Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 09/33/02. The contractual start date was in March 2012. The draft report began editorial review in May 2017 and was accepted for publication in January 2018. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Marc Serfaty is a member of the National Institute for Health Research Health Technology Assessment General Board.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2019. This work was produced by Serfaty et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2019 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Introduction

Background

The CanTalk trial was devised in response to a specific call from the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR)’s Health Technology Assessment (HTA) programme to provide evidence on the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of cognitive–behavioural therapy (CBT) for the treatment of depression in patients with advanced cancer. Those who took part had an estimated minimum clinically assessed prognosis of 4 months so as to maximise the potential to retain participants in the trial, deliver the intervention and collect outcome data.

Definition of advanced cancer

For this study, we defined ‘advanced cancer’ as cancer that is considered by oncology experts not to be amenable to cure. People vary in terms of prognosis and the impact of the disease on their physical functioning. Advanced cancer may include metastatic disease for which standard curative therapies have failed, disease that is already widespread at the time the patient presents and that is unlikely to be cured, and cancers with a poor prognosis, such as lung or pancreatic cancers.

Depression and advanced cancer

In this study, we defined ‘depression’ using the Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI). It is distinct from adjustment disorders that might be expected in those with a terminal illness, for whom appropriate sadness is a common response.

Depression is one of the most common mental disorders in people with cancer. 1 Among those with advanced cancer, the prevalence of depression measured using structured clinical interviews ranges from 5% to 45%2–4 and may vary with type of cancer. 5,6 A meta-analysis3 of depression in advanced cancer found the pooled prevalence of clinical depression to be 16.5%. There is a considerable burden on public finances presented by depression; the overall economic cost of depression generally in England was estimated to be £9B in 2000. 7

Depression in people with cancer is associated with several negative health outcomes. It undermines quality of life (QoL) for both patients and their carers,8–10 can reduce adherence to medications and treatment,10 and may prolong episodes of hospitalisation and increase health-care costs. 11 Psychological distress,12 and a diagnosis of depression in particular, predicts elevated mortality among cancer patients,13 as do higher levels of depressive symptoms. Among those with advanced cancer, untreated depression is an independent predictor of early death. 14

Therapy for depression in advanced cancer

There is a scarcity of evidence to guide the management of depressive symptoms in advanced cancer. 15–17 Among cancer patients with mixed prognoses (not limited to advanced cancer), evidence suggests that a nurse-led intervention including education about depression, problem-solving and behavioural activation is effective in treating depression in people with cancer (not advanced). 18,19 However, this intervention was also found to be effective among patients with poor-prognosis (lung) cancer. 20 Guidelines developed for the European Palliative Care Research Collaborative suggest that patients whose cancer is unlikely to be cured and who present with depression should be referred to specialist palliative care. 21 Treatment will include psychosocial support and the use of antidepressants and/or psychosocial therapy. 22

Three Cochrane reviews23–25 have looked at which psychosocial therapies are effective in advanced cancer. One of these, a meta-analysis23 of psychosocial therapies for depression in advanced cancer, cited six studies: four26–29 used supportive psychotherapy, one30 used group CBT and one31 used problem solving. The results of this meta-analysis23 were heterogeneous, and the authors concluded that further, well-designed trials were needed to evaluate if CBT is effective at treating depression in patients with advanced cancer. The other two Cochrane reviews24,25 looked at psychological interventions in women with metastatic breast cancer. One24 identified five well-designed studies. 26,30–33 The first two of these studies30,32 suggested that CBT resulted in a short-term improvement in the Profile Of Mood States (POMS) score; however, the effects were lost at the 6-month follow-up, possibly because group therapy did not sufficiently address the needs of specific individuals. An updated review of psychological interventions in women with metastatic breast cancer and depression25 identified 10 well-designed studies. 26,30–38 Three of these studies26,31,33 showed evidence of a small improvement in the POMS score among patients receiving group CBT, although this finding did not reach statistical significance.

Cognitive–behavioural therapy

Cognitive–behavioural therapy is an empirically effective treatment for major depression. The rationale behind CBT is that depression is associated with negative ways of thinking and unhelpful ways of behaving, and teaching the individual to challenge and modify negative thoughts and unhelpful behaviours helps to improve mood. CBT for treating depression compares favourably with antidepressant treatments and has been shown to be associated with significant therapeutic gains over time. Trials of CBT have demonstrated some evidence of efficacy in treating depression in cancer patients. A recent Cochrane review39 of trials of psychosocial interventions for women with non-metastatic breast cancer indicated that patients receiving CBT were less depressed than patients in control groups. CBT is an approach that may be pertinent to treating a population who may experience significant symptom burden from advanced cancer and palliative treatments, such as nausea and pain. A review40 of treatments for depression in patients with advanced cancer has suggested that CBT approaches are the best evaluated and show the most encouraging results; the studies are summarised here.

Screening and recruitment of advanced cancer patients

The European Association for Palliative Care calls for the screening and treatment of depression in patients with advanced cancer. 41 A number of different methods have been used and recommended to screen for depression in cancer patients. 42 The simplest method asks two simple questions43 that have been shown to exclude depression in non-depressed individuals in cancer and palliative care with a 97% negative predictive value. 44,45 The first two questions of the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9), known as the Patient Health Questionnaire-2 (PHQ-2), are routinely used to screen for depression in primary care. Such brief screening is acceptable if followed by a clinical interview to confirm the clinical diagnosis of depression. 46 The MINI47 provides a brief and reliable method for diagnosing depression according to Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition (DSM-IV) and International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Edition (ICD-10) criteria in cancer patients. 47–55 It has been validated against the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM,56 Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Third Edition, Revised57 and the Composite International Diagnostic Interview58 and has been widely used in cancer patients.

Recruitment into, and retention of participants in, palliative care studies can be difficult for several reasons. 59,60 First, associated mental and physical exhaustion present major hurdles to recruitment and retention. 61 Second, there may be high rates of attrition due to early death. 61 Third, well-meaning health professionals may be protective towards patients by discouraging them from making the extra effort required to participate in a study. For example, in previous trials of CBT for depression in advanced cancer, 9–19% of patients approached agreed to participate in the research. 30,62,63 Follow-up rates as low as 44% at 10 weeks have been reported in severely ill palliative care patients,62 although higher follow-up rates are possible and some studies have reported 75% follow-up at 3 months. 30,63 Previous research conducted by our research team within the London cancer networks have achieved follow-up rates of at least 65%. 64,65 A number of strategies and recommendations have since been made to increase recruitment of people with cancer in clinical trials. 59,60

In trials conducted in our research group to evaluate CBT in older people with depression,66 CBT in cancer patients67 and advance care planning discussions in cancer,68 follow-up rates of > 85% were recorded. In each of these studies we offered both treatment at home and telephone interview follow-ups, significantly minimising attrition. Telephone CBT has been shown to be both feasible and clinically effective and cost-effective. 69,70 Individualised, rather than group, CBT is likely to facilitate recruitment and minimise attrition. Individual CBT has been found to be preferred by patients with head and neck cancer. 15,71 Benefits of individualised CBT have also been reported in a study of CBT for depression in women with metastatic breast cancer. 63

Rationale for providing therapy for depression in advanced cancer through the NHS

The research outlined suggests that CBT is an effective treatment for depression and may be a promising treatment for depression among advanced cancer patients. However, advanced cancer patients are not routinely screened and treated for depression within the NHS, despite National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE)’s recommendations that this be done. 72 There is currently no manual-based therapy aimed at treating depression in this patient group and there is not currently a sufficient evidence base to determine that CBT is clinically effective and cost-effective in advanced cancer patients.

Our therapy, consistent with the evidence given, consisted of individual as opposed to group CBT. The UK agenda for treating depression is to widen access to psychological treatment through Improving Access to Psychological Therapies (IAPT) centres that operate in primary care and provide a stepped care approach provided by trained mental health practitioners. In order to provide a pragmatic trial of the effectiveness of CBT in treating patients with advanced cancer, we utilised this existing IAPT infrastructure to provide CBT to advanced cancer patients who screen positive for clinical depression.

Evaluation of cognitive–behavioural therapy provided, fidelity to the intervention and its principles

Moncher and Prinz73 proposed guidelines to enhance treatment fidelity, which have been further developed by Lichstein et al. 74 and Bellg et al. 75 They recommend assessing whether or not a psychological treatment is delivered by the therapist and is understood and carried out by the client; these stages have been respectively described as delivery, receipt and enactment. The primary purpose of the CanTalk trial was to evaluate the addition of CBT to treatment as usual (TAU) compared with TAU alone. We adopted a pragmatic approach within the constraints of the resources available by focusing on evaluation of the treatment delivery, and assessing whether or not the patient seemed to have understood the principles of CBT.

The first question, of treatment delivery, was assessed using quantitative methods. The second question, about whether or not the treatment was received, was explored using qualitative semistructured interviews with 10 participants who had received CBT. The background to this is reported in Background to qualitative work and the methodology in Chapter 3, with a summary of the findings in Chapter 5. A fuller report on qualitative experience of therapy will be prepared for publication elsewhere. The third question, relating to enactment and determining whether or not the CBT model prompted behaviour change in the patient, was beyond the aims of the study and, therefore, was not evaluated.

Concerning treatment delivery, two areas are worthy of consideration. The first important consideration is whether or not the CBT is being delivered competently, including whether or not the therapist is sufficiently flexible and able to use a range of techniques to engage the patient. Competent delivery of CBT, evaluated using the Cognitive Therapy Scale (CTS), has been shown to be related to outcome,76 although the relationship between therapist adherence and competence in determining symptom change is less clear cut than originally thought. 77 The second important consideration is whether or not the therapist adheres to the treatment manual described by Moorey, Mannix and Serfaty. The CanTalk treatment manual was intended to be made available for download on the NIHR webpage for this project. However, the manual was based on work published in Moorey78 and it was not possible to obtain permission from the publisher to make this document available. Please contact the corresponding author for more information about the manual. Indeed, we would like to point out that the revised Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) guidelines for reporting non-pharmacological trials79 have suggested that a description of different components of the intervention is to be provided when evaluating non-pharmacological interventions.

With respect to the first question concerning treatment delivery, we decided that two issues were worthy of consideration. First, an assessment of the therapist’s competence and, second, a measure to confirm that adherence to the CanTalk manual had taken place. In effectiveness studies such as the current one, it can be more difficult to ensure competence and adherence owing to the challenges inherent in delivering the treatment in a routine clinical service. Therapists may be time pressured, there may be differences between services in how CBT is delivered and, crucially in a study of patients with advanced cancer, therapists may not have experience in treating people with physical conditions.

