Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 10/101/02. The contractual start date was in December 2012. The final report began editorial review in August 2017 and was accepted for publication in February 2018. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Anthony P Morrison reports personal fees from the provision of training workshops in cognitive–behavioural therapy (CBT) for psychosis and royalties from books on the topic, outside the submitted work. Andrew Gumley reports grants from the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Health Technology Assessment (HTA) programme (grant number 13/15/04) outside the submitted work. Douglas Turkington reports personal fees from Insight–CBT partnership (Insight Healthcare, Newcastle upon Tyne), outside the submitted work. Gemma Shields reports grants from NIHR during the conduct of the study. Graeme MacLennan reports grants from the NIHR HTA programme during the conduct of the study. Hamish J MacLeod reports that he occasionally provides CBT for psychosis workshops and receives fees for this work. John Norrie reports personal fees from the NIHR Editors Board and grants from NIHR HTA General Board Deputy Chairperson, outside the submitted work, and has membership of the HTA Funding Boards Policy Group and Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis Impact Review Panel. Linda Davies reports grants from the NIHR HTA programme during the conduct of the study. Paul French has membership of the HTA prioritisation Panel. Paul Hutton reports that he sits on an Expert Steering Group for Professor Jill Stavert’s Centre for Mental Health and Incapacity Law Rights and Policy at Edinburgh Napier University, and that he is a member of a committee developing National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidelines on supporting decision-making for people who may lack mental capacity. Robert Dudley reports receiving a NIHR Comprehensive Local Research Network Greenshoots award to fund time to support his contribution to the FOCUS (Focusing on Clozapine Unresponsive Symptoms) trial, royalties from Guilford Press and personal fees from Trinity College Dublin, outside the submitted work. Samantha Bowe reports personal fees from Pennine Care NHS Foundation Trust and personal fees from Cheshire & Wirral Partnership NHS Foundation Trust, outside the submitted work. Thomas RE Barnes reports personal fees from Sunovion (Marlborough, MA, USA) and Otsuka (Tokyo, Japan)/Lundbeck (Copenhagen, Denmark), outside the submitted work.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2019. This work was produced by Morrison et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2019 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Introduction

Psychosis and schizophrenia

The term psychosis is used to refer to a mental health problem that can involve changes to a person’s perceptions and/or to their thoughts. A person who has experience of psychosis may report perceptual changes such as hearing a voice that another person cannot hear, or seeing something that another person cannot see. Perceptual changes may also occur to a person’s taste, smell and/or bodily sensations. Such perceptual changes are typically referred to as hallucinations. A person experiencing psychosis may also report beliefs that others around them consider unusual, that are out of keeping with their social or cultural background and that are lacking rational grounds (often referred to as delusions). Common delusional beliefs include feelings of being persecuted, ideas of reference and feelings of importance. 1 Persecutory beliefs are thought to be the most commonly occurring of the range of delusional beliefs. 2 Experiences of hallucinations and delusions can be distressing and confusing and can have a negative impact on functioning. In addition, a person with experience of psychosis may report changes in their ability to concentrate or may communicate in a manner that is hard for other people to understand, which is commonly referred to as thought disorder. In both clinical practice and research, delusions, hallucinations and thought disorder are typically referred to as positive symptoms of psychosis. In addition, people who experience psychosis may report flat affect (blunted affect), a decrease in verbal output and verbal expressiveness, loss of motivation (including social withdrawal) and loss of enjoyment. 3 These experiences are often referred to as negative symptoms. This term was originally proposed because these changes refer to the loss or absence of usually present functions or characteristics. 4–6 Estimates suggest that 15–20% of people who receive a schizophrenia diagnosis will experience persistent negative symptoms. 7,8

Psychosis is considered to exist on a continuum,9 from the occasional occurrence of psychotic phenomena in the general population9–12 to persistent and frequent psychotic symptoms resulting in distress and, in many cases, the need for care from a mental health service. Someone who experiences psychosis and presents to mental health services for care may receive a schizophrenia spectrum diagnosis. Experiences of psychosis are often categorised using a diagnostic classification system, namely the International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision (ICD-10),13 or the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-V). 14 Schizophrenia spectrum diagnoses include schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, delusional disorder and schizophreniform disorder. However, there has been considerable debate over the use of such diagnostic terms and classification systems. 15 One argument is that these classification systems suggest that psychosis difficulties are dichotomous rather than continuum based. 9 In addition, concerns have been raised regarding the reliability of the diagnostic classification systems used. 16 The diagnostic label of schizophrenia has become stigmatising, with intrinsic negative associations about prognosis17 leading some countries to drop the term schizophrenia. 18 The use of diagnostic terminology has, therefore, been contentious and Murray,19 in 2017, highlighted the burgeoning evidence that schizophrenia is not a dichotomous condition, but rather the severe end of a continuum. Murray19 expects to see the end of the concept of schizophrenia in the future. However, diagnosis and diagnostic terminology is commonly utilised throughout both clinical practice and research. For the purpose of this report, we wish to acknowledge this debate and, throughout, we will adopt respectful terminology. When reviewing the literature relevant to the Focusing on Clozapine Unresponsive Symptoms (FOCUS) trial, we use the terms psychosis and schizophrenia, depending on the sample of participants recruited to the studies being referred to. In relation to the sample of participants included in the FOCUS trial, we refer to the population as people who meet the criteria for a schizophrenia spectrum diagnosis or people who meet the criteria for clozapine-resistant schizophrenia (CRS).

Prevalence rates and the personal, social and economic impact of schizophrenia

A first episode of psychosis typically occurs in young adults; a review of the literature on the age at onset of mental health disorders by Kessler et al. 20 found that, for those with a schizophrenia diagnosis, the age at onset is usually between 15 and 35 years of age. Reports of the lifetime prevalence in the literature vary from 0.12 to 1.6 per 100 persons. 21 In the UK, a systematic review22 commissioned by the Department of Health and Social Care reported that the incidence rate for all clinically relevant psychosis diagnoses is 31.72 per 100,000 persons per year, and for schizophrenia is 15 per 100,000 persons per year; the incidence of the latter being the same as the international incidence rate for schizophrenia reported by McGrath et al. 23

Although the prevalence of schizophrenia is relatively low, the personal, social and economic costs are considerable and the management of schizophrenia is among one of the largest health challenges globally as well as for the UK NHS. For example, Kirkbride et al. 22 report that, in 2009, the estimated economic costs for services and society attributable to broadly defined schizophrenia amounted to £8.8B. The majority of the costs were attributable to lost employment (47%) and service costs (40%). Using disability-adjusted life-years lost as a measure of the overall number of years lost as a result of ill health, disability or early death, schizophrenia was ranked eighth among mental health diagnoses and brain disorders in Europe in 2010. 24

Considerable health inequalities are reported for people who have a schizophrenia diagnosis, with increased risk of serious diseases, such as diabetes mellitus, cardiovascular disease (CVD), a human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection and respiratory problems. 25 The prevalence of CVD among those with a schizophrenia diagnosis is estimated to be 75%, compared with an estimated 50% in the general population. 26 Of great concern is the mortality risk associated with schizophrenia. A recent systematic review and meta-analysis27 of the literature on potential life lost and life expectancy in schizophrenia found that, on average, people with a diagnosis of schizophrenia die 14.5 years earlier than those in the general population. The same authors27 report that the average life expectancy for people with a schizophrenia diagnosis is 64.7 years (for men and women combined); among men only, the average life expectancy is 8 years shorter than in the general population. The estimated risk of suicide in the general population is 1%, in comparison with 10% in those with a schizophrenia diagnosis. 26 In addition to the health inequalities outlined above, people with a schizophrenia diagnosis face widespread public stigma and discrimination, representing further inequalities and a major challenge to recovery. The incidence of anticipated, experienced and internalised stigma is high among people with psychosis. 28,29 A large-scale survey of people with schizophrenia diagnoses across 27 different countries found that nearly half of the respondents felt at a disadvantage as a result of having a diagnosis of schizophrenia, because of stigma. 29 Nearly half of the sample reported interpersonal/social difficulties with making or keeping friends and around one-quarter identified feeling at a disadvantage in terms of finding and keeping work and in relation to their personal safety. 29

Given the significant personal, societal and economic costs associated with schizophrenia, the treatment and care provided for people who meet the criteria for schizophrenia spectrum diagnoses should be a priority for policy-makers, commissioners and service providers.

Treatment options for people with a schizophrenia diagnosis

In this section of the report, we will consider the evidence base for treatments for people with a schizophrenia diagnosis considering both pharmacological and psychological interventions. We will begin the section with a consideration of the efficacy of antipsychotic medication, with a particular emphasis on treatment options for people with a schizophrenia diagnosis who have a poor response to antipsychotic medication. We will outline the psychological interventions recommended by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE), with a specific emphasis on cognitive–behavioural therapy (CBT), given that this is the intervention evaluated by the FOCUS trial. We will consider the efficacy of CBT in conjunction with antipsychotic medication with a particular emphasis on efficacy for CRS.

Antipsychotic medication

The NICE guideline30 for psychosis and schizophrenia in adults recommends, for people with a first episode of psychosis, an acute exacerbation or recurrence of psychosis or schizophrenia, that oral antipsychotic medication be offered. The NICE guideline30 does not make a specific recommendation for the type of antipsychotic offered, that is first-generation antipsychotics (FGAs) or atypical/second-generation antipsychotics (SGAs). The range of antipsychotic medications in both of these classes differ in their psychopharmacological properties, efficacy and adverse effect profiles. 31 A recent systematic review and meta-analysis32 of placebo-controlled antipsychotic medication trials identified a total of 167 double-blind randomised controlled trials (RCTs) with a total sample of 28,102 people with a schizophrenia diagnosis. Meta-analysis of the data found a small to medium effect size (ES) for overall efficacy of 0.47, but this reduced to a small ES of 0.38 when looking at rigorous trials. Leucht et al. 32 reported that 23% of the participants who received antipsychotic medication had a ‘good’ response (defined as ≥ 50% change on the primary outcome), compared with 14% in the placebo group, with an absolute difference of 9%. Although the percentage is greater for those who receive antipsychotic medication, the authors32 conclude that this is still only a minority of participants who have a good response. With regard to the superiority of FGAs versus SGAs, a meta-analysis31 of studies comparing FGAs and SGAs found that four SGAs demonstrated superiority over FGAs in reducing overall symptoms for people with a schizophrenia diagnosis, with small to moderate ESs; specifically, these were amisulpride (ES = 0.31), clozapine (ES = 0.52), olanzapine (ES = 0.28) and risperidone (Risperdal, McGregor Cory Ltd) (ES = 0.13). However, direct comparisons of FGAs with SGAs in large, rigorously conducted, publicly funded RCTs33,34 have found no differences in efficacy, leading some to conclude that the class of ‘atypical’ antipsychotics has been fabricated for marketing purposes and has no basis in science or clinical practice. 35

Antipsychotic medication is the mainstay of treatment for people who meet the criteria for a schizophrenia diagnosis; however, it has been argued that evidence from meta-analyses demonstrates that the superiority of antipsychotic medication over placebo has been overestimated. 36 In addition, antipsychotics have a wide range of side effects, such as metabolic effects (including weight gain), cardiovascular effects, hyperprolactinaemia, antimuscarinic side effects (dry mouth, blurred vision and cognitive impairment), sexual dysfunction and movement disorders. 37 The adverse effects of antipsychotic medication are associated with increased stigma, physical morbidity and mortality, poor adherence and reduced quality of life. 37 A systematic review38 of the effects of antipsychotic drugs on brain volume concluded that some of the structural brain changes found in people with a schizophrenia diagnosis may be the result of antipsychotic medication. The headline result from the largest study34 to date to compare FGAs with SGAs was that 74% of participants discontinued their study medication before 18 months, which indicates issues of tolerability and adherence to antipsychotic medication.

Morrison et al. 36 argue that the adverse effects of antipsychotic medication have been underestimated, and authors of a recent review39 of antipsychotic medication as a treatment for people with a schizophrenia diagnosis concluded that ‘we still remain a long way from being able to recommend with precision, specific treatments for individual patients, in terms of the clinical response and lack of adverse events’ (Lally and MacCabe39).

A choice of treatments for people with experience of psychosis or with a schizophrenia diagnosis and an evidence base for these treatments is, therefore, imperative.

Treatment-resistant schizophrenia

It is common for the symptoms experienced by someone with a diagnosis of schizophrenia to become progressively more unresponsive to medication with subsequent relapses. 40 Findings from a recent systematic review conducted by Kennedy et al. 41 indicate a 60% failure rate to achieve a response to treatment with standard antipsychotic medication after 23 weeks. The persistence of symptoms after adequate treatment with antipsychotic medication is commonly referred to in the literature and clinical practice as ‘treatment-resistant’ schizophrenia (TRS); for comparison with the literature, we will utilise the terminology ‘people with experience of TRS’ throughout this report. Global estimates of the prevalence of TRS would suggest that 7.8 million people worldwide are experiencing TRS. 42 As outlined in Prevalence rates and the personal, social and economic impact of schizophrenia, people with a schizophrenia diagnosis frequently experience health inequalities; for the TRS group, these health inequalities are inflated. The mean quality of life score for those who meet TRS criteria is 20% lower than for people with a diagnosis of schizophrenia whose symptoms are considered to be in remission. 41 Moreover, in comparison with other mental health diagnoses that are considered to be ‘severe and enduring’, those with TRS have worse outcomes in terms of both symptoms, as measured by the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS), and social/functional outcomes, with TRS being a predictor for poor community functioning. 43 For the person experiencing TRS, the continued presence of symptoms represents a barrier to recovery and improvements in quality of life, and increased personal social/economic costs. 41 In sum, the importance of identifying effective treatments for this group cannot be overstated.

