Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 11/129/109. The contractual start date was in March 2013. The draft report began editorial review in September 2018 and was accepted for publication in March 2019. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Rustam Al-Shahi Salman is a member of the Efficacy and Mechanism Evaluation Funding Board panel. Lelia Duley reports grants from the Nottingham Clinical Trials Unit during the conduct of the study. Christian Ovesen reports grants from the Velux Foundation (Søborg, Denmark), the Hojmosegaard Grant/Danish Medical Association (Copenhagen, Denmark), the Axel Muusfeldt’s Foundation (Albertslund, Denmark), the University of Copenhagen (Copenhagen Denmark) and non-financial support from Merck Sharp & Dohme (MSD; Kenilworth, NJ, USA) outside the submitted work. Robert A Dineen reports grants from the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Health Technology Assessment (HTA) programme (project number 11/129/109) during the conduct of the study. Timothy J England reports grants from the NIHR HTA programme during the conduct of the study. Thompson G Robinson reports grants from the University of Leicester. Christine Roffe has been a member of the HTA General Board since 2017. David Werring reports personal fees from Bayer AG (Leverkusen, Germany) outside the submitted work. Philip M Bath reports grants from the British Heart Foundation and the NIHR HTA programme during the conduct of the study, others from Platelet Solutions Ltd (Nottingham, UK) and personal fees from Diamedica (UK) Ltd (Bratton Fleming, UK), Nestlé SA (Vevey, Switzerland), Phagenesis Ltd (Manchester, UK), ReNeuron Group plc (Bridgend, UK), Athersys Inc. (Cleveland, OH, USA) and Covidien (Dublin, Ireland) outside the submitted work.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2019. This work was produced by Sprigg et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2019 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Introduction

Sections of text of this report are reproduced from Sprigg et al. 1 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

Scientific background

Haemorrhagic stroke

Haemorrhagic stroke or intracerebral haemorrhage (ICH), caused by bleeding in the brain, can be devastating and is a common cause of death and disability, both in the UK and worldwide. 2 Despite the development of effective treatments for ischaemic stroke (thrombolysis, mechanical thrombectomy, aspirin, hemicraniectomy), there is no proven effective treatment for spontaneous ICH (SICH).

Haematoma expansion

Outcome after ICH is closely related to whether brain bleeding expands after onset, so-called haematoma expansion, or whether rebleeding occurs; both are associated with a bad outcome (i.e. death and disability). 3,4 Contrast extravasation during contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) and CT angiography (CTA), known as the spot sign, have been shown to predict haematoma expansion. 5 Nevertheless, there is currently wide variation in the use of these techniques in routine clinical practice.

Haematoma expansion is related to both haemostatic factors and blood pressure. Furthermore, haematoma volume (HV) can be reduced surgically; all these approaches are potential targets for treatment of ICH.

Intensive blood pressure treatment

Lowering blood pressure in patients with ICH is a potential therapeutic option to limit haematoma expansion and improve outcome. The Intensive Blood Pressure Reduction in Acute Cerebral Hemorrhage Trial (INTERACT) assessed intensive blood pressure treatment in 404 ICH patients. The study showed that aggressively lowering blood pressure appeared safe and may limit haematoma expansion, but did not change outcome. 6 In the INTERACT-2 trial, the largest intervention trial of SICH that involved 2839 patients, intensive blood pressure lowering to a systolic blood pressure (SBP) of < 140 mmHg is safe and resulted in a significant shift in ordinal analysis of the modified Rankin Scale (mRS) score, although there was no significant improvement in primary outcome of death and disability (i.e. a mRS score of 3–6). 7 In view of this result, the European Stroke Organisation’s (ESO’s) 2014 guideline and the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association’s (AHA/ASA’s) 2015 guideline suggest that lowering blood pressure to a SBP of 140 mmHg is safe and may have a beneficial effect on functional outcome. 8,9

The most recent development of blood pressure treatment in SICH is the Antihypertensive Treatment of Acute Cerebral Hemorrhage II (ATACH II) trial, which was stopped early in view of futility after recruiting 1000 patients. There was no significant difference in death or dependency between the intensive and guideline treatment groups. In addition, there were higher renal adverse events in those participants treated with intensive blood pressure reduction. 10 There are several potential reasons why the ATACH II trial had different findings compared with previous trials. Patients in the trial received intravenous antihypertensive medication pre randomisation to ensure compliance with guidelines. Furthermore, the blood pressure reduction was much larger than seen in previous trials; from a baseline SBP of approximately 200 mmHg, the intensive arm achieved a mean minimum SBP of 129 mmHg, whereas the standard treatment arm attained a mean minimum SBP of 141 mmHg. In contrast, the baseline blood pressure was approximately 179 mmHg in the INTERACT-2 trial, with the intensive and standard treatment groups achieving a SBP of 150 mmHg and 164 mmHg at 1 hour post randomisation, respectively. These results suggest that the degree of blood pressure reduction in the standard arm of the ATACH II trial is similar to the intensive arm of the INTERACT-2 trial. 11 In addition, all patients in the ATACH II trial were treated with intravenous nicardipine, which has a weak antiplatelet effect, possibly negating the benefit achieved by blood pressure reduction. 11,12 The UK’s 2016 national clinical guideline for stroke recommends lowering blood pressure to a SBP of 140 mmHg, whereas the 2017 American guideline suggests that lowering blood pressure to a SBP of < 140 mmHg may be harmful. 13,14

Surgery for intracerebral haemorrhage

The current role of surgery is limited to patients with cerebellar haematoma. Posterior decompression in patients with cerebellar haematoma of > 3 cm and that result in hydrocephalus or brainstem compression is life-saving. 15,16 In addition, in ICH complicated with hydrocephalus, the placement of an external ventricular drain lowers intracranial pressure and may reduce mortality. 17

The role of routine surgery in patients with supratentorial haematoma is unclear. The international Surgical Trial in IntraCerebral Haemorrhage (STICH) was a prospective, open-label, blinded, end point, randomised controlled trial (RCT) that randomised 1033 patients with ICH to early surgical haematoma evacuation and initial conservative treatment. There was no significant difference in outcome between the two trial groups. 18 This may be because patients were recruited only when the surgeon was in equipoise and time to surgery was delayed (mean time 30 hours) and, thus, surgery was unlikely to be able to limit haematoma expansion. However, a subgroup analysis of the trial showed that patients with superficial haematoma (i.e. < 1 cm from the surface) benefited from early surgery. The trial also found that patients with a poor initial Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) score of < 8 and intraventricular haemorrhage (IVH) had poor outcomes despite surgery. 18

The subsequent early surgery versus initial conservative treatment in patients with spontaneous supratentorial lobar ICHs (STICH II) trial randomised 601 patients with superficial lobar haematomas, with a HV of 10–100 ml and without intraventricular extension to undergo early surgery or initial conservative management. There was an absolute reduction in mortality of 6% and a 4% increase in favourable outcome in the early surgery arm, although the difference was not statistically significant. 19 One reason that may explain this neutral result is that the trial recruited patients who were conscious or mildly confused who might not have benefited from surgery. Patients with poorer GCS scores of between 9 and 12 benefited from early surgery. 19 A meta-analysis including STICH II and 14 other trials (3366 patients), concluded that there was an overall benefit for early surgery [odds ratio (OR) 0.74, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.64 to 0.86]. 19 However, the meta-analysis should be interpreted with caution, as there was significant heterogeneity in the trials. It is unclear whether or not the surgical intervention benefited certain subgroups of patients. The current ESO guideline8 does not recommend routine surgery for supratentorial haematoma, although early surgery may be considered in patients with GCS scores of 9–12. Similarly the AHA/ASA guideline does not recommend routine surgery for supratentorial haematoma except in patients who are deteriorating. 9

Haemostatic therapy

In anticoagulant-related ICH, haemostatic therapy plays an important role. In vitamin K antagonist-related ICH, the four-factor prothrombin complex concentrate (4F-PCC) normalised the international normalised ratio (INR) to < 1.2 within 3 hours in 67% of patients compared with only 9% of patients with fresh-frozen plasma (FFP). 20 Where 4F-PCC is not available, FFP can be given as an alternative. In addition, intravenous vitamin K should be given. In ICH related to direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs; e.g. dabigatran, rivaroxaban, apixaban, edoxaban), reversal agents are now available. Idarucizumab is a specific reversal agent for the direct thrombin inhibitor, dabigatran. 21 Idarucizumab normalises diluted thrombin time and ecarin and thrombin clotting time within 15 minutes in almost 100% of patients. 21 Andexanet alfa, a reversal agent for direct (rivaroxaban, apixaban, edoxaban) and indirect factor Xa inhibitor (enoxaparin), was found to reverse the anti-Xa activities of rivaroxaban and apixaban within minutes of administration. Andexanet alfa was tested in a single-arm study among 67 patients who had intracranial and other major bleeding secondary to rivaroxaban, apixaban and enoxaparin. Effective haemostasis was achieved in 79% of the patients within 12 hours. However, 18% (12/67) of the patients had thromboembolic events. 22 Andexanet alfa was approved as a reversal agent by the US Food and Drug Administration in May 2018. The role of an antifibrinolytic agent, that is, tranexamic acid in DOAC-related ICH, is being examined.

The role of haemostatic therapy in ICH not related to anticoagulant is less clear. The most widely studied agent is recombinant factor VIIa (rFVIIa). In a Phase IIb trial with 399 patients, rFVIIa restricted haematoma expansion, improved functional outcome and reduced mortality despite a significant increase in arterial thromboembolic events. 23 However in a larger Phase III study with 841 patients, rFVIIa had no effect on functional outcome or mortality despite restricting haematoma expansion. 24 A meta-analysis comparing blood clotting factors versus placebo or open control, including 1480 patients from seven RCTs, found no significant benefit on mortality, or death or dependency. 25 There was a trend to improved outcome which was offset by an increase in thromboembolic events. Two RCTs recruited only ICH patients with positive CTA spot sign, that is, those patients at risk of haematoma expansion and most likely to benefit from rFVIIa. 26,27 However, the trials were stopped as a result of poor recruitment and the data have not yet been published, except in abstract form. 28

Platelet transfusion in antiplatelet-related ICH was found to be harmful in the platelet transfusion versus standard care after acute stroke due to spontaneous cerebral haemorrhage associated with antiplatelet therapy (PATCH) trial. The odds of death or dependence at 3 months were higher in the platelet transfusion group than in the standard care group [adjusted common OR 2.05, 95% CI 1.18 to 3.56; p = 0.011]. 29

Tranexamic acid

Tranexamic acid is a licensed antifibrinolytic drug that can be administered intravenously or orally and is used in a number of bleeding conditions to reduce bleeding. In the Clinical Randomisation of an Antifibrinolytic in Significant Haemorrhage – 2 (CRASH-2) trial involving 20,211 patients with major bleeding following trauma, tranexamic acid significantly reduced mortality (OR 0.91, 95% CI 0.85 to 0.97), with no increase in vascular occlusive events. Treatment was most effective when given rapidly; delayed administration was associated with a lack of efficacy and potential harm. In a subgroup analysis of patients with traumatic ICH, tranexamic acid showed a non-significant trend to reduced mortality (OR 0.47, 95% CI 0.21 to 1.04), and death or dependency (OR 0.66, 95% CI 0.32 to1.36). However, patients in the CRASH-2 trial were younger and had fewer comorbidities than those with SICH. In another RCT in traumatic ICH, tranexamic acid reduced death (OR 0.69, 95% CI 0.35 to 1.39) and death or dependency (0.76, 95% CI 0.46 to 1.27), without an increase in thromboembolic events. A meta-analysis of tranexamic acid in traumatic intracranial haemorrhage showed that it was associated with a significant reduction in subsequent intracranial bleeding and a larger trial is ongoing. 30,31

In the WOrld Maternal ANtifibrinolytic (WOMAN) trial, involving 20,060 women, tranexamic acid reduced death due to bleeding in women with postpartum haemorrhage [risk ratio (RR) 0.81, 95% CI 0.65 to 1.00; p = 0.045], with the effect greatest in women given treatment within 3 hours of childbirth (RR 0.69, 95% CI 0.52 to 0.91; p = 0.008). 32 The need to administer tranexamic acid immediately in bleeding conditions was again highlighted in an individual patient data meta-analysis combining data from the CRASH-2 and WOMAN trials. Immediate treatment improved survival by > 70% (OR 1.72, 95% CI 1.42 to 2.10; p < 0.0001) and the survival benefit decreased by 10% for every 15 minutes of treatment delay until 3 hours, after which there was no benefit. 33

Tranexamic acid has been tested in aneurysmal subarachnoid haemorrhage, where it reduced the risk of rebleeding at the expense of increased risk of cerebral ischaemia. 34 However, many of the trials of tranexamic acid in subarachnoid haemorrhage involved giving high doses of up to 6 g per day for a prolonged duration of 3–6 weeks, and this could have accounted for the increased number of ischaemic events. 34

Tranexamic acid has been found to restrict haematoma expansion in acute SICH in a small non-randomised study, although this study did not report on safety. 35 In another small study (n = 156), rapid administration of a bolus of tranexamic acid within 24 hours of stroke was observed to reduce haematoma expansion (17.5% vs. 4.3%). 36 In this study, tranexamic acid was given in combination with intensive blood pressure control, suggesting that it may be possible to combine haemostatic and haemodynamic approaches. The authors subsequently reported a study of an additional 95 patients treated with a rapid infusion of tranexamic acid with haematoma expansion occurring in 4.2% of these patients. 37

Systematic review of randomised controlled trials of tranexamic acid in intracerebral haemorrhage

The Cochrane Stroke Trials Register, the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, MEDLINE (via Ovid) and EMBASE (via Ovid) were searched from inception to 27 November 2017 for RCTs of antifibrinolytics and tranexamic acid. The search terms were published previously. 25 In November 2017, to identify further published, ongoing and unpublished RCTs, bibliographies were scanned and international registers of clinical trials were searched for relevant articles. Trials published in all languages were searched. The quality of the evidence was assessed using the Grades of Recommendation, Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) approach. Two small RCTs of tranexamic acid, with a total of 54 participants, were found with no clear evidence of benefit or harm associated with tranexamic acid. 38,39 Therefore, the systematic review concluded that there is a lack of evidence for the use of tranexamic acid in SICH. At the time of publication, five further RCTs are ongoing. 25,40

Rationale for trial

Haematoma expansion is a not uncommon complication of ICH and is associated with devastating consequences of early death and severe disability in those who survive. There is no effective drug treatment to prevent haematoma expansion. Tranexamic acid, an antifibrinolytic drug, is effective at reducing bleeding and death due to bleeding in other conditions. Tranexamic acid is widely available, affordable and appears to be safe in studies in other bleeding conditions conducted to date. The rationale for this study was to test the safety and efficacy of tranexamic acid in ICH, the hypothesis being that tranexamic acid will prevent haematoma expansion and reduce death and disability after ICH.

