Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 13/96/07. The contractual start date was in March 2015. The draft report began editorial review in February 2019 and was accepted for publication in July 2019. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Oliver Rivero-Arias, Ursula Bowler, Edmund Juszczak, Marian Knight, Louise Linsell and Julia Sanders report receipt of funding from the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) outside the submitted work. Edmund Juszczak reports Clinical Trials Unit infrastructure support funding received from NIHR and active membership of the Health Technology Assessment (HTA) Commissioning Board and the HTA General Board while the study was being undertaken.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2019. This work was produced by Knight et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2019 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Introduction

Sepsis is a leading cause of direct and indirect maternal death in the UK, and, globally, is estimated to cause almost 20,000 maternal deaths annually. 1,2 In addition to very maternal death, an estimated 70 women have severe sepsis (requiring level 2 or 3 critical care) but survive. 3 An increased risk of sepsis in association with caesarean section has been recognised for many years,4 and the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE)’s guidance recommends the use of prophylactic antibiotics at all caesarean births,5 based on substantial randomised controlled trial (RCT) evidence of clinical effectiveness. 6 Three separate studies, conducted as part of a previous National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Programme Grants for Applied Research programme, using both UK and US data, have documented an additional risk associated with operative vaginal birth (forceps or ventouse/vacuum extraction),3,7–9 particularly in relation to group A streptococcal infection, one of the most rapidly progressive causes of maternal infection. 2,3 A Cochrane review,10 updated in 2017, identified only one small previous trial of prophylactic antibiotics following operative vaginal birth, including a total of 393 women, with a relative risk of 0.07 [95% confidence interval (CI) 0.00 to 1.21] for post-partum endometritis; given the small study size and extreme result, the authors suggested that further robust evidence is needed.

Further work suggests that the burden of localised infection following operative vaginal birth is also significant,11 with > 10% of women experiencing symptoms of perineal wound infection in the 3 weeks after giving birth. Women prioritising childbirth-related perineal trauma outcomes have rated ’fear of perineal infection’ as the most important outcome they are concerned about in the first few weeks after childbirth. 12

Latest figures show that approximately 12% of women have an operative vaginal (forceps or ventouse) birth in England, representing a significant burden of potentially preventable morbidity. 13 Current NICE guidelines for intrapartum care make no reference to prophylactic antibiotics following instrumental vaginal birth. 14 The Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (RCOG)’s guidance on operative vaginal delivery15 states that there are insufficient data to justify the use of prophylactic antibiotics in operative vaginal birth, referencing the Cochrane review10 identified above. Recognising the importance of antibiotic stewardship, the World Health Organization (WHO)’s recommendations on prevention and treatment of maternal peripartum infections explicitly state that routine antibiotic prophylaxis is not recommended for women undergoing operative vaginal birth, again citing a lack of evidence of benefit. 16 The RCOG’s guidance on bacterial sepsis following pregnancy does not identify operative vaginal birth as a risk factor for post-partum infection;17 a lack of awareness of the associated risk may contribute to a delay in diagnosis. Evidence suggests that progression to severe sepsis following birth, particularly in association with group A streptococcal infection, can be very rapid. 2,3 This emphasises the importance of urgent investigation of potential prophylactic measures.

Women with generalised and localised infection following operative vaginal birth incur additional health-care resources compared with those without infection. Although there are no studies quantifying these additional resources accurately, women with post-surgical infection after undergoing caesarean section follow a similar treatment pathway to women with localised infection after instrumental vaginal birth. Research has estimated that infection after caesarean section costs, annually, an additional £226 per patient compared with women with no post-surgical infection. 18 These extra health-care costs are attributable to additional hospital length of stay, re-admissions and community care. Therefore, there remains the potential for a reduction in health-care costs if routine antibiotic prophylaxis prevents post-partum infection.

Presentations of the data from the NIHR programme studies3,7–9 at national meetings clearly showed that the natural response of the clinical community is to introduce prophylactic management with antibiotics, without clear evidence for the effectiveness of this approach following operative birth, because antibiotic prophylaxis been shown to be effective in reducing the risk of infection following caesarean birth. 10 Giving antibiotic prophylaxis after operative vaginal birth has thus been introduced into local guidance unsupported by evidence. Although similar in some ways, there are clear differences between the wound sites and potential contaminating organisms at caesarean section and instrumental birth, so it cannot be assumed that single-dose prophylactic antibiotics will be equally effective in both circumstances. In addition, in the context of growing concerns about antibiotic resistance,19–21 it is vital that there is robust evidence behind any prophylactic use of antibiotics.

Recent recommendations suggest that antibiotic prophylaxis for caesarean section should be given prior to delivery. This trial specifically aimed to investigate the use of antibiotic prophylaxis after operative vaginal birth of the infant for the following reasons:

-

The potential risks of in utero exposure to antibiotics are now widely recognised. The risk of necrotising enterocolitis22 and cerebral palsy23 is known to be increased among the children of women managed with antibiotics for suspected preterm labour. Maternal antibiotic use in late pregnancy has also been associated with an increased risk of asthma in early childhood24 and with very early-onset inflammatory bowel disease. 25 Reports have identified differences in the infant microbiome with maternal antibiotic administration and the potential for long-term impacts on other disease states is a concern. 26

-

The major difference between the episiotomy wound and the caesarean section wound is the fact that there is ongoing contamination of the surgical field. Thus, with caesarean section, as soon as the operation is completed and a wound dressing applied, the major risk of infection is over. In contrast, an episiotomy wound is impossible to cover and, therefore, our rationale is to actually increase the length of time that there would be therapeutic levels of antibiotic from a single dose by giving it post delivery, to cover for ongoing contamination for as long as possible.

-

There have been several cases of anaphylaxis relating to antibiotics given prophylactically for caesarean birth identified in a NIHR-funded study. 27 Although the incidence is extremely low, this is of concern, particularly with antenatal administration, in which there is the potential for fetal compromise.

Twelve per cent of women in the UK undergo forceps or ventouse deliveries,13 which is an estimated 90,000 women annually. The conservatively estimated incidence of maternal infection following operative vaginal birth is 4%, based on the one previous trial,10 which results in an estimated 3600 women potentially having an infection after instrumental vaginal birth. Of these women, around 200 will be diagnosed with severe infection7 and up to four may die from their infection. 28 There is, therefore, considerable scope for direct patient benefit from an effective preventative strategy. Other non-randomised studies suggest higher infection rates of up to 16%,29 which would correspondingly lead to an even greater potential benefit from a preventative therapy.

Objective

The objectives of this research were to investigate whether or not a single dose of prophylactic antibiotic following operative vaginal birth is clinically effective for preventing confirmed or presumed maternal infection and to investigate the associated impact on health-care costs.

Chapter 2 Methods

The trial protocol28 and results30 have been previously published and parts of the published articles are reproduced throughout this report. These have been reproduced with permission from Knight et al. 28 [This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.] and Knight et al. 30 [This article is available under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0) ‘Beyond maternal death’. You may copy and distribute the article, create extracts, abstracts and new works from the article, alter and revise the article, text or data mine the article and otherwise reuse the article commercially (including reuse and/or resale of the article) without permission from Elsevier. You must give appropriate credit to the original work, together with a link to the formal publication through the relevant DOI and a link to the Creative Commons user license above. You must indicate if any changes are made but not in any way that suggests the licensor endorses you or your use of the work.]

Design

The A randomised controlled trial of prophylactic ANtibiotics to investigate the prevention of infection following Operative vaginal DElivery (ANODE) trial was a multicentre, randomised, blinded, placebo-controlled trial conducted in the UK.

Ethics approval and research governance

The ANODE trial protocol was approved by the Health Research Authority National Research Ethics Service Committee South Central – Hampshire B (study reference number 15/SC/0442).

Local approval and site-specific assessments were obtained from each NHS hospital site.

Patient and public involvement

The research question was initially prioritised by the user advisory group to the NIHR ‘Beyond maternal death’ programme, which generated the initial information about sepsis risk in association with operative vaginal birth. 9 To obtain the perspective of a group more representative of the wider maternity population, we contacted the PRIME (Public and Researchers Involvement in Maternity and Early pregnancy) group. PRIME is a patient and public involvement group that was set up in collaboration with the University of Birmingham Collaborations for Leadership in Applied Health Research and Care (CLAHRC). PRIME group members helped design the trial processes and materials, particularly assisting with designing our approach to consent. The group was represented among the co-applicant group to continue to advise throughout the trial.

Participants

Inclusion criteria

-

Women aged ≥ 16 years who were willing and able to give informed consent.

-

Women who had had an operative vaginal delivery at ≥ 36+0 weeks’ gestation.

Exclusion criteria

Women were not eligible to enter the trial if any of the following applied:

-

A clinical indication for ongoing antibiotic administration post delivery [e.g. because of a confirmed antenatal or intrapartum infection, third- or fourth-degree tears (obstetric anal sphincter injury)]. Note that receiving antenatal antibiotics (e.g. for maternal group B streptococcal carriage or prolonged rupture of membranes) was not considered a reason for exclusion if there was no indication for ongoing antibiotic prescription post delivery.

-

Known allergy to penicillin or to any of the components of co-amoxiclav, as documented in hospital notes.

-

History of anaphylaxis (a severe hypersensitivity reaction) to another β-lactam agent (e.g. cephalosporin, carbapenem or monobactam), as documented in hospital notes.

Setting

The trial was conducted in 27 consultant-led obstetric units in England and Wales (see Appendix 1).

Informed consent and recruitment

Information about the trial was made widely available throughout the maternity units in the form of posters and leaflets [with QR (Quick Response) codes to the trial website]. Written information about the trial was available to all women at participating centres during their pregnancy through different routes, depending on the centre, for example at their antenatal booking visit, as part of their hand-held notes or at their 19- to 21-week scan visit.