In defining criteria for TRS, many researchers and clinicians have referred to the following conceptualisation of TRS, outlined by Kane et al. :44 two periods of treatment with different antipsychotics at an adequate dose for ≥ 4 weeks without a ≥ 20% reduction in symptoms. Since the publication of the Kane et al. 44 study, there have been numerous investigations of treatments for people with TRS; however, these studies often use different definitions of TRS. A systematic review45 of the TRS literature highlights the fact that the definition of TRS has been inconsistent across numerous clinical trials for TRS, and it is argued that the lack of clarity regarding the definition of TRS is a limiting factor for translating the research findings into clinical practice. It also increases heterogeneity across the studies and, therefore, reduces the conclusions that can be drawn from meta-analyses. 45 Furthermore, the international guidelines utilised by clinicians working in the field use varying definitions of TRS (e.g. NICE guidelines30). In the UK, NICE does not specify a duration of treatment of an episode that it deems adequate, unlike the American Psychiatric Association, which specifies a duration of ≥ 6 weeks. In response, the Treatment Response and Resistance in Psychosis (TRRIP) working group was convened to develop criteria for treatment resistance in schizophrenia. This work represents an important development in research and practice in the field of TRS. Howes et al. 45 note that, of the 42 studies identified as eligible for their systematic review, only two, from the same research group, used identical TRS criteria. Based on the systematic review conducted by Howes et al. ,45 an online survey of the TRRIP group members (identifying agreements and disagreements) and meetings of the TRRIP group members, the following criteria for TRS have been recommended: (1) current symptoms of a minimum duration and severity determined by a standardised rating scale that includes both positive and negative symptoms, that is, the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS) or PANSS; (2) moderate or worse functional impairment; (3) prior treatment of at least two different antipsychotics, each for a minimum duration and dosage; (4) systematic monitoring of adherence and meeting of minimum adherence criteria; (5) at least one prospective treatment trial; and (6) criteria that clearly separate responsive from treatment-resistant patients. 45

The NICE guideline30 treatment recommendation for people diagnosed with TRS is to review diagnosis and adherence to medication, ensure that the medication prescription is at an adequate dose for the correct period of time, consider possible causes of non-response, such as substance misuse and physical health problems, and offer psychological intervention [CBT and family intervention (FI)]. For those who experience persistent symptoms of schizophrenia following adequate treatment with at least two different antipsychotic drugs (at least one of which should be a non-clozapine SGA), a trial of clozapine should be offered. 30 Clozapine is a SGA and it is currently considered to be the treatment of choice for people with TRS,46 as demonstrated by the NICE guideline recommendation. 30 However, clozapine has a number of adverse effects and, in comparison with FGAs, clozapine is associated with more frequent haematological problems, drowsiness, hypersalivation and temperature increases. 47 The most dangerous adverse effect associated with clozapine is agranulocytosis, which is a haematological disorder of the white blood cells that help fight infection. The unwanted side effects of clozapine can prevent the optimal dose of clozapine being reached or tolerated over time, and data from a cohort study in the UK showed that 45% of people discontinued treatment with clozapine within the first 2 years of the drug being initiated. 48 Results of the same study also suggest that tolerability and adverse drug reactions play a key role in patient-led decisions to discontinue clozapine: in just over half of cases, the reason given for discontinuation was adverse drug reactions, with sedation being the most frequently reported. 48

The use of clozapine as a treatment for TRS grew in popularity following the highly influential double-blind study of clozapine versus chlorpromazine conducted by Kane et al. 44 Since this study, there has been an increased number of RCTs comparing clozapine with FGAs, paving the way for subsequent meta-analyses of these trials. Essali et al. 47 conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis of trials comparing clozapine with FGAs, identifying a total of 42 eligible trials with 3950 participants. Although there was no difference in mortality or employment status between those on clozapine and those receiving FGAs, clozapine was superior in relation to clinical improvements, reduced relapse rates and greater reduction in BPRS scores. Although the meta-analysis conducted by Essali et al. 47 suggests superiority of clozapine over FGA, the authors note problems of heterogeneity with the data and the high risk of bias across the studies. 47

There has been some debate regarding the efficacy of clozapine in comparison with other antipsychotic medications. Two meta-analyses49,50 of clozapine versus treatment with standard antipsychotic medication were published in 2016. Both meta-analyses found that clozapine was no more effective in the long term for total psychotic symptoms than other antipsychotic medications. However, Siskind et al. 49 report that for positive symptoms clozapine is superior to other antipsychotic medications in both the short and the long term. Given the absence of superiority over other antipsychotic medications for total symptoms in the long term, Siskind et al. 49 recommend that, for patients who do not respond to clozapine by 6 months, other antipsychotic medications with lower side effect profiles should be considered. The network meta-analysis by Samara et al. ,50 which integrated all published and unpublished single- and double-blind RCTs of all antipsychotic medications for TRS, found that there was little evidence of efficacy of antipsychotic medications other than clozapine, haloperidol, olanzapine and risperidone. The authors50 concluded that there is, however, insufficient evidence to determine which of these medications are most effective for people with TRS, commenting that ‘The most surprising finding was that clozapine was not significantly more efficacious than most other drugs’ (Samara et al. 50) and arguing that there is a need for blinded studies of antipsychotic medication for TRS. 50 Howes et al. 45 note that the conclusions that can be drawn from the network meta-analysis by Samara et al. 50 may be limited by the heterogeneity across the studies included in the review. Clearly, it is challenging when two meta-analyses with similar research questions are published within the same year, making it difficult for clinicians, researchers and commissioners to interpret the data; however, clozapine remains the mainstay of treatment for TRS.

Clozapine-resistant schizophrenia

Around 30–40% of people who trial clozapine will experience a poor response to this medication. 51 Moreover, the range of adverse effects from clozapine means that the optimal dose may not always be reached or clozapine may not be tolerated long term. In both the research literature and clinical practice, a person who experiences a poor response to clozapine is typically said to have ‘clozapine-resistant schizophrenia’ (CRS) and, for this reason, we use that term in this report. CRS is defined as the persistence of symptoms after treatment with clozapine for ≥ 12 weeks at a stable dose of ≥ 400 mg per day, unless the dose was limited by side effects. 52

The most frequent approach to the treatment of CRS is to augment clozapine with another antipsychotic medication. 53,54 This is an approach taken frequently in clinical practice. 53,54 Clozapine has low antidopaminergic properties and, therefore, is often combined with an antipsychotic medication that has dopaminergic properties. 53 There is some evidence of small but significant benefits of clozapine augmentation with a second antipsychotic,54,55 but studies are scarce. 56 There is some indication that augmentation with risperidone may have adverse effects, as evidence from the Cochrane review57 comparing risperidone with placebo suggests that adding risperidone to clozapine treatment leads to reduced functioning. Not only are antipsychotic augmentation studies infrequent, but their results are highly heterogeneous, which limits the conclusions that can be drawn from meta-analyses. 54 Many of the studies to date are subject to detection bias, with concealment of allocation unclear in eight of the studies included in the meta-analysis of antipsychotic augmentation conducted by Taylor et al. 55 With this representing just over 50% of the studies included in the review, findings may be compromised by the risk of detection bias. Moreover, several of the studies included in the systematic review conducted by Porcelli et al. 54 were rated as being of low quality, with the mean quality assessment score across the 24 studies being 5.43 points (SD 1.88 points, range 3–8 points), with 0 points being the minimum score and 9 points being the maximum score.

A systematic review and meta-analysis conducted by Taylor et al. 55 identified 14 RCTs, with a total sample of 734 participants, that compared clozapine plus a second antipsychotic with clozapine plus placebo for ≥ 6 weeks’ duration. Augmentation with a second antipsychotic was found to have a small but significant effect over placebo, with an ES of 0.239. The long-term adverse effects of clozapine augmentation with a second antipsychotic are unclear from the Taylor et al. 55 review because 11 of the 14 trials followed up participants for only ≤ 10 weeks. Potential long-term adverse effects include hyperprolactinaemia and increased striatal dopamine blockade. 55 There is scarce evidence to answer the question of which combination strategy of clozapine and another antipsychotic medication is more effective. Sommer et al. 56 conducted a systematic review of 29 randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trials of clozapine augmentation with a second drug, including augmentation with drugs from a different class (i.e. not an antipsychotic). Of these, 10 trials evaluated the efficacy of augmentation with another antipsychotic and included amisulpride, aripiprazole, haloperidol, risperidone and sulpiride. Only clozapine augmented with sulpiride proved superior to placebo in reducing symptom severity, and this finding was from one small trial (with a sample size of n = 28).

The most recent review of clozapine augmentation with another antipsychotic medication was carried out by Barber et al. 58 The aim was to evaluate the efficacy and tolerability (in terms of side effects) of clozapine combined with various antipsychotic medications. The search yielded a limited number of studies, which were of low quality and high heterogeneity. In total, five studies met the inclusion criteria, yielding a total of 309 participants. Findings from the review demonstrated that there are a very limited number of studies that can indicate the superiority of one clozapine combination strategy over another, and the evidence that is available is of low quality. The current evidence does not allow a specific clozapine augmentation strategy to be recommended; individual pragmatic trials may be indicated, but, given the increased risk of adverse effects from polypharmacy, augmentation with a second antipsychotic should be discontinued if the benefits do not outweigh the risks.

An alternative strategy that has been evaluated is augmenting clozapine with another medication of a different class, namely benzodiazepines or antidepressants. In a review, Dold and Leucht53 argued that there is currently insufficient evidence for this approach, although they do recognise that targeted use of augmentation may be indicated in specific cases, such as the use of medication to target agitation.

In summary, the literature regarding the efficacy of treatments for TRS indicates that a significant proportion of people will experience CRS and continue to experience persistent difficulties. The evidence base for treatments for CRS is sparse59 and augmentation strategies with a second antipsychotic demonstrate small effects. 55

Psychological interventions

Psychological therapies for people with psychosis have been extensively evaluated in recent years. Clinical trials and subsequent meta-analyses have evaluated individual and group treatments (including CBT, supportive counselling, befriending, narrative therapies and psychodynamic approaches), FIs (individual or multifamily) and art therapies (including music therapies, dance therapy and art therapy). After thoroughly reviewing the evidence base, the NICE guideline30 currently recommends that all people with experience of psychosis or with a schizophrenia diagnosis should be offered CBT and FI, and for those who experience TRS or CRS it is recommended that the care team review the person’s engagement with and use of both of these psychological treatments. 30

Cognitive–behavioural therapy

The generic cognitive model60 has been applied to our understanding and treatment of schizophrenia. This cognitive model suggests that the way in which we interpret events has consequences for how we feel and behave, and that such interpretations are often maintained by unhelpful thinking biases and behavioural responses. Cognitive models of psychosis and psychotic experiences suggest that it is the way in which people interpret and respond to psychotic phenomena that accounts for distress and disability, rather than the psychotic experiences themselves. 61–63

Key elements of CBT include a shared, individualised formulation of the problem, which can include consideration of life events that may contribute to the development and/or maintenance of psychosis, such as trauma and deprivation; evaluating unhelpful thoughts; and conducting behavioural experiments. 64 Morrison et al. 64 place emphasis on the importance of CBT being conducted via a strong therapeutic relationship for people who experience psychosis and schizophrenia, the use of normalising information, collaboration between the client and the therapists, and therapy being based on a client’s problem list and idiosyncratic goals.

The importance of delivering CBT in an empowering and recovery-orientated manner has been highlighted in a 2016 article by Brabban et al. ,65 who suggest 10 key considerations to ensure that CBT is delivered ethically, in a manner that is recovery orientated and promotes therapeutic relationships: (1) collaboration, (2) use of everyday language, (3) acknowledging the historical and developmental context of the client’s difficulties, namely adverse life experiences, so as not to minimise the impact of these, (4) evaluating rather than challenging beliefs, (5) applying caution with use of the stress vulnerability model of psychosis and schizophrenia, (6) validating the client’s experience using a cognitive formulation, (7) delivering hope to the client, (8) offering informed choice about engaging with CBT, (9) ensuring that CBT training is extensive and specialist and (10) ensuring that there is access to continued supervision.

