Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 15/10/37. The contractual start date was in November 2016. The draft report began editorial review in October 2019 and was accepted for publication in March 2020. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Anthony Byrne reports grants from Marie Curie (London, UK), Health and Care Research Wales, the End of Life Board for Wales and the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Health Technology Assessment (HTA) programme outside the submitted work; he is also a member of the End of Life Board for Wales, which is responsible to the Welsh Government for developing and implementing strategy for end-of-life care in Wales. Bee Wee reports that she is National Clinical Director for End of Life Care, Chairperson of the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence Quality Standards Advisory Committee and has a NIHR-funded grant outside the submitted work. She has also received royalties for a book published by Oxford University Press (Oxford, UK). Dyfrig Hughes reports that he was a member of the HTA Programme Pharmaceuticals Panel (2008–12) and member of the HTA Programme Clinical Evaluation and Trials Board (2010–16). Marlise Poolman was a member of the HTA Prioritisation Committee: Integrated Community Health and Social Care (A) from 2013 to 2019. Zoe Hoare reports that she is an associate member of NIHR Health Services and Delivery Research board. Clare Wilkinson reports that she was chairperson of the HTA Commissioning Panel – Primary Care, Community, Preventive Interventions (2013–18) and a member of the HTA Rapid and Add-0n Trials Board (2012–13).

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2020. This work was produced by Poolman et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2020 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Introduction

Background

Caring for people who are dying during their last few days of life in a place of their preference is an essential part of health and social care. The majority of people who are dying express a wish to die at home (79%); however, only half of those achieve this. 1 The likelihood of patients remaining at home often depends on the availability of able and willing informal carers. 2–4 These carers take on numerous care tasks, including the responsibility of assisting patients to have their oral as-needed medications. Extending the role of carers to include administering subcutaneous (SC) medication has proven to be key to achieving home death in other countries. 5

Pain, nausea/vomiting, restlessness/agitation and noisy breathing (rattle) are common symptoms in people who are dying. 6,7 In addition to regular (background) medication, which is given via continuous SC infusion using a syringe pump, guidelines suggest using additional (‘as-needed’) medication for symptoms that ‘break through’. 8,9 As dying patients are commonly unable to take oral medication, as-needed medication is most often given as a SC injection by a health-care professional (HCP),8 in the UK usually a district nurse (DN).

Medication for breakthrough symptoms is commonly prescribed in advance (anticipatory prescribing) and kept in the patient’s home. Medication administration can be severely delayed by the HCP’s travel time to the patient’s home and/or the non-availability of anticipatory medication in the home. Delays happen even with dedicated out-of-hours (OOH) ‘rapid response’ nursing services for patients dying at home. Our local audit revealed long waiting times. The median waiting time from the call to OOH services for symptom control to the administration of as-needed medication by a HCP was 86 minutes (range 35–167 minutes), not including the time from administration to the onset of action or symptom control. Breakthrough pain is usually difficult to predict; it is quick in onset and has a median duration of 30 minutes. 10 Long waits mean that pain is often not adequately managed in the home setting, as shown in the National Survey of Bereaved People (VOICES). 1

The CARiAD trial is about exploring and developing:

-

a legal practice in the UK of carer administration of injectable medication (including strong analgesia) to patients who are unable to take oral medication and may not be able to make decisions for themselves (see Appendix 1)

-

a practice that is not yet routine in the UK and needs careful testing to see whether or not the carer role can routinely be extended to include training in the administration of SC medication to a dying patient who is unable to swallow their usual medication.

The CARiAD trial is not about:

-

control of background symptoms that are usually managed by a continuous SC infusion when a patient becomes unable to swallow their usual medication

-

pressurising carers to take on the extended role if that is not right for either the carer or their loved one

-

hastening death or replacing best-quality palliative care from HCPs.

This study focuses on timely administration of as-needed medication for dying patients who are being cared for at home, in particular whether or not lay carer role extension (to be trained to give as-needed SC injections) is feasible and acceptable in the UK.

Rationale

Although carer administration of injectable medication (including strong opioids) is lawful and practical,1 it is not currently part of usual care everywhere in the UK. The national Palliative and End of Life Care Priority Setting Partnership (PeolcPSP) surveyed 1403 people, including patients in the last years of their life, current and bereaved carers and HCPs, on their unanswered questions about palliative and end-of-life care. They accorded highest priority to research into the provision of palliative care, including symptom management outside working hours to avoid crises and help patients to stay in their place of choice. The survey noted the information and training needs of carers and families to provide the best care for their loved one who was dying, including training for administering medicines at home. 11 Data from the PeolcPSP indicated that UK patients may be denied the opportunity to die at home owing to the lack of access to adequate symptom relief. 12,13

Carers across the world embrace this as an option, as evidenced through the published literature. In Australia, the practice is well established (> 30 years) and highly acceptable. 5 A manualised educational package and evidence-based guidelines are available. 14

This practice appears acceptable and has become embedded in Queensland, Australia. However, as per our rapid review (unpublished),5,15–22 to our knowledge there have been no randomised studies testing the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of carer-administered non-oral medication in the last days of life for patients dying at home anywhere in the world.

Equipoise is emerging on this topic in the UK. Carer administration of as-needed non-oral (including SC) medication for breakthrough symptoms in patients dying at home is practised in a limited way in some areas in the UK, and has been for a number of years. For this to be widely available to more carers who are considering supporting a loved one at home, testing was required in a UK environment with the support of an evidence-based carer education programme and resources. Not all family, carers or patients at home will want to be involved in this practice. This research will help to ascertain the proportion of those who are interested and how to train and support those who are willing to be involved.

How does the existing literature support this study?

Carers prioritise rapid symptom control and are willing and able to administer injectable drugs, including controlled drugs such as morphine: a narrative literature review of family carer perspectives on supporting a dying person at home illustrated the desire of families to be able to provide immediate symptom relief. 23 Our review found that caregivers are willing to learn to overcome their reservations about administering SC medications. 5,15–22 The ability to alleviate their loved one’s symptoms and support them to stay at home was paramount.

There is an existing evidence-based education package and medication resources; a Brisbane group developed and evaluated an educational package and a randomised trial was completed of who prepares the SC injections (carer, nurse or pharmacist). 5,14,24 In Singapore, a colour-coded ‘Comfort Care Kit’ is in use,25 with oral and non-oral as-needed medication provided for caregiver administration. A telephone survey of 49 family carers showed that 67% of them used this kit, all family members found it easy to use and 98% of them found it effective for symptom management. All except one patient died at home. In Canberra, the provision of an emergency medical kit (including for use by lay carers) was largely viewed as an effective strategy to achieve timely symptom control and to prevent inpatient admissions. 19

There is growing UK evidence around the carer role for patients who are in the last months/year of their life, but few studies focus on the last days of life (as reiterated by the Neuberger Review into the Liverpool Care Pathway26). The evidence that is beginning to accumulate mostly focuses on patients who have capacity in the last year of their life. UK and Australian research includes ‘Unpacking the home’,27,28 the Cancer Carers Medication Management work,29,30 the SMART (Self-Management of Analgesia and Related Treatments) study31 and ImPaCCT (Improving Palliative Care through Clinical Trials). 32 Our study, by contrast, focuses on the last days of life at home, when the individual’s capacity is likely to be limited or absent, with very different implications and issues for carer administration.

Community receptivity

The UK was ready for testing this extended lay carer role:

-

Primary care teams and families are used to similar practices in other areas of medicine (e.g. insulin for diabetes mellitus and intravenous antibiotics for children with cystic fibrosis).

-

The PeolcPSP report incorporated the views of 1403 people across the UK and placed great emphasis on empowerment of family carers and symptom management during the last days of life. 11

-

Ambitions for Palliative and End of Life Care: A Framework for Local Action was published in September 2015. 33 It was jointly developed and published by the National Partnership for Palliative and End of Life Care (27 national organisations) and has widespread support in the UK, especially as the partnership included the Patients’ Association and charities with large public contributor groups. They identified eight foundations for their six ambitions; one of these foundations relates to ‘Involving, supporting and caring for those important to the dying person’, acknowledging the importance of lay carers in the caring team. Each ambition has a set of building blocks; the building block of ‘practical support’ in ambition 6 is particularly applicable to the CARiAD trial as it calls for ‘new ways to give the practical support, information and training that enables families . . . to help’. There has been a strong positive response to the framework, and many localities are using it to consider their local strategies. The message about shared ownership and responsibility is particularly pertinent.

-

In the UK, this practice is not widely accepted as usual care; however, over the past few years, we have identified a small number of geographically distinct sites where the practice occurs (< 10 sites). Recently, the Lincolnshire project was showcased on national radio as part of a series of talks on dying. 21,34,35 Since the conception of the CARiAD trial, at least seven other areas have, unsolicited, expressed interest in exploring the practice, including joining as potential recruitment sites in a future definitive trial.

Pressure on health and care services in the UK

Health-care professionals in all three sites were universally positive about testing the intervention; if found to be beneficial, it could make their patients more comfortable and their jobs more manageable. In the longer term, this innovation could relieve some pressure on emergency departments by reducing inappropriate emergency (crisis) admissions due to uncontrolled symptoms. 36,37

Pressure on DN time could also be relieved as extra visits (in addition to the daily check) to administer as-needed medication would decrease, which would contribute to the sustainability of services.

Choice of design

Our team was aware of the challenges that are associated with research in the last days to weeks of life in general, including recruitment and ethics considerations. Although we recognised the benefits of conducting an internal pilot trial with progression rules to a full trial, we felt that an external pilot and feasibility study was more appropriate. Regarding recruitment, an external pilot trial required three sites recruiting 50 patients. A full trial would require at least 30 sites recruiting 520 patients. Although our three sites were confident about recruitment, and a number of other areas had already expressed interest in participating in a future trial, we could not disregard the effect of the other complex factors affecting a broader roll-out.

These specific additional considerations added to the decision to propose a stand-alone (external) pilot trial:

-

The current UK context (post Shipman,38 post Liverpool Care Pathway26 and with the ongoing euthanasia public debate) – this called for careful attention to its affect on consent mechanisms and attitudes of carers, patients and clinicians to this innovation.

-

The lack of clear UK-wide guidance on carer administration of as-needed SC medication to patients dying at home – the practice is legal but current guidance was not detailed or specific enough for wide adoption (see Appendix 1).

-

The lack of a clear and widely accepted training package for lay carers, adapted for the UK context.

