Notes

Article history

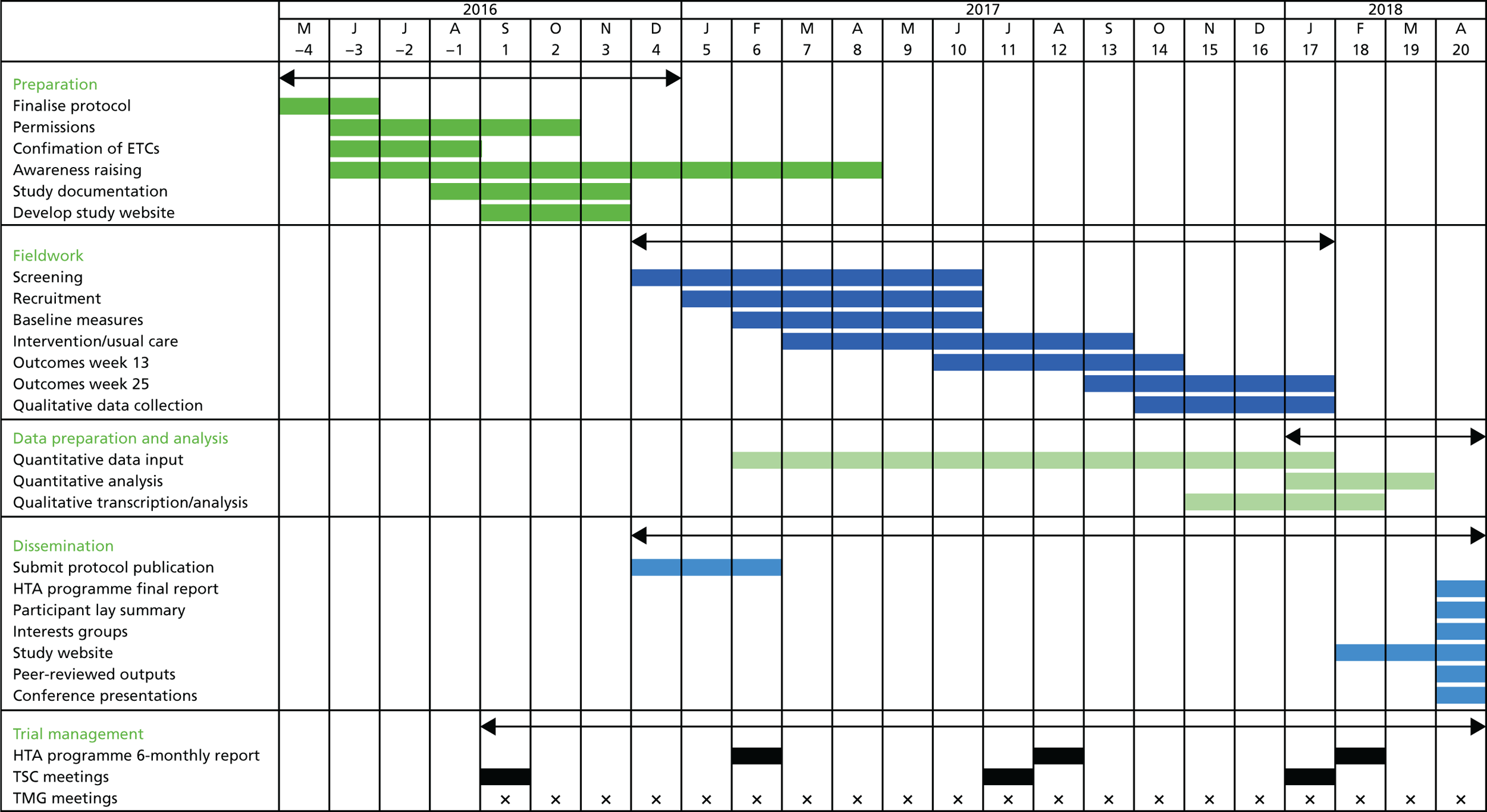

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 14/176/12. The contractual start date was in September 2016. The draft report began editorial review in May 2018 and was accepted for publication in October 2018. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Paul Ewings is a member of the National Institute for Health Research Health Technology Assessment Clinical Evaluation and Trials Board.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2019. This work was produced by Gunn et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2019 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Introduction

Background

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is an incurable, unpredictable but typically progressive, life-long neurological condition, affecting approximately 100,000 people in the UK. 1 It is the most common cause of neurological disability in young adults, with an estimated cost of £1.4B per annum to the NHS and society. 2 More recently, new insights into the burden and costs of MS in Europe have demonstrated that, on average, costs are €22,800 in mild, €37,100 in moderate and €57,500 in severe disease (adjusted for purchasing power parity). 3 Although most people start with a relapsing–remitting (RR) disease course, approximately two-thirds move to a progressive phase, with a gradual rise in the total percentage of progressive cases as the disease advances. 4 At this point, medical interventions are limited and further disease progression is usually inevitable. 5 People in this phase, the majority of whom have limited mobility, are often excluded from clinical trials, which tend to focus on the RR stage. 6

Balance and falls in multiple sclerosis

Eighty-five per cent of people with MS report gait disturbance as their main problem. 7 Within approximately 15 years of diagnosis, 50% of people are unable to walk unaided, and over time an estimated 25% are dependent on a wheelchair. 8 It is, therefore, unsurprising that mobility is a major concern for people with MS and the health professionals involved in their care, and an area that is consistently highlighted by research, policy and service user fora. Surveys of people with MS consistently rank mobility as their highest priority9 and the most important, yet most challenging, daily function. 10 Furthermore, mobility has been correlated with employment status, earnings and quality of life (QoL). 11,12 An important contributor to difficulties in mobility is impaired balance, which is reported by approximately 75% of people with MS13 and has been shown to be more compromised in people with secondary progressive multiple sclerosis (SPMS) than in those with relapsing–remitting multiple sclerosis (RRMS). 14 Our own work suggests that falls may be an early marker of mobility deterioration associated with disease progression. 15 Rehabilitation interventions that improve balance and physical activity and decrease the risk of falls may slow this deterioration, providing a persuasive argument for ensuring that optimal physical management is a clinical priority. With only limited medical interventions available for this patient group, such rehabilitation programmes are considered key to the treatment of SPMS but currently lack a robust evidence base. 5

Our research,16 in line with that of others, demonstrates that, alongside impaired mobility and balance, falls are a common issue for people with SPMS, who are twice as likely to fall as those with RRMS. 17 The evidence shows that approximately 70% of people with MS fall regularly,15 at a rate of > 26 falls per person per year with SPMS. 16 More than 10% of these falls lead to injuries18 and people with MS are three times more likely to sustain a fracture than the general population. 19 Falling and fear of falling have a profound impact on individuals, leading to activity curtailment, social isolation and a downwards spiral of immobility, deconditioning and disability accumulation. 20 This has significant implications for an individual’s health, well-being and QoL. Unsurprisingly, 4 out of the 10 research priorities identified by the James Lind MS Priority Setting Partnership relate directly to this area. 21 This trial has provided an opportunity for people with SPMS, whose limited mobility often excludes them from clinical trials, to participate in a trial targeting what they themselves consider to be a key concern.

Implications of impaired mobility and falls for society and for health practice

There are substantial economic and social costs related to increasing immobility, impaired balance and falls in people with MS. Costs of health and social care have been shown to increase steeply with increasing disease severity/immobility. 2 By this stage of the disease, rehabilitation interventions form the mainstay of treatment and drug therapy options are limited. The mean cost per wheelchair-dependent patient is four to five times higher than that for an ambulatory patient. 22 This, together with the associated costs of falls for those who continue to ambulate, underlines the importance of optimising safe mobility for as long as possible: a key aim of our work. This is particularly relevant given recent evidence that people with MS are living longer, leading to a rising population living with the disease. 23 This has important implications for resource provision in the UK and for the NHS, as highlighted in a national audit of neurological services,24 which demonstrated a significant increase in emergency hospital admissions in people with progressive neurological disability, including MS. The importance of mobility and falls is emphasised by their consistent prominence in recent policy documents for long-term neurological conditions. 25

An overwhelming proportion of a physiotherapist’s MS caseload comprises people who have balance and mobility impairments, many of whom are falling. Improving balance and mobility in people with SPMS and reducing falls is likely to have a significant impact on QoL and independence. Our recent literature reviews, however, demonstrate that there is a lack of available evidence to support this assertion, although data from mixed samples of patients with RRMS or SPMS are suggestive. 5,26 Furthermore, professionals and patients have identified serious problems with the feasibility and sustainability of a traditional weekly outpatient model of programme delivery. 27 The emphasis on evidence-based practice heavily influences whether or not interventions are provided, as does local policy. These decisions rely on the availability of robust evidence of clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness. Currently, there is minimal evidence-based guidance to inform optimal mobility management and none to inform falls management in people with MS. This paucity of evidence is highlighted in the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) clinical guideline 186,25 which nominates the rehabilitation of mobility as one of its five key research recommendations. Although evidence is available for older people and for other neurological conditions, research suggests that translating existing interventions to people with MS is likely to be ineffective. 28,29 Small, limited-duration studies have evaluated single elements of MS balance and falls interventions, individually demonstrating short-term improvements in mobility, balance or falls awareness,13,30,31 but these elements have not yet been implemented or evaluated collectively. Moreover, no studies have focused on people with SPMS.

The BRiMS programme

Development of the BRiMS programme

Health-care policy prioritises the need to empower patients to self-manage through partnership working and self-management programmes,32 with emphasis placed on a future NHS that implements interventions that promote self-care and lifestyle behavioural change and are community based. 33

In partnership with service users, providers, other key stakeholders (including commissioners) and international collaborators, our ongoing research programme systematically developed Balance Right in MS (BRiMS), an innovative, evidence-based, user-focused self-management programme, designed to improve safe mobility and reduce falls for people with MS. The development of BRiMS has been based on the Medical Research Council framework34 for the development and evaluation of complex interventions and supplementary guidance identifying specific tasks to be undertaken in the development process. 35 It was informed by input from a number of internationally recognised experts,36 which is explicitly acknowledged in the programme documentation. The programme’s underlying philosophy is based on the premise that interventions must promote lifestyle behavioural change, be community based and focus on prevention and self-care, an approach in line with the future direction of the NHS. 33

Overview of the BRiMS programme

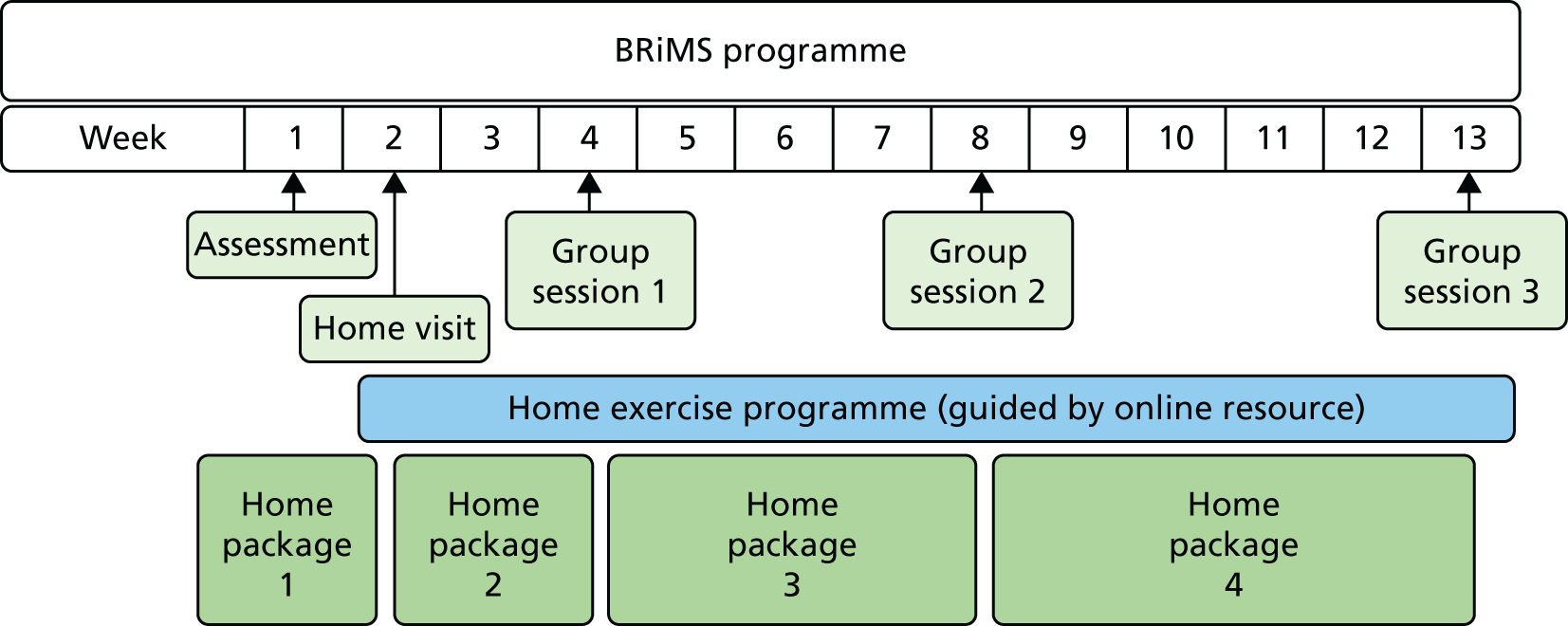

BRiMS is a novel 13-week, therapy-led personalised education and exercise programme structured to maximise the development of self-efficacy and support participant engagement (Figure 1). It addresses modifiable risk factors, enabling self-management by individualised mobility, safety and falls risk management strategies.

