Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 10/37/01. The contractual start date was in December 2012. The draft report began editorial review in November 2018 and was accepted for publication in May 2019. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Gary A Ford declares personal fees from AstraZeneca (Cambridge, UK), Bayer AG (Leverkusen, Germany), Medtronic (Dublin, Ireland), Pfizer (New York, NY, USA), Pulse Therapeutics Euphrates Vascular (St Louis, MO, USA), Stryker Corporation (Kalamazoo, MI, USA) and Amgen (Thousand Oaks, CA, USA), and grants from Daiichi Sankyo (Tokyo, Japan), Medtronic and Pfizer outside the submitted work. Anne Forster declares grants from the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) and The Stroke Association (London, UK) outside the submitted work. She reports membership of the Health Services and Delivery Research (HSDR) Researcher-led Prioritisation Committee. Denise Howel was a member of the NIHR Programme Grants for Applied Research panel (2016 to present) and NIHR HSDR Commissioning Board (2012–15) during this research project. Luke Vale was a member the NIHR Health Technology Assessment (HTA) Clinical Evaluation and Trials panel (2014–18) during this research project. Helen Rodgers declares fees from Bayer and that during this research project she was a member of the British Association of Stroke Physicians (president) (2014–17), NIHR HTA Clinical Evaluation and Trials Board (2010–14), Intercollegiate Stroke Working Party (2002 to present), National Stroke Programme (chairperson of rehabilitation and ongoing care working group) (2018 to present) Joint Stroke Medicine Committee Royal College of Physicians London (chairperson) (2018 to present) and Steering Group member VISTA (Virtual International Stroke Trials Archive) (2015 to present).

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2020. This work was produced by Shaw et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2020 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Introduction

Some parts of this report are based on Rodgers et al. 1 © 2019 The Authors. Stroke is published on behalf of the American Heart Association, Inc., by Wolters Kluwer Health, Inc. This is an open access article under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided that the original work is properly cited. In 2010, the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Health Technology Assessment (HTA) programme identified the need to evaluate the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of rehabilitation interventions that aimed to improve ability to perform extended activities of daily living (EADL) in the longer term after stroke. EADL include mobility, housework, hobbies and leisure interests. 2 This report describes findings of the research commissioned for this evaluation.

Problems after stroke

In the UK, approximately 113,000 strokes currently occur per year. 3 Although the incidence of stroke has fallen, survival rates have improved and the prevalence of stroke has increased. 4 At present, there are over 1.2 million stroke survivors living in the UK. 5

The effects of stroke are diverse and, despite recent improvements in acute treatments (e.g. stroke unit care, thrombolysis and thrombectomy), currently around two-thirds of survivors leave hospital with a disability. 5 Some people will make a full recovery but for others disabilities persist long term. 6,7 At the time of planning this research project in 2010, a national survey of stroke survivors more than 1 year after stroke had shown that nearly half of respondents reported unmet needs in relation to issues such as personal care, mobility, emotional problems and leisure activities. 8,9 Later work continues to report similar findings. 10–12 Stroke survivors, carers and health-care professionals are repeatedly requesting that this situation is improved.

Rehabilitation after stroke

Rehabilitation is a broad term that encompasses specific interventions to target specific issues (e.g. robot-assisted training for upper limb function) through to complex care systems that involve teams of health-care professionals delivering a package of interventions. 13

It is well established that hospital stroke unit care and early supported discharge (ESD) services are both effective and cost-effective ways to improve patient outcomes following stroke. 14,15 The ESD services provide ongoing rehabilitation in a patient’s own home following the period of stroke unit care. They enable patients to leave hospital earlier than would be possible without such a service.

Stroke units and the ESD services are referred to as ‘organised stroke care’ and their key features are multidisciplinary stroke specialist expertise and co-ordination of care. 16,17 The National Clinical Guideline for Stroke recommends specialist stroke unit care for the duration of the inpatient stay unless stroke is not the main illness. 16 In 2016/17, 83.8% of patients spent at least 90% of their stay In a stroke unit. 18 ESD is recommended for patients with mild to moderate disability16 and in 2016 81% of stroke units had access to an ESD service. 19

Evidence and guidelines also continue to grow about specific rehabilitation interventions for different problems after stroke. 13,16,20 However, most research to date has focused on the acute and subacute phases of stroke, and there is less evidence to guide rehabilitation in the longer term following stroke. 16 When planning this research project, several publications were noting this lack of evidence for longer-term rehabilitation and the need for further research. 21,22

A 2008 Cochrane review of therapy-based rehabilitation services for patients living at home > 1 year after stroke found only five trials suitable for inclusion and reported that there was inconclusive evidence about whether or not these services improved patient outcomes. 21 Although a 2010 Cochrane review of community stroke liaison workers reported that there was no evidence that this intervention could improve outcomes for all stroke patients, it showed that people with milder disability had a reduction in death and dependence. 23 Another Cochrane review, which included 14 trials of non-ESD therapy-based rehabilitation services, which were provided at home for patients within 1 year of stroke, reported that these services decreased the odds of a poor outcome (defined as death or deterioration in ability to perform activities of daily living) and had a beneficial effect on performance of activities of daily living. 24 However, most of the services included in this review commenced soon after discharge rather than later after stroke.

Probably in part a result of the lack of evidence of the effectiveness of rehabilitation in the longer term after stroke, at the time of planning this research project, it was recognised that provision of longer-term services for stroke patients was limited and varied across the UK. 25 Following discharge from ESD services, the concept of ‘organised stroke care’ disappears and patients who have ongoing rehabilitation needs may be referred to a range of services, if available (e.g. neurorehabilitation teams, day hospital and community rehabilitation services). Reports from both the National Audit Office and Care Quality Commission highlighted that the longer-term care after stroke needed to be improved. 22,25

The literature about interventions to improve longer-term outcomes after stroke has of course expanded since 2010; however, the evidence is still mixed. For example, a 2014 review of several specific physical therapy interventions concluded that those involving repetitive task practice improved outcomes, including outcomes for patients later after stroke. 26 A 2015 Cochrane review that examined interventions that aimed to improve ambulation in the community reported that there was insufficient evidence to determine if these interventions were beneficial. 27 A review examining the effect of physiotherapy interventions that aimed to improve mobility or independence in activities of daily living in patients at least 6 months after stroke showed a significant improvement in mobility but no improvement in independence in activities of daily living. 28 A 2016 Cochrane review of self-management programmes for stroke survivors living in the community found that these interventions led to improved quality of life, but not to improvements in activities of daily living or mood. 29 A large cluster randomised controlled trial published in 2015 evaluated a system of Longer-Term Stroke (LoTS) care in which stroke care co-ordinators, who were community-based health-care professionals with experience in stroke care, were trained to follow a structured assessment and treatment plan working with patients and carers after discharge from hospital (29 centres, 800 patients, 208 carers). 30 Follow-up was at 6 months and 12 months following patient recruitment, and included assessment of quality of life and performance in EADL. Neither patients nor carers in the intervention group had improved outcomes compared with usual care.

Although improvements in stroke services have taken place since this research was commissioned,18 the evidence base supporting longer-term rehabilitation is still limited and post acute stroke care remains variable. 31

The EXTRAS trial

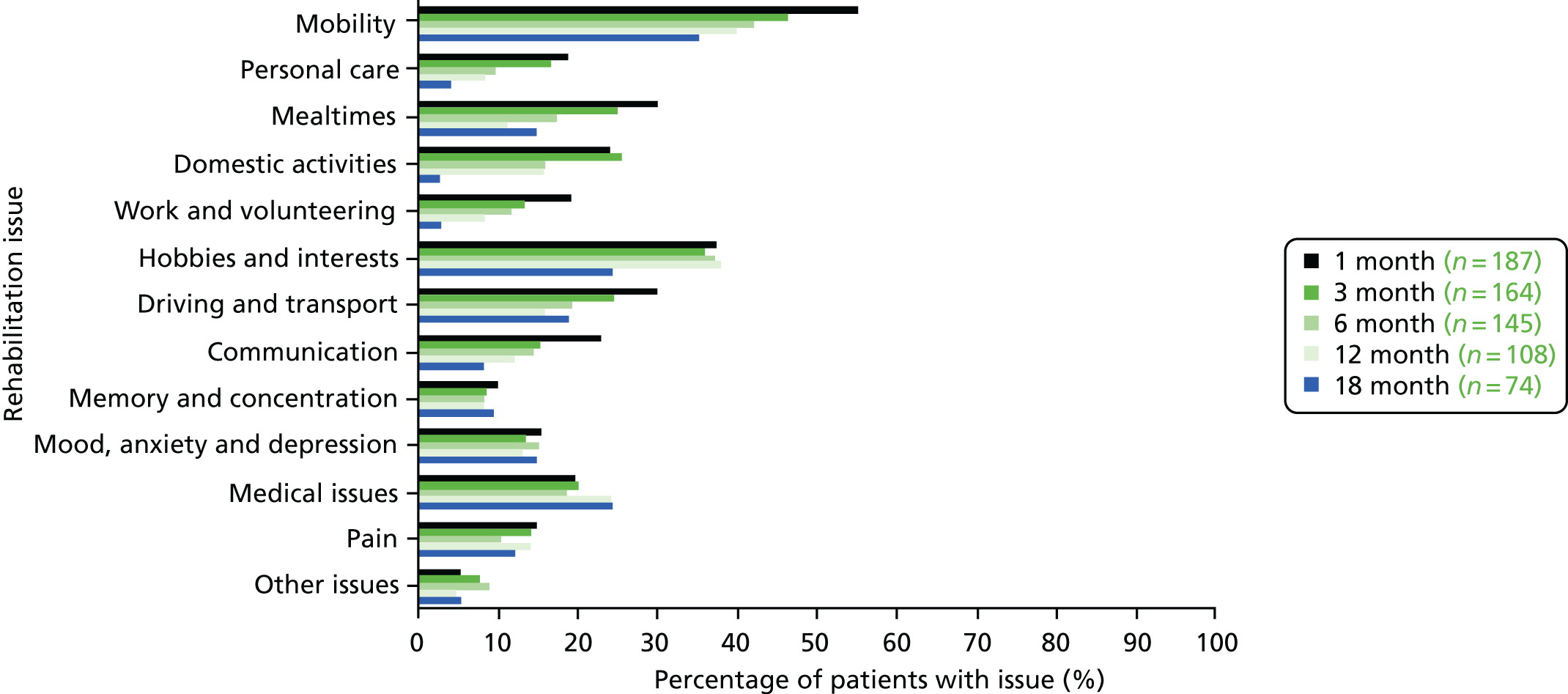

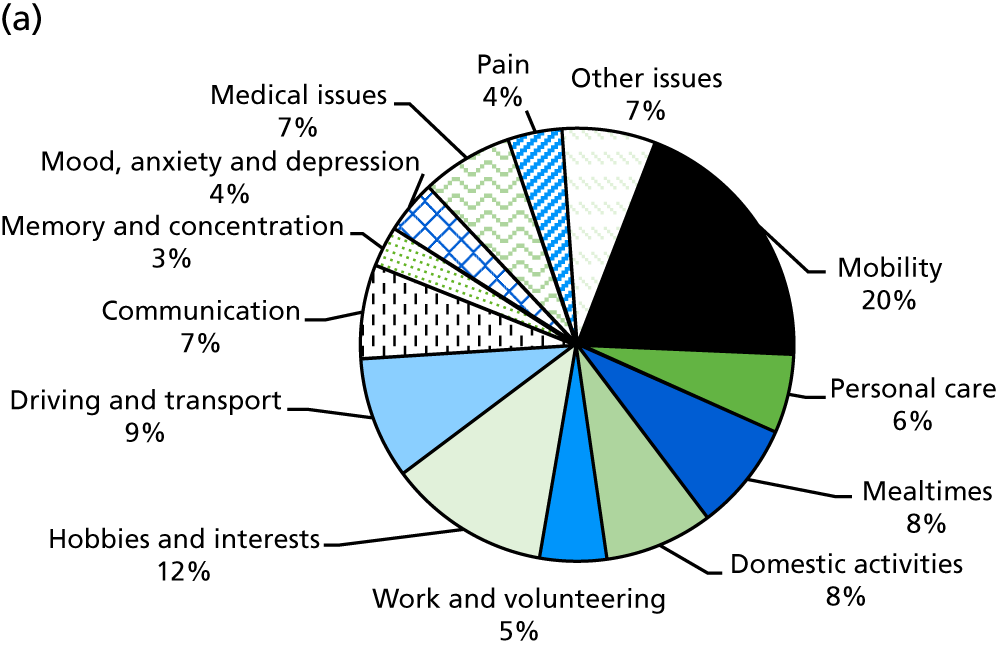

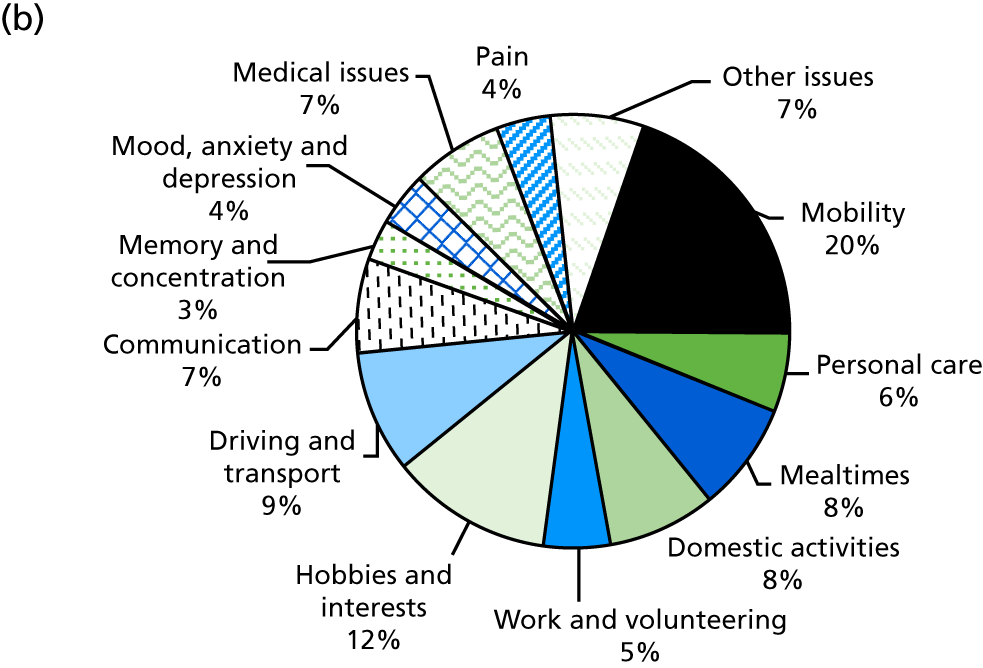

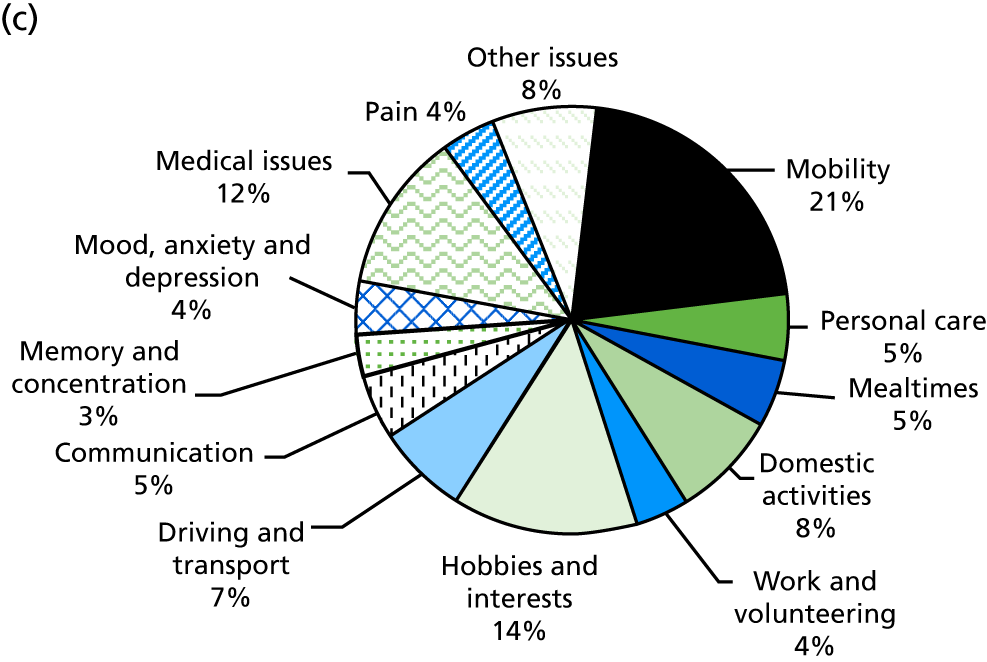

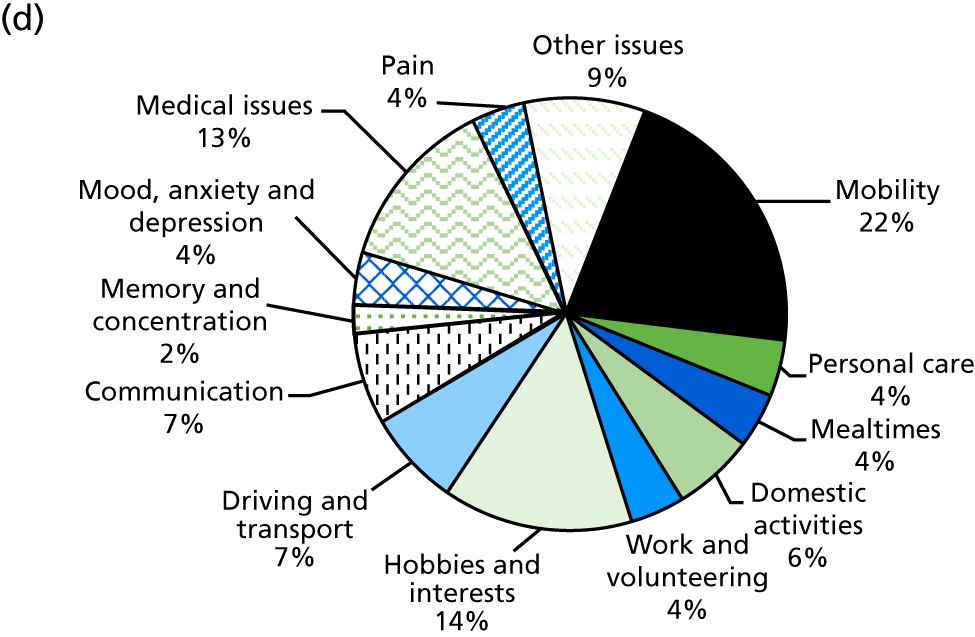

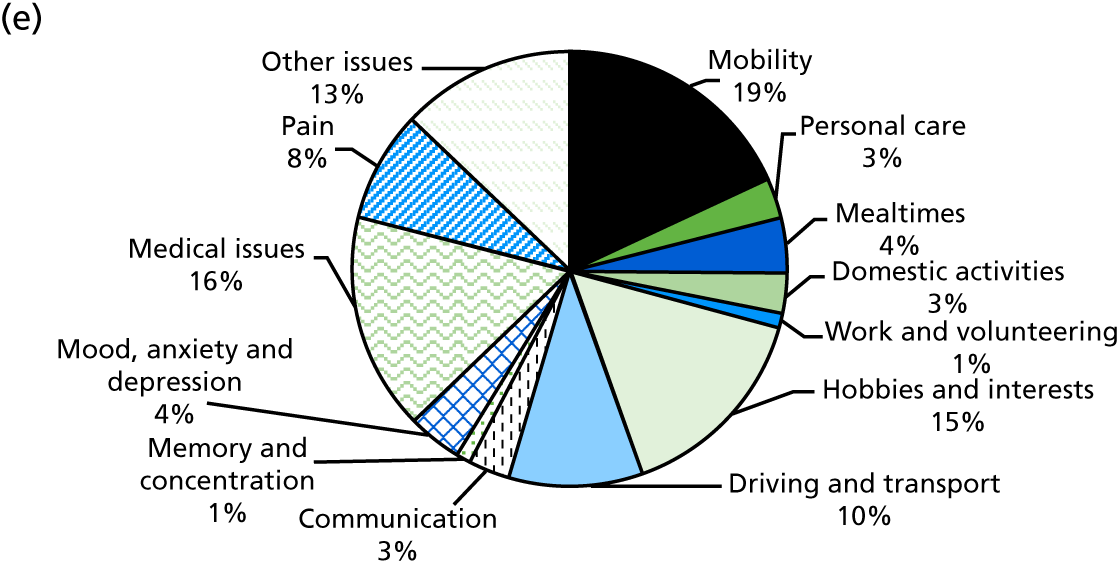

This research project has evaluated an extended stroke rehabilitation service (EXTRAS). The service consisted of five rehabilitation reviews conducted at 1, 3, 6, 12 and 18 months post discharge from ESD services. Reviews were undertaken by senior members of ESD teams and consisted of a structured assessment of rehabilitation needs, goal-setting and action-planning. Reviews covered mobility; personal care; mealtimes; domestic activities; work and volunteering; hobbies and interests; driving and transport, communication; memory and concentration; mood, anxiety and depression; medical issues; pain and other issues. Both stroke patients and their carers were included in the study and outcomes were assessed at 12 and 24 months post randomisation. Although EXTRAS did not include any assessment of carer needs or specific interventions for carers, we hypothesised that the new service may also influence carer outcomes. An evaluation of a longer-term stroke specialist service was undertaken because of the strong evidence showing that stroke units and ESD services improve patient outcomes and are cost-effective. If EXTRAS is effective and affordable, it could extend ‘organised stroke care’ and improve longer-term outcomes after stroke.

Chapter 2 Methods

Parts of this chapter have been reproduced from Rodgers et al. 32 © 2015 Crown copyright; licensee BioMed Central. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly credited. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

Study aim and objectives

1. Aim

To determine the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of an extended stroke rehabilitation service (EXTRAS).

2. Objectives

-

To determine whether and extended stroke rehabilitation service (intervention) improved patient outcomes compared to usual care (control). The primary outcome was extended activities of daily living at 24 months following randomisation. Secondary outcomes were health status, quality of life, mood and experience of services (12 and 24 months following randomisation).

-

To determine whether an extended stroke rehabilitation service improved carer outcomes compared to usual care. Outcomes were quality of life, carer stress, experience of services (12 and 24 months following randomisation).

-

To determine the cost-effectiveness of an extended stroke rehabilitation service.

-

To document how the extended stroke rehabilitation service was implemented and delivered in different settings.

-

To seek the views and experiences of patients, carers and rehabilitation staff about the community rehabilitation that they received or provided.

-

To explore the impact of the severity of activity limitation, pre-stroke health status and comorbidity on the effectiveness of the intervention.

Study design

The study was a pragmatic, observer-blind, parallel-group, multicentre randomised controlled trial with health economic and process evaluations. The study protocol has been published. 32

Study setting

The study was conducted in 19 NHS study centres in the UK. All study centres provided an ESD service. To be eligible to take part, the ESD service had to meet the following criteria:

-

had a multidisciplinary stroke team that provided community rehabilitation following discharge from hospital

-

was able to provide stroke rehabilitation at home within 48 hours of patient discharge from hospital

-

was able to provide stroke rehabilitation for a specified period of time and/or had clear criteria for discharge of patients from the service.

Study participants

Adults with a stroke who fulfilled the following criteria were eligible.

1. Inclusion criteria

-

Aged ≥ 18 years.

-

Confirmed diagnosis of new stroke (first ever or recurrent).

-

Planned discharge from hospital under the care of ESD or currently receiving ESD.

2. Exclusion criteria

-

Unable to participate in a rehabilitation programme that focused on EADL.

A carer was the main family member or friend who provided support after stroke. He or she was not required to be a co-resident of the patient. If an eligible patient had no carer or a carer who did not wish to participate in the study, the patient was still able to take part.

Case ascertainment, recruitment and consent

1. Patients

Potential patients were identified and recruited by NHS staff (clinicians, staff from the Local Clinical Research Network and senior members of an ESD team). Potential patients could be recruited prior to discharge from hospital or while receiving care from an ESD service. Although EXTRAS did not commence until routine ESD services ended, identification and recruitment of patients in hospital or during ESD was used to maximise recruitment opportunities.

It was intended that screening data would be collected to report eligibility and subsequent recruitment or reason for lack of recruitment. Unfortunately, collecting these data was not possible owing to workload at the NHS study centres.

As stroke survivors can have impairments that result in difficulties with communication and/or cognition, a number of consent methods were used to facilitate participation.

For patients with mental capacity to consent to research, a standard research information sheet and consent form were used by NHS staff. If a person had capacity to consent to research but was unable to sign the consent form (e.g. because of weakness of the dominant hand due to stroke), consent was confirmed orally in the presence of a witness (an individual not involved in the trial) who signed the consent form on behalf of the participant. For patients with communication difficulties owing to aphasia, an ‘easy access’ study information sheet and consent form were used. For patients without mental capacity to consent to research, a personal consultee was identified, was provided with a consultee information sheet and signed a consultee declaration form if they believed that the patient would have no objection to taking part in the study. Due to the nature of this study, potential patients lacking in capacity also needed to have a relative/friend (carer) who was prepared to assist with EXTRAS reviews and outcome assessments, as these were unlikely to be possible without their support.

2. Carers

Potential carers were identified by ESD senior team members while the patient was receiving routine ESD care. At the time of patient discharge from routine ESD services, if the patient had an identified carer, she/he was provided with an invitation letter, study information sheet, study carer baseline questionnaire and prepaid envelope (addressed to the study co-ordinating centre). Provision of the invitation letter and study documents could be in person by an ESD senior team member, by post by the local study team, or by a consented patient. These three options were used to maximise potential opportunities for carers to take part in the study, as carers were not always present at staff visits. The invitation letter asked the carer to complete and return the baseline questionnaire if she/he was willing to participate in the study.

Recruitment and baseline assessments

Patient baseline data were collected during face-to-face recruitment and baseline assessments. Both assessments were performed by NHS staff after informed consent had been obtained. The recruitment assessment could be performed within 4 days prior to planned discharge from hospital, or during routine ESD care. The baseline assessment was performed at discharge from routine ESD services and immediately prior to randomisation. Both assessments could be conducted together at discharge from ESD if preferred. Data collection was divided in this format for logistical ease. As patient recruitment could be during hospital stay, data that were more easily obtainable by hospital staff were collected in the recruitment assessment. Data pertaining to patient characteristics at discharge from ESD were collected at the baseline assessment.

The following data were collected during the recruitment assessment: demographic data, pre-stroke performance in EADL [Nottingham Extended Activities of Daily Living (NEADL) Scale33], pre-stroke health status [Oxford Handicap Scale (OHS)34], date of hospital admission, date of stroke, stroke type and subtype,35 National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS),36 comorbidity and pre-stroke resource usage [adaptation of the Client Service Receipt Inventory (CSRI)37–39].

The following data were collected during the baseline assessment: date of hospital discharge, date of ESD discharge, Abbreviated Mental Test Score,40 Sheffield Aphasia Screening Test,41 EADL (NEADL Scale),33 health status (OHS),34 mood [Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS)42] and quality of life [EuroQol-5 Dimensions, five-level version (EQ-5D-5L)43].

Carers received a baseline questionnaire with the study invitation letter. The questionnaire collected the following data: demographic, carer stress [Caregiver Strain Index (CSI)44] and quality of life (EQ-5D-5L). 43

Randomisation

Randomisation was conducted by NHS staff at participating study centres using a central independent web-based service hosted by Newcastle University Clinical Trials Unit. Participants were stratified according to study centre and randomised to intervention and control in a 1 : 1 ratio using permuted block sequences. Stroke patients and their carers were randomised as a single unit.

