Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was commissioned and funded by the HTA programme on behalf of NICE as project number 17/10/01. The protocol was agreed in July 2017. The assessment report began editorial review in January 2018 and was accepted for publication in July 2018. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Andrew Shennan is an investigator in a number of trials/studies related to preterm birth (the GlaxoSmithKline-funded NEWBORN tocolytic trial, the National Institute for Health Research-funded PETRA and QUIDS prediction studies, the Guy’s and St Thomas’ charity-funded EQUIPPT, the preterm management study and Tommy’s charity-funded preterm birth studies). These studies include comparing PartoSure™ (Parsagen Diagnostics Inc., Boston, MA, USA) and the quantitative Fetal Fibronectin (fFN) Test (Hologic, Inc., Marlborough, MA, USA) and have been supported by free PartoSure samples from QUIAGEN and received financial support from Hologic, Inc. (fFN), paid to his institution to cover expenses of this comparison only. He has given lectures to internal staff at BioMedica [Actim® Partus (Medix Biochemica, Espoo, Finland)] and Hologic, Inc. (fFN), in the last 5 years and received financial support to cover expenses only for this when travelling to the USA and Finland.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2019. This work was produced by Varley-Campbell et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2019 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Background and definition of the decision problem(s)

Conditions and aetiologies

Preterm (premature) birth, as defined by the World Health Organization (WHO), refers to babies born alive before 37 weeks and 0 days of gestation (37 + 0 weeks). 1

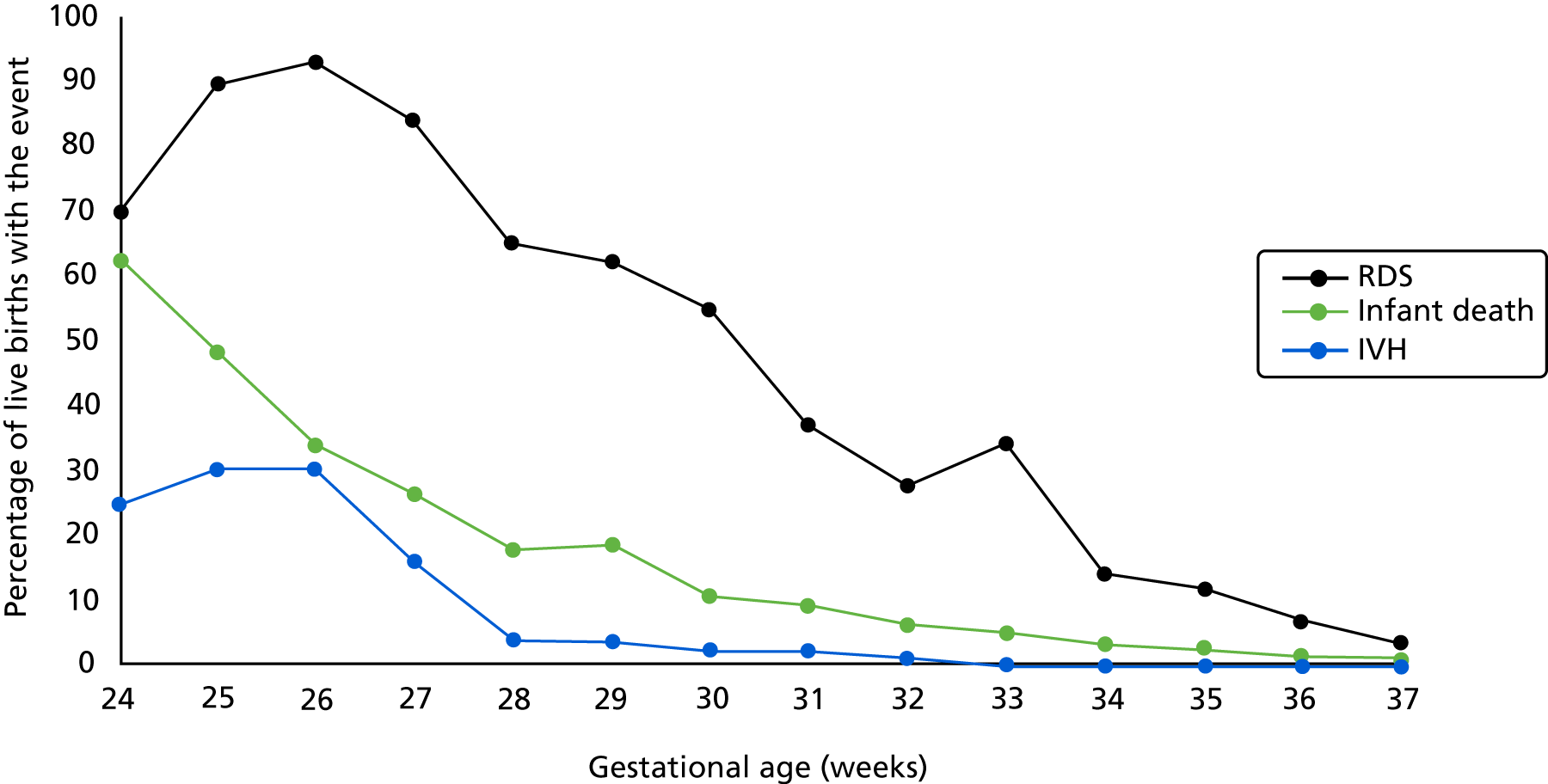

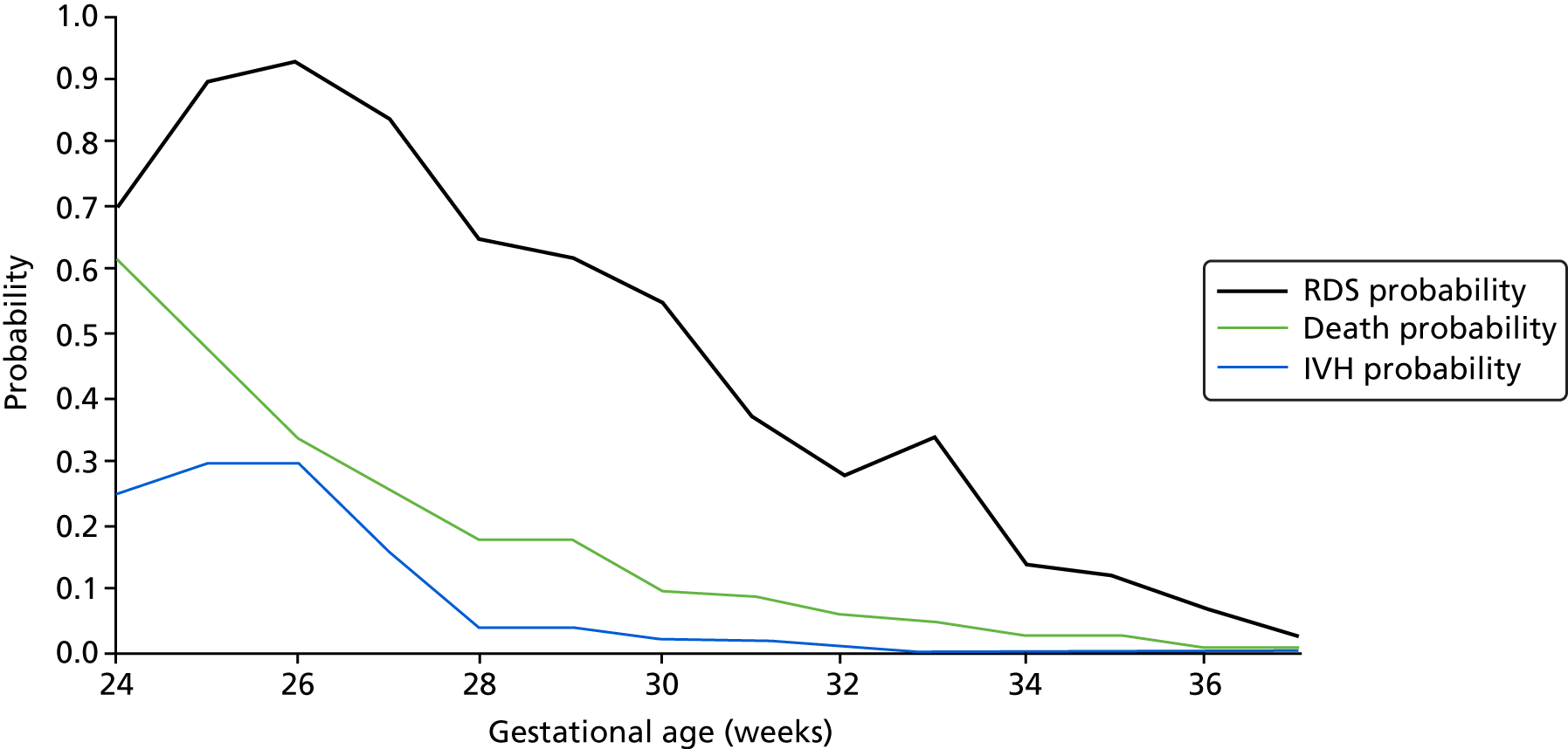

Preterm birth can be serious for an infant in terms of both short- and long-term health problems and an increased risk of mortality. For example, short-term problems include difficulties with breathing [respiratory distress syndrome (RDS)] and feeding and an increased risk of infections and bleeding within the brain [intraventricular haemorrhages (IVHs)]. Meanwhile, long-term problems include an increased risk of cerebral palsy, cognitive and visual impairment and respiratory illnesses. 2,3

Aetiology, pathology and prognosis

The WHO1 subcategorises preterm birth based on gestational age as:

-

extremely preterm – < 28 weeks’ gestational age

-

very preterm – ≥ 28 weeks’ and < 32 weeks’ gestational age

-

moderate to late preterm – ≥ 32 weeks’ and < 37 weeks’ gestational age.

Iatrogenic preterm births are medically instigated deliveries, such as early labour induction or caesarean section. 4 These elective deliveries aim to reduce health risks to the mother or fetus owing to complications such as hypertension, intrauterine growth restriction or pre-eclampsia. 4

Spontaneous preterm labour is a multifactorial condition with various underlying pathologies including infection, breakdown of fetal–maternal tolerance, stress, decidual senescence and uterine distension (commonly associated with multifetal pregnancies). 5 Spontaneous preterm deliveries can be broadly categorised as either spontaneous labour with intact membranes or those following preterm premature rupture of membranes (PPROMs). 4 Factors associated with an increased risk of preterm delivery include stress, tobacco use, drug abuse, trauma, multifetal gestations, in vitro fertilisation, low body mass index (BMI) before pregnancy, extremes of maternal age, diabetes mellitus, high blood pressure and infection. 6,7 However, previous preterm delivery is the greatest risk factor for preterm birth. 8

Symptoms of suspected preterm labour include painful contractions or cramps, abdominal and low-back pain and an increase or change in vaginal discharge. 9 Symptoms do not always result in progression to established labour and birth; they may occur but then settle, allowing the pregnancy to continue towards term. It is understood that > 90% of women presenting with symptoms of preterm labour do not go on to deliver in the next 2 weeks and, of these, 50% will continue with pregnancy until full term. 10,11 It is important to determine whether or not preterm labour is the cause of the symptoms and to assess the risk of preterm delivery to allow appropriate management to begin as soon as possible. 12

The focus population for this report is women presenting with signs and symptoms of spontaneous preterm labour with intact membranes.

Epidemiology

Data from the England and Wales 2016 birth cohort13 report 54,143 live, preterm deliveries in accordance with the WHO definition of preterm birth (< 37 weeks’ gestational age), corresponding to 7.8% of all live births. Of these deliveries, 5.9% were categorised as extremely preterm (< 28 weeks’ gestation), 10.4% were very preterm (gestational age of ≥ 28 to < 32 weeks) and 83.7% were moderate to late preterm (≥ 32 to < 37 weeks’ gestation). 13

The 2016 UK birth cohort data collected by the Office for National Statistics (ONS)13 show that the rate of preterm births varies between ethnic populations, with the highest proportion of preterm births occurring in black Caribbean and Indian populations (10.4% and 8.03% of pregnancies in these populations, respectively) and the lowest rate of preterm births occurring in women of ‘white other’ ethnicity (6.6%). The rate of preterm delivery in the population in which ethnicity was ‘not stated’ was 8.3%. 13 In the UK, preterm labour, particularly extreme preterm labour, disproportionately affects women from low socioeconomic backgrounds. 14,15

Incidence and/or prevalence

Improvements in perinatal health-care services have resulted in vastly improved outcomes for babies born preterm, yet the prevalence of preterm birth continues to rise. 1,16

Preterm birth rates vary between countries, with higher prevalence and poorer outcomes in lower-income countries. 16 However, preterm birth is a global issue that also affects developed countries.

Impact of the health problem

Globally, preterm birth complications are directly responsible for 35% of all neonatal deaths and are the second leading cause of death in children aged < 5 years. 16,17

Morbidities associated with preterm birth are both acute and chronic and can affect all organ systems. Respiratory distress can progress to bronchopulmonary dysplasia18 and cerebral pathology (e.g. IVHs and ischaemia can lead to neurodevelopmental disorders including learning and behavioural difficulties). 19,20 In addition, gastrointestinal disorders and immunodeficiencies are also associated with preterm birth. 21,22

Although mortality and morbidity rates are higher for infants delivered at lower gestational ages and lower birthweights, near-term premature infants remain at a considerably higher risk of complications than their full-term counterparts. 20

Preterm deliveries place a significant cost burden on the NHS. In addition to initial hospitalisation, rehospitalisation and rehabilitation, other direct medical costs include medication, aids and devices such as wheelchairs, visits to physicians and home care. 23 Direct non-medical costs such as special education, adaptations to homes or cars, special meal requirements, higher insurance premiums and other disease-associated costs are an expensive burden on both families and the state. 23

Current guidelines

The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guideline24 on preterm labour (Figure 1) and birth states that women reporting symptoms of preterm labour who have intact membranes should have a clinical assessment that includes:

-

clinical history-taking

-

observations of the woman, including the length, strength and frequency of her contractions; any pain she is experiencing; pulse, blood pressure and temperature; and urinalysis

-

observations of the unborn baby, including asking about the baby’s movements in the last 24 hours; palpation of the woman’s abdomen to determine the fundal height, the baby’s lie, presentation, position, engagement of the presenting part, and frequency and duration of contractions; and auscultation of the fetal heart rate for a minimum of 1 minute immediately after a contraction

-

a speculum examination (followed by a digital vaginal examination if the extent of cervical dilatation cannot be assessed).

