Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 13/115/62. The contractual start date was in April 2016. The draft report began editorial review in June 2019 and was accepted for publication in October 2019. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Matthew L Costa is a National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Senior Investigator and a member of the NIHR Health Technology Assessment (HTA) General Board (1 November 2016 to present). Rebecca S Kearney is a member of the NIHR HTA Clinical Evaluation and Trials Board (8 November 2018–present) and the NIHR Integrated Clinical Academic Doctoral Panel (29 November 2017–present) and was a member of NIHR Research for Patient Benefit Board (28 January 2016–24 January 2019). Sarah E Lamb reports that she was a member of the following boards: HTA Additional Capacity Funding Board (2012–15); HTA Clinical Trials Board (2010–15); HTA End of Life Care and Add on Studies (2015); HTA Funding Boards Policy Group (formerly Clinical Specialty Group) (2010–15); HTA Maternal, Neonatal, Child Health Methods Group (2013–15); HTA Post-board funding teleconference (2010–15); HTA Primary Care Themed Call Board (2013–14); HTA Prioritisation Group (2012–15); and the NIHR Clinical Trials Unit Standing Advisory Committee (2012–16). Stavros Petrou is a NIHR Senior Investigator.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2020. This work was produced by Costa et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2020 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Introduction

Background

The Achilles tendon is the largest tendon in the human body and transmits the powerful contractions of the calf muscles that are required for walking and running. A rupture of this tendon is painful and has an immediate and serious detrimental impact on daily activities of living. 1 In the longer term, tendon rupture results in prolonged periods off work and time away from sporting activity (average time away from work is between 4 and 8 weeks and time away from sport is between 26 and 39 weeks). 1 This results in lost income and restricted daily activities in the early phase and reduced physical activity, with associated negative health and social consequences, in the long term. For high-level sportsmen it is frequently a ‘career-ending’ injury.

Achilles tendon rupture affects > 11,000 people each year in the UK, and the incidence is increasing as the population remains more active into older age. 2 It affects all age groups in a bimodal distribution, with the first peak in patients aged 30–40 years and the second in patients aged 60–80 years. 2 The first peak in incidence is often associated with participation in sport, such as football and racquet sports, whereas the second peak often occurs during normal daily activities, such as climbing stairs. 2,3 However, all Achilles tendon ruptures are associated with a pre-existing ‘tendinopathy’, which is attributed to failures in the protective/regenerative functions that respond to repeated microscopic injury. 4,5

Historically, the main question in relation to the management of patients with rupture of the Achilles tendon has been whether or not to perform a surgical repair of the tendon. In 1981, Nistor6 designed and published the first randomised controlled trial (RCT) to address this clinical question. This study was followed by a series of RCTs that were pooled in a meta-analysis by the Cochrane review group in 2004. 7 The results suggested that surgical repair reduced the risk of re-rupture, but this came with an increased cost and a greatly increased risk of other complications, most of which were associated with infection and wound healing. There were few data on functional outcome at the time of this review. More recent trials comparing surgical repair and non-operative treatment have found no difference in functional outcome. 8,9 As surgery carries considerable costs, and carries considerable risks to the patient in terms of complications,7 there is an increasing trend towards non-operative treatment. However, some surgeons have been reluctant to advocate non-operative treatment because of concerns about the lack of evidence to guide early rehabilitation for this group of patients,10 specifically whether or not functional bracing is safe and effective if the tendon has not been not surgically repaired.

Traditionally, patients have been treated in plaster casts after rupture of the Achilles tendon, with the cast immobilising the foot and ankle while the tendon heals. 11 However, there are potential problems with this approach. First, there is the immediate impact on mobility for a period of around 8 weeks, affecting activities of daily life. Second, there are the complications and risks associated with prolonged immobilisation: muscle atrophy, deep-vein thrombosis (DVT) and joint stiffness. 12,13 Finally, there are the potential long-term consequences, which include prolonged gait abnormalities, persistent calf muscle weakness and an inability to return to previous activity levels. 14 Functional bracing, involving immediate, protected weight-bearing in a brace, was designed to address these issues.

In patients having a surgical repair, seven RCTs,1,15–20 directly comparing plaster casts with early movement and/or weight-bearing in a ‘functional brace’, had been conducted at the time that the protocol was developed for the UK Study of Tendo Achilles Rehabilitation (UKSTAR). The results favoured functional bracing in terms of re-rupture rate, functional outcome and quality-of-life (QoL) measures. Therefore, in the first guideline produced on this topic in 2009,21 the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons recommended functional bracing for patients undergoing surgical repair of their tendon.

What about patients managed non-operatively?

Although there are clear guidelines for rehabilitation of patients who have a surgical repair, there is no clarity about the use of functional bracing in non-operatively managed patients. Does functional bracing provide improved function and QoL if the tendon is not surgically repaired? Or, in the context of a tendon that has not been stitched together, does a plaster cast provide greater protection and therefore improved healing? Does functional bracing facilitate faster return to work and is this cost-effective? Or, is the tendon more vulnerable to re-rupture in a brace, with the subsequent risk and cost of reconstructive surgery?

At the time that UKSTAR was developed, we supplemented the 2004 Cochrane review7 with an updated literature search and found that in total only two additional studies22,23 had been performed that compared functional bracing with plaster cast for patients managed non-operatively following rupture of the Achilles tendon. Both studies suggested potential benefits from bracing. However, the data from the studies should be interpreted with caution because patient numbers were small (90 in total), patients received different functional bracing regimes and the reporting of outcomes was minimal.

This gap in the evidence was recognised by the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons in their 2009 guideline,21 which stated that they were unable to make a recommendation with regards the use of immediate functional bracing. With the incidence of Achilles tendon rupture on the rise, and in the light of the high associated personal and societal cost, this evidence gap is a clear priority. A Versus Arthritis (formerly known as Arthritis Research UK) multidisciplinary ‘Think Tank’ (Arthritis Research UK, Birmingham, 2013) on tendon injuries reported that rehabilitation following non-operative treatment of acute Achilles tendon rupture was ‘the top research priority’ in this area.

Since the start of the UKSTAR, a number of small randomised trials have investigated both the mechanistic and the functional effects of early weight-bearing in a brace compared with cast immobilisation. A trial of 56 patients indicated that tendon healing at a molecular level may be enhanced by early mobilisation, but, given the small number of participants, there was no difference in objective functional outcome (heel raise testing in this study). 24 A second trial investigated the biomechanical properties of the healing tendon in patients randomised to early weight-bearing or delayed weight-bearing. 25 The investigators noted that there was less tendon stiffness in the group treated with early weight-bearing. However, in terms of functional outcomes, the authors reported no evidence of a difference in Achilles Tendon Rupture Score (ATRS), although they did report a statistically significant improvement in health-related quality of life (HRQoL) at 1 year in the group treated with early weight-bearing. 25 Another trial included 47 patients treated non-operatively for an acute Achilles tendon rupture. Half of the patients were treated with partial weight-bearing beginning on the first day of treatment and the other half were treated with non-weight-bearing for the first 4 weeks. 26 The authors concluded that early weight-bearing was ‘safe’ in terms of the incidence of re-rupture, but there was no evidence of a difference in functional outcome (ATRS or Physical Activity Scale) in the first 12 months after the rupture. Finally, another trial compared two types of cast immobilisation of Achilles tendon rupture. 27 Half of the patients wore a traditional cast, which restricted weight-bearing, whereas the other group wore a modified cast, which included a heel ‘iron’ to facilitate weight-bearing. The authors found no evidence of a difference in functional outcome (Leppilahti Score), but there were only 84 patients in the trial. One further study, published very recently, randomised patients to cast immobilisation or ‘early controlled motion’ and involved 130 patients at a single centre. The authors found no evidence that early controlled motion was of benefit compared with immobilisation in any of the investigated outcomes. 28

Pre-pilot data

Before UKSTAR, we completed four phases of pilot and preparatory work to establish the following.

External pilot study

We randomised 48 patients receiving non-operative treatment for acute rupture of the Achilles tendon to either functional bracing or plaster cast. This trial1 showed that patients and clinicians had equipoise for this question and were happy to take part. However, the trial identified that although plaster casting was a mature intervention, the important facets of the complex intervention, namely functional bracing, were inadequately defined, and that this needed to be addressed before a larger trial was undertaken.

Defining the functional brace intervention

In keeping with the Medical Research Council framework for developing complex interventions, our group and collaborators performed a UK survey of current practice, a systematic review of published rehabilitation methods, gait analysis experiments using different functional brace and heel wedge combinations, and qualitative interviews to define the optimal functional bracing regime and refine the trial design. 29,30 The rehabilitation strategy proposed in UKSTAR was the summation of that work that identified the optimal type of orthosis (brace), the optimal foot position within the orthosis and the duration of application of the orthosis.

To investigate the number of patients potentially eligible for UKSTAR, we carried out a UK-wide survey of orthopaedic trauma clinicians. 10 This clearly showed that clinicians were enthusiastic about the study and that the number of eligible patients was large enough for a full trial.

Research objectives

The primary objective was to quantify and draw inferences about observed differences in ATRS between the trial treatment groups at 9 months post injury.

The secondary objectives were to:

-

quantify and draw inferences about observed differences in ATRS between the trial treatment groups at 8 weeks and 3 and 6 months post injury

-

identify any differences in HRQoL between the trial treatment groups in the first 9 months post injury

-

determine the complication rate of the trial treatment groups in the first 9 months post injury

-

investigate, using appropriate statistical and economic analytical methods, the resource use, costs and comparative cost-effectiveness of the trial treatment groups in the first 9 months post injury.

Patient and public involvement

We have been working with and listening to the views of patients with Achilles tendon injuries for many years. However, as well as this informal contribution, a series of formal qualitative interviews with patients and clinicians were carried out in the development of the UKSTAR (ISRCTN68273773). 11 The views of patients were used to inform and refine the trial interventions and processes, in particular the development of the trial information and materials. The patient perspective was key during the development of the trail protocol to ensure that the interventions, and participation in the trial, would be acceptable.

Two of the patients who contributed to our development work agreed to act as lay representatives on the Trial Management Group (TMG) and as co-applicants on the research grant award. Mrs Richmond later had to leave the research team for personal reasons, but Mr Grant attended TMG meetings throughout the trial and contributed to all trial process and paperwork, with particular input on patient information leaflets. Mr Grant will be crucially involved in the dissemination of the study findings to the wider public. He will lead the development of any materials, leaflets and website information to be used for this purpose. Mr Grant has reviewed the Plain English summary of this report.

Mr Grant was supported by the chief investigator and the trial co-ordination team. He had peer support from the UK musculoskeletal trauma patient and public involvement (PPI) group, hosted in Oxford. He also had access to and support from the University/User Teaching and Research Action Partnership network through University of Warwick, an organisation that promotes the engagement and involvement of service users and carers from the local community in research and teaching in health and social care.

Chapter 2 Clinical trial methods

Summary of study design

UKSTAR was a multicentre, randomised, pragmatic, two-group superiority trial. Patients presenting at 39 NHS hospitals in England and Scotland with an acute primary Achilles tendon rupture for non-surgical treatment were randomised 1 : 1 to receive either functional brace or plaster cast.

Settings and locations

The 39 NHS hospital orthopaedic or trauma clinics in England and Scotland that screened and recruited participants for this trial were:

-

King’s College Hospital NHS Foundation Trust

-

Nottingham University Hospitals NHS Trust

-

Royal Berkshire Hospital, Royal Berkshire NHS Foundation Trust

-

Aberdeen Royal Infirmary, NHS Grampian

-

Ninewells Hospital and Medical School, NHS Tayside

-

Glasgow Royal Infirmary, NHS Greater Glasgow and Clyde

-

Pilgrim Hospital, United Lincolnshire Hospitals NHS Trust

-

University Hospital of North Tees, North Tees and Hartlepool Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust

-

Airedale NHS Foundation Trust

-

Salisbury District Hospital, Salisbury NHS Foundation Trust

-

The Rotherham NHS Foundation Trust

-

George Eliot Hospital NHS Trust

-

James Paget University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust, Great Yarmouth

-

Southampton General Hospital, University Hospital Southampton NHS Foundation Trust

-

Lister Hospital, East and North Hertfordshire NHS Trust

-

Royal Cornwall Hospital, Royal Cornwall Hospitals NHS Trust

-

Tunbridge Wells Hospital, Maidstone and Tunbridge Wells NHS Trust

-

Addenbrooke’s Hospital, Cambridge University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust

-

Derriford Hospital, University Hospitals Plymouth NHS Trust

-

Hull Royal Infirmary, Hull University Teaching Hospitals NHS Trust

-

Luton and Dunstable University Hospital NHS Foundation Trust

-

Salford Royal NHS Foundation Trust

-

Scunthorpe General Hospital, Northern Lincolnshire and Goole NHS Foundation Trust

-

Pinderfields Hospital, The Mid Yorkshire Hospitals NHS Trust

-

Leeds General Infirmary, Leeds Teaching Hospitals NHS Trust

-

Worcestershire Royal Hospital, Worcestershire Acute Hospitals NHS Trust

-

Doncaster Royal Infirmary, Doncaster and Bassetlaw Teaching Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust

-

St Helier Hospital, Epsom and St Helier University Hospitals NHS Trust

-

St Mary’s Hospital, Imperial College Healthcare NHS Trust

-

Raigmore Hospital, NHS Highland

-

Whiston Hospital, St Helens and Knowsley Hospitals NHS Trust

-

Milton Keynes University Hospital NHS Foundation Trust

-

Warwick Hospital, South Warwickshire NHS Foundation Trust

-

Queen’s Hospital, Burton Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust

-

Hereford County Hospital, Wye Valley NHS Trust

-

Queen Elizabeth Hospital, University Hospitals Birmingham NHS Foundation Trust

-

John Radcliffe Hospital, Oxford University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust

-

University Hospital of South Manchester NHS Foundation Trust

-

Musgrove Park Hospital, Taunton and Somerset NHS Foundation Trust.

Participants

Participant screening

All adult patients presenting at a trial centre with a primary (first-time) rupture of the Achilles tendon were screened. The patient, in conjunction with their surgeon, decided whether or not non-surgical treatment was appropriate, as per normal clinical practice. If they decided not to have surgery, they were potentially eligible to take part in the trial.

Participant eligibility

In order that the trial findings would be generalisable to a UK-wide population, the eligibility criteria were broad. Patients with acute rupture of the Achilles tendon were eligible if they met all of the inclusion criteria and none of the exclusion criteria.

The inclusion criteria were:

-

being aged ≥ 16 years

-

having a primary rupture of the Achilles tendon

-

having decided to have non-operative treatment.

The exclusion criteria were:

-

presenting to the treating hospital > 14 days after injury

-

likely to be unable to adhere to trial procedures or complete questionnaires

-

having had a previous rupture of the Achilles tendon.

The first exclusion criterion related to patients with late presentation, which is not uncommon after this injury. Patients who present late may have problems with chronic tendon lengthening, irrespective of treatment, and are frequently offered surgical intervention. The limit of 14 days since injury has been widely used to define ‘acute’ rupture.

If a patient taking part in the study sustained a contralateral rupture during the trial period, the second rupture was not included in the study because the result of an intervention for the second injury would not be independent from that of the first injury. However, the patient remained in the trial, with both previous and future data related to the initial rupture included in the final analysis.

Screening logs were completed at recruiting centres and collected by the UKSTAR office throughout the trial to assess the main reasons for patient exclusion at each recruitment centre and the number of patients who were unwilling to participate.

Members of the local research team informed the patient of the study and carried out the informed consent process, baseline data collection and randomisation.

Baseline assessment

Potential participants were allowed as much time as they needed to consider the trial information and had the opportunity to ask questions of the attending clinical team and a member of the research team. The trial information was delivered verbally and in writing, detailing the exact nature of the study, the implications and constraints of the protocol, what to expect as a participant and any risks involved in taking part. It was stated clearly that the participant was free to withdraw from the study at any time, for any reason, without prejudice to future care and with no obligation to give the reason for withdrawal. If the patient was happy to participate, they were asked to sign and date a consent form, which was also signed and dated by the person who obtained consent. Consent was obtained by an appropriately trained member of the research team who had been delegated to do so by the local principal investigator.

A copy of the signed consent form was given to the participant and another copy was sent to the study co-ordinating team in Oxford to facilitate central monitoring. The original signed consent form was retained in the medical notes and a copy was held in the investigator site file. Consent forms were held in a secure location separately from study data. Permission was obtained to inform the participant’s general practitioner (GP) about study participation.

Participants were asked for their consent for their name and contact details (including address, telephone numbers and e-mail address) to be collected to facilitate follow-up, data collection and reporting of results, and for a copy of their contact details to be sent to the UKSTAR central office team in Oxford. The study team used these details to contact participants for follow-up at the 3-, 6- and 9-month time points, to resolve queries and to send a thank-you letter when a participant’s involvement in the trial ended.

Permission was sought to allow members of the University of Oxford or the NHS trust who were responsible for monitoring or audit of the study to access participant data, to ensure compliance with regulations.

Following consent, baseline data were collected and the participant was randomised. The treatment took place at the same visit. A Good Clinical Practice-trained member of the local research team oversaw the participant’s completion of the paper baseline questionnaire, which included:

-

date, mechanism and side of injury

-

baseline demographics – height, weight, smoking and alcohol status, employment status

-

current medication

-

medical history – diabetes mellitus, rheumatoid arthritis, lower limb fracture, ligament, tendon or nerve injury to lower limb in last 12 months, arthritis, Achilles tendinopathy or other relevant conditions.

Randomisation

Participants were randomly allocated (1 : 1) to either functional bracing or plaster cast using a computer-generated allocation sequence, stratified by recruitment centre, via a secure, centralised web-based randomisation service provided by the Oxford Clinical Trials Research Unit (OCTRU). The research associate informed the treating clinical team of the allocated treatment.

Stratification by recruitment centre helped to ensure that any cluster effect related to the recruitment centre itself was equally distributed between the trial groups. The catchment area was similar for all of the recruitment centres (each recruitment centre was a trauma unit dealing with these injuries on a daily basis). All of the recruitment centres were familiar with both techniques (i.e. the clinical staff used both plaster casts and functional bracing as part of their routine clinical practice).

Post-randomisation withdrawals

Participants were free to decline to take part in, consent to take part in or withdraw from the trial at any time without prejudice and without affecting the standard of care that they received. Participants had two options for withdrawal:

-

to withdraw from completing further questionnaires, but allow the trial team to view and record de-identified data are recorded as part of the normal standard of care

-

to withdraw wholly from the study and permit data obtained only up to the point of withdrawal to be included in the final analysis.