Chapter 2 Methods

Objectives

Purpose

To assess in a pragmatic Phase III prospective double-blind randomised placebo-controlled trial whether tranexamic acid is safe and reduces death or dependency after SICH. The results will determine whether or not tranexamic acid should be used to treat SICH, which currently has no proven therapy.

Primary objective

To assess whether or not tranexamic acid is safe and improves functional status (i.e. reduces death and dependency) after SICH.

Secondary objectives

To assess the effect of tranexamic acid on secondary outcomes: clinical outcomes, safety outcomes, costs and radiological efficacy.

Design

The Tranexamic acid in IntraCerebral Haemorrhage 2 (TICH-2) study was an international, double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled, parallel-group, Phase III trial performed in two phases: an 18-month start-up phase (with an aim to activate 30 centres and recruit a minimum of 300 participants) and then a main phase (with 120 centres and to recruit to a total of 2000 participants). There was no break in recruitment as the trial proceeded from the start-up phase to the main phase because the stopping criteria were not met.

Participants were enrolled by investigators from acute stroke units at 124 hospital sites in 12 countries: Denmark, Georgia, Hungary, Ireland, Italy, Malaysia, Poland, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, Turkey and the UK. Ethics approval was obtained in each site and country prior to commencement of the study. The trial was adopted in the UK by the National Institute for Health Research Clinical Research Network and registered with the International Standard Randomised Controlled Trial Number (ISRCTN) Registry as ISRCTN93732214. The full TICH-2 trial protocol41 and statistical plan42 have been published.

Study settings

The study was set in acute stroke units at 124 hospitals in 12 countries (as detailed in Design). A full listing of sites and investigators can be found in Report Supplementary Material 1.

Participants

Inclusion criteria

Adult patients (aged ≥ 18 years) with acute SICH within 8 hours of stroke onset were included in the study. (Where stroke onset time is unknown, the time of when last known well was used.)

Exclusion criteria

Patients with ICH secondary to anticoagulation, thrombolysis or known underlying structural abnormality, such as arterial venous malformation, aneurysm, tumour, trauma, venous thrombosis as cause for the ICH, were excluded. Note that it was not necessary for investigators to exclude underlying structural abnormality prior to enrolment, but where an underlying structural abnormality was already known, these patients would not be recruited.

Other exclusion criteria were patients for whom tranexamic acid is thought to be contraindicated, patients with premorbid dependency (i.e. a mRS score of > 4), prestroke life expectancy < 3 months (e.g. advanced metastatic cancer), a GCS score of < 5, female patients of childbearing potential either pregnant or breastfeeding at randomisation, geographical or other factors that prohibited follow-up at 90 days (e.g. no fixed address or telephone contact number or overseas visitor) and participation in another drug or devices trial concurrently, with the exception of the secondary prevention trial, REstart or STop Antithrombolics Randomised Trial (RESTART).

Data collected at baseline

Investigators recorded the participants’ age, sex, ethnic group, medical history and whether or not they were taking antiplatelet agents, as well as their assessment of ICH location, IVH, spot sign and blood pressure. Investigators assessed prestroke dependence with the mRS, and stroke severity using the National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS) and GCS.

Interventions

The intervention, tranexamic acid, was given intravenously as a 1-g loading dose in 100 ml of 0.9% normal saline infused over 10 minutes, followed by another 1 g in 250 ml of 0.9% normal saline, which was infused over 8 hours. The comparator was a matching placebo (i.e. 0.9% normal saline), administered with an identical regimen.

The dosing regimen selected (1-g bolus and 1-g infusion) was chosen to achieve plasma concentrations sufficient to inhibit fibrinolysis. Studies in cardiac surgery have shown that use of a dose > 10 mg/kg bolus and 1 mg/kg infusion does not provide any additional haemostatic benefit. 43 In the emergency situation, administration of a fixed dose is more practicable and the fixed dose chosen is efficacious for patients weighing > 100 kg and it is safe for patients weighing < 50 kg. The short duration of treatment allows for the full effect of tranexamic acid on the immediate risk of haematoma expansion without extending too far into the acute phase response seen after stroke.

Randomisation

All participants eligible for inclusion were randomised centrally using a secure internet site in real time. Randomisation involved stratification by country and minimisation on key prognostic factors: age; sex; time since onset; SBP; stroke severity (as assessed via the NIHSS); presence of IVH; and known history of antiplatelet treatment used immediately prior to stroke onset. This approach ensured concealmentof allocation, minimises differences in key baseline prognostic variables, and slightly improves statistical power.

Randomisation allocated a number corresponding to a treatment pack and the participants received treatment from the allocated numbered pack.

In the event of computer failure (e.g. server failure), investigators would follow the working practice document for computer system disaster recovery, which will allow the participant to be randomised manually following a standardised operating procedure.

Blinding

Clinicians, patients and outcome assessors (i.e. research nurse and radiologist) were blind to treatment allocation. In general, there should be no need to unblind the allocated treatment. If some contraindication to antifibrinolytic therapy developed after randomisation (e.g. clinical evidence of thrombosis), the trial treatment would simply be stopped. Unblinding was to be done only in those rare cases when the doctor believed that clinical management depended importantly on the knowledge of whether or not the patient received antifibrinolytic or placebo. For those few patients for whom urgent unblinding was considered necessary, the emergency telephone number was telephoned, giving the name of the doctor authorising unblinding and the treatment pack number. The caller was then told whether the patient received antifibrinolytic or placebo. The rate of unblinding was monitored and audited.

In the event of breaking the treatment code, this was recorded as part of managing a serious adverse event (SAE; see Chapter 2, Methods, Secondary outcomes, Safety for more details) and such actions were reported in a timely manner. The chief investigator (delegated the sponsor’s responsibilities) was informed immediately (within 24 hours) of any SAEs and determined seriousness and causality in conjunction with any treating medical practitioners.

Adherence

Adherence was assessed by examining the participant’s drug chart and recording the trial treatment administered at day 2 (i.e. whether or not all treatment was given, the time and date of the two doses and any other comments). Adherence was verified by both the central review of the drug chart and pharmacies recording returns of residual or unused trial medications.

Assessments after randomisation

Participants were reviewed at days 2 and 7, and on the day of death or hospital discharge, whichever came first, to gather information on clinical assessment (i.e. the NIHSS score), the process-of-care measures (e.g. blood-pressure-lowering treatment, neurosurgical intervention) and discharge date and destination (e.g. home or institution). A second research CT scan was carried out after 24 hours of treatment to assess haematoma expansion.

The central assessors, who were trained and certified in administration of the mRS and masked to treatment allocation, carried out the final follow-up at 90 days by telephone from the co-ordinating centre in each country. If the participant or carer could not be contacted, they received a questionnaire covering the same outcome measures by post.

Primary efficacy outcome

Functional status, death or dependency (ordinal shift on the mRS) at day 90 was compared between tranexamic acid and placebo by intention to treat using ordinal logistic regression (OLR), with adjustment for stratification and minimisation factors. The assumption of proportional odds was tested using the likelihood ratio test.

Secondary outcomes

Clinical

Clinical outcomes

Neurological impairment was measured (using the NIHSS44) at day 7 (or discharge if sooner).

Day 90 outcomes

The outcomes measured at day 90 were disability (using the Barthel index45), dependency (using the mRS46), quality of life [using the EuroQol-5 Dimensions (EQ-5D) questionnaire and the EuroQol Visual Analogue Scale (EQ-VAS47)], cognition [using the Telephone Interview Cognitive Score – Modified (TICS-M) questionnaire48] and mood (using the Zung Depression Scale49).

Costs

Cost outcomes included length of stay in hospital, readmission and institutionalisation.

Radiological

Radiological outcomes included relative and absolute haematoma growth and haematoma expansion.

Safety

Safety outcomes included:

-

death (cause)

-

venous thromboembolism (VTE)

-

vascular occlusive events [stroke/transient ischaemic attack/myocardial infarction (MI)/peripheral artery disease]

-

seizures

-

SAEs in first 7 days.

In addition, any safety interaction between the treatment effect and time to randomisation was assessed. Definitions of evidence required for adjudication of safety outcomes can be found in Appendix 1.

Study oversight

The trial was overseen by a Trial Steering Committee (TSC) and an International Advisory Committee comprising each national co-ordinator. A Trial Management Committee, based at the Stroke Trials Unit in Nottingham, UK, was responsible for the day-to-day conduct of the trial. Study data were collected, monitored and analysed in Nottingham. The trial was performed according to the principles of good clinical practice and the Declaration of Helsinki. 50

Data Safety Monitoring Committee

An independent Data Safety Monitoring Committee (DSMC) was established. The DSMC received safety reports every 6 months, and performed a total of six unblinded reviews of efficacy and safety data. The DSMC performed a formal interim analysis after 818 participants had been recruited (comprising both trial phases) and followed up at 90 days.

A DSMC charter was prepared containing information on the membership, terms and conditions and full details of the stopping guidelines. The DSMC reported its assessment to the independent chairperson of the TSC, who reported to the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Health Technology Assessment (HTA) programme.

Missing data

Any missing data were reported. For participants to have been included in the primary analysis they must have had their mRS score at day 90 recorded along with values for all of the minimisation criteria; if not, then they were excluded from the analysis. To include as many of the participants as possible, any missing minimisation criteria were backfilled from their randomisation form. The first step was to contact the recruiting centre and ask if it had this information, if not then imputation was used. If any of the individual NIHSS measures were missing, then the highest risk value was imputed to ensure that a total NIHSS score could be calculated for each participant. If the history of antiplatelet treatment was not known and could not be found, then the highest risk value was imputed, as would have been used in the randomisation process. Participants who died before day 90 were given death scores for outcome measures: a mRS score of 6, an EQ-5D score of 0, a Barthel Index of –5, an EQ-VAS of –1, a TICS-M score of –1, an Animal Naming Test score of –1 and a Zung Depression Scale score of 102. Missing outcome data from other follow-ups were excluded from any analyses. If a participant withdrew consent, no further information was collected; however, data collected thus far from follow-up assessments were used for any of the analyses.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed according to the published statistical analysis plan by Katie Flaherty and Polly Scutt, with oversight by Stuart J Pocock using SAS® software (version 9.4; SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA). Analyses were by intention to treat for all comparisons. Data shown are number (%), median [interquartile range (IQR)], mean [standard deviation (SD)] and odds ratio (95% CIs).

Death or dependency (ordinal shift on mRS) at day 90 was analysed between tranexamic acid and placebo by intention to treat using OLR, with adjustment for stratification and minimisation factors, which include: age (< 70 years, ≥ 70 years), sex (female, male), time from stroke onset to randomisation (< 3 hours, ≥ 3 hours), mean SBP (< 170 mmHg, ≥ 170 mmHg), stroke severity (NIHSS score of < 15, ≥ 15), presence of IVH (no, yes), known history of antiplatelet therapy used prior to stroke onset (no, yes) and country. As a sensitivity analysis, the primary outcome was also analysed unadjusted and as a binary outcome (a mRS score of > 3 vs. a mRS score of ≤ 3). The heterogeneity of the treatment effect on the primary outcome was assessed in prespecified subgroups and by adding an interaction term into the adjusted OLR model.

For secondary outcomes, binary logistic regression will be used for binary outcomes, including death, SAEs and thromboembolic events. Multiple linear regression will be used for continuous measures, including haematoma expansion. Wilcoxon rank-sum test will be used for continuous measures, which are not normally distributed, including the Barthel Index. Cox proportional hazards regression will be used for time-to-event analyses, including death. All regression analyses will be performed with adjustment for stratification and minimisation factors, as stated above. To review the overall trend of the data a global test (i.e. a Wei–Lachin test) was used on a combination of outcome measures. The impact of tranexamic acid on quality of life was assessed using the EuroQoL measure. Comparisons between the treatments will be performed in prespecified subgroups, the low-risk groups are given first in the brackets, as follows; minimisation criteria; CTA (yes, no); haematoma location (deep, lobar); and ethnicity (other, white).

The subgroup analysis did not constitute the primary analysis and, thus, has not informed the sample size calculation. The interpretation of any subgroup effect was based on interaction tests (i.e. evidence of differential treatment effects in the different subgroups) and there was no adjustment for multiple testing. The minimisation criteria were chosen and included in the subgroup analysis, as they are independent prognostic indicators of ICH.

The nominal level of significance for all analyses was a p-value of < 0.05. No adjustment was made for multiplicity of testing.

Sample size

The null hypothesis (H0) is that tranexamic acid does not alter death or dependency in participants with acute primary ICH. The alternative hypothesis (HA) is that death or dependency differs between those participants randomised to tranexamic acid and those randomised to saline. A total sample size of 2000 (1000 per group) participants with acute primary ICH is required, assuming:

-

an overall significance of (alpha) = 0.05

-

a power of (1 – beta) = 0.90

-

a distribution in mRS score (mRS 0 = 4%, 1 = 17%, 2 = 16%, 3 = 19%, 4 = 24%, 5 = 7% and 6 (death) = 13%; based on data from participants with primary ICH in the Efficacy of Nitric Oxide in Stroke (ENOS) trial

-

an ordinal OR of 0.79

-

increases due to losses to follow-up of 5%

-

a reduction of 20% for baseline covariate adjustment. 51

In summary, a trial of 2000 participants (1700 from the main phase and 300 from the start-up phase) will have 90% power to detect an ordinal shift of mRS outcome with an OR of 0.79.

