Notes

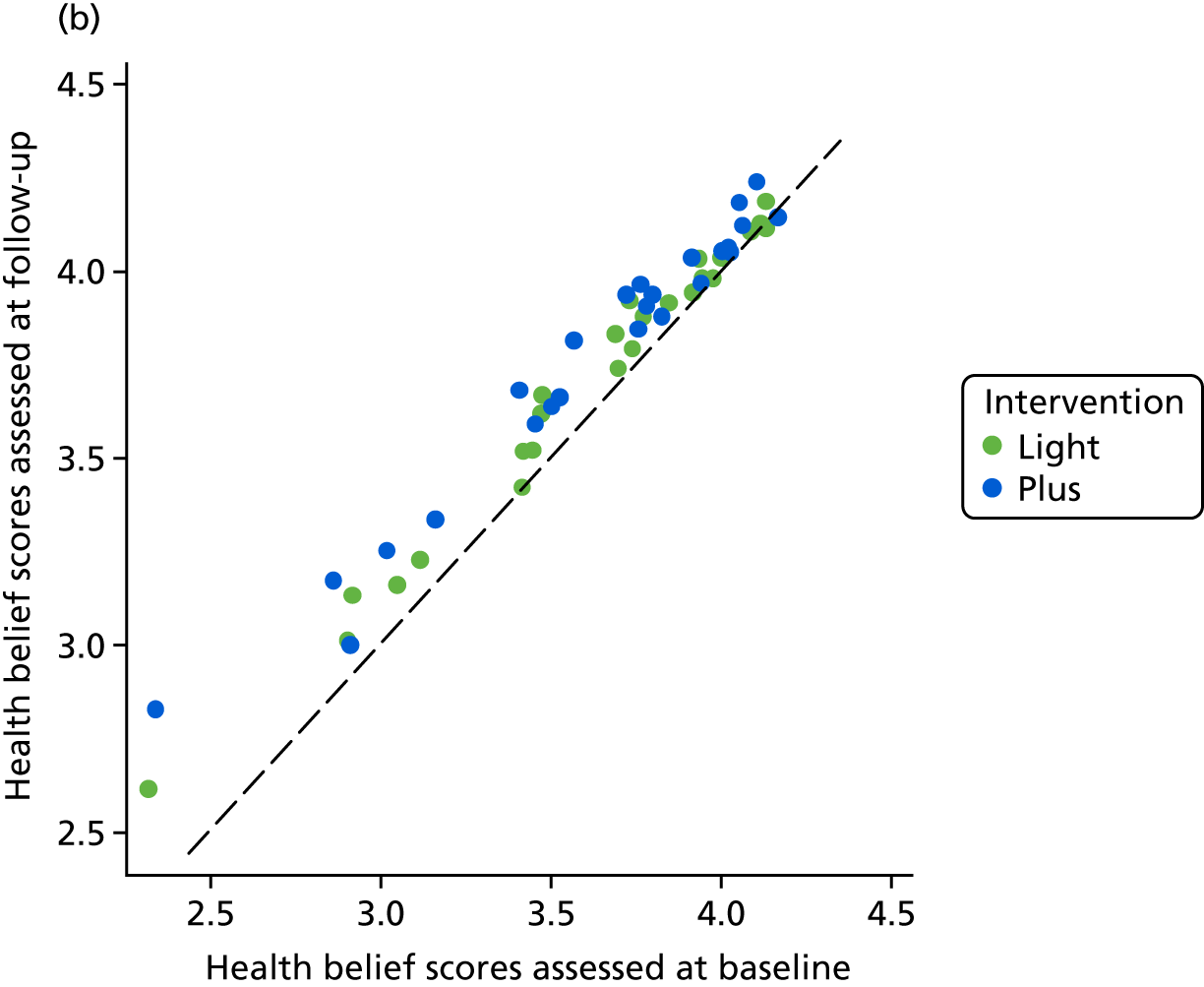

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 11/94/01. The contractual start date was in June 2013. The draft report began editorial review in December 2017 and was accepted for publication in April 2019. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Ira Madan reports being the chairperson of the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR)’s Health Technology Assessment (HTA) Mental Health panel from 1 January 2018 to December 2020. Vaughan Parsons reports personal fees from the magazine Occupational Health at Work during the conduct of the trial. Alison Wright reports other grants from the NIHR HTA programme during the conduct of the study. Julia Smedley reports other grants from NIHR via Guy’s and St Thomas’ NHS Foundation Trust (lead centre) during the conduct of the study (HTA reference number 15/107/02). Hywel Williams is Director of the HTA programme and chairperson of the HTA Commissioning Board. From 1 January 2016, he became Programme Director for the HTA programme.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2019. This work was produced by Madan et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2019 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Introduction

Parts of this chapter have been adapted from Madan et al. 1 This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The text below includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original text.

Scientific background

Irritant hand dermatitis is an important occupational disease in health professionals. A study in Sweden found the 1-year prevalence of self-reported hand dermatitis among 9051 health-care workers to be 21%,2 slightly lower than the 24% found among health-care workers in an earlier study in the Netherlands. This compares to < 10% in the general population. 3 Past history of atopy (childhood or adult eczema, asthma or allergic rhinitis), female sex and occupational exposure are well recognised as predictive risk factors for future hand dermatitis,4,5 with studies showing that history of atopy can also negatively affect the prognosis of hand dermatitis in later life. 6,7

Among health professionals, nurses are the group at highest risk of hand dermatitis, with an estimated point prevalence of 12–30%;8–10 this is often attributed to frequent exposure to wet work, including hand-washing. 11 Moreover, in a study of German geriatric nurses, two-thirds of those who reported hand dermatitis stated that it had developed after they had joined the profession. 8 Consistent with this, among Korean nursing students, the prevalence of self-reported hand dermatitis increased from 7% in the first year to 23% in the fourth year of training. 12 The costs of hand dermatitis to the individual and employer are high. It not only affects quality of life, but also can lead to loss of employment. 13,14 Once an individual has developed irritant hand dermatitis, the prognosis is poor. In a 15-year follow-up study of a Swedish general population sample, about one-third of those people with hand dermatitis needed ongoing medical treatment and 5% experienced long periods of sickness absence, loss or change of job, or retirement due to ill health. 6 Affected individuals may also experience negative psychosocial consequences, such as sleep disturbance and interference with leisure activities,6 as well as economic implications. 15 Recent evidence from the UK suggests that, although the incidence of allergic contact dermatitis is decreasing, probably because of an improvement in working practices, the incidence of irritant contact dermatitis remains unchanged. 16

Health-care settings are known to expose health-care workers to a variety of irritants that can cause and exacerbate skin abnormalities. Current hand-cleansing improvement policies in the NHS are driven by efforts to reduce colonisation and transmission of infections, and the emphasis is on frequent use of hand rubs before and after patient contact, and washing with soap and water if the hands are visibly soiled or potentially contaminated with bodily fluids. 17 However, to date, little attention has been paid to the prevention of hand dermatitis.

For a nurse who develops irritant hand dermatitis, the condition is likely to be aggravated by exposure to recommended hand-hygiene measures. The presence of hand dermatitis may discourage nurses from undertaking adequate hand decontamination because of discomfort or concern about exacerbating skin lesions. It is known that 50% of people with hand dermatitis are colonised with Staphylococcus aureus18 and, accordingly, there is a risk that nurses with hand dermatitis infected with S. aureus or indeed antimicrobial-resistant strains, such as those resistant to meticillin [i.e. meticillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA)], could transmit these organisms and cause infections in patients. 19 Occupational health-care workers often have to advise nurses with active dermatitis to refrain from working in clinical areas until the lesions are healed, as it is difficult for them to avoid frequent hand-washing unless they are redeployed to a non-clinical area. This workplace adjustment may become temporary or permanent.

Existing literature and interventional studies

Several studies on the primary and secondary prevention of hand dermatitis have been conducted in the last decade, with variable success, as detailed in the following section.

Moisturisers

Two systematic reviews of the management of occupational dermatitis20,21 have concluded that moisturisers contributed importantly to both prevention and treatment of hand dermatitis at work. The review commissioned by NHS Plus focused on the evidence for managing established occupational dermatitis and found a small body of consistent evidence that hand moisturisers used before and during work improved skin condition in health-care workers with damaged skin,22,23 and concluded that there was sufficient evidence to recommend that skin-care programmes should include the use of hand moisturisers. 24,25

Guidelines produced by the British Occupational Health Research Foundation21 recommended the regular application of emollients to help prevent the development of occupational dermatitis, citing three high-quality studies: a systematic review26 and two randomised controlled trials (RCT). 27,28 One RCT found an improvement in all outcomes, including visible dermatitis. In the other RCT, transepidermal water loss improved among construction workers who used pre- and after-work creams compared with controls, but there was no difference in the workers’ clinically assessed skin condition. 28 Moisturisers also improved skin condition in health-care workers with damaged skin. 29 More recent reviews, including a Cochrane review,30 concluded that there is some evidence to support the use of educational interventions that include moisturisers to prevent occupational hand dermatitis, but, as the evidence came from only a small number of studies, the authors strongly recommended that larger high-quality RCTs in different occupational groups were needed. 30,31 Following these recommendations, Soltanipoor et al. 11 conducted a RCT in the Netherlands that examined the effectiveness of an educational programme together with the provision of moisturisers in dispensers. The dispensers were fitted with electronic usage monitors, allowing the researchers to give feedback to the participants on their moisturiser use. The effectiveness of the intervention was measured from the assessment of skin conditions in participants before and after the interventions. The study found higher levels of self-reported use of hand moisturising cream among nurses before and during shifts in the intervention group than in the control group. However, the self-reported prevalence of hand dermatitis was similar in both study groups at follow-up. Notwithstanding, evidence from the study suggests that electronic tracking of hand cream usage coupled with feedback has a positive impact on skin-care behaviour among health-care workers.

In the experience of the dermatologists and occupational health physicians in this research team, moisturisers are not widely used by health-care workers in the UK. This anecdotal observation is supported by a study of nurses working in intensive care units (ICUs) in Germany that found that only 15% of the 204 respondents reported that they applied moisturising creams after hand-washing and only 2% after skin disinfection with hand rubs. Furthermore, 9% of respondents never applied skin care to their hands and 72% reported that they did not perform final skin care after the last hand wash of the day. 32

Hand cleansing

The use of antibacterial (alcohol-based) hand rubs, with the addition of moisturisers for hand hygiene, reduces the drying and cracking of the skin that commonly results from repeated hand cleansing with soap and water. 33,34 This has the added benefit of also reducing rates of some health-care-associated infections, such as S. aureus bacteraemia and Clostridium difficile infections. 35 Moreover, antibacterial hand rubs have been associated with increased hand-hygiene compliance and reduced rates of nosocomial infection. 17,36 Although the benefits of using antibacterial hand rubs as a safe and effective dermatitis prevention strategy have now been established,2 a notable difficulty faced by occupational health-care workers and dermatologists is to challenge the misconceptions among nurses that antibacterial hand rubs are more damaging to the skin integrity than hand-washing and, therefore, more likely to cause hand dermatitis. 37 There is a misconception among some health-care workers that alcohol-based hand rubs are more irritating and drying than cleaning hands using soap and water; therefore, they are less likely to use them. 38 Accordingly, Stutz et al. 37 argue that hand-hygiene education and training should focus on promoting the use of antibacterial hand rubs as an effective protective behaviour for reducing the prevalence of hand dermatitis in nurses. The implementation of the World Health Organization (WHO)’s guidelines among physicians working in Ireland, which promoted the use of alcohol-based hand rubs by senior management and infection control teams, had a positive impact on changing attitudes and practices towards the use of hand rubs without damaging the epidermis. 39

Hand drying and glove use

The appropriate use of gloves during clinical work and proper drying of the hands after washing is pivotal to good hand hygiene and care, particularly as wet skin is more likely than dry skin to facilitate the transmission of bacteria. A recent review of hand-drying processes,40 which included 12 studies, concluded that paper towels are superior to electric air dryers in drying hands in clinical environments. The ensuing recommendation that paper towels should be used for hand drying in clinical environments, where hand hygiene is vital, was supported by The Royal College of Physicians20 and WHO. 17

Effectiveness of skin-care programmes

Various skin-care programmes that incorporated the provision of hand moisturisers, hand rubs and paper towels have shown a beneficial effect in the prevention of hand dermatitis in health-care workers. 22,23,41–44 However, as John and Kezic45 pointed out, although effective preventative strategies are available, these are often limited by poor understanding of the causes of occupational skin diseases among at-risk workers. Furthermore, others have argued the need to reconsider what is deemed acceptable levels of hand-hygiene compliance, as, for example, a 70% hand-hygiene compliance rate among health-care workers is as effective at reducing infections as 90% compliance. 46

Educational programmes (individual or part of hand health programmes)

Previous studies examining the effectiveness of educational programmes designed to influence and encourage optimal hand-care behaviours among health-care workers22 including ICU nurses47 have yielded only moderately promising results. However, Ibler et al. 43 found that an educational programme coupled with individual counselling focusing on good hand dermatitis prevention behaviours had a positive impact on the secondary prevention of hand dermatitis. The intervention reduced the frequency with which participants washed their hands and increased the frequency of their use of protective gloves during wet work, when compared with their usual treatment. However, this intervention was delivered on a one-to-one basis and so might be difficult to scale up across the health service.

A recent systematic review suggested that educational programmes could benefit from being more strongly informed by psychological theories of behaviour, as programme success relies on employees adopting appropriate preventative and protective behaviours. 31 Furthermore, other studies have also investigated interventions specifically designed to facilitate behaviour change, with an emphasis on improving hand care among health professionals. The Hands4U RCT trial in the Netherlands examined a multifaceted intervention that comprised (1) a leaflet containing evidence-based hand dermatitis prevention recommendations, (2) a participatory working group to explore facilitators of and barriers to adopting recommendations, (3) provision of trained role models (dermacoaches) to encourage and model good hand dermatitis prevention behaviours at a departmental level and (4) provision of education and training to promulgate preventative measures in the workplace. 44 The main outcome measures assessed were self-reported hand dermatitis and adoption of preventative behaviours over a 12-month period. The study found that health-care workers in the intervention group were significantly more likely to engage in positive preventative behaviours to protect themselves from hand dermatitis. That is, the health-care workers reported significantly less hand-washing and more frequent use of hand moisturisers and wearing of cotton under gloves than colleagues in the control arm. However, the intervention group reported a higher prevalence of hand dermatitis than the control group at 12 months. This may have been due to an increased awareness of hand dermatitis as a consequence of the intervention. A notable limitation of this study was the use of self-reported measures to assess hand dermatitis, as opposed to more objective measures. Moreover, no cost-effectiveness analysis of the intervention was undertaken. A prominent observation with many skin-protection programmes is that sustained compliance among at-risk workers is poor and so programmes that promote sustained behaviour change are required. 48

Although there are good reasons to expect that well-designed skin-care programmes would be beneficial for nurses, their clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness remain uncertain. Trials to date have been limited by size and the possibility that the control group was aware of the intervention,44 or by a failure to address cost-effectiveness. 49 Furthermore, trials have been hampered by lack of sustainability of behaviour change. Psychological theory suggests that knowledge transfer coupled with a behaviour change programme would be effective in changing the beliefs and behaviours of at-risk nurses in relation to hand care and, if accompanied by provision of hand moisturisers, would lead to a reduction in the prevalence of hand dermatitis.

The use of psychological theory to improve hand hygiene and hand care

Hand dermatitis prevention requires the adoption and maintenance of several protective behaviours. Changing behaviour requires an understanding of its determinants. Interventions to prevent hand dermatitis have not always drawn sufficiently on psychological theories of behaviours. 31 Psychological theory has, however, proved useful in understanding the behavioural determinants of hand hygiene among health-care workers. 17,50–52 Several trials have employed behavioural theoretical frameworks to modify and improve hand-hygiene behaviours among health-care workers,51,53 including one study of critical care nurses that used the theory of planned behaviour (TPB) as a theoretical framework. 54 Moreover, a meta-analysis of internet-based behaviour change interventions found that interventions that focused more on behaviour were more effective,55 suggesting that theories may help interventions better target key influences on the behaviour they wish to change. In contrast, hand dermatitis prevention interventions have often focused only on improving nurses’ knowledge of the condition. Larger effects on behaviour, and so on hand dermatitis prevention, might be achieved if a broader range of the psychological determinants of behaviour were targeted. One of the few studies applying psychological theory to occupational hand dermatitis examined the ability of the TPB to predict the behaviour of a sample of German patients with occupational hand dermatitis receiving an inpatient tertiary prevention programme. 56 The TPB57 suggests that behaviour is directly influenced by intentions (motivation, in the form of a conscious plan or decision to try to perform the behaviour) and perceived behavioural control (the individual’s belief concerning how easy or difficult performing the behaviour will be). Moreover, intentions are influenced by three constructs: attitudes (the degree to which the person has a favourable or unfavourable evaluation of the behaviour), subjective norms (beliefs about whether important others want one to perform the behaviour) and perceived behavioural control. In the study of German patients with occupational dermatitis, the TPB variables explained 30% of the variance in post-intervention dermatitis prevention behaviour and 38% of the variance in intentions for preventative behaviours. 56 Therefore, an intervention targeting attitudes, subjective norms and perceived behavioural control over hand dermatitis prevention behaviours may lead to risk-reducing behaviour change and reduced prevalence of hand dermatitis. Systematic review evidence suggests that the TPB may perform somewhat better at predicting intentions than behaviour. 58 One particular issue is ‘inclined abstainers’, individuals with positive intentions who subsequently fail to act in line with those intentions. 59 However, systematic review evidence shows that forming implementation intentions and specific plans about how, when and where health-promoting behaviours will be performed increases the likelihood of individuals acting on their positive intentions. Furthermore, evidence suggests that reminding individuals of their implementation intentions can facilitate longer-term behaviour change. 60,61 Therefore, adding an implementation intentions component to a dermatitis prevention behaviour change intervention may promote greater protective behaviour change.