Training of therapist for CanTalk to deliver cognitive–behavioural therapy specific for people with advanced cancer

To maximise competence and adherence to the protocol, mental health therapists with existing CBT skills were selected and trained to apply these skills to people with advanced cancer. This seemed appropriate given that the Five Year Forward View for Mental Health80 aims to expand the IAPT services for people with long-term conditions (LTCs). However, we chose to stipulate that, within IAPT services, therapists would need to be accredited by the professional organisation of the British Association for Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapies (BABCP). Accreditation is not in itself sufficient assurance that high-quality treatment is delivered; however, it does improve the likelihood. When adherence is concerned, it needs to be acknowledged that accreditation cannot ensure that therapists deliver the therapy in accordance with a specific protocol for the treatment of depression associated with cancer. However, selecting high-level therapists minimises any distraction caused by needing to learn CBT techniques and allows them to apply their skills to cancer patients. This was done by training all therapists and some of the supervisors on how to assess and deliver the Moorey, Mannix and Serfaty model to advanced cancer patients; more details are provided in Chapter 3, Training Improving Access to Psychological Therapies therapists.

Background to qualitative work

In the CanTalk trial, we explored both patients’ experience of receiving CBT and and therapists’ experience of delivering it, as well as clinicians’ views of referring into CanTalk. As this work was not commissioned or funded by the HTA programme, we have included only a summary in this report. Nevertheless, we would suggest that findings from this qualitative work are likely to guide practice. The full background, methodology, results and discussion are to be reported elsewhere.

Clinicians’ experience of the CanTalk trial

During the course of the study, we became aware that cancer clinicians involved in identifying patients who did not come from a mental health background had a wide range of views about psychological research in people with advanced cancer. We informally detected a range of views about the relevance of psychological research in advanced cancer patients. Some clinicians were strongly supportive and others suggested that CanTalk was outside their remit or that they felt uncomfortable with the psychological nature of the trial. Further examination of the literature suggested that there was a dearth of research in the area. As cancer clinicians play an essential role in facilitating recruitment, we decided to conduct qualitative work to determine the views of clinicians about psychological research in advanced cancer, their experience of referring into the CanTalk trial, any obstacles they may have experienced and how to improve recruitment into similar trials.

Therapists’ views of treating people with advanced cancer

Both the client and therapist play a role in the outcome of CBT,81 with the therapeutic alliance having an impact on the outcome of therapy. 82 When randomised controlled trials (RCTs) have failed to demonstrate an impact on cancer populations,83,84 interpretations of the findings are purely theoretical. Empirical literature suggests that a number of therapist-specific factors play a major role in the outcome of CBT. 85,86 Despite the importance of the therapists’ role in this type of therapy, there is a dearth of qualitative research conducted from a therapist perspective that addresses their personal experiences of delivering therapy. Indeed, most of published research into experiences of CBT has used quantitative methods, and concerns about such methods have been raised,87 with the focus being purely on client perspectives of CBT with no attempts to explain things qualitatively and directly from a therapist perspective.

In order to determine whether or not the costs outweigh the benefits of this particular treatment in this population, we took a holistic approach so that, as well as quantitatively addressing the effectiveness of treatment, we undertook a qualitative assessment (not required in the brief) of treatment from the therapists’ perspectives on (1) their overall views and experiences of delivering CBT, (2) how services and therapy may be improved, (3) specific training requirements and (4) issues in delivering therapy sessions. This was to help inform the optimum use of resources.

Experience of cognitive–behavioural therapy in people with advanced cancer

There is evidence to suggest that CBT is an effective treatment for people with depression and advanced cancer63 but little is known about how patients in this group perceive CBT or about their thoughts and experiences of it.

For cancer patients attending group CBT, their experiences have been positive; patients enjoy the interpersonal and social environment of the group88 and learn skills to challenge and solve problems. 89 Feedback from patients receiving individual CBT has also been encouraging. Omylinska-Thurston and Cooper90 interviewed eight patients with primary cancers who had received a course of psychological therapy within a NHS service for cancer patients and found that participants found talking about their feelings to someone outside their family and problem solving helpful. In a study in Australia,91 cancer patients with metastatic disease commented that CBT allowed them to share their thoughts and feelings with an understanding, caring therapist. Finally, Anderson et al. 92 found that hospice patients reported CBT to be acceptable and effective.

Although qualitative work has focused on cancer patients’ experience of individual CBT, there is little information about the experience of advanced cancer patients. The remit of IAPT services in the UK is to be expanded to cover patients with chronic health conditions,93 including cancer. Despite the London Cancer Alliance94 having some reservations about the ability of IAPT therapists with brief training to treat older people with complex needs, there are few data evaluating how patients should best be managed.

The qualitative work was designed to elucidate what aspects of CBT participants found helpful, their thoughts about their therapist and the impact of CBT on their QoL, and patients’ views about the best way to support them emotionally.

Chapter 2 Objectives

The study aimed to test, within a RCT, the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of IAPT-delivered manualised individual CBT together with TAU for people with a depressive disorder and advanced cancer compared with TAU alone on depressive symptoms over a 6-month period.