Protecting against bias, including blinding

Numerous steps were taken to protect against bias in this double-blind RCT, with allocation concealed from all staff throughout the study.

Neuroimaging and scan adjudication

Brain imaging by CT was done as part of routine care before enrolment; a second research CT scan was done after 24 hours of treatment to assess haematoma expansion. When multiple scans were done, the scan closest to 24 hours after randomisation was used. Central independent expert assessors, who were masked to treatment assignment, assessed CT scans for the location of the ICH using a web-based adjudication system. Semi-automated segmentation of the ICH was done on Digital Imaging and Communications in Medicine [DICOM®; Medical Imaging & Technology Alliance (MITA), Arlington, VA, USA]-compliant images to give ICH volumes. The user-guided three-dimensional active contour tool in the itk-SNAP software (version 3.6; www.itksnap.org/pmwiki/pmwiki.php, accessed 3 May 2019) was used for segmentation and, as required, one of the three assessors did manual editing. All assessments were masked to treatment assignment.

Haematoma expansion was defined as an absolute increase of > 6 ml or a relative growth of > 33%.

Sites, investigators and monitoring

Investigators were trained in trial procedures, via a site initiation teleconference, after obtaining all of the necessary regulatory approvals. New investigators who joined the study after the site initiation training were required to complete and pass an online training test covering the trial protocol. Monitoring of trial data included confirmation of informed consent in all participants; source data verification; data storage and data transfer procedures; local quality control checks and procedures, back-up and disaster recovery of any local databases; and validation of data manipulation. The trial co-ordinator carried out monitoring of trial data throughout the study; entries on case report forms (CRFs) were verified by inspection against the source data. A sample of CRFs (10% as per the trial risk assessment) were checked for verification of all entries made. In addition, the subsequent capture of the data on the trial database was checked. Where corrections were required, a full audit trail and justification was documented.

Protocol amendments

During the course of the trial there was a number of amendments to the study protocol, which are detailed in Chapter 2, Methods, Substudies. In summary, these amendments were to add a number of substudies [i.e. a day 365 follow-up, a magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) substudy and a biomarker substudy], make minor changes to trial documentation and allow co-enrolment to the ongoing RCT, RESTART. Full details of protocol amendments can be found in Appendix 2.

Substudies

Three substudies were performed and will be presented elsewhere. First, an additional follow-up at day 365 was performed and, second, a MRI substudy (funded by the British Heart Foundation) was performed, which will be presented separately. Finally, a single-centre plasma biomarker substudy examined the effect of tranexamic acid on markers of haemostasis and inflammation.

Meta-analysis

In due course, data from TICH-2 will be added to summary and individual patient data meta-analyses in acute stroke. This will include data being used in a Cochrane review25 and in an individual patient data meta-analysis of all tranexamic acid effects in ICH by the Antifibrinolytics Triallists Collaboration (ATC). 52

Chapter 3 Results

Recruitment

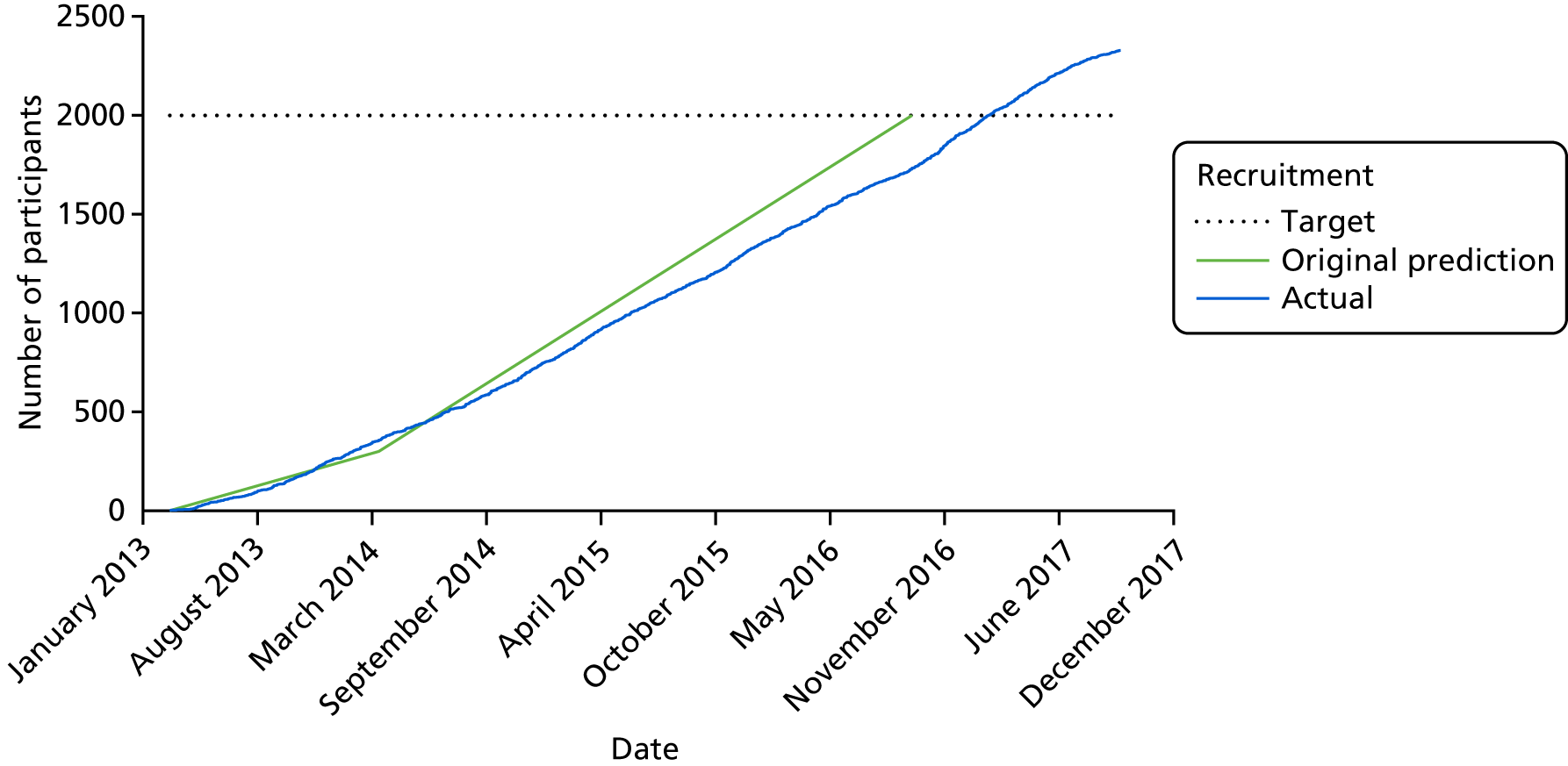

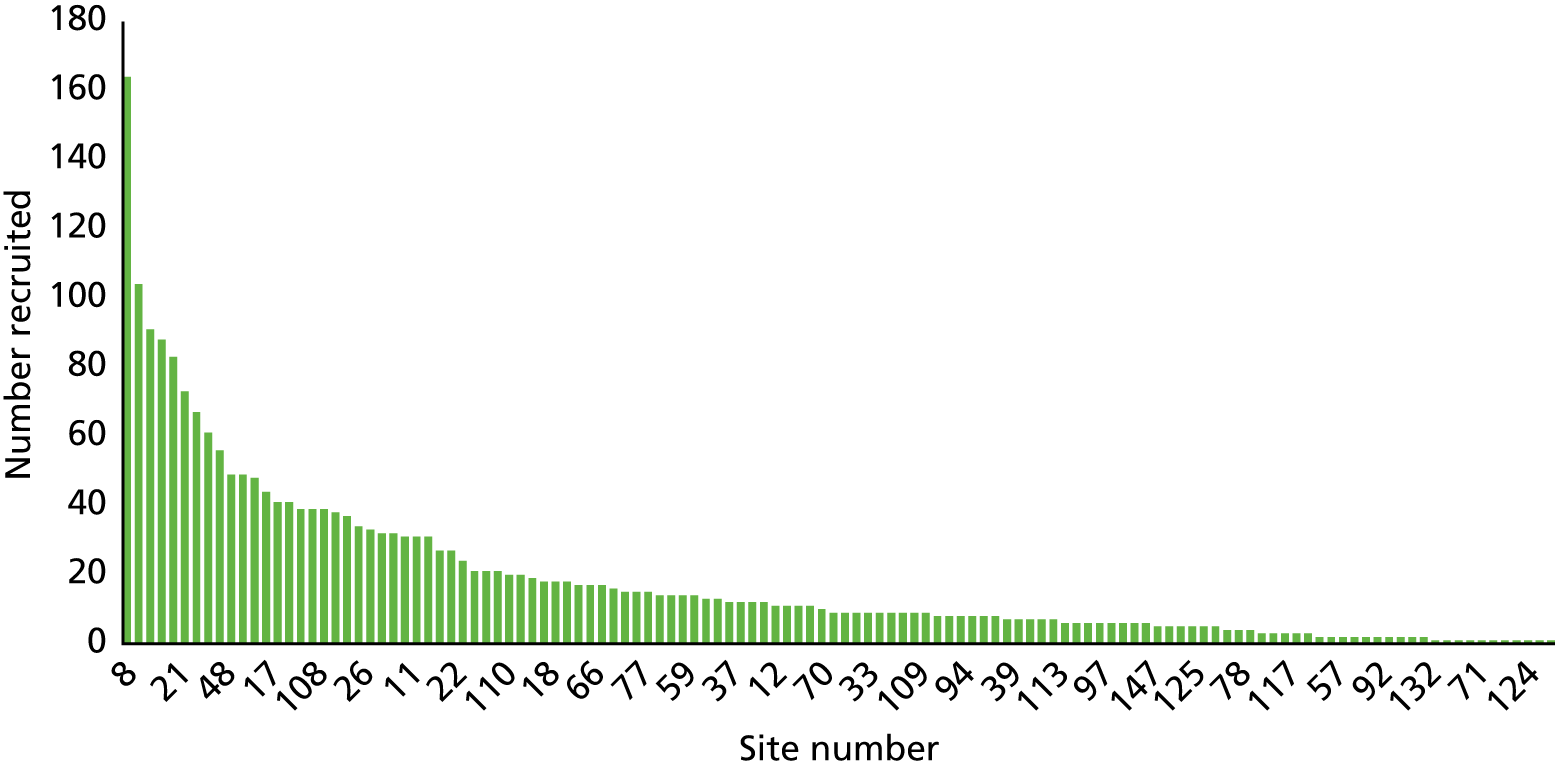

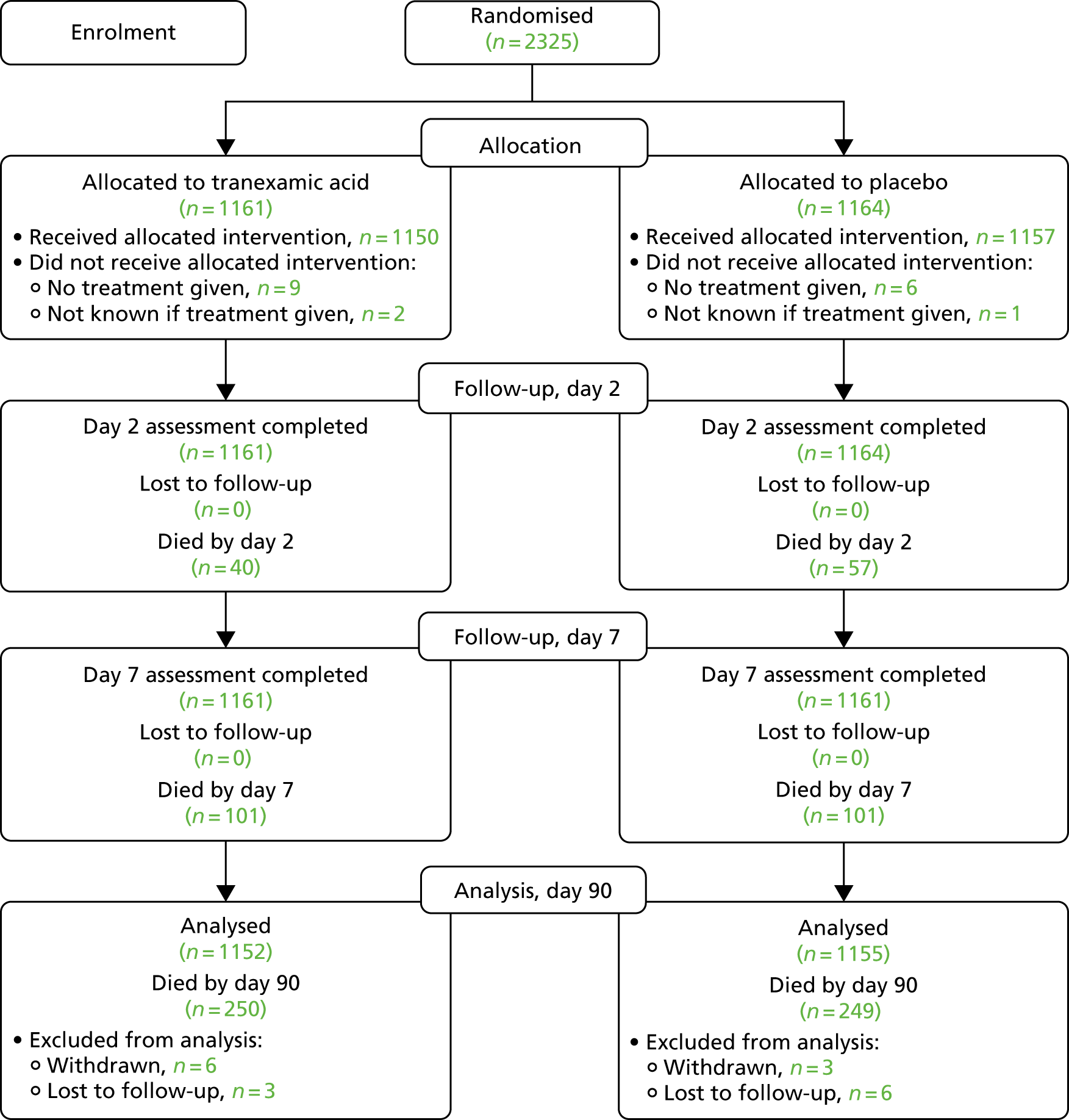

Recruitment started on 1 March 2013 and ended on 30 September 2017, after a 12-month extension was sought and approved to enable the trial to reach its target sample size (Table 1). This slower-than-planned recruitment was due to delays in opening trial sites outside the UK. Subsequently, recruitment increased and the TSC agreed that the study should exceed the target of 2000 and continue until the end of the extension. Therefore, a total of 2325 participants (1161 randomised to tranexamic acid and 1164 to placebo) were recruited from 124 sites in 12 countries over 55 months (Tables 1 and 2 and Figures 1–3).