Approaches to diagnosing hand dermatitis and use of photographic methods as a diagnostic tool

Various techniques have been used to diagnose hand dermatitis in dermatological research. Some studies have relied on visual inspections of hands by clinicians, whereas others have based diagnoses on information collected about symptoms from questionnaires or used self-diagnosis by participants. 37,62,63 The merits of these different techniques, in terms of sensitivity and specificity, were evaluated by Smit et al. 62 Smit et al. 62 found a prevalence of hand dermatitis of 18% based on visual examination, 19% based on self-diagnosis and 48% by symptom-based diagnosis. The study also found varying degrees of overestimation regarding disease prevalence, namely that, although there was 100% sensitivity in the symptom-based questionnaire, the specificity was found to be low, at 64%, whereas the sensitivity of the self-diagnosis questionnaire was found to be lower (65%), with a higher degree of specificity (93%).

Teledermatology (a method of assessing and diagnosing skin conditions from photographic images) is a validated procedure, which yields results similar to those from face-to-face consultations64–67 and can be used by patients to self-assess their own hand dermatitis severity. 65,68 Researchers have found that face-to-face (‘live’) diagnoses by specialist dermatologists were in agreement with retrospective diagnoses by resident dermatologists based on digital photographs in 22 of the 29 cases (76% of the time). 65 Furthermore, the ‘live’ diagnoses by the specialist dermatologists agreed with the definitive diagnoses (by biopsy) in 73% of occasions. Interpretation of digital photographs is sufficiently sensitive to detect early signs of dermatitis. 66 Teledermatology has been shown to have high intra- and inter-rater reliability when compared with face-to-face assessment in NHS ICU nurses and nursery nurses,64 with a slight tendency to overestimate the prevalence of hand dermatitis. 64,66 Teledermatology based on images from a mobile phone camera has been shown to have > 70% diagnostic agreement with face-to-face assessments by dermatologists. 69,70 Furthermore, Shin et al. 70 found that images taken on mobile phones for diagnosing dermatitis had a sensitivity of 78% [standard deviation (SD) 0%] and a specificity of 93.1% (SD 5.2%). 70

Rationale for research

Hand dermatitis in nurses is an important clinical and occupational issue in the NHS: treatment is costly, and hand dermatitis affects service delivery. It may increase in importance in the future given that hand-hygiene measures will continue to be rigorously enforced in health care. At the same time, retention of highly trained nurses in the workforce is likely to become increasingly important as fewer people are being trained to become nurses. Given the current economic climate, it is vital that new interventions implemented in the NHS are both clinically effective and cost-effective. As there was genuine equipoise about the suggested intervention, the study assembled a multidisciplinary team to deliver a high-quality study to test whether or not an intervention based on the TPB and implementation intentions could lead to enhanced hand-care behaviours and reduce the incidence of hand dermatitis in the NHS. We chose to employ a cluster RCT design to avoid contamination during the study as we recognised the potential problems that would occur if individual nurses at each site were randomised to either the intervention plus or the intervention light arm.

Objectives

-

The study tested the hypothesis that a bespoke, web-based behaviour change intervention to improve hand care, together with provision of hand moisturisers, could produce a clinically useful reduction in the prevalence of hand dermatitis after 1 year, when compared with standard care, among nurses working in the NHS who are particularly at risk.

-

Secondary aims were to assess impacts on participants’ beliefs and behaviour regarding hand care, days off sick over a 1-year follow-up period and use of hand moisturisers.

-

In addition, the study assessed the cost-effectiveness of the intervention compared with normal care.

Chapter 2 Trial design and methods

Parts of this chapter have been adapted from Madan et al. 1 This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The text below includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original text.

Design overview

The study used a cluster RCT design, with sites as the unit of randomisation. This was a pragmatic multicentre study in which participating sites were randomly allocated to the ‘intervention light’ or ‘intervention plus’ arm. See Madan et al. 1 for a full description of the trial protocol. Participants were newly recruited student nurses and ICU or special-care baby unit (SCBU) nurses.

Inclusion criteria

Included individuals were:

-

student nurses who –

-

were first-year student nurses, and

-

had a history of atopic tendency (i.e. had ever had, or received treatment for, asthma, hay fever, eczema anywhere on the body or dermatitis of the hands)

-

-

ICU nurses (including SCBU nurses) who –

-

worked on ICUs (or SCBUs)

-

worked full-time (i.e. ≥ 30 hours per week)

-

had no extended periods of leave of > 3 months in the following 12 months.

-

Exclusion criteria

The study excluded individuals who:

-

were first-year mental health student nurses

-

were ICU nurses (or SCBU nurses) working on a part-time basis (i.e. < 30 hours per week), or

-

had extended periods of leave of > 3 months planned in the following 12 months.

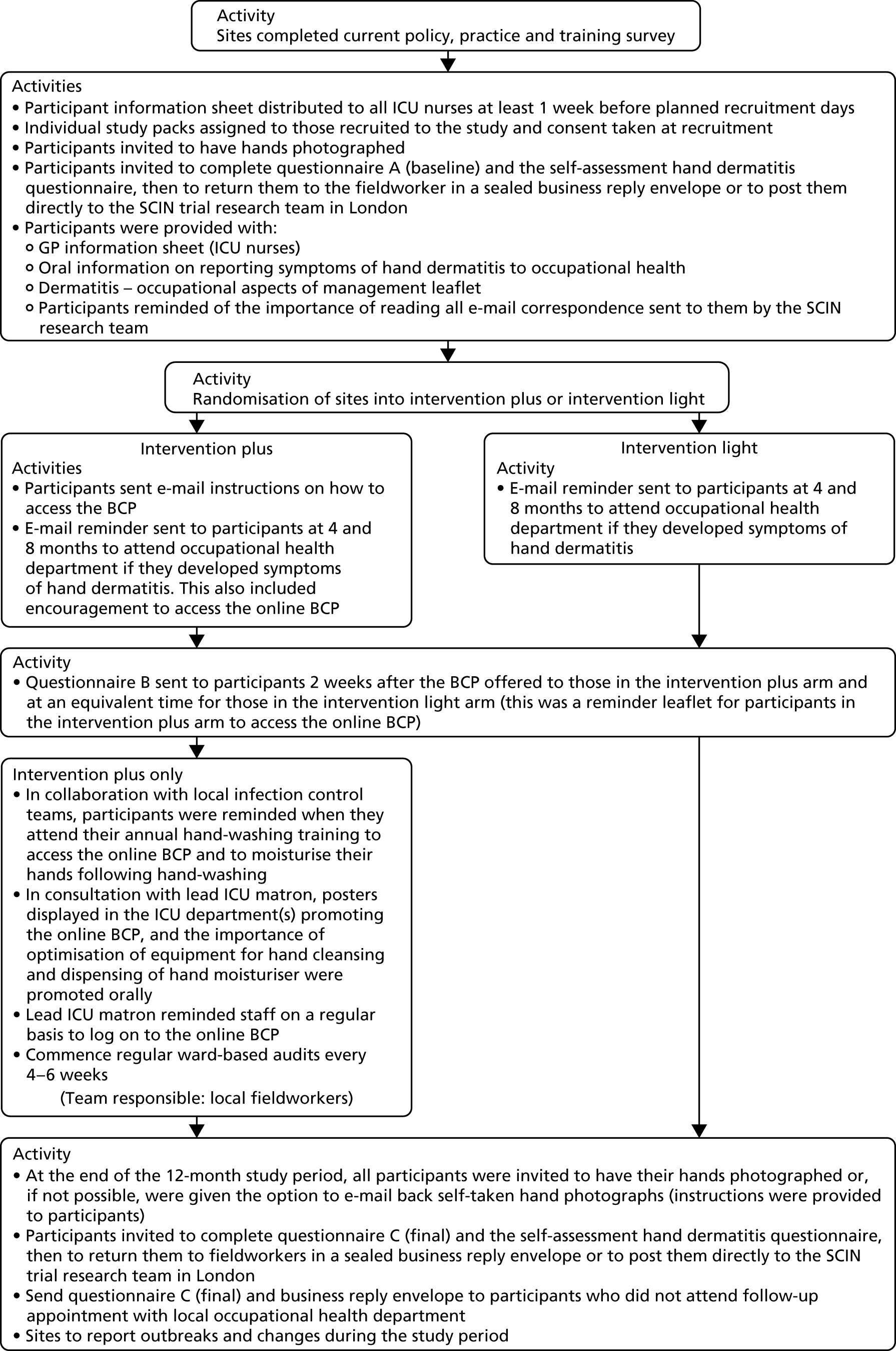

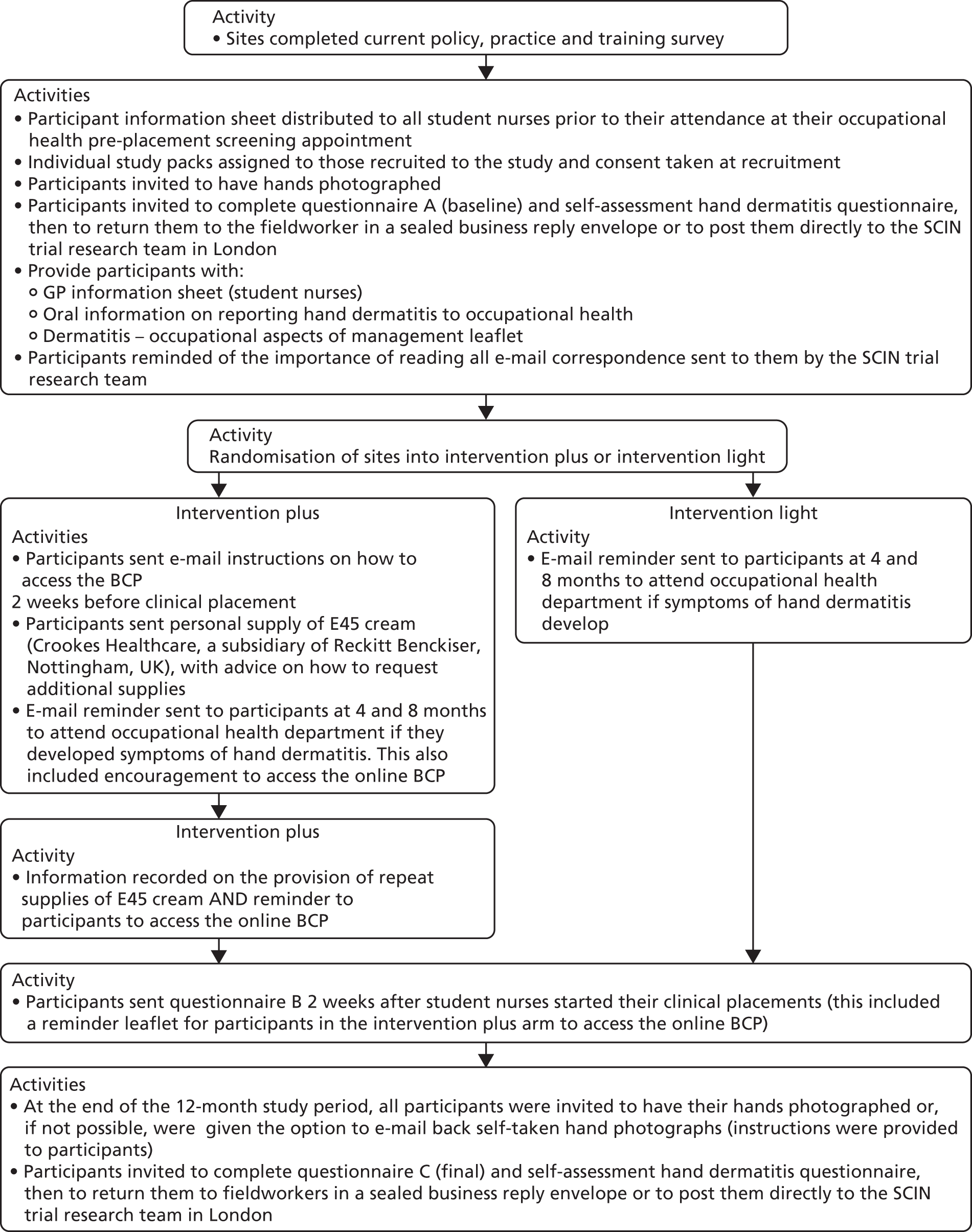

Student nurses were recruited during their occupational health pre-placement screening appointments in the occupational health departments located at either their local NHS trusts/health boards or their respective universities. ICU/SCBU nurses were recruited on-site at their respective NHS trust/health board. Figures 1 and 2 outline the trial procedures for ICU/SCBU nurses and student nurses, respectively.

FIGURE 1.

Flow chart of the trial procedures for ICU/SCBU nurses. BCP, behaviour change package; GP, general practitioner; SCIN, Skin Care Intervention in Nurses.

FIGURE 2.

Flow chart for the trial procedures for student nurses. BCP, behaviour change package; GP, general practitioner; SCIN, Skin Care Intervention in Nurses.

Preliminary work

Questionnaire development and management

Careful consideration was given when designing the study questionnaires to ensure that the study was able to collect reliable measures of TPB variables in relation to hand dermatitis prevention behaviours among the study participants, for example ‘When I start clinical work I intend to apply hand cream before and after work and during each of my breaks’ (intentions), ‘Contacting occupational health if I get symptoms which I think might be hand dermatitis would be worthwhile’ (behavioural belief) and ‘Other nurses at my placement would approve of me using hand rubs, when appropriate for infection control, instead of washing my hands with soap and water’ (subjective norms).

Three study questionnaires were developed and administered at 0, 3 and 12 months during the study. Participant questionnaires comprised a modified version of the Nordic Occupational Skin Questionnaire – 2002 (NOSQ-2002) to measure, before and after randomisation, participants’ self-reported behaviours relating to hand care and dermatitis prevention practices, and activities both inside and outside the workplace. The questionnaires also asked about participants’ rating of their overall health status using the validated EuroQol-5 Dimensions (EQ-5D) questionnaire and their views on the behaviour change package (BCP) (participants in the intervention plus arm of the study only). In addition, the study separately gathered site-level data on the use of moisturising cream (i.e. ad hoc requests for further personal supplies by student nurses and monthly estimates of moisturising creams available in each dispenser on the ICUs and SCBUs).

Local fieldworkers at each participating site made use of individual ‘study packs’ when recruiting participants to the study. Study packs contained each of the research documents (e.g. data collection worksheets, consent forms, questionnaire A booklet, a one-page self-assessment dermatitis questionnaire, business reply envelope) that required completion at the time of recruitment. The second questionnaire booklet (i.e. questionnaire B) was not included in these packs as these were posted directly to participants by the SCIN trial research team based in London. A matching preassigned participant identification number (PIN) was recorded on all research documents contained in each pack and these were numbered sequentially to reflect the order in which they were to be completed. A unique PIN was allocated to each participant as they were recruited to the study. The local fieldworkers then recorded the PIN, participant initials and date of birth on a separate participant registration log sheet as participants were recruited to the study.

Hand photography protocol development

Photographs of hands that were taken by trained personnel using high-resolution digital cameras were considered to be a cost-effective and practical method for collecting data on the presence or absence and severity of dermatitis. Developing a photographic guide to assist with diagnosing hand dermatitis and for use when assessing self-taken photographs of hands (i.e. ‘selfies’) was previously proposed by van der Meer et al. 44 In developing this photographic guide for diagnosing hand dermatitis and assessing its severity, the study team had the following requirements:

-

The method had to measure presence or absence of any form of hand dermatitis, as well as severity.

-

The method could not involve physical examination of the participants, as that would be logistically very difficult, expensive and likely to result in poor response rates.

-

The method had to be objective and not based on self-report as self-reporting tends to over-report hand dermatitis.

-

The severity scale needed to be able to distinguish dermatitis towards the milder end of the disease spectrum.

For the purpose of this study, three distinct stages were undertaken when developing the new hand photography method for use in the study. Accordingly, this new method for diagnosing hand dermatitis and assessing its severity offered a multidisciplinary method for diagnosing hand dermatitis and its severity. The method relied solely on dermatologist and research nurse inspection of hand photographs from research participants (in lieu of physical examinations), with comparisons from standardised images contained in Coenraads et al. ’s photographic guide. 71 The stages were:

-

developing a standardised procedure for hand photography

-

a stepwise validation process of rules for the study dermatologists to diagnose and determine the severity of the hand dermatitis

-

training, by a dermatologist, of the research nurse to screen out hand photographs of study participants without dermatitis (‘clear cases’).

The method for taking high-resolution digital photographs of the participants’ hands was developed in conjunction with a medical photographer and is consistent with the views required for the photographic assessment scale, for use in clinical trials, described by Coenraads et al. 71 When participants were unable to return to have their hands photographed by the trained fieldworkers, they were asked to provide, via e-mail, self-taken photographs of their hands, with a stipulation that self-taken photographs were taken against a grey or white background.

