Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 14/172/01. The contractual start date was in February 2016. The draft report began editorial review in August 2018 and was accepted for publication in January 2019. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Catherine Hewitt reports being a member of the National Institute for Health Research Health Technology Assessment Commissioning Board.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2019. This work was produced by Hughes et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2019 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Introduction and background

This report presents the findings from a Health Technology Assessment programme commissioned study that aimed to establish the feasibility of a novel sexual health promotion intervention for people with serious mental illness (SMI). This study had two main aims:

-

to develop a novel evidence-informed and co-produced sexual health promotion intervention that could be routinely delivered in community mental health services

-

to assess the feasibility and acceptability of both the intervention and the randomised controlled trial (RCT).

Secondary aims were to gain a better understanding of the sexual health needs of people with SMI who use mental health services, and to explore the cost-effectiveness of the intervention in preparation for a future large-scale fully powered trial.

This chapter provides the background and rationale for developing a sexual health intervention for people with SMI, and describes the research objectives. The remainder of the report is divided into the following seven chapters, each representing specific phases of the study:

-

Chapter 2 describes the process undertaken to develop the intervention manual and the selection and training of mental health workers to deliver the intervention in the NHS sites. The content and format of the intervention is described.

-

Chapter 3 describes the method and procedure of both the trial and the nested qualitative study.

-

Chapter 4 outlines changes to the protocol, which were implemented after the study had commenced.

-

Chapter 5 presents the main feasibility trial results and reports on the numbers screened and eligible, and the numbers recruited and retained. It reports on data completeness. It also presents descriptive data on demographics, participants and the outcome data by gender and study arm (intervention arm and control arm).

-

Chapter 6 presents the qualitative analysis and, following this, the data obtained from the recruitment stage feedback:

-

recruitment stage questionnaire and study exit questionnaire

-

Clinical Research Network (CRN) staff feedback.

-

-

Chapter 7 presents details of the dissemination events and engagement activities in which the research team have been involved.

-

Chapter 8 presents the overall discussion and conclusion.

Background

People with SMI (e.g. psychosis, schizophrenia and bipolar affective disorders) account for approximately 1% of the population. 1 SMI includes mental disorders such as schizophrenia-spectrum disorders, bipolar disorders and severe major depression where there is significant functional impairment and limitation of major life activities. 1 In the UK, people with these needs typically require the care of secondary mental health services. Some people with SMI may require the services of secondary mental health care over an extended period of time because of the impact that these disorders have on functioning and the activities of daily life. In addition to their mental health needs, this population experiences significant inequalities in physical health compared with the general population, with their life expectancy approximately 15–20 years less than the general population. 2 To address this disparity, the physical health and well-being of those with SMI has been recently prioritised in mental health services3 and there is some evidence that the sexual health of this group has not been addressed as effectively as other aspects of health. 4

The nature of the problem

The World Health Organization’s (WHO’s) definition of sexual health5 includes not just freedom from sexually acquired infections; it defines it as experiencing one’s own sexuality that is satisfying, positive and respectful, and free from exploitation and violence.

Most people with SMI live in the community and many are sexually active throughout their adult life. It is hard to estimate the level of sexual activity of people with SMI in the UK as there have been no studies undertaken; however, in a systematic review of 52 studies (predominantly conducted in the USA, with a few in Australia, India and Canada),6 it was estimated that just under half (44%) of people with SMI were sexually active in the preceding 12 months. In a reanalysis of data from a previous study, Bonfils et al. 7 found that 30% of people with SMI had been sexually active in the last 3 months prior to data collection.

Although sexual activity is generally less frequent than levels reported in data for the general adult population6 for a range of reasons (impact of mental illness, medication and/or lack of sexual partner), sexual practices seem to involve a greater proportion of ‘high-risk behaviour’ such as condomless vaginal and anal sex. 8

Human immunodeficiency virus

People with SMI have an elevated risk of infection with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), hepatitis B and hepatitis C. A systematic review and meta-analysis of 91 prevalence studies of blood-borne viruses9 (BBVs) (hepatitis B and C, and HIV) found that pooled HIV prevalence estimates were elevated in every area of the world for people with SMI, and much higher than expected in that area’s general population. Pooled data for the prevalence of HIV infection in people with SMI in the USA were 10 times higher than for the general population (6% vs. 0.6%). 10

Sexually transmitted infections

There is less research attention paid to sexually transmitted infection (STI) prevalence in people with SMI than in people with HIV. However, studies from the USA and Brazil have indicated that STI rates are also elevated for people with SMI. In the USA, Vanable et al. 11 found that 38% of 464 psychiatric outpatients reported having had STI. In a study of sexual health interviews for 2475 psychiatric patients in Brazil, Dutra et al. 12 found that 26% had a lifetime history of STIs. In the questionnaires, participants were asked about STI symptoms as well as whether or not they had any medical diagnosis of a STI; the majority of participants reported symptoms as opposed to medically diagnosed STIs (although 10% reported having had a diagnosis of gonorrhoea).

Reproductive health

Pregnancy rates are lower in women with SMI, yet the rates of terminations of pregnancy are higher than in the general population. 13 Simoila et al. 14 undertook a comparison of termination of pregnancy rates in Finland for women with schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder, and matched healthy women using large health data sets. They found that the numbers of terminations of pregnancy were similar between the two groups; however, as pregnancy was a rarer event in the women with schizophrenia, the risk of abortion was twofold. Terminations in the group with SMI were associated with being younger, being single and having a lack of contraception. Therefore, women with SMI should have access to advice about a range of contraception and the planning of pregnancies in order to have control over their fertility, as well as having support around decisions regarding whether or not to continue with a pregnancy.

People with SMI experience higher levels of exploitation and violence in sexual relationships. 15 Elkington et al. 16 have suggested that one factor that mediates exploitative relationships is stigma (from self as well as others) regarding mental illness. People who feel that they are less attractive because of their mental health diagnosis may be more likely to be vulnerable to exploitative and abusive partners, as they perceive that they have limited choices of partners. High scores on the Mental Illness Stigma Scale (MISS-Q) have been associated with risky sexual behaviour. 17

In addition, people with SMI are more likely to have a history of childhood sexual abuse. Abuse histories are associated with sexual risk-taking as adults such as condomless anal and vaginal sex with multiple partners, sex working and sex trading. 8,12 Another factor that could be mediating risky sexual behaviour is that many people with SMI have co-occurring drug and/or alcohol use and drug and/or alcohol problems. This can lead to unsafe sex as a result of intoxication (poor decision-making, being unprepared) as well as trading sex for drugs and/or alcohol. During an acute phase of illness, some people are more likely to engage in unsafe sex as a result of hyper-sexuality, sexual disinhibition and poor judgement and planning. 8

Informed about sexual health

Several studies indicate that there are gaps in information and awareness related to sexual health issues for people with SMI (Table 1).

| Author and year of study | Location | Type of participants | Method | Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Grassi 200118 | Italy | Inpatient psychiatric units and two mental health outpatient clinics in Ferrara, in north-eastern Italy, and a control group | AIDS risk behaviour knowledge test | Knowledge was lower in the SMI group than in the control group:

|

| Shield 200519 | Early intervention psychosis, Sydney, NSW | Young people using the service, n = 62 | Paper survey: mail and in person |

School was the main source of sex information Gender difference in the knowledge of transmission of infection – males had poorer knowledge Risks – in terms of rating rate sexual practices as low, medium or high – responses were reasonably accurate (but some rated oral sex as ‘high’ risk and a small percentage rated anal sex moderate to low (15%) 31% reported a concern about unsafe sex in the past 12 months Sexually active women in this sample reported more than three sexual partners in last 12 months Safer sex attitudes: women were more concerned than men regarding STIs: |

| McCann 201020 | Community mental health team, London | Schizophrenia and schizotypal, n = 30: 15 men, 15 women | Qualitative interviews |

Anxiety about HIV No past sex education – basic education at school Rarely talk about issues with health-care staff, knowledge is patchy |

| Ngwena 201121 | Acute psychiatric hospital, London, UK | Patients on acute wards, able to give consent, aged 18–65 years, n = 30 | Questionnaire survey |

Knowledge – ‘from TV’ Doctors and nurses were least likely to be sources of info Risk knowledge: |

Mental health service response to sexual health

Sexuality and sexual health issues are rarely discussed with service users in mental health settings. 22–24 Service users themselves value positive sexual relationships,20 yet because of ‘self-stigma’ and other vulnerabilities they feel limited in their choices of sexual partners and, therefore, more vulnerable to sexual exploitation and abuse in relationships. 16

In focus group discussions held in two different NHS services in England,4 mental health clinicians reported awareness of a range of sexual health needs of the people in their care, but some reported that they would usually avoid raising the topic of sexuality, sexual health and abuse. The reasons for this ranged from fear of offending the person, concerns about destabilising their mental state, feeling that they lacked the knowledge to address the sexual health issues that may be raised, and lack of knowledge about local sexual health services. Despite this, the participants recognised that sexual health is an important aspect of people’s lives. They were able to describe a number of issues that they had become aware of related to the topic and they saw promotion of sexual health, as well as facilitating access to appropriate family planning and sexual health clinics, as part of their clinical role. In addition, they recognised that they could play an advocacy role in terms of assisting people to get access to appropriate family planning and sexual health clinics. However, they also acknowledged that their knowledge regarding sexual health and sexual health services was limited. These findings were echoed in a survey of mental health staff in England and Australia about sexual health provision. 25 Participants from both countries reported that very limited sexual health work was being undertaken in routine practice but they did see it as part of their role. Therefore, in order to address this issue, mental health staff require training and guidance in relation to sexual health issues in SMI and in how to engage people in conversations about sexual behaviour, and offer advice about where to access help for contraception and sexual health concerns.

Despite experiencing significant health disparities, people with SMI struggle to get their wider physical needs assessed and treated. 2 Therefore, promoting the sexual health of people with SMI could fall into routine practice in mental health services that can often be the only health service that some people with SMI are engaged with.

Current sexual health concerns in England

Sexual health is an important public health concern in England26 and there are key areas that require attention for the promotion of sexual health in the general population. Overall, the incidence of new diagnoses of many STIs has remained stable in recent years but there are some disproportionate rises in STIs in specific populations. Chlamydia is the most common STI (almost half of all STIs diagnosed are chlamydia) and the impact of STIs remains greatest in young people aged under 25 years. There has been a 21% rise in gonorrhoea and a 19% increase in syphilis in men who have sex with men (MSM), and this is possibly as a result of an increase in condomless sex. 27

HIV rates are declining for the first time since it was first identified 30 years ago. 28 The mortality of someone diagnosed promptly (shortly after infection) with HIV is comparable with the general population for the first time. This is because of access to effective treatments to suppress the virus. However, this is not the case for late diagnosis and those diagnosed late have a greater risk of death within the first 12 months of diagnosis. Therefore, people engaging in condomless sex with new or casual partners of unknown HIV status should be tested for HIV every 3 months, and gay/bisexual men and other MSM should be tested for HIV every year.

In summary, in the general population, STIs are most prevalent in young people and in specific groups, such as MSM (who may be more likely to engage in high-risk sexual behaviours). Early detection and treatment of STIs is crucial, not only to improve the prognosis and prevent further harms (e.g. untreated chlamydia leading to fertility problems) but, in some cases, to prevent mortality (e.g. late diagnosis of HIV is associated with death from AIDS within 12 months of diagnosis). In addition, the treatment of STIs (and HIV) can also prevent onward transmission, hence the term ‘testing as treatment’. Therefore, it is essential that all health professionals are aware of the current issues in sexual health, able to ask questions about sex and sexuality as part of routine care, able to offer advice about testing and treatment, and able to offer access to condoms in the local area.