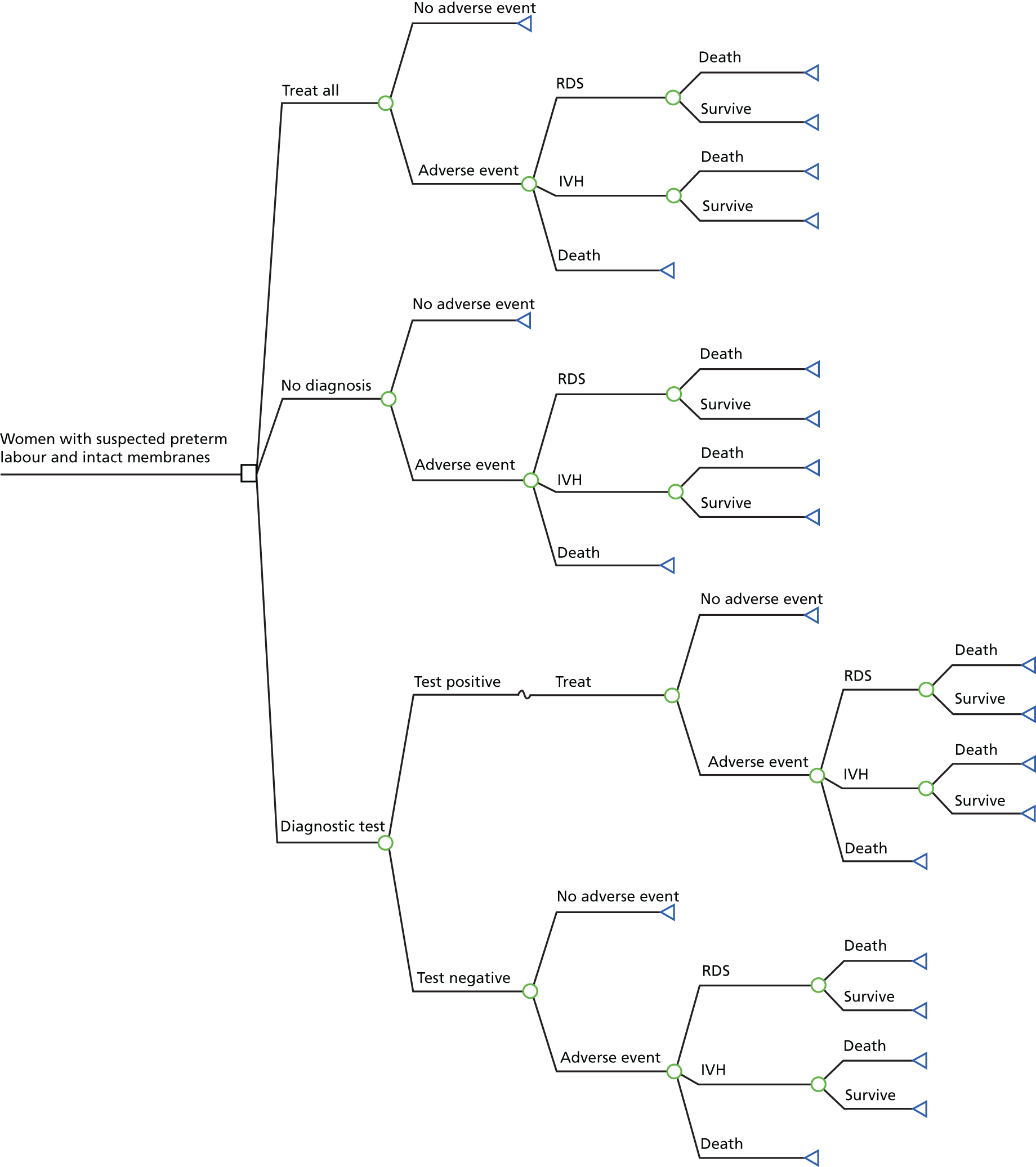

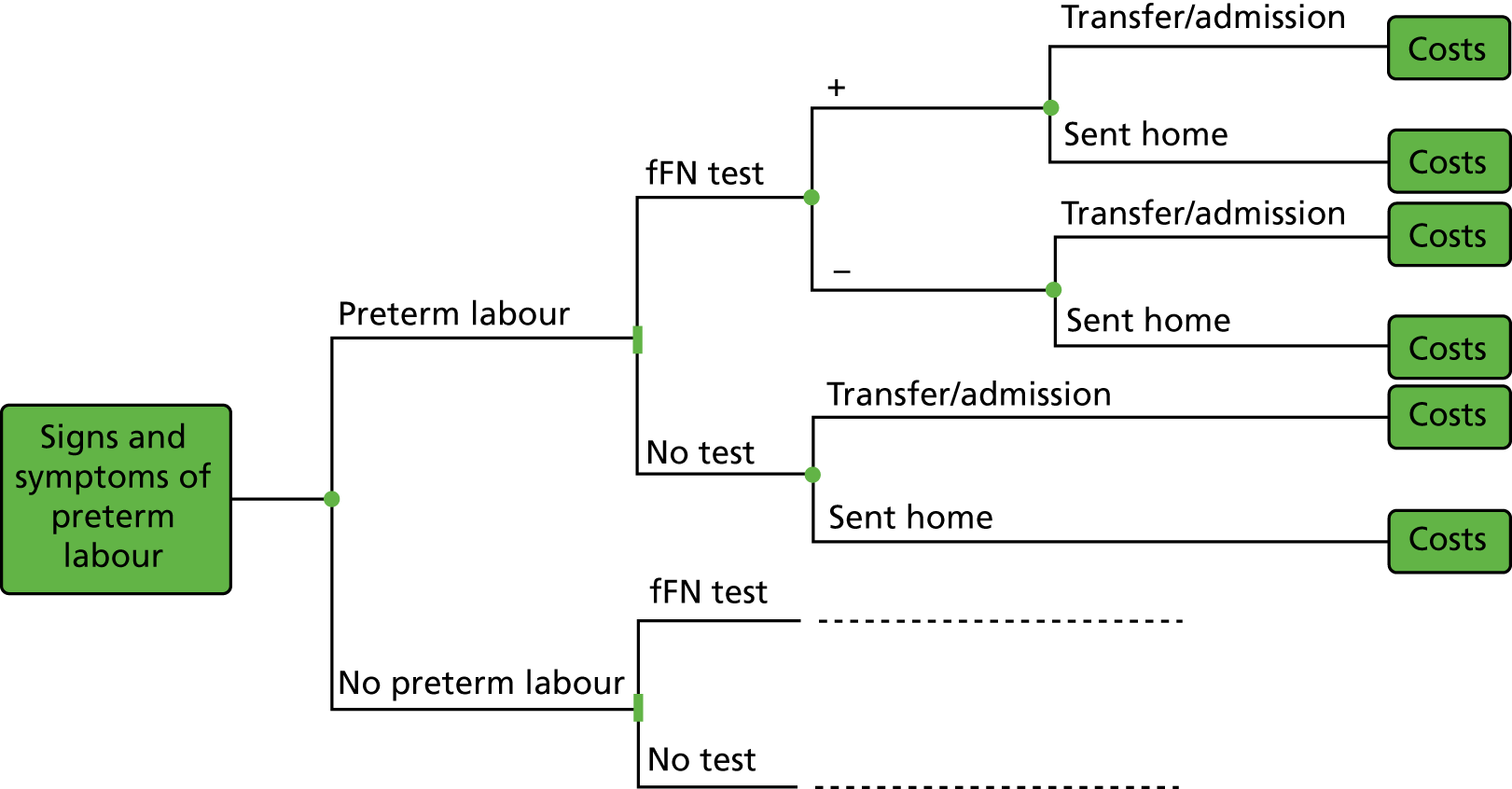

FIGURE 1.

Diagnosis of preterm labour from section 9 of the 2015 NICE guidance on preterm labour and birth. 24 FN, fetal fibronectin; PTL, preterm labour. Reproduced from: Royal College of Obstetricians NICE Guideline 25 Preterm Labour and Birth, London, ROCG, November 2015, with the permission of the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists. 24

If the clinical assessment suggests that the woman is in suspected preterm labour and she is 29 + 6 weeks pregnant or less, treatment for preterm labour is recommended. 24

If the clinical assessment suggests that the woman is in suspected preterm labour and she is ≥ 30 + 0 weeks pregnant then the following tests should be conducted:24

-

Transvaginal ultrasound scan measurement of cervical length (as a diagnostic test to determine likelihood of birth within 48 hours).

-

If cervical length is > 15 mm, the woman is unlikely to be in preterm labour and could be discharged home with routine follow-up in the community and advised to return if symptoms reappear.

-

If cervical length is ≤ 15 mm, the woman is diagnosed as being in preterm labour and should be offered treatment.

-

-

If transvaginal ultrasound scan measurement of cervical length is indicated but is not available or not acceptable, then fetal fibronectin (fFN) testing as a diagnostic test may be used for women who are ≥ 30 + 0 weeks pregnant.

-

If the fFN test result is negative (concentration of < 50 ng/ml), the woman is unlikely to be in preterm labour and could be discharged home with routine follow-up in the community and advised to return if symptoms reappear.

-

If the fFN test result is positive (concentration of ≥ 50 ng/ml), the woman is diagnosed as being in preterm labour and should be offered treatment.

-

It is not recommended to use transvaginal ultrasound scan measurement of cervical length and fFN testing in combination to diagnose preterm labour.

Description of the technologies under assessment

Accurate diagnoses of preterm birth using a biomarker test could prevent unnecessary, or ensure appropriate, admissions into hospitals, transfers to specialist units and/or treatment.

Summary of the technologies

Following the NICE guidance, the technologies under assessment in this review would appear in the treatment pathway where the fFN test (at the threshold of 50 ng/ml) is currently being used. A summary of information relating to the tests is given in Table 1.

| Category | Actim® Partus (Medix Biochemica, Espoo, Finland)26 | PartoSure™ (Parsagen Diagnostics Inc., Boston, MA, USA)27 | Rapid fFN® 10Q Cassette Kit (Hologic, Inc., Marlborough, MA, USA)28 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gestational age | From 22 weeks | From 20 + 0 weeks to 36 + 6 weeks | From 22 + 0 weeks to 35 + 6 weeks |

| Contraindications | Ruptured membranes, vaginal bleeding (moderate or heavy), amniotic fluid | Significant blood on the swab, within 6 hours of vaginal disinfectant solutions or medicines. Inaccurate results may be likely with previous placenta previa or digital examination or in presence of meconium, antifungal creams, suppositories, lubricants, moisturisers, talcum powder or baby oil | Advanced cervical dilatation (≥ 3 cm), ruptured membranes, cervical cerclage, placental abruption, placenta previa (moderate) or vaginal bleeding (heavy). Inaccurate results may be likely with sexual intercourse, digital cervical examination or transvaginal ultrasound scan and bacteria, bilirubin and semen. A negative test result is still valid if in the presence of semen |

| Instructions |

Negative results (one blue line) should be confirmed at 5 minutes: highly unlikely that patient will deliver within the next 2 weeks Positive results (two blue lines) can be read as soon as it becomes visible (if before 5 minutes). Risk of a preterm delivery is elevated |

Negative results (one line) should be confirmed at 5 minutes Positive results (two lines) can be read as soon as it becomes visible (if before 5 minutes) |

|

| Kit components |

|

|

|

| Cost | £15 per test excluding VAT | £32 per test excluding VAT | £35 per test excluding VAT |

| Storage | The kit should be stored between 2 °C and 25 °C | The kit should be stored in a dry place between 4 °C and 25 °C |

The kit should be stored at room temperature between 15 °C and 30 °C Transport specimens at 2 °C to 25 °C, or frozen. Specimens are stable for up to 8 hours at room temperature Specimens not tested within 8 hours of collection must be stored refrigerated at 2 °C to 8 °C and assayed within 3 days of collection, or frozen and assayed within 3 months to avoid degradation of the analyte. Specimens arriving frozen should be subject to a single freeze–thaw cycle only |

| Test range | The test has a limit of detection of 10 µg/l and a measuring range of 10 to 8000 µg/l | The test has a limit of detection of 1 ng/ml and a measuring range of 1–40,000 ng/ml | The test has a detection range of 0–500 ng/ml, concentrations of > 500 ng/ml will be displayed as > 500 ng/ml |

| User personnel | The test is intended for professional use and results must be interpreted in the light of other clinical findings | The test is designed to be used in conjunction with clinical assessment and by health-care professionals | The test is intended to be used in conjunction with other clinical information |

PartoSure

PartoSure™ (Parsagen Diagnostics Inc., Boston, MA, USA) is a CE-marked qualitative lateral flow, immunochromatographic point-of-care test that detects placental alpha microglobulin-1 (PAMG-1) in vaginal secretions. PAMG-1 is a protein produced by decidual cells lining the uterus and is secreted into amniotic fluid, its concentration in vaginal discharge is usually low and studies have shown that the presence of PAMG-1 in vaginal discharge is predictive of imminent delivery. 25

Actim Partus

Actim® Partus (Medix Biochemica, Espoo, Finland; distributed by Alere Inc.) is a CE-marked qualitative immunochromatographic point-of-care test that detects phosphorylated insulin-like growth factor binding protein-1 [ph(IGFBP-1)] in cervical secretions. ph(IGFBP-1) is made by cells lining the uterus and leaks into the cervix when delivery is imminent. 12

Rapid Fetal Fibronectin 10Q Cassette Kit

The Rapid fFN® 10Q Cassette Kit (Hologic, Inc., Marlborough, MA, USA) is a CE-marked point-of-care test for use in the PeriLynx system or the Rapid fFN 10Q system. This test quantifies the concentration of fFN present in cervicovaginal fluid. fFN is a glycoprotein that connects membranes of the uterus and fetal membranes, which begins to degrade after 35 weeks of pregnancy or soon before preterm birth.

Population

For the purpose of this report, the population of interest is women with signs and symptoms of preterm labour with intact amniotic membranes, who are not in established labour and for whom a transvaginal ultrasound scan is not available or acceptable.

Identification of important subgroups

The following women are at different risks of preterm delivery and consequently adverse neonatal outcomes. The clinical utility of the test may vary across these groups and the relative value of accurate identification of true-positive and true-negative cases is different from that in the overall population:24

-

women with history of preterm delivery

-

women presenting with symptoms at < 28 weeks’ gestation

-

women presenting with symptoms at ≥ 28 and < 32 weeks’ gestation

-

women presenting with symptoms at ≥ 32 weeks’ gestation

-

women with multiple fetuses

-

women from lower socioeconomic groups (i.e. in most disadvantaged decile).

Current usage in the NHS

Current NICE guidelines are described in Current guidelines.

Advising clinicians report that the guidelines are not always followed in typical clinical practice. Symptomatic women presenting irrespective of gestational age will usually have the fFN test administered. In addition, clinicians advise that transvaginal ultrasound scan is rarely used in routine practice owing to a lack of trained staff available, experience or equipment availability.

Anticipated costs associated with the intervention

The cost of the Rapid fFN 10Q System is usually £35 per test, not including value-added tax (VAT). The cost per control is £40 and this is usually incurred twice per year for each site. Additional costs associated with equipment maintenance and test consumables are negligible (request for information from NICE to Hologic, Inc., 2017, personal communication from NICE).

The cost per Actim Partus test is £15, not including VAT. No other costs are associated with this test (request for information from NICE to Alere Inc., 2017, personal communication from Alere Inc.).

The cost per PartoSure test (PAMG-1) is £32, not including VAT. No other costs are associated with this test (request for information from NICE to Parsagen Diagnostics Inc., 2017, personal communication from Parsagen Diagnostics Inc.).

Comparators

The two comparators from the NICE scope (for the clinical and cost-effectiveness reviews) are fFN, used at a threshold of 50 ng/ml, and clinical assessment.

