Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 12/190/05. The contractual start date was in September 2014. The draft report began editorial review in September 2018 and was accepted for publication in February 2019. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Alan A Montgomery reports grants from the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) and membership of the NIHR Health Technology Assessment (HTA) Clinical Evaluation and Trials Funding Board during the conduct of the study. Roshan das Nair reports membership of the NIHR Health Services and Delivery Research Board, the HTA End of Life Care and Add-on Studies Board and the NIHR Research for Patient Benefit (East Midlands), and personal fees from Biogen Inc. (Cambridge, MA, USA). Avril ER Drummond reports membership of the NIHR Clinical Lectureships panel. Cris S Constantinescu reports grants, personal fees and other from Bayer AG (Leverkusen, Germany); Biogen Inc.; Merck, Sharp & Dohme (Kenilworth, NJ, USA); Novartis International AG (Basel, Switzerland), Sanofi Genzyme (Cambridge, MA, USA) and Teva Pharmaceuticals Industries Ltd (Petah Tikva, Israel). He also reports grants and personal fees from GW Pharmaceuticals (Cambridge, UK), Morphosys (Planegg, Germany), Roche (Basel, Switzerland); and grants from Sanofi-Pasteur-MSD (Lyon, France), outside the submitted work.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2020. This work was produced by Lincoln et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2020 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Introduction

Background

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is a progressive neurological condition that affects ≈127,000 people in the UK. 1 It is an incurable, progressive disease usually diagnosed in young adulthood or early middle age, and is a leading cause of neurological disability in young adults. 2 Cognitive problems are common in people with MS, affecting about 70% of people with MS, and include impairments of attention, information processing, executive function and memory. 3–6 Impairment of memory and impairment of information processing speed are the most common cognitive deficits in people with MS. 7–10

Cognitive impairment has a detrimental effect on daily life activities and quality of life. People with MS with cognitive problems are less independent in activities of daily living than those with MS without cognitive problems. 11–14 In particular, cognitive problems have a detrimental effect on employment. 15–18 There is also some evidence that they also negatively affect overall quality of life. 16,19–21

People with cognitive problems may be offered cognitive rehabilitation to retrain cognitive skills or to improve their ability to cope with cognitive problems in daily life. Cognitive rehabilitation is a structured set of therapeutic activities designed to improve cognitive function and to reduce the impact of cognitive impairment on daily life. There are recommendations for the provision of rehabilitation for specific symptoms for people with MS in The National Service Framework for Long-term Conditions. 22 The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) clinical guidelines for the management of adults with MS23 mention the need to refer people with MS and persisting memory or cognitive problems to both an occupational therapist and a neuropsychologist to assess and manage these symptoms. They also identify the need for research on the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of cognitive rehabilitation for people with MS. 23

In clinical practice in the UK, people with MS may receive an assessment of their cognitive abilities and general advice on strategies to cope with their cognitive problems. In addition, information is available on the web pages of MS charities, such as the MS Society and MS Trust. Very few people with MS receive a systematic retraining of cognitive skills or structured training in strategies to cope with their cognitive difficulties. A recent survey of professionals and clinical staff in the UK24 found that ≈58% of those surveyed used some cognitive assessment to screen for cognitive problems and ≈49% of those surveyed provided some form of cognitive rehabilitation when problems were identified, but only about 3% used a manualised rehabilitation approach.

Research evidence

An early systematic review by O’Brien et al. 25 considered a range of evidence from randomised trials, non-randomised trials and case series studies. The authors found low-level evidence for positive effects of neuropsychological rehabilitation in people with MS, but suggested that more high-quality randomised trials were needed. More recent reviews (in the years 2013–18)3,10,26–28 have reached similar conclusions. Amato et al. 3 considered a broad range of evidence for cognitive rehabilitation, including non-randomised trials, and concluded that some interventions showed promise, but that further evaluations were needed. D’Amico et al. 27 highlighted that targeted training in specific cognitive domains improved the trained function in studies with people with mixed types of MS and in people with relapsing–remitting MS. Mitolo et al. 28 reviewed 33 studies and considered controlled clinical trials and before-and-after studies, in addition to randomised controlled trials (RCTs). They highlighted that recent studies, which have focused on cognitive domains other than memory (i.e. attention, speed of processing and executive abilities), seem to provide the best evidence for beneficial effects of intervention. Goverover et al. 26 identified 16 RCTs published between 2007 and 2016, but did not include a statistical analysis of results.

Systematic reviews restricted to RCTs of cognitive rehabilitation have generally concluded that, overall, there is insufficient evidence to support the effectiveness of cognitive rehabilitation for people with multiple sclerosis. 29–31 Both Cochrane reviews29,31 reported that there was some evidence of benefit on measures of cognitive function. Das Nair et al. 29 also found some evidence of benefit on measures of quality of life. However, neither review29,31 found any evidence of benefit on emotional outcomes. These conclusions were not supported by a more selective review that was confined to RCTs with a low risk of bias,30 but this review included only five studies. Hämäläinen and Rosti-Otajärvi10 also suggested that the weak evidence emerging from the Cochrane reviews29,31 may stem from the strict analysis methods used, and that such methods may not be best suited for the evaluation of rehabilitation studies. They advocate more consideration for a more qualitative analysis of best evidence.

Research has also examined the evidence for effectiveness according to the type of intervention. Some controlled trials32–43 have demonstrated the effectiveness of computerised cognitive rehabilitation to retrain cognitive skills in people with MS and some have also shown changes in brain activation on imaging outcomes. 44–48 However, these studies have rarely included any long-term follow-up to assess whether or not the observed benefits persist. A few studies have evaluated whether or not the effects of computerised cognitive rehabilitation continue for up to 1 year. Some have shown persisting effects on cognitive abilities and quality of life41,49,50 but some have not. 32,45 In addition, some non-computerised strategies have been used to retrain cognitive skills, such as the Story Memory Technique,51,52 self-generated learning53 and paper-and-pencil exercises. 54 These studies have demonstrated the short-term effects of retraining cognitive skills and provide limited evidence that the benefits persist. However, it has been questioned whether or not interventions that involve retraining of cognitive skills produce clinically meaningful effects. 55

An alternative approach in cognitive rehabilitation is to teach people skills to cope with the cognitive impairment and provide aids to enable them to compensate for the loss of cognitive abilities. These skills may be taught early in cognitive decline to prevent the functional consequences of cognitive decline affecting daily life, or later on to enable people to cope better with their cognitive impairments.

One study evaluated using an electronic memory aid as a compensatory strategy for people with MS. 56 It found that participants receiving reminder text messages encountered fewer problems in daily life as recorded in a daily diary and were less distressed than those receiving non-specific text messages. Some studies have combined this compensatory approach with either computerised cognitive training57,58 or non-computerised practice on cognitive tasks. 59,60

The studies that combined computerised cognitive rehabilitation with strategy training showed a few benefits on cognitive outcomes but also reported differences in the number of perceived cognitive deficits58 and in the use of memory strategies. 57 However, neither study57,58 found any evidence of effects on mood or quality of life.

The two trials59,60 that combined non-computerised activities with compensatory strategy training both used a similar cognitive rehabilitation programme. The Rehabilitation of Memory in Neurological Disabilities (ReMiND) trial59 was conducted with people with a range of neurological disabilities, including many who had MS. This trial evaluated the effectiveness of group memory rehabilitation programmes in participants with memory problems by comparing compensation strategy training, restitution strategy training and a self-help control. Both quantitative and qualitative data from the study indicated that the interventions were worthy of further evaluation. 59,61,62 The ReMIND-MS trial60 was a modified version of the group intervention, combining restitution and compensation strategies, compared with a control group receiving usual care (total participants, n = 48); all participants had MS. The results showed a significant effect on mood, favouring the intervention.

Thus, overall, despite the suggestion that compensatory strategy training may be the most appropriate intervention for people who have not benefited from retraining,63 the evidence to support the provision of such an intervention is weak. Therefore, the present trial was designed to assess the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of a group cognitive rehabilitation programme, which combined training in strategies to restore cognitive function with compensatory strategies for people with MS.

Rationale

Currently, people with MS with attention or memory problems do not routinely receive cognitive rehabilitation. This is in part because of the current lack of evidence for the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of cognitive rehabilitation, and also because of resource limitations.

Research question

What is the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of cognitive rehabilitation for people with MS with attention and memory problems?

Objectives

Primary objective

The primary objective was to determine whether or not attending a cognitive rehabilitation programme (the intervention) in addition to usual care was associated with reduced psychological impact of MS on quality of life, as measured on the Multiple Sclerosis Impact Scale – Psychological Subscale64 (MSIS-Psy) compared with usual care alone (control).

Secondary objectives

The secondary objectives were to assess cost-effectiveness of the intervention, and whether or not the intervention was associated with improvements in participants’ attention and memory abilities or in self-reported memory problems in daily life, mood, fatigue, employment status and carer strain.

Chapter 2 Methods

Parts of this chapter have been reproduced from the Cognitive Rehabilitation for Attention and Memory in people with Multiple Sclerosis (CRAMMS) trial protocol. 65 This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (https://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

Design

This was a multicentre, parallel-group, pragmatic RCT of a cognitive rehabilitation programme, provided in addition to usual care and compared with usual care alone.

An economic analysis was conducted to determine the costs and cost-effectiveness of cognitive rehabilitation compared with usual care (see Chapter 6). Treatment fidelity was assessed (see Chapter 4) and a qualitative study was conducted to explore participants’ experiences of the cognitive rehabilitation and usual care (see Chapter 5).

Trial setting and participants

Sites

The trial was conducted in five sites in England (see Appendix 1, Table 25). Each site was an NHS trust providing neurology services for people with MS.

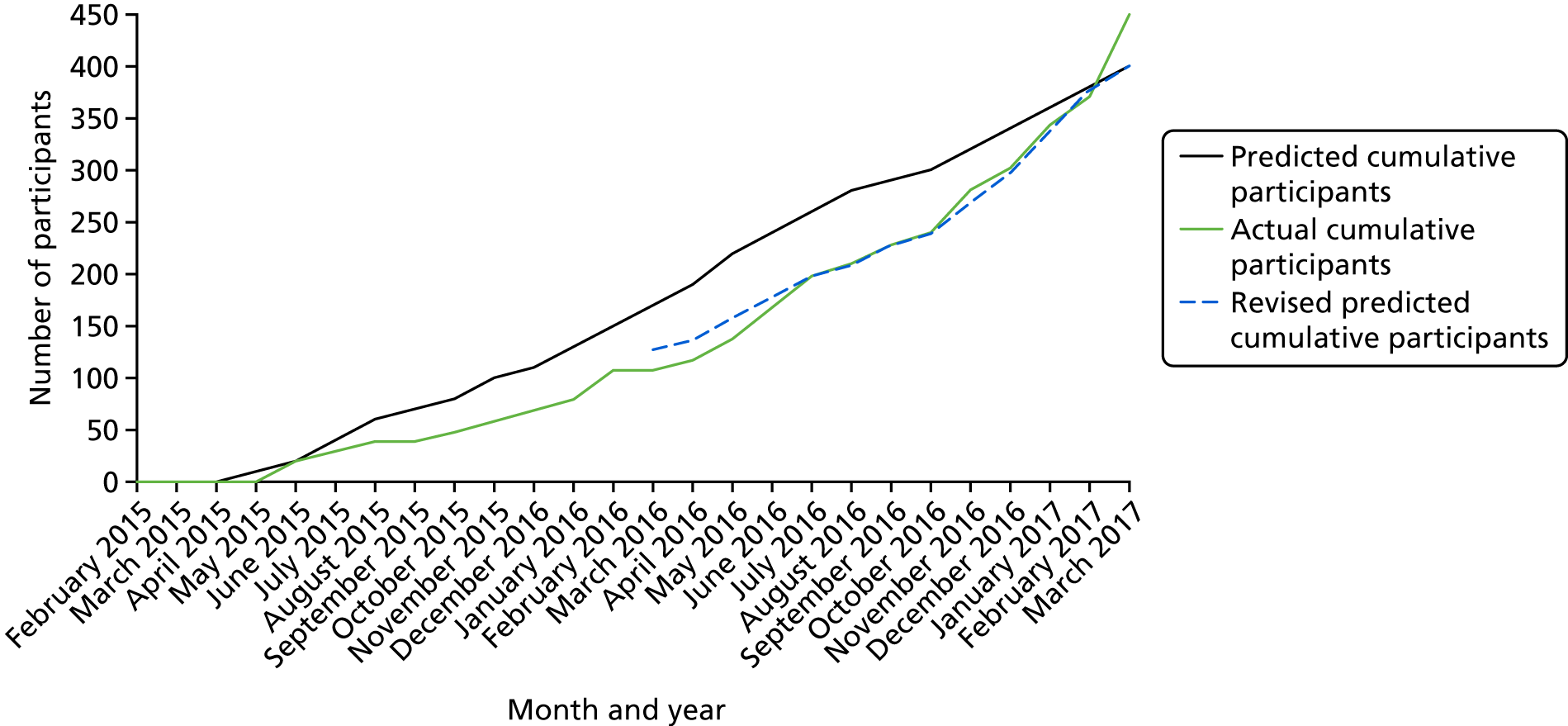

Three sites were opened to recruitment between March 2015 and May 2015. A fourth site opened in February 2016 and a fifth site in September 2016. All sites were open to recruitment until March 2017.

Identification of participants

Participants were identified through NHS hospitals and participant identification centres (PICs) near to sites. An invitation pack – which included a letter of invitation, a participant information sheet, a consent form, a contact details slip and a prepaid reply envelope – was sent to individuals with MS on hospital neurology and neuropsychology databases. Those who were interested in taking part were asked to return the contact slip to the assistant psychologist (AP) at their nearest site. In addition, people with MS attending neurology and rehabilitation clinics were invited to take part by members of the clinical teams. The clinician asked for permission to pass on their contact details to the AP at the site, who then sent them the invitation pack.