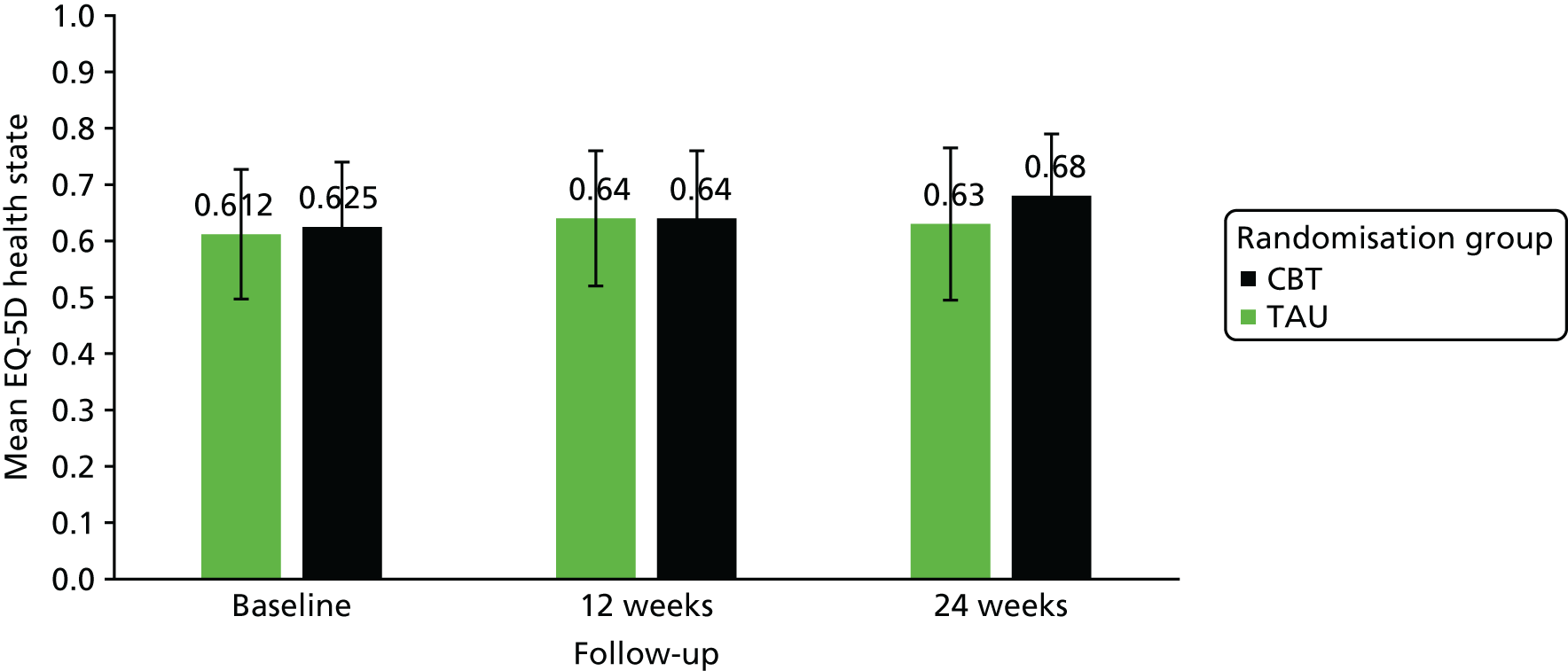

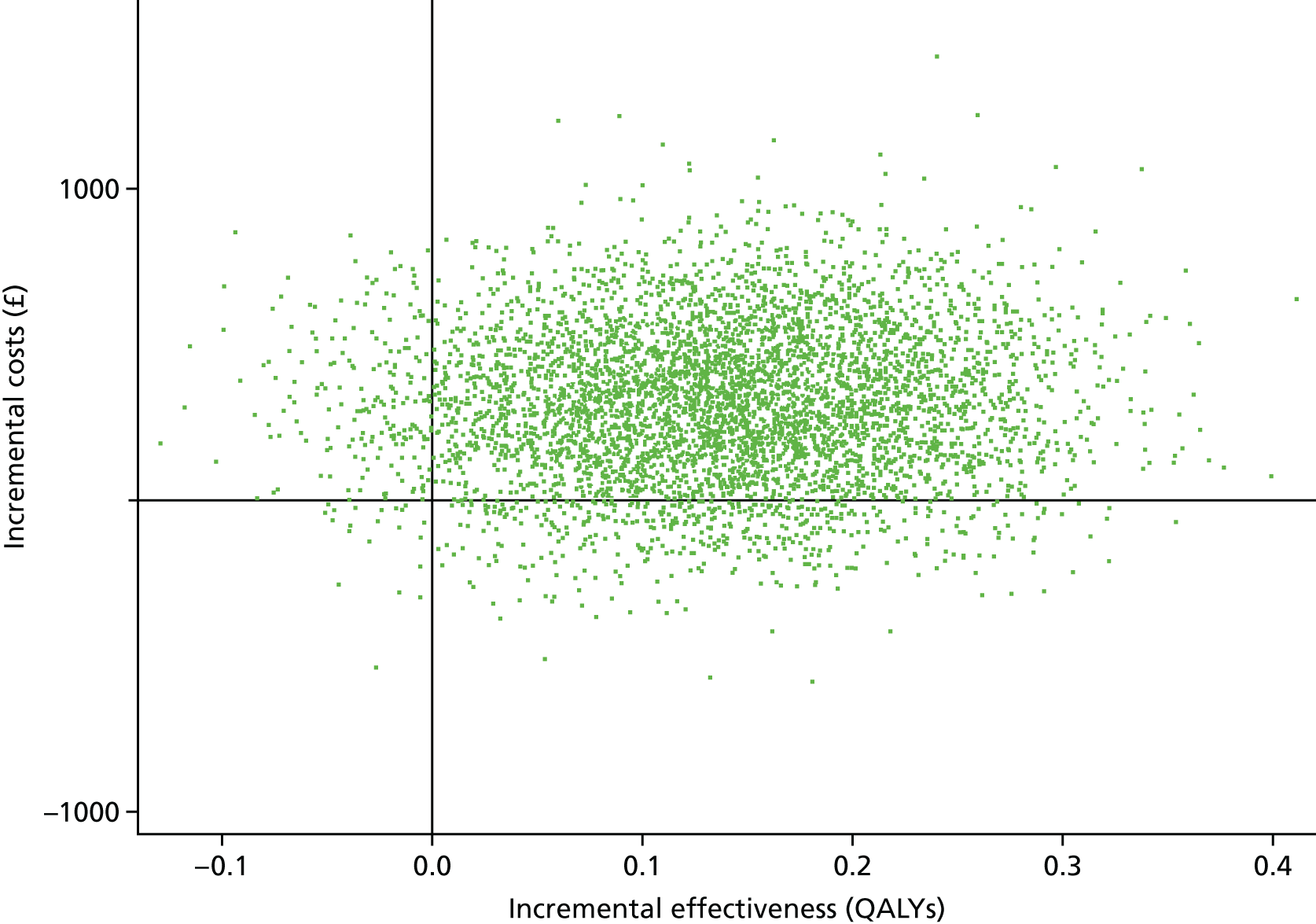

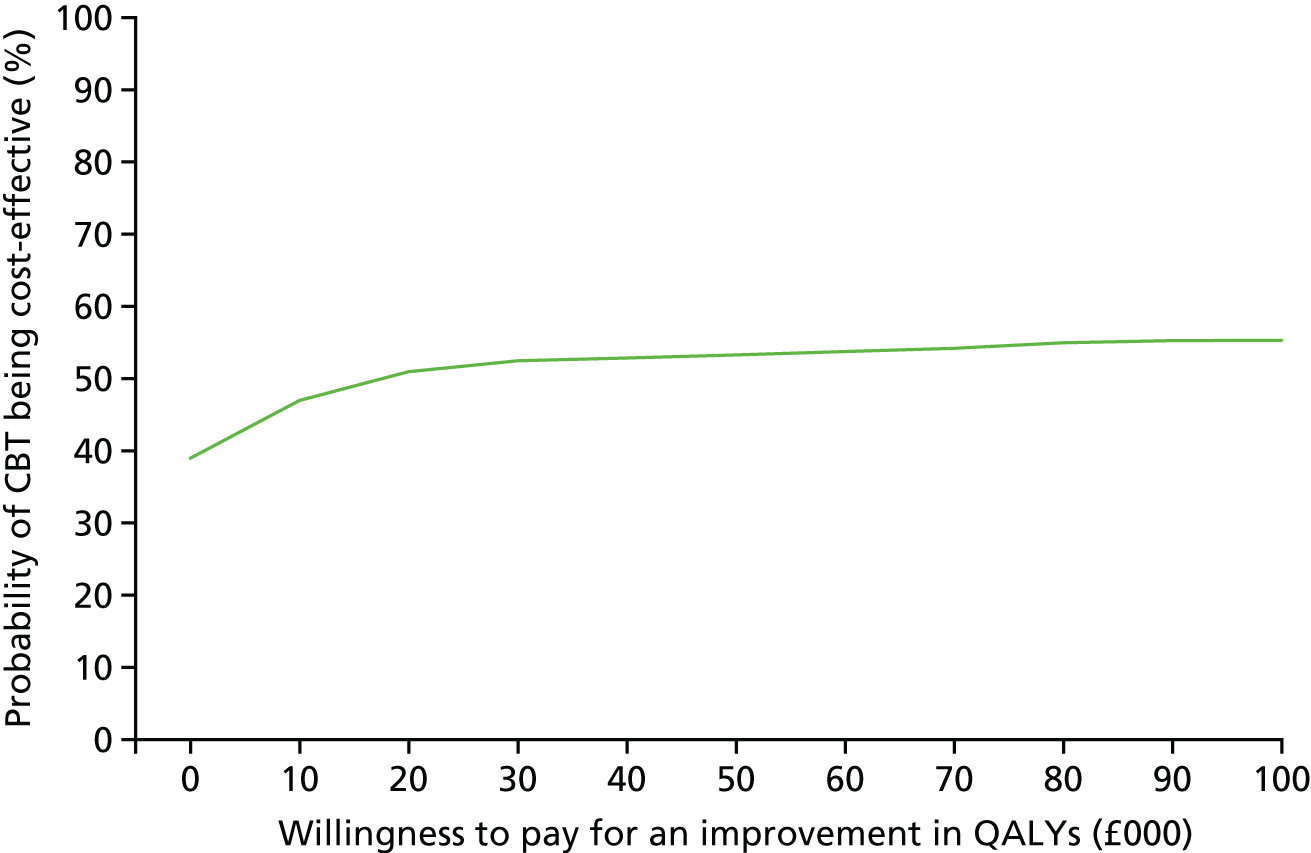

An economic evaluation was undertaken using a cost-effectiveness analysis comparing differences in treatment costs for patients receiving the CBT intervention with quality-adjusted life-years (QALYs) computed from the EuroQol-5 Dimensions (EQ-5D) and societal weights over a 6-month follow-up.

Chapter 3 Methods

Acknowledgement

This chapter contains information previously published by Serfaty et al. 95 © 2016 Serfaty et al. Open Access. This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

Trial design and governance

Trial registration

This trial is registered as ISRCTN07622709. The full protocol is available online and published in Trials. 95

Trial design

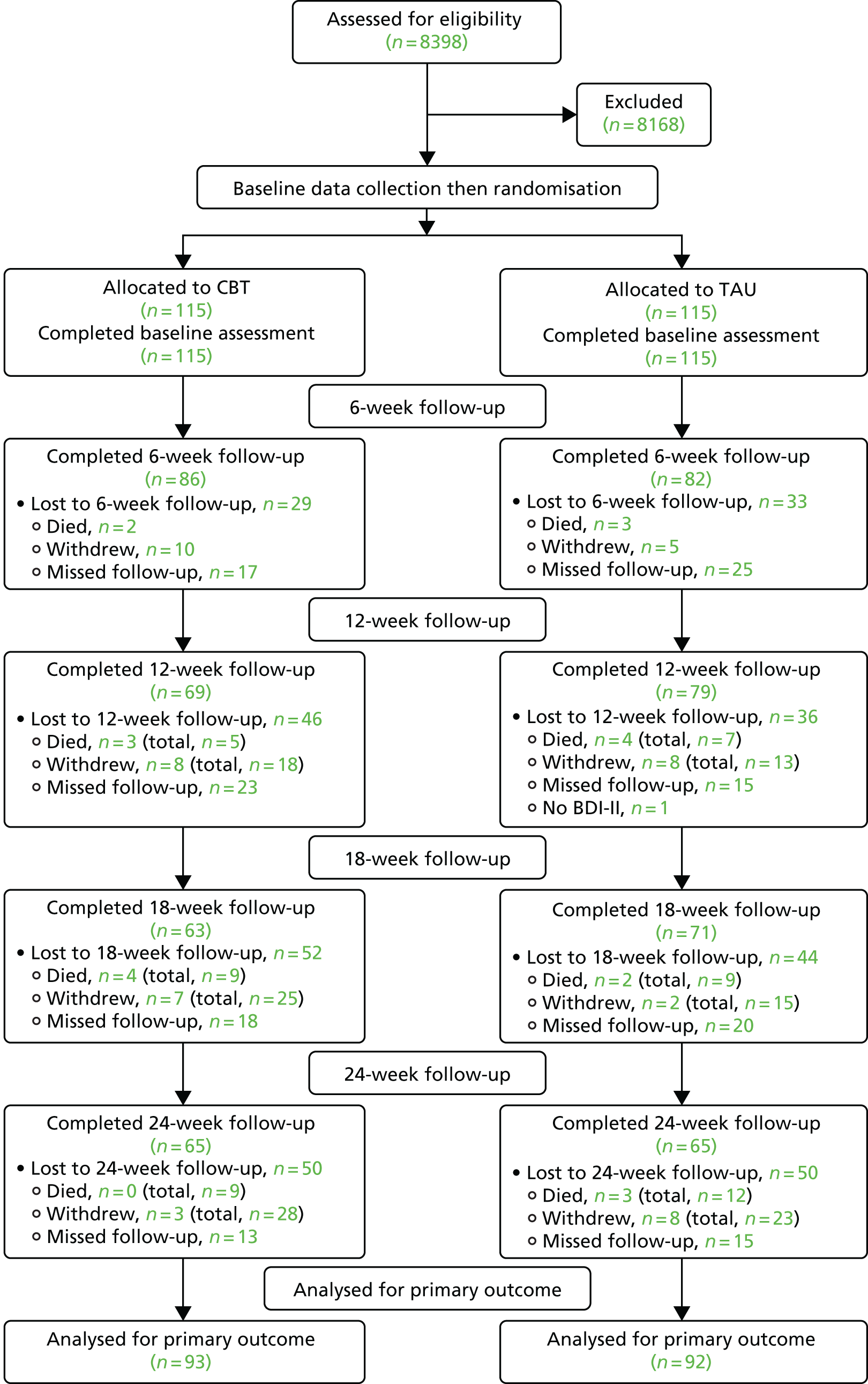

This is a parallel-group RCT, stratified by antidepressant prescribed at baseline (yes/no), comparing TAU with TAU plus up to 12 sessions of manualised CBT. Allocation ratio for the two trial arms was 1 : 1.

Patient and public involvement

The trial was designed in response to a HTA programme call. Janet St.John-Austen, a user of cancer services, was an active contributor to the design of the project, the preparation of the materials (including the layout and wording for clarity and sensitivity) and ethical considerations. She attended regular steering group meetings and was invaluable in commenting on methods to boost recruitment. She also contributed to the interpretation of the results and write-up.

Ethics approval

A favourable opinion for the conduct of the study was granted by the London–Camberwell St Giles National Research Ethics Service committee, Central London (REC3 reference number 11/LO/0376). This study formed part of the National Cancer Research Network (NCRN) clinical trials portfolio (registration number 10255, ISRCTN07622709). The trial was conducted in compliance with the Declaration of Helsinki. 96 Informed written consent was obtained from all participants.

Changes to protocol

Several amendments were made to the study’s procedures during the course of the study, including changes to streamline recruitment methods and the addition of three qualitative substudies. These amendments are outlined in Table 1.

| Amendment number | Date of amendment approval | Summary of changes |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 4 December 2012 |

|

| 2 | 28 October 2014 |

|

| 3 | 22 January 2015 |

|

| 4 | 1 July 2015 |

|

| 5 | 14 September 2015 |

|

| 6 | 21 September 2015 |

|

Eligibility criteria for participants

Inclusion criteria

-

People with a diagnosis of cancer not amenable to curative treatment as assessed by their clinician and defined as those receiving palliative radiotherapy or chemotherapy, and those with metastatic disease or subsequent incurable recurrence. The diagnosis was verified by oncologists or general practitioners (GPs).

-

A DSM-IV diagnosis of depressive disorder using the MINI. 47

-

Sufficient understanding of English judged by clinic staff to enable them to engage in CBT.

