Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 09/06/01. The contractual start date was in March 2011. The draft report began editorial review in March 2018 and was accepted for publication in November 2018. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Paul D Griffiths was a member of Health Technology Assessment Commissioning Board (2014–18) and Cindy L Cooper is a member of National Institute for Health Research Clinical Trials Unit Standing Advisory Committee (2015 to present).

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2019. This work was produced by Griffiths et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2019 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Introduction

Scientific and clinical background

Ultrasonography and fetal screening

For many years, fetal imaging with ultrasonography has been the mainstay of antenatal screening programmes in the UK. However, no imaging method is perfect and various technical factors and physical limitations of ultrasonography may result in suboptimal images of the fetus being obtained. Suboptimal images may lead to incorrect diagnoses of structural abnormalities and inaccurate counselling and prognostic information being given to parents. The fetal brain is a particular area of concern because of the relatively high frequency of developmental abnormalities (approximately 3/1000 pregnancies). 1 A wide spectrum of neuropathologies can be shown, many of which are associated with serious clinical morbidities.

Development of magnetic resonance imaging

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) technology has advanced over the years and because of significant improvements in spatial and contrast resolution, highly reliable and accurate diagnoses of comparable pathology can now be made for children. In the 1990s, MRI became a realistic clinical possibility because of advances in hardware and software. The Academic Unit of Radiology at the University of Sheffield was a pioneer in this field. 2 Clinical magnetic resonance sequences have been developed that do not require maternal sedation or fetal neuromuscular blockade, allowing several groups, including our own, to believe that in utero magnetic resonance imaging (iuMRI) may be a powerful adjunct to ultrasonography for detecting fetal brain abnormalities from 18 weeks’ gestational age.

Magnetic resonance imaging in the literature: diagnostic accuracy

Much of the early literature focused on describing the techniques required to perform iuMRI and relied on anecdotal cases to compare the additional information provided with ultrasonography alone. 3–8 A key limitation of the majority of the literature was the lack of an outcome reference diagnosis (ORD), with discrepancies between iuMRI and ultrasonography generally assumed as errors on the part of the latter. Doing so inevitably leads to bias in favour of iuMRI, and fetal ultrasonography experts have criticised these studies for the artificially high detection rates for iuMRI that resulted from biased patient selection,9,10 although the extent of this bias is unknown. One such study was published by our group;11 it was a study of 100 singleton pregnancies in which a fetal brain abnormality was suspected on ultrasonography but for which optimal diagnostic information had not been obtained. When iuMRI was used in conjunction with ultrasonography, an increase in diagnostic accuracy of 48% was observed. Although these findings are clearly prone to the aforementioned bias, they nevertheless demonstrate the potential for a significant improvement in diagnoses based on ultrasonography and provide an upper limit on the improvement attributable to the introduction of iuMRI.

Ventriculomegaly (VM) has been the focus of much research in the field of fetal neuroimaging with iuMRI because of the high prevalence of the finding (1 or 2 out of 1000 pregnancies) following a screening ultrasonography. In our more recent study, 147 fetuses were diagnosed with isolated VM on ultrasonography, with high confidence and no technical limitations. 12 When iuMRI was performed in these cases, additional clinically important brain findings were detected in 17% of cases. In a second study of 61 fetuses with cerebral VM, iuMRI was found to provide more information than ultrasonography in 33% of cases and was able to identify the cause of the VM in 21% of cases. 13 A further study of 185 fetuses with isolated VM in the third trimester found that 11 out of 185 (5.94%) fetuses had other brain abnormalities. 14 The use of iuMRI as an adjunct to ultrasonography for detecting fetal brain abnormalities has been further supported by recent studies and systematic reviews;15–18 however, the extent of diagnostic improvement remains unclear.

Magnetic resonance imaging in the literature: clinical management

The literature on the clinical impact of iuMRI on the counselling and management of pregnancies complicated by fetal brain abnormalities is limited. One prospective study of fetuses with a suspected central nervous system abnormality observed that 24 out of 52 (46%) pregnancies were managed differently after iuMRI,19 and a further prospective study found that the counselling and management of pregnancies were changed after iuMRI in 49.7% and 13.5% of cases, respectively. 20 Our study of fetuses with isolated VM found significant changes in clinical management after iuMRI in the majority of cases when additional brain abnormalities were identified. Changes in management more frequently happened between the gestational ages of 20 and 24 weeks. 12 Our group conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis18 including 34 studies, of which only 11 reported on the changes in counselling or management of pregnancies brought about by the iuMRI. These 11 studies11,21–30 comprised 186 fetuses and changes were observed in 78 (41.9%) cases. Our review concluded that the clinical impact of iuMRI through changes to the counselling and management of pregnancies remains unclear owing to being reported in only a small proportion of studies.

It is important to recognise that iuMRI is unlikely to be incorporated as a routinely used diagnostic tool for pregnancies. Constraints on resources, both financial and human, mean that iuMRI is likely to be used selectively, in combination with ultrasonography and other tests, for fetuses that are considered to be at a high risk of severe developmental abnormalities. The term ‘high risk’ can be interpreted in many different ways and may legitimately incorporate genetic features and/or a previous pregnancy with a fetal abnormality, but the most obvious risk factor is when the fetus has an abnormality diagnosed by the ultrasonography. Therefore, the project set out to determine whether or not adding iuMRI to the usual diagnostic pathway helps to improve the diagnosis and appropriate management of fetuses with a suspected brain abnormality based on previous ultrasonography.

Rationale for the MERIDIAN study

In the light of the uncertainties surrounding the extent of improvement in diagnostic accuracy associated with iuMRI as an adjunct to ultrasonography and its impact on clinical management and counselling, a large prospective study with a representative population of fetal brain abnormalities was required to inform clinical practice in the UK.

For a full evaluation of the use of iuMRI in clinical practice, it was essential that patient acceptability was assessed. New technologies in fetal medicine can raise ethical and social dilemmas for the patients involved and, therefore, the views of patients and their partners are important when considering the implementation of iuMRI. 31 A survey of 227 women who were not pregnant but underwent MRI suggests that it is perceived positively in terms of comfort and impact on care;32 however, other studies have shown a potential association between MRI and anxiety33,34 and that patients may find it less acceptable than ultrasonography. 35 A study published in 2007 found that overall satisfaction with the prenatal diagnosis (PND) is high in women carrying a fetus with a congenital abnormality. 36 Satisfaction with prenatal care has been found to be associated with the attitude of the medical staff,37,38 the amount of information provided38 and the patient’s involvement in decision-making. 37 Data on the use of MRI in fetomaternal medicine are limited but do suggest that MRI may cause additional distress, especially in women for whom the prognosis for the fetus is poor,39,40 and can lead to more anxiety than that of undergoing an ultrasonography. 41

The research described in this report was a logical extension of our previous work and essential in providing definitive data on the diagnostic accuracy, clinical impact and acceptability of iuMRI in clinical practice in the UK.

Study aims and objectives

The aim of the research was to assess iuMRI as a technology to aid the PND of fetal developmental brain abnormalities.

The objectives were to:

-

assess diagnostic accuracy of iuMRI compared with antenatal ultrasonography through the –

-

measurement of the diagnostic accuracy of antenatal ultrasonography alone (i.e. prior to iuMRI) relative to an ORD (postnatal imaging or postmortem examination)

-

measurement of the diagnostic accuracy of iuMRI (following antenatal ultrasonography) relative to an ORD (postnatal imaging or postmortem examination).

-

-

assess the clinical effectiveness of iuMRI through the –

-

change in clinical diagnostic confidence before and after an iuMRI study

-

effect of iuMRI on prenatal counselling and management intent.

-

-

assess the acceptability of the clinical care package with the use of MRI included via quantitative and qualitative psychosocial measures

-

undertake an economic analysis to evaluate the cost consequence of the use of iuMRI scans.

Chapter 2 Methods

This report is concordant with the Standards for the Reporting of Diagnostic Accuracy Studies (STARD) guidelines updated in 2015. 42

Study design

The MERIDIAN study was a prospective, multicentre, observational cohort study.

Participants and eligibility criteria

Participants were pregnant women aged ≥ 16 years and carrying a fetus with a suspected brain abnormality on detailed ultrasonography as diagnosed by a fetal medicine consultant. The potential participants were screened against the following criteria.

Inclusion criteria

A participant was eligible for the trial if the following criteria were met:

-

The participant had an ongoing singleton or multifetal pregnancy of ≥ 18+0 weeks’ gestation by ultrasonography dating.

-

The participant was thought to be carrying a fetus with a brain abnormality following detailed specialist ultrasonography examination.

Exclusion criteria

A participant was excluded from the trial if any of the following criteria were met:

-

The participant was unable to give informed consent.

-

The participant had a cardiac pacemaker, had an intraorbital metallic foreign body or recently had surgery with metallic sutures or an implant.

-

The participant had previously experienced or is likely to suffer from severe anxiety or claustrophobia in relation to a MRI examination.

-

The participant was unable or unwilling to travel to Belfast, Birmingham, Leeds, Newcastle, Nottingham or Sheffield for specialist MRI.

-

The participant was unable to understand the English language (except where satisfactory translation services were available).

-

The participant was aged < 16 years.

Participant identification and recruitment

Potentially eligible participants were identified from 16 participating fetal medicine units that acted as research sites. Following a detailed ultrasonography examination that confirmed the suspicion of a fetal brain abnormality, consecutive patients were screened by the referring clinician or local research midwife according to the inclusion and exclusion criteria listed above. Written informed consent was obtained after the confirmation of eligibility and after the patient had been given the opportunity to consider participation and ask any questions. Data collection and management provides details of the referral process once consent had been obtained.

Test methods

Detailed ultrasonography

The protocol did not specify the exact requirements for the ultrasound technique. All ultrasonographies were performed by fetal medicine consultants working within the UK NHS who reported the suspected fetal brain abnormalities using nomenclature from the ViewPoint™ antenatal ultrasonography-reporting software (GE Healthcare, Chalfont St Giles, UK). Recruiting clinicians were asked to record their certainty of the diagnosis alongside each brain abnormality using a five-point Likert scale43 as follows: very unsure (10% certain), unsure (30% certain), equivocal (50% certain), confident (70% certain) and highly confident (90% certain). Following the detailed ultrasonography, participants underwent iuMRI at one of the six collaborating sites.

In utero magnetic resonance imaging

Magnetic resonance imaging protocols could not be matched exactly across all the scanning sites because of the different manufacturers of MRI systems being used. However, all examinations were performed at 1.5 T and there was an absolute requirement to obtain T2-weighted images of the fetal brain in the three orthogonal planes using the best, ultrafast method available (maximum slice thickness of 5 mm) and a T1-weighted ultrafast sequence in at least one plane (usually axial). 44 The attending radiologist could add further sequences to the case as appropriate to obtain thorough diagnostic information. To reflect clinical practice, the radiologist was aware of the diagnoses and the level of certainty made by the fetal medicine consultant prior to the iuMRI being performed and had access to the full clinical ultrasonography report. The radiologist was required to comment on each brain abnormality diagnosed by the ultrasonography. If the radiologist did not agree with a diagnosis made by ultrasonography then ‘diagnosis excluded’ could be used and an additional diagnosis could be added if appropriate. The radiologists were also required to indicate their certainty for each diagnosis using the same five-point Likert scale43 as the ultrasonography assessment.

Data collection and management

After the detailed ultrasonography performed by a fetal medicine consultant, participants were recruited into the study and referred for an iuMRI scan at the Academic Unit of Radiology at the University of Sheffield or at one of the five collaborating sites (Belfast, Birmingham, Leeds, Newcastle or Nottingham).

The referral form was completed by the referring clinician and a copy was sent to the MRI site through the standard referral pathway. The referral form collected details of the type of brain abnormalities suspected, confidence of diagnosis and the prognosis for the outcome of the pregnancy. It also collected data on whether or not termination of pregnancy (TOP) was discussed or offered because the abnormalities on ultrasonography were sufficient to consider that option under Ground E of the Abortion Act 1967 [section 1(1)(d) – substantial risk of serious mental or physical disability]. 45

The reporting radiologist completed a similar iuMRI feedback form and was required to comment on all suspected diagnoses along with their diagnostic confidence. Additional diagnoses could be added or excluded when required, as detailed previously.

Following the iuMRI examination, the participant attended a follow-up appointment with the referring fetal medicine consultant. The iuMRI report was available to the clinician at this appointment and the clinical feedback form was completed. The purpose of the clinical feedback form was to assess the changes in the clinical management and prognosis of the pregnancy after the iuMRI. In addition, further details of diagnostic and prognostic information were collected, along with the management plan for the pregnancy. From a diagnostic perspective, participants were asked if iuMRI had provided additional information and, if so, if the ‘new’ pathology was visible when the clinician performed a follow-up ultrasonography. To assess the prognosis, the clinicians were asked if iuMRI had changed the prognostic information given to the patient and to regrade the prognosis in the light of the iuMRI information using the same five categories used at referral. The clinicians also recorded whether or not TOP had been discussed or offered. Finally, the clinicians were requested to state if the iuMRI had altered the counselling and management of the pregnancy and, if so, what the degree of change was.

The pregnancy was then followed up for up to 6 months post delivery and data were collected on the outcome of the pregnancy, as described in Statistical analysis. The outcome data form was used to collect relevant information.

Statistical methods

Sample size

A recruitment target of 750 pregnant women was set, from whom we anticipated 504 fetuses would have a complete ORD. It was assumed that 336 of these fetuses would be 18 to < 24 weeks’ gestation at the time of iuMRI. A diagnostic accuracy of 70% in ultrasonography46–54 and 80% in iuMRI was assumed, and it was further assumed that iuMRI would correctly contradict the ultrasonography in 20% of cases and erroneously contradict the ultrasonography in 10% of cases. A sample size of 336 participants allowed the confidence interval (CI) for the difference to be estimated to within a standard error of 3%, and ensured that any improvement in diagnostic accuracy of < 5% with 90% power and at 85% confidence could be ruled out. A change of 5% was deemed to be clinically important as it would lead to changes in fetal prognostic information and management intent in ≈5% of all cases. A total recruitment target of 504 fetuses with complete ORDs was set, assuming that one woman with a fetus of > 24 weeks’ gestation would be scanned for every two fetuses in the 18 to < 24 weeks’ gestation age group.

Statistical analysis

The diagnostic strategies are referred to as ultrasonography (diagnostic ultrasonography alone) and iuMRI (iuMRI following diagnostic ultrasonography).

Statistical analysis was conducted using R version 3.3.3 (The R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria) and Stata® version 14 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA).

Analysis populations

Owing to the nature of the study, some outcomes were collected at the mother level (e.g. other diagnostic tests, participant feedback). In some instances, more than one record was available for the same mother because of repeat ultrasonography and/or MRI scans, multiple pregnancies or repeat pregnancies. The denominator used is outlined throughout the methods and the results.

The primary analysis of diagnostic accuracy was undertaken on all fetuses for which a successful iuMRI scan had been undertaken within 2 weeks of their diagnostic ultrasonography and for whom an ORD was available. The 2-week time window was chosen so as to minimise the bias arising because of the evolving brain and, in some cases, the evolving diagnosis. A long delay between scans may favour iuMRI because diagnoses may become more apparent as the brain matures. Secondary analyses of diagnostic accuracy were undertaken on fetuses:

-

with successful ultrasonography and iuMRI scans (irrespective of their timing) and with ORD

-

with successful ultrasonography and iuMRI scans undertaken within 2 weeks, with or without ORD

-

with successful ultrasonography and iuMRI scans, irrespective of timing and availability of ORD.

For all these analysis populations, the analyses were based on the first diagnostic ultrasonography and iuMRI scan unless otherwise stated. When groups were large enough, analyses were conducted on different subsets (i.e. analysis populations) of the data. Details of which population was assessed for each outcome are described in this section.

Within each of these populations, when appropriate, analyses were repeated on the following subgroups:

-

first pregnancies (i.e. excluding any pregnancies subsequent to their first within the MERIDIAN study)

-

singleton pregnancies

-

first and singleton pregnancies

-

repeat pregnancies

-

repeat scans (i.e. second ultrasonography and iuMRI for the same pregnancy).

Finally, analyses of diagnostic accuracy were intended to be undertaken separately for pregnancies at < 22 weeks’, 22–24 weeks’ and > 24 weeks’ gestational age at the time that the MRI scan was performed. However, these three categories were condensed to 18–24 weeks’ and > 24 weeks’ gestational age because of small numbers in the first two subgroups.

Summaries and analyses of diagnostic confidence were undertaken on the primary analysis population and on all fetuses undergoing scans. Summaries and analyses of changes in prognosis and management were undertaken on all mothers undergoing both scans. Summaries of safety and adverse outcomes were undertaken separately for all mothers undergoing a scan and all fetuses undergoing a scan.