Study control treatment

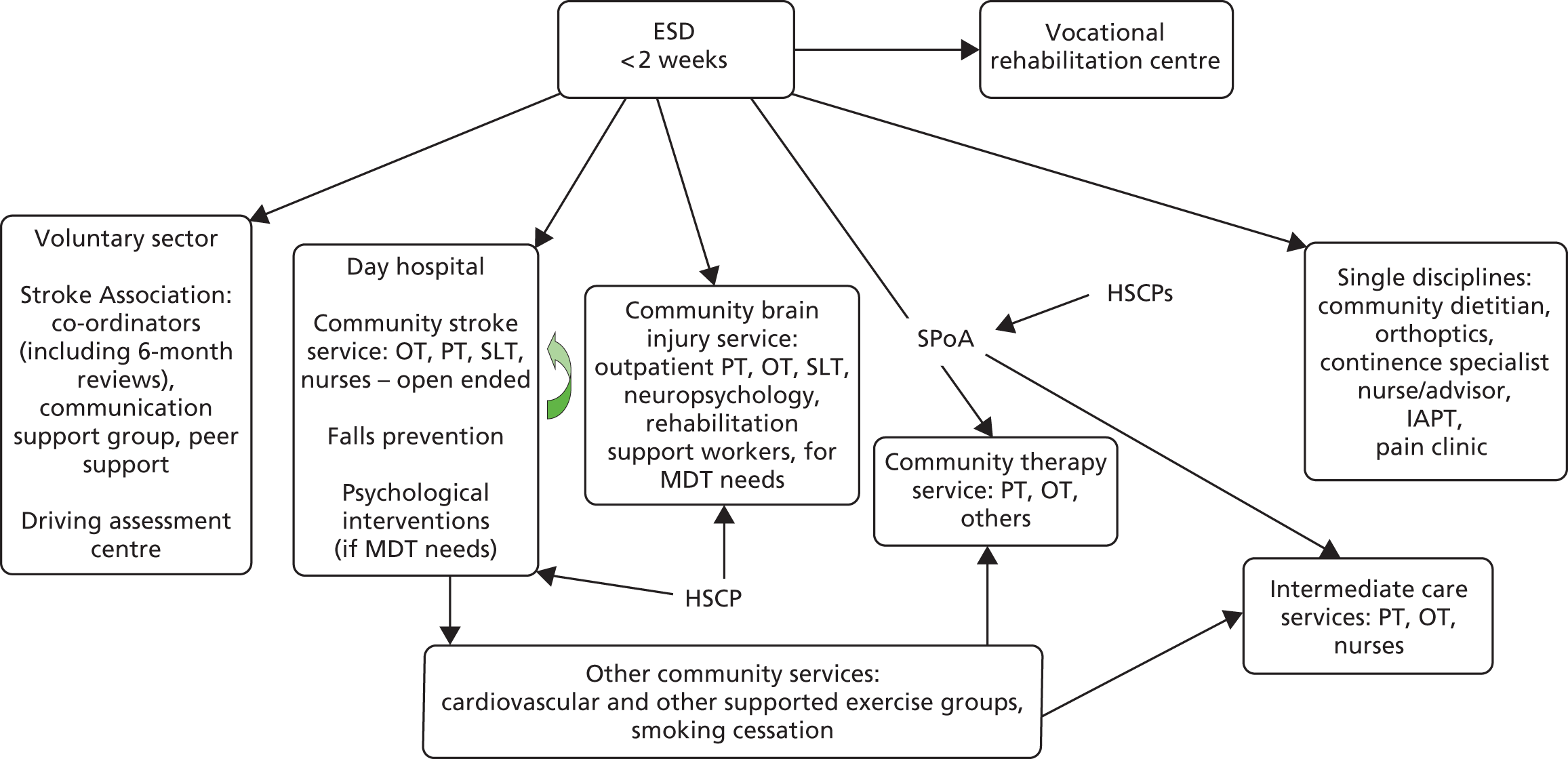

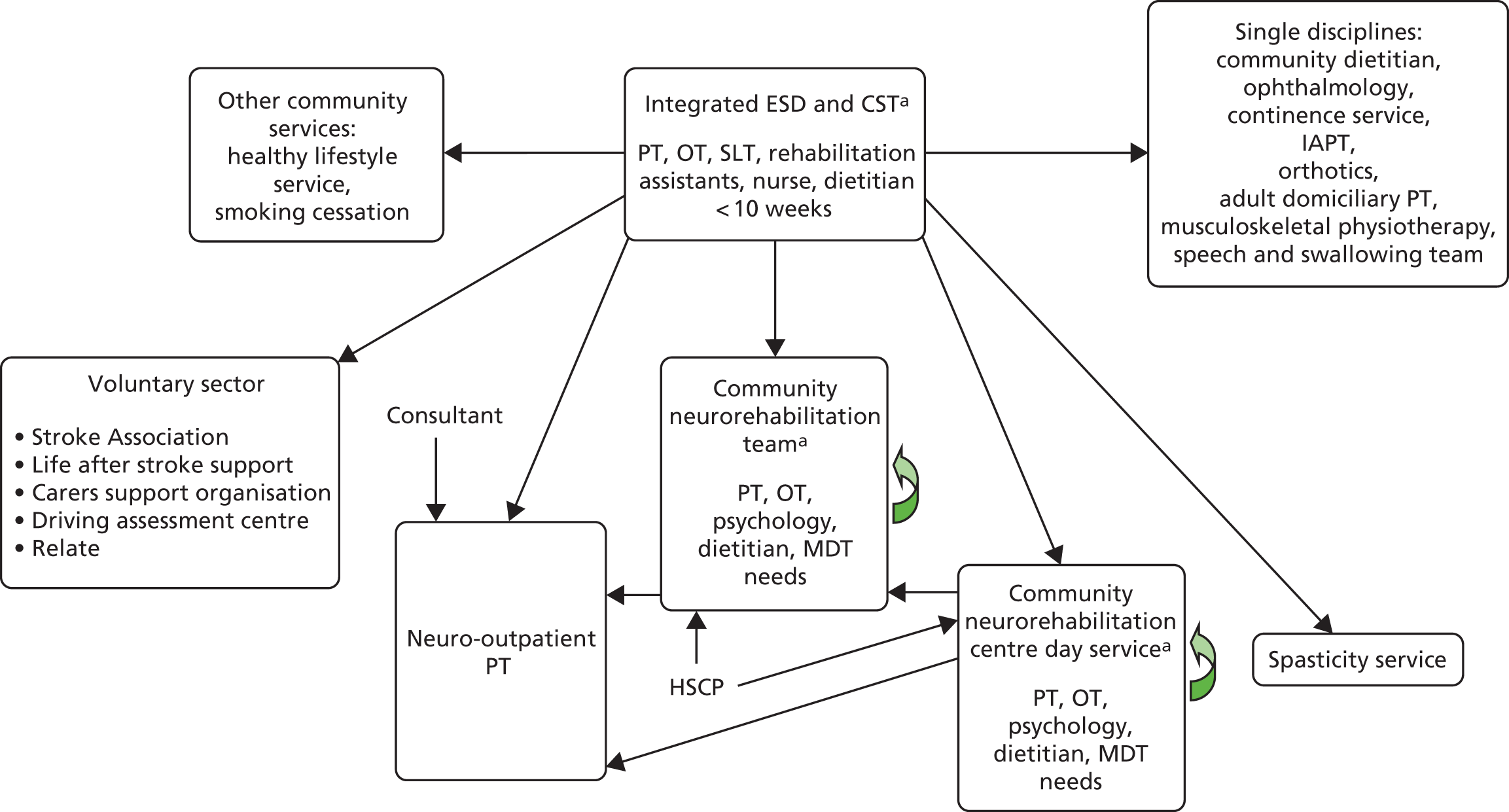

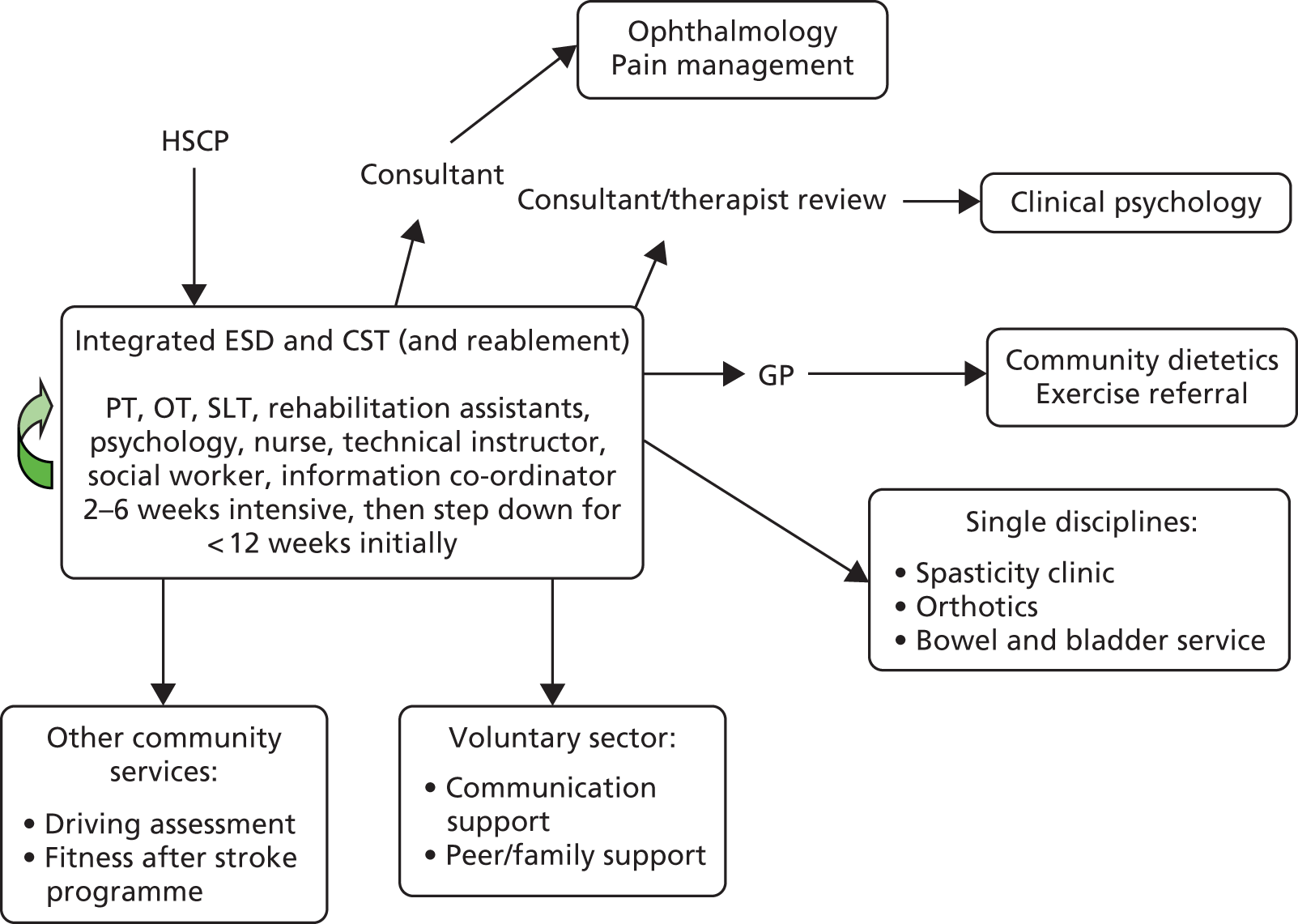

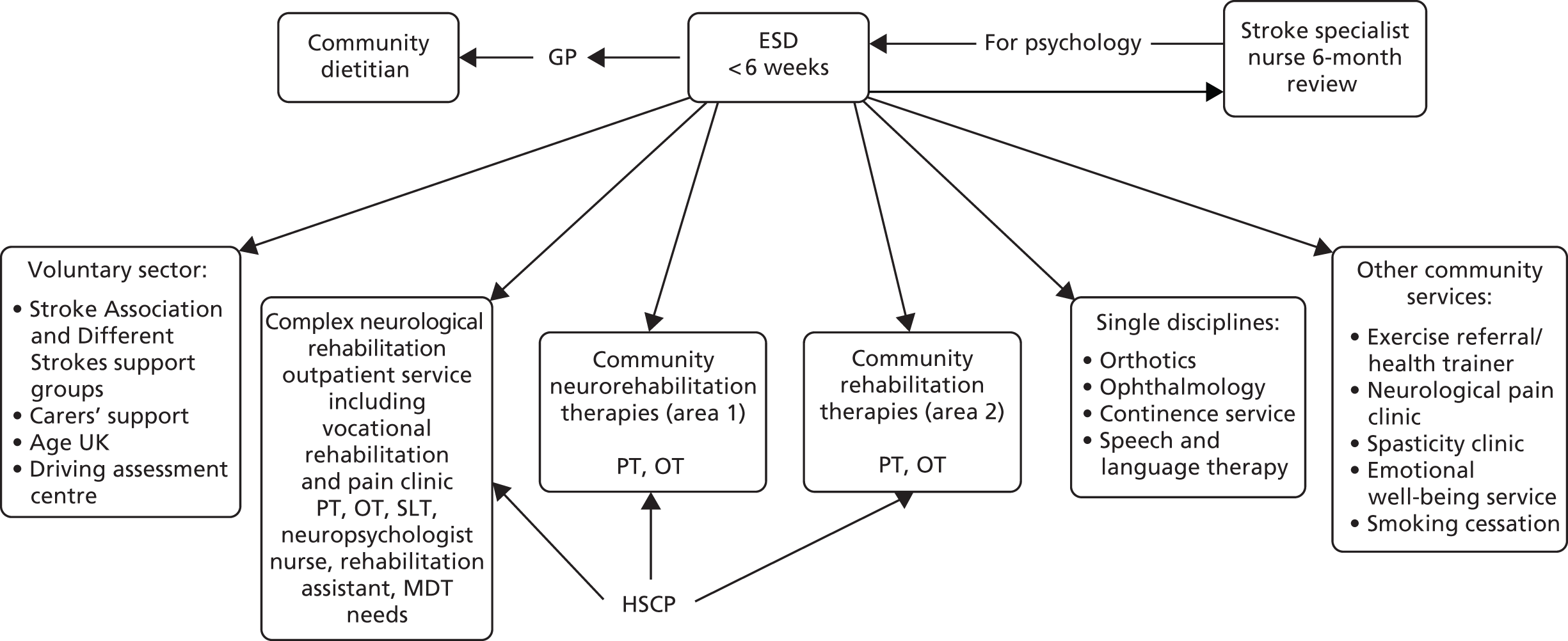

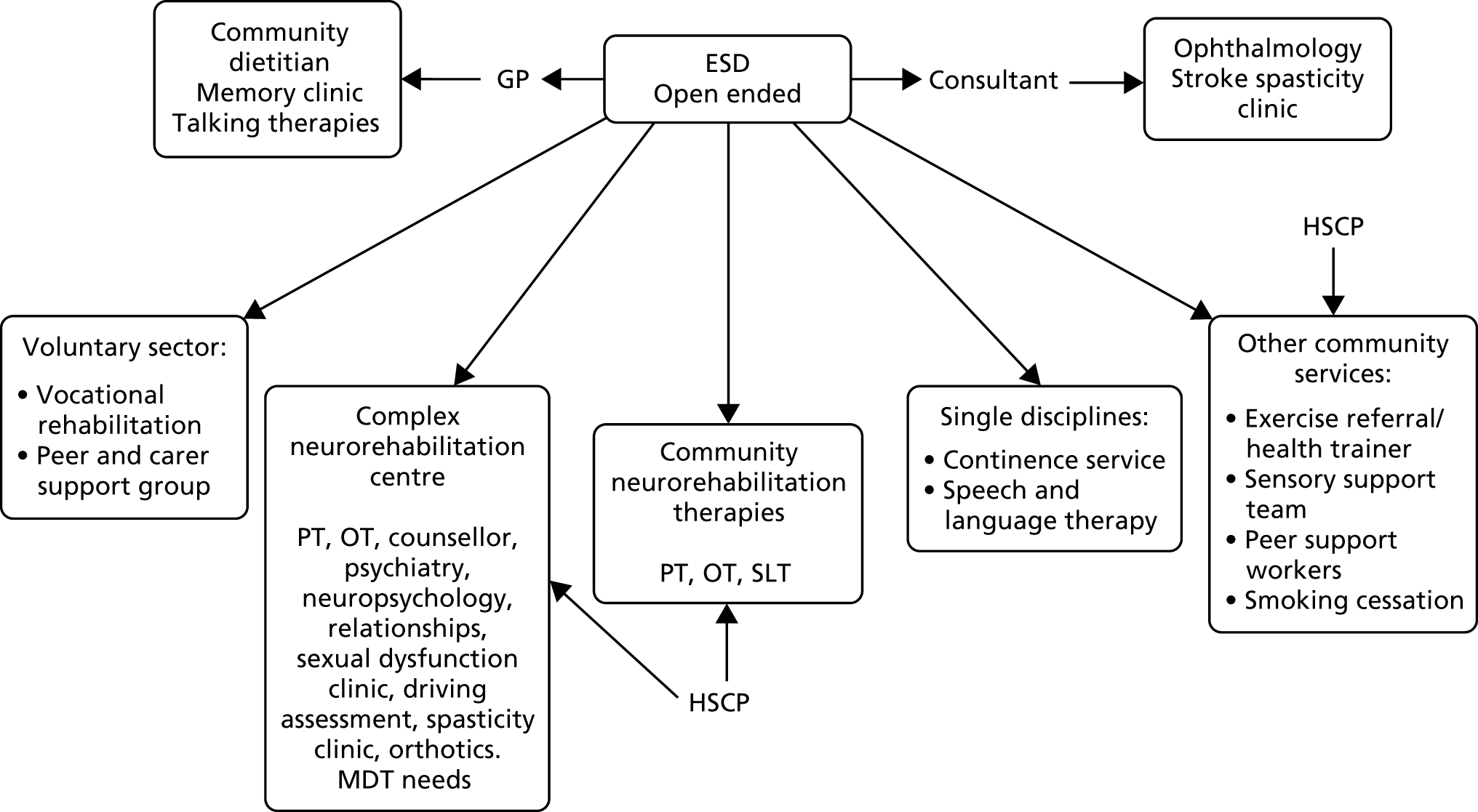

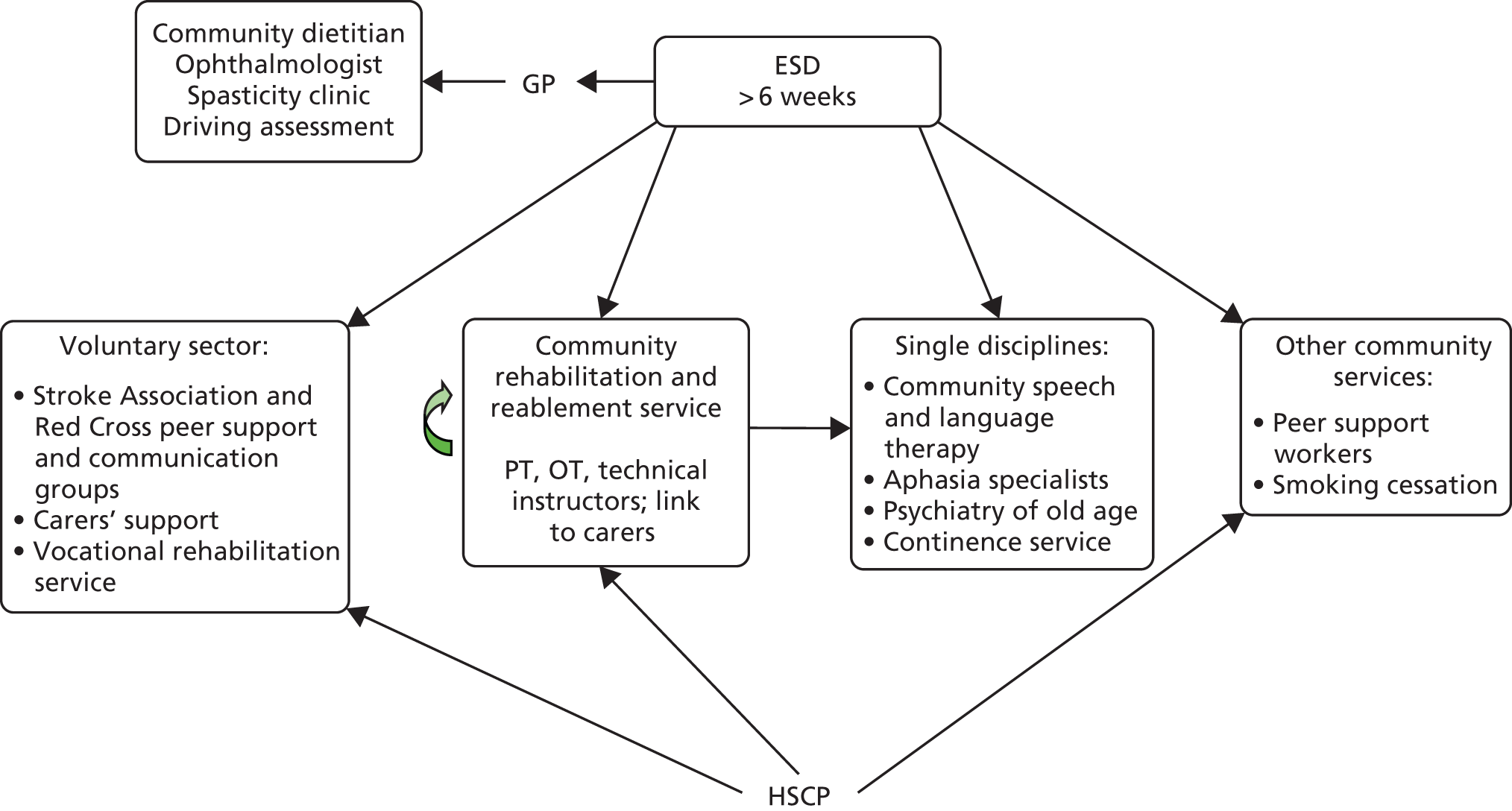

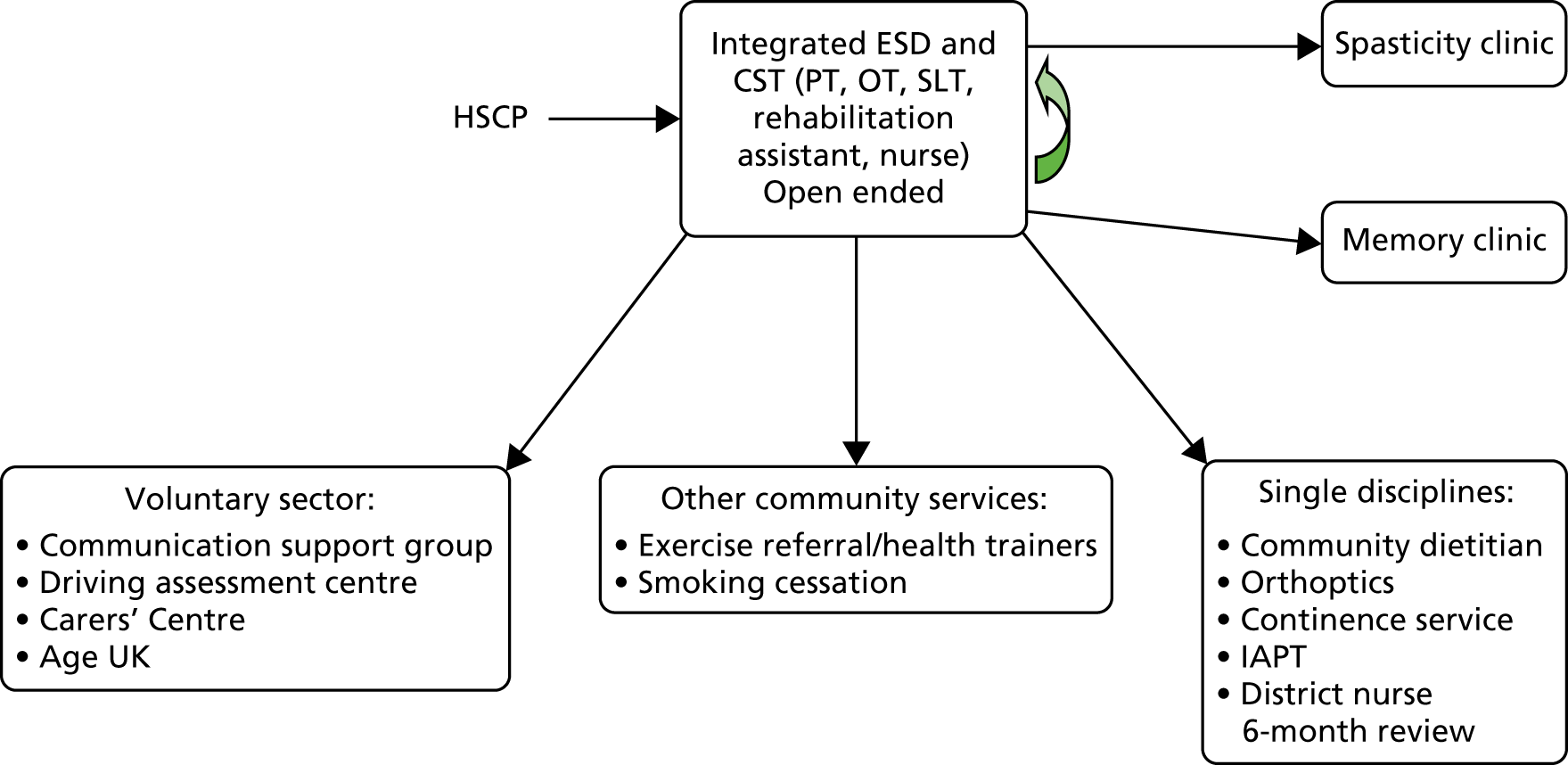

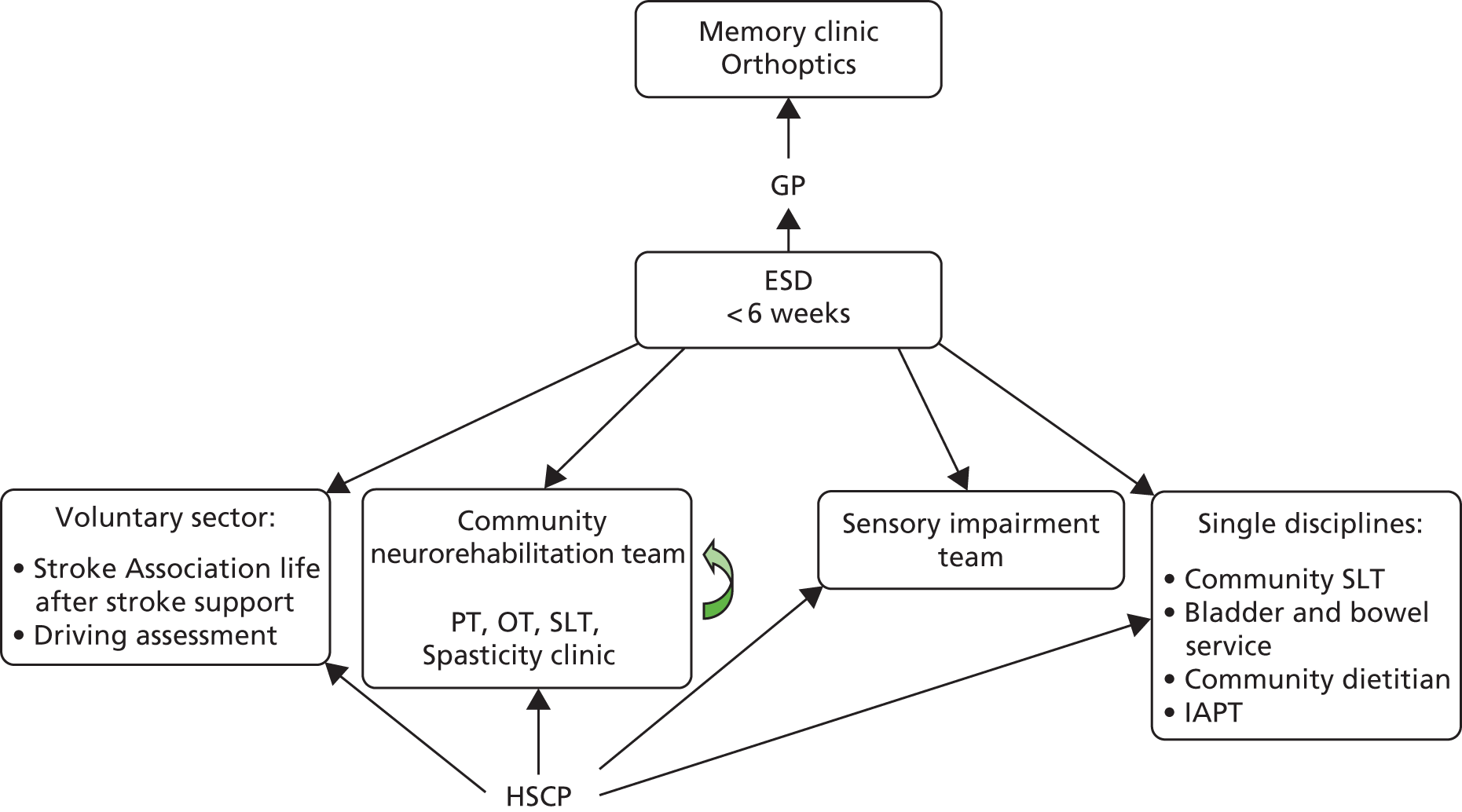

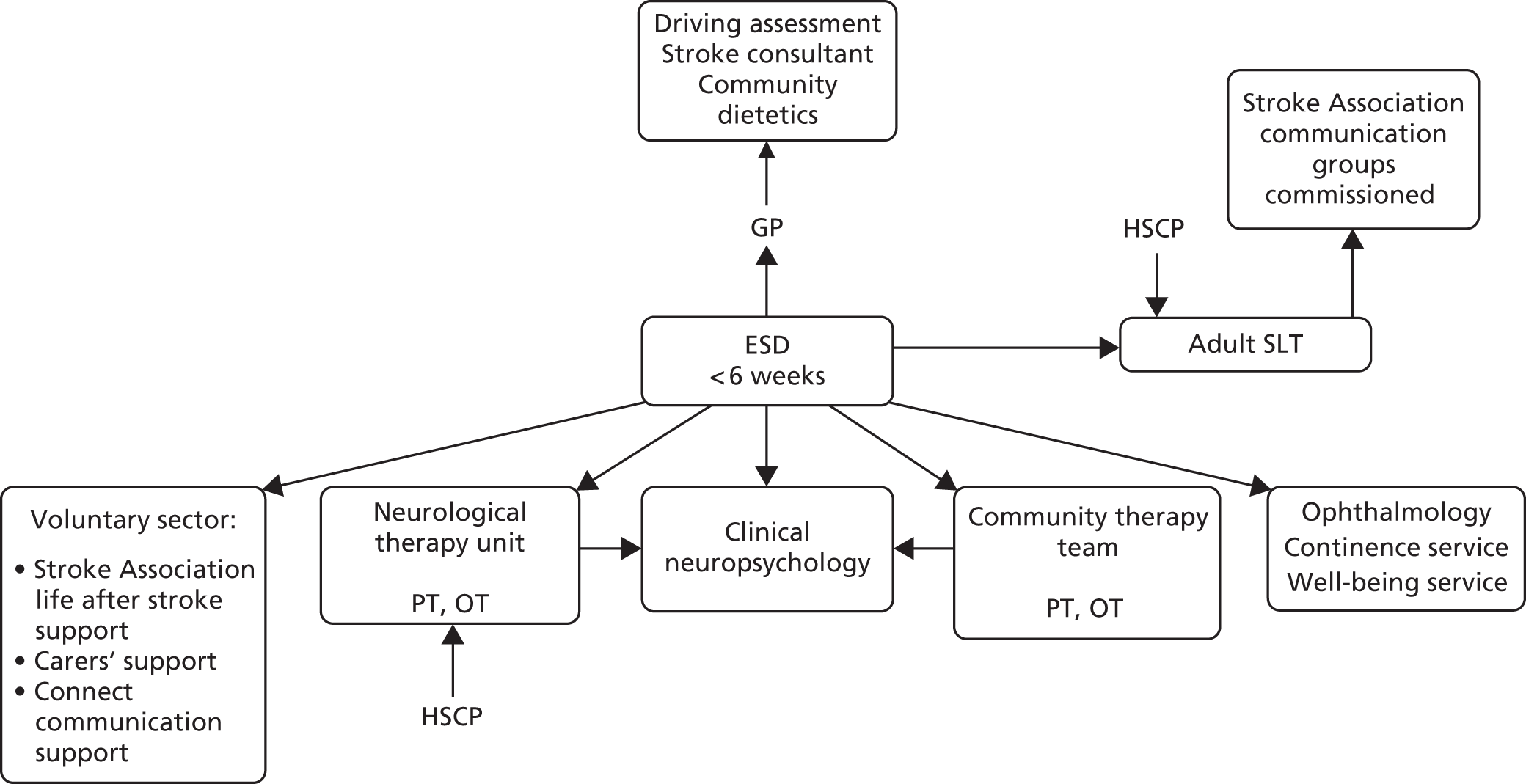

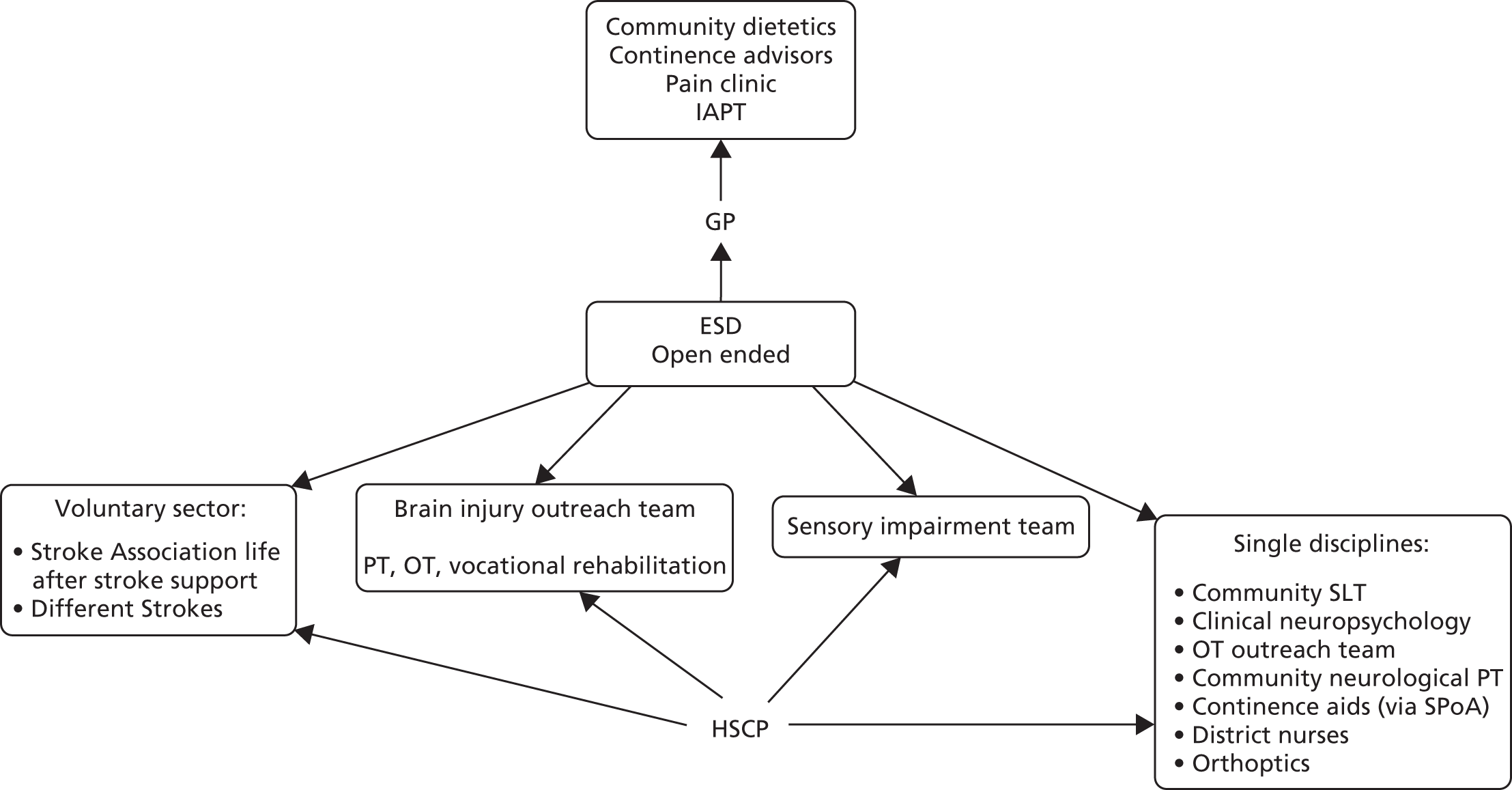

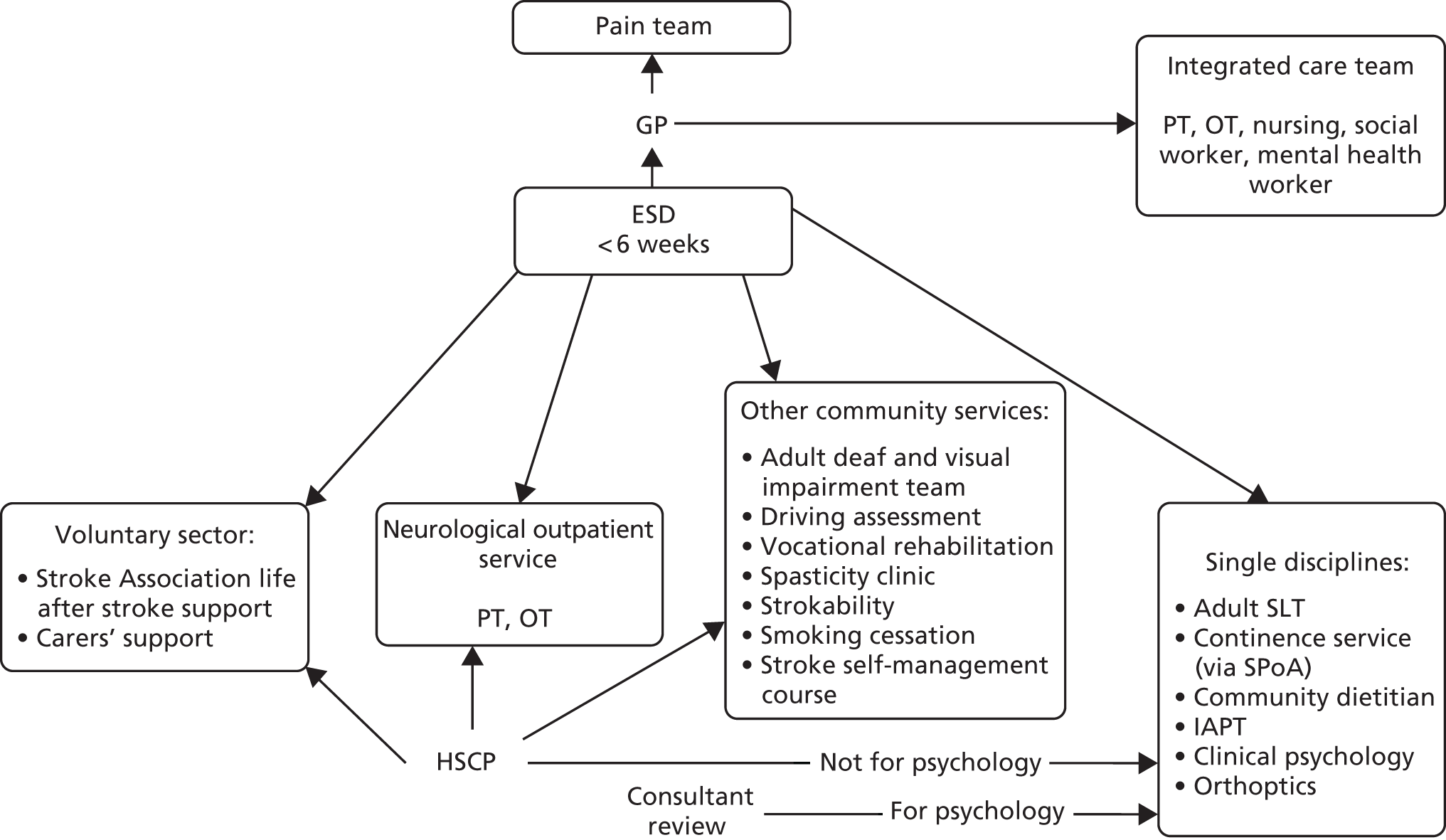

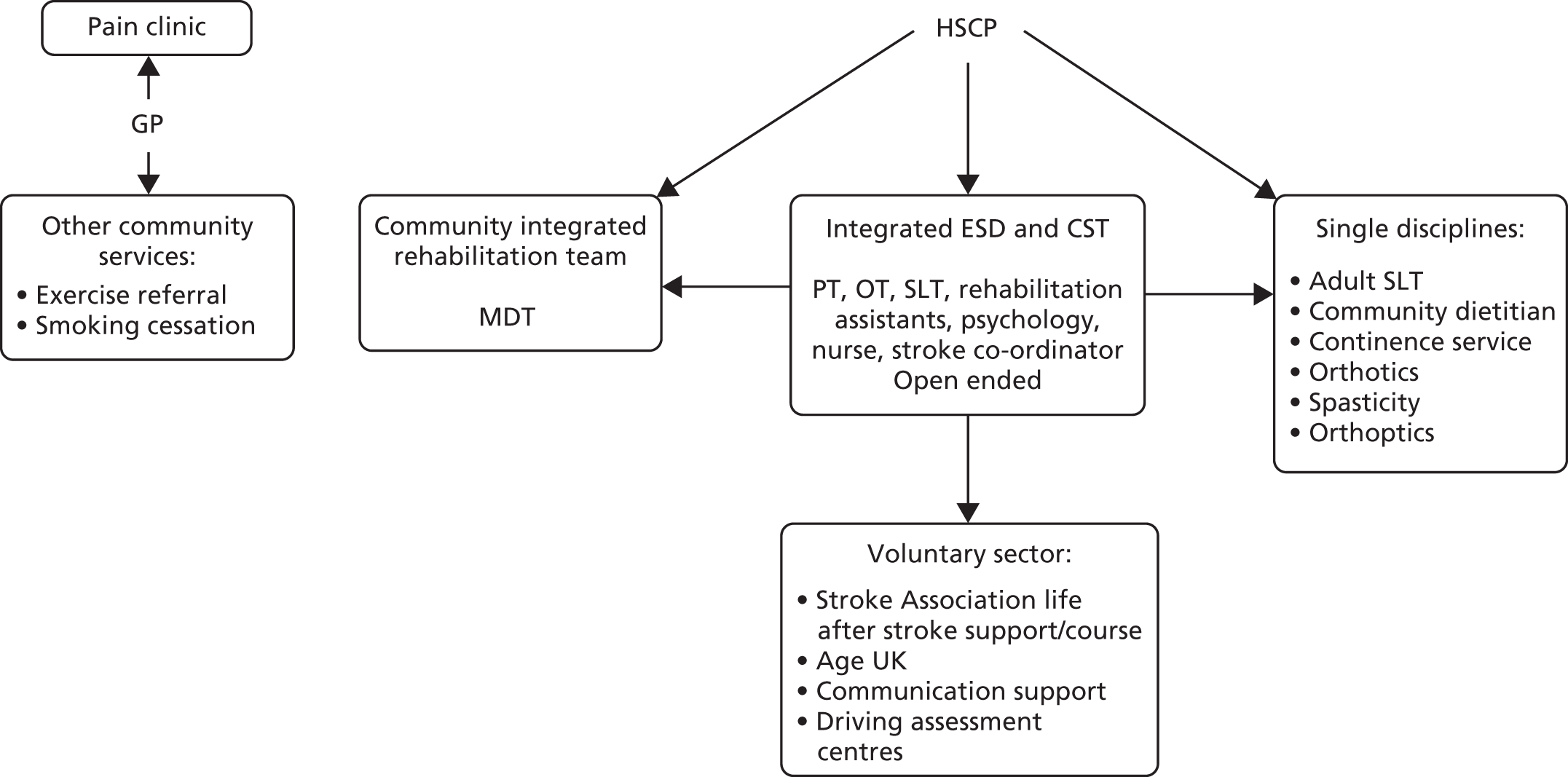

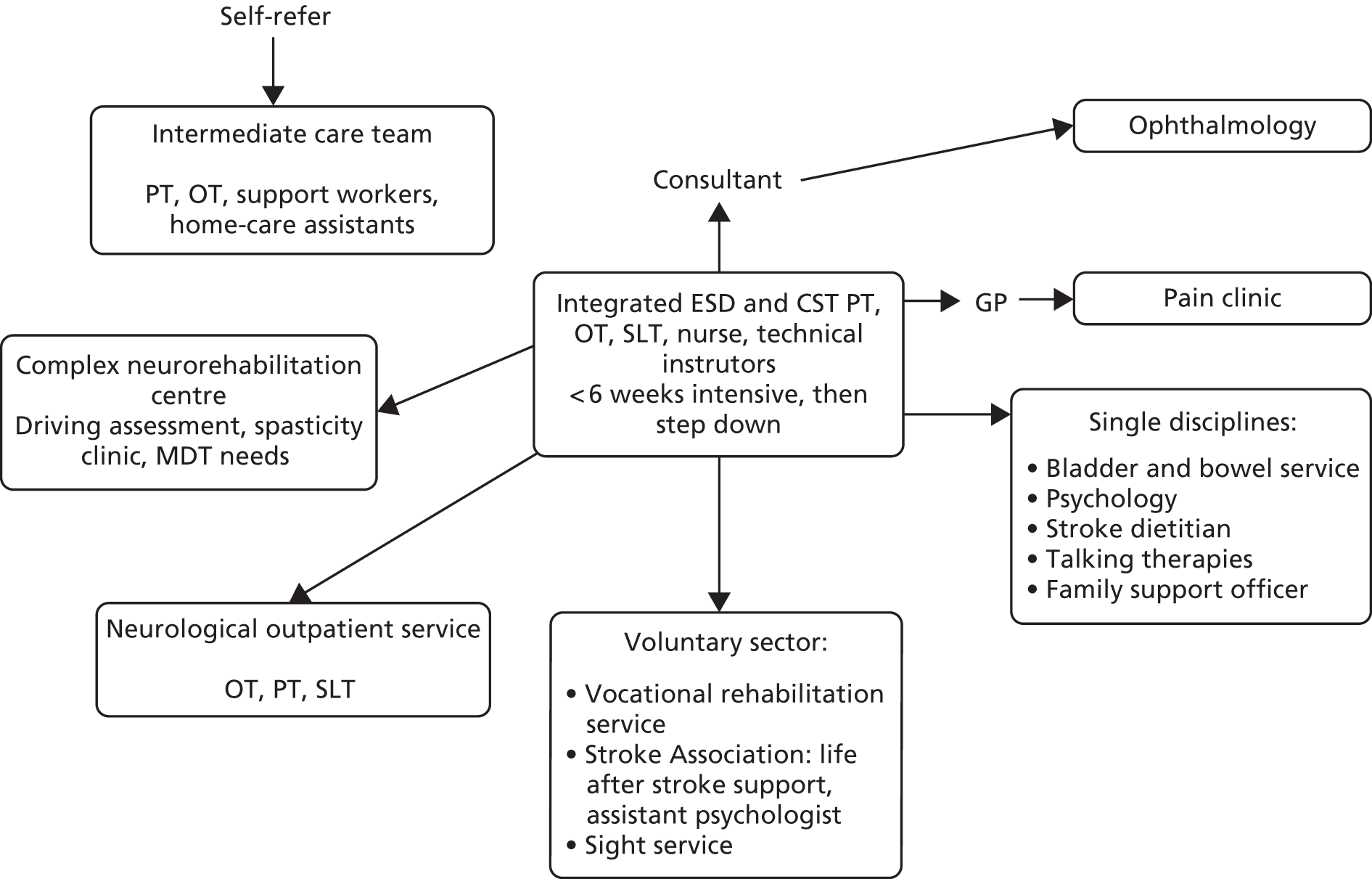

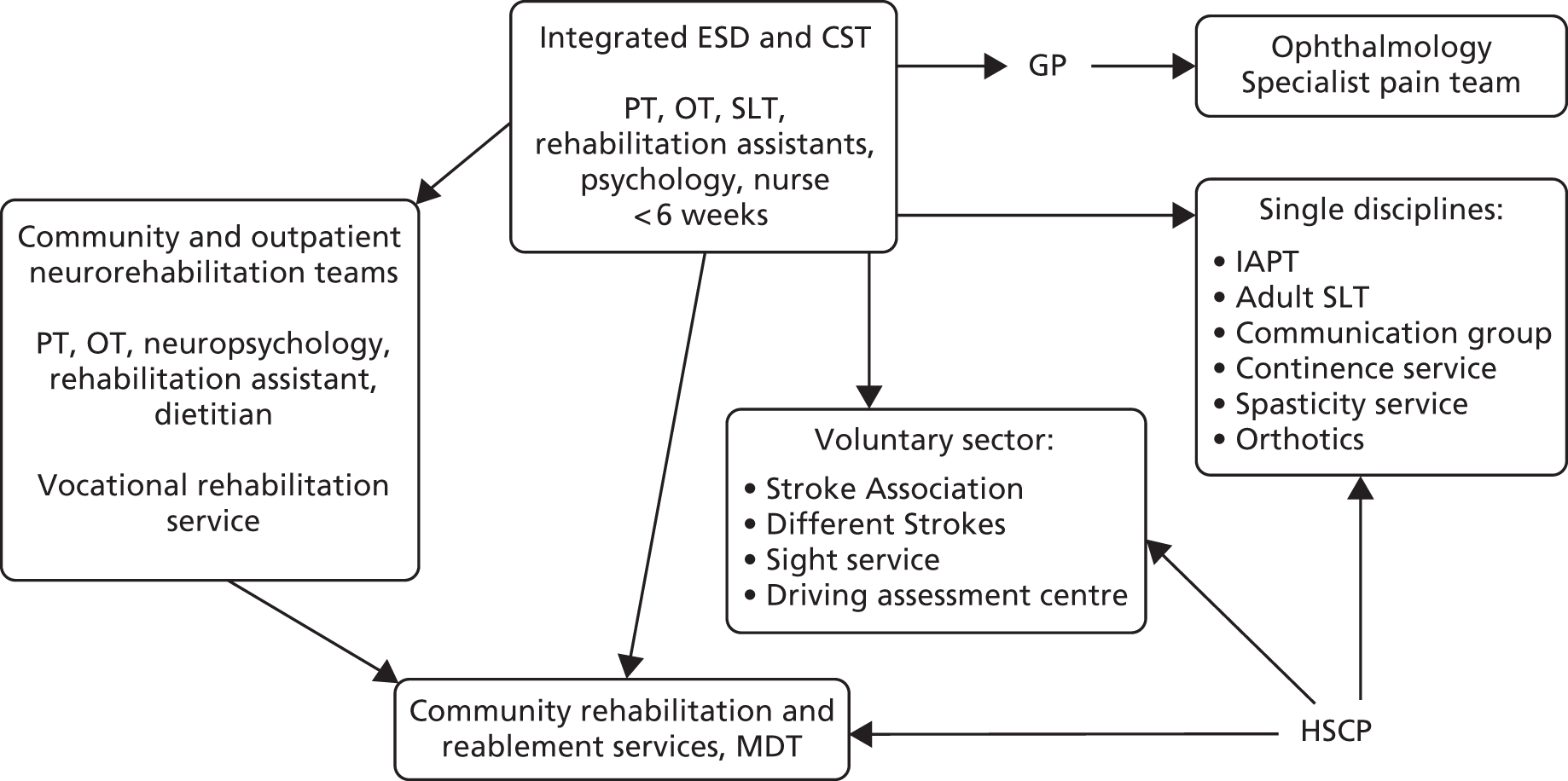

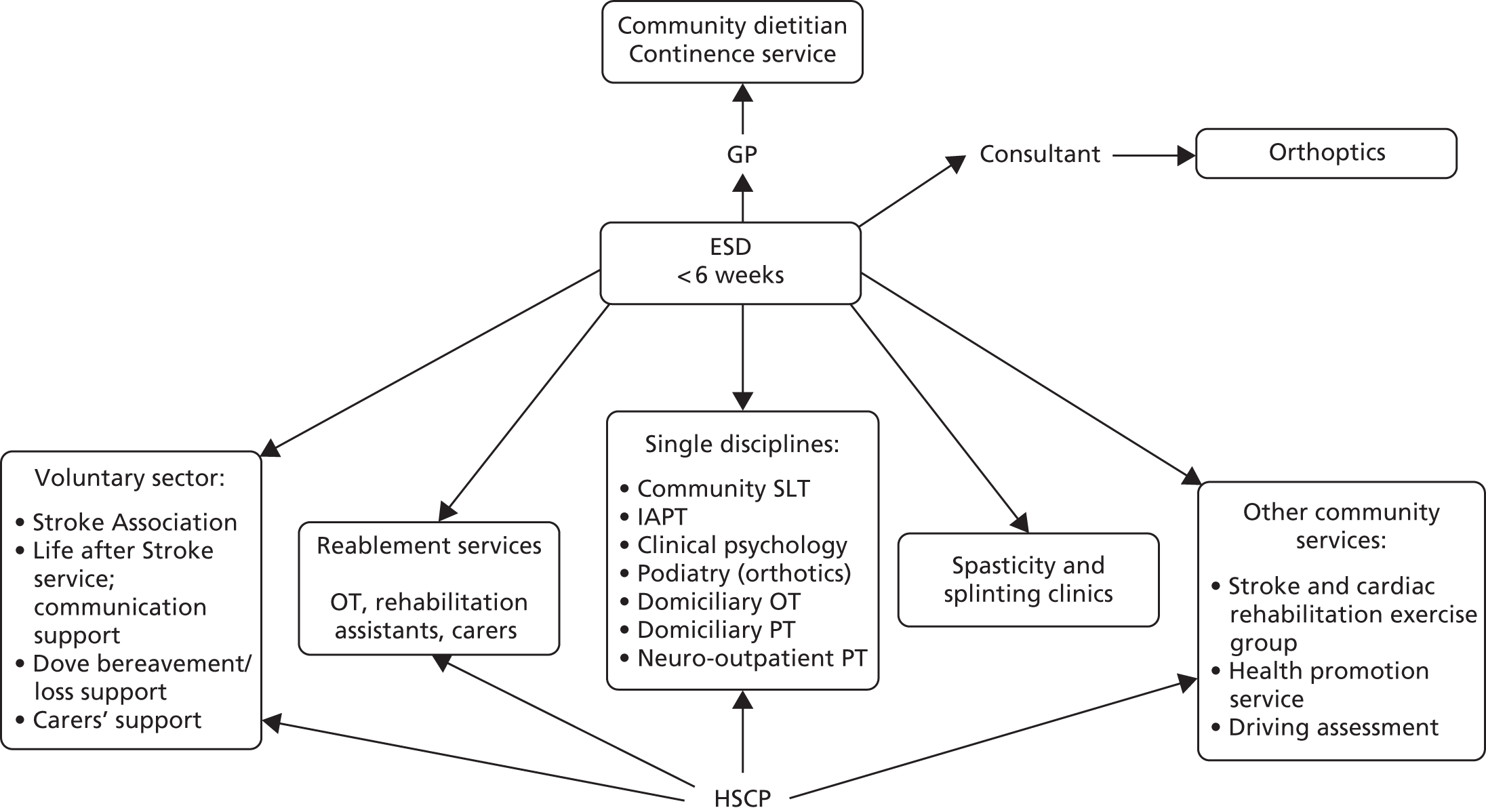

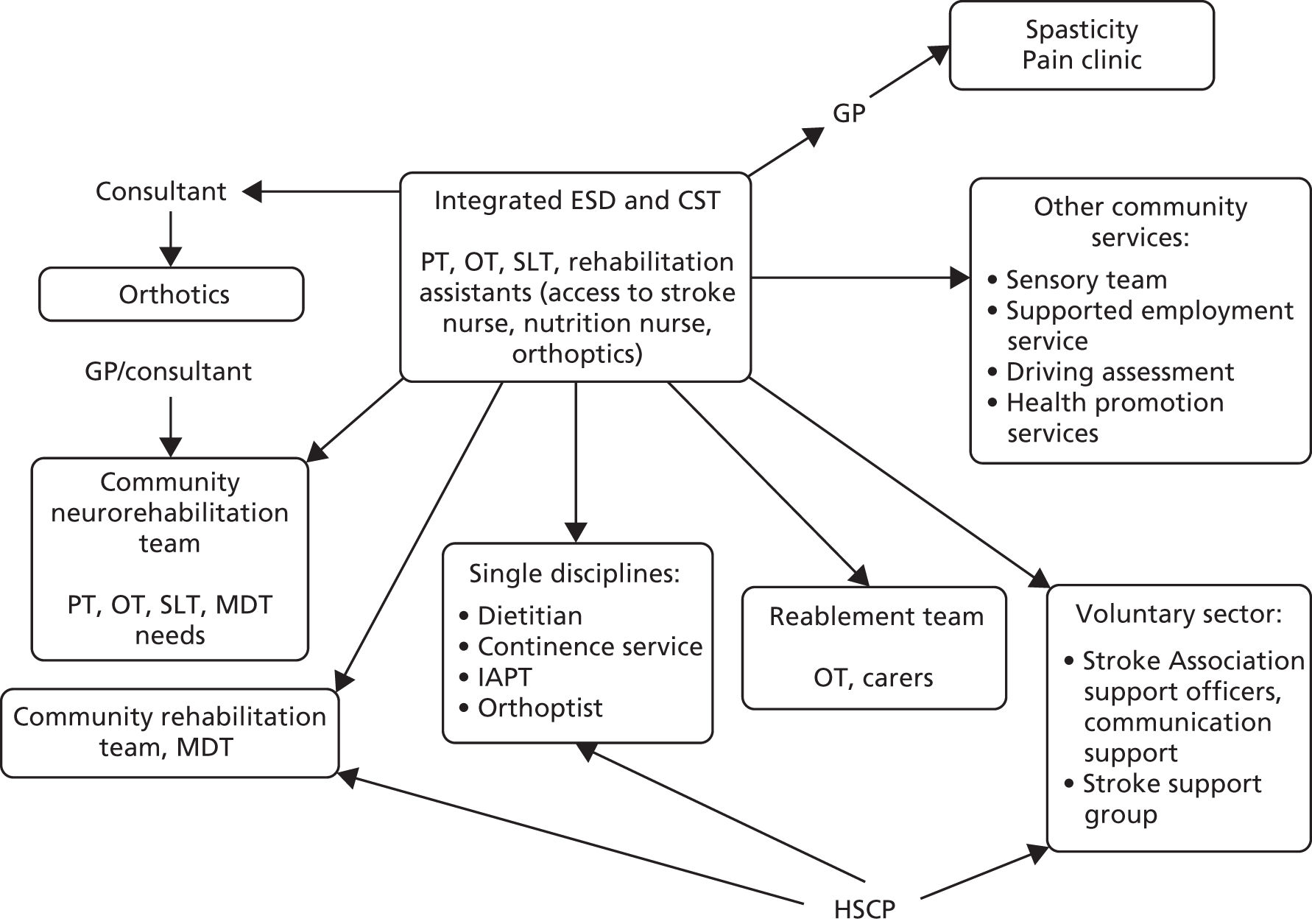

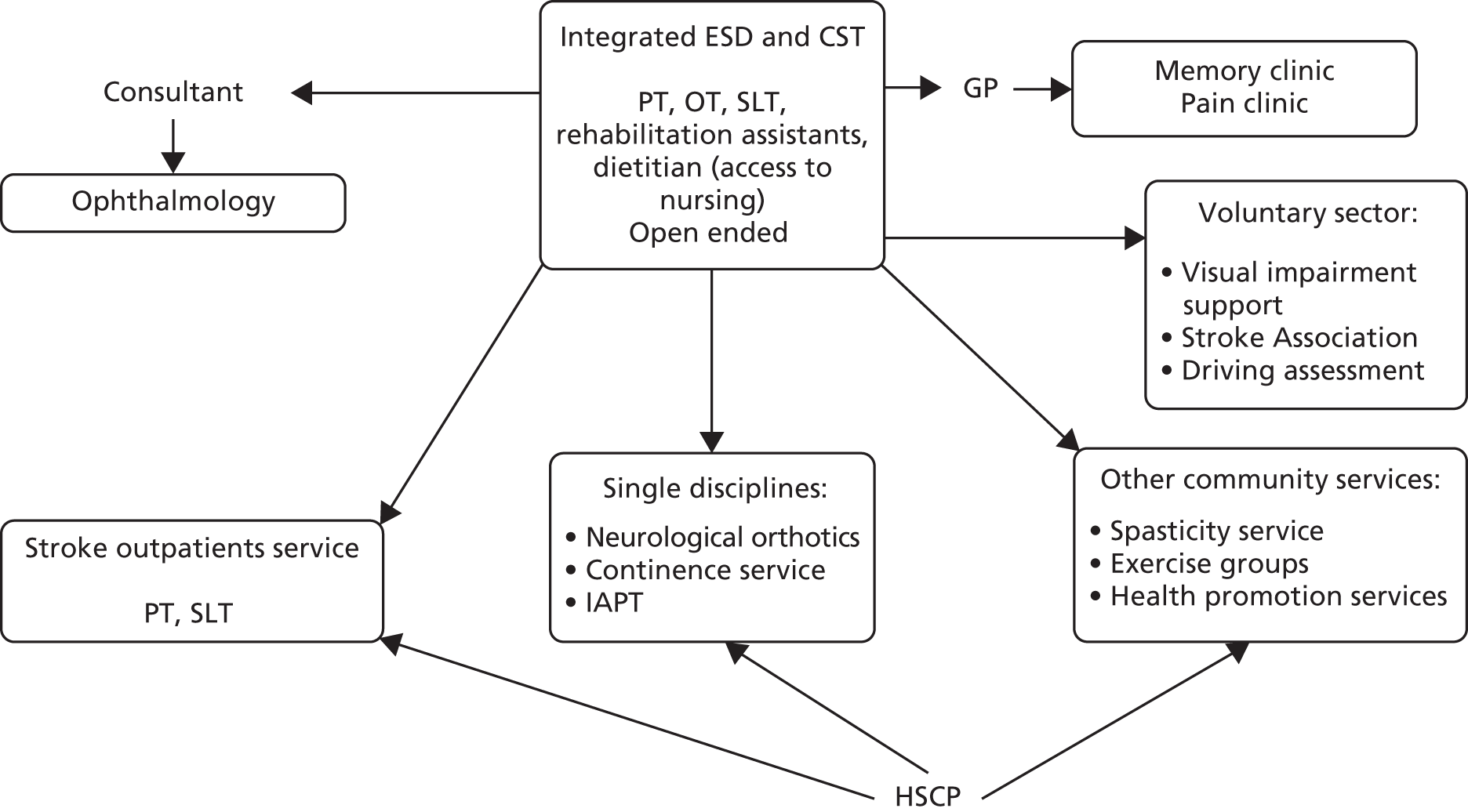

Stroke patients in the control group received usual ESD care with subsequent referral to other rehabilitation services post discharge from ESD if required, and in accordance with the local usual care. Patients who had ongoing rehabilitation needs following completion of ESD could be referred to a range of services, for example neurorehabilitation teams, day hospital and community rehabilitation services. The availability of rehabilitation services for patients taking part in this study was recorded during a mapping exercise (see Chapter 7).

Control participants also received the booklet Care After Stroke or Transient Ischaemic Attack. Information for Patients and their Carers written by the Intercollegiate Stroke Working Party. 45 This booklet described what a stroke is and its assessment, acute management and rehabilitation. It was based on the National Clinical Guideline for Stroke in 200846 updated in 2012. 47

Study intervention treatment

Stroke patients in the intervention group received EXTRAS for 18 months following completion of rehabilitation with their ESD team. This was in addition to usual care. They also received the Intercollegiate Stroke Working Party booklet about stroke care and rehabilitation. 45

EXTRAS was developed by the investigator team and consisted of reviews conducted by a senior member of the ESD team at 1, 3, 6, 12 and 18 months post discharge from routine ESD (randomisation).

Each EXTRAS review consisted of:

-

Identification of rehabilitation needs. A semistructured interview was conducted to determine the patient’s progress, current rehabilitation needs and service provision. The interview addressed daily activities (mobility, personal care, mealtimes, domestic activities), social participation (work and volunteering, hobbies and interests, driving and transport) and wider issues (communication, memory and concentration, mood, medical issues, pain), which may be problematic for stroke survivors. The views of both the patient and the carer (where appropriate) could be sought. The interview topics were based on the literature about stroke survivors’ long-term needs including the UK Stroke Survivor Needs Survey8 and input from stroke survivors, carers and health-care professionals.

-

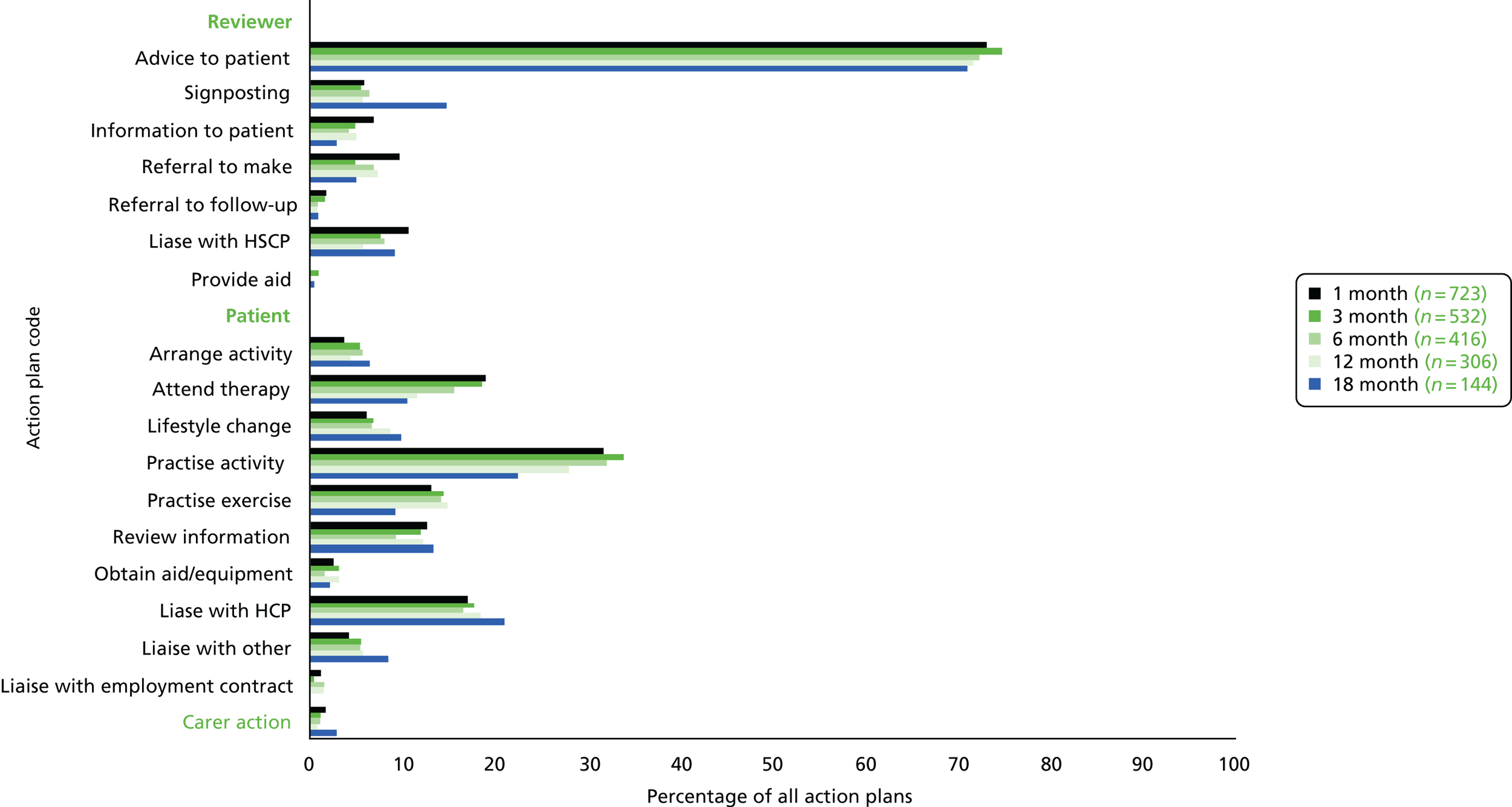

Joint rehabilitation goal-setting. From the identified progress and rehabilitation needs, up to five individual rehabilitation goals could be set by the patient (and carer) in collaboration with the senior ESD team member who conducted the review. The focus of joint goal-setting was intended to be on increasing participation in everyday activities. From the second review, progress towards the goals set previously was assessed prior to further goal-setting. Achievement of goals was recorded using a Goal Attainment Scale. 48

-

Action-planning. The patient (and carer) agreed an action plan for each rehabilitation goal. Action plans could include:

-

Verbal advice and encouragement.

-

Discussion with the stroke team, rehabilitation team, primary care team or social services involved in care.

-

Signposting to local activities, community organisations or voluntary services.

-

Referral to stroke services, rehabilitation services or primary care services for further assessment and treatment if required according to local guidelines and/or service provision.

-

Subsequent to each review, the ESD therapist/nurse could contact the services currently involved in the patient’s care to discuss progress, goals and care plan.

The EXTRAS reviews were intended to be predominantly undertaken by telephone. The senior ESD team member would know the patient and carer, as he/she had treated the patient as part of the ESD service. However, if the patient and/or carer was unable to participate in a telephone review, a home visit could be undertaken. On randomisation to the intervention group, patients were given a study appointment card that also contained a short checklist of rehabilitation issues to be covered in each review. This was intended to allow patients (and carers) time to consider the topics to be discussed prior to each review. Patients with aphasia received an ‘easy access’ version of the appointment card. Following each review, a summary of the interview and recommendations for rehabilitation were sent to the patient by post and could be copied to other health-care professionals involved in care as appropriate. Patients with aphasia received an ‘easy access’ version of the summary.

On opening a study centre, all senior ESD staff taking part in delivery of the new service received face-to-face training from the trial co-ordinating centre team. As delivery of the intervention for this study was conducted for almost 5 years (recruitment commenced in late 2012 and delivery of the intervention ceased in mid-2017), inevitable staffing changes took place in ESD teams. New members of staff received cascade training from existing trained staff and/or further training visits from the trial co-ordinating centre.

A manual describing EXTRAS was also provided to each member of staff. This manual described how to conduct the reviews and included guidance on exploring rehabilitation needs, goal-setting and appropriate interventions to meet a patient’s needs. Study-specific paperwork was completed for each review, including documentation of identified needs, goals set and action plans made.

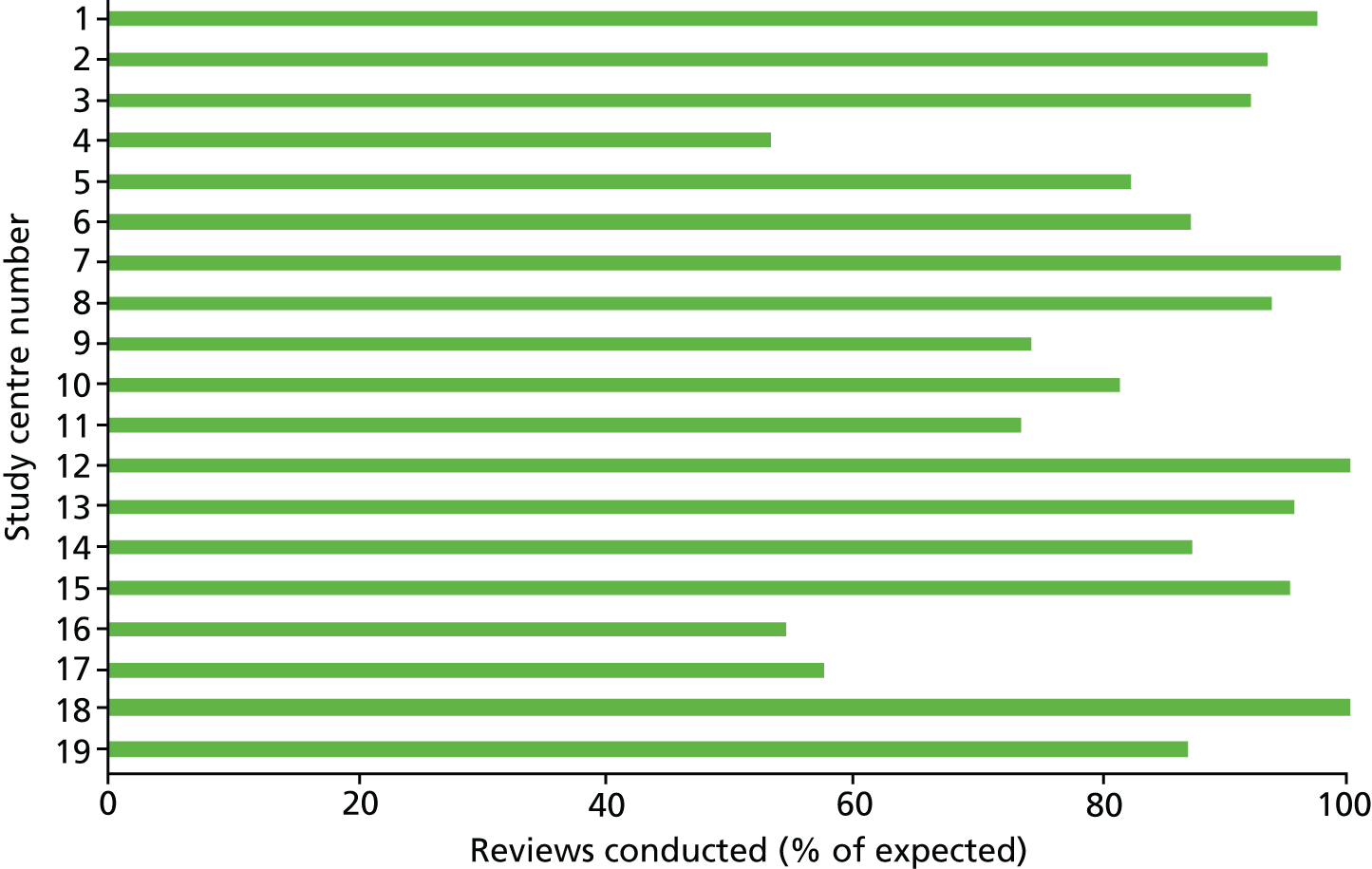

The choice of ESD team staff member (e.g. physiotherapist, occupational therapist, nurse) to conduct each individual review was at the discretion of each participating centre. The trial co-ordinating centre sent all participating study centres weekly reminders about forthcoming reviews and a regular data report that illustrated which review data were entered onto the study database, therefore highlighting overdue or missing reviews.