Posters about the CRAMMS trial, giving contact details of the AP at the nearest site, were displayed in MS therapy centres and at MS Society branch offices in areas covered by the recruiting sites. There was information about the trial on the MS Society and MS Trust websites. Members of the research team also attended MS Society branch meetings to talk about the study and invite those who were interested to take part. Self-referral was possible for those who accessed public-facing information on the study website, newsletters and posters. Those who contacted the sites were then sent the information pack.

An invitation to complete the Multiple Sclerosis Neuropsychological Screening Questionnaire (MSNQ)66 was sent to those who were enrolled on the UK MS Register who were in the study age range and had a registered postcode in the areas covered by the sites. The replies were reviewed anonymously and those who scored > 27 on the MSNQ were sent an invitation pack through the MS Register.

Informed consent

Written informed consent was obtained by the AP, and participants were given a copy for their records. Participant information sheets and consent forms were based on those developed for the pilot study and had been checked for clarity and readability by a service user representative. Potential participants had the opportunity to read and discuss the study with other clinical staff, family and friends, and the research team before they decided to take part. They were given at least 24 hours to do this.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

The inclusion and exclusion criteria were based on those used in the pilot studies. 59,60

Inclusion criteria

People with MS were eligible for the trial if they met the following inclusion criteria:

-

Aged 18–69 years. The upper age limit was to ensure that memory problems were likely to be because of MS rather than age-related memory impairments.

-

Reported having relapsing–remitting or progressive MS.

-

Diagnosed with MS at least 3 months prior to the screening assessment.

-

Reported having cognitive problems as determined by a cut-off score of > 27 on the patient version of the MSNQ. 66 The cut-off score was based on the original validation study by Benedict et al. 66 with 50 participants with MS. The cut-off score was used to identify those with cognitive impairment on a neuropsychological test battery.

-

Had cognitive deficits, defined as performance more than one standard deviation (SD) below the mean of healthy control participants corrected for age and education67 on at least one of the Brief Repeatable Battery of Neuropsychological Tests (BRBN). 68

-

Able to travel to one of the centres to attend group sessions. Participants had to live in the geographical area covered by the sites and be able to get to the sites independently. Travel expenses were offered to those who needed them.

-

Willing to receive treatment in a group if allocated to intervention.

-

Able to speak English sufficiently to complete the cognitive assessments and take part in group sessions.

-

Gave informed consent.

Exclusion criteria

Potential participants were excluded if they:

-

had vision or hearing problems, such that they were unable to complete the cognitive assessments

-

had concurrent severe medical or psychiatric conditions that prevented them from engaging in treatment

-

were involved in other psychological intervention trials.

Initial screening assessment

The AP conducted an initial telephone screening with those who expressed an interest in taking part in the trial. The screening included confirmation of the diagnosis of MS and a participant’s age. The MSNQ was administered to those who were willing to complete the questionnaire over the telephone. If it was not administered over the telephone, it was administered at the screening visit. For those recruited through the UK MS Register, the MSNQ was included in the online form to identify potential participants, but repeated at the screening visit, as scores were not available for specific individuals from the online version. The scale comprises 15 questions about the frequency of cognitive failures in daily life. Each question is rated on a four-point scale from ‘never’ to ‘very often’. Scores range from 0 to 60 and higher scores indicate more cognitive complaints. There is some evidence to support the reliability and validity of the scale. 57,69–72

Initial screening visit

At the screening visit, the AP explained the trial and obtained written consent.

Assessments were completed in the participant’s home, unless they preferred to be seen elsewhere. A quiet room was used whenever possible and an attempt was made to keep distractions to a minimum. The AP explained that the initial assessments were required to check that the participant met the inclusion criteria, and to obtain demographic and clinical data.

Demographic information included gender, date of birth, ethnicity, marital status, living arrangements and years of education. Clinical information included type of MS and number of relapses in the previous 6 months.

All assessment measures were selected on the basis of their clinical utility, relevant psychometric properties and ease of use for participants. Furthermore, the measures reflect the three levels of the International Classification of Function domains: impairment, activity limitations and participation restrictions. 73

The following assessments were completed:

-

The BRBN. 68 This is a cognitive screening battery that mainly assesses attention and memory and takes motor problems into consideration. It consists of the Selective Reminding, 10/36 Spatial Recall, Symbol Digit Modalities, Paced Auditory Serial Addition and Controlled Oral Word Association tests. The BRBN is a brief cognitive screening measure for people with MS, which is sensitive to detect cognitive impairment more so than other similar batteries and has been widely used in trials of medical interventions with people with MS. Higher scores indicate better cognitive function.

-

Guy’s Neurological Disability Scale (GNDS). 74 The self-report postal version of this measure75 was used to document the symptoms of MS. It comprises questions on 11 domains, including cognition and mood; the optional sexual function domain was excluded. Higher scores indicate greater disability. There is evidence to support its reliability and validity,76,77 responsiveness to change78 and to support the use of a total score. 79 It was chosen in preference to the more commonly used Expanded Disability Status Scale (EDSS)80 because it covers a wider range of activities and is less focused on mobility. The EDSS has also been criticised for being insensitive to cognitive dysfunction. 81 The GNDS has been compared directly with the EDSS and demonstrated good validity. 75,82

The results from the MSNQ and BRBN were used to assess the inclusion criteria. Participants who met the inclusion criteria were given the following questionnaires to complete in their own time, to be collected at the baseline assessment visit:

-

Multiple Sclerosis Impact Scale (MSIS). 64 This is a MS-specific quality-of-life scale that encompasses both the physical and psychological effects of MS on everyday life. It comprises 29 questions: 20 on the physical subscale and 9 on the psychological subscale. Each item is rated in four categories: ‘not at all’, ‘a little’, ‘moderately’ and ‘extremely’. Scores on the physical impact scale range from 20 to 80 and scores on the psychological impact scale range from 9 to 36, with higher scores indicating greater negative impact of MS. The scale has good psychometric properties83–88 and has been used as an outcome measure in rehabilitation trials. 89–92 The psychological and physical subscales of version two93 were both used.

-

Everyday Memory Questionnaire – patient version (EMQ-p). 94 This assesses the frequency of participants’ everyday attention and memory problems in daily life. It has good ecological and face validity and has been previously used as an outcome measure in cognitive rehabilitation studies. 59,60,95 The EMQ-p consists of 28 items asking about the frequency of memory failures in everyday life over the previous month. Each item is rated on a five-point Likert scale (from ‘once or less in the last month/never’ to ‘once or more a day’). Total scores range from 0 to 112, with higher scores indicating more frequent memory problems.

-

Fatigue Severity Scale (FSS). 96 The five-item, Rasch-analysed version of the FSS97 was used to document the severity of fatigue. This assesses patient-perceived fatigue over the previous week. Each item was scored from 0 to 7, with higher scores indicating more severe fatigue. The sum of the five items was then converted to the Rasch person location using the table provided by Mills et al. ,97 and ranged from –3.4 to 3.4. Several studies have supported the reliability and validity of the FSS in people with MS. 98,99

-

The 30-Item General Health Questionnaire (GHQ-30). 100 This questionnaire was designed to detect psychological distress in the general population. It assesses a participant’s mood over the previous few weeks compared with their usual mood. The GHQ-30 was chosen as it is suitable for postal administration and is easy to complete. The GHQ (12-, 28- or 30-item versions) has also been shown to be responsive to the effects of psychological interventions in people with neurological conditions. 60,89,101 Likert scoring was used for the clinical outcome, with scores ranging from 0 to 90; higher scores indicate more psychological distress.

Participants who did not meet the eligibility criteria following the initial screening visit were notified by letter to thank them for their interest in the trial; a brief report of their test results was also provided, if requested. Those who met the inclusion criteria were invited to complete the baseline assessment visit.

Participants were asked to nominate a relative or friend who knew about their cognitive problems in daily life. A questionnaire booklet for the relative or friend was sent to participants following the initial screening visit and they were asked to pass this on to their friend or relative. The questionnaire booklet consisted of the Everyday Memory Questionnaire – relative version (EMQ-r). The EMQ-r is identical to the patient version, but is completed by a relative or friend who knows the participant and their cognitive problems. This version tends to correlate more highly with the presence of ‘objectively’ identified cognitive problems than participant self-report, which can be influenced by mood102 or fatigue. 103 The EMQ-r was included to identify any effect of treatment on daily life problems as observed by another person, which might not have been detected by participants themselves. EMQ-r scores range from 0 to 112, with higher scores indicating more frequent memory problems. Participants were asked to return completed relative/friend questionnaires at the baseline assessment visit or they could be returned by post.

Baseline assessment visit

The participant questionnaires that had been completed were collected at the baseline visit, which was conducted within 2 weeks of the screening visit. If they had not been completed, they were administered at the visit if time allowed, or the participant was asked to complete them after the visit and return them by post.

In addition, the following assessments were completed:

-

Doors and People. 104 This is a measure of memory function in four domains: verbal, visual, immediate and delayed. This was used to determine the type of memory problems and was used when planning treatment sessions to ensure that the treatment was adjusted according to the nature of each participant’s memory problems. Higher scores indicate better memory ability.

-

Trail Making Test from the Delis–Kaplan Executive Function System. 105 This was administered as a measure of attention and executive abilities. Conditions two (letter sequencing) and four (letter–number sequencing) were used. The difference in the time taken between the two conditions was used. A smaller difference indicates less interference effect, which indicates better executive functioning.

-

EuroQol-5 Dimensions, five-level version (EQ-5D-5L). 106 This is a generic health-related quality-of-life measure, used for health economic evaluations. Utility scores were derived from the EQ-5D-5L descriptive system and used to estimate quality-adjusted life-years (QALYs) and incremental cost-effectiveness ratios (ICERs).

-

Use of Health and Social Services Questionnaire (UHSSQ). This bespoke self-report questionnaire was used to assess NHS health-care use. It included questions on the frequency with which participants accessed NHS services, such as visits to general practitioners (GPs), neurologists and MS nurses, and services provided by charities, such as MS Society groups. Use of hospital services, including outpatient appointments, rehabilitation services and hospitalisation, were recorded. Current medication and medications prescribed over the previous 3 months were recorded. The period covered by the questionnaire was the previous 3 months; this time period was chosen so that people would have received a range of services, and they would still remember what they had received. The UHSSQ was adapted from previous studies. 107

Current employment status and the number of relapses in the previous 3 months were also documented.

If a participant was randomised to receive cognitive rehabilitation, the AP checked whether or not that participant could attend groups on certain days. Participants were randomised only if they were able to attend on the days that groups were due to take place. Those who were unable to attend on the planned days were held in reserve until such time that a new group, matching their availability, was formed. While participants were waiting for sufficient participants to form a group, the AP remained in regular contact to keep individuals aware of probable timescales.

The AP also checked whether participants would prefer to receive the outcome questionnaires by post or to complete them online.

Randomisation

Clusters of between 9 and 11 participants were formed by the AP at each site; in case they would be allocated to the cognitive rehabilitation group, cluster formation was based on participants’ availability to attend for treatment at the same time and same venue. Randomisation took place once there were 9–11 individuals in a cluster.

Participants were individually randomised to the intervention or control group on a 6 : 5 ratio, to allow for clustering in the intervention group. Allocation was stratified by recruitment site, and minimised by MS type (relapsing–remitting or progressive) and gender. Those who were allocated to the intervention group were offered cognitive rehabilitation. Those who were allocated to the control condition were not offered cognitive rehabilitation and received only their usual care.

The allocation algorithm was created by the Nottingham Clinical Trials Unit (NCTU), in accordance with their standard operating procedure, and held on a secure server. A remote, internet-based randomisation system was used by APs to obtain the group allocation for each participant. Access to the sequence was confined to the NCTU information technology (IT) manager. The sequence of group allocations was concealed from the trial statistician until all participants had been allocated, and recruitment, data collection and all other trial-related assessments were complete.

Participants who were waiting to be randomised at the time their site closed to recruitment were sent a letter informing them that the AP had not been able to recruit enough people to create a group at a time and place that was convenient for that participant, and that their participation in the trial was at an end.

Interventions

Usual care

All participants received their usual clinical care. In the standard NHS care pathway, people with MS with cognitive problems may get general advice from MS specialist nurses and occupational therapists on how to manage any cognitive difficulties. There are information sheets available on web pages of MS charities, which include suggestions for coping with cognitive problems. However, usual care does not normally include any specific intervention for cognitive problems or cognitive rehabilitation.

Other clinical services available to participants included employment rehabilitation services, self-help groups and support from specialist charities, such as the MS Society. Any input, including psychological or medical interventions, that participants received during the trial was recorded on the UHSSQ.

Cognitive rehabilitation

Cognitive rehabilitation is a structured set of therapeutic activities designed to improve cognitive function and to reduce the impact of cognitive impairment on daily life. 65 The emphasis of the intervention was on identifying the most appropriate strategies to help individuals overcome their cognitive problems and in providing participants with a range of techniques that they could use and adapt in accordance with their own needs. Although the intervention was delivered in a group format, every effort was made to ‘personalise’ or ‘individualise’ the intervention to meet the needs of each participant. For instance, if a participant found it particularly difficult and stressful to remember faces, the strategies taught were focused on this problem.

Each cognitive rehabilitation group consisted of four to six participants. Sessions were held at NHS sites or community venues. Participants received 10 sessions, each of 1.5 hours’ duration, which included a break mid-way through. Sessions were held once a week for 10 weeks. The content of each session was defined in a treatment manual. 60 The intervention included restitution strategies to retrain attention and memory functions., and methods to improve encoding and retrieval. In addition, participants were taught compensation strategies, such as internal mnemonics (e.g. chunking, first letter cues and rhymes), the use of external memory aids (e.g. diaries, notebooks and mobile phones) and methods of coping with attention and memory problems in daily life. The programme was adjusted according to each participant’s cognitive abilities, as determined during the baseline assessment, yet it also provided a systematic framework for addressing problems with attention and memory. Homework assignments were set at the end of each session to help participants practise the strategies learnt in their everyday life. These were reviewed each week at the following session. Carers and family members were invited to attend the final session, if participants agreed, and this session was used to summarise the previous sessions.

