Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 16/94/02. The contractual start date was in April 2018. The draft report began editorial review in October 2019 and was accepted for publication in January 2020. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Lyvonne N Tume was a National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Health Technology Assessment (HTA) panel member during the conduct of the study and is the deputy chairperson of the HTA Prioritisation Committee. Chris Gale reports grants from the Medical Research Council during the conduct of the study; and grants from the NIHR (research grant and fellowship for a Doctor of Philosophy student), the Mason Medical Research Foundation (London, UK), Rosetrees Trust (Edgware, UK) and from the Canadian Institute for Health Research (Ottawa, ON, Canada), outside the submitted work. Chris Gale also reports grants and personal fees from Chiesi Pharmaceuticals (Parma, Italy), outside the submitted work (the grant is for a research study and the personal fee was to support attendance at an educational meeting). Chris Gale is vice-chairperson of the NIHR Research for Patient Benefit London Regional Assessment Panel (2016–present). Frederic V Valla reports personal fees from Baxter International (Deerfield, IL, USA) and personal fees from Nutricia (Zoetermeer, the Netherlands), outside the submitted work. Jon Dorling reports grants from the NIHR and from Nutrinia (Nazareth, Israel), outside the submitted work (the grant from Nutrinia in 2018 was for part of his salary to work as an expert advisor on a trial). Jon Dorling was a member of the NIHR HTA General Board (2017–18) and the NIHR HTA Maternity, Neonatal and Child Health Panel (2013–18).

Disclaimer

This report contains transcripts of interviews conducted in the course of the research and contains language that may offend some readers.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2020. This work was produced by Tume et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2020 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Surveys to establish standard practice

Introduction

Work package (WP) 1 involved an electronic survey for all UK paediatric intensive care units (PICUs) and neonatal units (NNUs), to describe ‘standard care practices’ around enteral feeding and gastric residual volume (GRV) measurement.

Study management

This WP was led by LNT (for PICU) and JD (for NNUs). The Study Management Group (SMG) was responsible for providing input into the survey questions and design, with the SMG statistician (BA) analysing the descriptive results, LNT and JD summarising the guidelines, and members of the qualitative SMG (KW and ED) undertaking qualitative analysis of the free-text responses.

Aims and objectives

To describe current unit (PICU and NNU) practices around the measurement of GRV.

Methods

Two separate cross-sectional surveys were developed by the study team, one for PICUs and one for NNUs, in REDCap,1 an online electronic data-capture tool. The surveys were tested for clarity and face validity on clinicians who did not go on to respond to the final surveys. Minor wording adjustments were made to improve clarity, then the surveys were tested again within the study team. Ethics approval for the surveys was provided by the University of the West of England (reference HAS.18.04.144). The Paediatric Intensive Care Society (PICS) Study Group also reviewed and endorsed the PICU survey, as did the Neonatal Nutrition Network.

All UK PICUs (n = 27) and NNUs (n = 184) were invited to complete a survey. Between May and July 2018, each unit was contacted via professional networks and e-mailed an invitation link. Units were asked to complete the survey as a team consisting of a senior clinical nurse, a consultant and a dietitian (or equivalent leads in these three areas of expertise). They were also asked to upload any written guidance that their unit had around enteral feeding. The target response rate was > 70%. This was maximised by sending out three reminders, 1 week apart. Data were summarised using descriptive statistics for quantitative data and content analysis for qualitative free-text data. 2 The unit guidelines were reviewed and summarised.

The paediatric intensive care unit survey

The PICU survey [see project web page: www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/programmes/hta/169402/#/documentation (accessed 13 February 2020)] consisted of 31 closed questions (tick-box responses, with room for free-text responses whenever a tick-box response ‘other’ was chosen), a ranking question and 19 open-ended questions. It was piloted on 10 PICU clinicians (a mix of doctors, dietitians and nurses). The survey focused on three domains: (1) general enteral feeding and nutrition practices in the respondents’ unit, (2) the GRV measurement technique used in the respondents’ unit and (3) clinical management in response to GRV. Twenty-seven UK PICUs were approached: these were units that admit children for at least 24 hours of intensive care and that are part of the national research network (PICS Study Group).

The neonatal unit survey

The NNU survey [see project web page: www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/programmes/hta/169402/#/documentation (accessed 13 February 2020)] consisted of 10 closed questions (tick-box responses, with room for free-text responses whenever a tick-box response ‘other’ was chosen) and nine open-ended questions. It was piloted on 10 NNU staff (doctors, dietitians and nurses). The survey focused on three domains: (1) general enteral feeding and nutrition practices in the respondent’s unit, (2) the GRV measurement technique used in the respondent’s unit and (3) clinical management in response to GRV. One hundred and eighty-four UK NNUs [special care baby units (SCBUs), local neonatal units (LNUs) and neonatal intensive care units (NICUs) who looked after both medical and surgical babies] were approached. These are NHS units that admit babies for at least 24 hours of neonatal care.

Results

Paediatric intensive care unit

Twenty-four of 27 (89%) UK PICUs completed the survey. These were a mixture of general PICUs (13/24, 54%), mixed cardiac surgical and general PICUs (7/24, 29%) and standalone cardiac intensive care units (ICUs) (4/24, 17%). Collective unit responses were completed by senior doctors (22/24, 92%), nurses (23/24, 96%) and dietitians (23/24, 96%). Almost all (23/24, 96%) responding PICUs reported written guidance regarding enteral feeding and most of these (19/23, 83%) were uploaded for review.

All responding PICUs undertook some nutritional assessment at PICU admission (Table 1).

| Nutritional parameter assesseda | Number (%) assessed (n = 24) |

|---|---|

| Actual weight | 20 (83) |

| Estimated weight | 14 (58) |

| Height or length | 13 (54) |

| z-score/weight | 4 (17) |

| Centile chart | 15 (62) |

| Weight for age | 4 (17) |

| Nutritional assessment score | 9 (37) |

| STAMP | 3/9 (33) |

| PYMS | 5/9 (56) |

| BCH | 1/9 (11) |

The first part of the PICU survey consisted of questions regarding general nutrition practices in units. Most PICUs (15/24, 63%) used the Schofield Equation to predict energy requirements and aimed to achieve full energy targets within 48–72 hours. Over half (14/24, 58%) of PICUs had a target time to initiate enteral feeding, and for half (7/14, 50%) of these this was within 6 hours of admission (total range 2–24 hours). Continuous feeding was delivered in the majority of PICUs (15/24, 63%), and 34% (9/24) used intermittent bolus via the gastric route. Continuous feeding was mostly delivered over 24 hours a day (10/15, 66.6%) or over 20 hours a day (5/15, 33%). When feeding was by intermittent bolus, this was predominantly every 2 hours (6/9, 67%). Most units (15/24, 63%) reported using standard rigid gastric tubes, with eight units (33%) using soft silicone tubes as their standard feeding tube. Most PICUs (18/24, 75%) defined feed tolerance or intolerance in their guidance and, of these, definitions included GRV (18/18, 100%), vomiting (12/18, 67%), diarrhoea (9/18, 50%) and abdominal appearance (8/18, 44%). (See Report Supplementary Material 1 for a table of results and the full qualitative analysis of the text responses.)

The rest of the survey asked questions about GRV technique and management in units. Table 2 presents the key findings and further results are given in Report Supplementary Material 1. Table 3 is a summary of the 19 guidelines that were received.

| Practice | Frequency (N = 24), n (%) |

|---|---|

| GRV is routinely measured | 23 (96) |

| There is an agreed feed intolerance definition | 18 (75) |

| The feed intolerance definition includes GRV | 18/18 (100) |

| Frequency of GRV measurement | |

| Before every bolus feed | 2 (8) |

| 4-hourly | 18 (75) |

| 5-hourly or 6-hourly | 3 (12) |

| Only when child is vomiting | 1 (4) |

| Guidance is in place for GRV measurement technique | 8 (33) |

| The syringe size is specified | 17 (70) |

| Size of syringea | |

| 20 ml | 5/17 (29) |

| 50 ml or 60 ml | 10/17 (59) |

| Size varies according to circumstance | 2/17 (12) |

| GRV is used to define maximum threshold | 21 (88) |

| Type of threshold | |

| Maximum volume in ml/kg body weight | 11/21 (52) |

| Maximum volume percentage of administered feed | 6/21 (29) |

| Other | 4/21 (19) |

| GRV maximal threshold to define ‘intolerance’a | |

| 5 ml/kg | 12 (50) |

| Other: ml/kg threshold (up to 10 ml/kg/other) | 2 (8) |

| Gastric aspirate > 2 hours/4 hours/6 hours | 4 (17) |

| > 50% of previous 4 hours of feed | 3 (13) |

| Reason for discarding GRVa | |

| Abnormal colour | 17 (70) |

| PICU number and type | Default feeding method and route | GRV check frequency | Threshold for stopping feeds | Actions if threshold exceeded | Actions if still not tolerating feeds | Feeding defined by risk level: low- vs. high-risk abdomen |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mixed general and cardiac PICU | Bolus gastric | 3-hourly | 5 ml/kg | Return GRV, stop feeds at 3 hours and recheck GRV | Consider continuous feeding, post-pyloric feeding, PN or prokinetics | No |

| Mixed general and cardiac PICU | Continuous gastric | 4-hourly | 5 ml/kg | Return GRV, stop feeds at 2 hours and recheck GRV | Change to post-pyloric feeding | Yes |

| Mixed general and cardiac PICU | Bolus gastric | 4-hourly | > 4 hours of feed volume given | Replace GRV, continue feeding at same rate, recheck GRV at 4 hours | Stop feeds and review by doctor and dietitian | No |

| Mixed general and cardiac PICU | Continuous gastric, but also uses bolus | 4-hourly | > 4 hours of feed volume given or 200 ml | Return GRV, stop feeds at 2 hours and recheck GRV, restart feed at 0.5–1 ml/hour | Change to post-pyloric feeding | Yes |

| Mixed general and cardiac PICU | Bolus gastric | 2- to 6-hourly to first determine the child’s gastric emptying time and prior to every bolus feed | > 50% of last bolus feed volume | Return GRV, stop feeds at 2 hours and recheck GRV | If GET delayed > 6 hours start post-pyloric feeding | No |

| Mixed general and cardiac PICU | Continuous gastric | 4-hourly | 5 ml/kg or 200 ml | Return GRV, stop feeds at 2 hours and recheck GRV | Withhold and discuss regarding post-pyloric feeding | No |

| Mixed general and cardiac PICU | Bolus gastric | Minimum 8-hourly, but done before every 2-hour feed | 5 ml/kg or 300 ml | Return GRV, stop feeds at 2 hours and recheck GRV | Change to continuous feeds, add oral prokinetic or consider post pyloric feeding | No |

| Mixed general and cardiac PICU | Continuous gastric | 4-hourly | 5 ml/kg | Return GRV, stop feeds at 2 hours and recheck GRV | If in first 48 hours stop feeds, after 48 hours change to post-pyloric feeding | Yes |

| Cardiac ICU | Continuous gastric | 4-hourly | 5 ml/kg | Return GRV, stop feeds at 2 hours and r-check GRV | Discuss with doctor and dietitian | Yes |

| Cardiac ICU | Continuous gastric with somatic NIRS monitoring | 4-hourly | > 4 hours of feed volume given | Replace half GRV, stop feeds at 2 hours and recheck GRV | Consider post-pyloric feeding | Yes |

| General PICU | Continuous gastric | 4-hourly | > 4 hours of feed volume given | Return GRV, stop feeds at 1 hour and recheck GRV | No mention | No |

| General PICU | Continuous gastric | 4-hourly | 5 ml/kg or 200 ml | Return GRV and maintain rate of feed | Consider alternative feed, post-pyloric feeding or PN | No |

| General PICU | Continuous gastric, but do use bolus | 4-hourly | 5 ml/kg or 200 ml | Return GRV, stop feeds 2 hours and recheck GRV | Consider post-pyloric feeding | No |

| General PICU | Continuous gastric | 4-hourly | 5 ml/kg or 200 ml | Change to non-fibre feed then return to half GRV and continue same rate for 4 hours | Consider post-pyloric feeding and prokinetics | No |

| General PICU | Bolus gastric | 4-hourly | > 50% of the feed volume given in last 4 hours | Discard GRV and give the previous amount of feed again, recheck GRV | If still > 50%, change to continuous feeding. If still not tolerating, use IV prokinetic and by 72 hours start post-pyloric feeding | No |

| General PICU | Continuous gastric | 4-hourly | 5 ml/kg | Return GRV, stop feeds at 1 hour and recheck GRV | Start prokinetics and post-pyloric feeding | No |

| General PICU | Continuous or bolus feeds | 4-hourly | 5 ml/kg or 250 ml | Return GRV, stop feeds at 2 hours and recheck GRV | Consider prokinetics, rule out constipation and consider post-pyloric feeding | Yes |

| General PICU | Continuous gastric | 4-hourly | > 50% of the feed given in last 4 hours | Notify medical professional/dietitian, stop feed or reduce rate and recheck GRV | Consider post-pyloric feeding if not tolerating by 24 hours | No |

| General PICU | Continuous gastric | 6-hourly | > 6 hours of feed given | Return GRV, stops feeds at 1 hour and recheck GRV | Does not specify | No |

All but one (23/24, 96%) responding PICU measured GRV routinely as part of their standard practice, and none reported that the policy was different for invasively ventilated compared with non-ventilated children. The frequency of GRV measurement was most commonly reported as 4-hourly (18/24, 75%) in the survey and (15/19, 79%) in the unit guidelines. However, most PICUs (16/24, 67%) reported little guidance around the technique of measuring GRV. Only 71% (17/24) of responding units indicated a specific syringe size to use with GRV measurement (but this was rarely written in their guidelines). When this was specified, this was most commonly (10/17, 59%) a 50- to 60-ml syringe. Most units (15/24, 63%) reported that the feeding method (continuous or intermittent) did not influence the frequency of GRV measurement. Half of responding units (12/24, 50%) reported that the size of the child (i.e. > 40–50 kg) did not affect the frequency of GRV measurement.