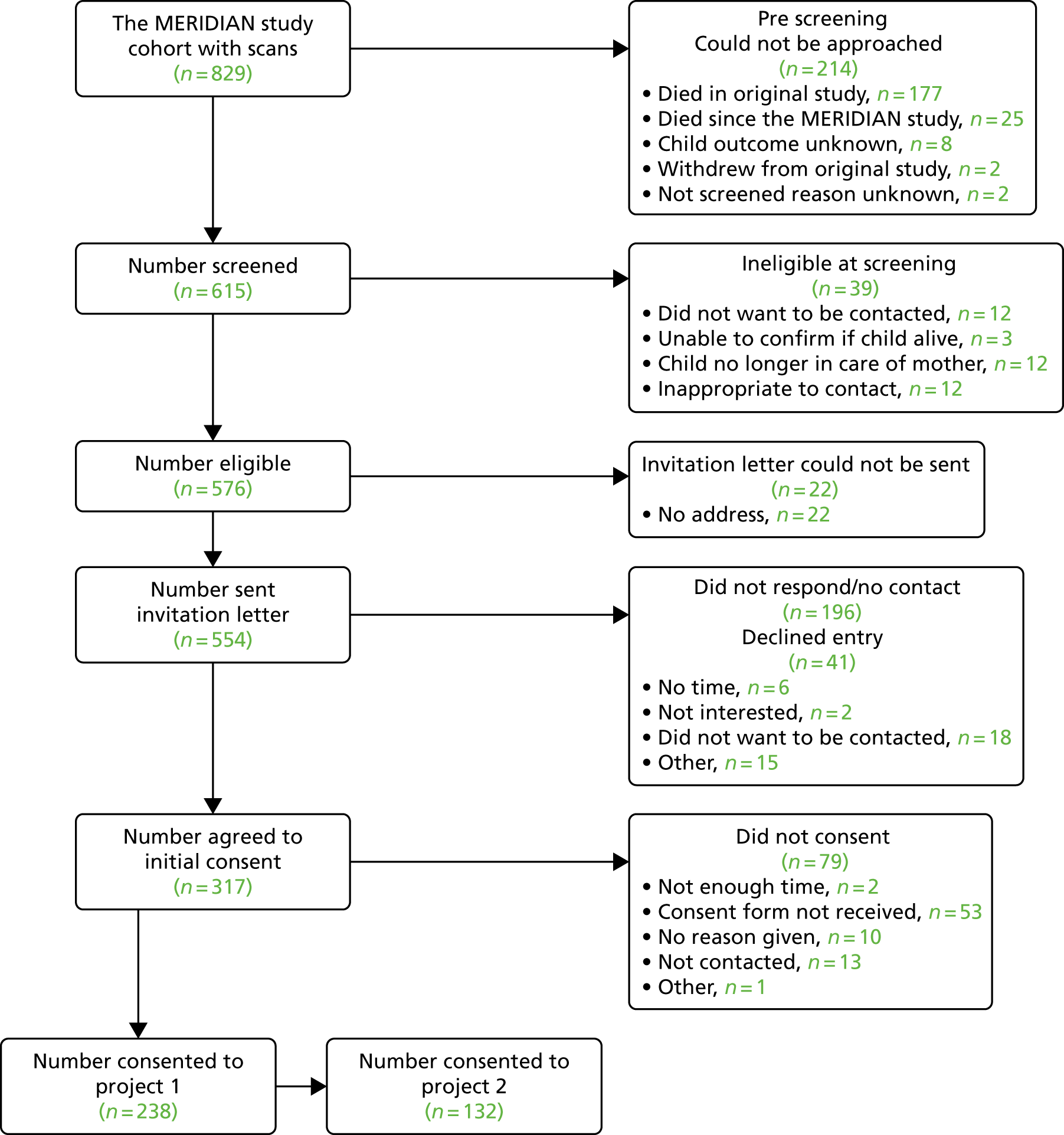

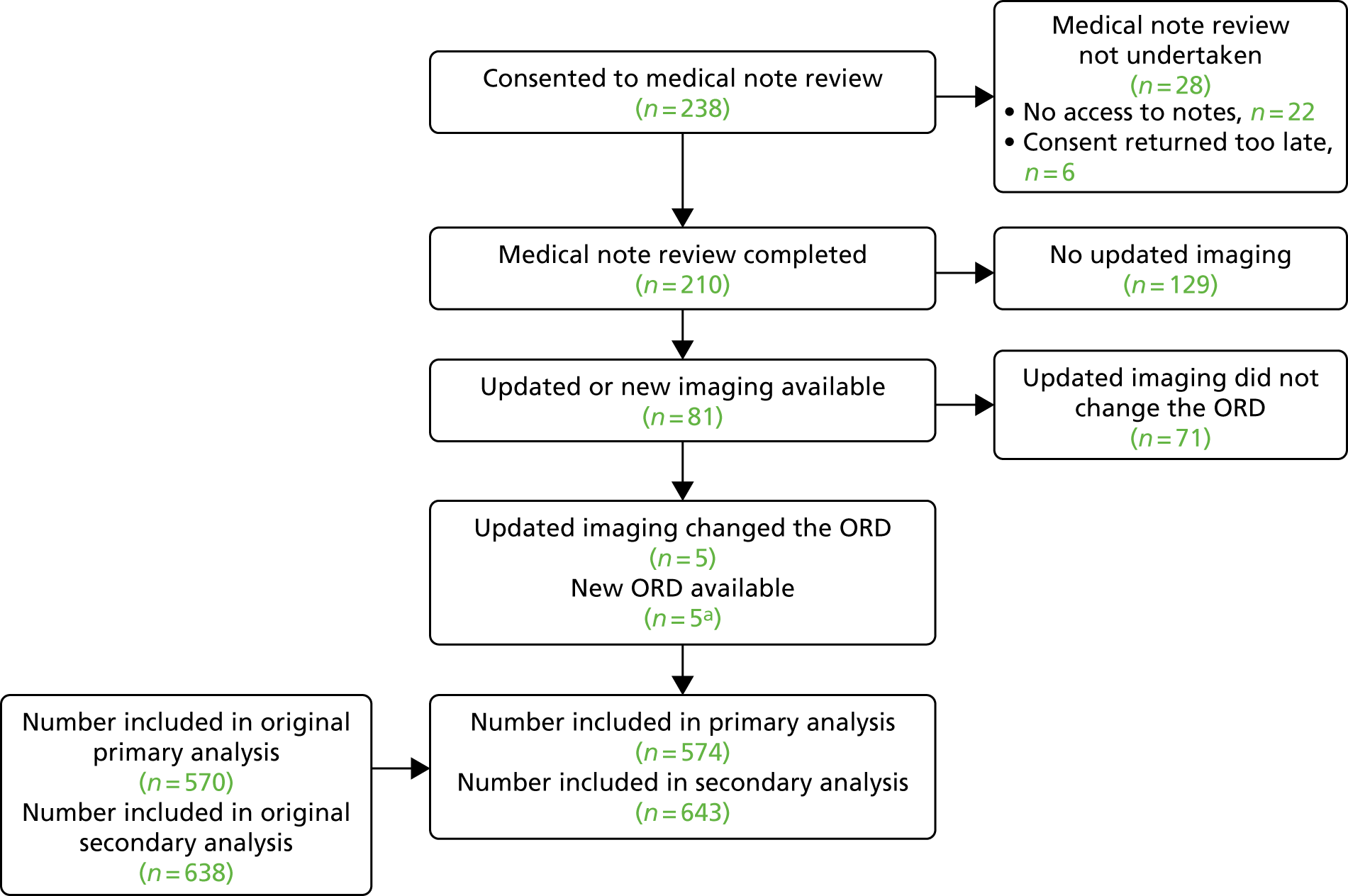

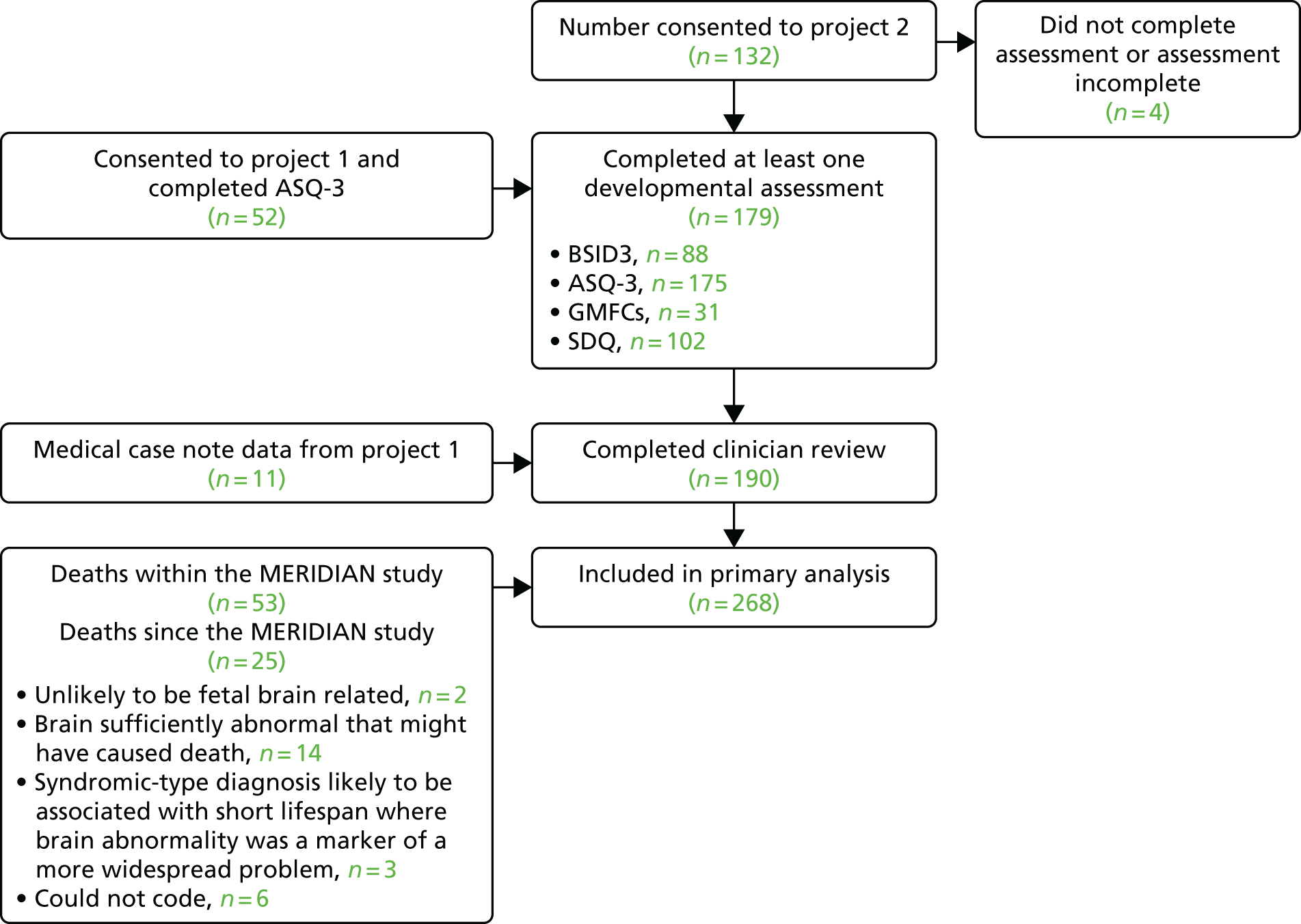

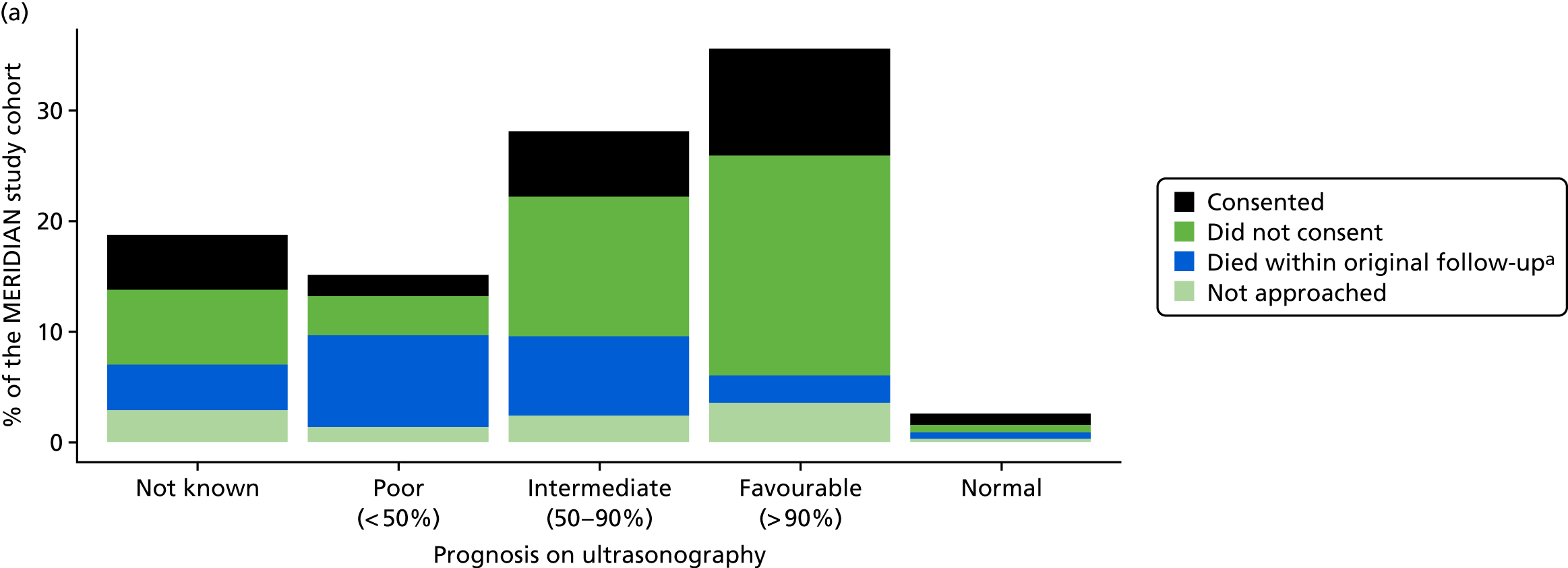

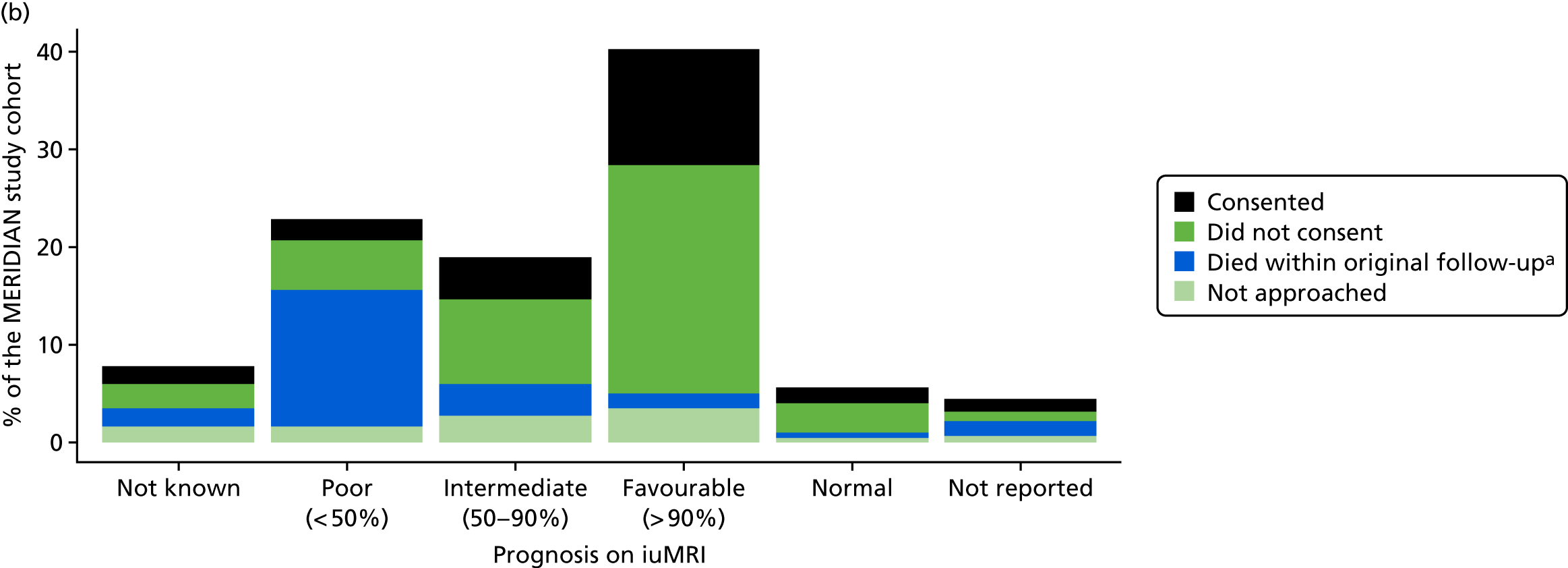

Approach/consent

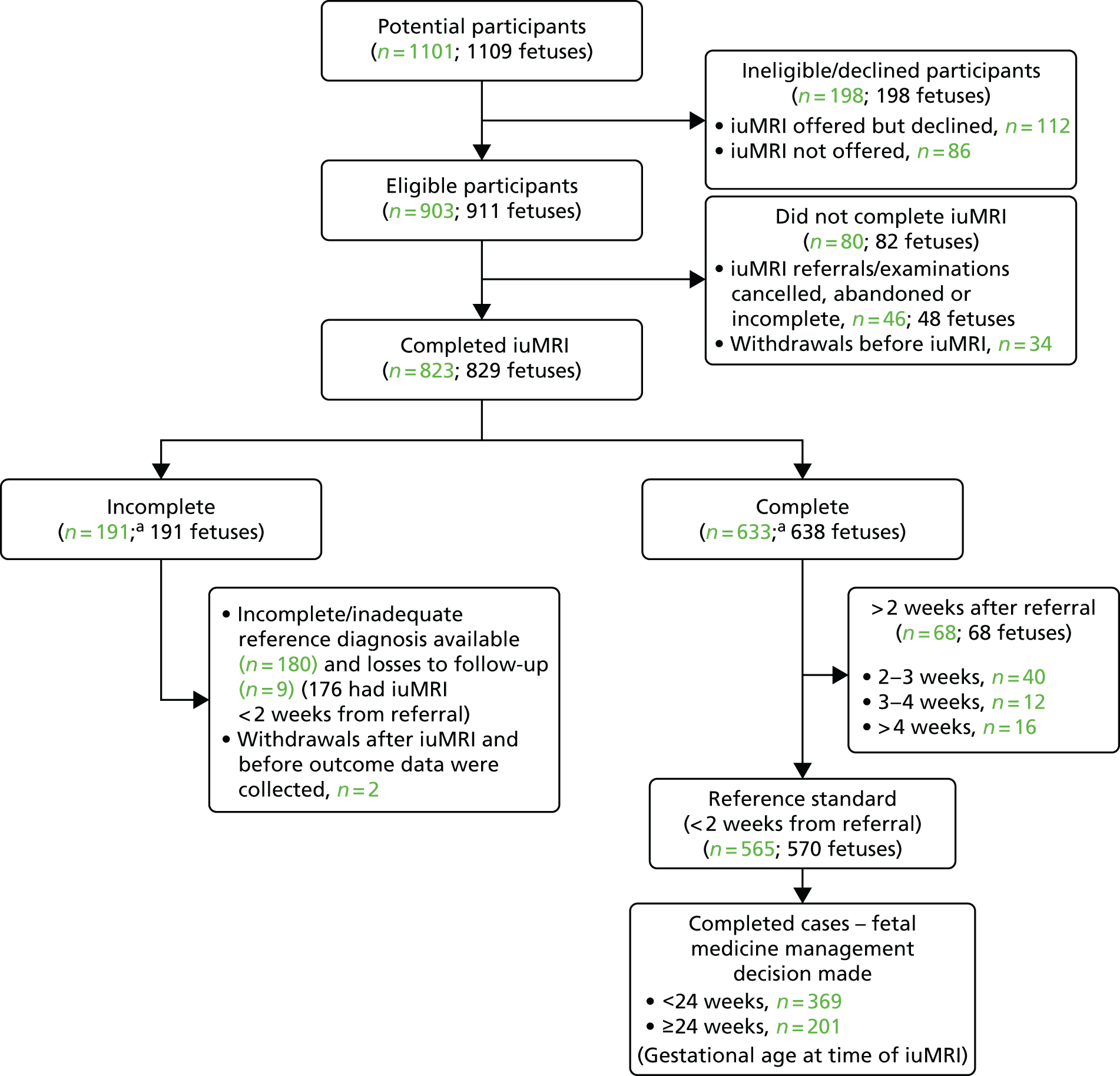

The number of mothers who were approached and consented is presented in the STARD flow diagram (Figure 1). When given, the reasons for not offering iuMRI and reasons for not consenting to join the study have been presented.

FIGURE 1.

Flow diagram to show the pathway and recruitment numbers in the MERIDIAN study. a, One participant carried two fetuses, only one of which had an ORD. Therefore, the participant is counted in both the incomplete and complete participant groups.

Data completeness

The number of participants who completed data collection at each stage of the study is presented in the STARD flow diagram (see Figure 1). This included the number of participants who completed iuMRI, the number of those with a reference diagnosis available, the number of participants who withdrew or were lost to follow-up, the number of complete cases and at what gestational age a management decision was made.

Characteristics

The following summaries were presented for all mothers who entered the trial:

-

iuMRI centre

-

maternal age

-

gestational age at initial approach

-

whether the pregnancy was single or multiple

-

dominant diagnosis of brain abnormality based on screening ultrasonography.

The number and percentage in each category were presented for categorical variables and appropriate summary statistics were presented for continuous variables. These figures were presented by population groups 1–3 (i.e. primary, ORD unavailable and excluded).

Diagnostic accuracy

Diagnostic accuracy was defined as the percentage of true-positive diagnoses for ultrasonography and the percentage of true-positive and true-negative diagnoses for iuMRI. This percentage is equivalent to the positive predictive value (PPV) for ultrasonography screening.

Primary analysis (agreement)

For the purposes of our trial, the ORD was defined as follows:

-

For delivered neonates, the reference used was the neuroanatomical diagnosis recorded in the child’s clinical notes at 6 months of age, based on all available follow-up imaging (i.e. postnatal MRI, computed tomography when performed for clinical purposes or postnatal transcranial ultrasonography). The exceptions were (1) cases of isolated VM, for which a resolved diagnosis made via third trimester ultrasonography was acceptable, and (2) isolated microcephaly, for which clinical examination was sufficient.

-

For terminated fetuses, the reference diagnosis was based on postmortem data (i.e. autopsy and/or postmortem MRI when available).

Agreement between the PND and the reference diagnosis was determined by a two-level review process. The first-level review was carried out by one of two neuroradiologists, who were not associated with the MERIDIAN study. Their role was to determine whether or not a full review by the Multidisciplinary Independent Expert Panel (MIEP), described below, was required, based on the ORD. A full review by the MIEP was required unless the following criteria were met: (1) there was complete and unequivocal agreement between the anatomical findings on ultrasonography, iuMRI and the ORD, or (2) VM was the only finding described on both ultrasonography and iuMRI examinations, but the size of the ventricles had returned to normal as shown on ultrasonography later in pregnancy or on neonatal imaging. The latter was counted as agreement because the enlargement of ventricles can commonly resolve spontaneously during pregnancy. 55

The second-level review (by the MIEP) consisted of three NHS consultants (i.e. a neuroradiologist, a fetal and maternal medicine specialist and a paediatric neurologist) from a single centre, independent of the MERIDIAN study. The MIEP was provided with the diagnostic results for each fetus and members were blinded to knowing if it was an ultrasonography or iuMRI report. The MIEP was responsible for deciding whether or not each report agreed completely with the ORD (all listed diagnoses correct) and, when it was judged that there was disagreement between ultrasonography and iuMRI, which one indicated the more severe pathology. The MIEP could request additional information if required to assess a case and could be given access to the full report. In the small number of cases when the full clinical report was required to assess a case, blinding was no longer possible. The research team at the Sheffield Clinical Trials Research Unit (CTRU) was able to unblind the results for the MIEP for analysis purposes.

The number of fetuses diagnosed, diagnostic accuracy (i.e. the proportion of fetuses correctly diagnosed) and its 95% CIs were presented for ultrasonography and iuMRI in the primary analysis population by gestational age (i.e. 18–23 weeks and ≥ 24 weeks). The differences in diagnostic accuracy between ultrasonography and iuMRI and the 95% CIs were presented along with associated p-values calculated using McNemar’s test.

Missing data

To examine the effect of missing data on the primary analysis, two sensitivity analyses were undertaken on the subset of fetuses whose iuMRI was undertaken within 2 weeks of their ultrasonography. The first sensitivity analysis was to assume that outcome data are missing at random,56 which means that the reason for missing data can be predicted based on measurable covariates. A bivariate Probit analysis was undertaken, in which the two outcomes (ultrasonography correct, iuMRI correct) were modelled with the same covariates for both outcomes but with their coefficients allowed to differ. The covariates were chosen based on their association with missingness and diagnostic accuracy. The predicted probabilities of ultrasonography and iuMRI being correct, conditional on their covariates, were then derived for fetuses both with and without ORD; these predictions are unbiased under the assumption of data missing at random. 57 The difference between ultrasonography and iuMRI was calculated as the difference between the two predicted probabilities, with a 95% CI derived using bootstrap methods with 10,000 simulations. The second sensitivity analysis estimated the impact of missing data worst-case assumptions about the diagnostic ability of iuMRI. The differences in diagnostic accuracy between ultrasonography and iuMRI were calculated under both assumptions.

Secondary analysis of agreement

Repeat in utero magnetic resonance imaging

The primary analysis was repeated using repeat iuMRI scans. When mothers had more than one repeat scan, the latest iuMRI report was used.

Anatomical subgroup analysis

The primary analysis was repeated on three subgroups of the primary analysis population. These subgroups were defined by the diagnosis at ultrasonography.

Definition of subgroups

Isolated ventriculomegaly

Cases were included in this group if they were diagnosed with isolated VM as the only finding on ultrasonography. No other brain abnormality was diagnosed on ultrasonography in this subgroup. These cases were further categorised into three types based on the largest trigone on ultrasonography: mild (10–12 mm), moderate (13–15 mm) and severe (≥ 16 mm).

Posterior fossa

Cases were included in this group if they were diagnosed with abnormalities confined to the posterior fossa (with or without associated VM) on ultrasonography. These cases were further divided into two specific diagnosis categories: those involving the brain stem or cerebellum (i.e. parenchymal abnormalities including Dandy–Walker spectrum malformations, Chiari II malformation and cerebellar hypoplasia) and those involving cerebrospinal fluid (CSF)-containing lesions (i.e. enlarged cisterna magna, Blake’s pouch cyst and arachnoid cysts). In the first ‘overall’ group, correctness was judged by the presence of any diagnosis of isolated posterior fossa abnormality on ORD. For a diagnosis in the two subsequent groups to be deemed correct, an ORD included the same specific diagnosis described above.

Failed commissuration

Fetuses were included in this group if they were diagnosed with either agenesis or hypogenesis of the corpus callosum (CC) as the sole diagnosis or in conjunction with VM on ultrasonography only. These fetuses were further categorised into their specific diagnosis category of ‘agenesis of the CC’ or ‘hypogenesis of the CC’. In the first ‘overall’ group, correctness was judged only by either the presence of CC abnormality or the absence of another brain lesion. For a diagnosis in the two subsequent groups to be deemed correct, an ORD included the same specific diagnosis (i.e. ‘agenesis of the CC’ or ‘hypogenesis of the CC’), regardless of any other brain lesion.

Subgroup analysis

Fetuses were categorised into one of the three anatomical subgroups described above if they were diagnosed on ultrasonography. The number of fetuses diagnosed within these groups for whom the diagnoses were correct on ORD were used to calculate the diagnostic accuracy of ultrasonography. The diagnostic accuracy of iuMRI was calculated on the same subgroup as defined using ultrasonography diagnosis.

Diagnostic accuracy was also calculated for the subgroups within each of the three anatomical subgroups. The number of incorrectly diagnosed cases on ultrasonography and iuMRI were presented along with the difference in diagnostic accuracy and its associated 95% CI and p-value from McNemar’s paired test.

Diagnostic confidence

Diagnostic confidence was defined for each diagnosis on a five-point scale (10% = very unsure to 90% = highly confident) on ultrasonography. Diagnostic confidence by iuMRI is similar but has one addition (‘diagnosis excluded’). Ultrasonographers were also asked which method of ultrasonography was used and which factors contributed to low confidence in the diagnosis. High confidence was defined as a score of 70% or 90% and low confidence was defined as a score of 10%, 30% or 50%.

The numbers of missed diagnoses (false negatives) have been presented by confidence category following ultrasonography alone and ultrasonography plus MRI for the primary population. Changes in confidence were categorised into five categories: no change, ultrasonography with more confidence by one category, ultrasonography with more confidence by two or more categories, MRI with more confidence by one category and MRI with more confidence by two or more categories. The number and percentage of fetuses in each category were presented. A Wilcoxon signed-rank test was carried out to compare the difference in confidence on ultrasonography with the difference in confidence on MRI.

