Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 10/50/42. The contractual start date was in August 2012. The draft report began editorial review in November 2018 and was accepted for publication in May 2019. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Ramon Luengo-Fernandez reports grants from the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Health Technology Assessment (HTA) programme outside the submitted work. Najib M Rahman reports personal fees from Rocket Medical plc (Watford, UK) outside the submitted work. Nick A Maskell is a member of the NIHR HTA Commissioning Board.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2020. This work was produced by Bhatnagar et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2020 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Introduction

Scientific background

Pathophysiology of malignant pleural effusion

In a healthy individual, only a potential space exists between the two pleural layers (visceral and parietal). A small volume of fluid is continuously produced and absorbed in equal measure. Absorption occurs via a series of channels and pores, which are concentrated in the dependent portions of the parietal pleura. 1

Malignancy can affect the pleura in a number of ways, all of which are likely to contribute to the formation of malignant pleural effusion (MPE) through the disruption of the normal cycle of fluid production and resorption. Direct tumour effects, typically as a result of primary tumour formation (mesothelioma) or metastatic deposition, can lead to physical obstruction of drainage outlets. Indirect effects are thought to arise as a result of cytokines, for example vascular endothelial growth factor, that either are secreted locally or exert their influence via the bloodstream. Indirect effects are thought to arise as a result of cytokines, for example vascular endothelial growth factor, which either are secreted locally or exert their influence via the bloodstream, resulting in increased vascular permeability and/or pleural neoangiogenesis, both of which predispose an individual to pleural fluid formation. 2–4 The end result of these processes is a net increase in the volume of fluid in the pleural space, resulting in an effusion that may, in certain cases, lead to physical restriction and the development of associated symptoms. 5 A particular hallmark of MPE is the tendency to recur or to progress despite treatment or drainage.

Burden of malignant pleural effusion

Autopsy series have suggested that as many as 15% of cancers will lead to some form of macroscopically evident pleural invasion. 6 Despite this, it is probable that the incidence of MPE is under-reported, as detection of malignant cells in fluid may be challenging7 and not all patients develop symptoms.

Data suggest that there are around 40,000 new cases of MPE in the UK each year,8 although these figures may well prove to be conservative as improved detection techniques and life-prolonging treatments become increasingly available. In addition, projections would estimate that there will be a year-on-year rise in the number of newly diagnosed malignancies over the coming decade, driven largely by increases in population. 9

Survival in malignant pleural effusion

Malignant pleural effusion is usually a result of a metastatic process; therefore, patient survival is typically poor. In general, average survival is quoted as being 4–6 months from diagnosis, although these data are drawn from highly heterogeneous patient groups. 10–12 In addition, there are a number of factors that appear to influence survival, meaning that this figure may be less applicable to a number of patients. The underlying cancer type, in particular, appears to exert a strong influence on outcome, with some series reporting that those patients with mesothelioma (12 months) or breast cancer (> 2 years) survived longer. 11,13

General approaches to malignant pleural effusion management

For many patients, MPE can lead to debilitating symptoms, such as breathlessness or chest pain. 5 General management of both of these symptoms, and others that may be associated with the underlying cancer, form the cornerstone of all treatment strategies; however,14 in those patients with clinically significant volumes of fluid, drainage is usually indicated in addition to broader symptomatic management. Therapeutic aspiration of pleural fluid, whereby fluid is drawn off using simple apparatus, such as a needle and syringe, can lead to rapid relief for many patients and is readily performed in the outpatient setting, although the volumes that can be removed in a single sitting are limited by the potential adverse effects of rapid, high-volume lung re-expansion. 15 For this reason, thoracocentesis is usually considered to be a temporising measure rather than a definitive treatment, with recurrent aspirations reserved for those patients with a very short life expectancy. 5

Broadly, definitive MPE treatment can be divided into two approaches: (1) long-term fluid management and (2) attempted fluid prevention. The fluid management approach accepts that fluid will recur and prioritises treatments that will minimise patient time spent in hospital; in the UK, this typically involves the insertion of an indwelling pleural catheter (IPC). IPCs are inserted as a day-case procedure under local anaesthetic and are then drained regularly in the community by nursing teams, family members or the patient themselves. Despite their potential benefits, an IPC cannot be relied on to stop fluid forming. Recent data suggest that this occurs in approximately 20% of cases when drained at a typical frequency. 16,17 In addition, for some, the inconvenience of a permanently sited tube, and the regular drainages it demands, preclude IPC use. 18 Furthermore, treatment with an IPC requires the infrastructure to insert and manage the devices alongside the financial capability to support the regular use of the consumables they require, factors that prevent their use in several countries.

The more traditional and established approach to MPE treatment is fluid prevention, or pleurodesis. An attempt at pleurodesis begins with emptying the chest of as much fluid as possible, which is usually accomplished following insertion of an intercostal chest drain (at the bedside under local anaesthetic) or during a thoracoscopic procedure (which may be performed under either light sedation or general anaesthesia). Once the pleural cavity is evacuated, an irritant is applied to the pleural linings with the intention of stimulating a local inflammatory response, resulting in fibrosis and adhesion, effectively obliterating the pleural space and, hopefully, preventing any further effusion formation. The primary perceived benefit of the pleurodesis approach is that a single intervention period can lead to long-term fluid prevention. A number of small series have described success rates in excess of 80%. 5 However, as with the alternative, a degree of compromise is necessary as pleurodesis approaches usually require a period of inpatient treatment and may lead to more pain. 19,20

In terms of patients’ symptoms, recent randomised controlled trial (RCT) evidence suggest that there is parity between the pleurodesis approach and the fluid management approach with an IPC, with both interventions improving symptoms to a clinically meaningful degree. 20 Many centres, therefore, will choose to offer patients the choice of how they wish their recurrent fluid to be managed: as an outpatient with an IPC or as an inpatient with an attempt at pleurodesis.

Selecting a pleurodesis agent

In 2016, a Cochrane network meta-analysis21 examining the efficacy of various treatments for the management of MPE was published. This study identified 62 RCTs for inclusion and used pleurodesis failure rate as its primary outcome measure, but noted that there was an extremely high degree of heterogeneity in the design and outcome reporting of the included studies, with a high risk of bias in many of them. With these limitations, the conclusion was that talc is likely to be the most efficacious agent, overall, for inducing pleurodesis and, in particular, it was suggested that talc given in the form of poudrage (sprayed directly onto the pleural as a dry powder during a thoracoscopic procedure) was the best approach. 21 It was recommended, however, that a more effective comparison between this method and the alternative delivery method for talc – as a slurry following drainage via bedside chest tube – be undertaken in the future. 21

Talc slurry via chest tube is the current standard treatment approach for pleurodesis in the UK. 5 This method has become ubiquitous, as it is easily undertaken in the ward setting, with chest drain insertion possible at the bedside and not typically requiring anything other than local anaesthesia. Talc poudrage requires the capability to perform a thoracoscopy and for the patient to be able to tolerate such a procedure. Thoracoscopy may be undertaken by surgeons under general anaesthetic [video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery (VATS)] or, as is increasingly the case in the UK, under light sedation [local anaesthetic thoracoscopy (LAT)], the latter usually being performed by respiratory physicians in a dedicated procedural environment. 22

Current evidence comparing the use of talc poudrage with slurry

Previous randomised controlled trials

Three studies have directly compared talc slurry with talc poudrage in a randomised setting, totalling 599 patients, and describe conflicting results. 23–25 All of these studies delivered poudrage using VATS under general anaesthesia; to the best of our knowledge, there are no studies that have examined talc poudrage delivered at LAT.

The earliest of these, Yim et al. ,23 which included 57 patients from a single centre, concluded that there was no significant difference between the two treatments and thus, because of the likelihood of increased resources being required, recommended that talc slurry be the treatment of choice. This study, however, as well as being significantly underpowered, chose to exclude all patients who were taking anticancer therapies, which makes the study population less applicable to the typical patient presenting with MPE. 23

In 2009, Terra et al. 24 randomised 60 patients from a single centre, with the primary intention of examining post-pleurodesis lung expansion. Although this was found to be better in the poudrage arm, this did not translate into a meaningful clinical difference over longer-term follow-up. Once again, however, the wider applicability of this study’s results may be questioned, as the population had an unusually low average age (55 years) and the majority of patients were female, a trait also shared by the earlier Yim et al. 23 study.

To the best of our knowledge, the largest study addressing the question of talc delivery for pleurodesis was performed by Dresler et al. ,25 reported in 2005. Participants were drawn from multiple North American centres over a 5-year recruitment period and had to meet entry criteria that included being suitable for general anaesthetic, having a performance status score of 0–2 and having an expected survival of ≥ 2 months. Participants were excluded if they had received any previous intrapleural therapy, if they had recently received systemic anticancer treatment or if they had bilateral effusions. Following randomisation, patients would proceed on protocol only if there was evidence of adequate lung expansion. Patients in the slurry arm had a chest tube (of unspecified size) inserted prior to 4–5 g of ungraded talc being instilled. Those patients undergoing poudrage received the same dose of talc if the operating surgeon was satisfied with a visual assessment of lung expansion, followed by drain insertion. 25

The primary outcome for the Dresler et al. study25 was successful pleurodesis at 30 days. Secondary outcomes included patient-reported breathlessness using a visual analogue scale (VAS), patient satisfaction, complications, time to recurrence and quality of life using the Quality of Life Questionnaire – Cancer 30 (QLQ-C30). Interpretation of the primary end point was based on the reviewing surgeon’s interpretation of the chest radiograph, although the authors state that a radiological opinion was also sought to corroborate this. 25

After withdrawals and exclusions, a total of 482 patients (slurry, n = 240; poudrage, n = 242) were included in the final analysis. Based on intention to treat, no significant difference was found between the two arms at 30 days. Following a per-protocol analysis, whereby trapped-lung patients were excluded, a significant difference (p = 0.045) was found, favouring poudrage, although this effect disappeared when only patients who were alive at 30 days (slurry, n = 130; poudrage, n = 152) were included. Of note, a high number of complications were reported, including a perioperative mortality rate of 8.4% and a respiratory failure rate of 8.1% in the poudrage arm. A post hoc analysis suggested that poudrage might be more effective in those patients with MPE due to breast and lung malignancies. 25

Although undoubtedly important, the Dresler et al. study25 has not defined practice as it was felt to have encompassed several potentially important flaws and barriers to wider generalisability, particularly in the UK. With the benefit of hindsight, these included a lack of detail regarding how randomisation, concealment or powering of the trial occurred; the use of ungraded talc; the use of VATS and general anaesthetic; the lack of an economic evaluation to inform broader utility and cost-effectiveness; poor retention to follow-up; major differences in treatment arms, such as assessing trapped lung using radiology in the slurry arm and intraoperatively in the other; no attempt at stratification prior to randomisation; the use of post hoc analyses to draw and report study conclusions; and, perhaps most importantly, a lack of what may be seen to be a clinically relevant or patient-centred definition of pleurodesis success. 25,26

Health economic analyses comparing slurry with poudrage

No published studies have directly measured the costs or cost-effectiveness of talc poudrage compared with talc slurry for MPE; the limited number of studies in this area have tended to focus on the comparative costs of IPC use following their introduction approximately 15 years ago. 27–29 Two of these studies,27,29 however, used theoretical modelling to compare treatments and included slurry and poudrage in their analyses. The first,27 published as a 2011 conference abstract, is the only study to include LAT-delivered poudrage as well as VATS poudrage, suggesting both that the latter was dramatically less cost-effective than the former and that LAT poudrage and that talc slurry were very similar in terms of cost-effectiveness. 27 The second study, a further modelling exercise by Puri et al. ,29 suggested that talc slurry is the optimal approach for patients with a life expectancy of ≥ 1 year, when compared with either IPC or thoracoscopic poudrage (the authors do not specify LAT or VATS). 29

Local anaesthetic thoracoscopy in the UK

In the UK, over the last 20 years, there has been an expansion in the number of centres able to offer physician-delivered LAT services. 22 The wider availability of LAT services, and, by extension, of talc poudrage, potentially opens up the possibility of treatment of MPE to a broader geographical range of patients than VATS allows, as well as opening up the possibility of treatment to those patients who would perhaps be unsuitable for general anaesthesia. It should be noted, however, that LAT is currently used primarily as a diagnostic tool, with the overwhelming majority of procedures being performed in patients with a suspected, but not yet established, diagnosis of pleural malignancy. In such a scenario, talc poudrage may still be performed prior to conclusion of the procedure in order to reduce the likelihood of a patient needing a further intervention for MPE later in their disease course.

Rationale for research

How best to deliver talc into the pleural space remains an unanswered but important question, with the relatively poor-quality data described in Current evidence comparing the use of talc poudrage with slurry failing to provide robust evidence to drive standardised clinical practice. This is particularly the case in the UK, where the pleurodesis approach offered will often be based on the individual preferences or beliefs of the treating clinician and the locally available facilities. Advocates for thoracoscopy and poudrage suggest that this procedure, despite being more involved for patients and requiring greater health-care infrastructure, offers a higher chance of long-term pleurodesis success (due to a more even powder distribution) and a shorter initial stay in hospital (as all fluid is drained immediately prior to poudrage, rather than waiting for it to drain gradually). Opponents to poudrage argue that there is a lack of evidence to support the view that poudrage is better than slurry, and that the probable excess costs, lower availability and requirement for greater baseline patient fitness make it the less preferable approach in routine care.