FIGURE 1.

The BRiMS programme delivery plan.

The programme includes two individual and three group sessions addressing physical, behavioural and environmental aspects of mobility and falls management. These are supplemented by a home-based package delivered via an established web-based interactive resource to ensure integration into daily life from the outset. As emphasised in the NICE guideline,25 this combined approach (which was developed in collaboration with people with MS, physical therapists, sports scientists, occupational therapists and psychologists) aims to equip the person with MS with the knowledge, skills and motivation to sustain long-term behaviour change. Developing and supporting motivation is addressed throughout using new functional imagery techniques37,38 to supplement established motivational techniques.

The BRiMS education component aims to improve exercise self-efficacy and develop individualised falls prevention and management practices through the acquisition and application of relevant knowledge and skills. 39 This component is delivered through a mix of home and group activities embedded throughout the programme. It utilises a number of evidence-based self-management practices, specifically group brainstorming, problem-solving and action-planning. 40 It also applies the principles of cognitive–behavioural therapy to facilitate self-efficacy enhancement. In group sessions, BRiMS utilises peer modelling, vicarious learning, social persuasion and guided mastery to boost self-efficacy41 and encourages the setting and imagery of short-term exercise goals to boost the desire to achieve them. 42

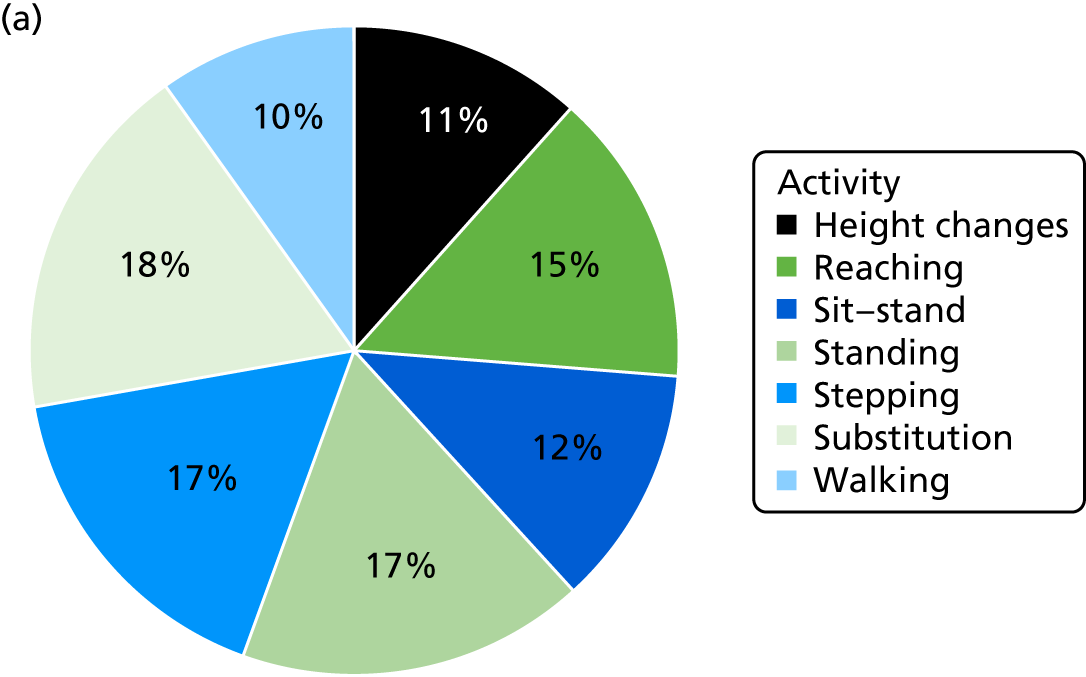

The BRiMS exercise component is designed to achieve a minimum of 120 minutes of individualised, progressive, gait, balance and functional training per week. The content is guided by a comprehensive literature review of MS balance exercise interventions,43 while the structure and format are informed by comprehensive stakeholder input. 27

The BRiMS exercise component is designed to be predominantly home-based, with exercise planning and progression undertaken in partnership between the participant and the programme leader. The group sessions include exercise activities to encourage peer support and problem-solving. Motivational support is built into both elements. Additionally, BRiMS integrates an online exercise prescription resource (https://webbasedphysio.com)44 to support and guide participants’ home-based practice. The resource can be customised to the participant’s individual exercise prescription and remotely amended during the programme to maintain an appropriate level of challenge.

Intervention description and standardisation

The BRiMS programme has been manualised to provide a detailed description of the intervention and to ensure consistency of content, approach and delivery of sessions across time, region and groups. The manual includes identification of the critical elements of each part of the programme, key objectives of each session and detailed guidance/scripts for programme leaders along with accompanying participant resources.

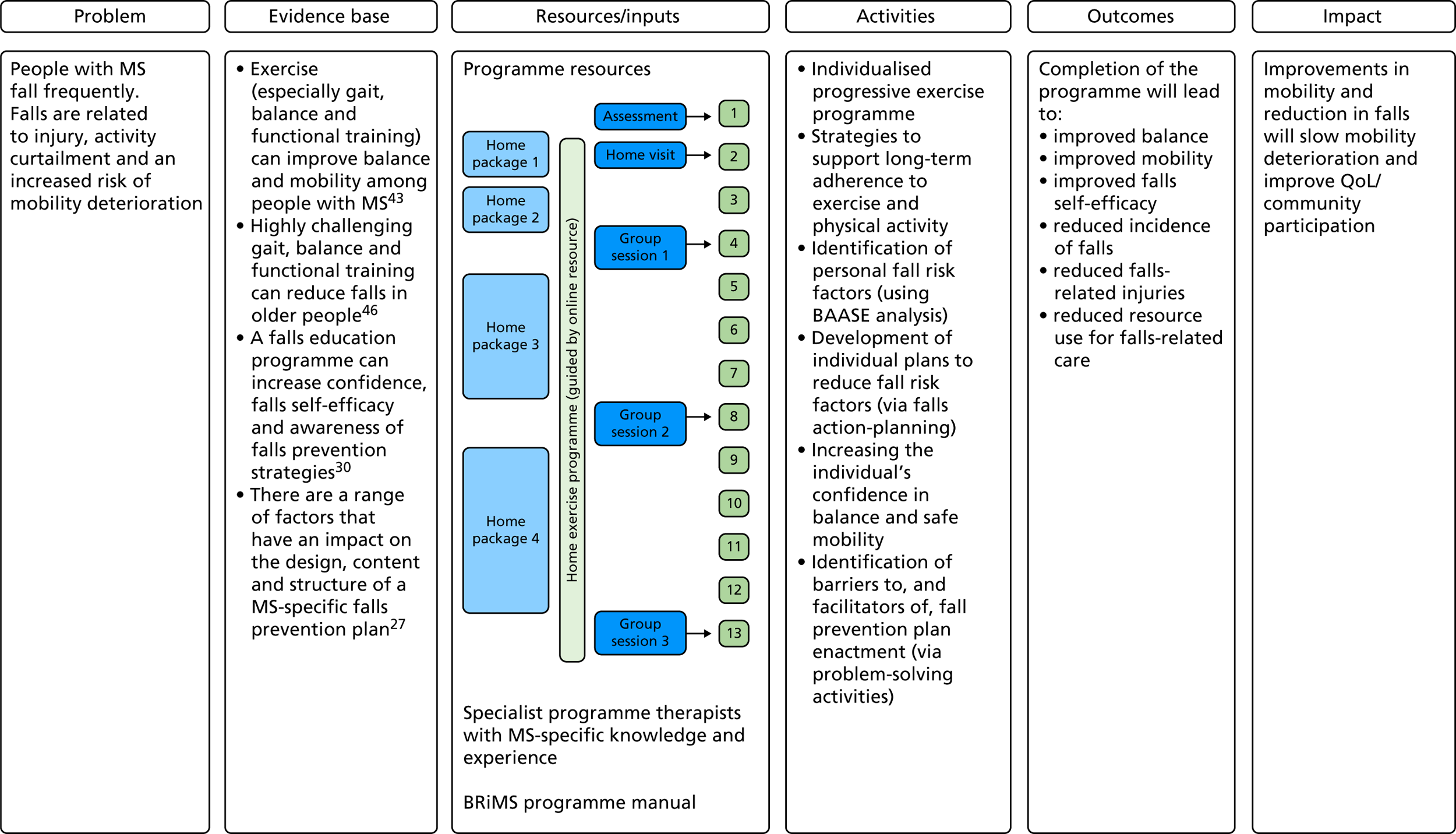

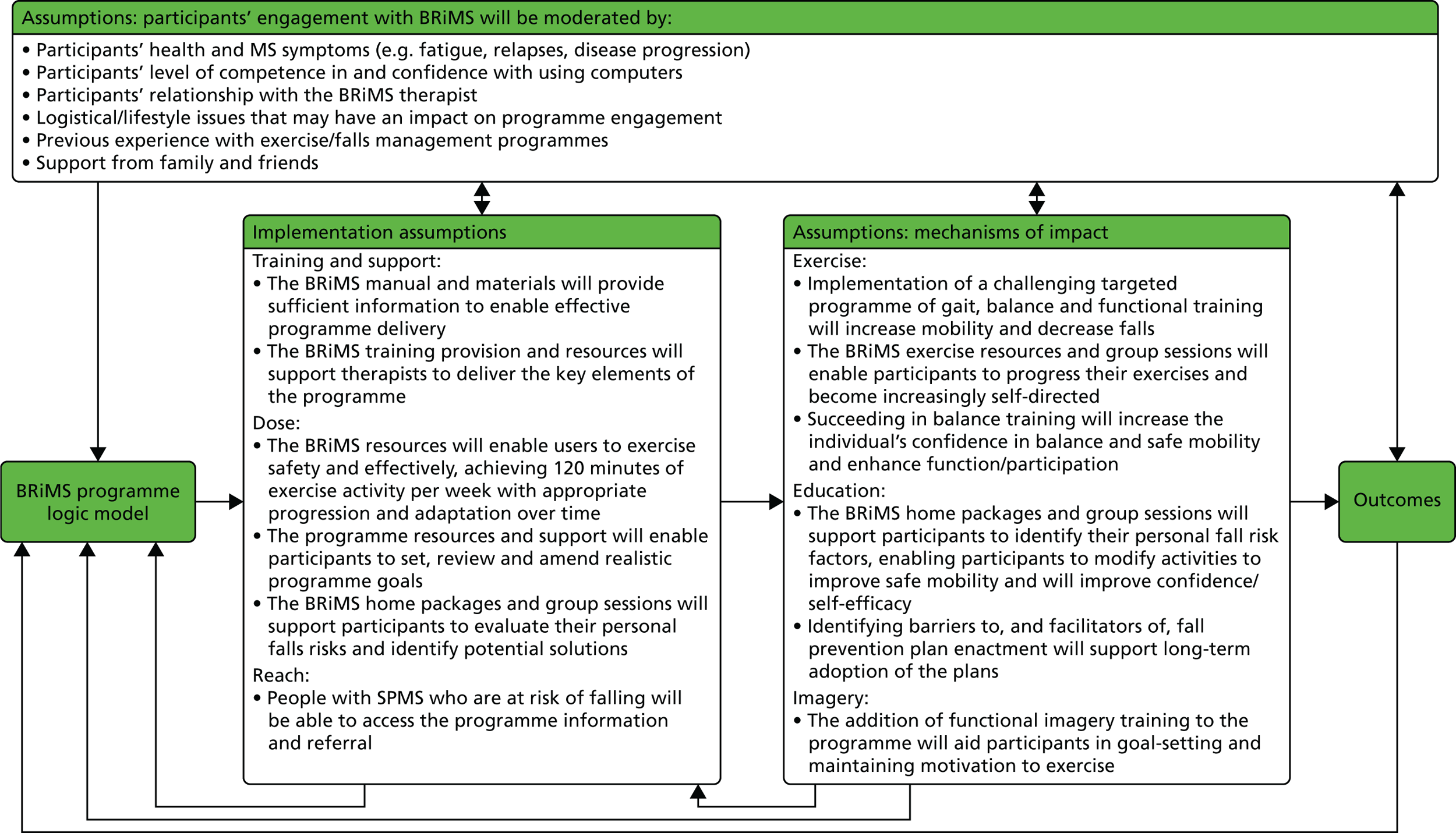

Figure 2 shows the BRiMS ‘logic model’,45 which maps the programme content and delivery methods, along with causal assumptions, the mechanisms that are theorised to drive the programme and any expected external factors that may affect the outcomes. Table 1 provides an overview of the schedule of content delivery.

FIGURE 2.

