Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 14/157/06. The contractual start date was in January 2016. The draft report began editorial review in May 2017 and was accepted for publication in September 2018. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Roz Shafran is on the Health Technology Assessment Mental, Psychological and Occupational Health Panel and Stuart Logan is on the Open Call Assessment Board – Medicines for Children.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2019. This work was produced by Moore et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2019 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Preface

Watching a child suffer from a long-term health condition is awful. They may be in pain, feel ill or be unable to do the things that other young people do. They may need surgery and lengthy stays in hospital. They need medication, the side effects of which can be a challenge all by themselves. Watching a child have to cope with all this, and then put their fist through their bedroom door in anger, refuse to leave the house for weeks through social isolation or be unable to sleep/eat properly because of anxiety, is heartbreaking.

Children and young people with long-term health conditions – be it cancer, brain injury, muscular dystrophy or any of a myriad of physical conditions that cannot be cured, only managed – face enormous challenges. As well as their physical illness, many of these young people suffer from mental health problems as a consequence of their condition. These include anxiety, depression, anger, social isolation and poor self-esteem. Children and young people with long-term health conditions may be four times more likely to suffer mental health problems than their physically healthy peers.

It is vital that the mental ill health of these young people is treated alongside their physical condition. A range of strategies are currently in use, and this study aims to evaluate how effective different types of intervention are in improving mental health.

The quality, and accessibility, of these strategies vary greatly. Those young people lucky enough to have accessed top-quality mental health provision may overcome their anxieties and worries completely. They may recover to become confident and happy once again. Others may still not be able to attend school, engage socially or live without dark thoughts years after their physical condition began. There is no justification for this disparity. Every single child or young person suffering from a long-term health condition must receive top-quality interventions to improve their mental health – it should not be down to chance as to which technique or provider they are given. Some parents have been able to see their child’s anguished mental state healed. Others, on a daily basis, do not know what they will find when they return home each day.

In looking at the effectiveness of the various strategies, it is hoped that excellent practice can be identified and used to improve all mental health provision for our young people with long-term physical conditions. They deserve nothing less.

Fiona Lockhart

Chapter 1 Background

Description of the health problem

Defining long-term physical conditions

A 2007 systematic review1 of definitions of chronic health conditions in childhood found 25 different definitions of long-term physical conditions (LTCs), with relatively few appearing across multiple publications. For the current project, the team drew from some of the most frequently cited definitions2–4 to define LTCs as any diagnosed physical health condition with an expected duration of at least 3 months for which a cure is considered unlikely and which results in limitations in ordinary activities and necessitates the use of medical care or related services beyond what is usual for someone of the age of the affected individual.

This definition was used to select conditions that were included in searches for the systematic reviews. To fit the definition, physical conditions could not be psychiatric disorders found in Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders – Fifth Edition. 5 Aside from this, the definition was inclusive, with conditions including structural or functional central nervous system disorders [e.g. acquired brain injury (ABI), epilepsy], disability (e.g. cerebral palsy, spina bifida) or those with unclear aetiology [e.g. chronic pain, inflammatory bowel disease (IBD)]. It is acknowledged that LTCs may be referred to as chronic illness/disease/conditions or complex/special health needs and that most often these terms include mental health conditions. In the current review LTC refers to children and young people’s (CYP’s) physical health conditions only.

Defining mental health

The term ‘mental health’ captures far more than the absence of psychiatric disorders6 to include adjustment, well-being and coping. 7 Although we take this view of mental health, for the purposes of this project we needed to define mental health in different ways. When we refer to mental health conditions or psychiatric illness, we use the term ‘mental health disorder’, for instance depression or conduct disorder. As the reviews conducted do not focus only on mental health disorders, we use the term ‘mental ill health’ to refer to elevated symptoms that may or may not relate to a particular mental health disorder, but indicate difficulties experienced by an individual, for example anxiety or stress. Finally, we use the term ‘mental health and well-being’ to refer to mental health in its broad sense as indicated above, to include coping and adjustment. This is necessary when we have been inclusive in terms of how interventions may aim to improve mental health and the wide range of mental health outcomes that such interventions may affect.

Prevalence

Despite advances in medicine leading to improved prognosis and/or cures for many conditions, LTCs continue to be common in CYP. van der Lee et al. 1 considered a range of definitions of chronic conditions, but identified an overall prevalence of around 15% in CYP in the international literature. In the USA, prevalence of LTCs is high and has increased over time; the US National Health Interview Survey (NHIS) has annually collated information about the health of CYP across the nation, and, in 2014, 42% of CYP suffered from one or more LTCs (NHIS data, childhealthdata.org; accessed 9 February 2017), whereas in 1988 this figure stood at 31%. 8 Although the majority of reported data relate to the USA, a high prevalence of LTCs is experienced across the globe. In England, 23% of secondary school age pupils reported that they had a long-term medical illness or disability in 2014,9 with similar proportions of youths reporting a LTC in New Zealand in 200710 as well as in Canada and Finland in 2002. 11 Inconsistency in the methods used to survey the health of CYP exists, for example in the definition of LTCs, the sample inclusion criteria or the reporting method; in spite of uncertainty regarding the prevalence of LTCs according to our definition, there is strong evidence that there is an international burden related to LTCs in CYP. 12

Having a LTC places strain on the individual and their family, as well as placing demands on societal systems such as health care and education. A mental health disorder in addition to the LTC therefore poses a significant problem for some CYP and those around them. The challenges associated with childhood mental disorders alone can be significant and have the potential to exert a more negative impact than certain LTCs. 13

There is extensive evidence that links the presence of a LTC with increased risk of the development of a mental health diagnosis in CYP. Although the overall risk of a mental health disorder is reportedly around four times greater in CYP with LTCs than in their physically healthy counterparts,14,15 this risk varies because of a number of factors. For example, the duration,10,16,17 severity and progression11,18,19 of a LTC are associated with the risk of mental ill health or of mental health disorder.

For a variety of LTCs, there is evidence to support increased risk of mental health disorder, for example asthma,20,21 gastrointestinal disorders,22 functional abdominal pain,23 kidney disease,17,24,25 chronic headache,26 type 1 diabetes mellitus (T1DM)27 and epilepsy. 28 However, for a range of LTCs there is limited evidence of any association with mental health disorders and many studies suffer from poor quality. For example, the literature regarding CYP with cancer is particularly equivocal. There is research showing little difference in depressive symptoms between CYP with cancer and healthy comparators (e.g. Weschler and Sánchez-Iglesias,29 Arabiat et al. ,30 Myers et al. 31), although some aspects, such as the stage of treatment32 or undertaking certain distressing procedures, such as stem cell transplants,33,34 can influence the mental health of cancer patients.

How long-term physical conditions may increase risk of mental ill health

Although the prevalence of mental health disorder in populations with LTCs may be greater than in populations without such physical health concerns, the mechanisms for this are not fully understood. Physical and mental health conditions can share the same pathology,35 or the stress and/or treatment associated with having a LTC can adversely affect mental health. For instance, LTCs and their treatment may involve pain; invasive, complicated or time-consuming treatment regimens; time away from school and peers for hospital visits; restrictions on activity or diet; and a sense of isolation from friends and family. 36

There are several empirical models that attempt to explain why children with a LTC are at risk of mental ill health, including the risk resistance model developed by Wallander and Varni. 37,38 This model was intended to guide interventions to support children to adapt to living with a LTC. It suggests that aspects of disease severity, the impact a LTC has on the child’s functional independence and other psychosocial stressors within the child’s life are a set of risk factors that can increase the risk of a child developing some form of mental, social or physical maladjustment associated with their LTC. The model also proposes a set of personal and family factors that may act as factors protecting against mental ill health. Both risk and protective factors identified by this model are proposed to be applicable across different types of LTC, but their relevance to specific illness groups has not been widely tested.

An alternative theory is Thompson and Gustafson’s39 transactional stress and coping model, which views chronic illness using a systems theory approach and sees a LTC as a stressor requiring adaptation. This model identifies processes that contribute to the adjustment of both children with chronic disorders and their mothers. Adaptation to a LTC is seen to involve psychological, biomedical and developmental processes and, therefore, there are similarities to Wallander and Varni’s model. 38 Thompson’s model has been tested primarily with sickle cell disease and cystic fibrosis. 40

Moos and Holahan’s41 conceptual model for the determinants of health-related outcomes of chronic illness and disability builds on the previous models by integrating the influence of personal and social factors on the course of illness. It demonstrates how different adaptive tasks can influence the development of coping skills and mediate potential health outcomes. The model emphasises the inter-relationship between risk and protective factors and health-related outcomes, resulting in the concept of adjustment to a LTC as a process rather than an end point. Although aimed at adults and thus omitting the important influences of developmental stage and family and social dynamics for CYP, the model notes the importance of building relationships with health-care providers as one of seven ‘adaptive tasks’ for the chronically ill person to complete.

Haase et al. 42 put forward a resilience in illness model, which focuses on adolescents and young adults, identifying risk and protective factors that influence the resilience shown by those experiencing illness-related distress. In common with the above models, the model considers family factors and coping capabilities, which have been the subject of exploratory and confirmatory evaluations among young people with cancer.

Aside from theoretical models of the interaction between physical and mental ill health, aspects of the experience of living with a LTC highlight the stress that CYP face. The initial diagnosis of a LTC is often very distressing for both the child and their family, and is associated with feelings of shock, sadness and confusion. 43 At the time of diagnosis, children and families must take in information regarding the child’s immediate treatment needs, which can feel confusing and frustrating, but also consider the possible impact of the diagnosis on the child’s future. 44

The daily experience of living with a LTC can be physically unpleasant for CYP, and this may have a detrimental effect on their mental health via several mechanisms. Venning et al. 45 conducted a qualitative metasynthesis focusing on the experiences of children diagnosed with a LTC and noted how LTCs made children ‘feel uncomfortable in their body and the world’.

Impact of mental health on physical health and economic consequences

Cottrell46 describes the vicious cycle of comorbid LTCs and mental health diagnosis, in which one condition exacerbates the other. Mental ill health may also be associated with poor treatment adherence, which may exacerbate the physical condition, impair self-management and worsen long-term outcomes. 47,48 For example, depression in children with diabetes mellitus is associated with poorer control of blood sugar, increasing the risk of later serious complications such as loss of vision. 49 It is estimated that between 12% and 18% of all NHS spending on LTCs is linked to poor mental health and well-being50 and that psychological interventions can reduce care costs by up to 20%. 51

Interventions

Numerous highly effective psychological interventions for mental ill health in CYP are available but pay no explicit regard to physical illnesses, with > 750 treatment protocols cited in one systematic review. 52 For instance, the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) recommends the use of group or individual parenting interventions for children with conduct disorder53 and cognitive–behavioural therapy (CBT) for children with depression. 54 It is important to know whether or not such interventions are also effective in children with physical illnesses. However, children with some LTCs are often excluded from trials of such interventions; for example, in a large trial of CBT for children with anxiety disorders, children with a disabling medical condition were excluded. 55

Various characteristics of a LTC may make traditional interventions for mental ill health more challenging and/or less effective, necessitating a modified approach to treatment. Cottrell46 suggests that, although existing evidence-based treatments for mental health diagnoses in CYP should be effective in the presence of LTCs, there are circumstances in which this may not be the case. For example, in CYP with T1DM, the strong link between blood glucose control and mood disorders56 may mean that management of diabetes mellitus should be targeted first. 57 In CYP with epilepsy in whom seizure control is challenging, it is recommended that any treatment for depression is carefully managed by an interdisciplinary team and adapted to the individual’s needs, particularly when pharmacological management is warranted for either condition. 58 Patients with comorbid gastrointestinal disorders and depression may be unsuitable candidates for pharmacological treatments, as these treatments may exacerbate physical symptoms, whereas approaches such as CBT may need to be adapted to focus on maladaptive thinking related to the LTC. 59 The additional costs of treatment for mental ill health can be significant. For example, one study60 suggested that, in the USA, the presence of comorbid depression increases the treatment cost in adolescents with asthma by 51%. This was largely attributable to non-asthma and non-mental health costs related to primary care and laboratory/radiology expenditure.

Treatment guidance

The closer integration of mental and physical health care is a priority for the NHS,61 and the NHS Confederation has highlighted the social, health and economic benefits that arise from the integration of physical and mental health treatments. 62 NICE calls for access to mental health professionals with an understanding of diabetes mellitus to address psychological and social issues in CYP with diabetes mellitus63 and states that the psychological needs of children with epilepsy should be considered as part of routine care. 64 A 2014 Department of Health and Social Care (DHSC) policy paper65 builds on the government’s mental health strategy for mental and physical health to have ‘parity of esteem’. 61 It explicitly states the DHSC’s ambition for mental health care and physical health care to be better integrated at every level and mandates best practice approaches to caring for patients to include potential psychological care needs. 65 However, at present we do not know what ‘best practice’ consists of in relation to the treatment of mental ill health in CYP with LTCs.

In 2015, the DHSC and NHS England released a policy document, Future in Mind,66 which aimed to comprehensively evaluate the current picture of children’s mental health in the UK and outline plans to improve the care provided. Within this document, the prevalence of comorbid mental health diagnosis in CYP with LTCs is highlighted, but the associated treatment difficulties are not discussed and the only recommendations related to this topic are aimed at holistic school-based promotion of mental and physical self-care. NICE has not produced any general guidance for the treatment of CYP with LTCs and comorbid mental health diagnosis, although it exists for the treatment of adults with LTCs and depression. 67 One document specifically considers mental health services referral in diabetes mellitus patients,63 but this is focused more on management of the physical condition. Specifically, NICE guideline NG1863 acknowledges the increased risk of emotional and behavioural difficulties in CYP with T1DM, and promotes awareness of these risks in health-care professionals. The availability of mental ill health screening and referral to mental health professionals with expertise in diabetes mellitus is recommended in the NICE guidelines. 63

This represents a gap in policy development and research activity. In adults with cancer, the collaborative care model implemented by Sharpe et al. 68 led to large improvements in depressive symptoms compared with usual care. The model involved the integration of cancer nurses and psychiatrists into the hospital environment alongside primary care physicians, and, given the improvements shown in treatment of depression in the adult population, primary evidence is needed to assess such an approach with CYP with LTCs.

Evidence for adults cannot simply be applied to CYP. A wide range of factors may influence the clinical effectiveness of interventions for CYP,69 for example the developmental stage of the child; aspects relating to parents; accessibility requirements, such as relying on others to access treatment; attentional requirements, such as keeping children engaged and interested; the need to work around education; and different social aspects of being a child compared with being an adult. It is clear that separate research is required for CYP with LTCs.

Measurement of mental health and other outcomes

A range of different outcome measures can be used to measure the clinical effectiveness of mental health interventions for CYP with LTC. There are several reasons for this. First, the range of mental health disorders that might coexist with LTCs is wide and, likewise, the varied symptoms of mental ill health can be measured using a large number of validated scales. Second, there are no gold standard outcome measures. For example, a Cochrane review70 of CBT for anxiety in CYP that was restricted to studies using validated and reliable diagnostic interviews and symptom rating scales identified four diagnosis tools and more than eight different outcome measures in 41 studies. Third, some more generic measures of mental health and well-being are used to measure clinical effectiveness. Finally, interventions that aim to improve the mental health of CYP might also be predicted to improve markers of physical health, whether as a result of improved mental health or components of the intervention.

Previous systematic reviews

Systematic reviews of mental health interventions rarely separately consider the clinical effectiveness of these interventions in populations with LTCs. A Cochrane systematic review by James et al. 70 included 41 studies to assess the effectiveness of CBT for anxiety in CYP. Despite this relatively large number of studies, none considered a sample or subgroup in which a comorbid LTC was present. Similarly, systematic reviews of non-pharmacological treatments for depression in CYP with traumatic brain injury71 and congenital heart disease72 found no relevant randomised controlled trials (RCTs) in CYP.

There are a number of existing, well-executed systematic reviews in the broader area of psychological interventions for people with LTCs, including several Cochrane reviews. 73–76 However, these reviews are highly targeted, focusing on, for example, one particular physical and/or one particular psychiatric comorbidity, rather than exclusively on CYP or parenting interventions.

The majority of other reviews in this area have concerned either adult populations or specific disorders, and have often focused on the distress arising from having a LTC rather than the treatment of a comorbid mental health disorder. 57,77 Reviews of psychological interventions in CYP with LTC have been undertaken, but many of these have focused on coping, treatment adherence and/or use of health-care resources in populations without elevated mental ill health (e.g. Yorke et al. ,78 Sansom-Daly et al.,79 Thompson et al. 80). There have been some reviews81 of pharmacological interventions for children with mental health diagnoses and physical illness that have considered particular physical illnesses and mental health symptoms (e.g. depression in epilepsy).

The most relevant attempt to systematically review psychological interventions to treat symptoms of mental health disorder in CYP with LTCs was by Bennett et al. 82 This review targeted only psychotherapeutic interventions in which child-related mental health measures were the primary outcome. A total of 10 relevant studies were identified, of which two were RCTs. These RCTs trialled CBT for subthreshold depression in CYP with epilepsy83 or IBD. 84 Although the review provides preliminary evidence that CBT can be a clinically effective treatment for depression and anxiety in CYP with LTCs, the reviewers concluded that the existing evidence base was weak.

The current review fills a gap in the literature by synthesising studies investigating interventions aiming to improve mental health in CYP with LTCs who exhibit elevated symptoms of mental ill health and studies reporting cost and cost-effectiveness evidence. In addition, this review synthesises evidence from qualitative research studies in order to understand how children with LTCs experience interventions aimed at improving their mental health and well-being and their attitudes towards them.

Aim and research questions

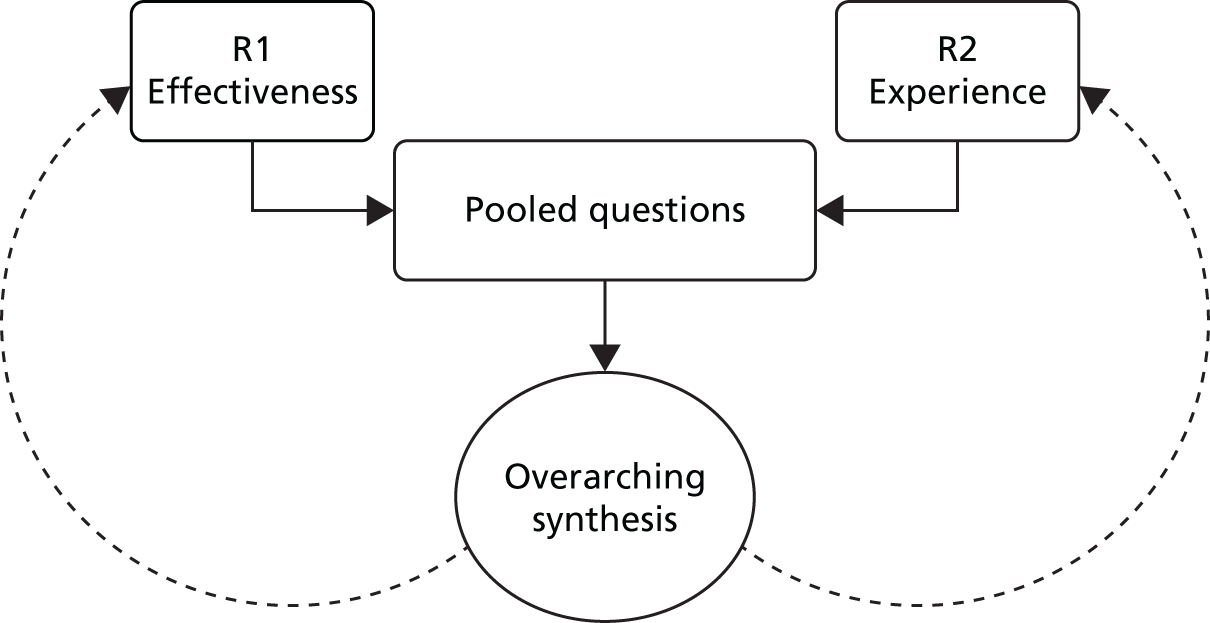

We aimed to evaluate the effectiveness of interventions aimed at improving the mental health of children and young people with LTCs and to explore the factors that may enhance or limit the delivery of such interventions. This necessitated reviewing both quantitative and qualitative research. The systematic reviews addressed the following research questions:

-

What are the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of interventions targeting mental health for CYP with LTCs and symptoms of mental ill health?

-

What are the effects of such interventions on other key aspects of individual and family functioning?

-

What are the factors that may enhance, or hinder, the clinical effectiveness of interventions and/or the successful implementation of interventions intended to improve mental health for CYP with LTCs?

Chapter 2 Review 1: clinical effectiveness of interventions aiming to improve mental health in children and young people with long-term physical conditions

Research questions

This chapter describes the first systematic review and addresses the following research questions:

-

What are the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of interventions aiming to improve mental health for CYP with LTCs and symptoms of mental ill health?

-

What are the effects of such interventions on other key aspects of individual and family functioning?

Methods

The methods used to identify and select evidence followed recommended best practice. 85,86 A protocol for the systematic reviews across the project was registered on the PROSPERO database (PROSPERO CRD42011001716).

Identification of evidence

Inclusion/exclusion criteria

The following inclusion and exclusion criteria were used to determine eligibility of articles. The inclusion criteria specified RCTs or economic evaluations involving CYP aged 0–25 years with LTCs and symptoms of mental ill health. Participants needed to have received any type of intervention that targeted their mental health. Clinical effectiveness had to be measured in terms of impact on at least one measure of the young person’s mental health. Additional details of inclusion and exclusion criteria are shown in Report Supplementary Material 1, Table 1.