Primary research aim

The evaluating the efficacy of Thoracoscopy And talc Poudrage versus Pleurodesis using talc Slurry (TAPPS) trial aimed to be the first adequately powered, robustly designed trial to compare the efficacy of talc poudrage (administered using LAT) with the current standard treatment of a chest drain followed by talc slurry, for the management of patients with MPE in the UK.

Research questions

The primary research question was, for patients with a confirmed MPE and good performance status, does thoracoscopy and talc poudrage increase the proportion of patients with successful pleurodesis at 3 months post procedure when compared with the standard therapy of chest drain insertion and talc slurry instillation?

The secondary research questions were as follows:

-

Does talc poudrage reduce the time to pleurodesis failure at 1 and 6 months post randomisation when compared with talc slurry?

-

Does talc poudrage at thoracoscopy improve chest radiographic appearances after initial drain removal and at 1, 3 and 6 months post randomisation when compared with talc slurry?

-

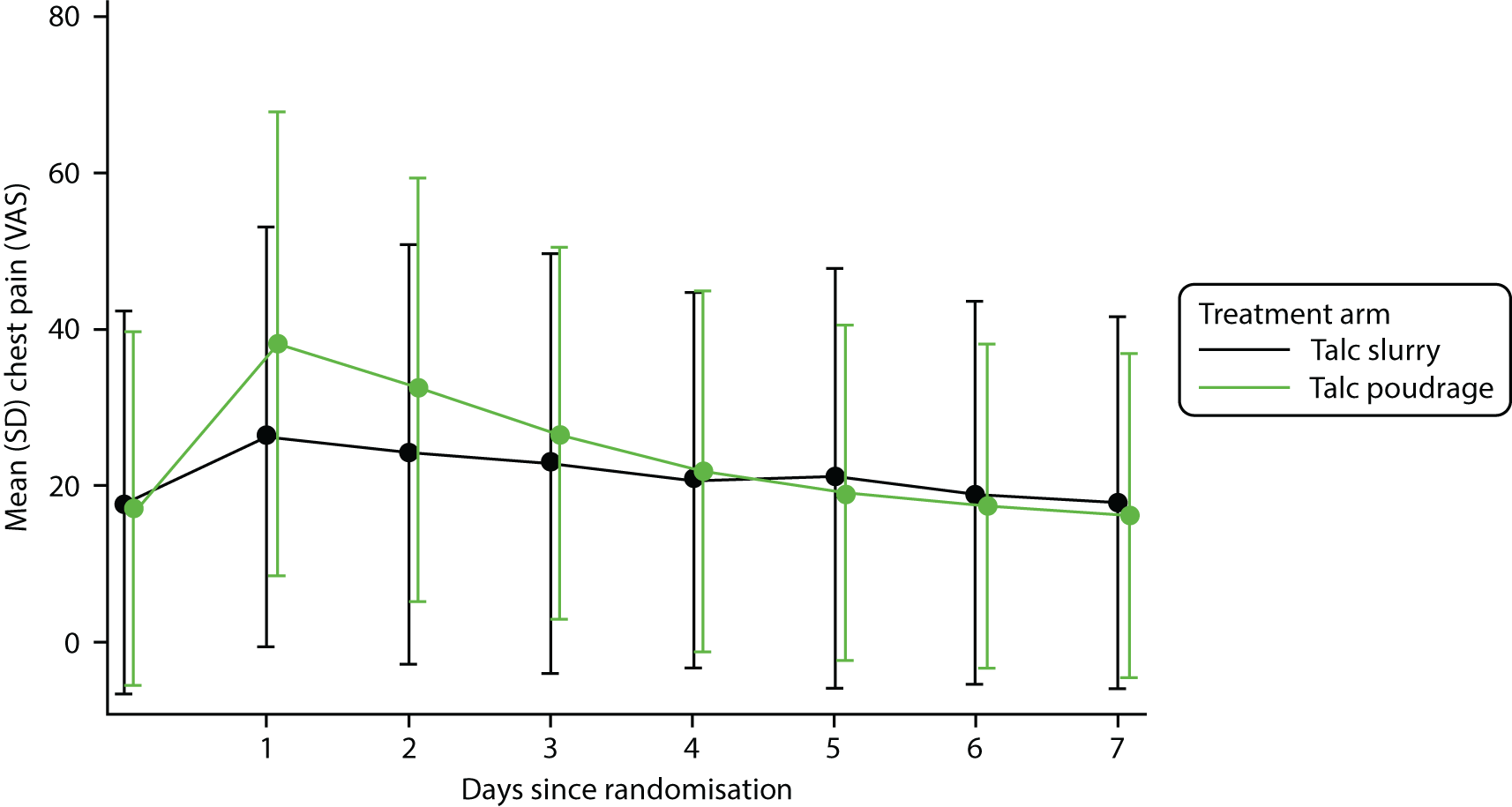

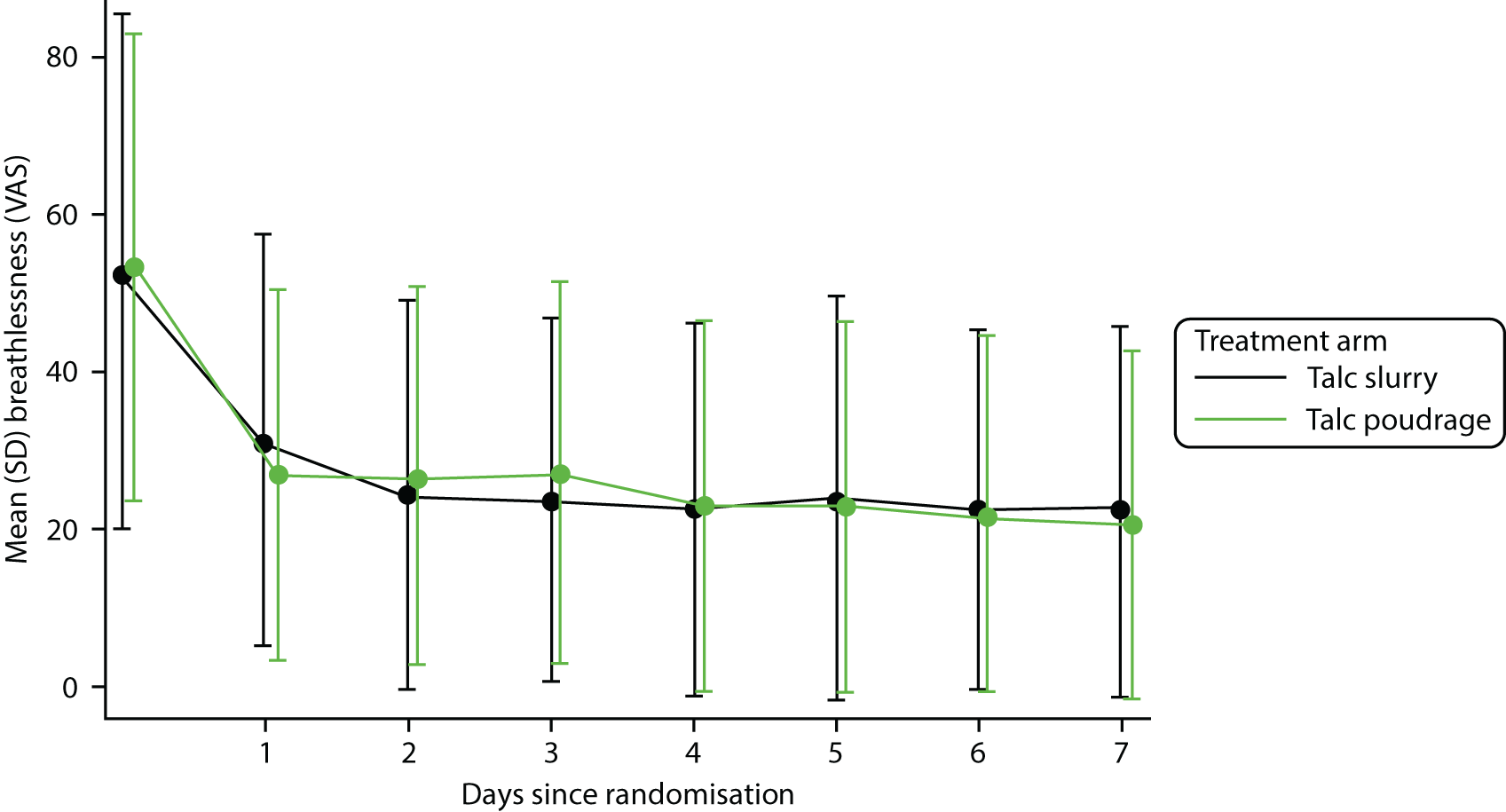

Does talc poudrage cause less breathlessness and thoracic pain for the first 7 days post randomisation when compared with talc slurry?

-

Does talc poudrage improve health-related quality of life (HRQoL) over the 6 months post randomisation when compared with talc slurry?

-

Does talc poudrage reduce health-care utilisation during the 6 months post randomisation when compared with talc slurry instillation?

-

Is talc poudrage cost-effective over 6 months when compared with talc slurry instillation?

Chapter 2 Main trial design and methods

Trial design

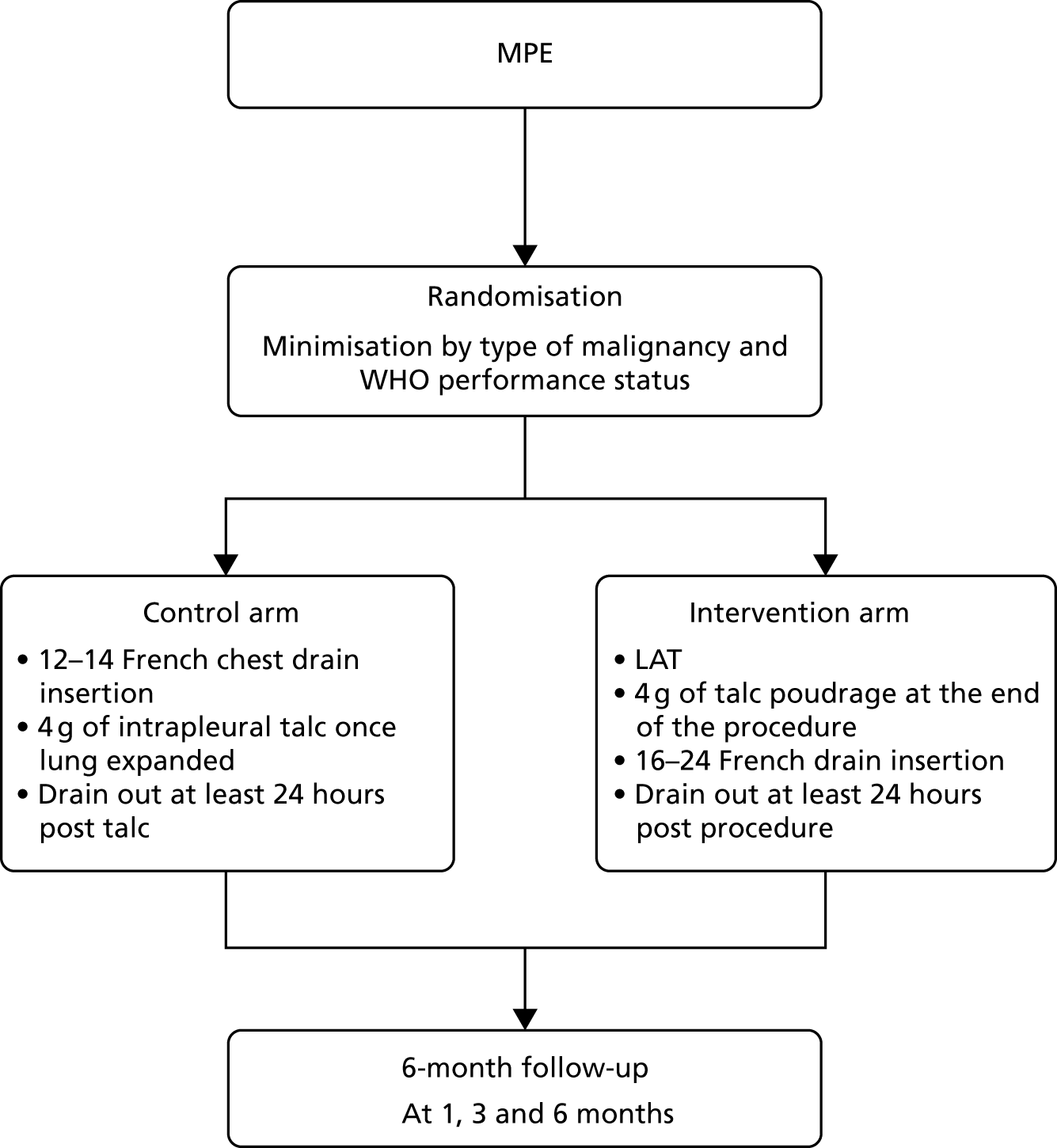

The trial was a pragmatic, multicentre, UK-based, open-label RCT comparing two methods for delivering talc for the management of MPE: (1) bedside chest drain and talc slurry and (2) LAT and talc poudrage. The trial was not registered as a Clinical Trial of an Investigational Medicinal Product following discussion with the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency. A within-trial economic evaluation was conducted to assess the cost-effectiveness of both approaches.

