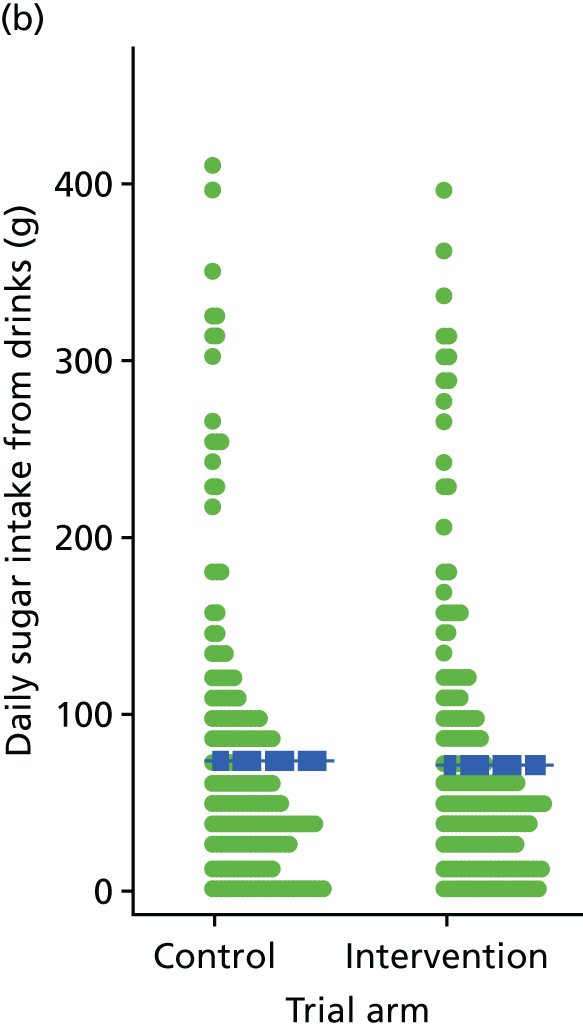

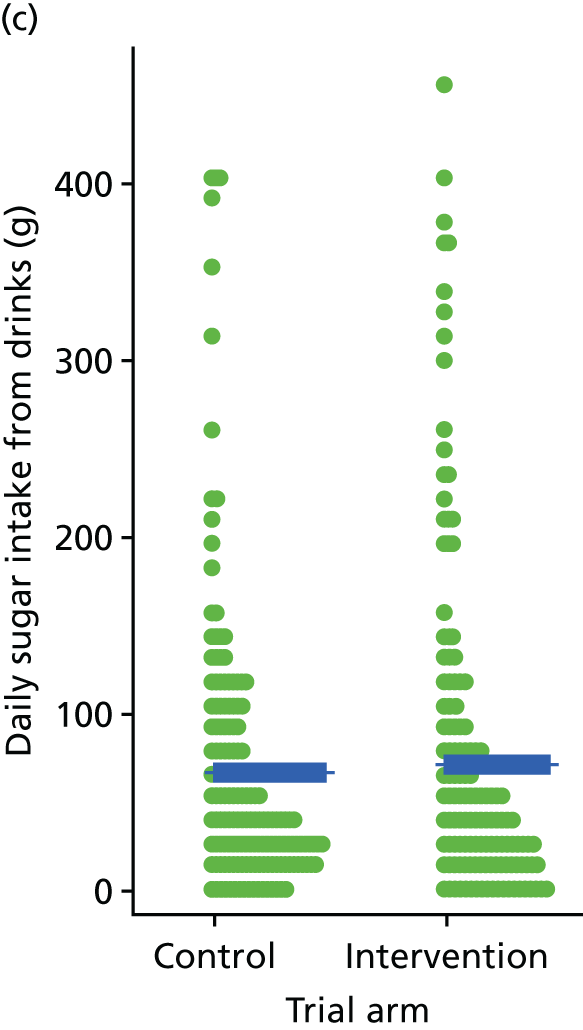

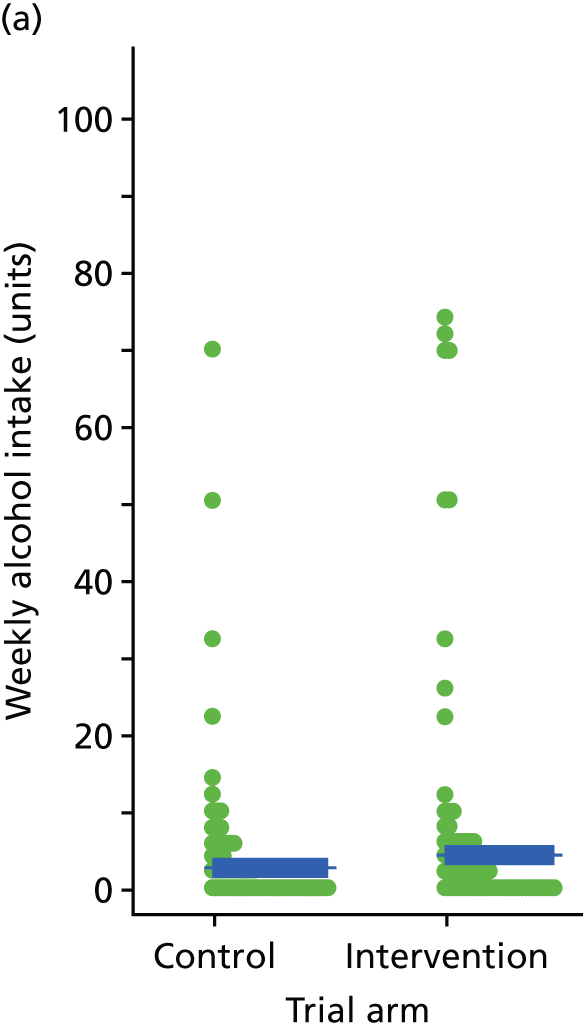

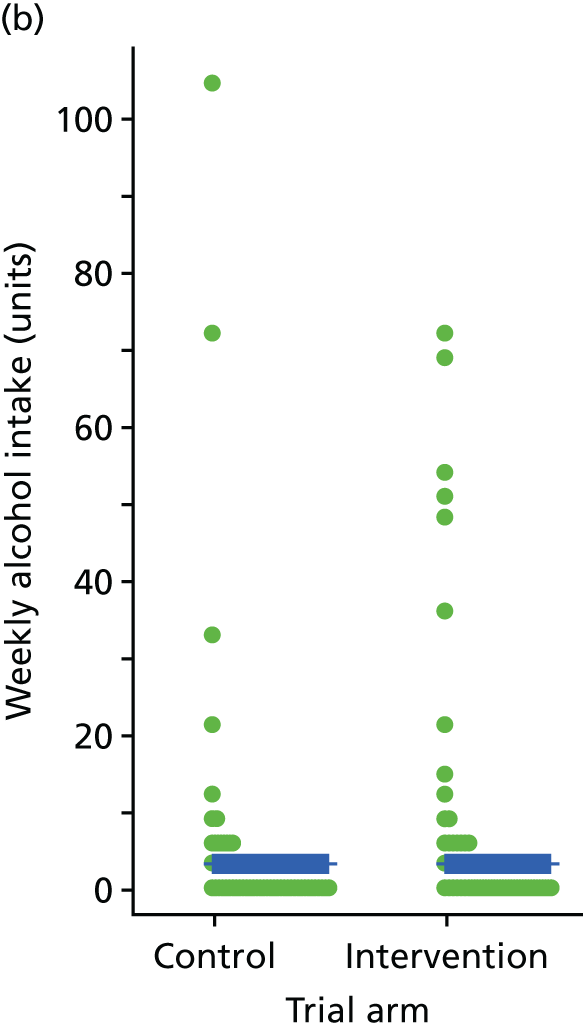

Three lifestyle measures were collected. These were the adapted Dietary Instrument for Nutrition Education (DINE) questionnaire,38 smoking status and use of weight loss programmes:

-

The adapted DINE questionnaire measures diet on six items – fibre intake, fat intake, unsaturated fat intake, sugar intake, alcohol intake and meal type. Scores and ratings were calculated only when all constituent items had been reported for the particular item.

-

Smoking status was measured by the number and percentage of participants who smoke, smoking category [light (< 10 cigarettes per day), moderate (10–19 cigarettes per day) or heavy (≥ 20 cigarettes per day)], interventions offered to aid smoking cessation and interventions taken to aid smoking cessation.

-

Use of weight loss programmes (follow-up only); the number and percentage of participants who reported enrolling in any weight loss programme.

Patient-reported outcome measures

Four patient-reported outcome measures were collected:

-

EuroQol-5 Dimensions, five-level version (EQ-5D-5L) health utility,46 comprising a health state and thermometer scale. Higher scores indicate a better health state.

-

The Short Form questionnaire-36 items (SF-36),47 from which eight domains of quality of life (QoL) were derived. Higher scores indicate a higher QoL.

-

The Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9),44 a measure of depressive symptoms. Higher scores indicate more severe depressive symptoms.

-

The adapted Brief Illness Perception Questionnaire (B-IPQ),41 a measure of illness perception. Higher scores reflect a more threatening view of the obesity.

Clinician-assessed outcome measure

Participants were assessed using the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS), a clinician-rated measure that evaluates the psychopathology of patients with schizophrenia. 42 Higher scores indicate greater psychiatric concern.

The OPCRIT+ was completed by the research team, using case note review, within 10 weeks of the baseline visit. This was to provide comparable baseline characteristics for all participants across the study. The protocol allowed baseline fasting blood samples and accelerometry data to be collected after randomisation when recruitment occurred close to a scheduled intervention course.

Cardiovascular and diabetes mellitus risk

The 10-year cardiovascular risk was calculated using the Framingham Cardiovascular Risk Score. 48 An analysis using a second cardiovascular risk score for people with severe mental illness (PRIMROSE)49 was planned but not used, as a problem emerged with the algorithm during the analysis. The 10-year type 2 diabetes mellitus risk was calculated by the Leicester score. 50

Derivation of outcome measures

The EuroQol-5 Dimensions (EQ-5D) tariff was scored using the EQ-5D-5L for UK population norms;51 no score was calculated if any of the five items were missing. The eight subscales of the SF-36 were calculated as per McHorney et al. ;40 subscores were calculated when at least half of the questions within the domain had been answered. When all eight domains were completed, the aggregate physical and mental component scores were calculated. The adapted B-IPQ was scored by summing the responses to items into a single score41 if at least six of the eight questions were answered. The BPRS was scored by summing up the responses into a single score42 and was calculated if at least 14 of the 18 items had been answered.

Sample size

The sample size calculation was based on data from two sources, both of which assessed behavioural interventions for weight loss in people prescribed antipsychotics for schizophrenia. First, a systematic review undertaken by Das et al. 52 examined both randomised and non-randomised controlled trials, and reported between-group differences of 1.5–6 kg (SD ≈5 kg). Data on overweight and obese UK patients with severe mental illness from a second study also contributed to the sample size calculation. A total of 51 people with schizophrenia were followed up for at least 1 year, and the weight change reported was 7.7 kg (SD 6.5 kg). 53