| Recruitment | |

|---|---|

| Date recruitment started | 14 March 2013 |

| Date recruitment stopped | 30 September 2017 |

| Randomisation | |

| Number of patients randomised | 2325 |

| Number of centres that randomised patients | 124 |

| Number of countries that randomised patients | 12 |

| Country | Recruitment | |

|---|---|---|

| Number (%) of participants randomised | Average number of participants randomised per month | |

| Total number recruited | 2325 | |

| UK | 1910 (82.2) | 32.93 |

| Georgia | 141 (6.1) | 3.28 |

| Italy | 96 (4.1) | 1.92 |

| Malaysia | 46 (2.0) | 1.64 |

| Switzerland | 46 (2.0) | 1.53 |

| Denmark | 39 (1.7) | 2.17 |

| Republic of Ireland | 17 (0.7) | 0.65 |

| Hungary | 9 (0.4) | 0.64 |

| Turkey | 9 (0.4) | 0.33 |

| Sweden | 8 (0.3) | 0.29 |

| Poland | 3 (0.1) | 0.19 |

| Spain | 1 (0.0) | 0.06 |

FIGURE 1.

Recruitment graph.

FIGURE 2.

Recruitment by centre.

FIGURE 3.

Participant Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) flow diagram.

There was good data completion, with nine patients lost to follow-up or withdrawn in each of the treatment groups (see Figure 3).

Baseline data

The majority of participants were recruited in the UK (1910, 82.2%). The mean age of participants was 68.9 years (SD 13.8 years); 1301 participants (56%) were male. The median time from stroke onset to randomisation was 3.6 hours [IQR 2.6–5.0 hours] and one-third of participants (833, 36%) were recruited within 3 hours (Table 3). The mean baseline blood pressure was 173/93 mmHg. The majority of participants had a haematoma that was deep and supratentorial (1371, 59.0%), with 738 (31.7%) participants having a lobar supratentorial haematoma; one-third of participants had IVH. The mean HV was 24.0 ml (SD 27.2 ml) and the median HV was 14.1 ml (IQR 5.9–32.4 ml). Contrast-enhanced imaging, conducted as CTA, was performed in 249 (10.9%) of the participants. Twenty-four out of 121 (19.8%) participants in the tranexamic acid group and 32 out of 128 (25%) in the placebo group were spot positive. Treatment groups were well balanced at baseline.

| Baseline variable | N | Treatment group | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tranexamic acid | Placebo | ||

| Patients randomised, n | 1161 | 1164 | |

| Age (years) | |||

| Mean (SD) | 2325 | 69.1 (13.7) | 68.7 (13.9) |

| Sex, n (%) | |||

| Male | 2325 | 642 (55.30) | 659 (56.62) |

| Ethnic origin, n (%) | |||

| White | 2324 | 986 (85.00) | 992 (85.22) |

| Black | 2324 | 49 (4.22) | 47 (4.04) |

| Asian | 2324 | 107 (9.20) | 111 (9.53) |

| Other | 2324 | 18 (1.55) | 14 (1.20) |

| Country, n (%) | |||

| UK | 2325 | 954 (82.17) | 956 (82.13) |

| Onset to randomisation (hours) | |||

| Median (IQR) | 2325 | 3.6 (2.6–5.1) | 3.7 (2.6–5.0) |

| History of, n (%) | |||

| Antiplatelet therapy | 2324 | 316 (27.24) | 295 (25.34) |

| Statin use | 2307 | 319 (27.69) | 303 (26.23) |

| Previous stroke or TIA | 2301 | 174 (15.17) | 156 (13.52) |

| IHD | 2298 | 110 (9.62) | 92 (7.97) |

| Thromboembolism | 2296 | 15 (1.31) | 19 (1.65) |

| Hypertension | 2310 | 700 (60.66) | 721 (62.37) |

| Pre-stroke mRS score | |||

| Median (IQR) | 2325 | 0.0 (0.0–1.0) | 0.0 (0.0–1.0) |

| > 2, n (%) | 2325 | 104 (8.96) | 103 (8.85) |

| GCS score | |||

| Mean (SD) | 2325 | 13.4 (2.2) | 13.5 (2.1) |

| NIHSS score | |||

| Mean (SD) | 2325 | 13.1 (7.5) | 12.9 (7.5) |

| Systolic blood pressure (mmHg) | |||

| Mean (SD) | 2325 | 171.7 (27.5) | 173.5 (26.8) |

| > 170, n (%) | 2325 | 571 (49.18) | 602 (51.72) |

| Diastolic blood pressure (mmHg) | |||

| Mean (SD) | 2325 | 92.9 (18.4) | 93.6 (17.8) |

| Advanced imaging performed, n (%) | 2277 | 121 (10.60) | 128 (11.28) |

| Spot positive | 249 | 24 (19.83) | 32 (25.00) |

| Spot negative | 249 | 97 (80.17) | 96 (75.00) |

| Haematoma location, n (%) | |||

| Supratentorial – lobar | 2325 | 379 (32.64) | 359 (30.84) |

| Supratentorial – deep | 2325 | 675 (58.14) | 696 (59.79) |

| Infratentorial | 2325 | 73 (6.29) | 76 (6.53) |

| Combination | 2325 | 34 (2.93) | 33 (2.84) |

| Haematoma characteristics | |||

| IVH, n (%) | 2325 | 382 (32.90) | 363 (31.19) |

| Intracerebral HV (ml), mean (SD) | 2273 | 24.7 (27.9) | 23.3 (26.4) |

Adherence/tranexamic acid treatment

Adherence to the allocated treatment was high, that is, 2207 (94.9%) participants received all of their randomised treatment, whereas only 15 (0.6%) participants received no treatment. There was no difference in adherence rates between the treatment groups. The median time from randomisation to treatment was 21 minutes (IQR 13–33 minutes) (Table 4).

| Adherence | Treatment group | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tranexamic acid | Placebo | ||

| Number of participants randomised | 1161 | 1164 | |

| Treatment, n (%) | |||

| All treatment received | 1101 (94.8) | 1106 (95.0) | 0.96 |

| Some treatment received | 49 (4.2) | 51 (4.4) | 0.66 |

| No treatment received | 9 (0.8) | 6 (0.5) | 0.48 |

| Not known | 2 (0.2) | 1 (0.1) | 0.54 |

| Incorrect drug administration,a n (%) | 31 (2.7) | 26 (2.2) | 0.56 |

| Time (minutes) until first dose, median (IQR) | 21 (13–33) | 21 (13–32) | 0.49 |