Withdrawn participants were not replaced, as the target sample size allowed for losses to follow-up.

Interventions

Participants received their allocated treatment (plaster cast or functional brace) following randomisation.

Although the principles of application of both plaster casts and functional brace are inherent in the technique, there are different types of plaster cast material and functional brace design. Each patient underwent the allocated intervention as specified below (see Table 9), but the details of application and materials used for the plaster and brace were left to the discretion of the treating clinician, as per their usual practice. This was intended to ensure that the results could be generalised across the NHS.

Plaster cast

Participants randomised to plaster cast received a cast in the ‘gravity equinus’ position (i.e. the position that the foot naturally adopts when unsupported). In this position, with the toes pointing down towards the floor, the ends of the ruptured tendon are roughly approximated. Ultrasonography to assess the approximation of the tendon ends is not routine in the NHS10 and this was left to the discretion of the treating clinician. The participant was permitted to mobilise with crutches immediately, using their toes for balance (toe-touch), but was advised not to bear weight on the injured hindfoot. Over the first 8 weeks, as the tendon was healing, the position of the plaster cast was changed until the foot achieved plantigrade (i.e. the foot flat to the floor). At this point the patient was permitted to start to bear weight in the plaster cast. The number of changes of plaster cast and the time to weight-bearing were left to the discretion of the treating clinician, as per their usual practice. The cast was removed at 8 weeks.

The plaster cast provided maximum protection for the healing tendon, specifically restricting upwards movement (dorsiflexion) of the ankle, which may stretch the healing tendon, but it did not allow the patient to bear weight on the foot immediately or to move the ankle.

Functional brace

Participants randomised to functional brace received a rigid brace, as opposed to a flexible brace. 29 Initially, two solid heel wedges (or equivalent) were inserted into the brace to replicate the ‘gravity equinus’ position of the foot. 29 The patient was able to mobilise with immediate full weight-bearing within the functional brace. The brace also permitted some movement at the ankle joint. The number of wedges and foot position were reduced over 8 weeks until the patient reached plantigrade. Again, the timing of the removal of wedges and change in foot position were left to the discretion of the treating clinician, as per their usual practice. The brace was removed at 8 weeks, as per routine clinical care.

Monitoring intervention delivery and compliance

Clinic staff recorded the participant’s treatment in clinic records, as per usual practice. At the 8-week follow-up visit, research staff recorded on the 8-week trial case report form (CRF):

-

the intervention to which the patient was randomised

-

the intervention that they received

-

the date of the 8-week follow-up appointment

-

for participants treated with a functional brace, irrespective of their randomisation allocation, the:

-

number of heel wedges inserted into the heel of the functional brace at baseline (date of treatment), and at 2, 4, 6 and 8 weeks after treatment

-

number of weeks after treatment when the patient was allowed to fully weight bear

-

number of weeks after treatment when the functional brace was removed

-

brand of functional bracing

-

-

for participants treated with a plaster cast, irrespective of their randomisation allocation, the number of:

-

plaster cast changes over the 8 weeks since treatment

-

weeks after treatment when the patient was allowed to fully weight bear

-

weeks after treatment when the plaster cast was removed

-

-

whether or not the patient switched to another intervention during the 8 weeks after treatment, the date of switching and the reason for switching

-

whether or not the participant received treatment with venous thromboembolism (VTE) prophylaxis and, if so, the type and duration.

Rehabilitation

At the patient’s 8-week clinic appointment, the plaster cast or functional brace was removed unless the clinical team directed otherwise. All participants were provided with the same standardised written physiotherapy advice, detailing the exercises that they needed to perform for rehabilitation. This advice was based on a published systematic review of current rehabilitation protocols. 30 All of the participants were advised to move their toes, ankle and knee joints fully, within the limits of their comfort, and walking was encouraged. In this pragmatic trial, any other rehabilitation input beyond the written physiotherapy advice (including a formal referral to physiotherapy) was left to the discretion of the treating clinician. A record of any rehabilitation input (type and number of additional appointments), as well as other investigations or interventions, was collected as part of the 8-week and 3-, 6- and 9-month follow-up questionnaires.

Outcome measures

Primary outcome measure

The primary outcome measure for this study was the ATRS31 at 9 months post injury. The ATRS is a validated questionnaire32 that is completed by the participant. It has 10 items, assessing symptoms and physical activity specifically related to the Achilles tendon. It measures strength, fatigue, stiffness, pain, activities of daily living, walking on uneven surfaces, walking upstairs or uphill, running, jumping and physical labour. Each ATRS item is rated on an 11-point scale from 0 (major limitations/symptoms) to 10 (no limitations/symptoms). The final ATRS is derived from the sum of the 10 questions, with a total possible score ranging between 0 and 100 (100 being the best possible score).

Secondary outcome measures

The secondary outcome measures were:

-

The ATRS, collected at 8 weeks and 3 and 6 months post injury.

-

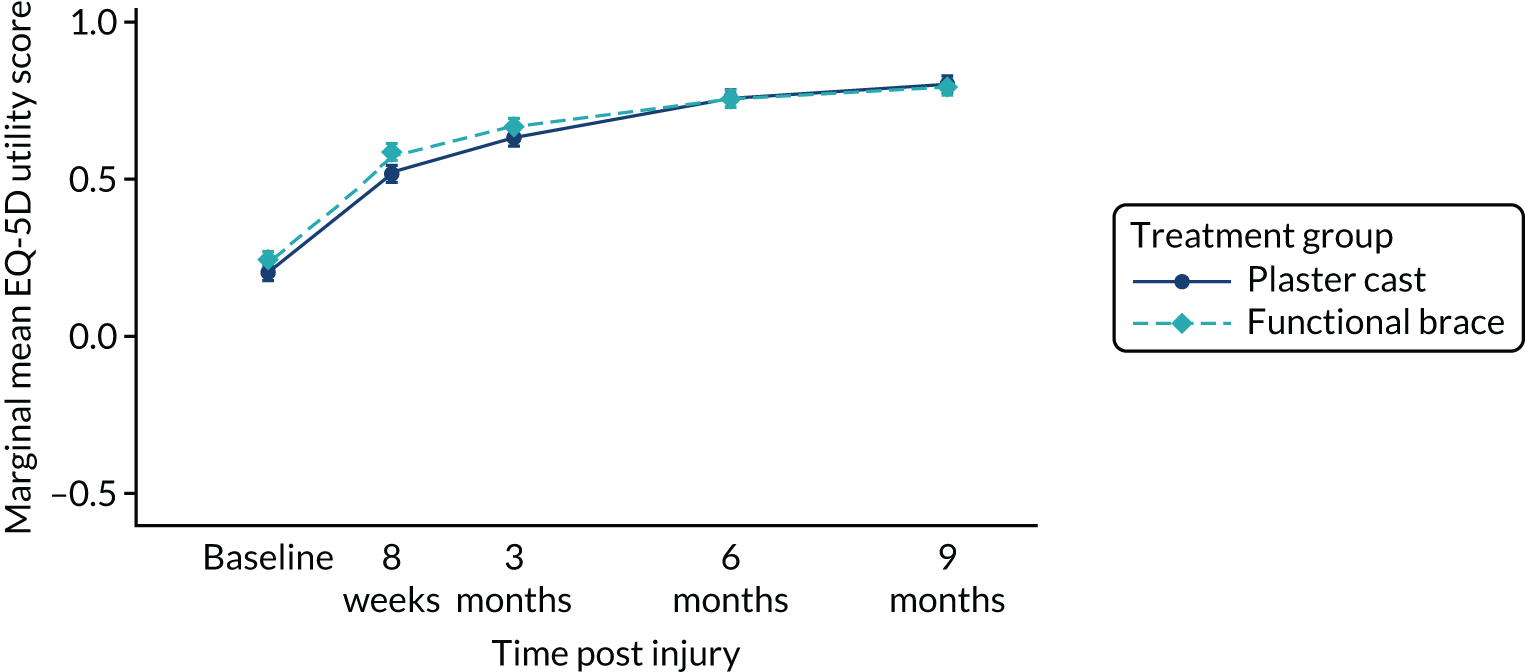

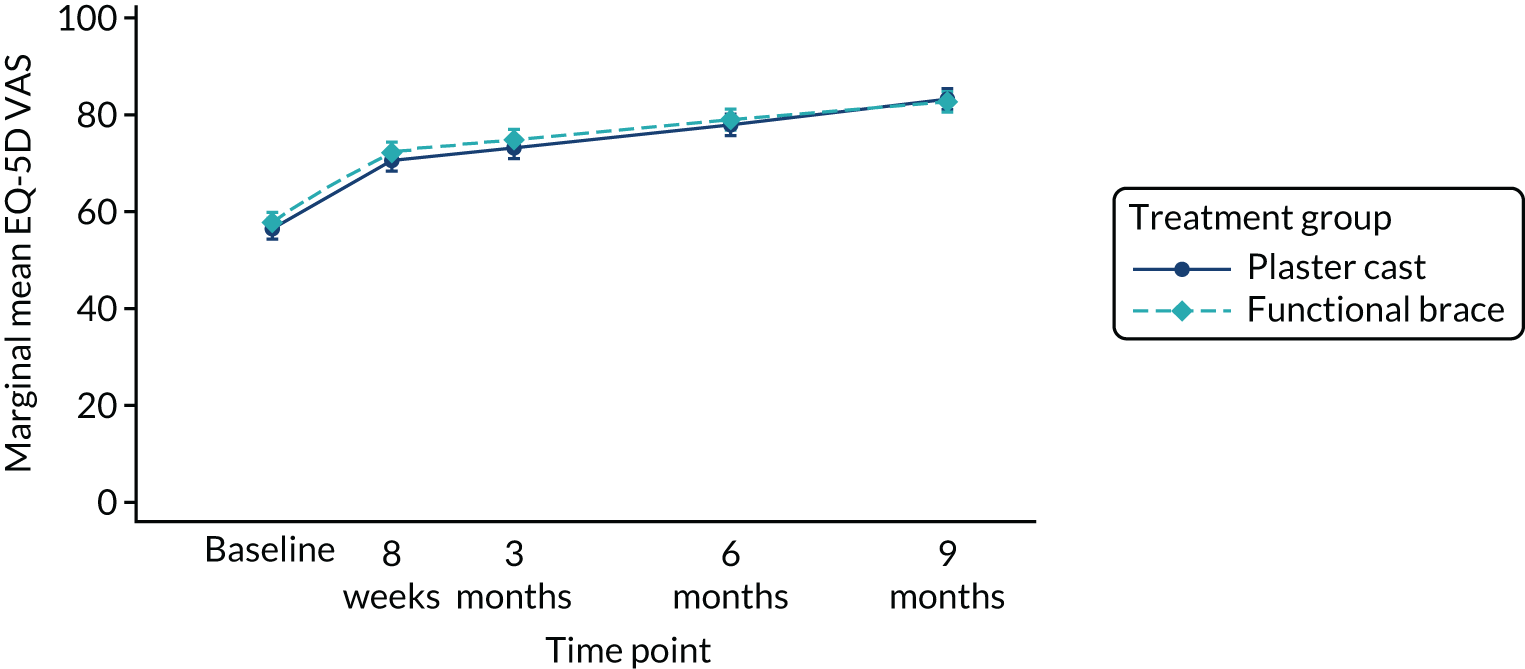

The EuroQol-5 Dimensions (EQ-5D)/EuroQol-5 Dimensions, five-level version (EQ-5D-5L), which is a validated, generic HRQoL measure consisting of five dimensions, each with a five-level answer possibility, and a visual analogue scale (VAS). 33 The EQ-5D can be used to report HRQoL in each of the five dimensions and each combination of answers can be converted into a health utility score, with 1 representing perfect health and 0 indicating death. The EQ-5D VAS takes values between 0 and 100, with 0 representing worst imaginable health and 100 representing best imaginable health. It has good test–retest reliability, is simple for patients to use and gives a single preference-based index value for health status that can be used for broader cost-effectiveness comparative purposes.

-

Complications were recorded from medical notes at the 8-week review and were patient reported at the 3-, 6- and 9-month follow-ups. The predefined complication categories were tendon re-rupture, DVT, pulmonary embolism (PE), non-injurious falls, injurious falls, pain under the heel, numbness around the foot and pressure sores. In addition, three categories were created based on the recorded text and included skin condition requiring medication, surgery related to Achilles rupture and fractured toe.

Adverse events

An adverse event (AE) is defined as any untoward medical occurrence in a clinical trial subject and does not necessarily have a causal relationship with the treatment. All AEs were listed on the CRF for routine return to the UKSTAR central office.

A serious adverse event (SAE) is defined as any untoward and unexpected medical occurrence that:

-

results in death

-

is life-threatening

-

requires hospitalisation or prolongation of existing hospitalisation

-

results in persistent or significant disability or incapacity

-

is a congenital anomaly or birth defect

-

is any other important medical condition that, although not included in the above, may require medical or surgical intervention to prevent one of the outcomes listed.

All SAEs were recorded by recruitment centre staff on the trial SAE reporting form and e-mailed to a secure NHS.net account, which was accessed only by the research team within 24 hours of the investigator becoming aware of the SAE. Once the information was received, causality and expectedness were confirmed by the chief investigator. SAEs deemed unexpected and related to the trial were notified to the Research Ethics Committee within 15 days. All such events were reported to the Trial Steering Committee (TSC) and Data and Safety Monitoring Committee (DSMC) at their next meetings.

Some AEs were foreseeable as part of the proposed treatment – including those that met the definition of ‘serious’ as described above – and did not need to be reported immediately to the UKSTAR central office, provided that they were recorded in the ‘complications’ section of the CRF or participant questionnaire. These events were re-rupture, blood clots/emboli, pressure areas/hindfoot pain, falls and neurological symptoms in the foot.

All participants experiencing a SAE were followed up as per protocol until the end of the trial.

All unexpected SAEs or suspected unexpected SAEs that occurred between the date of consent and the date of the 9-month follow-up time point were reported.

Blinding

As the type of rehabilitation used was clearly visible, participants could not be blinded to their treatment. In addition, the treating clinician was not blinded to the treatment but took no part in the post-injury assessment of the participants. The outcome data were collected and entered onto the trial central database via questionnaire by a research assistant or a data entry clerk in the trial central office, which reduced the risk of assessment bias.

Follow-up

The UKSTAR office staff contacted the participants directly for follow-up at 3, 6 and 9 months using the contact details that the participant had supplied. Participants were contacted by post, by e-mail or by short message service (SMS), according to their preference; if no response was received, they were telephoned. All follow-up contacts and attempted contacts were logged without personal identifying details.

Participants who had supplied an e-mail address were sent a link to an online questionnaire. Participants who had supplied a mobile phone number were sent the same link by SMS. Participants who had supplied both an e-mail address and a mobile phone number were sent the link via both mechanisms. If a participant did not respond to any of these initial approaches, they were sent a reminder 1 week later. If there was still no response after another week, the participant was sent a paper questionnaire. If the paper questionnaire was not returned within 2 weeks, UKSTAR office staff telephoned the participant. If the participant was uncontactable during working hours, attempts were made to telephone them during the evening, as many participants were of working age.

Participants who had specified that they preferred to be contacted by post, or who had not supplied an e-mail address or mobile phone number, were sent a questionnaire in the post and sent a second postal questionnaire if no response was received within 2 weeks. UKSTAR office staff attempted to telephone the participant for follow-up if the second postal questionnaire was not returned within 2 weeks.

Deep-vein thrombosis, PE and re-rupture were reported by participants through completing a questionnaire or directly to the study office, or by recruitment centre staff after participants had returned to the centre for further treatment. These reports underwent validation, as follows. In the case of a patient-reported DVT or PE, recruitment centres were requested to complete a DVT/PE form, which detailed symptoms, results of any ultrasonography, results of any computerised tomography pulmonary angiogram imaging, treatment received and treatment duration. In the case of a patient-reported re-rupture, recruitment centres were requested to provide details of diagnosis and treatment. If the patient underwent surgery for a re-rupture, an operation note was requested. All information submitted in connection with a re-rupture was reviewed by the chief investigator, blinded to the treatment allocation, to confirm the diagnosis.