Cognitive–behavioural therapy has been shown to have small to moderate effects when delivered in combination with antipsychotic medication, with several meta-analyses showing support for this approach. 66–68 The most conservative ES estimate for total symptoms is 0.33, demonstrating small but significant effects of CBT for psychosis over treatment as usual (TAU); however, the ES for total symptoms reduces to 0.15 for studies with a low risk of bias from masking. 69 The same meta-analysis69 reports small ESs for positive symptoms (ES = 0.25) and negative symptoms (ES = 0.13). A 2014 meta-analysis conducted by Turner et al. ,70 which compared CBT for psychosis with other psychological therapies, found that, across the 48 included studies, CBT was more efficacious in improving overall and positive symptoms of psychosis than in improving other psychological therapies. van der Gaag et al. 71 note that there has been a focus on positive and negative symptoms in meta-analyses of CBT; however, CBT is a formulation-based approach that aims not necessarily to reduce the frequency or severity of positive and negative symptoms, but rather to help service users make sense of distressing hallucinatory experiences and delusional beliefs, with the aim of reducing distress and increasing coping. In a meta-analysis of treatment effects of individually tailored case-formulation CBT on auditory hallucinations and delusions, van der Gaag et al. 71 found modest and significant ESs for auditory hallucinations at the end of treatment (ES = 0.44), and this increased when contrasted with active treatment (ES = 0.49) and for blinded studies (ES = 0.46). Although modest significant ESs were found for delusions at the end of treatment (ES = 0.36), these ESs lost significance when (1) contrasted with active treatment and (2) the ES was reduced for blinded studies (ES = 0.24). Findings from the meta-analysis conducted by van der Gaag et al. 71 suggest that CBT can be effective in treating auditory hallucinations, but that the evidence for treating delusions is less robust.

Although meta-analyses suggest small to moderate ESs for CBT, in comparison with other psychological approaches, there remains debate in the literature about CBT’s value for psychosis and schizophrenia. 69,72 In particular, McKenna,72 in the 2014 Maudsley Debate, suggest that the meta-analysis carried out by NICE in 2009 for the schizophrenia guideline was methodologically flawed, leading to an increased chance of type I error and the probability that any positive findings were as a result of chance. In addition, Jauhar et al. 69 suggest that the conclusions regarding efficacy of CBT are mistaken, because the most large, well-conducted trials have failed to demonstrate a significant effect at the end of treatment, and the supportive meta-analyses overestimate the effects from smaller, low-quality trials. They also argue that their finding of ‘non-significant effects on positive symptoms in a relatively large set of 21 masked studies also suggests that claims that CBT is effective against these symptoms of the disorder are no longer tenable’. 69

Cognitive–behavioural therapy for treatment-resistant schizophrenia

In relation to TRS, the efficacy of CBT has been evaluated in a number of RCTs with some encouraging evidence; key details of these studies are presented below. Tarrier et al. 73 conducted one of the earliest trials of CBT for TRS using a three-arm RCT design in which participants were randomly allocated to CBT, supportive counselling or TAU. In total, 87 eligible participants were randomised, and those who received CBT exhibited significantly greater improvements in positive symptoms at the 3-month assessment than those who received supportive counselling or TAU. Because the authors did not provide further definition of ‘stable medication’, it is difficult to establish whether or not this group would meet strict TRS criteria. Augmenting clozapine with CBT was first evaluated by Pinto et al. 74 In their RCT74 of CBT with social skills training compared with supportive therapy as an adjunct to clozapine, 41 treatment-resistant participants who had recently started taking clozapine were recruited. Treatment resistance was defined as non-response to at least two antipsychotic medication trials, each ≥ 6 weeks in duration, at a dose of > 600 mg per day of chlorpromazine equivalents. At the end of treatment, both the CBT plus social skills training and supportive counselling groups showed statistically significant improvement in total BPRS score and positive and negative symptom ratings. However, comparisons between the groups showed that, post intervention, participants who had received CBT plus social skills training had lower total BPRS score and lower negative symptoms scores than participants who had received supportive therapy. 74 This study74 provided preliminary evidence for augmenting clozapine with a psychological intervention; however, as this study is non-blind there is a risk of bias that limits the conclusions that be drawn from the findings. In another RCT of CBT for TRS, Kuipers et al. 75 found that the CBT group had a significant improvement on the BPRS, as defined by a 25% reduction in the BPRS score; however, significant differences were not observed between the CBT and control groups on any of the other clinical outcomes. Findings from the study75 also suggested that CBT was considered an acceptable treatment, because participants had a low drop-out rate from therapy (11%), and 80% of those who received CBT expressed high levels of satisfaction with the intervention. Sensky et al. 76 recruited 90 participants to a RCT comparing CBT with befriending for people with TRS. For this study, treatment resistance was defined as the persistence of symptoms resulting in distress or dysfunction for ≥ 6 months despite an adequate trial of antipsychotic medication. 76 Analysis of the data demonstrated no significant difference between the groups at the end of treatment, but an effect was observed at follow-up for positive and negative symptom ratings and depression for the CBT group. A 5-year follow-up study77 of these participants indicated some evidence for the medium-range effectiveness of CBT: participants who received CBT had significantly lower overall symptom severity scores than those in the befriending group. A three-arm RCT78 of CBT versus supportive psychotherapy (SP) versus TAU, for people with a schizophrenia diagnosis who experienced persistent delusions and/or hallucinations after treatment with antipsychotic medication for 6 months, found greater improvement in PANSS total score among those allocated to CBT. In addition, the results of the study demonstrated that those in the psychological intervention arms (CBT or SP) experienced a greater reduction in the severity of delusions and that more people in the CBT arm than in the SP and TAU arms achieved a ≥ 25% reduction in PANSS scores. 78 Although the study indicates promise for the acceptability of CBT for this group, and promise for the effects of CBT on total PANSS score and delusion severity, this was a small study with between 19 and 23 participants in each arm. Valmaggia et al. 79 carried out a small RCT of manualised CBT for psychosis versus a time-matched control intervention of supportive counselling for people with TRS, matching the Kane et al. 44 definition. Sixty-two participants were randomised and the between-group analyses at the end of treatment demonstrated no significant difference between the CBT and supportive counselling groups on positive, negative or general subscale of the PANSS, or the delusion subscale of the Psychotic Symptom Rating Scale (PSYRATS). There was however, a significant improvement in the CBT group on two items of the PSYRATS voices subscale (the physical characteristics and interpretation of voices). These differences were not sustained at follow-up, indicating some short-term effects of CBT on voices for the TRS group.

To date, there have been no published meta-analyses of CBT specifically for TRS. However, a meta-analysis of CBT and FIs for people with a diagnosis of schizophrenia reported that the majority of the studies included in the review included participants who would appear to meet TRS criteria, that is, they were prescribed an antipsychotic medication and had a long duration of illness (DI), and concluded that CBT may be useful for those with TRS. 66 A more recent systematic review80 of the literature on interventions for TRS found 13 studies investigating CBT for TRS. This review included any paper in which the authors had considered the participants to be experiencing TRS, and so did not follow a strictly defined definition of TRS, with the result that the samples included are likely to be highly heterogeneous; this raises the question of whether or not the studies included are reflective of intervention studies for the TRS group. In addition, closer inspection of the CBT studies included in the review80 reveals that the CBT intervention usually targeted specific symptoms of psychosis (i.e. command hallucinations81 and auditory hallucinations82) or was aimed at improving outcomes that were not directly related to symptoms, such as therapeutic alliance. 83

Cognitive–behavioural therapy for clozapine-resistant schizophrenia

To date, only one study has examined the efficacy of CBT for CRS. 84 In this controlled trial, treatment resistance was evaluated using Kane et al. ’s44 criteria and, to meet trial inclusion criteria, participants were required to have taken clozapine for ≥ 6 months without improvement of symptoms of psychosis. Twenty-two participants who met the inclusion criteria were allocated to either CBT (n = 10) or befriending (n = 12). CBT was found to be significantly more effective in reducing BPRS total score, PANSS total score and PANSS general psychopathology subscale score at the end of treatment and at the 6-month follow-up. However, an effect was not found for the reduction of positive symptoms. Although the result of the study by Barretto et al. 84 is encouraging, there are significant methodological limitations. The sample size was very small, limiting the power of the study to detect an effect of CBT for positive symptoms. Moreover, the study design is limited by the absence of randomisation.

Predictors of response to cognitive–behavioural therapy

In addition to understanding the overall efficacy of CBT relative to standard treatment, a further important research consideration is determining predictors of response to CBT, to better understand who will benefit from CBT. In determining who will have a good response to CBT, secondary analyses of CBT trials have indicated that patient characteristics including sex, ethnicity and baseline symptom severity may moderate the outcomes of CBT for people with a schizophrenia diagnosis. 85–88 More specifically in relation to TRS, studies of CBT in this group have indicated that fewer recent hospital admissions,89 greater cognitive flexibility concerning delusions89 and less severe symptoms on allocation73 are associated with a better response to CBT. The DI has been shown to be associated with response to CBT,90–92 and this has also been demonstrated in TRS groups. 73 Similarly, insight at baseline has been shown to be associated with good outcomes in CBT for psychosis. 93

It is likely that the way in which events are appraised will be dependent on the experiences a person has had in life and the way in which they view themselves and other people. 63 Experience of traumatic life events, such as abuse, could lead to the development of a view that other people are threatening, causing later experiences to be interpreted in this light. 62,63 Research in the general population that has found an association between negative life events and unusual beliefs or perceptual experiences has provided support for this view. 94 There is increasing evidence of a link between abuse and psychosis95 as well as other types of traumatic or difficult life experiences and psychosis, for example being held hostage,96 living in highly urbanised areas,97 refugee migrant status,98 low social capital99 and racial discrimination. 100 A 2012 meta-analysis101 of 41 studies found a significant relationship between adversity in childhood and risk of psychosis later in life. The types of traumatic childhood experience that were included in the review101 were emotional, physical and sexual abuse; neglect; bullying; and death of a parent. It was found that, apart from parental death, each of these factors was significantly related to psychosis. Loss of a parent was also found to be significantly related to psychosis when the data from one paper with outlying results were removed from the analysis. This review,101 therefore, concluded that the experience of trauma in childhood is strongly related to an increased risk of psychosis. Specific types of traumatic experience have also been found to relate to specific psychotic experiences. It has been found that sexual abuse is related to voice-hearing, whereas growing up in care is related to experience of paranoia. 102 A longitudinal study103 found that experience of psychosis in children aged 12 years was particularly associated with traumatic events, characterised by intention to harm. This suggests that it could be the perception of threat that is of significance to the development of psychotic experiences. 103 Experiences, such as those described above, could lead to beliefs that others are dangerous, and increase the likelihood that future experiences will be interpreted as threatening. 2 Use of a longitudinal formulation within CBT can, therefore, provide validation of the experiences that an individual has suffered and make sense of current experiences in the context of a traumatic history. 104 This process can also foster hope of recovery by identifying specific areas in which change strategies could be applied. 104

Cognitive difficulties, that is, difficulties with attention, memory and working memory, are frequently experienced by people with a schizophrenia diagnosis. 105,106 Working memory has been described as a system for temporarily storing information while using it to complete tasks involving cognitive function, such as problem-solving. 107 A large meta-analysis investigating working memory in schizophrenia consistently found that participants with a diagnosis of schizophrenia performed worse than control groups on a range of tests of working memory. 108 Furthermore, it has been found that those individuals with a longer-term diagnosis and receiving antipsychotic medication are likely to be the most seriously affected. For example, it has been shown that participants with a greater DI demonstrate the poorest performance on working memory tasks. 108 In relation to spatial working memory, it was found that participants’ performances significantly worsened after receiving clozapine for just 17 weeks. 109 It has previously been demonstrated that anticholinergic drugs, including clozapine, affect memory performance. 110

It has been proposed that neurocognitive deficits in people with a diagnosis of depression are likely to predict outcome from CBT. 111 The same is likely to be true for people with a schizophrenia diagnosis, given that CBT relies on skills, such as memory and generating alternative hypotheses. 112 Neurocognition is also known to be associated with functional outcomes, such as social skills and ability to perform daily activities. 113 Neuropsychological impairment has been found to be predictive of poorer outcome among participants receiving Cognitive Behavioural Social Skills Training. 112 It was hypothesised that neuropsychological inpairment could be related to poorer attendance and reduced engagement with homework in this group. Memory difficulties could make engaging with homework tasks, a factor thought to improve outcome, more problematic. 114 However, few studies have formally evaluated the impact of neurocognitive variables on outcome with CBT, and a clear relationship has not been identified. 115

Although some researchers have endeavoured to identify who has a good response to CBT, the current evidence for predictors of a good response to CBT is limited and the findings are often unreliable because of insufficient statistical power, with very few findings surviving replication. There is a clear benefit to understanding how best to target CBT at those who are most likely to respond, and further research is required.