Time to treatment

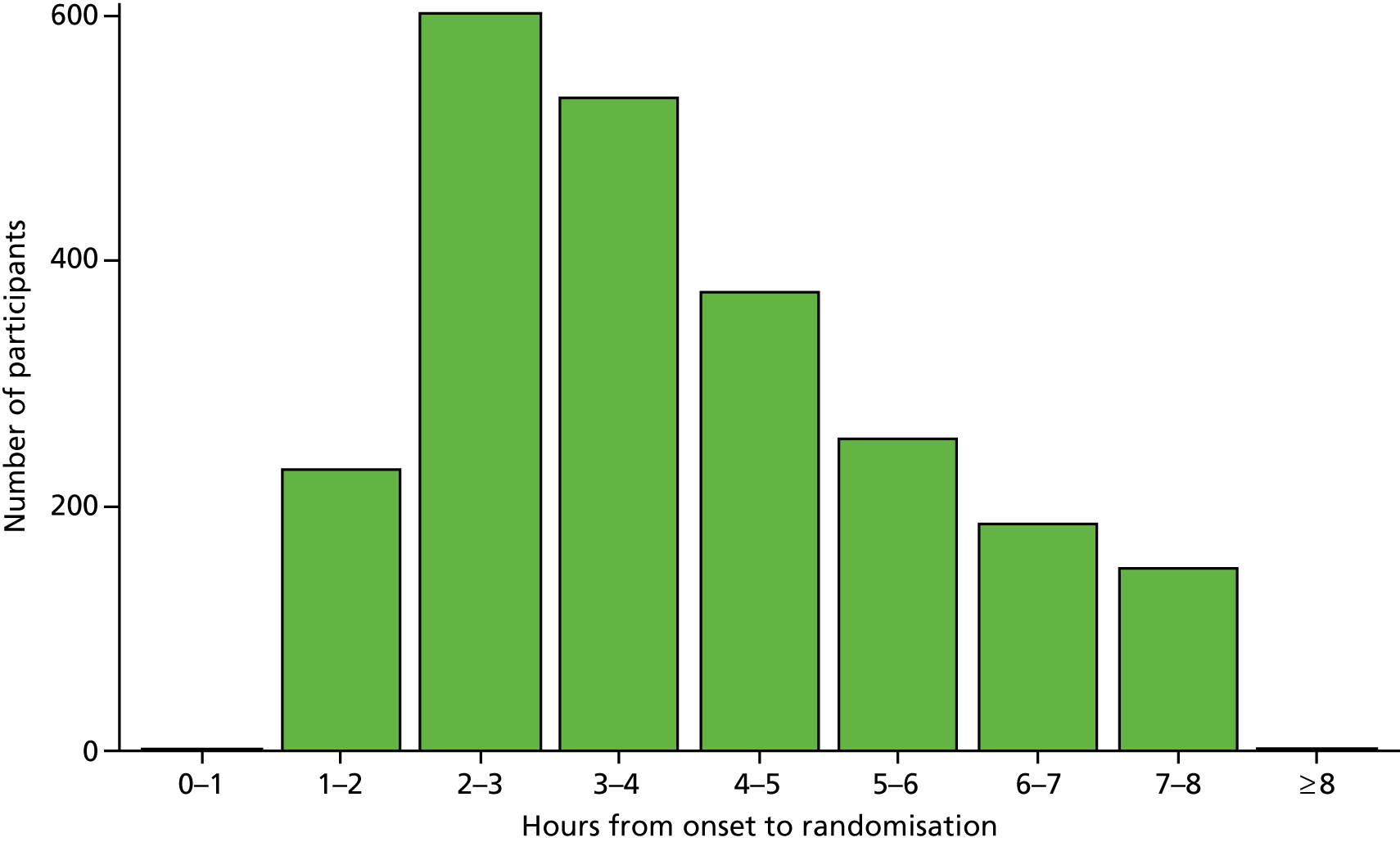

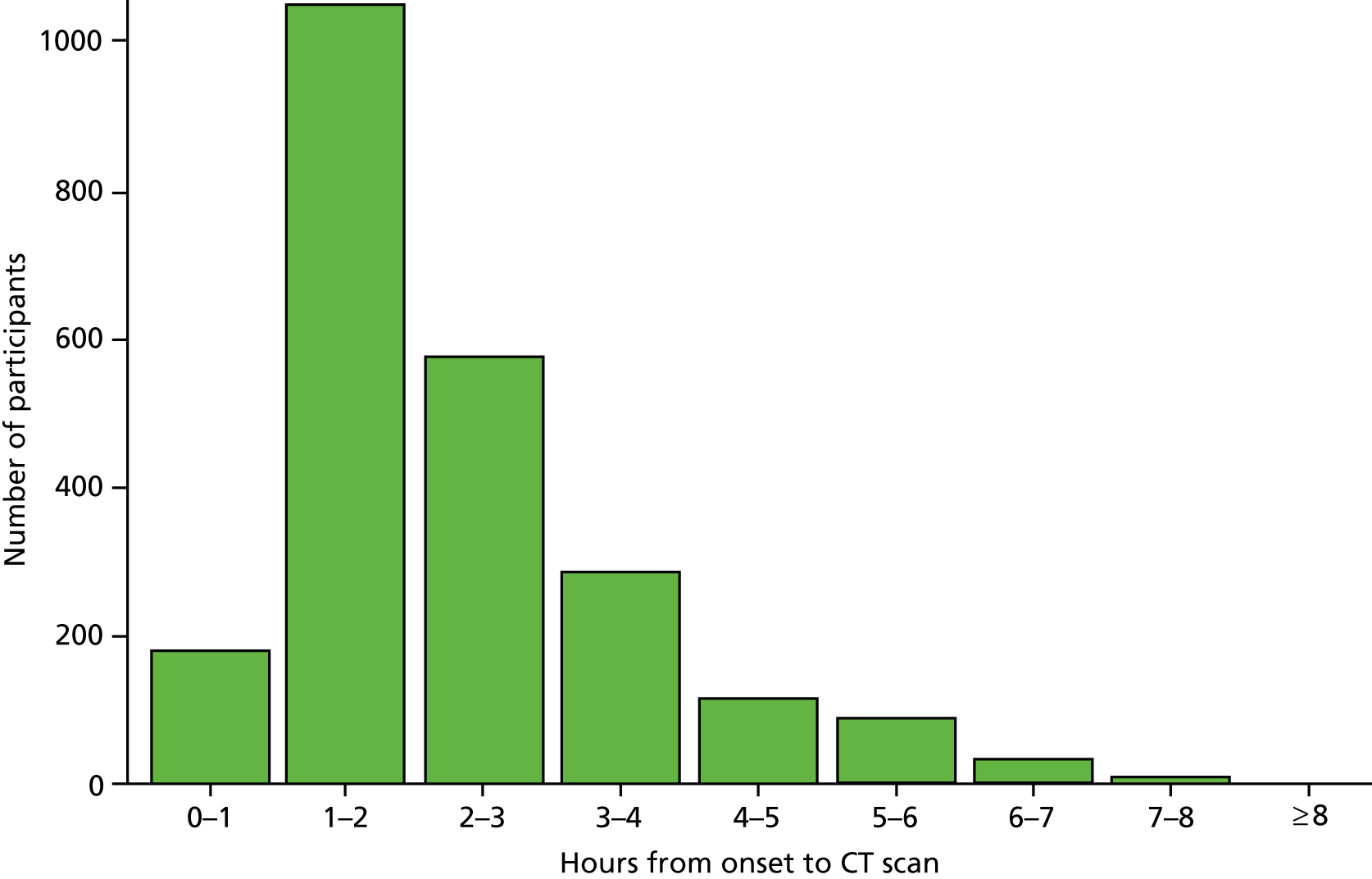

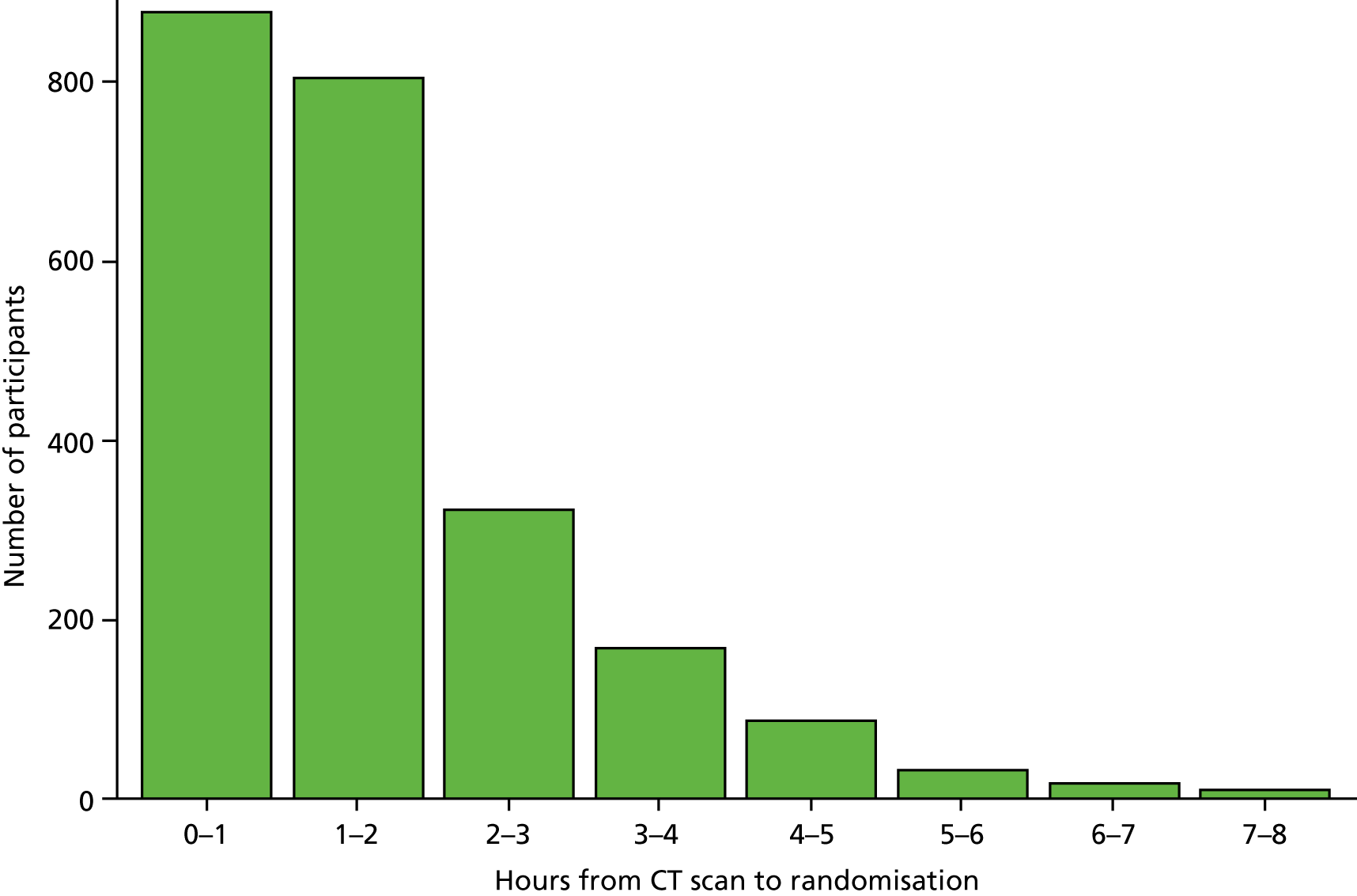

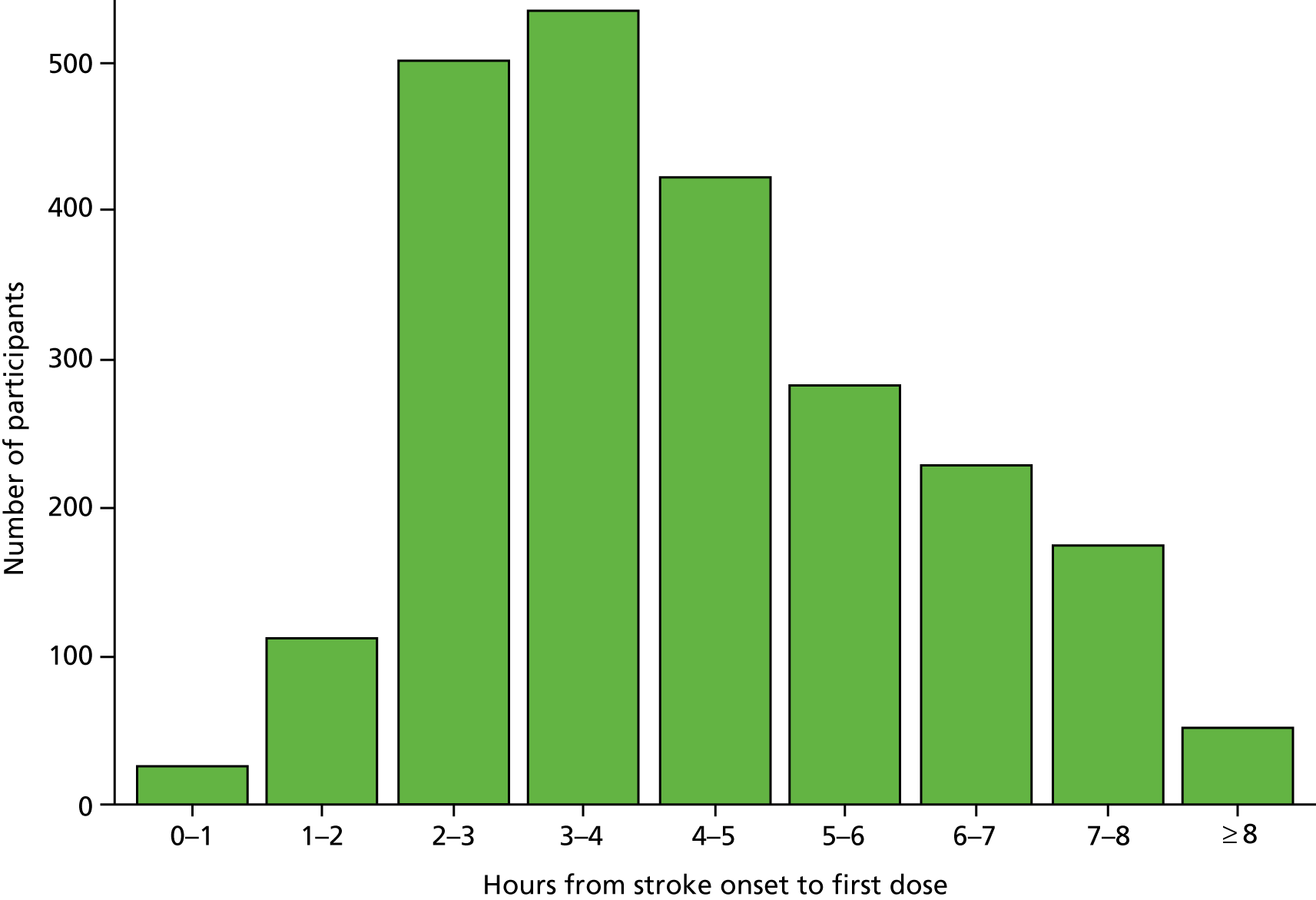

The median time for stroke onset to randomisation was 3.6 hours (IQR 2.6–5.0 hours) (Figure 4), with 827 (35.6%) participants enrolled within 3 hours and 1571 (67.6%) participants enrolled within 4.5 hours. The median time to a CT scan was 1.9 hours (IQR 1.4–2.9 hours); 77% of participants had a CT scan within 3 hours of symptom onset and 93% had a CT scan within 4.5 hours (Figure 5). The median time from a CT scan to randomisation was 1.3 hours (IQR 0.8–2.1 hours) (Figure 6), with 861 (37%) participants randomised within 1 hour of a CT scan and 1681 (72.3%) participants randomised within 2 hours of a CT scan. The majority of participants took more than 1 hour to enrol in the trial after a CT scan was performed. The median time to first dose was 4.1 hours after stroke onset (Figure 7), 25% of participants were treated within 3 hours of stroke onset and 58% within 4.5 hours.

FIGURE 4.

Time from stroke onset to randomisation.

FIGURE 5.

Time from stroke onset to CT scan.

FIGURE 6.

Time from CT scan to randomisation.

FIGURE 7.

Time from stroke onset to treatment.

Consent

The majority of participants were enrolled in the trial after consent by a relative (Table 5). Participants with more severe stroke (i.e. a higher NIHSS score) were more likely to use relative or doctor consent. Independent doctor consent had the shortest time from onset to randomisation (3.25 hours) compared with full informed consent from a relative, which took the longest (4.21 hours).

| Consent type | n (%) | NIHSS mean score | OTR mean time (hours) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Patients with data | 2325 | 13 | 3.94 |

| Fully informed participant | 558 (24.0) | 7.58 | 3.97 |

| Brief participant | 260 (11.2) | 9.03 | 3.59 |

| Fully informed relative | 996 (42.8) | 15.1 | 4.21 |

| Brief relative | 323 (13.9) | 16.1 | 3.75 |

| Doctor | 188 (8.1) | 18 | 3.25 |

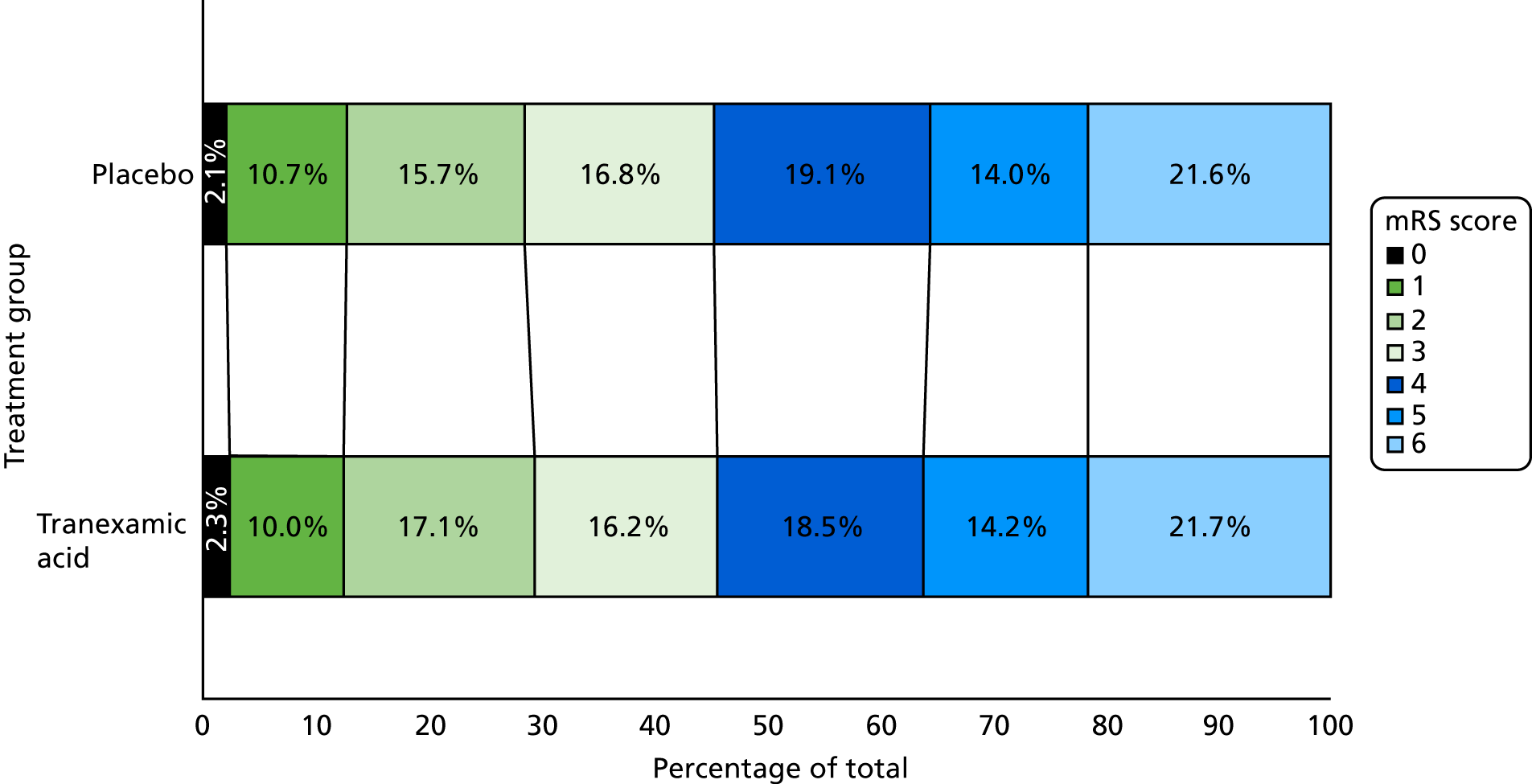

Primary efficacy outcome

The primary outcome of mRS score at day 90 was determined in 2307 (99.2%) participants; 9 (0.4%) were lost to follow-up and 9 (0.4%) withdrew from their day 90 follow-up (see Figure 3). There was no difference in the distribution (i.e. shift) in the mRS score at day 90 after adjustment for stratification and minimisation criteria [adjusted odds ratio (aOR) 0.88, 95% CI 0.76 to 1.03; p = 0.11] (Figure 8). A formal goodness-of-fit test gave no evidence that the proportional odds assumption was violated (p = 0.97). There was no difference between the tranexamic acid and placebo treatment groups in the proportion of participants who were dead or dependent (mRS score of > 3: aOR 0.82, 95% CI 0.65 to 1.03; p = 0.08).