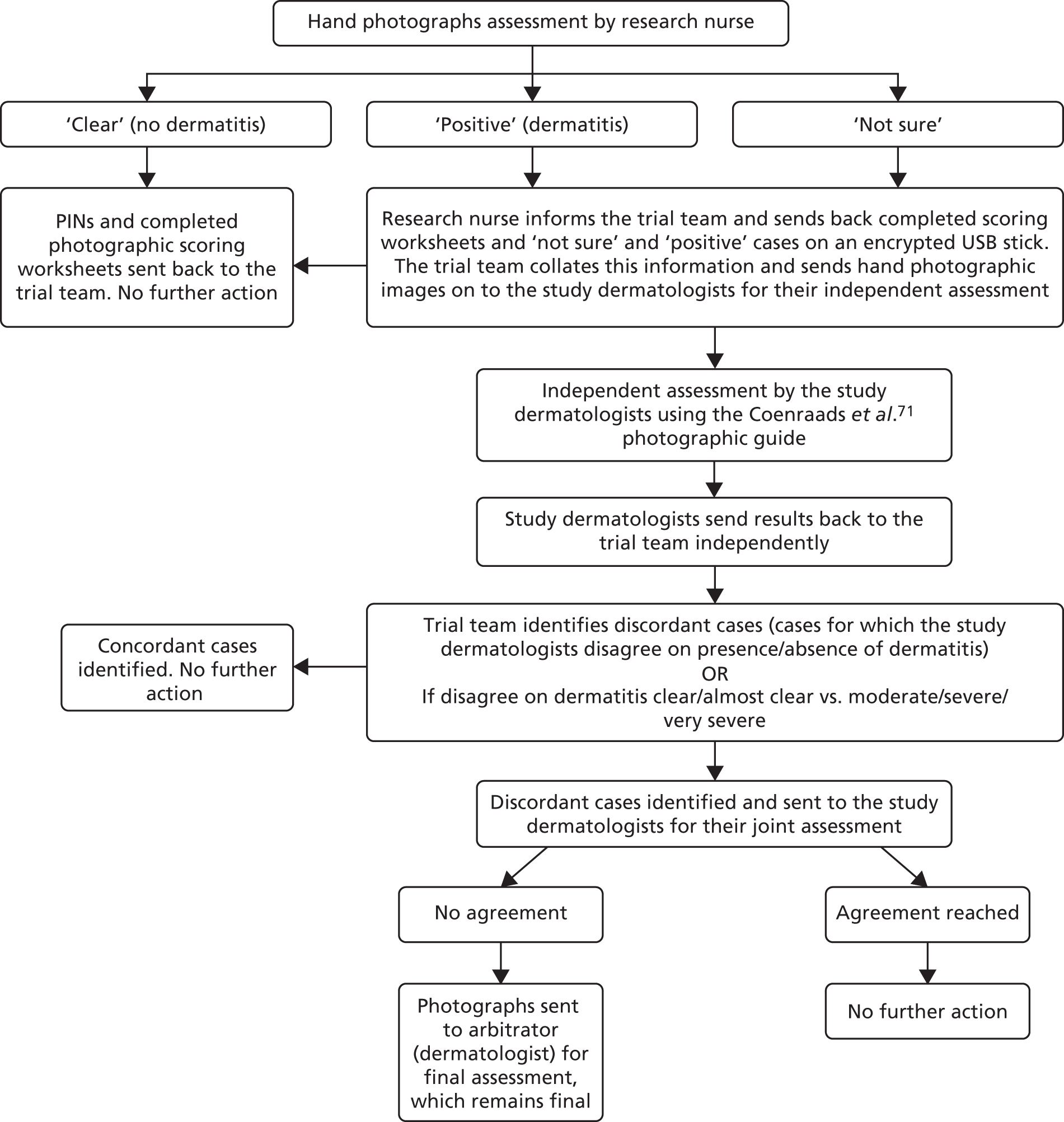

Hand dermatitis was assessed through photographs taken of each of the two sides of both hands (i.e. palm and dorsum). The presence of hand dermatitis was based on comparisons made with the standardised images of severity at various stages of diseases, which were contained in Coenraads et al. ’s photographic severity guide. 71 In accordance with this guide, for each combination of sides of the hand, the study dermatologists were required to indicate whether dermatitis was clear (absent), almost clear, moderate, severe or very severe. These four variables (i.e. dermatitis in the right hand at the dorsum, right hand in the palm, left hand at the dorsum and left hand in the palm) were then dichotomised as clear versus almost clear/moderate/severe/very severe. A single binary variable was generated for the presence of dermatitis (i.e. no/yes). Agreement or disagreement on the severity of hand dermatitis was not assessed during the validation process, as it was realised early on in the study that the likelihood of two dermatologists agreeing on the severity grading (five grades) at four different sites was likely to be poor and that perfect agreement on each site was not necessary for this study, which sought to establish a global estimate of hand dermatitis severity. Therefore, a pragmatic view was taken that severity would be defined as the combined score from the two dermatologists. Agreement between the two dermatologists on the binary rating (yes/no) was assessed using Cohen’s kappa statistic. Each participant’s overall severity of hand dermatitis was defined as the most severe combined score from both dermatologists on Coenraads et al. ’s scale from their four hand photographs. The levels of severity of dermatitis, as these were assessed by the two dermatologists, were 1 = clear, 2 = almost clear, 3 = moderate, 4 = severe and 5 = very severe. For each participant positive for dermatitis, a severity score by each of the two dermatologists was defined as the maximum score across the four photographs, then an overall severity of dermatitis score was derived as the average value of the two severity scores given by the two dermatologists. Overall severity was dichotomised using 3 as a cut-off point. Overall severity scores of < 3 (including those without dermatitis) indicated no severe dermatitis, whereas scores of ≥ 3 indicated severe dermatitis. Only two participants had severe dermatitis at baseline and only three participants had severe dermatitis at follow-up. As the prevalence of severe dermatitis was so low, this secondary outcome was not analysed further.

Figure 3 outlines the procedure that the dermatologists and dermatology research nurses used for assessing the hand photographs.

FIGURE 3.

Flow chart for assessing hand photographs. USB, universal serial bus.

Development of the behaviour change package

A key component of the study’s intervention was the BCP, which provided nurses with evidence-based information on good hand dermatitis prevention behaviours and encouraged them to form implementation intentions regarding specific hand-care behaviours, such as when and where they would use hand moisturising cream and when they would regularly check their hands for signs of hand dermatitis. The BCP employed the TBP, supplemented by implementation intentions, as its key theoretical framework. As described previously, the TPB postulates that a person’s behaviour is influenced by their intentions and perceived behavioural control (PBC). For example, whether or not a nurse uses hand moisturiser at the start and end of a shift is influenced by his/her intentions (e.g. ‘I strongly intend to use hand moisturiser at the start and end of a shift’) and his/her PBC (e.g. ‘I find it quite easy to use hand moisturiser at the start and end of a shift’). Intentions are influenced by attitudes towards the behaviour (e.g. ‘I believe using hand moisturiser at the start and end of a shift will be beneficial’) and subjective norms (e.g. ‘the matron wants me to use hand moisturiser at the start and end of a shift’) as well as PBC (as before).

Prior to the development of the BCP, the trial’s health psychologist conducted a focus group meeting with first-year student nurses, exploring their beliefs about the different hand dermatitis prevention behaviours likely to be targeted by the intervention. This work partly used open-ended belief elicitation questions recommended by Ajzen,57 but also explored student nurses’ perceptions of the practicality of performing behaviours frequently and their understanding of the consequences of hand dermatitis. For practising nurses, similar work was performed using an online questionnaire (with open-ended questions), so that the data could be collected at a time that was convenient for each nurse. Importantly, the early work revealed that nurses perceived that applying hand cream more frequently than at the start and end of shifts and before going on breaks was an impractical recommendation; therefore, making such a recommendation would damage the credibility of the BCP. It also allowed the health psychologist to identify misconceptions relating to hand dermatitis, such as alcohol-based hand rubs being more harmful to skin than hand-washing, and to ensure that specific information was included in the BCP to help to challenge these beliefs.

The BCP was designed to target four key hand dermatitis prevention behaviours:

-

using hand moisturising cream

-

using disinfectant hand rubs rather than hand-washing, while remaining in line with infection control guidance

-

using gloves for the shortest time possible while still conforming with infection control guidance

-

checking oneself regularly for hand dermatitis symptoms and seeking support from occupational health if required.

Different versions were developed for student nurses with an atopic tendency and ICU/SCBU nurses, given their differing levels of nursing experience and working environments.

The intervention was intended to be delivered primarily online, as this would allow good scalability if it proved to be effective. A web-based intervention standardises treatment delivery, thereby enhancing intervention fidelity. 72 Moreover, given that nurses work a variety of shift patterns, an online intervention allowed participants to access the BCP at a time that was convenient for them. Given the demands on nurses’ time, the intervention consisted of a single session with two brief follow-up reminder e-mails to access the intervention.

The intervention aimed to increase each of the behaviours by targeting relevant attitudes, subjective norms, PBC and implementation intentions. Specific change techniques73 were selected to target each construct, based on published expert consensus regarding which behaviour change techniques (BCTs) were most effective at changing particular psychological constructs. Where the expert consensus suggested a number of possible BCTs, the ultimate selection was based on feasibility of delivery in an online intervention and likely acceptability to participants. 73

Content of the BCP was intended to reflect current evidence-based guidelines and scientific literature on hand dermatitis prevention and infection control, at the time the intervention was developed, and to be appropriate for nurses working in NHS settings.

Patient and public involvement

The patient involvement in this study differs from that in other studies in that the ‘patients’ are NHS nurses. During the set-up and conduct of the trial, the research team actively consulted with representatives from the nursing (including student) profession. In particular, the trial involved a patient representative, Wendy Taylor, who:

-

ensured that the proposed interventions and data collection tools were acceptable

-

provided her expertise on the planning and management of the trial

-

provided her expertise on the optimum dissemination of the trial results to ensure that they reach the target audience.

Wendy Taylor is a midwife with a history of hand dermatitis acquired during her nurse training. She commented on the draft proposal, was a member of the Trial Steering Committee and attended one of the training workshops for fieldworkers.

During the intervention development stage, the study also conducted focus group sessions involving student nurses and registered nurses for the purpose of seeking their views on hand dermatitis, including prevention strategies, approaches to hand hygiene in the workplace and their preference for hand moisturisers to use during the trial.

Participating sites

The study identified all NHS sites in the UK that train nurses and have an in-house occupational health service and at least one ICU. The lead occupational physician in each eligible site was written to in December 2011, asking their willingness, in principle, to collaborate in a trial; again, the lead occupational physician was written to in May 2012 and January 2014 asking them to confirm their willingness to collaborate. In addition, additional sites were invited to sign up to the study via national occupational health newsletters. This included some sites that had an ICU but did not train nurses, and vice versa. To avoid the risk of student nurses moving placements from an intervention to a control site (or vice versa) during the study period, only one site, in general, was invited in each city or town to participate in the study. The exceptions were London and Manchester. In London, three sites were identified in which student nurses did not move to neighbouring sites during their training. In Manchester, sites were identified where students at three local universities undertake their clinical placements during their first year of nursing training, and it was ensured that these sites were clustered appropriately to prevent cross-contamination in the study:

-

12 sites recruiting both ICU nurses (including SCBU nurses) and student nurses

-

18 sites recruiting ICU nurses (including SCBU nurses) only

-

five sites recruiting student nurses only.

Participant recruitment procedure

Study group 1 student nurses

All student nurses are required to attend an occupational health assessment before starting their clinical work. At participating sites, with permission from the universities concerned, all student nurses in one or more year groups (excluding mental health nursing students) who were due to start their first clinical placement were provided with a participant information sheet by their university or their occupational health department, before or at the time of their mandatory assessment. Those student nurses who had a history of atopic tendency or hand dermatitis were identified by the occupational health department at the assessment from information that they provided in a generic pre-placement health screening questionnaire or during screening conversations the fieldworkers had with potential participants. An occupational health clinician explained to the student nurses that, because of their constitution, they are at increased risk of hand dermatitis. Student nurses who met the inclusion criteria were then invited to participate in the study. The local fieldworker obtained written consent from those nurses who agreed to take part in the study (the lead occupational health practitioner at the study site and the trial manager were available to answer questions when necessary). The consent form asked participants to provide a preferred e-mail address and telephone number to facilitate follow-up, and so that those at intervention plus sites could be sent a link to the online BCP. Paper copies of the BCP were provided at sites where participants were unable to access the online version. One copy of the signed consent form was filed in the nurse’s occupational health notes, one copy was sent to the trial manager and a third copy was given to the participant. Participants were also provided with an information sheet to give to their general practitioner (GP).

Study group 2 intensive care unit nurses (including special-care baby unit nurses)

The investigators, trial manager and lead occupational health clinicians from each site identified all critical care nurses who were suitable for the study. A local occupational health clinician or senior ICU nurse explained to all nurses working on the selected ICUs that they are at increased risk of hand dermatitis because of frequent hand-washing with cleansers and water. Full-time ICU nurses (i.e. those working ≥ 30 hours per week) were provided with a participant information sheet and, when possible, given a week to decide whether or not they wished to participate in the study. Consent to take part was obtained by the fieldworker, who, along with the trial manager, was available to answer any queries about the study. The consent form asked participants to provide a preferred e-mail address to facilitate follow-up, and so that those participants at the intervention plus sites could be sent a link to the online BCP. Paper copies of the BCP were provided at sites where participants were unable to access the online version. Participants were provided with an information sheet to give to their GP.

The study was presented to both study groups as research to assess the causes, consequences and ways of managing hand dermatitis in nurses who are at increased risk, either because of a personal history of atopy disease or because of the type of work that they do. However, to minimise the chance of bias, the nurses were not told that they were in an intervention plus or intervention light group. During the recruitment phase, fieldworkers reinforced the importance of participants being able to commit fully to the study, particularly with respect to the completion of the study questionnaires.

To check that rates of participation did not differ importantly between sites randomised to the two arms of the study, the recruitment process was carefully documented. The total number of eligible student and critical care nurses was recorded, as was the number who were consented to take part. In addition, the numbers and dates of those who dropped out of the study were recorded.

The recruitment period was between September 2014 and December 2015 and the follow-up period was between September 2015 and March 2017.

Informed consent

Participants were provided with an opportunity to read through the participant information sheet and to ask any clarifying questions before consent for entry into the study was taken. Informed written consent was obtained from participants at the time they were recruited into the study. In addition, all participants were required to provide written consent for the collection of hand photographs at the time of recruitment in the study (i.e. t = 0) and when photographs were collected during the follow-up period (i.e. t = 12 months). The participants who provided self-taken hand photographs via e-mail were taken to have provided consent by way of their self-initiated e-mail correspondence to the research team. Participants were provided with a copy of the consent forms and copies were also retained in the site file, the trial management file and occupational health records. All participants were provided with a GP information sheet, so that their GPs were aware of their participation in the trial.

Interventions

Intervention plus

The intervention plus in both staff groups centred on a bespoke BCP that targeted the behaviours of appropriate glove use, use of antibacterial hand rubs versus hand-washing, regular use of moisturising cream and contacting occupational health early if hand dermatitis occurred.

The BCP was developed by members of the study team with expertise in dermatology, occupational medicine, nursing and health psychology. As described earlier in this report, the intervention aimed to change relevant attitudes, subjective norms, PBC and implementation intentions. Copies of the BCP interventions screenshots (from the online platform: see Report Supplementary Materials 1 and 2) for the student nurses and ICU nurses are provided as supplementary documents. When participants were asked to form implementation intentions for performing the behaviours in their workplace, a record of each participant’s implementation intentions was generated by the online BCP package and e-mailed to her/him.

If a participant reported being unable to access the online BCP, she/he was posted a paper-based magazine version of the BCP, which reflected the information provided in the online BCP. Participants were asked to read through the material provided and write down their action plans in the spaces provided. The participants were then asked to keep the paper-based BCP in a convenient place so that, as required, they could refer back to it. The BCP was supported by provision of facilities to encourage adherence. These included personal supplies of moisturising cream for at-risk student nurses and provision of (1) optimal equipment for cleaning hands and (2) moisturising cream dispensers on ICUs and SCBUs.

The BCP was made available to ICU/SCBU nurse participants within 12 weeks of their recruitment to the study and for student nurse participants 2 weeks before they started their first clinical attachment. However, for many participants, access to the BCP occurred within a shorter timeframe (i.e. 2–4 weeks from their recruitment). It was actively reinforced over the course of the study by consistent messages on skin care from the local occupational health and control of infection teams, and from local line management. Research has shown that senior role models have important effects on more junior health professionals’ hand-hygiene behaviours,74,75 and it seemed reasonable to assume that this influence would extend to behaviours preventing dermatitis. To facilitate this, when implementing intervention plus, a dialogue was engaged in with local occupational health staff and line managers about the nature and purpose of the study and information was provided to them on the content provided in the BCP to ensure that they promoted consistent messages on skin care.

The online BCP was offered to allow nurses to access it at a time convenient to their schedules, to permit standardisation of the delivery of key information across all intervention plus sites and to reduce the potential burden on occupational health staff. Moreover, it was considered that, if the BCP was found to be effective in this trial, it would be simple to scale up access to the website to deliver the BCP across the country.

In the early stages of the trial, responses from the intermediate questionnaires and electronic user activity data showed that the initial uptake of the BCP was poor for both study groups. The most commonly cited reasons for this were that most participants forgot to, or did not have time to, access the BCP. In response to this, the research team implemented a targeted strategy to further promote and encourage uptake of the BCP. This comprised attaching a leaflet to the intermediate questionnaire that contained the website link and encouragement for participants to access the material; additional specific information in the follow-up reminder e-mails that were sent to participants; and displaying BCP information on posters in prominent locations in clinical areas.

Intervention light

Nurses at the intervention light sites were managed in accordance with what was currently regarded as best practice, with the provision of an advice leaflet about optimal hand care entitled Dermatitis: Occupational Aspects of Management. Evidence-based Guidance for Employees (which was also provided to the intervention plus group) and encouragement to contact their occupational health department early if hand dermatitis occurred. However, the nurses did not receive the BCP or active reinforcement of its messages. Nor were the nurses routinely offered supplies of moisturising cream over and above what was already standard practice at their site.

During the recruitment phase, fieldworkers reinforced to participants the importance of being able to fully commit to the study, particularly with respect to the completion of each of the study questionnaires.