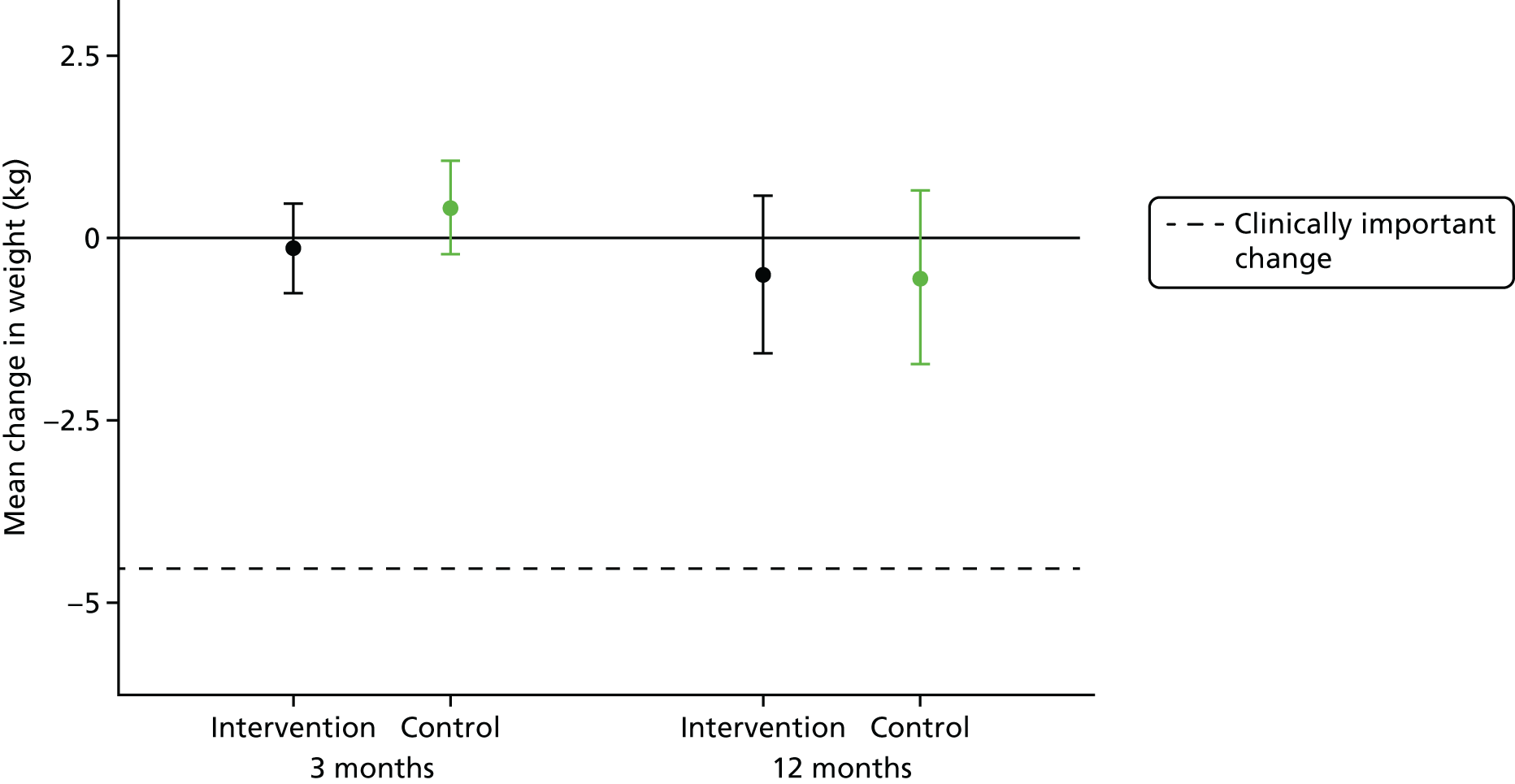

The sample size used in STEPWISE aimed to detect a difference of 4.5 kg, which is clinically meaningful (average ≈5% reduction in body weight)54 and also appears to be compatible based on previous work. A conservative estimate of a SD of 10 kg, 95% study power and a two-sided significance level of 5% was assumed, meaning that 130 participants per intervention arm (260 participants in total) were required to detect a minimum clinically important difference of 4.5 kg.

Owing to the group nature of the intervention, it is possible that the outcomes of participants within the same group may be correlated. Therefore, an average group size of seven participants was assumed, with an intraclass correlation of 5% in the intervention arm. For this reason, the sample size was inflated by a design effect of 1.3 in the intervention arm, which gives revised sample sizes of 169 participants in the intervention arm and 130 participants in the control arm (299 in total).

To ensure a 1 : 1 allocation, 158 participants were required per arm to reproduce this power. Assumptions were made for a conservative dropout rate of 20%, which is higher than that observed in similar studies,55 giving a final sample size of 198 participants per trial arm. This equates to 40–50 participants at each centre, with 20–25 of these receiving the intervention in up to four groups per site.

Randomisation

Sequence generation

The randomisation list was generated using the CTRU’s web-based system, which provided central randomisation and ensured that the study team was blinded to the allocation. The list was generated using permuted blocks of random sizes to allocate participants to either TAU plus the STEPWISE lifestyle education programme or TAU alone in a 1 : 1 ratio, stratified by site and time since the start of antipsychotic medication (< 3 months or ≥ 3 months). When the exact duration was unknown, an approximate duration was considered to be acceptable for the purposes of randomisation.

Implementation

After the baseline assessments were completed and consent was provided, participants were randomised using the STEPWISE randomisation system. Once randomised, an unblinded member of the site research team informed the participant and their general practitioner (GP) of the treatment allocation.

Blinding

All research team members performing outcome assessments were blind to treatment allocation. Blind (or suspected) breaks were recorded. Owing to the nature of the intervention, participants were not blinded.

Ethics aspects

The study received a favourable opinion from the National Research Ethics Committee, Yorkshire & the Humber – South Yorkshire on 4 February 2014 (reference 14/YH/0019).

Patient and public involvement

Angela Etherington (a person with severe mental illness and experience of taking antipsychotic medication) and David Shiers (the carer of a family member with schizophrenia) were involved in the design of the study and the intervention, management meetings, the qualitative research analysis and the drafting of the report. They reviewed, made changes to and approved the final lay summary.

Statistical methods

Outcome measures

Primary outcome measure

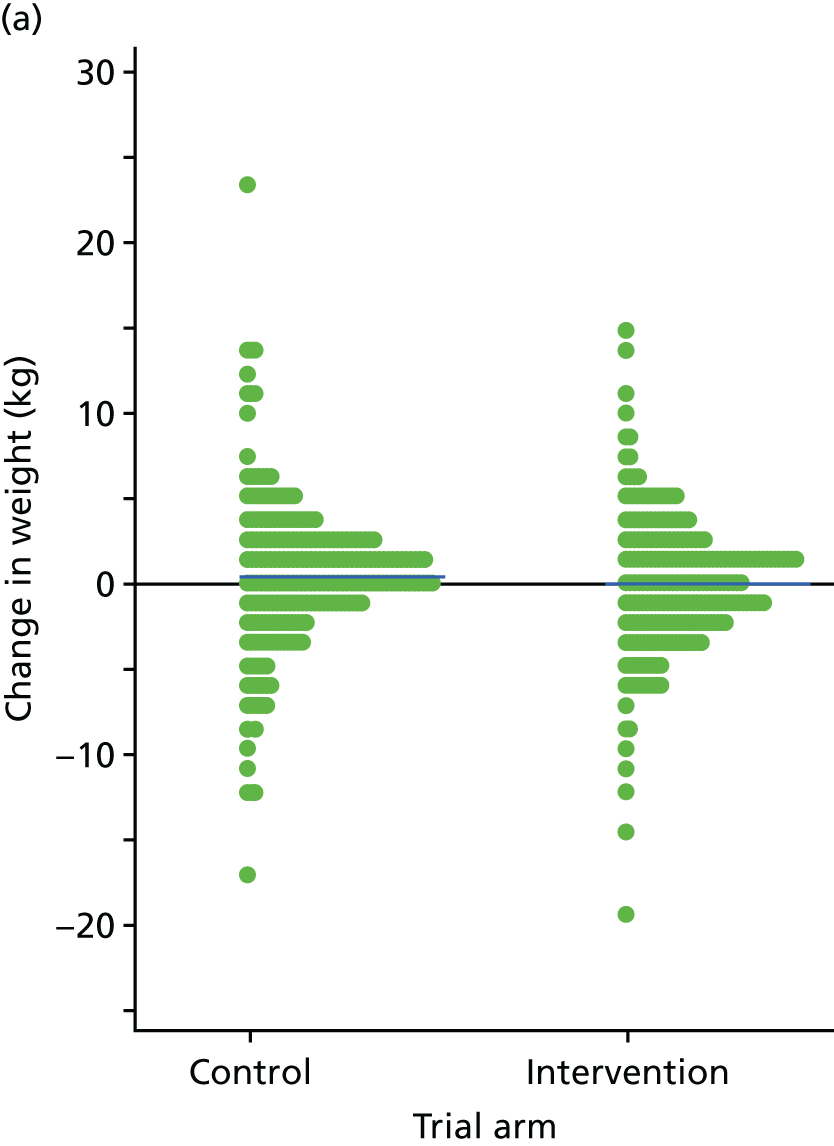

The primary end point of the STEPWISE trial was the change in weight (kg) at 12 months after randomisation.

Secondary outcome measures

Secondary outcomes included biomedical measurements, physical activity, dietary components and psychosocial factors, including QoL, health beliefs and cost-effectiveness. All secondary outcome measures were assessed at baseline and after 3 and 12 months (except when stated), to measure if there was an effect at the end of the intervention and, if so, whether or not this was sustained over the longer term.