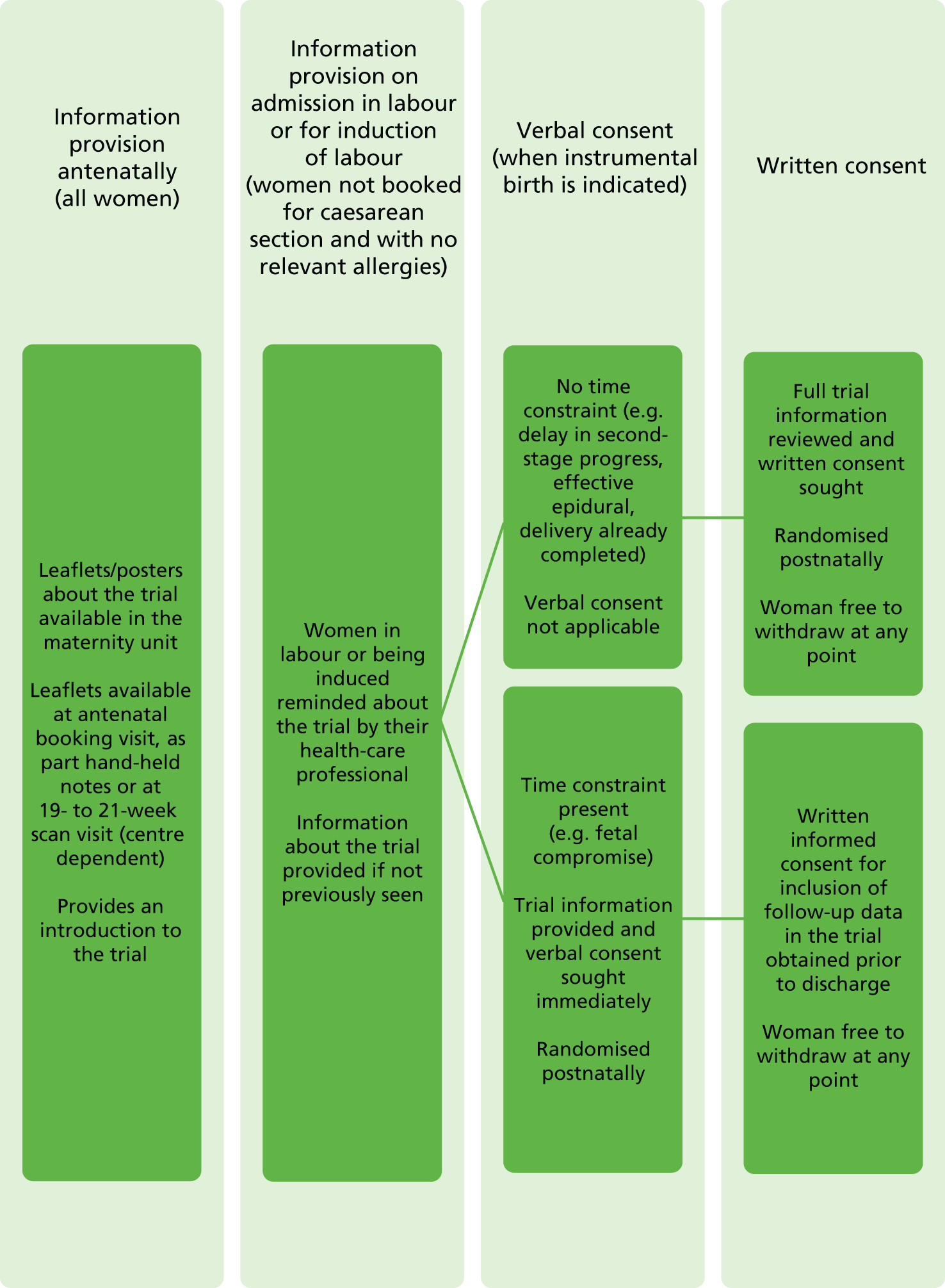

On admission, women in labour or admitted for induction were reminded about the trial by their health-care professional and information about the trial could be provided if not previously seen. After the clinical decision for operative vaginal birth had been made, the following approaches were used by the woman’s midwife, obstetrician or anaesthetist to obtain informed consent, depending on the clinical circumstances (Figure 1):

-

If there was no time constraint (e.g. in cases of operative vaginal birth for delayed second-stage progress or if birth was already completed), the health-care professional discussed the trial with the woman and provided her with the participant information leaflet. If she was happy to join the trial, then informed written consent was obtained.

-

If there was a time or other constraint (e.g. in cases of operative vaginal birth for suspected fetal compromise, or if an approach for written consent was considered inappropriate by the health professionals in attendance), women were approached to give verbal consent. It is possible that urgent deliveries are associated with a lower standard of asepsis, and so it was particularly important that these women were able to participate in the trial. If the attending obstetrician or midwife felt that it was appropriate, the woman was provided with verbal information about the trial and asked if she was willing to participate, in principle; if she agreed, she was randomised. Verbal consent was documented by the clinician recruiting the woman and countersigned by a witness. All women enrolled under this procedure were approached before discharge by trial midwives to give full written consent for inclusion of their data in the trial and for participation in the planned follow-up.

FIGURE 1.

Consent and randomisation processes. Reproduced from Knight et al. 28 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The text includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original text.

Intervention

Centres were supplied with sealed sequentially numbered indistinguishable packs containing trial treatment [a single dose of intravenous co-amoxiclav (1 g of amoxicillin/200 mg of clavulanic acid)] or placebo (a single dose of intravenous sterile saline), as designated. Bottles of 1000 mg/200 mg of co-amoxiclav, in the form of sterile powder for solution, were supplied for making up as an injection reconstituted with sterile water, which was also supplied. The placebo (0.9% saline) was supplied as 20 ml single-use vials of clear liquid. Reconstitution was not required.

As co-amoxiclav, when reconstituted, has a distinct colour and odour, it was impossible to blind those preparing and checking the intervention to women’s allocation. The investigational medicinal product (IMP) (co-amoxiclav or placebo) was made up in an opaque-coloured syringe so that the woman herself remained blinded to allocation. To ensure that awareness of allocation could not influence outcomes, it was specified that the research nurse/midwife conducting telephone follow-up should not have prepared or checked the intervention. Sites were instructed to give the intervention as soon as possible after women had given birth, and no later than 6 hours after birth of the baby.

Randomisation, blinding and code-breaking

A randomisation list was generated by the Senior Trials Statistician at the National Perinatal Epidemiology Unit Clinical Trials Unit (NPEU CTU) using permuted blocks of variable size to ensure balance and unpredictability overall. Pack numbers were added by the Senior Trials Programmer at the NPEU CTU, who liaised directly with the packaging and distribution company. Sites were provided with a series of sequential packs and stocks were replenished from the global sequence as required. Women were randomised by the allocation of the next sequentially numbered indistinguishable pack once consent and eligibility were established. Pack use was recorded by the recruiting site and reviewed by NPEU CTU.

An emergency code-breaking procedure was not required. As only a single dose of co-amoxiclav was administered, there was no need to code-break if further antibiotics were required. Centres were advised that if a woman had an anaphylactic reaction, she should be treated as if she had been given the active drug.

Internal pilot

We conducted an internal pilot during the first 9 months of the trial, when 1034 recruits were predicted, to test our recruitment and retention assumptions. The predefined stop–go criteria were:

-

If recruitment was ≥ 75% (n ≥ 775), then the target sample size was clearly achievable and Trial Steering Committee (TSC) recommendation to Health Technology Assessment (HTA) programme would be to continue directly with the main trial.

-

If recruitment was between 50% and 75% (517 ≤ n ≤ 775), then the TSC recommendation to the HTA programme would be to recruit more centres and review again in 6 months.

-

If recruitment was < 50% (n < 517), then urgent discussions were required between the Project Management Group and the TSC to undertake a detailed review of options to subsequently recommend to the HTA programme.

Outcomes

Primary outcome

Confirmed or suspected maternal infection within 6 weeks of delivery, as defined by one of the following:

-

a new prescription of antibiotics for presumed perineal wound-related infection, endometritis or uterine infection, urinary tract infection with systemic features or other systemic infection

-

confirmed systemic infection on culture

-

endometritis, as defined by the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). 31

An episode of endometritis defined according to the CDC required meeting at least one of the following criteria:

-

Organisms are cultured from fluid (including amniotic fluid) or tissue from endometrium obtained during an invasive procedure or biopsy.

-

The woman exhibits at least two of the following signs or symptoms: fever (> 38 °C), abdominal pain (with no other recognised cause), uterine tenderness (with no other recognised cause) or purulent drainage from uterus (with no other recognised cause).

Secondary outcomes

Systemic sepsis

This was defined according to modified systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS) criteria for pregnancy used in previous population-based surveillance studies,3,32 namely:

-

any woman dying from infection or suspected infection

-

any woman requiring level 2 or 3 critical care (or obstetric high-dependency unit-type care) because of severe sepsis or suspected severe sepsis

-

a clinical diagnosis of severe sepsis (two or more of the following) –

-

a temperature of > 38 °C or < 36 °C measured on two occasions at least 4 hours apart

-

a heart rate of > 100 beats per minute measured on two occasions at least 4 hours apart

-

a respiratory rate of > 20 breaths per minute measured on two occasions at least 4 hours apart

-

a white cell count of > 17 × 109/l or < 4 × 109/l or with > 10% immature band forms, measured on two occasions.

-

Perineal wound infection

This was defined according to the Public Health England Surveillance definition of surgical site infection (SSI),33 which falls under the following headings.

Superficial incisional infection

Superficial incisional infection is a SSI that occurs within 30 days of surgery, involves only the skin or subcutaneous tissue of the incision and meets at least one of the following criteria:

-

purulent drainage from superficial incision

-

culture of organisms and pus cells present in fluid/tissue from superficial incision or wound swab from superficial incision

-

at least two symptoms of inflammation – pain, tenderness, localised swelling, redness, heat AND EITHER (1) incision deliberately opened to manage infection OR (2) clinician’s diagnosis of superficial SSI.

Deep incisional infection

Deep incisional infection is a SSI involving the deep tissues (i.e. fascial and muscle layers) within 30 days of surgery (or 1 year if an implant is in place), and the infection appears to be related to the surgical procedure and meets at least one of the following criteria:

-

purulent drainage from deep incision (not organ space)

-

organisms from culture and pus cells present in fluid/tissue from deep incision or wound swab from deep incision

-

deep incision dehisces or deliberately opened and patient has at least one symptom of fever or localised pain/tenderness

-

abscess or other evidence of infection in deep incision – re-operation/histopathology/radiology

-

clinician’s diagnosis of deep incisional SSI.

Organ/space infection

Organ/space infection is a SSI involving the organ/space (other than the incision) opened or manipulated during the surgical procedure, that occurs within 30 days of surgery and the infection appears to be related to the surgical procedure and meets at least one of the following criteria:

-

purulent drainage from drain (through stab wound) into organ space

-

organisms from culture and pus cells present in fluid or tissue from organ/space or swab from organ/space

-

abscess or other evidence of infection in organ/space – re-operation/histopathology/radiology

-

clinician’s diagnosis of organ/space infection.