The AP recorded whether or not participants attended each of the intervention sessions and the reasons why any sessions were not attended. Participants who missed sessions were offered a half-hour catch-up session prior to the next session. If a participant was no longer able to attend their allocated group for the remaining number of treatment sessions, they could attend another group, provided the sessions were completed by the 6-month outcome assessment and the same AP was delivering the sessions. Participants’ travel expenses were reimbursed.

Treatment fidelity

The fidelity of the cognitive rehabilitation programme was assured in two ways:

-

Manualised treatment – the cognitive rehabilitation programme followed a manual that was developed and tested in a pilot study. 60 A detailed description of the manual has been published elsewhere108 and in the Template for Intervention Description and Replication (TIDieR)109 checklist (see Appendix 2, Table 26).

-

Training and supervision – staff delivering the intervention (i.e. APs) were psychology graduates with clinical experience. They received supervision from a clinical psychologist based at their site. A clinical psychologist provided training on the delivery of the intervention. Monthly teleconferences were conducted to provide peer group supervision. In addition, individual telephone supervision was provided monthly with a clinical psychologist for the discussion of specific challenges relating to treatment or assessment. When staff changes occurred, former staff completed a ‘handover’ document for new staff, to ensure continuity. The new staff were trained by the same trainers to ensure consistency.

Formal assessment of the fidelity of the cognitive rehabilitation was undertaken through analysis of video-recordings of treatment sessions. This is described in detail in Chapter 4.

Outcome assessment

Outcomes were assessed at 6 and 12 months after randomisation to determine the immediate and longer-term effects of the intervention. The primary outcome was 12 months after randomisation, in order to determine whether or not any treatment gains had been maintained over time. The 6-month assessment was to determine the immediate effects of the intervention, allowing time for completing 10 sessions, including allowing for sessions to be rescheduled if they had to be cancelled through illness or holidays.

Outcomes were assessed by questionnaire and at an outcome assessment visit.

Questionnaire outcomes

A questionnaire pack was posted to each participant 2 weeks before the 6- and 12-month appointments were due. They were asked to complete this questionnaire pack at home and hand it to the research assistant (RA) during the follow-up visit. Those who requested to complete questionnaires online were sent an e-mail with a link to open the questionnaires. Prior to the follow-up visit, the RAs checked if the questionnaires had been returned or competed online.

The pack included the following:

-

the MSIS

-

the EMQ-p

-

the GHQ-30

-

the FSS

-

GNDS

-

a question about the number of relapses in the previous 6 months.

In addition, the EMQ-r and Modified Carer Strain Index (MCSI) were posted for completion by the participant’s nominated relative/friend.

The MCSI110 is a measure of burden on carers and family members. It comprises 13 items from the Carer Strain Index111 that, in the modified version, are rated according to the frequency of their occurrence as ‘yes, on a regular basis’ (score 2), ‘yes, sometimes’ (score 1) and ‘no’ (score 0). Scores range from 0 to 26; the higher the score, the higher the level of caregiver strain. The internal reliability and test–retest reliability are high. 110

Returned questionnaires were checked for completeness at the visit so that if items were missing or clarification was needed about responses (e.g. unclear marking on questionnaires), these could be corrected. The RA also took a copy of the questionnaires to the visit so that these could be completed during the visit if they had not already been completed. If there was not sufficient time to complete the questionnaires during the visit, and they had not been done previously, the RA left a copy of the questionnaires and a prepaid envelope so that these could be completed and returned to the co-ordinating centre after the visit.

Outcome assessment visits

Research assistants were responsible for conducting outcome visits 6 and 12 months after randomisation. The RAs were not involved in recruitment to the trial of or delivery of the intervention to any of the participants that they followed up, and were blind to treatment allocation. At the start of the appointment, the RA reminded the participants of the importance of them remaining blind to group allocation and asked participants not to discuss any aspects of their involvement in the trial. Before conducting the outcome visit assessments, the RA recorded whether or not they had been unblinded and their opinion as to which group the participant had been allocated to, using the categories definitely usual care, probably usual care, probably intervention or definitely intervention. At the end of the visit, the RA recorded whether or not they had been unblinded during the visit and also what treatment they thought the participant had received.

The following assessments were completed at the follow-up visits:

-

the EQ-5D-5L

-

the UHSSQ

-

the BRBN

-

Doors and People

-

Trail Making.

The schedule of outcome assessments is summarised in Appendix 3, Table 27.

All participants were contacted in order to complete all assessments. Participants were initially contacted by telephone when follow-up visits were due. If telephone contact failed, then a letter was sent to the participant’s last known address, asking the participant to contact the outcome assessor. Any changes in contact details were recorded.

Feedback interviews

A feedback interview was conducted between the 6- and 12-month appointments, with 36 purposefully selected and willing participants: this qualitative component of the trial is described in detail in Chapter 5.

End of the study

Participants completed the trial when the 12-month follow-up was completed. The end of the trial was defined as being the last 12-month follow-up appointment. However, questionnaires returned after completion of the final visit were accepted to allow for any delays in the post.

If participants discontinued the intervention or withdrew from follow-up, this was reported and the reasons were documented, if they were given. Outcome data collection was completed if a participant discontinued treatment but agreed to remain in the trial. Participants were informed at the start of the trial that data collected up to the point of withdrawal would be retained and used in the final analysis. Participants who withdrew from the trial were not replaced with other participants.

Assessment of safety and adverse events

The risks of taking part in the trial were assessed as being low. However, non-specific risks for participants involved travelling to the research sites. In addition, participants may have experienced some distress if they found that they were not performing as well as they expected on cognitive assessments. However, such distress was considered improbable and likely to be mild. Any distress was managed by the APs, who were trained to deal with such situations. They discussed any concerns with the supervising clinical psychologists and made referrals to a participant’s GP, if needed. Distress during the course of the intervention was managed similarly. As the risk, overall, was assessed as being low, no adverse events or serious adverse events were reported. However, as a safety outcome, the number of participants who showed an increase in scores on the GHQ-30 of > 30 points between baseline and the 6-month assessment were monitored by the independent Data Monitoring Committee (DMC), and any concerns were discussed with the clinical teams. In addition, adverse outcomes, such as hospitalisation, distress and death, were recorded.

‘Notable events’ occurring during assessments or the intervention were recorded by the APs or RAs throughout the trial. Notable events were any events that were considered to be out of the ordinary, such as problems arising during cognitive rehabilitation sessions or any events that may pose a risk to either the participants or the researchers. These were reviewed during supervision.

Research governance

The trial was conducted in accordance with the recommendations for clinicians involved in research on human subjects adopted by the 18th World Medical Association General Assembly, Helsinki, 1964,112 and later revisions, the UK Policy Framework for Health and Social Care Research113 and the principles of the International Conference on Harmonisation of Technical Requirements for Registration of Pharmaceuticals for Human Use – Good Clinical Practice (ICH-GCP) guidelines. 114

Trial registration

The trial was prospectively registered as ISRCTN09697576 (International Standard Randomised Controlled Trial Number) on 14 August 2014.

Ethics

The National Research Ethics Service West Midlands, South Birmingham Committee gave ethics approval for the study (reference number 14/WM/1083).

Site initiation and training

Prior to the commencement of the trial, a meeting was held between members of the central research team (i.e. the chief investigator, the co-chief investigator and NCTU staff) and trial collaborators from the initial three sites to discuss implementation and training issues to ensure that all members were familiar with all aspects of the trial. For sites that were involved after this initial meeting, training was carried out on an individual basis. NCTU staff provided trial-specific training on the trial documentation and database, a clinical neuropsychologist provided training on conducting baseline assessments and, as part of ensuring treatment fidelity, a clinical psychologist provided training on the delivery of the intervention (as detailed in Treatment fidelity).

Protocol deviations

A protocol deviation was defined as an unanticipated or unintentional divergence or departure from the expected conduct of the trial that was inconsistent with the protocol, consent document or other trial procedures This was based on standard practice within NCTU.

The APs and RAs recorded protocol deviations on the electronic case report form. Protocol violations were reviewed by the Trial Management Group (TMG) and defined as those deviations that affected participant eligibility or outcome measures.

Oversight

A number of oversight groups monitored the progress and conduct of the trial. The roles and responsibilities of these groups were described in the protocol,65 and specific charters were developed for the independent Trial Steering Committee (TSC) and DMC.

Trial Management Group

The TMG comprised the co-chief investigators, members of NCTU responsible for the running of the trial and the health economists. They met regularly to monitor the day-to-day running of the trial.

Trial Steering Committee

The TSC was responsible for the overall conduct of the trial. The TSC had an independent chairperson and four independent members. The independent members were rehabilitation professionals and service user representatives who were not otherwise involved in the trial. Members of the trial team, including the chief investigator, co-chief investigator and trial manager, were also part of the TSC. The TSC advised on recruitment strategies, monitored progress with recruitment and checked adherence to the trial protocol. Representatives of the sponsor were also invited to TSC meetings.

Data Monitoring Committee

The DMC was an independent group, the members of which had no other involvement with the trial. Members of the DMC included two rehabilitation professionals and a professor of health service research with expertise in statistics. The role of the DMC was to safeguard the interests of trial participants, with particular reference to the safety of the intervention; monitor the overall progress and conduct of the trial; and protect the validity and credibility of the trial.

The TSC and the DMC met independently of each other, with the DMC providing reports to the TSC.

Patient and public involvement

During the planning of the trial, four service users were identified through the MS Society research network and one service user co-applicant had been involved in the pilot study for the trial. All commented on the trial design and documentation, particularly the participant information sheet and consent form. Two service user representatives were directly involved in the trial as members of the TSC. In addition, one of the service user representatives assisted with interviewing participants as part of the qualitative component of the trial. This service user representative was also involved in preparing a video to disseminate the results to participants and to people with MS. Three participants also contributed to the dissemination of results by taking part in a video to illustrate the cognitive rehabilitation sessions. All service users were invited to comment on the lay summary.

Statistical methods

The primary outcome was the psychological impact of MS on everyday life at 12 months, as a reflection of health-related quality of life (HRQoL), as measured using the MSIS-Psy.

Sample size

The sample size was estimated using the primary outcome of the MSIS-Psy scores at 12 months post randomisation. A clinically meaningful effect using this outcome is probably in the range of 3.0–3.5 (using version 1 of the MSIS-Psy, scored 9–45). Based on a two-sample test, 143 participants per group were required for analysis in order to detect a difference of 3 points on the MSIS-Psy, assuming a SD of 9 points, with 80% power and 5% two-sided alpha. However, a clustering effect may be expected to occur in the intervention group as a result of the cognitive rehabilitation being delivered in groups. Based on an average cluster size of five evaluable participants (those providing primary outcome data at 12 months after randomisation), an intracluster correlation (ICC) of 0.1 in the intervention group and an optimal allocation ratio of 6 : 5 in favour of the intervention group, a total of 336 evaluable patients would provide 80% power to detect such a difference (182 to the intervention and 154 to usual care). A sample size of 400 randomised participants was set (216 to the intervention and 184 to usual care) to allow for non-collection of primary outcome data for 15% of participants.

Version 2 of the MSIS-Psy was used in this trial, with scores ranging from 9 to 36. The SD of the MSIS-Psy version 2 in the UK South West Impact of Multiple Sclerosis (SWIMS) cohort was 6.4 points. 115 Differences of between 2 and 3 points on version 2 of the MSIS-Psy are detectable based on the effect size specified above (assuming a SD of between 6 and 9), with assumed similar clinical importance as for version 1.

Statistical analysis

The planned analyses were described in the statistical analysis plan (SAP), which was finalised prior to database lock and release of the treatment allocation codes for analysis. All analyses were carried out using Stata®/SE version 15.1 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA) and R studio version 3.4.2 (The R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).

Preliminary analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to examine balance between the two groups on demographic and clinical measures.

Analysis populations

The main approach for the analysis was to analyse participants as randomised, regardless of the number of cognitive rehabilitation sessions attended for all primary and secondary outcomes.

The data used at each time point were as follows:

-

questionnaires/visits completed within 9 months of randomisation (i.e. within 275 nights of randomisation) for the outcomes at 6 months

-

questionnaires/visits completed within 15 months of randomisation (i.e. within 456 nights of randomisation) for the outcomes at 12 months.

Outcomes completed outside these time periods were used only in a sensitivity analysis for the primary outcome and for the safety outcome. The main analyses were conducted on data from participants with available data; no imputation was undertaken for participants who had missing outcomes.

Descriptive analyses

The adherence to the intervention was described by tabulating the attendance at each session and summarising the number of sessions that each participant attended (with and without catch-up sessions). The reasons for non-attendance at sessions were also described and summarised.

The number of participants returning the questionnaire booklet/completing the follow-up visit at 6 and 12 months was summarised in the two groups, along with the number of days between randomisation and completion. The pattern of missing outcome data was explored, overall and in the two groups, and the baseline characteristics were compared between participants with and participants without primary outcome data.

Unblinding of RAs at a follow-up visits was reported descriptively. The kappa statistic was used to assess the agreement between a participant’s actual treatment allocation and the RA’s opinion of treatment allocation, collapsing probably and definitely into one category.

Missing data in questionnaires

Missing items in questionnaires were imputed with the mean of the completed items if ≥ 8 of the 9 items on the MSIS-Psy were completed, ≥ 17 of the 20 items on the Multiple Sclerosis Impact Scale – Physical Subscale (MSIS-Phy) were completed, ≥ 25 of the 28 items on the Everyday Memory Questionnaire (EMQ) were completed, ≥ 27 of the 30 items on the GHQ-30 were completed and ≥ 12 of the 13 items on the MCSI were completed. Otherwise, scores from questionnaires were treated as missing.