-

Eligible for treatment in an IAPT centre. Either the patient or their GP had to be located in an appropriate IAPT catchment area.

Exclusion criteria

-

Clinician-estimated survival of < 4 months, verified by the patients’ oncologists or GPs.

-

People at high risk of suicide, established through module C of the MINI.

-

Currently receiving, or having received in the last 2 months, a psychological intervention recommended by NICE aimed at treating depression (e.g. interpersonal psychotherapy, CBT).

-

Suspected alcohol dependence using the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test. 97

We did not recruit in areas where the local palliative care service includes routine access to CBT, to avoid contamination of TAU arm by non-study CBT.

Recruitment methods and procedures

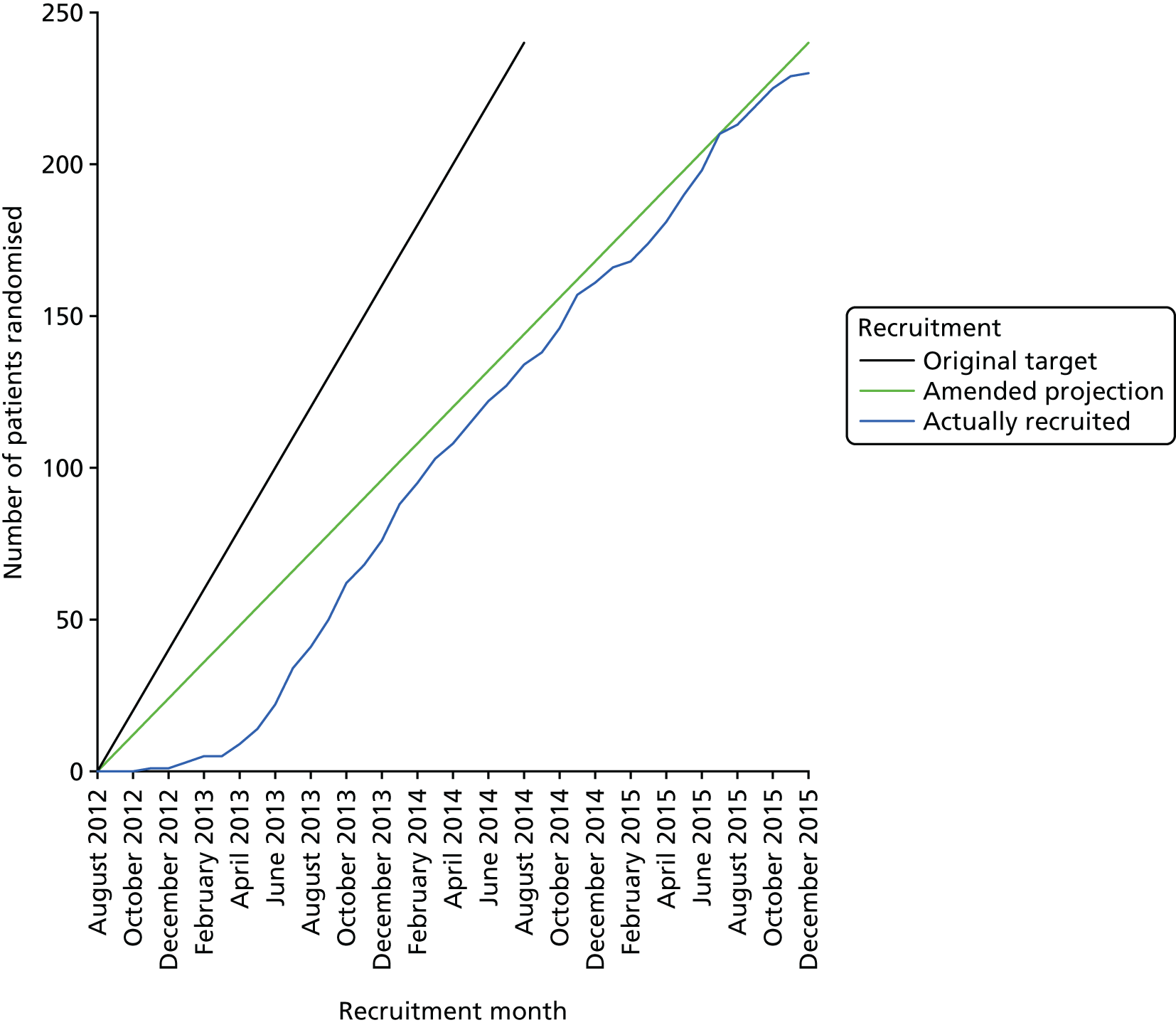

Timeline and setting

Recruitment of participants commenced on 1 September 2012. Recruitment finished on 14 December 2015 (the end of the study’s agreed recruitment period). The first participant was recruited into the study on 27 November 2012. The first 6-week follow-up took place on 15 January 2013 and the final 24-week follow-up took place on 19 May 2016.

Participants were identified in four ways: (1) from oncology centres, (2) through GP practices, (3) through the Marie Curie Hospice, Hampstead and (4) through self-referral using leaflets left in GP surgeries and oncology clinics.

Outpatient oncology clinics

National Cancer Research Network support staff working with University College London (UCL) researchers facilitated recruitment from oncology outpatient clinics. Patients’ GP addresses were checked to determine that they were eligible to be referred to an IAPT service before they were approached. UCL researchers collected accurate data about the number of patients screened and the proportion of whom satisfied the entry criteria. However, NCRN support staff or research nurses could not always commit to collecting data on the number of people screened for eligibility. In addition, UCL researchers attempted to collect patients’ reasons for not wishing to take part in the study; however, this information was not always available as the ethics application stipulated that patients did not need to give a reason.

We selected oncology services to represent a variety of patients from the main tumour groups: breast, gastrointestinal (GI), lung, haematology, prostate and other. Patients attending radiotherapy and chemotherapy clinics came from all tumour groups. Oncology centres were identified across England and represented a variety of services, and we recruited from the following hospitals and clinics. Screening data and numbers of participants recruited, when available, are presented in Chapter 5.

Unless otherwise specified, UCL research staff attended in the following clinics.

North London

-

Royal Free Hospital: breast, radiotherapy, lung, urology, lymphoma, melanoma, head and neck, and renal.

-

Whittington Hospital: the clinic research nurses approached, screened and then sent screen-positive details about patients from the following clinics – colorectal, upper GI, lung and breast.

-

University College London Hospital: myeloma, lymphoma, melanoma, gynaecology and radiotherapy, breast, lung, GI and sarcoma.

-

North Middlesex University Hospital: lung, chemotherapy (all tumours), GI and breast. A cancer researcher also screened from breast and lung clinics.

East London

-

Homerton University Hospital: lung clinics.

-

Barts and The London: prostate, GI, lung, breast (Barts) and melanoma (The Royal London Hospital).

South London

-

University Hospital Lewisham: the clinic research nurses approached, screened and then sent screen-positive details about patients from the following clinics – lung, colorectal and breast.

-

Guy’s and St Thomas’ Hospital: myeloma, breast, upper GI, colorectal, hepatopancreatobiliary (HPB), lung (Guy’s) and Neurology (St Thomas’).

-

Princess Royal University Hospital (PRUH): UCL research staff attended the lung clinic. Research nurses at the PRUH approached, screened and sent screen-positive patients to contact from the breast and haematology clinics.

-

King’s College Hospital: breast, myeloma and neurology, and a research nurse screened in the haematology, lung, breast and colorectal clinics.

-

Queen Elizabeth Hospital: the clinic research nurses approached, screened and then sent screen-positive details about patients from the following clinics – breast, lung, GI and colorectal, and urology.

Out-of-London sites

Patients in all of the out-of-London sites were identified, screened, recruited and followed up by research nurses. The following clinics participated in the study:

-

South-west England (Weston Super Mare) – participants were identified from the Weston General Hospital haematology and prostate oncology clinics.

-

Midlands (Coventry and Warwick) – oncology clinics (breast, colorectal, prostrate, GI, neurological, and head and neck).

-

The south of England (Brighton General Hospital) – identified patients for the study in the Midhurst Macmillan multidisciplinary team meeting. Patients identified were then approached in their clinics and screened.

-

The north of England (South Tyneside) – patients were identified from oncology clinics (colorectal and urology).

-

The north-west of England – patients were identified in oncology clinics (gynaecology, HPB, breast, palliative care and chemotherapy) at oncology centre 14.

General practitioner practices

Reeve et al. 98 have used methods to identify those patients from registers of people with advanced metastatic cancer who are receiving only palliative treatment. However, our preliminary examination of general practice data prior to the study suggested that < 10% of all cancer patients are placed on palliative care registers even though 60% of cancer patients may have advanced disease. Identifying patients from palliative care registers approaches a restricted population; for example, only the sickest patients may be placed on such registers and they may have been too ill to respond to the authors’ survey. Indeed, psychological and psychiatric morbidity associated with cancer goes undetected and undertreated in > 80% of people. 99,100 Given these varied data, for the purposes of our study, we assumed a more conservative prevalence rate for major depression in advanced cancer patients with rates of depression of 15% in oncology outpatients and 10% in GP patients.

General practitioner practices were identified from areas where collaborating IAPT/well-being services were located and were approached if they had previously expressed an interest in research and had ≥ 55 patients on their cancer register. We used our established links with the Primary Care Research Network (PCRN) in south London and the North Central London Research Consortium in north London to approach practices that expressed an interest in research. Cancer registers were used rather than palliative care registers as the latter include a significant number of people with non-cancer diagnoses.

Marie Curie Hospice, Hampstead

The Marie Curie Hospice, Hampstead, is purpose built and cares for around 450 registered patients. Hospice clinic staff identified potential participants attending the hospice day-care, outpatients services and the hospice gym and asked them if they could be approached by UCL researchers to see whether or not they were eligible to take part in a research study.

Self-referral

With the permission of clinical leads in each service, posters and leaflets about the study were placed in approved oncology clinics and GP practices.

Set-up procedures

The time taken for sites to become active was an important element of the research process as such procedures may delay the start of recruitment and escalate the costs of research. In Chapter 5, we will report when research and development (R&D) applications were made, when R&D approval was received and when sites became active. In one centre, approval was required by the hospital board prior to submitting an application for R&D approval.

Screening methods

Participants were screened for entry into the study between 1 September 2012 and 14 December 2015.

Oncology centres

Either support staff or UCL researchers screened suitable patients for depression using the PHQ-2,101,102 the first two questions of the PHQ-9,103 a valid screening measure for depression routinely used in general practice.