A description of EXTRAS using the Template for Intervention Description and Replication (TIDieR) checklist49 is shown in Appendix 1, Table 31.

EXTRAS did not include any assessment of carer needs or specific interventions for carers.

Outcome assessments

Outcomes were intended to be assessed at 12 months (± 7 days) and 24 months (± 7 days) post randomisation.

1. Patients

Patient outcome assessments could be undertaken over the telephone, by postal questionnaire or during a face-to-face visit. The preferred method was telephone questionnaire but postal or face-to-face options were possible where use of a telephone was unfeasible. Postal questionnaires were also used when it had not been possible to make contact by telephone.

Telephone interviews were conducted by a researcher based in the study co-ordinating centre at Newcastle University, Newcastle upon Tyne, UK. This researcher also co-ordinated any postal questionnaires and conducted any required face-to-face visits for patients in north-east England. When patients required a face-to-face visit outside north-east England, this was undertaken by staff from the local participating centre following training by the co-ordinating centre researcher.

The following data were collected: EADL (NEADL Scale),33 health status (OHS),34 mood (HADS),42 experience of services (adaption of an experience survey designed by Northumbria Healthcare NHS Foundation Trust based on Picker Institute questions,50 quality of life (EQ-5D-5L)43 and resource utilisation (adaptation of the CSRI). 37–39 The primary outcome was the NEADL Scale. 33 The OHS,34 HADS42 and experiences of services survey were secondary outcome data. The EQ-5D-5L43 and resource utilisation were collected for the economic evaluation.

The NEADL Scale is a 22-item scale to assess performance in carrying out EADL. The items are ordered as four subscales covering ‘mobility’, ‘in the kitchen’, ‘domestic tasks’ and ‘leisure activities’. Respondents are asked to indicate what they have actually done, not what they perceive they could do, ought to do or would like to do. Each item is scored as follows: 0 is ‘no’, 1 is ‘with help’, 2 is ‘on my own with difficulty’ and 3 is ‘on my own’. Responses are summed, giving a score of 0–66, where higher scores indicate greater activity.

The OHS34 is a derivative of the Modified Rankin Scale,51 which, in turn, is a derivative of the original Rankin Scale. 52 The OHS used in this study was a self-report version. The scale has ordinal scale scoring: 0 is ‘I have no symptoms at all and cope well with life’, 1 is ‘I have a few symptoms but these do not interfere with my everyday life’, 2 is ‘I have symptoms which have caused some changes in my life but I am still able to look after myself’, 3 is ‘I have symptoms which have significantly changed my life, prevent me coping fully on my own, and I need some help in looking after myself’, 4 is ‘I have quite severe symptoms which mean I need to have help from other people but I am not so bad as to need attention day and night’, 5 is ‘I have major symptoms which severely handicap me and I need constant attention day and night’. A score of 6 is used to indicate death.

The HADS42 is made up of anxiety and depression subscales of seven items each. Each item is scored 0–3, so patients can score from 0 to 21 on each subscale. Higher scores are indicative of anxiety and depression. In addition, ‘cut-off’ scores have been defined as follows: a score of 0–7 is ‘non-case’, 8–10 is ‘doubtful case’ and 11–21 is ‘definite case’.

The experience of services scale was an adaptation of an experience survey designed by Northumbria Healthcare NHS Foundation Trust based on Picker Institute questions. 50 It had three parts. Part 1 involved 15 questions about services received with responses on a five-point Likert scale: ‘strongly disagree’, ‘disagree’, ‘agree’, ‘strongly agree’ and ‘does not apply’. Part 2 was about overall satisfaction. Participants were asked ‘Overall, how satisfied are you with the services you received?’. There were five responses from ‘extremely satisfied’ to ‘extremely unsatisfied’. Part 3 contained three questions about meeting needs in relation to speaking, mobility and emotional problems. Responses were ‘yes, definitely’, ‘yes, to some extent’, ‘no I did not get enough help from the NHS’ and ‘I did not have any difficulties’. There was no numerical scoring for this questionnaire, so questions were dichotomised to create proportions of patients answering ‘strongly agree’ and ‘agree’, for comparison with ‘disagree’ and ‘strongly disagree’; or, ‘extremely satisfied’, ‘very satisfied’ and ‘quite satisfied’, for comparison with ‘not very satisfied’ and ‘extremely unsatisfied’.

The EQ-5D-5L43 instrument has two parts: a descriptive system comprising five dimensions (i.e. mobility, self-care, usual activities, pain/discomfort and anxiety/depression) and a visual analogue scale (VAS). In the descriptive system, each dimension has five responses: no problems, slight problems, moderate problems, extreme problems and unable to do. The VAS is vertical with ‘the best health you can imagine’ at the top (score of 100) and ‘the worst health you can image’ at the bottom (score of 0). Responses to the EQ-5D-5L were converted into utility values, which were combined with observed mortality to create quality-adjusted life-years (QALYs). Data are presented in Chapter 8.

An adaption of the CSRI37–39 was used to measure resource utilisation. This instrument captures data about accommodation and living, hospital care, primary care, other NHS services (e.g. physiotherapy, occupational therapy) and social services.

2. Carers

Carers’ outcome assessments were undertaken by a postal questionnaire sent by and returned to the study co-ordinating centre. The following data were collected from carers: carer stress (CSI),44 experience of services (adaption of an experience survey designed by Northumbria Healthcare NHS Foundation Trust based on Picker Institute questions)50 and quality of life (EQ-5D-5L). 43 Responses to the EQ-5D-5L were used to create QALYs, and these data are presented in the health economic evaluation chapter (see Chapter 8).

The CSI44 is a tool used to identify strain in informal carers for physically ill and functionally impaired elderly adults. It comprises 13 items, each answered as ‘no’ (score of 0) or ‘yes’ (score of 1). Scores are summed and a higher score indicates more strain. Because the CSI asks some sensitive questions about the impact of stroke on the carer, it was not felt appropriate to conduct telephone interviews as carers may have modified their answers if they could be overheard on the telephone by the patient.