The trial protocol has been published and is available on an open-access basis. 26 A general summary of the trial processes can be found in Figure 1.

FIGURE 1.

Trial summary flow chart. WHO, World Health Organization.

Table 1 describes the main differences between the TAPPS trial and the 2005 Dresler et al. study. 25

| Dresler et al.25 | TAPPS trial |

|---|---|

| VATS only | Medical LAT |

| Radiological outcome | Clinical definition of pleurodesis |

| No health economics | Full health economics |

| 1-month primary end point | 3-month primary end point |

| No stratification | Minimisation |

| Disparity between pleurodesis methods | Standardisation of therapy as best as possible |

| Ungraded talc | Graded talc |

| Post hoc subgroup analysis | A priori subgroup analysis |

Ethics approval

The TAPPS trial was given initial ethics approval by the National Research Ethics Service Committee (North West – Preston) on 26 June 2012. The ethics approval number was 12/NW/0467.

All subsequent substantial amendments were reviewed and approved by the same committee.

Trial registration

The TAPPS trial was prospectively registered on the publicly accessible International Standard Randomised Controlled Trial Number (ISRCTN) database prior to recruitment beginning (ISRCTN47845793). 30 A comprehensive lay summary was also prepared and made available on the Cancer Research UK website. 31

Trial oversight and management

The trial was sponsored by North Bristol NHS Trust (local identification number 2843).

The TAPPS trial was managed jointly by research teams based at the University of Bristol and the University of Oxford. The chief investigator, trial co-ordinator and lead trial nurse were based at the Academic Respiratory Unit at the University of Bristol. The trial manager, trial database and data entry team were based at Oxford Respiratory Trials Unit at the University of Oxford.

A Trial Management Group met and communicated regularly to ensure efficient day-to-day running of the trial, protocol adherence, and that adverse events (AEs) and safeguarding issues were identified and acted on swiftly.

The Trial Steering Committee (TSC) met at regular intervals (at least twice per year) and, in addition to the chief investigator and trial statistician, consisted of independent physician and lay members in accordance with the funder’s requirements.

An Independent Data and Safety Monitoring Committee met at regular intervals during the trial. After reviewing the necessary data, they provided a recommendation to the chairperson of the TSC with regards to trial continuation.

Participant selection and trial recruitment centres

Inclusion criteria

-

Clinically confident diagnosis of MPE requiring pleurodesis, defined as:

-

pleural effusion with histocytologically proven pleural malignancy, or

-

pleural effusion in the context of histocytologically proven malignancy elsewhere, without a clear alternative cause for fluid, or

-

pleural effusion with typical features of malignancy with pleural involvement on cross-sectional imaging without a clear alternative cause for fluid.

-

-

Fit enough to undergo LAT.

-

Expected survival of > 3 months.

-

Written, informed consent to trial participation.

Exclusion criteria

-

Patients in whom thoracoscopy is the only reasonable approach to making a diagnosis and in whom such a diagnosis would significantly influence further management.

-

Aged < 18 years.

-

Female patients who were pregnant or lactating.

-

Evidence of extensive lung entrapment on chest X-ray (CXR) or computed tomography, or significant fluid loculation on ultrasound, to a level that would normally be a contraindication to attempted talc pleurodesis.

-

Insufficient volume or position of pleural fluid on lateral decubitus thoracic ultrasound to safely perform LAT without further intervention being necessary.

-

Previously documented adverse reaction to talc.

-

Clear contraindication to thoracoscopy or chest tube insertion.

Recruitment centre selection

To be considered for participation in the TAPPS trial, all recruitment centres needed to:

-

have a local principal investigator (PI) with an interest in pleural disease

-

have an established medical thoracoscopy service

-

expect to see at least 20 potentially eligible patients per year.

[The original ethics submission included eight sites based in England. Subsequently, an additional nine sites (including centres in Wales and Scotland) were added. All site additions and removals were considered and approved by the TSC.]

Changes to the original trial protocol

All changes to the trial protocol were made following consideration and approval by the TSC and, when necessary, the Independent Data Monitoring Committee and ethics committee. Changes were typically made in response to poorer-than-expected recruitment rates and these are summarised in Table 2.

| Study amendment number | Details of significant alterations to protocol | Resulting protocol version and date |

|---|---|---|

| 1 |

Clarified various sections in the protocol Altered the time window for a patient to consider trial entry Updated flow charts Clarified the use of suction and telephone follow-ups |

2.0; 1 December 2012 |

| 2 | No alterations as part of this amendment | |

| 3 |

Adjustments to the follow-up visit windows Administrative details were updated throughout the protocol |

3.0; 14 August 2013 |

| 4 |

Change of time allowance between the randomisation and the trial procedure from 24 to 72 hours Minor administration changes and clarifications to the protocol |

4.0; 26 September 2013 |

| 5 | No alterations as part of this amendment | |

| 6 |

Edited the safety reporting section of the protocol Updated administrative details throughout the protocol Added protocol appendix 6 |

5.0; 1 June 2014 |

| 7 |

Updated secondary end points following ratification of SAP version 1.0 Updated trial end date Updated trial recruitment centre and PI details Minor clarifications |

6.0; 6 October 2014 |

| 8 |

Clarified that the first 7 days of VAS measurements were to be taken post procedure, not post randomisation Removed Leicester as recruiting site |

7.0; 5 December 2014 |

| 9 |

Updated the PI at Wythenshawe Hospital Added information regarding new sites Updated the change in TSC membership information |

8.0; 2 October 2015 |

| 10 |

Updated the PI at Addenbrooke’s Hospital Removed Birmingham and Wrexham as active recruiting sites Updated trial recruitment end date |

9.0; 5 October 2016 |

Sample size

The sample size calculation and all statistical analyses were performed using Stata® v15.1 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA). Previous literature and local audit data suggested that patients with a European Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status score of 2 or better have approximate pleurodesis failure rates of 10% with a thoracoscopy, and 30% with standard chest tube and talc slurry pleurodesis. 5,25

Therefore, in order to detect a 15% difference in pleurodesis failure at 3 months (10% thoracoscopy and poudrage vs. 25% chest drain and talc slurry), with 90% power, a 5% significance level and 10% loss to follow-up, a total of 325 patients would be required.

The final recruitment target was rounded up to 330 patients, with 165 patients to be allocated equally to each treatment arm.

No interim analyses were planned.

Participant recruitment

Patient identification and screening

Potential participants were identified locally from a range of sources, including:

-

discussions at local multidisciplinary team meetings

-

routine outpatient appointments

-

inpatient ward reviews

-

referrals from colleagues in oncology or acute medical settings.

Patients were assessed against the inclusion and exclusion criteria on a consecutive basis. A patient information sheet was provided at the earliest opportunity, with each individual given enough time (in their own opinion) to consider trial entry.

Each site maintained a local screening log. These were sent to the trial management team on a regular basis and were used to identify potential challenges to recruitment and/or general patterns of behaviour among patients and clinicians.

Informed consent

All participants provided written, informed consent to trial participation. It was suggested that consent be taken as close as possible to the proposed date of randomisation, but these could occur up to 7 days apart when necessary. A separate consent form was signed if the patient was willing to agree to sample collection and storage for possible genetic testing in the future.

In addition to the above, all sites were expected to obtain separate consent for whichever procedure the patient was allocated to, as per standard NHS practice.

Randomisation, concealment and blinding

Following consent, patients were randomly assigned, in a 1 : 1 ratio, to one of the treatment allocations detailed below (see Treatment groups). Randomisation was performed centrally by the Trial Management Team in Oxford. The team accessed an external computer-based system (Sealed Envelope™, London, UK) on behalf of the randomising site, with local investigators required to confirm eligibility verbally over the telephone before being notified of the allocation. Strict allocation concealment was maintained, with treatment allocations becoming available only after the participant was enrolled and entered into the randomisation system.

Minimisation with a random component of 80% was utilised. The minimisation factors were:

-

type of underlying malignant disease (mesothelioma, lung cancer, breast cancer, other)

-

World Health Organization (WHO)/ECOG performance status (0 or 1, 2 or 3).

It was intended that randomisation occur as close as possible to the intended procedure time.

Because of the inherent and substantial differences between the two methods being tested, this trial could not be performed ethically or safely in a blinded manner using dummy or sham procedures. The trial was undertaken in an open-label manner, such that both the trial participant and the research team were aware of the allocated intervention; however, the trial management team, including the TSC and Trial Management Group, were blind to patient-level data throughout.