Policy context

There is no specific mention of people with mental illness in the recent Public Health England sexual health policy. 29 However, there is some emerging awareness of this issue in mental health policy, specifically within the ‘improving physical health for people with mental illness’ agenda. A recent document from the Department of Health3 (Improving the physical health of people with mental health problems. Actions for mental health nurses) includes a chapter on sexual health, outlining sexual health needs, and care responses to those needs, by mental health nurses. In addition, sexual health is mentioned (albeit very briefly) in a recent joint report by the Academy of Medical Royal Colleges and the Royal Colleges of General Practitioners, Nursing, Pathologists, Psychiatrists, Physicians, the Royal Pharmaceutical Society and Public Health. 30 Both of these documents support the role of mental health nurses and psychiatrists in promoting sexual health in mental health care settings.

Justification for sexual health promotion in mental health

Sexual health promotion activities such as regular check-ups, increasing knowledge and awareness of risky sexual behaviour and how to keep oneself and sexual partners protected are essential in terms of prevention of STIs, as well as in detection. Untreated STIs can lead to significant health problems (e.g. the human papilloma virus can lead to cervical cancer, and other STIs such as chlamydia can result in infertility). BBV such as hepatitis B and hepatitis C can result in premature death through the development of cirrhosis and liver cancer in the long term. Comorbidity of HIV and SMI, such as schizophrenia, poses significant challenges for both the person themselves as well as in the provision of treatment. 31 The treatment and management of HIV requires early detection and adherence to a complex medicine regime to suppress the virus. This requires engagement with services and treatment adherence. Early diagnosis and treatment has resulted in people living well with HIV and has the potential to reduce onward transmission (treatment as prevention) by suppressing the virus to the extent that it is not present in sufficient quantities in blood and body fluids. However, many people are receiving a late diagnosis of HIV and are starting treatment after the point of maximum benefit. 28 This latest data suggests that 13% of HIV diagnoses occur at a later stage of the disease and the prognosis is likely to be poorer. 28

Evidence to support sexual health promotion interventions

Current evidence around improving sexual health for people with SMI has been conducted in the USA and Brazil, where a different set of cultural, organisational and socioeconomic factors exist from those in the UK.

Simply providing information (e.g. leaflets) alone is insufficient to bring about health behavioural change, and behavioural interventions that address knowledge, confidence, attitudes/motivations and behavioural skills are recommended. 19 There have been two recent literature reviews that have examined the evidence for sexual health promotion interventions and found that the evidence is currently equivocal. 32,33 All studies were conducted in the USA and most were group-based interventions. Some studies34,35 demonstrated a significant reduction in condomless sex, when compared with a control group, and some studies showed no overall effect. 36,37 Both reviews32,33 recommended that further research should be undertaken in the UK to develop and evaluate an intervention, as well as the feasibility of undertaking a study that addresses sexual health needs in SMI.

Rationale

The overall aim of the project was to design a sexual health intervention for people with SMI and to establish the feasibility and acceptability of undertaking a RCT in order to establish key parameters to inform a future trial of effectiveness.

Research objectives

The main objectives of the Randomised Evaluation of Sexual health Promotion Effectiveness informing Care and Treatment (RESPECT) study were as follows.

Stage 1: intervention development

-

To undertake a stakeholder consultation to inform the development of an intervention.

-

To use intervention mapping to develop an evidence-informed and co-produced manualised sexual health promotion intervention.

Stage 2: feasibility randomised controlled trial

Objective 1 was to assess the feasibility and acceptability of undertaking a trial by:

-

quantitatively assessing the numbers screened, numbers eligible and those agreeing to participate

-

qualitatively assessing the feasibility and acceptability of the randomisation process, as well as the intervention

-

quantitatively evaluating the acceptability of the intervention by assessing retention in treatment (number of sessions attended)

-

quantitatively evaluating the acceptability of the proposed method of data collection and data collection tools by assessing overall questionnaire response rates and for each data collection tool.

Objective 2 was to identify the key parameters to inform the sample size calculation for the main trial: the standard deviation (SD) of the primary outcome measure, quantify the average caseload per therapist and tentatively explore clustering within therapist using intracluster correlation coefficients (ICCs).

In addition, a number of secondary aims were anticipated to be met by this study, especially as this was the first UK study to our knowledge to collect data specifically about sexual health and service use of people with SMI:

-

to develop an understanding of the sexual health needs of people with SMI who use NHS mental health services

-

to establish the use and uptake of sexual health services by people with SMI

-

to establish the barriers to accessing information and service provision

-

to establish workforce capacity to undertake such an intervention in mental health services

-

to explore cost-effectiveness in preparation for a future large trial

-

to develop recommendations for care pathways between mental health and sexual health service.

Chapter 2 Stage 1: intervention development

The overall aim of the RESPECT study was to undertake a feasibility study of an intervention designed to promote sexual health for people who have SMI. This chapter will outline the theoretical underpinning and the process that was adopted to develop the manualised behavioural intervention for the RESPECT study.

Background and theoretical basis

It was important that all stakeholders (including service users and clinicians) were involved in the development of an intervention in order to ensure that it addressed specific challenges faced by this population and that it was feasible and acceptable to participants. 38,39

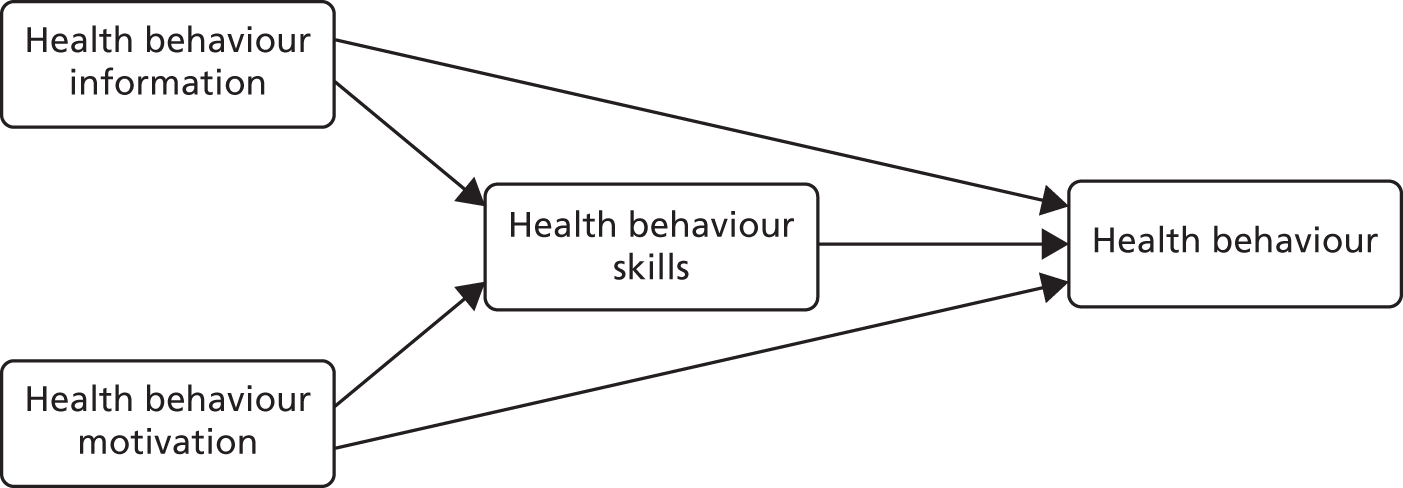

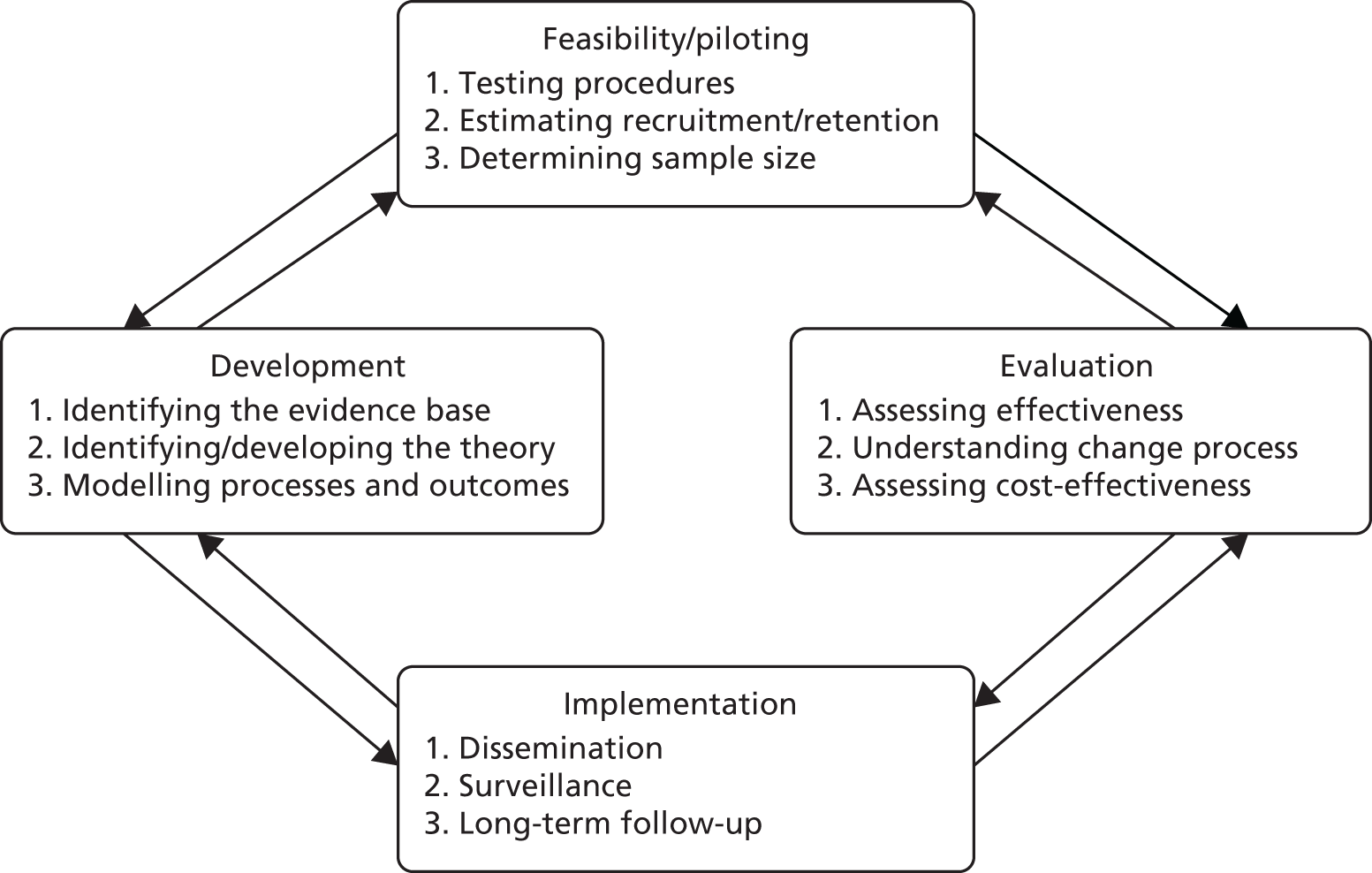

The Medical Research Council (MRC) framework for the development of complex interventions38 is an iterative process to guide the development of interventions in the real-world health-care setting (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

Key elements of the development and evaluation process. 38 Reproduced from Developing and evaluating complex interventions: the new Medical Research Council guidance, Craig P, Dieppe P, Macintyre S, Michie S, Nazareth I, Petticrew M, Medical Research Council Guidance, 337, a1655, 2008, with permission from BMJ Publishing Group Ltd.