Almost all (21/24, 88%) responding units reported that GRV was the main indicator to withhold enteral feeding. The decision to withhold feeds was determined most frequently by a maximum volume in ml/kg body weight (11/21, 52%). Twenty-nine per cent (6/21) of units reported using a maximum percentage of volume of feed given, but this was higher (8/19, 42%) in the unit guidelines. The volume above which feeds were withheld was reported as 5 ml/kg by 52% (11/21) of units in the survey and by 58% (11/19) of guidelines. In the seven units whose guidelines stipulated an upper absolute level (for children > 40–50 kg), this was most frequently 200 ml (5/7, 71%). Of the six guidelines that used a percentage of volume of feed given in previous hours to determine whether or not to withhold feeds, this varied from > 50% of feed given in the previous 4 hours to 100% of the feed given in the previous 2–6 hours. A percentage of the volume of the previous 4 hours of feed given was used in 5 out of 19 (26%) guidelines. More than half (14/24, 58%) of responding units reported that they did not vary the threshold according to the size of the child.

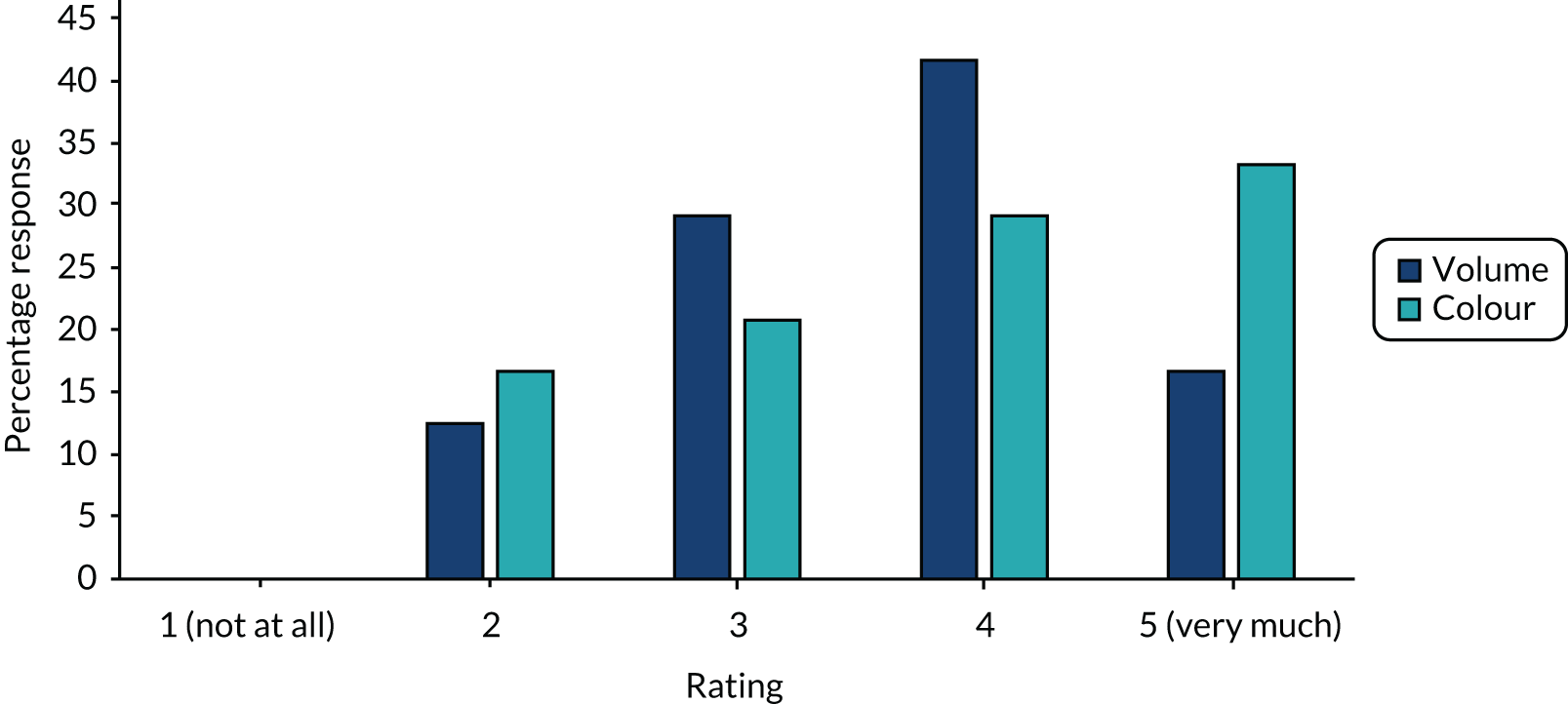

Both volume and/or colour of aspirates affected decisions to stop feeds. Figure 1 shows that most units rated both volume (14/24, 58%) and colour (15/24, 63%) as fairly important.

FIGURE 1.

How much does aspirate volume and aspirate colour affect your decision to stop feeds? (n = 24 paediatric intensive care units.)

Guideline analysis and free-text responses all cited abnormal colour aspirates being green (bilious), red (bloody) or brown (faecal) in appearance and, even if the volume was not large, aspirates of this appearance would be discarded and indicate the withholding of feeds. Most (15/24, 63%) units reported returning GRV. None reported that GRVs were routinely discarded, but that this was dependent on individual patient factors and aspirate appearance. However, most guidelines (16/19, 84%) required to return the GRV in all patients unless it was abnormal in appearance. In response to obtaining ‘high’ GRVs, PICUs reported their actions by free text and then actions were ranked by frequency in the survey. Qualitative responses indicated that for the majority of PICUs, in the first instance, enteral feeds would be withheld for a period of time (commonly 2 hours) and GRV reassessed. After this, actions ranked by order of priority were most commonly (1) changing the feeding method from bolus to continuous feeds, (2) changing to post-pyloric feeding and/or changing the feed formula, (3) adding prokinetics and persisting with gastric feeding and, lastly, (4) stopping enteral feeds and commencing parenteral nutrition.

For 79% of units (15/19), the initial action in response to a large GRV was to stop feeds for a period of time and recheck the GRV. From the guideline review (see Table 3), six units had defined levels of abdominal risk for enteral feeding of children. Five out of these six units admitted cardiac surgical neonates (83%) and defined low- and high-risk abdomens in their protocols based on the patient profile. Defining features of a high-risk abdomen included infants with hypoplastic left heart syndrome, aortic arch abnormalities, shunts and duct-dependent circulations, gut concerns, including confirmed necrotising enterocolitis (NEC) in the last 4 weeks, high vasopressor support, high lactate concentrations, low somatic near-infrared spectroscopy, and after cardiac arrest and extracorporeal life support. In all situations, even when different feeding regimes were specified in relation to risk, both protocols (for low and high risk) still used routine GRV measurement, but the rate of feed delivery and the speed of advancement was much slower in the high-risk patients.

Neonatal units

Ninety-five of 184 (52%) NNUs in the UK, excluding Northern Ireland, completed the survey. These consisted of 40 NICUs, 42 LNUs and 13 SCBUs,3 giving response rates of 71%, 47% and 33%, respectively. Seventeen of a possible 18 NICUs that routinely care for both immediate postoperative surgical and medical patients responded, as did 23 NICUs that routinely care for only medical cases. LNUs and SCBUs do not provide early postoperative care in the UK. 4,5 Survey responses were received from senior doctors (81/95, 85%), nurses (51/95, 54%) and dietitians (9/95, 10%). Table 4 gives a summary of general feeding practices. Most (81/95, 85%) responding units reported written enteral feeding guidance and 28 unit or local neonatal network guidelines were sent to the authors. Enteral feeding was typically delivered intermittently (90/95, 95%), rather than continuously (5/95, 5%). Forty-two out of 95 units (44%) reported having written guidance for measurement and interpretation of GRVs.

| Practice | Frequency (N = 95), n (%) |

|---|---|

| Units had written feeding guidelines/protocol | 81 (85) |

| Standard gastric feeds were intermittent bolus (not continuous) | 90 (95) |

| There was specific guidance about how GRV should be measured and interpreted (e.g. a protocol or guideline) | 42 (44) |

| NICUs that care for surgical and medical babies (n = 17) | |

| GRV measurement differs between the medical and surgical babies | 5/17 (29) |

Ninety units answered questions about the management of non-surgical babies (Table 5). When asked about how often GRV is measured, 20 out of 90 units (22%) measured aspirates before every feed, 26 (29%) units measured aspirates when it was felt to be clinically indicated and 39 (43%) units measured GRV at regular time intervals [most commonly 4- to 6-hourly, 35/39 (90%), but all more frequently than once per day]. One unit had no guidelines on this and four (4%) reported that they did not measure GRV. Among units that reported having written GRV measurement guidance, 13 out of 39 (33%) indicated that the guidance was ‘always’ followed and 17 (39%) indicated that the guidance was ‘usually’ followed; however, free-text responses suggested that practice was ‘very variable depending on the nurse looking after the baby’ (unit 3, surgical and medical unit). The bedside nurse most commonly made decisions in relation to GRV results (56/90, 62%), followed by middle grade doctors (41/90, 46%) and the senior nurse in charge of the shift (26/90, 29%).

| Practice | Frequency (N = 90), n (%) |

|---|---|

| Frequency that staff in your unit measure GRV | |

| Once a day | 0 (0) |

| Before every feed | 20 (22) |

| Only when clinically indicated | 26 (29) |

| At regular intervals | 39 (43) |

| At least every 3, 4 or 6 hours | 35/39 (90) |

| GRV is not measured | 4 (4) |

| How often is specific guidance for GRV measurement followed and undertaken as per protocol [asked only of units with specific guidance for GRV measurement (n = 39)]? | |

| Always | 13 (43) |

| Usually | 17 (39) |

| Often | 4 (10) |

| Rarely/never | 5 (13) |

| Who usually decides what to do with concerning GRV aspirates in the first instance (more than one response allowed)? | |