Blinding

Owing to the nature of the study intervention, it was not possible to blind stroke patients or carers to treatment allocation. Where patient outcome assessments were undertaken by telephone or face-to-face visit, it was intended that they were conducted blinded to treatment allocation. After each assessment, the assessor was asked to record whether or not they had unintentionally become aware of treatment allocation as a result of conversation with the participant.

Study withdrawal

No specific study withdrawal criteria were pre-set. Stroke patients and/or carers could withdraw from the study at any time for any reason. Reasons for withdrawal were sought but participants could withdraw without providing an explanation. Investigators, senior ESD team members and/or a patient’s consultee (in the case of mental incapacity) could also withdraw participants from the study at any time if they felt that it was no longer in their interest to continue, for example because of intercurrent illness. Participants were informed that data collected prior to withdrawal would be used in the study analysis, unless consent for this was specifically withdrawn. Participants who wished to receive no further intervention were not withdrawn from study follow-up unless they specifically requested this.

Safety evaluation

Adverse events were collected by including the following questions in the study outcome questionnaires at 12 and 24 months:

-

Have you suffered any new medical illnesses in the last 12 months?

-

Have you suffered any falls resulting in injury in the last 12 months?

Any event potentially fulfilling the criteria to be a serious adverse event (SAE) was further investigated by local study centre staff who had access to medical records, and fully detailed on a separate study SAE form as appropriate. As local study centre staff could become aware of events fulfilling the criteria to be SAEs at any time during a participant’s involvement in the study, the study SAE form was also used to directly capture any such events. A causality and expectedness assessment was undertaken for all SAEs.

The standard definition for SAE was used. A SAE is an untoward occurrence that:

-

results in death

-

is life-threatening

-

requires hospitalisation, or prolongation of existing hospitalisation

-

results in persistent or significant disability or incapacity

-

consists of a congenital anomaly or birth defect

-

is otherwise considered medically significant by the investigator.

Data management

Study data were collected onto study-specific paper case-record forms and subsequently entered onto an online database by NHS staff at participating centres and/or staff at the study co-ordinating centre.

Sample size

A difference of 6 points on the NEADL Scale (scored 0–66, SD 18) is considered to be clinically important, and power calculations for previous multicentre rehabilitation trials had been based on this difference. 38,53 Responses from 382 patients who were split equally between intervention and control groups would provide 90% power to detect a difference in mean NEADL Scale of 6 points. Based on attrition in other stroke rehabilitation trials, it was estimated that there could be up to 25% attrition between study randomisation and the 24-month (primary) outcome assessment. To allow for this, 510 patients were required to be randomised into the study.

Because patients could be recruited at any time from within 4 days prior to hospital discharge to discharge from ESD, there could be several weeks between recruitment and randomisation. As dropout was observed during this time interval, it was planned that recruitment would cease when it was estimated that at least 510 patients would be randomised. Reasons for loss from the trial were recorded.

Statistical analysis of primary and secondary outcome data

1. Analysis populations

Analyses were carried out on an intention-to-treat (ITT) basis, retaining patients and carers in their randomisation groups, and including protocol violators and ineligible patients.

2. Analysis data sets

The pattern and extent of missing observations because of loss to follow-up was examined. Unless specified by the scale developers, where no more than 20% of questions were missing or uninterpretable on specific scales, the score was calculated by using the mean or median value (as appropriate) of the respondent-specific completed responses on the rest of the scale to replace the missing items (i.e. simple imputation). 54 It was planned to investigate the use of multiple imputation techniques if the primary outcome was still missing for > 20% of patients after the use of simple imputation; however, this was not necessary. Complete-case, simple imputation and a sensitivity analysis data set were analysed. The sensitivity analysis data set excluded data from patients who had follow-up conducted 1 month before and 3 months after the due date for their 12- and 24-month assessments, and patients whose NEADL Scale scores recorded post stroke were higher than those recorded prior to their stroke.

3. Descriptive analyses

Characteristics of study patients and carers were summarised separately for each randomisation group. This included primary and secondary outcome variables and covariates. Continuous variables were summarised by the numbers of observations and the mean and SD, or the median and interquartile range (IQR), depending on whether or not the distribution was symmetric. Numbers of observations and percentages were reported for categorical variables. No significance testing for any baseline imbalance was carried out, but any noted differences were reported descriptively.

4. Inferential analyses

Mean scores on the NEADL Scale (the primary outcome) were compared at 24 months between the intervention and the control groups using multiple linear regression, including terms for centre, baseline OHS, age and sex. Mean scores with bootstrapped confidence intervals (CIs) are reported for:

-

data with complete-case NEADL Scale scores

-

a complete-case set adjusted for centre, baseline OHS, age and sex

-

data with simple imputation for partially completed NEADL Scale scores

-

a simple imputation set, adjusted for centre, baseline OHS, age and sex (primary analysis)

-

a sensitivity analysis of above, excluding data from patients outside –1 and + 3 months of their expected visit date and those whose NEADL Scale scores appeared to be unlikely as they had increased (improved) post stroke.