Interventions should be developed based on the best available evidence (previous studies, stakeholder consultation and expert opinion) and based on an appropriate theory. The rationale for the intervention (i.e. what changes are expected and how that change will be achieved) should be based on that theory but may be refined by development work such as stakeholder consultations. Once an intervention is developed, feasibility work should be undertaken to obtain vital information about recruitment and retention, barriers and practical challenges, as well as further feedback on the intervention. Once feasibility is established, a full-scale definitive trial (or other appropriate design) can be undertaken. It is always important to keep in mind the implementation of the intervention at every stage of the process and consider how it could be integrated into wider health care should it prove effective. This is why it is crucial to involve key stakeholders in the development and evaluation process.

For the purposes of the RESPECT study, the MRC Framework38 stages that will be focused on are the development and feasibility/piloting stages. This chapter will describe the stage 1 development process including the theory underpinning the intervention and the process undertaken to combine evidence from previous studies as well as stakeholder consultations to finalise the content and mode of delivery (techniques). The feasibility study itself will address the second stage of the MRC framework,38 that is, assessing recruitment, retention and the acceptability of the study in order to prepare for a fully powered trial, which would assess clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness (stage 3).

To develop an intervention, it is important to consider what end point (behaviour change) it hopes to have an impact on and how intervention components can be designed with that end point in mind. It is useful at this point to reflect on what is meant by sexual health and how people assess if their sexual health is good or if they have any unmet needs in this area. The promotion of sexual health is by definition a complex intervention as it covers a range of activities and topics as well as requiring a range of intended outcomes.

Sexual health is defined by the WHO5 as not just simply the absence of disease (e.g. HIV or STIs); it is more broadly about the right to freely express one’s own sexuality and to have safe, satisfying sexual relationships, free from exploitation or discrimination:

. . . a state of physical, emotional, mental and social well-being in relation to sexuality; it is not merely the absence of disease, dysfunction or infirmity. Sexual health requires a positive and respectful approach to sexuality and sexual relationships, as well as the possibility of having pleasurable and safe sexual experiences, free of coercion, discrimination and violence. For sexual health to be attained and maintained, the sexual rights of all persons must be respected, protected and fulfilled.

WHO, 2006. 5

Theoretical model: the information–motivation–behavioural skills model of health behaviour change

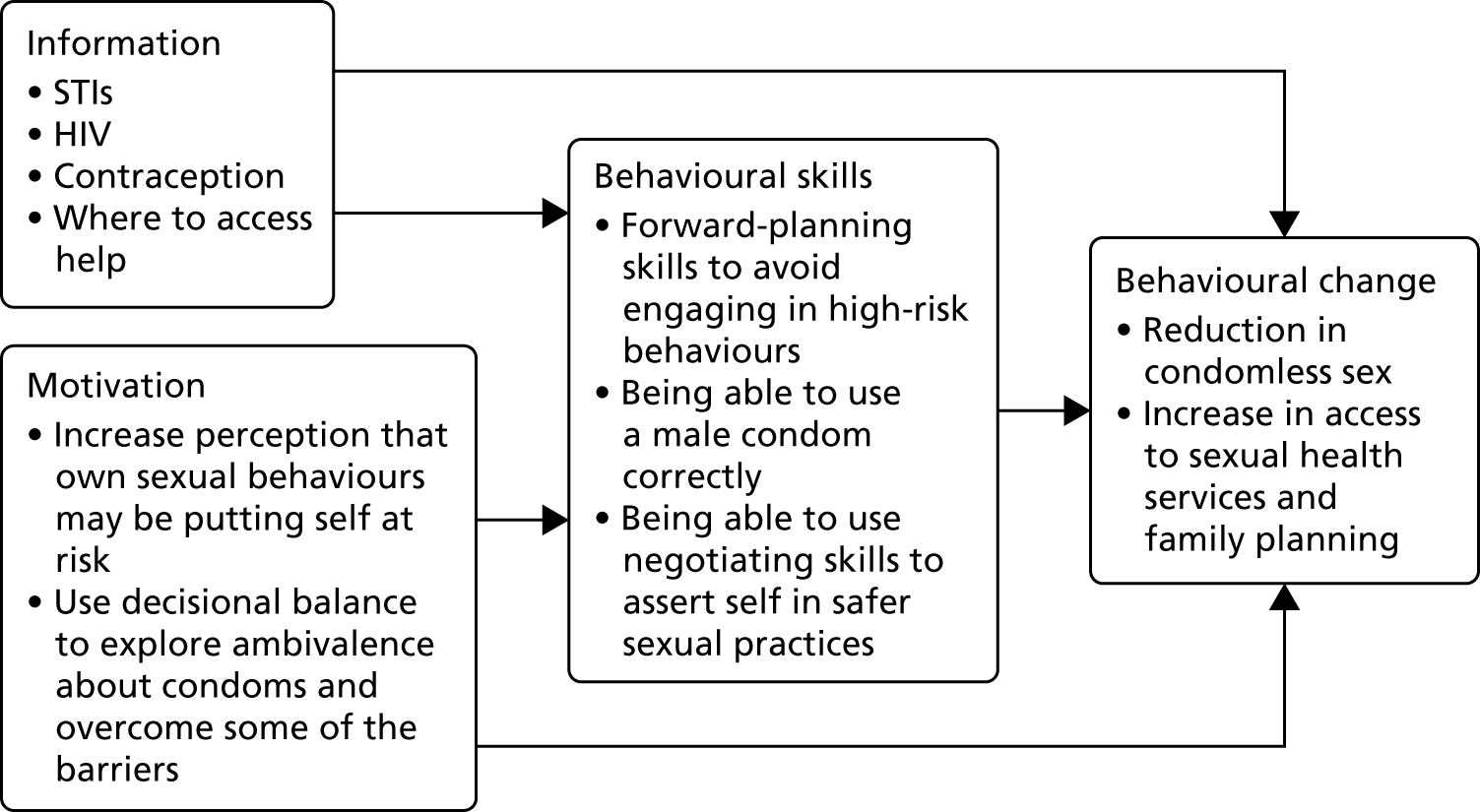

The theoretical model adopted was the information–motivation–behavioural skills (IMB) model. 39 This model has been used to inform the development of HIV prevention (and other sexual health interventions) and has demonstrated good predictive qualities with a wide range of participants including young people, MSM and people with SMI. 35

The IMB model is a social cognitive model of health behaviour change. It proposes that although information (about the impact of a particular behaviour) is important, it is not sufficient on its own to influence behaviour change. In addition, it is important that individuals can personalise the information about health risk to their own situation and adjust their cognitions to be concerned about the consequences of their behaviour for their own well-being and the well-being of others (perceptions of risk). However, there is a third and crucial step in the process of behaviour change: putting the intention into action. This requires significant behaviour and cognitive skills such as self-efficacy, communication skills (e.g. asserting oneself in negotiating for safer sex with sexual partners), belief in success and practical skills (e.g. in the case of sexual health, being able to use a condom correctly). A theoretical model should guide the developer in considering the components of an intervention and the choice of outcome measures that relate to those components.

In this model, three constructs (i.e. information, motivation and behavioural skills) are needed to engage in a specific health behaviour (Figure 2). Motivation is comprised of personal motivation (which includes beliefs about the outcome and attitudes) as well as social motivation (which is the perceived social support for engaging in a particular behaviour). According to the IMB model, behaviour change is facilitated by an increase in self-efficacy (confidence in one’s own ability to do something) through an enhancement of practical skills.

Process of intervention development

To develop the intervention, a process called intervention mapping was used. 40 This methodology identifies barriers to, facilitators of and motivators for adoption of a specific intervention derived from an analysis of the literature, as well as input from key stakeholders drawn from the given ‘at risk’ group and service providers. It provides a framework on which to base development that includes theory and stakeholder input in decision-making.

Intervention mapping consists of six stages:

-

needs assessment

-

mapping

-

selecting techniques

-

selecting intervention components

-

planning for intervention adoption

-

evaluation.

Note that as the RESPECT study is a feasibility study stages 5 and 6 will not be covered, as it was not the intention to be able to undertake widespread adoption or evaluation of effectiveness in this particular study.

Step 1: needs assessment

Chapter 1 presented the background literature related to sexual health issues for people with SMI. A needs assessment sets out the context and the target population and defines their specific needs in order to design a targeted and relevant intervention.

Context

Setting: community mental health services.

Population: people who experience SMI such as psychosis, bipolar affective disorder, schizophrenia or severe depressive disorders.

Needs: people with SMI have needs in relation to the following –

-

information about sexual health, STIs and how to prevent transmission

-

information about where to access help and advice in relation to sexual health

-

perceptions of self as at risk for STIs, HIV, unplanned pregnancy, etc.

-

behavioural skills to be able to implement intentions to engage in safer sex.

Step 2: mapping

The first step involved mapping the key elements from manualised interventions that were identified in the literature review33 in terms of behaviour change objectives and underpinning mechanisms of change and corresponding change techniques and implementation strategies. Walsh et al. 33 undertook a systematic review of interventions to promote sexual health for people with SMI. Eleven studies were identified and synthesised. All were group interventions with people who were defined as living with SMI and all took place in mental health provider settings.

-

State the expected outcomes for behaviour and environment:

-

increased use of sexual health services

-

reduced unprotected sex (increased use of contraception including condoms).

-

-

Specify performance objectives for behavioural and environmental outcomes:

-

planning skills

-

problem-solving

-

assertive communication in negotiating safer sex.

-

-

Select determinants for behavioural and environmental outcomes:

-

increased knowledge of sexual health issues

-

increased motivation to adopt safer sexual practices

-

more positive attitudes to using condoms.

-

Steps 3 and 4: selecting techniques and intervention components

Manuals from previous trials were obtained (note that an adapted version of the Susser et al. Sex, Games and Video-tapes34 manual was also used in the Berkman et al. 36 and Berkman et al. 41 RCTs) and the content was coded according to the IMB model in terms of anticipated impact on information, motivation and behavioural skills (Table 2).

| Components of the intervention | Information | Motivation | Behavioural skills | Susser et al.34 (1998) | Carey et al.35 (2004) | Rosenberg et al.42 (2010) | Wainberg et al.17 (2016) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Warm-up/introduction | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ||

| Ground rules | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ||||

| Knowledge of HIV | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ||

| Dispelling myths about HIV | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ||||

| Knowledge of STIs | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ||

| Knowledge of risk behaviours | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ||

| Rationale for condom use to keep safe | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | |||

| Pros and cons of using condoms | ✗ | ✗ | |||||

| Pros and cons of risk taking | ✗ | ||||||

| Pros and cons of HIV testing | ✗ | ✗ | |||||

| Behavioural skill: male condom | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | |||

| Behavioural skill: female condom | ✗ | ✗ | |||||

| Negotiating skills: use of condom | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | |||

| Assertive communication | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ||||

| How to eroticise using condoms | ✗ | ✗ | |||||

| Risk perception exercise (high, low, no risk) | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | |||

| Problem-solving skills | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ||||

| Avoiding/dealing with high-risk situations | ✗ | ✗ | |||||

| Goal setting and planning skills | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ |

Selecting intervention components

The components of the intervention were chosen based on components from previous manuals. This involved a small group of the RESPECT study researchers and the people with lived experience (PWLE) representatives. Pragmatic decisions were made to choose the ones that were directly related to the change objectives and were then included in a prototype manual.