Sample size

The minimum clinically important difference (MCID) for the primary outcome ATRS was 8 points. At an individual patient level, a difference of 8 points represents the ability to walk upstairs or run with ‘some difficulty’ compared with ‘great difficulty’. At a population level, 8 points represents the difference between a ‘healthy patient’ and a ‘patient with a minor disability’. 32

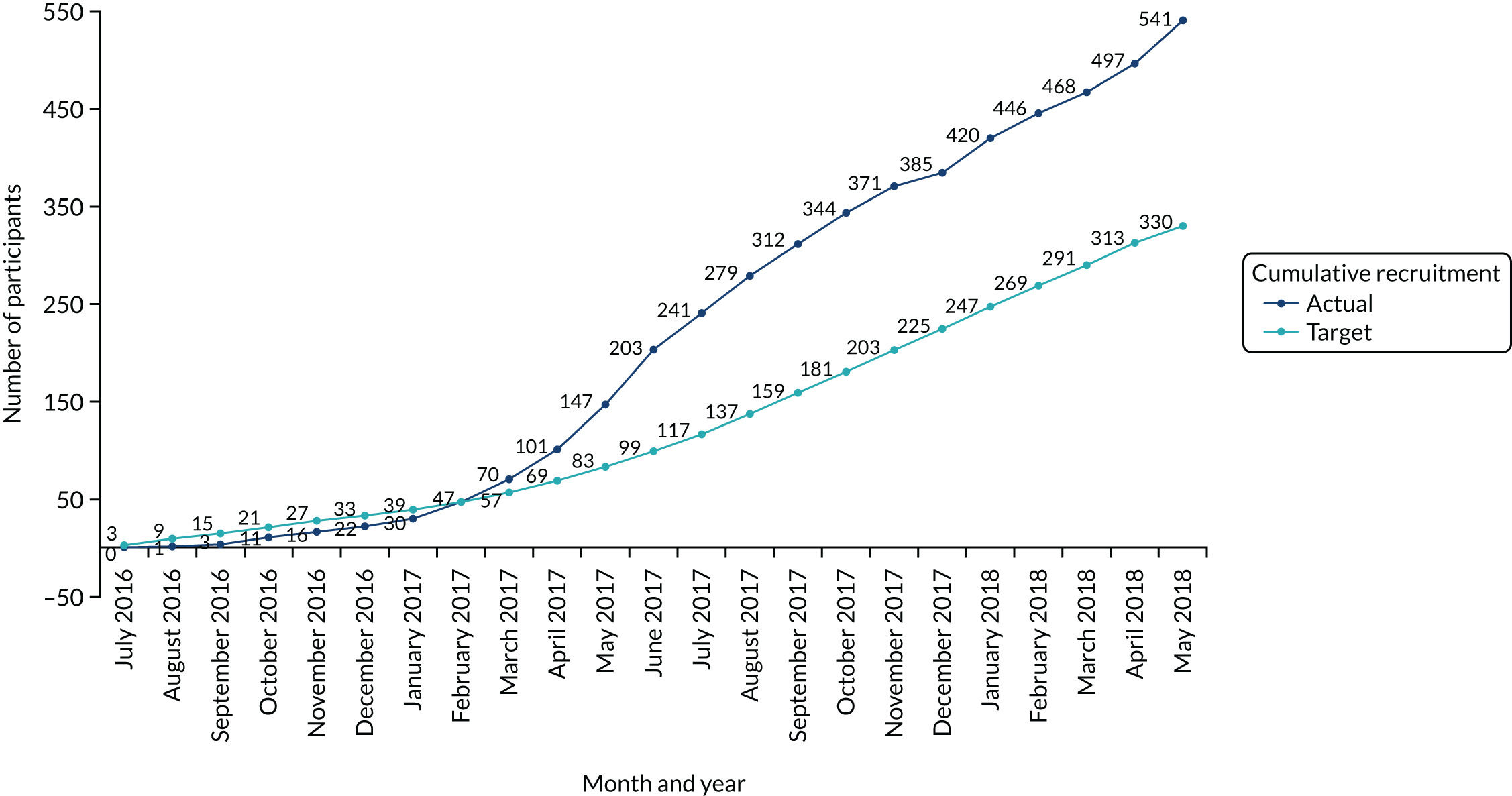

In previous work, the standard deviation (SD) of the ATRS at 9 months post injury was 20 points. 34 Assuming a likely population variability of 20, MCID value of 8 and 90% power to detect the selected MCID, 264 participants needed to be randomised. Allowing a margin of 20% loss of primary outcome data to include patients who would cross over between interventions and those lost to follow-up led to a requirement of 330 participants. We intended to recruit a minimum of 330 patients from at least 22 centres over 16 months. The trial reached its primary recruitment target of 330 participants before the end of the proposed recruitment window and therefore the sample size was recalculated based on a larger population variability equivalent to a SD of 25 points, following a blinded review of the variability by the DSMC. As per Table 1 calculations for a SD of 25, MCID value of 8, 5% two-sided tests and 20% loss to follow-up, 516 participants were required. The maximum number of participants to be recruited for the trial was set at 550.

| MCID/SD | 80% power | 90% power | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MCID | 6 | 8 | 10 | 6 | 8 | 10 |

| SD | ||||||

| 15 | 198 | 112 | 72 | 264 | 150 | 96 |

| 20 | 350 | 198 | 128 | 468 | 264 | 170 |

| 25 | 548 | 308 | 198 | 732 | 412 | 264 |

Statistical analysis

Software used

All analyses outlined here were undertaken using Stata® version 15.0 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA).

Blinded analysis

The distribution of variables, missing data distributions and outliers were assessed as part of a blinded analysis of data (not separated by treatment group) prior to the final data lock. This analysis was also used to help confirm the key prognostic variables to be included in the adjusted analysis. The treatment code was added to the database after the data cleaning had been completed and all subsequent analyses described were conducted on an unblinded data set. The statistical analysis plan was updated to incorporate necessary changes.

Data validation

To ensure consistency, validation checks of the data were conducted. These included checking for duplicate records, checking the range of variable values or missing items and validating potential outliers by comparing with CRFs and referring back to recruitment centres, when necessary. Calculations for derived variables, such as the ATRS, were checked by hand calculations on 20 randomly selected participants from the data set. These checks confirmed that the data had been imported into the statistical software correctly, calculation of derived variables had been performed correctly and merging of different data to form an analysis data set had been verified.

Study populations

Two populations were considered for analysis: the intention-to-treat (ITT) population and the complier-average causal effect (CACE) population. 35 The ITT population comprised all participants in their randomised groups and the CACE population comprised all randomised participants compliant with treatment. Participants were considered compliant with the intervention if they wore their allocated treatment for a period of ≥ 6 weeks without any change of treatment during this period.

Descriptive analysis

All available data from both treatment groups (functional brace and plaster cast) were used in a descriptive analysis. The flow of participants through each stage of the trial, including numbers of participants eligible for randomisation, those randomised, those receiving intended treatment, those completing the study protocol and those analysed for the primary outcome, was assessed. Reporting of the results was in accordance with the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) for patient-reported outcomes (PROs) statement using the extension for non-pharmacologic treatment interventions and PROs. 36 Any protocol deviations and violations were investigated.

Participant baseline characteristics were reported by treatment group and overall, and included recruitment centre stratification, demographic variables (age, sex, site of injury and mechanism of injury, body mass index, smoking status, alcohol consumption, medication, diagnoses, employment status) and baseline values for ATRS and EQ-5D-5L before and after the injury. Numbers (with percentages) for categorical variables and means (and SDs) or medians [and interquartile ranges (IQRs)] for continuous variables were presented for each treatment group and overall. There were no tests of statistical significance or confidence intervals (CIs) for differences between randomised groups on any baseline variable.

Data collected at the 8-week and 3-, 6- and 9-month post-injury follow-ups were summarised and the proportion of missing items from completed questionnaires was examined. The patterns of data availability for primary and secondary outcomes from baseline to end of follow-up were summarised for the two treatment groups, as well as reasons for missingness, when known. The nature and pattern of missing data [missing completely at random, missing at random (MAR) or missing not at random (MNAR)] were explored. Differentiation was made between partially completed and fully missing outcome data. Validation rules for the primary outcome ATRS ensured that data were entered in the correct format, within valid ranges, minimising the chance of missing data. When ATRS item responses were missing and at least half of the items were present, a pro rata estimation of the final ATRS score was imputed based on the average of the available ATRS item responses. No pre-injury ATRS values were imputed, two ATRS scores were imputed at 8 weeks, five were imputed at 3 months, four were imputed at 6 months and eight were imputed at 9 months.

Withdrawals and losses to follow-up were compared between the groups at each time point and the reasons were reported when known. Absolute risk differences (with 95% CIs) between the groups were calculated, and the importance of differences was determined using chi-squared tests or Fisher’s exact test, if appropriate. When participants were identified as having tendon re-ruptures followed by surgery, the participant was not treated as lost to follow-up. Deaths and their causes were reported separately.

Quality assurance and compliance with treatment was assessed. The treatment received was reported by group and summarised, with reasons for not receiving the assigned treatment given when possible.

For all analyses, tests were two sided and considered to provide evidence of a significant statistical difference if p-values to three decimal places were < 0.05 (5% significance level). In addition, any reported treatment estimates will be presented with their associated 95% CI.

Analysis of primary outcome

The primary outcome ATRS at 9 months post injury was reported for each of the treatment groups. The main findings of the trial show the difference in the ATRS between the two treatment groups, estimated with a linear mixed-effects regression model, including outcome information from all follow-up points and adjusting for age, sex and baseline ATRS as fixed effects, and centre and observations within participants as random effects.

An additional fully adjusted model included age, sex, baseline ATRS, smoking status and diabetic condition as prognostic variables, with random effects for centre and repeated measures within participants. Important clinician-specific effects were not expected as each clinician treated only a small number of patients, but recruitment centre was included in the model as a random-effect factor to adjust for potential cluster differences. Estimates of treatment effects were presented with 95% CIs. Histograms and residual checks were used to assess an approximate normal distribution of the ATRS and, when relevant, the medians and IQRs reported for each treatment group.

An unadjusted analysis was also undertaken to assess the differences between treatment groups using Student’s t-test, based on a normal approximation of the ATRS score. Estimates of treatment effects were presented with 95% CIs for both unadjusted and adjusted analyses. The ITT adjusted analysis of the primary outcome ATRS was used to determine the success, or otherwise, of the trial.

Sensitivity analyses to examine the robustness of conclusions to different assumptions were conducted for the CACE population. Compliance was defined as using the allocated intervention for a minimum of 6 weeks, and further sensitivity analysis was undertaken using different definitions of compliance, namely minimum of 4 weeks and minimum of 2 weeks. Adherence to the allocated treatment can affect the interpretation of the impact of what was offered to patients. This may be a particular issue in an ITT analysis, which includes all patients as they were expected to be treated and does not take into account if patients received or adhered to the intervention allocated to them.

Supplementary analysis

To explore recovery in the two treatment groups over time, a further analysis of the ATRS was conducted. This summarised longitudinal data collected at all four time points to a single value, the area under the curve (AUC),37 to facilitate a comparison of the ATRS between the treatment groups over time. Parameter estimates from the mixed-effects models were used to calculate AUCs for each treatment group from baseline to the 9-month post-injury follow-up. This provided an overall estimate of recovery over time in each group. Higher ATRS scores were associated with fewer limitations and difficulties related to the injured Achilles tendon, and therefore larger AUCs were suggestive of improved function. The AUC for each treatment group and their differences, calculated using a t-test, were presented, together with their associated 95% CIs. The lincom command in Stata was used to calculate the AUC for each group. This analysis was also conducted for the EQ-5D utility score and the EQ-5D VAS.

Analysis of secondary outcomes

The continuous secondary outcomes ATRS at 8-week and 3- and 6-month post-injury follow-up and EQ-5D-5L were evaluated and analysed for the ITT population using the methodology described for the primary outcome (see Analysis of primary outcome). Histograms and residual checks were used to assess whether or not these variables were approximately normally distributed. Means and SDs were reported at the 8-week and 3-, 6- and 9-month post-injury follow-up time points, and medians and IQRs were reported when appropriate. A linear mixed-effects regression model with random effects for recruitment centre and participant outcome information from all time points, and fixed effects for age, sex and baseline pre-injury outcome values, was used to examine the difference between the treatment groups.

Complications in each of the treatment groups were reported as numbers (with percentages) and compared over the 9-month study period using chi-squared tests or Fisher’s exact test. The results were reported with their associated 95% CI and p-values for comparison between the two treatment groups. The population for this analysis was ITT. Complications were further grouped to identify the number of patients with one or more complications at each time point.

Sensitivity analyses were also conducted for the secondary outcome EQ-5D-5L analysis using the CACE population.

Health economics methods

Overview

The main objective of the health economic evaluation was to assess the comparative cost-effectiveness of the two non-surgical treatment options (plaster cast and functional brace) for patients with a primary (first-time) rupture of the Achilles tendon. To achieve this, a systematic comparison of the cost of resource inputs used by participants in the two groups of the trial and the consequences associated with the interventions was conducted. The primary analysis adopted an NHS and Personal Social Services (PSS) perspective, in accordance with National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) recommendations. 38 A societal perspective for costs was adopted for the sensitivity analysis, and this included private costs incurred by trial participants and their families, as well as productivity losses and loss of earnings as a result of work absences.

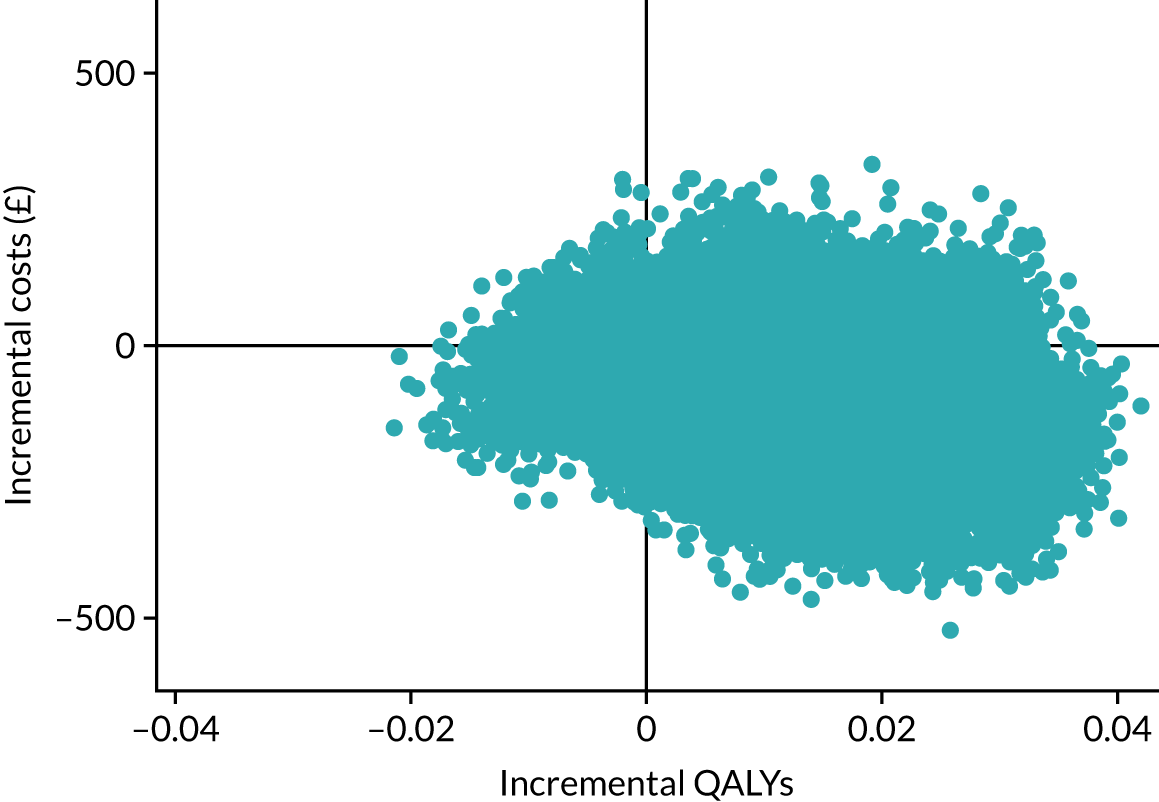

The economic evaluation took the form of a cost–utility analysis, expressed in terms of incremental cost per quality-adjusted life-year (QALY) gained. The time horizon covered the period from randomisation to end of follow-up at 9 months post injury. Costs and outcomes were not discounted because of the short (i.e. 9 months) time horizon adopted for this within-trial evaluation.

Measuring resource use and costs

Data were collected on:

-

resource use and costs associated with delivery of the interventions (direct intervention costs)

-

broader health and social care service use during the 9 months of follow-up

-

broader societal resource use and costs (this encompassed private medical costs and lost productivity costs, such as lost income over the 9 months of follow-up).

All costs were expressed in Great British pounds and valued in 2017–18 prices. When appropriate, costs were inflated or deflated to 2017–18 prices using the Hospital and Community Health Services Pay and Prices Inflation Index. 39

Direct intervention costs

Direct intervention costs were costs associated with the application of the two interventions. These included cost of the walking boot and wedges, materials used for plaster cast, the cost associated with fitting the interventions to patients (hospital staff time) and the costs associated with any changes required to either plaster cast or functional bracing (Table 2). Information on how long it took to deliver each intervention and the type and volume of materials used was collected at each recruitment centre using a questionnaire completed by recruitment centre staff in consultation with the staff responsible for fitting the functional brace or applying the plaster cast. Unit costs for staff were obtained from the Personal Social Services Research Unit (PSSRU) Unit Costs of Health and Social Care 2018 compendium39 and were multiplied by the median time it takes to deliver each intervention. The median time to fit a functional brace was 10, 11 and 17.5 minutes for a plaster technician, nurse and other staff (including physiotherapists, orthotists and occupational therapists), respectively. The median time to change wedges was 5 minutes for a plaster technician and a nurse and 10 minutes for other staff. The median time to change a plaster cast was 15 minutes for a plaster technician and 17.5 minutes for a nurse. The base-case analysis assumed the costs of a plaster technician. Unit costs of plaster cast materials, walking boots and wedges were obtained from the 2018 NHS Supply Chain catalogue. 40 The total direct intervention cost for each patient was calculated by combining the resource inputs with their unit cost values.

| Direct intervention costs: resource item | Unit cost (£) | Unit of analysis | Source of unit cost |

|---|---|---|---|

| Functional brace: walking boota cost by brand | |||

| Samson walking boot (AliMed Inc., Dedham, MA, USA) | 15.00 | Per walking boot | John Radcliffe Hospital, Oxford (Claire Granville, Outpatients Manager, Trauma Unit, 2017, personal communication); NHS Supply Chain Catalogue 201840 |

| Donjoy walking boot (DJO UK, Guildford, UK) | 19.24 | ||

| Airstep walking boot (DJO UK) | 68.66 | ||

| Plaster cast materialsb | |||

| Poly rolls: 2 × 7.5 cm | 2.83 | Per roll | NHS Supply Chain catalogue 201840 |

| Poly rolls: 2 × 10 cm | 6.69 | ||

| Fibreglass casting tape: 5 inches × 3.6 m | 11.48 | Per roll | NHS Supply Chain catalogue 201840 |

| 1-m stockinette | 3.23 | Per roll | NHS Supply Chain catalogue 201840 |

| Wool bandage: 2 × rolls of 5 inches | 3.00 | Per roll | NHS Supply Chain catalogue 201840 |

Measuring broader resource use

Broader resource use data were collected using follow-up questionnaires completed by trial participants at the four follow-up assessment points: 8 weeks and 3, 6 and 9 months post injury. The questionnaires captured details of inpatient and day-case admissions, outpatient and emergency care attendances, contacts with primary or community health and social care services, medication use and walking aids provided/self-purchased, as well adaptations to home environments. In addition, the questionnaires captured the direct non-medical costs (including travel expenses) incurred by patients and their carers, as well as the number of days off work and gross loss of earnings attributable to the participant’s health state or contacts with care providers.

Valuing of resource use

Resource inputs were valued by attaching unit costs derived from national compendia in accordance with NICE’s Guide to the Methods of Technology Appraisal. 38 The key databases for deriving unit cost data included the Department of Health and Social Care’s Reference Costs 2017–18 schedules,41 the PSSRU’s Unit Costs of Health and Social Care 2018 compendium,39 the 2018 NHS Prescription Cost Analysis database for England,42 the 2016 volume of the British National Formulary43 and the NHS Supply Chain catalogue 2018. 40 Table 24 (see Appendix 1) gives a summary of the unit costs values and data sources for broader resource use categories identified within the follow-up questionnaires.

