Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 11/129/16. The contractual start date was in March 2013. The draft report began editorial review in August 2017 and was accepted for publication in January 2019. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Hugh S Markus is supported by a National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Senior Investigator award and his work is supported by the Cambridge University Hospitals Trust NIHR Comprehensive Biomedical Research Centre. He reports personal fees from AstraZeneca plc (Cambridge, UK) for teaching outside the submitted work. Peter M Rothwell is supported by Wellcome Trust and NIHR Senior Investigator awards and his work is supported by the NIHR Biomedical Research Centre, Oxford, UK. He reports personal fees from Bayer AG (Leverkusen, Germany) outside the submitted work.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2019. This work was produced by Markus et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2019 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Introduction

Scientific background and rationale

Stroke in the posterior circulation accounts for 20% of all ischaemic stroke,1 and about 25% of cases of posterior circulation stroke are due to stenosis in the vertebral and/or the basilar arteries. 1 Despite the high proportion of posterior circulation stroke caused by vertebral and basilar stenosis, information about optimal management is lacking in comparison with that available for anterior circulation stroke. A similar proportion of anterior circulation stroke is caused by stenosis of the carotid arteries, associated with carotid artery stenosis. Large international trials in patients with symptomatic carotid stenosis [presenting with both transient ischaemic attack (TIA) and non-disabling stroke] have shown that carotid endarterectomy is associated with a reduced risk of recurrent stroke. 2 Carotid stenting has also been shown to be effective, although it is associated with a slightly higher risk of perioperative stroke than carotid endarterectomy. 3

It has been shown that patients with recently symptomatic vertebrobasilar stenosis have a similarly high risk of recurrent stroke to that in patients with symptomatic carotid stenosis, with the highest risk being in the first month. In a pooled analysis of two prospective studies, 90-day risk of stroke was 24.6%, with the risk higher with intracranial (33%) than with extracranial stenosis (16.2%). 4

Surgical access to the vertebral arteries is more difficult than that to the carotid artery, and, although vertebral stenosis can be treated surgically, such procedures have not been widely adopted worldwide. 1 By contrast, vertebral artery (VA) stenosis can more easily be treated with angioplasty and/or stenting. In early studies, proximal lesions were treated primarily with angioplasty; however, this was associated with a high restenosis rate, leading to the use of stenting for such lesions. 2 Several series have reported very low periprocedural complication rates for extracranial vertebral stenosis. Two systematic reviews were published in 2011 and 2012 with similar results. 5,6 Stayman et al. 5 identified 27 articles of series of cases of extracranial stenting meeting their inclusion criterion, with a total of 980 of 993 patients treated with stents. The majority of patients (56%) were noted to have contralateral VA stenosis or occlusion, and 92% were symptomatic at the time of treatment. A total of 11 patients (1.1%) experienced a stroke and eight (0.8%) experienced a TIA within 30 days of the procedure. Drug-eluting stents were associated with lower restenosis rates (11%) than bare metal stents (30%) at a mean of 24 months’ follow-up.

The VA comprises both an extracranial section (segments V1–V3) and an intracranial segment (V4). The complication rate following angioplasty and stenting is higher for intracranial than for extracranial vertebral stenosis. In a systematic review,7 perioperative stroke rates were 1.3% in 313 extracranial stents, 7.1% in intracranial vertebral angioplasties and 10.6% in intracranial vertebral stents. That review7 included data from the prospective multicentre Stenting of Symptomatic Atherosclerotic Lesions in the Vertebral or Intracranial Arteries study,8 which included 61 vertebral and intracranial lesions. However, many of the studies included in previous reviews are now old and technology has significantly improved. Furthermore, as intracranial stenosis has a higher recurrent stroke rate if treated medically,4 it may still benefit from stenting.

In contrast to the considerable data from case series, there are far fewer data from randomised trials. The Carotid And Vertebral Artery Transluminal Angioplasty Study (CAVATAS)9 included both carotid and vertebral stenosis. However, only 16 patients were randomised between vertebral angioplasty or stenting and best medical treatment (BMT), and this used angioplasty as the trial was performed before the routine use of stents for treating arterial stenosis. The Stenting and Aggressive Medical Management for Preventing Recurrent Stroke in Intracranial Stenosis (SAMMPRIS) trial10 reported that outcomes among patients with stenosis in a variety of intracranial cerebral arteries were worse in the stent group than in the BMT group. Basilar artery stenting was associated with a particularly high complication rate, but few patients with VA stenosis were enrolled. However, a recent analysis suggested that outcomes after stenting are as poor in patients with VA stenosis as in patients with stenoses in other intracranial arteries. 11 Furthermore, the SAMMPRIS trial used the Wingspan stent system (Boston Scientific, Fremont, CA, USA), which has been associated with a higher complication rate. The Vertebral Artery Stenting Trial (VAST) included both patients with intracranial and those with extracranial VA stenosis and randomised them between stenting and BMT. It found no significant difference between the two groups. Although VAST was designed as a Phase II trial, it was terminated early owing to regulatory issues and because it was underpowered to detect a difference. 12

Specific objectives

The Vertebral artery Ischaemia Stenting Trial (VIST) was established to compare the risks and benefits of vertebral angioplasty and stenting plus BMT with those of BMT alone for recently symptomatic VA stenosis.

Chapter 2 Methods

Trial design

VIST was a prospective, randomised, open, parallel, blinded end-point clinical trial performed at 14 hospitals, with both specialised stroke and interventional radiology services, in the UK. VIST sites and recruitment rates are shown in Appendix 1. It was planned to extend the study to other countries; however, after funding was ceased because of slower than anticipated recruitment, only 182 of the planned 540 patients, all from the UK, were recruited. VIST was initially established as a pilot (with a sample size of 100 participants), and was funded by the Stroke Association. The plan was to extend the pilot to a definitive Phase III trial if recruitment was feasible. After further funding from the National Institute for Health Research Health Technology Assessment programme, the pilot phase was extended to a Phase III trial.

Eligibility

Patients were identified from stroke and neurology services in secondary and tertiary care, with the following inclusion and exclusion criteria applied.

Inclusion criteria

-

Women or men aged > 20 years.

-

Symptomatic vertebral stenosis resulting from presumed atheromatous disease.

-

Symptoms within the last 3 months.

-

Severity of stenosis at least 50% as determined by magnetic resonance angiography (MRA), computed tomography angiography (CTA) or intra-arterial angiography.

-

Symptoms of TIA or stroke within the previous 6 months.

-

Patients able to provide written informed consent, willing to be randomised to either treatment, and willing to participate in follow-up.

Exclusion criteria

-

Patients unwilling or unable to give informed consent.

-

Patients unwilling to accept randomisation to either treatment group.

-

Vertebral stenosis caused by acute dissection (as this has a different natural history and usually spontaneously improves).

-

Patients in whom vertebral stenting is felt to be technically not feasible (e.g. access problems).

-

Previous stenting in the randomised artery.

-

Women who are pregnant or lactating.

Key protocol changes

During the pilot phase (recruitment of the first 100 patients), patients had to have had symptoms within the previous 6 months. However, this was changed to 3 months when the pilot phase was extended to the full trial, in view of data showing that stroke risk was highest in the first 3 months.

The primary end point was changed on 6 February 2013 from fatal or disabling stroke in any arterial territory (including periprocedural stroke), defined by a modified Rankin Scale score of ≥ 3, at 3 months post stroke, to any fatal or non-fatal stroke in any arterial territory (including periprocedural stroke) during trial follow-up.

Imaging inclusion criteria

Prior to randomisation, the likely presence of a VA stenosis had to be demonstrated on imaging and confirmed by at least two experienced neuroradiologists. The following imaging modalities were acceptable: MRA (preferably contrast enhanced); contrast-enhanced CTA; and intra-arterial digital subtraction angiography (DSA). It was recommended that, if there was any doubt about the result of a non-invasive screening test, an additional imaging modality should be used. Only if the two methods provided concordant and appropriate results was the patient to be considered for randomisation. The extent of VA stenosis was calculated by a method based on the North American Symptomatic Carotid Endarterectomy Trial (NASCET),13 in which the residual luminal diameter (R) was divided by the vessel diameter (D) at a point distal to the stenosis where normal vessel calibre had been restored, applying the formula:

If normal distal vessel was not available (e.g. for distal stenosis), the proximal normal artery diameter was used as the denominator, a method based on Warfarin–Aspirin Symptomatic Intracranial Disease (WASID) measurement of intracranial stenosis. 14

Settings and locations where the data were collected

The study was carried out at stroke centres in the UK. These centres had both a specialised stroke service and facilities for interventional radiology. It was planned to extend the study to centres outside the UK; however, only one overseas centre (Prince of Wales Hospital, Hong Kong) had opened to recruitment by the time recruitment was stopped and this had not recruited any patients by that time. To be allowed to participate, a centre had to have both a consultant neurologist or physician with an interest in stroke and a designated consultant interventional radiologist with experience in cerebral angioplasty/stenting. Interventionists were expected to have performed a minimum of 50 stenting procedures, of which at least 10 were on cerebral vessels. Centres with less than this level of experience joined for a probationary period, during which time procedures were proctored by an experienced interventionist until 10 procedures had been satisfactorily performed.

The study was approved by the Multicentre Ethics Committee in England (reference number 08/H0711/2) and all patients gave written informed consent.

Randomisation and masking

Patients were randomly assigned (1 : 1) to vertebral angioplasty/stenting plus BMT or BMT alone via an online randomisation service provided by the King’s College London Clinical Trials Unit. Authorised researchers at recruiting study sites who were delegated to request randomisation were provided with unique login details by the Clinical Trials Unit to access the system. Once the participant was confirmed as consenting and eligible to proceed into the study, the authorised researchers accessed the system and entered the relevant data, which included participant identifiers and stratifiers. The system then allocated the participant to treatment group using the method of block randomisation with randomly varying block sizes of two and four, stratified by site of VA stenosis (origin V1 vs. other extracranial V2 and V3 vs. intracranial V4). To account for the differing recurrent stroke risk associated with site of VA stenosis, randomisation was stratified by the site of VA stenosis (V1 vs. V2/V3 vs. V4). E-mails confirming the randomisation were automatically generated by the system and sent to relevant authorised researchers in the study site and central co-ordinating team; the e-mail revealed or concealed the treatment allocation depending on the recipient’s role in the study. Both patients and clinicians were aware of treatment allocation, but an independent adjudication committee, masked to treatment allocation, assessed all primary and secondary end points.