Search strategy

A search strategy was developed and tested in the databases to be searched. The strategy used both controlled headings [e.g. medical subject heading (MeSH)] and free-text searching. Terms were grouped according to four concepts:

-

children and young people terms

-

mental health terms

-

long-term physical conditions terms

-

study design terms (using a Cochrane filter for locating RCT87).

The LTC terms were informed by previous reviews that included studies with populations with LTCs or chronic conditions,79,82,88–105 as well as discussion with experts among the wider project team. Thirteen electronic databases were searched: MEDLINE including MEDLINE in-process (via OvidSP), EMBASE (via OvidSP), PsycINFO (via OvidSP), Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (CDSR) (via The Cochrane Library), Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) (via The Cochrane Library), Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects (DARE) (via The Cochrane Library), Health Technology Assessment (HTA) database (via The Cochrane Library), NHS Economic Evaluation Database (NHS EED) (via The Cochrane Library), Cumulative Index of Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL) (via EBSCOhost), British Nursing Index (via ProQuest), Health Management Information Consortium (HMIC) (via OvidSP), Conference Proceedings Citation Index (via Web of Science) and Science Citation Index (via Web of Science). No language or date restrictions were applied. Searches were conducted between 28 January and 4 February 2016. An example search strategy used for the MEDLINE database is shown in Appendix 1. All references identified by the searches were exported into EndNote X7 (Thomson Reuters, New York, NY, USA) prior to deduplication and screening.

A second search strategy was designed to locate studies relating to cost-effectiveness using the University of York’s Centre for Reviews and Dissemination (CRD) search strategy for economic evaluations in place of the RCTs filter. 106 The economic evaluation filter for this search was applied to MEDLINE and EMBASE from April 2015 only as the NHS EED was updated using these databases up until 31 March 2015. Searches for economic evaluations were carried out on 3 May 2016. The search strategy used for EMBASE to locate economic evaluations is shown in Appendix 2.

Supplementary searches were also conducted. Backward citation-chasing (searching the references of included articles) was conducted by three researchers (DM, MN and LS) to locate further potentially relevant articles. Alongside backward citation-chasing, these researchers checked lists of included studies from related reviews. Forward citation-chasing (searching articles citing included articles) was conducted by an information specialist (JTB) using Web of Science and Google Scholar (Google Inc., Mountain View, CA, USA). In addition, three researchers (DM, LS and MN) searched websites that had been identified by the project team and the children and young people advisory group (CYPAG) for relevant research (see Appendix 3 for a list of websites searched). Targeted searches to identify ‘sibling’ papers (further outcomes, process evaluations, economic studies and qualitative research) associated with included trials and based on trial names and first and last authors were conducted by Juan Talens-Bou. Michael Nunns e-mailed all contact authors of included studies to request any articles associated with included articles. The databases CINAHL, HMIC and Conference Proceedings Citation Index were searched, all of which index grey literature. The website OpenGrey was also searched via www.opengrey.eu/ on 23 June 2016.

Study selection

Relevant studies were identified in two stages based on the inclusion/exclusion criteria given above. First, independent double screening of titles and abstracts for each record was conducted (seven researchers shared this screening: MN, LS, DM, JTC, MR, VB and IR). Endnote X7 was used to perform this screening. Disagreements were resolved through discussion between two reviewers, with referral to a third reviewer as necessary (DM, MN and LS). Full texts of records that appeared to meet the inclusion criteria on the basis of titles and abstracts were then obtained whenever possible via the University of Exeter online library, web searching and the British Library. Each full-text article was screened independently by two reviewers (six researchers shared this screening: MN, LS, DM, JTC, VB and IR). Reasons for exclusion at this stage were recorded. Disagreements were again resolved as for title and abstract screening. To assess population eligibility at full-text screening, reviewers often needed to locate information regarding cut-off scores for validated measures of mental health outcomes. These were rarely reported in screened records and, therefore, reviewers searched for publications including cut-off scores for these measures or manuals for the scale in question. Whenever possible a threshold indicating symptoms of clinical distress in a previous CYP sample was used. These thresholds were collated so that reviewers applied them consistently. Screening for the additional economic search proceeded in the same manner.

Methods of analysis/synthesis

Data extraction

A data extraction form was developed and piloted. Three researchers (MN, LS and DM) each extracted one article and checked one colleague’s extraction before discussing and amending the form. Data on article details and aims, participants, mental health measures at baseline, intervention, outcome measures, findings and study quality were extracted into Microsoft Office Excel® 2010 (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA) by three researchers (MN, DM and LS) and checked (by either DM or MN). When data were missing that would have allowed for meta-analysis, authors were contacted for information alongside our request for sibling papers.

Quality appraisal

Quality appraisal was conducted simultaneously with data extraction using criteria adapted from the Cochrane risk-of-bias tool. 86 In addition to criteria on randomisation, allocation concealment, blinding of assessors and selective outcome reporting from the existing tool, we included items on intention-to-treat analysis, between-group similarities at baseline, dropouts, response rates, intervention details and manuals, adherence, follow-up measures and psychometric properties of outcome measures (see Richardson et al. 107). This gave 15 items on which risk of bias and quality of included articles were assessed, providing additional insight into study quality and reporting. Assessment of quality and risk of bias was performed at the article level to evaluate any differences on account of the different outcomes reported in articles from the same study. Quality appraisal decisions were made by two reviewers (from DM, MN and LS) and disagreements resolved through discussion. The appraisals were used to evaluate risk of bias and study quality and were not used to exclude papers.

Categorisation of interventions and outcomes

During data extraction, interventions were categorised according to similarities in terms of broad intervention type and intervention content. The label and definition of these intervention categories were developed using the descriptions of interventions in the included studies and with reference to previous general classifications of interventions. The categories were developed by Darren Moore and Michael Nunns and discussed with the wider team. The categorisation was primarily used to organise the presentation of the synthesis by intervention type, with sections synthesising the findings from studies relating to each intervention category.

Owing to the diversity of outcomes used to measure the clinical effectiveness of interventions in the included studies, outcome categories were determined in response to the constructs measured by the instruments used. These categories and, therefore, each measure were also categorised at a broad level as either a ‘CYP mental health outcome’ or ‘other outcome’, given that the focus of the review is on interventions that aim to improve CYP mental health. Outcomes were categorised as CYP mental health when they appeared to meet our broad definitions of mental health and well-being given in Chapter 1. Other outcomes were extracted and analysed in order to include all clinical effectiveness outcomes and, therefore, address our second research question (what are the effects of such interventions on other key aspects of individual and family functioning?). These categories and the measures used within included studies are shown in the tables in Analysis of included study findings. These outcome categories were refined after data extraction by Michael Nunns and then reduced by Darren Moore before they were shared with experts among the wider team. These outcome categories were primarily used to determine when results for outcomes measuring similar constructs could be meta-analysed and as a way to compare similar outcomes for each intervention category, without necessitating knowledge of individual measures.

Data analysis and synthesis

The principal summary measure used to compare clinical effectiveness findings in included studies was differences in mean between intervention and control group post test and, when available, at the longest follow-up time point. For each outcome, mean, standard deviation (SD) and sample size (or figures that could be used to derive these when available) for the relevant intervention and control groups were used to assess differences between groups. When we did not receive necessary data for outcomes from either articles or correspondence with authors, we did not synthesise these outcomes. When such figures were not available for any CYP mental health outcomes in a study, we synthesised findings narratively. Effect sizes for each study were calculated post intervention using Cohen’s d, that is, the difference between the means in the two groups divided by their pooled SD. 108 Ninety-five per cent confidence intervals (CIs) for the effect sizes were also calculated, along with p-values. Effect sizes and CIs were calculated using the ‘metan’ command in Stata® v13 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA). The p-values for each effect size were calculated using the ‘ttesti’ command in Stata. Cohen’s guidelines were used to aid interpretation of effect sizes. 108 Thresholds above which effect sizes are considered to be ‘small’, ‘medium’ and ‘large’ are d = 0.20, d = 0.50 and d = 0.80, respectively. Although these classifications are widely used, it is acknowledged that these guidelines do not take account of how the clinical or practical importance of effects might vary between outcome measures. 109

Meta-analysis was considered feasible if multiple studies examined the same intervention type and used the same outcome category and a similar comparator and participant LTC. Random-effects meta-analysis models were fitted to pool effect sizes across the studies, based on the assumption that no two studies were addressing the same research questions in exactly the same way. We calculated 95% CIs for each pooled effect size estimate. The I2 statistic (possible range 0–100%) was used to quantify statistical heterogeneity, with higher values indicating greater heterogeneity. 110 When two or more measures assessing the same outcome category were reported in a study, the effects were combined into a single summary effect for that study, calculating the standard error for this effect using the correlation between the measures obtained from the paper itself or other research. 111 When different studies used identical measures, we conducted additional meta-analysis using raw mean differences. All meta-analyses and associated forest plots were produced using the ‘metan’ command in Stata.

We intended to assess publication bias by examining funnel plots for asymmetry using the ‘metafunnel’ command in Stata. However, we were unable to assess funnel plots properly or use more advanced regression-based assessments to assess publication bias owing to the substantial heterogeneity identified across studies and the small number of studies with similar characteristics that could be entered into a given meta-analysis. 112 Therefore, we cannot comment on publication bias in this review.

Results

Tables and figures described below are available in Report Supplementary Material 1.

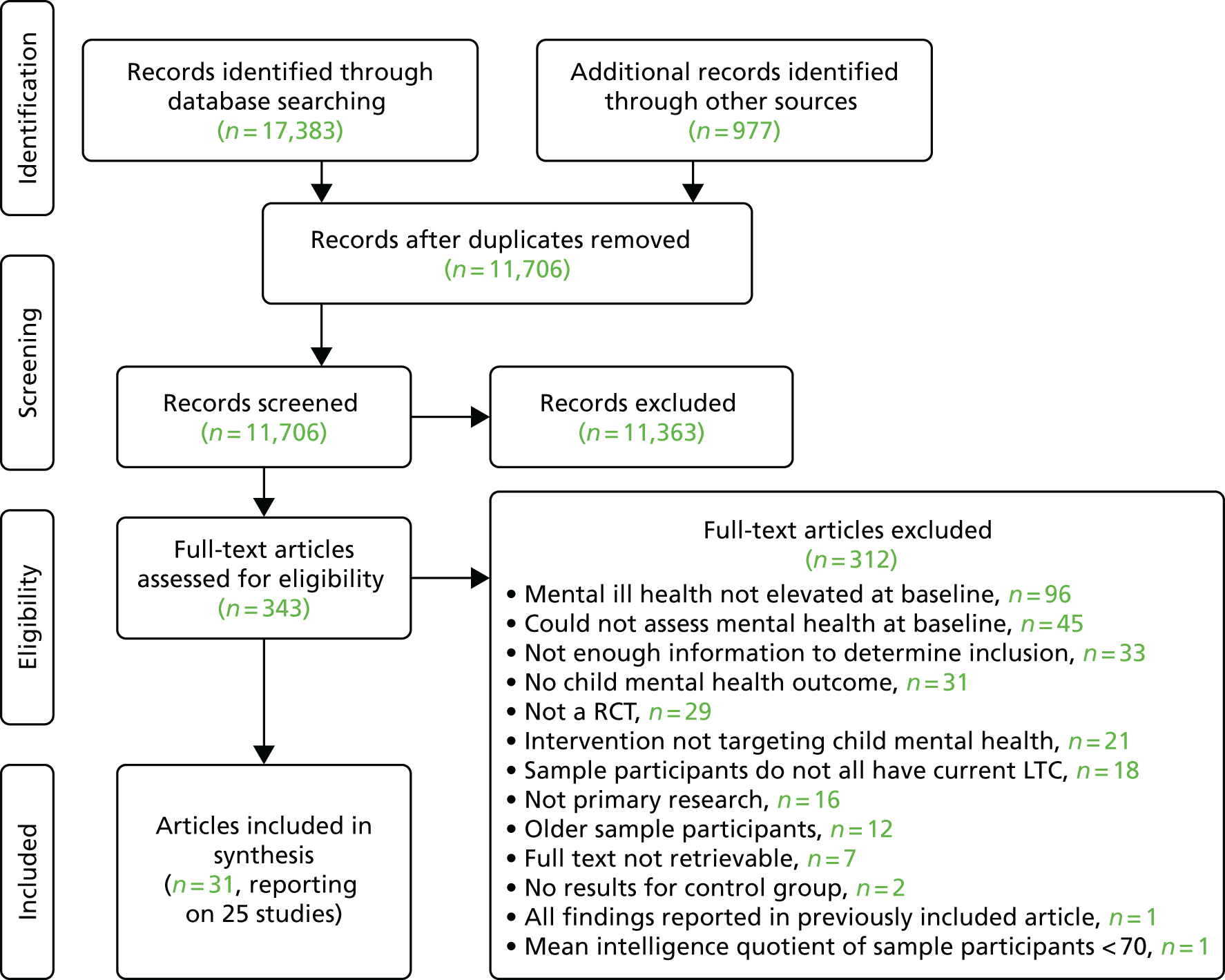

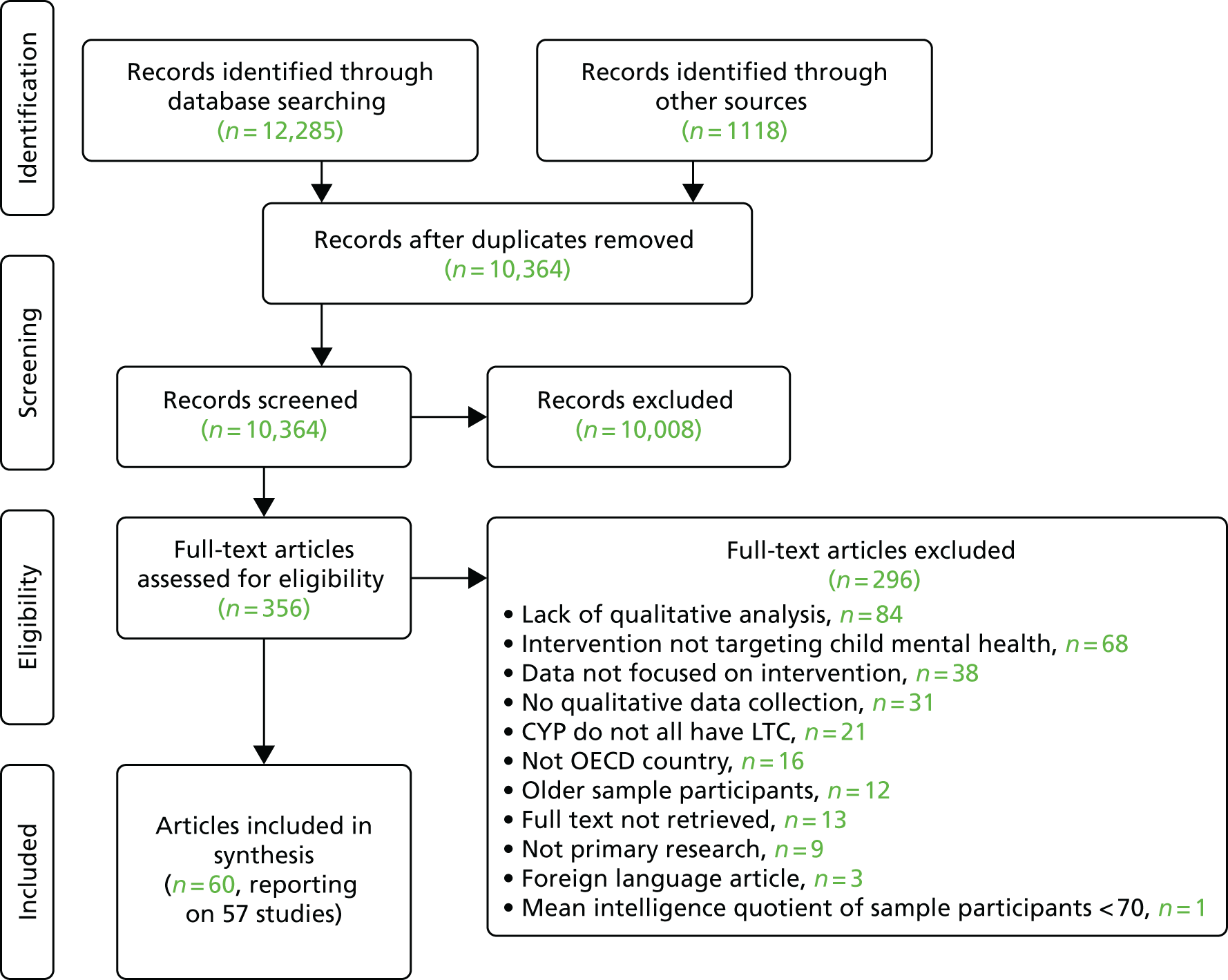

Study selection

The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) flow diagram113 in Figure 1 summarises the process of study selection. Approximately 5% of the 18,360 records were identified by methods other than searches of academic databases, including citation-chasing searches, searching relevant reviews and websites, searches for sibling papers and author contact. After the removal of duplicates, a total of 11,706 records were screened at title and abstract stage. We attempted to retrieve the full text of 343 records for further consideration, and were successful in 336 cases (98%). After full-text screening, 312 articles were excluded for reasons provided in Figure 1. The majority of articles were excluded because CYP mental health measures did not indicate that the sample was above an established cut-off at baseline, no recognised cut-off was available for the measures used or there was not enough information to determine inclusion because only an abstract had been published. A number of articles were excluded because they did not meet inclusion criteria for one of intervention target, population or study design. Only one paper was excluded on account of the sample having moderate intellectual disabilities. A list of reasons for the exclusion of each article screened at full-text screening is given in Report Supplementary Material 1, Table 2.

FIGURE 1.

The PRISMA flow chart recording review 1’s study selection.

Thirty-one articles met our inclusion criteria and were included in the synthesis. Six of the articles were additional papers relating to studies already reported in included papers. These papers were included if they provided any additional relevant data not seen in other study articles. Eight of the 31 included articles were located through additional searching (forward citation-chasing, backward citation-chasing, author contact, included in previous reviews). We e-mailed 22 authors from the 25 included studies to ask for details of any other articles associated with the studies. Ten authors responded. Ten e-mails to authors included specific data queries. Six authors replied to the data queries, allowing additional effect sizes to be calculated. None of the 31 articles that met the full-text screening criteria reported economic outcomes such as costs or cost-effectiveness.

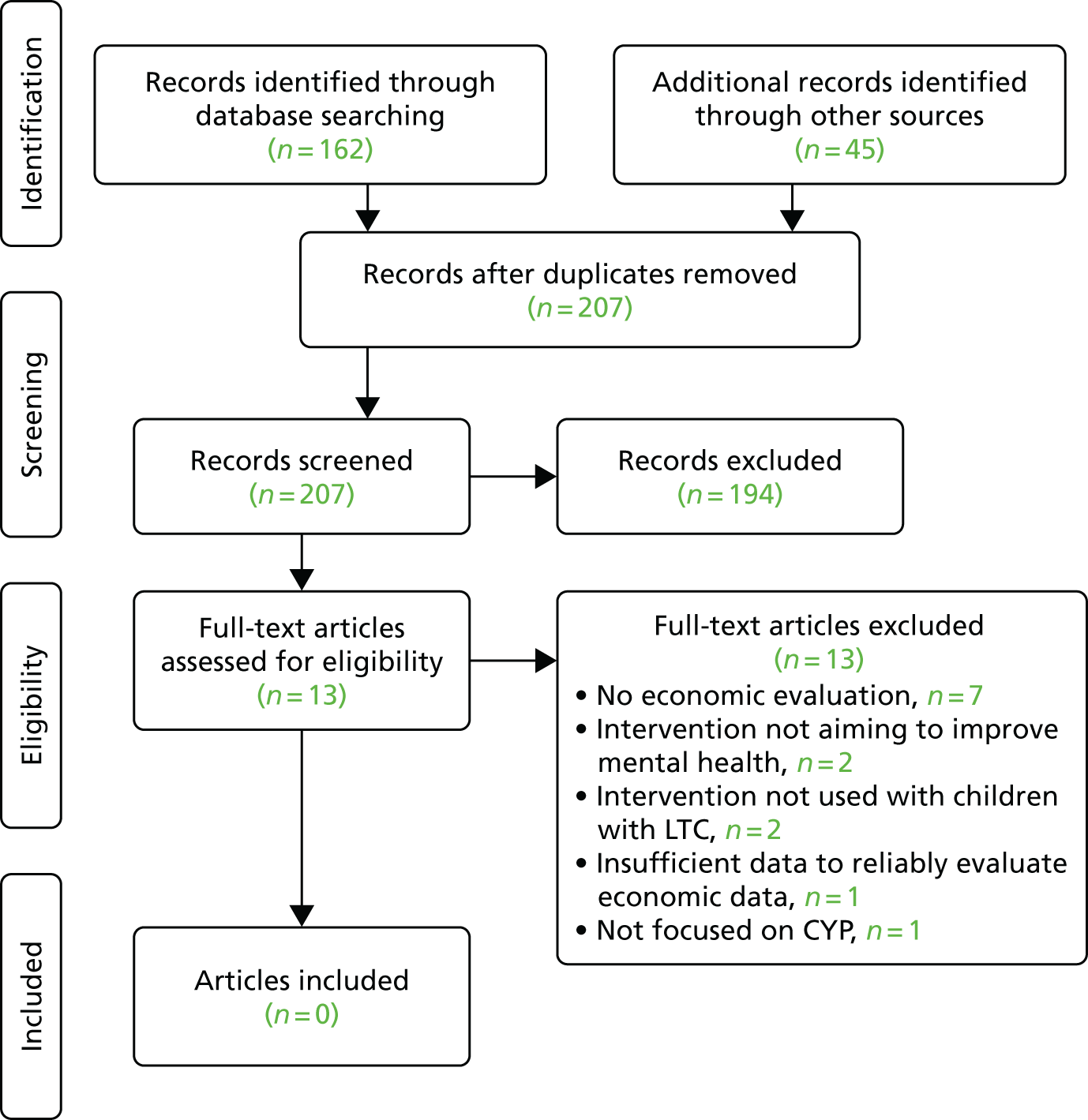

Economic evaluation

The PRISMA flow diagram in Figure 2 summarises the study selection after the second database search for economic evaluations and targeted search for sibling studies of the 31 articles included in the review. The majority (78%) of the 207 records were identified from the search of databases. Thirteen records were considered relevant after title and abstract screening. Both reviewers agreed that none of the 13 articles met the inclusion criteria for this part of the review. Two studies identified among the screened articles are worthy of note. Whittemore et al. 114 provided a single-cost estimate of providing a 5-week Teencope intervention that met the intervention inclusion criteria (see Report Supplementary Material 2, Table 5), but provided no breakdown of this cost or description of how it was calculated. In another study,115 figures on the use of ‘integrated psychological therapies’ to increase treatment adherence (the Shine intervention; see Report Supplementary Material 2, Table 5) allowed us to estimate the cost of providing the intervention/therapy to 12 patients as £4260. However, some costs (such as hospital staff training and costs of staff from the social enterprise) appear to have been excluded, and there were insufficient data presented for the stated net cost savings to be seen as reliable.