| Senior doctor (consultant) | 13 (14) |

| Middle-grade doctor (specialist registrar) | 41 (46) |

| Junior-grade doctor (senior house officer) | 18 (20) |

| Bedside nurse | 56 (62) |

| Nurse in charge of shift (senior nurse) | 26 (29) |

| What is usually done with obtained GRV? | |

| Returned | 44 (49) |

| Discarded | 7 (8) |

| Other | 39 (43) |

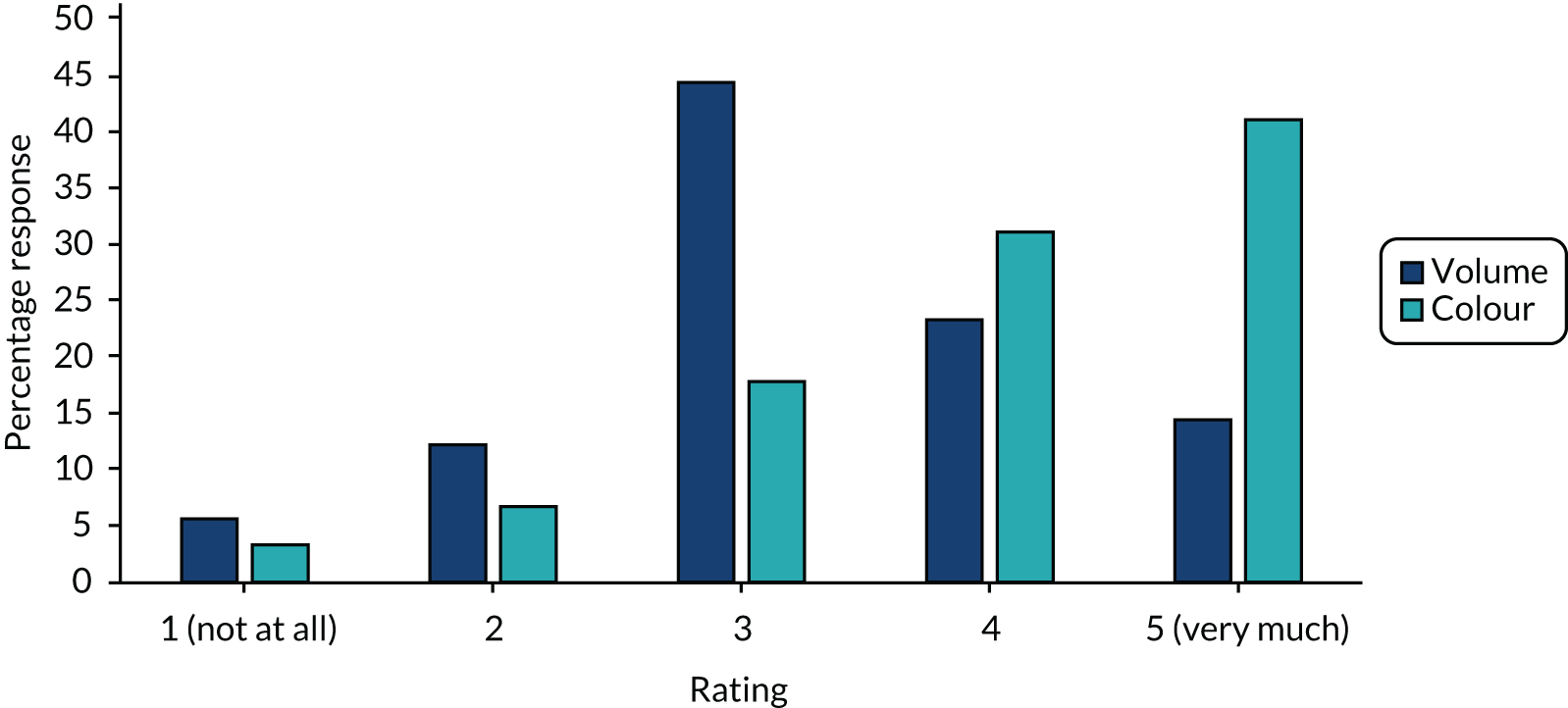

Responding units had mixed views on how useful the volume of the aspirate was for guiding feeding decisions (Figure 2), with 13 out of 90 (14%) units reporting that volume affected clinical decision-making ‘very much’ and the most frequent response was an intermediate score. The colour of the aspirate was felt to be more important, with 37 out of 90 (41%) units reporting that colour influenced clinical decisions ‘very much’ and this was the most frequent response. More detail was obtained from 74 open-text responses to this question. A large volume of aspirate was commonly described as a concern, which would often lead to a clinical review of a baby’s condition and subsequent consideration of how much milk the baby is receiving. The threshold for prompting a feeding review was reported to vary. Some units stated that aspirates > 50% of the feed would ‘prompt a review’ (unit 8, NICU surgical and medical), whereas others stated ‘> 25% of the feed given in previous 6 hours’ (unit 18, NICU medical only), if exceeds ‘25% of the previous 4 hours’ feed volume’ (unit 22, NICU medical only) or ‘if > 25% of the feed volume given since the last assessment was made’ (unit 25, NICU medical only).

FIGURE 2.

How much does aspirate volume and aspirate colour affect your decision to stop feeds? (n = 90 NNUs.)

Almost half (44/90, 49%) routinely returned aspirates to the stomach. Seventy-two nurses gave reasons for seeking medical advice, with 55 (76%) citing increased or large GRVs and 52 (72%) citing bilious colour of the residual or a change in colour. Other reasons were blood-stained aspirates (16/72, 22%), concerns about the condition of the baby, such as arterial oxygen desaturations (16/72, 22%), abdominal distension (11/72, 15%) and vomiting (5/72, 7%). In free-text responses, units stated that that a dark or bilious colour would ‘trigger medical review [by a] middle grade or consultant’ (unit 22, NICU medical only), whereas some described how feeds would be stopped, ‘green aspirate – assess baby and feeds withheld’ (unit 60, LNU). Full summaries of qualitative analyses are presented in Report Supplementary Material 1.

The 28 guidelines received are summarised in Table 6. This shows that 19 out of 28 (68%) guidelines specified a volume of aspirate at which to consider stopping feeds, using a defined proportion of the previous feed. Six guidelines specified this threshold as ≥ 25% of the previous feed, eight guidelines specified ≥ 50% of the previous feed, whereas five guidelines used a level between these. Fourteen guidelines mentioned the bilious green colouring of GRV being an indication to stop enteral feeds, whereas five mentioned blood staining as being important. Vomiting and abdominal distension were also considered important for guiding management, being mentioned by 13 and 12 guidelines, respectively.

| NNU number and levela | Default feeding method | GRV checking | Threshold for stopping feeds |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. NICU | Bolus feeds | Routinely measured, but no mention of frequency or technique | Aspirate > 50% feed volume in previous 6 hours or bilious aspirates |

| 2. NICU | Bolus feeds | Measured, but no mention of frequency or how | Aspirates > 50% or > 1 ml if aspirate contains blood or bile: discard GRV, stop feeds, wait 2 hours and reassess |

| 3. NICU | Bolus feeds | No mention of frequency or technique | Consider stopping if pre-feed aspirate > 4 ml/kg, heavily bile-stained aspirates or two vomits after consecutive feeds |

| 4. NICU | No mention | No mention | No mention |

| 5. NICU | Bolus feeds and advanced as per SIFT | Check GRV no more than 6-hourly unless concerns | Withhold feeds for 6–12 hours if GRV > 40% of feed given, 2 ml or 3 ml (dependent on infant weight) heavily bile/blood stained or abdominal distension |

| 6. NICU | Bolus feeds | Not stated | GRV > 50% volume of feeds over last 6 hours or vomit of this size |

| 7. NICU | 2-hourly bolus feeds advanced as per SIFT | 4- to 6-hourly | Action with gastric residuals, if:

|

| 8. NICU | Bolus feeds, two risk levels, advanced as per SIFT | Routine measurement of full gastric residuals should be avoided. This should only be done, with discussion, as a part of a full medical review by a doctor or ANNP | Signs of feed intolerance may include clinical observations, such as desaturation and bradycardia events, and increased work of breathing, vomiting, abdominal distension and discolouration |

| 9. NICU | Bolus feeds | Not specified |

Medical babies: 2 ml/kg of milky gastric residual is not important and should simply be replaced. When the gastric residual at higher volumes is equivalent to 100% of the bolus feeds, then the feeds should be stopped and a clinical review should be undertaken Surgical babies: aspirate less than half feed volume since last aspirate, replace the aspirate itself and continue feeding. If aspirate is greater than half feed volume but less than whole feed volume, replace half of the aspirate and discard the rest. If aspirate is greater than whole feed volume since previous aspirate, do not replace the aspirate, stop feeding and obtain senior medical and surgical review |

| 10. NICU | Bolus feeds | 4- to 6-hourly |

Examine and assess the baby if vomiting, GRV is > 25% of the previous 4 hours total feed volume, residuals are persisting or increasing Small milky/yellow aspirates up to 2–3 ml are frequently normal. They can be replaced and feeds continued |

| 11. NICU | Bolus feeds | 4- to 6-hourly |

When babies are on any enteral feeds, only aspirate the stomach contents via a gastric tube every 4–6 hours, to check the residual volume. The assessment of the baby should include any abdominal distension, dark green (bilious) aspirates and bowel opening If < 50% of the previous 4- to 6-hour total feed volume is aspirated, then replace the aspirate and continue enteral feeding, provided the baby is otherwise clinically stable If > 50% of the previous 4- to 6-hour total feed volume is aspirated, then discuss with medical staff; often reasonable to replace the aspirate and omit the feed. If necessary, stop the feeds for 4–6 hours and a senior member of the medical/nursing team should then review |

| 12. NICU | Bolus feeds | 6-hourly until infant is fully fed | Signs of intolerance: vomiting, gastric residuals > 25% of previous 6 hours feed volume, persistent or increasing, abdominal distension/increasing abdominal girth, increase in stool frequency |

| 13. NICU | Bolus feeds | Not specified | Large-volume aspirates or dark-green bile-stained aspirates, particularly in association with abdominal distension and/or tenderness are a cause for concern. Small milky/yellow aspirates up to 2–3 ml are frequently normal. They can be replaced and feeds continued |

| 14. NICU | Bolus feeds | No more than 4- to 6-hourly | If vomit or GRV exceeds 33% of the last feed volume or 3.5 ml in a single aspirate, then examine baby. Small residuals normal |

| 15. NICU | Bolus feeds | Not specified |

Isolated large GRV in the absence of other clinical signs and symptoms should not prevent continued feeding Signs of intolerance: vomiting, GRV > 30% of previous 5 hours feed, abdominal distension, unwell baby |

| 16. LNU | Bolus feeds with advancement strategy as per SIFT | Not specified | Aspirate > 50% feed volume or green aspirates |

| 17. LNU | Bolus feeds with advancement as per SIFT | GRV aspirated 4-hourly | GRV > 25% feeds in previous 4 hours combined with abdominal distension and/or vomiting |

| 18. LNU | Not stated | Not specified | 4-hourly NG aspirates are < 25% of total infused in the preceding 4 hours. No significant abdominal distension. No significant vomiting. No bile-stained aspirates |

| 19. LNU | Bolus feeds | Not specified |

Aspirates up to 2–3 ml or 50% of the previous 4 hours, feed can be normal if the baby is well Aspirates > 50% of the previous 4 hours feed or 2–3 ml (whichever is greater) discard aspirate, hold feed and try again in 2 hours If aspirate contains blood or bile then stop feeds |

| 20. LNU | Bolus feeds | Not specified |

If the aspirates are non-bilious and less than half the volume of previous feed then they can be replaced and feeding continued while observing the infant closely If the aspirates are bilious or > 50% of the previous feed volume, consider withholding the feeds on that occasion and assess for any signs of NEC |

| 21. LNU | Bolus feeds | Not specified | No mention |

| 22. LNU | Bolus feeds | 4- to 6-hourly |

If GRV is 25–50% of total, replace the hourly amount, omit the feed and do not increase If GRV is > 50% of total, stop feeds and medical review |

| 23. SCU | Bolus feeds | Not specified | GRV > 2-hourly amount, vomiting or abdominal distension |

| 24. Mixed network | Bolus feeds | Not specified | GRV > 25% (some > 50%) in previous 4 hours in combination with vomiting and abdominal distension plus bilious aspirates |

| 25. Mixed network | Bolus feeds | 4-hourly | Stop feeds if GRV heavily blood or bile stained. No mention of volume |

| 26. Mixed network | Bolus feeds | Not specified |

GRV should not be used in isolation to determine feed tolerance Intolerance: vomiting plus GRV > 50% in the last 4 hours (especially if increasing) plus abdominal distension |

| 27. Mixed network | Bolus feeds advanced as per SIFT | Not specified |

Infants ‘feed tolerance’ assessed with each set of cares (high risk), assess twice daily (moderate risk) and before making changes in feed volumes (standard risk) Assessing tolerance: undigested gastric residuals using a colour chart, GRV not used in isolation If vomiting, GRV > 25% of feed volume in last 4 hours + bloody or bilious residuals + abdominal distension |

| 28. Mixed network | Bolus feeds | Assess GRV 4- to 6-hourly depending on cares |

If GRV > 50% of total, stop feeds and medical review If GRV 25–50% of total, replace the hourly amount, omit the feed and do not increase An appropriate GRV is < 25% of preceding volume since last replacement of GRV Replace GRV in full A GRV > 25% but < 1.5 ml is unlikely to be problematic A GRV of 25–50% is high, but acceptable if well, replace only normal hourly volume and continue feeds but do not increase A GRV > 50% is excessive, perform a clinical exam and if acceptable hourly volume can be replaced, but with feed withheld |