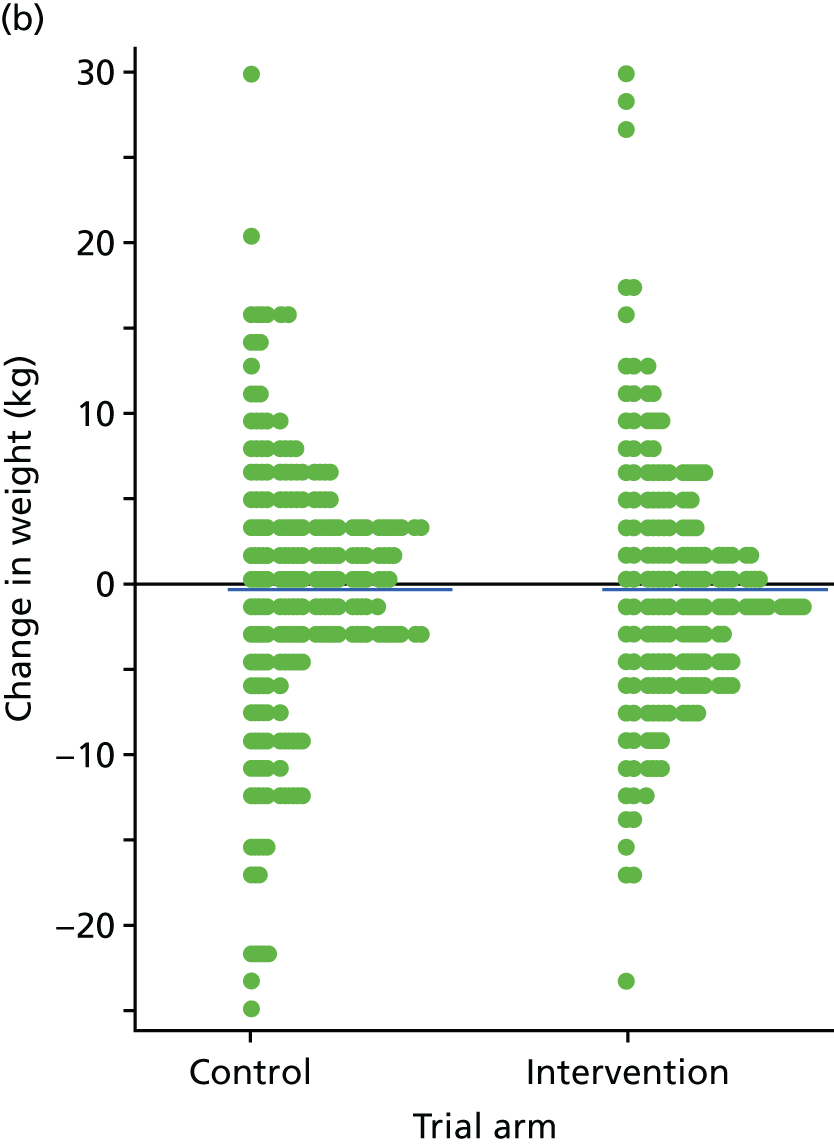

Analysis of weight change

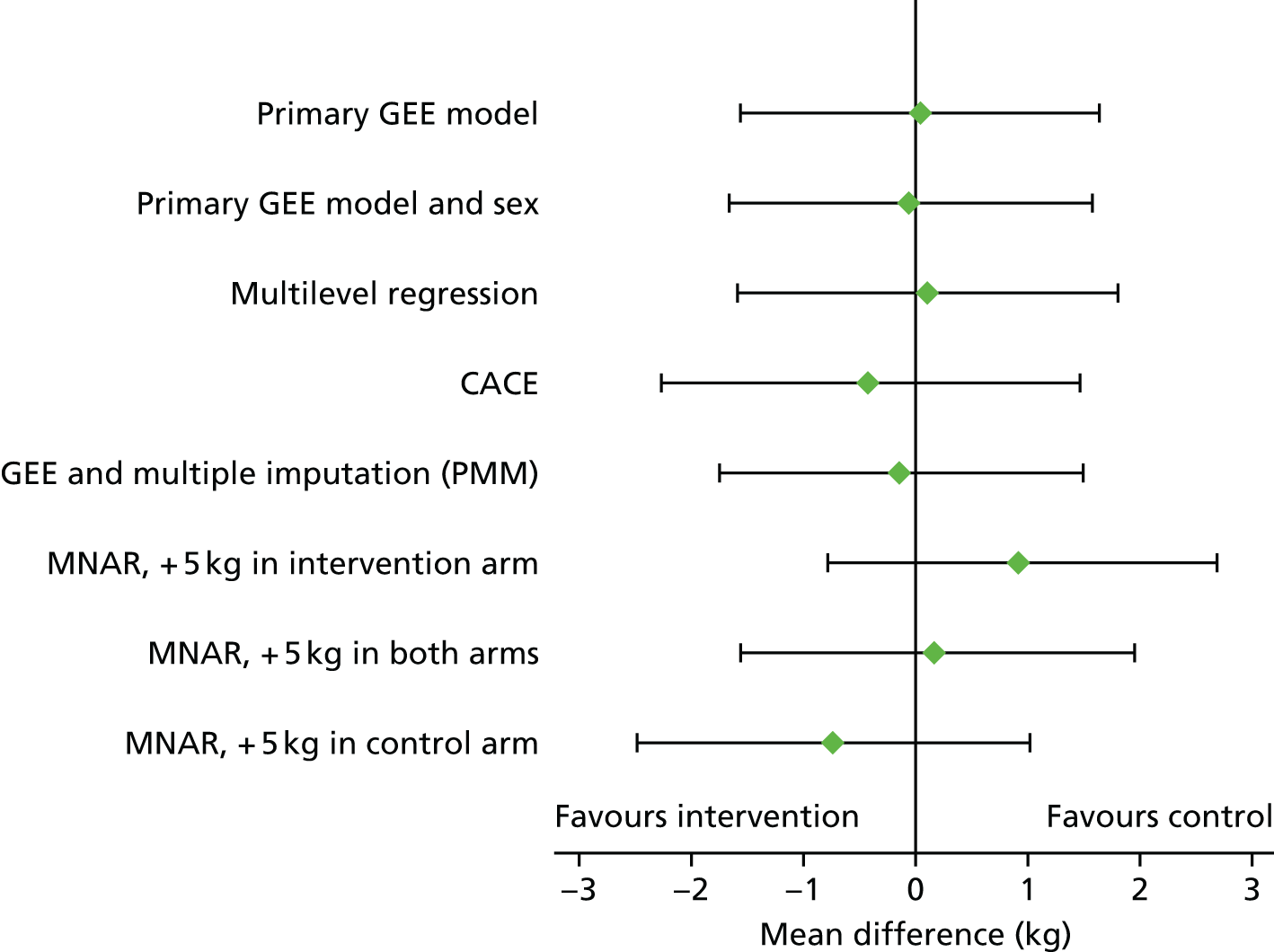

The primary objective (weight change at 1 year post randomisation) was assessed by fitting a marginal generalised estimating equation (GEE) model using robust standard errors and an exchangeable correlation structure. The difference between intervention and control arms was adjusted for baseline weight, site and years since antipsychotic medication initiation. The intraclass correlation coefficient (i.e. the ‘cluster’ term) was derived from the correlation matrix of the GEE model. The following preplanned sensitivity analyses were undertaken:

-

alternative covariates (in which any imbalanced baseline characteristics were added into the GEE model)

-

alternative model structure (multilevel model in place of the GEE to estimate the cluster effect)

-

alternative assumptions for missing data.

The last of these analyses used approaches proposed by von Hippel,56 Carpenter et al. 57 and White et al. 58 The complete-case analyses were augmented with a reanalysis assuming a missing-at-random (MAR) mechanism, achieved by incorporating all baseline covariates that were associated with the probability of missing weight at 12 months and/or with weight change among those who were followed up; these included baseline demographics, disease characteristics, recruiting site, treatment group, weight, BPRS score, B-IPQ score and physical domains of the SF-36 at baseline and 3 months.

The first model incorporated baseline measures as covariates, following which the treatment effect was re-estimated (model MAR 1). Following this, predictive mean matching multiple imputation via chained estimation incorporated all available baseline and 3-month values to impute missing 12-month weight using the original model covariates (model MAR 2). Thereafter, the sensitivity to missing not at random (MNAR) was assessed by adding a range of fixed quantities (delta) to the MAR prediction; for example, delta = 1 corresponds to the assumption that an individual with no 12-month data has a weight change of 1 kg more than predicted. The values of delta used ranged from –5 to + 5 kg and included different values of delta for the two treatment groups.

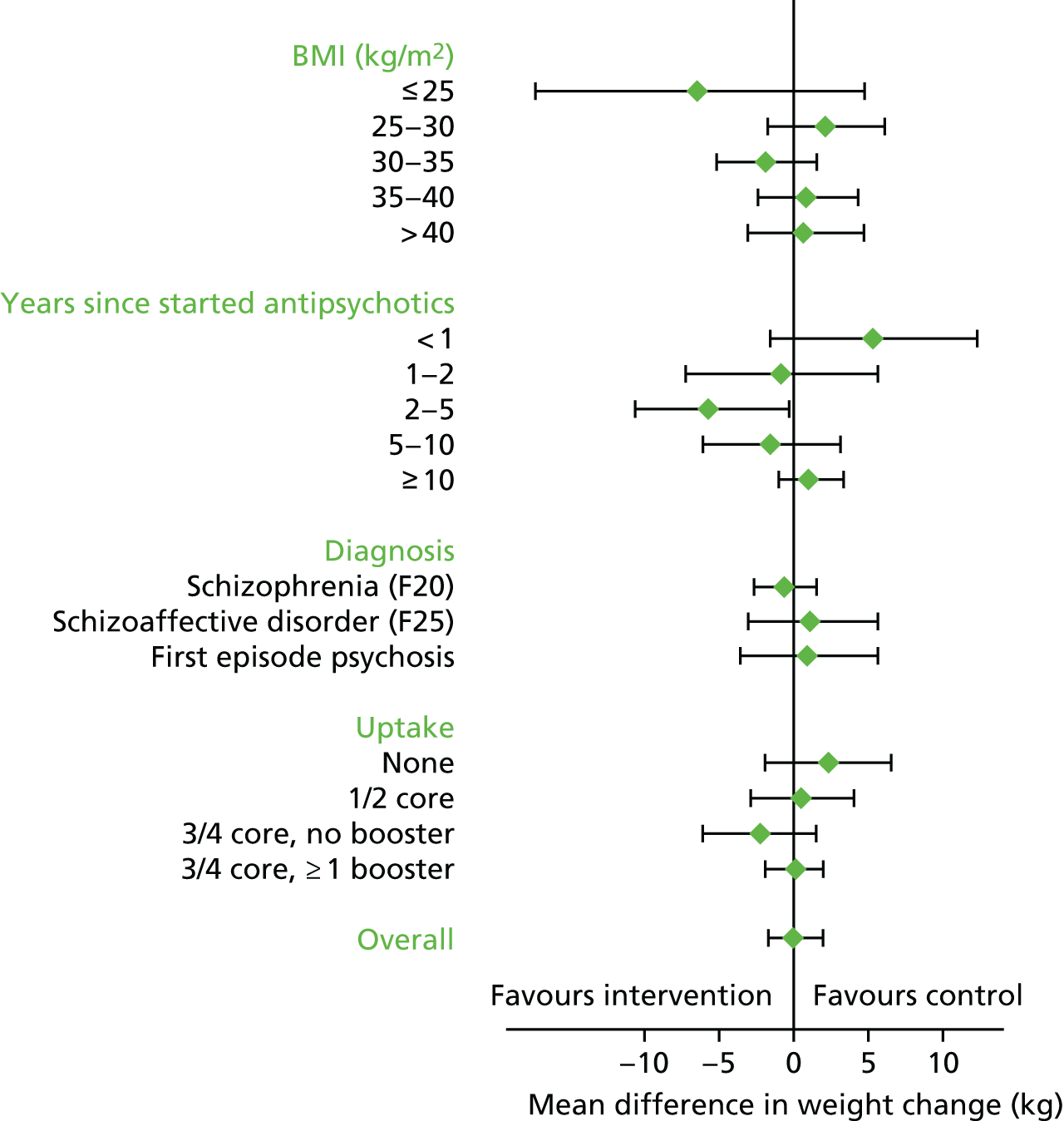

The treatment comparison was calculated in the following preplanned subgroups:

-

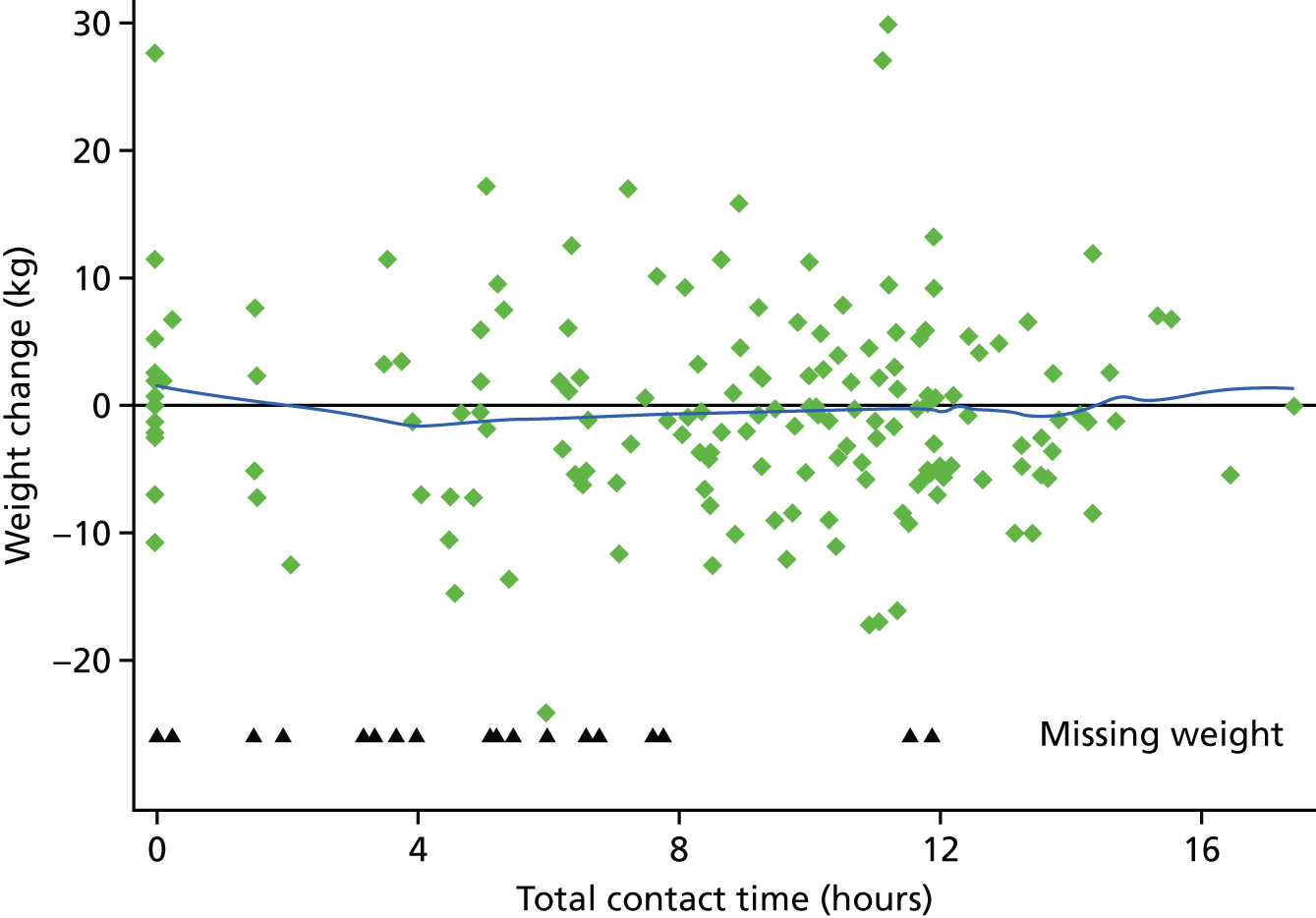

uptake of therapy (non-attender; attended one or two foundation sessions; attended three or four foundation sessions but no booster sessions; attended at least three foundation sessions and one booster session)

-

recruiting centre

-

clinical diagnosis (first episode vs. other diagnoses)

-

time since starting antipsychotic medication (≤ 12 months, > 12 to ≤ 24 months and > 24 months)

-

BMI (≤ 25 kg/m2, > 25 to ≤ 30 kg/m2, > 30 to ≤ 35 kg/m2, > 35 to ≤ 40 kg/m2 and > 40 kg/m2)

-

principal reason for dietary concern, as assessed by the B-IPQ.

Analysis of other outcomes

Other outcomes were analysed using a GEE model, with the covariates being treatment group, site, years since antipsychotic medication initiation and the baseline measurement of the respective outcome.

General considerations

A comprehensive statistical analysis plan was developed before the database freeze and while the statistician was blinded to treatment allocation. Data were reported and presented in accordance with the revised CONSORT statement. 31,59 Analyses were performed on an intention-to-treat basis, unless otherwise stated. Analyses of outcome in relation to protocol compliance were undertaken by looking at the level of course attendance (a subgroup analysis in Analysis of other outcomes) and by complier-average causal effect (CACE), using two-stage least squares regression; the latter defined compliance as attendance of at least one foundation course.

