Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 12/200/04. The contractual start date was in June 2014. The final report began editorial review in January 2018 and was accepted for publication in July 2018. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The EME editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Chris A Rogers reports grants from the British Heart Foundation to April 2017, outside the submitted work. Chris A Rogers is a member of Clinical Trials Units funded by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) and the Health Technology Assessment (HTA) Commissioning Board. Melanie J Calvert reports personal fees from Ferring Pharmaceuticals (Saint-Prex, Switzerland), outside the submitted work. Rhiannon C Macefield has a patent Wound Healing Questionnaire pending to the University of Bristol. Stephen O’Brien reports grants from Saving Lives at Birth Partners, outside the submitted work. Tim Draycott reports personal fees from Ferring Pharmaceuticals, outside the submitted work. Barnaby C Reeves reports membership of the HTA Commissioning Board (up to 31 March 2016), the Systematic Reviews Programme Advisory Group (up to 5 July 2017) and Interventional Procedures Panel Methods Group, the HTA Efficient Study Designs Board, SRP – Cochrane Programme Grant Funding Meeting and Systematic Reviews NIHR Cochrane Incentive Awards (all current).

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2019. This work was produced by Reeves et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2019 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Introduction

Background and definition of the clinical problem

Each year there are > 4.5 million hospital admissions for surgery in England. 1 At the end of each procedure the skin edges of the wound are approximated using sutures or clips. Closing a surgical incision in this way creates what is called ‘a closed primary wound’. Following most surgery in adults, it is standard practice to cover closed primary wounds with a dressing.

Up to 25% of closed primary wounds may be complicated by a surgical site infection (SSI). 2 A SSI requires treatment with antibiotics and dressings and it may require further investigation and treatment. Interventions for SSI may lead to complications, which can delay recovery and reduce quality of life. SSIs therefore have a significant impact on patients and the health service. 3–7

The risk of developing a SSI is multifactorial. Major factors include the contamination level of the wound and whether surgery is performed in the elective or the emergency setting. 8–10 The site of the operation plays an important part in the likelihood of developing a SSI. Abdominal surgery carries one of the highest rates of SSI, particularly if the operation involves the colon or rectum. 11,12 Caesarean section is another procedure that carries a high rate of SSI. Another factor associated with an increased risk of SSI is a compromised immune system (e.g. diabetes mellitus, malnutrition, immunosuppressive therapy or human immunodeficiency virus). 13

Possible ways for reducing SSI include modification of preoperative, perioperative and postoperative factors. The role of the method of wound dressing in minimising SSI is of major interest. 14

The health technology being assessed: dressings for primary surgical wounds

Dressings are widely used in the postoperative care of wounds, theoretically to promote healing and prevent infection and for convenience to absorb blood or tissue fluid. Several attributes of an ideal wound dressing have been described and include the absorbency of wound exudates without leakage or strike-through, the absence of particulate contaminant, the suitability of the dressing for use with different skin closures, minimal wound trauma on removal of the dressing, minimal requirements for dressing changes and optimal cosmesis. 15 More recently, interactive dressings have been developed that, in addition to these passive roles, deliberately interact with the wound-bed components to potentially further enhance wound healing. These interactive dressings are often called ‘complex’ or ‘advanced’. (In this report, we follow the terminology of the brief, describing such dressings as complex.) They tend to be more expensive than their simple counterparts, but their use is increasing, despite the absence of robust evidence supporting their efficacy in preventing SSI.

Although it is standard to use a dressing in adult surgery, with the dressing type varying substantially by organisation and practitioner, it is standard practice in paediatric surgery not to use dressings following surgery. 14,16 Discussions with paediatric staff suggest that reasons for not doing so include a belief that children may be afraid of what is underneath a dressing and that the removal is painful. A systematic review [including randomised controlled trials (RCTs) in adult and paediatric practice] available when this study was planned summarised evidence for the effects of simple and interactive wound dressings, as well as no dressing, on the risk of SSI. 17 It found no differences between types of dressings, or no dressing at all. The review highlighted the need for better studies addressing this important and common issue and it recommended in-depth exploratory work to examine the culture and practices associated with the use of wound dressings.

Rationale for the study

The burden placed on health-care systems and patients by SSI means that all possible interventions to reduce the incidence or severity of SSI warrant detailed exploration. A particular advantage of optimising postoperative dressings is the potential for a major impact on clinical outcomes.

Surgical site infection has been shown to be an independent predictor of mortality. 18 In 2002 there were 8205 deaths in the USA attributable to SSI, accounting for 8% of all deaths caused by a nosocomial infection. 19 SSI has been shown to increase the duration and cost of patient hospitalisation, predominantly as a result of reoperation, additional nursing care and drug treatment costs. 20 In a case–controll US study4 of 255 patient pairs, it was found that, in those patients with SSI, hospital discharge was delayed by a mean of 6.5 days [95% confidence interval (CI) 5 to 8 days], with an additional direct cost of US$3089 per patient. In a later Swiss study7 of 6283 surgical procedures, the researchers found that the mean additional hospital cost in patients with SSI was 19,638 Swiss francs (95% CI 8492 to 30,784 Swiss francs) and the mean additional days in hospital was 16.8 days (95% CI 13 to 20.6 days). In the UK, length of stay is typically doubled, with additional costs of £814–10,523 incurred in patients with SSI. 3,5,6 The indirect costs of SSI as a result of loss of productivity, patient dissatisfaction and litigation, and reduced quality of life are very important but have been studied less extensively.

There are at least 30 different types of wound dressings, with variable unit costs and requirements for frequency of replacement. 13 Manufacturers are keen to extol the relative benefits of their products but high-quality evidence to support these claims is lacking. No recommendations were made in the last national UK guidelines13 on the treatment and prevention of SSI, which reviewed five RCTs available up to September 2007 and concluded that no differences in SSI rates were evident. As described above, a Cochrane review17 examined data from 16 RCTs and found no evidence to suggest either that one dressing type was better than another or that covering wounds with dressings was better at preventing SSI than not covering wounds. The authors noted that many trials were of poor quality. Other recent publications have reviewed evidence about risk factors for SSI. 21,22

We aimed to carry out initial feasibility and pilot work across several NHS sites, to maximise generalisability of the findings and to demonstrate practical issues that researchers would be likely to have to address in a definitive trial. We did not stipulate specific dressings within dressing types described in the brief in order to avoid constraining the dressing types in common use. We made these decisions to allow the trial to evaluate the strategy of using one or other of these various broad types of dressing (simple, complex or no dressing) rather than the relative efficacy of specific products.

Chapter 2 Aims and objectives

We conceived this feasibility study with reference to a future definitive trial to establish the effectiveness, acceptability and cost-effectiveness of complex, simple and/or no dressings in elective and unplanned abdominal surgery. In this feasibility study, we aimed to establish the methods and infrastructure required for the main trial, including the development of new methods where we found them to be necessary. The study involved two programmes of work: the preliminary work (Phase A), which we considered to be a necessary precursor of the pilot RCT, and the pilot RCT (Phase B).

Phase A objectives

The aims of Phase A of the Bluebelle study were to assess the scope for comparisons of simple, complex and/or no dressings in a pilot trial and to develop and pre-test a comprehensive patient-centred measure to assess SSI. Phase A also included work with professional groups and the literature to define and categorise dressing types into three groups (complex, simple and no dressing).

The specific objectives of Phase A were as follows:

-

understand the reasons underpinning the current choice and use of dressings (e.g. simple vs. complex) across elective abdominal, obstetric and paediatric surgery, including perspectives on the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of dressings, patients’ expectations and experience of wound care and dressing use and how these issues vary by patient, clinical and procedure-related factors

-

explore patients’ and health-care professionals’ (HCPs’) attitudes towards a trial of dressing type, including the range of procedures and comparisons (simple, complex, no dressing) that would be deemed acceptable for inclusion in a trial, perspectives on random allocation to dressing type and views on the important outcomes to measure in a trial of dressing use

-

identify dressings commonly used in the NHS

-

develop the method for SSI assessment to use in the main trial

-

develop and test a patient-centred measure of practical wound measurement

-

define and categorise dressing into pragmatic groups with agreed boundaries: (1) complex, (2) simple and (3) no dressing; agree protocols for the application and removal of the dressings; identify their costs and contextual information

-

investigate the feasibility of photographing wounds in theatre and assessing the quality of wound closure

-

analyse the value of information (VoI) to the NHS that would be provided by a definitive trial

-

bring together the results of the above objectives to design Phase B of the study (i.e. a randomised external pilot trial).

Phase B objectives

The overall aim of Phase B of the Bluebelle feasibility study was to establish whether or not it is possible to carry out a large definitive RCT to compare the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of simple dressings, tissue adhesive used as a dressing (glue-as-a-dressing) and no dressing to reduce the risk of a SSI following elective and unplanned surgery, to improve aspects of wound management and to improve participants’ experiences of the care of their surgical wounds. The specific objectives of Phase B were as follows:

-

establish the numbers of potential participants at different hospitals who are likely to be eligible and who can be approached about the trial, and the proportions confirmed as eligible, recruited and randomised

-

pilot the randomisation process and investigate reasons for any difficulties that affect recruitment (through conducting a ‘qualitative recruitment investigation’), so that issues can be tackled before progressing to a main trial

-

assess the acceptability of trial interventions and processes to participants and clinical staff using qualitative research methods

-

assess adherence to dressing type allocation and the follow-up protocol through detailed reports, qualitative research methods and follow-up

-

assess the appropriateness and feasibility of collecting a range of secondary outcomes and resource use data

-

establish the validity and reliability of the developed tools for assessing wounds for SSI, practical wound management and participants’ experience of wound care

-

explore the feasibility of obtaining digital photographs of wounds in theatre after wound closure by theatre personnel and after discharge by participants

-

work with the patient and public involvement (PPI) group to inform the conduct of Phase B and the design of a future main trial

-

design a large, definitive RCT based on information from the pilot trial and from integrated and interactive meetings with nurses/midwives, surgeons, methodologists and patient partners.

Additional objectives

Objectives A3, A7 and A8 were not in the protocol for Phase A. The need for these additional objectives emerged during the conduct of Phase A and they were included as objectives of a funded extension to Phase A. As part of this extension, we also collaborated with the Cochrane Wounds Group to update its 2011 review of dressings for the prevention of SSI, primarily with respect to the inclusion of tissue adhesive as a dressing. The review did not identify any eligible trials that studied tissue glue. It has been recently published and no further details are included in this report. 17 Findings from the survey to address objective A3 led to the inclusion of unplanned surgery, as well as elective surgery, as part of our general aim and in the pilot RCT.

Chapter 3 Study methods

Objectives A1 and A2: understand practice and views in relation to dressings

Study design

Qualitative research methods, using semistructured interviews with HCPs and patients, were used to address objectives A1 and A2:

-

understand the reasons underpinning the current choice and use of dressings (e.g. simple vs. complex) across elective abdominal, obstetric and paediatric surgery

-

explore patients’ and HCPs’ attitudes towards a trial of dressing type, including the range of procedures and comparisons (e.g. simple, complex, no dressing) that will be deemed acceptable for inclusion in a trial, perspectives on random allocation to dressing type, and views on the important outcomes to measure in a trial of dressing use.

Scope: clinical specialties

The qualitative research integrated throughout the Bluebelle study (i.e. Phases A and B) focused on abdominal [upper and lower gastrointestinal (GI)] and obstetric (caesarean section) surgery, as these were surgical specialties specified in the description of the study population in the funding application. Interviews were also conducted in paediatric surgery as a means of comparing dressing practices with those in adult surgery. This was because informal preliminary enquiries and the literature14,16 had indicated that dressings are not routinely used in paediatric surgery, thus providing the potential to further the team’s understanding of clinical practice related to dressing use.

Setting

Interviews were conducted across six university and district NHS hospitals in the South West and West Midlands regions of England.

Sampling strategy

Health-care professionals

Sampling was purposeful, based on a prior intention to interview a wide range of health-care professionals with expertise in abdominal, paediatric and obstetric surgery. Prior discussion with clinical members of the Study Management Group (SMG) established that dressing practice would be relevant to a wide range of professionals who provided care at various stages of the patient pathway for surgery. Relevant informants were identified by clinical members of the SMG based on the above criteria. Further potential interviewees were identified partly on a snowball sampling basis. Sampling was also guided by intentions to explore new lines of enquiry; for instance, ‘tissue viability experts/nurses’ were identified as a key group to target, based on emerging findings from prior interviews. Sampling proceeded using a hybrid of the above approaches until the point of saturation.

Patients

Patients eligible for interview were aged > 18 years and had undergone or were scheduled to undergo an abdominal surgical procedure within 3 months of the interview date. Eligible patients were identified by research nurses and surgical trainee collaboratives. Initially, recruitment was guided by these criteria alone. As interviews progressed, sampling became increasingly purposeful to achieve maximum variation according to age, sex and type of surgery.

Data collection

Interviews were conducted by Leila Rooshenas, Christel M McMullan, Daisy Elliott and Jonathan M Mathers over a 7-month period (July 2014–January 2015), either via telephone or in person. Face-to-face interviews took place on NHS premises or in informants’ homes. The qualitative researchers obtained written consent to conduct and audio-record all interviews. Separate topic guides were used for HCPs and patients to ensure that broad topics were consistently covered across each set of interviews. The topic guides evolved as data collection proceeded, either through rewording of questions to elicit more detailed responses or through the addition of new topics based on emerging lines of enquiry from earlier interviews (see Results, Objectives A1 and A2: Understand practice and views in relation to dressings). The initial and final topic guides used are shown in Report Supplementary Material 1. All interviews were transcribed ‘smart verbatim’ [i.e. a full transcript of the recording with some amendments to spoken content to ease readability (e.g. removal of filler utterances such as ‘um’)].

Approach to analysis

Interview transcripts were analysed thematically using the constant comparison method adopted from grounded theory methodology. 23 This involved line-by-line coding of text, whereby descriptive words or phrases were attached to lines of transcript and arranged into themes. Themes were subsequently arranged into hierarchies (with overarching themes and subthemes). Data collection and analysis proceeded in tandem, with the coding frame evolving as new data were collected and analysed. Previously coded interviews were reread in the light of the evolving coding frame to ensure that this comprehensively captured data across the full set of interviews. HCP interviews and patient interviews were analysed separately (i.e. with distinct coding frames).

The analysis of Phase A interviews was conducted primarily by the researchers who led each interview. A subset of interviews (10%) were double-coded by two members of the qualitative team in the early stages of analysis. This helped to inform the earlier versions of the coding frame. The coding frame was regularly discussed among the team as it evolved during the study. Given the wider study aims, the team agreed that themes that had implications for the pilot RCT protocol would be prioritised and coded in greater detail.

Descriptive accounts summarising emerging themes and overall study findings were prepared for the SMG throughout the analytical process. One researcher took responsibility for collating and synthesising findings from all sites for the purpose of producing final report(s) of Phase A findings. These tasks involved consulting descriptive accounts from individual sites and referring to coding frames and raw data (transcripts/recordings) where needed. There was an attempt to search for ‘negative cases’ in relation to particular themes or theories; where present, these are fully reported in the findings. All final reports were scrutinised by all members of the qualitative team.

Presentation of findings

The key Phase A findings that had implications for the pilot RCT design are summarised in Chapter 4, Objectives A1 and A2: Understand practice and views in relation to dressings, and cover HCPs’ accounts of current wound-dressing practice, HCPs’ perspectives on the proposed pilot RCT and patients’ perceived acceptability of the proposed pilot RCT.

Objective A3: identify dressings commonly used in the NHS

Initial findings for objectives A1 and A2 revealed that key words used in the commissioning brief to describe the intervention dressing of interest (i.e. ‘interactive’ and ‘complex’) were not recognised by professionals in the context of closed primary surgical wounds. There was also evidence to suggest that informants had variable interpretations of what constituted a ‘dressing’, and in some cases used products (e.g. tissue glue) that were not marketed as ‘dressings’ to cover primary wounds. After discussion, the SMG decided to carry out a survey on dressings used for primary surgical wounds, in collaboration with the Severn and Peninsula Audit and Research Collaborative for Surgeons (SPARCS)24,25 and the West Midlands Research Collaborative (WMRC).

Survey design

A prospective multicentre study was undertaken. All hospitals located in the two trainee-led research collaborative networks were invited to participate by e-mail and personal communication. A surgical trainee-level principal investigator, responsible for local co-ordination of data collection and entry, was identified within each participating hospital. The study was registered with the clinical audit department in each hospital.

Survey population

Abdominal wounds created during elective or unplanned abdominal surgery, and closed wounds primarily, were surveyed during a 2-week interval in January 2015. We considered a wound to be a closed primary wound if the edges of the incised skin were apposed (using suture material, tissue adhesive or clips) at the end of the procedure. Vascular, gynaecological, urological and paediatric procedures were excluded. Cases were included only if trainees were present (and therefore able to collect the data prospectively).

Data collected

Trainees completed anonymised data collection forms at the end of each surgical procedure, recording information about skin closure and dressings. Dressings were categorised as complex (those with advanced practical and/or therapeutic properties, including amorphous material, silicone, hydrocolloid, foam, antimicrobials or negative pressure) or basic (those without therapeutic properties that are adherent around the perimeter or entire surface, with or without a pad to absorb exudate). ‘No dressing’ was documented when an already closed wound was left without a covering at the end of the operation. The use of tissue adhesive to cover an already closed wound (i.e. when it was used as a dressing rather than wound closure technique) was categorised separately.

Operative and patient-related risk factors that might influence dressing selection were recorded. Operative risk factors included the type of procedure performed and access (open, laparoscopic or laparoscopically assisted), whether or not a stoma was formed and the degree of wound contamination (clean, clean-contaminated, contaminated and dirty). 26,27 Procedures were classified as planned (elective) or unplanned (emergency). The following patient-related risk factors were recorded: age, sex, body mass index (BMI), diabetic status and American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) fitness grade.

The reason for dressing selection (by the surgeon responsible for closing the wound) was recorded in the following three categories: (1) personal preference, (2) selected for specific wound characteristics or (3) the dressing was simply handed to the surgeon at the end of the procedure, without discussion. Dressings could be selected for multiple reasons and space was provided for free-text answers. To supplement this, procurement officers from each hospital were contacted to obtain information about local policies for purchasing dressings.

Data analysis

Data were entered into a password-protected online database held on a server [developed and maintained by the Bristol Clinical Trials and Evaluation Unit (CTEU)] in one of the participating hospitals. Analyses summarised the frequency of different dressing types using descriptive statistics. Descriptive statistics were also used to examine whether patient characteristics or the type and urgency of surgery were associated with particular dressing strategies. Analyses were performed in Stata® version 13 (StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA).