Interventions

Stenting procedure

It was recommended that stenting, rather than angioplasty, be the preferred procedure for proximal vertebral stenosis; however, for distal stenosis the choice of angioplasty alone or stenting was at the discretion of the interventional radiologist. Stent choice was also at the discretion of the interventional radiologist, but the stents used were Conformité Européenne (CE) marked for use for treatment of arterial stenosis. The recommended antiplatelet therapy during the procedure was clopidogrel and aspirin, with a loading dose of clopidogrel (300–600 mg) administered at least 12 hours before the procedure if the patient was not already taking clopidogrel. It was recommended that clopidogrel and aspirin be continued for at least 1 month post procedure, after which standard antiplatelet therapy for stroke prevention was used.

Medication during trial

All patients were expected to receive BMT (including antiplatelet therapy or anticoagulation, when appropriate) and control of medical risk factors (including hypertension, smoking and hyperlipidaemia). Use of antiplatelet agents was recorded. The specific drugs to be used were not mandated.

Follow-up

Both entry and follow-up data were collected via an online electronic case report form hosted by King’s College London. Participants were seen at the time of the procedure (if allocated to stenting) and at 1 month and 1 year post randomisation by the local neurologist/stroke physician. In addition, telephone follow-up was performed at 6 months and 2 years, and after that on a yearly basis, at the co-ordinating centre by a designated stroke physician or neurologist using a standard pro forma. If patients experienced possible outcome events during follow-up, an end-point form was completed, the results of imaging were obtained and the data were reviewed by the adjudication committee. Members of the adjudication committee reviewed cases independently and were blinded to subject identity. Repeat imaging with either MRA or CTA at 1 year to check for vessel patency was encouraged but not mandated.

Angiographic imaging at baseline and at 12 months was assessed by central reading of the images by an experienced interventional neuroradiologist (AC). Restenosis was defined as any residual or recurrent stenosis of at least 50% or occlusion of the VA on CTA or MRA during follow-up.

Outcomes

The primary end point was fatal or non-fatal stroke in any arterial territory (including periprocedural stroke) during trial follow-up.

The secondary end points were:

-

fatal or non-fatal stroke in any arterial territory (including periprocedural stroke) within 3 months post randomisation

-

posterior circulation stroke (including periprocedural stroke) during follow-up

-

periprocedural stroke or death (within 30 days of the procedure)

-

posterior circulation stroke or TIA during follow-up

-

death from any cause during follow-up

-

restenosis in treated artery during follow-up.

An additional exploratory end point of fatal or non-fatal stroke and TIA was added. There were two reasons for this. First, as the trial was to be terminated early, we wanted an end point that would include the maximum number of ischaemic events. Second, it proved difficult to determine unequivocally whether or not some strokes were posterior circulation.

Stroke was defined as a rapid-onset focal disturbance of cerebral function, lasting > 24 hours or leading to death, with no apparent cause other than that of vascular origin. The diagnosis did not mandate imaging confirmation of a cerebral infarct.

It was intended that data would be collected and analysed on cost-effectiveness, and the following additional secondary end points were included in the statistical analysis plan:

-

NHS and Personal Social Services costs

-

quality-adjusted life-years

-

within-trial and long-run incremental cost-effectiveness.

However, owing to the early termination of recruitment and the withdrawal of funding for this analysis, data were not available for these secondary analyses.

Adverse events were collected on a dedicated form and reviewed by the co-ordinating centre prior to unbinding of the treatment group.

Patient and public involvement in study design

The trial design was reviewed by the St George’s Patient and Carer Stroke Group. The group felt that it was an important topic to investigate further. The group helped to ensure that the design was feasible. In particular, there was significant input from one member (Mr John Dennis), who had experience of vertebral stenting and played a key role throughout the trial. He commented on study design and patient materials, assisted with preparation of the grant application, on which he was a co-applicant, and was a member of the Trial Steering Committee.

Sample size

For sample size estimates the following figures were used: a stroke risk in the medically treated group of 24% over a 3-year period; and a risk reduction in the stented group of 45% (including periprocedural rate).

Estimate of medical risk

To determine short-term risk (up to 90 days), we used data from the pooled individual patient meta-analysis of the Oxford Vascular Study (OXVASC) and St George’s data sets, which provide prospective data from unselected groups of patients presenting with posterior circulation stroke in whom routine imaging of the vertebral arteries was performed with CTA and/or contrast-enhanced MRA in all cases. 4 From these data, a 90-day recurrent stroke risk of 24.6% was determined. However, many recurrences will be very early, before intervention could take place, and we estimated that half of this recurrent risk (i.e. 12%) will have occurred before randomisation. These data were used in the calculations and conservatively estimated a total risk over the first year of 12%. For longer-term risk over a mean 3-year follow-up, there were limited data from patients with imaging-proven vertebral stenosis. Therefore, data for carotid stenosis (for which there are many more data) were used because there are now increasing data that carotid and vertebral stenosis have a similar recurrent stroke risk profile. Therefore, it was estimated that the stroke risk in the medically treated group would be of the order of 12% in year 1, 7% in year 2 and 5% in year 3 (i.e. 24% over a 3-year period).

Effect of treatment

Owing to limited previous data on efficacy of stenting for vertebral stenosis, we based a possible treatment benefit effect on trials of intervention for symptomatic carotid stenosis. There are considerable data on this from the European Carotid Surgery Trial (ECST) and the NASCET,13 which compared carotid endarterectomy with BMT. In subsequent trials it was shown that carotid stenting is broadly similar in efficacy to, although probably marginally worse than, carotid endarterectomy. 3 In the pooled analysis of NASCET and ECST, the relative risk reduction for any stroke or operative death for 70–99% stenosis at 5 years was 0.52 (48% reduction). 2 Based on this, 45% was used as an estimate of the risk reduction in the stented group (including periprocedural rate).

Sample size calculations were performed by the National Institute for Health Research Stroke Research Network Statistical Support Unit (Professor Ian Ford), using a chi-squared test comparing two proportions with nQuery Advisor software version 6.02 (Statistical Solutions, Saugus, MA, USA). Table 1 shows how these varied by effect size and event rate. With a risk reduction with stenting of 45% [a hazard ratio (HR) of 0.55] and an event rate of 24% in medically treated patients over 3 years, the number of patients needed was estimated to be 245 per group (490 in total), assuming a significance level of 5% and power of 80%. Sample size was increased by 10% to take account of any crossovers or loss to follow-up for reasons other than stroke, giving us a sample size of 540.

| HR | Control group event rate | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 20% | 24% | 28% | |

| 0.65 | 521 | 433 | 370 |

| 0.60 | 387 | 321 | 274 |

| 0.55 | 296 | 245 | 210 |

| 0.50 | 232 | 192 | 164 |

| 0.45 | 185 | 154 | 131 |

| 0.40 | 150 | 125 | 107 |

However, owing to slow recruitment, support for continued recruitment by the funder was withdrawn after 182 patients were recruited, and, at that point, analysis was planned after every patient had been followed up for at least 1 year.

Statistical methods

The main analyses performed were on an intention-to-treat basis. Per-protocol analyses including patients who received the assigned treatment and had at least 50% VA stenosis confirmed by angiography were also conducted. HRs with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were estimated using Cox proportional hazards regression models. Each patient accrued follow-up time from the date of randomisation until the time of first event of each type, death or 1 March 2016 (the time by which follow-up of at least 1 year was available for all patients). The proportional hazards assumption was tested using scaled Schoenfeld residuals and was found to be satisfactory. Kaplan–Meier survival analysis was used to construct time-to-event curves and the log-rank test was used to compare the cumulative events between groups.

All statistical tests were two-sided and a p-value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. The statistical analyses were performed using Stata® version 14.1 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA).

Meta-analysis of results with those of other randomised controlled trials

The results of VIST were meta-analysed with those of previous randomised controlled trials (RCTs) of stenting for vertebral stenosis. Randomised trials investigating the effect of stenting and/or angioplasty on recurrent stroke or TIA in symptomatic VA stenosis patients were identified by searching PubMed (including MEDLINE) until 9 June 2017. Abstracts were reviewed by one author (SL). The search terms used were ‘stenting’ or ‘angioplasty’ or ‘stent’; ‘VA stenosis’ or ‘extracranial stenosis’ or ‘intracranial stenosis’; ‘stroke’ or ‘transient ischemic attack’; and ‘randomized trial’ or ‘randomized controlled trial’ or ‘clinical trial’. No language or other restrictions were imposed. The primary end point was any stroke. Analyses were performed separately for extra- and intracranial stenosis. Data were extracted by one author (SL) and included the name of the trial, number of outcome events, total number of patients in the stenting/angioplasty and medical groups, and the relative risk estimate (HR or odds ratio), comparing stenting/angioplasty with BMT. Relative risk estimates were combined using a random-effects model, and heterogeneity among estimates was evaluated using the Q-test and I2-statistic.

Chapter 3 Results

Recruitment

Owing to slow recruitment, support for continued recruitment by the funder was withdrawn after 182 patients were recruited, and, at that point, analysis was planned after every patient had been followed up for at least 1 year. Each patient accrued follow-up time from the date of randomisation until the time of first event of each type, death or 1 March 2016.