-

The uncertainty about the primary outcome measure for a definitive trial.

These were unpredictable barriers until we began to introduce the reworked Australian manualised intervention and tested the trial processes. If the intervention was proven to be feasible and acceptable, we anticipated a phase of ensuring that new guidance is developed and put in place at national level in UK health systems to enable the practice, prior to rolling out a full trial.

We aimed to demonstrate a clear path towards a definitive randomised controlled trial (RCT), as per Medical Research Council Framework, for the evaluation of complex intervention principles, further informed by the MORECare guidance developed for palliative care research. 39,40

Aims and objectives

The research question was ‘is carer administration of as-needed SC medication for common breakthrough symptoms in patients dying at home feasible and acceptable in the UK, and is it feasible to test this intervention in a future definitive randomised controlled trial?’

-

P (Patient) = patients in the last days of their life who are becoming unable to take their usual oral as-needed medication for breakthrough symptoms and are being cared for at home, and their carers.

-

I (Intervention) = carer administration of as-needed SC medication for common breakthrough symptoms, such as pain, restlessness/agitation, nausea/vomiting, and noisy breathing/rattle, supported by tailored education.

-

C (Control) = usual care (HCP administration of as-needed SC medication).

-

O (Outcome) = main outcomes of interest – feasibility and acceptability, recruitment, attrition and contamination.

To inform the design of a Phase III trial we aimed to:

-

Tailor a successful Australian intervention as a standardised, manualised intervention for UK carer administration of as-needed SC medication for breakthrough symptoms in patients dying at home.

-

Establish the feasibility of this standardised manualised package and carer role extension by assessing acceptability, ability to recruit, attrition rates and suitability to UK context. This will be carried out by conducting an external randomised pilot trial with an embedded qualitative component.

-

Identify attributes pertinent to carers’ preferences for HCP versus own administration of as-needed SC medications for patients dying at home (as part of the qualitative component) and to establish the feasibility of completion of the Carer Experience Scale (CES) (assessed in the pilot trial).

The aim of the public contribution was to:

-

conduct the study and be informed and influenced by the lived experience of bereaved carers

-

facilitate meaningful involvement of patient representatives

-

provide an exemplar of a highly integrated and proactive public contributor role in care of the dying trials.

Chapter 2 Developing the intervention

Manualised education package

Introduction

From discussion with our Australian co-investigators, we developed a good understanding of the Caring Safely at Home resources, which consist of carer and HCP resources. When the CARiAD study commenced, carer resources that were part of the Caring@Home study comprised:

-

Illustrated step-by-step guides that provided a simple structured approach to the preparation and administration of SC injections –

-

opening and drawing up from an ampoule

-

10-step plan – blunt needle technique

-

10-step plan – no-needle technique

-

injection via cannula – blunt needle technique

-

injection via cannula – no-needle technique.

-

-

A practice demonstration kit, including a cannula and other equipment that are required for the preparation and delivery of SC injections.

-

Colour-coded medication labels for labelling prepared syringes.

-

A fridge magnet that was colour coded to help the clinician or caregiver match the relevant medication with the patient’s symptoms.

-

A daily diary to document aspects of medication administration.

-

A series of videos, ‘Palliative subcutaneous medication administration: a guide for carers’, that demonstrated aspects of SC medication preparation and administration.

-

A booklet, ‘Subcutaneous medication and palliative care: a guide for caregivers’, that covered topics including frequently asked questions, the importance of symptom control, management of common palliative symptoms, commonly used SC medications and injecting processes.

The HCP resources comprised:

-

the Caring Safely at Home Standardised Education Framework

-

detailed instruction guidelines for the Caring Safely at Home resources and education framework

-

a competency checklist that provides the clinician with a mechanism to ensure that the caregiver is competent to safely inject SC medications

-

a clinician lanyard that provides a useful overview of the educational framework and the colour-coding scheme utilised for the medications.

The Queensland materials continue to be freely available on the project website (www.caringathomeproject.com.au/; accessed 5 January 2020) and are updated frequently (most recent update 12 June 2019). The materials are now available for use in all Australian jurisdictions.

In this chapter, we describe the development of the manualised training package that was used in the CARiAD trial. It does not cover all of the supporting trial documents, for example the participant information sheets (PISs), screening log or daily DN checklist.

Methods

We developed the manualised training package materials in three distinct stages:

-

clarifying focus and scope

-

developing the content

-

deciding the design, colour scheme and layout.

The final materials would be used in the trial and feedback would be obtained on their utility, acceptability and feasibility via qualitative interviews and informal feedback processes.

A more detailed description of each of the three stages is as follows:

-

Clarifying focus and scope.

After detailed review of the suite of Australian materials (including any updates during the time the CARiAD trial materials were developed), and after accounting for practice differences between Australia and the UK, the materials were adapted for a UK trial setting. All references to the Australian practice of drawing as-needed medication up in advance, labelling with colour-coded labels and storing in the fridge (with supporting aide memoires such as fridge magnets and lanyards) were removed. All references to the Queensland-wide framework Guidelines for the Handling of Medication in Community-Based Palliative Care Services in Queensland (March 2015) were removed. Wording was scrutinised and, if needed, aligned with the UK practice of carer administration being tested in the trial. Details in the Australian framework pertinent to the CARiAD trial were included in the trial protocol.

Permission was granted by our Australian co-applicants for us to use the graphics in their materials as appropriate.

The Quality of Life in Life-Threatening Illness--Family Carer Version (QOLLTI-F) questionnaire was added to the diary, to be completed every 48 hours following the first administration of SC as-needed medication (see Appendix 2). 41

-

Developing the content.

This stage required detailed, word-for-word consideration of the Australian materials and adjustments as appropriate. In the first instance this was carried out by the core CARiAD team, who also cross-checked the content against other available documents (specifically the Lincolnshire policy and supporting documentation and the risk assessment tools for self-medicating). 35,42 This was reviewed by the co-applicants who are clinicians. As a final check prior to discussion at the expert consensus workshops, it was considered by our public contributor co-applicants. Overall, minimal adaptation was needed, including of terminology and drug names. Detail included in the Australian Standard Education Framework was incorporated into the training that HCPs received on the trial.

-

Deciding the final design, colour scheme and layout.

The final design stage was an iterative process between the core team and the design company, with invaluable input from the public contributor co-applicants, especially on colour scheme choice (distinctive enough but not intrusive, i.e. not using too strong colours and using different colours for different trial booklets to support ease of recognition for carers and HCPs) and cover graphics.

Results

The final set of documents included in the CARiAD trial manualised training pack for carers comprised:

-

‘Subcutaneous medication for breakthrough symptoms in the last days of life: a guide for carers’ (see Report Supplementary Material 1).

This was adapted from the booklet ‘Subcutaneous medication and palliative care: a guide for caregivers’ and covered similar topic areas. In addition, it included information on how to know which medication to give, how long to wait for medication to work, how often to give medication, which symptoms medication can be given for in the trial, how many doses could be given, what to do if too much medication is given and what to do if the carer is not available to give medications. A section was also included broaching the concept of the ‘last injection’. After careful discussion with our public contributor co-applicants, the following paragraph was added –

There may come a time when you are giving the injections when the person you are caring for is very ill and will soon die. This might mean that the time when they die is near to when you have last given them medication. It is very important for you to know that these two things are not related and the medication has not ended their life. The nurse training you to give injections will discuss any worries or concerns you may have about this.

Rather than leaving it to individual clinicians to find their own way of explaining this, the text was intended to provide a script on which the HCP’s explanation to the carer could be based.

-

A carer diary (intervention or usual care), which was A5 size (see Report Supplementary Material 1). This was divided into the following sections –

-

introduction, explaining provenance and focus

-

contact details of the teams involved in the dying person’s care and space to record medical appointments

-

instructions for use of the diary when recording symptom management

-

information on the prescribed as-needed medication (intervention group diary only)

-

record of symptoms and subsequent management (one page per entry, 15 entries per booklet)

-

QOLLTI-F questionnaire (three copies per diary, additional diaries provided by DN teams as required).

-

Changes to the carer diary included assigning a full A5 page to each administration entry (rather than five administration entries per page, as in the Australian carer diary) and amending the medication information table to align with commonly used medication in the UK. The context of a RCT necessitated the need for carer diaries with different content for the two trial groups; therefore, two versions of the diary were produced.

-

Step-by-step guides with images illustrating the required actions (see Report Supplementary Material 1) –

-

step-by-step guide to opening and drawing-up medications from an ampoule

-

10-step plan for preparing and giving as-needed SC injections using a blunt needle technique

-

10-step plan for preparing and giving as-needed SC injections using a no-needle technique.

-

An injection training pack was also included so that the carer could practise giving needle-less injections (i.e. via a cannula). We listed the suggested content to be assembled by the HCP from their stocks (see Report Supplementary Material 1). Given that ampoule openers are not in widespread use, these were provided to the HCPs for inclusion in the training packs.

In relation to carer resources, we were advised that the video resources were not often used and that carers preferred the printed resources; therefore, video resources were not developed.

More extensive changes were required to the HCP resources, as it was outside the scope of the trial to generate a standardised education framework for a UK context. The framework was therefore removed from the HCP resources along with the detailed instruction guidelines, as HCPs delivering the intervention would be comprehensively trained by the core CARiAD trial team. Additional resources were developed to support HCPs and ensure the safety of patients and carers (see Report Supplementary Material 2) and comprised:

-

risk assessment (RA) tool

-

information for prescribers (intervention group only)

-

daily checklist for DNs – this document was an aide memoire of all the trial-related tasks to be carried out at DN visits

-

adverse event (AE) record – to be kept in the patient’s notes and returned to the trial team at the end of the study. It defined AEs, serious adverse events (SAEs) and related events, included a table to record AEs and provided a prompt of the circumstances in which a separate SAE form should be recorded.

The competency checklist was amended to include the following questions about the nominated carer:

-

Is aware of the symptoms of pain, restlessness/anxiety, nausea/vomiting and noisy breathing and which medications to use for each of these symptoms?

-

Can reconstitute drugs if required?

-

Understands the importance of completing all associated study paperwork?

-

Is aware of how many as-needed doses can be administered of each drug in 24 hours?

-

Understands the importance of contacting the health-care team immediately if an error is made with medications or unusual symptoms develop?

The date, signature and name of the HCP were also included in the competency checklist. In addition, two columns were added so that ongoing checks of competency could be recorded if needed.