This analysis was repeated for the 12-month NEADL Scale scores for:

-

data with simple imputation for partially completed NEADL Scale scores

-

a simple imputation set adjusted for centre, baseline OHS, age and sex

-

a sensitivity analysis of above, excluding data from patients outside –1 and +3 months of their expected visit date and those whose NEADL scores appeared to be unlikely as they had increased (improved) post stroke.

In terms of secondary outcomes, ordinal regression was used to analyse the 12- and 24-month OHS scores by randomisation group, using the same covariates as for the primary analysis. This was carried out for categories 0–5, with category 0 set as the reference group. To come closer to a full ITT analysis, patients who had died were included in a second analysis in a separate category, as a score of 6. Odds ratios with 95% CIs were reported for an unadjusted model and one adjusted for centre, baseline OHS, age and sex.

The HADS scores were analysed as the two separate domains of anxiety and depression. Multiple linear regression was used to compare the intervention and the control groups at 12 and 24 months. Mean scores with bootstrapped CIs were reported for data with simple imputation for partially completed HADS scores, and the simple imputation set adjusted for centre, baseline OHS, age and sex. In addition, a post hoc analysis considered those patients scoring ≥ 8 to have cases of anxiety or depression, and logistic regression was used to compare the randomisation groups on this binary variable at 12 and 24 months. Odds ratios with 95% CIs were reported for an unadjusted model and one adjusted for centre, baseline OHS, age and sex. The HADS can be presented as either scores or ‘cases’, with the latter being more meaningful to a clinical audience. During the trial, the Trial Steering Committee (TSC) and the Data Monitoring Committee (DMC) reports had included both methods as they are considered to be of equal importance. This post hoc analysis of ‘cases’ was undertaken owing to an omission from the statistical analysis plan. This was the only post hoc analysis that was undertaken for this report.

Experience of service questions for both patients and carers at 12 and 24 months were reported as a difference in the proportion of patients and carers satisfied or in agreement between the control and the intervention groups with a 95% CI. No adjustment for covariates was undertaken for this scale analysis.

For the CSI, mean scores at 12 and 24 months were compared between carers whose patients were in the control group and those whose patients were in the intervention group, using multiple linear regression and adjusting for the age and sex of the carer, and using the patients’ baseline OHS score as a measure of the patient’s health status.

5. Exploratory analyses

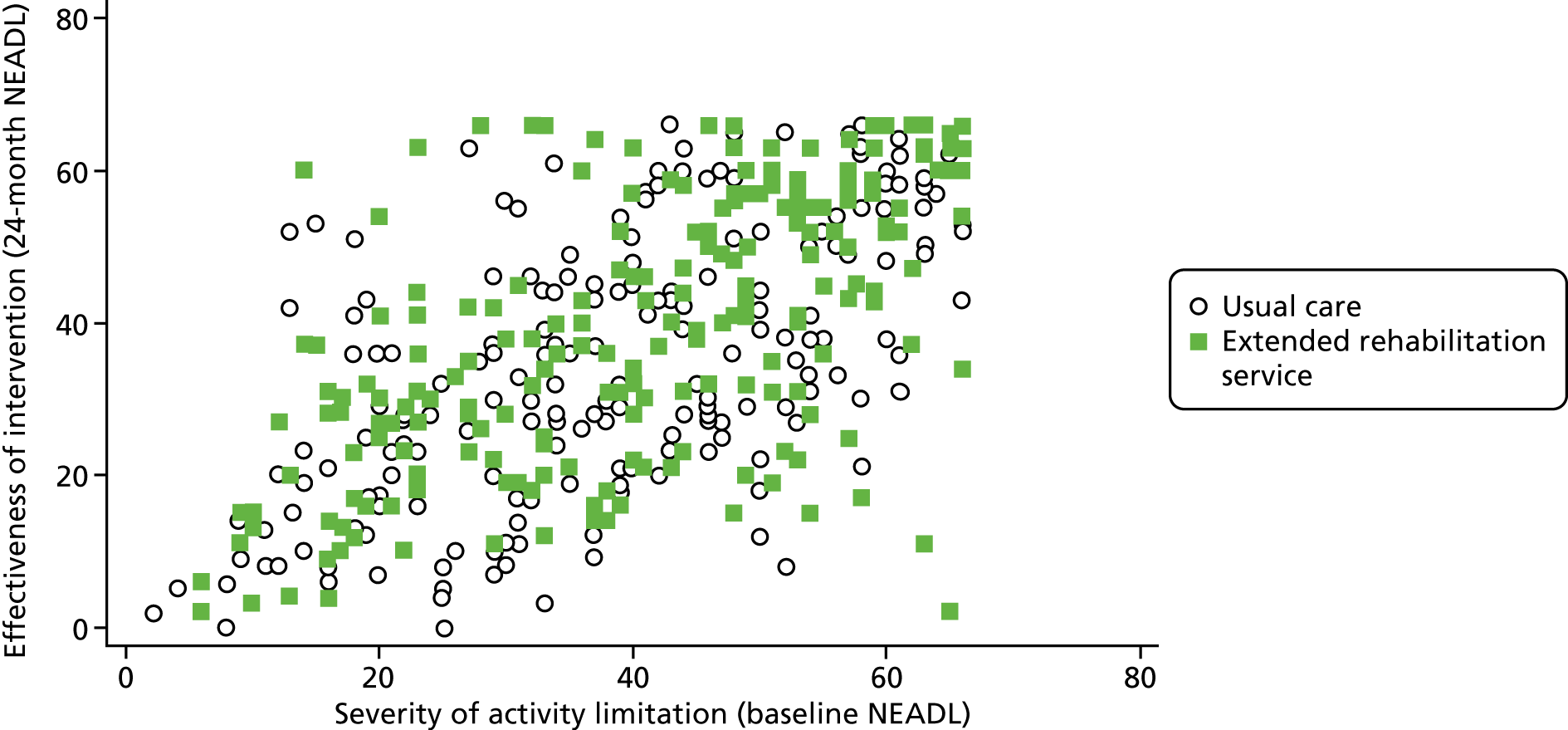

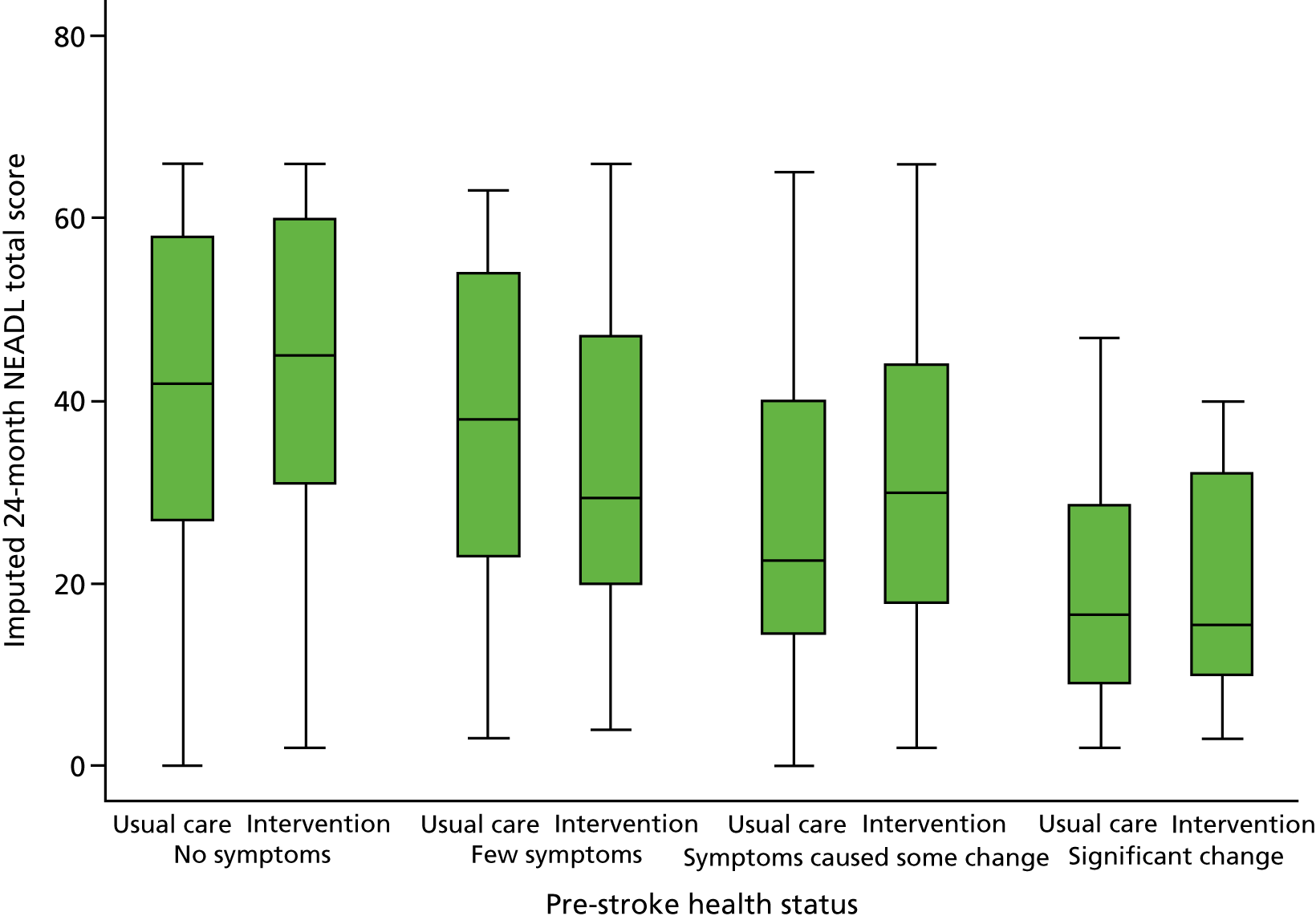

Pre-planned exploratory descriptive analyses examined the association of the severity of activity limitation measured by the baseline NEADL Scale score and the pre-stroke health status measured by the pre-stroke OHS, with the effectiveness of the intervention (24-month NEADL Scale score). These are reported as separate scatterplots of the 24-month NEADL Scale score against the severity variables. A boxplot showing 24-month NEADL Scale scores by pre-stroke OHS category and randomisation group is also reported.

The study protocol included a third pre-planned exploratory analysis, which was to examine the impact of comorbidity on the effectiveness of the intervention. On preparing the detailed statistical analysis plan, it was decided that this would not be conducted because although free-text comorbidity had been recorded for patients, a quantifiable measure of comorbidity had not been included.

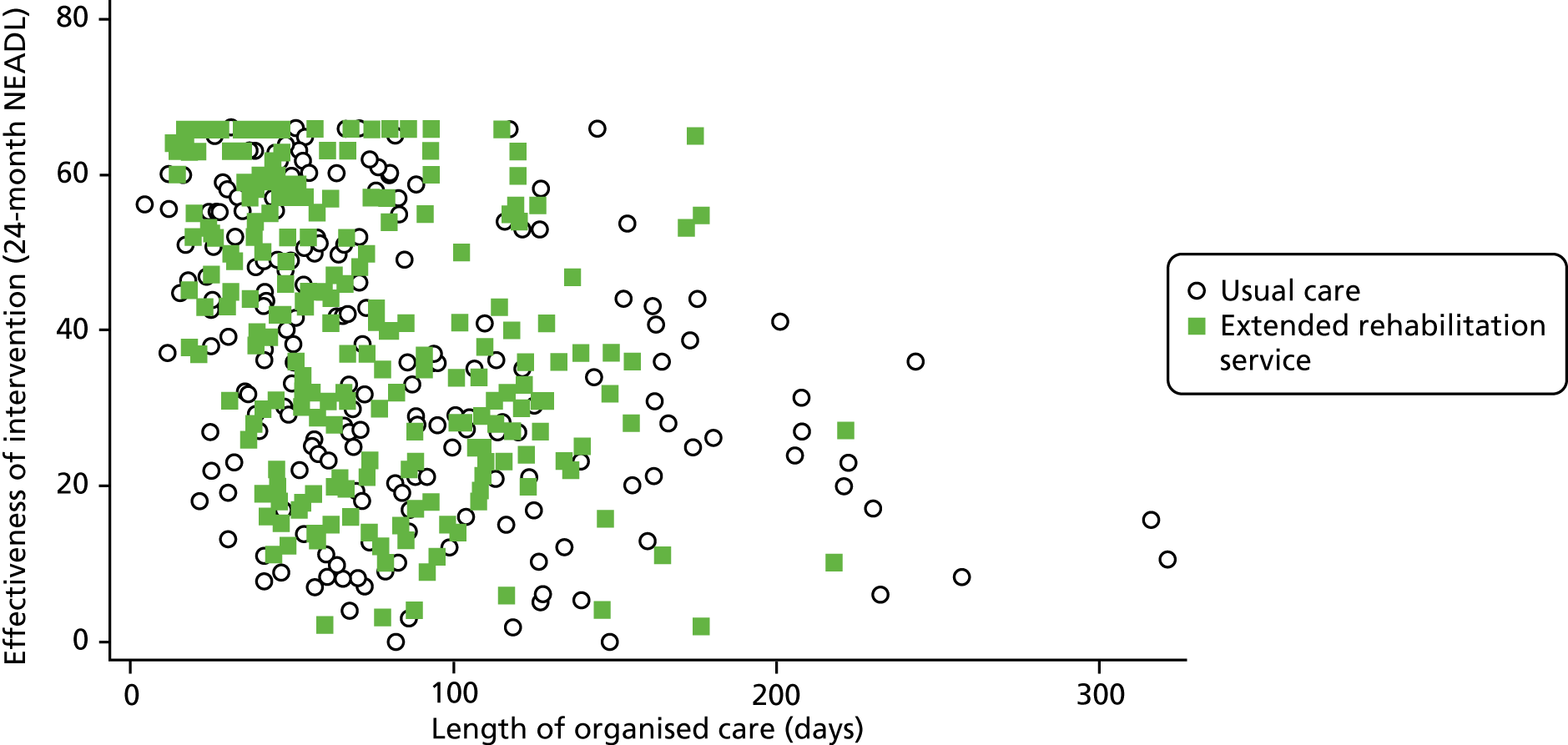

In preparing the detailed statistical analysis plan, it was decided to include an additional analysis to examine the effect of time in organised stroke care (time as an inpatient plus the time in ESD) on the effectiveness of the intervention. This is illustrated as a scatterplot of the 24-month NEADL Scale score against the duration of organised stroke care.

All analyses were carried out using Stata® version 15 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA).

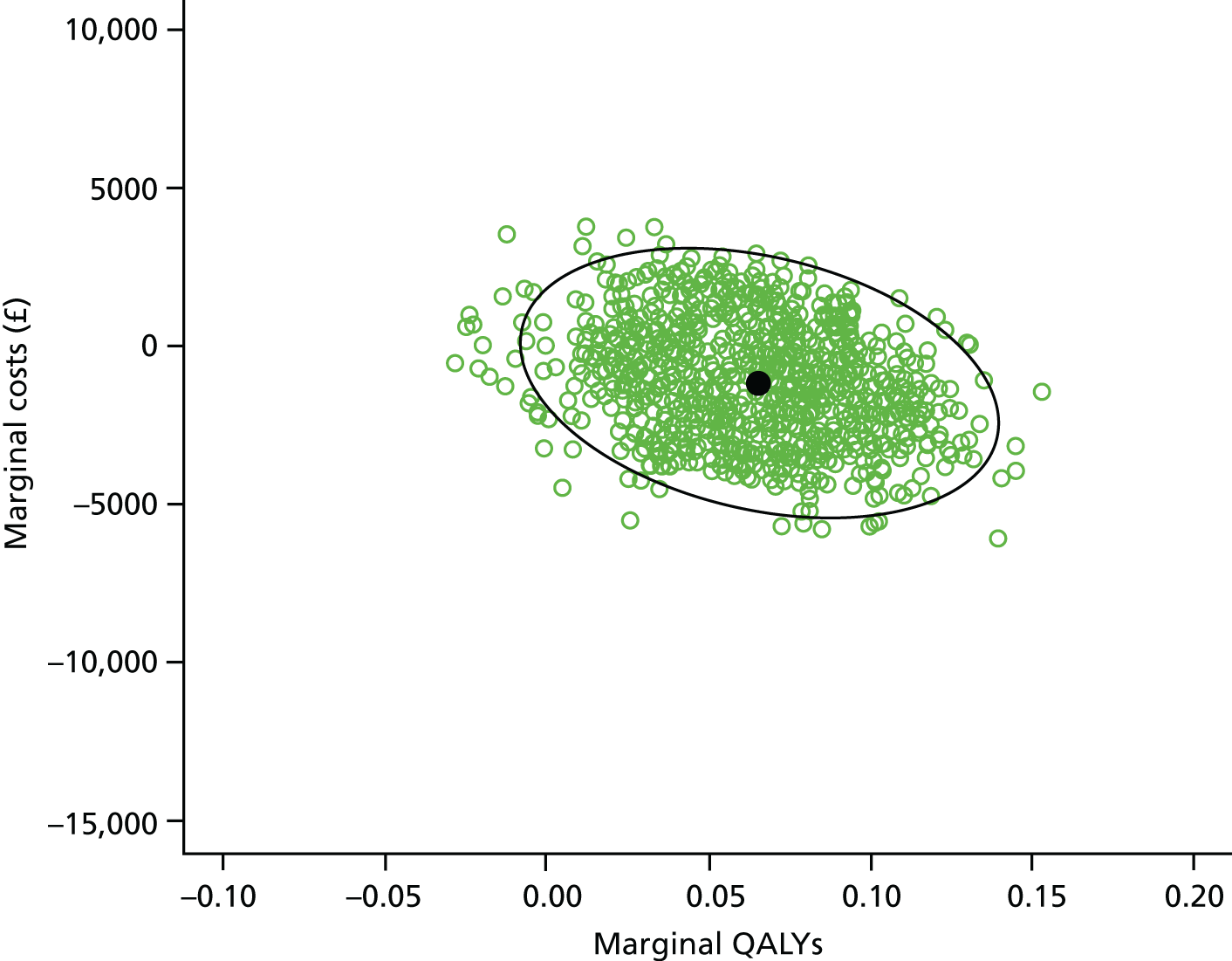

Economic analysis

The economic evaluation consisted of a cost-effectiveness analysis (CEA) and a cost–utility analysis. 55 Methods are described in the health economic evaluation chapter (see Chapter 8).

Parallel process evaluation

Parallel process evaluations of complex interventions being tested by randomised controlled trials are increasingly recommended. 56 They can provide information about unanticipated consequences, reasons for success and how an intervention can be improved, and can identify contextual factors associated with variations in outcome. 57 The study process evaluation consisted of the following components, and the methods are described at the start of each respective chapter:

-

mapping the routine rehabilitation and follow-up services provided for stroke patients in each study centre (see Chapter 7)

-

analysis of the study intervention paperwork completed by ESD staff to understand implementation and delivery of the new service in the different study settings (see Chapter 5)

-

conducting interviews to seek the views and experiences of patients and carers about the rehabilitation services they received (see Chapter 6)

-

conducting interviews to seek the views and experiences of senior members of the ESD teams and community rehabilitation staff about the services provided to the intervention and control groups (see Chapter 6).

Ethics and regulatory issues

The study sponsor was Northumbria Healthcare NHS Foundation Trust. Ethics approval was granted by the National Research Ethics Committee North-East – Newcastle and North Tyneside 1 (reference 12/NE/0217). Local NHS approvals were obtained from all participating NHS organisations. The study was conducted in accordance with the Research Governance Framework for Health and Social Care58 and Good Clinical Practice. 59 Monitoring of study conduct and data collection was performed by regular visits to all participating study centres. The trial was managed by a co-ordinating centre based at Newcastle University, Newcastle upon Tyne, UK. An independent DMC and TSC were in place for the duration of the project.

Amendments made to the study after it commenced

1. Modification of the enrolment process for carers

When the study commenced, carer enrolment was in keeping with the patient enrolment procedures described above. There was a face-to-face approach and written consent to participate in the study was sought. This was followed by a face-to-face recruitment assessment and then a separate self-completion baseline questionnaire. It was soon noted that carer recruitment rates were not as high as had been anticipated and it appeared that this may have been due to the enrolment procedures. The procedures appeared to be proving logistically challenging due to carers and NHS staff not being available at mutually convenient times. The carer enrolment procedure was, therefore, amended to invitation by letter and return of one self-completion baseline questionnaire (as described above).

2. Inclusion of stroke patients with communication difficulties (aphasia)

The study commenced without inclusion of patients with significant communication difficulties. The documentation required to support their involvement (‘easy access’) was developed during the first year of the trial.

3. Widening of options for patient outcome assessments

The original study protocol did not include postal questionnaires when telephone contact had failed or the option to mail reminder questionnaires for non-response. These options were later included.

4. Revision of recruitment target

The sample size of 510 patients included inflation for 25% attrition. This was based on the estimated loss between study randomisation and the 24-month (primary) outcome assessment. Randomisation for this study was at discharge from ESD services, but to maximise recruitment opportunities, patients could be recruited from 4 days prior to hospital discharge until discharge from ESD services. This could lead to a delay of up to several weeks between recruitment and randomisation, and dropout was observed during this time, which had not been anticipated. The protocol was therefore revised to clarify that 510 patients would need to be randomised to a study group and that recruitment would be kept under review, ceasing when it was estimated that this would be achieved.

In total, 573 patients were randomised. This is a larger number of participants than described in the sample size calculation, as during the study we felt that there was a risk that attrition at 24 months could be greater than anticipated and, as a result, the primary analysis would be underpowered. The ethics committee approved a minor amendment to increase the number of participants recruited and randomised.

5. Increasing number of study centres

The original study protocol proposed 12 study centres. The number of centres was increased to maintain the proposed recruitment rate.

Chapter 3 Randomised controlled trial results: patients

Patient recruitment and randomisation

Between 15 November 2012 and 6 July 2015, 674 patients were recruited to the trial from 19 participating study centres. Patients could be invited and consent to take part in the trial from 4 days prior to hospital discharge to discharge from an ESD service. Randomisation to a study group was conducted at discharge from an ESD service. The duration of ESD services ranged from a few days to several months. A total of 101 patients dropped out of the trial during the time between recruitment and randomisation. Reasons for this included the choice of patients [49/101 (49%)] and study centre staff [20/101 (20%)] to discontinue involvement. Full details about reasons for dropout are shown in Appendix 2, Table 32.

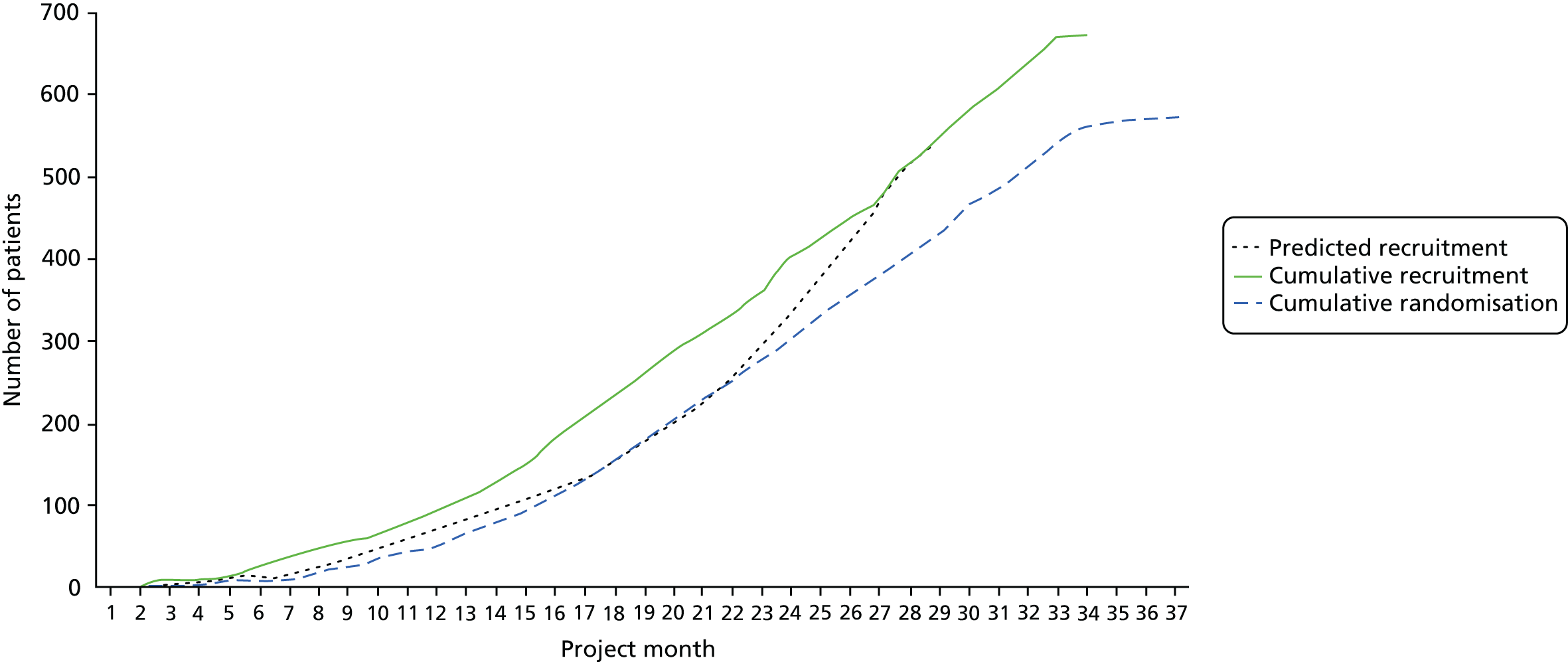

A total of 573 patients were randomised to a study group. Randomisation occurred at a median of 73 days (IQR 48–111.5 days) post stroke in the intervention group and 70 days (IQR 48–106.5 days) post stroke in the control group. Predicted and actual cumulative recruitment and actual cumulative randomisation are shown in Figure 1. Recruitment and randomisation per study centre are illustrated in Appendix 2, Table 33.

FIGURE 1.

Predicted and actual cumulative recruitment, and actual cumulative randomisation.

Patient retention and follow-up

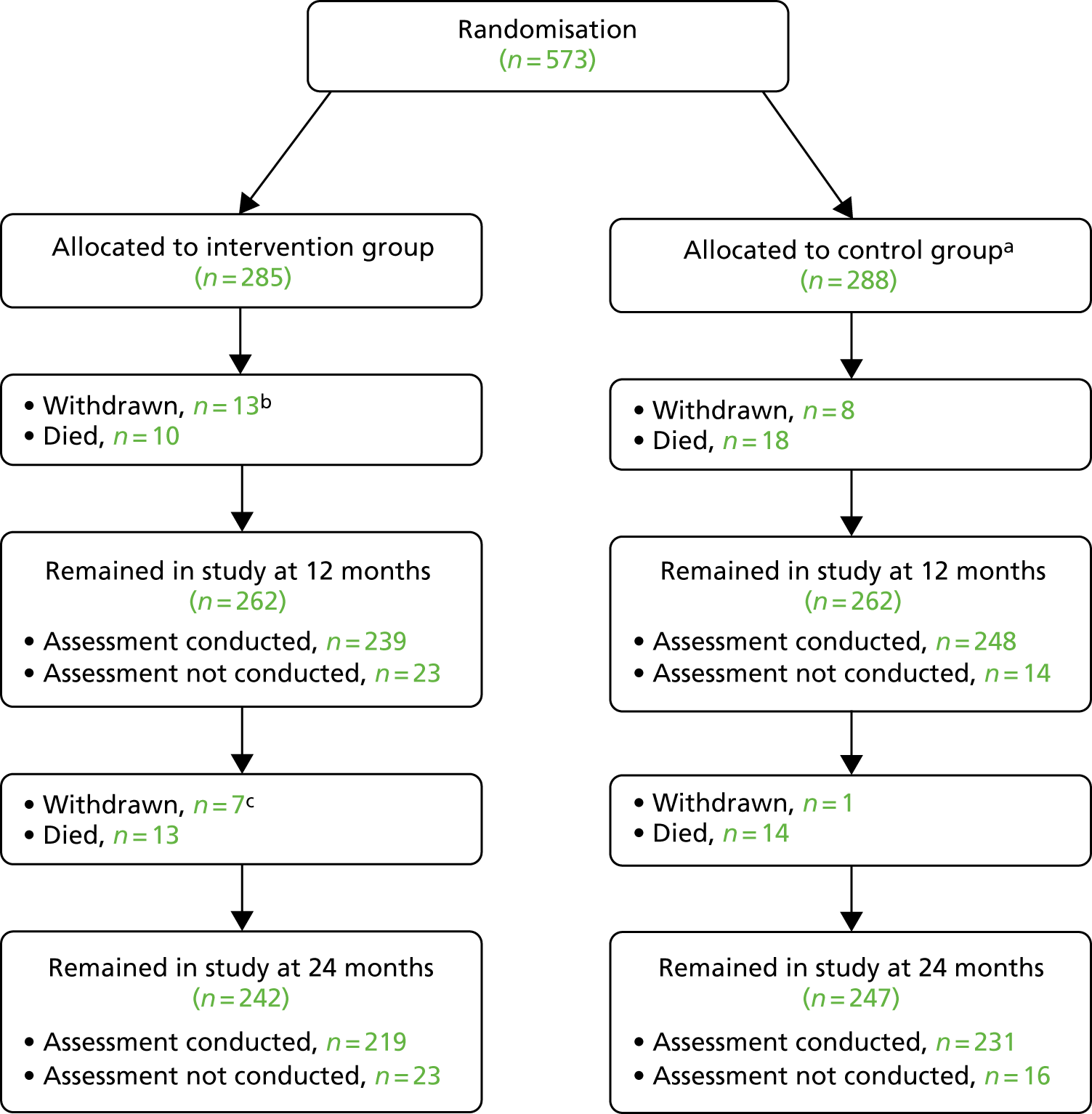

Of the 573 randomised patients, 285 were allocated to the intervention group and 288 were allocated to the control group. Patient retention is illustrated in Figure 2. Outcome data were collected for 487 out of 573 (85%) patients at 12 months and 450 out of 573 (78%) patients at 24 months. Further detail about the patients who were alive and did not have follow-up data collected is shown in Appendix 2, Table 34.