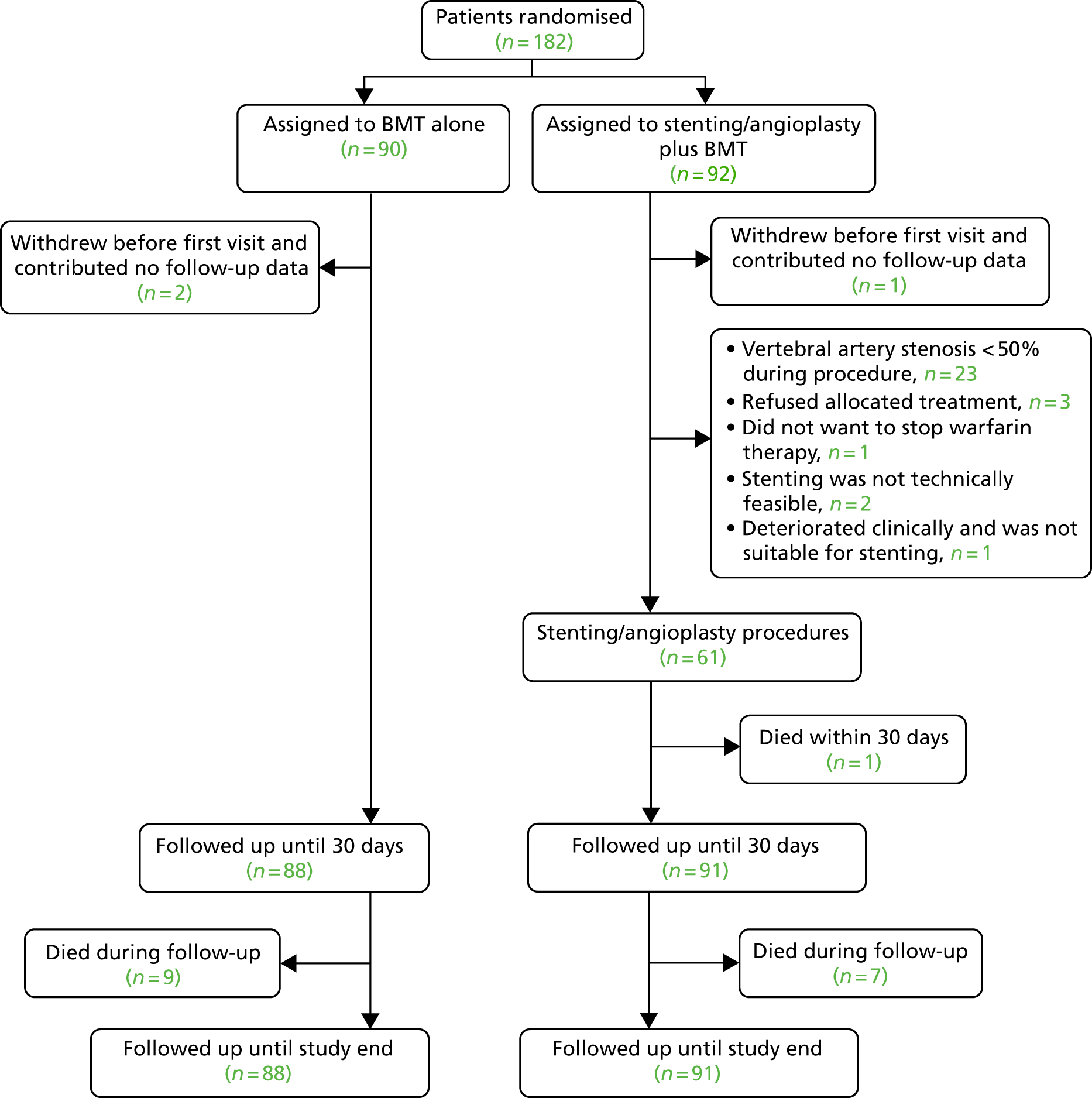

The trial profile is shown in Figure 1. Between 23 October 2008 and 4 February 2015, 182 patients were enrolled. Three patients (two who withdrew after randomisation and one who did not attend after the initial randomisation visit) did not contribute any follow-up data and were excluded. None of these three patients had outcome events. Of the 179 remaining patients, 88 were assigned to BMT alone (‘medical’ group) and 91 were assigned to stenting or angioplasty plus BMT (‘stent’ group). Follow-up data until March 2016 were available for all 179 patients.

FIGURE 1.

Patient flow in the two groups of the study.

Baseline characteristics

At baseline patients were well matched for age, sex and cardiovascular risk factors (Table 2). Similar proportions in both groups had stroke and TIA as the qualifying event, and the location of the vertebral stenosis was similar in both groups. The location of the VA target stenosis was extracranial in 83% and intracranial in 17%; most extracranial stenosis affected the V1 segment.

| Characteristic | Group | |

|---|---|---|

| Medical (N = 88) | Stent (N = 91) | |

| Age (years), mean (SD) [range] | 66.6 (10.2) [45–86] | 68.3 (9.2) [44–89] |

| Male, n (%) | 75 (85) | 73 (80) |

| Treated hypertension, n (%) | 60 (68) | 66 (73) |

| Systolic blood pressure (mmHg), mean (SD) | 139.3 (2.3) | 138.4 (2.0) |

| Diastolic blood pressure (mmHg), mean (SD) | 79.5 (1.3) | 77.0 (1.3) |

| Treated hyperlipidaemia, n (%) | 77 (88) | 77 (85)a |

| Total cholesterol (mmol/l), mean (SD) | 4.5 (0.14) | 4.4 (0.13) |

| Treated diabetes mellitus, n (%) | 19 (22) | 20 (22) |

| Current smoker, n (%) | 25 (29) | 18 (20) |

| Ischaemic heart disease, n (%) | 9 (10) | 19 (21) |

| Peripheral artery disease, n (%) | 4 (4.6) | 9 (9.9) |

| Atrial fibrillation, n (%) | 8 (9.1) | 10 (11) |

| Qualifying event | ||

| Ischaemic stroke | 58 (66) | 63 (69) |

| TIA | 30 (34) | 28 (31) |

| Days between last vertebrobasilar event and randomisation, median | 24.5 | 14.0 |

| ≤ 14 days since last vertebrobasilar event | 30 (34) | 47 (52) |

| Days from randomisation to stenting, mean (SD) | – | 16.1 (1.9) |

| Location of VA target stenosis | ||

| Extracranial (V1–V3), n (%) | 74 (84) | 74 (81) |

| V1, n | 70 | 71 |

| V2 or V3, n | 4 | 3 |

| Intracranial (V4), n (%) | 14 (16) | 17 (19) |

| Modified Rankin Scale score,b median (IQR) | 1 (1–2) | 2 (1–2) |

However, the time from last symptoms to randomisation was shorter in the stenting group by a mean of 12.8 days, and this could introduce a potentially important imbalance as a result of the previously noted association between time from symptoms and risk of recurrent stroke. 4 This implies that patients in the medical group were exposed to the highest stroke risk for 13 days fewer than those in the stent group. The percentage of patients randomised within 14 days of last symptoms was 47% in the stent group and 30% in the medical group. To account for this imbalance, two exploratory analyses were performed: first, controlling for time from symptoms; and, second, controlling for time in those subjects randomised within 2 weeks of symptoms. The 2-week cut-off point was chosen as this had been identified as the high-risk period for symptomatic carotid stenosis during which patients with moderate (50–70% stenosis) benefit from intervention (with carotid revascularisation), and after which there is no significant benefit. 15

Details of intervention

Ninety-one patients were randomised to stenting; however, stenting was not performed in 30 of those patients (33.0%) (see Figure 1). The most common reason, applying to 23 (76.7%) participants, was the finding of stenosis < 50% on intra-arterial angiography carried out at the time of the planned stenting. Of the 61 patients in the stent group, the stenosis was extracranial in 48 (78.7%) and intracranial in 13 (21.3%). Fifty-eight (63.7%) patients had a stent placed (56 balloon-expandable and two self-expanding) and three patients had angioplasty alone (no distal protection devices were used). Mean stenosis in the treated VA of stented patients was 78.7 [standard deviation (SD) 1.6%] pre stent and 9.6 (SD 1.8%) post stent.

Follow-up and characteristics of the two groups during follow-up

The median follow-up was 3.5 (interquartile range 2.1–4.7) years. Medical treatment and risk factors were recorded at each follow-up visit and were similar between groups, except for slightly higher dual antiplatelet use in the stent group in the first year, particularly at month 1 (57% vs. 33%) (Table 3).

| Medical treatment, blood pressure and smoking status | Time point | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | 1 month | 6 months | 1 year | 2 years | ||||||

| Medical group (N = 88a) | Stent group (N = 91a) | Medical group (N = 82a) | Stent group (N = 88a) | Medical group (N = 83a) | Stent group (N = 85a) | Medical group (N = 79a) | Stent group (N = 84a) | Medical group (N = 62a) | Stent group (N = 70a) | |

| Aspirin, n (%) | 51 (58) | 60 (66) | 42 (51) | 60 (68) | 27 (33) | 43 (51) | 24 (30) | 45 (54) | 17 (27) | 21 (30) |

| Clopidogrel, n (%) | 62 (70) | 63 (69) | 62 (76) | 75 (85) | 59 (71) | 69 (81) | 55 (70) | 62 (74) | 45 (73) | 49 (70) |

| Dual antiplatelet therapy, n (%)b | 30 (34) | 38 (42) | 27 (33) | 50 (57) | 14 (17) | 32 (38) | 12 (15) | 29 (35) | 9 (15) | 10 (14) |

| Dipyridamole, n (%) | 10 (11) | 9 (10) | 7 (9) | 4 (5) | 5 (6) | 6 (7) | 4 (5) | 5 (6) | 2 (3) | 4 (6) |

| Oral anticoagulants, n (%) | 4 (4.6) | 3 (3.3) | 8 (10) | 4 (5) | 11 (13) | 5 (6) | 12 (15) | 6 (7) | 9 (15) | 13 (19) |

| Statin therapy, n (%) | 82 (93) | 84 (92) | 80 (98) | 83 (94) | 79 (95) | 82 (96) | 74 (94) | 78 (93) | 56 (90) | 63 (90) |

| Antihypertensive medication, n (%) | 65 (74) | 70 (77) | 66 (80) | 69 (78) | 64 (77) | 69 (82) | 60 (76) | 71 (85) | 49 (79) | 59 (84) |

| SBP (mmHg), mean (SD) | 139.3 (2.3) | 138.4 (2.0) | 138.4 (2.0)c | 140.0 (2.2)d | NA | NA | 139.1 (2.3)e | 141.8 (2.6)f | NA | NA |

| DBP (mmHg), mean (SD) | 79.5 (1.3) | 77.0 (1.3) | 77.4 (1.2)c | 77.7 (1.2)d | NA | NA | 78.3 (1.4)e | 79.1 (1.3)f | NA | NA |

| Diabetes mellitus therapy, n (%) | 19 (22) | 20 (22) | 20 (24) | 21 (24)g | NA | NA | 19 (24)h | 19 (23)i | NA | NA |

| Current smoker, n (%) | 25 (29) | 18 (20) | 20 (24) | 11 (12)g | NA | NA | 16 (20) | 13 (16)i | NA | NA |