Per diem costs for hospital inpatient admissions during the follow-up period were calculated individually as a weighted average of Healthcare Resource Group (HRG) codes of related procedures and/or clinical diagnoses. For example, the average cost per day of an inpatient stay in a medical ward to treat a PE was calculated as the sum total of weighted average HRG codes (DZ09J–DZ09Q; PE with or without interventions), divided by the average length of stay across elective and non-elective inpatient services. The individual HRG codes were derived using the NHS HRG4 2017/18 Reference Cost Grouper software version RC1718 (NHS Digital, Leeds, UK). The Department of Health and Social Care’s Reference Costs 2017–1841 schedule was used to assign the costs of each of the derived HRG codes.

Costs of community-based health and social care services were calculated by applying unit costs extracted from national tariffs, primarily the PSSRU Unit Costs of Health and Social Care 2018 compendium,39 to resource volumes. Costs of medications for individual participants were estimated based on their reported doses and frequencies, when these were available, or based on assumed daily doses using British National Formulary43 recommendations. When a dose range was reported as ‘as required’, or when the quantities were not recorded, we assumed a mean cost of that medication item based on the prescription cost analysis values (net ingredient cost per item). When medication dosages were missing, we conservatively assumed that the patient received the same dosage as other trial participants who reported taking the same medication.

The costs of walking aids and adaptations (equipment participants receive to manage their injury and make daily lives easier) were derived by combining data on the number and type of items received with their unit cost values. Unit cost values were derived from the NHS Supply Chain catalogue40 if equipment was provided by a health provider during the trial follow-up period. When aids and adaptations were self-financed, the costs were provided by participants.

We used data on sex- and employment status-specific median earnings from the UK national annual survey of hours and earnings44 to derive the costs of time taken off work. The employment status of trial participants was derived from self-reported information. Broader societal costs were calculated by combining the productivity losses and the income losses attributable to work absences.

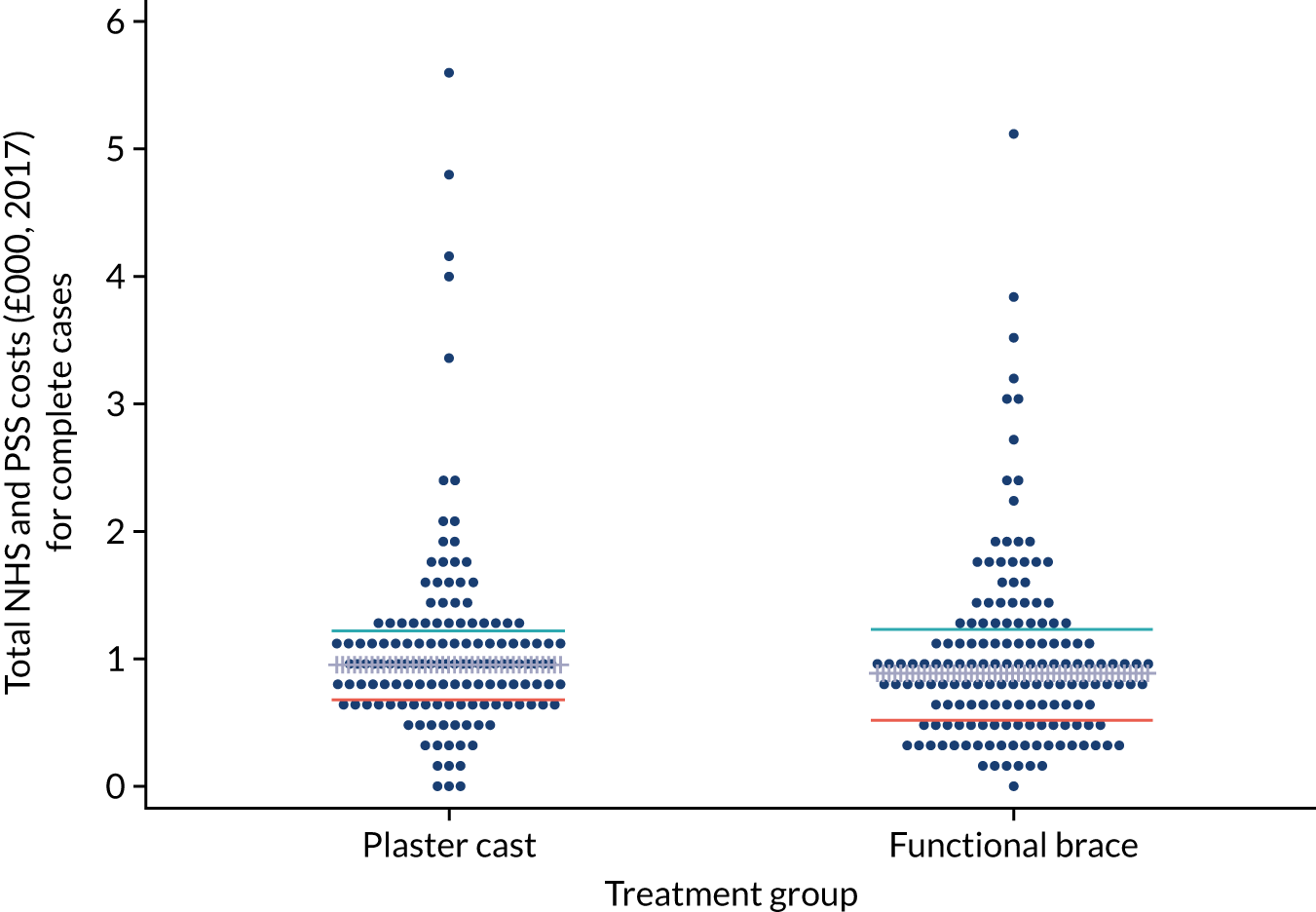

Summary statistics were generated for resource use variables by treatment allocation and assessment point. Between-group differences in resource use and costs at each assessment point were compared using the two-sample t-test. Statistical significance was assessed at the 5% significance level. Standard errors are reported for treatment group means and bootstrap 95% CIs for the between-group differences in mean resource use and cost estimates.