The intervention under scrutiny in the CARiAD trial was carer administration of as-needed SC medication and, for this reason, the training to enable carers in this practice was key. The printed documents described supported carer training and, therefore, there was ongoing review of these materials throughout the trial, resulting in minor changes.

Expert consensus work

Introduction

The aim of the expert consensus workshops was to refine trial processes, guide the adaptation of the existing Australian training materials for use in a UK context and inform the development of other supporting documents. The chosen format was based on the successful model used in the Early Lung Cancer Identification and Diagnosis (ELCID) trial. 43

Methods

Two workshops were planned with invited UK experts: one in North Wales and one in the southern part of the UK (either south Wales or Gloucestershire). The invited experts from the three recruitment sites were to include public contributors, primary care clinicians [general practitioners (GPs) and DNs], specialist palliative care (SPC) clinicians, research nurses (RNs), pharmacists and representatives of other support services [including hospice at home and Marie Curie (London, UK)]. Workshops were facilitated by two members of the core CARiAD trial team, one of whom made notes throughout the workshop. Workshop attendees were given background to the trial, including detail on how the question for the research was developed and the existing Australian training package that was to be adapted for the CARiAD trial. The facilitators then led discussions on the following areas:

-

identifying and approaching participants

-

consent processes

-

prescription, supply and storage of drugs

-

delivery of the intervention

-

monitoring and accountability

-

follow-up measures

-

post-bereavement interviews

-

ethics concerns

-

resource pack.

Attendees were given the opportunity to freely discuss, ask for clarification on or raise any queries or concerns about these areas. In addition, the core CARiAD team raised specific questions that required input.

Workshops were audio-recorded and a summary of discussions and resultant actions from each workshop was produced.

Results

Following the first workshop in North Wales, the decision was taken to have two separate workshops in the southern part of the UK (i.e. for both south Wales and Gloucestershire recruitment sites), as it became apparent that the specific details of the local ways of working would be vital in understanding how to deliver the trial intervention. Discussions at each workshop built on and refined those from previous workshops, interpreting them in a local context. There were 10–12 attendees at each of the three workshops, with at least one representative of each of the invited groups present at each meeting. A co-chief investigator for the study (MP) facilitated two of the workshops, supported by the trial manager (JR). The third workshop was facilitated by the principal investigator (PI) for the site (AB) and the qualitative lead for the study (AN).

Identifying and approaching participants

All sites agreed that specific DN teams who were deemed to be stable and had the capacity to take on research should be chosen to take part and be responsible for identifying eligible patient/carer dyads. This decision was to be made with the input of the local DN matrons or equivalent. HCPs who were linked with these teams were to be made aware of the study and that the named DN team was involved. They had to have knowledge of the RA tool (see Report Supplementary Material 2) and would be asked to flag potential patients to the DN team. No concerns were raised about difficulties in identifying dyads suitable for the CARiAD trial by the DN teams, and discussion focused on the practicalities of how, when and where patients and their carers should be approached.

There was considerable discussion around the content of the RA tool. It was noted that there was no need for the RA tool to exclude patients who were known to have human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) or hepatitis as, first, universal precautions should be taken and, second, there was no risk of needle-stick injury as needles would not come into contact with the patient’s blood owing to the no-needle administration technique. It was also suggested that RA using the RA tool should be ongoing to account for changes in circumstances. Other factors discussed included how to include GPs in the RA process, what to do if there was more than one carer, whether or not a question about social support for the carer was appropriate, the inclusion of a free-text box for additional issues and the need for a question about a suitable environment for drug storage.

Consent processes

The benefit of research staff being responsible for the consent process was discussed, as they have experience in explaining trial-specific procedures, such as equipoise and randomisation, to ensure that consent was fully informed and that dyads were clear that agreeing to take part did not guarantee that they would be able to administer as-needed SC medications.

Attendees were asked to consider the balance between the benefits of a RN obtaining informed consent and the potential burden caused by introducing a new colleague (i.e. the RN) to a dyad during such a sensitive time. Public contributors suggested that an acceptable course of action was that, first, the DNs introduced the concept of the study and gave the information sheets and, second, if the dyad was interested in participating, the DN could attend a joint visit with the RN to introduce the RN to the dyad. During subsequent discussion in Gloucestershire, it was suggested that a joint visit might not be necessary and that it would be appropriate for the DNs to ask the dyad if they would be happy for a RN to visit independently.

Prescription, supply and storage of drugs

The legal responsibilities of the prescribers was discussed. If all usual prescribing procedures are followed correctly, training to competency of carers evidenced by the DNs and the delegation of administration duties clearly demonstrated, the legal responsibilities for all HCPs involved remain the same as in usual care. However, as the anticipatory medications prescribed for patients in the intervention group may be administered by a carer rather than a HCP, it was felt that all GPs (the usual prescribers) in the area covered by the DN teams involved in identifying potential participants for CARiAD would need to agree in principle to their patients being approached. Potential other prescribers who should be informed of the study were also identified across the three sites; these included advanced nurse practitioners, DNs, pharmacists and SPC nurses.

The CARiAD team raised the issue of reconstitution of drugs for discussion, as diamorphine is a commonly used drug and needs reconstitution (morphine does not need reconstitution). The workshop attendees confirmed that morphine is used as first-line SC opioid and the use of diamorphine would be limited to a small percentage of cases in which exceptions apply. In North Wales, this was supported by a recent change in the local health board’s official prescribing policy. Therefore, it was felt that these small number of patients should be dealt with on a case-by-case basis, with the DNs liaising with the prescriber to negotiate the use of morphine as an alternative and being able to train carers to reconstitute diamorphine when needed.

It was also noted that because all drugs would be in glass ampoules, blunt filter needles should be used for drawing up medications and it was agreed that a reusable ampoule opener should be provided in the injection training kit, alongside the step-by-step guide to opening an ampoule, to minimise the risk of injury.

Delivery of the intervention

No major concerns were raised about the delivery of the intervention; however, there were certain factors that attendees felt that the research team needed to take into consideration. These mainly centred around support for the carer, including ensuring that they are able to access as-needed support 24/7, and being mindful of carer burden.

Practical issues raised included the need for a second SC butterfly administration site and that carers would need to know how to check when the administration site is compromised. It was also noted that the use of a second SC butterfly site may not be routine in all areas, so this should be emphasised to the DN teams. Similarly, as the research team are relying on DNs to undertake daily visits to these patients, this should be checked with individual teams as this may not always be the case.

Monitoring and accountability

Practicalities around how carer administration of medications would be recorded in patient notes were discussed. It was suggested that information could be transferred to the medication administration chart by the DNs and marked as ‘carer administered’ during the daily checks. Some members felt that a copy of the RA and competency checklist should also be included in the patient notes.

Limits of how many doses of carer-administered as-needed medication that could be given in 24 hours for the same indication were discussed. The agreement was three doses to balance pragmatism and safety considerations. If a further dose of medication for the same indication was needed within 24 hours, this could not be carer administered and a review by a HCP should be sought. The frequency of carer administration of commonly used medication was discussed and agreed that they should, in general, not be given more frequently than every 4 hours. The attendees noted that failure to respond fully to medication may sometimes indicate a different reason for the symptom (e.g. pain could be caused by a new urinary retention, for which a catheter, and not increasing doses of pain relief, is needed) and that clinical review should be sought if symptoms are not settling or are persisting or increasing. This concern was carefully weighed against the need to give timely symptom relief, which is often achieved by increased doses of pain relief medication. Attendees, drawing on experiences of public contributor carers and current usual care in the community setting, agreed that a carer could be given specific permission by the prescriber to give one further dose of morphine or midazolam 1 hour after the previous administration, if required.

For safety reasons, it was felt that prescribers and OOH services should be made aware that dose steps/options should not be prescribed for patients in the intervention group and that dose changes could not be suggested to the carer over the telephone. If the as-needed dose of medication was adjusted, this had to be communicated to the clinical team and the carer. It was suggested that space should be provided in the medication table at the front of intervention carer diaries for updating dose information. A SPC pharmacist at the North Wales workshop suggested including a dose–volume column to aid carers in giving the correct dose of medication.

The patchwork of OOH services available was discussed in some detail, showing the challenges involved in ensuring that there was awareness of the CARiAD study across the board. The group advised that the CARiAD team can flag inclusion on the study to the OOH services themselves, using current mechanisms.

Follow-up measures and post-bereavement interviews

The proposed plans for conducting the post-bereavement follow-up and qualitative interview with the carer were deemed to be an acceptable balance between not overburdening the carer and being soon enough that they would still have accurate recall. Feedback from attendees suggested that earlier time points may also be acceptable. The workshops emphasised the importance of signposting to bereavement services at this visit when appropriate. It was generally felt that the best way to do this would be to signpost via the GP.

It was agreed that, ideally, the follow-up visit should be conducted by the same person who completed the baseline visit, but that if this was not possible it would be acceptable for a different person to do this. As the intention was for the baseline visit to be conducted by the RN, this would require the RN to remain blinded to the randomisation allocation. RNs attending the workshop expressed a strong preference for being unblinded, as it is usually part of the RN role to deliver the randomisation allocation news to a participant and it was felt that their knowledge of allocation would be beneficial to the management of the study processes.

Ethics concerns

No concerns were raised that posed a significant risk to the commencement of the study. For all points raised, the attendees were asked to consider if this was something that was specific to the CARiAD intervention or something that would also be relevant to usual practice in the UK.

The main concern was the potential for carer burden, which was raised in all workshops. This included concerns about randomisation and the potential for distress when families were not randomised to the intervention group. Strategies for minimising this risk were discussed, which focused mainly on establishing an open dialogue between participants and RNs/DNs to allow an explanation of equipoise and the randomisation process. The importance of the initial approach and explanation of the study was discussed, and the reliance on the experience of RNs to do this effectively to ensure that patients and carers understood all of the trial processes as well as difficult events such as the ‘last injection’.

There was a general view that the risk of overdose was no different from the usual risk involved when carers administer oral opioids at home. Similarly, with regard to patients who may attempt to coerce a carer into giving an increased dose, the risk was deemed to be comparable with that in usual practice, as drugs are already present in the home.

There were questions about what would happen if the carer gave the wrong drug, but attendees were reassured by the CARiAD team who reported that there were no recorded incidents of this in the Australian study and that if this were to happen it should be noted by DNs during drug stock checks, which attendees reported were part of usual practice.