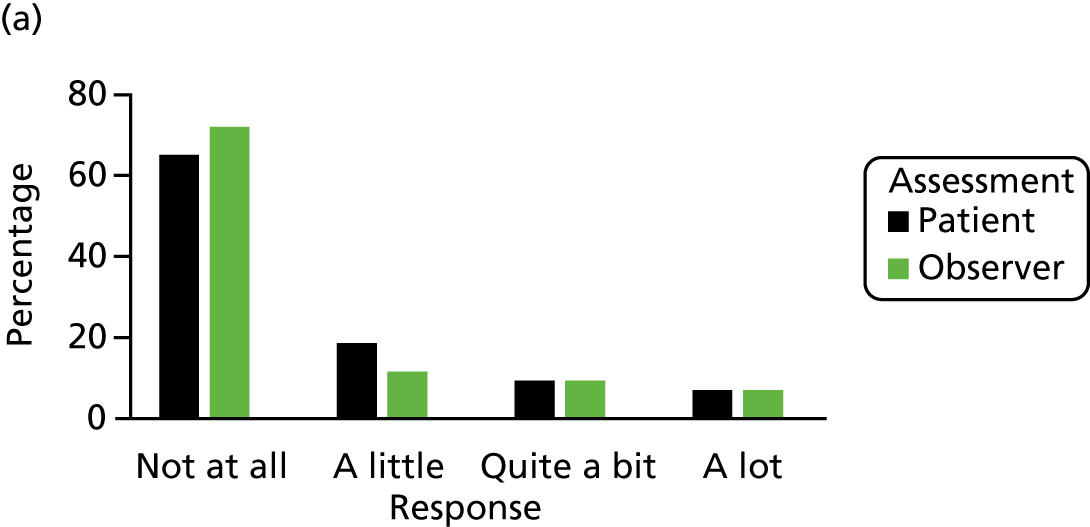

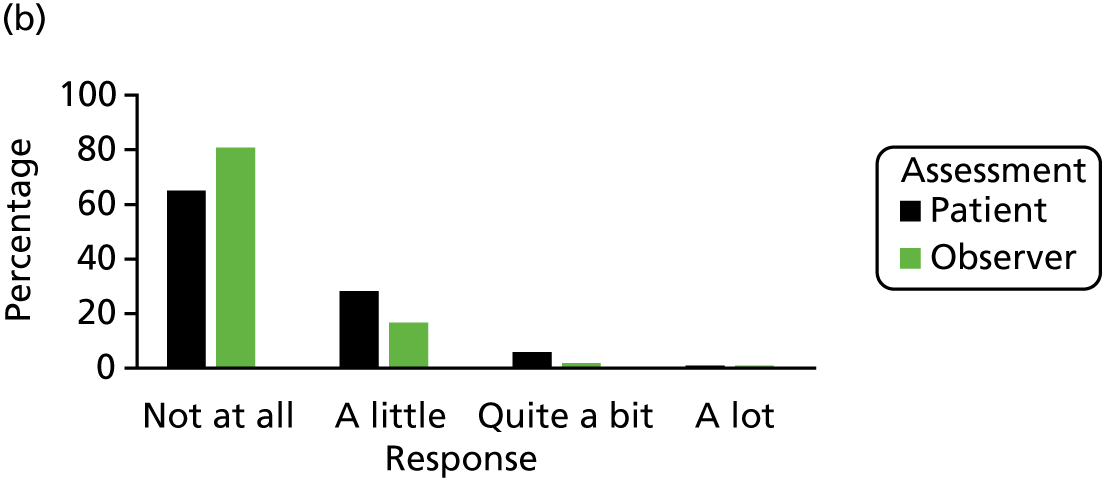

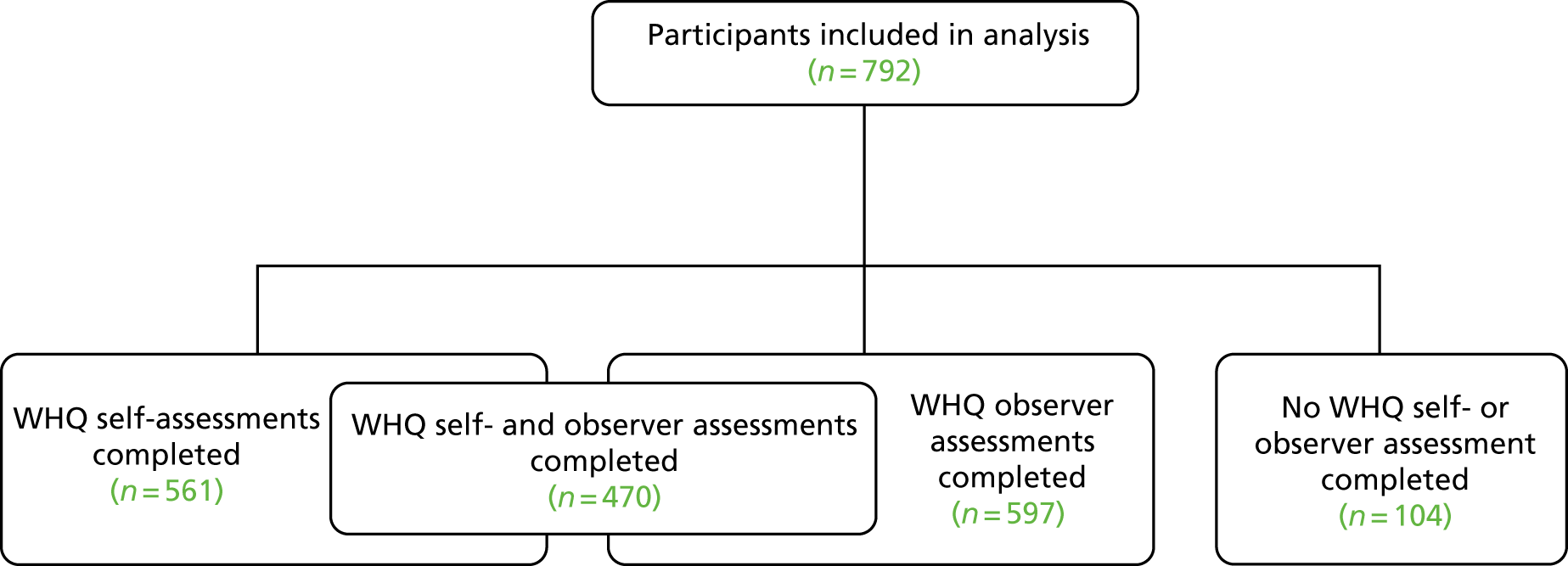

Objective A4: develop a patient-centred comprehensive measure of surgical site infection

This objective sought to develop a questionnaire to capture information on wound healing after a patient has been discharged from hospital. The questionnaire was intended for patient use (self-assessment of wounds) and/or HCP completion (observer assessment).

Study design

A mixed-methods study was conducted in three steps:

-

analysing existing tools and in-depth interviews with patients and HCPs to establish the content of the questionnaire

-

developing questionnaire items and designing the tool

-

pre-testing the questionnaire for content validity, acceptability and understanding using cognitive interviews with patients and HCPs.

Step 1: generation of questionnaire content

Analysis of existing tools

A previous systematic review28 identified the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) criteria and the ASEPSIS (Additional treatment, the presence of Serous discharge, Erythema, Purulent exudate, and Separation of the deep tissues, the Isolation of bacteria, and the duration of inpatient Stay) grading scale as the most commonly used definitions and grading scales for assessing SSI. 29,30 In the UK, the Public Health England (PHE) SSI surveillance programme has designed a checklist based on the CDC criteria (including signs, symptoms and wound care interventions) to collect information to determine incidence of SSI. 31 The surveillance programme also uses a questionnaire for patients to complete to collect information to ascertain post-discharge SSI. 31

The ASEPSIS grading scale is a clinical tool designed for use in hospital to aid HCPs to identify and grade the severity of SSI. 30 ASEPSIS also has an associated questionnaire for patients to collect information post discharge. 32

We undertook a detailed content analysis of the PHE clinical data sheet and post-discharge patient questionnaire, and the ASEPSIS grading scale and associated patient questionnaire. The purpose was to ascertain the important signs, symptoms and criteria for diagnosing SSI. First, individual criteria or items were extracted from the tools and recorded verbatim. Next, criteria and items referring to the same issue or underlying construct were grouped together into SSI ‘domains’ based on the sign, the symptom or the intervention carried out to manage infection.

In-depth interviews

General abdominal surgery patients identified as having had a SSI, and staff involved in post-surgical wound care, were interviewed. The purpose of interviews was to elicit information on the signs, symptoms and interventions relevant to SSI occurrence and to identify any new domains relevant to SSI diagnosis that were not covered in the CDC and ASEPSIS clinical tools and patient questionnaires.

Patient participants were identified and approached by research nurses and surgical trainees at one UK NHS trust. Contact details of interested participants were given to the SSI study team so that they could arrange an interview. HCP participants were identified and approached directly by the SSI study team. Written consent was taken at the time of interview. Sampling and eligibility criteria were similar to those reported previously (see Objectives A1 and A2: Understand practice and views in relation to dressings).

Semistructured interviews were conducted to explore SSI experiences and opinion on relevant aspects for SSI diagnosis. Views on the PHE and ASEPSIS clinical tools and associated questionnaires were also sought, asking participants to comment on their suitability, relevance and practicality for completion. Pre-designed topic guides were used (see Report Supplementary Material 2). Interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed in full.

Interview data were analysed using an inductive approach. Data were coded and grouped into themes (thematic content analysis). A descriptive account of the common identified themes was generated as an ongoing iterative document and updated with subsequent interview data. Accounts concluded with a summary of points to consider when designing the new questionnaire.

Themes identified from the analysis of interviews were mapped to SSI domains derived from the analysis of the existing tools. Any new themes emerging from the interview data that were not found in the analysis of the existing tool were listed separately.

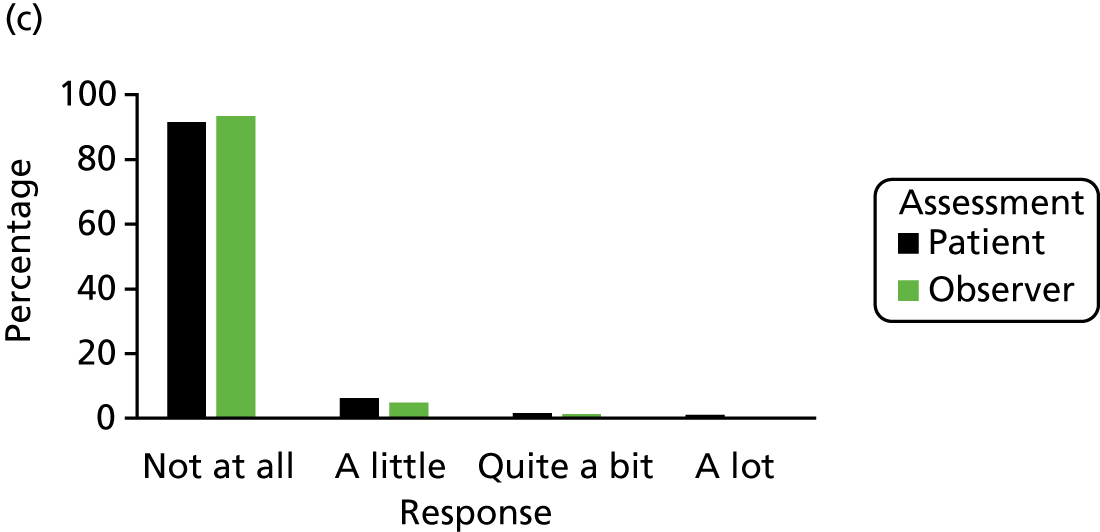

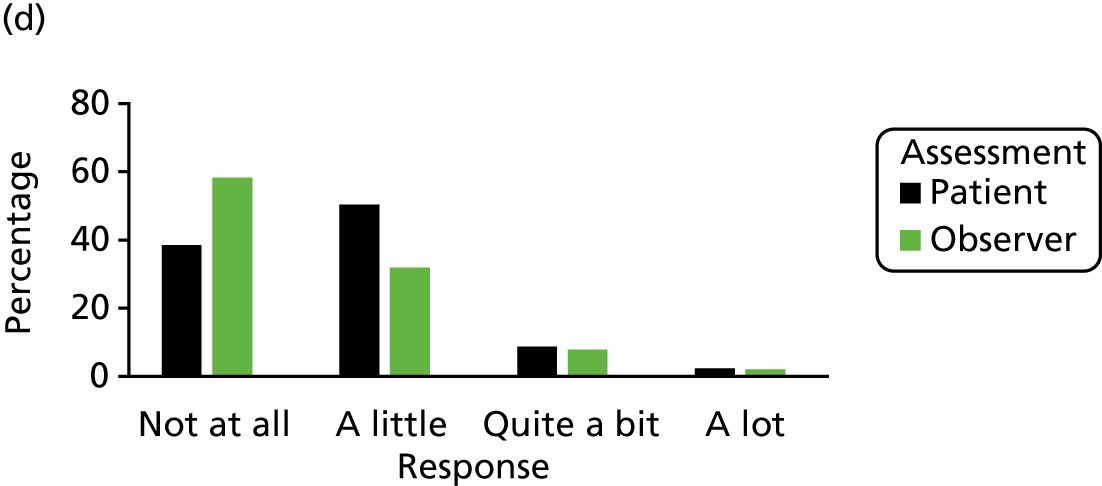

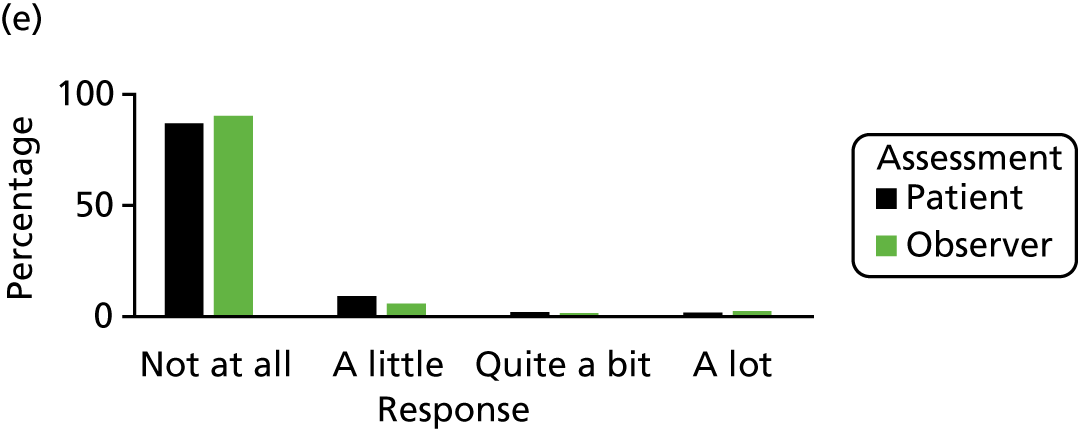

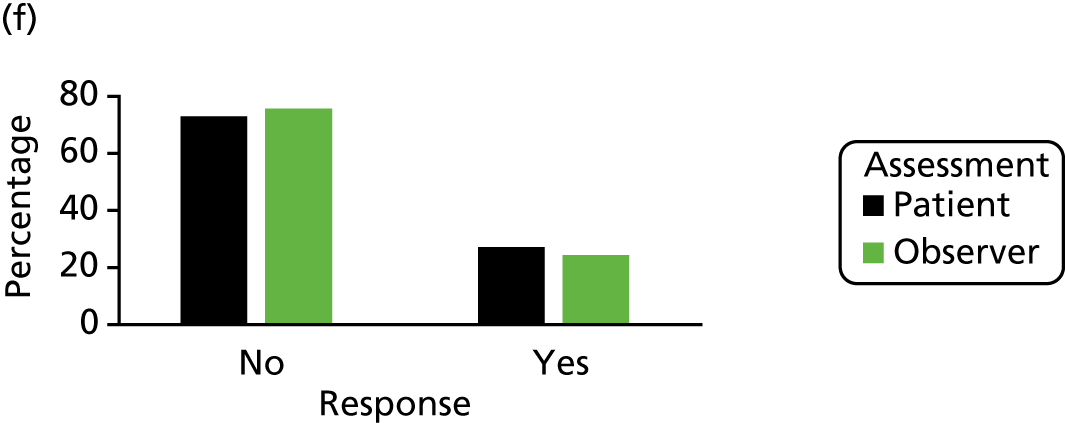

Step 2: designing the questionnaire

A comprehensive list of all possible domains identified from step 1 was considered for inclusion in the new questionnaire by the study team, surgeons and methodological experts in trial design and outcome data collection. Domains unsuitable for a patient-reported questionnaire were dropped and those retained were constructed into items for a questionnaire. Domains were ‘operationalised’ into items for a questionnaire. Items were designed to be clear and unambiguous, written using plain language targeted at a lay audience without technical or medical terms. At the end of the item, where possible, the medical term for the underlying domain that the item was intended to measure was included in parentheses. Response categories took the format of either a ‘yes/no’ option or an ordinal scale (initially ‘not at all’, ‘a little’, ‘moderately’, ‘quite a bit’, ‘very much’), depending on what was most appropriate for the individual item. Options for ‘do not know’ were available for some signs and symptoms and wound care interventions anticipated to be potentially unclear to patients. Instructions for questionnaire completion were written, and adapted for patient and professional use. The only other difference between the questionnaires for patients and professionals was use of the first- or third-person pronoun in the phrasing of the items.

Step 3: pre-testing the questionnaire

The provisional questionnaire was pre-tested in cognitive interviews.

Participants

General abdominal surgery patients and women who had had a caesarean section were identified from two UK NHS trusts. Research nurses, midwives and surgical trainees identified and approached patients for participation. Contact details were passed on to the SSI study team so that they could follow up and arrange an interview. HCP participants were identified and approached directly by the SSI study team. Participants were purposively sampled to include a range of surgeries and specialties.

Data collection

Cognitive interviews were conducted by two members of the research team. Participants were asked to complete the provisional questionnaire using a ‘think aloud’ technique. Interviewers used probes to explore issues further such as ‘What does that word mean to you?’. Detailed memoranda were written up for each interview with summary points of key issues and suggested improvements to the questionnaire.

Analysis

Interviews and revisions to the questionnaire were made as an iterative process so that new versions of the questionnaire could be tested in subsequent interviews. Suggested improvements were considered; substantial or recurring problems were addressed by revisions to the questionnaire. The study team met at regular intervals throughout steps 1–3 to discuss findings and revise the questionnaire.

Objective A5: develop and test a patient-centred measure of practical wound management

This objective was included to address an observation of the 2011 Cochrane review,33 namely that dressings may need to be evaluated on the basis of their wound management attributes because trials to evaluate the effect of dressings on the risk of SSI would have to be very large. The intention was that an initial measure would be developed in time for inclusion the pilot RCT, while recognising that further development and validation would be likely to be required.

Study design

We planned to develop a measure based on an existing framework for developing patient-reported outcome measures,34,35 incorporating guidance on eliciting health domain concepts using qualitative methods. 36,37 Step 1 aimed to produce a comprehensive list of potential issues relating to wound and dressing experience and practical management issues. Step 2 developed issues identified from step 1 into questionnaire items. Step 3 evaluated the measures for acceptability and relevance using cognitive interviews with patients and HCPs. Steps 1–3 were overseen by a working group (DE, JB, LR, RM and CMM) that was part of the wider SMG. The SMG met before and between each step to discuss progress and make decisions about how the measures should be adapted.

Step 1: generating relevant issues

Interviews

Eligible patients who had undergone abdominal general surgery or caesarean section were identified and approached by research nurses and surgical trainees. Contact details of interested participants were passed on to members of the working group so that they could arrange an interview. HCP participants were identified and approached directly by the SSI study team. A purposeful sampling strategy ensured that perspectives were captured from a range of participants. 37 Within this sampling approach, maximum variation was sought in relation to age, sex, ethnicity, type of surgery, dressing type and location.

Interviews were conducted by Leila Rooshenas, Daisy Elliott and Christel M McMullan and explored and characterised participants’ experiences of wounds and dressings. A topic guide was developed (based on literature and views of HCPs in the Bluebelle study team) to ensure that discussions covered the same core issues but with sufficient flexibility to allow new issues of importance to the informants to emerge (see Report Supplementary Material 3).

Interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed in full. Transcripts were imported into NVivo (version 10; QSR International, Melbourne, VIC, Australia). All data relating to outcomes and issues of importance to patients that were relevant to dressing use and the practical management of the wound in the initial period after surgery were assigned labels (coded) by two experienced qualitative researchers. Data were analysed using techniques of constant comparison derived from grounded theory methodology, and emerging codes across the data set were then compared to look for shared or disparate views among participants. 38 A subset of approximately half of the interviews (n = 19) was double coded by a third researcher to highlight any differences in the interpretation of codes. 36 Data collection and analysis continued until the team were confident that saturation had been reached (i.e. no more patterns or themes emerged from the data).

Extraction of information from three systematic reviews

Three systematic reviews39–41 were used to identify RCTs that included outcomes relating to wounds and dressings. Papers were scrutinised for outcomes relating to practical wound management or symptoms and patient experience. Relevant data from the RCT reports were then extracted on the outcome (as described by the authors), the verbatim wording to measure the outcome, who reported the outcome, the measurement scale and the assessment time point. Attempts were made to contact the authors for more information.

Synthesis of literature and qualitative data

A list of issues from the analysis of the interviews and literature search was collated into an item-tracking matrix (see Report Supplementary Material 4). 42 The working group agreed on a set of words or phrases to reflect each issue and also noted additional phrasing used by participants in a subsequent column. 36 Issues that were conceptually similar were organised into categories. For instance, issues such as ‘itchiness/irritation’, ‘presence of pulling sensation’ and ‘tightness of wound’ were mapped into a ‘wound comfort’ category.

Step 2: designing the questionnaire

The working group used the item-tracking matrix to agree on those issues that should be written into questionnaire items. Items featured words and phrases used by patients in the interviews to enhance content validity. 37,43

Step 3: pre-testing the questionnaire

Cognitive interviews, with a new sample of patients who had undergone surgery, were conducted. Cognitive interviews are used widely in questionnaire development36 and involve asking respondents to verbalise their thoughts while answering questions. This methodology enabled us to explore the acceptability of the measure and coverage of patients’ and HCPs’ concerns (in terms of language, accuracy and relevance, as well as layout).

Patients who had undergone abdominal general surgery or caesarean section at one of five hospitals in two cities in the UK were identified and approached by research nurses and surgical trainees. Contact details were passed on to members of the working group to follow up and arrange an interview. HCP participants were identified and approached directly by the working group. As in step 1, sampling was purposeful to achieve maximum variation in relation to clinical role, age, sex and geographic location (for HCPs) and age, sex, ethnicity, type of surgery, dressing type and location (for patients).

