Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 15/59/22. The contractual start date was in June 2016. The draft report began editorial review in March 2018 and was accepted for publication in June 2018. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Matthew L Costa is a member of the UK National Institute for Health Research Health Technology Assessment General Board.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2019. This work was produced by Griffin et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2019 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Introduction

Background

Fractures of the distal femur are increasingly common injuries. They account for 5% of all fractures of the femur with an estimated incidence of 10 per 100,000. 1 The optimal management of these fractures remains controversial. There is a bimodal distribution of the incidence of these fractures with age. 2 The majority, approximately 85%, are fragility fractures sustained by elderly patients after a fall from a standing height, and the remainder are typically sustained by multiply injured patients after massive trauma. 2 This study will investigate the most common fracture subtype: fragility fractures sustained in the elderly population, often as a consequence of osteoporosis.

Fragility fractures of the distal femur occur in the same population as hip fractures. 3 Similar to hip fractures, these are significant injuries in a vulnerable group of patients, causing considerable morbidity and mortality as well as placing a major financial burden on the NHS. 4 Hip fracture is approximately 10 times more common than fracture of the distal femur. 1 However, the overall incidence of fragility fractures associated with osteoporosis is rising steadily, promising an increasing challenge to future health-care provision. 5

It is current practice to manage displaced fractures with operative fixation if the patient is medically fit enough to undergo surgery. 3,6 Surgery reduces the substantial complications associated with non-operative treatment, such as prolonged immobilisation and bed rest, as well as the problems of non-union and malunion. 7

Since the operative treatment of these fractures was popularised, a wide variety of implants have been employed to achieve fixation. Despite the significant advancements in implant design and manufacture, operative fixation is still associated with substantial complications similar to those seen with hip fractures. 6,8 This reflects the common pathology underlying these injuries, that the bone is weakened by osteoporosis, undermining the stability of the bone–implant construct.

There has been very little research comparing operative technologies for treating distal femoral fractures in this population. A recent Cochrane review9 found few trials in this area, most of which compared outdated implants, such as non-anatomical, non-locking plating systems or earlier-generation nails. Furthermore, important limitations in the methodology of each of the trials were identified, leading to substantial risks of bias. 9 It was suggested that in order to optimise patient functional recovery following this debilitating injury ‘a well-designed, adequately powered, randomised controlled trial (RCT) comparing modern treatments is required’. 9

The two interventions most commonly used in UK practice are intramedullary fixation with a locked retrograde nail (nail) and extramedullary fixation with an anatomical locking plate (plate). 3 Nails offer twin theoretical advantages: the mechanical impact of a long, intramedullary device that is close to the axis of the femur10 and the biological advantages of minimum disruption of the fracture site and stimulation of blood supply through reaming. 11 However, nails provide only limited options for distal locking screws, as all screws must pass through the centre of the nail, so the stability of the bone–implant construct may be suboptimal. Locking plate fixation has been facilitated by recent advances in implant technology that allow the screws to be screwed into the bone as well as the plate itself (‘locked’). This produces a ‘fixed-angle’ bone–plate construct. These plates were designed specifically for use in osteoporotic bone and have been shown to exhibit excellent biomechanical properties. 12 However, they are more expensive than nails and require larger surgical wounds to apply. There are few clinical data available to guide clinicians9 and it is clear that there is no current consensus concerning the best management of these injuries. 3

Relevance of the research

We performed a multicentre retrospective study to review the current management of distal femoral fractures at four UK major trauma centres. 3 We found that only two devices are now used for fixation: retrograde nails and locking plates. In addition, > 80% of these injuries in a population were fragility fractures, which matched those sustaining hip fracture. Furthermore, mortality in this frail elderly group of patients was 20% at 1 year and the prevalence of cognitive impairment was 30% as reported at baseline. 3 The overall annual incidence in each centre was 20 fractures per year. This retrospective study shows the patient demographics, the variability in treatment of these fractures in the UK and the considerable morbidity associated with the injury.

Crucially, we have found that there may be an important difference in outcomes following the choice of surgical management of these patients. The mean benefit of a nail over locking plates may be as great as 0.12 in EuroQol-5 Dimensions (EQ-5D) (p = 0.019). 13 The minimum clinically important difference in EQ-5D score is estimated to be 0.08. 14 Similar effect sizes are demonstrated in other measures of function and quality of life, such as the Glasgow Outcome Scale (extended) and Short Form questionnaire-12 items. 13 These findings have also been reported by other groups. A small pilot study in the USA comparing these technologies found some evidence of a similar benefit in quality of life in favour of nails (mean difference in EQ-5D score was 0.1; p = 0.07). 15

Below we present the null hypothesis and trial objectives for both the proposed definitive trial and the current feasibility trial.

Definitive trial null hypothesis

There is no difference in the EuroQol-5 Dimensions, five-level version (EQ-5D-5L), at 4 months after injury between adults aged > 18 years with an acute, extra-articular fragility fracture of the distal femur treated with ‘locking’-plate fixation (plate) versus retrograde intramedullary nail fixation (nail).

Definitive trial objectives

The objectives of any subsequent definitive trial will be to:

-

quantify and draw inferences on observed differences in health-related quality of life (HRQoL) at 4 months between the study intervention groups (nail versus plate)

-

quantify and draw inferences on observed differences in functional status at 4 weeks, 4 months and 12 months

-

quantify and draw inferences on observed differences in the radiological outcomes of non-union, malalignment and shortening

-

determine the complication profile associated with nail fixation versus locking plate fixation in the first year after the injury

-

investigate, using appropriate statistical and economic analytical methods, the resource use, costs and comparative cost-effectiveness of nail fixation versus locking plate fixation.

Feasibility trial objectives

The objectives of this feasibility study were to:

-

estimate the number of eligible patients in the UK population and the proportion of those eligible who are willing to consent to take part in the study

-

optimise the protocol, procedures and CRFs in preparation for a future definitive trial

-

perform a process evaluation to better understand the implementation, mechanisms of impact and context of the interventions and the generalisability and likely success of any future definitive trial

-

explore the validity of self and proxy reporting of the primary outcome measure in this specific population.

Strict recruitment criteria, against which a decision to determine the feasibility of a definitive trial can be judged, are given below. If these criteria are not met a full trial will not be pursued. These criteria were:

-

an average recruitment rate of 1.0 participants per month per centre

-

appropriate recruitment performance across all feasibility sites.

Chapter 2 Methods

Trial design

Phase I (feasibility study) was designed to determine the expected rate of recruitment in a large-scale multicentre RCT in this complicated area of trauma research. Phase II (definitive trial) is a proposed multicentre RCT in the UK. This report concerns Phase I only.

This feasibility study was a multicentre controlled trial, stratified by centre and cognitive impairment, with balanced randomisation 1 : 1.

In parallel with the conduct of the feasibility study, we also performed a process evaluation in line with the recommendations of the Medical Research Council (MRC)’s guidance. 16 The evaluation focused on investigating the fidelity and quality of implementation, clarifying the causal mechanisms and identifying the contextual factors that might be important in variation of outcome.

Important changes after commencement

Eligibility criteria

The trial protocol17 aimed to include all patients with fragility fracture. Fragility was initially defined using age as a surrogate marker. After reviewing the screening data during recruitment, the Trial Steering Committee (TSC) recommended that an assessment of the feasibility of using a mechanistic definition of fragility should be made within the trial. The minimum age was therefore revised from 50 to 18 years to ensure that all possible fragility fractures were included. The mechanism of injury was recorded during screening and defined using the World Health Organization (WHO)’s definition as a fall from standing height or less.

Participants

Inclusion criteria

Patients were eligible for this study if they:

-

were ≥ 18 years

-

had a fracture of the femur involving the distal two ‘Müller’ squares18

-

would, in the opinion of the attending surgeon, benefit from internal fixation of the fracture.

Many of the patients who sustain this injury have some degree of cognitive impairment, similar to patients sustaining hip fracture. Some have chronic cognitive impairment3 and some develop acute delirium at the time of presentation to hospital. 19 Cognitive status is an important independent predictor of patients’ baseline functional, quality-of-life status and likely outcome in this population. 19,20 This is possibly related to patients’ pre-injury independence, post-injury expectations and ability to participate fully in their rehabilitation. Inclusion of these patients was essential to determine specific effect sizes in this subgroup and so that the sample properly reflected the population sustaining this injury.

Exclusion criteria

Patients were excluded from this trial if they had:

-

a loose knee or hip arthroplasty requiring revision

-

pre-existing femoral deformity

-

an arthroplasty that precluded nail fixation.

Patients who sustained injuries to areas of the body other than the lower limbs, which may affect the primary outcome measure, were still included in the analysis. For patients with bilateral fractures of the distal femur, a rare event, both fractures were recorded but only one fracture was included in the trial. The treating surgeon decided which injury to include in the study prior to randomisation.

All patients who were eligible for inclusion in Trial of Acute Femoral Fracture Fixation (TrAFFix) and their personal consultees, as well as all staff members involved in the research and intervention delivery, were eligible to be approached about participating in qualitative interviews as part of the process evaluation.

Screening and trial recruitment

The clinical care team notified the research team of any potentially eligible patients. Non-identifiable patient details were then used for screening in the emergency department and trauma wards at the trial centres. Reasons for patients’ exclusion or ineligibility were recorded.

Consent to trial participation

The nature of these injuries meant that the great majority of patients were operated on immediately or on the next available trauma operating list, depending on access to an appropriate operating theatre. Some patients were unconscious, all were distracted by the injury to their lower limb and its subsequent treatment and all had large doses of opiates for pain relief, potentially affecting their ability to process information. Similarly, patients’ next of kin, carers and friends were often anxious at this time and had difficulty in weighing the large amount of information that they were given about the injury and plan for treatment. In this emergency situation, the focus was on obtaining consent for surgery (when possible) and informing the patient and any next of kin about immediate clinical care. The consent procedure for this trial reflected that of the surgery, with the clinical team assessing capacity before taking consent for the surgical procedure and this capacity assessment then being used to decide on the proper approach to consenting to the research. The appropriate method, as described below, was used to gain either prospective or retrospective consent from the patient or appropriate consultee by a good clinical practice-trained, appropriately delegated, member of the research team.

Conducting research in this ‘emergency setting’ is regulated by the Mental Capacity Act 2005. 21 As patients may have lacked capacity as described above, and because the urgent nature of the treatment limited access to and appropriate discussion with personal consultees, we proposed to act in accordance with section 32, subsection 9b of the Mental Capacity Act 2005 following a process approved by the relevant Research Ethics Committee (REC): the clinical team would make an assessment of capacity as per usual procedures for obtaining consent for a surgical procedure. The clinical team then provided guidance to the research team as to whether the patient had capacity to consent prospectively or if consultee agreement should be sought.

When the clinical team advised that prospective patient consent was appropriate, this was sought by the research team. If the clinical team advised that prospective patient consent was not appropriate, the research team approached an appropriate consultee. When a personal consultee was available, they were provided with the study information. The personal consultee was given the opportunity to ask questions and discuss the study, after which their written agreement was recorded. When a personal consultee was not available then a nominated consultee was identified to advise the research team. The nominated consultee was the patient’s treating surgeon. If that surgeon was a member of the research team, another independent surgeon was identified. Consent or agreement for further participation into the study after surgery was then sought by the patient themselves or a personal/nominated consultee.