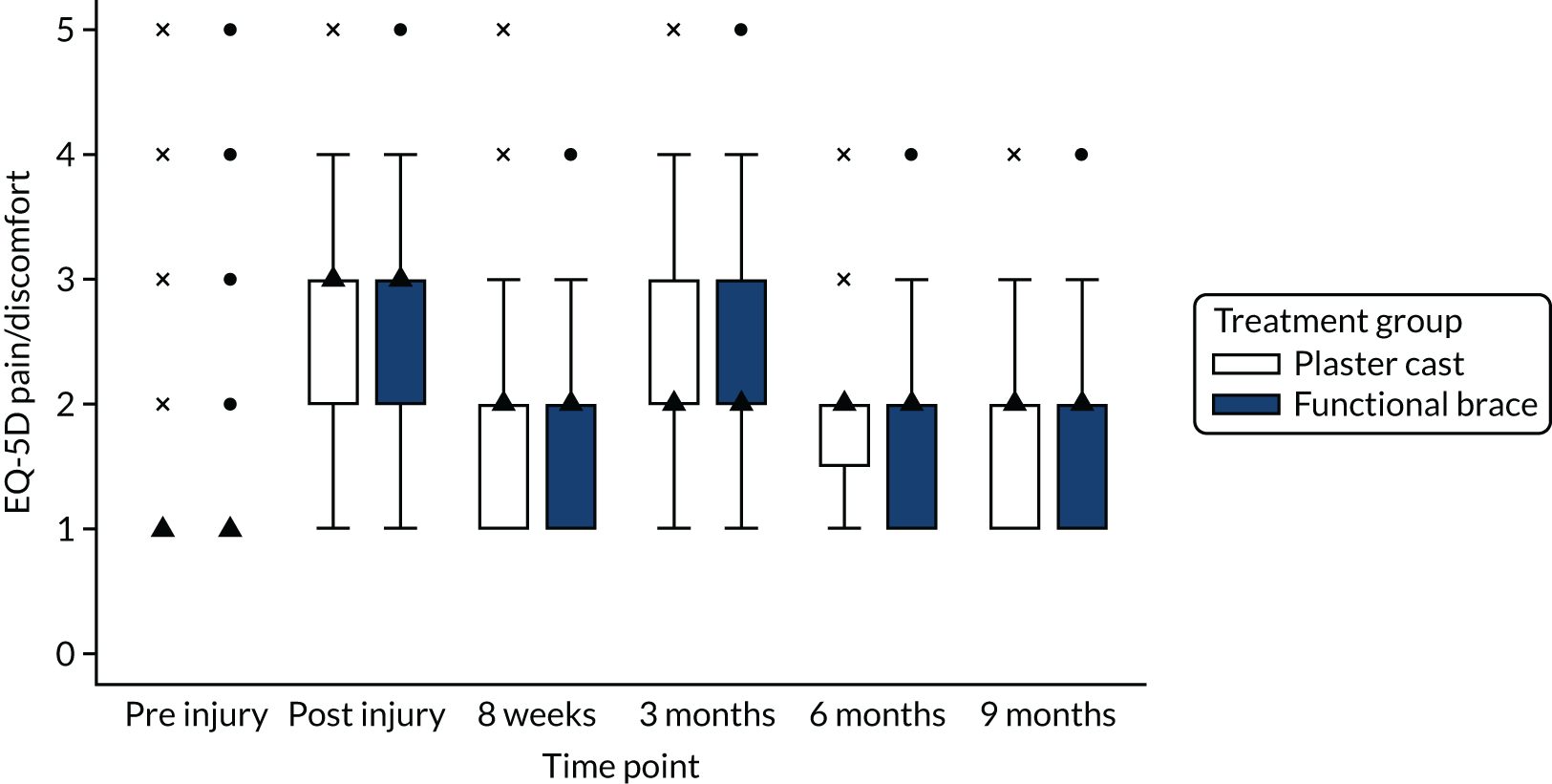

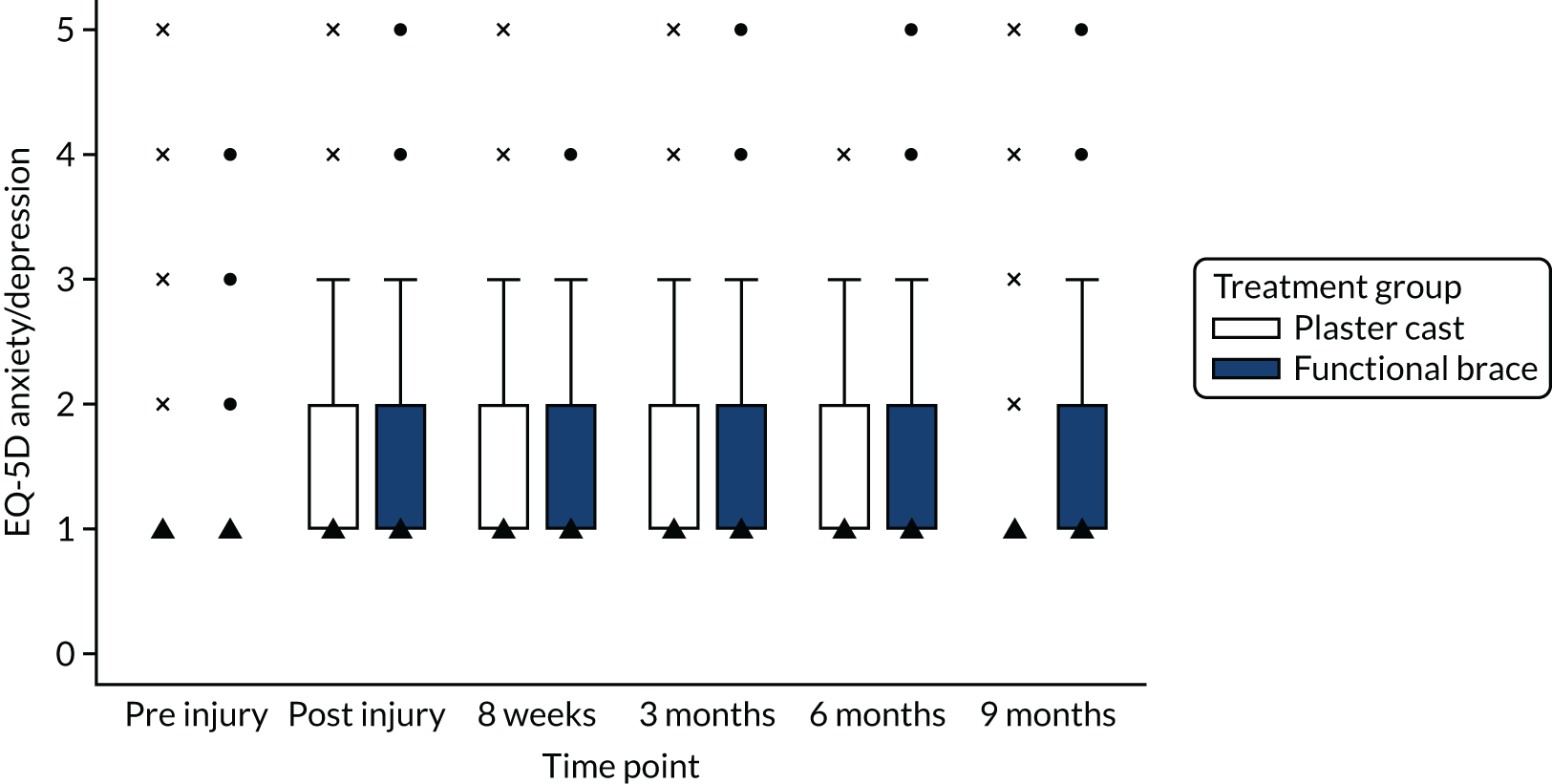

Measuring outcomes

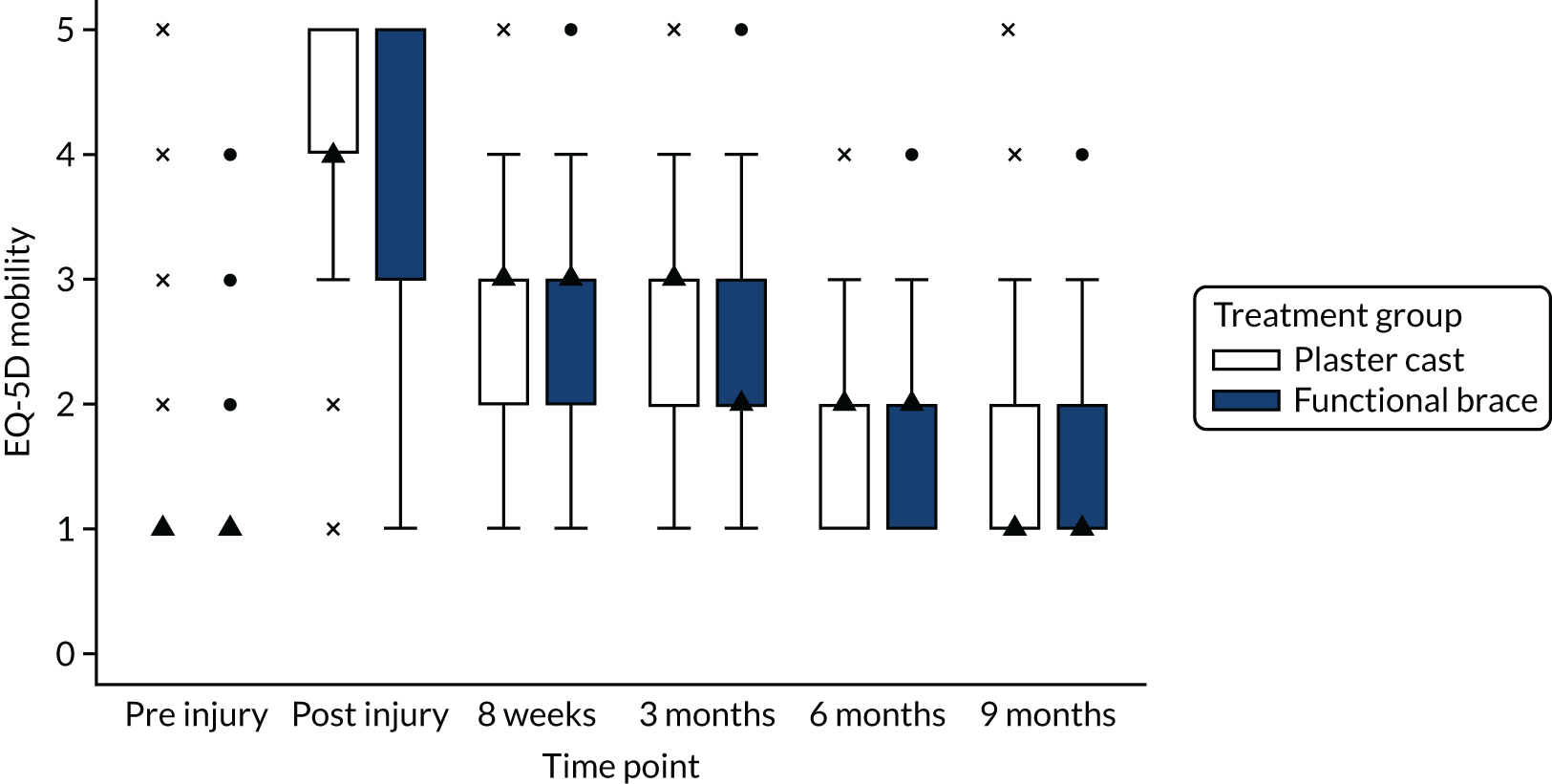

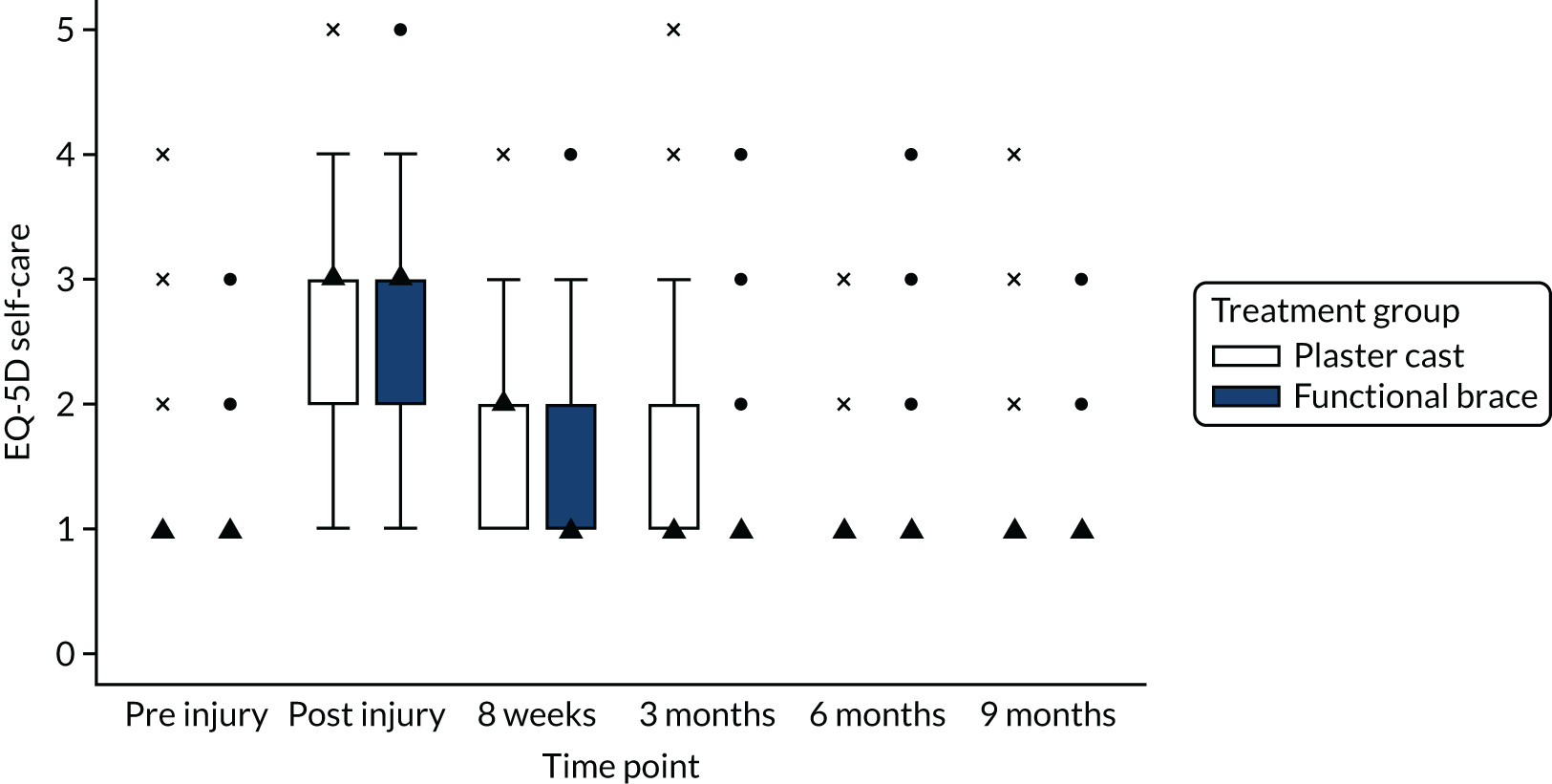

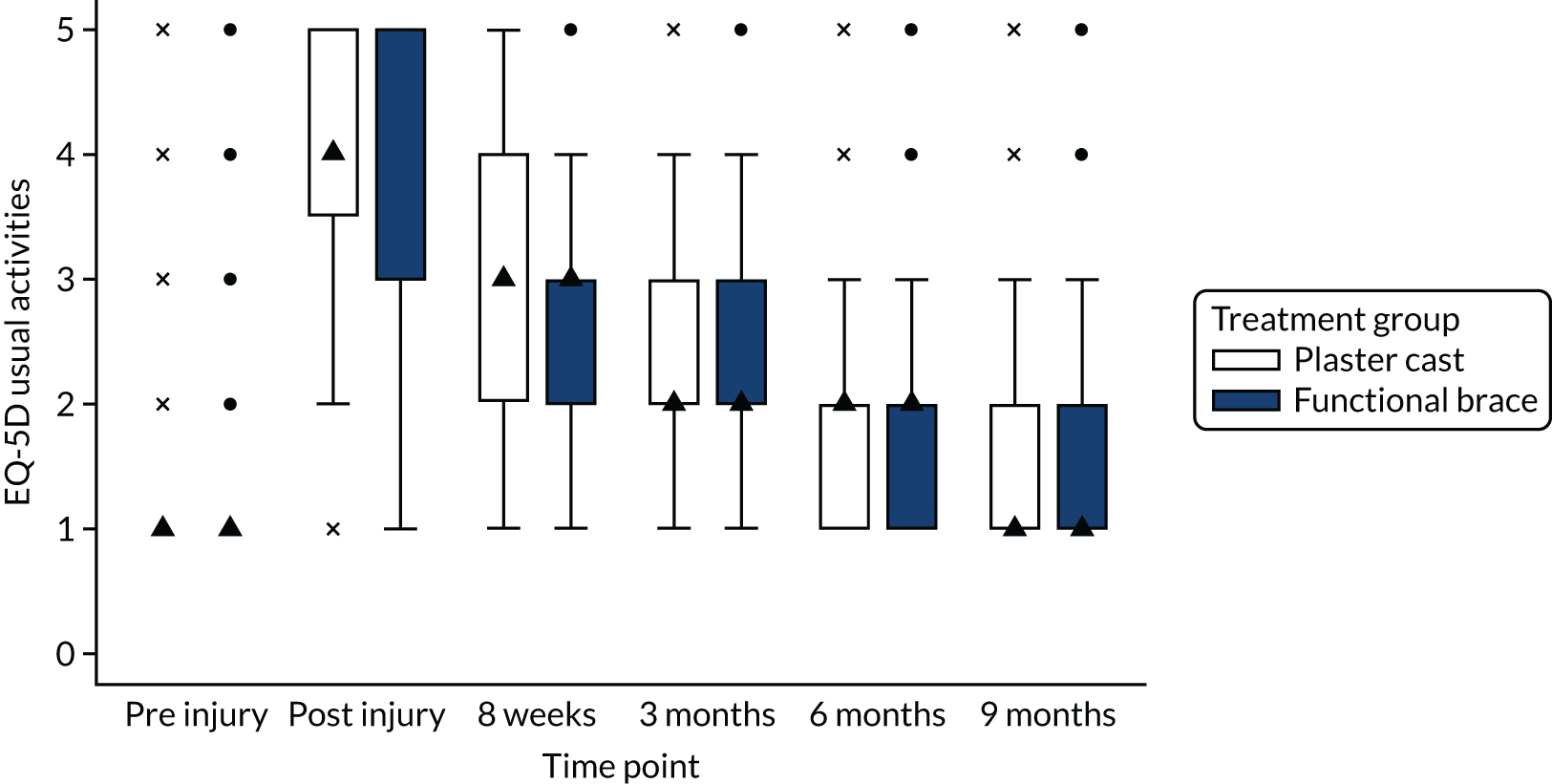

In accordance with NICE guidelines, the primary health outcome of the health economic evaluation was the QALY metric. 38 The QALY is a measure that combines quantity of life and preference-based HRQoL into a single metric. To calculate QALYs, it is imperative to obtain health state values for participants within the trial. The HRQoL of trial participants was assessed at baseline (both pre and post injury) and at 8 weeks and 3, 6 and 9 months post injury using the EQ-5D-5L. 38 The EQ-5D-5L defines HRQoL in terms of five dimensions: (1) mobility, (2) self-care, (3) usual activities, (4) pain/discomfort and (5) anxiety/depression. Responses in each dimension are divided into five ordinal levels, coded (1) no problems, (2) slight problems, (3) moderate problems, (4) severe problems and (5) extreme problems. Responses to each health dimension were categorised as optimal or suboptimal with respect to function, where optimal function indicates no impairment (e.g. ‘no problems in walking about’ for the mobility dimension) and suboptimal function refers to any functional (below level 1) impairment. Between-group differences in optimal compared with suboptimal function for each health dimension were compared at each time point using chi-squared tests.

Responses to the EQ-5D-5L instrument were converted into health utility scores using the EQ-5D-5L Crosswalk Index Value Calculator currently recommended by NICE,42 which maps the EQ-5D-5L descriptive system data onto the EQ-5D-3L valuation set. A detailed description of the mapping methodology is described elsewhere. 42 QALYs were generated for each patient using the area under the baseline-adjusted utility curve, assuming linear interpolation between health utility measurements across assessment points.

The health utility values and QALYs accrued over the 9-month follow-up period were summarised by treatment group and assessment point, and presented as means and associated standard errors. Between-group differences were compared using the two-sample t-test, in a similar way to the descriptive analyses of resource inputs and costs.

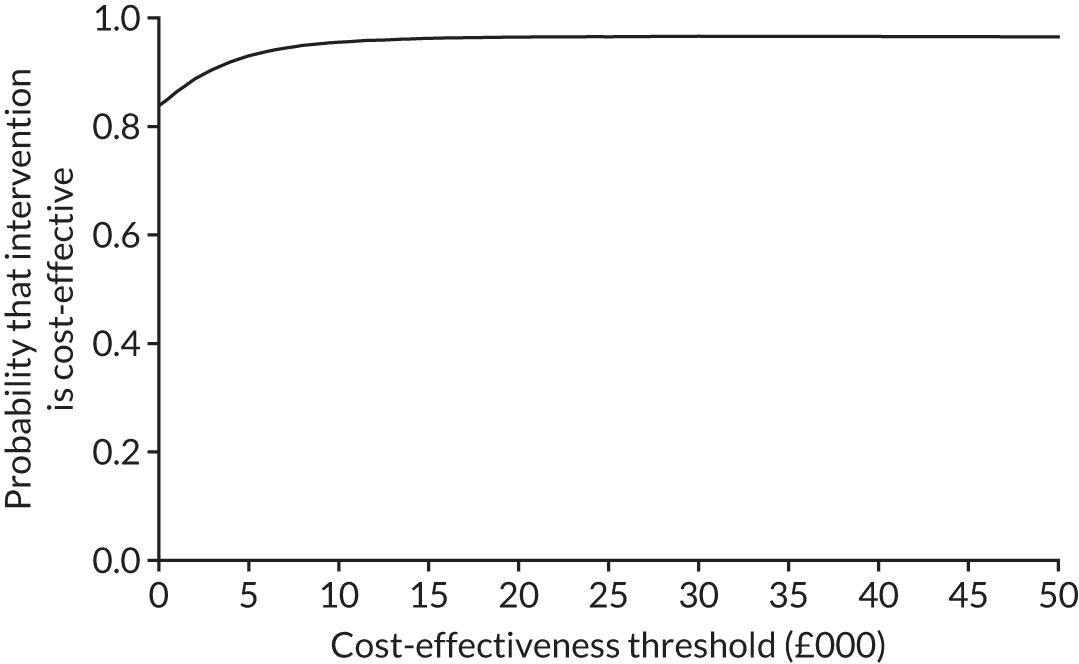

Cost-effectiveness analysis methods

Missing data

Missing data are common in RCTs: participants may be lost to follow-up, questionnaires may be unreturned or responses to individual questionnaire items may be missing. 45 As costs and outcomes of individuals with missing data may differ systematically from those of individuals with fully observed data, it is important to handle missing data using a principled approach that is justified by, among other factors, the missing data mechanism. Missing costs and health utility data were imputed at each time point using fully conditional multiple imputation by chain equations, implemented through the MICE package (run within Stata version 15.0; http://fmwww.bc.edu/RePEc/bocode/m) under the MAR assumption. The appropriateness of the MAR assumption was assessed by (1) investigating the missing data patterns (monotonic vs. non-monotonic) and (2) comparing the attributes of participants with and those of participants without missing costs and HRQoL data at each follow-up time point.

Regression models were used to generate multiple imputed data sets, in which missing values were predicted drawing on predictive covariates (age, sex and baseline pre-injury HRQoL scores). Costs and EQ-5D utility scores at each time point contributed as both predictors and imputed variables. Imputations were generated separately by treatment group using predictive mean matching drawn from the five knh-nearest-neighbours (knn = 5); predictive mean matching preserves distribution of the data and is more robust to violations of the normality assumption. The multiple imputation was run 50 times, generating 50 complete data sets that reflected the distributions of and correlations between variables.

Bivariate regressions using a seemingly unrelated regression model (Sureg) were used to independently analyse the multiply imputed data sets so as to estimate the costs and QALYs in each treatment group over the 9-month trial horizon. Joint distributions of costs and outcomes from the original data set were generated through non-parametric bootstrapping and changes in costs and QALYs were calculated for each sample. A total of 1000 bootstrap samples were drawn and means for both incremental costs and incremental QALYs (with associated 95% CIs) were calculated. Estimates from each imputed data set were combined using Rubin’s rules38 to generate overall mean estimates of costs and QALYs and their standard errors. The standard errors reflect the variability within and across imputations. The imputation model was validated by assessing the distributions of imputed and observed values. A mixed model with adjustment made for baseline pre-injury EQ-5D health utility scores is also presented for comparison.