Patients who scored ≥ 3 points were provided with a pre-screening information pack and asked if they would be willing to be assessed for the study. If they scored ≥ 3 points but did not wish to participate, their permission was sought for their GP or oncology team to be informed that they may be depressed. If they agreed in principle to take part, a researcher undertook a further assessment, using the MINI to establish a DSM-IV diagnosis of depressive disorder. If a DSM-IV diagnosis of depression was confirmed, the patient was given an information pack. The patient was then given at least 48 hours to reflect on whether or not they wished to participate in the study before giving written consent for participation. If a patient consented to take part, the researcher then conducted baseline assessments and passed the participant’s details to an independent trial administrator, who arranged randomisation through the PRImary care and MENTal health (PRIMENT) Clinical Trials Unit (CTU). The study administrator informed the participant by telephone of their group allocation. For those randomised to the treatment arm, the administrator liaised with IAPT to set up the therapeutic sessions. Both administrator and PRIMENT were situated separately from the trial research team to maximise masking of trial arm allocation from the researchers.

General practitioner practices

University College London researchers attended the practice and trained a practice research nurse in the standard operating procedure on how to identify potential suitable participants. Practice administrators identified people on the cancer register and consulted the GP on whether or not the patient had advanced cancer as defined in the protocol. By mutual agreement according to availability at the practice, either the practice nurse or PCRN staff contacted the patient by telephone or face to face in practices to explore whether or not they were willing to answer the two PHQ-9 screening questions for depression. The procedure was then the same as for the oncology centres but, in this case, the practice nurses/PCRN nurses collected follow-up data at the relevant time points.

Marie Curie Hospice, Hampstead

University College London researchers consulted clinic records and checked the eligibility criteria for those identified as suitable by hospice staff. They then approached potential participants for screening as outlined above. Those suitable were then told about the trial and consented once they had had 48 hours to consider participation.

Self-referral

The leaflet contained the PHQ-2 for patients to conduct a quick assessment of their mood themselves, suggesting to people with a score of ≥ 3 points that they may have depression and that they should either (1) approach the clinical team within the site or (2) contact the study team directly using the reply slip attached to the leaflet. The process of recruitment was the same as that previously outlined.

Screening data

In instances in which the UCL researchers undertook the screening, they were able to collect data about the number of patients screened – the proportion of whom satisfied entry criteria – and, if patients declined to take part, the reasons (if given). It is important to highlight that the ethical principle that patients are free to decline to take part or withdraw from a study without giving a reason was included in the project’s ethics approval submission. When Comprehensive Local Research Networks (CLRNs) were undertaking identification, selecting and screening of patients, comprehensive data for numbers of people screened and reasons for declining to take part in research were not always available as CLRNs indicated that they did not have the resources to collect these data.

Randomisation

Participants were randomised to one of two conditions, (1) TAU or (2) TAU plus CBT, with an equal allocation to each treatment arm. Randomisation occurred after patients had been assessed to meet the eligibility criteria and had consented to participate and baseline measures had been collected. Once a participant had been randomised, the trial administrator called the participant to inform them of their group allocation. For participants randomised to the group receiving CBT, the trial administrator then sent an e-mail to a contact in the relevant treatment centre providing details of the participant.

Randomisation was conducted by the trial administrator using Sealed Envelope (Sealed Envelope Ltd, London, UK), an automated online randomisation system supplied by the PRIMENT CRU (a UK Clinical Research Collaboration registered CTU). This system was pre-populated with a randomisation list using a randomisation algorithm developed by the trial statisticians. The randomisation was tested using a test version of the Sealed Envelope randomisation system. Randomisation was conducted using permuted blocks with block sizes of four or six, stratified for antidepressant use (yes or no). Antidepressants are a predictor of outcome. 104 In cancer, tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs) may be preferentially prescribed over selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors because they have fewer relevant side effects, such as nausea, and may be used for both mood and, in lower doses, for pain. Indeed, even low doses of TCAs may be effective. 105 Therefore, we stratified our randomisation according to whether or not participants were prescribed an antidepressant, irrespective of dose. We did not have the resources to measure compliance with medication through pill counts or by taking blood levels, but we did ask participants what they were taking, estimated their antidepressant doses and converted them to equivalent doses of fluoxetine using methods previously described by Hayasaka et al. 106 to assess whether or not the doses of prescribed antidepressants were similar in both arms of the trial at randomisation (see Chapter 4, Analysis plan).

Masking

Once a participant had been randomised, the trial administrator unblinded that participant by clicking on an ‘unblind’ link on the Sealed Envelope system that generated an e-mail to themselves with details of the group allocation.

It is not possible for patients or therapists to remain blind to the treatment group. The trial manager was unblinded only if needed, for example if there was a problem referring a patient to therapy. The trial team worked at UCL and was based in a different location to the therapy teams that conducted the trial intervention.

Assessment of blindness

The UCL researchers who were blinded were asked to guess group allocation (TAU alone, TAU plus CBT or do not know) at 3 months (post intervention) and 6 months (follow-up). Although the PCRN assessors were blinded, they requested that any additional data collection was kept to a minimum and, therefore, they did not make an assessment of blindness.

Unmasking for those conducting the analysis did not occur until databases were closed.

Intervention

Treatment as usual

All participants received TAU from all clinicians involved in their care. This consisted of routine support, such as appointments with GPs, clinical nurse specialists, oncologists and palliative care clinicians. Participants’ physical health and medication were reviewed and treatment was modified according to symptoms, such as pain. Psychotropic medication was allowed to be prescribed as necessary, by either the GP or the oncologist. In line with NICE’s guidance,107 specific psychological support should have been available for those who presented with psychological needs at any time, and study participants were not exempt from receiving external psychological support. We discouraged specific psychological interventions aimed at treating symptoms of depression (e.g. CBT or interpersonal psychotherapy), but, ultimately, we could not interfere with usual care for ethical reasons. We recorded the numbers of participants receiving any psychological therapy during the trial, although we predicted that the numbers were likely to be small. 66 We did not stipulate post randomisation that antidepressant medication could not be used or that the dose should be fixed. Withholding a recognised treatment for depression would be unethical and would not reflect TAU.

Cognitive–behavioural therapy (in addition to treatment as usual)

The CBT was delivered through IAPT93 and well-being centres. IAPT/well-being centres train, supervise and supply therapists to treat people in primary care with mental health problems. For the purpose of the study, only step 3 and 4 (high-intensity) therapists who had experience of CBT were used. They were given 1 day’s training by the CanTalk team (SM, MS and KM) so that their existing CBT skills could be adapted to use a specially developed treatment manual for people with advanced cancer. The manual detailed modifications in the structure of therapy and its content; in particular, it took into account physical health problems, existential issues and communication with loved ones.

Structure of cognitive–behavioural therapy sessions

The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence recommends 16–20 sessions of CBT to treat severe depression in secondary care. Experience shows that, in primary care, considerably fewer sessions are taken up. People with advanced cancer may have difficulty coping with longer therapy as their health may be deteriorating. Our intervention consisted of up to 12 sessions of individual CBT, which was delivered either face to face or over the telephone over 3 months. Although telephone CBT was not delivered as a substitute for face-to-face treatment, it was used to facilitate engagement and minimise dropout. Twice-weekly sessions could be offered for the first 2 weeks, weekly sessions for weeks 3–9 and then two sessions within weeks 10–12. The timing of sessions was flexible and pragmatic to fit in with the existing commitments of the IAPT service and with patient availability, taking their other medical clinics and treatments into account.

In order to facilitate engagement for those who may not be able to attend sessions face to face, telephone CBT was offered if at least three sessions of face-to-face therapy had already been received. Telephone CBT was already being used by IAPT therapists. Stirling Moorey, Marc Serfaty and Kathryn Mannix taught CBT therapists how to adapt their CBT techniques for telephone-based therapy using similar methods to Tutty et al. 108

Content of cognitive–behavioural therapy sessions, guided by a written manual

Improving Access to Psychological Therapies guidelines recommend that patients with moderate to severe depression and complex needs receive high-intensity (step 3) work. This is consistent with the level 4 psychological interventions recommended by NICE72 for people with cancer. The CBT intervention used a flexible approach, adapted for use with people with advanced illness who face a poor prognosis. In the manual, developed by Stirling Moorey, Kathryn Mannix and Marc Serfaty, therapists adapted their work to patients with advanced cancer. The key shift was to identify whether thinking and behaviour are ‘helpful’ or ‘unhelpful’ rather than solely a reality-testing approach, thereby enabling patients to adopt adaptive strategies to cope with adverse and often unpredictable health circumstances.

The intervention broadly covered the following:

-

Session 1 – an assessment of problems, psychoeducation about depressive disorder and an introduction to the cognitive model was undertaken. A simple cross-sectional formulation of current emotional distress was established, and the triggers to emotional distress and how to manage them were identified, with steps towards one of the patient’s goals. A list of enjoyable activities was instigated, and unhelpful thinking styles were identified, using specific examples from recent events.

-

Session 2 – aimed to help patients develop an understanding of their problems within a cognitive behavioural framework and began the process of therapy using cross-sectional formulation. This included a discussion of past strengths and coping abilities. Behavioural activation techniques were used within the constraints of the person’s physical illness.

-

Session 3 – consisted of a review of the formulation, identifying any new insights/changes. Guided discovery, through a deeper discussion of the patient’s thoughts/beliefs around their illness and their resilience, was used to help them apply their resilience under current circumstances. A start was made on identifying ‘helpful’ versus ‘unhelpful’ thinking and behaviours.

-

Sessions 4 and 5 – helped the patient to apply new learning to current difficulties, recent successful experiences were reformulated and helpful changes were identified. Guided discovery was used to help the person notice successful experiences and build resilience. The triggers to emotional distress and strategies for responding were explored. These included thought-testing and an in-session experiment of allowing intrusive thoughts to pass.

-

Sessions 6 and 7 – focused on thought-testing and finding ‘helpful’ alternative thoughts. This was done within sessions, supplemented by homework completed by the patient between sessions, when logs of patients’ mood, the associated thoughts and behaviours were reviewed. Thoughts and behaviours could then be challenged and more helpful alternatives considered. Examples of recent success experiences were added to successes lists and exploration of these for their associated ‘helpful’ thoughts.

-

Session 8 – focused on problem solving and worry time. Confirmation was made that the thought-testing/’helpful’ thoughts concept had been understood. Examples of realistic concerns were identified to generate a ‘problems to address’ list. An example of one problem was taken to illustrate the problem-solving approach. The concept of ‘worry time’ was introduced to reduce rumination.

-

Session 9 – consolidated CBT strategies and reviewing and prioritising a problem list. Planning on how to tackle harder problems was undertaken, identifying unhelpful thoughts and behaviours with consideration of the pros and cons of potential solutions and the commitment to this process. The use of worry management strategies was also reviewed.

-

Session 10 – consisted of a review of the person’s perceived progress, including successes and difficulties.

-

Session 11 – consisted of relapse prevention. This included reviewing presenting difficulties, the progress and personal achievement made, personal resilience and successes and the development of a relapse prevention checklist.

-

Session 12 – consisted of future planning, reviewing a relapse-prevention checklist, making concrete plans for action if emotional distress recurred or unhelpful behaviours/thinking returned.