Diagnostic accuracy and diagnostic confidence

A score-based weighted-average analysis was conducted58 that combined changes in diagnostic accuracy, diagnostic confidence and management to provide a summary measure of the clinical impact attributable to iuMRI. The scores were defined for each individual diagnosis by its presence/absence and the assigned diagnostic confidence. The scores for the overall impact (i.e. at the level of the fetus rather than the condition) were assigned by the expert panel on a case-by-case basis. The null hypothesis, that the impact scores are zero (no impact), was tested by a one-sample t-test in the primary analysis population. The mean, standard deviation (SD) and 95% CI of difference in confidence was presented overall and also by anatomical subgroup.

Clinical impact

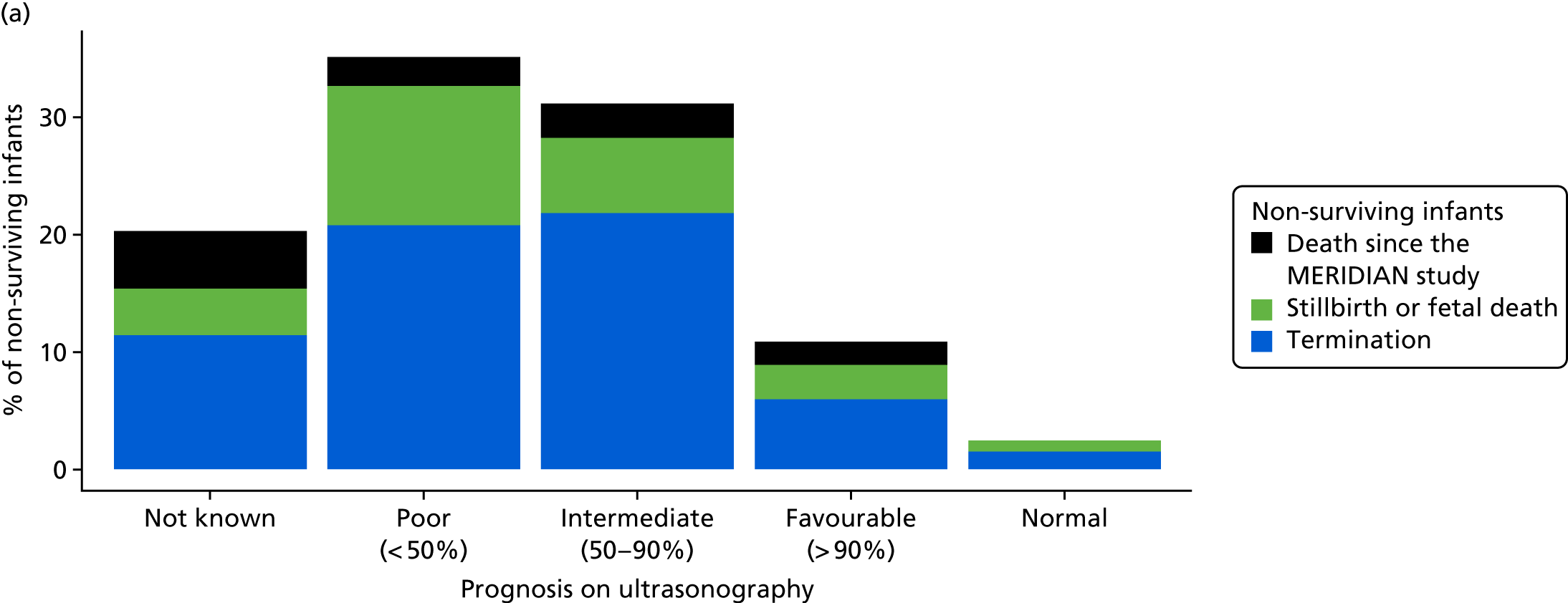

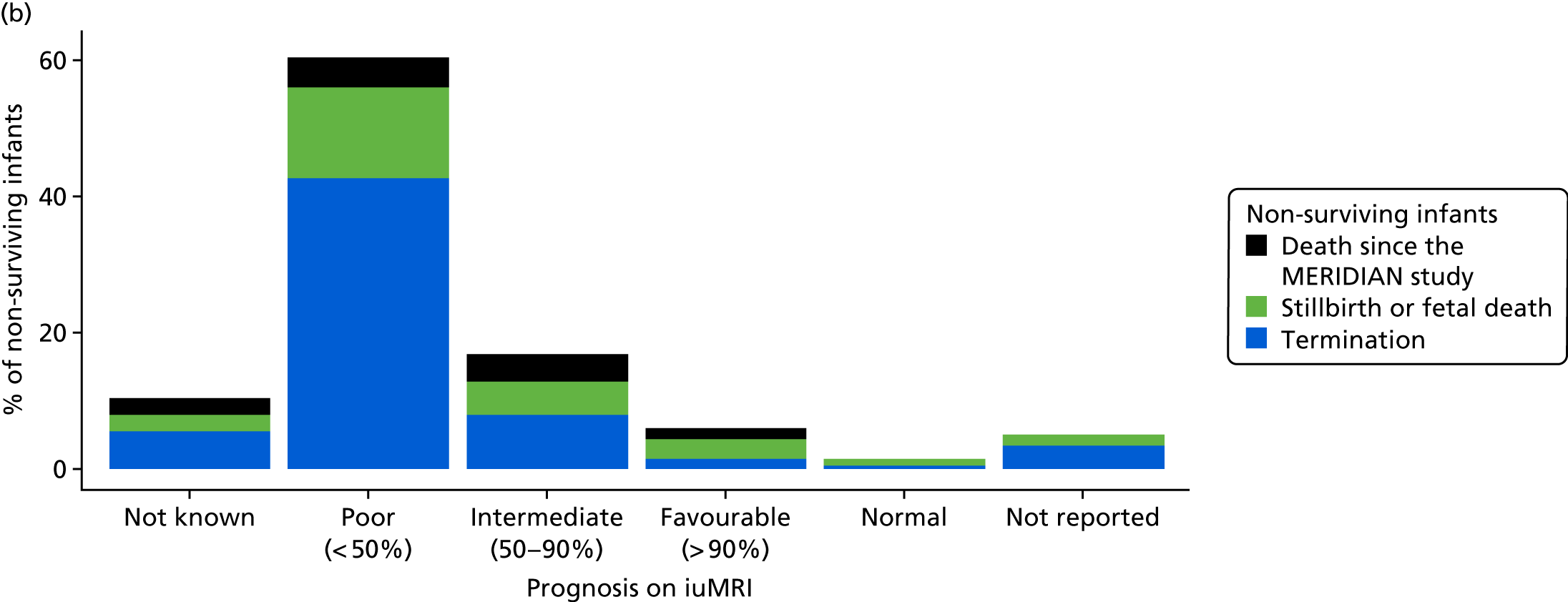

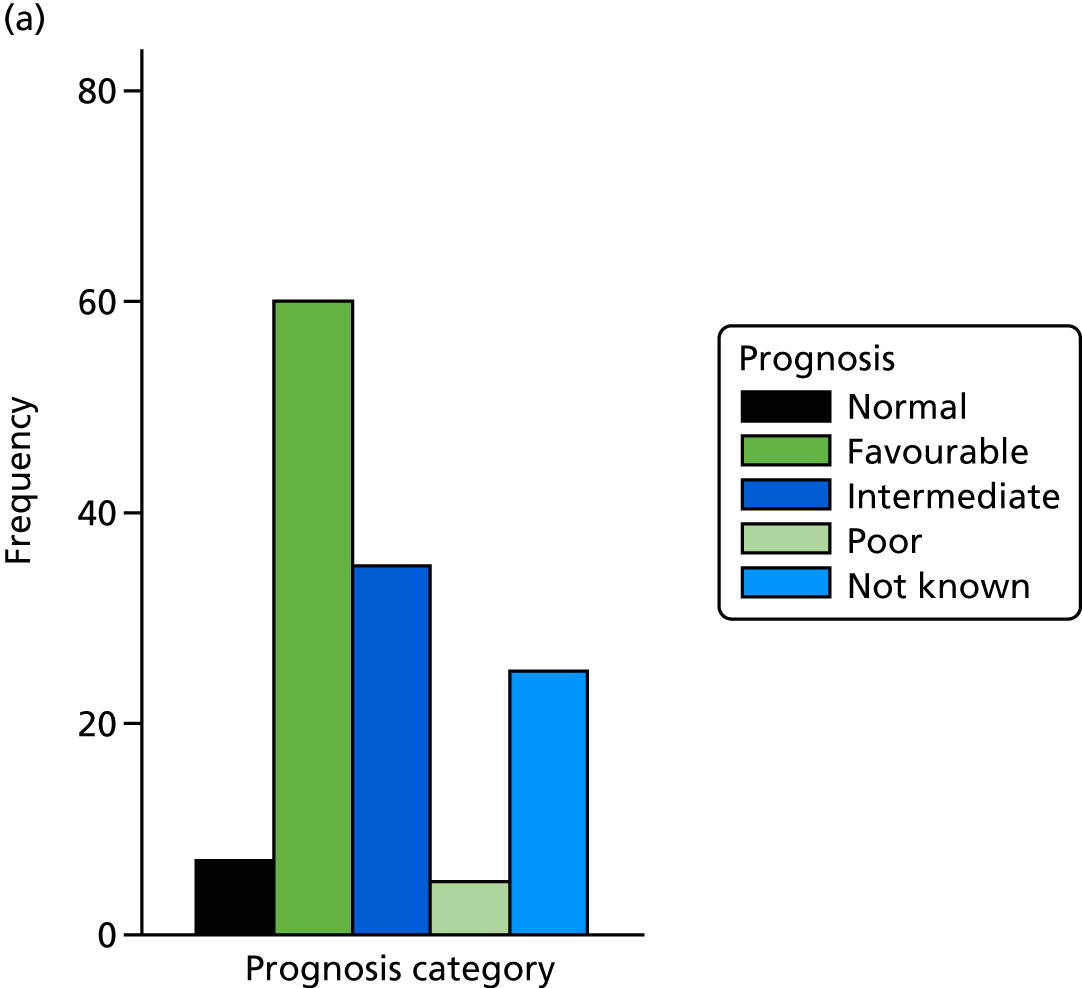

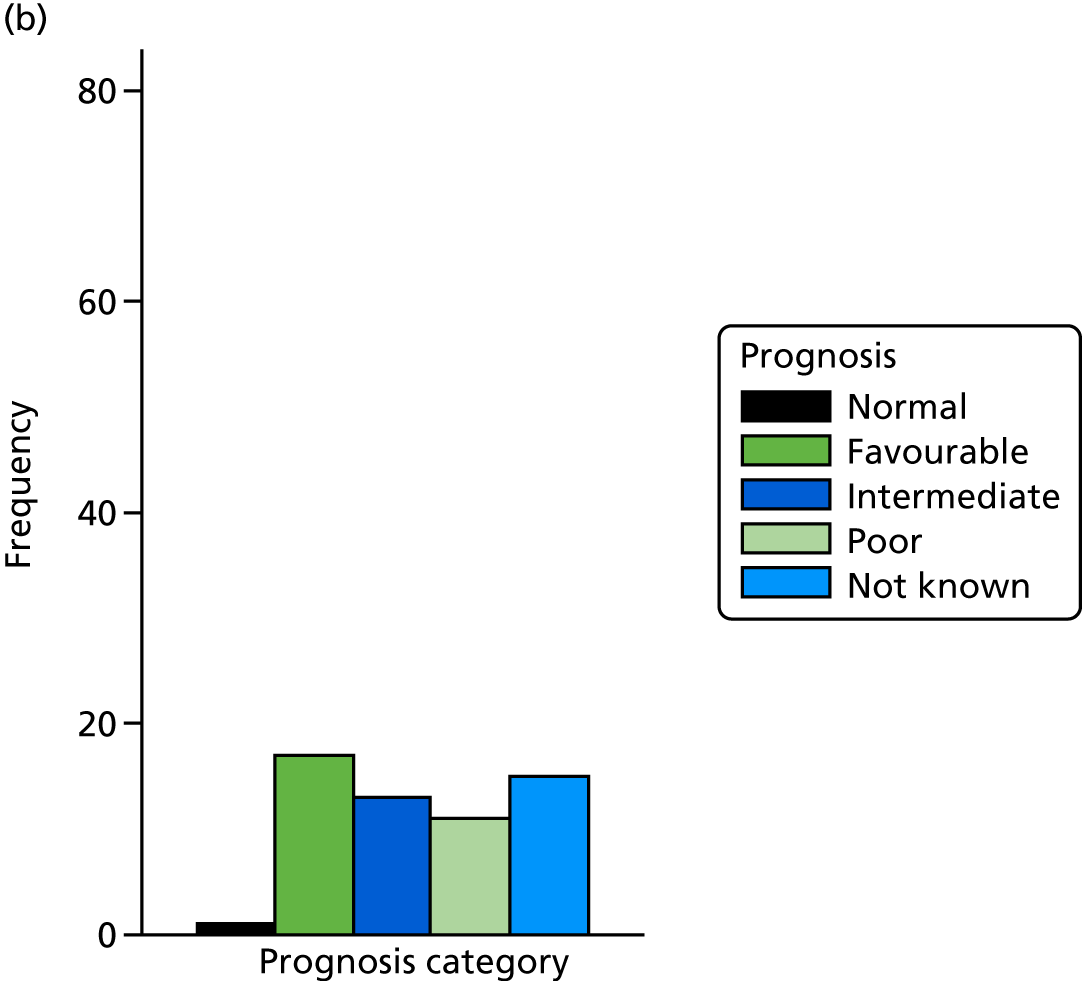

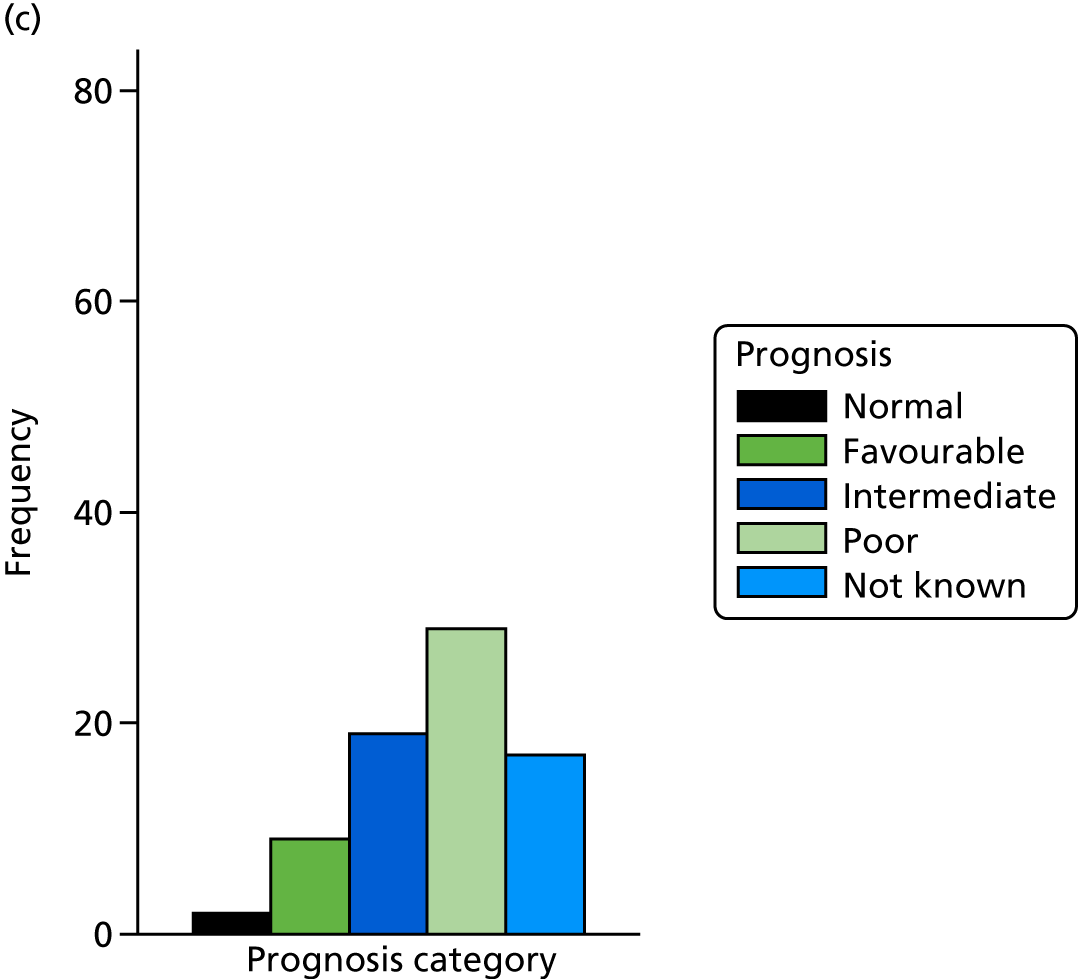

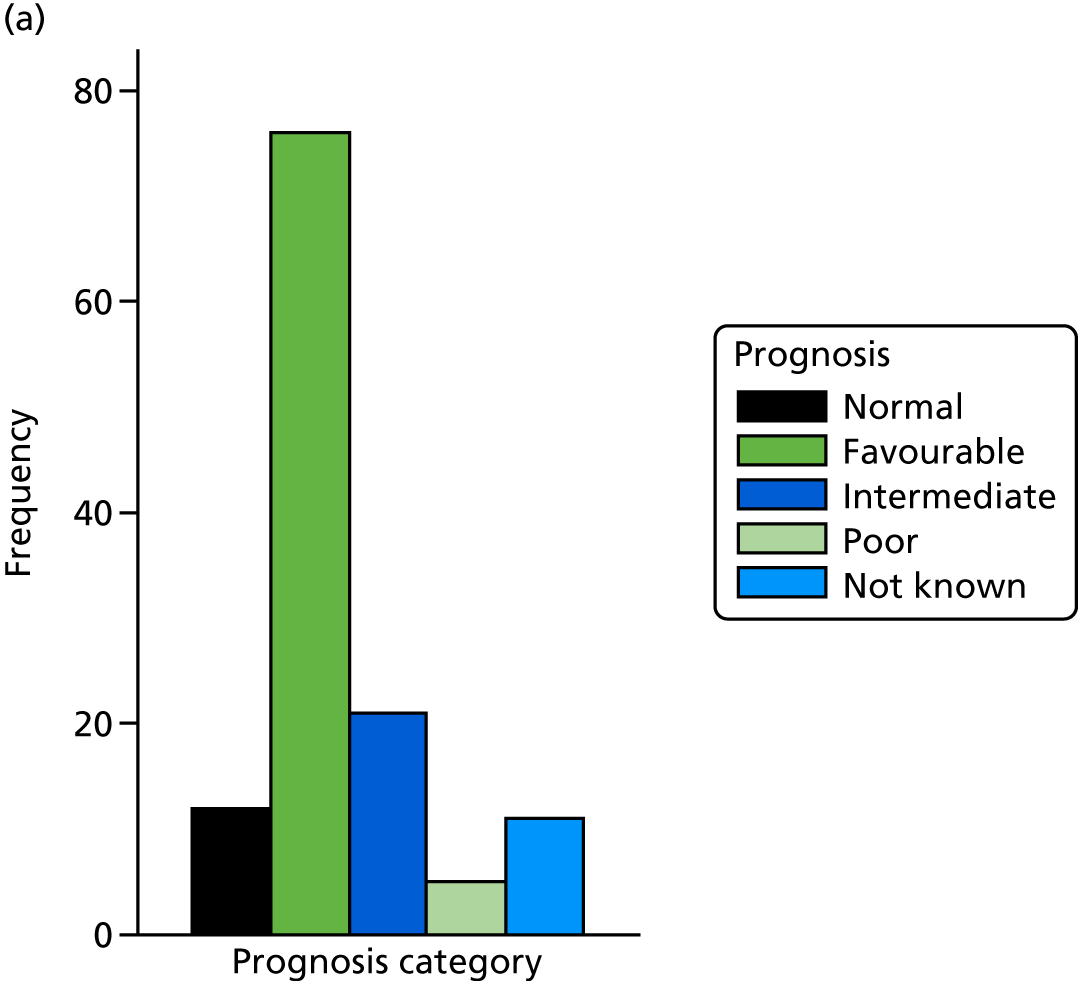

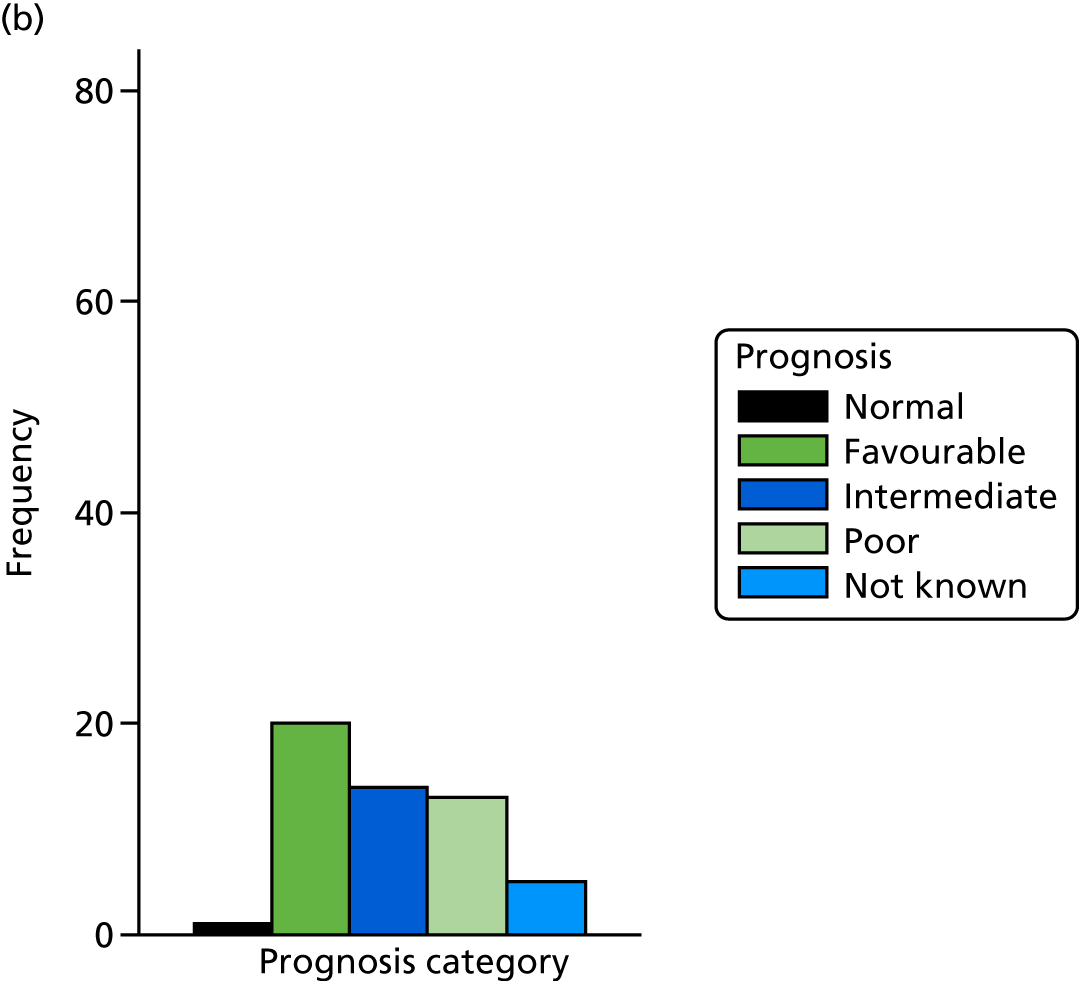

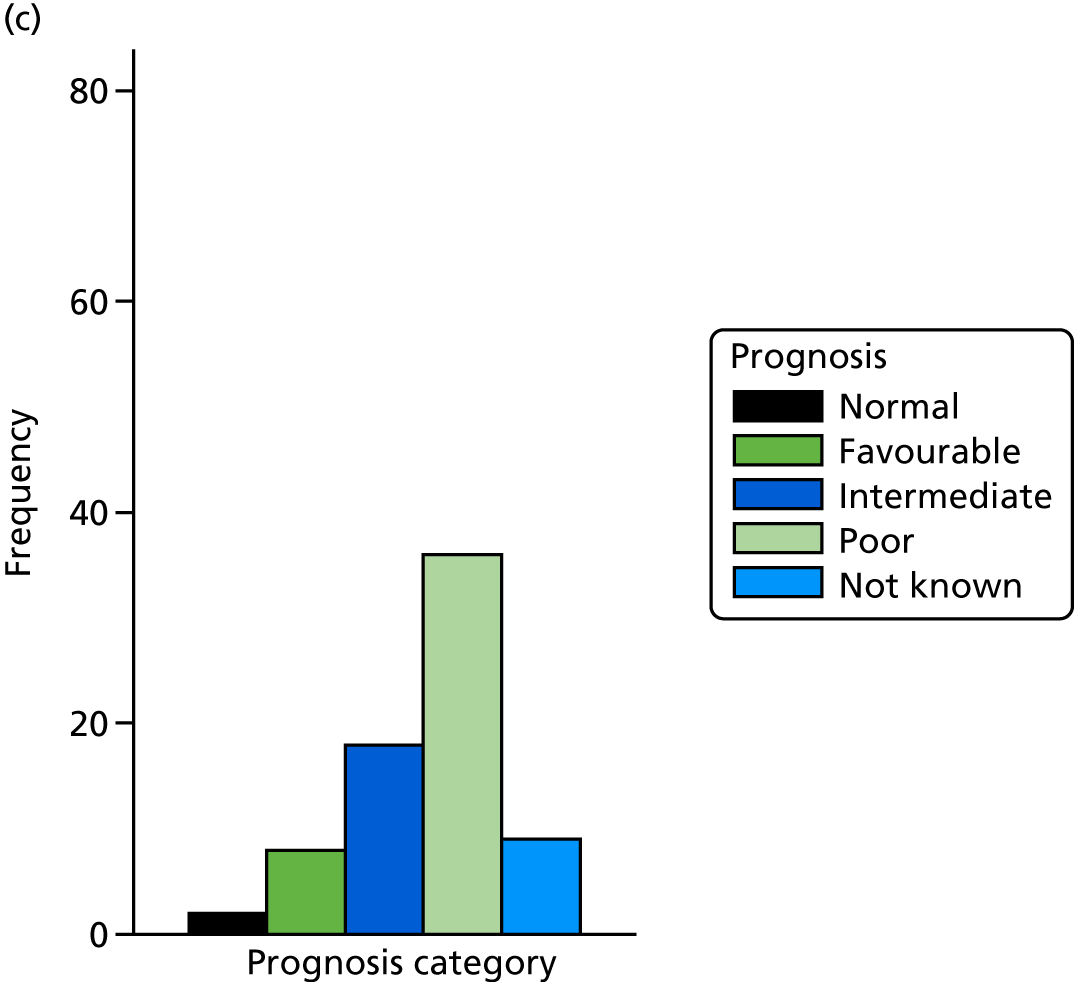

Change in prognosis

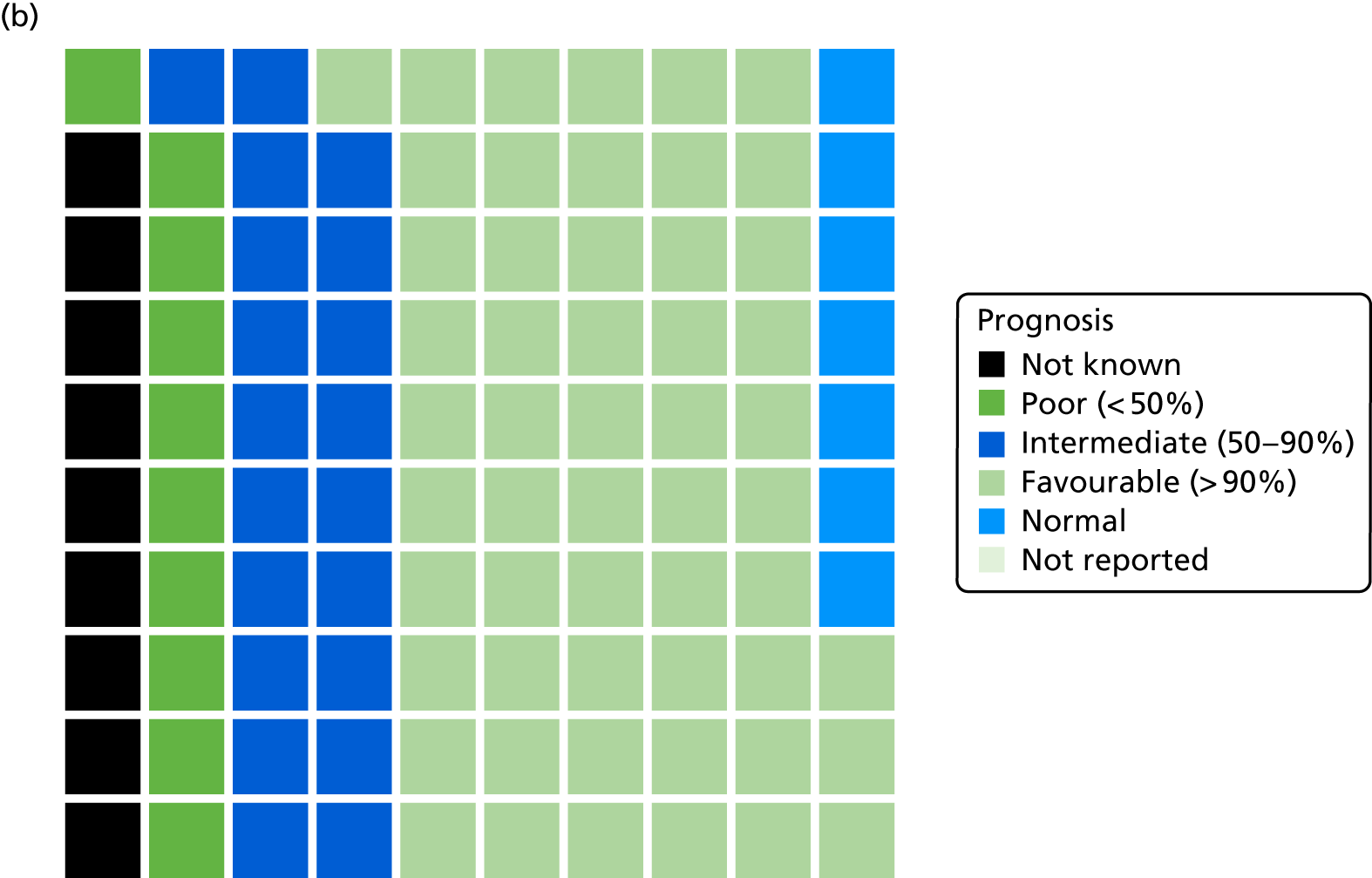

The prognosis was defined at the pregnancy (mother) level, rather than the fetal level. Following ultrasonography, the prognosis was recorded by using a four-point scale of severity (i.e. poor, intermediate, favourable and normal) and if the ultrasonographer was unable to offer a prognosis on the basis of the scan this was recorded as not known. The same process was undertaken following iuMRI and the two were compared in a 5 × 5 contingency table, with the number and percentage of pregnancies in each group presented.

When a fetus had a known prognosis for both ultrasonography and ultrasonography plus iuMRI, the change in prognosis category was categorised as no change, more favourable with ultrasonography by one category, more favourable with ultrasonography by two or more categories, more favourable with iuMRI by one category or more favourable with iuMRI by two or more categories. The number and percentage of fetuses in each of these categories were presented and their distribution compared using a Wilcoxon signed-rank test.

When a prognosis was unknown on either ultrasonography or ultrasonography plus iuMRI, these fetuses were presented separately and further grouped into nine categories: no change, not known to known (i.e. poor, intermediate, favourable or normal) or known (poor, intermediate, favourable or normal) to not known.

Counselling and management of pregnancy