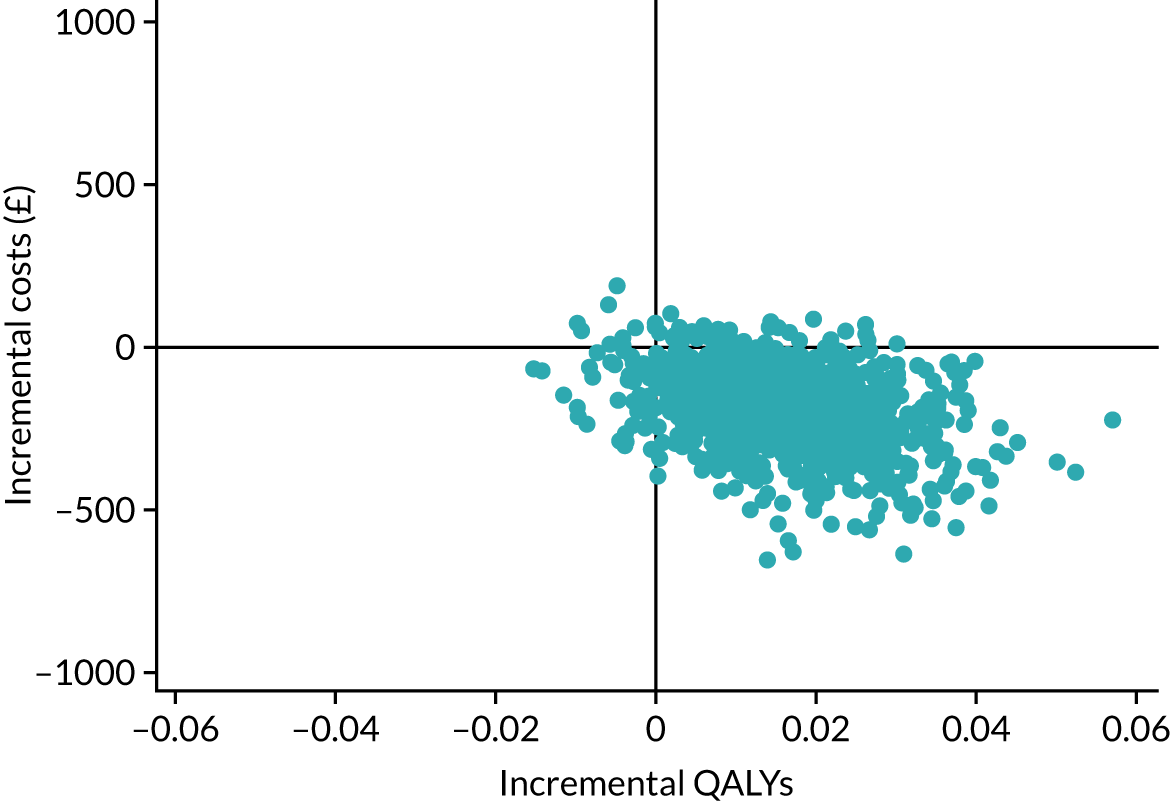

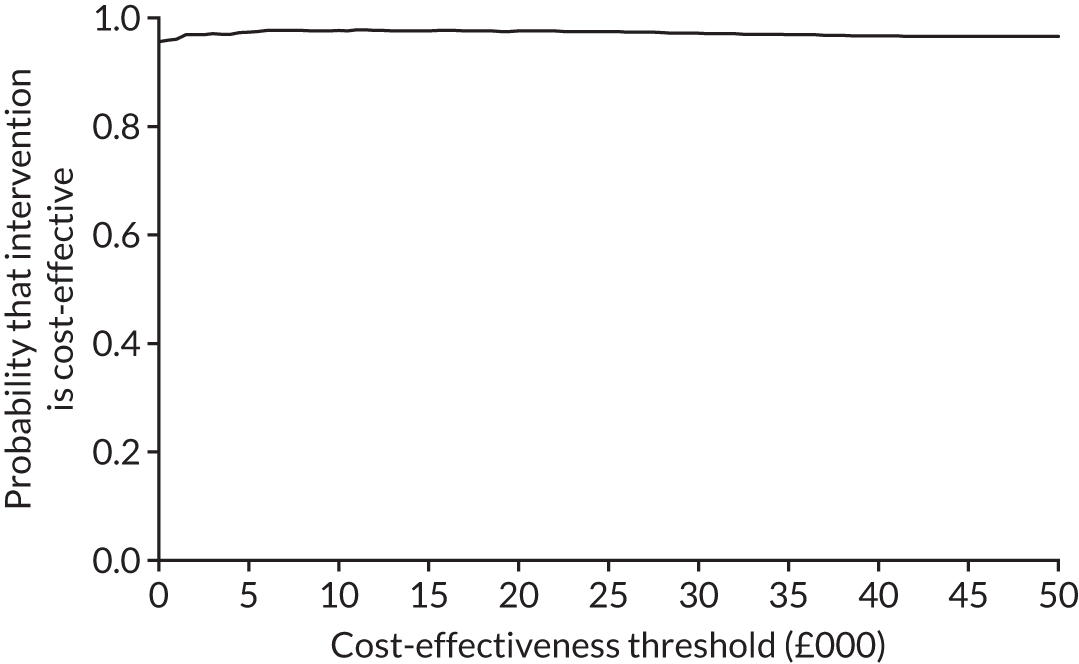

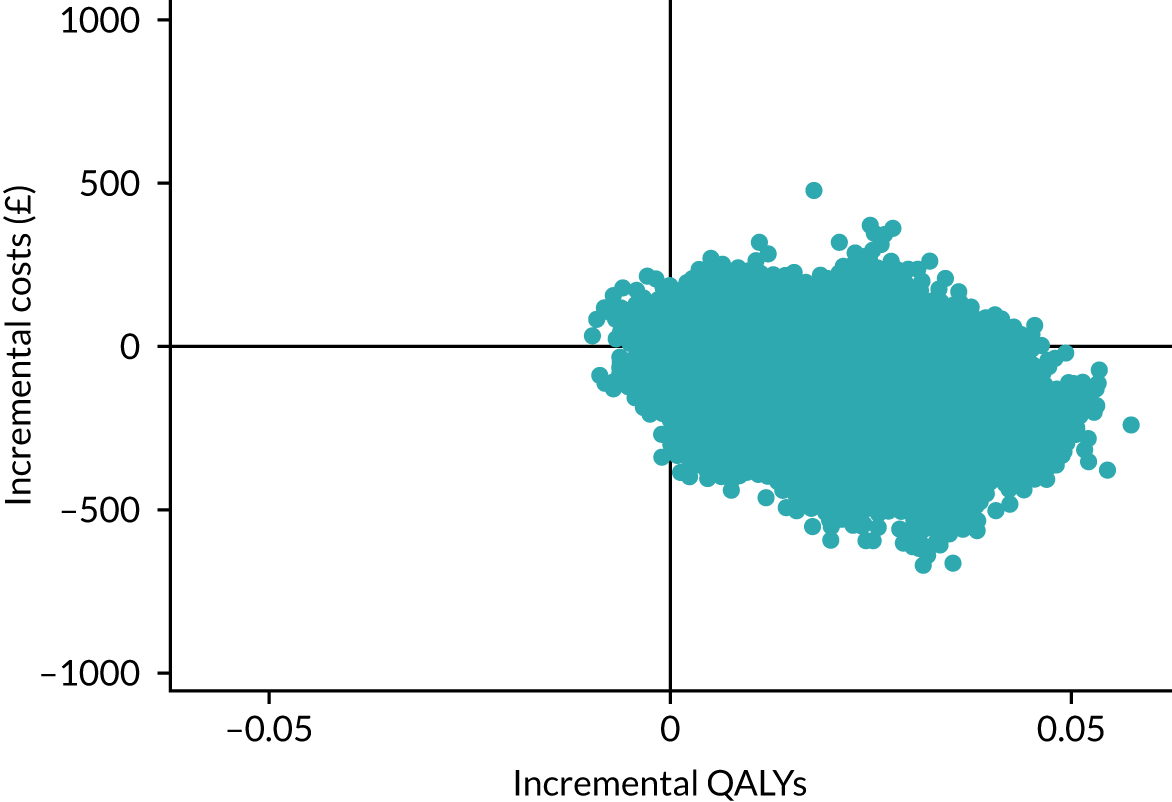

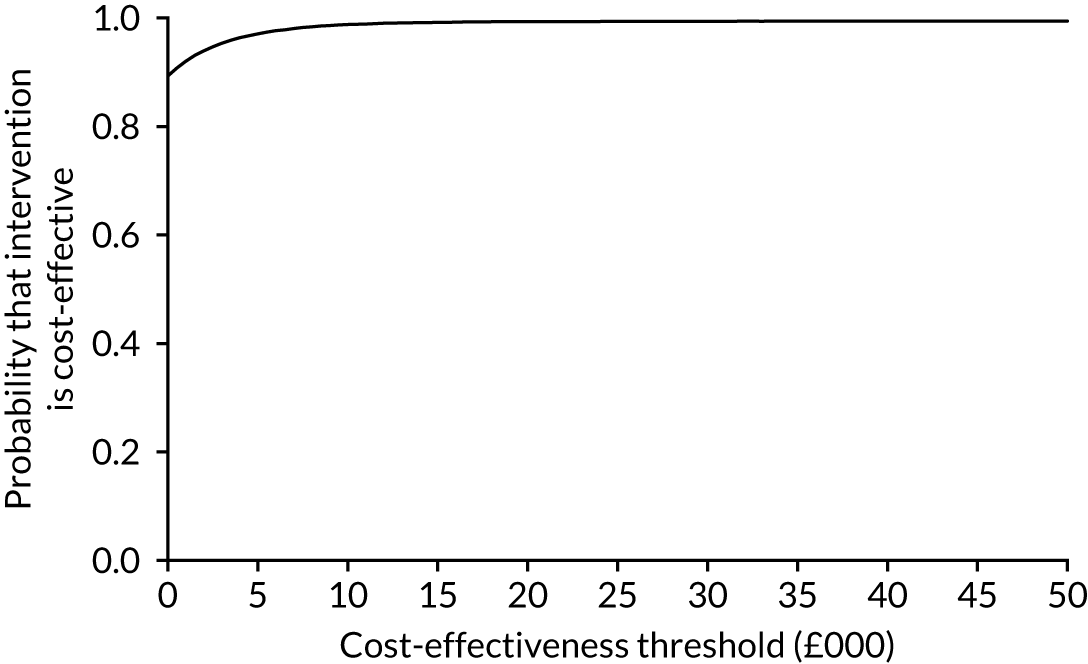

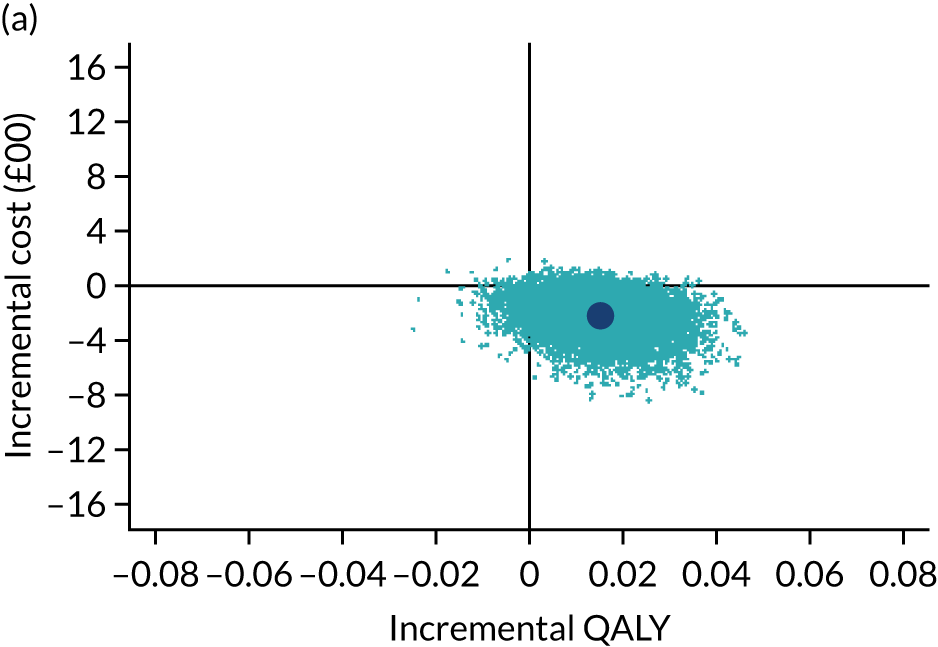

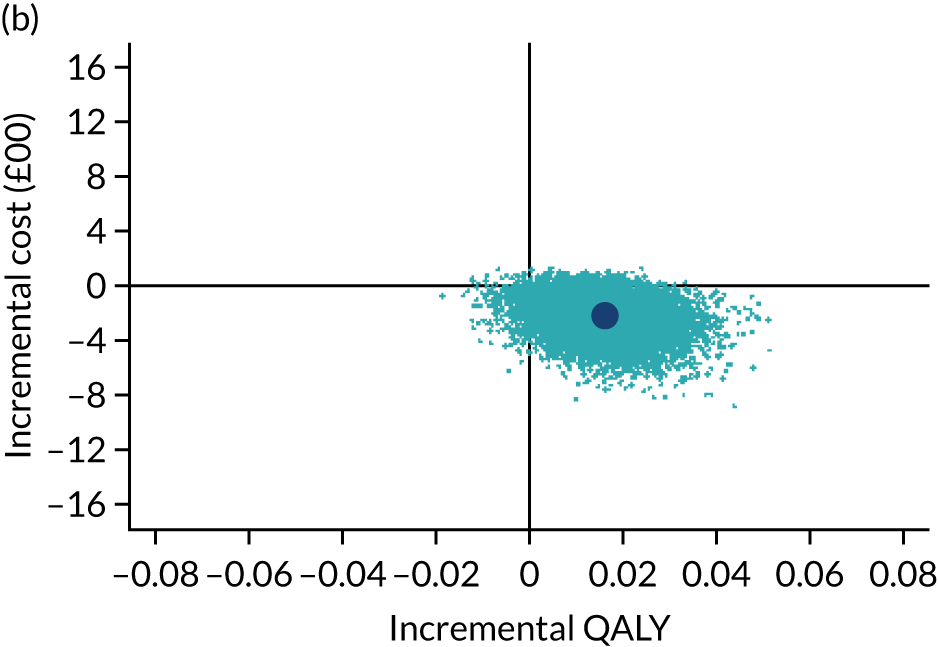

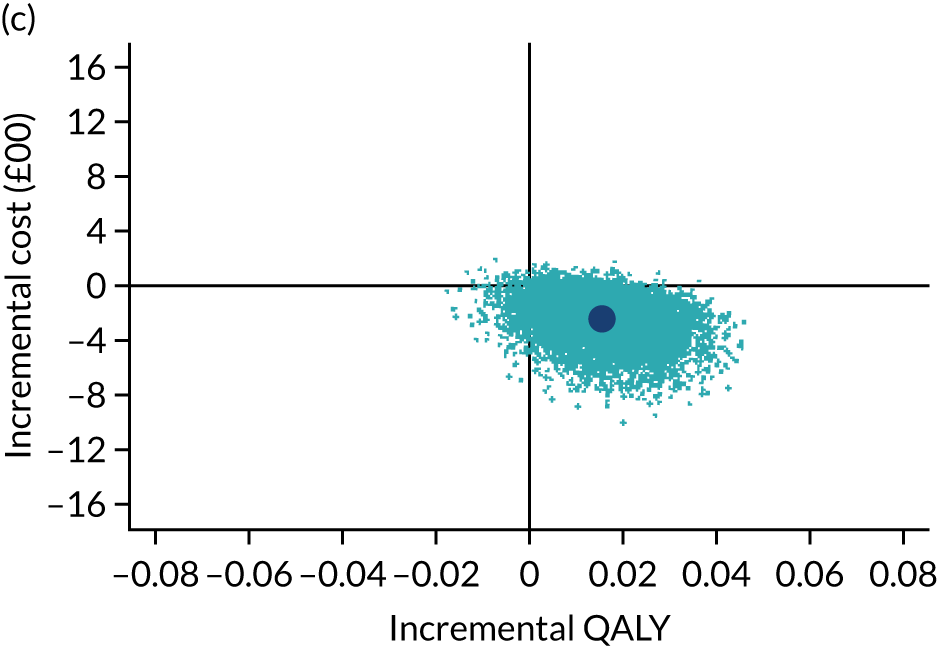

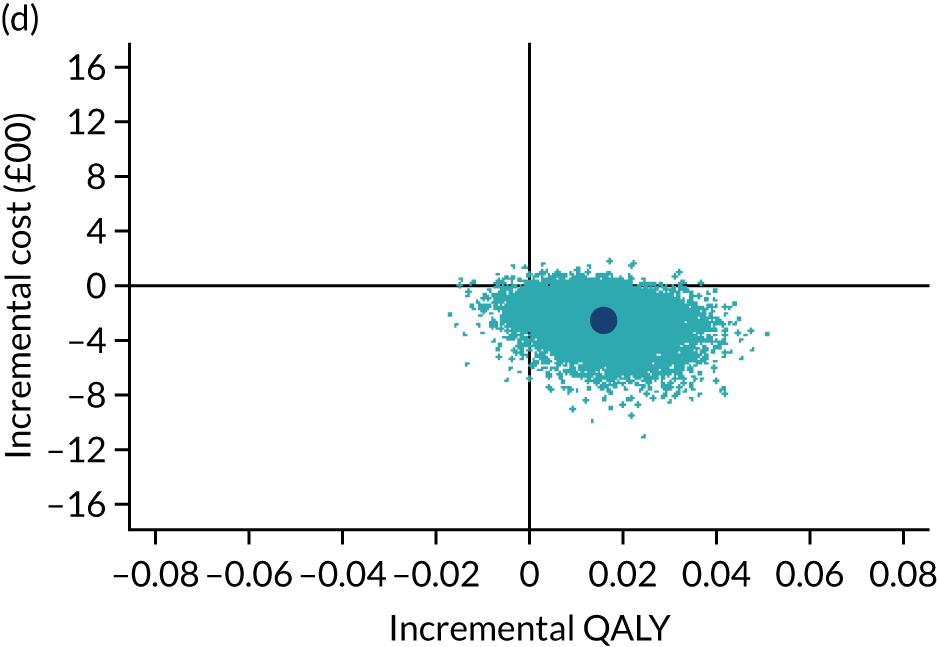

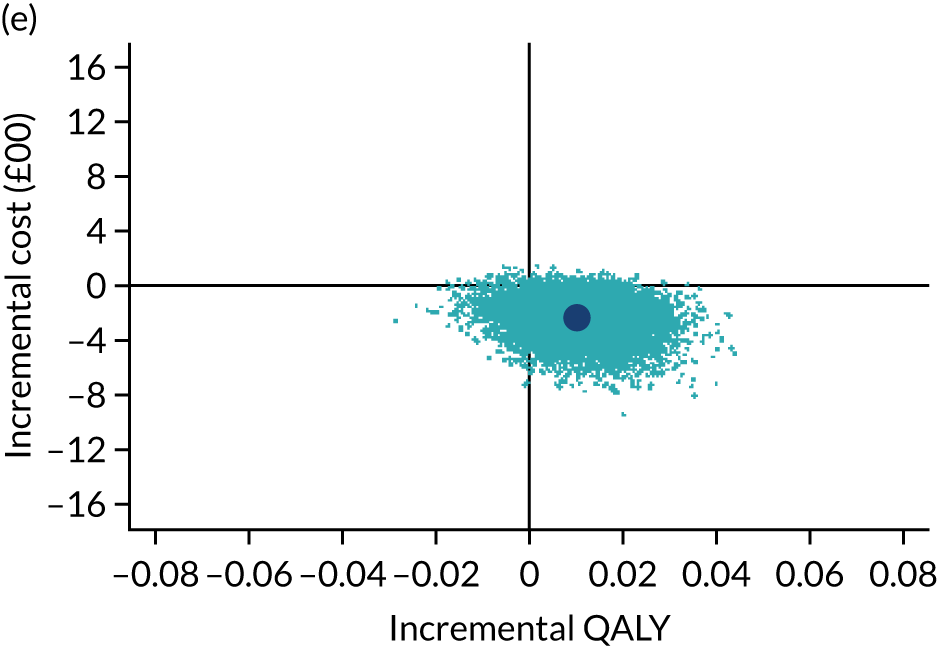

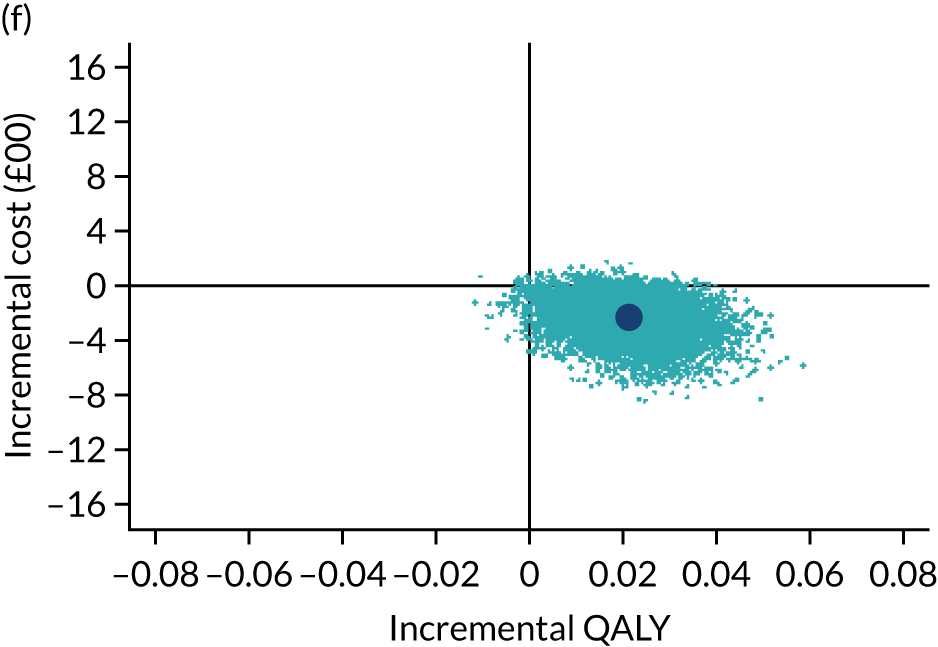

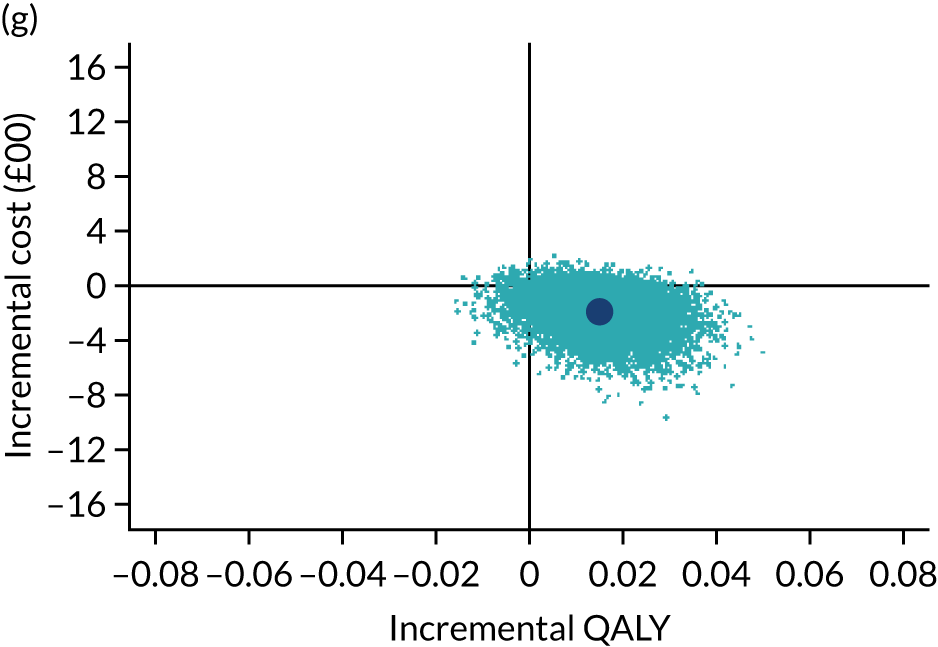

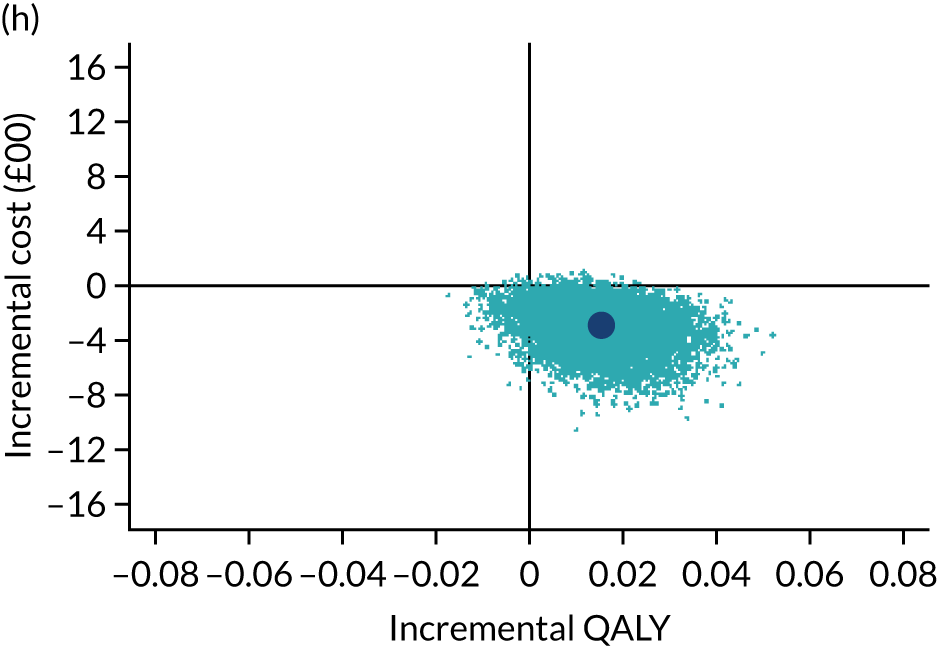

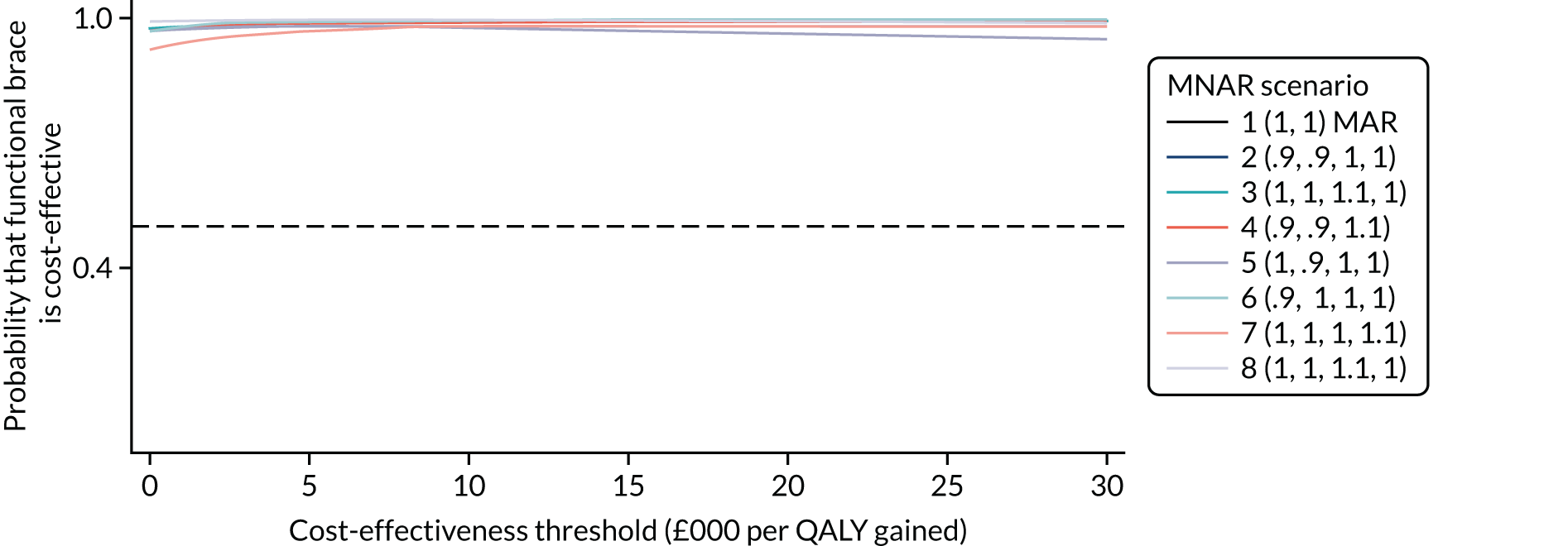

Presentation of cost-effectiveness results

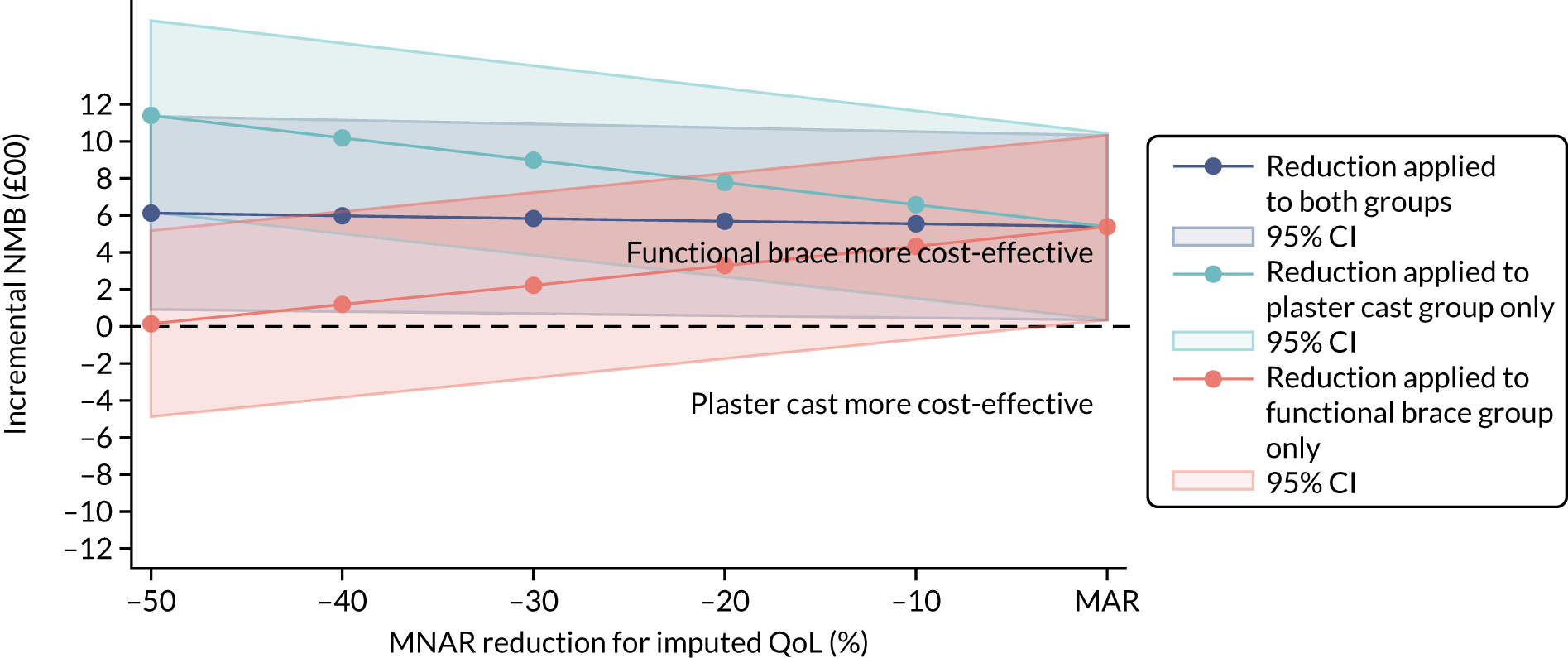

The cost-effectiveness results are expressed in terms of the incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER) and calculated as the difference between treatments in mean total costs divided by mean total QALYs. Given the pattern of results, plaster cast has been selected as the referent and functional brace as the comparator (i.e. functional brace minus plaster cast) for the estimation of ICER values. The bootstrap replicates generated by the non-parametric bootstrapping, described in Missing data, were used to populate cost-effectiveness scatterplots. Cost-effectiveness acceptability curves, which showed the probability that functional brace is cost-effective relative to plaster cast across a range of cost-effectiveness thresholds, were also generated based on the proportion of bootstrap replicates with positive incremental net benefits. The net monetary benefit (NMB) of using functional brace compared with plaster cast was also calculated across three prespecified cost-effectiveness thresholds, namely £15,000 per QALY,44 £20,000 per QALY and £30,000 per QALY. 46 A positive incremental NMB indicates that functional brace is cost-effective compared with plaster cast at the given cost-effectiveness threshold. For the secondary analysis that adopted the ATRS as the health outcome measure of interest, the NMB was estimated at cost-effectiveness thresholds of £100–500 per unit change in ATRS score. We failed to identify any external evidence on economic values for changes in ATRS score and therefore a range of arbitrary threshold values had to be selected for this analysis.

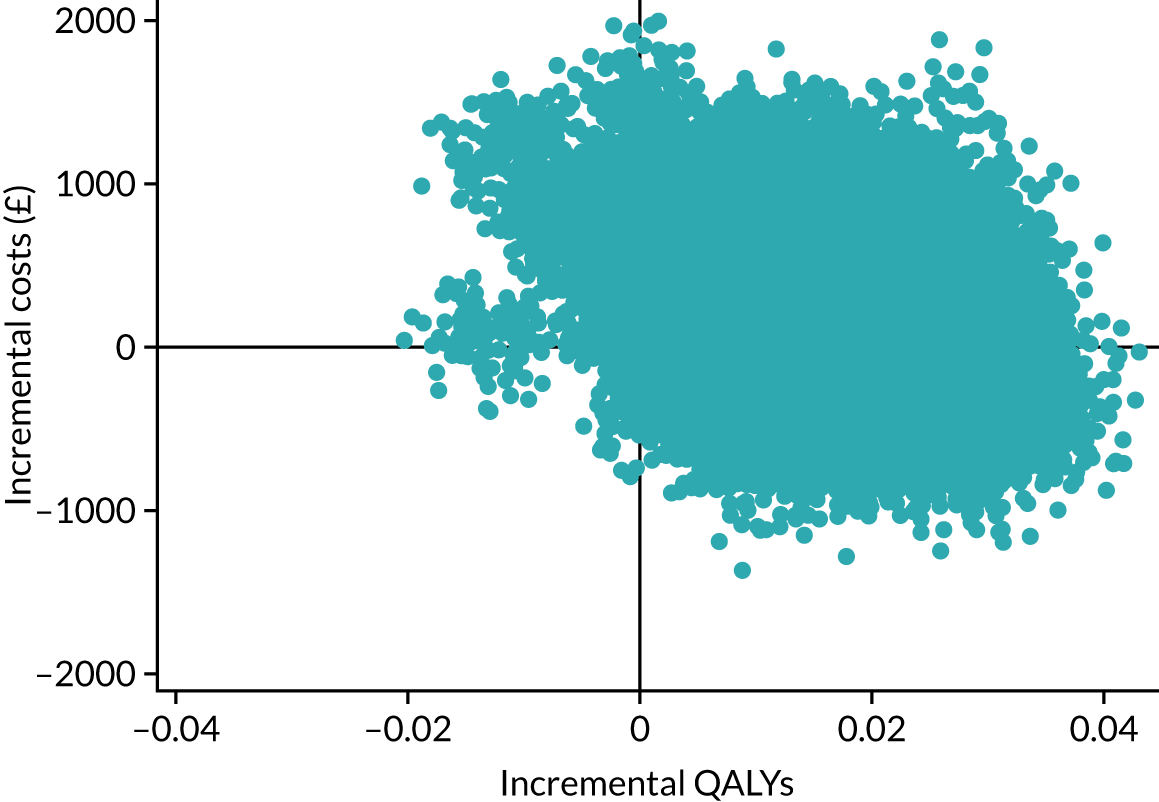

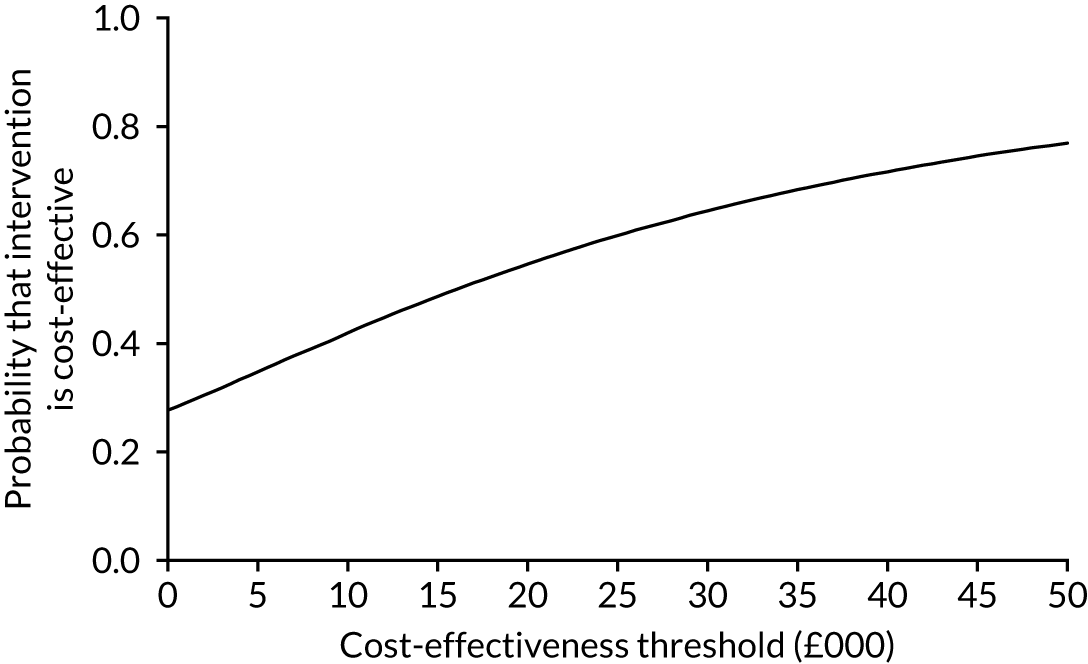

Sensitivity and secondary outcomes analyses

Several sensitivity analyses were conducted to test the robustness of the cost-effectiveness estimates. These involved re-estimating the main cost-effectiveness outcomes under the following scenarios: (1) restricting the analyses to complete cases (i.e. those participants with complete cost and outcome data over the 9-month follow-up period); (2) adopting a wider societal perspective that included private costs incurred by trial participants and their families, as well as economic losses attributable to work absences; (3) estimating incremental cost-effectiveness using a CACE population; and (4) evaluating the impact on cost-effectiveness results of assuming that data may be MNAR, rather than MAR, as the tests for exploring missing data mechanisms described above cannot rule out MNAR. Data are MNAR when the probability of missingness is directly linked to the unobserved value itself. To explore this assumption in sensitivity analyses, we used pattern mixture models with