Summary of findings to inform the GASTRIC trial

Paediatric intensive care unit current practice

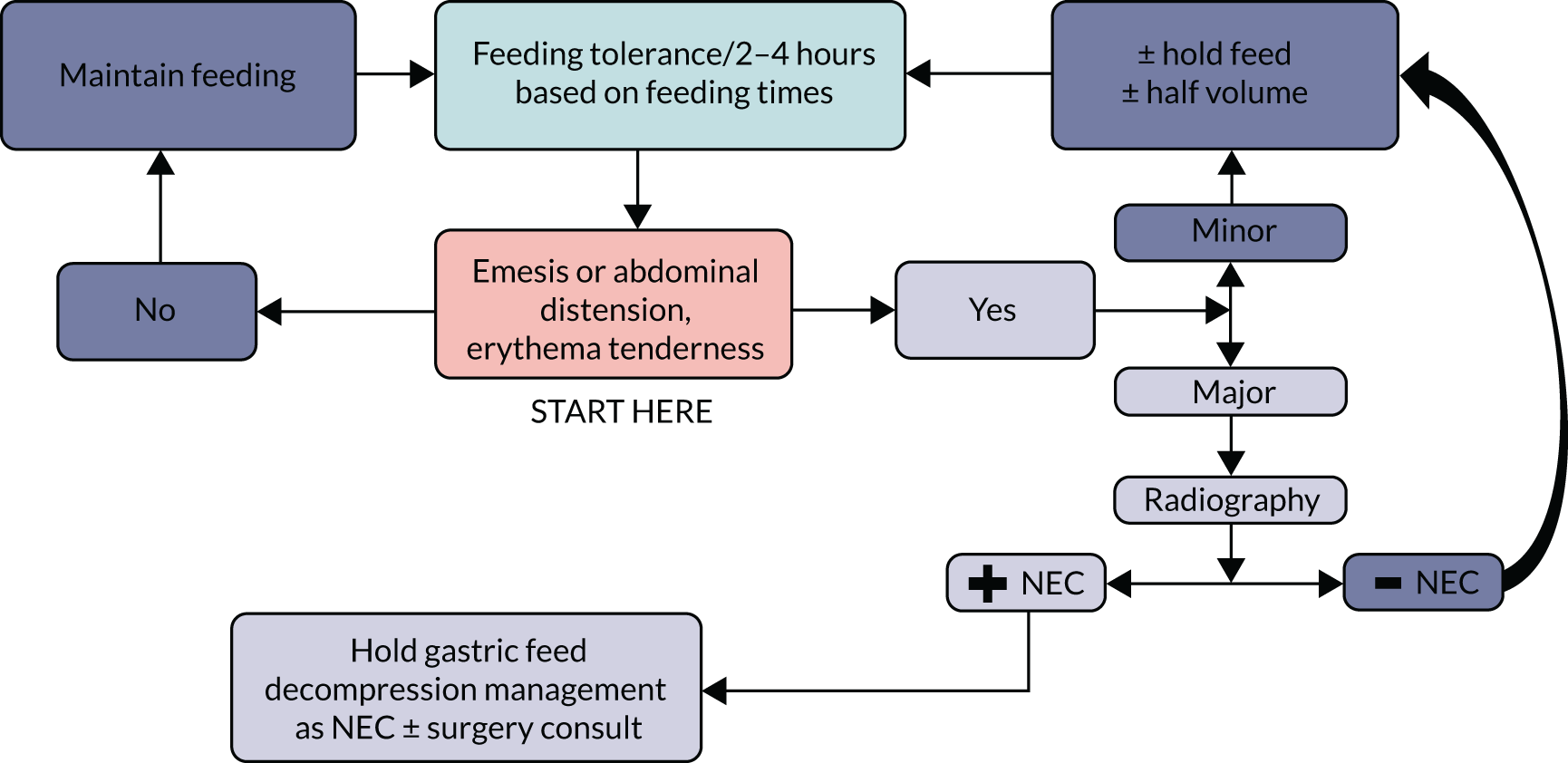

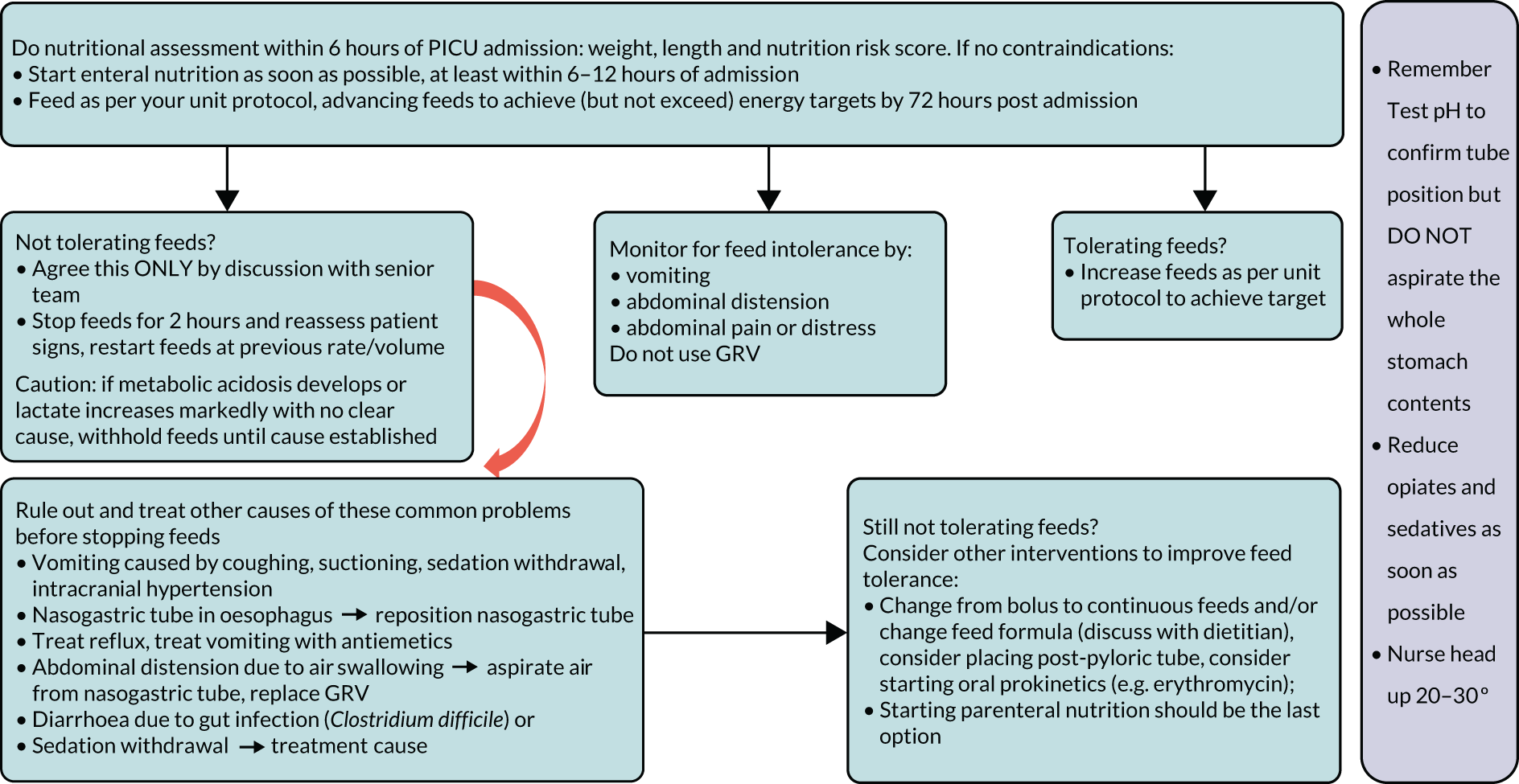

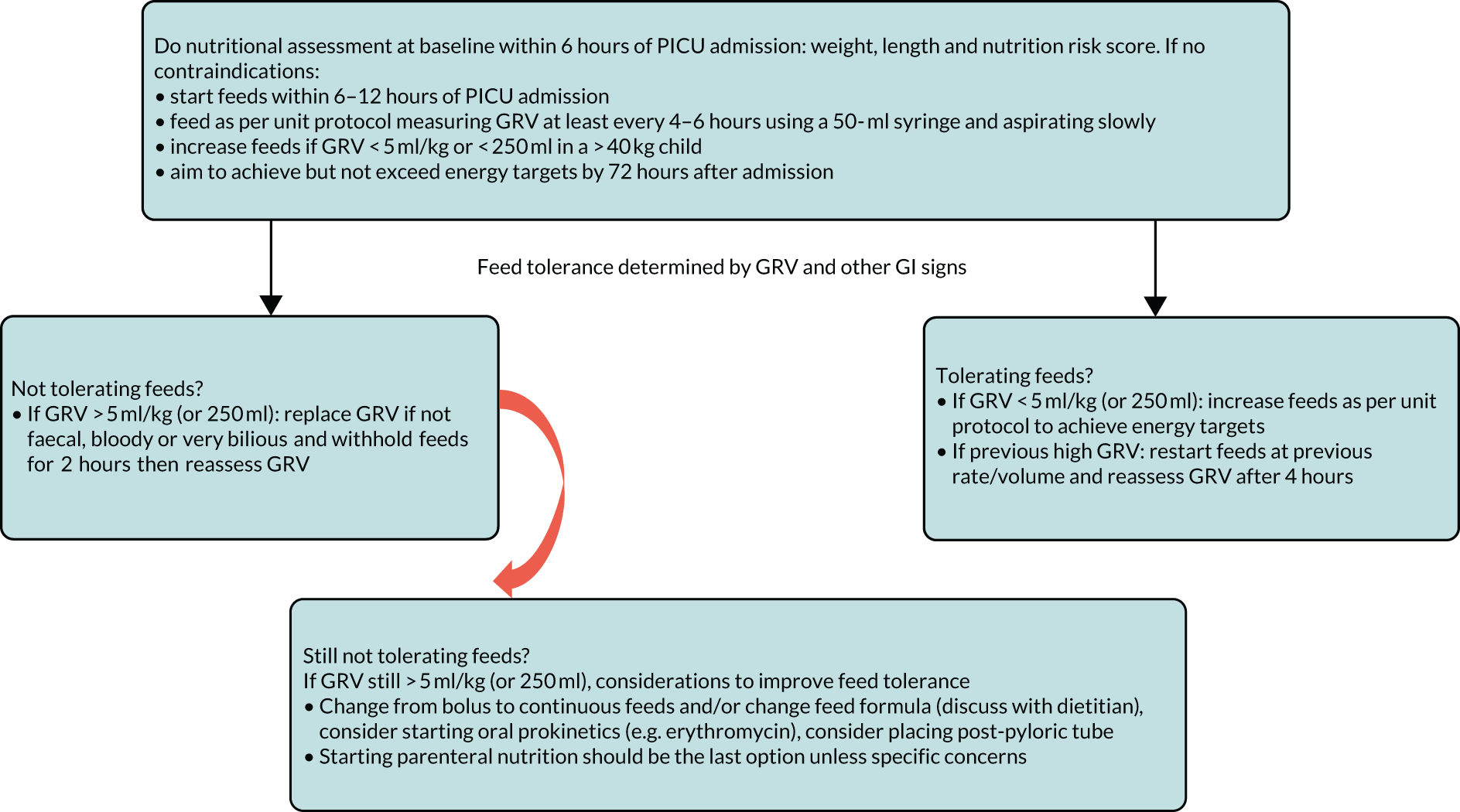

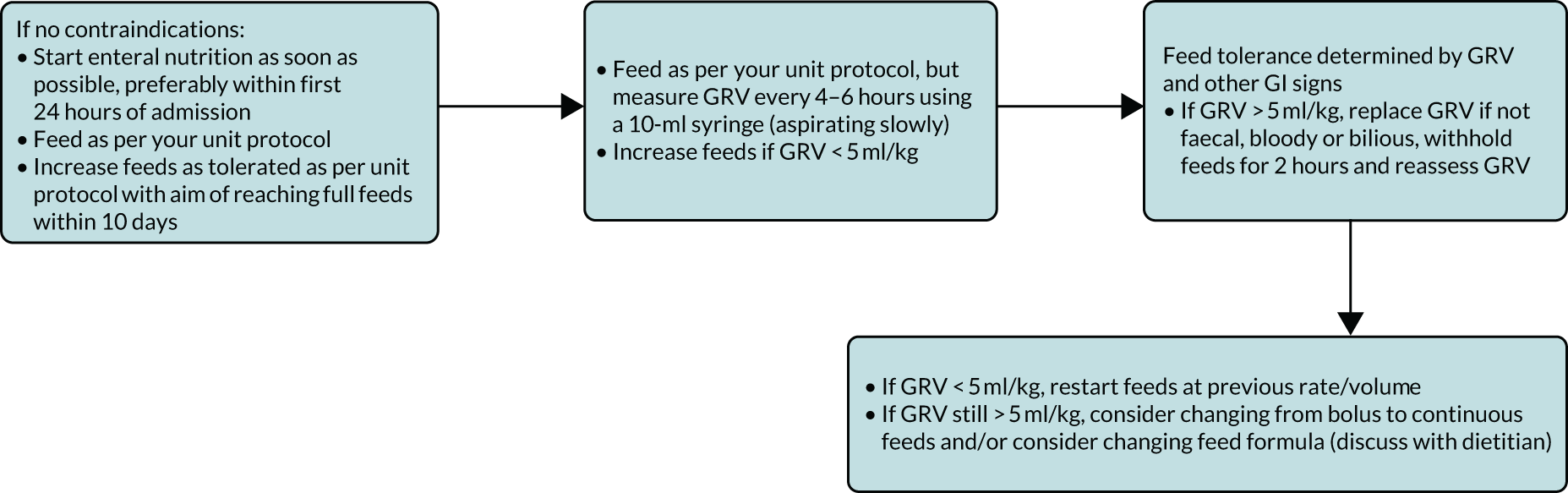

The routine and frequent measurement of GRV is embedded into enteral feeding practice and guidelines in UK PICUs, yet little specific guidance is provided about the technique. This is despite a lack of evidence and questionable accuracy of this parameter. For most units, GRV is the main defining assessment of feed tolerance or intolerance and the most commonly used threshold is a GRV ≥ 5 ml/kg. Colour was as important as volume in the decision-making regarding whether to return or discard GRV and to withhold feeds. This survey has established current practice around GRV measurement in UK PICUs, which enabled us to develop a ‘control’ arm of a future trial of not routinely measuring GRV in critically ill children (see Appendix 1 for flow chart). These results have been published. 6