Fetal fibronectin used with a threshold of 50 ng/ml

Point-of-care, qualitative fFN tests currently in use in the UK include QuikCheck fFN™ (Hologic, Inc., Marlborough, MA, USA) and Rapid fFN for the TLiIQ® System (Hologic, Inc., Marlborough, MA, USA). 29

QuikCheck fFN

QuikCheck fFN is a CE-marked, lateral flow immunoassay. The test kit includes a sterile applicator, test strip and a tube containing an extraction buffer. Additional materials required are a test tube rack and timer. 29

The specimen is obtained from the posterior fornix using the applicator provided. The tip of the applicator is inserted into the extraction buffer and vigorously mixed for 10–15 seconds, the applicator tip is pressed against the side of the tube to remove as much liquid as possible and discarded. The ‘dip area’ of the test strip is suspended in the extraction mixture for 10 minutes and then removed. Two lines indicate a positive result and a high risk of preterm delivery within 7–14 days; one line indicates a negative result and a low risk of delivery within 7–14 days; if no lines appear, the test result is invalid. The detection limit of the test is 50 ng/ml. 29

The QuikCheck fFN test must be run within 15 minutes of the sample collection. The sample should be obtained before digital examination is conducted as cervix disruption may affect the test results. The presence of semen and gross vaginal bleeding may also affect the test results. The test is indicated for women presenting with threatened preterm labour and intact amniotic membranes. 29

Rapid Fetal Fibronectin for the TLiIQ System

Rapid fFN for the TLiIQ System (Hologic, Inc., Marlborough, MA, USA) is a CE-marked immunochromatographic assay. The Rapid fFN test kit includes cassettes and a directional insert. Other materials required include a 200-µL pipette, a Rapid fFN Control Kit (includes positive control, negative control and directional insert) and the TLiIQ System, which contains an analyser, printer and TLiIQ QCette. 29

A cervicovaginal sample is obtained from the posterior fornix or the ectocervical region of the external cervical os using a swab. The swab is rolled against the inside of the specimen transport tube to express the liquid into the extraction buffer and the swab is then discarded. The TLiIQ analyser is set to internal incubation mode and the cassette containing the sample is inserted. Thereafter, 200 µl of the patient sample is dispensed into the sample application well of the Rapid fFN Cassette. After 20 minutes, the TLiIQ analyser will display a result: positive, negative or invalid. The detection limit of the test is 50 ng/ml. 29

This test is indicated for use in routine prenatal visits between 22 + 0 weeks’ and 30 + 6 weeks’ gestation, to assess the risk of delivery at ≤ 7 or ≤ 14 days from testing. Disruption to the cervix (i.e. through sexual intercourse, digital vaginal examination or transvaginal ultrasound scan) may result in a false-positive result. Douches, semen, white blood cells, red blood cells, bacteria and bilirubin may interfere with test results. However, if the patient reports sexual intercourse within the previous 24 hours, a negative fFN test result is still valid. 29

Clinical assessment of symptoms alone

Clinical assessment consists of taking a clinical history, observations of the woman and unborn baby and a speculum examination. See Current guidelines for more details.

Care pathways

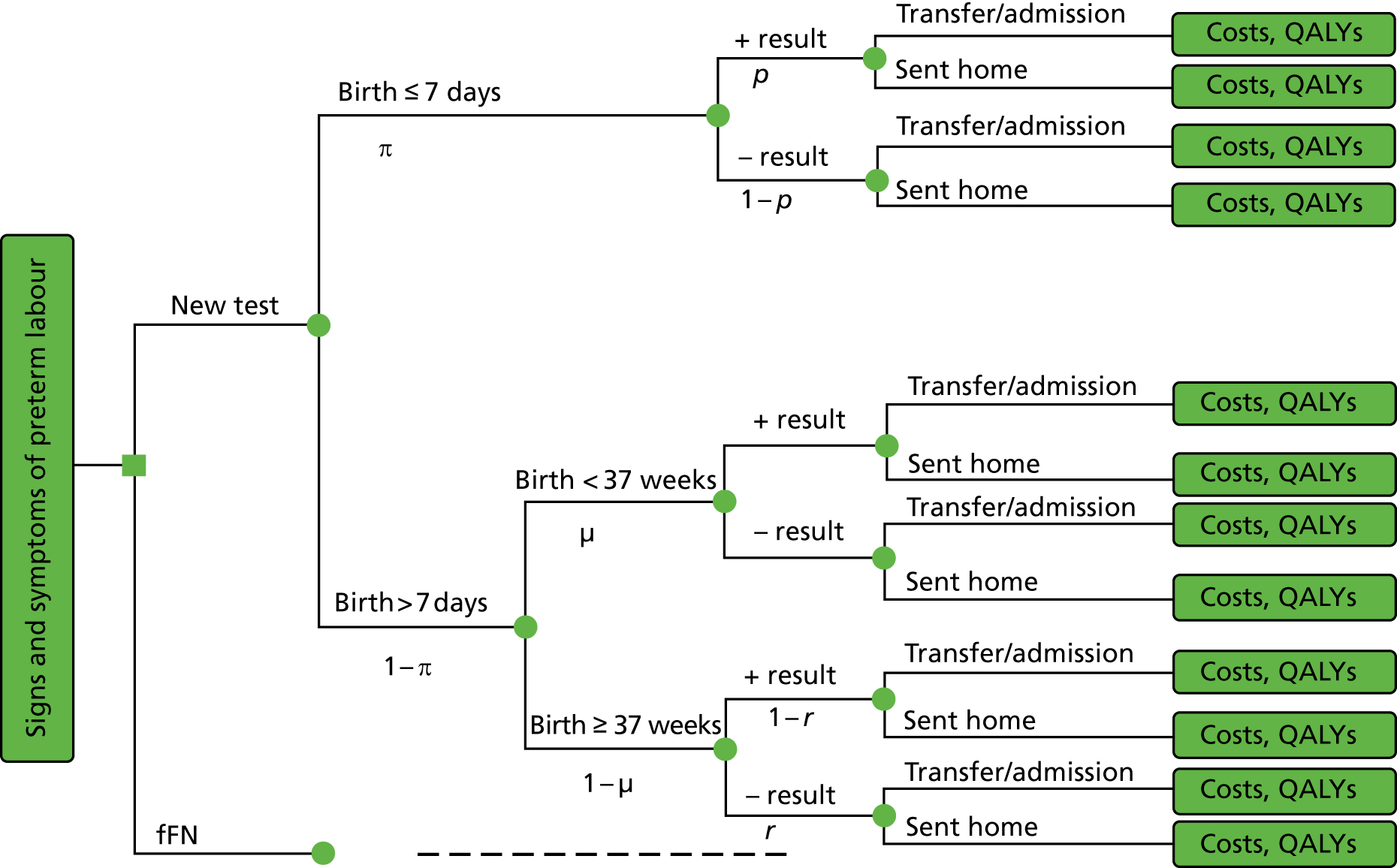

Clinical assessment and use of the biomarker tests aid clinicians in their decisions regarding whether women presenting with signs and symptoms of preterm labour can be safely sent home or need to be admitted to hospital for treatment to delay birth and improve neonatal outcomes. 24 Typically, the results would be used in combination with clinical judgement. For example:

-

If the test result is negative and the symptoms of preterm labour have settled, the woman would be discharged home with routine follow-up in the community and advised to return if symptoms reappear.

-

If the test result is negative but symptoms of preterm labour continue, the woman would be admitted and monitored and symptoms treated as appropriate and monitored. If symptoms were managed successfully, the woman would be discharged home.

-

If the test result is positive, the woman would be admitted and symptoms managed as appropriate and monitored.

Once a woman has been diagnosed with threatened preterm labour, she will typically be offered tocolytic therapy, corticosteroids and magnesium sulphate. 24

Tocolytic therapy

Tocolytic therapies increase the latency period for up to 48 hours. The aim of this therapy is to allow time for neonatal transfers and to complete the course of antenatal corticosteroids (ACSs). 30 There are many classes of tocolytic drugs with different mechanisms of action. 30

The NICE guidelines24 recommend nifedipine for women between 24 + 0 and 33 + 6 weeks’ gestation in suspected or diagnosed labour with intact membranes. If nifedipine is contraindicated, NICE recommends oxytocin receptor antagonists [e.g. Atosiban (Sun Pharmaceuticals UK Ltd)] for tocolytic therapy.

Our clinical advisors suggest that tocolytic therapy is not commonly used in routine clinical practice. This may be attributable to recent evidence on the potential harms to the fetus and infant. 30,31

Antenatal corticosteroids

Antenatal corticosteroids {e.g. dexamethasone [Alliance Healthcare (Distribution) Ltd] or betamethasone (AAH Pharmaceuticals Ltd)} are prescribed in cases of threatened preterm labour to stimulate fetal lung development to reduce infant mortality and morbidity. 32 Following administration of steroids, there is a window within which the steroids appear to be most beneficial for the infant (Figure 1C, Norman et al.). 33 The primary documented negative effect of giving steroids is a negative reduction in birthweight of approximately 100 g. 34

The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence currently recommends ACSs for women between 26 + 0 and 33 + 6 weeks’ gestation in suspected, diagnosed or established preterm birth, PPROM or undergoing planned preterm delivery. ACSs should be considered for extremely preterm (between 24 + 0 and 25 + 6 weeks’ gestation) and near-term (34 + 0 and 35 + 6 weeks’ gestation) women in suspected, diagnosed and established preterm labour, PPROM or undergoing iatrogenic deliveries. 24 However, evidence regarding the effectiveness of corticosteroid treatment at very low gestational ages remains uncertain. 24 NICE recommends that clinicians should discuss the benefits and risks associated with ACSs with the patient and their family. Repeat doses are contentious owing to possible risks, although this needs to be weighed against potential benefits of reduced RDS and serious adverse infant outcomes. 32,35 For this reason, some cases of repeat dosing may be acceptable depending on the interval since last dose, gestational age and likelihood of delivery within 48 hours. 24

Magnesium sulphate

Magnesium sulphate is a neuroprotective agent that significantly reduces neurological morbidities such as cerebral palsy in preterm infants. 36

The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence recommends magnesium sulphate for women at 24 + 0 to 29 + 6 weeks’ gestation in established labour or with iatrogenic delivery planned within 24 hours. Magnesium sulphate should also be considered for women between 30 + 0 and 33 + 6 weeks’ gestation. A 4-g intravenous bolus dose of magnesium sulphate should be administered over 15 to 20 minutes, followed by an intravenous infusion of 1 g per hour for 24 hours or until delivery. Patients should be routinely monitored for signs of magnesium toxicity.

Outcomes

The accuracy of biomarker testing for predicting preterm labour has been evaluated against the reference standard of preterm delivery within 48 hours or 7 days. Clinically important outcomes relevant to test accuracy include:

-

Sensitivity – the probability of correctly identifying someone who will deliver preterm:

-

Specificity – the probability of correctly identifying someone who will not deliver preterm:

-

Likelihood ratio (LR) – the likelihood of a given test result in a patient who has a preterm delivery compared with the likelihood of that same result in a patient who does not deliver preterm.

-

Likelihood ratio for a positive test result (LR+) – how much more often a positive test result occurs in people who do deliver preterm compared with those who do not:

-

-

Likelihood ratio for a negative test result (LR–) – how much less likely a negative test result is in people with preterm delivery compared with those without preterm delivery:

-

Positive predictive value (PPV) – the probability of someone with a positive result actually having a preterm delivery:

-

Negative predictive value (NPV) – the probability of someone with a negative test result actually not having a preterm delivery:

-

Diagnostic yield (also known as test positivity rate or apparent prevalence) – the number of positive test results divided by the number of samples.

-

Concordance – the proportion of cases in which the result of the test agrees with the clinical outcome.

-

Prevalence – the proportion of women actually having a preterm delivery.

-

Test failure (non-informative test result) rate.

-

Time (required) to (obtain a) test result.

Chapter 2 Assessment of test accuracy

This report contains reference to confidential information provided as part of the NICE appraisal process. This information has been removed from the report and the results, discussions and conclusions of the report do not include the confidential information. These sections are clearly marked in the report.

Methods for reviewing test accuracy

The diagnostic accuracies of PartoSure, Actim Partus and Rapid fFN 10Q Cassette Kit [at thresholds other than 50 ng/ml, referred to in the remainder of this report as quantitative fFN (qfFN)] were assessed by conducting a systematic review of the research evidence for these three index tests. This review was undertaken following the general principles published by the University of York Centre for Reviews and Dissemination. 37 The protocol was registered on PROSPERO (reference number CRD42017072696).

Methods of the systematic review

The aim of this systematic review was to identify and summarise the diagnostic test accuracy (DTA) data for PartoSure, Actim Partus and qfFN (at thresholds other than 50 ng/ml) from test accuracy studies that provide data for one or more of these index tests.

Identification of studies

Study sources and searches

To identify studies, the following bibliographic databases were searched from inception until July 2017 (the search was conducted in July 2017): MEDLINE (R), MEDLINE(R) Epub Ahead of Print, MEDLINE In-Process & Other Non-Indexed Citations, MEDLINE (R) Daily and EMBASE (all via Ovid), Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL) (via EBSCOhost); BioSciences Information Service and Web of Science (via Clarivate Analytics) and The Cochrane Library [Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects (DARE), Health Technology Assessment (HTA) database and NHS Economic Evaluation Database (NHS EED) (all via Wiley Interface)]. The search strategies were developed by a senior information specialist (CC), and comprised terms designed to identify the index tests. Methodological filters for test accuracy studies were not used to limit the study designs retrieved as these have been shown to reduce sensitivity38 and also because the search results were used to screen studies for the other two reviews described in this report (see Chapters 3 and 4). Search results were limited to English-language studies. The full search strategies for each database are reproduced in Appendix 1. The search results were exported to EndNote X8 [Clarivate Analytics (formerly Thomson Reuters), Philadelphia, PA, USA] and deduplicated using automatic and manual checking.

Additional sources were searched:

-

Systematic reviews identified by the bibliographic database searches were screened for includable studies. For the purpose of this review, a systematic review was defined as one that had a focused research question; explicit search criteria that are available to view; explicit inclusion/exclusion criteria; sufficient data on included and excluded studies to populate a PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) flow diagram; a critical appraisal of included studies, including consideration of internal and external validity of the research; and a synthesis of the included evidence (narrative or quantitative).

-

Trial registries were searched via the ClinicalTrials.gov website [https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/home (accessed July 2017)] and ISRCTN (International Standard Randomised Controlled Trial Number) [www.isrctn.com/editAdvancedSearch (accessed July 2017)] using terms designed to identify the index tests (see Appendix 1).

-

Google Advanced Search (Google Inc., Mountain View, CA, USA) was used to conduct web searching (September 2017), using terms designed to identify the index tests (see Appendix 1). For each term searched using Google Advanced Search, the first 50 hits were screened.

-

Items included after full-text screening were forward citation chased and screened using Scopus (Elsevier).

-

The reference lists of included studies were screened.

-

The industry submissions to NICE were cross-checked for additional studies.

Study selection

Relevant studies were screened in two stages. First, titles and abstracts returned by the search strategy were examined independently by two reviewers (two of JVC, SD, MB and HC) and screened for possible inclusion, using prespecified inclusion and exclusion criteria (see Inclusion and exclusion criteria). Disagreements were resolved by discussion within the review team. Full texts of studies included at the title and abstract screening stage were obtained, as were full texts of studies identified from systematic reviews, from trial registry searches, from forward and backward citation chasing, from references provided by the companies and from web searching. Two researchers (two of JVC, SD, MB and HC) independently examined full texts for inclusion or exclusion. Disagreements were again resolved by discussion within the review team.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Population

In line with the NICE scope,12 studies were included if they recruited pregnant women with signs and symptoms of preterm labour who were not in established labour and who had intact amniotic membranes. Studies were eligible regardless of whether they were based on samples that were at high or low risk for preterm labour. Studies were also eligible regardless of whether or not it was stipulated that the recruited population had access to transvaginal ultrasound scans. There were no specific inclusion criteria relating to the number of weeks of gestation of the women recruited; however, the study was required to define its population as preterm. The unit of assessment was individual women with a single result for each test.

Initially, studies were included only if all participants were expecting a singleton pregnancy. However, owing to the lack of evidence, a protocol amendment was made to include studies in which twin or multiple pregnancies were included but made up ≤ 20% of the total population recruited. We are not aware of any published evidence to suggest that multifetal pregnancies would alter the DTA of any of the tests.

Index tests

In accordance with the NICE scope,12 the index tests to be considered were:

-

PartoSure (with or without a clinical assessment)

-

Actim Partus (with or without a clinical assessment)

-

Rapid fFN 10Q Cassette Kit (qfFN), used with a threshold other than 50 ng/ml (with or without a clinical assessment).