To be able to include all participants in the regression analysis of the outcome score, if scores from the questionnaires remained missing at baseline after the process outlined above, baseline data were imputed for the analysis using the mean score at each centre. These simple imputation methods are better than more complicated imputation methods in which baseline variables are included in an adjusted analysis to improve the precision of the treatment effect. 116 This imputation was done only for the regression analyses and not for summarising the baseline scores.

Primary outcome

The primary analysis estimated the difference in the mean MSIS-Psy score at 12 months between the two groups using a multilevel linear model, with baseline MSIS-Psy score, gender, MS type and centre as covariates. Participants in the usual-care group had no contact with each other; therefore, outcomes in this group were assumed to be independent. However, participants in the intervention group received cognitive rehabilitation sessions together, which needed to be taken into account in the analysis. A fully heteroscedastic model was used, which estimates group-level residual variance in the intervention group and also permits individual-level residual variance to differ between intervention and control groups. 117,118 The assumptions for the multilevel linear model were checked using diagnostic plots. The ICC coefficient in the intervention group was estimated using the estimates of the group-level residual variance and individual-level residual variance in the intervention group.

Sensitivity analyses for the primary outcome

The following sensitivity analyses were conducted:

-

Including all 12-month questionnaires – the analysis was repeated including participants whose 12-month questionnaires were returned after the 15-month post-randomisation window.

-

Using different methods for missing baseline MSIS-Psy score – the analysis was repeated restricting the analysis to participants with the MSIS-Psy completed at baseline and using the missing indicator method for missing baseline MSIS-Psy values.

-

Multiple imputation of missing primary outcome data – multiple imputation was performed using multivariate multilevel linear regression using the pan procedure in R, under the assumption that missing data were missing at random. Variables included in the imputation model were centre, age, gender, MS type, MSIS-Psy score at baseline and at 6 months, MSNQ score, Doors and People overall age-scaled score at baseline, Symbol Digit Modalities Test from the BRBN, whether or not the participant had reported a MS relapse at 6 and 12 months, the number of cognitive rehabilitation sessions attended and the following scores from baseline, 6 months and 12 months: GHQ-30 total score, EMQ-p score and EuroQol-5 Dimensions visual analogue scale (EQ-5D VAS) score. Thirty data sets were imputed and the results of the analyses on the imputed data sets were combined using Rubin’s rules.

-

The complier average causal effect was estimated in a secondary analysis of the primary outcome. Instrumental variable regression was used to estimate the effect of the intervention for participants who would comply with the allocated treatment for whichever group they were randomised to. 119,120 Participants in the intervention group were classified as adherent if they attended at least three cognitive rehabilitation sessions. The instrumental variable regression model included baseline MSIS-Psy score, gender, MS type and centre. The complier average causal effect was estimated using both the observed data and the multiply imputed data.

Earlier effects on the primary outcome were investigated in a secondary analysis by comparing the MSIS-Psy at 6 months after randomisation in the two groups using the same analysis model as for the primary outcome.

Subgroup analyses for the primary outcome

Four exploratory subgroup analyses for the primary outcome were performed by including an interaction term in the model for the primary analysis between allocated group and the following variables:

-

MS type (progressive or relapsing–remitting)

-

MSNQ score (i.e. according to cognitive problems at baseline)

-

Doors and People score (overall score, i.e. according to memory function at baseline)

-

Symbol Digit Modalities Test score from the BRBN (i.e. according to speed of processing of information).

The MSNQ score, the overall Doors and People score and Symbol Digit Modalities Test score were split into three categories, according to the tertiles at baseline.

Secondary outcomes at 6 and 12 months

The difference in means between the two groups at 6 and 12 months was estimated, using the same analysis model described for the primary outcome, for the following outcomes:

-

memory problems in everyday life, measured using the EMQ-p and EMQ-r

-

mood, measured using the GHQ-30

-

fatigue, measured using the Rasch-transformed FSS

-

carer strain, measured using the MCSI

-

quality of life, measured using the EQ-5D VAS (from the EQ-5D-5L), which asks participants to rate their current health status

-

attention and memory abilities, using the Selective Reminding total and delayed recall scores; 10/36 Spatial Recall Test total correct and delayed recall scores; the Symbol Digit Modalities total score; the Paced Auditory Serial Addition Test, Easy and Hard total scores; and the Word Fluency total score from the BRBN

-

overall age-scaled score, verbal total score, non-verbal total score and forgetting score from the Doors and People test

-

the difference between the number of seconds to complete parts A and B of the Trail Making test (derived as B – A)

-

physical impact of MS on quality of life, measured using the MSIS-Phy.

The number of participants in any form of employment (full or part-time) was used for the analysis for employment status. The odds ratio for any form of employment at 6 and 12 months in the two groups was estimated using a generalised estimating equation with a logistic link function and robust standard errors to account for potential clustering in the intervention group. 121

The secondary outcomes for disability (as measured using GNDS) and the number of reported relapses in the previous 6 months are reported descriptively.

The safety outcome, defined as an increase of ≥ 30 points on the GHQ-30 (using Likert scoring) between baseline and 6 months, is also reported descriptively. All participants completing the 6-month questionnaire were included in the analysis population for the safety outcome.

Chapter 3 Results

Recruitment

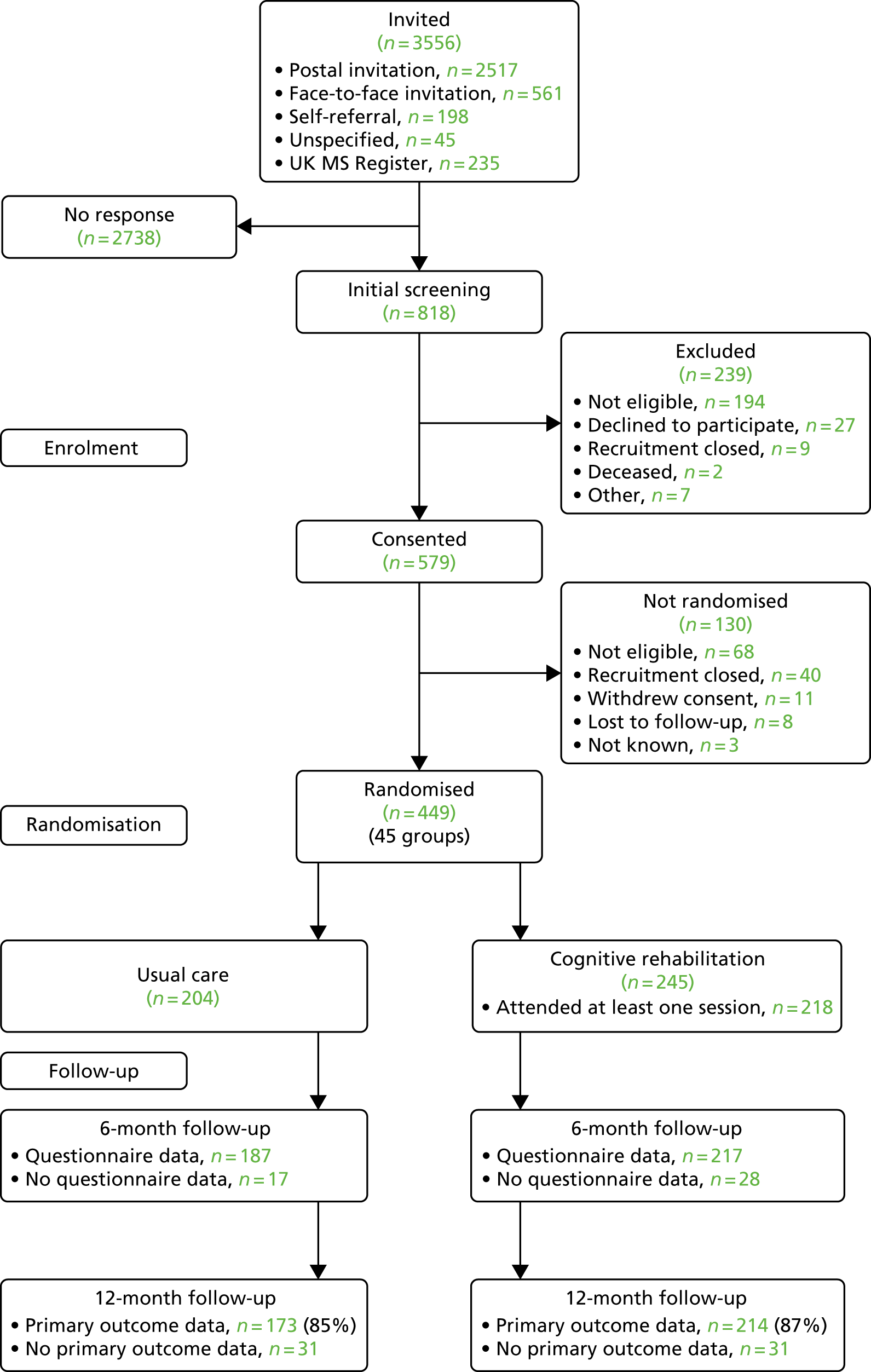

Participants were recruited between April 2015 and March 2017 (see Appendix 4, Figure 10). Of the 3556 people with MS who were invited to participate or expressed an interest in the trial, 818 had an initial telephone eligibility screening and, of these, 579 consented. The majority of the patients screened initially who did not consent were not eligible (n = 194; 81%). The breakdown of reasons for exclusion is shown in Appendix 5, Table 28.

Of the 579 participants who gave consent, 449 were randomised (78%). Non-randomisation after consent was mainly as a result of not being eligible (n = 68; 52%) or the trial being closed to recruitment (n = 40; 31%); the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) flow diagram is shown in Figure 1 and reasons participants were not eligible are shown in Appendix 5, Table 29. The randomisation target was exceeded because there was a pool of eligible participants who had been screened, consented and were awaiting randomisation at the time the target was reached, as a result of the requirement to form groups of 9–11 participants who could all attend for cognitive rehabilitation sessions at the same time and place (if allocated).

FIGURE 1.

The CONSORT flow diagram. Reproduced with permission from Lincoln et al. 122 This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/) which permits non-commercial use, reproduction and distribution of the work without further permission provided the original work is attributed as specified on the SAGE and Open Access pages (https://us.sagepub.com/en-us/nam/open-access-at-sage).

Of the 449 participants randomised, 204 were randomised to usual care and 245 to cognitive rehabilitation in addition to usual care (allocation ratio of 6 : 5 to the cognitive rehabilitation group, as planned). There were 45 cognitive rehabilitation groups: two groups of four participants (4%), 21 groups of five participants (47%) and 22 groups of six participants (49%).

Participants waited a median of 42 days between the baseline assessment and randomisation. However, a few participants (n = 25; 6%) waited for ≥ 6 months to be randomised as a result of waiting for other participants who could attend the intervention sessions at the same time or awaiting the availability of an AP to deliver the intervention.

Baseline data

The mean age of participants was 49 years (SD 9.9 years), 326 (73%) were women and almost all were white (96%) (Table 1). Approximately two-thirds of participants reported that they had relapsing–remitting MS with a mean time since diagnosis of 11.7 years (SD 8.4 years). One-third of participants reported being in employment, one-third reported being retired and one-third reported not being in either employment or education.

| Characteristic | Usual care (N = 204) | Cognitive rehabilitation (N = 245) |

|---|---|---|

| Age at randomisation (years) | ||

| Mean (SD) | 48.9 (10.0) | 49.9 (9.8) |

| Minimum, maximum | 25, 69 | 18, 69 |

| Gender, n (%) | ||

| Men | 56 (27) | 67 (27) |

| Women | 148 (73) | 178 (73) |

| Ethnicity, n (%) | ||

| White | 195 (96) | 237 (97) |

| Black | 3 (1) | 3 (1) |

| Asian | 2 (1) | 3 (1) |

| Mixed | 4 (2) | 2 (1) |

| Marital status, n (%) | ||

| Single/divorced/widowed | 66 (32) | 81 (33) |

| Married/with partner | 138 (68) | 164 (67) |

| Participant-reported time since MS diagnosis (years) | ||

| Mean (SD) | 11.1 (8.7) | 12.1 (8.0) |

| Minimum, maximum | 0, 40 | 0, 36 |

| Type of MS (participant reported), n (%) | ||

| Relapsing–remitting | 132 (65) | 159 (65) |

| Primary progressive | 24 (12) | 22 (9) |

| Secondary progressive | 48 (24) | 64 (26) |

| Number of relapses in the previous 6 months, as assessed at screening (participant reported), n (%) | ||

| 0 | 155 (76) | 186 (76) |

| 1 | 31 (15) | 47 (19) |

| 2 | 13 (6) | 5 (2) |

| ≥ 3 | 5 (2) | 7 (3) |

| Relapse between baseline and randomisation (participant reported), n (%) | ||

| No | 190 (93) | 220 (90) |

| Yes | 12 (6) | 24 (10) |

| Not known | 2 (1) | 1 (< 0.5) |

| Years of education | ||

| Mean (SD) | 13.9 (2.9) | 14.2 (3.4) |

| Minimum, maximum | 10, 30 | 10, 35 |

| Employment status, n (%) | ||

| Retired | 64 (31) | 80 (33) |

| Not employed or in education | 70 (34) | 83 (34) |

| Employed part time | 31 (15) | 44 (18) |

| Employed full time | 38 (19) | 31 (13) |

| In education full time | 0 (0) | 1 (< 0.5) |

| In education part time | 0 (0) | 6 (2) |

| Not knowna | 1 (< 0.5) | 0 (0) |

| Any employment (full or part time) | 69 (34) | 75 (31) |

| Living arrangements, n (%) | ||

| Lives alone | 38 (19) | 49 (20) |

| Lives with others | 166 (81) | 196 (80) |

| Living in care home | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

The characteristics assessed at baseline were well balanced between groups, including the minimisation stratification variables of gender and MS type. However, a slightly higher percentage of participants in the cognitive rehabilitation group than in the usual-care group reported a relapse between baseline and randomisation (10% vs. 6%, respectively). Attention and memory abilities, psychological and physical impact of MS on quality of life, frequency of memory problems, and mood and fatigue were similar in the two groups at baseline (Table 2).