After identifying the core common components of the previous interventions, a prototype outline of the suggested intervention was presented to stakeholders to aid in the discussion of what the RESPECT intervention should contain as well as what methods should be used in the intervention.

Stakeholder consultation

Several consultation meetings were held during the stage 1 phase of the RESPECT study. The aim of these events was to obtain views from a range of stakeholders in order to refine the content and mode of delivery to meet the needs of people with SMI (Table 3). In these meetings, the prototype of the intervention was provided and the discussion was then focused on how best to adapt these components to suit both the service users’ needs as well as the service setting, feasibility and the likely uptake of intervention components. Modifications based on these discussions were then made. The range of participants included:

-

people with lived experience of SMI, people who cared for people with SMI, mental health nurses, sexual health workers, drug and alcohol workers, and support workers.

| Themes | Feedback | How feedback influenced manual development |

|---|---|---|

| Who should be included? | Discussion about who the manual would be suitable for. Consensus that all people interested in taking part will be included regardless of current relationship status | Eligibility criteria were wide to include as many people as possible |

| Number and length of sessions | Original plan suggested was 6 × 30-minute sessions. Some variation in numbers suggested, and suggestion to reduce number of sessions but increase the time of them | The manual was designed to be delivered in 3 × 1-hour sessions. However, it was divided into components within the session so that there could be flexibility in delivery |

| Frequency | Frequency should be weekly to space out the intervention enough for people to absorb information and to not be too intense | The intervention was recommended to be delivered weekly but also allowed some flexibility (holidays, work commitments, etc.). We also allowed interventionists to offer less sessions but more content per session to cover the material |

| Mode of delivery |

We asked whether or not it should be over telephone or face to face: consensus was face to face Be flexible in the delivery so that people can opt-out of some sessions if felt irrelevant or if they just did not want to do them |

We changed the plan to only being delivered face to face |

| Recording intervention | Be able to record important or interesting observations from the sessions in a more systematic way so that participants’ progress can be tracked. For example, might it be useful to rate how well people do in the condom demonstration? This could be in a column next to each section in the session guide, in addition to the notes section at the end | We decided not to assess people’s skill as this was felt too threatening and stressful |

| Location of delivery |

Location? Appropriate to deliver in people’s homes? Need for privacy Factors in who can be present (e.g. family or a partner) |

We offered the choice of location dependent on participant preference. We advised the interventionists to check out the privacy or otherwise of the home visit (being mindful of other people being present, or children, etc. Advised to use a clinic room if that was an issue) |

| Modifications for the SMI population | Provide intervention sequentially and offer a recap at the start of the next session and at the end; promote cohesiveness between the sessions to help learning and retention | Incorporated introduction and recap into each session |

| Training for interventionists | Sexual health services involved to deliver awareness training | We included a sexual health practitioner in the development of the manual and also attendance at the initial intervention training event |

| Qualities of interventionists | It was deemed important that the person delivering the intervention should be aware of all types of sexual behaviour and sexual relationship and to be non-judgemental, be able to build rapport at the start of the intervention and avoid jargon | We incorporated this into the interventionist training |

| Safety and confidentiality | There was a need for the boundaries of confidentiality in the intervention to be clarified and also for the interventionists to understand what to do regarding disclosures that related to safeguarding | This was attended to in the training and the interventionists were advised that in the first instance as employees of the NHS service that they follow NHS trust processes first (especially if the issue was urgent) and then inform their local research and development department or the RESPECT study researcher |

| Information on STIs and HIV | There would need to be some content related to increasing the awareness of and knowledge about various STIs and HIV | The decision was made to include quizzes on the transmission of both STIs and HIV |

| Contraception |

Make sure that there is discussion of other forms of contraception The nurses delivering the intervention should be aware of how certain forms of contraception can affect those with diabetes and are contraindicated for people on some antipsychotic medication because of the associated risk It was felt that use of female condoms should be demonstrated Need for demonstration of female condoms, preferably with model vagina |

A section on the whole range of contraceptives was included: ‘what’s in the bag’ We did not include any input on sexual dysfunction as the HTA commissioning brief was specifically to exclude sexual dysfunction We did not include a specific component on female condom use (because they are not commonly used and they are expensive). However, we did advise people to seek advice regarding female condom use from local family planning services |

| Condoms |

There was a consensus that the person demonstrating how to put on a condom should not hold the condom demonstrator between their legs There should be more emphasis on the importance of getting the condom on the right way round. Discuss more explicitly about what it should look like. If it’s on right it looks like a Mexican hat or bobble hat. Discuss what should be done if you put it on the wrong way round (i.e. throw it away). If you notice it is difficult to roll down it is probably on the wrong way Using other forms of contraception other than condoms. Without acknowledging this the intervention could be taken as suggesting that you will have to use condoms for the rest of your life. This is both demoralising and could stigmatise mental health service users by denying them the usual progression of a relationship that others experience Gel charging should be included in the condom use section. This is when a pea-sized amount of lubricant is placed in the tip of the condom before putting it on. Not too much though as this will make it slip off. This is helpful for men who say they do not like the feel of condoms Warnings about fingernails and rings ripping the condoms should be included in the intervention |

Condom demonstrator not to be held between legs Specific advice regarding getting the condom the right way round was included in a script and the interventionists all practised putting a condom on and off as part of the training We incorporated gel charging and also gave out some condoms and lubricant gel sachets to participants in the intervention We covered all forms of contraception |

| Assertiveness skills | Generally in this assertiveness section there needs to be some flexibility over the thing being negotiated depending on the individual participant’s circumstances. Suggest role play within sessions as a good way of building confidence | We used discussion exercises and a role play if the person was comfortable doing so |

| Relationships |

There was a discussion over the use of the word ‘friend’ in the relationship game and it was suggested to change it to ‘friend or partner’ There should be a section dedicated to how relationships progress |

We used ‘friend’ at the request of our patient and public involvement group We did not include a section on ‘how relationships progress’ as it was felt that this could be drifting away from a sexual health focus |

| Range of sexual practices | There should be more information about the alternatives to penetrative sex. This is helpful for the times when a condom is not available and also for building confidence to explore sexuality | There is an exercise (traffic lights) in which alternatives to penetrative sex are discussed |

| Local information and signposting | Information be supplied regarding sexual health clinics as an external resource | All participants received a localised advice sheet regarding services for sexual health, intimate partner violence and family planning |

At each event, notes were taken of the discussion and passed to the chief investigator. A simple thematic framework was developed based on the content of the discussions.

Table 3 summarises the range of issues discussed in the stakeholder events and the response to these issues in the intervention development. The overall responses were positive and feedback from each discussion was used to modify the intervention procedures and information packs.

In summary, there was significant overlap in the content identified from a thematic analysis of the previous study intervention manuals (see Table 2) and the content suggested in the stakeholder and PWLE discussions. The addition was the suggestion of the inclusion of contraception more broadly than just a focus on condoms. In addition, people generally felt that the tone of the intervention should be positive and focusing on ‘health’, ‘being safer’ and having ‘positive intimate relationships’.

Two main behavioural changes were anticipated for the intervention: a reduction in condomless sex and an increase in access to sexual health and family planning services. Stakeholder feedback had been clear that they wanted a broader view of sexual health that included contraception within a monogamous relationship and that they wanted the content to reflect the positive aspects of intimate relationships.

The intervention content has been aligned with the IMB model (Figure 3). To achieve those behavioural outcomes, it is postulated that the person requires knowledge of HIV and STIs, as well as the range of contraception available (and what services are available locally). As well as having that information, increasing perceptions of self as potentially at risk is important. In the IMB model, information and motivation to adopt safer sexual practices is mediated by behavioural skills. In the intervention, key skills were included and were demonstrated by the interventionist and then the person was invited to try it out for themselves. There were also exercises in developing problem-solving skills and planning skills, which are important for supporting self-efficacy for new behavioural strategies.

FIGURE 3.

Content of the intervention mapped on to the IMB model.

The outcome measures chosen for the study related to the components of the model:

-

information – measured with the knowledge about HIV questionnaire (HIV-KQ)

-

motivation – measured with the ‘motivations to engage in safer sex’ scale

-

behaviour – measured with the Sexual Risk Behaviour Assessment Schedule (SERBAS), self-reported condomless sex acts, the Behavioural Intentions for Safer Sex measure and the Condom Use Self-Efficacy Scale (see Chapter 3 for more information about the measures).

Training for intervention delivery

At each site, mental health staff were identified to deliver the intervention and were invited to attend a 2-day training event. The criteria for inclusion in the training were:

-

experience of delivering clinical care to people with SMI

-

availability to be able to deliver the intervention during the specified study period.

The training took place over 2 consecutive working days. It covered the rationale, aims and design of the study eligibility and data collection, the background literature regarding sexual health in mental health and the evidence from previous studies. The rest of the training was focused on familiarising the staff with the content of the intervention and providing an opportunity to practise the delivery. Each component was explained in terms of why it was there and what purpose it served, and there was an accompanying script within the manual to promote consistency of delivery. In the training the interventionists were able to complete each exercise as a participant would and then discuss the outcomes. The trainees were also informed of the intervention monitoring paperwork that would be required to be completed by them.

Intervention: frequency and length of session

Timing: there were three intervention sessions each lasting 60 minutes or these could be delivered in two (longer) sessions.

Location: the intervention was delivered at the local clinical service where the person usually attended or at home.

Interventionist: the intervention was delivered by a mental health worker from the same service (as the service user) who had received the bespoke RESPECT intervention training.

Monitoring: a checklist was completed at every session by the interventionist for each component of that session. All interventionists were able to access advice at any time from the RESPECT intervention team during the delivery phase by telephone or e-mail.

There are three main areas to focus on in the intervention based on the needs assessment: (1) knowledge and perception of risk (session 1); (2) ways to keep safe, focusing on safe condom use as well as a whole range of contraceptive choices and where to seek advice and help (session 2); and (3) negotiating safer sex in relationships including communication skills and focus on ‘mutual respect’ (session 3). The person will be encouraged to develop their own ‘action plan’ based on the needs and goals identified, which (with permission) will be shared with the care co-ordinator to incorporate into their overall care plan.

Outline of intervention

The intervention manual can be seen on the National Institute for Health Research journals library website.

Session 1: knowledge of human immunodeficiency virus, sexually transmitted infections and safer sex

The first part of session 1 involved introducing the intervention and building a rapport. This is always a requirement for any new intervention, but especially so when discussing a potentially sensitive topic. Interventionists were advised to spend a bit of time on this, getting to know the person first; a suggested ice-breaker was to ask why the person had been interested in taking part in the study. In addition to this, some ground rules were discussed including:

The interventionist promises that –

-

I will be non-judgemental

-

I will listen

-

if I do not know something, I will find out and let you know

and

-

there is no such thing as a ‘stupid question’

-

if anything at all concerns you, flag it up and we can stop and discuss

-

none of the activities are compulsory

-

talk about the boundaries of confidentiality – everything discussed during the intervention is completely confidential (except the disclosure of risk to self/others).

Information giving about sexual health

In some of the previous group interventions,34,35 the information had been imparted using didactic methods as well as interactive exercises. It was felt by PWLE that a didactic approach would be too intensive for an individually delivered intervention, so a set of quizzes was developed to be used to help establish what is already known and where any knowledge gaps exist. The interventionist allowed time to complete the quizzes and then went through the responses, and addressed the items that were incorrect. In terms of introducing the quiz it was really important to make it clear that most people in the general population have things to learn about sexual health and that it is OK not to get it all correct.