The BRiMS programme logic model. BAASE, Behaviours and Attitudes, Activities, MS Symptoms, Environment.

| Week | BRiMS activities |

|---|---|

| 1 |

Session 1: individual assessment and introduction to the programme. The therapist develops a personalised exercise programme based on assessment findings and agreed outcomes Takes place at a local health-care establishment Home activities: patient receives BRiMS manual and website login, and completes first home package |

| 2 | Session 2: home visit by BRiMS therapist to explain and set up the exercise programme |

| 2–4 |

Home-based individual practice of exercise programme, plus education activities, with online support from the BRiMS therapist Therapist undertakes online review and adjustment of web-based exercise prescription every 2 weeks |

| 4 |

Group session 1: group exercise and education activities Takes place at a local health-care establishment |

| 5–8 | Home-based practice of exercise programme, plus education activities |

| 8 |

Group session 2: group exercise and education activities Takes place at a local health-care establishment |

| 9–13 | Home-based practice of exercise programme, plus education activities |

| 13 |

Group session 3: group exercise and education activities Takes place at a local health-care establishment |

Trial rationale and objectives

The National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) commissioning brief (Health Technology Assessment 15/47) requested applications for studies undertaking primary research in rehabilitation therapies to improve QoL in patients with SPMS. Having previously developed BRiMS, it was critical, and timely, to assess the feasibility of delivering this programme and the proposed evaluation methods before undertaking a definitive trial to assess the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of the programme.

There were a number of uncertainties about the optimal parameters for the definitive trial. This current trial tested the feasibility of conducting such a trial, providing estimates of recruitment, attrition and concordance, completion rates of measures, and baseline scores and standard deviations (SDs) of proposed outcomes. We also assessed the acceptability of the intervention, and of participating in the trial, from both the participants’ and the health professionals’ perspectives, and the process of delivering BRiMS.

This feasibility trial aimed to obtain the necessary data and operational experience to finalise the planning of an intended future definitive multicentre randomised controlled trial (RCT) to compare a manualised 13-week education and exercise programme (BRiMS) plus usual care with usual care alone in improving mobility, improving QoL and reducing falls in people with SPMS. The intention was to learn lessons to enable a definitive trial to be successfully delivered with confidence. The objectives were divided into four areas, as follows.

Trial feasibility objectives

To determine the:

-

feasibility, utility and acceptability of the trial procedures

-

suitability and feasibility of eligibility criteria

-

numbers of eligible participants from the target population

-

willingness of clinicians to recruit patients

-

willingness of patients to be randomised

-

likely recruitment and retention rates as participants move through the trial.

Potential full trial outcome objectives

To determine the:

-

completion and performance of proposed outcome measures, including rates of outcome measure completion, baseline scores, distributional properties and SDs of outcome measures, and responsiveness to inform selection of primary outcome (and refine the number of secondary outcomes) for a definitive trial

-

baseline factors most strongly associated with outcomes, as potential stratification factors in a definitive trial

-

sample size required for a fully powered RCT to evaluate the effectiveness of the BRiMS intervention.

BRiMS programme feasibility (process evaluation) objectives

To determine:

-

the optimum way of delivering the BRiMS programme

-

intervention fidelity and application between sites

-

the acceptability of, and adherence to, the 13-week BRiMS programme.

Health economics objectives

To determine:

-

estimates of resource use and related costs associated with delivery of the BRiMS intervention

-

a framework for assessing the cost-effectiveness of the BRiMS intervention in a future economic evaluation alongside a full trial.

Chapter 2 Trial design and methods

This was a pragmatic, multicentre, feasibility RCT with blinded outcome assessment. Participants were randomised either to a manualised 13-week education and exercise programme (BRiMS) plus usual care (intervention group), or to usual care alone (usual-care group). The protocol for the trial has been published previously. 47

Trial participants

The target population was English-speaking men and women aged ≥ 18 years who had a confirmed diagnosis of SPMS and reported having walking difficulties and experiencing falls. This population constitutes an estimated 70% of all individuals with SPMS, as, by the time this phase has been reached, balance, mobility and physical activity levels are usually compromised.

The trial was explicitly designed to have high applicability to people with SPMS, and so it used broad inclusion criteria and relatively few exclusion criteria.

Inclusion criteria

The patient:

-

Had a confirmed diagnosis of MS as determined by a neurologist; and, in the secondary progressive phase, as confirmed by a MS specialist clinician.

-

Was aged ≥ 18 years.

-

Was willing and able to understand/comply with all trial activities.

-

Had an Expanded Disability Status Scale (EDSS) score of between ≥ 4.0 and ≤ 7.0 points.

-

Had self-reported two or more falls in the past 6 months.

-

Was willing and able to travel to and participate in BRiMS group sessions at local sites and to commit to undertaking their individualised home-based programme.

-

Had access to a computer or tablet and to the internet.

Exclusion criteria

The patient:

-

Had reported relapse or receiving steroid treatment within the past month (patient-reported relapse is defined as ‘the appearance of new symptoms, or the return of old symptoms, for a period of 24 hours or more – in the absence of a change in core body temperature or infection’). 48

-

Had any recent changes in disease-modifying therapies. More specifically, patients were excluded if they:

-

had ever had previous treatment with alemtuzumab (Lemtrada®, Sanofi Genzyme, Cambridge, MA, USA) because it was felt to be a major disease modifier that had long-term effects after the usual courses given 12 months apart; or

-

had ceased nataluzimab (Tysabri®, Biogen, Cambridge, MA, USA) in the previous 6 months; or

-

were within 3 months of ceasing any other MS disease-modifying drug.

-

-

Had participated in a falls management programme (e.g. for older people) within the previous 6 months.

-

Had comorbidities that may have influenced their ability to participate safely in the programme or that were likely to have an impact on the trial (e.g. uncontrolled epilepsy).

-

Had been recruited to a concurrent interventional trial.

Trial settings

The sites involved were based in two geographical regions of the UK: south-west England (Devon/Cornwall) and Ayrshire.

Research activity took place at four sites:

-

Plymouth

-

Exeter

-

Cornwall

-

Ayrshire and Arran.

All sites implemented the trial protocol in the same manner. Physiotherapists (treating therapists) from each of these sites performed the interventions (as part of their NHS role) and two BRiMS research therapists (employed specifically for the trial) undertook the blinded assessments.

Sample size

In accordance with relevant best-practice,49 we wanted to test processes within and across the three sites to ensure that this feasibility trial gave a realistic indication of the practicalities for conducting the intended full trial. This included gaining robust information on likely recruitment and retention rates and full testing of the procedures involved in all trial processes. Therefore, the more common sample size calculation, based on considerations of power for detecting a between-group clinically meaningful difference in a primary clinical outcome, was not appropriate. 18

From other studies in similar settings, it was estimated that retention rates would be in the region of 80%. 19,20 A target sample size of 60 participants in total would allow estimation of the overall retention rate with precision of at least ± 13%; for example, if the 6-month follow-up rate was around 80%, the estimate would have precision of ± 10%. Assuming a non-differential follow-up rate at 6 months of 80%, it was estimated that recruiting 60 participants would provide outcome data on a minimum of 24 participants in each of the two allocated groups, enabling reasonable estimates to be made of the variability (i.e. SD) in each of the proposed outcomes.