In 2012, the study opened to recruitment in Belfast. Under Northern Irish law, TOP is permissible only in very specific circumstances that are more limited than in the rest of the UK or Western Europe. The incidence of TOP and the grounds for it being performed are, therefore, likely to be very different between Belfast and other centres, and findings in Belfast would not be expected to generalise to other study centres. Therefore, the main summaries of counselling and management included all mothers who completed iuMRI but excluded patients recruited from Belfast.

Following both ultrasonography and MRI, the clinician was asked to record if they discussed TOP with the mother, offered TOP to the mother, or neither. If TOP was offered, the clinician recorded whether or not this was due to there being a substantial risk of disability. The clinician was also asked whether or not MRI changed their counselling from ultrasonography only to ultrasonography plus iuMRI. A cross-tabulation of counselling categories (i.e. TOP not discussed, TOP discussed but not offered, TOP discussed and offered, TOP offered based on substantial risk of disability) on ultrasonography and counselling on ultrasonography plus iuMRI has been presented in Appendix 9.

Following iuMRI, the chosen management plan was recorded (i.e. continued pregnancy, continued pregnancy with further imaging, fetal demise, termination, unable to decide). If further imaging was used, the type was recorded (i.e. ultrasonography, iuMRI or both) and a rating of iuMRI’s contribution was recorded (i.e. none, minor, significant, major, decisive). The number and percentage of mothers in each category has been presented.

Magnetic resonance imaging errors

The number of iuMRI errors and the total number of scans were presented by central and non-central reporters for the primary analysis population. The overall error rate (number of errors/total number of scans) was calculated by central and non-central reporters along with the difference in error rate. Errors were also assessed in relation to their chronological order within the study (i.e. errors within the first 25 scans, errors in scans 26–50, errors in scans 51–75 and errors thereafter).

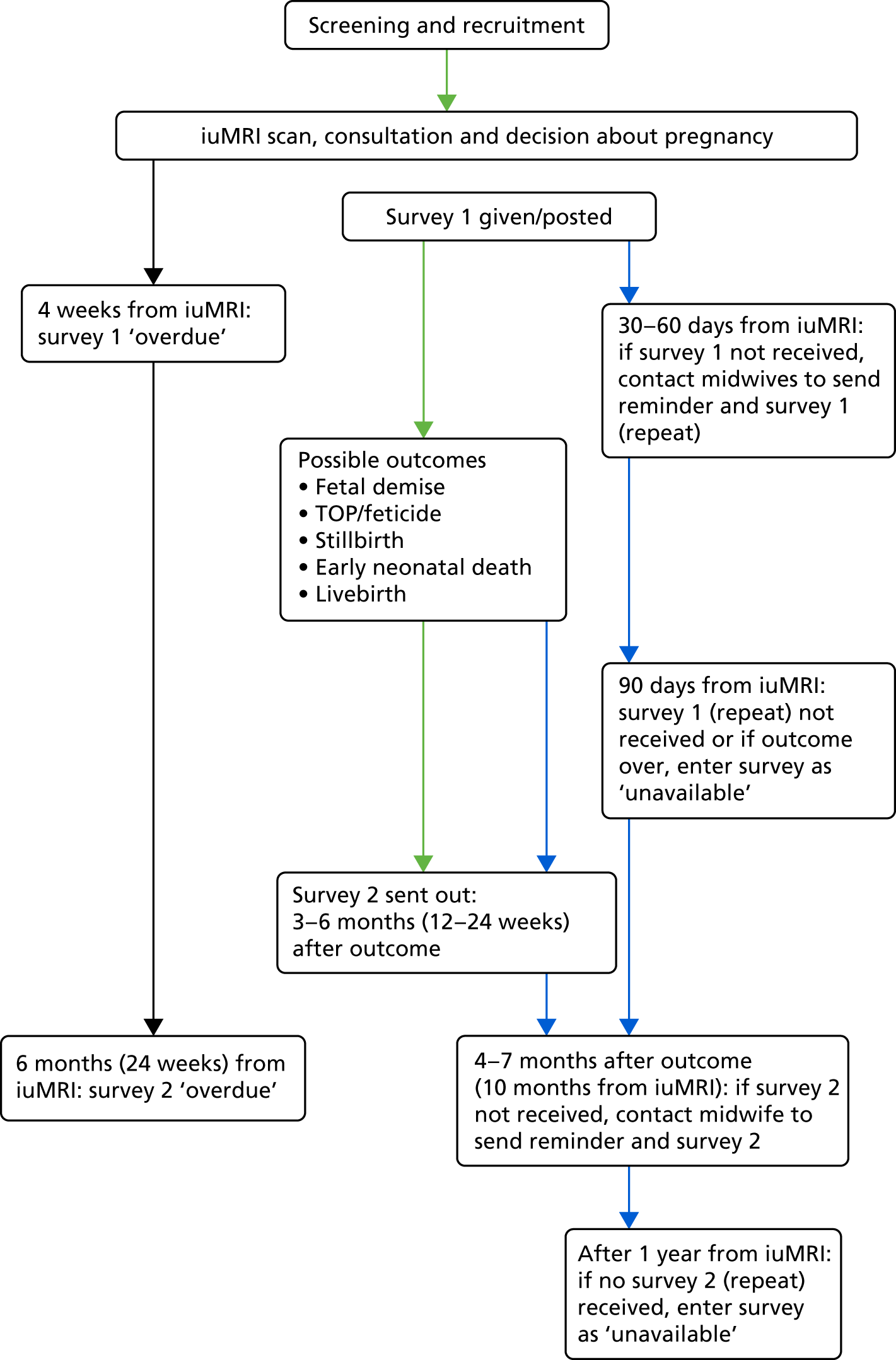

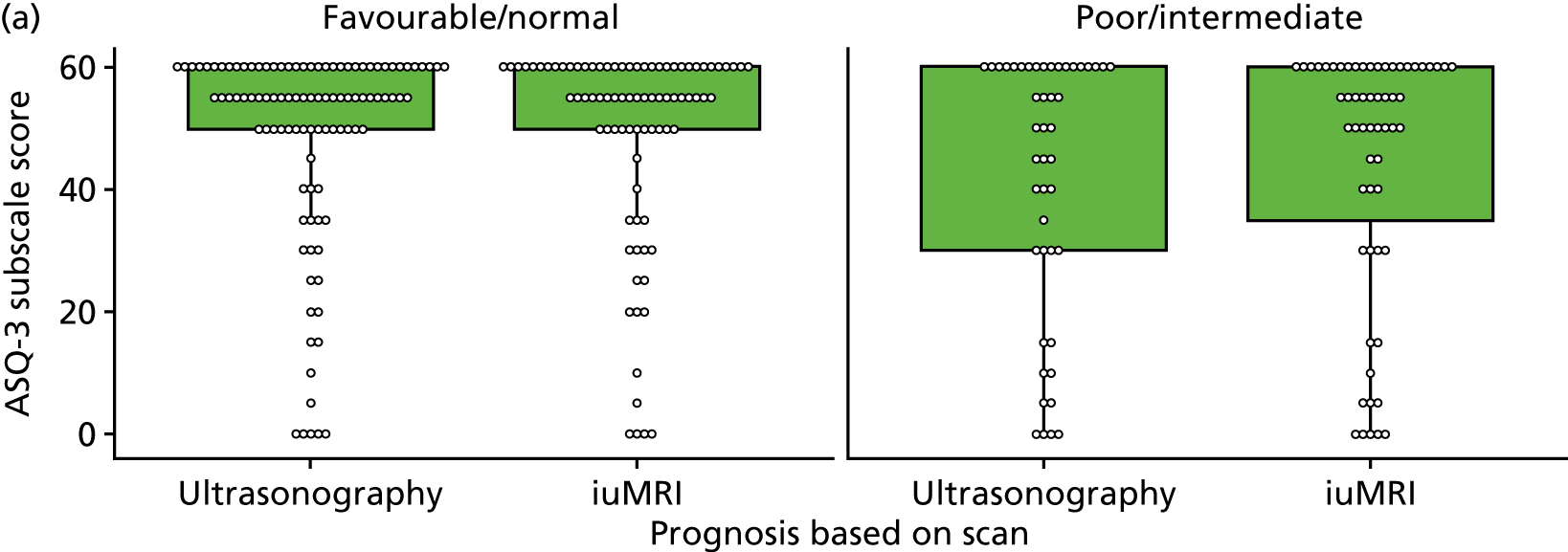

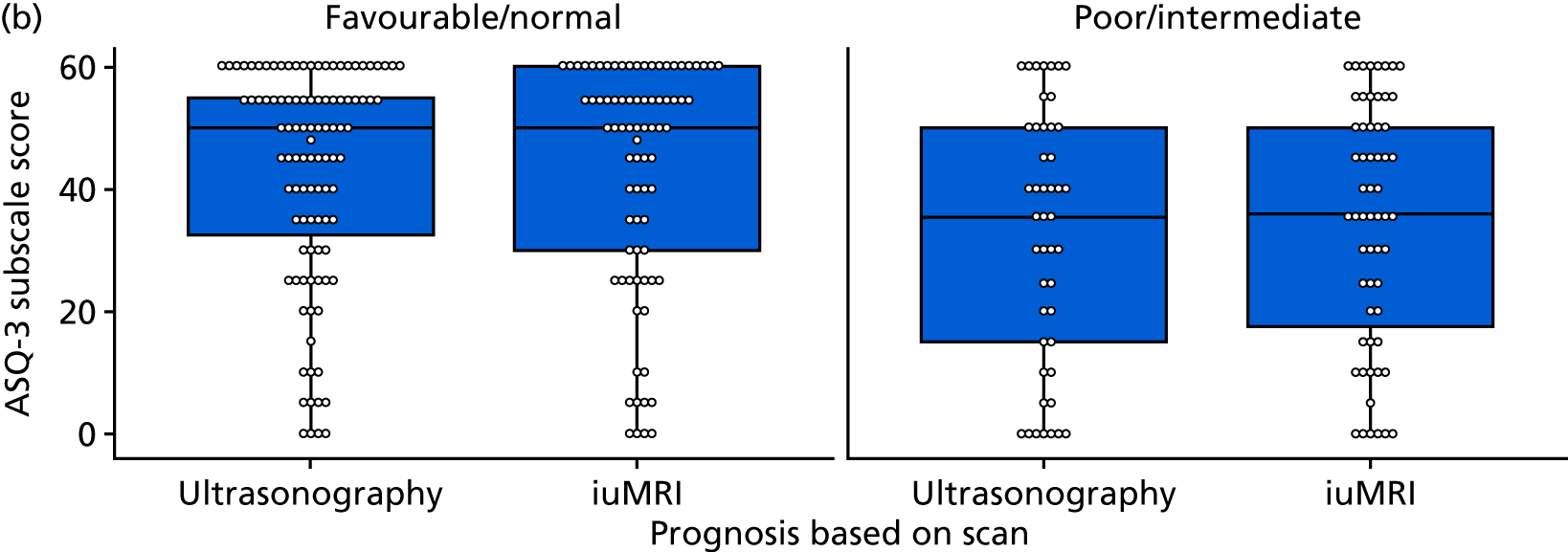

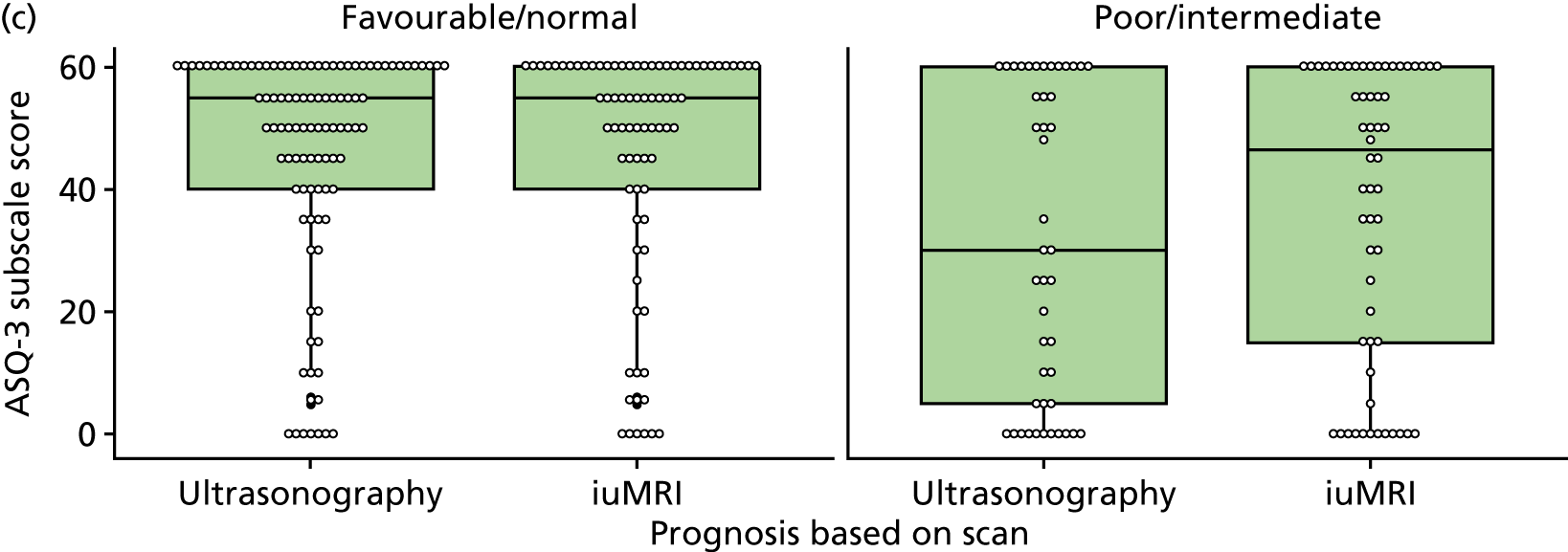

Patient acceptability

Participants were invited to complete two surveys to evaluate their satisfaction with the care received. The methods and results relating to this are outlined in Chapter 4.

Patient outcomes

Outcome of pregnancy

The outcome of pregnancy was categorised and the number and percentage of fetuses that were categorised as livebirth, perinatal, neonatal, infant death, stillbirth, spontaneous intrauterine fetal demise or terminated have been presented by each of the four analysis populations described in Statistical analysis.