Interviews explored the acceptability of the measure and coverage of patients’ and HCPs’ concerns (in terms of language, accuracy and relevance, as well as layout). 37 During each interview, participants were asked to complete the measure by reading each item aloud and commenting on their understanding. Interviews were guided by a series of probes (e.g. ‘What does this item mean to you?’, ‘Are there other ways you would describe it?’). 44 Participants’ body language was also observed and prompted further discussion about specific items (such as the participant nodding in agreement or frowning). 36 A copy of the topic guide is available.

Operationalisation and modification of the measures was an iterative process. Findings from cognitive interviews and suggestions for amendments were regularly disseminated to the Bluebelle SMG. Each stage of feedback informed amendments to modify and reword items to improve understanding, which was repeated following efforts to revise questions and eliminate problems. 44 This process continued until no new issues were identified and no further refinements were believed to be necessary.

Objective A6: use the literature and views of experts to define and categorise commonly used dressings into three pragmatic groups

The primary literature source for this objective was the 2011 Cochrane review and the ongoing collaboration to update the review,17,33 and the British National Formulary (BNF). 45 A summary of the dressing types that were evaluated in previous trials was compiled and draft definitions were circulated to the SMG before a meeting on 21 October 2014. Findings from the literature were supplemented by emerging findings from qualitative interviews carried out during Phase A. The draft definitions were discussed in detail at that meeting and at the subsequent one (24 February 2015), at which definitions for the pilot RCT were finalised.

Objective A7: investigate the feasibility of photographing wounds in theatre and assessing the quality of wound closure

Feasibility of photographing wounds in theatre

We attempted to collect wound photographs in theatre at three of the participating hospitals. This required obtaining approvals from the hospitals, separately from the research ethics approval for doing this. Special safeguards were in place at NHS trust level in all three hospitals. We were ultimately successful in gaining approval to take photographs in theatre but the process was time-consuming and cumbersome. The challenges encountered are described under the results for this objective.

Feasibility of assessing the quality of wound closure

Poor wound closure may be a contributory factor to SSI development that has not previously been investigated. The reasons why poor wound closure may increase the risk of SSI include the presence of gaps in the wound allowing either exudate to leak out or contamination to enter, subcutaneous suture material visible on the skin acting as a nidus for infection, tethering or puckering of the skin edges that may invite bacterial colonisation and even tension and poor vascularisation increasing wound ischaemia. These issues have not been intensively studied but it is notable that cosmetic and plastic surgeons (wound experts) take great care to ensure that primary surgical wounds are closed well and heal well to optimise cosmesis and it is plausible that the quality of wound closure also affects the risk of SSI.

Therefore, we sought to investigate markers that constitute good-quality wound closure, in the context of such markers providing the basis for the development of a metric to measure the quality of wound closure and its relevance to the development of a SSI.

We were also interested in measuring the quality of wound closure in the Phase B pilot RCT because of concern about the feasibility of randomising after wound closure and the risk of performance bias. Randomising after wound closure was preferred to avoid knowledge of dressing allocation influencing how a surgeon closed the wound. For example, if a surgeon is aware that the patient has been allocated to ‘no dressing’, then the surgeon may take extra care to ensure that the wound edges are well approximated and that there is no puckering and tethering. Conversely, if the surgeon is aware that the patient has been allocated to a simple dressing, then the surgeon may take less care, knowing that the dressing will cover the wound.

Study design

We used a mixed-methods design to address this objective, comprising literature reviews, qualitative interviews with surgeons and observation of wound closure in the operating theatre. Mixed methods were selected to enable an in-depth exploration of a complex phenomenon (closure of surgical wounds) within its original setting (the operating theatre).

Literature review

We searched for literature pertaining to wound closure, with the aim of identifying theories about ‘what makes a good wound closure’, and how wound closure might influence wound healing and the development of SSI. Relevant articles were identified using snowballing techniques, and by reviewing the grey literature.

Snowballing

Preliminary searches in PubMed identified a RCT in which the quality of wound closure was assessed. Starting with this citation, forwards and backwards snowballing was used to identify further relevant articles. ‘Forwards snowballing’ refers to the identification of relevant articles based on papers citing the paper being examined. ‘Backwards snowballing’ involved searching reference lists of included papers to identify new papers of relevance to the review. The snowballing process ended when no new information about wound closure emerged from the papers.

Grey literature

Sources such as training videos and surgical textbooks were searched alongside the snowballing process.

Interviews and observations

Sampling and recruitment

For the observations, surgical procedures performed at three centres were purposively sampled to include a variety of approaches (laparoscopic and open surgery), disease types (cancer and non-cancer) and anatomical areas (upper and lower GI surgery). Surgeons who were observed were also invited to take part in an interview. Additional surgeons (from the same three centres) were purposefully selected for interview, with the intention of including a range of clinical experience (e.g. consultant and trainee level) and subspecialty interests (e.g. GI and plastic surgery). Observations and interviews continued up to the point of data saturation (i.e. the point at which additional data were not adding anything new to the analytical framework).

Data collection

Non-participant observation of the operation was undertaken to enable documentation of the operative steps of wound closure, as well as contextual factors that were thought to potentially influence wound closure. As the project progressed, visits to the operating theatre were also used as an opportunity to establish the feasibility of capturing the characteristics of a well-closed wound (which were identified within the literature work and during surgeon interviews). Observations were recorded by hand on an observation schedule, which was developed during preparatory visits to the operating theatre. Handwritten notes were later transferred into an electronic Microsoft Word (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA) document.

All surgeons whose operations were observed were invited to participate in an interview immediately after the operation to discuss whether or not the wound closure had progressed smoothly and to identify and explore reasons behind any unusual events or deviations from the usual procedure. Interviews that took place without a preceding observation were arranged at the surgeon’s convenience and were conducted by a second interviewer. Interviews were semistructured and topics were based on existing literature and clinical knowledge. The topics were adapted as interviews and analyses progressed to explore emergent findings. Interviews were guided by a list of open-ended questions to ensure that all topics were covered in each interview but were sufficiently flexible to enable unanticipated emerging topics to be explored (e.g. issues important to the participants). Questions encouraged surgeons to reflect on their wound closure (and incision) practices, their rationale for these, and whether or not, in their opinion, these may affect wound healing. Surgeons were also asked for their interpretations of what constitutes a well-closed wound and whether or not, and how, this may be assessed in a photograph of a freshly closed wound.

Interviews were conducted face to face by two medically qualified trainees with limited direct surgical experience of wound closure, between 2014 and 2015. The interviewers were not familiar with the research participants or the operating theatre environments in which the research was conducted.

Data analysis

Data collection and analysis ran in parallel. NVivo version 10, Microsoft Excel® (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA) and Microsoft Word were used to aid the storage and analyses of all types of data. Notes from the observations were written up as soon as possible afterwards. Patterns noted across series of observations were developed into themes, which in turn were refined through further observations and exploration through interviews. Interview data were used to confirm, challenge and clarify findings from the observations. For example, if an unexpected event or step was identified, this was explored with the surgeon in the postoperative interview. The term ‘unexpected’ was defined in relation to patterns across observed surgeons, and the medical knowledge of the observer.

Interviews were transcribed and analysed as previously described (see Objective A4: Develop a patient-centred comprehensive measure of surgical site infection), generating themes and forming an early coding framework. The coding framework was added to, and coded material regrouped, with further data collection and analysis. Further analysis involved scrutinising the textual data for differences and similarities within themes and relating findings back to the observational analyses.

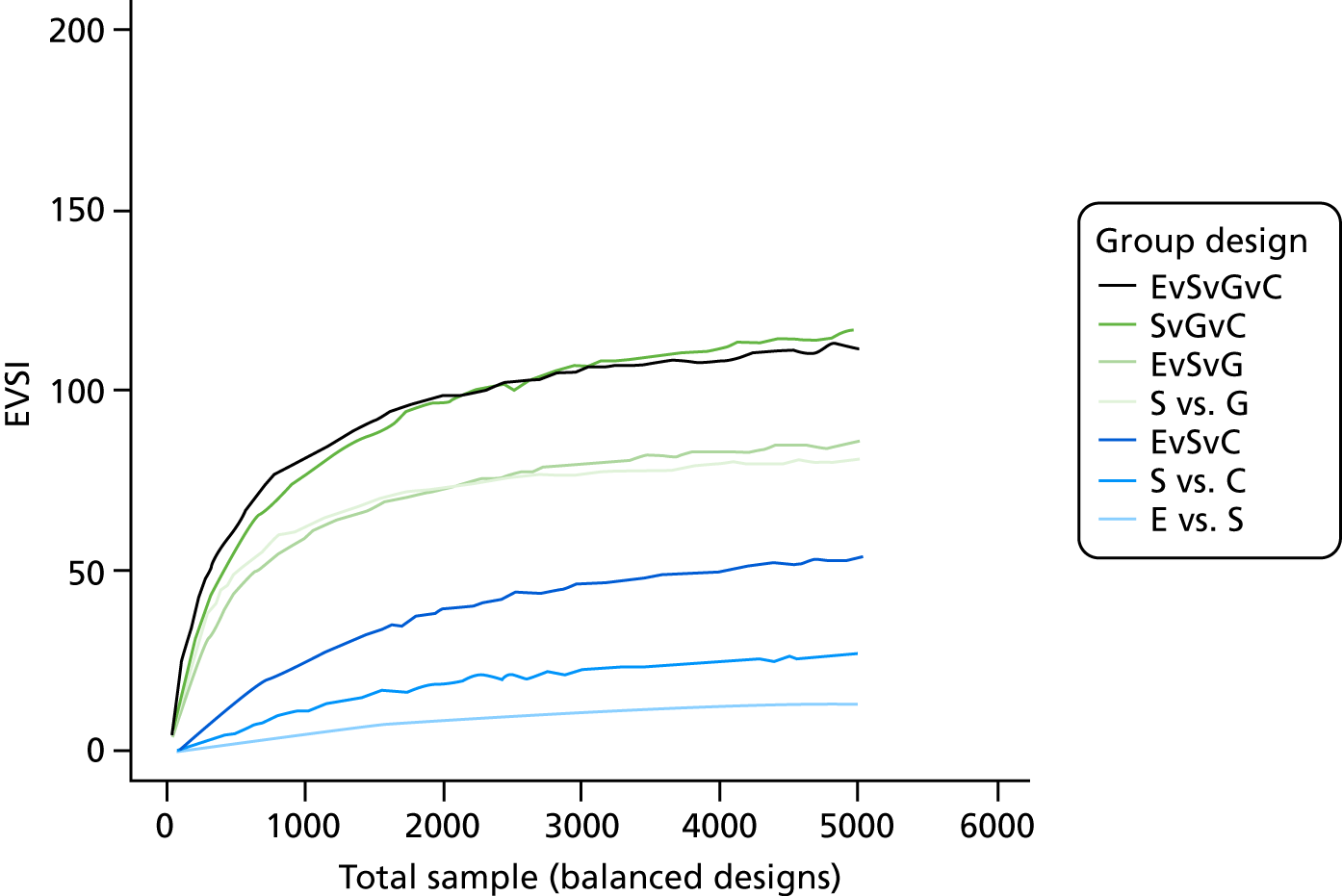

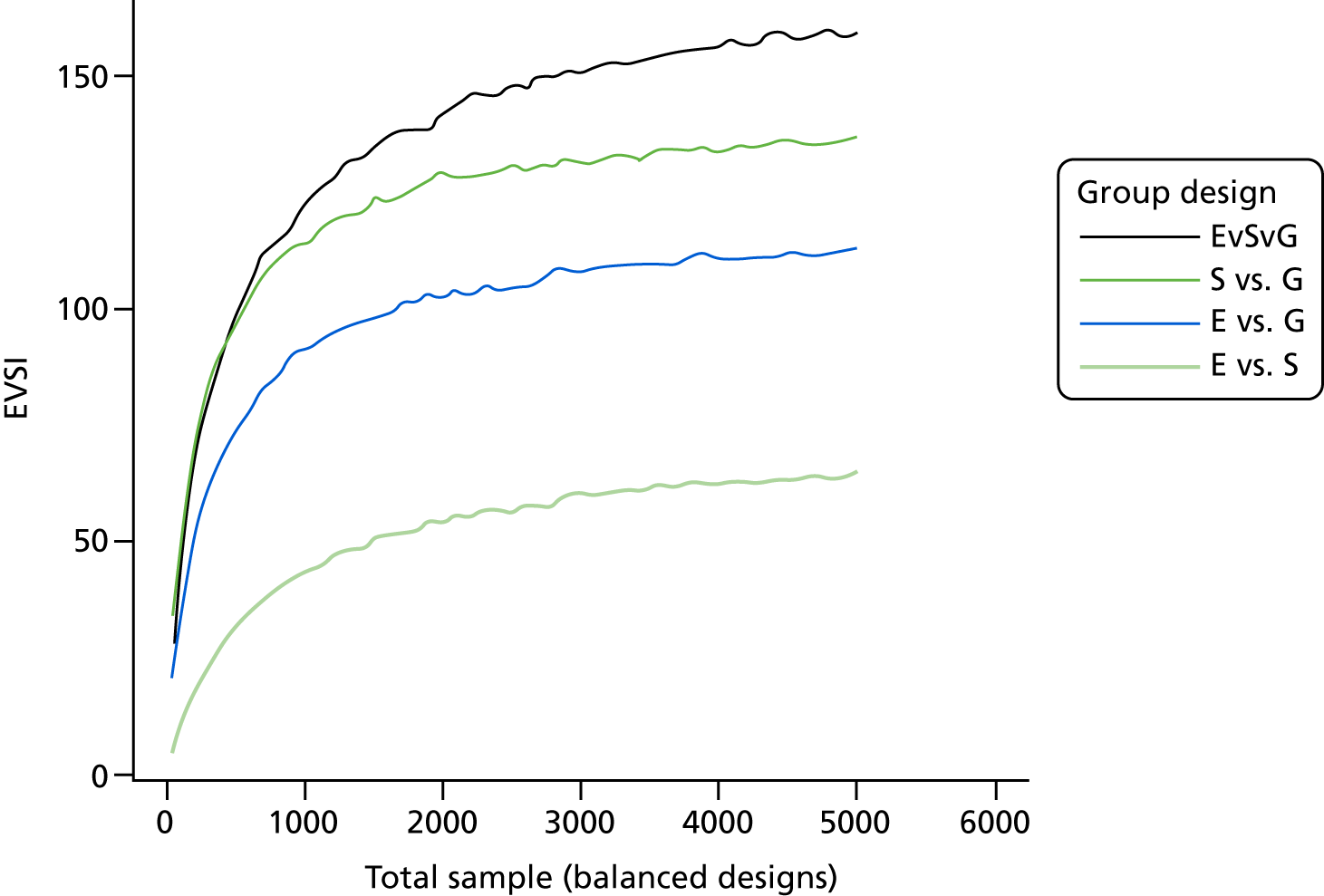

Objective A8: analyse the value of information to the NHS that would be provided by a definitive trial

By carrying out a VoI analysis,46 this objective sought to establish whether or not a main trial of alternative surgical wound-dressing methods would be a worthwhile NHS investment.