In addition, therapists were taught about materials contained in three sections in the manual, so that, if relevant, these may be addressed with participants. These sections covered (1) existential issues in addition to eliciting and discussing the patient’s fears about death, including their mode of dying, fears about the effect of their death on others and fears about what happens after death; (2) applying CBT when health is poor, which included running shorter sessions, and discussing how to deal with fatigue and coping with loss of function; and (3) facilitating communication with a partner, families and carers. This provided CBT therapists with confidence in adapting their skills to people with advanced cancer.

Please contact the corresponding author for more information about the CanTalk treatment manual.

Improving Access to Psychological Therapies involvement

Identifying and contacting Improving Access to Psychological Therapies centres

The following methods were used to identify IAPT/well-being collaborating centres where the intervention could take place. IAPT/well-being leads were approached for selected boroughs across London for the pilot stage and further areas within, and outside, London for the definitive trial. Areas were selected for several reasons: first, where study team personnel had existing links with oncology teams, hospices and GP centres for recruitment to be feasible; second, where study personnel had existing links with IAPT/well-being services and IAPT/well-being leads expressed an interest in research; third, IAPT/well-being services were approached if they had a mature service running for ≥ 2 years and, therefore, would be more likely to be able to participate in the delivery of specialist CBT; and fourth, we were also approached by a number of services who identified the CanTalk trial through trust research co-ordinators.

Our approaches were initially made by telephone to IAPT/well-being leads, identified from websites and by personal contact. These were followed by an e-mail summarising the project with the advantages to IAPT/well-being services highlighted as follows:

-

free training for IAPT/well-being high-level CBT practitioners

-

improvement in IAPT/well-being therapists’ CBT skills

-

developing the delivery of IAPT to patients with long-term physical health conditions, which is consistent with national aims

-

effective publicity for IAPT/well-being so that services are properly funded

-

demonstration that, if effective, CBT, delivered through IAPT, would represent a good model of care for LTCs.

Training Improving Access to Psychological Therapies therapists

The IAPT/well-being services were asked to supply at least two high-intensity IAPT/well-being therapists for manualised training. IAPT/well-being supervisors were also encouraged to attend.

Training was delivered by Stirling Moorey, Marc Serfaty and Kathryn Mannix. Therapists were supplied with a therapists’ manual, presented with Microsoft PowerPoint® 2010 (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA) slides giving an overview of sessions in the manual as well as videos and role plays and were asked to participate in practising skills using a variety of scenarios. How they could access the resources online was also explained. Finally, they were taken through processes required for, and associated with, the research.

Training took place at the following sites: UCL for London, the south of England, the Midlands and the west of England (SM and MS); Chester for the North West (MS and KM); and Newcastle upon Tyne for the North East (KM).

Training took place in 27 IAPT/well-being services. Of these, 25 participated in the study. Chester and Newcastle upon Tyne did not participate as we could not set up recruitment centres in these areas. Details of the 25 services engaged in the study, including the number of therapists (124 in total) represented from each service and the IAPT/well-being leads, are presented below.

The number of people trained in applying CBT skills to patients with cancer came from the following services.

-

London:

-

North London – 13 people from five IAPT services from Barnet, Camden and Islington, Enfield and Haringey.

-

East London – 19 people from nine IAPT services from City and Hackney, St Bartholomew’s and The London (Hospital), Tower Hamlets, Redbridge, Homerton, Newham, Waltham Forrest, Havering, Barking and Dagenham.

-

South London – 30 people from seven IAPT services from Lambeth, Lewisham, Bromley, Bexley, Croydon, Southwark and Greenwich.

-

-

Outside London:

-

the south of England – four people from two IAPT services (Sussex and Brighton and Hove).

-

the west of England – two people from one IAPT service (Avon and Wiltshire).

-

Midlands – four people from Coventry and Warwick IAPT services.

-

North East – 11 people from one IAPT service (South Tyneside).

-

North West – five people from one IAPT service (Stockport).

-

Evaluation of training

Training was evaluated using a feedback questionnaire with a Likert scale asking about specific aspects of training; boxes enabled additional free-text comments. These findings are presented in Chapter 5.

Location of therapy

Patients were offered the opportunity for face-to-face therapy in their local IAPT/well-being centre. In some cases, this was at a local GP practice, depending on the set-up of the service. We did consider delivering therapy in the patients’ own homes but were constrained by limits on safe lone working and, thus, therapy could not be delivered in this way through the IAPT/well-being service. When patients were too frail or reluctant to continue to attend therapy in an IAPT/well-being centre, we allowed for the delivery of telephone CBT, providing the patient had seen the therapist at least three times and it was deemed by the therapist to be consistent with safe working practices. We asked therapists to record whether therapy was delivered face to face or by telephone.

Supervision of Improving Access to Psychological Therapies therapists

Supervision structures are well set up within IAPT services. Routine supervision of therapy in IAPT takes place at least monthly but is flexible within this period. However, in this trial, we recommended flexibility, so that if any immediate issues needed attention, the therapists could consult their IAPT supervisors. Stirling Moorey, Kathryn Mannix and Marc Serfaty were also available, by e-mail or by telephone, to discuss any difficulties related to interventions in people with cancer. The CanTalk trial supervisors were also accessible to the local IAPT supervisors by e-mail to answer any additional queries that arose between supervision sessions. Flexibility in the ‘practice stage’ was used to learn about how clarification about the CBT intervention might be required. Audio recordings of all therapy sessions are routinely made in IAPT and these were also made available for the independent assessment of quality.

Delivery of cognitive–behavioural therapy

We decided that CanTalk should be a pragmatic approach, which aimed to determine whether or not our target population would benefit from CBT delivered through IAPT. If the CanTalk approach were to be rolled out across the UK, we decided that, for the findings to be generalisable, therapists should be managed in the usual way.

We kept a record of which IAPT services and which therapist within the service delivered the intervention, and of how many sessions were delivered to each patient.

Quantitative assessment of delivery of cognitive–behavioural therapy

The quality of therapy was assessed using mixed methods. Quantitatively, the Cognitive Therapy Scale – Revised (CTS-R) was used to assess the delivery of CBT and adherence to the therapy manual was assessed using an adherence checklist (described in Measure of adherence to cognitive–behavioural therapy in cancer manual). Qualitatively, the patients’ experience of therapy and the therapists’ experience of delivering CBT to people with advanced cancer with depression was explored through interview. Although this work was not commissioned by the HTA programme, we felt that this would provide a useful addition to this report and the findings are summarised accordingly in Chapter 5.

Measure to assess competence of delivery of cognitive–behavioural therapy

A scale for measuring therapist competence in cognitive therapy, based on the original CTS,109 is the 12-item CTS-R. 110

This revised version improves on the original CTS by eliminating the overlap between items, improves on the scaling system and defines items more clearly. In this trial, we assessed competence by having an independent rater listen to audio recordings of therapy sessions using the CTS-R.

Scoring

The CTS-R consists of 12 items: (1) agenda setting and adherence, (2) feedback, (3) collaboration, (4) pacing and efficient use of time, (5) interpersonal effectiveness, (6) eliciting of appropriate emotional expression, (7) eliciting key cognitions, (8) eliciting and planning behaviours, (9) guided discovery, (10) conceptual integration, (11) application of change methods and (12) homework setting. Although the CTS-R is more specific than the original CTS, in that therapist competence is defined very precisely, the CTS-R has poorer inter-rater reliability. In the CTS-R, each item is rated from 0 to 6 on a visual analogue scale (VAS) encompassing the following competencies: incompetent, novice, advanced beginner, competent, proficient and expert. The total score ranges from 0 to 72 points, with a minimum score of 36 points taken as competency for the delivery of therapy. We would expect therapists to achieve a minimum score of 36 points, which is the standard criterion for competence within IAPT services.

How the quantitative measures of delivery of therapy were collected

Assessment of the quality of therapy to the manualised treatment was assessed as follows:

-

Quality of delivery of CBT – a total of 194 therapy sessions were audio recorded. In accordance with our plan to sample 1 in 10 of the therapy recordings, we selected 55 out of 543 audio recordings to rate the therapy. As the sample was skewed, with the mode being one session, we purposefully sampled recordings to obtain a balance of therapy sessions from the different phases of the intervention (early, sessions 1–4; middle, sessions 5–8; or late, sessions 9–12). Tapes were allocated a random identification number, but it enabled identification of the therapy session number (1–12) so that a range of phases of therapy could be assessed.

-

Therapists were asked to upload recordings of therapy, when possible, onto a secure database using encryption software. Local health-care trust policy and therapists’ experience of information technology (IT) systems may limit this process. Recordings of therapy were rated by an accredited member of the BABCP using the updated version of the CTS109 (the CTS-R110), which is a reliable measure of the delivery of CBT. 76

Measure of adherence to cognitive–behavioural therapy in cancer manual

In this context, we defined therapist adherence as the extent to which the therapist adhered to the essential ingredients described within the treatment manual developed for use in the trial by Marc Serfaty, Stirling Moorey and Kathryn Mannix.

Detailed information about the content of the intervention was collected using a ‘Therapy Components Checklist’ (TCC) (Table 2). The role of the TCC was threefold. First, it provided the therapist with a guide to which elements were delivered (or not) from the manual. Second, it provided information about which elements had been delivered by therapists during the course of the trial. Third, it enabled us to evaluate whether a therapist’s self-report of what they said they did was consistent with what they actually did, judged by an independent rater.

| Component | Session the component was covered | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | |

| General procedures | ||||||||||||

| Initial assessment | ||||||||||||

| Describe Beck’s model and concept of CBT | ||||||||||||

| Agree goals of therapy | ||||||||||||

| Present a shared formulation | ||||||||||||

| Goal-setting | ||||||||||||

| Review of shared formulation | ||||||||||||

| Review of success list | ||||||||||||

| Relapse prevention/future planning | ||||||||||||

| Behavioural techniques | ||||||||||||

| Relaxation training | ||||||||||||

| Breathing space | ||||||||||||

| Activity schedule | ||||||||||||

| Pleasure experiences sheet | ||||||||||||

| Cognitive techniques | ||||||||||||

| Refocusing techniques | ||||||||||||

| Mindfulness | ||||||||||||

| Four-step process for resilience and coping | ||||||||||||

| Coping map | ||||||||||||

| List of strengths and resources | ||||||||||||

| Reattribution | ||||||||||||

| Decatastrophising | ||||||||||||

| Advantages/disadvantages | ||||||||||||

| Success list | ||||||||||||

| Thoughts diary | ||||||||||||

| Personal rule (pros/cons) | ||||||||||||

| Managing worry (worry tree handout) | ||||||||||||

| Blueprint for coping | ||||||||||||

| Cognitive–behavioural techniques | ||||||||||||

| Guided discovery | ||||||||||||

| Pleasure prediction sheet | ||||||||||||

| Pleasure experiences sheet | ||||||||||||

| Negative triad/negative automatic thoughts | ||||||||||||

| Applying resilience | ||||||||||||

| Thinking traps handout | ||||||||||||

| Reality testing | ||||||||||||

| Searching for alternatives | ||||||||||||

| ABC form | ||||||||||||

| Specific cancer topics | ||||||||||||

| Impact of physical illness | ||||||||||||

| Beliefs and expectations about illness | ||||||||||||

| Plans and hopes for care as disease advances | ||||||||||||

| Relationship between emotions and physical symptoms | ||||||||||||

| Concerns about current and future ability to cope | ||||||||||||

| Concerns about loss of control | ||||||||||||

| Concerns about accepting help | ||||||||||||

| Concerns about dying (mode/afterwards/life expectancy) | ||||||||||||

| Impact of disease and mood on behaviour | ||||||||||||

| Impact of disease/death on loved ones | ||||||||||||

| Discussion of ‘the meaning’ of the illness | ||||||||||||

| Acceptance of unfinished business | ||||||||||||

The general procedures and main interventions for successful treatment are as follows:

-

general procedures (eight elements)

-

behavioural techniques (four elements)

-

cognitive techniques (13 elements)

-

cognitive–behavioural techniques (nine elements)

-

specific cancer topics (12 elements).