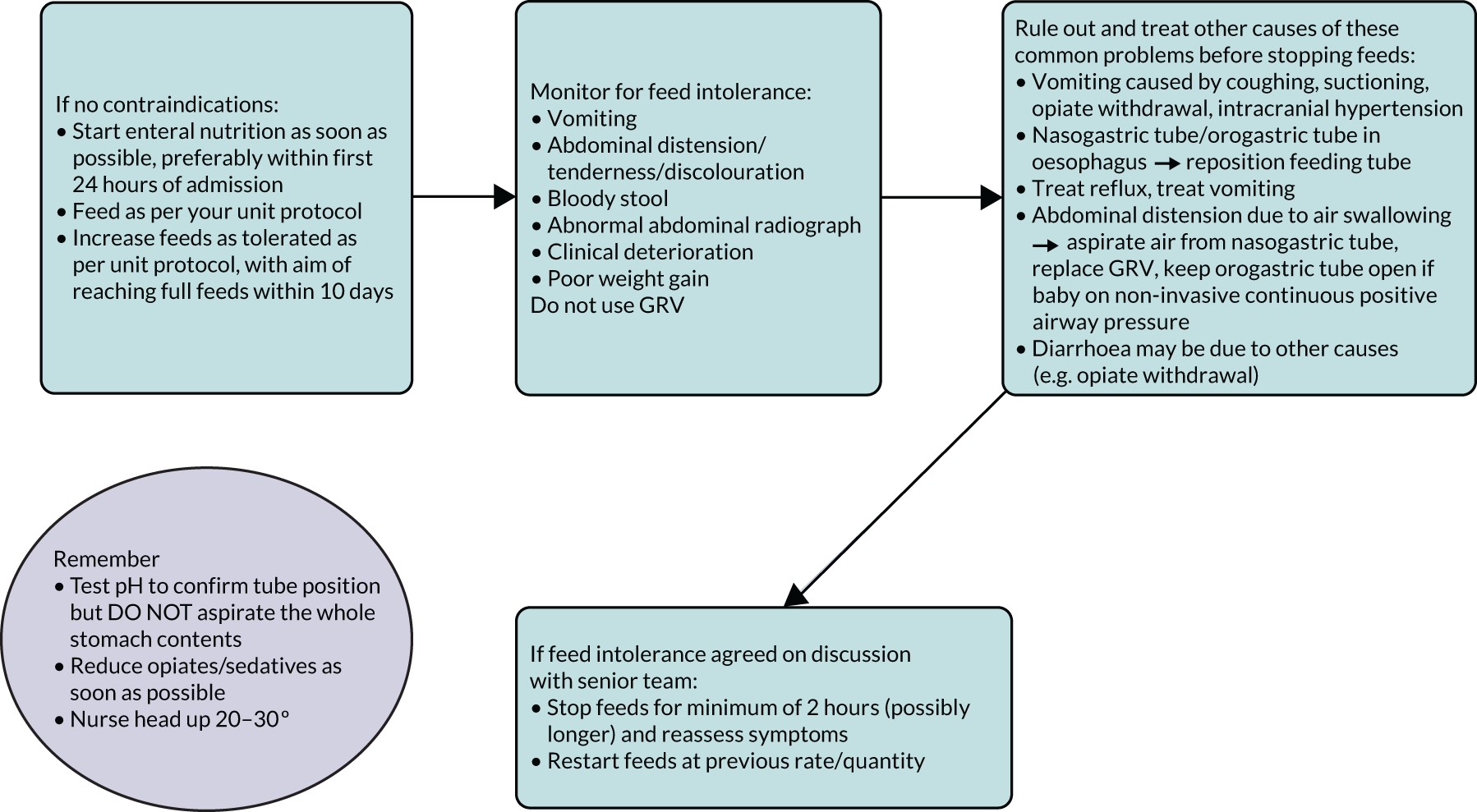

Neonatal unit current practice

Neonatal units show a more mixed practice for both measuring GRV and in how GRV is used to make decisions about enteral feeding. However, around half of UK NNUs still routinely use GRV as a parameter to guide enteral feeding advancement. Health professionals’ views around the importance of the volume compared with colour of the GRV were inconsistent, and importance was defined at different thresholds. Aspirate colour was often cited as more important than volume; however, the importance placed on this was inconsistent. Some unit guidelines specified actions based on bilious or blood staining of the secretions, whereas others did not.

Understanding current practice in both settings has enabled us to construct a ‘control arm’ for a future trial in both settings, which reflects the most prevalent practices across the units (see Appendices 1 and 2).

Chapter 2 Interviews and focus groups involving parents and health-care professionals

Study design

Work package 2 was a mixed-method study involving interviews with parents with relevant PICU or NNU experience, as well as focus groups and interviews with NNU and PICU health-care professionals (HCPs), including nurses, doctors, surgeons and dietitians.

Objectives

To explore the views of parents with NNU and PICU experience on:

-

the acceptability of the proposed trial

-

potential barriers to recruitment

-

participant information

-

whether or not they would be happy to consent to their child’s participation in the trial

-

potential parent-centred outcome measures.

To explore HCPs’ views on:

-

the acceptability of the trial, including the proposed inclusion and exclusion criteria and equipoise

-

the acceptability of not measuring GRV and other measures used to assess feeding tolerance

-

the willingness to randomise to a future trial, including potential barriers to recruitment consent

-

associated training needs.

Study management

The WP 2 team was led by co-investigator (KW). Two experienced research associates (LR and ED) were employed to organise, conduct and analyse interviews and focus groups. The SMG was responsible for overseeing day-to-day management of the entire GASTRIC feasibility study, including the WP 2 qualitative work.

Design and development of the protocol

The design and development of the protocol, including sample estimation, recruitment strategy, information sheets [see project web page: www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/programmes/hta/169402/#/documentation (accessed 13 February 2020)] and interview topic guide [see project web page: www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/programmes/hta/169402/#/documentation (accessed 13 February 2020)], were informed by previous research. 7–11 A review of previous studies of GRV in different populations was conducted prior to this study to develop a list of outcomes to inform outcome-related discussions with parents during interviews. A voting system, using TurningPoint software (Turning Technologies, Youngstown, OH, USA), was used alongside verbally administered questions in practitioner focus groups. This involved some of the key questions [see project web page: www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/programmes/hta/169402/#/documentation (accessed 13 February 2020)] being presented to the group and each participant using a wireless handset to select their answer from those shown on the screen. This method enabled the collection of data from all participants, as well as a means of generating statistical data from all sites alongside qualitative data from group discussions. The same quantitative questions were verbally administered during HCP telephone interviews and recorded by the researcher using a questionnaire [see project web page: www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/programmes/hta/169402/#/documentation (accessed 13 February 2020)], allowing for collation of interview and focus group data.

Recruitment

Participants

Based on our team’s previous relevant studies,7–10 it was anticipated that 20–30 parents (10–15 in each setting) would be recruited to reach data saturation point. This is when the major themes identified in new data are recurring from previous participants or transcripts and no new major themes are being discovered in analysis. 12,13 We aimed to hold between two and four focus groups for HCPs [e.g. two focus groups (one NNU, one PICU) in the north of England and two focus groups (one NNU, one PICU) in the south of England]. It was expected that each focus group would involve 8–12 practitioners. 14 We anticipated conducting up to 10 telephone interviews with HCPs unable to attend the focus groups.

Eligibility criteria

Inclusion criteria

Parents of children with experience of tube feeding in NNU and/or PICU in the last 3 years and HCPs with involvement in decisions about feeding (nurses, doctors or dietitians) currently working in NNUs and PICUs in the UK were included.

Exclusion criteria

Parents who were unable to speak English and HCPs not working in the specialty were excluded.

Recruitment and sampling procedure

Parents

We recruited parents through three routes to maximise the potential sample in the recruitment period and to encourage sample diversity.

Recruitment route 1: social media or website advertising

An advertisement was posted on Twitter (URL: www.twitter.com; Twitter, Inc., San Francisco, CA, USA) and Facebook (URL: www.facebook.com; Facebook, Inc., Menlo Park, CA, USA), which invited parents to register interest in participating in the study. Relevant charities and support groups were asked to place an advertisement on their website and social media [e.g. Bliss (URL: www.bliss.org.uk), Sepsis Trust (URL: https://sepsistrust.org), hospital charities, GASTRIC study (URL: www.grvstudy.com) and Mumsnet (URL: www.mumsnet.com)]. In addition, the study team posted the media advert in relevant university internal newsletters.

Recruitment route 2: national contacts and existing database

E-mails were sent from the study team to their professional national contacts. In addition, e-mail invitations were sent to eligible parents from the FEVER feasibility study7 who had given consent to be contacted about related studies.

Recruitment route 3: national newspaper

To assist recruitment and sample variance, we placed an advertisement in the London Metro newspaper. This helped to balance the predominantly northern sample that was available at that point in recruitment (September 2018).

Health-care professionals

Focus groups were held in different geographical locations (north, north-west and south) to encourage the involvement of HCPs from across the country. We purposively targeted individuals, to include those unable to attend a focus group and include all key professional groups (e.g. doctors, nurses, dietitians and surgeons). We recruited through e-mail invitations and networks known to the co-applicants of the study, including the PICS and British Dietetic Association. HCPs were invited to participate in a telephone interview and if no response was made to the researcher, they were not contacted again.

Screening and conduct of interviews and focus groups

Parent interviews

Screening

Parents’ expressions of interest to participate were responded to in sequential order. Once eligibility was confirmed, an interview date and time was scheduled. A participant information sheet (PIS), a draft GASTRIC randomised controlled trial (RCT) PIS [see project web page: www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/programmes/hta/169402/#/documentation (accessed 13 February 2020)] and list of potential outcomes (see Appendix 3) were e-mailed to parents to read prior to interview. Screening and interview conduct stopped when data saturation and sample variation (e.g. recruitment of parents via multiple recruitment routes) was achieved.

Informed consent

Audio-recorded verbal consent was sought over the telephone before the interview. This involved reading each aspect of the consent form to parents, including consent for audio-recording and to receive a copy of the findings when the study was complete.

Conduct of parent interviews

Interviews began with a discussion about the aims of the study, and included an opportunity for questions and checking that the parent had had enough time to read the information sheet and list of potential outcomes. Interviews commenced using the interview topic guide to explore:

-

experience of having a child with a feeding tube in a NNU or a PICU

-

any previous experience of participation in clinical trials

-

the length and content of the draft GASTRIC study PIS

-

the acceptability of measuring GRV

-

the acceptability of not measuring GRV

-

potential barriers to participation in the trial and how these could be addressed

-

potential facilitators of trial participation

-

trial design, including the selection of outcome measures and randomisation method

-

whether or not parents would (hypothetically) consent to their child taking part in the proposed GASTRIC study.

Respondent validation14 was used to add unanticipated topics to the topic guide as interviewing and analysis progressed. After the interview, participants were sent a copy of the consent form and a thank you letter, including a £30 Amazon voucher (Amazon.com, Inc., Bellevue, WA, USA), to thank them for their time. A copy of the consent form was retained by the University of Liverpool. Researchers (LR and ED) conducted a similar number of parent interviews.

Health-care professional focus groups and interviews

Informed consent

At the start of the focus group or interview the researcher checked that all participants had read the PIS. The focus group or interview aims and topics to be covered were discussed, followed by an opportunity for questions. Participants were asked to provide written consent before the focus group began. Using the same procedure as the parent interviews, audio-recorded verbal consent was sought over the telephone before the HCP interviews.

Conduct of health-care professional focus groups and interviews

Three researchers were involved in the focus group facilitation (LR, n = 3; KW, n = 1; ED, n = 2) and two researchers were involved in conducting interviews (LR, n = 8; ED, n = 2). An ‘ice breaker’ question was used at the beginning of the focus group to help demonstrate how the voting system would work alongside verbally administered questions. Staff were then asked to introduce themselves, their role within the ICU and their experience of recruiting to clinical trials.

Focus group and interviews explored site HCPs’ views and experiences on:

-

the current approach to GRV measurement

-

the acceptability of measuring GRV

-

the acceptability of not measuring GRV

-

potential barriers to the trial and how these could be addressed

-

potential facilitators of trial participation

-

trial design, including randomisation method, inclusion and exclusion criteria

-

perceived training needs

-

the acceptability of the proposed GASTRIC study.

Transcription

Digital audio-recordings were transcribed verbatim by a professional transcription company (Voicescript Ltd., Bristol, UK) in accordance with the Data Protection Act 1998. 15 Transcripts were anonymised and checked for accuracy. All identifiable information (e.g. names of patients, family members or the hospital where their child was admitted) was removed.