Study groups

Study group 1 student nurses

At both the intervention plus and the intervention light sites, all first-year student nurses were given the participant information sheet about the study. Student nurses who agreed to take part were invited to complete a consent form, a self-administered baseline questionnaire booklet and a one-page hand dermatitis self-assessment form (t = 0 months). The completed questionnaires were then placed into a sealed business reply envelope and returned to the fieldworker, who forwarded them on to the SCIN trial research team in London. If the student nurses preferred, they could send the completed questionnaires directly back to the SCIN trial team in London. After the two questionnaires had been completed, all student nurses were invited to have their hands photographed as per a standard operating procedure developed for use in the study. Separate consent was obtained from the participating nurses each time their hands were photographed. In addition, the fieldworkers provided participants with oral information about hand dermatitis and with the Dermatitis: Occupational Aspects of Management. Evidence-based Guidance for Employees written leaflet. Participants were also told that they may be sent a link to access a BCP that they should undertake in the week before starting their first clinical attachment. Participants were required to log on to the online BCP package and register as a first-time user. At that time, the nurses would also be sent (by post) three personal tubes of moisturising cream, with guidance on how to request further supplies if needed.

All participants in both the intervention plus and the intervention light sites were encouraged (orally, through the written advice leaflet and by e-mail reminders at 4 and 8 months) to attend their local occupational health department at an early stage if they developed hand dermatitis during the study period. One week after starting their first clinical attachment, all nurses were asked to complete a further short self-administered questionnaire booklet (t = 3 months), covering beliefs and plans regarding dermatitis prevention behaviours. At intervention plus sites, it also asked about participation in, and views on, the BCP. The intermediate questionnaire was sent by post to participants by the SCIN trial research team along with a business reply envelope so that completed questionnaires could be returned. E-mail reminders were also sent to participants containing a positive reinforcement message to encourage ongoing participation in the study. At the intervention sites, the e-mail reminders also reinforced the BCP.

To account for seasonal variations in the prevalence of dermatitis, the final study data collection tools were administered 12 months after questionnaire A. All participants were asked to complete the final self-administered questionnaire booklet and a one-page dermatitis self-assessment form and to have their hands photographed. The questionnaires were sent out in the post to fieldworkers 2 months before the end of the study by the SCIN trial research team. The fieldworkers gave the student nurses the questionnaires at the time that they recalled them to have their hands photographed. The questionnaire C booklet covered clinical attachments undertaken in the previous year; hours worked per week over the previous year; beliefs and plans regarding dermatitis prevention behaviours; participation in, and views about, the BCP (only at intervention plus sites); activities outside work that predispose to hand dermatitis; recent practices regarding use of gloves; recent practices regarding hand cleansing; recent use of moisturising creams; history of hand dermatitis in the previous 12 months (including its investigation and treatment, and any consequent loss of time from work or restriction of duties); and the EQ-5D questionnaire.

At the follow-up time point (i.e. t = 12 months), participants who were unable to attend to have hand photographs taken by a fieldworker were provided with an opportunity to send the SCIN trial research team self-taken photographs, taken with their mobile phones, of their hands. If it was not possible for a student nurse to complete the questionnaire at the time, then they were asked to return the completed questionnaire to the SCIN trial team directly using a business reply envelope.

Information on the number of attendances at occupational health with symptoms of hand dermatitis and requests for extra provisions of emollients was also recorded.

Study group 2 intensive care unit nurses (including special-care baby unit nurses)

At both the intervention plus and the intervention light sites, all nurses who worked on selected ICU/SCBU wards were given the participant information sheet. Those who agreed to participate were asked to complete a consent form and self-administered questionnaire booklet (t = 0 months). This was similar to the baseline questionnaire booklet administered to student nurses, but also included items on current occupation; recent practices regarding the use of gloves; recent practices regarding hand cleansing; recent use of moisturising creams; and any sickness absence or modification of duties during the previous 12 months because of hand dermatitis. At the time of the photograph, ICU/SCBU nurses were asked to complete a one-page dermatitis self-assessment form evaluating whether or not they considered themselves to have dermatitis and the extent to which it interfered with work and hobbies. ICU/SCBU nurses were asked to return the completed questionnaires either to the fieldworkers or (by post) directly back to the SCIN trial research team in London. All ICU/SCBU nurses had their hands photographed as per protocol. All ICU/SCBU nurses, including those at intervention light sites, were provided with the Dermatitis: Occupational Aspects of Management. Evidence-based Guidance for Employees written leaflet. Participants were also told that they may be sent a link to access a BCP in due course that they should use. Participants were required to log on to the online BCP package and register as a first-time user.

At the intervention plus sites, once participants had been recruited, fieldworkers (occupational health clinicians) promoted the importance of optimisation of equipment for hand cleansing and use of moisturising cream. An e-mail was also sent via the lead ICU/SCBU nurses to all staff on the wards, with a link to the BCP. Two weeks after the BCP was offered (or at a similar interval after recruitment in the intervention light sites), participants were asked to complete an intermediate questionnaire about beliefs regarding prevention of dermatitis and (at intervention plus sites) participation in and views on the BCP. Questionnaire B was sent by post to participants by the SCIN trial research team along with a business reply envelope. All participants, at both the intervention plus and intervention light sites, were encouraged (orally, through the written advice leaflet and by e-mail reminders sent out by the SCIN trial research team at 4 and 8 months) to attend their local occupational health department at an early stage should they develop hand dermatitis. E-mail reminders were also sent to participants containing a positive reinforcement message to encourage ongoing participation in the study. At the intervention sites, the e-mail reminders also reinforced the BCP.

To account for seasonal variations in the prevalence of dermatitis, the final study data collection tools were administered 12 months after questionnaire A. All participants were asked to have their hands photographed and invited to complete questionnaire C. At the time of the photograph, ICU/SCBU nurses were asked to complete a one-page dermatitis self-assessment form evaluating whether or not they considered themselves to have dermatitis and the extent to which it interfered with work and hobbies. The questionnaires were sent to fieldworkers 2 months before the end of the study by the SCIN trial research team. The fieldworkers gave the ICU/SCBU nurses the questionnaires at recall for hand photographs. Completed questionnaires were returned to the fieldworker or directly (by post) to the SCIN trial research team in London. If it was not possible for an ICU/SCBU nurse to complete the questionnaires at the time, then they were asked to return the completed questionnaire to the SCIN trial team directly using a business reply envelope. At the follow-up time point (i.e. t = 12 months), participants who were unable to attend to have hand photographs taken by the fieldworker could send the SCIN trial research team self-taken photographs of their hands.

All participants who decided to withdraw from the study were asked to complete a shortened version of questionnaire C and were invited to have follow-up hand photographs taken after giving further consent. The collection of these data enabled the researchers to report further on the study’s primary objective measure (i.e. changes in the point prevalence of visible hand dermatitis from baseline).

Optimising response date to questionnaires and follow-up hand photographs

Study questionnaires were identified by the unique PIN assigned at the time of recruitment. For security reasons, contact details were kept separately. The content of the questionnaire was described above. Throughout the study, non-responders to any of the three study questionnaires were sent an e-mail reminder from the SCIN trial research team. If questionnaires remained outstanding, another copy of the paper questionnaire and a reply envelope were posted to participants’ preferred postal address. Non-responding participants were sent up to two reminder text messages (or landline telephone messages). 76

At the end of the study period, participants who had completed and returned all three study questionnaire booklets (i.e. questionnaires A, B and C) were entered into a prize draw for one study camera (a total of 26 cameras were offered). Information about the draw and prizes had been provided on the participant information sheets.

If local fieldworkers were unable to follow up participants at the end of the trial, the central research team then sent participants an information sheet with easy step-by-step instructions to follow on how to take and send in self-taken photographs of their hands.

Extension to the follow-up period

To optimise the response rate at follow-up, the research team felt that it was important to adopt a pragmatic approach that encouraged fieldworkers to try and follow up as many participants as practicable beyond the 12- to 15-month time point. As described in Chapters 3 and 4, an ancillary analysis (sensitivity analysis II) was conducted for the purpose of excluding the sample of participants who were followed up between 12 and 15 months.

Measure outcomes

Primary outcome

-

Difference between intervention plus and intervention light sites in the change in point prevalence of visible hand dermatitis from baseline to the end of follow-up, as assessed by two dermatologists.

Secondary outcomes

-

The difference between intervention and control sites in the change in point prevalence of severity of visible hand dermatitis from baseline to the end of follow-up (as ascertained by the dermatologists).

-

Days lost from sickness absence and days of modified duties because of hand dermatitis per 100 days of nurse time during the 12 months of follow-up.

-

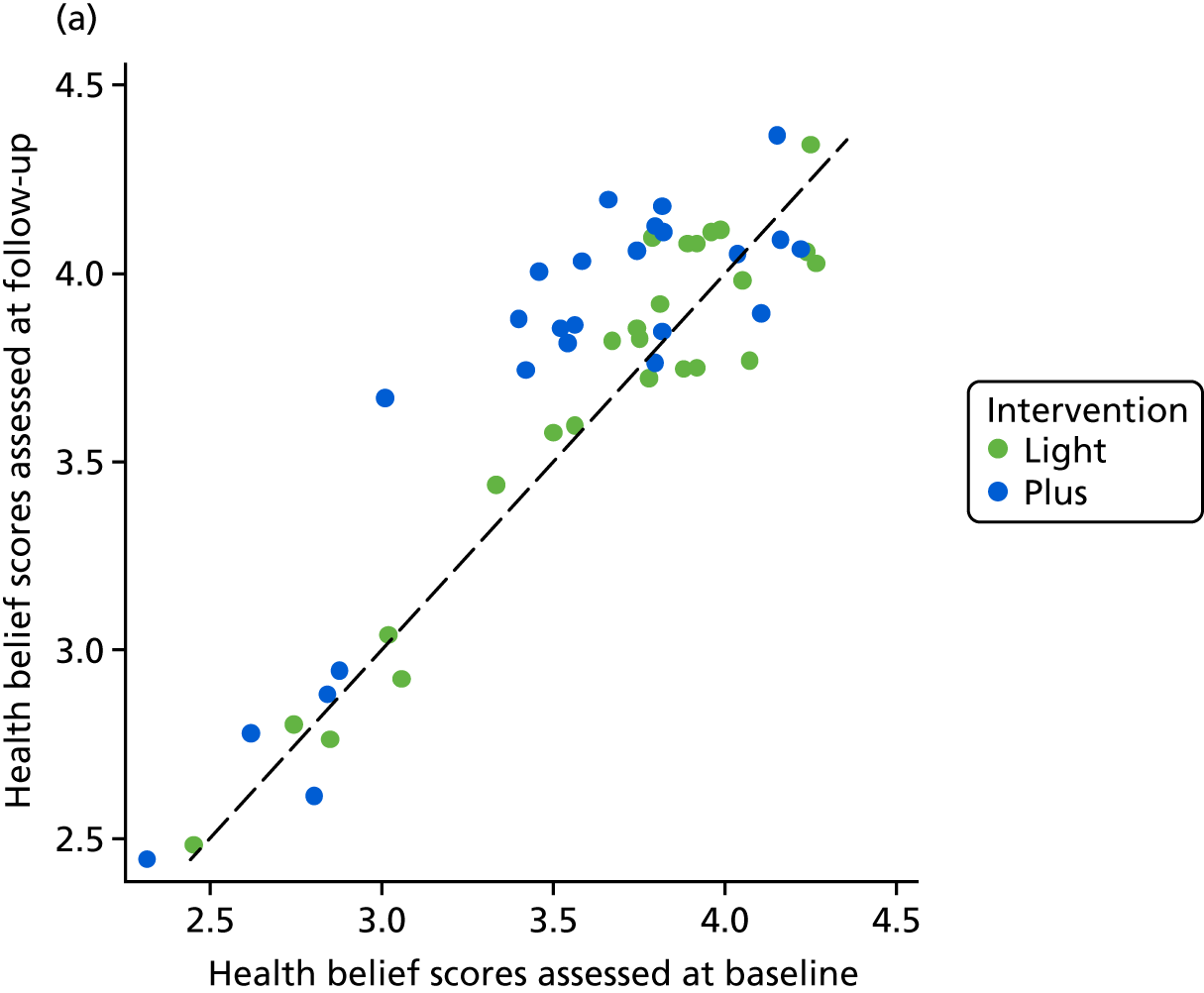

The change from baseline to after completion of the BCP, and to the end of the 12-month follow-up period, in beliefs about dermatitis prevention behaviours.

-

The change from baseline to the end of follow-up in the reported frequency of:

-

use of hand rubs for hand cleansing

-

hand-washing with water

-

use of moisturising creams (for student nurses, who had not started clinical attachments at the beginning of the study, this was reduced to differences between the intervention and control sites at the end of the follow-up).

-

-

The change from baseline to the end of follow-up in quality-of-life score.

-

The use of moisturiser provided for the intervention (in terms of requests for further supplies by student nurses and orders for supplies of moisturisers by ICUs).

Sample size

Original sample size calculations

The aim was to recruit at least 40 student nurses and 40 nurses from the ICUs at each trust. To give an indication of power, it was assumed that:

-

the expected baseline prevalence of hand dermatitis, overall, was 5% in student nurses and 25% in ICU nurses

-

the expected rates, overall, at the control trusts at the end of follow-up were 25% for student nurses and 23% for ICU nurses; these estimated rates allow for limited impact in control trusts

-

the expected prevalence rates for individual trusts varied by a multiplying factor, which was normally distributed with a mean of 1.0 and a SD of 0.2

-

after allowance for other variables, hand dermatitis at baseline in an individual carried a relative risk of 2.5 for the presence of hand dermatitis at follow-up.

With these assumptions and a 5% level of statistical significance (two-sided), the study would have approximately 89% power to detect a prevalence at follow-up in the intervention trusts of 10% in student nurses and 95% power to detect a prevalence of 10% at follow-up in ICU nurses. For final prevalence rates of 12%, the corresponding power values would be 73% for student nurses and 82% for ICU nurses.

Revised sample size calculations

Fieldworkers were encouraged to recruit as many eligible student nurses and ICU/SCBU nurses as possible, with the expectation that they would recruit at least 40 student nurses and 40 critical care nurses at each site. From the outset it was acknowledged that, as a result of the low workforce populations, a number of smaller sites would not reach this target. To give an indication of power, it was assumed that, at the end of follow-up, the expected prevalence rates overall at the intervention light sites would be 24% in both student and ICU/SCBU nurses, the intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) would be 0.05 and 20% of participants would be lost to follow-up. With a 5% level of statistical significance (two-sided), the study would have approximately 83% power to detect a reduction in prevalence of dermatitis at follow-up in the intervention plus sites to 10% in student nurses and a 91% power to detect a reduction in prevalence to 10% at follow-up in ICU nurses. For final prevalence rates of 12%, the power values would be 68% for student nurses and 78% for ICU/SCBU nurses, whereas for final prevalence rates of 14%, the corresponding power values would be 51% and 61%, respectively. The power would be higher if the ICC was < 0.05. [These calculations were carried out using the ‘clustersampsi’ command in Stata® (version 12.1; StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA) for difference in proportions.]

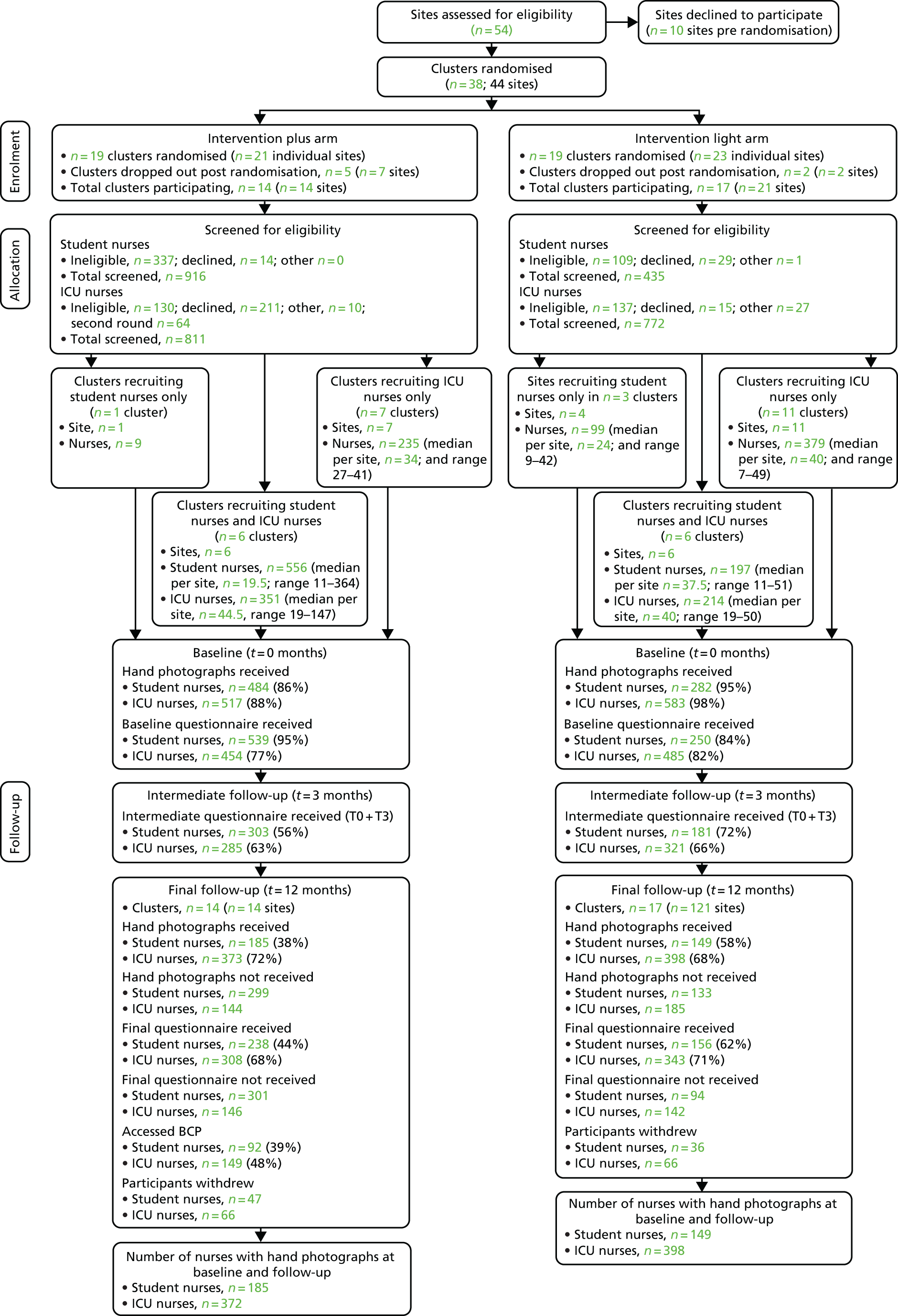

Randomisation

A total of 54 sites were assessed as eligible for entry into the study. However, 10 sites subsequently declined to participate, citing capacity reasons. No site-level data were collected from these 10 sites. Following this, the trial methodologist and statistician developed a formal strategy for randomisation based on the remaining list of 44 participating sites, and King’s Clinical Trials Unit (CTU) was responsible for conducting the randomisation procedure. Randomisation was carried out in four blocks as a single step at the beginning of the study. The blocks were defined according to the types of nurses who the centres planned to recruit (i.e. student nurses, ICU nurses or both) and by the size of the centres to ensure an approximate balance of numbers of nurses in the two arms of the trial. Five clusters contained more than one site, as the sites were geographically close to each other and student nurses may go on placement to another. This was done to avoid contamination between sites. The three clusters that comprised more than one site were all randomised to the control arm. If the sites in these clusters recruited ICU nurses only or student nurses only, the clusters were recorded twice on the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) flow diagram, which needs to be taken into account in its interpretation (see Figure 5).