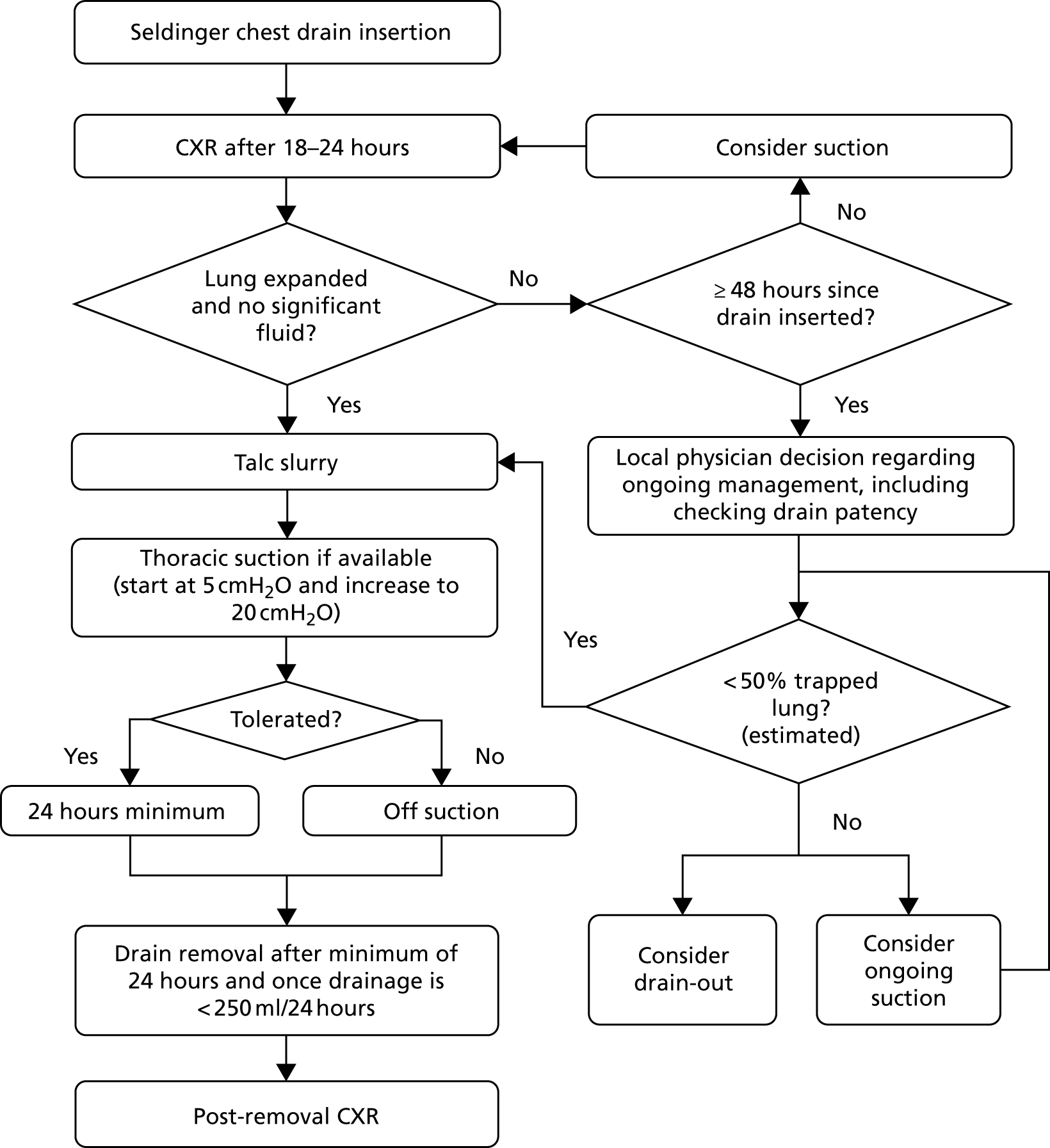

Treatment groups

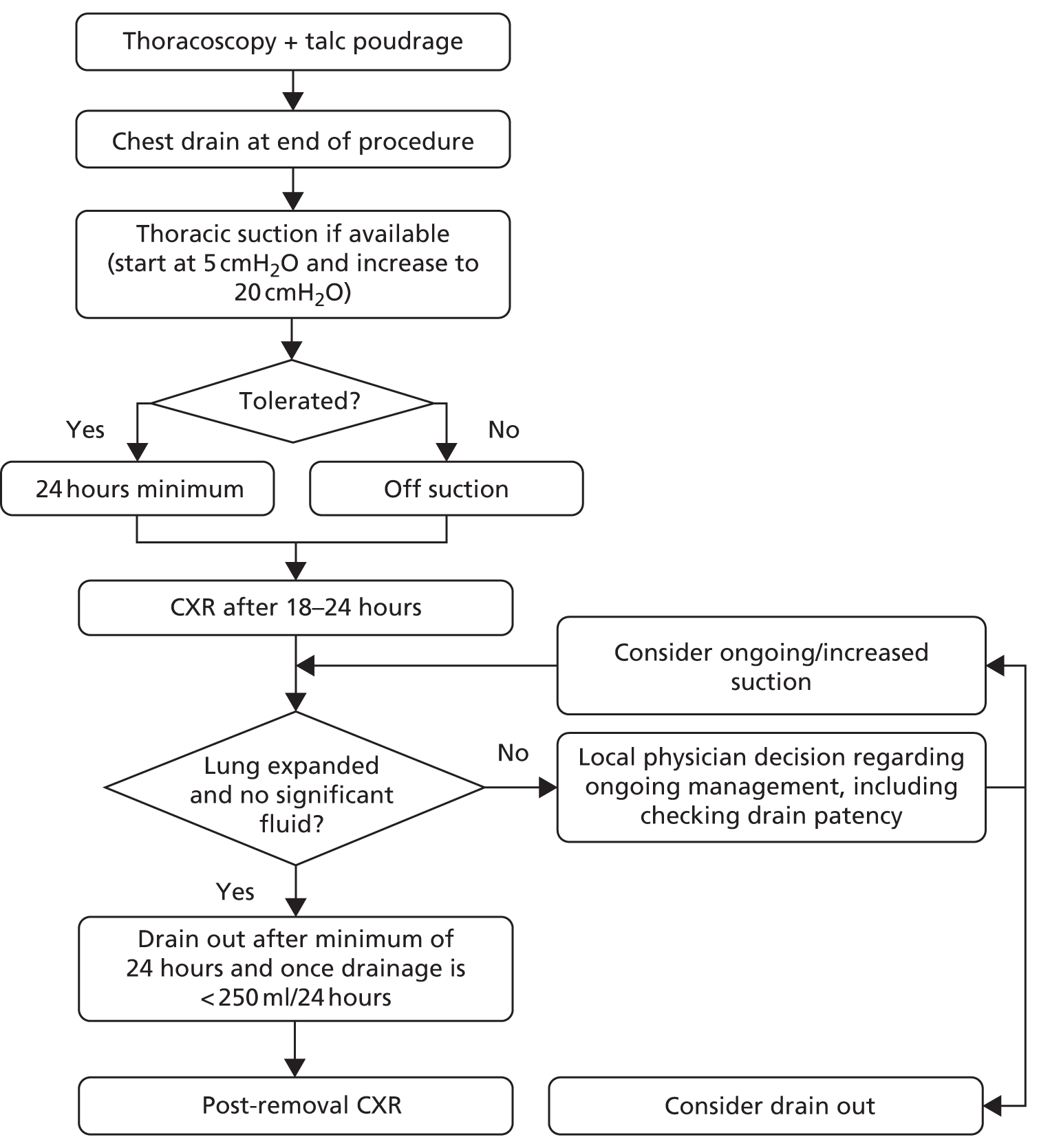

A summary of the treatments given in each group can be found in Figures 2 and 3.

FIGURE 2.

Summary of treatments in control (slurry) arm.

FIGURE 3.

Summary of treatments in intervention (poudrage) arm.

Control (slurry) group

Post randomisation, patients allocated to the control group underwent the following:

-

Admission to an appropriate clinical area.

-

Contemporaneous thoracic ultrasonography to guide drain placement.

-

Pre-medication with analgesia as required.

-

Instillation of local anaesthesia to proposed drain site.

-

12–14 French gauge chest drain insertion, using Seldinger technique, by an individual of adequate training and experience.

-

Assessment with CXR between 18 and 24 hours post drain insertion.

-

Those patients without significant ongoing pleural opacification and/or unexpanded lung were given 4 g of sterile talc slurry (see Appendix 1 for full procedure). Those patients with ongoing opacification or unexpanded lung could be placed onto thoracic suction at the discretion of the treating physician. When on suction, patients underwent CXR every 24 hours with local teams instructed to consider talc slurry instillation when there was evidence of at least 50% pleural apposition (by visual estimation).

-

Thoracic suction (if available and tolerated) for a minimum of 24 hours post talc instillation.

-

Drain removal, CXR and consideration for discharge once < 250 ml of fluid output was recorded in a 24-hour period.

Intervention (poudrage) group

Post randomisation, patients allocated to the intervention group underwent the following:

-

Admission to an appropriate clinical area and listing for LAT at the earliest opportunity.

-

LAT as per local standard practice (to include ultrasound guidance and light sedation), with complete fluid drainage and diagnostic pleural sampling as required, performed by an individual of appropriate training and experience.

-

Talc poudrage with 4 g of sterile talc slurry (see Appendix 1 for full procedure).

-

Insertion of a 16–24 French gauge chest drain at the end of the procedure.

-

Thoracic suction (if available and tolerated) for a minimum of 24 hours immediately after the procedure.

-

Assessment with CXR between 18 and 24 hours post procedure (with ongoing use of suction if deemed to be necessary).

-

After a minimum of 24 hours, drain removal, CXR and consideration for discharge once < 250 ml of fluid output was recorded in a 24-hour period.

Standard care and co-enrolment during the trial period

During the trial, for all issues other than those pertaining to the drainage and management of the MPE, treatment discretion lay with the primary clinician.

Normal clinical review during the trial period was to take place in the usual outpatient or inpatient setting. The frequency of clinical review depended on patient choice, severity of symptoms and clinical discretion.

Patients could withdraw from the trial at any time without their clinical care being affected.

An individual patient could be enrolled into the TAPPS trial only once. Once entered, patients were not to be enrolled in any other trial that looked to directly influence the production of pleural fluid until the end of their trial participation. Patients could still be considered for other studies, such as chemotherapy trials, but discussion was to take place prior to enrolment to ensure compatibility between protocols.

Trial assessments and timings

Baseline assessment

Participants underwent a baseline assessment prior to their trial procedure. The standardised assessment was to include:

-

relevant current and past medical history

-

symptom scores for pain and dyspnoea

-

recent blood results

-

quality-of-life assessments.

Intervention and inpatient period

Standardised data collection regarding the trial intervention was obtained, along with details of AEs in the early post-procedure period.

Documentation of inpatient trial activity and outcomes was recorded in a standardised fashion at the time of discharge.

Follow-up period and assessment of increasing breathlessness

Trial follow-up appointments took place at:

-

1 month (day 28 ± 7 days)

-

3 months (day 84 ± 10 days)

-

6 months (day 168 ± 14 days) post randomisation.

These appointments took place in the patient’s local trial hospital or an appropriate satellite centre, and consisted of a standardised assessment and CXR.

All patients who were felt to have increasing breathlessness during the follow-up period were recommended to undergo CXR. Any CXR that showed a degree of pleural opacification ipsilateral to the pleurodesis attempt led to further imaging to confirm the presence of fluid. If fluid was confirmed and the CXR showed pleural opacification to be one-third or greater than the volume of the hemithorax (by visual estimation), the primary physician could undertake any further investigations or interventions as deemed appropriate.

In patients who had less than one-third of the hemithorax occupied by pleural fluid, the primary physician was to discuss with another local physician, who was blinded to treatment arm, whether or not pleural intervention was required. In the event of disagreement, or being unable to find a blinded physician, the chief investigator could be contacted to make a casting decision (without being informed of the treatment arm).

Patient-reported outcomes

Trial participants were asked to complete two forms of patient-reported outcome measure:

-

VAS score for chest pain and dyspnoea

VAS scores were recorded at baseline and then daily for the first 7 days post procedure; following this, scores were recorded on a weekly basis and at each follow-up visit

-

quality-of-life questionnaires

the EuroQol-5 Dimensions, five-level version (EQ-5D-5L), and Short Form questionnaire-36 items (SF-36) HRQoL questionnaires were completed by all participants at baseline and at each subsequent trial visit.

Health economic diaries

Patients were provided with pre-printed diaries to keep with them for the duration of their trial involvement. They were asked to record details of all personal contact with medical professionals (excluding trial visits) in a basic standardised manner. These data were reviewed at each follow-up appointment.

An example of a standardised diary may be found in Report Supplementary Material 1.

Data acquisition and management

Data were collected in a variety of ways, depending on the type of information being acquired. All information from trial visits was recorded locally on a series of paper case report forms, which were copied and sent to the trial data team for screening, transcription and entry into the main database, which was run using the OpenClinica 3.12.2 platform (OpenClinica LLC, Waltham, MA, USA).

The case report forms were supplemented by VAS collection booklets (see Report Supplementary Material 2) and health-care utilisation diaries, as described above, which patients completed at home and brought to each trial visit.

Outcome measures

Primary outcome

The primary end point was the number of patients who experienced pleurodesis failure up to 3 months (90 days) post randomisation.

A patient was defined as experiencing pleurodesis failure if they underwent any of the following procedures on the side ipsilateral to their trial intervention:

-

therapeutic pleural aspiration of ≥ 100 ml

-

insertion of an intercostal drain for fluid drainage

-

insertion of an IPC

-

medical or surgical thoracoscopy.

A patient was also deemed to have failed pleurodesis if their primary physician decided that they required one of the above pleural interventions, but the intervention was not performed (e.g. in the event of death or patient choice against procedure).

The 90-day end point was chosen with a view to providing useful clinical information to patients with a presumed average life expectancy of 4–6 months, as was expected in the target trial population. Although failure rate at 30 days had previously been used in a major study,25 this was felt, in general, to be too short an interval. Conversely, we believed a primary outcome measured later, at 180 days post randomisation, would increase the risk of insufficient data being available due to mortality from underlying malignancy. Nonetheless, pleurodesis failure at both 30 and 180 days were included as secondary outcomes.

Secondary outcomes

In addition to the above, the following secondary outcomes were assessed:

-

the number of patients with pleurodesis failure up to 30 days post randomisation

-

the number of patients with pleurodesis failure up to 180 days post randomisation

-

percentage radiographic (CXR) pleural opacification at the 1-, 3- and 6-month post-randomisation follow-up visits, and after initial drain removal

-

self-reported HRQoL at the 1-, 3- and 6-month follow-up post-randomisation visits, as measured using the SF-36 and EQ-5D-5L questionnaires

-

self-reported thoracic pain and breathlessness at 7 days post procedure, and at 30, 90 and 180 days post randomisation, measured using VAS scores

-

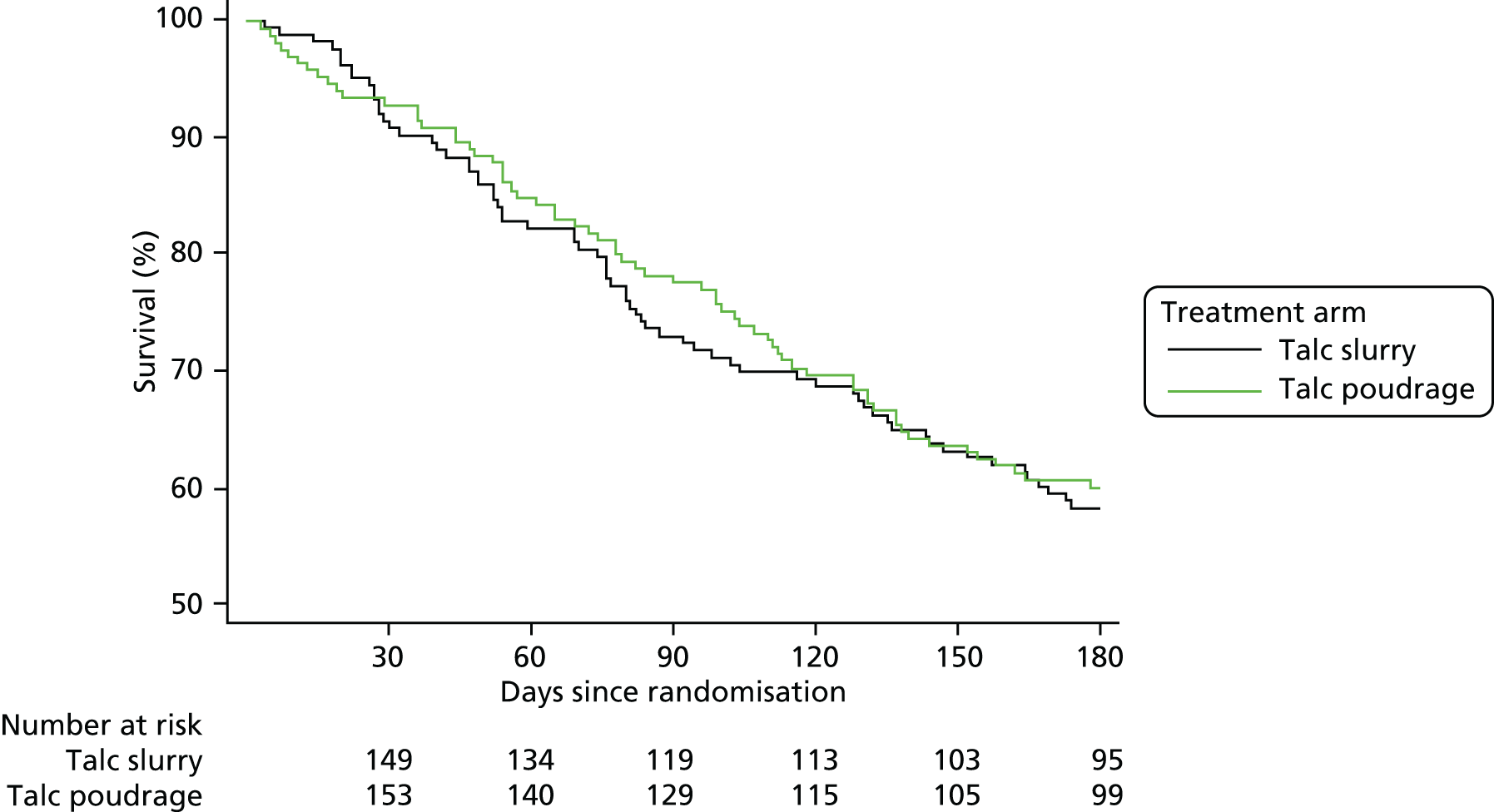

all-cause mortality up to 180 days post randomisation

-

time to pleurodesis failure, censored at 180 days post randomisation

-

number of nights spent as a hospital inpatient up to 90 days post randomisation, including length of initial stay.