Perineal pain/use of pain relief/dyspareunia/ability to sit comfortably to feed the baby/need for additional perineal care/breastfeeding

This was identified using standard questions developed for the HOOP study34 and the PREVIEW study. 35

Maternal quality of life

This was elicited by the EuroQol-5 Dimensions, five-level version (EQ-5D-5L), questionnaire. 36

Hospital bed stay/hospital and general practitioner visits/wound breakdown/antibiotic side effects

This was identified through specific questions included in the maternal questionnaire.

Sample size

Observational studies of operative vaginal birth estimate postnatal infection to occur in between 2% and 16% of women. 29 The single existing trial of antibiotic prophylaxis at operative vaginal birth found a 4% rate of postnatal infection. 10 We therefore used this more conservative estimate of the maternal infection rate following operative vaginal birth. We assumed an estimated relative risk reduction of 50% in this rate with antibiotics to 2% in the treatment arm. The single trial relating to operative vaginal birth suggests a greater reduction than this, but this rate of reduction is based on that seen in the more robust antibiotic prophylaxis for caesarean section trials. 6 We used the absolute difference (i.e. a reduction from 4% to 2%) to calculate the sample size. To detect such a difference with 90% statistical power at the two-sided 5% level of significance required 1626 participants per group; with an estimated 5% loss to follow-up, the trial required 1712 participants per group, which was a total of 3424 women.

Statistical analyses

Statistical analyses were carried out according to a prespecified statistical analysis plan finalised and agreed prior to unblinding. In summary, demographic and clinical data were summarised with counts and percentages for categorical variables, means [standard deviations (SDs)] for normally distributed continuous variables and medians (with interquartile or simple ranges) for other continuous variables. Women were analysed in the groups to which they were randomly assigned, comparing the outcome of all women allocated to active treatment with all those allocated to placebo, regardless of deviation from the protocol or treatment received (referred to as the intention-to-treat population). Binary outcomes were analysed using risk ratios, while continuous outcomes were analysed using either a mean or a median difference, as appropriate. As randomisation did not involve stratification or minimisation, the primary analysis was based on unadjusted estimates of effect. Two-sided statistical testing was performed throughout. A 5% level of statistical significance was used for analyses of the primary outcome, and 1% for secondary outcomes. 95% CIs are presented for analyses of the primary outcome and 99% CIs for secondary outcomes.

Sensitivity analyses

Four planned sensitivity analyses were carried out:

-

examining the primary outcome restricted to women who had not received antibiotics in the 7 days prior to birth, in case any masking of a prophylactic effect occurred by inclusion of pre-treated women

-

examining the primary outcome excluding women prescribed antibiotics (other than the trial intervention) within 24 hours of birth in case these women were already infected prior to administration of the intervention

-

a repeat analysis of the primary outcome restricted to women whose primary outcome was obtained based on data obtained between 6 and 10 weeks after women had given birth

-

a sensitivity analysis including centre as a random effect.

Data collection

Data were collected at hospital discharge by extraction of information from a woman’s clinical records by the research midwife and at 6 weeks post partum by telephone interview with a research midwife to obtain information on the primary outcome. Following this, each woman was sent a postal or online questionnaire (as preferred by each woman) for collection of data on secondary outcomes.

Text reminders for completion of the questionnaire were sent and women were offered the option for telephone completion in the event of a delayed response to ensure a high response rate. Information about any hospital re-admissions and results of any microbiological investigations when a woman indicated that she had a suspected or confirmed infection were collected from hospital records by the site research midwife.

Basic demographic, medical and obstetric details were collected for all women, including details of any antibiotic treatment in the 7 days before women gave birth and the indication for antibiotic prescription.

Data on maternal anaphylaxis were collected up until hospital discharge. Data on other secondary outcomes were collected at 6 weeks post partum using standard instruments, when possible, as detailed below.

Surgical site infection (perineal)

This was identified using the items included in the Public Health England ’surgical wound healing post discharge questionnaire’. 33

Perineal pain/use of pain relief/dyspareunia/ability to sit comfortably to feed the baby/need for additional perineal care/breastfeeding

This was identified using standard questions developed for the HOOP (Hands On Or Poised) study34 and the PREVIEW (PREVention of diabetes through lifestyle intervention and population studies In Europe and around the World) study. 37

Maternal quality of life

This was elicited by the EQ-5D-5L. 36

Hospital bed stay/hospital and general practitioner visits/wound breakdown/antibiotic side effects

This was identified through specific questions included in the maternal questionnaire, to include medications prescribed, critical care admission, hospital inpatient admissions, outpatient visits, and midwife and practice nurse visits. All side effects of the IMP were recorded.

Indications for maternal antibiotic prescription and causes of infection were independently coded by two clinical reviewers, blinded to allocation, into the following categories:

-

perineal wound-related infection (including deep infections, such as abscess)

-

endometritis/uterine infection

-

urinary tract infection with systemic features (e.g. pyelonephritis)

-

other systemic infection (sepsis)

-

uncomplicated lower urinary tract infection (urinary tract infection with no other features specified)

-

breast infection/mastitis

-

respiratory infection (e.g. chest/throat)

-

other infection (e.g. meningitis)

-

other reason (non-infective)

-

unknown reason.

Any discrepancies or disagreements between the two reviewers were resolved by discussion or referral to a third reviewer.

A ’blinded end-point review’ (BER) was conducted to derive the primary outcome for women who returned a questionnaire but did not complete a telephone interview. Two clinical reviewers, who were blinded to allocation, independently assessed each questionnaire to see if there was any evidence that might indicate that the woman had experienced the primary outcome (i.e. evidence of any condition that might have led to antibiotic prescription, endometritis or any hospital re-admission). Any discrepancies or disagreements between the two reviewers were resolved by discussion or referral to the BER committee chairperson. If there was a potential, but not definite, indication that a woman had experienced the primary outcome, information about any hospital re-admissions and the results of any microbiological investigations were collected from hospital records by the site research midwife.

Adverse event reporting

The safety reporting window for this trial was from administration of intervention to 6 hours post administration or discharge (whichever was sooner). Non-serious adverse events were not routinely recorded as the IMP is a licensed product being given at a standard dose. However, adverse events that were part of the trial outcomes were recorded in the case report form.

All serious adverse events (SAEs) were reported immediately, at least within 24 hours, except the following SAEs (which were not considered to be causally related to the trial intervention because these events occurred prior to the trial intervention being administered):

-

birth defect/congenital anomaly

-

hypertensive disorder of pregnancy (e.g. pre-eclampsia/eclampsia)

-

post-partum haemorrhage with onset before the intervention.

Development safety update report

A development safety update report was submitted each year to the Competent Authority, the Ethics Committee and the sponsor.

Health-care resource use and cost analysis

As an additional analysis, not specified in the trial protocol, we conducted a within-trial comparison of health-care resource use and associated costs between trial arms. The perspective of the analysis was that of the UK NHS and the following categories of resource use were collected using the telephone interview and postal questionnaire at 6 weeks post delivery: antibiotic use (co-amoxiclav prophylaxis and new prescriptions), health-care professional visits [general practitioner (GP), nurse, midwife, health visitor and district nurse], outpatient hospital visits and all-cause hospital re-admissions.

Unit costs for co-amoxiclav were collected and estimated using the British National Formulary 2017. 38 We did not have details of the antibiotics used for new prescriptions and, therefore, assumed that all new prescriptions were co-amoxiclav, a low-cost generic antibiotic, so that our estimate of costs was conservative. Although some women may have received more than one course of antibiotics, we assumed that all women who had a new prescription of antibiotics had a single 7-day course of co-amoxiclav with three daily doses, again so that our estimate of costs was conservative. Unit costs for GP visits and nurse/midwife services at general practice were collected from Unit Costs of Health and Social Care 2017. 39 For other health-care resource categories, the unit cost was taken from NHS Reference Costs 2017/18. 40 More details on sources and associated estimates of unit costs (expressed in 2017/18 Great British pounds) for the different categories of resource use are presented in Appendix 2, Tables 17 and 18. The costs associated with each category of resource use were estimated by multiplying resource use by unit costs.

We calculated the mean and SD of resource uses (number of visits for health-care professional and outpatient hospital visits, number of days for re-admissions) and costs for each category by trial arms. We also calculated overall mean (SD) costs at 6 weeks following delivery by adding up all individual cost categories, together with the cost for intervention (a single dose of intravenous co-amoxiclav). Mean differences in health-care resource use and costs were calculated and associated 99% parametric CIs were estimated.

The main analysis was based on complete cases among women who returned the postal questionnaire at 6 weeks post delivery and completed questions on usage for each specific health-care resource category. We compared the characteristics of women who returned the postal questionnaire with those who did not using the t-test for continuous variables and Pearson’s chi-squared test for categorical variables. A sensitivity analysis using multiple imputation with chained equations was conducted to evaluate the impact of missing data on our complete-case results. Fifty values were imputed for each missing data point by specifying separate regression models for each variable with missing data. Within each model, the remaining variables with missing data were used as predictors along with selected patient characteristics [maternal age, gestational age at randomisation in weeks, ethnic group, body mass index (BMI), any previous pregnancies of ≥ 22 weeks’ gestation, labour induction, episiotomy in current delivery, perineal tear in current delivery]. Imputation was performed using prediction mean matching (using five nearest neighbours) and for each trial arm separately.

Governance and monitoring

A monitoring plan for the trial, including responsibilities, was developed prior to the start of recruitment. Remote monitoring was carried out, with at least one monitoring assessment of each site. Site monitoring visits were carried out if remote monitoring identified any discrepancies.

The trial was supervised on a day-to-day basis by a Project Management Group. A TSC was convened comprising an independent chairperson, four other independent members, a patient and public involvement representative, the NPEU CTU Director and the chief investigator. A Data Monitoring Committee (DMC), independent of the applicants and of the TSC, reviewed the progress of the trial annually and provided the TSC with advice on the conduct of the trial.

Summary of changes to the trial protocol

The initial planned primary outcomes were defined as follows.

Confirmed or suspected maternal infection within 6 weeks of delivery, as defined by one of:

-

a new prescription of antibiotics

-

confirmed systemic infection on culture

-

endometritis as defined by the US CDC. 31

Following an interim review of the data by the DMC in February 2017, a change to the primary outcome was recommended to exclude women who were prescribed antibiotics for unrelated indications. This was because of concerns that the noise arising from antibiotic prescriptions for unrelated indications would mask the effect of the intervention. The primary outcome was therefore revised to the following.