Those patients who were able to consent before their operation were always approached for consent before surgery. For those patients who did not consent prior to surgery, the research associate (RA) provided the patients with all of the study information at the first appropriate time when the patient regained capacity. The patients were given the opportunity to ask questions and discuss the study with their family and friends. They were then asked to provide written consent for continuation in the study. Patients were asked to consent to long-term follow-up and data linkage to routine NHS data sets.

For those patients who did not prospectively consent or who had a nominated consultee give prospective agreement and still lacked capacity after their surgery, a personal consultee was contacted to advise the research team about the patient’s continued participation in the study.

Patients or personal consultees who preferred not to be actively involved in the study follow-up were asked if they were willing to consent to the research team using their routinely collected NHS data for the study.

Responsibility for recording and dating both oral and written informed consent or agreement was with the investigator, or persons delegated by the investigator, who conducted the informed consent discussion. Permission was sought to inform the patient’s general practitioner (GP) of their participation in the study.

Recruitment and consent to process evaluation

As part of the initial consent process, patients and their personal consultees were asked whether or not they could be approached about participating in interviews regarding their views on participating in this trial. Written agreement from participants or their personal consultees to be approached for an interview was sent to the TrAFFix research office. Participants who did not consent to the main trial were also given the opportunity to participate in an interview with a member of the research team.

Participants who agreed to be approached underwent a separate informed consent discussion for the interviews with a member of the research team either in person, by telephone, or by post. Written informed consent was provided when the interviews were face to face and verbal informed consent was recorded if the interviews took place by telephone.

NHS staff were initially invited for an interview by telephone or e-mail, and if they agreed to be approached an informed consent discussion took place with a researcher from the TrAFFix office by telephone or in person.

As part of the process evaluation, conversations between researchers and participants or personal consultees were audio recorded. This included the initial discussion about TrAFFix, before informed consent for the main study has been given. When patients agreed, their verbal consent was recorded at the start of the recording. When patients did not agree, the informed consent conversation continued as usual without being recorded.

Settings

The trial was run in seven NHS hospitals across the UK (Box 1).

John Radcliffe Hospital, Oxford University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust (PI: Mr David Noyes).

Leeds General Infirmary, The Leeds Teaching Hospitals NHS Trust (PI: Professor Peter Giannoudis).

Queen’s Medical Centre, Nottingham University Hospitals NHS Trust (PI: Professor Ben Ollivere).

Queen Alexandra Hospital, Portsmouth Hospitals NHS Trust (PI: Ms Charlotte Lewis).

Royal Berkshire Hospital, Royal Berkshire NHS Foundation Trust (PI: Mr Andrew McAndrew).

Royal Stoke Hospital, University Hospitals of North Midlands NHS Trust (PIs: Mr Haroon Majeed and Mr Damian McClelland).

Leicester Royal Infirmary, University Hospitals of Leicester NHS Trust (PI: Mr Ashwin Kulkarni).

PI, principal investigator.

Sample size

Data from this feasibility study can be used to calculate estimates of the standard deviation (SD) of the primary outcome measure (EQ-5D-5L) to drive a formal power analysis and sample size calculation for a definitive trial. Evidence from other relevant sources for EQ-5D-5L22,23 can also be used to inform this process.

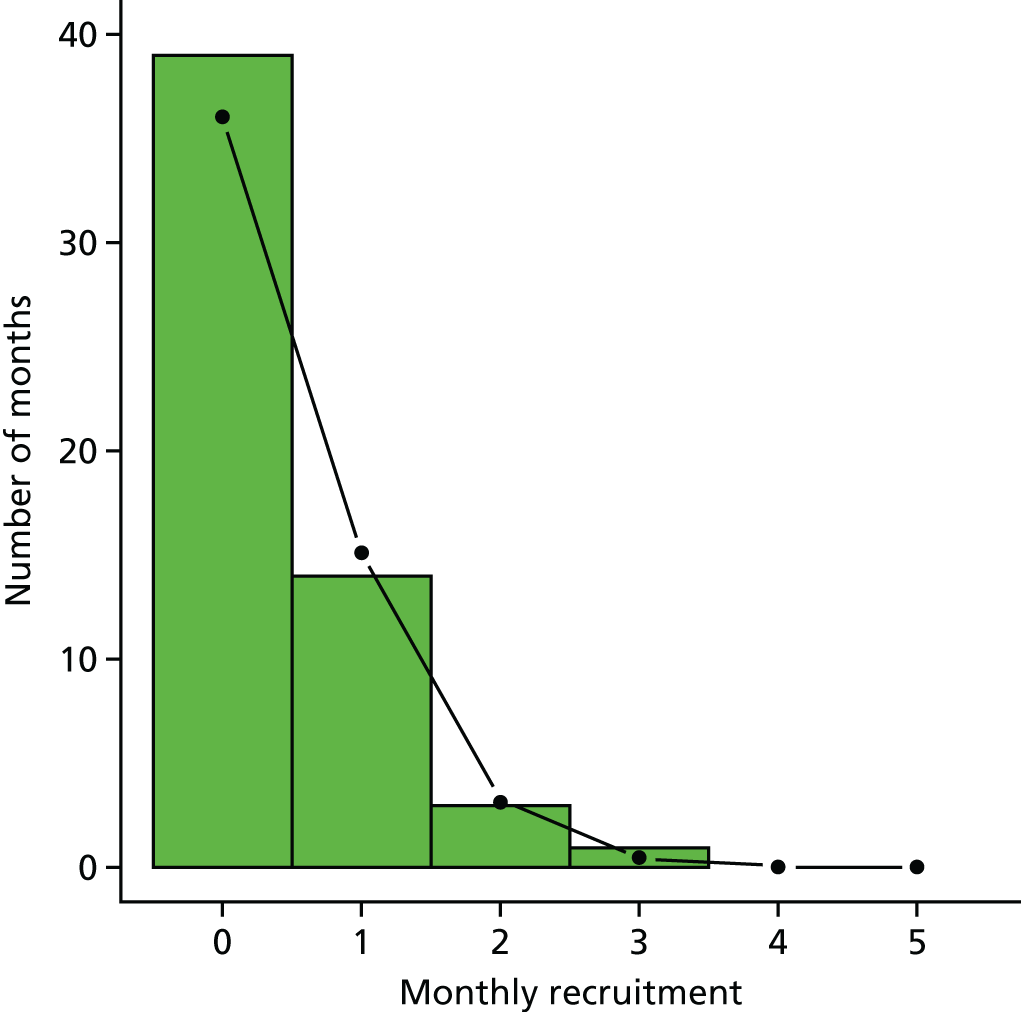

We anticipated that each of the participating centres would treat approximately 1.5 eligible patients per month. 3 Taking a conservative approach, we expected, to ensure feasibility, to be able to recruit 1.0 patients per month per centre. Given our schedule for centre opening times and recruitment length, we had 52 centre.months available to recruit for this study. Assuming that the recruitment rate was 1.0 per month per centre, and that monthly centre counts of patient recruitment numbers were approximately Poisson distributed and independent of one another, would allow us to estimate the recruitment rate with a 95% confidence interval (CI) of 0.73 to 1.28. 24 Therefore, recruiting 52 patients in total would provide sufficiently precise estimates of the monthly recruitment rate to decide if a definitive trial was feasible.

For the qualitative interviews with participants, convenience sampling was used. We intended to sample participants until data saturation was achieved; however, as there were fewer than anticipated potential participants, we approached all participants who were willing to be interviewed. For the interviews with staff, we used a purposive sampling strategy that included an interview with at least one surgeon [i.e. the principal investigator (PI)] and a RA at each of the seven participating centres.

Randomisation

Sequence generation

Stratification by centre ensured that any clustering effects related to the centre itself were equally distributed across the trial arms. This would not eliminate centre- or surgeon-specific effects, but, because between 10 and 30 surgeons were likely to be involved in the management of the patient group, any one surgeon would treat only two or three patients enrolled in the trial. Patients were also stratified by chronic cognitive impairment, which was judged by the clinical team on randomisation, to ensure that participants with cognitive impairment were allocated evenly across the treatment groups.

Allocation implementation

Eligible participants were recruited by a trial RA or member of the clinical team using a secure online registration and randomisation system provided by the Oxford Clinical Trials Research Unit (OCTRU). Basic information, including the patient’s initials and age and eligibility checks, was entered. The patient then received a trial identifier (ID) that was used on all non-public-facing trial documentation. The treatment allocation was generated prior to surgery, allowing randomisation outside working hours.

Blinding

Participants were informed of their treatment allocation only at the end of the trial. For this trial, surgical scars were evident, which could have given informed participants knowledge of their allocation. The treating surgeons were not blind to the treatment but took no part in the post-operative assessment of the patients. The functional outcome data were collected and entered onto the trial central database by a research assistant/data clerk in the trial central office. The radiographs collected were reviewed by independent assessors.

Post-randomisation withdrawals

Participants could decline to continue to take part in the trial at any time without prejudice. A decision to decline consent or withdraw did not affect the standard of care the patient received. Once withdrawn, the patients were advised to discuss their further care plan with their surgeon. Data collected up to the point of withdrawal were included in the final analysis. Post-randomisation withdrawals were not replaced.

Interventions

Participants were usually assessed in the emergency department. Diagnosis of a fracture of the distal femur was confirmed from plain radiographs of the femur. When there was doubt over the radiological pattern of the fracture, for example whether or not it extends into the knee, participants were reviewed by the on-call orthopaedic surgeon and, if clinically indicated, computed tomography (CT) was performed; this constituted standard of care practice.

As a minimum, all participants underwent electrocardiography, had a full blood count, underwent group and save investigations, had a coagulation screen, and underwent urea, creatinine and electrolytes tests. Routine thromboprophylaxis was started in all participants who were not already receiving anticoagulant therapy. Pharmaceutical and mechanical prophylaxis measures were used in accordance with the current practice agreed at each centre. A regional or general anaesthesia technique was used and routine analgesia was provided in accordance with local practice.

All participants received perioperative prophylactic antibiotics in accordance with the current practice agreed at each centre. Appropriate preparation, positioning and fracture reduction were left to the discretion of the operating surgeon, as per their normal clinical practice. Participants were randomly allocated to fixation using either intramedullary nailing or locking plate fixation.

All of the hospitals involved in this trial used both methods of fixation3 and all of the consulting surgeons involved will be familiar with both techniques.

Retrograde intramedullary nailing

Fixation of the fracture was achieved with a proximally and distally locked nail that spanned the entire diaphysis of the femur. All nails were introduced retrograde through the knee joint. In this pragmatic trial, the details of surgical incision and approach, fracture reduction and supplementary fixation with wires or screws were at the surgeon’s discretion as per their normal clinical practice.

Locking plate fixation

Fixation of the fracture was achieved with anatomical distal femoral locking plate and screws. Locking plates were defined as those in which at least one fixed-angle locking screw was placed distal to the fracture. The operating surgeon determined the length, number and type of additional screws. Additional fixation with lag screws and cerclage wires was at the surgeon’s discretion. In this pragmatic trial, the details of surgical incision and approach, fracture reduction, number and type of other screws and supplementary fixation with wires or screws were at the surgeon’s discretion as per their normal clinical practice.