Important outcomes for trials

A further criticism of these studies is the absent or limited focus on outcome measures that service users consider meaningful and important to their recovery. A review116 of 24 measures commonly used to evaluate psychosis and mood disorders found that service user preference was for measures that were patient rated rather than clinician rated and that evaluated side effects of both pharmacological and psychological interventions; interestingly, measures of social functioning were rated particularly low because of the assumptions made about ‘good’ social functioning. However, it is interesting to note that the PANSS, a commonly used outcome measure, was rated as the most acceptable of the psychosis outcome measures. 116 Although this suggests that measuring these symptom-based domains is important to service users, there is also clear evidence that recovery-orientated outcomes are a priority. 117 A recovery-orientated model of care engenders values of hope, independence and control over one’s life following a mental health problem, connection with a self-identity and having meaning to life and being able to take responsibility for one’s recovery. 117 The emphasis is not on the remission or absence of symptoms. 118 A qualitative study119 investigating how service users with experience of psychosis or schizophrenia diagnoses defined recovery identified three key themes: (1) rebuilding self, (2) rebuilding life and (3) hope for a better future. Within these key themes, processes of recovery included understanding oneself, empowerment, participation in life activities and social support, understanding a personal process for change and a personal desire for change. Importantly, Pitt et al. 119 emphasised that recovery is a journey, not a linear process with a clear end point. A 2011 systematic review120 of the literature on personal recovery from a mental health problem identified a total of 97 papers; synthesis of the findings from these papers resulted in five key processes of recovery: (1) connectedness, (2) hope and optimism for the future, (3) identity, (4) meaning and (5) empowerment.

It has also been argued, especially in relation to the evaluation of psychological therapies for people with psychosis, that affective processes or emotional distress or dysfunction should be the outcomes that are evaluated in trials. For example, CBT for psychosis trials have been criticised as inappropriately conceiving CBT as a quasi-neuroleptic on the basis of adopting methodologies designed to evaluate antipsychotic medication, including use of psychiatric symptoms as the primary outcome rather than affective dysfunction. 121

The importance of recovery-orientated services and treatments for people with experience of psychosis or for people with a schizophrenia diagnosis is in the NICE guideline,30 which emphasises the importance of recovery-orientated values in the treatment of psychosis and schizophrenia. The Schizophrenia Commission report122 makes a call for all mental health services working with people with experience of psychosis and schizophrenia to work in a person-centered approach that embraces the interests and opinions, as well as the strengths and aspirations of the person with psychosis.

Arguably, the lack of specific focus on outcome measures that evaluate these domains, which are important to service users, limits any conclusions that can be drawn from previous treatment studies, both psychological and pharmacological. Similarly, trials that use symptom-focused measures, such as the PANSS, often fail to demonstrate clinically significant change, even if treatments demonstrate statistical superiority. This has led to attempts to define clinically significant response,123 and meta-analyses of trials often use a > 50% improvement on the PANSS as an operational definition of a good outcome. 32

Summary

To summarise, there is clear evidence from the CBT trials that people with TRS and CRS can be engaged in CBT, and that CBT can have small to moderate effects on overall symptoms and may be particularly beneficial for auditory hallucinations. However, it has been highlighted in a 2014 meta-analysis69 that the large and methodologically robust trials of CBT for psychosis have not demonstrated a significant advantage of CBT for either symptoms or relapse, and to date there have been no large high-quality trials of CBT for people with CRS. Moreover, CBT trials have been criticised for poor reporting of adverse effects,124 and future trials should report adverse effects as an outcome. Klingberg et al. 125,126 have provided a useful template for assessing adverse effects that includes death caused by suicide, suicide attempt, suicidal crisis [as defined in the Calgary Depression Rating Scale for Schizophrenia (CDSS), item 8, rating 2] and severe symptomatic exacerbation, defined by the Clinical Global Impression (CGI) scale, which includes ratings of illness severity, changes in overall clinical status, and therapeutic effects. In addition, further research is needed to identify factors that predict a good outcome from CBT.

Rationale for the research/trial aims and objectives

The objectives of this RCT were to provide evidence of the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of CBT for people with CRS and to utilise baseline data from the RCT to develop a risk model that identifies factors that predict good outcome from CBT. Using the patient-level data available from the trial, the objectives for the economic evaluation were to:

-

estimate the costs of health and social care in the intervention and TAU groups, and assess whether or not there were differences between the groups

-

estimate the quality-adjusted life-years (QALYs) of participants in the intervention and TAU groups, and assess whether or not there were differences between groups

-

assess whether or not any additional benefit is worth any additional cost.

The research objectives of this RCT were to test the following hypotheses:

-

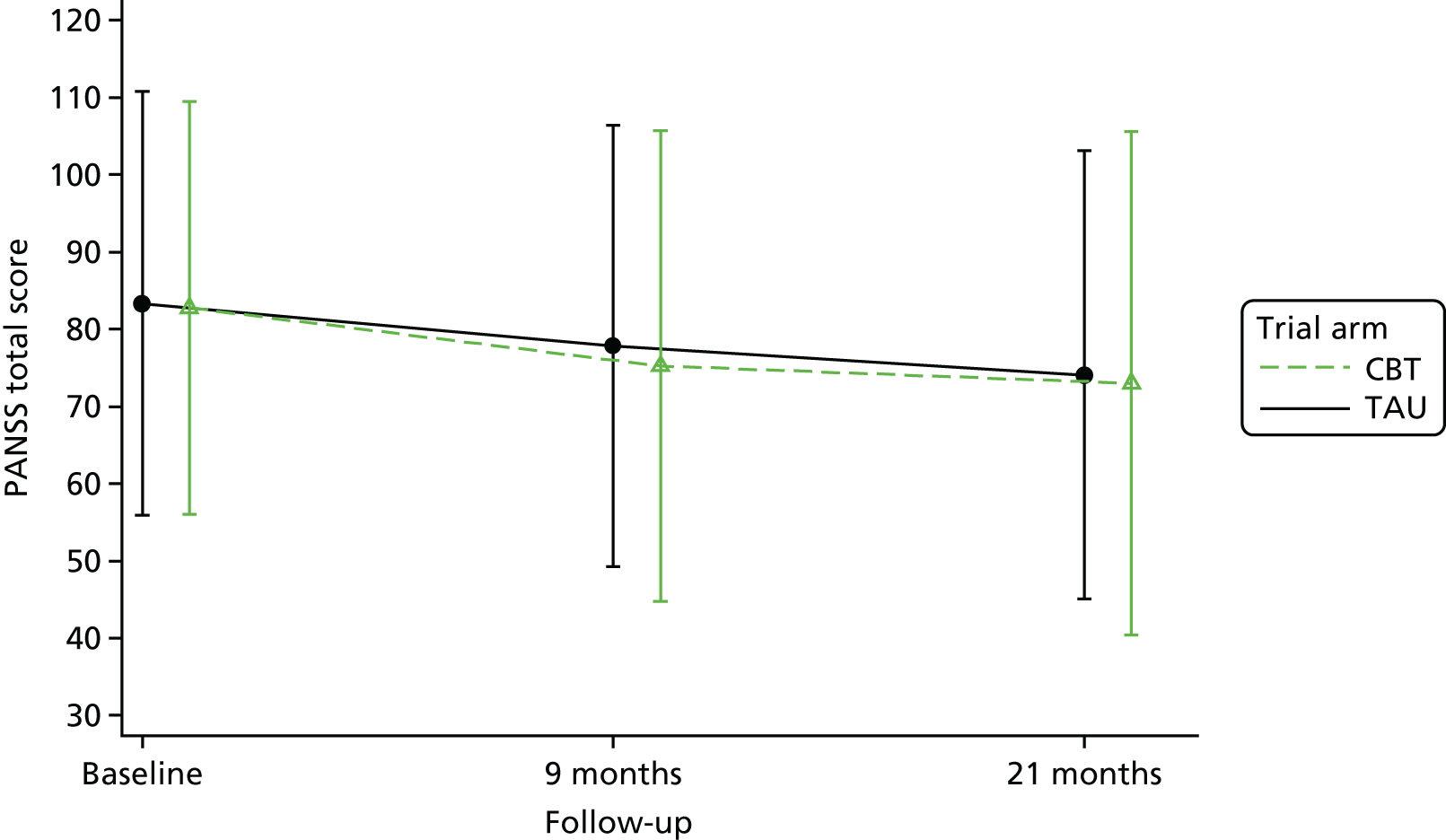

In people with a diagnosis of a schizophrenia spectrum disorder who have an inadequate response to or are unable to tolerate clozapine, CBT plus TAU will lead to improvement in psychotic symptoms, measured using a psychiatric interview (PANSS) over a 21-month follow-up period compared with TAU alone.

-

Cognitive–behavioural therapy plus TAU will lead to improved quality of life and user-defined recovery compared with TAU alone.

-

Cognitive–behavioural therapy plus TAU will lead to a reduction in affective symptoms and negative symptoms compared with TAU alone.

-

Cognitive–behavioural therapy plus TAU will be cost-effective compared with TAU alone.