Confirmed or suspected maternal infection within 6 weeks of delivery, as defined by one of:

-

a new prescription of antibiotics for presumed perineal wound-related infection, endometritis or uterine infection, urinary tract infection with systemic features or other systemic infection

-

confirmed systemic infection on culture

-

endometritis as defined by the US CDC. 31

Indications for antibiotic prescription were coded independently as described in Data collection by two clinically qualified staff, based on responses to the telephone questionnaire, the infection form or the postal questionnaire. The revised primary outcome could, therefore, be derived for all women already recruited into the trial and no additional processes were needed.

A summary of the other changes made to the original protocol is presented in Appendix 3.

Chapter 3 Results

Recruitment and retention

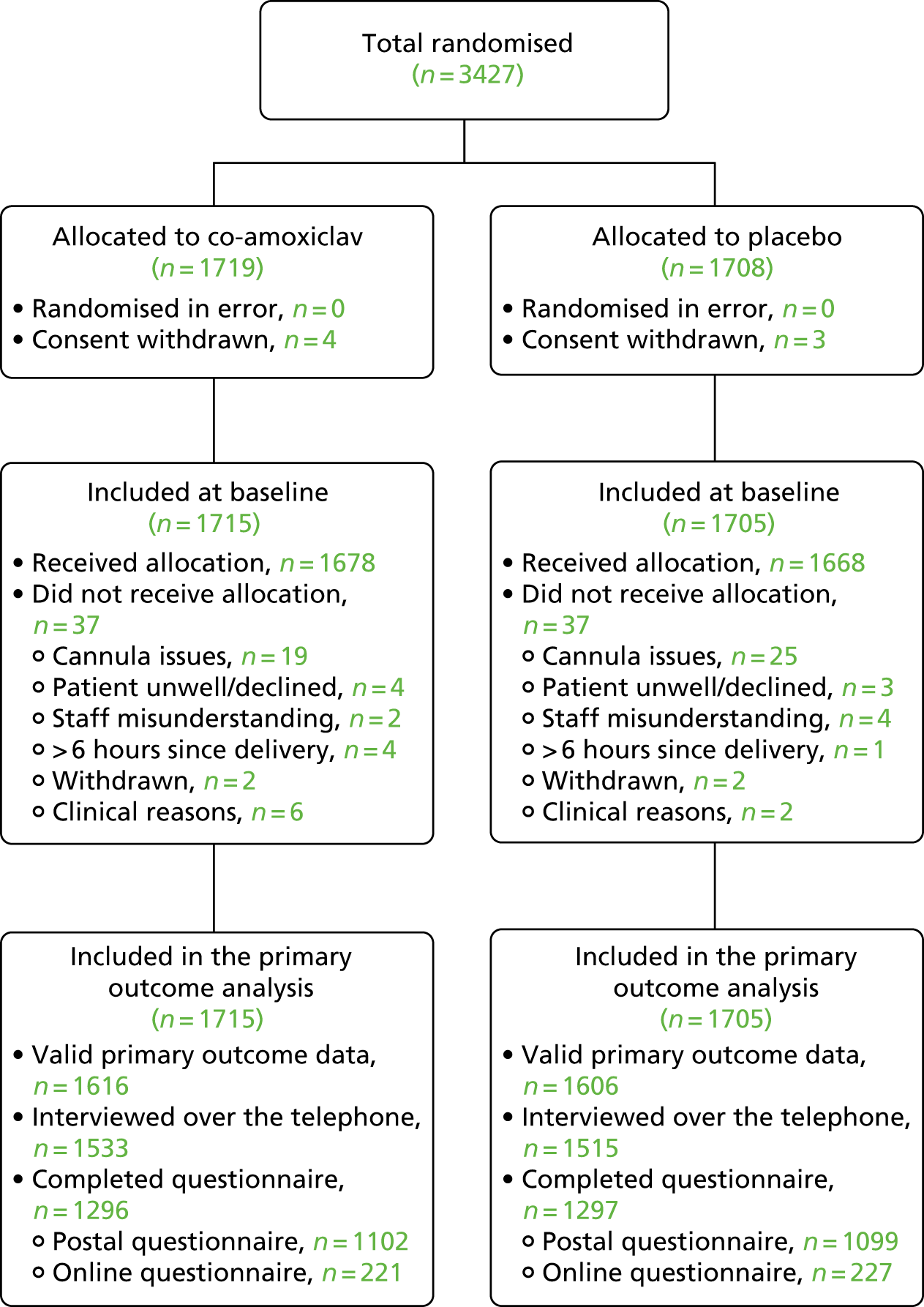

Between March 2016 and June 2018, 3427 women were randomised: 1719 to the antibiotic arm and 1708 to the placebo arm (Figure 2).

FIGURE 2.

Flow of participants. Figure modified from Knight et al. 30 This article is available under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). You may copy and distribute the article, create extracts, abstracts and new works from the article, alter and revise the article, text or data mine the article and otherwise reuse the article commercially (including reuse and/or resale of the article) without permission from Elsevier. You must give appropriate credit to the original work, together with a link to the formal publication through the relevant DOI and a link to the Creative Commons user license above. You must indicate if any changes are made but not in any way that suggests the licensor endorses you or your use of the work.

The number of participants recruited at each site varied from 22 to 388 (Table 1).

| Site | Co-amoxiclav (N = 1715), n (%) | Placebo (N = 1705), n (%) |

|---|---|---|

| James Cook University Hospital | 128 (7.5) | 132 (7.7) |

| Royal Berkshire Hospital, Reading | 30 (1.7) | 31 (1.8) |

| Sunderland Royal Hospital | 191 (11.1) | 197 (11.6) |

| Royal Victoria Infirmary, Newcastle upon Tyne | 150 (8.7) | 148 (8.7) |

| University Hospital of North Tees | 50 (2.9) | 51 (3.0) |

| John Radcliffe Hospital, Oxford | 86 (5.0) | 88 (5.2) |

| Bradford Royal Infirmary | 111 (6.5) | 103 (6.0) |

| Burnley General Hospital | 12 (0.7) | 10 (0.6) |

| Darlington Memorial Hospital | 59 (3.4) | 58 (3.4) |

| Derriford Hospital, Plymouth | 42 (2.4) | 40 (2.3) |

| East Surrey Hospital, Redhill | 28 (1.6) | 24 (1.4) |

| Liverpool Women’s Hospital | 111 (6.5) | 114 (6.7) |

| Princess Anne Hospital, Southampton | 83 (4.8) | 85 (5.0) |

| Princess of Wales Hospital, Bridgend | 21 (1.2) | 17 (1.0) |

| Queen Elizabeth Hospital, Gateshead | 53 (3.1) | 56 (3.3) |

| Royal Devon and Exeter Hospital | 25 (1.5) | 20 (1.2) |

| Singleton Hospital, Swansea | 32 (1.9) | 30 (1.8) |

| South Tyneside District General Hospital | 23 (1.3) | 22 (1.3) |

| St Thomas’ Hospital, London | 90 (5.2) | 89 (5.2) |

| Stoke Mandeville Hospital, Aylesbury | 40 (2.3) | 39 (2.3) |

| University Hospital of North Durham | 41 (2.4) | 37 (2.2) |

| University Hospital of Wales | 114 (6.6) | 113 (6.6) |

| Warrington Hospital | 21 (1.2) | 22 (1.3) |

| Whittington Hospital, London | 27 (1.6) | 30 (1.8) |

| Royal Stoke University Hospital | 17 (1.0) | 17 (1.0) |

| Croydon University Hospital | 110 (6.4) | 111 (6.5) |

| Northumbria Specialist Emergency Care Hospital | 20 (1.2) | 21 (1.2) |

Characteristics of participants

Characteristics of participants were similar between the two trial arms (Table 2) and appeared to be representative of the general population of women undergoing operative vaginal birth. Women had a mean age of 30 years, approximately half were of normal BMI and more than four-fifths were of white ethnicity. Overall, 77% of women were primiparous, and 49% had labour induced. Sixty-five per cent of births were assisted by forceps and 35% were assisted by vacuum extraction. Eighty-eight per cent of women had an episiotomy, 31% had a perineal tear and > 99% of women had suturing of a perineal wound.

| Characteristic | Allocated to co-amoxiclav (N = 1715), n (%) unless otherwise indicated | Allocated to placebo (N = 1705), n (%) unless otherwise indicated |

|---|---|---|

| Maternal age (years) mean (SD) | 30.3 (5.37) | 30.2 (5.49) |

| Missing | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Gestational age at randomisation (weeks) | ||

| Median (IQR) | 40 (39–41) | 40 (39–41) |

| 36+ 0 to 37+ 6 | 136 (7.9) | 123 (7.2) |

| 38+ 0 to 39+ 6 | 568 (33.1) | 555 (32.6) |

| 40+ 0 to 41+ 6 | 964 (56.2) | 968 (56.8) |

| ≥ 42+ 0 | 46 (2.7) | 59 (3.5) |

| Missing | 1 (0.1) | 0 (0) |

| Ethnic group | ||

| White | 1436 (84.1) | 1474 (86.8) |

| Indian | 36 (2.1) | 34 (2.0) |

| Pakistani | 73 (4.3) | 54 (3.2) |

| Bangladeshi | 8 (0.5) | 14 (0.8) |

| Black Caribbean | 6 (0.4) | 8 (0.5) |

| Black African | 32 (1.9) | 29 (1.7) |

| Any other ethnic group | 116 (6.8) | 85 (5.0) |

| Missing | 8 (0.5) | 7 (0.4) |

| BMI at booking (kg/m2) | ||

| Median (IQR) | 25 (22–28) | 25 (22–29) |

| < 18.5 | 46 (2.8) | 48 (2.9) |

| 18.5 to 24.9 | 851 (51.0) | 842 (50.6) |

| 25 to 29.9 | 460 (27.5) | 446 (26.8) |

| 30 to 34.9 | 207 (12.4) | 216 (13.0) |

| 35 to 39.9 | 74 (4.4) | 77 (4.6) |

| ≥ 40 | 32 (1.9) | 34 (2.0) |

| Missing | 45 (2.6) | 42 (2.5) |

| Twin pregnancy | 11 (0.6) | 9 (0.5) |

| Missing | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Any previous pregnancies of ≥ 22 weeks’ gestation | 402 (23.5) | 373 (21.9) |