Patients received the same standardised written physiotherapy advice detailing the exercises they need to perform for rehabilitation following their injury regardless of which group they were randomised to. All of the patients were advised to move their toes, ankle and knee joints fully within the limits of their comfort. Weight-bearing status was decided by the treating surgeon, with a preference for early weight-bearing mobilisation immediately or as soon as the surgeon felt appropriate. In this pragmatic trial, any other rehabilitation input beyond the written physiotherapy advice (including a formal referral to physiotherapy) was left to the discretion of the treating clinicians. However, a record of any additional rehabilitation input (type of input and number of additional appointments) together with a record of any other investigations/interventions was requested as part of the 6-week and 4-month postal follow-ups and formed part of the trial data set.

Outcomes

Primary

The primary outcome measures for this study were the participant recruitment rate and the completion rate of the EQ-5D-5L at 4 months post surgery.

Other measurements

Other measurements that were made during the trial are summarised in Table 1.

| Pre-randomisation | Time point | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-surgery | Baseline | 6 weeks | 4 months | |

| Fracture classification18 | ✓ | |||

| Cognitive impairment | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Age | ✓ | |||

| Personal details | ||||

| Contact details | ✓ | |||

| Baseline characteristics | ||||

| Date of birth | ✓ | |||

| Sex | ✓ | |||

| Current medications | ✓ | |||

| Comorbidities | ✓ | |||

| Current/previous occupation | ✓ | |||

| Educational attainment | ✓ | |||

| Grip strength | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Self-efficacy report | ✓ | |||

| Rockwood Frailty Scale score | ✓ | |||

| MOS social support | ✓ | |||

| Government benefits | ✓ | |||

| Residential status | ✓ | |||

| Discharge destination | ✓ | |||

| Mobility | ✓ | |||

| Treatment | ||||

| Additional fixation | ✓ | |||

| Anaesthesia | ✓ | |||

| Grade of surgeon | ✓ | |||

| Prescribed medications | ✓ | |||

| Rehabilitation assessment | ✓ | |||

| Outcomes | ||||

| EQ-5D-5L | Pre and post injury | ✓ | ✓ | |

| DEMQoLa | Pre and post injury | ✓ | ✓ | |

| DRIb | Pre and post injury | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Radiographs | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Complications | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Resource use | ✓ | |||

| Qualitative interviewsc | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

Baseline characteristics

Routine baseline characteristics were recorded for all participants to describe the nature of the participants. Additional measurements (described below) were made to more fully describe the groups.

Grip strength

Grip strength is a measure of muscle strength and gives an indication of sarcopenia, a predictor of frailty, and was measured as previously described by Roberts et al. 25

Frailty

The degree of frailty can provide useful predictive information26 and was measured using the Rockwood Frailty Scale. The Rockwood Frailty Scale is a quick nine-point index used to measure frailty. 26

Social support

The Medical Outcomes Survey social support survey is a brief multidimensional, self-administered social support survey. 27

Self-efficacy

Self-efficacy is a measure of an individual’s confidence in their ability to accomplish tasks and overcome problems. Low levels of self-efficacy are associated with less optimal health behaviours. 28

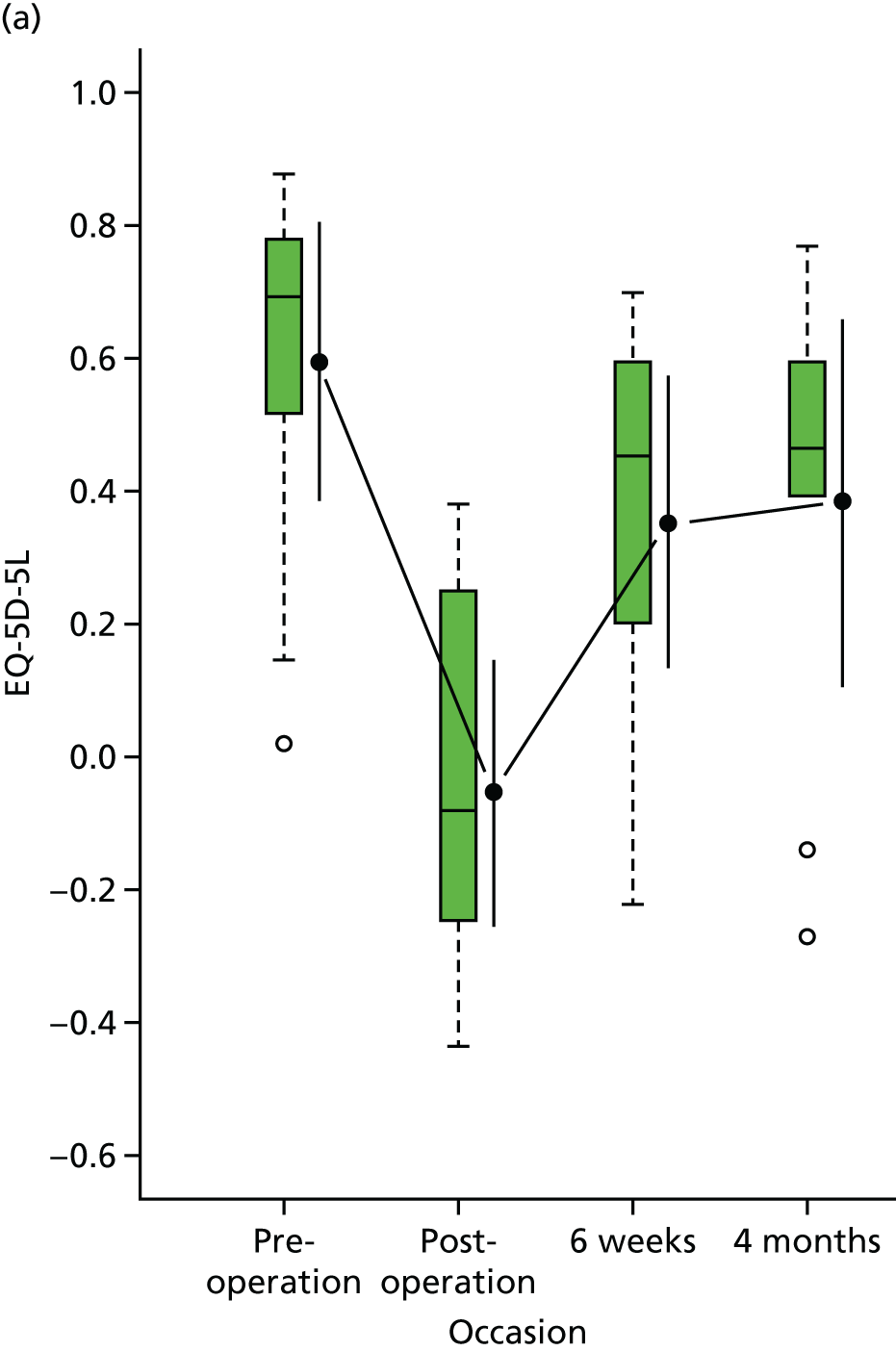

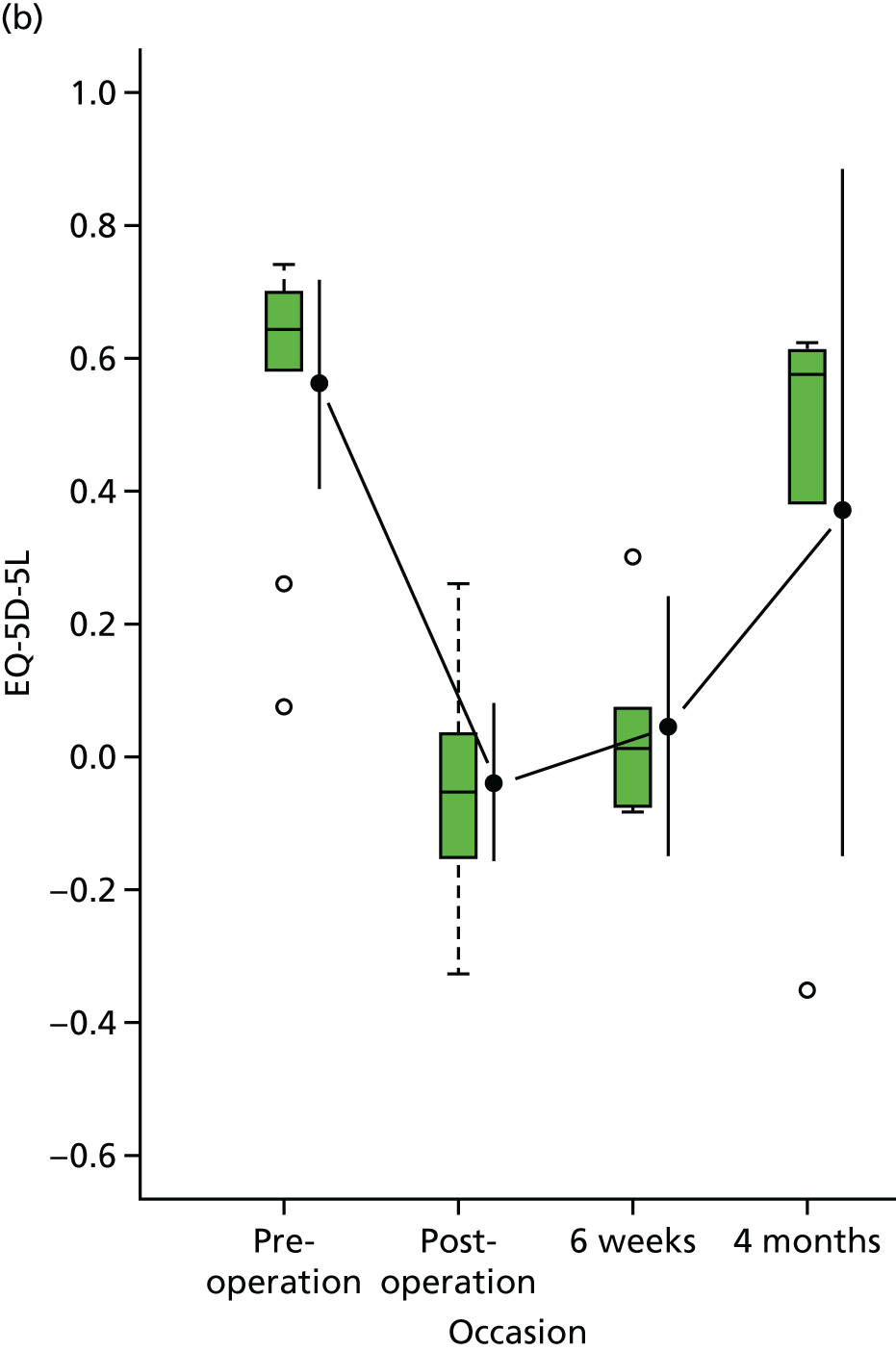

Health-related quality of life

The EQ-5D-5L29 is a validated generalised and standardised instrument comprising a visual analogue scale measuring self-rated health and a health status instrument, consisting of a five-level response (no problems, some problems, moderate problems, severe problems and unable) for five domains related to daily activities:29 (1) mobility, (2) self-care, (3) usual activities, (4) pain and discomfort and (5) anxiety and depression. Responses to the health status classification system are converted into an overall score using a published utility algorithm for the UK population. 30 The EuroQol visual analogue scale scores self-rated health on a scale on which the end points are labelled ‘best imaginable health state’ (100) and ‘worst imaginable health state’ (0). The EQ-5D-5L has some important advantages in this study. It has been validated for use in patients with cognitive impairment, for whom an appropriate proxy may respond to the questions. 31 It can be administered by mail or by telephone. Our recent work has demonstrated it to have excellent measurement properties in comparison with other commonly used disease- and region-specific outcome tools in the similar cohort of patients with fragility hip fracture. 22,23 The EQ-5D-5L scores were collected at baseline (for pre and post surgery), 6 weeks post surgery and 4 months post surgery.