multiple imputation, following the published tutorial by Leurent et al. 47 Using this approach, missing values were first imputed using multiple imputation under a MAR assumption. Second, the MAR-imputed data were modified by a scale parameter (c) to reflect that HRQoL and cost data may be MNAR under a range of plausible scenarios. Specifically, we assumed that participants with missing HRQoL were likely to be in poorer health, whereas those with missing cost data were likely to have used more resources. In the absence of expert data on what the likely reduction could be, we assumed conservatively that a participant with missing HRQoL values would, on average, have a 10% lower HRQoL than a trial participant with similar characteristics who had available data. We applied the same reasoning for costs, but this time assuming a 10% higher cost. The combination of scenarios is shown in Table 3. The resulting multiply imputed data set was analysed as explained above for multiple imputation under MAR, combining the results using Rubin’s rules. Results are presented as cost-effectiveness scatterplots and cost-effectiveness acceptability curves for the different scenarios (see Figures 15 and 16). Furthermore, we present a graph to show NMB over a range of MNAR parameter values, specifically 0–50% reduction in imputed HRQoL values (see Figure 17) in order to show when a tipping point (change in cost-effectiveness decision) might occur.

| Scenario description | MNAR rescaling parameter | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HRQoL in plaster cast group | HRQoL in functional brace group | Cost in plaster cast group | Cost in functional brace group | |

| 1. MAR | ||||

| Same parameters in both treatment groups | ||||

| 2. 10% reduction in HRQoL in both groups | –10% | –10% | 1 | 1 |

| 3. 10% increase in costs in both groups | 1 | 1 | +10% | +10% |

| 4. 10% increase in costs and 10% reduction in HRQoL | –10% | –10% | +10% | +10% |

| Different parameters by treatment group | ||||

| 5. 10% reduction in HRQoL in functional brace group | 1 | –10% | 1 | 1 |

| 6. 10% reduction in HRQoL in plaster cast group | –10% | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 7. 10% increase in cost in functional brace group | 1 | 1 | 1 | +10% |

| 8. 10% increase in cost in plaster cast group | 1 | 1 | +10% | 1 |

In addition, as this was a secondary analysis, cost-effectiveness was estimated using the ATRS, rather than the QALY, as the health outcome measure of interest.

Longer-term economic modelling

The study protocol also allowed for decision-analytic modelling to estimate longer-term cost-effectiveness of functional brace or plaster cast, provided that the costs and health outcomes did not converge at the end of the 9-month post injury follow-up period.

Data management

In accordance with the standard operating procedures of the OCTRU, data management procedures were defined in a data management plan. This covered trial databases and data handling, definition of critical data fields, forms and questionnaires used, data collection, how protocol deviations were recorded, data rulings, handling data deviations, data security and confidentiality, data set closure, archiving and data sharing. Each data management plan version was signed off by the chief investigator and the trial statistician.