Studies were eligible for inclusion if one or more index test was assessed against a reference standard.

Reference standard

Studies using one or more of the following reference standards were eligible for inclusion:

-

preterm delivery within 48 hours or within 7 days

-

clinical assessment of symptoms alone

-

fetal fibronectin at a threshold of 50 ng/ml (qualitative or quantitative test).

In addition, studies that provided test accuracy data by comparing the results of one index test with another (i.e. by using one of the index tests as a reference standard) were also eligible for inclusion. It was, however, expected that most studies would use preterm delivery within 48 hours, or within 7 days, as the reference standard.

Outcomes

In accordance with the NICE scope,12 the outcomes assessed for index tests were:

-

sensitivity – true positive/(true positive + false negative)

-

specificity – true negative/(false positive + true negative)

-

likelihood ratio for positive test result

-

likelihood ratio for negative test result

-

positive predictive value – true positive/(true positive + false positive)

-

negative predictive value – true negative/(true negative + false negative)

-

diagnostic yield (also known as test positivity rate or apparent prevalence)

-

concordance

-

prevalence (or incidence) of preterm delivery within 7 days and/or within 48 hours

-

test failure (non-informative test result) rate

-

time to test result.

Study design

Single-gate prospective or retrospective diagnostic studies with random or consecutively recruited participants were considered the optimal design for evaluating test accuracy of the index tests and were, therefore, eligible for inclusion. Ideally, studies assessing two or more index tests in the same population were sought, but studies assessing the accuracy of only one index test were also included. Studies assessing an index test and a test out of scope would be eligible for inclusion providing that data were reported specifically for all women receiving the index test. Two-gate diagnostic studies were also eligible for inclusion.

Studies in which the index test was conducted within 7 days of the reference standard were included. In addition, a protocol amendment was made to include studies using frozen samples (i.e. use not in line with clinical practice), even when the test was analysed outside the window stipulated in the manufacturers’ guidelines owing to a lack of evidence.

Studies were eligible for inclusion in the DTA review whether or not the index test results were used in the clinical management of patients.

We did not consider unpublished data without sufficient study methodology for quality appraisal.

Data extraction strategy

Data were extracted by one reviewer (SD) using a standardised data extraction form and checked by a second reviewer (JVC). Disagreements were resolved by discussion, with involvement of a third reviewer (HC) as necessary. Data were then transferred to standardised tables.

Critical appraisal strategy

The methodological quality of the studies was assessed by one reviewer (SD) and judgements were checked by a second reviewer (HC), in accordance with criteria specified by phase 3 of the QUADAS-2 tool (see Appendix 2). 39 Any disagreements were resolved by discussion, with involvement of a third reviewer (JVC) as necessary.

Methods of data synthesis

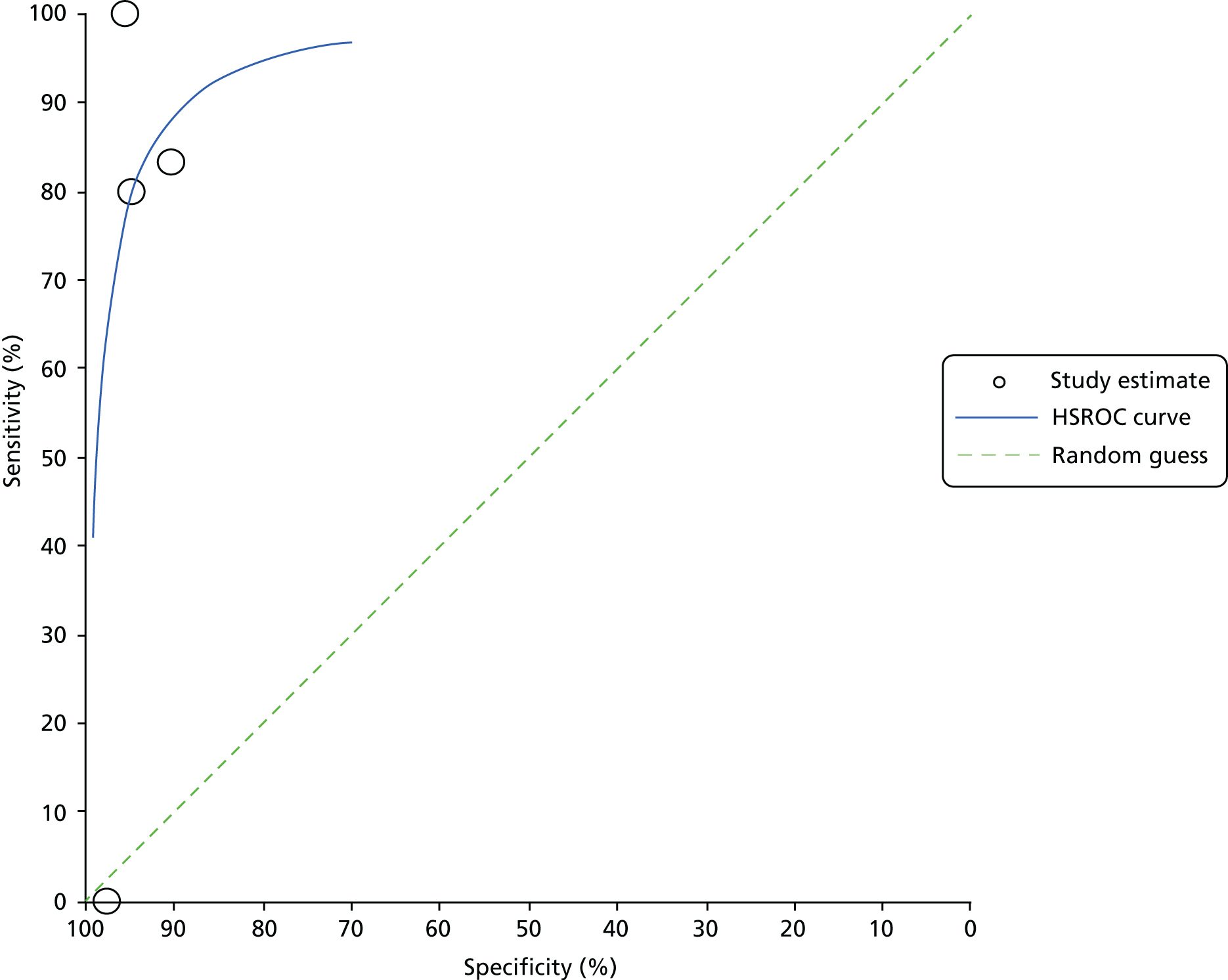

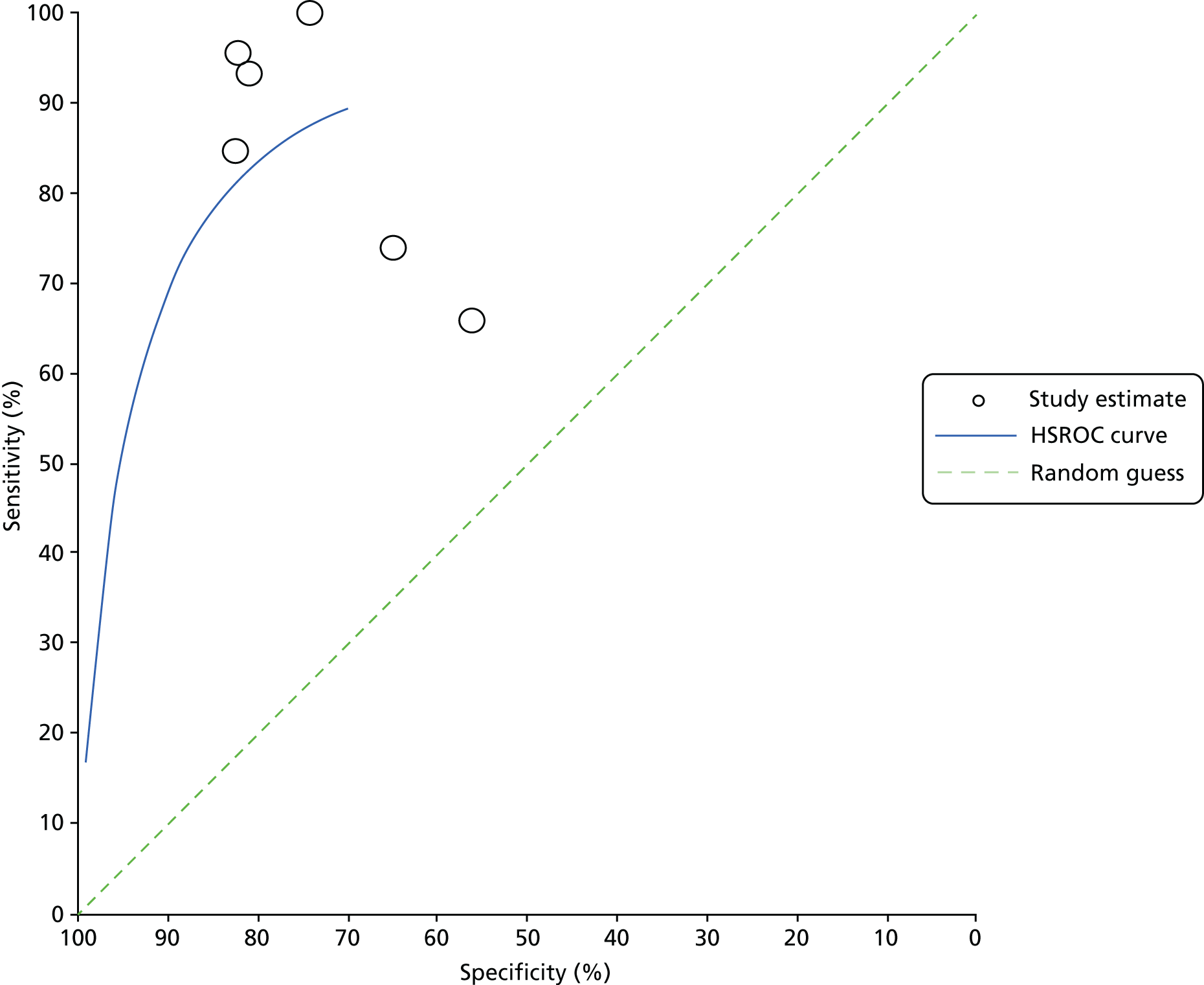

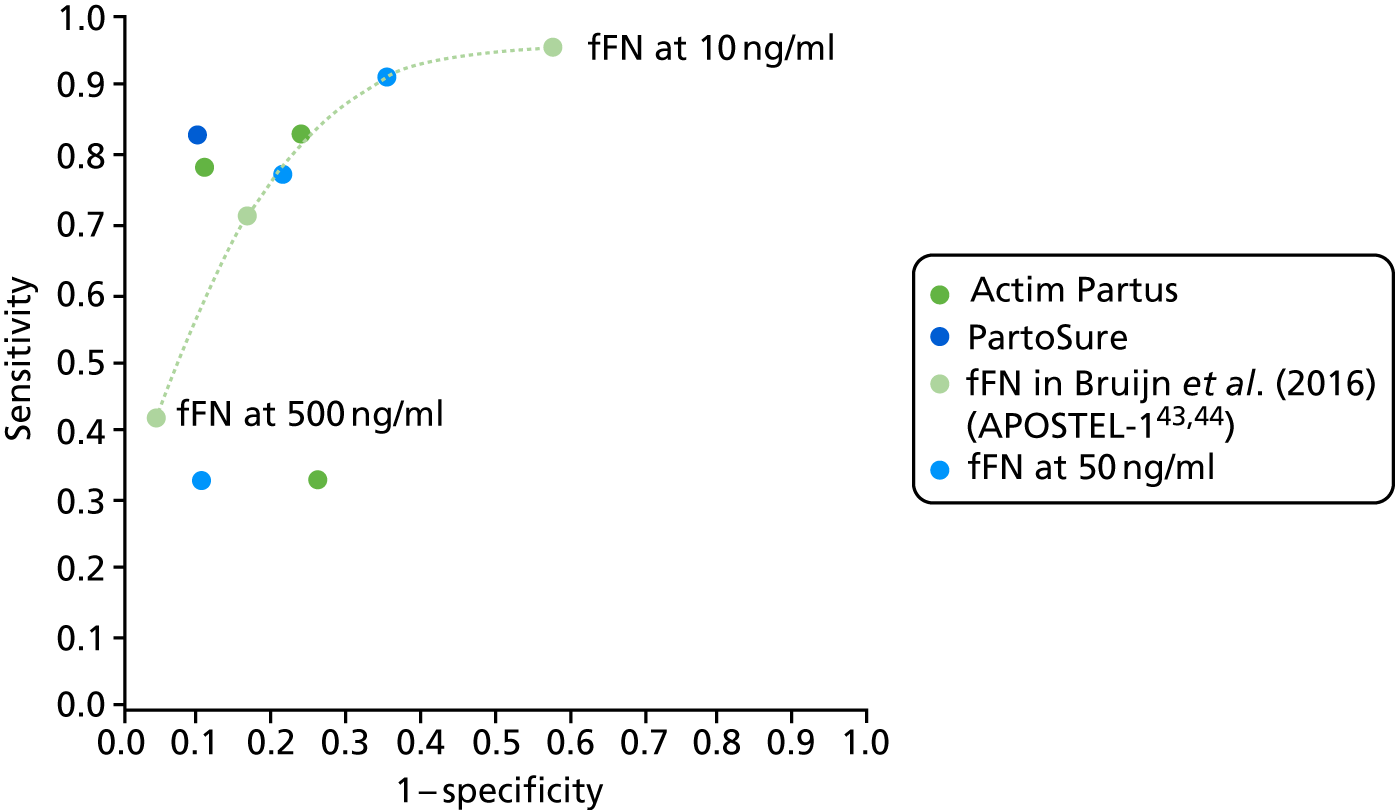

For all included studies, sensitivity, specificity, positive and negative predictive value, positive and negative LR, prevalence, concordance and diagnostic yield for delivery within 48 hours and 7 days were calculated from true-positive, true-negative, false-positive and false-negative values. Where the raw values were not provided, they were derived using back-calculation from other suitable available data. Summary receiver operating characteristic (ROC) plots were generated to provide graphical depiction of the sensitivity and specificity data. These were produced for each test separately against the 48-hour and 7-day reference standards, and for qfFN they were also produced separately for each testing threshold.

Summary ROC plots were generated subject to a minimum of three studies per plot. In accordance with Stata® requirements, the minimum number of studies for a diagnostic meta-analysis was four. Whenever this requirement was met, consideration was given to conducting meta-analysis. According to the Cochrane DTA handbook,40 heterogeneity cannot be assessed for diagnostic meta-analysis in the same way as for meta-analysis of interventions, and no quantitative summary statistic for heterogeneity can be derived.

Meta-analysis against the 7-day delivery reference standard for Actim Partus was conducted using the metandi command for sensitivity and specificity. Meta-analysis against the 48-hour delivery reference standard for Actim Partus and against the 7-day reference standard for PartoSure was conducted using a mixed-effects multilevel logistic regression to refine the parameters used in metandi to improve model convergence in the presence of a low proportion of preterm births in the study by Werlen et al. 41 No meta-analysis was undertaken for qfFN at any threshold or for the 48-hour reference standard for PartoSure.

Stata® version 14.11 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA) software was used for all statistical analysis. Graphs were made using Stata or Review Manager version 5.3 (Nordic Cochrane Centre, Copenhagen) software.

Results of the systematic review

In this section, the results of the systematic review of PartoSure, Actim Partus and qfFN are presented. Studies providing DTA data for one or more of these index tests are included (see Inclusion and exclusion criteria for specific details on inclusion and exclusion criteria).