The output of the randomisation resulted in 19 clusters being randomised to be intervention plus sites and 19 clusters being randomised to be intervention light sites. The 19 clusters comprised the 44 participating sites. Following randomisation, nine sites either lost interest in taking part or withdrew from participating in the trial for capacity reasons. This included two clusters that contained more than one site, that is, the number of clusters taking part reduced by seven. No participant data were collected from the nine sites that withdrew after randomisation, as no participants were recruited at these sites. Of these nine sites, five completed a site survey of current policy, practice and training. Regarding the dropout of sites, it is important to note that the original list of proposed sites was devised as part of the initial funding application period in 2012. However, there was a period of > 12 months between their commitment and the commencement of the trial, and the sites that dropped out did so because they no longer felt that they had the capacity to participate in trial. Furthermore, the nature of occupational health departments is such that business contracts are usually awarded on a short-term basis and it is not uncommon for frequent changes of management to occur. With these factors in mind, there is no reason to believe that the dropout of these sites was influenced by concerns related to the potential uptake of the intervention.

The final number of clusters in the trial was 31, comprising 35 individual sites. Of the 31 clusters, 14 were randomised to intervention plus and 17 were randomised to intervention light. As the three clusters that contained more than one site were randomised to intervention light, the final ratio of intervention plus to intervention light sites was 21 : 14.

(When possible, before randomisation, the fieldworkers at each participating site provided information about current arrangements to minimise the occurrence of hand dermatitis in nurses and the procedure to manage it when it occurs. Among other things, this covered general training regarding dermatitis; guidance on when and when not to use gloves; guidance on washing and drying hands and on use of hand rubs; information on the use of moisturising creams; and provision of moisturising creams for staff. Sites were stratified to ensure that sample sizes were similar in the intervention light and intervention plus arms. This helped to address issues such as low recruitment numbers at specific sites, which were anticipated.)

As described above, to ensure that the nurses were not influenced by prior knowledge of treatment allocation, the study ensured that only the CTU knew if sites had been randomised to the intervention light or intervention plus arm of the study at the time when study participants were recruited and completed baseline questionnaire A. At all sites, we recorded the number of nurses who did not participate in the study for whatever reason (e.g. those who declined or who were not eligible). Numbers of all potential participants in each site were obtained so that assessment could be undertaken to see if there had been differential uptake in intervention plus and intervention light sites.

For the purpose of the intention-to-treat (ITT) analysis, the date of entry into the study for all participants was the date when they signed the consent form for the research study. Although the research team acknowledged that student nurses could contribute useful information only once they started clinical work, in practice, very few failed to start their clinical work once they commenced their nursing studies.

Fieldworkers at sites were informed of the outcome of the randomisation via e-mail, when practicable, after all of the participants had been recruited into the trial. Study team members were informed of the randomisation in a blinded or unblinded manner, depending on their role in the trial. The trial statistician (GN), methodologist (DC), infection control expert (BC), dermatologists (HW and JE) and health economist (PM) remained blinded to treatment allocation until after the primary analysis.

Ethics approval and research governance

Ethics approval to conduct the trial was granted by the National Research Ethics Service (NRES) Committee London – City Road and Hampstead (Research Ethics Committee reference number 13/LO/0981). Subsequent substantial and minor amendments are outlined in Appendix 1. Ethics approval applied to all research sites taking part in the study. In addition, local site-specific assessments were conducted at participating research sites and approval obtained by their respective research and development departments. A full list of participating sites is given in Table 4. The trial was registered with the International Standard Randomised Controlled Trial Number (ISRCTN) registry, on 21 June 2013, as ISRCTN53303171.

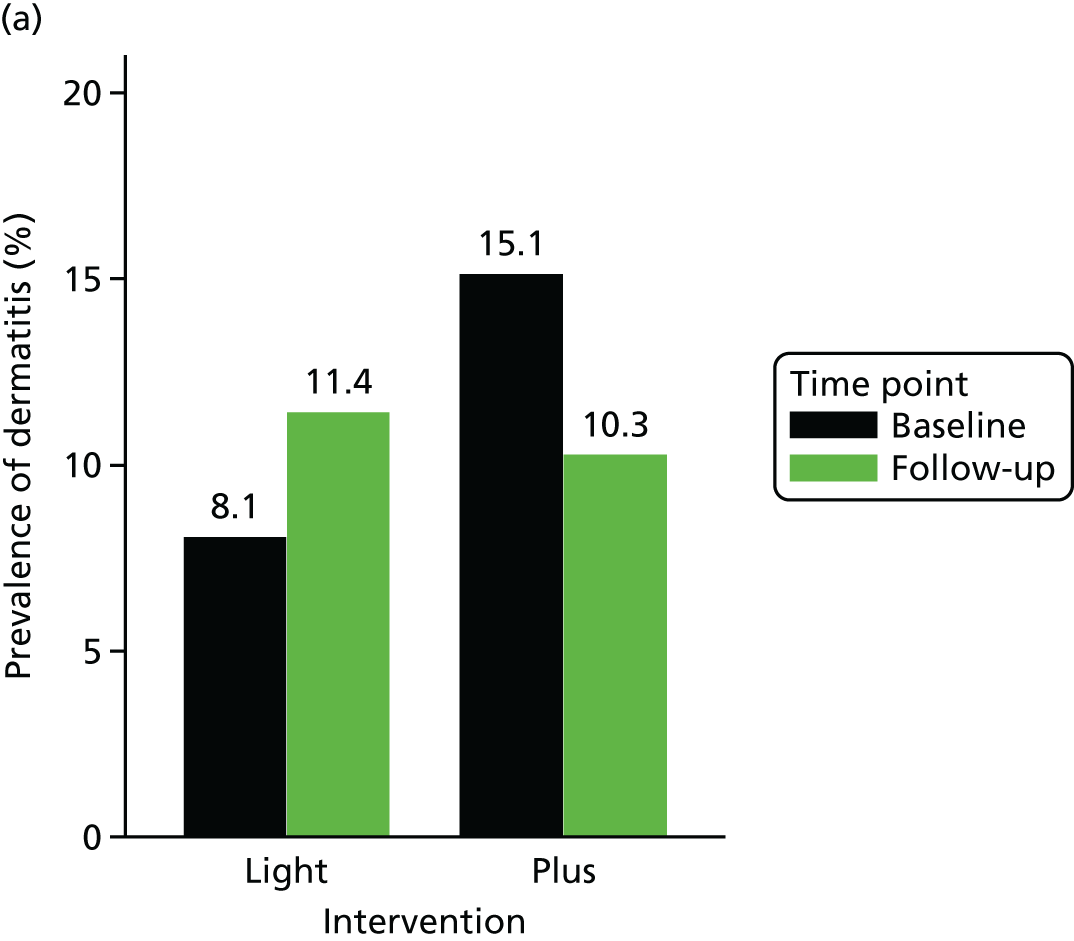

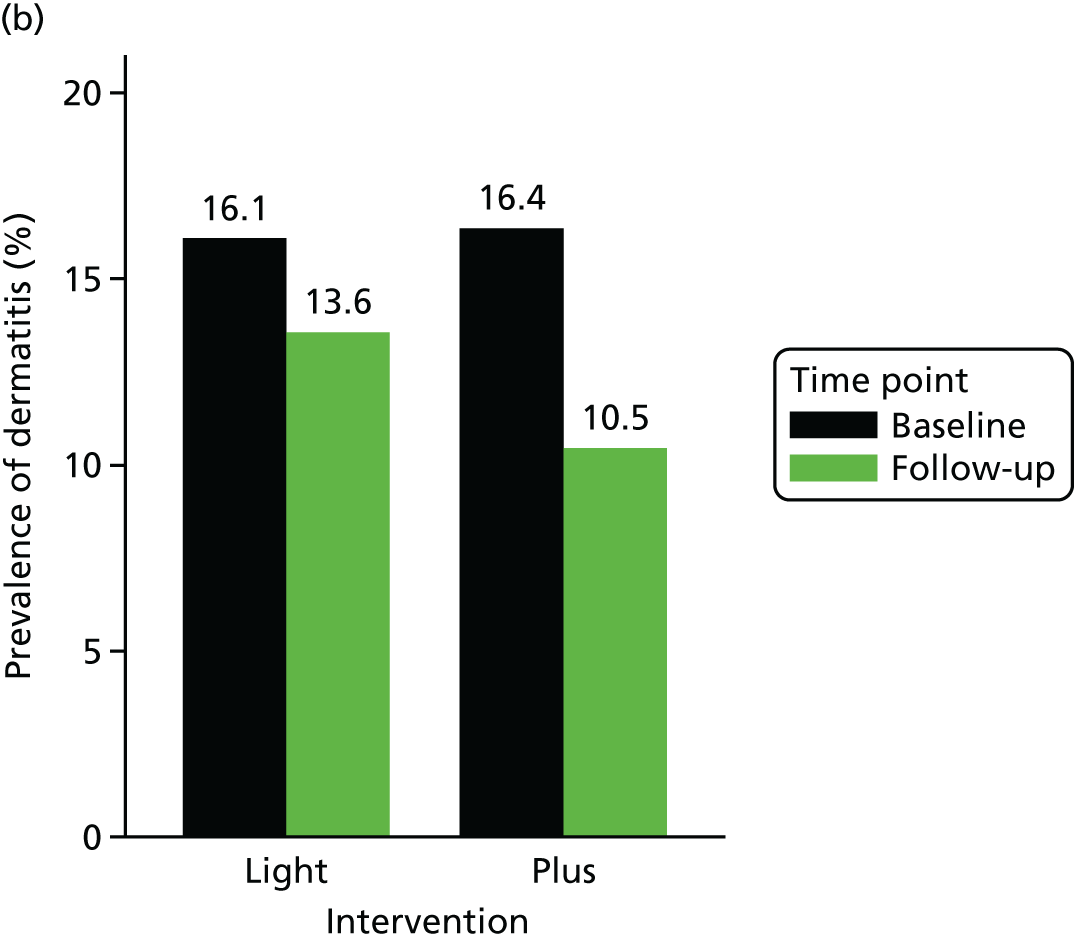

Statistical methods

The primary analysis was an ITT comparison of the two study arms (i.e. intervention plus and intervention light) in change of objectively assessed dermatitis, health beliefs and health prevention measures, and was run separately for student and ICU nurses. All outcomes, primary and secondary, were initially described using means, SDs and percentages, separately for each of the trial arms.

The difference between the two trial arms in change in the primary outcome of the trial (i.e. prevalence of objectively assessed dermatitis) from baseline to follow-up was assessed using logistic regression modelling, with hand dermatitis assessed at follow-up used as an outcome variable after adjusting for hand dermatitis assessed at baseline. The effect of intervention on change in prevalence of hand dermatitis was summarised by odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs).

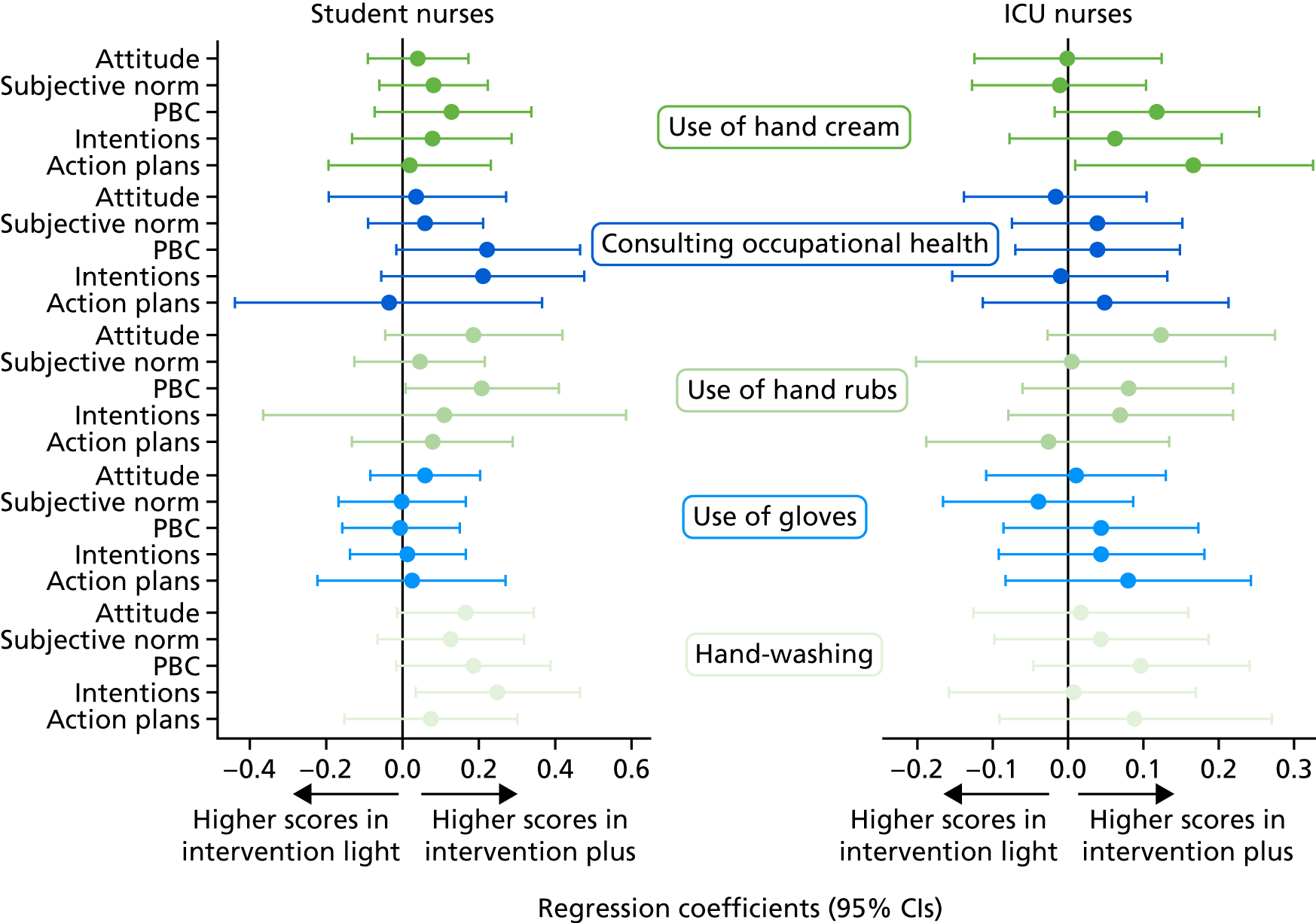

Health belief variables were used as continuous measures with their scores ranging from 1 to 5, with higher scores indicating more positive beliefs. The difference between the two trial arms in change in health beliefs was assessed using linear regression models, with all of the 25 measures assessed at follow-up used as outcome variables in separate regression models after adjusting for the corresponding measures assessed at baseline. The effect of the intervention on change in health beliefs from baseline to follow-up was summarised by regression coefficients and 95% CIs.