FIGURE 8.

Primary outcome: shift plot of the day 90 mRS score (aOR 0.88, 95% CI 0.76 to 1.03; p-value = 0.11). mRS score level descriptions: 0 = no symptoms; 1 = no disability despite symptoms; 2 = slight disability, but able to look after own affairs; 3 = moderate disability, but able to walk without assistance; 4 = moderately severe disability – unable to walk or attend to own bodily needs; 5 = severely disabled – bedridden and requiring constant nursing care; and 6 = death. Reproduced from Sprigg et al. 1 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

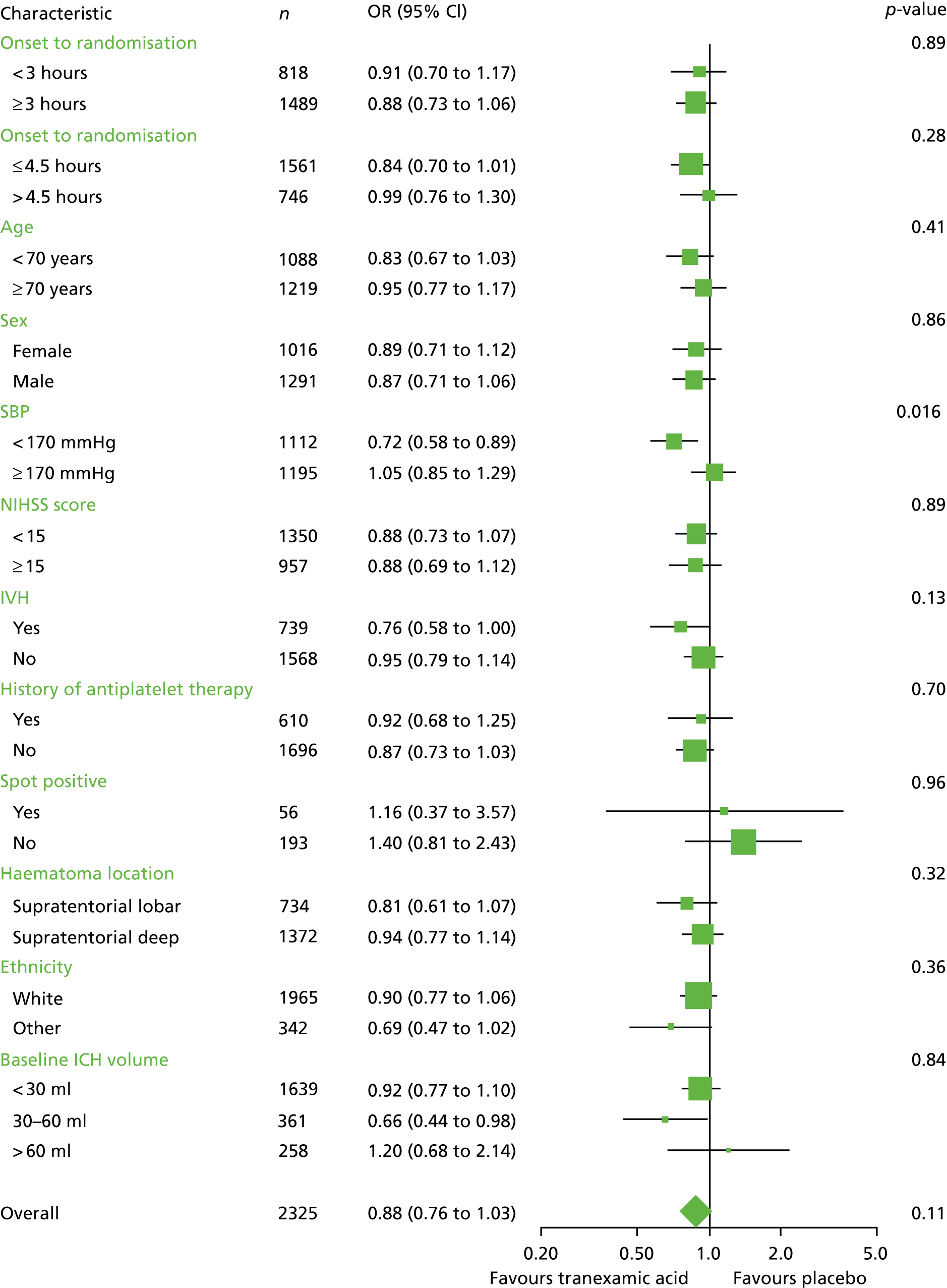

Subgroup analysis

When the primary outcome was assessed in prespecified subgroups (Figure 9), the only significant interaction was between mRS score and baseline SBP (interaction p = 0.016). Participants with a baseline SBP of < 170 mmHg had a favourable shift in mRS score with tranexamic acid compared with those participants with a SBP of ≥ 170 mmHg. There was no heterogeneity of treatment effect by time to enrolment (see Figure 9) whether dichotomised at < 3 hours versus ≥ 3 hours (interaction p = 0.89) or ≤ 4.5 hours versus > 4.5 hours (interaction p = 0.28); similarly, there was no interaction between treatment effect and time when analysed as a continuous variable (aOR 0.98, 95% CI 0.90 to 1.07; p = 0.69).

FIGURE 9.

Forest plot of the day 90 mRS scores in the subgroups. Haematoma volume was not prespecified and was an exploratory post hoc analysis.

In exploratory post hoc analysis, participants with a moderate haematoma size (i.e. 30–60 ml) have a favourable shift in mRS score with tranexamic acid treatment (aOR 0.66, 95% CI 0.44 to 0.98, p = 0.039), but the interaction between haematoma size and treatment was not statistically significant (p = 0.84). This difference was statistically significant when studying 1350 participants with a haematoma size of ≤ 60ml who were enrolled within 4.5 hours of onset (aOR 0.821, 95% CI 0.67 to 0.9; p = 0.031). However, the interaction between haematoma size and treatment in patients randomised within 4.5 hours was not statistically significant (p = 0.55).

Secondary outcomes

Radiological outcomes

There were fewer participants with a haematoma expansion at day 2 in the tranexamic acid group (265, 25.1%) than in the placebo group (304, 28.7%; aOR 0.80, 95% CI 0.66 to 0.98; p = 0.030) (Table 6). The mean increase in HV from baseline to 24 hours was also less in the tranexamic acid group [3.72 ml (SD 15.9 ml)] than in the placebo group [4.90 ml (SD 16.0 ml); adjusted mean difference (aMD) –1.37 ml, 95% CI –2.71 to –0.04 ml; p = 0.043].

| Outcome | n | Treatment group | OR/MD (95% CI) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tranexamic acid | Placebo | ||||

| Radiological outcomes | |||||

| Change in HV (ml) (SD) from baseline to 24 hoursa | 2112 | 3.72 (15.9) | 4.90 (16.0) | MD: –1.37 (–2.71 to –0.04) | 0.043 |

| Participants with haematoma expansion,b n (%) | 2112 | 265 (25.1) | 304 (28.7) | Binary OR: 0.80 (0.66 to 0.98) | 0.030 |

| Clinical outcomes day 7 | |||||

| Death by day 7, n (%) | 2325 | 101 (8.7) | 123 (10.6) | Binary OR: 0.73 (0.50 to 0.99) | 0.041 |

| NIHSS at day 7, mean score (SD) | 1829 | 10.13 (8.3) | 10.29 (8.3) | MD: –0.43 (–0.94 to 0.09) | 0.10 |

Clinical outcomes

Neurological impairment (i.e. mean NIHSS score at day 7) did not differ between the tranexamic acid group (10.1) and the placebo group (10.3) (aMD –0.43, 95% CI –0.94 to 0.09; p = 0.10) (see Table 6).

Clinical outcomes day 90

There were no significant differences in any of the day 90 functional outcomes between treatment groups: activities of daily living (as measured by the Barthel Index), mood [as measured by the Zung Depression Scale (ZDS)], cognition (as measured by TICS-M, verbal fluency), or quality of life [as measured by EQ-5D health utility score (HUS) and EQ-VAS; Table 7].

| Secondary outcome | N | Treatment group | OR/MD (95% CI) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tranexamic acid | Placebo | ||||

| Death by day 90, n (%) | 2325 | 250 (21.5) | 249 (21.4) | HR: 0.92 (0.77 to 1.10) | 0.37 |

| EQ-5D HUS, day 90 | 2244 | 0.34 (0.4) | 0.34 (0.4) | MD: 0.01 (–0.01 to 0.04) | 0.30 |

| EQ-VAS, day 90 | 2081 | 48.81 (33.8) | 48.34 (33.1) | MD: 1.75 (–0.52 to 4.02) | 0.13 |

| Barthel Index, day 90 | 2231 | 52.92 (44.0) | 53.21 (43.7) | MD: 1.70 (–0.90 to 4.31) | 0.20 |

| TICS-M, day 90 | 1216 | 13.57 (12.5) | 13.94 (12.8) | MD: –0.19 (–1.12 to 0.74) | 0.69 |

| ZDS score, day 90 | 1319 | 67.28 (29.5) | 67.29 (29.9) | MD: –0.35 (–2.60 to 1.90) | 0.76 |

| Global analysis (Wei–Lachin test), day 90 | 2307 | NA | NA | MWD: 0.00 (–0.05 to 0.04) | 0.85 |

| Length of stay (days) in hospital | 2312 | 63.12 (47.1) | 63.73 (48.1) | MD: 1.09 (0.97 to 1.24) | 0.16 |

| If discharged, days well at home | 1007 | 69.94 (28.6) | 72.15 (29.1) | MD: –0.72 (–3.73 to 2.28) | 0.64 |

| Home discharge, n (%) | 2325 | 465 (40.1) | 453 (38.9) | Binary OR: 1.14 (0.93 to 1.40) | 0.20 |

| Institutionalisation, n (%) | 2325 | 505 (43.5) | 506 (43.5) | Binary OR: 0.99 (0.83 to 1.18) | 0.90 |

| Died by discharge, n (%) | 2325 | 190 (16.4) | 205 (17.6) | Binary OR: 0.83 (0.65 to 1.07) | 0.15 |

Cost outcomes

Length of hospital stay and discharge disposition did not differ between treatment groups (see Table 7).

Process-of-care measures

The majority of participants received intravenous blood pressure-lowering treatment (i.e. 75.3% in the tranexamic acid group and 74.5% in the placebo group) on the first day. By day 7 nearly all participants had received blood pressure-lowering treatment (i.e. 81.6% in the tranexamic acid group and 83.5% in the placebo group).

The use of do not attempt resuscitation (DNAR) orders increased from 17% in the first 24 hours, to 22% by day 7, but there was no difference between the treatment groups (Table 8).

| Day | N | Treatment group | All | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tranexamic acid | Placebo | ||||

| Day 2 | |||||

| Participants, n | 2325 | 1161 | 1164 | 2325 | |

| Blood pressure, n (%) | |||||

| Treatment | 2325 | 851 (73.3) | 886 (76.1) | 1737 (74.7) | 0.39 |

| Treatment route (i.v.) | 1737 | 641 (75.3) | 660 (74.5) | 1301 (74.9) | 0.78 |

| DNAR orders, n (%) | 2325 | 193 (16.6) | 199 (17.1) | 392 (16.9) | 0.26 |

| Day 7 | |||||

| Participants, n | 2325 | 1161 | 1164 | 2325 | |

| Blood pressure, n (%) | |||||

| Treatment | 2325 | 947 (81.6) | 972 (83.5) | 1919 (82.5) | 0.59 |

| Treatment route (i.v.) | 1919 | 545 (57.6) | 585 (60.2) | 1130 (58.9) | 0.21 |

| DNAR orders, n (%) | 2325 | 255 (22.0) | 254 (21.8) | 509 (21.9) | 0.59 |

| Neurosurgery received, n (%) | 2325 | 57 (4.9) | 64 (5.5) | 121 (5.2) | 0.60 |

| ICU, n (%) | 2325 | 113 (9.7) | 119 (10.2) | 232 (10.0) | 0.84 |

| Invasive ventilation, n (%) | 2325 | 82 (7.1) | 84 (7.2) | 166 (7.1) | 0.92 |

Only 5% of participants underwent neurosurgery, with similar rates for both treatment groups. A total of 10% of participants were transferred to intensive care units (ICUs), with 7% of participants undergoing ventilation. Rates of ICU transfer and ventilation did not differ between the treatment groups.

Safety outcomes

There were fewer deaths by day 7 in the tranexamic acid group (101, 8.7%) than in the placebo group (123, 10.6%; aOR 0.73, 95% CI 0.53 to 0.99; p = 0.041).