Overview of the quantity and quality of research available

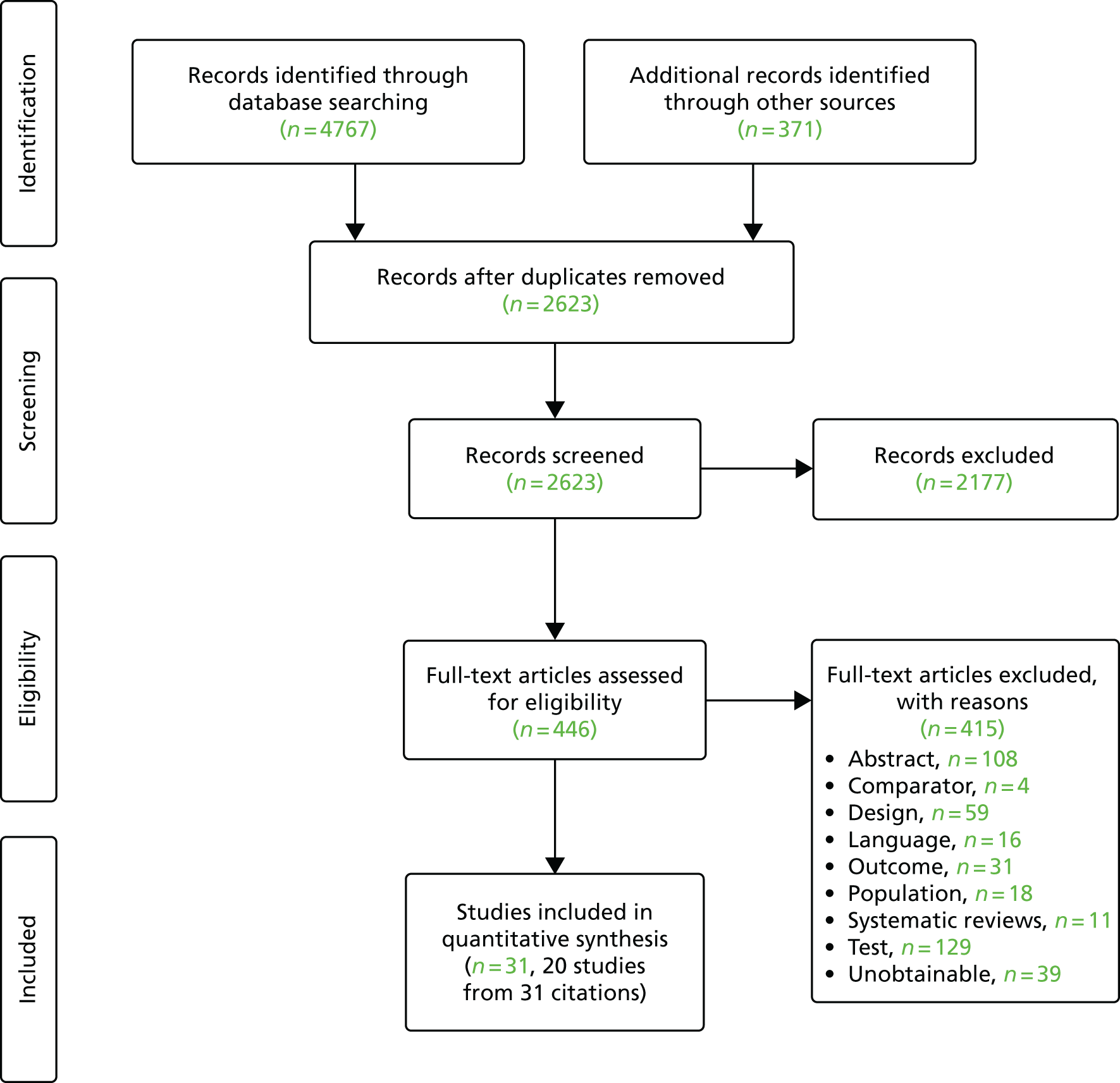

The searches retrieved a total of 2619 unique titles and abstracts. A total of 2177 articles were excluded, based on screening titles and abstracts. The remaining 442 articles were requested as full texts for more in-depth screening.

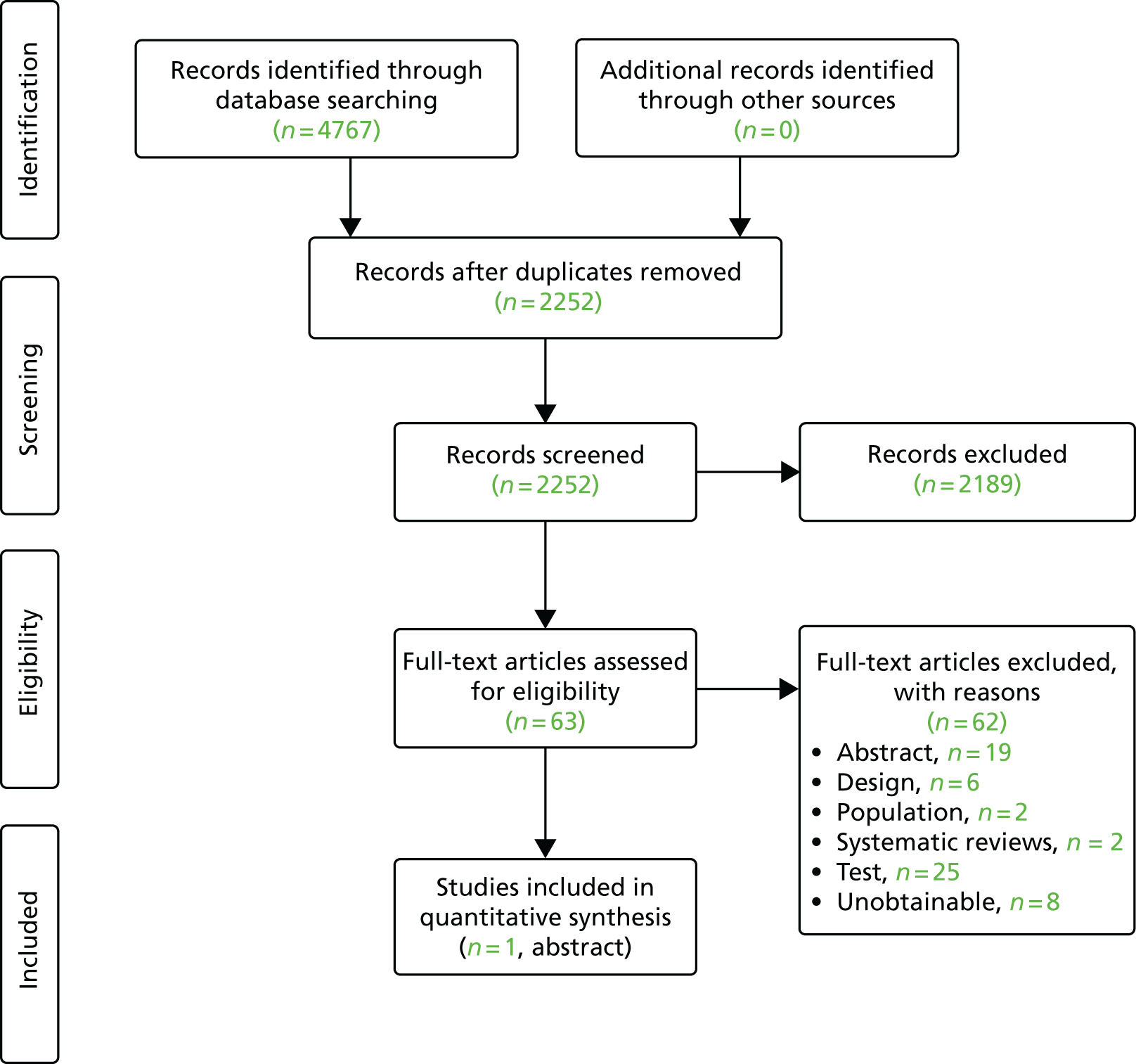

Of the 442 articles retrieved as full texts, 415 were excluded. The primary reasons for exclusion were use of an irrelevant test, typically qualitative fFN (n = 129), the study design (n = 59), that outcomes did not match the review inclusion criteria (n = 31) or that the article was an abstract that both had insufficient information to be included in the review and was unconnected to any of the included studies (n = 108). Abstracts were included if they were connected (by reporting data from the same study) to a full-text included study. The bibliographic details of studies retrieved as full papers and subsequently excluded, along with the reasons for their exclusion, are detailed in Appendix 3. Additional tables (see Tables 28–30) are provided in Appendix 3, listing all the citations provided by the industry to NICE along with whether or not the citation was included, and, if not, the reason for exclusion. After screening relevant systematic reviews (n = 11; see Appendix 3, Included systematic reviews), and forward and backward citations of the included studies, no further new included studies were identified. Twenty studies from 31 citations met the review inclusion criteria. The process of study selection is shown in Figure 2.

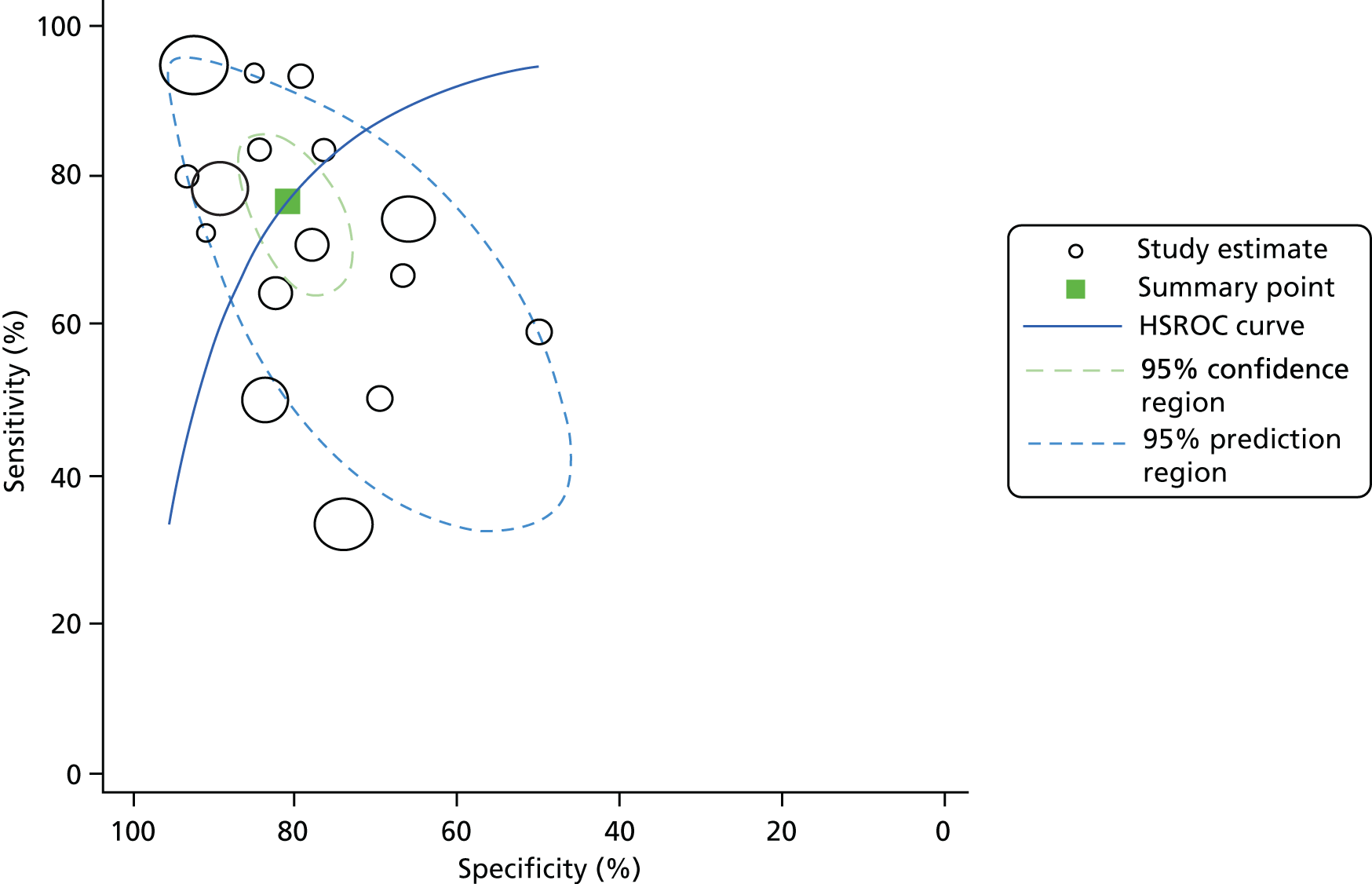

FIGURE 2.

Summary of the selection process.

Ongoing trials

A search of trial registries and company submissions identified seven ongoing trials that may be relevant to this review of DTA. These trials are summarised in Table 2.

| Study | Title | Sponsor | Status | Location | Estimated enrolment | Test(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NCT01987024 | Advantage of Detection of phIGFBP-1 to Reduce Hospitalization Time for Stable Patients With a Risk of Preterm Labour | Assistance Publique Hôpitaux De Marseille | Unknown | France | 420 | Actim Partus |

| NCT01868308 | Screening To Obviate Preterm Birth (STOP) | University of Pennsylvania | Completed | USA | 568 | fFN |

| NCT02853656 | Time to Delivery of Preterm Birth | Basildon and Thurrock University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust | Currently recruiting | UK | 242 | Actim Partus and fFN |

| NCT02904070 | Interest of Placental Alpha-microglobulin-1 Detection Test to Assess Risk of Premature Delivery in Reunion Island (PARTOSURE-OI) | Centre Hospitalier Universitaire de La Réunion | Currently recruiting | Réunion Island, France | 300 | PartoSure, Actim Partus and fFN |

| ISRCTN41598423 | Can a test of preterm labour (qfFN) help diagnosis and clinical decision making? (QUIDS and QUIDS-2) | HTA programme (UK) | Currently recruiting | UK | 2100 | PartoSure, Actim Partus and fFN |

| IRAS ID 111142 | Threatened preterm labour: a prospective cohort study of a clinical risk assessment tool and a qualitative exploration of women’s experiences of risk assessment and management (PETRA) | King’s College London | Currently recruiting | UK | 1181 | fFN |

| (Confidential information has been removed) | (Confidential information has been removed) | (Confidential information has been removed) | (Confidential information has been removed) | (Confidential information has been removed) | (Confidential information has been removed) | (Confidential information has been removed) |

Four of the ongoing trials are based in the UK, two of which are planning to enrol > 1000 participants (ISRCTN41598423, n = 2100, and Integrated Research Application System ID 111142, n = 1181). However, it was not possible to include data from these ongoing trials in this review of test accuracy.