All statistical tests were two-tailed at a 5% significance level and CIs were two-sided, with 95% intervals. No adjustment was made for multiplicity, but the number of outcome measures used necessitates cautious interpretation of statistical significance. All analyses were performed in the Stata® version 14.2 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA) statistical software, using the user-written Stata package rctmiss for the first MNAR model. 60

Process evaluation

Overview

The process evaluation was undertaken ‘to explain discrepancies between expected and observed outcomes, to understand how context influences outcomes, and to provide insights to aid implementation’. 30 Specifically, we investigated whether or not (1) treatment is consistent with the underpinning behaviour change theories (treatment theory or theory of change) and (2) contextual factors affected implementation. The process evaluation used a pipeline logic model, showing causal links between resources, activities and outcomes, integrating the National Institutes for Health Behaviour Change Consortium (NIHBCC)’s approach to treatment fidelity24 and a modified version of Linnan and Steckler’s framework for process evaluation. 61 We described context qualitatively and took a mixed-methods approach to characterising recruitment, reach, dose delivered/received and fidelity both qualitatively and quantitatively, with triangulation between data sources. 62 Interviews were held with intervention designers, health professionals and RCT participants, and the analyses were combined with RCT data and quantitative fidelity data.

Researchers

The qualitative researchers, Rebecca Gossage-Worrall, a female graduate sociologist [Master of Arts (MA); Research Associate], and Daniel Hind, a male graduate anthropologist [Doctor of Philosophy (PhD), Reader], had 8 and 10 years’ experience of interviewing, respectively. No relationship was established with any participant outside or before the interview. The interview purpose was explained to participants twice, at consent to trial and at interview. Two facilitators had a prior relationship with Rebecca Gossage-Worrall (through their study research role) before participating in the interviews. Daniel Hind knew two intervention developers prior to interview via project meetings.

Theoretical and thematic framework

Rationale and worldview63/epistemology64

We incorporated qualitative research to understand the implementation of, and response to, the intervention,65–67 to propose causal pathways to success or failure. 65–68 However, our rationale was primarily pragmatic rather than explanatory;69 we were pursuing a basis for ‘organising future observations and experiences’70 by ‘investigating conceivable practical consequences’71 of future decisions, rather than advancing, building or testing social science theory. 68,72

Research design63/methodology64/approach73

We used a single-case design,74 with the unit of analysis variably at the participant level (n = 24 participants) and at the level of the experimental intervention programme (n = 20 facilitator interviews). In participant case studies, the embedded units of analysis were (1) post-course interview and (2) quantitative CRFs, especially weight at 0, 3 and 12 months.

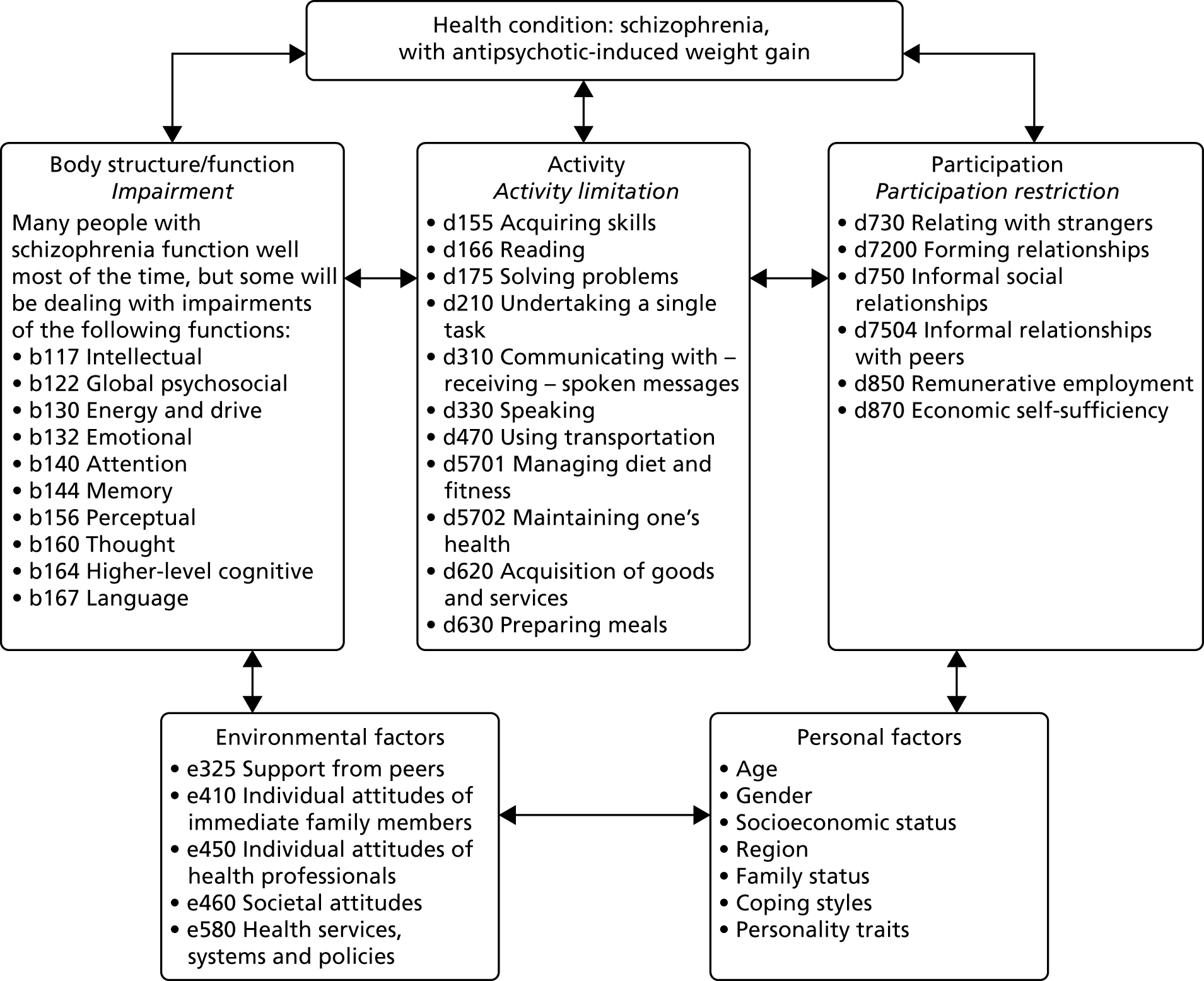

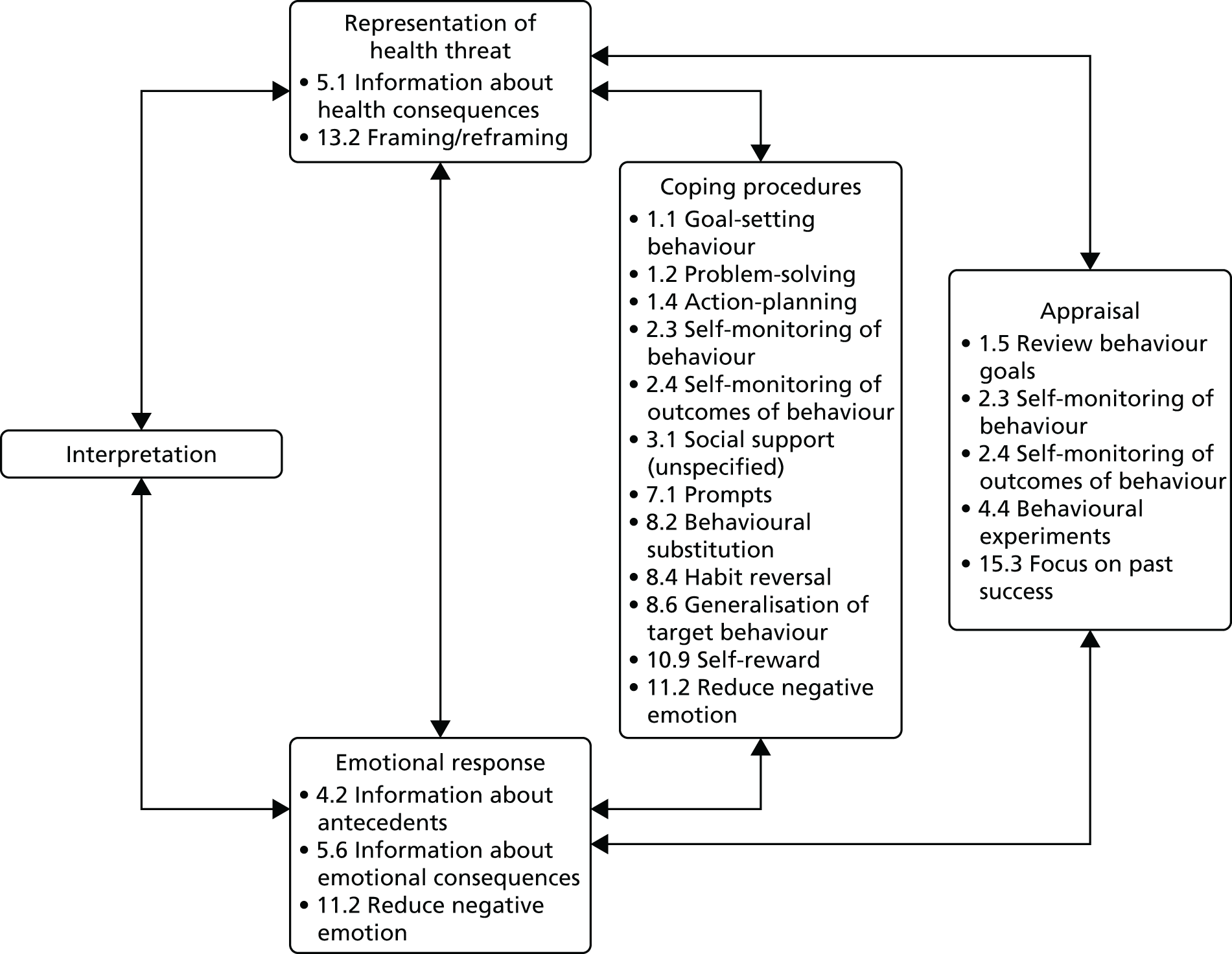

Theory

We used the International Classification of Functioning (ICF) as a conceptual framework for describing the schizophrenia-specific context for implementation. 75,76 We used an a priori framework, based on similar studies,77,78 to inform the topic guide for interviews with participants (Table 3). Topic guides for interviews with health professionals were designed around the normalisation process theory (NPT). 80–83 We used the theoretical domains framework (TDF)84 to characterise stakeholder understandings of the intervention. Codes from the TDF were later mapped to constructs from the principal theories underpinning the STEPWISE intervention: Bandura’s self-efficacy theory,85 the self-regulation theory of Leventhal et al. 86 and Marlatt and George’s relapse prevention model. 87 We used the NIHBCC’s framework for understanding intervention fidelity79 and the framework of Sekhon et al. for understanding the acceptability of health-care interventions. 88