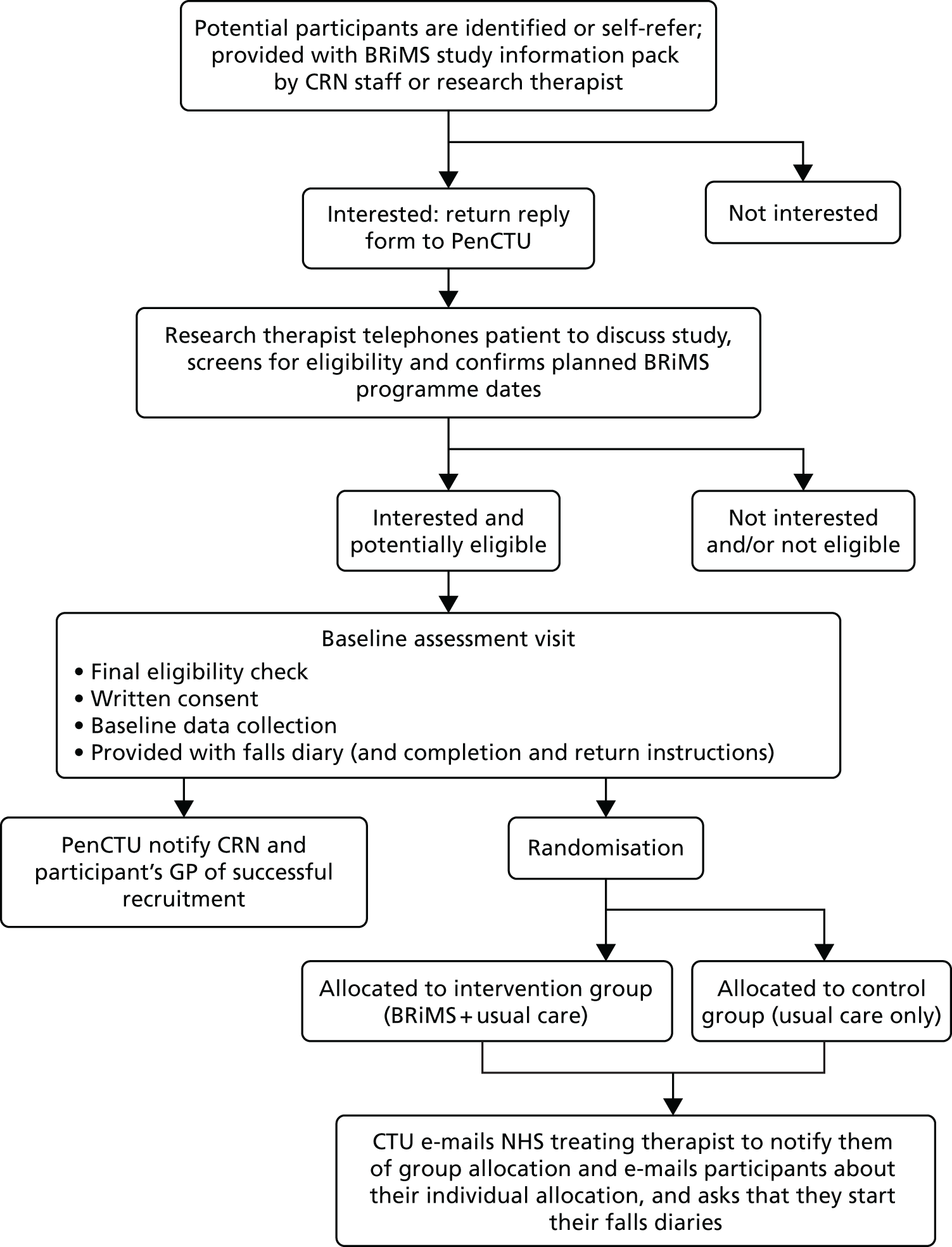

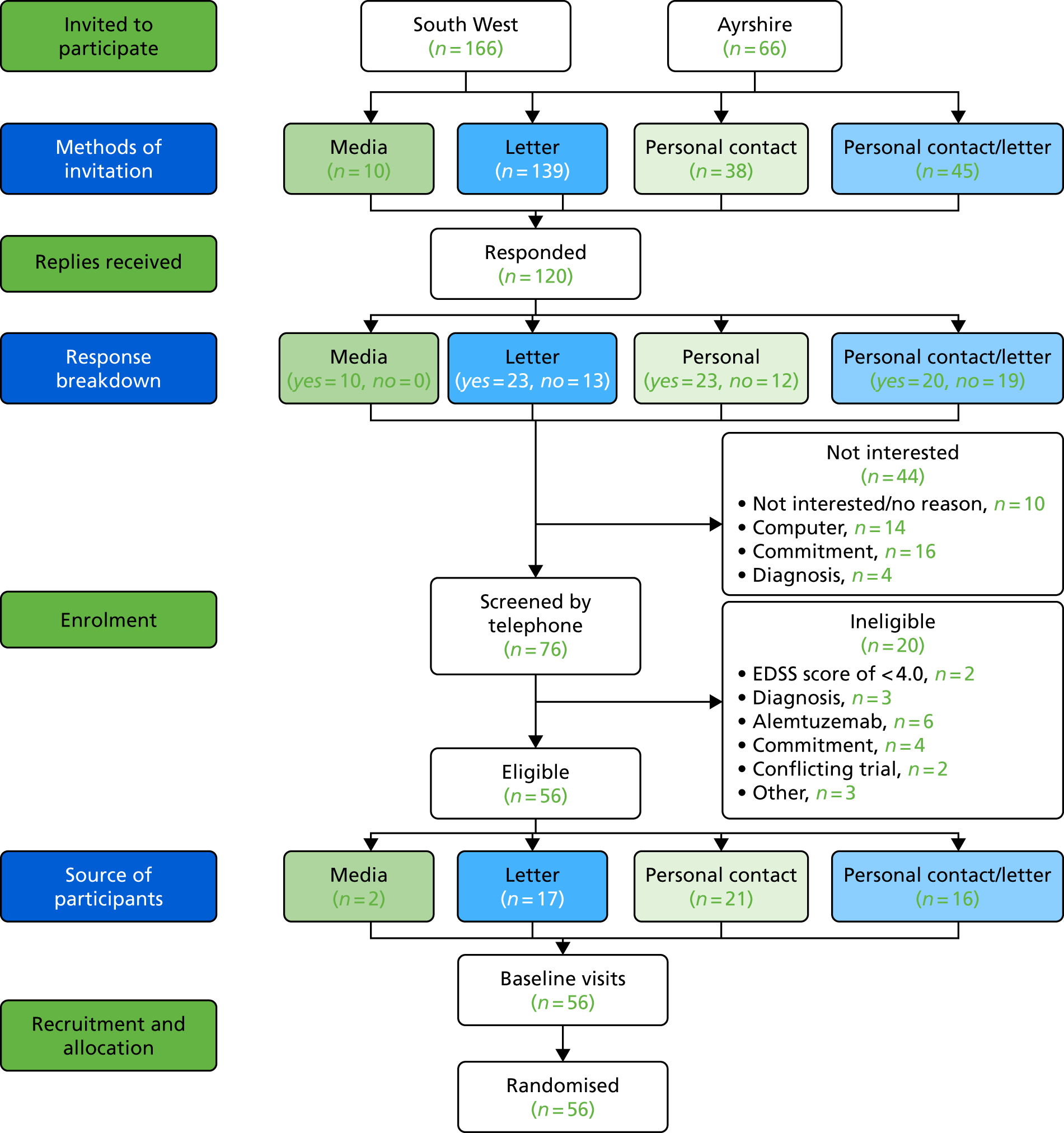

Recruitment and screening

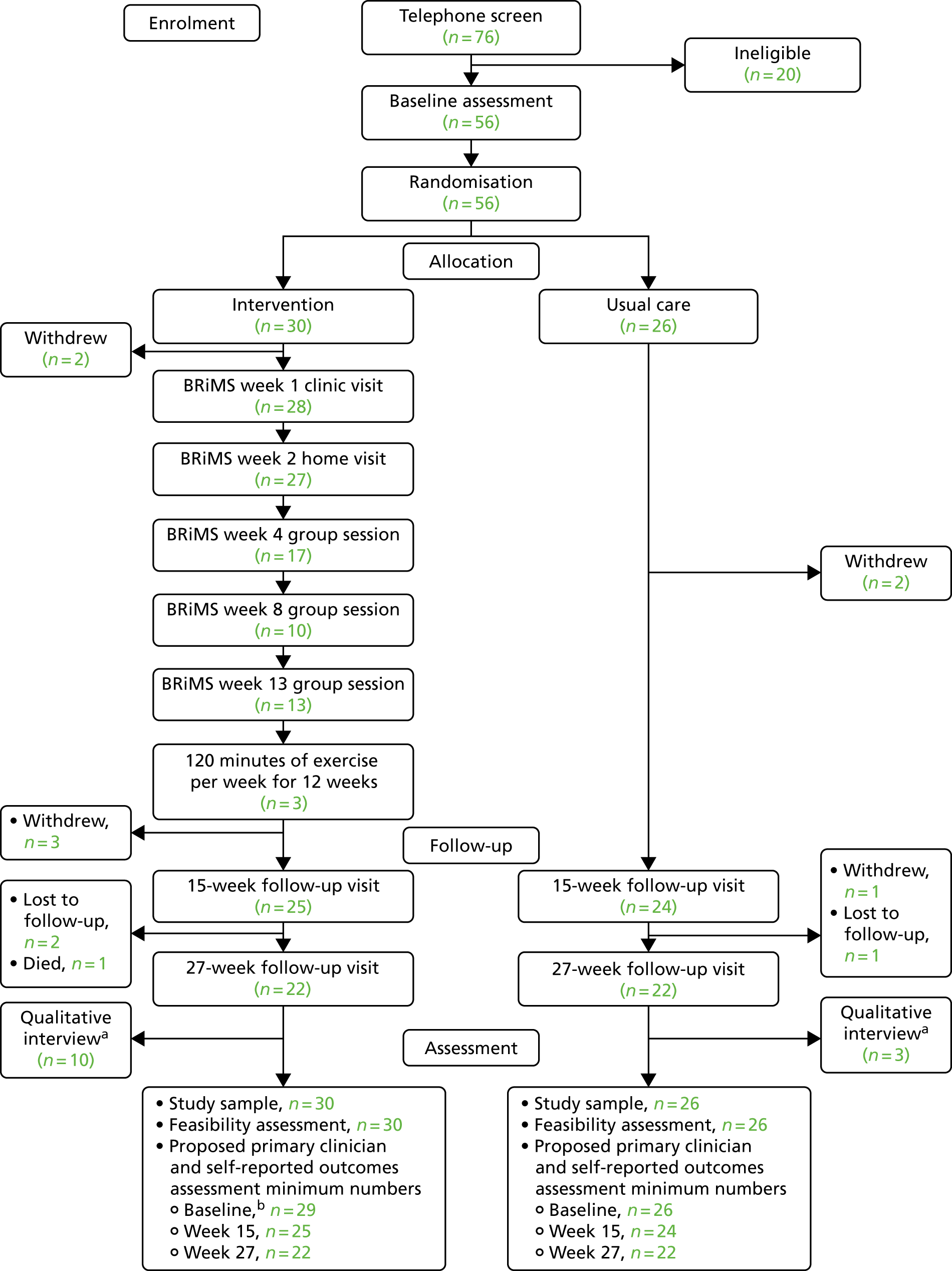

A summary of the recruitment and screening process is shown in Figure 3.

FIGURE 3.

Recruitment pathway. CRN, Clinical Research Network; GP, general practitioner; PenCTU, Peninsula Clinical Trials Unit.

Recruitment

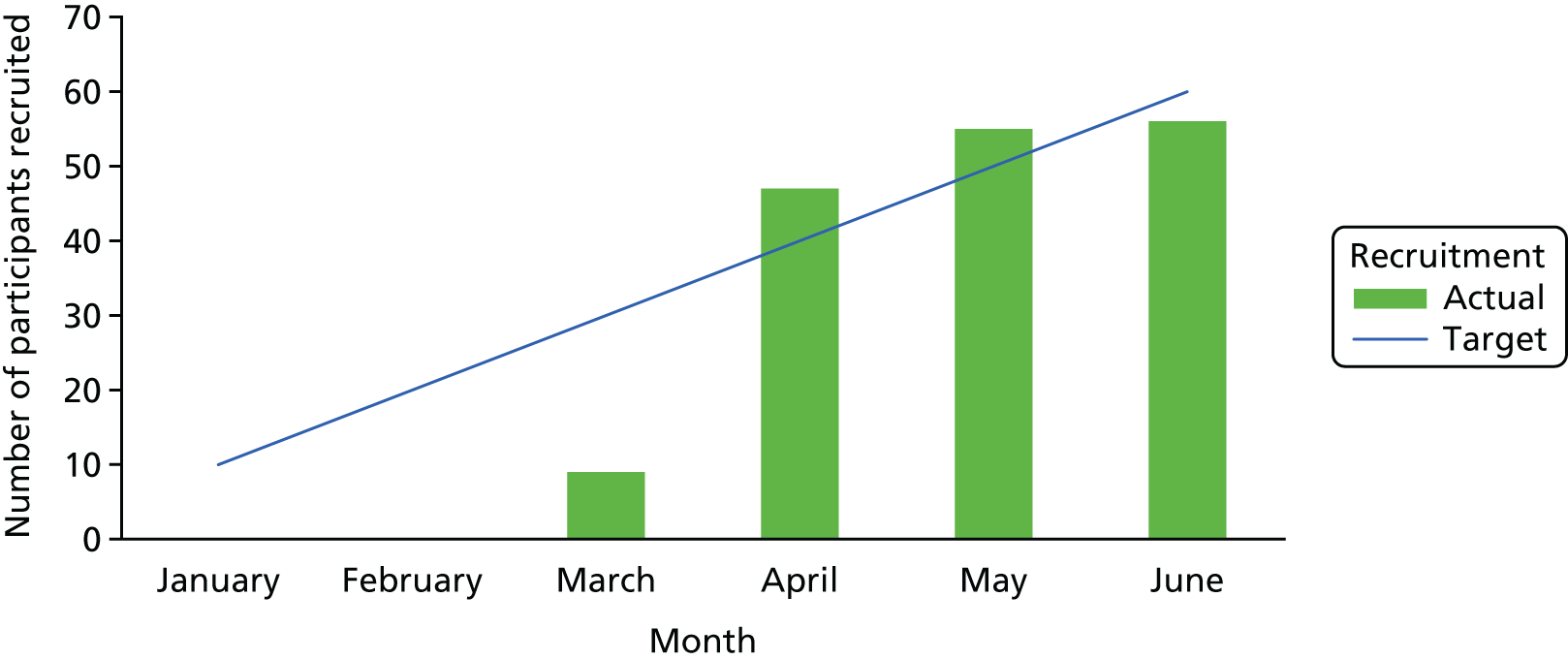

To our knowledge, there are no data that report recruitment rates to MS clinical trials from national sources and so it was difficult to estimate what these would be. This feasibility trial aimed to elucidate this, as we recorded the sources of recruitment for all participants. However, for this feasibility trial, we could be more confident of recruitment rates from the local sites involved. For example, our previous work15,50 in ambulant individuals with MS, using similar local recruitment methods, demonstrated high recruitment rates, with 60–65% of those who were eligible participating. However, given that BRiMS involved attendance at three group sessions and the commitment to undertake a home-based exercise programme and work package, we believed that a 50% local recruitment rate was more realistic. Based on this, and on a conservative estimate of approximately 600 eligible local participants (Devon/Cornwall, n = 284; Ayrshire, n = 330), our data demonstrated that sufficient numbers of eligible people would be available within our two recruiting regions from whom to recruit our target sample.

For this feasibility trial, the aim was to recruit 60 participants across the four sites (40 in the south-west and 20 in Ayrshire) over 6 months. This meant running six intervention groups, each with approximately five participants. It was anticipated that, to recruit these 60 participants, around 240 people would need to be screened, assuming that around 80% would agree to participate (n = 190), of whom approximately 35% (n = 70) would be found to be ineligible after screening, leaving around 120 eligible people. Following this screening, it was anticipated that approximately 50% of eligible people would consent to participate, leaving around 60 participants to be randomised.

Our recruitment period was relatively short, at 6 months. Our rationale for this was efficiency: to minimise the overall length and, therefore, the cost of this feasibility trial. Trial awareness-raising activities commenced during the 4-month set-up period. In line with recommendations from Treweek et al. ’s51 systematic review, a multifaceted recruitment approach was undertaken using both national and local routes. In doing this, we anticipated that we would have a list of potential participants to screen as soon as sites confirmed research capacity and capability. As necessary, during the recruitment period we complemented this approach by utilising direct recruitment strategies. Our first priority was to send out consultant invitation letters, as this has been demonstrated to be a cost-effective strategy for recruitment in other MS rehabilitation trials. 52–54

Nationally, recruitment was promoted via a number of sources:

-

the UK MS Register via their quarterly newsletter and social networking sites

-

promotion through the MS charitable bodies’ regular open access newsletters (i.e. MS Society ‘Research Matters’)

-

promotion through the MS Society online resources that alert people with MS to studies they may be interested in participating in

-

promotion and support from the NIHR Clinical Research Network (CRN) and national specialty lead for neurology

-

the trial’s website (www.brims.org.uk), which included generic e-mail contact details.

All promotional materials included information inviting people to make contact via the trial’s generic e-mail address. These e-mails were monitored by the Peninsula Clinical Trials Unit (PenCTU), which triaged enquiries and redirected them to the appropriate research therapist.

Local recruitment was also promoted via a number of routes, which included:

-

adoption onto the UK CRN Portfolio; the local Clinical Research specialty lead also promoted the trial through existing clinical networks

-

through the caseloads of neurologists, MS specialist nurses and NHS therapists who discussed the trial with interested patients, or wrote a letter of invitation to potential participants

-

leaflets and posters placed in relevant outpatient clinics of the participating health establishments

-

promotion through local initiatives where they existed, for example the South West Impact of MS (SWIMS) project55

-

local MS centres and MS Society branches, via posters, newsletters, personal contact with the regional and branch leaders, and informal presentations at local MS branch meetings.

All people with MS who expressed an interest in participating were sent a BRiMS trial information pack by the CRN staff or research therapists at the appropriate site. The pack consisted of a letter of invitation, the participant information sheet, a list of local pre-scheduled BRiMS programme dates and venues, a reply form and a reply-paid envelope. Where packs were distributed through direct contact (either face to face or by telephone), potential participants were given the option to be contacted by the local research therapist to verbally discuss the project and ask any questions. If the potential participant opted in to this option, the member of staff passed the person’s name and contact details (e-mail address or telephone number) to the local research therapist.

All patients were asked to read the participant information sheet and return the reply form to indicate their interest, to confirm that they felt they were eligible, and to give consent for the staff undertaking screening to contact their treating team to confirm their diagnosis of SPMS. This also gave the CRN staff or research therapists permission to contact the potential participant to establish fully whether or not the individual met the trial’s eligibility criteria.

Screening

On receipt of the completed reply form, the research therapist telephoned the person with MS to answer any further questions and to screen them for eligibility using a pre-formatted screening checklist based on the eligibility criteria. This included determining the person’s disability level using a telephone version of the EDSS. 56 During this screening telephone call, the participant’s preferred contact details were confirmed and the planned dates of the BRiMS programme were discussed to ensure that they were able to attend if they were allocated to the BRiMS group. Screen failures (i.e. patients who did not meet the eligibility criteria at time of screening) were informed if they were eligible for re-screening at a later date and, in this case, the research therapist arranged a follow-up screening call for a suitable date.