Description of the included studies

Characteristics of the included studies are summarised in Table 3. Two studies, Assessment of Perinatal Outcome after Sustained Tocolysis in Early Labour (APOSTEL-1)42,43 and Hadzi-Lega et al. ,44 assessed the DTA of two different index tests in the same population: APOSTEL-142,43 assessed both Actim Partus and qfFN whereas the study by Hadzi-Lega et al. 44 assessed Actim Partus and PartoSure. APOSTEL-142,43 was one of the larger studies (n = 350), conducted in 10 centres around the Netherlands, whereas the study by Hadzi-Lega et al. 44 was smaller (n = 57), from one centre in Macedonia.

| Study (first author/study name and year) | Other tests used | Number included (number recruited) | Country (number of centres) | Definition of preterm labour symptoms | Weeks of gestation | Dilatation threshold for exclusion | Other exclusion criteria |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study assessing Actim Partus and qfFN | |||||||

| APOSTEL-1 (2016)42,43 | Cervical length | 350 (714) | The Netherlands (10) | Uterine contractions (> 3/30 minutes), abdominal pain,back pain and vaginal bleeding | 24–34 | > 3 cm | Contraindications for tocolysis, Iatrogenic deliveries and tocolytic treatment prior to testing |

| Study assessing Actim Partus and PartoSure | |||||||

| Hadzi-Lega (2017)44 | Cervical length | 57 (72) | Macedonia (1) | Uterine contractions and abdominal pain | 22–34 + 6 | > 3 cm | Antepartum haemorrhage, cervical cerclage and multiple gestations |

| Actim Partus | |||||||

| Abo El-Ezz (2014)45 | N/A | 57 (80) | Kuwait (2) | Uterine contractions (≥ 8/hour), back pain, pelvic pressure, vaginal discharge and 50% effacement | 24–34 | > 3 cm | Cervical cerclage, chorioamnionitis, fetal abnormalities, intrauterine growth restriction, multiple gestations, placenta praevia, prior cervical examination, sexual intercourse in previous 24 hours, uterine anomalies and vaginal bleeding |

| Altinkaya (2009)46 | N/A | 105 (NR) | Turkey (1) | Uterine contractions | 24–34 | ≥ 2 cm | Fetal abnormalities, history of preterm delivery, intrauterine growth restriction, multiple gestations, preeclampsia, smokers, uterine anomalies and vaginal bleeding |

| Azlin (2010)47 | Cervical length | 51 (51) | Malaysia (NR) | Uterine contractions | 24–36 | ≥ 3 cm | Abruptio placenta, cervical cerclage, cervical incompetence, multiple gestations and placenta praevia |

| Brik (2010)48 | N/A | 276 (325) | Spain (1) | Uterine contractions, abdominal pain, back pain, leaking of fluid and other | 24–34 | > 3 cm | Abruptio placenta, cervical cerclage, fetal abnormalities, fetal distress and vaginal bleeding (active labour) |

| Cooper (2012)49 | Qualitative fFN (unclear which test) | 349 (366) | Canada (2) | Symptoms judged by physician to be indicative of labour | 24 + 0 to 34 + 6 | NR | Antepartum haemorrhage and chorioamnionitis (active labour) |

| Danti (2011)50 | Cervical length | 60 (102) | Italy (1) | Uterine contractions (≥ 4/20 minutes) | 24 + 0 to 32 + 6 | > 3 cm | Abruptio placenta, cervical cerclage, fetal abnormalities, intrauterine growth restriction, multiple gestations, placenta praevia, preeclampsia, uterine anomalies and vaginal bleeding |

| Eroglu (2007)51 | QuikCheck fFN, cervical length | 51 (51) | Turkey (1) | Uterine contractions (> 10/hour) | 24–35 | ≥ 3 cm | Abruptio placenta, fetal abnormalities, intrauterine growth restriction, multiple gestations, placenta praevia, preeclampsia, sexual intercourse in previous 24 hours, uterine anomalies and vaginal bleeding |

| Goyal (2016)52 | Cervical length | 60 (95) | India (1) | Uterine contractions (> 4/20 minutes) and abdominal pain | 24–36 | NR | Fetal abnormalities, fetal growth restrictions, preeclampsia, multiple gestations and vaginal bleeding |

| Lembet (2002)53 | N/A | 36 (36) | Turkey (1) | Uterine contractions (> 10/hour) | 20–36 | N/A | Fetal abnormality, intrauterine growth restriction, preeclampsia, multiple gestations, uterine anomalies and vaginal bleeding |

| Riboni (2011)54 | fFN by ELISA | 210 | Italy (2) | Uterine contractions (> 10/hour) | 24–34 | > 2 cm | Fetal abnormalities, multiple gestations, placenta praevia, prior cervical examination, sexual intercourse in previous 24 hours, uterine anomalies and vaginal bleeding |

| Tanir (2009)55 | N/A | 68 (121) | Turkey (1) | Uterine contractions (> 4/20 minutes), changes in cervix, back pain and increased discharge | 24–37 | ≥ 3 cm | Asthma, cervical cerclage, diabetes mellitus, digital examination in previous 24 hours, hyperthyroidism, multiple gestations, preeclampsia, sexual intercourse in previous 24 hours, tocolytic treatment prior to testing, vaginal bleeding and vaginal douche in previous 24 hours |

| Ting (2007)56 | Qualitative fFN (unclear which test) | 94 (108) | Singapore (1) | NR | 24–34 | ≥ 3 cm | Cervical cerclage, chorioamnionitis, fetal asphyxia, fetal abnormalities, intrauterine growth restrictions, multiple gestations, placenta praevia and preeclampsia |

| Tripathi (2016)57 | QuikCheck fFN | 468 (550) | India (1) | Uterine contractions (> 1/10 minutes) and labour pains | 28 + 1 to 36 + 6 | > 3 cm | Blood-mixed cervical secretions, diarrhoea, prepartum haemorrhage, previous preterm delivery, sexual intercourse in previous 24 hours, urinary tract infection and vaginal leakage |

| Vishwekar (2017)58 | N/A | 30 (NR) | India (1) | Uterine contractions and vaginal discharge | 28–37 | NR | Blood-mixed cervical secretions, fetal distress, hypertension and intrauterine growth restrictions (active labour) |

| PartoSure | |||||||

| Bolotskikh (2017)59 | Cervical length | 99 (100) | Russia (1) | Uterine contractions, abdominal pain, back pain, pelvic pressure, menstrual-like cramping and diarrhoea | 22 + 0 to 36 + 6 | > 3 cm | Maternal age < 18 years, multiple gestations, prior cervical examination, placenta praevia, symptoms unrelated to threatened preterm delivery (e.g. trauma), tocolytic treatment prior to testing and vaginal bleeding |

| Nikolova (2014/15)60,61 | Cervical length, QuikCheck fFN | 203 (219) | Macedonia and Russia (2) | Uterine contractions, abdominal pain and pelvic pressure | 20 + 0 to 36 + 6 | > 3 cm | Cervical cerclage, placenta praevia, maternal age < 18 years and multiple gestations |

| Werlen (2015)41 | N/A | 41 (42) | France (1) | Uterine contractions and cervical changes | 24–34 | > 3 cm | Blood-mixed cervical secretions, multiple gestations and vaginal infection |

| qfFN | |||||||

| Bruijn (2016)62 | Cervical length | 455 (484) | The Netherlands, Switzerland, Belgium, Germany and Austria (10) | Uterine contractions (> 3/30 minutes), abdominal pain, back pain and vaginal bleeding | 24–34 | > 3 cm | Contraindications for tocolysis, fetal distress, iatrogenic deliveries, tocolytic treatment prior to testing and triplet or higher gestations |

A further 14 studies45–58 assessed the DTA for Actim Partus only. Three studies41,59–61 assessed PartoSure only and one62 assessed qfFN only.

For Actim Partus, study sizes ranged from 30 in Vishwekar et al. 58 to 468 in Tripathi et al. 57 and covered the following countries: Kuwait,45 Turkey,46,51,53,55 Malaysia,47 Spain,48 Canada,49 Italy,50,54 India52,57,58 and Singapore. 56 The three studies assessing PartoSure were conducted in Russia,59 Macedonia60,61 and France41 and the study size ranged from 41 in Werlen et al. 41 to 203 in Nikolova et al. 61 Finally, the Bruijn study62 assessed qfFN only and recruited 455 participants from 10 centres across Austria, Belgium, Germany, the Netherlands and Switzerland.

Key differences between studies

It was notable that the prevalence rates of preterm birth differed greatly between studies (see Tables 6 and 7). In addition, there were differences between studies in the mode of delivery for included women. The participant inclusion/exclusion criteria also differed between studies. For example, although all studies included women presenting with symptoms of preterm labour with intact membranes, the definition of ‘preterm’ (i.e. the number of weeks of gestation) differed between studies. The inclusion/exclusion criteria of the studies also differed regarding the presenting symptoms of the women, the proportion of women with singleton gestations, the risk status of included women, dilatation thresholds applied and other specific exclusion criteria.

Differences between studies in prevalence of preterm birth

There was clear variation between studies regarding the prevalence of the reference standard (i.e. the prevalence of preterm birth within 7 days and within 48 hours). Across all 20 studies, prevalence of preterm birth within 7 days ranged from 1.7% [95% confidence interval (CI) 0.6% to 3.7%] in Cooper et al. 49 to 73.3% (95% CI 60.3% to 83.9%) in Goyal et al. 52 Both of these studies assessed the test accuracy of Actim Partus. Therefore, the studies assessing Actim Partus had a larger range of prevalence (of preterm birth within 7 days) than the studies assessing PartoSure and qualitative fFN. However, in the studies assessing PartoSure, prevalence of preterm birth within 7 days still ranged widely (from 2.4%, 95% CI 0.1% to 12.9% in Werlen et al. 41 to 17.2%, 95% CI 12.3% to 23.2% in Nikolova et al. 61). In the studies assessing qfFN, prevalence of preterm birth within 7 days was slightly higher in APOSTEL-142,43 than in EUIFS62 (19.7%, 95% CI 15.7% to 24.3% vs. 10.5%, 95% CI 7.9% to 13.7%, respectively).

Seven studies provided DTA data for the index tests against preterm birth within 48 hours. 41,48,52,53,56–58 Across these seven studies, the prevalence of preterm birth within 48 hours ranged from 2.4% (95% CI 0.1% to 12.9%) in Werlen et al. 41 to 58.3% (95% CI 44.9% to 70.9%) in Goyal et al. 52 The study by Werlen et al. 41 was the only study assessing PartoSure against preterm birth within 48 hours, with the other six studies48,52,53,56–58 assessing Actim Partus. The lowest prevalence of preterm birth within 48 hours within these six Actim Partus studies was 5.3% (95% CI 1.7% to 12.0%) in Ting et al. 56

These differences in prevalence displayed between studies are probably attributable to differences in the populations recruited into the studies (e.g. differences in gestational age and in presenting symptoms of preterm labour; see Differences between studies in inclusion/exclusion criteria) and will also probably have an impact on the DTA data presented in Results of quantitative data synthesis (test accuracy data) and the generalisability of these data to the NHS in England.

Differences between studies in mode of delivery

It is important to know whether women who had non-spontaneous deliveries within the time frame of the reference standard were included or excluded from the test accuracy data; if iatrogenic delivery takes place within this time frame, it remains unclear whether or not a spontaneous delivery may have occurred, which thus makes it impossible to accurately assess the reference standard in these women. Nine of the included studies41,45,46,50–52,54,56,57 did not report the mode of delivery (i.e. whether or not birth was spontaneous, or whether or not there were any planned caesarean sections or inductions).

The other 11 studies42–44,47–49,53,55,58–62 provided some data regarding mode of delivery (Table 4). Four of these studies (APOSTEL-1,42,43 Hadzi-Lega et al. ,44 EUIFS62 and Bolotskikh et al. 59) reported that women who had a non-spontaneous delivery within the time frame of the reference standard were excluded from the test accuracy data. Women who had a non-spontaneous delivery outside the time frame of the reference standard should not be excluded as these women would be considered to be reference-standard negatives in any case (i.e. they did not deliver within 48 hours or within 7 days). In a further three studies (Vishwekar et al. ,58 Brik et al. 48 and Nikolova et al. 60,61), iatrogenic delivery was mentioned as a reason for exclusion, but it is unclear how many of these deliveries took place within the time frame of the reference standard, and in another study (Lembet et al. 53) the number of iatrogenic deliveries could not be ascertained.

| Study (first author/study name and year) | Participants (n) | Maternal age (years), mean (SD) [range] | Gestational age at presentation (weeks), mean (SD) [range] | Multiple gestations, n (%) | BMI (kg/m2), mean (SD) | Gravidity, mean (SD) | Parity, mean (SD) | Previous preterm delivery, n (%) | Previous miscarriage/stillbirth, n (%) | Mode of delivery, n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study assessing Actim Partus and qfFN | ||||||||||

| APOSTEL-142,43 | 350 | 29.9 (5.4) | 29.0 (2.7) | 71 (20) | 23.1 (4.3) | NR | NR | 79 (23) | NR | Non-spontaneous deliveries within reference-standard time frame excluded |

| Study assessing Actim Partus and PartoSure | ||||||||||

| Hadzi-Lega (2017)44 | 57 | Median 27 [IQR 23.0–30.5] | Median 31 [IQR 28.8–32.4] | 0 (0) | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | Non-spontaneous deliveries within reference-standard time frame excluded |

| Actim Partus | ||||||||||

| Abo El-Ezz (2014)45 | 57 | 27.40 (6.1) | 29.70 (2.5) | 0 (0) | NR | NR | 2.91 (NR) | NR | NR | NR |

| Altinkaya (2009)46 | 105a | 24.52 (5.16) | 29.63 (4.4) | 0 (0) | 24.1 (3.5) | NR | 0.65 (0.95) | 0 (0) | NR | NR |

| Azlin (2010)47 | ||||||||||

| phIGFBP-1 (+) | 7 | 29.57 (3.99) | 32.96 (3.07)b | 0 (0) | NR | 2.43 (1.27) | 1.00 (1.16) | NR | 0.43 (1.13) |

|

| phIGFBP-1 (–) | 44 | 28.34 (4.32) | 32.38 (2.64)b | 0 (0) | NR | 2.59 (1.59) | 0.91 (0.96) | NR | 0.68 (1.25) | |

| Brik (2010)48 | 276 | 29.4 (5.9) [15–46] | 29.9 (2.8) [23–34] | 0 (0) | NR | NR | Nulliparous = 58.3% | 26 (9.4) | NR | Unclear |

| Cooper (2012)49 | 349 | 29 (5.0) [17–46] | Median 29 + 6 (4 + 6) [IQR 24–34] | 20 (5.7)c | NR | NR | Nulliparous = 43.3% | 56 (16.1) | NR |

|

| Danti (2011)50 | 60d | Median 31 [IQR 28–34] | Median 30.0 [IQR 28.7–31.4] | 0 (0) | NR | NR | Nulliparous = 63% | NR | NR | NR |

| Eroglu (2007)51 | 51a | 27.6 (3.5) | 29.5 (2.6) | 0 (0) | 22.6 (2.9) | NR | 0.4 (0.6) | 2 (3.9) | 2 (3.9) | NR |

| Goyal (2016)52 | 60 | 29.92 (5.14) | 32.84 (3.24) | 0 (0) | 23.61 (2.45) | NR | 0.9 (0.3) | 18 (30) | NR | NR |

| Lembet (2002)53 | 36a | 28.4 (5.3) | 31.3 (3.3) | 0 (0) | < 19.6, n = 7; > 26, n = 29 | 2.2 (1.6) | 0.7 (1.1) | 7 (16) | 3 (7) | Unclear |

| Riboni (2011)54 | 210 | 28.7 (NR) | 0 (0) | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | ||

| Delivering term | 30.4 (5.6) | 23.36 (3.99) | ||||||||

| Delivering preterm | 30.7 (5.1) | 22.72 (3.7) | ||||||||

| Tanir (2009)55 | ||||||||||

| phIGFBP-1 (+)e | 25 | 28.4 (4.6) | 30.6 (3.5) | 0 (0) | 25.1 (3.5) | 2.1 (1.3) | 0.7 (0.3) | NR | 1.8 (0.8) | |

| phIGFBP-1 (–)g | 43 | 28.4 (5.3) | 29.6 (2.3) | 0 (0) | 26.9 (4.4) | 2.2 (1.3) | 0.6 (0.4) | NR | 1.5 (0.5) | |

| Ting (2007)56 | ||||||||||

| phIGFBP-1 (+)e | 28 | 27 | 30.5 | 0 (0) | NR | 2 | 0.5 | NR | NR | NR |

| phIGFBP-1 (–)g | 66 | 27 | 32.2 | 0 (0) | NR | 2 | 1 | NR | NR | |

| Tripathi, 201657 | 468 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | 0 (0) | NR | NR |

| Vishwekar 201758 | 25 [19–35] | 2 (6.7) | ‘Normal limits’ | NR | NR | 4 (13.3) | NR | Unclear | ||

| phIGFBP-1 (+) | 14 | 32 | ||||||||

| phIGFBP-1 (–) | 16 | 32.5 | ||||||||

| PartoSure | ||||||||||

| Bolotskikh (2017)59 | 99 (100) | Median 25 [IQR 23–38] | Median 32 [IQR 29–36] | 0 (0) | NR | NR | Nulliparous = 32% | 15 (15) | 27 (27) | Non-spontaneous deliveries within reference-standard time frame excluded |

| Nikolova (2014 and 2015)60,61 | 203 | Median 27 [range 18–43] | Median 32.0 [range 20.5–36.6] | 0 (0) | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | Patients with non-spontaneous delivery excluded (n = 8); unclear when these happened |

| Werlen (2015)41 | 41 | 27.6 (5.3) [18–39] | 29.5 (2.91) [24–34] | 0 (0) | NR | NR | 0.54 (0.71) | NR | NR | NR |

| qfFN | ||||||||||

| EUIFS62 | 455 | 29.5 (5.2) | Median 29.6 [IQR 26.7–31.6] | 67 (15) | Median 24.5 (IQR 22.0–28.0) (n = 429) | NR | Nulliparous = 55% | 72 (16) | NR | Non-spontaneous deliveries within reference-standard time frame excluded |