Outcome events during stenting

There were two major complications during the stenting procedure, both in patients with intracranial stenosis. One died from subarachnoid haemorrhage during stenting due to vessel rupture. A second had a non-fatal periprocedural brainstem stroke. Among patients with extracranial stenosis, one stented patient had a non-fatal stroke within 30 days of intervention.

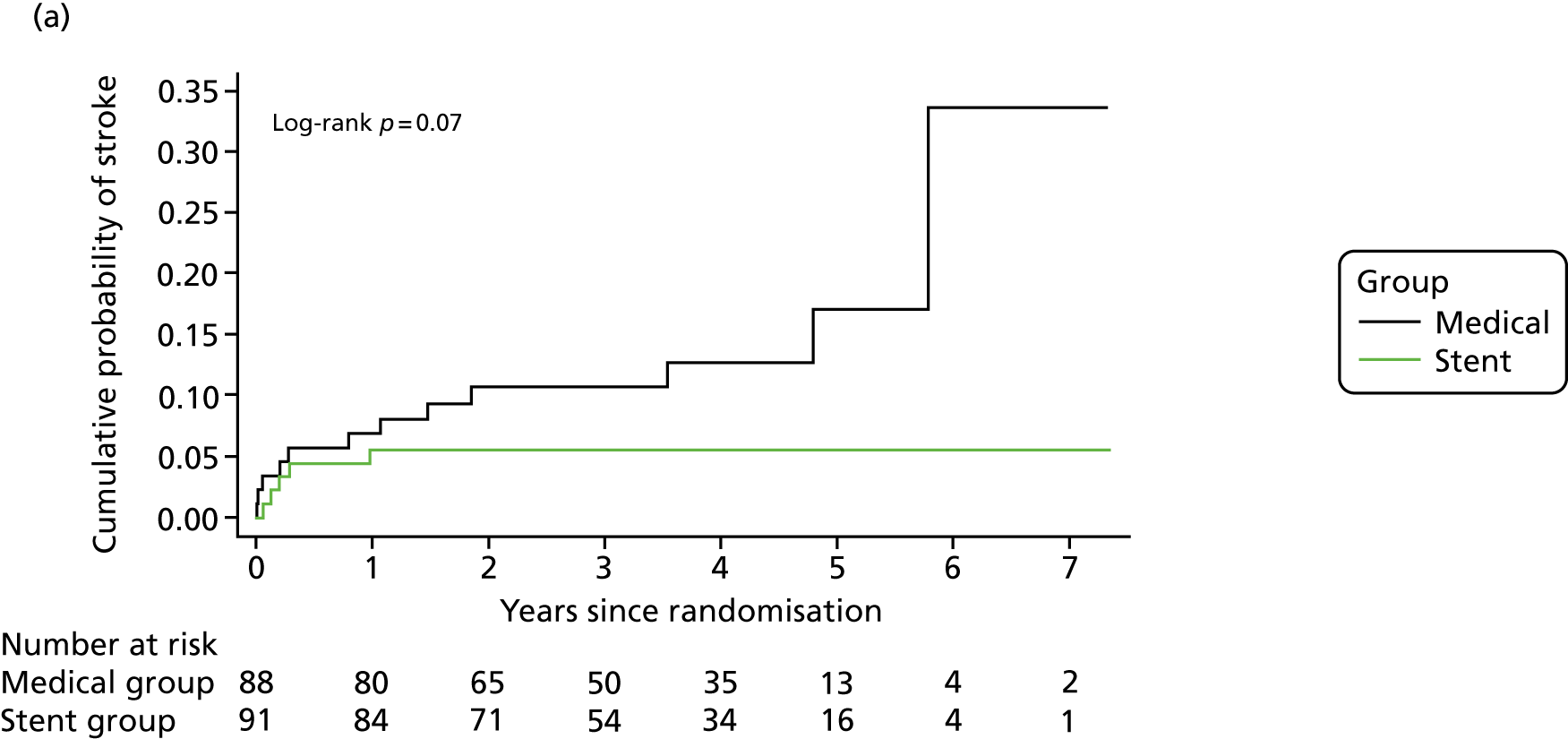

Primary outcome

The primary end point was fatal or non-fatal stroke, which occurred in five patients (including one fatal stroke) in the stent group and in 12 patients (including two fatal strokes) in the medical group (HR 0.40, 95% CI 0.14 to 1.13; p = 0.08) (Table 4 and Figure 2). For the primary end point there were 41 strokes per 1000 person-years in the medical group compared with 16 strokes per 1000 person-years in the stent group. Therefore, the absolute risk benefit was 25 strokes per 1000 person-years.

| End point | Analysis | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intention-to-treat | Per-protocol | |||||||

| Group, n events/person-year | HR (95% CI)b | p-value | Group, n events/person-year | HR (95% CI)b | p-value | |||

| Medical (N = 88) | Stent (N = 91) | Medical (N = 88) | Stent (N = 61) | |||||

| Primary | ||||||||

| Fatal or non-fatal stroke in any arterial territory | 12/291 | 5/308 | 0.40 (0.14 to 1.13) | 0.08 | 12/291 | 4/208 | 0.47 (0.15 to 1.46) | 0.19 |

| Extracranial VA target stenosisc | 8/246 | 3/258 | 0.37 (0.10 to 1.38) | 0.14 | 8/245 | 2/173 | 0.37 (0.08 to 1.73) | 0.21 |

| Intracranial VA target stenosisd | 4/45 | 2/50 | 0.47 (0.08 to 2.60) | 0.39 | 4/45 | 2/35 | 0.60 (0.11 to 3.33) | 0.56 |

| Secondary | ||||||||

| Posterior circulation stroke | 8/291 | 4/308 | 0.47 (0.14 to 1.58) | 0.39 | 8/291 | 3/208 | 0.53 (0.14 to 1.99) | 0.35 |

| Posterior circulation stroke or TIA | 19/255 | 11/291 | 0.53 (0.25 to 1.11) | 0.09 | 19/255 | 8/192 | 0.59 (0.26 to 1.35) | 0.22 |

| Periprocedural stroke or death (within 30 days of procedure) | 3/7.0 | 3/7.2 | 0.98 (0.20 to 4.84) | 0.98 | 3/7.0 | 3/4.7 | 1.47 (0.30 to 7.30) | 0.64 |

| Fatal or non-fatal stroke within 90 days | 4/21 | 3/22 | 0.71 (0.16 to 3.18) | 0.66 | 4/21 | 3/15 | 1.07 (0.24 to 4.76) | 0.93 |

| Death from any cause during follow-up | 9/316 | 8/323 | 0.86 (0.33 to 2.22) | 0.76 | 9/316 | 7/218 | 1.12 (0.41 to 3.01) | 0.82 |

| Exploratory | ||||||||

| Fatal or non-fatal stroke or TIA | 22/255 | 12/291 | 0.50 (0.25 to 1.01) | 0.05 | 22/255 | 9/192 | 0.57 (0.26 to 1.24) | 0.16 |