Clinical Research Network staff and research therapists maintained a screening log of potential participants who made contact with the research team to be considered for entry to the trial. Anonymised data from the screening log were transferred to PenCTU as required for the purpose of monitoring recruitment. These data included the reason individuals were not eligible for trial participation, if they were eligible but declined, and their reason(s) for declining if they were happy to divulge this. Furthermore, a record was kept of all people who were sent invitation letters to determine the proportion of those who expressed an interest in the trial.

Once initial eligibility checks were completed, the individual’s details were forwarded on to the research therapist (if screening had been undertaken by CRN staff). The research therapist telephoned the participant to confirm eligibility and send an appointment e-mail for the baseline assessment. It was the intention that the final face-to-face screening and the baseline assessment would be undertaken up to 2 weeks before the participant commenced the pre-scheduled BRiMS programme, should they subsequently be allocated to the intervention group. To minimise travel costs and burden on the participants, this baseline assessment was undertaken at a local health-care establishment. Reasonable travel expenses were reimbursed for all visits additional to normal care, namely for the three research assessments at the local health-care establishments at day 0, 15 weeks (± 1 week) after randomisation and 27 weeks (± 1 week) after randomisation. All participants were reminded that the allocation to either group of the trial was by chance and would occur after baseline assessment (see the next section).

Randomisation, concealment and blinding

The group-based element of the BRiMS intervention necessitated the confirmed recruitment and participation of a sufficient number of patients within a recruiting site before randomisation was undertaken. Each of the four sites aimed to recruit 10 participants per block/BRiMS delivery, but there was flexibility to recruit 8–12 participants. After the completion of the block of participants, each participant within the block was randomised (i.e. all participants within a block were simultaneously randomised). A participant was deemed recruited once they had provided written informed consent, confirmed their ability to attend a BRiMS group and completed the baseline assessment.

Once the decision was taken to declare a block of participants complete, randomisation was undertaken a minimum of 3 and a maximum of 7 working days before the BRiMS programme commenced. Individuals in the block were randomised approximately 1 : 1 to the intervention or usual-care arm following a strict and auditable protocol. When the block size was 9 or 11, allocation was forced to have one more participant in the intervention group than the usual-care group to maximise learning opportunities in this feasibility trial. Randomisation was conducted via a secure web-based system. The randomised allocations were computer-generated by PenCTU in conjunction with a statistician independent to the trial team, in accordance with PenCTU’s relevant standard operating procedure. An automatic e-mail was sent by PenCTU to the NHS treating therapist leading the BRiMS programme to notify them of those participants allocated to the BRiMS programme plus usual care (intervention).

Access to the randomisation process was confined to the PenCTU data programmer only. This ensured effective allocation concealment from every other member of the trial team. Following randomisation, only appropriate members of the trial team were made aware of the allocations to the intervention or usual-care arm [e.g. clinical trials unit (CTU) trial manager, chief investigator and site principal investigators]. Clearly, the participants and the NHS treating therapists leading the BRiMS programme could not be blinded to which treatment the participants were receiving. However, the research therapist (outcome assessor) remained blinded to the allocated treatment arm at all stages. In addition, the trial statisticians remained blinded until the database was locked for analyses.

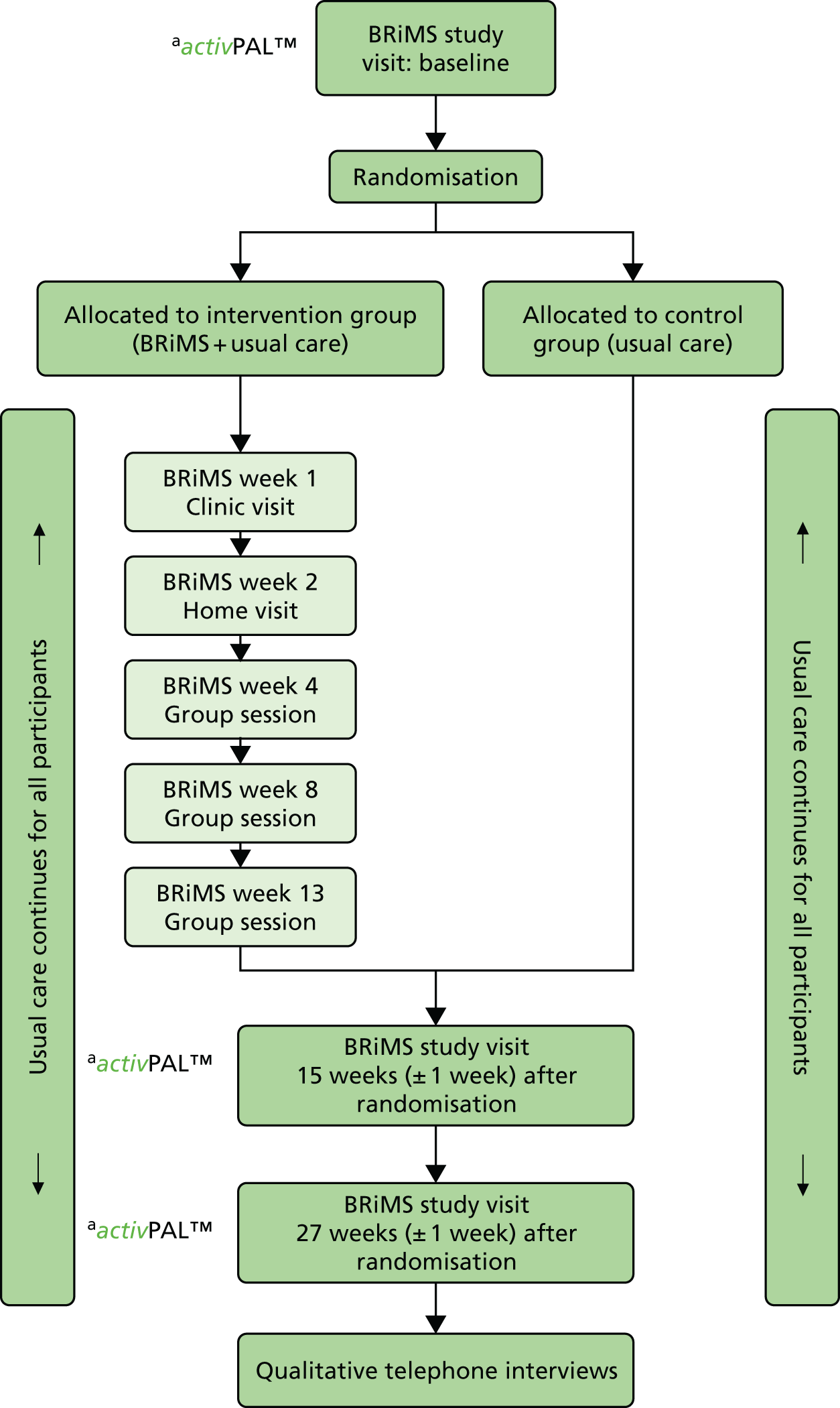

Treatment

The two trial groups are shown in Figure 4, which includes a summary of the participant pathway.

FIGURE 4.

Participant pathway. activPAL™ (Paltechnologies Ltd, Glasgow, UK). a, All participants wear the activity monitor for 1 week from visit and then return it to the research therapist.

Usual care (usual-care group)

All participants allocated to this group continued to receive their usual clinical care; thus, with the exception of the trial assessments, they were not asked to attend any additional visits or sessions. Although usual care varies across the country,57 it rarely involves regular ongoing physiotherapy intervention in the community or as an outpatient on either an individual or a group basis. As a general rule, for those with SPMS, physiotherapy input is provided when an event has caused a significant deterioration in the person’s ability to function (e.g. a respiratory infection or an injurious fall). The standard physiotherapy care pathway usually comprises short, intermittent episodes of face-to-face intervention, which are generally limited to a few sessions. The typical approach and content of these sessions is one wherein presenting problems are managed (e.g. providing mobility aids, a written home exercise programme and advice) rather than focusing on the promotion of long-term self-management strategies.

For people with mobility impairment who are at risk of falling, physiotherapy regimes typically consist of gait re-education and the provision of a written home exercise programme, which is aimed at strengthening muscles and/or optimising balance. In line with NICE guidelines,7 for individuals with mild to moderate disability, advice may also be given to enhance cardiovascular fitness, as this has been demonstrated to optimise general physical and emotional well-being and minimise deconditioning. For individuals whose mobility is more severely impaired, advice and information to support their carer in terms of facilitating movement (e.g. manual handling advice to enhance the safety of assisted transfers) may be given.

Usual care may also involve appointments with a variety of other health professionals (e.g. an occupational therapist, a general practitioner, a MS nurse specialist, a neurologist or a rehabilitation consultant). As with physiotherapy, multidisciplinary interventions are usually short term as resource restrictions limit the provision of long-term maintenance therapy.

Falls programmes for older people exist in most locations across the UK;58 however, anecdotal evidence highlights that people with MS are seldom referred to these services. 27 Some programmes specifically exclude those with neurological conditions from attending, and have lower minimum age restrictions, which present further barriers.

This trial recorded the content of usual care on the participant resource-use questionnaire at each trial assessment. Details of actual use for both groups are in see Table 41.

Usual care plus BRiMS (intervention group)

During the trial, six deliveries of the BRiMS programme were undertaken. The dates were planned in advance to secure the services of the NHS treating therapists at each site and to facilitate participants’ advance diary planning. The intervention groups were conducted by band 7 NHS physiotherapists who were experienced clinical specialist neurological therapists (see Table 25). The therapist training took the form of a 1-day workshop delivered by two members of the research team (HG and JA), which all treating therapists attended. The workshop included an overview of the key elements of the programme, interactive sessions to introduce therapists to less familiar activities and an opportunity to practise setting up and amending the online exercise activities. Ongoing support was provided in the form of an online forum, promoting peer support and with additional input from a member of the research team (JA).

As participants were recruited in blocks that were related to each programme delivery, they were already aware of the expected programme dates. Therefore, when participants received confirmation that they had been allocated to the intervention group, they were simply contacted by the relevant treating therapist to arrange the one-to-one sessions and to confirm their ongoing availability for the group sessions. All BRiMS programmes were delivered in accordance with the programme manual and plan (see Chapter 1, The BRiMS programme). In addition to participating in the BRiMS programme, all of those allocated to this group were encouraged to continue utilising their usual clinical care and services.

Data collection and outcome measures

The BRiMS trial had four main analytical strands:

-

evaluation of trial feasibility

-

clinical outcomes

-

health economics evaluation

-

BRiMS programme process evaluation.

All of the required data, assessment tools, collection time points and processes are summarised in Table 2.

| Outcome group/measure | Objective | Evaluation time point(s) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | 13 weeks ± 1 weeka | 27 weeks ± 1 weeka | Post trial | ||

| Trial feasibility | |||||

|

i–vi | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | |

|

✗ | ||||

|

→ | ||||

| Potential full trial outcomes | |||||

| Participant characteristics | |||||

|

✗ | ||||

|

✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ||

| Primary outcomes | |||||

|

vii–ix | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | |

|

✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ||

|

✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ||

| Secondary outcomes | |||||

|

vii–ix | → | |||

|

✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ||

|

✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ||

|

✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ||

|

✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ||

|

✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ||

|

✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ||

| BRiMS programme feasibility (process evaluation) | |||||

| Programme acceptability and feasibility (participant and therapist interviews) | x, xii | ✗ | |||

|

x–xii | → | |||

|

|||||

|

|||||

| Health economics | |||||

|

xiii–xv | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | |

|

✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ||

Evaluation of trial feasibility (objectives i–vi)

Feasibility outcomes

-

Recruitment, retention and attrition rates [Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) data]: number of patients assessed for eligibility, reasons for exclusion, numbers lost to follow-up, numbers discontinuing (with reasons) and numbers analysed and excluded from the analysis. Research staff invited participants who withdrew from the intervention or research procedures to provide a reason.

-

Participants’ and therapists’ views on the acceptability of the trial procedures were obtained through qualitative methods (see Methods of evaluation for details).

Participant safety and adverse events

Adverse events

An adverse event (AE) was defined as any unfavourable and unintended sign (e.g. including an abnormal laboratory finding), symptom or disease that developed or worsened during the trial, whether or not it was considered to be related to the trial intervention. The risk of an AE from participating in this trial was assessed to be low. 1 AEs such as chest infections and urinary tract infections, which are common in people with MS, were not intentionally monitored for any participants (intervention or usual-care group). However, all participants were asked to report any new or worsening problems that they perceived to be related to participation in activity and/or exercise, as well as any relapses and falls, in the daily pre-formatted paper diaries. These were completed from the day of randomisation until the final assessment (27 weeks ± 1 week following randomisation), and returned in the reply-paid envelope on a fortnightly basis to PenCTU for data entry. AEs may also have been discovered by treating therapists or research therapists during questioning, physical examinations or during another intervention. When this was the case, the therapist took appropriate action and also asked the participant to record the AE in their diary to ensure it was reported as part of the trial data. To avoid double counting AEs, the therapist was requested not to report these to the PenCTU.

On receipt of the diary returns, PenCTU recorded any AEs in the trial database, with collated reports being (of the whole group, i.e. not according to group allocation) regularly presented at the Trial Management Group (TMG) meeting for review.

Adverse events considered related to the trial intervention were followed until resolution or until the event was considered stable.

