Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was commissioned and funded by the HTA programme on behalf of NICE as project number 16/30/05. The protocol was agreed in March 2018. The assessment report began editorial review in October 2018 and was accepted for publication in January 2019. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Howard Thom reports personal fees from Novartis Pharmaceuticals UK Ltd (Camberley, UK), Pfizer Inc. (New York, NY, USA), F. Hoffman-La Roche AG (Basel, Switzerland), Bayer AG (Leverkusen, Germany) and Janssen (Beerse, Belgium), all unrelated to the submitted work. Tom Marshall was a member of the National Institute for Health Research Health Technology Assessment and Efficacy and Mechanism Evaluation Editorial Board (2009–11).

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2020. This work was produced by Duarte et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2020 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Background

Description of the target condition

Atrial fibrillation (AF) refers to a disturbance in heart rhythm (arrhythmia) that is caused by abnormal electrical activity in the upper chambers of the heart (atria). 1 The arrhythmia reduces the efficiency of the heart to move blood into the ventricles, increasing the risk of blood clots and consequent stroke. 1 AF is associated with conditions such as hypertension, heart failure, coronary artery disease, valvular heart disease, obesity, diabetes mellitus and chronic kidney disease. 2

Types of atrial fibrillation

Three types of AF (based on presentation and duration of the arrhythmia) are described in Table 1.

| Type of AF | Description |

|---|---|

| Paroxysmal (intermittent) | Intermittent episodes that usually last < 7 days and stop without treatment |

| Persistent | Episodes that last > 7 days and do not stop without treatment |

| Permanent | Present all the time |

Atrial fibrillation can be categorised as valvular or non-valvular for the purposes of choosing the most suitable treatment. Categorisation as valvular or non-valvular refers to the underlying condition causing AF (i.e. whether or not there is valve disease present) rather than the duration of AF episodes. Both valvular AF and non-valvular AF can be paroxysmal, persistent or permanent. Patients diagnosed with paroxysmal AF can develop persistent or permanent AF. 2 It is also possible, but most unusual, for patients with persistent AF to revert to normal sinus rhythm. 2

Symptoms of atrial fibrillation

Patients with AF may experience palpitations, dizziness, shortness of breath and tiredness. However, AF can be asymptomatic and may be identified only during medical appointments for other conditions. Because the symptoms are intermittent, many cases of paroxysmal AF remain undiagnosed. 2 Cases of paroxysmal AF may be detected only after a prolonged monitoring period, rather than from a single examination. 2

Epidemiology

Atrial fibrillation is the most common type of cardiac arrhythmia. Estimates from 2010 suggest that, worldwide, 20.9 million men and 12.6 million women are living with AF. 2 Higher rates of AF are recorded in developed countries than in undeveloped countries; however, this may be explained by differences in reporting. 2 Higher rates of AF are recorded in people living in Western countries (estimated incidence rate of 9.03 per 1000 patient-years)4 than in people living in Asian countries (estimated incidence rate of 5.38 per 1000 patient-years). 5 Despite a higher exposure to potential AF risk factors, such as hypertension and obesity, African American people were found to have a lower age- and sex-adjusted risk of being diagnosed with AF than white American people. 6

In the 2016 European Society of Cardiology (ESC) guidelines,2 the prevalence of AF in the European Union was reported to be 3%.The ESC also notes that one in four middle-aged people in Europe and the USA will develop AF. 2 The prevalence of AF in Europe is projected to increase over time because of the ageing population, an increase in incidence of conditions associated with AF and the improvements in the detection of AF. 2

The overall age-adjusted incidence of AF per 1000 patient-years in the primary care setting in the UK has increased from 1.11 [95% confidence interval (CI) 1.09 to 1.13] in 1998–2001 to 1.33 (95% CI 1.31 to 1.35) in 2007–10, with a constant increase in incidence reported in people aged ≥ 75 years. 7

In the NHS Quality and Outcomes Framework for 2015–16,8 the prevalence of AF in England is estimated to be 1.7%, which equates to 985,000 people. However, as noted, AF can be asymptomatic, which suggests that 1.7% may be an underestimate of the true prevalence. 9 Based on a reference population in a region of Sweden, Public Health England has estimated that the true prevalence of AF in England is likely to be 2.5% and that 1.4 million people in England are living with AF. 10 In the most recent data from the NHS Quality and Outcomes Framework for 2016–17, the prevalence of AF in England is estimated to be 1.8%, equating to 1,066,000 people. 11 An assessment of electronic primary care records identified an increase in the prevalence of AF in the UK from 2.14% in 2000 to 3.29% in 2016 in those aged ≥ 35 years. 12

The prevalence of AF increases with age and a higher proportion of men than women live with the condition (2.9% and 2.0%, respectively). 10 The median age at which people are diagnosed with AF is 75 years. 10 The largest numbers of AF diagnoses in men and women occur between the ages of 75 and 79 years and 80 and 84 years, respectively. 10 Although fewer women than men have AF, women experience higher mortality rates owing to AF-related strokes. 10

Paroxysmal AF is estimated to account for between 25% and 62% of patients with AF treated in hospitals and general practitioner (GP) practices. 13 Patients with paroxysmal AF tend to be younger and have fewer comorbidities (e.g. hypertension or congestive heart failure) than patients with persistent or permanent AF. 13,14

Impact of atrial fibrillation

Untreated AF is a major risk factor for stroke. AF is associated with a fivefold increase in the risk of stroke and a threefold increase in the risk of congestive heart failure. 15 Strokes with AF as the underlying cause may be more severe than strokes unrelated to AF. 16 Furthermore, each year in the UK, 100,000 people have a stroke and one in five of those strokes has AF as the underlying cause. 17

There is evidence to suggest that there are differences in the risk of stroke between patients with paroxysmal, persistent and permanent AF, with patients with paroxysmal AF having a lower risk of stroke than those with persistent or permanent AF. 18,19 The risk of stroke in patients with symptomatic AF is similar to that in patients with asymptomatic AF. 20

The ESC reports that, annually, between 10% and 40% of patients with AF are hospitalised and that patients with AF have impaired health-related quality of life (HRQoL), regardless of co-existing cardiovascular conditions. 2 Cognitive decline and vascular dementia are conditions suggested to develop from the onset of AF. 2

Current diagnostic and treatment pathways

The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) clinical guideline CG1803 provides recommendations for the diagnosis and management of AF. An update of CG1803 is in progress.

Diagnosis of atrial fibrillation

In CG180,3 NICE recommends the use of manual pulse palpation (MPP) to detect the presence of an irregular pulse that may indicate underlying AF in people who have symptoms such as breathlessness/dyspnoea, palpitations, syncope/dizziness, chest discomfort, previous stroke or suspected transient ischaemic attack (TIA).

During the scoping stage of this assessment, clinical experts commented that people presenting with a stroke or TIA would undergo electrocardiogram (ECG) testing for AF in secondary care and are, therefore, outside the scope of an assessment that focuses on diagnosis in primary care.

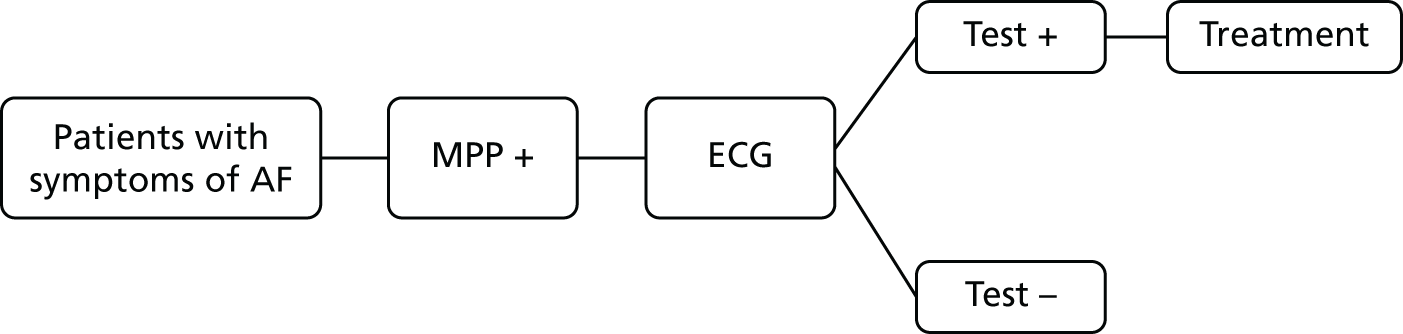

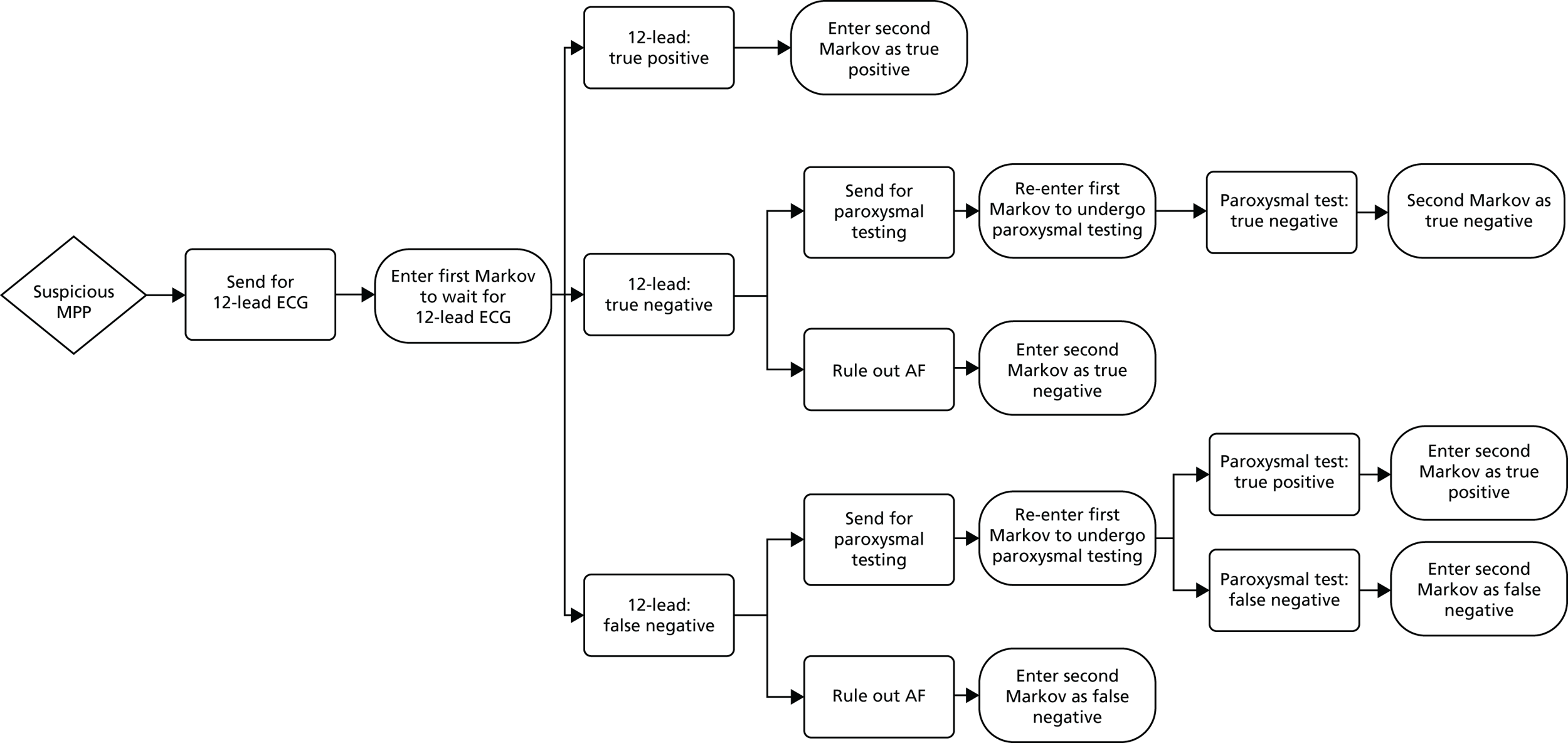

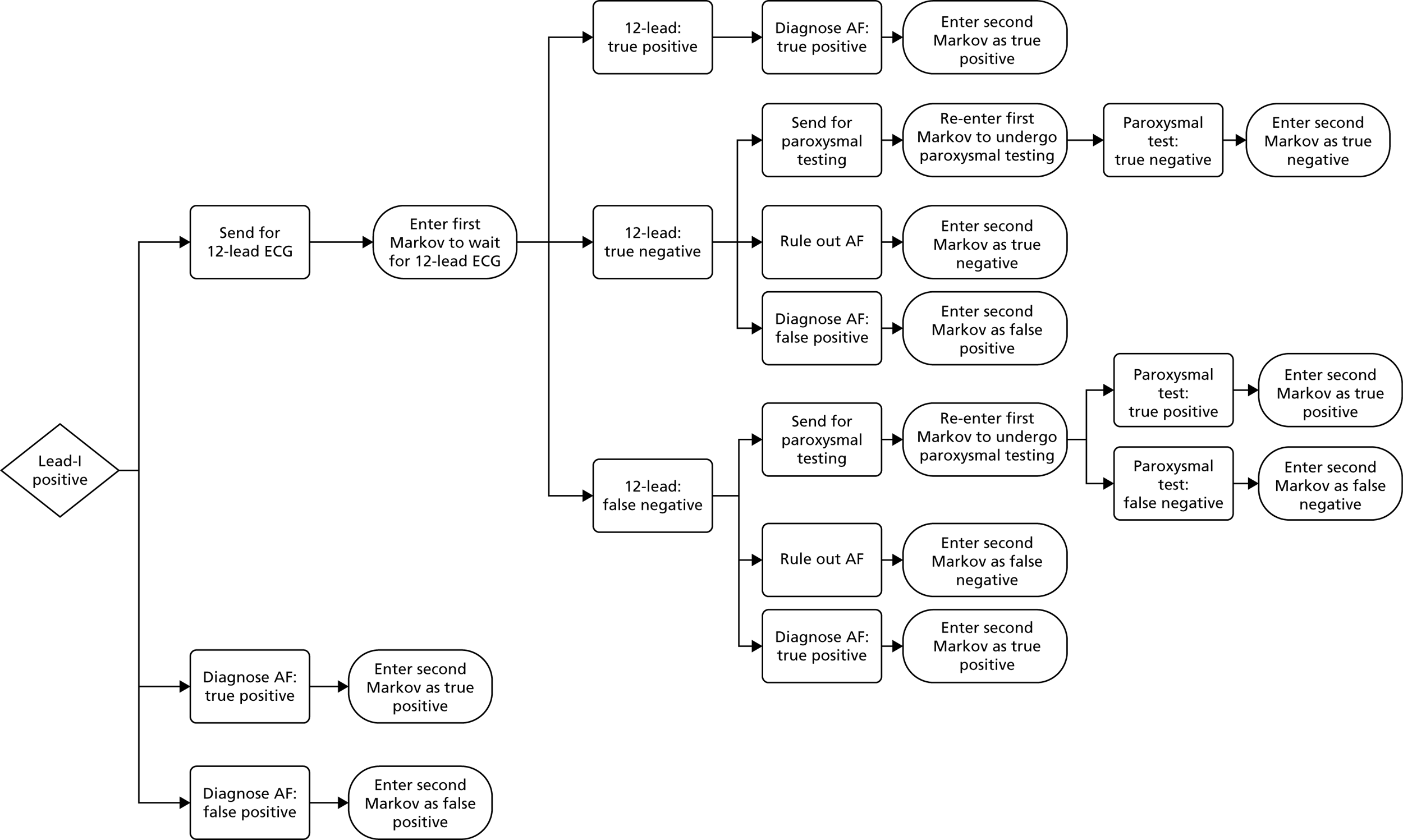

If AF is suspected because of an irregular pulse, NICE3 recommends that the diagnosis should be confirmed based on the results of an ECG. Patients who are suspected of having paroxysmal AF that is not detected by the ECG should be monitored using either a 24-hour ambulatory monitor or an event recorder ECG. Patients with confirmed AF may also undergo echocardiography to further inform the management of their condition. The current diagnostic pathway for people presenting to primary care with signs or symptoms of the condition and who have an irregular pulse is depicted in Figure 1.

FIGURE 1.

Current diagnostic pathway.