| Missing | 1 (0.1) | 3 (0.2) |

| Previous caesarean section | 137 (8.0) | 123 (7.2) |

| Missing | 2 (0.1) | 3 (0.2) |

| Previous episiotomy | 147 (8.7) | 141 (8.4) |

| Missing | 26 (1.5) | 25 (1.5) |

| Previous tear | 81 (4.8) | 80 (4.8) |

| Missing | 24 (1.4) | 26 (1.5) |

| Rupture of membranes before giving birth | 1692 (98.7) | 1683 (98.7) |

| < 24 hours | 1461 (85.2) | 1466 (86.0) |

| ≥ 24 to < 48 hours | 191 (11.1) | 175 (10.3) |

| ≥ 48 hours | 35 (2.0) | 36 (2.1) |

| Unknown | 5 (0.3) | 6 (0.4) |

| Missing | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Labour induction | 819 (47.8) | 852 (50.0) |

| Missing | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Actual mode of birtha | ||

| Spontaneous vaginalb | 7 (0.4) | 3 (0.2) |

| Forceps | 1086 (62.9) | 1148 (67.0) |

| Vacuum extraction | 633 (36.7) | 563 (32.8) |

| Caesarean section | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Missing | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Sequential instruments used | 77 (4.5) | 78 (4.6) |

| Missing | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Reason for instrumental birth (non-exclusive) | ||

| Failure to progress | 855 (49.9) | 870 (51.0) |

| Fetal compromise | 861 (50.3) | 817 (47.9) |

| Other medical reason | 134 (7.8) | 131 (7.7) |

| Missing | 2 (0.1) | 0 (0) |

| Episiotomy in current birth | 1519 (88.6) | 1525 (89.4) |

| Missing | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Perineal tear in current birth | 493 (28.7) | 560 (32.8) |

| Missing | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Perineal wound sutured | 1645 (99.0) | 1665 (99.6) |

| Missing | 54 (3.1) | 33 (1.9) |

| Location suturing carried out | ||

| Operating theatre | 571 (34.7) | 588 (35.3) |

| Delivery ward/room | 1074 (65.3) | 1076 (64.7) |

| Missing | 70 (4.1) | 41 (2.4) |

Outcomes

Primary outcome data were available for 3225 out of 3420 women (94.3%). There were no substantive differences between women for whom primary outcome data were available (Table 3). Questionnaires were received for 2593 women (75.8%).

| Characteristic | Missing primary outcome data (N = 195), n (%) unless otherwise indicated | Complete primary outcome data (N = 3225), n (%) unless otherwise indicated |

|---|---|---|

| Maternal age (years) | ||

| Mean (SD) | 28.2 (5.97) | 30.4 (5.37) |

| Missing | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Gestational age at randomisation (weeks) | ||

| Median (IQR) | 40 (39–41) | 40 (39–41) |

| 36+ 0 to 37+ 6 | 18 (9.2) | 241 (7.5) |

| 38+ 0 to 39+ 6 | 68 (34.9) | 1055 (32.7) |

| 40+ 0 to 41+ 6 | 104 (53.3) | 1828 (56.7) |

| ≥ 42+ 0 | 5 (2.6) | 100 (3.1) |

| Missing | 0 (0) | 1 (0) |

| Ethnic group | ||

| White | 164 (84.1) | 2746 (85.5) |

| Indian | 2 (1.0) | 68 (2.1) |

| Pakistani | 7 (3.6) | 120 (3.7) |

| Bangladeshi | 3 (1.5) | 19 (0.6) |

| Black Caribbean | 1 (0.5) | 13 (0.4) |

| Black African | 5 (2.6) | 56 (1.7) |

| Any other ethnic group | 13 (6.7) | 188 (5.9) |

| Missing | 0 (0) | 15 (0.5) |

| BMI at booking (kg/m2) | ||

| Median (IQR) | 24 (22–30) | 25 (22–28) |

| < 18.5 | 8 (4.2) | 86 (2.7) |

| 18.5 to 24.9 | 93 (49.2) | 1600 (50.9) |

| 25 to 29.9 | 45 (23.8) | 861 (27.4) |

| 30 to 34.9 | 32 (16.9) | 391 (12.4) |

| 35 to 39.9 | 9 (4.8) | 142 (4.5) |

| ≥ 40 | 2 (1.1) | 64 (2.0) |

| Missing | 6 (3.1) | 81 (2.5) |

| Twin pregnancy | 3 (1.5) | 17 (0.5) |

| Any previous pregnancies of ≥ 22 weeks’ gestation | 57 (29.2) | 718 (22.3) |

| Missing | 0 (0) | 4 (0.1) |

| Previous caesarean section | 15 (7.7) | 245 (7.6) |

| Missing | 0 (0) | 5 (0.2) |

| Previous episiotomy | 20 (10.3) | 268 (8.4) |

| Missing | 1 (0.5) | 50 (1.6) |

| Previous tear | 17 (8.8) | 144 (4.5) |

| Missing | 1 (0.5) | 49 (1.5) |

| Rupture of membranes before giving birth | 195 (100.0) | 3180 (98.6) |

| < 24 hours | 178 (91.3) | 2749 (85.2) |

| ≥ 24 to < 48 hours | 14 (7.2) | 352 (10.9) |

| ≥ 48 hours | 1 (0.5) | 70 (2.2) |

| Unknown | 2 (1.0) | 9 (0.3) |

| Missing | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Labour induction | 101 (51.8) | 1570 (48.7) |

| Missing | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Actual mode of birtha | ||

| Spontaneousb | 0 (0) | 10 (0.3) |

| Forceps | 129 (65.2) | 2105 (65.3) |

| Ventouse | 69 (34.8) | 1127 (34.9) |

| Caesarean section | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Missing | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Sequential instruments used | 7 (3.6) | 148 (4.6) |

| Missing | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Reason for instrumental birth (non-exclusive) | ||

| Failure to progress | 82 (42.1) | 1643 (51.0) |

| Fetal compromise | 111 (56.9) | 1567 (48.6) |

| Other medical reason | 16 (8.2) | 249 (7.7) |

| Missing | 0 (0) | 2 (0.1) |

| Episiotomy in current birth | 174 (89.2) | 2870 (89.0) |

| Missing | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Tear in current birth | 50 (25.6) | 1003 (31.1) |

| Missing | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Wound sutured | 184 (98.9) | 3126 (99.3) |

| Missing | 9 (4.6) | 78 (2.4) |

| Location suturing carried out | ||

| Operating theatre | 61 (33.2) | 1098 (35.1) |

| Delivery ward/room | 123 (66.8) | 2027 (64.9) |

| Missing | 11 (5.6) | 100 (3.1) |

Primary outcomes

There was a 42% reduction in the risk of the overall primary outcome (risk difference 7.9%, 95% CI 5.5% to 10.4%) among the antibiotic arm compared with the placebo arm, noting that the overall primary outcome rate was substantially higher in the placebo arm than we had hypothesised (19% vs. an estimated 4%) (Table 4). The primary outcome was principally driven by one of the three components of the primary outcome: new prescription of antibiotics with specific indication. However, all components of the primary outcome showed the same direction of effect, and there was a statistically significant 56% reduction in confirmed systemic infection on culture from 1.5% (25/1606) in the placebo arm to 0.6% (11/1619) in the antibiotic arm.

| Outcome | Co-amoxiclav (N = 1715), n (%) | Placebo (N = 1705), n (%) | Risk ratioa (95% CI unless otherwise indicated) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Confirmed or suspected maternal infection | 180 (11.1) | 306 (19.1) | 0.58 (0.49 to 0.69) | < 0.001 |

| Missing | 96 (5.6) | 99 (5.8) | ||

| Confirmed systemic infection on culture | 11 (0.6) | 25 (1.5) | 0.44 (0.22 to 0.89) | 0.018 |

| Missing | 1 (0.1) | 1 (0.1) | ||

| Endometritis | 15 (0.9) | 23 (1.3) | 0.65 (0.34 to 1.24) | 0.186 |

| Missing | 1 (0.1) | 1 (0.1) | ||

| New prescription of antibiotics with relevant indication | 180 (11.1) | 306 (19.1) | 0.58 (0.49 to 0.69) | < 0.001 |

| Missing | 96 (5.6) | 99 (5.8) | ||

| Systemic sepsis according to modified SIRS criteria for pregnancy | 6 (0.4) | 10 (0.6) | 0.59 (0.16 to 2.24)b | 0.307 |

| Missing | 9 (0.5) | 16 (0.9) | ||

| Perineal wound infection | ||||

| Superficial incisional infection | 75 (4.4) | 141 (8.3) | 0.53 (0.37 to 0.76)b | < 0.001 |

| Missing | 3 (0.2) | 5 (0.3) | ||

| Deep incisional infection | 36 (2.1) | 77 (4.5) | 0.46 (0.28 to 0.77)b | < 0.001 |

| Missing | 5 (0.3) | 11 (0.6) | ||

| Organ/space infection | 0 | 4 (0.2) | 0.00 | 0.044 |

| Missing | 7 (0.4) | 11 (0.6) | ||

Secondary outcomes

There were statistically significant reductions in the secondary outcomes superficial perineal infection and deep perineal wound infection in the antibiotic arm. There was no significant difference in the incidence of systemic sepsis according to the modified SIRS criteria for pregnancy (see Table 4).