Serious adverse events

A serious adverse event (SAE) was defined as an untoward occurrence that:

-

resulted in death

-

was life-threatening

-

required hospitalisation or prolongation of existing hospitalisation

-

resulted in persistent or significant disability or incapacity

-

consisted of a congenital anomaly or birth defect, or

-

was otherwise considered medically significant by the investigator.

It was not anticipated that there would be any SAEs related to this feasibility trial. Any SAE, whether or not thought to be related to any trial intervention, was reported to the CTU by the local principal investigator or another member of the research team by telephone or e-mail within 24 hours of the research team becoming aware of it. SAEs were recorded from the time of the baseline assessment until the date the participant completed follow-up or withdrew from the trial. SAEs could be directly reported by the participant or another informant (e.g. by telephone) or discovered by the treating therapist or research therapist through questioning, physical examination or another investigation. In addition, the 2-weekly diaries were reviewed to check for potential SAEs that had not otherwise been reported. Within 7 days of a local research team becoming aware of such an event, it was required that a SAE form was completed, signed by the principal investigator and returned to PenCTU. Completion of the SAE form included the principal investigator’s assessment of causality (i.e. whether or not there was a reasonable causal relationship between the SAE and the trial intervention). If the available information was incomplete at the time of reporting, all appropriate information relating to the SAE was forwarded to PenCTU as soon as possible.

If the principal investigator considered that the SAE was not, or was unlikely to be, related to the trial, PenCTU obtained a second assessment of causality either from the Scottish regional co-ordinator (for SAEs at the Plymouth site) or from the chief investigator (for SAEs at other participating sites).

It was protocolised that, if SAEs were adjudicated as being possibly related to the trial intervention and unexpected, then they would be reported by PenCTU to the Research Ethics Committee within 15 days of the local research team becoming aware of the event. This situation did not arise in this feasibility trial.

All SAEs were followed until resolution. PenCTU routinely notified the chief investigator by e-mail of all reported SAEs as they occurred and reported organ system listings of all SAEs to the Trial Steering Committee (TSC) and sponsor on a quarterly basis. PenCTU was responsible for the preparation and submission of an annual safety report to the Research Ethics Committee.

Trial outcome objectives (vii–ix)

Potential primary outcome for the definitive trial

A key aim of this feasibility trial was to inform the selection of a primary outcome measure and provide potential sample size estimates for the definitive trial. In line with the remit of a feasibility trial, a variety of outcome measures were undertaken to determine their performance and to identify those that may be most appropriate to use in the definitive trial. The selection of potential outcomes was informed by best practice guidance,59,60 and refined by the findings of our previous stakeholder activities (which involved service users, providers and commissioners),27 collaboration with our trial patient and public involvement (PPI) representatives and guidance from methodological experts. This led to the decision to propose mobility and quality-of-life measures as potential primary outcomes rather than as falls outcomes. There were two main reasons for this: (1) the recognition that a reduction in falls without a corresponding improvement in mobility or QoL outcomes would be undesirable, and (2) concern about possible issues associated with relying on self-report falls diaries as a data collection mechanism.

As this process led to the proposal of several potential primary outcomes, one of the key objectives was to establish what would be the most sensible choice for use in a main trial. In particular, our aim was to select a primary outcome that, as well as being meaningful to patients, ensured that the main trial would be feasible and provide good value for money; for example, the selected outcome should demonstrate good completion rates and lead to a realistic sample size requirement.

Outcome time points

Standardised, validated, clinician-rated and patient self-reported clinical outcomes were measured at baseline, at 15 ± 1 weeks after randomisation (coinciding with the end of intervention period for participants allocated to receive BRiMS) and at 27 ± 1 weeks after randomisation (coinciding with the 12-week post-intervention period). In a definitive trial, we would ideally like to follow up participants for 6 months post intervention to determine whether long-term behaviour change (such as sustained engagement in exercise) occurs once therapy support is withdrawn.

Procedures

All research procedures were protocolised and any deviations were documented. A research therapist (this was always a physiotherapist) in each region undertook all of the outcome assessments, independently of treatment, at separate research visits at local health-care establishments. Before recruitment commenced, the research therapists from the two regions met with each other and members of the research team to ensure a consistent approach and to standardise procedures. Every effort was made to ensure that these assessments were blinded, and participants were asked to not discuss whether they were attending a group session or undertaking any exercise programme. We carefully chose the battery of measures on the basis of proven psychometric properties, our previous research in this area, recommendations from the International Multiple Sclerosis Falls Prevention Network, and discussions held with people with MS/carers, as well as health professionals working in this field, to ensure acceptability and relevance. Previous trials of the assessment protocol demonstrated that the assessment would take approximately 60 minutes. This is the typical duration for NHS physiotherapy assessments for complex neurological conditions and well within the maximum 90 minutes that people with MS have told us is acceptable for such assessments.

Baseline measures

The following demographic clinical characteristic data were collected by participant self-report: age, sex, educational attainment, marital status, employment status, length of time since diagnosis, disease course, MS relapse history (within the past 3 months), number of falls/related injuries in the past 6 months, currently prescribed drugs and comorbid medical conditions. The diagnosis was corroborated by the research therapists or CRN staff with the participant’s medical records.

Information about changes to health and medication use was also collected at the follow-up assessments.

Potential primary outcomes

Multiple Sclerosis Walking Scale (12-item) version 2

An important outcome to evaluate in this study was walking from the patient’s perspective. We chose the MS Walking Scale (12-item) version 2 (MSWS-12vs2)61 to achieve this because it is a widely used, psychometrically robust, patient-reported questionnaire that assesses the impact of MS on walking ability, which is a key goal of the BRiMS programme. This questionnaire evaluates the impact on 12 aspects of walking function and quality (walking, running, climbing stairs, standing, balance, distance, effort, support needed indoors, support needed outdoors, speed, smoothness, and concentration needed to walk) identified as important by people with MS. The original Multiple Sclerosis Walking Scale (MSWS-12) has been robustly evaluated in terms of its psychometric properties,62–65 and the revised version 250,61,66,67 has minor modifications to response options. Of the 12 items, three are scored 1–3 and the other nine are scored 1–5. The category descriptors range from 1 (‘not at all limited’) to 5 (‘extremely limited’). Scores on the 12 items are summed, giving a total raw score whose range is 12–54. To ease interpretation, this raw score is transformed to 0–100 (minimum to maximum walking disability) by subtracting the minimum score from the sum, dividing the result by 42 and then multiplying by 100. 68

Quality of life (EuroQol-5 Dimensions, five-level version)

The EuroQol-5 Dimensions, five-level version (EQ-5D-5L)69 is a standardised self-report measure of health status, recommended for use in UK health technology appraisals and health policy decision-making. 70 Taking approximately 5 minutes to complete, the EQ-5D-5L collects data across five dimensions; mobility, self-care, usual activities, pain/discomfort and anxiety/depression. Each dimension is scored by the participant as no problems, slight problems, moderate problems, severe problems or extreme problems. From the initial collection of the EQ-5D-5L, data can be mapped to be reported as the EuroQol-5 Dimensions, three-level version (EQ-5D-3L), in accordance with relevant guidance (see Health economics analyses). The EQ-5D-5L would also be used to inform the economic evaluation in a follow-on definitive trial, wherein it is expected that it would be used in combination with a UK tariff of health state values71 to estimate quality-adjusted life-years (QALYs) for use as the primary economic end point.

Quality of life [Multiple Sclerosis Impact Scale (29-item) version 2]

The MS Impact Scale (29-item) version 2 (MSIS-29vs2)61,72,73 is a condition-specific measure of health-related QoL. This widely used self-report questionnaire was devised specifically for people with MS and was founded on interviews with patients exploring how MS affects their QoL. The original Multiple Sclerosis Impact Scale (MSIS-29) has been robustly evaluated in terms of its psychometric properties,61,74–77 and the revised version 2 has minor modifications to response options. 67,73 It consists of 29 items, all of which have four response categories numbered 1 (‘not at all limited’) to 4 (‘extremely limited’); a higher score indicates greater impact on the individual’s life. The MSIS-29vs2 provides domain scores for QoL and summary scales for physical and psychological elements. There is an accumulating body of evidence to support the internal consistency, reproducibility, validity and responsiveness of this later version. 67,73 Furthermore, the MSIS-29vs2 data can be used to derive a MS-specific preference-based measure, the Multiple Sclerosis Impact Scale (8-dimensions) (MSIS-8D),73,78,79 which may be used in assessment of cost-effectiveness.