The monitoring plan determined the need for central and on-site data monitoring. All recruitment centres were monitored centrally. The monitoring plan specified that on-site monitoring was not required for this trial and no monitoring visits were conducted.

Statistics on data collection, data entry and query management were presented at each TMG meeting for oversight.

UK legislation requires data to be anonymised as soon as it is practical to do so. Participants were identified only by their initials and a participant number on UKSTAR questionnaires and in the study database. All documents were stored securely and accessible only by study staff and authorised personnel. Personal data and sensitive information required for the study were collected directly from trial participants and hospital notes. All personal information received in paper format for the trial was held securely and treated as strictly confidential. Personal data were stored separately from study outcomes in lockable cabinets in secure keycard-accessed rooms in the Kadoorie Centre in the John Radcliffe Hospital and in the Botnar Research Centre, University of Oxford. All paper and electronic data will be retained for at least 5 years after completion of the trial.

Patient and public involvement

The UKSTAR TSC and TMG both included a patient representative as a PPI member. Mrs S Webb was TSC PPI representative and attended meetings from the initial meeting and Mr R Grant was PPI representative at TMG meetings from September 2017.

Ethics approval and monitoring

Ethics approval

The study received favourable opinion from the South Central – Oxford B Research Ethics Committee on 7 April 2016 (reference 16/SC/0109) and each recruitment centre was granted site-specific approval from its NHS trust research and development department before the trial commenced.

Data and Safety Monitoring Committee

The DSMC was a group of independent experts external to the trial who assessed the progress, conduct, participant safety and critical end points of the trial. The UKSTAR DSMC adopted a DAMOCLES (DAta MOnitoring Committees: Lessons, Ethics, Statistics) charter,48 which defined its terms of reference and operation in relation to oversight of the trial. It reviewed copies of data accrued to date, including information on allocation balance, data quality and participant safety summarised by treatment group, and assessed the screening algorithm against the eligibility criteria. No formal interim analysis of the outcome data was requested for review by the DSMC. During the period of recruitment to the trial, all information was supplied to the DSMC members in strict confidence. The DSMC also considered emerging evidence from other related trials or research and reviewed related SAEs that have been reported. It was able to advise the chairperson of the TSC at any time if, in its view, the trial should be stopped for ethical reasons, including concerns about participant safety. DSMC meetings were held at least annually during the recruitment phase of the study.

Trial Steering Committee

The TSC, which included independent members and had an independent chairperson, provided overall supervision of the trial on behalf of the funder. Its terms of reference were defined in a TSC charter, agreed with the Health Technology Assessment programme, which also approved the appointment of TSC members. The TSC’s remit was to:

-

monitor and supervise the progress of the trial towards its interim and overall objectives

-

review, at regular intervals, relevant information from other sources

-

consider the recommendations of the DSMC

-

inform the funding body of the progress of the trial.

Trial Steering Committee meetings were held at least annually during the recruitment phase of the study.

Trial Management Group

The TMG was made up of the study investigators and staff working on the project. This group oversaw the day-to-day running of the trial and met regularly throughout the study.

Summary of changes to the trial protocol

All protocol versions can be found on the NIHR Journals Library website at www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/programmes/hta/1311562/#/ (accessed 11 November 2019).

The changes to the project protocol are summarised in Table 4.

| Protocol version number | Date | Details of changes made |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 27 January 2016 | The first version |

| 2 | 18 August 2016 |

References to fax removed; replaced with description of sending confidential documents to a secure nhs.net e-mail address Addition of resource use questionnaire at 8 weeks Clarification of data collection roles of recruitment centre staff and UKSTAR office staff Update to the statistical analysis section of the protocol so that it reflects the statistical analysis plan for the trial Clarification of the consent process Correction of typographical errors and clarifications |

| 3 | 10 July 2017 | Clarification that questionnaires at the 3-, 6- or 9-month time points may be sent electronically to patients via e-mail or SMS, as an alternative to by post |

| 4 | 19 September 2017 (not issued) | Update of sample size to a maximum of 550 patients |

| 5 | 23 October 2017 | Correction of protocol version number from 4.1 to 5.0 |

| 6 | 16 May 2018 |

Addition of ‘study within a trial’ to assess the effect of thank-you e-mails on follow-up rates Updates to study personnel, TSC membership and sponsor address details Correction of minor typographical errors |

| 7 | 13 November 2018 |

Removal of ‘study within a trial’ Addition of thank-you letter to participants after final follow-up |

Chapter 3 Clinical trial results

Study participants

Patients with an Achilles tendon rupture typically attend the emergency department at their local hospital and, following their diagnosis, are referred to the next available fracture/trauma clinic to discuss the management of their injury.

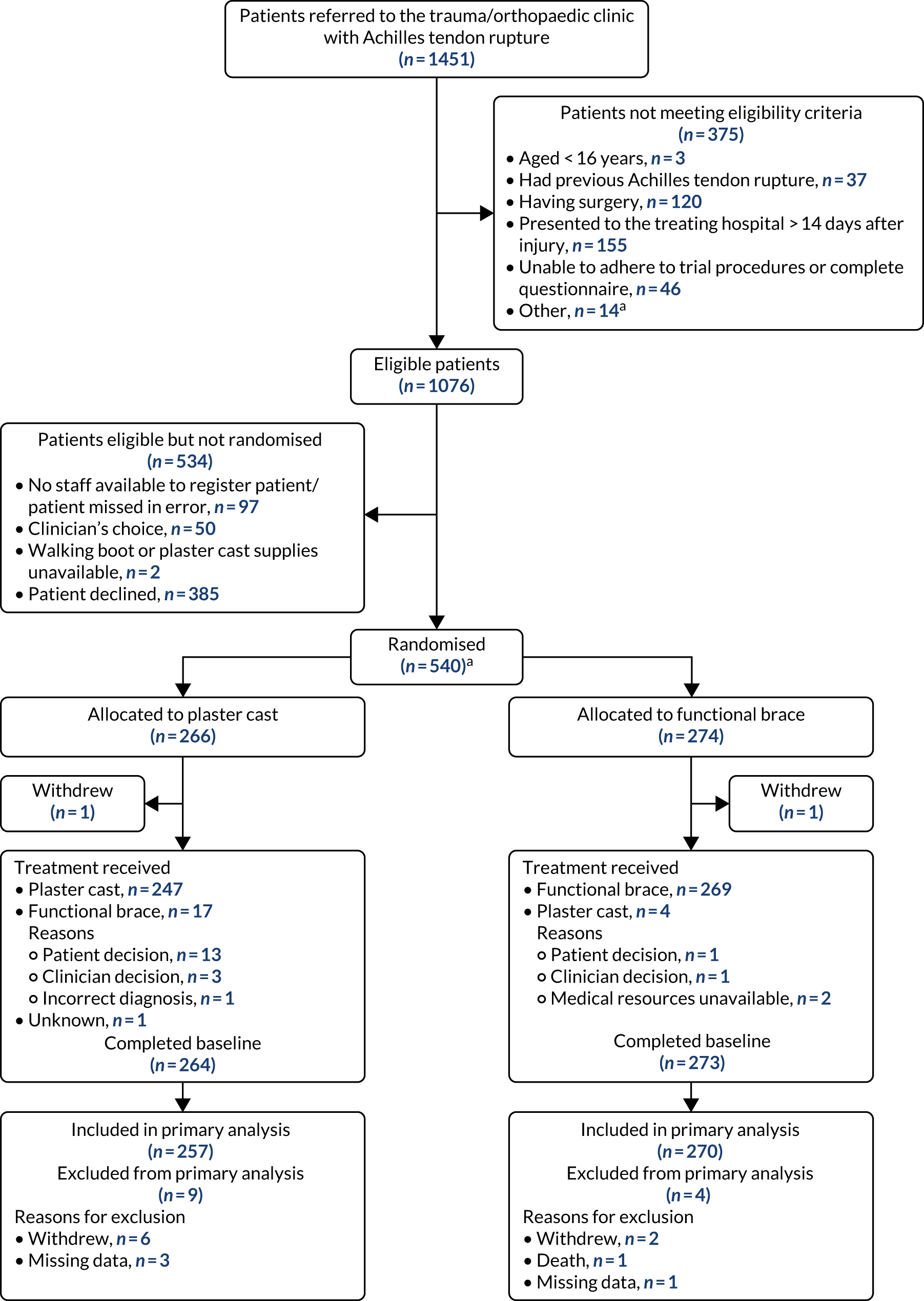

The flow of participants through the study is summarised in Figure 1. This includes details on the total number of patients referred to the trauma clinic with an Achilles tendon rupture and those randomised. The availability of the primary outcome for analysis is also reported by treatment group, as is the total number of patients excluded from the primary outcome analysis.

FIGURE 1.

The UKSTAR CONSORT flow diagram. a, Two additional patients were randomised in error without giving consent to be in the study. These participants were excluded from all data analyses. Reproduced from Costa et al. 49 © 2020 The Author(s). Published by Elsevier Ltd. This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

Recruitment

A total of 1076 eligible participants were screened from July 2016 to May 2018 from 39 NHS hospitals across England and Scotland (see Figure 1). Of these, 540 participants consented to take part in the trial. Reasons why patients were not included in the trial are presented. Participants attended clinic visits at the time of randomisation (baseline) and at the 8-week follow-up. Participants were also contacted by the trial team by post, e-mail or telephone to complete follow-up questionnaires at 3, 6 and 9 months post injury. Two participants were randomised in error before consenting and are therefore not included in the numbers allocated to each treatment group.

Baseline characteristics

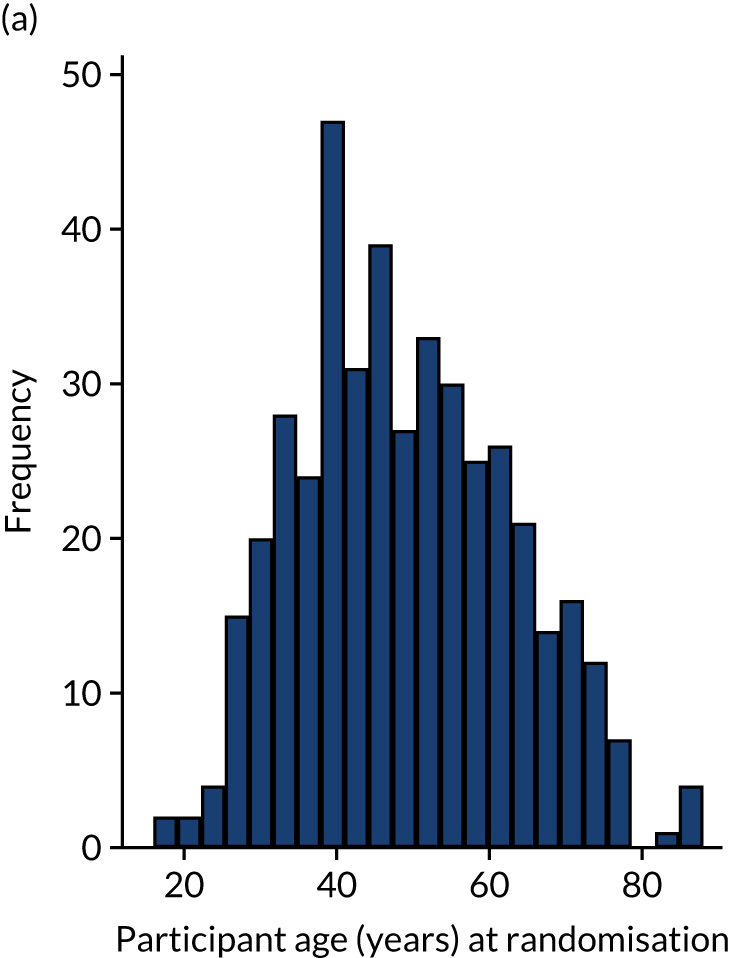

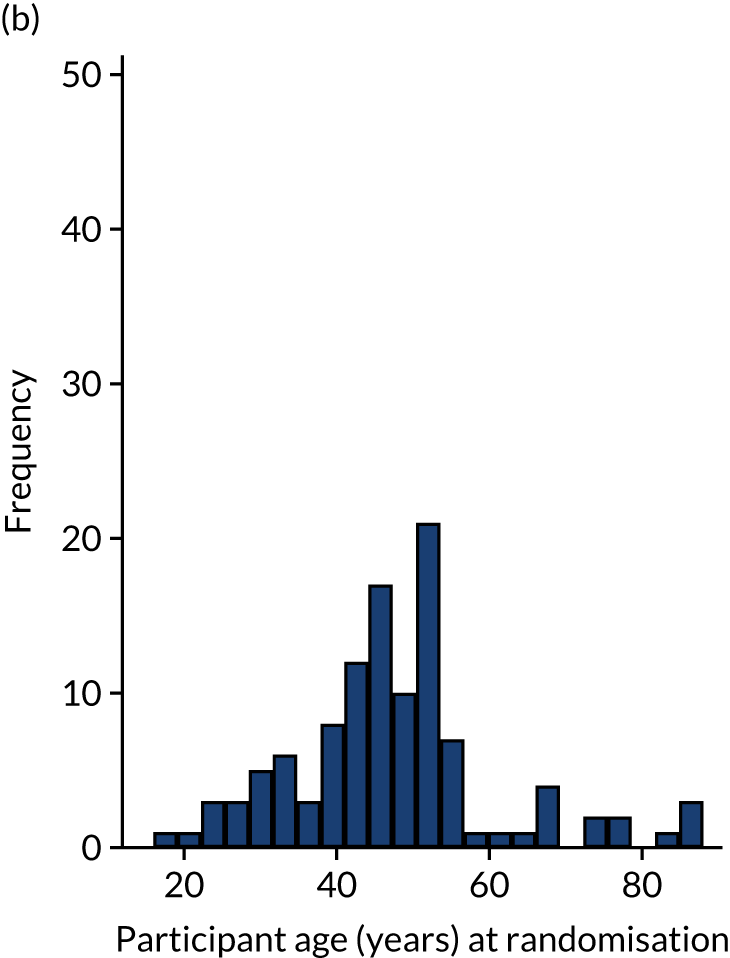

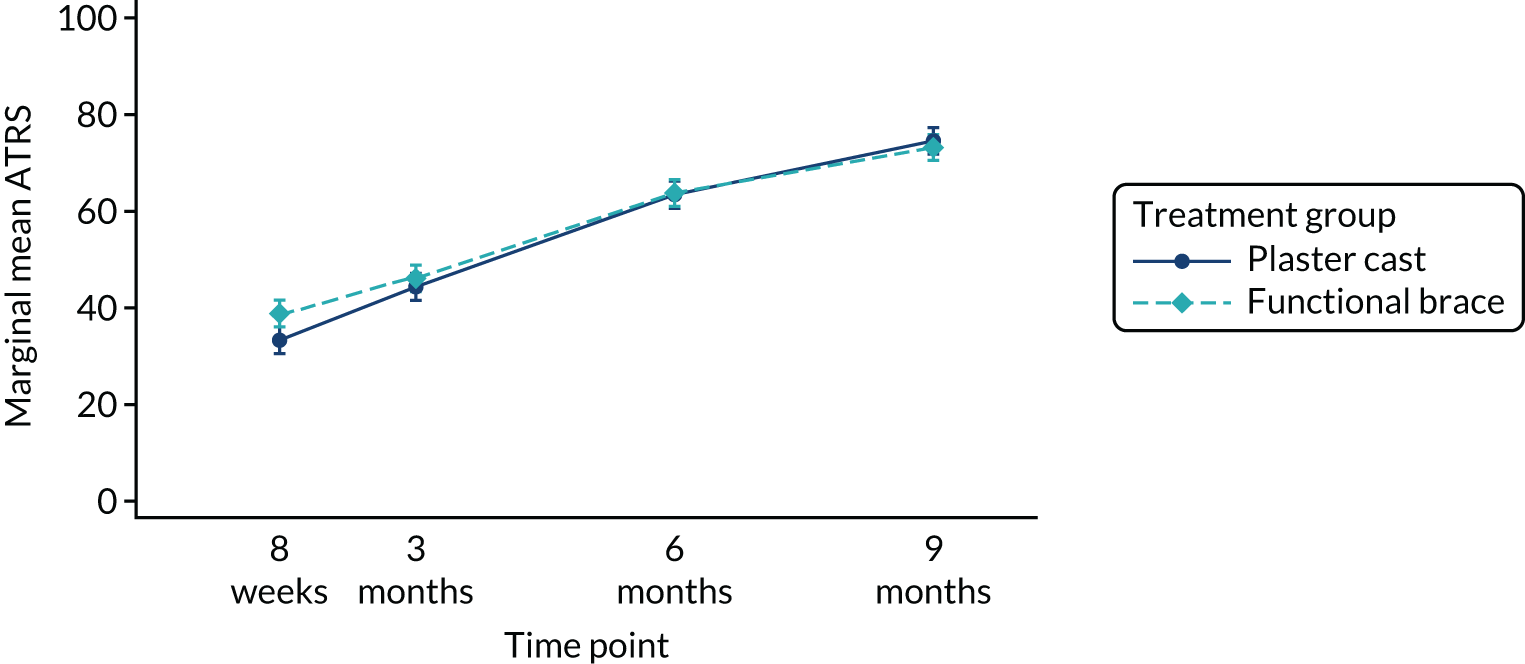

The randomisation was stratified by centre, and the allocation of participants to the treatment groups in each centre and the overall numbers is given in Table 5. The descriptive characteristics of the participants included in the ITT population are summarised by treatment group and overall in Table 6. These values are presented as numbers and percentages for categorical factors and as means and SD or medians and IQR, as appropriate, for continuous variables. These variables all appear well balanced between the two treatment groups. The distribution of participant ages by sex at enrolment is shown in Figure 2. This distribution has a peak in male patients aged 30–40 years and in female patients aged 40–60 years. Baseline values of patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs), ATRS and EQ-5D-5L are summarised by group in Table 7. ATRS values range from 0 to 100, with lower scores indicating more functional limitations; EQ-5D utility scores range from –0.511 to 1, with higher scores indicating better QoL and 0 being equivalent to death; and EQ-5D VAS scores range from 0 to 100, with higher scores indicating better QoL. The values reported are similar in the two treatment groups.

| Trial centrea | Plaster cast group (N = 266) | Functional brace group (N = 274) | Overall (N = 540) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % | |

| ABD | 31 | 11.7 | 33 | 12.0 | 64 | 11.9 |

| AIR | 11 | 4.1 | 12 | 4.4 | 23 | 4.3 |