Considering the secondary outcomes reported on the postal/online questionnaire (Table 5), women in the antibiotic arm reported significantly lower levels of perineal pain, less use of pain relief for perineal pain, a less frequent need for additional perineal care and lower rates of wound breakdown than those in the placebo arm. There were no differences in reported dyspareunia between the groups, noting that only 41% of women had resumed intercourse at the time of returning their questionnaire. There was no statistically significant difference in breastfeeding rates between the two groups, but a greater proportion of women in the placebo arm reported times at which their perineum was too uncomfortable to feed their baby. Women in the antibiotic arm had fewer primary care or home visits, or hospital outpatient visits, in relation to their perineum than women in the placebo arm. There was no statistically significant difference in hospital re-admissions between the two arms, and no difference in mean EQ-5D-5L score (using the significance level p < 0.01 for secondary outcomes).

| Outcome | Co-amoxiclav (N = 1296), n (%) unless otherwise indicated | Placebo (N = 1297), n (%) unless otherwise indicated | Effect measurea (99% CI) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Perineal pain | 592 (45.7) | 707 (54.5) | 0.84 (0.76 to 0.93) | < 0.001 |

| Missing | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | ||

| Use of pain relief for perineal pain | 99 (7.7) | 138 (10.8) | 0.72 (0.52 to 0.99) | 0.007 |

| Missing | 13 (1.0) | 18 (1.4) | ||

| Need for additional perineal care | 390 (31.1) | 543 (43.1) | 0.72 (0.63 to 0.83) | < 0.001 |

| Missing | 42 (3.2) | 38 (2.9) | ||

| Wound breakdown | 142 (11.0) | 272 (21.1) | 0.52 (0.41 to 0.67) | < 0.001 |

| Missing | 4 (0.3) | 7 (0.5) | ||

| Dyspareuniab | 299 (55.0) | 280 (54.5) | 1.01 (0.87 to 1.17) | 0.873 |

| Missing | 5 (0.4) | 8 (0.6) | ||

| Breastfeeding at 6 weeks | 662 (51.2) | 657 (50.8) | 1.01 (0.91 to 1.11) | 0.828 |

| Missing | 4 (0.3) | 4 (0.3) | ||

| Perineum ever too painful/uncomfortable to feed baby | 136 (11.3) | 198 (16.5) | 0.69 (0.53 to 0.90) | < 0.001 |

| Missing | 96 (7.4) | 98 (7.6) | ||

| Hospital bed stay to discharge | ||||

| Median (IQR) | 1 (1–2) | 1 (1–2) | 0.00 (0.00 to 0.00) | 0.318 |

| Missing | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | ||

| Any primary care or home visits in relation to perineum | 361 (27.9) | 496 (38.4) | 0.73 (0.63 to 0.84) | < 0.001 |

| Missing | 3 (0.2) | 5 (0.4) | ||

| Any outpatient visits in relation to perineum | 95 (7.4) | 173 (13.4) | 0.55 (0.40 to 0.75) | < 0.001 |

| Missing | 5 (0.4) | 6 (0.5) | ||

| Maternal hospital re-admission | 63 (5.0) | 84 (6.7) | 0.75 (0.49 to 1.14) | 0.072 |

| Missing | 47 (3.6) | 51 (3.9) | ||

| Maternal health-related quality of life | ||||

| EQ-5D-5L score, mean (SD) | 0.935 (0.098) | 0.927 (0.111) | 0.008 (–0.003 to 0.019) | 0.048 |

| Missing | 16 (1.2) | 18 (1.4) | ||

Adverse events and side effects

Only three women reported side effects of the intervention: 2 out of 1715 in the antibiotic arm (0.12%) and 1 out of 1705 (0.06%) in the placebo arm (risk difference 0.06%, 95% CI –0.14% to 0.25%). The woman in the placebo arm reported a skin rash, and the women in the antibiotic arm reported other reactions (e.g. itching, swollen throat). There were no cases of anaphylaxis. Three SAEs were reported (Table 6), but only one was thought to be causally related to the intervention.

| Treatment allocation | Description | Severity | Related |

|---|---|---|---|

| Co-amoxiclav | Immediate reaction to the active IMP: itching and swollen throat. | Moderate | Definitely |

| Placebo | Woman admitted to intensive care unit 15 days post natal with severe sepsis | Severe | Not related |

| Placebo | Post-partum haemorrhage with blood transfusion | Moderate | Not related |

Adherence

The intervention was administered a median of 3 hours after women had given birth (Table 7). Thirty-three women (1.0%) received the intervention > 6 hours after giving birth. Overall, 33 telephone follow-up interviews (1.0%) were conducted by staff who had prepared or checked the ANODE intervention and may, theoretically, have been unblinded to allocation. Similarly, as antibiotic prescription was part of the primary outcome, we checked whether or not the person prescribing antibiotics was also the person who had checked or prepared the ANODE intervention and would therefore have been unblinded. Only one woman, in the antibiotic arm, was prescribed further antibiotics by a member of staff who may have been unblinded.

| Adherence factor | Co-amoxiclav (N = 1715), n (%) unless otherwise indicated | Placebo (N = 1705), n (%) unless otherwise indicated |

|---|---|---|

| Time between giving birth and the administration of the intervention (hours) | ||

| Median (IQR) | 3.2 (2.2–4.5) | 3.1 (2.1–4.4) |

| ≤ 6 | 1649 (98.9) | 1651 (99.2) |

| > 6 | 19 (1.1) | 14 (0.8) |

| Missing | 47 (2.7) | 40 (2.3) |

| Telephone interviewer at 6 weeks prepared or checked the ANODE intervention | 14 (0.9) | 19 (1.2) |

| Missing | 130 (7.6) | 132 (7.7) |

| Same person who prescribed further antibiotics prepared or checked the trial intervention | 1 (0.1) | 0 (0.0) |

| Missing | 1 (0.1) | 4 (0.2) |

Sensitivity analyses

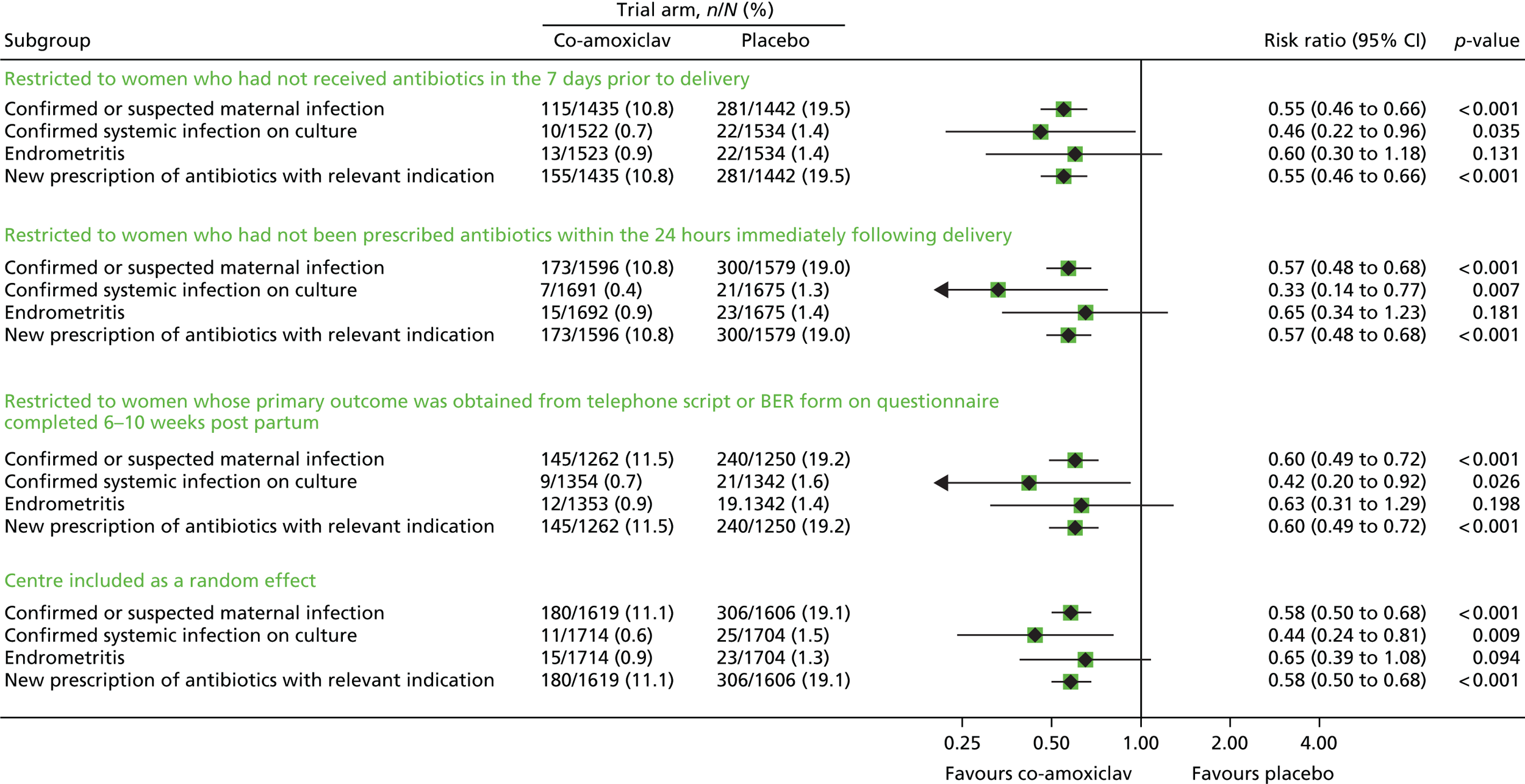

There were no material changes to the primary outcome with any of the sensitivity analyses (Tables 8–11 and Figure 3).

| Outcome | Co-amoxiclav (N = 1523), n (%) | Placebo (N = 1535), n (%) | Risk ratio (95% CI) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Confirmed or suspected maternal infection | 155 (10.8) | 281 (19.5) | 0.55 (0.46 to 0.66) | < 0.001 |

| Missing | 88 (5.8) | 93 (6.1) | ||

| Confirmed systemic infection on culture | 10 (0.7) | 22 (1.4) | 0.46 (0.22 to 0.96) | 0.035 |

| Missing | 1 (0.1) | 1 (0.1) | ||

| Endometritis | 13 (0.9) | 22 (1.4) | 0.60 (0.30 to 1.18) | 0.131 |

| Missing | 0 (0) | 1 (0.1) | ||

| New prescription of antibiotics with relevant indication | 155 (10.8) | 281 (19.5) | 0.55 (0.46 to 0.66) | < 0.001 |

| Missing | 88 (5.8) | 93 (6.1) |

| Outcome | Co-amoxiclav (N = 1692), n (%) | Placebo (N = 1676), n (%) | Risk ratio (95% CI) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Confirmed or suspected maternal infection | 173 (10.8) | 300 (19.0) | 0.57 (0.48 to 0.68) | < 0.001 |

| Missing | 96 (5.7) | 97 (5.8) | ||

| Confirmed systemic infection on culture | 7 (0.4) | 21 (1.3) | 0.33 (0.14 to 0.77) | 0.007 |

| Missing | 1 (0.1) | 1 (0.1) | ||

| Endometritis | 15 (0.9) | 23 (1.4) | 0.65 (0.34 to 1.23) | 0.181 |

| Missing | 0 (0) | 1 (0.1) | ||

| New prescription of antibiotics with relevant indication | 173 (10.8) | 300 (19.0) | 0.57 (0.48 to 0.68) | < 0.001 |