Potential secondary outcomes

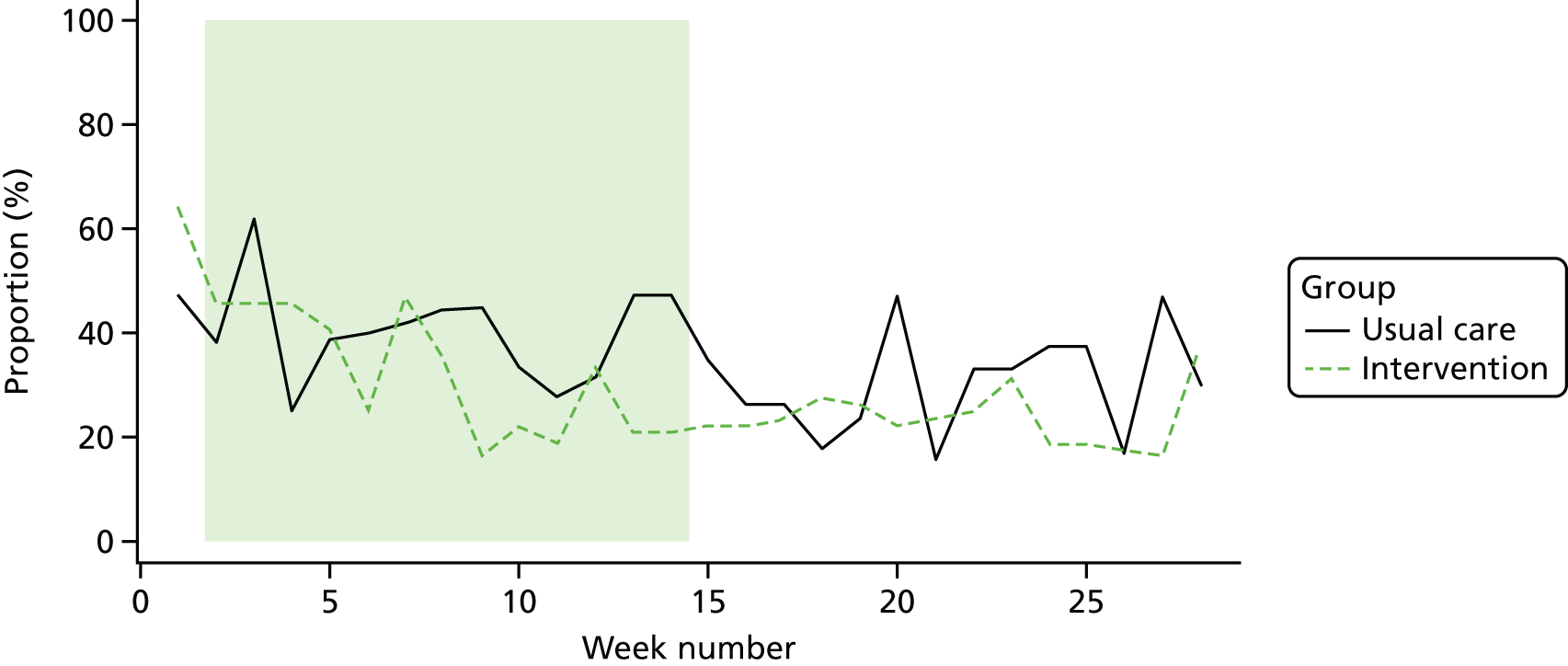

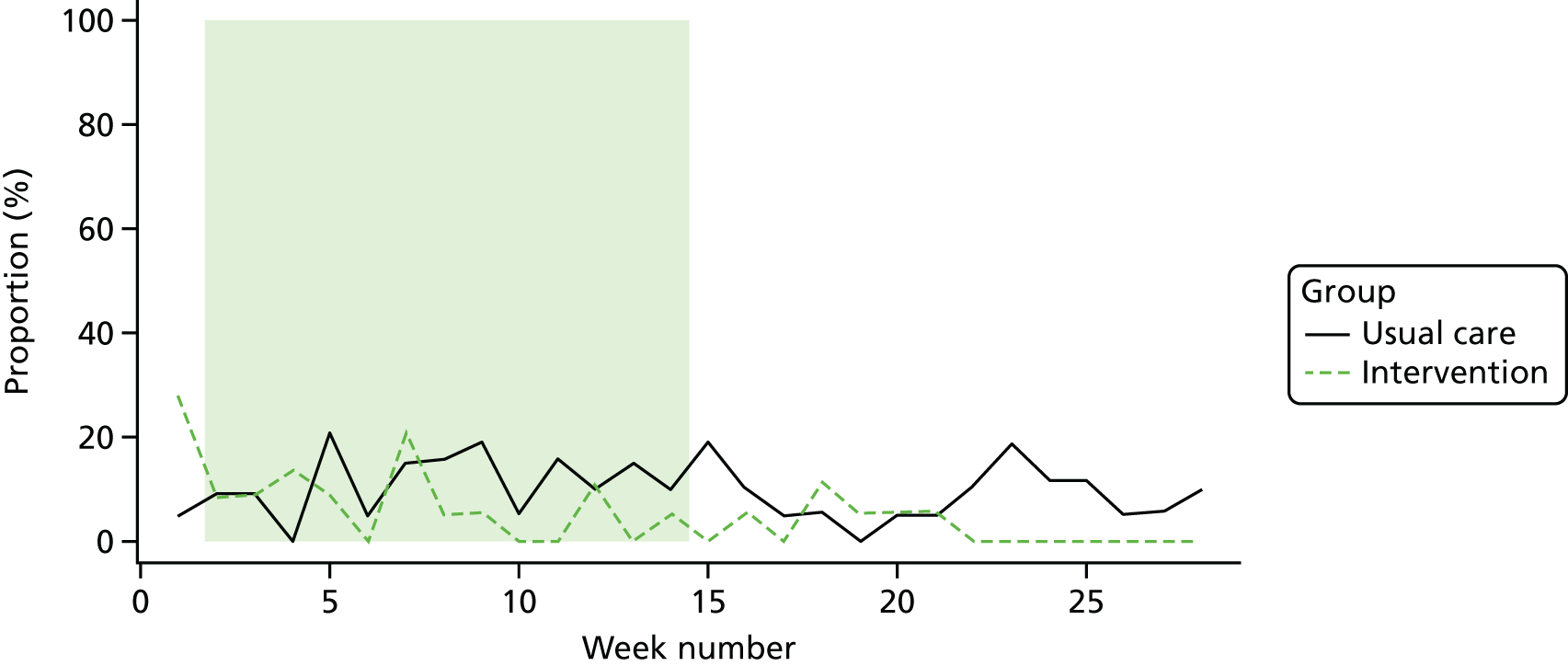

Falls frequency and injury rates

Evaluation of falls status is important, as there is a known link between falls status and activity curtailment20 that may, in turn, have an impact on mobility and QoL. In this trial, falls were assessed by prospective direct measurement, as it is widely acknowledged that other methods lack reliability and validity. 80,81 In line with best practice guidance,59 participants were asked to complete the pre-formatted daily paper diaries throughout the trial to record falls and any related injuries (see Appendix 1). A fall was defined as ‘an unexpected event in which you come to rest on the floor or ground or lower level’. 60 In addition, participants were asked to record any injuries and the related use of medical services as a result of each fall. In line with recommendations from Coote et al. ,59 participants were asked to complete the diary daily and return a batch of 14 completed daily diaries in a reply-paid envelope every 2 weeks throughout the trial. Participants received an automatic e-mail on six occasions throughout the trial to thank them for their engagement and to prompt ongoing diary returns. Returned diaries were reviewed by the trial managers and the data were entered into the trial database. Automatic e-mail reminders were triggered when diary returns fell more than 2 weeks behind schedule. Up to two reminders were sent to participants to remind them to complete and return their diary. Pre-formatted diaries to record falls and related injuries have been used in a number of MS studies. 16,82,83 Previous studies using this method have indicated that high completion and return rates are consistently gained (75–99%), with our own previous study demonstrating a 93% completed diary return rate. 16

Physical activity level

It is important to measure levels of physical activity, as these reflect much more than simply walking, and potentially provide a clearer indication of the impact of both the disease and the intervention on the physical dimensions of an individual’s daily life. For instance, although falls may reduce if people remain sitting (appearing to be a positive outcome from a falls perspective), this would not generally be considered a positive outcome for the person with MS. The intention of BRiMS is to encourage increased levels of safe mobility/physical activity, which has been demonstrated to enhance people’s QoL and minimise secondary complications such as deconditioning.

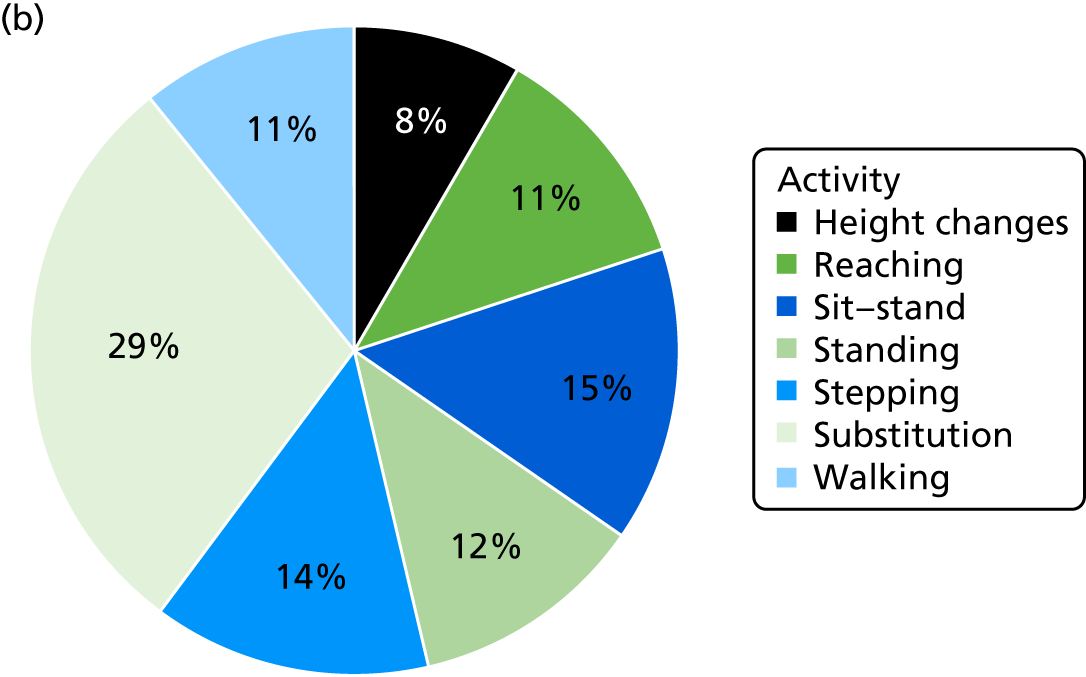

The level of physical activity was measured objectively over 7 days using an activity monitor (activPAL™, Paltechnologies Ltd, Glasgow, UK). 84 The activPAL is a tri-axial accelerometer, worn on the thigh, which can record data continuously for up to 21 days. It is smaller and lighter than other accelerometers and attaches securely to the skin. The activPAL, and its accompanying manufacturer’s software, classifies activity in terms of the time spent sitting or lying, standing and stepping, the number of steps taken, the cadence, and the number of sit-to-stand and stand-to-sit transitions. To our knowledge, these are features that no other comparable device offers. To ensure that the data collected are a true representation of the individual’s physical activity, 5 consecutive days of data are required. 85 Thus, to improve the likelihood of achieving 5 full days of data, participants were asked to wear the monitor continuously (24 hours a day) for 7 consecutive days and to undertake normal daily activity. The device was not removed during the data collection period. The time spent in each posture and the number of steps were averaged over the 5-day period. The activity monitor was fitted to the participant at each assessment session and participants were instructed to remove the device after 7 days and post it back to the research team in the pre-paid addressed envelope provided. This methodology has been successfully used in previous studies,86 including several undertaken by some of the co-applicants. 87,88

Walking capacity

To complement the self-report MSWS-12vs2, we also undertook an objective clinician-rated measure of walking capacity: the Two-Minute Walk Test (2MWT). This determines the longest distance an individual can walk (using walking aids if required) over 2 minutes on a hard, flat surface. 89 This measure was chosen as it is strongly correlated with community mobility levels,90 which is a potentially important outcome of the BRiMS programme. There is evidence to support the reliability, validity and responsiveness of the 2MWT in a range of rehabilitation studies, and reference values are available regarding clinically meaningful improvement, according to disability level, in people with MS. 50,90,91 The 2MWT has been recommended as the timed walking measure of choice for evaluating rehabilitation interventions in people with MS who have moderate disability. 91 In this study, the 2MWT was undertaken using a 5-metre track set up in a quiet corridor. Participants were instructed to walk as many lengths as possible in the time allowed, taking breaks if required.

Balance

Poor balance has been identified as a key modifiable risk factor for falls in MS15 and is one of the primary targets of the BRiMS exercise component. The multidimensional nature of balance means that some measures have been criticised for lacking responsiveness. 92 In this trial, balance was evaluated using the following two measures:

-

The Mini-Balance Evaluation Systems Test (Mini-BEST),93 a 14-item clinician rated balance assessment tool that aims to target and identify the contributions of six different balance control systems to functional stability: anticipatory postural adjustments, reactive postural correction and dynamic balance during gait (including cognitive effects). Each item is scored on a three-level ordinal scale (0–2), with higher scores indicating better performance; the maximum possible score is 28 points. The Mini-BEST has established psychometric properties, including excellent internal consistency, reliability, validity and responsiveness. 94 It is recommended for inclusion as part of a core outcome set for measuring balance in adult populations. 95

-

The Functional Reach and Lateral Reach Tests are clinician-rated measures of standing balance that mirror the everyday activity of reaching for objects beyond arm’s length. The person stands adjacent to a wall with their shoulder flexed (forwards reach) or abducted (lateral reach) to 90 degrees, and leans forward (or laterally) as far as possible without stepping, thereby testing the limits of stability. Measurements are taken with a metre rule and an average of three repetitions is used. 96 The Functional Reach and Lateral Reach Tests are considered psychometrically robust for use in neurological clinical practice97 and have been used in a number of studies to evaluate the effect of exercise interventions that aim to improve the balance of people with MS. 66,98

Fear of falling

Fear of falling has been highlighted as a risk factor for falls99 and is also associated with activity curtailment in MS. 20 A reduction in fear of falling is, therefore, a potentially important outcome of BRiMS, given the recognised association between physical activity levels and QoL. 100 We measured fear of falling with the Falls Efficacy Scale – International (FES-I),101 which has been recommended by the European falls network ProFane (www.profane.eu.org) as the preferred measure of fear of falling for clinical and research use because of its speed and simplicity of completion. 60 The FES-I has also been validated for use in ambulant people with MS, demonstrating excellent internal reliability and construct validity. 102 The FES-I produces a single score based on the summed total of the individual responses to the 16 questions; the maximum possible score is 64, with higher scores indicating a greater degree of anxiety.

Community Integration

The World Health Organization’s focus on participation as a key construct in the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health103 recognises that high-quality health care looks beyond mortality and disease to focus on how people live with their conditions within their environments. As a result, participation is increasingly a focus of measurement in rehabilitation studies. 104,105 We measured participation using the Community Participation Indicators (CPI),105 a self-report measure that evaluates participation using three key indicators: engagement (20 items), involvement in life situations (14 items) and control over participation (13 items). There is preliminary evidence supporting the validity of the CPI; however, its use has been relatively small-scale to date. The CPI was recommended for use in an expert review paper published by members of the International MS Falls Prevention Research Network;106 this feasibility trial provided an opportunity to evaluate its performance before its potential inclusion in the definitive trial.

Programme feasibility objectives (x–xii)

Evaluation of programme feasibility: BRiMS process evaluation

There is growing recognition of the complexity of designing, implementing and evaluating rehabilitation interventions and the challenges of moving programmes from the research setting into clinical practice. The updated Medical Research Council guidance on the evaluation of complex interventions calls for researchers to combine assessment of outcomes alongside evaluation of process. 34 This reflects the recognition that for evaluations to inform policy and practice, emphasis is needed not only on whether interventions ‘work’ but also on how they are implemented, their causal mechanisms and the impact of the ‘real world’ on programme uptake, delivery and engagement.