The Dementia Quality of Life Measure (DEMQoL)32 score is a validated questionnaire specifically designed to assess quality of life in patients with dementia. A large minority of the participants in this study are expected to have coexisting dementia. The score can be self- or proxy-reported and comprises 28 or 31 items, respectively. These data were collected at baseline and at 6 weeks and 4 months post surgery in participants who had cognitive impairment. Recently, preference-based utility scores for a UK population have also been published. 33

Lower limb function

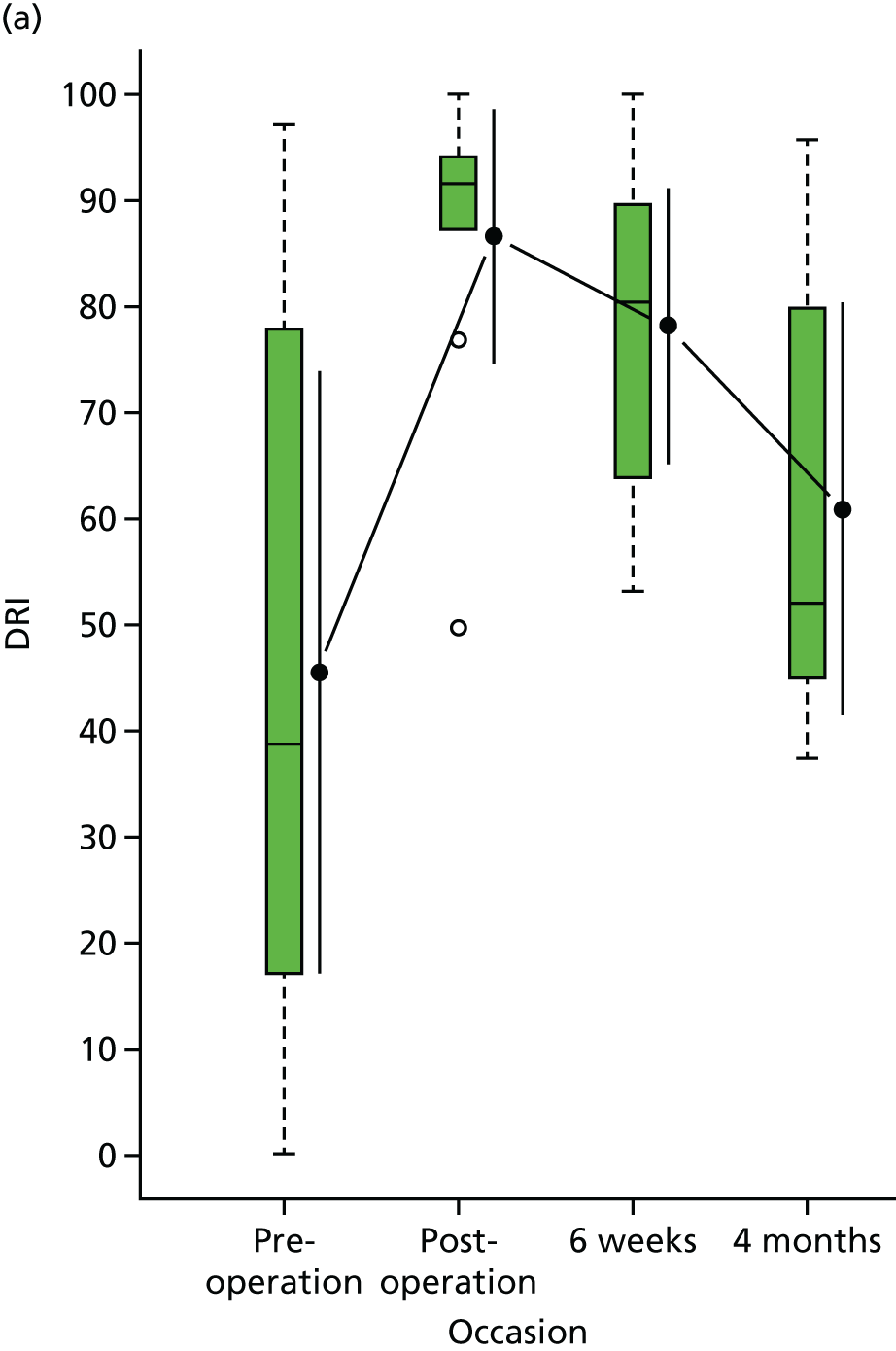

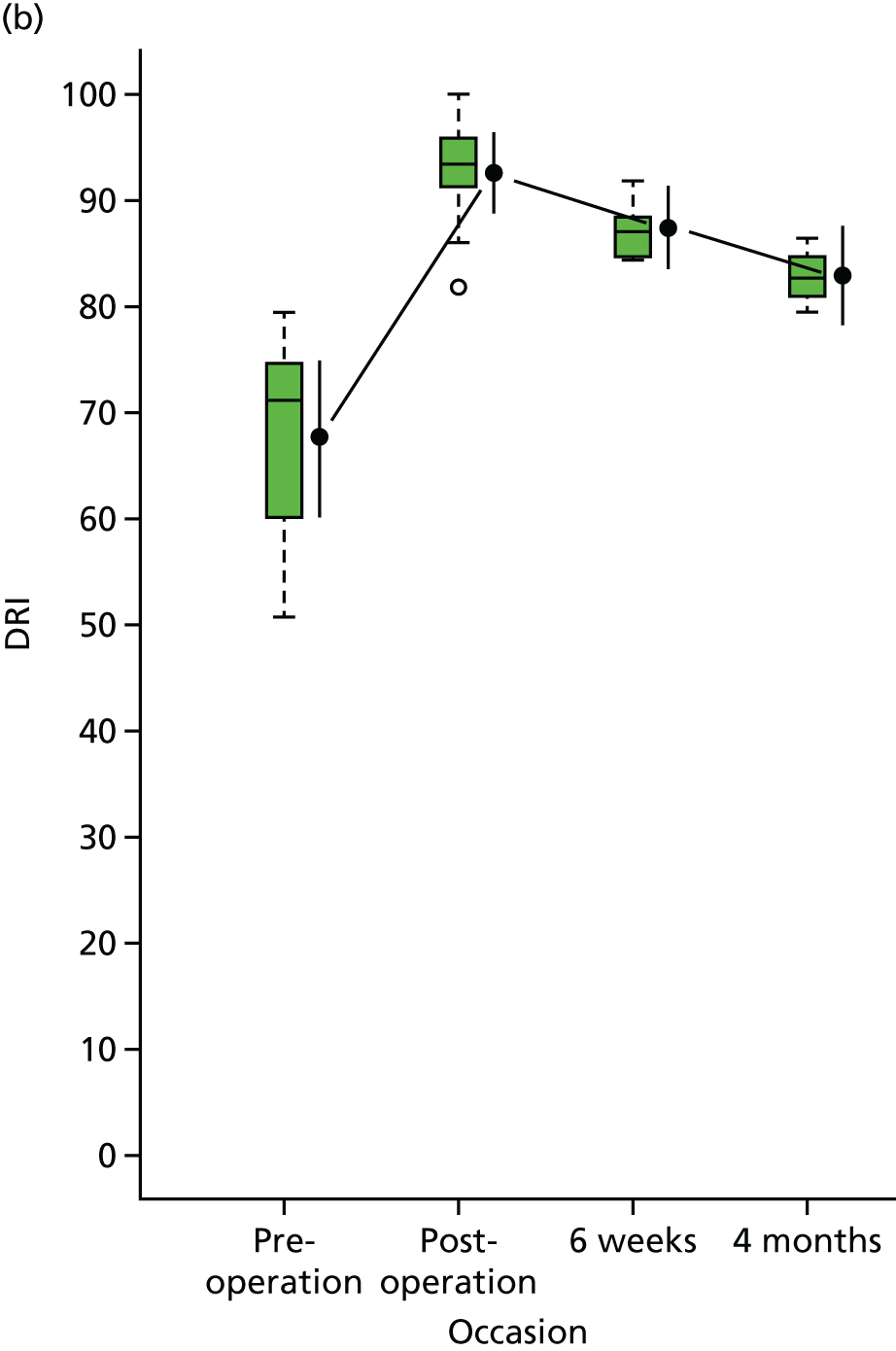

The Disability Rating Index (DRI)34 score is a validated self-reported questionnaire. It comprises 12 items specifically related to function of the lower limb. These data will be collected at baseline and at 6 weeks and 4 months post surgery in participants who do not have cognitive impairment. The DRI34 has been proven to be a robust, practical clinical and research instrument with good responsiveness and acceptability for assessment of disability caused by impairment in the lower limb. 35

Complications

All complications were recorded. Complications were classified as either:

-

unrelated to the trial protocol

-

related systemic complications (including venous thromboembolic phenomena, death, pneumonia, urinary tract infection, blood transfusion, acute cerebrovascular accident, acute cardiac event, other)

-

related local complications (superficial/deep infection, non-/mal-union, failure/removal/revision of metalwork, injury to adjacent structures, such as nerves/tendons/blood vessels, other).

Radiographic evaluation

Standard anteroposterior and lateral radiographs of the femur were assessed for malunion at 6 weeks post injury. Radiographs were those routinely used for the investigation of patients with a suspected fracture of the distal femur and for the follow-up of such patients following any intervention, so that there would be no need for any additional or special investigations. Radiographs were assessed by an independent researcher at each site for:

-

evidence of early loss of fixation

-

varus/valgus of > 5°

-

re/procurvatum of > 10°

-

shortening of > 1 cm.

Semistructured interviews

Patients, carers and staff were asked to participate in qualitative interviews to discuss their experience of participating in the trial and the intervention. Interviews were semistructured, based on a semistructured interview guide (see Appendix 1).

Adverse event management

An adverse event (AE) was defined as any untoward medical occurrence in a clinical trial subject that did not necessarily have a causal relationship with the treatment. All AEs were listed on the appropriate clinical reporting form (CRF) for routine return to the TrAFFix central office. A serious adverse event (SAE) was defined as any untoward and unexpected medical occurrence that:

-

resulted in death

-

was life-threatening

-

required hospitalisation or prolongation of existing inpatients’ hospitalisation

-

resulted in persistent or significant disability or incapacity

-

was a congenital anomaly or birth defect

-

was any other important medical condition that, although not included in the above, may have required medical or surgical intervention to prevent one of the outcomes listed.

Some SAEs were expected as part of the surgical interventions and did not need to be reported to the trial co-ordinating centre, provided that they were recorded on the ‘complications’ section of the CRFs. These included:

-

wound infection

-

venous thromboembolic phenomena

-

blood transfusion

-

death

-

pneumonia

-

urinary tract infection

-

cerebrovascular accident

-

myocardial infarction/acute coronary syndrome

-

damage to a nerve, tendon or blood vessel.