FIGURE 2.

The PRISMA flow chart recording review 1’s economic evaluation study selection.

It was noted that two of the screened economic studies assessed the cost of the Positive Parenting Programme (Triple P) parenting intervention (i.e. Foster et al. 116 in the USA and Mihalopoulos et al. 117 in Australia), which was also evaluated in one of the effectiveness studies included in review 1 (i.e. Westrupp et al. 118). However, some features of the intervention used in these two studies differed from that used in the study by Westrupp et al. 118 (which would have made the costs different). In addition, both the study by Foster et al. 116 and that by Mihalopoulos et al. 117 targeted all families with at least one child below a particular age, rather than specifically families with children with LTCs. For these reasons, their findings would not be comparable to the findings of Westrupp et al. 118 or the results of similar parenting interventions targeting only families with children with LTCs. Therefore, this study was also excluded.

Descriptive statistics

Report Supplementary Material 1, Table 3, provides details about the study location, participants’ LTC, intervention type, comparator, qualifying baseline mental health status and other reported CYP mental health outcomes for the 25 studies included in this review. Studies were conducted in eight different countries, with the USA (n = 10)84,119–127 most common, followed by Australia (n = 5)118,128–131 and Iran (n = 4). 132–135 Studies included children and/or young people with 12 different LTCs, with cancers (n = 5)123,133,135–137 receiving the most attention. T1DM (n = 4),118,120,122,130 asthma (n = 3),119,138,139 IBD (n = 3)84,125,126 and hearing loss (n = 2)132,134 were also the subject of multiple studies, with all other LTCs featuring in one study each. Only one article was published before 2000,120 with 13 articles (52%) being published since 2010. 118,119,123–128,130–134,137,138

Five included studies were reported in more than one included journal article reporting on different study details or findings. Brown et al. 140 reported additional parent and family function outcomes from their 2014 trial. 128 We excluded one article associated with this study as it did not provide any effectiveness outcomes that were not seen in the previous articles. 128 Lyon et al. 123 included detailed information about the content of their intervention in 2013, with outcome data reported in the 2014 article. 123 The earliest Szigethy et al. 84 trial was linked with two additional papers. These reported on correlates of treatment with individual items on the Child Depression Inventory (CDI)141 and long-term follow-up data for the original trial. 142 For Szigethy et al. ’s143 later trial, the article reported secondary outcomes from a subset (those with Crohn’s disease) of the 2014 sample, which included both Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis patients. 126 Finally, the two papers from Whittingham et al. 131,144 reported different outcomes from their trial of a parenting and acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT) for children with cerebral palsy. The 2014 paper131 focused directly on child behaviour outcomes and parenting skills, whereas the 2015 paper144 reported child quality of life (QoL) related to physical functioning, and further parenting and parent mental health outcomes.

A range of interventions was evaluated, with those categorised as CBT the most frequent (n = 7). 83,84,124–126,130,145 After CBT, interventions categorised as parenting programmes133,142,145–147 and group play therapy148–150 were most commonly evaluated. Emotional intelligence training,132,134 stress management programmes120,122 and palliative care123,137 also featured in two studies each. Most often, the comparator involved ‘usual care’ (e.g. regular schooling, usual sedation, usual hospital care) within a given setting (n = 20),83,84,118,120,122–124,127,128,130–139,145 with five of these studies employing a waiting list control group. 122,124,127,131,137 Active comparators in the remaining five studies included asthma education,119 progressive muscle relaxation,121 aerobic exercise129 and non-directive supportive therapy. 125,126

Two studies contained in their inclusion criteria a mental health diagnosis (principal anxiety disorder in Masia-Warner et al. ,124 mild or major depression in Szigethy et al. 126). All other studies included samples from which reviewers found that symptoms of mental ill health were above an established threshold or included a sample at risk of a mental health disorder. 83 At baseline, elevated symptoms of anxiety119,121–125,127,136,137,139 and depression83,84,121,126,129,133,135,137,139,145 were most common, each present in 10 studies. The participants in seven studies showed elevated symptoms in more than one mental health domain. 84,121,124,132,134,137,139 Additional CYP mental health outcomes were reported in 15 studies,84,120,122,123,126–128,130–133,137,138,140,144,145 crossing a wide range of categories including anxiety and depression, coping measures, emotional difficulties, adjustment and general mental health.

Sample characteristics

The studies included a total of 1198 participants, of whom 48.1% were female, with a mean age of 12.2 years (when data were available: gender not reported by Gordon et al. 129 and mean age not reported by Hains et al. 122 and Zareapour et al. 135). The ethnicity of the sample was predominantly (> 66%) white in seven studies84,120,122,124–126,128 and predominantly black or African American in two studies. 119,121 Lyon et al. 123 and Yetwin127 recruited samples from a more diverse mix of ethnicities, but ethnicity was not reported in 12 studies. Report Supplementary Material 1, Table 4, provides details about the sample size, gender, age, ethnicity and inclusion criteria for each study.

Eleven studies provided some information about the socioeconomic status of participants. 84,118,120,121,123–126,128,131,137 The method of classifying socioeconomic status was inconsistent, with family income,84,124–126,128,131 federal poverty level,123 parental education,84,123,128,131 parental employment status,128 social class,137 a socioeconomic index118 and the Hollingshead Index120,121 all reported, preventing comparison across the included studies.

Thirteen studies recruited subjects from hospitals. 84,118,120–123,126,130,133,135–137,145 Referrals by specialists or general practitioners, with or without additional advertising in clinics or waiting rooms (flyers, online posts, etc.), was the second most common method of recruitment, used in six studies. 83,124,125,127–129 Three further studies recruited from schools119,132,134 and two by consulting patient databases. 131,139 In total, 111 (9.2%) participants dropped out from studies after the intervention delivery had commenced, which appears low. 151

Typically, inclusion criteria in included studies required diagnosis of the relevant LTC, lack of intellectual disability that would prevent understanding of interventions or assessments and willingness/availability to participate. Five studies had specific requirements of elevated mental health symptoms for inclusion. 83,84,124,126,128 Martinović et al. 83 required ‘subthreshold’ depression scores (just below a validated cut-off point on three scales) whereas Szigethy et al. 84 required a minimum score of 9 on the CDI. In the 2014 study by Szigethy et al. ,126 diagnosis of minor or major depression was required and confirmed using the Kiddie-Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia-Present and Lifetime Version (K-SADS-PL) diagnostic interview. Brown et al. 128 included parents who subjectively considered their child to have behavioural problems. Masia-Warner et al. 124 recruited participants with a previously diagnosed principal anxiety disorder. However, 13 studies excluded participants with certain mental health diagnoses or issues. 83,84,118,123–127,130,132,135,138,139 Therefore, some studies excluded particular mental health diagnoses, even when other diagnoses or elevated symptoms were required.

Intervention characteristics

Report Supplementary Material 1, Table 5, provides details about the interventions reported in the included studies. The intervention aims and structure, as well as details of the delivery site and personnel, the intended recipients and the comparator group, are shown. Eleven intervention categories were used to group together similar interventions. The label and definition of these intervention categories are shown, along with the studies evaluating them, in Appendix 4. Interventions based on CBT were the most frequently studied (n = 7),83,84,124–126,130,145 with 267 participants randomised to this type of intervention. The two studies reported by Szigethy et al. 84,126 explored the effects of the CBT programme PASCET-PI (Primary and Secondary Control Enhancement Therapy-Physical Illness) on various outcomes in children with IBD84 or Crohn’s disease. 143 Masia-Warner et al. 124 and Reigada et al. 125 used versions of TAPS (treatment of anxiety and physical symptoms), the latter authors modifying the intervention to include management of specific symptoms of IBD. Adapted intervention content was seen in eight studies. 84,119,120,124–126,130,145 All but two of these were trials of CBT, with Bignall et al. ’s119 relaxation intervention and Boardway et al. ’s120 stress management training also including adapted content. For each study, Appendix 5 describes the content of each intervention, and whether it was adapted or delivered flexibly. Only Szigethy et al. 126 specifically allowed flexibility in delivery, allowing for individual changes to content based on the developmental stage of the recipient.

The parenting programmes Triple P118 and its modified subsidiary for families in which a child has a disability and behavioural problems, Stepping Stones Triple P (SSTP),128,131 were assessed in three studies, with 93 parents randomised to these intervention conditions. The study by Whittingham et al. 131 was the only one to include more than one intervention condition, as both SSTP with and without additional ACT featured. Group play therapy featured in three studies,133,135,138 with 44 participants randomised to these treatment arms. Palliative care (n = 49),123,137 emotional intelligence training (n = 40)132,134 and stress management programmes (n = 16)120,122 featured in two studies each.

Progressive muscle relaxation (PMR) techniques featured in three studies. 119,133,139 However, they formed part of only two intervention arms, with 47 participants receiving such interventions. Specifically, Bignall et al. 119 trialled an intervention containing breathing retraining with PMR, asthma education and guided imagery, whereas Yang et al. 139 used 30 minutes of audio-recorded guided muscle relaxation nightly before going to sleep. PMR was also an active comparator in the intervention trialled by Diego et al. ,121 in which the intervention was massage therapy. Sometimes the intervention label used in the study indicated that more than one intervention category might be relevant, for instance Hains et al. ’s122 cognitive restructuring and problem solving and Nekah et al. ’s133 structured cognitive–behavioural group play therapy both suggest CBT. The descriptions of interventions provided in articles were used to assess which category was most suitable.

The most common comparator involved treatment as usual (TAU) or usual care (e.g. regular schooling, usual sedation, usual hospital care) within a given setting (n = 20),83,84,118,120,122–124,127,128,130–139,145 with five of these studies employing a waiting list design. 122,124,127,131,137 In total, 393 participants were randomised to standard or usual care control groups. Active comparators in the remaining six studies (n = 157 participants) included asthma education,119 PMR,121 aerobic exercise129 and non-directive supportive therapy. 125,126 Standard care/TAU was often described only roughly and varied considerably between studies, to the extent that determining common components was not possible. During the waiting period of studies with waiting list designs, all participants received usual care.

Interventions were received by parents alone in three studies,118,128,131 by parents and children together in five studies84,123,125,126,145 and by CYP alone in the remainder. When both parents and CYP received the intervention, the goal was usually to give parents skills to help them encourage positive behaviours at home and develop skills to maintain positive effects beyond the intervention end. This occurred as a component of CBT interventions, with the exception of Lyon et al. ’s123 palliative care intervention, in which the aim was to include the family in decision-making. The delivery of interventions occurred across a variety of settings and through a range of personnel. Twelve studies delivered at least part of their intervention in a hospital setting. 84,118,120,122,123,126,128–130,133,136,145 Five interventions took place in other medical centres or university outpatient departments,83,124,125,127,135 three were delivered in school settings119,132,134 and one at home. 139 In Shoshani et al. ’s137 study, which assessed the Make-A-Wish (Make-A-Wish Foundation® UK, Reading, UK) intervention, children’s wishes were ascertained in their own home, but the nature of their delivery was not reported. Seven studies included some component that required delivery, receipt or practice of the intervention at home. 84,119,123,126–128,131

Interventions were delivered by researchers, clinicians, therapists, psychologists, postgraduate students and teachers. Specific training in the delivery of the intervention was reported in 12 studies. 84,123,125–128,131,132,136,137,139,145 Intervention manuals were referred to in only nine studies. 84,118,123,125–128,130,131

Quality appraisal and risk of bias

Table 1 provides a summary of the quality and risk-of-bias appraisal of included articles. Risk of bias was performed at the article, rather than study, level, as data collection and/or outcomes differed across articles and, therefore, risk of bias may vary where there were several publications reporting on a single study. Eight of the 15 criteria allowed a rating of ‘Yes’, ‘No’ or ‘unclear’. An additional ‘not applicable’ option was available for four criteria (whether or not intention-to-treat analysis was performed, the longest follow-up was at ≥ 6 months, dropouts were described and missing data were explained). For comparative purposes, a response rate at the longest follow-up of ≥ 85% was considered high, 70–84% as moderate and < 70% was considered a poor response rate. For the assessment of outcome measures, only when all outcomes had good psychometric properties was the score deemed positive.

| Study author and year of publication | Adequate method of randomisation? | Allocation concealed? | Intention-to-treat analysis performed? | Blinding of outcome assessor in at least one measure? | Group outcomes similar at baseline, or imbalances accounted for? | Response rate at longest follow-up (%) | Intervention well described? | Adherence, compliance or fidelity measured? | Included follow-up beyond post treatment? | Longest follow-up ≥ 6 months? | Were any dropouts and attrition described? | Proportion of outcome measures with good psychometric properties? | Was missing data explained? | Is the study free of suggestion of selective outcome reporting? | Was there a treatment manual for the intervention? |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ashori et al.,132 2013 | ? | ? | n/a | N | Y | ≥ 85 | N | N | N | n/a | n/a | 1/1 | n/a | Y | N |

| Bignall et al.,119 2015 | Y | ? | N | N | N | ≥ 85 | Y | N | N | n/a | Y | 4/4 | n/a | Y | N |

| Boardway et al.,120 1993 | ? | ? | N | ? | Y | ≥ 85 | Y | N | Y | N | N | 11/12 | N | Y | N |

| Brown et al.,128 2014 | Y | Y | Y | N | N | < 70 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | 3/3 | Y | Y | Y |

| Brown et al.,140 2015 | Y | Y | Y | N | N | < 70 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | 7/7 | Y | Y | Y |

| Bufalini136 2009 | ? | ? | n/a | N | N | ≥ 85 | N | N | N | n/a | n/a | 3/4 | n/a | Y | N |

| Diego et al.,121 2001 | ? | ? | n/a | ? | ? | ≥ 85 | Y | N | N | n/a | n/a | 4/4 | n/a | Y | N |

| Gordon et al.,129 2010 | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | ≥ 85 | N | N | N | n/a | Y | 5/7 | Y | Y | N |

| Hains et al.,122 2000 | N | ? | N | ? | Y | ≥ 85 | Y | N | Y | N | n/a | 5/5 | N | Y | N |

| Lyon et al.,123 2014 | Y | ? | Y | N | Y | ≥ 85 | Y | N | N | n/a | n/a | 4/4 | Y | Y | Y |

| Lyon et al.,123 2014 | Y | ? | Y | N | Y | ≥ 85 | Y | Y | N | n/a | n/a | 2/3 | Y | Y | Y |

| Martinović et al.,83 2006 | Y | ? | n/a | N | Y | ≥ 85 | N | N | Y | N | N | 4/5 | n/a | Y | N |

| Masia-Warner et al.,124 2011 | Y | ? | N | Y | Y | ≥ 85 | N | N | Y | N | Y | 4/5 | Y | Y | N |

| Nekah et al.,133 2015 | ? | ? | N | N | Y | 70–84 | Y | N | N | N | Y | 1/1 | n/a | Y | N |

| Pourmohamadreza-Tajrishi et al.,134 2013 | ? | ? | n/a | N | Y | ≥ 85 | N | N | N | n/a | n/a | 1/1 | n/a | Y | N |

| Reigada et al.,125 2015 | Y | ? | Y | Y | Y | ≥ 85 | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | 4/4 | N | Y | Y |

| Serlachius et al.,130 2016 | Y | Y | Y | ? | Y | < 70 | Y | N | Y | Y | N | 4/4 | N | Y | Y |

| Shoshani et al.,137 2016 | Y | ? | N | N | Y | ≥ 85 | N | N | Y | N | Y | 5/5 | N | Y | N |

| Szigethy et al.,84 2007 | ? | ? | N | Y | Y | < 70 | Y | Y | N | n/a | Y | 6/6 | N | Y | Y |

| Szigethy et al.,141 2009 | ? | ? | N | Y | Y | < 70 | Y | Y | N | n/a | N | 3/3 | N | Y | Y |

| Szigethy et al.,126 2014 | ? | ? | Y | Y | Y | 70–84 | Y | Y | N | n/a | N | 7/7 | N | Y | Y |

| Szigethy et al.,143 2015 | ? | ? | Y | Y | Y | 70–84 | Y | Y | N | n/a | N | 5/5 | N | N | Y |

| Thompson et al.,142 2012 | ? | ? | N | Y | Y | 70–84 | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | 3/3 | N | Y | Y |

| Wang et al.,138 2012 | Y | ? | N | N | Y | ≥ 85 | Y | N | N | n/a | Y | 2/2 | n/a | Y | N |

| Westrupp et al.,118 2015 | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | 70–84 | N | N | Y | Y | N | 9/9 | N | Y | Y |

| Whittingham et al.,131 2014 | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | < 70 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | 3/3 | Y | Y | Y |

| Whittingham et al.,144 2016 | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | < 70 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | 4/4 | Y | Y | Y |

| Wicksell et al.,145 2009 | Y | ? | Y | N | Y | 70–84 | Y | N | Y | Y | N | 7/9 | N | Y | N |

| Yang et al.,139 2004 | ? | ? | n/a | Y | Y | ≥ 85 | N | N | N | n/a | n/a | 2/8 | n/a | Y | N |

| Yetwin,127 2011 | N | ? | N | ? | Y | 70–84 | N | N | N | n/a | Y | 8/8 | N | N | Y |

| Zareapour,135 2009 | ? | ? | N | N | Y | ≥ 85 | N | N | N | N | Y | 1/1 | n/a | Y | N |

The included articles were often free from risk of bias on freedom from selective outcome reporting, with 33 out of 35 papers rated ‘yes’. Lack of differences or adjustment for differences between groups at baseline was present in 28 out of 35 articles. Twenty-seven articles included only outcomes with good psychometric properties, and five of the eight articles not meeting this criterion were marked down on only one outcome measure. 83,120,123,124,136 Seventeen articles reported a response rate at the longest follow-up of ≥ 85%; however, none of these articles collected follow-up data at a period ≥ 6 months following the intervention. For those eight articles that did include longer follow-ups, response rates were 70–84% in three articles118,142,145 and < 70% in the rest. 128,130,131,140,144

The criteria that indicated risk of bias most often across articles were the assessment of adherence, compliance or fidelity (20/31 ‘no’); explaining missing data (13/31 ‘no’); blinding of assessors and inclusion of a follow-up after treatment (both 17/31 ‘no’). In addition, only half of those articles including a follow-up assessment did this at ≥ 6 months. The selection bias domains scored poorly, largely because of a lack of clarity in reporting.

Four articles were rated as being at a particularly high risk of bias (were judged to be of poor quality in relation to ≥ 50% criteria). 83,127,135,136 There were five other articles in which < 50% of criteria scored positively and > 15% of criteria were unclear, indicating potential risk of bias. 120,121,132,133,139 In all five articles, it was not possible to determine whether or not randomisation was adequate or allocation was concealed. However, these articles were rated as being free from bias in relation to the suggestion of selective reporting, and had a ≥ 85% response rate at follow-up (except Nekah et al. 133), although none included a follow-up assessment at ≥ 6 months.

The articles by Yetwin127 and Hains et al. 122 were rated as being at risk of bias on adequacy of randomisation because both allowed two participants to swap groups after allocation.

The articles demonstrating as being at the lowest risk of bias were by Whittingham et al. ,131,144 both of which were rated positively on 13 criteria. The only risk of bias in the Whittingham articles arose because outcomes were self-reported, therefore assessors were not blinded, and the response rate at the longest follow-up was < 70%. This poor response rate was symptomatic of the few studies to collect data at the 6-month follow-up interval. The two articles reporting on the study by Brown et al. 128,140 performed similarly to the Whittingham articles. The article by Reigada et al. 125 was also rated as being at low risk of bias overall, with only two negative scores.