This trial provided an opportunity to evaluate the implementation of BRiMS as the next step in the complex intervention development process. 35 The BRiMS process evaluation was developed in accordance with best practice guidelines45 and with reference to key theoretical and evaluation frameworks. The overarching approach to the BRiMS PE is one of realist evaluation, as laid down by Pawson and Tilley. 107 The paradigm driving the evaluation is one of pragmatism, recognising the influence of historical, cultural and political contexts on programme design, implementation and user experience. 108

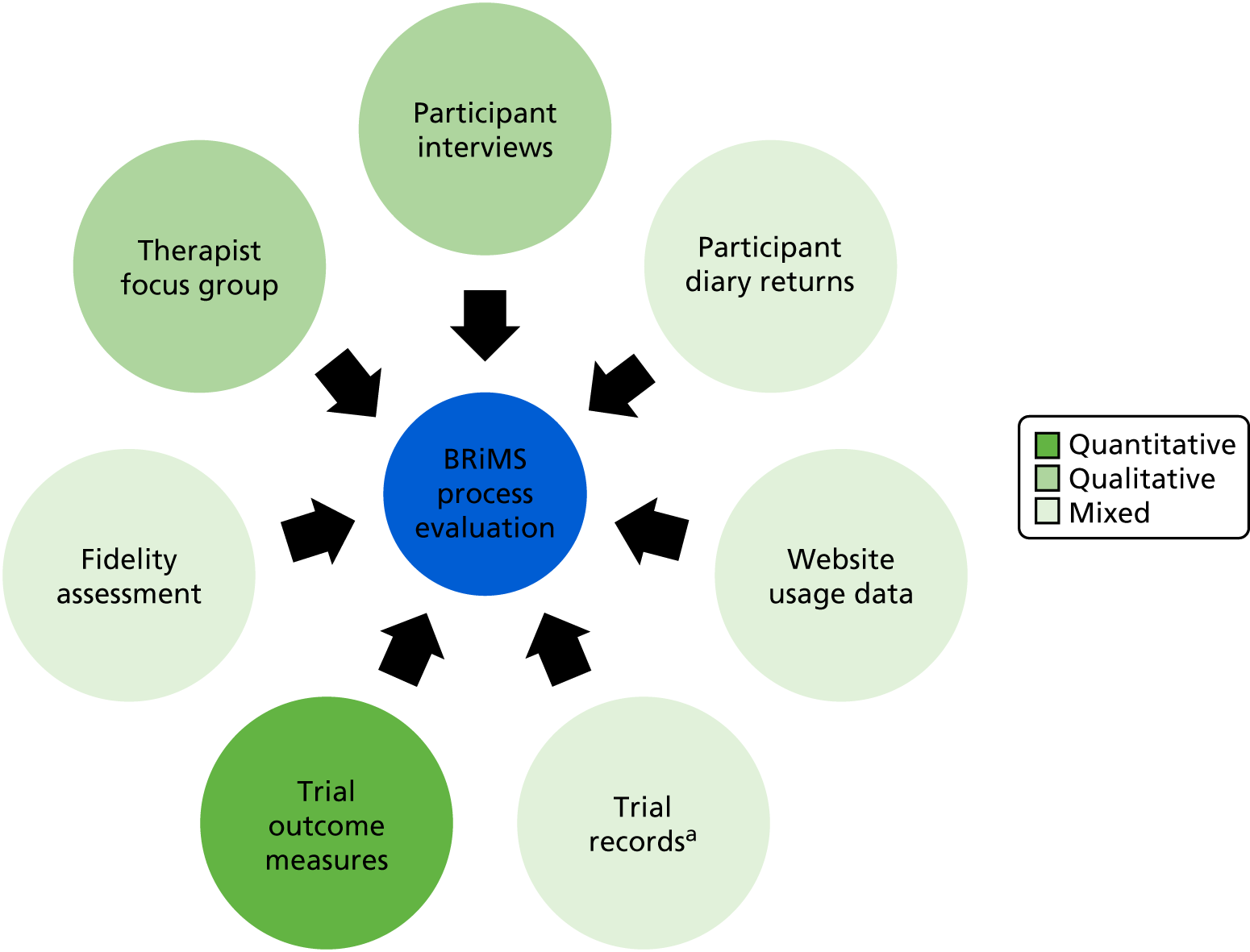

The process evaluation explored three main areas of programme delivery (Figure 5):

-

intervention implementation

-

mechanisms of impact

-

context.

FIGURE 5.

The BRiMS process evaluation framework.

The process evaluation plan

The overarching methodological approach to the BRiMS process evaluation is that of mixed methods. A mixed-methods approach allows a number of strategies to be employed concurrently or sequentially. Each element supports the findings of the other methods to create a coherent whole109 to inform the development of holistic, realistic recommendations. 110

Sources of data

The sources of data for the process evaluation are detailed in Figure 6.

FIGURE 6.

Sources of data for the BRiMS process evaluation. a, Treating therapist contact sheets, withdrawal and adverse event data.

Methods of evaluation

Intervention fidelity

The assessment of intervention fidelity aimed to measure the degree of concordance between the BRiMS manual and the actual programme delivery. The BRiMS fidelity assessment was carried out by three members of the research team who had a range of expertise relevant to the programme:

-

assessor 1 – consultant neurological physiotherapist; expertise in clinical management of MS, site principal investigator for the Ayrshire site

-

assessor 2 – professor of psychology; lead for the development of functional imagery and motivational support aspects of BRiMS

-

assessor 3 – lecturer in physiotherapy; developer of BRiMS programme and BRiMS trial co-ordinator.

Fidelity assessments, customised according to the content of each session, were undertaken by scoring audio-recordings of a sample of BRiMS sessions against the relevant checklist rating scale. The items scored included both generic behaviours and session-specific content. The checklists were based on the Dreyfus system for assessing skill acquisition111 and an adaptation of the Motivational Interviewing Treatment Integrity scale. 112

The fidelity checklist rating scales

The fidelity assessment for every session type included four common items that were scored according to the criteria specific to the item (see Fidelity assessment; full manual available from the authors on request). In addition, session-specific items were included that were scored according to the generic criteria (see Appendix 2). Thus, the scale assessed adherence to the content of the intended intervention techniques, the depth of coverage and the delivery approach. Each item was rated according to a four-point Likert scale; to aid with the rating of items, an outline of the key features of each item was provided. The tool was piloted, and scoring comparisons were made between the three reviewers, for three session recordings. This enabled a consensus to be reached about its application before its use in the full evaluation.

Method

With the participants’ permission, all face-to-face BRiMS sessions were audio-recorded (clinic assessment, home visit and all group sessions). The recorded sessions were used to measure fidelity by comparing the session audio recording against the checklist for that session. A random sample of 25% of the audio-recordings was scored. No patient identifiable information was recorded on the fidelity checklist and the audio-recordings were destroyed at the earliest opportunity after the checklist was completed. The recorded sessions were used to evaluate the quality of the intervention delivery and the degree of concordance with the BRiMS manual.

Participant engagement and adherence to the BRiMS programme

The BRiMS programme comprises five face-to-face sessions (two individual and three group based); attendance at these face-to-face sessions was monitored and recorded. Participants were also advised to undertake a minimum of 120 minutes of home-based exercise per week for a minimum of 12 weeks, utilising a web-based physiotherapy programme, completing a web-based exercise diary each time. Thus, adherence to the home-based programme was monitored based on the number of web-based log-in sessions and the exercise diary data recorded online by the participant during the programme; adherence to each element was calculated as a percentage. For example, with regard to adherence to the requested time spent exercising, the optimum duration of exercise was 24 hours (2 hours per week for 12 weeks); if a participant reported completing 18 hours, then they had 75% adherence. In addition, the weekly adherence was monitored throughout the programme, as evidence suggests that adherence to internet-delivered interventions reduces over time. 113

Participants’ and therapists’ views on acceptability of the BRiMS intervention

The BRiMS programme has not yet been trialled for use by therapists in the clinical setting, and nor has it been fully evaluated in a clinical trial. Therefore, a qualitative component was included in the process evaluation to enable an exploration about the experience of participating in the trial (for both allocated groups) and engaging in the BRiMS intervention (for the intervention group only), from the perspective of both people with MS and the therapists delivering the intervention.

Procedures

The qualitative data from BRiMS participants were collected through one-to-one telephone interviews, and a telephone focus group114 with treating therapists was held at the end of the programme. For the participant interviews, a purposive sample of 13 participants was recruited, including people from different regions and different BRiMS intervention groups, together with a sample of usual-care group participants. At the end of the trial period, participants were contacted and a mutually convenient time was agreed to undertake a telephone interview within 2 weeks of the completion of the BRiMS final trial visit.

All four treating therapists were invited to participate in the telephone focus group, which was convened within 10 weeks of the completion of the final BRiMS programme delivery. All qualitative interviews were facilitated by members of the research team (participant interviews, HG or JF; therapist focus group, HG and JA). All interviews were digitally recorded and transcribed verbatim before being thematically analysed (see Qualitative analyses) and synthesised into the process evaluation.

Health economics objectives (xiii–xiv)

Health economics outcomes

The main aims of the health economics analyses were to (1) provide an estimate of the resource use and associated cost of delivering the BRiMS intervention; (2) develop a framework for collecting data on costs and outcomes, and (3) develop methods for conducting cost-effectiveness analyses (CEA) in a future full trial.

Methods for future conduct of economic evaluation were developed and tested, within this feasibility trial, on the collection of resource use, cost and outcome data. The data on resource use associated with the set-up and delivery of the BRiMS intervention were collected via within trial reporting, including participant-level contact and non-contact time for staffing input on delivery, equipment and consumable costs, training and supervision for delivery staff. Data on health and social care resource use were collected at participant level using a resource-use questionnaire, developed for this trial based on resource-use forms used successfully in previous studies in people with MS. 67

The EQ-5D-5L was used to assess health outcomes from an economic viewpoint. The EQ-5D-5L is used to derive health state values associated with the health status (states) described by trial participants. A future economic evaluation would be expected to use the EQ-5D-5L as the primary economic end point (over a6-month follow-up) to estimate the cost per QALY and, accordingly, EQ-5D-5L data were collected in this trial. However, given some debate and uncertainty over the appropriateness of the EQ-5D-5L for people with MS, the MSIS-29vs2 data collected during the trial were also used to estimate health state values (QALYs) via the MS-specific preference-based measure developed by Goodwin and Green. 79

Progression to definitive trial

We pre-defined a number of progression criteria for consideration as part of the decision about whether we would either progress to a full trial application, or need to undertake further developmental work. These criteria, described below, were designed to address the key aims and objectives of this feasibility trial. The progression criteria were finalised in discussion with the TSC, with whom we were also able to discuss whether or not there was sufficient evidence, with appropriate changes, to move forwards to a definitive trial. The criteria were:

-

A minimum of 80% recruitment of the intended 60 participants within the planned 6-month recruitment window.

-

A minimum of 80% of consented participants randomised to the intervention group fulfilling the minimum engagement criteria of engaging with the 13-week BRiMS intervention, which was to attend the initial face-to-face clinic appointment where the participant was assessed, their individualised home programme was designed and explained, and the paper-based BRiMS participant manual was provided to them.

-

A minimum of 80% completion rate of at least one of the proposed primary outcome measures among participants attending the planned primary end point of 27 weeks (± 1 week).

-

The total resource estimated to conduct the definitive trial at a level that is likely to attract funding.

We considered that there would most likely be unforeseen issues raised during the trial that could affect the decision to progress, but we anticipated that the process evaluation data and input from PPI team members would be helpful in finding potential solutions and indicating remedial action.

Trial governance

Ethics and research governance

Application for ethics review via NHS and university ethics was submitted during the pre-trial period (January–September 2016) in time for the commencement of the trial in September 2016. During this period, relevant NHS trust research and development department and Clinical Commissioning Group approvals were also obtained.

Patient and public involvement

From the outset, the programme was informed by people with SPMS. In 2010, this topic was identified by participants in the chief investigator’s longitudinal study evaluating mobility. A survey (n = 116) asked for views about what future research should focus on: safe mobility and falls were priorities. Subsequently, two discussion groups confirmed this and were used to focus research questions, determine acceptable study designs and problem-solve implementation issues. People with SPMS have sat on advisory committees in our subsequent studies: the BRiMS programme is a direct output. They were intimately involved in the development of BRiMS through participation in the nominal group study [n = 36 (50%) people with MS],27 which was innovative in how it facilitated people with MS, health professionals, commissioners and the research team to work together. Dedicated training sessions (facilitated by the local NIHR user involvement group) supported people with MS to engage fully and confidently in the process. This high level of user engagement continued throughout this feasibility trial: Ben Marshall (who has MS) was a co-applicant on the trial and had input on the development of the qualitative interview schedule/evaluation/validation checks. John Kendrick, who also has SPMS, sat on the TSC. They provided advice on issues such as recruitment, on participant materials such as the information sheet and plain English summary, and on publications designed for patient/general public consumption such as MS organisation newsletters. Participants from the nominal group phase, who helped us to design the BRiMS intervention, gave permission for us to involve them in related discussion groups, and we contacted some of these individuals again to use them as a ‘sounding board’ for materials during this study. In line with INVOLVE guidance, lay members were financially reimbursed for attending discussion groups, TSC and TMG meetings, as well as for the associated preparation time (included in the trial costs). The project team has a well-established relationship with the MS Trust and the MS Society; both organisations were consulted about the development of the trial protocol application and were highly supportive, playing a key role in ensuring that it was possible to access people with SPMS through local branches.

Human and data management

As chief investigator, Jenny Freeman assumed overall responsibility for the trial, ensuring that it finished on time and within budget. The trial was sponsored by University Hospitals Plymouth NHS Trust (formerly Plymouth Hospitals NHS Trust). It was managed by the UKCRC-registered PenCTU, which co-ordinated the development of the trial protocol and trial-specific documentation, managed the approvals process, liaised with both trial sites, monitored recruitment and was responsible for the day-to-day conducting of the trial in conjunction with the chief investigator. The CTU also provided a bespoke web-based randomisation system, database and data management services for the trial.

Trial Management Group

A TMG, chaired by Jenny Freeman and including the co-applicants, the PenCTU trial manager, the PenCTU data manager, patient representatives and sponsor representative, met monthly to monitor general progress/timelines, recruitment, retention, adherence to the trial intervention and budgetary issues and to discuss any problems as they arose.

Trial Steering Committee

Make-up

The TSC was a group of experienced triallists with majority independent representation: the chairperson (independent), an external statistician (independent), the chief investigator (non-independent) and a lay member (independent).

Frequency of meetings

The TSC met before the start of the trial in person and subsequently by teleconference on four occasions. In addition, the TSC received a quarterly report of SAEs and injurious falls.

Responsibilities

The responsibility for calling and organising the TSC meetings lay with PenCTU in association with the chairperson.

Degree of independence from sponsor and investigators

Confirmation that independent members of the TSC were unconnected to either the trial sponsor or the investigators was made through the completion of conflict of interests documents by all TSC members.

Minutes of meetings were sent to all members, the sponsor and the funder, and were retained in the trial master file.

Data Monitoring Committee

Make-up