The original trial protocol also included the following secondary outcome: requirement for further pleural procedures up to 180 days post randomisation, based on an independent, blinded assessment. However, following approval from the TSC, this outcome was removed prior to the trial database being locked. The reason and justification for this change can be found in Table 3.

| Change | Notes/justification |

|---|---|

| Changed method of analysis for pleurodesis failure from competing risk time-to-event model to logistic regression model | To match what was specified in the protocol |

| Removed secondary outcome ‘requirement for further pleural procedures up to 180 days post randomisation, based on an independent, blinded assessment’ | Blinded assessment and corroboration of the need for pleural intervention were already required for any case, which is likely to be contentious. Without clinical contact, the information on which specified assessment would be made was felt to be insufficient to determine whether or not a further pleural procedure would have been necessary; thus, the clinical relevance of the outcome was felt to be doubtful. It is probable that this assessment would have relied primarily on the patient’s CXR appearance, which is being addressed as another secondary outcome |

| Restricted subgroup analyses to only the primary outcome | |

| Updated Stata command for analysing CXR pleural opacification, EQ-5D-5L, SF-36, thoracic pain and breathlessness, from ‘xtmixed’to ‘mixed’ | The command ‘mixed’ replaced ‘xtmixed’ in more recent versions of Stata |

| Removed sensitivity analysis for primary outcome based on measuring pleurodesis failure from date of procedure rather than date of randomisation | |

| Removed the subgroup analysis for use of NSAIDs at baseline | This question has now been addressed more comprehensively in the TIME1 trial |

| Removed the subgroup analysis for previous radiotherapy at baseline | This was not felt likely to be of clinical relevance |

| Added additional exploratory outcomes | |

| Specified that AEs and SAEs would be summarised and analysed within 7 days of randomisation (in addition to within 30 and 180 days) | To better reflect the immediate post-procedure and inpatient period |

Exploratory outcomes

The following outcomes were added during the trial on a purely exploratory basis:

-

categorical version of percentage radiographic (CXR) pleural opacification at the 1-, 3- and 6-month post-randomisation follow-up visits and after initial drain removal, with categories –

-

no fluid visible

-

1–24% opacification due to fluid (small effusion)

-

25–49% due opacification due to fluid (moderate effusion)

-

≥ 50% opacification due to fluid (large effusion)

-

-

degree of visible lung entrapment on CXR at 6 months post randomisation, with categories –

-

no lung entrapment

-

minor lung entrapment (1–24% unexpanded lung)

-

moderate lung entrapment (25–49% unexpanded lung)

-

severe lung entrapment (≥ 50% unexpanded lung).

-

These additions occurred without the Trial Management Team being aware of any results, following completion of recruitment but before database lock.

Adverse events

Adverse events and serious adverse events (SAEs) were defined, documented and assessed in line with standard practice. All SAEs were independently reviewed with regards to safety (by the sponsor) as close as possible to the time of occurrence. On completion of the trial, all AEs and SAEs were independently reviewed and coded.

Statistical analysis

The primary analysis for each outcome was performed using intention-to-treat principles, meaning that all patients on whom an outcome was available were included in the analysis, and were analysed according to the treatment group to which they were randomised. 32 Patients with missing outcome data were excluded from the analysis. All tests were two sided and were considered statistically significant at the 5% level.

All analyses were adjusted for the minimisation variables, with these included as covariates in the regression model for each outcome33,34 [type of underlying malignant disease (mesothelioma, lung cancer, breast cancer, other) and WHO performance status (0–1 or 2–3)].

Primary outcome

The primary outcome (pleurodesis failure at 90 days post randomisation) was analysed using a logistic regression model. As specified above, the model was adjusted for the minimisation variables and excluded patients with missing outcome data.

Subgroup analyses

Subgroup analyses were prespecified and performed for the primary outcome. Results from subgroup analyses were viewed as hypothesis-generating only. The following analyses were performed:

-

patients receiving anticancer therapy at baseline compared with those patients not receiving anticancer therapy at baseline

-

WHO performance status (0 vs. 1 vs. 2 vs. 3)

-

patients on steroids at baseline compared with those patients not on steroids at baseline

-

previous attempt at pleurodesis in the previous month compared with no attempt in the previous month

-

patients with primary malignancy of breast cancer compared with mesothelioma, lung cancer and other cancer.

Secondary outcomes

-

Pleurodesis failure at 30 and 180 days was analysed in the same manner as the primary outcome, using a logistic regression model adjusted for the minimisation factors.

-

Percentage chest radiographic opacification was analysed using a mixed-effects linear regression model. Fixed effects were treatment group, time point, a treatment-by-time interaction and the minimisation factors. An unstructured correlation matrix was used to model the correlation between outcomes at different time points.

-

HRQoL, using the EQ-5D-5L and SF-36 questionnaires, was analysed using the same approach as percentage chest radiographic opacification above (i.e. using mixed-effects linear regression model, adjusted for treatment, time point and a treatment-by-time interaction). In addition to the minimisation factors, the analyses also adjusted for baseline questionnaire scores.

-

Chest pain and dyspnoea were analysed using the same approach as above and adjusted for the baseline VAS scores.

-

All-cause mortality was analysed using a logistic regression model.

-

The time to pleurodesis failure was analysed using a Fine–Gray competing risk time-to-event model, with mortality as the competing risk. 35

-

The number of days spent in hospital was analysed using a negative binomial regression model, with the number of days of follow-up included in the model as an offset.

Exploratory outcomes

-

The exploratory outcome of the categorical version of percentage radiographic pleural opacification was analysed using a mixed-effects ordinal logistic regression model, with a random intercept for patient. The model was adjusted for the minimisation variables.

-

The exploratory outcome of the degree of visible lung entrapment was analysed using an ordinal logistic regression model, adjusted for the minimisation variables.

Bias reduction

Because of the open-label nature of this trial, the potential for introducing bias into data collection and analysis was considered inherently greater than if the trial was performed in a fully blind fashion, especially given that the local trial research teams were typically also responsible for the clinical management of participants. Therefore, in order to minimise the possibility of bias in the primary outcome, the decision to undertake further pleural intervention in patients who develop breathlessness and have a small-volume recurrent effusion was discussed with a blinded assessor. This blinded assessor could be a clinician at the local recruiting site or, if necessary, the chief investigator.

Changes to original statistical analysis plan

All changes to the original statistical analysis plan were agreed by the TSC and occurred prior to the trial database being locked.

A summary of the changes can be found in Table 3.

Sensitivity analyses

Sensitivity to missing data for the primary outcome was assessed under a range of missing-not-at-random scenarios. For each scenario, a treatment effect and 95% confidence interval (CI) were calculated and compared with results from the main analysis of the primary outcome to see if conclusions were affected by different assumptions regarding the missing data.

Chapter 3 Health economic analysis design and methods

Objective

The objective of the health economic element to the trial was to determine whether or not a LAT-delivered talc poudrage was more cost-effective than standard chest tube talc slurry pleurodesis in patients with MPE.

Analysis perspective and aims

The health economic analysis took place from a UK NHS and Personal Social Services perspective. HRQoL data and health-care resource use and cost data were used to examine the following:

-

the cost of performing both trial interventions

-

the follow-up health-care resource use and costs for trial participants in both groups

-

HRQoL, through calculation of utility values using the EQ-5D-5L and Short Form questionnaire-6 Dimensions (SF-6D)

-

the incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER) when thoracoscopy-delivered talc poudrage was compared with standard chest tube talc slurry pleurodesis.

Data collection

Quality of life

Generic HRQoL was measured using the SF-36 and the EQ-5D-5L. 36,37

In the EQ-5D-5L, patients are asked to think about their health on the day that they are completing the questionnaire and to report any problems (none, slight, moderate, severe and unable/extreme) on five attributes (mobility, self-care, usual activities, pain/discomfort and anxiety/depression). Patients are then required to rate their health using a 100-point VAS (0 = worst health you can imagine to 100 = best health you can imagine). The EuroQoL-5 Dimensions (EQ-5D) is a standardised measure of health, providing a simple generic measure of health for clinical and economic appraisal.

In the SF-36, patients are asked to think about their health in terms of eight health concepts: (1) physical functioning (10 items); (2) social functioning (two items); (3) role limitations due to physical problems (four items); (4) role limitations due to emotional problems (three items); (5) mental health (five items); (6) energy/vitality (four items); (7) pain (two items); and (8) general health perceptions (five items). It also includes questions providing an indication of perceived change in health.

Both quality-of-life questionnaires were completed at randomisation and then at 1, 3 and 6 months post randomisation.

Resource use

As part of the NHS and Personal Social Services perspective adopted, we included the following health and hospice care resource-use categories over the 6-month follow-up:

-

Resource use involved with trial procedures, including time in surgical theatre; health-care staff involved; surgical disposables (e.g. surgical gowns, gloves, drapes, syringes, sutures and drains); medication (including talc) and sedation; capital equipment (e.g. video stack use, warmer, thoracoscopes and light cables); and investigations (e.g. thoracic ultrasound and CXRs).

-

Initial hospitalisation after trial intervention. For each hospitalisation, information was recorded on the date of admission and discharge, and the dates of transfers between different specialty wards.

-

Follow-up hospital resource use, including outpatient visits; visits to accident and emergency (A&E); ambulance use; outpatient visits; and day cases and length of stay in hospital, including stays in an intensive treatment unit.

-

Community care use, including visits to a general practitioner (at surgery, home or through the telephone); nurse (at surgery or at home); physiotherapist; occupational therapist; psychologist; and counsellor.

-

Palliative and hospice care, including contacts with a palliative care nurse and number of nights spent as an inpatient in a hospice.

Resource use involved with trial procedures was obtained by observing a number of trial interventions at the trial site at the Churchill Hospital (NHS Oxford University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust). Details about the initial hospitalisation were obtained through a staff questionnaire to be completed once the patient had been discharged.

All other follow-up resource use was collected using patient questionnaires administered at 1, 3 and 6 months. As an aide memoire, patients were also provided with a resource-use log designed for them to fill in every time they had a contact with the health-care system. In the questionnaires, we did not distinguish whether the contacts with the health-care service were through the NHS, Personal Social Services or private providers, and we assumed that all contacts were financed by the NHS or Personal Social Services, in a bid to keep the questionnaires as simple as possible. For missing values (e.g. patients who died halfway through follow-up), clinical staff completed some of the questions, including ambulance and A&E use, outpatient visits and hospitalisations, through review of patients hospital records.

Unit costs

Unit costs for the initial hospital admission were derived from NHS reference costs for the year 2013/14,38 as they contained information on costs by medical specialty. Unit costs for consultations with general practitioners and nurses were obtained from the Personal Social Services Research Unit’s Unit Costs of Health and Social Care publications for 2015 and 2017. 39,40

For all other contacts, unit costs were derived from the NHS National Schedule of Reference Costs 2016 to 2017. 41 For outpatient visits, we used the weighted average of all consultant-led, non-admitted, face-to-face attendances, either first or follow-up. For physiotherapists, occupational therapists and psychologists, we also used the weighted average of all consultant-led, non-admission, face-to-face attendances for each of these three therapists. In the absence of specific unit costs for counsellors, we assumed that these would be the same as for a psychologist. For visits to A&E, we used the weighted average of all emergency medicine contacts, excluding dental care and patient dead on arrival. For ambulance transport to A&E, the unit cost of a call to the emergency services was included as well as that for ambulance transport.