Correct use of the male condom

After the knowledge quizzes, the interventionist picked up on a specific item from one of the quizzes (‘using condoms always prevents pregnancy’) and linked this to the fact that condoms can fail if used incorrectly. The next section focused on the correct use of condoms and (if the person agrees) the interventionist runs through a (scripted) description and physical demonstration of how to correctly put on and off a condom using a plastic condom demonstrator. Session 2 went into condom use in more detail, but it was felt that if there was poor attendance at the subsequent sessions then having the condom demonstration in session 1 would ensure that all participants received this.

Types of contraception

The final part of session 1 was a general discussion of contraception using ‘what’s in the bag’, which was a bag containing information and photos of all the variants of contraception available. They were grouped as barrier, non-hormonal and hormonal. At the end of the session the next appointment was arranged.

Session 2: keeping safe – focus on the role of condoms and contraception choices

Session 2 started with a recap of session 1, and the participants were asked to recall anything they had remembered or had been thought-provoking from session 1. After that was discussed, the session 2 content was introduced. The aim of session 2 was to increase the motivation to adopt safer sexual practices by becoming aware of different levels of risk posed by a range of sexual practices. This was delivered by an exercise that involved three coloured circles: red was high risk, yellow was some (low) risk and green was no risk. The participant was given a set of sexual acts and they had to sort them by placing them on the correct circle. Any errors were then discussed. This exercise was designed to reinforce understanding of the behaviours that are high risk and that the person should consider using protection (e.g. a condom) if their or their partner’s sexual health status is unknown. In addition, the lists of behaviours that carry no risk were then reinforced as options for sexual expression if there are no condoms available. The second aim of session 2 was to explore motivation to use condoms by addressing some of the perceived barriers to use of and some of the myths about condoms in the hope that the participant would become more motivated to use them. This was undertaken by a discussion of the less good things about condoms followed by the good things about using condoms. Following this, there was an exercise on identifying ‘triggers for unsafe sex’ using two scenarios. The participant then brainstormed possible options and solutions for each scenario about how to adopt safer sex in the future. This was followed by a practical exercise in which the person was offered the chance to demonstrate the correct use of a condom using a plastic demonstrator.

Session 3: the RESPECT intervention – relationships and communication

The final session focused on relationships: feeling safe in those relationships and having control and choice in those relationships. The first exercise was for participants to sort a set of cards that had statements on them about feelings, behaviours and experiences in relationships and whether they were compatible with a ‘good relationship’ or a ‘bad relationship’. This aimed to increase the awareness of power dynamics in relationships and link it to autonomy and choice about sex in that relationship. This exercise then links to sexual behaviour and being able to be assertive in a relationship. Assertive communication was discussed and then practised with the interventionist. There was an exercise using scenarios and the participant was asked to think about assertive responses to the situation when a partner does not want to use a condom. Finally, there was an exercise that aims to bring the strands of the intervention together in a planning and goal-setting exercise. At the end of the session the participant and the interventionist recap on the three sessions and, if the person is in agreement, design an action plan for any outstanding needs that they would like to address (such as access to contraception). This plan was shared with their care co-ordinator but only with signed consent.

Chapter 3 Feasibility trial

Trial design

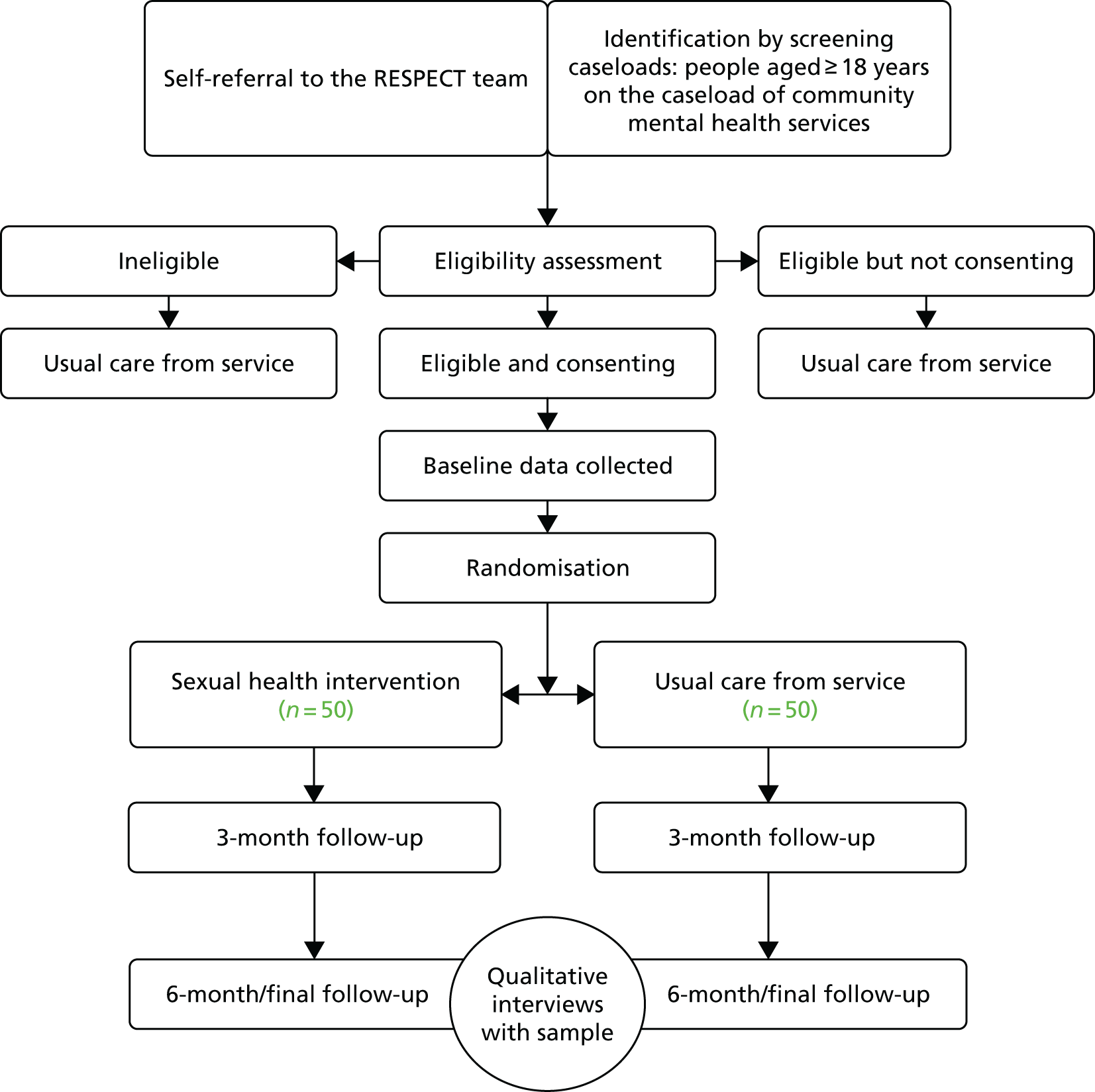

We conducted a pragmatic, multicentred, open feasibility RCT. Participants meeting the eligibility criteria were individually randomised (1 : 1) to receive one of the following:

-

The control arm – treatment as usual (TAU), which consisted of usual mental health care. All participants were free to pursue reproductive health and sexual health services via general services in their local area.

-

The intervention arm – in addition to TAU, participants were invited to participate in a manualised intervention designed to promote sexual health, which was delivered in the NHS service where the person usually attended (or at their home) in three sessions of 1 hour, on a one-to-one basis, by a suitably experienced mental health worker employed by the NHS trust and who had received the specific training.

All participants received written information on local sexual health services, contraceptive services and national helplines at the baseline appointment irrespective of the arm to which they were allocated.

The study summary can be seen in Figure 10 (see Appendix 1).

Sample size

The sample size calculations were based on estimating the attrition rates and SD of the primary outcome. Assuming that 30% of participants were lost to follow-up (as in the SCIMITAR trial43) with a sample size of 100, then the 95% confidence interval for this level of attrition would be the observed difference ± 9 percentage points (i.e. between 21% and 39%44). Hence, an external pilot trial of 100 participants would ensure robust estimates of follow-up in this population. Furthermore, an external feasibility study of at least 70 measured subjects provides robust estimates of the SD of the outcome measure to inform the sample size calculation for the subsequent larger definitive fully powered trial. 45

Approvals obtained

This study was approved by the NHS East Midlands – Derby Research Ethics Committee (REC) on 30 September 2016 (reference number 16/EM/0334) and Health Research Authority (HRA) approval was obtained on 10 November 2016. Confirmation of capacity and capability was sought for each trial centre thereafter. This trial was assigned the number ISRCTN15747739.

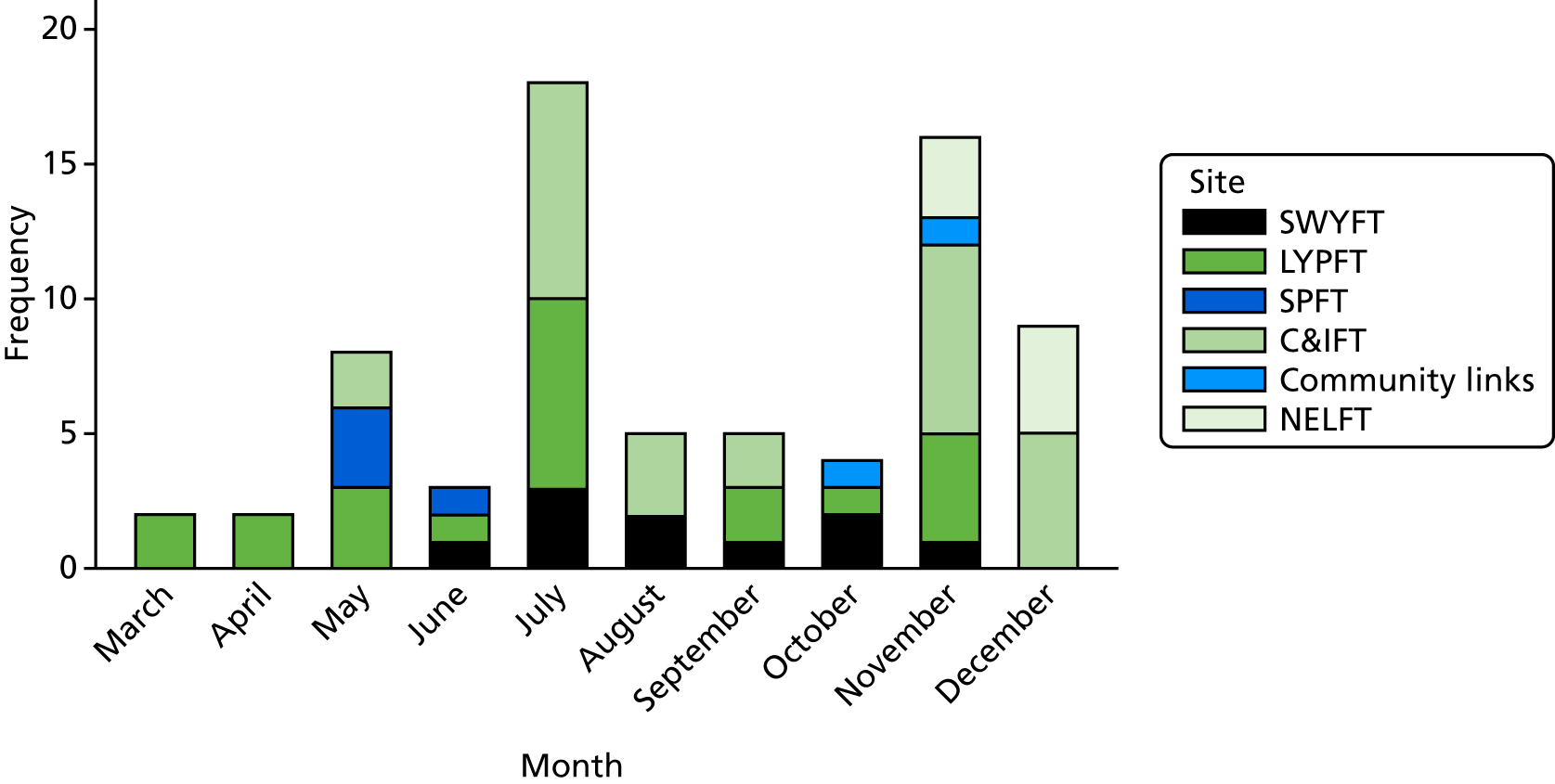

Trial centres

Initially four (later five) NHS trusts were selected as trial sites in four UK cities across England: Leeds and York Partnership NHS Foundation Trust (LYPFT); Community Links – aspire service for Early Intervention Psychosis in Leeds [a third-sector provider of the NHS contract and part of LYPFT research and development (R&D) provision]; South West Yorkshire Partnership NHS Foundation Trust (SWYFT) (Barnsley only); Sussex Partnership NHS Foundation Trust (SPFT) (Brighton only); Camden and Islington NHS Foundation Trust (C&IFT); and North East London NHS Foundation Trust (NELFT).