All other SAEs were entered onto the SAE reporting form and sent to the TrAFFix office by e-mail within 24 hours of the principal investigator (or delegated clinician) becoming aware of them. Once received, causality and expectedness were confirmed by the chief investigator. The SAEs that were deemed to be unexpected and related to the trial were notified to the REC within 15 days of being reported to the TrAFFix office. Any such events were be reported to the TSC and Data Monitoring Committee at its next meeting.

All participants experiencing SAEs were followed up as per protocol until the end of the trial.

Risks and benefits

The risks associated with this study were predominantly the risks associated with the surgery: infection, bleeding and damage to the adjacent structures, such as nerves, blood vessels and tendons. Participants in both groups underwent surgery and were potentially at risk from any/all of these complications. There were no data to suggest that the risk is greater in one group than another. We believe that the overall risk profile was similar for the two interventions.

Statistical analysis

Analysis plan

The statistical analysis plan was agreed with the Data Safety Monitoring Committee (DSMC) at the start of the study.

Software

The main analyses were conducted using specialist mixed-effects modelling functions available in the software package R (The R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria), for which EQ-5D-5L29 data were assumed to be normally distributed, possibly after appropriate variance-stabilising transformation.

Data validation

Data returned to the trial office were entered into an OpenClinica database (version 3.7; OpenClinica LLC, Waltham, MA, USA) and data that were missing or failed to pass automatic validation checks were queried with researchers at participating sites. A random sample of 10% of CRFs were checked against the database to ensure accuracy of data entry.

Missing data

The reasons and patterns of any missing data, loss to follow-up and participant withdrawals were carefully considered and reported.

Final statistical analyses

The primary outcome measures for this feasibility study were the participant recruitment rate and the completion rate of the EQ-5D-5L during follow-up. The overall monthly recruitment rate was estimated using Poisson regression analysis, with 95% CIs to assess the likely range of rates in a future main study. Data completeness for the primary EQ-5D-5L outcome was calculated as the percentage of randomised participants completing the HRQoL at baseline and at 6 weeks and 4 months after operation.

Baseline demographics (e.g. age, sex, cognitive status) were compared between groups to ensure that an approximate balance was achieved. This was a small study so group treatment effects were unlikely to be estimated with much precision and, consequently, inferences were tentative and reported as such.

The main analysis of the effects of the intervention investigated differences in the primary outcome measure, EQ-5D-5L29 score at 4 months, between the two treatment groups (nail and plate) on an intention-to-treat basis. In addition, a per-protocol analysis was also reported and early EQ-5D-5L status assessed and reported at 6 weeks. Differences between groups were based on a normal approximation for EQ-5D-5L. 22,23 Tests were two-sided and considered to provide evidence for a significant difference if p-values were < 0.05 (5% significance level). The stratified randomisation procedure ensured a balance in cognitive impairment and recruiting centre between test treatments. Although generally we had no reason to expect that clustering effects would be important for this study, in reality the data would be hierarchical in nature, with patients naturally clustered into groups by recruiting centre. Therefore, we accounted for this by generalising the conventional linear (fixed-effects) regression approach to a mixed-effects modelling approach, in which participants are naturally grouped by recruiting centres (random effects). This model formally incorporated terms that allowed for possible heterogeneity in responses for patients from different recruiting centres, in addition to the fixed effects of the treatment groups, cognitive impairment and other participant characteristics that might prove to be important moderators of the treatment effect (e.g. age and sex).

Secondary analyses were undertaken using the above strategy for approximately normally distributed outcome measures, such as DRI. 34 For dichotomous outcome variables, such as complications related to the trial interventions, mixed-effects logistic regression analyses were undertaken with results presented as odds ratios (and 95% CIs) between the trial groups.

In order to assess the relative performance and merits of EQ-5D-5L and DEMQoL in the study population, we planned to compare the two measures in the subgroup of study participants who were unable to self-report EQ-5D. Given the relatively small size of this study, and minority of participants who were unable to self-report, we anticipated that there would be insufficient data to undertake formal statistical testing for differences between measures. However, graphical presentation of the distribution and relationship (correlation) between measures for individuals would provide some assessment of the merits and metric properties (e.g. variance) of the two measures. Agreement or moderate to strong correlation between measures would indicate that the instruments measure the same underlying trait, which we take to be the true HRQoL of the study participants.

Null hypothesis

For the purposes of analysis for the data collected in the feasibility study the following null hypothesis was proposed:

-

There is no difference in EQ-5D-5L score at 4 months after injury between adults aged > 18 years with an acute, extra-articular fragility fracture of the distal femur treated with ‘locking’-plate fixation (plate) and those treated with retrograde intramedullary nail fixation (nail).

Health economics analysis

The economic analysis investigated the feasibility of a definitive economic evaluation within a large RCT of treatment with modern intramedullary nails or anatomical locking plates for fragility fractures of the distal femur.

A NHS and Personal Social Services perspective was adopted for the costing component of the feasibility study. The main analysis reports the practicalities and difficulties associated with an assessment of the cost to providers, to individuals and, more broadly, to society consequent on the intervention, along with the identification of appropriate sources of unit cost data.

Process evaluation

We evaluated intervention implementation, mechanisms of impact and context in line with the MRC guidance on process evaluation of complex interventions using a mixed-methodology approach. 16 Process evaluation enables us to understand how the interventions work and under what circumstances effectiveness is achieved.

In this feasibility study, we developed and tested methods for process evaluation that might then be modified in the subsequent definitive trial. The findings of the process evaluation could also lead to modifications in the plan for outcomes evaluation and so we did not separate research team members conducting process and outcomes evaluation in the way that might be appropriate in a definitive trial.

Implementation

Evaluation of intervention implementation focused on four areas. These were (1) the reach of the interventions, (2) the fidelity of delivering the interventions, (3) the acceptability of the interventions and study procedures and (4) understanding how delivery was achieved.

The reach of the intervention, that is whether or not the intended audience came into contact with the intervention, was assessed through the rates of screening and recruitment at each centre over the 10-month period. The fidelity of delivering the intervention considered the procedures for screening patients and application of the study eligibility criteria, the content of consent discussions, deviations from the study protocol and delivery and compliance with post-operative rehabilitation instructions. In addition to our evaluation of intervention implementation, we examined the implementation of the study processes in order to inform the development of a definitive trial.

Mechanisms of impact

Process evaluations seek to identify how the delivered intervention produces change. From our process evaluation data and patient and public involvement (PPI) workshop, we identified relevant intermediate outcomes that might be associated with the effect of the interventions on the primary outcomes of interest. These were used to develop a logic model for the feasibility study that worked from the hypothesis that nail fixation is associated with better outcomes then locking plate fixation.

Context

Understanding of the context in which the intervention is delivered is important to understand how the outcome was achieved. Our evaluation of context focused on three areas. These were the national context, contextual similarities and differences between the participating centres and patient factors.

Screening logs and enhanced screening

Screening logs were kept at each site to determine the number of patients assessed for eligibility. As fewer than expected fractures of the distal femur were recorded on the screening logs, the TSC recommended further screening to ascertain whether or not any distal femoral fractures had been missed. Trainee PIs at each participating centre were asked to review hospital records and rescreen all patients who were admitted with fractures of the distal femur during the recruitment window for their institution. It was recommended that this was done by searching electronic records for fractures of both intra- and extra-articular distal femur [Arbeitsgemeinschaft für Osteosynthesefragen (AO)/Orthopaedic Trauma Association (OTA) 33]. 18

Trauma Audit and Research Network data

We requested admissions data from Trauma Audit and Research Network (TARN)36 in order to monitor the accuracy of the screening logs and enhanced screening. This allowed us to compare the screening information returned by the participating centres with the information returned to TARN. Clinical leads for TARN at each site gave us permission to receive anonymised aggregate patient demographic data that corresponded to our screening data. These screening data were compared with screening data supplied by research teams at each site to help confirm the completeness of the screening logs. The TARN database was queried using a search string that included the site ID, the recruitment window for which the site was open for TrAFFix and the AO/OTA classification 33A, B and C.

We also requested some additional data, such as operation(s) performed, injury severity score and comorbidity index, in order to determine whether or not recruitment may have been biased against certain patient groups. We collected some basic information about the provision of rehabilitation for patients after a distal femoral fracture, specifically the rehabilitation recommended and received.

Clinical reporting forms

The CRFs, comprising data collected from participants and their medical notes, were completed at the time of recruitment (which included pre- and post-injury information) and at 6 weeks and 4 months post injury.

NHS data

We used data from NHS Digital, NHS England Statistics and the annual reports of the participating NHS trusts to describe the context for each participating hospital. From NHS Digital, we used the NHS Hospital and Community Health Service (HCHS) Workforce Statistics in England, Summary of staff in the NHS 2003–201337 and Hospital Admitted Patient Care Activity. 38 This provides details on workforces within NHS organisations, including numbers of consultants, registrars and other doctors in training by specialty. It is provisionally published monthly and data are extracted from NHS human resources and payroll system. Hospital-admitted patient care activity reports the number of finished consultant episodes and admissions. It is published annually and uses data collected from the Hospital Episodes Statistics, which contains records of all admissions, appointments and attendances for patients at NHS hospitals in England. From NHS England Statistics, we used The NHS Quarterly Bed Availability39 and Supporting Facilities Dataset. 40 The former gives data on the number of available beds and occupied beds. The latter provides information on operating theatres and dedicated day case theatres. These data sets are published quarterly; we looked for information about the populations they serve from the annual reports of the participants NHS trusts.

Questionnaire

A brief questionnaire, comprising six questions, was used to assess surgical expertise and preference. The questionnaire was sent to consultant trauma and orthopaedic surgeons by e-mail using the distribution lists of the Orthopaedic Trauma Society and PIs at each of the participating centres. The questionnaire content can be found in Appendix 2.

Interviews

Qualitative interviews adopted a phenomenological approach that has been used successfully in other trauma studies. 41,42 This approach seeks to understand individuals’ lived experience of a phenomenon of interest, and in this study staff and participants’ experience of TrAFFix and participants’ experience of being injured was explored. To enable interviewees to tell us what was important to them, the interviews were semistructured and used a brief topic guide. Topics covered during participant interviews were their experience of (1) injury, (2) recovery and (3) taking part in TrAFFix. Interviews with RAs covered (1) their experience of recruiting to TrAFFix and other trauma trials, (2) their experience of explaining research studies to patients, (3) their experience of nominated consultee consent, (4) their experience of follow-up questionnaires and (5) their views on their colleagues’ engagement with research and TrAFFix. Surgeon interviews covered the following topics: (1) their experience of recruiting to TrAFFix and other trauma trials, (2) their experience of the two interventions, (3) their views on rehabilitation, (4) their views on blinding and (5) their colleagues’ engagement with research and TrAFFix. Owing to the small number of patients recruited to the study, staff interviews explored experiences of trauma trials in general, as well as staff experiences of TrAFFix. Interviews were conducted face to face or by telephone. The majority of staff were interviewed towards the end of the recruitment period or shortly after, with 22 of the 24 interviews conducted between May and October 2017.