| A priori theme | Example interview question |

|---|---|

| Acceptability77,78 |

|

| Being in a group77,78 |

|

| Presentation of content78 |

|

| Changes in behaviour77,78 |

|

| Processes of change78 |

|

| Types of interventions78 |

|

| Fidelity79 |

|

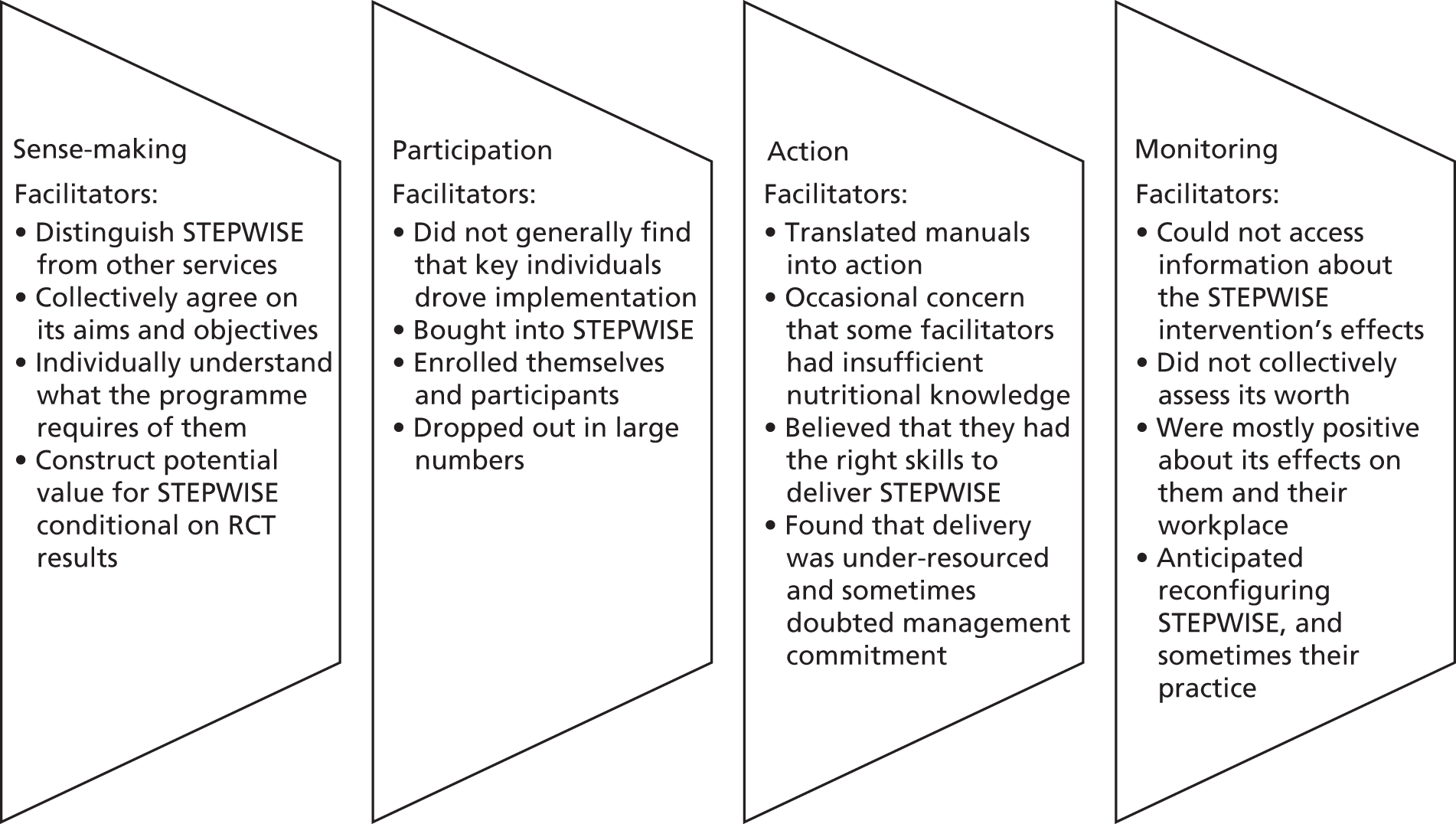

We developed a programme theory to identify essential elements for the successful replication and causes of failure in the contracts, actions, interactions and emergent relationships between people and organisations that surround the STEPWISE intervention. 89–91 The programme theory development was deductive, through literature review and by articulating mental models in discussion with the LDC team, and inductive, through interviews with participants and professionals. 92 To illustrate how sequences of events were to bring about desirable outcomes, as per the programme theory, we developed a logic model (Figure 5). 93,94

FIGURE 5.

Logic model for the implementation of the STEPWISE intervention.

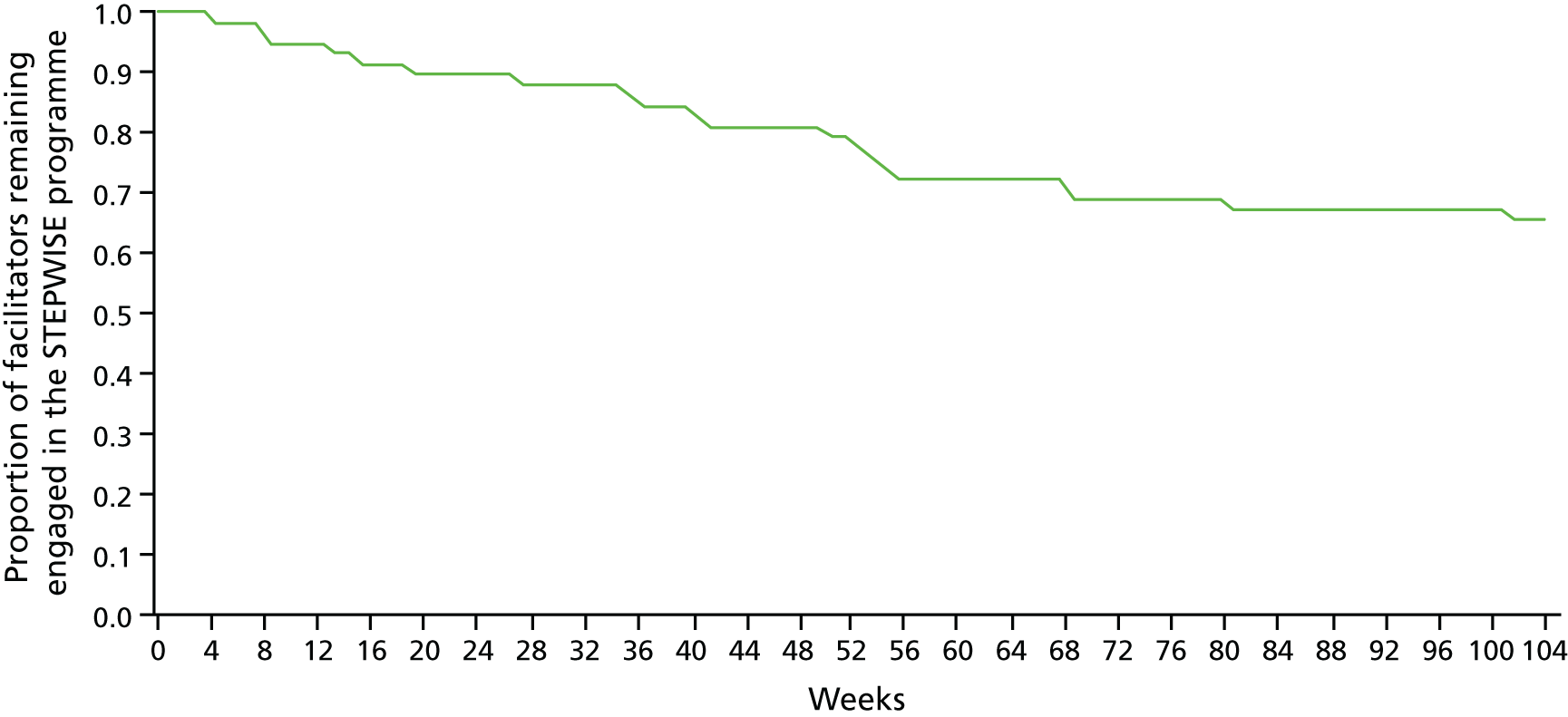

Participant selection and setting

Consent for participant interviews was requested, face to face, at the time of consent to the RCT (when participants specified a preferred method of approach) and reconsented immediately before interview. The majority of participants were approached by telephone. Professionals were approached directly by telephone, e-mailed the information sheet and consented by telephone; intervention designers were approached during project meetings and by e-mail. The RCT intervention arm participants were purposively sampled (n = 24) from those consenting and allocated to the intervention (n = 188) to reflect different study centre, gender and age (Table 4). A total of 63 participants (34%) were sampled, of whom 22 (35%) were non-responsive, despite a minimum of three attempts to contact. Ten participants declined when invited to participate, one declined at (re-)consent and six consented but did not attend the appointment. Forty professionals were purposively sampled to reflect differences in site, occupation, sex and prior group facilitation characteristics (derived from a short survey after completing facilitator training) for invitation to study, of whom 20 were interviewed (Table 5); none formally declined, but many left their employment or were non-responsive, or it became unnecessary to interview them because of accrual of the target sample. All those involved with the intervention design were interviewed. All interviews were conducted by telephone.

| ID | Sex | Age (years) | Diagnosisa | Ethnicity | BPRS score | Sessions | Weight in kg | Weight change in kg | Interview took place after (session) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Foundation | Booster | 0 months | 3 months | 12 months | 0–3 months | 3–12 months | 0–12 months | |||||||

| Clinically important weight loss over 12 months | ||||||||||||||

| S03/Q06 | M | 35 | F20 | White British | 34 | 4 | 3 | 115.5 | 111.7 | 98.3 | –3.8 | –13.4 | –17.2 | Booster 2 |

| S01/Q01 | F | 40 | F20 | African | 27 | 3 | 2 | 106.7 | 101.0 | 94.0 | –5.7 | –7.0 | –12.7 | Foundation |

| S08/Q05 | F | 28 | F25 | White British | 41 | 4 | 3 | 103.4 | 104.9 | 94.1 | 1.5 | –10.8 | –9.3 | Booster 1 |

| S04/Q02 | F | 33 | FEP | African | 34 | 4 | 0 | 92.2 | 93.4 | 86.1 | 1.2 | –7.3 | –6.1 | Foundation |

| S06/Q01 | M | 23 | F20 | White British | 27 | 3 | 2 | 92.7 | 92.6 | 87.5 | –0.1 | –5.1 | –5.2 | Foundation |

| S01/Q05 | M | 40 | F20 | White British | 24 | 4 | 2 | 110.4 | 105.4 | 105.2 | –5.0 | –0.2 | –5.2 | Foundation |

| S02/Q04 | F | 40 | F25 | White British | 31 | 4 | 3 | 74.0 | 71.0 | 69.3 | –3.0 | –1.7 | –4.7 | Booster 2 |

| Weight loss that is not clinically important | ||||||||||||||

| S10/Q03 | F | 39 | F20 | White British | 23 | 3 | 3 | 110.8 | 108.2 | 107.4 | –2.6 | –0.8 | –3.4 | Booster 1 |

| S04/Q09 | M | 48 | F20 | White British | 47 | 3 | 1 | 70.1 | 71.9 | 68.7 | 1.8 | –3.2 | –1.4 | Foundation |

| S09/Q04 | M | 43 | F20 | White British | 25 | 4 | 2 | 125.1 | 110.0 | 123.7 | –15.1 | 13.7 | –1.4 | Foundation |

| S09/Q02 | F | 49 | F25 | White British | 21 | 4 | 3 | 105.5 | 104.4 | 104.2 | –1.1 | –0.2 | –1.3 | Foundation |

| S08/Q06 | F | 44 | F20 | White British | 28 | 2 | 2 | 92.0 | 93.6 | 90.8 | 1.6 | –2.8 | –1.2 | Foundation |

| S01/Q04 | M | 43 | F20 | White British | 33 | 3 | 3 | 96.7 | 97.0 | 96.6 | 0.3 | –0.4 | –0.1 | Booster 1 |

| Weight gain that is not clinically important | ||||||||||||||

| S05/Q03 | F | 54 | F25 | White British | 53 | 4 | 3 | 92.4 | 90.0 | 92.9 | –2.4 | 2.9 | 0.5 | Foundation |

| S06/Q02 | M | 34 | FEP | White British | 32 | 3 | 2 | 121.8 | 126.0 | 123.9 | 4.2 | –2.1 | 2.1 | Booster 1 |

| S03/Q01 | F | 36 | F20 | Bangladeshi | 24 | 4 | 2 | 101.5 | 103.3 | 103.7 | 1.8 | 0.4 | 2.2 | Foundation |

| S04/Q10 | M | 19 | FEP | White British | 36 | 2 | 0 | 84.6 | 83.9 | 87.7 | –0.7 | 3.8 | 3.1 | Foundation |

| S08/Q09 | F | 31 | F25 | White British | 23 | 4 | 1 | 92.4 | 96.4 | 95.5 | 4.0 | –0.9 | 3.1 | Foundation |

| S09/Q01 | M | 54 | F20 | White British | 29 | 3 | 3 | 86.3 | 87.3 | 90.4 | 1.0 | 3.1 | 4.1 | Foundation |

| Clinically important weight gain | ||||||||||||||

| S04/Q12 | M | 30 | FEP | Indian | 26 | 4 | 3 | 120.0 | 124.3 | 125.5 | 4.3 | 1.2 | 5.5 | Foundation |

| S07/Q06 | M | 25 | FEP | White British | 34 | 3 | 2 | 131.6 | 140.0 | 142.9 | 8.4 | 2.9 | 11.3 | Foundation |

| S04/Q08 | F | 32 | FEP | White British | 44 | 4 | 3 | 126.2 | 139.8 | 155.9 | 13.6 | 16.1 | 29.7 | Booster 1 |

| Qualitative participants without weight data | ||||||||||||||

| S04/Q06 | F | 25 | FEP | White British | 34 | 4 | 0 | 86.0 | 94.0 | ND | 8.0 | ND | ND | Booster 1 |

| S06/Q06 | M | 21 | FEP | White other | 39 | 3 | 2 | 91.3 | 79.0 | ND | –12.3 | ND | ND | Booster 1 |

| ID | Professional category | Education | Worked in | Groups facilitated | Confidence in skills (0 = low; 5 = high) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mental health | Physical health | |||||||

| Years | Months | Years | Months | |||||

| S01/F02 | Support worker | City and Guilds of London Institute | 29 | 0 | ND | ND | 1 | 4 |

| S01/F04 | Mental health nurse | PG degree | 8 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 |

| S02/F02 | Healthy living advisor | UG degree | ND | ND | ND | ND | 10 | 4 |

| S02/F03 | Physiotherapist | UG degree | 2 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 10 | 4 |

| S02/F06 | Dietitian | UG degree | 3 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 99 | 4 |

| S03/F02 | Occupational therapist | UG degree | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 24 | 4 |

| S03/F04 | Mental health nurse | UG degree | 11 | 4 | ND | ND | ND | 5 |

| S03/F05 | Community development | UG degree | 8 | 10 | 3 | 11 | 15 | 4 |

| S04/F02 | Support worker | No data | 38 | 4 | 14 | ND | ND | 4 |

| S04/F03 | Clinical studies officer | PG diploma | 6 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 4 |

| S05/F02 | Mental health nurse | PG degree | 17 | 0 | 17 | 0 | 2 | 5 |

| S06/F01 | Research assistant | PG degree | 2 | 0 | ND | ND | 0 | 3 |

| S06/F04 | Mental health nurse | Diploma (college) | 24 | 11 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 4 |

| S06/F05 | Mental health nurse | PG diploma | 7 | 8 | ND | ND | 0 | 3 |

| S07/F05 | Mental health nurse | UG degree | 7 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 |

| S08/F03 | Mental health nurse | UG degree | 26 | 9 | ND | ND | 0 | 4 |

| S08/F05 | Occupational therapist | UG degree | 20 | 0 | ND | ND | ND | 4 |

| S09/F01 | Mental health nurse | Diploma (college) | 25 | 4 | ND | ND | 0 | 3 |

| S09/F03 | Occupational therapist | UG degree | 6 | 7 | ND | ND | 5 | 4 |

| S09/F04 | Pharmacy technician | BTEC degree in Pharmaceutical Science | 8 | 0 | ND | ND | 1 | 3 |