Patient and public involvement in the feasibility trial

People with lived experience were integral to all stages of this study (design, development and training for the intervention, decisions about outcome measures, recruitment, analysis and dissemination). There was PWLE representation in the Trial Management Group. Four experienced researchers and trainers with ‘lived experience’ of mental health service use acted as the patient and public involvement advisory group. Specific meetings were convened to review the battery of outcome measures and how to collect the data with participant comfort in mind. The PWLE and researchers have delivered presentations on the study at the Leeds R&D conference. There were also meetings to discuss the methods of engaging potential participants in the study. The information sheet was written by one of the PWLE. The PWLE were also involved in undertaking the qualitative interviews for participants to discuss the experience of being in the study, focusing on acceptability and feasibility aspects. They have been involved in the analysis as well as the report.

Additionally, the research team engaged the NHS service users from each site in focus groups alongside other stakeholders, such as clinicians for the development of the intervention.

Recruitment

Participant eligibility

Inclusion criteria

The following people were eligible for inclusion in the trial:

-

those on the caseload of selected community mental health services in each NHS site

-

those diagnosed with a ‘severe mental illness’ (defined as schizophrenia, other psychosis, bipolar affective disorder, schizoaffective disorder or major depressive disorder)

-

those aged ≥ 18 years

-

those willing to provide written informed consent

-

those able to provide written informed consent.

Exclusion criteria

Potential participants were excluded if they were identified as:

-

having an acute exacerbation of their mental illness that precludes them from active participation (as indicated by hospitalisation and/or being under the crisis/home treatment team at the time of consenting)

-

having a case note diagnosis that did not meet the criteria of SMI (see Inclusion criteria)

-

having a severe physical illness that precludes them from active participation

-

having a significant cognitive impairment (e.g. an organic brain disorder) as determined by case notes

-

being a non-English speaker (adapting the intervention is currently beyond the scope of this study)

-

lacking capacity to consent (as guided by the Mental Capacity Act 200546)

-

being unable or unwilling to give written informed consent

-

being on the Sex Offenders Register, or having a history of inappropriate sexual behaviour.

All case managers in the selected community mental health teams (CMHTs) were informed of the inclusion and exclusion criteria, and were contacted regarding potential participants to check that there were no areas for concern regarding researcher safety (e.g. on home visits) prior to entry into the study.

Recruitment into the trial

Potentially eligible participants were identified using three main methods: screening of caseloads for potentially eligible people, direct approach by research staff in clinic waiting rooms and self-referral (via study e-mail, telephone or via an online form on the study website). The details for self-referral were provided on all participant-facing materials such as the posters and leaflets.

Caseload screening and eligibility assessment process

Local researchers [known as Clinical Studies Officers (CSOs)] employed by the CRN based in each site’s R&D office worked with the trust’s clinical staff to promote the study and undertake caseload screening for potentially eligible participants using the eligibility criteria. Screening was undertaken in two main ways. The initial approach was to visit CMHTs and talk through each individual case manager’s caseload with them, creating a list of people for the case manager to informally approach. They were given one study information pack for every person identified. The second method was the CSO staff screening caseloads via the electronic records system and then verifying the list with case managers. Once a member of the team had verified that it was appropriate to make an approach, the CSO sent out a study information pack with a letter signed from their case manager or the team manager.

Participant-facing information and study information pack

A simple leaflet and poster introducing the study were developed and distributed widely in each study site. In addition, potentially eligible people received a ‘pack’ (either face to face or by post). The information pack included an invitation letter, a participant information sheet (PIS), a consent to contact (CtoC) form and a baseline feedback questionnaire.

Completed CtoC forms were returned (by fax scanned, by hard copy or verbally) to the CSO research team at each NHS site. Once a CtoC form was received by post at the York Trials Unit, the details were passed to the relevant RESPECT study researcher: either one in the north of England (based at the University of Huddersfield) or one in the south of England (based at University College London).

Self-referral

The participant-facing materials were all designed to offer an option of self-referral to the study. The study posters and leaflets about the study contained a Quick Response code (QR code) and website address to the project website. This website was designed to provide information about the study for staff and potential participants, as well as other interested parties. The posters and leaflets provided a brief description of the study and methods for contacting the RESPECT study research team directly. Local CRN staff and RESPECT study researchers attended various service user groups/events (e.g. recovery colleges, creative groups and clinics) to give out leaflets. At those events, CtoC (by a researcher) was obtained verbally or with the CtoC form. This method of recruitment was utilised to ensure that all potentially eligible participants had the opportunity to take part. The method of recruitment was recorded to inform the most effective recruitment strategies for the main trial. A study e-mail address was set up specifically to manage enquiries regarding the study that was managed by the RESPECT study research team. By contacting the RESPECT study research team directly, it was assumed that the potential participant had implicitly agreed to contact by the research team and, therefore, a CtoC form was not required. However, a record of the contact and any contact information was recorded by the research team.

Once a self-referral had been received, one of the research team made contact by e-mail or telephone to determine interest and eligibility, and to answer any initial queries and concerns that the potential participant had about participating. If they were interested in pursuing involvement, they were sent a study information pack (information sheet and consent form). They were also informed verbally that the researcher would be in touch with their local NHS service R&D team to inform them of the person’s interest, and that their case manager would also be contacted by the CSO in the R&D team to check the person’s eligibility for the study. The RESPECT researchers confirmed that no information would be shared other than their expression of interest in taking part, and the fact that they had self-referred to the research team. In addition, no clinical information would be shared from the NHS back to the RESPECT study team other than whether or not the potential participant met the eligibility criteria.

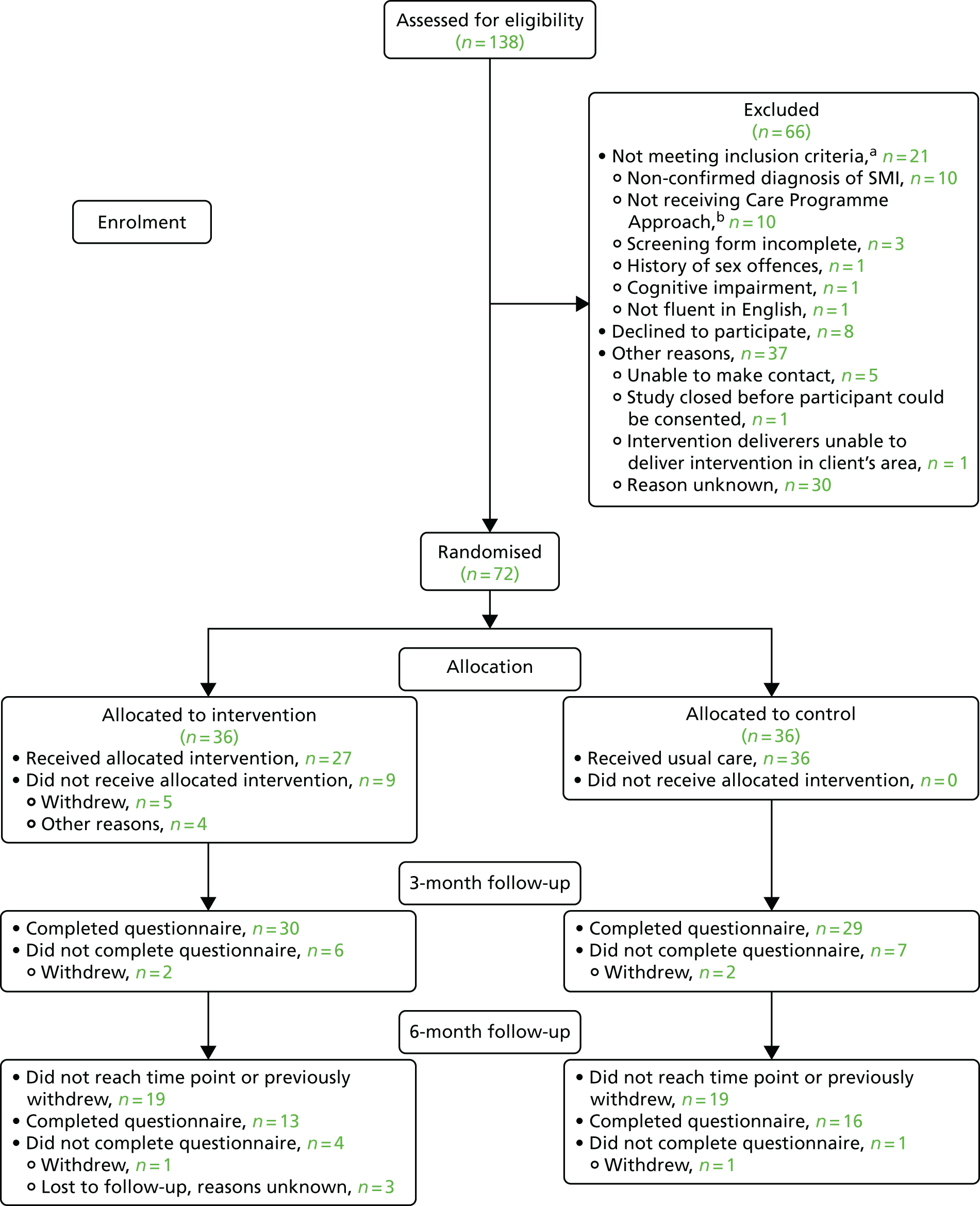

Flow of participants from identification to entry into study

The numbers of people who were screened, eligible and had consented to participate were recorded when possible. Eligible patients who did not wish to take part (i.e. were unwilling to give consent) and those found to be ineligible went on to receive usual care from the service without prejudice.

As the primary objective of this trial was feasibility, reasons for participation and non-participation were collected by various means to inform future studies. Clinicians handed out feedback forms to those with whom they discussed the study. Service users who received a study information pack by post were contacted by CSOs by telephone 2 weeks later to discuss the information and gauge if there was any interest in participating or not. The feedback form was completed over the telephone for both potential participants and for those who declined to pursue this.