Patient and public involvement workshop

We held a 1-day workshop with PPI representatives to learn about the factors other than surgery that influence patients’ recovery from this injury. The workshop aimed to identify what is important for patients and their families/carers during treatment and recovery. Factors identified form this workshop contributed to the development of a logic model for the feasibility study. The patient pathway, from before the fracture to returning home from hospital, was used as a guide to discuss what might be important for patients at each stage. The PPI representatives from the Oxford Trauma PPI group were invited to attend the workshop by e-mail. The workshop was also advertised on the Patients Active in Research (PAIR) website. Six PPI representatives and four members of the study team attended. The workshop was audio-recorded with consent from the attendees.

Audio-recordings of consent discussion

The intention was for RAs to record their discussions with patients about the study, with agreement from the patient. However, there were limited opportunities for RAs to do this and it proved difficult in a trauma setting. Consequently, only one discussion about the study was audio-recorded.

Data analyses

Quantitative data

Discrete data were summarised as absolute values and proportions; continuous data as means and SDs. No inferential statistical tests were performed but comparisons were facilitated through tabulation of the data.

Qualitative data

When participants agreed, interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim. Data analysis was conducted alongside data collection to enable refinement of the interview topic guide. NVivo 10 (QSR International, Warrington, UK) was used to manage the data. All data relating to trauma trials and the study processes were analysed inductively using thematic analysis. 43 This involved grouping sentences or paragraphs of similar meaning into codes. Similar codes were then grouped together into categories by comparing within and across the codes. For example, the category enabling participation comprised codes that described involving family or nominated consultee consent procedures. Three themes relating to trial recruitment were developed by comparing within and across the emerging categories. Within this approach, we acknowledge that the researcher’s interpretation of codes, categories and themes is shaped by their own experience and knowledge. To enable reflection on this process throughout analysis, Emma Phelps, Elizabeth Tutton, Janis Baird and Xavier L Griffin met regularly to discuss the emerging themes. Data saturation occurred when the team agreed that no new elements were arising from the interviews or within the themes. Data saturation was achieved within the staff interviews but the degree of frailty in the patient population limited the degree of saturation that was achieved. The thematic framework and the themes and categories within it are presented in Table 2. The audio-recorded consent discussion was transcribed verbatim. The transcript was used to see what information patients were given about the study and how patients responded.

| Item | Component | Data sources | Indicator |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reach |

|

|

|

| Fidelity |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Acceptability |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| How is delivery achieved? |

|

|

|

Integration

Qualitative and quantitative data relating to each aspect of the process evaluation are presented within the process evaluation framework. The themes and categories identified from the thematic analysis were also mapped onto the process evaluation framework to demonstrate how they relate to each aspect of the process evaluation. Tables 2–4, which summarise the process evaluation results, demonstrate how the qualitative themes relate to the process evaluation findings.

| Item | Component | Data sources | Indicator |

|---|---|---|---|

| Existing factors | Factors relating to the patients, such as health, social support, levels of self-efficacy, which may influence their recovery |

|

|

| Injury and treatment | Factors relating to the injury, treatment and time in hospital, which may influence patients’ recovery |

|

|

| Post-discharge factors | Factors relating to the patients, such as access to support and place of discharge, which may influence their recovery |

|

|

| Item | Component | Data sources | Indicator |

|---|---|---|---|

| National context |

|

|

|

| Contextual similarities and differences between the participating centres |

|

|

|

| Patient factors |

|

|

|

Ethics approval and monitoring

Ethics committee approval

TrAFFix was approved by the Wales REC (reference number 16/WA/0225), study-wide NHS approval was given by the Health Research Authority (Integrated Research Application System 206745) and participating NHS trusts provided local approvals. The study protocol has been published. 17

Trial Management Group

The day-to-day management of the trial was the responsibility of the trial co-ordinator, based at Nuffield Department of Orthopaedics, Rheumatology and Musculoskeletal Sciences (NDORMS), and supported by the OCTRU administrative staff. This was overseen by the Trial Management Group, which met monthly to assess progress. It was also the responsibility of the trial co-ordinator to undertake training of the RAs at each of the trial centres. The trial statistician and health economist were closely involved in the setting up of data capture systems and the design of databases and CRFs.

Trial Steering Committee

A TSC, which included independent members, was responsible for monitoring and supervising the progress of TrAFFix. The terms of reference were agreed with the Health Technology Assessment (HTA) programme manager and was drawn up in a TSC charter that outlined its roles and responsibilities. Meetings of the TSC took place at the beginning and end of the feasibility study and once during recruitment.

An outline of the remit of the TSC was to:

-

monitor and supervise the progress of the trial towards its interim and overall objectives

-

review, at regular intervals, relevant information from other sources

-

consider the recommendations of the DSMC

-

inform the funding body on the progress of the trial.

The TSC consisted of five independent experts, a lay member and the chief investigator. Membership of the TSC is given in Acknowledgements.

Data Safety and Monitoring Committee

The study DSMC agreed and adopted an appropriate charter, structured in accordance with DAMOCLES principles,45 which defined its terms of reference and operation in relation to oversight of the trial. The DSMC was not asked to perform any formal interim analyses of effectiveness. The committee did, however, review accruing data and summaries of the data presented by treatment group and assessed the screening algorithm against the eligibility criteria. The DSMC reviewed all related SAEs that were reported and could advise the TSC if, in its view, the trial should be stopped for ethics reasons. The DSMC meetings were held once during the recruitment phase of the study and once at the end of the trial. The trial statistician provided data and analyses requested by the DSMC at each of the meetings. Membership of the DSMC is given in Acknowledgements.

Chapter 3 Results of the process evaluation

Introduction

This section is divided into three parts. We will first present the logic model developed for this feasibility study. Second, we will describe the characteristics of the patients and staff groups who were interviewed during the process evaluation. This will be followed by our evaluation of implementation, mechanisms of impact and context.

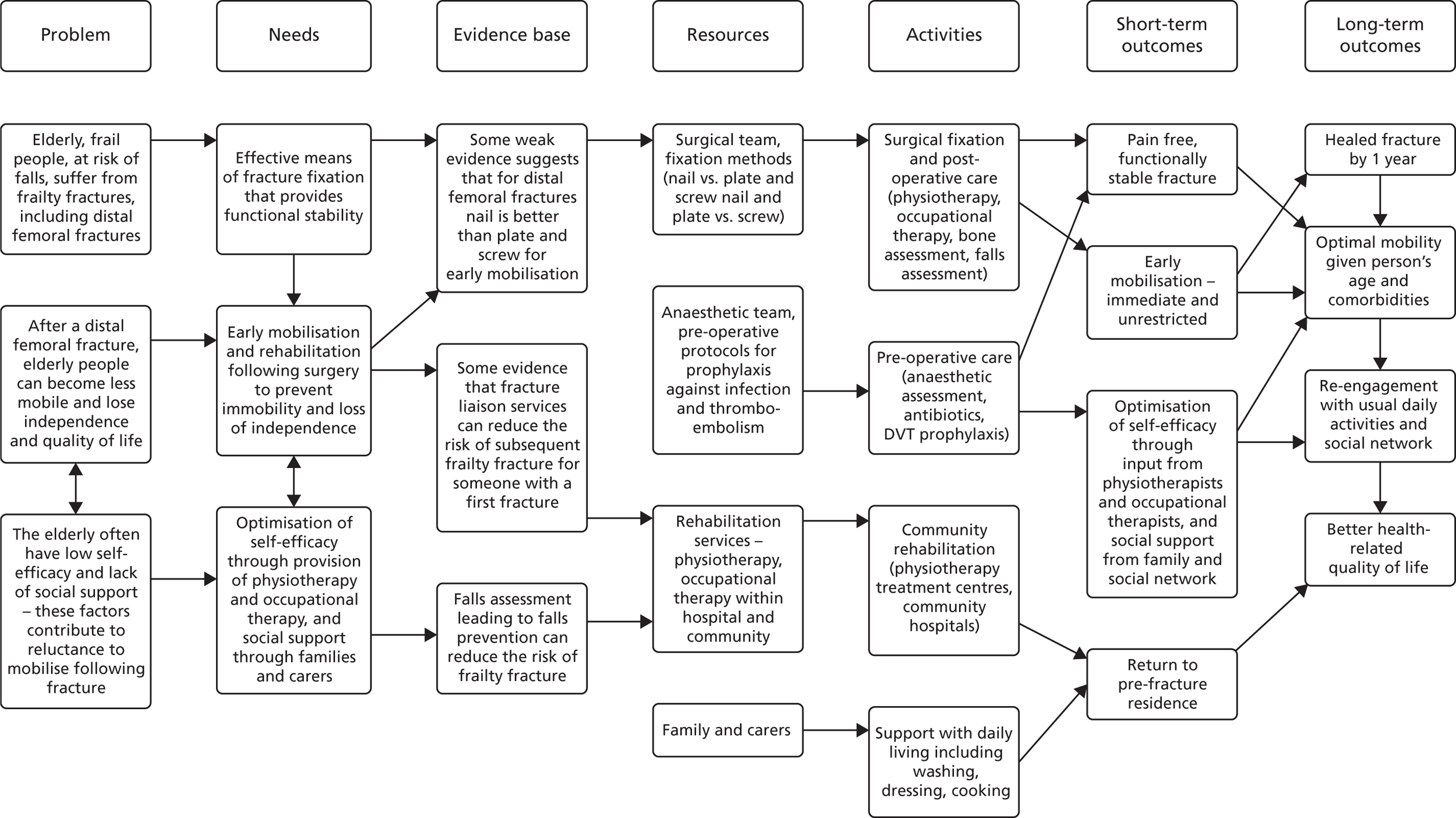

Logic model

We developed a draft logic model for TrAFFix through discussions with clinical members of the research team. The model summarised the problem posed by fractures of the distal femur, which tend to occur in frail older patients, and the resulting need for effective methods of fixation combined with support for rehabilitation and recovery in this group of patients. Logic models provide a diagrammatic representation of the relationships between an intervention’s resources, activities and intended outcomes. 46 The model outlined the evidence in support of the two approaches to fracture fixation and the resources and activities required to deliver the treatment. Short- and long-term outcomes were identified. We then used the content of the draft logic model to inform discussion at a 1-day workshop with PPI representatives. The workshop aimed to identify factors, other than surgery, that are important for patients and their families/carers during treatment and recovery from this injury (see Chapter 2). The themes that emerged from the workshop informed our findings relating mechanisms of impact summarised in Tables 5–7, but also fed into the logic model. Many of the factors that the clinical team had identified as potentially important pre- and post-operatively, such as patient frailty, lack of confidence (self-efficacy) and comorbidities, were also identified by the PPI representatives. The resulting version of the logic model (Figure 1) will form the basis for the full-scale trial of acute femoral fracture fixation.

| Item | Component | Data sources | Findings | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quantitative | Qualitative | |||

| Reach |

|

|

|

|

| Fidelity |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Acceptability |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| How is delivery achieved? |

|

|

|

|

| Item | Component | Data source | Findings | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quantitative | Qualitative | |||

| Existing factors | Factors relating to the patients, such as health, social support, levels of self-efficacy, which may influence their recovery |

|

|

|

| Injury and treatment | Factors relating to the injury, treatment and time in hospital, which may influence patients’ recovery, for example grade of operating surgeon |

|

|

|

| Post-discharge factors | Factors relating to the patients, such as access to support and place of discharge, which may influence patients’ recovery |

|

|

|

| Item | Component | Data source | Findings | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quantitative | Qualitative | |||

| National context |

|

|

|

|

| Contextual similarities and differences between the participating centres |

|

|

|

|

| Patient factors |

|

|

|

|

FIGURE 1.