There was much discussion at the south Wales workshop about professional accountability and the responsibilities and legal position if things went wrong. The group was informed of research insurance and the sponsor’s role.

There was uncertainty about whether or not there was any issue in taking part in the trial for carers who were also HCPs, and if the relevant medical or nursing councils held a view on their eligibility to take part. It was generally felt that, although HCPs who found themselves in a caring role should not be excluded, it would be beneficial to obtain a supporting statement from the relevant councils if possible.

Discussion

The consensus workshops provided rich, site-specific information from a range of expert stakeholders to inform the trial processes and the development of carer training materials. Attendees were positive and supportive about the trial and its aims, and the majority of concerns that were expressed were addressed by the trial team or other attendees by sharing their experiences.

Suggestions made in the workshops were considered by the core CARiAD team and were incorporated into training materials and other trial documents accordingly. It was apparent that clear guidelines for prescribing for intervention patients would be required and that an information sheet for prescribers should be compiled to enable prescribers to adhere to these. This summarised the issues raised in the workshop and suggested dose regimens for as-needed medications. As reconstitution was not likely to be common, it was felt that no step-by-step guide for this would be needed. Specific changes that were required to the RA tool were removing reference to the risk of transmissible disease, adding a check that there was a suitable place to store medications and amending it to allow it to be used as an ongoing document. Carer burden concerns were addressed as much as possible in the carer handbook and through signposting to OOH services as well as by ensuring that during training carers were aware that there was no obligation to administer as-needed medications, even when trained.

The importance of GP support for the study, particularly regarding the prescribing requests for intervention patients, required all general practices in the areas covered by the chosen DN teams to indicate that they had no objections to patients being approached to take part. Although some DN teams planned to involve the GP in the initial RA, this was unlikely to happen in every case, and for this reason the general practices were targeted by the core CARiAD team prior to opening trial recruitment.

The issue of whether or not the RNs could be unblinded was not resolved, and further discussion of this with the core CARiAD team and trial steering committee was required.

After DN teams were identified at each site, they were trained by the trial manager in how to recruit participants and how to train carers in the intervention group. They were provided with all of the materials and information, and the purpose of the documents was clearly explained, particularly the RA tool and the competency checklists. When usual-care processes already existed and there had been no strong views in the consensus workshops about the need for any changes to these, and as long as there was no impact on safety, DN teams were encouraged to continue with these processes. For this reason, no trial paperwork was provided for drug stock checks because these checks were already being carried out as part of current practice. When DN teams felt that it was appropriate and feasible for the carer, the carer was trained to complete the Medication Administration Record along with the carer diaries.

The General Medical Council (GMC) and Nursing and Midwifery Council (NMC) were contacted to establish their stance on recruiting carers to the CARiAD study who were also HCPs. Although they were unable to offer complete clarity, they did not object to HCPs being included in the study. As all carer participants were to be trained as lay carers, regardless of their background, they were not excluded from taking part.

Chapter 3 Randomised pilot trial design and methods

Design

We conducted a two-arm, parallel-group, individually randomised, multicentre pilot trial of carer-administered as-needed SC medication for common breakthrough symptoms in patients dying at home compared with usual care, with a 1 : 1 allocation ratio and using convergent mixed methods. 44

Qualitative and quantitative data were seen as complementary and were given equal importance. Data analysis of the two data sources was undertaken independently and then combined during the interpretation stage, during which the data were examined for convergence, divergence, contradictions and relationships between the two data sets.

The study was funded by the Health Technology Assessment programme of the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR). It received a favourable ethics opinion from the Wales 1 National Research Ethics Committee (REC) (reference: 17/WA/0208; IRAS project ID: 227970) and the Bangor University REC (project ID: 2016–15826). The UK Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency has advised that the CARiAD trial was not a Clinical Trial of an Investigational Medicinal Product (CTIMP). The study was registered on the International Standard Randomised Controlled Trials Number (ISRCTN) registry (ISRCTN11211024). Approval was granted from the NHS research and development departments of all three sites. Standard Protocol Items: Recommendations for Interventional Trials (SPIRIT) 201345 recommendations and Consolidating Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) 2010 statements46 (including those specific to randomised pilot and feasibility trials) guided protocol development. The current version of the trial protocol can be accessed from the NIHR project web page. 47

Trial flow chart

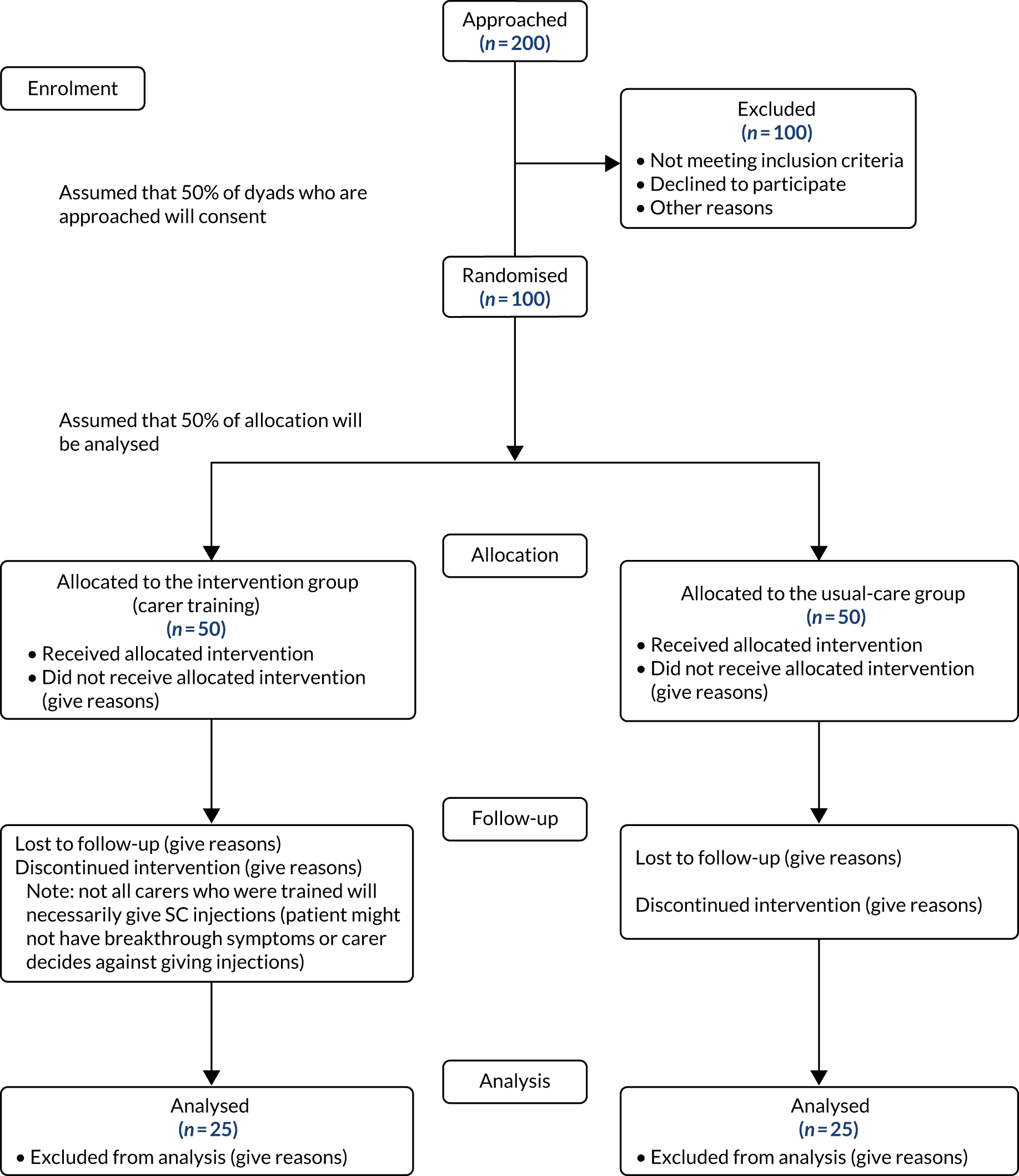

Figure 1 details planned participant flow in the trial.

FIGURE 1.

Anticipated trial flow chart.