Informed consent and baseline assessment

After eligibility was confirmed by the NHS Trust, a RESPECT study researcher arranged a convenient time and venue to meet with the potential participant. At this meeting, the RESPECT study researcher explained the study in full and gave the potential participant an opportunity to ask any questions. Participants were assured of confidentiality regarding the information that they provided as part of the research, advised about the boundaries of confidentiality (i.e. under what circumstances that would have to be breached), told what to expect after the study ceases, and given contact details in the event of a complaint or the need for further information. They were also given a localised information sheet with local sexual health services and contact details. They were informed that participation is not compulsory and that they could withdraw from the intervention and/or data collection at any time without affecting their care. Written informed consent was then obtained, and (if convenient for the participant) baseline data were collected at this appointment (see Report Supplementary Material 1).

When the questionnaires had been completed, the RESPECT study researcher then contacted the independent randomisation service at York Trials Unit by telephone, and the person was randomised independently to either intervention as an adjunct to TAU or TAU. The participant was then informed of their allocation face to face. If it was not possible to access the randomisation line at that time, randomisation was completed later and the participant was then informed by telephone.

Participant follow-up

The original plan was that all participants in the RESPECT study would be followed up with a repeat of the questionnaires/interview at 3 months and 6 months post randomisation (see Report Supplementary Material 2). However, as a result of requiring an extension to the recruitment period, and balancing the need to complete the study within a new time frame, an agreement was reached between the research team and the funder to only collect 3-month data on any participants who entered the trial after October 2017 and for all recruitment to be completed by 31 December 2017. This allowed for all the follow-up data collection to be completed by 31 March 2018.

Outcomes

The main outcome of the RESPECT study was to establish the feasibility and acceptability of an evidence-based intervention to promote sexual health, and to establish key parameters to inform a future main trial. In conjunction with the qualitative study, this was to be established by measuring recruitment rates, retention rates and follow-up completion rates.

Secondary outcome assessment

The following outcome measures were collected at baseline, 3 months and (for some participants) 6 months post randomisation:

-

SERBAS34 – a validated HIV risk behaviour measure that was developed in the USA and has been validated for use with populations who have SMI. It gathers information on sexual activity in the last 3 months and records frequency of high-risk behaviours (for HIV infection), such as intercourse without a condom, sexual activity under the influence of drugs and alcohol, and sex work/sex trading. It takes into account sexuality and gender in the schedule.

-

The National Survey of Sexual Attitudes and Lifestyle (Natsal) – we have included specific items that cover broader aspects of sexual health including contraception use, STI and HIV tests, and knowledge on family planning advice.

-

HIV-KQ35 – a 17-item measure that assesses knowledge about HIV. (This originally comprised 18 items but we removed one question about lamb-skin condoms as this is now outdated.)

-

Motivations to Engage in Safer Sex35 – a four-item scale to assess people’s own perception of their risk of infection with a STI.

-

Condom Use Self-Efficacy Scale35 – an 18-item Likert scale to assess attitudes towards the use of condoms as well as questions on self-efficacy in the use and negotiation of use.

-

Behavioural Intentions for Safer Sex35 – a six-item measure in which patients are presented with a scenario describing a possible sexual encounter and asked to rate how likely it was that they would engage in six risky or protective behaviours (e.g. ‘I will tell the person I don’t want to have sex without a condom’). Patients responded to each behaviour using a six-point scale (ranging from 0 ‘definitely will not do’ to 5 ‘definitely will do’).

-

MISS-Q17 – a 32-item tool that has been developed and validated to measure a person’s perceived stigma as a result of their mental health problem and its impact on perceptions of attractiveness and opportunities for intimate relationships.

-

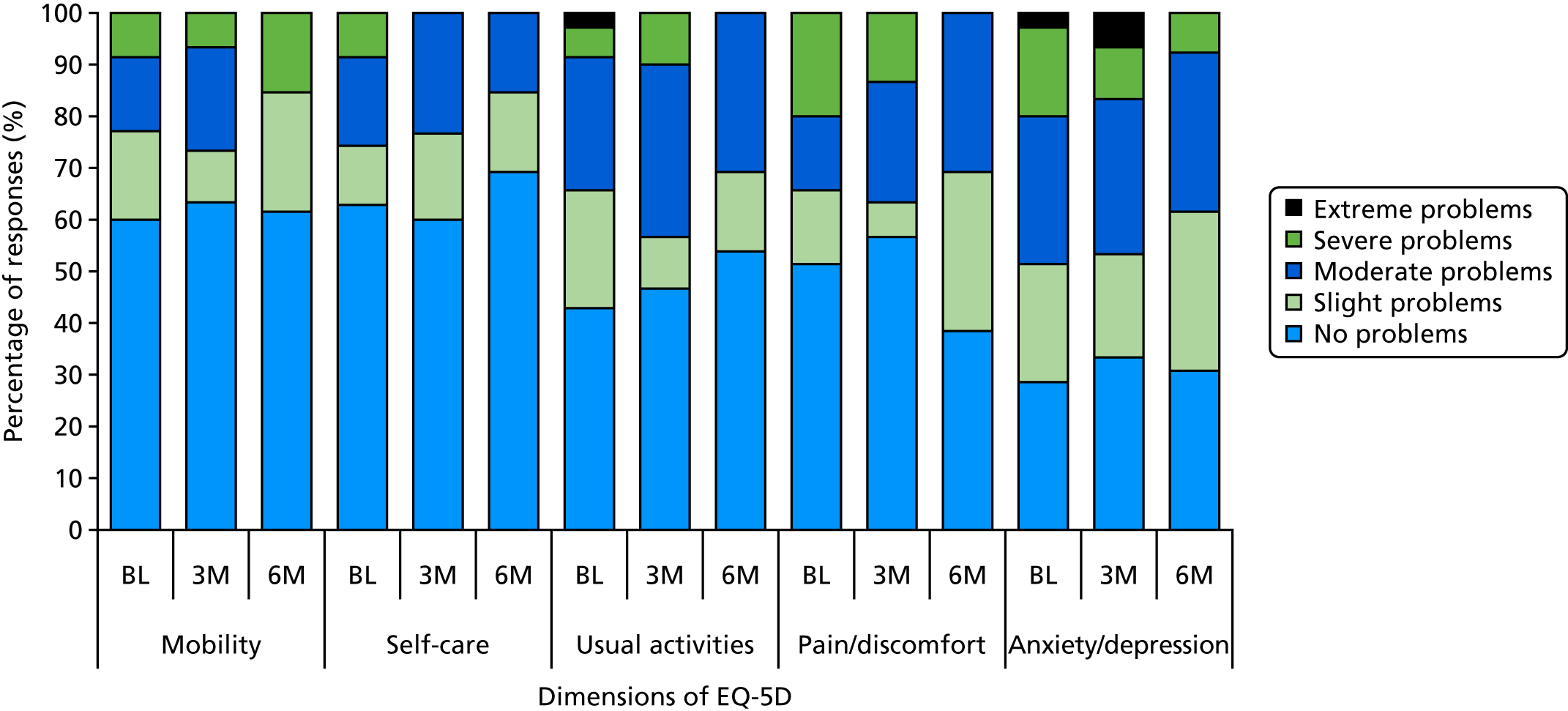

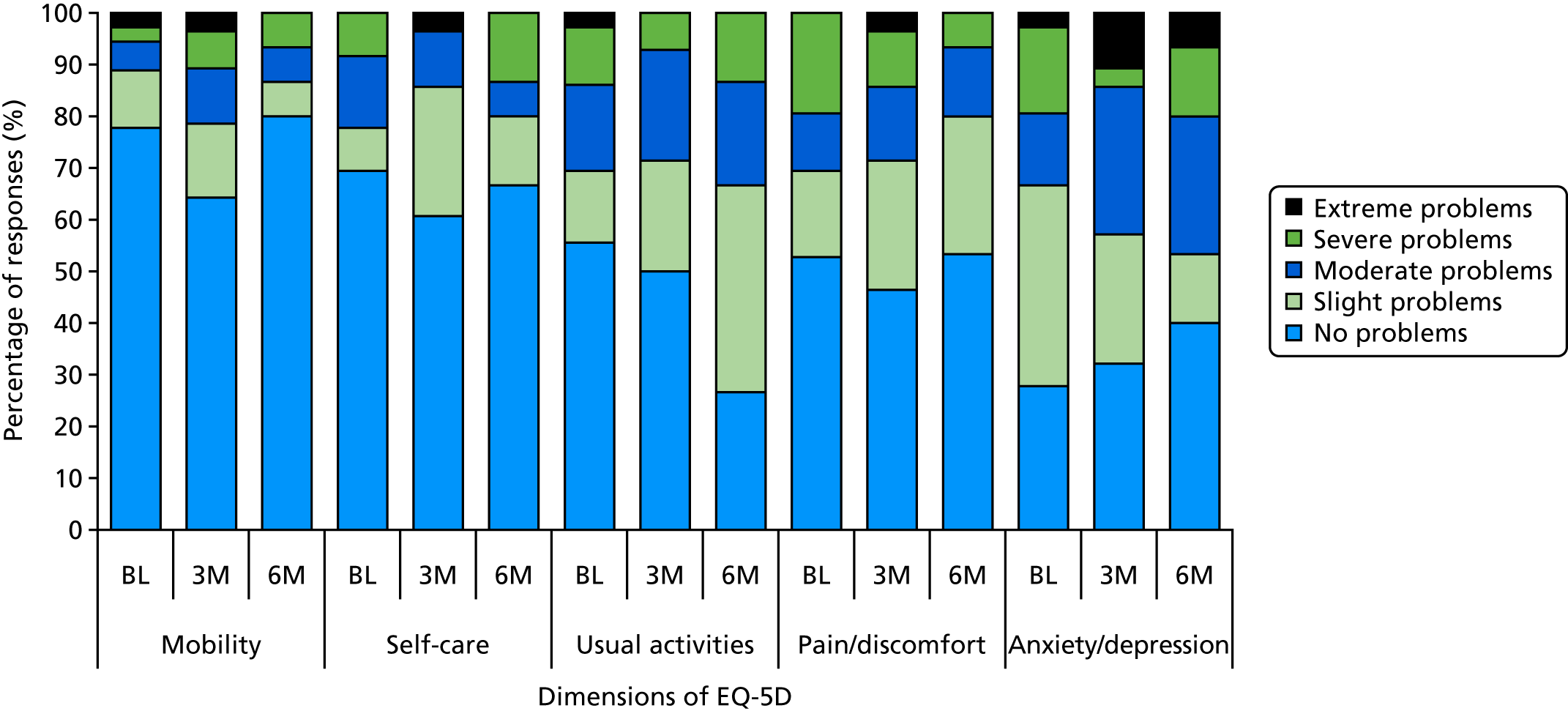

EQ-5D-5L (EuroQol-5 Dimensions, five-level version) – a standardised instrument for use as a measure of health outcome that is applicable to a wide range of health conditions and treatments (https://euroqol.org; accessed 5 September 2019).

-

The Alcohol, Smoking and Substance Involvement Screening Test (ASSIST)47 – developed for the WHO by an international group of substance abuse researchers to detect and manage substance use and related problems in primary and general medical care settings.

-

Recovering Quality of Life (ReQoL)48 – a new 20-item patient-reported outcome measure that has been developed to assess the quality of life for people with different mental health conditions.