| Missing | 96 (5.7) | 97 (5.8) |

| Outcome | Co-amoxiclav (N = 1354), n (%) | Placebo (N = 1343), n (%) | Risk ratio (95% CI) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Confirmed or suspected maternal infection | 145 (11.5) | 240 (19.2) | 0.60 (0.49 to 0.72) | < 0.001 |

| Missing | 92 (6.8) | 93 (6.9) | ||

| Confirmed systemic infection on culture | 9 (0.7) | 21 (1.6) | 0.42 (0.20 to 0.92) | 0.026 |

| Missing | 0 (0) | 1 (0.1) | ||

| Endometritis | 12 (0.9) | 19 (1.4) | 0.63 (0.31 to 1.29) | 0.198 |

| Missing | 1 (0.1) | 1 (0.1) | ||

| New prescription of antibiotics with relevant indication | 145 (11.5) | 240 (19.2) | 0.60 (0.49 to 0.72) | < 0.001 |

| Missing | 92 (6.8) | 93 (6.9) |

| Outcome | Co-amoxiclav (N = 1715), n (%) | Placebo (N = 1705), n (%) | Risk ratio (95% CI) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Confirmed or suspected maternal infection | 180 (11.1) | 306 (19.1) | 0.58 (0.50 to 0.68) | < 0.001 |

| Missing | 96 (5.6) | 99 (5.8) | ||

| Confirmed systemic infection on culture | 11 (0.6) | 25 (1.5) | 0.44 (0.24 to 0.81) | 0.009 |

| Missing | 1 (0.1) | 1 (0.1) | ||

| Endometritis | 15 (0.9) | 23 (1.3) | 0.65 (0.39 to 1.08) | 0.094 |

| Missing | 1 (0.1) | 1 (0.1) | ||

| New prescription of antibiotics with relevant indication | 180 (11.1) | 306 (19.1) | 0.58 (0.50 to 0.68) | < 0.001 |

| Missing | 96 (5.6) | 99 (5.8) |

FIGURE 3.

Forest plot showing the results of the sensitivity analyses.

Health-care resource use and cost analysis

Among the 2593 women who returned the questionnaire, we found evidence that, at 6 weeks post delivery, women randomised to the antibiotic arm consumed fewer NHS health-care resources than those in the placebo arm (Table 12). The mean difference in all categories of resource use favoured the antibiotic arm, with the number of visits to the GP (p < 0.001), nurse or midwife home visits (p < 0.001) and outpatient hospital visits (p < 0.001) being statistically significantly different between groups. No statistically significant mean differences were detected in the length of stay for all-cause hospital re-admissions.

| Health-care resource use category | Co-amoxiclav (N = 1296) | Placebo (N = 1297) | Mean difference (99% CI) | p-value | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | Minimum | Maximum | Mean (SD) | n | Minimum | Maximum | Mean (SD) | |||

| Health-care professional number of visits in relation to perineum | ||||||||||

| GP | 1235 | 0 | 4 | 0.161 (0.500) | 1239 | 0 | 7 | 0.266 (0.689) | –0.11 (–0.17 to –0.04) | < 0.001 |

| Midwife/nurse at general practice | 1240 | 0 | 23 | 0.115 (0.771) | 1243 | 0 | 6 | 0.142 (0.546) | –0.03 (–0.10 to 0.04) | 0.298 |

| Midwife/nurse at home | 1219 | 0 | 15 | 0.373 (1.079) | 1226 | 0 | 10 | 0.551 (1.189) | –0.18 (–0.30 to –0.06) | < 0.001 |

| Health visitor/district nurse | 1240 | 0 | 23 | 0.071 (0.731) | 1253 | 0 | 11 | 0.081 (0.550) | –0.01 (–0.08 to 0.06) | 0.710 |

| Outpatient hospital number of visits | 1229 | 0 | 12 | 0.168 (0.828) | 1231 | 0 | 17 | 0.310 (1.042) | –0.14 (–0.24 to –0.04) | < 0.001 |

| Length of stay hospital re-admissions (in days) | 1234 | 0 | 29 | 0.079 (0.954) | 1235 | 0 | 10 | 0.124 (0.761) | –0.05 (–0.14 to 0.04) | 0.192 |

Similar results were found for costs. Among different health-care categories, the highest cost was estimated for hospital re-admissions, followed by nurse or midwife home visits and outpatient hospital visits (Table 13). Compared with the women allocated to the placebo arm, the health-care costs for women in the antibiotic arm were, on average, a significant £0.40 (99% CI £0.20 to £0.50) less for new prescriptions of antibiotic, £3.90 (99% CI £1.60 to £6.20) less for GP visits, £12.10 (99% CI £4.00 to £20.10) less for nurse or midwife home visits and £15.40 (99% CI £5.20 to £25.50) less for outpatient hospital visits. The mean cost of hospital re-admissions was also found to be lower in the antibiotic arm (£50.30 vs. £81.60), but the difference was not statistically significant (p = 0.164). The total mean cost at 6 weeks following delivery was estimated to be £102.50 (SD £652.40) per woman in the antibiotic arm and £155.10 (SD £497.40) per woman in the placebo arm. The mean difference in the total health-care cost was –£52.60 (99% CI –£115.10 to £9.90) per woman, which was not statistically significantly different at the 1% level (p = 0.030).

| Health care cost | Co-amoxiclav (N = 1296) | Placebo (N = 1297) | Mean difference (99% CI) | p-value | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | Minimum | Maximum | Mean (SD) | n | Minimum | Maximum | Mean (SD) | |||

| Health-care cost category | ||||||||||

| Co-amoxiclav for prevention | 1296 | 2.3 | 2.3 | 2.3 (0.0) | 1297 | 0 | 0.0 | 0.0 (0.0) | 2.3 (2.3 to 2.3) | – |

| New prescription of antibiotic | 1283 | 0 | 4.8 | 0.5 (1.5) | 1281 | 0 | 4.8 | 0.9 (1.9) | –0.4 (–0.5 to –0.2) | < 0.001 |

| Health-care professional number of visits | ||||||||||

| GP | 1235 | 0 | 148.0 | 6.0 (18.5) | 1239 | 0 | 259.0 | 9.9 (25.5) | –3.9 (–6.2 to –1.6) | < 0.001 |

| Midwife/nurse at general practice | 1240 | 0 | 250.7 | 1.2 (8.4) | 1243 | 0 | 65.4 | 1.6 (5.9) | –0.3 (–1.1 to 0.4) | 0.298 |

| Midwife/nurse at home | 1219 | 0 | 1020.0 | 25.4 (73.4) | 1226 | 0 | 680.0 | 37.4 (80.8) | –12.1 (–20.1 to –4.0) | < 0.001 |

| Health visitor/district nurse | 1240 | 0 | 874.0 | 2.7 (27.8) | 1253 | 0 | 418.0 | 3.1 (20.9) | –0.4 (–2.9 to 2.2) | 0.710 |

| Outpatient hospital number of visits | 1229 | 0 | 1303.1 | 17.3 (84.1) | 1231 | 0 | 1846.1 | 32.7 (109.3) | –15.4 (–25.5 to –5.2) | < 0.001 |

| Hospital re-admissions | 1234 | 0 | 18568.7 | 50.3 (610.6) | 1235 | 0 | 6403.0 | 81.6 (498.7) | –31.3 (–89.1 to 26.6) | 0.164 |

| Total health-care costsa | ||||||||||

| Total costs at 6-weeks following delivery | 1148 | 2.3 | 19084.0 | 102.5 (652.4) | 1144 | 0.0 | 6403.0 | 155.1 (497.4) | –52.6 (–115.1 to 9.9) | 0.030 |

On the basis of the estimated number of doses of co-amoxiclav used for the costs analysis (see Table 13), we estimated the potential effect of a policy of universal prophylaxis with a single dose of co-amoxiclav after operative vaginal birth on overall antibiotic use. In the placebo arm, 19% of women had a confirmed or suspected infection and 1297 women received an estimated 5166 doses of co-amoxiclav to treat infection (three daily doses for 7 days in 246 women). In the antibiotic arm, 11% of women had a confirmed or suspected infection and 1296 women received an estimated 3003 doses of co-amoxiclav to treat infection (three daily doses for 7 days in 143 women), as well as 1296 prophylactic doses; therefore, a total of 4299 doses. A policy of universal prophylaxis would therefore be associated with an estimated net reduction of 867 doses of antibiotic (17% reduction).

There were statistically significant differences in the characteristics of women who had missing secondary resource outcomes compared with those who did not (Table 14). However, the comparisons of post-delivery health-care resource use and costs after multiple imputation were similar to those generated by using complete cases (Tables 15 and 16). Compared with women allocated to the placebo arm, women in the antibiotic arm had significantly fewer GP visits, nurse or midwife visits at home, and outpatient hospital visits. The total mean costs after multiple imputation were estimated to be £117.30 (SE £20.23) in the co-amoxiclav group and £168.30 (SE £15.07) in the placebo group. The mean difference in the total cost was –£50.90 (99% CI–£114.70 to £12.90; p = 0.040).