FIGURE 2.

Patient retention. a, One patient allocated to control received intervention in error; b, study SAE information indicates that 2 out of 13 patients died after withdrawal and within the 24-month follow-up period; and c, study SAE information indicates that one out of seven patients died after withdrawal and within the 24-month follow-up period.

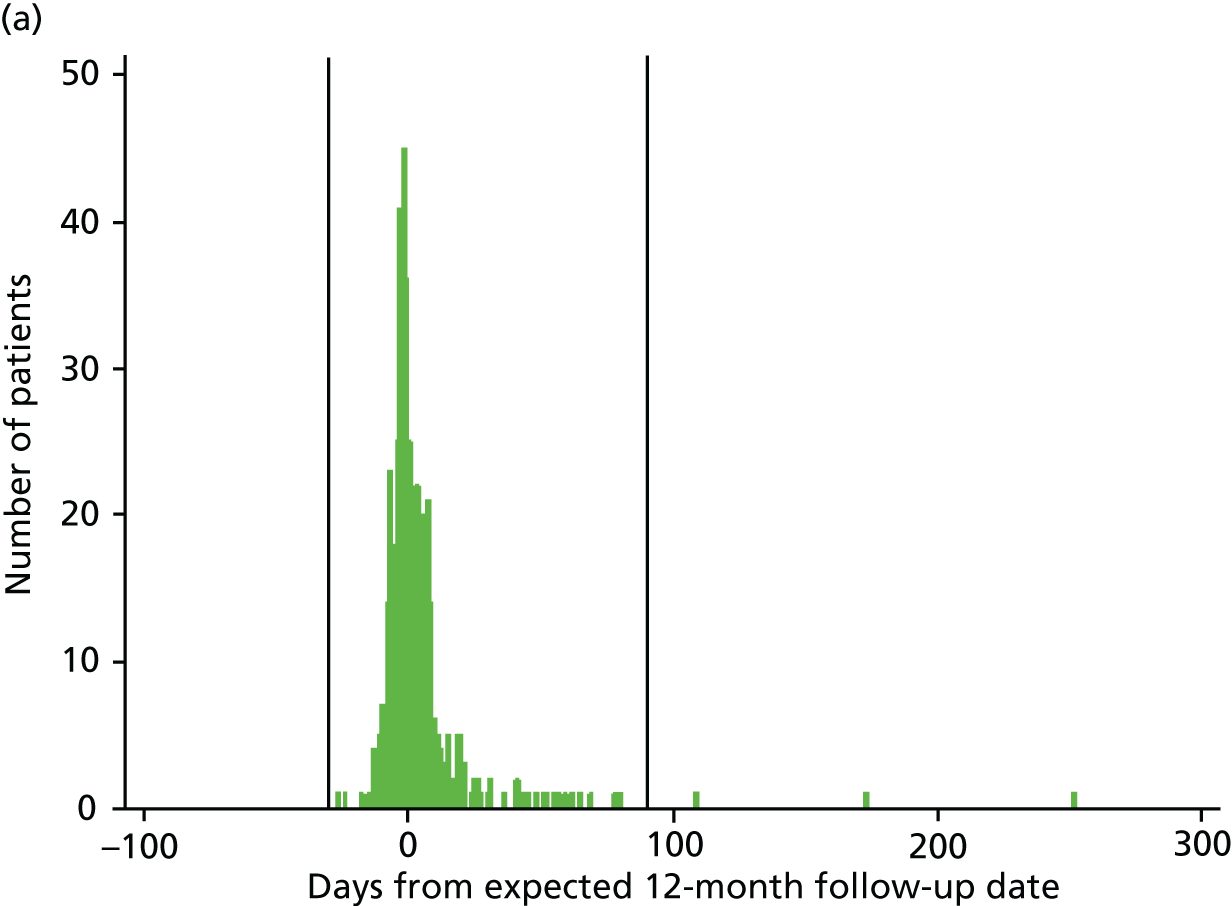

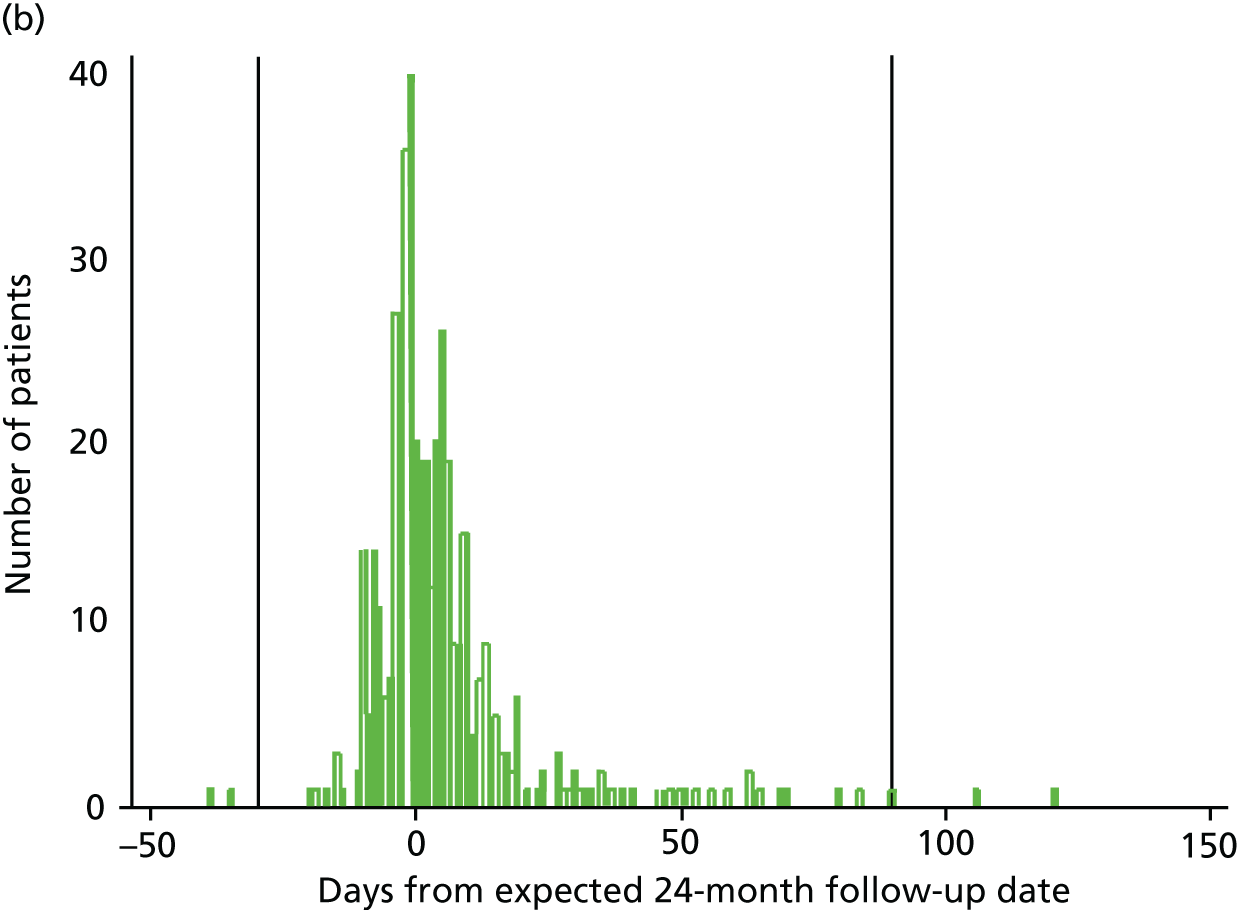

Timing of patient outcome assessments

According to the study protocol, assessments were due at 12 and 24 months (± 7 days) post randomisation. At 12 months, 351 out of 487 (72%) assessments took place within this time frame; at 24 months this was 295 out of 450 (66%). The investigators felt that data collected more than 1 month before the assessment was due and 3 months after it was due may not reflect the outcomes that would have been collected at the planned time points. Figures 3a and 3b show how closely data were collected in relation to the 12-month and 24-month due dates, with reference lines indicating the –1/+3 months outside the time window. A sensitivity analysis was conducted excluding people whose data collection fell outside the –1/+3 months.

FIGURE 3.

Time from randomisation to patient outcome assessments. (a) 12-month follow-up date; and (b) 24-month follow-up date.

Patient baseline characteristics

Demographic, stroke and baseline characteristics for the 573 randomised patients are shown in Table 1. The groups were well matched. Most people had suffered a cerebral infarction that was a first stroke. Just over half of the patients were male, with a median age of 71 years at the stroke. The median duration of hospital stay was 14 days and the median duration of ESD services was 43 days, and the time between stroke and randomisation was 72 days. Most people were living in their own home at randomisation.

| Characteristic | Intervention | Control |

|---|---|---|

| Sex, n (%) | n = 285 | n = 288 |

| Male | 174 (61.1) | 168 (58.3) |

| Female | 111 (39.0) | 120 (41.7) |

| Age (years) | n = 285 | n = 288 |

| Median (IQR) | 71 (60–77) | 71 (62–79) |

| Pre-stroke NEADL Scale, mean (SD) | n = 285 | n = 288 |

| Mobility (scored 0–18) | 16.7 (3.1) | 16.1 (3.8) |

| Kitchen (scored 0–15) | 14.7 (1.5) | 14.5 (2.1) |

| Domestic tasks (scored 0–15) | 13.7 (2.8) | 13.5 (3.3) |

| Leisure activities (scored 0–18) | 16.0 (3.1) | 15.6 (3.4) |

| Total (scored 0–66) | 61.0 (8.6) | 59.7 (10.6) |

| Pre-stroke OHS (scored 0–5) score, n (%) | n = 285 | n = 287 |

| 0 | 179 (62.8) | 170 (59.2) |

| 1 | 52 (18.3) | 56 (19.5) |

| 2 | 39 (13.7) | 43 (15.0) |

| 3 | 14 (4.9) | 15 (5.2) |

| 4 | 1 (0.4) | 3 (1.1) |

| 5 | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Stroke type, n (%) | n = 285 | n = 288 |

| Cerebral infarction | 250 (87.7) | 253 (87.9) |

| Intracerebral haemorrhage | 30 (10.5) | 29 (10.1) |

| Subarachnoid haemorrhage | 5 (1.8) | 5 (1.8) |

| Unknown | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.4) |

| Stroke subtype, n (%) | n = 284 | n = 286 |

| TACS | 55 (19.4) | 60 (21.0) |

| PACS | 125 (44.0) | 133 (46.5) |

| LACS | 56 (19.7) | 44 (15.4) |

| POCS | 47 (16.6) | 49 (17.1) |

| Uncertain | 1 (0.4) | 0 (0.0) |

| First ever stroke, n (%) | n = 285 | n = 288 |

| Yes | 235 (82.5) | 227 (78.8) |

| NIHSS scorea | n = 285 | n = 288 |

| Median (IQR) | 2 (1–4) | 2 (1–4) |

| Comorbidity, n (%) | n = 285 | n = 288 |

| Ischaemic heart disease | 45 (15.8) | 47 (16.3) |

| Previous myocardial infarction | 25 (8.8) | 29 (10.1) |

| Peripheral arterial occlusive disease | 11 (3.9) | 9 (3.1) |

| Previous transient ischaemic attack | 46 (16.1) | 53 (18.4) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 51 (17.9) | 53 (18.4) |

| Hypertension | 166 (58.3) | 170 (59.0) |

| Hyperlipidaemia | 92 (32.4) | 98 (34.2) |

| Atrial fibrillation | 59 (20.7) | 65 (22.6) |

| Congestive heart failure | 15 (5.3) | 7 (2.4) |

| Thromboembolism | 15 (5.3) | 13 (4.5) |

| Valvular heart disease | 15 (5.3) | 7 (2.4) |

| Other | 205 (71.9) | 199 (69.1) |

| Duration of hospital stay (days) | n = 282 | n = 286 |

| Median (IQR) | 13.5 (6–33) | 14 (6–35) |

| Duration of ESD (days) | n = 283 | n = 285 |

| Median (IQR) | 43 (36–68) | 43 (31–68) |

| Time (days) from stroke to randomisation | n = 284 | n = 288 |

| Median (IQR) | 73 (48–111.5) | 70 (48–106.5) |

| Residence at randomisation, n (%) | n = 283 | n = 283 |

| Own house | 261 (92.2) | 261 (92.2) |

| Living with family/friends | 13 (4.6) | 14 (5.0) |

| Sheltered accommodation | 4 (1.4) | 5 (1.8) |

| Residential care/nursing home | 2 (0.7) | 2 (0.7) |

| Other | 3 (1.1) | 1 (0.4) |

| Lived alone at randomisation, n (%) | n = 283 | n = 284 |

| Yes | 94 (33.2) | 78 (27.5) |

| Total patients | 283 | 284 |

| Abbreviated Mental Test Score (scored 0–10) | n = 281 | n = 285 |

| Median (IQR) | 9.9 (9–10) | 9 (9–10) |

| Sheffield Screening test for acquired language disorders | ||

| Receptive (scored 0–9) | n = 282 | n = 285 |

| Median (IQR) | 8 (7–9) | 8 (7–9) |

| Expressive (scored 0–11) | n = 282 | n = 285 |

| Median (IQR) | 11 (10–11) | 11 (10–11) |

| Total (scored 0–20) | n = 282 | n = 285 |

| Median (IQR) | 19 (18–20) | 19 (18–20) |

| Baseline NEADL Scale | ||

| Mobility (scored 0–18) | n = 283 | n = 285 |

| Mean (SD) | 10.5 (5.5) | 10.3 (5.5) |

| Kitchen (scored 0–15) | n = 283 | n = 286 |

| Mean (SD) | 12.1 (4.0) | 11.8 (4.3) |

| Domestic tasks (scored 0–15) | n = 283 | n = 285 |

| Mean (SD) | 8.0 (5.2) | 7.8 (5.2) |

| Leisure activities (scored 0–18) | n = 281 | n = 284 |

| Mean (SD) | 9.3 (4.2) | 9.3 (4.1) |

| Total (scored 0–66) | n = 281 | n = 282 |

| Mean (SD) | 39.8 (16.1) | 39.1 (16.1) |

| Baseline OHS (scored 0–5) score, n (%) | n = 283 | n = 285 |

| 0 | 9 (3.2) | 8 (2.8) |

| 1 | 42 (14.8) | 43 (15.1) |

| 2 | 104 (36.8) | 95 (33.3) |

| 3 | 100 (35.3) | 99 (34.7) |

| 4 | 18 (6.4) | 34 (11.9) |

| 5 | 10 (3.5) | 6 (2.1) |

| HADS | ||

| Anxiety (scored 0–21) | n = 282 | n = 285 |

| Mean (SD) | 5.7 (4.2) | 5.6 (3.9) |

| Score, n (%) | ||

| 0–7 (non-case) | 203 (72.0) | 201 (70.5) |

| 8–10 (doubtful case) | 39 (13.8) | 50 (17.5) |

| 11–21 (definite case) | 40 (14.2) | 34 (11.9) |

| Depression (scored 0–21) | n = 282 | n = 285 |

| Mean (SD) | 5.4 (3.8) | 5.4 (3.7) |

| Score, n (%) | ||

| 0–7 (non-case) | 215 (76.2) | 211 (74.0) |

| 8–10 (doubtful case) | 40 (14.2) | 42 (14.7) |

| 11–21 (definite case) | 27 (9.6) | 32 (11.2) |

The distributions of performance in EADL (NEADL Scale), health status (OHS) and mood (HADS) at baseline (and pre stroke for NEADL Scale and OHS) were well matched between the intervention and the control groups. The majority of people had a high level of performance in activities of daily living before their stroke and this decreased post stroke.

A comparison of the characteristics of patients who dropped out of the trial between recruitment and randomisation with those of patients who were randomised is shown in Appendix 2, Table 35. Patients who were not randomised tended to be slightly older and have poorer function prior to stroke (pre-stroke NEADL Scale and OHS).

Primary outcome

The distribution of the NEADL Scale scores (primary outcome) at pre stroke, baseline, 12 months and 24 months is shown in Table 2. Patients reported that they undertook the most activities before their stroke, but the mean scores at baseline decreased to 39.9 in the intervention group and 39.1 in the control group. Thereafter, the mean scores remained very similar over time for those patients still providing data in the intervention group and decreased very slightly in the control group.

| Time point | Intervention | Control | Difference in mean score (intervention – control) (95% CI) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | Mean (SD) | n | Mean (SD) | Unadjusted | Adjusted for centre, baseline OHS, age and sex | |

| Pre stroke | 285 | 61.0 (8.6) | 288 | 59.7 (10.6) | NA | NA |

| Baseline: simple imputation | 281 | 39.8 (16.1) | 282 | 39.1 (16.1) | NA | NA |

| 12 months: simple imputation | 239 | 40.6 (17.7) | 247 | 38.3 (17.0) | 2.3 (–0.5 to 5.2) | 1.5 (–0.8 to 3.7) |

| 12 months: simple imputation and sensitivity | 229 | 40.9 (17.7) | 228 | 38.5 (17.2) | 2.5 (–0.8 to 5.7) | 1.5 (–1.0 to 4.0) |

| 24 months: complete cases | 217 | 39.9 (18.1) | 230 | 37.3 (18.4) | 2.5 (–0.5 to 5.6) | 1.6 (–0.7 to 3.8) |

| 24 months: simple imputation | 219 | 40.0 (18.1) | 231 | 37.2 (18.5) | 2.8 (–0.6 to 6.2) | 1.8 (–0.7 to 4.2) |

| 24 months: complete case and sensitivity | 208 | 40.4 (17.9) | 214 | 37.6 (18.3) | 2.9 (0.0 to 5.7) | 2.0 (–0.9 to 4.9) |

| 24 months: simple imputation and sensitivity | 210 | 40.5 (17.9) | 215 | 37.4 (18.4) | 3.1 (–0.4 to 6.6) | 2.2 (–0.7 to 5.2) |

The primary comparison was at 24 months, adjusting for covariates and using simple imputation for partially completed scores. The mean NEADL Scale scores at 24 months were 40.0 in the intervention group and 37.2 in the control group: an adjusted difference in means of 1.8 (95% CI –0.7 to 4.2). The minimum clinically important difference on the NEADL Scale is 6 units, so the results were not consistent with a meaningful change on this scale.

Other analyses of the NEADL Scale were complete-case data and a sensitivity analysis that excluded both patients providing data outside the –1 and +3 months of the expected assessment date and those with improbable NEADL Scale scores. The differences in means between trial groups remained similar at both time points and for each analysis group.

The distribution of the subscales of the NEADL Scale at each time point is shown in Appendix 2, Table 36.

Patient secondary outcomes

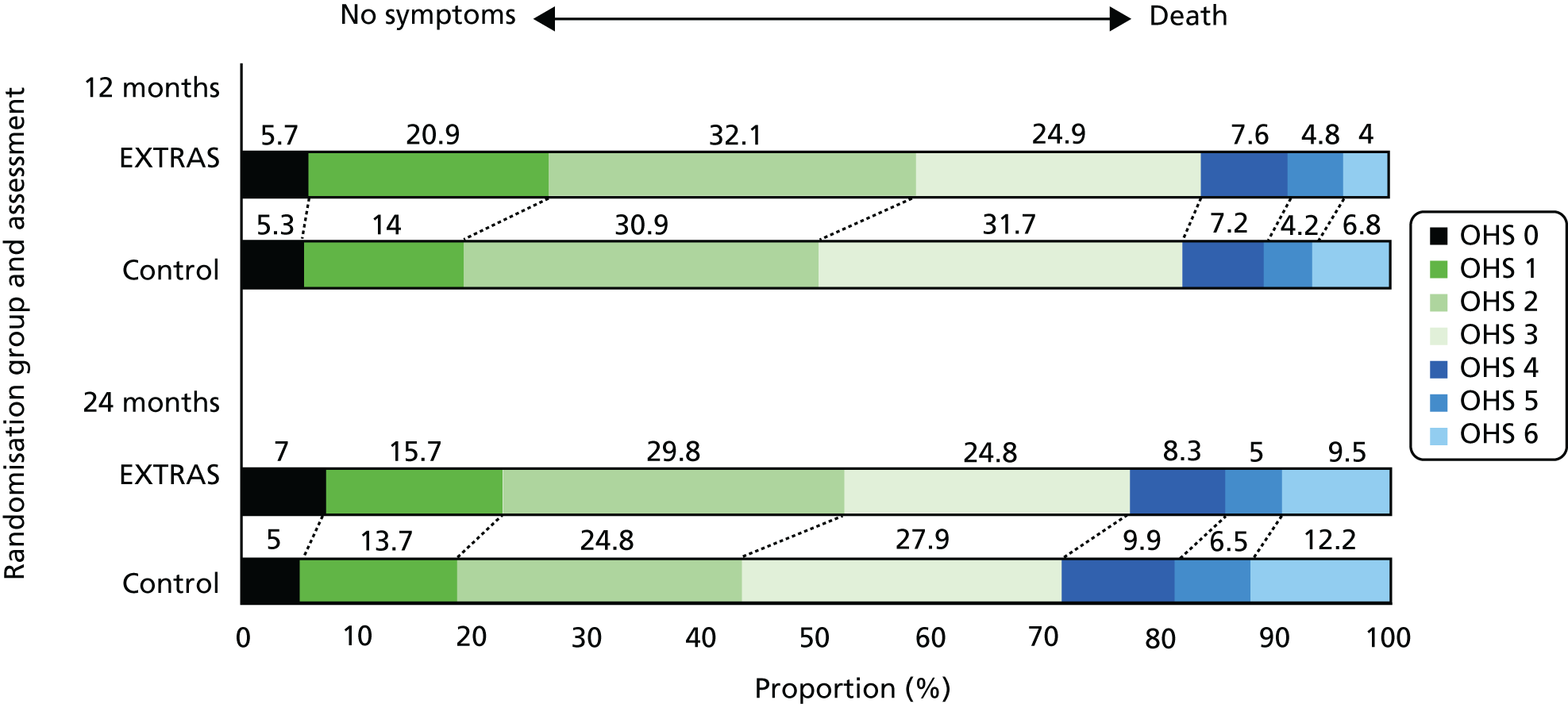

1. Health status (Oxford Handicap Scale)

The distribution of the health status score (OHS) at pre stroke, baseline, 12 months and 24 months is shown in Table 3. Relatively few patients reported significant symptoms or disability pre stroke, but by baseline the majority of patients reported symptoms that were affecting their well-being. This distribution changed little over time in those providing data, except for a small number of deaths.

| Oxford Handicap Scale (score) | Time point, n (%) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre stroke | Baseline | 12 months | 24 months | |||||

| Intervention | Control | Intervention | Control | Intervention | Control | Intervention | Control | |

| Total patients, n | 285 | 287 | 283 | 285 | 249 | 265 | 242 | 262 |

| No symptoms (0) | 179 (62.8) | 170 (59.2) | 9 (3.2) | 8 (2.8) | 14 (5.7) | 14 (5.3) | 17 (7.0) | 13 (5.0) |

| Few symptoms (1) | 52 (18.3) | 56 (19.5) | 42 (14.8) | 43 (15.1) | 52 (20.9) | 37 (14.0) | 38 (15.7) | 36 (13.7) |

| Symptoms caused some change (2) | 39 (13.7) | 43 (15.0) | 104 (36.8) | 95 (33.3) | 80 (32.1) | 82 (30.9) | 72 (29.8) | 65 (24.8) |

| Symptoms caused significant change (3) | 14 (4.9) | 15 (5.2) | 100 (35.3) | 99 (34.7) | 62 (24.9) | 84 (31.7) | 60 (24.8) | 73 (27.9) |

| Severe symptoms (4) | 1 (0.4) | 3 (1.1) | 18 (6.4) | 34 (11.9) | 19 (7.6) | 19 (7.2) | 20 (8.3) | 26 (9.9) |

| Major symptoms (5) | 0 | 0 | 10 (3.5) | 6 (2.1) | 12 (4.8) | 11 (4.2) | 12 (5.0) | 17 (6.5) |

| Death (6) | – | – | – | – | 10 (4.0) | 18 (6.8) | 23 (9.5) | 32 (12.2) |

| Intervention: control, OR (95% CI) | Intervention: control, OR (95% CI) | |||||||

| Unadjusted | NA | NA | 0.8 (0.6 to 1.1) | 0.7 (0.5 to 1.0) | ||||

| Unadjusted including death | NA | NA | 0.7 (0.5 to 1.0) | 0.7 (0.5 to 1.0) | ||||

| Adjusteda | NA | NA | 0.8 (0.5 to 1.1) | 0.7 (0.5 to 1.0) | ||||

| Adjusteda including death | NA | NA | 0.7 (0.5 to 1.0) | 0.7 (0.5 to 1.0) | ||||

The OHS scale was compared in two ways: first using the 0–5 scale (i.e. not including death) and second including deaths (i.e. scoring 6 for death). At 24 months, ordinal regression adjusting for covariates and using the 0–6 scale estimated that the odds of the intervention group patients having a worse health status (compared with better) was 0.7 times as high as those for control patients (95% CI 0.5 to 1.0). This was not significantly different from equal odds in both groups. There were very similar results at both time points and for each analysis group. Figure 4 shows the unadjusted distribution of OHS scores at 12 and 24 months.

FIGURE 4.

Distribution of OHS scores at 12 and 24 months.