Data analysis

Quantitative data from the practitioner-closed interview and focus group questions were entered into Statistical Product and Service Solutions (SPSS) version 20.0 (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA) and examined using descriptive statistics. Qualitative interview and focus group data analysis was interpretive and iterative. 16,17 Utilising a thematic analysis approach18 (Table 7), the aim was to provide an accurate representation of views on trial design and acceptability. Thematic analysis is a method for identifying, analysing and reporting patterns (or themes) within data. Analysis was informed by the work of Braun and Clarke2 and their guide to thematic analysis. This approach allows for themes to be identified at a semantic level (i.e. surface meanings or summaries) or at a latent level (i.e. interpretive, theorising the significance of the patterns and their broader meanings and implications). 19 NVivo 10 software (QSR International, Warrington, UK) was used to assist in the organisation and coding of data. The researchers (ED and LR) led the analysis and 10% of the analysis was second coded by the qualitative lead (KW).

| Phase | Description |

|---|---|

| 1. Familiarising with data | ED (parents) and LR (practitioners) read and reread transcripts noting down initial ideas |

| 2. Generating initial codes | Initially, two data coding frameworks were developed using a priori codes identified from the project proposal and the interview topic guide. During the familiarisation stage, LR and ED identified additional data-driven codes and concepts not previously captured in the initial coding frame |

| 3. Developing the coding framework | 10% of the transcripts were double coded. LR, ED and KW all reviewed and discussed both initial coding frames (practitioner and parent), making notes on any new themes identified and how the framework could be refined |

| 4. Defining and naming themes | Following review and reconciliation by ED, LR and KW, revised coding frames were subsequently developed and ordered into themes (nodes) within the NVivo database |

| 5. Completing coding of transcripts | LR and ED completed coding of all transcripts in preparation for further analysis |

| 6. Producing the report | ED, LR and KW developed the manuscript using themes that related back to the study aims to ensure key findings and recommendations were relevant to the GASRTIC study. Final discussion and development of selected themes occurred during the write-up phase |

| 7. Participant validation | During PPI webinars and consensus meetings, findings were presented back to parents and practitioners who then had a chance to discuss, validate or disagree with the presented results |

Outcomes analysis

To rank parents’ prioritised outcome measures, we conducted an additional analysis step involving content analysis. 20 Outcomes identified during the thematic analysis were cross-referenced by participant and by question and entered into an Excel® version 1908 (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA) database. The number of times each outcome was prioritised was then counted. A weighted point-based system was used to combine findings from all outcome questions and determine the top prioritised outcomes by group. For example, each time an outcome was ranked first it received 6 points, if it was ranked second it received 5 points and if it was mentioned as an important outcome but subsequently not included in the ranked list it received 1 point.

Results

Participants: parents

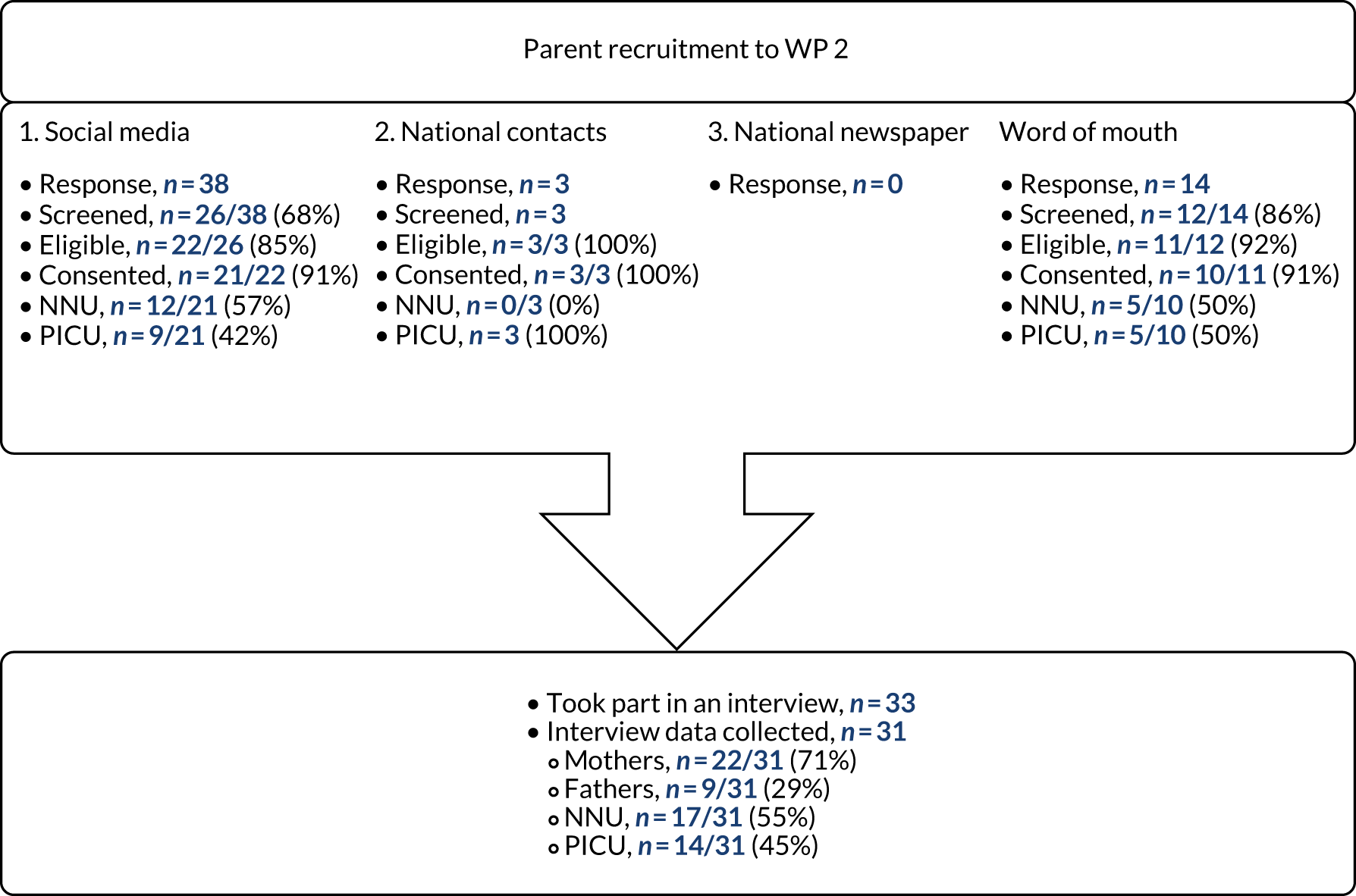

A total of 55 parents registered interest (Figure 3), of whom 41 were screened. Five parents were deemed ineligible and five parents did not respond to contact. Two PICU parents were interviewed, but not included in the sample because of recording equipment failure and seven parents were not interviewed as data saturation had been reached. Our sample of 31 parents included 17 parents with experience of NNUs and 14 parents with experience of PICUs. Interviews took place between May and November 2018.

FIGURE 3.

Parent recruitment to WP 2.

Most participants were recruited through social media (19/31, 61%) and despite advertising nationally, a large proportion of expressions of interest came from the North West. This geographical clustering was reinforced by the WP 2 team’s location in Liverpool and the second most effective recruitment method was word of mouth (9/31, 29%). Although not originally planned as a recruitment route, several parents expressed an interest in taking part in the study after hearing about it from friends, family and other participants. The newspaper advert did not yield any response.

Parent characteristics

The sample included 22 mothers (n = 12, NNU; n = 10, PICU; n = 4, bereaved) and nine fathers (n = 5, NNU; n = 4, PICU; n = 1, bereaved). Most parents lived in the north-west of England (23/31, 74%) and the remainder were from across England (Yorkshire and the Humber, n = 3; South East, n = 2; South West, n = 1; North East, n = 1) and Scotland (n = 1, 3%). The majority (26/31, 84%) of parents did not have medical backgrounds or related occupations. The five parents with health-care-related occupations had roles that included ambulance dispatcher, health-care assistant, physiotherapist, paediatric research nurse and a speech and language specialist.

Neonatal unit parent interviews (n = 17) related to 19 children. Three mothers had twins who were both admitted to NNU and one set of parents were interviewed separately regarding the same child (Table 8). PICU parent interviews (n = 14) related to 10 children, with four sets of parents interviewed separately regarding the same child (see Table 8). Six out of 10 children had also been admitted to NNU at birth and five children had had multiple PICU admissions.

| Characteristic | NNU | PICU |

|---|---|---|

| Child age at hospital admission (or birth) | Median 29 gestational weeks at birth (range 24–41 weeks) | Median 8 months (range 3 weeks to 12 years) |

| Days in unit | Median 21 (range 1–140, missing n = 1) | Median 8 (range 2–72) |

| Days in hospital | Median 57 (range 7–152) | Median 39 (range 3–196) |

| Days on feeding tube | Median 58 (range 2–210) | Median 127.5 (range 5–547) |

| Days on breathing support | Median 56 (range 0–370) | Median 6 (range 0–168) |

| Main reason for admittance |

Prematurity (n = 18) Meconium aspiration syndrome (n = 1) |

Heart conditions (e.g. congenital heart defect, hypoplastic left heart syndrome) (n = 4) Sepsis (n = 2) Reconstruction of airway (n = 1) Complications linked to chronic conditions (e.g. holoprosencephaly, Noonan syndrome, prematurity) (n = 3) |

Collectively, parents had experience of ICU and tube feeding spanning 21 hospitals. This experience varied from hospital admissions due to short-term acute health conditions to chronic conditions, when children had been placed on feeding tubes at birth and were still on them at hospital discharge (see Table 8). Although ventilation was not a separate inclusion criterion, most of the sample (28/31, 90%) had experience of their child being ventilated. Sixteen parents (50%) had experience of their child being approached to take part in a clinical trial (NNU n = 10, PICU n = 6). Telephone interviews took place, on average, 11 months (range 0.8–37 months) from admission to hospital and took a mean of 68 [standard deviation (SD) 12.7] minutes.

Participants: health-care professionals

Five focus groups were conducted at three UK hospitals: two in NNUs and three in PICUs. Forty-two HCPs (NNU, n = 16; PICU, n = 26) participated in one of the five focus groups. As most focus group participants were nursing staff, we purposively contacted doctors (n = 10), surgeons (n = 3) and dietitians (n = 5) and invited them to take part in a telephone interview. Five additional dietitians expressed interest in being interviewed after receiving study information through their professional networks. Of those we directly targeted, 12 out of 21 (57%) did not respond. A total of nine interviews were conducted. Ten hospitals from across England and Wales were represented in the combined interview and focus group sample. Focus groups and interviews were conducted between May 2018 and November 2018.

Health-care professional characteristics

Sixty-two per cent (26/42) of focus group participants were nurses. The remainder were research nurses (5/42, 12%), senior doctors (3/42, 7%) and dietitians (2/42, 5%). Six participants (6/42, 14%) categorised themselves as ‘other’. Three were student nurses and three did not specify. The interview sample included three consultant doctors (NNU, n = 2; PICU, n = 1), four dietitians (NNU, n = 1; PICU, n = 3) and two consultant surgeons (both worked with NNU and PICU patients).

The majority (45/51, 88%) of HCPs were involved in the direct clinical care of children and/or had experience of conducting paediatric clinical trials (39/51, 76%). Focus groups took, on average, 55 minutes (range 49–68 minutes) and telephone interviews took, on average, 32 minutes (range 26–45 minutes).

Parent perspectives

Prior to interviews, parents were sent copies of the draft PIS for a future RCT and a list of potential outcome measures to read. At the start of each interview, parents were asked questions about their experiences of their child’s hospital admission and tube feeding. The interview then moved on to discussions about the proposed GASTRIC RCT.

Views on feeding

Parents’ views around GRV measurement and the perceived acceptability of a future GASTRIC trial was intrinsically linked to their views on the importance of feeding in the ICU. The extent to which parents viewed feeding as a priority appeared to be influenced by their child’s prognosis and associated comorbidities or complications. For example, parents of children who experienced an imminently life-threatening condition, such as sepsis, had not considered feeding to be a priority in the ICU:

Bottom of the pile, yes, you know, the fact is they needed to – well initially we needed to try and get these feet not being black, erm, erm . . . Well initially obviously they were trying to keep her alive, erm, but, but, but the next thing was trying to get these feet, erm, to not be black as I, as, so I’ve said and, and make sure, you know, things like peeing for England, make sure everything was working as it should, and that the, the, the sepsis had gone.

P24, mother, PICU

Once the immediate threat to life had been addressed, parents described how feeding increased in importance, as it was a sign that their child was getting better:

But obviously the main concern at that point was getting her better and then, when we went into HDU [high dependency unit], I was like more worried about like her weight and her getting back to normal.