Chapter 2 Methods

Trial design

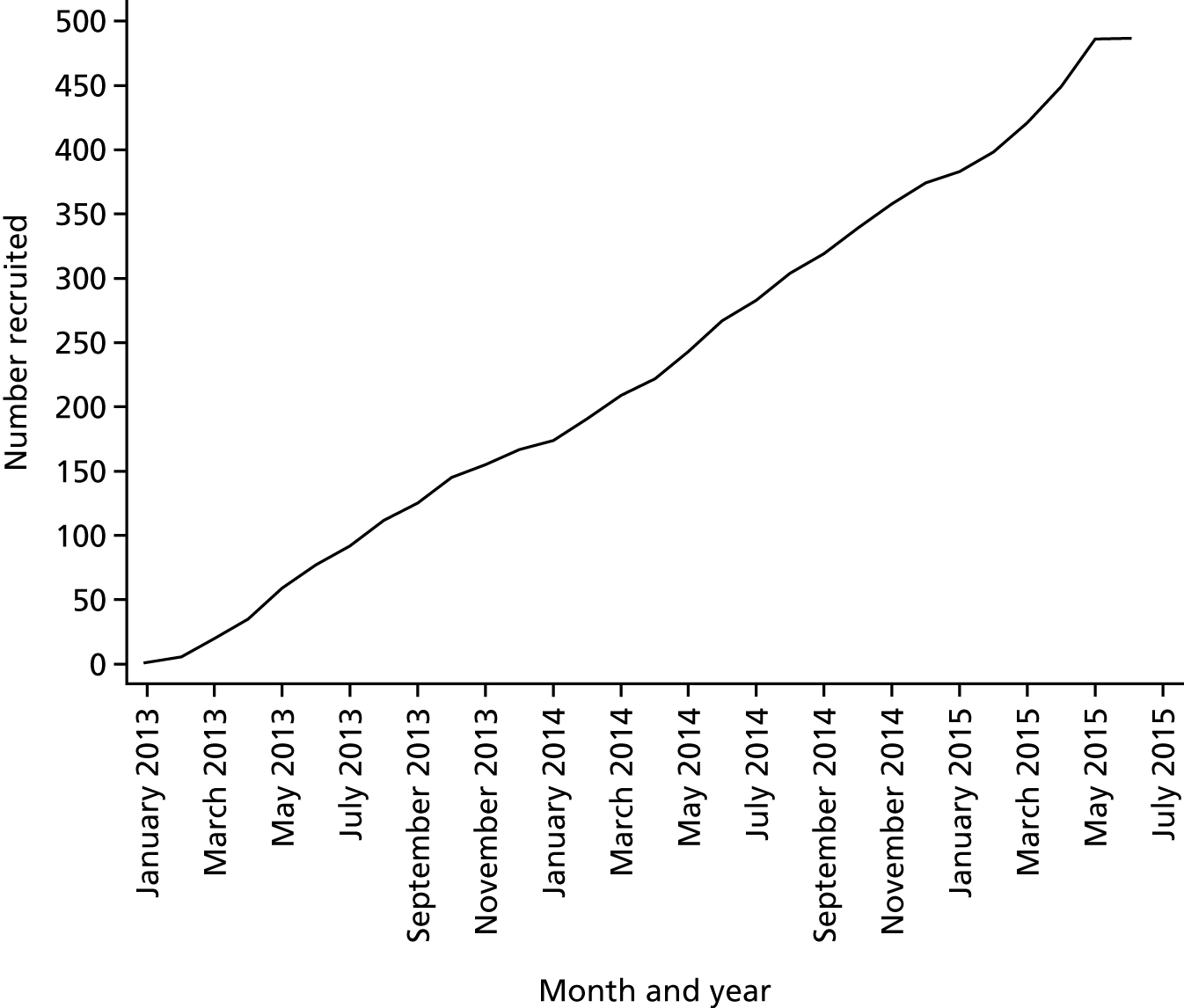

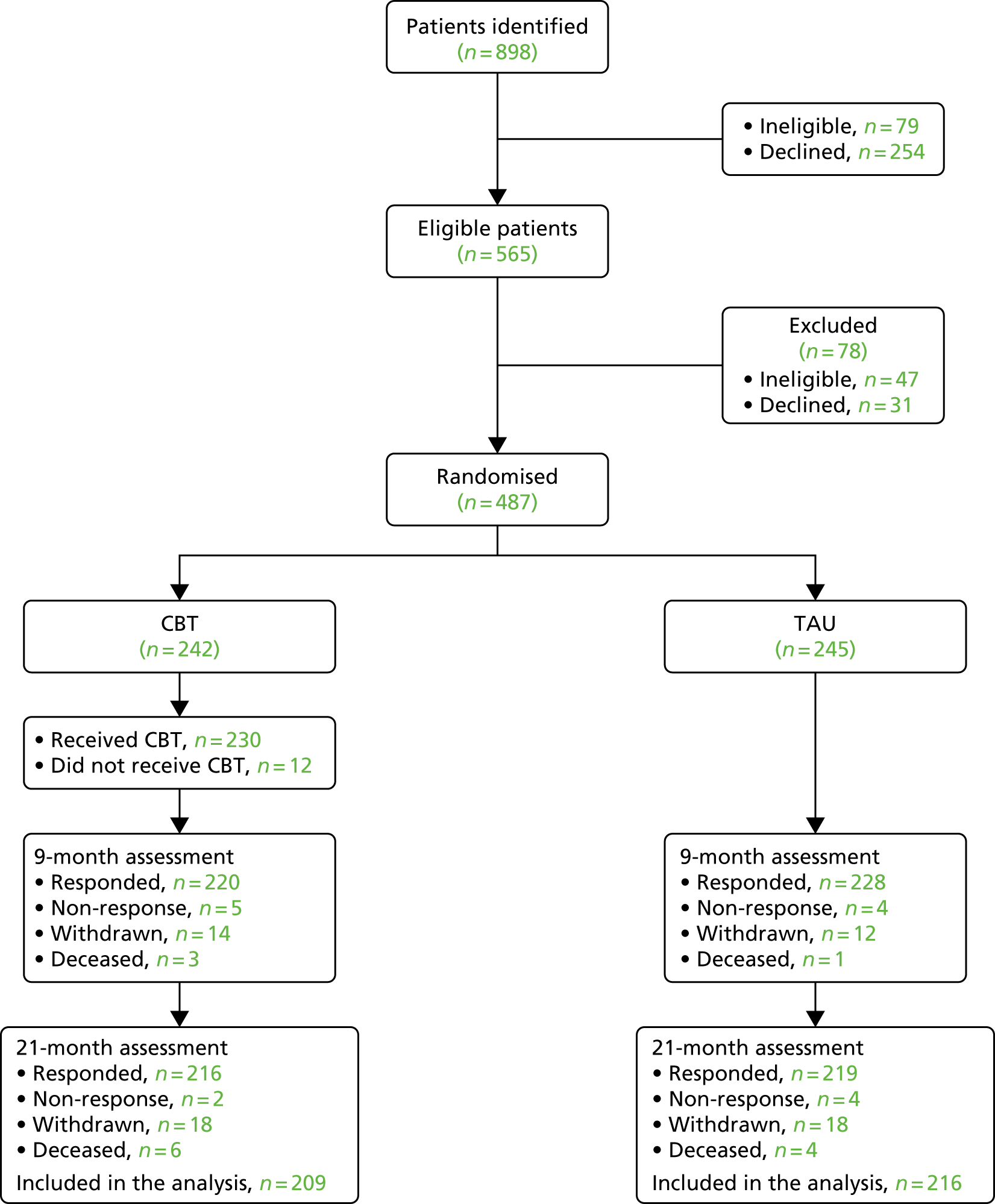

The FOCUS trial was a parallel-group, randomised, outcome-blinded evaluation (PROBE) to evaluate the addition of a standardised CBT intervention to TAU for individuals who are unable to tolerate or have had an inadequate response to clozapine. The comparison group received TAU only. The trial was intended to be a definitive, pragmatic clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness trial. It was conducted over 4 years across five sites within the UK, with recruitment commencing on 1 January 2013 and ending on 1 June 2015. The follow-up phase for the trial ended in February 2017. A copy of the full ethics-approved trial protocol can be found on the project web page: www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/programmes/hta/1010102#/. In addition, the study protocol has been published in a peer-reviewed journal. 127

Role of funding source

The FOCUS trial was funded as a result of a National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Health Technology Assessment-commissioned call. The call specified the design in PICO (population, intervention, comparator and outcome) terms, requiring that the population be patients with schizophrenia who had not responded to an adequate dose of clozapine or were unable to tolerate it, the intervention was CBT, the comparator was TAU and the outcome was psychiatric symptoms.

Approval

The National Research Ethics Service (NRES) Committee North West – Lancaster (reference 12/NW/0520) approved the FOCUS trial. Ethics approval was granted on 13 August 2012. The trial was also registered on the International Standard Randomised Controlled Trial Number (ISRCTN) clinical trial registry (reference ISRCTN99672552). The trial was registered on 29 November 2012, before recruitment was started in January 2013.

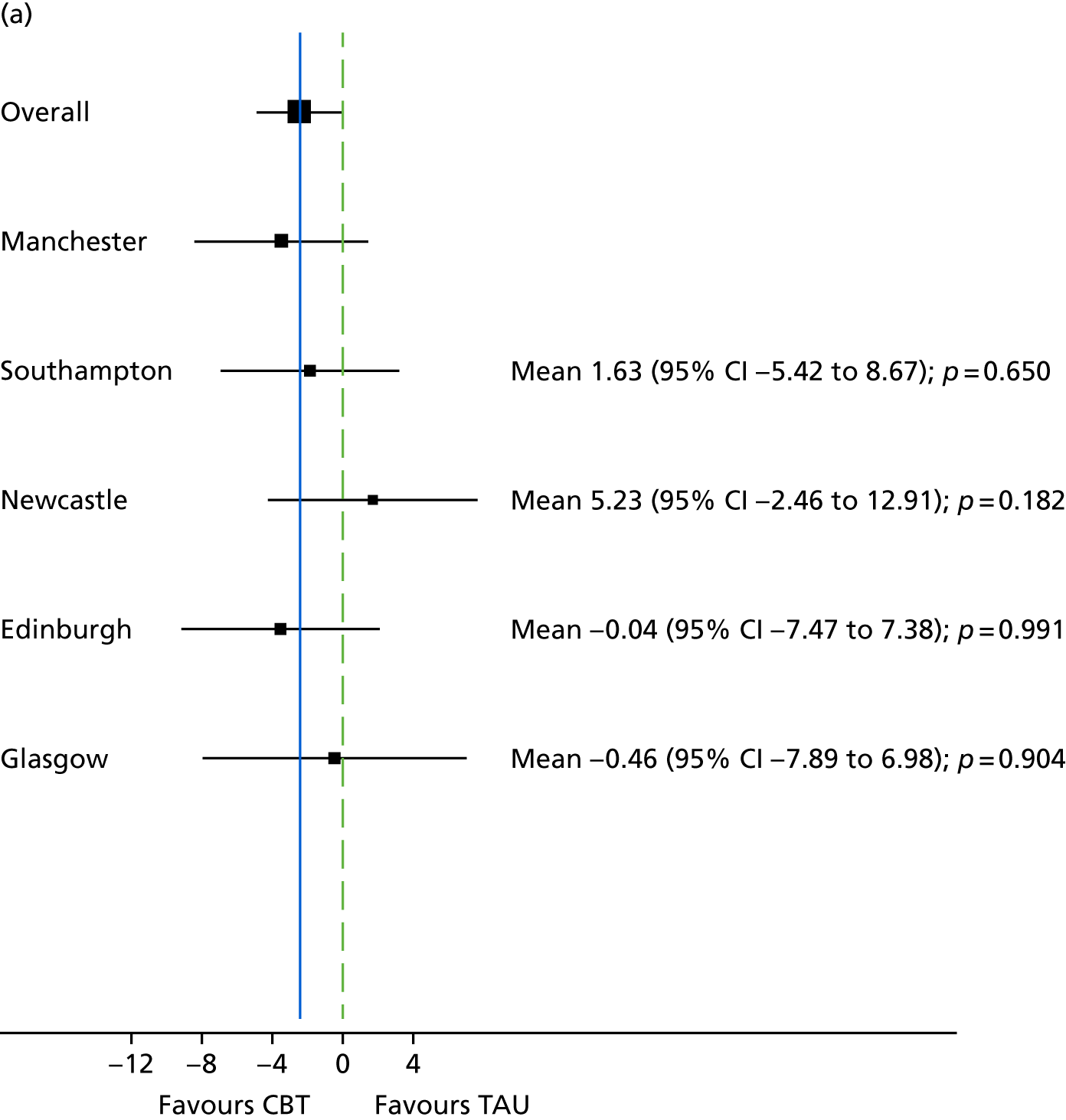

Trial sites

The study was conducted in secondary care mental health services (community mental health, residential rehabilitation and inpatient settings) at five UK centres. These were (1) Manchester, (2) Edinburgh, (3) Glasgow, (4) Newcastle upon Tyne and (5) Southampton.

Participants

A total of 487 participants were recruited across the five sites between 1 January 2013 and 1 June 2015. The Manchester site recruited 108 of the total participants, Southampton recruited 105, Edinburgh recruited 94, Newcastle upon Tyne recruited 92 and Glasgow recruited 88. Participants were recruited from a range of services and settings including community mental health teams (CMHTs), early intervention teams, recovery teams and inpatient services.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Participants were eligible to take part in the FOCUS trial if they were considered to have had an inadequate response to a trial of clozapine treatment, specifically treatment with clozapine at a stable dose of ≥ 400 mg (unless limited by tolerability) for ≥ 12 weeks, or, if currently augmented with a second antipsychotic, for ≥ 12 weeks, without remission of psychotic symptoms. This criterion was selected as a review of medication trials found 400 mg to be the minimum dose necessary for effective treatment with clozapine. 128 Other clinical trials looking at CRS have employed the same criteria. 52 Alternatively, participants were eligible for the trial if they had discontinued clozapine in the preceding 2 years because of side effects, lack of efficacy or a problem identified during routine blood monitoring appointments.

Participants were also required to have been given an ICD-10 diagnosis on the schizophrenia spectrum, or to meet criteria for an Early Intervention in Psychosis (EIP) service.

To be included, participants were also required to achieve a minimum total score on the PANSS of 58 (equivalent to a CGI scale of at least mild difficulties),129 as well as a score of ≥ 4 on items for delusions or hallucinations, or of ≥ 5 for items on suspiciousness or grandiosity, to ensure that symptoms of psychosis had not remitted. The research assistant (RA) assessed this at baseline. Participants had to be aged ≥ 16 years and have an identified care co-ordinator or consultant psychiatrist. In additional, participants were required to be competent and willing to provide written informed consent to take part.

Exclusion criteria were having a primary diagnosis of substance or alcohol dependence if this could be the cause of the psychotic experiences, having a diagnosis of developmental disability or organic impairment and being non-English-speaking. Individuals who were currently receiving or had received structured CBT from a qualified psychological therapist within the preceding 12 months were also excluded from the trial. This was operationalised as CBT delivered in line with the NICE guidelines30 for the treatment of psychosis and schizophrenia as ≥ 16 sessions of CBT that is delivered in line with a CBT treatment manual. 30

Data collection

In accordance with the approved protocol, potential participants were initially informed about the study by a member of their care team and, if they expressed interest, were asked to consent to being contacted by the FOCUS trial research team. If they did so, a member of the research team briefly described the study and sent the participant information sheet (PIS) by post. The individual was then given a minimum of 24 hours to consider the information. Following this, the RA arranged to meet the participant at a place of their choosing; in the majority of cases this was the participant’s own home. Some preferred to meet within a mental health service or, if there were any possible risk issues, a meeting at a NHS site would be arranged. Participants who were current inpatients were visited on the ward. The RA talked through the PIS with the individual and ensured that the information was understood by asking the participant to reflect it back to them. When both the RA and the participant were satisfied that all the information about the trial had been provided and understood, the participant was asked to sign the consent form. The RA then read through each point and the participant initialled the boxes provided if they agreed to the information. Both the RA and the participant signed their names underneath.

The RA would then commence the baseline assessment. In the majority of cases, this was conducted across two visits, but this was at the participant’s preference. On average, to complete all assessment measures in full would take approximately 2 hours. The assessment would begin with the PANSS interview and then move on to the self-report measures (outlined below). Each participant was also provided with a personalised crisis card at the baseline assessment. This included contact details for their care team and general practitioner (GP) as well as other helpline numbers, such as the Samaritans. Finally, participants were compensated with £10 for their time and contribution to the research process.

Face-to-face follow-up assessments were completed at 9 and 21 months. The participant was contacted by telephone and an appointment was arranged. Ongoing consent was confirmed with participants at each follow-up. The RA conducted a PANSS interview and asked the participant to complete the self-report measures at each of these time points. Participants were compensated £10 for their time and contribution to the research process at these time points.

Follow-up assessments were completed by telephone at 3, 6, 13 and 17 months. These telephone assessments focused only on obtaining health economics data – no clinical outcome data were collected. The participants were sent £5 gift vouchers in the post on completion of these follow-ups. ‘Keeping in touch’ cards were also posted to the participant on two occasions between these telephone calls.