Analysis of included study findings

Effectiveness of cognitive–behavioural therapy interventions

Interventions categorised as CBT were the most common type of intervention, featuring in 10 articles reporting on seven studies across a range of LTCs: epilepsy, persistent functional somatic complaints, IBD, T1DM and chronic pain. 83,84,124–126,130,145 Across the seven studies, 531 participants were randomised. Comparators were TAU, waiting list or non-directive supportive therapy (NDST). 84,125,126 Despite being the most common intervention type, there was no opportunity to meta-analyse data because of differing LTCs, control groups and outcomes. The included studies were also characterised by small samples and varying risk of bias. Six different CBT interventions were assessed across the seven studies. All interventions in this category shared components of typical CBT interventions and/or were identified as a CBT intervention. All of these interventions aimed to improve both mental and physical health. Mental health variables included depression,83,84,126,145 anxiety124,125 and stress. 130 Parent sessions were included in all but two of the interventions. 83,130 Exposure and ACT in Wicksell et al. ’s study145 were categorised as CBT because exposure exercises were seen in other CBT interventions,124,125 and the authors145 characterised ACT as a development of CBT.

Five of the interventions [Best of Coping (BOC),130 TAPS,124 TAPS+IBD,125 PASCET-PI84,126 and Exposure and ACT145] contained content adapted for the LTC of the sample in the study (T1DM,130 persistent functional somatic complaints,124 IBD84,125,126 or chronic pain145) by the inclusion of intervention content such as tasks identifying IBD-specific stressors and developing ways to cope with symptoms,125 addressing fears specifically related to physical pain124 and integrating illness narratives and working on the development of healthy IBD-related cognitions and behaviours. The intervention trialled by Martinović et al. 83 targeted depressive thoughts and did not contain any LTC-specific (epilepsy) content.

Children and young people mental health outcomes

Depression was assessed in the four studies whose intervention aimed to improve this outcome. 83,84,126,145 Three of the studies measured depression using multiple measures,83,84,126 meaning that this was the most frequently occurring outcome category for CBT interventions. General mental health was assessed in four studies,84,124,126,145 and two studies whose interventions aimed to improve anxiety also measured it as an outcome. 124,125

Report Supplementary Material 1, Table 6, displays means and SD for control and intervention groups for each CYP mental health outcome assessed post intervention, in which sample size, mean and SD were reported or calculable. Effect sizes (Cohen’s d), 95% CIs and p-values are included, with a positive effect size representing improvement on the measure.

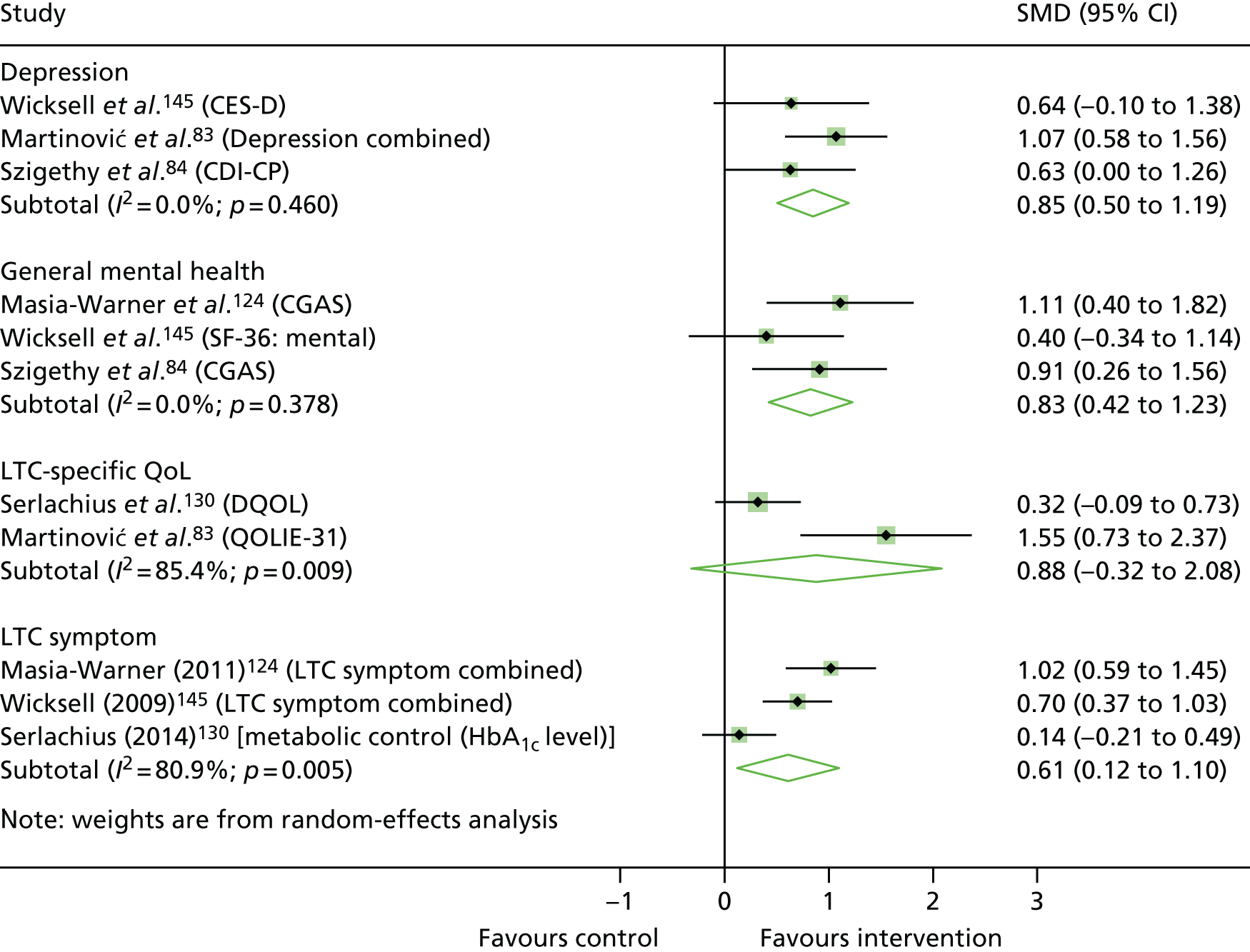

Evidence of the beneficial effect of CBT for measures of CYP mental health can be found in six out of the seven studies featuring this type of intervention. Evidence of the beneficial effect of CBT on depression across all outcomes is provided by one study83 in which large positive effect sizes are seen for all depression measures, although wide 95% CIs for two of the measures include negligible effect sizes, reflecting the imprecision of the estimate of effect [Beck Depression Inventory (BDI): d = 0.85, 95% CI 0.10 to 1.60; p = 0.03; Centre for Epidemiological Studies Depression scale (CES-D): d = 0.86, 95% CI 0.11 to 1.61; p = 0.03]. Evidence for the beneficial effect of CBT on depression from other studies is less clear; although small to large positive effect sizes were seen for the other studies reporting depression outcomes, these effects tended to be imprecise, with 95% CIs typically including negligible or even slightly harmful effects. Reigada et al. 125 provide evidence of a large beneficial effect of CBT on IBD-specific anxiety (d = 1.31, 95% CI 0.36 to 2.27; p = 0.007). However, there was little evidence for a beneficial effect of CBT on anxiety in the study by Masia-Warner et al. 124 (d = 0.27, 95% CI –0.38 to 0.92; p = 0.41). There was some evidence for a large beneficial effect of CBT on general mental health according to Masia-Warner et al. 124 (d = 1.11, 95% CI 0.42 to 1.81; p = 0.002) and Szigethy et al. 84 (d = 0.91, 95% CI 0.25 to 1.56; p = 0.007), although the wide CIs in the latter study include small effect sizes reflecting the imprecision of the estimate of effect. However, Wicksell et al. 145 report a lack of evidence for the beneficial effect of CBT on general mental health (d = 0.40, 95% CI –0.40 to 1.13; p = 0.41) in their trial. There was no opportunity to meta-analyse CYP mental health outcomes for these interventions evaluating CBT because of differing LTCs or comparators across studies in which outcome categories were shared.

Other outcomes

Report Supplementary Material 1, Table 7, displays findings for other outcomes assessed post intervention. Conflicting evidence regarding the beneficial effect of CBT on LTC-specific QoL and LTC symptoms can be seen across the studies featuring CBT interventions. For instance, although the study by Martinović et al. 83 provides evidence of a large beneficial effect of CBT for epilepsy-specific QoL (d = 1.55, 95% CI 0.72 to 2.37; p < 0.001), a lack of evidence for such a beneficial effect on diabetes mellitus control was reported by Serlachius et al. 130 (d = 0.32, 95% CI –0.08 to 0.73; p = 0.12). The study by Masia-Warner et al. 124 provides evidence of some medium to large beneficial effect sizes for CBT on measures of LTC symptoms. Large beneficial effect sizes for self-reported (d = 1.33, 95% CI 0.61 to 2.05; p < 0.001) and parent-reported (d = 0.98, 95% CI 0.30 to 1.67; p = 0.005) pain were found, as well as a medium beneficial effect on somatisation (d = 0.75, 95% CI 0.08 to 1.42; p = 0.03), although the wide CI for somatisation includes negligible effect sizes, reflecting the imprecision of this estimate of effect. The study by Wicksell et al. 145 provides evidence of large beneficial effects of CBT for pain (d = 1.25, 95% CI 0.45 to 2.05; p = 0.002) and pain-related emotional discomfort (d = 1.46, 95% CI 0.63 to 2.28; p < 0.001). However, there was little evidence for a beneficial effect of CBT on other pain and LTC symptoms outcomes measured by Wicksell et al. 145 There was little evidence for a beneficial effect of CBT on LTC symptoms in other studies. 125,126,130