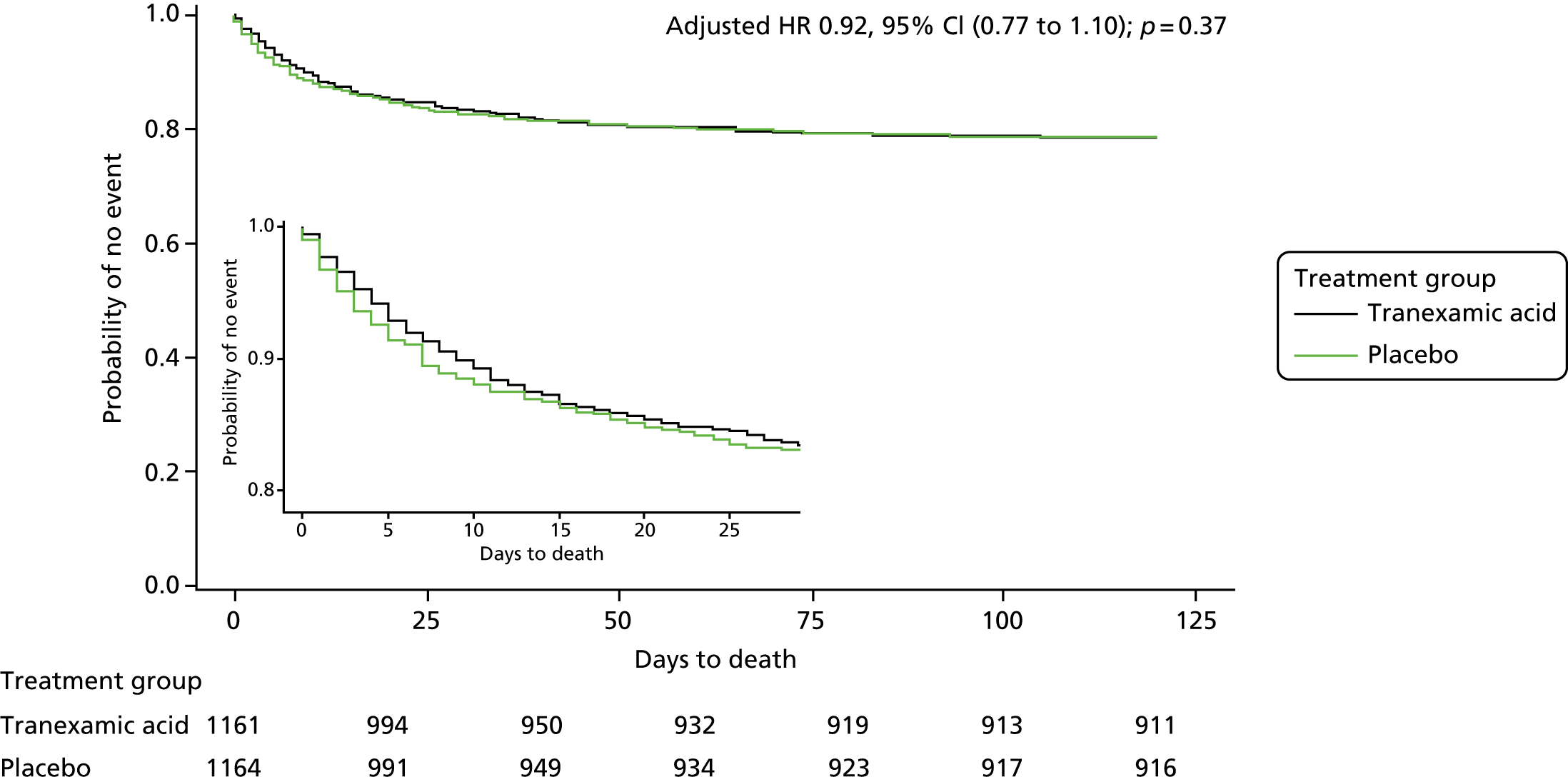

The number of deaths by day 90 did not differ between the tranexamic acid group (250/1161, 21.5%) and the placebo group (249/1164, 21.4%; see Table 7). There was no difference in survival between treatment groups over 90 days (adjusted hazard ratio 0.92, 95% CI 0.77 to 1.10; p = 0.37) (Figure 10).

FIGURE 10.

Plot of cumulative mortality. HR, hazard ratio.

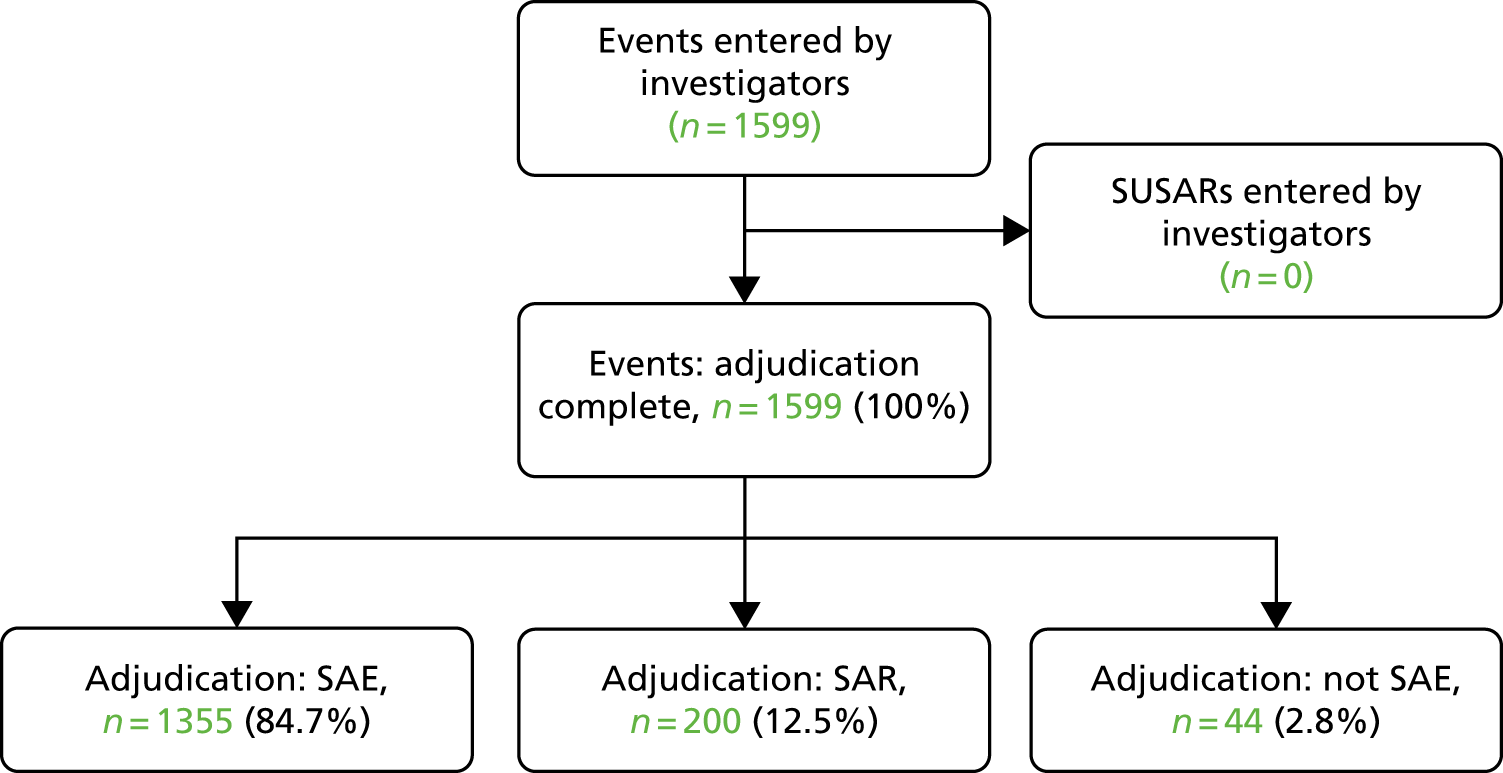

Serious adverse events

A total of 1599 events were reported as SAEs, of which 1355 were SAEs and 200 serious adverse reactions (SARs) (Figure 11). There were no suspected unexpected SAR (Table 9).

FIGURE 11.

Serious adverse events reported by investigators. SUSAR, suspected unexpected serious adverse reaction.

| Event | Median (IQR) days to event | Treatment group, n (%) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tranexamic acid (n = 1161) | Placebo (n = 1164) | |||

| By day | ||||

| By day 2 | 379 (32.6) | 417 (35.8) | 0.027 | |

| By day 7 | 456 (39.3) | 497 (42.7) | 0.020 | |

| By day 90 | 521 (44.9) | 556 (47.8) | 0.039 | |

| By classification | ||||

| SAE | 1 (0–3) | 493 (42.5) | 517 (44.4) | 0.11 |

| SAR | 2 (1–4) | 92 (7.9) | 95 (8.2) | 0.69 |

| Safety outcomes | ||||

| Death | 1 (0–15) | 250 (21.5) | 249 (21.4) | 0.60 |

| ACS or MI | 5 (1–53) | 11 (0.9) | 6 (0.5) | 0.24 |

| DVT | 15 (10–34) | 19 (1.6) | 14 (1.2) | 0.41 |

| PE | 16 (8–29) | 20 (1.7) | 23 (2.0) | 0.58 |

| VTE (combined DVT/PE) | 16 (10–30) | 39 (3.4) | 37 (3.2) | 0.98 |

| Seizure/convulsions | 1 (0–3) | 77 (6.6) | 85 (7.3) | 0.44 |

| Ischaemic stroke or TIA | 9 (2–52) | 16 (1.4) | 11 (0.9) | 0.27 |

| SAEs by subcategory | ||||

| Blood and lymphatic system disorders | 0 (0–4) | 1 (0.1) | 2 (0.2) | 0.41 |

| Cardiac disorders | 1 (1–2) | 14 (1.2) | 10 (0.9) | 0.48 |

| Gastrointestinal disorders | 1 (0–2) | 12 (1.0) | 9 (0.8) | 0.59 |

| General disorders and administration site conditions | 2 (1–3) | 2 (0.2) | 2 (0.2) | 0.95 |

| Immune system disorders | 0 (0–1) | 1 (0.1) | 2 (0.2) | 0.51 |

| Infections and infestations | 2 (1–3) | 98 (8.4) | 116 (10.0) | 0.14 |

| Injury, poisoning and procedural complications | 1 (1–3) | 7 (0.6) | 10 (0.9) | 0.53 |

| Metabolism and nutrition disorders | 4 (1–7) | 0 | 2 (0.2) | 0.99 |

| Musculoskeletal and connective tissue disorders | 1 (1–1) | 0 | 1 (0.1) | 0.99 |

| Neoplasms benign, malignant and unspecified | 4 (1–5) | 3 (0.3) | 3 (0.3) | 0.89 |

| Nervous system disorders | 1 (0–1) | 171 (14.7) | 189 (16.2) | 0.24 |

| Psychiatric disorders | 4 (3–5) | 1 (0.1) | 4 (0.3) | 0.26 |

| Renal and urinary disorders | 2 (1–4) | 14 (1.2) | 17 (1.5) | 0.66 |

| Respiratory, thoracic and mediastinal disorders | 1 (1–2) | 4 (0.3) | 3 (0.3) | 0.72 |

| Skin and subcutaneous tissue disorders | 5 (5–5) | 2 (0.2) | 0 | 0.99 |

| Vascular disorders | 1 (0–2) | 7 (0.6) | 9 (0.8) | 0.64 |

| Miscellaneous | 1 (0–3) | 7 (0.6) | 6 (0.5) | 0.81 |

Fewer participants experienced safety outcomes and SAEs at day 2 (32.6% vs. 35.8%), 7 (39.3% vs. 42.7%) and 90 days (44.9% vs. 47.8%) were significantly lower in the tranexamic acid group (see Table 9). There was no increase in the number of venous thromboembolic events (3.4% in the tranexamic acid group vs. 3.2% in the placebo group; p = 0.98), or arterial occlusions (MI, acute coronary syndrome or peripheral arterial occlusion) in the tranexamic acid group (see Table 9).

Seizure was the most common safety outcome, but there was no difference between the treatment groups [77 (7%) patients in the tranexamic acid group vs. 85 (7%) patients in the placebo group]. Nervous system disorders were the most common SAEs [149 (13%) in the tranexamic acid group vs. 163 (14%) in the placebo group], followed by infections [98 (8%) in the tranexamic acid group vs. 116 (10%) in the placebo group].

Protocol violations

A total of 331 protocol violations were reported by investigators, with 87 meeting the protocol definition of a protocol violation (Table 10). The commonest protocol violation was failure of a participant to receive all of the allocated treatment, which occurred in 1% of participants.

| Protocol violation | Treatment group, n (%) | All, n (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tranexamic acid | Placebo | ||

| Patients with data | 1161 | 1164 | 2325 |

| Number of protocol violations entered by investigators | 164 | 167 | 331 |

| Number adjudicated to not be a protocol violation | 129 | 115 | 244 |

| Number of protocol violations | 35 | 52 | 87 |

| Baseline characteristics | |||

| Randomisation over 8 hours from onset of symptoms | 1 (0.1) | 0 | 1 (0.0) |

| Baseline cranial imaging shows underlying structural abnormality, for example a tumour or arterial venous malformation | 1 (0.1) | 2 (0.2) | 3 (0.1) |

| On anticoagulation | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.1) | 1 (0.0) |

| Randomising event was secondary to trauma | 1 (0.1) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.0) |

| Not a primary ICH | 1 (0.1) | 1 (0.1) | 2 (0.1) |

| Practice during the trial | |||

| Subsequent randomisation into another drug or devices trial | 1 (0.1) | 0 | 1 (0.0) |

| Participant does not receive all of the randomised treatment | 13 (1.1) | 15 (1.3) | 28 (1.2) |

| Consent and reconsent | |||

| Failure to obtain any consent – neither brief information sheet/assent nor fully informed consent | 0 (0.0) | 3 (0.3) | 3 (0.1) |

| Failure to obtain appropriate, fully informed consent (following brief or independent physician consent) | 0 (0.0) | 5 (0.4) | 5 (0.2) |

| Individual taking consent not authorised to take consent on delegation log | 2 (0.2) | 5 (0.4) | 7 (0.3) |

| Wrong consent form used to obtain fully informed consent | 2 (0.2) | 4 (0.3) | 6 (0.3) |

| Follow-up assessments performed | |||

| Day 2 follow-up – over 2 days past due date | 1 (0.1) | 1 (0.1) | 2 (0.1) |

| Day 7 follow-up – over 7 days past due date | 2 (0.2) | 1 (0.1) | 3 (0.1) |

| Day 90 follow-up – over 30 days past the due date | 2 (0.2) | 6 (0.5) | 8 (0.3) |

| Miscellaneous | |||

| Any other major deviation from the trial protocol | 8 (0.7) | 8 (0.7) | 16 (0.7) |

Chapter 4 Discussion and conclusion

Interpretation

In this international multicentre RCT of tranexamic acid after acute ICH, there was no statistically significant difference in the primary outcome of functional status at day 90. Despite no significant improvement in primary outcome, there were statistically significant yet modest reductions in the prespecified secondary outcomes of early death, haematoma expansion and SAEs. There was no increase in thromboembolic events or seizures.