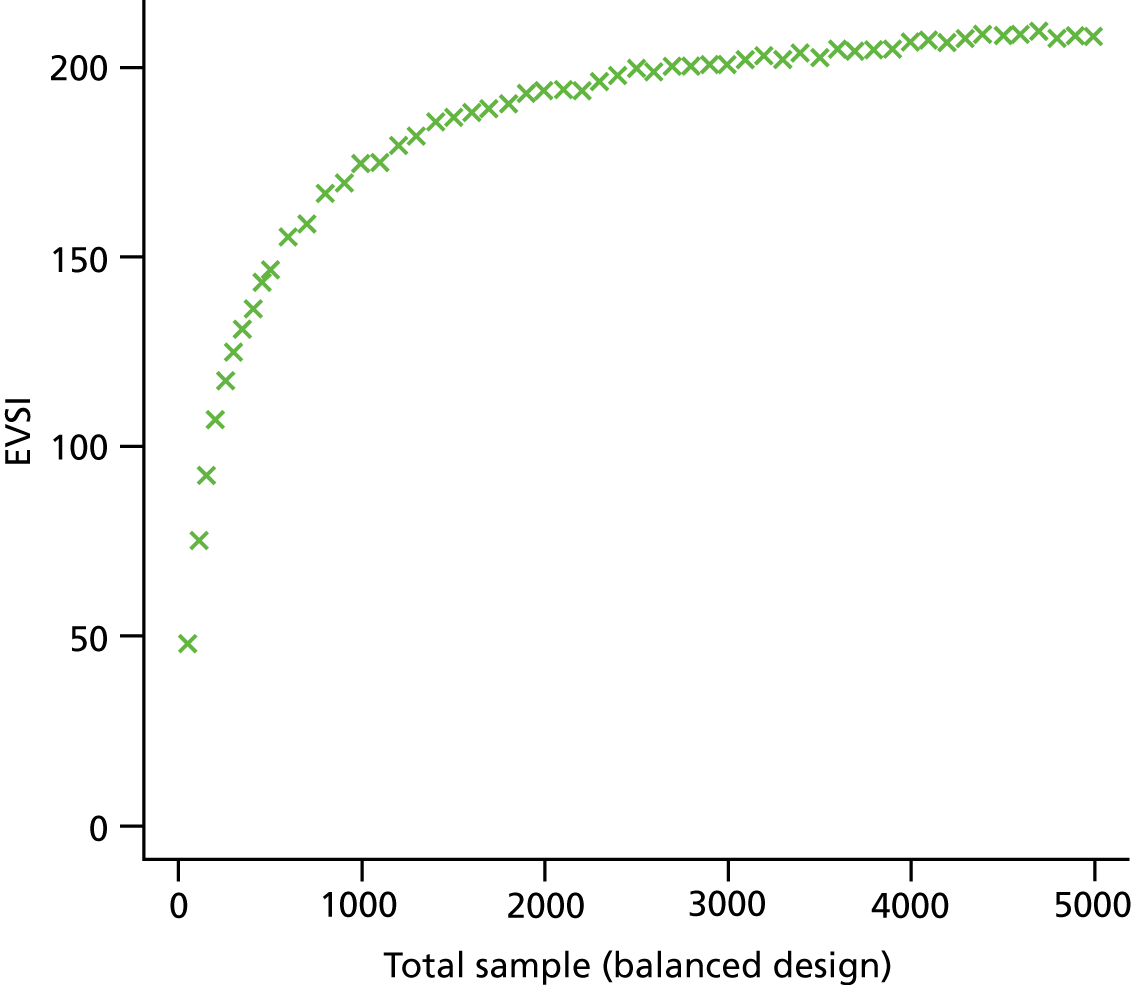

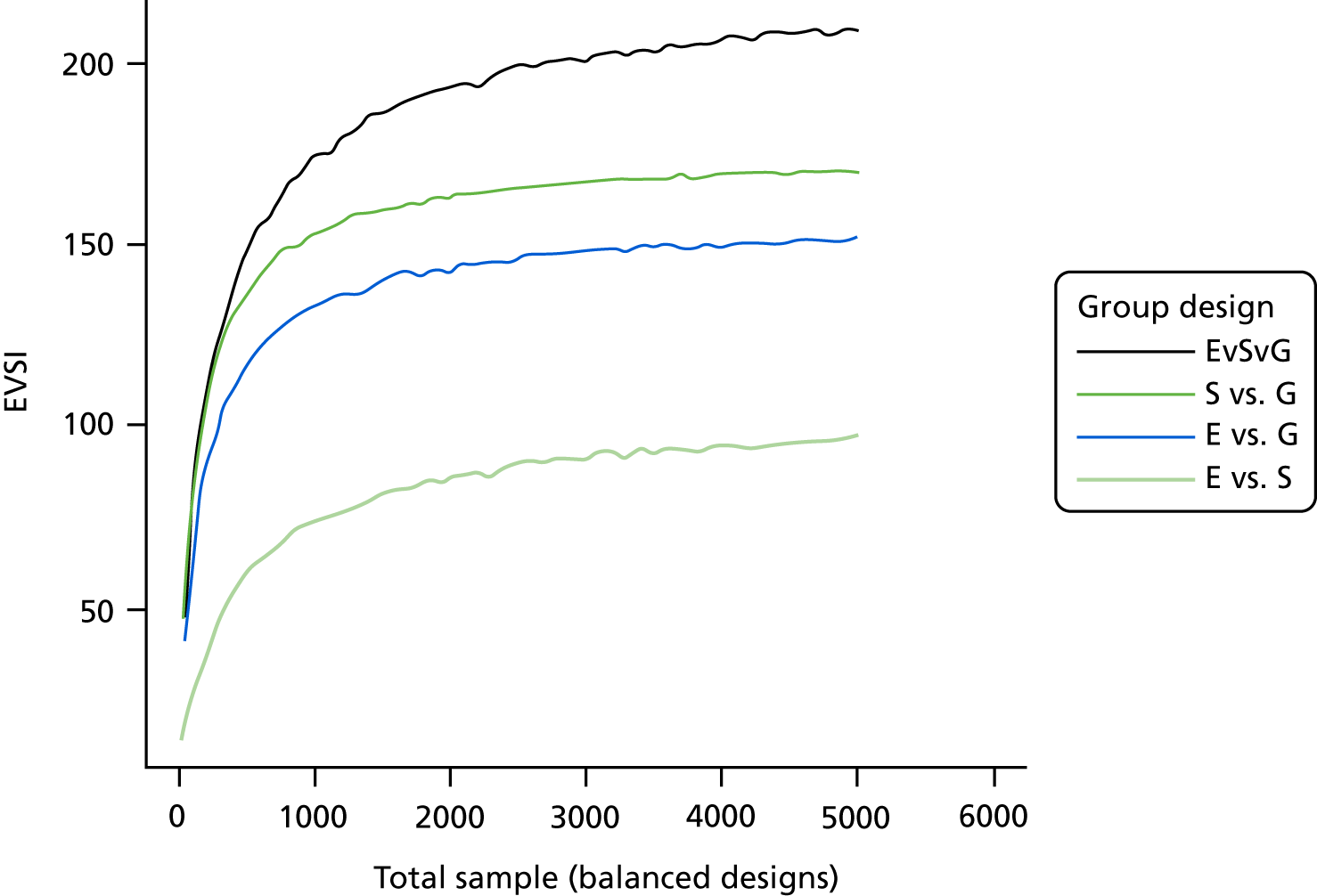

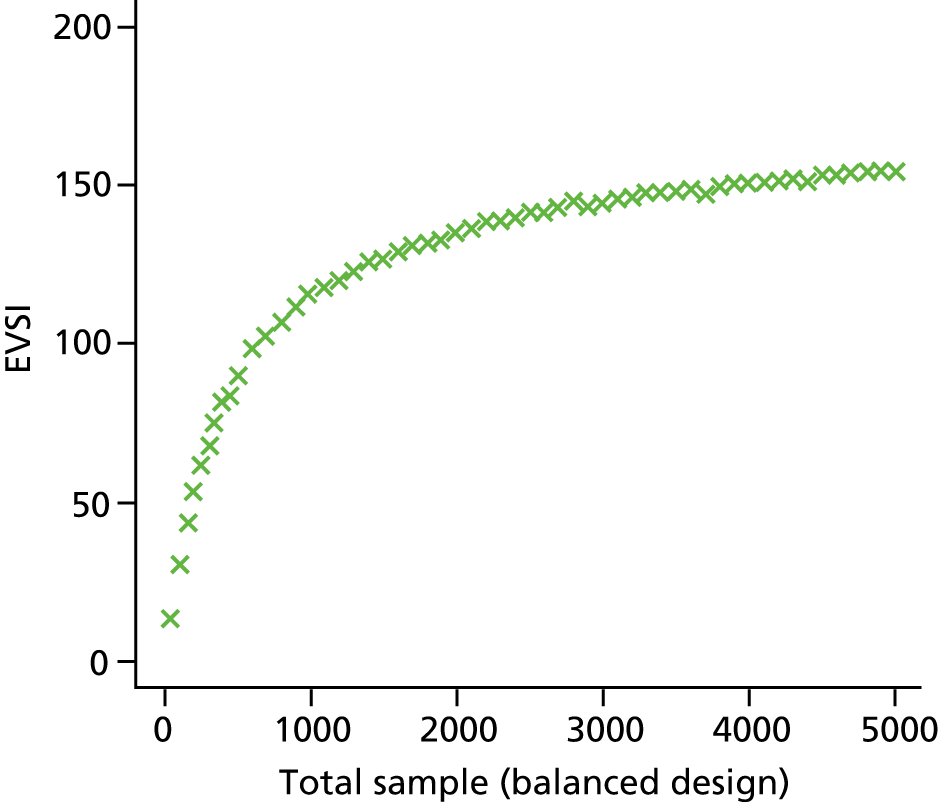

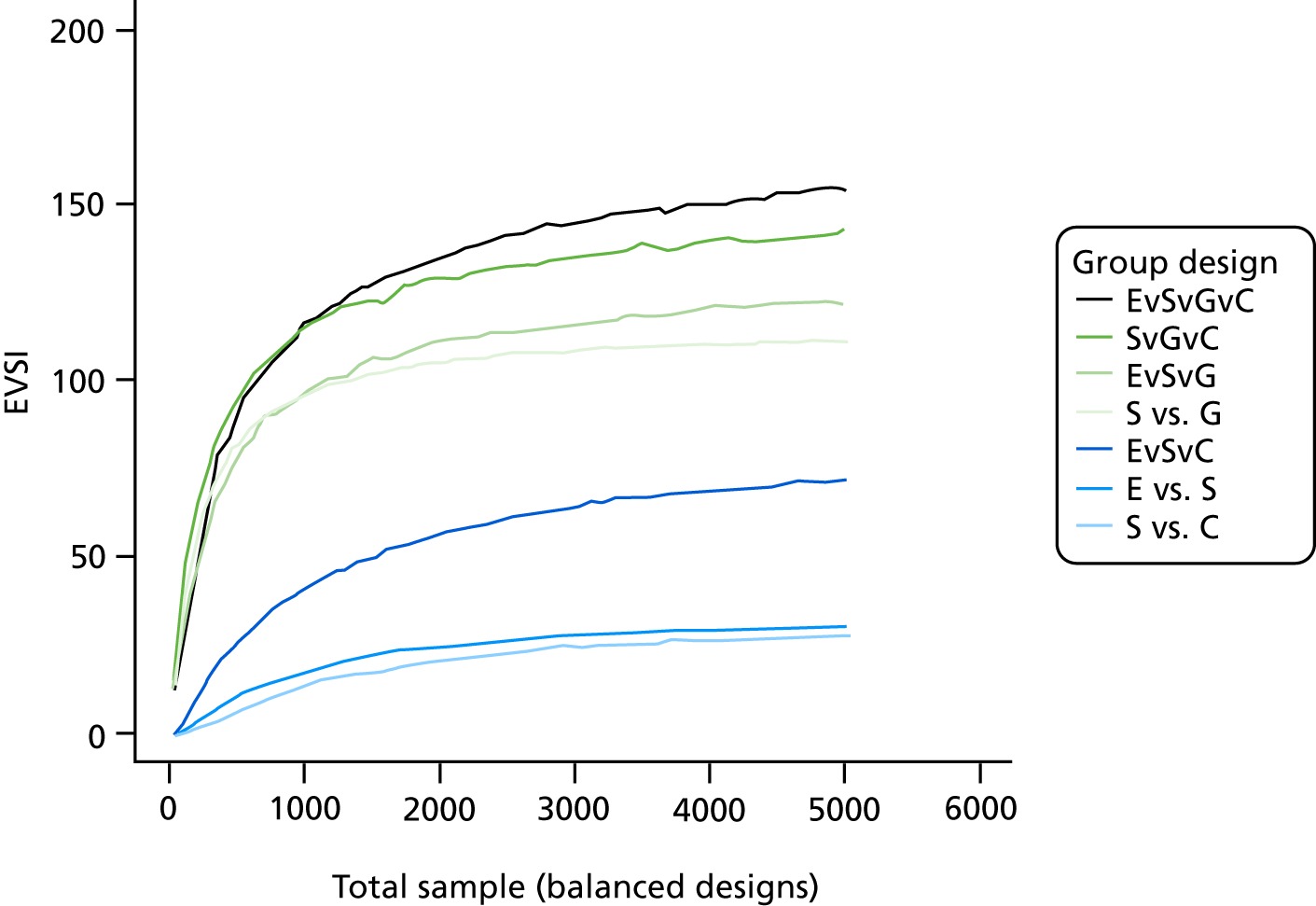

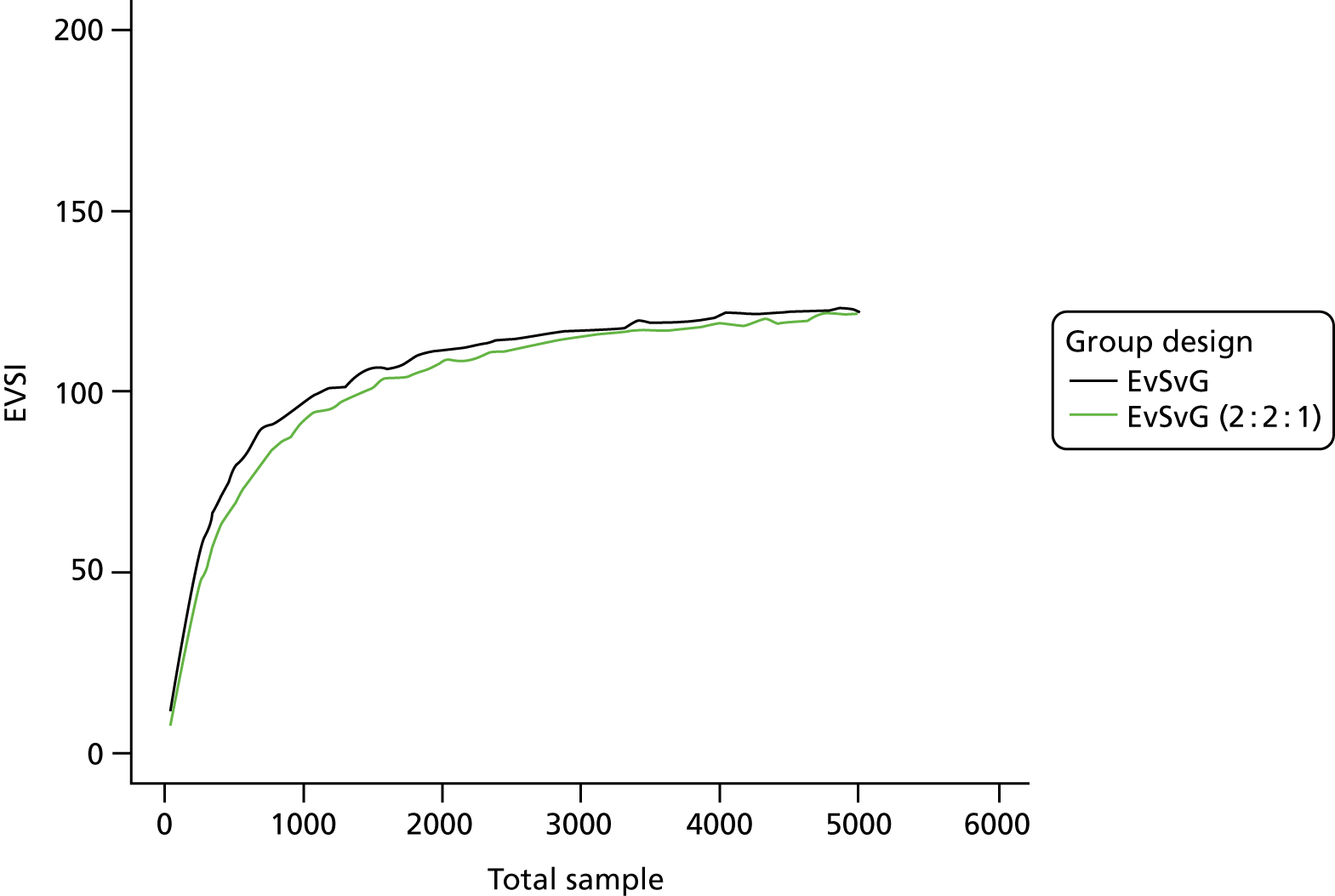

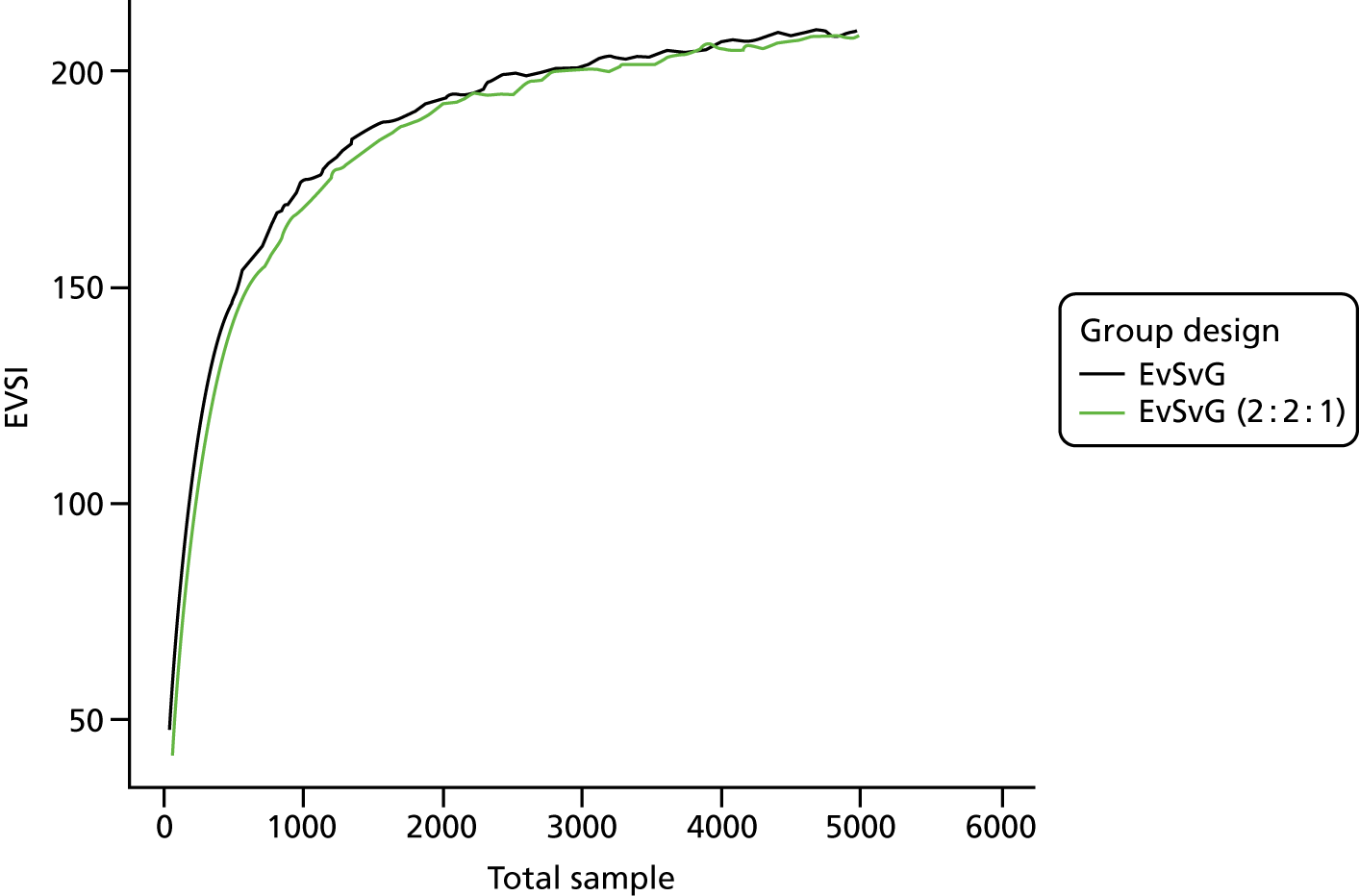

The VoI analysis was based on a simple decision model, which depended on SSI rates and costs and dressing costs. Network meta-analysis (NMA) was used to combine the available RCT evidence on relative effects identified in the updated Cochrane review17 and other studies identified. Expected value of partial perfect information (EVPPI) was computed to give an upper bound on the value of research on particular model inputs. Expected value of sample information (EVSI) was computed for various sample sizes to identify (1) if a trial is worthwhile and (2) the relative benefit of trial designs, which differ in the included intervention groups and samples sizes. We first calculated results based on existing evidence, and then updated the results incorporating the results from the Bluebelle Phase B study.

Decision question

Patient population

The population of interest was patients having elective or unplanned general surgery. This population includes patients having surgical procedures involving the abdomen, oesophagus, stomach, small bowel, colon, liver, pancreas, gall bladder, bile ducts, thyroid, head and neck, breast and chest. These procedures are primarily conducted on adults.

Interventions

Simple, complex and no dressing categories were defined in accordance with the Bluebelle definitions (see Chapter 4, Objective A6: use the literature and views of experts to define and categorise commonly used dressings into three pragmatic groups). Tissue adhesive (glue-as-a-dressing; see Objective B1: establish the numbers of potential participants at different hospitals who are considered likely to be eligible and who can be approached about the trial, and the proportions confirmed as eligible, recruited and randomised) was considered as a fourth category.

Because the category of complex dressing was not included in the Phase B pilot RCT and may not be relevant in the context of closed primary wounds, we present results for two scenarios:

-

where all four dressing categories (no dressing, simple dressing, glue-as-a-dressing, complex dressing) are decision options

-

where only the non-complex dressing categories (no dressing, simple dressing, glue-as-a-dressing) are decision options.

In Phase B, glue-as-a-dressing replaced the ‘complex’ dressing specified in the commissioning brief. Technically, it does not satisfy the definition of a complex dressing adopted in Phase B (see Chapter 4, Objective A6: use the literature and views of experts to define and categorise commonly used dressings into three pragmatic groups) because it does not have an ‘intended therapeutic property’. Nevertheless, it has a similar cost to complex dressings and has complex properties, in that it is adhesive in a different way from simple dressings and does not require removal.

In both cases, evidence on relative effectiveness comes from a NMA of all four dressing categories because this allows as much evidence as possible to be incorporated; the evidence on the complex dressing category can indirectly strengthen the estimates of the other dressing categories.

Outcomes

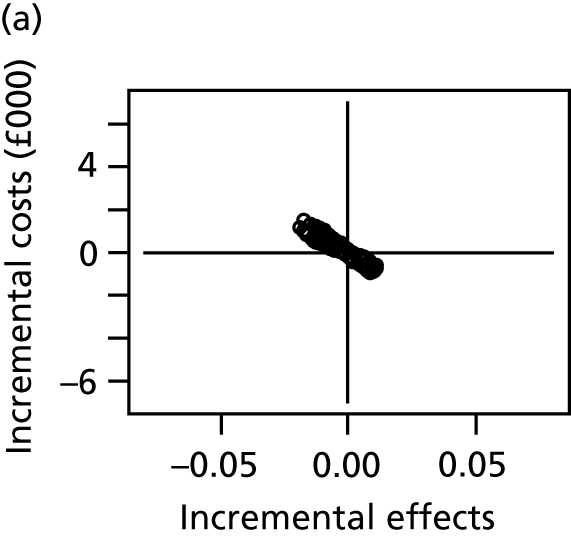

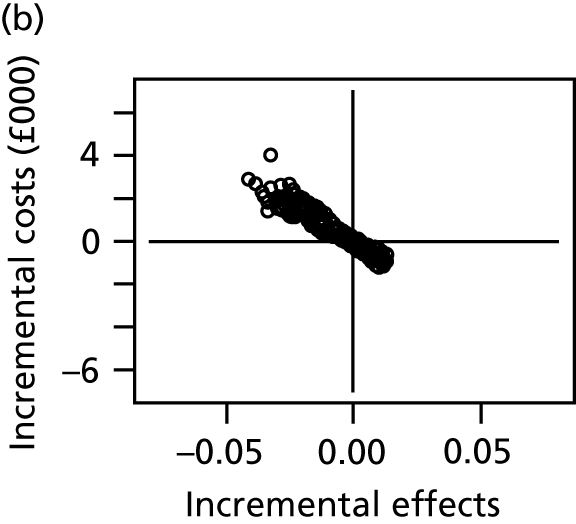

The main economic analysis included the costs of dressings, nurse time, SSI treatment and management, and the quality-of-life impact of a SSI. We did not include any impact of dressings on quality of life as a result of wound management, for example reducing exudates, making it easier to shower and dress, ease of dressing removal and scarring. This is because it is expected that any effects of wound management on quality of life will be small in comparison with the costs and disutility associated with a SSI.