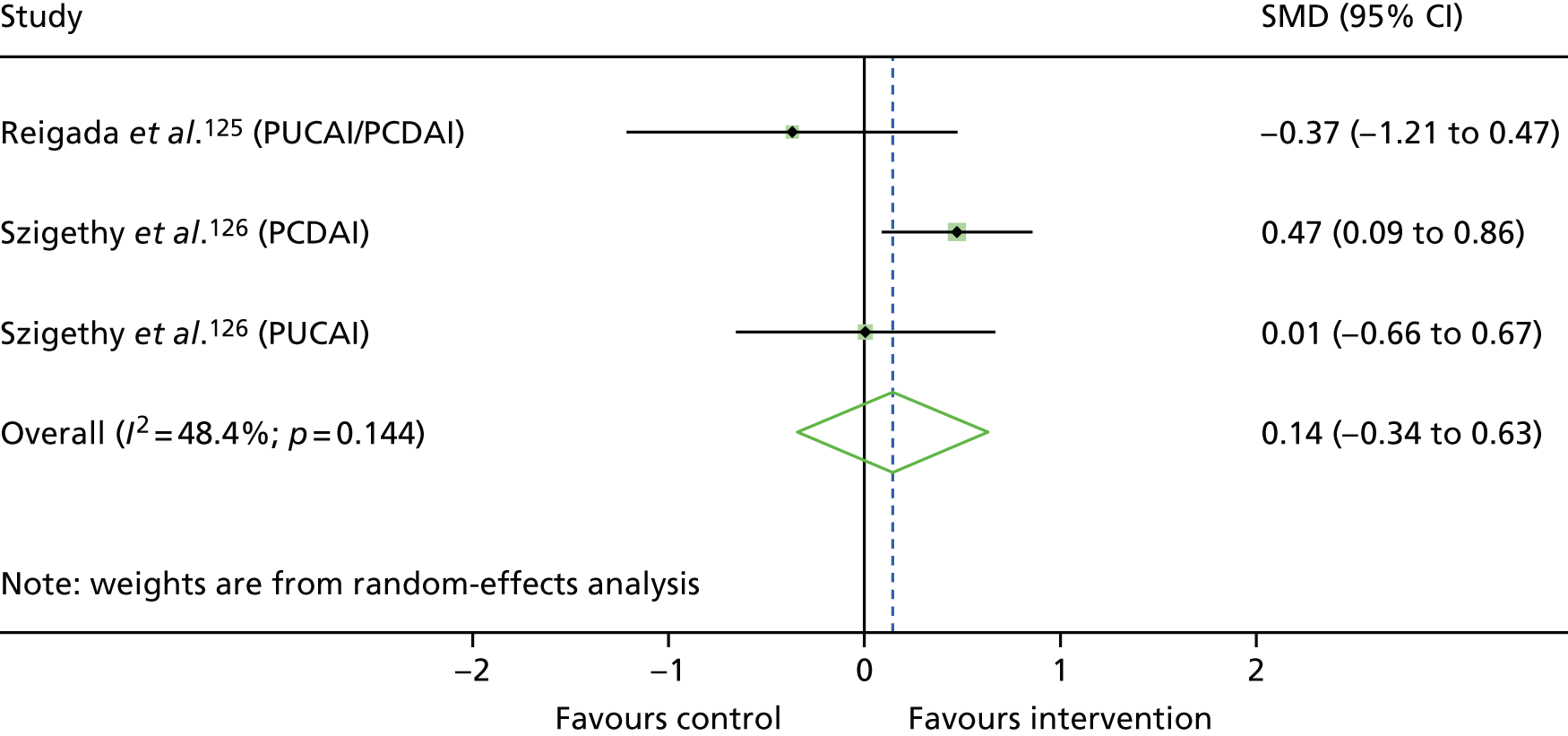

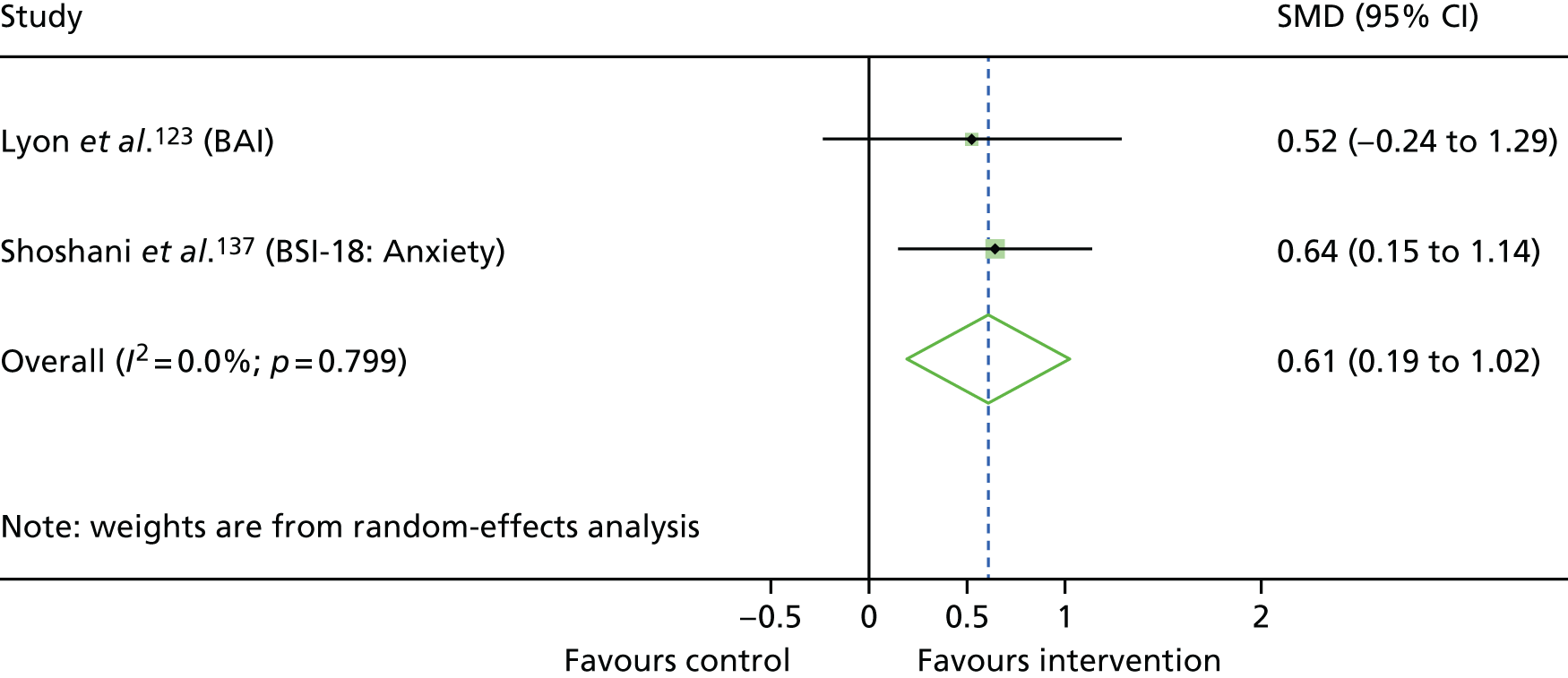

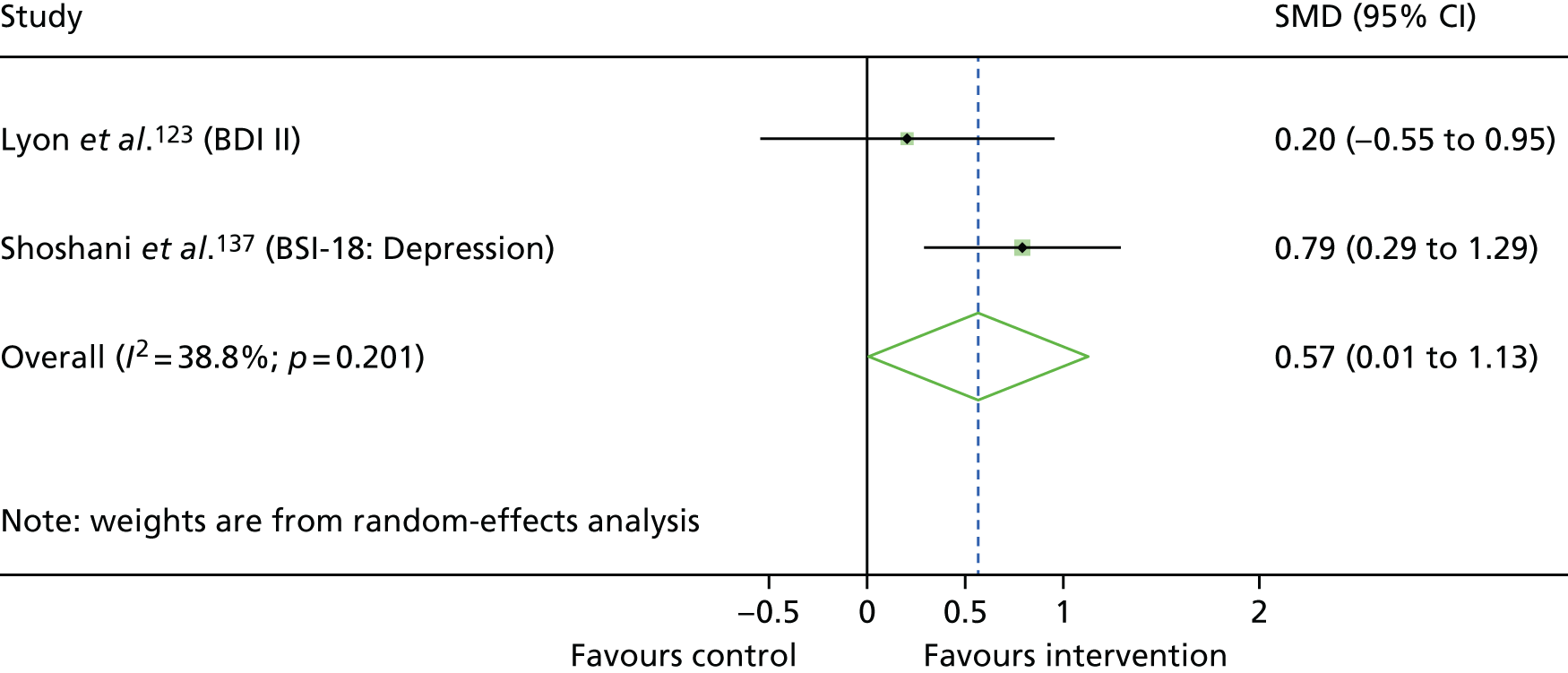

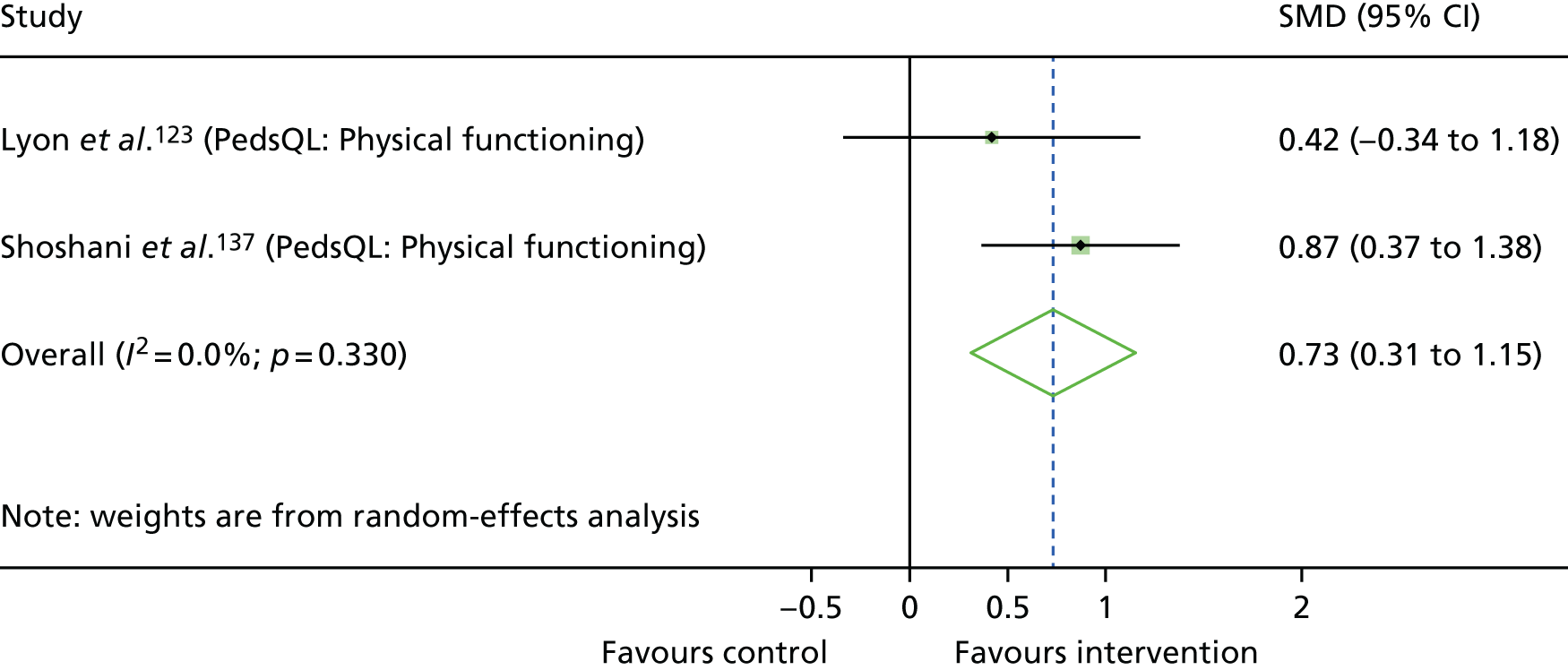

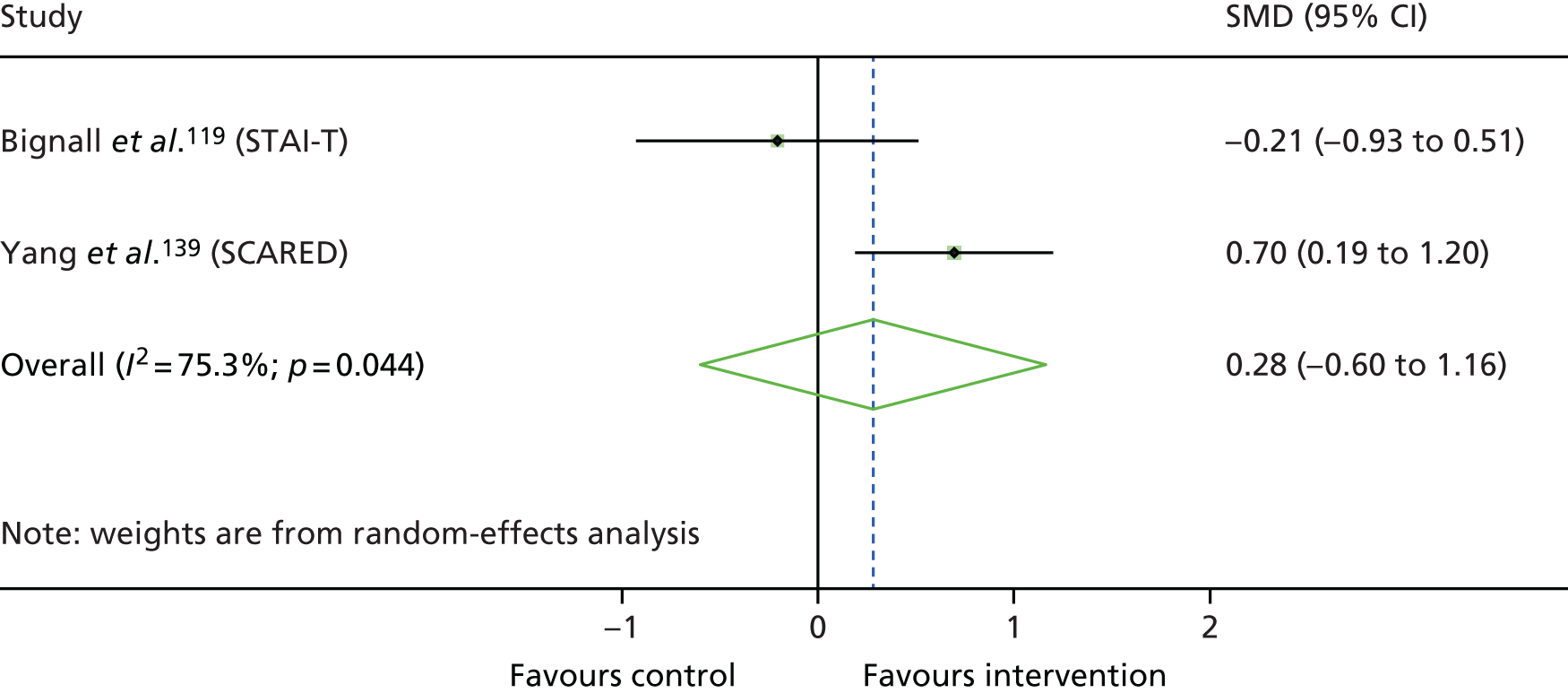

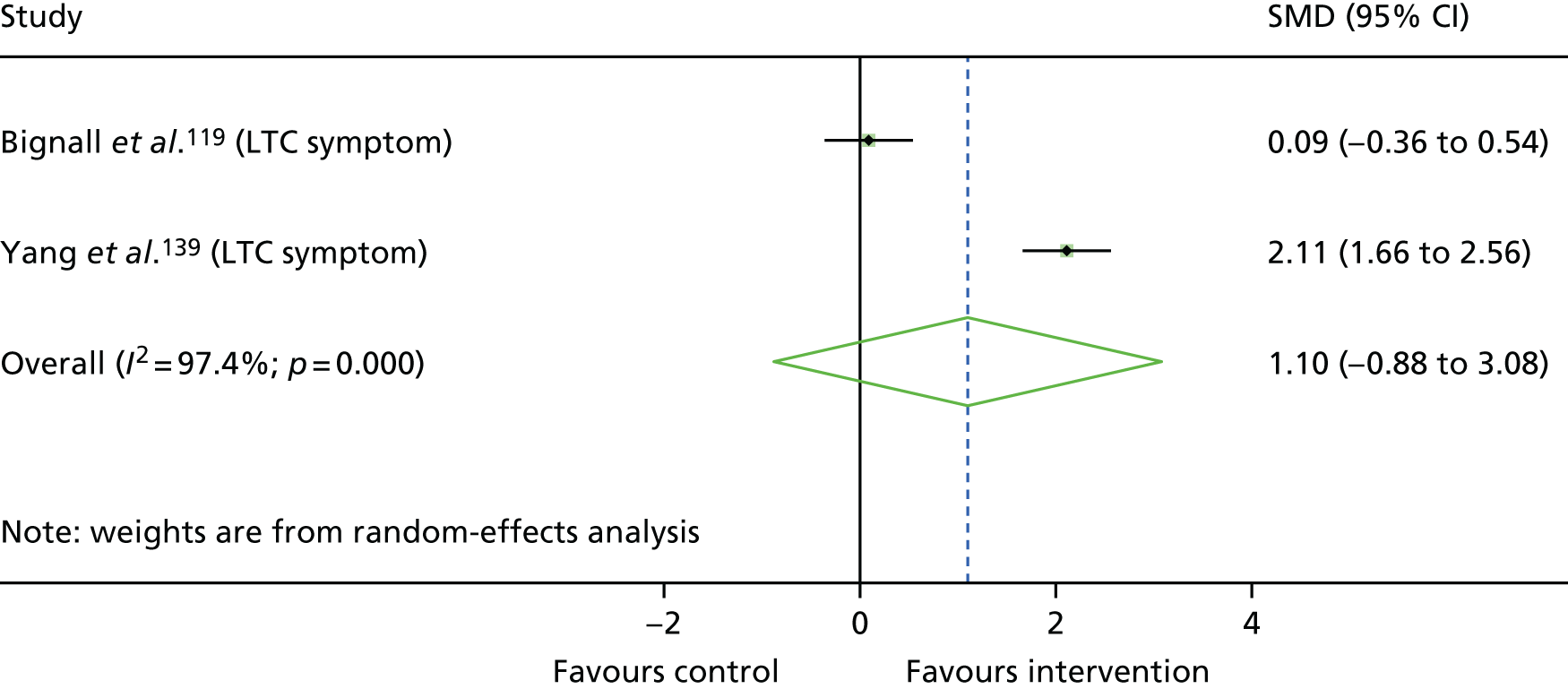

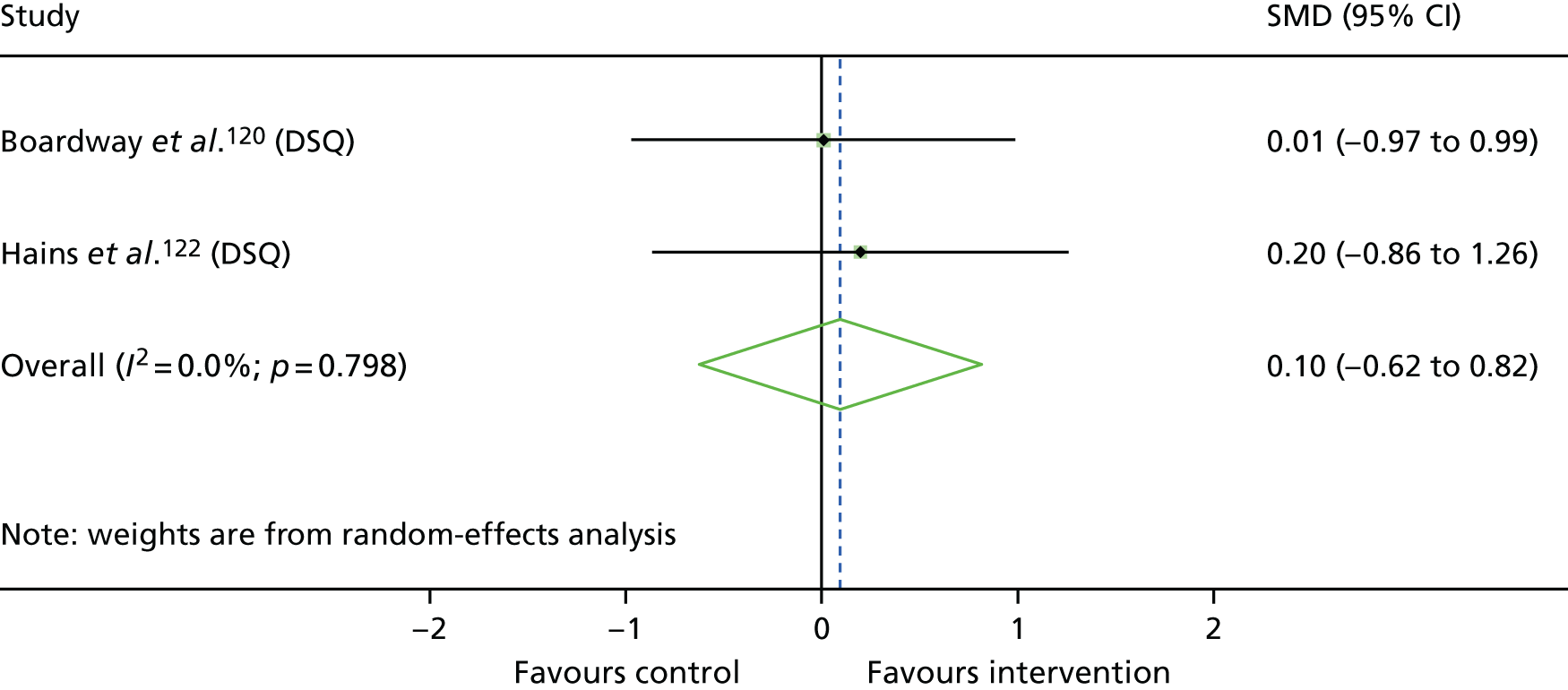

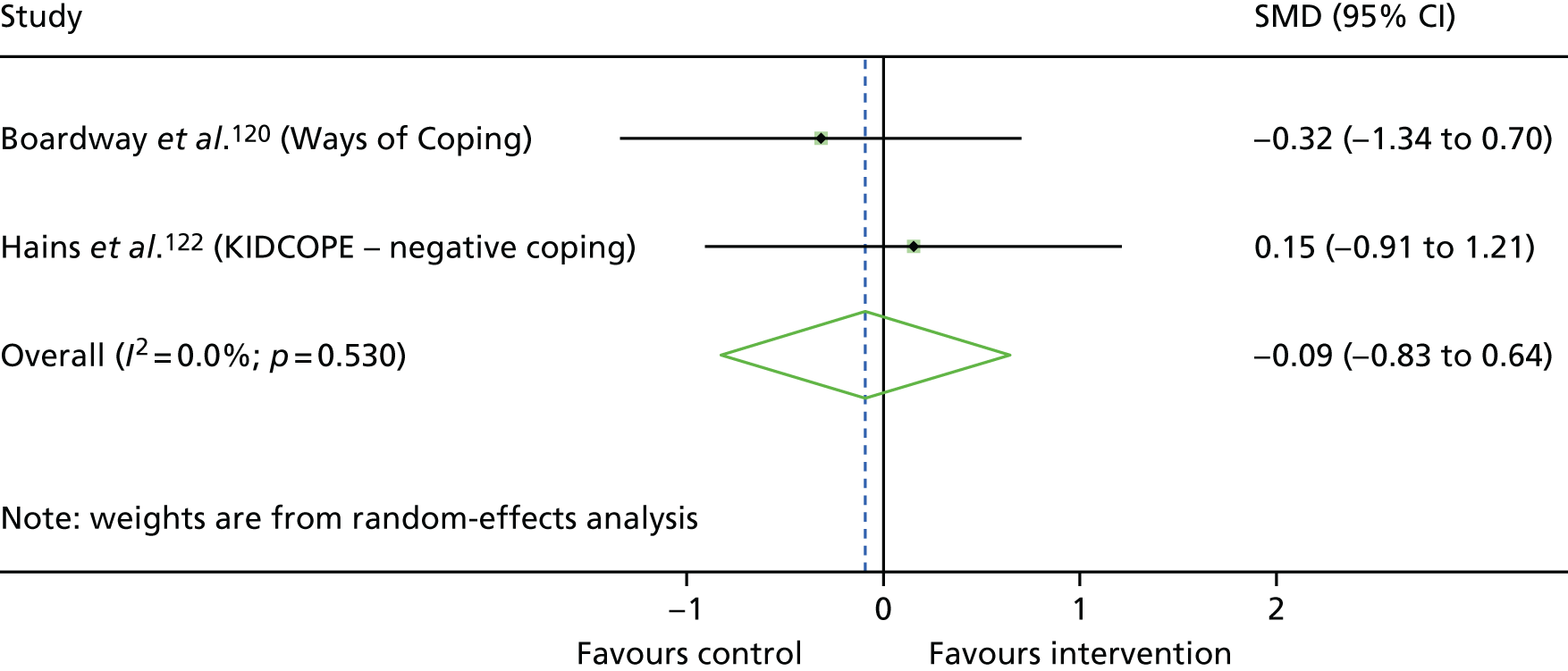

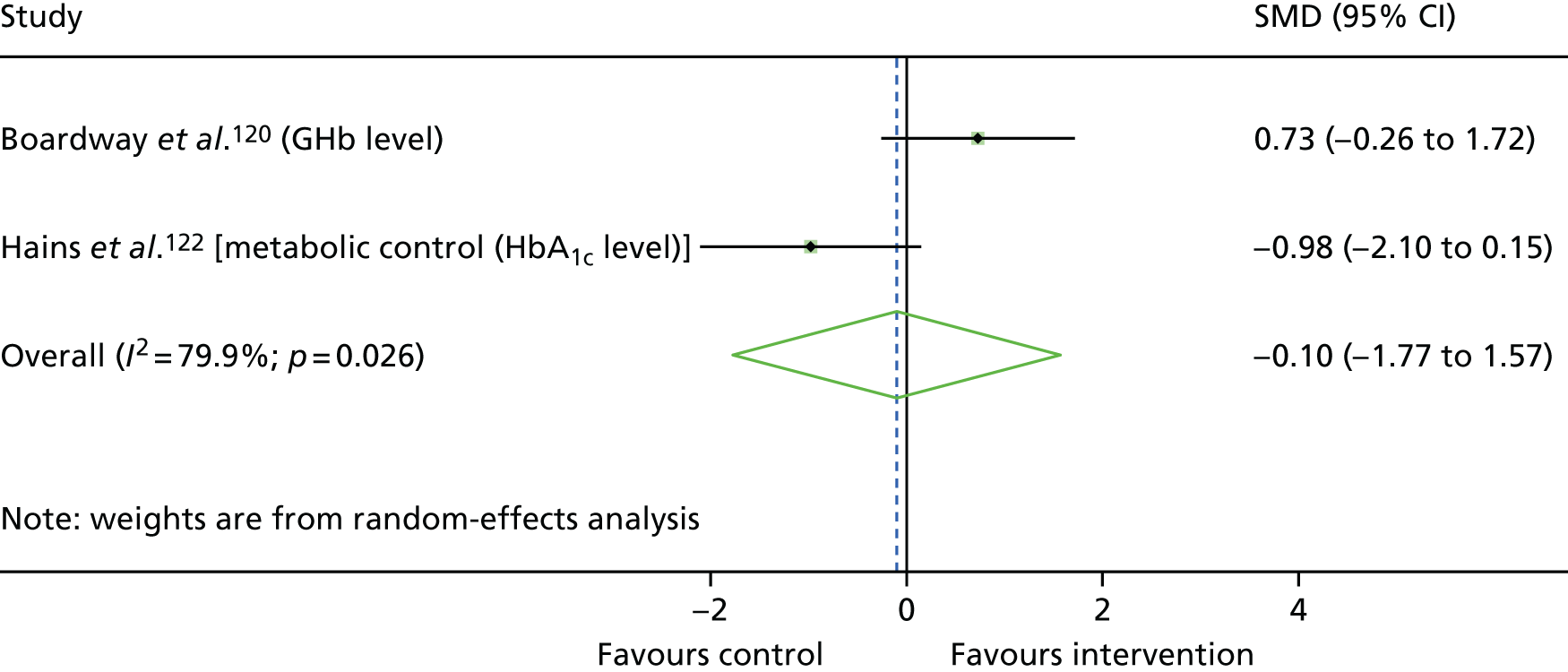

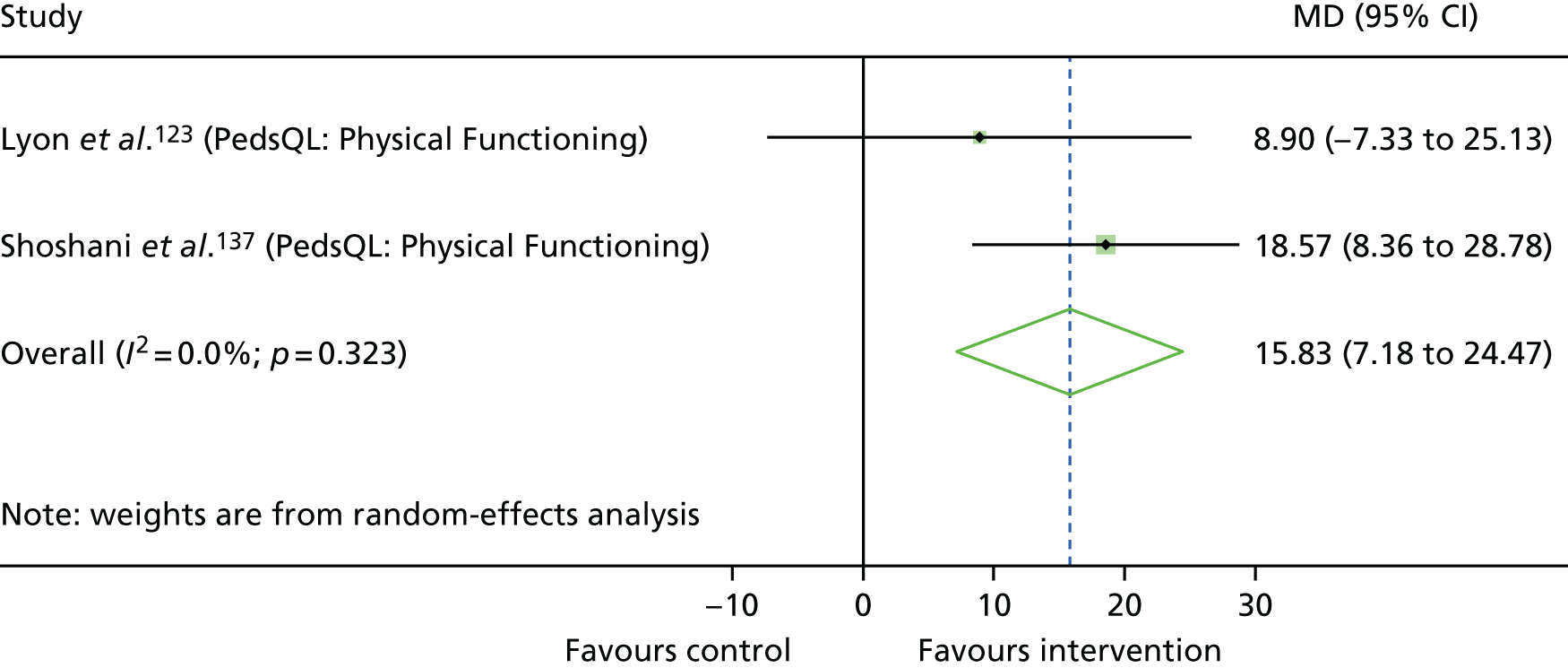

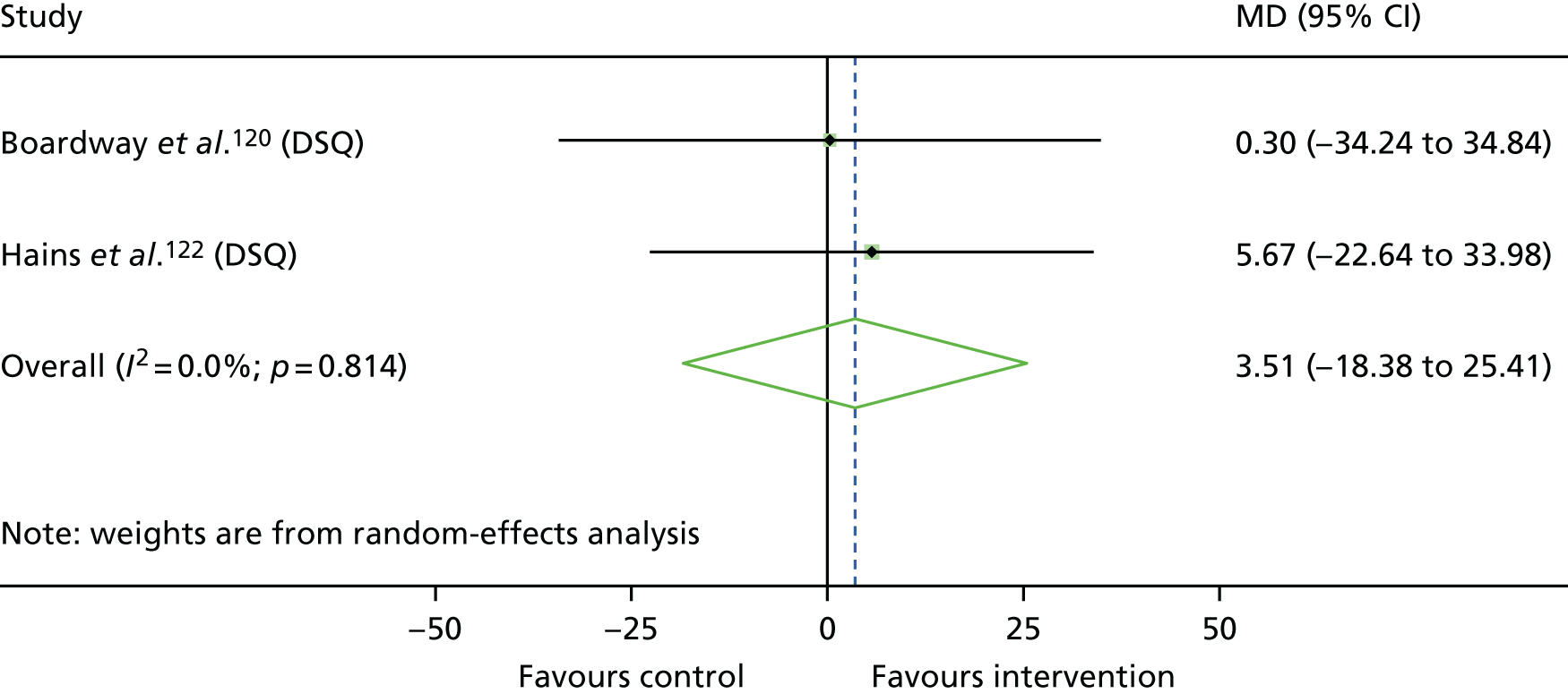

Evidence for the effect of CBT on LTC symptom severity could be investigated further by meta-analysing outcomes from Szigethy et al. 126 and Reigada et al. ,125 both of which studied patients with IBD and used NDST as the comparator. Reigada et al. 125 reported pooled data for the Paediatric Ulcerative Colitis Activity Index (PUCAI) and Paediatric Crohn’s Disease Activity Index (PCDAI) outcomes,125 whereas Szigethy et al. 126 reported separately for participants with ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease. Figure 3 is a forest plot of the effects of CBT on these disease activity measures reported in these studies. This meta-analysis demonstrated little evidence of an effect of CBT on LTC symptoms (d = 0.14, 95% CI –0.34 to 0.63; p = 0.56).

FIGURE 3.

Forest plot showing the results of meta-analysis of the effects of CBT on IBD symptoms post intervention for included studies. SMD, standardised mean difference (Cohen’s d).

Overall, the seven included studies that evaluated the clinical effectiveness of interventions categorised as CBT aiming to improve the mental health of CYP with LTCs show some promising effects. A number of large beneficial effects for CYP mental health and other outcomes were seen, although effects for particular outcomes were rarely consistent across all studies. The heterogeneity in study characteristics prevented meta-analysis of CYP mental health outcomes. The available sample of studies is small, targeting different aspects of mental health for children with different LTCs. There was also diversity in quality and risk of bias across these studies.

Effectiveness of parenting interventions

Parenting interventions without acceptance and commitment therapy

Of the four parenting interventions assessed in included studies, two were parenting without ACT (Westrupp et al. 118 and Whittingham et al. 131,144). Westrupp et al. 118 assessed the Triple P in families with a child with diabetes mellitus, whereas one of the intervention arms in Whittingham et al. 131,144 was SSTP alone. SSTP is tailored towards families with pre-adolescent children with a disability, which may be physical or intellectual, and behavioural problems. 148 The sample in the study by Whittingham et al. 131,144 had cerebral palsy. Both studies had similar aims, including improving aspects of CYP mental health, with a focus on behavioural and emotional problems in Whittingham et al. 131,144 as well as improving parenting. A total of 50 participants were randomised to intervention or control arms, with all control participants (n = 32) receiving TAU (Whittingham et al. 131,144 used a waiting list control). In both studies, the primary aim was to reduce child behavioural problems through improved parenting skills. Westrupp et al. 118 examined the effects of Triple P in a group of families with children who had elevated behavioural problems at baseline, as well as a group without elevated behavioural symptoms. We were unable to obtain raw data for the subgroup analysis of families with children with behaviour problems and, therefore, could not calculate effect sizes for the study.