Participants

Trial setting/context

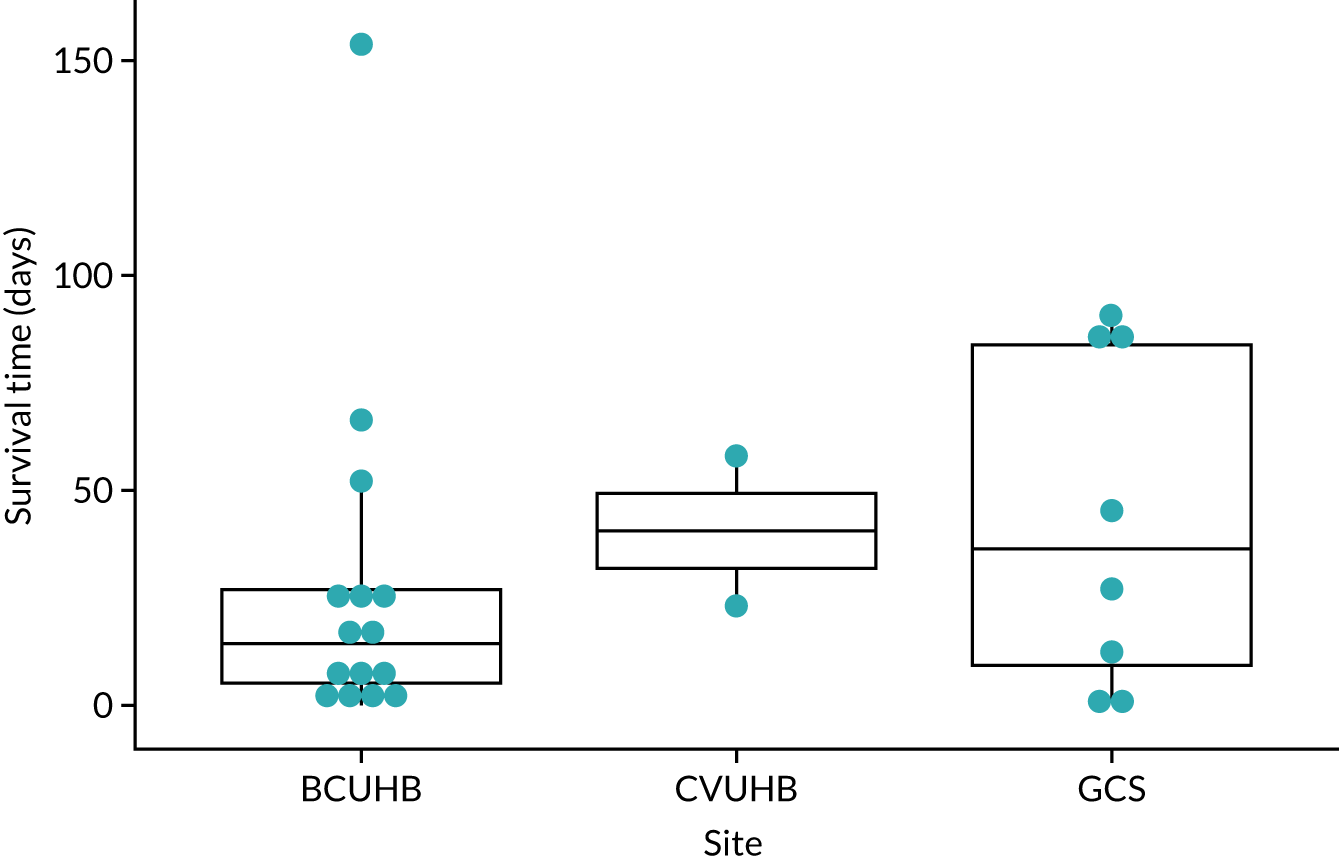

The trial was carried out in community settings in North Wales {Betsi Cadwaladr University Health Board [BCUHB], the Vale of Glamorgan [i.e. Cardiff and surrounding areas, Cardiff & Vale University Health Board (CVUHB)] and Gloucestershire [Gloucester Care Services (GCS)]}, where patients were likely to die at home in accordance with their wishes and without the provision of round-the-clock paid care. The three pilot study sites were chosen as they are representative of the range of sites for a future definitive study.

Eligibility criteria

Inclusion criteria

Inclusion criteria for dyads were:

-

an adult (i.e. aged ≥ 18 years) patient in the last weeks of their life who was likely to lose the oral route for administration of medication and who had expressed a preference to die at home

-

their adult (unpaid) lay/family carer, who was willing to have this extended role and receive SC injection training.

Patient inclusion was not reliant on cognitive status.

Prognostication was reliant on the professional judgement of and agreement among the attending HCP team (i.e. clinical estimate of survival). There is an assumption that the carer will spend a significant amount of time with the patient.

In cases where more than one carer was available, we asked the patient to identify which carer they wanted to be included in the study.

Exclusion criteria

A dyad was excluded if any one of the following criteria were present:

-

A patient who –

-

had only paid/formal care

-

had a known allergy/adverse reaction to any one of the usually prescribed anticipatory medication with no suitable alternative

-

had a known history of substance abuse

-

had an objection to the concept of lay carer administration of SC medication

-

was unwilling for available health-care support systems to be accessed (e.g. OOH services).

-

-

A carer who –

-

had cognitive problems (i.e. who was confused, disorientated or forgetful or unable to understand the importance of medications and the information relating to them)

-

had significant visual problems

-

had insufficient literacy skills to understand and complete the study documentation

-

had insufficient dexterity to prepare and give SC injections

-

had a known history of substance abuse

-

had an objection to the concept of lay carer administration of SC medication

-

was unable and unwilling to engage with and access available health-care support systems (e.g. OOH services).

-

-

A context/environment in which –

-

there were known relational issues between the carer and the patient that contraindicated carer administration of medications (e.g. when either the patient or the carer could have assumed this practice supports assisted dying)

-

there were known issues of substance misuse in the immediate circle of family and/or friends

-

there was no suitable place for medications to be stored.

-

The inclusion and exclusion criteria were incorporated in the RA tool (see Report Supplementary Material 2). The aim was to complete the tool:

-

prior to approaching a dyad (if the criteria were not met, dyads were not approached for consent to participate)

-

at intervals (at the discretion of the HCP or local research teams) for dyads included in the trial (if the criteria were not continued to be met, dyads were withdrawn from the trial).

Recruitment

Patient identification

Potential patient/carer dyads were identified consecutively from clinical caseloads in a number of ways: through the hospice, SPC service or DN teams. When a patient was deemed by the HCP team to be in the last weeks of their life and they had expressed a wish to be cared for and die at home, they were screened for approach.

Screening

To be eligible, dyads must have satisfied the RA criteria. A RA screening tool was refined for the CARiAD trial, which was based on existing self-medication tools (see Report Supplementary Material 2). 42 RA took into account several factors as detailed above, and was conducted by the health-care team involved in the patient’s care. If a dyad did not satisfy the RA criteria, they were not approached.

Approach

The patient was approached with written material (PIS; see project web page at www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/programmes/hta/151037/#/documentation; accessed 5 January 2020) by a member of their health-care team. The initial patient approach was carried out separately from that of the carer, unless otherwise requested by the patient and if the attending HCP deemed this appropriate, that is when there was no perceived risk of patient–carer coercion. As the study involved sites in Wales, the PISs (see project web page at www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/programmes/hta/151037/#/documentation ; accessed 5 January 2020) and consent forms (see project web page at www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/programmes/hta/151037/#/documentation; accessed 5 January 2020) were translated into Welsh for the Welsh centres and offered bilingually to comply with the Welsh Language Act 1993. 48 Dyads were given as much time as they needed to consider the information sheets and to discuss with family, friends or the health-care team whether or not to take part. They were told that they could decline to participate without giving reasons.

Informed consent

A RN sought consent at a time that was judged to be suitable by the attending HCP. This gave the patient and carer as much time as they needed to understand the nature of the research, ask questions and make their feelings clear on trial participation. 49,50 If the patient was unable to consent or they had lost the capacity to do so after they had previously given consent, the assent of a personal consultee was sought (as required by the Mental Capacity Act 200551) to the patient’s participation in the trial. 49,50 As the RA excluded dyads for whom there were concerns about relational issues between the patient and the carer, the carer could act as personal consultee.

If the carer did not wish to act as the personal consultee and there was no additional family member or close friend to take on this role, we appointed a nominated consultee (e.g. a HCP not associated with the research) who would act for all patients in this situation in the trial.

The PI retained overall responsibility for the informed consent of participants at their site and was mandated to ensure that any person who was delegated responsibility to participate in the informed consent process was duly authorised, trained and competent to participate according to the ethically approved protocol, principles of Good Clinical Practice and Declaration of Helsinki. 52,53

Randomisation

Method of implementing the allocation sequence

Once the dyad had consented and baseline data collection had been completed, the dyad was randomised to one of the trial arms. Secure online randomisation hosted by the North Wales Organisation for Randomised Trials in Health (NWORTH) Clinical Trials Unit was carried out by the researcher who obtained consent or the trial manager. The system used a dynamic adaptive method of randomisation in which it stratified for recruitment centre and diagnosis (cancer/non-cancer). 54 Confirmation of allocation was sent only to those members of study staff who needed to be aware of the result.

Blinding

The CARiAD trial was an open-label trial in which blinded-outcome assessment was not feasible; therefore, it was important that outcomes were as robust as possible in the light of the lack of blinding. See Appendix 2 and Table 27 for details of the primary outcome contenders, methods of assessment, strategies to reduce bias (by increasing subjectivity) and criteria for assessing feasibility as a primary outcome measure for a future definitive trial. Outcome assessors were experienced RNs.

Data entry was completed unblinded; the trial statistician who carried out the data analysis was the only individual who was blinded to randomisation allocation. The analysis was unblinded at a combined Trial Steering Committee (TSC) and Data Monitoring and Ethics Committee (DMEC) meeting, with independent members present.

Withdrawal criteria

Participants were free to withdraw from the trial at any time without giving reasons and without prejudicing their further treatment. This was made clear to all potential participants at the time that they consented and throughout their time in the trial. Non-completion of the follow-up questionnaires did not constitute formal withdrawal from the trial; unless the participant requested withdrawal of their data completely, all data collected were used for analysis. The RA was reviewed at intervals based on the HCP’s judgement, and if the criteria were not met the dyad was withdrawn from the trial.

Duration of the feasibility study

The study opened to recruitment in BCUHB on 10 January 2018, in CVUHB on 21 March 2018 and in GCS on 1 April 2018. Recruitment closed on 15 March 2019.

Interventions

Schedule of study procedures

Table 1 details the planned study procedures.

| Procedures | Time point | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Screening | Baseline | Study period (last days of life) | Post bereavement | |

| Eligibility assessment | As per dyad inclusion/exclusion criteria | As per dyad inclusion/exclusion criteria | As per dyad inclusion/exclusion criteria | |

| Informed consent | Advance consent from dyad | Check consent | Check consent (personal consultee assent might be required when patient loses capacity) | |

| Demographics | CRF | |||

| Medical history | CRF | |||

| Concomitant medications | CRF | CRF | ||

| Randomisation | ||||

| Assessment | ||||

| Symptom control | ||||

| Symptom scores | Tool: carer diary

|

|||

| Overall symptom burden | Tool: Family MSAS-GDI

|

|||

| Time to symptom relief | Measure: episodes resolved in 30 minutes

|

Tool: qualitative interviewing

|

||

| Safety | ||||

| RA tool | Tool: adapted tool based on Fuller and Watson’s42 self-medication RA screening tool

|

|||

| Competency checklist | Tool: competency checklist

|

Tool: competency checklist

|

||

| SAE reporting | Including appropriateness of administration, proportionality, side effects, drug accountability and carer events | |||