We also collected information from the therapist about what they thought were the three most important aspects of the therapy and why, whether or not they felt that there was anything missing from therapy and whether or not they had any general comments.

How adherence was assessed

Adherence to the therapist manual was undertaken using two methods:

-

Self-report by therapists – therapists were asked to upload the TCC (see Table 2), which they completed at the end of each therapy session. The therapy components were generated by the trial team (MS, SM, KM and MK) to help identify the main elements thought to be important in this intervention. A checklist was piloted in a previous study,66 and, in the present trial, was adapted for people with cancer.

-

Independent ratings of adherence – the assessor described in point 1 (above) was also asked to complete the TCC so that it could be compared with the therapists’ reports of what their intervention comprised.

Analysis

Cognitive Therapy Scale – Revised

For normally distributed data, we have presented the means and standard deviations (SDs) of the CTS-R. We chose a threshold of ≥ 36 points for competence on the 12-item CTS-R and also indicated the proportion of therapists who fall under this score. A score of 36 points is also the accepted pass mark for the postgraduate diploma in CBT that IAPT trainees take.

We have also presented the means and SDs for CTS-R scores for different phases of therapy (early, sessions 1–4; middle, sessions 5–8; and late, sessions 9–12).

Therapy Components Checklist

-

Elements of the adherence checklist that have been covered are presented as a proportion of the total score for each of the five subsets: (1) general procedures, (2) behavioural techniques, (3) cognitive techniques, (4) cognitive–behavioural techniques and (5) specific cancer topics.

We also provided a description of the various elements covered for all the TCCs submitted by therapists. An independent assessor conducted an objective rating of 1 in 10 therapy sessions to see what elements were delivered and we compared these with the therapists’ self-reports.

For each component of therapy, we calculated agreement between the independent assessor and the therapist’s own assessment of whether or not the component was covered, providing the four possible outcomes: (1) both rate that the component was delivered; (2) both rate that the component was not delivered; (3) the therapist, but not observer, rated the component as being delivered; and (4) the observer, but not therapist, rated the component as being delivered. Using these possible agreement outcomes, we then calculated the prevalence-adjusted and bias-adjusted kappa111 (PABAK) for each component.

Therapist supervision and workload

We recommended that two IAPT therapists would be required from each primary care trust to each treat approximately 4.5 participants per year. We have experience in delivering a training programme for palliative care nurses in CBT skills,112 which improves confidence in managing patients. 113 Relevant sections of this have been adapted to provide CBT therapists with confidence in adapting their skills to people with advanced cancer.

Ensuring safety

This study was not a drug trial and our main concern was centred around risk of self-harm or suicide. UCL researchers and the research nurses screening in oncology centres were given training by Marc Serfaty covering the serious adverse events (SAEs) protocol (see Appendix 1), detailing what action should be taken if patients assessed were considered to be high risk, even though they would be excluded from entry into the study. These appropriate governance procedures and good clinical practice applied to all patients seen, to ensure safety at all times. For those who were detected as being at high risk at follow-up, similar procedures were actioned.

Examples of good practice and the difficulties associated with risk were discussed, including ensuring that there was an opportunity for individual supervision on request with a senior member of the team who was always available. This culture of transparency ensures that researchers are able to always raise concerns about their participants. Time was also taken within supervision to highlight the importance of behaving ethically and safely in all aspects of clinical work.

We considered the possibility that patients being seen by IAPT/well-being therapists may be detected as being at increased risk. However, practitioners are bound by their own governance procedures in their assessment of risk and are very familiar with managing suicidal patients. Because of the number of IAPT/well-being centres collaborating in this study and minor variations in the procedures on how to manage risk, we stipulated that IAPT/well-being therapists adopt their own governance procedures, as this is what would happen if the intervention were to be rolled out across the country, but that they also complete and return a SAE form. The chief investigator, Marc Serfaty, would then contact the IAPT/well-being team within 2 working days to discuss the case and consider whether or not the participant should be withdrawn from the study.

Research staff support

It is recognised that working with patients with cancer and at the end of life could be distressing for field researchers, particularly when it is likely that staff may have had direct personal experience of cancer. Therefore, several systems were put in place to ensure the pastoral care of staff. First, scheduled weekly meetings took place with the chief investigator and the team to discuss particularly distressing cases, and research staff were also offered the opportunity to discuss any cases individually with the chief investigator. Second, there was good cohesiveness among team members for peer support, enabling sharing of difficult situations. Third, there was the opportunity for UCL researchers to meet monthly with Liz Cort, an experienced palliative care nurse, at oncology centre 13. Liz Cort is not only independent from UCL but is also very experienced in issues frequently faced with the often distressing day-to-day lives of people with cancer. An important dimension of this support was to help researchers develop self-reflexivity, exploring and making sense of their own responses to the people and situations that they were assessing. The combination of group and individual supervision meant that researchers felt that their experiences were validated by their shared experiences.

Cancer research nurses are very experienced in conducting research in this client group. Their support was provided in the usual way, through group and individual supervision within different services.

Qualitative methods

Embedded qualitative study

In this report, we have included information about a qualitative substudy exploring clinicians’ views on referring into the CanTalk trial, which we conducted independently. However, as qualitative research was not commissioned by the HTA programme, only a brief summary of the methodology and results has been provided (see relevant sections of this report):

-

an evaluation of clinicians’ experience of referring into the CanTalk trial evaluated through qualitative interviews (described in Clinicians’ views of the CanTalk trial)

-

an evaluation of the patient experience of therapy was evaluated through qualitative interviews (described in Patient interviews to determine experience of cognitive–behavioural therapy)

-

an evaluation of the therapists’ experience of delivering CBT to advanced cancer patients using semistructured interviews (described in Therapists’ views of delivering cognitive–behavioural therapy to people with advanced cancer).

General interview procedures for qualitative data capture

Semistructured, one-to-one interviews using topic guides (presented in Appendices 2–4) ensured that all participants within these three groups were asked the same questions to minimise researcher effects. The topic guide initially consisted of a number of open-ended, non-leading questions. We aimed to cover the six types of questions described by Patton114 for qualitative interviews. These include experience/behaviour questions, opinion/belief questions, feeling questions, knowledge questions, sensory questions and background/demographic questions.

The interview began with introductory questions in order to help establish a good relationship with interviewees to encourage rapport. The topic guide followed a logical sequence with topics being grouped together with corresponding categories. The questions were formulated to avoid influencing the participant. We attached probes to each question to aid rapport building. The topic guide ended with a closing question to encourage participants to discuss topics or issues that were not mentioned previously. Individual interviews were audio recorded and transcribed verbatim. Flexibility allowed the interviewer or interviewee to divert from questions to pursue other areas where necessary. 115

The interviews took place where there were minimum distractions for the participant and for the researcher to aid the dialogue. All interviews were audio recorded for transcription at a later date. We aimed to recruit up to 20 interviewees for each of the three areas of interest from the CanTalk trial to allow a sufficient number to generate themes from the data until no new themes emerged from the interviews.

Clinicians’ views of the CanTalk trial

Any clinician who had been involved in referring patients to the CanTalk trial was considered eligible for inclusion. The study aimed to obtain a good cross-section of participants including consultants, registrars, nurses and radiotherapists. The study also aimed to include the views of 15 clinicians from each of the referring sites.

Clinicians were asked to describe their role in oncology clinics, their previous involvement in research, their views on non-drug trials, the CanTalk trial, any patient feedback and their views about future psychological studies. A detailed topic guide is provided in Appendix 2.

Therapists’ views of delivering cognitive–behavioural therapy to people with advanced cancer

We used a purposive sampling frame and contacted all therapists who delivered CBT as part of the CanTalk trial. We aimed to recruit up to 20 IAPT therapists for one-to-one, face-to-face, semistructured interviews in a quiet setting agreed by both the researcher and therapist.

The therapists were asked to describe their role and how it applied to the CanTalk trial, what they knew about the patient, their views on working with patients with advanced cancer and, with CanTalk patients in particular, any components of CBT that were or were not useful, and any other important views. A detailed topic guide is given in Appendix 3.

Patient interviews to determine experience of cognitive–behavioural therapy

All participants recruited from London sites who had reached the 24-week follow-up who had not died or withdrawn from the study and who had received at least one session of CBT were approached by a member of their clinical team via post and asked for permission to contact them. Those agreeable to being contacted or who had already provided consent to contact were sent an invitation letter offering them the chance to provide feedback about their experiences of CBT.

Interviews took place in the participants’ homes or within the department where the research was taking place. The interview schedule was as follows: participants were asked to describe what therapy they had, what knowledge they had of CBT, what they found helpful or not, their views of the therapist, how CBT had an impact on their life and their views about CBT for low mood in cancer patients. The precise topic guide is provided in Appendix 4.

Qualitative analysis

All interviews were audio recorded and transcribed. Thematic analysis was used to analyse data using NVivo version 11 software (QSR International, Warrington, UK) by two researchers who were ‘immersed’ in the data before proceeding with data analysis, as this can strengthen data analysis. 116

Researchers used a matrix-based analytical method of framework analysis to analyse the data. 117 The method of ‘complete line-by-line coding’ was used to broadly identify any code or theme that emerged without restricting analyses to detecting particular themes. 116 Codes were then grouped into broader themes. For the purposes of triangulation, researchers compared their findings with each other once they had identified broader themes. Any discrepancies were discussed until agreement was reached.

Chapter 4 Outcomes

Acknowledgement

This chapter contains information previously published by Serfaty et al. 95 © 2016 Serfaty et al. Open Access. This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

Assessments

Screening measures

Patient Health Questionnaire-2

The PHQ-2101 consists of the first two questions of the PHQ-9,103 a valid screening measure of depression that has also been used in cancer services.

Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview

The MINI is a short structured diagnostic interview that takes 15 minutes to complete. It was developed jointly by psychiatrists and clinicians in the USA and Europe for DSM-IV and ICD-10 psychiatric disorders47 and has been widely used in cancer patients.