Data collection

Semistructured interview guides for participants (see Appendix 1) and professionals (see Appendix 2) were pilot-tested with the relevant project team members. No topic guide was used for the unstructured interviews with intervention designers, although sections from the behaviour change wheel,95 the logic model and the NIHBCC framework24 were used as prompts. Interviews were recorded on an encrypted digital recorder and field notes were made during and after the interview. The median (range) length of the interviews was 18:57 minutes (13:06–30:33 minutes) for participant interviews, 46:13 minutes (29:29–76:32 minutes) for facilitator interviews and 39:20 minutes (43:39–64:00 minutes) for intervention designer interviews. Data saturation was achieved in the participant, professional and intervention designer data sets. No repeat interviews were carried out and transcripts were not returned to participants for comment/correction.

Data analysis

Two coders (RG-W and DH) coded participant interviews systematically in NVivo version 11 (QSR International, Warrington, UK) to behaviour change theory, intervention functions, theoretical domains95 and dimensions of acceptability,88 as well as opportunistically to the NIHBCC framework79 (see Table 6) and logic model constructs (see Figure 5). Staff interviews were coded systematically to NPT constructs and opportunistically to the NIHBCC framework and logic model constructs. Developer interviews were coded systematically to intervention functions, logic model and NIHBCC framework constructs (see Table 6).

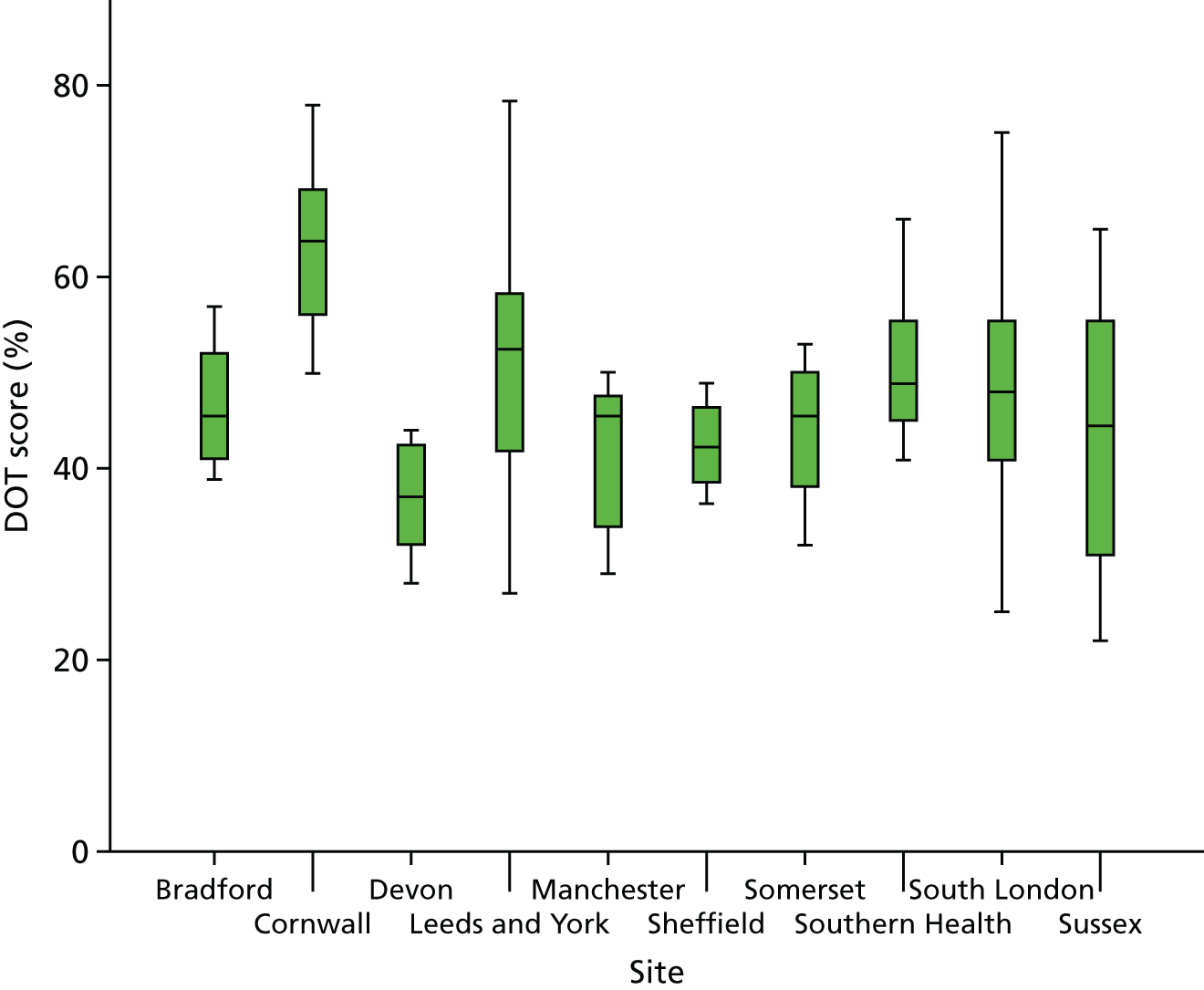

Fidelity assessment

Leicester Diabetes Centre staff monitored the fidelity of intervention delivery through direct observation of sessions, using two instruments. First, the STEPWISE Core Facilitator Behavioural Observation Sheet assesses the relative presence or absence of 35 behaviours in six domains: non-judgemental engagement of participants (five items); eliciting and responding to emotions/feelings (two items); facilitating reflective learning (eight items); behavioural change, planning and goal-setting (nine items); overall group management (nine items); and other behaviours (two items). Second, LDC staff objectively assessed participant–educator interaction during observation visits by means of the DOT (DESMOND Observation Tool). The coder sat at the back of the room, with a compact disc playing in a headphone, from which a beep sounded every 10 seconds, whereupon the coder recorded whether an educator or a participant was currently talking at that point. Silence, laughter or multiple conversations were classed as ‘miscellaneous’. In self-management programme research, a link has been proposed between less facilitator talk and a more effective participant receipt of the education process, defined as a less didactic/more facilitative approach. 96 The national and local infrastructure available for quality control and mentoring in education programmes such as DESMOND was not available for STEPWISE, so feedback of observations in pursuit of accreditation was conducted. Other steps to ensure intervention fidelity are described in Table 6.

| Goal | STEPWISE fidelity strategies |

|---|---|

| Design | |

| Ensure the same treatment dose within conditions |

|

| Ensure an equivalent dose across conditions | Not applicable (no active control) |

| Plan for implementation setbacks |

|

| Training | |

| Standardise training |

|

| Ensure provider skill acquisition |

|

| Minimise ‘drift’ in provider skills | Not applicable (no benchmark established) |

| Accommodate provider differences |

|

| Delivery | |

| Control for provider differences |

|

| Reduce differences within treatment |

|

| Ensure adherence to treatment protocol |

|

| Minimise contamination between conditions |

|

| Receipt | |

| Ensure participant comprehension |

|

| Ensure participant ability to use cognitive skills |

|

| Ensure participant ability to perform behavioural skills |

|

| Enactment | |

| Ensure participant use of cognitive skills |

|

| Ensure participant use of behavioural skills |

|

Triangulation protocol

Different methods and informants were used and a formal framework was employed for comparison of the findings to comprehensively address different questions, increase confidence in findings and provide a basis for feedback from participants and professionals on the project team. 97 No priority was granted to either quantitative or qualitative methods, which were used concurrently to assess the intervention. A modified triangulation protocol62 was employed for the methodological triangulation of data sets, in five stages:

-

Data sets were reviewed to compare for presence and examples (‘sorting’) of logic model constructs.

-

The level of convergence between data types was coded for each of the 22 logic model components as ‘agreement’ (full interpretive agreement between data sets); partial agreement (some disagreement within/between data sets); silence (a logic mode component covered by only one data set); and dissonance [disagreement between data sets (‘convergence coding’)].

-

The global level of convergence was characterised (‘convergence assessment’).

-

Differences in the data set contribution to the case study were summarised (‘completeness comparison’).

-

The triangulated results were shared and points of disagreement were discussed with stakeholders at a face-to-face meeting on 14 July 2017 (‘feedback’), with changes in interpretation being incorporated when supported by the data. A formal comparison of researcher coding was not conducted, owing to time constraints and a rapidly evolving analysis strategy.