2. Mood (Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale)

Tables 4 and 5 show the distribution of the anxiety and depression scores (HADS) at baseline, 12 months and 24 months. Scores at baseline showed relatively low levels of both anxiety and depression, and the mean scores changed very little over time in those who remained in the trial.

| Time point | Intervention | Control | Difference in means (intervention – control) (95% CI) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | Mean score (SD) | n | Mean score (SD) | Unadjusted | Adjusted for centre, baseline, OHS, age and sex | |

| Anxiety at baselinea | 282 | 5.7 (4.2) | 285 | 5.6 (3.9) | NA | NA |

| Anxiety at 12 monthsa | 238 | 5.8 (4.3) | 246 | 6.5 (4.7) | –0.7 (–1.5 to 0.0) | –0.7 (–1.3 to 0.0) |

| Anxiety at 24 monthsa | 217 | 5.5 (4.3) | 230 | 6.4 (4.6) | –0.9 (–1.8 to 0.0) | –0.6 (–1.4 to 0.1) |

| Depression at baselinea | 282 | 5.4 (3.8) | 285 | 5.4 (3.7) | NA | NA |

| Depression at 12 monthsa | 239 | 5.7 (4.3) | 247 | 6.5 (4.2) | –0.8 (–1.6 to 0.0) | –0.7 (–1.5 to 0.0) |

| Depression at 24 monthsa | 217 | 5.9 (4.3) | 230 | 6.7 (4.6) | –0.8 (–1.5 to –0.1) | –0.7 (–1.4 to 0.0) |

| Time point | Intervention | Control | OR (intervention/control) (95% CI)a | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | Cases (%)b | n | Cases (%)b | Unadjusted | Adjusted for centre, baseline, OHS, age and sex | |

| Anxiety at baselinea | 282 | 28 | 285 | 29 | NA | NA |

| Anxiety at 12 monthsa | 238 | 34 | 246 | 39 | 0.79 (0.55 to 1.15) | 0.83 (0.55 to 1.25) |

| Anxiety at 24 monthsa | 217 | 28 | 230 | 38 | 0.62 (0.41 to 0.92) | 0.64 (0.41 to 0.99) |

| Depression at baselinea | 282 | 24 | 285 | 26 | NA | NA |

| Depression at 12 monthsa | 239 | 29 | 247 | 40 | 0.61 (0.42 to 0.89) | 0.59 (0.39 to 0.90) |

| Depression at 24 monthsa | 217 | 34 | 230 | 39 | 0.80 (0.55 to 1.18) | 0.81 (0.52 to 1.24) |

The mean scores at 24 months for anxiety were 5.5 in the intervention group and 6.4 in the control group: an adjusted difference in means of –0.6 (95% CI –1.4 to 0.1). The mean scores for depression at 24 months were 5.9 in the intervention group and 6.7 in the control group: an adjusted difference in means of –0.7 (95% CI –1.4 to 0.0). The differences at 12 months were very similar. The differences in means between trial groups were consistently small with narrow CIs.

3. Experience of services (experience survey)

Table 6 shows the dichotomised responses to the experiences of services questionnaire at 12 and 24 months. There were high levels of satisfaction for all aspects of experiences of care. The difference in the percentage of patients who were satisfied between study groups was usually quite small, but the 95% CIs were quite wide. The wider CIs occurred when there was a high proportion of patients either not completing that question or saying that it did not apply. The detailed breakdown of scores is shown in Appendix 2, Tables 37 and 38. These tables show that by 24 months, approximately half of the patients were reporting that each question ‘did not apply’. This means that the comparisons between study groups were based on much reduced sample sizes.

| About the services received in the last 12 months, to what extent do you agree that | 12 months | 24 months | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patients satisfied/in agreement | Difference in proportion of patients satisfied (intervention – control) (95% CI) | Patients satisfied/in agreement | Difference in proportion of patients satisfied (intervention – control) (95% CI) | |||

| Intervention, n (%) | Control, n (%) | Intervention, n (%) | Control, n (%) | |||

| Staff were welcoming and friendly | 230 (99.1) | 230 (97.5) | 1.7 (–0.7 to 4.0) | 114 (98.3) | 123 (96.9) | 1.4 (–2.4 to 5.3) |

| Staff treated you with dignity and respect | 227 (98.3) | 230 (97.1) | 1.2 (–1.5 to 4.0) | 117 (100.0) | 122 (96.8) | 3.2 (0.1 to 6.2) |

| Staff assessed your needs | 219 (95.6) | 229 (96.6) | –1.0 (–4.5 to 2.5) | 113 (96.6) | 114 (92.7) | 3.9 (–1.8 to 9.6) |

| Staff met your needs | 217 (93.9) | 222 (93.7) | 0.3 (–4.1 to 4.6) | 114 (97.4) | 111 (88.8) | 8.6 (2.4 to 14.9) |

| You have been involved as much as you wanted to be in decisions about your care | 211 (91.3) | 213 (91.4) | –0.1 (–5.2 to 5.0) | 110 (94.0) | 108 (89.3) | 4.8 (–2.2 to 11.8) |

| You were able to discuss your preferences, beliefs and concerns as part of your care | 211 (93.0) | 208 (92.4) | 0.5 (–4.3 to 5.3) | 106 (93.0) | 112 (91.8) | 1.2 (–5.6 to 7.9) |

| You were told who to contact if you had any worries or concerns | 220 (94.4) | 218 (93.6) | 0.9 (–3.5 to 5.2) | 110 (94.0) | 116 (92.8) | 1.2 (–5.0 to 7.5) |

| You were confident that the staff you saw had the right skills and knowledge to help you | 223 (97.0) | 223 (94.1) | 2.9 (–0.9 to 6.6) | 116 (97.5) | 119 (94.4) | 3.0 (–1.9 to 7.9) |

| You were treated fairly, regardless of your age, race, sex, belief, sexual orientation or disability | 223 (96.5) | 228 (96.6) | –0.1 (–3.4 to 3.2) | 116 (99.2) | 124 (96.9) | 2.3 (–1.2 to 5.7) |

| You were given the information you wanted | 220 (94.8) | 219 (93.6) | 1.2 (–3.0 to 5.5) | 114 (96.6) | 115 (92.0) | 4.6 (–1.2 to 10.4) |

| You were able to see the same health-care professional/team whenever possible | 211 (92.5) | 203 (87.1) | 5.4 (–0.1 to 10.9) | 103 (92.0) | 107 (87.7) | 4.3 (–3.4 to 12.0) |

| If you had important questions to ask, you got answers that you could understand | 212 (93.0) | 212 (95.5) | –2.5 (–6.8 to 1.8) | 107 (93.0) | 113 (92.6) | 0.4 (–6.1 to 7.0) |

| If you needed more than one service, staff made sure they were well co-ordinated | 196 (91.2) | 189 (88.7) | 2.4 (–3.3 to 8.1) | 91 (91.9) | 95 (91.4) | 0.6 (–7.0 to 8.2) |

| If you needed more than one service, staff made sure that your care information was clearly and accurately shared | 197 (92.1) | 192 (89.7) | 2.3 (–3.1 to 7.8) | 91 (91.0) | 94 (90.4) | 0.6 (–7.4 to 8.6) |

| You were told who to contact if you had any ongoing health-care needs | 217 (93.1) | 215 (91.5) | 1.6 (–3.2 to 6.5) | 110 (94.8) | 115 (92.7) | 2.1 (–4.0 to 8.2) |

| Overall, how satisfied are you with the services you received? | 228 (95.4) | 227 (92.3) | 3.1 (–1.1 to 7.4) | 208 (97.7) | 189 (87.5) | 10.2 (5.3 to 15.0) |

| In the last 12 months, have you had enough help with speaking difficulties from the NHS? | 79 (87.8) | 89 (84.8) | 3.0 (–6.6 to 12.7) | 29 (69.1) | 35 (63.6) | 5.4 (–13.5 to 24.3) |

| In the last 12 months, have you had enough treatment to help improve your mobility from the NHS? | 167 (82.7) | 166 (76.2) | 6.5 (–1.2 to 14.2) | 95 (67.4) | 81 (48.5) | 18.9 (8.0 to 29.7) |

| In the last 12 months, have you had enough help with emotional problems from the NHS? | 80 (70.8) | 112 (76.7) | –5.9 (–16.7 to 4.9) | 52 (71.2) | 59 (62.1) | 9.1 (–5.1 to 23.4) |

Nevertheless, there were 4 out of 19 aspects of care at 24 months where the 95% CI for the differences in percentage satisfied between groups did not cover the value zero. These were ‘staff treated you with dignity and respect’, ‘staff met your needs’, ‘overall satisfaction’ and ‘help with mobility’. However, these must be interpreted with some caution because of multiple significance testing. In addition, the largest difference at 24 months came from the question about overall satisfaction (‘Overall, how satisfied are you with the services you received?’): 97.7% in the intervention group compared with 87.5% in the control group, which is a difference of 10.2% (95% CI 5.3% to 15.0%).

Patient post hoc analysis

Post hoc analyses of the HADS used established ‘cut-off’ scores where patients scoring ≥ 8 on a subscale are considered to have a case of anxiety or depression (see Tables 4 and 6). For anxiety, the proportion of cases was slightly lower in the intervention group (34%) than in the control group (39%) at 12 months, with an adjusted OR of 0.83 (95% CI 0.55 to 1.25). This proportion was lower again by 24 months with 28% of the intervention group versus 38% of the control group considered to be cases, with an adjusted OR of 0.64 (95% CI 0.41 to 0.99). For depression, the proportion of cases was lower in the intervention group (29%) than the control group (40%) at 12 months, with an adjusted OR of 0.59 (95% CI 0.39 to 0.90), but only slightly lower by 24 months, with 34% in the intervention group versus 39% in the control group adjusted OR 0.64, (95% CI 0.52 to 1.24).

Patient exploratory analyses

A set of prespecified exploratory analyses investigated whether or not there was an association between the effectiveness of EXTRAS and pre-stroke health status (OHS), and baseline performance in activities of daily living (NEADL Scale) and time in organised stroke care (inpatient and ESD).

Figure 5 shows the NEADL Scale scores at 24 months plotted against baseline NEADL Scale scores with different symbols for study groups. Although this shows, not surprisingly, that those who had higher NEADL Scale scores at baseline tended to have higher scores at 24 months, there does not seem to be an indication that the relationship differs between study groups.

FIGURE 5.

Association between severity of activity limitation and effectiveness of EXTRAS.

Figure 6 shows the NEADL Scale scores at 24 months plotted against pre-stroke health status (OHS) as pairs of boxplots for intervention and control groups. Those patients with better health status pre stroke tended to have higher NEADL Scale scores at 24 months, but there was little indication that the relationship differed between study groups.

FIGURE 6.

Association between pre-stroke health status and effectiveness of EXTRAS.

Figure 7 shows the NEADL Scale scores at 24 months plotted against length of organised stroke care with different symbols for study groups. This shows, not surprisingly, that those who had experienced longer organised stroke care tended to have lower (worse) NEADL Scale scores at 24 months, but there does not seem to be an indication that the relationship differs between study groups.

FIGURE 7.

Association between length of time of organised care and effectiveness of EXTRAS.

Patient outcome assessment blinding

Outcome assessments were conducted by telephone interview [12 months: n = 408/487 (84%); 24 months: n = 371/450 (82%)], face-to-face assessment [12 months: n = 8/487 (2%); 24 months: n = 10/450 (2%)] or postal questionnaire [12 months: n = 71/487 (15%); 24 months: n = 69/450 (15%)]. For assessments conducted by telephone and face to face, it was intended that the researcher was blinded to study group. At 12 months, 371 out of 416 (89%) assessments undertaken by phone or face to face were conducted blinded to study group and at 24 months this was 363 out of 450 (81%). Data are shown in Appendix 2, Table 39.

Patient safety data

1. Serious adverse events

Serious adverse events were reported for 125 out of 285 (43.9%) patients in the intervention group (total 250 events) and 130 out of 288 (45.1%) patients in the control group (total 254 events). The number of events per patient is shown in Table 7. No significant differences were seen between the study groups.

| Number of SAEs per patient | Number of patients, n (%) | Difference in proportion (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Intervention (N = 285) | Control (N = 288) | ||

| 0 | 160 (56.1) | 158 (54.9) | 1.3 (–6.9 to 9.4) |

| 1 | 70 (24.6) | 69 (24.0) | 0.6 (–6.4 to 7.6) |

| 2 | 30 (10.5) | 31 (10.8) | –0.2 (–5.3 to 4.8) |

| 3 | 11 (3.9) | 17 (5.9) | –2.0 (–5.6 to 4.8) |

| 4 | 4 (1.4) | 3 (1.0) | 0.3 (–1.4 to 2.2) |

| 5 | 3 (1.1) | 3 (1.0) | For > 4 events: 0.0 (–2.9 to 3.0) |

| 6 | 2 (0.7) | 4 (1.4) | |

| 7 | 1 (0.4) | 3 (1.0) | |

| 8 | 2 (0.7) | 0 (0.0) | |

| 9 | 1 (0.4) | 0 (0.0) | |

| 12 | 1 (0.4) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Total events | 250 | 254 | |

The reasons for the reported events being considered to be SAEs are shown in Appendix 2, Table 40. The most common reason for an event to be reported as a SAE was because it resulted in hospitalisation (intervention group, n = 163; control group, n = 168). A total of 58 reported events resulted in death (intervention group, n = 26; control group, n = 32). Note that in the retention flow diagram (see Figure 2), 23 participants in the intervention group and 32 participants in the control group are reported to be deceased. The SAEs in the control group (n = 32) match the control group deaths (n = 32). In the intervention group, the cause of death for two participants could not be established and no SAE form was received. However, for a further five participants, a SAE was initially reported during their involvement in the study but the date of death from this event was after their involvement ceased. For two out of five participants, the date of death was after the 24-month outcome assessment; for three out of five participants, the date of death was after withdrawal but within the study period.

A summary of the events that resulted in death is shown in Appendix 2, Table 41. A summary of all other events is shown in Appendix 2, Table 42.

During SAE reporting, a standard causality assessment was undertaken for all SAEs and none were reported to be related to the study intervention.

As safety monitoring started from participant consent and this could be several weeks before randomisation to a study group, some patients had SAEs reported before randomisation (16 patients, 19 events). These data are shown in Appendix 2, Tables 43–45. In addition, some patients who were recruited but dropped out of the study before randomisation had SAEs reported before their involvement in the study ended (14 patients, 22 events). These data are shown in Appendix 2, Tables 46–48.

2. Non-serious adverse events

At each outcome assessment, patients were asked to self-report adverse events by means of the following question: ‘Have you suffered any new medical illnesses in the last 12 months?’. Any events potentially fulfilling the criteria to be a SAE were investigated and reported as SAEs, as appropriate. Such events are included in Serious adverse events. All other events are reported here.

At 12 months, 66 out of 239 (27.6%) participants in the intervention group who had the assessment conducted reported at least one non-serious AE. For the control group, this was 57 out of 248 (22.9%) participants. The difference in proportions was 4.6% (95% CI –3.1% to 12.3%).

At 24 months, 53 out of 219 (24.2%) participants in the intervention group who had the assessment conducted reported at least one non-serious AE. For the control group, this was 50 out of 231 (21.6%) participants. The difference in proportions was 2.6% (95% CI –5.2% to 10.3%).

The number of events per participant is shown in Appendix 2, Table 49, and events are summarised in Appendix 2, Table 50.