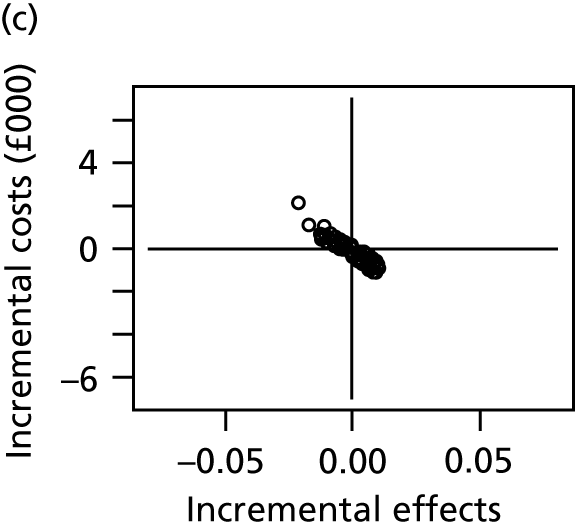

We conducted a probabilistic analysis, whereby probability distributions are used to represent the uncertainty in model inputs. We report the expected net benefit, which is the mean quality-adjusted life-years (QALYs), monetarised by multiplying by willingness to pay per QALY, minus the mean total costs. Because the key outcome is SSI risk, which is both costly and detrimental to quality of life, we anticipate that the expected net benefit will be negative, representing the overall health costs for a given dressing type. We prefer dressing types that minimise these costs (i.e. the least negative net benefits). We display uncertainty in the decision by plotting the joint distribution of incremental costs and effects (relative to the reference intervention, simple dressing) in the cost-effectiveness plane. We also present the probability that each intervention is the most cost-effective. All results are shown for a willingness to pay per QALY threshold of £20,000. 47

In the VoI analyses we report:

-

expected value of perfect information, which measures the maximum amount a decision-maker would be willing to pay to eliminate uncertainty in all the inputs to the economic model

-

EVPPI, which measures the maximum amount a decision-maker would be willing to pay to eliminate uncertainty in a subset of the model input parameters (e.g. the relative effects of the different interventions on SSI risk, or the cost of a SSI)

-

EVSI, which measures the value to a decision-maker of reducing uncertainty in a subset of parameter by collecting data in a given study design (e.g. a RCT with a balanced three-group design with a given sample size per group).

Details on computational methods used in the VoI analyses are given in Report Supplementary Material 5.

Economic model

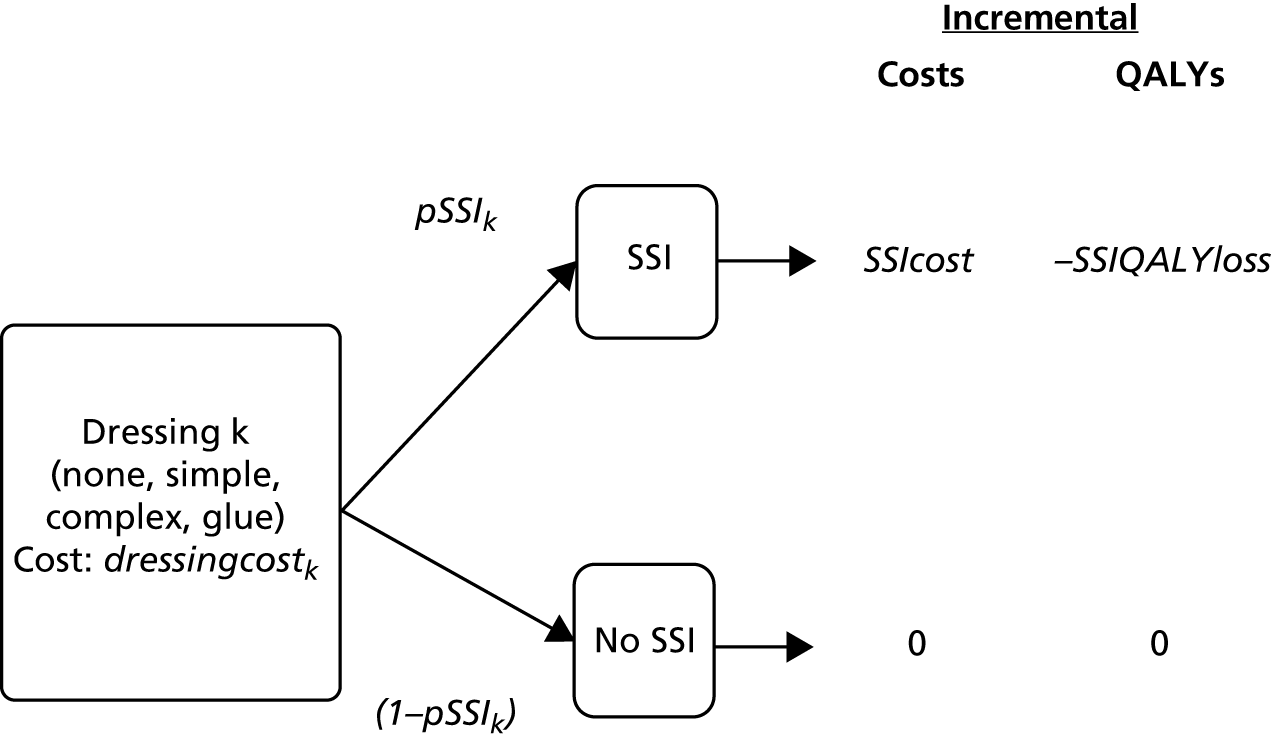

The total cost of dressing k, costk, is the sum of the cost of dressing k and the probability of a SSI (pSSI) using dressing k multiplied by the cost of a SSI. We also include a utility decrement associated with a SSI, so that the decision model is to identify the dressing k that maximises net benefit:

where NB is net benefit, SSIQALYloss is the QALY decrement resulting from a SSI and WTP is the willingness to pay per QALY threshold.

This model is shown as a decision tree in Appendix 1 (see Figure 13).

Model inputs

Prevalence of selective and emergency and general surgery procedures and wounds

The Royal College of Surgeons of England quotes 1.2 million general surgery procedures in 2013/14. 48 Data from our survey (see Objective A3: identify dressings commonly used in the NHS, and Chapter 4, Objective A3: identify dressings commonly used in the NHS) found that patients who would have been eligible for the pilot RCT had a mean of 1.84 wounds per procedure. 49 Assuming that this rate of wounds per procedure can be generalised to the whole population of England and Wales, we estimate a total of 1.84 × 1.2 million = 2.208 million wounds resulting from general surgery per year.

Appendix 1 (see Table 39) shows the number of elective operations in a single large hospital in 2 years50 and the number of procedures in the PHE surveillance data in 2014/15. 51 The PHE data include both elective and unplanned procedures, but it is optional for hospitals to report these figures to PHE; approximately 70 hospitals contributed data. Assuming that the proportion of operations described as missing in the PHE report is the same as those seen in Jenks et al. ,50 we have predicted the proportions of operations in all categories using the PHE data.

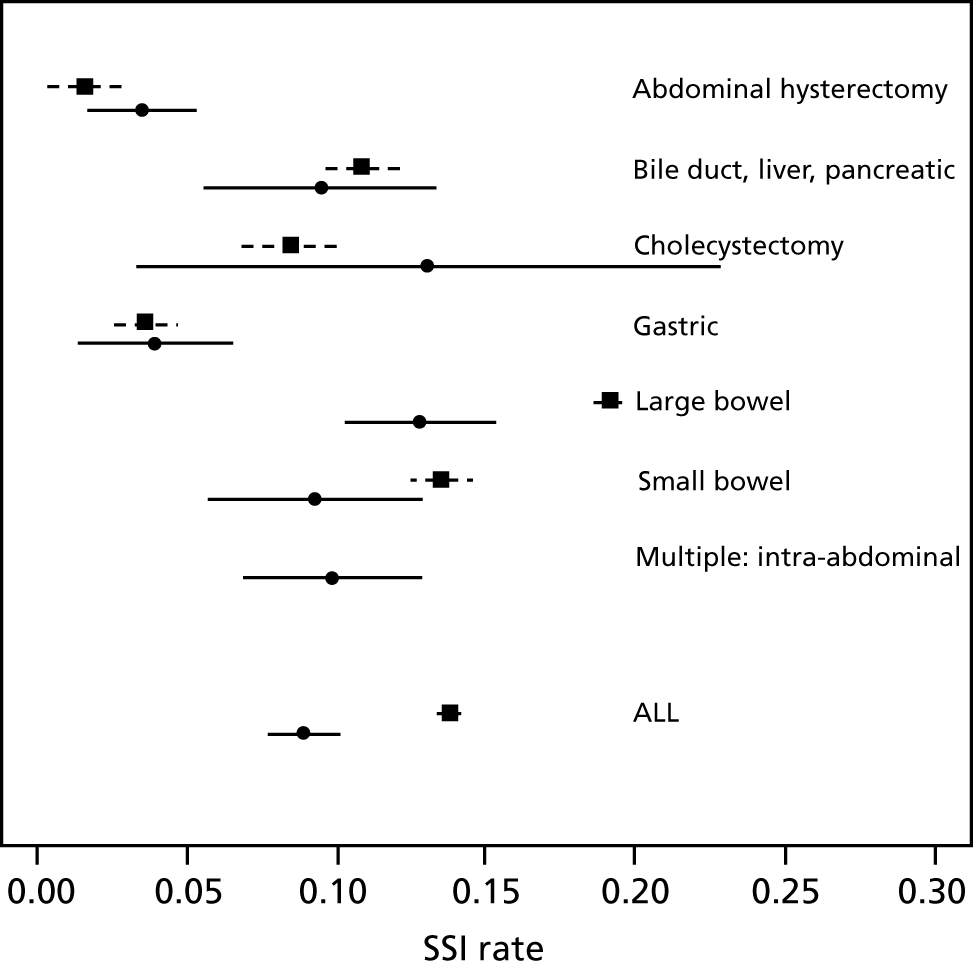

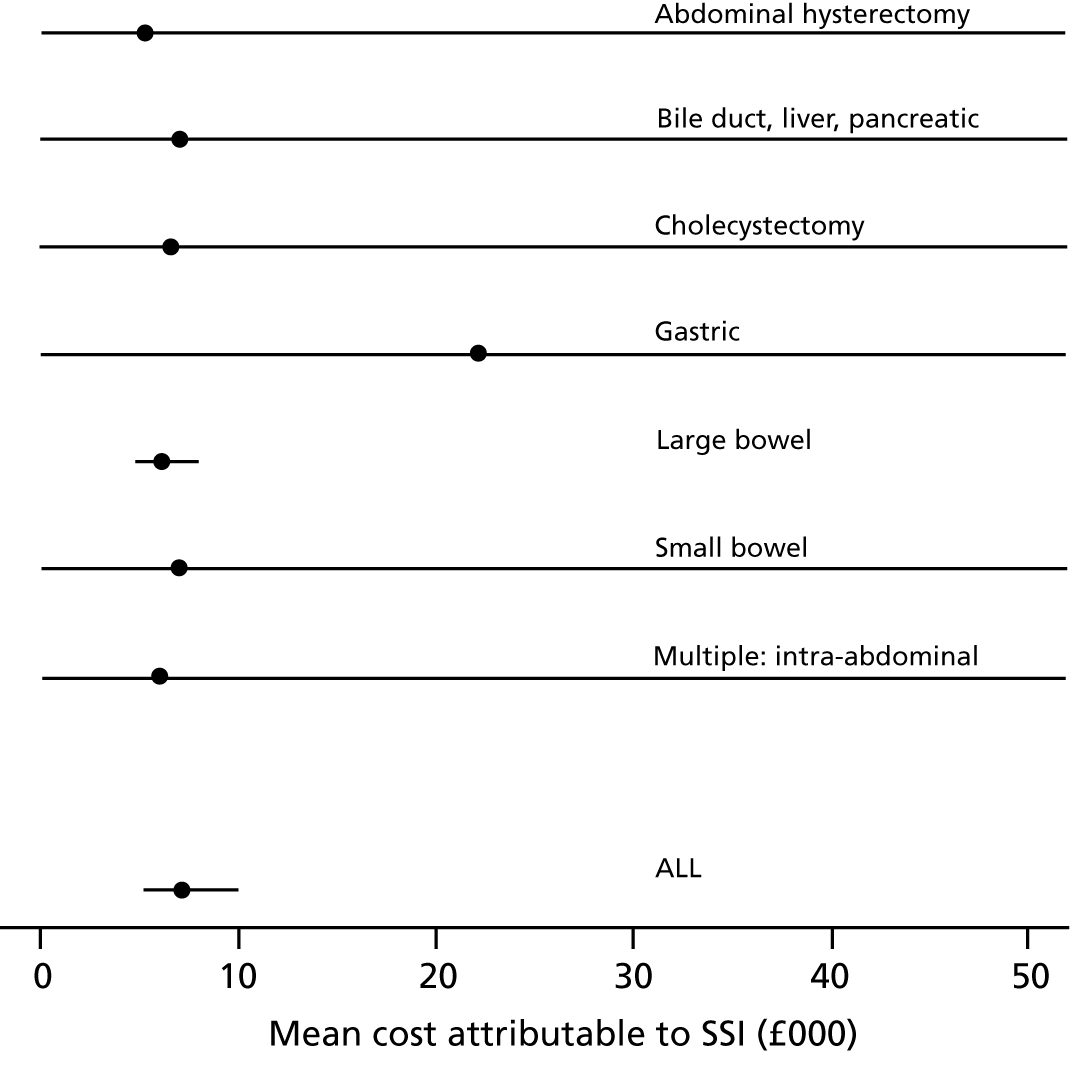

Surgical site infection risk with simple dressings (standard practice)

Surgical site infection risk is variable across surgery types, and Jenks et al. 50 and the PHE SSI surveillance programme51 report this risk by surgery type (Figure 1). The two different data sources are broadly comparable, although the risk of SSI following large bowel surgery was higher in PHE surveillance survey than in Jenks et al. 50 The PHE survey is optional and the data may not be representative of all hospitals, and it is not clear how the selective inclusion of data may have had an effect; hospitals may have wished to report good results, but managers may also have wanted to report poorer results to encourage improvements. The data in the Jenks et al. 50 study may be unrepresentative (i.e. expected to be better than average owing to awareness of SSI risk in participating hospitals and to the restriction to elective surgery only). PHE includes more hospitals and regions than the Jenks et al. 50 study (multiple hospitals in the University Hospitals Plymouth NHS Trust) and PHE covers a broader and more recent time period. We therefore prefer to use the SSI risk estimate from the PHE survey but, because PHE does not give information for the ‘multiple: intra-abdominal’ surgery type included in Jenks et al. ,50 we have used the Jenks et al. 50 data on the proportion of procedures and SSI risk for this category. The overall SSI risk under this assumption across all surgery types of interest was estimated to be 13.8% (95% CI 13.45% to 14.15%). We use this estimate in our base case but use the estimate from Jenks et al. 50 of 8.94% (95% CI 7.75% to 10.13%) in a sensitivity analysis.

The Jenks et al. 50 study is based on data from April 2010 to March 2012, whereas the PHE survey covers the period from April 2010 to March 2015 (between 50 and 70 hospitals per year). The estimated risk across all these surgery types is labelled ‘ALL’ for Jenks et al. ;50 this is the overall SSI risk, but for PHE, this is calculated on the basis of the above assumption for the surgery type multiple: intra-abdominal.

Odds ratios of surgical site infection comparing different dressing types

To estimate the odds ratios of SSI comparing different dressing types, we use results from a recent update of the Cochrane review of dressings for the prevention of SSI. 17 Appendix 1 (see Table 40) shows the included studies that report the SSI outcome, surgery type and interventions (I) with their classifications according to the Cochrane review classes (C) and according to the Bluebelle definition.