| Characteristic | Secondary outcome missing (N = 827), n (%) unless otherwise indicated | Secondary outcome present (N = 2593), n (%) unless otherwise indicated | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mother’s age at randomisation (years), mean (SD) | 28.2 (5.8) | 30.9 (5.1) | < 0.001 |

| Gestational age at randomisation (weeks) | |||

| 36+0 to 37+6 | 74 (8.9) | 185 (7.1) | 0.036 |

| 38+0 to 39+6 | 294 (35.6) | 829 (32.0) | |

| 40+0 to 41+6 | 438 (53.0) | 1494 (57.6) | |

| > 42 | 21 (2.5) | 84 (3.2) | |

| Ethnic group | |||

| Bangladeshi | 12 (1.5) | 10 (0.4) | < 0.001 |

| Black African | 25 (3.0) | 36 (1.4) | |

| Black Caribbean | 9 (1.1) | 5 (0.2) | |

| Indian | 26 (3.2) | 44 (1.7) | |

| Other | 47 (5.7) | 154 (6.0) | |

| Pakistani | 54 (6.6) | 73 (2.8) | |

| White | 648 (78.9) | 2262 (87.5) | |

| BMI at booking (kg/m2) | |||

| < 18.5 | 30 (3.7) | 64 (2.5) | < 0.001 |

| 18.5 to 24.9 | 383 (47.3) | 1310 (51.9) | |

| 25 to 29.9 | 199 (24.6) | 707 (28.0) | |

| 30 to 34.9 | 133 (16.4) | 290 (11.5) | |

| 35 to 39.9 | 41 (5.1) | 110 (4.4) | |

| ≥ 40 | 23 (2.8) | 43 (1.7) | |

| Multiple pregnancy | |||

| No | 821 (99.3) | 2579 (99.5) | 0.54 |

| Yes | 6 (0.7) | 14 (0.5) | |

| Previous pregnancies of ≥ 22 weeks’ gestation | |||

| No | 587 (71.1) | 2054 (79.3) | < 0.001 |

| Yes | 239 (28.9) | 536 (20.7) | |

| Previous caesarean section | |||

| No | 744 (90.1) | 2411 (93.1) | 0.004 |

| Yes | 82 (9.9) | 178 (6.9) | |

| Previous episiotomy | |||

| No | 727 (89.4) | 2354 (92.1) | 0.017 |

| Yes | 86 (10.6) | 202 (7.9) | |

| Previous tear | |||

| No | 758 (93.2) | 2451 (95.9) | 0.002 |

| Yes | 55 (6.8) | 106 (4.1) | |

| Rupture of membranes before giving birth | |||

| < 24 hours | 718 (87.9) | 2209 (86.4) | 0.36 |

| 24 to < 48 hours | 76 (9.3) | 290 (11.3) | |

| ≥ 48 hours | 20 (2.4) | 51 (2.0) | |

| Unknown | 3 (0.4) | 8 (0.3) | |

| Labour induced | |||

| No | 401 (48.5) | 1348 (52.0) | 0.080 |

| Yes | 426 (51.5) | 1245 (48.0) | |

| Sequential instruments used | |||

| No | 796 (96.3) | 2469 (95.2) | 0.21 |

| Yes | 31 (3.7) | 124 (4.8) | |

| Episiotomy in current birth | |||

| No | 101 (12.2) | 275 (10.6) | 0.20 |

| Yes | 726 (87.8) | 2318 (89.4) | |

| Tear in current birth | |||

| No | 603 (72.9) | 1764 (68.0) | 0.008 |

| Yes | 224 (27.1) | 829 (32.0) | |

| Wound sutured | |||

| No | 8 (1.0) | 15 (0.6) | 0.22 |

| Yes | 786 (99.0) | 2524 (99.4) | |

| Health-care resource | Co-amoxiclav | Placebo | Mean difference (99% CI) | p-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | Mean (SE) | n | Mean (SE) | |||

| Health-care professional number of visits in relation to perineum | ||||||

| GP | 1715 | 0.170 (0.014) | 1705 | 0.270 (0.018) | –0.100 (–0.161 to –0.039) | < 0.001 |

| Midwife/nurse at general practice | 1715 | 0.114 (0.018) | 1705 | 0.152 (0.015) | –0.038 (–0.098 to 0.022) | 0.101 |

| Midwife/nurse at home | 1715 | 0.404 (0.031) | 1705 | 0.568 (0.032) | –0.163 (–0.277 to –0.049) | < 0.001 |

| Health visitor/district nurse | 1715 | 0.073 (0.016) | 1705 | 0.082 (0.015) | –0.009 (–0.067 to 0.049) | 0.699 |

| Outpatient hospital number of visits | 1715 | 0.173 (0.022) | 1705 | 0.317 (0.028) | –0.145 (–0.236 to –0.053) | < 0.001 |

| Duration of stay for hospital re-admissions (in days) | 1715 | 0.099 (0.031) | 1705 | 0.134 (0.022) | –0.035 (–0.131 to 0.060) | 0.339 |

| Health-care cost | Co-amoxiclav | Placebo | Mean difference (99% CI) | p-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | Mean (SE) | n | Mean (SE) | |||

| Health-care cost category | ||||||

| Co-amoxiclav for prevention | 1715 | 2.3 (0.0) | 1705 | 0.0 (0.0) | 2.3 (2.3 to 2.3) | – |

| New prescription of antibiotic | 1715 | 0.5 (0.038) | 1705 | 0.9 (0.047) | –0.4 (–0.5 to –0.2) | < 0.001 |

| Health-care professional visits in relation to perineum | ||||||

| GP | 1715 | 6.3 (0.524) | 1705 | 10.0 (0.681) | –3.7 (–5.9 to –1.4) | < 0.001 |

| Midwife/nurse at general practice | 1715 | 1.2 (0.194) | 1705 | 1.7 (0.164) | –0.4 (–1.1 to 0.2) | 0.101 |

| Midwife/nurse at home | 1715 | 27.5 (2.084) | 1705 | 38.6 (2.203) | –11.1 (–18.9 to –3.4) | < 0.001 |

| Health visitor/district nurse | 1715 | 2.8 (0.625) | 1705 | 3.1 (0.579) | –0.3 (–2.5 to 1.9) | 0.699 |

| Outpatient hospital visits | 1715 | 13.6 (1.826) | 1705 | 26.0 (2.487) | –12.4 (–20.3 to –4.5) | < 0.001 |

| Hospital re-admissions | 1715 | 63.1 (19.634) | 1705 | 88.0 (14.216) | –24.9 (–86.4 to 36.7) | 0.296 |

| Total health-care costs | ||||||

| Total costs at 6 weeks following delivery | 1715 | 117.3 (20.228) | 1705 | 168.3 (15.069) | –50.9 (–114.7 to 12.9) | 0.040 |

Chapter 4 Discussion and conclusions

Summary of main findings

This trial showed clear evidence of benefit of a single dose of intravenous co-amoxiclav administered to women a median of 3 hours after operative vaginal birth. Women in the antibiotic arm had a 42% relative reduction, from 19% to 11%, in the risk of suspected or confirmed infection. This was principally driven by the prescription of antibiotics for presumed perineal wound-related infection, endometritis or uterine infection, urinary tract infection with systemic features or other systemic infection, but women in the antibiotic arm also had a statistically significant 56% reduction in the risk of confirmed systemic infection on culture, from 1.5% to 0.6%. Secondary outcomes also favoured the active (co-amoxiclav) arm, with significant reductions in rates of both deep and superficial perineal infection, perineal pain, wound breakdown and the need for additional perineal care.

At 6 weeks post delivery, women who were randomised to the antibiotic arm consumed fewer NHS health-care resources than women randomised to the placebo arm, with significantly fewer visits to the GP, midwife/nurse home visits and outpatient hospital visits. The mean total health-care cost per woman was £52.60 lower in the antibiotic arm than in the placebo arm, but this was not statistically significantly different at the 1% level.

Limitations

We took the pragmatic approach in this trial of defining suspected or confirmed maternal infection using a composite outcome, including a new prescription of antibiotics for confirmed or suspected infection, which can be interpreted as equating to a clinical diagnosis of infection. This clinical diagnosis of infection drove the overall outcome and resulted in a substantially higher than anticipated event rate, which may suggest overprescription of antibiotics in the postnatal period. The use of this clinical definition rather than microbiologically confirmed infection could be regarded as a limitation; however, we observed a statistically significant decrease in the rate of microbiologically confirmed systemic infection following culture from a sterile site, which supports the assumption that the findings represent a genuine decrease in infection, despite our pragmatic primary outcome definition.

We achieved a 76% follow-up rate for the majority of our secondary outcomes, which represents the main limitation of this trial. There were statistically significant differences in the characteristics of the women who completed the 6-week questionnaire and those who did not. Most notably, a greater proportion of women who returned the 6-week questionnaire were primiparous. It is possible that their consultation behaviour differed from multiparous women; thus, rates of some of the reported secondary outcomes may be higher than would be seen in the general population. This difference in characteristics between those with follow-up data and those without is, however, unlikely to account for the magnitude of difference we observed between the antibiotic and placebo arms.

The population of women included in the trial was representative of the population of women undergoing operative vaginal birth and thus appear broadly generalisable. The trial was limited to women who were not penicillin-allergic and, therefore, is not directly applicable to women who are allergic to penicillin. However, it would be anticipated that another antibiotic with a similar spectrum of activity would have a similar protective effect in women for whom co-amoxiclav is contraindicated. Options for penicillin-allergic women that offer a comparable spectrum of activity to co-amoxiclav would include cefuroxime with metronidazole or clindamycin with gentamicin. Similarly, we included only women giving birth at ≥ 36 weeks’ gestation. However, there are no clear reasons why the results would not also be generalisable to women who had an instrumental vaginal birth at lower gestations than this.

We asked sites to administer the intervention as soon as possible after women had given birth, and no later than 6 hours after women had given birth. In practice, it was administered a median of 3 hours after women had given birth. It is possible that administration this length of time after women had given birth made the co-amoxiclav less effective than it might have been, given that caesarean section trials suggest that pre-delivery administration is more effective at preventing wound infection and endometritis. 41 However, as noted earlier, the perineal wound, which is highly likely to become contaminated, is very different from the caesarean section wound, and later administration may have allowed for a longer duration of protective effect and greater efficacy. Further analyses are needed to investigate the mechanism of effect, as described in Implications for research.

Comparison with existing literature

The single previous trial of antibiotic prophylaxis after operative vaginal birth42 reported on endometritis only, noting a rate of 4% in the no antibiotic arm. This is considerably lower than the rate of suspected or confirmed infection we observed in the ANODE trial but, interestingly, using the strict CDC surveillance definition,31 we observed a lower endometritis rate. The estimate of effect we observed for endometritis (relative risk 0.65, 95% CI 0.34 to 1.24) in the ANODE trial is compatible with the effect estimate in the Heitmann and Benrubi trial42 (relative risk 0.07, 95% CI 0.00 to 1.17). Combining the results of the two trials using Mantel–Haenszel fixed-effect meta-analysis gives an overall relative risk 0.50 (95% CI 0.27 to 0.93) for endometritis.

Women in the ANODE trial who received placebo had a 19% rate of confirmed or suspected infection at 6 weeks post partum. This is higher than the infection rate reported in most other studies of complications following instrumental vaginal birth. 29 As noted previously, very few of these observational studies followed women beyond discharge, yet post-partum wound infections and endometritis have been reported to occur at a peak of 7 days post discharge in large data-linkage studies. 43 The ANODE trial shows very clearly a significant burden of confirmed or suspected infection and, most notably, both superficial and deep perineal wound infection after initial hospital discharge.