Management of atrial fibrillation

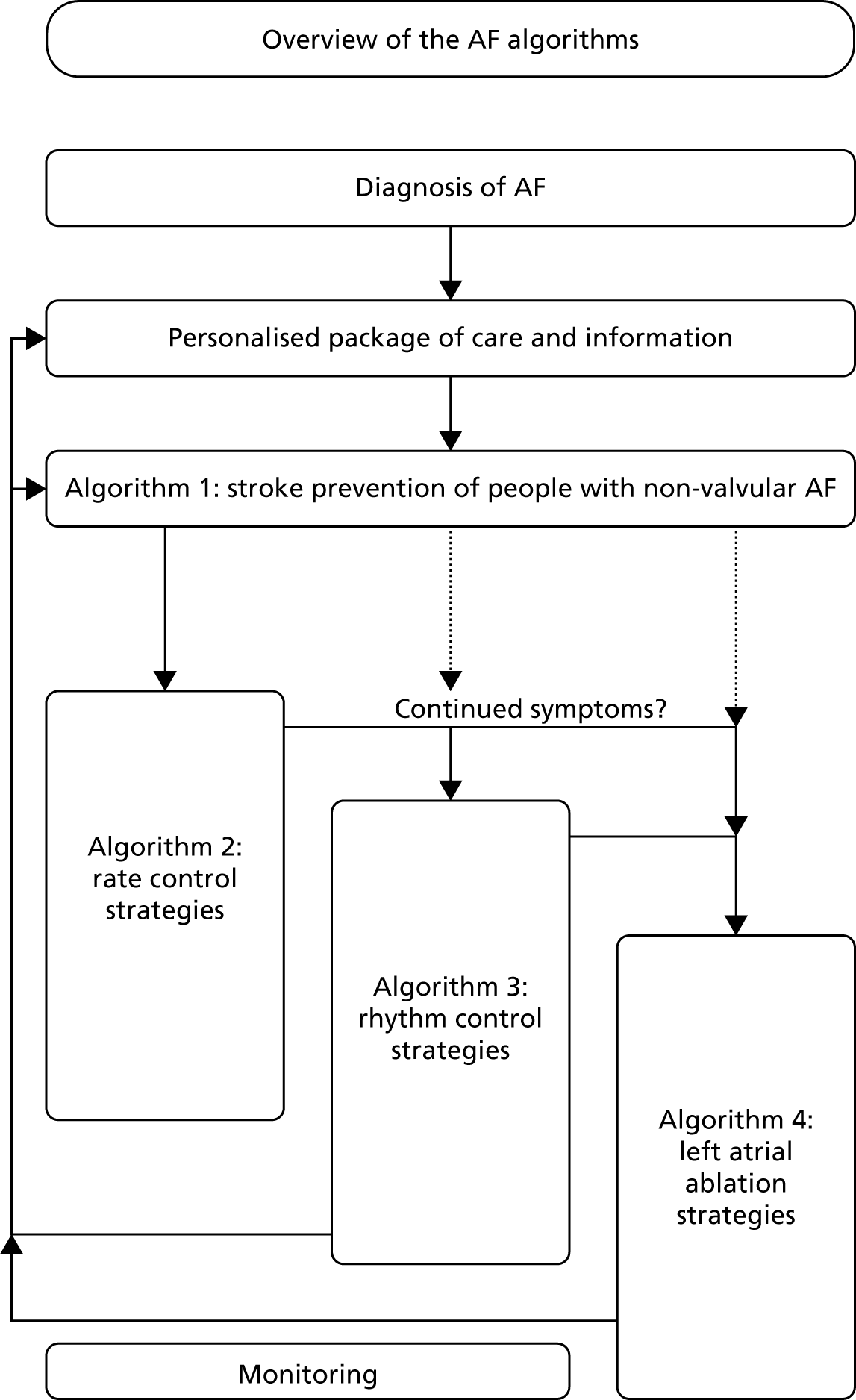

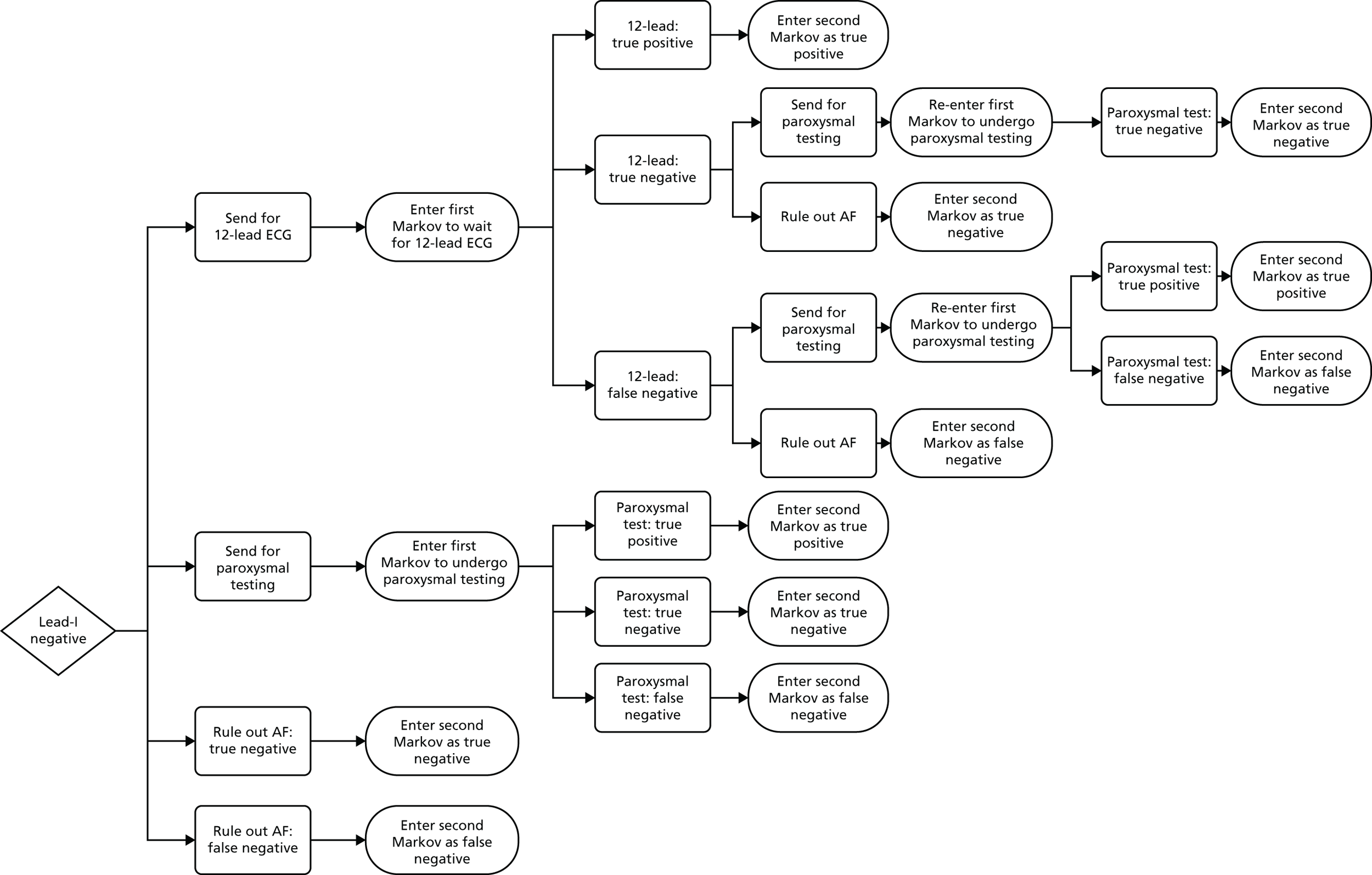

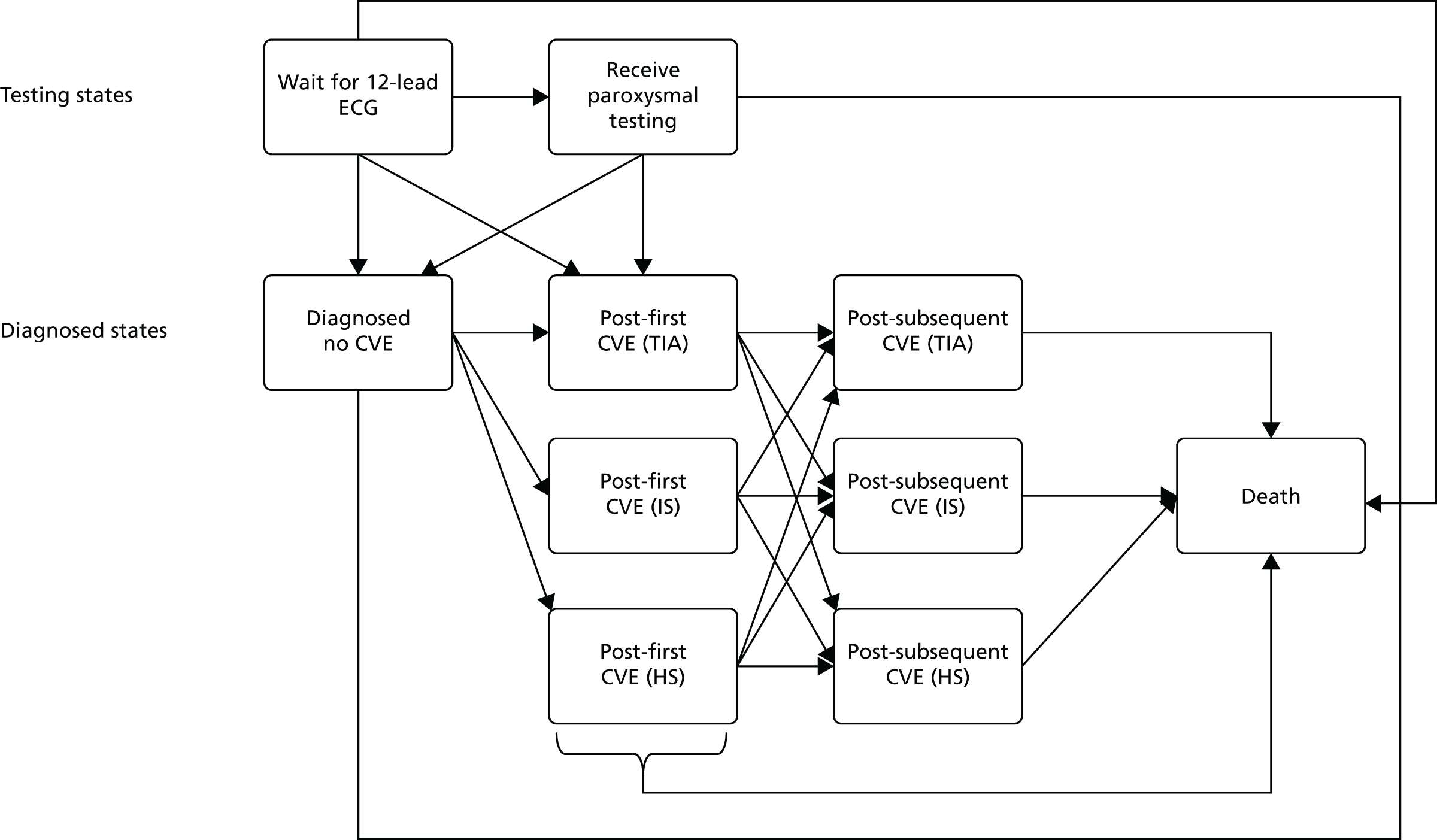

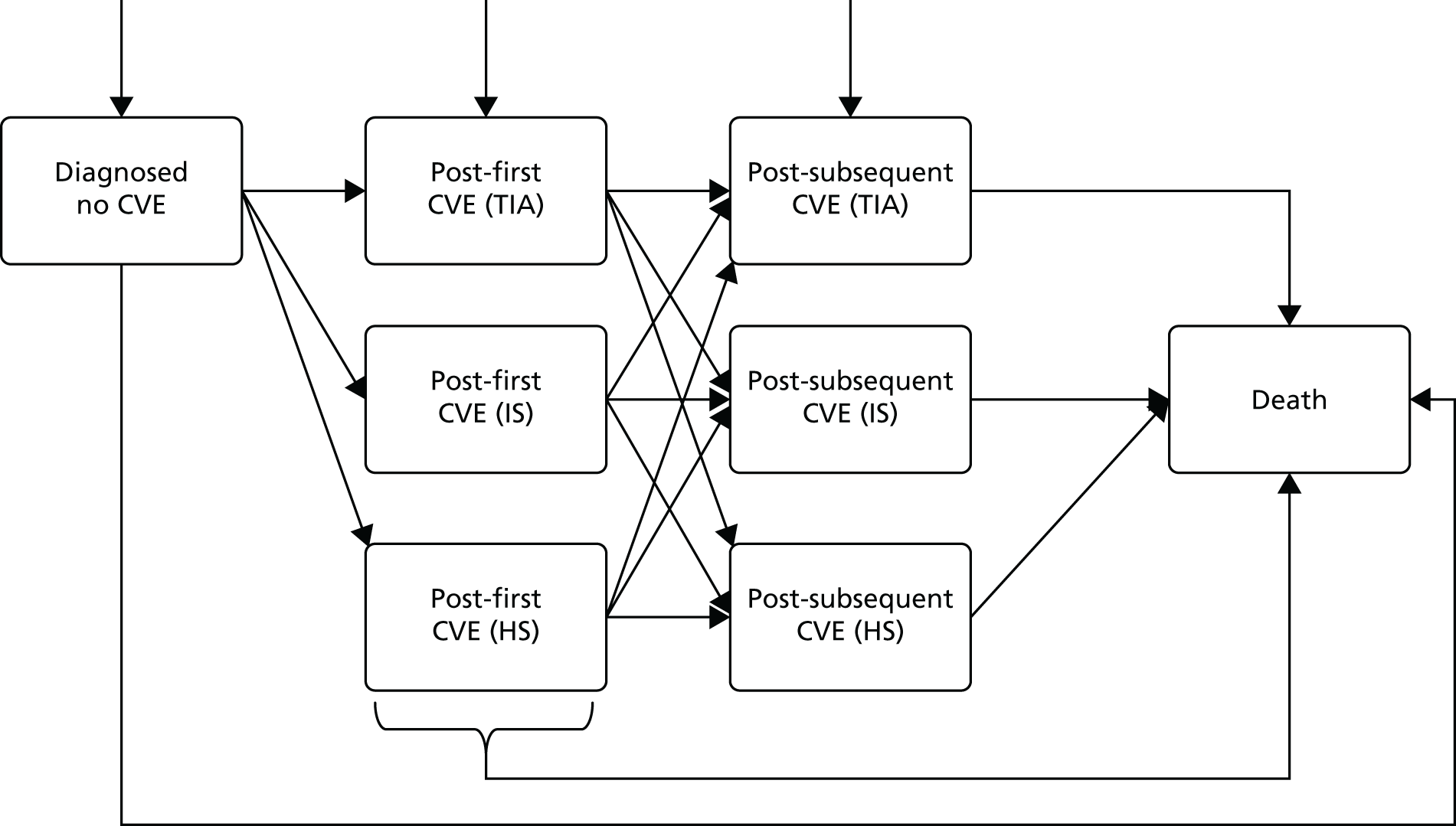

An overview of the treatment pathway described in CG1803 is provided in Figure 2. As shown in Figure 2, the management of AF is subdivided into four algorithms.

FIGURE 2.

Overview of AF algorithms. Source: NICE CG180. 3 © NICE 2014 Atrial fibrillation: management. Available from www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg180. All rights reserved. Subject to notice of rights (www.nice.org.uk/terms-and-conditions#notice-of-rights).

The aim of treatment is to reduce the symptoms of AF and prevent the potential consequences of undiagnosed AF, such as stroke. 3

Reducing stroke risk

In CG180,3 NICE recommends that patients with AF should be assessed for both their risk of stroke and their risk of bleeding. The risk of stroke should be assessed using the CHA2DS2-VASc21 algorithm [history of congestive heart failure, hypertension, age ≥ 75 years (doubled), diabetes mellitus, prior stroke or TIA (doubled), vascular disease, age 65–74 years, female] and the risk of bleeding should be assessed using the HAS-BLED22 algorithm (hypertension, abnormal liver/renal function, stroke history, bleeding predisposition, labile international normalised ratio, age, drug/alcohol use).

Depending on the age of the patient, the results of the CHA2DS2-VASc21 assessment and the results of the HAS-BLED22 assessment, patients with non-valvular AF may be offered stroke prevention treatment with either a vitamin K antagonist (usually warfarin) or a non-vitamin K antagonist oral anticoagulant (NOAC) [i.e. apixaban (Eliquis®; Bristol–Myers Squibb, NY), dabigatran etexilate (Pradaxa®, Prazaxa®, Pradax®; Boehringer Ingelheim GmbH, Germany), rivaroxaban (Xarelto®; Bayer Health Care, Germany) or edoxaban (Lixiana®; Daiichi Sankyo, Japan)].

Rate and rhythm control

In CG180,3 NICE recommends (with some exceptions) that people with AF who need drug treatment as part of their rate-control strategy should be offered either a standard beta-blocker or a rate-limiting calcium-channel blocker. Exceptions include people whose AF has a reversible cause, those who have heart failure thought to be primarily caused by AF, those with new-onset AF, those with an atrial flutter whose condition is considered suitable for an ablation strategy to restore sinus rhythm or for those whom a rhythm control strategy would be more suitable based on clinical judgement. Digoxin may be offered to sedentary people who have non-paroxysmal AF. If monotherapy does not control the AF symptoms, and the symptoms are a result of poor ventricular rate control, dual therapy with any two of a beta-blocker, diltiazem and digoxin is recommended. 3 For rhythm control, NICE3 recommends pharmacological treatment with or without electrical rhythm control (cardioversion).

In CG180,3 NICE also recommends strategies for left atrial ablation to control AF.

Description of technologies under assessment

The technologies assessed (i.e. index tests) were lead-I ECG devices. Lead-I ECG devices are handheld instruments that can be used in primary care to detect AF at a single time point in people who present with relevant signs or symptoms (i.e. palpitations, dizziness, shortness of breath and tiredness). Although lead-I ECG devices may also be used for ongoing or repeated testing for AF, and for the diagnosis of non-AF conditions, this use is outside the scope of this assessment.

Lead-I ECG devices feature touch electrodes and internal storage for ECG recordings, as well as software with an algorithm to interpret the ECG trace and indicate the presence of AF. Data from the lead-I ECG device can be uploaded to a computer to allow further analysis if necessary (e.g. in cases of paroxysmal AF).

The manufacturers of lead-I ECG devices all state that the diagnosis of AF should not be made using the algorithm alone, and that the ECG traces measured by the devices should be reviewed by a qualified health-care professional. The use of lead-I ECG devices following the detection of an irregular pulse by MPP may allow people with AF to initiate and benefit from earlier treatment with anticoagulants instead of waiting for the results of a confirmatory 12-lead ECG as per current practice.

Five different lead-I ECG devices are included in the final scope issued by NICE: imPulse (Plessey Semiconductors, Ilford, UK),23 Kardia Mobile (AliveCor Inc., Mountain View, CA, USA),24 MyDiagnostick (MyDiagnostick Medical B.V., Maastricht, the Netherlands),25 RhythmPad GP (Cardiocity, Lancaster, UK)26 and Zenicor ECG (Zenicor Medical Systems AB, Stockholm, Sweden). 27 The features of each device are described in imPulse, Kardia Mobile, MyDiagnostick, RhythmPad GP and Zenicor-ECG, respectively. All devices are CE (Conformité Européenne) marked.

imPulse

The lead-I ECG device is provided with downloadable software for data analysis (imPulse Viewer) and a cable for charging the device. The ECG readings are taken by holding the device in both hands and placing each thumb on a separate sensor on the device for a pre-set length of time (from 30 seconds to 10 minutes). To be operated, the device requires the associated software to be installed on a nearby PC or tablet. Data are transferred to hardware hosting the analytical software using Bluetooth (Bluetooth Special Interest Group, WA, USA), with the recorded ECG trace being displayed in real time.

Once the recording has finished, the generated ECG trace can be saved in the imPulse viewer. Previously recorded readings can also be loaded into this viewer and ECG traces can be saved as a PDF (Portable Document Format). The software has an AF algorithm that analyses the reading and states whether AF is unlikely, possible or probable. In the event of a ‘possible’ or ‘probable’ result, the company recommends that the person should undergo further investigation, and that the algorithm should not be used for a definitive clinical diagnosis of AF.

Kardia Mobile

The Kardia Mobile lead-I ECG device works with the Kardia Mobile app to record and interpret ECGs. In addition to the Kardia Mobile device and app [www.alivecor.com/ (accessed January 2018)], a compatible Android (Google Inc., Mountain View, CA, USA) or Apple (Apple Inc., Cupertino, CA, USA) smartphone or tablet is required.

Two fingers from each hand are placed on the Kardia Mobile device to record an ECG that is sent wirelessly to the device hosting the Kardia Mobile app. The default length of recording is 30 seconds; however, this can be extended up to 5 minutes. The measured ECG trace is then automatically transmitted as an anonymous file to a European server for storage as an encrypted file.

The app uses an algorithm to classify measured ECG traces as (1) normal, (2) possible AF detected or (3) unclassified. The instructions for use state that the Kardia Mobile app assesses the patient for AF only, and the device will not detect other cardiac arrhythmias. Any detected non-AF arrhythmias, including sinus tachycardia, are labelled as unclassified. The company states that any ECG labelled as ‘possible AF’ or ‘unclassified’ should be reviewed by a cardiologist or trained health-care professional. ECG traces measured by the device can be sent from a smartphone or tablet by e-mail as a PDF attachment and stored in the patient’s records. The first version of the Kardia app did not have automatic diagnostic functionality. The AF algorithm was added to the app in January 2015. The Kardia Mobile has previously been available as the AliveCor Heart Monitor.

MyDiagnostick

The MyDiagnostick lead-I ECG recording is generated after a patient holds the metal handles at each end of the device for 1 minute. A light on the device will turn green if no AF is detected or turn red if AF is detected. If an error occurs during the reading, the device produces both an audible warning and a visible warning from the light on the device. Up to 140 ECG recordings can be recorded on the device before it starts to overwrite previous recordings. The MyDiagnostick device can be connected to a computer via a USB (universal serial bus) connection to download the generated ECG trace for review and storage using free software that can be downloaded from the MyDiagnostick website [www.mydiagnostick.com (accessed January 2018)].

RhythmPad GP

The RhythmPad GP lead-I ECG readings are taken by placing the palms of both hands on the surface of the device for 30 seconds. Alternative configurations can be used if a person is unable to place their hands flat on the device, for example if they have arthritis. The software needs to be installed on a device running Windows XP (Microsoft, WA, USA) or a later version, and that has a USB port. Data are transferred directly to a computer using the USB connection to be stored on the device’s hard drive in PDF format.

The software includes an algorithm that can determine if a person has AF, and can additionally detect if a person has bradycardia, tachycardia, sinus arrhythmia, premature ventricular contractions or right bundle branch block. The recorded ECG trace is also available for further analysis by a health-care professional. The company recommends that a 12-lead ECG device is used to confirm a case of AF detected by the RhythmPad GP device.

Zenicor-ECG

The Zenicor-ECG is a system with two components: a lead-I ECG device (Zenicor-EKG 2) and an online system for analysis and storage (Zenicor-EKG Backend System version 3.2). The online system is not locally installed; the device transmits data to a remote server that can be accessed using a web browser, without prior installation of software, and requires a user licence. ECG readings are taken by placing both thumbs on the device for 30 seconds. The instructions for use state that the electrodes in the Zenicor EKG-2 should be replaced after every 500 measurements. The device is powered by three alkaline batteries that the company states are expected to last for at least 200 measurements and transmissions.

Once a measurement is made using the Zenicor-EKG 2 device, the ECG measurement can be transferred from the device (using a built-in mobile network modem) to a Zenicor server in Sweden. Here, the ECG trace is analysed using the Zenicor-EKG Backend System, which includes an automated algorithm. The algorithm categorises an ECG into one of 12 groups corresponding to potential arrhythmias, one of which includes AF. The algorithm will also report if the recorded ECG trace cannot be analysed. The company states that a clinician needs to manually interpret the ECG trace generated by the Zenicor-ECG to make a final diagnosis of AF.

The measured ECG trace can be downloaded or printed as a PDF report. The company states that the ECG is available via the web interface approximately 4–5 seconds after the ECG has been transmitted from the device.

The company states that the Zenicor EKG-2 does not store, contain or transmit any patient-identifying information. ECGs are sent via the built-in mobile network modem to the Zenicor server labelled with the device’s identity number. Communication between the Zenicor server and the web browser accessing it is encrypted.

Comparator

To evaluate the diagnostic accuracy of lead-I ECG devices, the comparator of interest is other lead-I ECG devices as described above or no comparator (Table 2). To evaluate the clinical impact of lead-I ECG devices, the comparator of interest is MPP followed by a 12-lead ECG in primary or secondary care prior to initiation of anticoagulation therapy.

| Characteristic | Description | |

|---|---|---|

| Population | (1) People with signs or symptoms that may indicate underlying AF and who have an irregular pulse; or (2) asymptomatic populationa if no evidence for (1) is available | |

| Setting | Primary care (ideal), secondary or tertiary care | |

| Index tests | Lead-I ECG using one of the following technologies:

|

|

| Clinical impact | DTA | |

| Comparator | Manual pulse palpation followed by a 12-lead ECG in primary or secondary care prior to initiation of anticoagulation therapy or other lead-I ECG devices as specified in Description of technologies under assessment | Other lead-I ECG devices as specified above, or no comparator |

| Reference standard | Not applicable | 12-lead ECG performed and interpreted by a trained health-care professional |

| Outcomes | Intermediate outcomes

|

DTA

|

Clinical outcomes

|

||

Patient-reported outcomes

|

||

| Study design | RCTs, cross-sectional, case–control, cohort and uncontrolled single-arm studies. Qualitative studies were considered to evaluate the ease of use of the devices | Diagnostic cross-sectional and case–control studies |

Reference standard

The index test results are compared with the results of a reference standard for an assessment of DTA. The reference standard is used to verify the presence or absence of the target condition (i.e. AF). The reference standard for this assessment is 12-lead ECG performed and interpreted by a trained health-care professional.

Aim of the assessment

The aim of this assessment was to evaluate whether or not the use of lead-I ECG devices to detect AF in people presenting to primary care with signs or symptoms of the condition and who have an irregular pulse represents a cost-effective use of NHS resources compared with MPP followed by a 12-lead ECG in primary or secondary care prior to initiation of anticoagulation therapy.

Chapter 2 Methods for assessing diagnostic test accuracy and clinical impact

Two systematic literature reviews were conducted to evaluate (1) the DTA of single-time point lead-I ECG for the diagnosis of AF, using 12-lead ECG as the reference standard, in people with signs or symptoms that may indicate underlying AF and who have an irregular pulse, and (2) the clinical impact of single time point lead-I ECG devices compared with MPP followed by a 12-lead ECG in both primary care and secondary care. The methods for the systematic review followed the general principles outlined in the Centre for Reviews and Dissemination guidance for conducting reviews in health care,28 NICE’s Diagnostics Assessment Programme manual29 and the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Diagnostic Test Accuracy. 30 The systematic review is reported in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines for DTA studies. 31 The PRISMA-DTA checklist and PRISMA-DTA for abstracts checklist are presented in Appendices 1 and 2, respectively.

Search strategy

The search strategies were designed to focus on the specified devices (i.e. imPulse, Kardia Mobile, MyDiagnostick, RhythmPad GP and Zenicor ECG) and the target condition (i.e. AF). No study design filters were applied and all electronic databases were searched from inception to 9 March 2018. The search strategy used for the MEDLINE database is presented in Appendix 3. The MEDLINE search strategy was adapted to enable similar searches of the other relevant electronic databases. The following databases were searched for relevant studies:

-

MEDLINE (via Ovid)

-

MEDLINE Epub Ahead of Print and MEDLINE In-Process & Other Non-Indexed Citations (via Ovid)

-

EMBASE (via Ovid)

-

PubMed

-

CDSR

-

CENTRAL

-

DARE (via The Cochrane Library)

-

Health Technology Assessment (HTA) database (via The Cochrane Library).

The results of the searches were uploaded to, and managed, using EndNote X8 software [Clarivate Analytics (formerly Thomson Reuters), Philadelphia, PA, USA]. The reference lists of relevant systematic reviews and eligible studies were hand-searched to identify further potentially relevant studies. Data submitted by the manufacturers of the five lead-I ECG devices that are the focus of this assessment were considered for inclusion in the review.

Eligibility criteria

The eligibility criteria for the inclusion of studies assessing the clinical impact or DTA of lead-I ECG devices are presented in Table 2.

Although the index test (i.e. the test being evaluated) should be performed in a primary care setting, studies in which the index tests were performed and interpreted by a cardiologist in a secondary or tertiary care setting were also considered eligible for inclusion. This is because it is plausible that in clinical practice (primary care setting) the test results could be sent for remote interpretation by a cardiologist.

Studies that assessed the DTA or the clinical impact of lead-I ECG devices used at a single time point to detect AF in an asymptomatic population were considered for inclusion if no studies were identified in a symptomatic population. An asymptomatic population was considered to be people not presenting with symptoms of AF, with or without a previous diagnosis of AF. These patients could have other cardiovascular comorbidities, or could be attending a clinic for cardiovascular-related reasons, but not be presenting with signs or symptoms of AF. The use of lead-I ECG devices for ongoing or repeated testing for AF is outside the scope of this assessment.

Studies that did not present original data (i.e. reviews, editorials and opinion papers), case reports and non-English language studies were excluded from the review. Conference proceedings published from 2013 onwards were considered for inclusion.

Study selection

The citations identified were assessed for inclusion in the review using a two-stage process. First, two reviewers independently screened all of the titles and abstracts identified by the electronic searches to distinguish the potentially relevant studies to be retrieved. Second, full-text copies of these studies were obtained and assessed independently by two reviewers for inclusion using the eligibility criteria outlined in Table 2. Any disagreements were resolved through discussion at each stage, and, if necessary, in consultation with a third reviewer.

Data extraction

A data extraction form was designed, piloted and finalised to enable data extraction relating to study authors, year of publication, study design, characteristics of study participants, prevalence of comorbidities, prevalence of AF by type, characteristics of the index, comparator and reference standard tests (including length of monitoring, who performed and interpreted the test), the order in which the index and comparator/reference standard tests were performed, whether or not the person who interpreted the reference standard test was blind to the results of the index test, and the outcome measures as described in Table 2.

Data extraction was performed by one reviewer and checked for accuracy by a second reviewer. Any disagreements were resolved through discussion, and, if necessary, in consultation with a third reviewer. The manufacturers of the index tests and the corresponding authors of the studies selected for assessment of DTA were contacted for missing data or clarification of the data presented.

Quality assessment

The methodological quality of DTA studies was assessed using the QUality Assessment of Diagnostic Accuracy Studies–2 (QUADAS-2) tool tailored to the review question. 32 The QUADAS-2 tool considers four domains: (1) patient selection, (2) index test(s), (3) reference standard and (4) flow of patients through the study and the timing of the tests.

The methodological quality of cross-sectional and case–controlled studies that evaluated the clinical impact of lead-I ECG devices was assessed using the Newcastle–Ottawa quality assessment scale. 33,34 We had planned to use the Cochrane Risk of Bias tool35 to assess the methodological quality of randomised controlled trials (RCTs) of clinical impact, but no RCTs were identified. 35 Qualitative studies were assessed using the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) tool. 36

Quality assessment of the included studies was undertaken by one reviewer and checked by a second reviewer. Any disagreements were resolved by discussion, and, if necessary, in consultation with a third reviewer.

Methods of analysis/synthesis of diagnostic test accuracy studies

Statistical analysis and data synthesis

Individual study results

The sensitivity and specificity of each index test from studies of diagnostic accuracy were summarised in forest plots and plotted in receiver operating characteristic (ROC) space.

Meta-analysis

The bivariate model was used to obtain pooled estimates of sensitivity and specificity for lead-I ECG devices. 37 The pooled estimates for sensitivity and specificity were plotted in ROC space with a 95% confidence region around this summary estimate. The 95% confidence region depicts a range of sensitivity and specificity values within which the analyst can be 95% confident that the true sensitivity and specificity values for the index test lie.

The analyses were stratified by whether the diagnosis of AF was made by a trained health-care professional interpreting the lead-I ECG trace, or by the lead-I ECG algorithm. Within these stratified analyses, it was not possible to compare the diagnostic accuracy of different types of lead-I ECG device by adding a covariate for device type owing to the sparsity of the data. We were also unable to perform subgroup analyses to assess the impact of potential sources of heterogeneity on the diagnostic accuracy of lead-I ECG devices owing to the sparsity of the data.

For one study38 that reported data for two types of lead-I ECG device (MyDiagnostick and Kardia Mobile) and for two different interpreters of lead-I and 12-lead ECG traces for the same patient cohort, we performed multiple analyses so that we could investigate the impact of varying both the type of lead-I ECG device and the interpreter on the results of the overall pooled analysis. Therefore, no set of patients was double-counted in any of the meta-analyses performed. The data for the lead-I ECG device (MyDiagnostick defined as device 1 and Kardia Mobile defined as device 2) and the electrophysiologist (EP) (EP1 or EP2) that were included in the main analysis were randomly selected by using the command r(uniform) in Stata version 14 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA) to randomly generate the number 1 or 2 first for device and then for EP. Additional analyses are presented as sensitivity analyses.

One study39 reported data for one lead-I ECG device (Kardia Mobile) and two different interpreters (a cardiologist and a GP with an interest in cardiology) of lead-I and 12-lead ECG traces. The data interpreted by the cardiologist were used in the main analysis because the interpreters in the other included studies were either cardiologists or EPs. The analysis with data interpreted by the GP is presented as a sensitivity analysis.

The bivariate model was fitted using the metandi and xtmelogit commands in Stata version 14 where at least four studies could be included in meta-analysis. Summary receiver operating characteristic (SROC) plots were produced using RevMan 5.3 (RevMan; The Cochrane Collaboration, The Nordic Cochrane Centre, Copenhagen, Denmark). When there were fewer than four studies, the bivariate model was reduced to two univariate random-effect logistic regression models by assuming no correlation between sensitivity and specificity across studies. 40 When little or no heterogeneity was observed on forest plots and SROC plots, the models were further simplified into fixed-effect models by eliminating the random-effects parameters for sensitivity and/or specificity. 40 Judgement of heterogeneity was based on the visual appearance of forest plots and SROC plots in addition to clinical judgement regarding potential sources of heterogeneity.

Sensitivity analyses

We had planned to conduct sensitivity analyses by excluding studies judged as having a high risk of bias or studies where the appropriateness of inclusion in the primary meta-analyses was uncertain. Sensitivity analyses stratified by risk of bias were not performed owing to the small number of studies included in the meta-analysis with similar risk-of-bias judgements.

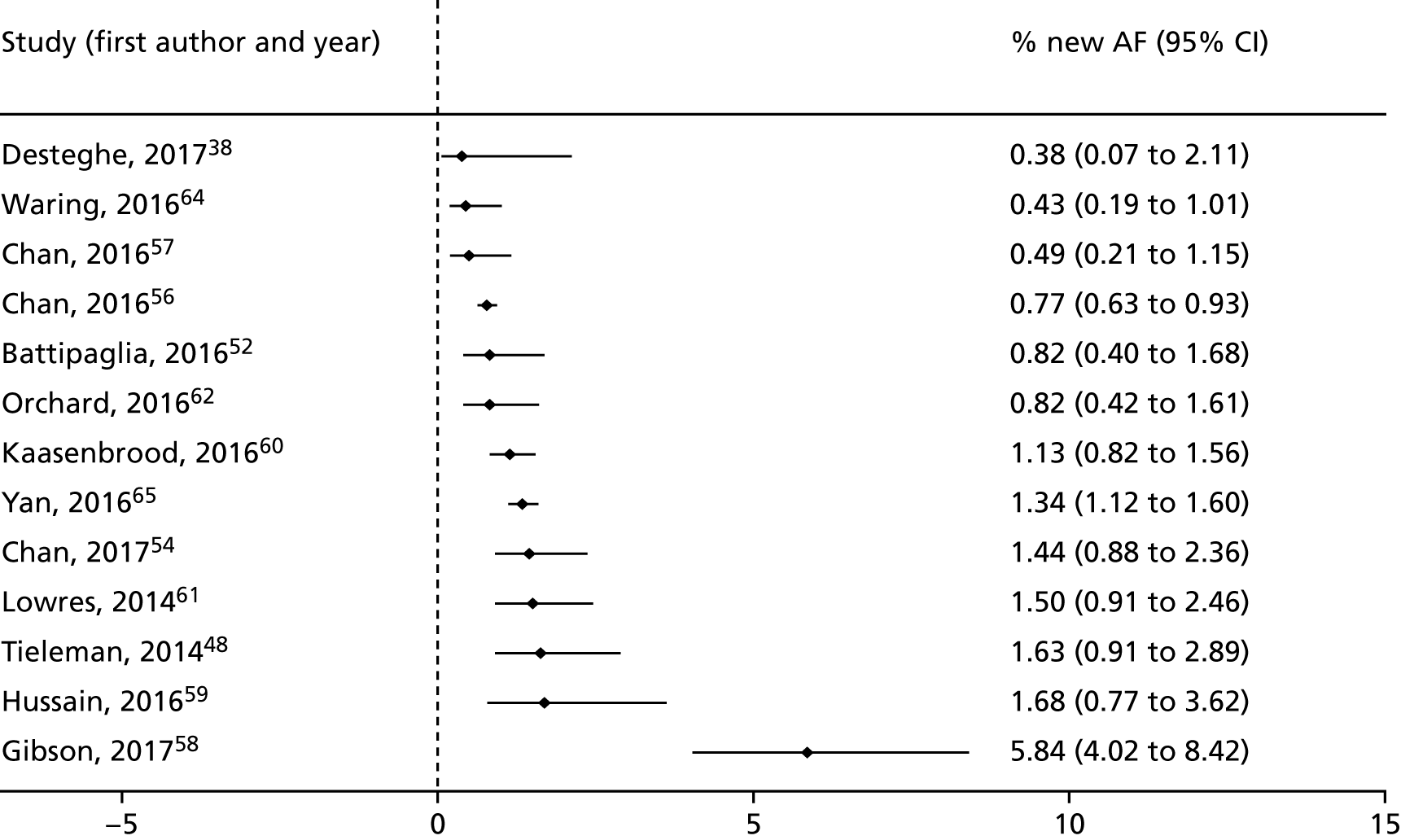

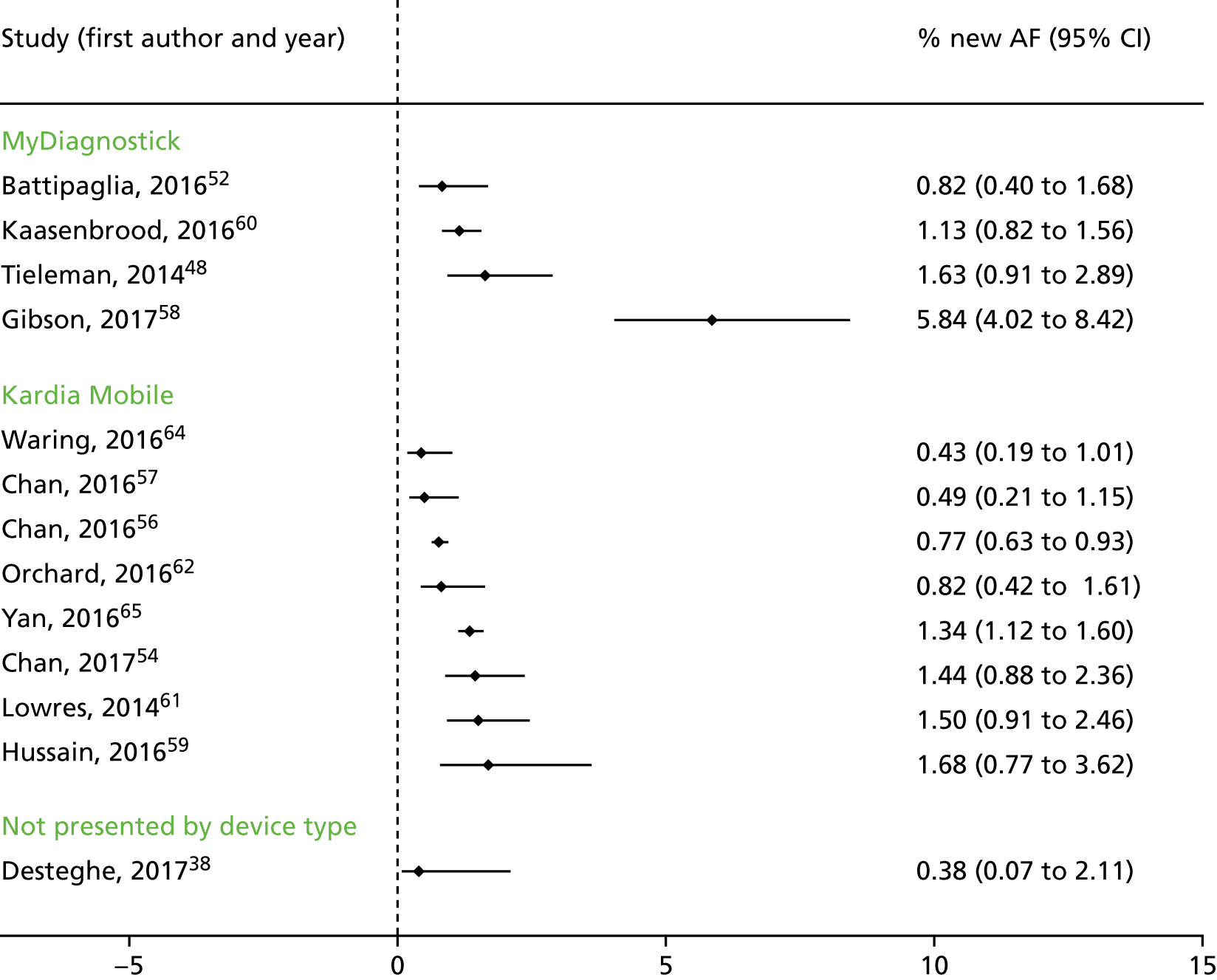

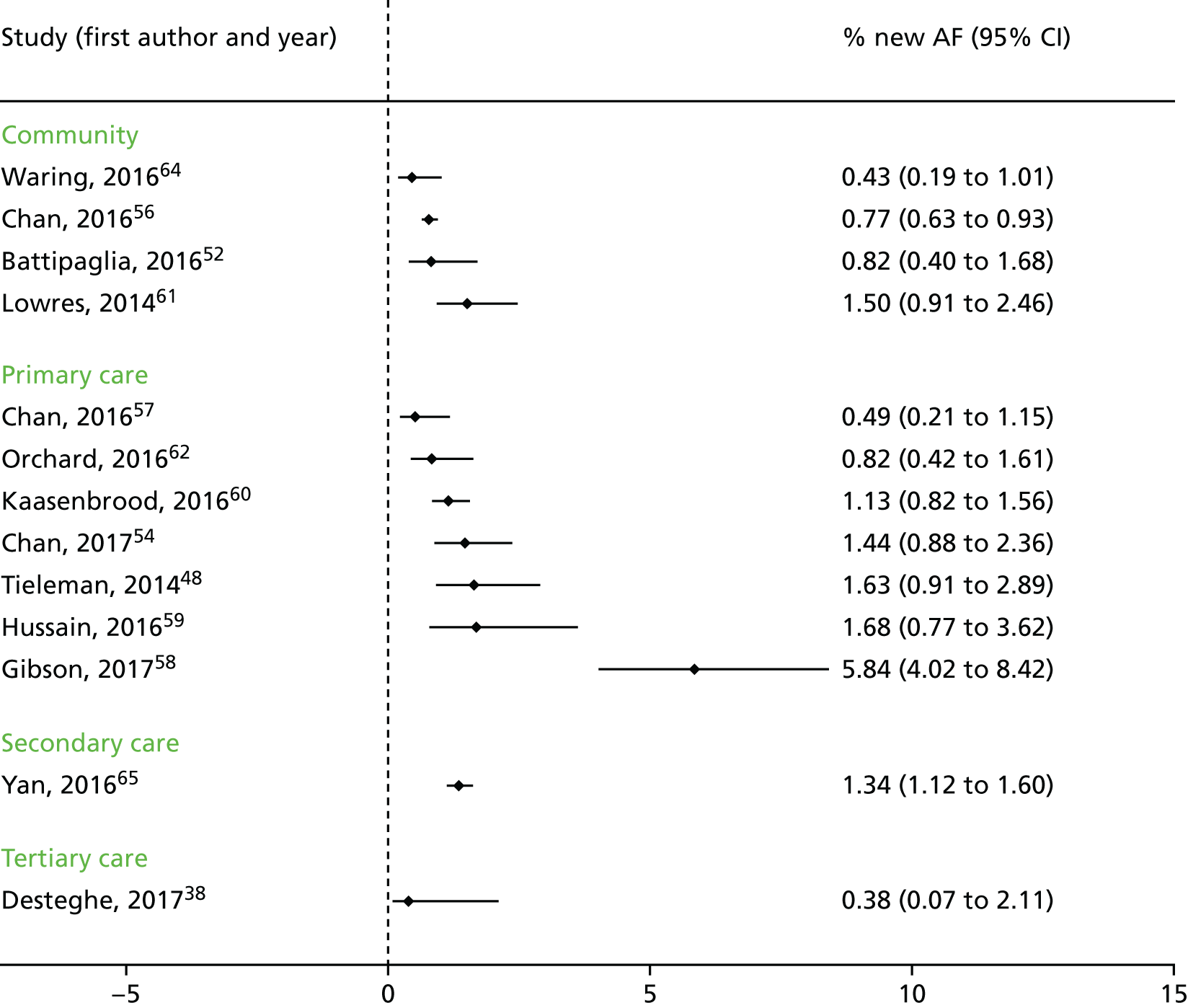

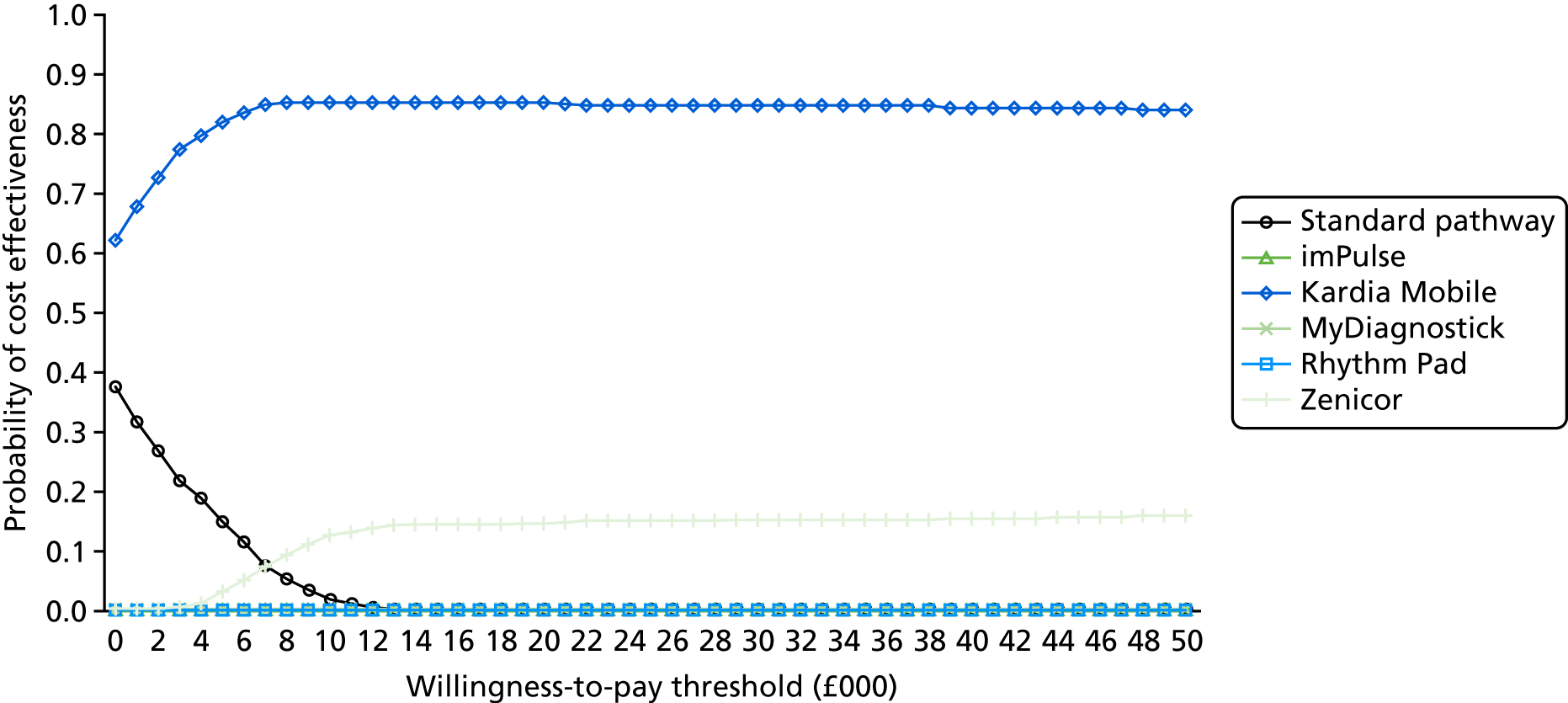

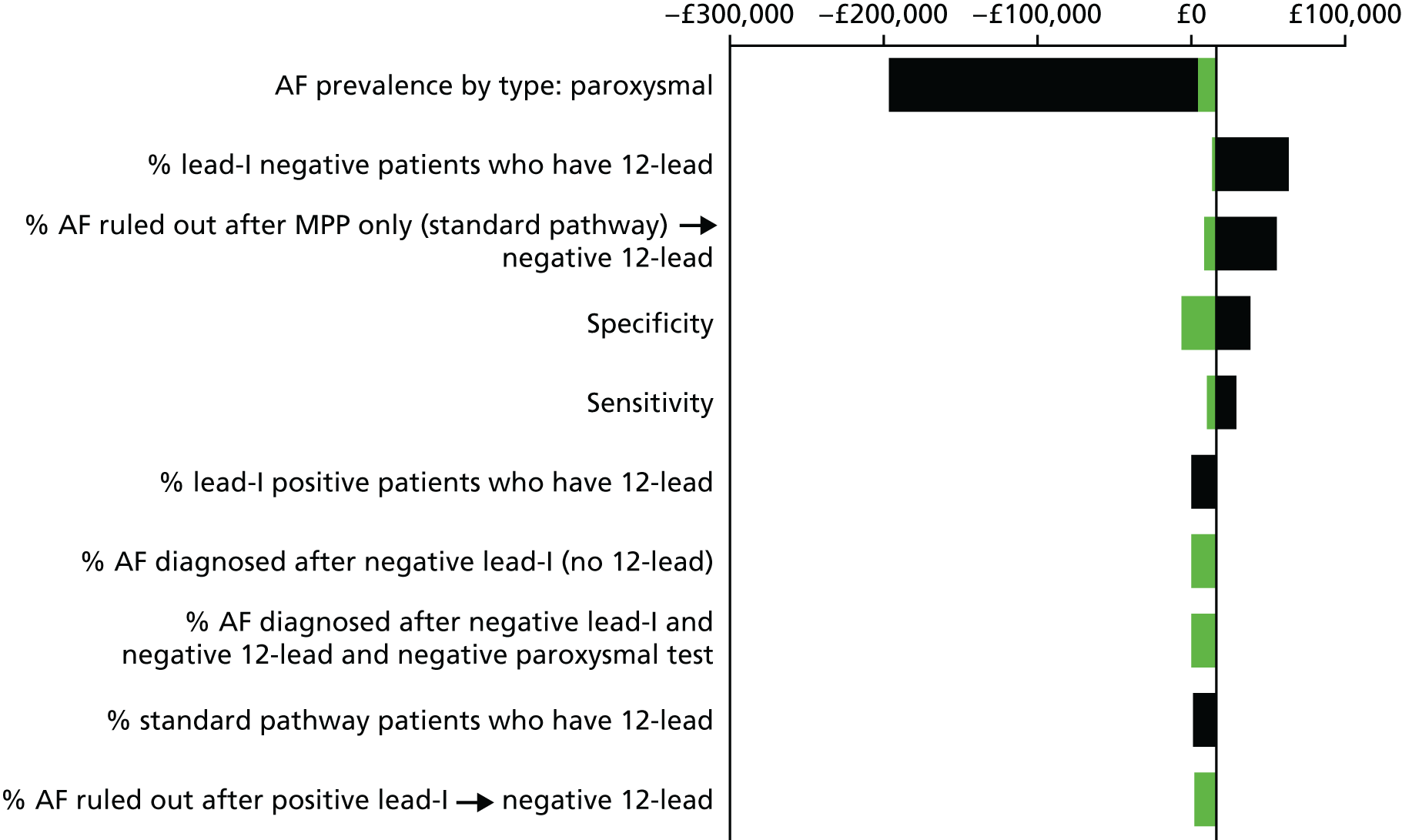

Methods of analysis/synthesis of clinical impact studies

We had planned to perform a meta-analysis of the clinical and intermediate outcomes stated in Table 2. After data extraction, we considered pooling data for the outcome of diagnostic yield; however, on examination of the forest plots displaying diagnostic yield data for the included studies, we judged the data to be too heterogeneous for pooling to give clinically meaningful results. Therefore, we produced forest plots displaying individual study results from all included studies and additional forest plots displaying individual study results stratified by device type and by setting. These forest plots were produced in Stata 14 using the metaprop command.

Other considerations

‘Real-world’ data describing the clinical impact of lead-I ECG devices were received from the Kent Surrey Sussex Academic Health Science Health Network (AHSN) and these are included in Chapter 3, Clinical impact results.

Chapter 3 Results of the assessment of diagnostic test accuracy and clinical impact

Study selection

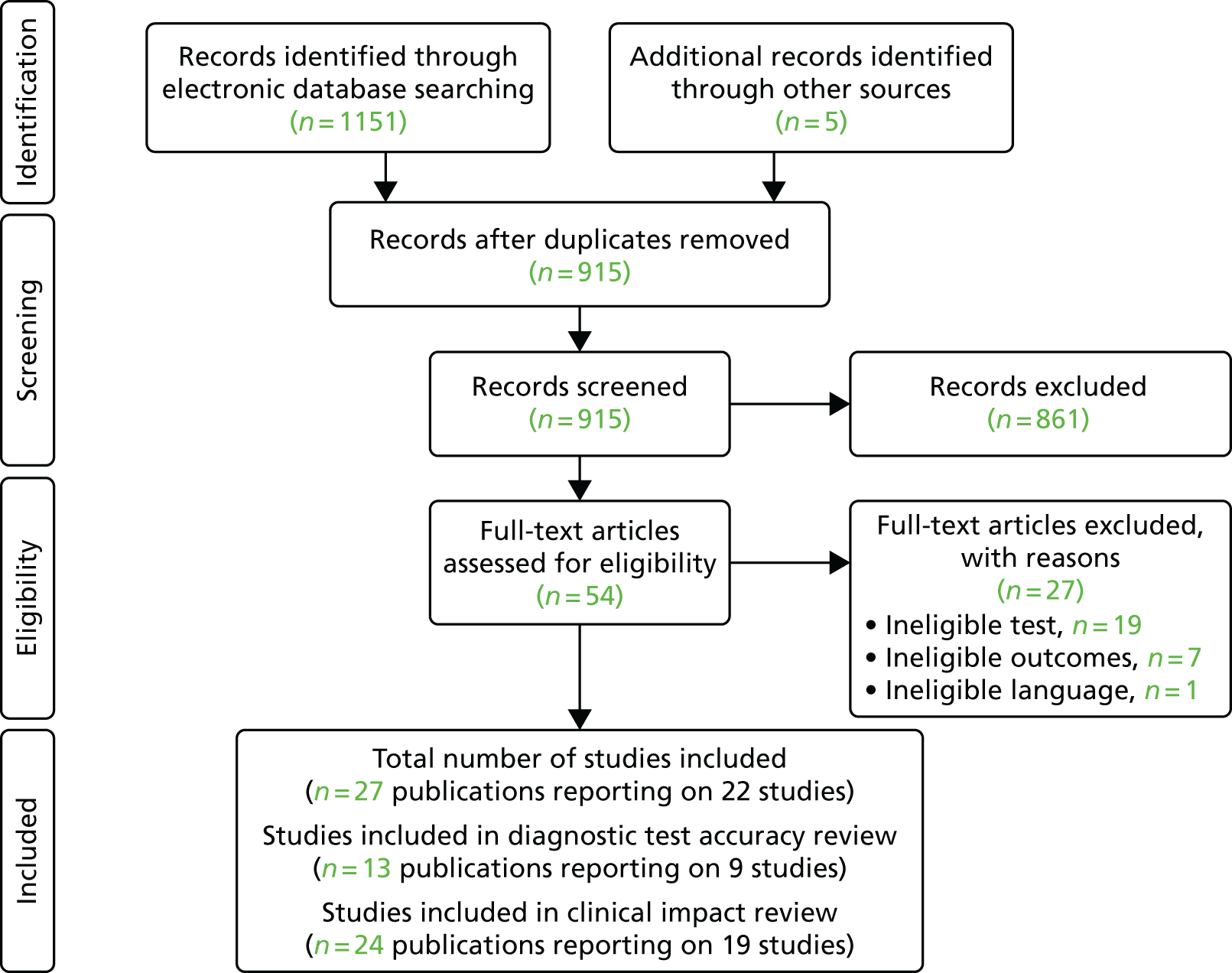

The searches of the electronic databases identified 1151 citations. After the removal of duplicate records, 915 potential citations remained. Following initial screening of titles and abstracts, 54 publications were considered to be potentially relevant and were retrieved to allow assessment of the full-text publication.