Using the reasons for hospitalisation reported by patients in the resource-use questionnaires, we obtained diagnosis and procedure codes. These were then translated into a Healthcare Resource Group (HRG) using the HRG4+ 2016/17 Reference Costs Grouper (NHS Digital). Each HRG was then linked to a series of elective, non-elective and day-case reference costs obtained from the 2016/17 schedule of reference costs. All costs were updated to 2016/17 using the Hospital and Community Health Service index. 40

Statistical analysis

Quality of life

At each follow-up, responses to each of the five questions in the EQ-5D-5L were presented. As recommended by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE),42 EQ-5D-5L responses were converted into utilities using the validated mapping function to derive utility values for the EQ-5D-5L from the existing EuroQol-5 Dimensions, three-level version. 43

For each follow-up, the score for each of the eight dimensions of the SF-36 were coded, summed and transformed on to a scale from 0 (worst possible health state) to 100 (best possible health state). We also estimated the two standardised summary scores of the SF-36: the physical component score and the mental health component score. 37 SF-36 responses were then converted into utilities using the SF-6D algorithm developed by Brazier et al. 44

The SF-36 items scores, utility values (both for the EQ-5D-5L and SF-6D) and EQ-5D VAS scores at each follow-up are presented as mean [standard deviation (SD)]. Mean differences across the two treatment groups are presented alongside 95% CIs, with statistical significance assessed using two-sided t-tests.

Quality-adjusted life-years

Survival was estimated using the Kaplan–Meier survival function 6 months post randomisation. A quality-adjusted survival curve was generated by plotting, against time, the product of the mean utility of patients living at time t and the probability of surviving to time t, in order to create three periods (i.e. randomisation to 1-month follow-up, 1- to 3-month follow-up and 3- to 6-month follow-up). The area under this quality-adjusted survival curve then gave the mean quality-adjusted survival in each treatment group. Utility was assumed to change linearly between each follow-up, rather than changing at the mid-point between follow-ups or being maintained from one follow-up to another.

For each treatment group, results are reported as quality-adjusted life-years (QALYs) with 95% CIs calculated non-parametrically from 1000 bootstrap differences. Mean QALY differences between the two patient groups were also presented with 95% CIs, estimated using the 1000 bootstrap differences. Results are presented for the whole patient sample (i.e. when patients who withdrew from the analysis were treated as censored and missing utility estimates were assumed to be the same as the mean for that treatment group).

Resource use

Initial length of stay and all follow-up contacts, at each follow-up visit, with health or social care services were reported as means (SD), with differences between the two groups assessed using a Student’s t-test. Six-month resource-use totals were evaluated using an available-case analysis (i.e. for each treatment group, average resource use was summed over the three follow-up periods). Results are then presented as means together with 95% CIs, generated through 1000 bootstrap estimates. Mean differences were also estimated, as well as the 95% CI of the difference using bootstrapping.

Costs of providing the trial procedures

Time spent by participants in theatre was costed using Scottish information on theatre services,45 excluding costs for medical, nursing and other staff, drugs and other supplies (as this information was collected directly by the trial). For participants undergoing standard chest tube talc slurry pleurodesis, we also excluded central sterile supply department costs, as all equipment used was disposable. Capital equipment (including video stack, thoracoscopes, light cable, pre-heater and tube inserts) costs used to perform the thoracoscopy-delivered talc poudrage were obtained directly from the manufacturer. To obtain an equivalent annual cost for all capital equipment, we depreciated the acquisition costs over their assumed 5-year lifetime, using an annual rate of 3.5%. To obtain per-minute costs, we assumed that this equipment would be used for 4 hours per week over 50 weeks per year.

Costs of staff time

This included the consultant physician, specialist registrar, nurse and health-care assistant and was valued using average salaries for that position. 40 Unit costs of disposables was valued using prices obtained from the NHS Supply Chain. 46 Costs of medications and sedation drugs were obtained from the British National Formulary. 47 Finally, costs of investigations undertaken as part of the intervention, including CXRs and thoracic ultrasonography, were obtained from NHS reference costs. 41

Total costs

Costs of the initial hospitalisation, and costs incurred between each follow-up visits, are presented as means (SD), with differences between the two patient groups assessed using a Student’s t-test. Six-month total costs were evaluated using an available-case analysis (i.e. for each treatment group, average total costs were summed over the three follow-up periods), as well as initial hospitalisation and intervention costs. Results are then presented as means with 95% CIs, generated through 1000 bootstrap estimates. Mean differences were also estimated, as well as the 95% CI of the difference, using bootstrapping.

Cost-effectiveness

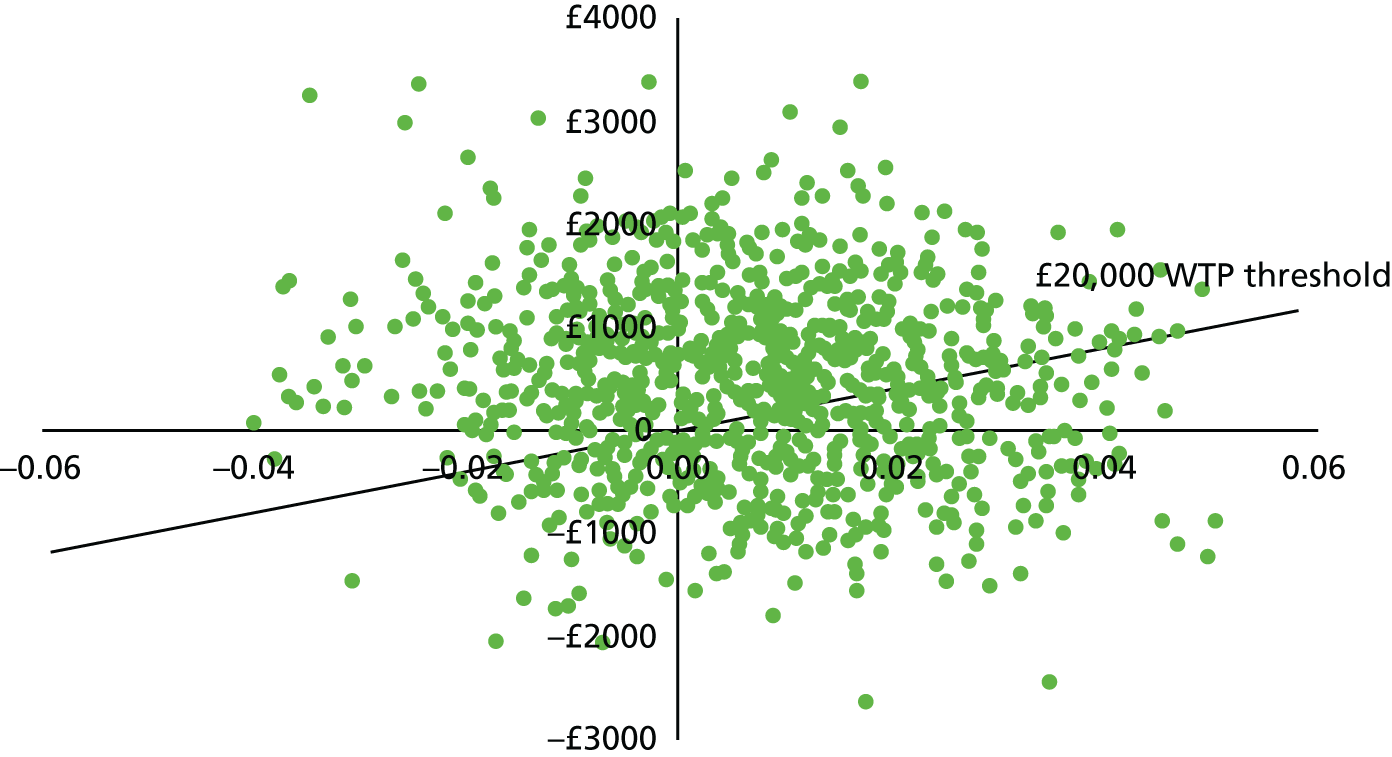

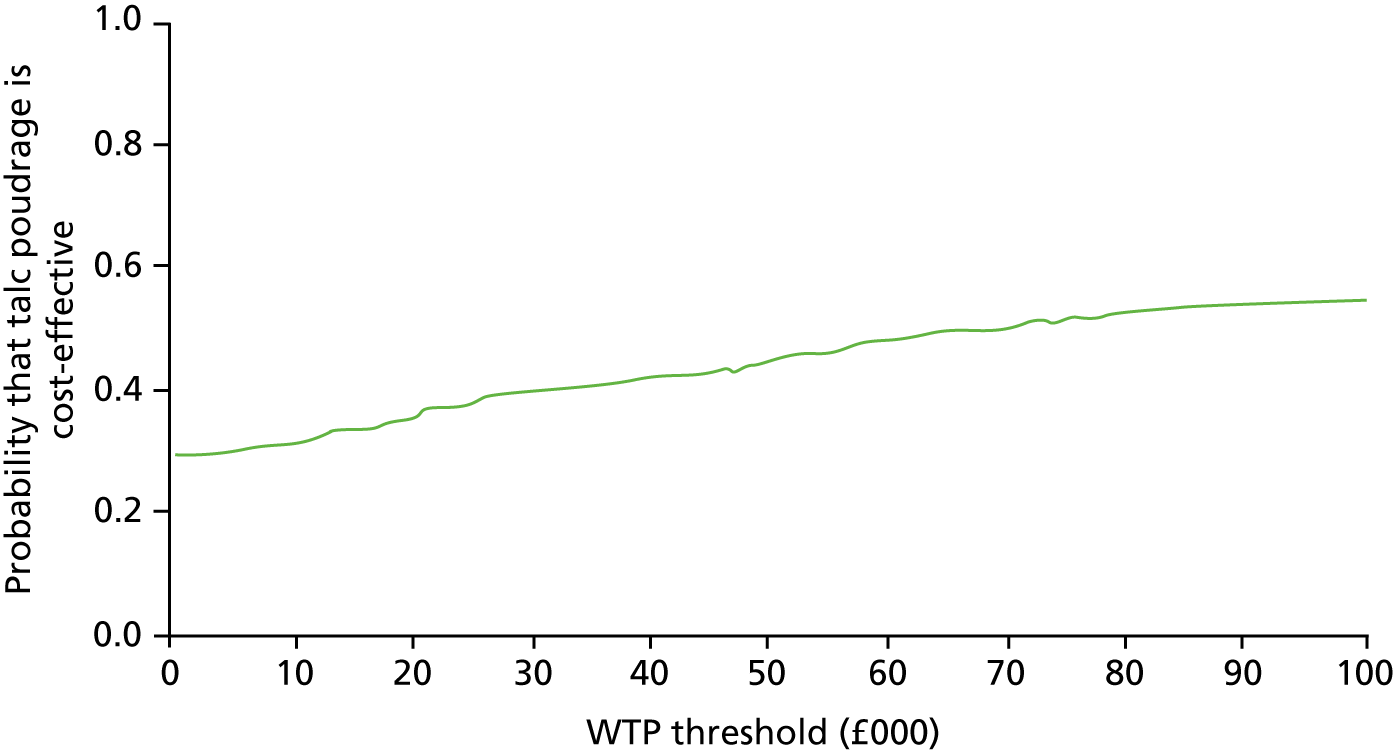

In order to evaluate if thoracoscopy-delivered talc poudrage was cost-effective when compared with standard chest tube talc slurry pleurodesis, we carried out an incremental analysis, with the mean cost difference between thoracoscopy-delivered talc poudrage and standard chest tube talc slurry pleurodesis divided by the mean QALY difference to give the ICER. As per NICE recommendations,48 we judged an intervention to be cost-effective if the ICER was ≤ £20,000 per QALY gained.

However, given that average life expectancy in patients enrolled in the TAPPS trial was < 1 year, it could be argued that NICE’s end-of-life criteria for assessing cost-effectiveness might apply. 49 As a result, in sensitivity analyses, we evaluated the impact of increasing the cost-effectiveness threshold to £50,000 per QALY gained. 50

We used the non-parametric percentile method for calculating the CI around the ICER, using 1000 bootstrap estimates of the mean cost and QALY differences. 51 Results of the 1000 bootstrap estimates are also presented in the cost-effectiveness plane. We used the cost-effectiveness acceptability curve to show the probability that thoracoscopy-delivered talc poudrage is cost-effective at 6 months for the £20,000 and £50,000 per QALY NICE thresholds, and also for different values of the NHS’s willingness to pay for an additional QALY. 52

To account for the possibility that LATs performed during the trial were of a longer duration than those LATs that might be performed in clinical practice, we undertook a one-way sensitivity analysis to examine the impact on the results of shortening the duration of thoracoscopy-delivered talc poudrage by 10 minutes.

Multiple imputation

As the analysis of the TAPPS trial data were undertaken on an intention-to-treat basis, multiple imputation was used to impute missing cost and utility values. 53–55 As per recommended best practice, imputation was implemented separately by randomised treatment allocation. 56 Costs were imputed at the most disaggregated level at which the model would converge. As a result, we imputed values for general practice consultation costs (at practice, home and telephone); hospitalisation costs (outpatient visits, A&E and ambulance, inpatient stays and day cases); hospice and nursing costs (hospice stays, and hospice and other nurse visits); and other health-care costs (physiotherapy, occupational therapy, counselling and psychologist visits).