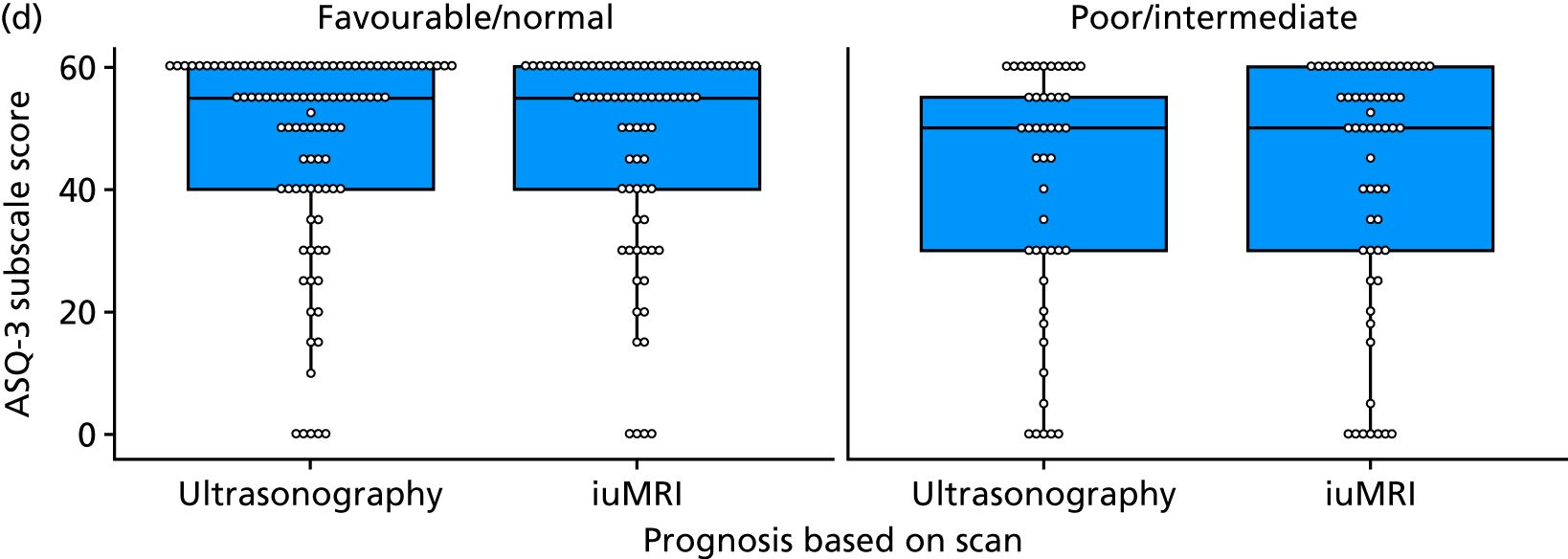

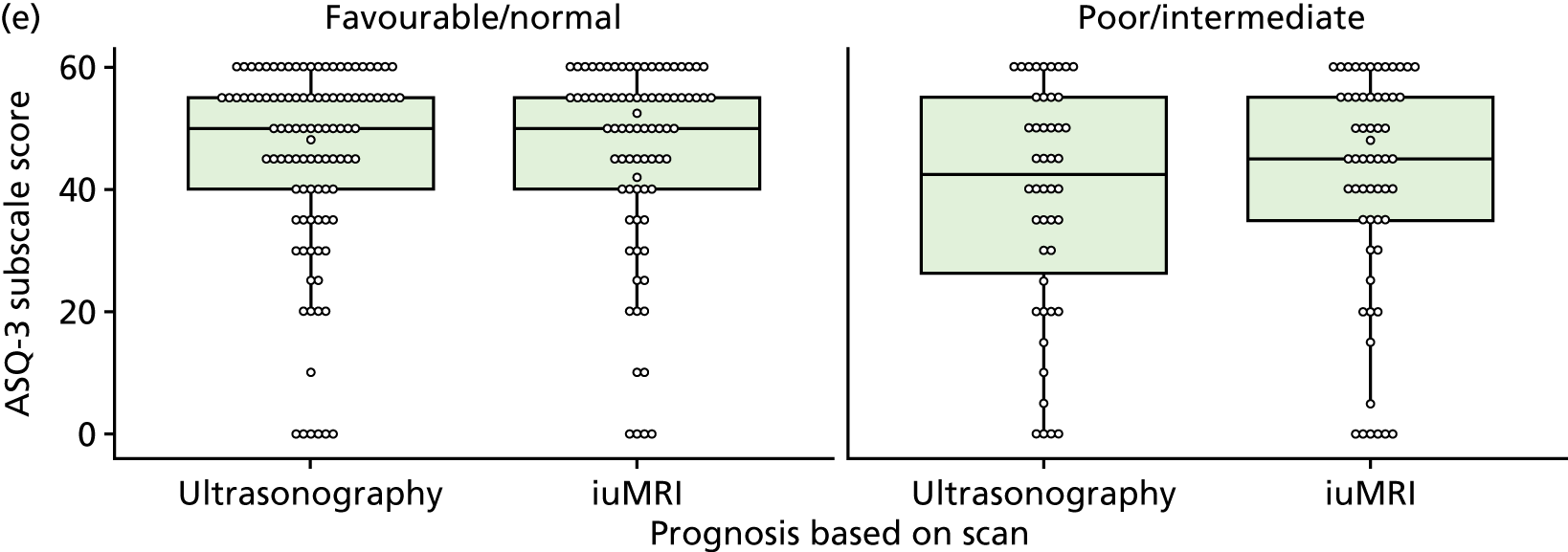

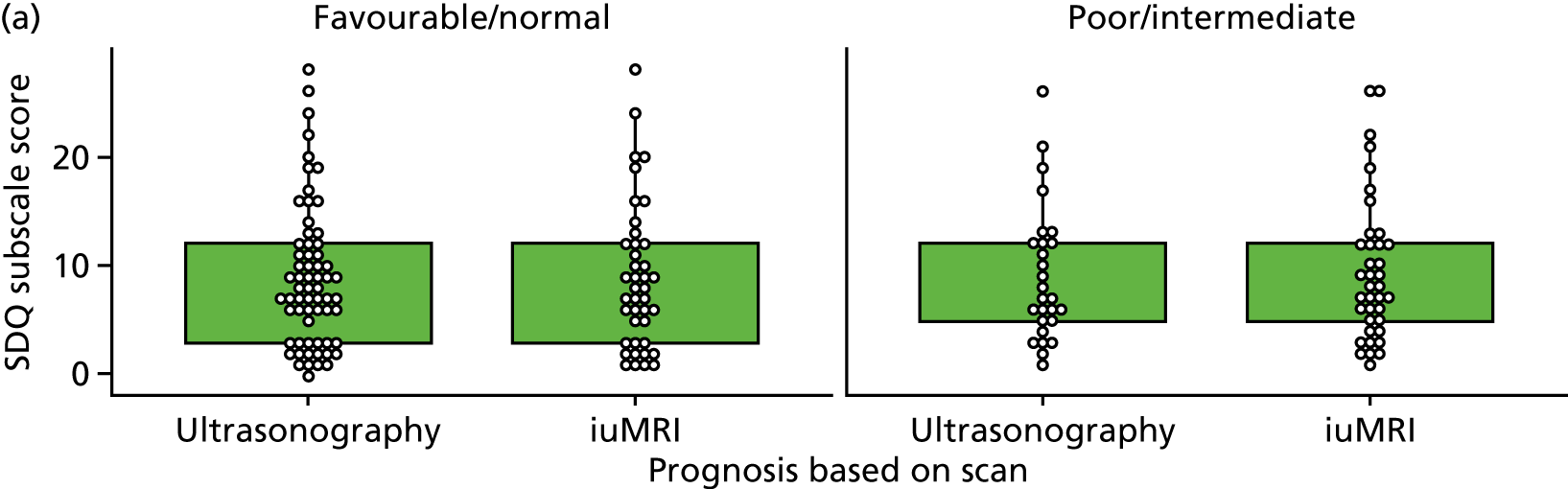

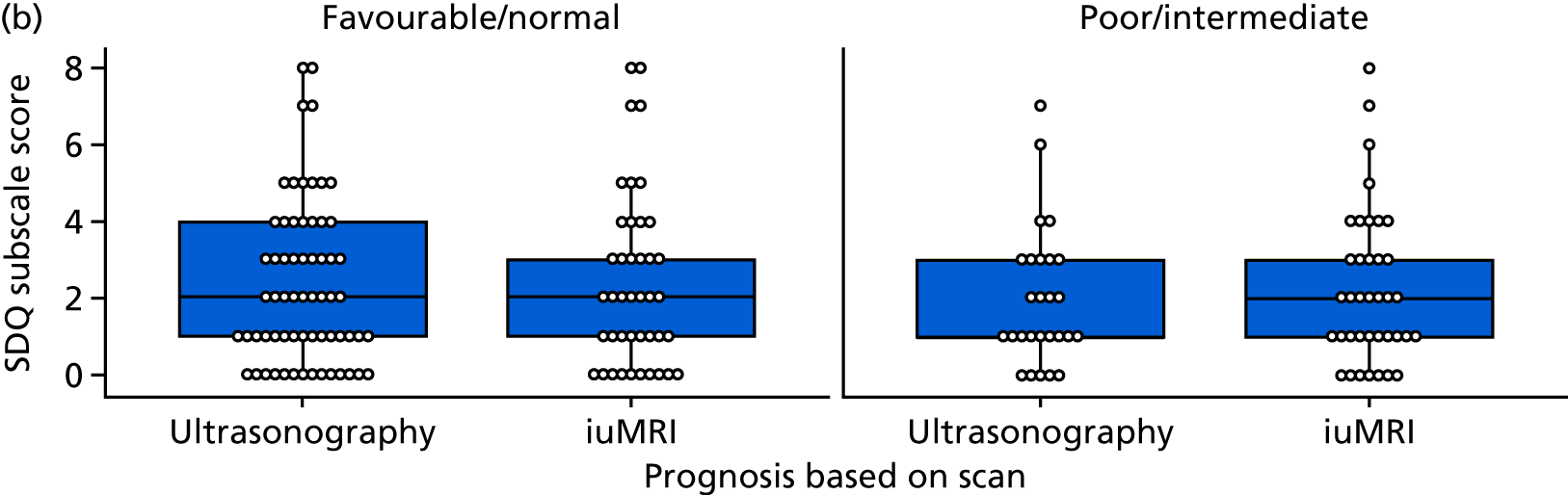

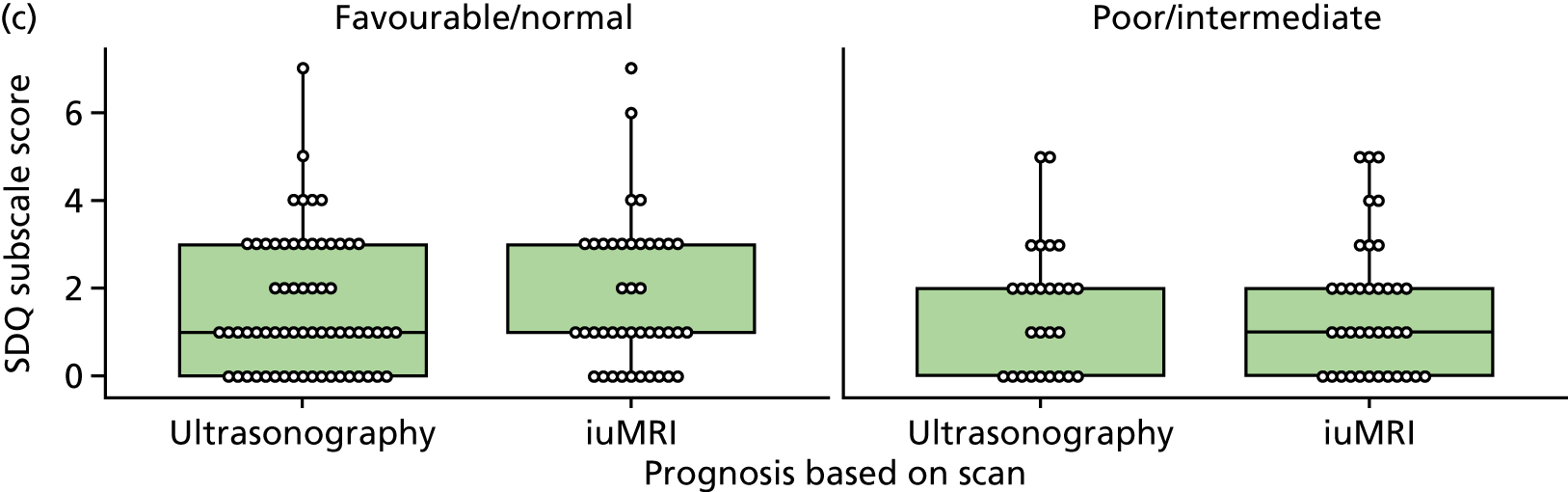

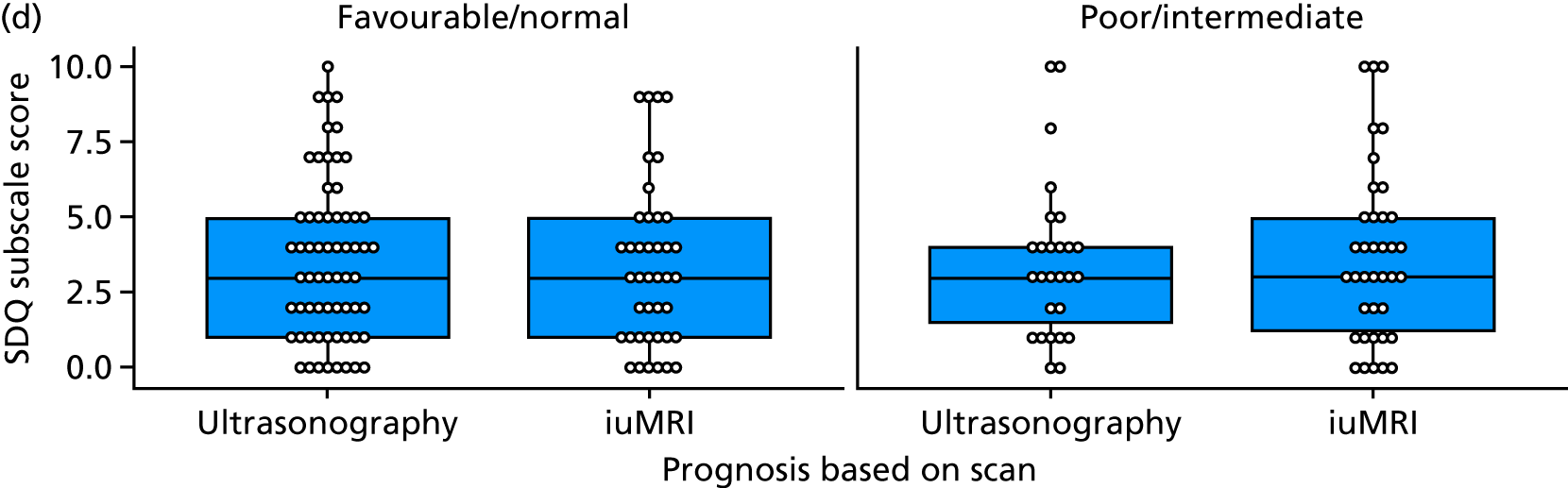

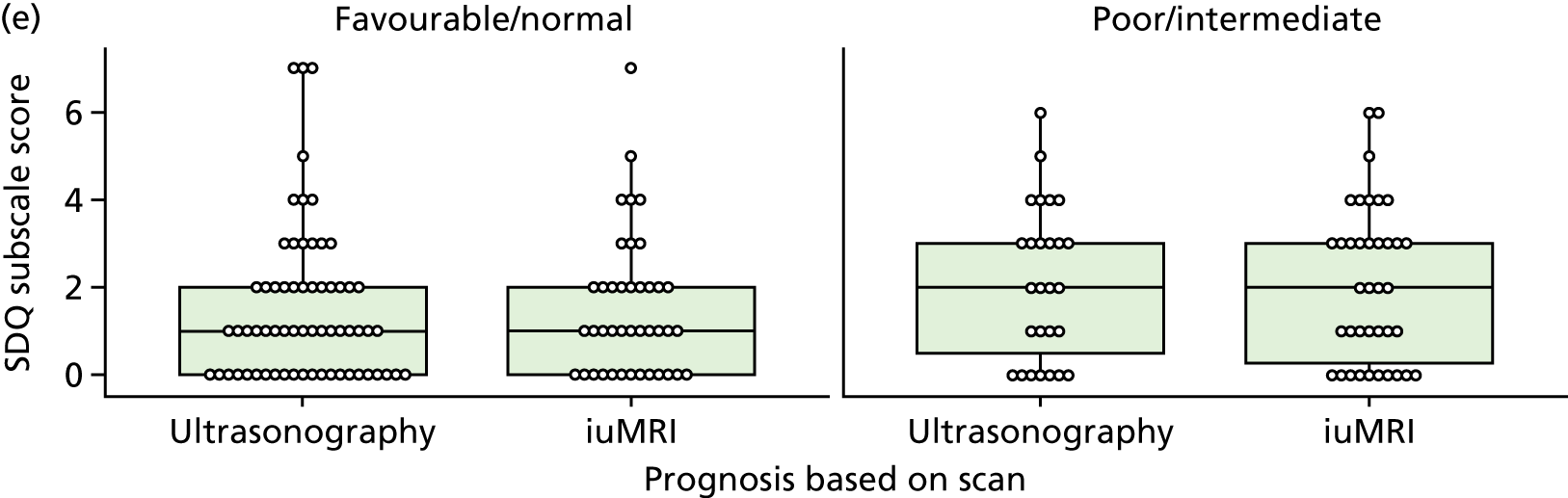

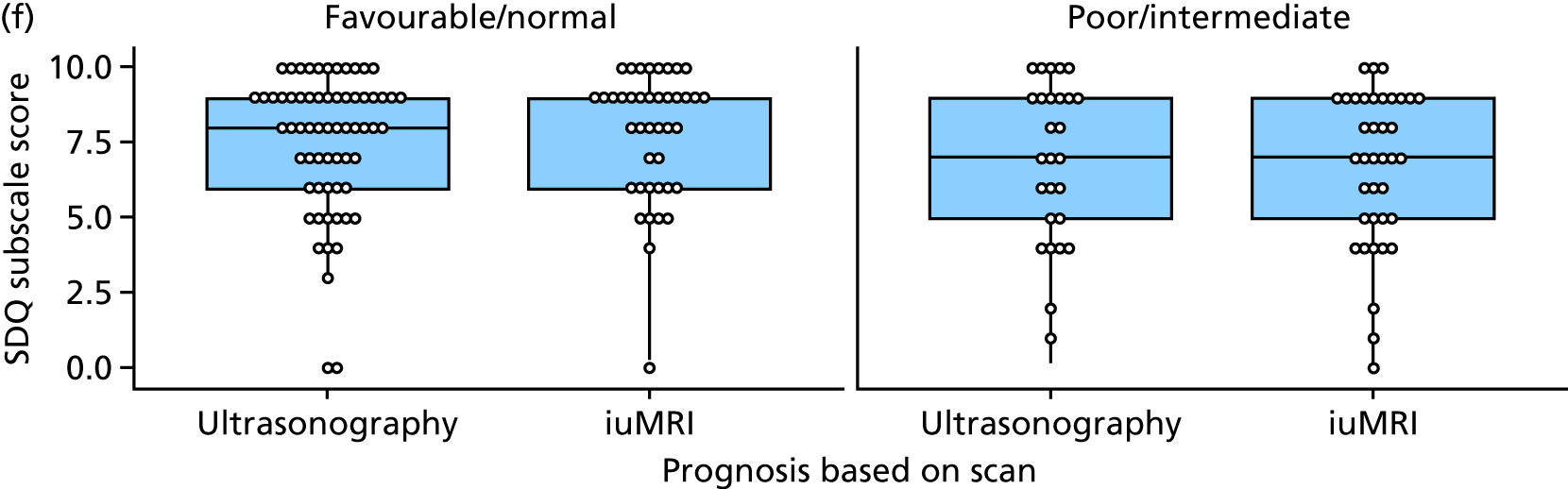

The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale questionnaire

The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) questionnaire was used to measure anxiety and depression, each being scored from 0 to 21, with higher scores indicating greater severity. 59 Prorating was used for partially answered questionnaires, provided that at least four of the seven questions within the domain had been answered. The change from survey 1 to survey 2 was calculated among mothers who completed both surveys and the difference was tested using the Wilcoxon signed-rank test.

Mothers were also classified separately for anxiety and depression as ‘in the normal range’ (0–7.5), ‘cause for concern’ (7.51–10.5) or ‘probable clinical case’ (> 10.5). The change in response categorisations from survey 1 to survey 2 was analysed using McNemar’s test generalised to a three-point scale (also known as Bowker’s test for symmetry).

Mean, SD, median, interquartile range (IQR) and minimum and maximum values were presented for anxiety and depression scores from each survey. The number and percentage of mothers in each category were also presented. When mothers completed both surveys, the mean, SD, median and IQR of the difference between scores was presented. The difference in the percentage by category for those completing both surveys was also presented.

Additional tests and resource use

When additional tests were used, the number and percentage of each type of test was presented for the whole cohort. The median and IQR of additional tests per mother were presented. The impact of these additional tests was presented by category.

A summary of clinic visits has not been presented because of inconsistent reporting; however, full resource use has been reported as part of the health economic evaluation.

Ultrasonography technical factors

The type of ultrasonography used was recorded (i.e. two or three dimensional) and the number and percentage of mothers were presented. Technical factors affecting the confidence of the sonographer (e.g. high body mass index of the patient, fetal position, oligohydramnios or other) were also reported.

Safety analysis

Adverse events (AEs) and serious adverse events (SAEs) were reported separately for all mothers and fetuses.

The number and percentage of mothers and fetuses experiencing an AE have been presented separately. Owing to the small number of AEs, they were reported descriptively by the participants. AEs related to the iuMRI procedure were reported separately. The AEs have also been presented by the type of AE and whether or not it was attributable to the procedure. The same summaries have been presented for SAEs. Descriptions of all AEs and SAEs have been presented in Table 20.

Health economic methods

Background

Introducing iuMRI to diagnose fetal brain abnormalities during pregnancy will introduce additional direct costs to the NHS. However, iuMRI may also lead to cost savings in other areas and may improve outcomes. Therefore, there is a need for health economic analysis to assess the cost-effectiveness of iuMRI in the diagnosis of fetal brain abnormalities.

Overview

This section considers an economic evaluation based on data collected as part of the MERIDIAN study. Information on resource use and outcomes is analysed for participants in the MERIDIAN study, to estimate the total additional costs and the change in outcomes associated with iuMRI in the diagnosis of fetal brain abnormalities.

A health economic analysis involves the comparison of two or more alternative courses of action. One of the comparators should be usual care, so that it can be determined whether or not the new intervention represents good value for money compared with current practice. The MERIDIAN study is not a randomised controlled trial with an intervention and a comparator, but instead it reports the diagnostic accuracy of iuMRI. In the base case, the economic analysis compares the costs and outcomes associated with iuMRI with those of single ultrasonography. In scenario analyses, iuMRI is compared with repeat ultrasonography.