Logic model for TrAFFix.

Interview participant characteristics

A convenience sample of 11 study participants, or their personal consultees, from five out of the seven centres participating in the study were interviewed. Seventeen participants agreed to be approached about taking part in an interview. One participant died and another withdrew from the study prior to being contacted about the interview. Two participants declined to be interviewed when contacted by the researcher and two could not be reached. The sample of participants interviewed included two consultees who provided consent for their relative to participate in the study. Of the participants who were interviewed or whose consultee was interviewed on their behalf, two were male and nine were female. All participants, or their carers where interviewed, were of white ethnicity and aged between 54 and 93 years (mean age of participants 76.3 years). Participants were interviewed up to 5 months after surgery. Three participants were interviewed twice. The majority of participant interviews were conducted by telephone (n = 9). One participant went through the interview questions with her daughter, who gave the answers to the researcher in writing.

A purposive sample of 24 members of staff from each of the seven sites were also interviewed. Of the 24 members of staff interviewed, 10 were surgeons. The remaining 14 members of staff, hereafter referred to as RAs to protect anonymity, included research nurses, a RA, a physiotherapist, a research manager and a trial co-ordinator. The majority of staff were interviewed face to face (n = 21).

Process evaluation results

For each aspect of the process evaluation framework we present a brief synopsis of the relevant quantitative and qualitative findings at the beginning of the section (see Tables 5–7). Within these tables we also demonstrate how the themes developed from the qualitative analysis relate to the process evaluation framework.

Implementation

Our evaluation of implementation considered the implementation of the surgical and rehabilitative components of the intervention and the implementation of the study procedures.

In relation to intervention implementation, we evaluated whether or not potentially eligible patients received the interventions. This is described within the sections Reach, Applying the study eligibility criteria, Protocol deviations and Patient compliance with rehabilitation instructions. Our evaluation of intervention implementation also explored the acceptability of the interventions as presented in the sections Acceptability of the interventions to staff and patients (referring to fixation with nail or plate) and Patient compliance with rehabilitation instructions.

In order to inform the development of a definitive trial, we also examined the fidelity of applying the study procedures and the acceptability of the study procedures, as described within the sections Reach, Applying the study eligibility criteria, Consent discussions, How was delivery achieved? and Acceptability of study procedures.

Our evaluation of intervention implementation and implementation of the study procedures overlaps with some components, such as ‘reach’, aiding our understanding of both areas. For reason this, we have not separated these two areas within our results. For a summary of our findings regarding implementation, see Table 5.

Reach

Screening and recruitment

[The quotations throughout this chapter were produced in the course of research and also appear in Griffin et al. 44 © Author(s) (or their employer(s)) 2019. Re-use permitted under CC BY. Published by BMJ. This is an open access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 Unported (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to copy, redistribute, remix, transform and build upon this work for any purpose, provided the original work is properly cited, a link to the licence is given, and indication of whether changes were made. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.]

Ninety-one patients were screened and recorded on screening logs during the 10-month recruitment period. Of these, 54 were eligible to participate in the study. After review by the TSC, this number seemed too small given the assumptions made in the development of the protocol. The TSC recommended revisiting screening with the sites to confirm the incident fracture population size. Trainee PIs and PIs at each of the sites were asked to revisit their local clinical databases to confirm the number of potentially eligible patients and, when additional patients were identified, to conduct screening based on the clinical records. This enhanced screening found a further 82 unscreened patients with distal femur fractures who were not included on the screening logs. Of these, 31 met the eligibility criteria for inclusion in the study.

The number of patients added from enhanced screening varied by centre, with between 0 and 34 patients added. In four centres, ≥ 40% of distal femoral fractures were not included on the screening logs and were added after enhanced screening. At interview, staff were confident that few patients were eligible for the study, suggesting that they were unaware that potentially eligible patients were being missed. Some staff appeared confident that they were not missing patients, even in centres that were subsequently found to have missed many patients. Some research teams were unable to provide a fully integrated daily provision to the clinical teams:

With the TrAFFix study, well we just never had the numbers come through and I think the only two that we actually missed were during weekends and I think one was when I was on annual leave and obviously, research nurses don’t work 7 days a week and that was the issue for recruiting.

Staff (RA) 19

Differences in the number of patients missed from screening logs may relate to the experience of the research teams and the research culture within the centres, which are discussed further in the sections Procedures for screening patients and Contextual similarities and differences between the participating centres. For example, in some centres, not all surgeons within the team screened and identified eligible patients and this may have contributed to patients being missed:

Generally it is mainly the PI that screens for them and that would be identifying them. We do if we find them on the trauma list but it would be mainly the PI that would be identifying if the patient was eligible for us and obviously the PI wants to have people in the trial.

Staff (RA) 4

In addition, patients deemed ineligible might not have been recorded on the screening logs in some centres. One surgeon felt he had ‘a very big screening log to actual recruitment’ (staff, surgeon 18) despite having very few patients recorded on the log.