P21, mother, PICU

By contrast, parents of children with a long-lasting condition, such as prematurity, viewed feeding as very important from the onset of their experience. Weight gain and calorie consumption were seen to have a direct causal relationship with short- and longer-term outcomes. These included reduced length of time on breathing support, time in the PICU or NNU, number of infections, improved kidney function, ability to undertake and survive medical procedures, reduced chance of NEC, and overall health and development:

With our two being premature and being quite small, um, we knew that gaining weight was central to them going home and we also knew that the greater their weight, the less risk there was of an infection or something having a serious impact upon them. We knew that once they got up to full feeds the incidences of NEC reduced greatly as well.

P05, father, NNU

So they just wanted to make sure that she was having enough calories intake in her so that she could thrive basically and, um, she’d get bigger and stronger and, you know, hopefully the, the heart would stabilise.

P27, mother, PICU and NNU

Feeding was particularly pertinent to NNU and PICU parents whose children had experienced difficulties with feeding (e.g. reflux, vomiting, unsafe swallow, aspiration and oral aversion), weight gain or problems related to the child’s bowels (e.g. suspected NEC, bowel loops, bowel perforations, stoma) and breathing. Both NNU and PICU parents also described concerns about their children being force fed or overfed, leading to discomfort, vomiting, aspiration and oral aversion:

He always used to scream after his feeds, and, um, I said, it just feels like I’m force-feeding him; I actually said that to her, I said I feel like, you know, he’s like foie gras or something . . . he’s obviously in pain.

P02, mother, NNU

Yeah, it was a big, big issue, um, for me, because of him being sick. I felt like I was force feeding my child, um, to the point of him being sick and because of the pressure put upon us, um, by kind of the dietitians obviously to get certain amounts . . . of food needed, he needed to be getting his calories, especially as he had more surgery. It was really difficult for me.

P18, mother, PICU and NNU

In addition to being viewed as medically important, feeding of young children was something that parents, particularly mothers, felt was a key part of their parental role and responsibilities:

I think as a mother, it just feels like my primary role in a way, I was supposed to provide milk and ensure he grew.

P19, mother, PICU

During interviews, parents often described how feeding was also one of the few areas of their child’s care that they felt they could be actively involved in within the ICU:

. . . cause everything’s done for your baby other than like you can change a nappy. A lot of the practical care you can’t do, which is . . . it’s quite powerless, isn’t it, so it’s nice to be able to have like some hands-on time so yeah, it was really good.

P16, father, NNU

Children of parents in our NNU sample had a higher proportion of long-lasting illnesses and associated comorbidities than children of parents in the PICU sample. Consequently, it follows that feeding was more of a priority for NNU parents than for PICU parents. However, this prioritisation was formed on experiential knowledge of the importance of feeding gained during their hospital stay. In the first few days of NNU (which would be the point at which children would be eligible for inclusion in the proposed GASTRIC trial), parents would not have such experience. As the following quote illustrates, parents were initially unaware of how difficult, yet important, establishing feeds was at the beginning of their NNU stay and would still be in what feels like an acute situation:

I remember them saying, oh, they’ve coped really well with the last feed, and you think, coped really well? How hard is eating? And they don’t explain to you that it can have a huge a huge impact on their, on their kidneys and everything, because if they’re so premature, then their insides are immature as well, and so they might not even be able to filter through the nutrients, and you’re just left there with your mouth open going, what?

P11, mother, NNU

By comparison, over half of the PICU parents had past NNU experience and would therefore have already developed views on feeding in the early phase of their PICU stay.

Views on gastric residual volume measurement

Twenty-one parents recalled their child’s GRV being measured (NNU, n = 15; PICU, n = 6). Eight reported watching stomach contents being checked for pH and tube placement, but not GRV measurement (NNU, n = 3; PICU, n = 5). Three PICU parents stated that they were certain that GRV measurement had not taken place during the period in which their child was receiving tube feeding in NNU, PICU or at home. Those who did recall GRV being measured had varying understanding of its utility. Some were aware of GRV measurement, but had no understanding of its purpose, risks or benefits, as clinicians had not explained the procedure:

I mean obviously when the procedure was done whilst we were in the NNU, no one really explained why they were doing it, you know, what the benefits were or, um, I suppose what the negatives were for not doing it. I don’t think anyone ever discussed it, it was just a procedure that, er, was carried out.

P07, mother, NNU

Most parents had a basic understanding of its function, which they described as to see if their child’s bowels were working, to check milk tolerance, to guide food volumes or to help detect infections. Some had developed medicalised knowledge of the process and in some cases had performed GRV measurement themselves:

I remember a nurse explaining that they were doing it to see how much milk had been digested and that if all of the milk had been digested it was a good sign that they’re, um, bowels were working normally.

P05, father, NNU

They were, erm, sort of like take it out, erm, and then write it into the computer, erm, and they work it out but if there was so much, if there was too much left then they wouldn’t do the next one as much.

P21, mother, PICU

Some parents noted that GRV process differed between and within hospitals, in terms of frequency and execution. Such differences led parents to comment on how GRV measurement was not a ‘scientific’ (P30, mother, bereaved, PICU and NNU) or consistent process:

I would say it differs quite considerably between hospital to hospital, what the actual practice is. So in [hospital 1] they check the pH of the aspirates. So they take a little aspirate every feed and check the pH, um, to make sure that actually the tube is still located in the stomach, um, and they will check the, um, GRV every 4 hours. So if feeding hourly then they’d check it every fourth feed, then when it goes to two hourly feeds you check it every other feed. So you’re checking the full, um, volume in the stomach at that point. In [hospital 2] it’s completely the opposite. They rarely check the pH of the aspirate and I would say they never check the volume of the fluids in the stomach at all. And in [hospital 3] it is kind of a bit hit and miss. So they would check the pH at every feed, but they only check the volume probably twice a day, yeah, regardless of what kind of, yeah, feeding regime they’re on.

P13, father, NNU

Although GRV measurement was holistically viewed as being a low-risk standard practice, performed for the benefit of the child, some parents also perceived it to be invasive and felt that it had caused vomiting and discomfort:

I don’t see it as being high, high risk. but, um, my husband was quite, um, he was sort of quite worried them actually taking and, taking the fluid out, pulling it out . . . because when you’re, when you, you see your, um, your tiny baby in an incubator, hooked up to tubes and then having it, it, it’s quite invasive when you see, sort of, medical staff going in again, in the incubator when they’re trying to keep them warm and regulate the temperature. It’s sort of quite sort of daunting, um, whereas I’m quite, I’m quite, sort of, matter of fact. If it needs to be done, it needs to be done, and let them crack on.

P03, mother, NNU

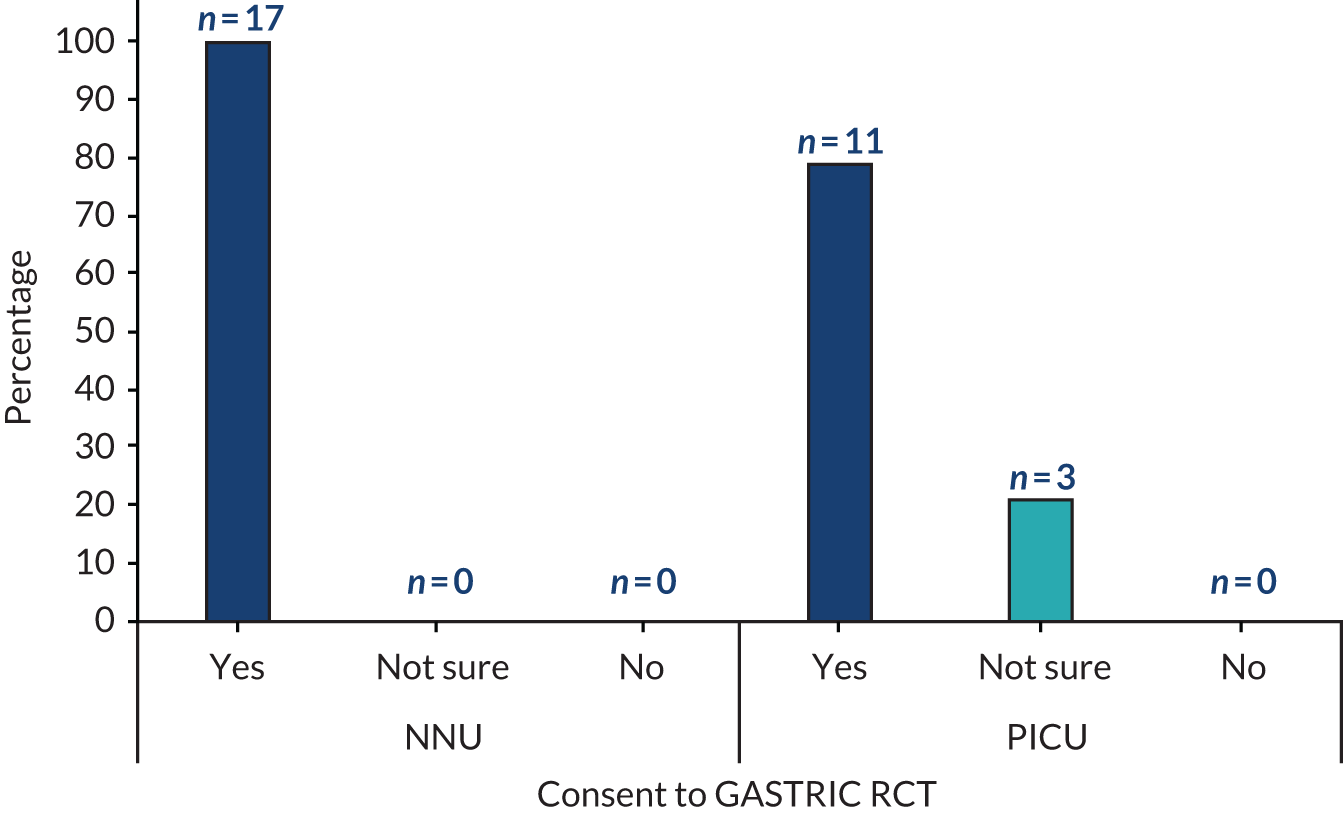

Perceived acceptability of the proposed GASTRIC randomised controlled trial

Interviews then explored perceived acceptability of the proposed GASTRIC RCT. Overall, parents supported the trial, with the majority (28/31, 90%) stating that they would hypothetically provide consent for their child to take part if they were approached about the trial (Figure 4).

FIGURE 4.

Parents’ views on whether or not they would have consented to the proposed GASTRIC RCT.

While considering trial acceptability and whether or not they would consent, many parents noted that they would not have pre-existing knowledge or beliefs about tube feeding or GRV measurement at the point they would be approached about the study:

I wouldn’t have known anything about feeding, so I wouldn’t have known any different.

P19, mother, PICU

Consequently, they would not have been aware it was a change in practice or, indeed, its consequences:

A lot of the time you wouldn’t know any different, it was all, all very new to me and if you said, we’re doing a trial where we’re not measuring it and if the nurse said, you know, we can’t see any effect, it wouldn’t, it wouldn’t bother me.

P15, father, NNU

Building on this situational equipoise, acceptability appeared to be influenced by a belief that the proposed study question ‘makes perfect sense’ (P23, father, PICU). NNU and PICU parents described how not measuring GRV might be beneficial because it would reduce potentially unnecessary interventions that may cause infections, discomfort and pain. Some also described how not measuring GRV may improve overall health, due to increased calorie consumption:

I just think that extra intervention, if it’s not actually doing anything positive, then is it really necessary? It’s, you know, it’s, it’s just another issue that can occur, another point of infection, um, and also another thing that the nurses are having to deal with on top of everything else.

P18, mother, PICU and NNU

It is a huge thing for them, to get the feeding established and get the calories on board, because that helps them get better faster as well. So, if you can get them better faster, you’re going to cut down, possibly that they’re blocking a bed as well. You know, like because if they’re getting calories on board quicker, they’ll start to feel better quicker . . . so it’ll have a knock-on effect in that respect. But again, you know, like these wee babies, feeding was one of the issues then that would kind of, I think, have an all-round effect on the overall condition of the, the baby.

P09, mother, NNU

Conversely, measuring GRV was also seen as acceptable, as their child would be receiving normal or ‘standard’ clinical care, because most units in the UK measure GRV:

Well that’s just the way it is. So would they be, would they be told that they’re in a trial and we’re just carrying on doing what we’re doing anyway?

P20, mother, PICU

Two parents described how no GRV measurement was acceptable and ‘normal’ care because, ‘if I was in France, this is what would be happening [not measuring GRV] so I wouldn’t, I wouldn’t worry based on that’ (P17, mother, NNU).

Some parents viewed GRV measurement or no measurement as of little importance, which was potentially influenced by the low significance associated with feeding during a critical care situation. These parents highlighted how, at the beginning of their child’s NNU or PICU stay, their child’s acute condition was the main priority and how a trial involving measuring or not measuring GRV would be seen as ‘low risk’ and therefore acceptable:

Obviously if they weren’t measuring the contents, it wouldn’t bother me ‘cause that’s what we do at home anyway. As I say, I don’t think I’d even be thinking about that at that stage. I don’t think I’d be worried that they weren’t checking it, um, ‘cause I’d be worried about other different, other things. So, um, I think that would be the last thing on me mind. So no, it wouldn’t bother me.