Costs

The base-case analysis considers the costs incurred until the end of pregnancy. This includes costs of delivery for continued pregnancies and costs of termination for terminated pregnancies. Scenario analyses consider the exclusion of costs of delivery and termination.

In the base-case analysis, resource use is calculated from the analysis of MERIDIAN study data. Costs in the analyses include costs of ultrasonography scans, iuMRI scans, consultations, further investigations and TOP. Resource use is multiplied by unit costs to calculate total costs. Unit costs considered in the base case are shown in Appendix 1. All costs are reported for 2016; when necessary, costs were inflated using the Unit Costs of Health and Social Care 2016 by Curtis and Burns. 60

There are several NHS costs available for TOP. 61 In almost all cases within the study (96.1%), gestational age at termination was > 20 weeks, so ‘Medical or surgical termination of pregnancy, over 20 weeks’ gestation’ (MA20Z) appears to be the most appropriate classification. Clinicians advised that terminations would be planned and so elective inpatient costs are appropriate. Clinicians further advised that the majority of women would stay in hospital for 2 days, with 10% of women staying in hospital for longer and none staying for < 2 days. The elective inpatient cost of £1232 per patient corresponds to an average length of stay of 1.26 days, so additional excess bed-days were included (costed at £277 per day), such that the total average stay was 2.1 days, costing £1581 per patient. From the NHS costs it is unclear whether or not the total costs include feticide, which clinicians advised would be required for gestational ages of > 21+6 weeks. 61 Clinicians advised that the cost of feticide would be similar to the cost of a specialised fetal diagnostic procedure, which is £366 on average per procedure (NZ72Z). The NHS reference cost for an elective inpatient medical termination at 14–20 weeks’ gestation (MA18D) would not include feticide and is £322 less than the equivalent cost category for > 20 weeks’ gestation. 61 This suggests that the cost for termination at > 20 weeks’ gestation already includes a feticide cost (at least for a proportion of admissions). Therefore, we used our cost for termination at 20 weeks’ gestation for a 2.1-day stay for terminations that involved a feticide. For validation, clinicians advised that this cost should be similar to the cost of a normal delivery, which costs an average of £1643 per procedure (NZ30C0). 61

For terminations that did not require feticide, we assumed that a 2.1-day stay cost for 14–20 weeks’ gestation was appropriate, which was calculated as £1136.

Scenario analysis additionally considers the inclusion of costs borne by participants, such as travel (valued at £0.45 per mile as per UK Government expenses62) and time (valued using earnings by age taken from the 2016 Annual Survey of Hours and Earnings63). A further scenario analysis includes the long-term costs associated with caring for children born with disabilities.

Costs for the pathway with iuMRI and with ultrasonography alone are reported separately for participants who had and for those who did not have TOP. Resource use differs for participants who have TOP, there is the cost of TOP itself, and further imaging or consultation costs may differ. The proportion of participants having a TOP is required to calculate the total cost of iuMRI and ultrasonography. The proportion of participants having a TOP following iuMRI was observed, but because the MERIDIAN study was not a comparative trial, the proportion of TOP for ultrasonography alone was not directly available and had to be estimated (see Analyses).

Outcomes

Health economic analysis from an NHS perspective typically uses the quality-adjusted life-year (QALY) as the measure of benefit. However, the relevance of the QALY in iuMRI is questionable as decision-makers may be uncomfortable with the use of QALYs to reflect the value of an unborn child. Furthermore, incorporating QALYs for unborn children may lead to the perverse situation whereby the intervention with the lowest rate of true-negative detections maximises QALY gain.

In utero magnetic resonance imaging is intended to provide information, additional to ultrasonography, that is of value to parents and treating clinicians. This additional information is of value only if it is both accurate and leads to changes in the management of pregnancy. Therefore, the primary outcome selected for the economic analysis is ‘appropriate management decisions’. The decision for an individual mother is classified as appropriate if the revised decision is consistent with the presence or otherwise of neuro-developmental abnormalities at birth or postmortem. Therefore, appropriate management decisions are:

-

TOP advised following ultrasonography, continuation of pregnancy advised following iuMRI. Continuation of pregnancy chosen and infant exhibits no abnormalities at birth.

-

TOP advised following ultrasonography, continuation of pregnancy advised following iuMRI. TOP chosen and the fetus exhibits no abnormalities at postmortem.

-

Continuation of pregnancy advised following ultrasonography, TOP advised following iuMRI. Continuation of pregnancy chosen and infant exhibits abnormalities at birth.

-

Continuation of pregnancy advised following ultrasonography, TOP advised following iuMRI. TOP chosen and the fetus exhibits abnormalities at postmortem.

In the base-case and scenario analyses, the reported cost-effectiveness estimate is the cost per management decision appropriately revised. The proportion of management decisions appropriately revised is calculated by cross-tabulating the number of cases in which iuMRI was correct with the number of cases in which iuMRI changed the diagnosis. The proportion of management decisions appropriately revised is equal to the number of cases in which iuMRI was correct and iuMRI changed the diagnosis, divided by the total number of cases for which both outcomes were available.

Analyses

All analyses were conducted using Stata to calculate resource use and outcomes, and data were analysed in Microsoft Excel® (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA) to calculate total costs and cost-effectiveness. All analyses used completed cases with the exception of the imputed missing data, which used bootstrapping in Stata. The analyses conducted are summarised in Table 1 and explained further in the sections that follow.

| Scenario | Population | iuMRI: proportion of TOP | Ultrasonography: proportion of TOP | Effectiveness data | Costs included |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Base case | All women with outcomes | Proportion of women who had TOP | Proportion of women offered TOP after ultrasonography | Proportion of cases for which iuMRI was correct and changed the prognosis | NHS costs only |

| Scenario 1 | Same as base case | Proportion of women offered TOP after iuMRI | Same as base case | Same as base case | Same as base case |

| Scenario 2 | Same as base case | Same as base case | Proportion of women offered TOP after ultrasonography, multiplied by the proportion of women offered TOP after iuMRI who had TOP | Same as base case | Same as base case |

| Inclusion of participant-borne costs 1 | Same as base case | Same as base case | Same as base case | Same as base case | NHS costs plus costs for time and mileage |

| Inclusion of participant-borne costs 2 | All women with outcomes whose total mileage was < 40 miles | Same as base case | Same as base case | Same as base case | NHS costs plus costs for time and mileage |

| Gestational age at iuMRI of < 22 weeks | Gestational age of < 22 weeks | Same as base case | Same as base case | Same as base case | Same as base case |

| Gestational age at iuMRI of 22–24 weeks | Gestational age of 22–24 weeks | Same as base case | Same as base case | Same as base case | Same as base case |

| Gestational age at iuMRI of > 24 weeks | Gestational age of > 24 weeks | Same as base case | Same as base case | Same as base case | Same as base case |

| Comparison with the second ultrasonography | All women with outcomes | Same as base case | Adjusted to account for a proportion of cases in which ultrasonography identified the same information as iuMRI, and a proportion of cases for which TOP was offered (after iuMRI) and occurred | Proportion of cases in which iuMRI was correct and changed the prognosis, multiplied by the proportion of cases in which additional iuMRI provided information that was not visible on follow-up ultrasonography | Ultrasonography arm patients: additional cost for one two-dimensional ultrasonography and one subsequent consultation |

| Delivery costs excluded | Base case, scenario 1 and scenario 2 | Base case, scenario 1 and scenario 2 | Base case, scenario 1 and scenario 2 | Base case, scenario 1 and scenario 2 | Same as base case but delivery costs excluded. Termination costs included |

| Delivery and termination costs excluded | Base case, scenario 1 and scenario 2 | Base case, scenario 1 and scenario 2 | Base case, scenario 1 and scenario 2 | Base case, scenario 1 and scenario 2 | Same as base case but delivery and termination costs excluded |

| Increased cost for termination | Base case, scenario 1 and scenario 2 | Base case, scenario 1 and scenario 2 | Base case, scenario 1 and scenario 2 | Base case, scenario 1 and scenario 2 | Same as base case, termination costs increased |

Base case, scenario 1 and scenario 2

The MERIDIAN study recorded if participants were offered a TOP following the ultrasonography, if participants were offered a TOP following the iuMRI and if participants had a TOP. In the base-case analysis, the proportion of participants who had a TOP is used for iuMRI and the proportion of participants who had a TOP following ultrasonography alone is assumed to be equal to the proportion of participants who were offered TOP following ultrasonography. This approach may overestimate the proportion of participants having a TOP following ultrasonography alone. After iuMRI, 189 out of 537 participants were offered a TOP but only 58 participants had a TOP. Therefore, two further scenarios are considered. In scenario 1, the proportion of participants having TOP following iuMRI is assumed to be the proportion of participants who were offered TOP following iuMRI. In scenario 2, the proportion of participants having TOP following ultrasonography is the proportion of participants offered TOP following ultrasonography adjusted by the proportion of those who were offered TOP following iuMRI who had a TOP.

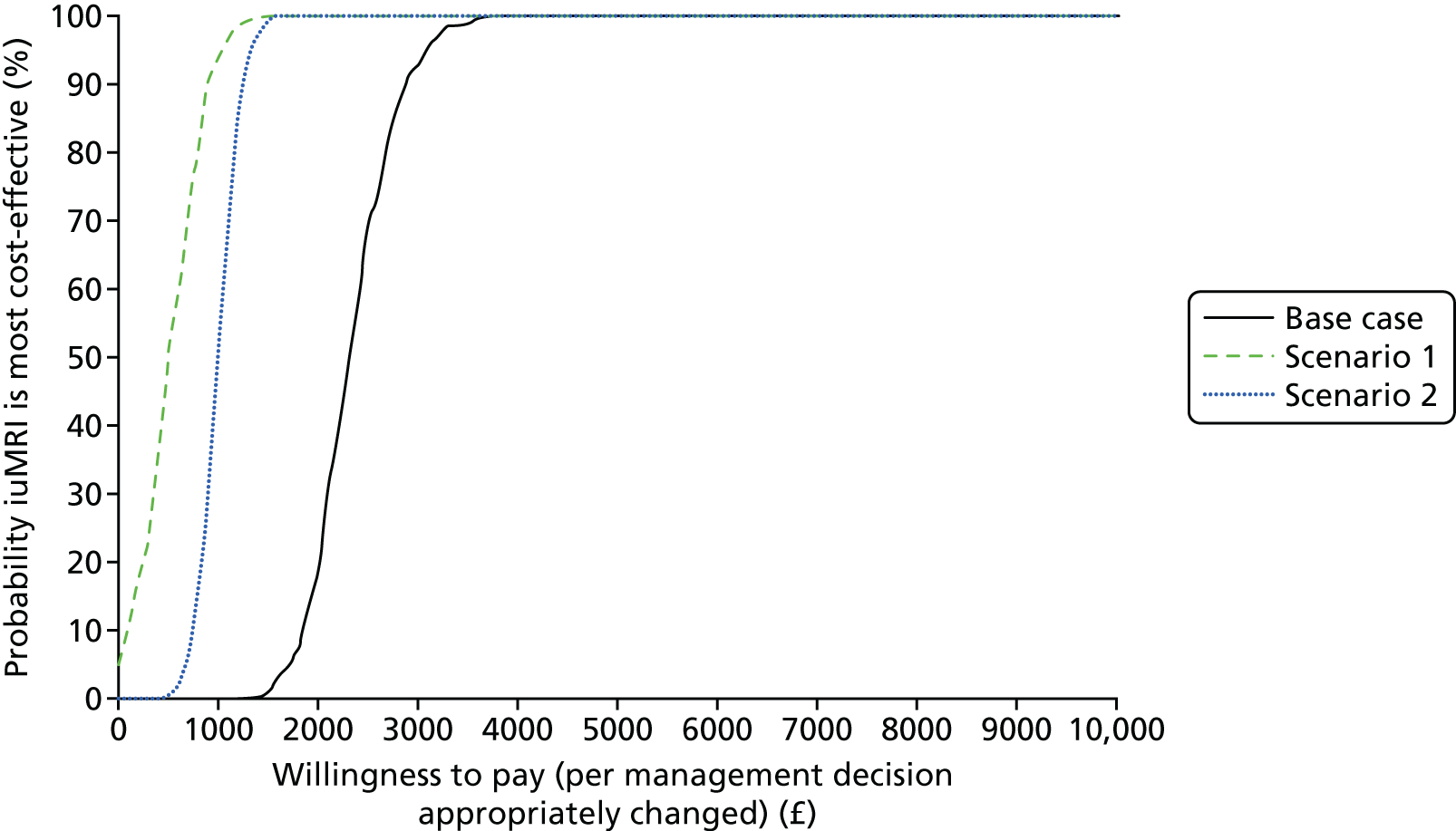

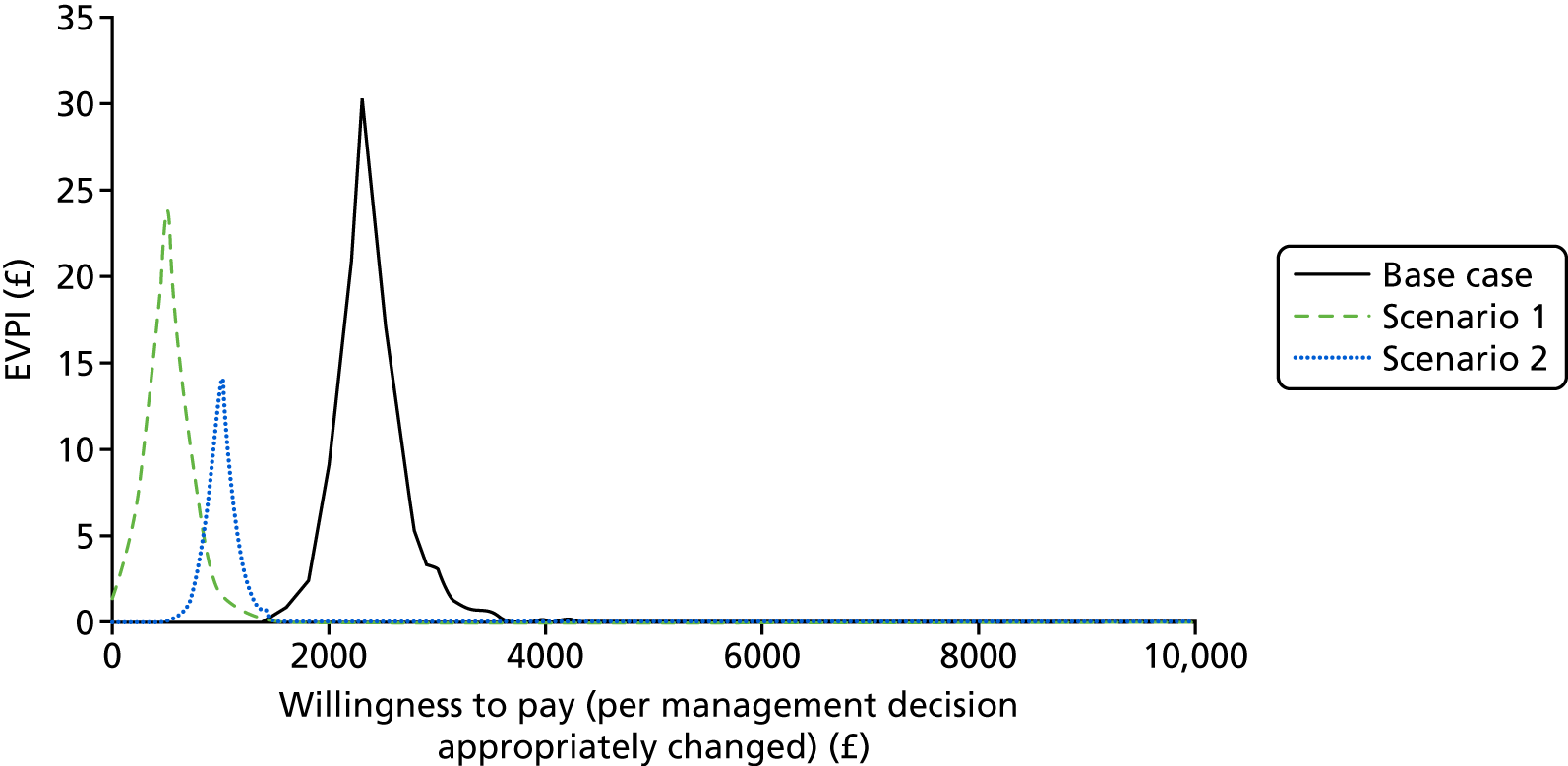

Deterministic analysis and probabilistic sensitivity analysis were conducted for the base case and for the two scenarios. The deterministic analysis reports total costs, incremental cost and incremental cost per management decision appropriately revised. The probabilistic sensitivity analysis samples each uncertain value from its associated probability distribution (i.e. normal for mean costs, log-normal for resource use, beta for proportions; see Appendix 2) simultaneously and reports the probabilistic mean cost per management decision appropriately revised. Cost-effectiveness acceptability curves are presented for a range of willingness-to-pay thresholds for appropriate management decisions. The cost-effectiveness acceptability curves are calculated from the proportion of simulations for which the cost per management decision is below each willingness-to-pay threshold and summarise the uncertainty associated with the cost-effectiveness results. The expected value of perfect information (EVPI) analysis is conducted on a per-person basis for varying willingness-to-pay thresholds. The EVPI is the price we would be willing to pay for perfect information about all of the factors that determine which intervention is cost-effective. This is calculated from the difference in monetary benefit when the choice between interventions is made on current information and when the choice is made based on perfect information with no uncertainty. EVPI is calculated at each willingness-to-pay threshold (per management decision appropriately changed, from £0 to £10,000):

-

Each uncertain parameter is sampled from its associated distribution – this is called ‘one run’.

-

For each run, the following are calculated:

-

the net benefit of iuMRI (appropriate management decisions are valued using the willingness-to-pay threshold and the cost of the iuMRI strategy, for TOP and continued pregnancies)

-

the net benefit of ultrasonography

-

the net benefit with perfect information (the maximum of the net benefit of iuMRI and the net benefit of ultrasonography).

-

-

The mean over all the runs is calculated for:

-

the net benefit of iuMRI

-

the net benefit of ultrasonography

-

the net benefit with perfect information.

-

-

The expected outcome with current information is calculated as:

-

the maximum of the mean net benefit of iuMRI and the mean net benefit of ultrasonography.

-

-

The EVPI is calculated as:

-

the difference between the mean net benefit with perfect information and the expected outcome with current information.

-

Some participant records were missing data on some elements of resource use. In order to include as many participants as possible in the analysis, imputed missing data were analysed. The imputation used multivariate normal regression with 75 replicate data sets with age (years), distance from iuMRI unit, the total number of fetal unit visits and gestational age at iuMRI as predictors of missing costs. Imputed missing data are analysed for the base case, scenario 1 and scenario 2.

Inclusion of participant-borne costs

Two scenarios considered participant-borne costs, including costs for mileage and costs for participant time to travel to and undergo an iuMRI procedure. The first analysis considered the whole population. The second analysis considered only patients whose mileage was < 40 miles to estimate the potential results of reconfiguring services so that iuMRI could be locally available. Outcome data were the same as in the base case.

Subgroups by gestational age

Subgroup analyses separately considered participants with a gestational age at iuMRI of < 22 weeks, 22–24 weeks and > 24 weeks. Total costs, the proportion of TOPs and the proportion of management decisions correctly revised following iuMRI are analysed separately for the subgroups.

Comparison with second ultrasonography

This analysis compares iuMRI with repeat ultrasonography, as recommended by the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (RCOG) pathway. In the RCOG pathway, if an abnormality is suspected, the woman should be referred for a second opinion as soon as possible, ideally within 3 working days. 64 As described in Data collection and management, after an iuMRI examination, participants attended a follow-up appointment that included a follow-up ultrasonography to determine whether or not the additional information from iuMRI was visible on follow-up ultrasound scans.

In this scenario, the proportion of management decisions appropriately revised following iuMRI is adjusted to account for the improved diagnostic accuracy of a second ultrasonography. This downgrades the effect of iuMRI to take into account the proportion of abnormalities that would have been detected by a repeat ultrasonography. The proportion of management decisions appropriately revised is multiplied by the proportion of cases in which the additional diagnostic information obtained from iuMRI was not visible on follow-up ultrasonography. The proportion of participants having a TOP following a second ultrasonography is calculated using the following approach:

-

Cross-tabulating the number of cases when TOP was offered following ultrasonography by the number of cases when TOP was offered following iuMRI to calculate the number of cases in which the management decisions agreed or disagreed.

-

Multiplying the number of cases when ultrasonography and iuMRI do not agree by the proportion of cases when the new information from iuMRI was not visible on follow-up ultrasonography, to calculate the proportion of cases when the second ultrasonography and iuMRI would agree or disagree.

-

Calculating the proportion of cases when TOP would be offered following the second ultrasonography.

-

Multiplying the proportion of cases when TOP would be offered following the second ultrasonography by the proportion of cases for which TOP was offered following iuMRI in which TOP happened.

In this scenario, the same costs for the iuMRI and ultrasonography pathway (whether or not the participant had a TOP) are used, but there is a cost for one additional two-dimensional ultrasonography and consultation for all participants in the second ultrasonography pathway.