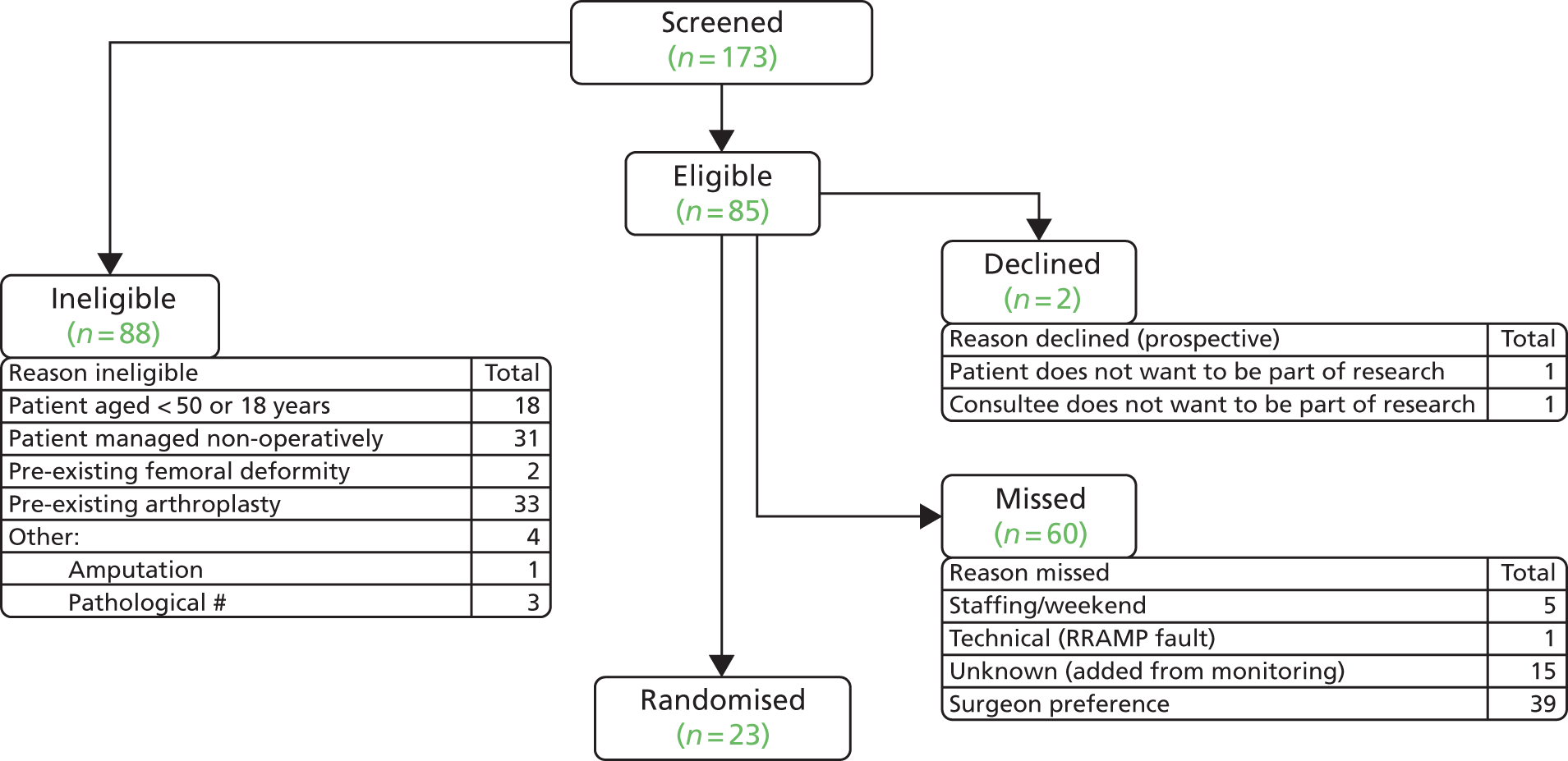

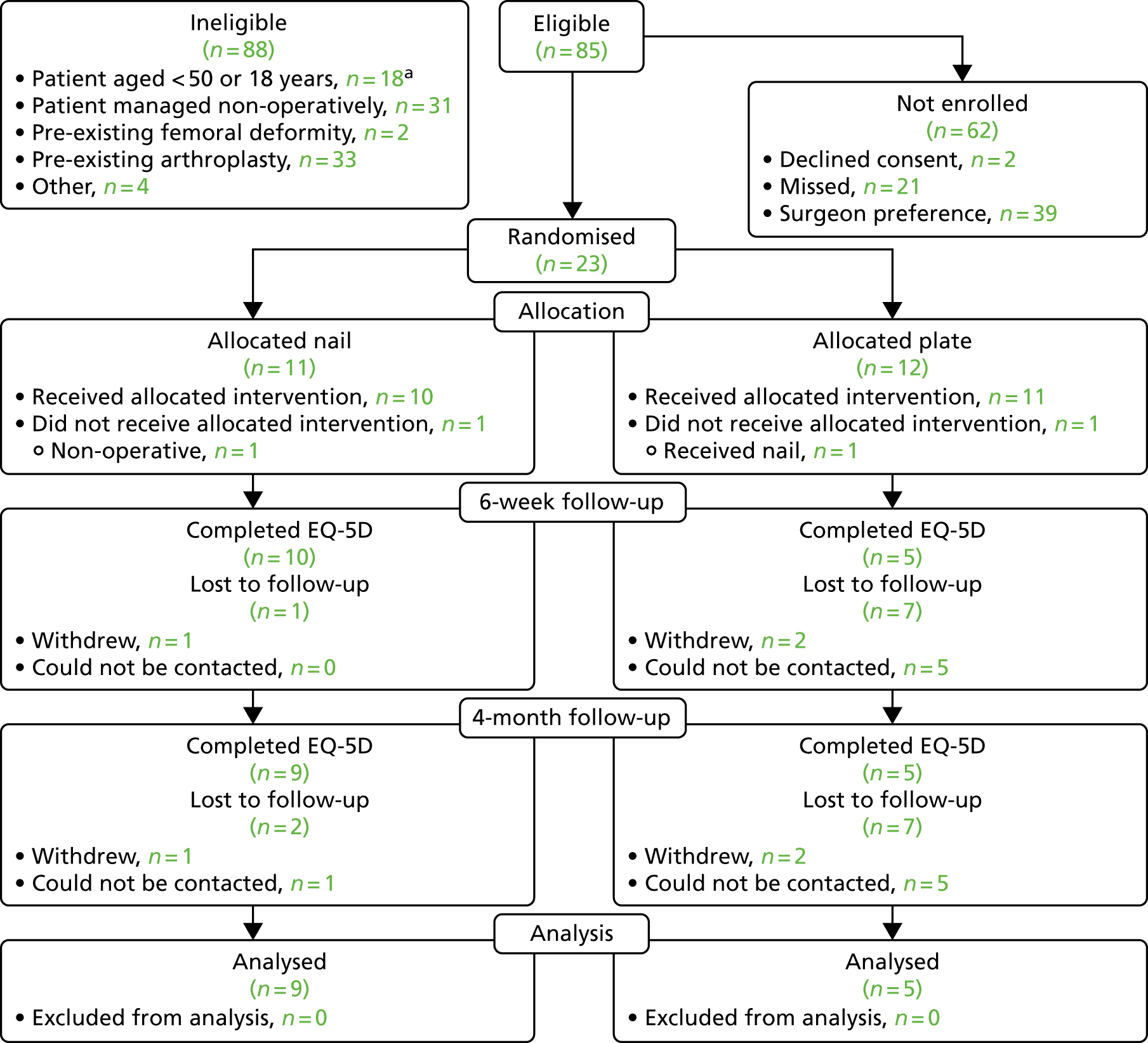

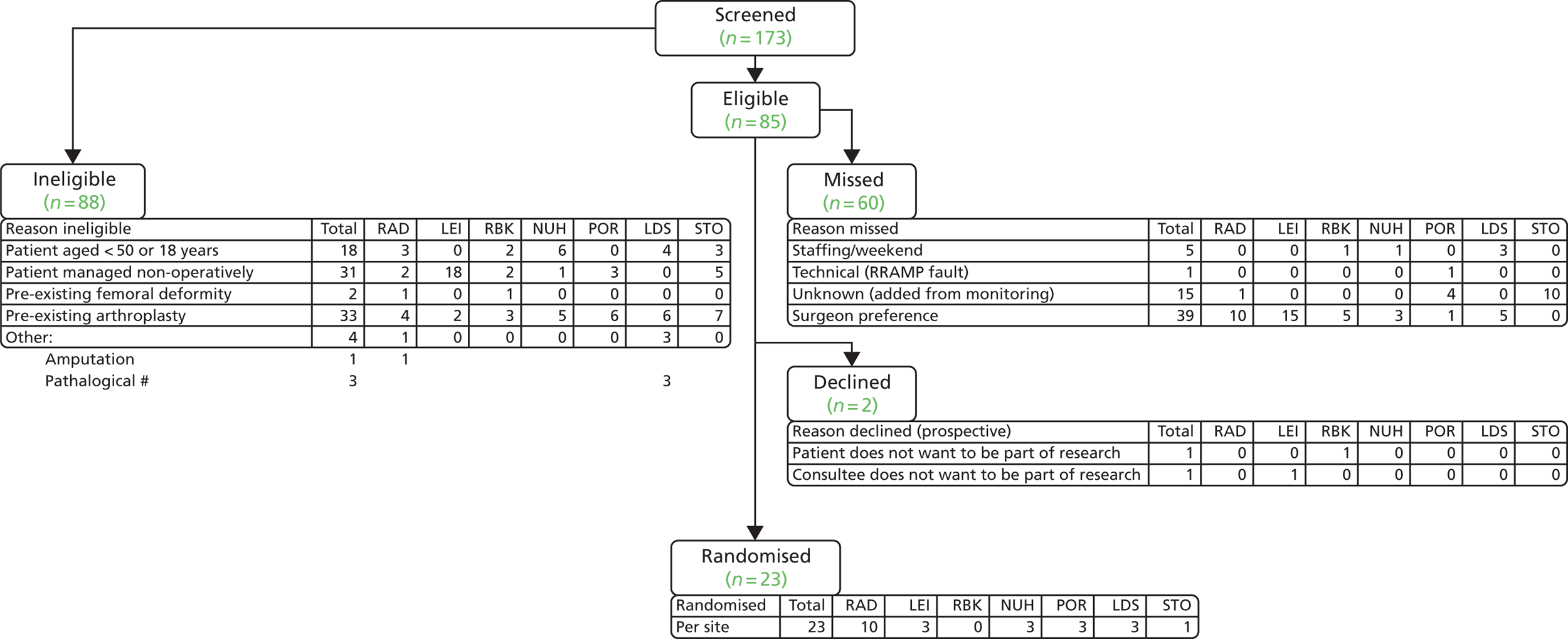

Figure 2 shows the number of patients screened, the number of patients deemed eligible for inclusion in the study and the reasons for exclusion. Of the 85 eligible patients, 23 were included in the study. Thirty-nine eligible patients were excluded because of surgeon preference, two declined to participate, five were missed as a result of staffing (e.g. the PI was not present to confirm eligibility, or the patient was admitted and operated on over the weekend) and one was missed owing to failure of the randomisation programme. The reasons for missing the remaining 15 patients are unknown. Further details of screening are reported by site in Appendix 3.

FIGURE 2.

Summary of screening. RRAMP, Registration/Randomisation and Management of Product. Adapted from Griffin et al. 44 © Author(s) (or their employer(s)) 2019. Re-use permitted under CC BY. Published by BMJ. This is an open access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 Unported (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to copy, redistribute, remix, transform and build upon this work for any purpose, provided the original work is properly cited, a link to the licence is given, and indication of whether changes were made. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

After the TSC recommended that the age limit be lowered, a further 69 patients were screened. In this group, eligibility increased from 44% to 60% but this did not translate into an increase in successful recruitment into the study. Only 18 out of the 88 ineligible patients were excluded because of age. After the change in eligibility criteria, only two participants were recruited who were < 50 years of age. Only 3 of the 69 patients screened after the change sustained their fracture from an injury involving more energy transfer than a fall from standing height.

The reasons for ineligibility and missed patients varied between sites. Of the 39 patients treated non-operatively, 18 were from a single site, whereas another site did not report any patients treated non-operatively. Similarly, the proportion of eligible patients excluded because of surgeon preference ranged from 0–10 to 15–19 between sites, although two sites did not completely report the reasons why patients were not included as some patients were screened retrospectively during monitoring activities after the study had closed.

Two centres did not record reasons for missing the majority of patients eligible for inclusion in the study. In the remaining five centres, surgeon preference was the most common reason for eligible patients not being included. The proportion of eligible patients excluded because of surgeon unwillingness to randomise in these five centres varied from 43% (three out of seven eligible patients) to 79% (15 out of 19 eligible patients). In three centres, < 50% of eligible patients were excluded because of surgeon preference, and in two centres > 70% of eligible patients were excluded because of surgeon preference. Several factors may have contributed to this variation. Differences in surgeons’ interpretation of the eligibility criteria were evident at interview and are discussed fully in Applying the study eligibility criteria. Some surgeons felt that patients could be ‘borderline’ or not appropriate for both of the treatments and this might have influenced the number of patients they excluded. Research culture and the experience of the research teams may have also influenced the number of patients excluded because of surgeon preference. In addition, of these five centres, the three that were major trauma centres excluded a smaller proportion of eligible patients because of surgeon preference, perhaps reflecting a greater willingness among specialist trauma surgeons to use both technologies.

Combining the baseline demographic data collected for all screened patients with the hospital data supplied from TARN demonstrated that the screened population was over two-thirds women, one-fifth of whom had cognitive impairment and were aged approximately 70 years. Although a little younger than the hip fracture population, which has a mean age in the UK of 83 years,47 this cohort was similar to a hip fracture population.

Fidelity

Procedures for screening patients

The ideal method of screening patients was for the clinical care teams to identify eligible patients in the emergency department and trauma wards and notify the research team during the daily trauma meeting. Interviews with surgeons and RAs revealed that in several centres the clinical teams tended not to notify the research teams of eligible patients. These centres relied on strong research teams to screen patients and promote studies. The presence of members of the research team (PIs and RAs) in the daily trauma meeting also facilitated screening, as they were able to prompt the clinical teams to consider whether or not patients were eligible. PIs were usually unable to attend every trauma meeting because of other commitments and RA attendance varied. In one centre, the RA attended two or three times per week but was supported by a specialist trainee, while in two centres RAs did not attend the trauma meeting. For one centre, this was as a result of staffing. Staff interviewed at this site felt that RA attendance at this meeting was important for identifying eligible patients, promoting studies and building a rapport with clinical teams:

We have a research nurse in the trauma meeting every morning to screen for patients and so yes they are infrequent and as such the treating surgeons don’t necessarily have it in mind but the research team always do. They have 8–10 studies on their list and they screen the trauma meeting for those patients so . . . I think from the surgeons perspective, because they are not very common, they wouldn’t necessarily phone up the research nurses as we would like them to do and just say someone has come in, I have already mentioned the study to them, so there is a little bit of a scuffle round in the morning because obviously the consultant concerned needs to say to the patient would you mind if the research team approach you about this study and so on, so on that side of logistics yes but not terrible. I think if we didn’t have enough studies running to have a fully funded research team then it would be tricky.

Staff (surgeon) 20

I’m keen to see what is going to happen when we do get the other research nurses going to the trauma meeting because I feel that that’s going to make a big difference and I think our recruitment will increase quite a lot but I might be completely wrong in thinking that. It’s just that I always think having somebody there and having a face to face and having a nurse that is going to see. We have orthopaedic nurse practitioners as well who run the department in the daytime clinically with beds and things and they always know what’s coming in, but they also do some of the clinical stuff for the patients that is more advanced as well. They know everybody that’s coming in and if we get them on boards as well to tell us when patients come in that’s even better. Through emails and just popping in every now and then it’s just difficult to get that rapport whereas actually if you really get to know somebody then they’ll let you know if anybody comes in . . . I’m hoping that they’ll just get to know them because they’ll see them every day and it should help with building that relationship with them as well and the consultants seeing a research nurse every day.

Staff (RA) 4

In addition to the trauma meeting, building relationships with staff who have up-to-date knowledge of admissions could aid RAs in finding eligible patients.

Given the rarity of eligible patients, some centres found it difficult for the clinical care team to keep the study in mind. Other, unspecified, research studies being conducted at the same time as TrAFFix, in which eligible patients were common, were more easily remembered and in one centre were prioritised over TrAFFix:

So I think because we’ve been trying to put more effort into an area that we know is going to guarantee a better outcome. We’ve put more effort into that and sacrificed a study that’s a bit more complicated and harder to recruit to. So yes, it has gone a little bit into the background I would say.

Staff (RA) 16

More often than not they’ve not discussed whether or not the patient is eligible for TrAFFix in their morning meeting and so I’m then ringing them and chasing it up and you’re racing against time and when you are given an answer that they are going to do this one that’s better I don’t know whether that’s because it is better or whether it wasn’t discussed early in the meeting, it’s now half eight and we just need to get on with it and we’ve decided it’s too much hassle to think about randomising them now. I don’t know the reasons behind that and it is sort of infrequent, it’s not in the front of their mind.

Staff (RA) 11

One team described using anonymised instant messaging to prompt and engage surgeons in recruitment to trauma trials. This meant that the PI could encourage recruitment even when unable to attend the trauma meeting in person.

Applying the study eligibility criteria