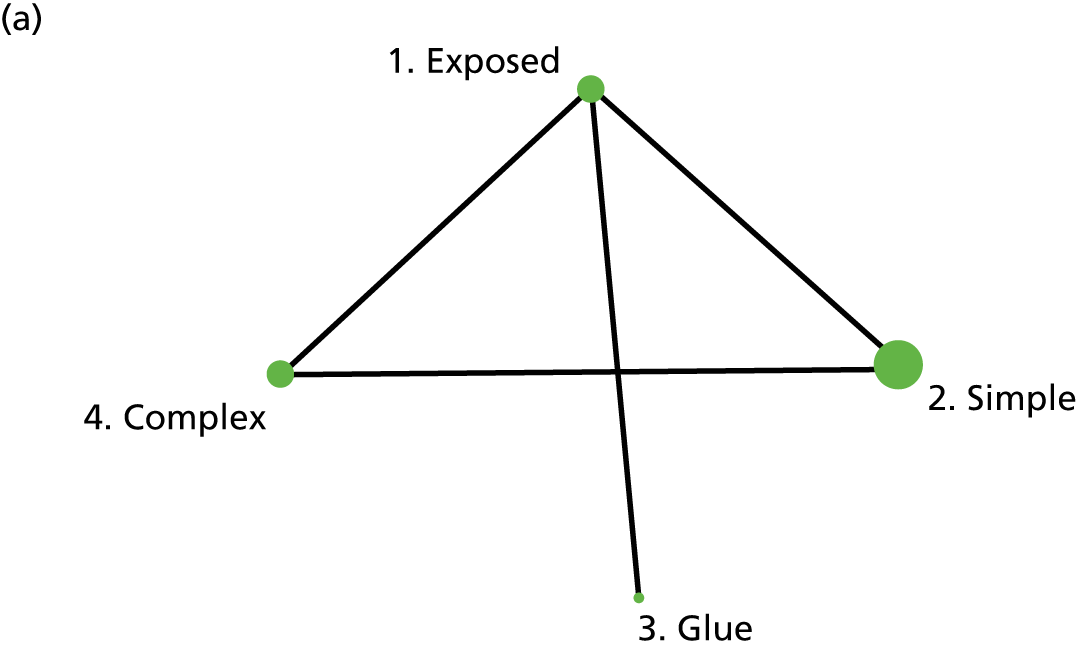

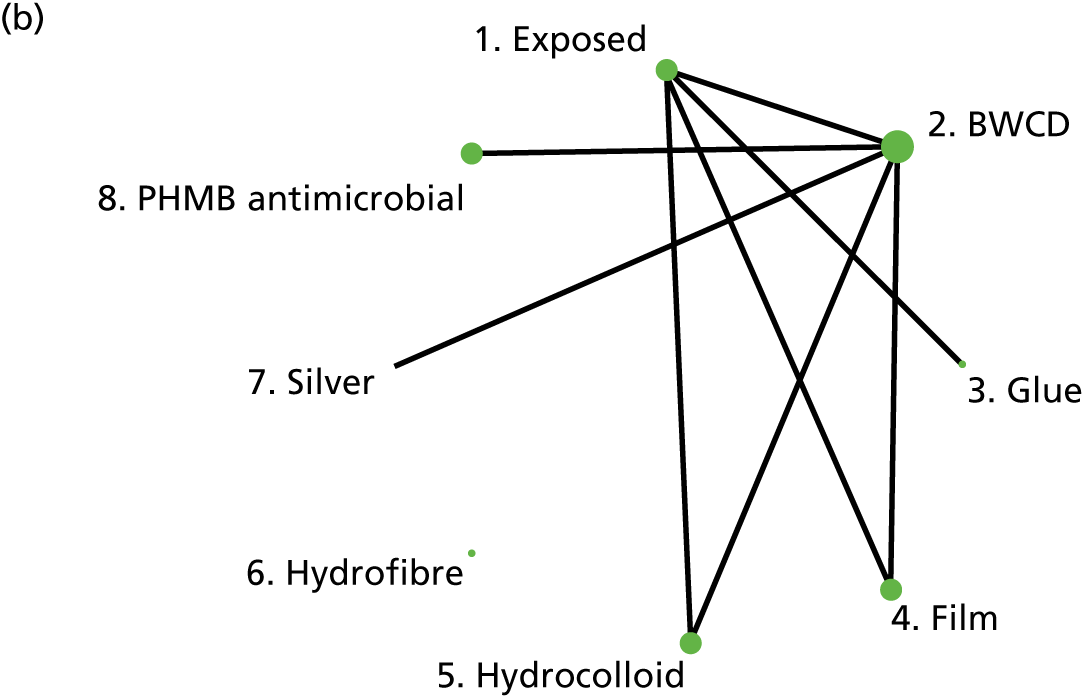

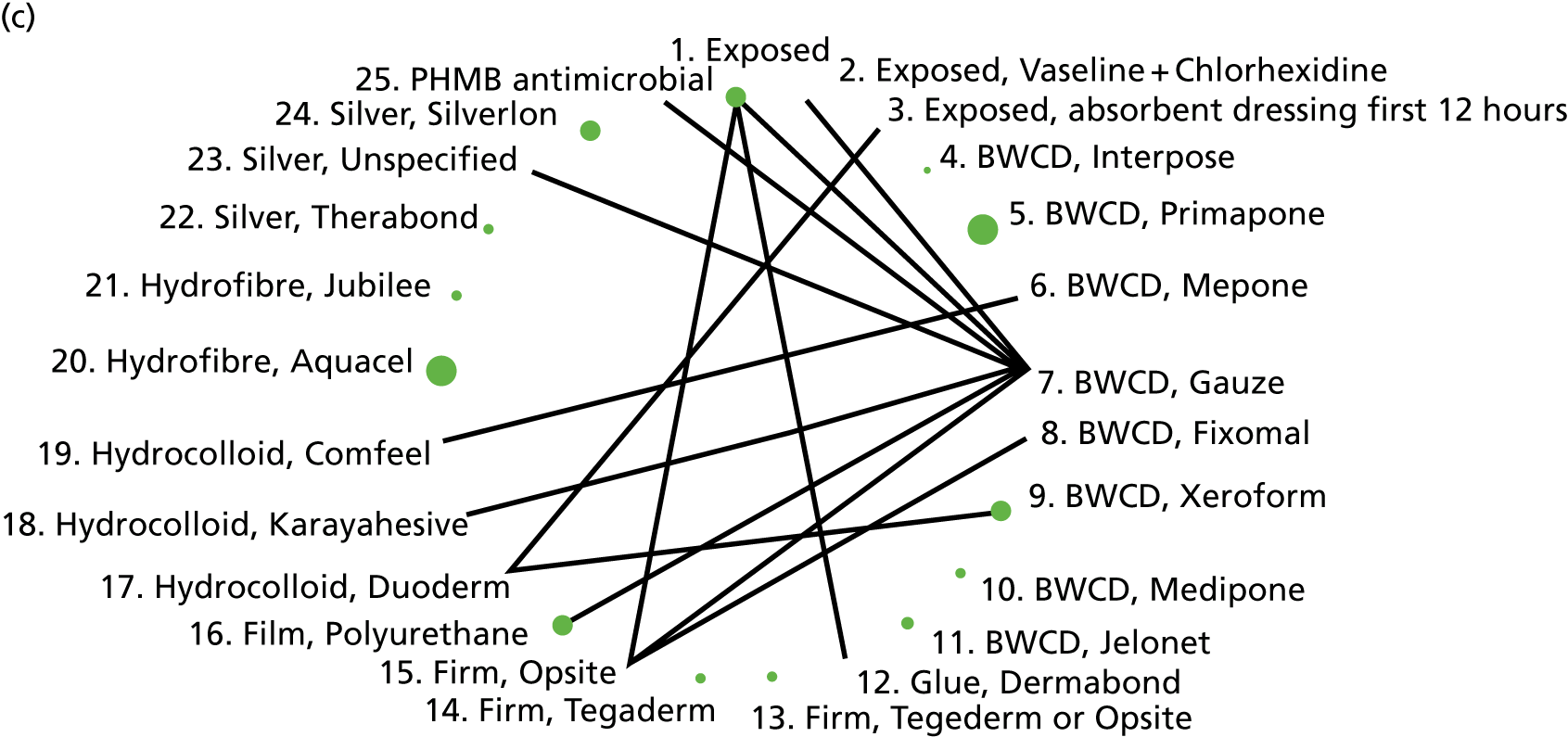

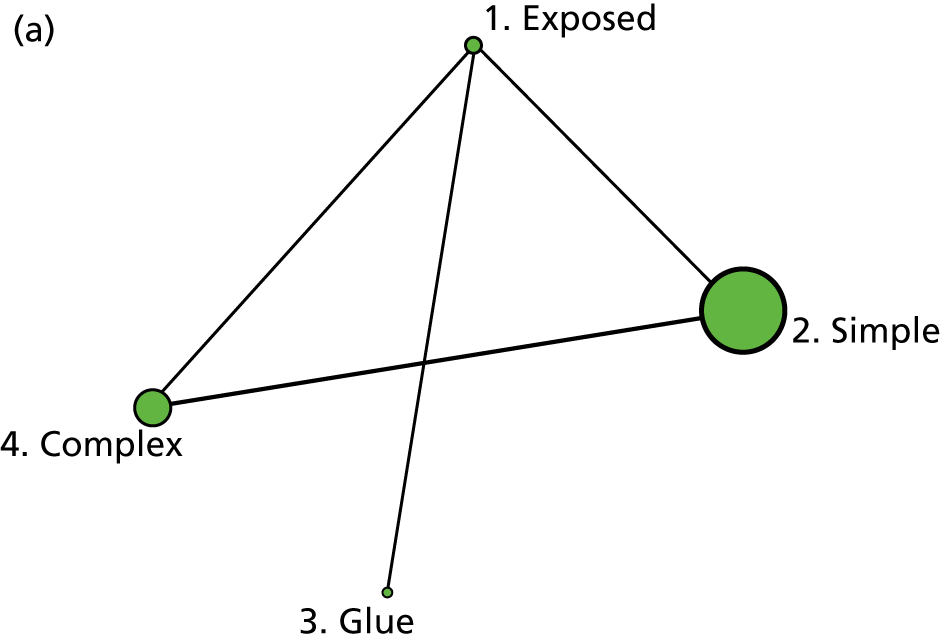

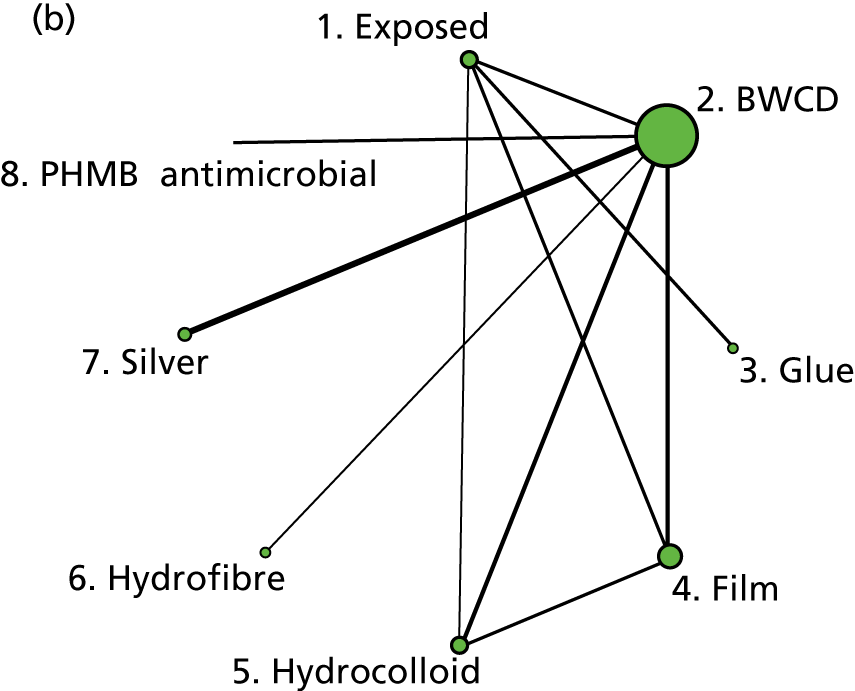

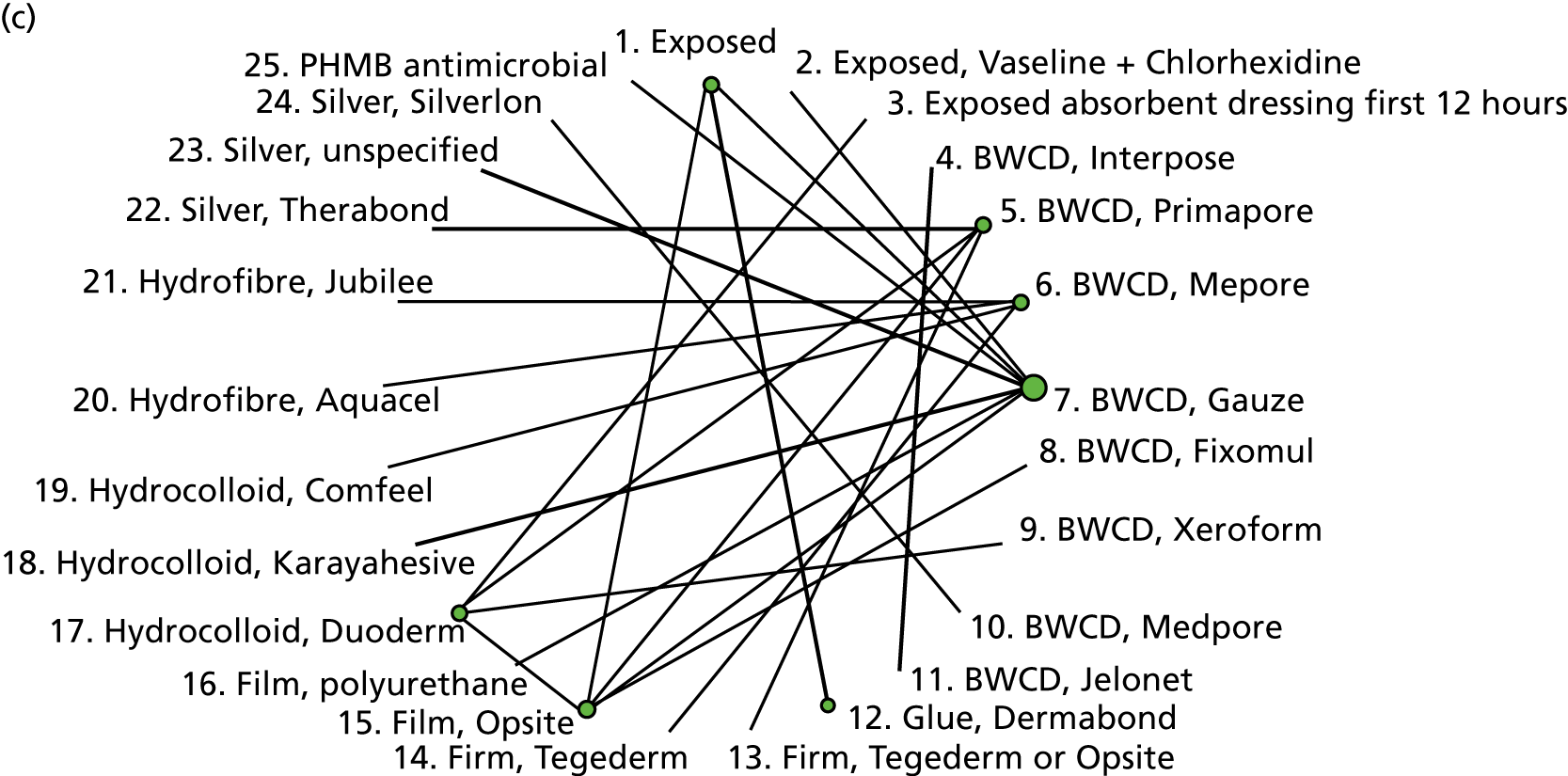

The intervention comparisons made in the included studies can be represented pictorially in a network plot, in which interventions are joined by lines if there is a RCT comparing those two interventions, and the thickness of the lines indicates the number of RCTs making that comparison. We display these plots for the surgery types representative of the Bluebelle population (Figure 2) and for all surgery types (see Appendix 1, Figure 14). Each figure shows network plots at three different classification levels of the interventions: Bluebelle project classification, intervention level and Cochrane review classification (see Appendix 1, Table 40). It is apparent that some level of grouping of the interventions is necessary because the networks are ‘unconnected’ when using the most detailed level of intervention definition; comparisons cannot be made between interventions when there is no connecting path.

FIGURE 2.

Network plots showing comparisons that have been made between interventions (for three different classification schemes) in RCTs included in the Cochrane update review17 where surgery type was representative of the Bluebelle population of interest. The term ‘exposed’ in the figure presents leaving the wound uncovered, described as ‘no dressing’ in the pilot Bluebelle trial. BWCD, basic wound contact dressing; PHMB, polyhexamethylene biguanide.

We considered two different NMA models to estimate the relative efficacy of wound dressings according to the Bluebelle classification: (1) a random-effects model with intervention effects defined by the Bluebelle classification and (2) a hierarchical model with three levels: studies nested within interventions defined using the Cochrane classification, which in turn are nested within the coarser Bluebelle classification. The fit of these two models was practically identical, and heterogeneity was not decreased by including the additional level of hierarchy. Therefore, we present only results from the simpler random-effects model using the Bluebelle classification. To put credible bounds on the estimates of intervention efficacy, we used informative priors on relative effects, chosen to give a 99% prior credible interval that the odds ratios lie between a factor of 3 either way (i.e. between 0.33 and 3, which represent extremes of effect). This corresponds to a 95% prior credible interval of 0.43 to 2.3. Any posterior intervals similar to this indicate comparisons where evidence is lacking, so that results are dominated by the prior.

Table 1 shows results from the NMA for each dressing type compared with simple dressings (Bluebelle definitions). Owing to the low SSI event rate and relatively small sample sizes in the included studies, all estimates have wide credible intervals, and all include 1 (no effect). The results for the ‘all surgery’ population are comparable to those for Bluebelle population surgery types. There is very little improvement in model fit by allowing for surgery type and heterogeneity increases. We therefore use the estimates from all surgery types because they are more precisely estimated.

| Surgery type | Odds ratio (95% credible interval) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Exposed vs. simple | Glue vs. simple | Complex vs. simple | |

| All surgery types | |||

| All wound types | 0.979 (0.561 to 1.546) | 1.049 (0.371 to 2.413) | 0.858 (0.535 to 1.263) |

| Clean wounds | 0.787 (0.403 to 1.388) | 0.847 (0.278 to 2.001) | 0.740 (0.397 to 1.277) |

| Mixed/unclear/contaminated | 1.153 (0.608 to 1.92) | 1.263 (0.392 to 3.029) | 1.068 (0.534 to 1.865) |

| Only surgery types representative of Bluebelle population | |||

| All wound types | 0.889 (0.465 to 1.497) | 0.956 (0.315 to 2.214) | 0.726 (0.329 to 1.382) |

| Clean wounds | 0.805 (0.348 to 1.629) | 0.860 (0.245 to 2.232) | 0.753 (0.224 to 1.908) |

| Mixed/unclear/contaminated | 1.064 (0.532 to 1.841) | 1.172 (0.353 to 2.887) | 0.902 (0.394 to 1.757) |

Results are shown for all surgery types included in Dumville et al. 17 and also restricting to studies with surgery types representative of the Bluebelle population of interest. Results are also shown on the basis of whether or not there were clean wounds only. Some of the estimates are associated with considerable uncertainty (posterior approximately equal to the prior), reported in grey font.

Most of the evidence is for complex versus simple dressings and shows a trend for reduced SSI rates with complex dressings, although the credible interval crosses 1 (no effect). Exposed wounds, that is wounds left uncovered with no dressing, show similar effectiveness to simple dressings and a trend towards a reduced SSI rate when used on clean wound types, although credible intervals are wide and cross 1 (no effect). There is no direct evidence for glue versus simple wound dressings, and, although an indirect comparison can be formed, this estimate is extremely imprecise, so there is effectively no evidence for this comparison. Similarly, there is effectively no evidence for wounds that are non-clean.

In the economic model we use the results for ‘all wound types’ and ‘all surgery types’ in the base case, but note in interpreting the results that these results apply mainly to clean wounds. We use the results for ‘all wound types’ and ‘Bluebelle population surgery types’ in a sensitivity analysis.