Rather than imputing missing responses for each of the five domains in the EQ-5D-5L, we imputed the overall EQ-5D-5L utility. 57 The imputation of costs and utility was conducted using predictive mean matching (i.e. imputes data from similar patients with complete data) to account for the skewed nature of both cost and utility data. Imputation was conducted using age, sex, baseline utility levels and the trial minimisation criteria (i.e. type of underlying malignant disease and WHO/ECOG performance status). We generated 60 replacement values for each missing case, generating 60 imputed data sets.

Using the Stata ‘mi estimate command’, we obtained mean estimates of cost and utility and SD. Differences across patients groups were obtained using ordinary least squares regression using the ‘mi estimate: reg’ command.

Chapter 4 Main trial results

Recruitment

Recruitment took place between August 2012 and October 2017, with 17 centres contributing participants.

Table 4 shows the distribution of recruitment by site.

| Site | Approval date | Final recruitment total |

|---|---|---|

| Taunton | 2 November 2012 | 54 |

| South Manchester | 15 March 2013 | 38 |

| Oxford | 9 November 2012 | 30 |

| Nottingham | 22 October 2012 | 27 |

| Bristol | 26 September 2012 | 26 |

| Glasgow | 5 September 2014 | 26 |

| King’s Mill | 23 October 2012 | 24 |

| Cambridge | 3 April 2013 | 22 |

| Glan Clwyd | 24 February 2015 | 19 |

| Preston | 9 January 2013 | 13 |

| Doncaster | 19 March 2014 | 13 |

| St Thomas’ (London) | 18 December 2013 | 10 |

| North Tees | 26 June 2014 | 9 |

| Medway | 30 October 2012 | 7 |

| Milton Keynes | 24 October 2014 | 7 |

| Aintree | 2 September 2014 | 4 |

| Birmingham | 20 October 2014 | 1 |

| Total | – | 330 |

Flow of participants in the trial

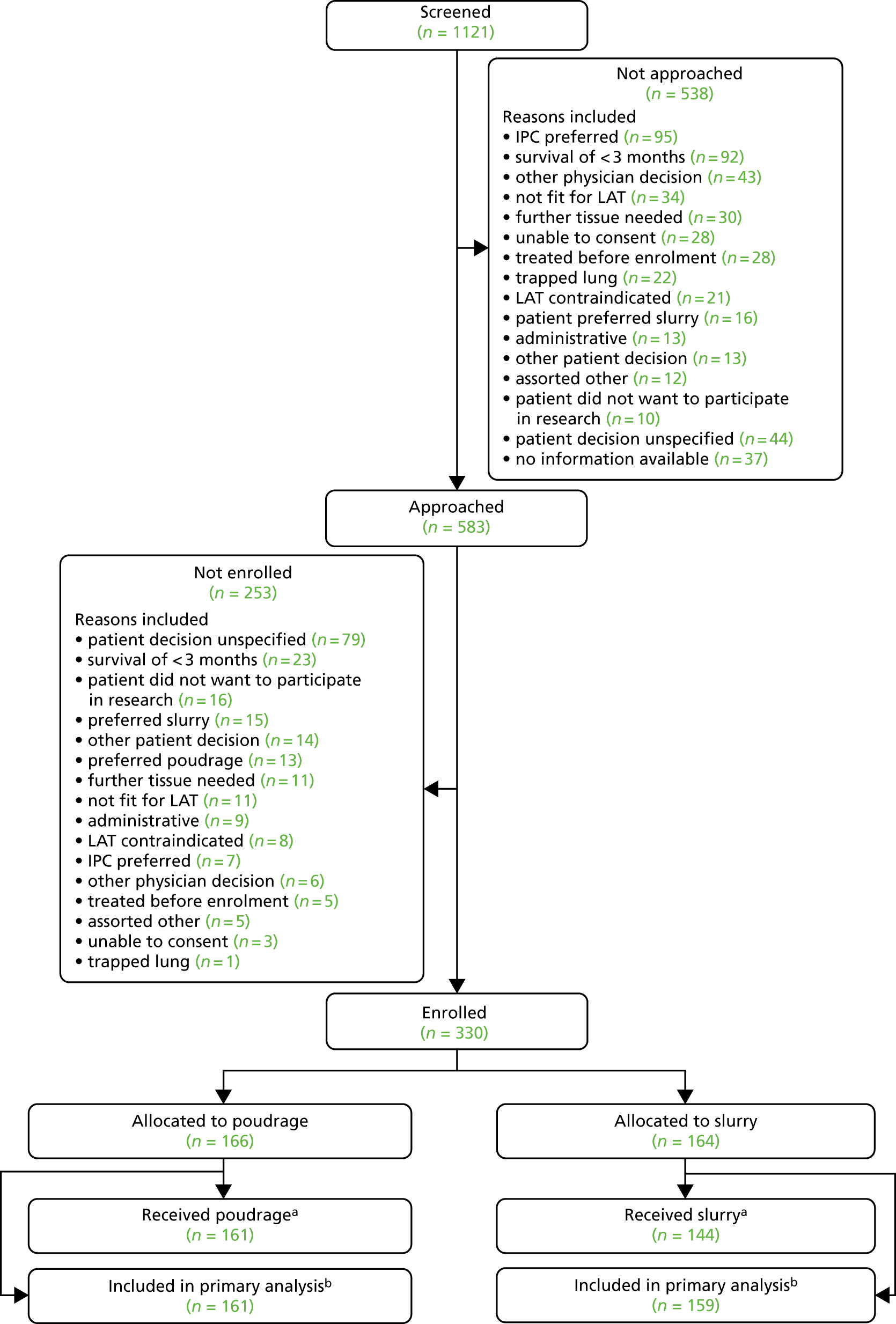

The target of 330 participants was achieved, with 164 participants allocated to the control (slurry) arm and 166 participants to the intervention (poudrage) arm. A total of 159 (97.0%) and 161 (97%) participants, respectively, were included in the primary outcome analysis. Fourteen (8.5%) and 15 (9.0%) participants, respectively, withdrew during the 6-month follow-up period.

A comprehensive overview of participant flow, including screening activity, is given in the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) flow diagram in Figure 4.

FIGURE 4.

The trial CONSORT flow diagram. a, Reasons for not receiving allocated treatment: poudrage arm – thoracoscopy not attempted (n = 2), procedure abandoned before talc (n = 2), talc not given because of rapid lung expansion on coughing (n = 1); slurry arm – chest drain not attempted (n = 2), talc not given (n = 18) because of lung expansion (n = 6), lung entrapment (n = 5), excessive fluid production (n = 1), drain dislodgement (n = 1), early drain removal (n = 1), loculated pleural space (n = 1), missing data (n = 3); and b, patients were not included in the primary outcome analysis if there were no data available regarding pleurodesis failure at 90 days post randomisation.

Baseline characteristics

In general, both treatment groups were well matched at baseline. A higher proportion of participants in the control group (33/164, 20%) were noted to be receiving chemotherapy at enrolment than in the intervention group (15/166, 9%). The mean age at enrolment was 68 years in both groups. The majority of participants (79% control, 78% intervention) were of ECOG performance status 1 or 2. The commonest underlying cancer types were lung and breast cancer.

Table 5 describes the full set of baseline characteristics.

| Characteristic | Treatment arm, summary measure | Treatment arm, number with missing data | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Thoracoscopy and poudrage | Chest drain and slurry | Thoracoscopy and poudrage (N = 166) | Chest drain and slurry (N = 164) | |

| Age (years), mean (SD) | 68 (11) | 68 (12) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Chest pain (VAS), mean (SD) | 17 (23) | 18 (25) | 1 (1) | 1 (1) |

| Breathlessness (VAS), mean (SD) | 53 (29) | 53 (33) | 1 (1) | 1 (1) |

| Percentage radiographic (CXR) pleural opacification, mean (SD) | 54 (20) | 47 (20) | 129 (78) | 127 (77) |

| Blood measurements | ||||

| Hb, mean (SD) | 131 (20) | 129 (19) | 3 (2) | 3 (2) |

| Sodium, mean (SD) | 136 (10) | 137 (4.0) | 3 (2) | 2 (1) |

| INR, median (IQR) | 1.0 (1.0–1.1) | 1.0 (1.0–1.1) | 38 (23) | 38 (23) |

| WCC, mean (SD) | 9.8 (14) | 9.5 (9.4) | 2 (1) | 3 (2) |

| Potassium, mean (SD) | 5.0 (5.1) | 4.5 (2.2) | 6 (4) | 7 (4) |

| APTT, mean (SD) | 27 (14) | 28 (12) | 30 (18) | 22 (13) |

| Platelets, mean (SD) | 342 (119) | 334 (124) | 3 (2) | 3 (2) |

| Urea, mean (SD) | 5.8 (3.0) | 6.6 (7.6) | 5 (3) | 9 (5) |

| CRP, mean (SD) | 46 (60) | 46 (53) | 35 (21) | 26 (16) |

| Creatinine, mean (SD) | 74 (29) | 75 (28) | 4 (2) | 2 (1) |

| General categorical variables, n (%) | ||||

| Female | 96 (58) | 85 (52) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Smoking status | 1 (1) | 0 (0) | ||

| Current smoker | 13 (8) | 12 (7) | ||

| Ex-smoker | 104 (63) | 98 (60) | ||

| Never smoker | 48 (29) | 54 (33) | ||

| WHO score | 1 (1) | 0 (0) | ||

| 0 | 17 (10) | 18 (11) | ||

| 1 | 82 (50) | 81 (49) | ||

| 2 | 46 (28) | 49 (30) | ||

| 3 | 20 (12) | 16 (10) | ||

| Effusion on right-hand side | 91 (55) | 91 (55) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Pleural intervention in previous 3 months | 117 (70) | 121 (74) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Pleurodesis attempt in previous month | 2 (1) | 3 (2) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Length of symptoms (weeks) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | ||

| < 1 | 5 (3) | 6 (4) | ||

| 1–3 | 40 (24) | 35 (21) | ||

| > 3 | 121 (73) | 123 (75) | ||

| Percentage radiographic (CXR) pleural opacification | 129 (78) | 127 (77) | ||

| 1–24 | 3 (8) | 4 (11) | ||

| 25–49 | 15 (41) | 18 (49) | ||

| ≥ 50 | 19 (51) | 15 (41) | ||

| Underlying cancer type | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | ||

| Lung | 59 (36) | 54 (33) | ||

| Mesothelioma | 15 (9) | 19 (12) | ||

| Breast | 50 (30) | 49 (30) | ||

| Ovarian | 6 (4) | 7 (4) | ||

| Lymphoma | 3 (2) | 2 (1) | ||

| Upper GI | 4 (2) | 4 (2) | ||

| Lower GI | 6 (4) | 9 (5) | ||

| Renal | 5 (3) | 11 (7) | ||

| Other | 15 (9) | 5 (3) | ||

| Unknown | 3 (2) | 4 (2) | ||

| Analgesia | ||||

| Oral steroids | 22 (13) | 24 (15) | 0 (0) | 1 (1) |

| NSAIDs | 21 (13) | 29 (18) | 0 (0) | 1 (1) |

| Analgesic | 118 (71) | 107 (66) | 0 (0) | 1 (1) |

| Cancer treatment | ||||

| One or more anticancer treatment | 44 (27) | 55 (34) | 0 (0) | 1 (1) |

| Radiotherapy | 48 (29) | 40 (25) | 0 (0) | 1 (1) |

| Cancer-modulating hormone therapy | 27 (16) | 17 (10) | 0 (0) | 1 (1) |

| Anticancer monoclonal antibodies | 5 (3) | 6 (4) | 0 (0) | 1 (1) |

| Chemotherapy | 15 (9) | 33 (20) | 0 (0) | 2 (1) |

| Other anticancer therapy | 2 (1) | 6 (4) | 0 (0) | 1 (1) |

| Anticoagulant therapy | 29 (17) | 35 (21) | 0 (0) | 1 (1) |

| Comorbidities | ||||

| COPD/asthma | 20 (12) | 18 (11) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Interstitial lung disease | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | 0 (0) | 1 (1) |

| Bronchiectasis | 1 (1) | 2 (1) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Pulmonary hypertension | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Other respiratory disease | 4 (2) | 5 (3) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Ischaemic heart disease | 11 (7) | 13 (8) | 1 (1) | 0 (0) |

| Atrial fibrillation | 14 (8) | 10 (6) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Heart failure | 1 (1) | 2 (1) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Other cardiac disease | 27 (16) | 19 (12) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Minimisation factors, n (%) | ||||

| Underlying malignancy | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | ||

| Lung | 57 (34) | 57 (35) | ||

| Breast | 50 (30) | 48 (29) | ||

| Mesothelioma | 16 (10) | 17 (10) | ||

| Other | 43 (26) | 42 (26) | ||

| Grouped WHO score | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | ||

| 0–1 | 99 (60) | 99 (60) | ||

| 2–3 | 67 (40) | 65 (40) | ||

Adherence to interventions

A total of 144 out of 164 (88%) of participants received their treatment as intended in the control arm, compared with 161 out of 166 (97%) of participants in the intervention arm. Of those patients in the control arm, 18 out of 20 participants did not receive talc after chest drain insertion.