The UCL researchers gave the assessors 1 day’s training on how to use the MINI. We did not have the resources to make assessments of inter-rater reliability.

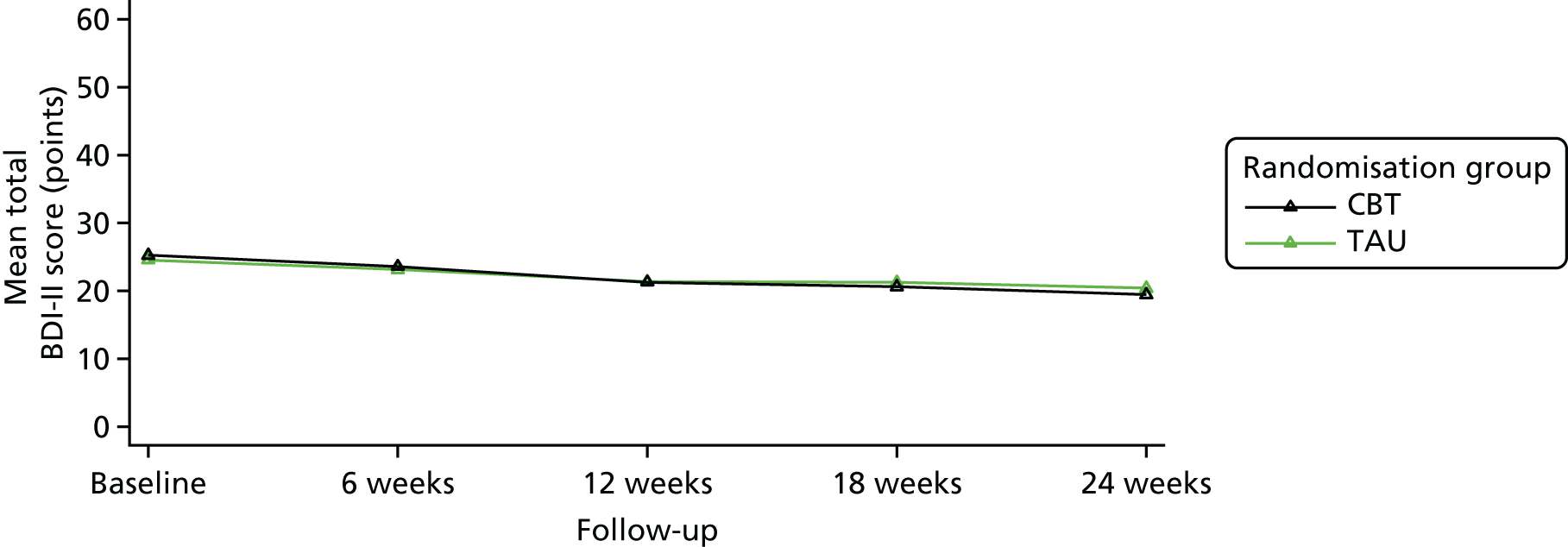

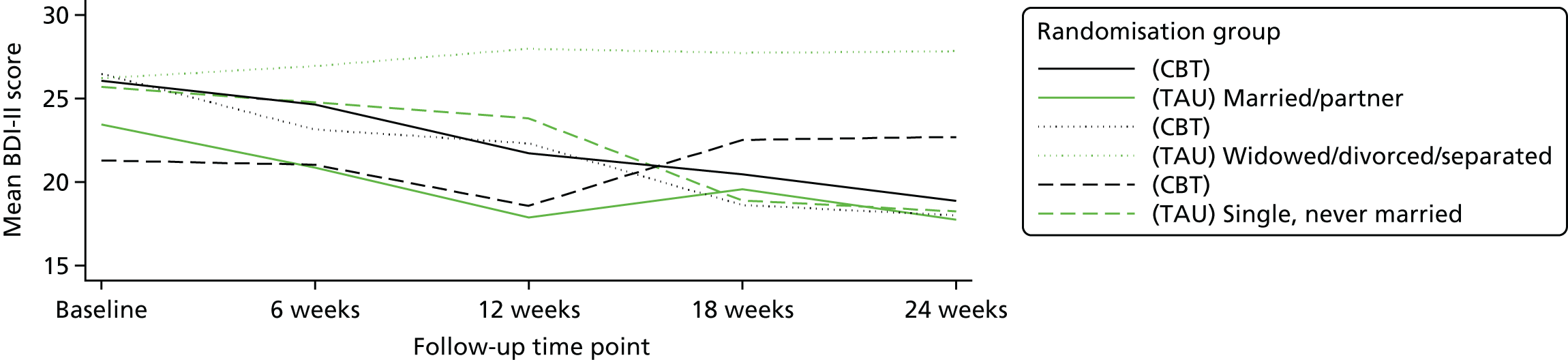

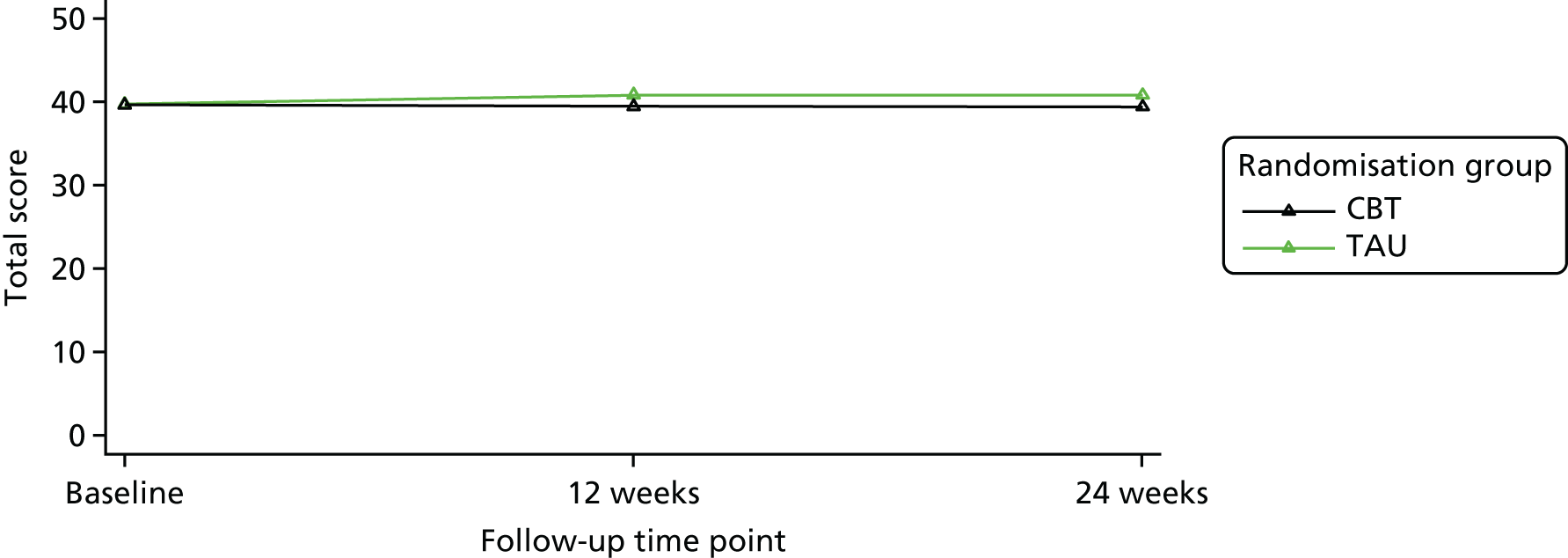

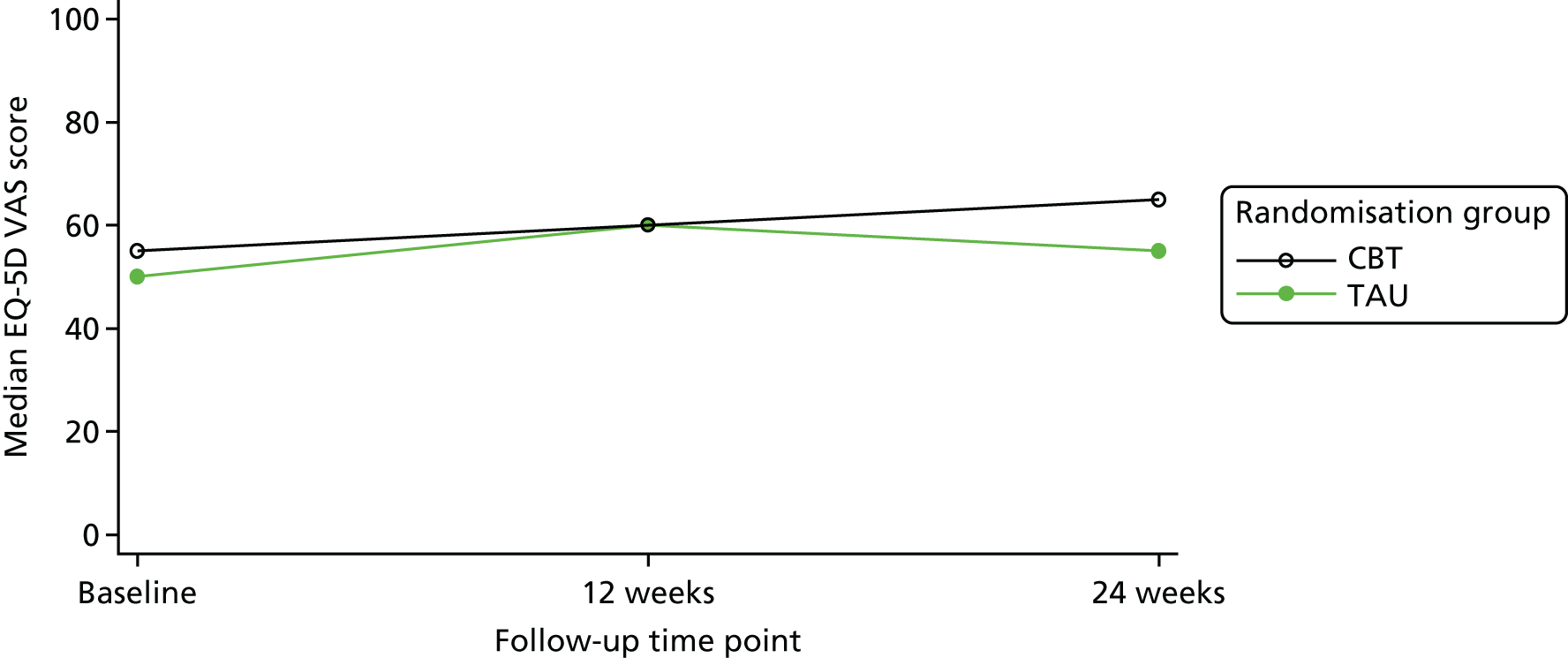

Demographic information