Report Supplementary Material 1, Table 8, shows the findings for each CYP mental health outcome assessed post intervention by Whittingham and colleagues. 131,144 Despite a medium-sized beneficial effect for the Eyberg Child Behavior Inventory (ECBI): Problems subscale (d = 0.72, 95% CI 0.04 to 1.40; p = 0.04), there was a lack of evidence for the beneficial effect of a parenting programme on child behaviour, with 95% CIs on the other measures of child behaviour all including harmful effects. There was conflicting evidence of the effect of parenting on social dysfunction, with a large beneficial effect seen for the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ) peer problems subscale, although a wide 95% CI includes negligible effect sizes, reflecting the imprecision of the estimate of effect (d = 0.88, 95% CI 0.19 to 1.57; p = 0.01), but there was little evidence of a beneficial effect on the prosocial subscale (d = –0.19, 95% CI –0.84 to 0.47). A medium effect size was also found in this study for the SDQ emotional behaviour subscale (d = 0.64, 95% CI –0.03 to 1.31; p = 0.06), but the imprecise 95% CI includes negligibly harmful effects. Although it was not possible to calculate effect sizes for the outcomes reported by Westrupp et al. ,118 the article reports medium to large and statistically significant beneficial effects for externalising problems, internalising problems and disruptive behaviours for the participants with behaviour problems receiving the intervention. Because of the different LTCs in the two studies and the lack of necessary statistics reported in the study by Westrupp et al. ,118 a meta-analysis was not performed for these CYP mental health outcomes or others reported below.

Numerous secondary outcomes were also reported. Given the parent-focused nature of the interventions, the studies by both Westrupp et al. 118 and Whittingham et al. 131,144 assessed parenting styles and parent mental health. A number of outcomes related to LTC symptoms and LTC-specific QoL were also reported. Report Supplementary Material 1, Table 9, displays findings for these other outcomes. Overall, the study by Whittingham et al. 131,144 demonstrates a lack of evidence of a beneficial effect of this parenting intervention on other outcomes, except parenting confidence, which recorded a medium-sized beneficial effect, but the wide 95% CI included negligible effect sizes (d = 0.69, 95% CI 0.02 to 1.37; p < 0.05). 131,144 Westrupp et al. 118 found statistically significant medium effect sizes for parent mental health, but only evidence of the benefit of a parenting intervention for some measures of parenting and family functioning for participants with behaviour problems.

Westrupp et al. 118 included follow-up assessments of all outcomes 12 months post intervention. They reported large statistically significant favourable effects for parent anxiety and stress at 12 months, but not for the CYP mental health and other outcomes assessed.

These two studies investigated the effect of parenting programmes on a wide range of outcomes, yet clear evidence for benefits was rarely seen. The study by Whittingham et al. 131,144 provides conflicting evidence relating to child behaviour and social dysfunction across different measures used. For other outcomes, reported effect sizes were typically small with wide CIs, reflecting imprecision in effect estimates. Overall, with only two RCTs assessing parenting interventions without an ACT component and only one providing data that allowed the calculation of effect sizes, there is weak evidence relating to the effectiveness of parenting programmes for improvement of child or parent outcomes.