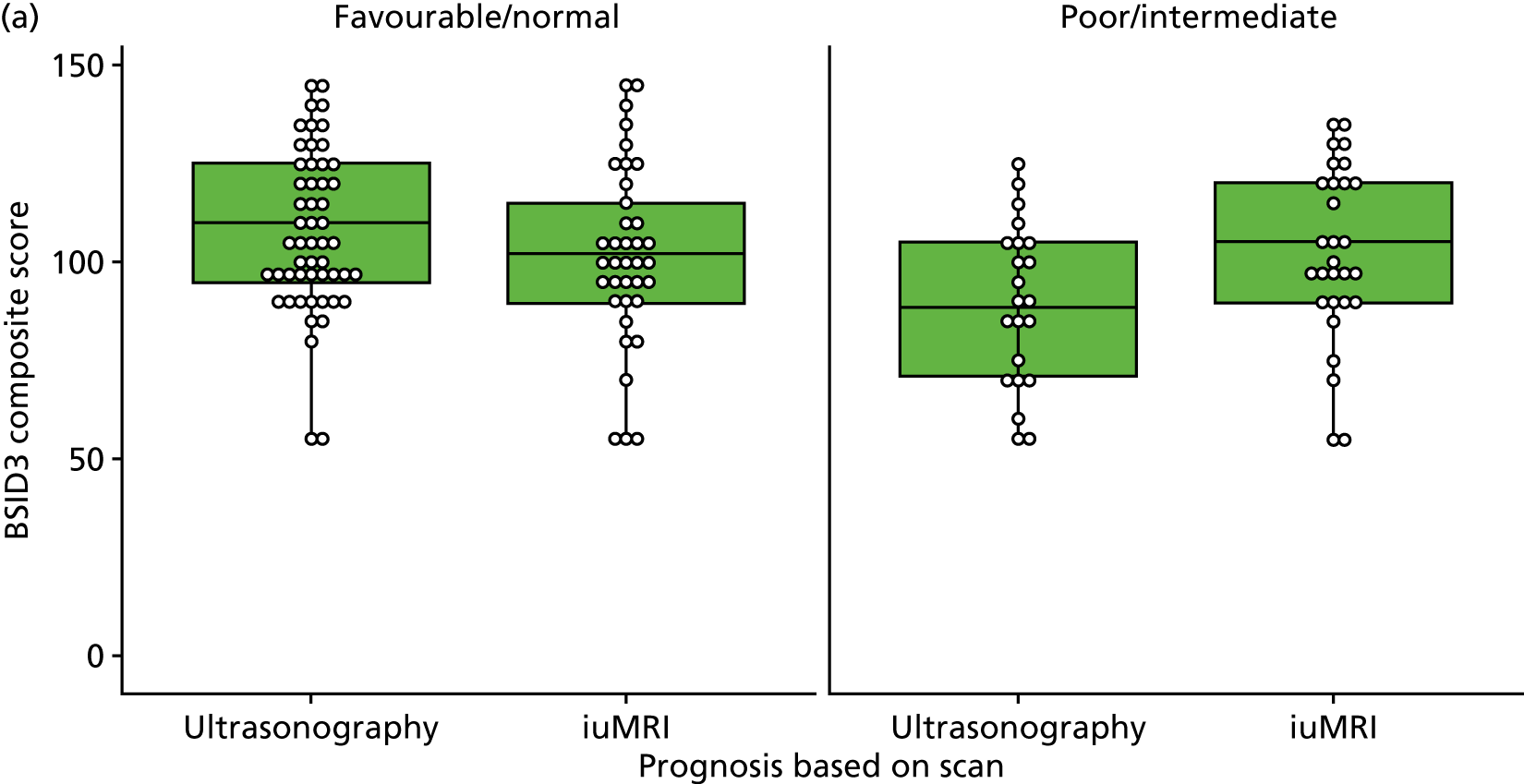

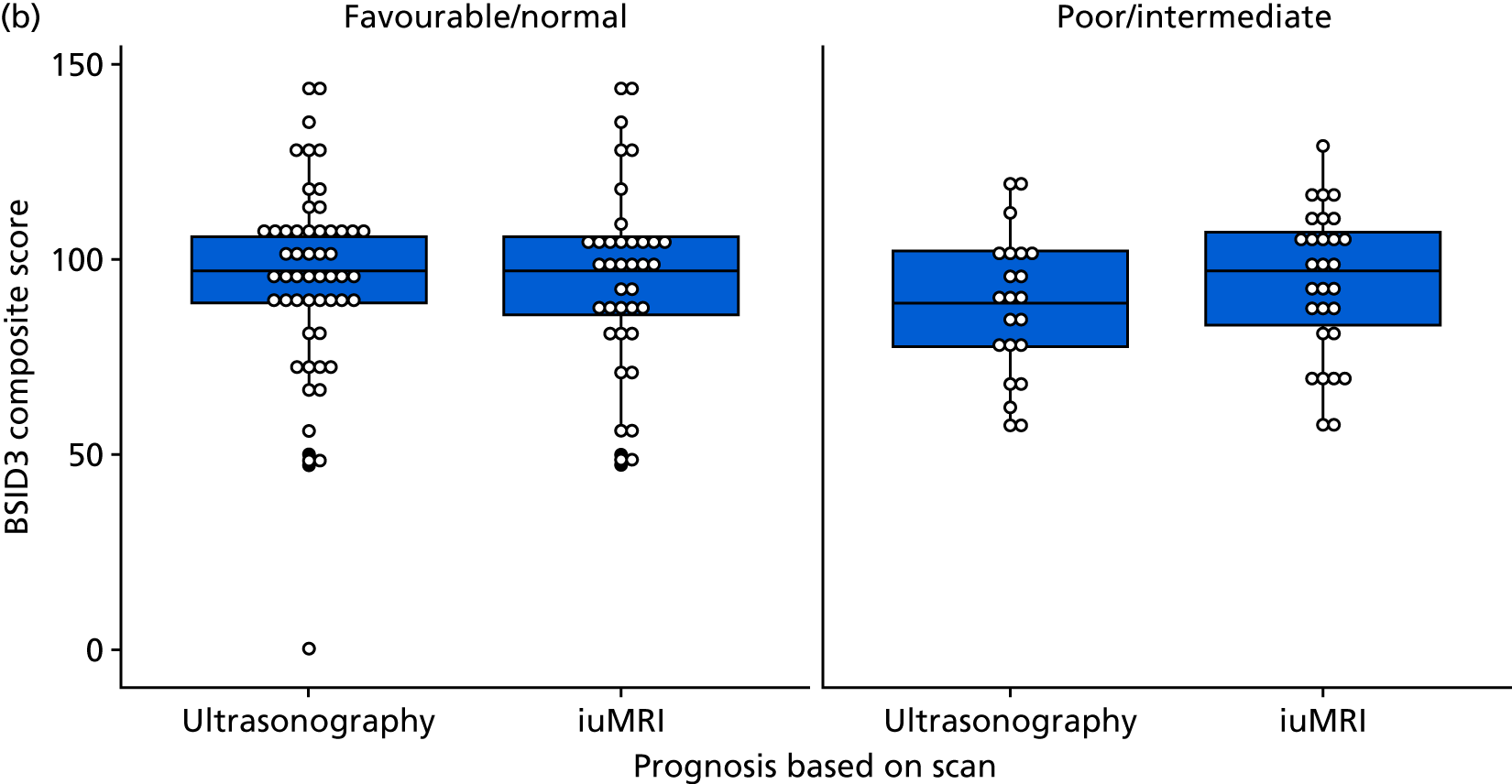

Longer time horizon

This scenario considers costs over a longer time period, to include the cost of additional care for children born with disabilities. This analysis uses the proportions of children with abnormalities, borderline abnormalities and no abnormalities from the follow-up study to estimate the long-term costs associated with continued pregnancies. In the follow-up study, at 2–3 years, 31% of children had abnormalities, 14% of children had borderline abnormalities and 56% of children had no abnormalities (see Table 38).

A published study of the economic costs of childhood psychiatric disorders reports the mean public sector costs over the previous year of life for children with and without psychiatric disorders by level of cognitive impairment. 65 The costs were estimated by collecting resource use data from parents when the child was 11 years of age. The annual costs for moderate and severe impairment without psychiatric disorders were £5529 and £5842, respectively, inflated to 2016 prices. 60 Our analysis assumed that these costs would be applicable each year up until the age of 11 years, and so considered long-term cost for 11 years. Beyond the age of 11 years, it is anticipated that the costs could change substantially as children enter adolescence and their needs change. Children born with no abnormalities are assumed to incur no additional costs, children with abnormalities incur the costs associated with severe cognitive impairment and children with borderline abnormalities incur the costs associated with moderate cognitive impairment. Costs are discounted at 3.5% per annum. 66

Costing scenarios

The following three scenarios consider changes to the costs included in the analysis. These were applied to the base case, scenario 1 and scenario 2 to explore the sensitivity of the variation in results to the costing assumptions.

Delivery costs excluded

This scenario considers the same costs as the base case, except that it excludes the costs for the delivery of continued pregnancies.

Delivery and termination costs excluded

This scenario considers the same costs as the base case, except that it excludes the costs for TOP and the costs for the delivery of continued pregnancies.

Increased termination cost

This scenario considers a higher cost of termination, assuming that the cost for termination at 20 weeks’ gestation for a 2.1-day stay did not involve feticide and that feticide would incur an additional cost of £366. In this scenario, the cost for a termination without feticide was £1581 and the cost for a termination with feticide was £1947.

Patient and public involvement

Representatives from Antenatal Results and Choices (ARC) and the Spina Bifida, Hydrocephalus, Information, Networking, Equality (SHINE) charities were involved in the study oversight throughout the project through the Trial Steering Committee (TSC). This included the review and development of the study protocol and patient documents, monitoring the study progress and review and discussion of the final results of the study. Feedback from the patient and public involvement (PPI) members informed our approach to potential participants and the content of the participant information sheets. The PPI members also had input in the content of the results summary/participant debrief letter and the method for disseminating results to participants.

Study governance and management

Study governance

The study conduct was governed by a number of oversight committees: the Trial Management Group (TMG), the TSC and the Data Monitoring and Ethics Committee (DMEC). The trial was conducted in accordance with Sheffield CTRU standard operating procedures (SOPs) and the committees convened at appropriate intervals as dictated by both study requirements and SOPs.

The TMG was composed of the chief investigator (chairperson), study collaborators and key staff within the CTRU and Newcastle University. The TMG met monthly or bimonthly via teleconference during trial recruitment and follow-up.

The TSC members were approved and appointed by the funder. The TSC was composed of a professor of fetal and maternal medicine as the independent chairperson, an independent consultant in neuroradiology, experts in antenatal screening and supporting families who provided expert advice and acted as PPI representatives. The DMEC consisted of an independent statistician, a professor of health-care research (chairperson) and a fetal medicine consultant. The TSC received formal recommendations from the DMEC.

Ethics arrangements and regulatory approvals

The study and subsequent amendments were approved by the Yorkshire and The Humber – South Yorkshire Research Ethics Committee (REC) (reference number 11/YH/0006). Each participating site gave UK NHS Research and Development approval. The study was conducted in accordance with the principles of good clinical practice.

Protocol amendments after study initiation

Details of substantial amendments submitted to the REC, which were important changes to trial methodology, are listed below.

Multidisciplinary independent expert panel

The original protocol stated that agreement between the PND and the outcome diagnosis would be judged independently by two fetal medicine experts and that a third expert would arbitrate if there was a discrepancy in opinion. In June 2011, the protocol was revised to state that an independent expert panel would be appointed to assess agreement rather than two independent experts. The independent expert panel was to consist of a fetal medicine clinician, a paediatric neuroradiologist and a paediatric neurologist or neurosurgeon.

Outcome data collection

A number of measures were introduced to assist with the collection of follow-up data about the outcome of the pregnancy. First, a data-collection sheet for handheld notes was developed; this sheet requested basic details of where and when the participant delivered. This meant that the research midwife could be notified of the delivery and could subsequently request the appropriate outcome data.

We also implemented the option of a postmortem MRI. When a woman opted for TOP, or when there was a neonatal death, we aimed to gather the results of any postmortem autopsies performed for clinical purposes. However, the offer of a postmortem is often declined; therefore, we introduced the option of a non-invasive postmortem MRI examination that could be performed in addition to, or instead of, a postmortem autopsy.

Following feedback from sites where, in some cases (e.g. mild VM that resolved during pregnancy), clinicians did not advocate postnatal imaging, we modified our ORD to include a third-trimester ultrasonography in cases of resolved VM.

Recruitment target

The recruitment target was changed on the advice of the DMEC and TSC from 750 participants to ‘at least 750 participants’ to ensure that the required 504 complete cases were obtained.

Chapter 3 Study results

Recruitment and participant flow

Between July 2011 and August 2014, 1101 women carrying 1109 fetuses were identified as potentially eligible. Of those, 198 women (198 fetuses) were deemed to be ineligible on further screening or declined participation, resulting in 903 participants (911 fetuses) being recruited. A total of 80 participants (82 fetuses) did not complete ultrasonography and iuMRI (see Figure 1). A total of 64% of all participants attended the Academic Unit of Radiology at the University of Sheffield for their iuMRI and the remaining 36% of participants attended one of the five collaborating centres. ORD was available in 638 out of 829 (77%) fetuses, of which 570 out of 638 (89%) had the iuMRI performed within 2 weeks of the referral ultrasonography. A total of 369 fetuses (65%) were in the 18–23 weeks’ gestational age group (110% of required) and 201 fetuses (35%) were in the ≤ 24 weeks’ gestational age group (120% of required). The three commonest ultrasonography diagnoses were isolated VM (306/570, 54%), an abnormality restricted to the contents of the posterior fossa (81/570, 14%) and failed commissuration (79/570, 14%).

Of the 1101 potential participants, 198 women were ineligible or declined participation. A total of 86 of these potential participants were not asked to be part of the study. The most common reason for this was that the consultant considered it to be clinically inappropriate or unhelpful (n = 50, 58%). A total of 112 potential participants were offered to participate but declined. There were several reasons for refusal that were all reported with a similar frequency [i.e. decision had already been made (n = 18), unwilling to travel (n = 13), does not want iuMRI (n = 28) and too upset or distressed (n = 11)]. A full summary of these reasons can be found in Appendix 3.

Characteristics

Participant characteristics are shown in Table 2. The majority of participants completed their iuMRI in the host institution (Sheffield, 67% of the ‘ORD available cohort’). Belfast had a large number of participants who were excluded (n = 14, 17%) because of the time delay between the ultrasonography referral and the iuMRI. The median maternal age of the ‘ORD available’ cohort was 29 years (IQR 24–33 years). The median gestational age of the ‘ORD available’ cohort was 22.5 weeks (IQR 21.4–26.5 weeks). A total of 95% of the ‘ORD available’ cohort were singleton pregnancies. The majority (56%) of this cohort had a dominant diagnosis of VM.

| Characteristic | ORD available (N = 570) | ORD unavailable (N = 175) | Excludeda (N = 84) |

|---|---|---|---|

| iuMRI site, n (%) | |||

| Sheffield | 380 (67.0) | 120 (69.0) | 31 (37.0) |

| Birmingham | 75 (13.0) | 34 (19.0) | 15 (18.0) |

| Newcastle | 66 (12.0) | 6 (3.4) | 9 (11.0) |

| Leeds | 34 (6.0) | 12 (6.9) | 11 (13.0) |

| Nottingham | 12 (2.1) | 3 (1.7) | 1 (1.2) |

| Belfast | 3 (0.5) | 0 (0.0) | 17 (20.0) |

| Maternal age at approach (years), median (IQR) | 29 (24–33) | 28 (24–33) | 30 (25–35) |

| Gestational age at iuMRI (weeks), median (IQR) | 22.5 (21.4–26.5) | 22.0 (21.2–24.7) | 24.8 (23.1–28.5) |

| Singleton pregnancy, n (%) | 539 (94.6) | 165 (94.3) | 80 (96.4) |

| Dominant diagnosis on ultrasonography, n (%) | |||

| Isolated VM | 321 (56.0) | 33 (19.0) | 51 (63.0) |

| ACC | 89 (16.0) | 51 (29.0) | 9 (11.0) |

| Posterior fossa | 81 (14.0) | 44 (25.0) | 9 (11.0) |

| Other | 79 (14.0) | 47 (27.0) | 12 (15.0) |

Uptake of in utero magnetic resonance imaging

The iuMRI was successful in and diagnostic images were obtained from 823 participants (829 fetuses). Second iuMRI studies were performed on 97 participants and seven of these had a third iuMRI study. All follow-up studies were successful and useful diagnostic images were obtained.

Uptake of ultrasonography

A total of 681 mothers had two-dimensional ultrasonography and 140 mothers had both two-dimensional and three-dimensional ultrasonography. Technical factors experienced during ultrasonography are summarised in Appendix 4.

Outcome of pregnancy

Of the 829 fetuses undergoing both ultrasonography and iuMRI, 642 (77%) were livebirths, 124 (15%) underwent TOP and 53 (6.4%) were categorised as stillbirths, miscarriages, intrauterine demise or deaths within the postnatal follow-up (Table 3). Data were not available for 10 (1.2%) fetuses.

| Outcome of pregnancy | ORD available, n (%) (N = 570) | ORD unavailable, n (%) (N = 175) | Excluded, n (%) (N = 84) | Overall, n (%) (N = 829) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Livebirth | 482 (84.6) | 90 (51.4) | 70 (83.3) | 642 (77.4) |

| Stillbirth or miscarriage/fetal demise | 20 (3.5) | 27 (15.4) | 6 (7.1) | 53 (6.4) |

| Terminated | 68 (11.9) | 51 (29.2) | 5 (6.0) | 124 (15.0) |

| Not available | 0 (0.0) | 7 (4.0) | 3 (3.6) | 10 (1.2) |

Diagnostic source for outcome reference diagnosis

The most frequently used diagnostic source for ORD in the primary cohort was transcranial ultrasonography (n = 261, 46%; Table 4). Postnatal MRI was used in one-quarter of cases (n = 144, 25%).

| Diagnostic source for ORD | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Transcranial ultrasonography | 261 (46.0) |

| Postnatal MRI | 144 (25.0) |

| Postmortem autopsy | 70 (12.0) |

| Third-trimester ultrasonography | 63 (11.0) |

| Postnatal computed tomography | 19 (3.3) |

| Abnormality visible on postnatal inspection | 11 (1.9) |

| Postmortem MRI | 2 (0.4) |

Agreement

Overall

The overall diagnostic accuracies of ultrasonography and iuMRI were 68.1% and 93.0%, respectively, with a difference of 24.9% (95% CI 21.1% to 28.7%; Table 5). The difference between ultrasonography and iuMRI increased with gestational age: in the 18–23 week group, the diagnostic accuracies were 69.9% for ultrasonography and 92.4% for iuMRI (difference of 22.5%, 95% CI 17.8% to 27.2%); in the ≥ 24 week group, the diagnostic accuracies were 64.7% for ultrasonography and 94.0% for iuMRI (difference of 29.3%, 95% CI 22.6% to 36.1%).

| Gestational age | Ultrasonography correct, n (%) | iuMRI correct, n (%) | Percentage difference (95% CI) | p-valuea |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 18–23 weeks (N = 369) | 258 (69.9) | 341 (92.4) | 22.5 (17.8 to 27.2) | < 0.0001 |

| ≥ 24 weeks (N = 201) | 130 (64.7) | 189 (94.0) | 29.3 (22.6 to 36.1) | < 0.0001 |

| Combined (N = 570) | 388 (68.1) | 530 (93.0) | 24.9 (21.1 to 28.7) | < 0.0001 |

In 386 out of 570 cases (67.7%), both the ultrasonography and iuMRI reports were correct, and in 144 out of 570 cases (25.3%), the ultrasonography report was incorrect but the iuMRI report was correct. There were two fetuses (0.4%) for whom the ultrasonography was correct and the iuMRI was incorrect and 38 (6.7%) fetuses for which both the ultrasonography and the iuMRI were incorrect.

Missing data

Of the 175 fetuses with no ORD, ultrasonography and iuMRI agreed in 86 cases and disagreed in 89 cases. In the most conservative assumption possible, ultrasonography would be correct in all 175 cases, with iuMRI incorrect in all cases of disagreement, resulting in a diagnostic accuracy for ultrasonography of 76.6% and for iuMRI of 82.7%. The difference of 7.1% (95% CI 3.0% to 11.2%), although vastly reduced, remains highly statistically significant (p = 0.0007). The improved diagnostic accuracy of iuMRI over ultrasonography was, therefore, not attributable to missing data.

A less extreme method of handling a missing ORD was to assume that it was missing at random and then to predict what the outcome would have been based on other, similar fetuses for which ORDs were available. The prediction model took into account the relationship between diagnostic accuracy, the probability of missing ORD data and the following characteristics: maternal age, fetal age (weeks) at time of iuMRI, single/multiple pregnancy, outcome (TOP/no TOP) and prognosis.

A missing ORD was more commonly encountered among individuals with a normal, poor or unknown prognosis, but was similar in relation to whether or not iuMRI changed the prognosis. The association of missing data with a prognosis was similar regardless of whether the prognosis was based on ultrasonography or iuMRI. As there were no missing data for the ultrasonography prognosis, it was used in the prediction model. Missing data were also more commonly observed among individuals who underwent TOP, although this was highly associated with the prognosis. Missing data were slightly more common among younger fetuses but showed little association with maternal age or single/multiple pregnancy. Because gestational age was associated with diagnostic accuracy (the diagnostic accuracy of ultrasonography was reduced in those of older gestational age), this was retained in the prediction model along with the prognosis based on ultrasonography.

Using the prediction model to predict missing outcomes (under the assumption of missing at random), the diagnostic accuracy of ultrasonography was 66.9% and iuMRI was 92.8%, resulting in a slightly greater difference of 25.9% (95% CI 22.3% to 29.7%).

All participants with outcome reference diagnosis

The primary analysis was repeated on all participants who had scans and an ORD (Table 6). Similar results to the primary analysis were observed and the overall diagnostic accuracies of ultrasonography and iuMRI, at 68.8% and 92.3%, respectively, resulted in a difference of 23.5% (95% CI 20.0% to 27.1%; p < 0.0001).

| Gestational age | Ultrasonography correct, n (%) | iuMRI correct, n (%) | Percentage difference (95% CI) | p-valuea |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 18–23 weeks (N = 399) | 279 (69.9) | 365 (91.5) | 21.6 (17.1 to 26.0) | < 0.0001 |

| ≥ 24 weeks (N = 239) | 160 (66.9) | 224 (93.7) | 26.8 (20.6 to 32.9) | < 0.0001 |

| Combined (N = 638) | 439 (68.8) | 589 (92.3) | 23.5 (20.0 to 27.1) | < 0.0001 |

Repeat in utero magnetic resonance imaging

There were 65 fetuses for which repeat ultrasonography and iuMRI were undertaken and an ORD was obtained. As with the primary analysis, the majority (46/65) underwent iuMRI at the host institution. The median gestational age was 31 weeks with just five fetuses under 24 weeks. The overall diagnostic accuracies of ultrasonography and iuMRI were 67.7% and 87.7%, respectively, indicating a difference of 20.0% (95% CI 7.8% to 32.2%; p < 0.0001; Table 7).

| Gestational age | Ultrasonography correct, n (%) | iuMRI correct, n (%) | Percentage difference (95% CI) | p-valuea |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 18–23 weeks (N = 5) | 4.0 (80.0) | 4.0 (80.0) | 0.0 (20.0 to 20.0) | N/A |

| ≥ 24 weeks (N = 60) | 40.0 (66.7) | 53.0 (88.3) | 21.6 (8.6 to 34.7) | < 0.0001 |

| Repeat MRI (N = 65) | 44.0 (67.7) | 57.0 (87.7) | 20.0 (7.8 to 32.2) | < 0.0001 |

A summary of the analysis repeated on first, single and repeat pregnancies can be found in Appendix 5.

Anatomical subgroup analysis

Isolated ventriculomegaly

Ventriculomegaly was the most common brain abnormality for referral to the MERIDIAN study. 67 In 421 out of 570 (74%) fetuses, VM formed part of the ultrasonography diagnosis; in 306 out of 570 (54%) fetuses, VM was the only brain abnormality diagnosed on ultrasonography. This analysis is based on the 306 cases with isolated VM on ultrasonography.