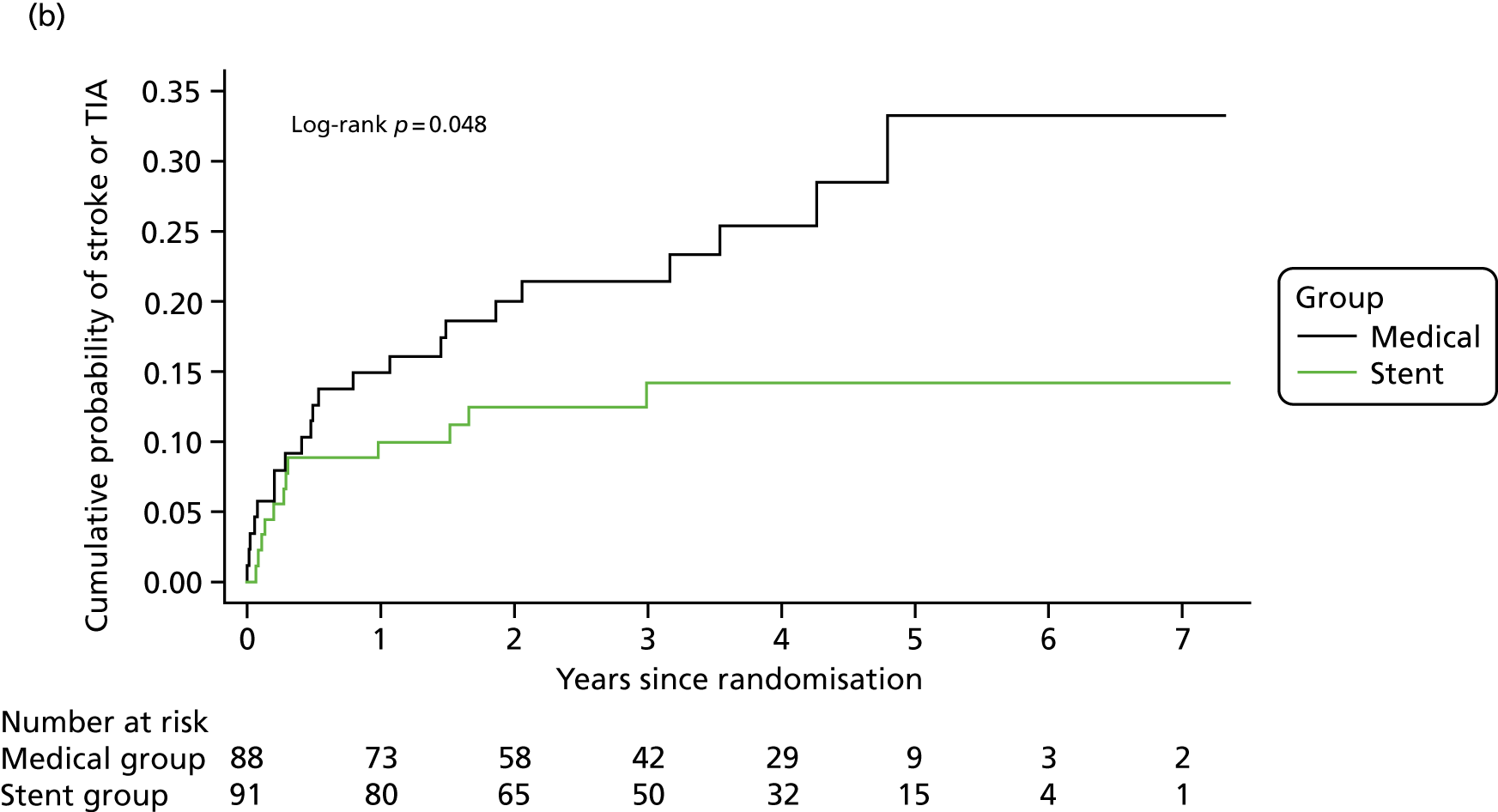

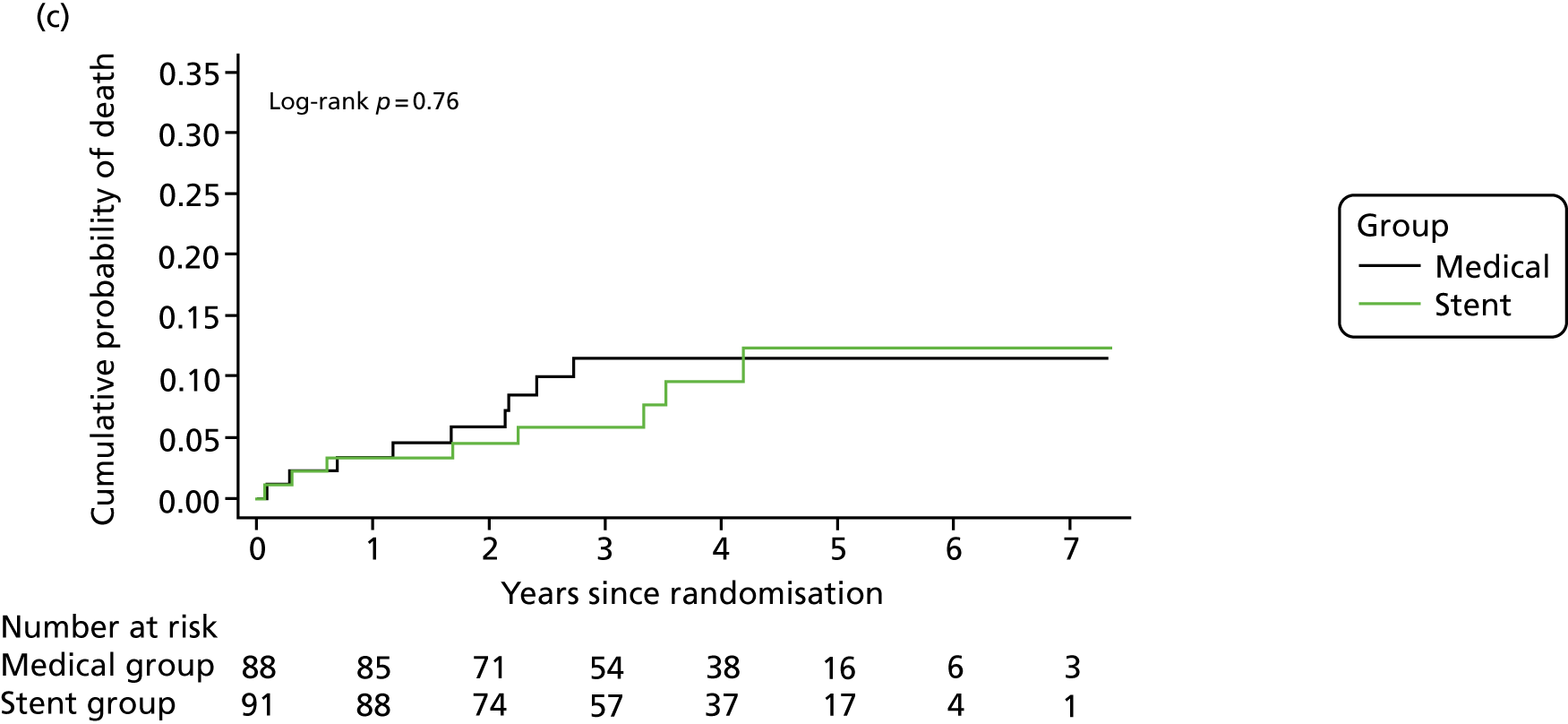

FIGURE 2.

Kaplan–Meier curves for the cumulative probability of (a) fatal or non-fatal stroke in any arterial territory (primary end point), (b) fatal or non-fatal stroke in any arterial territory or TIA and (c) death from any cause during follow-up, according to treatment group (intention-to-treat population). A log-rank test was used to test the hypothesis that stroke incidence, stroke or TIA incidence, or mortality rate between groups was the same.

Key secondary outcomes

The HR in patients with extracranial and intracranial VA stenosis was 0.37 (95% CI 0.10 to 1.36) and 0.47 (95% CI 0.08 to 2.60), respectively (see Table 4). Other secondary end points, fatal or non-fatal stroke within 90 days and death from any cause (see Figure 2), did not differ between the groups (see Table 4). The per-protocol analyses yielded similar results (see Table 4).

We were unable to accurately classify stroke severity at 3 months to allow division of stroke into disabling and non-disabling according to the predefined modified Rankin Scale score. This is because a number of strokes were picked up some months after they occurred. For this reason we have not included the secondary end point of disabling stroke.

Exploratory (post hoc) analyses

The HR of the composite secondary end point of fatal or non-fatal stroke or TIA was 0.50 (95% CI 0.25 to 1.01; p = 0.05) (see Table 4 and Figure 2).

Owing to the imbalance in time between last symptoms and randomisation between the two groups, as described in Figure 2, an exploratory post hoc analysis was carried out, adjusting for days from last symptoms (i.e. from last vertebrobasilar TIA or stroke) to randomisation. The HR of the primary end point was 0.34 (95% CI 0.12 to 0.98; p = 0.046). In addition, a second post hoc analysis limited to those patients randomised within 2 weeks after the last symptom was carried out; the HR of the primary end point was 0.30 (95% CI 0.09 to 0.99; p = 0.048; medical group, 8/30; stent group, 4/47).

Adverse events

Adverse events are listed in Table 5. There was no difference between the two treatment groups.

| Adverse event type | Group, n (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Medical (N = 88) | Stent (N = 91) | |

| Adverse events, any | 29 (33.0) | 34 (37.4) |

| Cardiovascular events, any | 6 (6.9) | 7 (7.7) |

| Angina | 1 (1.1) | 2 (2.2) |

| Atrial fibrillation | 2 (2.3) | 1 (1.1) |

| Brachial artery dissecting aneurysm | 0 (0) | 1 (1.1) |

| Cardiac failure | 1 (1.1) | 2 (2.2) |

| Coronary artery bypass graft | 1 (1.1) | 0 (0) |

| Myocardial infarction | 0 (0) | 1 (1.1) |

| Ventricular tachycardia | 1 (1.1) | 0 (0) |

| Other events, any | 23 (26.1) | 27 (29.7) |

| Abdominal pain | 1 (1.1) | 1 (1.1) |

| Acoustic neuroma | 0 (0) | 1 (1.1) |

| Acute kidney injury | 1 (1.1) | 0 (0) |

| Bone fracture | 0 (0) | 2 (2.2) |

| Cancer | 0 (0) | 1 (1.1) |

| Cervical spondylosis | 1 (1.1) | 0 (0) |

| Chest infection | 5 (5.7) | 4 (4.4) |

| Chest pain non-ischaemic | 1 (1.1) | 2 (2.2) |

| Collapse, unknown cause | 0 (0) | 2 (2.2) |

| Confusion, unknown cause | 1 (1.1) | 0 (0) |

| Dizziness | 1 (1.1) | 0 (0) |

| Dizziness and vomiting | 0 (0) | 2 (2.2) |

| Diarrhoea and vomiting | 0 (0) | 1 (1.1) |

| Epididymitis | 0 (0) | 1 (1.1) |

| Fall | 1 (1.1) | 2 (2.2) |

| Gastrointestinal bleeding | 1 (1.1) | 1 (1.1) |

| Grip haematoma | 0 (0) | 1 (1.1) |

| Hemicolectomy | 1 (1.1) | 0 (0) |

| Multiple sclerosis | 1 (1.1) | 0 (0) |

| Numbness | 1 (1.1) | 0 (0) |

| Pancreatitis | 2 (2.3) | 0 (0) |

| Pain during stenting | 0 (0) | 1 (1.1) |

| Presyncope, unknown cause | 1 (1.1) | 0 (0) |

| Psychosis | 1 (1.1) | 0 (0) |

| Road traffic accident | 0 (0) | 1 (1.1) |

| Sciatica | 1 (1.1) | 0 (0) |

| Seizure | 1 (1.1) | 1 (1.1) |

| Unconsciousness following stenting | 0 (0) | 1 (1.1) |

| Urinary retention | 0 (0) | 2 (2.2) |

| Urinary tract infection | 1 (1.1) | 0 (0) |

Follow-up angiographic imaging

Follow-up angiographic imaging with CTA or MRA was carried out in 47 of the 61 the patients undergoing stenting. This showed three stent occlusions: two in V1 and one in V2. Because the stent obscured the lumen on CTA and MRA, it was not possible to accurately measure the degree of stenosis on the follow-up imaging and, therefore, only report on whether or not the artery was occluded, which we were able to reliably determine.