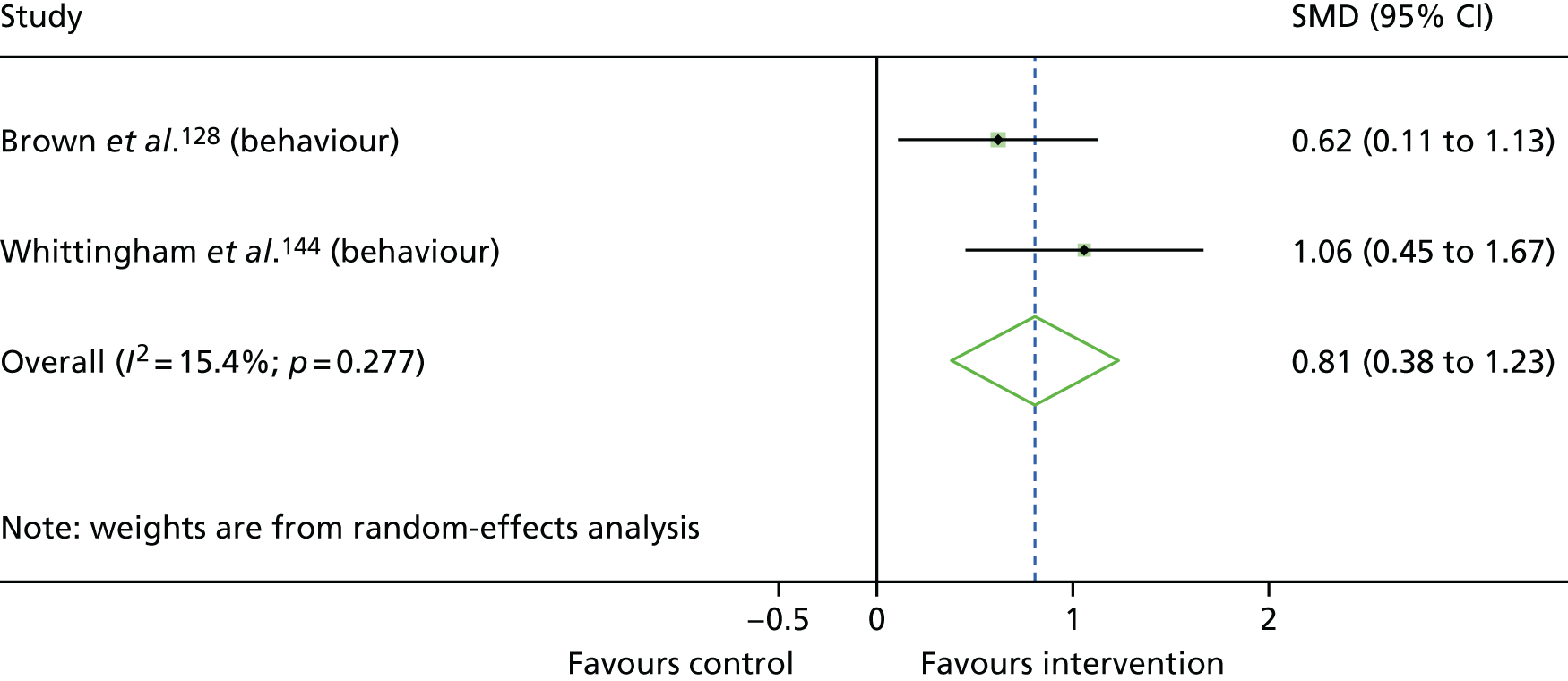

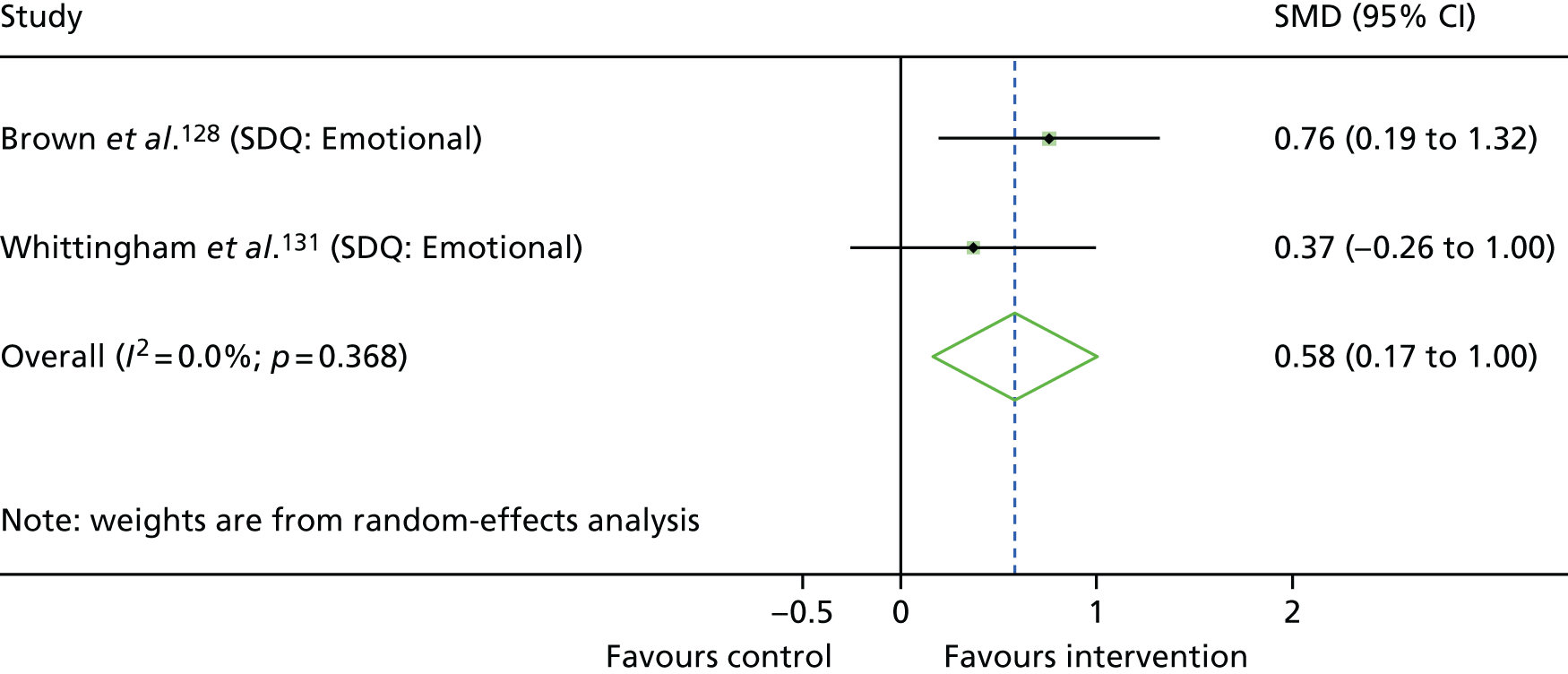

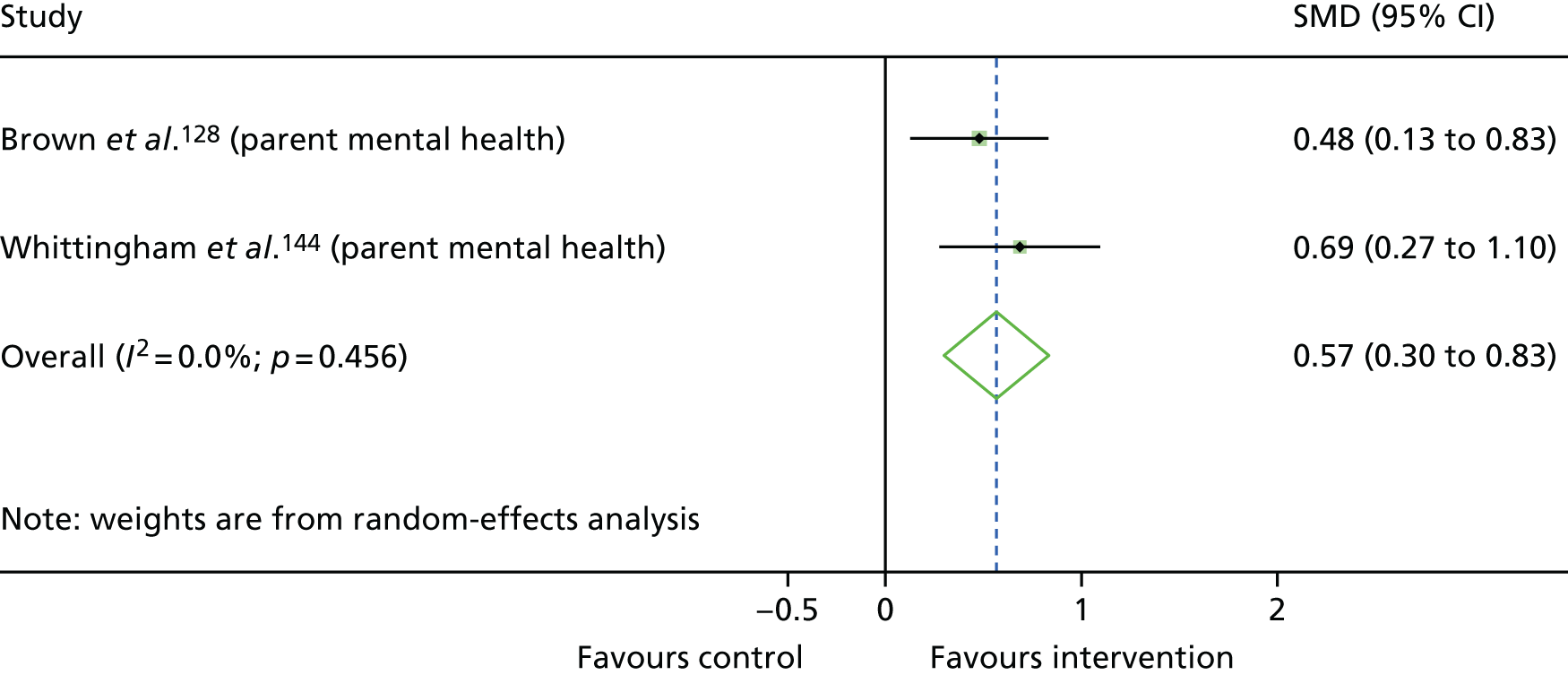

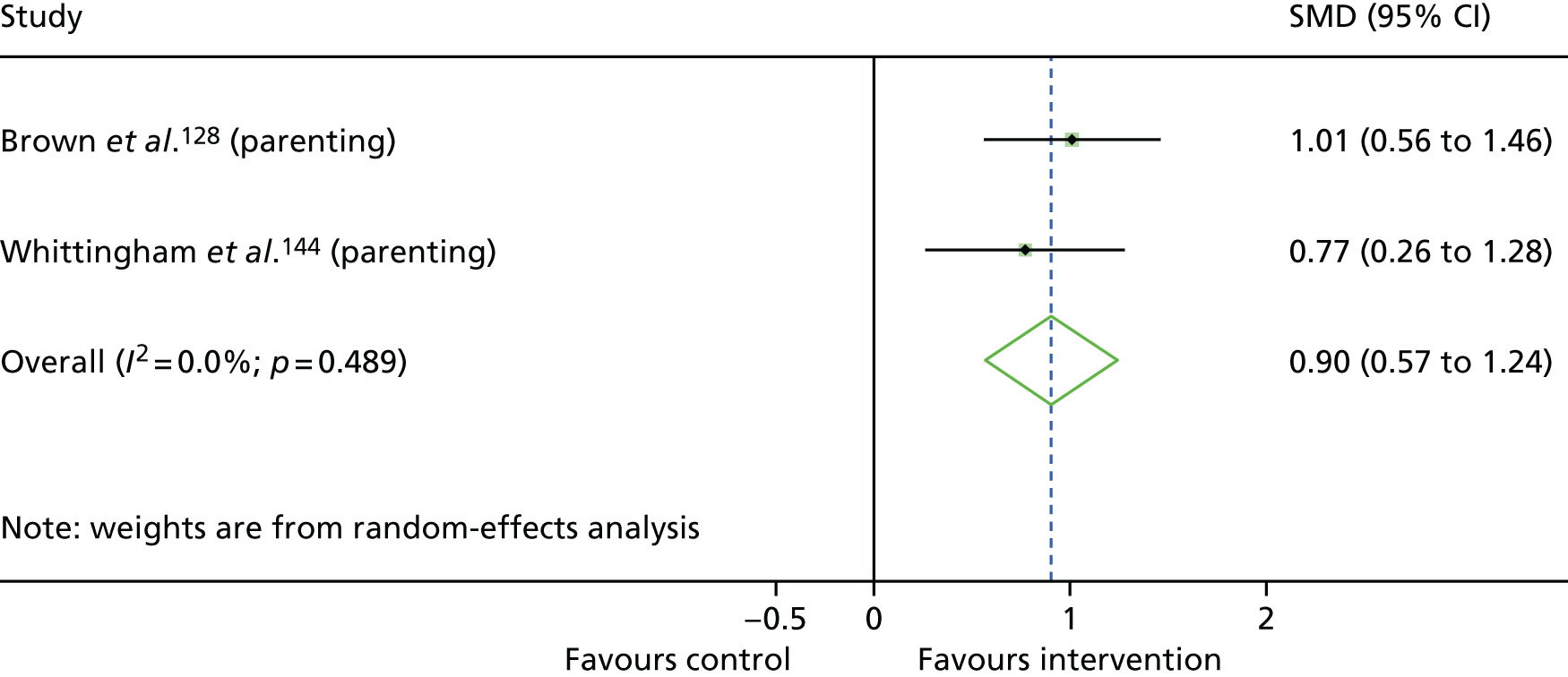

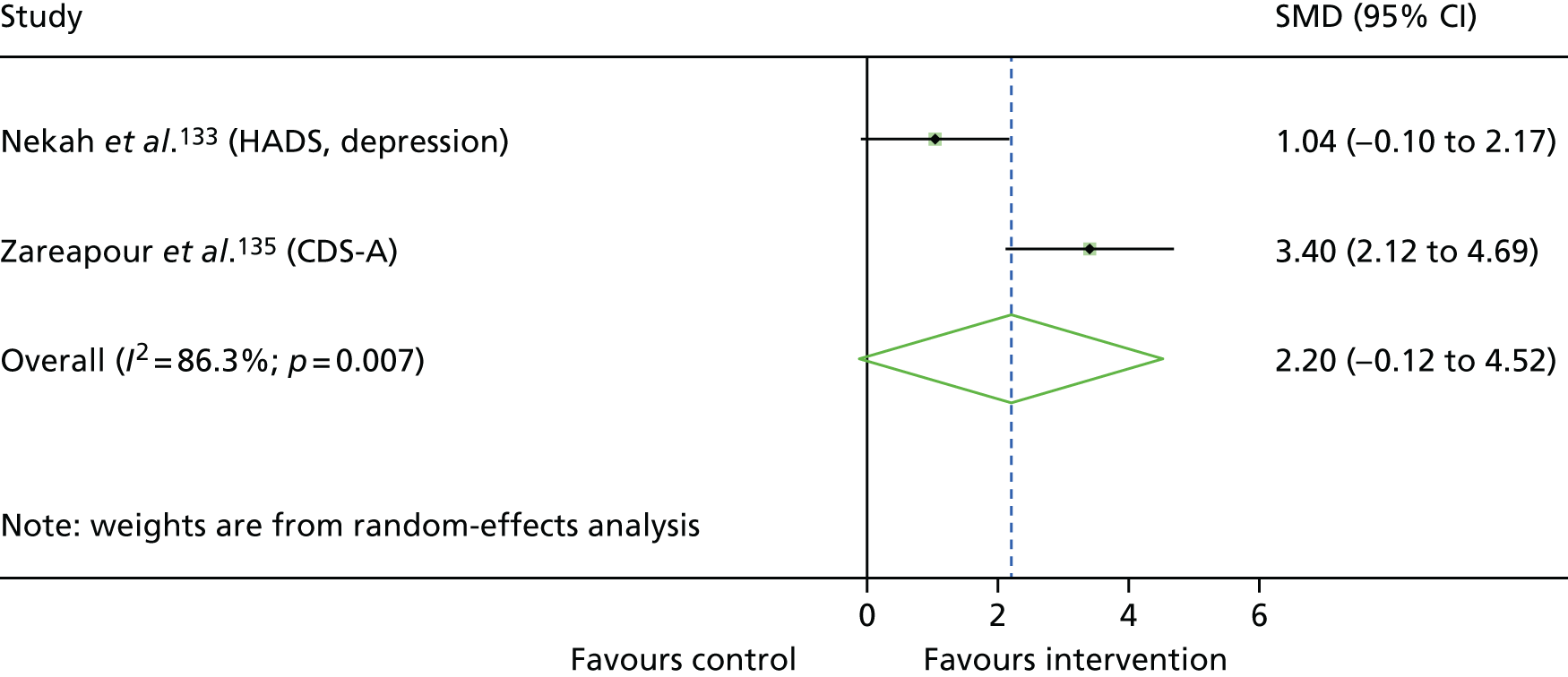

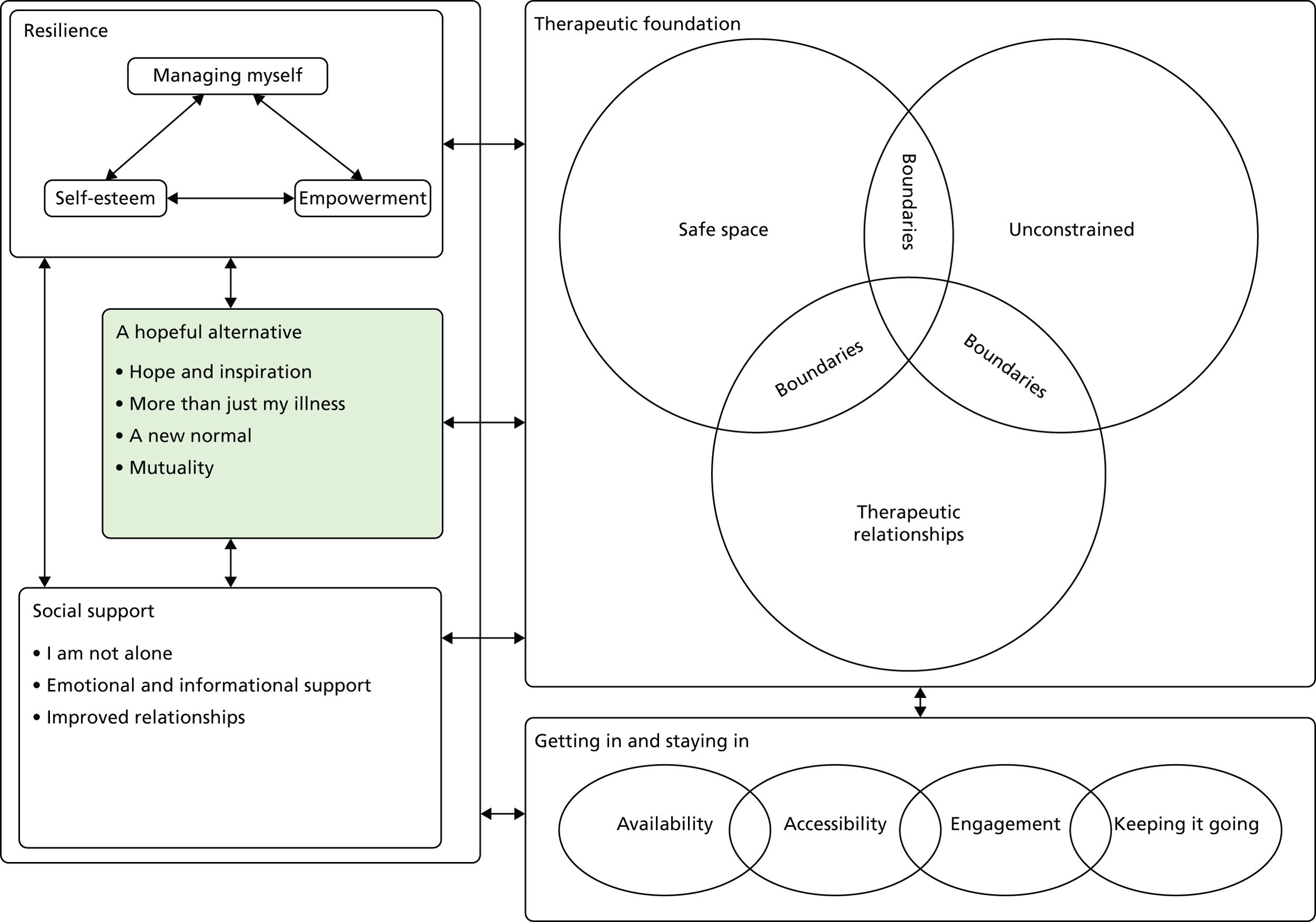

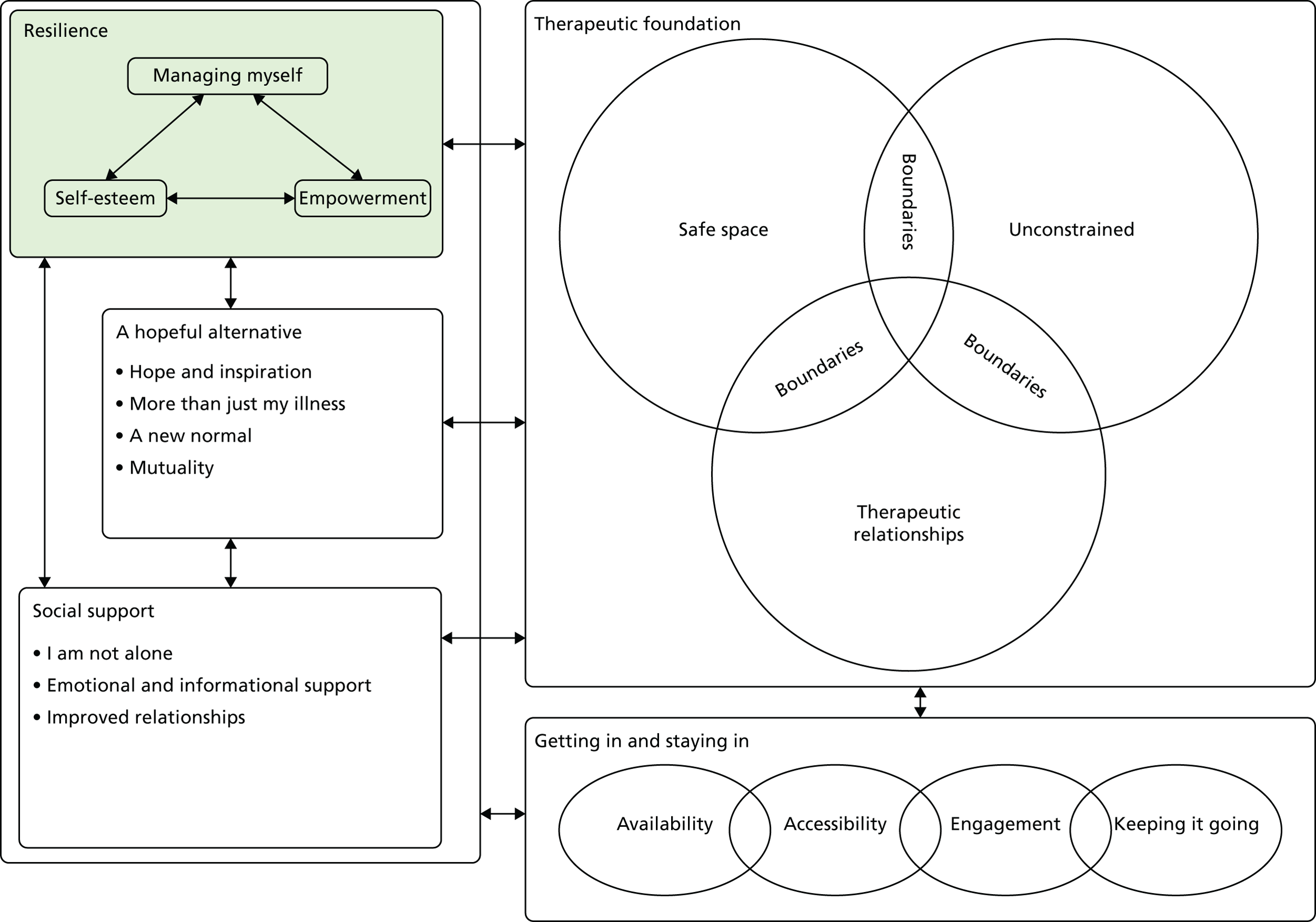

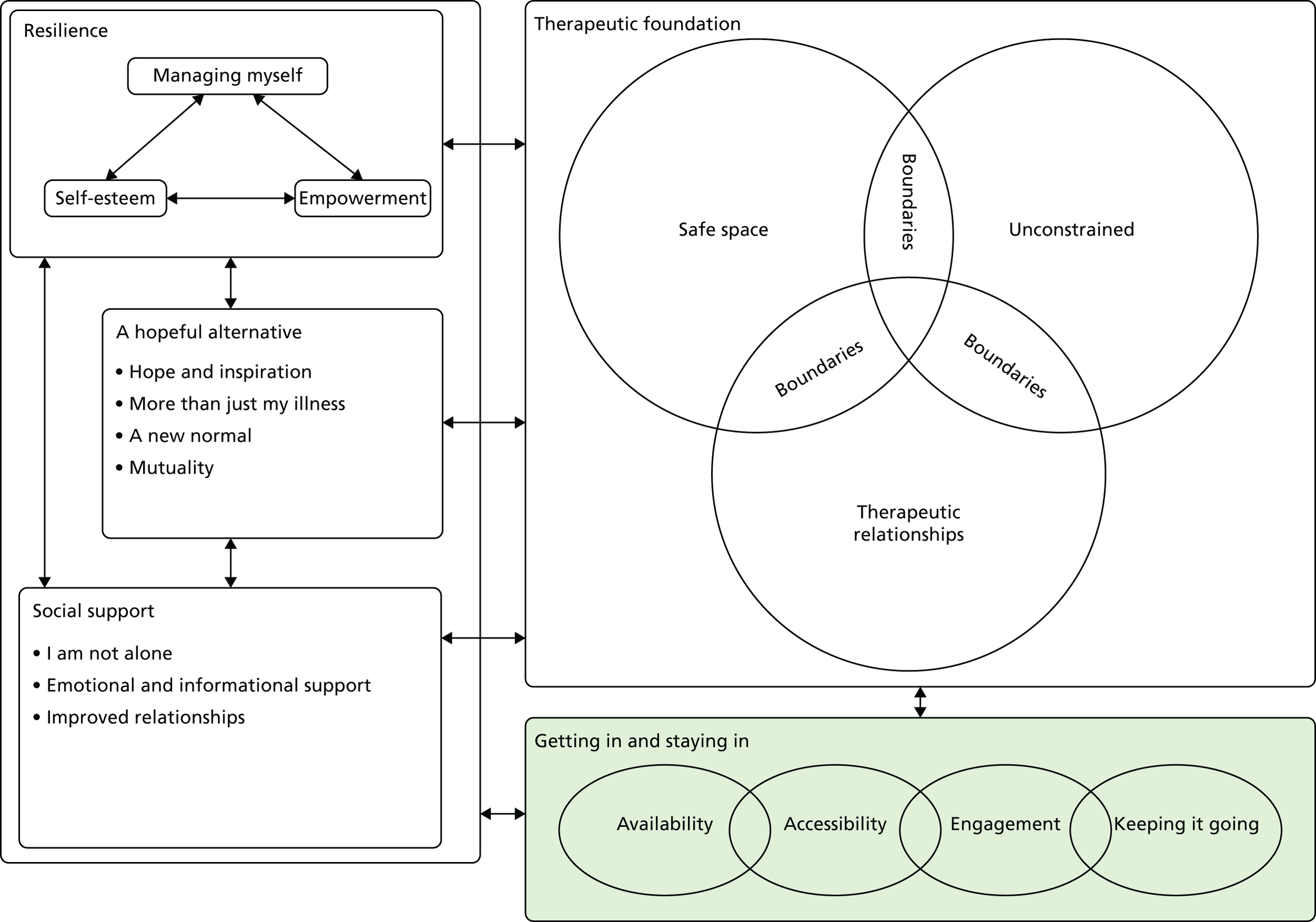

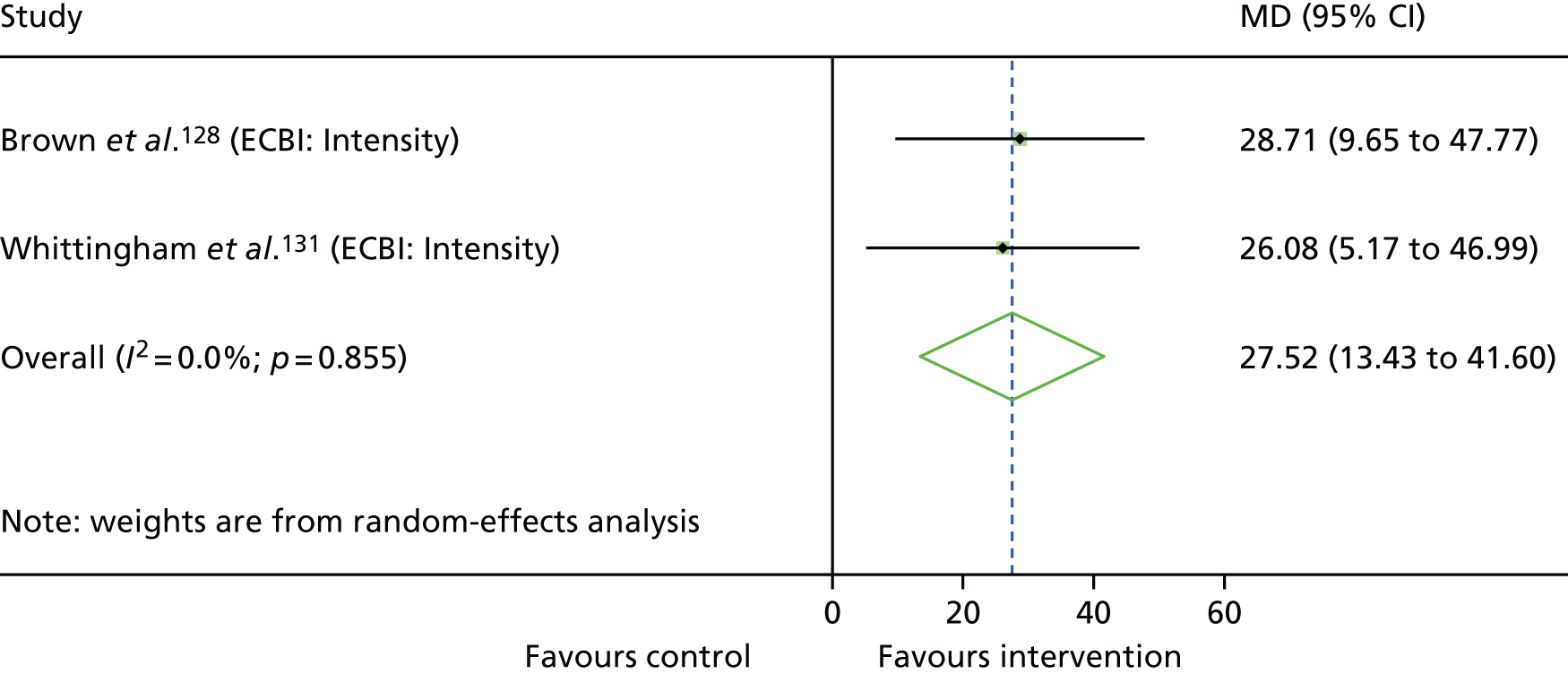