Outcome measures

Primary outcome

Although there is considerable debate regarding the most appropriate or important outcome measures (e.g. whether to focus on specific psychiatric symptoms or broader recovery and quality of life), the FOCUS trial was funded as a result of a commissioned call that specified the PICO. The commissioned call specified the important outcome as psychiatric symptoms and, therefore, PANSS,130 a reliable and valid, semistructured interview to assess the severity of symptoms associated with psychosis, was chosen as the primary outcome. It is widely used as the primary outcome measure in studies of treatments for people with a schizophrenia diagnosis and research indicates that a 15-point change on the total PANSS score translates to minimal clinical improvement. 123 This allows comparison with other published trials and inclusion of these results in any future systematic reviews and meta-analyses of treatment evidence. PANSS has 30 items that are scored between 1 (absent) and 7 (extreme), and includes seven items that map on to the positive symptoms (such as hallucinations and delusions), seven items relating to negative symptoms (such as blunted affect and emotional withdrawal) and 16 items assessing general psychopathology (such as anxiety and depression). This three-factor model of PANSS was originally proposed by Kay et al. 130 However, multiple-factor structures have been suggested for PANSS, including the original three-factor model, a four-factor model and, more commonly, a five-factor model. 131 Using confirmatory factor analysis on a large data set (n = 5769), van der Gaag et al. 131 tested the fit of 25 published five-factor models; the results indicated that it was not possible to find a fit of these models. Further analysis of the same data set using a 10-fold cross-validation identified a five-factor model with the following subscales: (1) positive, (2) negative, (3) agitation–excitement, (4) depression–anxiety and (5) cognitive. 132 This model of PANSS was used for the FOCUS trial. As the PANSS has a 1 (absent) to 7 (severe) rating scale, each participant is allocated a minimum score of 30 even if they have no symptomology. As noted by Leucht et al. ,133 this poses a significant challenge to understanding percentage change on PANSS, as percentage change is underestimated if 30 minimum points are not subtracted from the total score before calculating percentage change. Therefore, for the analysis of PANSS percentage change for the FOCUS trial, we rescaled the PANSS as recommended by Leucht et al. 133 The commissioned call specified that the minimum duration of follow-up should be 12 months. The primary outcome was therefore specified as PANSS total score at 12-month follow-up from the end of the 9-month treatment window.

Secondary outcomes

Positive and negative symptoms

These were measured by PANSS as described in the preceding section.

Hallucinations and delusions

The PSYRATS134 is a semistructured interview consisting of 12 items assessing aspects of voice-hearing, such as frequency, volume, distress and disruption caused, and six items assessing aspects of unusual beliefs, such as preoccupation, distress and disruption. All items are scored from 0 to 4, with higher scores indicating greater severity. Both sections include cognitive and emotional subscales, and the voices section also includes a physical subscale.

Recovery

The Process of Recovery Questionnaire (QPR) was developed in collaboration with service users to assess recovery from psychosis. 135 A shortened 15-item version was used here. 136 Participants respond using a five-point scale ranging from ‘disagree strongly’ to ‘agree strongly’. Items include ‘I feel better about myself’ and relate to the preceding 7 days.

Social and occupational function

The Personal and Social Performance (PSP) scale137 assesses functioning in four key areas: (1) socially useful activities, (2) personal and social relations, (3) self-care and (4) disturbing and aggressive behaviour. A score is allocated out of 100, with higher scores indicating better functioning.

Depression

The CDSS138 is a structured interview measure with nine items. The items include assessment of hopelessness, feelings of guilt and suicidal ideation. For each section, the assessor can score the client between a score of zero (absent) and three (severe). Therefore, possible scores range from 0 to 27. The measure was incorporated into the PANSS interview during the assessment of depression.

Anxiety

The Anxious Thoughts Inventory (AnTI)139 is a 22-item, self-report questionnaire designed to measure aspects of worry. Each question is scored from one (almost never) to four (almost always). The measure has a three-factor structure comprising (1) social worry, (2) health worry and (3) meta-worry. The seven-item meta-worry scale only was included in the FOCUS trial. This subscale includes statements, such as ‘I worry that I cannot control my thoughts as well as I would like to’.

Substance use

The Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT) was developed by the World Health Organization (WHO). It consists of 10 questions relating to alcohol use, with cut-off scores to identify hazardous drinking levels. Scores range from 0 to 4 on each item, with total AUDIT scores ranging from 0 to 40. 140 The higher the score, the more severe the alcohol use-related problems. AUDIT has been found to be reliable when used with participants with first-episode psychosis. 140

The Drug Abuse Screening Test (DAST)141 consists of 10 items relating to recent drug use. Participants are asked to provide a dichotomous yes/no response to such questions as ‘Are you always able to stop using drugs when you want to?’. DAST has been found to reliably identify substance abuse issues in participants with first-episode psychosis. 140

Clinical Global Impression

The CGI consists of three items, each scored on a seven-point scale. The RA was required to rate the severity of the participant’s current difficulties from one (not at all ill) to seven (extremely ill). This was completed at all time points. At 9 and 21 months only, the RA also rated change in the participant’s presentation since baseline. This was rated from one (very much improved) to seven (very much worse). In addition, at each time point, the participant was asked to rate the perceived severity of their own difficulties from one (no mental health problems) to seven (very severe mental health problems).

Measurement of adverse events and effects

To ensure a thorough review of adverse events (AEs) and effects, we used a number of methods to identify and report AEs including Health Research Authority (HRA) standard operating procedure (SOP), guidance from our Trial Steering Committee (TSC) and Data Monitoring and Ethics Committee (DMEC) and guidance recommended by Klingberg et al. 126 and a bespoke patient-rated adverse effects measure, developed for the FOCUS trial. Each will be outlined in more detail.

The HRA requires all non-Clinical Trials of an Investigational Medicinal Product (CTIMPs) to report the following AEs, when the chief investigator considers the event related and unexpected: death, is life-threatening, requires hospitalisation or prolongation of existing hospitalisation, results in persistent or significant disability or incapacity, consists of a congenital anomaly or birth defect and is otherwise considered medically significant by the investigator. In addition to this list of AEs, our DMEC and TSC advised that self-harm and harm to others also be included. All such events were reported by RAs and therapists to the chief investigator. As per HRA policy, serious adverse events (SAEs) were reported to the Research Ethics Committee (REC) if they were deemed by the chief investigator to be related to trial proceedings and unexpected. To minimise the potential for bias, all AEs were also reviewed by an independent clinician who was a member of the independent DMEC. If the independent clinician considered the event both related and unexpected, then it was reported to the REC.

In addition to the above, for the purpose of the trial, we also defined adverse effects in the trial protocol in line with Klingberg et al. 125,126 as:

-

death caused by suicide

-

suicide attempt

-

suicidal crisis (explicit plan for serious suicidal activity without suicide attempt) as defined in CDSS, item 8, rating 2)

-

severe symptomatic exacerbation, defined by the CGI, which includes ratings of illness severity, changes in overall clinical status, and therapeutic effects. A rating of CGI 2 as six or more and CGI 1 as six or more would be regarded as a severe AE.

In order to better evaluate the adverse effects of trial participation, the adverse effects measure was developed for the FOCUS trial. Participants rated 27 statements on a five-point scale from ‘not at all’ to ‘very much’. Statements included ‘taking part took up too much time’ and ‘I did not like or feel I could trust the FOCUS team members’. A free-text box was also provided for participants to record any additional details about their experience of taking part in the FOCUS trial. This measure was either provided following the final assessment, or at the point of withdrawal for participants who left the trial early. The measure was completed anonymously and was optional.

Other measures including psychological processes

Appraisals of voices

The Interpretation of Voices Inventory (IVI)142 is a 26-item measure consisting of cognitive and metacognitive appraisals of voice-hearing. The IVI has three subscales that relate to (1) positive beliefs about voices, (2) metaphysical beliefs and (3) beliefs about loss of control. Participants respond on a four-point scale from ‘not at all’ to ‘very much’ to indicate how much they endorse each belief. Items include ‘they will take over my mind’ and ‘they are a sign that I am evil’.

Appraisals of paranoia

The Beliefs about Paranoia Scale143 contains 18 items relating to paranoia, such as ‘my paranoid thoughts worry me’ and ‘paranoia is normal’. The scale has been found to have three subscales, namely (1) negative beliefs about paranoia, (2) beliefs about paranoia as a survival strategy and (3) normalising beliefs. The three-factor structure has been validated in a large clinical sample. 144

Beliefs about self and others

The Brief Core Schema Scale (BCSS)145 is a 24-item measure assessing beliefs about self and others. It consists of four subscales: (1) positive beliefs about self, (2) negative beliefs about self, (3) positive beliefs about others and (4) negative beliefs about others. Participants respond ‘yes’ or ‘no’ to a question about whether or not they endorse each belief and then, if they reply ‘yes’, state how much they believe this on a scale from 1 (believe it slightly) to 4 (believe it totally).

Working memory

The letter–number span (LNS)146 was completed at baseline and 9 months only and was read aloud to the participant by the RA. In this test, a participant is presented with a string of letters and numbers and asked to respond by reciting first the numbers in ascending numerical order and then the letters in alphabetical order. The sequences provided begin with two items (e.g. D-6) and increase until they are seven items long (e.g. C-7-G-4-Q-1-S). There are four sequences of each length and the test is stopped when the participant answers all four of any one length incorrectly. The highest possible score is 24.

Attachment

The Psychosis Attachment Measure (PAM-SR)147 is a 16-item measure of adult attachment styles that was developed specifically for use with individuals with psychosis. The PAM-SR has two subscales relating to anxious attachment and avoidant attachment styles. It has been found to be a reliable and valid measure. 147

Stigma

The Internalised Stigma of Mental Illness (ISMI) scale148 assesses the individual’s experience of stigma. It consists of 29 items, each rated on a four-point scale between strongly disagree and strongly agree. The measure includes items such as ‘others think that I can’t achieve much in life because I have a mental illness’. It has five subscales – (1) alienation, (2) stereotype endorsement, (3) perceived discrimination, (4) social withdrawal and (5) stigma resistance – and has been found to be reliable and valid. 148

Childhood trauma

The Childhood Trauma Questionnaire (CTQ)149 was designed to retrospectively assess childhood trauma. It has 28 items on a five-point scale, ranging from ‘never true’ to ‘very often true’. It consists of five subscales – (1) physical abuse, (2) emotional abuse, (3) sexual abuse, (4) emotional neglect and (5) physical neglect – and is thought to be a reliable and valid measure. 149 This measure was administered at 9 months only and delivered in line with a protocol developed in collaboration with members of a service user reference group for managing any distress that could arise from completing this measure. Participants were all offered a list of support services in relation to experience of abuse and offered a follow-up telephone call for the next day.