| Evaluation of training package | Tool: qualitative interviewing

|

|||

| Impact on carer | ||||

| Self-efficacy | Tool: QOLLTI-F

|

Tool: QOLLTI-F

|

Tool: qualitative interviewing

|

|

| Confidence | Tool: carer diary

|

|||

| Health economic outcomes | ||||

| Impact on carers | Tool: CES

|

Tool: CES

|

||

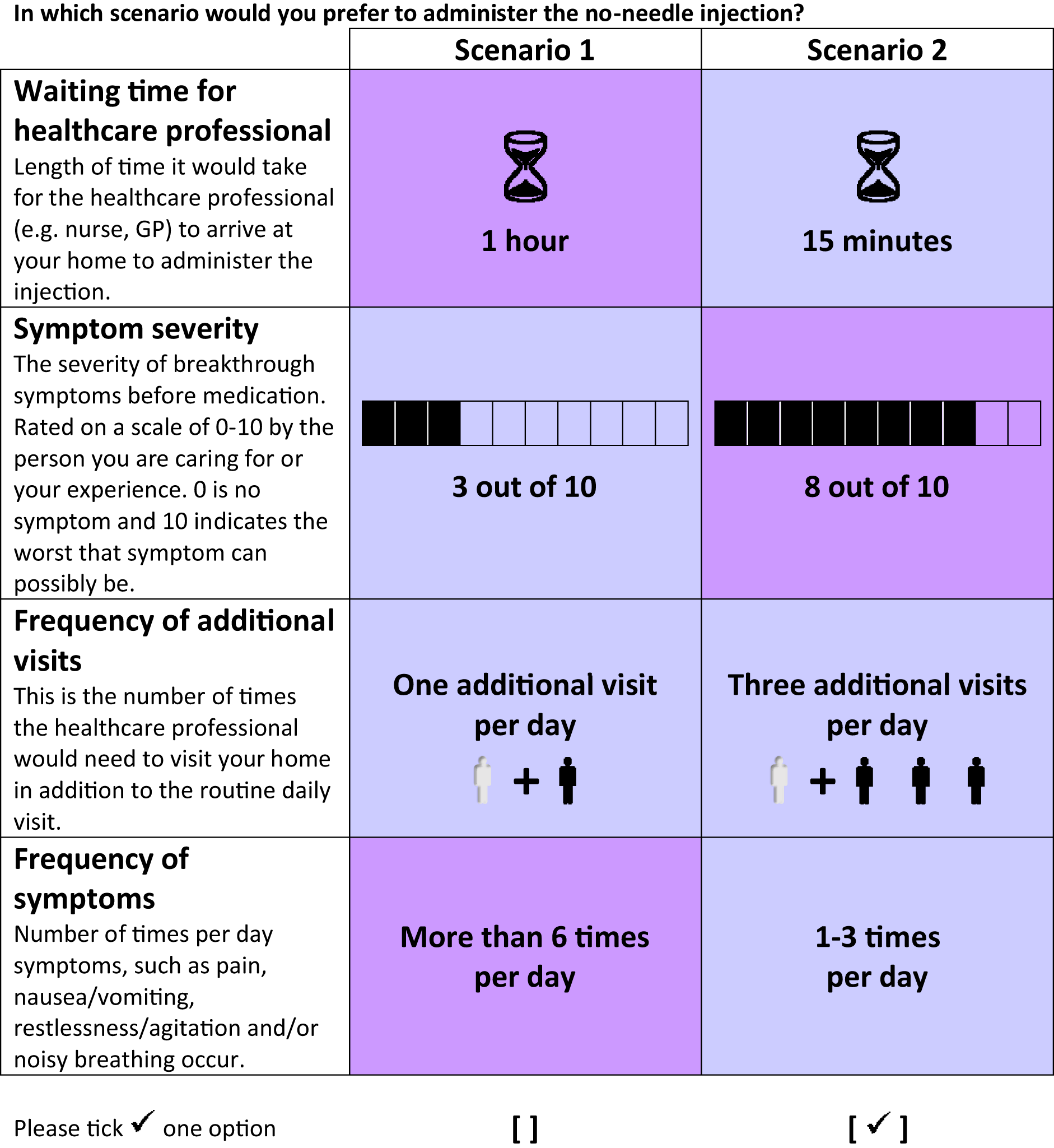

| DCE attribute selection | Tool: qualitative interviewing

|

|||

Health technologies being assessed

The technology under scrutiny was the extended role of lay carers to administer as-needed SC medication for common symptoms to a person who was dying at home. Lay carers were trained in this practice, and their training was supported by a manualised training package that was based on the Australian package Caring Safely at Home (see Chapter 2 for details of the development of the intervention).

Of note, it is usual practice in the UK to ensure that there is provision of as-needed medicines for breakthrough symptoms in the patient’s home for administration by the attending HCP. 55–57 The difference in this technology is that lay carers were trained and, therefore, had the option to administer these medicines (instead of and/or in addition to HCP administration).

Carer training

Carers in both groups received training on the trial materials. This was carried out by a DN or RNs at their visit to the dyad’s home to collect baseline information.

In addition, carers in the intervention group received one-to-one face-to-face training that was delivered by a HCP (usually a DN or SPC nurse) and was supported by written materials. The training covered common symptoms that may occur in the last days of life and how to assess if their loved one needed medication for a particular symptom; how to prepare (draw up) medication and dispose of sharps (glass ampoules and drawing-up needles); how to administer SC medication by needle-less technique (using a butterfly SC catheter); how to assess the effect of the medication; and the support that was available, including the primary care team as well as dedicated 24/7 SPC support. If a symptom occurred for which medication was deemed necessary (either as expressed by the patient, if able, or as assessed by the carer), the carer could use the training outlined above to administer the appropriate medication.

Training was to be tailored to the individual lay carer. As competence and confidence in practical tasks develop over time,24 HCPs were asked to be ready to deliver the training over the course of a few visits until the carer attained competency.

When carer competency in the task was attained, HCPs offered ongoing support in building confidence:

-

The first time that the patient needs an injection, the carer should call a HCP and observe administration.

-

The carer should then administer an injection at a subsequent opportunity, while a HCP is present.

-

Finally, the carer should administer an injection and call the HCP.

Medication regimens

Guidelines for anticipatory prescribing for care in the last days of life are in place across the UK. 55,56 They cover common symptoms in the dying phase, such as pain, nausea and/or vomiting, restlessness/agitation and noisy breathing/rattle. The CARiAD trial recruitment sites were advised to follow usual prescribing practice for dosing anticipatory medication. For example, in Wales, as-needed SC medication prescribing advice includes:58

-

for pain – morphine or diamorphine at one-sixth of the 24-hour dose, or if a patient is not on background strong opioids a starting dose of diamorphine of 2.5 mg or morphine of 2.5 mg

-

for nausea and/or vomiting – 50 mg of cyclizine (maximum dose in 24 hours = 150 mg), 6.25 mg of levomepromazine (maximum dose in 24 hours = 25 mg) or 1.25 mg of haloperidol

-

for restlessness/agitation –2.5 mg or 5 mg of midazolam

-

for noisy breathing/rattle – 400 µg of hyoscine hydrobromide (maximum dose in 24 hours = 2.4 mg) or 200 µg of glycopyrronium (maximum dose in 24 hours = 1.2 mg).

For patients in the intervention group only, prescribers were provided with specific additional advice, including instructions not to prescribe dose ranges/steps and that dose changes could be made only after a face-to-face assessment (not remotely, e.g. over the telephone) (see Report Supplementary Material 2).

Care pathways

In both groups, the following aspects of the current care pathway remained in place:

-

Patients were visited regularly (ideally daily) by a member of the health-care team, usually a DN. ‘Usual routes’ for support applied. These usual routes were different across the recruitment sites. For some areas, there was direct access to a 24/7 SPC advice line for carers in addition to support from the patient’s primary care team or OOH. In other areas, support for the carer was via their primary care team, and the GPs and DNs could ask for advice from the SPC clinicians.

-

As per local guidelines for anticipatory care of common symptoms in the last days of life, there was a supply of drugs in the patient’s home and the apparatus needed to administer them. 55,56

-

Measures for managing background symptoms were unchanged (usually through medication delivered via continuous SC infusion). If a patient requires several doses of as-needed medication for a particular symptom in a 24-hour period, it is usual practice for a prescriber to review and either start a continuous SC infusion of a medication or increase the dose if the medication is already given, to reduce the likelihood of further as-needed doses.

In summary, the usual-care group followed an unchanged care pathway for dealing with breakthrough symptoms at home, with the usual palliative care in place and DNs administering as-needed SC medication.

In the intervention group, carers were trained to administer as-needed SC medication, although they were not obliged to actually administer medication. If the carer needed the support of a HCP, either because they would feel more confident having a HCP present when they administered the medication or because they wished the HCP to assess and give the medication, they could obtain it via the usual routes in their area. If the carer had reached the limit of the number of administrations of medication that could be given in 24 hours (maximum of three medication administrations for each indication per 24-hour period, unless the prescribing clinician advised a maximum of fewer than three), they were asked to contact a HCP as review was required. Usual routes for support included the DN team, the GP, the GP/DN OOH, the hospice at home team or a hospice advice line. The use of such support was captured in carer diaries.

For each recruitment site, the following were clearly set out as standard operating procedures:

-

clinical support for dyads and for their primary care HCPs regarding SPC advice (relevant contact details will be recorded in the carer diary)

-

research support, including when, how and in what circumstances the research team should be accessed.

If a patient in the intervention group was admitted to an inpatient unit (including a hospital, hospice or nursing home), carers were made aware that they should not administer SC medications to the patient during the admission.

Health-care professional training requirements

All DNs (or SPC nurses) who were providing carer training had undertaken detailed standardised training on:

-

trial background, including why it is needed, the legal framework (see Appendix 1), ethics considerations and the research support team in their area

-

detailed trial processes, including inclusion/exclusion criteria, screening and approach, consent, randomisation, trial assessments and outcome measurements, safety, recruitment targets, post-trial care and the delegation log

-

training carers in the intervention group, based on the framework developed in Australia detailing the step-by-step processes and materials (see Report Supplementary Material 1 and Report Supplementary Material 2)

-

training the trainers, including detailed guidance on how to disseminate the training within their team and maintain training records.

Training was designed to be delivered by the trial manager to the DN team leads, the DN educator or another nominated individual who would be able to disseminate the training to the rest of the DN team. A record of attendance was kept for each training session. Standardised training documents [Microsoft PowerPoint® (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA) slides and training materials] were made available to the DN team leads for disseminating training.

Randomised pilot trial outcomes

The main outcomes of interest were those appropriate to a pilot trial, including feasibility, acceptability, recruitment rates, attrition and selection of the most appropriate outcomes measures. Outcomes were measured for patients, their lay carers and HCPs. System barriers were also noted. These measurements were made at baseline, on a daily basis for symptom control and lay carer confidence, and at 6–8 weeks post bereavement.

Recruitment measurements

Recruitment measurements were the number of eligible patients who fulfilled the inclusion criteria and were willing to be randomised, which was expressed as a percentage of the number of patients screened, the number who withdrew after baseline assessment and randomisation, the number who completed the various outcome measurements at baseline and at later time points, and reasons for any non-completion.