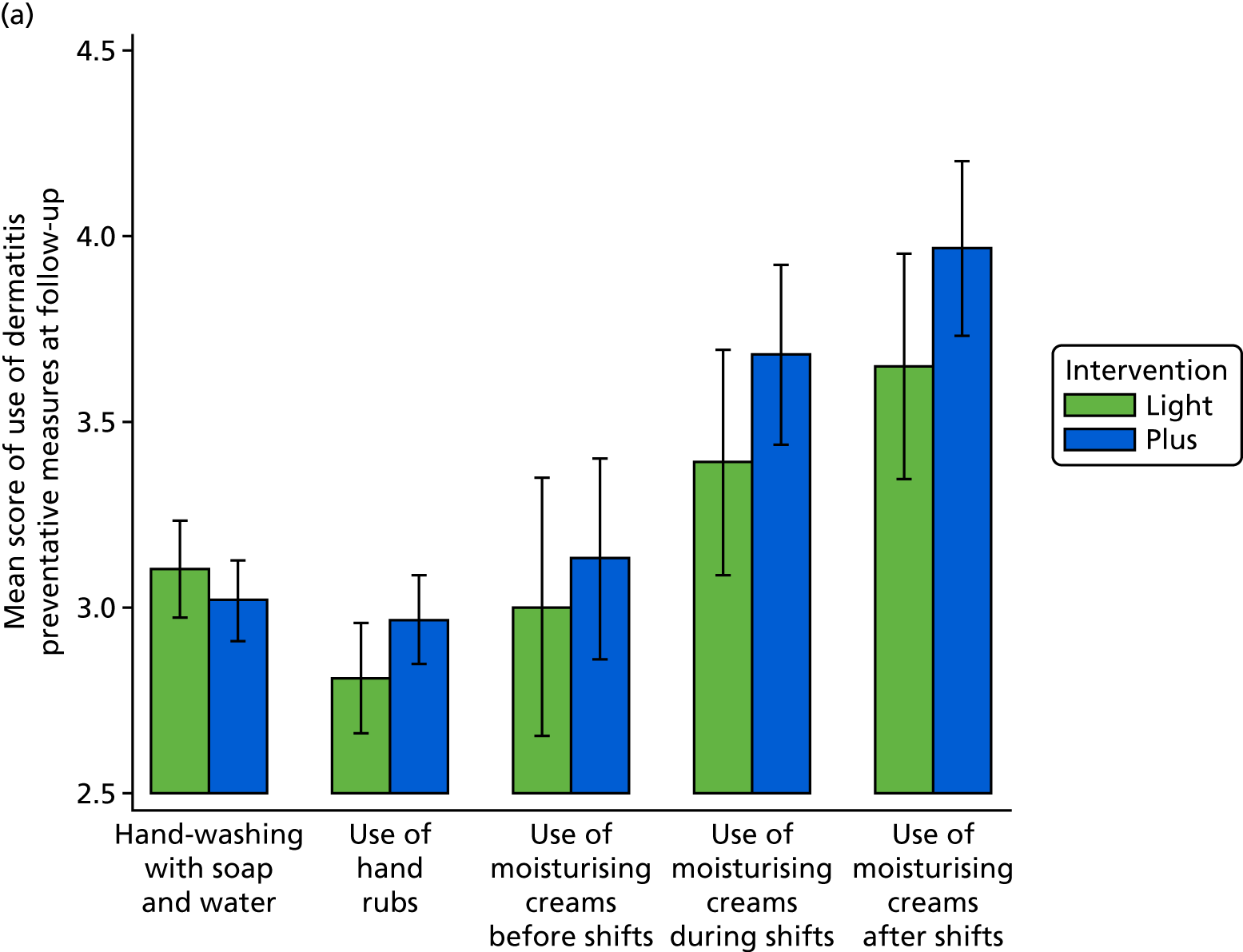

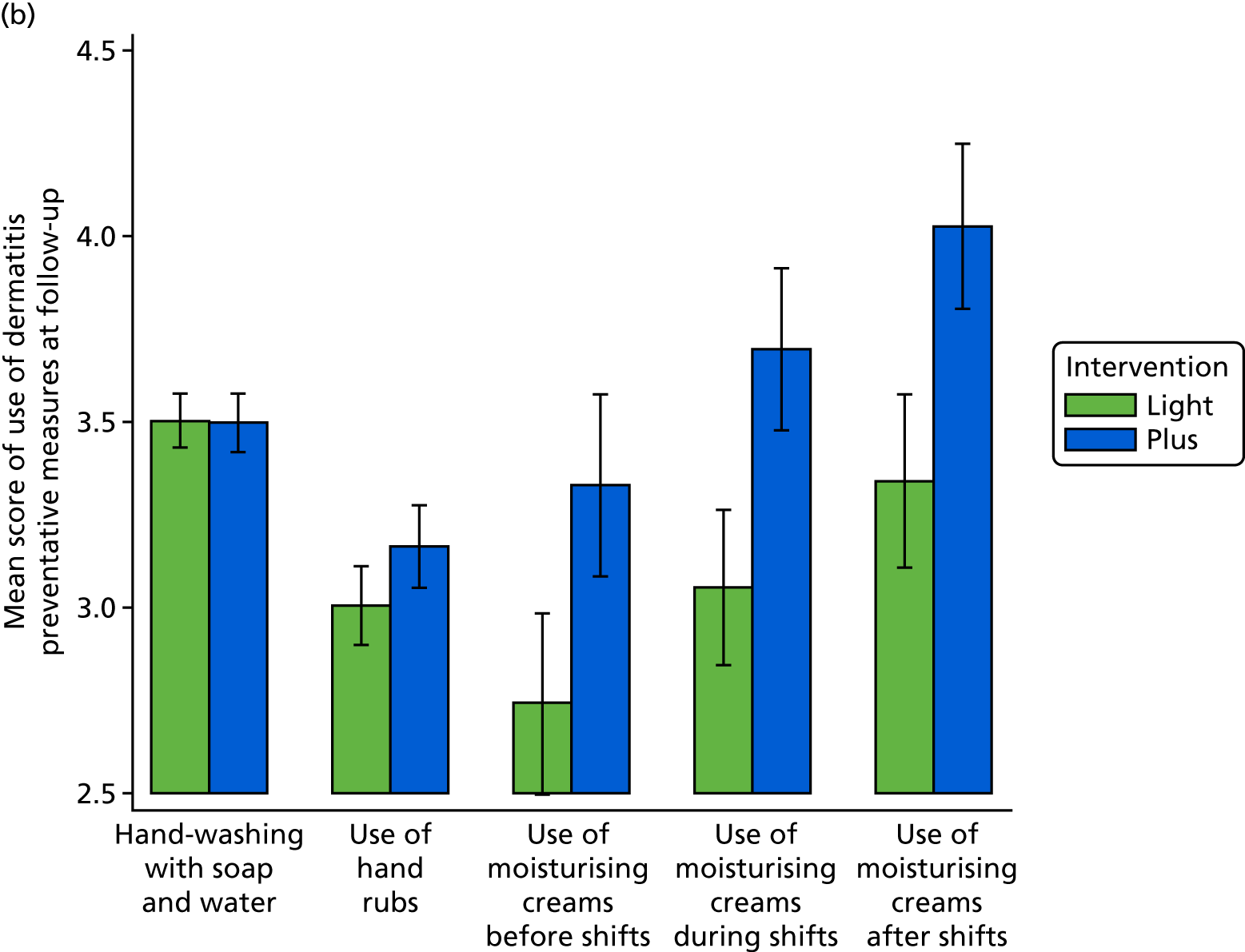

The variables for use of dermatitis prevention measures were used in their ordinal form; scores for hand-washing with soap and water and for the use of hand rubs ranged from 1 to 4 and scores for use of moisturising creams (before, during and after shifts) ranged from 1 to 6. Higher scores for dermatitis prevention measures indicated more frequent use. The difference between the two trial arms in change in frequency of use of dermatitis prevention measures from baseline to follow-up in ICU nurses was assessed using ordinal logistic regression models, with each measure assessed at follow-up used as an outcome variable and adjusting for the measure assessed at baseline. As student nurses started their clinical placement at the beginning of the trial, the difference in frequency of use of dermatitis prevention measures from baseline to follow-up could not be assessed. Thus, for student nurses, the differences in the two trial arms were explored in relation to the frequency of use of dermatitis prevention measures at the end of the study. The effect of intervention was summarised by ORs and 95% CIs.

All analyses were further adjusted for participants’ age, sex and follow-up time, and were repeated after excluding those nurses who reported that they did not access the BCP intervention. Clustering of the outcome among student nurses was very low, so that the ICC approximated zero. Therefore, the final model fitted was a single-level model, adjusted for sex, age and follow-up time. For ICU nurses, a random-intercept model was used to account for clustering by site. The estimated ICCs were 0.01 (95% CI 0.00 to 0.95) and 0.03 (95% CI 0.00 to 0.36) for the ‘adjusted for baseline dermatitis’ and the ‘adjusted for baseline dermatitis, sex, age and follow-up time’ models, respectively. All analyses were run using Stata (version 12.1).

With respect to the approach used for missing data, all analyses were restricted to participants with data on the relevant outcomes. The main adjusted analysis of the primary outcome (i.e. presence of dermatitis at follow-up) was further restricted to participants with complete data on all relevant independent variables.

To explore potential attrition biases in the results, the numbers of participants who completed the baseline, intermediate and the 12-month follow-up questionnaires were compared by categories of their characteristics and the primary outcome variable assessed at baseline and separately for the two intervention arms. In addition, health behaviour and belief variables assessed at baseline were compared between those nurses who completed the baseline, intermediate and follow-up questionnaires using medians, interquartile ranges (IQRs) and ranges, and separately for the two intervention arms.