Semistructured clinical interview for psychosis subgroups

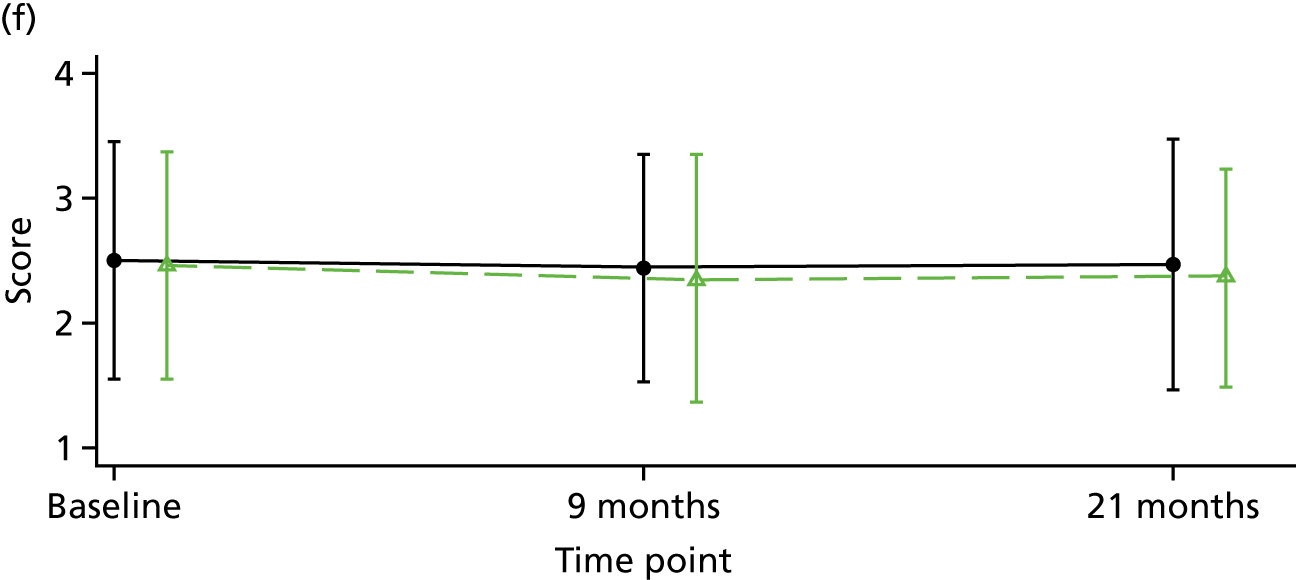

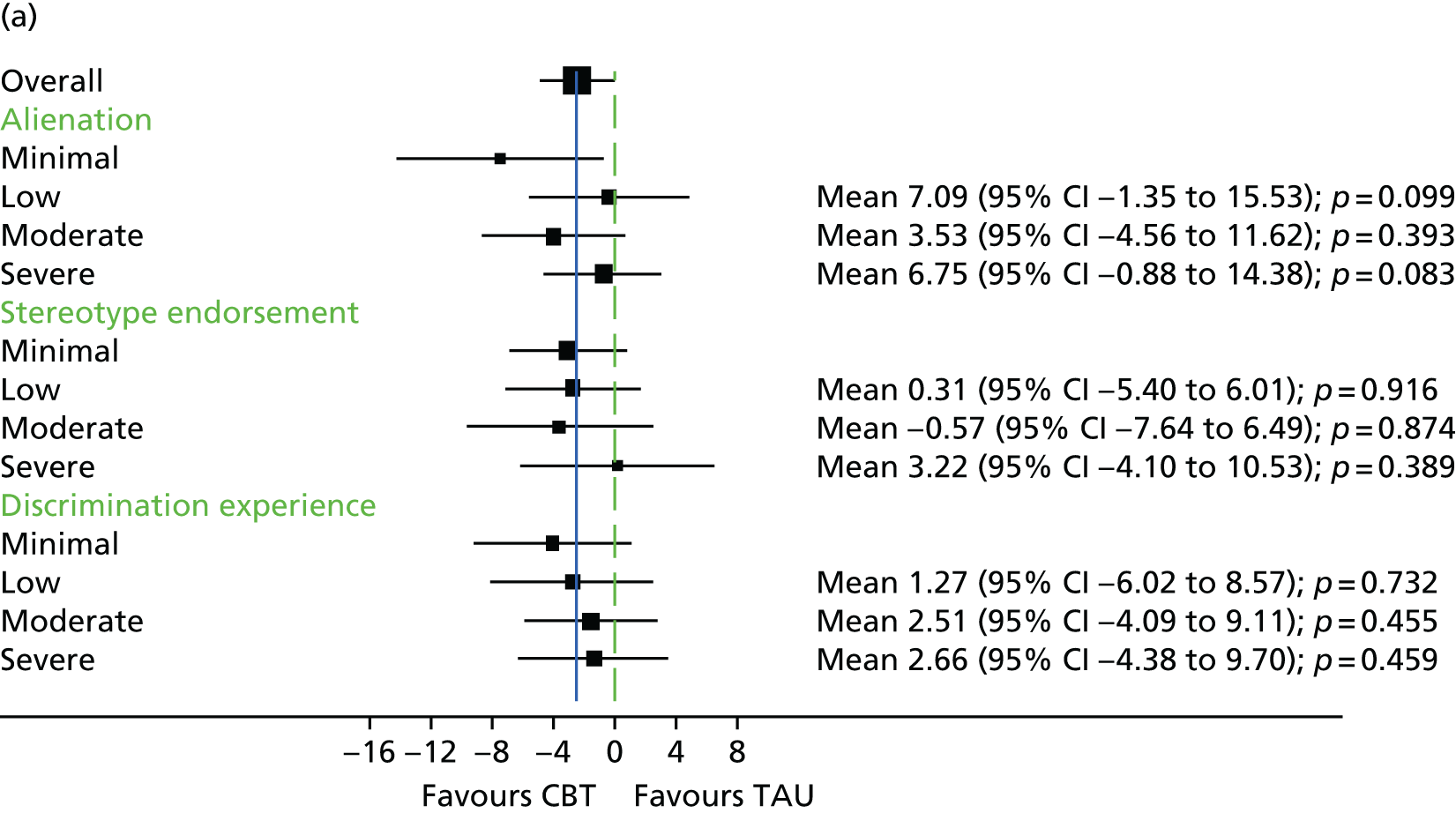

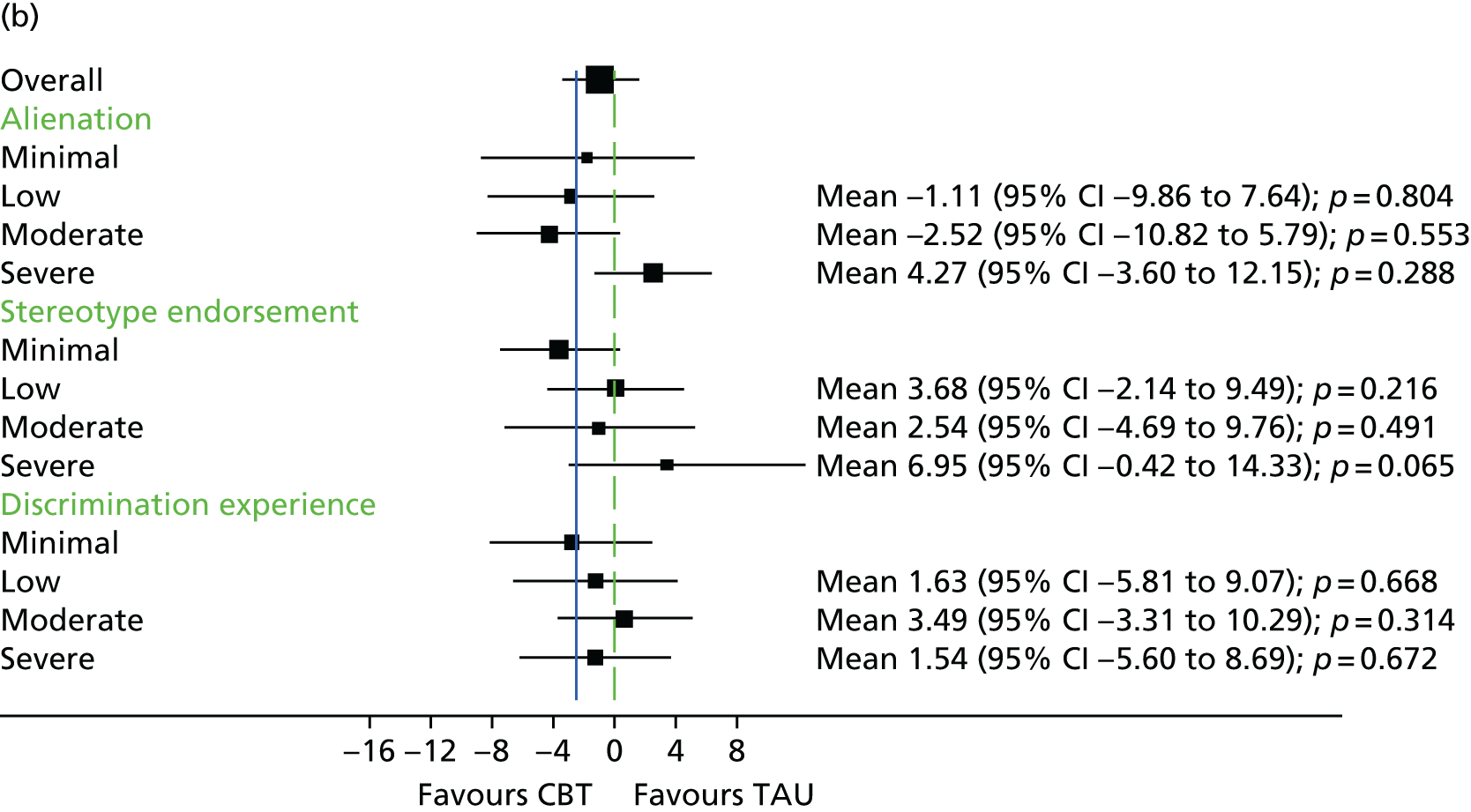

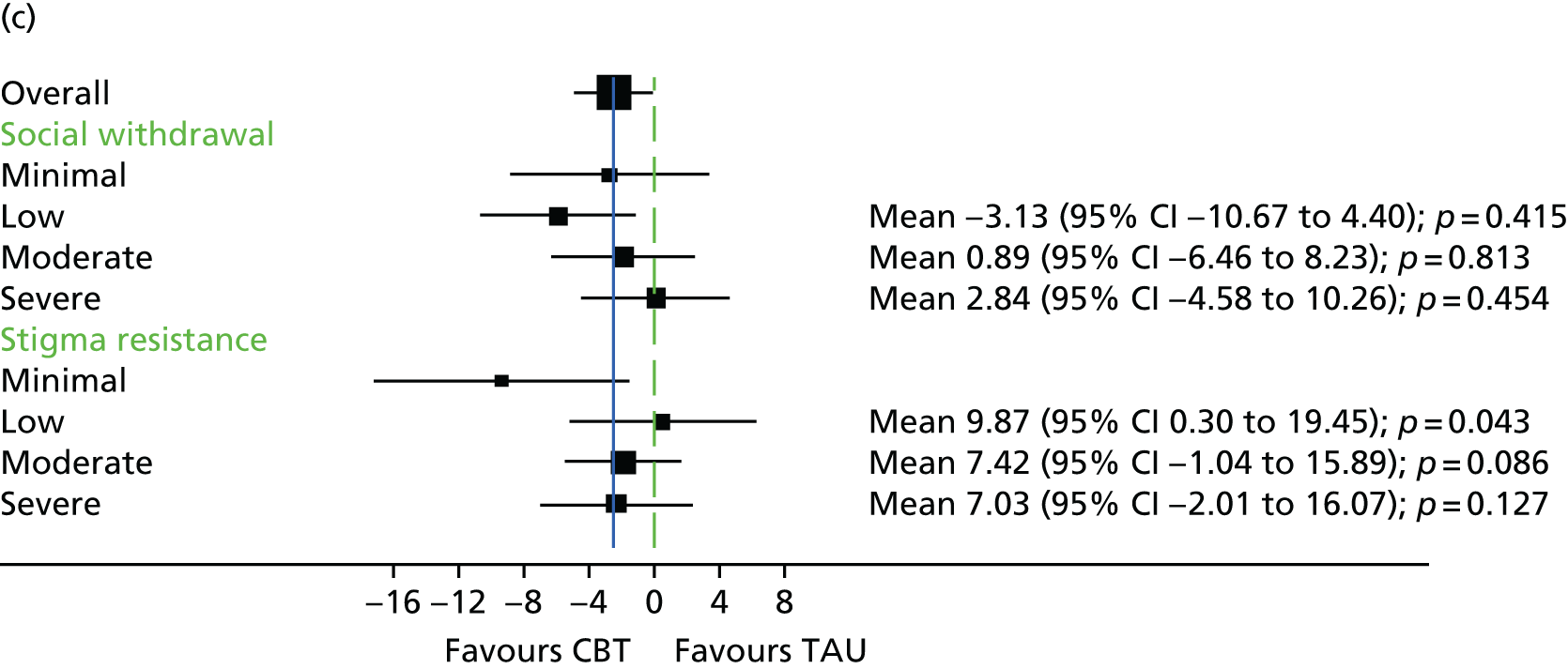

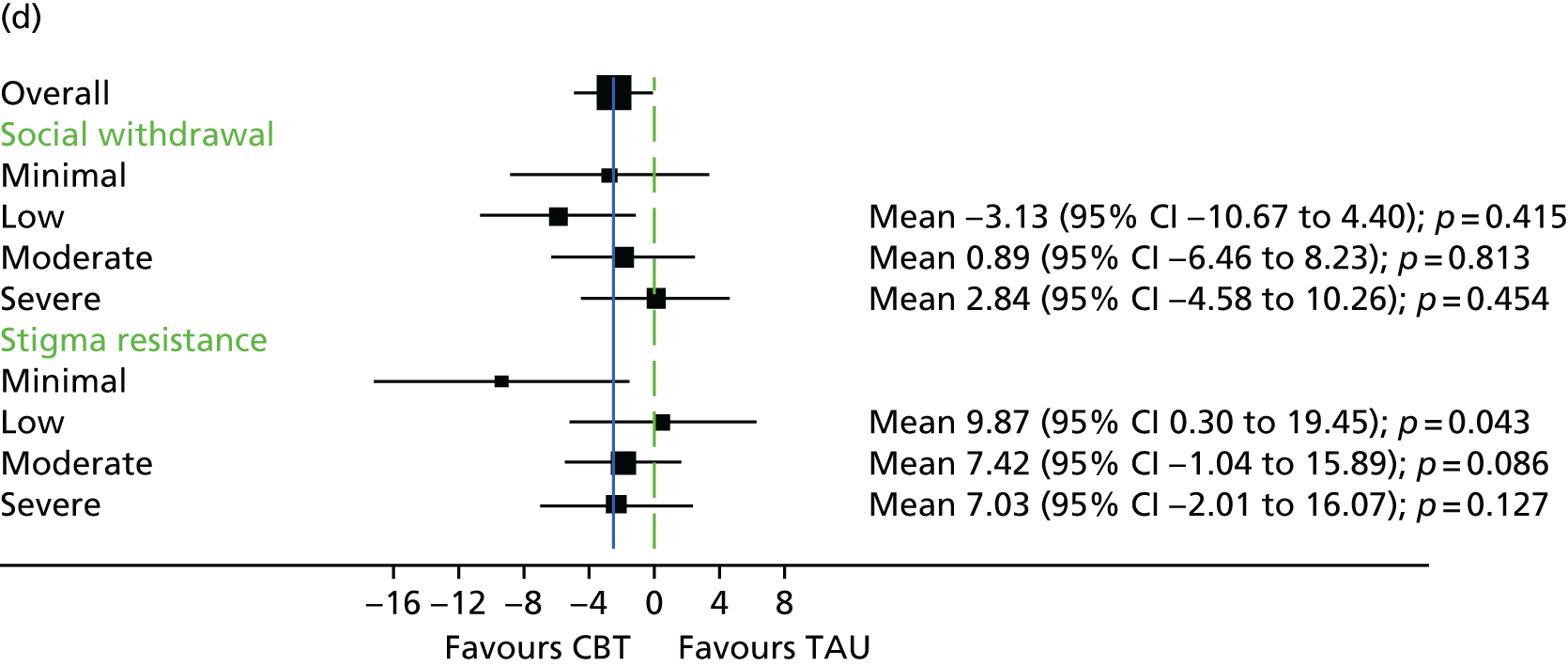

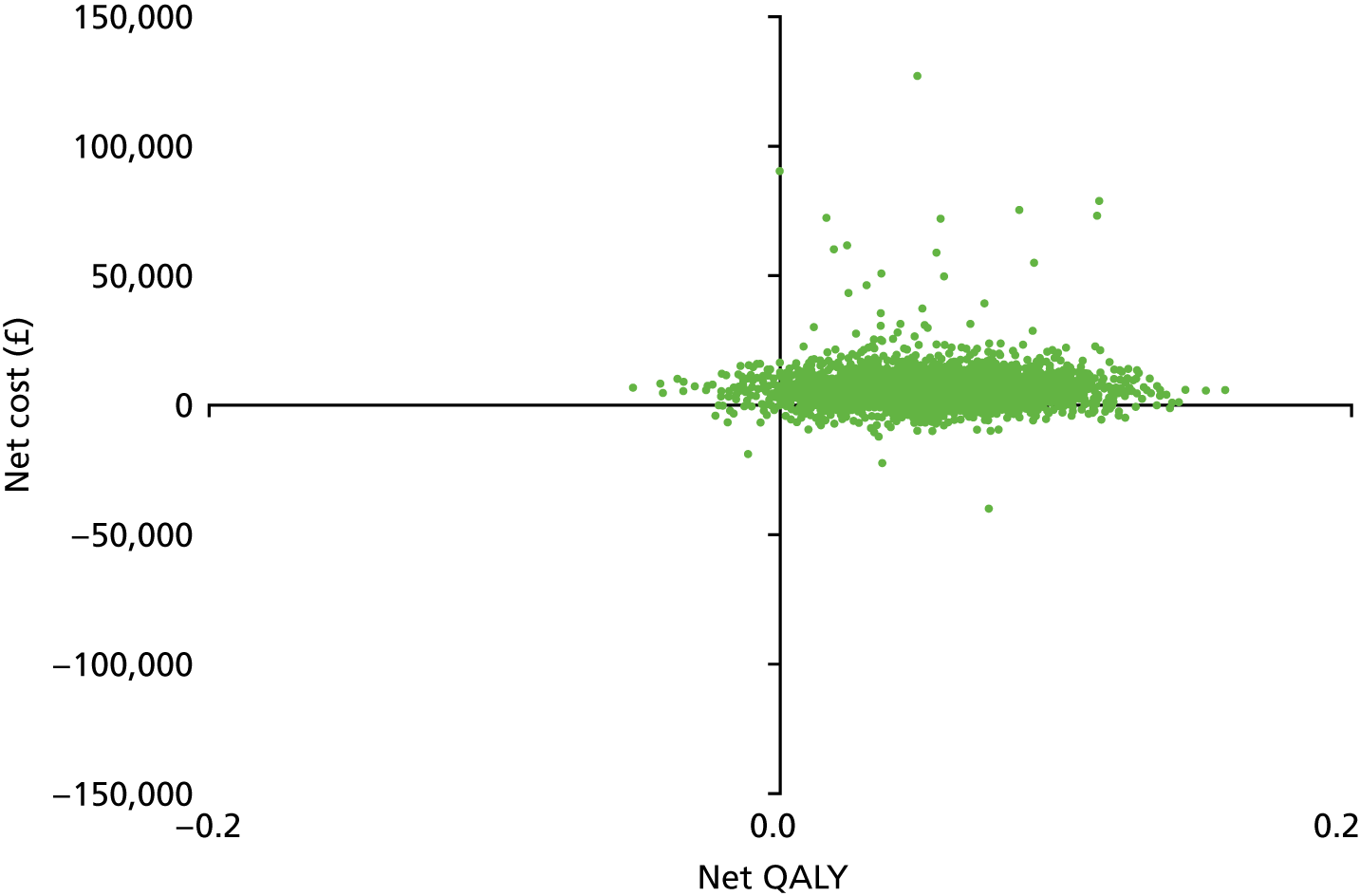

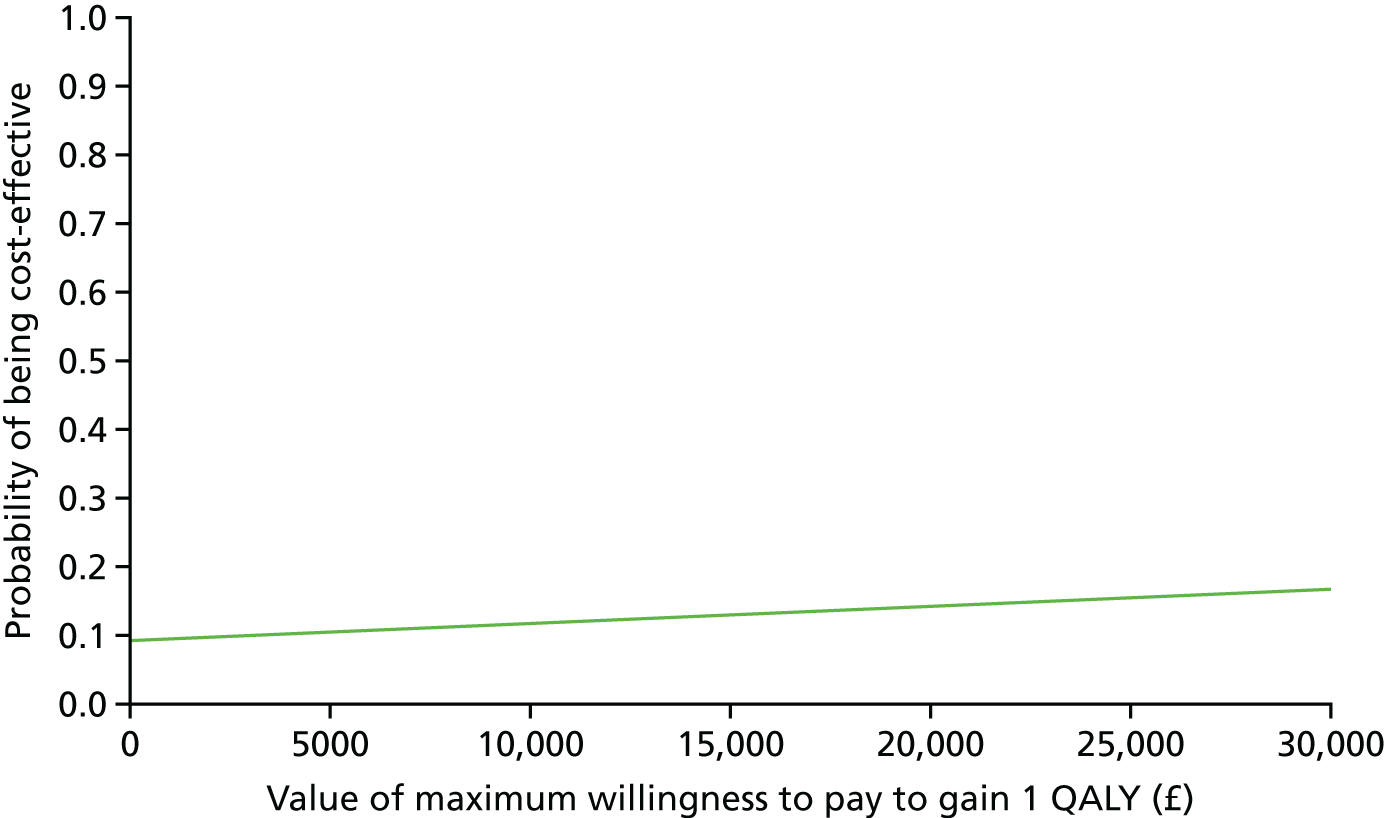

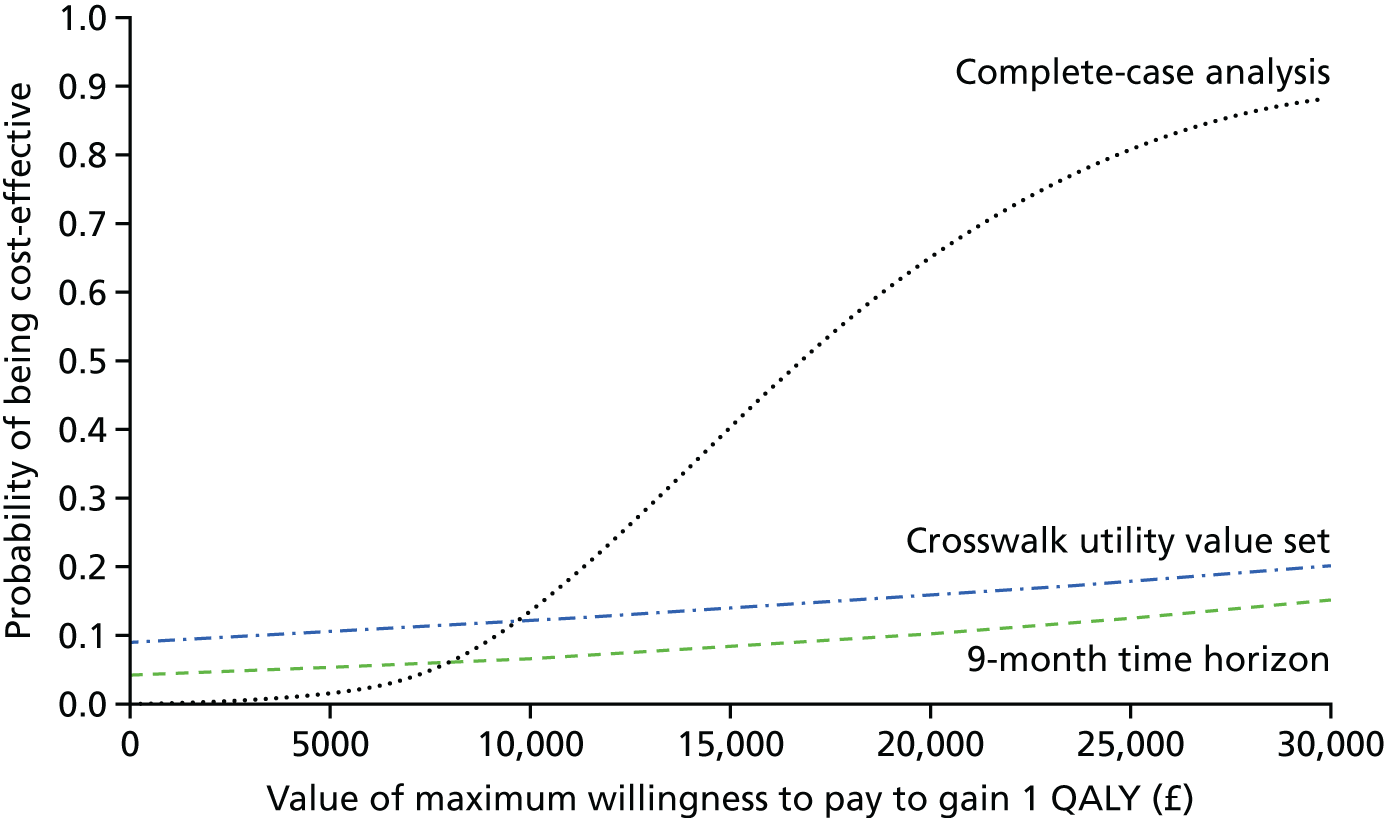

The semistructured clinical interview for psychosis subgroups (SCIPS)150 assesses areas of life and events before the onset of psychotic symptoms. The items cover psychosocial factors and comorbid conditions that have been proven to be associated with psychosis to allow for the classification of a specified subgroup: traumatic, drug related, anxiety or stress sensitivity. SCIPS was administered at 12-month follow-up (21 months) for participants who reached this time point by October 2015; all other participants completed SCIPS at the end-of-treatment assessment (9 months).