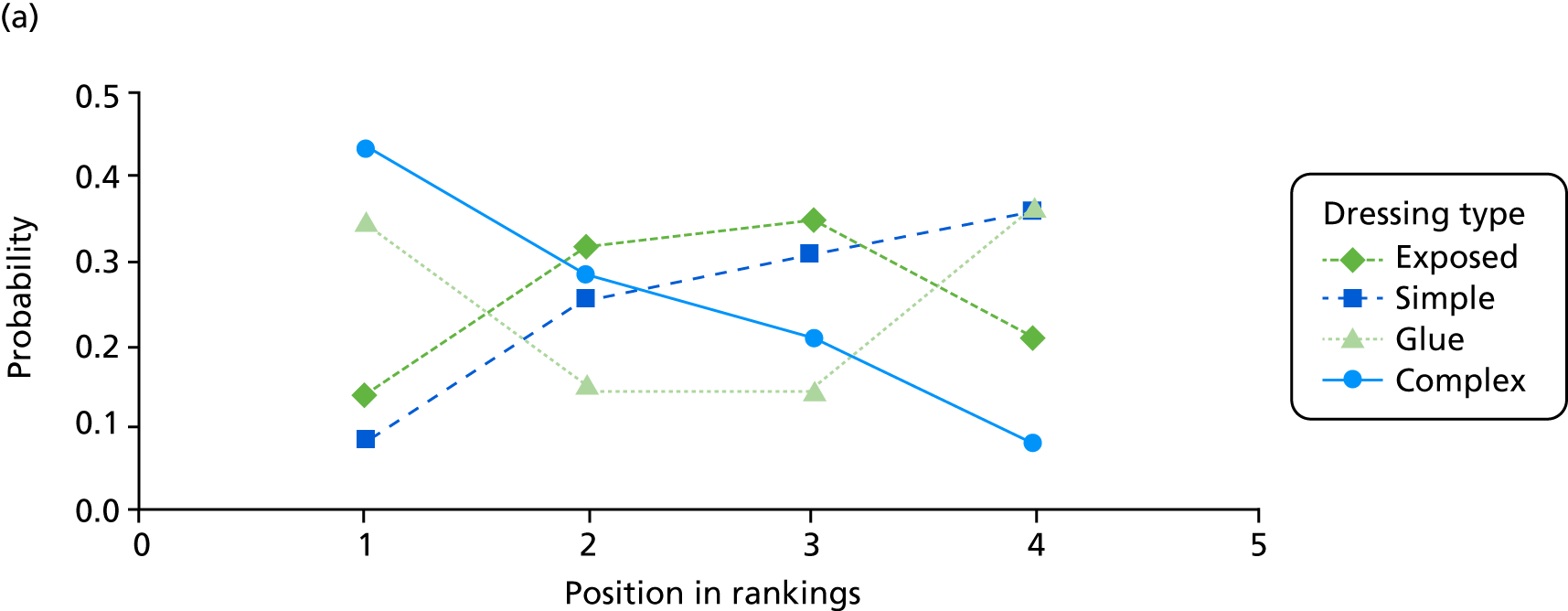

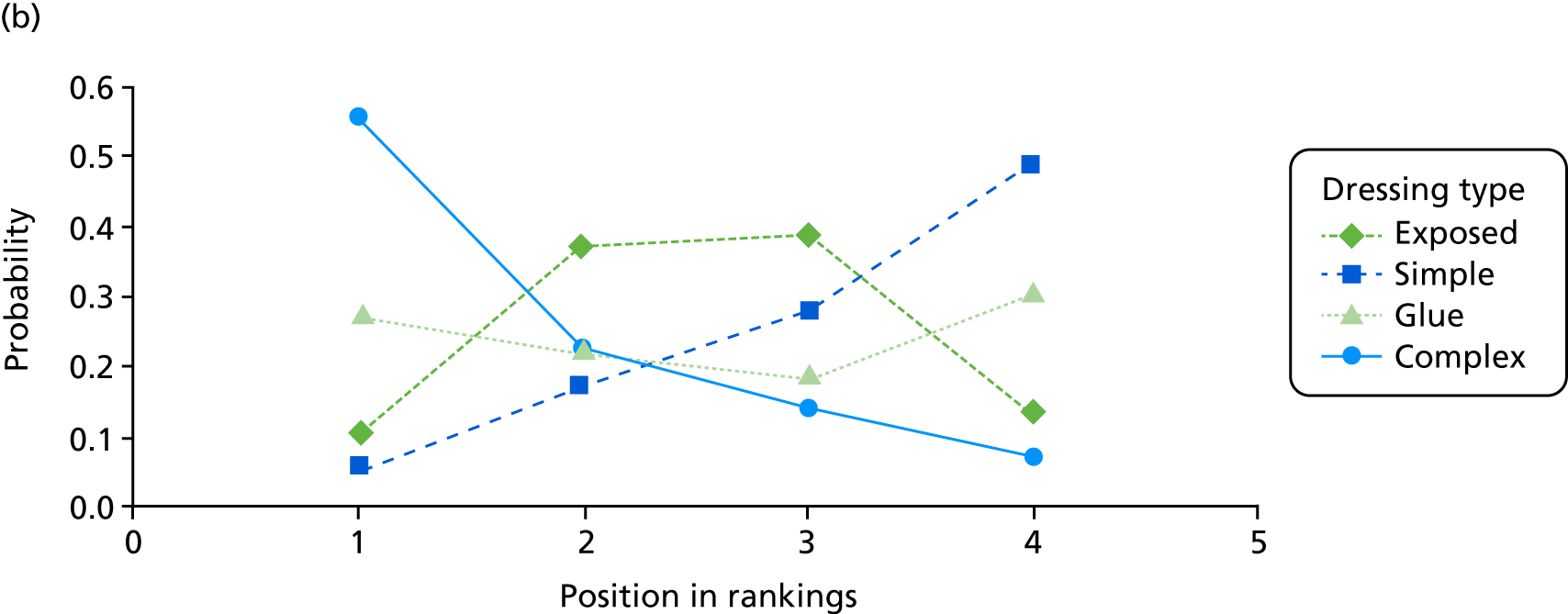

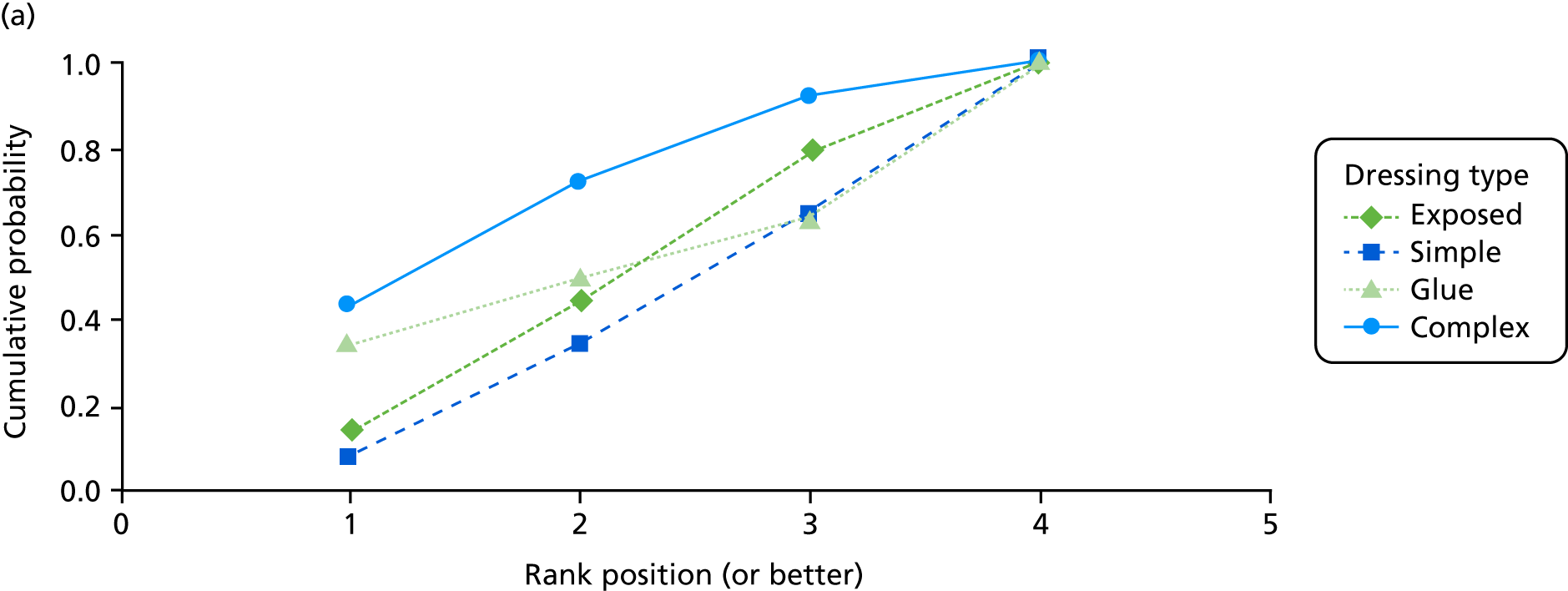

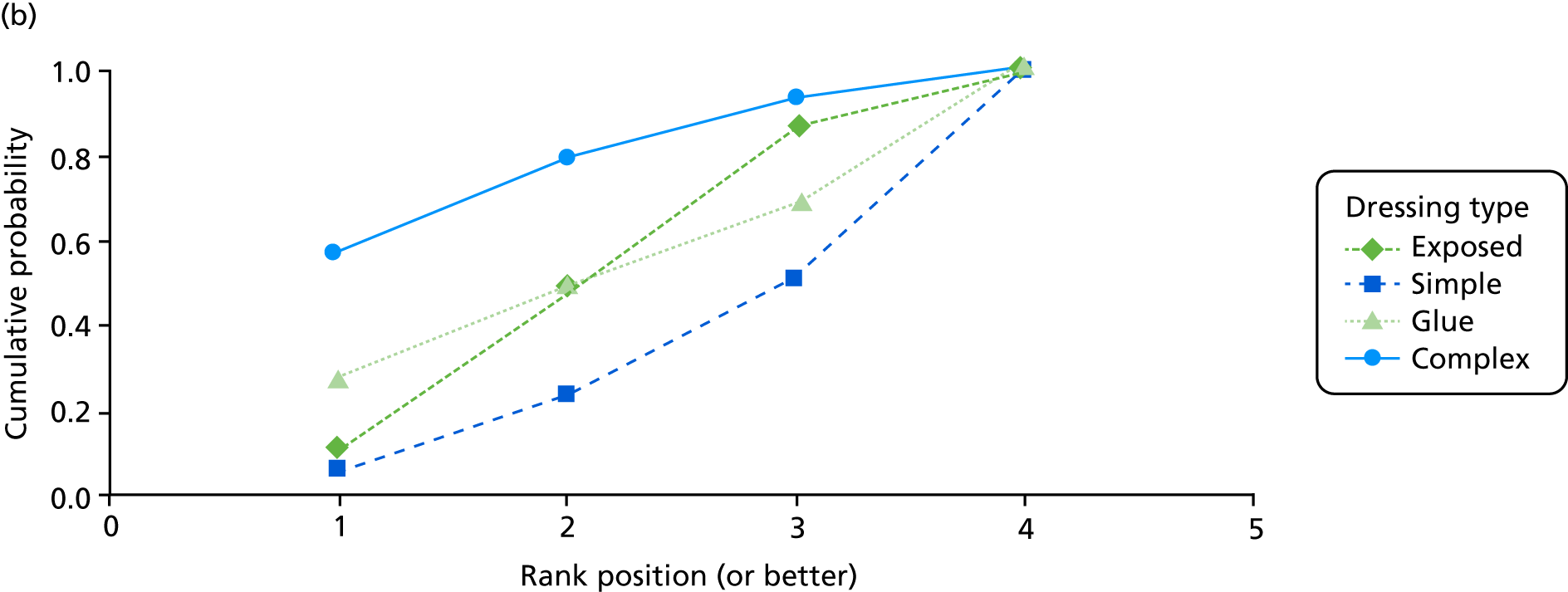

The probabilities of each dressing being ranked first, second, third or fourth in terms of effectiveness in preventing SSIs are shown in Appendix 1 (see Figure 15). Complex dressings have the highest probability of being most effective for SSI outcomes, but this probability is < 0.5 for ‘all surgery’ and only just over 0.5 for the Bluebelle population surgery types, suggesting a high level of uncertainty. Appendix 1 (see Figure 16) also presents these probabilities cumulatively (i.e. the probability that each dressing is ranked in each position or better, so all dressings have a probability 1 of being fourth or better). The ideal curve would go straight to 1 and stay there, and we prefer dressings with curves above the others. Complex dressings are preferred according to the cumulative ranking curves, but the curves are all close to each other. Simple dressings perform least well. Table 2 gives the mean rank (where rank 1 is best and 4 is worst). Complex dressings have the best mean rank and simple dressings have the worst; however, these are very similar and 95% credible intervals span all ranks from 1 to 4 for each dressing type, reflecting the high degree of uncertainty.

| Dressing type | Mean rank (95% credible interval) | |

|---|---|---|

| All surgery types | Bluebelle population surgery types | |

| Complex | 1.93 (1 to 4) | 1.71 (1 to 4) |

| Glue | 2.52 (1 to 4) | 2.53 (1 to 4) |

| Exposed | 2.62 (1 to 4) | 2.56 (1 to 4) |

| Simple | 2.94 (1 to 4) | 3.20 (1 to 4) |

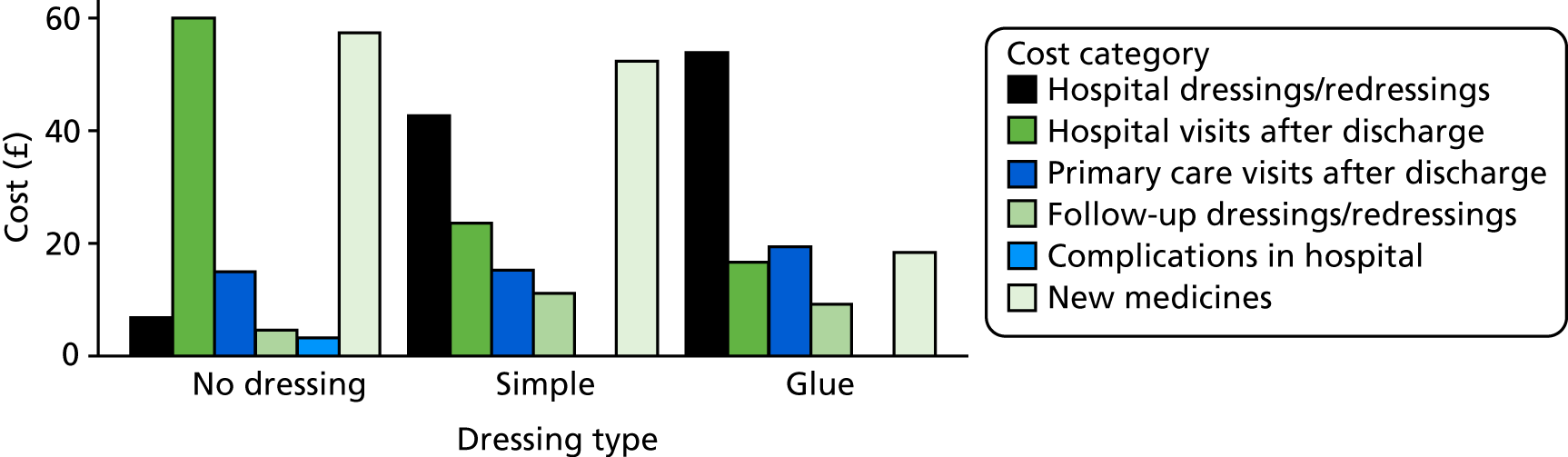

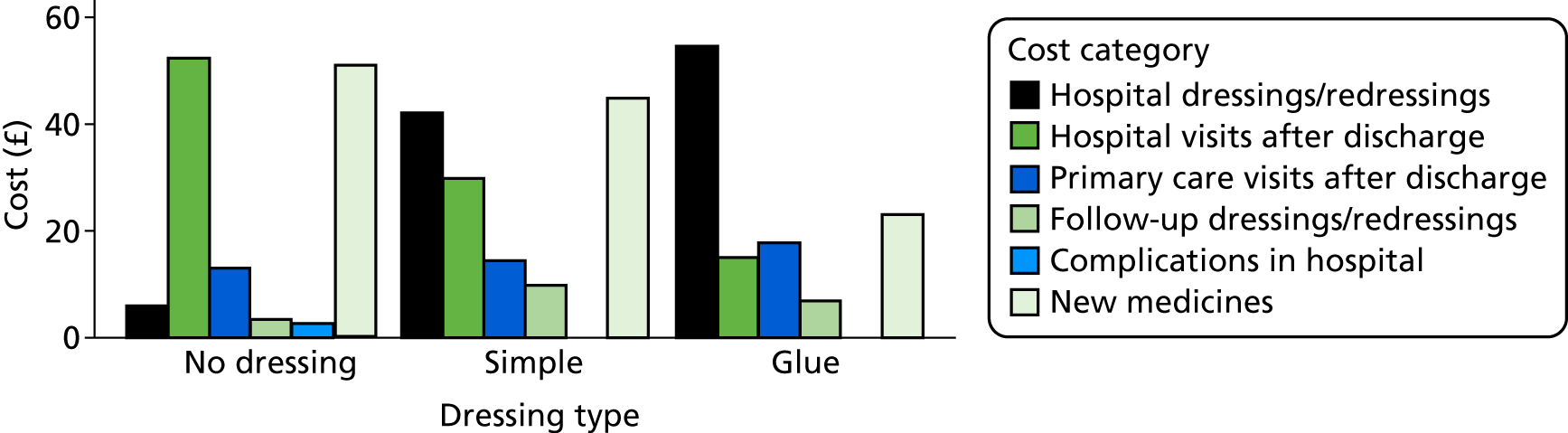

Surgical site infection cost

Jenks et al. 50 provide estimates of mean costs attributable to SSI, shown in Figure 3. Some of these estimates are very uncertain (very wide or incalculable CIs). SSI costs associated with gastric surgery are estimated to be much higher than those associated with other surgery types, although this estimate is based on only six patients. It is possible that gastric surgery included bariatric surgery (not our population of interest), which involves prosthetic ‘bands’ and may have led to higher costs. With the exception of gastric surgery, mean costs are quite similar across surgical sites. The estimated mean cost over all surgery types is £7179.79 with a 95% CI of £5225.01 to £9865.88. Assuming that these costs were correct for 2012, we inflate them to 2015/16 prices using an inflation factor of 1.097694841. 52 This gives a mean cost of £7881.22 with a 95% CI of £5724.25 to £10,850.95 in our model, described by a log-normal distribution with a mean of 8.972 and a standard error of 0.1631 on the log-scale.

FIGURE 3.

Mean cost (GBP) attributable to SSI by surgery type based on University Hospitals Plymouth NHS Trust data April 2010–March 2012 (Jenks et al. 50), assumed 2012 prices. CIs for the mean cost are obtained from reported confidence limits on the median cost, assuming that costs can be described by a log-normal distribution.

Dressing costs

Table 3 summarises the computation of dressing costs, based on the BNF15 and Personal Social Services Research Unit unit costs, 2015 prices. 53 We assume that a wound requires a large dressing (10 × 20 cm or 15 × 15 cm) or two vials of tissue adhesive; that simple or complex dressings may require changing (once), so that two dressings are required in total; and that the nurse time required to perform the change of dressing is as advised (clinical opinion). Dressing types on the BNF typical of each Bluebelle definition were chosen, and the product with the lowest cost within those types was chosen.

| Cost component | Exposed | Simple | Glue | Complex |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unit cost (BNF) (£) | 0 | 0.29 [10 × 20 cm absorbent perforated dressing with adhesive border (Cutiplast® Steril, Smith & Nephew, Zaventem, Belgium)] | 6.93 [1 × 500 mg vial Histoacryl® (B. Braun Melsungen AG, Hessen, Germany)] | 8.36 [15 × 15 cm hydrocolloid with silver antimicrobial (Aquacel® Ag Extra™, ConvaTec, Deeside, UK)] |

| Number of dressings per wound (including changes) | N/A | 2 | 2 vials | 2 |

| Total dressing cost (£) | 0 | 0.58 | 13.86 | 16.72 |

| Nurse cost to change dressing (£) | 0 | 4.67 | 0 | 4.67 |

| Total cost (£) | 0 | 5.25 | 13.86 | 21.39 |

Total cost is equal to the dressing cost plus the cost of nurse time to administer dressings. Dressing costs are computed as the number of dressings multiplied by the dressing unit cost. Nurse time is computed as £4.67 for 5 minutes based on a general practice-based nurse with qualifications patient contact time. 53

Quality-adjusted life-year decrement attributable to surgical site infection

Gheorghe et al. 54 systematically reviewed SSI utility values reported in patient-level and decision modelling studies. Only 6 out of the 28 studies identified related to the Bluebelle population surgery types. Most modelling studies used utility decrements based on the authors’ assumptions or on assumptions made in previous modelling studies. Only one study was conducted in a population relevant to Bluebelle (UK patients undergoing upper abdominal surgery laparotomy) and reported utility decrements based on patient-level EuroQol-5 Dimensions, three-level version, data attributable to superficial SSI. 2 Estimated SSI decrements were 0.05 and 0.12 at 7 days and 30 days, respectively. 2,54 The 30-day estimate is consistent with estimates from studies in other surgical areas reporting at 1 year55 and postoperatively. 56 We therefore assume a fixed utility decrement of 0.12 QALYs resulting from a SSI in our base case (SSIQALYloss = 0.12). We were concerned, however, that this may be an overestimate due to confounding (those with worse outcomes in general are more likely to get a SSI, and so reduction in quality of life may be due to other factors as well as SSI). We therefore used values SSIQALYloss = 0.06 and SSIQALYloss = 0 in sensitivity analyses.

Quality-adjusted life-year gain as a result of wound management compared with ‘no dressing’

We assume that there is no quality-of-life benefit of dressing a wound compared with leaving a wound exposed (which allows a gauze covering to be applied as long as it is not sealed around the perimeter). The model inputs are summarised in Table 4.

| Parameter | Base-case valuea | Source (base case) | Sensitivity analysis | Source (sensitivity analysis) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prevalence of general surgery wounds | 2.208 million | Royal College of Surgeons,48 SPARCS49 | ||

| Proportion of surgery types | See Table 39 |

Jenks et al. 50 PHE51 |

||

| SSI risk with simple dressings | 0.1380 (0.1345 to 0.1415) |

Jenks et al. 50 PHE51 |

0.0894 (0.0775 to 0.1013) | Jenks et al.50 |

| Mean SSI cost | £7881.22 (£5724.25, £10,850.95) (log-normal mean = 8.972, SE = 0.1631 on log-scale) | Jenks et al.,50 inflated to 2015 prices | ||

| OR exposed vs. simple | 0.979 (0.561 to 1.546) | NMA (see Table 40), all surgery types | 0.889 (0.465 to 1.497) | NMA (see Table 40), Bluebelle population |

| OR glue vs. simple | 1.049 (0.371 to 2.413) | NMA (see Table 40), all surgery types | 0.956 (0.315 to 2.214) | NMA (see Table 40), Bluebelle population |

| OR complex vs. simple | 0.858 (0.535 to 1.263) | NMA (see Table 40), all surgery types | 0.726 (0.329 to 1.382) | NMA (see Table 40), Bluebelle population |

| Utility decrement resulting from a SSI | SSIQALYloss = 0.12 |

Pinkney et al. 20132 Gheorghe et al. 201554 |

0.06 and 0 | Assumption |

| Cost exposed (£) | 0.00 | Assumption | ||

| Cost simple (£) | 10.13 | BNF,15 PSSRU53 | ||

| Cost glue (£) | 13.86 | BNF,15 PSSRU53 | ||

| Cost complex (£) | 26.05 | BNF,15 PSSRU53 |

Time horizon and discounting

We assume a 1-year time horizon as adequate to capture all the cost and quality-of-life benefits attributable to the choice of wound dressing following a surgical procedure. It is, therefore, unnecessary to discount costs and QALYs in the economic model.

In the VoI analysis, we multiply per patient-year results by the population prevalence of general surgery wounds (2.208 million per annum) and by the ‘lifetime’ of the dressing intervention (assumed to be 5 years discounted at a rate of 3.5% to give a multiplier of 4.673) to obtain the population VoI. The ‘lifetime’ of the dressing can be thought of as the length of time until it is superseded by new evidence/innovations, or as a proxy for other uncertainties about the future. The VoI will increase as the ‘lifetime’ of the intervention increases.

Incorporating results from Bluebelle Phase B Study

We updated the NMA model (all wound types, all surgery types) incorporating the Bluebelle Phase B results using denominators based on either (1) intention to treat (ITT) or (2) per protocol (PP). We also updated the base-case EVPPI and EVSI results incorporating the Bluebelle results.

Computation

The WinBUGS code used to compute the NMAs is described in Report Supplementary Material 6. The methods used to compute the VoI, and the R-code used to compute all cost-effectiveness and VoI estimates, are also described in Report Supplementary Material 5 and 7. It was necessary to make a multivariate normal approximation to the NMA estimates used in the computation of EVSI. Making this approximation did not much alter any of the other model outputs and we therefore present all results under the multivariate normal approximation.

Objective A9: bring together the results of the above objectives to design Phase B of the study

The results of the research to address objectives A1–8 were presented to the SMG as Phase A progressed. The results were discussed and informed the design of the pilot trial, as described below (see the next section).