A summary of treatment adherence (and the reasons for non-adherence) can be found in Tables 6 and 7.

| Treatment adherence | Treatment arm, n (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Thoracoscopy and poudrage (N = 166) | Chest drain and slurry (N = 164) | |

| Treatment given as intended | ||

| No | 5 (3) | 20 (12) |

| Yes | 161 (97) | 144 (88) |

| Reason treatment not given as intended | ||

| Procedure not attempted | 2 (1) | 2 (1) |

| Procedure abandoned | 2 (1) | 0 (0) |

| Talc not given | 1 (1) | 18 (11) |

| Reason | Treatment arm (n) | |

|---|---|---|

| Thoracoscopy and poudrage (N = 1) | Chest drain and slurry (N = 18) | |

| Poor lung expansion/trapped lung | 0 | 9 |

| Excessive pleural production | 0 | 1 |

| Othera | 1 | 5 |

| Missing | 0 | 3 |

Details of interventions

The median [interquartile range (IQR)] duration of the control procedure was 30 (IQR 20–40) minutes. The median duration of the intervention procedure was 49 (IQR 40–60) minutes. A total of 110 of 164 (67%) of LAT procedures, compared with 62 of 163 (38%) control procedures, were performed by consultant-grade doctors. A total of 111 of 153 (73%) and 120 of 161 (75%) of participants in the control and intervention groups, respectively, had thoracic suction applied during their post-procedure period. A comprehensive summary of intervention details can be found in Table 8.

| Characteristic | Treatment arm, summary measure | Treatment arm, number of participants without data | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Thoracoscopy and poudrage | Chest drain and slurry | Thoracoscopy and poudrage (N = 166) | Chest drain and slurry (N = 164) | |

| Duration of procedure (minutes), mean (SD) | 51 (22) | 32 (13) | 15 (9) | 26 (16) |

| Grade of operator, n (%) | 2 (1) | 1 (1) | ||

| CT1/CT2 | 0 (0) | 10 (6) | ||

| Consultant | 110 (67) | 62 (38) | ||

| F1/F2 | 0 (0) | 4 (2) | ||

| Other | 0 (0) | 9 (6) | ||

| Registrar | 54 (33) | 78 (48) | ||

| Total fluid (ml) drained as an inpatient, mean (SD) | 3442 (1831) | 2890 (2094) | 11 (7) | 10 (6) |

| Evidence of lung entrapment: 18–24 hours, n (%) | 60 (36) | 55 (34) | ||

| None | 85 (80) | 90 (83) | ||

| Mild | 8 (8) | 8 (7) | ||

| Moderate | 8 (8) | 7 (6) | ||

| Severe | 5 (5) | 4 (4) | ||

| Evidence of lung entrapment: discharge, n (%) | 61 (37) | 66 (40) | ||

| None | 92 (88) | 90 (92) | ||

| Mild | 1 (1) | 4 (4) | ||

| Moderate | 4 (4) | 1 (1) | ||

| Severe | 8 (8) | 3 (3) | ||

| Thoracic suction used, n (%) | 120 (75) | 111 (73) | 5 (3) | 11 (7) |

| Time drain removed, n (%) | 13 (8) | 7 (4) | ||

| On time | 113 (74) | 126 (80) | ||

| Early | 12 (8) | 11 (7) | ||

| Late | 28 (18) | 20 (13) | ||

The frequency of complications during both trial procedures was low. Of note, 12 out of 161 (7%) and 8 out of 161 (5%) participants in the intervention arm were documented as experiencing new hypotension and a drop in transcutaneous oxygen saturations, respectively, after talc was given. No participants in the control arm experienced either of these events either before or after talc was given. A comprehensive summary of recorded procedural complications can be found in Table 9.

| Complication | Treatment summary measure, n (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Thoracoscopy and poudrage (N = 166) | Chest drain and slurry (N = 164) | |

| During procedure | 164 with data available | 162 with data available |

| Bleeding | 1 (1) | 0 (0) |

| Significant cough | 4 (2) | 2 (1) |

| Syncope | 2 (1) | 1 (1) |

| Significant pain | 0 (0) | 3 (2) |

| Pleural space not entered | 1 (1) | 0 (0) |

| New hypoxia | 2 (1) | 0 (0) |

| Dysrhythmia | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| New hypotension | 4 (2) | 0 (0) |

| Other | 3 (2) | 1 (1) |

| After talc | 161 with data available | 144 with data available |

| Nausea | 3 (2) | 2 (1) |

| Respiratory distress | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| GCS score drop of > 2 points | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Uncontrolled pain | 7 (4) | 1 (1) |

| New hypotension | 12 (7) | 0 (0) |

| Saturation drop | 8 (5) | 0 (0) |

| Allergic reaction | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| New confusion | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Bleeding | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Other | 6 (4) | 5 (3) |

Primary outcome

Treatment efficacy at 90 days

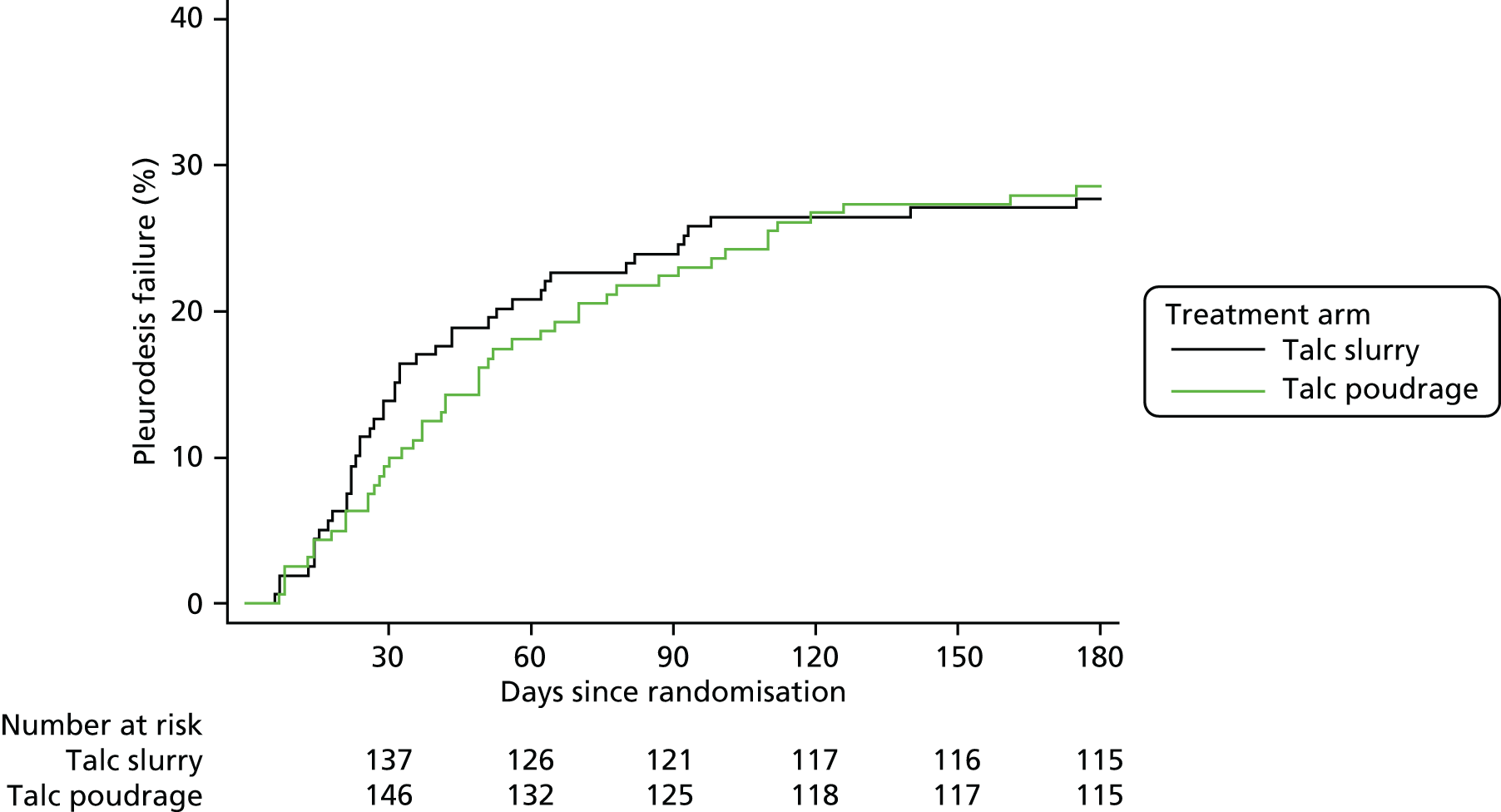

A total of 97% of participants in both arms (159/164 control, 161/166 intervention) were included in the primary outcome analysis. No significant difference in pleurodesis failure was observed between the treatment groups at 90 days, with failure rates of 22% (36/161) and 24% (38/159) noted in the poudrage and slurry groups, respectively [adjusted odds ratio (OR) 0.91, 95% CI 0.54 to 1.55; p = 0.74].

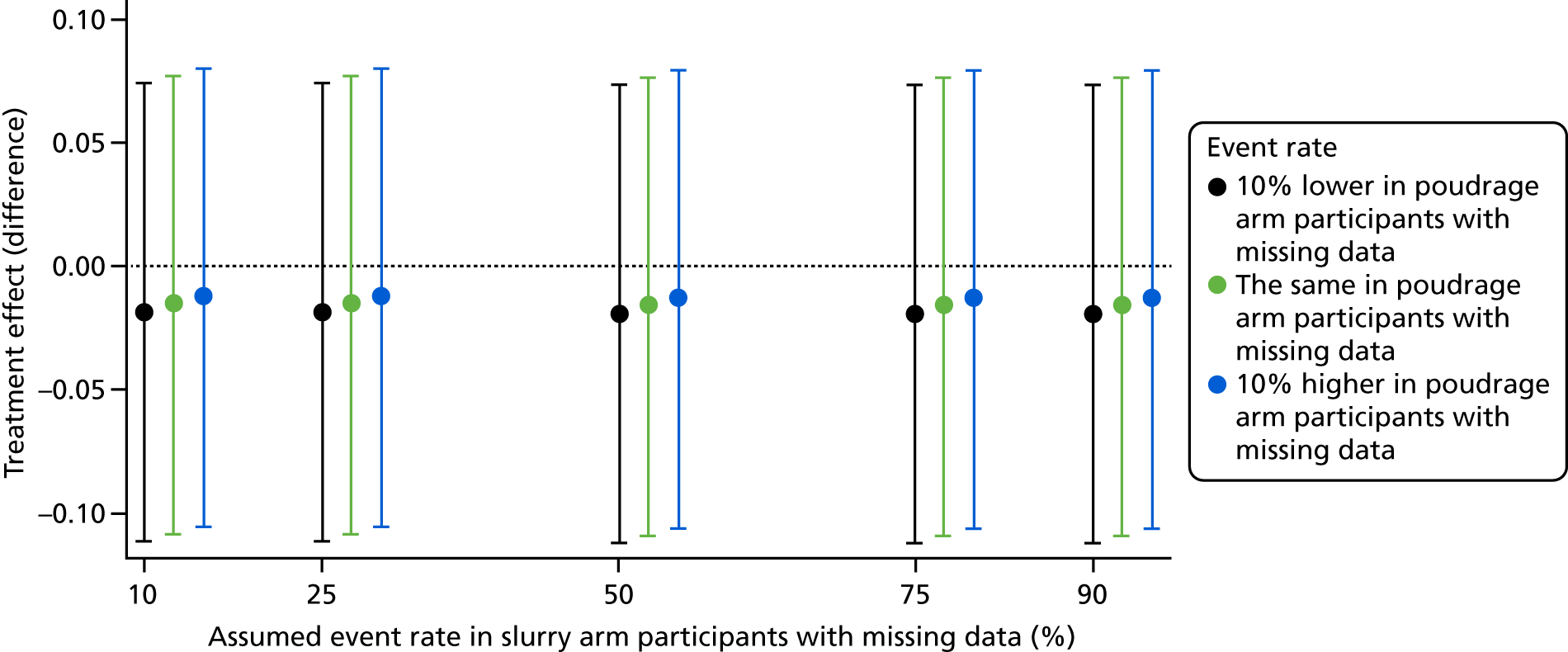

Sensitivity analysis

Sensitivity analyses for the primary outcome evaluated how sensitive results were to departures from the missing-at-random assumption described above by conducting various missing-not-at-random analyses; these analyses made different assumptions about the event rates for participants with missing data in the control and intervention arms. Results are shown in Figure 5, which shows the treatment effect as a difference in proportions. Results were very robust to alternative assumptions regarding the missing data.

FIGURE 5.

Sensitivity analysis for the primary outcome.

Subgroup analyses

We found moderate evidence of a subgroup effect between participants taking oral steroids at baseline and those participants not taking oral steroids (p-value for interaction 0.04). In the subgroup on oral steroids, there was a lower rate of pleurodesis failure (6/24, 25%) in the control group than in the intervention group (10/20, 50%) (adjusted OR 3.13, 95% CI 0.84 to 11.61). Conversely, in the subgroup not on oral steroids, there was a slightly higher rate of pleurodesis failure in the control arm (32/134, 24%) than in the intervention arm (26/141, 19%) (adjusted OR 0.71, 95% CI 0.39 to 1.29).