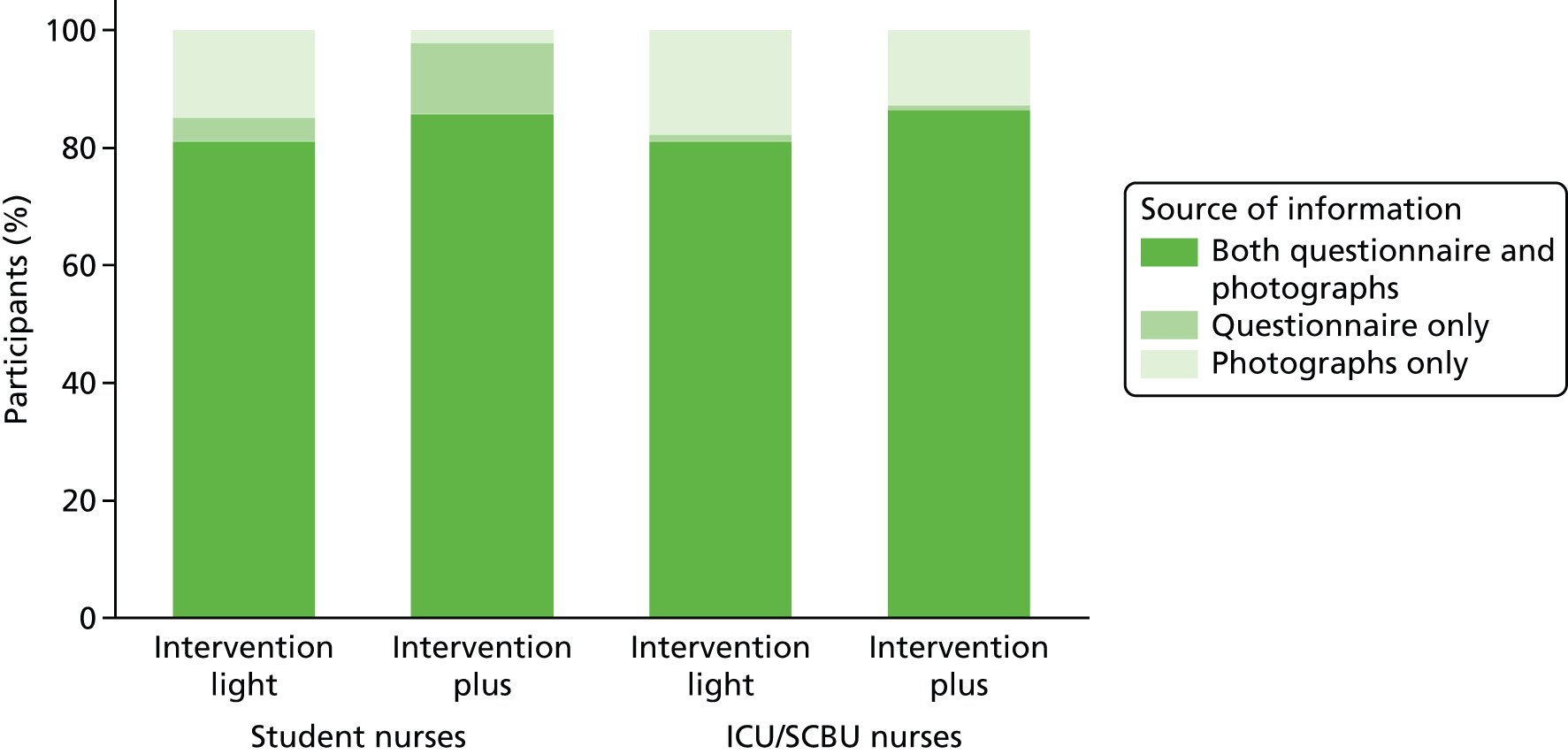

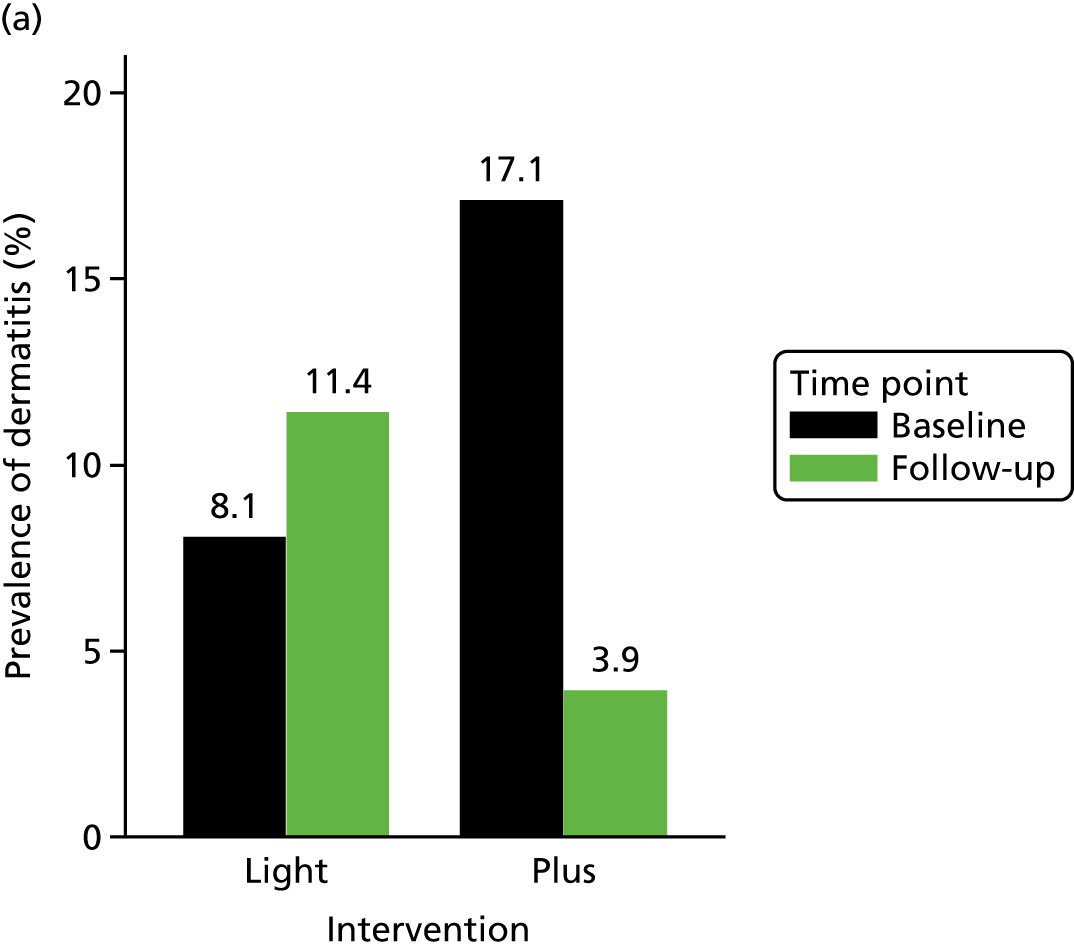

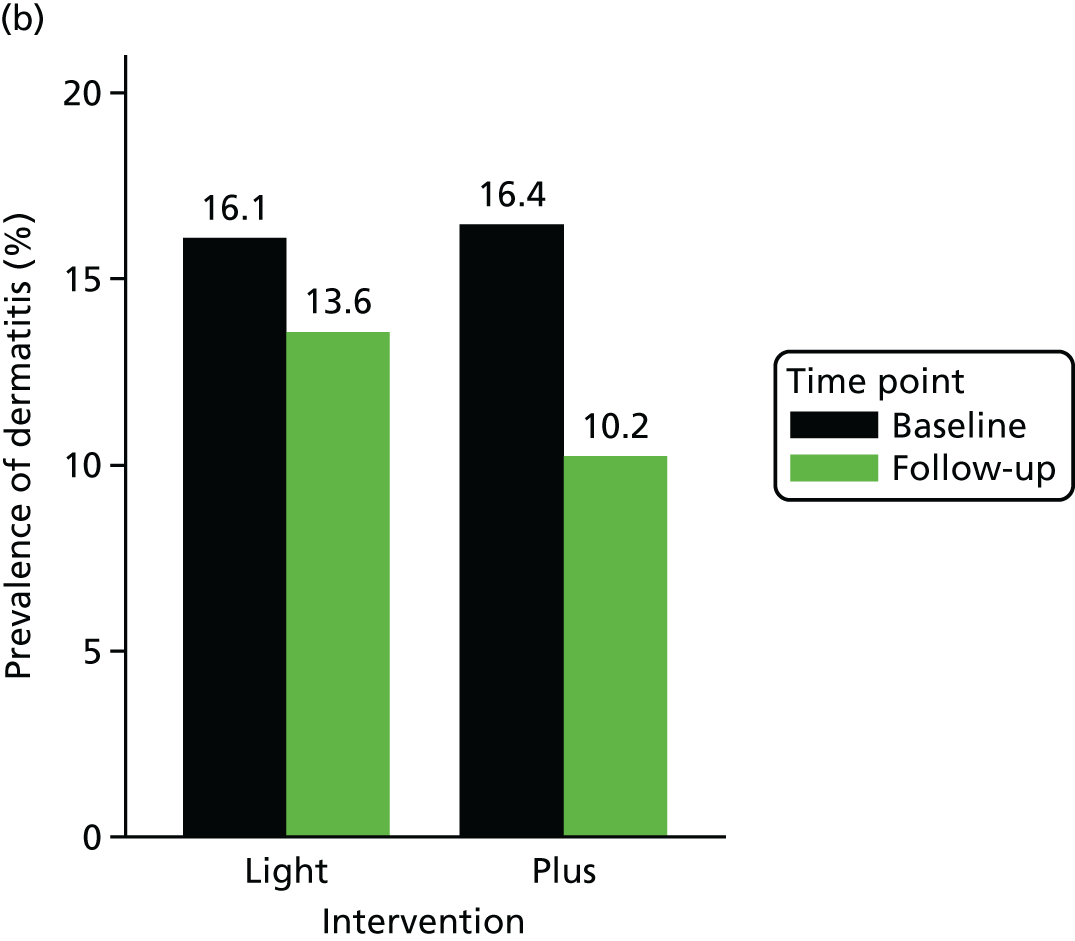

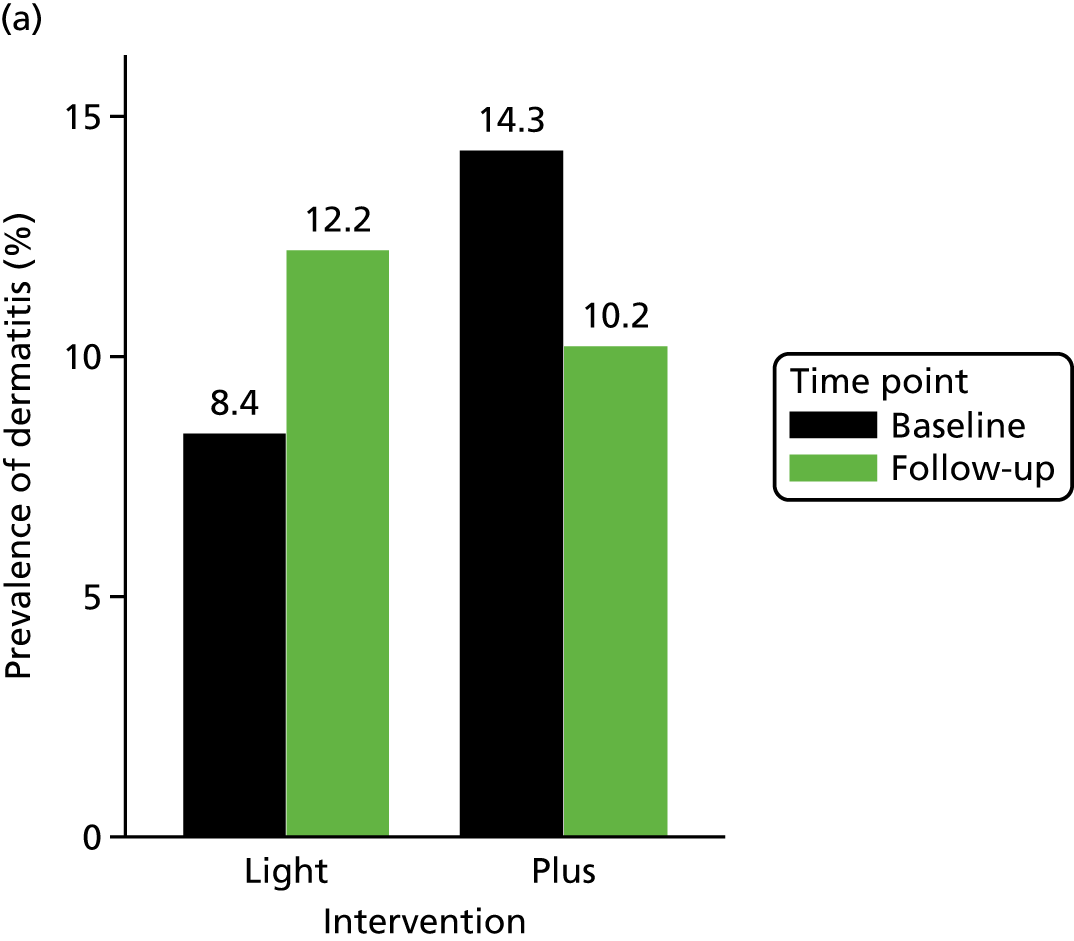

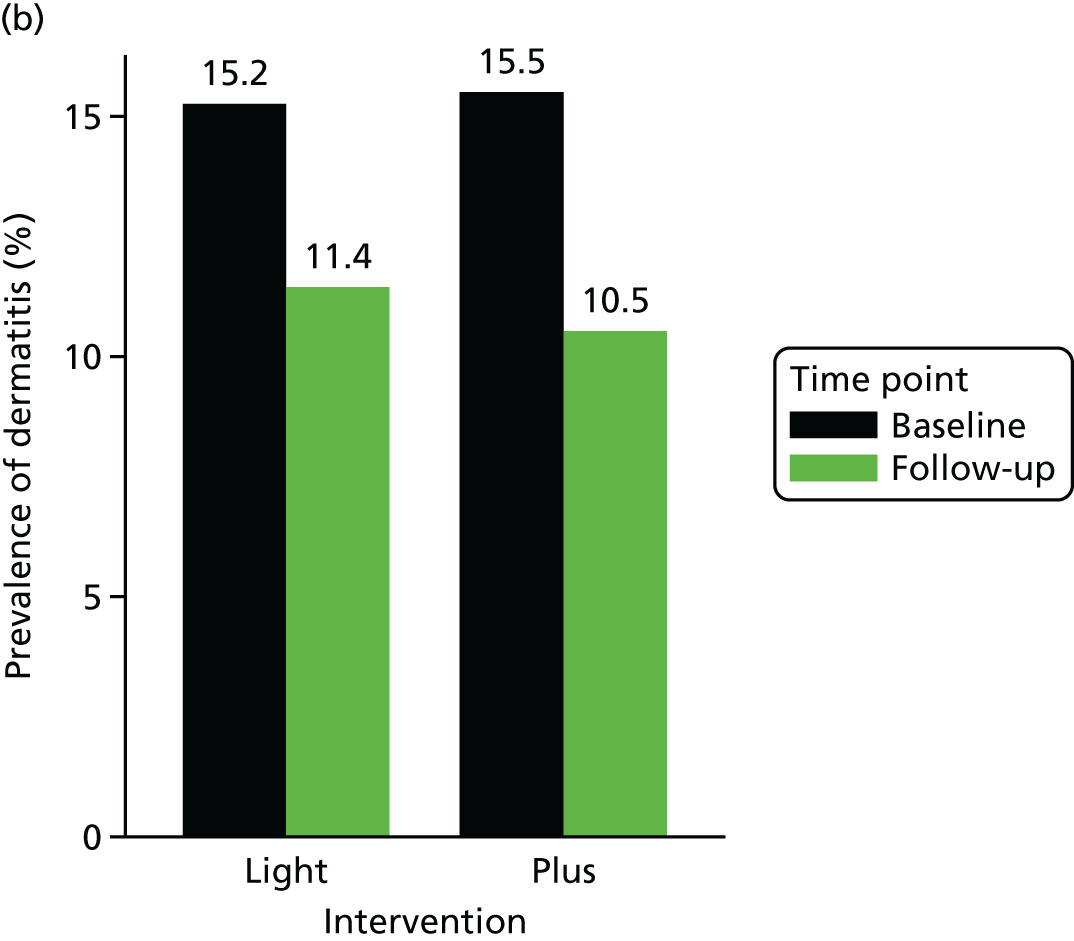

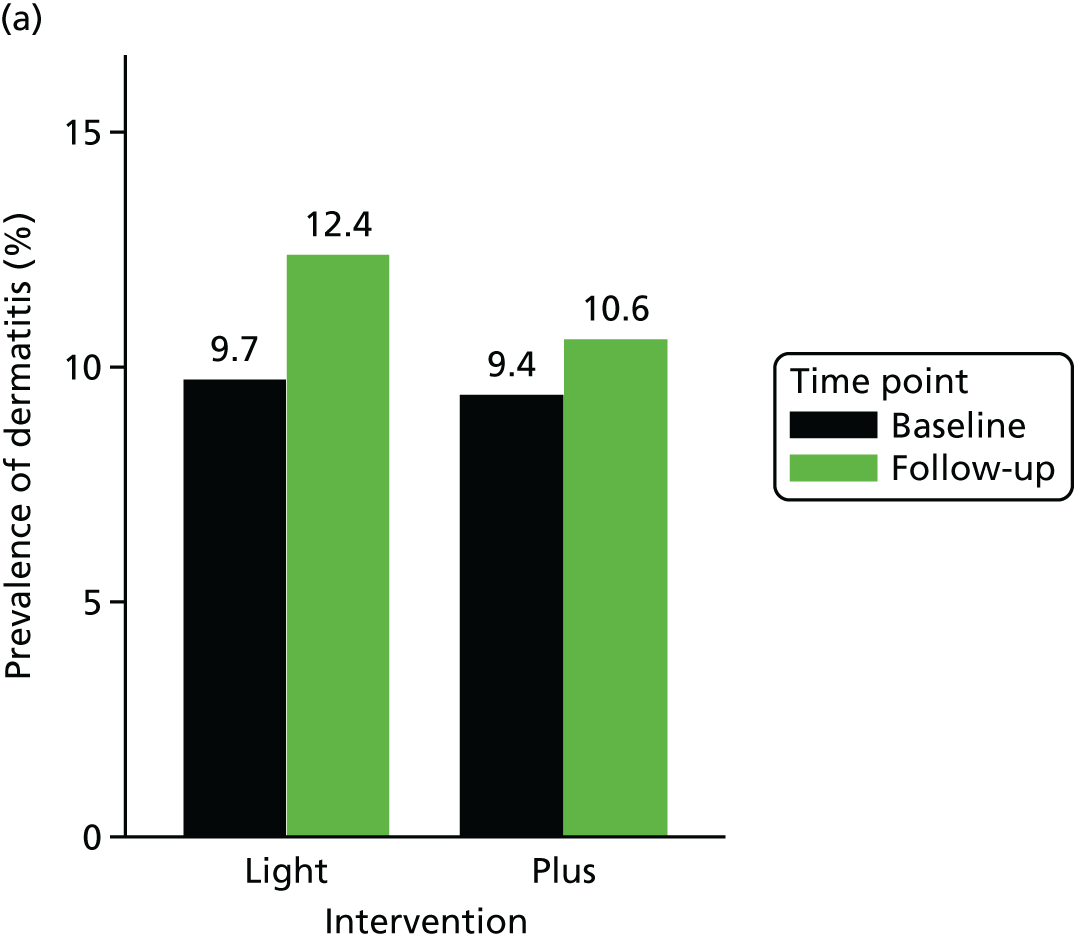

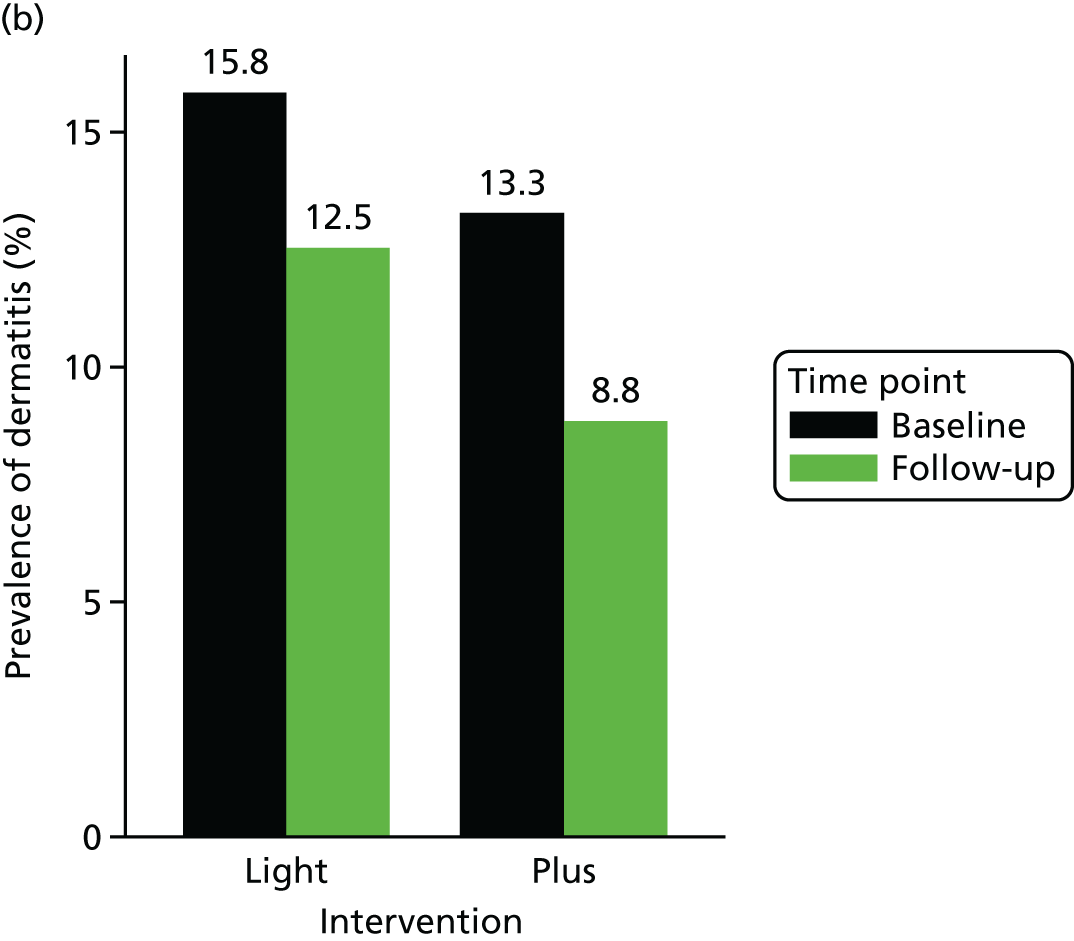