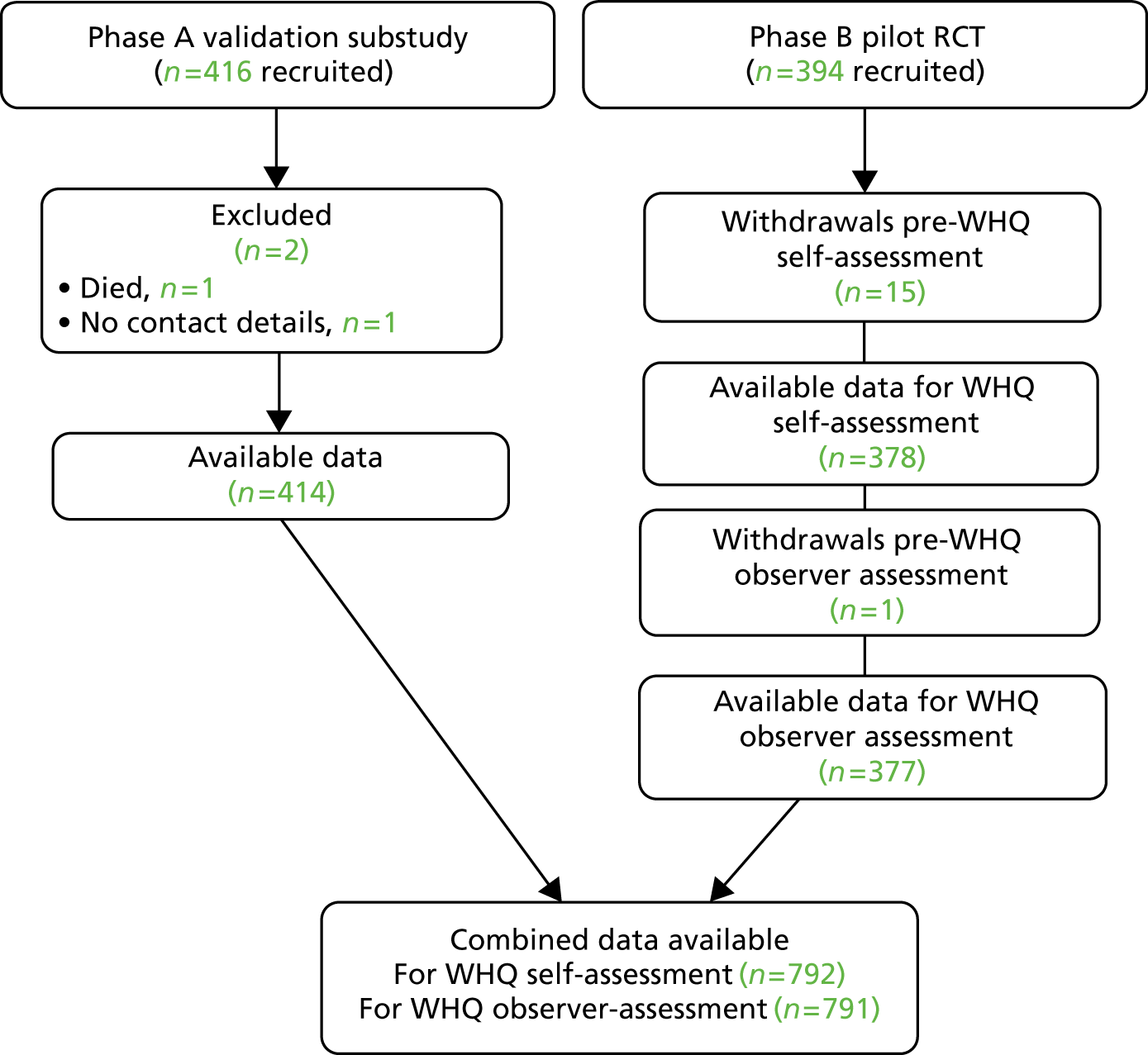

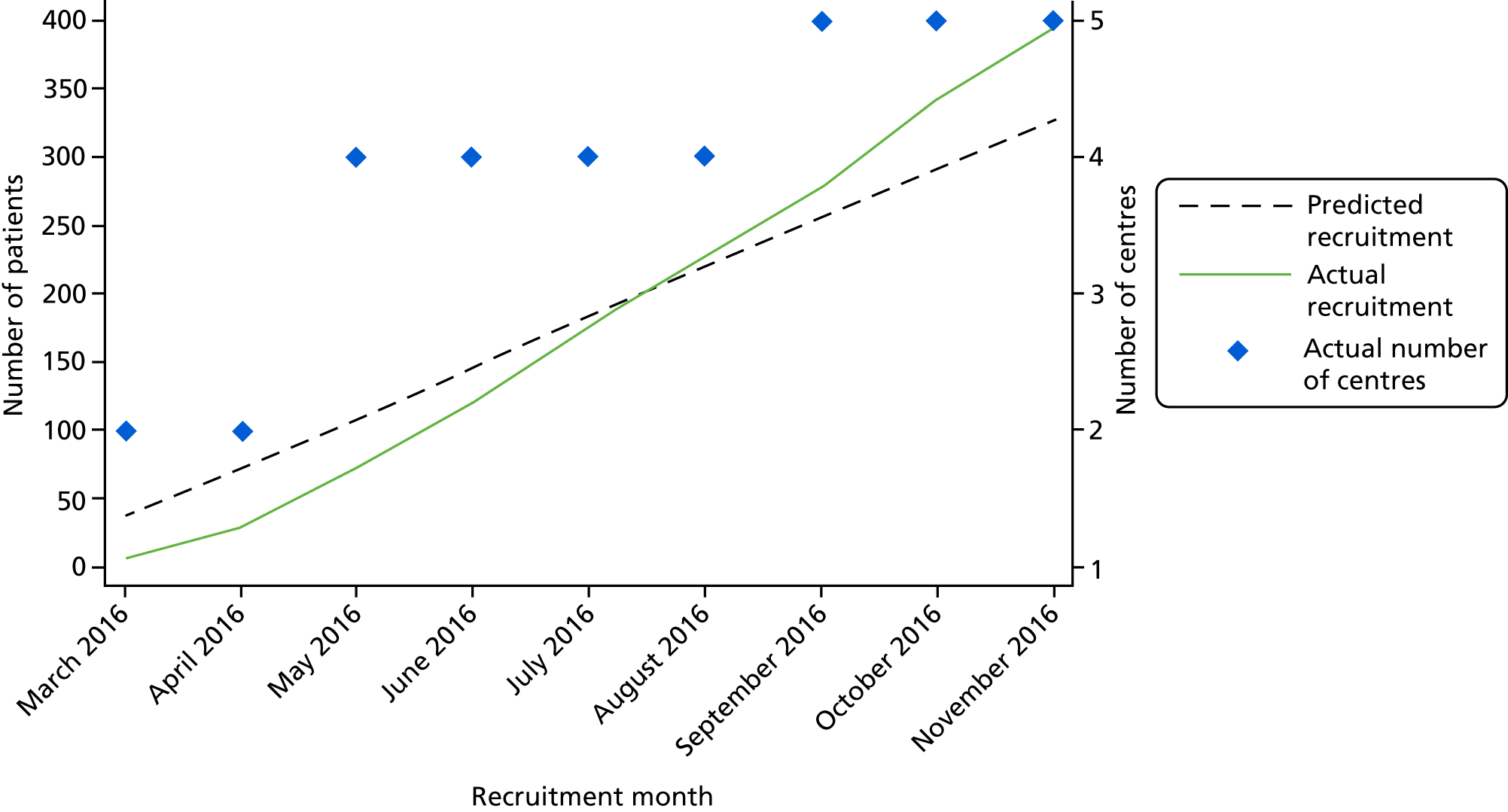

Objective B1: establish the numbers of potential participants at different hospitals who are considered likely to be eligible and who can be approached about the trial, and the proportions confirmed as eligible, recruited and randomised

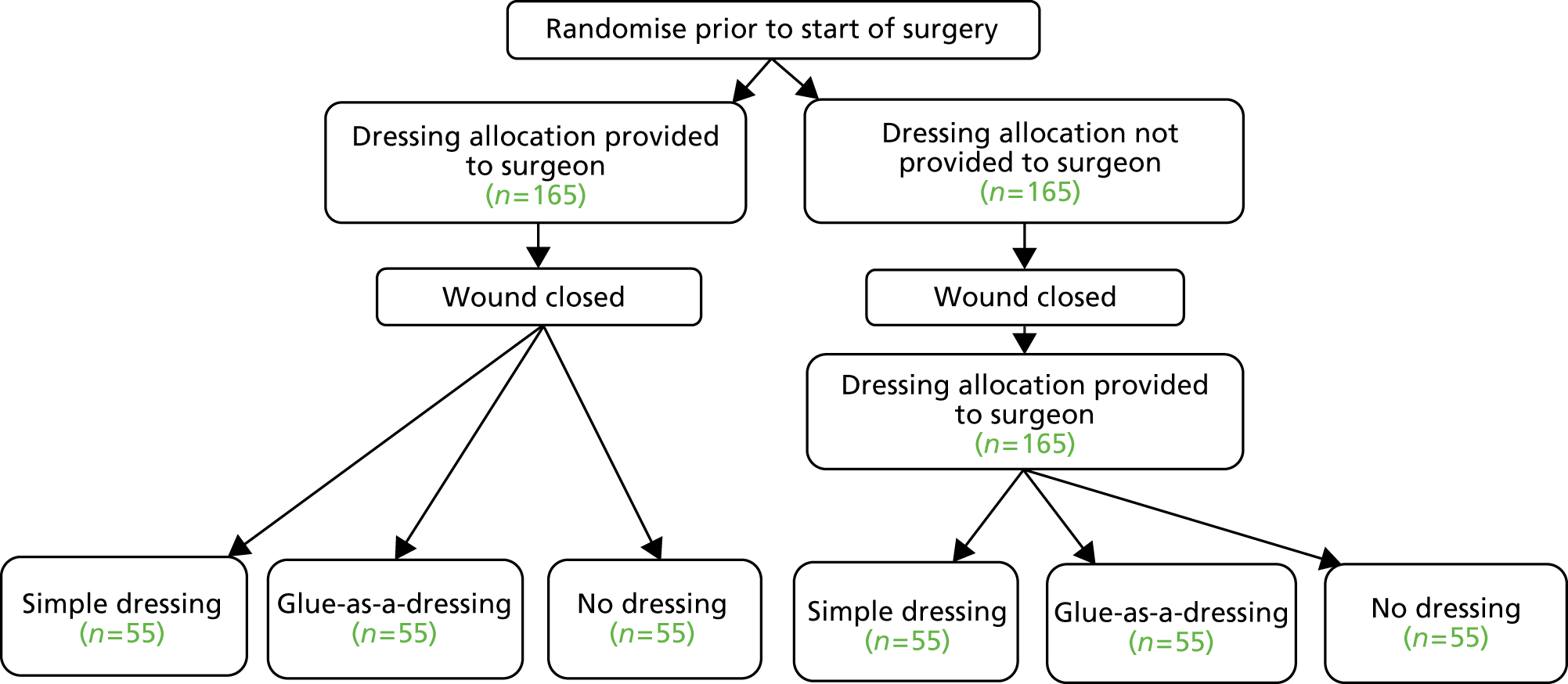

Study design

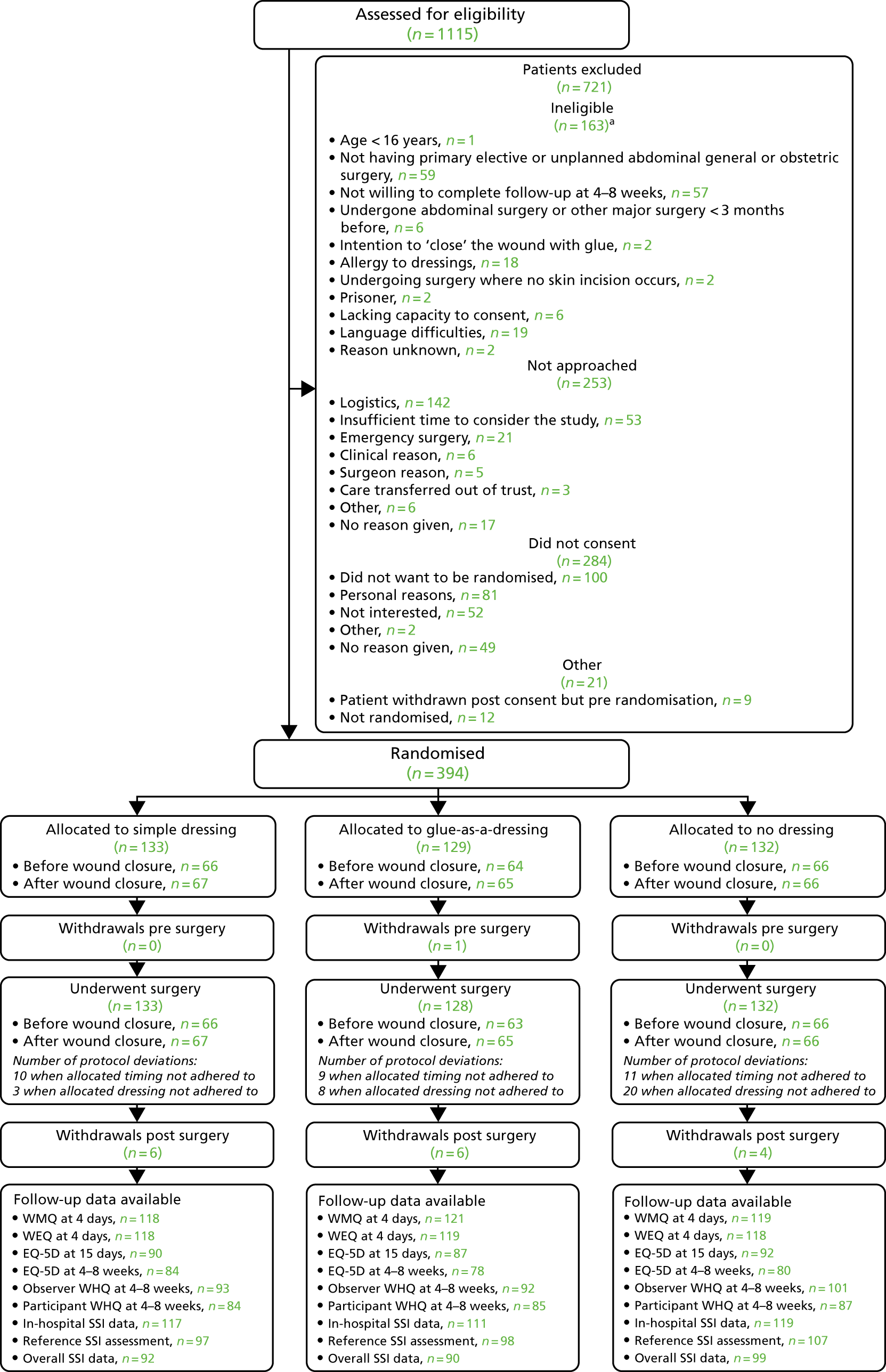

Phase B was a pragmatic feasibility and pilot parallel group RCT, using mixed methods. The trial used a factorial design, allocating participants to one of three dressing types and to disclosure of the dressing allocation before or after wound closure (Figure 4). If a participant had multiple closed primary wounds, all wounds were intended to be managed on the basis of the allocation.

FIGURE 4.

Trial schema for the Bluebelle Phase B external pilot trial, showing the double randomisation.

The time-of-disclosure factor was included because disclosing allocation after wound closure was preferred, to prevent surgeons closing the wound in different ways depending on the allocation, but was considered likely to be problematic by surgeons. This factor allowed the trial to test (1) the feasibility of randomising after wound closure and if photographs of the closed wound could be obtained in the operating theatre and subsequently assessed for the quality of wound closure and (2) the effect of timing of disclosure of dressing allocation on wound closure. This effect was potentially important as an indicator of the risk of performance bias if randomisation after wound closure proved impossible.

Study setting and population

The trial was set in secondary care (i.e. acute and maternity NHS hospitals). Patients aged ≥ 16 years undergoing primary elective or unplanned open or laparoscopic abdominal general surgery [including, but not limited to, gastrectomy for benign or malignant disease, cholecystectomy, anti-reflux procedures, hepatic resection, small or large bowel resection for benign or malignant conditions, abdominal wall hernia surgery (inguinal, femoral, incisional, epigastric and para-umbilical)] or elective or unplanned obstetric surgery (caesarean section) were eligible. Patients undergoing simultaneous abdominal and chest surgery were eligible but only those with abdominal wounds were allocated to one of the study interventions. At the time of recruitment, research nurses emphasised the need to attend a follow-up clinic 4–8 weeks after surgery and did not recruit patients who said that they would be unable to do so.

Patients with any of the following characteristics were ineligible:

-

abdominal or other major surgery < 3 months before the index operation

-

those for whom the surgeon intends to ‘close’ the wound with tissue adhesive (glue)

-

any contraindication to one of the dressing allocations, including allergy to dressings

-

undergoing surgery where no skin incision occurs

-

lacking capacity to consent

-

an inability to complete patient-reported outcome questionnaires

-

detained in the prison service.

Reasons for ineligibility were recorded.

Eligible patients were provided with a participant information leaflet (PIL), either at a clinic visit before the operation or sent in advance of admission. They were given as long as possible to consider the study before being approached for consent (usually > 4 hours for elective surgery and usually > 1 hour for unplanned surgery). Consent was not requested if a patient asked for longer thinking time or appeared visibly distressed.

Participants were also asked to consent to four optional aspects of the trial, designed to explore feasibility:

-

willing to be interviewed about the acceptability of, and adherence to, the allocated dressing type (objective B3)

-

willing for a member of the research team to take a photograph of the wound(s) in the operating theatre

-

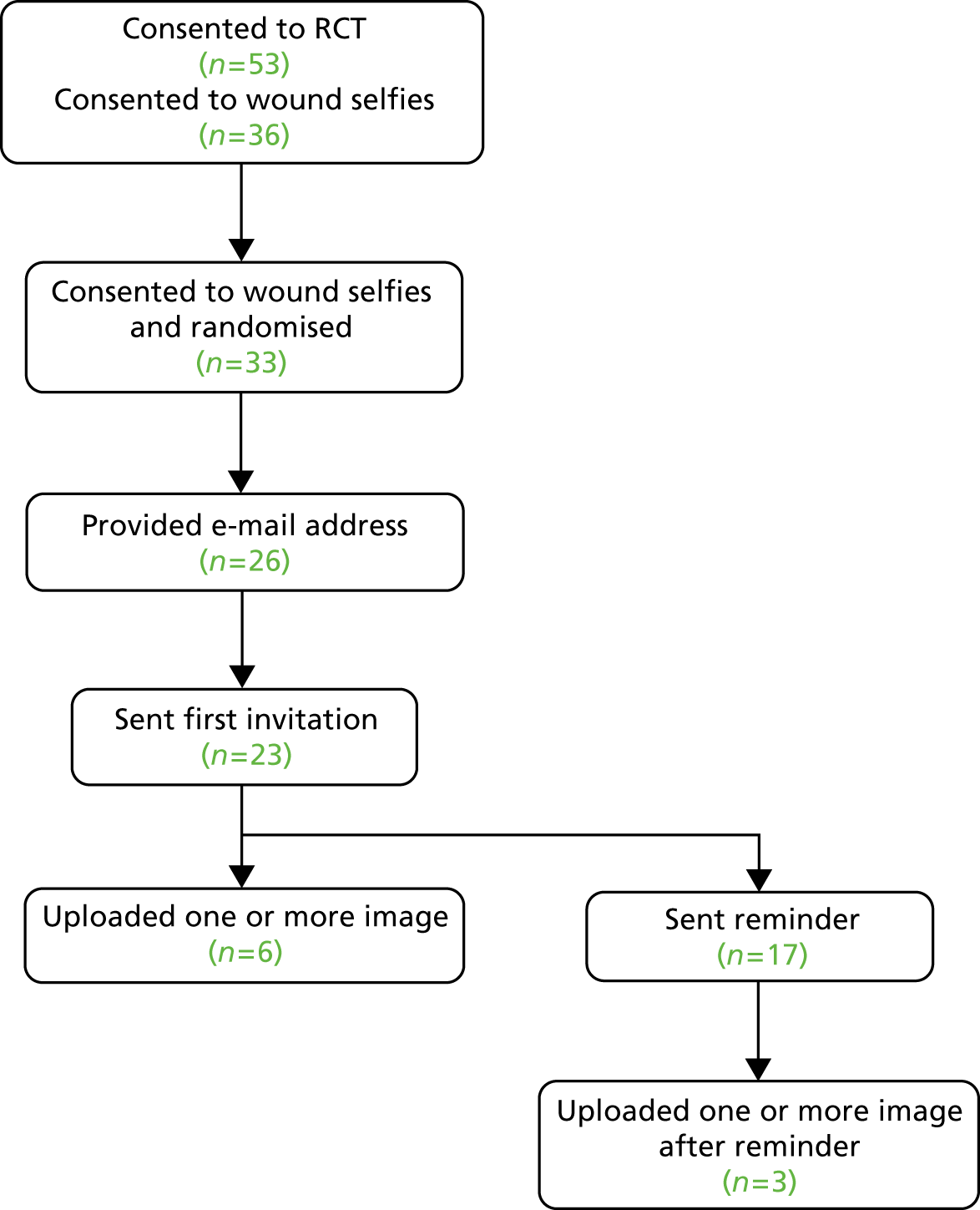

willing to take a photograph of their wound(s) themselves 4–8 weeks after the operation and to send it to the research team (described to participants as a ‘wound selfie’, a term that was readily understood; objective B7)

-

willing for a skin transfer to be applied after the operation to remind staff that the participant was in the study.