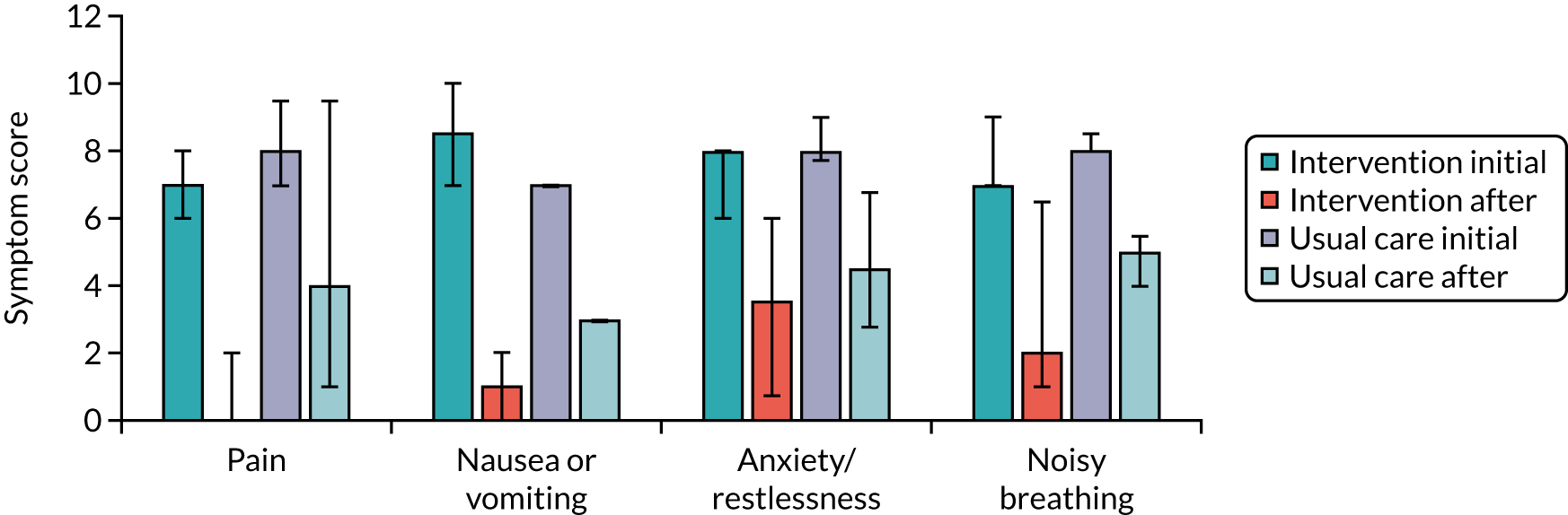

Patient measurements

Patient measurements were baseline information (including demographic information, medical history, capacity assessment, preferred place of care in the last days of their life and current drug management) and a daily carer diary during the study that was related to the presence and treatment of breakthrough symptoms (for use in both trial groups). Data points in each medication administration diary entry included the initial time when the breakthrough symptom triggered a perceived need for an additional SC dose; whether this was noted by the patient or the lay carer; medication and dose, and time given; reason for medication (e.g. pain, nausea, restlessness or noisy breathing); symptom score before and 30 minutes after medication administration; and when symptom control/reduction of the symptom to an acceptable level was achieved. Hospital or hospice admissions during last illness and the actual place of death were also recorded. Approximately 6–8 weeks post bereavement, carers were asked to complete the Family Memorial Symptom Assessment Score – General Distress Index (MSAS-GDI). 10,59–61

Carer measurements

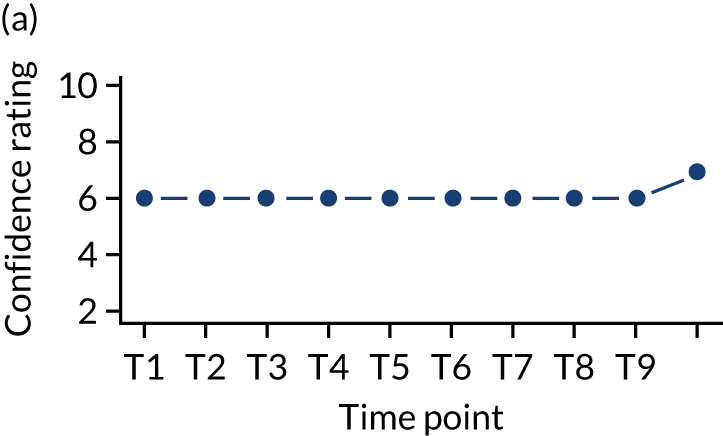

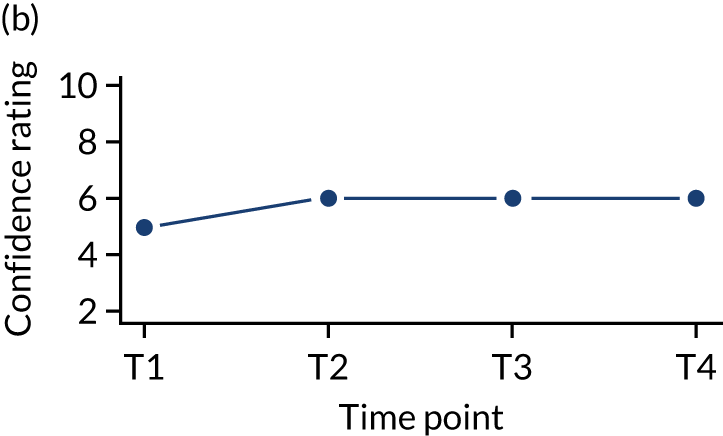

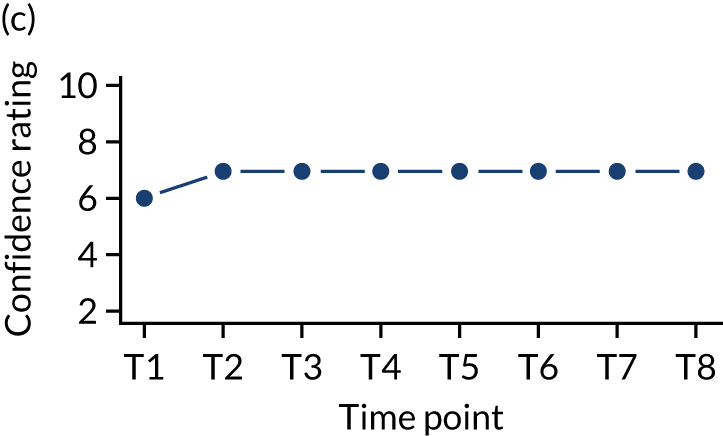

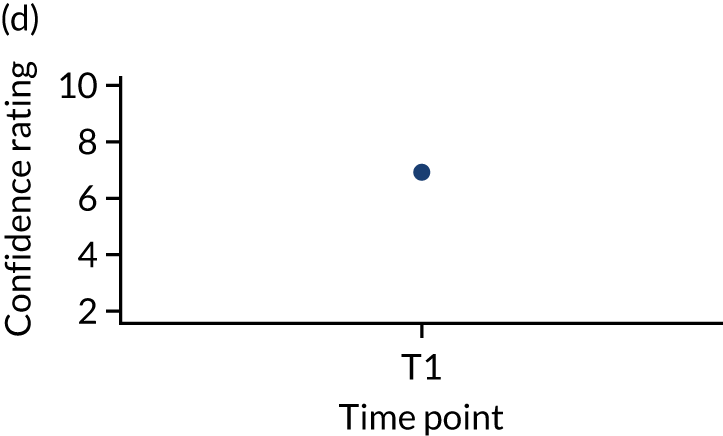

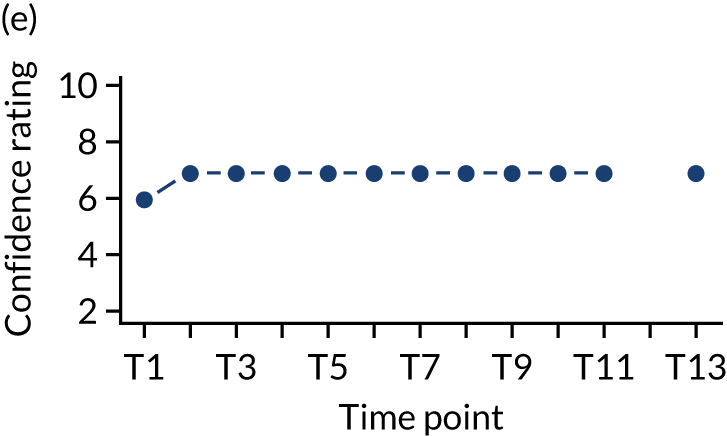

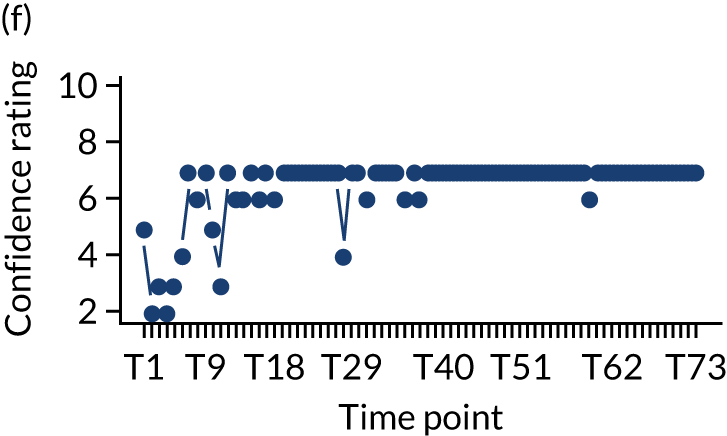

Carer measurements were demographic information at baseline; QOLLTI-F questionnaire (at baseline, after the first as-needed SC medication, then every 48 hours thereafter until the patient’s death); whether or not HCP support was sought; and Family MSAS-GDI (a measure of the patient’s symptom distress in the last 7 days of life) at the 6–8 week post-bereavement visit. In the intervention group, the confidence in administering SC medication and competence at intervals after training were recorded.

Health-care professional measurements

Health-care professional measurements were the baseline measurements of attending team structure, primary prescriber and carer trainer.