-

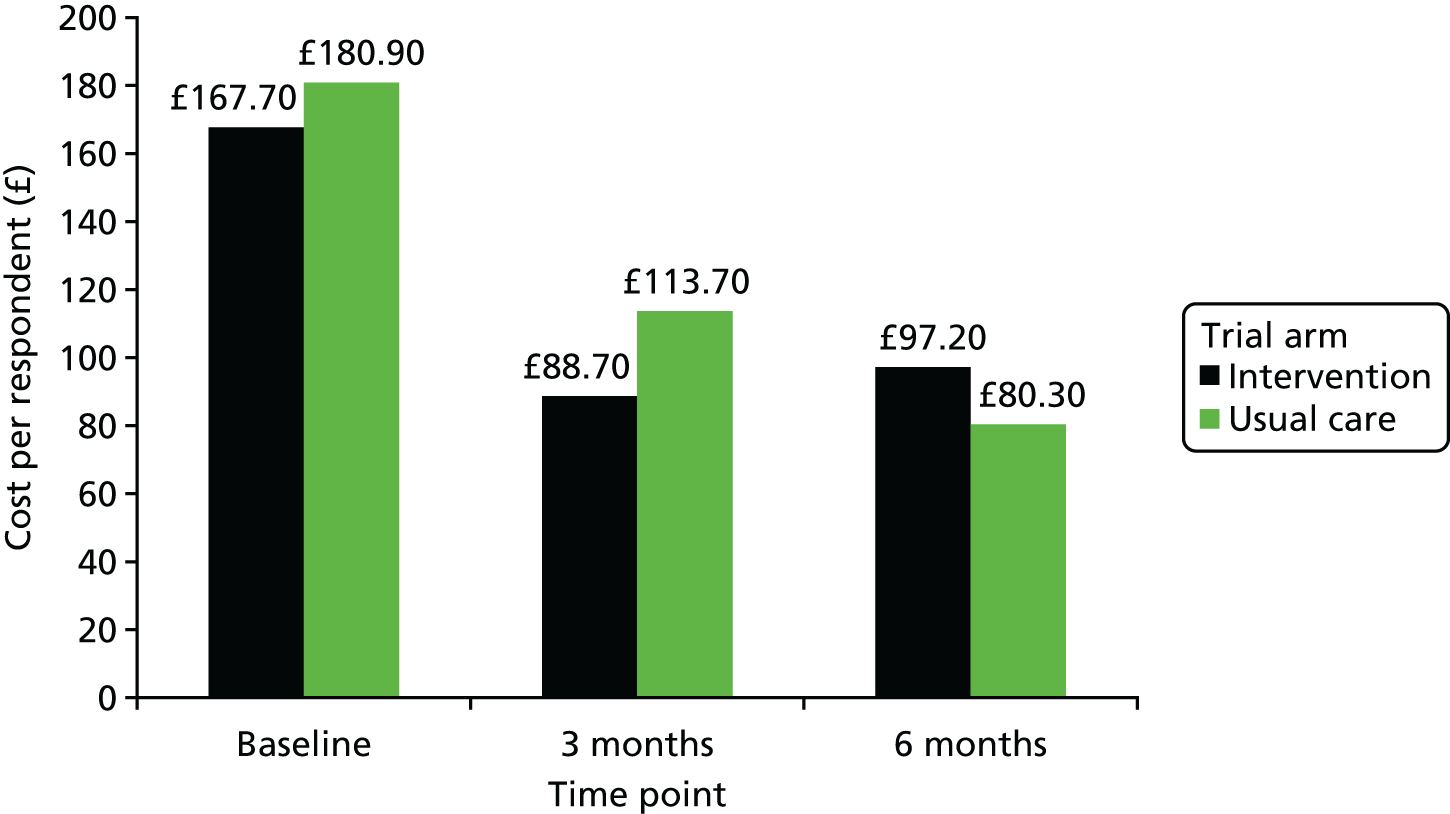

Cost assessment – commonly used generic instruments to measure health-related quality of life (e.g. EQ-5D-5L) will be used and assessed for completion rates at various time points and for patterns of missing data. Sensitivity of generic instruments will be evaluated against sexual health-specific clinical outcomes. A bespoke resource use questionnaire has been designed and piloted in the target population and responses will be evaluated to identify the key cost drivers (incorporated into participant-completed questionnaires; see Report Supplementary Material 1).

Randomisation

Randomisation was performed by a secure, remote, telephone randomisation service based at York Trials Unit. An independent statistician at the University of York undertook the generation of the randomisation sequence. Randomisation was on a 1 : 1 basis using stratified block randomisation with stratification by centre and variable block sizes. Periodic checks were made on the computerised randomisation system during the trial following standard operating procedures. Baseline data were collected prior to randomisation; therefore, treatment allocation was concealed at this point. Owing to the nature of the intervention, it was not possible to conceal treatment allocation from the participant or the professional delivering the intervention.

Trial interventions

Participants were randomised to receive either:

-

TAU or

-

the RESPECT intervention, as an adjunct to TAU.

Once randomised, participants were informed of their allocation at the face-to-face baseline interview, or by telephone shortly afterwards (the researchers did not always have access to a private telephone line at the time of data collection).

Intervention arm

In addition to usual care, people who were randomised to receive the intervention were offered three 1-hour sessions of a manualised intervention. This was delivered by a specifically trained mental health worker based in the NHS sites (specific training was provided by the RESPECT study team) and was supported by a specifically devised manual and intervention pack. The sessions were delivered in a private room at the local clinical service or at their home. The intervention was delivered as soon as possible following randomisation and before the 3-month follow-up point. The intervention is described in more detail in Chapter 2.

Control arm

Participants randomised to receive TAU continued to receive their usual care. The TAU for sexual health (including contraception) included their local primary care and/or specialist sexual health services. All participants, irrespective of allocation, received a leaflet listing the local sexual health, family planning and domestic abuse services relevant to their local area, and some condoms at the point of baseline data collection.

The participants’ general practitioners (GPs) were sent a letter informing them that the named person was taking part in the trial and also notifying them of the arm of the trial to which they had been allocated. The RESPECT study information leaflets and sheets contained a link to the study website that also contained links to national helplines and resources related to sexual health and relationships (www.respectstudy.co.uk; accessed 5 September 2019).

Trial completion and exit

Participants were considered to have exited the trial when they:

-

withdrew consent

-

had been withdrawn by an interventionist/researcher for reasons of risk or harm to self and/or others

-

had reached the end of the trial

-

died.

Withdrawals

Withdrawals were possible at any point during the study at the request of the participant. When a participant expressed that he or she wished to withdraw from the study, a researcher would speak to them to clarify their level of withdrawal (i.e. to confirm withdrawal from the intervention only, from follow-up only, or from all aspects of the study). If the participant requested to be withdrawn from the intervention only, follow-up data continued to be collected. All data were retained for all participants until the date of withdrawal unless a participant specifically requested that these be destroyed.

A participant could also be withdrawn without their consent from the intervention and/or the trial for reasons of risk or harm to self and/or others. This was actioned only when there was evidence of serious and significant risk. In these instances, the risk protocol (see Report Supplementary Material 3) guided the interventionist and/or researcher to the appropriate action to be taken in conjunction with the lead research clinician and the duty worker in the organisation.

Adverse events

General clinical decisions remained the responsibility of the participant’s care team, and participation in the study had no bearing on this process. When participants sought an opinion on their care/medication from a member of the RESPECT study team, they were strongly advised to seek advice from a member of their clinical team.

During the study, adverse events (AEs) were monitored and, at each data collection point, the participants were asked if anything significant had happened to them with regards to their mental well-being (such as psychiatric admission or an escalation of the level of care needing input from the crisis team). A study-specific AE protocol described the process by which a potential AE would be notified and assessed before being passed to the Data Monitoring and Ethics Committee (DMEC).

Adverse events were monitored by an independent DMEC and the Trial Steering Committee (TSC). The DMEC/TSC would be immediately notified and asked to review any reported serious adverse events (SAEs) that were deemed to be study and/or intervention related.

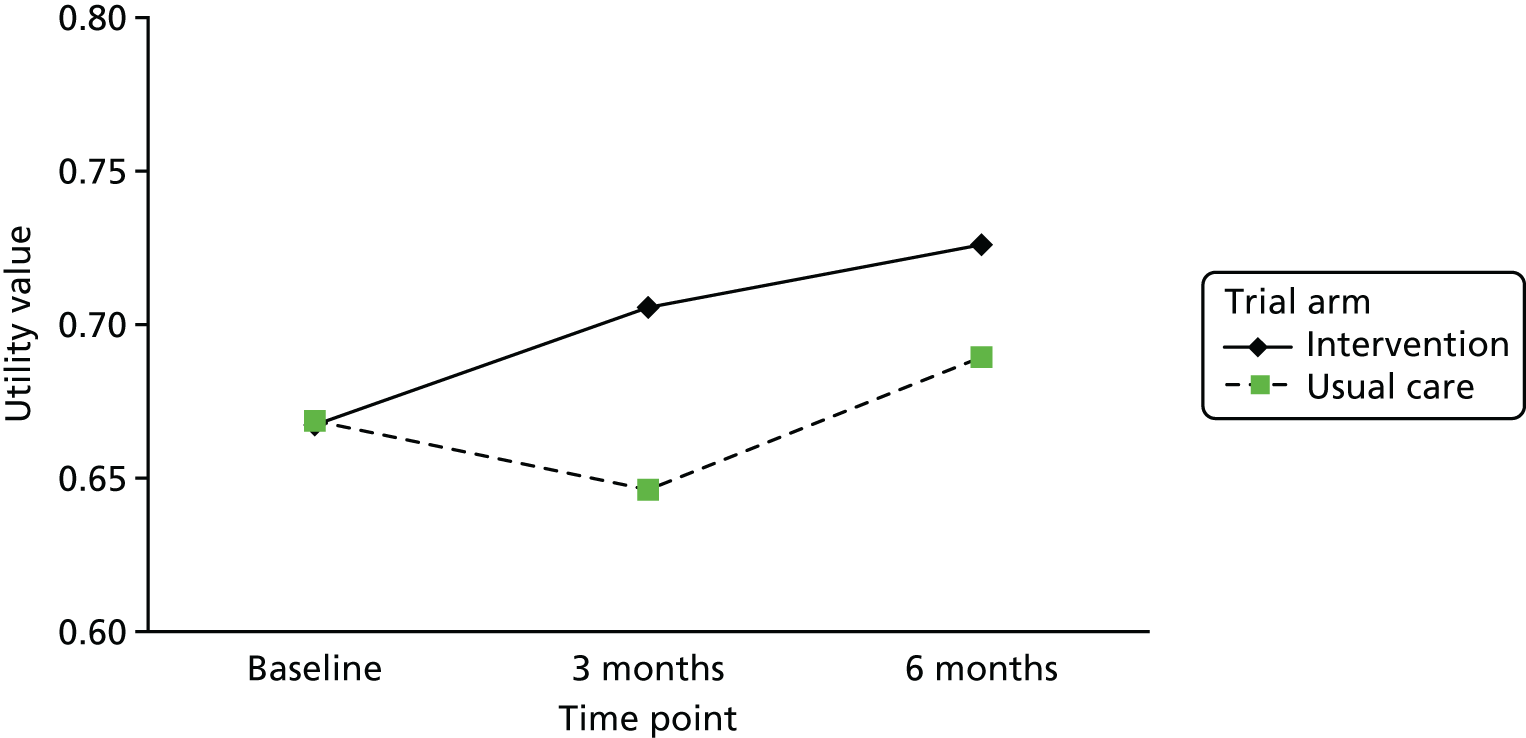

Statistical analysis