P27, mother, PICU and NNU

Despite parents describing their support for the study, many also voiced concerns and stated that their views on trial acceptability and consent decision-making would be influenced by how such concerns would be addressed. Parents described how they would not have capacity or desire to be approached about a trial in the early stages of their child being admitted to PICU or NNU. They referred to their emotional distress, uncertainty and generally being ‘overwhelmed by everything that’s going on’ (P14, father, NNU) at that point in time. They believed this incapacity would limit their ability to take on board study information and reach an informed decision. Some stated that being approached in the first 24 hours after ICU admission could have led to them to decline consent to a trial, which in different circumstances they would have consented to. Parents stated that any conversations about research in this early phase, when their child was still critically ill, ‘would have to be very carefully approached’ (P15, father, NNU). They also reflected on how the nature of the situation would enhance their desire to protect their child from any perceived risk, and that any trial or change from standard care would be viewed as a risk:

The fear of the impact. I think it’s quite different to ask for that consent for your child than it is like if it was for yourself. I think I’d be more likely to give that consent than I would be for one of my children. Just because, I don’t know. Same reason why you walk on the side of the pavement where the cars are, isn’t it?

P31, father, PICU

I don’t, I don’t feel that those, sort of, children who are in intensive care, I think they should be left alone, you know, because there’s some babies that are being fed by tubes that are absolutely tiny, really, sort of, you know, ill.

P03, mother, NNU

Some parents had described a preference for the ‘standard’ care arm:

Kind of trusting in older practices if that makes sense, especially in that kind of situation, kind of do what you’ve always done to make my child better type, er, feeling towards it.

P30, mother, bereaved, PICU and NNU

However, parents’ consideration of risk appeared to be influenced by the draft trial information provided to parents, which outlined potential risks of GRV measurement (standard care). The PIS raised questions and concerns about a practice that would not otherwise have been brought to their attention. Parents felt that this may result in the need for practitioners to fully explain and be prepared to answer questions on the motivation for both measuring GRV and not measuring GRV:

. . . ’cause it sounds really odd, doesn’t it, sucking up the contents of the stomach. I think it probably would, probably would have drawn more attention to something they do that’s standard practice; I might have been quite, a bit disturbed about that thought, and, and . . . questioned around whether it hurts and so on.

P19, mother, PICU

I suppose in, in general I’m all for, um, no intervention where it’s not necessary and so I think then learning that there was a study, exploring whether, um, we actually needed to measure in the way that it’s being done and she was being measured in the traditional way but there was now some question marks potentially about it because I was made aware of this study. Um, then that, that might make me ask a few extra questions.

P12, mother, NNU

This information was particularly important to PICU parents whose child had been on a feeding tube before admission and who had no previous experience of GRV. From their perspective, GRV measurement was not standard practice, but an additional, invasive and unnecessary procedure:

I would be kind of saying why? He’s never had this done before. This is not something I really want him to have done just for the sake of doing. It’s not necessary . . . But I possibly would say no unless there was some specific benefit to him [from GRV measurement] . . . I’m always kind of aware of not creating an aversion, not doing any more poking and prodding than is strictly necessary because he has plenty already. So I guess I’m probably just weighing it up on, yeah, was it gonna ’cause him any more, sort of any unnecessary discomfort, which I would avoid. Um, but in the main, I would be wanting to take part, I think.

P26, mother, PICU and NNU

Although situational incapacity, risk aversion and concerns about the impact of study participants may be applicable to most trials conducted in an ICU, there were three main trial-specific factors that concerned parents about the proposed GASTRIC trial. First, NNU parents were concerned about the risk of delayed diagnosis of bowel or stomach problems, or missing signs of an infection. Second, NNU and PICU parents worried about the risk of vomiting into lungs, which, as well as being potentially distressing for the child, may cause chest infections and breathing difficulties. Third, both groups of parents focused on the risk of increased pain or discomfort:

I think you’d just be concerned that, like, infections would go unnoticed or that their tube wasn’t in the baby’s stomach and it could be pumping milk in somewhere else.

P01, mother, NNU

Interestingly, parent accounts suggested that both measuring and not measuring GRV may lead to vomiting. Returning stomach contents may cause a child to vomit, ‘9 times out of 10 if they shot it back in, she was sick’ (P15, NNU, father), whereas not measuring GRV may result in overfeeding and vomiting. Similarly, not measuring GRV is believed to cause discomfort or pain if the child cannot be winded, the tube placement is incorrect or increased vomiting, whereas measuring GRV may cause discomfort and pain. In addition, NNU parents were particularly concerned about the risk of NEC not being detected because of not measuring GRV. This information was provided in the information sheet:

From nurses in passing that they’d mention NEC it, it seemed to be, you know, it was quite like, you know, a really, oh god, you don’t want your baby getting NEC and stuff like that, so that spread quite quickly I think, you know, amongst other parents. It was like, oh god NEC, you know, and stuff like that and it was something that god forbid that, that your child would get. So I think, if I was getting this, my question would be, if I hadn’t heard already within those 48 hours, what is NEC and how serious is it?

P14, father, NNU

However, as the previous quote from a father (P14, NNU) helps to illustrate, parents may not be aware of what NEC is at the time of their child’s hospital admission, as this knowledge is often gained from discussions with clinical staff during their child’s hospital stay. Therefore, a concern in retrospect may not influence parents’ views on trial acceptably at the point of consent discussions.

The three PICU parents who were unsure whether or not they would provide consent stated that there was not enough information about the possible benefits of each trial arm for them to predict whether or not they would consent. They described how if additional verbal information, such as the potential benefits of participation, was provided by a trial recruiter then they would potentially consent. However, based on the details provided in the draft PIS alone, they were uncertain about their consent decision:

I don’t think there’s anything you can put in your leaflet in that, in that moment that would have made me sign up to something that effectively felt like a trial or something that is deviating from current practice. Maybe if the doctor had said, had talked through a potential, potential benefit, in terms of the actual ability to get better or fight the infection. If that, if that was, if they were saying, you know, if your child’s taking in those calories he’s going to better fight the infection whatever it is, then maybe I’d have felt differently but the strength of the wording on that doesn’t, doesn’t sort of lead to a conclusion that would have sold it to me at the time, I don’t think.

P31, father, PICU

I think it depends how it, hmm, how it’s explained. There are the other questions I want to know. Sorry, it’s hard to say.

P19, mother, PICU

The proposed GASTRIC randomised controlled trial participant information sheet and consent discussion

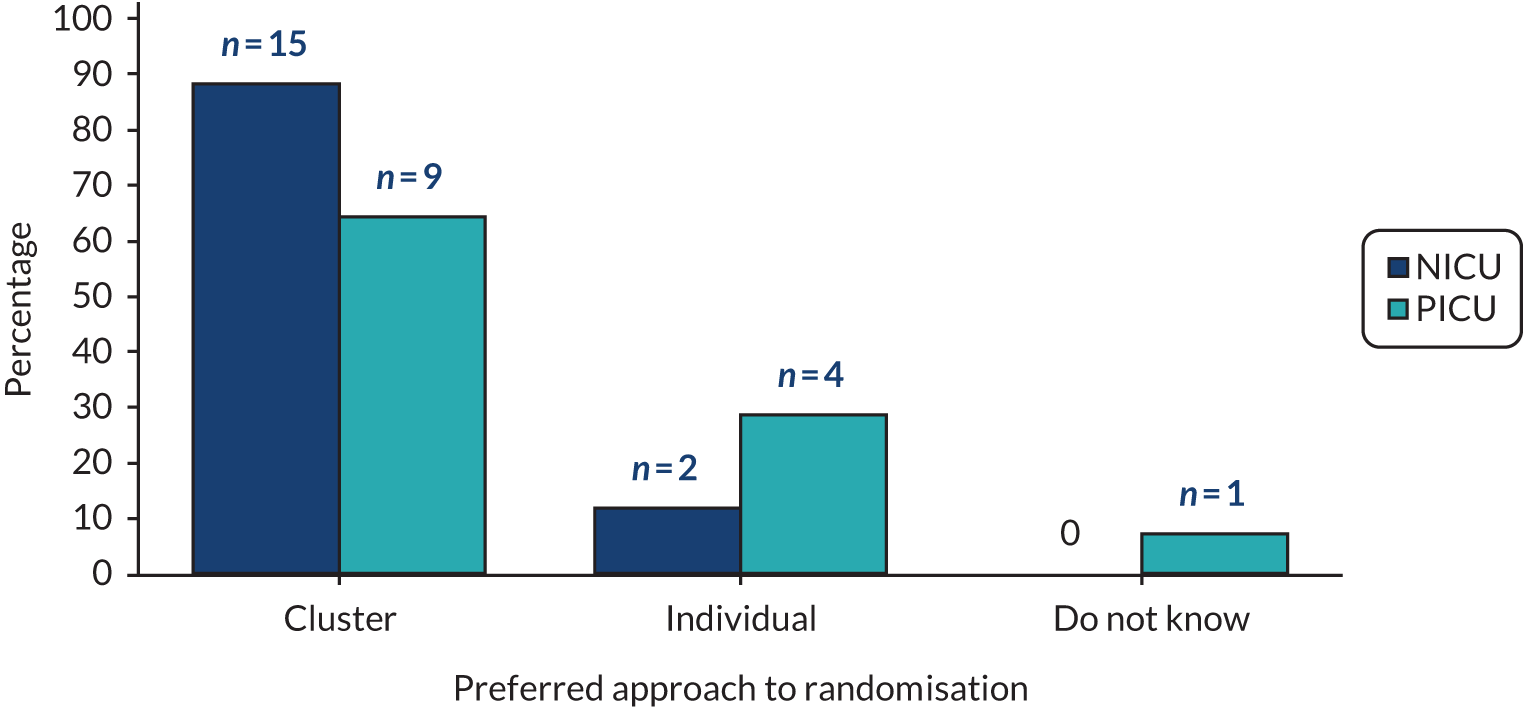

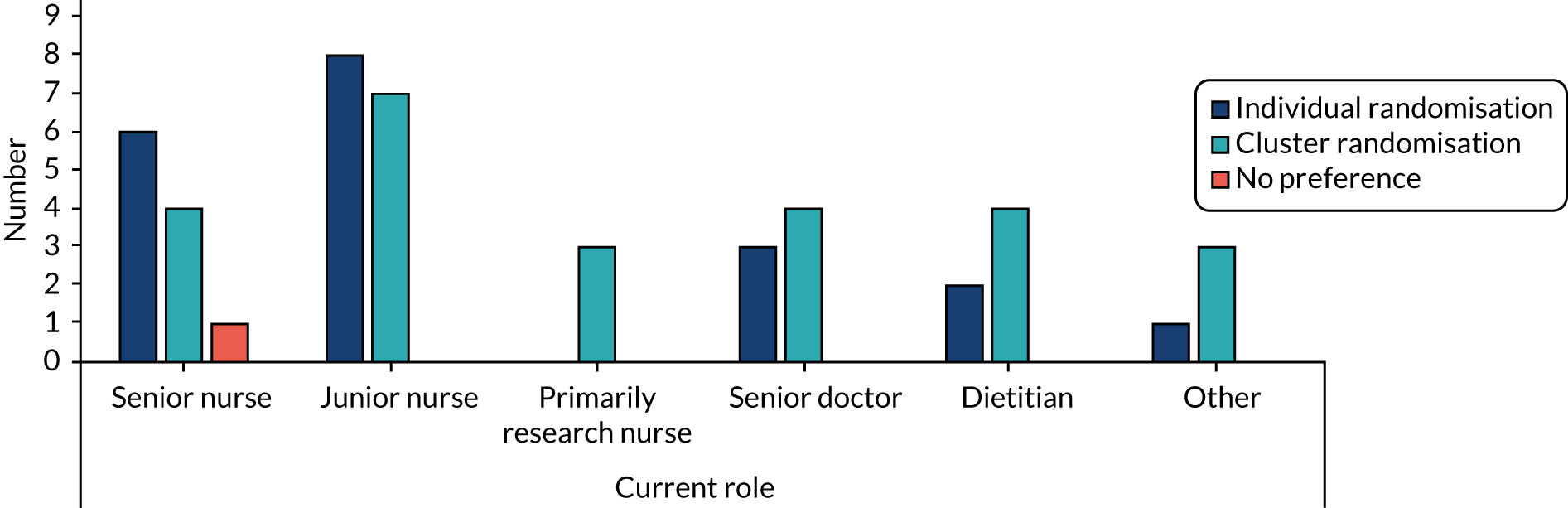

Overall, NNU and PICU parents considered the draft PIS [see project web page: www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/programmes/hta/169402/#/documentation (accessed 13 February 2020)] to be ‘very clear’ (P23, father, PICU), ‘very straightforward’ (P01, mother, NNU) and written in a way that would be comprehensible to someone with no pre-existing medical knowledge: