Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 10/104/30. The contractual start date was in December 2012. The draft report began editorial review in April 2019 and was accepted for publication in November 2019. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Michael J Griffiths has a patent 068347A1 pending for a novel method of detection of bacterial infection. Tom Solomon reports grants from the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) outside the submitted work and other support from the Data Safety and Monitoring Committee of the GlaxoSmithKline plc (London, UK) study to evaluate the safety and immunogenicity of a candidate ebola vaccine in children (GSK3390107A) (ChAd3 EBO-Z), outside the submitted work. He also chairs the Siemens Healthineers (Munich, Germany) Clinical Advisory Board. Dyfrig Hughes was member of the Health Technology Assessment (HTA) programme Pharmaceuticals Panel (2008–12) and the HTA programme Clinical Evaluation and Trials board (2010–16). Carrol Gamble reports grants from NIHR outside the submitted work and is a member of the NIHR Efficacy and Mechanism Evaluation programme committee (January 2015–present).

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2020. This work was produced by Mallucci et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2020 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Introduction

Parts of this chapter have been reproduced from Jenkinson et al. 1 This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. The text below includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original text.

Parts of this chapter have been reproduced from Mallucci et al. 2 This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nd/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. The text below includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original text.

Current practice

Hydrocephalus affects one in every 500 births,3 and is thus one of the most common developmental disabilities in children. The condition also affects older children and adults of all ages, and can be secondary to a variety of causes, including intracranial tumours, haemorrhage and infection. In the late 1950s, the development of a treatment with cerebral shunts revolutionised the management of these patients.

Standard treatment for hydrocephalus remains the ventriculoperitoneal shunt (VPS) catheter. A VPS comprises silicone tubing with the addition of an in-line valve that is designed to control the rate of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) flow. The tubing passes from the brain fluid cavities (ventricles) under the skin to the peritoneum (abdominal cavity). The shunt drains CSF from the ventricles to the peritoneal cavity.

Insertion of a VPS to treat hydrocephalus is now one of the most common procedures performed in neurosurgical units, and between 3000 and 3500 shunt operations are carried out per year in the UK in adults and children. 4 Once inserted, a shunt is generally required for life; it will inevitably be susceptible to failure, in terms of both infection (as it remains an implanted foreign body) and mechanical failure, usually due to blockage of tubing or valve failure. Thus, patients with shunts will need lifelong follow up and usually require multiple surgeries. Therefore, VPS treatment for hydrocephalus is a major health burden to the NHS.

Industry produces a number of different VPS types, and costs associated with these can vary. The market comprises a wide variety of different valves and, more recently, different types of shunt catheter. The treating surgeon and hospital often chooses the type of valve and shunt tubing based on personal preference and/or associated costs.

There are three types of VPS catheter available (standard, antibiotic impregnated and silver impregnated). There is no standard practice or guidance in the UK as to which shunt catheter is the most effective at reducing infection. Practice is variable across the UK and the world. There are no current National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidelines, nor is there a position statement from the Society of British Neurological Surgeons regarding the use of any type of VPS.

As an infection in a newly implanted shunt can have such devastating consequences for the patient, with far-reaching health economic sequelae,5 the industry has led the way in trying to develop types of shunt catheters that will reduce infection. It is incumbent on clinical researchers to assess the effectiveness of these developments; this study attempts to answer this question.

Rationale

Shunt failure due to infection has plagued this neurosurgical advance ever since it was developed. The reported incidence of shunt infection varies markedly in the literature from 3% to 27%6–10 and is higher in certain groups, for example neonates and children aged < 1 year, and patients treated with a previous temporary external ventricular drain (EVD). Episodes of shunt infection have a major impact on both patients and the NHS and require prolonged inpatient hospitalisation, additional surgery to remove the infected hardware, placement of a temporary EVD, intravenous and intrathecal antibiotics and further surgery to place a new shunt once the infection has been treated. Other clinical consequences of infection, including epilepsy, reduced intelligence quotient (IQ) and loculation, have often been reported8 but never formally studied in the context of a prospective clinical trial. The number of shunt infections is an independent predictor of death in patients requiring CSF shunts [hazard ratio (HR) 1.66, 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.02 to 2.72]. 11

The most common pathogens detected were staphylococcus species, but, in a proportion of patients with suspected infection, the organism is never determined, especially if the patient has already received antimicrobial treatment or if there was a delay in culturing the organism, both of which hamper microbiological treatment. 5 However, newer molecular approaches are being developed,12 including the substudy within this trial.

Data from the UK shunt registry (to which most neurosurgical units contribute) report that 15% of shunt revisions are for infection. 13 In the largest randomised controlled shunt trial worldwide, the infection rate was 8.4% for primary VPSs. 14

Impregnated VPS catheters have been introduced as a means to reduce VPS infection, in addition to the usual surgical site infection prevention care bundles that are not standardised across neurosurgery clinical practice.

There are three types of VPS catheters available, and there are cost implications associated with impregnated shunt catheters that, typically, are more than double the cost of the standard non-impregnated VPS catheters:

-

standard VPSs are made of silicone and are available and supplied by a number of different companies

-

antibiotic-impregnated VPSs are made of silicone and are impregnated with antibiotics (0.15% clindamycin and 0.054% rifampicin) [available as Bactiseal® (Codman®; Integra LifeSciences Holdings Corporation, Plainsboro, NJ, USA) and Ares™ (Medtronic plc, Dublin, Ireland)]

-

silver-impregnated VPSs are made of silicone and impregnated with silver [available as Silverline® (Spiegelberg GmbH & Co. KG, Hamburg, Germany)].

Despite a large number of publications15–22 prior to our study, there has been limited evidence to date indicating the clinical effectiveness of these impregnated shunt catheters. Prior to our study, a systematic review and meta-analysis23 of the Bactiseal VPS identified one randomised controlled trial (RCT)15 and 11 observational studies. The RCT,15 conducted in a single centre in South Africa, demonstrated a trend favouring impregnated VPSs, but did not show a statistically significant difference between the two trial groups [relative risk (RR) 0.38, 95% CI 0.11 to 1.30; p = 0.12]; however, meta-analysis of the 11 observational studies showed a statistically significant difference favouring the Bactiseal VPS (RR 0.37, 95% CI 0.23 to 0.60; p < 0.01). 23 Research on the Bactiseal VPS conducted in Liverpool, UK, has shown that, over a 2-year period, the infection rate reduced among paediatric patients who were given the Bactiseal VPS compared with historical controls. 16 However, continued data collection over 3.5 years, published as part of a Liverpool-led multicentre observational study in collaboration with two other UK paediatric neurosurgical units, showed no significant reduction in infection. 17 Indeed, the reduction in infection achieved by the Bactiseal VPS in the multicentre observational study17 was seen only in neonates and was heavily weighted by the results from one unit. This study17 was not part of the published systematic review. 23

Silver-impregnated shunts were launched in the UK in March 2011. There is little doubt that silver ions have antimicrobial effects and they elute from Silverline shunt catheters. However, the efficacy of Silverline shunt catheters at preventing VPS infections is not proven. In vitro models have shown varying results and clinical studies are limited. 18,19 There is one observational study of the Silverline VPS,20 in which the Silverline VPS was used to successfully treat seven patients with active CSF infection. There are no observational studies comparing Silverline VPS infection rates with those of either standard or Bactiseal VPSs. However, in a RCT of EVDs (an EVD is a temporary tube placed in the ventricles that is prone to infection) in children and adults, Silverline EVDs have been shown to reduce infection from 21.4% (30/140) with standard shunt catheters to 12.3% (17/138) (p = 0.043) for silver shunt catheters. 22 Two further observational studies comparing standard with Silverline EVDs also show a reduction in infection rates. 21,24

Risks and benefits

The potential beneficial effect on health status of these impregnated shunt catheters is reduced shunt infection and its negative sequelae. Prior to this study, approximately 70%4,13 of shunt operations in the UK were with Bactiseal shunts (verified by feasibility screening logs) and it was felt that, just like Bactiseal, there was likely to be a significant uptake of Silverline shunts by neurosurgeons, despite the lack of evidence of clinical or cost benefit.

The potential adverse effects of impregnated shunt catheters has never been studied prospectively, to our knowledge. One of the potential concerns of antibiotic-impregnated shunt catheters is the potential for selecting out resistant organisms or missing potential infections owing to an inability to culture them.

Thus, before the wide adoption of these impregnated shunt catheters, an adequately powered RCT is needed to assess their effectiveness at reducing infection and to determine their safety (including the type of organisms cultured), antibiotic sensitivities and antibiotic resistances.

Aims and objectives

Primary objective

The primary objective was to determine whether or not antibiotic- or silver-impregnated VPSs reduce infection compared with standard VPSs in patients with hydrocephalus, following insertion of a de novo VPS.

Secondary objectives

-

To determine the proportion of first VPS infections occurring > 6 months after insertion of a de novo VPS.

-

To determine whether or not antibiotic- or silver-impregnated VPSs reduce shunt failure due to any cause compared with standard VPSs in patients with hydrocephalus following insertion of a de novo VPS.

-

To assess whether or not the reason for shunt failure is different across the three different types of VPS.

-

To determine which organisms and their resistances/sensitivities subsequently infect three alternative VPSs.

-

To determine whether or not antibiotic- or silver-impregnated VPSs reduce infection following first (non-infected) clean VPS revision for mechanical failure, compared with standard VPSs in patients with hydrocephalus, following insertion of a de novo VPS.

-

To assess the impact of VPS infection on patients in terms of quality of life.

-

To assess the cost-effectiveness of antibiotic- and silver-impregnated VPSs compared with standard VPSs.

Chapter 2 Trial design and methods

Parts of this chapter have been reproduced from Jenkinson et al. 1 This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. The text below includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original text.

Parts of this chapter have been reproduced from Mallucci et al. 2 This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nd/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. The text below includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original text.

Trial design

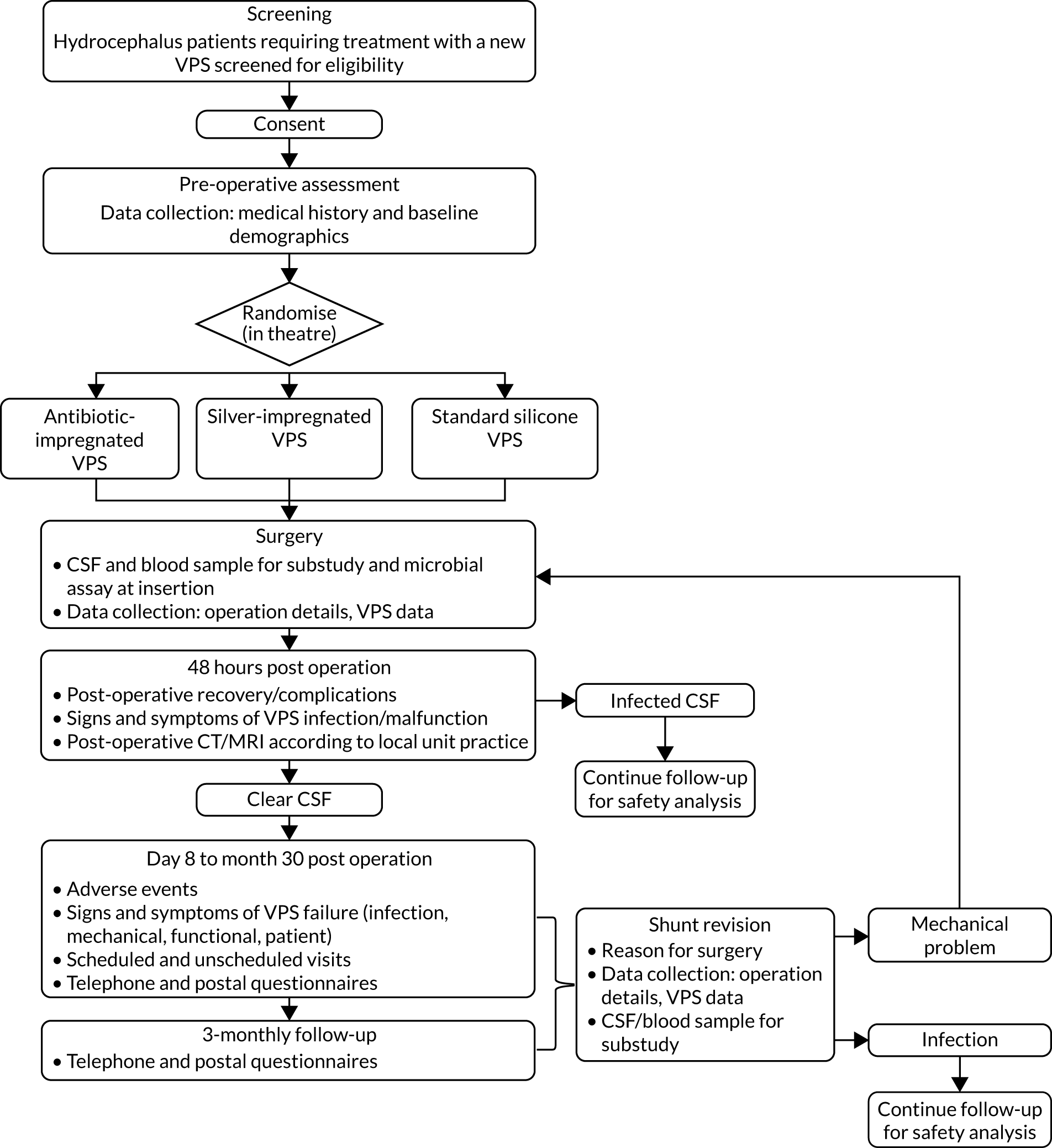

A schematic representation of the trial design is given in Figure 1.

FIGURE 1.

Trial design. CT, computerised tomography; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging. Reproduced from Jenkinson et al. 1 This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. The figure includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original.

Ethics approval and research governance

The protocol was approved by the Greater Manchester South Research Ethics Committee (reference number 12/NW/0790). The trial was funded by the National Institute for Health Research Health Technology Assessment programme (number 10/104/30) and included on the International Standard Randomised Controlled Trial Number registry (ISRCTN49474281). Centre-specific approval was obtained at all of the recruiting centres.

The protocol has been published previously. 1 The trial opened on protocol version 3.0, and the final approved version of the protocol was version 13.0, which contains a complete list of protocol changes [see www.fundingawards.nihr.ac.uk/award/10/104/30 (accessed 22 January 2020)]. A summary of substantial protocol amendments are provided in Table 1.

| Protocol version and date | Key amendments |

|---|---|

| 2.0 (21 November 2012) |

|

| 3.0 (22 March 2013) |

|

| 4.0 (25 July 2013) |

|

| 5.0 (20 December 2013) |

|

|

|

| 6.0 (1 April 2014) |

|

| 8.0 (10 August 2015) |

|

| 9.0 (10 August 2016) |

|

| 10.0 (11 August 2017) |

|

|

|

| 11.0 (5 April 2018) | Section added to the protocol to access HES data for patients with a Welsh postcode |

| 13.0 (25 September 2018) |

|

Selection of trial centres

Participants were recruited from 21 regional adult and paediatric neurosurgery centres in the UK and the Republic of Ireland. To be eligible to participate in the trial, centres had to meet the British Antibiotic and Silver Impregnated Catheters for ventriculoperitoneal Shunts (BASICS) trial centre suitability assessment criteria:

-

minimum of three patients per month

-

neurosurgical unit treating adults or paediatrics

-

evidence of a team to undertake trial activities

-

principal investigator (PI) had previous experience of RCTs or a significant role

-

no local issues to prevent trial set-up

-

completion of prospective screening log.

Participants

The trial was open to all patients (children and adults) who had hydrocephalus requiring treatment with a first permanent VPS who met the eligibility criteria.

Inclusion criterion

Patients were considered for inclusion in the trial if they met the following criterion:

-

Hydrocephalus of any aetiology [including idiopathic intracranial hypertension (IIH)] requiring a first VPS.

Note that failed primary endoscopic third ventriculostomy was allowed, indwelling ventricular access devices (e.g. Ommaya or Rickham reservoir or ventriculosubgaleal shunt or similar) were allowed and indwelling EVDs were allowed.

Exclusion criteria

Patients with the following characteristics were excluded from the trial:

-

previous indwelling ventricular or lumbar peritoneal or atrial shunt

-

active and ongoing CSF or peritoneal infection (previously infected cases were allowed once they were clear of infection)

-

multiloculated hydrocephalus requiring multiple VPS or neuroendoscopy

-

ventriculoatrial or ventriculopleural shunt planned

-

allergy to antibiotics associated with the antibiotic shunt

-

allergy to silver.

Recruitment procedure

Screening

Screening was performed daily by clinical staff or the designated research nurse (throughout this report, ‘research nurse’ means either the research nurse or someone who has been delegated that duty) to identify potentially eligible patients. This was carried out on the daily ward rounds or at an appropriate time point, depending on the clinical setting.

All patients having a first VPS for hydrocephalus of any aetiology (including IIH) were screened for eligibility and recorded on the screening log. Reasons for non-recruitment were documented (e.g. not eligible, declined consent) and the information was used for monitoring purposes.

Informed consent

Eligible patients were provided with patient information sheets. In the case of children or adults who lacked mental capacity to consent, the parents, consultee or legal representative were approached to discuss participation. When feasible, this was at a clinic visit prior to admission. The research nurse gave the family sufficient time to discuss the trial and to decide whether or not to consent to trial entry.

Patients were eligible to be randomised to the trial if written consent was provided by the patient, parent, legal representative or consultee.

Randomisation, concealment and blinding

Patients were randomised to standard silicone or antibiotic- or silver-impregnated VPS catheters in a ratio of 1 : 1 : 1 in random permuted blocks of three and six. The randomisation sequence was generated by an independent statistician and was stratified by neurosurgical unit, age group (adult or paediatrics was defined according to unit practice) and envelope storage room within the neurosurgical unit. Randomisation was undertaken in the operating theatre at the time when the VPS was required. Pressure-sealed envelopes were opaque and tamper-proof: they were opened by tearing perforated edges. Patients and a central review panel, but not surgeons or operating staff, were blinded to the type of VPS inserted. VPS type was not recorded in the operating record and was not disclosed outside the operating room. Training on non-disclosure of VPS type was provided to all investigators. All VPS types were medical devices used in accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions for their intended purpose.

Trial assessments

Table 2 provides the schedule of trial assessments. Participants were followed up for a minimum of 6 months and a maximum of 2 years, dependent on their randomisation date.

| Time point | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Screening | Baselinea (pre-operative assessment) | Randomisation (first surgery) | Early post-operative assessment | First routine post-operative assessmentb | 12-weekly follow up assessment | Subsequent routine post-operative assessment(s) | End-of-trial telephone call | Unscheduled visit/admission | Shunt revision/removal | |

| Informed consentc | ✗ | |||||||||

| Assessment of eligibility criteria | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | |||||||

| Review of relevant medical history | ✗ | ✗ | ||||||||

| Collect demographic data | ✗ | ✗ | ||||||||

| Review of concomitant medications | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | |

| Weight | ✗ | |||||||||

| Heart rate | ✗ | ✗ | (✗) | |||||||

| Head circumference | (✗) | (✗) | (✗) | (✗) | (✗) | |||||

| Neurological assessment (Glasgow Coma Scale) | ✗ | ✗ | (✗) | |||||||

| Temperature | ✗ | (✗) | ||||||||

| Randomisation | ✗ | |||||||||

| Trial intervention | ✗ | ✗ | ||||||||

| Wound check | ✗ | (✗) | (✗) | (✗) | ||||||

| CSF sample taken | ✗d | (✗e) | ✗d | |||||||

| Additional CSF and blood taken for substudy | (✗) | (✗) | ||||||||

| CSF results reviewed | ✗f | (✗) | ||||||||

| Health economics questionnaire | ✗ | ✗ | ✗g | ✗ | ||||||

| Health service diary | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | |||||||

| Post-operative CT/MRI | (✗) | (✗) | (✗) | (✗) | ||||||

| Assessment of AEs | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | |||

Data collection

Data were collected on paper-based case report forms (CRFs) completed by centre staff who were authorised to do so and returned to the Liverpool Clinical Trials Centre (LCTC) Clinical Trials Unit (CTU). Participants were issued with diaries to record their health-care utilisation every 12 weeks and administered questionnaires to measure quality of life. A planned analysis of data from NHS Digital could not be achieved as the sponsor was unable to meet NHS Digital requirements for obtaining Hospital Episode Statistics data within the project timeline. Electronic health-care data were therefore obtained from Patient-Level Information and Costing Systems (PLICS).

Data were collected at baseline, randomisation, the peri-operative assessment, the early post-operative assessment, the first routine post-operative assessment and the subsequent post-operative assessment, and at the time points described in the remainder of this section.

The 12-weekly follow-up assessment

The 12-weekly follow-up was conducted face to face if there was a routine appointment scheduled at the same time point; if not, the follow-up was conducted by telephone. The following data were recorded:

-

related adverse events (AEs)

-

concomitant medications

-

pregnancy.

At the first 12-week assessment, the research nurse completed the relevant quality-of-life questionnaire (Table 3) with the participant over the telephone.

| Age (years) | Completed by | |

|---|---|---|

| Participant | Parent/carer | |

| < 5 | None administered | None administered |

| 5 to < 8 | None administered | HOQ (parent version) |

| EQ-5D-3L (proxy 1)a | ||

| 8 to < 18 | HOQ (child version) | EQ-5D-3L (proxy 1)a (including EQ-VAS) |

| EQ-5D-Y (including EQ-VAS) | ||

| ≥ 18 years | EQ-5D-3L (including EQ-VAS) | EQ-5D-3L (proxy 1)b (including EQ-VAS) |

Unscheduled visit/admission assessment

The ‘unscheduled visit/admission’ CRF was completed for any non-routine attendance at the treating neurosurgical centre and the following data were recorded:

-

source of unscheduled visit

-

reason for return

-

physical examination

-

microbiology

-

blood samples

-

imaging

-

wound check

-

CSF leak

-

related AEs

-

concomitant medications

-

pregnancy

-

outcome of visit.

Shunt revision/removal

If a patient was admitted for a clean VPS revision (for mechanical shunt failure, functional shunt failure or failure due to the patient) or removal (for suspected infection), the following data were recorded:

-

surgery details (separate sections for revision/removal)

-

surgeon details

-

CSF sample details (including samples for substudies, if patient is taking part)

-

related AEs

-

concomitant medications.

In addition, the shunt surgery log was completed for all surgeries that took place after the initial surgery when the randomised shunt was inserted.

For instances in which the shunt was removed for suspected infection, concomitant medications were reported up until 14 days after removal and the patient was reviewed for 48 hours for AEs and serious adverse events (SAEs).

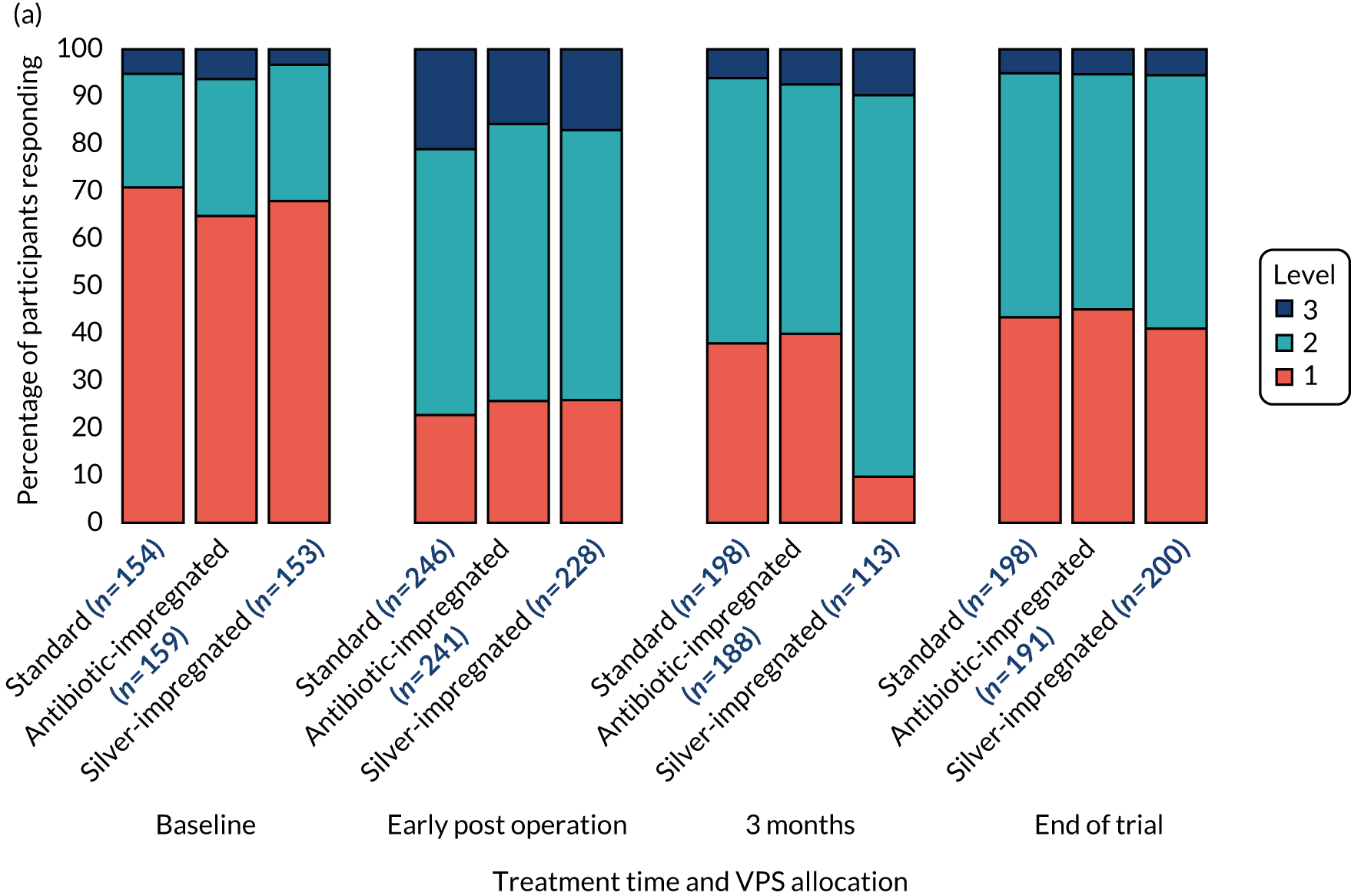

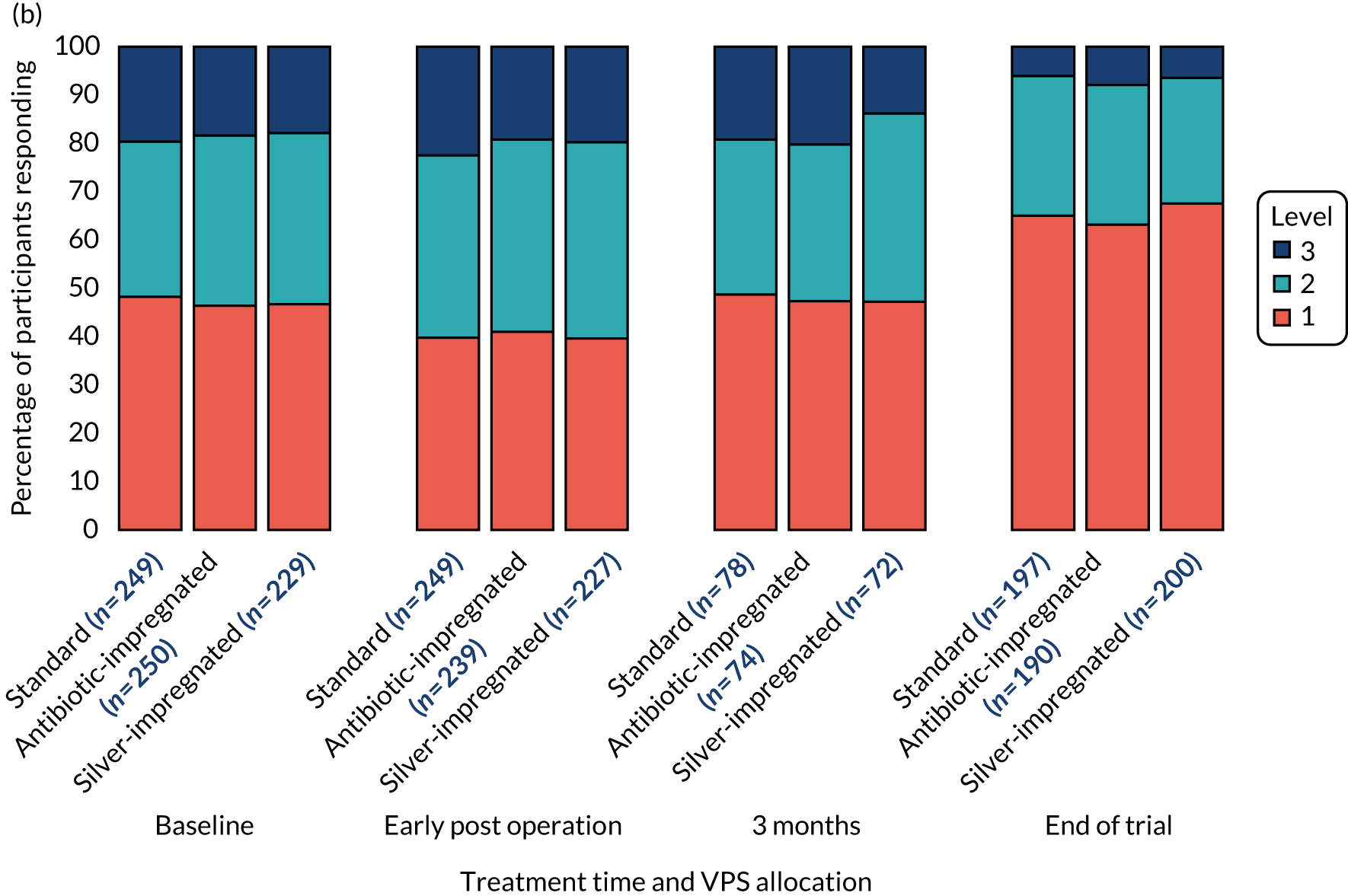

Quality of life and health service diaries

Questionnaires

The EuroQol-5 Dimensions, three-level version (EQ-5D-3L), the EQ-5D-3L Proxy, the EuroQol-5 Dimensions Youth (EQ-5D-Y) (youth version), the EuroQol Visual Analogue Scale (EQ-VAS) or the Hydrocephalus Outcome Questionnaire (HOQ)25 were administered to participants, or their parent or carer, according to age (see Table 3) to measure participants’ health outcome and quality of life.

Resource use questionnaires were given/posted out to participants every 12 weeks for participants to complete and return to the centres 12 weeks later. Participants were reminded by the research nurse to return diaries during the 12-weekly assessments if they had not done so.

Measures

Primary outcome

The primary outcome was time to VPS infection as assessed by the central review panel, which comprised the chief investigator (or delegate for participants treated at the centre of the chief investigator) and a microbiologist, who were masked to participant allocation. Each VPS revision was classified as infection or no infection. Infections were further classified as definite (culture positive), probable (culture uncertain), probable (culture negative), possible (culture uncertain) or VPS deep incisional infection according to the microbiological samples sent and the criteria in the trial protocol.

Secondary outcomes

Secondary outcomes were as follows:

-

time to removal of the first VPS due to suspected infection, as defined by the treating surgeon at the time of revision

-

time to VPS failure of any cause (infection, mechanical, patient or functional)

-

reason for failure (infection, mechanical, patient, functional) as classified by the treating surgeon

-

types of bacterial VPS infection (organism, antibiotic resistances)

-

time to VPS infection following first clean (non-infected) revision, as classified by the central review panel

-

quality of life measured using the HOQ25

-

health economics outcomes – incremental cost per VPS failure averted and quality-adjusted life-year (QALY) gained, measured using the EQ-5D-3L, EQ-5D-3L Proxy and EQ-5D-Y questionnaires.

Data on complications and SAEs were also collected.

Sample size

The sample size for the primary outcome was calculated using the Pintilie26 method with the following assumptions: (1) failure for infection was the event of interest, with all other reasons for failure a competing risk, (2) the rate of infection was 8% in the standard silicone arm14 and 4% in the impregnated shunt catheter arms, (3) the competing risk event rate was 30% and (4) there was a 5% loss to follow-up. A total sample size of 1200 participants with 119 events demonstrated good statistical power (88%), with leverage for a lower event rate if required (Table 4). A feasibility study conducted in trial centres for 1 month indicated an annual eligible participant figure of 1200; a conservative estimate of consent of 50% suggested that the sample size would be achievable within a 2-year recruitment period, with participants followed up for a minimum of 6 months.

| Infection rate | HR | Power (%) | Total sample size (across the three trial arms) (n) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control arm | Treated arms | |||

| 0.1 | 0.05 | 0.48 | 94 | 1140 |

| 0.08 | 0.04 | 0.49 | 80 | 942 |

| 0.08 | 0.04 | 0.49 | 88 | 1157 |

| 0.05 | 0.025 | 0.49 | 67 | 1144 |

An interim analysis was planned after 50% of the total events had been observed, using the Haybittle–Peto method. 27

Monitoring of the infection rate during the trial demonstrated that the majority of events occur within 1 month of VPS insertion (i.e. they are not exponentially distributed), and that the rates of infection, competing risk and loss to follow-up were lower than expected. In January 2016, the Independent Data and Safety Monitoring Committee (IDSMC) reviewed the sample size calculations and recommended increasing recruitment to a target of 1606 participants with 101 events, to provide 80% power; the Trial Steering Committee (TSC) agreed and approved this change. The early occurrence of events and assumption of exponential risk were managed in the Pintilie26 method assumptions by reducing the accrual and follow-up rates to 1 month.

Statistical methods

The main features of the analysis plan were specified in the protocol; the final analyses were undertaken according to a more detailed and prespecified statistical analysis plan (see Report Supplementary Material 1), consistent with the protocol.

Efficacy outcomes were analysed according to the intention-to-treat principle as far as practically possible; AEs and SAEs were reported according to the type of VPS in situ. A Bonferroni adjustment28 was made to allow for multiple comparisons (antibiotic-impregnated vs. standard VPS, and silver-impregnated vs. standard VPS) and a 2.5% level of statistical significance and 97.5% CIs were used throughout.

Outcomes with infection as the event of interest used Fine and Gray29 survival regression models with cause-specific hazard ratios (csHRs) and subdistribution hazard ratios (sHRs) presented. 30,31 Cox regression models were used to analyse time to VPS failure due to any cause. Reason for VPS failure is presented descriptively (see Chapter 3, Secondary outcome 3: reason for shunt failure) and with a chi-squared test. Types of organisms and their resistances and sensitivities are presented descriptively in Chapter 3, Secondary outcome 4: types of bacterial infection. Quality-of-life outcomes were analysed using mixed models. All survival models were adjusted for the age category of the recruiting centre (paediatric or adult), with adult centres further categorised by age > 65 years. A post hoc analysis was conducted that explored revision rates, and reason for revision, by aetiology of the hydrocephalus, type of valve and operative approach. Results of the post hoc analysis are presented descriptively in Chapter 3, Post hoc analyses.

Primary outcome and safety analyses were validated by independent programming from the point of raw data extraction. All analyses were carried out with SAS® software version 9.4 with SAS/STAT package 14.3 (SAS Institute Inc, Cary, NC, USA).

Patient and public involvement

The trial team collaborated with young people and parent contributors throughout the trial:

-

Advice was sought from the Medicines for Children Research Network Young Person’s Group on the content and presentation of patient information leaflets and consent forms. The Medicine for Children’s Research Network is a division of the LCTC, part of the Liverpool Clinical Trials Collaborative.

-

Three lay members were invited at the trial outset to join the Trial Management Group (TMG) and TSC; one was recruited to be a member of the TMG.

-

Members of the TMG, including the lay member, met via teleconference with the patient and public involvement co-ordinator for the LCTC early in the trial to establish the timings for return of the patient-completed diaries and to identify ways to maximise the return rate of these diaries. They decided that it would be appropriate for the centre team to contact the participant or representative via telephone every 3 months as a reminder to complete and return the diaries.

-

The charity Shine (Spina bifida Hydrocephalus Information Networking Equality) was continually supportive of the trial. A Shine representative was a member of the TSC.

Trial oversight and role of funders

The TMG, comprising the chief investigator, other lead investigators (clinical and non-clinical) and members of the LCTC CTU, was responsible for the day-to-day running and management of the trial. The membership of the oversight committees was suggested by members of the TMG to the trial funders and appointed by the funders with their constitution following funder requirements.

The TSC consisted of an independent chairperson, an independent microbiologist, a lay representative from the Shine charity and an independent statistician. The chief investigator was a non-independent member of the TSC. The role of the TSC was as the executive decision-making committee, considering the recommendations of the IDSMC. Monitoring reports viewed by the TSC were not split by treatment group.

The IDSMC consisted of an independent chairperson, plus two independent members: an expert in the field of microbiology and an expert in medical statistics. The IDSMC was responsible for reviewing and assessing recruitment, interim monitoring of safety and effectiveness, trial conduct and external data. The IDSMC provided recommendations to the TSC concerning the continuation of the trial and viewed accumulating data split by treatment group.

All protocol amendments were approved by the funder prior to ethics submission.

Chapter 3 Results

Parts of this chapter have been reproduced from Mallucci et al. 2 This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nd/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. The text below includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original text.

Recruitment and screening

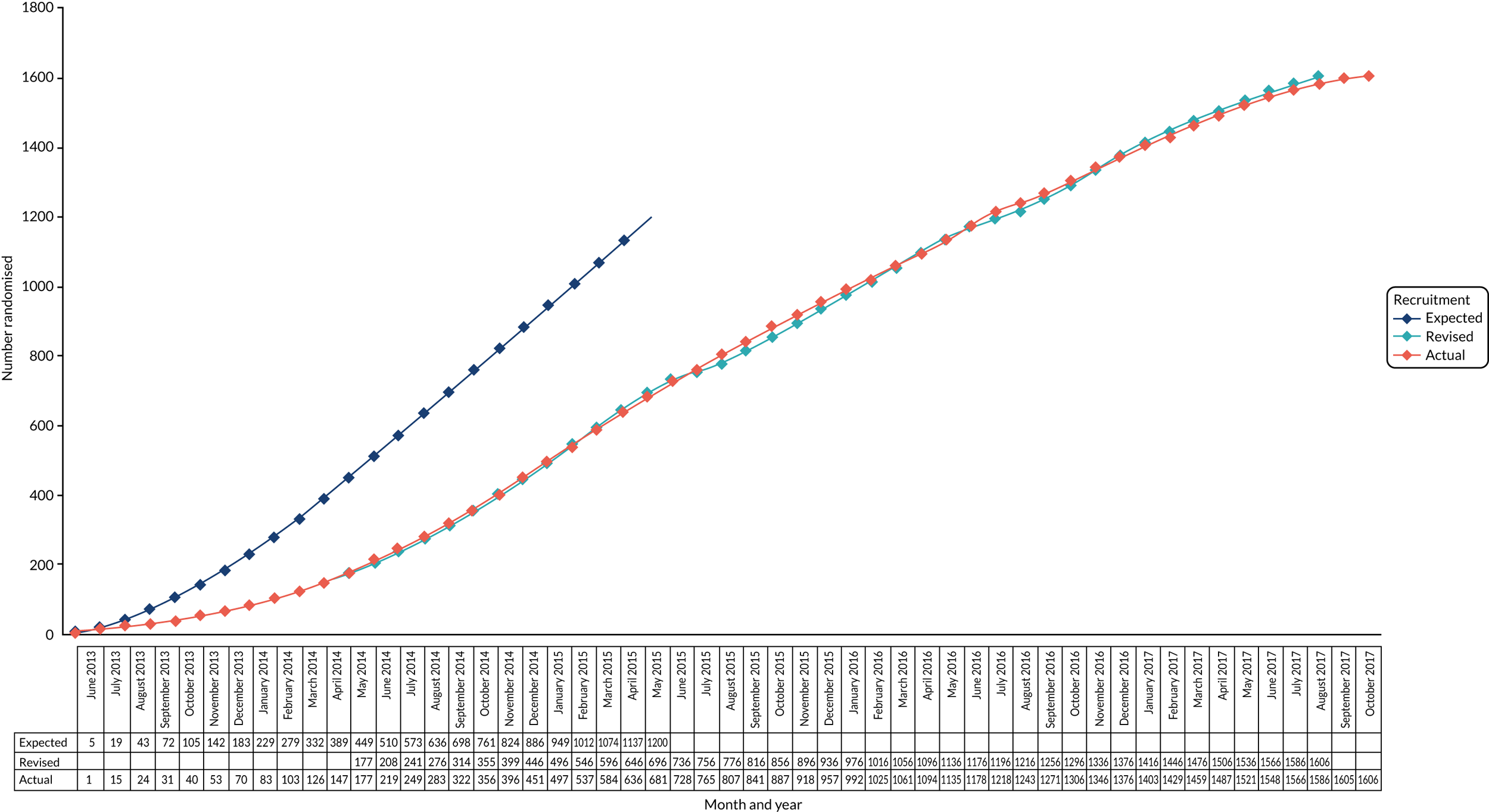

The trial opened to recruitment on 26 June 2013 and closed on 9 October 2017.

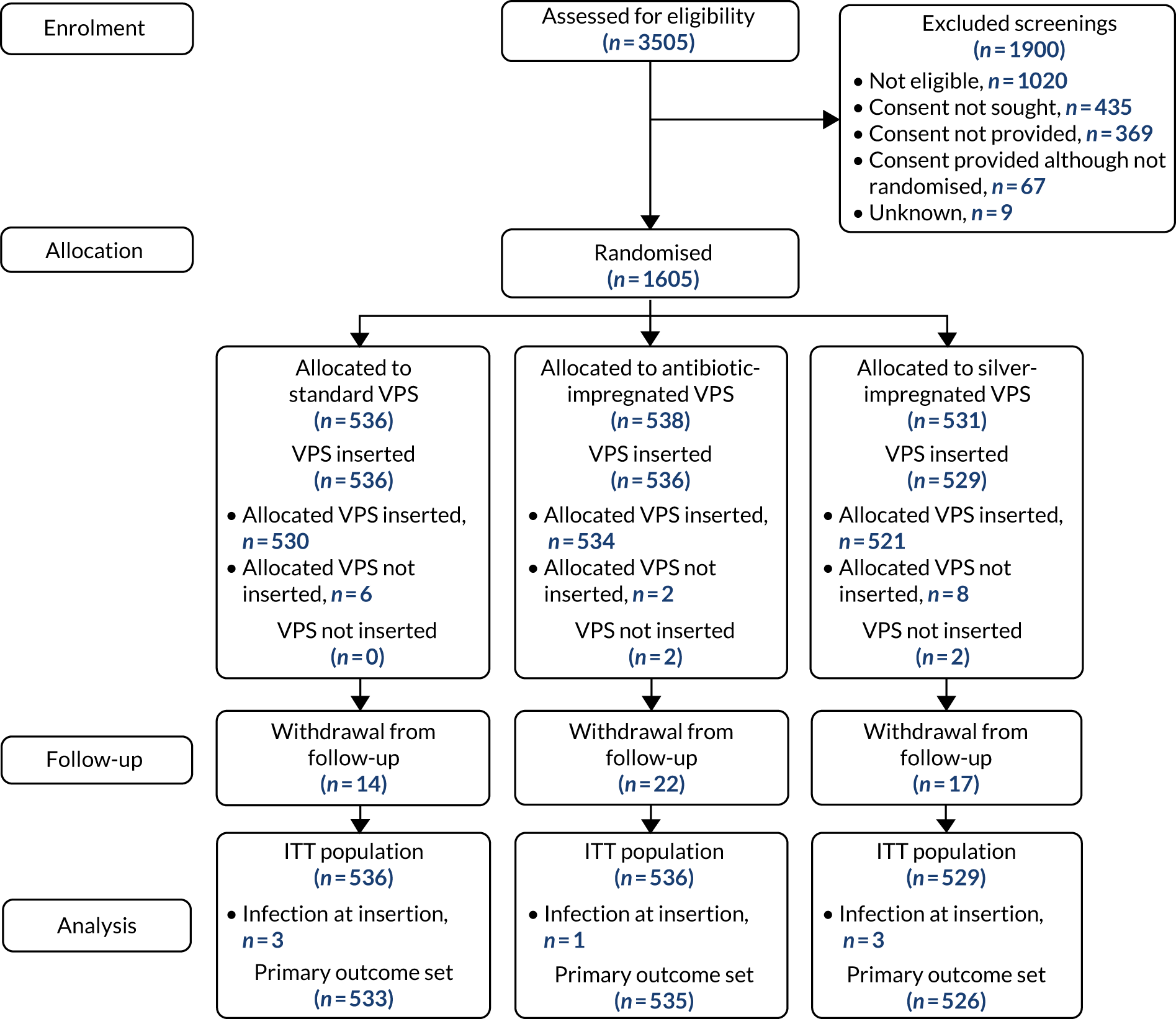

During this period, 3505 patients were screened for eligibility, of whom 1605 patients were randomised from 21 centres. One patient was randomised twice and their data contributed from the first randomisation only. See Appendix 2, Figure 8 and Tables 32 and 33, for screening and recruitment data.

Screened patients who were not randomised fell into four categories: the patient did not meet eligibility criteria (n = 1020); the patient was eligible but consent was not sought (n = 435); consent was sought but the patient declined (n = 369); and the patient was not randomised for another reason (n = 67). The overall consent rate in patients who were approached for participation was 82%.

A Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) flow diagram illustrating the pathway of patients from screening to consent and randomisation is provided in Figure 2.

FIGURE 2.

The CONSORT flow chart. ITT, intention to treat.

Baseline comparability

The three groups were similar in their baseline characteristics (Table 5) and baseline risk assessment (Table 6). Approximately 40% of all participants were paediatric patients, with one-quarter of all participants being aged < 1 year at the time of randomisation. The factors recorded on the baseline risk assessment were those regarded within the literature as being associated with a high risk of infection.

| Characteristic | Trial group | Total | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Standard VPS | Antibiotic-impregnated VPS | Silver-impregnated VPS | ||

| Number randomised | 536 | 538 | 531 | 1605 |

| Age (years) | ||||

| n (n missing) | 536 (0) | 538 (0) | 531 (0) | 1605 (0) |

| Median (IQR) | 42.5 (0.8–69.7) | 43.9 (1.1–70.8) | 41.1 (0.5–68.8) | 42.5 (0.8–69.6) |

| Minimum, maximum | 0.0, 90.3 | 0.0, 88.9 | 0.0, 91.1 | 0.0, 91.1 |

| Age category | ||||

| n (n missing) | 536 (0) | 538 (0) | 531 (0) | 1605 (0) |

| Paediatric, n (%) | 200 (37.3) | 201 (37.4) | 198 (37.3) | 599 (37.3) |

| Adult (≤ 65 years), n (%) | 174 (32.5) | 156 (29.0) | 172 (32.4) | 502 (31.3) |

| Adult (> 65 years), n (%) | 162 (30.2) | 181 (33.6) | 161 (30.3) | 504 (31.4) |

| Sex | ||||

| n (n missing) | 535 (1) | 538 (0) | 531 (0) | 1605 (0) |

| Female, n (%) | 246 (46.0) | 260 (48.3) | 282 (53.1) | 788 (49.1) |

| Male, n (%) | 289 (54.0) | 278 (51.7) | 249 (46.9) | 816 (50.9) |

| Weight (kg) | ||||

| n (n missing) | 523 (13) | 523 (15) | 515 (16) | 1561 (44) |

| Median (IQR) | 64.0 (8.8–82.7) | 63.0 (9.6–82.0) | 63.0 (7.3–80.0) | 63.1 (8.7–81.5) |

| Minimum, maximum | 1.1, 161.0 | 0.8, 163.0 | 1.3, 145.0 | 0.8, 163.0 |

| Heart rate (BPM) | ||||

| n (n missing) | 530 (6) | 532 (6) | 521 (10) | 1583 (22) |

| Median (IQR) | 84 (72–120) | 85 (70–116.5) | 84 (70–124) | 84 (70–121) |

| Minimum, maximum | 48, 190 | 44, 185 | 43, 185 | 43, 190 |

| Risk indicator | Trial group | Total | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Standard VPS (N = 536) | Antibiotic-impregnated VPS (N = 538) | Silver-impregnated VPS (N = 531) | ||

| Previous Staphylococcus aureus infection (requiring treatment in the previous 6 months) | ||||

| n (n missing) | 534 (2) | 538 (0) | 531 (0) | 1603 (2) |

| Yes, n (%) | 18 (3.4) | 15 (2.8) | 16 (3.0) | 49 (3.1) |

| No, n (%) | 516 (96.6) | 523 (97.2) | 515 (97.0) | 1554 (96.9) |

| Active skin/wound infection | ||||

| n (n missing) | 534 (2) | 538 (0) | 530 (1) | 1602 (3) |

| Yes, n (%) | 7 (1.3) | 8 (1.5) | 5 (0.9) | 20 (1.2) |

| No, n (%) | 527 (98.7) | 530 (98.5) | 525 (99.1) | 1582 (98.8) |

| MRSA infection in the previous 6 months | ||||

| n (n missing) | 535 (1) | 537 (1) | 529 (2) | 1601 (4) |

| Yes, n (%) | 6 (1.1) | 4 (0.7) | 5 (0.9) | 15 (0.9) |

| No, n (%) | 529 (98.9) | 533 (99.3) | 524 (99.1) | 1586 (99.1) |

| Pre-term at birth | ||||

| n (n missing) | 513 (23) | 522 (16) | 505 (26) | 1540 (65) |

| Yes, n (%) | 78 (15.2) | 82 (15.7) | 76 (15.0) | 236 (15.3) |

| No, n (%) | 435 (84.8) | 440 (84.3) | 429 (85.0) | 1304 (84.7) |

| Abdominal surgery in the previous month | ||||

| n (n missing) | 533 (3) | 538 (0) | 531 (0) | 1602 (3) |

| Yes, n (%) | 3 (0.6) | 3 (0.6) | 8 (1.5) | 14 (0.9) |

| No, n (%) | 530 (99.4) | 535 (99.4) | 523 (98.5) | 1588 (99.1) |

| Tracheotomy | ||||

| n (n missing) | 534 (2) | 538 (0) | 531 (0) | 1603 (2) |

| Yes, n (%) | 32 (6.0) | 13 (2.4) | 21 (4.0) | 66 (4.1) |

| No, n (%) | 502 (94.0) | 525 (97.6) | 510 (96.0) | 1537 (95.9) |

| Percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy | ||||

| n (n missing) | 534 (2) | 538 (0) | 531 (0) | 1603 (2) |

| Yes, n (%) | 14 (2.6) | 7 (1.3) | 15 (2.8) | 36 (2.2) |

| No, n (%) | 520 (97.4) | 531 (98.7) | 516 (97.2) | 1567 (97.8) |

| CSF leak in the previous month | ||||

| n (n missing) | 534 (2) | 538 (0) | 531 (0) | 1603 (2) |

| Yes, n (%) | 57 (10.7) | 51 (9.5) | 35 (6.6) | 143 (8.9) |

| No, n (%) | 477 (89.3) | 487 (90.5) | 496 (93.4) | 1460 (91.1) |

| EVD in previous 3 months | ||||

| n (n missing) | 532 (4) | 538 (0) | 531 (0) | 1601 (4) |

| Yes, n (%) | 105 (19.7) | 95 (17.7) | 90 (16.9) | 290 (18.1) |

| No, n (%) | 427 (80.3) | 443 (82.3) | 441 (83.1) | 1311 (81.9) |

Retention and adherence

Table 7 summarises compliance with the randomly allocated shunt. Of the 1605 participants randomised, four (0.2%) had no VPS inserted and 16 (1%) received a different VPS to the one that was randomly allocated. Reasons for participants having an alternative trial VPS inserted or no VPS are provided in Appendix 2, Tables 35 and 36, respectively. Participants receiving no VPS were excluded from the intention-to-treat population; for the safety analysis, participants were analysed according to the VPS received. The analysis sets are summarised in Table 8.

| Randomised VPS | Number randomised | Allocated VPS inserted, n (%) | Other VPS inserted, n (%) | No VPS inserted, n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Standard | 536 | 530 (98.9) | 6 (1.1) | 0 (0.0) |

| Antibiotic impregnated | 538 | 534 (99.3) | 2 (0.4) | 2 (0.4) |

| Silver impregnated | 531 | 521 (98.1) | 8 (1.5) | 2 (0.4) |

| Total | 1605 | 1585 (98.8) | 16 (1.0) | 4 (0.2) |

| Population | Trial group, n (%) | Total, n (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Standard VPS | Antibiotic-impregnated VPS | Silver impregnated-VPS | ||

| Randomised | 536 (33.4) | 538 (33.5) | 531 (33.1) | 1605 (100) |

| Intention to treat | 536 (33.5) | 536 (33.5) | 529 (33.0) | 1601 (99.8) |

| Safety | 531 (33.2) | 545 (34.0) | 525 (32.8) | 1601 (99.8) |

In total, 53 (3.3%) randomised participants withdrew from the trial. No participants withdrew consent to use collected data. Table 9 summarises the level of and reasons for withdrawal.

| Withdrawal summary | Trial group, n (%) | Total, n (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Standard VPS | Antibiotic-impregnated VPS | Silver-impregnated VPS | ||

| Randomised | 536 (33.4) | 538 (33.5) | 531 (33.1) | 1605 (100) |

| Withdrawals | 14 (2.6) | 22 (4.1) | 17 (3.2) | 53 (3.3) |

| Level of withdrawal | ||||

| Withdrawal of dataa | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Consent revoked to use data collected | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Withdrawal from follow-upb | 14 (2.6) | 22 (4.1) | 17 (3.2) | 53 (3.3) |

| Consent revoked for trial-specific data to be collected | 6 (1.1) | 9 (1.7) | 9 (1.7) | 24 (1.5) |

| Consent revoked for any trial data to be collected | 8 (1.5) | 13 (2.4) | 8 (1.5) | 29 (1.8) |

| Consent revoked for additional substudy samples to be taken | 3 (0.6) | 1 (0.2) | 1 (0.2) | 5 (0.3) |

| Reasons for withdrawal | ||||

| Unexpected related AE or SAE | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Burden of additional trial data collection | 4 (0.7) | 9 (1.7) | 5 (0.9) | 18 (1.1) |

| Other | 10 (1.9) | 16 (3) | 13 (2.4) | 39 (2.4) |

| Decision for withdrawal made by | ||||

| Participant (aged ≥ 16 years) | 1 (0.2) | 5 (0.9) | 5 (0.9) | 11 (0.7) |

| Parent/guardian/consultee | 8 (1.5) | 12 (2.2) | 7 (1.3) | 27 (1.7) |

| Clinical | 4 (0.7) | 5 (0.9) | 5 (0.9) | 14 (0.9) |

| None listed | 1 (0.2) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.1) |

Unblinding

A total of 32 participants from 10 centres were unblinded during the course of the trial.

Unblinding could be accidental or intentional. Accidental unblinding was defined as an unplanned occurrence; for example, the allocation was incorrectly recorded in the participant notes. Intentional unblinding occurred when the unblinding envelope was opened; for example, if a patient was transferred to another hospital and staff needed to be aware of their allocation. Twenty-five participants from eight centres were accidentally unblinded and seven participants from four centres were intentionally unblinded. Table 10 summarises unblinding events, both overall and by randomised VPS.

| Type of unblinding | Level | Trial group (n) | Total (n) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Standard VPS | Antibiotic-impregnated VPS | Silver-impregnated VPS | |||

| Accidental | Patient | 10 | 5 | 10 | 25 |

| Centre | 6 | 3 | 7 | 8 | |

| Intentional | Patient | 1 | 1 | 5 | 7 |

| Centre | 1 | 1 | 4 | 4 | |

| Total | Patient | 11 | 6 | 15 | 32 |

| Centre | 7 | 4 | 4 | 10 | |

Protocol deviations

Prespecified protocol deviations are summarised in Appendix 2, Table 37. The most common major protocol deviation was that shunt components were not taken for culture at shunt revision/removal (n = 320, 19.9%). This was not routine practice in many units, and the impact of this deviation on the identification of infections for the primary outcome was mitigated by the low numbers of missing CSF at revision (n = 14), as CSF analysis and culture was the primary factor used for defining shunt infection (not culture of the shunt tubing or components).

Antibiotic sensitivity data were not returned on many isolates.

Primary outcome: time to ventriculoperitoneal infection as assessed by the central review panel

The primary outcome was time to VPS infection, as assessed by the central review panel.

Four participants received no shunt and seven participants had an infection at insertion; these participants were excluded from the primary analysis set (see Figure 2).

A summary of the first VPS revisions and infections among participants in the primary intention-to-treat analysis set is provided in Table 11. The overall revision rate of first VPS was 25% (398/1594), and was approximately equal between each of the three VPS groups.

| Primary VPS revisions | Trial group, n (%) | Total, n (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Standard VPS (N = 536) | Antibiotic-impregnated VPS (N = 538) | Silver-impregnated VPS (N = 531) | ||

| Summary of surgeries | ||||

| Eligible for primary outcomea | 533 (99.4) | 535 (99.8) | 526 (99.4) | 1594 (99.6) |

| No VPS removal/revision | 403 (75.6) | 403 (75.3) | 390 (74.1) | 1196 (75.0) |

| VPS removal/revision (for any cause) | 130 (24.4) | 132 (24.7) | 136 (25.9) | 398 (25.0) |

| Reason for revision as classified by central review | ||||

| Reason for revision | ||||

| Revision for infection | 32 (6.0) | 12 (2.2) | 31 (5.9) | 75 (4.7) |

| Revision for other reason (no infection) | 98 (18.4) | 120 (22.4) | 105 (20.0) | 323 (20.3) |

| Type of infection | ||||

| VPS CSF or peritoneal infection | ||||

| Definite: culture positive | 22 (68.8) | 6 (50.0) | 25 (80.6) | 53 (70.7) |

| Probable: culture uncertain | 1 (3.1) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (6.5) | 3 (4.0) |

| Probable: culture negative | 3 (9.4) | 3 (25.0) | 1 (3.2) | 7 (9.3) |

| Possible: culture uncertain | 1 (3.1) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (3.2) | 2 (2.7) |

| Clinically classified infectionb | 1 (3.1) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (1.3) |

| VPS deep incisional infection | 4 (12.5) | 3 (25.0) | 2 (6.5) | 9 (12.0) |

All first revisions were classified as to whether or not the revision was for suspected infection by the central review panel. If there was insufficient information for the central review panel to classify an infection (n = 1/398; see Table 11), the clinical classification, as recorded on the CRFs by the treating surgeon, was used.

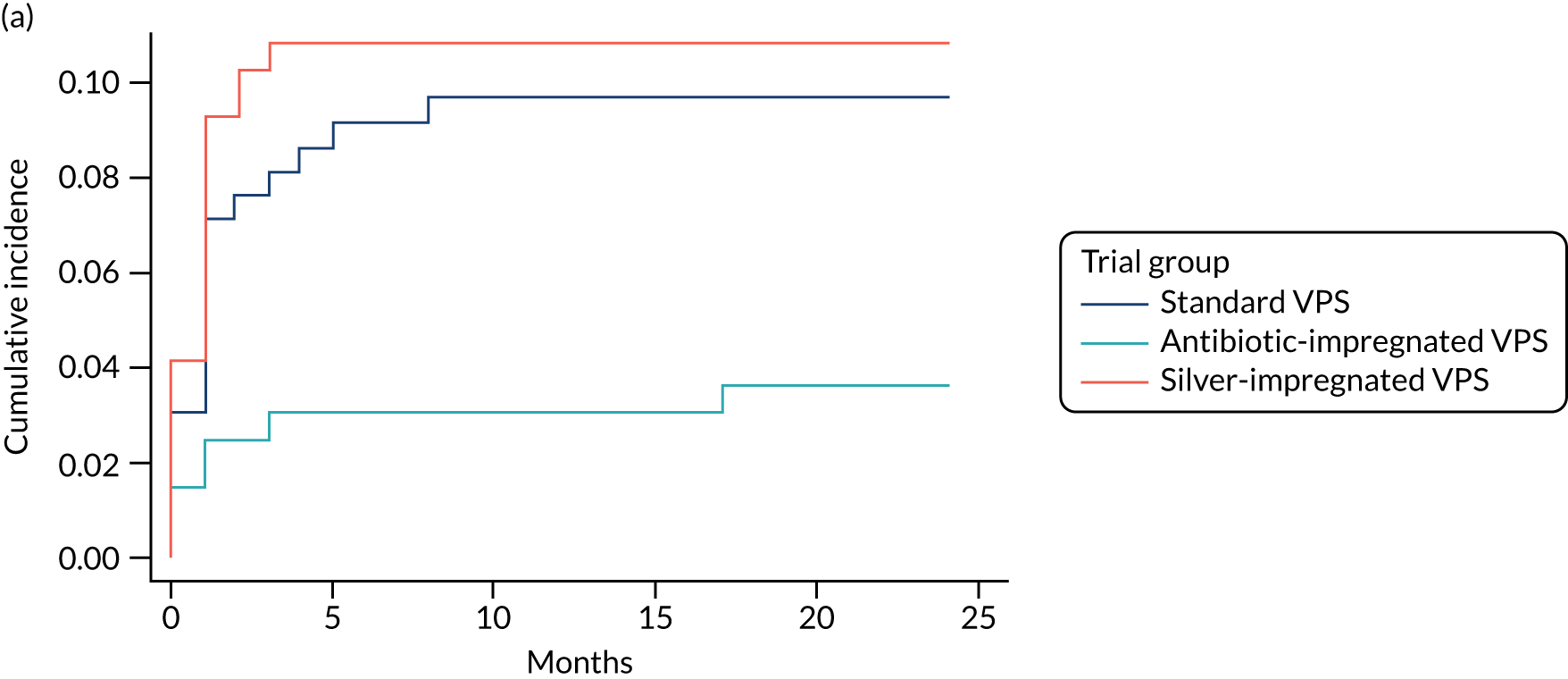

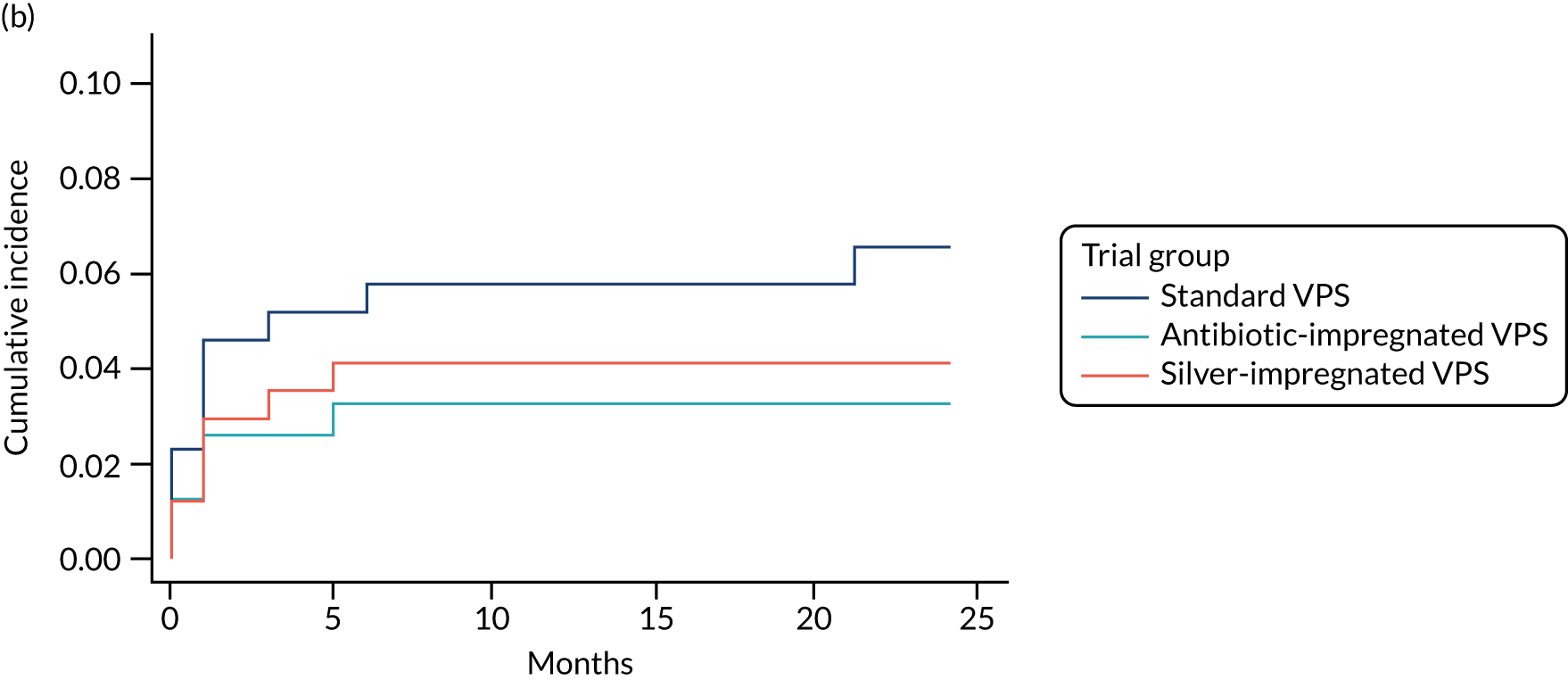

Of the total number of first revisions, 75 were classified infections (4.7%). The infection rate was approximately equal in the standard and silver-impregnated VPS arms (6.0% and 5.9%, respectively) and lowest in the antibiotic-impregnated VPS arm (2.2%). The time to infection was similar across all treatment arms {standard VPS arm: median 1 month [lower quartile (LQ)–upper quartile (UQ) 0–1.5 months]; antibiotic-impregnated VPS arm: median 1 month [LQ–UQ 0–2 months]; silver-impregnated VPS arm: median 1 months [LQ–UQ 0–1 months]}.

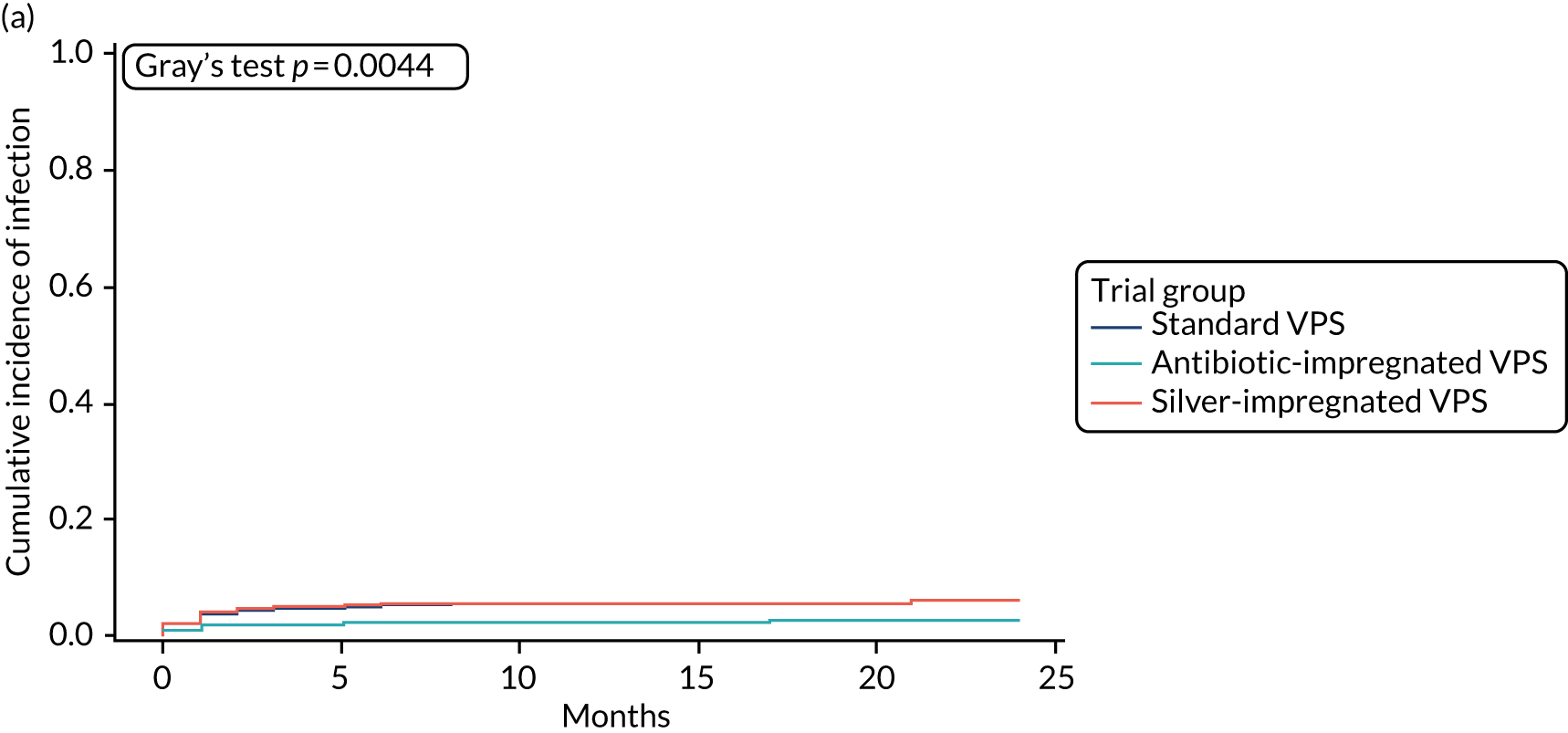

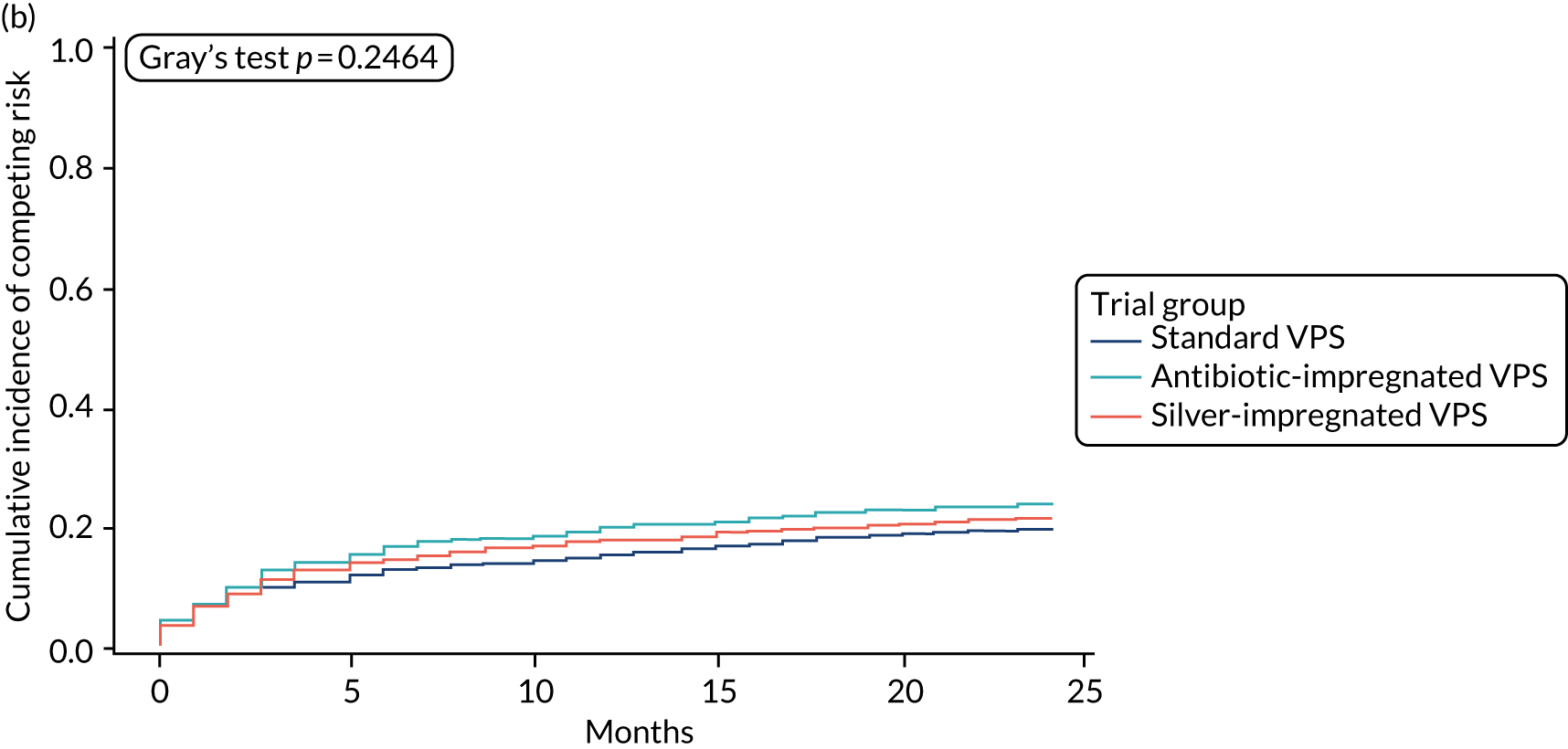

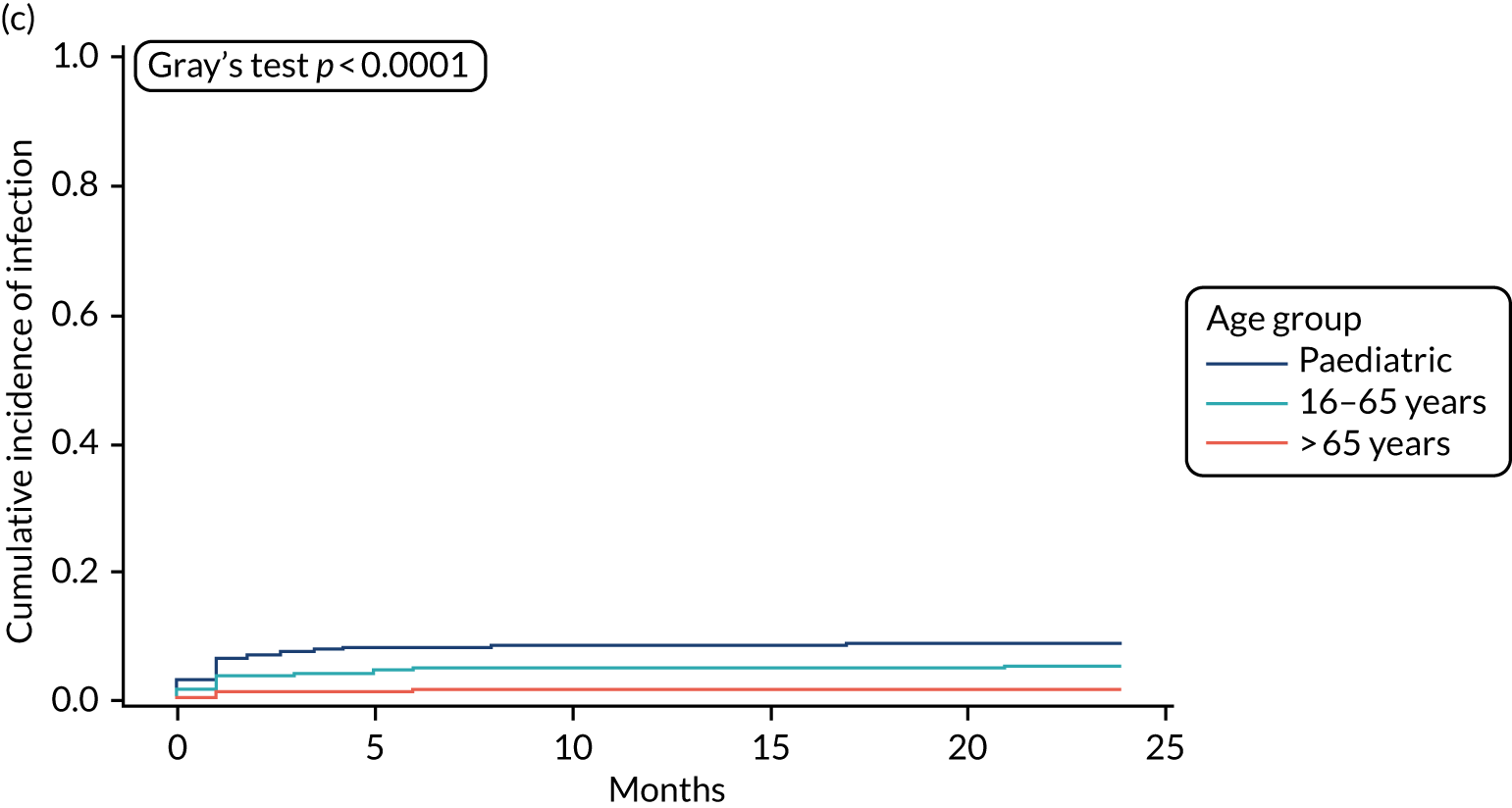

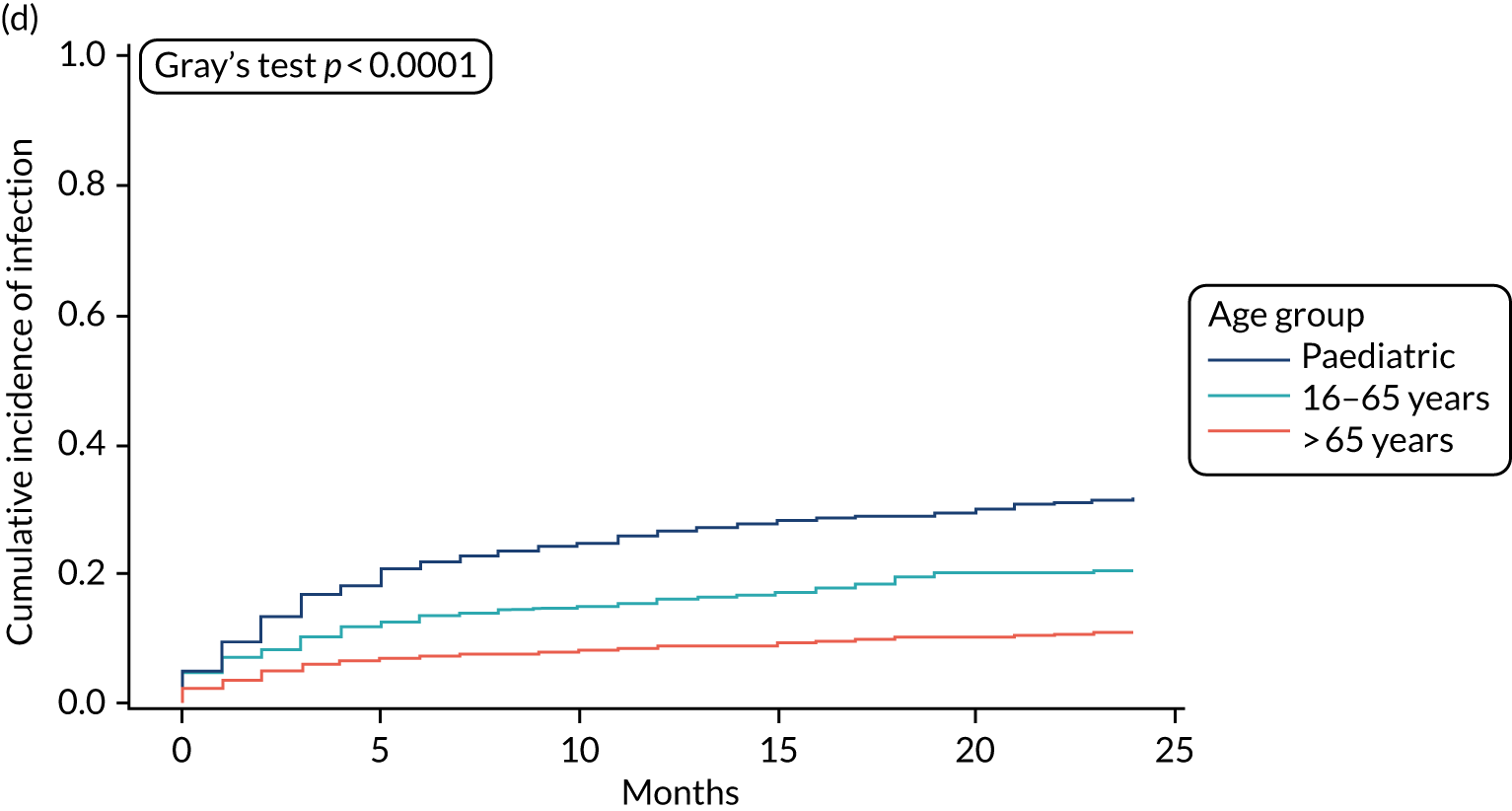

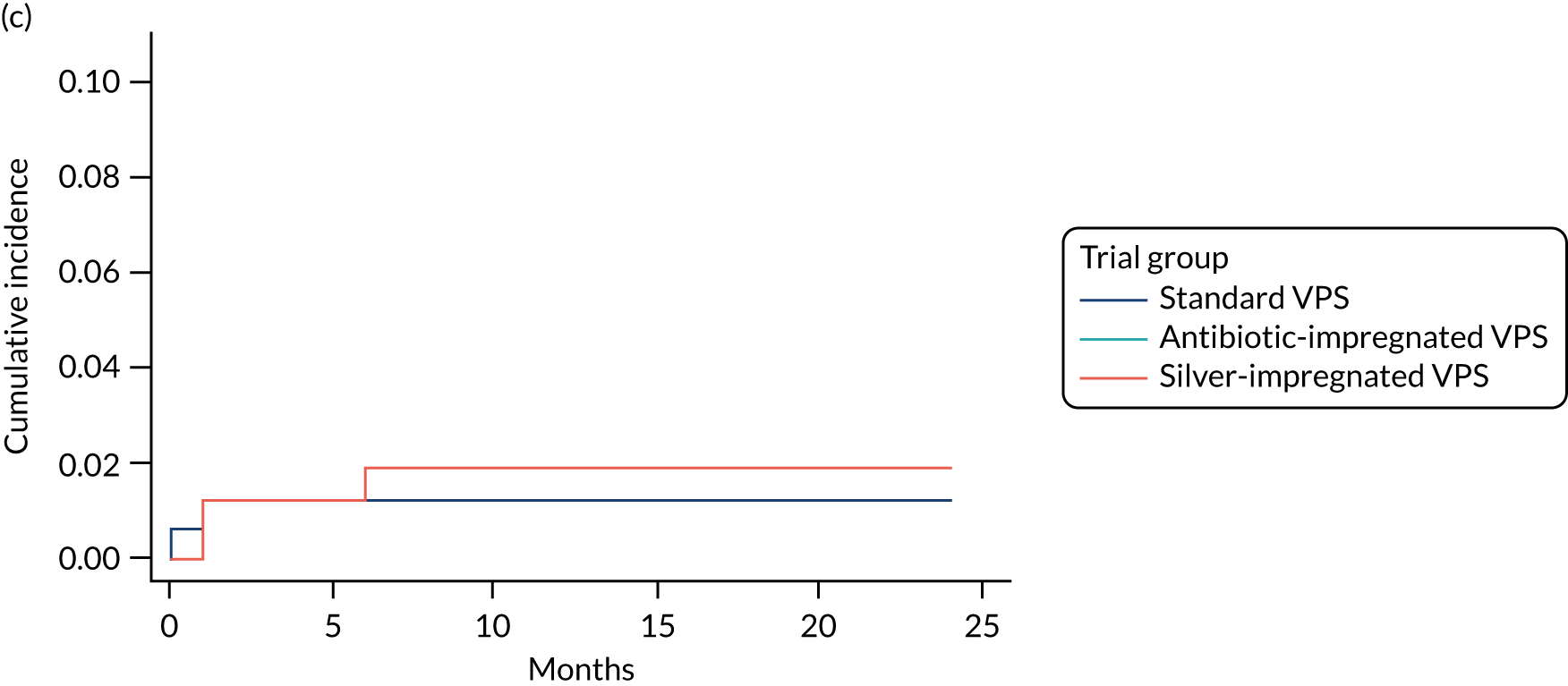

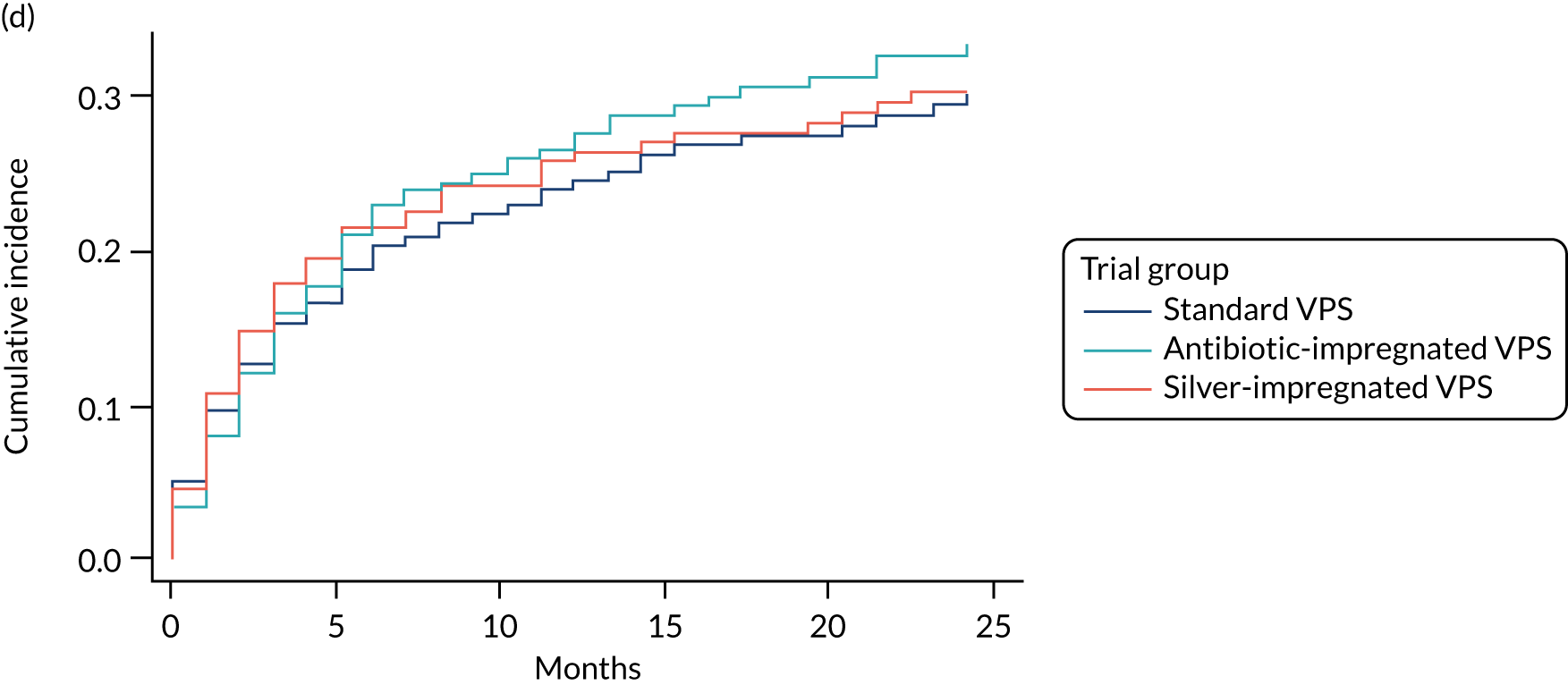

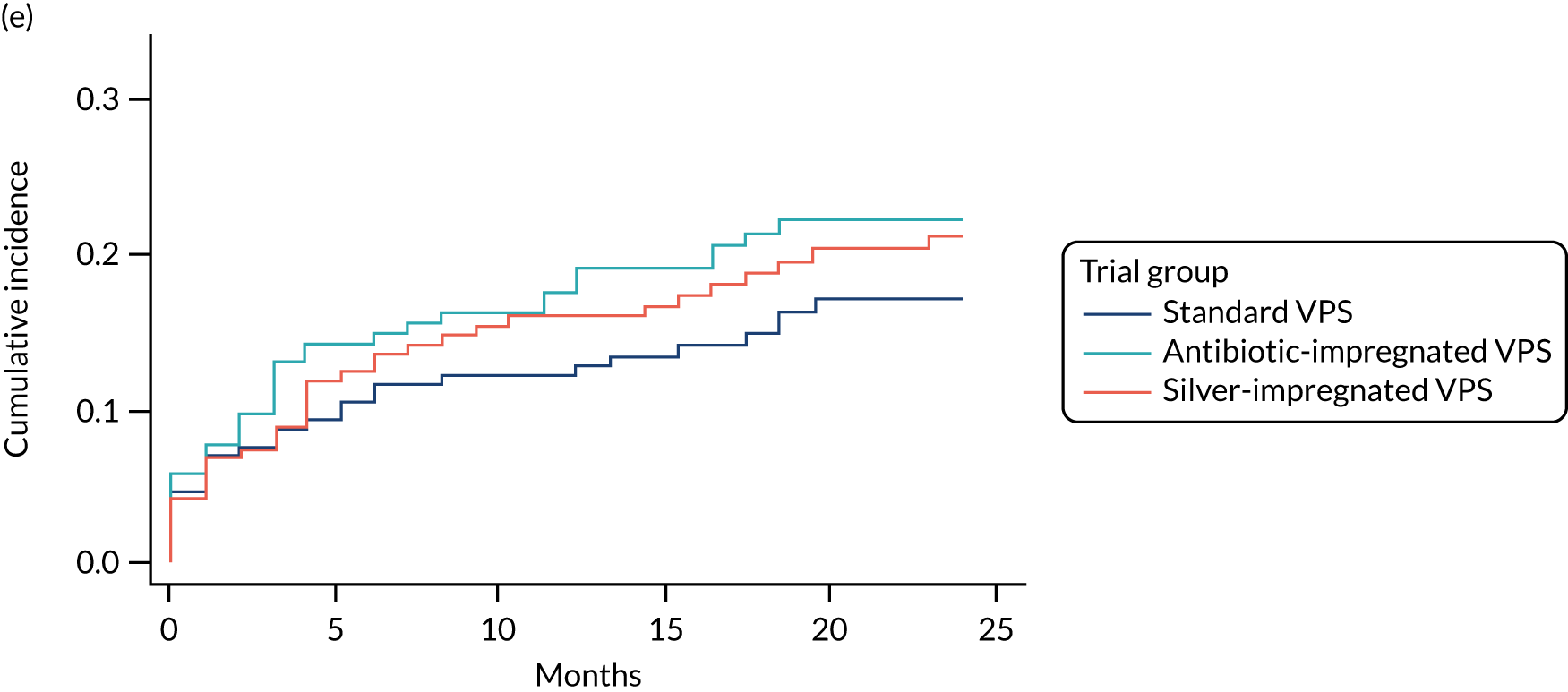

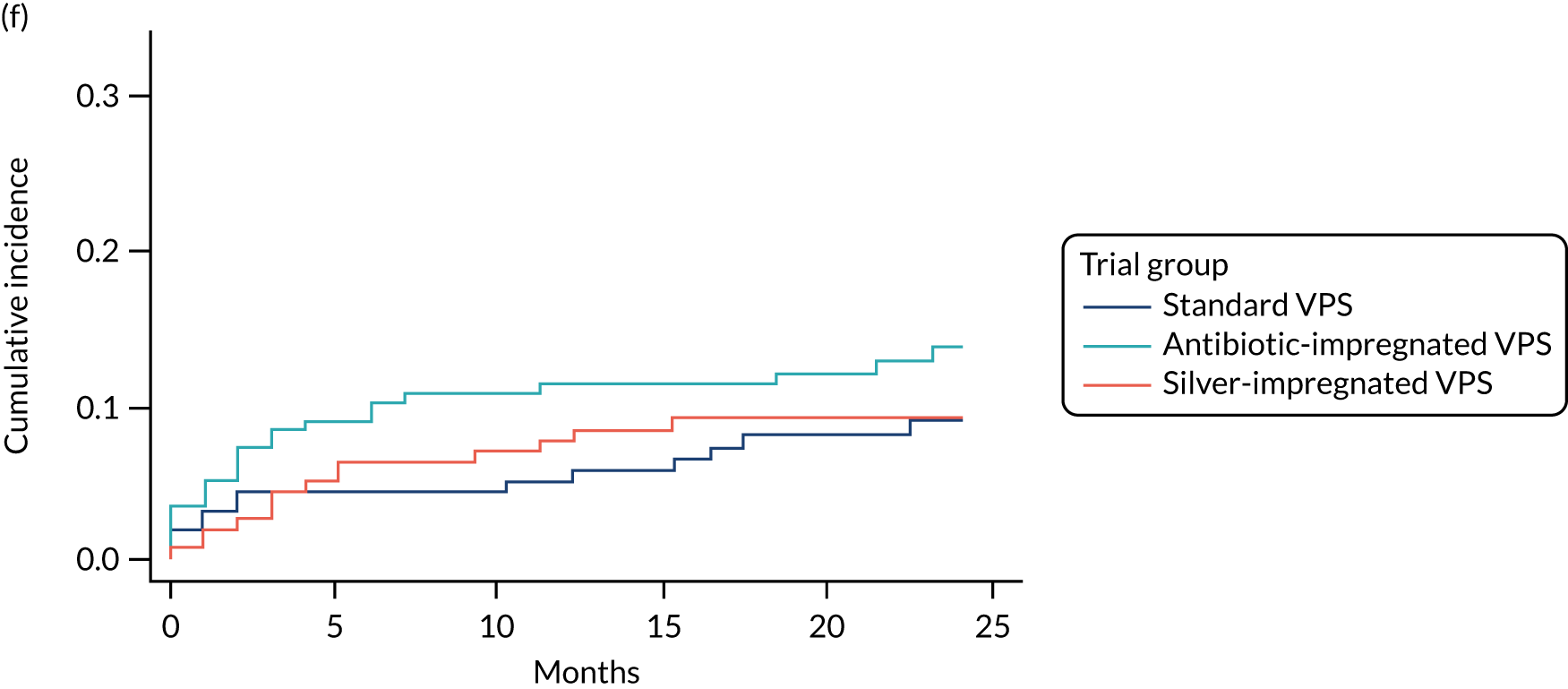

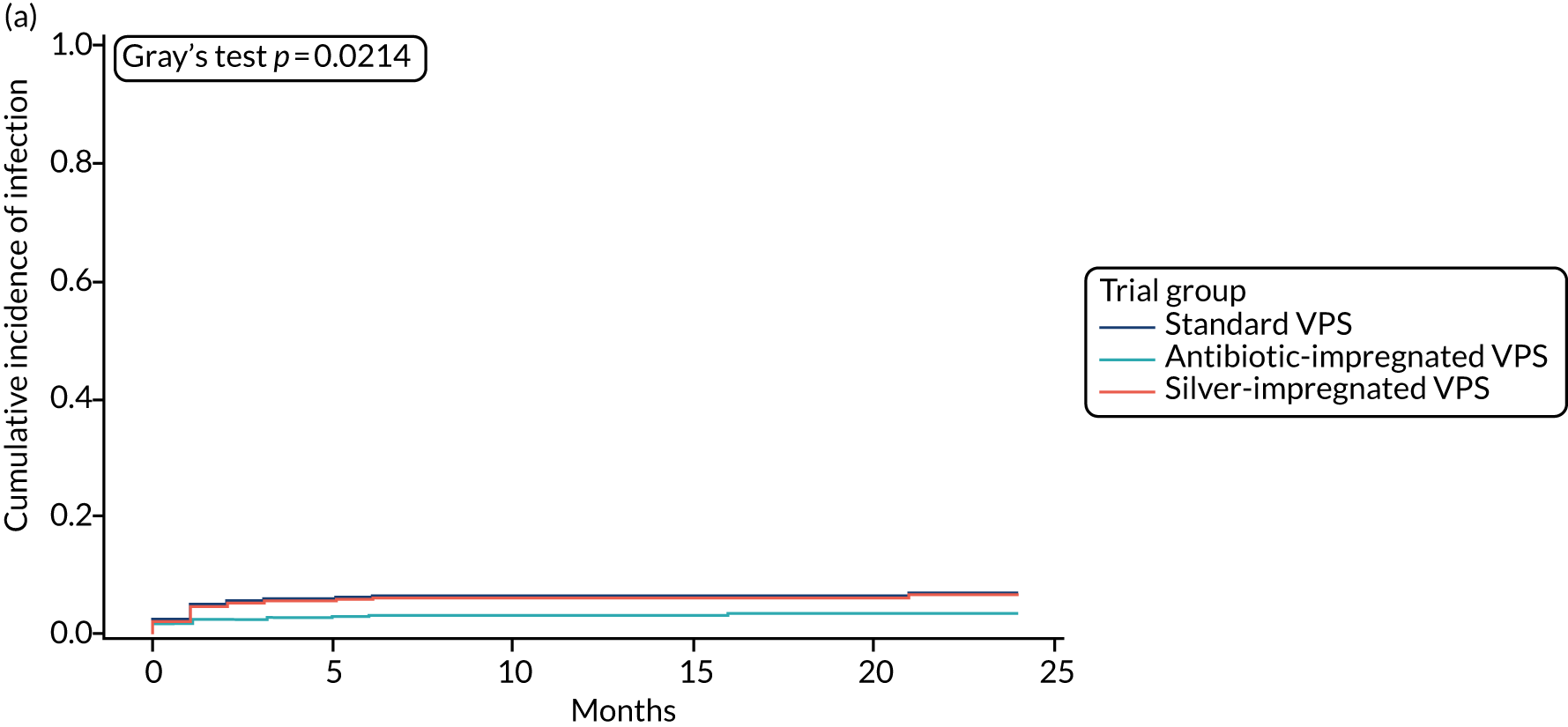

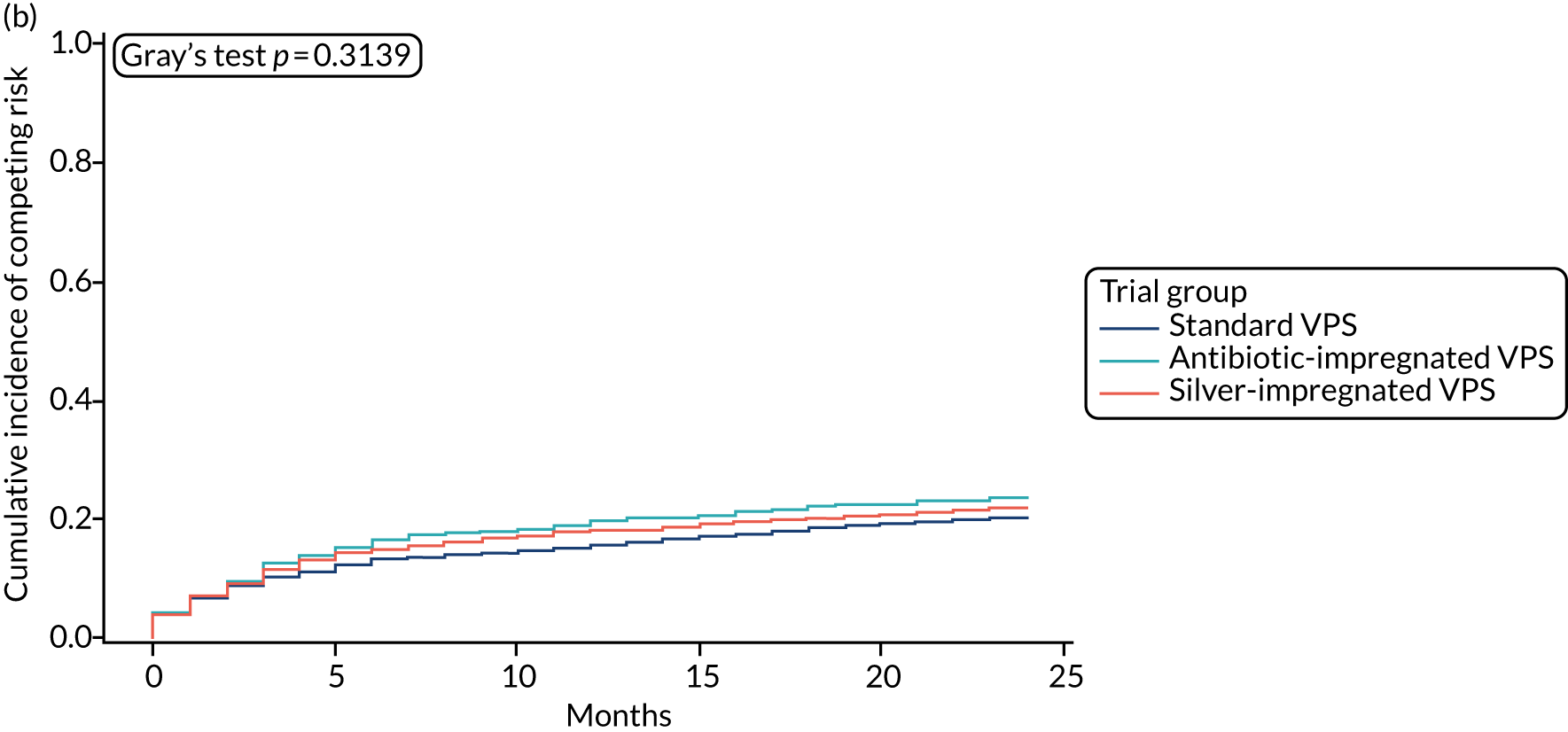

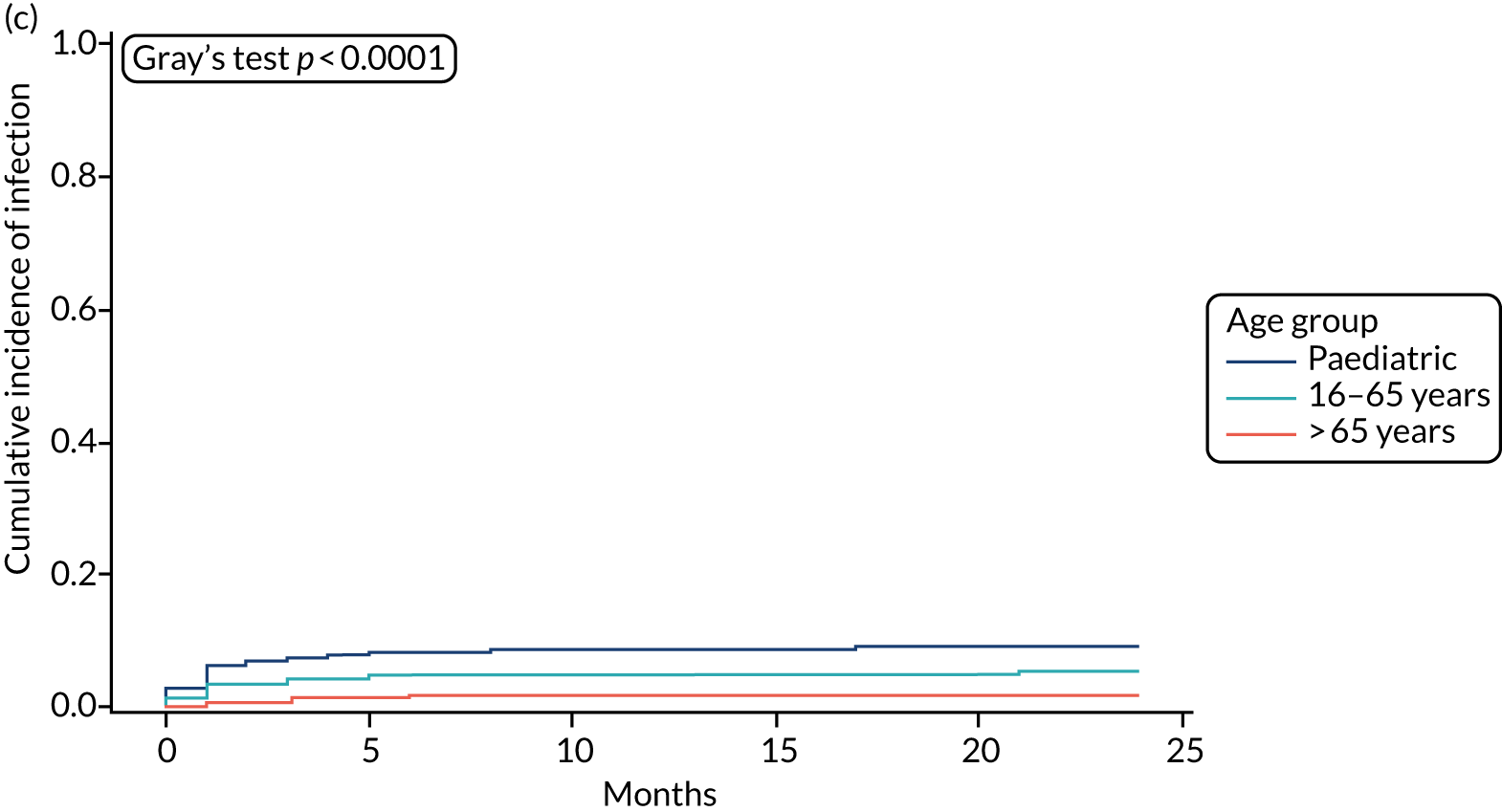

When compared with the standard VPS, antibiotic-impregnated VPSs decreased the risk of infection (csHR 0.38, 97.5% CI 0.18 to 0.80; p < 0.01) (Table 12). Silver-impregnated VPSs were comparable to standard VPSs (csHR 0.99, 97.5% CI 0.56 to 1.74; p = 0.96) (see Table 12). Figure 3 displays the cumulative incidences of infection and no infection by VPS and age group. Figure 4 displays the cumulative incidence plots of infection or no infection by VPS group, stratified by age group.

| Covariate | Infection, HR (97.5% CI); p-value | Competing risk, HR (97.5% CI); p-value |

|---|---|---|

| Cox: csHR | ||

| VPS | ||

| Standard | – | – |

| Antibiotic-impregnated | 0.38a (0.18 to 0.80); < 0.01 | 1.22b (0.90 to 1.65); 0.15 |

| Silver-impregnated | 0.99a (0.56 to 1.74); 0.96 | 1.11b (0.81 to 1.51); 0.47 |

| Age group | ||

| Paediatric | – | – |

| Adult (≤ 65 years) | 0.55a (0.31 to 0.97); 0.02 | 0.58b (0.44 to 0.77); < 0.01 |

| Adult (> 65 years) | 0.12a (0.04 to 0.34); < 0.01 | 0.28b (0.20 to 0.40); < 0.01 |

| Fine–Gray: sHR | ||

| VPS | ||

| Standard | – | – |

| Antibiotic-impregnated | 0.38c (0.18 to 0.80); < 0.01 | 1.26d (0.93 to 1.70); 0.08 |

| Silver-impregnated | 0.99c (0.56 to 1.72); 0.95 | 1.10d (0.81 to 1.50); 0.50 |

| Age group | ||

| Paediatric | – | – |

| Adult (≤ 65 years) | 0.56c (0.32 to 0.99); 0.02 | 0.60d (0.45 to 0.80); < 0.01 |

| Adult (> 65 years) | 0.12c (0.04 to 0.35); < 0.01 | 0.30d (0.21 to 0.43); < 0.01 |

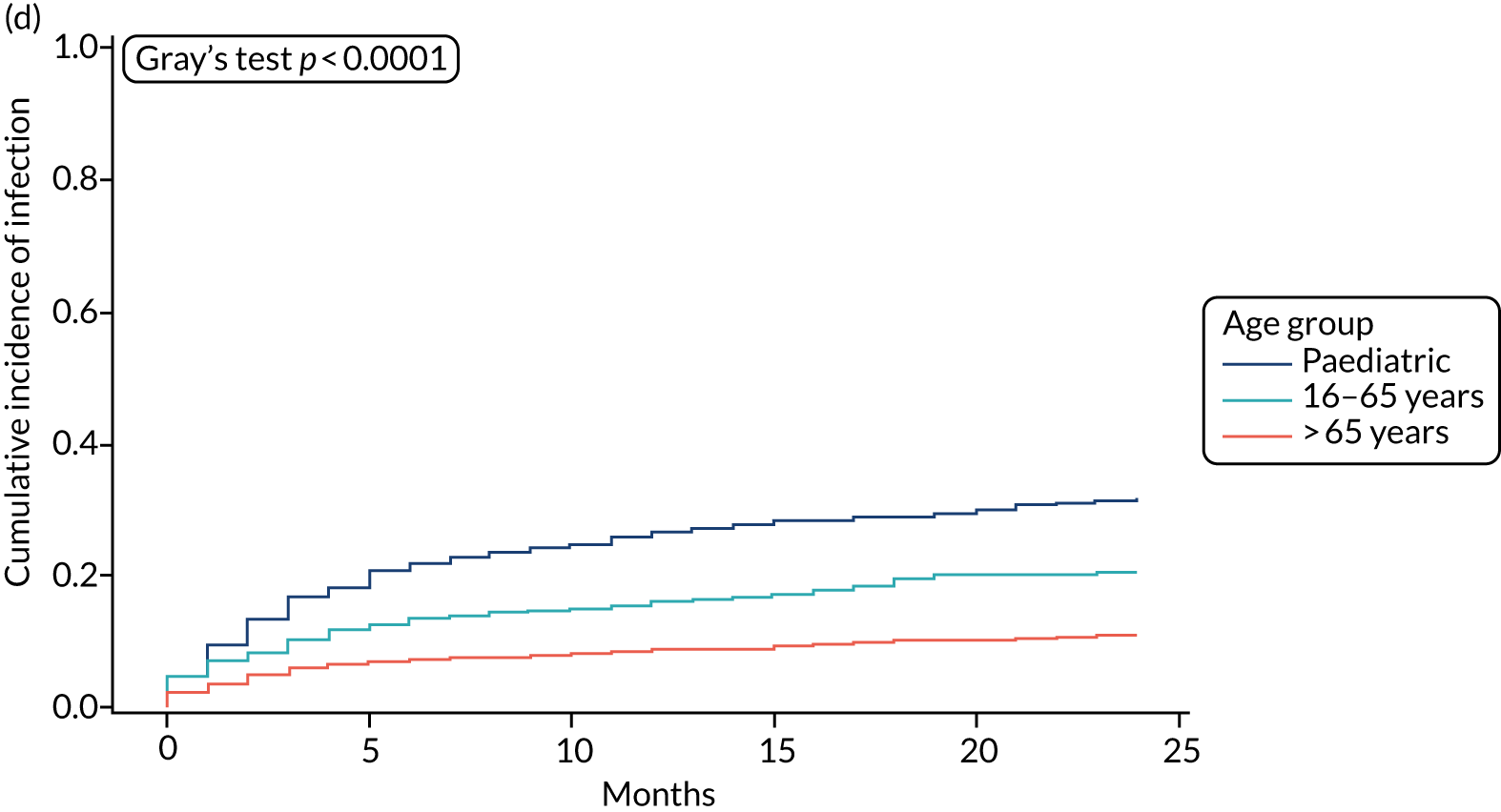

FIGURE 3.

Cumulative incidence plots of revisions for infection and competing risk by VPS group and age group. (a) Infection by VPS group; (b) competing risk by VPS group; (c) infection by age group; and (d) competing risk by age group.

FIGURE 4.

Cumulative incidence plots of revisions for infection and competing risk by VPS group, stratified by age group. (a) Infection in the paediatric group; (b) infection in those aged ≤ 65 years; (c) infection in those aged > 65 years; (d) competing risk in the paediatric group; (e) competing risk in those aged ≤ 65 years; and (f) competing risk in those aged > 65 years.

All revisions for infection were further classified by type, with the majority being classified as ‘definite: culture positive’ across all arms (standard VPS arm: 22/32, 68.8%; antibiotic-impregnated VPS arm: 6/12, 50%; silver-impregnated VPS arm: 25/31, 80.6%).

Secondary outcomes

Secondary outcome 1: time to removal of first ventriculoperitoneal shunt due to suspected infection as assessed by treating surgeon

This secondary outcome, time to removal of first VPS due to suspected infection, complemented the primary outcome of revision for infection classified by central review by defining revision for infection according to the treating surgeon, as reported on the CRFs.

Of the total number of revisions, 78 (4.9%) were classified as infections by the treating surgeon. As with the primary outcome, when revisions were centrally classified, the infection rate was approximately equal in the standard and silver-impregnated VPS arms (6.2% and 5.7%, respectively), and was lowest in the antibiotic-impregnated arm (2.8%) (Table 13).

| Reason for revision | Trial group, n (%) | Total, n (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Standard VPS | Antibiotic-impregnated VPS | Silver-impregnated VPS | ||

| VPS removal/revision (for any cause) | 130 (100) | 132 (100) | 136 (100) | 398 (100) |

| Suspected infection | 33 (6.2) | 15 (2.8) | 30 (5.7) | 78 (4.9) |

| Revision for other reason (no infection) | 97 (18.2) | 117 (21.9) | 106 (20.2) | 320 (20.1) |

When compared with the standard VPS, antibiotic-impregnated VPSs decreased the risk of infection (csHR 0.45, 97.5% CI 0.23 to 0.91; p = 0.01) (Table 14). Silver-impregnated VPSs were comparable to standard VPSs (csHR 0.93, 97.5% CI 0.53 to 1.64; p = 0.77) (see Table 14). Appendix 2, Figure 9, displays the cumulative incidences of infection and no infection by VPS and age group.

| Covariate | Infection, HR (97.5% CI); p-value | Competing risk, HR (97.5% CI); p-value |

|---|---|---|

| Cox: csHR | ||

| VPS | ||

| Standard | – | – |

| Antibiotic impregnated | 0.45a (0.23 to 0.91); 0.01 | 1.20b (0.88 to 1.63); 0.19 |

| Silver impregnated | 0.93a (0.53 to 1.64); 0.77 | 1.13b (0.82 to 1.54); 0.39 |

| Age group | ||

| Paediatric | – | – |

| Adult (≤ 65 years) | 0.51a (0.29 to 0.91); < 0.01 | 0.59b (0.44 to 0.79); < 0.01 |

| Adult (> 65 years) | 0.11a (0.04 to 0.31); < 0.01 | 0.29b (0.20 to 0.41); < 0.01 |

| Fine–Gray: sHR | ||

| VPS | ||

| Standard | – | – |

| Antibiotic-impregnated | 0.45c (0.23 to 0.91); 0.01 | 1.24d (0.92 to 1.68); 0.11 |

| Silver-impregnated | 0.92c (0.53 to 1.61); 0.74 | 1.13d (0.83 to 1.54); 0.38 |

| Age group | ||

| Paediatric | – | – |

| Adult (≤ 65 years) | 0.53c (0.30 to 0.93); 0.01 | 0.61d (0.46 to 0.81); < 0.01 |

| Adult (> 65 years) | 0.12c (0.04 to 0.33); < 0.01 | 0.31d (0.21 to 0.44); < 0.01 |

Secondary outcome 2: time to ventriculoperitoneal shunt failure due to any cause

The overall revision rate was 25.0% (398/1594), which was approximately equal between each of the three VPS groups (standard VPS arm: 130/533, 24.4%; antibiotic-impregnated VPS arm: 132/535, 24.7%; silver-impregnated VPS arm: 136/526, 25.9%) (see Table 11).

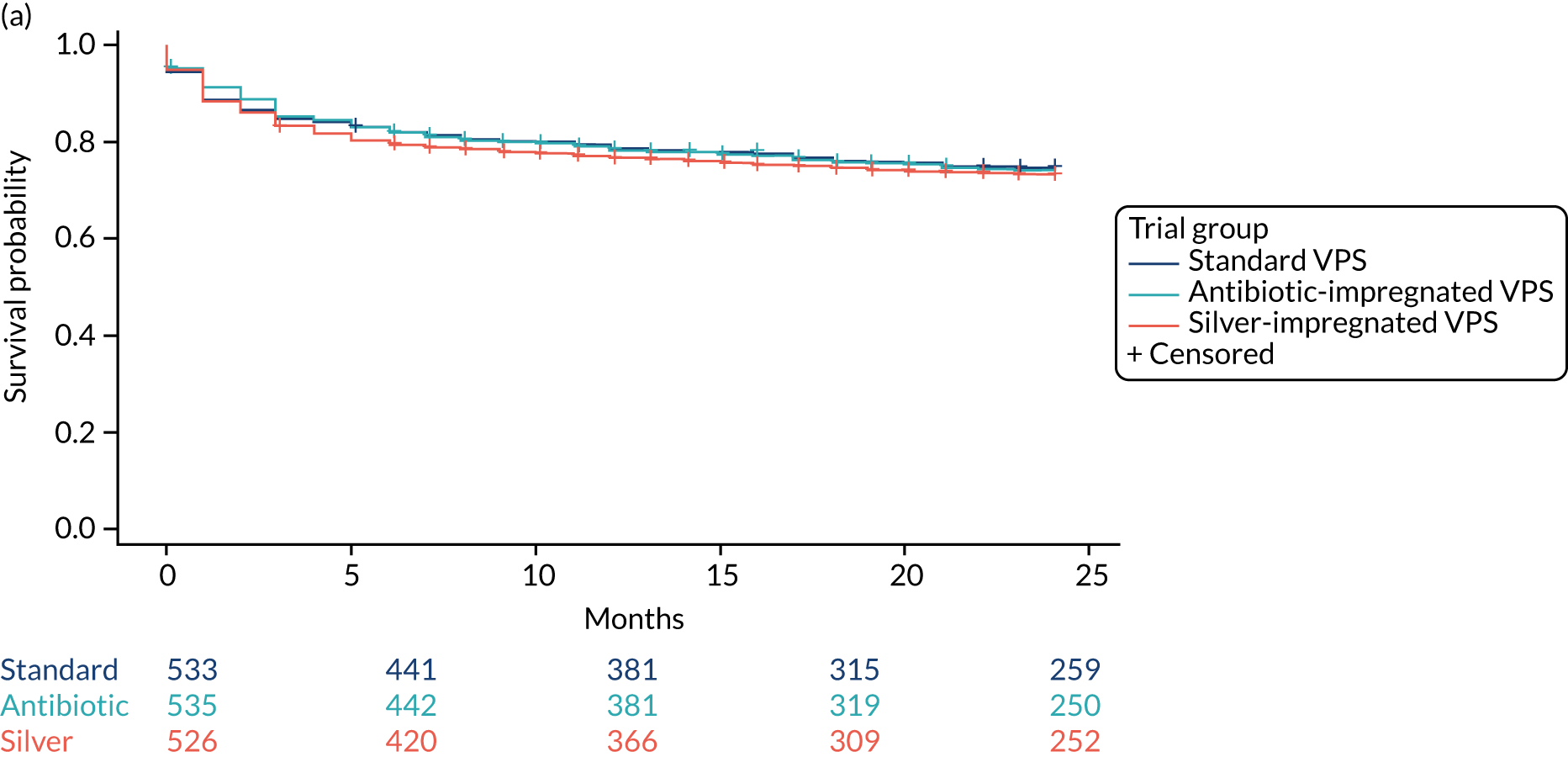

There was no significant difference for time to failure between the antibiotic-impregnated or silver-impregnated VPS arms when compared with the standard VPS arm (Table 15). Figure 5 shows the Kaplan-Meier curve for time to VPS failure for any cause, split by VPS and age group.

| Covariate | Revision, HR (97.5% CI); p-value |

|---|---|

| VPS | |

| Standard | – |

| Antibiotic impregnated | 1.01 (0.77 to 1.33); 0.94 |

| Silver impregnated | 1.08 (0.82 to 1.42); 0.54 |

| Age group | |

| Paediatric | – |

| Adult (≤ 65 years) | 0.57 (0.44 to 0.74); < 0.01 |

| Adult (> 65 years) | 0.25 (0.18 to 0.35); < 0.01 |

FIGURE 5.

Kaplan–Meier curves for time to VPS failure for any cause, split by (a) VPS group and (b) age group.

Secondary outcome 3: reason for shunt failure

At the time of revision, the treating surgeon recorded the reason for shunt failure on the CRFs. The reason for shunt failure could fall into one of four categories: suspected shunt infection, mechanical shunt failure, functional shunt failure and failure due to the patient. The outcome explored the reasons for shunt failure in the antibiotic-impregnated and silver-impregnated VPS arms, compared with the standard VPS arm.

The reasons for shunt failure, according to VPS type, are summarised in Table 16. Although the number of revisions across the VPS groups is similar, comparing the reasons within group indicates:

-

Failures due to suspected shunt infections are lower in the antibiotic-impregnated group (n = 15/132, 11.4%) than in the standard (n = 33/130, 25.4%) or the silver-impregnated VPS groups (n = 30/136, 22.1%).

-

Mechanical shunt failures are higher in the antibiotic-impregnated VPS group (n = 69/132, 52.3%) than in the standard (n = 52/130, 43.0%) or the silver-impregnated VPS groups (n = 64/136, 47.1%).

| Comparator | Reason for VPS failure, n observed failures (row %,a column %b) | Total (n) | Chi-squared test results | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Suspected infection | Mechanical shunt failure | Functional shunt failure | Failure due to patient | Test | Result | ||

| Antibiotic-impregnated vs. standard VPS | |||||||

| Standard | 33 (25.4, 68.8) | 52 (40.0, 43.0) | 40 (30.8, 47.6) | 5 (3.8, 55.6) | 130 | Value | 9.4 |

| Antibiotic-impregnated | 15 (11.4, 31.3) | 69 (52.3, 57.0) | 44 (33.3, 52.4) | 4 (3.1, 44.4) | 132 | Degrees of freedom | 3 |

| Total (n) | 48 | 121 | 84 | 9 | 262 | p-value | 0.02 |

| Silver-impregnated vs. standard VPS | |||||||

| Standard | 33 (25.4, 52.4) | 52 (40.0, 44.8) | 40 (30.8, 51.9) | 5 (3.8, 50.0) | 130 | Value | 1.4 |

| Silver-impregnated | 30 (22.1, 47.6) | 64 (47.1, 55.2) | 37 (27.2, 48.1) | 5 (3.7, 50.0) | 136 | Degrees of freedom | 3 |

| Total (n) | 63 | 116 | 77 | 10 | 266 | p-value | 0.71 |

These results indicate that, although the number of VPS failures is similar between the three groups, the underlying reason for failure differs when comparing standard with antibiotic-impregnated VPSs (p = 0.02), with fewer infections with antibiotic-impregnated VPSs, but a higher frequency of failure for other causes.

Secondary outcome 4: types of bacterial infection

The proportion of ‘definite – culture positive’ infections was 68.8% in the standard VPS group, 50.0% in the antibiotic-impregnated VPS group and 80.6% in the silver-impregnated VPS group. The central review panel classified all shunt infections that were ‘definite – culture positive’ and ‘probable – culture uncertain’ (n = 56/75; see Table 11) by the organism that was cultured.

The organisms cultured are summarised by species in Tables 17 and 18. Coagulase-negative staphylococci (37.5%) and Staphylococcus aureus (30%) accounted for the majority of cultured organisms in ‘all VPS infection’ but not in the antibiotic-impregnated VPS group. Culture results show a reduction in staphylococcal/Gram-positive infections for the antibiotic-impregnated VPS group, compared with the standard and the silver-impregnated VPS groups. All three VPS types have a similar number of Gram-negative infections.

| Summary of Gram-positive organisms cultured | Standard VPS | Antibiotic-impregnated VPS | Silver-impregnated VPS | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total number of infectionsa | 23b | 6 | 27c | 56 |

| Gram-positive organisms isolated (n) | 20 | 2 | 23 | 45 |

| Gram-positive organism cultured, n (%)d | ||||

| Staphylococcus aureus | 6 (26.1) | 0 (0.0) | 11 (40.7) | 17 (30.4) |

| Coagulase-negative staphylococci | ||||

| Coagulase-negative staphylococci, species not given | 5 (21.7) | 1 (16.7) | 3 (11.1) | 9 (16.1) |

| Staphylococcus epidermidis | 4 (17.4) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (11.1) | 7 (12.5) |

| Staphylococcus capitas | 3 (13.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (3.7) | 4 (7.1) |

| Staphylococcus hominis | 1 (4.3) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (1.8) |

| Other Gram-positive organisms | ||||

| Enterococcus faecalis | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (7.4) | 2 (3.6) |

| Propionibacterium acnes | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (7.4) | 2 (3.6) |

| Propionibacterium species | 0 (0.0) | 1 (16.7) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (1.8) |

| Streptococcus mitis | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (3.7) | 1 (1.8) |

| Streptococcus salivaris | 1 (4.3) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (1.8) |

| Summary of Gram-negative organisms cultured | Standard VPS | Antibiotic-impregnated VPS | Silver-impregnated VPS | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total number of infectionsa | 23b | 6 | 27c | 56 |

| Gram-negative organisms isolated (n) | 6 | 4 | 5 | 15 |

| Gram-negative organisms cultured, n (%)d | ||||

| Enterobacteriaceae | ||||

| Enterobacter cloacae | 0 (0.0) | 1 (16.7) | 2 (7.4) | 3 (5.4) |

| Escherichia coli | 0 (0.0) | 1 (16.7) | 2 (7.4) | 3 (5.4) |

| Klebsiella pneumoniae | 3 (13.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (5.4) |

| Citrobacter species | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (3.7) | 1 (1.8) |

| Serratia marcescens | 1 (4.3) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (1.8) |

| Serratia species | 1 (4.3) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (1.8) |

| Proteus mirabilis | 0 (0.0) | 1 (16.7) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (1.8) |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa | 1 (4.3) | 1 (16.7) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (3.6) |

Line listings of details of each infection against their organism cultured and antibiotic sensitivities are provided in Appendix 2, Table 38. Antibiotic sensitivity data were not consistently returned, so displayed data are limited.

Secondary outcome 5: time to removal of ventriculoperitoneal shunt because of suspected infection

Following first clean revision

This outcome explored revisions for infections in patients who had their first VPS revised for a reason other than infection (clean revision), that is those with a competing risk in the primary outcome set (n = 323; see Table 11). Participants in this group, who subsequently had a second revision, had their data centrally assessed by the panel and had the reason for revision classified as infection, or no infection, based on the data available. As with the primary outcome, for which there was insufficient information for the central panel to classify, the clinical classification was used (n = 4/128; Table 19).

| Second VPS revisions | Standard VPS, n (%) | Antibiotic-impregnated VPS, n (%) | Silver-impregnated VPS, n (%) | Total, n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Summary of revisions | ||||

| Eligible for primary outcomea | 98 (100) | 120 (100) | 105 (100) | 323 (100) |

| No VPS removal/revision | 61 (62.2) | 69 (57.5) | 65 (61.9) | 195 (60.4) |

| VPS removal/revision (for any cause) | 37 (37.8) | 51 (42.5) | 40 (38.1) | 128 (39.6) |

| Reason for revisions as classified by central review | ||||

| Revision for infection | 9 (9.2) | 6 (5.0) | 5 (4.8) | 20 (6.2) |

| Revision for other reason (no infection) | 28 (28.6) | 45 (37.5) | 35 (33.3) | 108 (33.4) |

| VPS CSF or peritoneal infection | ||||

| Definite – culture positive | 7 (18.9) | 3 (5.9) | 5 (12.5) | 15 (11.7) |

| Probable – culture uncertain | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Probable – culture negative | 1 (2.7) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.8) |

| Possible – culture uncertain | 1 (2.7) | 2 (3.9) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (2.3) |

| Clinically classified infectionb | 0 (0.0) | 1 (2.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.8) |

| VPS deep incisional infection | ||||

| VPS deep incisional infection | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (2.5) | 1 (0.8) |

There were 128 secondary revisions following a first clean revision, of which 20 were classified as an infection (6.2%; see Table 19). The infection rate was approximately equal in the antibiotic-impregnated and silver-impregnated VPS groups (5.0% and 4.8%, respectively), and was higher in the standard VPS group (9.2%). However, these differences were not statistically significant when survival models were applied to the data (Table 20).

| Covariate | Infection, HR (97.5% CI); p-value | Competing risk, HR (97.5% CI); p-value |

|---|---|---|

| Cox: csHR | ||

| VPS | ||

| Standard | – | – |

| Antibiotic-impregnated | 0.55a (0.17 to 1.81); 0.26 | 1.38b (0.80 to 2.36); 0.19 |

| Silver-impregnated | 0.47a (0.13 to 1.63); 0.17 | 1.11b (0.63 to 1.97); 0.67 |

| Age group | ||

| Paediatric | – | – |

| Adult (≤ 65 years) | 1.64a (0.58 to 4.61); 0.28 | 0.80b (0.49 to 1.30); 0.30 |

| Adult (> 65 years) | 0.34a (0.03 to 3.64); 0.14 | 0.43b (0.19 to 0.95); 0.10 |

| Fine-Gray: sHR | ||

| VPS | ||

| Standard | – | – |

| Antibiotic-impregnated | 0.55c (0.17 to 1.75); 0.25 | 1.40d (0.83 to 2.37); 0.16 |

| Silver-impregnated | 0.48c (0.14 to 1.67); 0.19 | 1.14d (0.65 to 1.99); 0.61 |

| Age group | ||

| Paediatric | – | – |

| Adult (≤ 65 years) | 1.72c (0.62 to 4.81); 0.24 | 0.80d (0.50 to 1.28); 0.29 |

| Adult (> 65 years) | 0.38c (0.04 to 3.91); 0.14 | 0.44d (0.20 to 0.97); 0.11 |

Seventy-five per cent of the secondary revisions for infection were classified by the committee as ‘definite – culture positive’ (n = 15/20).

Additional analysis

Comparing the identification of infections between assessors

The reason for revision (infection or no infection), as classified by the central panel, was the primary outcome (see Primary outcome: time to ventriculoperitoneal infection as assessed by the central review panel), and the reason for revision, as classified by the treating surgeon, was a complementary secondary outcome (see Secondary outcome 1: time to removal of first ventriculoperitoneal shunt due to suspected infection, as assessed by the treating surgeon). The classification made by these two independent assessors was the same in 95.7% (381/398) of revisions. Appendix 2, Table 39, provides further detail.

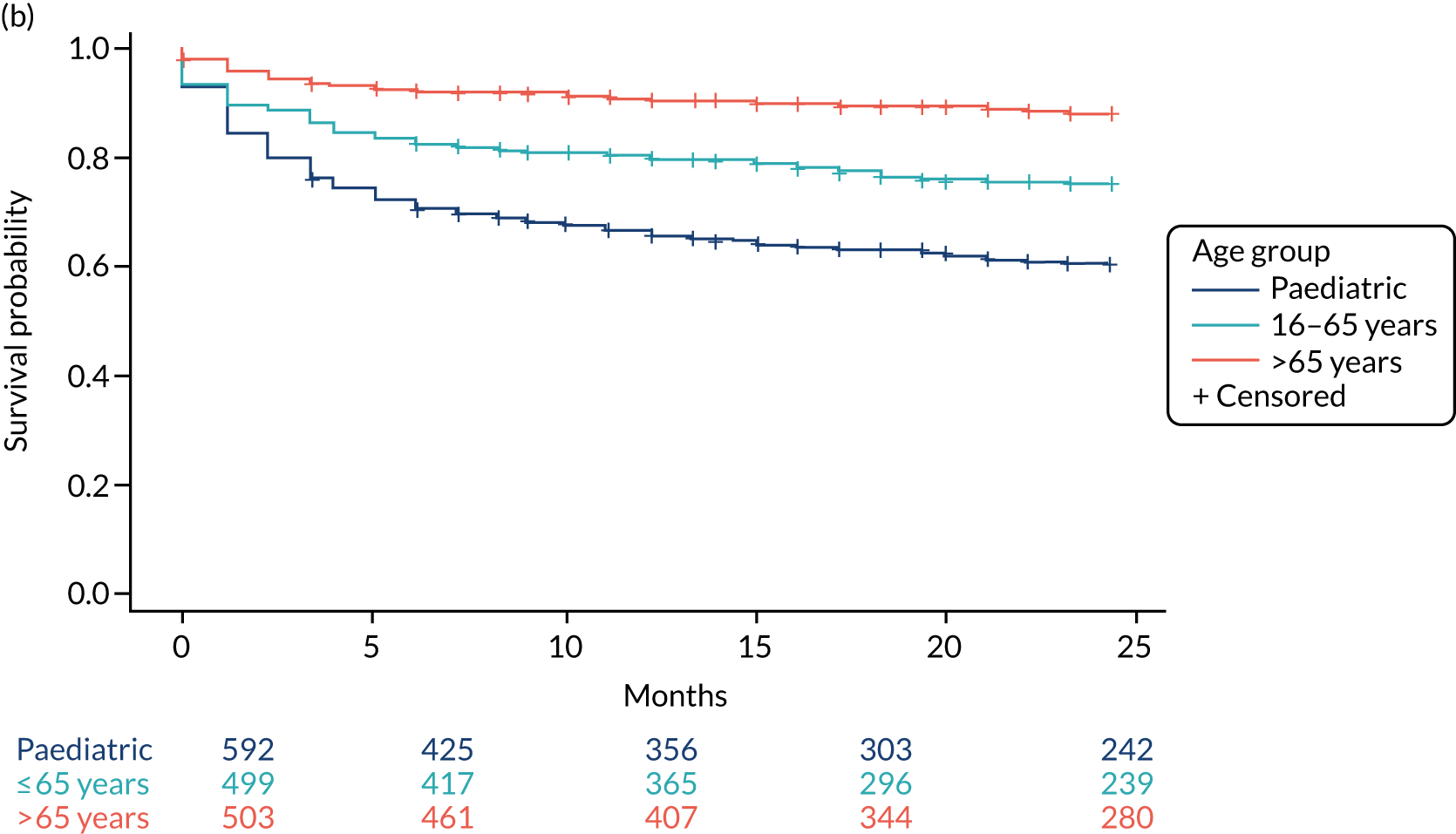

Revision and infection rates by age group

The proportion of revisions of first VPS for any cause ranged from 38.0% (n = 225/592) for paediatrics to 10.9% (n = 55/503) for those aged > 65 years. The proportion of infections, as classified by the central review panel, was also higher for paediatrics than for older participants. Table 21 provides more detail.

| Summary of revisions | Age group | Total | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Paediatric | ≤ 65 years | > 65 years | ||

| Eligible for primary outcome | 592 (100) | 499 (100) | 503 (100) | 1594 (100) |

| No VPS removal/revision | 367 (62.0) | 381 (76.4) | 448 (89.1) | 1196 (74.5) |

| Revision for other reason (no infection) | 178 (30.1) | 95 (19.0) | 50 (9.9) | 323 (20.3) |

| Revision for infection | 47 (7.9) | 23 (4.6) | 5 (1.0) | 75 (4.7) |

All survival models were adjusted for age category of the recruiting centre (paediatric or adult), with adult centre being further categorised by age > 65 years. The risk of infection was significantly lower for participants aged 16–65 years (csHR 0.56, 97.5% CI 0.32 to 0.99; p = 0.02) and for those aged > 65 years (csHR 0.12, 97.5% CI 0.04 to 0.35; p < 0.01) than for paediatric participants (see Table 12). See Figure 3 for the cumulative incidence of infection by age category; see Figure 4 for the cumulative incidence of infection by VPS type, stratified by age group.

Revision and infection rates by centre

Heterogeneity between centres in revision rates and infection rates was explored by summary statistics.

Revision rates varied from a minimum of 4.8% (97.5% CI 0.0% to 15.2%, adult-only centre) to a maximum of 75.0% (97.5% CI 40.7% to 100.0%, paediatric-only centre), as presented in Appendix 2, Table 41. Infection rates, presented in Appendix 2, Table 41, varied from 0.0% (97.5% CI 0.0% to 0.0%, adult-only centre) to 25.0% (97.5% CI 0.0% to 59.3%, paediatric-only centre). Paediatric-only centres generally had higher rates of revisions and infections than adult-only centres and centres that treated both adults and paediatrics.

Post hoc analyses

A post hoc analysis explored revision rates, and reason for revision, by aetiology of the hydrocephalus, type of valve, operative approach and component replaced at first revision.

Revision and infection rates by aetiology

Table 22 and Appendix 2, Table 42, summarise aetiologies of the hydrocephalus, overall and split by treatment group, respectively. The rates of revision for infection and mechanical failure varied within certain aetiologies. For example, the revision and infection rates for participants with congenital malformations was 38.4% and 9.2%, respectively, both higher than the equivalent overall rates of 25.0% and 4.7% (see Table 11). Similarly, participants with idiopathic normal pressure hydrocephalus had much lower revision and infection rates of 10.0% and 1.1%, respectively, than the rates for patients with other aetiologies of hydrocephalus.

| Summary of aetiology | Clean insertion,a n (%) | Revision required | Reason for revision | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No revision, n (%) | Revision,b n (%) | Failure due to patient, n (%) | Functional shunt failure, n (%) | Mechanical shunt failure, n (%) | Failure due to infection, n (%) | Failure – no infection,c n (%) | ||

| Total number of patients | 1594 | 1196 | 398 | 14 | 121 | 185 | 78 | 320 |

| Congenital malformations | ||||||||

| Patients with congenital malformations | 294 (18.4) | 181 (61.6) | 113 (38.4) | 2 (0.7) | 36 (12.2) | 48 (16.3) | 27 (9.2) | 86 (29.3) |

| Type of congenital malformation | ||||||||

| Aqueduct stenosis | 68 (23.1) | 46 (67.6) | 22 (32.4) | 0 (0.0) | 8 (11.8) | 7 (10.3) | 7 (10.3) | 15 (22.1) |

| Dandy–Walker | 7 (2.4) | 6 (85.7) | 1 (14.3) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (14.3) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (14.3) |

| Chiari | 62 (21.1) | 43 (69.4) | 19 (30.6) | 0 (0.0) | 7 (11.3) | 7 (11.3) | 5 (8.1) | 14 (22.6) |

| Spina bifida | 111 (37.8) | 62 (55.9) | 49 (44.1) | 1 (0.9) | 11 (9.9) | 25 (22.5) | 12 (10.8) | 37 (33.3) |

| Other | 72 (24.5) | 38 (52.8) | 34 (47.2) | 1 (1.4) | 12 (16.7) | 13 (18.1) | 8 (11.1) | 26 (36.1) |

| Not known | 1 (0.3) | 1 (100.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Acquired hydrocephalus | ||||||||

| Patients with acquired hydrocephalus | 819 (51.4) | 615 (75.1) | 204 (24.9) | 9 (1.1) | 54 (6.6) | 102 (12.5) | 39 (4.8) | 165 (20.1) |

| Type(s) of acquired hydrocephalus | ||||||||

| Cysts (colloid or arachoid) | 32 (3.9) | 24 (75.0) | 8 (25.0) | 0 (0.0) | 4 (12.5) | 3 (9.4) | 1 (3.1) | 7 (21.9) |

| Trauma | 30 (3.7) | 25 (83.3) | 5 (16.7) | 1 (3.3) | 1 (3.3) | 3 (10.0) | 0 (0.0) | 5 (16.7) |

| Tumour: benign | 124 (15.1) | 96 (77.4) | 28 (22.6) | 2 (1.6) | 9 (7.3) | 14 (11.3) | 3 (2.4) | 25 (20.2) |

| Tumour: malignant | 133 (16.2) | 105 (78.9) | 28 (21.1) | 2 (1.5) | 6 (4.5) | 14 (10.5) | 6 (4.5) | 22 (16.5) |

| Post haemorrhagic/intracranial haemorrhage | 337 (41.1) | 244 (72.4) | 93 (27.6) | 2 (0.6) | 21 (6.2) | 45 (13.4) | 25 (7.4) | 68 (20.2) |

| Infection: meningitis | 32 (3.9) | 23 (71.9) | 9 (28.1) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (6.3) | 5 (15.6) | 2 (6.3) | 7 (21.9) |

| Infection: cerebral abscess | 8 (1.0) | 7 (87.5) | 1 (12.5) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (12.5) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (12.5) |

| Infection: other | 21 (2.6) | 17 (81.0) | 4 (19.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 4 (19.0) | 0 (0.0) | 4 (19.0) |

| Other factors | 140 (17.1) | 99 (70.7) | 41 (29.3) | 3 (2.1) | 16 (11.4) | 17 (12.1) | 5 (3.6) | 36 (25.7) |

| Idiopathic condition | ||||||||

| Patients with idiopathic condition | 496 (31.1) | 408 (82.3) | 88 (17.7) | 4 (0.8) | 32 (6.5) | 38 (7.7) | 14 (2.8) | 74 (14.9) |

| Type(s) of idiopathic condition | ||||||||

| Idiopathic normal pressure hydrocephalus of the elderly | 361 (72.8) | 325 (90.0) | 36 (10.0) | 1 (0.3) | 15 (4.2) | 16 (4.4) | 4 (1.1) | 32 (8.9) |

| IIH | 98 (19.8) | 63 (64.3) | 35 (35.7) | 2 (2.0) | 10 (10.2) | 16 (16.3) | 7 (7.1) | 28 (28.6) |

| Other | 38 (7.7) | 20 (52.6) | 18 (47.4) | 1 (2.6) | 7 (18.4) | 7 (18.4) | 3 (7.9) | 15 (39.5) |

Rates between VPS groups also differed according to aetiology. For example, the infection rate in participants with spina bifida in the antibiotic-impregnated VPS group was 2.9%, compared with 14.3% each for the standard and silver-impregnated VPS groups. The infection rate in participants with idiopathic normal pressure hydrocephalus was 13.6% in the standard VPS group and 2.9% in the antibiotic-impregnated VPS group.

Revision and infection rates by operative approach

Table 23 and Appendix 2, Table 43, summarise valve type and operative approach at insertion, both overall and split by treatment group.

| Summary of operative approach/valve type | Clean insertion,a n (%) | Revision required | Reason for revision | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No revision, n (%) | Revision,b n (%) | Failure due to patient, n (%) | Functional shunt failure, n (%) | Mechanical shunt failure, n (%) | Failure for infection, n (%) | Failure – no infection,c n (%) | ||

| Total number of patients | 1594 | 1196 | 398 | 14 | 121 | 185 | 78 | 320 |

| Use of guidance system | ||||||||

| Patients for whom guidance system was used for VPS placement | 653 (41.0) | 489 (74.9) | 164 (25.1) | 7 (1.1) | 45 (6.9) | 78 (11.9) | 34 (5.2) | 130 (19.9) |

| Type of guidance system | ||||||||

| Electromagnetic | 413 (63.2) | 309 (74.8) | 104 (25.2) | 4 (1.0) | 26 (6.3) | 50 (12.1) | 24 (5.8) | 80 (19.4) |

| Ultrasonography | 128 (19.6) | 88 (68.8) | 40 (31.3) | 3 (2.3) | 16 (12.5) | 14 (10.9) | 7 (5.5) | 33 (25.8) |

| Optical | 46 (7.0) | 37 (80.4) | 9 (19.6) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (4.3) | 6 (13.0) | 1 (2.2) | 8 (17.4) |

| Stereotactic frame | 63 (9.6) | 52 (82.5) | 11 (17.5) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (1.6) | 8 (12.7) | 2 (3.2) | 9 (14.3) |

| Not known | 3 (0.5) | 3 (100.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Placement of proximal shunt catheter | ||||||||

| Frontal | 134 (8.4) | 93 (69.4) | 41 (30.6) | 0 (0.0) | 13 (9.7) | 15 (11.2) | 13 (9.7) | 28 (20.9) |

| Parietal, occipital or parietal/occipital | 1453 (91.2) | 1100 (75.7) | 353 (24.3) | 14 (1.0) | 107 (7.4) | 167 (11.5) | 65 (4.5) | 288 (19.8) |

| Combination | 3 (0.2) | 2 (66.7) | 1 (33.3) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (33.3) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (33.3) |

| Not known | 4 (0.3) | 1 (25.0) | 3 (75.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (75.0) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (75.0) |

| Type of valve | ||||||||

| Fixed | 935 (58.7) | 652 (69.7) | 283 (30.3) | 10 (1.1) | 91 (9.7) | 126 (13.5) | 56 (6.0) | 227 (24.3) |

| Programmable | 627 (39.3) | 525 (83.7) | 102 (16.3) | 4 (0.6) | 26 (4.1) | 52 (8.3) | 20 (3.2) | 82 (13.1) |

| Not known | 32 (2.0) | 19 (59.4) | 13 (40.6) | 0 (0.0) | 4 (12.5) | 7 (21.9) | 2 (6.3) | 11 (34.4) |

The rate of revisions when there was no evidence of infection (the competing risk in the primary outcome analysis) was > 10% lower among participants with a programmable valve (n = 82/627, 13.1%) than among those with a fixed valve (n = 227/935, 24.3%). On the other hand, revision rates for no infection were equivalent when comparing frontal placement of proximal shunt catheter with parietal and/or occipital placement: 20.9% and 19.8%, respectively.

Revision and infection rates by component replaced at first revision

Table 24 and Appendix 2, Table 44, summarise the component replaced in participants who had their VPS revised for reason other than infection, as classified by the treating surgeon.

| Summary of shunt components replaced | Failure – no infection,a n (%) | Reason for revision for no infection | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Failure due to patient, n (%) | Functional shunt failure, n (%) | Mechanical shunt failure, n (%) | ||

| Total number of patients | 320 | 14 | 121 | 185 |

| Was a complete new shunt inserted? | ||||

| No | 268 (83.8) | 12 (4.5) | 99 (36.9) | 157 (58.6) |

| If no, which component was replaced? | ||||

| Ventricular shunt catheter only | 72 (26.9) | 0 (0.0) | 22 (30.6) | 50 (69.4) |

| Peritoneal shunt catheter only | 31 (11.6) | 3 (9.7) | 5 (16.1) | 23 (74.2) |

| Valve only | 76 (28.4) | 3 (3.9) | 35 (46.1) | 38 (50.0) |

| Combination | 38 (14.2) | 1 (2.6) | 19 (50.0) | 18 (47.4) |

| Not known | 51 (19.0) | 5 (9.8) | 18 (35.3) | 28 (54.9) |

Most commonly, when a shunt is revised for a reason other than infection, the component replaced is the ventricular shunt catheter (n = 72/268, 26.9%) or the valve (n = 76/268, 28.4%). The component replaced was similar between VPS groups, although valve changes were more common in the antibiotic-impregnated VPS group than in the standard or silver-impregnated VPS groups.

Safety analysis

Efficacy outcomes were analysed by the intention-to-treat analysis population as much as possible. For AEs and SAEs, participants are reported according to the type of VPS in situ at the time of the event. The shunt in situ was known for all patients up to the first revision. However, events occurring following a revision whereby the shunt was not replaced like for like are reported in under ‘other VPS’ group.

The total number of AEs experienced and the number of participants experiencing at least one AE are provided, both overall and split according to the VPS in situ at the time of the event. Of the 1601 participants who received a trial shunt, 413 (25.8%) experienced 654 events. Summarising these events, split by VPS in situ at the time of event, indicates the following:

-

Standard VPS – 135 out of 531 participants (25.4%) experienced 201 events.

-

Antibiotic-impregnated VPS – 136 out of 545 participants (25.0%) experienced 210 events.

-

Silver-impregnated VPS – 140 out of 525 participants (26.7%) experienced 191 events.

-

Other VPS – when the initial trial shunt was removed and not replaced like for like, 35 out of 136 participants (25.7%) experienced 52 events.

Common events were ventricular shunt catheter obstruction (96 events in 79 participants), shunt valve obstruction (65 events in 52 participants) and valve change for symptomatic overdrainage (54 events in 50 participants).

Appendix 2, Table 45, provides the summary of related AEs.

No participant experienced a SAE.

Chapter 4 Economic evaluation

Parts of this chapter have been reproduced from Mallucci et al. 2 This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nd/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. The text below includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original text.

Introduction

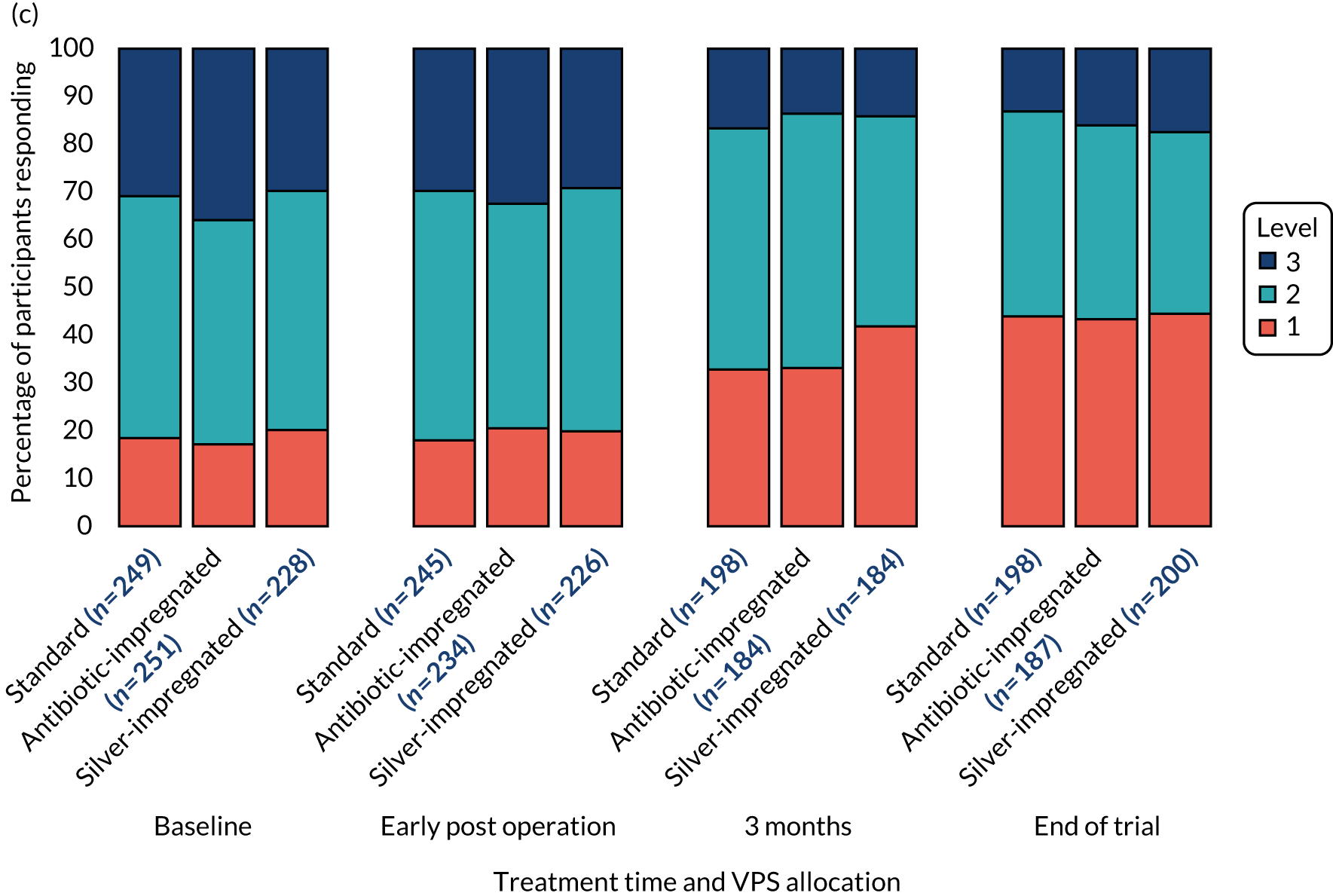

A number of studies32–36 (although none from the UK) have estimated the costs of managing patients with VPS infections. These often combine cost estimates with observed differences in infection rates, between antibiotic-impregnated and standard VPS catheters, in rudimentary cost-effectiveness analyses, to calculate the incremental cost (saving) per VPS infection avoided. This is relevant to inform the best use of health-care resources, given that impregnated VPS catheters are about twice as expensive as standard shunt catheters, but are limited in not assessing all-cause VPS failure or impacts on patients’ health-related quality of life.