Meta-analysis of VIST results with those of other published randomised controlled trials

The systematic review identified four other trials: CAVATAS,9 the SAMMPRIS trial,10,11 VAST12 and the Vitesse Intracranial Stent Study for Ischemic Stroke Therapy (VISSIT). 16 CAVATAS9 randomised 16 patients with vertebral stenosis: eight to angioplasty and eight to medical therapy alone. There were no outcome events during follow-up and, therefore, this study did not contribute data to the meta-analysis. The SAMMPRIS trial10,11 randomised patients with a stenosis in a variety of intracranial vessels, but only data for vertebral stenosis were included in the meta-analysis. VAST12 recruited only patients with vertebral stenosis and therefore all of its data were included in the meta-analysis. VISSIT,16 like the SAMMPRIS trial,10,11 randomised patients with a stenosis in a variety of intracranial arteries. We were unable to separate data for vertebral stenosis and the corresponding author did not respond to a request for additional data. Therefore, VISSIT16 could not be included in the meta-analysis.

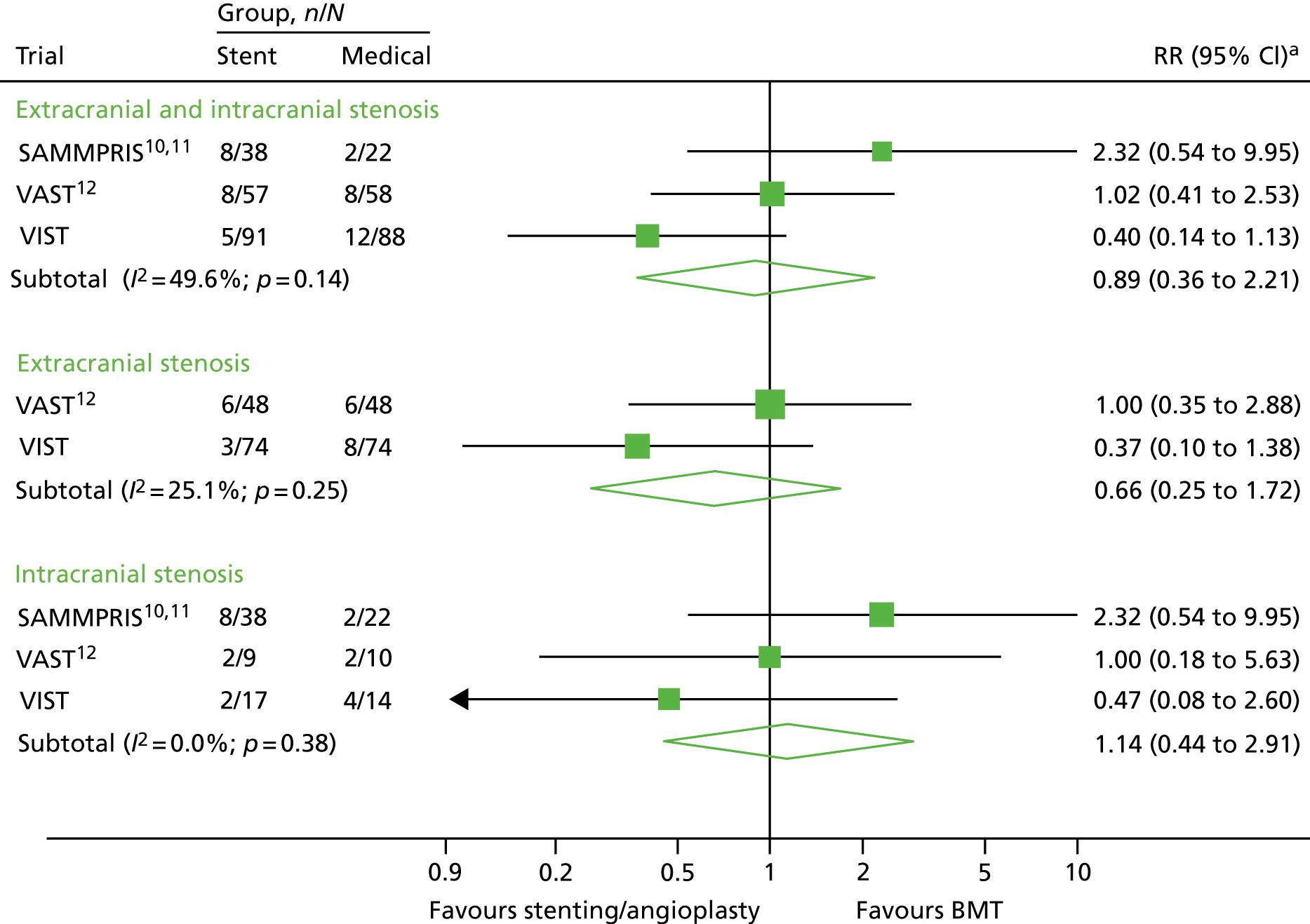

The results of the meta-analysis are shown in Figure 3. For any vertebral stenosis there was no benefit of stenting, with a relative risk (RR) of 0.89 (95% CI 0.36 to 2.21). There was no evidence of any benefit when analysis was limited to intracranial stenosis (RR 1.14, 95% CI 0.44 to 2.91). Likewise, there was no significant benefit when analysis was limited to extracranial stenosis, although there was a possible trend towards benefit (RR 0.66, 95% CI 0.25 to 1.72).

FIGURE 3.

Relative risk of stroke among patients randomised to stenting/angioplasty vs. BMT alone in randomised trials of VA stenosis. Note that the results of CAVATAS9 are not included because there were no end points in either group of the trial. Squares represent trial-specific RRs (the size of the square reflects the trial-specific statistical weight); horizontal lines represent 95% CIs; and diamonds represent the combined RR with its 95% CI from a random-effects meta-analysis. a, The RR estimates are odds ratios in the SAMMPRIS trial10,11 and in VAST,12 and HRs in VIST.

Chapter 4 Discussion

VIST is the largest RCT comparing stenting with medical treatment alone in patients with symptomatic VA stenosis. Stenting, particularly for extracranial stenosis, appeared safe. There was no significant difference in risk of stroke between the treatment groups. Over a median follow-up of 3.5 years, the stent group showed a non-statistically significant 60% lower risk of the primary end point of fatal or non-fatal stroke than the medical group. Despite randomisation, there was a shorter time between last symptoms and randomisation in the stent group. As the risk of recurrent stroke is strongly related to time since last symptoms,4 Cox regression, controlling for time from last symptoms to randomisation, was carried out and showed a significant benefit for stenting. However, caution should be taken in interpretation of these post hoc analyses.

Natural history data have shown that the risk of recurrent stroke following TIA or minor stroke due to vertebral stenosis is much greater in the first days and few weeks following the event. 4 This is a similar pattern to that seen in symptomatic carotid stenosis. 2 Therefore, any intervention is likely to have greater potential benefit if administered early. Consistent with this, an analysis of patients randomised within 2 weeks of last symptoms, chosen because this covers the initial very high-risk period,3 showed a significant treatment benefit.

We performed a systematic review of the literature and found four previous RCTs that included patients with vertebral stenosis and compared stenting and/or angioplasty with medical therapy. CAVATAS9 randomised 16 patients with extracranial VA stenosis between angioplasty (not including stenting) and medical therapy. 9 However, patients were randomised a long time after their last symptoms, with a mean interval between symptom onset and randomisation of 92 days and between randomisation and endovascular treatment of 45 days. There were no stroke end points in either group. The SAMMPRIS trial10,11 randomised patients with a variety of intracranial stenosis between stenting and BMT. There was a high early risk of stroke in the stented group, contributing to a worse outcome in this group. 10 Sixty (13%) patients had intracranial VA stenosis, and in this group the outcome was similar to the outcome among those with intracranial stenosis in other arteries, the 2-year primary event rate being 9.5% in the medical group and 21.1% in the stent group. 11 VISSIT16 randomised 112 patients with symptomatic intracranial stenosis in a variety of intracerebral arteries to stenting or BMT and reported risk similar to that in the SAMMPRIS trial. 10,11 However, the number of patients with VA stenosis is not documented and we were unable to obtain this information from the corresponding author. 16 VAST12 randomised 115 patients, of whom 83% had extracranial stenoses. 12 There was a trend towards a higher risk of early outcomes (at 30 days) in the stented group. However, the risk of any stroke after a median follow-up of 3 years was 14% in both groups. The rate of complications in the stented group was lower in VIST than in VAST,12 and the mean duration of follow-up was longer in VIST than in VAST. 12 We performed a meta-analysis of the results of the SAMMPRIS trial,10,11 VAST12 and VIST, and found no significant benefit of stenting in the group as a whole.

Previous non-randomised case series have shown that the risk of stenting is low with extracranial VA stenosis (1% vs. 7–10% for intracranial stenosis). 5–7 Prospective natural history studies have also shown that the risk of early recurrent stroke is higher for intracranial stenosis. 4 Therefore, it is possible that any treatment benefit of stenting will vary for extra- and intracranial vertebral stenosis. For this reason, randomisation was stratified according to location of stenosis in VIST.