Health economic methods

Introduction

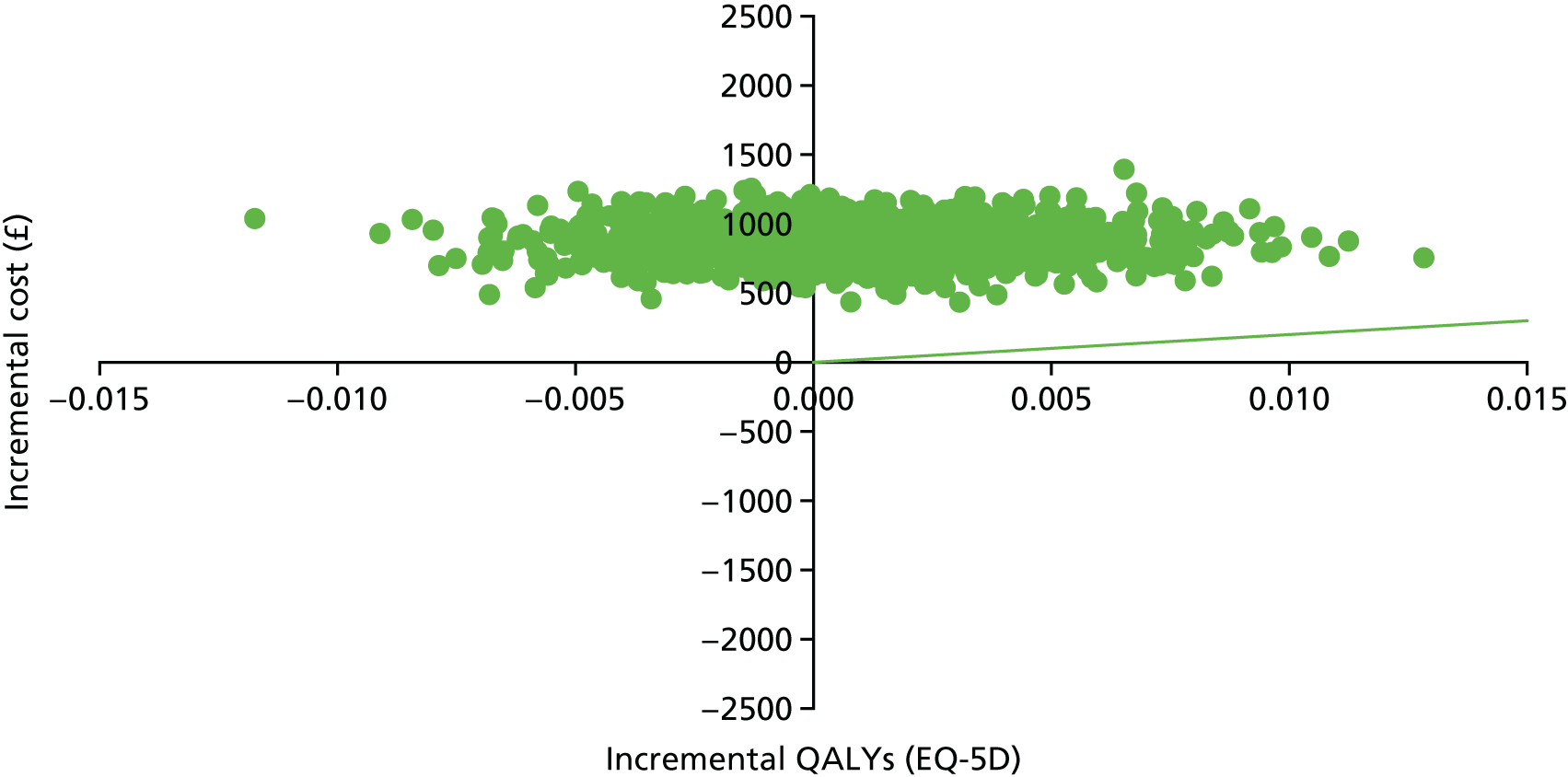

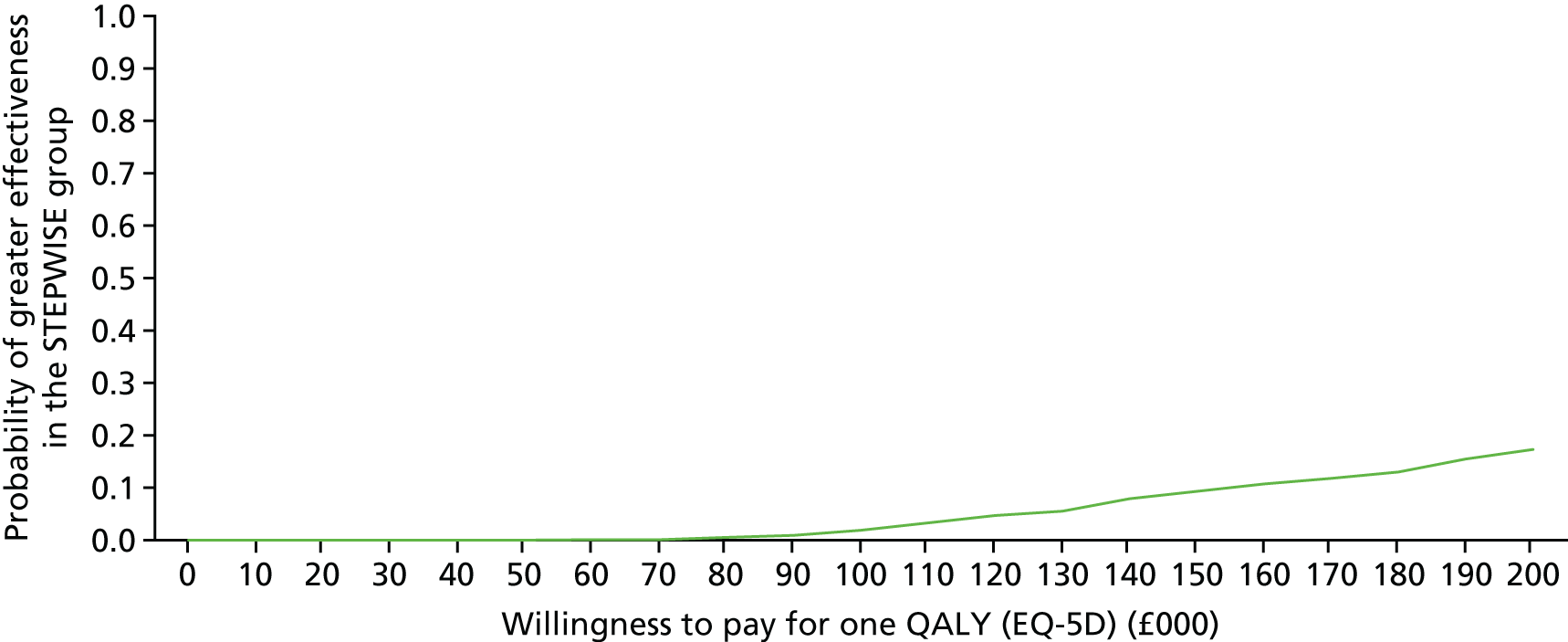

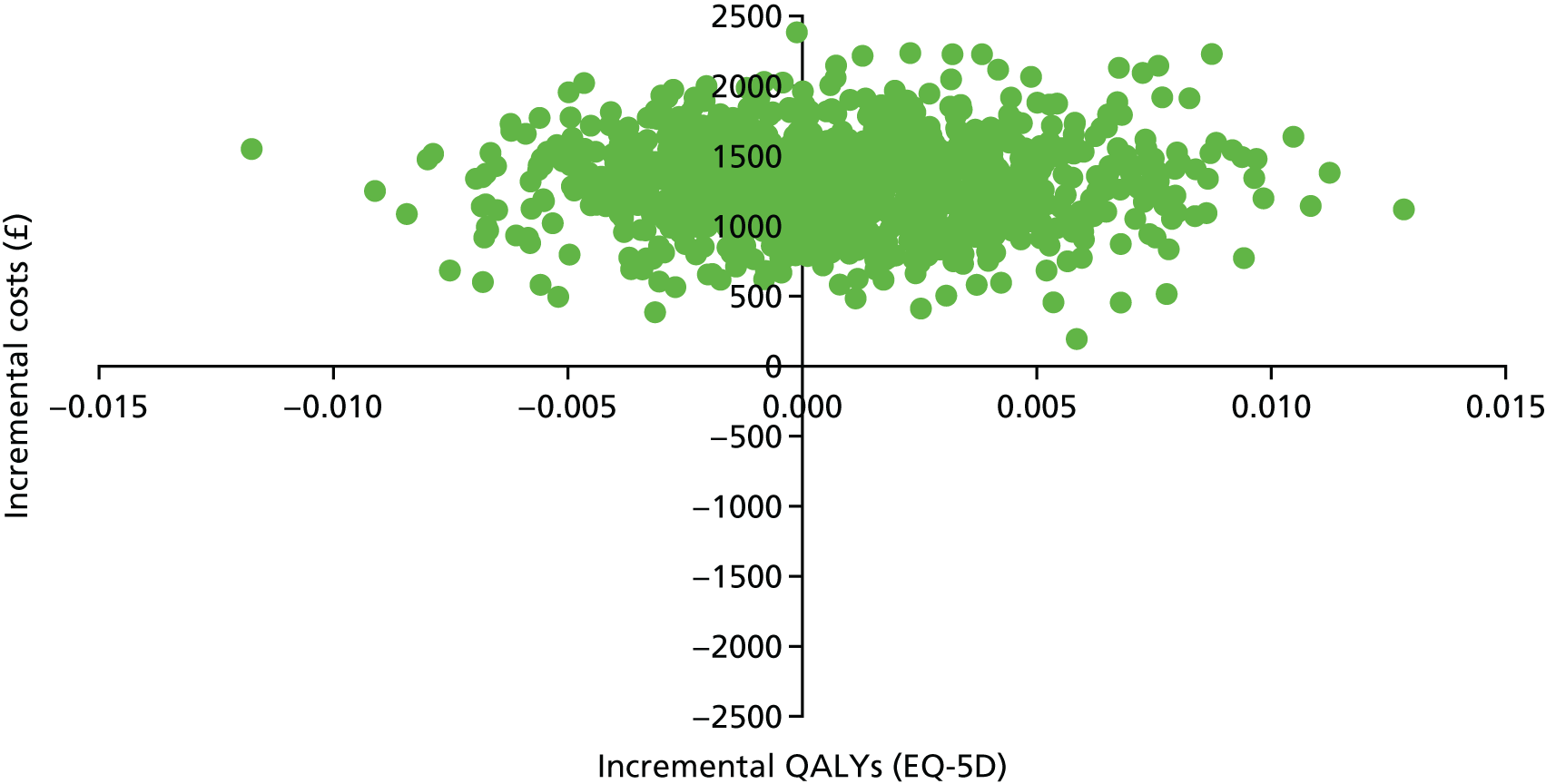

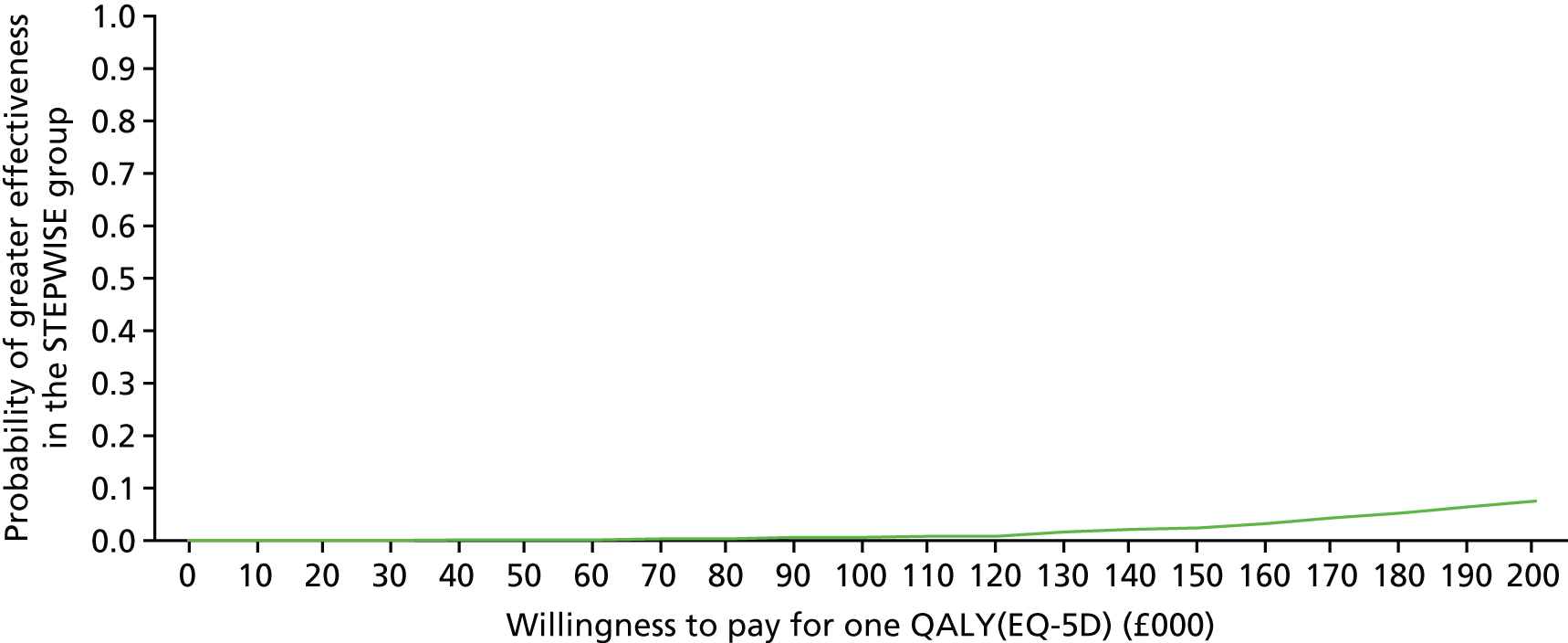

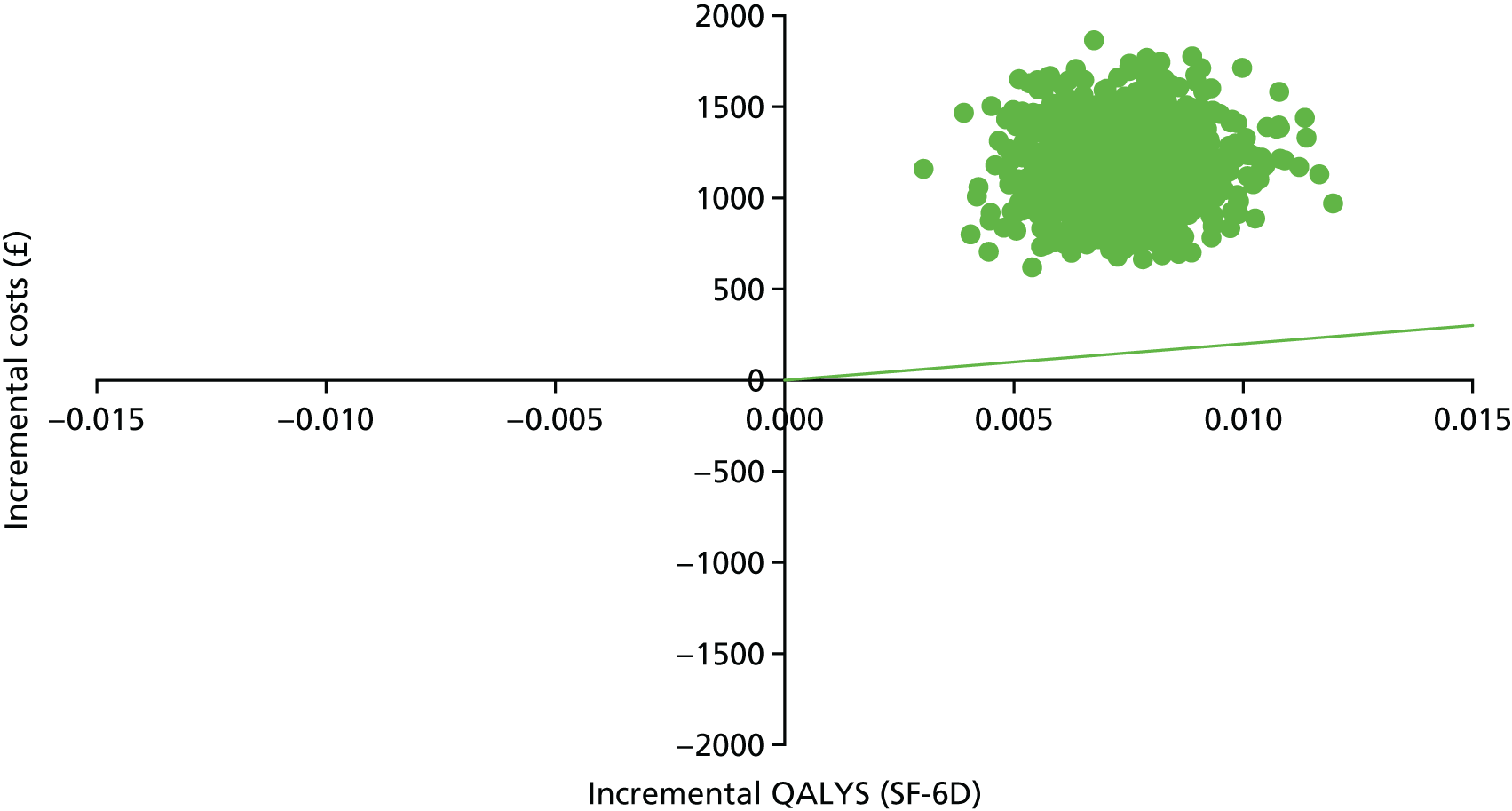

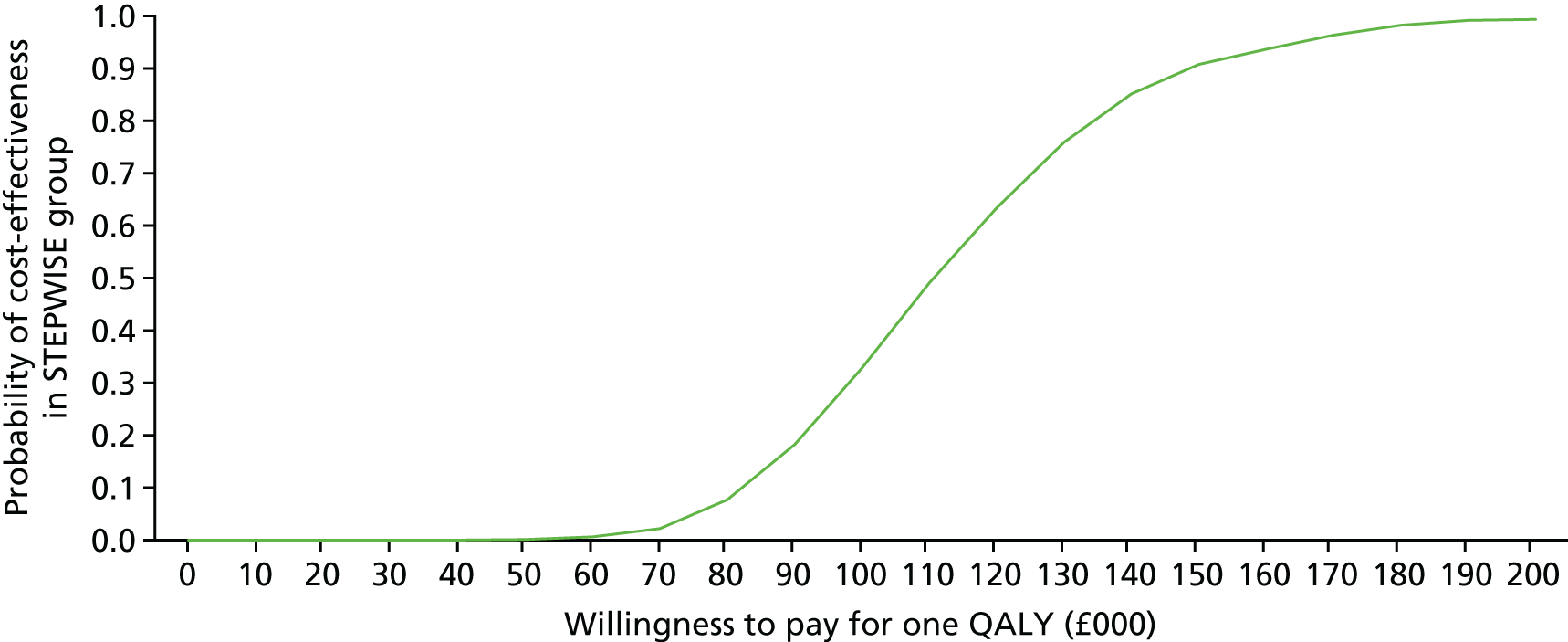

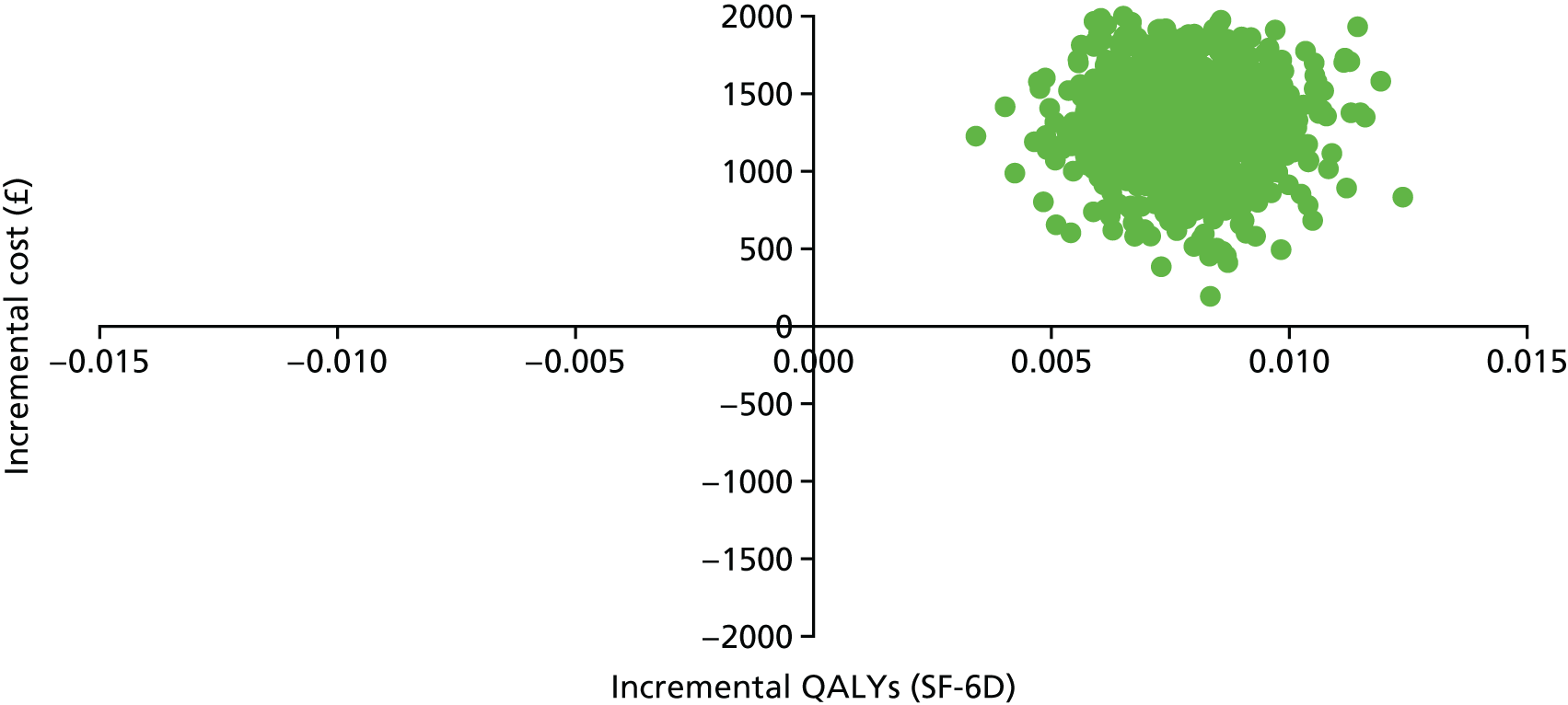

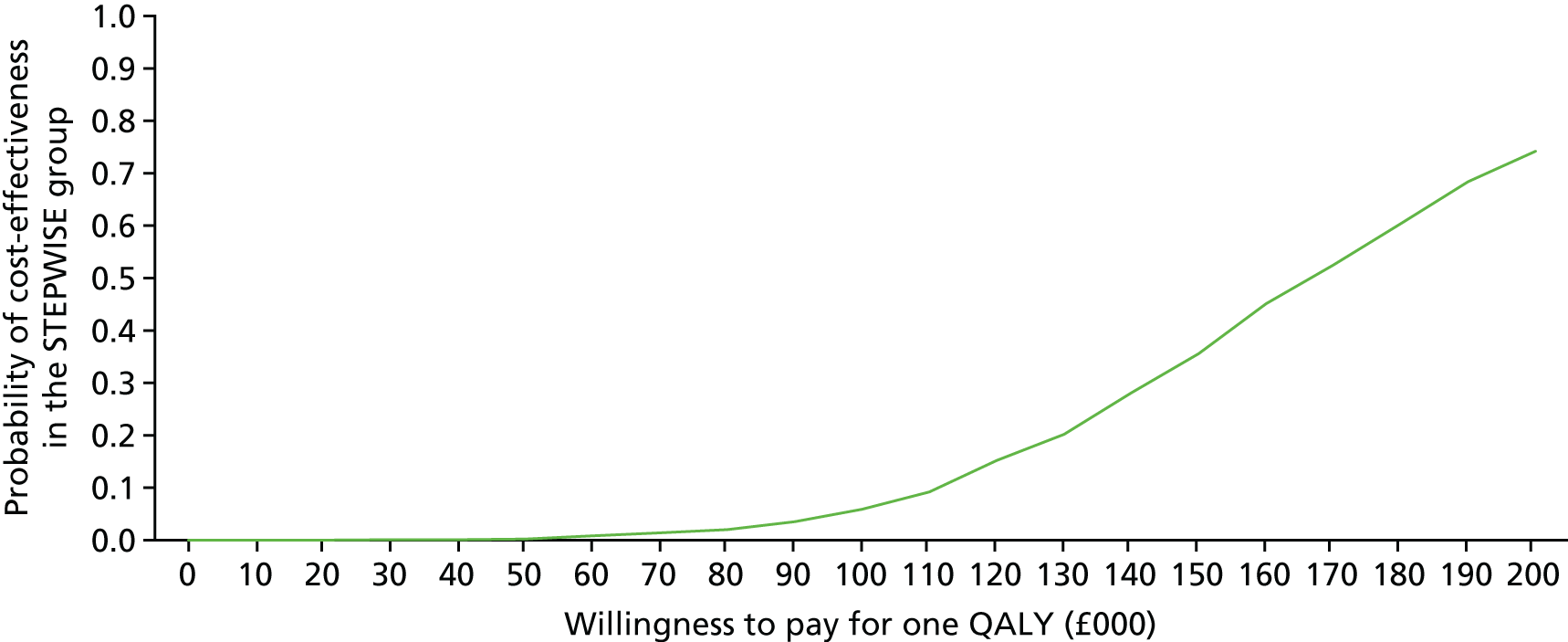

The economic evaluation of the STEPWISE trial was conducted using both health and social care and societal perspectives. Individual participant data were used in the analysis to generate results for the cost-effectiveness of the intervention regarding its impact on cost-relative quality-adjusted life-years (QALYs), derived from the EQ-5D-5L and the SF-36 questionnaires, and weight change. The time horizon of the trial (3- and 12-month follow-up) was the same in the economic evaluation. The economic analyses included all trial participants. The comparison was between the group receiving the STEPWISE intervention and the group receiving a leaflet with advice. This analysis determined cost-effectiveness using the £20,000-per-QALY-gained threshold set by NICE. A sensitivity analysis was used to establish the effect of changes in costs and QoL measurement (comparing results using utility values from the EQ-5D and the SF-36)51,98 on the results. Value sets for health-related QoL measures related to value sets containing preferences from a population in England for the EQ-5D-5L51 and in the UK for the SF-36. 98

Health and social care costs