In keeping with an antifibrinolytic effect, tranexamic acid was associated with a modest yet statistically significant reduction in haematoma expansion and smaller growth in HV, key factors known to influence outcome after ICH. However, the small reduction in HV growth (i.e. 1.4 ml), and proportion of participants experiencing haematoma expansion (29% in the placebo group compared with 25% in the tranexamic acid group) may have been too small to translate into improved functional status in this population.

Therefore, although it is possible that tranexamic acid is not effective at improving outcome after ICH, an alternative explanation for the study’s findings is that the observed treatment effect was too modest. The study’s sample size calculation was based on an estimated effect size of an OR of 0.79, which the trial did not detect. The observed OR was 0.88 and a much larger sample size would be required to detect this. Indeed, previous RCTs of tranexamic acid in other settings have randomised more than 10-fold the number of participants to identify more modest effects on bleeding-related deaths after trauma (i.e. an OR of 0.85)23 and postpartum haemorrhage (i.e. an OR of 0.81). 13 Furthermore, an individual patient data meta-analysis of two RCTs (with > 40,000 participants), published after enrolment in TICH-2 had completed, has subsequently confirmed that commencing tranexamic acid within 3 hours of the start of bleeding is necessary to obtain the benefit of tranexamic acid after trauma or postpartum haemorrhage. 15 Despite repeated efforts to encourage investigators to reduce the time to enrolment, the majority of the study’s participants were enrolled after 3 hours. Recent meta-analysis of individual patient data in 5435 patients has demonstrated that the probability of haemorrhage growth declines mostly steeply 3 hours after symptom onset,53 highlighting the need for urgent treatment.

In the same meta-analysis, baseline HV was the strongest predictor of outcome after SICH. The probability of haematoma growth increased with baseline HV, but peaked at 75 ml. 53 In TICH-2, in an exploratory post hoc analysis, participants with a baseline HV of between 30 and 60 ml, who received tranexamic acid appeared to have better outcome (aOR 0.66, 95% CI 0.44 to 0.98; p = 0.039; see Figure 9), but the interaction between HV and treatment was not significant (p = 0.84). Although this could be due to chance and caution is needed when interpreting subgroups, it is also compatible with the hypothesis that patients with moderate-size haematomas may be more likely to benefit from haemostatic therapies and, hence, could be targeted for future studies, as has been postulated with rFVIIa. 23,24

The statistically significant interaction demonstrated in this study between baseline SBP and treatment suggests participants with lower blood pressure were more likely to benefit from tranexamic acid. This finding could have been confounded by stroke severity, as larger haematomas have increased blood pressure and worse outcomes. 22,26 Despite being the only intervention to date to improve functional outcome after ICH, early intensive blood pressure-lowering treatment3 remains controversial. 11 Although there were no significant effects on haematoma growth in INTERACT-2,3 secondary analysis suggested blood pressure lowering did attenuate bleeding in a dose-dependent manner. 25 The interaction demonstrated in this study between SBP and tranexamic acid suggests complementary approaches to reduce haematoma expansion, with haemostatic and haemodynamic therapies warranting further investigation.

Unlike other acute ICH studies with rFVIIa24 and aggressive lowering of blood pressure,10 the study found no evidence of adverse effects. Notably, there was no increase in VTE or seizures in this significantly older population with more comorbidities than in participants in previous studies of tranexamic acid. 13,23 It is therefore unlikely that any potential benefit of tranexamic acid was offset by harm, as has been suggested with rFVIIa. 24 In a Phase 3 trial, there was no evidence of clinical benefit of rFVIIa, with a reduction in haematoma expansion but an increased risk in arterial occlusive events. 24 Although tranexamic acid and rFVIIa are both haemostatic agents, tranexamic acid has antifibrinolytic mechanisms and rFVIIa is a procoagulant and, hence, they have different risk–benefit profiles. Recent studies with rFVIIa have attempted to use the spot sign to identify those patients at risk of haematoma expansion and, as such, most likely to benefit from rFVIIa. 26,27 However, the trials were stopped as a result of poor recruitment. 28 The study has also demonstrated that selecting large numbers of patients based on the spot sign is not practicable, as only 10% of participants had advanced imaging performed. Although the presence of the spot sign does improve prediction of ICH growth, time from onset, antithrombotic therapy and baseline HV remain the strongest predictors. 53

Generalisability

The study’s inclusion criteria were deliberately broad, with recruitment from international sites, across secondary and tertiary care, reflective of the clinical population. However, the study was unable to collect screening logs across such a large number of sites and, as such, was unable to determine the proportion of population who would be eligible for haemostatic therapy if it were effective.

Overall evidence

In the systematic review,25 two small RCTs of tranexamic acid with a total of 54 participants were found, with no clear evidence of benefit or harm associated with tranexamic acid. 38,39 Several smaller RCTs of tranexamic acid in ICH are ongoing,54–58 with a total enrolment of < 1000 participants across all the trials. A number of these ongoing trials are targeting participants likely to be at greater risk of haematoma expansion, based on an earlier time window,54,55 spot sign status55,58 and anticoagulation. 59 Although an individual patient data meta-analysis is planned,33 further large randomised trials are needed to confirm or refute a clinically significant treatment effect of tranexamic acid.

Strengths

The strengths of this study include double-blinding and strong allocation concealment, with low risk of bias, high adherence to treatment and high completion of follow-up, with very few missing primary outcomes. The use of an approved brief (see Report Supplementary Material 1) and proxy consent processes allowed rapid enrolment of patients without capacity, who are important in acute stroke studies. Independent doctor consent was the most rapid form of consent and may be appropriate in emergency studies, especially when relatives struggle to make informed decisions. Minimisation techniques were effective, and the treatment groups were well matched at baseline. The sample size was large, making this the largest haemostatic therapy RCT after ICH. Pre-study support from the Nottingham Clinical Trials Unit ensured that approvals were obtained rapidly once the grant was activated, allowing recruitment to begin in a timely manner. This rapid set-up process led to a large number of sites being activated ahead of schedule, with recruitment in the UK exceeding initial expectations, which led to early achievement of the stop–go criteria. The large number of sites participating in the UK would not have been possible without the support of the NIHR Clinical Research Network in England and adoption of TICH-2 on the study portfolio. The absence of an effective drug therapy for ICH, in combination with streamlined processes of acute stroke care to facilitate reperfusion therapies in ischaemic stroke and the absence of competing trials, led to TICH-2 fitting well into the acute stroke clinical pathway and ensured good engagement with clinicians. Finally, permission was sought and granted to allow co-enrolment into RESTART; an investigator-led, randomised trial comparing starting versus avoiding antiplatelet drugs for adults surviving antithrombotic-associated ICH. 60 The TSCs for both studies felt that co-enrolment did not affect the safety of participants or the quality of the scientific data and yet allowed for both important clinical questions to be answered, something that the patient and public involvement group strongly supported (20 participants were co-enrolled, 10 in the tranexamic acid group, 10 in the placebo group).

Limitations

The wide inclusion criteria led to a heterogeneous population of patients, with multiple comorbidities, more severe strokes, larger HVs and a greater proportion of participants with lobar haematomas and IVH as compared with other ICH trials. 3,22,24,27 This inclusion of older participants with more comorbidities and larger haematomas, in particular, could have diluted any treatment effect.

As already highlighted, the majority of participants were enrolled more than 3 hours after ICH onset, which could explain the absence of a significant interaction with time in the subgroup analysis. In 2016, the protocol for the ongoing RCT CRASH-3 (testing tranexamic acid in traumatic brain injury) was amended to reduce the time window for eligibility (originally within 8 hours of injury) to patients within 3 hours of injury. 61 The TSC for TICH-2 discussed on a number of occasions whether or not the inclusion criteria should be amended to limit recruitment to participants within 3 hours of symptom onset in line with other tranexamic acid studies. However, as the majority of recruitment had been completed, and there are important pathophysiological differences between ICH and traumatic brain injury, the decision was taken to leave the inclusion criteria unchanged but to focus on efforts to ensure rapid treatment. Had this been an adaptive trial design, enrichment could have allowed further recruitment within subgroups where tranexamic acid was most likely to be effective, such as those patients presenting < 3 or < 4.5 hours after the onset of symptoms, or those with moderate-sized haematomas. Furthermore, sample size reassessment to account for the fact that the observed effect size was lower than predicted in the original sample size calculation may have been beneficial. 62

The study did not seek to explore mechanistic approaches by which tranexamic acid could improve outcome. First, this could be done by addressing how tranexamic acid may reduce haematoma expansion, and it is thus unclear whether the reduction in number of participants experiencing haematoma expansion is related to attenuation of primary bleeding, secondary vessel rupture, both or neither. More research is needed to understand the time course of changes after acute ICH and differences between lobar and deep haematomas. Although the study collected data on haematoma location and local investigators assigned a final diagnosis, it is acknowledged that recognising cerebral amyloid angiopathy (CAA) is a challenge and many of the participants, particularly elderly participants, may have undiagnosed CAA. Further work is currently being undertaken to analyse participants’ brain images and will be presented at a later date. Second, beyond antifibrinolytic effects there is increasing recognition that because of its inhibition of plasmin, tranexamic acid has anti-inflammatory properties. This anti-inflammatory action has been speculated to be important for the efficacy of tranexamic acid. 63 Inflammation is a key contributor to secondary brain injury after ICH and the effects of tranexamic acid on this warrant further investigation.

Although the recruitment process was simple and enrolment could be done by a doctor, the majority of participants were enrolled during working hours, due in part to a reliance on clinical research network staff. Only a small number of hyperacute stroke research centres in the UK have coverage from clinical research network staff in the evenings and at weekends. It is therefore likely that a large number of potential participants were not considered for enrolment as they presented with stroke symptoms outside normal working hours.

Furthermore, requiring the NIHSS score to be measured before randomisation reduced the number of participants enrolled in the emergency department because of a lack of availability of trained staff, again, particularly out of hours. For this reason, the study did not collect HV at baseline, as measuring HV is not currently part of standard clinical care in the majority of hospitals. It was therefore not possible to minimise on the basis of HV.

Finally, although the study set up and recruitment in the UK exceeded expectations, set up in international sites took longer than expected, with governance issues contributing to significant delays. This was the main contributing factor that necessitated the 1-year contract extension in order to allow recruitment targets to be met. This delay in starting the study in international sites meant that the majority of participants were recruited from the UK, limiting international generalisability.

Public and patient involvement

Haemorrhagic stroke was highlighted as a research priority by the Stroke Association and stroke survivors have been involved throughout the trial, since the conception of the study. The Nottingham Stroke Research Partnership, comprising stroke survivors and carers, reviewed the proposed study, in an iterative process, commented on its design and conduct. In particular, the Nottingham Stroke Research Partnership influenced the approach to taking informed consent within the study. The group felt strongly that everything should be done to allow as many people suffering from stroke as possible to take part in the study. In particular, the group recognised that in the emergency situation of an acute stroke it is often impossible to take in information to allow people to fully decide whether or not they wish to take part in the study, as a result of speech and processing problems caused by the acute stroke. In this instance, it was believed that the person would want to be included in such a study, unless there was a medical reason not to or if they had pre-expressed a desire not to want to take part. The group also recognised that many people arrive in hospital alone after a stroke without family members present. It was for this reason that the study sought permission for enrolment after consultation with an independent physician when no family or friends are present.

Malcom Jarvis and Christine Knott, both stroke survivors, were members of the TSC throughout the duration of the trial. In addition to shaping the informed consent processes, stroke survivors (i.e. the Nottingham Stroke Research Partnership group) provided advice on how best to inform participants of the study results, which included developing a lay summary for the trial, which is available on the study website. Malcolm Jarvis and Christine Knott helped prepare the primary publication and this report.

Conclusions

The TICH-2 study is the first large multicentre international RCT of tranexamic acid, in acute SICH. There was no statistically significant improvement in functional status at 90 days. Significant yet modest reduction in the number of participants with haematoma expansion and fewer early deaths in those allocated tranexamic acid are consistent with tranexamic acid having an antifibrinolytic effect after ICH. Tranexamic acid was safe, with fewer SAEs and no increase in thromboembolic events or seizures. Prespecified subgroup analyses suggested that treatment for participants with lower blood pressure may be beneficial. Although the analysis did not demonstrate an interaction with time to enrolment, earlier treatment in those patients with a modest haematoma size (excluding those with very large haematomas, who may have already undergone haematoma expansion) may be optimal.

Implications for health care

Although there is insufficient evidence to support the routine use of tranexamic acid in clinical practice for SICH, the results do not exclude a modest but clinically important treatment effect.

Tranexamic acid is affordable, widely available, easy to administer and appears to be safe. Even a modest benefit could have a global impact on the excessive burden of mortality and morbidity after ICH.

Recommendations for research