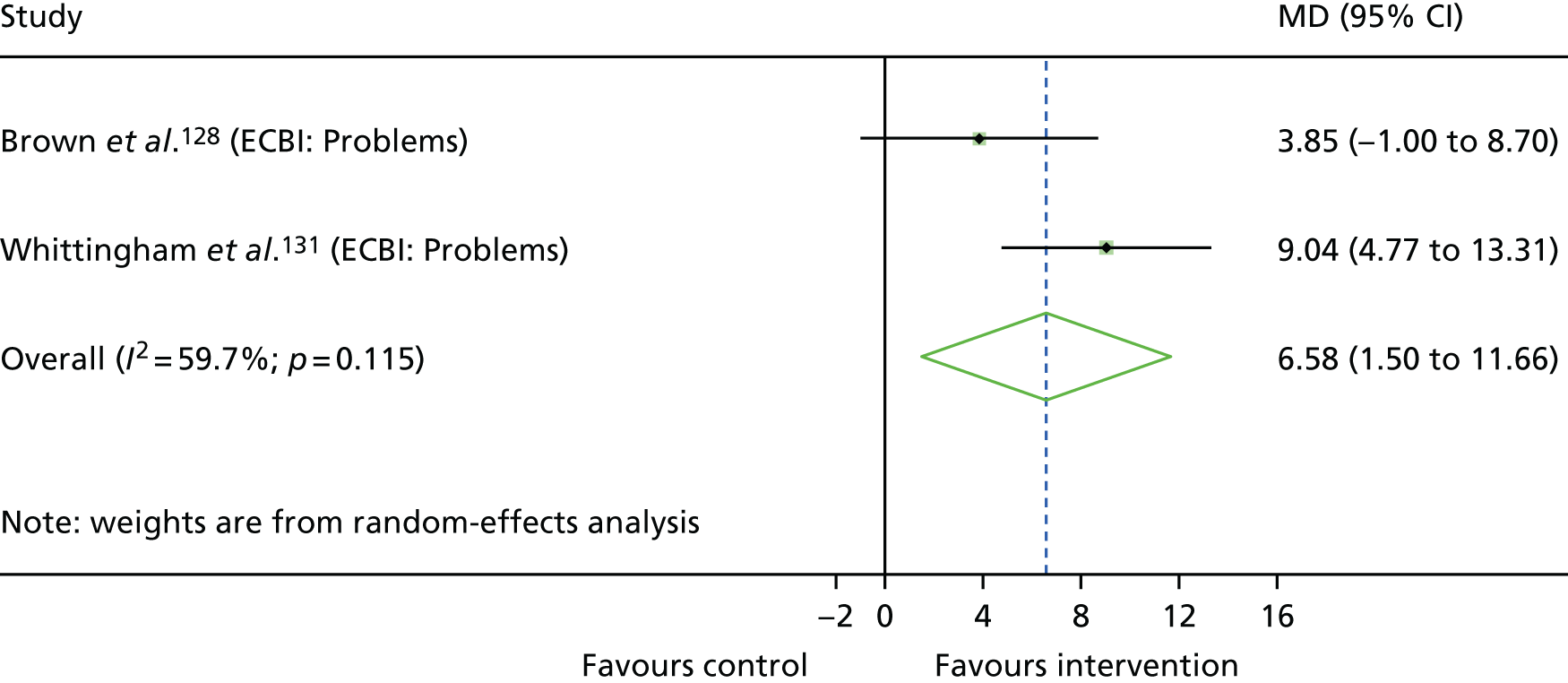

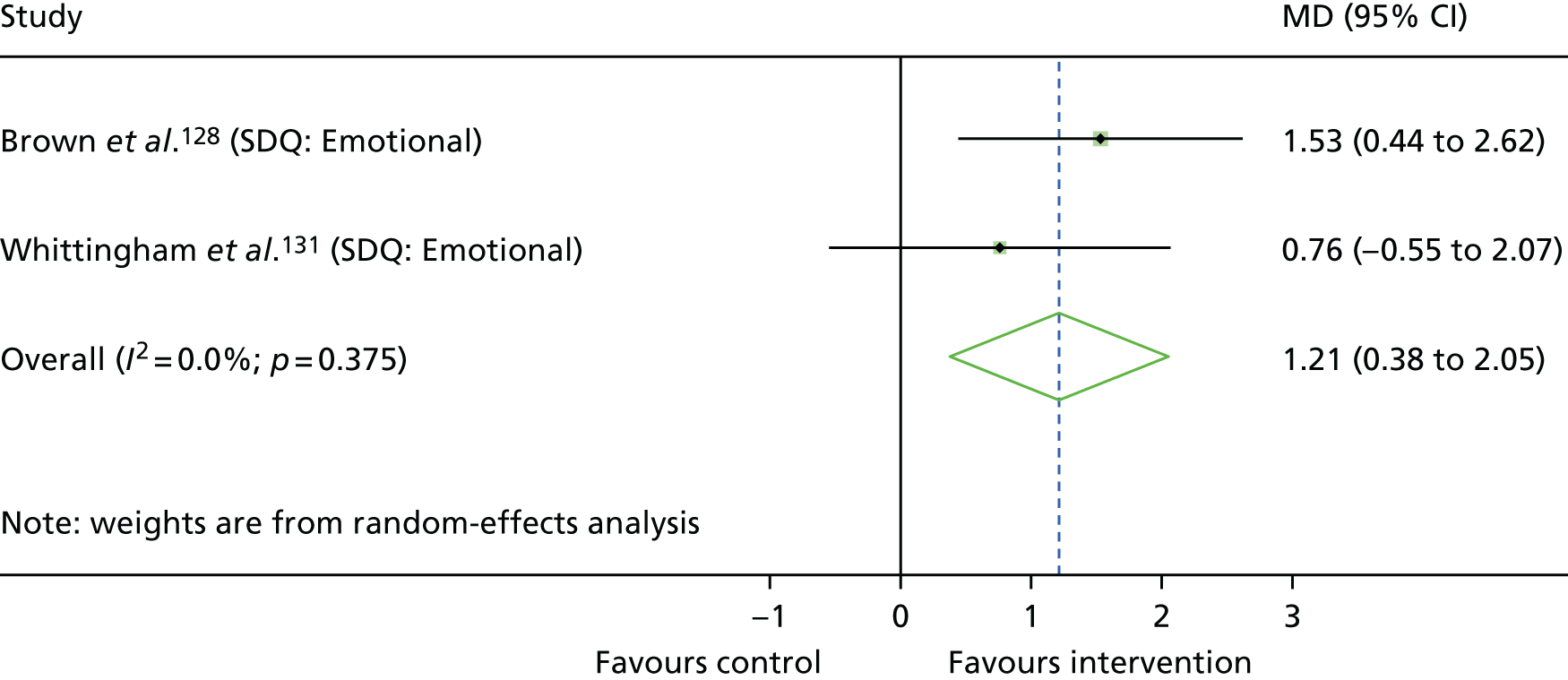

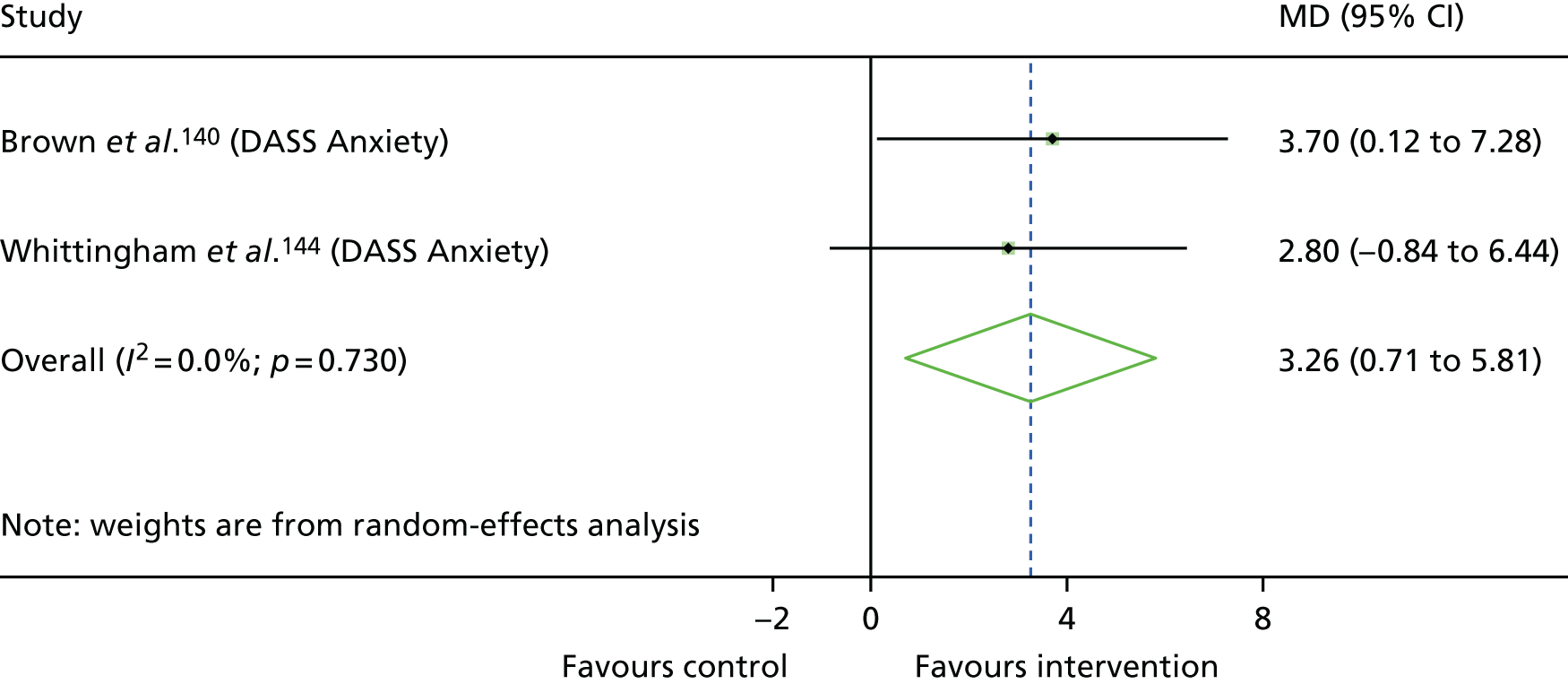

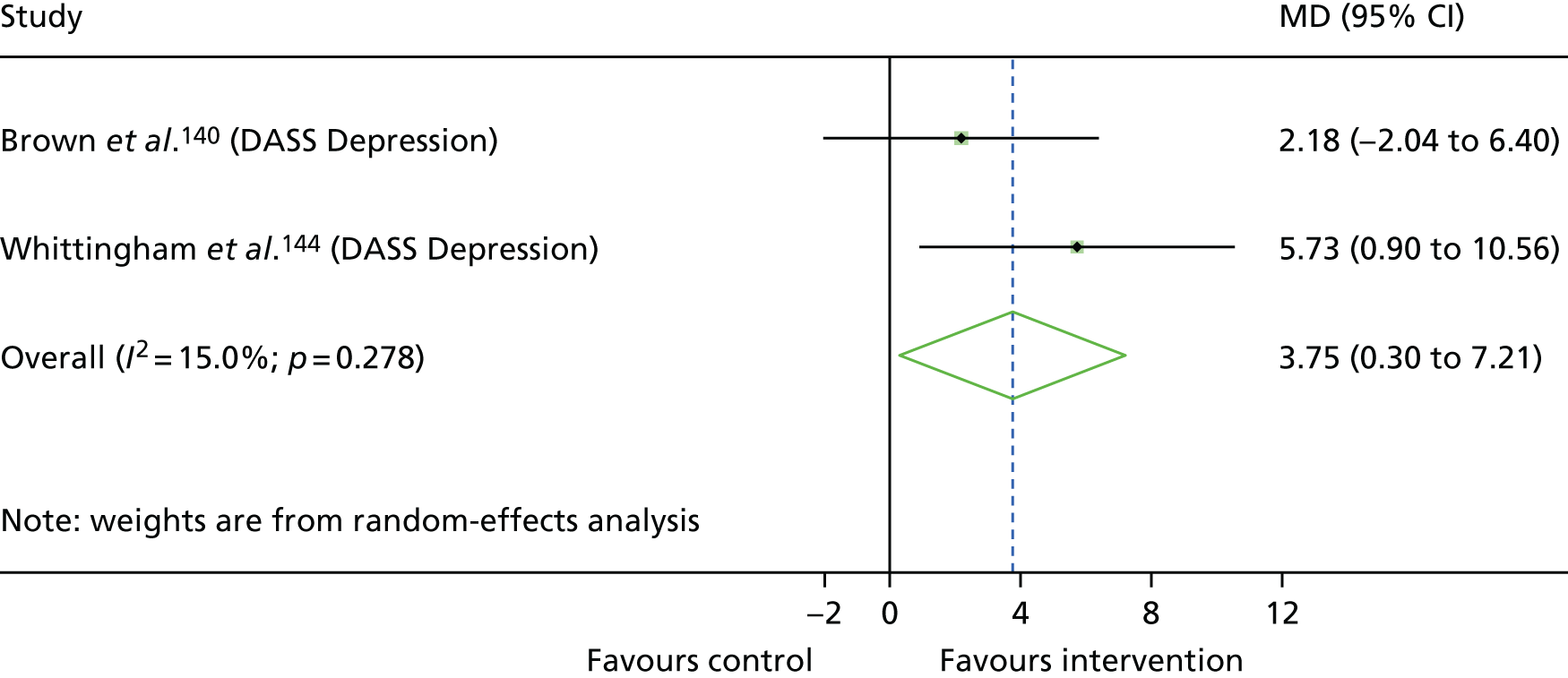

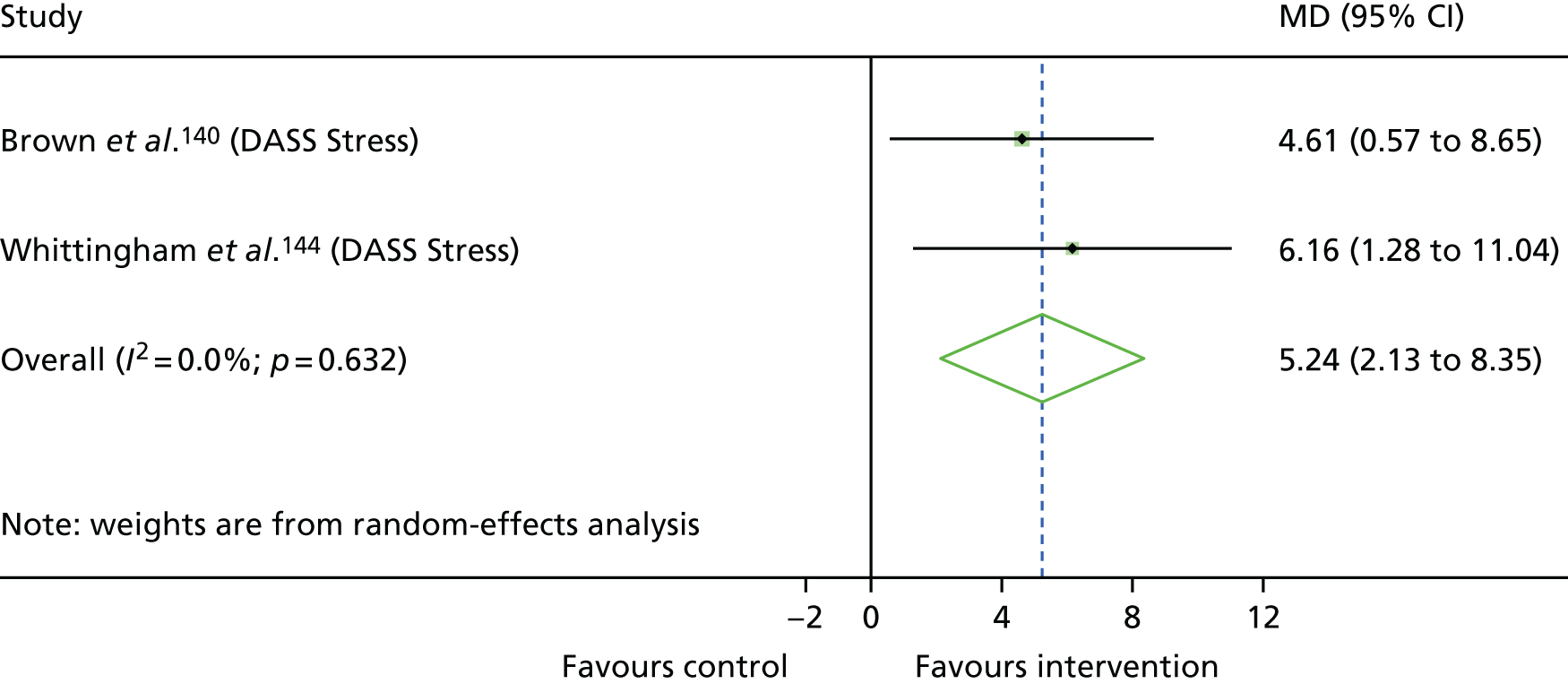

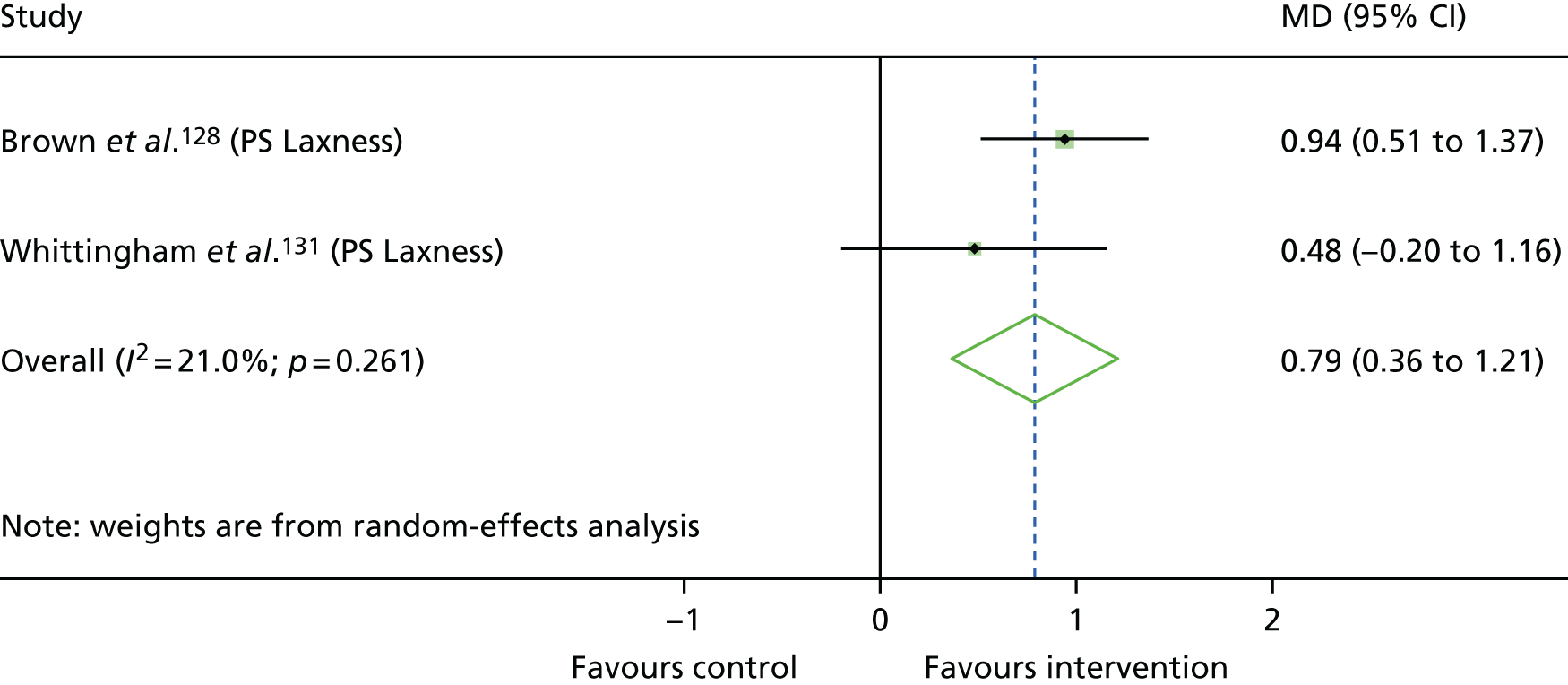

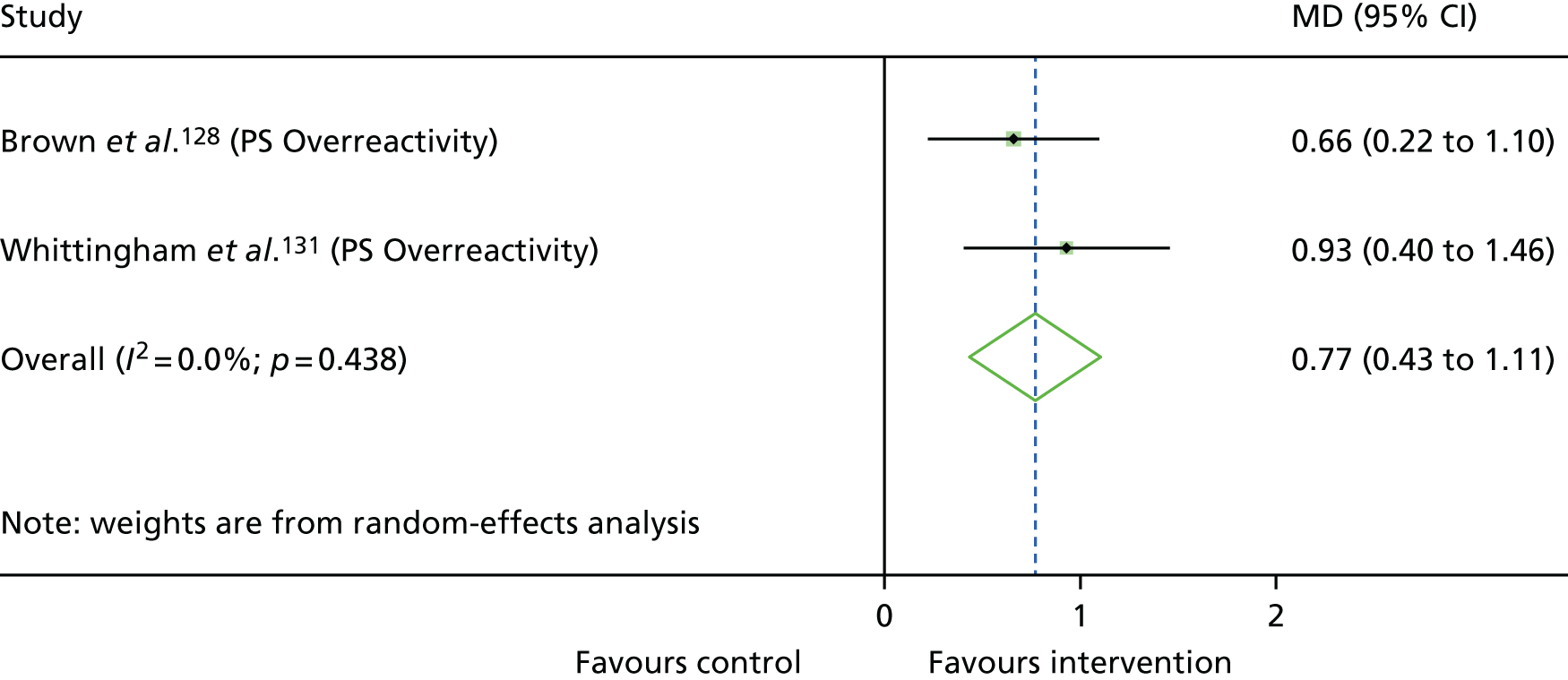

Parenting interventions with acceptance and commitment therapy