The majority of patients in VIST had extracranial stenosis. In this group, stenting was performed with a very low perioperative risk; there were no perioperative strokes. There was no significant benefit for stenting over medical therapy alone; however, there did appear to be a trend in favour of stenting. In the meta-analysis we performed an analysis of published trials of stenting for extracranial stenosis and found that there was no significant benefit, although there was a possible trend in favour of stenting. The CIs were wide, emphasising the need for more data.

Because the vast majority of patients in VIST had extracranial stenosis, drawing firm conclusions on the benefit for those with intracranial stenosis is difficult, although the risk of perioperative stroke in VIST appeared to be higher for intracranial stenosis. The results are in line with those from the SAMMPRIS trial,10,11 which exclusively recruited patients with intracranial stenosis and found a higher risk in stented-treated patients than in medically treated patients. The meta-analysis showed no significant difference, but there was a possible trend in favour of medical therapy for intracranial stenosis. Again, the CIs were wide, emphasising the need for more data.

VIST has a number of strengths, including the randomised design; the fact that all patients were followed up, with none lost to follow-up; and the fact that it is the largest study of stenting for VA stenosis to our knowledge.

However, VIST also has a number of limitations. A major limitation is that recruitment was stopped due to funding issues before the planned sample size was recruited. An additional limitation is the high proportion of patients in the stent group who were found not to have stenosis (> 50% on DSA at the time of stenting). Owing to the small size of the vertebral arteries compared with the carotid arteries, non-invasive imaging with CTA or MRA in the former is not as accurate. 1 However, studies comparing these two non-invasive modalities with intra-arterial DSA have shown high sensitivity and specificity. 17 A central review of non-invasive entry imaging failed to confirm a stenosis in approximately half of the cases in which stenosis was not confirmed. In other cases, entry imaging was judged to be of insufficient quality to confirm stenosis. This emphasises the need for very careful quality control of both the technical quality and the interpretation of non-invasive imaging in any future VA stenting study. A further consideration is the intensity of medical treatment in the two groups. There was no difference in the use of statins or antihypertensive agents between the groups either early or during long-term follow-up. There was a slightly increased use of antiplatelet agents at the 1-month follow-up in the stented group; however, the difference was small, reflecting the advice given that both groups should be prescribed intensive medical therapy.

Recruitment to VIST was slower than expected. During the initial feasibility phase of the trial, funded by the Stroke Association, we met the recruitment target of 100 patients in the planned recruitment period. However, to reach the target for a definitive trial, it was clear that we needed to extend the study to additional centres. To achieve this, in view of the limited number of neurointerventional sites in the UK, the plan in the grant was to extend the trial to overseas centres, as described in the Health Technology Assessment grant awarded for funding, to allow the main phase of the study to be performed. A number of centres in Europe, Asia and Australia were keen to join, but set-up of these sites took longer than anticipated owing to regulatory, insurance and contract issues, and sites were not opened (with the exception of one site in Hong Kong, which was opened shortly before trial closure and did not recruit any patients). Although the investigators and the patient and public involvement representative were keen to continue the trial, the funder withdrew funding before the overseas sites could be opened, and at this stage a decision was made to terminate recruitment and to continue follow-up for a minimum of 1 year. Major issues delaying the set-up of overseas sites included the following.

-

The cost of the stenting procedure itself was not reimbursed as part of the grant. This prevented some countries taking part, although others were prepared to take part despite this.

-

The chief investigator, and therefore the sponsor of the trial, moved to another institution during the trial. The second sponsor required insurance to be in place not only for the trial protocol but also to cover any medical negligence claims arising from the stenting procedure itself. This was a considerable cost and one not covered in the grant. It took the chief investigator some time to obtain funding for this, although it was eventually obtained to cover a number of overseas centres.

-

It took a long time for the relevant contracts offices to set up contracts between the co-ordinating centre and overseas centres.

The trial illustrated the challenges of conducting such research studies across countries, and highlighted that the time scales required to overcome these challenges are sometimes longer than allowed in fixed-term grant funding. We also found that, in the UK, recruitment rates widely between centres. One factor that influenced this was that not all patients with posterior circulation stroke received CTA or MRA as part of their routine care. This would be likely to change if further data show that stenting is associated with improved outcome.

It is important to note that a number of seminal trials of surgical interventions for cerebral artery stenosis, which have transformed stroke prevention, have taken longer than planned to recruit, and have required extension of original funding. This includes the ECST18 and the NASCET13 in symptomatic carotid stenosis, which the Asymptomatic Carotid Surgery Trial19 in asymptomatic carotid stenosis. For example, the ECST18 demonstrated that carotid endarterectomy reduced stroke risk for recently symptomatic carotid stenosis, which has transformed clinical practice. However, recruitment took much longer than anticipated, taking 13 years (from 1981 to 1994), and had to be extended well beyond the period estimated in the initial grant application. 18 This emphasises that funders should be very cautious about terminating recruitment to such trials mid-way, as without extension these trials would not have had a major transforming effect on health care.

Patient and public involvement input played a major role in identifying that better management of vertebral stenosis is an area of research that is important to people who have had stroke and their families. The trial design was reviewed by the St George’s Patient and Carer Stroke Group, its input helped to ensure that the design was feasible and that the patient materials were easily understandable. In particular, there was significant input from one member (Mr John Dennis), who had experience of vertebral stenting and played a key role throughout the trial. He commented on study design and patient materials, assisted with preparation of the grant application, on which he was a co-applicant, and was a member of the Trial Steering Committee.

Chapter 5 Conclusions

VIST has demonstrated that stenting of extracranial symptomatic vertebral stenosis can be carried out in a multicentre study with a low periprocedural risk and appears safe when compared with BMT alone. There was a non-significant reduction in recurrent stroke risk in the stent group compared with the medical group. Owing to early termination of recruitment, the projected sample size was not reached, and further, larger trials are now required to confirm this finding.

Although the number of patients randomised to intracranial stenosis was small, this procedure was associated with a higher perioperative risk, which is consistent with data from other trials. This suggests that, at least based on current data, medical treatment is the preferred first-line treatment for intracranial vertebral stenosis.

If stenting could be demonstrated to reduce the risk of recurrent stroke in symptomatic vertebral stenosis, this would have a major impact on clinical practice in future. Although the VIST results suggest that stenting of extracranial vertebral stenosis can be carried out with a low perioperative risk, and may be effective in reducing recurrent stroke risk in symptomatic VA stenosis, further trial data are required before routine clinical practice is likely to change. VIST confirms that, if possible, recruitment in RCTs should be continued until the full sample size is obtained.

The VIST results suggest that further trials of stenting for extracranial vertebral stenosis are warranted. If such trials are to be performed, a number of lessons could be learnt from VIST. First, any benefit is likely to be greater for extracranial than for intracranial stenosis. Second, careful attention needs to be given to ensuring that non-invasive imaging is accurate prior to randomisation; alternatively, patients could be randomised after the results of intra-arterial angiography.

Acknowledgements

VIST investigators

Steering and grantholders’ committee

John Bamford (independent chairperson), Gavin Young (independent member), Thompson Robinson (independent member), Peter Rothwell, Hugh Markus (principal investigator), Ian Ford, Andrew Clifton, Wilhelm Kuker, Caroline Murphy, John Dennis (patient and public involvement representative) and Ursula Schulz.

Writing committee

Hugh Markus, Susanna Larsson, Peter Rothwell and Andrew Clifton.

Adjudication committee

Kath Pascoe, Ajay Bhalla and Kirsty Harkness.

Data monitoring committee

Peter Sandercock (chairperson), Robin Sellar and Catriona Graham.

Co-orientating office

Study co-ordinators – Melina Wilson, Cara Hicks, Jennifer Lennon and Lindsay Davies; interim analysis – Loes Rutten-Jacobs; follow-up – Usman Khan, Hugh Markus and Robert Hurford.

Study neuroradiologists

Andrew Clifton (lead extracranial stenting) and Wilhelm Kuker (lead intracranial stenting).

Statistical design and analysis

Susanna Larsson and Ian Ford.

VIST centres (and numbers of patients recruited)

St George’s University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust (Barry Moynihan, Hugh Markus, Andrew Clifton and Jeremy Madigan), n = 77; Oxford University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust (Peter Rothwell, Ursula Schulz and Wilhelm Kuker), n = 38; University Hospitals of North Midlands NHS Trust (Christine Roffe and Sanjeev Nayak), n = 14; Sheffield Teaching Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust (Ralf-Bjoern Lindert and Peter Gaines), n = 11; The Walton Centre NHS Foundation Trust, Liverpool (Alakendu Sekhar and Hans Nahser), n = 8; King’s College Hospital NHS Foundation Trust (Bartlomiej Piechowski-Jozwiak and Timothy Hampton), n = 8; Newcastle upon Tyne Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust (Anand Dixit and Anil Gholkhar), n = 7; University College Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust (David Werring and Stefan Brew), n = 6; Imperial College Healthcare NHS Trust (Pankaj Sharma and Maneesh Patel), n = 4; Cambridge University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust (Hugh Markus and Nick Higgins), n = 2; Leeds Teaching Hospitals NHS Trust (Ahamad Hassan and Anthony Goddard), n = 2; North Bristol NHS Trust (Neil Baldwin and Marcus Bradley), n = 2; Nottingham University Hospital NHS Trust (Senthil Raghunathan and Robert Crossley), n =2; and Royal Preston Hospital (Hedley Emsley and Siddhartha Wuppalapati), n = 1.

Contributions of authors

Hugh S Markus (Professor of Stroke Medicine and Honorary Consultant Neurologist) contributed to the study design, obtaining funding, study organisation, patient recruitment, data interpretation and writing the first draft of the paper.

Susanna C Larsson (Postdoctoral Research Associate) contributed to developing the statistical analysis, data analysis and writing the first draft of the paper.