In three studies,47,49,55 the numbers of spontaneous/iatrogenic deliveries were reported, but no exclusion of data from non-spontaneous deliveries was made. In the study by Azlin et al. ,47 70.6% of women delivered spontaneously, 7.8% underwent an emergency caesarean section and for a further 7.8% there were no data available on mode of delivery. Although 13.7% of women delivered by a planned caesarean section, it is unclear whether or not these took place within the time frame of the reference standard, and these women were not excluded from the test accuracy data. 47 In Cooper et al. ,49 52.1% of women delivered spontaneously, 14.9% had an operative delivery and 33.0% had a caesarean section, although, again, it was unclear how many of these procedures were planned and how many took place within the time frame of the reference standard. Finally, Tanir et al. 55 report the proportion of women who delivered by caesarean section or from vaginal delivery; however, these data do not appear to be correct (see Table 4).

Differences between studies in inclusion/exclusion criteria

There are several ways in which the participant inclusion/exclusion criteria differed between studies (see Table 3). It is likely that many of these differences had an impact on the prevalence of preterm labour and, thus, test accuracy data. However, insufficient data were provided to fully assess these relationships.

Of the 20 included studies, 14 recruited women from 24 weeks’ gestation onwards (see Table 3). 41–43,45–52,54–56,62 In these 14 studies, the upper limit of gestation varied widely: eight studies recruited women at gestation of up to 34 weeks,41–43,45,46,48,54,56,62 with the upper limit of gestation ranging from 32 + 6 weeks (Danti et al. 50) to 37 weeks (Tanir et al. 55) in the remaining six studies.

Of the remaining six studies, four recruited women at an earlier gestation: two studies53,61 recruited women from as early as 20 weeks’ gestation and two studies44,59 included women from 22 weeks’ gestation. Two of these studies recruited women up until 36 + 6 weeks,59,61 one recruited women up until 36 weeks53 and the other recruited women up until 34 + 6 weeks. 44 The other two studies57,58 recruited women at a later gestation (i.e. from 28 weeks’ gestation), with both recruiting up until 37 weeks (36 + 6 weeks for Tripathi et al. 57).

None of the studies presented test accuracy data between different gestational cut-off points. It was not possible, therefore, to make any within-study assessment, for any of the index tests, whether or not test accuracy differed based on gestation. 41–62

Other than stating that women had to be symptomatic, all studies except for Ting et al. 56 provided some further details about the presenting symptoms of preterm labour. However, one further study (Cooper et al. 49) added only that that ‘symptoms indicative of labour were to be determined by a physician’.

All other studies reported uterine contractions as a necessary indicator of preterm labour. 41–48,50–55,57–62 Ten studies additionally described the rate of uterine contractions necessary for inclusion: a rate of six contractions per hour was reported by Tripathi et al. ,57 Bruijn62 and APOSTEL-1,42,43 a rate of eight contractions per hour was reported by Abo El-Ezz et al. ,45 a rate of 10 contractions per hour was reported by Eroglu et al. ,51 Riboni et al. 54 and Lembet et al. 53 and a rate of 12 contractions per hour was reported by Danti et al. ,50 Goyal et al. 52 and Tanir et al. 55

Other commonly reported symptoms included in definitions of preterm labour were abdominal pain (in seven studies42–44,48,52,59–62), back pain (in six studies42,43,45,48,55,59,62), pelvic pressure (in three studies45,59–61), vaginal bleeding (in the APOSTEL-1 and Bruijn studies42,43,62) and vaginal discharge (in three studies45,55,58).

The majority of included studies were based on samples that only included women with singleton pregnancies. However, based on the protocol amendment, four studies were included that recruited women with multiple gestation pregnancies. One of these studies assessed two index tests in the same population [APOSTEL-1 (qfFN and Actim Partus)] and 20% of the included pregnancies were multiple pregnancies. 42,43 Two of these studies assessed only Actim Partus, with one (Cooper et al. 49) having 6% of included pregnancies as multiple pregnancies and the other (Vishwekar et al. 58) having 7% of included pregnancies as multiple pregnancies. The final study that included multiple pregnancies (Bruijn62) only assessed qfFN, and they made up 15% of the population. We are not aware of any published evidence to suggest that multifetal pregnancies would alter the DTA of either qfFN or Actim Partus.

Only one of the included studies (Bolotskikh et al. 59) clearly reported the risk status of included women (i.e. whether or not the women were at high or low risk for preterm labour prior to the onset of symptoms). In this study, the population was described as high risk because 15% of the participants had previously experienced preterm labour, 43% had mild preeclampsia and 51% were previously hospitalised during the pregnancy. 59 However, although none of the other studies explicitly stated that the populations were at high risk of preterm labour, eight additional studies42,43,48,49,51–53,58,62 also recruited some women who had previously experienced preterm delivery (see Table 4). In addition, two studies (APOSTEL-142,43 and Danti et al. 50) restricted their population by conducting tests in women presenting with a cervical length of < 30 mm. However, this high-risk status is associated with symptoms at presentation rather than the women being high risk prior to the onset of symptoms.

Recruiting high-risk women would be expected to have an impact on the prevalence of preterm birth. However, because almost all studies did not clearly report risk status, it is not possible to properly assess if or how this had an impact on prevalence rates (and, therefore, test accuracy data).

All studies except Cooper et al. ,49 Goyal et al. ,52 Lembet et al. 53 and Vishwekar et al. 58 included a dilatation threshold for exclusion; typically, the threshold was > 3 cm or ≥ 3 cm. However, Riboni et al. 54 had a dilatation threshold of > 2 cm and Altinkaya et al. 46 had a threshold of ≥ 2 cm.

Studies were not excluded on the basis of access to cervical length measurement (lack of access was unlikely to be reported in studies). Indeed, studies that did not report the use of cervical length measurement did not explicitly cite lack of access or discuss the suitability of cervical length measurement for the included population. Cervical length measurement was conducted in nine of the included studies. 42–44,47,50–52,59–62 In seven of these studies,44,47,51,52,59–62 no selection of women took place in accordance with cervical length measurement, and, therefore, it is not expected that the women in these studies would substantively differ from women who would not have access to cervical length measurement in clinical practice. However, in the other two studies (APOSTEL-142,43 and Danti et al. 50), all women included in final analyses of index test data had a transvaginal cervical length measurement of ≤ 30 mm, which would probably increase the prevalence of preterm birth in these studies. Both of these studies were assessing Actim Partus, with APOSTEL-1 additionally assessing qfFN. 42,43,50

Other criteria for exclusion differed substantially between studies (see Table 3 for specific details). Across studies, exclusion criteria included abruptio placenta, antepartum haemorrhage, contraindications for tocolysis, cervical cerclage, cervical incompetence, chorioamnionitis, diabetes mellitus, diarrhoea, digital examination in the previous 24 hours, fetal asphyxia, fetal abnormalities, fetal distress, history of preterm delivery, hypertension, hyperthyroidism, iatrogenic deliveries, intrauterine growth restriction, maternal age of < 18 years, multiple gestations, placenta praevia, preeclampsia, prior cervical examination, sexual intercourse in the previous 24 hours, smokers, symptoms unrelated to threatened preterm delivery (e.g. trauma), tocolytic treatment prior to testing, urinary tract infection, uterine anomalies, vaginal bleeding, vaginal douche in the previous 24 hours, vaginal infection and vaginal leakage. 41–62 All exclusion criteria were reasonable in the context of the index tests under consideration (see Quality appraisal summary).

Summary of the reference standard

In all studies, the reference standard was preterm birth, within 48 hours and/or within 7 days. 41–62 All 20 included studies evaluated the index tests against the 7-day reference standard. 41–62 Six of the Actim Partus studies48,52,53,56–58 and one PartoSure study41 also evaluated the index test against a 48-hour reference standard. qfFN was not evaluated against the 48-hour reference standard. 42,43,62

Summary of test administration

The manufacturers’ descriptions of the index tests and how they should be used are presented in Table 1. The quantity and quality of reported details regarding how each test was performed within a study varied considerably.

Actim Partus

In the 16 studies that used the Actim Partus test,43,45–58 the information provided on how the test was administered typically followed the manufacturer’s guidance; however, there were some differences. The reporting of detection-limit thresholds varied between studies, but it is likely that all studies used a threshold of 10 µg/l: eight studies clearly reported a detection limit of 10 µg/ml. 45,49,50,52–54,57,58 Two studies46,51 reported that samples higher than 30 µg/l give ‘a strong positive result’. It is unclear in both of these studies whether or not a weak positive at 10 µg/l would have been considered a positive result, although this appears to be the case. 46,51 One study48 states that a threshold of 30 µg/l was required for a positive result, and that this shows as two blue lines on the dipstick, but this is incorrect (two blue lines show at 10 µg/l). Finally, five studies41,43,44,47,55,56 did not report what detection limit they used; however, given the qualitative nature of the test, it appears most likely that a 10-µg/l threshold was used. Indeed, the manufacturer’s guidance indicates that a concentration of ≥ 10 µg/l in the cervical fluid causes a positive Actim Partus test reaction result.

All studies report taking their sample from around the external cervical orifice or cervical os or as a cervical specimen. 43–58 However, two studies43,56 report that the sample was taken from the posterior fornix. The instructions from the manufacturer state that the sample should be taken from the cervical os. Our obstetric clinical experts have advised that samples taken from the posterior fornix would probably yield a higher false-negative rate because the secretion samples differ between the two areas and concentrations are likely to be weaker from the posterior fornix. A difference in secretion sample concentration between cervical locations has been demonstrated by Kuhrt et al. ,63 although using the qfFN test, it is likely that Actim Partus would be affected in a similar manner.

The manufacturer’s instructions state that if the single (control) line does not appear then the test is invalid. However, one study55 interpreted no visible lines as a positive test result. This was their way of dealing with missing data owing to invalid results. This is unlikely to greatly alter results as only two tests from 68 results were invalid. 55 The remaining studies did not report details on how invalid tests were treated.

Two studies43,49 both froze their samples at –20 °C for future analysis. In APOSTEL-1,43 samples were reported to have been transferred and stored at –80 °C within 6 months. It is unknown how long after the transfer samples remained in storage before testing; however, it is likely that total storage time would have exceeded 6 months. 43 Likewise, in the study by Cooper et al. 49 it is unclear how long the tests remained frozen before testing. Both of these studies43,49 go on to describe that samples were thawed before the Actim Partus test was run. This protocol differs from the manufacturer’s guidance (and, of course, clinical practice), in which freezing a sample is not discussed in the instructions for use. We have received clinical input from our obstetricians to suggest that freezing is unlikely to affect the sample’s integrity and, therefore, is unlikely to have an impact on test accuracy.

PartoSure

All four studies assessing the PartoSure test appeared to conduct the test in a manner that was consistent with the manufacturer’s guidance. 41,44,59–61 However, Bolotskikh et al. 59 did not specifically report that samples were collected using a speculum.

Fetal fibronectin

Of the two studies that used the qfFN test, one study (Bruijn62) appeared to conduct the test in accordance with the manufacturer’s guidance. The other study (APOSTEL-142) froze the samples as reported in Studies evaluating more than one index test. This is not in accordance with the manufacturer’s guidance, which states that in order to avoid degradation of the analyte, frozen samples should be assayed within 3 months.

Time to test results

Based on the manufacturers’ instructions, the maximum time between taking the sample and receiving the test results (including time for mixing in solvents, etc.) is approximately 6 minutes for Actim Partus and PartoSure, and 12 minutes for qfFN. Some of the studies provided information within their methods relating to the maximum time that test personnel had to wait before reading the result from the test. This was always in accordance with the manufacturers’ guidance.

None of the 20 studies included in our review reported, in the study results, how long it took to conduct the test and receive a result; therefore, no further data can be presented on this outcome.

Test failure rates

Only two studies (Goyal et al. 52 and Tanir et al. 55), both of which evaluated Actim Partus, reported information about test failures: Goyal et al. 52 reported that there were no invalid tests and Tanir et al. 55 reported that there were two cases in which the Actim Partus test failed to show any visible lines. For these two women, the test result was not assigned as invalid and the tests were not re-run; they were instead assigned as positive Actim Partus results. 52,55 It was not clear whether these two women had a preterm delivery within 48 hours or within 7 days (i.e. whether they were assigned as true positive or false positive); therefore, it was not possible to conduct sensitivity analyses when these two cases were assigned as negative test results.

Frozen samples

Following the protocol amendment to include studies using frozen samples, two additional studies (APOSTEL-142 and Cooper et al. 49) were included. Methodological details on freezing of the samples are described in the previous sections Actim Partus and PartoSure, and are further discussed in Quality appraisal of included studies. We have received clinical input from our obstetricians to suggest that freezing of the sample is unlikely to affect the integrity of the sample, even if thawed outside the time frame suggested by the manufacturer’s guidance, and is, therefore, unlikely to have a major impact on test accuracy. However, it should be noted that we have no published data to verify this.

Description of included participants

Studies evaluating more than one index test

The APOSTEL-1 study, which evaluated both Actim Partus and qfFN in the same population, recruited 350 participants. 42,43 The characteristics of these participants are reported in Table 4. To summarise, the mean maternal age was 29.9 years [standard deviation (SD) 5.4 years] and the mean gestational age at presentation was 29.0 weeks (SD 2.7 weeks). In this study,42,43 20% of the participants (n = 71) had multiple gestations and 23% (n = 79) had previously delivered preterm.

The other study evaluating more than one index test in the same population was a much smaller study: Hadzi-Lega et al. 44 assessed both Actim Partus and PartoSure and recruited 57 participants. The characteristics of these participants are also reported in Table 4. In this study,44 the median maternal age was reported as 27 years [interquartile range (IQR) 23.0–30.5 years] and the median gestational age at presentation was reported as 31 weeks (IQR 28.8–32.4 weeks).