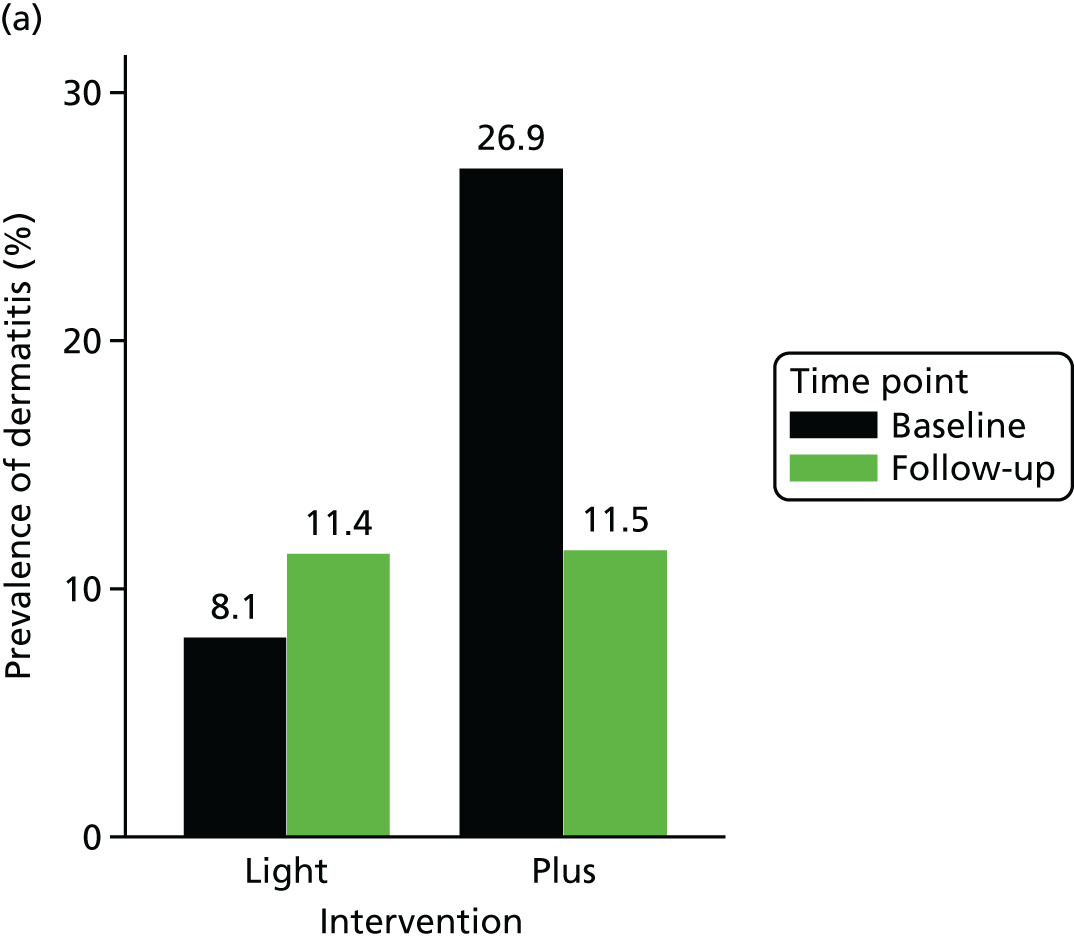

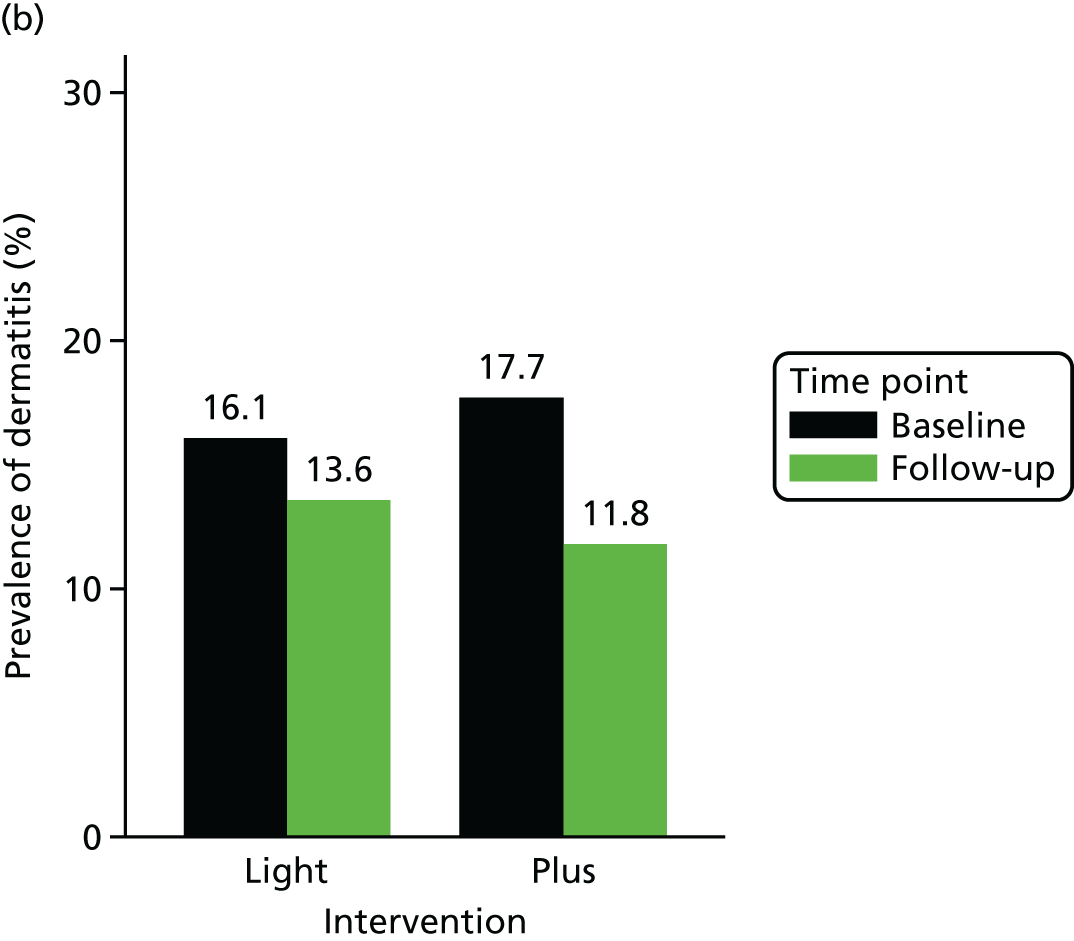

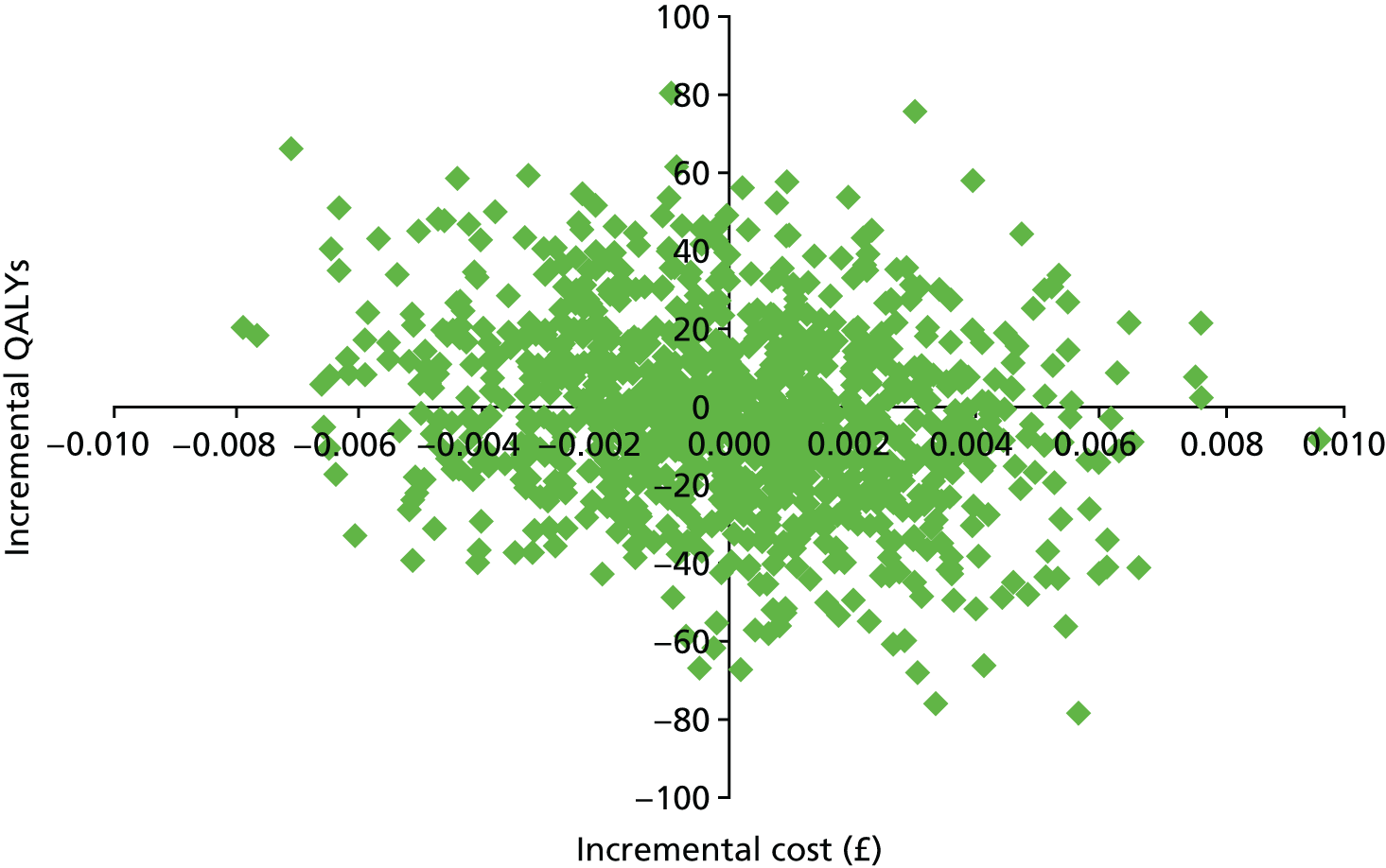

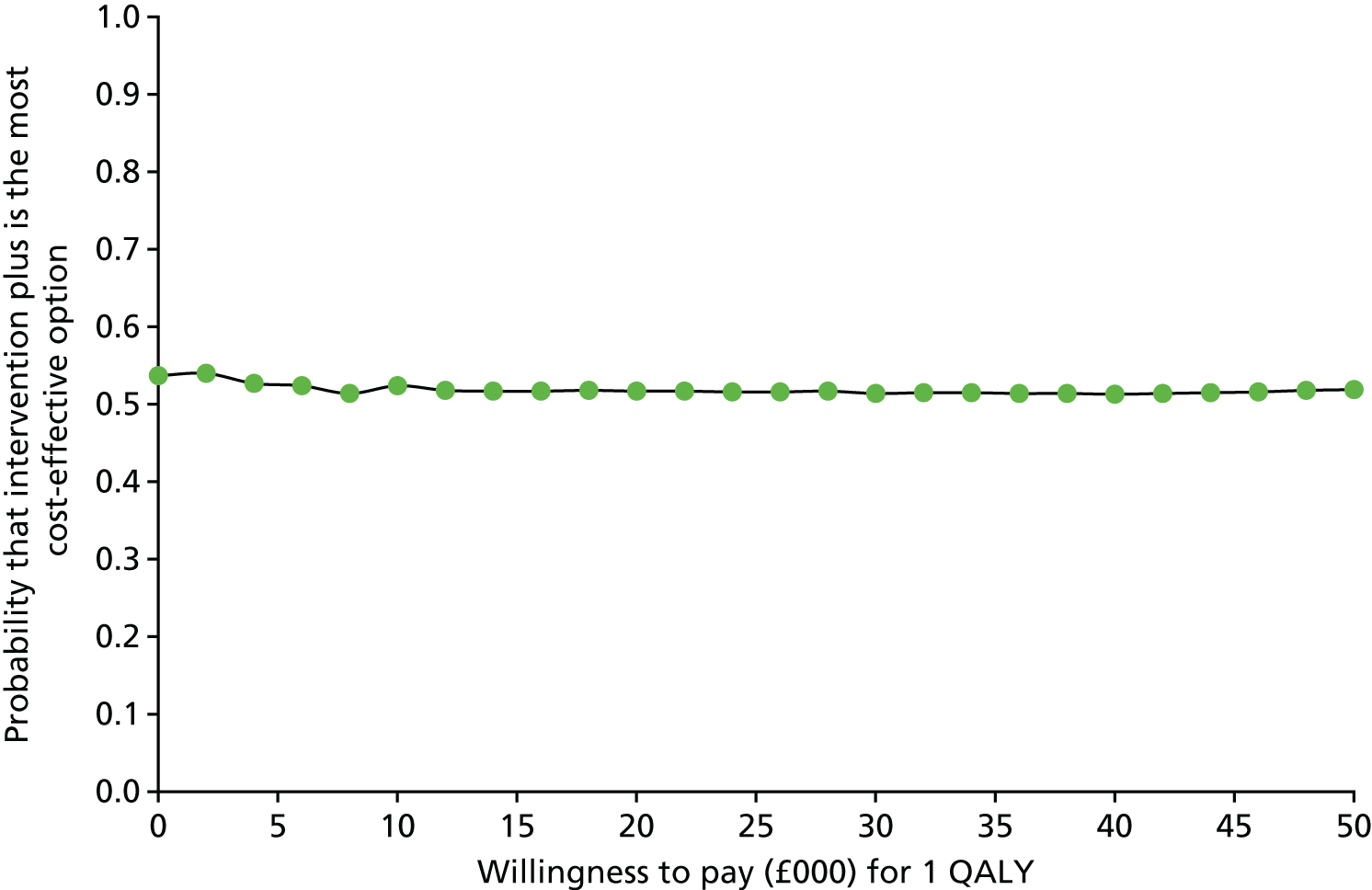

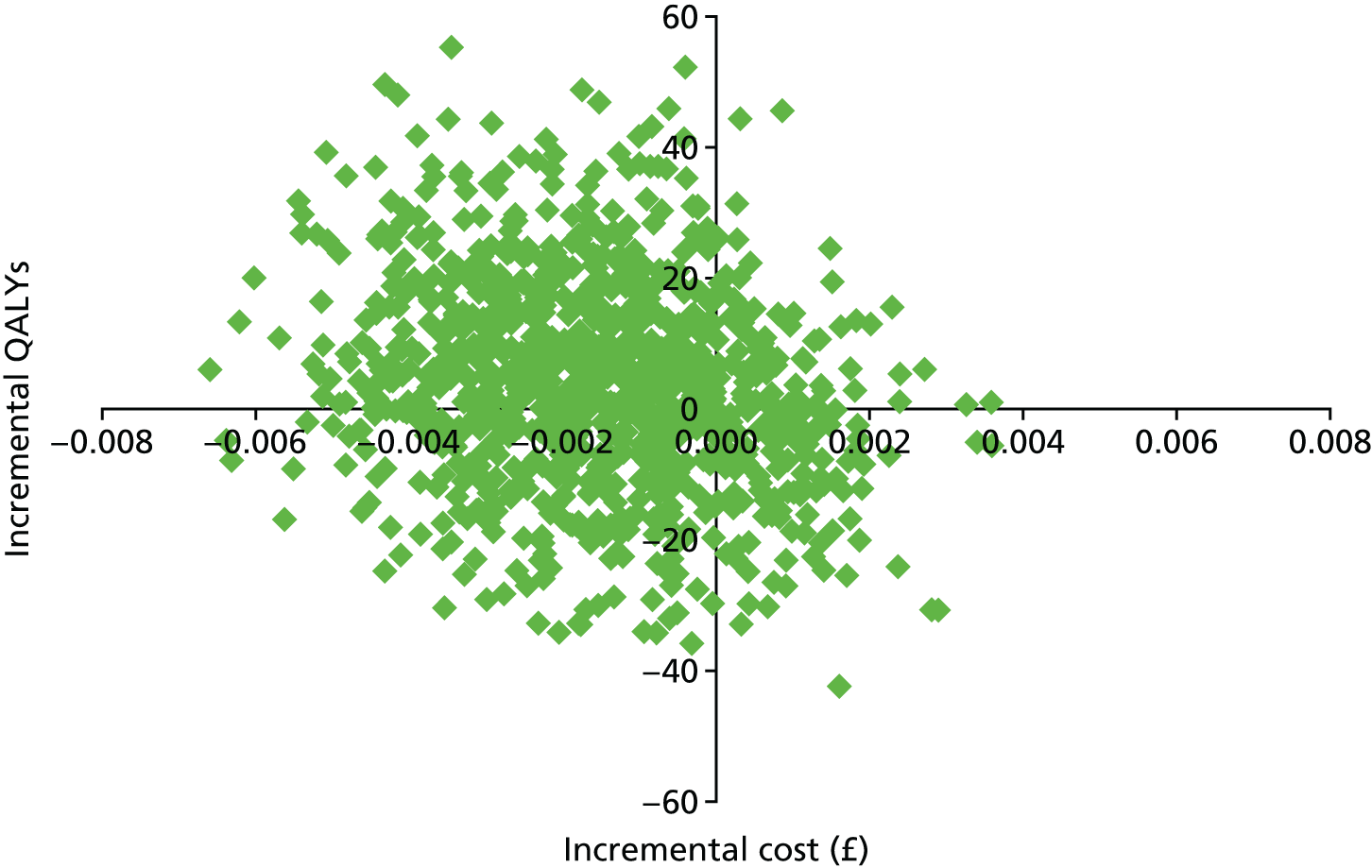

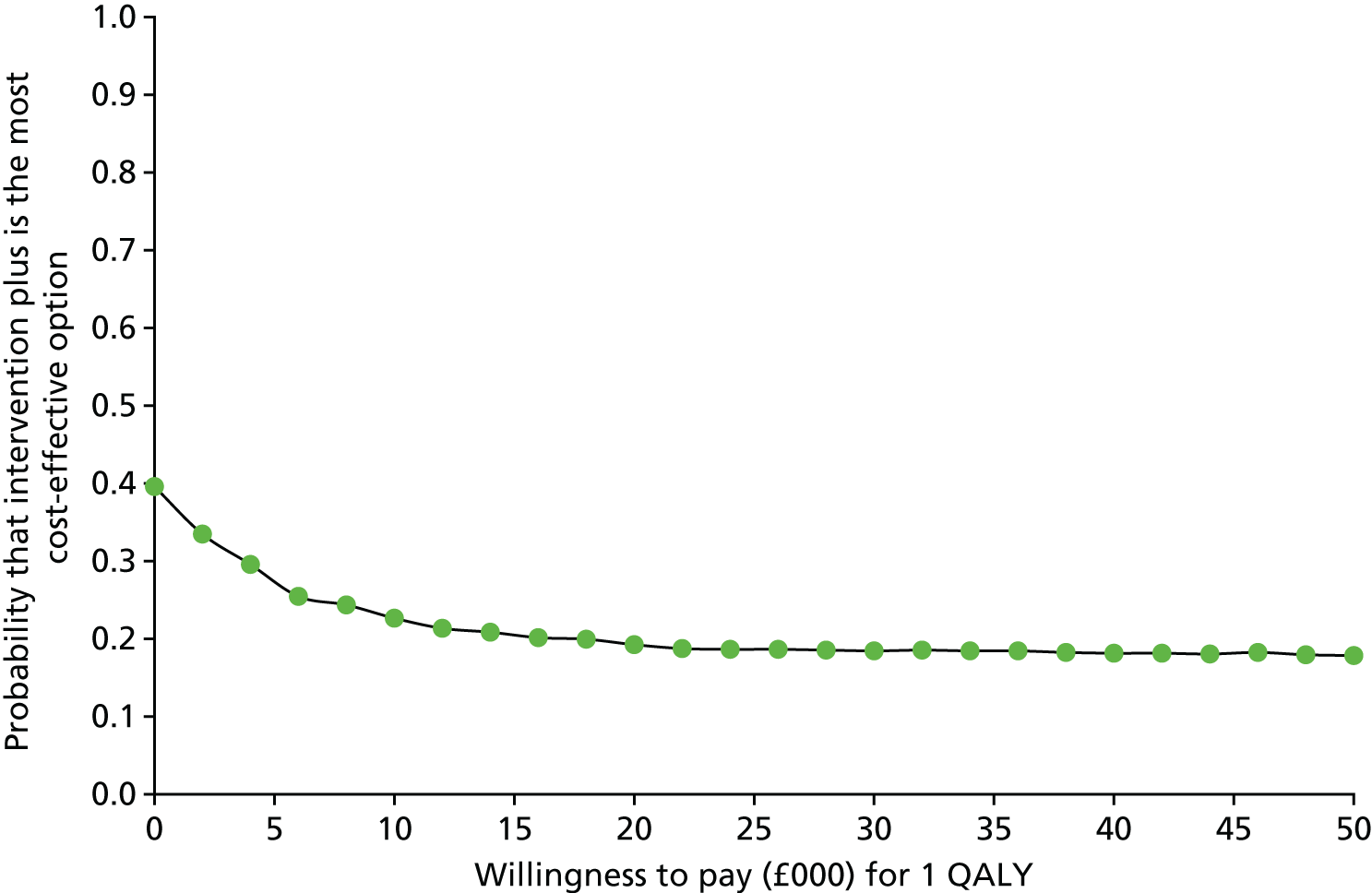

Per-protocol analysis