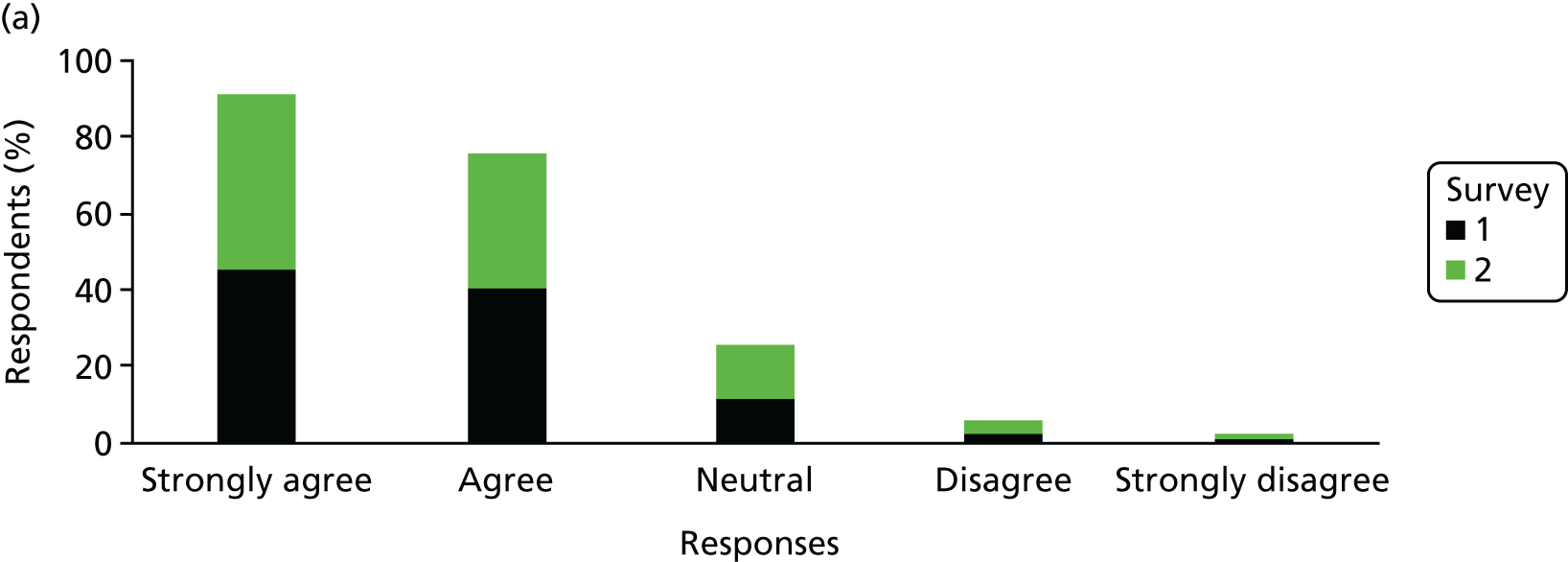

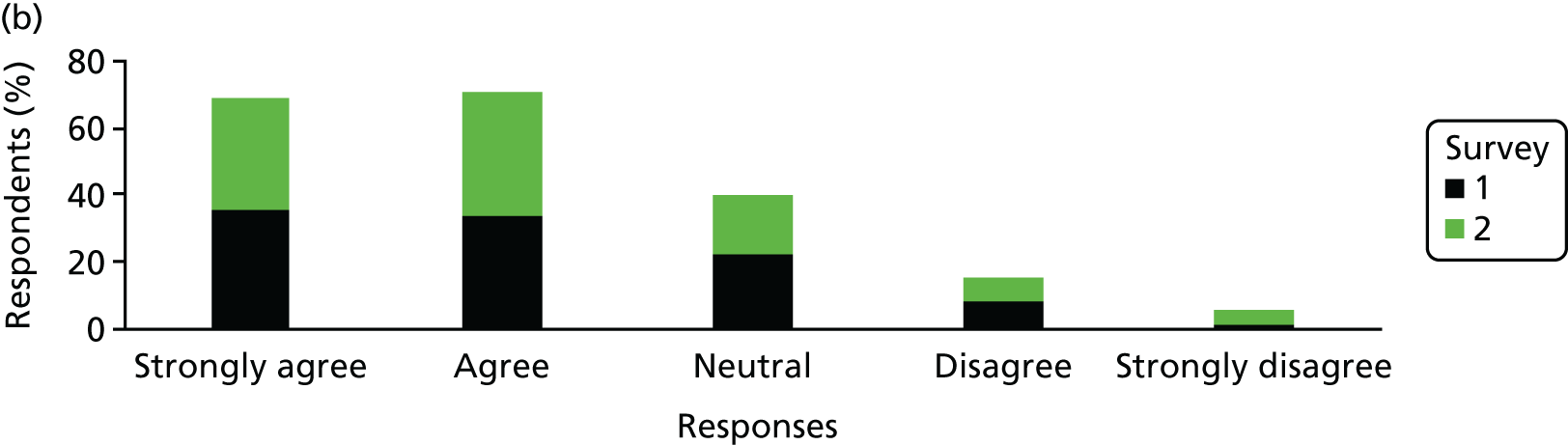

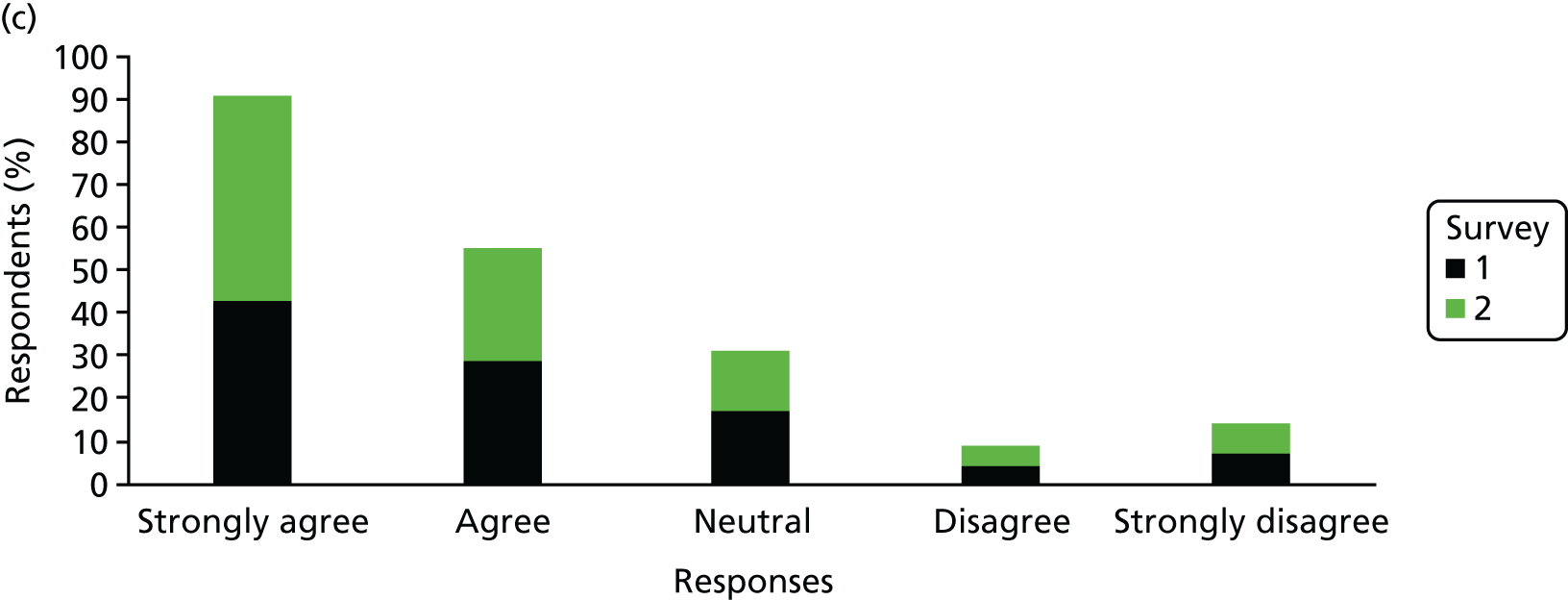

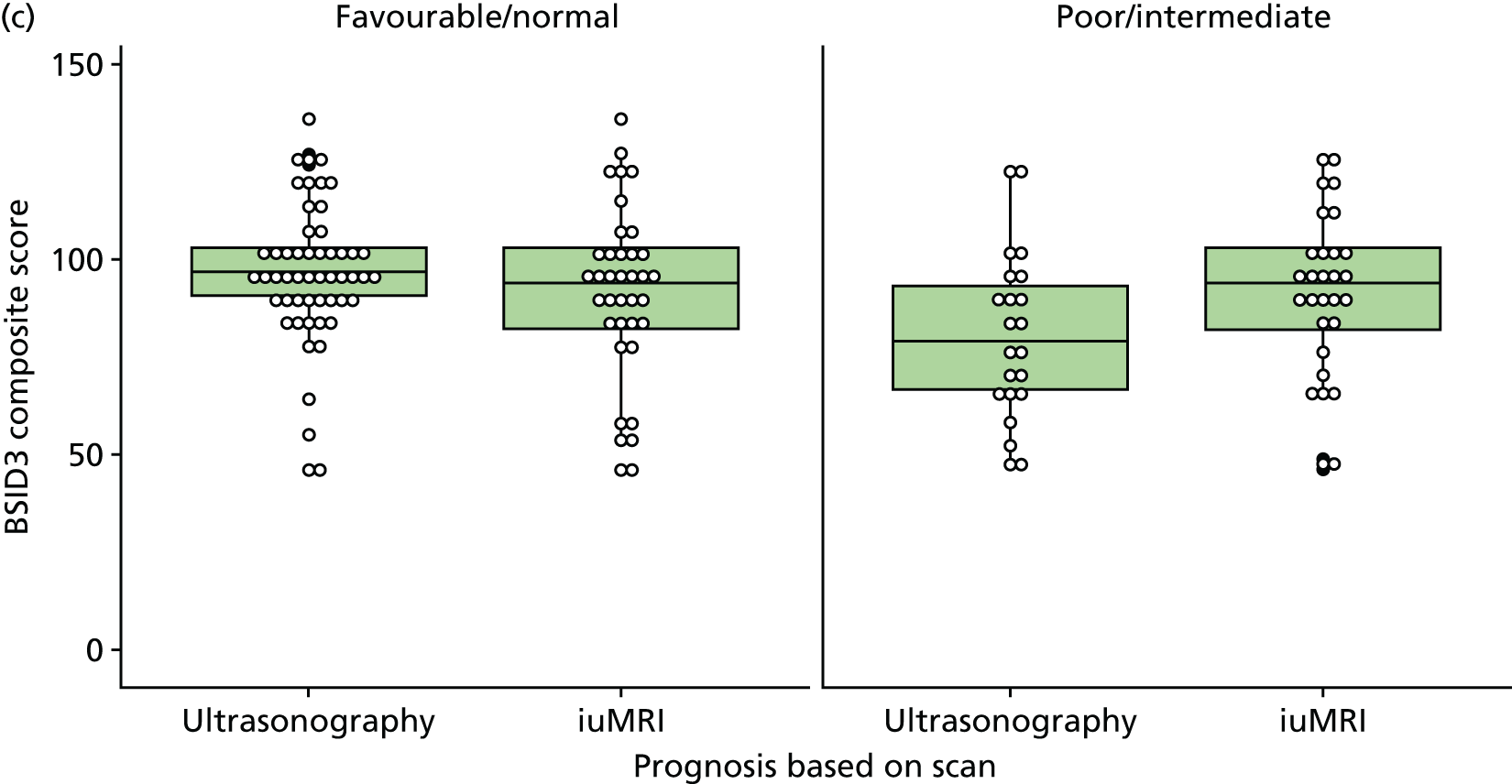

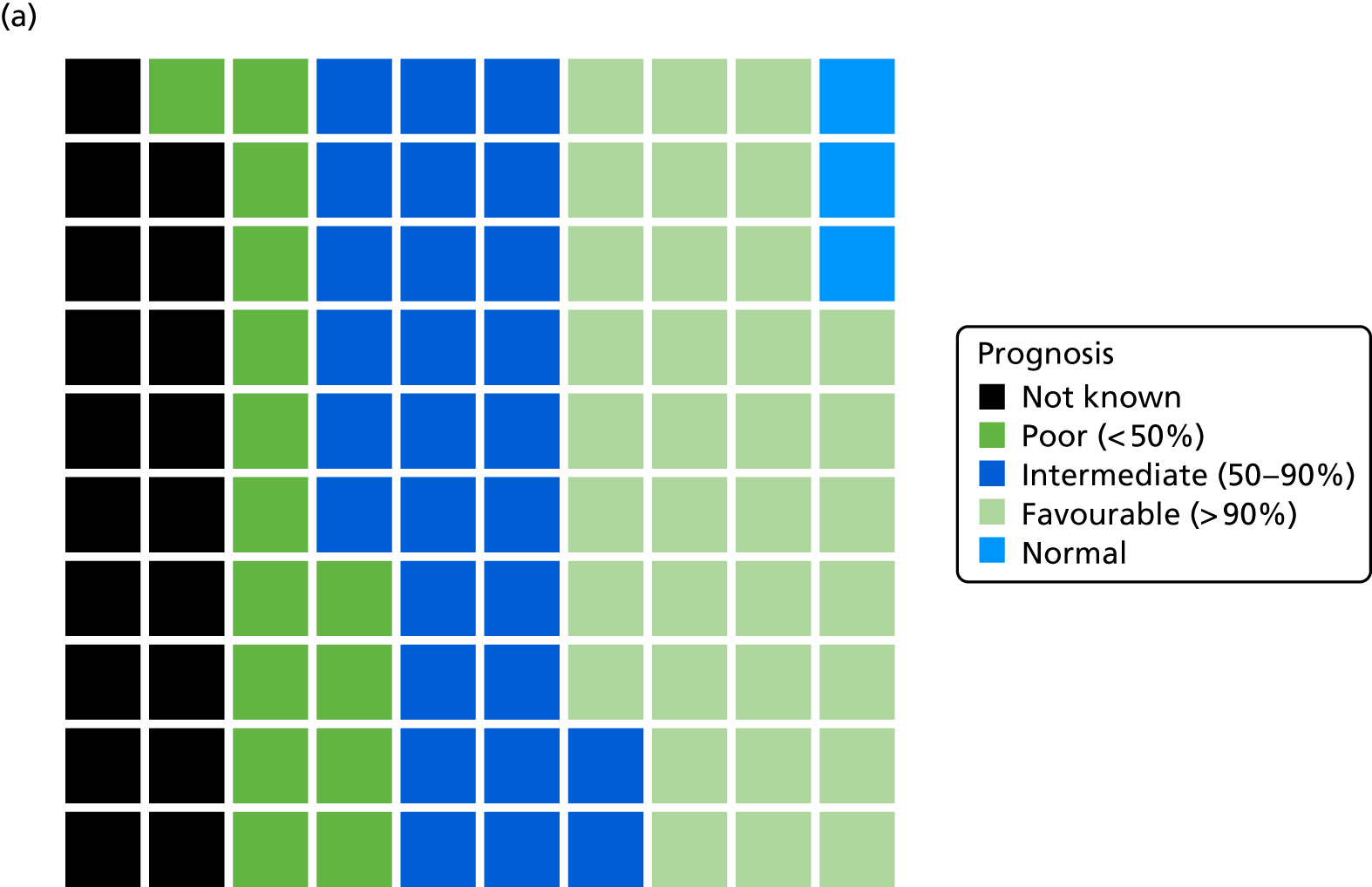

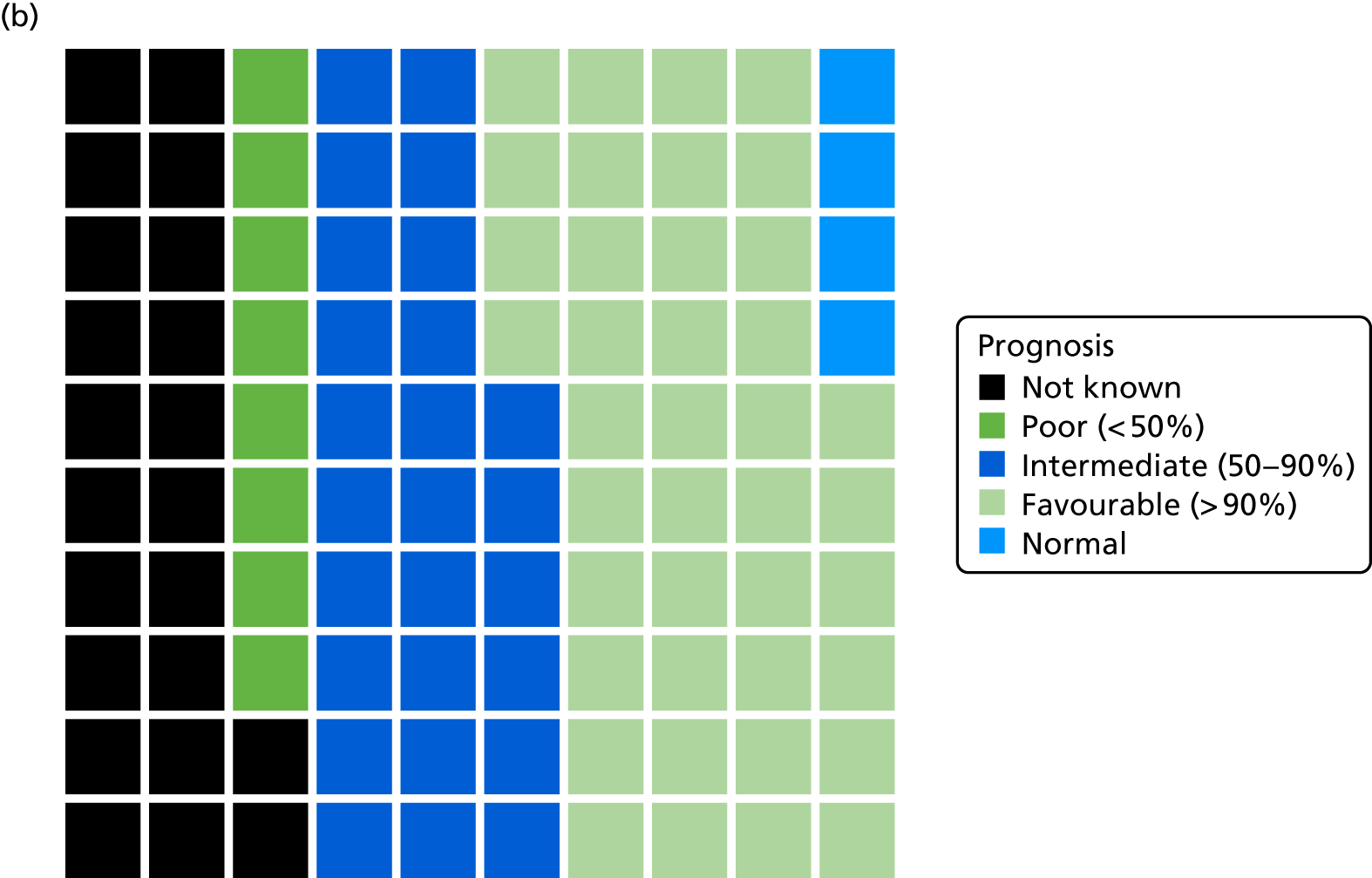

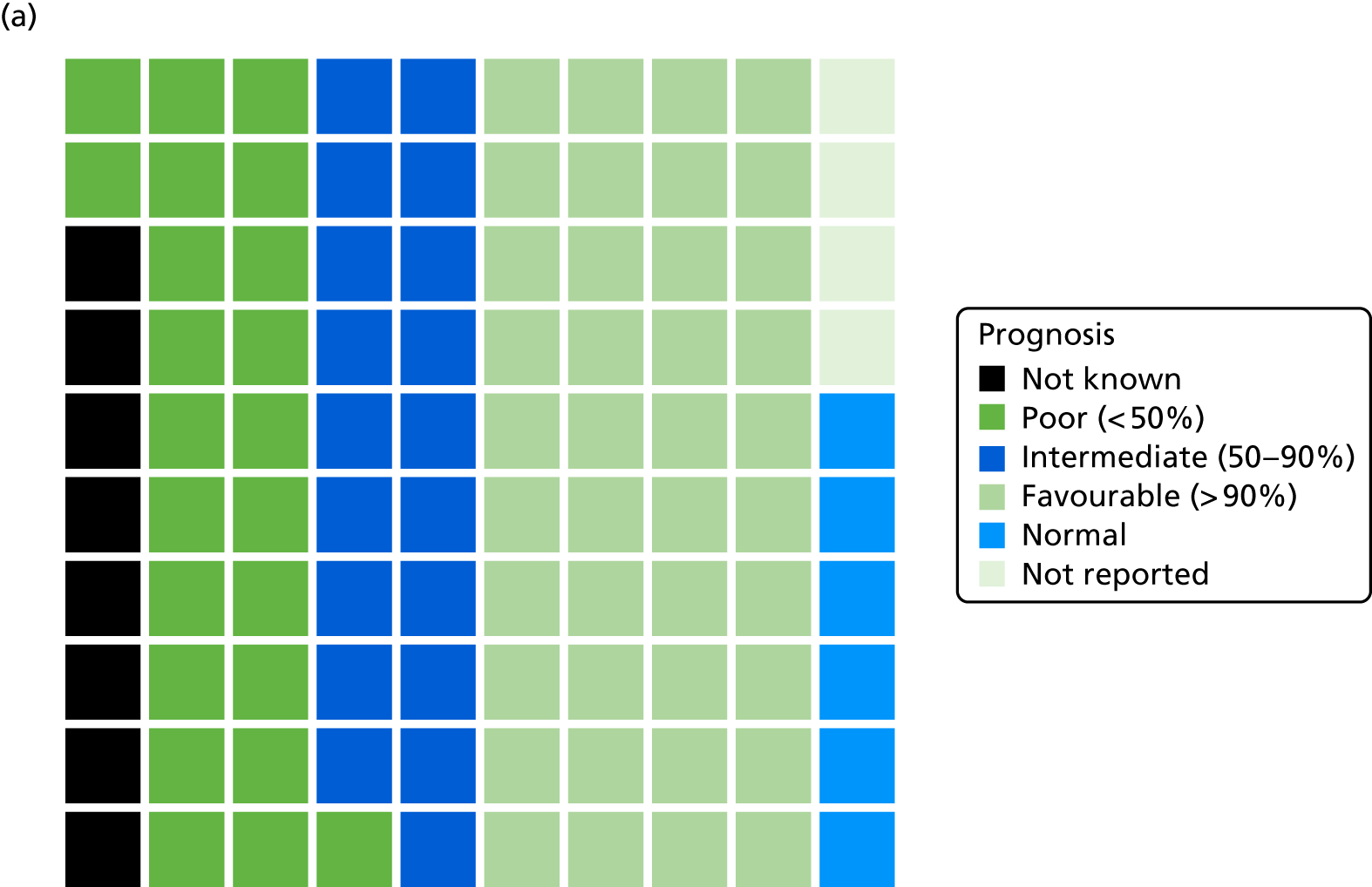

A total of 199 out of 306 (65%) cases were in the 18–23 weeks group at the time of iuMRI and 107 out of 306 (35%) cases were in the ≥ 24 weeks group. The category of VM was determined by the largest trigone measurement and were divided into mild (10–12 mm), moderate (13–15 mm) and severe (≥ 16 mm) categories. Ultrasonography diagnosed mild VM in 244 out of 306 (80%) fetuses, moderate VM in 36 out of 306 (12%) fetuses and severe VM in 26 out of 306 (8%) fetuses.