Actim Partus

In the 16 Actim Partus studies (including APOSTEL-142,43 and Hadzi-Lega et al. 44),42–44,57,58 sample sizes ranged from 30 in Vishwekar et al. 58 to 468 in Tripathi et al. 57 Reported maternal ages ranged from a mean of 24.5 years (SD 5.16 years) in Altinkaya et al. 46 to a median of 31 years (IQR 28–34 years) in Danti et al. 50 Gestation ranged from a mean of 28.7 weeks (SD not reported) in Riboni et al. 54 to 32.8 weeks (SD 3.24 weeks) in Goyal et al. 52 Further details describing the participant characteristics in each study are given in Table 4.

Three43,49,58 of the 16 studies assessing Actim Partus included participants with multiple gestations (20%, n = 71;43 6%, n = 20;49 and 7%, n = 258). Previous preterm delivery was reported in seven studies,43,48,49,51–53,58 and prevalence ranged from 3.9% (n = 2) in Eroglu et al. 51 to 30% (n = 18) in Goyal et al. 52

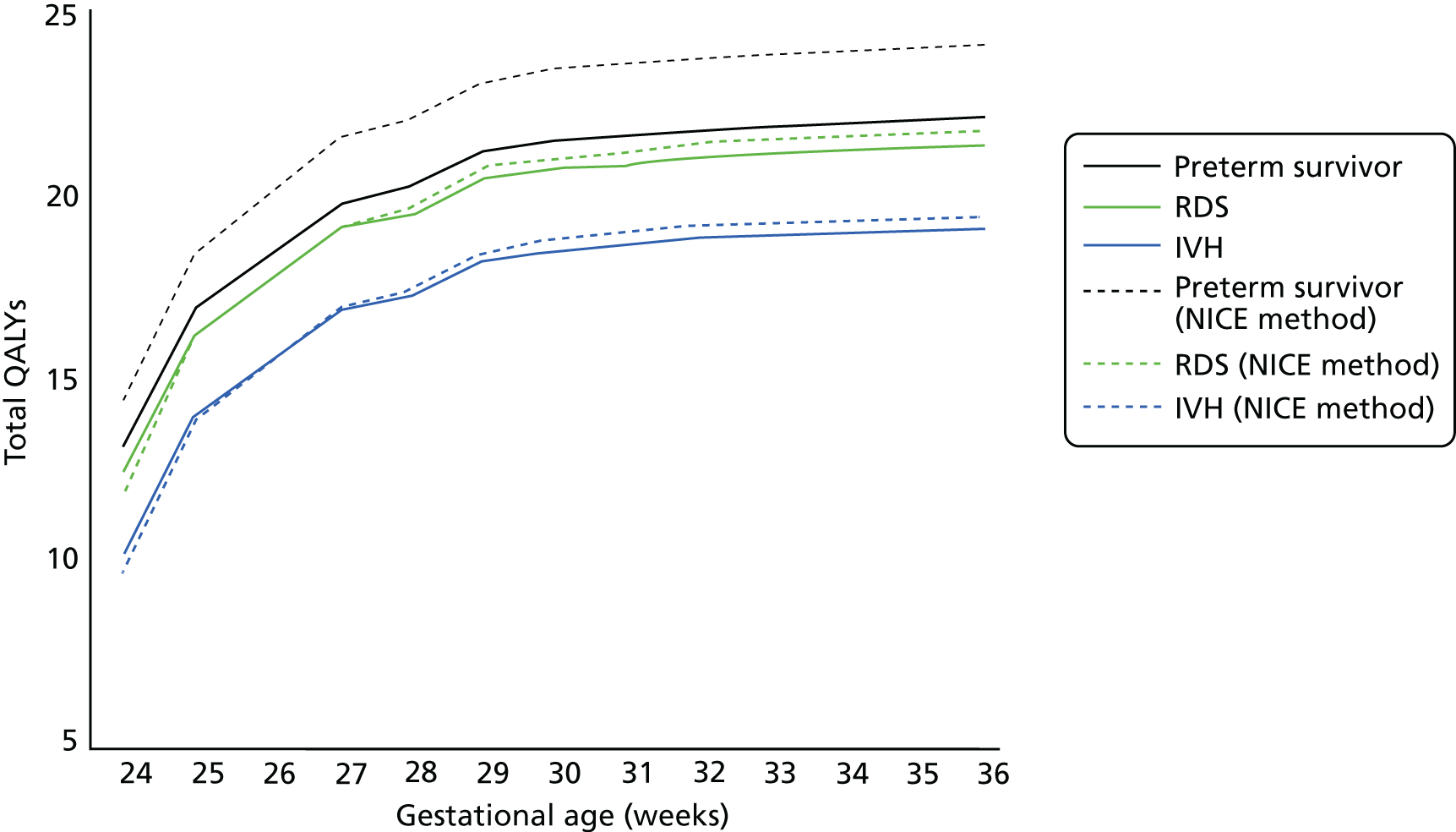

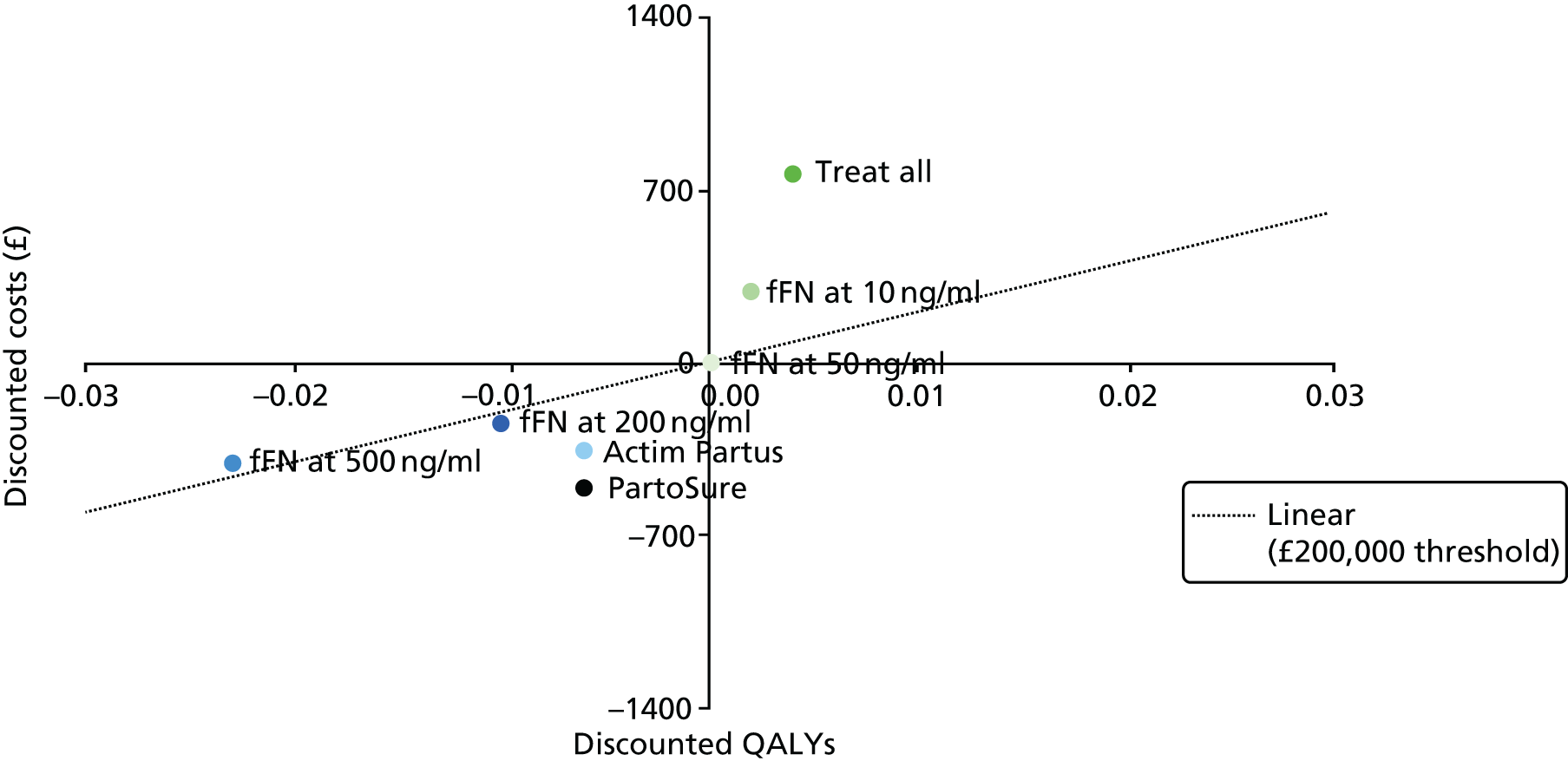

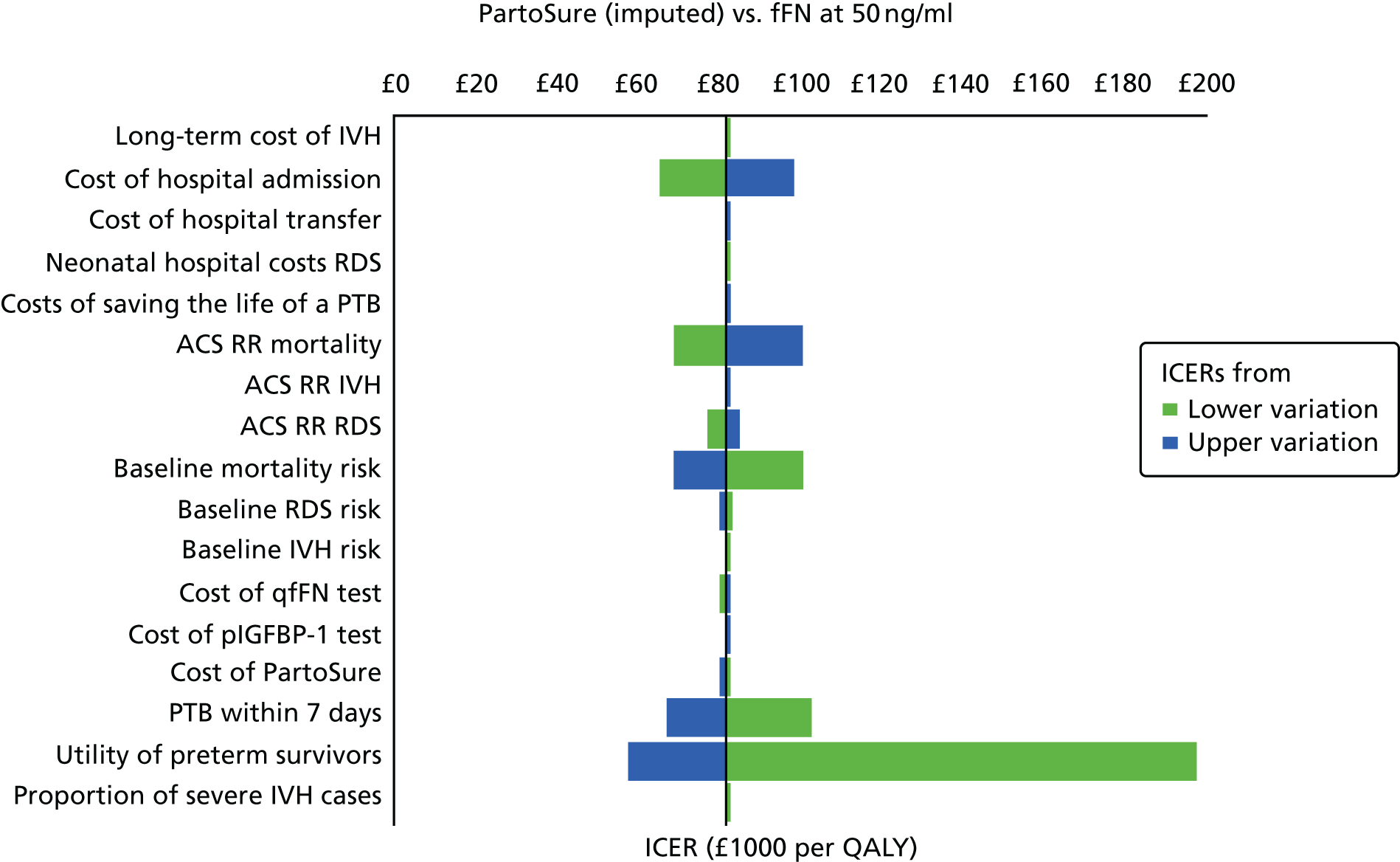

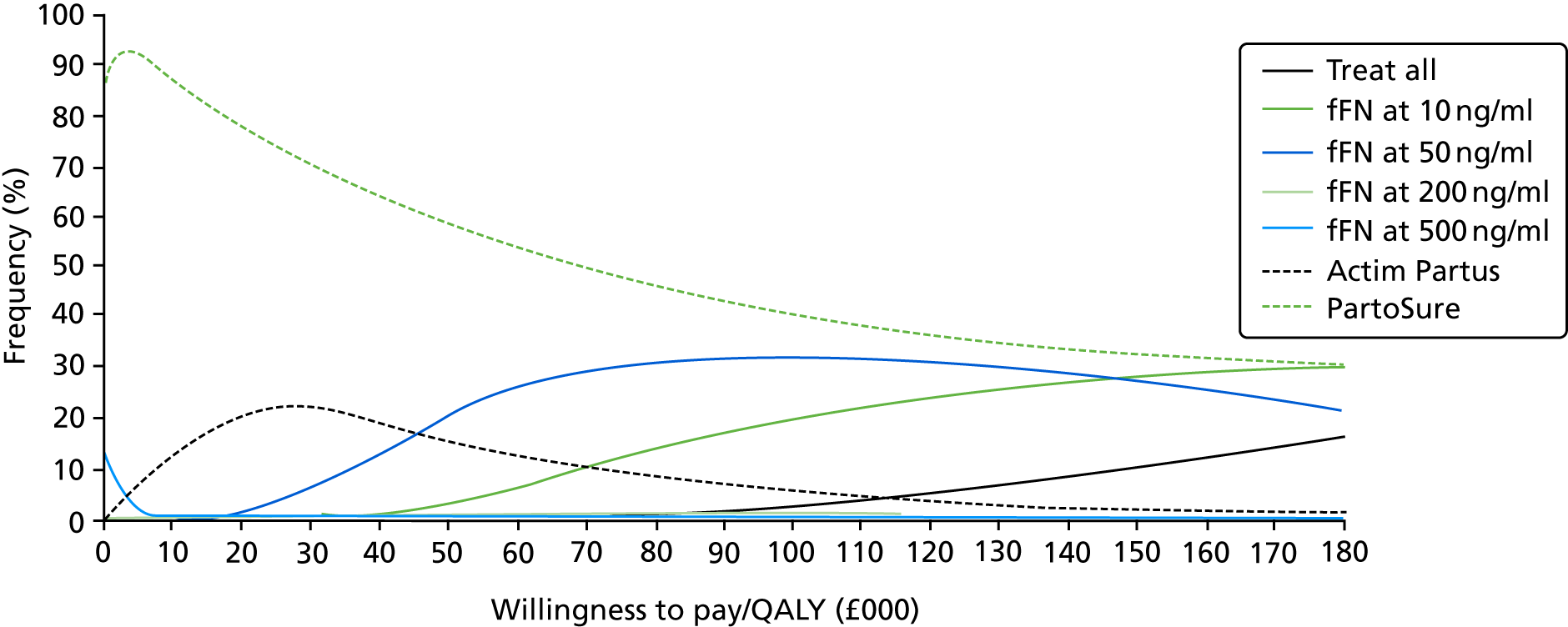

PartoSure