Safety

The CARiAD study contained a number of safety outcome measures at different stages of the clinical journey taken by the patient, carer and HCPs. Safety outcome measures include the RA tool, competency checklist and significant event reporting (see Report Supplementary Material 2). Significant event reporting included the following: the appropriateness of administration (is administration accompanied by evidence of need?); proportionality (has the correct dose been administered?); side effects both anticipated and not anticipated; drug accountability (do stocks tally?); and carer events (e.g. distress, injury, accidental or purposeful self-administration).

An AE was defined as any untoward medical occurrence in a trial participant (either the patient or the carer) and included incidents that were not necessarily caused by or related to the trial. A SAE was any untoward occurrence that resulted in death, was life-threatening, required inpatient hospitalisation or prolonged existing hospitalisation, resulted in persistent or significant disability/incapacity or was otherwise medically significant.

All AEs and SAEs were captured via the significant event form. SAEs were reported to the PI and sponsor within 24 hours. As this was a study involving patients who were close to the end of their lives, death was an expected outcome. It was recorded and reported to the sponsor but was not considered a SAE if, in the opinion of the PI, it was a natural conclusion to a patient’s life-limiting illness. Owing to the nature of the study, events of death did not require immediate reporting to the DMEC.

Exploratory end points/outcomes for a future definitive trial

Core Outcome Measures for Effectiveness Trials (COMET) in patients close to the end of their life were not available at the time of CARiAD trial planning. 2 After scrutiny of available outcome measures, the most likely candidates for primary outcome measures for a future definitive trial of this intervention were Family MSAS-GDI (a measure of overall symptom burden/distress in the last 7 days of life)10,59–61 and QOLLTI-F (a measure of the quality of life of carers looking after someone with a life-threatening illness, incorporating elements of control and self-efficacy). 41

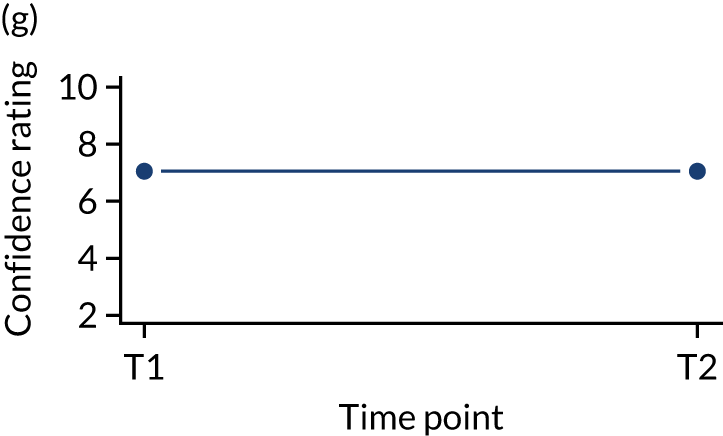

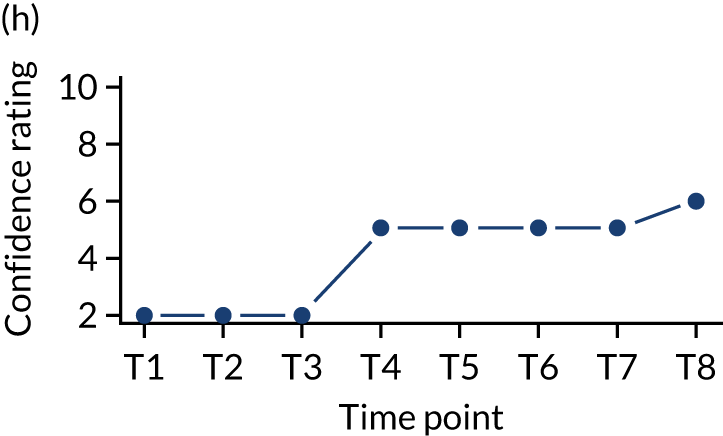

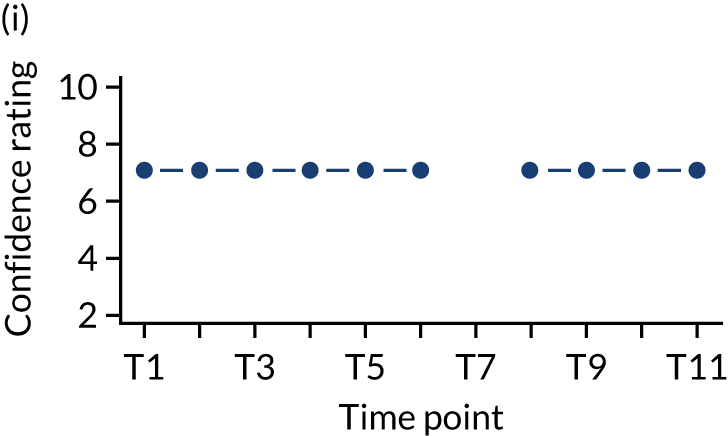

In addition, we measured carer confidence using a seven-point Likert scale, in which the carer is asked after administration of every as-needed SC injection to rate their level of confidence in administering this injection (1 = not at all confident, 7 = extremely confident). We planned to give quantitative and qualitative data equal importance and integrate these at the interpretation stage. For more detail on the rationale for choosing the Family MSAS-GDI and QOLLTI-F, see Appendix 2.

Criteria for assessing feasibility as primary outcome measure

All outcome measures were assessed on the same criteria for consistency.

Applicability:

-

This was assessed by an independent expert panel and was based on feedback from participants (HCPs and carers).

-

Each measure was assessed by the panel with regard to its relevance and applicability to the population, based on the outcomes of the pilot data collection phase.

-

The panel will recommend an ‘accept’ or ‘not accept’ status for each outcome based on the criteria below and their expert opinions, and taking into account the RATIONALE (Risk of Bias Justification Table) statements on outcome measures and assessment of bias risks in ultimate reporting. 62,63

Acceptability:

-

This was assessed by participants and HCPs during the qualitative aspects of the feedback interviews.

Level of completeness:

-

This was assessed by the frequency of missing data during the data collection phase. This would require potential primary outcome measures to have > 70% completeness.

-

An assessment will also be made of the reasons for missing data to establish whether or not anything systematic in the trial design could be adjusted to mitigate for the missing data.

Once the feasibility of the outcomes is established, the design of the definitive trial will consider whether a single or a combined primary outcome of interest is appropriate.

Secondary outcome measures

The potential suitability of the secondary outcomes will be considered, as detailed below.

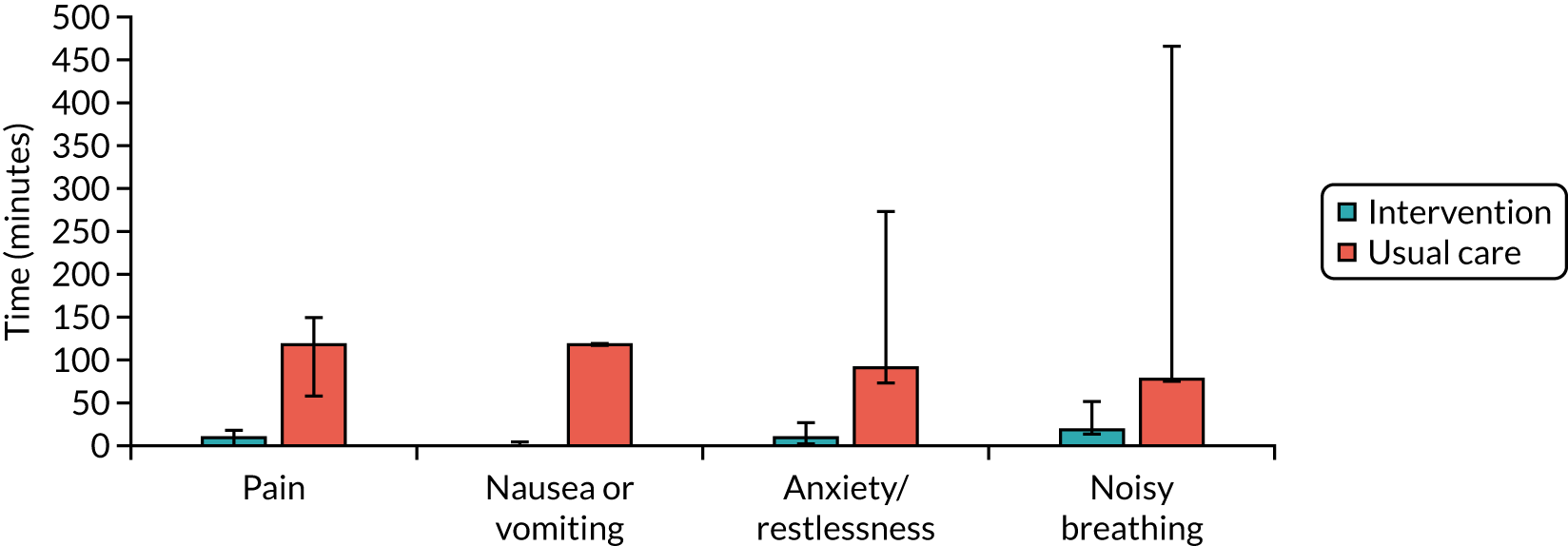

Time to symptom relief

This outcome measure was collected given the importance of this outcome to carers and patients. It does, however, present significant inherent challenges with potential bias and will not contend as a primary outcome measure for a future definitive trial, unless methodological concerns are resolved. The specific methodological concern is that it will be hard to demonstrate that the measurement of this outcome will be carried out in comparable ways in the two arms of the trials. We acknowledge that these problems arise because the individual who is measuring the outcome (the carer) cannot be blinded to the trial group. The intervention group will have lay carers deciding to dispense treatment, and this could systematically affect their judgement of this outcome.

Carer Experience Scale

See Chapter 7.

Sample size

A fully justified sample size was not required; sample size was justified by estimating what sample size a future definitive RCT will need.

Careful consideration was given to the size of effect that we could potentially see for the Family MSAS-GDI and QOLLTI-F in a potential future definitive trial. There was no definitive statement of what a minimal clinically important difference would be for either of these measures in this context; therefore, we had to make an assumption that was informed by both HCPs and public contributors. It may be that these estimates are considered too conservative/small; however, for the pilot trial we wanted to ensure that we had captured enough precision within any estimates to be confident of capturing any potential indication of a signal. Using a smaller effect size to ensure adequate precision when investigating at this stage would not preclude the use of a larger effect size (and possibly resultant smaller sample), if it were considered more appropriate when designing a definitive study.