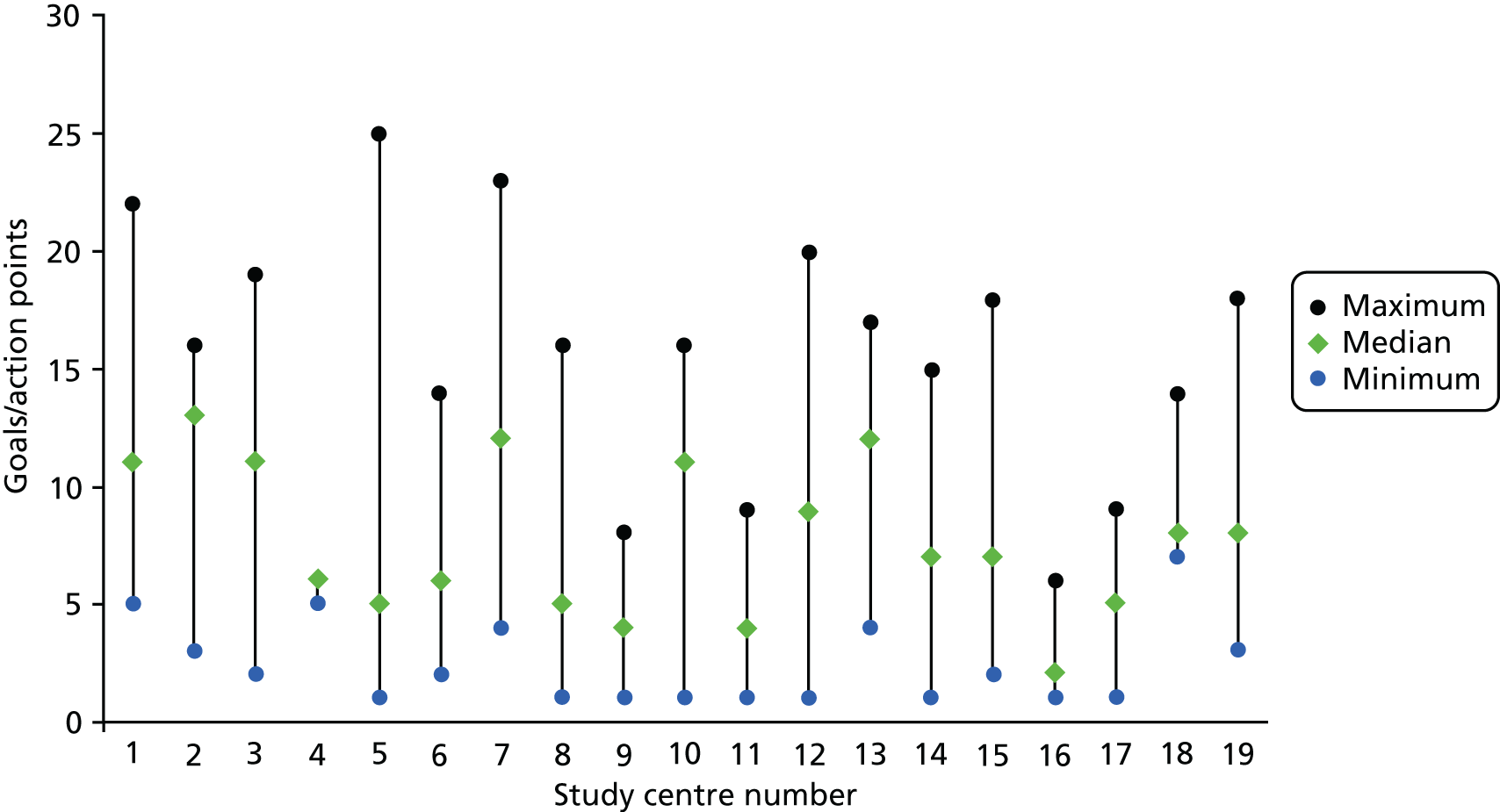

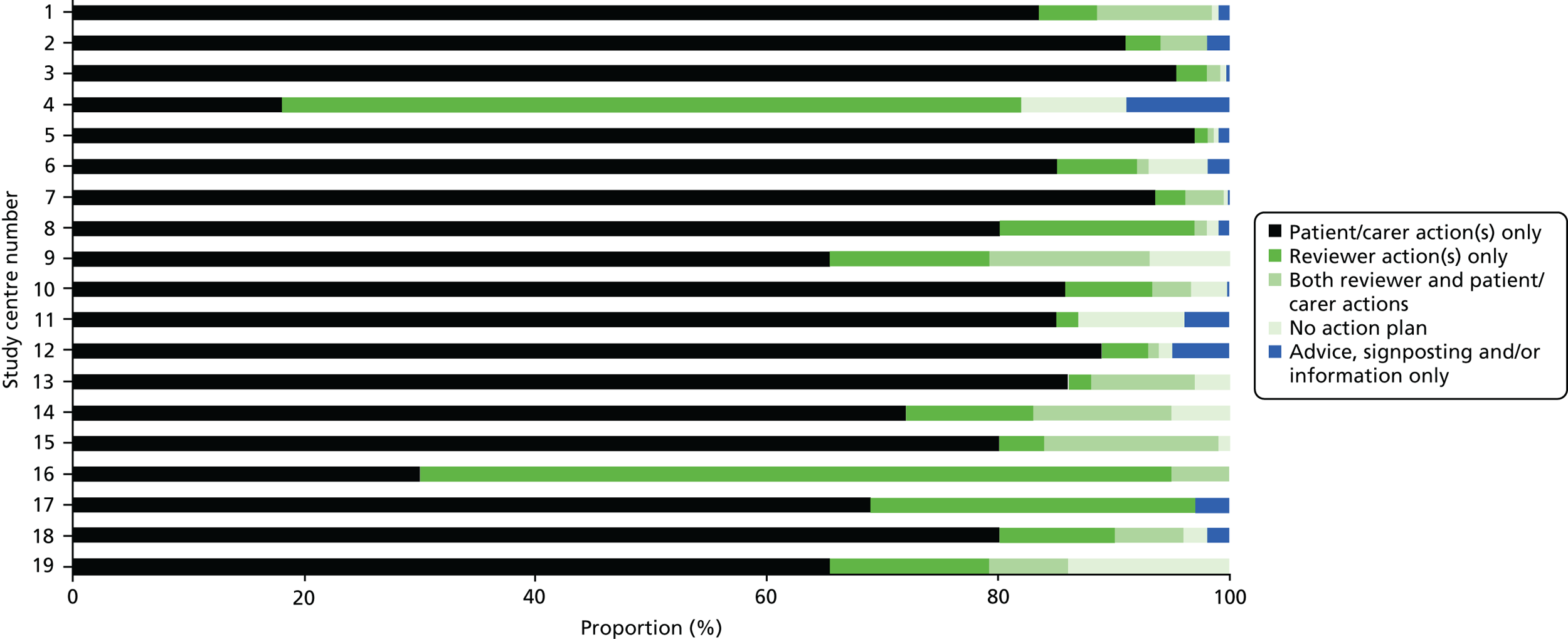

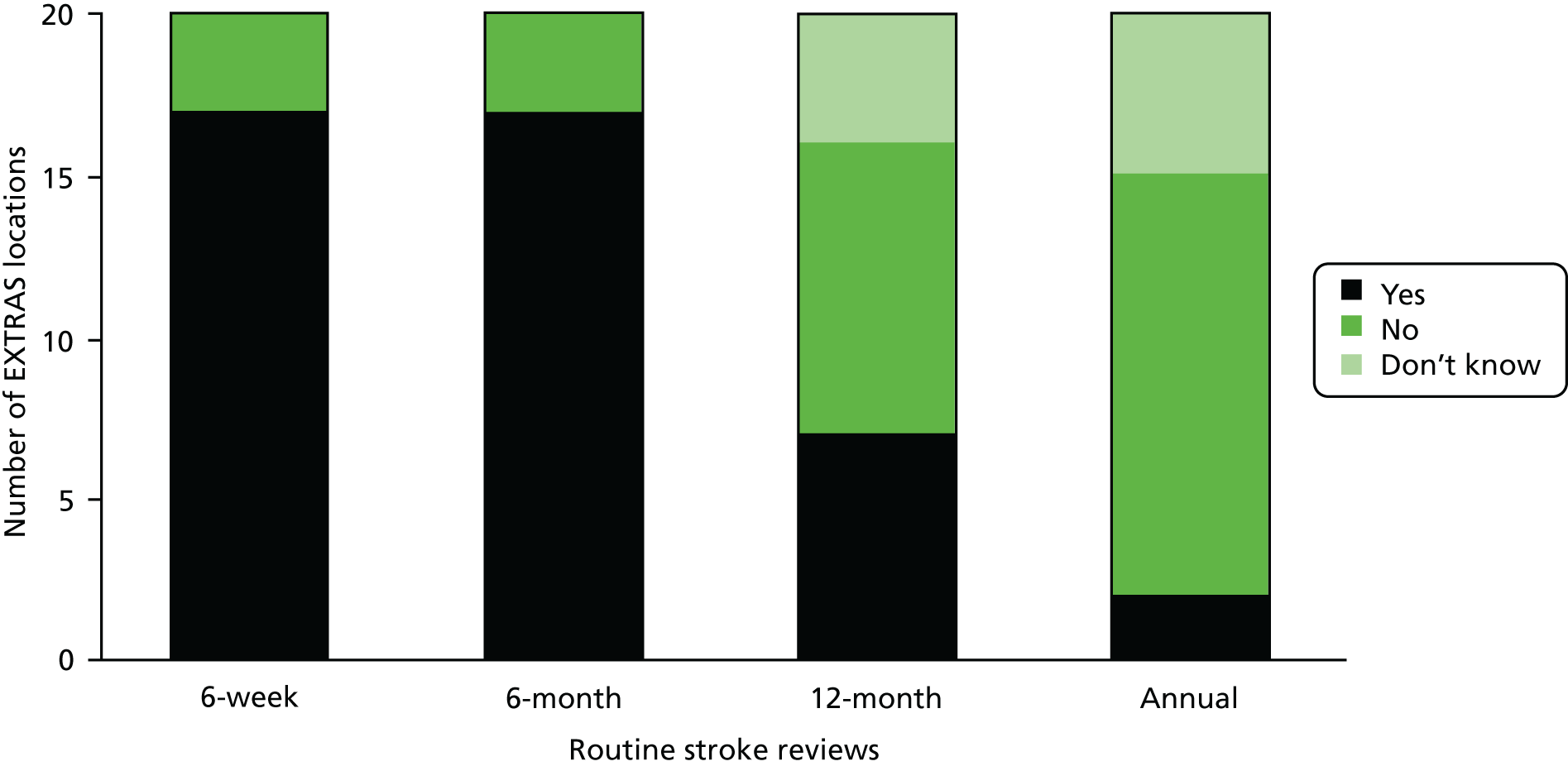

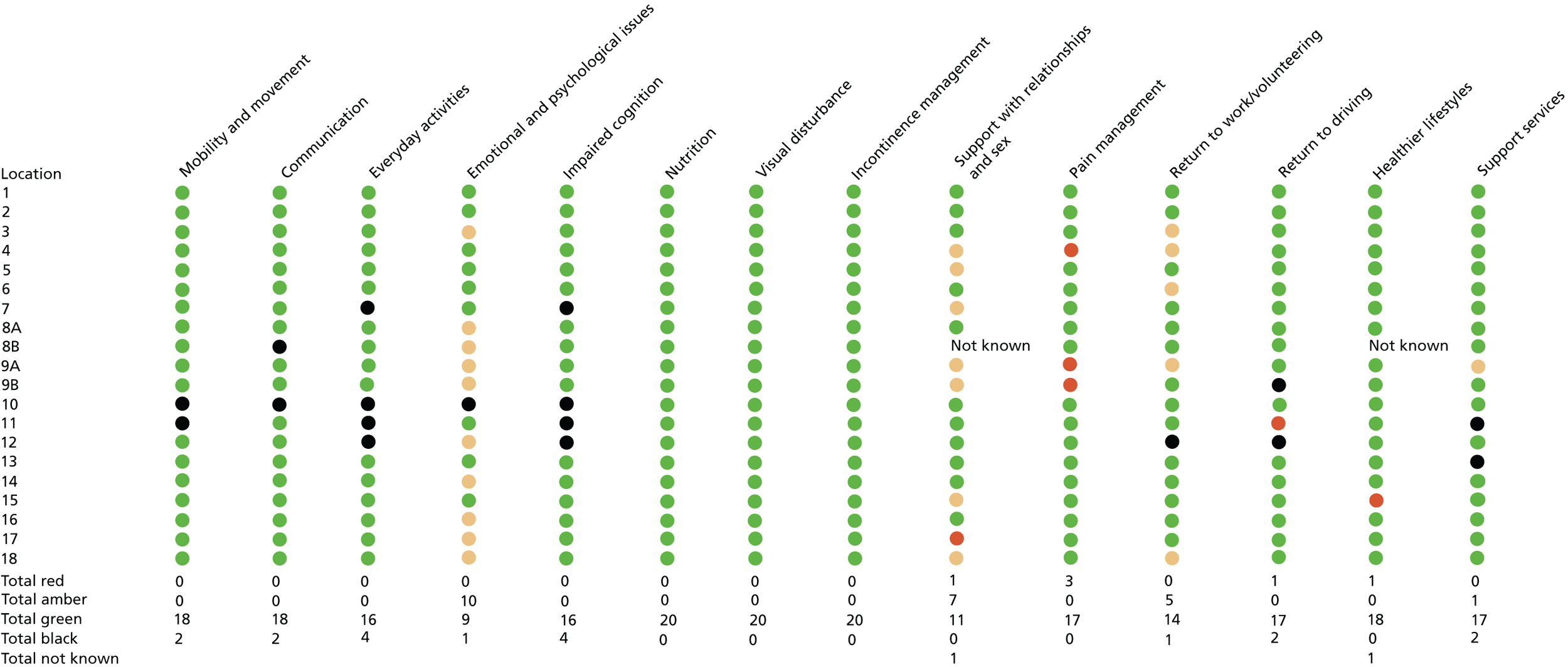

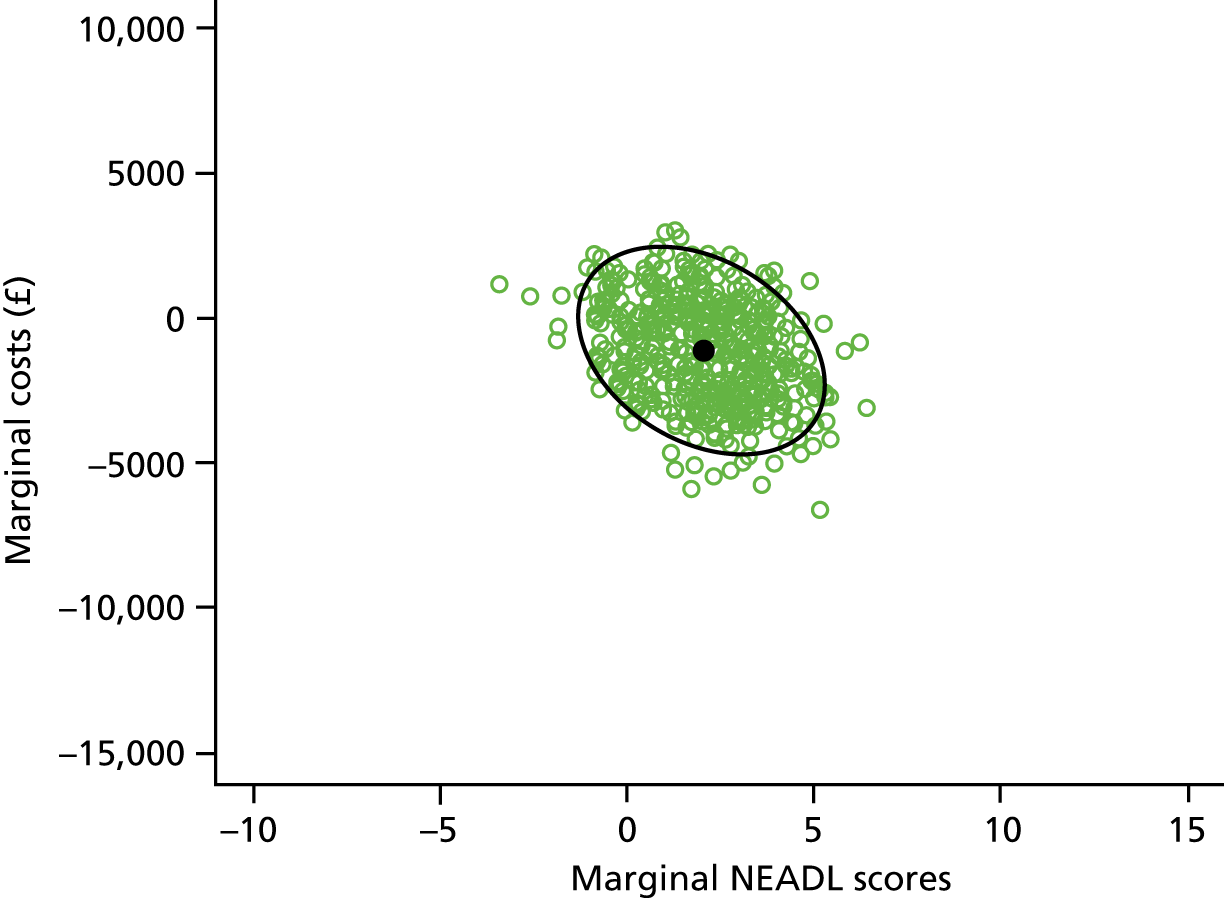

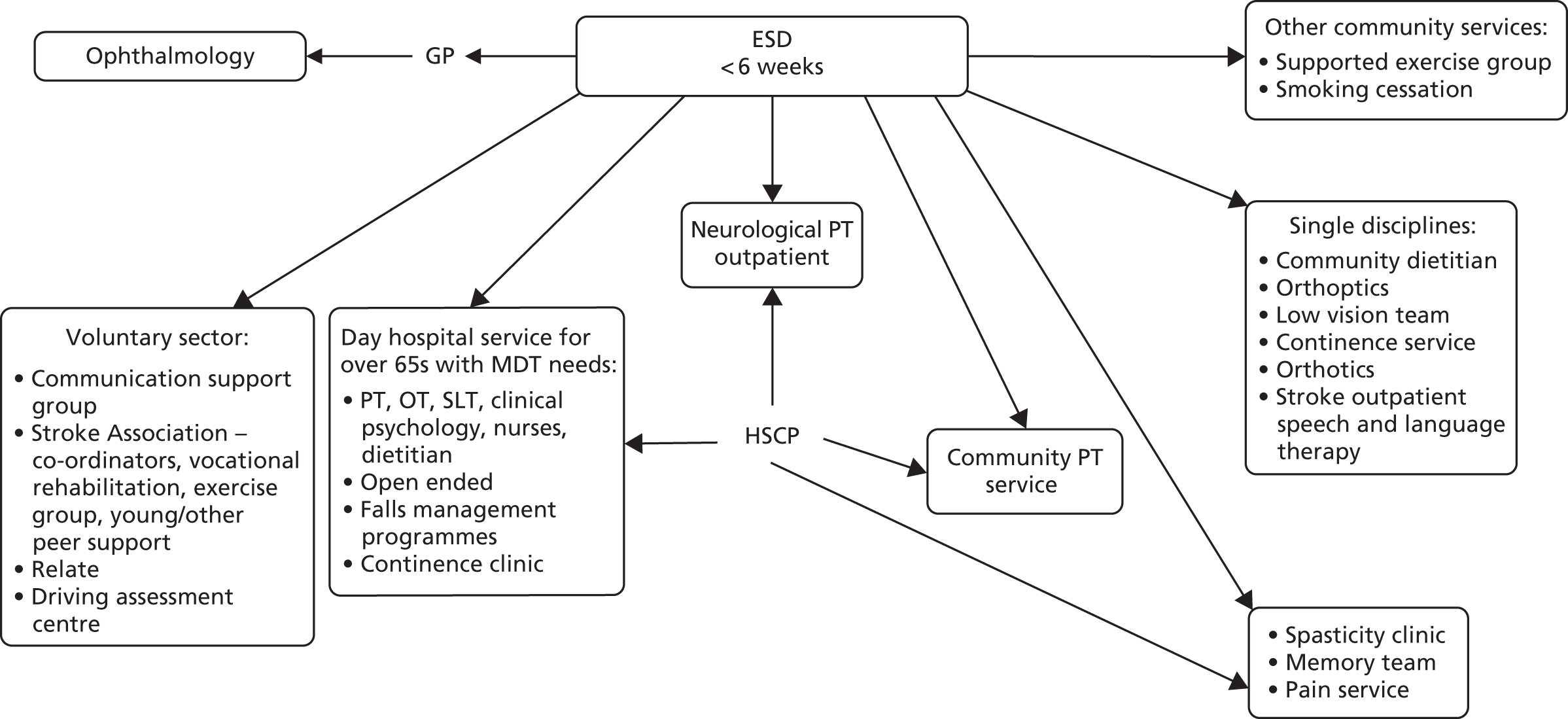

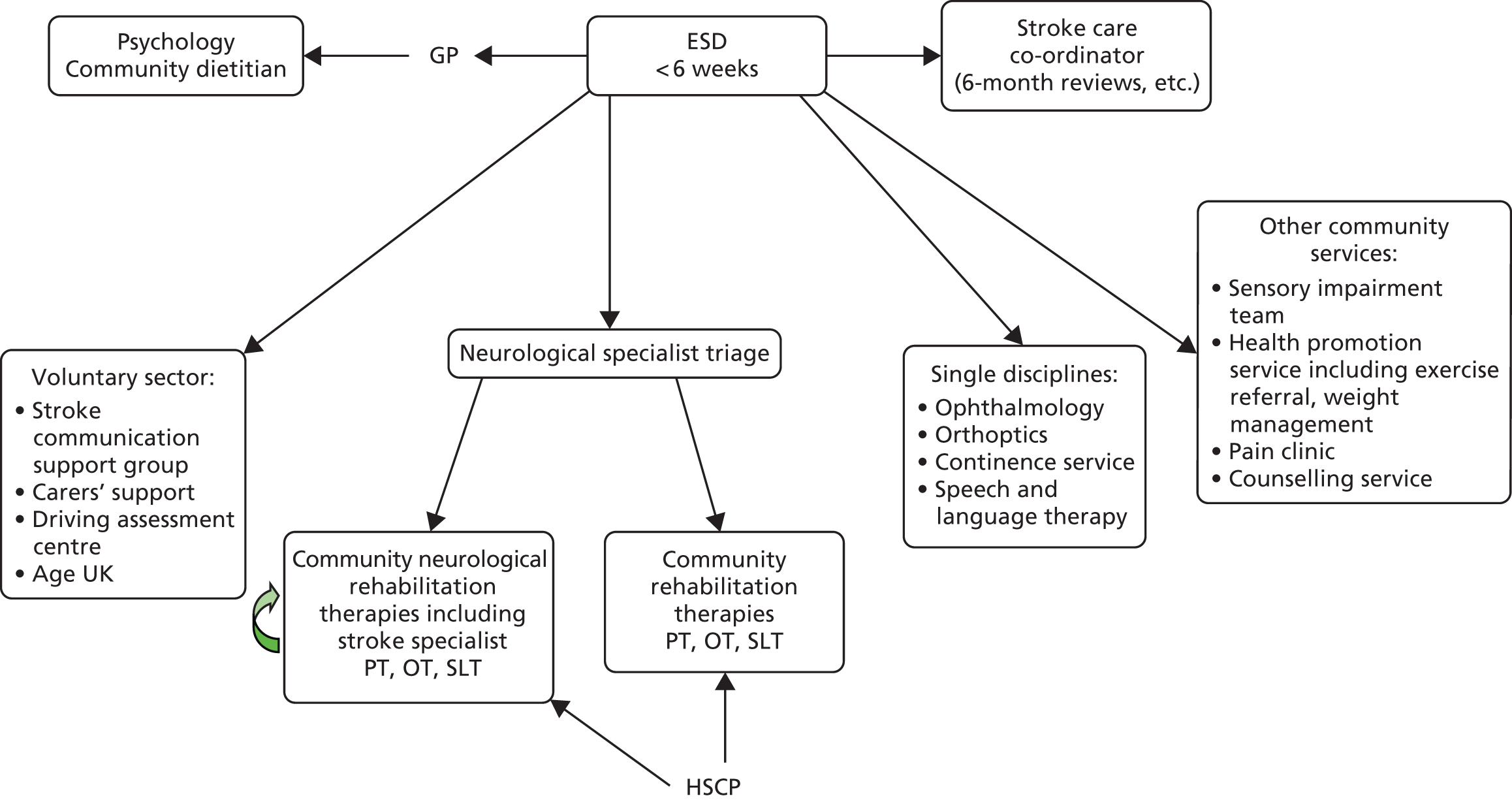

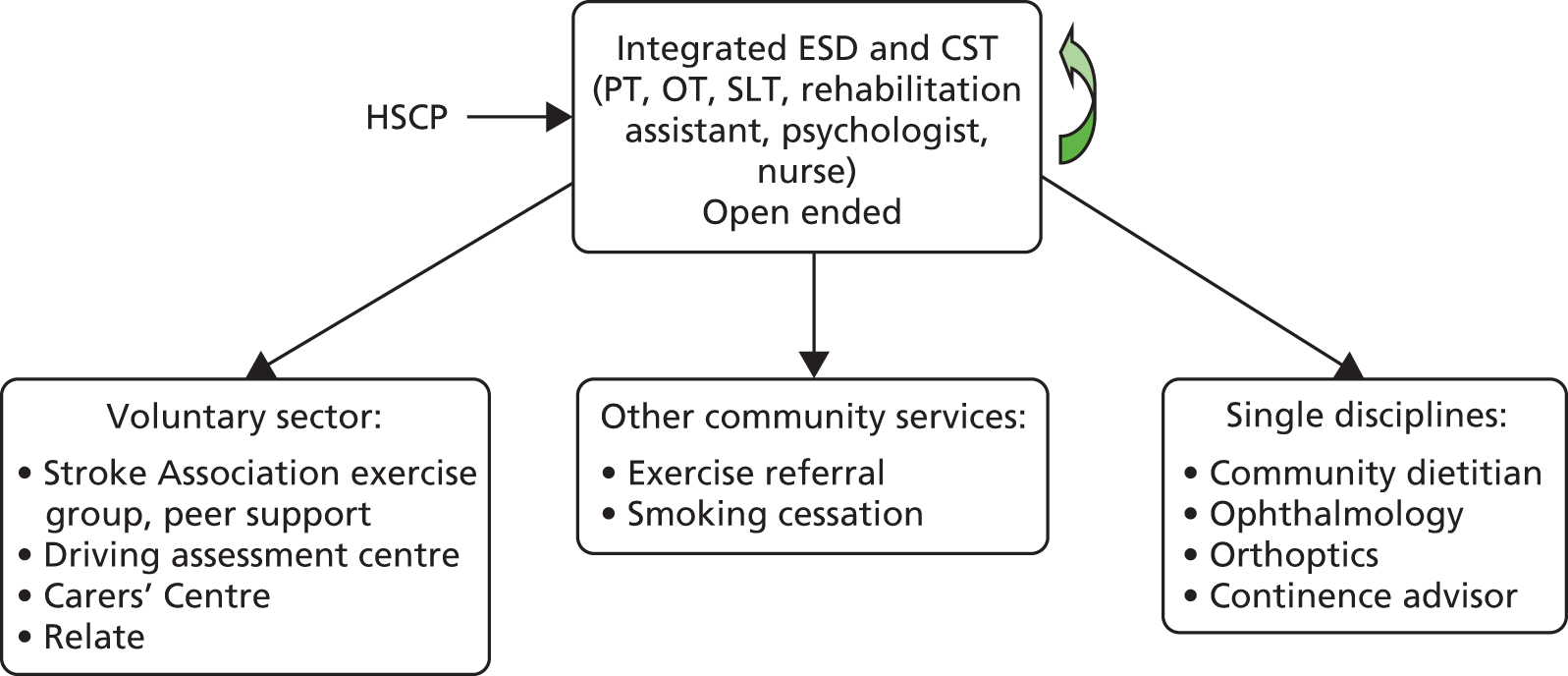

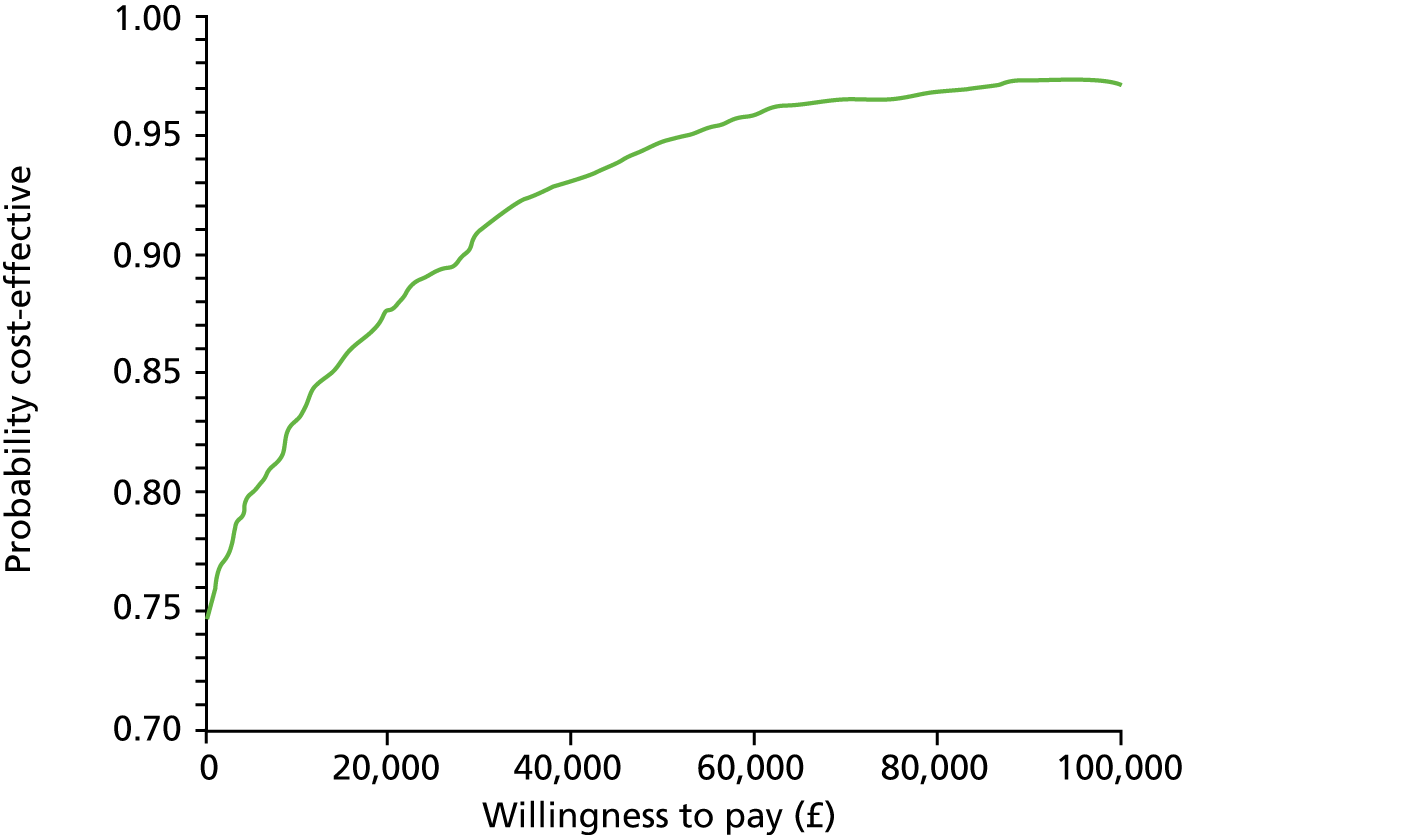

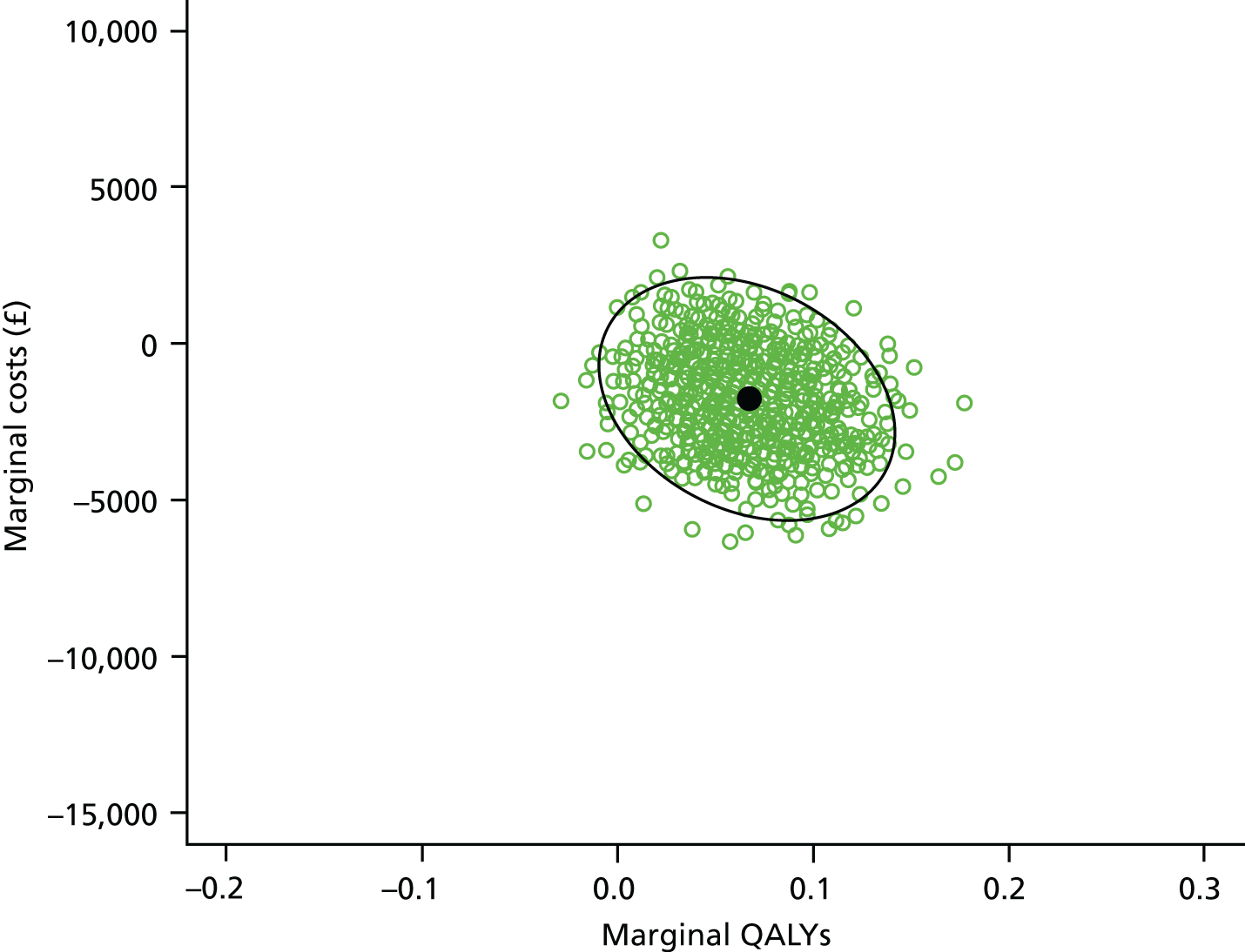

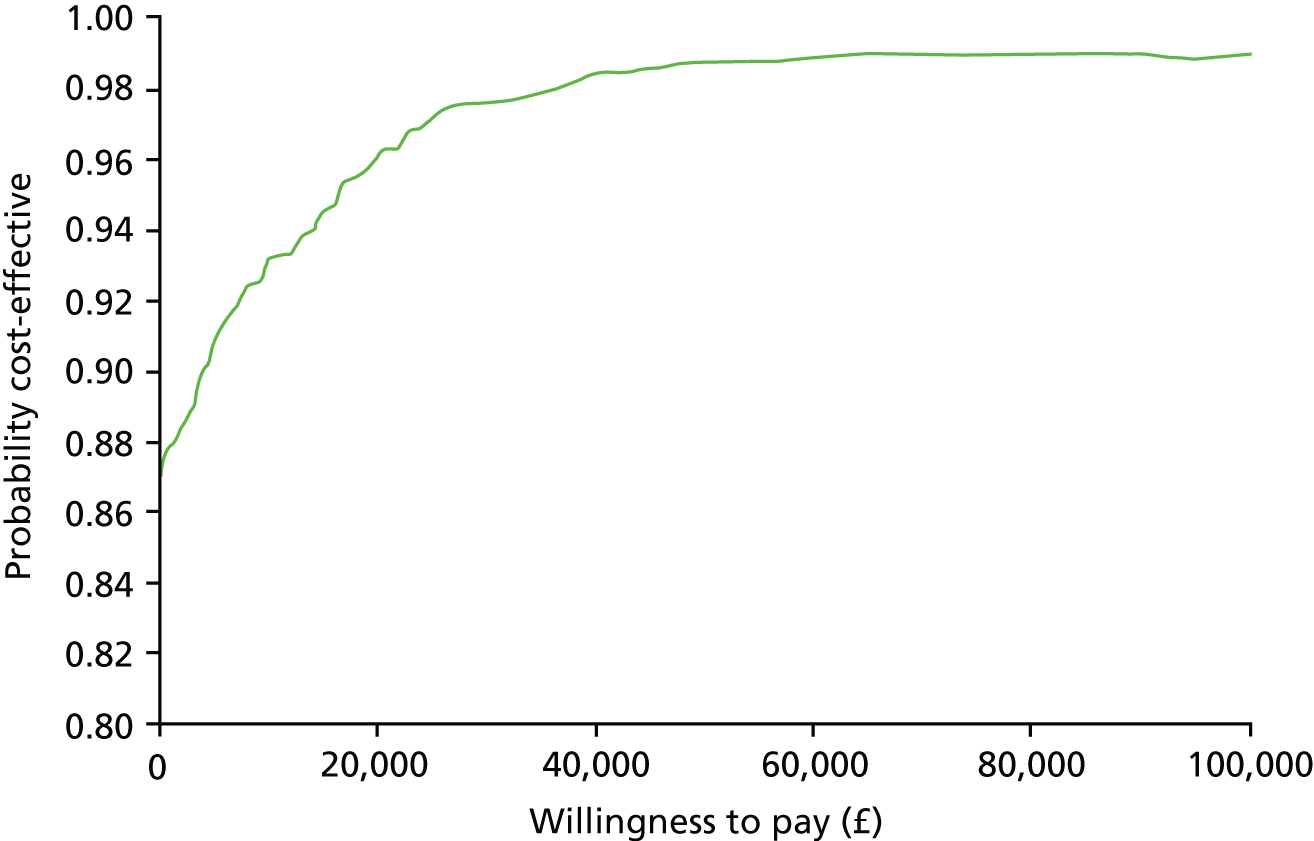

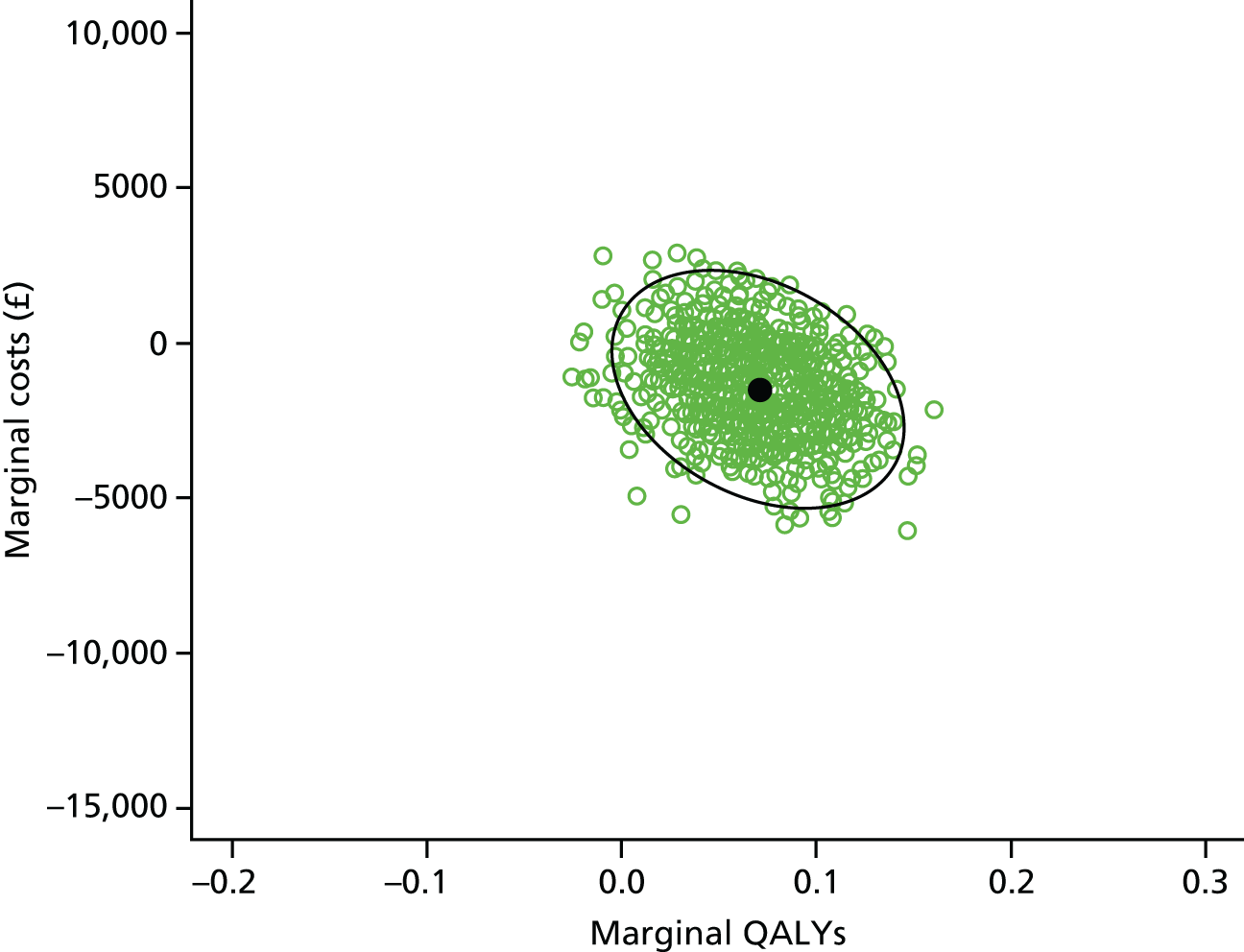

3. Injurious falls