| Assessment | Usual care, mean [SD] or n (%) (N = 204) | Cognitive rehabilitation, mean [SD] or n (%) (N = 245) |

|---|---|---|

| MSNQa | 39.0 (7.4) | 38.9 (7.1) |

| BRBNb | ||

| Selective Remindingc | ||

| Total recall | 40.2 [10.5] | 40.6 [11.0] |

| Long-term storage | 30.9 [14.5] | 31.2 [15.7] |

| Consistent long-term retrieval | 18.7 [13.6] | 19.0 [14.2] |

| Delayed recall | 5.7 [2.8] | 5.8 [2.8] |

| 10/36 Spatial Recalld | ||

| Total correct | 18.3 [4.9] | 18.1 [4.5] |

| Total confabulations | 11.3 [5.0] | 11.5 [4.6] |

| Delayed recall | 6.3 [2.1] | 6 [2.2] |

| Symbol Digit Modalitiese | 37.8 [12.1] | 36.3 [11.5] |

| Paced Auditory Serial Additionf | n = 199 | n = 239 |

| Easy total correct | 31.1 [16.4] | 31.6 [16.2] |

| Hard total correct | 15.9 [15.8] | 17.3 [16.5] |

| Word fluencyg | n = 203 | n = 244 |

| Total score | 25.1 [8.9] | 24.8 [8.8] |

| GNDSh | 20.0 [6.7] | 19.9 [7.1] |

| Doors and Peoplei | n = 203 | n = 245 |

| Overall age-scaled score | 7 [3.9] | 7 [3.7] |

| Verbal total score | 7.7 [3.9] | 7.8 [3.7] |

| Non-verbal total score | 7.7 [3.5] | 7.5 [3.4] |

| Total forgetting score | 8.8 [3.0] | 8.8 [3.0] |

| Trail Makingj | n = 200 | n = 244 |

| Part B – part A | 69.6 [41.4] | 71.7 [41.0] |

| EQ-5D VAS scorek | 59.6 [20.3] | 59.9 [21.2] |

| Baseline questionnaire booklet returned | 198 (97) | 233 (95) |

| MSIS-Psyl | 24.7 [6.0] (n = 197) | 23.3 [5.8] (n = 233) |

| MSIS-Phym | 53.4 [13.1] (n = 197) | 52 [13.6] (n = 232) |

| EMQ-pn | 47.1 [23.2] (n = 194) | 45.0 [22.8] (n = 229) |

| FSSo | 1.3 [1.3] (n = 197) | 1.4 [1.4] (n = 230) |

| GHQ-30p | ||

| Total score (Likert scoring) | 39.7 [15.8] (n = 197) | 36.5 [14.2] (n = 230) |

| GHQ score of ≥ 5 (GHQ scoring) | 136 (67) | 150 (61) |

| EMQ-rn | 38.2 [25.9] (n = 185) | 34.7 [23.4] (n = 213) |

The EMQ-r questionnaire was completed for 398 participants (89%) at baseline: 185 (91%) in the usual-care group and 213 (87%) in the cognitive rehabilitation group.

Baseline questionnaires should have been completed prior to randomisation; however, six participants (3%) in the usual-care group and 12 (5%) in the cognitive rehabilitation group were randomised without the questionnaires being completed.

Two randomised participants (one in each group) were found to not be eligible for the trial during checks of the BRBN scoring as they did not have any test scores more than one SD below the mean of healthy controls, corrected for age and years of education. These participants are included in all analyses.

Cognitive rehabilitation sessions

Attendance at sessions

Participants attended a mean of 7 sessions (SD 3.4 sessions) not including catch-up sessions, and a mean of 7.7 sessions (SD 3.5) when catch-up sessions were included (Table 3). Three or more sessions (including catch-up sessions) were attended by 208 participants (85%). The reasons that participants did not attend sessions are shown in Table 4. Twenty-four participants (10%) missed sessions as they did not want to continue and six participants (2%) stopped attending as they withdrew from the trial (not mutually exclusive); otherwise, sessions tended to be missed because of illness or other commitments.

| Sessions attended | (N = 245) |

|---|---|

| Including catch-up sessions | |

| Mean (SD) | 7.7 (3.5) |

| Median (25th, 75th centile) | 10 (7, 10) |

| Number of sessions attended, n (%) | |

| 0–2 | 37 (15) |

| 3–7 | 32 (13) |

| 8–10 | 176 (72) |

| Excluding catch-up sessions | |

| Mean (SD) | 7 (3.4) |

| Median (25th, 75th centile) | 8 (6, 10) |

| Reason scheduled session missed | Total number of sessions | Total number of participants |

|---|---|---|

| Did not want to continue | 162 | 24 |

| Withdrew from trial | 40 | 6 |

| Unable to contact | 92 | 26 |

| Forgot to attend | 14 | 13 |

| Unwell – MS relapse | 20 | 11 |

| Unwell – other | 119 | 66 |

| Holiday | 65 | 49 |

| Work commitments | 49 | 25 |

| Travel problems | 12 | 11 |

| Othera | 157 | 69 |

| Not known | 11 | 10 |

Follow-up

Participant follow-up was between November 2015 and April 2018. At the 6-month follow-up, 412 (92%) participants completed the assessment visit and 405 (90%) completed the questionnaire booklet (Table 5). Completion rates were similar in the two groups.

| Follow-up completion | 6-month follow-up | 12-month follow-up | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Usual care (N = 204) | Cognitive rehabilitation (N = 245) | Usual care (N = 204) | Cognitive rehabilitation (N = 245) | |

| Face-to-face visit | ||||

| Attended, n (%) | 187 (92) | 225 (92) | 175 (86) | 212 (87) |

| Not done,a n (%) | 5 (2) | 5 (2) | 3 (1) | 7 (3) |

| Discontinued with reasons, n (%) | 12 (6) | 15 (6) | 26 (13) | 26 (11) |

| Death (n) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Withdrawal of consent (n) | 9 | 10 | 16 | 13 |

| Lost to follow-up (n) | 3 | 4 | 10 | 12 |

| Other – not known (n) | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Days to assessment visit from randomisation | ||||

| Median (25th, 75th centile) | 182 (178, 188) | 184 (180, 188) | 365 (359, 370) | 364 (359.5, 370) |

| Minimum, maximum | 166, 261 | 167, 288 | 343, 546 | 334, 479 |

| Visit completed within 3 months of due date, n (%) | ||||

| No | – | 1 (< 0.5) | 2 (1) | 3 (1) |

| Yes | 187 (92) | 224 (91) | 173 (85) | 209 (85) |

| Questionnaire booklet, n (%) | ||||

| Returned | 187 (92) | 218 (89) | 176 (86) | 216 (88) |

| Not donea | 5 (2) | 12 (5) | 2 (1) | 3 (1) |

| Discontinued | 12 (6) | 15 (6) | 26 (13) | 26 (11) |

| Days to completion from randomisation | ||||

| Median (25th, 75th centile) | 177 (170, 187) | 178 (170, 184) | 357 (351, 366.5) | 358 (350, 366) |

| Minimum, maximum | 151, 260 | 152, 288 | 327, 532 | 313, 478 |

| Questionnaire completed within 3 months of due date, n (%) | ||||

| No | – | 1 (< 0.5) | 3 (1) | 1 (< 0.5) |

| Yesb | 187 (92) | 217 (89) | 173 (85) | 215 (88) |

At the 12-month follow-up, 387 (86%) participants completed the assessment visit and 392 (87%) completed the questionnaire booklet; completion rates were similar in the two groups (see Table 5). A total of 80% of questionnaire booklets at both time points were completed on paper rather than electronically.

Almost all of the visits and questionnaires were completed within 3 months of the scheduled time point (see Table 5).

Fifty-two participants did not complete the 12-month follow-up (12%; 26 participants in each group) because they either withdrew consent or were lost to follow-up (see Table 5). The main reasons for withdrawal (when given) were health problems or having too many other commitments.

Inclusion in primary analysis of the primary outcome

A total of 173 participants (85%) in the usual-care group and 214 (87%) participants in the cognitive rehabilitation group were included in the primary analysis of the primary outcome at 12 months. Three participants in the usual-care group and two participants in the cognitive rehabilitation group who completed questionnaires at 12 months were not included in the primary analysis of the MSIS-Psy because either they completed the questionnaire > 15 months after randomisation (n = 4) or there was more than one item missing on the MSIS-Psy (n = 1).

Participants in both groups with no primary outcome were slightly younger, more likely to report having relapsing–remitting MS and had poorer scores on cognitive assessments and questionnaires at baseline (see Appendix 6, Tables 30 and 31).

Relative/friend questionnaire follow-up

At 6 months relative/friend questionnaires were completed for 158 participants (77%) in the usual-care group and 185 participants (76%) in the cognitive rehabilitation group. All of the 6-month relative/friend questionnaires were completed within 9 months of a participant’s randomisation.

At 12 months, relative/friend questionnaires were completed for 147 participants (72%) in the usual-care group and 171 participants (70%) in the cognitive rehabilitation group. One relative/friend questionnaire in the usual-care group and three relative/friend questionnaires in the cognitive rehabilitation group were completed > 15 months after the participant’s randomisation.

Unblinding at follow-up visits

Research assistants reported being unblinded prior to the follow-up for 17 participants at 6 months (4% of completed visits) and for six participants at 12 months (2% of completed visits). The percentage of RAs who reported being unblinded prior to the visits were similar in the two groups at each follow-up time point.

Research assistants reported being unblinded during the visit more often in the cognitive rehabilitation group than in the usual-care group. At 6 months, RAs reported being unblinded during the visit for 36 participants (16%) in the cognitive rehabilitation group and for 16 participants (9%) in the usual-care group. At 12 months, RAs reported being unblinded during the visit for 17 participants (8%) in the cognitive rehabilitation group and for six participants in the usual-care group (3%).

Overall, there was little agreement between the RA opinion of treatment allocation and the actual treatment allocation as assessed using the kappa statistic. The kappa values were 0 at the start of the 6-month visit, 0.17 at the end of the 6-month visit, 0.02 at the start of the 12-month visit and 0.07 at the end of the 12-month visit. Details of the RA opinion of treatment allocation at the start and end of the visit are shown in Appendix 7, Table 32.

Primary outcome: MSIS-Psy at 12 months

Primary analysis

A total of 387 participants were included in the primary analysis at 12 months (86%); 376 of these completed the MSIS-Psy at baseline. There was a mean of 4.8 participants per cognitive rehabilitation group who had MSIS-Psy data at the 12-month follow-up.

There was no evidence of a difference between the two groups in the MSIS-Psy score at 12 months (Table 6). The adjusted difference in means was –0.6, with 95% confidence interval (CI) –1.5 to 0.3, which does not include the 2-point difference assumed to be clinically important on version 2.0 of the MSIS-Psy.

| Trial group | Time point, mean (SD); n | Adjusted difference in means (95% CI) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baselinea | 12 months | |||

| Usual care | 24.2 (5.9); 170 | 23.4 (6.0); 173 | ||

| Cognitive rehabilitation | 23.0 (5.7); 206 | 22.2 (6.1); 214 | –0.6 (–1.5 to 0.3) | 0.20 |

There was no evidence that the assumptions for the model were not met. The estimated ICC coefficient for the MSIS-Psy score from the model was 0 in the cognitive rehabilitation group.

Sensitivity analyses

The sensitivity analyses for the primary analysis were all consistent with the primary analysis, showing no clinically important difference between the groups in MSIS-Psy score at 12 months (Table 7).

| Sensitivity analysis | n | Adjusted difference in means (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|

| Including participants completing the 12-month questionnaire booklet > 15 months after randomisation | 391 | –0.5 (–1.4 to 0.4) |

| According to method used for missing baseline MSIS-Psy score | ||

| Participants with observed baseline MSIS-Psy score | 376 | –0.7 (–1.6 to 0.2) |

| Using missing indicator method | 387 | –0.7 (–1.6 to 0.2) |

| Multiple imputation for missing MSIS-Psy score at 12 monthsa | 449 | –0.5 (–1.5 to 0.5) |

Secondary analysis

The complier average causal effect estimate of the adjusted difference in means using the observed data was –0.7 (95% CI –1.7 to 0.4, n = 387), and using the multiply imputed data it was –0.6 (95% CI –1.7 to 0.4, n = 449), based on attending three or more cognitive rehabilitation sessions.

Subgroup analysis for the primary outcome

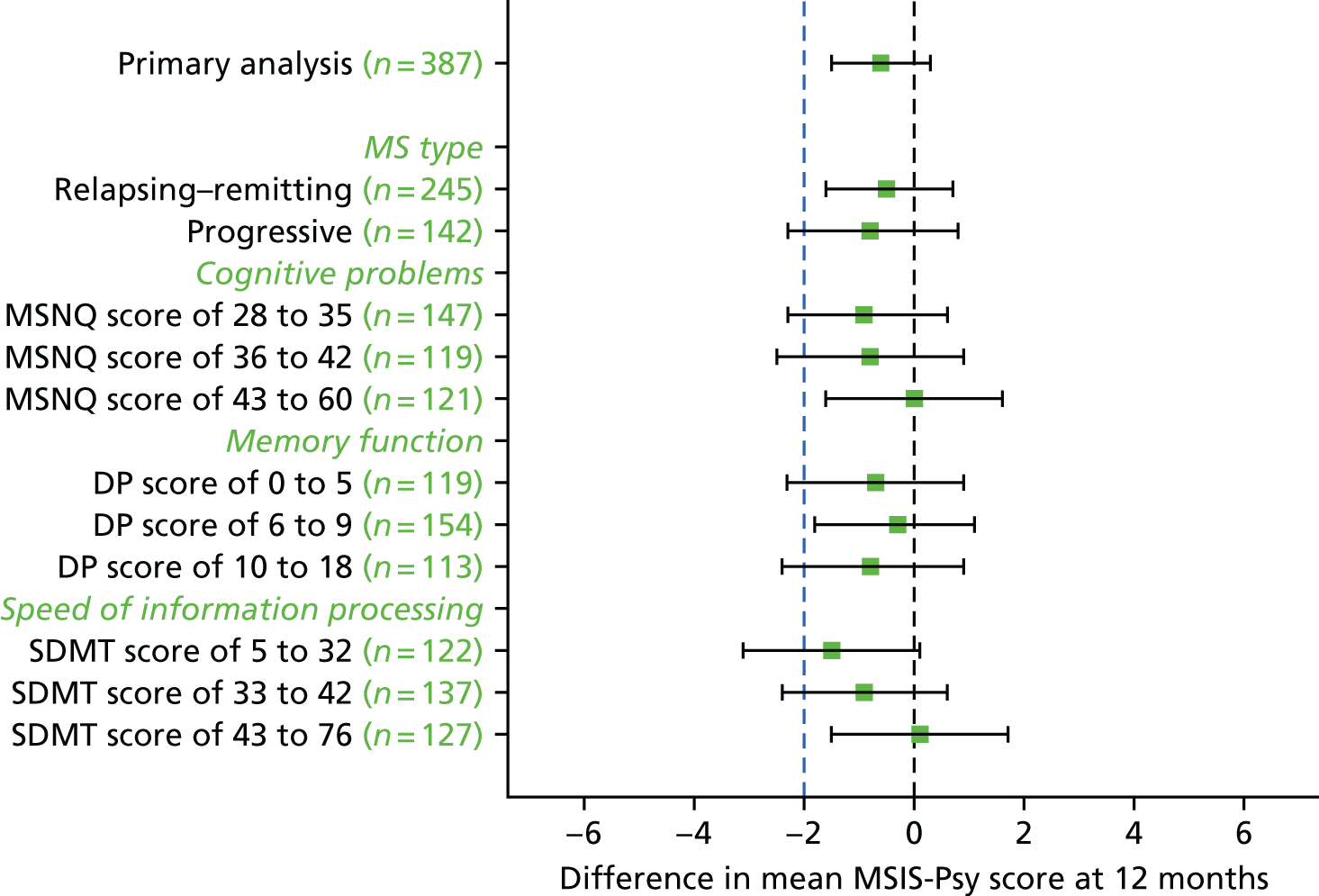

There was no evidence of a difference in the effect of cognitive rehabilitation according to MS type (p-value for interaction effect, 0.79), cognitive problems at baseline assessed on the MSNQ (p-value for interaction effect, 0.71), memory function at baseline using the Doors and People overall age-scaled score (p-value for interaction effect, 0.92) or speed of information processing at baseline using the Symbol Digit Modalities Test from the BRBN (p-value for interaction effect, 0.38) (Figure 2; see also Appendix 8, Table 33).

FIGURE 2.

Adjusted difference in mean MSIS-Psy score according to subgroup. DP, Doors and People; SDMT, Symbol Digit Modalities Test.

The MSIS-Psy score at 6 months

At 6 months, the adjusted difference in mean MSIS-Psy score and 95% CI favoured the cognitive rehabilitation group (Table 8). However, the 95% CI does not include the 2-point difference that is assumed to be clinically important.

| Trial group | Time point, mean (SD); n | Adjusted difference in means (95% CI) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baselinea | 6 months | |||

| Usual care | 24.5 (6.0); 181 | 24.1 (5.9); 187 | ||

| Cognitive rehabilitation | 23.2 (5.8); 210 | 22.3 (6.2); 217 | –0.9 (–1.7 to –0.1) | 0.03 |

Secondary outcomes

Secondary outcomes were considered to be supportive to the primary analysis. No formal adjustment for multiple significance testing was applied so the number of tests conducted should be taken into consideration when interpreting the results.

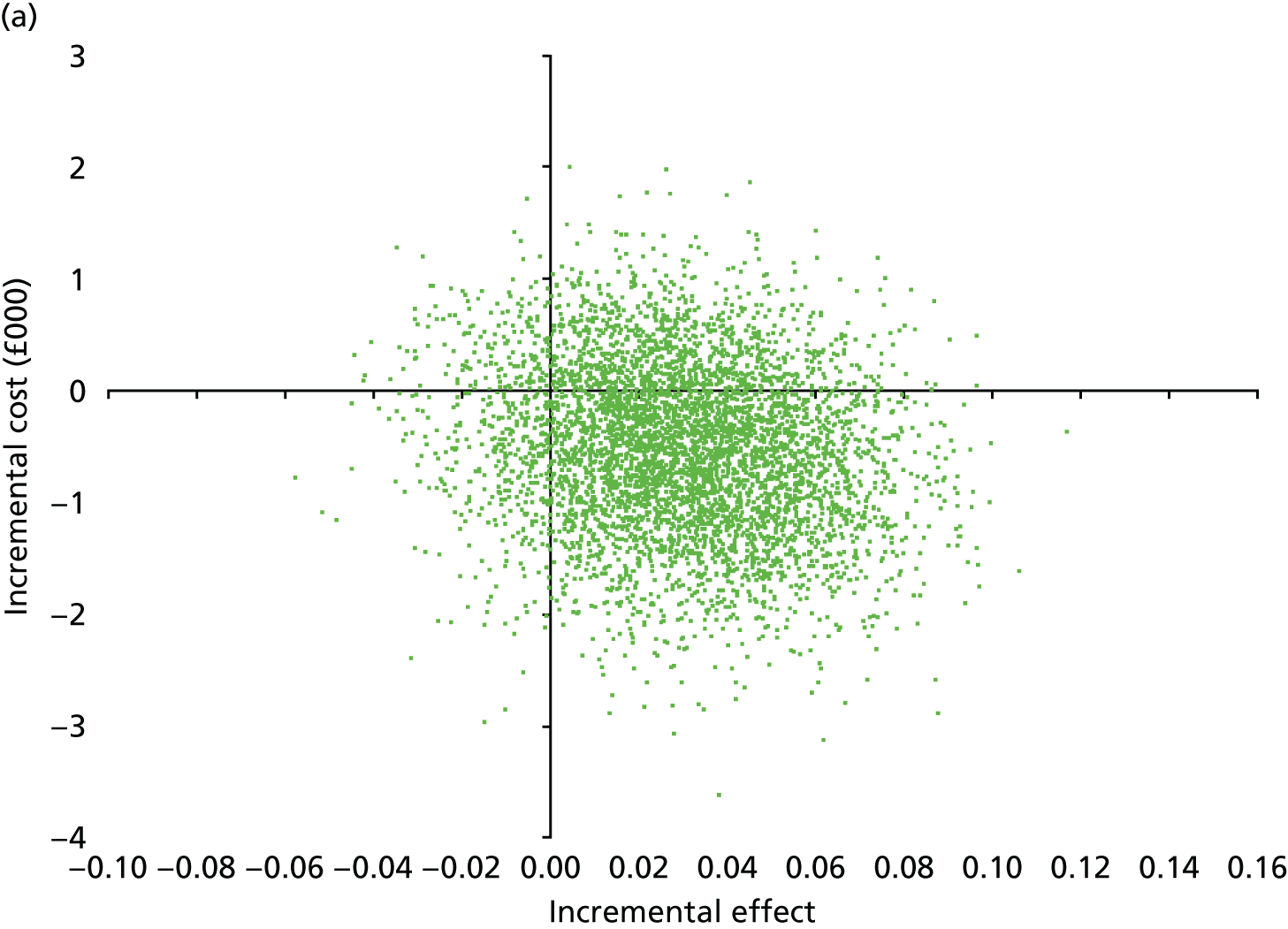

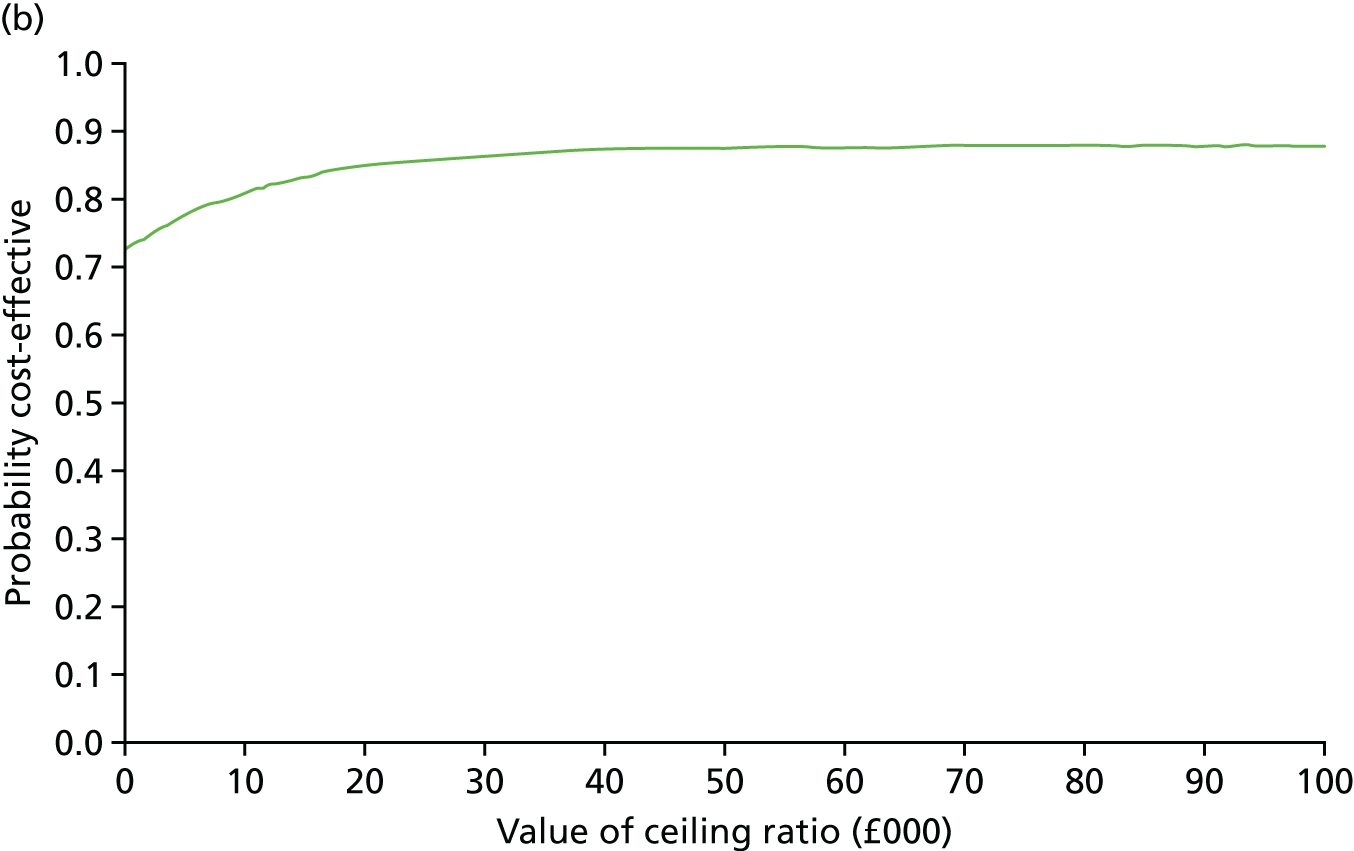

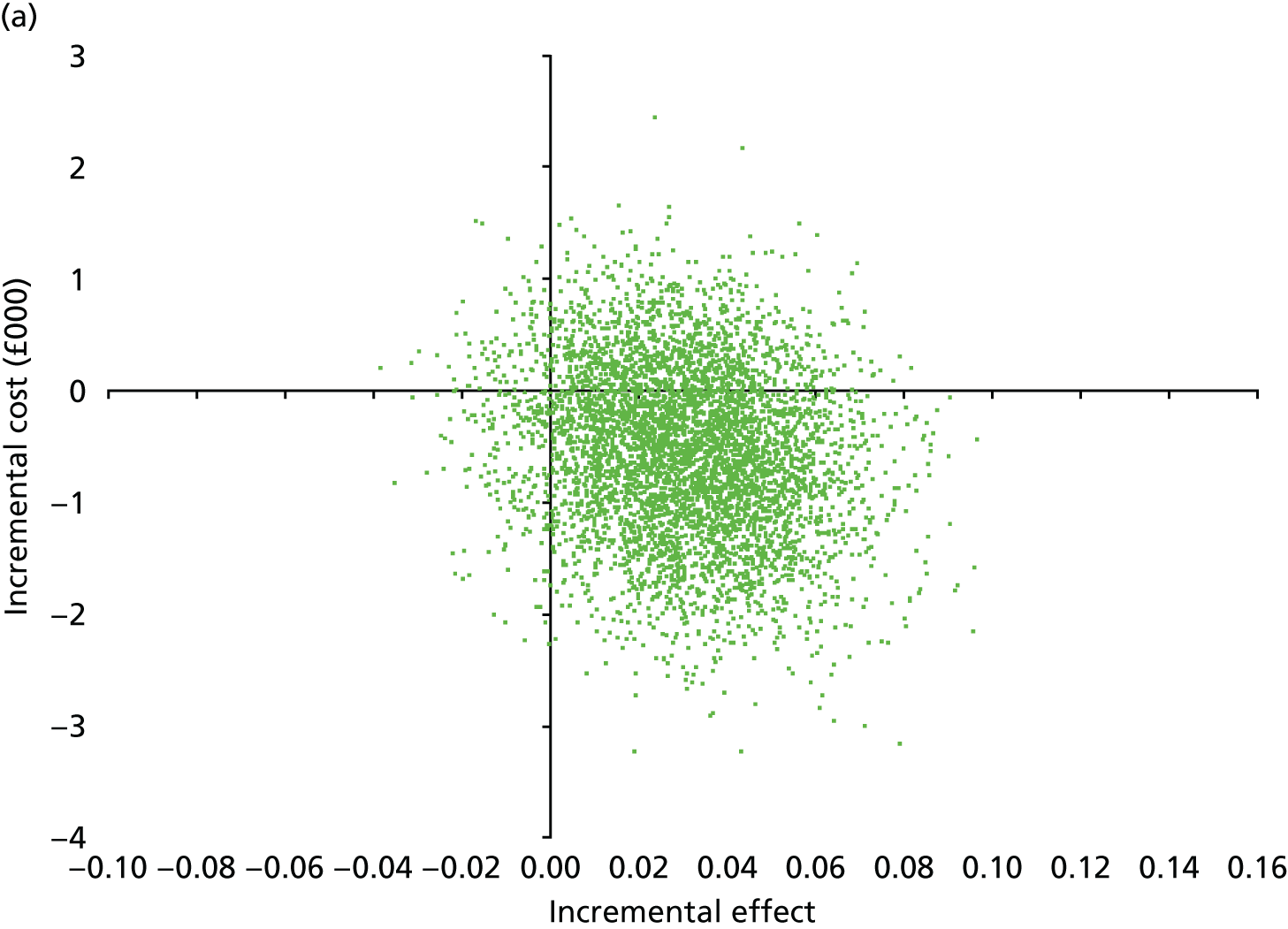

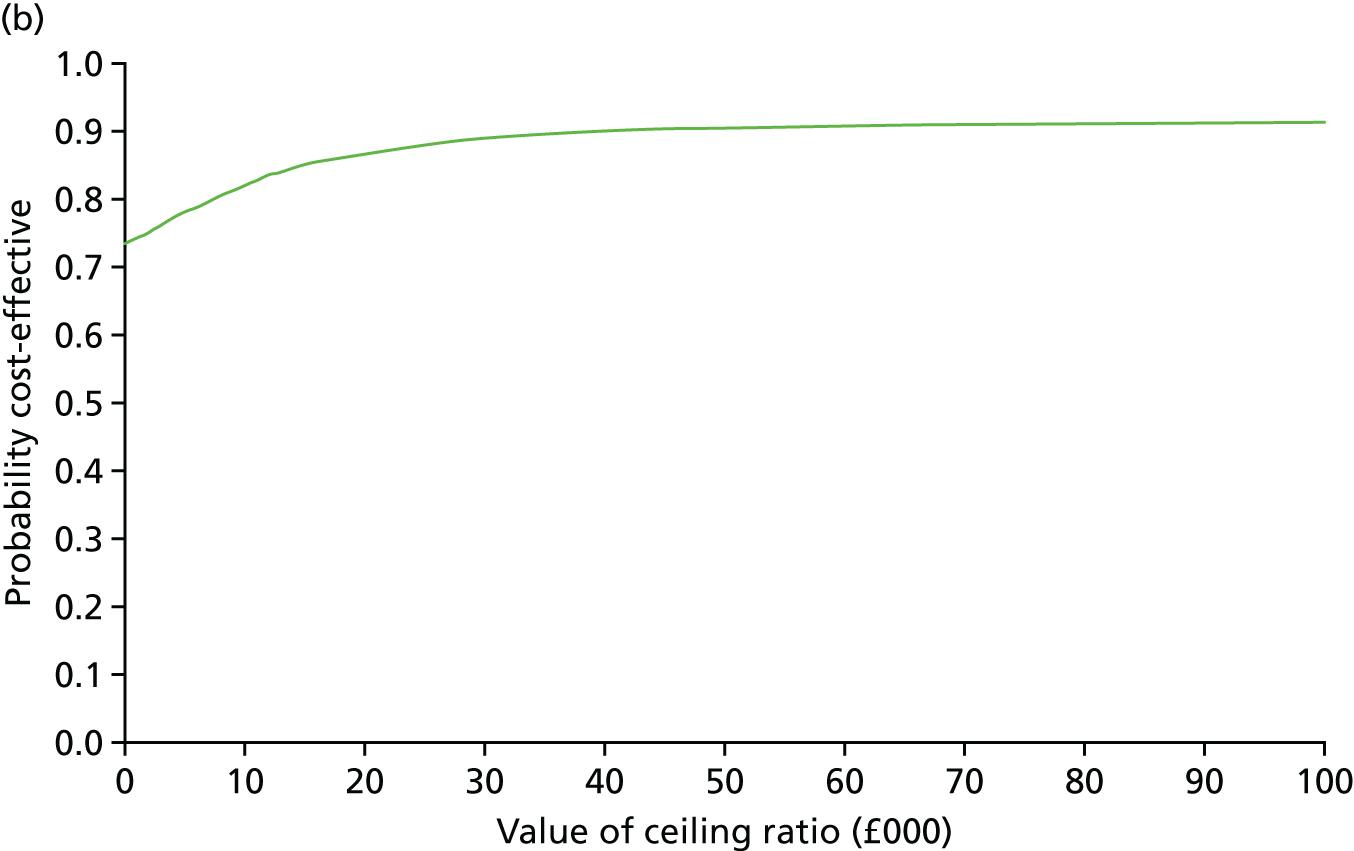

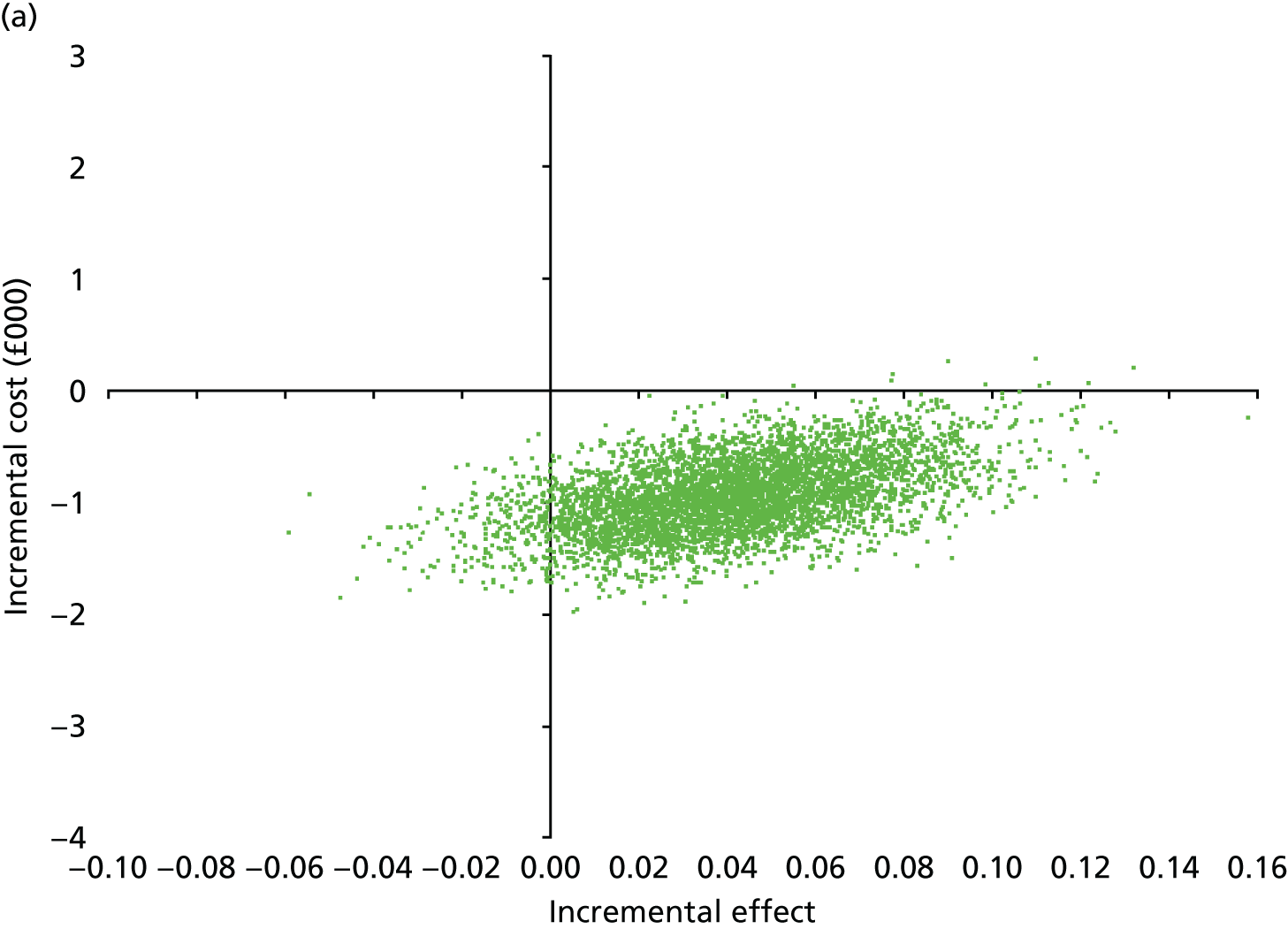

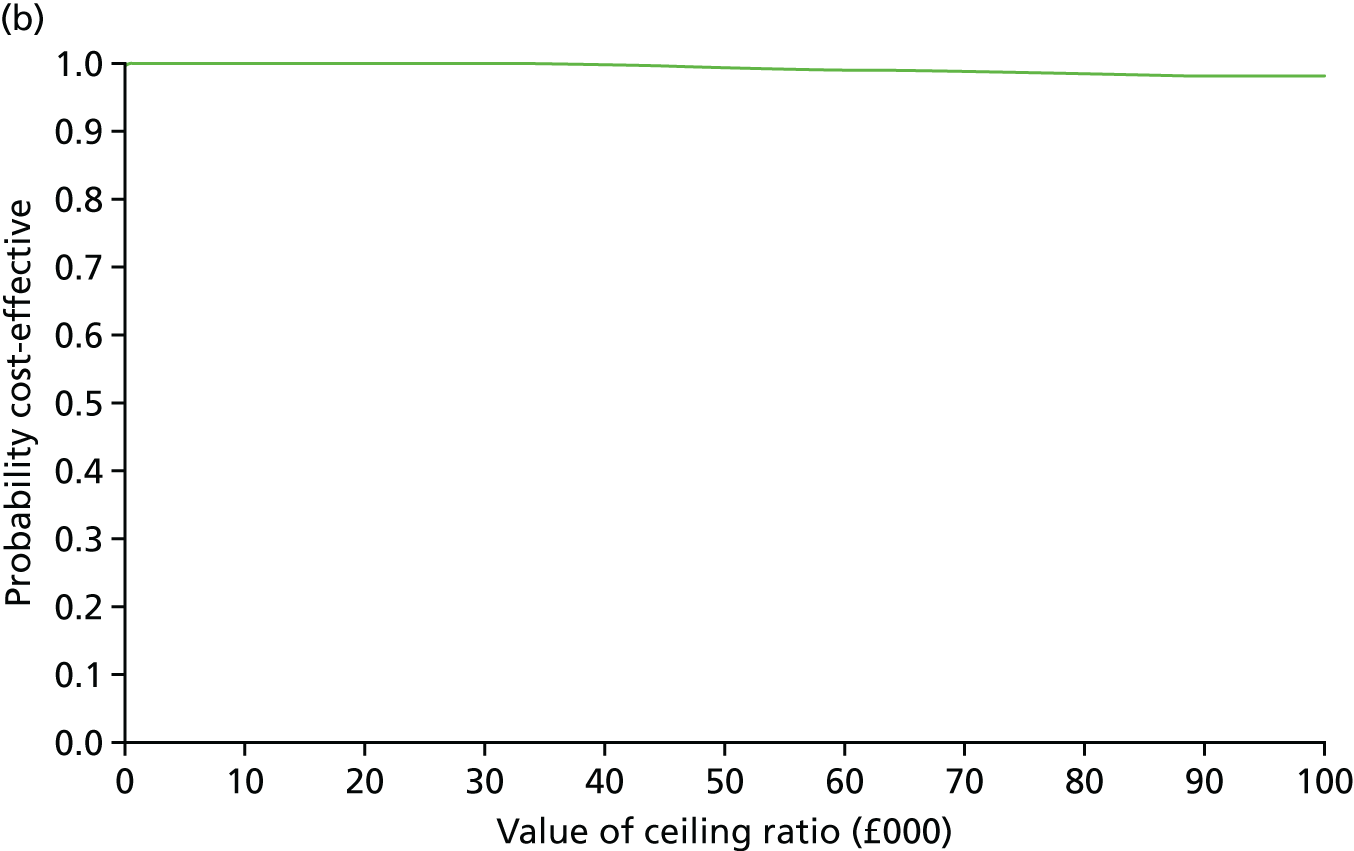

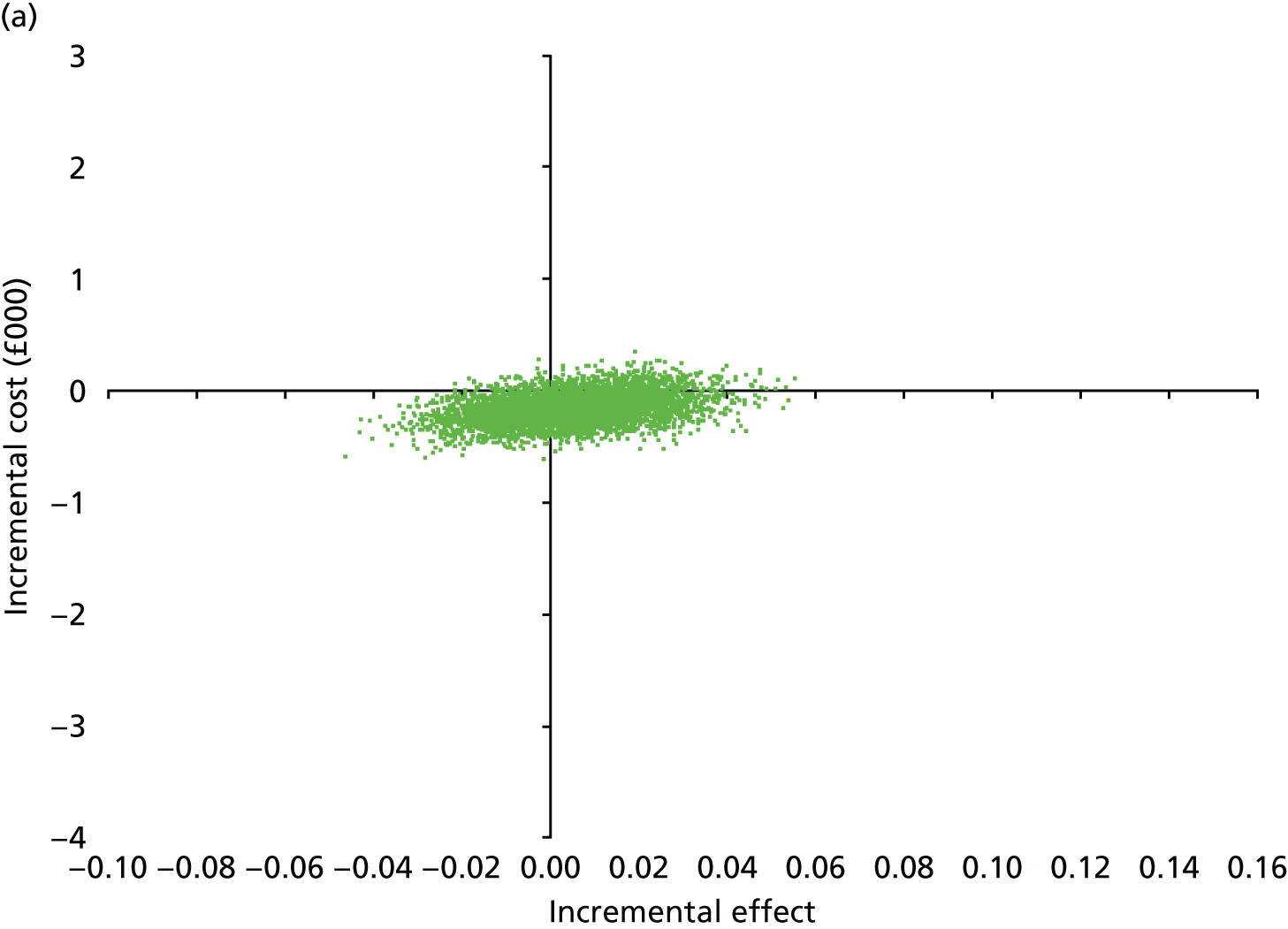

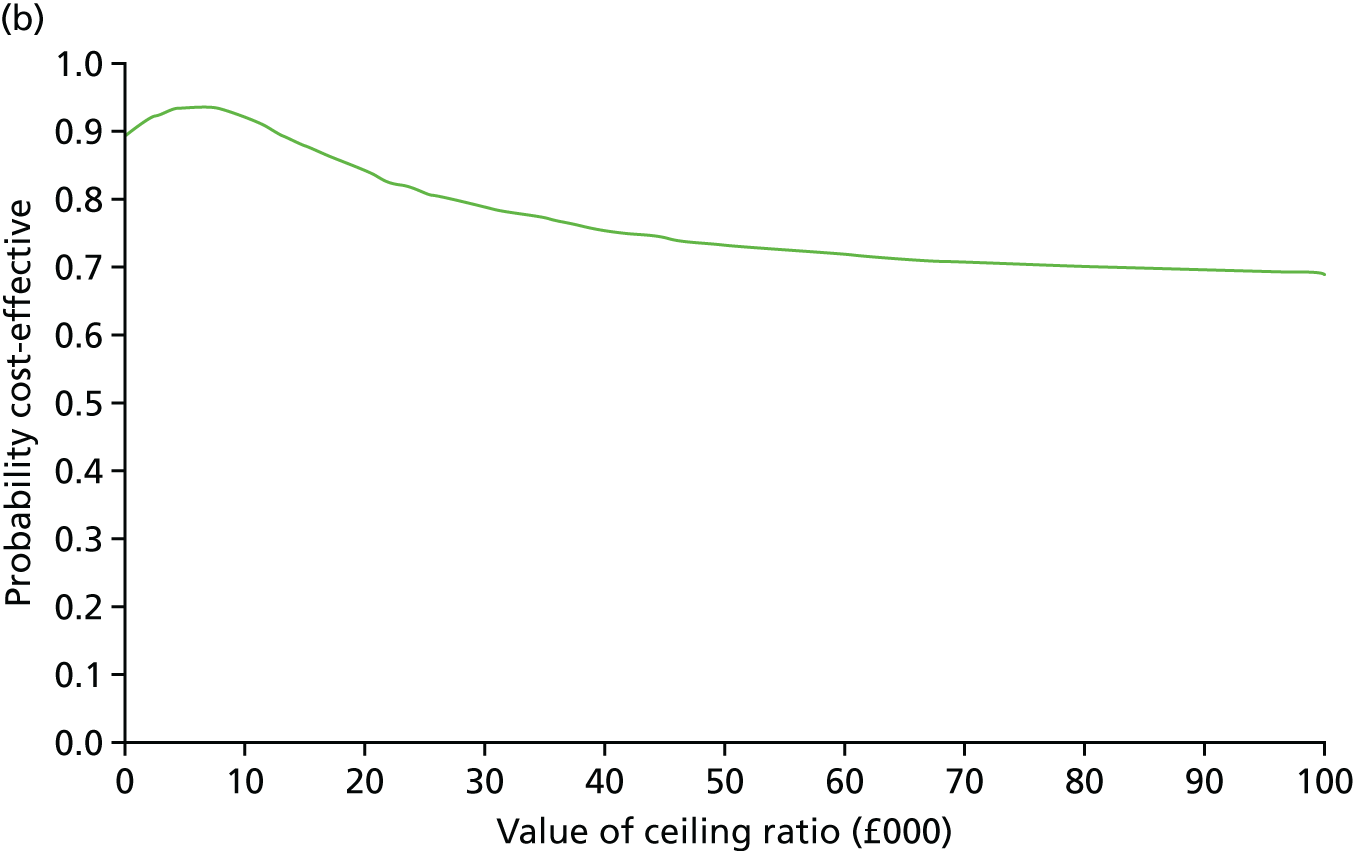

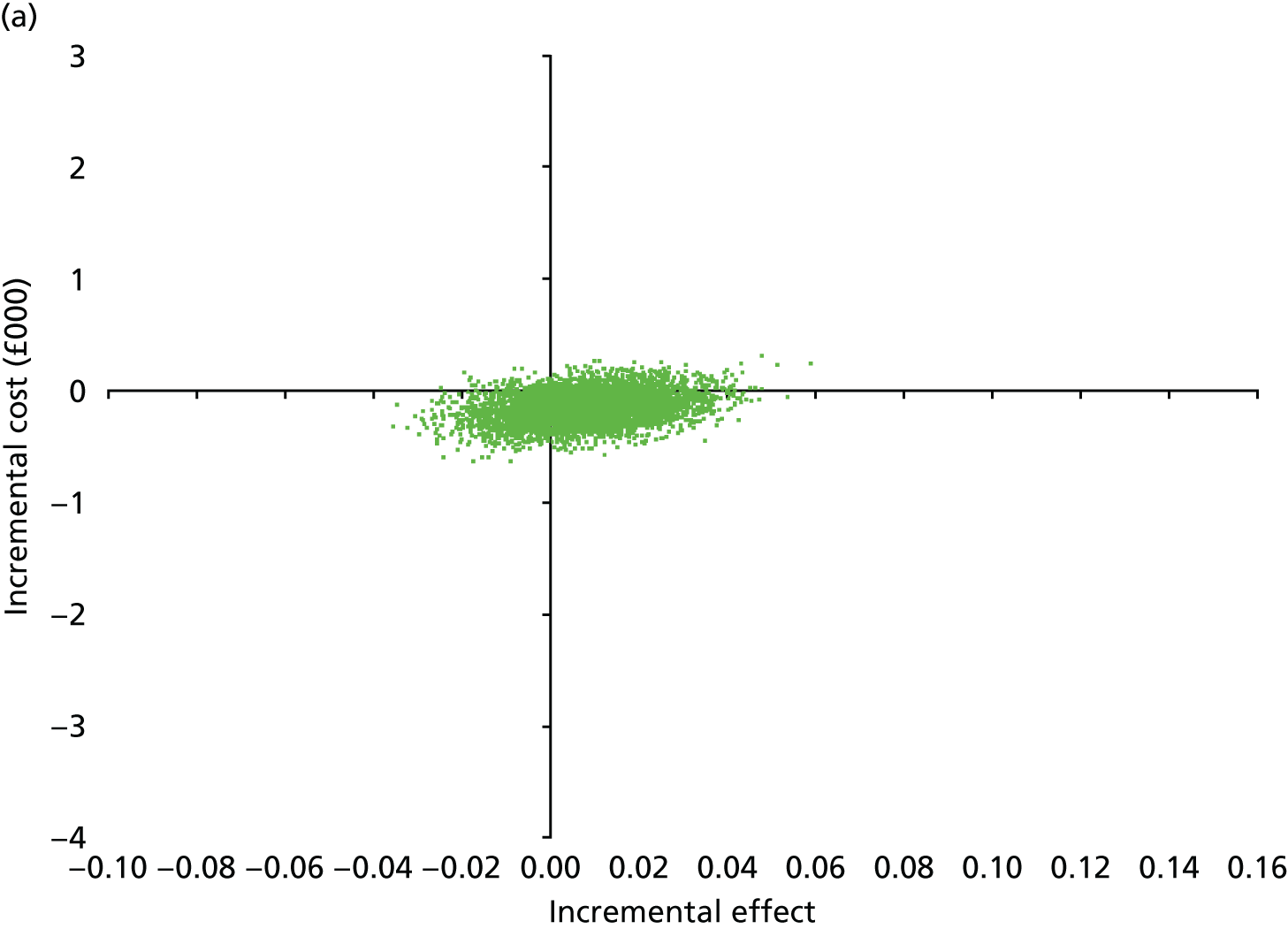

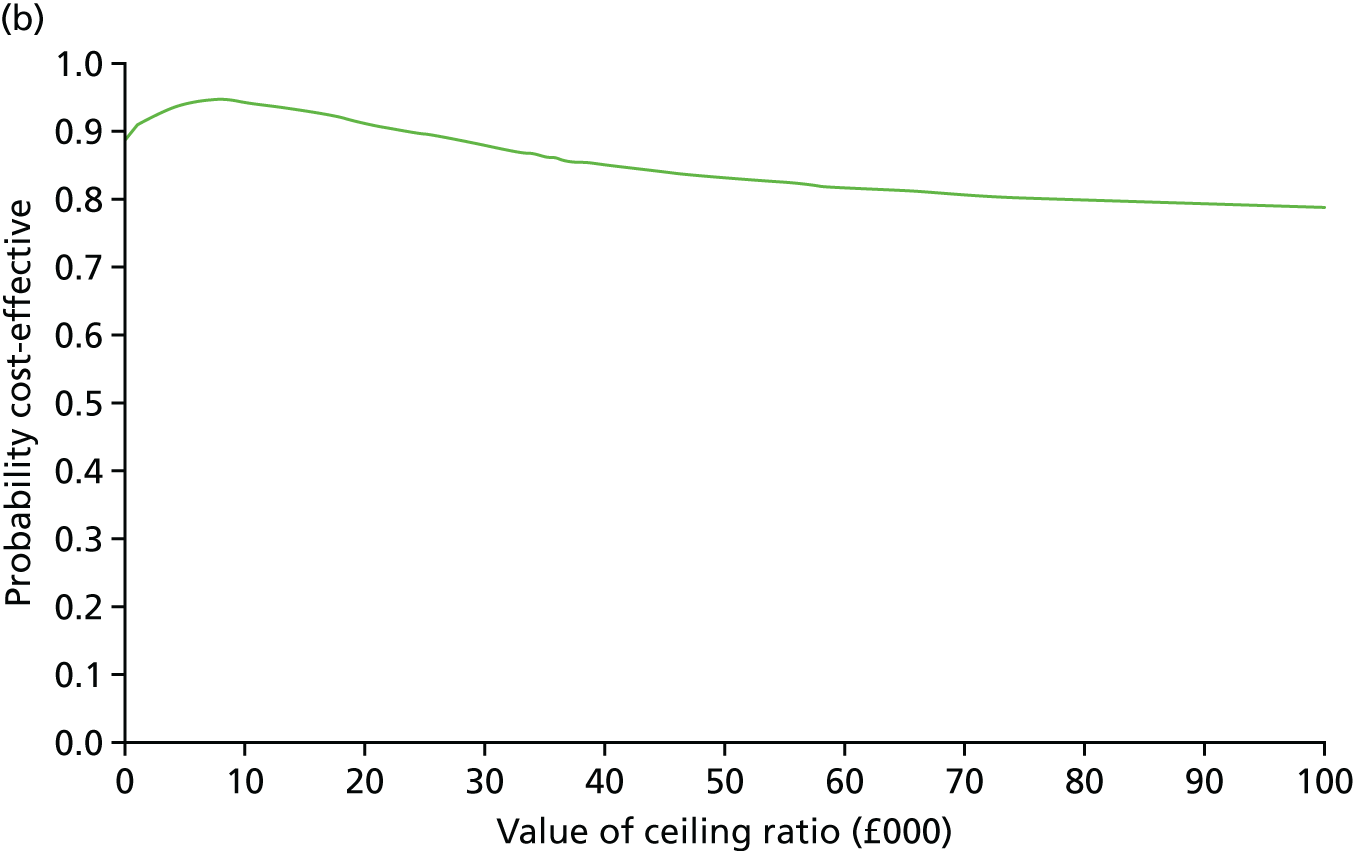

Secondary outcomes assessed on questionnaires