No studies were identified for the population of interest (i.e. people with signs or symptoms that may indicate underlying AF and who have an irregular pulse). Therefore, all of the included studies assessed the DTA and clinical impact of lead-I ECG devices used at a single time point to detect AF in an asymptomatic population (see Chapter 2, Eligibility criteria).

After review of the full-text publications, 13 publications38,39,41–51 reporting on nine studies were included in the DTA review and 24 publications38,41–48,51–65 reporting on 19 studies were included in the clinical impact review. Where there were overlaps in data and reporting as a result of studies being reported in several papers and abstracts, we selected the publication with the most complete data and treated it as the main publication. The PRISMA66 flow chart detailing the screening process for the review is shown in Figure 3. Studies excluded at the full-text paper screening stage and the reasons for exclusion are presented in Appendix 4.

FIGURE 3.

The PRISMA flow chart. Reproduced from Duarte et al. 67 © The Authors, 2019. This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

We contacted the authors of three studies47,50,51 to obtain additional data on DTA or to clarify the data on DTA reported in the publication. We did not receive a response from one set of authors. 51 One set of authors provided additional information that allowed their study47 to be included in the DTA meta-analysis. One set of authors also provided additional information on their study,50 but stated that the algorithm had been modified since the study was reported. For this reason, the sensitivity and specificity of the lead-I ECG device used are presented but are not included in the meta-analysis.

Assessment of diagnostic test accuracy

Characteristics of the included studies

The characteristics of the nine included DTA studies are summarised in Table 3.

| Study (first author, year) | Study design; country and setting | Population; number in analysis and recruitment details | Mean age and SD (years); sex; risk factors for AF | Lead-I ECG device | Interpreter of lead-I ECG | Test sequence |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Crockford, 201350 | Cross-sectional; UK; secondary care | Patients referred to an electrophysiology department; N = 176; NR | NR | RhythmPad GP | Algorithm | 12-lead ECG followed by lead-I ECG |

| Desteghe, 201738 | Case–control; Belgium; tertiary care | Inpatients at cardiology ward; N = 265; NR |

67.9 ± 14.6; female, n = 138 (43.1%); Pacemaker: 4 out of 55 (7.3%) were intermittently paced, and 18 out of 55 (32.7%) were not being paced during the recordings Known AF: 114 out of 320 (35.6%) AF at time of study: 11.9% on 12-lead ECG; 3.4% of all patients admitted because of symptomatic AF Paroxysmal AF: 54.4% |

MyDiagnostick and Kardia Mobile | Algorithm and two EPs (results presented separately for algorithm and two EPs) | 12-lead ECG followed by lead-I ECG (order for the use of the different lead-I ECG tests not specified) |

| Doliwa, 200943 | Case–control; Sweden; secondary care | People with AF, atrial flutter or sinus rhythm; N = 100; patients were recruited from a cardiology outpatient clinic | NR | Zenicor-ECG | Cardiologist | 12-lead ECG followed by lead-I ECG |

| Haberman, 201545 | Case–control; USA; community and secondary care | Healthy young adults, elite athletes and cardiology clinic patients; N = 130; NRa |

59 ± 15; male, n = 73 (56%); NR |

Kardia Mobile | EP | Lead-I ECG followed by 12-lead ECG |

| Koltowski, 201751 | Cross-sectional; Poland; tertiary care | Patients in a tertiary care centre; N = 100; NR | NR | Kardia Mobile | Cardiologist | Lead-I ECG followed by 12-lead ECG |

| Lau, 201347 | Case–control; Australia; secondary care | Patients at cardiology department; N = 204; NR |

NR; Known AF: n = 48 (24%) |

Kardia Mobile | Algorithm | Lead-I ECG followed by 12-lead ECG |

| Tieleman, 201448 | Case–control; Netherlands; secondary care | Patients with known AF and patients without a history of AF attending an outpatient cardiology clinic or a specialised AF outpatient clinic; N = 192; random selection of patients awaiting a 12-lead ECG |

69.4 ± 12.6; male, 48.4%; NR |

MyDiagnostick | Algorithm | Lead-I ECG followed by 12-lead ECG |

| Vaes, 201449 | Case–control; Belgium; primary care | Patients with known AF and patients without a history of AF; N = 181; GP invitation |

74.6 ± 9.7; female, n = 91 (48%); Known AF: n = 151 (83.4%) |

MyDiagnostick | Algorithm | Lead-I ECG followed by 12-lead ECG |

| Williams, 201539 | Case–control; UK; secondary care | Patients with known AF attending an AF clinic and patients with AF status unknown who were attending the clinic for non-AF-related reasons; N = 95; patients attending clinic appointments who were awaiting a 12-lead ECG | NR | Kardia Mobile | Cardiologist and GP with an interest in cardiology | 12-lead and lead-I ECG carried out simultaneously |

The studies included in the DTA review were either case–control studies38,39,43,45,47–49 or cross-sectional studies. 50,51 Two of the studies were based in the UK. 39,50 Only one study was conducted in primary care,49 with the remaining studies being conducted in either secondary39,43,45,47,48,50 or tertiary care. 38,51 All of the studies included either patients with a known history of AF or patients recruited from cardiology clinics. Only one study38 presented the reasons that patients were admitted to a cardiology department. Eleven patients (3.4%) were admitted because of symptomatic AF, all of whom had a known history of AF. The study by Haberman et al. 45 included a community-based population comprising healthy young adults and elite athletes. The results for the healthy young adults and elite athletes were excluded from the analysis because these participants did not meet the population inclusion criteria for this review and do not represent the typical population with AF (i.e. those aged > 75 years). 10 The study by Lau et al. 47 included a ‘learning set’ and data from this group were used to optimise the algorithm. The ‘learning set’ data were excluded from the analysis because, according to the author of the study (Ben Freedman, University of Sydney, 15 June 2018, personal communication), two separate cardiologists interpreted the rhythm strips, and the interpretation by cardiologist A seemed to have a bias towards sensitivity, with a resultant lower specificity, while the interpretation by cardiologist B had a slightly lower sensitivity, with a resulting higher specificity.

Only one study included results based on lead-I ECG interpretation by the device algorithm and a trained health-care professional presenting the results separately. 38 One study39 reported data for a lead-I ECG trace that was interpreted both by a cardiologist and by a GP with an interest in cardiology; the results were presented separately for each interpreter. In four studies,47–50 the lead-I ECG was interpreted by the device algorithm alone.

The lead-I ECG devices used in the included studies were Kardia Mobile,39,45,47,51 MyDiagnostick,48,49 RhythmPad GP50 and Zenicor-ECG. 43 The study by Desteghe et al. 38 used both Kardia Mobile and MyDiagnostick and presented the results separately for each device.

The trained health-care professional interpreting the 12-lead ECG in all of the studies included in the DTA review was a cardiologist,39,43,47–49,51 an EP38,45,50 or a GP with an interest in cardiology. 39

Quality assessment of diagnostic accuracy studies

All of the included studies were assessed for risk of bias and applicability using the QUADAS-2 tool. 32 A summary of the results that assessed risk of bias and applicability concerns across all studies is presented in Table 4. The full assessment for each included study is presented in Appendix 5.

| Study (first author, year) | Risk of bias | Applicability concerns | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient selection | Index test | Reference standard | Flow and timing | Patient selection | Index test | Reference standard | |

| aCrockford, 201350 | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | High | Unclear | Low |

| Desteghe, 201738 | Unclear | Low | Low | Low | High | Low | Low |

| Doliwa, 200943 | Unclear | Low | Low | Low | High | Low | Low |

| Haberman, 201545 | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Low | High | Low | Low |

| bKoltowski, 201751 | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Low | High | Unclear | Low |

| Lau, 201347 | Unclear | Low | Low | Low | High | High | Low |

| Tieleman, 201448 | Unclear | Low | Low | Low | High | High | Low |

| Vaes, 201449 | Unclear | Low | Low | Unclear | High | High | Low |

| Williams, 201539 | Unclear | Low | Low | Unclear | High | Low | Low |

All of the included studies were judged as being at an unclear risk of bias for the patient selection domain. Only one study48 reported the method used for patient inclusion. There was an overall lack of information regarding patient eligibility for participation in the studies, and whether or not any patients were excluded at the stage of study selection. All of the included studies were judged as having a high applicability concern for patient selection as none of these studies was performed in the population of interest. One study38 included a proportion (3.4%) of patients admitted to a cardiology department because of symptomatic AF; however, all of these patients had a known history of AF.

Three studies45,50,51 were judged as having an unclear risk of bias in the index test domain because there was lack of information regarding whether or not the index tests were interpreted without knowledge of the reference standard test result. The remaining six studies38,39,43,47–49 were judged as having a low risk of bias on the index test domain. Studies in which the index test was interpreted by a trained health-care professional were judged to be more applicable (low concern)38,39,43,45 than those interpreted by the lead-I ECG device algorithm alone. 47–49 Two studies50,51 were judged as having an unclear applicability concern because of a lack of information in the publication.

Three studies45,50,51 were judged as having an unclear risk of bias for the reference standard domain because they did not explicitly report whether or not the interpreters of the reference standard were blinded to the results of the index test. The reference standard for all of the included studies was the results of a 12-lead ECG, which were interpreted by a trained health-care professional; therefore, all of the studies were judged to have a low concern regarding applicability of the reference standard.

Risk of bias was judged as being unclear for three studies39,49,50 for the flow and timing domain because not all patients were included in the study analyses.

Diagnostic test accuracy results

Interpreter of lead-I electrocardiogram: trained health-care professional

All lead-I electrocardiogram devices: main analysis

We investigated the sensitivity and specificity of a lead-I ECG device when the trace was interpreted by a trained health-care professional and the reference standard was a 12-lead ECG interpreted by a trained health-care professional. Data from four studies38,39,43,45 were included in a meta-analysis. Two studies39,45 had data for Kardia Mobile alone, one study43 had data for Zenicor-ECG and one study38 had data for MyDiagnostick and Kardia Mobile. One additional study51 had data for Kardia Mobile but was not included in the pooled analysis because the numbers of true-positive, false-negative, false-positive and true-negative test results were not reported. The sensitivity and specificity values reported in this study51 were 92.8% and 100%, respectively.

Four meta-analyses were conducted to investigate the impact of using data for each combination of type of lead-I ECG device (MyDiagnostick or Kardia Mobile) and interpreter (EP1 or EP2) from the Desteghe et al. study38 from the results of the meta-analysis. Both EPs interpreted the lead-I ECG trace and the 12-lead ECG trace. The data based on the use of Kardia Mobile lead-I ECG device and interpretation by EP1 were randomly selected to be included in the main analysis. Additional meta-analyses are presented as sensitivity analyses (see Appendix 6, Figure 13).

One study39 reported data for one lead-I device (Kardia Mobile) and two different interpreters (a cardiologist and a GP with an interest in cardiology) of lead-I and 12-lead ECG traces. The data interpreted by the cardiologist were used in the main analysis because the interpreters in the other included studies were either cardiologists or EPs. The analysis with data interpreted by the GP is presented as a sensitivity analysis (see Appendix 6, Figure 17).

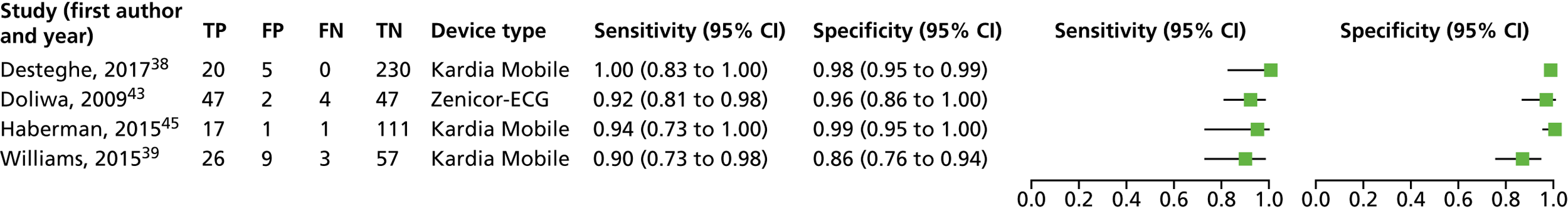

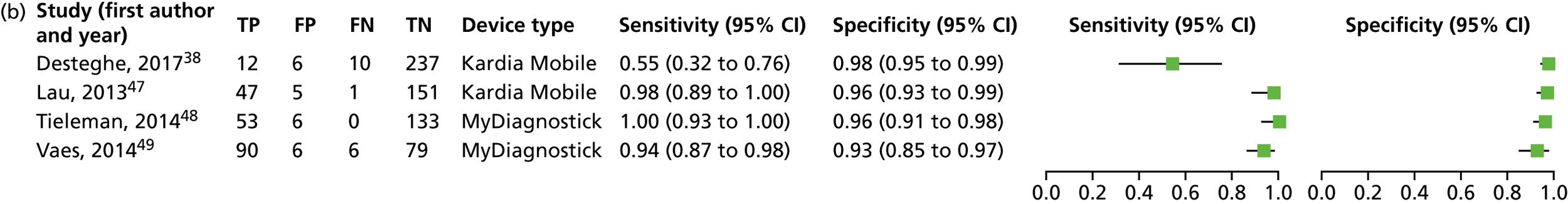

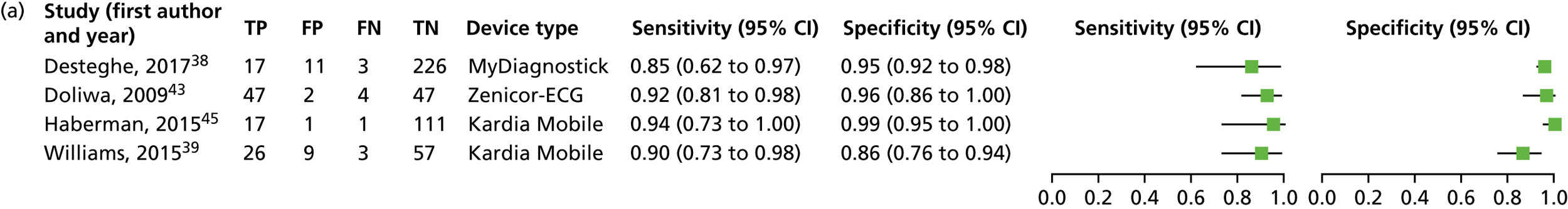

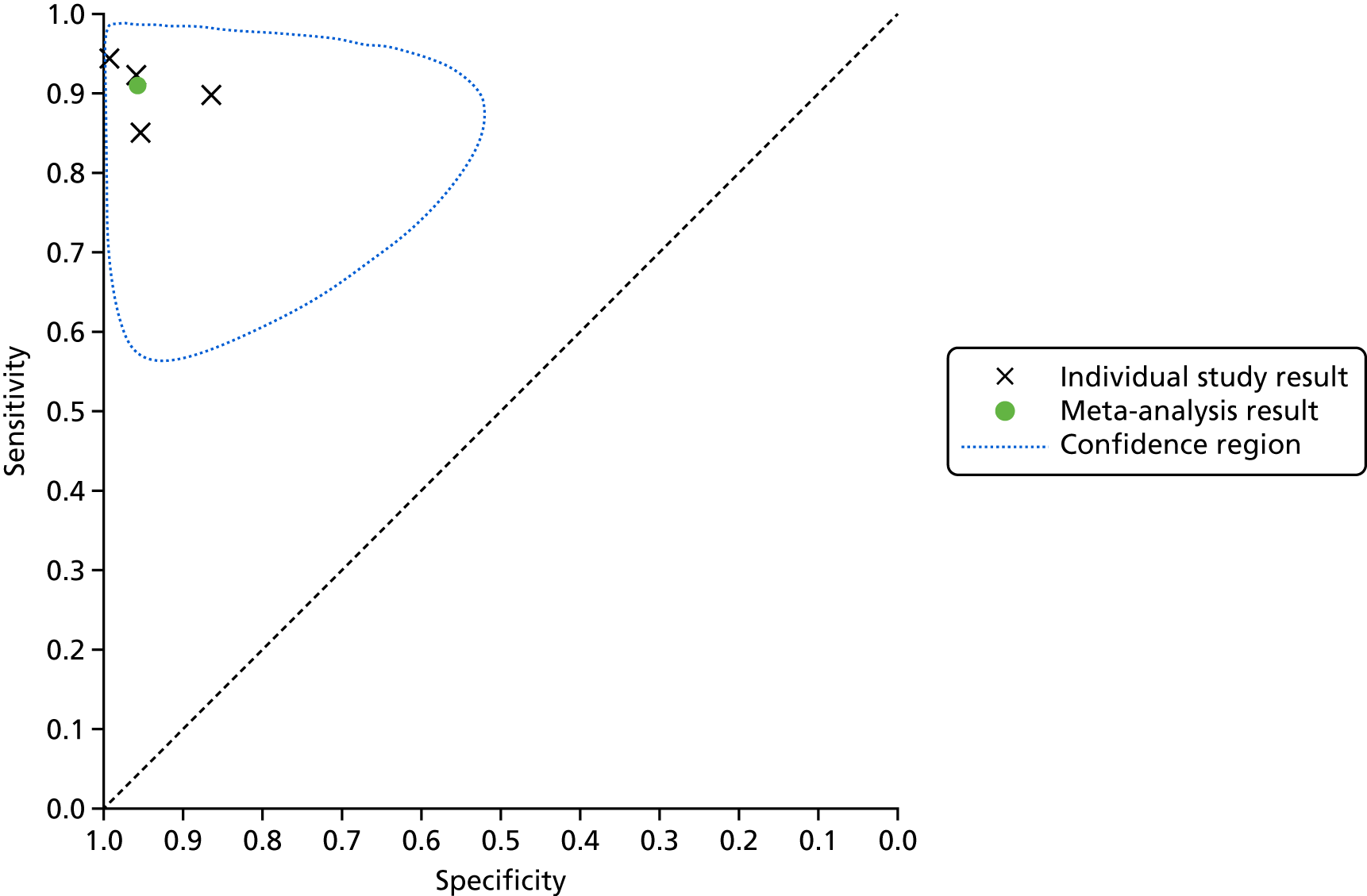

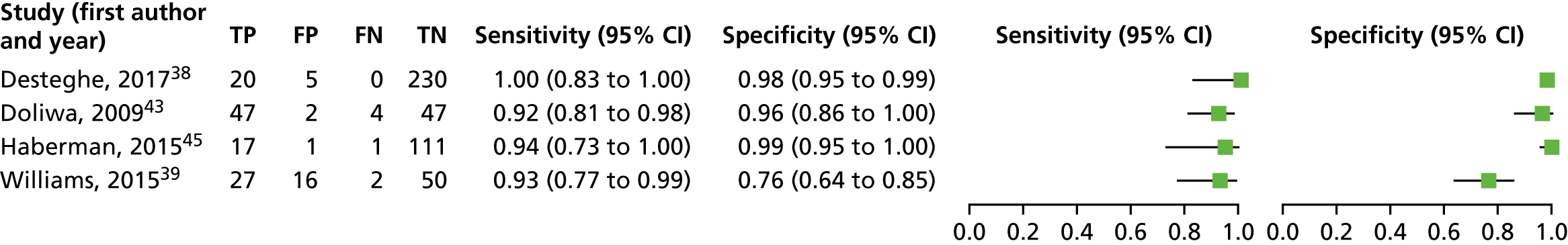

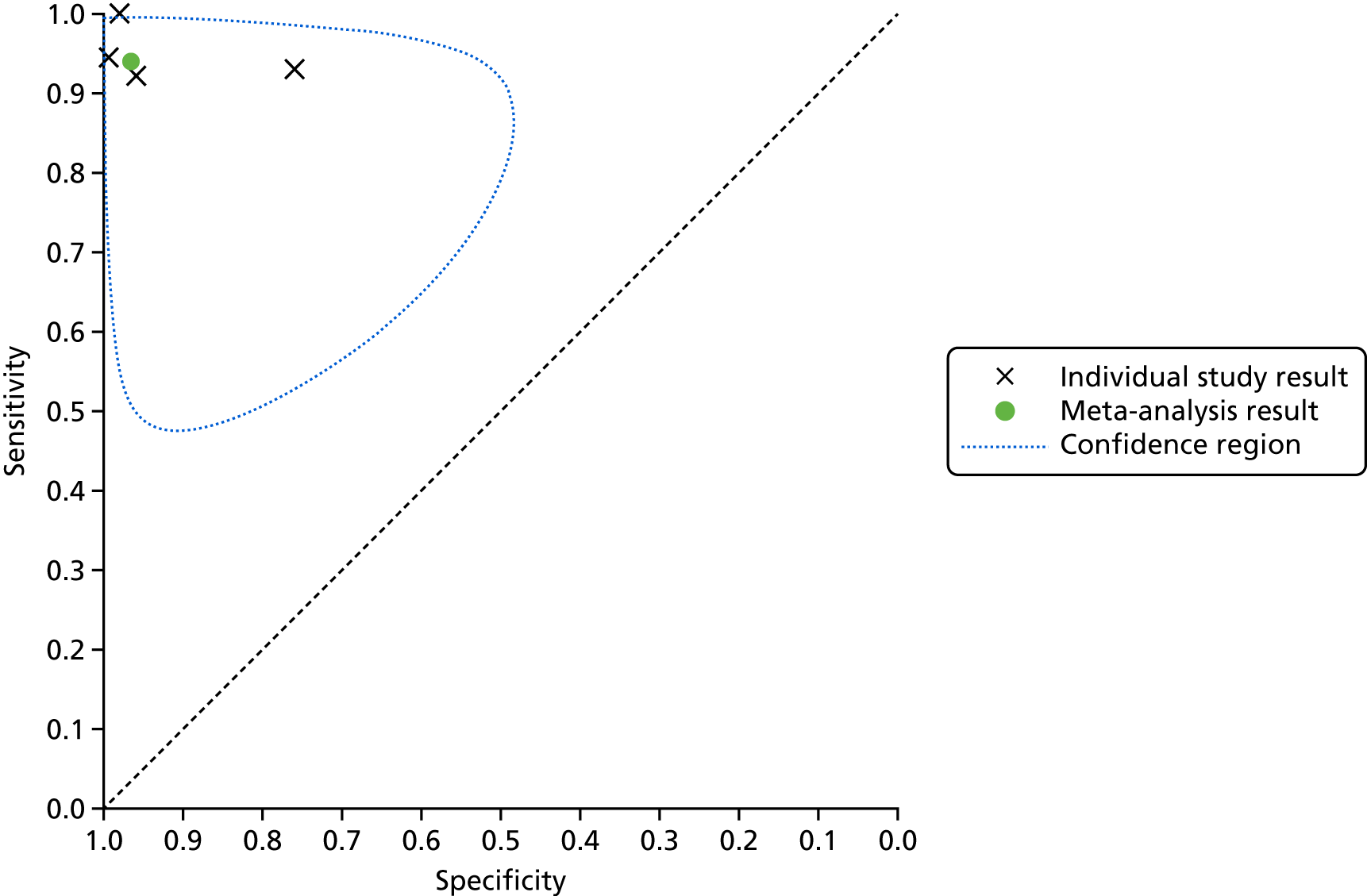

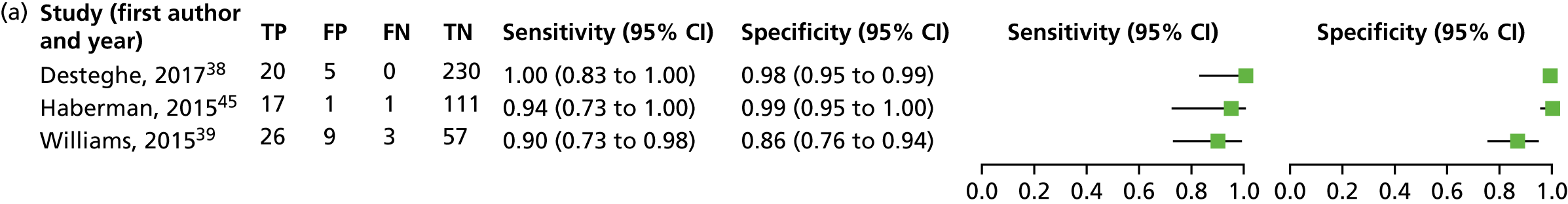

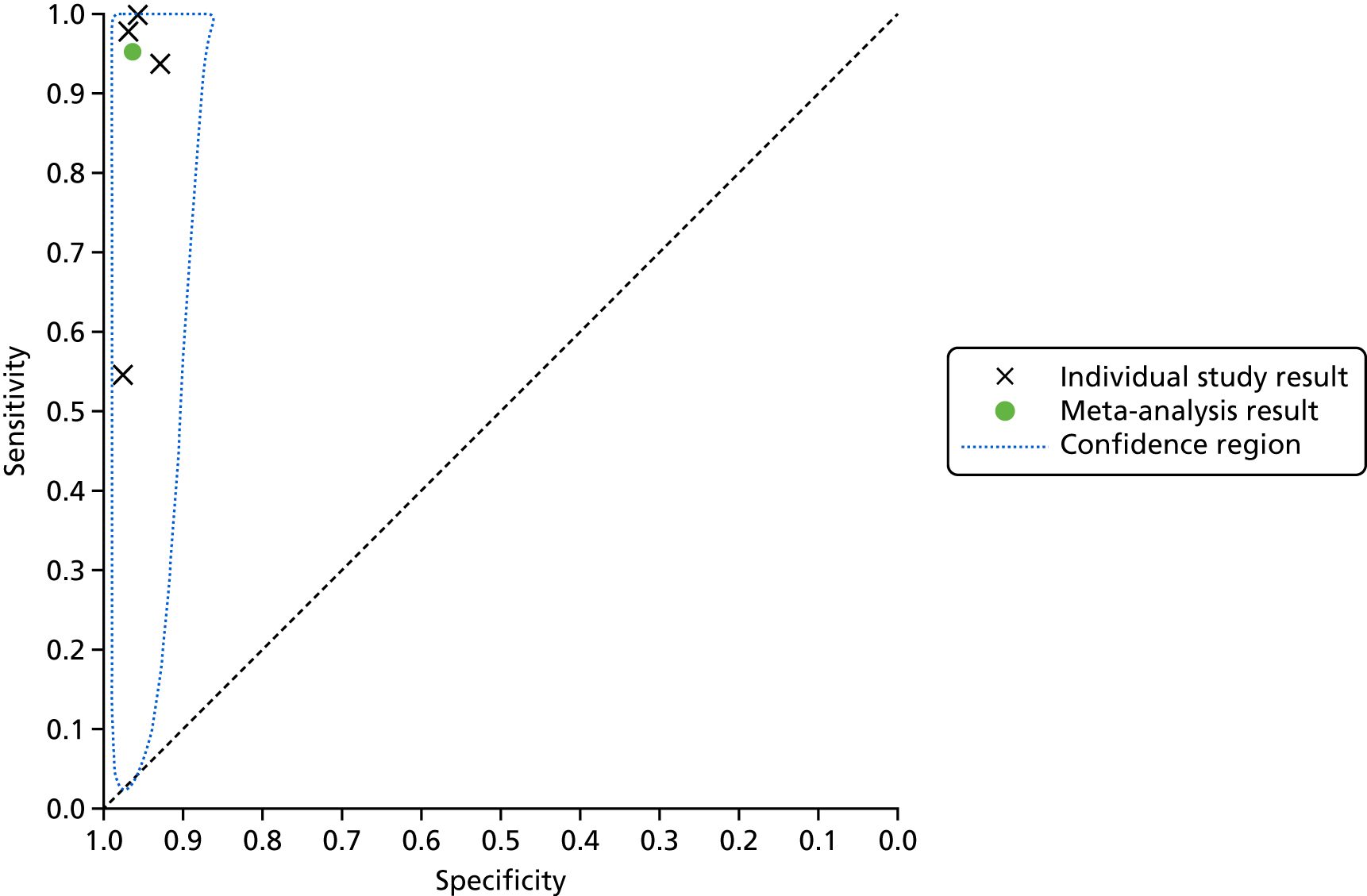

A forest plot displaying the results of the individual studies included in the meta-analysis is presented in Figure 4.

FIGURE 4.

Forest plot of individual studies included in the meta-analysis of all lead-I ECG devices; trace interpreted by a trained health-care professional (Kardia Mobile and EP1 data from the Desteghe study). FN, false negative; FP, false positive; TN, true negative; TP, true positive. Reproduced from Duarte et al. 67 © The Authors, 2019. This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

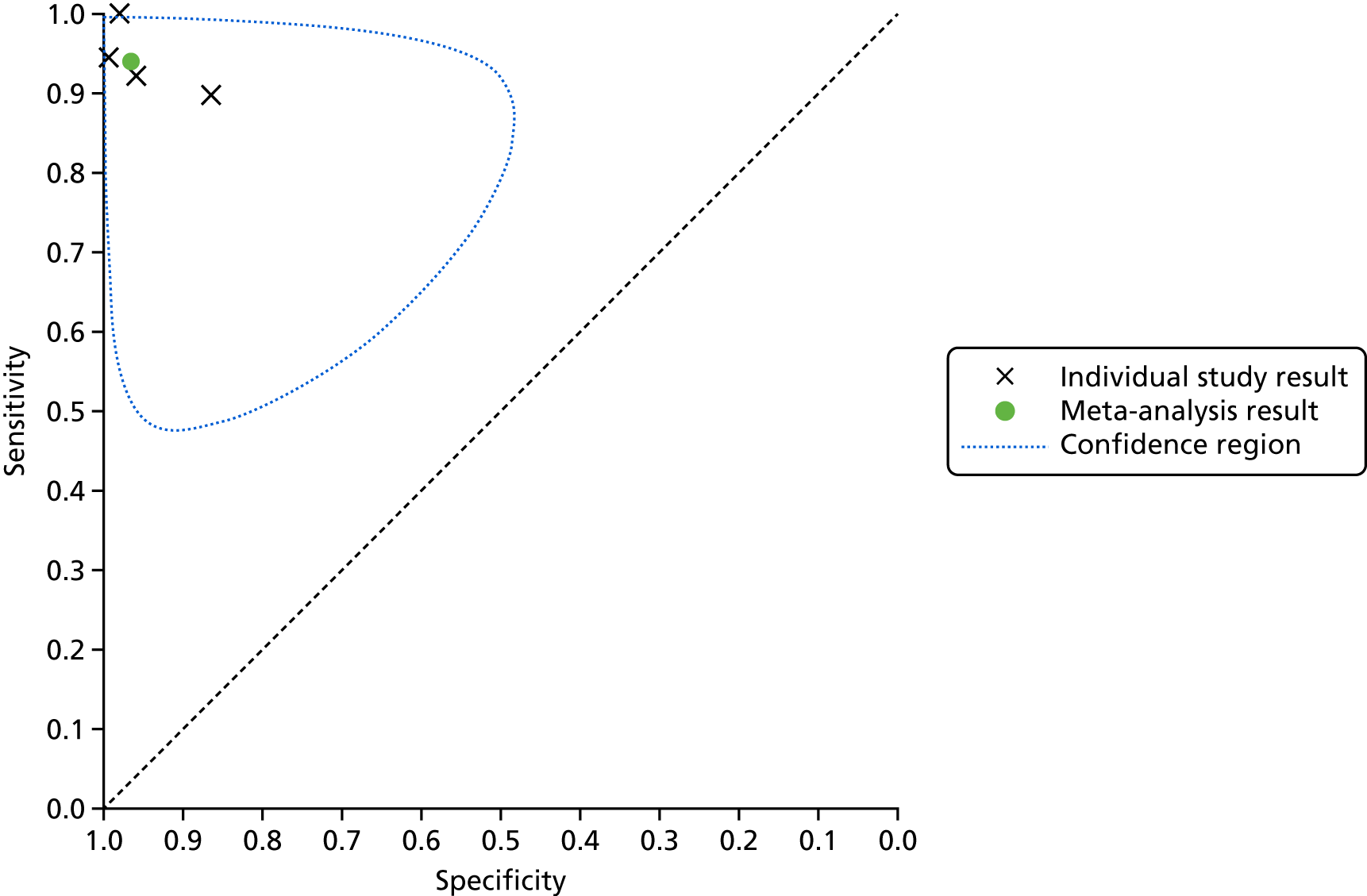

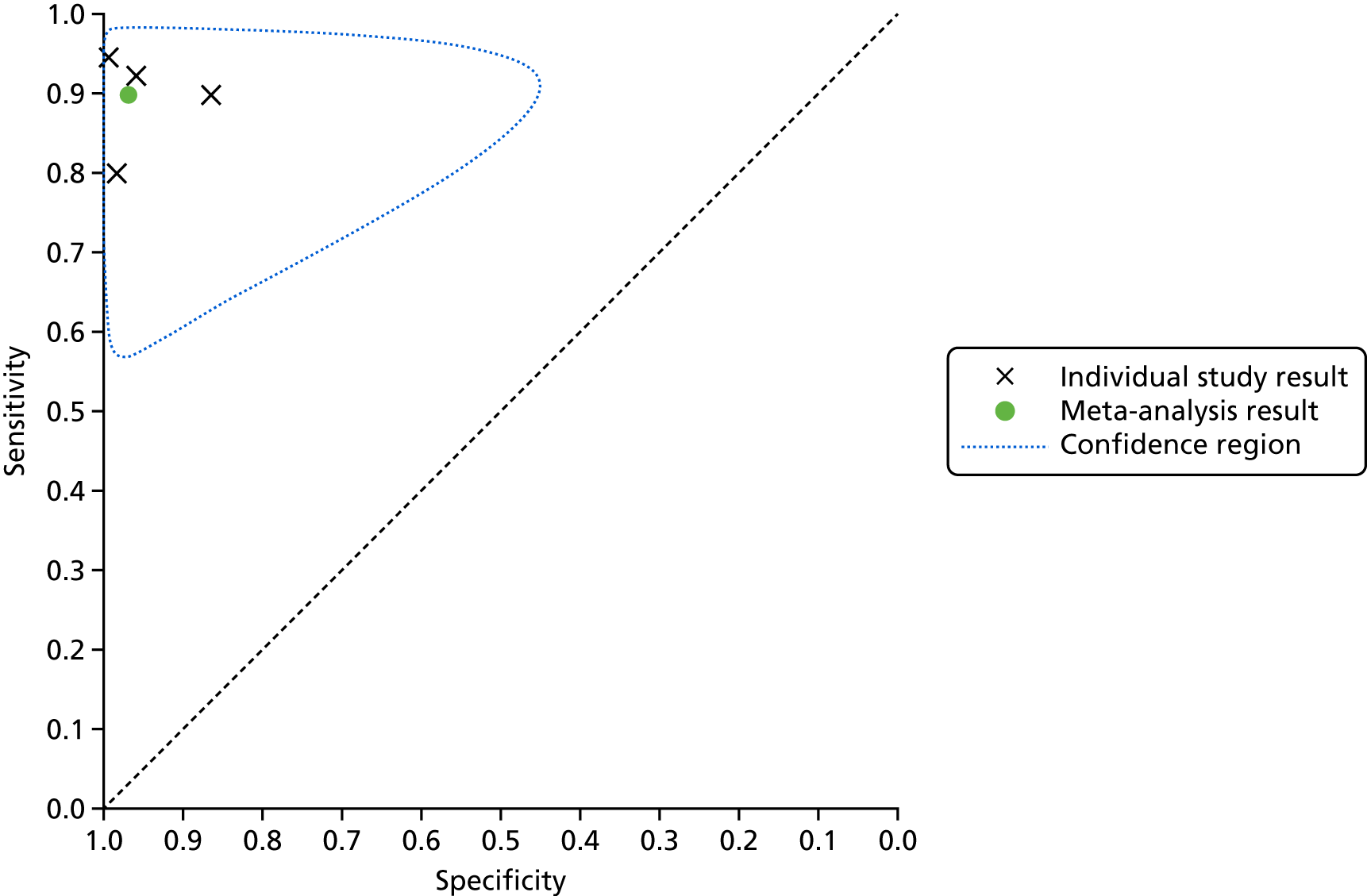

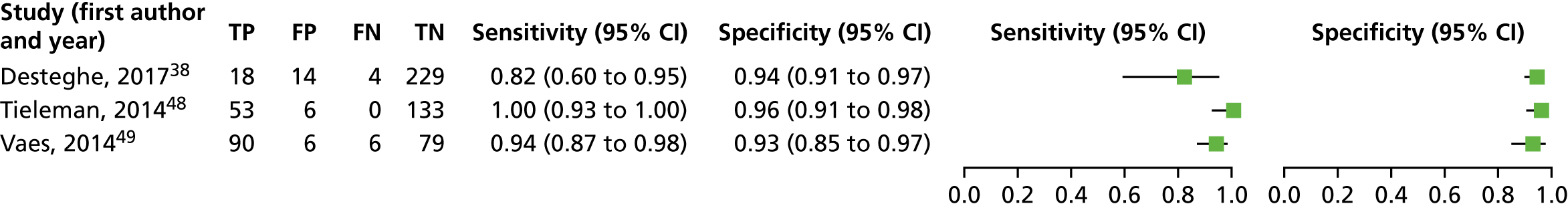

A SROC plot that displays the individual study results as well as the meta-analysis result is presented in Figure 5. A visual inspection of Figure 4 and the individual study results presented in Figure 5 shows that the results were relatively homogeneous across the included studies in this meta-analysis. However, owing to some potential heterogeneity between studies, we adopted a conservative approach and used a bivariate model with random effects in the meta-analysis.

FIGURE 5.

Summary receiver operating characteristic plot for lead-I ECG device as index test with trace interpreted by a trained health-care professional and 12-lead ECG interpreted by a trained health-care professional as reference standard (using Kardia Mobile lead-I ECG device and EP1 data from the study by Desteghe et al. 38).

This meta-analysis included 580 participants, of whom 118 had AF. The pooled sensitivity was 93.9% (95% CI 86.2% to 97.4%) and the pooled specificity was 96.5% (95% CI 90.4% to 98.8%).

All lead-I electrocardiogram devices: sensitivity analyses

Forest plots displaying the results of the individual studies included in the meta-analyses are presented in Appendix 6, Figure 13.

Summary receiver operating characteristic plots are presented in Appendix 6, Figure 14. A visual inspection of the forest plots (see Appendix 6, Figure 13) and the individual study results (see Appendix 6, Figure 14) shows that the results were relatively homogeneous across the included studies in these meta-analyses. However, owing to some potential heterogeneity between studies, we adopted a conservative approach and used a bivariate model with random effects in the meta-analysis.

Pooled sensitivity values from these additional meta-analyses ranged from 89.8% to 91.8%, while pooled specificity values ranged from 95.6% to 97.1% (Table 5). Overall, the use of either Kardia Mobile or MyDiagnostick lead-I ECG and an interpretation by different EPs does not seem to make a difference to the pooled results. Considering only the study by Desteghe et al. ,38 specificity is similar across all combinations, whereas the sensitivity of Kardia Mobile seems higher than the sensitivity of MyDiagnostick and EP1 seems to show slightly higher sensitivity than EP2.

| Data input from the study by Desteghe et al.38 | AF cases (n) | Total number of patients (N) | Pooled sensitivity (95% CI) | Pooled specificity (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MyDiagnostick device and EP1 data | 118 | 582 | 90.8% (83.8% to 95.0%) | 95.6% (89.4% to 98.3%) |

| MyDiagnostick device and EP2 data | 118 | 582 | 89.8% (82.7% to 94.1%) | 96.8% (90.6% to 99.0%) |

| Kardia Mobile device and EP2 data | 120 | 584 | 91.8% (85.1% to 95.7%) | 97.1% (90.8% to 99.1%) |

One study39 also presented data for one lead-I device (Kardia Mobile) that were interpreted by a GP with an interest in cardiology, and these data were included in a sensitivity analysis. The forest plot displaying the results of the individual studies included in the meta-analysis is presented in Appendix 6, Figure 17.

The SROC plot that shows the individual study results as well as the meta-analysis result is presented in Appendix 6, Figure 18. When the results presented in Appendix 6, Figure 17, and the individual study results presented in Appendix 6, Figure 18, were studied, they were found to be relatively homogeneous; however, in the study by Williams et al. ,39 specificity was lower when the lead-I ECG trace was interpreted by the GP (76%), than when it was interpreted by a cardiologist (86%) (see Figure 4). Owing to some potential heterogeneity between studies, we adopted a conservative approach and used a bivariate model with random effects in the meta-analysis.

For this meta-analysis (number of AF cases, 118; total number of patients, 580), the sensitivity was 94.3% (95% CI 87.9% to 97.4%) and the specificity was 96.0% (95% CI 85.4% to 99.0%).

Kardia Mobile lead-I electrocardiogram device

Data for the Kardia Mobile device were derived from only three studies. 38,39,45 We conducted two meta-analyses to investigate the impact of using data for each interpreter (EP1 or EP2) from the study by Desteghe et al. 38 on the results of the meta-analysis. Forest plots displaying the results of the individual studies included in each meta-analysis are presented in Appendix 6, Figure 19.

For both meta-analyses, we fitted a univariate random-effects logistic regression model for specificity and a univariate fixed-effects logistic regression model for sensitivity because minimal variability in sensitivity was observed across the studies.

For the meta-analysis that included EP1 data from the study by Desteghe et al. 38 (number of AF cases, 67; total number of patients, 480), sensitivity was 94.0% (95% CI 85.1% to 97.7%) and specificity was 96.8% (95% CI 88.0% to 99.2%). For the meta-analysis that included EP2 results from the study by Desteghe et al. 38 (number of AF cases, 69; total number of patients, 484), sensitivity was lower, at 91.3% (95% CI 82.0% to 96.0%), and specificity was slightly higher, at 97.4% (95% CI 88.3% to 99.5%). As only three studies38,39,45 were included in this analysis, it was not possible to produce confidence regions.

There were insufficient data to generate pooled estimates of sensitivity and specificity for other types of lead-I ECG device based on the interpreter of the lead-I ECG being a trained health-care professional, or to assess differences between types of devices. The sensitivity and specificity estimates for Zenicor-ECG and MyDiagnostick lead-I ECG devices are presented in Appendix 6, Figure 13.

Interpreter of lead-I electrocardiogram: algorithm

All lead-I electrocardiogram devices

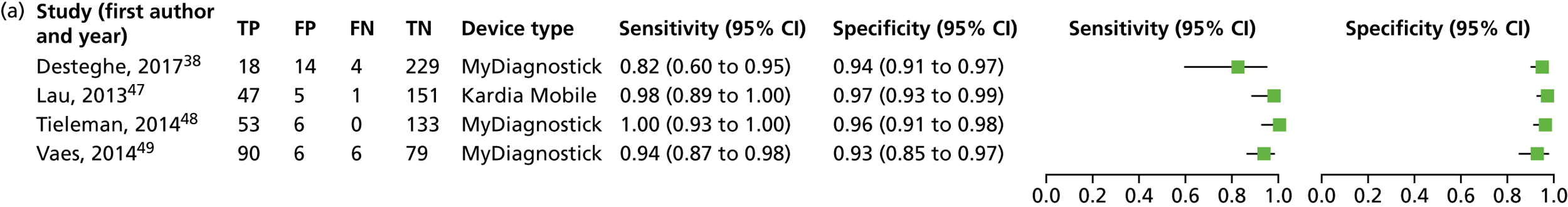

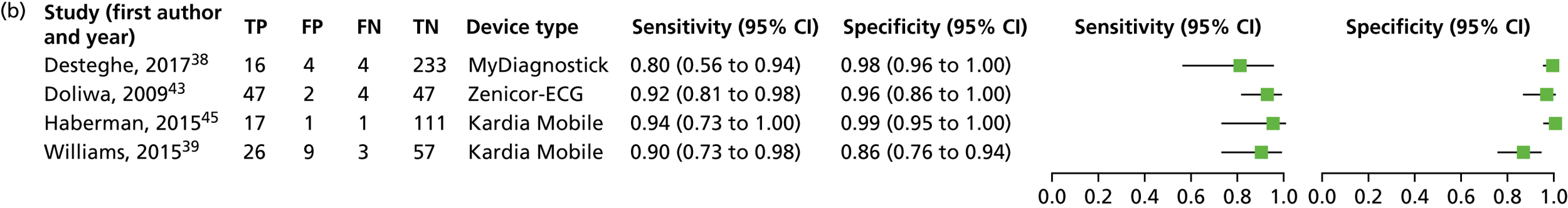

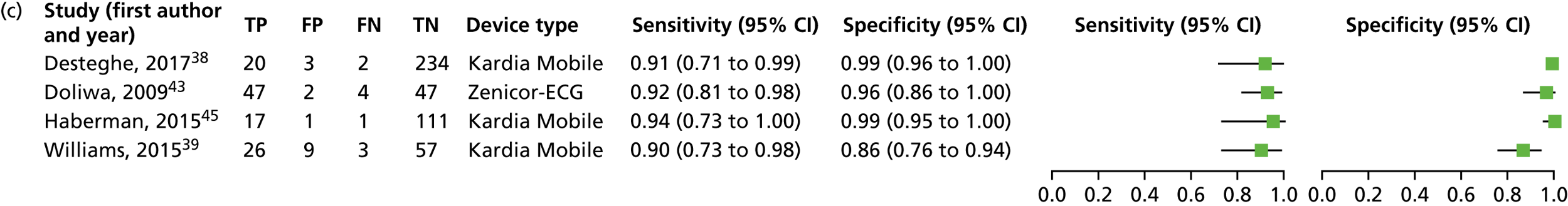

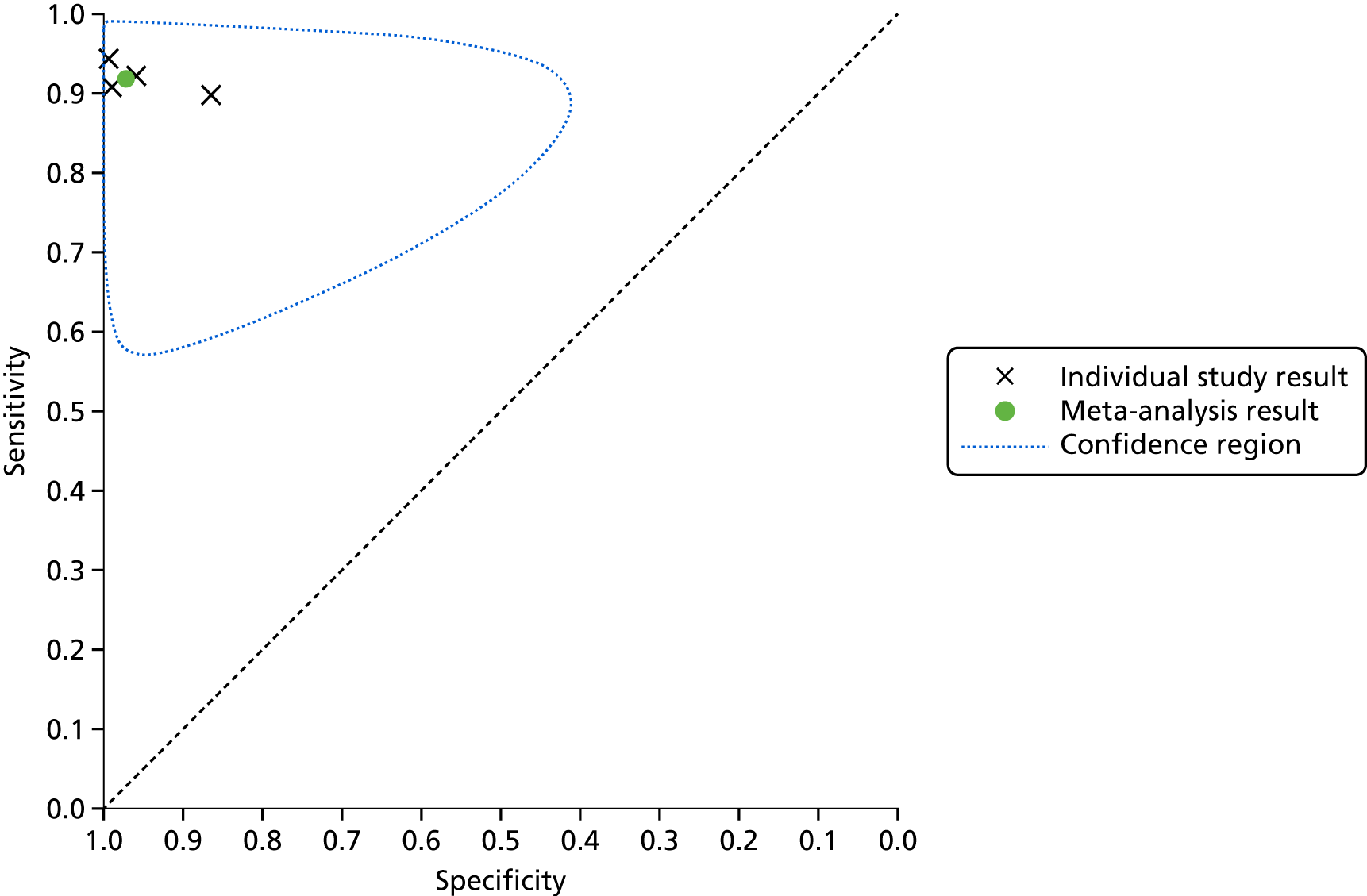

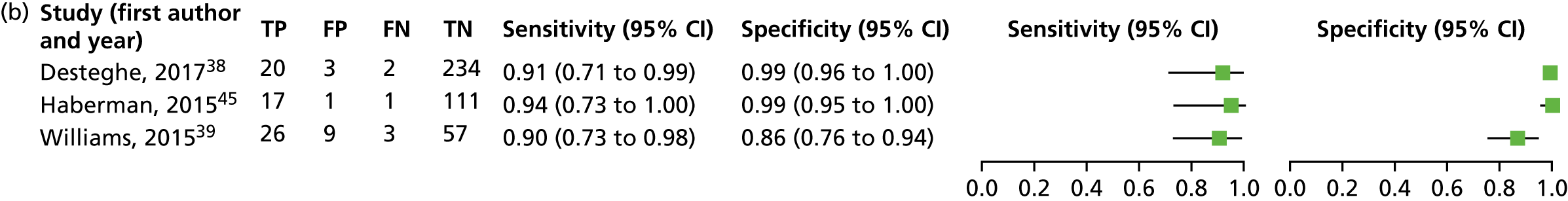

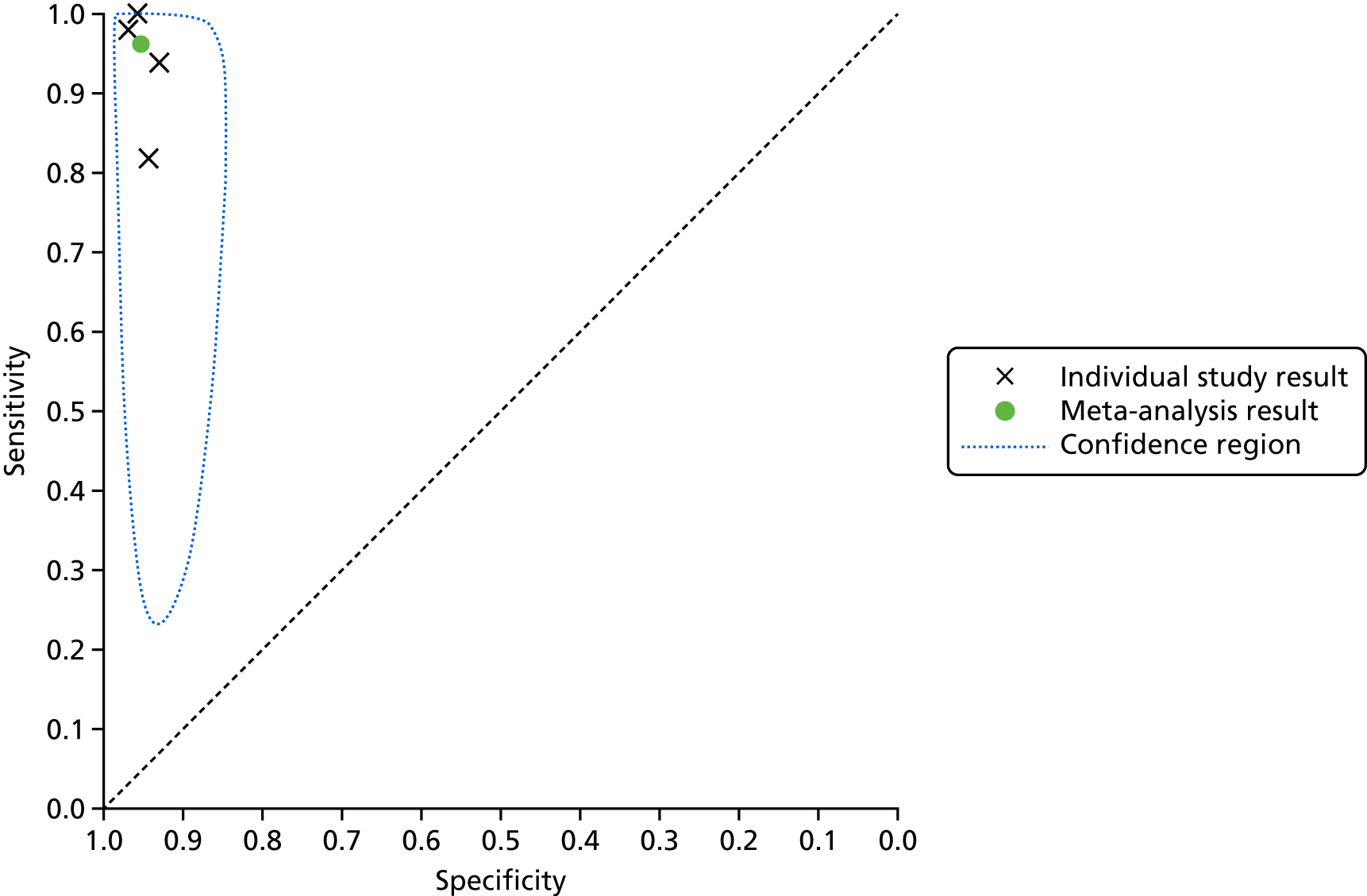

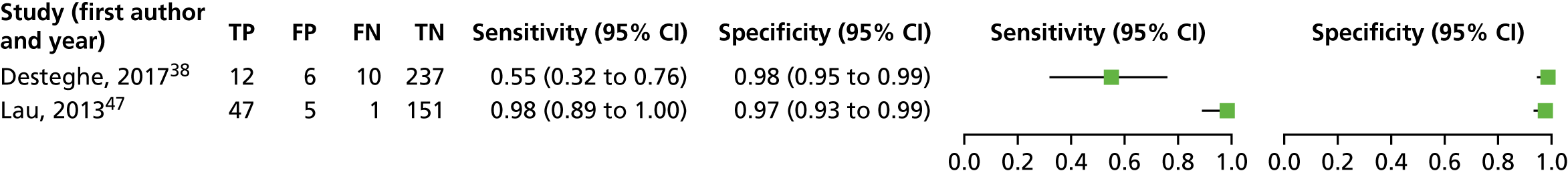

We investigated the sensitivity and specificity of the lead-I ECG device when the trace was interpreted by the device algorithm alone. The reference standard used was interpretation of the 12-lead ECG trace by a trained health-care professional. Data from four studies38,47–49 were included in a meta-analysis. Two studies48,49 had data for MyDiagnostick alone,48,49 one study47 had data for Kardia Mobile alone and one study38 had data for MyDiagnostick and Kardia Mobile. One study50 reported sensitivity (67%) and specificity (97%) for RhythmPad GP. Although the authors of this study50 provided the numbers for true-positive, false-negative, false-positive and true-negative test results, these were not included in the pooled analysis because the authors reported that the algorithm had since been modified (Chris Crockford, CardioCity, 3 August 2018, personal communication via NICE). We conducted two meta-analyses in order to investigate the impact of using data for each type of lead-I ECG device (MyDiagnostick or Kardia Mobile) from the study by Desteghe et al. 38 on the results of the initial meta-analysis. In the study by Desteghe et al. ,38 the same patient cohort was tested using both lead-I ECG devices. We performed multiple analyses in order to investigate the impact of varying the type of lead-I ECG device on the results of the overall pooled analysis with no set of patients double-counted. Forest plots displaying the results of the individual studies included in each meta-analysis are presented in Figure 6.

FIGURE 6.

Forest plots of individual studies included in each meta-analysis of all lead-I ECG devices (trace interpreted by the device algorithm). (a) MyDiagnostick data from the Desteghe study; and (b) Kardia Mobile data from the Desteghe study. FN, false negative; FP, false positive; TN, true negative; TP, true positive.

The SROC plots are presented in Appendix 6, Figures 20 and 21. The results were relatively homogeneous across the included studies in both meta-analyses. However, owing to some potential heterogeneity between studies, we adopted a conservative approach and used a bivariate model with random effects in the meta-analysis.

For the meta-analysis that included MyDiagnostick data from the study by Desteghe et al. 38 (number of AF cases, 219; total number of patients, 842), sensitivity was 96.2% (95% CI 86.0% to 99.0%) and specificity was 95.2% (95% CI 92.9% to 96.8%). For the meta-analysis that included Kardia Mobile data from the study by Desteghe et al. 38 (number of AF cases, 219; total number of patients, 842), the pooled estimates for sensitivity were 95.3% (95% CI 70.4% to 99.4%) and for specificity were 96.2% (95% CI 94.2% to 97.6%), which were similar to those obtained from the meta-analysis including MyDiagnostick data from the study by Desteghe et al. 38

MyDiagnostick lead-I electrocardiogram device

A forest plot displaying the results of the individual studies included in this meta-analysis is presented in Appendix 6, Figure 22.

As only three studies38,48,49 were included in this analysis, it was not possible to produce a SROC plot with a confidence region.

For MyDiagnostick, data from three studies38,48,49 (number of AF cases, 171; total number of patients, 638) were included in the meta-analysis; sensitivity was 95.2% (95% CI 79.0% to 99.1%) and specificity was 94.4% (95% CI 91.9% to 96.2%). For this meta-analysis, we fitted a univariate random-effects logistic regression model for sensitivity and a univariate fixed-effect logistic regression model for specificity because minimal variability in specificity was observed across the studies. The results were relatively homogeneous across the three included studies.

Kardia Mobile lead-I electrocardiogram device

We estimated sensitivity and specificity for the Kardia Mobile device, and for the MyDiagnostick device separately. A forest plot displaying the results of the individual studies included in this meta-analysis is presented in Appendix 6, Figure 23. In the study by Desteghe et al. ,38 sensitivity was 55% (95% CI 32% to 76%), much lower than that in the study by Lau et al. ,47 which was 98% (95% CI 89% to 100%).

As only two studies38,47 were included in this analysis, it was not possible to produce a SROC plot with a confidence region.

For Kardia Mobile, data from two studies (number of AF cases, 70; total number of patients, 469) were included in the meta-analysis; sensitivity was 88.0% (95% CI 32.3% to 99.1%), and specificity was 97.2% (95% CI 95.1% to 98.5%). For this meta-analysis, we fitted a univariate random-effects logistic regression model for sensitivity and a univariate fixed-effect logistic regression model for specificity, because minimal variability in specificity was observed across the studies.

Data were not sufficient to pool estimates of sensitivity and specificity for other types of lead-I device based on the interpreter of the lead-I ECG being a trained health-care professional, or to formally assess the differences between types of devices.

Summary of findings: diagnostic test accuracy

No studies were identified that evaluated the DTA of lead-I ECG devices in people presenting to primary care with signs or symptoms of AF and an irregular pulse.

Of the nine included studies, only one study49 was conducted in primary care. The remaining eight studies were conducted in secondary care, tertiary care or community settings.

Of the nine included studies, only one study38 explicitly stated that some patients (n = 11, 3.4%) had signs or symptoms of AF on admission to a cardiology ward. Another study49 included a large proportion of people with known AF (83.4%); however, it is not clear whether or not the patients had signs or symptoms of AF at the time of the assessment and/or if the patients had been previously diagnosed with AF.

As prespecified in the protocol,68 owing to a lack of evidence, we next focused the reviews on an asymptomatic population in any health-care setting. We considered an asymptomatic population to be people not presenting with signs or symptoms of AF, with or without a previous diagnosis of AF. These patients could have had co-existing cardiovascular conditions or could have been attending a cardiovascular clinic but did not present with signs or symptoms of AF. We identified 13 publications38,39,41–51 reporting on nine studies assessing the DTA of lead-I ECG devices in an asymptomatic population. However, all of these studies were judged as having a high applicability concern for patient selection, as none was performed in the population and setting of interest.

We included studies in which the interpreter of the lead-I ECG trace was a trained health-care professional38,39,43,45,51 and studies that included interpretations of the lead-I ECG trace by the lead-I ECG device algorithm only. 38,47–50 The lead-I ECG devices used in the studies were Kardia Mobile,39,45,47 MyDiagnostick48,49 and Zenicor-ECG. 43 The study by Desteghe et al. 38 used both Kardia Mobile and MyDiagnostick.

The results from the meta-analyses are summarised in Table 6. Across all meta-analyses where the interpreter of the lead-I ECG trace was a trained health-care professional, the sensitivity ranged from 89.8% to 94.3% and the specificity ranged from 95.6% to 97.4%. Across all meta-analyses where the interpreter of the lead-I ECG trace was the device algorithm, the sensitivity ranged from 88% to 96.2% and the specificity ranged from 94.4% to 97.2%. Pooled sensitivity and specificity values were similar across the different meta-analyses, irrespective of the interpreter of the lead-I ECG trace or the lead-I ECG device used. However, it should be noted that studies in which the index test was interpreted by the lead-I ECG device algorithm alone were judged as having a high applicability concern for the index test domain. This judgement was based on the consideration made by all manufacturers of the lead-I ECG devices that the diagnosis of AF should not be made using the algorithm alone, and that the ECG traces measured by the devices should be reviewed by a qualified health-care professional.

| Data input from the Desteghea and Williamsb studies | Studies of lead-I ECG devices in the meta-analyses (n) | AF cases (n) | Total number of patients (N) | Pooled sensitivity (95% CI) | Pooled specificity (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lead-I ECG trace interpreted by a trained health-care professional (main analysis) | |||||

| Kardia Mobile device, EP1a and cardiologistb data | Kardia Mobile (3), Zenicor-ECG (1) | 118 | 580 | 93.9% (86.2% to 97.4%) | 96.5% (90.4% to 98.8%) |

| Lead-I ECG trace interpreted by a trained health-care professional (sensitivity analyses, cardiologist datab) | |||||

| MyDiagnostick device and EP1a data | Kardia Mobile (2), Zenicor-ECG (1), MyDiagnostick (1) | 118 | 582 | 90.8% (83.8% to 95.0%) | 95.6% (89.4% to 98.3%) |

| MyDiagnostick device and EP2 data | Kardia Mobile (2), Zenicor-ECG (1), MyDiagnostick (1) | 118 | 582 | 89.8% (82.7% to 94.1%) | 96.8% (90.6% to 99.0%) |

| Kardia Mobile device and EP2a data | Kardia Mobile (3), Zenicor-ECG (1) | 120 | 584 | 91.8% (85.1% to 95.7%) | 97.1% (90.8% to 99.1%) |

| Lead-I ECG trace interpreted by a trained health-care professional (sensitivity analyses, GP datab) | |||||

| Kardia Mobile device, EP1a and GPb data | Kardia Mobile (3), Zenicor-ECG (1) | 118 | 580 | 94.3% (87.9% to 97.4%) | 96.0% (85.4% to 99.0%) |

| Lead-I ECG trace interpreted by a trained health-care professional (sensitivity analyses, Kardia Mobile) | |||||

| Kardia Mobile device and EP1a data | Kardia Mobile (3) | 67 | 480 | 94.0% (85.1% to 97.7%) | 96.8% (88.0% to 99.2%) |

| Kardia Mobile device and EP2a data | Kardia Mobile (3) | 69 | 484 | 91.3% (82.0% to 96.0%) | 97.4% (88.3% to 99.5%) |

| Lead-I ECG trace interpreted by lead-I ECG device algorithm alone | |||||

| MyDiagnostick devicea data | Kardia Mobile (1), MyDiagnostick (3) | 219 | 842 | 96.2% (86.0% to 99.0%) | 95.2% (92.9% to 96.8%) |

| Kardia Mobile devicea data | Kardia Mobile (2), MyDiagnostick (2) | 219 | 842 | 95.3% (70.4% to 99.4%) | 96.2% (94.2% to 97.6%) |

| MyDiagnostick device only | MyDiagnostick (3) | 171 | 638 | 95.2% (79.0% to 99.1%) | 94.4% (91.9% to 96.2%) |

| Kardia Mobile device only | Kardia Mobile (2) | 70 | 469 | 88.0% (32.3% to 99.1%) | 97.2% (95.1% to 98.5%) |

Details of the excluded studies that report sensitivity and specificity values for the lead-I ECG devices investigated in this assessment, and the reasons for exclusion, are presented in Appendix 7.

Assessment of clinical impact

Characteristics of the included studies

The characteristics of the 18 quantitative studies included in the clinical impact review are summarised in Table 7. One qualitative study53 included in the clinical impact review reported the results of semistructured interviews with patients, receptionists, practice nurses and GPs.

| Study (first author, year) | Study design; country and setting | Population; number in analysis and recruitment details | Mean age and SD (years); sex; risk factors for AF | Lead-I ECG device | Interpreter of lead-I ECG | Test sequence |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Battipaglia, 201652 | Cross-sectional; UK; community | General population without known AF or implanted pacemaker; N = 855; campaign for rhythm awareness in a shopping centre | NR | MyDiagnostick | Cardiologist | NA |

| Chan, 201756 | Cross-sectional; China; community | People aged ≥ 18 years; N = 13,122; screening programme publicised via channels including media promotion and placement of posters in community centres by non-governmental organisations |

64.7 ± 13.4; female, n = 9384 (71.5%) Hypertension: n = 5012 (38.2%) Diabetes: n = 1944 (14.8%) Hyperlipidaemia: n = 2613 (19.9%) Heart failure: n = 97 (0.7%) Stroke: n = 367 (2.8%) Coronary artery disease: n = 295 (2.2%) Valvular heart disease: n = 114 (0.9%) Peripheral vascular disease: n = 66 (0.5%) Obstructive sleep apnoea: n = 146 (1.1%) Thyroid disease: n = 517 (3.9%) COPD: n = 56 (0.4%) Cardiothoracic surgery: n = 354 (2.7%) |

Kardia Mobile | Cardiologist | NA |

| Chan, 201657 | Cross-sectional; China; primary care | People with history of hypertension and/or diabetes mellitus or aged ≥ 65 years; N = 1013; patients recruited from a general outpatient clinic |

68.4 ± 12.2; Sex: 539 (53.2%) female Hypertension: n = 916 (90.4%) Diabetes: n = 371 (36.6%) Coronary artery disease: n = 164 (16.2%) Previous stroke: n = 106 (10.5%) Mean CHA2DS2-VASc ± SD – 3.0 ± 1.5 |

Kardia Mobile | Algorithm and cardiologist | 12-lead ECG performed only when a diagnosis of AF was made by the algorithm (results not presented) |

| Chan, 201754 | Cross-sectional; Hong Kong; primary care | Patients aged ≥ 65 years attending primary care clinics; N = 1041; NR |

Aged ≥ 65 years; NR |

Kardia Mobile | Cardiologist | NA |

| Desteghe, 201738 | Case–control; Belgium; tertiary care | Inpatients at cardiology ward; N = 265; NR |

67.9 ± 14.6; female, n = 138 (43.1%); Pacemaker: 4 out of 55 (7.3%) were intermittently paced, and 18 out of 55 (32.7%) were not being paced during the recordings Known AF: 114 out of 320 (35.6%) AF at time of study: 11.9% (on 12-lead ECG) Paroxysmal AF: 54.4% |

MyDiagnostick and Kardia Mobile | Algorithm and EP | 12-lead ECG followed by lead-I ECG (order for the use of the different lead-I ECG tests not specified) |

| Doliwa, 200943 | Case–control; Sweden; secondary care | People with atrial fibrillation, atrial flutter or sinus rhythm; N = 100; patients were recruited from a cardiology outpatient clinic | NR | Zenicor-ECG | Cardiologist | 12-lead ECG followed by lead-I ECG |

| Gibson, 201758 | Cross-sectional; UK; primary care | Patients aged ≥ 65 years without a diagnosis of AF, attending a practice nurse or health-care assistant clinic; N = 445; NR | NR | MyDiagnostick | Algorithm | NA |

| Haberman, 201545 | Case–control; USA; community and secondary care | Healthy young adults, elite athletes and cardiology clinic patients; N = 130; NRa | 59 ± 15; male, n = 73 (56%); NR | Kardia Mobile | EP | Lead-I ECG followed by 12-lead ECG |

| Hussain, 201659 | Cross-sectional; UK; primary care | Patients attending a flu clinic; N = 357; lead-I ECG used while patients waited for flu vaccination |

Aged > 65 years: n = 257; NR |

Kardia Mobile | GP | NA |

| Kaasenbrood, 201660 | Case–control; Netherlands; primary care | Patients aged ≥ 60 years with and without known AF attending for flu vaccination; N = 3269; asked by nurses |

69.4 ± 8.9; male, n = 1602 (49%); NR |

MyDiagnostick | Algorithm and cardiologist | NA |

| Koltowski, 201751 | Cross-sectional; Poland; tertiary care | Patients in a tertiary care centre; N = 100; NR | NR | Kardia Mobile | Cardiologist | Lead-I ECG followed by 12-lead ECG |

| Lau, 201347 | Case–control; Australia; secondary care | Patients at cardiology department; N = 204; NR |

NR; Known AF: n = 48 (24%) |

Kardia Mobile | Algorithm | Lead-I ECG followed by 12-lead ECG |

| Lowres, 201461 | Cross-sectional; Australia; community | People aged ≥ 65 years entering the pharmacy without a severe coexisting medical condition; N = 1000; availability of screening in participating pharmacies was advertised through flyers displayed within each pharmacy, and pharmacists and staff also directly approached potentially eligible clients |

76 ± 7; male, n = 436 (44%); NR |

Kardia Mobile | Algorithm and cardiologist | Pulse palpation followed by lead-I ECG (12-lead ECG used for participants with suspected unknown AF indicated by lead-I device) |

| Orchard, 201662 | Case–control; Australia; primary care | Patients with known AF and patients without a history of AF attending for flu vaccination; N = 972 |

New AF: n = 7; 80 ± 3; male; 3 out of 7 male; Known AF: n = 29; 77.1 ± 1; male; n = 15 (52%) All AF (N = 36); 78 years ± 1; male, n = 18 (50%); NR |

Kardia Mobile | Algorithm and cardiologist | Lead-I ECG followed by 12-lead ECG in cases where AF was detected by lead-I (and was a new diagnosis) |

| Reeves, (NR)63 | Cross-sectional; UK; secondary care | Patients aged ≥ 18 years recovering in the cardiac intensive care unit or a cardiac surgery ward, following cardiac surgery, or who had been admitted to the coronary care unit or a cardiology ward after a cardiac related event; N = 53; research nurses working in one or other of the clinical settings identified and approached eligible patients |

23–90 (range); male, n = 37 (70%); NR |

imPulse | Two cardiology registrars, two cardiac physiologists and two specialist cardiac nurses | Lead-I ECG and 12-lead ECG recorded simultaneously |

| Tieleman, 201448 | Case–control; Netherlands; secondary care | Patients with known AF and patients without a history of AF visiting an outpatient cardiology clinic or a specialised AF outpatient clinic; N = 192; random selection of patients due to have a 12-lead ECG |

69.4 ± 12.6; male, 48.4%; NR |

MyDiagnostick | Algorithm | Lead-I ECG followed by 12-lead ECG |

| Primary care | People with unknown AF status; N = 676; people attending GP for flu vaccination |

74 ± 7.1; NR |

MyDiagnostick | Algorithm and cardiologist | NA | |

| Waring, 201664 | Cross-sectional; UK; community | People aged ≥ 65 years; N = 1153; NR | NR | Kardia Mobile | Cardiologist | NA |

| Yan, 201665 | Cross-sectional; Hong Kong; secondary care | People aged ≥ 65 years without a history of AF; N = 9046; consecutive patients attending clinics |

79 ± 12.1; male, 49.4%; NR |

Kardia Mobile | Cardiologist | NA |

Eleven of the studies included in the clinical impact review were cross-sectional studies,51,52,54,56–59,61,63–65 seven were case–control studies38,43,45,47,48,60,62 and one study was qualitative. 53 Seven studies were conducted in primary care,53,54,57–60,62 five were conducted in secondary care,43,47,48,63,65 two were conducted in tertiary care38,51 and the remaining four were conducted in a community setting. 52,56,61,64 One study45 included participants recruited from secondary care, but also included (as separate groups) elite athletes and healthy young adults. As discussed in Characteristics of the included studies, the results for these populations45 were excluded from the analysis as these participants did not meet our inclusion criterion for population and do not represent the typical population with AF (i.e. those aged ≥ 75 years).

Four studies included only people without known AF. 52,58,61,65 Three studies54,59,64 may have included only people without known AF as either participants were attending a primary care clinic or the study was conducted in a community setting. However, these studies were available only as conference abstracts and did not provide sufficient information to enable us to determine whether or not the population had a history of AF. The remaining 11 studies38,43,45,47,48,51,56,57,60,62,63 recruited people with known AF or cardiovascular comorbidities or who were attending a clinic for cardiovascular-related reasons.

Quality assessment

The methodological quality of the four cross-sectional52,56,57,61 and the two case–control studies60,62 included in the clinical impact review of lead-I ECG devices, was assessed using the Newcastle–Ottawa quality assessment scale. 33,34 The results of the quality assessment of cross-sectional and case–control studies are presented in Appendix 8, Table 40.

The methodological quality of the diagnostic accuracy studies included in the clinical impact review was assessed using the QUADAS-2 tool. 32 A summary of the results for the risk of bias in the studies38,43,45,47,48,51 that were included in the clinical impact review but had already been assessed as part of the DTA review is presented in Table 4 and a full assessment is reported in Appendix 5. A summary of the risk of bias for one diagnostic accuracy study63 not eligible for inclusion in the DTA review is presented in Appendix 8, Table 41; the full quality assessment for this study63 is presented in Appendix 5.

Five studies54,58,59,64,65 that were available only as conference abstracts and were assessed as meeting the study eligibility criteria for inclusion in the clinical impact review were subjected to data extraction only and not to quality assessment, because there was not enough information to allow a judgement to be made on some of the quality assessment criteria.

Overall, the quality of the four cross-sectional52,56,57,61 and the two case–control studies60,62 was similar across the different domains. None of the included studies was considered to be representative of the target population. Only one study61 included a sample size calculation. In all studies, the test failure rate was low; therefore, the response rate was considered satisfactory. All of the included studies described the intervention. None of the studies accounted for confounding factors in the analyses presented. An assessment of the outcome was described in all of the studies; however, those studies with independent blind assessment or record linkage were judged as being of better quality than the studies without blind assessment or record linkage. The statistical tests used to analyse the data were clearly described and appropriate in all included studies.

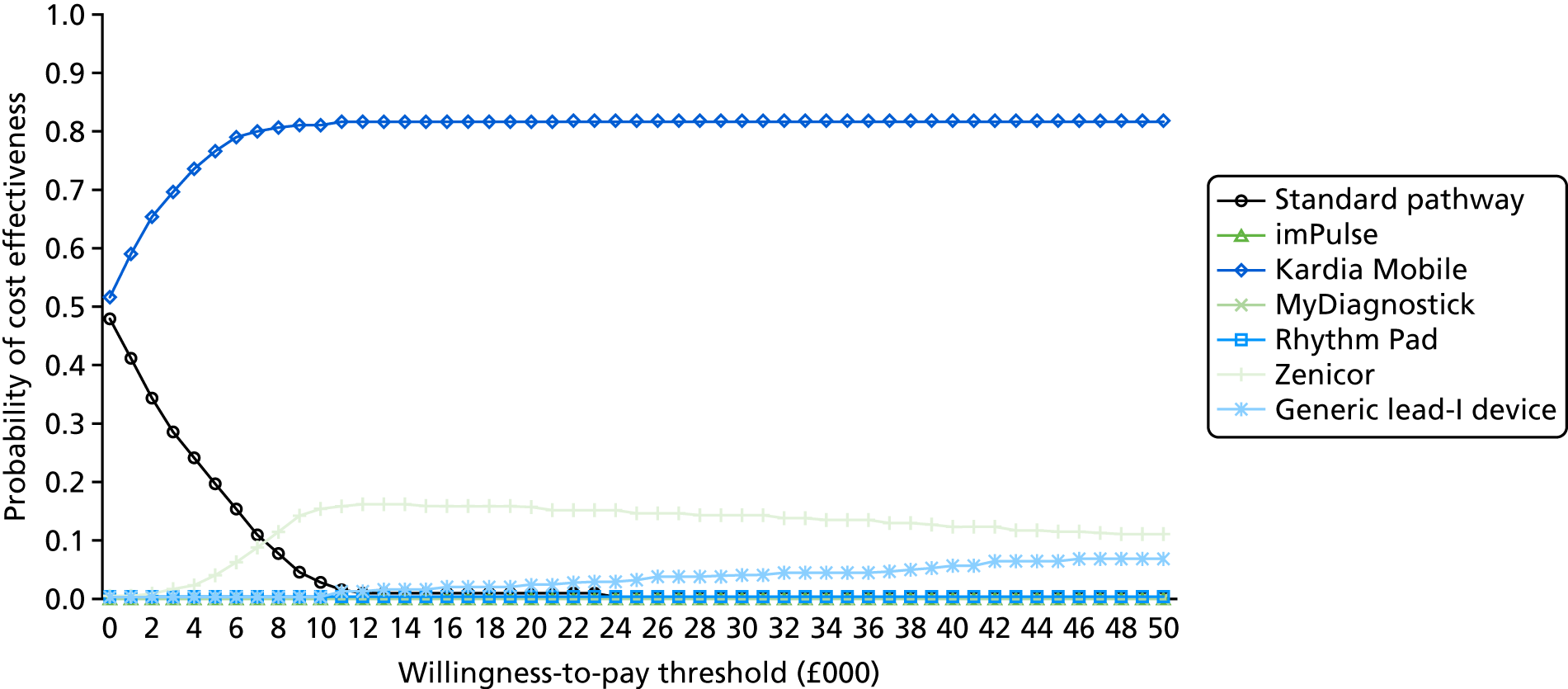

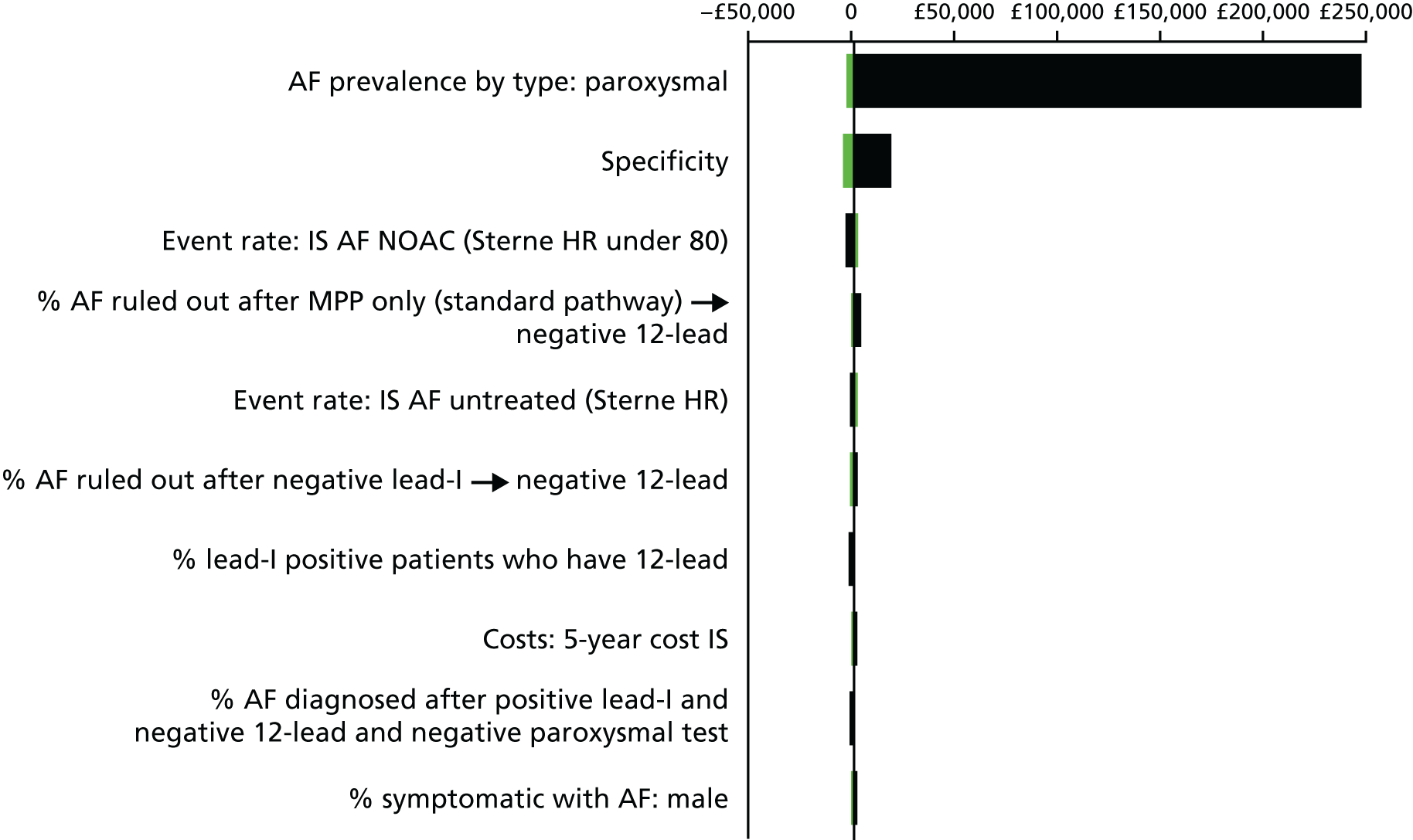

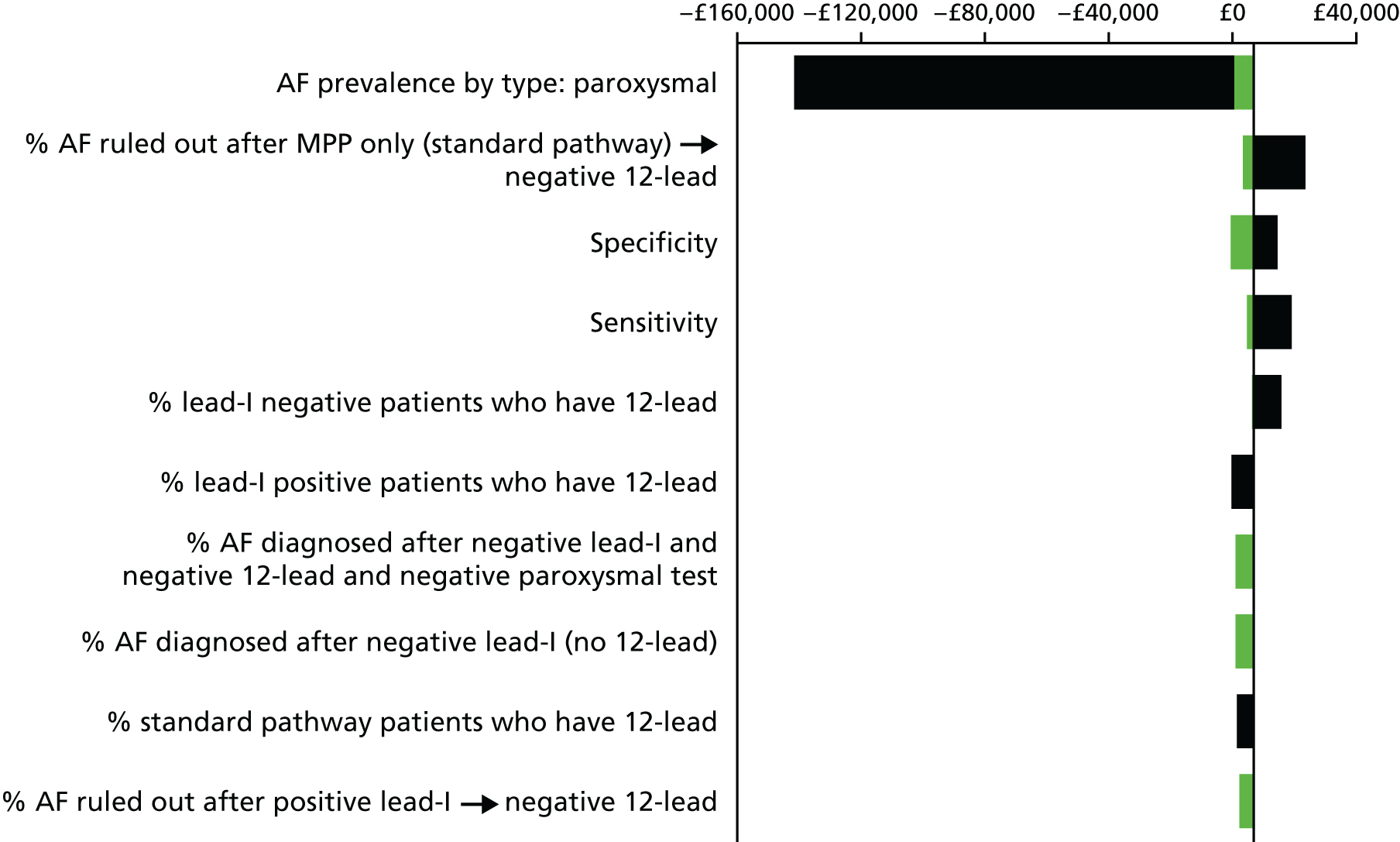

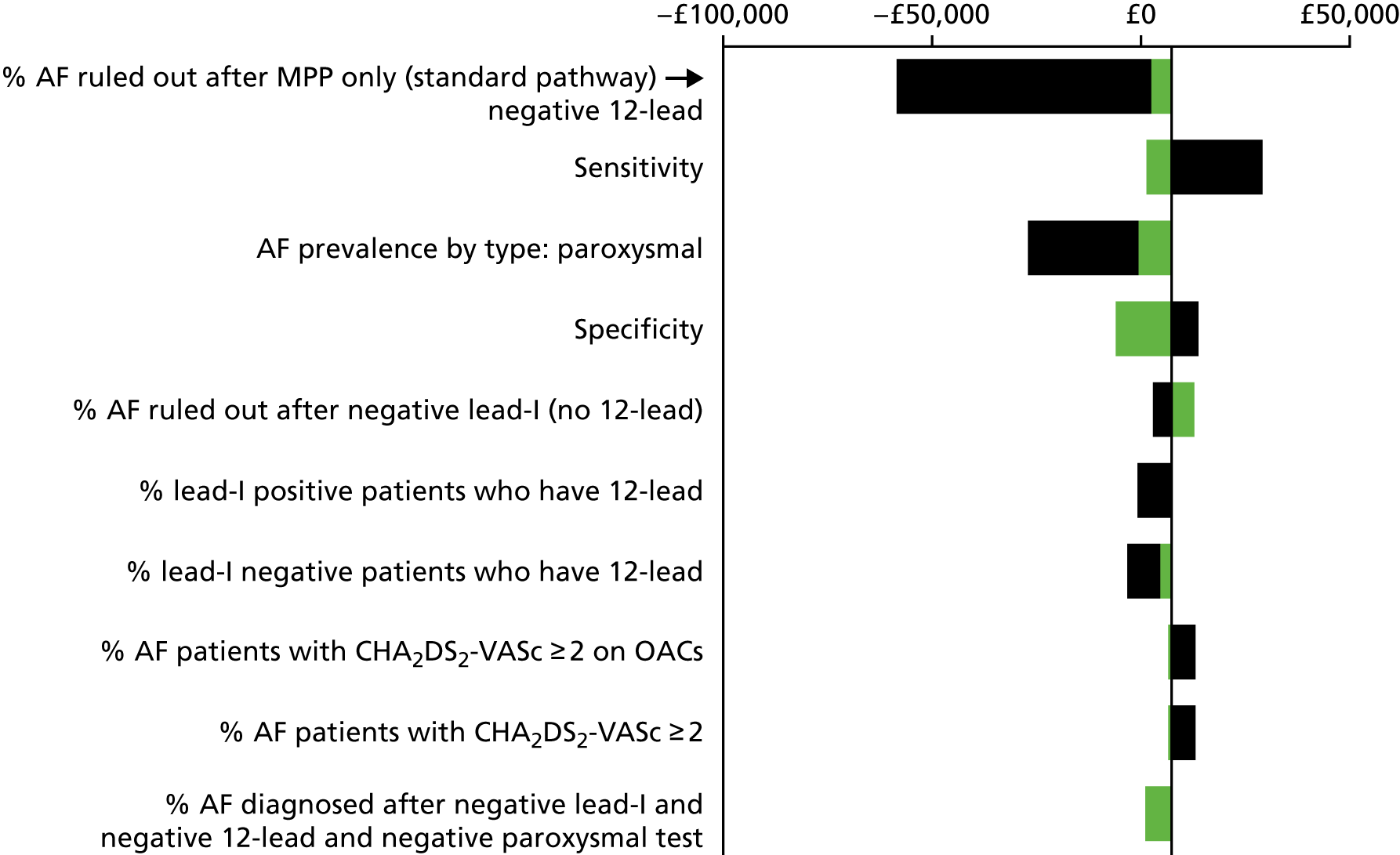

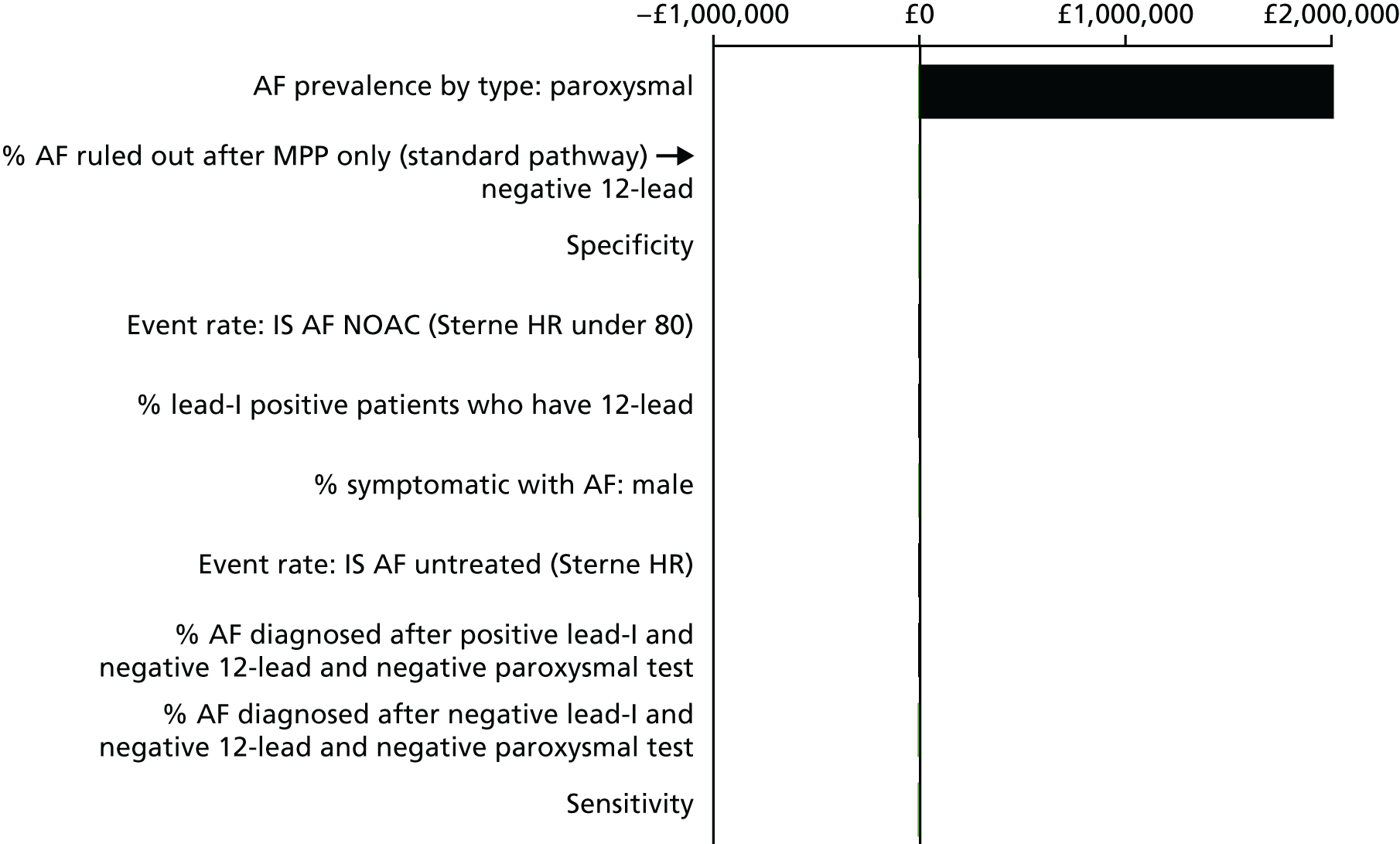

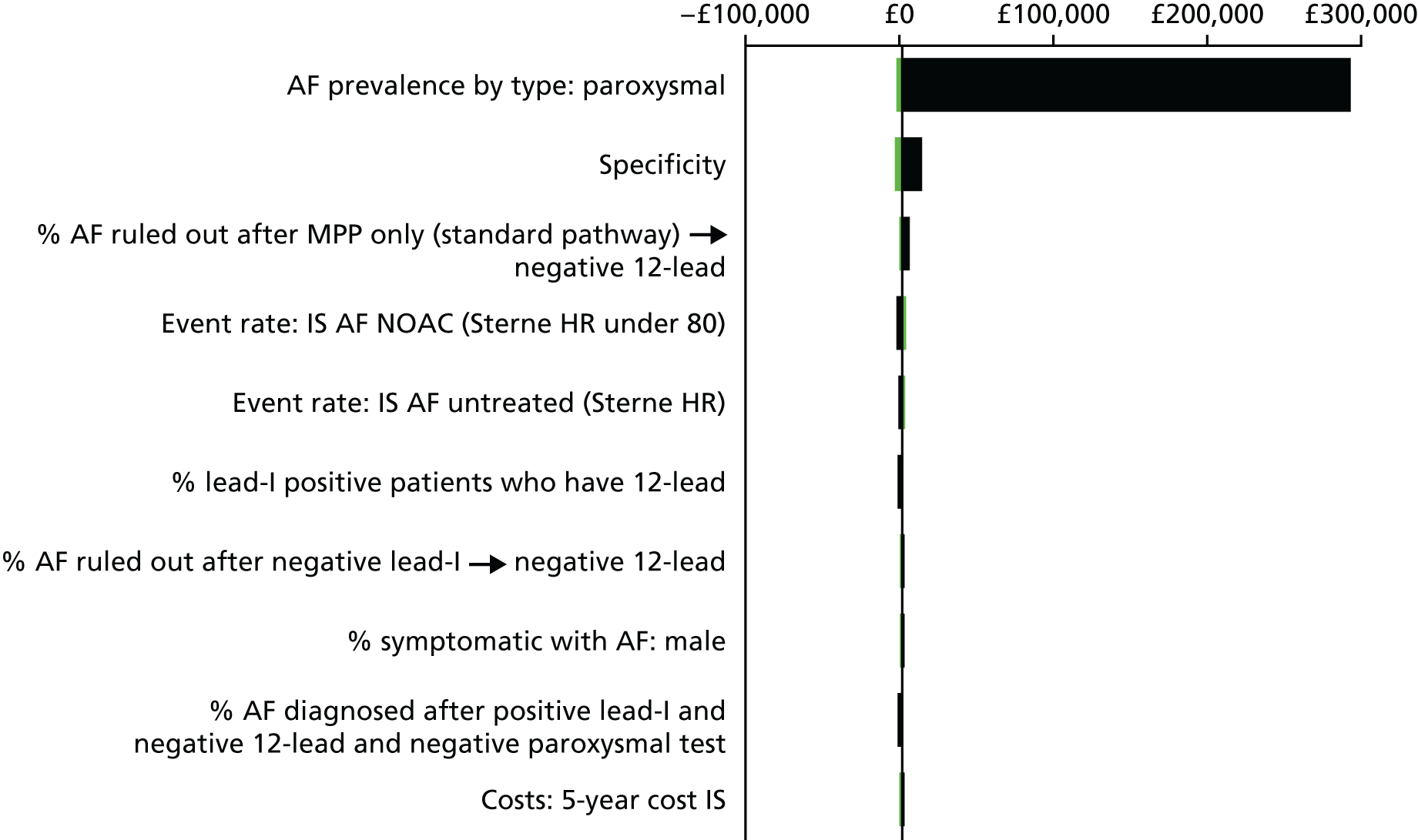

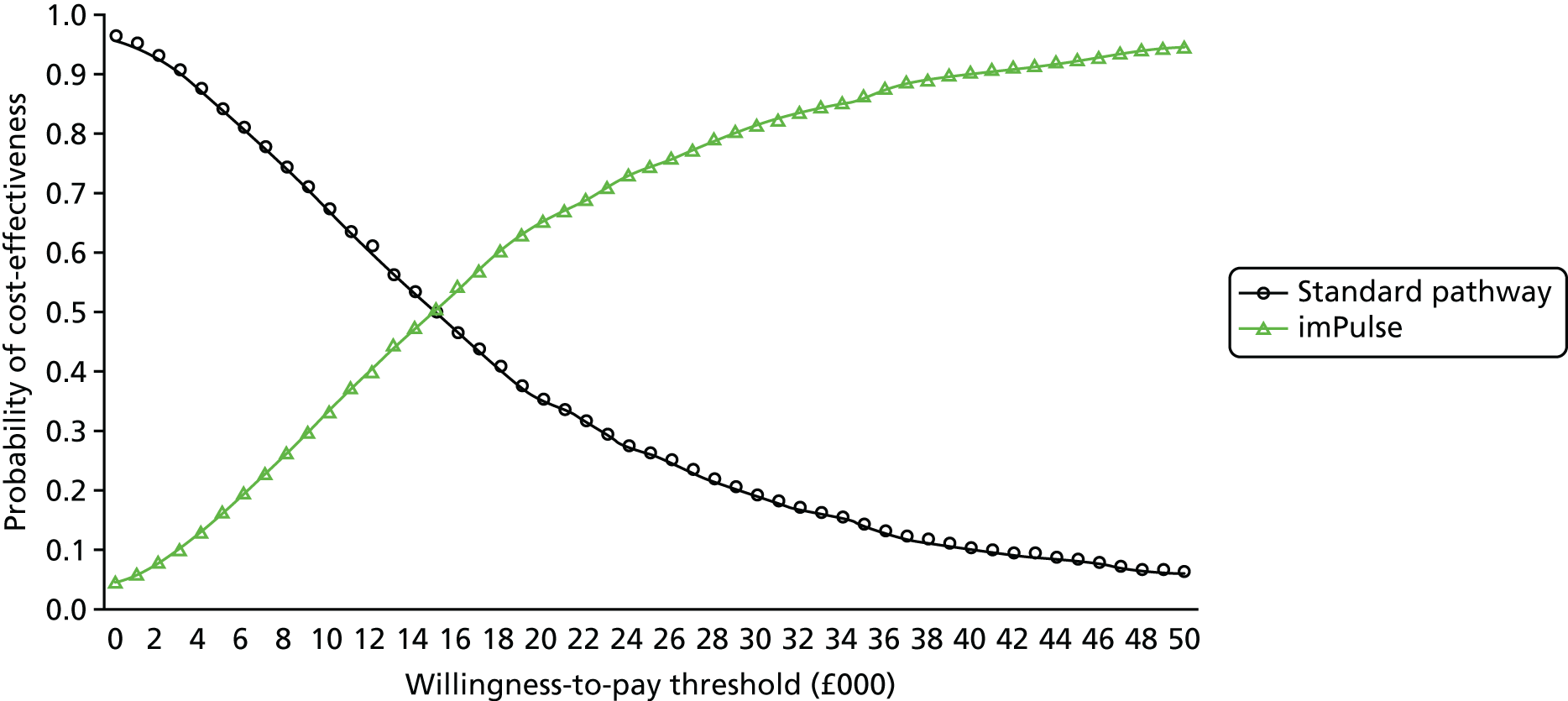

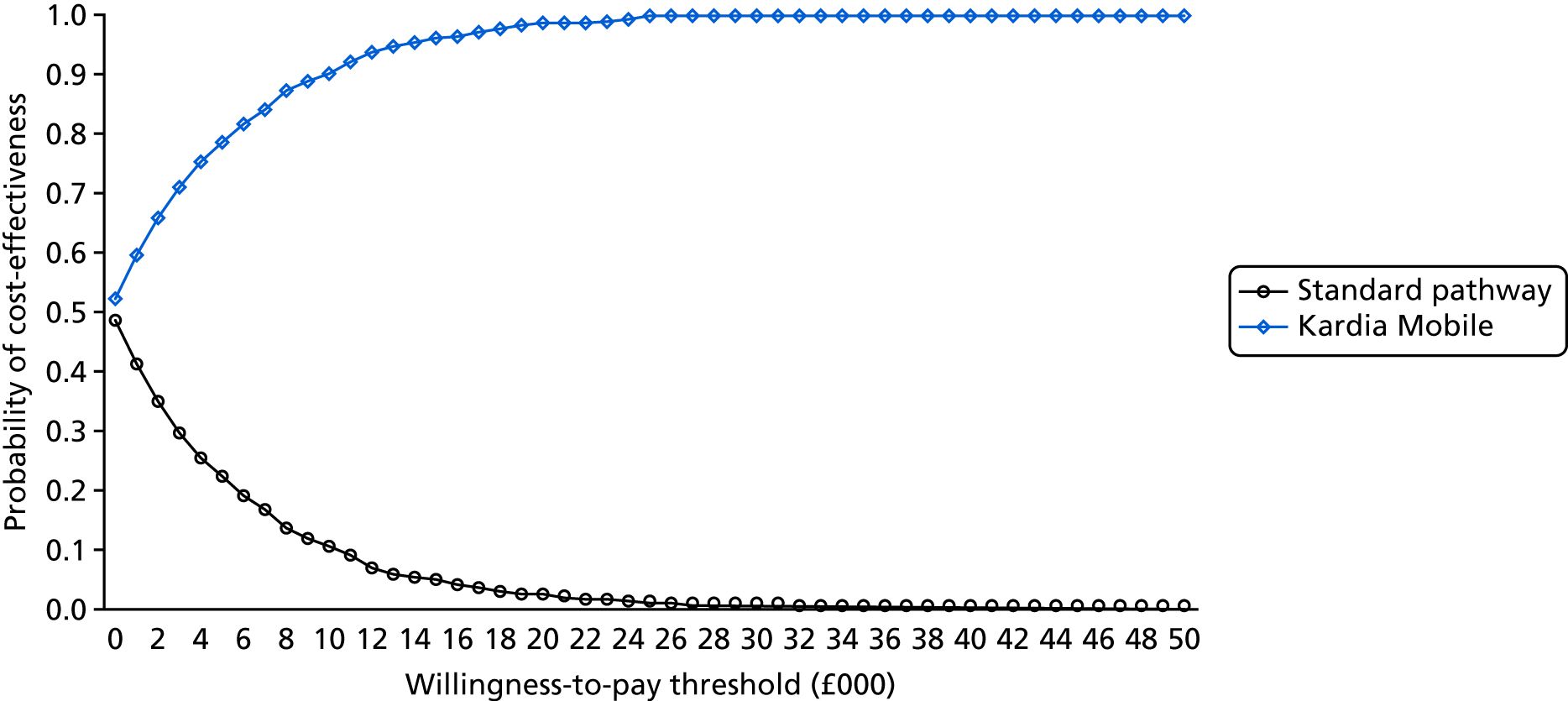

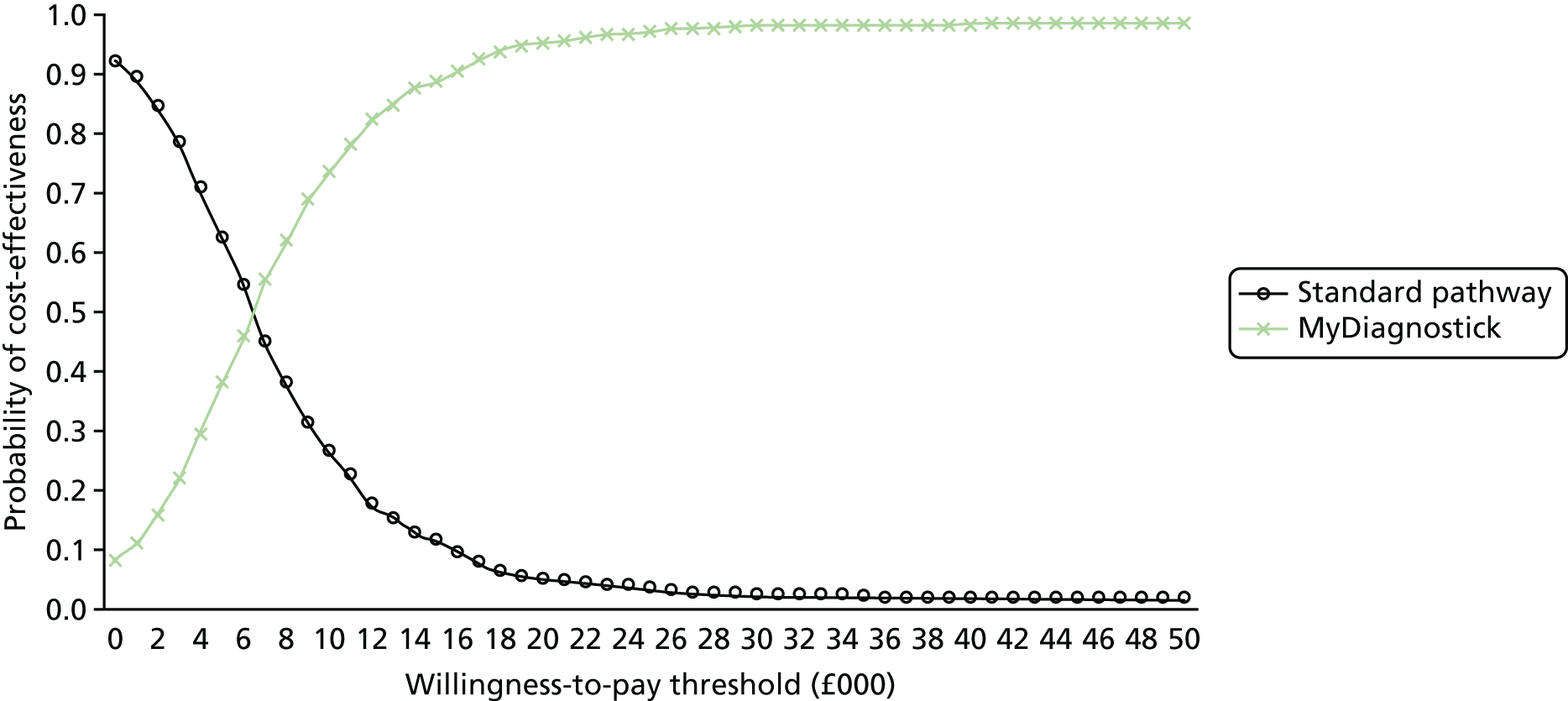

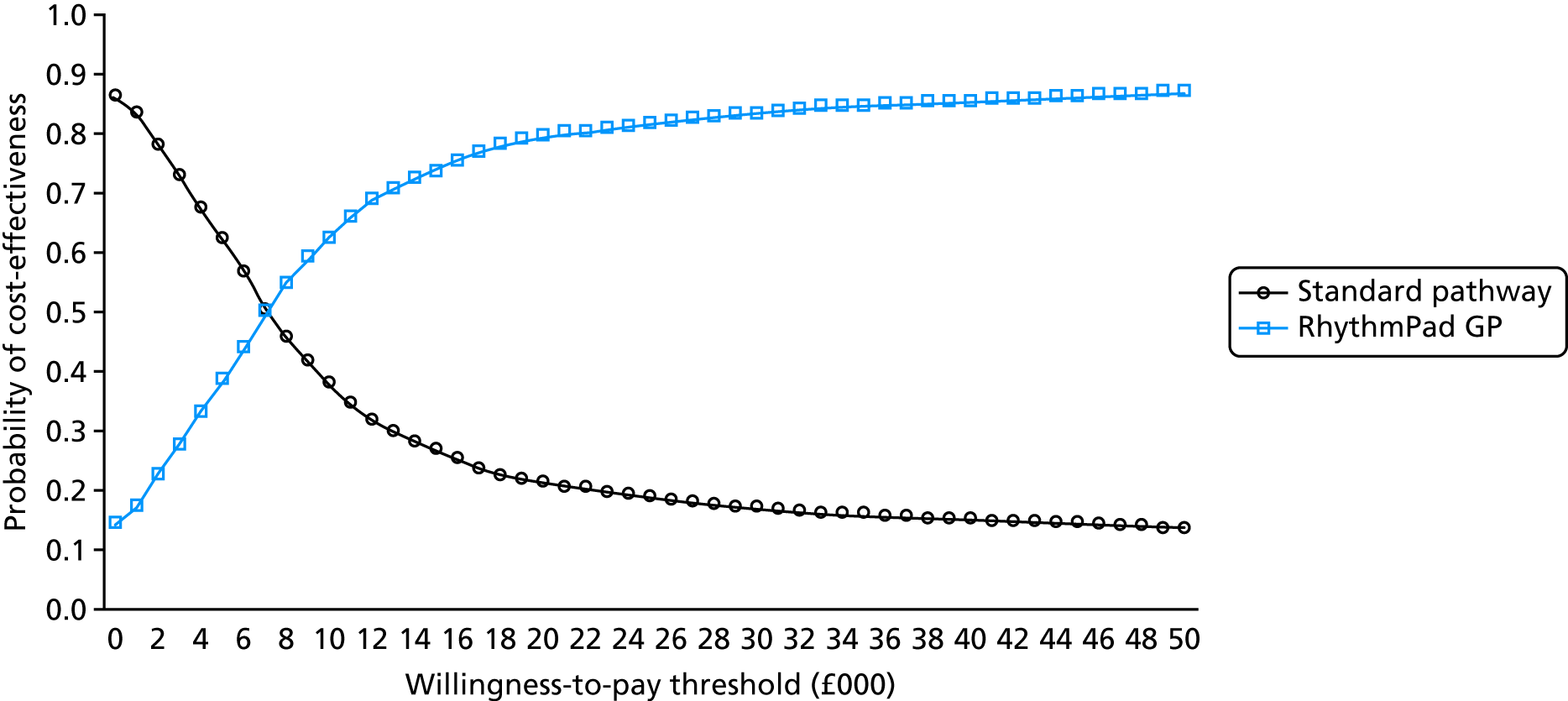

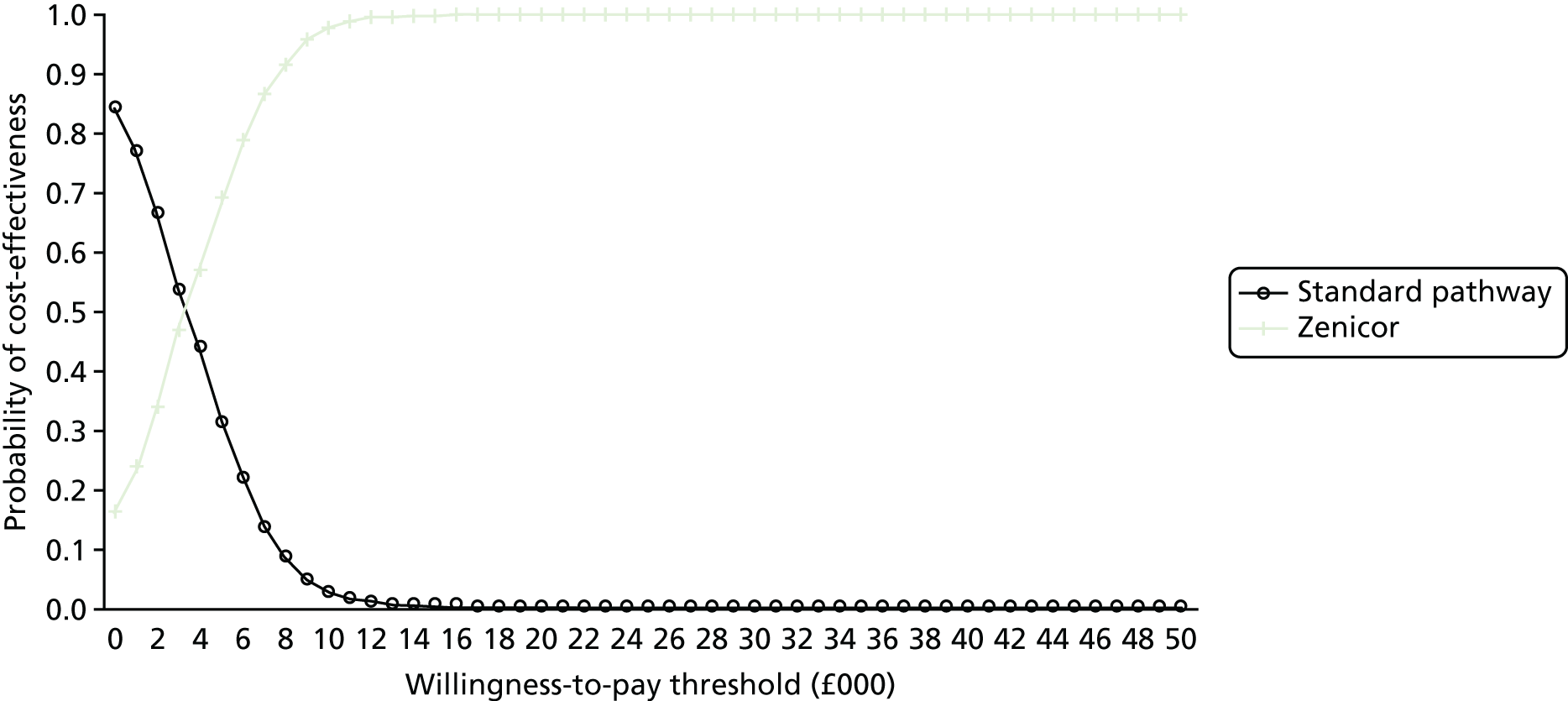

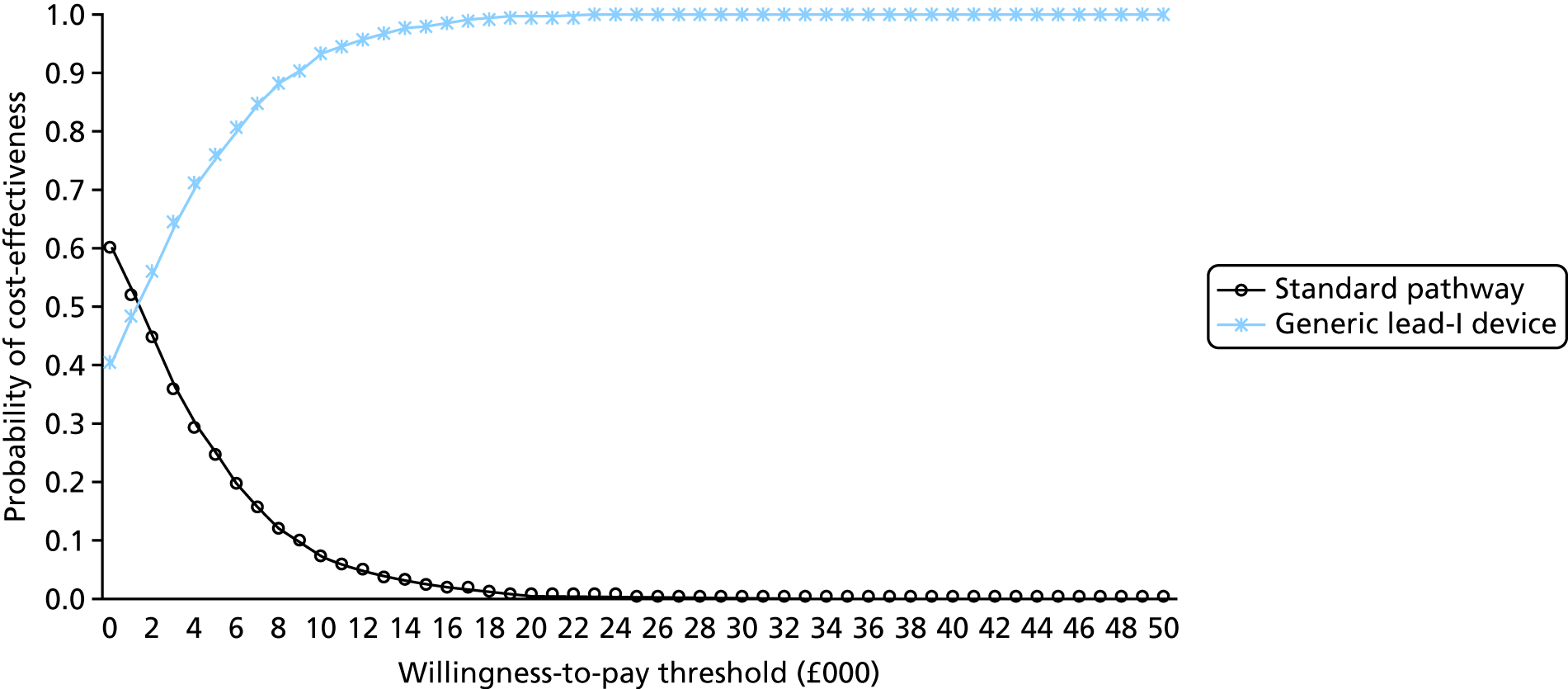

The diagnostic accuracy study63 was judged as being at an unclear risk of bias and having a high applicability concern for patient selection. This study63 was judged as being at low risk of bias on the index test domain as the test results were interpreted without knowledge of the reference standard test result and, therefore, there was also low applicability concern for this domain. All of the interpreters of the reference standard test results were blind to the results of the index test; therefore, the study63 was judged as being at low risk of bias for the reference standard domain. However, there were two reference standards: (1) a clinical ECG diagnosis based on additional information not available to the assessors, and (2) consensus (three of the four assessors) that matched this clinical ECG diagnosis. Therefore, this study63 was judged as having a high concern regarding applicability of the reference standard test.