John Dennis (patient and public involvement representative Trial and Steering Committee member) contributed to study design, study materials, presentation of results and revising the manuscript.

Wilhelm Kuker (Consultant Neuroradiologist) contributed to obtaining funding, study design and neuroradiological oversight.

Ursula G Schulz (Consultant Neurologist) contributed to obtaining funding, patient recruitment and follow-up, and revising the manuscript.

Ian Ford (Professor of Statistics) contributed to study design, advised on the statistical analysis and critically reviewed the paper.

Andrew Clifton (Consultant Neuroradiologist) contributed to study design, obtaining funding, neuroradiological analysis and oversight, and revising the manuscript.

Peter M Rothwell (Professor of Neurology) contributed to study design, obtaining funding, patient recruitment and revising the manuscript.

Publications

Markus HS, van der Worp HB, Rothwell PM. Posterior circulation ischaemic stroke and transient ischaemic attack: diagnosis, investigation, and secondary prevention. Lancet Neurol 2013;12:989–98.

Rothwell P, Markus HS. Improved medical treatment in secondary prevention of stroke. Lancet 2014;383:290–1.

Markus HS, Larsson SC, Kuker W, Schultz U, Ford I, Rothwell PM, Clifton A; VIST Investigators. Stenting for symptomatic vertebral artery stenosis: the Vertebral Artery Ischaemia Stenting Trial. Neurology 2017;89:1229–36.

Data-sharing statement

All data requests should be submitted to the corresponding author for consideration. Access to available anonymised data may be granted following review.

Patient data

This work uses data provided by patients and collected by the NHS as part of their care and support. Using patient data is vital to improve health and care for everyone. There is huge potential to make better use of information from people’s patient records, to understand more about disease, develop new treatments, monitor safety, and plan NHS services. Patient data should be kept safe and secure, to protect everyone’s privacy, and it’s important that there are safeguards to make sure that it is stored and used responsibly. Everyone should be able to find out about how patient data are used. #datasaveslives You can find out more about the background to this citation here: https://understandingpatientdata.org.uk/data-citation.

Disclaimers

This report presents independent research funded by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR). The views and opinions expressed by authors in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the NHS, the NIHR, NETSCC, the HTA programme or the Department of Health and Social Care. If there are verbatim quotations included in this publication the views and opinions expressed by the interviewees are those of the interviewees and do not necessarily reflect those of the authors, those of the NHS, the NIHR, NETSCC, the HTA programme or the Department of Health and Social Care.

References

- Markus HS, van der Worp HB, Rothwell PM. Posterior circulation ischaemic stroke and transient ischaemic attack: diagnosis, investigation, and secondary prevention. Lancet Neurol 2013;12:989-98. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1474-4422(13)70211-4.

- Rothwell PM, Eliasziw M, Gutnikov SA, Fox AJ, Taylor DW, Mayberg MR, et al. Analysis of pooled data from the randomised controlled trials of endarterectomy for symptomatic carotid stenosis. Lancet 2003;361:107-16. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(03)12228-3.

- Bonati LH, Lyrer P, Ederle J, Featherstone R, Brown MM. Percutaneous transluminal balloon angioplasty and stenting for carotid artery stenosis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2012;9. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD000515.pub4.

- Gulli G, Marquardt L, Rothwell PM, Markus HS. Stroke risk after posterior circulation stroke/transient ischemic attack and its relationship to site of vertebrobasilar stenosis: pooled data analysis from prospective studies. Stroke 2013;44:598-604. https://doi.org/10.1161/STROKEAHA.112.669929.

- Stayman AN, Nogueira RG, Gupta R. A systematic review of stenting and angioplasty of symptomatic extracranial vertebral artery stenosis. Stroke 2011;42:2212-16. https://doi.org/10.1161/STROKEAHA.110.611459.

- Antoniou GA, Murray D, Georgiadis GS, Antoniou SA, Schiro A, Serracino-Inglott F, et al. Percutaneous transluminal angioplasty and stenting in patients with proximal vertebral artery stenosis. J Vasc Surg 2012;55:1167-77. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvs.2011.09.084.

- Eberhardt O, Naegele T, Raygrotzki S, Weller M, Ernemann U. Stenting of vertebrobasilar arteries in symptomatic atherosclerotic disease and acute occlusion: case series and review of the literature. J Vasc Surg 2006;43:1145-54. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvs.2006.02.027.

- SSYLVIA Study Investigators . Stenting of Symptomatic Atherosclerotic Lesions in the Vertebral or Intracranial Arteries (SSYLVIA): study results. Stroke 2004;35:1388-92. https://doi.org/10.1161/01.STR.0000128708.86762.d6.

- Coward LJ, McCabe DJ, Ederle J, Featherstone RL, Clifton A, Brown MM, et al. Long-term outcome after angioplasty and stenting for symptomatic vertebral artery stenosis compared with medical treatment in the Carotid And Vertebral Artery Transluminal Angioplasty Study (CAVATAS): a randomized trial. Stroke 2007;38:1526-30. https://doi.org/10.1161/STROKEAHA.106.471862.

- Chimowitz MI, Lynn MJ, Derdeyn CP, Turan TN, Fiorella D, Lane BF, et al. Stenting versus aggressive medical therapy for intracranial arterial stenosis. N Engl J Med 2011;365:993-1003. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1105335.

- Lutsep HL, Lynn MJ, Cotsonis GA, Derdeyn CP, Turan TN, Fiorella D, et al. Does the Stenting Versus Aggressive Medical Therapy Trial support stenting for subgroups with intracranial stenosis?. Stroke 2015;46:3282-4. https://doi.org/10.1161/STROKEAHA.115.009846.

- Compter A, van der Worp HB, Schonewille WJ, Vos JA, Boiten J, Nederkoorn PJ, et al. Stenting versus medical treatment in patients with symptomatic vertebral artery stenosis: a randomised open-label phase 2 trial. Lancet Neurol 2015;14:606-14. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1474-4422(15)00017-4.

- Barnett HJM, Taylor DW, Haynes RB, Sackett DL, Peerless SJ, Ferguson GG, et al. Beneficial effect of carotid endarterectomy in symptomatic patients with high-grade carotid stenosis. N Engl J Med 1991;325:445-53. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJM199108153250701.

- Samuels OB, Joseph GJ, Lynn MJ, Smith HA, Chimowitz MI. A standardized method for measuring intracranial arterial stenosis. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2000;21:643-6.

- Rothwell PM, Eliasziw M, Gutnikov SA, Warlow CP, Barnett HJ. Carotid Endarterectomy Trialists Collaboration . Endarterectomy for symptomatic carotid stenosis in relation to clinical subgroups and timing of surgery. Lancet 2004;363:915-24. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(04)15785-1.

- Zaidat OO, Fitzsimmons BF, Woodward BK, Wang Z, Killer-Oberpfalzer M, Wakhloo A, et al. Effect of a balloon-expandable intracranial stent vs medical therapy on risk of stroke in patients with symptomatic intracranial stenosis: the VISSIT randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2015;313:1240-8. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2015.1693.

- Khan S, Rich P, Clifton A, Markus HS. Noninvasive detection of vertebral artery stenosis: a comparison of contrast-enhanced MR angiography, CT angiography, and ultrasound. Stroke 2009;40:3499-503. https://doi.org/10.1161/STROKEAHA.109.556035.

- European Carotid Surgery Trialists’ Collaborative Group . Randomised trial of endarterectomy for recently symptomatic carotid stenosis: final results of the MRC European Carotid Surgery Trial (ECST). Lancet 1998;351:1379-87. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(97)09292-1.

- Halliday A, Mansfield A, Marro J, Peto C, Peto R, Potter J, et al. Prevention of disabling and fatal strokes by successful carotid endarterectomy in patients without recent neurological symptoms: randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2004;363:1491-502. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16146-1.

Appendix 1 Rate of recruitment by UK site

| Site | Number of | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Recruited patients | Years of recruitment | Patients recruited per year | |

| St George’s University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust | 77 | 7.35 | 10.48 |

| Oxford University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust | 38 | 5.71 | 6.65 |

| University Hospitals of North Midlands NHS Trust | 14 | 4.87 | 2.87 |

| Sheffield Teaching Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust | 11 | 4.94 | 2.23 |

| The Walton Centre NHS Foundation Trust | 8 | 6.74 | 1.19 |

| King’s College Hospital NHS Foundation Trust | 8a | 3.33 | 2.40 |

| Newcastle upon Tyne Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust | 7 | 5.19 | 1.35 |

| University College Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust | 6b | 4.44 | 1.35 |

| Imperial College Healthcare NHS Trust | 4 | 3.46 | 1.16 |

| Cambridge University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust | 2 | 1.52 | 1.32 |

| North Bristol NHS Trust | 2 | 3.29 | 0.61 |

| Leeds Teaching Hospitals NHS Trust | 2 | 3.85 | 0.52 |

| Nottingham University Hospitals NHS Trust | 2 | 1.38 | 1.45 |

| Royal Preston Hospital | 1 | 2.95 | 0.34 |

List of abbreviations

- BMT

- best medical treatment

- CAVATAS

- Carotid And Vertebral Artery Transluminal Angioplasty Study

- CI

- confidence interval

- CTA

- computed tomography angiography

- DSA

- digital subtraction angiography

- ECST

- European Carotid Surgery Trial

- HR

- hazard ratio

- MRA

- magnetic resonance angiography

- NASCET

- North American Symptomatic Carotid Endarterectomy Trial

- RCT

- randomised controlled trial

- RR

- relative risk

- SAMMPRIS

- Stenting and Aggressive Medical Management for Preventing Recurrent Stroke in Intracranial Stenosis

- SD

- standard deviation

- TIA

- transient ischaemic attack

- VA

- vertebral artery

- VAST

- Vertebral Artery Stenting Trial

- VISSIT

- Vitesse Intracranial Stent Study for Ischemic Stroke Therapy

- VIST

- Vertebral artery Ischaemia Stenting Trial